User login

A Visiting Grandma Feels Short of Breath

ANSWER

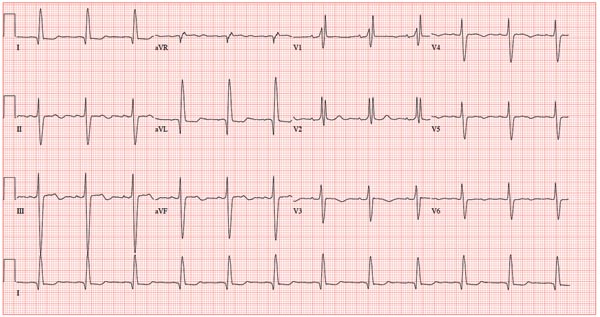

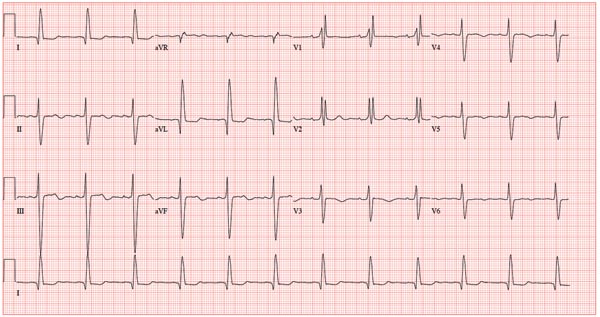

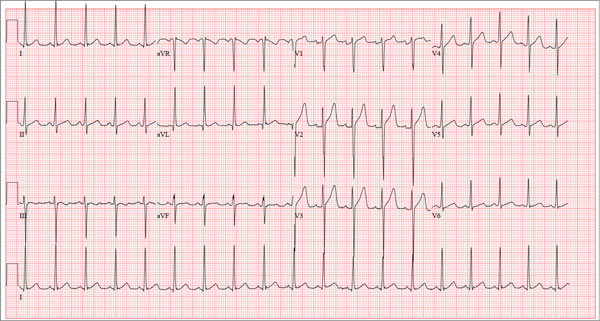

This ECG shows normal sinus rhythm, a right bundle branch block (RBBB), and a left anterior fascicular block (LAFB). RBBB and LAFB are consistent with bifascicular block.

Criteria for an RBBB include a prolonged total QRS complex of 120 ms or longer and an RSR’ complex (“rabbit ears”) in lead V1. LAFB criteria include a QRS of normal duration with an S wave greater than an R wave in leads II, III, and aVF and left-axis deviation (–48° in this case).

The astute reader may question the disparity between RBBB and LAFB, since the criteria for the former include a prolonged QRS interval and the criteria for the latter include a normal QRS interval. It should be noted that the requirements for QRS duration for RBBB vary.

Bifascicular block (RBBB and either LAFB or left posterior fascicular block [LPFB]) is indicative of more advanced conduction system disease. However, it is not an indication for permanent pacemaker placement in an asymptomatic patient.

This patient was treated for a community-acquired right lower lobe pneumonia and a UTI.

ANSWER

This ECG shows normal sinus rhythm, a right bundle branch block (RBBB), and a left anterior fascicular block (LAFB). RBBB and LAFB are consistent with bifascicular block.

Criteria for an RBBB include a prolonged total QRS complex of 120 ms or longer and an RSR’ complex (“rabbit ears”) in lead V1. LAFB criteria include a QRS of normal duration with an S wave greater than an R wave in leads II, III, and aVF and left-axis deviation (–48° in this case).

The astute reader may question the disparity between RBBB and LAFB, since the criteria for the former include a prolonged QRS interval and the criteria for the latter include a normal QRS interval. It should be noted that the requirements for QRS duration for RBBB vary.

Bifascicular block (RBBB and either LAFB or left posterior fascicular block [LPFB]) is indicative of more advanced conduction system disease. However, it is not an indication for permanent pacemaker placement in an asymptomatic patient.

This patient was treated for a community-acquired right lower lobe pneumonia and a UTI.

ANSWER

This ECG shows normal sinus rhythm, a right bundle branch block (RBBB), and a left anterior fascicular block (LAFB). RBBB and LAFB are consistent with bifascicular block.

Criteria for an RBBB include a prolonged total QRS complex of 120 ms or longer and an RSR’ complex (“rabbit ears”) in lead V1. LAFB criteria include a QRS of normal duration with an S wave greater than an R wave in leads II, III, and aVF and left-axis deviation (–48° in this case).

The astute reader may question the disparity between RBBB and LAFB, since the criteria for the former include a prolonged QRS interval and the criteria for the latter include a normal QRS interval. It should be noted that the requirements for QRS duration for RBBB vary.

Bifascicular block (RBBB and either LAFB or left posterior fascicular block [LPFB]) is indicative of more advanced conduction system disease. However, it is not an indication for permanent pacemaker placement in an asymptomatic patient.

This patient was treated for a community-acquired right lower lobe pneumonia and a UTI.

A 78-year-old woman presents to your urgent care clinic with a four-day history of lethargy. She lives in another state but currently is visiting her granddaughter, who happens to be your clinic manager. She says she felt weak prior to her trip but thought it was probably due to a urinary tract infection (UTI). Yesterday, however, she started feeling short of breath. The patient denies chest pain, orthopnea, paroxysmal nocturnal dyspnea, or productive cough. She reports feeling feverish this morning but did not record her temperature, adding that it seemed to subside after she got dressed. Her medical history is positive for frequent UTIs, a remote cholecystectomy, hypothyroidism, and paroxysmal atrial fibrillation. According to the patient’s daughter, who is present, her mother’s cardiologist recently mentioned some “funny” findings on an ECG; she didn’t really understand his explanation but they were told “not to worry.” The patient, a retired schoolteacher, lives in an assisted living center. She is independent and has been a widow for 14 years, since her husband died of an acute MI. She has two children who are in good health. She has never smoked, rarely consumes alcohol, and has never used recreational or homeopathic drugs. Her current medications include warfarin, levothyroxine, and conjugated estrogen. She was taking amiodarone for rhythm control of atrial fibrillation but stopped six months ago when her skin started turning blue. She is allergic to penicillin, which causes a true anaphylactic reaction, according to her daughter. Review of systems is positive for an infrequent, nonproductive cough, sun sensitivity due to amiodarone use, and infrequent burning with urination. Physical exam reveals a thin, elderly woman in no distress. Her blood pressure is 152/88 mm Hg; pulse, 70 beats/min and regular; respiratory rate, 14 breaths/min-1 with an infrequent, nonproductive cough; O2 saturation, 94% on room air; and temperature, 99°F. She is 5 ft 4 in tall and weighs 114 lb. Pertinent findings on physical exam include corrective lenses, pearly white skin with a blue hue on the nose and ears secondary to long-term amiodarone therapy, no evidence of thyromegaly or jugular distention, a regular rate and rhythm with a soft midsystolic murmur of mitral regurgitation, and no extra heart sounds. Her lungs are remarkable for consolidation in the right lower lobe, with crackles that change with coughing. Her abdomen is soft and nontender, and there is no peripheral edema. Her neurologic exam is intact. She is alert, attentive, and very witty in her responses to questions. Laboratory data include urinalysis findings suggestive of a UTI, a white blood cell count of 9.8 x 103/μL, and a hematocrit of 35%. A chest x-ray shows evidence of consolidation in the right lower lobe, which the radiologist says is strongly suggestive of pneumonia. An ECG shows a ventricular rate of 71 beats/min; PR interval, 152 ms; QRS duration, 142 ms; QT/QTc interval, 476/517 ms; P axis, 76°; R axis, –48°; and T axis, 161°. What is your interpretation of this ECG?

Nontender Nodules on the Lower Lip

The Diagnosis: Primary Systemic Amyloidosis

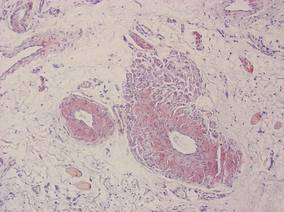

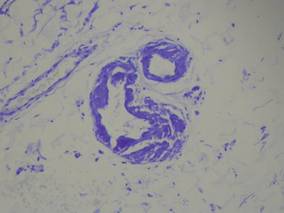

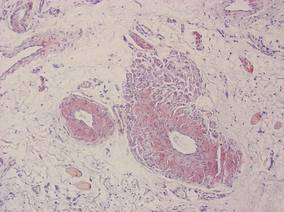

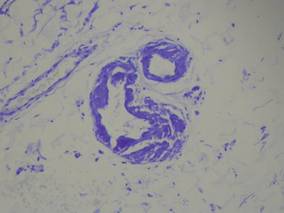

Our patient presented with multiple firm waxy nodules on the mucosal surface of the lower lip. Excision biopsy showed thickening of blood vessel walls with abundant amorphous material that was consistent with amyloid. Further staining with Congo red demonstrated brick red amorphous material within the vessel walls on routine light microscopy (Figure 1), and crystal violet stain showed metachromasia (Figure 2). Fine needle aspiration of the abdominal fat-pad showed amyloid. The final diagnosis was primary systemic amyloidosis (PSA).

|

| Figure 1. Congo red staining showed a brick red appearance of amyloid within the vessel walls on routine light microscopy (original magnification ×200). |

|

| Figure 2. Crystal violet staining around the blood vessels showed metachromasia (original magnification ×100). |

Amyloid is an ubiquitous fibrillar protein arranged in a cross-beta-pleated sheet that is confirmed with x-ray crystallography.1,2 More than 25 variants of amyloid have been identified.3 Pathologic deposition of amyloid-derived material results in a variable spectrum of clinical findings, collectively known as amyloidosis, with presentations ranging from nonspecific fever or fatigue to frank organ failure, depending on the organ involved. In PSA, immunoglobulin light chains are deposited throughout the body. Associated conditions include malignant or benign monoclonal gammopathy, multiple myeloma, Waldenström macroglobulinemia, malignant lymphoma, heavy chain disease, and chronic lymphocytic leukemia.2,4 The most commonly involved organ systems are the heart, lungs, liver, and kidneys. When patients present with unexplained heart failure, orthostatic hypotension, hepatomegaly, peripheral neuropathy, carpal tunnel syndrome, or renal insufficiency, amyloidosis should always be considered in the differential diagnosis.3

Cutaneous lesions of PSA tend to be vascular due to amyloid infiltration of blood vessel walls, manifesting as petechiae, purpura, ecchymoses, or nonhealing ulcers. Pinch purpura frequently are seen in the periorbital region after minor trauma and are recognized as a clinical indicator of PSA.2,4 Xerostomia from amyloid infiltrates in salivary glands is extremely common, and cases of amyloid in the eyes, bones, and thyroid gland have been reported.2 Macroglossia is seen in 12% to 40% of cases; coupled with xerostomia, it can lead to oropharyngeal dysphagia.2,5

Systemic amyloidosis can be further divided into primary (idiopathic or multiple myeloma associated) or secondary to chronic inflammatory conditions or infections; the key difference is the protein from which the abnormal amyloid is derived.1,4 The presence of cutaneous amyloidosis renders the need to rule out systemic disease because amyloidosis may be a purely localized or systemic process.4 Nodular amyloidosis is a localized form of amyloid that also has immunoglobulin light chain deposits and clinically appears exactly the same as PSA; however, the deposits are restricted to the skin.1,2,4,5

Characteristic biopsy findings in cutaneous amyloidosis include amorphous orange-red amyloid deposits on hematoxylin and eosin–stained sections. The gold standard for amyloid detection is apple green birefringence under polarized light with Congo red stain or electron microscopy.6,7 Other stains used to identify amyloid include crystal violet, methyl violet, periodic acid–Schiff, Sirius red, pagoda red, Dylon stain, and thioflavine T.1,2 Confirmation of systemic disease can be accomplished by fine needle aspiration of abdominal fat-pads or rectal mucosal biopsies.1,3,4 Biopsy of accessory salivary glands also has been reported to be very sensitive and specific.2

Treatment options remain limited; localized cutaneous disease may respond to topical corticosteroids, calcineurin inhibitors, or phototherapy. Primary systemic amyloidosis can be treated with a combination of steroids, melphalan, or colchicine often followed by autologous stem cell transplantation8; however, these regimens are not always curative and patients often have a poor prognosis.1

1. Black MM, Upjohn E, Albert S. Amyloidosis. In: Bolognia JL, Jorizzo JL, Rapini RP, eds. Dermatology. Vol 1. 2nd ed. Spain: Mosby Elsevier; 2008:623-631.

2. Steciuk A, Dompmartin A, Troussard X, et al. Cutaneous amyloidosis and possible association with systemic amyloidosis. Int J Dermatol. 2002;41:127-132.

3. Picken MM. Amyloidosis-where are we now and where are we heading? Arch Pathol Lab Med. 2010;134:545-551.

4. Schreml S, Szeimies RM, Vogt T, et al. Cutaneous amyloidoses and systemic amyloidoses with cutaneous involvement. Eur J Dermatol. 2010;20:152-160.

5. Breathnach SM. Amyloid and amyloidosis. J Am Acad Dermatol. 1988;18(1, pt 1):1-16.

6. Li WM. Histopathology of primary cutaneous amyloidoses and systemic amyloidosis. Clin Dermatol. 1990;8:30-35.

7. Lin CS, Wong CK. Electron microscopy of primary and secondary cutaneous amyloidoses and systemic amyloidosis. Clin Dermatol. 1990;8:36-45.

8. Dember LM. Modern treatment of amyloidosis: unresolved questions. J Am Soc Nephrol. 2009;20:469-472.

The Diagnosis: Primary Systemic Amyloidosis

Our patient presented with multiple firm waxy nodules on the mucosal surface of the lower lip. Excision biopsy showed thickening of blood vessel walls with abundant amorphous material that was consistent with amyloid. Further staining with Congo red demonstrated brick red amorphous material within the vessel walls on routine light microscopy (Figure 1), and crystal violet stain showed metachromasia (Figure 2). Fine needle aspiration of the abdominal fat-pad showed amyloid. The final diagnosis was primary systemic amyloidosis (PSA).

|

| Figure 1. Congo red staining showed a brick red appearance of amyloid within the vessel walls on routine light microscopy (original magnification ×200). |

|

| Figure 2. Crystal violet staining around the blood vessels showed metachromasia (original magnification ×100). |

Amyloid is an ubiquitous fibrillar protein arranged in a cross-beta-pleated sheet that is confirmed with x-ray crystallography.1,2 More than 25 variants of amyloid have been identified.3 Pathologic deposition of amyloid-derived material results in a variable spectrum of clinical findings, collectively known as amyloidosis, with presentations ranging from nonspecific fever or fatigue to frank organ failure, depending on the organ involved. In PSA, immunoglobulin light chains are deposited throughout the body. Associated conditions include malignant or benign monoclonal gammopathy, multiple myeloma, Waldenström macroglobulinemia, malignant lymphoma, heavy chain disease, and chronic lymphocytic leukemia.2,4 The most commonly involved organ systems are the heart, lungs, liver, and kidneys. When patients present with unexplained heart failure, orthostatic hypotension, hepatomegaly, peripheral neuropathy, carpal tunnel syndrome, or renal insufficiency, amyloidosis should always be considered in the differential diagnosis.3

Cutaneous lesions of PSA tend to be vascular due to amyloid infiltration of blood vessel walls, manifesting as petechiae, purpura, ecchymoses, or nonhealing ulcers. Pinch purpura frequently are seen in the periorbital region after minor trauma and are recognized as a clinical indicator of PSA.2,4 Xerostomia from amyloid infiltrates in salivary glands is extremely common, and cases of amyloid in the eyes, bones, and thyroid gland have been reported.2 Macroglossia is seen in 12% to 40% of cases; coupled with xerostomia, it can lead to oropharyngeal dysphagia.2,5

Systemic amyloidosis can be further divided into primary (idiopathic or multiple myeloma associated) or secondary to chronic inflammatory conditions or infections; the key difference is the protein from which the abnormal amyloid is derived.1,4 The presence of cutaneous amyloidosis renders the need to rule out systemic disease because amyloidosis may be a purely localized or systemic process.4 Nodular amyloidosis is a localized form of amyloid that also has immunoglobulin light chain deposits and clinically appears exactly the same as PSA; however, the deposits are restricted to the skin.1,2,4,5

Characteristic biopsy findings in cutaneous amyloidosis include amorphous orange-red amyloid deposits on hematoxylin and eosin–stained sections. The gold standard for amyloid detection is apple green birefringence under polarized light with Congo red stain or electron microscopy.6,7 Other stains used to identify amyloid include crystal violet, methyl violet, periodic acid–Schiff, Sirius red, pagoda red, Dylon stain, and thioflavine T.1,2 Confirmation of systemic disease can be accomplished by fine needle aspiration of abdominal fat-pads or rectal mucosal biopsies.1,3,4 Biopsy of accessory salivary glands also has been reported to be very sensitive and specific.2

Treatment options remain limited; localized cutaneous disease may respond to topical corticosteroids, calcineurin inhibitors, or phototherapy. Primary systemic amyloidosis can be treated with a combination of steroids, melphalan, or colchicine often followed by autologous stem cell transplantation8; however, these regimens are not always curative and patients often have a poor prognosis.1

The Diagnosis: Primary Systemic Amyloidosis

Our patient presented with multiple firm waxy nodules on the mucosal surface of the lower lip. Excision biopsy showed thickening of blood vessel walls with abundant amorphous material that was consistent with amyloid. Further staining with Congo red demonstrated brick red amorphous material within the vessel walls on routine light microscopy (Figure 1), and crystal violet stain showed metachromasia (Figure 2). Fine needle aspiration of the abdominal fat-pad showed amyloid. The final diagnosis was primary systemic amyloidosis (PSA).

|

| Figure 1. Congo red staining showed a brick red appearance of amyloid within the vessel walls on routine light microscopy (original magnification ×200). |

|

| Figure 2. Crystal violet staining around the blood vessels showed metachromasia (original magnification ×100). |

Amyloid is an ubiquitous fibrillar protein arranged in a cross-beta-pleated sheet that is confirmed with x-ray crystallography.1,2 More than 25 variants of amyloid have been identified.3 Pathologic deposition of amyloid-derived material results in a variable spectrum of clinical findings, collectively known as amyloidosis, with presentations ranging from nonspecific fever or fatigue to frank organ failure, depending on the organ involved. In PSA, immunoglobulin light chains are deposited throughout the body. Associated conditions include malignant or benign monoclonal gammopathy, multiple myeloma, Waldenström macroglobulinemia, malignant lymphoma, heavy chain disease, and chronic lymphocytic leukemia.2,4 The most commonly involved organ systems are the heart, lungs, liver, and kidneys. When patients present with unexplained heart failure, orthostatic hypotension, hepatomegaly, peripheral neuropathy, carpal tunnel syndrome, or renal insufficiency, amyloidosis should always be considered in the differential diagnosis.3

Cutaneous lesions of PSA tend to be vascular due to amyloid infiltration of blood vessel walls, manifesting as petechiae, purpura, ecchymoses, or nonhealing ulcers. Pinch purpura frequently are seen in the periorbital region after minor trauma and are recognized as a clinical indicator of PSA.2,4 Xerostomia from amyloid infiltrates in salivary glands is extremely common, and cases of amyloid in the eyes, bones, and thyroid gland have been reported.2 Macroglossia is seen in 12% to 40% of cases; coupled with xerostomia, it can lead to oropharyngeal dysphagia.2,5

Systemic amyloidosis can be further divided into primary (idiopathic or multiple myeloma associated) or secondary to chronic inflammatory conditions or infections; the key difference is the protein from which the abnormal amyloid is derived.1,4 The presence of cutaneous amyloidosis renders the need to rule out systemic disease because amyloidosis may be a purely localized or systemic process.4 Nodular amyloidosis is a localized form of amyloid that also has immunoglobulin light chain deposits and clinically appears exactly the same as PSA; however, the deposits are restricted to the skin.1,2,4,5

Characteristic biopsy findings in cutaneous amyloidosis include amorphous orange-red amyloid deposits on hematoxylin and eosin–stained sections. The gold standard for amyloid detection is apple green birefringence under polarized light with Congo red stain or electron microscopy.6,7 Other stains used to identify amyloid include crystal violet, methyl violet, periodic acid–Schiff, Sirius red, pagoda red, Dylon stain, and thioflavine T.1,2 Confirmation of systemic disease can be accomplished by fine needle aspiration of abdominal fat-pads or rectal mucosal biopsies.1,3,4 Biopsy of accessory salivary glands also has been reported to be very sensitive and specific.2

Treatment options remain limited; localized cutaneous disease may respond to topical corticosteroids, calcineurin inhibitors, or phototherapy. Primary systemic amyloidosis can be treated with a combination of steroids, melphalan, or colchicine often followed by autologous stem cell transplantation8; however, these regimens are not always curative and patients often have a poor prognosis.1

1. Black MM, Upjohn E, Albert S. Amyloidosis. In: Bolognia JL, Jorizzo JL, Rapini RP, eds. Dermatology. Vol 1. 2nd ed. Spain: Mosby Elsevier; 2008:623-631.

2. Steciuk A, Dompmartin A, Troussard X, et al. Cutaneous amyloidosis and possible association with systemic amyloidosis. Int J Dermatol. 2002;41:127-132.

3. Picken MM. Amyloidosis-where are we now and where are we heading? Arch Pathol Lab Med. 2010;134:545-551.

4. Schreml S, Szeimies RM, Vogt T, et al. Cutaneous amyloidoses and systemic amyloidoses with cutaneous involvement. Eur J Dermatol. 2010;20:152-160.

5. Breathnach SM. Amyloid and amyloidosis. J Am Acad Dermatol. 1988;18(1, pt 1):1-16.

6. Li WM. Histopathology of primary cutaneous amyloidoses and systemic amyloidosis. Clin Dermatol. 1990;8:30-35.

7. Lin CS, Wong CK. Electron microscopy of primary and secondary cutaneous amyloidoses and systemic amyloidosis. Clin Dermatol. 1990;8:36-45.

8. Dember LM. Modern treatment of amyloidosis: unresolved questions. J Am Soc Nephrol. 2009;20:469-472.

1. Black MM, Upjohn E, Albert S. Amyloidosis. In: Bolognia JL, Jorizzo JL, Rapini RP, eds. Dermatology. Vol 1. 2nd ed. Spain: Mosby Elsevier; 2008:623-631.

2. Steciuk A, Dompmartin A, Troussard X, et al. Cutaneous amyloidosis and possible association with systemic amyloidosis. Int J Dermatol. 2002;41:127-132.

3. Picken MM. Amyloidosis-where are we now and where are we heading? Arch Pathol Lab Med. 2010;134:545-551.

4. Schreml S, Szeimies RM, Vogt T, et al. Cutaneous amyloidoses and systemic amyloidoses with cutaneous involvement. Eur J Dermatol. 2010;20:152-160.

5. Breathnach SM. Amyloid and amyloidosis. J Am Acad Dermatol. 1988;18(1, pt 1):1-16.

6. Li WM. Histopathology of primary cutaneous amyloidoses and systemic amyloidosis. Clin Dermatol. 1990;8:30-35.

7. Lin CS, Wong CK. Electron microscopy of primary and secondary cutaneous amyloidoses and systemic amyloidosis. Clin Dermatol. 1990;8:36-45.

8. Dember LM. Modern treatment of amyloidosis: unresolved questions. J Am Soc Nephrol. 2009;20:469-472.

A 71-year-old woman presented with multiple 3×3-mm, firm, nontender nodules of 3 years’ duration on the mucosal surface of the lower lip that gradually enlarged. There was no macroglossia on presentation. The lip nodules were asymptomatic; however, they did interfere with eating and drinking, necessitating the use of a straw. Her medical history was remarkable for emphysema that required supplemental oxygen, rheumatoid arthritis, orthostatic hypotension, renal insufficiency, autonomic nervous system dysfunction, and Sjögren syndrome. She also had a recent thyroidectomy due to multiple thyroid nodules. An excision biopsy was performed of the lip nodules.

Tender Subcutaneous Nodules on the Back and Shoulders

The Diagnosis: Prostate Cancer Metastases

Cutaneous involvement of visceral tumors can occur indirectly, with the tumor causing changes in the skin without the presence of tumor cells (ie, paraneoplastic processes), or directly, with the presence of tumor cells in the skin (ie, metastasis).1 Cutaneous metastases from solid primary tumors are uncommon. The incidence of metastasis to the skin from visceral malignancies ranges from 0.3% to 9.0%.2 The most common primary internal tumors to metastasize to the skin are those arising from the breasts, lungs, colon, ovaries, and head and neck.3 Although prostate cancer is the most common cancer in males (making up 28% of new cancer diagnoses), excluding basal and squamous cell skin cancers, it rarely metastasizes to the skin, representing less than 1% of all cutaneous metastasis.4,5

There are 4 proposed mechanisms for metastatic dissemination to the skin: (1) direct invasion from underlying neoplasm; (2) implantation from a surgical scar; (3) spread through the lymphatics; and/or (4) hematogenous spread. The most common sites of prostate cancer cutaneous metastasis are the inguinal area, penis, and lower abdomen,2 which is likely due to spread via the lymphatic drainage. Cutaneous metastasis to distant sites such as the scalp or chest, as in our patient, may be secondary to hematogenous spread.

Generally, cutaneous metastases from visceral malignancies manifest as urticaria or a nonspecific macular rash.2 However, prostate cancer cutaneous metastases commonly present as papules or subcutaneous nodules but also can have inflammatory, cicatricial, sclerodermoid, telangiectatic, or zosteriform morphologies.2,5,6 The lesions of prostate cancer cutaneous metastases are typically well-circumscribed, flesh-colored or pink to red, oval plaques or nodules ranging in size from several millimeters to a few centimeters.2 The cutaneous lesions generally are multiple and can be localized or diffuse in distribution. The clinical differential diagnosis is broad in patients undergoing systemic treatment of prostate cancer and often includes drug reaction, cutaneous lymphoma, atypical mycobacterial or deep fungal infection, or paraneoplastic dermatosis.

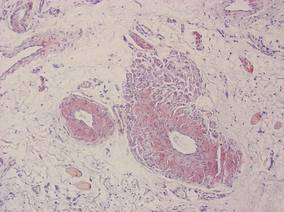

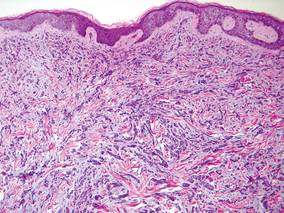

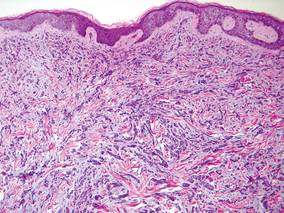

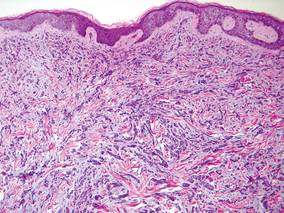

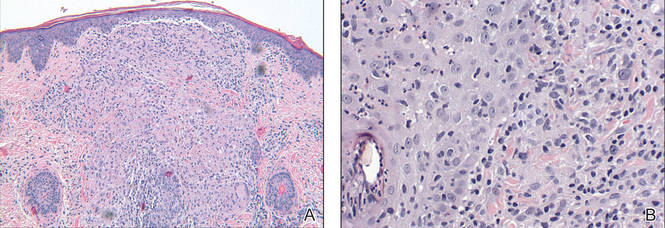

Laboratory studies often reveal an elevated serum prostate-specific antigen (PSA) level, a glycoprotein that functions in the liquefaction of seminal fluid made primarily by the prostate, often in benign hypertrophic and malignant prostatic processes.7 Definitive diagnosis of prostate cancer cutaneous metastasis can be established by histologic examination. Excisional or punch biopsy is preferred over superficial shave biopsy. Metastasis from prostate adenocarcinoma often reveals infiltrative growth of disorganized atypical epithelial cells along collagen bundles in the dermis and subcutis (Figure 1).2,8 The presence of lymphovascular invasion further increases the suspicion of metastasis. Metastatic lesions may resemble the primary lesion; however, they are often poorly differentiated, making histologic comparison difficult.

|

| Figure 1. Biopsy revealed cords of atypical epithelioid cells dissecting through dermal collagen bundles, accompanied by abundant mucin. Atypical cells displayed nuclear pleomorphism, and multiple mitotic figures were present (H&E, original magnification ×100). |

|

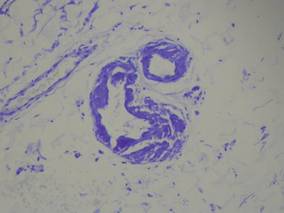

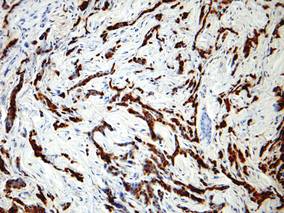

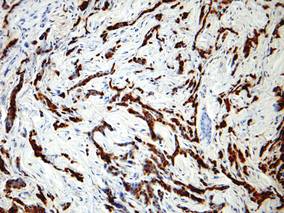

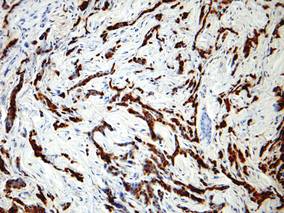

| Figure 2. Immunohistochemistry was strongly positive for prostate-specific antigen and focally positive for prostate-specific acid phosphatase (original magnification ×100). |

The diagnosis is confirmed immunohistochemically with PSA and/or prostate-specific acid phosphatase immunostaining (Figure 2), which together have nearly 100% specificity for prostate adenocarcinomas.9 Although rare, PSA and or prostate-specific acid phosphatase may be weakly positive in nephrogenic adenoma.10 Another biomarker, urinary prostate cancer antigen 3, is being evaluated to identify men with indolent prostate cancer.11 It is unknown how useful this marker will be in the immunohistochemical identification of prostate cancer cutaneous metastases.

A large review of reported cases of cutaneous metastases from internal malignancies revealed that the majority of patients had known systemic disease but enjoyed a good performance status at the time of diagnosis.2 As such, skin metastases may serve as the initial indicator of visceral recurrence. Prostate cancer is second only to lung cancer as the deadliest cancer in males,4 and cutaneous metastasis garners a particularly poor prognosis. The mean survival time after diagnosis of cutaneous metastasis is 7 months.8 Therefore, treatment of cutaneous metastases is largely palliative, including local excision and intralesional chemotherapy.

1. Thiers BH, Sahn RE, Callen JP. Cutaneous manifestations of internal malignancy. CA Cancer J Clin 2009;59:73-98.

2. Mueller TJ, Wu H, Greenberg RE, et al. Cutaneous metastases from genitourinary malignancies. Urology. 2004;63:1021-1026.

3. Brownstein MH, Helwig EB. Metastatic tumors of the skin. Cancer. 1972;29:1298-1307.

4. Jemal A, Siegel R, Xu J, et al. Cancer statistics, 2010. CA Cancer J Clin. 2010;60:277-300.

5. Schwartz RA. Cutaneous metastatic disease. J Am Acad Dermatol. 1995;33:161-182.

6. Reddy S, Bang RH, Contreras ME. Telangiectatic cutaneous metastasis from carcinoma of the prostate. Br J Dermatol. 2007;156:598-600.

7. Tosoian J, Loeb S. PSA and beyond: the past, present, and future of investigative biomarkers for prostate cancer. ScientificWorldJournal. 2010;10:1919-1931.

8. Wang SQ, Mecca PS, Myskowski PL, et al. Scrotal and penile papules and plaques as the initial manifestation of a cutaneous metastasis of adenocarcinoma of the prostate: case report and review of the literature. J Cutan Pathol. 2008;35:681-684.

9. Nadji M, Tabei SZ, Castro A, et al. Prostate-specific antigen: an immunohistochemical marker for prostatic neoplasms. Cancer. 1981;48:1229-1232.

10. Paner GP, Luthringer DJ, Amin MB. Best practice in diagnostic immunohistochemistry: prostate carcinoma and its mimics in needle core biopsies. Arch Pathol Lab Med. 2008;132:1388-1396.

11. Cooperberg MR, Carroll PR, Klotz L. Active surveillance for prostate cancer: progress and promise. J Clin Oncol. 2011;29:3669-3676.

The Diagnosis: Prostate Cancer Metastases

Cutaneous involvement of visceral tumors can occur indirectly, with the tumor causing changes in the skin without the presence of tumor cells (ie, paraneoplastic processes), or directly, with the presence of tumor cells in the skin (ie, metastasis).1 Cutaneous metastases from solid primary tumors are uncommon. The incidence of metastasis to the skin from visceral malignancies ranges from 0.3% to 9.0%.2 The most common primary internal tumors to metastasize to the skin are those arising from the breasts, lungs, colon, ovaries, and head and neck.3 Although prostate cancer is the most common cancer in males (making up 28% of new cancer diagnoses), excluding basal and squamous cell skin cancers, it rarely metastasizes to the skin, representing less than 1% of all cutaneous metastasis.4,5

There are 4 proposed mechanisms for metastatic dissemination to the skin: (1) direct invasion from underlying neoplasm; (2) implantation from a surgical scar; (3) spread through the lymphatics; and/or (4) hematogenous spread. The most common sites of prostate cancer cutaneous metastasis are the inguinal area, penis, and lower abdomen,2 which is likely due to spread via the lymphatic drainage. Cutaneous metastasis to distant sites such as the scalp or chest, as in our patient, may be secondary to hematogenous spread.

Generally, cutaneous metastases from visceral malignancies manifest as urticaria or a nonspecific macular rash.2 However, prostate cancer cutaneous metastases commonly present as papules or subcutaneous nodules but also can have inflammatory, cicatricial, sclerodermoid, telangiectatic, or zosteriform morphologies.2,5,6 The lesions of prostate cancer cutaneous metastases are typically well-circumscribed, flesh-colored or pink to red, oval plaques or nodules ranging in size from several millimeters to a few centimeters.2 The cutaneous lesions generally are multiple and can be localized or diffuse in distribution. The clinical differential diagnosis is broad in patients undergoing systemic treatment of prostate cancer and often includes drug reaction, cutaneous lymphoma, atypical mycobacterial or deep fungal infection, or paraneoplastic dermatosis.

Laboratory studies often reveal an elevated serum prostate-specific antigen (PSA) level, a glycoprotein that functions in the liquefaction of seminal fluid made primarily by the prostate, often in benign hypertrophic and malignant prostatic processes.7 Definitive diagnosis of prostate cancer cutaneous metastasis can be established by histologic examination. Excisional or punch biopsy is preferred over superficial shave biopsy. Metastasis from prostate adenocarcinoma often reveals infiltrative growth of disorganized atypical epithelial cells along collagen bundles in the dermis and subcutis (Figure 1).2,8 The presence of lymphovascular invasion further increases the suspicion of metastasis. Metastatic lesions may resemble the primary lesion; however, they are often poorly differentiated, making histologic comparison difficult.

|

| Figure 1. Biopsy revealed cords of atypical epithelioid cells dissecting through dermal collagen bundles, accompanied by abundant mucin. Atypical cells displayed nuclear pleomorphism, and multiple mitotic figures were present (H&E, original magnification ×100). |

|

| Figure 2. Immunohistochemistry was strongly positive for prostate-specific antigen and focally positive for prostate-specific acid phosphatase (original magnification ×100). |

The diagnosis is confirmed immunohistochemically with PSA and/or prostate-specific acid phosphatase immunostaining (Figure 2), which together have nearly 100% specificity for prostate adenocarcinomas.9 Although rare, PSA and or prostate-specific acid phosphatase may be weakly positive in nephrogenic adenoma.10 Another biomarker, urinary prostate cancer antigen 3, is being evaluated to identify men with indolent prostate cancer.11 It is unknown how useful this marker will be in the immunohistochemical identification of prostate cancer cutaneous metastases.

A large review of reported cases of cutaneous metastases from internal malignancies revealed that the majority of patients had known systemic disease but enjoyed a good performance status at the time of diagnosis.2 As such, skin metastases may serve as the initial indicator of visceral recurrence. Prostate cancer is second only to lung cancer as the deadliest cancer in males,4 and cutaneous metastasis garners a particularly poor prognosis. The mean survival time after diagnosis of cutaneous metastasis is 7 months.8 Therefore, treatment of cutaneous metastases is largely palliative, including local excision and intralesional chemotherapy.

The Diagnosis: Prostate Cancer Metastases

Cutaneous involvement of visceral tumors can occur indirectly, with the tumor causing changes in the skin without the presence of tumor cells (ie, paraneoplastic processes), or directly, with the presence of tumor cells in the skin (ie, metastasis).1 Cutaneous metastases from solid primary tumors are uncommon. The incidence of metastasis to the skin from visceral malignancies ranges from 0.3% to 9.0%.2 The most common primary internal tumors to metastasize to the skin are those arising from the breasts, lungs, colon, ovaries, and head and neck.3 Although prostate cancer is the most common cancer in males (making up 28% of new cancer diagnoses), excluding basal and squamous cell skin cancers, it rarely metastasizes to the skin, representing less than 1% of all cutaneous metastasis.4,5

There are 4 proposed mechanisms for metastatic dissemination to the skin: (1) direct invasion from underlying neoplasm; (2) implantation from a surgical scar; (3) spread through the lymphatics; and/or (4) hematogenous spread. The most common sites of prostate cancer cutaneous metastasis are the inguinal area, penis, and lower abdomen,2 which is likely due to spread via the lymphatic drainage. Cutaneous metastasis to distant sites such as the scalp or chest, as in our patient, may be secondary to hematogenous spread.

Generally, cutaneous metastases from visceral malignancies manifest as urticaria or a nonspecific macular rash.2 However, prostate cancer cutaneous metastases commonly present as papules or subcutaneous nodules but also can have inflammatory, cicatricial, sclerodermoid, telangiectatic, or zosteriform morphologies.2,5,6 The lesions of prostate cancer cutaneous metastases are typically well-circumscribed, flesh-colored or pink to red, oval plaques or nodules ranging in size from several millimeters to a few centimeters.2 The cutaneous lesions generally are multiple and can be localized or diffuse in distribution. The clinical differential diagnosis is broad in patients undergoing systemic treatment of prostate cancer and often includes drug reaction, cutaneous lymphoma, atypical mycobacterial or deep fungal infection, or paraneoplastic dermatosis.

Laboratory studies often reveal an elevated serum prostate-specific antigen (PSA) level, a glycoprotein that functions in the liquefaction of seminal fluid made primarily by the prostate, often in benign hypertrophic and malignant prostatic processes.7 Definitive diagnosis of prostate cancer cutaneous metastasis can be established by histologic examination. Excisional or punch biopsy is preferred over superficial shave biopsy. Metastasis from prostate adenocarcinoma often reveals infiltrative growth of disorganized atypical epithelial cells along collagen bundles in the dermis and subcutis (Figure 1).2,8 The presence of lymphovascular invasion further increases the suspicion of metastasis. Metastatic lesions may resemble the primary lesion; however, they are often poorly differentiated, making histologic comparison difficult.

|

| Figure 1. Biopsy revealed cords of atypical epithelioid cells dissecting through dermal collagen bundles, accompanied by abundant mucin. Atypical cells displayed nuclear pleomorphism, and multiple mitotic figures were present (H&E, original magnification ×100). |

|

| Figure 2. Immunohistochemistry was strongly positive for prostate-specific antigen and focally positive for prostate-specific acid phosphatase (original magnification ×100). |

The diagnosis is confirmed immunohistochemically with PSA and/or prostate-specific acid phosphatase immunostaining (Figure 2), which together have nearly 100% specificity for prostate adenocarcinomas.9 Although rare, PSA and or prostate-specific acid phosphatase may be weakly positive in nephrogenic adenoma.10 Another biomarker, urinary prostate cancer antigen 3, is being evaluated to identify men with indolent prostate cancer.11 It is unknown how useful this marker will be in the immunohistochemical identification of prostate cancer cutaneous metastases.

A large review of reported cases of cutaneous metastases from internal malignancies revealed that the majority of patients had known systemic disease but enjoyed a good performance status at the time of diagnosis.2 As such, skin metastases may serve as the initial indicator of visceral recurrence. Prostate cancer is second only to lung cancer as the deadliest cancer in males,4 and cutaneous metastasis garners a particularly poor prognosis. The mean survival time after diagnosis of cutaneous metastasis is 7 months.8 Therefore, treatment of cutaneous metastases is largely palliative, including local excision and intralesional chemotherapy.

1. Thiers BH, Sahn RE, Callen JP. Cutaneous manifestations of internal malignancy. CA Cancer J Clin 2009;59:73-98.

2. Mueller TJ, Wu H, Greenberg RE, et al. Cutaneous metastases from genitourinary malignancies. Urology. 2004;63:1021-1026.

3. Brownstein MH, Helwig EB. Metastatic tumors of the skin. Cancer. 1972;29:1298-1307.

4. Jemal A, Siegel R, Xu J, et al. Cancer statistics, 2010. CA Cancer J Clin. 2010;60:277-300.

5. Schwartz RA. Cutaneous metastatic disease. J Am Acad Dermatol. 1995;33:161-182.

6. Reddy S, Bang RH, Contreras ME. Telangiectatic cutaneous metastasis from carcinoma of the prostate. Br J Dermatol. 2007;156:598-600.

7. Tosoian J, Loeb S. PSA and beyond: the past, present, and future of investigative biomarkers for prostate cancer. ScientificWorldJournal. 2010;10:1919-1931.

8. Wang SQ, Mecca PS, Myskowski PL, et al. Scrotal and penile papules and plaques as the initial manifestation of a cutaneous metastasis of adenocarcinoma of the prostate: case report and review of the literature. J Cutan Pathol. 2008;35:681-684.

9. Nadji M, Tabei SZ, Castro A, et al. Prostate-specific antigen: an immunohistochemical marker for prostatic neoplasms. Cancer. 1981;48:1229-1232.

10. Paner GP, Luthringer DJ, Amin MB. Best practice in diagnostic immunohistochemistry: prostate carcinoma and its mimics in needle core biopsies. Arch Pathol Lab Med. 2008;132:1388-1396.

11. Cooperberg MR, Carroll PR, Klotz L. Active surveillance for prostate cancer: progress and promise. J Clin Oncol. 2011;29:3669-3676.

1. Thiers BH, Sahn RE, Callen JP. Cutaneous manifestations of internal malignancy. CA Cancer J Clin 2009;59:73-98.

2. Mueller TJ, Wu H, Greenberg RE, et al. Cutaneous metastases from genitourinary malignancies. Urology. 2004;63:1021-1026.

3. Brownstein MH, Helwig EB. Metastatic tumors of the skin. Cancer. 1972;29:1298-1307.

4. Jemal A, Siegel R, Xu J, et al. Cancer statistics, 2010. CA Cancer J Clin. 2010;60:277-300.

5. Schwartz RA. Cutaneous metastatic disease. J Am Acad Dermatol. 1995;33:161-182.

6. Reddy S, Bang RH, Contreras ME. Telangiectatic cutaneous metastasis from carcinoma of the prostate. Br J Dermatol. 2007;156:598-600.

7. Tosoian J, Loeb S. PSA and beyond: the past, present, and future of investigative biomarkers for prostate cancer. ScientificWorldJournal. 2010;10:1919-1931.

8. Wang SQ, Mecca PS, Myskowski PL, et al. Scrotal and penile papules and plaques as the initial manifestation of a cutaneous metastasis of adenocarcinoma of the prostate: case report and review of the literature. J Cutan Pathol. 2008;35:681-684.

9. Nadji M, Tabei SZ, Castro A, et al. Prostate-specific antigen: an immunohistochemical marker for prostatic neoplasms. Cancer. 1981;48:1229-1232.

10. Paner GP, Luthringer DJ, Amin MB. Best practice in diagnostic immunohistochemistry: prostate carcinoma and its mimics in needle core biopsies. Arch Pathol Lab Med. 2008;132:1388-1396.

11. Cooperberg MR, Carroll PR, Klotz L. Active surveillance for prostate cancer: progress and promise. J Clin Oncol. 2011;29:3669-3676.

A 57-year-old cachectic man with a history of metastatic, hormone-refractory adenocarcinoma of the prostate presented with multiple tender subcutaneous nodules on the back and shoulders that developed over the course of 12 months. During that time, he was treated with cyclophosphamide, leuprolide acetate, bicalutamide, zoledronic acid, and filgrastim. A punch biopsy specimen obtained from the left shoulder revealed cords of atypical epithelioid cells dissecting through dermal collagen bundles, accompanied by abundant mucin. The atypical cells displayed nuclear pleomorphism, and multiple mitotic figures were observed.

Shedding of the Fingernails

The Diagnosis: Onychomadesis

The nail changes were characteristic of onychomadesis. Systemic illness in this patient most likely resulted in temporary arrest of nail matrix activity, leading to separation of the proximal nail plate from the proximal nail fold, which gave rise to a deep transverse sulcus.1 Conversely, Beau lines are characterized by transverse grooves that move distally as the nail grows. Onychomadesis also is seen in pemphigus vulgaris, which could be due to an autoimmune disease inhibiting normal nail plate growth and development of blisters beneath the nail causing detachment of the nail plate.2 Drug-induced Beau lines or onychomadesis are most frequently caused by chemotherapeutic agents (taxanes) and retinoids, which reflect an arrest in epithelial proliferation.3 Familial cases also have been described.4 Management of the nail abnormality should focus on the underlying medical problem or triggering factor. In our patient, hypertension and kidney disease were managed by a low-salt diet, oral antihypertensives, and iron replacement.

1. Wolff K, Goldsmith LA, Katz SI, et al, eds. Fitzpatrick’s Dermatology in General Medicine. 7th ed. New York, NY: McGraw-Hill; 2008.

2. Engineer L, Norton LA, Ahmed AR. Nail involvement in pemphigus vulgaris. J Am Acad Dermatol. 2000;43:529-535.

3. Minisini AM, Tosti A, Sobrero AF, et al. Taxane-induced nail changes: incidence, clinical presentation and outcome. Ann Oncol. 2003;14:333-337.

4. Mehra A, Murphy RJ, Wilson BB. Idiopathic familial onychomadesis. J Am Acad Dermatol. 2000;43(2, pt 2):349-350.

The Diagnosis: Onychomadesis

The nail changes were characteristic of onychomadesis. Systemic illness in this patient most likely resulted in temporary arrest of nail matrix activity, leading to separation of the proximal nail plate from the proximal nail fold, which gave rise to a deep transverse sulcus.1 Conversely, Beau lines are characterized by transverse grooves that move distally as the nail grows. Onychomadesis also is seen in pemphigus vulgaris, which could be due to an autoimmune disease inhibiting normal nail plate growth and development of blisters beneath the nail causing detachment of the nail plate.2 Drug-induced Beau lines or onychomadesis are most frequently caused by chemotherapeutic agents (taxanes) and retinoids, which reflect an arrest in epithelial proliferation.3 Familial cases also have been described.4 Management of the nail abnormality should focus on the underlying medical problem or triggering factor. In our patient, hypertension and kidney disease were managed by a low-salt diet, oral antihypertensives, and iron replacement.

The Diagnosis: Onychomadesis

The nail changes were characteristic of onychomadesis. Systemic illness in this patient most likely resulted in temporary arrest of nail matrix activity, leading to separation of the proximal nail plate from the proximal nail fold, which gave rise to a deep transverse sulcus.1 Conversely, Beau lines are characterized by transverse grooves that move distally as the nail grows. Onychomadesis also is seen in pemphigus vulgaris, which could be due to an autoimmune disease inhibiting normal nail plate growth and development of blisters beneath the nail causing detachment of the nail plate.2 Drug-induced Beau lines or onychomadesis are most frequently caused by chemotherapeutic agents (taxanes) and retinoids, which reflect an arrest in epithelial proliferation.3 Familial cases also have been described.4 Management of the nail abnormality should focus on the underlying medical problem or triggering factor. In our patient, hypertension and kidney disease were managed by a low-salt diet, oral antihypertensives, and iron replacement.

1. Wolff K, Goldsmith LA, Katz SI, et al, eds. Fitzpatrick’s Dermatology in General Medicine. 7th ed. New York, NY: McGraw-Hill; 2008.

2. Engineer L, Norton LA, Ahmed AR. Nail involvement in pemphigus vulgaris. J Am Acad Dermatol. 2000;43:529-535.

3. Minisini AM, Tosti A, Sobrero AF, et al. Taxane-induced nail changes: incidence, clinical presentation and outcome. Ann Oncol. 2003;14:333-337.

4. Mehra A, Murphy RJ, Wilson BB. Idiopathic familial onychomadesis. J Am Acad Dermatol. 2000;43(2, pt 2):349-350.

1. Wolff K, Goldsmith LA, Katz SI, et al, eds. Fitzpatrick’s Dermatology in General Medicine. 7th ed. New York, NY: McGraw-Hill; 2008.

2. Engineer L, Norton LA, Ahmed AR. Nail involvement in pemphigus vulgaris. J Am Acad Dermatol. 2000;43:529-535.

3. Minisini AM, Tosti A, Sobrero AF, et al. Taxane-induced nail changes: incidence, clinical presentation and outcome. Ann Oncol. 2003;14:333-337.

4. Mehra A, Murphy RJ, Wilson BB. Idiopathic familial onychomadesis. J Am Acad Dermatol. 2000;43(2, pt 2):349-350.

A 70-year-old woman was referred to the dermatology department with abnormal-appearing fingernails of 6 months’ duration. Clinical examination showed complete shedding of the proximal nail plate and separation from the nail bed involving all the fingernails. There also was thickening of the distal nail plate. The patient also had diffuse thinning of the hair on the scalp. She had chronic kidney disease, likely from hypertensive nephrosclerosis, that was complicated by iron-deficient anemia. No new systemic medication had been given.

Man Falls on Buttocks

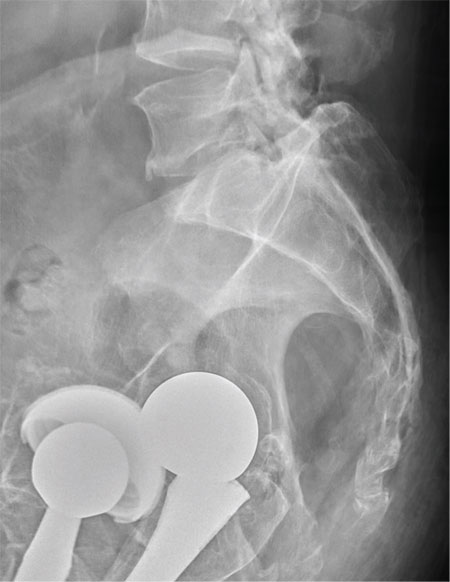

ANSWER

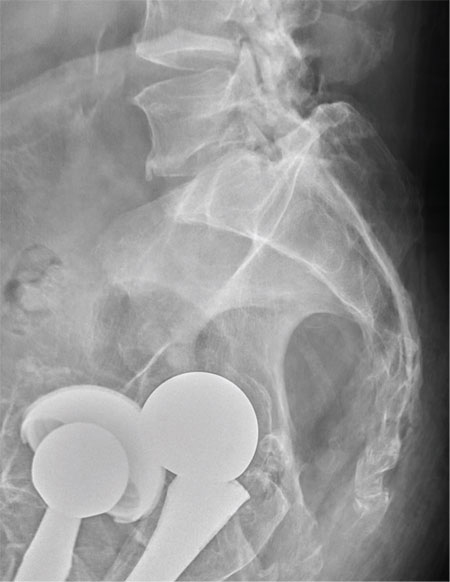

There are degenerative changes present. Bilateral hip prostheses are noted. Within the coccyx, there is bone remodeling and angulation that are likely chronic and related to remote trauma or injury (arrow). Below this, some cortical lucency (circled) is noted, most likely consistent with an acute fracture. The patient was prescribed a nonsteroidal medication and a mild narcotic pain medication.

ANSWER

There are degenerative changes present. Bilateral hip prostheses are noted. Within the coccyx, there is bone remodeling and angulation that are likely chronic and related to remote trauma or injury (arrow). Below this, some cortical lucency (circled) is noted, most likely consistent with an acute fracture. The patient was prescribed a nonsteroidal medication and a mild narcotic pain medication.

ANSWER

There are degenerative changes present. Bilateral hip prostheses are noted. Within the coccyx, there is bone remodeling and angulation that are likely chronic and related to remote trauma or injury (arrow). Below this, some cortical lucency (circled) is noted, most likely consistent with an acute fracture. The patient was prescribed a nonsteroidal medication and a mild narcotic pain medication.

A 75-year-old man presents to the urgent care center for evaluation of pain in his buttocks after a fall. He states he was walking when his “legs gave out” and he hit the ground. He landed squarely on his buttocks, causing immediate pain. He was eventually able to get up with some assistance. He denies any current weakness or any bowel or bladder complaints. His medical/surgical history is significant for coronary artery disease, hypertension, and bilateral hip replacements. Physical exam reveals an elderly male who is uncomfortable but in no obvious distress. His vital signs are stable. He has moderate point tenderness over his sacrum but is able to move all his extremities well, with normal strength. Radiograph of his sacrum/coccyx is shown. What is your impression?

Does Young Athlete Have Cause for Concern?

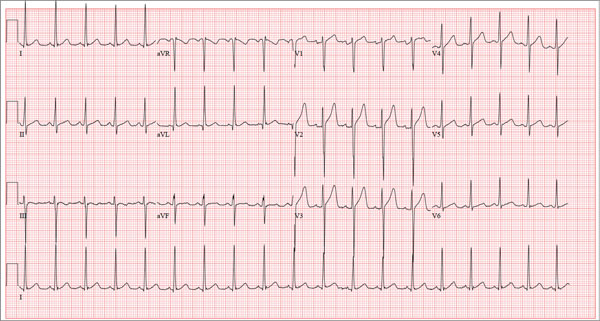

ANSWER

The correct interpretation of this ECG includes sinus tachycardia and left ventricular hypertrophy.

Sinus tachycardia is evidenced by an atrial rate greater than 100 beats/min with a P wave for every QRS complex and a QRS complex for every P wave.

Left ventricular hypertrophy is present when either the sum of the R wave voltage in lead I and the S wave in lead III is 25 mm or higher or the sum of the S wave in lead V1 and the R wave in either V5 or V6 is 35 mm or higher.

In follow-up to these findings, an echocardiogram was recommended and performed. It revealed a normal heart consistent with that of a young athlete.

The patient and his parents were reassured as to the young man’s condition but decided to seek a second opinion.

ANSWER

The correct interpretation of this ECG includes sinus tachycardia and left ventricular hypertrophy.

Sinus tachycardia is evidenced by an atrial rate greater than 100 beats/min with a P wave for every QRS complex and a QRS complex for every P wave.

Left ventricular hypertrophy is present when either the sum of the R wave voltage in lead I and the S wave in lead III is 25 mm or higher or the sum of the S wave in lead V1 and the R wave in either V5 or V6 is 35 mm or higher.

In follow-up to these findings, an echocardiogram was recommended and performed. It revealed a normal heart consistent with that of a young athlete.

The patient and his parents were reassured as to the young man’s condition but decided to seek a second opinion.

ANSWER

The correct interpretation of this ECG includes sinus tachycardia and left ventricular hypertrophy.

Sinus tachycardia is evidenced by an atrial rate greater than 100 beats/min with a P wave for every QRS complex and a QRS complex for every P wave.

Left ventricular hypertrophy is present when either the sum of the R wave voltage in lead I and the S wave in lead III is 25 mm or higher or the sum of the S wave in lead V1 and the R wave in either V5 or V6 is 35 mm or higher.

In follow-up to these findings, an echocardiogram was recommended and performed. It revealed a normal heart consistent with that of a young athlete.

The patient and his parents were reassured as to the young man’s condition but decided to seek a second opinion.

A 17-year-old male athlete recently graduated high school and received a full scholarship to play baseball for a major university. As part of his preparation for college, his parents bring him to your clinic for a complete physical examination, noting that he contracted several colds during the past school year. He has been symptom free for the past two months. The patient asks to be examined without his parents present. After they exit the room, he informs you that he has recently become sexually active, hasn’t used condoms on two occasions, and wants to be tested for sexually transmitted infections (STIs). Medical history is unremarkable, with the exception of a fractured left clavicle sustained when the patient was 12. He currently takes no medications, denies tobacco, alcohol, or recreational drug use, and has no known drug allergies. He lives at home with his parents and two siblings. A detailed review of systems reveals no complaints or symptoms. Vital signs include a blood pressure of 104/58 mm Hg; pulse, 100 beats/min; respiratory rate, 14 breaths/min-1; and temperature, 97.2°F. His weight is 204 lb and his height, 79 in. He appears anxious and apologizes for having sweaty palms. A thorough physical exam yields completely normal results, with the exception of a palpable callus over the mid portion of the left clavicle (consistent with his history of a fracture). Lung sounds are clear in all fields; there are no murmurs, bruits, rubs, or extra heart sounds; and a strong PMI (point of maximum impulse) is easily palpable over the left chest at the seventh and eighth intercostal spaces. The patient is sent to the lab, where blood is drawn for a routine chemistry panel, complete blood count, and STI surveillance panel. When he returns and his parents reenter the room, they insist on ECG for their son. You explain that there’s no clear indication for it; however, they insist and state they will pay out of pocket if not covered by insurance. You reluctantly agree. The ECG shows the following: a ventricular rate of 112 beats/min; PR interval, 132 ms; QRS duration, 756 ms; QT/QTc interval, 326/444 ms; P axis, 59°; R axis, –8°; and T axis, 26°. What is your interpretation?

Intergluteal Itching in Need of Relief

ANSWER

Admittedly, this is a bit of a trick question—but with a good teaching point to make. A course of oral fluconazole (choice “a”) is futile, since there’s no reason to think this problem is yeast-driven and since the patient has already demonstrated a lack of response to topical imidazoles.

Punch biopsy (choice “b”) would be a good choice, but not in this area, where it could quickly become a bigger problem than the one the patient presented with. Sutures would not likely hold the biopsy wound together, and resultant infection is all too likely.

A KOH test to detect fungal or yeast elements (choice “c”) is unlikely to shed any light on the problem, given the lack of response to antifungal creams. Finally, there’s no reason to suspect a bacterial origin, so oral antibiotics such as cephalexin (choice “d”) would be useless (and had already been tried unsuccessfully).

The correct answer is none of the above (choice “e”).

DISCUSSION

This case illustrates why dermatology seems so maddeningly difficult to the uninitiated. Any experienced derm provider would know the correct diagnosis, lichen sclerosus et atrophicus (LS&A), because it presents in such a distinctive way (in limited locations, predominantly in women) and because the differential is so limited. But if you’ve never heard of LS&A, you’re unlikely to diagnose it, let alone know how to treat it.

LS&A is an inflammatory condition of unknown origin that affects the upper epidermis. It can present in extragenital locations (particularly shoulders and legs) but is far more common in genital areas. As exhibited in this case, it presents with well-defined pigment loss, which is especially easy to see in patients with darker skin.

Although more commonly seen in women, LS&A can occur in men, usually manifesting on the penile glans and distal foreskin of uncircumcised patients. The dry atrophic changes seen on the glans can lead to stenosis of the urethral meatus and, proximally, to adhesions (phimosis) of the foreskin. (This condition was termed balanitis xerotica obliterans [BXO] long before its pathologic process was determined to be identical to LS&A’s. Tissue specimens obtained during circumcisions performed for chronic phimosis often yield evidence of BXO.)

In women, untreated chronic LS&A can lead to sclerotic changes in and around the urethra and labia minora and can cause introital stenosis. This case is a bit atypical; LS&A more often manifests in perivaginal and perirectal areas, where the intense hypopigmentation produces a classic “figure eight” appearance.

The differential includes lichen simplex chronicus, psoriasis, lichen planus, contact/irritant dermatitis, and seborrhea. Often, biopsy is necessary and appropriate to settle the issue, other factors being equal.

TREATMENT/PROGNOSIS

The patient was given a prescription for clobetasol 0.05% ointment for twice-daily application Monday through Friday (and no application for two consecutive days—in this case, the weekend—per week). Studies have established the efficacy and safety of this treatment regimen.

In a month or two, application can be reduced to once or twice a week to control the condition.

ANSWER

Admittedly, this is a bit of a trick question—but with a good teaching point to make. A course of oral fluconazole (choice “a”) is futile, since there’s no reason to think this problem is yeast-driven and since the patient has already demonstrated a lack of response to topical imidazoles.

Punch biopsy (choice “b”) would be a good choice, but not in this area, where it could quickly become a bigger problem than the one the patient presented with. Sutures would not likely hold the biopsy wound together, and resultant infection is all too likely.

A KOH test to detect fungal or yeast elements (choice “c”) is unlikely to shed any light on the problem, given the lack of response to antifungal creams. Finally, there’s no reason to suspect a bacterial origin, so oral antibiotics such as cephalexin (choice “d”) would be useless (and had already been tried unsuccessfully).

The correct answer is none of the above (choice “e”).

DISCUSSION

This case illustrates why dermatology seems so maddeningly difficult to the uninitiated. Any experienced derm provider would know the correct diagnosis, lichen sclerosus et atrophicus (LS&A), because it presents in such a distinctive way (in limited locations, predominantly in women) and because the differential is so limited. But if you’ve never heard of LS&A, you’re unlikely to diagnose it, let alone know how to treat it.

LS&A is an inflammatory condition of unknown origin that affects the upper epidermis. It can present in extragenital locations (particularly shoulders and legs) but is far more common in genital areas. As exhibited in this case, it presents with well-defined pigment loss, which is especially easy to see in patients with darker skin.

Although more commonly seen in women, LS&A can occur in men, usually manifesting on the penile glans and distal foreskin of uncircumcised patients. The dry atrophic changes seen on the glans can lead to stenosis of the urethral meatus and, proximally, to adhesions (phimosis) of the foreskin. (This condition was termed balanitis xerotica obliterans [BXO] long before its pathologic process was determined to be identical to LS&A’s. Tissue specimens obtained during circumcisions performed for chronic phimosis often yield evidence of BXO.)

In women, untreated chronic LS&A can lead to sclerotic changes in and around the urethra and labia minora and can cause introital stenosis. This case is a bit atypical; LS&A more often manifests in perivaginal and perirectal areas, where the intense hypopigmentation produces a classic “figure eight” appearance.

The differential includes lichen simplex chronicus, psoriasis, lichen planus, contact/irritant dermatitis, and seborrhea. Often, biopsy is necessary and appropriate to settle the issue, other factors being equal.

TREATMENT/PROGNOSIS

The patient was given a prescription for clobetasol 0.05% ointment for twice-daily application Monday through Friday (and no application for two consecutive days—in this case, the weekend—per week). Studies have established the efficacy and safety of this treatment regimen.

In a month or two, application can be reduced to once or twice a week to control the condition.

ANSWER

Admittedly, this is a bit of a trick question—but with a good teaching point to make. A course of oral fluconazole (choice “a”) is futile, since there’s no reason to think this problem is yeast-driven and since the patient has already demonstrated a lack of response to topical imidazoles.

Punch biopsy (choice “b”) would be a good choice, but not in this area, where it could quickly become a bigger problem than the one the patient presented with. Sutures would not likely hold the biopsy wound together, and resultant infection is all too likely.

A KOH test to detect fungal or yeast elements (choice “c”) is unlikely to shed any light on the problem, given the lack of response to antifungal creams. Finally, there’s no reason to suspect a bacterial origin, so oral antibiotics such as cephalexin (choice “d”) would be useless (and had already been tried unsuccessfully).

The correct answer is none of the above (choice “e”).

DISCUSSION

This case illustrates why dermatology seems so maddeningly difficult to the uninitiated. Any experienced derm provider would know the correct diagnosis, lichen sclerosus et atrophicus (LS&A), because it presents in such a distinctive way (in limited locations, predominantly in women) and because the differential is so limited. But if you’ve never heard of LS&A, you’re unlikely to diagnose it, let alone know how to treat it.

LS&A is an inflammatory condition of unknown origin that affects the upper epidermis. It can present in extragenital locations (particularly shoulders and legs) but is far more common in genital areas. As exhibited in this case, it presents with well-defined pigment loss, which is especially easy to see in patients with darker skin.

Although more commonly seen in women, LS&A can occur in men, usually manifesting on the penile glans and distal foreskin of uncircumcised patients. The dry atrophic changes seen on the glans can lead to stenosis of the urethral meatus and, proximally, to adhesions (phimosis) of the foreskin. (This condition was termed balanitis xerotica obliterans [BXO] long before its pathologic process was determined to be identical to LS&A’s. Tissue specimens obtained during circumcisions performed for chronic phimosis often yield evidence of BXO.)

In women, untreated chronic LS&A can lead to sclerotic changes in and around the urethra and labia minora and can cause introital stenosis. This case is a bit atypical; LS&A more often manifests in perivaginal and perirectal areas, where the intense hypopigmentation produces a classic “figure eight” appearance.

The differential includes lichen simplex chronicus, psoriasis, lichen planus, contact/irritant dermatitis, and seborrhea. Often, biopsy is necessary and appropriate to settle the issue, other factors being equal.

TREATMENT/PROGNOSIS

The patient was given a prescription for clobetasol 0.05% ointment for twice-daily application Monday through Friday (and no application for two consecutive days—in this case, the weekend—per week). Studies have established the efficacy and safety of this treatment regimen.

In a month or two, application can be reduced to once or twice a week to control the condition.

For almost a year, a 55-year-old African-American woman has experienced itchy skin changes in her perianal area. Treatment attempts with several topical creams—including clotrimazole, combination clotrimazole/betamethasone, and ketoconazole—have not helped. The patient has seen several primary care providers for the problem. All have told her that it was yeast-related, except the last clinician, who suspected psoriasis. When the topical medication prescribed by that provider did not yield a resolution, the patient decided to consult dermatology. Due to her lack of insurance, she had to wait four months to see a derm clinician, since her only option was a once-a-month free clinic in her community. Aside from mild hypertension, the patient claims to be in good health. Recent work-up indicated she does not have diabetes. She denies any family history of skin diseases, including psoriasis. She has had no previous complaints regarding her vaginal/perivaginal areas. The patient’s type V skin is free of notable changes except in the intergluteal and perianal areas. Specifically, no rash is noted on her extensor elbows or knees or in her scalp, and there are no changes in her fingernails. When the patient lies on her left side, extending her left leg and bringing her right knee toward her chest, the entire intergluteal and perianal areas can be visualized. Distinct loss of dark pigment is seen in the upper intergluteal/lower coccygeal areas. Closer inspection reveals that the pigment loss is complete, giving the affected skin a porcelain-like white appearance that also seems moderately atrophic. Palpation confirms this impression. No such changes are noted in the perianal or perineal areas. However, there is diffuse hyperpigmentation, as well as signs of mild chronic excoriation.

Nonpruritic Papular Facial Eruption

The Diagnosis: Granulomatous Periorificial Dermatitis

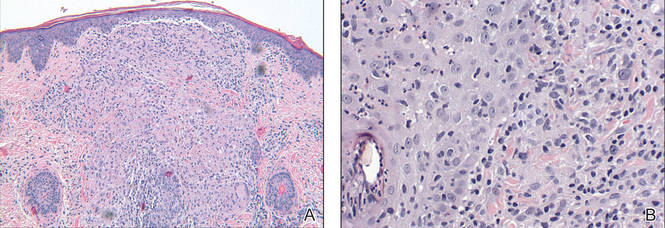

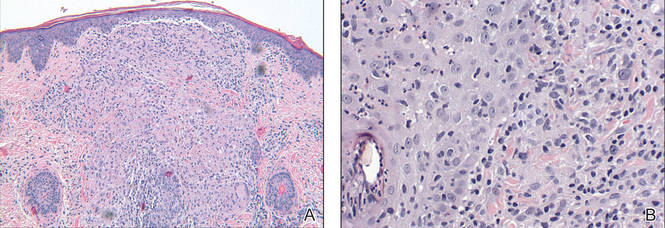

Review of the prior biopsy from the lower cutaneous lip revealed granulomatous perifolliculitis. The patient’s age combined with the morphology, distribution, and histopathologic features (Figure) of his eruption were characteristic of granulomatous periorificial dermatitis (GPD) of childhood. The patient was treated with oral erythromycin and topical metronidazole with immediate improvement, particularly with resolution of the erythema.

Granulomatous periorificial dermatitis is a benign, self-limited eruption in healthy prepubertal children that is characterized by coalescent, asymptomatic, dome-shaped, yellow-brown to erythematous papules.1,2 The monomorphous lesions are firm, measure 1 to 3 mm in diameter, and are most commonly located around the mouth.2,3 Other areas of involvement include the nostrils and alar creases as well as the periocular skin.4 Less commonly, GPD has been described on the scalp, ears, neck, trunk, extremities, and genital region.5 Slight peripheral scaling or erythema and small pitted scarring are variable.4,5 There may be a history of failed topical corticosteroid treatment that either caused no change or a flare in the rash.1-5 Patients have no systemic findings.3,5

Biopsy of GPD shows characteristic noncaseating granulomas in the dermis, typified by perifollicular localization.5 The granulomatous infiltrate consists of epithelioid histiocytes and multinucleated giant cells surrounded by lymphocytes, with focal collections of neutrophils and occasionally overlying parakeratosis.2,3

The nomenclature of GPD has varied since the 1970s and has included Gianotti-type perioral dermatitis,6 GPD of childhood,7 rosacealike eruption in children,8 FACE (facial Afro-Caribbean childhood eruption),9 and sarcoidlike granulomatous dermatitis.10

The etiology of GPD is unknown, though it has been associated with use of topical, inhaled, or systemic steroids; a personal history of skin problems; a family history of atopy; vaccination; and local reactions to allergens such as cosmetic preparations, antiseptic solutions, tartar control toothpaste, and bubble gum.4,5,11-13 Granulomatous periorificial dermatitis may represent a pediatric variant of granulomatous rosacea or a granulomatous variant of perioral dermatitis, but importantly, it is not related to sarcoidosis.1,4,5 Granulomatous periorificial dermatitis typically affects children of dark-skinned, African Caribbean ancestry, though it has been described in both white and Asian populations.1,2,5 Genders are equally affected.

Although generally a benign condition that spontaneously remits within a few months to 3 years,5 GPD can be quite disruptive to a patient’s self-image, necessitating therapy to hasten resolution. Prior to initiation of treatment, any topical corticosteroids being applied to the affected region should be discontinued. For children older than 9 years, a suggested regimen is oral tetracycline 250 mg twice daily; for those younger than 9 years, erythromycin 30 to 40 mg/kg daily in 2 divided doses is advised.14 Metronidazole 0.75% cream and gel also have shown efficacy in GPD and represent a topical adjunct or alternative to oral therapy.1,14,15

- Knautz MA, Lesher JL. Childhood granulomatous periorificial dermatitis. Pediatr Dermatol. 1996;13:131-134.

- Choi YL, Lee KJ, Cho HJ, et al. Case of childhood granulomatous periorificial dermatitis in a Korean boy treated by oral erythromycin. J Dermatol. 2006;33:806-808.

- Tarm K, Creel NB, Krivda SJ, et al. Granulomatous periorificial dermatitis. Cutis. 2004;73:399-402.

- Nguyen V, Eichenfield LF. Periorificial dermatitis in children and adolescents. J Am Acad Dermatol. 2006;55:781-785.

- Urbatsch AJ, Frieden I, Williams ML, et al. Extrafacial and generalized granulomatous periorificial dermatitis. Arch Dermatol. 2002;138:1354-1358.

- Gianotti F, Ermacora E, Bennelli MG, et al. Particuliere dermatite peri-orale infantile: observations sur cinq cas. Bull Soc Fr Dermatol Syph. 1970;77:341.

- Frieden IJ, Prose NS, Fletcher V, et al. Granulomatous perioral dermatitis in children. Arch Dermatol. 1989;125:369-373.

- Savin JA, Alexander S, Marks R. A rosacea-like eruption of children. Br J Dermatol. 1972;87:425-429.

- Marten RH, Presbury DG, Adamson JE, et al. An unusual popular and acneiform facial eruption in the Negro child. Br J Dermatol. 1974;91:435-438.

- Falk ES. Sarcoid-like granulomatous periocular dermatitis treated with tetracycline. Acta Derm Venereol. 1985;65:270-272.

- Hafeez ZH. Perioral dermatitis: an update. Int J Dermatol. 2003;42:514-517.

- Ferlito TA. Tartar-control toothpaste and perioral dermatitis. J Clin Oncol. 1992;27:43-44.

- Georgouras K, Kocsard E. Micropapular sarcoidal facial eruption in a child. Acta Derm Venereol. 1978;48:433-436.

- Laude TA, Salvemini JN. Perioral dermatitis in children. Semin Cutan Med Surg. 1999;18:206-209.

- Miller SR, Shalita AR. Topical metronidazole gel (0.75%) for the treatment of perioral dermatitis in children. J Am Acad Dermatol. 1994;31:847-848.

The Diagnosis: Granulomatous Periorificial Dermatitis

Review of the prior biopsy from the lower cutaneous lip revealed granulomatous perifolliculitis. The patient’s age combined with the morphology, distribution, and histopathologic features (Figure) of his eruption were characteristic of granulomatous periorificial dermatitis (GPD) of childhood. The patient was treated with oral erythromycin and topical metronidazole with immediate improvement, particularly with resolution of the erythema.

Granulomatous periorificial dermatitis is a benign, self-limited eruption in healthy prepubertal children that is characterized by coalescent, asymptomatic, dome-shaped, yellow-brown to erythematous papules.1,2 The monomorphous lesions are firm, measure 1 to 3 mm in diameter, and are most commonly located around the mouth.2,3 Other areas of involvement include the nostrils and alar creases as well as the periocular skin.4 Less commonly, GPD has been described on the scalp, ears, neck, trunk, extremities, and genital region.5 Slight peripheral scaling or erythema and small pitted scarring are variable.4,5 There may be a history of failed topical corticosteroid treatment that either caused no change or a flare in the rash.1-5 Patients have no systemic findings.3,5

Biopsy of GPD shows characteristic noncaseating granulomas in the dermis, typified by perifollicular localization.5 The granulomatous infiltrate consists of epithelioid histiocytes and multinucleated giant cells surrounded by lymphocytes, with focal collections of neutrophils and occasionally overlying parakeratosis.2,3

The nomenclature of GPD has varied since the 1970s and has included Gianotti-type perioral dermatitis,6 GPD of childhood,7 rosacealike eruption in children,8 FACE (facial Afro-Caribbean childhood eruption),9 and sarcoidlike granulomatous dermatitis.10

The etiology of GPD is unknown, though it has been associated with use of topical, inhaled, or systemic steroids; a personal history of skin problems; a family history of atopy; vaccination; and local reactions to allergens such as cosmetic preparations, antiseptic solutions, tartar control toothpaste, and bubble gum.4,5,11-13 Granulomatous periorificial dermatitis may represent a pediatric variant of granulomatous rosacea or a granulomatous variant of perioral dermatitis, but importantly, it is not related to sarcoidosis.1,4,5 Granulomatous periorificial dermatitis typically affects children of dark-skinned, African Caribbean ancestry, though it has been described in both white and Asian populations.1,2,5 Genders are equally affected.

Although generally a benign condition that spontaneously remits within a few months to 3 years,5 GPD can be quite disruptive to a patient’s self-image, necessitating therapy to hasten resolution. Prior to initiation of treatment, any topical corticosteroids being applied to the affected region should be discontinued. For children older than 9 years, a suggested regimen is oral tetracycline 250 mg twice daily; for those younger than 9 years, erythromycin 30 to 40 mg/kg daily in 2 divided doses is advised.14 Metronidazole 0.75% cream and gel also have shown efficacy in GPD and represent a topical adjunct or alternative to oral therapy.1,14,15

The Diagnosis: Granulomatous Periorificial Dermatitis

Review of the prior biopsy from the lower cutaneous lip revealed granulomatous perifolliculitis. The patient’s age combined with the morphology, distribution, and histopathologic features (Figure) of his eruption were characteristic of granulomatous periorificial dermatitis (GPD) of childhood. The patient was treated with oral erythromycin and topical metronidazole with immediate improvement, particularly with resolution of the erythema.

Granulomatous periorificial dermatitis is a benign, self-limited eruption in healthy prepubertal children that is characterized by coalescent, asymptomatic, dome-shaped, yellow-brown to erythematous papules.1,2 The monomorphous lesions are firm, measure 1 to 3 mm in diameter, and are most commonly located around the mouth.2,3 Other areas of involvement include the nostrils and alar creases as well as the periocular skin.4 Less commonly, GPD has been described on the scalp, ears, neck, trunk, extremities, and genital region.5 Slight peripheral scaling or erythema and small pitted scarring are variable.4,5 There may be a history of failed topical corticosteroid treatment that either caused no change or a flare in the rash.1-5 Patients have no systemic findings.3,5

Biopsy of GPD shows characteristic noncaseating granulomas in the dermis, typified by perifollicular localization.5 The granulomatous infiltrate consists of epithelioid histiocytes and multinucleated giant cells surrounded by lymphocytes, with focal collections of neutrophils and occasionally overlying parakeratosis.2,3

The nomenclature of GPD has varied since the 1970s and has included Gianotti-type perioral dermatitis,6 GPD of childhood,7 rosacealike eruption in children,8 FACE (facial Afro-Caribbean childhood eruption),9 and sarcoidlike granulomatous dermatitis.10

The etiology of GPD is unknown, though it has been associated with use of topical, inhaled, or systemic steroids; a personal history of skin problems; a family history of atopy; vaccination; and local reactions to allergens such as cosmetic preparations, antiseptic solutions, tartar control toothpaste, and bubble gum.4,5,11-13 Granulomatous periorificial dermatitis may represent a pediatric variant of granulomatous rosacea or a granulomatous variant of perioral dermatitis, but importantly, it is not related to sarcoidosis.1,4,5 Granulomatous periorificial dermatitis typically affects children of dark-skinned, African Caribbean ancestry, though it has been described in both white and Asian populations.1,2,5 Genders are equally affected.

Although generally a benign condition that spontaneously remits within a few months to 3 years,5 GPD can be quite disruptive to a patient’s self-image, necessitating therapy to hasten resolution. Prior to initiation of treatment, any topical corticosteroids being applied to the affected region should be discontinued. For children older than 9 years, a suggested regimen is oral tetracycline 250 mg twice daily; for those younger than 9 years, erythromycin 30 to 40 mg/kg daily in 2 divided doses is advised.14 Metronidazole 0.75% cream and gel also have shown efficacy in GPD and represent a topical adjunct or alternative to oral therapy.1,14,15

- Knautz MA, Lesher JL. Childhood granulomatous periorificial dermatitis. Pediatr Dermatol. 1996;13:131-134.

- Choi YL, Lee KJ, Cho HJ, et al. Case of childhood granulomatous periorificial dermatitis in a Korean boy treated by oral erythromycin. J Dermatol. 2006;33:806-808.

- Tarm K, Creel NB, Krivda SJ, et al. Granulomatous periorificial dermatitis. Cutis. 2004;73:399-402.

- Nguyen V, Eichenfield LF. Periorificial dermatitis in children and adolescents. J Am Acad Dermatol. 2006;55:781-785.

- Urbatsch AJ, Frieden I, Williams ML, et al. Extrafacial and generalized granulomatous periorificial dermatitis. Arch Dermatol. 2002;138:1354-1358.

- Gianotti F, Ermacora E, Bennelli MG, et al. Particuliere dermatite peri-orale infantile: observations sur cinq cas. Bull Soc Fr Dermatol Syph. 1970;77:341.

- Frieden IJ, Prose NS, Fletcher V, et al. Granulomatous perioral dermatitis in children. Arch Dermatol. 1989;125:369-373.

- Savin JA, Alexander S, Marks R. A rosacea-like eruption of children. Br J Dermatol. 1972;87:425-429.

- Marten RH, Presbury DG, Adamson JE, et al. An unusual popular and acneiform facial eruption in the Negro child. Br J Dermatol. 1974;91:435-438.

- Falk ES. Sarcoid-like granulomatous periocular dermatitis treated with tetracycline. Acta Derm Venereol. 1985;65:270-272.

- Hafeez ZH. Perioral dermatitis: an update. Int J Dermatol. 2003;42:514-517.

- Ferlito TA. Tartar-control toothpaste and perioral dermatitis. J Clin Oncol. 1992;27:43-44.

- Georgouras K, Kocsard E. Micropapular sarcoidal facial eruption in a child. Acta Derm Venereol. 1978;48:433-436.

- Laude TA, Salvemini JN. Perioral dermatitis in children. Semin Cutan Med Surg. 1999;18:206-209.