User login

Bringing you the latest news, research and reviews, exclusive interviews, podcasts, quizzes, and more.

Expected spike in acute flaccid myelitis did not occur in 2020

suggested researchers at the Centers for Disease Control and Prevention.

Acute flaccid myelitis (AFM) is an uncommon but serious complication of some viral infections, including West Nile virus and nonpolio enteroviruses. It is “characterized by sudden onset of limb weakness and lesions in the gray matter of the spinal cord,” they said, and more than 90% of cases occur in young children.

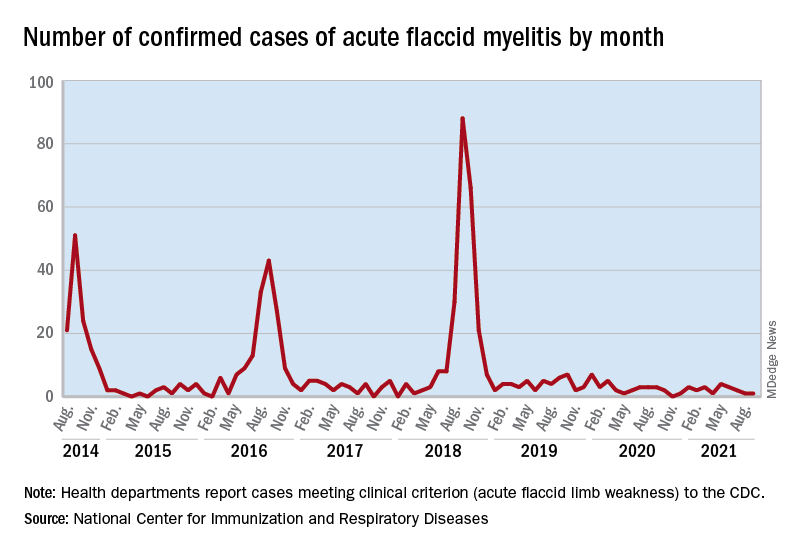

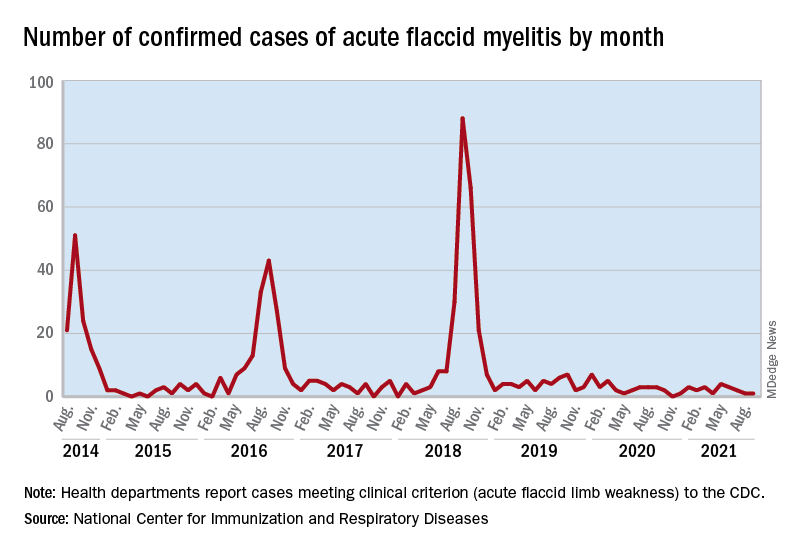

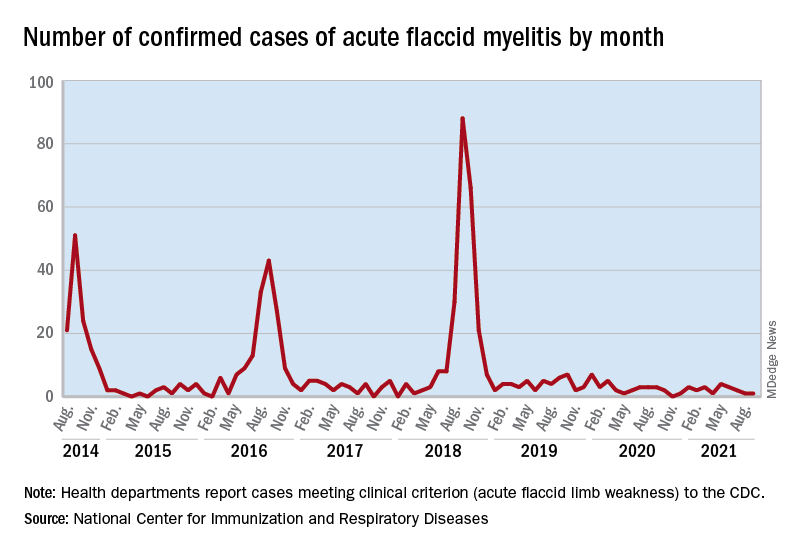

Cases of AFM, which can lead to respiratory insufficiency and permanent paralysis, spiked during the late summer and early fall in 2014, 2016, and 2018 and were expected to do so again in 2020, Sarah Kidd, MD, and associates at the division of viral diseases at the CDC’s National Center for Immunization and Respiratory Diseases, Atlanta, said in the Morbidity and Mortality Weekly Report.

Monthly peaks in those previous years – each occurring in September – reached 51 cases in 2014, 43 cases in 2016, and 88 cases in 2018, but in 2020 there was only 1 case reported in September, with a high of 4 coming in May, CDC data show. The total number of cases for 2020 (32) was, in fact, lower than in 2019, when 47 were reported.

The investigators’ main objective was to see if there were any differences between the 2018 and 2019-2020 cases. Reports from state health departments to the CDC showed that, in 2019-2020, “patients were older; more likely to have lower limb involvement; and less likely to have upper limb involvement, prodromal illness, [cerebrospinal fluid] pleocytosis, or specimens that tested positive for EV [enterovirus]-D68” than patients from 2018, Dr. Kidd and associates said.

Mask wearing and reduced in-school attendance may have decreased circulation of EV-D68 – the enterovirus type most often detected in the stool and respiratory specimens of AFM patients – as was seen with other respiratory viruses, such as influenza and respiratory syncytial virus, in 2020. Previous studies have suggested that EV-D68 drives the increases in cases during peak years, the researchers noted.

The absence of such an increase “in 2020 reflects a deviation from the previously observed biennial pattern, and it is unclear when the next increase in AFM should be expected. Clinicians should continue to maintain vigilance and suspect AFM in any child with acute flaccid limb weakness, particularly in the setting of recent febrile or respiratory illness,” they wrote.

suggested researchers at the Centers for Disease Control and Prevention.

Acute flaccid myelitis (AFM) is an uncommon but serious complication of some viral infections, including West Nile virus and nonpolio enteroviruses. It is “characterized by sudden onset of limb weakness and lesions in the gray matter of the spinal cord,” they said, and more than 90% of cases occur in young children.

Cases of AFM, which can lead to respiratory insufficiency and permanent paralysis, spiked during the late summer and early fall in 2014, 2016, and 2018 and were expected to do so again in 2020, Sarah Kidd, MD, and associates at the division of viral diseases at the CDC’s National Center for Immunization and Respiratory Diseases, Atlanta, said in the Morbidity and Mortality Weekly Report.

Monthly peaks in those previous years – each occurring in September – reached 51 cases in 2014, 43 cases in 2016, and 88 cases in 2018, but in 2020 there was only 1 case reported in September, with a high of 4 coming in May, CDC data show. The total number of cases for 2020 (32) was, in fact, lower than in 2019, when 47 were reported.

The investigators’ main objective was to see if there were any differences between the 2018 and 2019-2020 cases. Reports from state health departments to the CDC showed that, in 2019-2020, “patients were older; more likely to have lower limb involvement; and less likely to have upper limb involvement, prodromal illness, [cerebrospinal fluid] pleocytosis, or specimens that tested positive for EV [enterovirus]-D68” than patients from 2018, Dr. Kidd and associates said.

Mask wearing and reduced in-school attendance may have decreased circulation of EV-D68 – the enterovirus type most often detected in the stool and respiratory specimens of AFM patients – as was seen with other respiratory viruses, such as influenza and respiratory syncytial virus, in 2020. Previous studies have suggested that EV-D68 drives the increases in cases during peak years, the researchers noted.

The absence of such an increase “in 2020 reflects a deviation from the previously observed biennial pattern, and it is unclear when the next increase in AFM should be expected. Clinicians should continue to maintain vigilance and suspect AFM in any child with acute flaccid limb weakness, particularly in the setting of recent febrile or respiratory illness,” they wrote.

suggested researchers at the Centers for Disease Control and Prevention.

Acute flaccid myelitis (AFM) is an uncommon but serious complication of some viral infections, including West Nile virus and nonpolio enteroviruses. It is “characterized by sudden onset of limb weakness and lesions in the gray matter of the spinal cord,” they said, and more than 90% of cases occur in young children.

Cases of AFM, which can lead to respiratory insufficiency and permanent paralysis, spiked during the late summer and early fall in 2014, 2016, and 2018 and were expected to do so again in 2020, Sarah Kidd, MD, and associates at the division of viral diseases at the CDC’s National Center for Immunization and Respiratory Diseases, Atlanta, said in the Morbidity and Mortality Weekly Report.

Monthly peaks in those previous years – each occurring in September – reached 51 cases in 2014, 43 cases in 2016, and 88 cases in 2018, but in 2020 there was only 1 case reported in September, with a high of 4 coming in May, CDC data show. The total number of cases for 2020 (32) was, in fact, lower than in 2019, when 47 were reported.

The investigators’ main objective was to see if there were any differences between the 2018 and 2019-2020 cases. Reports from state health departments to the CDC showed that, in 2019-2020, “patients were older; more likely to have lower limb involvement; and less likely to have upper limb involvement, prodromal illness, [cerebrospinal fluid] pleocytosis, or specimens that tested positive for EV [enterovirus]-D68” than patients from 2018, Dr. Kidd and associates said.

Mask wearing and reduced in-school attendance may have decreased circulation of EV-D68 – the enterovirus type most often detected in the stool and respiratory specimens of AFM patients – as was seen with other respiratory viruses, such as influenza and respiratory syncytial virus, in 2020. Previous studies have suggested that EV-D68 drives the increases in cases during peak years, the researchers noted.

The absence of such an increase “in 2020 reflects a deviation from the previously observed biennial pattern, and it is unclear when the next increase in AFM should be expected. Clinicians should continue to maintain vigilance and suspect AFM in any child with acute flaccid limb weakness, particularly in the setting of recent febrile or respiratory illness,” they wrote.

FROM MMWR

Alopecia tied to a threefold increased risk for dementia

Alopecia areata (AA) has been linked to a significantly increased risk for dementia, new research shows.

After controlling for an array of potential confounders, investigators found a threefold higher risk of developing any form of dementia and a fourfold higher risk of developing Alzheimer’s disease (AD) in those with AA versus the controls.

“AA shares a similar inflammatory signature with dementia and has great psychological impacts that lead to poor social engagement,” lead author Cheng-Yuan Li, MD, MSc, of the department of dermatology, Taipei (Taiwan) Veterans General Hospital.

“Poor social engagement and shared inflammatory cytokines might both be important links between AA and dementia,” said Dr. Li, who is also affiliated with the School of Medicine and the Institute of Brain Science at National Yang Ming Chiao Tung University, Taipei.

The study was published online Oct. 26, 2021, in the Journal of Clinical Psychiatry (doi: 10.4088/JCP.21m13931).

Significant psychological impact

Patients with AA often experience anxiety and depression, possibly caused by the negative emotional and psychological impact of the hair loss and partial or even complete baldness associated with the disease, the authors noted.

However, AA is also associated with an array of other atopic and autoimmune diseases, including psoriasis and systemic lupus erythematosus (SLE).

Epidemiologic research has suggested a link between dementia and autoimmune diseases such as psoriasis and SLE, with some evidence suggesting that autoimmune and inflammatory mechanisms may “play a role” in the development of AD.

Dementia in general and AD in particular, “have been shown to include an inflammatory component” that may share some of the same mediators seen in AA (eg, IL-1 beta, IL-6, and tumor necrosis factor–alpha).

Moreover, “the great negative psychosocial impact of AA might result in poor social engagement, a typical risk factor for dementia,” said Dr. Li. The investigators sought to investigate whether patients with AA actually do have a higher dementia risk than individuals without AA.

The researchers used data from the Taiwan National Health Insurance Research Database, comparing 2,534 patients with AA against 25,340 controls matched for age, sex, residence, income, dementia-related comorbidities, systemic steroid use, and annual outpatient visits. Participants were enrolled between 1998 and 2011 and followed to the end of 2013.

The mean age of the cohort was 53.9 years, and a little over half (57.6%) were female. The most common comorbidity was hypertension (32.3%), followed by dyslipidemia (27%) and diabetes (15.4%).

Dual intervention

After adjusting for potential confounders, those with AA were more likely to develop dementia, AD, and unspecified dementia, compared with controls. They also had a numerically higher risk for vascular dementia, compared with controls, but it was not statistically significant.

When participants were stratified by age, investigators found a significant association between AA and higher risk for any dementia as well as unspecified dementia in individuals of all ages and an increased risk for AD in patients with dementia age at onset of 65 years and older.

The mean age of dementia diagnosis was considerably younger in patients with AA versus controls (73.4 vs. 78.9 years, P = .002). The risk for any dementia and unspecified dementia was higher in patients of both sexes, but the risk for AD was higher only in male patients.

Sensitivity analyses that excluded the first year or first 3 years of observation yielded similar and consistent findings.

“Intervention targeting poor social engagement and inflammatory cytokines may be beneficial to AA-associated dementia,” said Dr. Li.

“Physicians should be more aware of this possible association, help reduce disease discrimination among the public, and encourage more social engagement for AA patients,” he said.

“Further studies are needed to elucidate the underlying pathophysiology between AA and dementia risk,” he added.

No cause and effect

Commenting on the study, Heather M. Snyder, PhD, vice president of medical and scientific affairs, Alzheimer’s Association, said, “We continue to learn about and better understand factors that may increase or decrease a person’s risk of dementia.”

“While we know the immune system plays a role in Alzheimer’s and other dementia, we are still investigating links between, and impact of, autoimmune diseases – like alopecia areata, rheumatoid arthritis, and others – on our overall health and our brains, [which] may eventually give us important information on risk reduction strategies as well,” said Dr. Snyder, who was not involved in the research.

She cautioned that although the study did show a correlation between AA and dementia risk, this does not equate to a demonstration of cause and effect.

At present, “the message for clinicians is that when a patient comes to your office with complaints about their memory, they should, No. 1, be taken seriously; and, No. 2, receive a thorough evaluation that takes into account the many factors that may lead to cognitive decline,” Dr. Snyder said.

The study was supported by a grant from Taipei Veterans General Hospital and the Ministry of Science and Technology, Taiwan. Dr. Li, coauthors, and Dr. Snyder disclosed no relevant financial relationships.

A version of this article first appeared on Medscape.com.

Alopecia areata (AA) has been linked to a significantly increased risk for dementia, new research shows.

After controlling for an array of potential confounders, investigators found a threefold higher risk of developing any form of dementia and a fourfold higher risk of developing Alzheimer’s disease (AD) in those with AA versus the controls.

“AA shares a similar inflammatory signature with dementia and has great psychological impacts that lead to poor social engagement,” lead author Cheng-Yuan Li, MD, MSc, of the department of dermatology, Taipei (Taiwan) Veterans General Hospital.

“Poor social engagement and shared inflammatory cytokines might both be important links between AA and dementia,” said Dr. Li, who is also affiliated with the School of Medicine and the Institute of Brain Science at National Yang Ming Chiao Tung University, Taipei.

The study was published online Oct. 26, 2021, in the Journal of Clinical Psychiatry (doi: 10.4088/JCP.21m13931).

Significant psychological impact

Patients with AA often experience anxiety and depression, possibly caused by the negative emotional and psychological impact of the hair loss and partial or even complete baldness associated with the disease, the authors noted.

However, AA is also associated with an array of other atopic and autoimmune diseases, including psoriasis and systemic lupus erythematosus (SLE).

Epidemiologic research has suggested a link between dementia and autoimmune diseases such as psoriasis and SLE, with some evidence suggesting that autoimmune and inflammatory mechanisms may “play a role” in the development of AD.

Dementia in general and AD in particular, “have been shown to include an inflammatory component” that may share some of the same mediators seen in AA (eg, IL-1 beta, IL-6, and tumor necrosis factor–alpha).

Moreover, “the great negative psychosocial impact of AA might result in poor social engagement, a typical risk factor for dementia,” said Dr. Li. The investigators sought to investigate whether patients with AA actually do have a higher dementia risk than individuals without AA.

The researchers used data from the Taiwan National Health Insurance Research Database, comparing 2,534 patients with AA against 25,340 controls matched for age, sex, residence, income, dementia-related comorbidities, systemic steroid use, and annual outpatient visits. Participants were enrolled between 1998 and 2011 and followed to the end of 2013.

The mean age of the cohort was 53.9 years, and a little over half (57.6%) were female. The most common comorbidity was hypertension (32.3%), followed by dyslipidemia (27%) and diabetes (15.4%).

Dual intervention

After adjusting for potential confounders, those with AA were more likely to develop dementia, AD, and unspecified dementia, compared with controls. They also had a numerically higher risk for vascular dementia, compared with controls, but it was not statistically significant.

When participants were stratified by age, investigators found a significant association between AA and higher risk for any dementia as well as unspecified dementia in individuals of all ages and an increased risk for AD in patients with dementia age at onset of 65 years and older.

The mean age of dementia diagnosis was considerably younger in patients with AA versus controls (73.4 vs. 78.9 years, P = .002). The risk for any dementia and unspecified dementia was higher in patients of both sexes, but the risk for AD was higher only in male patients.

Sensitivity analyses that excluded the first year or first 3 years of observation yielded similar and consistent findings.

“Intervention targeting poor social engagement and inflammatory cytokines may be beneficial to AA-associated dementia,” said Dr. Li.

“Physicians should be more aware of this possible association, help reduce disease discrimination among the public, and encourage more social engagement for AA patients,” he said.

“Further studies are needed to elucidate the underlying pathophysiology between AA and dementia risk,” he added.

No cause and effect

Commenting on the study, Heather M. Snyder, PhD, vice president of medical and scientific affairs, Alzheimer’s Association, said, “We continue to learn about and better understand factors that may increase or decrease a person’s risk of dementia.”

“While we know the immune system plays a role in Alzheimer’s and other dementia, we are still investigating links between, and impact of, autoimmune diseases – like alopecia areata, rheumatoid arthritis, and others – on our overall health and our brains, [which] may eventually give us important information on risk reduction strategies as well,” said Dr. Snyder, who was not involved in the research.

She cautioned that although the study did show a correlation between AA and dementia risk, this does not equate to a demonstration of cause and effect.

At present, “the message for clinicians is that when a patient comes to your office with complaints about their memory, they should, No. 1, be taken seriously; and, No. 2, receive a thorough evaluation that takes into account the many factors that may lead to cognitive decline,” Dr. Snyder said.

The study was supported by a grant from Taipei Veterans General Hospital and the Ministry of Science and Technology, Taiwan. Dr. Li, coauthors, and Dr. Snyder disclosed no relevant financial relationships.

A version of this article first appeared on Medscape.com.

Alopecia areata (AA) has been linked to a significantly increased risk for dementia, new research shows.

After controlling for an array of potential confounders, investigators found a threefold higher risk of developing any form of dementia and a fourfold higher risk of developing Alzheimer’s disease (AD) in those with AA versus the controls.

“AA shares a similar inflammatory signature with dementia and has great psychological impacts that lead to poor social engagement,” lead author Cheng-Yuan Li, MD, MSc, of the department of dermatology, Taipei (Taiwan) Veterans General Hospital.

“Poor social engagement and shared inflammatory cytokines might both be important links between AA and dementia,” said Dr. Li, who is also affiliated with the School of Medicine and the Institute of Brain Science at National Yang Ming Chiao Tung University, Taipei.

The study was published online Oct. 26, 2021, in the Journal of Clinical Psychiatry (doi: 10.4088/JCP.21m13931).

Significant psychological impact

Patients with AA often experience anxiety and depression, possibly caused by the negative emotional and psychological impact of the hair loss and partial or even complete baldness associated with the disease, the authors noted.

However, AA is also associated with an array of other atopic and autoimmune diseases, including psoriasis and systemic lupus erythematosus (SLE).

Epidemiologic research has suggested a link between dementia and autoimmune diseases such as psoriasis and SLE, with some evidence suggesting that autoimmune and inflammatory mechanisms may “play a role” in the development of AD.

Dementia in general and AD in particular, “have been shown to include an inflammatory component” that may share some of the same mediators seen in AA (eg, IL-1 beta, IL-6, and tumor necrosis factor–alpha).

Moreover, “the great negative psychosocial impact of AA might result in poor social engagement, a typical risk factor for dementia,” said Dr. Li. The investigators sought to investigate whether patients with AA actually do have a higher dementia risk than individuals without AA.

The researchers used data from the Taiwan National Health Insurance Research Database, comparing 2,534 patients with AA against 25,340 controls matched for age, sex, residence, income, dementia-related comorbidities, systemic steroid use, and annual outpatient visits. Participants were enrolled between 1998 and 2011 and followed to the end of 2013.

The mean age of the cohort was 53.9 years, and a little over half (57.6%) were female. The most common comorbidity was hypertension (32.3%), followed by dyslipidemia (27%) and diabetes (15.4%).

Dual intervention

After adjusting for potential confounders, those with AA were more likely to develop dementia, AD, and unspecified dementia, compared with controls. They also had a numerically higher risk for vascular dementia, compared with controls, but it was not statistically significant.

When participants were stratified by age, investigators found a significant association between AA and higher risk for any dementia as well as unspecified dementia in individuals of all ages and an increased risk for AD in patients with dementia age at onset of 65 years and older.

The mean age of dementia diagnosis was considerably younger in patients with AA versus controls (73.4 vs. 78.9 years, P = .002). The risk for any dementia and unspecified dementia was higher in patients of both sexes, but the risk for AD was higher only in male patients.

Sensitivity analyses that excluded the first year or first 3 years of observation yielded similar and consistent findings.

“Intervention targeting poor social engagement and inflammatory cytokines may be beneficial to AA-associated dementia,” said Dr. Li.

“Physicians should be more aware of this possible association, help reduce disease discrimination among the public, and encourage more social engagement for AA patients,” he said.

“Further studies are needed to elucidate the underlying pathophysiology between AA and dementia risk,” he added.

No cause and effect

Commenting on the study, Heather M. Snyder, PhD, vice president of medical and scientific affairs, Alzheimer’s Association, said, “We continue to learn about and better understand factors that may increase or decrease a person’s risk of dementia.”

“While we know the immune system plays a role in Alzheimer’s and other dementia, we are still investigating links between, and impact of, autoimmune diseases – like alopecia areata, rheumatoid arthritis, and others – on our overall health and our brains, [which] may eventually give us important information on risk reduction strategies as well,” said Dr. Snyder, who was not involved in the research.

She cautioned that although the study did show a correlation between AA and dementia risk, this does not equate to a demonstration of cause and effect.

At present, “the message for clinicians is that when a patient comes to your office with complaints about their memory, they should, No. 1, be taken seriously; and, No. 2, receive a thorough evaluation that takes into account the many factors that may lead to cognitive decline,” Dr. Snyder said.

The study was supported by a grant from Taipei Veterans General Hospital and the Ministry of Science and Technology, Taiwan. Dr. Li, coauthors, and Dr. Snyder disclosed no relevant financial relationships.

A version of this article first appeared on Medscape.com.

Managing simple febrile seizures without lumbar puncture safe: 15-year study

Most children with simple febrile seizures (SFSs) can be safely managed without lumbar puncture or other diagnostic tests without risking delayed diagnosis of bacterial meningitis, new data gathered from a 15-year span suggest.

Vidya R. Raghavan, MD, with the division of emergency medicine at Boston Children’s Hospital and Harvard Medical School, also in Boston, published their findings in Pediatrics.

In 2011, researchers published the American Academy of Pediatrics simple febrile seizure guideline, which recommends limiting lumbar puncture to non–low-risk patients. The guidelines also specified that neuroimaging and hematologic testing are not routinely recommended.

Dr. Raghavan and coauthors studied evaluation and management trends of the patients before and after the guidelines. They identified 142,121 children diagnosed with SFS who presented to 1 of 49 pediatric tertiary EDs and met other study criteria. Changes in management of SFS had started years before the guideline and positive effects continued after the guideline publication.

Researchers found a significant 95% decline in rates of lumbar puncture between 2005 and 2019 from 11.6% (95% confidence interval, 10.8%-12.4%) of children in 2005 to 0.6% (95% CI, 0.5%-0.8%; P < .001) in 2019. The most significant declines were among infants 6 months to 1 year.

“We found similar declines in rates of diagnostic laboratory and radiologic testing, intravenous antibiotic administration, hospitalization, and costs,” the authors wrote.

“Importantly,” they wrote, “the decrease in testing was not associated with a concurrent increase in delayed diagnoses of bacterial meningitis.”

The number of hospital admissions and total costs also dropped significantly over the 15-year span of the study. After adjusting for inflation, the authors wrote, costs dropped from an average $1,523 in 2005 to $605 (P < .001) in 2019.

Among first-time presentations for SFSs, 19.2% (95% CI, 18.3%-20.2%) resulted in admission in 2005. That rate dropped to 5.2% (95% CI, 4.8%-5.6%) in 2019 (P < .001), although the authors noted that trend largely plateaued after the guideline was published.

“Our findings are consistent with smaller studies published before 2011 in which researchers found declining rates of LP [lumbar puncture] in children presenting to the ED with their first SFS,” the authors wrote.

Mercedes Blackstone, MD, an emergency physician at the Children’s Hospital of Philadelphia, said in an interview that the paper offers reassurance for changed practice over the last decade.

She said there was substantial relief in pediatrics when the 2011 guidelines recognized formally that protocols were outdated, especially as bacterial meningitis had become increasingly rare with widespread use of pneumococcal and Haemophilus influenzae vaccines. Practitioners had already started to limit the spinal taps on their own.

“We were not really complying with the prior recommendation to do a spinal tap in all those children because it often felt like doing a pretty invasive procedure with a very low yield in what was often a very well child in front of you,” she said.

In 2007, the authors noted, a few years before the guidelines, rates of bacterial meningitis had decreased to 7 per 100,000 in children aged between 2 and 23 months and 0.56 per 100,000 in children aged between 2 and 10 years.

However, Dr. Blackstone said, there was still a worry among some practitioners that there could be missed cases of bacterial meningitis.

“It’s very helpful to see that in all those years, the guidelines have been very validated and there were really no missed cases,” said Dr. Blackstone, author of CHOP’s febrile seizures clinical pathway.

It was good to see the number of CT scans drop as well, she said. Dr. Raghavan’s team found they decreased from 10.6% to 1.6%; P < .001, over the study period.

“Earlier work had shown that there was still a fair amount of head CTs happening and that’s radiation to the young brain,” Dr. Blackstone noted. “This is great news.”

Dr. Blackstone said it was great to see so many children from so many children’s hospitals included in the study.

The paper confirmed that “we’ve reduced a lot of unnecessary testing, saved a lot of cost, and had no increased risk to the patients,” she said.

Dr. Blackstone pointed out that the authors include a limitation that many children are seen in nonpediatric centers in community adult ED and she said those settings tend to have more testing.

“Hopefully, these guidelines have penetrated into the whole community,” she said. “With this paper they should feel reassured that they can spare children some of these tests and procedures.”

Dr. Raghavan and Dr. Blackstone declared no relevant financial relationships.

Most children with simple febrile seizures (SFSs) can be safely managed without lumbar puncture or other diagnostic tests without risking delayed diagnosis of bacterial meningitis, new data gathered from a 15-year span suggest.

Vidya R. Raghavan, MD, with the division of emergency medicine at Boston Children’s Hospital and Harvard Medical School, also in Boston, published their findings in Pediatrics.

In 2011, researchers published the American Academy of Pediatrics simple febrile seizure guideline, which recommends limiting lumbar puncture to non–low-risk patients. The guidelines also specified that neuroimaging and hematologic testing are not routinely recommended.

Dr. Raghavan and coauthors studied evaluation and management trends of the patients before and after the guidelines. They identified 142,121 children diagnosed with SFS who presented to 1 of 49 pediatric tertiary EDs and met other study criteria. Changes in management of SFS had started years before the guideline and positive effects continued after the guideline publication.

Researchers found a significant 95% decline in rates of lumbar puncture between 2005 and 2019 from 11.6% (95% confidence interval, 10.8%-12.4%) of children in 2005 to 0.6% (95% CI, 0.5%-0.8%; P < .001) in 2019. The most significant declines were among infants 6 months to 1 year.

“We found similar declines in rates of diagnostic laboratory and radiologic testing, intravenous antibiotic administration, hospitalization, and costs,” the authors wrote.

“Importantly,” they wrote, “the decrease in testing was not associated with a concurrent increase in delayed diagnoses of bacterial meningitis.”

The number of hospital admissions and total costs also dropped significantly over the 15-year span of the study. After adjusting for inflation, the authors wrote, costs dropped from an average $1,523 in 2005 to $605 (P < .001) in 2019.

Among first-time presentations for SFSs, 19.2% (95% CI, 18.3%-20.2%) resulted in admission in 2005. That rate dropped to 5.2% (95% CI, 4.8%-5.6%) in 2019 (P < .001), although the authors noted that trend largely plateaued after the guideline was published.

“Our findings are consistent with smaller studies published before 2011 in which researchers found declining rates of LP [lumbar puncture] in children presenting to the ED with their first SFS,” the authors wrote.

Mercedes Blackstone, MD, an emergency physician at the Children’s Hospital of Philadelphia, said in an interview that the paper offers reassurance for changed practice over the last decade.

She said there was substantial relief in pediatrics when the 2011 guidelines recognized formally that protocols were outdated, especially as bacterial meningitis had become increasingly rare with widespread use of pneumococcal and Haemophilus influenzae vaccines. Practitioners had already started to limit the spinal taps on their own.

“We were not really complying with the prior recommendation to do a spinal tap in all those children because it often felt like doing a pretty invasive procedure with a very low yield in what was often a very well child in front of you,” she said.

In 2007, the authors noted, a few years before the guidelines, rates of bacterial meningitis had decreased to 7 per 100,000 in children aged between 2 and 23 months and 0.56 per 100,000 in children aged between 2 and 10 years.

However, Dr. Blackstone said, there was still a worry among some practitioners that there could be missed cases of bacterial meningitis.

“It’s very helpful to see that in all those years, the guidelines have been very validated and there were really no missed cases,” said Dr. Blackstone, author of CHOP’s febrile seizures clinical pathway.

It was good to see the number of CT scans drop as well, she said. Dr. Raghavan’s team found they decreased from 10.6% to 1.6%; P < .001, over the study period.

“Earlier work had shown that there was still a fair amount of head CTs happening and that’s radiation to the young brain,” Dr. Blackstone noted. “This is great news.”

Dr. Blackstone said it was great to see so many children from so many children’s hospitals included in the study.

The paper confirmed that “we’ve reduced a lot of unnecessary testing, saved a lot of cost, and had no increased risk to the patients,” she said.

Dr. Blackstone pointed out that the authors include a limitation that many children are seen in nonpediatric centers in community adult ED and she said those settings tend to have more testing.

“Hopefully, these guidelines have penetrated into the whole community,” she said. “With this paper they should feel reassured that they can spare children some of these tests and procedures.”

Dr. Raghavan and Dr. Blackstone declared no relevant financial relationships.

Most children with simple febrile seizures (SFSs) can be safely managed without lumbar puncture or other diagnostic tests without risking delayed diagnosis of bacterial meningitis, new data gathered from a 15-year span suggest.

Vidya R. Raghavan, MD, with the division of emergency medicine at Boston Children’s Hospital and Harvard Medical School, also in Boston, published their findings in Pediatrics.

In 2011, researchers published the American Academy of Pediatrics simple febrile seizure guideline, which recommends limiting lumbar puncture to non–low-risk patients. The guidelines also specified that neuroimaging and hematologic testing are not routinely recommended.

Dr. Raghavan and coauthors studied evaluation and management trends of the patients before and after the guidelines. They identified 142,121 children diagnosed with SFS who presented to 1 of 49 pediatric tertiary EDs and met other study criteria. Changes in management of SFS had started years before the guideline and positive effects continued after the guideline publication.

Researchers found a significant 95% decline in rates of lumbar puncture between 2005 and 2019 from 11.6% (95% confidence interval, 10.8%-12.4%) of children in 2005 to 0.6% (95% CI, 0.5%-0.8%; P < .001) in 2019. The most significant declines were among infants 6 months to 1 year.

“We found similar declines in rates of diagnostic laboratory and radiologic testing, intravenous antibiotic administration, hospitalization, and costs,” the authors wrote.

“Importantly,” they wrote, “the decrease in testing was not associated with a concurrent increase in delayed diagnoses of bacterial meningitis.”

The number of hospital admissions and total costs also dropped significantly over the 15-year span of the study. After adjusting for inflation, the authors wrote, costs dropped from an average $1,523 in 2005 to $605 (P < .001) in 2019.

Among first-time presentations for SFSs, 19.2% (95% CI, 18.3%-20.2%) resulted in admission in 2005. That rate dropped to 5.2% (95% CI, 4.8%-5.6%) in 2019 (P < .001), although the authors noted that trend largely plateaued after the guideline was published.

“Our findings are consistent with smaller studies published before 2011 in which researchers found declining rates of LP [lumbar puncture] in children presenting to the ED with their first SFS,” the authors wrote.

Mercedes Blackstone, MD, an emergency physician at the Children’s Hospital of Philadelphia, said in an interview that the paper offers reassurance for changed practice over the last decade.

She said there was substantial relief in pediatrics when the 2011 guidelines recognized formally that protocols were outdated, especially as bacterial meningitis had become increasingly rare with widespread use of pneumococcal and Haemophilus influenzae vaccines. Practitioners had already started to limit the spinal taps on their own.

“We were not really complying with the prior recommendation to do a spinal tap in all those children because it often felt like doing a pretty invasive procedure with a very low yield in what was often a very well child in front of you,” she said.

In 2007, the authors noted, a few years before the guidelines, rates of bacterial meningitis had decreased to 7 per 100,000 in children aged between 2 and 23 months and 0.56 per 100,000 in children aged between 2 and 10 years.

However, Dr. Blackstone said, there was still a worry among some practitioners that there could be missed cases of bacterial meningitis.

“It’s very helpful to see that in all those years, the guidelines have been very validated and there were really no missed cases,” said Dr. Blackstone, author of CHOP’s febrile seizures clinical pathway.

It was good to see the number of CT scans drop as well, she said. Dr. Raghavan’s team found they decreased from 10.6% to 1.6%; P < .001, over the study period.

“Earlier work had shown that there was still a fair amount of head CTs happening and that’s radiation to the young brain,” Dr. Blackstone noted. “This is great news.”

Dr. Blackstone said it was great to see so many children from so many children’s hospitals included in the study.

The paper confirmed that “we’ve reduced a lot of unnecessary testing, saved a lot of cost, and had no increased risk to the patients,” she said.

Dr. Blackstone pointed out that the authors include a limitation that many children are seen in nonpediatric centers in community adult ED and she said those settings tend to have more testing.

“Hopefully, these guidelines have penetrated into the whole community,” she said. “With this paper they should feel reassured that they can spare children some of these tests and procedures.”

Dr. Raghavan and Dr. Blackstone declared no relevant financial relationships.

FROM PEDIATRICS

Which specialties get the biggest markups over Medicare rates?

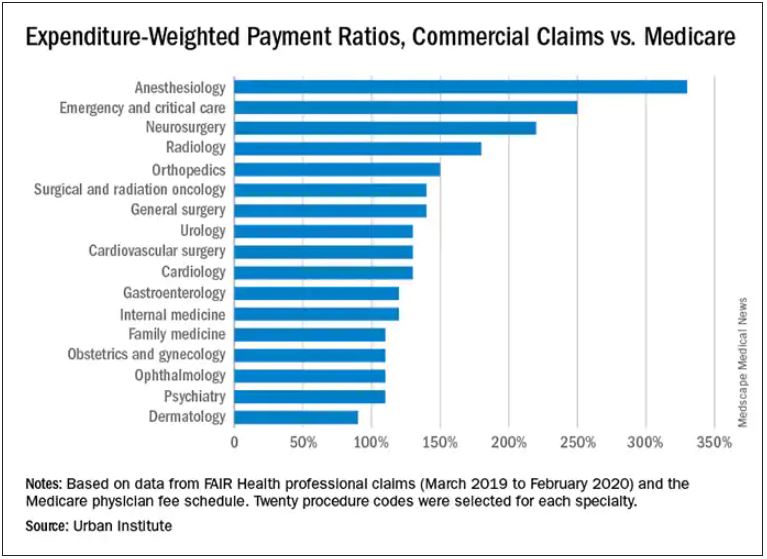

Anesthesiologists charge private insurers more than 300% above Medicare rates, a markup that is higher than that of 16 other specialties, according to a study released by the Urban Institute.

The Washington-based nonprofit institute found that the lowest markups were in psychiatry, ophthalmology, ob.gyn., family medicine, gastroenterology, and internal medicine, at 110%-120% of Medicare rates. .

In the middle are cardiology and cardiovascular surgery (130%), urology (130%), general surgery, surgical and radiation oncology (all at 140%), and orthopedics (150%).

At the top end were radiology (180%), neurosurgery (220%), emergency and critical care (250%), and anesthesiology (330%).

The wide variation in payments could be cited in support of the idea of applying Medicare rates across all physician specialties, say the study authors. Although lowering practitioner payments might lead to savings, it “will also create more pushback from providers, especially if these rates are introduced in the employer market,” write researchers Stacey McMorrow, PhD, Robert A. Berenson, MD, and John Holahan, PhD.

It is not known whether lowering commercial payment rates might decrease patient access, they write.

The authors also note that specialties in which the potential for a fee reduction was greatest were also the specialties for which baseline compensation was highest – from $350,000 annually for emergency physicians to $800,000 a year for neurosurgeons. Annual compensation for ob.gyns., dermatologists, and opthalmologists is about $350,000 a year, which suggests that “these specialties are similarly well compensated by both Medicare and commercial insurers,” the authors write.

The investigators assessed the top 20 procedure codes by expenditure in each of 17 physician specialties. They estimated the commercial-to-Medicare payment ratio for each service and constructed weighted averages across services for each specialty at the national level and for 12 states for which data for all the specialties and services were available.

The researchers analyzed claims from the FAIR Health database between March 2019 and March 2020. That database represents 60 insurers covering 150 million people.

Pediatric and geriatric specialties, nonphysician practitioners, out-of-network clinicians, and ambulatory surgery center claims were excluded. Codes with modifiers, J codes, and clinical laboratory services were also not included.

The charges used in the study were not the actual contracted rates. The authors instead used “imputed allowed amounts” for each claim line. That method was used to protect the confidentiality of the negotiated rates.

With regard to all specialties, the lowest compensated services were procedures, evaluation and management, and tests, which received 140%-150% of the Medicare rate. Treatments and imaging were marked up 160%. Anesthesia was reimbursed at a rate 330% higher than the rate Medicare would pay.

The authors also assessed geographic variation for the 12 states for which they had data.

Similar to findings in other studies, the researchers found that the markup was lowest in Pennsylvania (120%) and highest in Wisconsin (260%). The U.S. average was 160%. California and Missouri were at 150%; Michigan was right at the average.

For physicians in Illinois, Louisiana, Colorado, Texas, and New York, markups were 170%-180% over the Medicare rate. Markups for clinicians in New Jersey (190%) and Arizona (200%) were closest to the Wisconsin rate.

The authors note some study limitations, including the fact that they excluded out-of-network practitioners, “and such payments may disproportionately affect certain specialties.”

A version of this article first appeared on Medscape.com.

Anesthesiologists charge private insurers more than 300% above Medicare rates, a markup that is higher than that of 16 other specialties, according to a study released by the Urban Institute.

The Washington-based nonprofit institute found that the lowest markups were in psychiatry, ophthalmology, ob.gyn., family medicine, gastroenterology, and internal medicine, at 110%-120% of Medicare rates. .

In the middle are cardiology and cardiovascular surgery (130%), urology (130%), general surgery, surgical and radiation oncology (all at 140%), and orthopedics (150%).

At the top end were radiology (180%), neurosurgery (220%), emergency and critical care (250%), and anesthesiology (330%).

The wide variation in payments could be cited in support of the idea of applying Medicare rates across all physician specialties, say the study authors. Although lowering practitioner payments might lead to savings, it “will also create more pushback from providers, especially if these rates are introduced in the employer market,” write researchers Stacey McMorrow, PhD, Robert A. Berenson, MD, and John Holahan, PhD.

It is not known whether lowering commercial payment rates might decrease patient access, they write.

The authors also note that specialties in which the potential for a fee reduction was greatest were also the specialties for which baseline compensation was highest – from $350,000 annually for emergency physicians to $800,000 a year for neurosurgeons. Annual compensation for ob.gyns., dermatologists, and opthalmologists is about $350,000 a year, which suggests that “these specialties are similarly well compensated by both Medicare and commercial insurers,” the authors write.

The investigators assessed the top 20 procedure codes by expenditure in each of 17 physician specialties. They estimated the commercial-to-Medicare payment ratio for each service and constructed weighted averages across services for each specialty at the national level and for 12 states for which data for all the specialties and services were available.

The researchers analyzed claims from the FAIR Health database between March 2019 and March 2020. That database represents 60 insurers covering 150 million people.

Pediatric and geriatric specialties, nonphysician practitioners, out-of-network clinicians, and ambulatory surgery center claims were excluded. Codes with modifiers, J codes, and clinical laboratory services were also not included.

The charges used in the study were not the actual contracted rates. The authors instead used “imputed allowed amounts” for each claim line. That method was used to protect the confidentiality of the negotiated rates.

With regard to all specialties, the lowest compensated services were procedures, evaluation and management, and tests, which received 140%-150% of the Medicare rate. Treatments and imaging were marked up 160%. Anesthesia was reimbursed at a rate 330% higher than the rate Medicare would pay.

The authors also assessed geographic variation for the 12 states for which they had data.

Similar to findings in other studies, the researchers found that the markup was lowest in Pennsylvania (120%) and highest in Wisconsin (260%). The U.S. average was 160%. California and Missouri were at 150%; Michigan was right at the average.

For physicians in Illinois, Louisiana, Colorado, Texas, and New York, markups were 170%-180% over the Medicare rate. Markups for clinicians in New Jersey (190%) and Arizona (200%) were closest to the Wisconsin rate.

The authors note some study limitations, including the fact that they excluded out-of-network practitioners, “and such payments may disproportionately affect certain specialties.”

A version of this article first appeared on Medscape.com.

Anesthesiologists charge private insurers more than 300% above Medicare rates, a markup that is higher than that of 16 other specialties, according to a study released by the Urban Institute.

The Washington-based nonprofit institute found that the lowest markups were in psychiatry, ophthalmology, ob.gyn., family medicine, gastroenterology, and internal medicine, at 110%-120% of Medicare rates. .

In the middle are cardiology and cardiovascular surgery (130%), urology (130%), general surgery, surgical and radiation oncology (all at 140%), and orthopedics (150%).

At the top end were radiology (180%), neurosurgery (220%), emergency and critical care (250%), and anesthesiology (330%).

The wide variation in payments could be cited in support of the idea of applying Medicare rates across all physician specialties, say the study authors. Although lowering practitioner payments might lead to savings, it “will also create more pushback from providers, especially if these rates are introduced in the employer market,” write researchers Stacey McMorrow, PhD, Robert A. Berenson, MD, and John Holahan, PhD.

It is not known whether lowering commercial payment rates might decrease patient access, they write.

The authors also note that specialties in which the potential for a fee reduction was greatest were also the specialties for which baseline compensation was highest – from $350,000 annually for emergency physicians to $800,000 a year for neurosurgeons. Annual compensation for ob.gyns., dermatologists, and opthalmologists is about $350,000 a year, which suggests that “these specialties are similarly well compensated by both Medicare and commercial insurers,” the authors write.

The investigators assessed the top 20 procedure codes by expenditure in each of 17 physician specialties. They estimated the commercial-to-Medicare payment ratio for each service and constructed weighted averages across services for each specialty at the national level and for 12 states for which data for all the specialties and services were available.

The researchers analyzed claims from the FAIR Health database between March 2019 and March 2020. That database represents 60 insurers covering 150 million people.

Pediatric and geriatric specialties, nonphysician practitioners, out-of-network clinicians, and ambulatory surgery center claims were excluded. Codes with modifiers, J codes, and clinical laboratory services were also not included.

The charges used in the study were not the actual contracted rates. The authors instead used “imputed allowed amounts” for each claim line. That method was used to protect the confidentiality of the negotiated rates.

With regard to all specialties, the lowest compensated services were procedures, evaluation and management, and tests, which received 140%-150% of the Medicare rate. Treatments and imaging were marked up 160%. Anesthesia was reimbursed at a rate 330% higher than the rate Medicare would pay.

The authors also assessed geographic variation for the 12 states for which they had data.

Similar to findings in other studies, the researchers found that the markup was lowest in Pennsylvania (120%) and highest in Wisconsin (260%). The U.S. average was 160%. California and Missouri were at 150%; Michigan was right at the average.

For physicians in Illinois, Louisiana, Colorado, Texas, and New York, markups were 170%-180% over the Medicare rate. Markups for clinicians in New Jersey (190%) and Arizona (200%) were closest to the Wisconsin rate.

The authors note some study limitations, including the fact that they excluded out-of-network practitioners, “and such payments may disproportionately affect certain specialties.”

A version of this article first appeared on Medscape.com.

COVID-19: Can doctors refuse to see unvaccinated patients?

In June, Gerald Bock, MD, a dermatologist in central California, instituted a new office policy: He would not be seeing any more patients who remain unvaccinated against COVID-19 in his practice.

“[It is] the height of self-centered and irresponsible behavior,” he told me. “People who come in unvaccinated, when vaccination is widely available, are stating that their personal preferences are more important than their health, and are more important than any risk that they may expose their friends and family to, and also to any risk they might present to my staff and me. We have gone to considerable effort and expense to diminish any risk that visiting our office might entail. I see no reason why we should tolerate this.”

Other doctors appear to be following in his footsteps. There is no question that physicians have the right to choose their patients, just as patients are free to choose their doctors, but That is a complicated question without a clear answer. In a statement on whether physicians can decline unvaccinated patients, the American Medical Association continues to maintain that “in general” a physician may not “ethically turn a patient away based solely on the individual’s infectious disease status,” but does concede that “the decision to accept or decline a patient must balance the urgency of the individual patient’s need; the risk the patient may pose to other patients in the physician’s practice; and the need for the physician and staff, to be available to provide care in the future.”

Medical ethics experts have offered varying opinions. Daniel Wikler, PhD, professor of ethics and population health at the Harvard School of Public Health, Boston, wrote in an op-ed in the Washington Post that “ignorance or other personal failing” should not be factors in the evaluation of patients for health care. He argues that “doctors and hospitals are not in the blame and punishment business. Nor should they be. That doctors treat sinners and responsible citizens alike is a noble tradition.”

Timothy Hoff, professor of management, healthcare systems, and health policy at Northeastern University, Boston, maintains that, in nonemergency situations, physicians are legally able to refuse patients for a variety of reasons, provided they are not doing so because of some aspect of the patient’s race, gender, sexuality, or religion. However, in the same Northeastern University news release,Robert Baginski, MD, the director of interdisciplinary affairs for the department of medical sciences at Northeastern, cautions that it is vital for health authorities to continue urging the public to get vaccinated, but not at the expense of care.

Arthur L. Caplan, PhD, the head of the division of medical ethics at New York University, said in a Medscape commentary, that the decision to refuse to see patients who can vaccinate, but choose not to, is justifiable. “If you’re trying to protect yourself, your staff, or other patients, I think you do have the right to not take on somebody who won’t vaccinate,” he writes. “This is somewhat similar to when pediatricians do not accept a family if they won’t give their kids the state-required shots to go to school. That’s been happening for many years now.

“I also think it is morally justified if they won’t take your advice,” he continues. “If they won’t follow what you think is the best healthcare for them [such as getting vaccinated], there’s not much point in building that relationship.”

The situation is different in ED and hospital settings, however. “It’s a little harder to use unvaccinated status when someone really is at death’s door,” Dr. Caplan pointed out. “When someone comes in very sick, or whatever the reason, I think we have to take care of them ethically, and legally we’re bound to get them stable in the emergency room. I do think different rules apply there.”

In the end, every private practitioner will have to make his or her own decision on this question. Dr. Bock feels he made the right one. “Since instituting the policy, we have written 55 refund checks for people who had paid for a series of cosmetic procedures. We have no idea how many people were deterred from making appointments. We’ve had several negative online reviews and one woman who wrote a letter to the Medical Board of California complaining that we were discriminating against her,” he said. He added, however, that “we’ve also had several patients who commented favorably about the policy. I have no regrets about instituting the policy, and would do it again.”

Dr. Eastern practices dermatology and dermatologic surgery in Belleville, N.J. He is the author of numerous articles and textbook chapters, and is a longtime monthly columnist for Dermatology News. Write to him at dermnews@mdedge.com.

In June, Gerald Bock, MD, a dermatologist in central California, instituted a new office policy: He would not be seeing any more patients who remain unvaccinated against COVID-19 in his practice.

“[It is] the height of self-centered and irresponsible behavior,” he told me. “People who come in unvaccinated, when vaccination is widely available, are stating that their personal preferences are more important than their health, and are more important than any risk that they may expose their friends and family to, and also to any risk they might present to my staff and me. We have gone to considerable effort and expense to diminish any risk that visiting our office might entail. I see no reason why we should tolerate this.”

Other doctors appear to be following in his footsteps. There is no question that physicians have the right to choose their patients, just as patients are free to choose their doctors, but That is a complicated question without a clear answer. In a statement on whether physicians can decline unvaccinated patients, the American Medical Association continues to maintain that “in general” a physician may not “ethically turn a patient away based solely on the individual’s infectious disease status,” but does concede that “the decision to accept or decline a patient must balance the urgency of the individual patient’s need; the risk the patient may pose to other patients in the physician’s practice; and the need for the physician and staff, to be available to provide care in the future.”

Medical ethics experts have offered varying opinions. Daniel Wikler, PhD, professor of ethics and population health at the Harvard School of Public Health, Boston, wrote in an op-ed in the Washington Post that “ignorance or other personal failing” should not be factors in the evaluation of patients for health care. He argues that “doctors and hospitals are not in the blame and punishment business. Nor should they be. That doctors treat sinners and responsible citizens alike is a noble tradition.”

Timothy Hoff, professor of management, healthcare systems, and health policy at Northeastern University, Boston, maintains that, in nonemergency situations, physicians are legally able to refuse patients for a variety of reasons, provided they are not doing so because of some aspect of the patient’s race, gender, sexuality, or religion. However, in the same Northeastern University news release,Robert Baginski, MD, the director of interdisciplinary affairs for the department of medical sciences at Northeastern, cautions that it is vital for health authorities to continue urging the public to get vaccinated, but not at the expense of care.

Arthur L. Caplan, PhD, the head of the division of medical ethics at New York University, said in a Medscape commentary, that the decision to refuse to see patients who can vaccinate, but choose not to, is justifiable. “If you’re trying to protect yourself, your staff, or other patients, I think you do have the right to not take on somebody who won’t vaccinate,” he writes. “This is somewhat similar to when pediatricians do not accept a family if they won’t give their kids the state-required shots to go to school. That’s been happening for many years now.

“I also think it is morally justified if they won’t take your advice,” he continues. “If they won’t follow what you think is the best healthcare for them [such as getting vaccinated], there’s not much point in building that relationship.”

The situation is different in ED and hospital settings, however. “It’s a little harder to use unvaccinated status when someone really is at death’s door,” Dr. Caplan pointed out. “When someone comes in very sick, or whatever the reason, I think we have to take care of them ethically, and legally we’re bound to get them stable in the emergency room. I do think different rules apply there.”

In the end, every private practitioner will have to make his or her own decision on this question. Dr. Bock feels he made the right one. “Since instituting the policy, we have written 55 refund checks for people who had paid for a series of cosmetic procedures. We have no idea how many people were deterred from making appointments. We’ve had several negative online reviews and one woman who wrote a letter to the Medical Board of California complaining that we were discriminating against her,” he said. He added, however, that “we’ve also had several patients who commented favorably about the policy. I have no regrets about instituting the policy, and would do it again.”

Dr. Eastern practices dermatology and dermatologic surgery in Belleville, N.J. He is the author of numerous articles and textbook chapters, and is a longtime monthly columnist for Dermatology News. Write to him at dermnews@mdedge.com.

In June, Gerald Bock, MD, a dermatologist in central California, instituted a new office policy: He would not be seeing any more patients who remain unvaccinated against COVID-19 in his practice.

“[It is] the height of self-centered and irresponsible behavior,” he told me. “People who come in unvaccinated, when vaccination is widely available, are stating that their personal preferences are more important than their health, and are more important than any risk that they may expose their friends and family to, and also to any risk they might present to my staff and me. We have gone to considerable effort and expense to diminish any risk that visiting our office might entail. I see no reason why we should tolerate this.”

Other doctors appear to be following in his footsteps. There is no question that physicians have the right to choose their patients, just as patients are free to choose their doctors, but That is a complicated question without a clear answer. In a statement on whether physicians can decline unvaccinated patients, the American Medical Association continues to maintain that “in general” a physician may not “ethically turn a patient away based solely on the individual’s infectious disease status,” but does concede that “the decision to accept or decline a patient must balance the urgency of the individual patient’s need; the risk the patient may pose to other patients in the physician’s practice; and the need for the physician and staff, to be available to provide care in the future.”

Medical ethics experts have offered varying opinions. Daniel Wikler, PhD, professor of ethics and population health at the Harvard School of Public Health, Boston, wrote in an op-ed in the Washington Post that “ignorance or other personal failing” should not be factors in the evaluation of patients for health care. He argues that “doctors and hospitals are not in the blame and punishment business. Nor should they be. That doctors treat sinners and responsible citizens alike is a noble tradition.”

Timothy Hoff, professor of management, healthcare systems, and health policy at Northeastern University, Boston, maintains that, in nonemergency situations, physicians are legally able to refuse patients for a variety of reasons, provided they are not doing so because of some aspect of the patient’s race, gender, sexuality, or religion. However, in the same Northeastern University news release,Robert Baginski, MD, the director of interdisciplinary affairs for the department of medical sciences at Northeastern, cautions that it is vital for health authorities to continue urging the public to get vaccinated, but not at the expense of care.

Arthur L. Caplan, PhD, the head of the division of medical ethics at New York University, said in a Medscape commentary, that the decision to refuse to see patients who can vaccinate, but choose not to, is justifiable. “If you’re trying to protect yourself, your staff, or other patients, I think you do have the right to not take on somebody who won’t vaccinate,” he writes. “This is somewhat similar to when pediatricians do not accept a family if they won’t give their kids the state-required shots to go to school. That’s been happening for many years now.

“I also think it is morally justified if they won’t take your advice,” he continues. “If they won’t follow what you think is the best healthcare for them [such as getting vaccinated], there’s not much point in building that relationship.”

The situation is different in ED and hospital settings, however. “It’s a little harder to use unvaccinated status when someone really is at death’s door,” Dr. Caplan pointed out. “When someone comes in very sick, or whatever the reason, I think we have to take care of them ethically, and legally we’re bound to get them stable in the emergency room. I do think different rules apply there.”

In the end, every private practitioner will have to make his or her own decision on this question. Dr. Bock feels he made the right one. “Since instituting the policy, we have written 55 refund checks for people who had paid for a series of cosmetic procedures. We have no idea how many people were deterred from making appointments. We’ve had several negative online reviews and one woman who wrote a letter to the Medical Board of California complaining that we were discriminating against her,” he said. He added, however, that “we’ve also had several patients who commented favorably about the policy. I have no regrets about instituting the policy, and would do it again.”

Dr. Eastern practices dermatology and dermatologic surgery in Belleville, N.J. He is the author of numerous articles and textbook chapters, and is a longtime monthly columnist for Dermatology News. Write to him at dermnews@mdedge.com.

HEPA filters may clean SARS-CoV-2 from the air: Study

, researchers report in the preprint server medRxiv.

The journal Nature reported Oct. 6 that the research, which has not been peer-reviewed, suggests the filters may help reduce the risk of hospital-acquired SARS-CoV-2.

Researchers, led by intensivist Andrew Conway-Morris, MBChB, PhD, with the division of anaesthesia in the school of clinical medicine at University of Cambridge, United Kingdom, write that earlier experiments assessed air filters’ ability to remove inactive particles in carefully controlled environments, but it was unknown how they would work in a real-world setting.

Co-author Vilas Navapurkar, MBChB, an ICU physician at Addenbrooke’s Hospital in Cambridge, United Kingdom, said that hospitals have used portable air filters when their isolation facilities are full, but evidence was needed as to whether such filters are effective or whether they provide a false sense of security.

The researchers installed the filters in two fully occupied COVID-19 wards — a general ward and an ICU. They chose HEPA filters because they can catch extremely small particles.

The team collected air samples from the wards during a week when the air filters were on and 2 weeks when they were turned off, then compared results.

According to the study, “airborne SARS-CoV-2 was detected in the ward on all five days before activation of air/UV filtration, but on none of the five days when the air/UV filter was operational; SARS-CoV-2 was again detected on four out of five days when the filter was off.”

Airborne SARS-CoV-2 was not frequently detected in the ICU, even when the filters were off.

Cheap and easy

According to the Nature article, the authors suggest several potential explanations for this, “including slower viral replication at later stages of the disease.” Therefore, the authors say, filtering the virus from the air might be more important in general wards than in ICUs.

The filters significantly reduced the other microbial bioaerosols in both the ward (48 pathogens detected before filtration, 2 after, P = .05) and the ICU (45 pathogens detected before filtration, 5 after P = .05).

National Institute for Occupational Safety and Health (NIOSH) cyclonic aerosol samplers and PCR tests were used to detect airborne SARS-CoV-2 and other microbial bioaerosol.

David Fisman, MD, an epidemiologist at the University of Toronto, who was not involved in the research, said in the Nature article, “This study suggests that HEPA air cleaners, which remain little-used in Canadian hospitals, are a cheap and easy way to reduce risk from airborne pathogens.”This work was supported by a Wellcome senior research fellowship to co-author Stephen Baker. Conway Morris is supported by a Clinician Scientist Fellowship from the Medical Research Council. Dr. Navapurkar is the founder, director, and shareholder of Cambridge Infection Diagnostics Ltd. Dr. Conway-Morris and several co-authors are members of the Scientific Advisory Board of Cambridge Infection Diagnostics Ltd. Co-author Theodore Gouliouris has received a research grant from Shionogi and co-author R. Andres Floto has received research grants and/or consultancy payments from GSK, AstraZeneca, Chiesi, Shionogi, Insmed, and Thirty Technology.

A version of this article first appeared on Medscape.com.

, researchers report in the preprint server medRxiv.

The journal Nature reported Oct. 6 that the research, which has not been peer-reviewed, suggests the filters may help reduce the risk of hospital-acquired SARS-CoV-2.

Researchers, led by intensivist Andrew Conway-Morris, MBChB, PhD, with the division of anaesthesia in the school of clinical medicine at University of Cambridge, United Kingdom, write that earlier experiments assessed air filters’ ability to remove inactive particles in carefully controlled environments, but it was unknown how they would work in a real-world setting.

Co-author Vilas Navapurkar, MBChB, an ICU physician at Addenbrooke’s Hospital in Cambridge, United Kingdom, said that hospitals have used portable air filters when their isolation facilities are full, but evidence was needed as to whether such filters are effective or whether they provide a false sense of security.

The researchers installed the filters in two fully occupied COVID-19 wards — a general ward and an ICU. They chose HEPA filters because they can catch extremely small particles.

The team collected air samples from the wards during a week when the air filters were on and 2 weeks when they were turned off, then compared results.

According to the study, “airborne SARS-CoV-2 was detected in the ward on all five days before activation of air/UV filtration, but on none of the five days when the air/UV filter was operational; SARS-CoV-2 was again detected on four out of five days when the filter was off.”

Airborne SARS-CoV-2 was not frequently detected in the ICU, even when the filters were off.

Cheap and easy

According to the Nature article, the authors suggest several potential explanations for this, “including slower viral replication at later stages of the disease.” Therefore, the authors say, filtering the virus from the air might be more important in general wards than in ICUs.

The filters significantly reduced the other microbial bioaerosols in both the ward (48 pathogens detected before filtration, 2 after, P = .05) and the ICU (45 pathogens detected before filtration, 5 after P = .05).

National Institute for Occupational Safety and Health (NIOSH) cyclonic aerosol samplers and PCR tests were used to detect airborne SARS-CoV-2 and other microbial bioaerosol.

David Fisman, MD, an epidemiologist at the University of Toronto, who was not involved in the research, said in the Nature article, “This study suggests that HEPA air cleaners, which remain little-used in Canadian hospitals, are a cheap and easy way to reduce risk from airborne pathogens.”This work was supported by a Wellcome senior research fellowship to co-author Stephen Baker. Conway Morris is supported by a Clinician Scientist Fellowship from the Medical Research Council. Dr. Navapurkar is the founder, director, and shareholder of Cambridge Infection Diagnostics Ltd. Dr. Conway-Morris and several co-authors are members of the Scientific Advisory Board of Cambridge Infection Diagnostics Ltd. Co-author Theodore Gouliouris has received a research grant from Shionogi and co-author R. Andres Floto has received research grants and/or consultancy payments from GSK, AstraZeneca, Chiesi, Shionogi, Insmed, and Thirty Technology.

A version of this article first appeared on Medscape.com.

, researchers report in the preprint server medRxiv.

The journal Nature reported Oct. 6 that the research, which has not been peer-reviewed, suggests the filters may help reduce the risk of hospital-acquired SARS-CoV-2.

Researchers, led by intensivist Andrew Conway-Morris, MBChB, PhD, with the division of anaesthesia in the school of clinical medicine at University of Cambridge, United Kingdom, write that earlier experiments assessed air filters’ ability to remove inactive particles in carefully controlled environments, but it was unknown how they would work in a real-world setting.

Co-author Vilas Navapurkar, MBChB, an ICU physician at Addenbrooke’s Hospital in Cambridge, United Kingdom, said that hospitals have used portable air filters when their isolation facilities are full, but evidence was needed as to whether such filters are effective or whether they provide a false sense of security.

The researchers installed the filters in two fully occupied COVID-19 wards — a general ward and an ICU. They chose HEPA filters because they can catch extremely small particles.

The team collected air samples from the wards during a week when the air filters were on and 2 weeks when they were turned off, then compared results.

According to the study, “airborne SARS-CoV-2 was detected in the ward on all five days before activation of air/UV filtration, but on none of the five days when the air/UV filter was operational; SARS-CoV-2 was again detected on four out of five days when the filter was off.”

Airborne SARS-CoV-2 was not frequently detected in the ICU, even when the filters were off.

Cheap and easy

According to the Nature article, the authors suggest several potential explanations for this, “including slower viral replication at later stages of the disease.” Therefore, the authors say, filtering the virus from the air might be more important in general wards than in ICUs.

The filters significantly reduced the other microbial bioaerosols in both the ward (48 pathogens detected before filtration, 2 after, P = .05) and the ICU (45 pathogens detected before filtration, 5 after P = .05).

National Institute for Occupational Safety and Health (NIOSH) cyclonic aerosol samplers and PCR tests were used to detect airborne SARS-CoV-2 and other microbial bioaerosol.

David Fisman, MD, an epidemiologist at the University of Toronto, who was not involved in the research, said in the Nature article, “This study suggests that HEPA air cleaners, which remain little-used in Canadian hospitals, are a cheap and easy way to reduce risk from airborne pathogens.”This work was supported by a Wellcome senior research fellowship to co-author Stephen Baker. Conway Morris is supported by a Clinician Scientist Fellowship from the Medical Research Council. Dr. Navapurkar is the founder, director, and shareholder of Cambridge Infection Diagnostics Ltd. Dr. Conway-Morris and several co-authors are members of the Scientific Advisory Board of Cambridge Infection Diagnostics Ltd. Co-author Theodore Gouliouris has received a research grant from Shionogi and co-author R. Andres Floto has received research grants and/or consultancy payments from GSK, AstraZeneca, Chiesi, Shionogi, Insmed, and Thirty Technology.

A version of this article first appeared on Medscape.com.

Adolescents who exercised after a concussion recovered faster in RCT

After a concussion, resuming aerobic exercise relatively early on – at an intensity that does not worsen symptoms – may help young athletes recover sooner, compared with stretching, a randomized controlled trial (RCT) shows.

The study adds to emerging evidence that clinicians should prescribe exercise, rather than strict rest, to facilitate concussion recovery, researchers said.

Tamara McLeod, PhD, ATC, professor and director of athletic training programs at A.T. Still University in Mesa, Ariz., hopes the findings help clinicians see that “this is an approach that should be taken.”

“Too often with concussion, patients are given a laundry list of things they are NOT allowed to do,” including sports, school, and social activities, said Dr. McLeod, who was not involved in the study.

The research, published in The Lancet Child & Adolescent Health, largely replicates the findings of a prior trial while addressing limitations of the previous study’s design, researchers said.

For the trial, John J. Leddy, MD, with the State University of New York at Buffalo and colleagues recruited 118 male and female adolescent athletes aged 13-18 years who had had a sport-related concussion in the past 10 days. Investigators at three community and hospital-affiliated sports medicine concussion centers in the United States randomly assigned the athletes to individualized subsymptom-threshold aerobic exercise (61 participants) or stretching exercise (57 participants) at least 20 minutes per day for up to 4 weeks. Aerobic exercise included walking, jogging, or stationary cycling at home.

“It is important that the general clinician community appreciates that prolonged rest and avoidance of physical activity until spontaneous symptom resolution is no longer an acceptable approach to caring for adolescents with concussion,” Dr. Leddy and coauthors said.

The investigators improved on the “the scientific rigor of their previous RCT by including intention-to-treat and per-protocol analyses, daily symptom reporting, objective exercise adherence measurements, and greater heterogeneity of concussion severity,” said Carolyn A. Emery, PhD, and Jonathan Smirl, PhD, both with the University of Calgary (Alta.), in a related commentary. The new study is the first to show that early targeted heart rate subsymptom-threshold aerobic exercise, relative to stretching, shortened recovery time within 4 weeks after sport-related concussion (hazard ratio, 0.52) when controlling for sex, study site, and average daily exercise time, Dr. Emery and Dr. Smirl said.

A larger proportion of athletes assigned to stretching did not recover by 4 weeks, compared with those assigned to aerobic exercise (32% vs. 21%). The median time to full recovery was longer for the stretching group than for the aerobic exercise group (19 days vs. 14 days).

Among athletes who adhered to their assigned regimens, the differences were more pronounced: The median recovery time was 21 days for the stretching group, compared with 12 days for the aerobic exercise group. The rate of postconcussion symptoms beyond 28 days was 9% in the aerobic exercise group versus 31% in the stretching group, among adherent participants.

More research is needed to establish the efficacy of postconcussion aerobic exercise in adults and for nonsport injury, the researchers noted. Possible mechanisms underlying aerobic exercise’s benefits could include increased parasympathetic autonomic tone, improved cerebral blood flow regulation, or enhanced neuron repair, they suggested.

The right amount and timing of exercise, and doing so at an intensity that does not exacerbate symptoms, may be key. Other research has suggested that too much exercise, too soon may delay recovery, Dr. Emery said in an interview. “But there is now a lot of evidence to support low and moderate levels of physical activity to expedite recovery,” she said.

The study was funded by the American Medical Society for Sports Medicine. The study and commentary authors and Dr. McLeod had no disclosures.

After a concussion, resuming aerobic exercise relatively early on – at an intensity that does not worsen symptoms – may help young athletes recover sooner, compared with stretching, a randomized controlled trial (RCT) shows.

The study adds to emerging evidence that clinicians should prescribe exercise, rather than strict rest, to facilitate concussion recovery, researchers said.