User login

Hand Pain Following an Altercation

ANSWER

The radiograph shows moderate soft-tissue swelling with dislocation of the proximal interphalangeal joint. No definite fracture is seen. In addition, there are some metallic-appearing foreign bodies.

The patient was treated with closed reduction and splinting. He also received a referral to outpatient orthopedics for follow-up.

ANSWER

The radiograph shows moderate soft-tissue swelling with dislocation of the proximal interphalangeal joint. No definite fracture is seen. In addition, there are some metallic-appearing foreign bodies.

The patient was treated with closed reduction and splinting. He also received a referral to outpatient orthopedics for follow-up.

ANSWER

The radiograph shows moderate soft-tissue swelling with dislocation of the proximal interphalangeal joint. No definite fracture is seen. In addition, there are some metallic-appearing foreign bodies.

The patient was treated with closed reduction and splinting. He also received a referral to outpatient orthopedics for follow-up.

A 60-year-old man presents with a complaint of pain in his right fifth finger following an altercation. He is not sure exactly how the injury occurred, but he does recall that at one point his hand was twisted awkwardly. He denies any significant medical history. His vital signs are normal. Primary survey appears normal as well. On examination, you notice moderate swelling around the fifth finger of his right hand, which does appear to be slightly deformed. There are no obvious wounds or lacerations. He has moderate tenderness at the base of his finger. Range of motion is limited due to the swelling. Good capillary refill time is noted. The triage nurse already sent the patient for a radiograph of his finger (shown). What is your impression?

For Lethargic Patient, Trouble Is Brewing

ANSWER

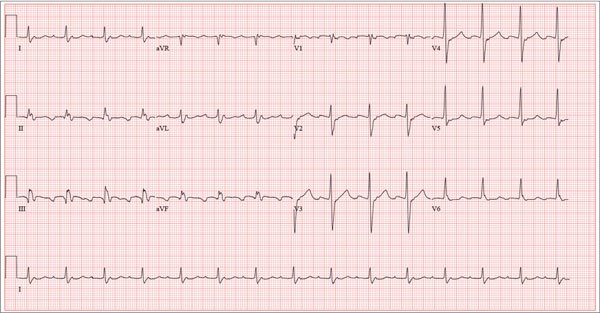

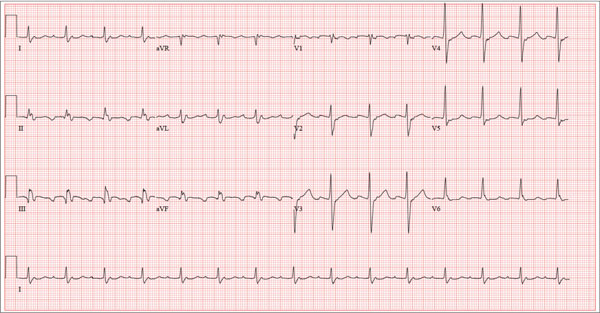

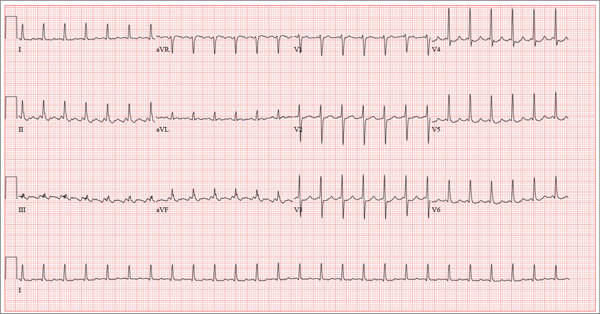

The correct interpretation is an atrial tachycardia with 2:1 ventricular conduction. The ventricular rate is 87 beats/min (690 ms), and the atrial rate is 174 beats/min (345 ms). Two P waves are present for each QRS, which excludes a first-degree atrioventricular block. The less obvious P wave is found in the terminal portion of the QRS complex. (You may convince yourself of this by using calipers to measure the R-R interval, dividing that measurement in half, and then applying it to the ECG. You will see the P waves march through without changing the ventricular response.)

A nonspecific intraventricular conduction delay is also present. The QRS duration is > 100 ms; however, the criteria for right or left bundle branch block are absent.

A thorough investigation revealed that the clerk formulating the herbs for the tea was using, among other things, dried foxglove. Foxglove has been used as a remedy for lethargy in the elderly, presumably because it inadvertently treats symptoms of congestive heart failure. It was the tea consumption that accounted for the presence of digoxin in the patient’s blood. (Recall that there is a substantial overlap between therapeutic and toxic serum concentrations of digoxin.) When the patient stopped consuming the tea, his atrial tachycardia resolved, as did his symptoms.

ANSWER

The correct interpretation is an atrial tachycardia with 2:1 ventricular conduction. The ventricular rate is 87 beats/min (690 ms), and the atrial rate is 174 beats/min (345 ms). Two P waves are present for each QRS, which excludes a first-degree atrioventricular block. The less obvious P wave is found in the terminal portion of the QRS complex. (You may convince yourself of this by using calipers to measure the R-R interval, dividing that measurement in half, and then applying it to the ECG. You will see the P waves march through without changing the ventricular response.)

A nonspecific intraventricular conduction delay is also present. The QRS duration is > 100 ms; however, the criteria for right or left bundle branch block are absent.

A thorough investigation revealed that the clerk formulating the herbs for the tea was using, among other things, dried foxglove. Foxglove has been used as a remedy for lethargy in the elderly, presumably because it inadvertently treats symptoms of congestive heart failure. It was the tea consumption that accounted for the presence of digoxin in the patient’s blood. (Recall that there is a substantial overlap between therapeutic and toxic serum concentrations of digoxin.) When the patient stopped consuming the tea, his atrial tachycardia resolved, as did his symptoms.

ANSWER

The correct interpretation is an atrial tachycardia with 2:1 ventricular conduction. The ventricular rate is 87 beats/min (690 ms), and the atrial rate is 174 beats/min (345 ms). Two P waves are present for each QRS, which excludes a first-degree atrioventricular block. The less obvious P wave is found in the terminal portion of the QRS complex. (You may convince yourself of this by using calipers to measure the R-R interval, dividing that measurement in half, and then applying it to the ECG. You will see the P waves march through without changing the ventricular response.)

A nonspecific intraventricular conduction delay is also present. The QRS duration is > 100 ms; however, the criteria for right or left bundle branch block are absent.

A thorough investigation revealed that the clerk formulating the herbs for the tea was using, among other things, dried foxglove. Foxglove has been used as a remedy for lethargy in the elderly, presumably because it inadvertently treats symptoms of congestive heart failure. It was the tea consumption that accounted for the presence of digoxin in the patient’s blood. (Recall that there is a substantial overlap between therapeutic and toxic serum concentrations of digoxin.) When the patient stopped consuming the tea, his atrial tachycardia resolved, as did his symptoms.

A 72-year-old man presents with a primary complaint of lethargy. He emigrated from Southeast Asia to the United States about a year ago and neither speaks nor understands English. His grandson, who is fluent, accompanies him to his appointment. Through his grandson, the patient explains that he has become increasingly tired in the past four months—to the extent that exercise and activities of daily living have become difficult. The patient’s libido also has been affected. In an effort to correct this, he visited a local Asian goods store, where he was given a mixture of herbs from which to brew tea to treat his symptoms. For three weeks, he consumed the tea twice daily. Initially, his energy, stamina, and libido improved. However, his symptoms eventually returned, so he doubled his tea consumption with the idea that this would improve his condition. Unfortunately, in addition to his lethargy, he is now experiencing palpitations, a fluttering sensation in his chest, and occasional dizziness. He denies chest pain, shortness of breath, nocturnal dyspnea, syncope, or near syncope. Medical history is difficult to elicit. He denies prior history of hypertension, myocardial infarction, congestive heart failure, or diabetes. Neither he nor his grandson understands the concept of arrhythmias (eg, atrial fibrillation). He was treated for tuberculosis as a child and has had no recurrence. He has had no surgeries. The patient takes no prescribed medications. He does, however, use herbal products including ginseng, horny goat weed, and fenugreek (in addition to his herbal tea). He has no known drug allergies. Social history reveals that the patient lives with his son’s family, having moved to the US from Thailand after his wife died of old age. He worked as a farmer his entire life. He drinks one ounce of whiskey daily and smokes 1 to 1.5 packs of cigarettes a day. The review of systems is noncontributory. His grandson is reluctant to ask the patient many questions regarding his health, once he notices his grandfather’s agitation at answering questions. The physical exam reveals a thin, elderly male with weathered skin who is in no acute distress. Vital signs include a blood pressure of 118/62 mm Hg; pulse, 80 beats/min and regular; respiratory rate, 16 breaths/min; and temperature, 97.8°F. His height is 62 in and his weight, 117 lb. The HEENT exam is remarkable for arcus senilis and multiple missing teeth. There is no jugular distention, and the thyroid is not enlarged. The lungs reveal coarse breath sounds that clear with coughing in all lung fields. (The patient has an occasional harsh cough.) The cardiac exam is positive for a grade II/VI systolic murmur best heard at the left upper sternal border, which radiates to the carotid arteries. The rhythm is regular at a rate of 80 beats/min, and there are no clicks or rubs. The abdomen is scaphoid, soft, and nontender, with no palpable masses. The peripheral pulses are strong and equal bilaterally. Extremities demonstrate full range of motion, and the neurologic exam is grossly intact. Routine laboratory tests including a complete blood count and electrolyte panel are obtained. Because you are unsure of his medication regimen, you order a toxicology screen. You are surprised to see a serum digoxin level of 0.7 ng/mL. Finally, given the patient’s symptoms of palpitations and dizziness, you order an ECG. It shows the following: a ventricular rate of 87 beats/min; PR interval, 218 ms; QRS duration, 130 ms; QT/QTc interval, 416/500 ms; P axis, 24°; R axis, 49°; and T axis, 45°. What is your interpretation of this ECG?

These Old Lesions? She’s Had Them for Years …

ANSWER

The correct answer is disseminated superficial actinic porokeratosis (DSAP; choice “a”). This condition, caused by an inherited defect of the SART3 gene, is seen mostly on the sun-exposed skin of middle-aged women.

Stasis dermatitis (choice “b”) can cause a number of skin changes, but not the discrete annular lesions seen with DSAP.

Seborrheic keratoses (choice “c”) are common on the legs. However, they don’t display this same morphology.

Nummular eczema (choice “d”) presents with annular papulosquamous lesions (as opposed to the fixed lesions seen with DSAP), often on the legs and lower trunk, but without the thready circumferential scaly border.

Continue reading for Joe Monroe's discussion...

DISCUSSION

Leg skin is prey to an astonishing array of problems; many have to do with increased hydrostatic pressure (eg, venous stasis disease), with the almost complete lack of sebaceous glands (eg, nummular eczema), or with the simple fact of being “in harm’s way.” And there is no law that says a given patient can’t have more than one problem at a time, co-existing and serving to confuse the examiner. Such is the case with this patient.

Her concern about possible blood clots is misplaced but understandable. Deep vein thromboses would not present in multiples, would not be on the surface or scaly, and would almost certainly be painful.

The fixed nature of this patient’s scaly lesions is extremely significant—but only if you know about DSAP, which typically manifests in the third decade of life and slowly worsens. The lesions’ highly palpable and unique scaly border makes them hard to leave alone. This might not be a problem except for the warfarin, which makes otherwise minor trauma visible as purpuric macules. Chronic sun damage tends to accentuate them as well. The positive family history is nicely corroborative and quite common.

The brown macules on the patient’s legs are solar lentigines (sun-caused freckles), which many patients (and even younger providers) erroneously call “age spots.” When these individuals become “aged,” they’ll understand that there is no such thing as an age spot.

This patient could easily have had nummular eczema, but not for 30 years! Those lesions, treated or not, will come and go. But not DSAP, about which many questions remain: If they’re caused by sun exposure, why don’t we see them more often on the face and arms? And why don’t we see them on the sun-damaged skin of older men?

If needed, a biopsy could have been performed. It would have been confirmatory of the diagnosis and effectively would have ruled out the other items in the differential, including wart, squamous cell carcinoma, and actinic or seborrheic keratosis.

ANSWER

The correct answer is disseminated superficial actinic porokeratosis (DSAP; choice “a”). This condition, caused by an inherited defect of the SART3 gene, is seen mostly on the sun-exposed skin of middle-aged women.

Stasis dermatitis (choice “b”) can cause a number of skin changes, but not the discrete annular lesions seen with DSAP.

Seborrheic keratoses (choice “c”) are common on the legs. However, they don’t display this same morphology.

Nummular eczema (choice “d”) presents with annular papulosquamous lesions (as opposed to the fixed lesions seen with DSAP), often on the legs and lower trunk, but without the thready circumferential scaly border.

Continue reading for Joe Monroe's discussion...

DISCUSSION

Leg skin is prey to an astonishing array of problems; many have to do with increased hydrostatic pressure (eg, venous stasis disease), with the almost complete lack of sebaceous glands (eg, nummular eczema), or with the simple fact of being “in harm’s way.” And there is no law that says a given patient can’t have more than one problem at a time, co-existing and serving to confuse the examiner. Such is the case with this patient.

Her concern about possible blood clots is misplaced but understandable. Deep vein thromboses would not present in multiples, would not be on the surface or scaly, and would almost certainly be painful.

The fixed nature of this patient’s scaly lesions is extremely significant—but only if you know about DSAP, which typically manifests in the third decade of life and slowly worsens. The lesions’ highly palpable and unique scaly border makes them hard to leave alone. This might not be a problem except for the warfarin, which makes otherwise minor trauma visible as purpuric macules. Chronic sun damage tends to accentuate them as well. The positive family history is nicely corroborative and quite common.

The brown macules on the patient’s legs are solar lentigines (sun-caused freckles), which many patients (and even younger providers) erroneously call “age spots.” When these individuals become “aged,” they’ll understand that there is no such thing as an age spot.

This patient could easily have had nummular eczema, but not for 30 years! Those lesions, treated or not, will come and go. But not DSAP, about which many questions remain: If they’re caused by sun exposure, why don’t we see them more often on the face and arms? And why don’t we see them on the sun-damaged skin of older men?

If needed, a biopsy could have been performed. It would have been confirmatory of the diagnosis and effectively would have ruled out the other items in the differential, including wart, squamous cell carcinoma, and actinic or seborrheic keratosis.

ANSWER

The correct answer is disseminated superficial actinic porokeratosis (DSAP; choice “a”). This condition, caused by an inherited defect of the SART3 gene, is seen mostly on the sun-exposed skin of middle-aged women.

Stasis dermatitis (choice “b”) can cause a number of skin changes, but not the discrete annular lesions seen with DSAP.

Seborrheic keratoses (choice “c”) are common on the legs. However, they don’t display this same morphology.

Nummular eczema (choice “d”) presents with annular papulosquamous lesions (as opposed to the fixed lesions seen with DSAP), often on the legs and lower trunk, but without the thready circumferential scaly border.

Continue reading for Joe Monroe's discussion...

DISCUSSION

Leg skin is prey to an astonishing array of problems; many have to do with increased hydrostatic pressure (eg, venous stasis disease), with the almost complete lack of sebaceous glands (eg, nummular eczema), or with the simple fact of being “in harm’s way.” And there is no law that says a given patient can’t have more than one problem at a time, co-existing and serving to confuse the examiner. Such is the case with this patient.

Her concern about possible blood clots is misplaced but understandable. Deep vein thromboses would not present in multiples, would not be on the surface or scaly, and would almost certainly be painful.

The fixed nature of this patient’s scaly lesions is extremely significant—but only if you know about DSAP, which typically manifests in the third decade of life and slowly worsens. The lesions’ highly palpable and unique scaly border makes them hard to leave alone. This might not be a problem except for the warfarin, which makes otherwise minor trauma visible as purpuric macules. Chronic sun damage tends to accentuate them as well. The positive family history is nicely corroborative and quite common.

The brown macules on the patient’s legs are solar lentigines (sun-caused freckles), which many patients (and even younger providers) erroneously call “age spots.” When these individuals become “aged,” they’ll understand that there is no such thing as an age spot.

This patient could easily have had nummular eczema, but not for 30 years! Those lesions, treated or not, will come and go. But not DSAP, about which many questions remain: If they’re caused by sun exposure, why don’t we see them more often on the face and arms? And why don’t we see them on the sun-damaged skin of older men?

If needed, a biopsy could have been performed. It would have been confirmatory of the diagnosis and effectively would have ruled out the other items in the differential, including wart, squamous cell carcinoma, and actinic or seborrheic keratosis.

A 65-year-old woman is referred to dermatology with discoloration of her legs that started several weeks ago. Her family suggested it might be “blood clots,” although she has been taking warfarin since she was diagnosed with atrial fibrillation several months ago. Her dermatologic condition is basically asymptomatic, but the patient admits to scratching her legs, saying it’s “hard to leave them alone.” On further questioning, she reveals that she has had “rough places” on her legs for at least 20 years and volunteers that her sister had the same problem, which was diagnosed years ago as “fungal infection.” Both she and her sister spent a great deal of time in the sun as children, long before sunscreen was invented. The patient is otherwise fairly healthy. She takes medication for her lipids, as well as daily vitamins. Her atrial fibrillation is under control and requires no medications other than the warfarin. A great deal of focal discoloration is seen on both legs, circumferentially distributed from well below the knees to just above the ankles. Many of the lesions are brown macules, but more are purplish-red, annular, and scaly. On closer examination, these lesions—the ones the patient says she has had for decades—have a very fine, thready, scaly border that palpation reveals to be tough and adherent. They average about 2 cm in diameter. There are no such lesions noted elsewhere on the patient’s skin. There is, however, abundant evidence of excessive sun exposure, characterized by a multitude of solar lentigines, many fine wrinkles, and extremely thin arm skin.

Verrucous Nodule on the Upper Lip

The Diagnosis: Disseminated Coccidioidomycosis

Fungi of the genus Coccidioides cause coccidioidomycosis and live in the soil of endemic areas including the southwestern United States (eg, Arizona, New Mexico, California) and Mexico. Coccidioides is a dimorphic fungus with parasitic and infectious saprophytic phases. Each year there are approximately 150,000 new infections of coccidioidomycosis in the United States, almost exclusively in the southwest.1 Coccidioidomycosis typically is an asymptomatic or mild infection in an immunocompetent patient. Although the lungs are nearly always the primary sites of infection, common sites of dissemination include the skin, meninges, bones, and joints. The skin is the most common site of disseminated, or secondary, coccidioidomycosis.2 Less commonly and usually caused by traumatic implantation, the skin is the site of primary infection.

Disseminated coccidioidomycosis occurs in approximately 1 in 200 infected individuals.2,3 Certain populations of patients are more likely to be affected by disseminated coccidioidomycosis, including specific ethnic groups such as black individuals, Filipinos, and Mexicans4,5; pregnant women6; and immunosuppressed patients such as those with human immunodeficiency virus, hematogenous malignancy, or organ transplantation.7-9 When skin lesions are present, they usually develop after the initial lung manifestation. The location of the lesion in cutaneous disseminated disease can be highly variable, but the face and head are the most common locations (30%).10

Cutaneous manifestations of coccidioidomycosis may be classified as being caused by the presence of the organism in the skin (organism specific) or a reactive process. Organism-specific cutaneous lesions are commonly due to systemic disease with secondary skin involvement, but they also may be due to a primary infection. These organism-specific lesions can present as papules, nodules, macules, verrucous plaques, abscesses, or pustules. Reactive cutaneous manifestations are only associated with disseminated disease; do not contain any organisms; and include manifestations such as erythema nodosum, acute exanthem, erythema multiforme, and possibly Sweet syndrome.11

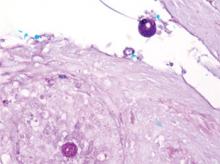

The clinical differential diagnosis of cutaneous coccidioidomycosis includes other

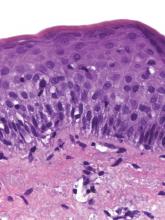

mycoses such as histoplasmosis and blastomycosis, as well as tuberculosis, sarcoidosis, basal cell and squamous cell carcinoma, and verruca vulgaris. The diagnosis of cutaneous coccidioidomycosis can be made with skin biopsy, culture, and serologic tests. The characteristic spherules can be visualized on routine hematoxylin and eosin stain or more readily with fungal stains (Figure). Spherules are thick walled and distinguishable from other fungi because of the characteristic endospores inside as well as their larger size. Organisms also may be detected via culture within 2 to 5 days.

Distinguishing primary cutaneous from disseminated skin lesions can be challenging but can have notable treatment implications. Although histology typically cannot distinguish primary from disseminated cutaneous infections, clinical history and serologic studies have been found to be useful. In disseminated disease, IgG antibodies are elevated, while in primary cutaneous disease, IgM antibodies are elevated but typically not IgG.12 Therefore, tube precipitin and latex particle agglutination tests that detect IgM antibodies should be positive in primary infections.13 Primary lesions can spontaneously resolve within months to years and may not require treatment if symptomatic, while secondary lesions must be therapeutically addressed.12 Despite the lack of treatment needed, primary cutaneous infections often are treated with azoles.14 In contrast, disseminated cutaneous infection requires systemic therapy. Treatment of disseminated infection with cutaneous coccidioidomycosis typically includes amphotericin B until a clinical response is achieved and antibody titers decline. Amphotericin B can then be replaced with an oral azole such as itraconozole or fluconazole.15

The patient discussed in this case demonstrates the typical clinical presentation of disseminated coccidioidomycosis with classical and diagnostic pathology. This case also highlights the importance of a detailed travel history; in the era of globalization, patients often present with diseases in nonendemic areas. Clinicians must consider the diagnosis of coccidioidomycosis, even in immunocompetent patients in nonendemic areas when their history and presentation are appropriate. The diagnosis should be confirmed with biopsy, culture, and/or serology.

1. Galgiani JN, Ampel NM, Blair JE, et al. Coccidioidomycosis [published online ahead of print September 20, 2005]. Clin Infect Dis. 2005;41:1217-1223.

2. Chiller TM, Galgiani JN, Stevens DA. Coccidioidomycosis. Infect Dis Clin North Am. 2003;17:41-57, vii.

3. Rance BR, Elston DM. Disseminated coccidioidomyclosis discovered during routine skin cancer screening. Cutis. 2002;70:70-72.

4. Einstein HE, Johnson RH. Coccidioidomycosis: new aspects of epidemiology and therapy [comment in Clin Infect Dis. 1994;18:470]. Clin Infect Dis. 1993;16:349- 354.

5. Crum NF, Ballon-Landa G. Coccidioidomycosis in pregnancy: case report and review of the literature. Am J Med. 2006;119:e11-e17.

6. Caldwell JW, Arsura EL, Kilgore WB, et al. Coccidioidomycosis in pregnancy during an epidemic in California. Obstet Gynecol. 2000;95:236-239.

7. Singh VR, Smith DK, Lawerence J, et al. Coccidioidomy-cosis in patients infected with human immunodeficiency virus: review of 91 cases at a single institution. Clin Infect Dis. 1996;23:563-568.

8. Blair JE, Logan JL. Coccidioidomycosis in solid organ transplantation [published online ahead of print October 4, 2001]. Clin Infect Dis. 2001;33:1536-1544.

9. Riley DK, Galgiani JN, O’Donnell MR, et al. Coccidioidomycosis in bone marrow transplant recipients. Transplantation. 1993;56:1531-1533.

10. Carpenter JB, Feldman JS, Leyva WH, et al. Clinical and pathologic characteristics of disseminated cutaneous coccidioidomycosis. J Am Acad Dermatol. 2010;62:831-837.

11. DiCaudo DJ. Coccidioidomycosis: a review and update. J Am Acad Dermatol. 2006;55:929-942; quiz 943-945.

12. Chang A, Tung RC, McGillis TS, et al. Primary cutaneous coccidioidomycosis. J Am Acad Dermatol. 2003;49:944-949.

13. Wilson JW, Smith CE, Plunkett OA. Primary cutaneous coccidioidomycosis: the criteria for diagnosis and report of a case. Calif Med. 1953;79:233-239.

14. Blair JE. State-of-the-art treatment of coccidioidomycosis: skin and soft-tissue infections [published online ahead of print March 1, 2007]. Ann N Y Acad Sci. 2007;1111:411-421.

15. Galgiani JN, Ampel NM, Catanzaro A, et al. Practice guidelines for the treatment of coccidioidomycosis. Infectious Diseases Society of America [published online ahead of print April 20, 2000]. Clin Infect Dis. 2000;30:658-661.

The Diagnosis: Disseminated Coccidioidomycosis

Fungi of the genus Coccidioides cause coccidioidomycosis and live in the soil of endemic areas including the southwestern United States (eg, Arizona, New Mexico, California) and Mexico. Coccidioides is a dimorphic fungus with parasitic and infectious saprophytic phases. Each year there are approximately 150,000 new infections of coccidioidomycosis in the United States, almost exclusively in the southwest.1 Coccidioidomycosis typically is an asymptomatic or mild infection in an immunocompetent patient. Although the lungs are nearly always the primary sites of infection, common sites of dissemination include the skin, meninges, bones, and joints. The skin is the most common site of disseminated, or secondary, coccidioidomycosis.2 Less commonly and usually caused by traumatic implantation, the skin is the site of primary infection.

Disseminated coccidioidomycosis occurs in approximately 1 in 200 infected individuals.2,3 Certain populations of patients are more likely to be affected by disseminated coccidioidomycosis, including specific ethnic groups such as black individuals, Filipinos, and Mexicans4,5; pregnant women6; and immunosuppressed patients such as those with human immunodeficiency virus, hematogenous malignancy, or organ transplantation.7-9 When skin lesions are present, they usually develop after the initial lung manifestation. The location of the lesion in cutaneous disseminated disease can be highly variable, but the face and head are the most common locations (30%).10

Cutaneous manifestations of coccidioidomycosis may be classified as being caused by the presence of the organism in the skin (organism specific) or a reactive process. Organism-specific cutaneous lesions are commonly due to systemic disease with secondary skin involvement, but they also may be due to a primary infection. These organism-specific lesions can present as papules, nodules, macules, verrucous plaques, abscesses, or pustules. Reactive cutaneous manifestations are only associated with disseminated disease; do not contain any organisms; and include manifestations such as erythema nodosum, acute exanthem, erythema multiforme, and possibly Sweet syndrome.11

The clinical differential diagnosis of cutaneous coccidioidomycosis includes other

mycoses such as histoplasmosis and blastomycosis, as well as tuberculosis, sarcoidosis, basal cell and squamous cell carcinoma, and verruca vulgaris. The diagnosis of cutaneous coccidioidomycosis can be made with skin biopsy, culture, and serologic tests. The characteristic spherules can be visualized on routine hematoxylin and eosin stain or more readily with fungal stains (Figure). Spherules are thick walled and distinguishable from other fungi because of the characteristic endospores inside as well as their larger size. Organisms also may be detected via culture within 2 to 5 days.

Distinguishing primary cutaneous from disseminated skin lesions can be challenging but can have notable treatment implications. Although histology typically cannot distinguish primary from disseminated cutaneous infections, clinical history and serologic studies have been found to be useful. In disseminated disease, IgG antibodies are elevated, while in primary cutaneous disease, IgM antibodies are elevated but typically not IgG.12 Therefore, tube precipitin and latex particle agglutination tests that detect IgM antibodies should be positive in primary infections.13 Primary lesions can spontaneously resolve within months to years and may not require treatment if symptomatic, while secondary lesions must be therapeutically addressed.12 Despite the lack of treatment needed, primary cutaneous infections often are treated with azoles.14 In contrast, disseminated cutaneous infection requires systemic therapy. Treatment of disseminated infection with cutaneous coccidioidomycosis typically includes amphotericin B until a clinical response is achieved and antibody titers decline. Amphotericin B can then be replaced with an oral azole such as itraconozole or fluconazole.15

The patient discussed in this case demonstrates the typical clinical presentation of disseminated coccidioidomycosis with classical and diagnostic pathology. This case also highlights the importance of a detailed travel history; in the era of globalization, patients often present with diseases in nonendemic areas. Clinicians must consider the diagnosis of coccidioidomycosis, even in immunocompetent patients in nonendemic areas when their history and presentation are appropriate. The diagnosis should be confirmed with biopsy, culture, and/or serology.

The Diagnosis: Disseminated Coccidioidomycosis

Fungi of the genus Coccidioides cause coccidioidomycosis and live in the soil of endemic areas including the southwestern United States (eg, Arizona, New Mexico, California) and Mexico. Coccidioides is a dimorphic fungus with parasitic and infectious saprophytic phases. Each year there are approximately 150,000 new infections of coccidioidomycosis in the United States, almost exclusively in the southwest.1 Coccidioidomycosis typically is an asymptomatic or mild infection in an immunocompetent patient. Although the lungs are nearly always the primary sites of infection, common sites of dissemination include the skin, meninges, bones, and joints. The skin is the most common site of disseminated, or secondary, coccidioidomycosis.2 Less commonly and usually caused by traumatic implantation, the skin is the site of primary infection.

Disseminated coccidioidomycosis occurs in approximately 1 in 200 infected individuals.2,3 Certain populations of patients are more likely to be affected by disseminated coccidioidomycosis, including specific ethnic groups such as black individuals, Filipinos, and Mexicans4,5; pregnant women6; and immunosuppressed patients such as those with human immunodeficiency virus, hematogenous malignancy, or organ transplantation.7-9 When skin lesions are present, they usually develop after the initial lung manifestation. The location of the lesion in cutaneous disseminated disease can be highly variable, but the face and head are the most common locations (30%).10

Cutaneous manifestations of coccidioidomycosis may be classified as being caused by the presence of the organism in the skin (organism specific) or a reactive process. Organism-specific cutaneous lesions are commonly due to systemic disease with secondary skin involvement, but they also may be due to a primary infection. These organism-specific lesions can present as papules, nodules, macules, verrucous plaques, abscesses, or pustules. Reactive cutaneous manifestations are only associated with disseminated disease; do not contain any organisms; and include manifestations such as erythema nodosum, acute exanthem, erythema multiforme, and possibly Sweet syndrome.11

The clinical differential diagnosis of cutaneous coccidioidomycosis includes other

mycoses such as histoplasmosis and blastomycosis, as well as tuberculosis, sarcoidosis, basal cell and squamous cell carcinoma, and verruca vulgaris. The diagnosis of cutaneous coccidioidomycosis can be made with skin biopsy, culture, and serologic tests. The characteristic spherules can be visualized on routine hematoxylin and eosin stain or more readily with fungal stains (Figure). Spherules are thick walled and distinguishable from other fungi because of the characteristic endospores inside as well as their larger size. Organisms also may be detected via culture within 2 to 5 days.

Distinguishing primary cutaneous from disseminated skin lesions can be challenging but can have notable treatment implications. Although histology typically cannot distinguish primary from disseminated cutaneous infections, clinical history and serologic studies have been found to be useful. In disseminated disease, IgG antibodies are elevated, while in primary cutaneous disease, IgM antibodies are elevated but typically not IgG.12 Therefore, tube precipitin and latex particle agglutination tests that detect IgM antibodies should be positive in primary infections.13 Primary lesions can spontaneously resolve within months to years and may not require treatment if symptomatic, while secondary lesions must be therapeutically addressed.12 Despite the lack of treatment needed, primary cutaneous infections often are treated with azoles.14 In contrast, disseminated cutaneous infection requires systemic therapy. Treatment of disseminated infection with cutaneous coccidioidomycosis typically includes amphotericin B until a clinical response is achieved and antibody titers decline. Amphotericin B can then be replaced with an oral azole such as itraconozole or fluconazole.15

The patient discussed in this case demonstrates the typical clinical presentation of disseminated coccidioidomycosis with classical and diagnostic pathology. This case also highlights the importance of a detailed travel history; in the era of globalization, patients often present with diseases in nonendemic areas. Clinicians must consider the diagnosis of coccidioidomycosis, even in immunocompetent patients in nonendemic areas when their history and presentation are appropriate. The diagnosis should be confirmed with biopsy, culture, and/or serology.

1. Galgiani JN, Ampel NM, Blair JE, et al. Coccidioidomycosis [published online ahead of print September 20, 2005]. Clin Infect Dis. 2005;41:1217-1223.

2. Chiller TM, Galgiani JN, Stevens DA. Coccidioidomycosis. Infect Dis Clin North Am. 2003;17:41-57, vii.

3. Rance BR, Elston DM. Disseminated coccidioidomyclosis discovered during routine skin cancer screening. Cutis. 2002;70:70-72.

4. Einstein HE, Johnson RH. Coccidioidomycosis: new aspects of epidemiology and therapy [comment in Clin Infect Dis. 1994;18:470]. Clin Infect Dis. 1993;16:349- 354.

5. Crum NF, Ballon-Landa G. Coccidioidomycosis in pregnancy: case report and review of the literature. Am J Med. 2006;119:e11-e17.

6. Caldwell JW, Arsura EL, Kilgore WB, et al. Coccidioidomycosis in pregnancy during an epidemic in California. Obstet Gynecol. 2000;95:236-239.

7. Singh VR, Smith DK, Lawerence J, et al. Coccidioidomy-cosis in patients infected with human immunodeficiency virus: review of 91 cases at a single institution. Clin Infect Dis. 1996;23:563-568.

8. Blair JE, Logan JL. Coccidioidomycosis in solid organ transplantation [published online ahead of print October 4, 2001]. Clin Infect Dis. 2001;33:1536-1544.

9. Riley DK, Galgiani JN, O’Donnell MR, et al. Coccidioidomycosis in bone marrow transplant recipients. Transplantation. 1993;56:1531-1533.

10. Carpenter JB, Feldman JS, Leyva WH, et al. Clinical and pathologic characteristics of disseminated cutaneous coccidioidomycosis. J Am Acad Dermatol. 2010;62:831-837.

11. DiCaudo DJ. Coccidioidomycosis: a review and update. J Am Acad Dermatol. 2006;55:929-942; quiz 943-945.

12. Chang A, Tung RC, McGillis TS, et al. Primary cutaneous coccidioidomycosis. J Am Acad Dermatol. 2003;49:944-949.

13. Wilson JW, Smith CE, Plunkett OA. Primary cutaneous coccidioidomycosis: the criteria for diagnosis and report of a case. Calif Med. 1953;79:233-239.

14. Blair JE. State-of-the-art treatment of coccidioidomycosis: skin and soft-tissue infections [published online ahead of print March 1, 2007]. Ann N Y Acad Sci. 2007;1111:411-421.

15. Galgiani JN, Ampel NM, Catanzaro A, et al. Practice guidelines for the treatment of coccidioidomycosis. Infectious Diseases Society of America [published online ahead of print April 20, 2000]. Clin Infect Dis. 2000;30:658-661.

1. Galgiani JN, Ampel NM, Blair JE, et al. Coccidioidomycosis [published online ahead of print September 20, 2005]. Clin Infect Dis. 2005;41:1217-1223.

2. Chiller TM, Galgiani JN, Stevens DA. Coccidioidomycosis. Infect Dis Clin North Am. 2003;17:41-57, vii.

3. Rance BR, Elston DM. Disseminated coccidioidomyclosis discovered during routine skin cancer screening. Cutis. 2002;70:70-72.

4. Einstein HE, Johnson RH. Coccidioidomycosis: new aspects of epidemiology and therapy [comment in Clin Infect Dis. 1994;18:470]. Clin Infect Dis. 1993;16:349- 354.

5. Crum NF, Ballon-Landa G. Coccidioidomycosis in pregnancy: case report and review of the literature. Am J Med. 2006;119:e11-e17.

6. Caldwell JW, Arsura EL, Kilgore WB, et al. Coccidioidomycosis in pregnancy during an epidemic in California. Obstet Gynecol. 2000;95:236-239.

7. Singh VR, Smith DK, Lawerence J, et al. Coccidioidomy-cosis in patients infected with human immunodeficiency virus: review of 91 cases at a single institution. Clin Infect Dis. 1996;23:563-568.

8. Blair JE, Logan JL. Coccidioidomycosis in solid organ transplantation [published online ahead of print October 4, 2001]. Clin Infect Dis. 2001;33:1536-1544.

9. Riley DK, Galgiani JN, O’Donnell MR, et al. Coccidioidomycosis in bone marrow transplant recipients. Transplantation. 1993;56:1531-1533.

10. Carpenter JB, Feldman JS, Leyva WH, et al. Clinical and pathologic characteristics of disseminated cutaneous coccidioidomycosis. J Am Acad Dermatol. 2010;62:831-837.

11. DiCaudo DJ. Coccidioidomycosis: a review and update. J Am Acad Dermatol. 2006;55:929-942; quiz 943-945.

12. Chang A, Tung RC, McGillis TS, et al. Primary cutaneous coccidioidomycosis. J Am Acad Dermatol. 2003;49:944-949.

13. Wilson JW, Smith CE, Plunkett OA. Primary cutaneous coccidioidomycosis: the criteria for diagnosis and report of a case. Calif Med. 1953;79:233-239.

14. Blair JE. State-of-the-art treatment of coccidioidomycosis: skin and soft-tissue infections [published online ahead of print March 1, 2007]. Ann N Y Acad Sci. 2007;1111:411-421.

15. Galgiani JN, Ampel NM, Catanzaro A, et al. Practice guidelines for the treatment of coccidioidomycosis. Infectious Diseases Society of America [published online ahead of print April 20, 2000]. Clin Infect Dis. 2000;30:658-661.

A 62-year-old black man presented to a dermatologist in the northeastern United States with a verrucous nontender nodule on the upper lip after traveling to southern California 1 month prior. The patient was not immunocompromised but reported a recent febrile upper respiratory illness.

Thick Plaques on the Foot

The Diagnosis: Prayer Callus

After our patient demonstrated his routine position for prayer (Figure), the

diagnosis of prayer callus was confirmed. We suggested he use a foam pad under his foot during prayer. The patient did not return for follow-up.

Prayer calluses have been documented in the literature as prayer nodules1-3 or marks.4 Callus is a preferred term, as it implies the act of repeated pressure or friction to an area of the skin. It is more descriptive than marks and avoids the inclusion of nodules caused by different prayer or religious activities such as ritual scarring.5

Abanmi et al4 studied a large group (N=349) of Muslim patients with regular praying habits and found a high prevalence of what they referred to as prayer marks, defined by lichenification and/or hyperpigmentation, on the knees, forehead, ankles, and dorsal aspects of the feet. They studied the histopathology of 33 marks. No statistical analysis was performed. They reported common histologic findings of compact orthokeratosis, hypergranulosis, dermal papillary fibrosis, and dermal vascularization. In contrast to lichen simplex chronicus, the authors found that the dermal fibrosis did not exhibit collagen bundles perpendicular to the epidermis.4

This study found that a higher prevalence of lichenification was observed on the left foot (males, 57%; females, 39%) than the right foot (males, 14%; females, 19%), which was attributed to a more typical prayer position that placed pressure on the left foot.4 Our patient only had calluses on his left foot, which was consistent with the prayer position.

Treatment options for prayer calluses include debridement, either mechanical or with topical keratolytic preparations. There is a high likelihood of recurrence if prayer practices are not changed. Optimally, more definitive treatment, which can be combined with initial debridement, would be position adjustment to lessen pressure or friction to the area or protection over the area with a cushion, as we attempted with our patient in the form of a foam pad.

1. Kahana M, Cohen M, Ronnen M, et al. Prayer nodules in Moslem men. Cutis. 1986;38:281-282.

2. Vollum DI, Azadeh B. Prayer nodules. Clin Exp Dermatol. 1979;4:39-47.

3. Kumar PV, Hambarsoomian B. Prayer nodules fine needle aspiration cytologic findings. Acta Cytol. 1988;32:83-85.

4. Abanmi AA, Al Zouman AY, Al Hussaini H, et al. Prayer marks. Int J Dermatol. 2002;41:411-414.

5. Bourrel P. Problems related to African customs and ritual mutilations [in French]. Contracept Fertil Sex (Paris). 1983;11:1351-1358.

The Diagnosis: Prayer Callus

After our patient demonstrated his routine position for prayer (Figure), the

diagnosis of prayer callus was confirmed. We suggested he use a foam pad under his foot during prayer. The patient did not return for follow-up.

Prayer calluses have been documented in the literature as prayer nodules1-3 or marks.4 Callus is a preferred term, as it implies the act of repeated pressure or friction to an area of the skin. It is more descriptive than marks and avoids the inclusion of nodules caused by different prayer or religious activities such as ritual scarring.5

Abanmi et al4 studied a large group (N=349) of Muslim patients with regular praying habits and found a high prevalence of what they referred to as prayer marks, defined by lichenification and/or hyperpigmentation, on the knees, forehead, ankles, and dorsal aspects of the feet. They studied the histopathology of 33 marks. No statistical analysis was performed. They reported common histologic findings of compact orthokeratosis, hypergranulosis, dermal papillary fibrosis, and dermal vascularization. In contrast to lichen simplex chronicus, the authors found that the dermal fibrosis did not exhibit collagen bundles perpendicular to the epidermis.4

This study found that a higher prevalence of lichenification was observed on the left foot (males, 57%; females, 39%) than the right foot (males, 14%; females, 19%), which was attributed to a more typical prayer position that placed pressure on the left foot.4 Our patient only had calluses on his left foot, which was consistent with the prayer position.

Treatment options for prayer calluses include debridement, either mechanical or with topical keratolytic preparations. There is a high likelihood of recurrence if prayer practices are not changed. Optimally, more definitive treatment, which can be combined with initial debridement, would be position adjustment to lessen pressure or friction to the area or protection over the area with a cushion, as we attempted with our patient in the form of a foam pad.

The Diagnosis: Prayer Callus

After our patient demonstrated his routine position for prayer (Figure), the

diagnosis of prayer callus was confirmed. We suggested he use a foam pad under his foot during prayer. The patient did not return for follow-up.

Prayer calluses have been documented in the literature as prayer nodules1-3 or marks.4 Callus is a preferred term, as it implies the act of repeated pressure or friction to an area of the skin. It is more descriptive than marks and avoids the inclusion of nodules caused by different prayer or religious activities such as ritual scarring.5

Abanmi et al4 studied a large group (N=349) of Muslim patients with regular praying habits and found a high prevalence of what they referred to as prayer marks, defined by lichenification and/or hyperpigmentation, on the knees, forehead, ankles, and dorsal aspects of the feet. They studied the histopathology of 33 marks. No statistical analysis was performed. They reported common histologic findings of compact orthokeratosis, hypergranulosis, dermal papillary fibrosis, and dermal vascularization. In contrast to lichen simplex chronicus, the authors found that the dermal fibrosis did not exhibit collagen bundles perpendicular to the epidermis.4

This study found that a higher prevalence of lichenification was observed on the left foot (males, 57%; females, 39%) than the right foot (males, 14%; females, 19%), which was attributed to a more typical prayer position that placed pressure on the left foot.4 Our patient only had calluses on his left foot, which was consistent with the prayer position.

Treatment options for prayer calluses include debridement, either mechanical or with topical keratolytic preparations. There is a high likelihood of recurrence if prayer practices are not changed. Optimally, more definitive treatment, which can be combined with initial debridement, would be position adjustment to lessen pressure or friction to the area or protection over the area with a cushion, as we attempted with our patient in the form of a foam pad.

1. Kahana M, Cohen M, Ronnen M, et al. Prayer nodules in Moslem men. Cutis. 1986;38:281-282.

2. Vollum DI, Azadeh B. Prayer nodules. Clin Exp Dermatol. 1979;4:39-47.

3. Kumar PV, Hambarsoomian B. Prayer nodules fine needle aspiration cytologic findings. Acta Cytol. 1988;32:83-85.

4. Abanmi AA, Al Zouman AY, Al Hussaini H, et al. Prayer marks. Int J Dermatol. 2002;41:411-414.

5. Bourrel P. Problems related to African customs and ritual mutilations [in French]. Contracept Fertil Sex (Paris). 1983;11:1351-1358.

1. Kahana M, Cohen M, Ronnen M, et al. Prayer nodules in Moslem men. Cutis. 1986;38:281-282.

2. Vollum DI, Azadeh B. Prayer nodules. Clin Exp Dermatol. 1979;4:39-47.

3. Kumar PV, Hambarsoomian B. Prayer nodules fine needle aspiration cytologic findings. Acta Cytol. 1988;32:83-85.

4. Abanmi AA, Al Zouman AY, Al Hussaini H, et al. Prayer marks. Int J Dermatol. 2002;41:411-414.

5. Bourrel P. Problems related to African customs and ritual mutilations [in French]. Contracept Fertil Sex (Paris). 1983;11:1351-1358.

A 60-year-old man presented to the dermatology clinic with 2 thick plaques on the top of the left foot of at least 5 years’ duration with no recent changes. The bumps were not itchy or painful. The patient had a medical history of diabetes mellitus and hypertension. He did not report any recent travel. He denied cough, shortness of breath, weight loss, and fatigue. The patient was asked about any hobbies or activities that involved repeated pressure to the dorsal aspect of the foot. He revealed that his religious obligations required him to pray 5 times daily.

Is Headache a Sign of a Larger Problem?

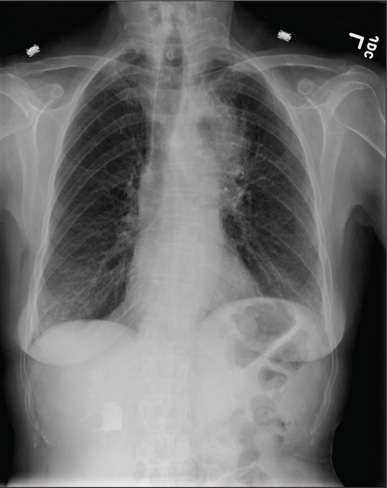

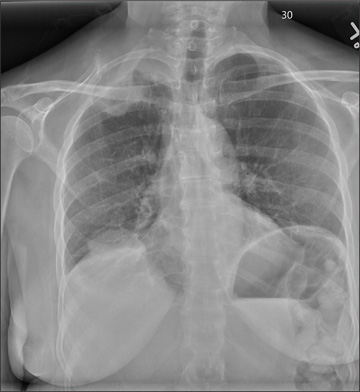

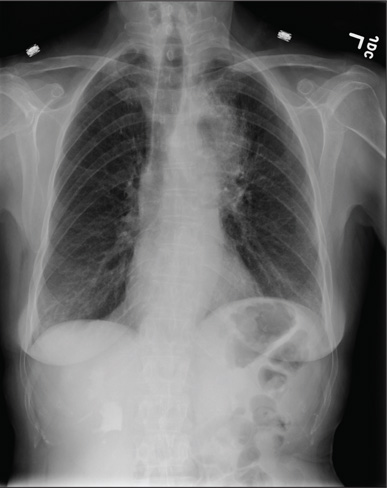

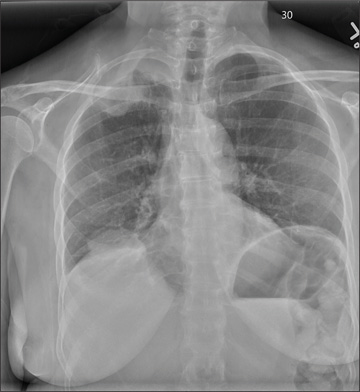

A 60-year-old woman presents with a complaint of severe headache, hoarseness, and weight loss, which have worsened in the past few days. Her headache is bifrontal, and at times she rates its severity as 10/10. She is not aware of any medical problems, but she admits she doesn’t have a primary care provider due to lack of insurance. She has a 30-year history of smoking one to one-and-a-half packs of cigarettes per day. Family history is positive for cancer. On examination, you note that she is uncomfortable but in no obvious distress. Her vital signs are normal. She is able to move all four extremities well and is neurovascularly intact. She has no other focal deficits. Noncontrast CT of the head is obtained. It shows a large right frontal lesion with surrounding vasogenic edema. You also order a chest radiograph (shown). What is your impression?

What Caused Patient’s Palpitations?

ANSWER

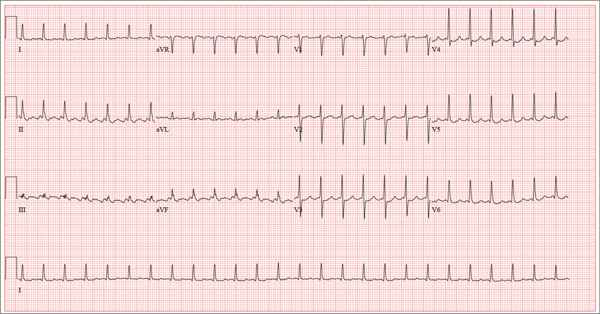

This ECG shows atrial flutter with 2:1 atrioventricular conduction. Additionally, ST depressions are seen in the anterior leads.

Typical sinus node P waves are absent, and atrial conduction at a rate of 310 beats/min is indicated by the sawtooth pattern in leads II and aVF. The ventricular rate is half that of the atrial rate (hence the 2:1 ratio). The ST depressions seen in the anterior leads, thought to be rate related, resolved upon cardioversion to terminate the atrial flutter.

Atrial flutter is uncommon in patients with structurally normal hearts and occurs far less frequently than atrial fibrillation. The etiology of this man’s arrhythmia may be due to pericarditis, based on his history and physical examination.

ANSWER

This ECG shows atrial flutter with 2:1 atrioventricular conduction. Additionally, ST depressions are seen in the anterior leads.

Typical sinus node P waves are absent, and atrial conduction at a rate of 310 beats/min is indicated by the sawtooth pattern in leads II and aVF. The ventricular rate is half that of the atrial rate (hence the 2:1 ratio). The ST depressions seen in the anterior leads, thought to be rate related, resolved upon cardioversion to terminate the atrial flutter.

Atrial flutter is uncommon in patients with structurally normal hearts and occurs far less frequently than atrial fibrillation. The etiology of this man’s arrhythmia may be due to pericarditis, based on his history and physical examination.

ANSWER

This ECG shows atrial flutter with 2:1 atrioventricular conduction. Additionally, ST depressions are seen in the anterior leads.

Typical sinus node P waves are absent, and atrial conduction at a rate of 310 beats/min is indicated by the sawtooth pattern in leads II and aVF. The ventricular rate is half that of the atrial rate (hence the 2:1 ratio). The ST depressions seen in the anterior leads, thought to be rate related, resolved upon cardioversion to terminate the atrial flutter.

Atrial flutter is uncommon in patients with structurally normal hearts and occurs far less frequently than atrial fibrillation. The etiology of this man’s arrhythmia may be due to pericarditis, based on his history and physical examination.

A 52-year-old man developed acute-onset palpitations, shortness of breath, and lightheadedness while sitting at his desk at work. He noticed his heart rate was rapid and asked a coworker to take his pulse for confirmation. He did not experience chest pain, syncope, or near syncope, but if he stood up and tried to walk, he very quickly became fatigued. His coworker tried to call 911; however, the patient asked to be driven to the urgent care center six blocks from their office instead. The patient’s heart rate and symptoms did not change en route. There is no previous history of heart disease. Although the patient works in an office, he is very active. He played hockey in high school and college and continues to play in an amateur league as well as coaching a youth group at the local ice rink. He is also an active member of a local bicycling club and recently completed a 150-mile recreational ride. He has no history of hypertension, diabetes, or pulmonary disease. Surgical history is remarkable for a medial meniscus repair of his right knee and a laparoscopic cholecystectomy, both performed more than 10 years ago. He works as a certified public accountant, does not smoke, and drinks one or two glasses of wine in the evening with meals. He is married and has two adult children. He denies using recreational drugs or herbal medicines. The only medication he uses is ibuprofen as needed for musculoskeletal aches and pains associated with his active lifestyle. He has no known drug allergies, and his immunizations are current. The review of systems is positive for a recent viral upper respiratory illness. He reports having vague, nonspecific substernal chest discomfort, but no pain, at the time of his illness. Symptoms have resolved. There are no other complaints. On arrival, the patient appears anxious and in mild distress, but without pain. Vital signs include a heart rate of 160 beats/min; blood pressure, 100/64 mm Hg; respiratory rate, 18 breaths/min-1; and temperature, 98.4°F. The HEENT exam is unremarkable except for corrective lenses. The chest is clear in all lung fields. There is no jugular venous distention, and carotid upstrokes are brisk. The cardiac exam reveals a regular rhythm at a rate of 150 beats/min with no murmurs or gallops; however, a rub is noted. The abdomen is soft and nontender with no organomegaly. Well-healed scars from his laparoscopic ports are present. The lower extremities show no evidence of edema. Peripheral pulses are strong and equal in both upper and lower extremities, and the neurologic exam is normal. Laboratory studies including a metabolic panel, complete blood count, and cardiac enzymes all yield normal results. An ECG reveals the following: a ventricular rate of 155 beats/min; PR interval, not measured; QRS duration, 78 ms; QT/QTc interval, 272/437 ms; P axis, unmeasurable; R axis, 34°; and T axis, –50°. What is your interpretation of this ECG?

Man Seeks Treatment for Periodic “Eruptions”

The correct answer is benign familial pemphigus (choice “b”). Also known as Hailey-Hailey disease, this is an unusual autosomally inherited blistering disease.

Benign familial pemphigus (BFP) is often mistaken for bacterial infection, such as pyoderma (choice “a”) or impetigo (choice “c”). Although it can become secondarily infected, its origins are entirely different.

Contact dermatitis (choice “d”) in its more severe forms can present in a similar manner. However, it would have shown entirely different changes (acute inflammation and spongiosis) on biopsy.

See next page for the discussion...

DISCUSSION

In 1939, two dermatologist-brothers in Georgia saw a patient with this previously unreported condition. They uncovered the family history and worked out the histologic basis, which they then described in the literature. They named the condition benign familial pemphigus, but it is now more commonly known as Hailey-Hailey disease in their honor.

Pemphigus vulgaris (PV), a serious blistering disease, was more common and far more feared at the time of the Hailey brothers’ discovery. Nearly 100% of PV patients died from the condition in that pre-steroid, pre-antibiotic era (most from secondary bacterial infection).

Fortunately, BFP is more benign, though it shares some features with PV. Both are said to be Nikolsky-positive, meaning the initial blisters can be extended with digital pressure. But BFP, unlike PV, does not involve deposition of immunoglobulins (IgA in the case of PV), nor is it accompanied by circulating auto-antibodies. BFP patients typically have no systemic symptoms, whereas in those with PV, the oral mucosae are often affected.

Herpes simplex virus, which was the primary care provider’s initial suspected diagnosis, can cause somewhat similar outbreaks, even in this area. However, it was effectively ruled out by the lack of response to treatment and by the biopsy results.

Although BFP is an inherited condition, it demonstrates variable penetrance, as in our case. It is rare enough that diagnosis is almost invariably delayed while other diagnoses are considered and treated. The actual “lesion” of BFP is still debated, but appears to involve the quality and quantity of desmosomes (microscopic structures that act as connecting fibers between layers of tissue) breaking down, often because of heat and friction, eventuating in blistering. This theory is bolstered by considerable research and by the fact that most cases present in intertriginous areas, such as the neck, axillae, and groin. Appearing episodically, it typically begins in the third to fourth decade of life, tending to diminish with age.

Biopsy is often necessary to confirm the diagnosis of BFP, with the sample best taken from perilesional skin to avoid separation of friable sample fragments. Additional specimens can be taken for special handling (Michel’s media) to detect immunoglobulins that might be seen in other blistering diseases.

See next page for treatment...

TREATMENT

BFP can be treated empirically with application of a soothing solution of aluminum acetate, or more specifically with topical corticosteroids (class III to IV) and topical antibiotics (eg, clindamycin 2% solution), plus/minus oral minocycline, which has potent anti-inflammatory as well as antimicrobial effects.

Difficult cases should be referred to dermatology, which has a number of treatments at its disposal. This includes diaminodiphenyl sulfone (dapsone), systemic glucocorticoids, methotrexate, systemic retinoids, and even local injection of botulinum toxin to decrease local hidrosis.

This patient is responding well to a regimen of oral minocycline 100 mg bid, topical clindamycin 2% bid application, and topical tacrolimus.

The correct answer is benign familial pemphigus (choice “b”). Also known as Hailey-Hailey disease, this is an unusual autosomally inherited blistering disease.

Benign familial pemphigus (BFP) is often mistaken for bacterial infection, such as pyoderma (choice “a”) or impetigo (choice “c”). Although it can become secondarily infected, its origins are entirely different.

Contact dermatitis (choice “d”) in its more severe forms can present in a similar manner. However, it would have shown entirely different changes (acute inflammation and spongiosis) on biopsy.

See next page for the discussion...

DISCUSSION

In 1939, two dermatologist-brothers in Georgia saw a patient with this previously unreported condition. They uncovered the family history and worked out the histologic basis, which they then described in the literature. They named the condition benign familial pemphigus, but it is now more commonly known as Hailey-Hailey disease in their honor.

Pemphigus vulgaris (PV), a serious blistering disease, was more common and far more feared at the time of the Hailey brothers’ discovery. Nearly 100% of PV patients died from the condition in that pre-steroid, pre-antibiotic era (most from secondary bacterial infection).

Fortunately, BFP is more benign, though it shares some features with PV. Both are said to be Nikolsky-positive, meaning the initial blisters can be extended with digital pressure. But BFP, unlike PV, does not involve deposition of immunoglobulins (IgA in the case of PV), nor is it accompanied by circulating auto-antibodies. BFP patients typically have no systemic symptoms, whereas in those with PV, the oral mucosae are often affected.

Herpes simplex virus, which was the primary care provider’s initial suspected diagnosis, can cause somewhat similar outbreaks, even in this area. However, it was effectively ruled out by the lack of response to treatment and by the biopsy results.

Although BFP is an inherited condition, it demonstrates variable penetrance, as in our case. It is rare enough that diagnosis is almost invariably delayed while other diagnoses are considered and treated. The actual “lesion” of BFP is still debated, but appears to involve the quality and quantity of desmosomes (microscopic structures that act as connecting fibers between layers of tissue) breaking down, often because of heat and friction, eventuating in blistering. This theory is bolstered by considerable research and by the fact that most cases present in intertriginous areas, such as the neck, axillae, and groin. Appearing episodically, it typically begins in the third to fourth decade of life, tending to diminish with age.

Biopsy is often necessary to confirm the diagnosis of BFP, with the sample best taken from perilesional skin to avoid separation of friable sample fragments. Additional specimens can be taken for special handling (Michel’s media) to detect immunoglobulins that might be seen in other blistering diseases.

See next page for treatment...

TREATMENT

BFP can be treated empirically with application of a soothing solution of aluminum acetate, or more specifically with topical corticosteroids (class III to IV) and topical antibiotics (eg, clindamycin 2% solution), plus/minus oral minocycline, which has potent anti-inflammatory as well as antimicrobial effects.

Difficult cases should be referred to dermatology, which has a number of treatments at its disposal. This includes diaminodiphenyl sulfone (dapsone), systemic glucocorticoids, methotrexate, systemic retinoids, and even local injection of botulinum toxin to decrease local hidrosis.

This patient is responding well to a regimen of oral minocycline 100 mg bid, topical clindamycin 2% bid application, and topical tacrolimus.

The correct answer is benign familial pemphigus (choice “b”). Also known as Hailey-Hailey disease, this is an unusual autosomally inherited blistering disease.

Benign familial pemphigus (BFP) is often mistaken for bacterial infection, such as pyoderma (choice “a”) or impetigo (choice “c”). Although it can become secondarily infected, its origins are entirely different.

Contact dermatitis (choice “d”) in its more severe forms can present in a similar manner. However, it would have shown entirely different changes (acute inflammation and spongiosis) on biopsy.

See next page for the discussion...

DISCUSSION

In 1939, two dermatologist-brothers in Georgia saw a patient with this previously unreported condition. They uncovered the family history and worked out the histologic basis, which they then described in the literature. They named the condition benign familial pemphigus, but it is now more commonly known as Hailey-Hailey disease in their honor.

Pemphigus vulgaris (PV), a serious blistering disease, was more common and far more feared at the time of the Hailey brothers’ discovery. Nearly 100% of PV patients died from the condition in that pre-steroid, pre-antibiotic era (most from secondary bacterial infection).

Fortunately, BFP is more benign, though it shares some features with PV. Both are said to be Nikolsky-positive, meaning the initial blisters can be extended with digital pressure. But BFP, unlike PV, does not involve deposition of immunoglobulins (IgA in the case of PV), nor is it accompanied by circulating auto-antibodies. BFP patients typically have no systemic symptoms, whereas in those with PV, the oral mucosae are often affected.

Herpes simplex virus, which was the primary care provider’s initial suspected diagnosis, can cause somewhat similar outbreaks, even in this area. However, it was effectively ruled out by the lack of response to treatment and by the biopsy results.

Although BFP is an inherited condition, it demonstrates variable penetrance, as in our case. It is rare enough that diagnosis is almost invariably delayed while other diagnoses are considered and treated. The actual “lesion” of BFP is still debated, but appears to involve the quality and quantity of desmosomes (microscopic structures that act as connecting fibers between layers of tissue) breaking down, often because of heat and friction, eventuating in blistering. This theory is bolstered by considerable research and by the fact that most cases present in intertriginous areas, such as the neck, axillae, and groin. Appearing episodically, it typically begins in the third to fourth decade of life, tending to diminish with age.

Biopsy is often necessary to confirm the diagnosis of BFP, with the sample best taken from perilesional skin to avoid separation of friable sample fragments. Additional specimens can be taken for special handling (Michel’s media) to detect immunoglobulins that might be seen in other blistering diseases.

See next page for treatment...

TREATMENT

BFP can be treated empirically with application of a soothing solution of aluminum acetate, or more specifically with topical corticosteroids (class III to IV) and topical antibiotics (eg, clindamycin 2% solution), plus/minus oral minocycline, which has potent anti-inflammatory as well as antimicrobial effects.

Difficult cases should be referred to dermatology, which has a number of treatments at its disposal. This includes diaminodiphenyl sulfone (dapsone), systemic glucocorticoids, methotrexate, systemic retinoids, and even local injection of botulinum toxin to decrease local hidrosis.

This patient is responding well to a regimen of oral minocycline 100 mg bid, topical clindamycin 2% bid application, and topical tacrolimus.

For three months, a 38-year-old man has been trying to resolve an “eruption” on his neck. The rash burns and itches, though only mildly, and produces clear fluid. His primary care provider initially prescribed acyclovir, then valacyclovir; neither helped. Subsequent courses of oral antibiotics (cephalexin 500 mg qid for three weeks, then ciprofloxacin 500 mg bid for two weeks) also had no beneficial effect. There is no family history of similar outbreaks. The patient, however, has had several of these eruptions—on the face as well as the neck—since his 20s. They typically last two to four weeks, then disappear completely for months or years. The eruptions tend to occur in the summer. He denies any history of cold sores and does not recall any premonitory symptoms prior to this eruption. He further denies any history of atopy or immunosuppression. His health is otherwise excellent, and he is taking no prescription medications. The denuded area measures about 8 x 4 cm, from his nuchal scalp down to the C6 area of the posterior neck. Discrete ruptured vesicles are seen on the periphery of the site. A layer of peeling skin, resembling wet toilet tissue, covers the partially denuded central portion, at the base of which is distinctly erythematous underlying raw tissue. There is no erythema surrounding the lesion, and no nodes are palpable in the area. A 4-mm punch biopsy is performed, with a sample taken from the periphery of the lesion and submitted for routine handling. It shows a hyperplastic epithelium, as well as intradermal and suprabasilar acantholysis extending focally into the spinous layer.

Atrophic Erythematous Facial Plaques

The Diagnosis: Atrophic Lupus Erythematosus

Cutaneous lupus erythematosus is divided into acute, subacute, and chronic cutaneous lupus erythematosus (CCLE). There are more than 20 subtypes of CCLE mentioned in the literature including atrophic lupus erythematosus (ALE).1 The most typical presentation is CCLE with discoid lesions. Most commonly, discoid CCLE is an entirely cutaneous process without systemic involvement.Discoid lesions appear as scaly red macules or papules primarily on the face and scalp.2 They may evolve into hyperkeratotic plaques with irregular hyperpigmented borders and develop a central hypopigmented depression with atrophy and scarring.2,3 Discoid CCLE has a female predominance and commonly occurs between 20 and 30 years of age. Triggers of discoid lesions include UV exposure, trauma, and infection.2

Our case of multiple atrophic plaques of the face, scalp, trunk, and upper extremities demonstrated a diagnostic challenge. Our patient presented with atrophic facial plaques, which are not typical of discoid lesions of CCLE. Our patient’s findings appeared clinically similar to acne scarring or atrophoderma. Histology showed common features of CCLE, including basal liquefactive degeneration, thickening of the basement membrane zone, increased melanin, and a lymphocytic inflammatory infiltrate (Figure).2,3 There was no evidence of hyperkeratosis, which often is seen in discoid lesions of CCLE.

Clinicopathologically, our case was consistent with ALE. A review of the literature revealed similar cases documented by Christianson and Mitchell4 in 1969; they described annular atrophic plaques of the skin of unknown diagnostic classification. Chorzelski et al5 reiterated the difficulty of defining diagnostically similar atrophic plaques of the face showing histopathologic features consistent with lupus and suggested these cases may represent an uncharacteristic presentation of discoid lupus erythematosus. Our patient demonstrated this rare subtype of discoid lupus erythematosus, known as ALE. There are few reports in the literature of ALE; thus we have managed our patient similar to other CCLE patients. Management of CCLE patients includes strict sun protection. Treatment options include corticosteroids, calcineurin inhibitors, antimalarial agents, and thalidomide.2 Our patient started using tacrolimus ointment 0.1% daily and hydroxychloroquine 200 mg twice daily. She also was practicing strict photoprotection. The patient was lost to follow-up. Topical steroids are not an option in ALE. It is important for dermatologists to recognize this rare variant of CCLE to prevent disfigurement.

1. Pramatarov KD. Chronic cutaneous lupus erythematosus—clinical spectrum. Clin Dermatol. 2004;22:113-120.

2. Rothfield N, Sontheimer RD, Bernstein M. Lupus erythematosus: systemic and cutaneous manifestations. Clin Dermatol. 2006;24:348-362.

3. Al-Refu K, Goodfield M. Scar classification in cutaneous lupus erythematosus: morphological description [published online ahead of print July 14, 2009]. Br J Dermatol. 2009;161:1052-1058.

4. Christianson HB, Mitchell WT. Annular atrophic plaques of the face. a clinical and histologic study. Arch Dermatol. 1969;100:703-716.

5. Chorzelski TP, Jablonska S, Blaszyczyk M, et al. Annular atrophic plaques of the face. a variety of atrophic discoid lupus erythematosus? Arch Dermatol. 1976;112:1143-1145.

The Diagnosis: Atrophic Lupus Erythematosus

Cutaneous lupus erythematosus is divided into acute, subacute, and chronic cutaneous lupus erythematosus (CCLE). There are more than 20 subtypes of CCLE mentioned in the literature including atrophic lupus erythematosus (ALE).1 The most typical presentation is CCLE with discoid lesions. Most commonly, discoid CCLE is an entirely cutaneous process without systemic involvement.Discoid lesions appear as scaly red macules or papules primarily on the face and scalp.2 They may evolve into hyperkeratotic plaques with irregular hyperpigmented borders and develop a central hypopigmented depression with atrophy and scarring.2,3 Discoid CCLE has a female predominance and commonly occurs between 20 and 30 years of age. Triggers of discoid lesions include UV exposure, trauma, and infection.2

Our case of multiple atrophic plaques of the face, scalp, trunk, and upper extremities demonstrated a diagnostic challenge. Our patient presented with atrophic facial plaques, which are not typical of discoid lesions of CCLE. Our patient’s findings appeared clinically similar to acne scarring or atrophoderma. Histology showed common features of CCLE, including basal liquefactive degeneration, thickening of the basement membrane zone, increased melanin, and a lymphocytic inflammatory infiltrate (Figure).2,3 There was no evidence of hyperkeratosis, which often is seen in discoid lesions of CCLE.

Clinicopathologically, our case was consistent with ALE. A review of the literature revealed similar cases documented by Christianson and Mitchell4 in 1969; they described annular atrophic plaques of the skin of unknown diagnostic classification. Chorzelski et al5 reiterated the difficulty of defining diagnostically similar atrophic plaques of the face showing histopathologic features consistent with lupus and suggested these cases may represent an uncharacteristic presentation of discoid lupus erythematosus. Our patient demonstrated this rare subtype of discoid lupus erythematosus, known as ALE. There are few reports in the literature of ALE; thus we have managed our patient similar to other CCLE patients. Management of CCLE patients includes strict sun protection. Treatment options include corticosteroids, calcineurin inhibitors, antimalarial agents, and thalidomide.2 Our patient started using tacrolimus ointment 0.1% daily and hydroxychloroquine 200 mg twice daily. She also was practicing strict photoprotection. The patient was lost to follow-up. Topical steroids are not an option in ALE. It is important for dermatologists to recognize this rare variant of CCLE to prevent disfigurement.

The Diagnosis: Atrophic Lupus Erythematosus

Cutaneous lupus erythematosus is divided into acute, subacute, and chronic cutaneous lupus erythematosus (CCLE). There are more than 20 subtypes of CCLE mentioned in the literature including atrophic lupus erythematosus (ALE).1 The most typical presentation is CCLE with discoid lesions. Most commonly, discoid CCLE is an entirely cutaneous process without systemic involvement.Discoid lesions appear as scaly red macules or papules primarily on the face and scalp.2 They may evolve into hyperkeratotic plaques with irregular hyperpigmented borders and develop a central hypopigmented depression with atrophy and scarring.2,3 Discoid CCLE has a female predominance and commonly occurs between 20 and 30 years of age. Triggers of discoid lesions include UV exposure, trauma, and infection.2

Our case of multiple atrophic plaques of the face, scalp, trunk, and upper extremities demonstrated a diagnostic challenge. Our patient presented with atrophic facial plaques, which are not typical of discoid lesions of CCLE. Our patient’s findings appeared clinically similar to acne scarring or atrophoderma. Histology showed common features of CCLE, including basal liquefactive degeneration, thickening of the basement membrane zone, increased melanin, and a lymphocytic inflammatory infiltrate (Figure).2,3 There was no evidence of hyperkeratosis, which often is seen in discoid lesions of CCLE.

Clinicopathologically, our case was consistent with ALE. A review of the literature revealed similar cases documented by Christianson and Mitchell4 in 1969; they described annular atrophic plaques of the skin of unknown diagnostic classification. Chorzelski et al5 reiterated the difficulty of defining diagnostically similar atrophic plaques of the face showing histopathologic features consistent with lupus and suggested these cases may represent an uncharacteristic presentation of discoid lupus erythematosus. Our patient demonstrated this rare subtype of discoid lupus erythematosus, known as ALE. There are few reports in the literature of ALE; thus we have managed our patient similar to other CCLE patients. Management of CCLE patients includes strict sun protection. Treatment options include corticosteroids, calcineurin inhibitors, antimalarial agents, and thalidomide.2 Our patient started using tacrolimus ointment 0.1% daily and hydroxychloroquine 200 mg twice daily. She also was practicing strict photoprotection. The patient was lost to follow-up. Topical steroids are not an option in ALE. It is important for dermatologists to recognize this rare variant of CCLE to prevent disfigurement.

1. Pramatarov KD. Chronic cutaneous lupus erythematosus—clinical spectrum. Clin Dermatol. 2004;22:113-120.

2. Rothfield N, Sontheimer RD, Bernstein M. Lupus erythematosus: systemic and cutaneous manifestations. Clin Dermatol. 2006;24:348-362.

3. Al-Refu K, Goodfield M. Scar classification in cutaneous lupus erythematosus: morphological description [published online ahead of print July 14, 2009]. Br J Dermatol. 2009;161:1052-1058.

4. Christianson HB, Mitchell WT. Annular atrophic plaques of the face. a clinical and histologic study. Arch Dermatol. 1969;100:703-716.

5. Chorzelski TP, Jablonska S, Blaszyczyk M, et al. Annular atrophic plaques of the face. a variety of atrophic discoid lupus erythematosus? Arch Dermatol. 1976;112:1143-1145.

1. Pramatarov KD. Chronic cutaneous lupus erythematosus—clinical spectrum. Clin Dermatol. 2004;22:113-120.

2. Rothfield N, Sontheimer RD, Bernstein M. Lupus erythematosus: systemic and cutaneous manifestations. Clin Dermatol. 2006;24:348-362.

3. Al-Refu K, Goodfield M. Scar classification in cutaneous lupus erythematosus: morphological description [published online ahead of print July 14, 2009]. Br J Dermatol. 2009;161:1052-1058.

4. Christianson HB, Mitchell WT. Annular atrophic plaques of the face. a clinical and histologic study. Arch Dermatol. 1969;100:703-716.

5. Chorzelski TP, Jablonska S, Blaszyczyk M, et al. Annular atrophic plaques of the face. a variety of atrophic discoid lupus erythematosus? Arch Dermatol. 1976;112:1143-1145.