User login

Cutis is a peer-reviewed clinical journal for the dermatologist, allergist, and general practitioner published monthly since 1965. Concise clinical articles present the practical side of dermatology, helping physicians to improve patient care. Cutis is referenced in Index Medicus/MEDLINE and is written and edited by industry leaders.

ass lick

assault rifle

balls

ballsac

black jack

bleach

Boko Haram

bondage

causas

cheap

child abuse

cocaine

compulsive behaviors

cost of miracles

cunt

Daech

display network stats

drug paraphernalia

explosion

fart

fda and death

fda AND warn

fda AND warning

fda AND warns

feom

fuck

gambling

gfc

gun

human trafficking

humira AND expensive

illegal

ISIL

ISIS

Islamic caliphate

Islamic state

madvocate

masturbation

mixed martial arts

MMA

molestation

national rifle association

NRA

nsfw

nuccitelli

pedophile

pedophilia

poker

porn

porn

pornography

psychedelic drug

recreational drug

sex slave rings

shit

slot machine

snort

substance abuse

terrorism

terrorist

texarkana

Texas hold 'em

UFC

section[contains(@class, 'nav-hidden')]

section[contains(@class, 'nav-hidden active')

A peer-reviewed, indexed journal for dermatologists with original research, image quizzes, cases and reviews, and columns.

Generalized Fixed Drug Eruptions Require Urgent Care: A Case Series

Recognizing cutaneous drug eruptions is important for treatment and prevention of recurrence. Fixed drug eruptions (FDEs) typically are harmless but can have major negative cosmetic consequences for patients. In its more severe forms, patients are at risk for widespread epithelial necrosis with accompanying complications. We report 1 patient with generalized FDE and 2 with generalized bullous FDE. We also discuss the recognition and treatment of the condition. Two patients previously had been diagnosed with systemic lupus erythematosus (SLE).

Case Series

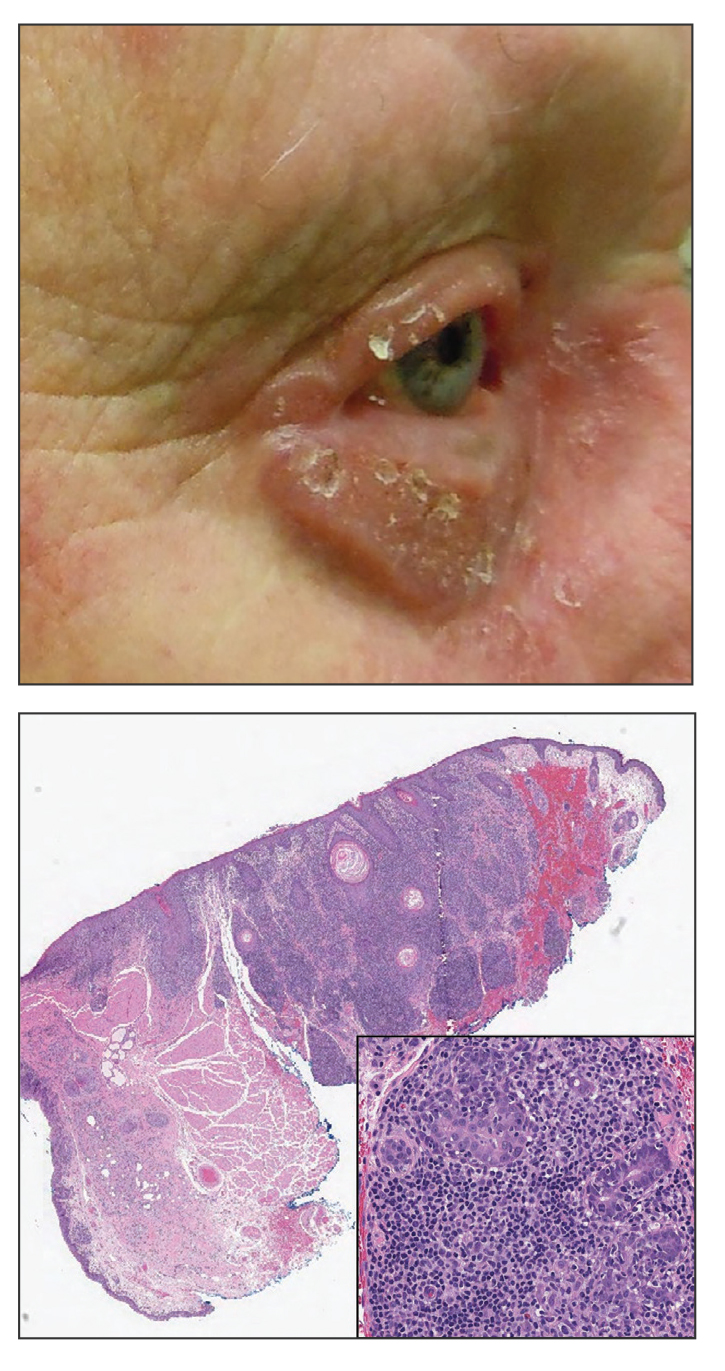

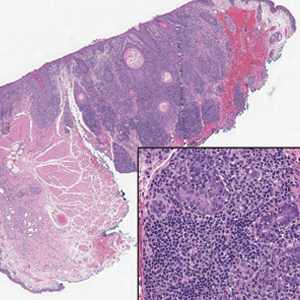

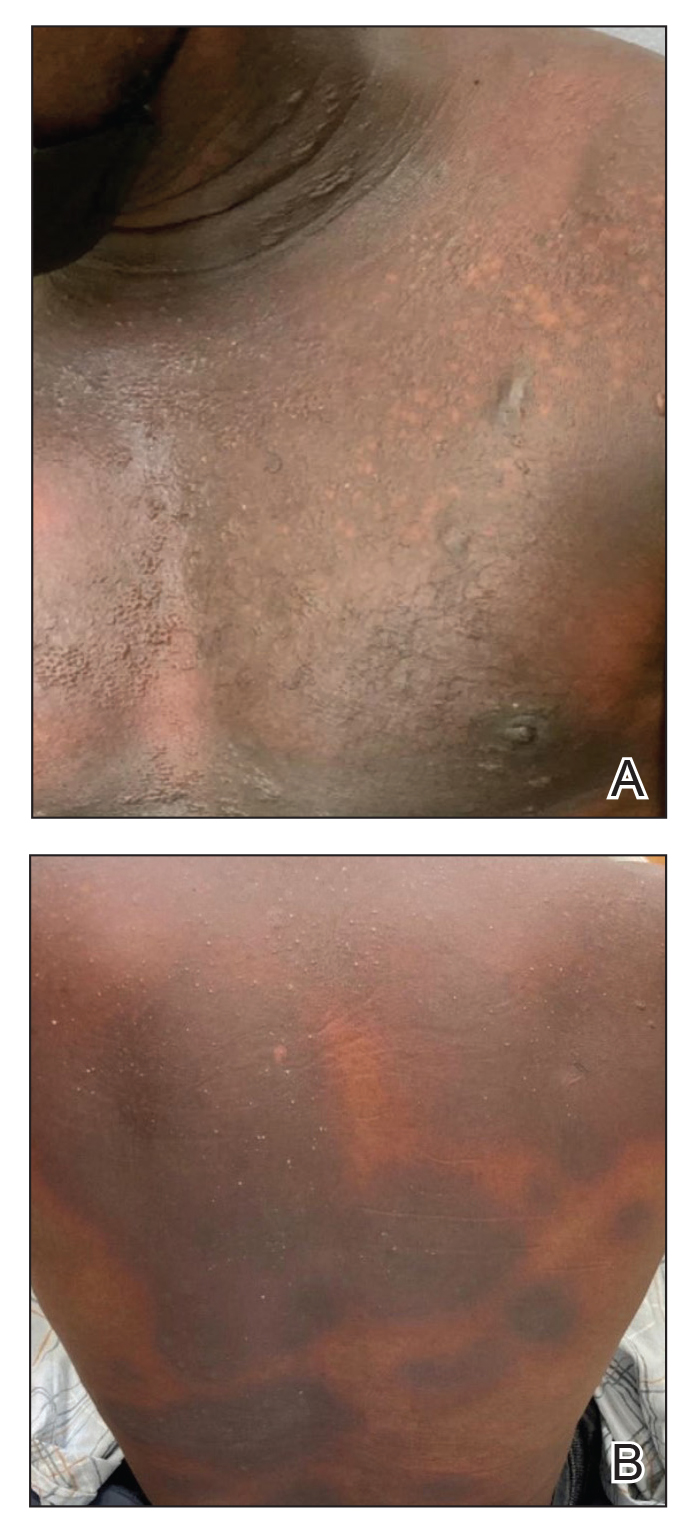

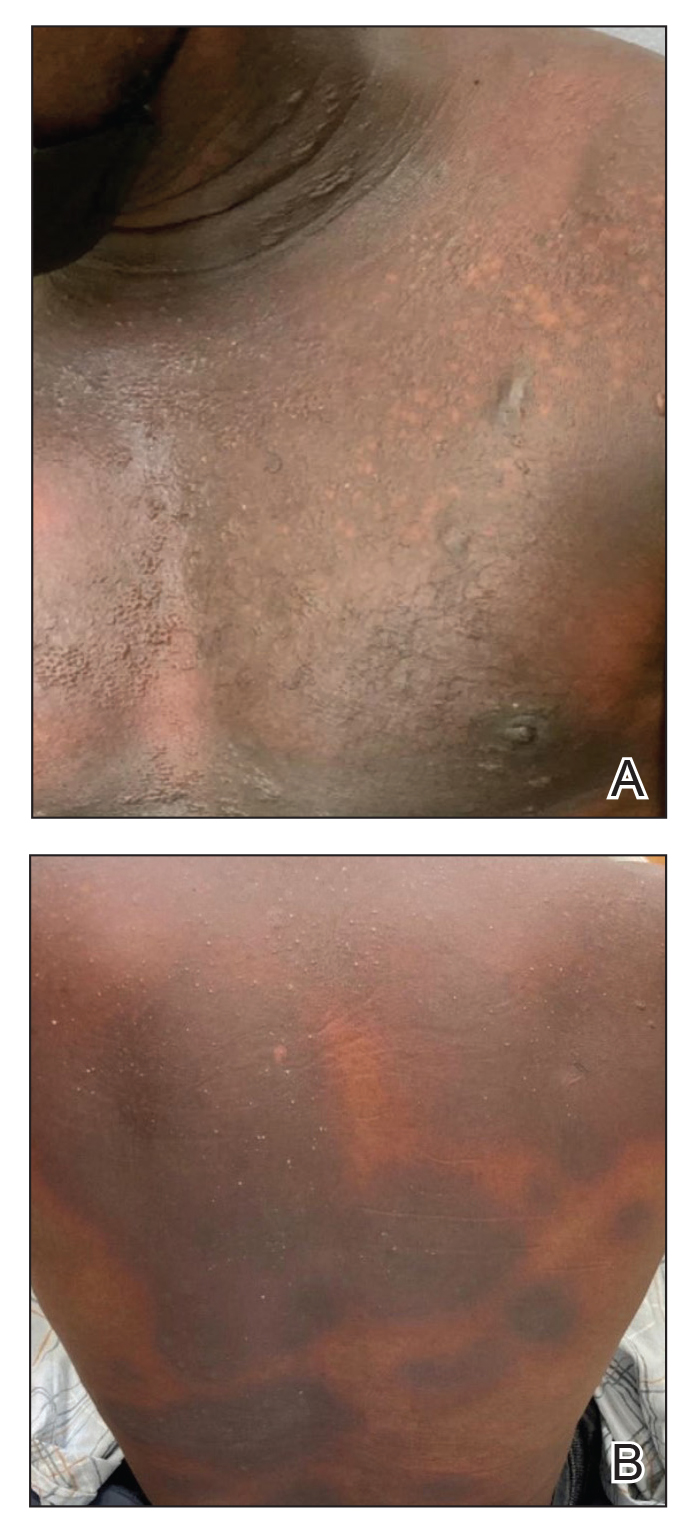

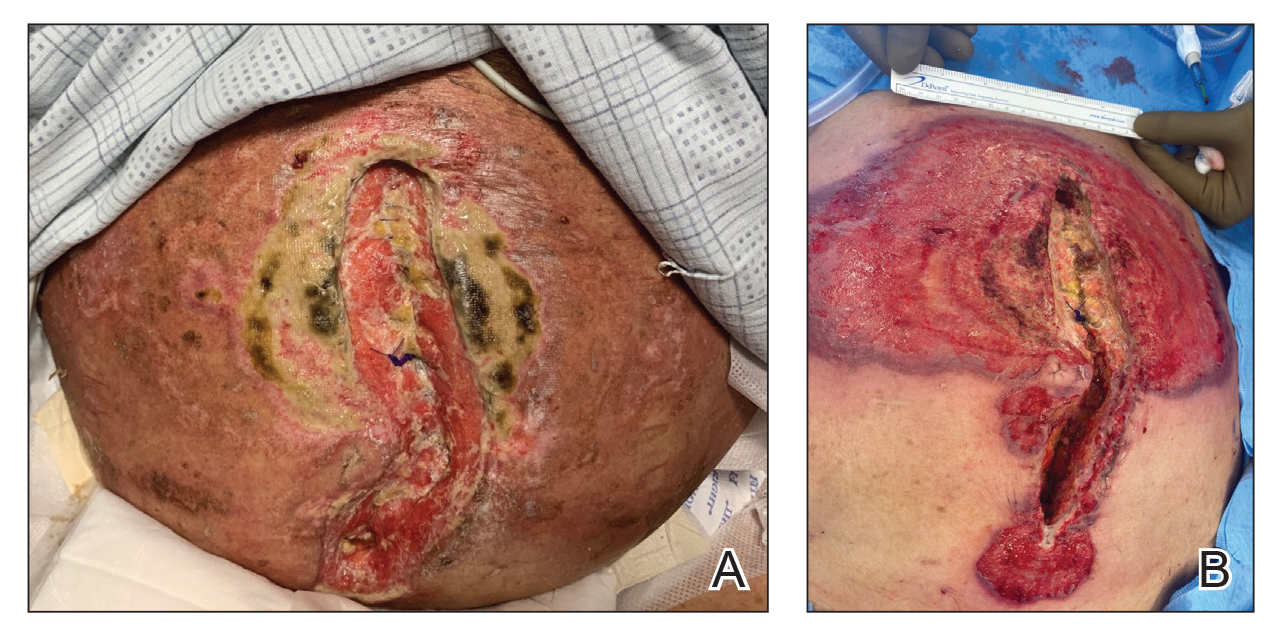

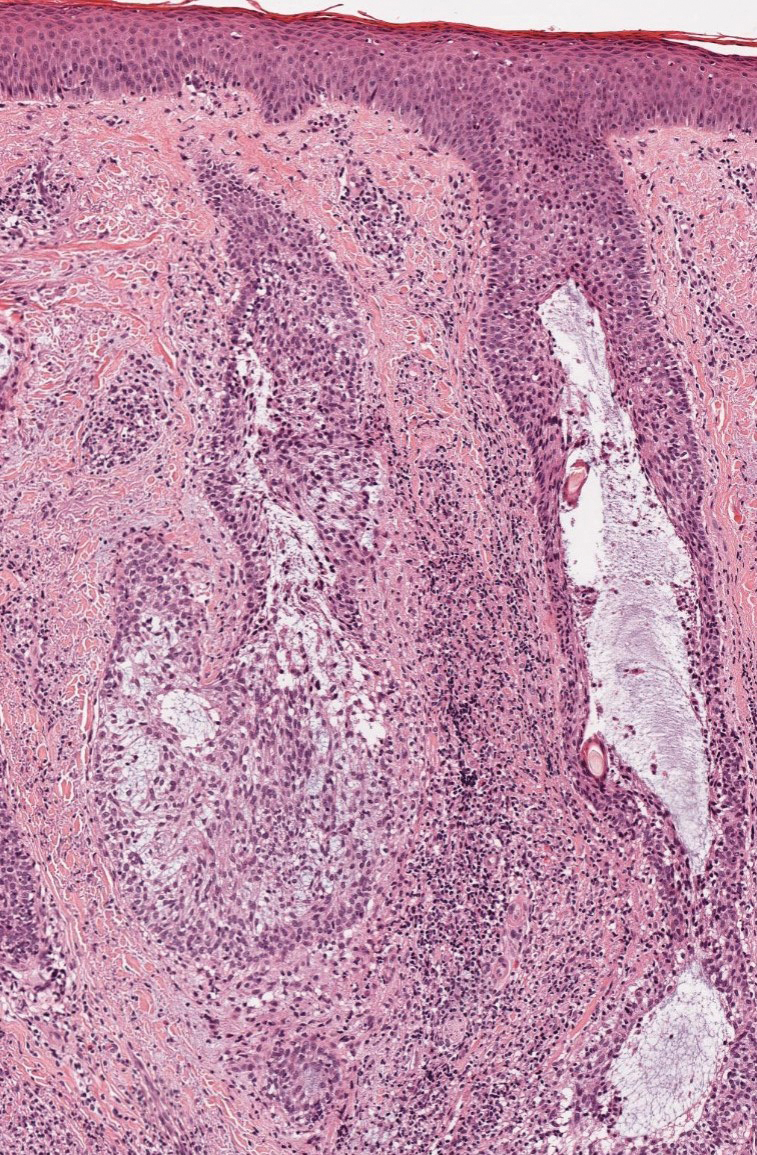

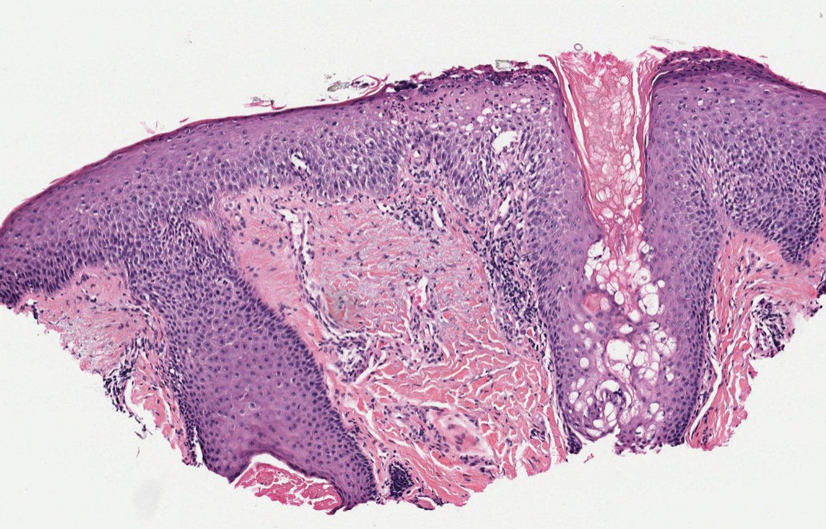

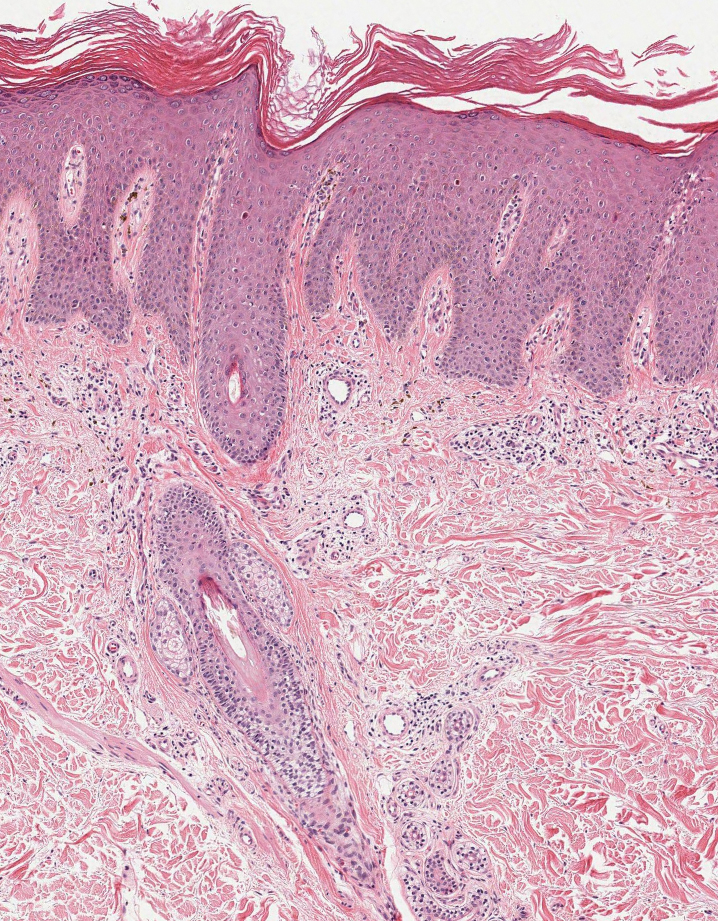

Patient 1—A 60-year-old woman presented to dermatology with a rash on the trunk and groin folds of 4 days’ duration. She had a history of SLE and cutaneous lupus treated with hydroxychloroquine 200 mg twice daily and topical corticosteroids. She had started sulfamethoxazole-trimethoprim for a urinary tract infection with a rash appearing 1 day later. She reported burning skin pain with progression to blisters that “sloughed” off. She denied any known history of allergy to sulfa drugs. Prior to evaluation by dermatology, she visited an urgent care facility and was prescribed hydroxyzine and intramuscular corticosteroids. At presentation to dermatology 3 days after taking sulfamethoxazole-trimethoprim, she had annular flaccid bullae and superficial erosions with dusky borders on the right posterior thigh, right side of the chest, left inframammary fold, and right inguinal fold (Figure 1). She had no ocular, oral, or vaginal erosions. A diagnosis of generalized bullous FDE was favored over erythema multiforme or Stevens-Johnson syndrome (SJS)/toxic epidermal necrolysis (TEN). Shave biopsies from lesions on the right posterior thigh and right inguinal fold demonstrated interface dermatitis with epidermal necrosis, pigment incontinence, and numerous eosinophils. Direct immunofluorescence of the perilesional skin was negative for immunoprotein deposition. These findings were consistent with the clinical impression of generalized bullous FDE. Prior to receiving the histopathology report, the patient was initiated on a regimen of cyclosporine 5 mg/kg/d in the setting of normal renal function and followed until the eruption resolved completely. Cyclosporine was tapered at 2 weeks and discontinued at 3 weeks.

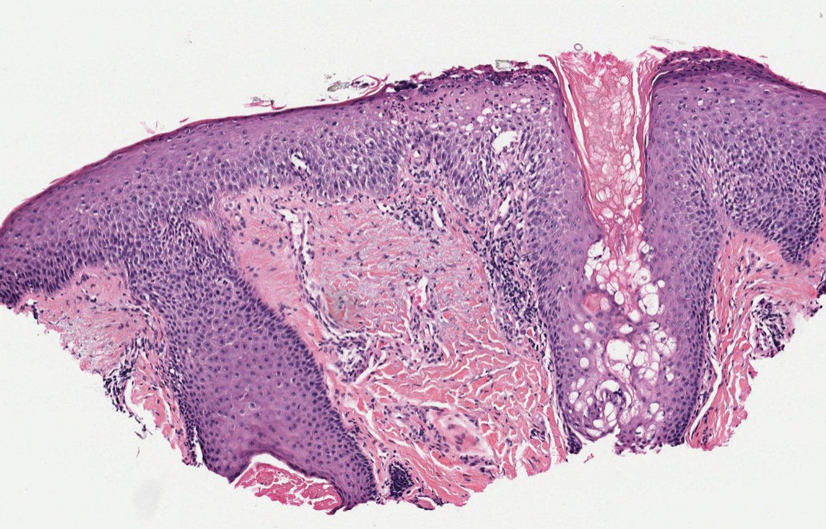

Patient 2—A 32-year-old woman presented for follow-up management of discoid lupus erythematosus. She had a history of systemic and cutaneous lupus, juvenile rheumatoid arthritis, and mixed connective tissue disease managed with prednisone, hydroxychloroquine, azathioprine, and belimumab. Physical examination revealed scarring alopecia with dyspigmentation and active inflammation consistent with uncontrolled cutaneous lupus. However, she also had oval-shaped hyperpigmented patches over the left breast, clavicle, and anterior chest consistent with a generalized FDE (Figure 2). The patient did not recall a history of similar lesions and could not identify a possible trigger. She was counseled on possible culprits and advised to avoid unnecessary medications. She had an unremarkable clinical course; therefore, no further intervention was necessary.

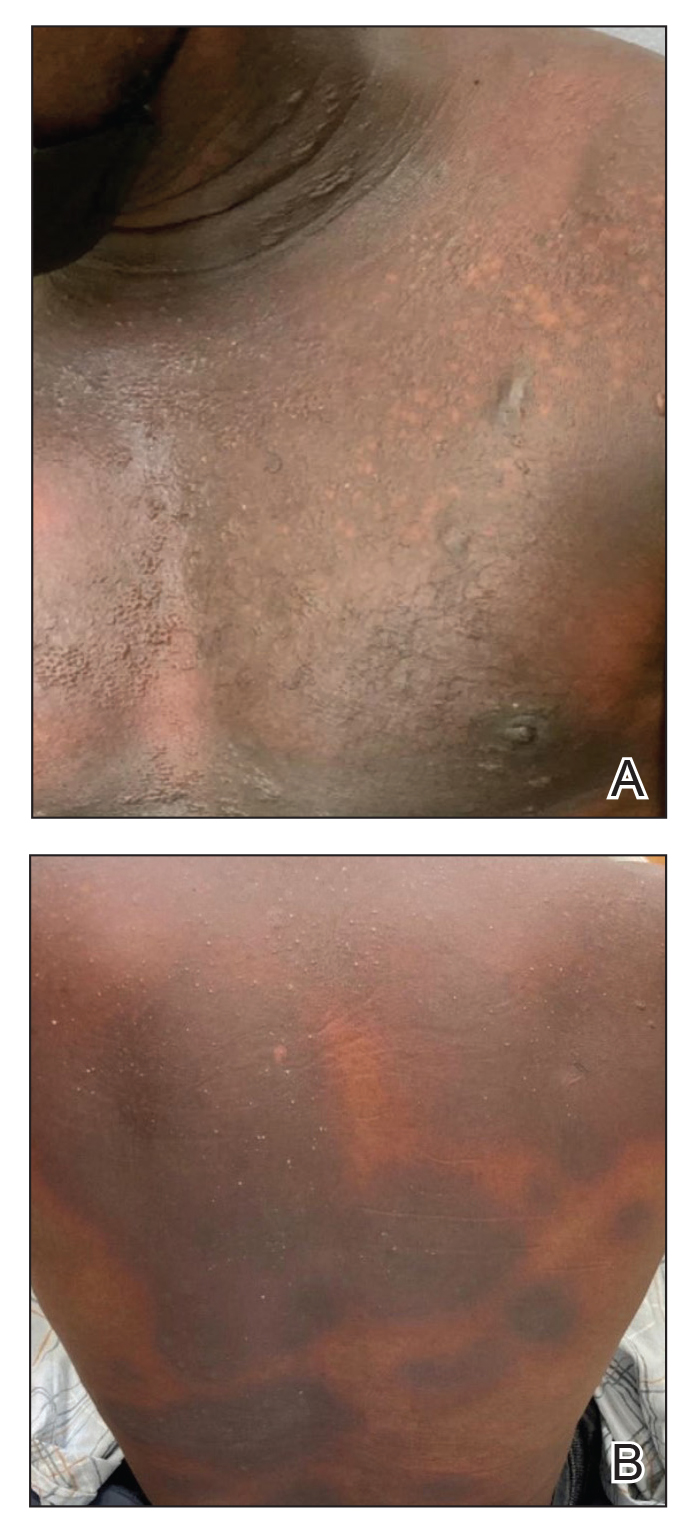

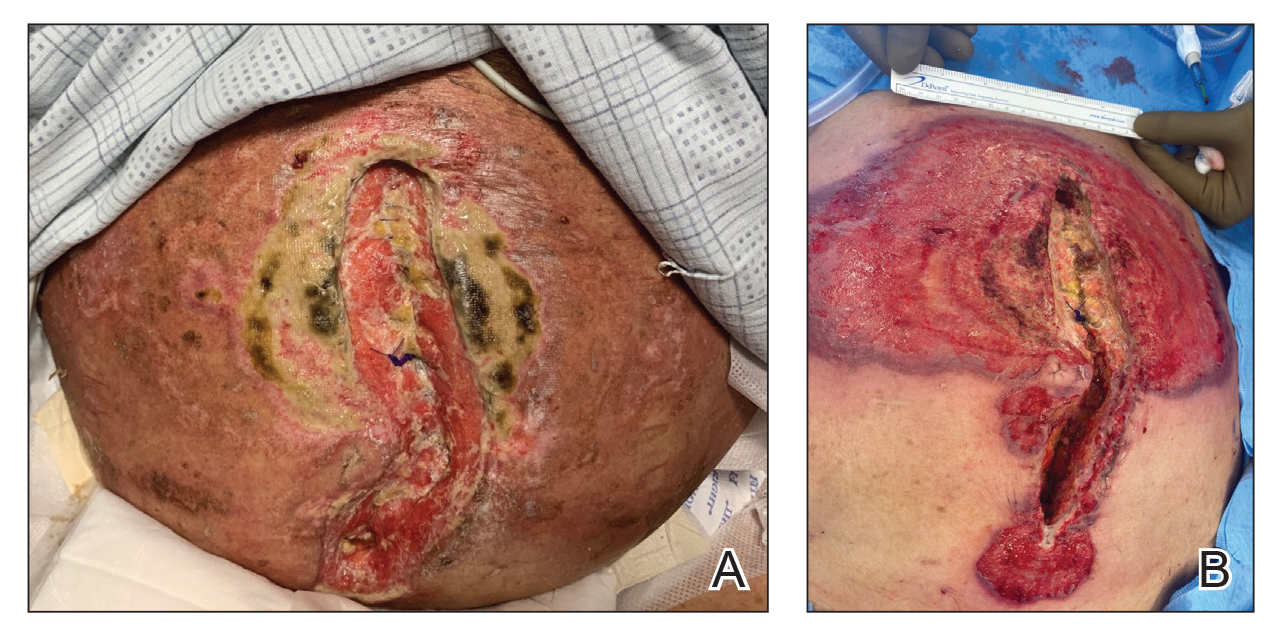

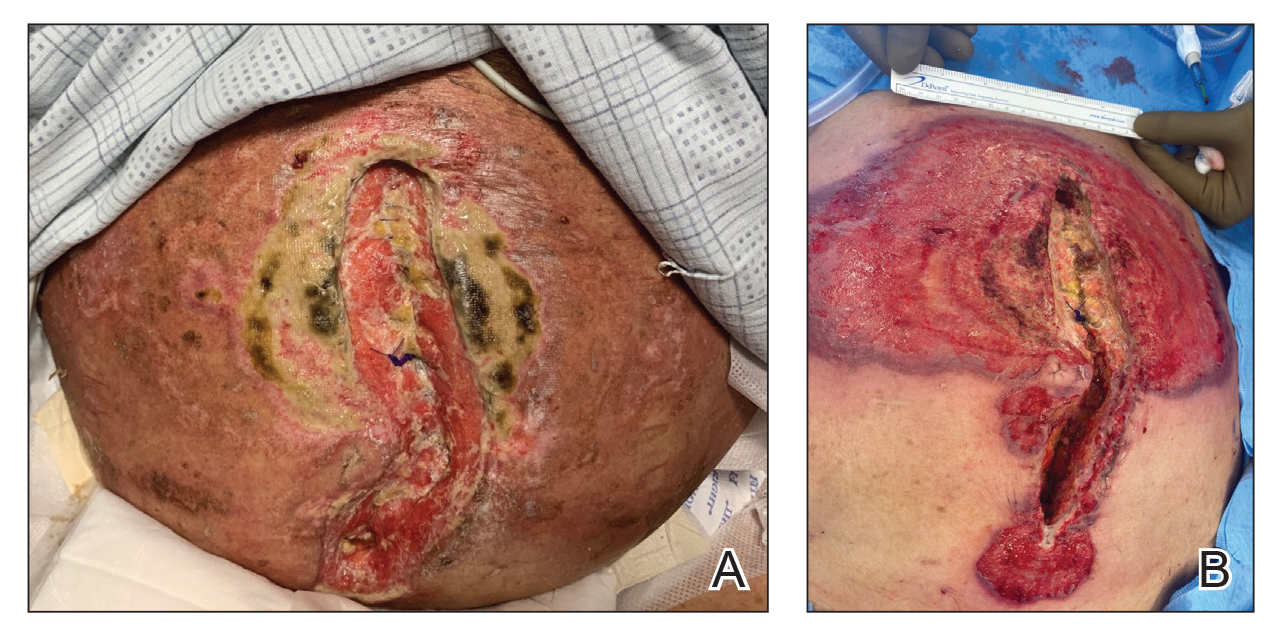

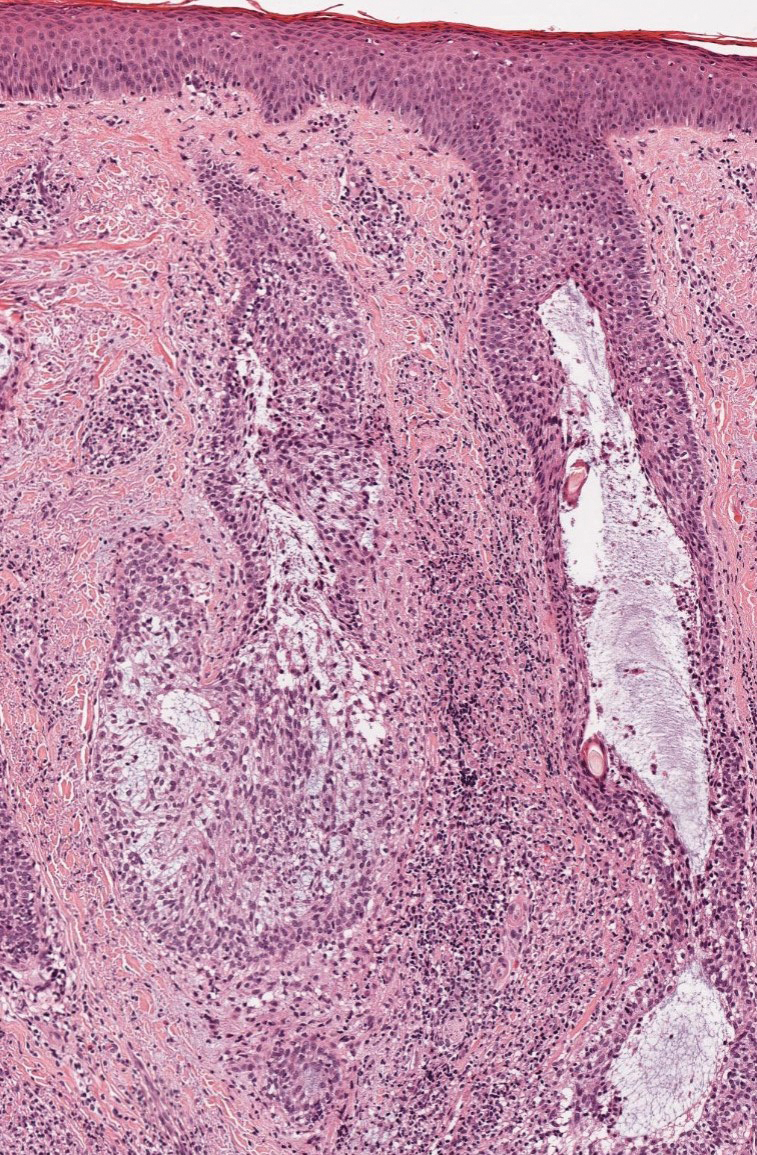

Patient 3—A 33-year-old man presented to the emergency department with a painful rash on the chest and back of 2 days’ duration that began 1 hour after taking naproxen (dosage unknown) for back pain. He had no notable medical history. The patient stated that the rash had slowly worsened and started to develop blisters. He visited an urgent care facility 1 day prior to the current presentation and was started on a 5-day course of prednisone 40 mg daily; the first 2 doses did not help. He denied any mucosal involvement apart from a tender lesion on the penis. He reported a history of an allergic reaction to penicillin. Physical examination revealed extensive dusky violaceous annular plaques with erythematous borders across the anterior and posterior trunk (Figure 3). Multiple flaccid bullae developed within these plaques, involving 15% of the body surface area. He was diagnosed with generalized bullous FDE based on the clinical history and histopathology. He was admitted to the burn intensive care unit and treated with cyclosporine 3 mg/kg/d with subsequent resolution of the eruption.

Comment

Presentation of FDEs—A fixed drug eruption manifests with 1 or more well-demarcated, red or violaceous, annular patches that resolve with postinflammatory hyperpigmentation; it occasionally may manifest with bullae. Initial eruptions may occur up to 2 weeks following medication exposure, but recurrent eruptions usually happen within minutes to hours later. They often are in the same location as prior lesions. A fixed drug eruption can be solitary, scattered, or generalized; a generalized FDE typically demonstrates multiple bilateral lesions that may itch, burn, or cause no symptoms. Patients can experience an FDE at any age, though the median age is reported as 35 to 60 years of age.1 A fixed drug eruption usually occurs after ingestion of oral medications, though there have been a few reports with iodinated contrast.2 Well-known culprits include antibiotics (eg, sulfamethoxazole-trimethoprim, tetracyclines, penicillins/cephalosporins, quinolones, dapsone), nonsteroidal anti-inflammatory drugs, acetaminophen (eg, paracetamol), barbiturates, antimalarials, and anticonvulsants. It also can occur with vaccines or with certain foods (fixed food eruption).3,4 Clinicians may try an oral drug challenge to identify the cause of an FDE, but in patients with a history of a generalized FDE, the risk for developing an increasingly severe reaction with repeated exposure to the medication is too high.5

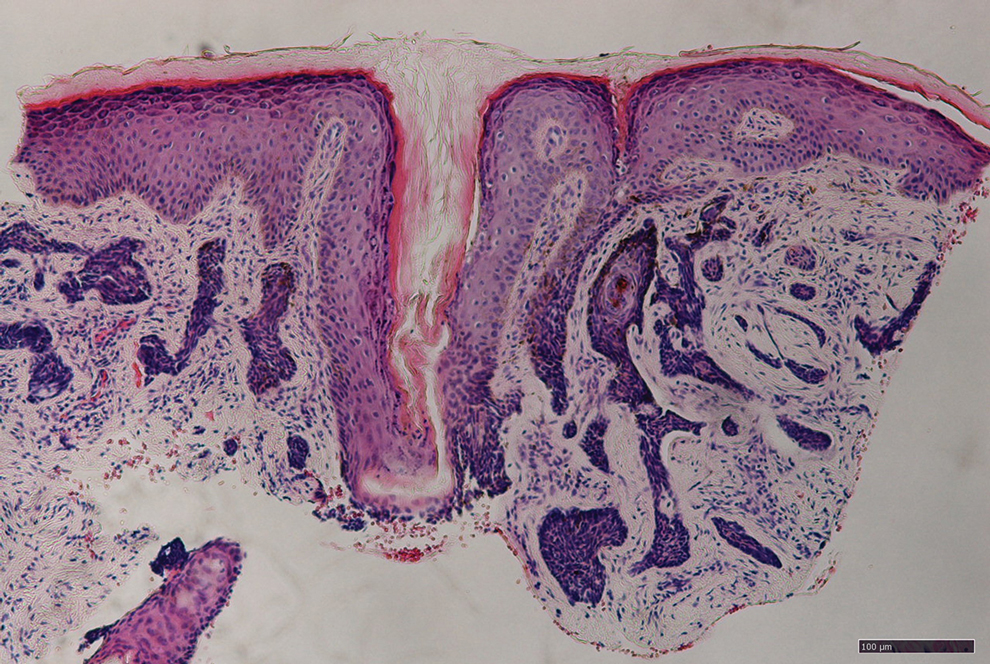

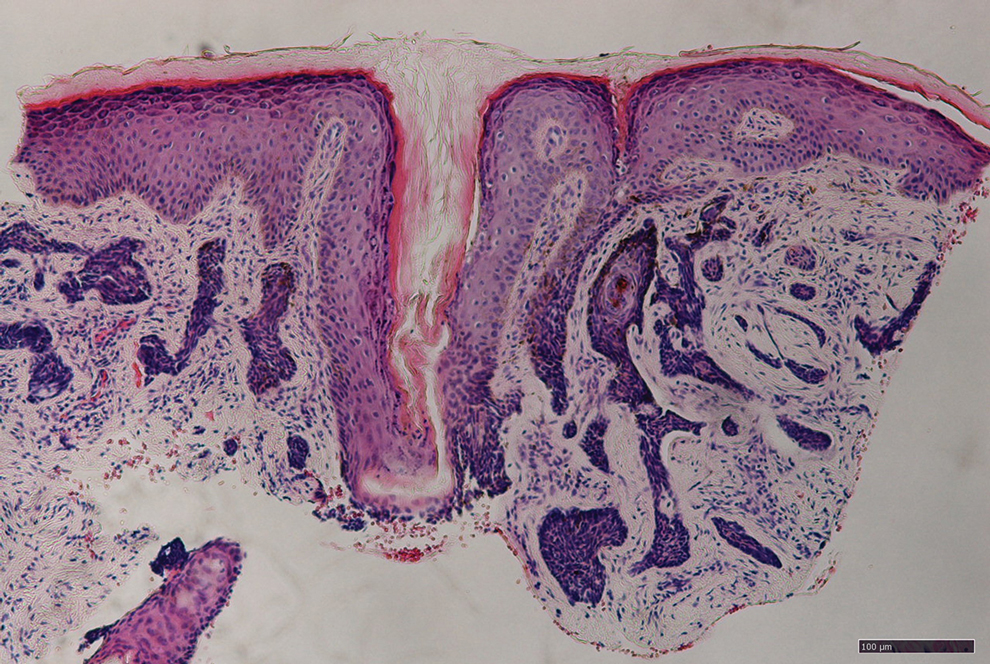

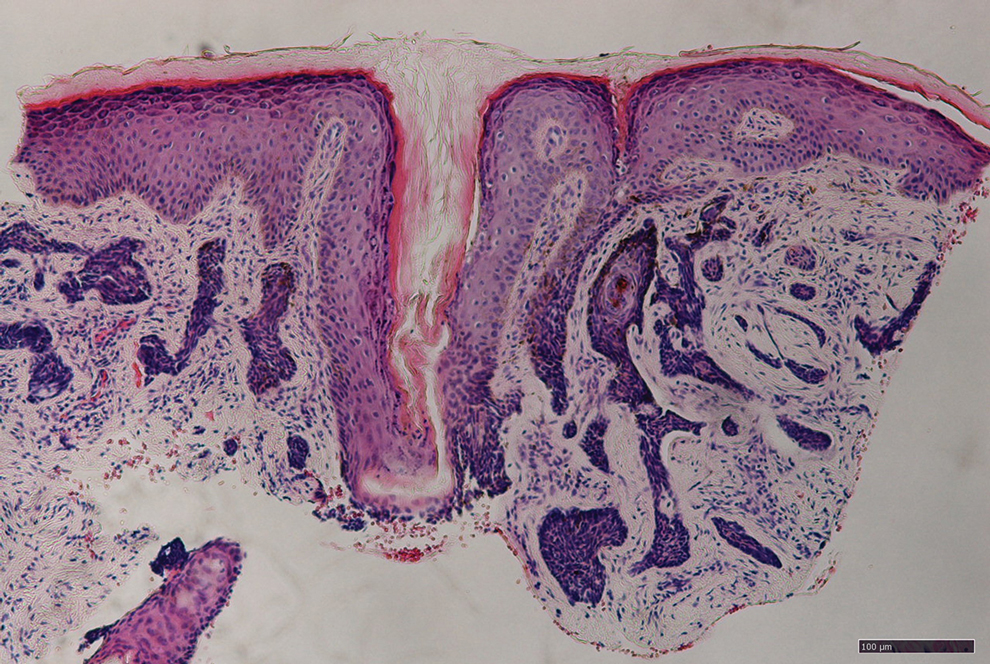

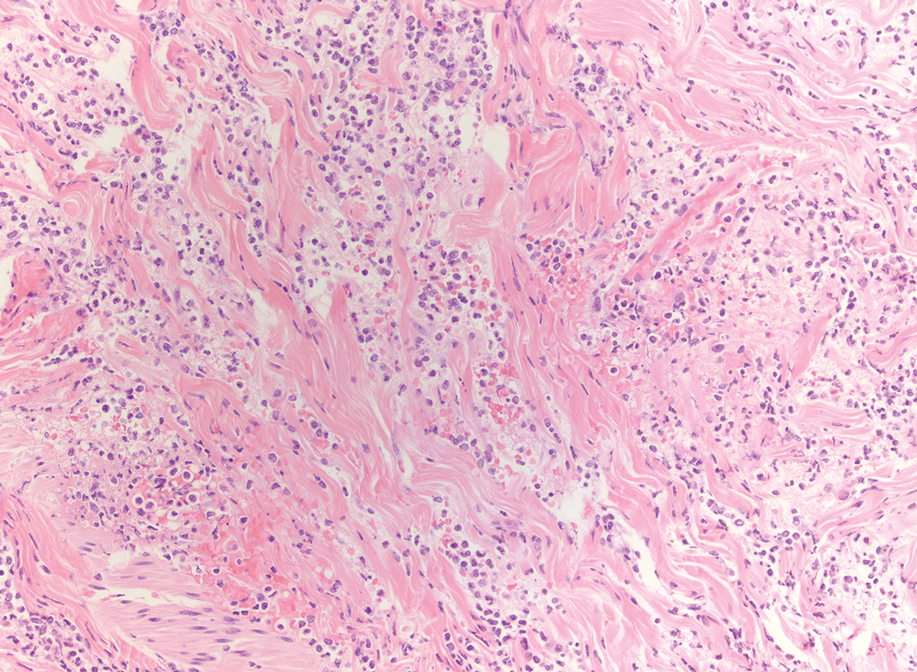

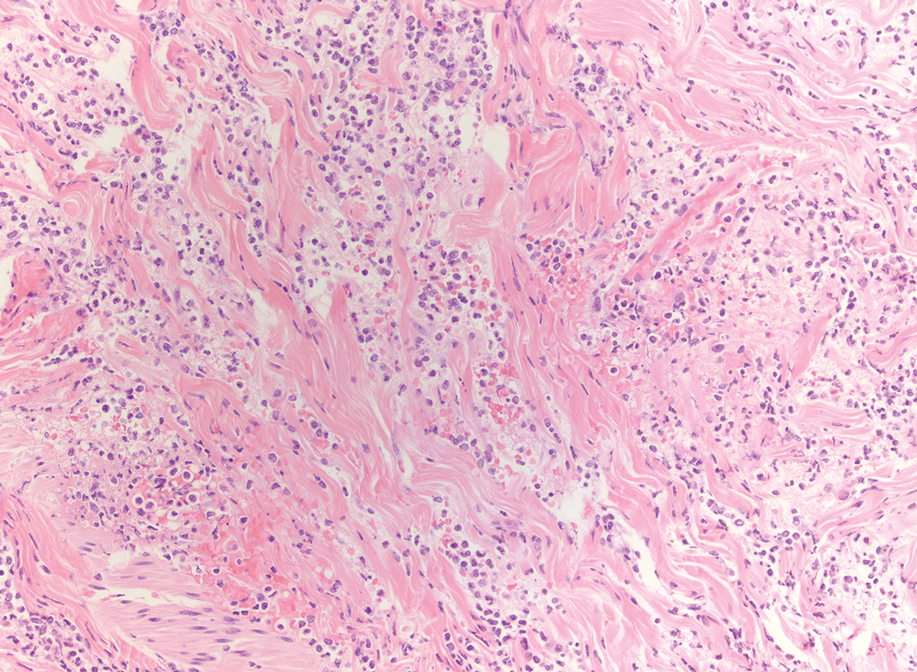

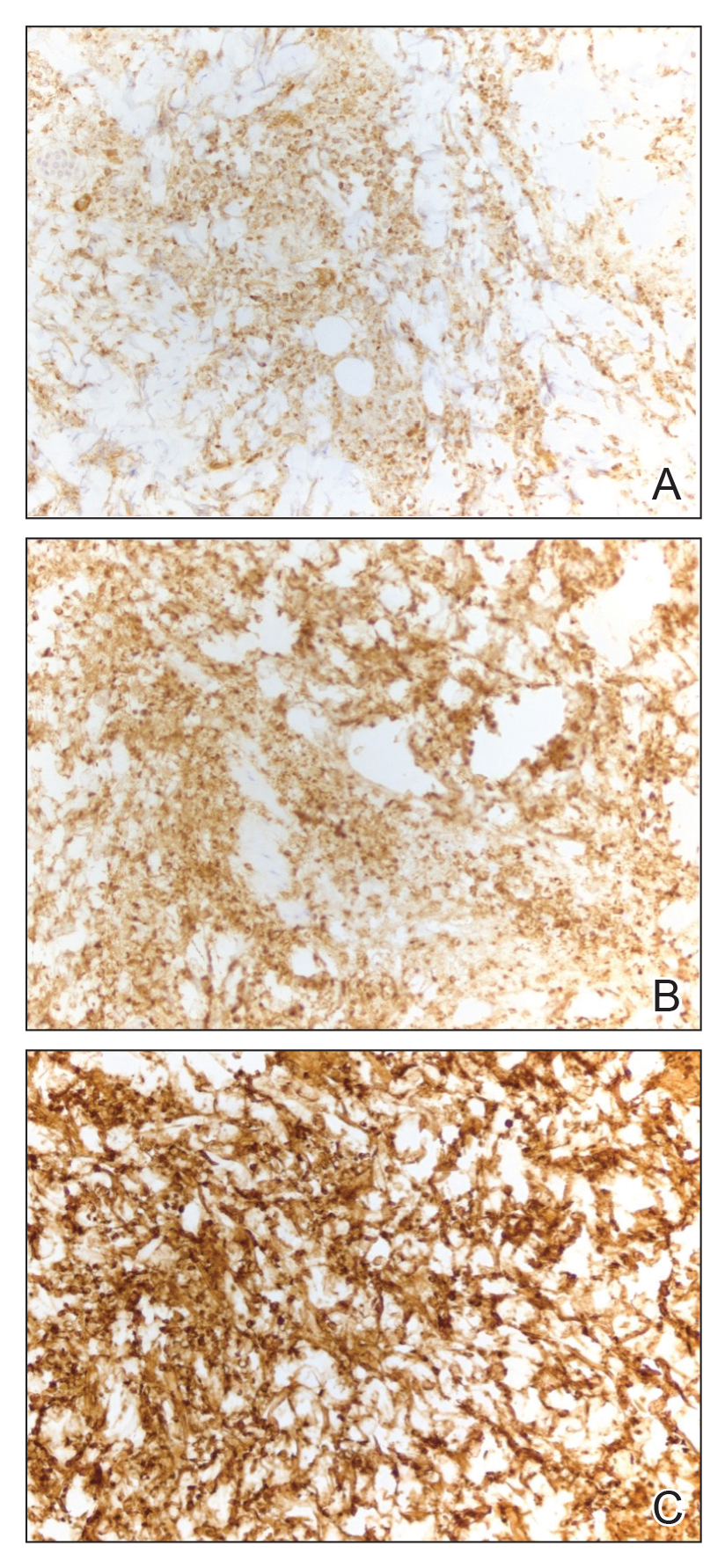

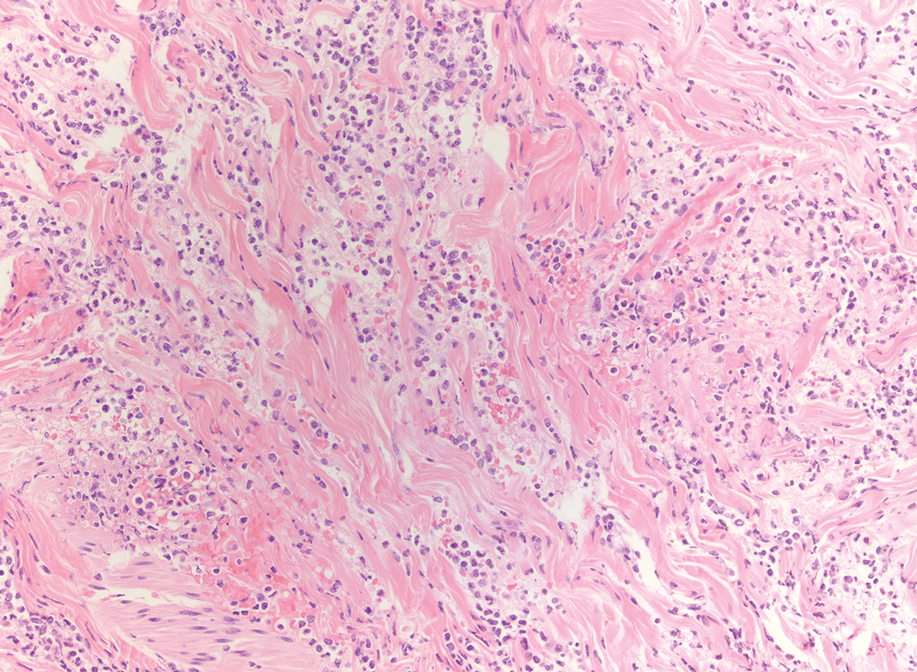

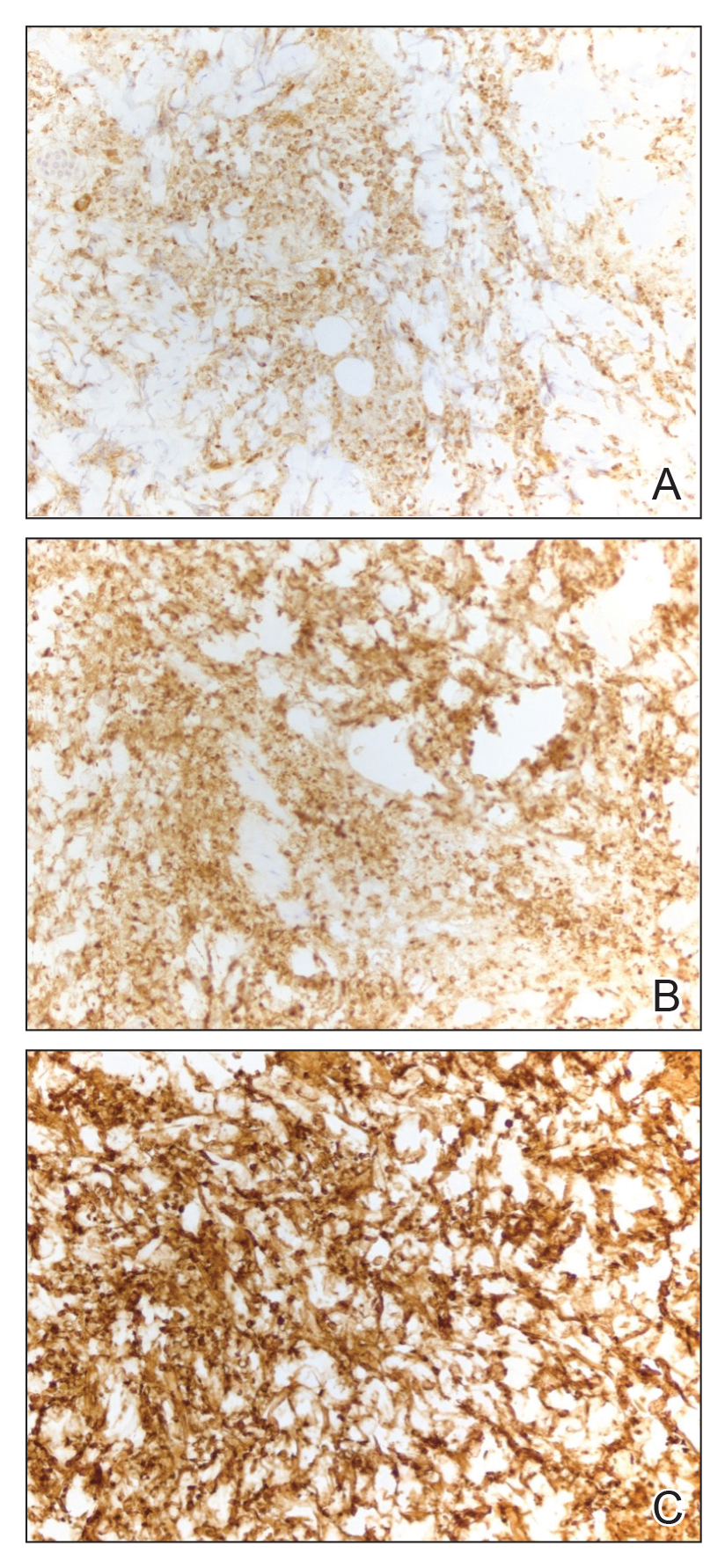

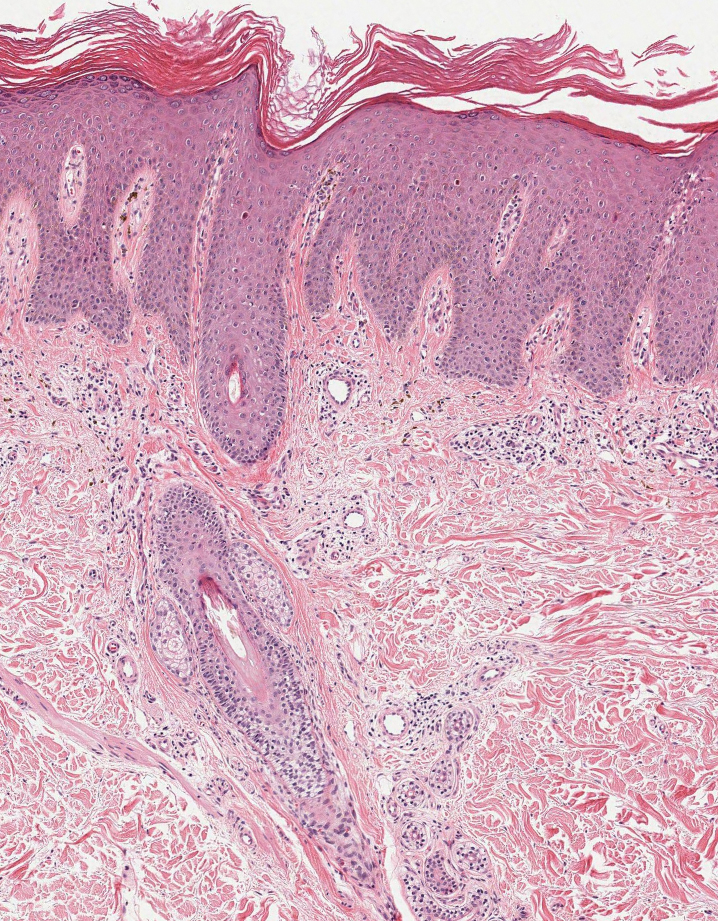

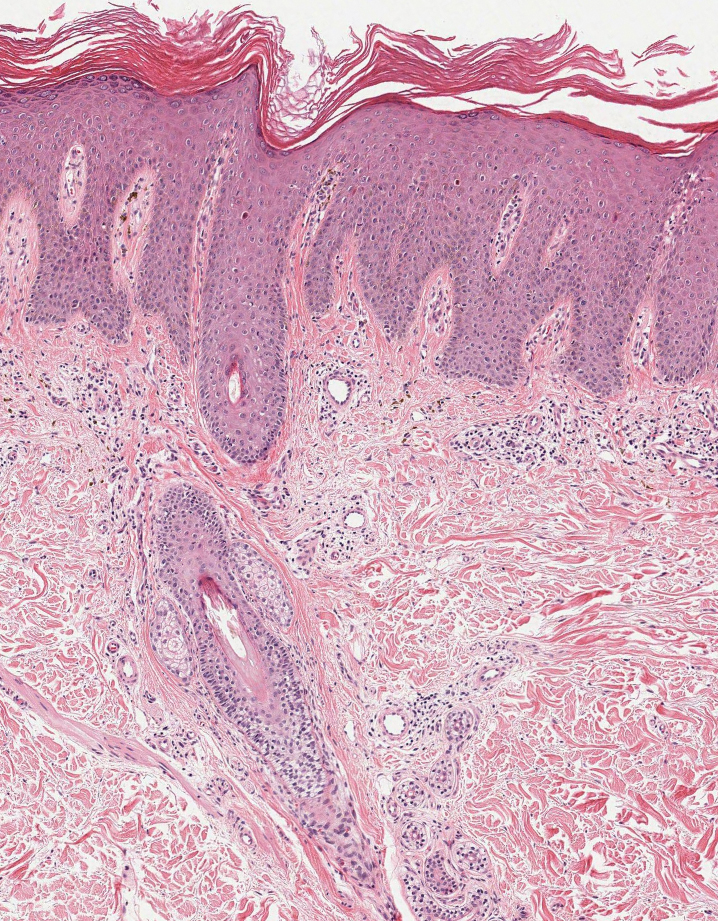

Histopathology—Patch testing at the site of prior eruption with suspected drug culprits may be useful.6 Histopathology of FDE typically demonstrates vacuolar changes at the dermoepidermal junction with a lichenoid lymphocytic infiltrate. Early lesions often show a predominance of eosinophils. Subepidermal clefting is a feature of the bullous variant. In an active lesion, there are large numbers of CD8+ T lymphocytes expressing natural killer cell–associated molecules.7 The pathologic mechanism is not well understood, though it has been hypothesized that memory CD8+ cells are maintained in specific regions of the epidermis by IL-15 produced in the microenvironment and are activated upon rechallenge.7Considerations in Generalized Bullous FDE—Generalized FDE is defined in the literature as an FDE with involvement of 3 of 6 body areas: head, neck, trunk, upper limbs, lower limbs, and genital area. It may cover more or less than 10% of the body surface area.8-10 Although an isolated FDE frequently is asymptomatic and may not be cause for alarm, recurring drug eruptions increase the risk for development of generalized bullous FDE. Generalized bullous FDE is a rare subset. It is frequently misdiagnosed, and data on its incidence are uncertain.11 Of note, several pathologies causing bullous lesions may be in the differential diagnosis, including bullous pemphigoid; pemphigus vulgaris; bullous SLE; or bullae from cutaneous lupus, staphylococcal scalded skin syndrome, erythema multiforme, or SJS/TEN.12 When matched for body surface area involvement with SJS/TEN, generalized bullous FDE shares nearly identical mortality rates10; therefore, these patients should be treated with the same level of urgency and admitted to a critical care or burn unit, as they are at serious risk for infection and other complications.13

Clinical history and presentation along with histopathologic findings help to narrow down the differential diagnosis. Clinically, generalized bullous FDE does not affect the surrounding skin and manifests sooner after drug exposure (1–24 hours) with less mucosal involvement than SJS/TEN.9 Additionally, SJS/TEN patients frequently have generalized malaise and/or fever, while generalized bullous FDE patients do not. Finally, patients with generalized bullous FDE may report a history of a cutaneous eruption similar in morphology or in the same location.

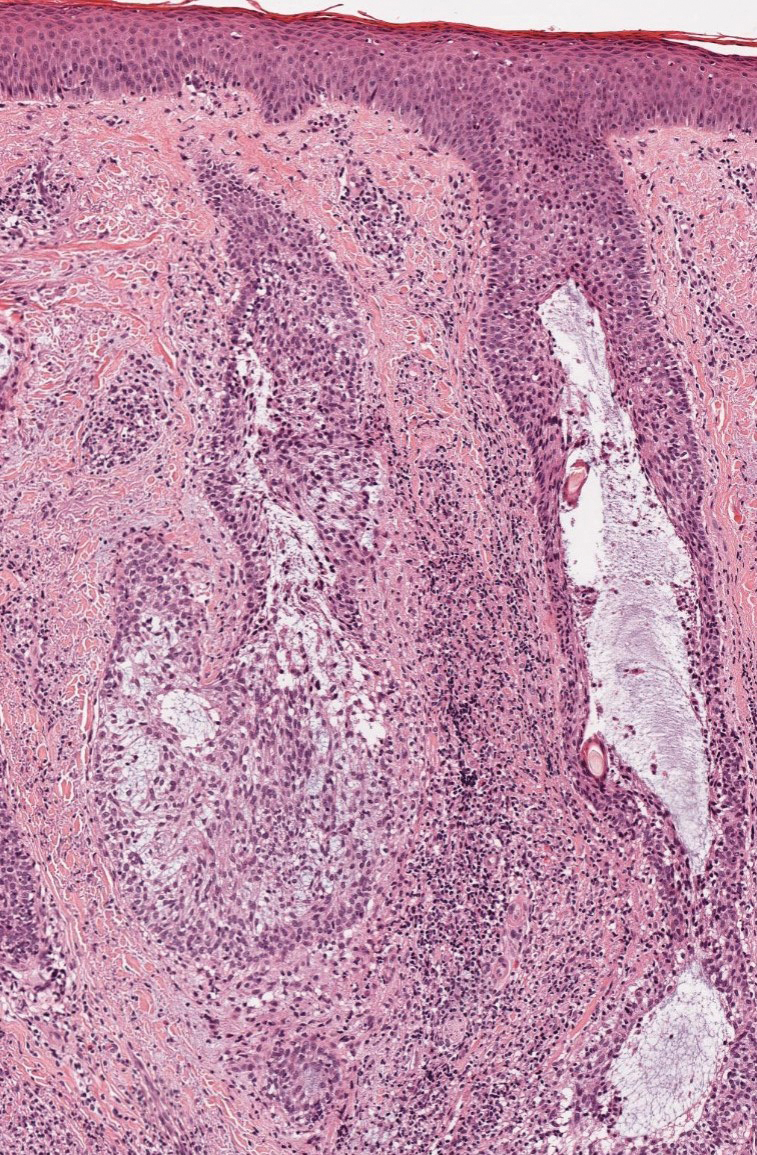

Histopathologically, generalized bullous FDE may be similar to FDE with the addition of a subepidermal blister. Generalized bullous FDE patients have greater eosinophil infiltration and dermal melanophages than patients with SJS/TEN.9 Cellular infiltrates in generalized bullous FDE include more dermal CD41 cells, such as Foxp31 regulatory T cells; fewer intraepidermal CD561 cells; and fewer intraepidermal cells with granulysin.9 Occasionally, generalized bullous FDE causes full-thickness necrosis. In those cases, generalized bullous FDE cannot reliably be distinguished from other conditions with epidermal necrolysis on histopathology.13

FDE Diagnostics—A cytotoxin produced by

Management—Avoidance of the inciting drug often is sufficient for patients with an FDE, as demonstrated in patient 2 in our case series. Clinicians also should counsel patients on avoidance of potential cross-reacting drugs. Symptomatic treatment for itch or pain is appropriate and may include antihistamines or topical steroids. Nonsteroidal anti-inflammatory drugs may exacerbate or be causative of FDE. For generalized bullous FDE, cyclosporine is favored in the literature15,16 and was used to successfully treat both patients 1 and 3 in our case series. A short course of systemic corticosteroids or intravenous immunoglobulin also may be considered. Mild cases of generalized bullous FDE may be treated with close outpatient follow-up (patient 1), while severe cases require inpatient or even critical care monitoring with aggressive medical management to prevent the progression of skin desquamation (patient 3). Patients with severe oral lesions may require inpatient support for fluid maintenance.

Lupus History—Two patients in our case series had a history of lupus. Lupus itself can cause primary bullous lesions. Similar to FDE, bullous SLE can involve sun-exposed and nonexposed areas of the skin as well as the mucous membranes with a predilection for the lower vermilion lip.17 In bullous SLE, tense subepidermal blisters with a neutrophil-rich infiltrate form due to circulating antibodies to type VII collagen. These blisters have an erythematous or urticated base, most commonly on the face, upper trunk, and proximal extremities.18 In both SLE with skin manifestations and lupus limited to the skin, bullae may form due to extensive vacuolar degeneration. Similar to TEN, they can form rapidly in a widespread distribution.17 However, there is limited mucosal involvement, no clear drug association, and a better prognosis. Bullae caused by lupus will frequently demonstrate deposition of immunoproteins IgG, IgM, IgA, and complement component 3 at the basement membrane zone in perilesional skin on direct immunofluorescence. However, negative direct immunofluorescence does not rule out lupus.12 At the same time, patients with lupus frequently have comorbidities requiring multiple medications; the need for these medications may predispose patients to higher rates of cutaneous drug eruptions.19 To our knowledge, there is no known association between FDE and lupus.

Conclusion

Patients with acute eruptions following the initiation of a new prescription or over-the-counter medication require urgent evaluation. Generalized bullous FDE requires timely diagnosis and intervention. Patients with lupus have an increased risk for cutaneous drug eruptions due to polypharmacy. Further investigation is necessary to determine if there is a pathophysiologic mechanism responsible for the development of FDE in lupus patients.

- Anderson HJ, Lee JB. A review of fixed drug eruption with a special focus on generalized bullous fixed drug eruption. Medicina (Kaunas). 2021;57:925.

- Gavin M, Sharp L, Walker K, et al. Contrast-induced generalized bullous fixed drug eruption resembling Stevens-Johnson syndrome. Proc (Bayl Univ Med Cent). 2019;32:601-602.

- Kabir S, Feit EJ, Heilman ER. Generalized fixed drug eruption following Pfizer-BioNtech COVID-19 vaccination. Clin Case Rep. 2022;10:E6684.

- Choi S, Kim SH, Hwang JH, et al. Rapidly progressing generalized bullous fixed drug eruption after the first dose of COVID-19 messenger RNA vaccination. J Dermatol. 2023;50:1190-1193.

- Mahboob A, Haroon TS. Drugs causing fixed eruptions: a study of 450 cases. Int J Dermatol. 1998;37:833-838.

- Shiohara T. Fixed drug eruption: pathogenesis and diagnostic tests. Curr Opin Allergy Clin Immunol. 2009;9:316-321.

- Mizukawa Y, Yamazaki Y, Shiohara T. In vivo dynamics of intraepidermal CD8+ T cells and CD4+ T cells during the evolution of fixed drug eruption. Br J Dermatol. 2008;158:1230-1238.

- Lee CH, Chen YC, Cho YT, et al. Fixed-drug eruption: a retrospective study in a single referral center in northern Taiwan. Dermatologica Sinica. 2012;30:11-15.

- Cho YT, Lin JW, Chen YC, et al. Generalized bullous fixed drug eruption is distinct from Stevens-Johnson syndrome/toxic epidermal necrolysis by immunohistopathological features. J Am Acad Dermatol. 2014;70:539-548.

- Lipowicz S, Sekula P, Ingen-Housz-Oro S, et al. Prognosis of generalized bullous fixed drug eruption: comparison with Stevens-Johnson syndrome and toxic epidermal necrolysis. Br J Dermatol. 2013;168:726-732.

- Patel S, John AM, Handler MZ, et al. Fixed drug eruptions: an update, emphasizing the potentially lethal generalized bullous fixed drug eruption. Am J Clin Dermatol. 2020;21:393-399.

- Ranario JS, Smith JL. Bullous lesions in a patient with systemic lupus erythematosus. J Clin Aesthet Dermatol. 2014;7:44-49.

- Perron E, Viarnaud A, Marciano L, et al. Clinical and histological features of fixed drug eruption: a single-centre series of 73 cases with comparison between bullous and non-bullous forms. Eur J Dermatol. 2021;31:372-380.

- Chen CB, Kuo KL, Wang CW, et al. Detecting lesional granulysin levels for rapid diagnosis of cytotoxic T lymphocyte-mediated bullous skin disorders. J Allergy Clin Immunol Pract. 2021;9:1327-1337.e3.

- Beniwal R, Gupta LK, Khare AK, et al. Cyclosporine in generalized bullous-fixed drug eruption. Indian J Dermatol. 2018;63:432-433.

- Vargas Mora P, García S, Valenzuela F, et al. Generalized bullous fixed drug eruption successfully treated with cyclosporine. Dermatol Ther. 2020;33:E13492.

- Montagnon CM, Tolkachjov SN, Murrell DF, et al. Subepithelial autoimmune blistering dermatoses: clinical features and diagnosis. J Am Acad Dermatol. 2021;85:1-14.

- Sebaratnam DF, Murrell DF. Bullous systemic lupus erythematosus. Dermatol Clin. 2011;29:649-653.

- Zonzits E, Aberer W, Tappeiner G. Drug eruptions from mesna. After cyclophosphamide treatment of patients with systemic lupus erythematosus and dermatomyositis. Arch Dermatol. 1992;128:80-82.

Recognizing cutaneous drug eruptions is important for treatment and prevention of recurrence. Fixed drug eruptions (FDEs) typically are harmless but can have major negative cosmetic consequences for patients. In its more severe forms, patients are at risk for widespread epithelial necrosis with accompanying complications. We report 1 patient with generalized FDE and 2 with generalized bullous FDE. We also discuss the recognition and treatment of the condition. Two patients previously had been diagnosed with systemic lupus erythematosus (SLE).

Case Series

Patient 1—A 60-year-old woman presented to dermatology with a rash on the trunk and groin folds of 4 days’ duration. She had a history of SLE and cutaneous lupus treated with hydroxychloroquine 200 mg twice daily and topical corticosteroids. She had started sulfamethoxazole-trimethoprim for a urinary tract infection with a rash appearing 1 day later. She reported burning skin pain with progression to blisters that “sloughed” off. She denied any known history of allergy to sulfa drugs. Prior to evaluation by dermatology, she visited an urgent care facility and was prescribed hydroxyzine and intramuscular corticosteroids. At presentation to dermatology 3 days after taking sulfamethoxazole-trimethoprim, she had annular flaccid bullae and superficial erosions with dusky borders on the right posterior thigh, right side of the chest, left inframammary fold, and right inguinal fold (Figure 1). She had no ocular, oral, or vaginal erosions. A diagnosis of generalized bullous FDE was favored over erythema multiforme or Stevens-Johnson syndrome (SJS)/toxic epidermal necrolysis (TEN). Shave biopsies from lesions on the right posterior thigh and right inguinal fold demonstrated interface dermatitis with epidermal necrosis, pigment incontinence, and numerous eosinophils. Direct immunofluorescence of the perilesional skin was negative for immunoprotein deposition. These findings were consistent with the clinical impression of generalized bullous FDE. Prior to receiving the histopathology report, the patient was initiated on a regimen of cyclosporine 5 mg/kg/d in the setting of normal renal function and followed until the eruption resolved completely. Cyclosporine was tapered at 2 weeks and discontinued at 3 weeks.

Patient 2—A 32-year-old woman presented for follow-up management of discoid lupus erythematosus. She had a history of systemic and cutaneous lupus, juvenile rheumatoid arthritis, and mixed connective tissue disease managed with prednisone, hydroxychloroquine, azathioprine, and belimumab. Physical examination revealed scarring alopecia with dyspigmentation and active inflammation consistent with uncontrolled cutaneous lupus. However, she also had oval-shaped hyperpigmented patches over the left breast, clavicle, and anterior chest consistent with a generalized FDE (Figure 2). The patient did not recall a history of similar lesions and could not identify a possible trigger. She was counseled on possible culprits and advised to avoid unnecessary medications. She had an unremarkable clinical course; therefore, no further intervention was necessary.

Patient 3—A 33-year-old man presented to the emergency department with a painful rash on the chest and back of 2 days’ duration that began 1 hour after taking naproxen (dosage unknown) for back pain. He had no notable medical history. The patient stated that the rash had slowly worsened and started to develop blisters. He visited an urgent care facility 1 day prior to the current presentation and was started on a 5-day course of prednisone 40 mg daily; the first 2 doses did not help. He denied any mucosal involvement apart from a tender lesion on the penis. He reported a history of an allergic reaction to penicillin. Physical examination revealed extensive dusky violaceous annular plaques with erythematous borders across the anterior and posterior trunk (Figure 3). Multiple flaccid bullae developed within these plaques, involving 15% of the body surface area. He was diagnosed with generalized bullous FDE based on the clinical history and histopathology. He was admitted to the burn intensive care unit and treated with cyclosporine 3 mg/kg/d with subsequent resolution of the eruption.

Comment

Presentation of FDEs—A fixed drug eruption manifests with 1 or more well-demarcated, red or violaceous, annular patches that resolve with postinflammatory hyperpigmentation; it occasionally may manifest with bullae. Initial eruptions may occur up to 2 weeks following medication exposure, but recurrent eruptions usually happen within minutes to hours later. They often are in the same location as prior lesions. A fixed drug eruption can be solitary, scattered, or generalized; a generalized FDE typically demonstrates multiple bilateral lesions that may itch, burn, or cause no symptoms. Patients can experience an FDE at any age, though the median age is reported as 35 to 60 years of age.1 A fixed drug eruption usually occurs after ingestion of oral medications, though there have been a few reports with iodinated contrast.2 Well-known culprits include antibiotics (eg, sulfamethoxazole-trimethoprim, tetracyclines, penicillins/cephalosporins, quinolones, dapsone), nonsteroidal anti-inflammatory drugs, acetaminophen (eg, paracetamol), barbiturates, antimalarials, and anticonvulsants. It also can occur with vaccines or with certain foods (fixed food eruption).3,4 Clinicians may try an oral drug challenge to identify the cause of an FDE, but in patients with a history of a generalized FDE, the risk for developing an increasingly severe reaction with repeated exposure to the medication is too high.5

Histopathology—Patch testing at the site of prior eruption with suspected drug culprits may be useful.6 Histopathology of FDE typically demonstrates vacuolar changes at the dermoepidermal junction with a lichenoid lymphocytic infiltrate. Early lesions often show a predominance of eosinophils. Subepidermal clefting is a feature of the bullous variant. In an active lesion, there are large numbers of CD8+ T lymphocytes expressing natural killer cell–associated molecules.7 The pathologic mechanism is not well understood, though it has been hypothesized that memory CD8+ cells are maintained in specific regions of the epidermis by IL-15 produced in the microenvironment and are activated upon rechallenge.7Considerations in Generalized Bullous FDE—Generalized FDE is defined in the literature as an FDE with involvement of 3 of 6 body areas: head, neck, trunk, upper limbs, lower limbs, and genital area. It may cover more or less than 10% of the body surface area.8-10 Although an isolated FDE frequently is asymptomatic and may not be cause for alarm, recurring drug eruptions increase the risk for development of generalized bullous FDE. Generalized bullous FDE is a rare subset. It is frequently misdiagnosed, and data on its incidence are uncertain.11 Of note, several pathologies causing bullous lesions may be in the differential diagnosis, including bullous pemphigoid; pemphigus vulgaris; bullous SLE; or bullae from cutaneous lupus, staphylococcal scalded skin syndrome, erythema multiforme, or SJS/TEN.12 When matched for body surface area involvement with SJS/TEN, generalized bullous FDE shares nearly identical mortality rates10; therefore, these patients should be treated with the same level of urgency and admitted to a critical care or burn unit, as they are at serious risk for infection and other complications.13

Clinical history and presentation along with histopathologic findings help to narrow down the differential diagnosis. Clinically, generalized bullous FDE does not affect the surrounding skin and manifests sooner after drug exposure (1–24 hours) with less mucosal involvement than SJS/TEN.9 Additionally, SJS/TEN patients frequently have generalized malaise and/or fever, while generalized bullous FDE patients do not. Finally, patients with generalized bullous FDE may report a history of a cutaneous eruption similar in morphology or in the same location.

Histopathologically, generalized bullous FDE may be similar to FDE with the addition of a subepidermal blister. Generalized bullous FDE patients have greater eosinophil infiltration and dermal melanophages than patients with SJS/TEN.9 Cellular infiltrates in generalized bullous FDE include more dermal CD41 cells, such as Foxp31 regulatory T cells; fewer intraepidermal CD561 cells; and fewer intraepidermal cells with granulysin.9 Occasionally, generalized bullous FDE causes full-thickness necrosis. In those cases, generalized bullous FDE cannot reliably be distinguished from other conditions with epidermal necrolysis on histopathology.13

FDE Diagnostics—A cytotoxin produced by

Management—Avoidance of the inciting drug often is sufficient for patients with an FDE, as demonstrated in patient 2 in our case series. Clinicians also should counsel patients on avoidance of potential cross-reacting drugs. Symptomatic treatment for itch or pain is appropriate and may include antihistamines or topical steroids. Nonsteroidal anti-inflammatory drugs may exacerbate or be causative of FDE. For generalized bullous FDE, cyclosporine is favored in the literature15,16 and was used to successfully treat both patients 1 and 3 in our case series. A short course of systemic corticosteroids or intravenous immunoglobulin also may be considered. Mild cases of generalized bullous FDE may be treated with close outpatient follow-up (patient 1), while severe cases require inpatient or even critical care monitoring with aggressive medical management to prevent the progression of skin desquamation (patient 3). Patients with severe oral lesions may require inpatient support for fluid maintenance.

Lupus History—Two patients in our case series had a history of lupus. Lupus itself can cause primary bullous lesions. Similar to FDE, bullous SLE can involve sun-exposed and nonexposed areas of the skin as well as the mucous membranes with a predilection for the lower vermilion lip.17 In bullous SLE, tense subepidermal blisters with a neutrophil-rich infiltrate form due to circulating antibodies to type VII collagen. These blisters have an erythematous or urticated base, most commonly on the face, upper trunk, and proximal extremities.18 In both SLE with skin manifestations and lupus limited to the skin, bullae may form due to extensive vacuolar degeneration. Similar to TEN, they can form rapidly in a widespread distribution.17 However, there is limited mucosal involvement, no clear drug association, and a better prognosis. Bullae caused by lupus will frequently demonstrate deposition of immunoproteins IgG, IgM, IgA, and complement component 3 at the basement membrane zone in perilesional skin on direct immunofluorescence. However, negative direct immunofluorescence does not rule out lupus.12 At the same time, patients with lupus frequently have comorbidities requiring multiple medications; the need for these medications may predispose patients to higher rates of cutaneous drug eruptions.19 To our knowledge, there is no known association between FDE and lupus.

Conclusion

Patients with acute eruptions following the initiation of a new prescription or over-the-counter medication require urgent evaluation. Generalized bullous FDE requires timely diagnosis and intervention. Patients with lupus have an increased risk for cutaneous drug eruptions due to polypharmacy. Further investigation is necessary to determine if there is a pathophysiologic mechanism responsible for the development of FDE in lupus patients.

Recognizing cutaneous drug eruptions is important for treatment and prevention of recurrence. Fixed drug eruptions (FDEs) typically are harmless but can have major negative cosmetic consequences for patients. In its more severe forms, patients are at risk for widespread epithelial necrosis with accompanying complications. We report 1 patient with generalized FDE and 2 with generalized bullous FDE. We also discuss the recognition and treatment of the condition. Two patients previously had been diagnosed with systemic lupus erythematosus (SLE).

Case Series

Patient 1—A 60-year-old woman presented to dermatology with a rash on the trunk and groin folds of 4 days’ duration. She had a history of SLE and cutaneous lupus treated with hydroxychloroquine 200 mg twice daily and topical corticosteroids. She had started sulfamethoxazole-trimethoprim for a urinary tract infection with a rash appearing 1 day later. She reported burning skin pain with progression to blisters that “sloughed” off. She denied any known history of allergy to sulfa drugs. Prior to evaluation by dermatology, she visited an urgent care facility and was prescribed hydroxyzine and intramuscular corticosteroids. At presentation to dermatology 3 days after taking sulfamethoxazole-trimethoprim, she had annular flaccid bullae and superficial erosions with dusky borders on the right posterior thigh, right side of the chest, left inframammary fold, and right inguinal fold (Figure 1). She had no ocular, oral, or vaginal erosions. A diagnosis of generalized bullous FDE was favored over erythema multiforme or Stevens-Johnson syndrome (SJS)/toxic epidermal necrolysis (TEN). Shave biopsies from lesions on the right posterior thigh and right inguinal fold demonstrated interface dermatitis with epidermal necrosis, pigment incontinence, and numerous eosinophils. Direct immunofluorescence of the perilesional skin was negative for immunoprotein deposition. These findings were consistent with the clinical impression of generalized bullous FDE. Prior to receiving the histopathology report, the patient was initiated on a regimen of cyclosporine 5 mg/kg/d in the setting of normal renal function and followed until the eruption resolved completely. Cyclosporine was tapered at 2 weeks and discontinued at 3 weeks.

Patient 2—A 32-year-old woman presented for follow-up management of discoid lupus erythematosus. She had a history of systemic and cutaneous lupus, juvenile rheumatoid arthritis, and mixed connective tissue disease managed with prednisone, hydroxychloroquine, azathioprine, and belimumab. Physical examination revealed scarring alopecia with dyspigmentation and active inflammation consistent with uncontrolled cutaneous lupus. However, she also had oval-shaped hyperpigmented patches over the left breast, clavicle, and anterior chest consistent with a generalized FDE (Figure 2). The patient did not recall a history of similar lesions and could not identify a possible trigger. She was counseled on possible culprits and advised to avoid unnecessary medications. She had an unremarkable clinical course; therefore, no further intervention was necessary.

Patient 3—A 33-year-old man presented to the emergency department with a painful rash on the chest and back of 2 days’ duration that began 1 hour after taking naproxen (dosage unknown) for back pain. He had no notable medical history. The patient stated that the rash had slowly worsened and started to develop blisters. He visited an urgent care facility 1 day prior to the current presentation and was started on a 5-day course of prednisone 40 mg daily; the first 2 doses did not help. He denied any mucosal involvement apart from a tender lesion on the penis. He reported a history of an allergic reaction to penicillin. Physical examination revealed extensive dusky violaceous annular plaques with erythematous borders across the anterior and posterior trunk (Figure 3). Multiple flaccid bullae developed within these plaques, involving 15% of the body surface area. He was diagnosed with generalized bullous FDE based on the clinical history and histopathology. He was admitted to the burn intensive care unit and treated with cyclosporine 3 mg/kg/d with subsequent resolution of the eruption.

Comment

Presentation of FDEs—A fixed drug eruption manifests with 1 or more well-demarcated, red or violaceous, annular patches that resolve with postinflammatory hyperpigmentation; it occasionally may manifest with bullae. Initial eruptions may occur up to 2 weeks following medication exposure, but recurrent eruptions usually happen within minutes to hours later. They often are in the same location as prior lesions. A fixed drug eruption can be solitary, scattered, or generalized; a generalized FDE typically demonstrates multiple bilateral lesions that may itch, burn, or cause no symptoms. Patients can experience an FDE at any age, though the median age is reported as 35 to 60 years of age.1 A fixed drug eruption usually occurs after ingestion of oral medications, though there have been a few reports with iodinated contrast.2 Well-known culprits include antibiotics (eg, sulfamethoxazole-trimethoprim, tetracyclines, penicillins/cephalosporins, quinolones, dapsone), nonsteroidal anti-inflammatory drugs, acetaminophen (eg, paracetamol), barbiturates, antimalarials, and anticonvulsants. It also can occur with vaccines or with certain foods (fixed food eruption).3,4 Clinicians may try an oral drug challenge to identify the cause of an FDE, but in patients with a history of a generalized FDE, the risk for developing an increasingly severe reaction with repeated exposure to the medication is too high.5

Histopathology—Patch testing at the site of prior eruption with suspected drug culprits may be useful.6 Histopathology of FDE typically demonstrates vacuolar changes at the dermoepidermal junction with a lichenoid lymphocytic infiltrate. Early lesions often show a predominance of eosinophils. Subepidermal clefting is a feature of the bullous variant. In an active lesion, there are large numbers of CD8+ T lymphocytes expressing natural killer cell–associated molecules.7 The pathologic mechanism is not well understood, though it has been hypothesized that memory CD8+ cells are maintained in specific regions of the epidermis by IL-15 produced in the microenvironment and are activated upon rechallenge.7Considerations in Generalized Bullous FDE—Generalized FDE is defined in the literature as an FDE with involvement of 3 of 6 body areas: head, neck, trunk, upper limbs, lower limbs, and genital area. It may cover more or less than 10% of the body surface area.8-10 Although an isolated FDE frequently is asymptomatic and may not be cause for alarm, recurring drug eruptions increase the risk for development of generalized bullous FDE. Generalized bullous FDE is a rare subset. It is frequently misdiagnosed, and data on its incidence are uncertain.11 Of note, several pathologies causing bullous lesions may be in the differential diagnosis, including bullous pemphigoid; pemphigus vulgaris; bullous SLE; or bullae from cutaneous lupus, staphylococcal scalded skin syndrome, erythema multiforme, or SJS/TEN.12 When matched for body surface area involvement with SJS/TEN, generalized bullous FDE shares nearly identical mortality rates10; therefore, these patients should be treated with the same level of urgency and admitted to a critical care or burn unit, as they are at serious risk for infection and other complications.13

Clinical history and presentation along with histopathologic findings help to narrow down the differential diagnosis. Clinically, generalized bullous FDE does not affect the surrounding skin and manifests sooner after drug exposure (1–24 hours) with less mucosal involvement than SJS/TEN.9 Additionally, SJS/TEN patients frequently have generalized malaise and/or fever, while generalized bullous FDE patients do not. Finally, patients with generalized bullous FDE may report a history of a cutaneous eruption similar in morphology or in the same location.

Histopathologically, generalized bullous FDE may be similar to FDE with the addition of a subepidermal blister. Generalized bullous FDE patients have greater eosinophil infiltration and dermal melanophages than patients with SJS/TEN.9 Cellular infiltrates in generalized bullous FDE include more dermal CD41 cells, such as Foxp31 regulatory T cells; fewer intraepidermal CD561 cells; and fewer intraepidermal cells with granulysin.9 Occasionally, generalized bullous FDE causes full-thickness necrosis. In those cases, generalized bullous FDE cannot reliably be distinguished from other conditions with epidermal necrolysis on histopathology.13

FDE Diagnostics—A cytotoxin produced by

Management—Avoidance of the inciting drug often is sufficient for patients with an FDE, as demonstrated in patient 2 in our case series. Clinicians also should counsel patients on avoidance of potential cross-reacting drugs. Symptomatic treatment for itch or pain is appropriate and may include antihistamines or topical steroids. Nonsteroidal anti-inflammatory drugs may exacerbate or be causative of FDE. For generalized bullous FDE, cyclosporine is favored in the literature15,16 and was used to successfully treat both patients 1 and 3 in our case series. A short course of systemic corticosteroids or intravenous immunoglobulin also may be considered. Mild cases of generalized bullous FDE may be treated with close outpatient follow-up (patient 1), while severe cases require inpatient or even critical care monitoring with aggressive medical management to prevent the progression of skin desquamation (patient 3). Patients with severe oral lesions may require inpatient support for fluid maintenance.

Lupus History—Two patients in our case series had a history of lupus. Lupus itself can cause primary bullous lesions. Similar to FDE, bullous SLE can involve sun-exposed and nonexposed areas of the skin as well as the mucous membranes with a predilection for the lower vermilion lip.17 In bullous SLE, tense subepidermal blisters with a neutrophil-rich infiltrate form due to circulating antibodies to type VII collagen. These blisters have an erythematous or urticated base, most commonly on the face, upper trunk, and proximal extremities.18 In both SLE with skin manifestations and lupus limited to the skin, bullae may form due to extensive vacuolar degeneration. Similar to TEN, they can form rapidly in a widespread distribution.17 However, there is limited mucosal involvement, no clear drug association, and a better prognosis. Bullae caused by lupus will frequently demonstrate deposition of immunoproteins IgG, IgM, IgA, and complement component 3 at the basement membrane zone in perilesional skin on direct immunofluorescence. However, negative direct immunofluorescence does not rule out lupus.12 At the same time, patients with lupus frequently have comorbidities requiring multiple medications; the need for these medications may predispose patients to higher rates of cutaneous drug eruptions.19 To our knowledge, there is no known association between FDE and lupus.

Conclusion

Patients with acute eruptions following the initiation of a new prescription or over-the-counter medication require urgent evaluation. Generalized bullous FDE requires timely diagnosis and intervention. Patients with lupus have an increased risk for cutaneous drug eruptions due to polypharmacy. Further investigation is necessary to determine if there is a pathophysiologic mechanism responsible for the development of FDE in lupus patients.

- Anderson HJ, Lee JB. A review of fixed drug eruption with a special focus on generalized bullous fixed drug eruption. Medicina (Kaunas). 2021;57:925.

- Gavin M, Sharp L, Walker K, et al. Contrast-induced generalized bullous fixed drug eruption resembling Stevens-Johnson syndrome. Proc (Bayl Univ Med Cent). 2019;32:601-602.

- Kabir S, Feit EJ, Heilman ER. Generalized fixed drug eruption following Pfizer-BioNtech COVID-19 vaccination. Clin Case Rep. 2022;10:E6684.

- Choi S, Kim SH, Hwang JH, et al. Rapidly progressing generalized bullous fixed drug eruption after the first dose of COVID-19 messenger RNA vaccination. J Dermatol. 2023;50:1190-1193.

- Mahboob A, Haroon TS. Drugs causing fixed eruptions: a study of 450 cases. Int J Dermatol. 1998;37:833-838.

- Shiohara T. Fixed drug eruption: pathogenesis and diagnostic tests. Curr Opin Allergy Clin Immunol. 2009;9:316-321.

- Mizukawa Y, Yamazaki Y, Shiohara T. In vivo dynamics of intraepidermal CD8+ T cells and CD4+ T cells during the evolution of fixed drug eruption. Br J Dermatol. 2008;158:1230-1238.

- Lee CH, Chen YC, Cho YT, et al. Fixed-drug eruption: a retrospective study in a single referral center in northern Taiwan. Dermatologica Sinica. 2012;30:11-15.

- Cho YT, Lin JW, Chen YC, et al. Generalized bullous fixed drug eruption is distinct from Stevens-Johnson syndrome/toxic epidermal necrolysis by immunohistopathological features. J Am Acad Dermatol. 2014;70:539-548.

- Lipowicz S, Sekula P, Ingen-Housz-Oro S, et al. Prognosis of generalized bullous fixed drug eruption: comparison with Stevens-Johnson syndrome and toxic epidermal necrolysis. Br J Dermatol. 2013;168:726-732.

- Patel S, John AM, Handler MZ, et al. Fixed drug eruptions: an update, emphasizing the potentially lethal generalized bullous fixed drug eruption. Am J Clin Dermatol. 2020;21:393-399.

- Ranario JS, Smith JL. Bullous lesions in a patient with systemic lupus erythematosus. J Clin Aesthet Dermatol. 2014;7:44-49.

- Perron E, Viarnaud A, Marciano L, et al. Clinical and histological features of fixed drug eruption: a single-centre series of 73 cases with comparison between bullous and non-bullous forms. Eur J Dermatol. 2021;31:372-380.

- Chen CB, Kuo KL, Wang CW, et al. Detecting lesional granulysin levels for rapid diagnosis of cytotoxic T lymphocyte-mediated bullous skin disorders. J Allergy Clin Immunol Pract. 2021;9:1327-1337.e3.

- Beniwal R, Gupta LK, Khare AK, et al. Cyclosporine in generalized bullous-fixed drug eruption. Indian J Dermatol. 2018;63:432-433.

- Vargas Mora P, García S, Valenzuela F, et al. Generalized bullous fixed drug eruption successfully treated with cyclosporine. Dermatol Ther. 2020;33:E13492.

- Montagnon CM, Tolkachjov SN, Murrell DF, et al. Subepithelial autoimmune blistering dermatoses: clinical features and diagnosis. J Am Acad Dermatol. 2021;85:1-14.

- Sebaratnam DF, Murrell DF. Bullous systemic lupus erythematosus. Dermatol Clin. 2011;29:649-653.

- Zonzits E, Aberer W, Tappeiner G. Drug eruptions from mesna. After cyclophosphamide treatment of patients with systemic lupus erythematosus and dermatomyositis. Arch Dermatol. 1992;128:80-82.

- Anderson HJ, Lee JB. A review of fixed drug eruption with a special focus on generalized bullous fixed drug eruption. Medicina (Kaunas). 2021;57:925.

- Gavin M, Sharp L, Walker K, et al. Contrast-induced generalized bullous fixed drug eruption resembling Stevens-Johnson syndrome. Proc (Bayl Univ Med Cent). 2019;32:601-602.

- Kabir S, Feit EJ, Heilman ER. Generalized fixed drug eruption following Pfizer-BioNtech COVID-19 vaccination. Clin Case Rep. 2022;10:E6684.

- Choi S, Kim SH, Hwang JH, et al. Rapidly progressing generalized bullous fixed drug eruption after the first dose of COVID-19 messenger RNA vaccination. J Dermatol. 2023;50:1190-1193.

- Mahboob A, Haroon TS. Drugs causing fixed eruptions: a study of 450 cases. Int J Dermatol. 1998;37:833-838.

- Shiohara T. Fixed drug eruption: pathogenesis and diagnostic tests. Curr Opin Allergy Clin Immunol. 2009;9:316-321.

- Mizukawa Y, Yamazaki Y, Shiohara T. In vivo dynamics of intraepidermal CD8+ T cells and CD4+ T cells during the evolution of fixed drug eruption. Br J Dermatol. 2008;158:1230-1238.

- Lee CH, Chen YC, Cho YT, et al. Fixed-drug eruption: a retrospective study in a single referral center in northern Taiwan. Dermatologica Sinica. 2012;30:11-15.

- Cho YT, Lin JW, Chen YC, et al. Generalized bullous fixed drug eruption is distinct from Stevens-Johnson syndrome/toxic epidermal necrolysis by immunohistopathological features. J Am Acad Dermatol. 2014;70:539-548.

- Lipowicz S, Sekula P, Ingen-Housz-Oro S, et al. Prognosis of generalized bullous fixed drug eruption: comparison with Stevens-Johnson syndrome and toxic epidermal necrolysis. Br J Dermatol. 2013;168:726-732.

- Patel S, John AM, Handler MZ, et al. Fixed drug eruptions: an update, emphasizing the potentially lethal generalized bullous fixed drug eruption. Am J Clin Dermatol. 2020;21:393-399.

- Ranario JS, Smith JL. Bullous lesions in a patient with systemic lupus erythematosus. J Clin Aesthet Dermatol. 2014;7:44-49.

- Perron E, Viarnaud A, Marciano L, et al. Clinical and histological features of fixed drug eruption: a single-centre series of 73 cases with comparison between bullous and non-bullous forms. Eur J Dermatol. 2021;31:372-380.

- Chen CB, Kuo KL, Wang CW, et al. Detecting lesional granulysin levels for rapid diagnosis of cytotoxic T lymphocyte-mediated bullous skin disorders. J Allergy Clin Immunol Pract. 2021;9:1327-1337.e3.

- Beniwal R, Gupta LK, Khare AK, et al. Cyclosporine in generalized bullous-fixed drug eruption. Indian J Dermatol. 2018;63:432-433.

- Vargas Mora P, García S, Valenzuela F, et al. Generalized bullous fixed drug eruption successfully treated with cyclosporine. Dermatol Ther. 2020;33:E13492.

- Montagnon CM, Tolkachjov SN, Murrell DF, et al. Subepithelial autoimmune blistering dermatoses: clinical features and diagnosis. J Am Acad Dermatol. 2021;85:1-14.

- Sebaratnam DF, Murrell DF. Bullous systemic lupus erythematosus. Dermatol Clin. 2011;29:649-653.

- Zonzits E, Aberer W, Tappeiner G. Drug eruptions from mesna. After cyclophosphamide treatment of patients with systemic lupus erythematosus and dermatomyositis. Arch Dermatol. 1992;128:80-82.

Practice Points

- Although localized fixed drug eruption (FDE) is a relatively benign diagnosis, generalized bullous FDE requires urgent management and may necessitate intensive burn care.

- Patients with lupus are at increased risk for drug eruptions due to polypharmacy, and there is a wide differential for bullous eruptions in these patients.

Mycobacterium interjectum Infection in an Immunocompetent Host Following Contact With Aquarium Fish

To the Editor:

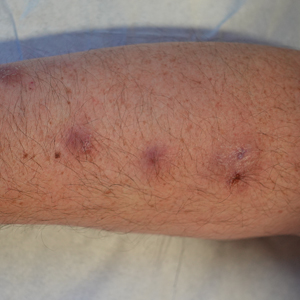

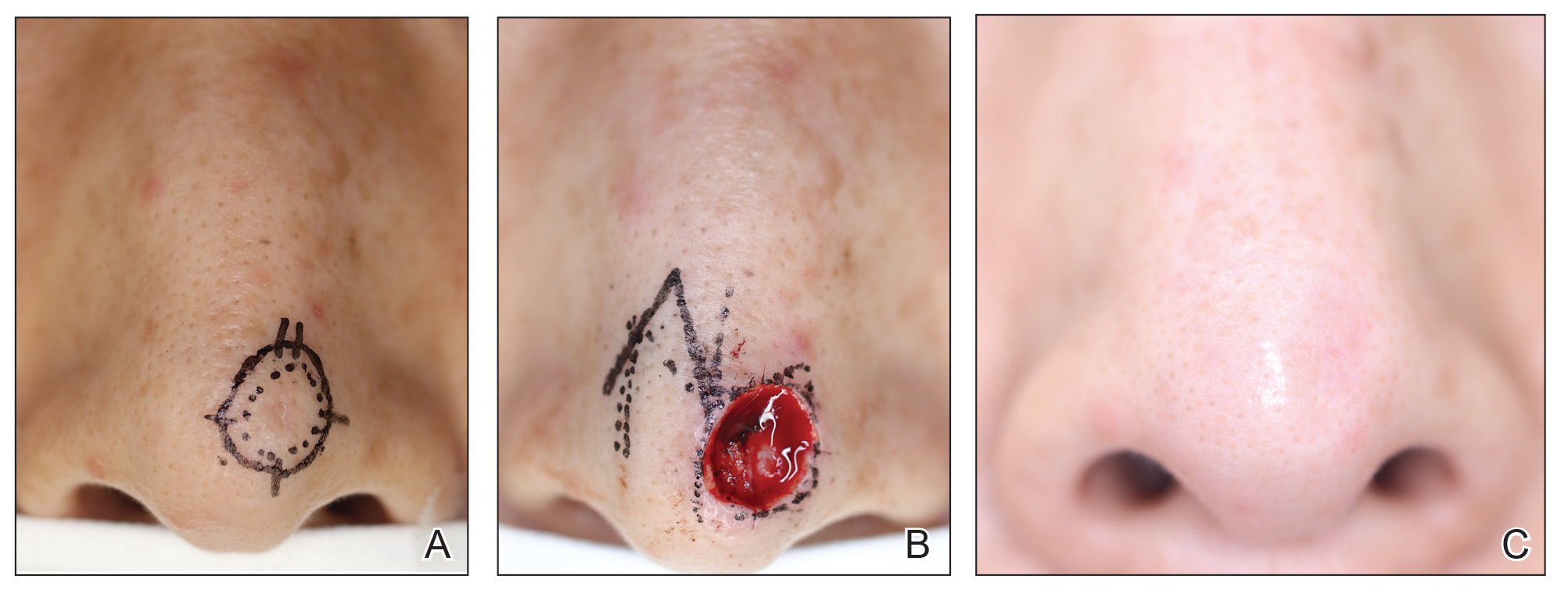

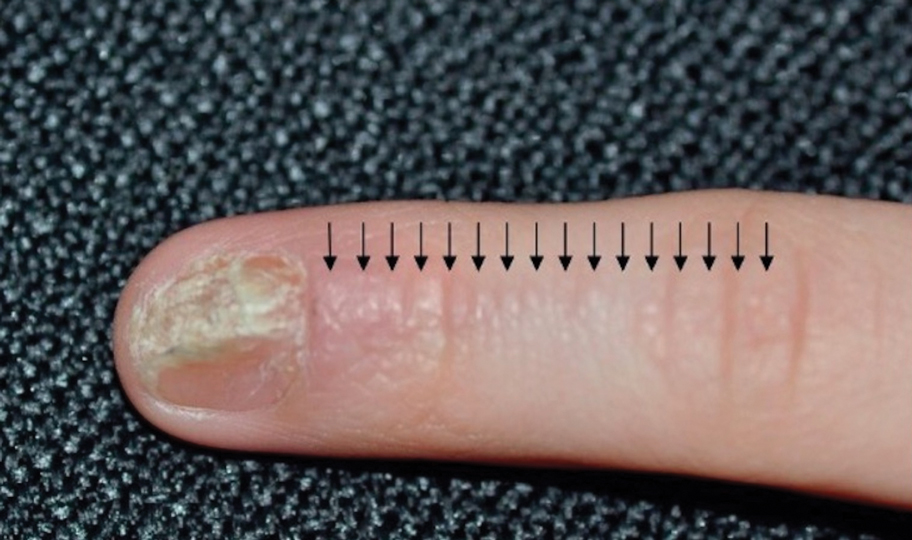

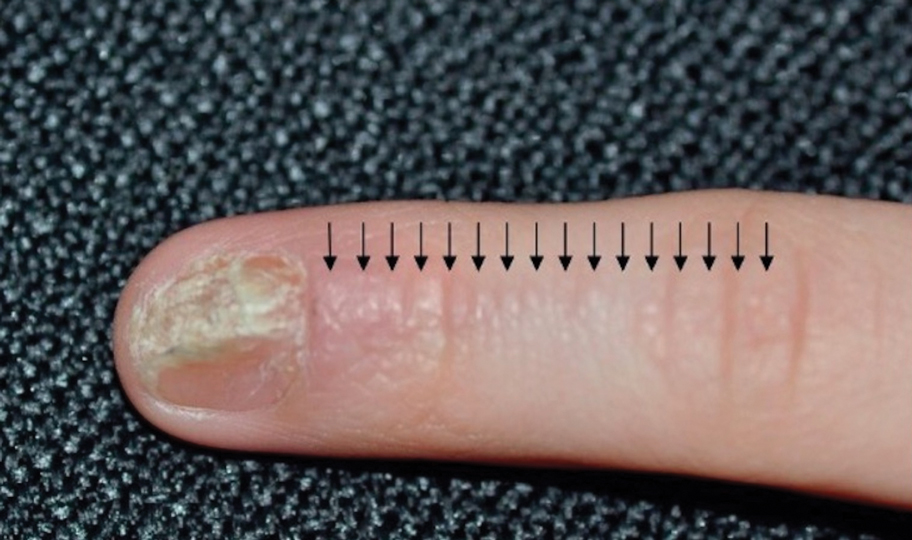

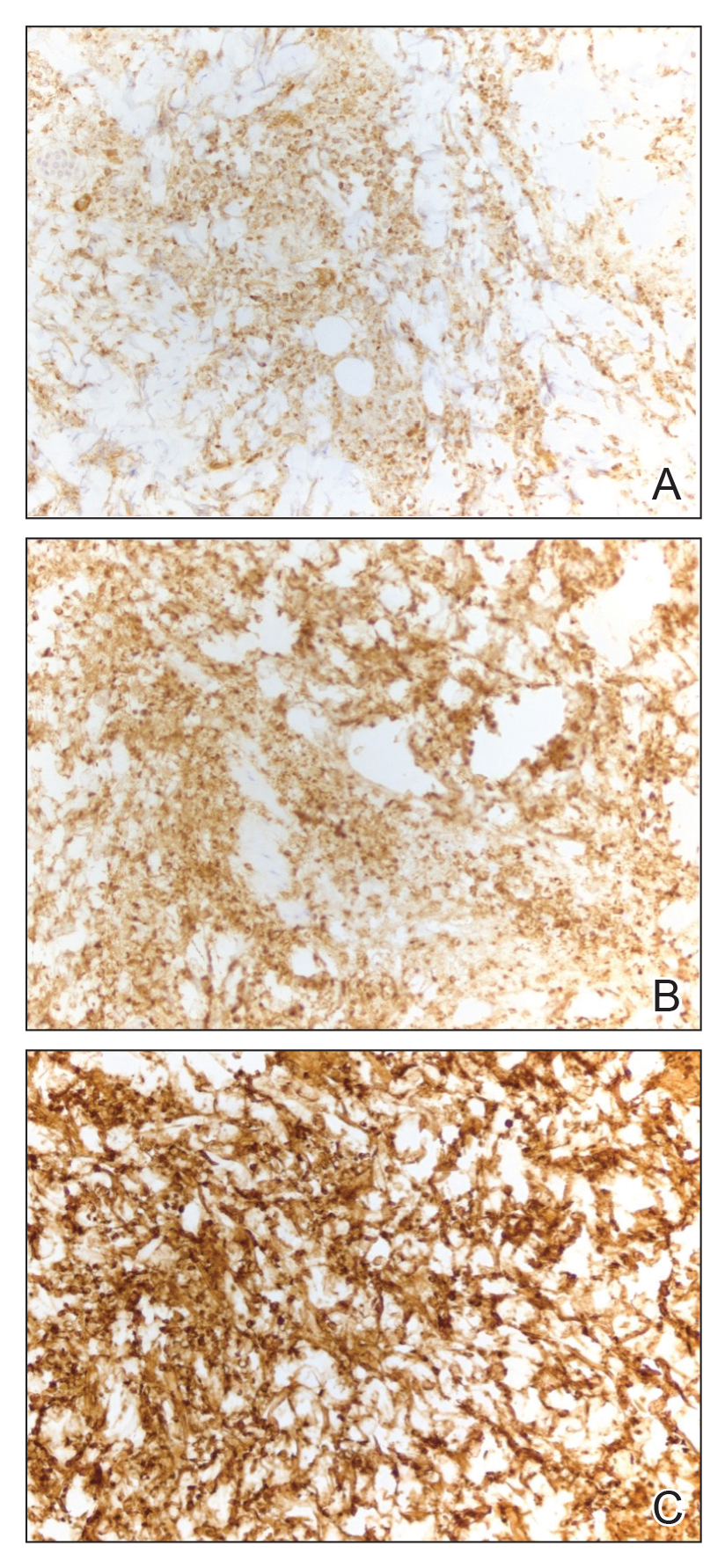

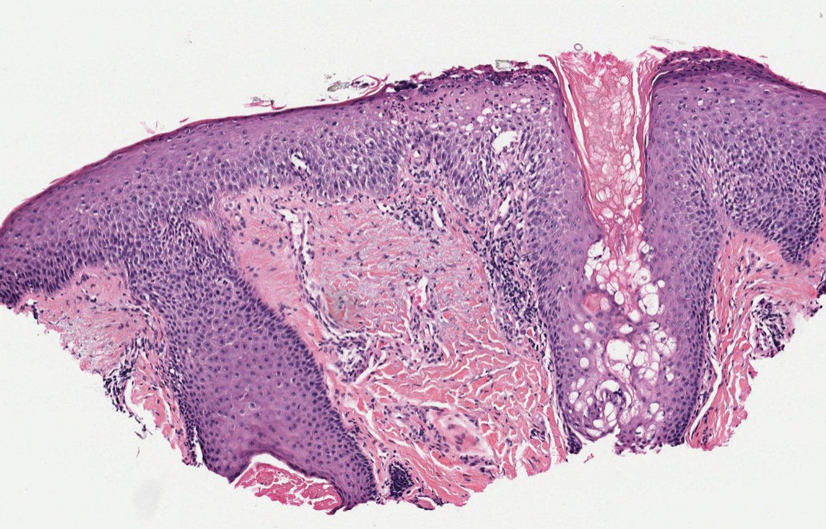

A 48-year-old man presented with nodular lesions in a sporotrichoid pattern on the right hand and forearm of 3 months’ duration (Figure). There were no lymphadeno-pathies, and he had no notable medical history. He denied fever and other systemic symptoms. The patient recently had manipulated a warm water fish aquarium. Although he did not recall a clear injury, inadvertent mild trauma was a possibility. He denied other contact or trauma in relation to animals or vegetables.

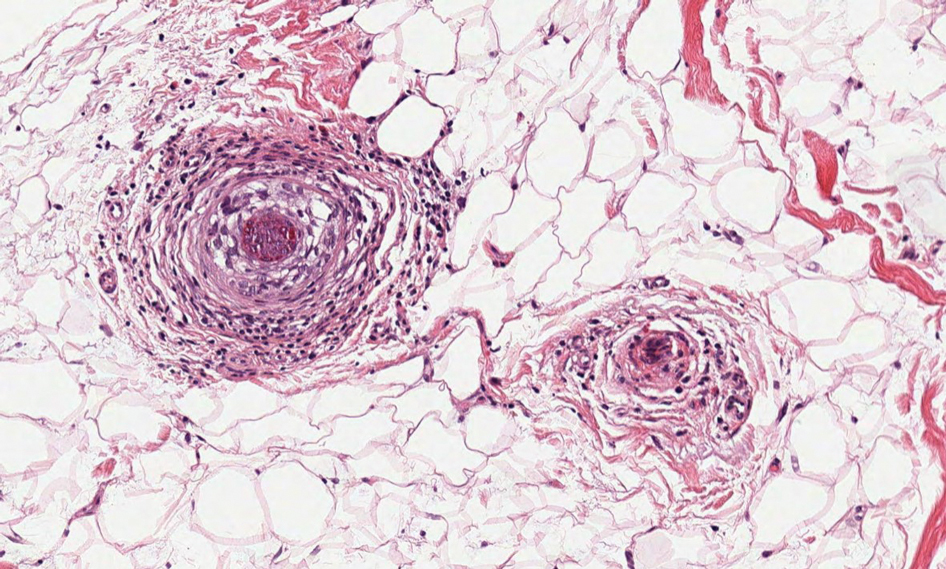

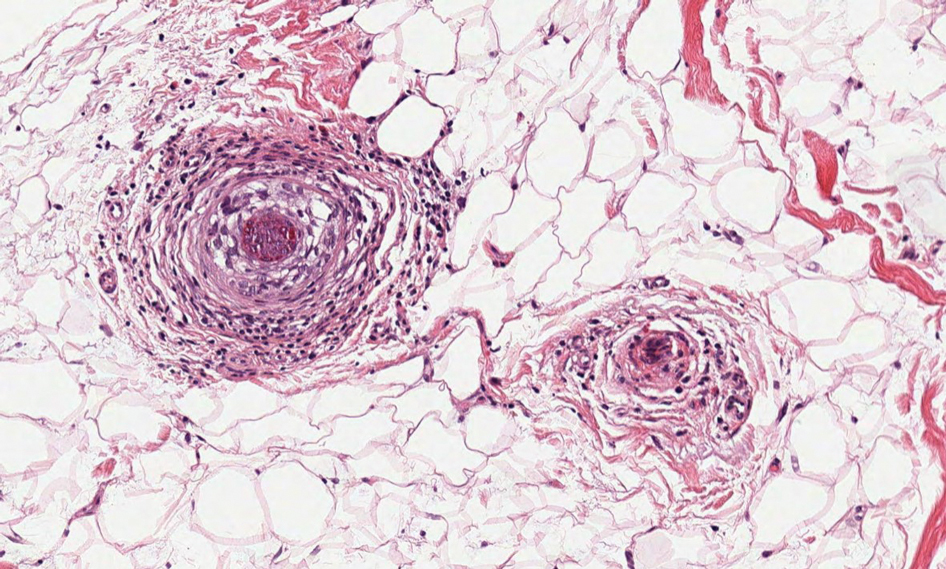

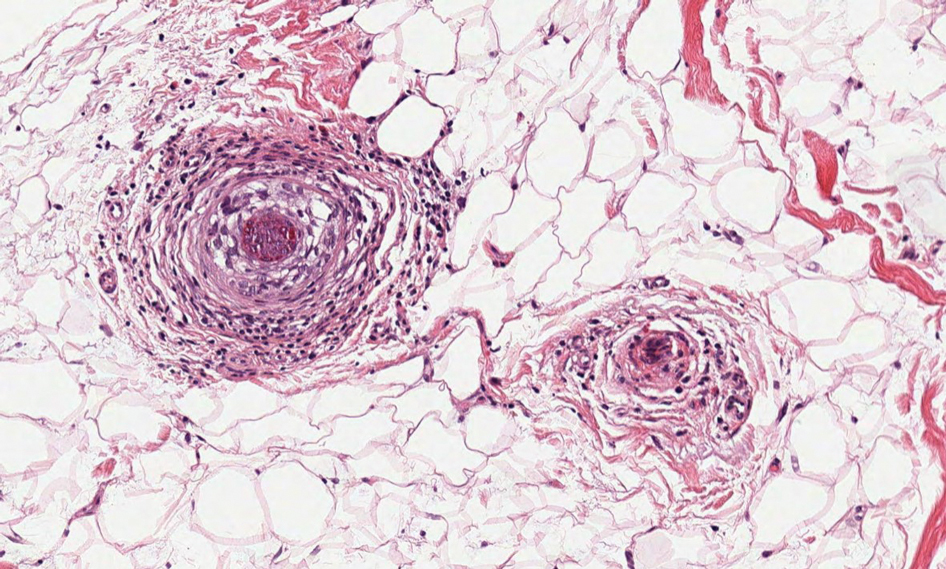

Histopathology from a punch biopsy of the forearm revealed a granulomatous infiltrate with necrosis at the deep dermis level at the interface with the subcutaneous cellular tissue that was composed of mainly epithelioid cells with a few multinucleated giant cells. No acid-fast bacilli or fungi were observed with special stains.

A polymerase chain reaction assay for atypical mycobacteria was positive for Mycobacterium interjectum. The culture of the skin biopsy was negative for fungi and mycobacteria after long incubation (6 weeks) on 2 occasions, and an antibiogram was not available. Complementary tests including hemogram, HIV serology, and chest and upper extremity radiographs did not reveal any abnormalities.

The patient was treated with rifampicin 600 mg/d, clarithromycin 500 mg every 12 hours, and co-trimoxazole 160/800 mg every 12 hours for 9 months with some resolution but persistence of some residual scarring lesions. There was no recurrence at 6-month follow-up.

Mycobacterium interjectum is a rare, slow-growing, scotochromogenic mycobacteria. Case reports usually refer to lymphadenitis in healthy children and pulmonary infections in immunocompromised or immunocompetent adults.1,2 A case of M interjectum with cutaneous involvement was reported by Fukuoka et al,3 with ulcerated nodules and abscesses on the leg identified in an immunocompromised patient. Our patient did not present with any cause of immunosuppression or clear injury predisposing him to infection. This microorganism has been detected in water, soil,3 and aquarium fish,4 the latter being the most likely source of infection in our patient. Given its slow growth rate and the need for a specific polymerase chain reaction assay, which is not widely available, M interjectum infection may be underdiagnosed.

No standard antibiotic regimen has been established, but M interjectum has proven to be a multidrug-resistant bacterium with frequent therapy failures. Treatment options have ranged from standard tuberculostatic therapy to combination therapy with medications such as amikacin, levofloxacin, rifampicin, and co-trimoxazole.1 Because an antibiogram was not available for our patient, empiric treatment with rifampicin, clarithromycin, and co-trimoxazole was prescribed for 9 months, with satisfactory response and tolerance. These drugs were selected because of their susceptibility profile in the literature.1,5

- Sotello D, Hata DJ, Reza M, et al. Disseminated Mycobacterium interjectum infection with bacteremia, hepatic and pulmonary involvement associated with a long-term catheter infection. Case Rep Infect Dis. 2017;2017:1-5.

- Dholakia YN. Mycobacterium interjectum isolated from an immunocompetent host with lung infection. Int J Mycobacteriol. 2017;6:401-403.

- Fukuoka M, Matsumura Y, Kore-eda S, et al. Cutaneous infection due to Mycobacterium interjectum in an immunosuppressed patient with microscopic polyangiitis. Br J Dermatol. 2008;159:1382-1384.

- Zanoni RG, Florio D, Fioravanti ML, et al. Occurrence of Mycobacterium spp. in ornamental fish in Italy. J Fish Dis. 2008;31:433-441.

- Emler S, Rochat T, Rohner P, et al. Chronic destructive lung disease associated with a novel mycobacterium. Am J Respir Crit Care Med. 1994;150:261-265.

To the Editor:

A 48-year-old man presented with nodular lesions in a sporotrichoid pattern on the right hand and forearm of 3 months’ duration (Figure). There were no lymphadeno-pathies, and he had no notable medical history. He denied fever and other systemic symptoms. The patient recently had manipulated a warm water fish aquarium. Although he did not recall a clear injury, inadvertent mild trauma was a possibility. He denied other contact or trauma in relation to animals or vegetables.

Histopathology from a punch biopsy of the forearm revealed a granulomatous infiltrate with necrosis at the deep dermis level at the interface with the subcutaneous cellular tissue that was composed of mainly epithelioid cells with a few multinucleated giant cells. No acid-fast bacilli or fungi were observed with special stains.

A polymerase chain reaction assay for atypical mycobacteria was positive for Mycobacterium interjectum. The culture of the skin biopsy was negative for fungi and mycobacteria after long incubation (6 weeks) on 2 occasions, and an antibiogram was not available. Complementary tests including hemogram, HIV serology, and chest and upper extremity radiographs did not reveal any abnormalities.

The patient was treated with rifampicin 600 mg/d, clarithromycin 500 mg every 12 hours, and co-trimoxazole 160/800 mg every 12 hours for 9 months with some resolution but persistence of some residual scarring lesions. There was no recurrence at 6-month follow-up.

Mycobacterium interjectum is a rare, slow-growing, scotochromogenic mycobacteria. Case reports usually refer to lymphadenitis in healthy children and pulmonary infections in immunocompromised or immunocompetent adults.1,2 A case of M interjectum with cutaneous involvement was reported by Fukuoka et al,3 with ulcerated nodules and abscesses on the leg identified in an immunocompromised patient. Our patient did not present with any cause of immunosuppression or clear injury predisposing him to infection. This microorganism has been detected in water, soil,3 and aquarium fish,4 the latter being the most likely source of infection in our patient. Given its slow growth rate and the need for a specific polymerase chain reaction assay, which is not widely available, M interjectum infection may be underdiagnosed.

No standard antibiotic regimen has been established, but M interjectum has proven to be a multidrug-resistant bacterium with frequent therapy failures. Treatment options have ranged from standard tuberculostatic therapy to combination therapy with medications such as amikacin, levofloxacin, rifampicin, and co-trimoxazole.1 Because an antibiogram was not available for our patient, empiric treatment with rifampicin, clarithromycin, and co-trimoxazole was prescribed for 9 months, with satisfactory response and tolerance. These drugs were selected because of their susceptibility profile in the literature.1,5

To the Editor:

A 48-year-old man presented with nodular lesions in a sporotrichoid pattern on the right hand and forearm of 3 months’ duration (Figure). There were no lymphadeno-pathies, and he had no notable medical history. He denied fever and other systemic symptoms. The patient recently had manipulated a warm water fish aquarium. Although he did not recall a clear injury, inadvertent mild trauma was a possibility. He denied other contact or trauma in relation to animals or vegetables.

Histopathology from a punch biopsy of the forearm revealed a granulomatous infiltrate with necrosis at the deep dermis level at the interface with the subcutaneous cellular tissue that was composed of mainly epithelioid cells with a few multinucleated giant cells. No acid-fast bacilli or fungi were observed with special stains.

A polymerase chain reaction assay for atypical mycobacteria was positive for Mycobacterium interjectum. The culture of the skin biopsy was negative for fungi and mycobacteria after long incubation (6 weeks) on 2 occasions, and an antibiogram was not available. Complementary tests including hemogram, HIV serology, and chest and upper extremity radiographs did not reveal any abnormalities.

The patient was treated with rifampicin 600 mg/d, clarithromycin 500 mg every 12 hours, and co-trimoxazole 160/800 mg every 12 hours for 9 months with some resolution but persistence of some residual scarring lesions. There was no recurrence at 6-month follow-up.

Mycobacterium interjectum is a rare, slow-growing, scotochromogenic mycobacteria. Case reports usually refer to lymphadenitis in healthy children and pulmonary infections in immunocompromised or immunocompetent adults.1,2 A case of M interjectum with cutaneous involvement was reported by Fukuoka et al,3 with ulcerated nodules and abscesses on the leg identified in an immunocompromised patient. Our patient did not present with any cause of immunosuppression or clear injury predisposing him to infection. This microorganism has been detected in water, soil,3 and aquarium fish,4 the latter being the most likely source of infection in our patient. Given its slow growth rate and the need for a specific polymerase chain reaction assay, which is not widely available, M interjectum infection may be underdiagnosed.

No standard antibiotic regimen has been established, but M interjectum has proven to be a multidrug-resistant bacterium with frequent therapy failures. Treatment options have ranged from standard tuberculostatic therapy to combination therapy with medications such as amikacin, levofloxacin, rifampicin, and co-trimoxazole.1 Because an antibiogram was not available for our patient, empiric treatment with rifampicin, clarithromycin, and co-trimoxazole was prescribed for 9 months, with satisfactory response and tolerance. These drugs were selected because of their susceptibility profile in the literature.1,5

- Sotello D, Hata DJ, Reza M, et al. Disseminated Mycobacterium interjectum infection with bacteremia, hepatic and pulmonary involvement associated with a long-term catheter infection. Case Rep Infect Dis. 2017;2017:1-5.

- Dholakia YN. Mycobacterium interjectum isolated from an immunocompetent host with lung infection. Int J Mycobacteriol. 2017;6:401-403.

- Fukuoka M, Matsumura Y, Kore-eda S, et al. Cutaneous infection due to Mycobacterium interjectum in an immunosuppressed patient with microscopic polyangiitis. Br J Dermatol. 2008;159:1382-1384.

- Zanoni RG, Florio D, Fioravanti ML, et al. Occurrence of Mycobacterium spp. in ornamental fish in Italy. J Fish Dis. 2008;31:433-441.

- Emler S, Rochat T, Rohner P, et al. Chronic destructive lung disease associated with a novel mycobacterium. Am J Respir Crit Care Med. 1994;150:261-265.

- Sotello D, Hata DJ, Reza M, et al. Disseminated Mycobacterium interjectum infection with bacteremia, hepatic and pulmonary involvement associated with a long-term catheter infection. Case Rep Infect Dis. 2017;2017:1-5.

- Dholakia YN. Mycobacterium interjectum isolated from an immunocompetent host with lung infection. Int J Mycobacteriol. 2017;6:401-403.

- Fukuoka M, Matsumura Y, Kore-eda S, et al. Cutaneous infection due to Mycobacterium interjectum in an immunosuppressed patient with microscopic polyangiitis. Br J Dermatol. 2008;159:1382-1384.

- Zanoni RG, Florio D, Fioravanti ML, et al. Occurrence of Mycobacterium spp. in ornamental fish in Italy. J Fish Dis. 2008;31:433-441.

- Emler S, Rochat T, Rohner P, et al. Chronic destructive lung disease associated with a novel mycobacterium. Am J Respir Crit Care Med. 1994;150:261-265.

Practice Points

- Mycobacterium interjectum can cause cutaneous nodules in a sporotrichoid or lymphocutaneous pattern and may affect immunocompromised and immunocompetent patients.

- This mycobacteria has been detected in water, soil, and aquarium fish. The latter could be a source of infection and should be taken into account in the anamnesis.

- There is no established therapeutic regimen for M interjectum infection. Combination therapy with rifampicin, clarithromycin, and co-trimoxazole could be an option, though it must always be adapted to an antibiogram if results are available.

Brazilian Peppertree: Watch Out for This Lesser-Known Relative of Poison Ivy

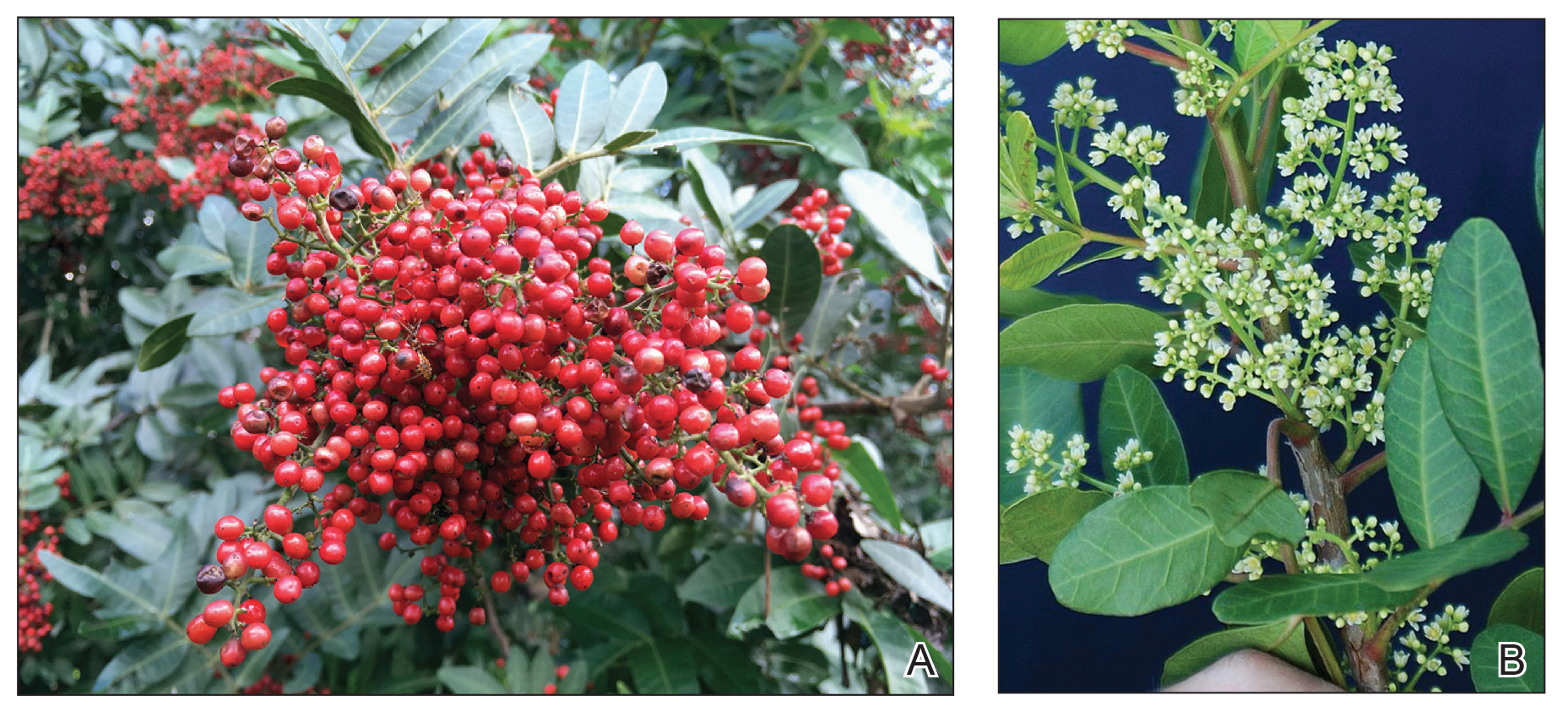

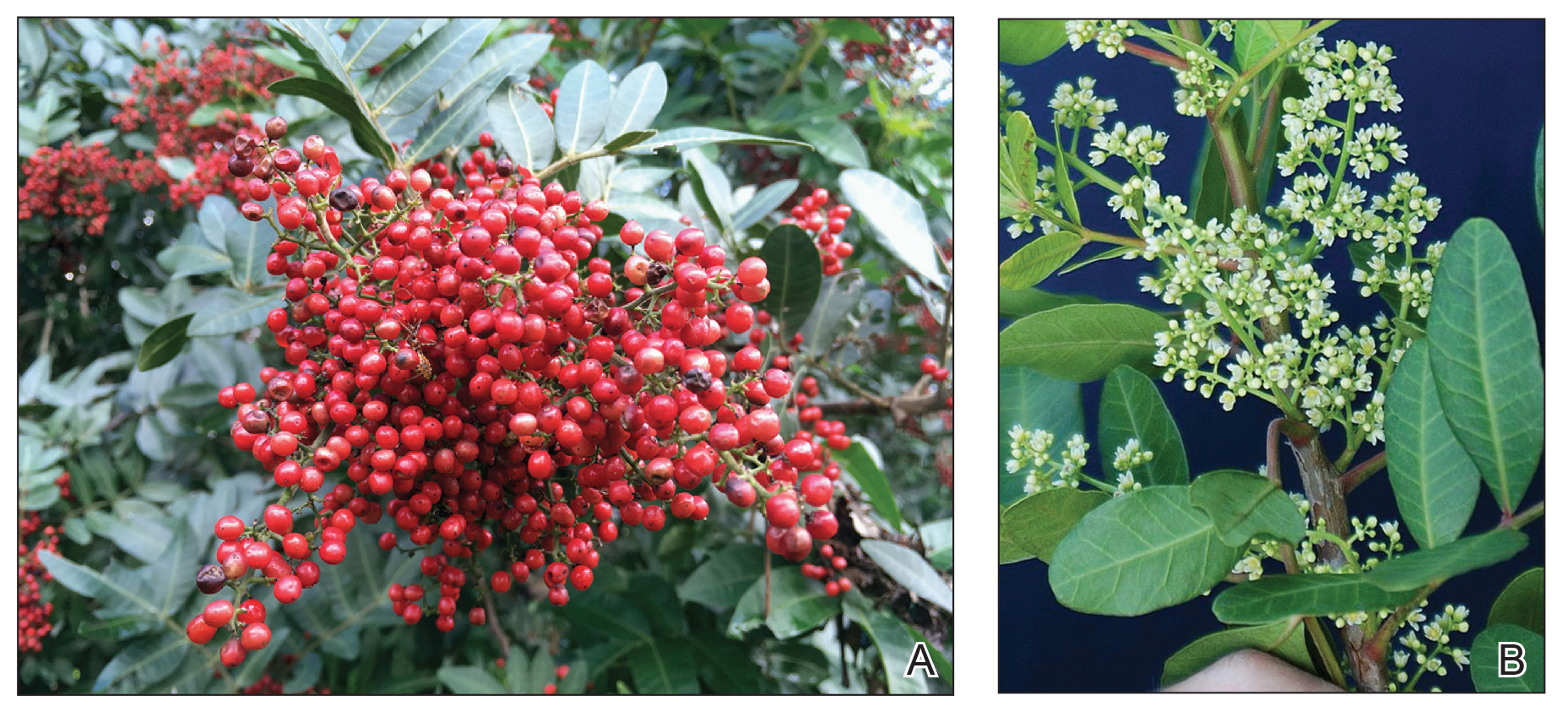

Brazilian peppertree (Schinus terebinthifolia), a member of the Anacardiaceae family, is an internationally invasive plant that causes allergic contact dermatitis (ACD) in susceptible individuals. This noxious weed has settled into the landscape of the southern United States and continues to expand. Its key identifying features include its year-round white flowers as well as a peppery and turpentinelike aroma created by cracking its bright red berries. The ACD associated with contact—primarily with the plant’s sap—stems from known alkenyl phenols, cardol and cardanol. Treatment of Brazilian peppertree–associated ACD parallels that for poison ivy. As this pest increases its range, dermatologists living in endemic areas should familiarize themselves with Brazilian peppertree and its potential for harm.

Brazilian Peppertree Morphology and Geography

Plants in the Anacardiaceae family contribute to more ACD than any other family, and its 80 genera include most of the urushiol-containing plants, such as Toxicodendron (poison ivy, poison oak, poison sumac, Japanese lacquer tree), Anacardium (cashew tree), Mangifera (mango fruit), Semecarpus (India marking nut tree), and Schinus (Brazilian peppertree). Deciduous and evergreen tree members of the Anacardiaceae family grow primarily in tropical and subtropical locations and produce thick resins, 5-petalled flowers, and small fruit known as drupes. The genus name for Brazilian peppertree, Schinus, derives from Latin and Greek words meaning “mastic tree,” a relative of the pistachio tree that the Brazilian peppertree resembles.1 Brazilian peppertree leaves look and smell similar to Pistacia terebinthus (turpentine tree or terebinth), from which the species name terebinthifolia derives.2

Brazilian peppertree originated in South America, particularly Brazil, Paraguay, and Argentina.3 Since the 1840s,4 it has been an invasive weed in the United States, notably in Florida, California, Hawaii, Alabama, Georgia,5 Arizona,6 Nevada,3 and Texas.5,7 The plant also grows throughout the world, including parts of Africa, Asia, Central America, Europe,6 New Zealand,8 Australia, and various islands.9 The plant expertly outcompetes neighboring plants and has prompted control and eradication efforts in many locations.3

Identifying Features and Allergenic Plant Parts

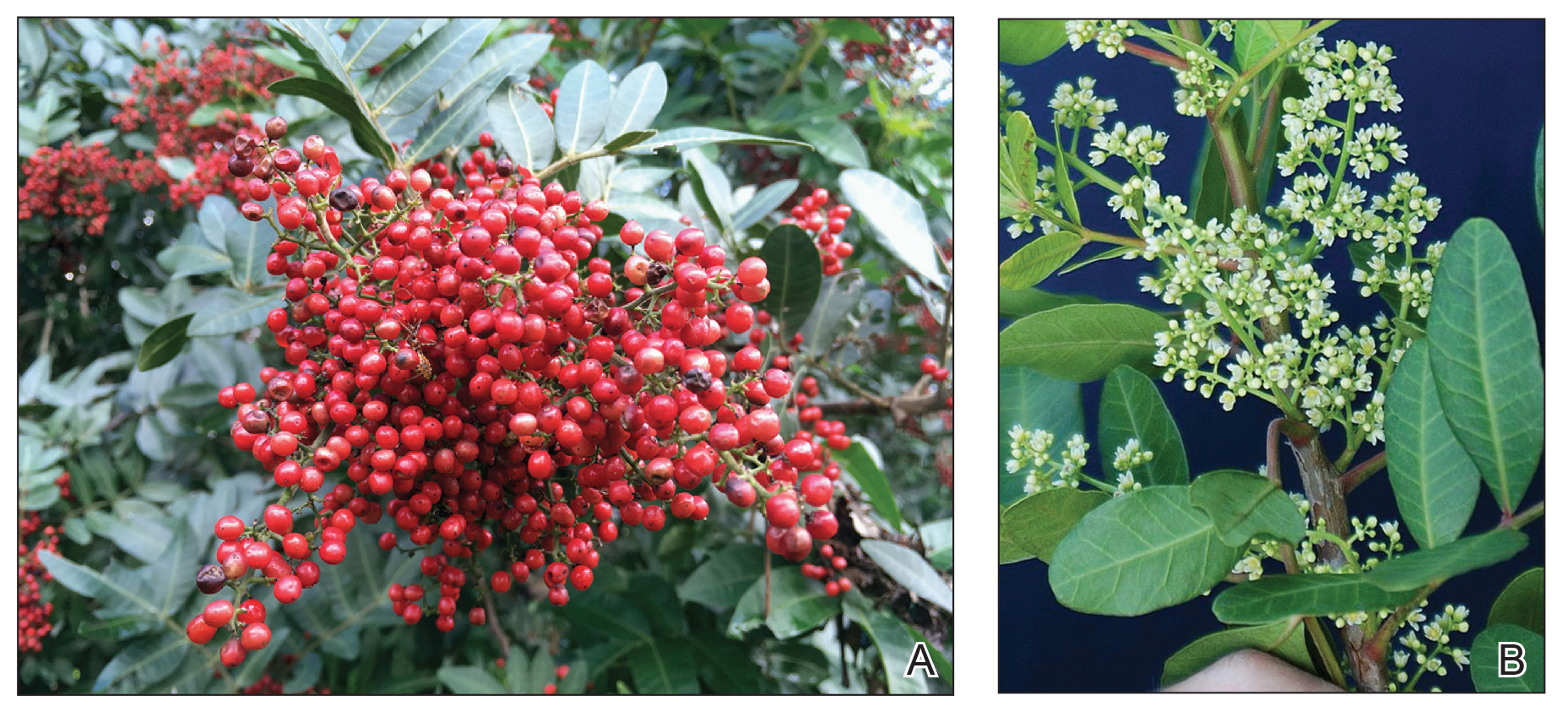

Brazilian peppertree can be either a shrub or tree up to 30 feet tall.4 As an evergreen, it retains its leaves year-round. During fruiting seasons (primarily December through March7), bright red or pink (depending on the variety3) berries appear (Figure 1A) and contribute to its nickname “Florida holly.” Although generally considered an unwelcome guest in Florida, it does display white flowers (Figure 1B) year-round, especially from September to November.9 It characteristically exhibits 3 to 13 leaflets per leaf.10 The leaflets’ ovoid and ridged edges, netlike vasculature, shiny hue, and aroma can help identify the plant (Figure 2A). For decades, the sap of the Brazilian peppertree has been associated with skin irritation (Figure 2B).6 Although the sap of the plant serves as the main culprit of Brazilian peppertree–associated ACD, it appears that other parts of the plant, including the fruit, can cause irritating effects to skin on contact.11,12 The leaves, trunk, and fruit can be harmful to both humans and animals.6 Chemicals from flowers and crushed fruit also can lead to irritating effects in the respiratory tract if aspirated.13

Urushiol, an oily resin present in most plants of the Anacardiaceae family,14 contains many chemicals, including allergenic phenols, catechols, and resorcinols.15 Urushiol-allergic individuals develop dermatitis upon exposure to Brazilian peppertree sap.6 Alkenyl phenols found in Brazilian peppertree lead to the cutaneous manifestations in sensitized patients.11,12 In 1983, Stahl et al11 identified a phenol, cardanol (chemical name 3-pentadecylphenol16) C15:1, in Brazilian peppertree fruit. The group further tested this compound’s effect on skin via patch testing, which showed an allergic response.11 Cashew nut shells (Anacardium occidentale) contain cardanol, anacardic acid (a phenolic acid), and cardol (a phenol with the chemical name 5-pentadecylresorcinol),15,16 though Stahl et al11 were unable to extract these 2 substances (if present) from Brazilian peppertree fruit. When exposed to cardol and anacardic acid, those allergic to poison ivy often develop ACD,15 and these 2 substances are more irritating than cardanol.11 A later study did identify cardol in addition to cardanol in Brazilian peppertree.12

Cutaneous Manifestations

Brazilian peppertree–induced ACD appears similar to other plant-induced ACD with linear streaks of erythema, juicy papules, vesicles, coalescing erythematous plaques, and/or occasional edema and bullae accompanied by intense pruritus.

Treatment

Avoiding contact with Brazilian peppertree is the first line of defense, and treatment for a reaction associated with exposure is similar to that of poison ivy.17 Application of cool compresses, calamine lotion, and topical astringents offer symptom alleviation, and topical steroids (eg, clobetasol propionate 0.05% twice daily) can improve mild localized ACD when given prior to formation of blisters. For more severe and diffuse ACD, oral steroids (eg, prednisone 1 mg/kg/d tapered over 2–3 weeks) likely are necessary, though intramuscular options greatly alleviate discomfort in more severe cases (eg, intramuscular triamcinolone acetonide 1 mg/kg combined with betamethasone 0.1 mg/kg). Physicians should monitor sites for any signs of superimposed bacterial infection and initiate antibiotics as necessary.17

- Zona S. The correct gender of Schinus (Anacardiaceae). Phytotaxa. 2015;222:075-077.

- Terebinth. Encyclopedia.com website. Updated May 17, 2018. Accessed July 9, 2024. https://www.encyclopedia.com/plants-and-animals/plants/plants/terebinth

- Brazilian pepper tree. iNaturalist website. Accessed July 1, 2024. https://www.inaturalist.org/guide_taxa/841531#:~:text=Throughout% 20South%20and%20Central%20America,and%20as%20a%20topical%20antiseptic

- Center for Aquatic and Invasive Plants. Schinus terebinthifolia. Brazilian peppertree. Accessed July 1, 2024. https://plants.ifas.ufl.edu/plant-directory/schinus-terebinthifolia/#:~:text=Species%20Overview&text=People%20sensitive%20to%20poison%20ivy,associated%20with%20its%20bloom%20period

- Brazilian peppertree (Schinus terebinthifolia). Early Detection & Distribution Mapping System. Accessed July 4, 2024. https://www.eddmaps.org/distribution/usstate.cfm?sub=78819

- Morton F. Brazilian pepper: its impact on people, animals, and the environment. Econ Bot. 1978;32:353-359.

- Fire Effects Information System. Schinus terebinthifolius. US Department of Agriculture website. Accessed July 4, 2024. https://www.fs.usda.gov/database/feis/plants/shrub/schter/all.html

- New Zealand Plant Conservation Network. Schinus terebinthifolius. Accessed July 1, 2024. https://www.nzpcn.org.nz/flora/species/schinus-terebinthifolius

- Rojas-Sandoval J, Acevedo-Rodriguez P. Schinus terebinthifolius (Brazilian pepper tree). CABI Compendium. July 23, 2014. Accessed July 1, 2024. https://www.cabidigitallibrary.org/doi/10.1079/cabicompendium.49031

- Patocka J, Diz de Almeida J. Brazilian peppertree: review of pharmacology. Mil Med Sci Lett. 2017;86:32-41.

- Stahl E, Keller K, Blinn C. Cardanol, a skin irritant in pink pepper. Plant Medica. 1983;48:5-9.

- Skopp G, Opferkuch H-J, Schqenker G. n-Alkylphenols from Schinus terebinthifolius Raddi (Anacardiaceae). In German. Zeitschrift für Naturforschung C. 1987;42:1-16. https://doi.org/10.1515/znc-1987-1-203.

- Lloyd HA, Jaouni TM, Evans SL, et al. Terpenes of Schinus terebinthifolius. Phytochemistry. 1977;16:1301-1302.

- Goon ATJ, Goh CL. Plant dermatitis: Asian perspective. Indian J Dermatol. 2011;56:707-710.

- Rozas-Muñoz E, Lepoittevin JP, Pujol RM, et al. Allergic contact dermatitis to plants: understanding the chemistry will help our diagnostic approach. Actas Dermosifiliogr. 2012;103:456-477.

- Caillol S. Cardanol: a promising building block for biobased polymers and additives. Curr Opin Green Sustain Chem. 2018;14: 26-32.

- Prok L, McGovern T. Poison ivy (Toxicodendron) dermatitis. UpToDate. Updated June 21, 2024. Accessed July 7, 2024. https://www.uptodate.com/contents/poison-ivy-toxicodendron-dermatitis#

Brazilian peppertree (Schinus terebinthifolia), a member of the Anacardiaceae family, is an internationally invasive plant that causes allergic contact dermatitis (ACD) in susceptible individuals. This noxious weed has settled into the landscape of the southern United States and continues to expand. Its key identifying features include its year-round white flowers as well as a peppery and turpentinelike aroma created by cracking its bright red berries. The ACD associated with contact—primarily with the plant’s sap—stems from known alkenyl phenols, cardol and cardanol. Treatment of Brazilian peppertree–associated ACD parallels that for poison ivy. As this pest increases its range, dermatologists living in endemic areas should familiarize themselves with Brazilian peppertree and its potential for harm.

Brazilian Peppertree Morphology and Geography

Plants in the Anacardiaceae family contribute to more ACD than any other family, and its 80 genera include most of the urushiol-containing plants, such as Toxicodendron (poison ivy, poison oak, poison sumac, Japanese lacquer tree), Anacardium (cashew tree), Mangifera (mango fruit), Semecarpus (India marking nut tree), and Schinus (Brazilian peppertree). Deciduous and evergreen tree members of the Anacardiaceae family grow primarily in tropical and subtropical locations and produce thick resins, 5-petalled flowers, and small fruit known as drupes. The genus name for Brazilian peppertree, Schinus, derives from Latin and Greek words meaning “mastic tree,” a relative of the pistachio tree that the Brazilian peppertree resembles.1 Brazilian peppertree leaves look and smell similar to Pistacia terebinthus (turpentine tree or terebinth), from which the species name terebinthifolia derives.2

Brazilian peppertree originated in South America, particularly Brazil, Paraguay, and Argentina.3 Since the 1840s,4 it has been an invasive weed in the United States, notably in Florida, California, Hawaii, Alabama, Georgia,5 Arizona,6 Nevada,3 and Texas.5,7 The plant also grows throughout the world, including parts of Africa, Asia, Central America, Europe,6 New Zealand,8 Australia, and various islands.9 The plant expertly outcompetes neighboring plants and has prompted control and eradication efforts in many locations.3

Identifying Features and Allergenic Plant Parts

Brazilian peppertree can be either a shrub or tree up to 30 feet tall.4 As an evergreen, it retains its leaves year-round. During fruiting seasons (primarily December through March7), bright red or pink (depending on the variety3) berries appear (Figure 1A) and contribute to its nickname “Florida holly.” Although generally considered an unwelcome guest in Florida, it does display white flowers (Figure 1B) year-round, especially from September to November.9 It characteristically exhibits 3 to 13 leaflets per leaf.10 The leaflets’ ovoid and ridged edges, netlike vasculature, shiny hue, and aroma can help identify the plant (Figure 2A). For decades, the sap of the Brazilian peppertree has been associated with skin irritation (Figure 2B).6 Although the sap of the plant serves as the main culprit of Brazilian peppertree–associated ACD, it appears that other parts of the plant, including the fruit, can cause irritating effects to skin on contact.11,12 The leaves, trunk, and fruit can be harmful to both humans and animals.6 Chemicals from flowers and crushed fruit also can lead to irritating effects in the respiratory tract if aspirated.13

Urushiol, an oily resin present in most plants of the Anacardiaceae family,14 contains many chemicals, including allergenic phenols, catechols, and resorcinols.15 Urushiol-allergic individuals develop dermatitis upon exposure to Brazilian peppertree sap.6 Alkenyl phenols found in Brazilian peppertree lead to the cutaneous manifestations in sensitized patients.11,12 In 1983, Stahl et al11 identified a phenol, cardanol (chemical name 3-pentadecylphenol16) C15:1, in Brazilian peppertree fruit. The group further tested this compound’s effect on skin via patch testing, which showed an allergic response.11 Cashew nut shells (Anacardium occidentale) contain cardanol, anacardic acid (a phenolic acid), and cardol (a phenol with the chemical name 5-pentadecylresorcinol),15,16 though Stahl et al11 were unable to extract these 2 substances (if present) from Brazilian peppertree fruit. When exposed to cardol and anacardic acid, those allergic to poison ivy often develop ACD,15 and these 2 substances are more irritating than cardanol.11 A later study did identify cardol in addition to cardanol in Brazilian peppertree.12

Cutaneous Manifestations

Brazilian peppertree–induced ACD appears similar to other plant-induced ACD with linear streaks of erythema, juicy papules, vesicles, coalescing erythematous plaques, and/or occasional edema and bullae accompanied by intense pruritus.

Treatment

Avoiding contact with Brazilian peppertree is the first line of defense, and treatment for a reaction associated with exposure is similar to that of poison ivy.17 Application of cool compresses, calamine lotion, and topical astringents offer symptom alleviation, and topical steroids (eg, clobetasol propionate 0.05% twice daily) can improve mild localized ACD when given prior to formation of blisters. For more severe and diffuse ACD, oral steroids (eg, prednisone 1 mg/kg/d tapered over 2–3 weeks) likely are necessary, though intramuscular options greatly alleviate discomfort in more severe cases (eg, intramuscular triamcinolone acetonide 1 mg/kg combined with betamethasone 0.1 mg/kg). Physicians should monitor sites for any signs of superimposed bacterial infection and initiate antibiotics as necessary.17

Brazilian peppertree (Schinus terebinthifolia), a member of the Anacardiaceae family, is an internationally invasive plant that causes allergic contact dermatitis (ACD) in susceptible individuals. This noxious weed has settled into the landscape of the southern United States and continues to expand. Its key identifying features include its year-round white flowers as well as a peppery and turpentinelike aroma created by cracking its bright red berries. The ACD associated with contact—primarily with the plant’s sap—stems from known alkenyl phenols, cardol and cardanol. Treatment of Brazilian peppertree–associated ACD parallels that for poison ivy. As this pest increases its range, dermatologists living in endemic areas should familiarize themselves with Brazilian peppertree and its potential for harm.

Brazilian Peppertree Morphology and Geography

Plants in the Anacardiaceae family contribute to more ACD than any other family, and its 80 genera include most of the urushiol-containing plants, such as Toxicodendron (poison ivy, poison oak, poison sumac, Japanese lacquer tree), Anacardium (cashew tree), Mangifera (mango fruit), Semecarpus (India marking nut tree), and Schinus (Brazilian peppertree). Deciduous and evergreen tree members of the Anacardiaceae family grow primarily in tropical and subtropical locations and produce thick resins, 5-petalled flowers, and small fruit known as drupes. The genus name for Brazilian peppertree, Schinus, derives from Latin and Greek words meaning “mastic tree,” a relative of the pistachio tree that the Brazilian peppertree resembles.1 Brazilian peppertree leaves look and smell similar to Pistacia terebinthus (turpentine tree or terebinth), from which the species name terebinthifolia derives.2

Brazilian peppertree originated in South America, particularly Brazil, Paraguay, and Argentina.3 Since the 1840s,4 it has been an invasive weed in the United States, notably in Florida, California, Hawaii, Alabama, Georgia,5 Arizona,6 Nevada,3 and Texas.5,7 The plant also grows throughout the world, including parts of Africa, Asia, Central America, Europe,6 New Zealand,8 Australia, and various islands.9 The plant expertly outcompetes neighboring plants and has prompted control and eradication efforts in many locations.3

Identifying Features and Allergenic Plant Parts

Brazilian peppertree can be either a shrub or tree up to 30 feet tall.4 As an evergreen, it retains its leaves year-round. During fruiting seasons (primarily December through March7), bright red or pink (depending on the variety3) berries appear (Figure 1A) and contribute to its nickname “Florida holly.” Although generally considered an unwelcome guest in Florida, it does display white flowers (Figure 1B) year-round, especially from September to November.9 It characteristically exhibits 3 to 13 leaflets per leaf.10 The leaflets’ ovoid and ridged edges, netlike vasculature, shiny hue, and aroma can help identify the plant (Figure 2A). For decades, the sap of the Brazilian peppertree has been associated with skin irritation (Figure 2B).6 Although the sap of the plant serves as the main culprit of Brazilian peppertree–associated ACD, it appears that other parts of the plant, including the fruit, can cause irritating effects to skin on contact.11,12 The leaves, trunk, and fruit can be harmful to both humans and animals.6 Chemicals from flowers and crushed fruit also can lead to irritating effects in the respiratory tract if aspirated.13

Urushiol, an oily resin present in most plants of the Anacardiaceae family,14 contains many chemicals, including allergenic phenols, catechols, and resorcinols.15 Urushiol-allergic individuals develop dermatitis upon exposure to Brazilian peppertree sap.6 Alkenyl phenols found in Brazilian peppertree lead to the cutaneous manifestations in sensitized patients.11,12 In 1983, Stahl et al11 identified a phenol, cardanol (chemical name 3-pentadecylphenol16) C15:1, in Brazilian peppertree fruit. The group further tested this compound’s effect on skin via patch testing, which showed an allergic response.11 Cashew nut shells (Anacardium occidentale) contain cardanol, anacardic acid (a phenolic acid), and cardol (a phenol with the chemical name 5-pentadecylresorcinol),15,16 though Stahl et al11 were unable to extract these 2 substances (if present) from Brazilian peppertree fruit. When exposed to cardol and anacardic acid, those allergic to poison ivy often develop ACD,15 and these 2 substances are more irritating than cardanol.11 A later study did identify cardol in addition to cardanol in Brazilian peppertree.12

Cutaneous Manifestations

Brazilian peppertree–induced ACD appears similar to other plant-induced ACD with linear streaks of erythema, juicy papules, vesicles, coalescing erythematous plaques, and/or occasional edema and bullae accompanied by intense pruritus.

Treatment

Avoiding contact with Brazilian peppertree is the first line of defense, and treatment for a reaction associated with exposure is similar to that of poison ivy.17 Application of cool compresses, calamine lotion, and topical astringents offer symptom alleviation, and topical steroids (eg, clobetasol propionate 0.05% twice daily) can improve mild localized ACD when given prior to formation of blisters. For more severe and diffuse ACD, oral steroids (eg, prednisone 1 mg/kg/d tapered over 2–3 weeks) likely are necessary, though intramuscular options greatly alleviate discomfort in more severe cases (eg, intramuscular triamcinolone acetonide 1 mg/kg combined with betamethasone 0.1 mg/kg). Physicians should monitor sites for any signs of superimposed bacterial infection and initiate antibiotics as necessary.17

- Zona S. The correct gender of Schinus (Anacardiaceae). Phytotaxa. 2015;222:075-077.

- Terebinth. Encyclopedia.com website. Updated May 17, 2018. Accessed July 9, 2024. https://www.encyclopedia.com/plants-and-animals/plants/plants/terebinth

- Brazilian pepper tree. iNaturalist website. Accessed July 1, 2024. https://www.inaturalist.org/guide_taxa/841531#:~:text=Throughout% 20South%20and%20Central%20America,and%20as%20a%20topical%20antiseptic

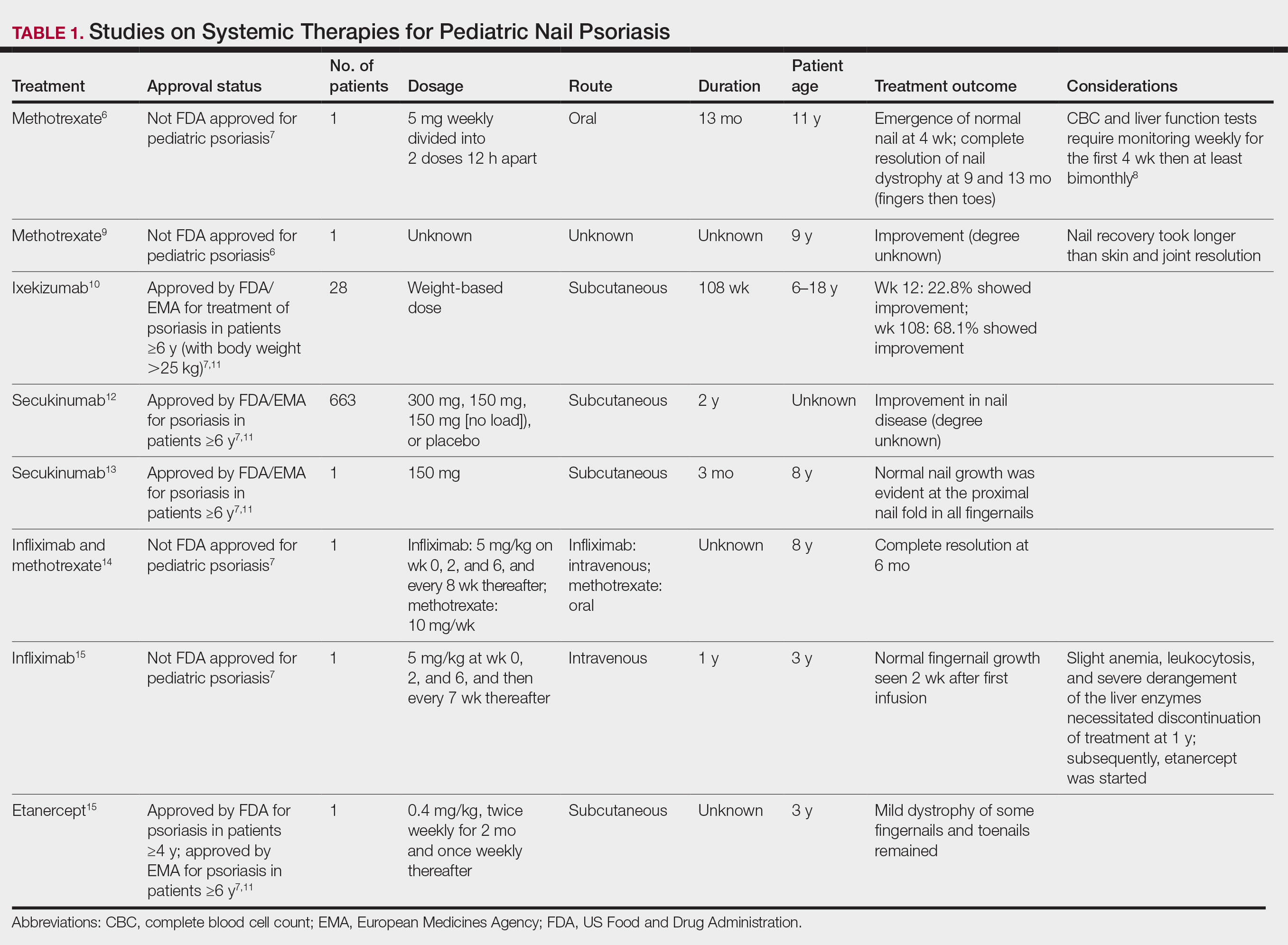

- Center for Aquatic and Invasive Plants. Schinus terebinthifolia. Brazilian peppertree. Accessed July 1, 2024. https://plants.ifas.ufl.edu/plant-directory/schinus-terebinthifolia/#:~:text=Species%20Overview&text=People%20sensitive%20to%20poison%20ivy,associated%20with%20its%20bloom%20period