User login

OTHER PEDIATRIC LITERATURE OF INTEREST

Enter text here

Enter text here

Enter text here

Calcitonin Precursors and IL-8 as a Screening Panel for Bacterial Sepsis

Enter text here

Enter text here

Enter text here

Practice Guidelines for the Management of Bacterial Meningitis

Enter text here

Enter text here

Enter text here

Issues in Determining Appropriate Levels of Hospitalist Staffing

Introduction

A major challenge for leaders of hospital medicine programs is determining appropriate staffing levels. Specifically, every hospitalist leader must answer the following question:

- What is the correct number of physician staff needed to meet the requirements of the work environment?

The Board of Directors of the Society of Hospital Medicine (SHM) asked the Benchmarks Committee to prepare a “white paper” on this subject. The Committee discussed hospitalist staffing and agreed that there is no simple formula or process for answering the question cited above. Instead, the Committee decided to prepare a paper that outlines the issues and suggests best practices for determining appropriate hospitalist staffing levels. A member of the Benchmarks Committee, Gale Ashbrener, Sr., Performance Consultant, Kaiser Permanente-Hawaii, has prepared a model for hospitalist staffing in her organization, and her work is the basis of this document.

NOTE: Most of the examples used in this document are from Kaiser-Hawaii. As such, the numbers cited are reflective of that particular organizational environment (i.e., a group model HMO). Readers should focus on the concepts and processes that are presented, recognizing that the numbers may be different for their environment.

Overview of the Issues

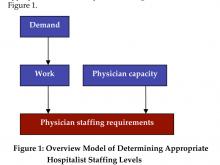

A process or simplistic model for determining the appropriate level of hospitalist staffing is summarized in Figure 1.

Staffing

Staffing is driven by demand: how many and what types of patients will the program expect to see in the upcoming year? Demand can then be converted to work: the tasks that the hospital medicine program must perform in order to treat these patients (the model must also quantify non-patient work). Once the total amount of work is described and quantified, the capacity of a hospitalist must be defined (e.g., in annual work hours). Then the number of hospitalists required to complete the projected work load can be computed.

Demand

The best practices for projecting patient demand are summarized in Box 1.

Hospitalist leaders should involve key stakeholders in the information gathering process. This helps establish the foundation for buy-in of the model down the road. You may want to pull together members of the hospitalist team and/or hospital administration to brainstorm on factors that may affect patient demand for inpatient services. At this point, keep an open mind for all considerations.

It is also critical to perform a comprehensive analysis of historical inpatient data. The analysis should examine all medical admissions at the hospital and specifically, in detail, those admissions cared for by the hospital medicine program. This analysis must look beyond the number of admissions and average length of stay (LOS). Several key characteristics of the hospitalized patients should be evaluated: age, diagnosis/severity, payer, and referring physician.

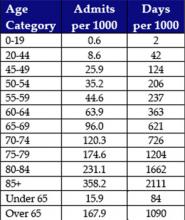

- Age: There are significant differences in inpatient utilization by age categories. It is important to further segment the “senior” Medicare (over age 65) population into several subgroups. Figure 2 (page 49) is based on data from Kaiser Permanente-Hawaii. As expected, there is a major difference in hospital utilization between the under age 65 population (15.9 admissions and 84 days per 1000) and the over age 65 population (167.9 admissions and 1,090 days per 1000). However, the differences within the Medicare subgroups are also substantial. For example, compare utilization by the population that is 65-69 years old (96.0 admissions and 621 days per 1000) with the population that is over age 85 (358.2 admissions and 2,111 days per 1000):

- Diagnoses/severity: There are acknowledged differences in LOS based on the patient’s reason for admission and many ways to characterize the reason of admission, including diagnosis and diagnostics-related groups (DRGs). Furthermore, patients with co-morbidities clearly require more coordination and patient management. There are several proprietary grouping methodologies that characterize the severity and intensity of an inpatient case, which include an assessment of co-morbidities. In analyzing historical data, the hospitalist leader should select a scheme that is used within the institution while minimizing the number of categories.

- Payer: In analyzing inpatient demand, it is also important to have an understanding of historical differences by payer (including uninsured patients). Health plans (or Medicaid programs) that are increasing or decreasing in size could affect the number of patients seen by a hospital medicine program.

- Referring physician: Community physicians (primary care, specialists, and surgeons) are a major source of inpatient cases for hospital medicine programs. It is important to analyze the historical impact of specific physicians or group practices on the patient load of the hospital medicine program.

The best way to project inpatient demand for hospitalist services is to identify and quantify what may change in the next year: what trends could increase or decrease the number of cases that will need to be treated? These change factors include the following:

- Population trends: Is the community growing? It there an influx of new residents? Is the community aging? Is it likely that there will be more seniors requiring inpatient services? Health plans and medical groups often can more easily assess population trends because they treat an enrolled population.

- Local health care factors: Will a hospital in the region be closing, resulting in additional inpatient demand? Is there a shortage of nursing home beds in the community that may affect the need for inpatient care? Is Medicaid reducing the number of covered recipients, potentially increasing the demand from uninsured patients?

- Changing referral patterns from community physicians: Do you expect additional community physicians to stop/start referring patients to the hospital medicine program? Are referring medical groups increasing or decreasing in size?

- Institution-specific factors: Does the hospital medicine program expect to assume new responsibilities in the next year – e.g., in the emergency department (ED), in the intensive care unit (ICU), providing night coverage, doing surgical co‑management, etc.?

Work

The best practices for measuring hospitalist output (work) are summarized in Box 2.

Determining how to quantify the labor of hospitalists can be the most controversial component of developing a staffing model. To ensure buy-in of these modeling decisions, participation by hospitalists and other key players (e.g., other physicians, physician leadership, and hospital/medical group administration) is crucial. Hospitalists and other key individuals must understand and agree on the quantification of time and labor.

It is critical that the analysis include ALL elements of work. Brainstorming with hospitalists can be helpful in this process. To build physician acceptance of and trust in the model, it is important to acknowledge the full set of hospitalist responsibilities in the initial stages of model development.

The services provided by a hospitalist team can vary from program to program and hospital to hospital. For example, at Kaiser Permanente-Hawaii, the dedicated hospitalist triage physician may direct patients coming from the clinic or ED to the ambulatory treatment center. A hospitalist then sees the patient in the center and an admission is often avoided. This physician labor must be captured in the model even though an admission did not occur. If your program includes a day team and a night team, you may want to handle these two teams as separate models.

Based on an analysis performed at Kaiser Permanente-Hawaii, some examples of hospitalist labor components are noted in Box 3 (page 50).

To measure the work performed by hospitalists, the model needs to recognize that there are differences in the labor components that have been identified (i.e., they are “weighted” differently). “Conventional wisdom” describes the work that hospitalists perform in terms of the number of patients seen per day (e.g., 15 patients per day). However, the work involved in a hospitalist seeing the following categories of patients is very different:

- Admitting a patient

- Rounding on a patient already admitted

- Discharging a patient

- Performing a consultation

Kaiser Permanente Hawaii developed the example in Box 4 to illustrate differences in the work required for admissions, rounding, and discharges, and how reductions in LOS do not lead to corresponding reductions in physician staffing levels.

There are basically two options in weighting the different elements of work performed by a hospitalist: time or relative value units (RVUs). Although the amount of time it takes to do a task seems to be the most sensible measurement of labor, it can be fraught with obstacles. The amount of time it takes a physician to round on a patient, for example, is not straightforward:

- Are all the patients located on one floor?

- Does the physician have to chase down test results routinely?

- Are all physicians the same, taking the same average amount of time to see a patient?

- Are all patients the same? Do older patients take more time due to social and medical complexity?

These are all factors that affect time. Furthermore, individuals are limited by their own experiences and frame of reference. Acceptance of a specific time allocation (e.g., a discharge takes 45 minutes) by those not doing the work is subjective. Despite these obstacles, it is valuable for hospitalist leaders to attempt to quantify the amount of time required to do inpatient work. Figure 3 shows example times used by a Kaiser Permanente-Hawaii medical group.

A hospital medicine program leader can use RVUs as a compliment to or as an alternative to time as the basis of weighting the work components performed by hospitalists. RVUs may account for patient acuity in a way that is hard to measure using time as the basis of measurement. Figure 4 illustrates RVUs by CPT-IV code.

Physician Capacity

The best practices for determining physician capacity are summarized in Box 5.

When determining the work capacity for a hospitalist (typically defined by the number of hours worked per year), it is critical to clearly define the unique aspects of the hospital medicine program that affect work capacity. These factors include:

- Staffing model: shift vs. call

- Scheduling approach: number of days on/off

- Non-patient care responsibilities: teaching, research, committees, etc.

- Staffing philosophy: part-time vs. full-time preference

Benchmark information is extremely helpful in determining physician capacity for a hospital medicine program. These benchmarks provide a point of comparison for hospitalist leaders developing staffing models. Medians for inpatient, non-patient, and on-call hours from the 2004 SHM Productivity and Compensation Survey are documented in Figure 5 (page 52).

The simplified example in Box 6, based on Kaiser time estimates, illustrates how demand, work, and physician capacity can be used to determine the number of hospitalists required to support a program.

As an alternative methodology or for comparative purposes, RVUs can be used rather than time. Box 7 uses RVUs from Figure 4 (initial hospital care: 1.28 RVUs; subsequent hospital care: .64 RVUs; hospital discharge < 30 minutes: 1.28 RVUs). The lowest level RVU values are used because they are consistent with the Kaiser example. Also, the median RVUs per year from Figure 5 are used (2961 for a hospital-based program).

Understand Your Work Environment

When a hospitalist program leader begins the process of developing a staffing model, it is important that he or she understands how the unique goals and characteristics of the program affects staffing. For example:

- Hospitalist-only groups are often driven by revenue. It is likely that these programs will expect hospitalists to do more billable work (i.e., see more patients)

- Academic programs typically have a broad range of other, non-patient care responsibilities, including teaching, research, and committee work. The hospitalists in these programs may see fewer patients.

The data from the 2004 SHM Productivity and Compensation Survey (Figure 5) confirms these differences. For inpatient hours worked, the national medians for these two different employment models differ by 23% (1700 vs. 2210). For RVUs worked, the national medians for the two different employment models differ by 17% (3000 vs. 3600).

Summary

Determining the right level of hospitalist staffing is important because it can positively or negatively affect the hospital medicine program and the hospital. Understaffing can lead to physician burn-out and adversely affect physician performance and hospital utilization. Overstaffing can affect the program’s financial performance and undercut the credibility of the program. The right staffing models and formulas, however, can help create a successful hospitalist work environment.

Summary of Recommendations

- There is no industry standard for a hospitalist staffing model. The analysis can be time-based or RVU-based, census driven, or based on any combination of output measures.

- Inpatient utilization drives the requirements for hospitalist staffing. A thorough analysis of historical inpatient utilization data is critical to developing a staffing model.

- In addition to understanding past utilization, projecting future inpatient demand is also important. Critical change factors include trends in: 1) the age and severity of patients; 2) population growth or decline; 3) payer sources; and 4) referral patterns.

- The services (work) performed by the hospital medicine program should be clearly identified and factored into the staffing formula. Brainstorming with the hospitalist group can be an effective technique for ensuring that the analysis is credible.

- Stakeholders should be involved early and often in developing a staffing model and in making staffing decisions.

- In developing a staffing model, particularly in the beginning stages, focus on the process and the methodology and not on the outcome (i.e., “my program needs 6 physicians”).

- Understand how the unique goals and characteristics of your hospital medicine program affect your staffing model.

Introduction

A major challenge for leaders of hospital medicine programs is determining appropriate staffing levels. Specifically, every hospitalist leader must answer the following question:

- What is the correct number of physician staff needed to meet the requirements of the work environment?

The Board of Directors of the Society of Hospital Medicine (SHM) asked the Benchmarks Committee to prepare a “white paper” on this subject. The Committee discussed hospitalist staffing and agreed that there is no simple formula or process for answering the question cited above. Instead, the Committee decided to prepare a paper that outlines the issues and suggests best practices for determining appropriate hospitalist staffing levels. A member of the Benchmarks Committee, Gale Ashbrener, Sr., Performance Consultant, Kaiser Permanente-Hawaii, has prepared a model for hospitalist staffing in her organization, and her work is the basis of this document.

NOTE: Most of the examples used in this document are from Kaiser-Hawaii. As such, the numbers cited are reflective of that particular organizational environment (i.e., a group model HMO). Readers should focus on the concepts and processes that are presented, recognizing that the numbers may be different for their environment.

Overview of the Issues

A process or simplistic model for determining the appropriate level of hospitalist staffing is summarized in Figure 1.

Staffing

Staffing is driven by demand: how many and what types of patients will the program expect to see in the upcoming year? Demand can then be converted to work: the tasks that the hospital medicine program must perform in order to treat these patients (the model must also quantify non-patient work). Once the total amount of work is described and quantified, the capacity of a hospitalist must be defined (e.g., in annual work hours). Then the number of hospitalists required to complete the projected work load can be computed.

Demand

The best practices for projecting patient demand are summarized in Box 1.

Hospitalist leaders should involve key stakeholders in the information gathering process. This helps establish the foundation for buy-in of the model down the road. You may want to pull together members of the hospitalist team and/or hospital administration to brainstorm on factors that may affect patient demand for inpatient services. At this point, keep an open mind for all considerations.

It is also critical to perform a comprehensive analysis of historical inpatient data. The analysis should examine all medical admissions at the hospital and specifically, in detail, those admissions cared for by the hospital medicine program. This analysis must look beyond the number of admissions and average length of stay (LOS). Several key characteristics of the hospitalized patients should be evaluated: age, diagnosis/severity, payer, and referring physician.

- Age: There are significant differences in inpatient utilization by age categories. It is important to further segment the “senior” Medicare (over age 65) population into several subgroups. Figure 2 (page 49) is based on data from Kaiser Permanente-Hawaii. As expected, there is a major difference in hospital utilization between the under age 65 population (15.9 admissions and 84 days per 1000) and the over age 65 population (167.9 admissions and 1,090 days per 1000). However, the differences within the Medicare subgroups are also substantial. For example, compare utilization by the population that is 65-69 years old (96.0 admissions and 621 days per 1000) with the population that is over age 85 (358.2 admissions and 2,111 days per 1000):

- Diagnoses/severity: There are acknowledged differences in LOS based on the patient’s reason for admission and many ways to characterize the reason of admission, including diagnosis and diagnostics-related groups (DRGs). Furthermore, patients with co-morbidities clearly require more coordination and patient management. There are several proprietary grouping methodologies that characterize the severity and intensity of an inpatient case, which include an assessment of co-morbidities. In analyzing historical data, the hospitalist leader should select a scheme that is used within the institution while minimizing the number of categories.

- Payer: In analyzing inpatient demand, it is also important to have an understanding of historical differences by payer (including uninsured patients). Health plans (or Medicaid programs) that are increasing or decreasing in size could affect the number of patients seen by a hospital medicine program.

- Referring physician: Community physicians (primary care, specialists, and surgeons) are a major source of inpatient cases for hospital medicine programs. It is important to analyze the historical impact of specific physicians or group practices on the patient load of the hospital medicine program.

The best way to project inpatient demand for hospitalist services is to identify and quantify what may change in the next year: what trends could increase or decrease the number of cases that will need to be treated? These change factors include the following:

- Population trends: Is the community growing? It there an influx of new residents? Is the community aging? Is it likely that there will be more seniors requiring inpatient services? Health plans and medical groups often can more easily assess population trends because they treat an enrolled population.

- Local health care factors: Will a hospital in the region be closing, resulting in additional inpatient demand? Is there a shortage of nursing home beds in the community that may affect the need for inpatient care? Is Medicaid reducing the number of covered recipients, potentially increasing the demand from uninsured patients?

- Changing referral patterns from community physicians: Do you expect additional community physicians to stop/start referring patients to the hospital medicine program? Are referring medical groups increasing or decreasing in size?

- Institution-specific factors: Does the hospital medicine program expect to assume new responsibilities in the next year – e.g., in the emergency department (ED), in the intensive care unit (ICU), providing night coverage, doing surgical co‑management, etc.?

Work

The best practices for measuring hospitalist output (work) are summarized in Box 2.

Determining how to quantify the labor of hospitalists can be the most controversial component of developing a staffing model. To ensure buy-in of these modeling decisions, participation by hospitalists and other key players (e.g., other physicians, physician leadership, and hospital/medical group administration) is crucial. Hospitalists and other key individuals must understand and agree on the quantification of time and labor.

It is critical that the analysis include ALL elements of work. Brainstorming with hospitalists can be helpful in this process. To build physician acceptance of and trust in the model, it is important to acknowledge the full set of hospitalist responsibilities in the initial stages of model development.

The services provided by a hospitalist team can vary from program to program and hospital to hospital. For example, at Kaiser Permanente-Hawaii, the dedicated hospitalist triage physician may direct patients coming from the clinic or ED to the ambulatory treatment center. A hospitalist then sees the patient in the center and an admission is often avoided. This physician labor must be captured in the model even though an admission did not occur. If your program includes a day team and a night team, you may want to handle these two teams as separate models.

Based on an analysis performed at Kaiser Permanente-Hawaii, some examples of hospitalist labor components are noted in Box 3 (page 50).

To measure the work performed by hospitalists, the model needs to recognize that there are differences in the labor components that have been identified (i.e., they are “weighted” differently). “Conventional wisdom” describes the work that hospitalists perform in terms of the number of patients seen per day (e.g., 15 patients per day). However, the work involved in a hospitalist seeing the following categories of patients is very different:

- Admitting a patient

- Rounding on a patient already admitted

- Discharging a patient

- Performing a consultation

Kaiser Permanente Hawaii developed the example in Box 4 to illustrate differences in the work required for admissions, rounding, and discharges, and how reductions in LOS do not lead to corresponding reductions in physician staffing levels.

There are basically two options in weighting the different elements of work performed by a hospitalist: time or relative value units (RVUs). Although the amount of time it takes to do a task seems to be the most sensible measurement of labor, it can be fraught with obstacles. The amount of time it takes a physician to round on a patient, for example, is not straightforward:

- Are all the patients located on one floor?

- Does the physician have to chase down test results routinely?

- Are all physicians the same, taking the same average amount of time to see a patient?

- Are all patients the same? Do older patients take more time due to social and medical complexity?

These are all factors that affect time. Furthermore, individuals are limited by their own experiences and frame of reference. Acceptance of a specific time allocation (e.g., a discharge takes 45 minutes) by those not doing the work is subjective. Despite these obstacles, it is valuable for hospitalist leaders to attempt to quantify the amount of time required to do inpatient work. Figure 3 shows example times used by a Kaiser Permanente-Hawaii medical group.

A hospital medicine program leader can use RVUs as a compliment to or as an alternative to time as the basis of weighting the work components performed by hospitalists. RVUs may account for patient acuity in a way that is hard to measure using time as the basis of measurement. Figure 4 illustrates RVUs by CPT-IV code.

Physician Capacity

The best practices for determining physician capacity are summarized in Box 5.

When determining the work capacity for a hospitalist (typically defined by the number of hours worked per year), it is critical to clearly define the unique aspects of the hospital medicine program that affect work capacity. These factors include:

- Staffing model: shift vs. call

- Scheduling approach: number of days on/off

- Non-patient care responsibilities: teaching, research, committees, etc.

- Staffing philosophy: part-time vs. full-time preference

Benchmark information is extremely helpful in determining physician capacity for a hospital medicine program. These benchmarks provide a point of comparison for hospitalist leaders developing staffing models. Medians for inpatient, non-patient, and on-call hours from the 2004 SHM Productivity and Compensation Survey are documented in Figure 5 (page 52).

The simplified example in Box 6, based on Kaiser time estimates, illustrates how demand, work, and physician capacity can be used to determine the number of hospitalists required to support a program.

As an alternative methodology or for comparative purposes, RVUs can be used rather than time. Box 7 uses RVUs from Figure 4 (initial hospital care: 1.28 RVUs; subsequent hospital care: .64 RVUs; hospital discharge < 30 minutes: 1.28 RVUs). The lowest level RVU values are used because they are consistent with the Kaiser example. Also, the median RVUs per year from Figure 5 are used (2961 for a hospital-based program).

Understand Your Work Environment

When a hospitalist program leader begins the process of developing a staffing model, it is important that he or she understands how the unique goals and characteristics of the program affects staffing. For example:

- Hospitalist-only groups are often driven by revenue. It is likely that these programs will expect hospitalists to do more billable work (i.e., see more patients)

- Academic programs typically have a broad range of other, non-patient care responsibilities, including teaching, research, and committee work. The hospitalists in these programs may see fewer patients.

The data from the 2004 SHM Productivity and Compensation Survey (Figure 5) confirms these differences. For inpatient hours worked, the national medians for these two different employment models differ by 23% (1700 vs. 2210). For RVUs worked, the national medians for the two different employment models differ by 17% (3000 vs. 3600).

Summary

Determining the right level of hospitalist staffing is important because it can positively or negatively affect the hospital medicine program and the hospital. Understaffing can lead to physician burn-out and adversely affect physician performance and hospital utilization. Overstaffing can affect the program’s financial performance and undercut the credibility of the program. The right staffing models and formulas, however, can help create a successful hospitalist work environment.

Summary of Recommendations

- There is no industry standard for a hospitalist staffing model. The analysis can be time-based or RVU-based, census driven, or based on any combination of output measures.

- Inpatient utilization drives the requirements for hospitalist staffing. A thorough analysis of historical inpatient utilization data is critical to developing a staffing model.

- In addition to understanding past utilization, projecting future inpatient demand is also important. Critical change factors include trends in: 1) the age and severity of patients; 2) population growth or decline; 3) payer sources; and 4) referral patterns.

- The services (work) performed by the hospital medicine program should be clearly identified and factored into the staffing formula. Brainstorming with the hospitalist group can be an effective technique for ensuring that the analysis is credible.

- Stakeholders should be involved early and often in developing a staffing model and in making staffing decisions.

- In developing a staffing model, particularly in the beginning stages, focus on the process and the methodology and not on the outcome (i.e., “my program needs 6 physicians”).

- Understand how the unique goals and characteristics of your hospital medicine program affect your staffing model.

Introduction

A major challenge for leaders of hospital medicine programs is determining appropriate staffing levels. Specifically, every hospitalist leader must answer the following question:

- What is the correct number of physician staff needed to meet the requirements of the work environment?

The Board of Directors of the Society of Hospital Medicine (SHM) asked the Benchmarks Committee to prepare a “white paper” on this subject. The Committee discussed hospitalist staffing and agreed that there is no simple formula or process for answering the question cited above. Instead, the Committee decided to prepare a paper that outlines the issues and suggests best practices for determining appropriate hospitalist staffing levels. A member of the Benchmarks Committee, Gale Ashbrener, Sr., Performance Consultant, Kaiser Permanente-Hawaii, has prepared a model for hospitalist staffing in her organization, and her work is the basis of this document.

NOTE: Most of the examples used in this document are from Kaiser-Hawaii. As such, the numbers cited are reflective of that particular organizational environment (i.e., a group model HMO). Readers should focus on the concepts and processes that are presented, recognizing that the numbers may be different for their environment.

Overview of the Issues

A process or simplistic model for determining the appropriate level of hospitalist staffing is summarized in Figure 1.

Staffing

Staffing is driven by demand: how many and what types of patients will the program expect to see in the upcoming year? Demand can then be converted to work: the tasks that the hospital medicine program must perform in order to treat these patients (the model must also quantify non-patient work). Once the total amount of work is described and quantified, the capacity of a hospitalist must be defined (e.g., in annual work hours). Then the number of hospitalists required to complete the projected work load can be computed.

Demand

The best practices for projecting patient demand are summarized in Box 1.

Hospitalist leaders should involve key stakeholders in the information gathering process. This helps establish the foundation for buy-in of the model down the road. You may want to pull together members of the hospitalist team and/or hospital administration to brainstorm on factors that may affect patient demand for inpatient services. At this point, keep an open mind for all considerations.

It is also critical to perform a comprehensive analysis of historical inpatient data. The analysis should examine all medical admissions at the hospital and specifically, in detail, those admissions cared for by the hospital medicine program. This analysis must look beyond the number of admissions and average length of stay (LOS). Several key characteristics of the hospitalized patients should be evaluated: age, diagnosis/severity, payer, and referring physician.

- Age: There are significant differences in inpatient utilization by age categories. It is important to further segment the “senior” Medicare (over age 65) population into several subgroups. Figure 2 (page 49) is based on data from Kaiser Permanente-Hawaii. As expected, there is a major difference in hospital utilization between the under age 65 population (15.9 admissions and 84 days per 1000) and the over age 65 population (167.9 admissions and 1,090 days per 1000). However, the differences within the Medicare subgroups are also substantial. For example, compare utilization by the population that is 65-69 years old (96.0 admissions and 621 days per 1000) with the population that is over age 85 (358.2 admissions and 2,111 days per 1000):

- Diagnoses/severity: There are acknowledged differences in LOS based on the patient’s reason for admission and many ways to characterize the reason of admission, including diagnosis and diagnostics-related groups (DRGs). Furthermore, patients with co-morbidities clearly require more coordination and patient management. There are several proprietary grouping methodologies that characterize the severity and intensity of an inpatient case, which include an assessment of co-morbidities. In analyzing historical data, the hospitalist leader should select a scheme that is used within the institution while minimizing the number of categories.

- Payer: In analyzing inpatient demand, it is also important to have an understanding of historical differences by payer (including uninsured patients). Health plans (or Medicaid programs) that are increasing or decreasing in size could affect the number of patients seen by a hospital medicine program.

- Referring physician: Community physicians (primary care, specialists, and surgeons) are a major source of inpatient cases for hospital medicine programs. It is important to analyze the historical impact of specific physicians or group practices on the patient load of the hospital medicine program.

The best way to project inpatient demand for hospitalist services is to identify and quantify what may change in the next year: what trends could increase or decrease the number of cases that will need to be treated? These change factors include the following:

- Population trends: Is the community growing? It there an influx of new residents? Is the community aging? Is it likely that there will be more seniors requiring inpatient services? Health plans and medical groups often can more easily assess population trends because they treat an enrolled population.

- Local health care factors: Will a hospital in the region be closing, resulting in additional inpatient demand? Is there a shortage of nursing home beds in the community that may affect the need for inpatient care? Is Medicaid reducing the number of covered recipients, potentially increasing the demand from uninsured patients?

- Changing referral patterns from community physicians: Do you expect additional community physicians to stop/start referring patients to the hospital medicine program? Are referring medical groups increasing or decreasing in size?

- Institution-specific factors: Does the hospital medicine program expect to assume new responsibilities in the next year – e.g., in the emergency department (ED), in the intensive care unit (ICU), providing night coverage, doing surgical co‑management, etc.?

Work

The best practices for measuring hospitalist output (work) are summarized in Box 2.

Determining how to quantify the labor of hospitalists can be the most controversial component of developing a staffing model. To ensure buy-in of these modeling decisions, participation by hospitalists and other key players (e.g., other physicians, physician leadership, and hospital/medical group administration) is crucial. Hospitalists and other key individuals must understand and agree on the quantification of time and labor.

It is critical that the analysis include ALL elements of work. Brainstorming with hospitalists can be helpful in this process. To build physician acceptance of and trust in the model, it is important to acknowledge the full set of hospitalist responsibilities in the initial stages of model development.

The services provided by a hospitalist team can vary from program to program and hospital to hospital. For example, at Kaiser Permanente-Hawaii, the dedicated hospitalist triage physician may direct patients coming from the clinic or ED to the ambulatory treatment center. A hospitalist then sees the patient in the center and an admission is often avoided. This physician labor must be captured in the model even though an admission did not occur. If your program includes a day team and a night team, you may want to handle these two teams as separate models.

Based on an analysis performed at Kaiser Permanente-Hawaii, some examples of hospitalist labor components are noted in Box 3 (page 50).

To measure the work performed by hospitalists, the model needs to recognize that there are differences in the labor components that have been identified (i.e., they are “weighted” differently). “Conventional wisdom” describes the work that hospitalists perform in terms of the number of patients seen per day (e.g., 15 patients per day). However, the work involved in a hospitalist seeing the following categories of patients is very different:

- Admitting a patient

- Rounding on a patient already admitted

- Discharging a patient

- Performing a consultation

Kaiser Permanente Hawaii developed the example in Box 4 to illustrate differences in the work required for admissions, rounding, and discharges, and how reductions in LOS do not lead to corresponding reductions in physician staffing levels.

There are basically two options in weighting the different elements of work performed by a hospitalist: time or relative value units (RVUs). Although the amount of time it takes to do a task seems to be the most sensible measurement of labor, it can be fraught with obstacles. The amount of time it takes a physician to round on a patient, for example, is not straightforward:

- Are all the patients located on one floor?

- Does the physician have to chase down test results routinely?

- Are all physicians the same, taking the same average amount of time to see a patient?

- Are all patients the same? Do older patients take more time due to social and medical complexity?

These are all factors that affect time. Furthermore, individuals are limited by their own experiences and frame of reference. Acceptance of a specific time allocation (e.g., a discharge takes 45 minutes) by those not doing the work is subjective. Despite these obstacles, it is valuable for hospitalist leaders to attempt to quantify the amount of time required to do inpatient work. Figure 3 shows example times used by a Kaiser Permanente-Hawaii medical group.

A hospital medicine program leader can use RVUs as a compliment to or as an alternative to time as the basis of weighting the work components performed by hospitalists. RVUs may account for patient acuity in a way that is hard to measure using time as the basis of measurement. Figure 4 illustrates RVUs by CPT-IV code.

Physician Capacity

The best practices for determining physician capacity are summarized in Box 5.

When determining the work capacity for a hospitalist (typically defined by the number of hours worked per year), it is critical to clearly define the unique aspects of the hospital medicine program that affect work capacity. These factors include:

- Staffing model: shift vs. call

- Scheduling approach: number of days on/off

- Non-patient care responsibilities: teaching, research, committees, etc.

- Staffing philosophy: part-time vs. full-time preference

Benchmark information is extremely helpful in determining physician capacity for a hospital medicine program. These benchmarks provide a point of comparison for hospitalist leaders developing staffing models. Medians for inpatient, non-patient, and on-call hours from the 2004 SHM Productivity and Compensation Survey are documented in Figure 5 (page 52).

The simplified example in Box 6, based on Kaiser time estimates, illustrates how demand, work, and physician capacity can be used to determine the number of hospitalists required to support a program.

As an alternative methodology or for comparative purposes, RVUs can be used rather than time. Box 7 uses RVUs from Figure 4 (initial hospital care: 1.28 RVUs; subsequent hospital care: .64 RVUs; hospital discharge < 30 minutes: 1.28 RVUs). The lowest level RVU values are used because they are consistent with the Kaiser example. Also, the median RVUs per year from Figure 5 are used (2961 for a hospital-based program).

Understand Your Work Environment

When a hospitalist program leader begins the process of developing a staffing model, it is important that he or she understands how the unique goals and characteristics of the program affects staffing. For example:

- Hospitalist-only groups are often driven by revenue. It is likely that these programs will expect hospitalists to do more billable work (i.e., see more patients)

- Academic programs typically have a broad range of other, non-patient care responsibilities, including teaching, research, and committee work. The hospitalists in these programs may see fewer patients.

The data from the 2004 SHM Productivity and Compensation Survey (Figure 5) confirms these differences. For inpatient hours worked, the national medians for these two different employment models differ by 23% (1700 vs. 2210). For RVUs worked, the national medians for the two different employment models differ by 17% (3000 vs. 3600).

Summary

Determining the right level of hospitalist staffing is important because it can positively or negatively affect the hospital medicine program and the hospital. Understaffing can lead to physician burn-out and adversely affect physician performance and hospital utilization. Overstaffing can affect the program’s financial performance and undercut the credibility of the program. The right staffing models and formulas, however, can help create a successful hospitalist work environment.

Summary of Recommendations

- There is no industry standard for a hospitalist staffing model. The analysis can be time-based or RVU-based, census driven, or based on any combination of output measures.

- Inpatient utilization drives the requirements for hospitalist staffing. A thorough analysis of historical inpatient utilization data is critical to developing a staffing model.

- In addition to understanding past utilization, projecting future inpatient demand is also important. Critical change factors include trends in: 1) the age and severity of patients; 2) population growth or decline; 3) payer sources; and 4) referral patterns.

- The services (work) performed by the hospital medicine program should be clearly identified and factored into the staffing formula. Brainstorming with the hospitalist group can be an effective technique for ensuring that the analysis is credible.

- Stakeholders should be involved early and often in developing a staffing model and in making staffing decisions.

- In developing a staffing model, particularly in the beginning stages, focus on the process and the methodology and not on the outcome (i.e., “my program needs 6 physicians”).

- Understand how the unique goals and characteristics of your hospital medicine program affect your staffing model.

Resident Work Hours, Hospitalist Programs, and Academic Medical Centers

In July of 2003, the Accreditation Council for Graduate Medical Education (ACGME) implemented new rules that restricted resident work hours to no more than 80 per week and restricted continuous duty to no more than 30 hours (24 hours plus 6 hours for transfer of care, the “24+6” rule). As a result, many major academic medical centers face the problem of handling increasing inpatient volume and ensuring compliance with these new work-hours regulations. The problem has become more pressing as several major academic centers have been cited for work-hours violations by the ACGME, and significant public attention has focused on the impact of excessive work hours on patient safety (1, 2).

Given the success of hospitalists in efficiently managing patents in many non-academic environments, one proposed solution has been the creation of hospitalist services to care for patients independent of residents. These services reduce the volume on resident-based services and therefore reduce resident work hours. We have recently implemented our own non-housestaff service at the University of Michigan and in this article describe the challenges and lessons learned.

Planning a Program

The first step for any institution contemplating the creation of a non-resident service is to establish clear goals. Frequently, decisions on the level and scope of uncovered services are made without any rigorous analysis of the data or without a clear idea of what it is that your program should be doing.

Goals for Resident-Service Census and Volume

The first task for any program is to understand what patient volume must be removed to ensure work-hours compliance without impeding the educational experience of the housestaff . Unfortunately, there is little published opinion on optimal resident workload, and the ACGME is surprisingly silent on this vital issue. While the ACGME does proscribe exceeding theoretical maximum workloads for internal medicine, they cite no minimum or ideal patient census (3). In the absence of firm guidelines, it is important to gather data on both the day-to-day variation of inpatient admissions and volume along with peak admission times (usually early evening). The residency program is likely to offer monthly data or a rough guess at what they think is needed. This can be misleading and does not appreciate the variability of patient flow. It is the “peaks’ that are often remembered, whereas the “troughs” are easily forgotten. Vital data elements that should be obtained include the daily admission volume for each resident-service over the course of the past year. We used this data to calculate average per-intern admission volumes and to project what future volume would be under a variety of possible scenarios, including removing a fixed number of patients per day, creating intern-admissions caps or alternating admissions between residents and hospitalists. We then discussed these models and their projected impact on the residents with residency leadership before settling upon our final model.

Structural Reform of the Resident Services

Besides the question of volume, there is also the issue of whether the new service will also be used to create other structural changes in the resident services. Some areas that programs may consider include modification of the existing call rotation such as reducing or eliminating short-call, changing the frequency of long-call, or implementing limitations on night-time admissions to the housestaff.

Each of these possibilities comes with its own structural needs, so it is vital to decide whether any of these changes are to be attempted.

Patient Complexity

There is significant temptation to use established hospitalist workload standards and apply them to non-resident services in academia. To do so is to invite disaster. The complexity of patients on most academic internal medicine services is quite different from the average community service. One big variable to address here is whether or not the new hospitalist service will have a selected patient population (such as low-complexity or “non-teaching” cases). Without specifically selected low-complexity cases, most hospitalist programs will realize that established community work standards do not apply.

Academic Inefficiencies and Workload

Much of what residents do on a day-to-day basis involves pushing their patients through the inefficient and complex maze of an academic medical center. It seems ridiculous to think that one faculty member can replace the work that was previously performed by an attending, a senior resident, and two interns, yet this is what many programs are actually proposing when they suggest that the “established” work load of 15 patients per day per hospitalist could work in academia.

What is an ideal workload in academia? Our answer is based both on our experience and on work-flow analysis of residents, which suggests that less than 20% of their time is actually spent in direct educational activities (4). We suggest that the acceptable workload for a hospitalist in a major academic center managing patients of equivalent complexity as the residents is slightly higher than what a senior resident alone can reasonably handle. In our institution we have had a service without interns, staffed with senior residents and one attending for several years. In institutions without this structure, one could look at what senior residents do on their intern’s days off. In our experience approximately 8-10 patients/day seems to be an acceptable workload that allowed the residents to provide quality care within the confines of a 10 to 12 hour day. This translates into an attending workload of 9-11 patients/day. We acknowledge that with time, an attending may develop more efficient practices than a senior resident but do not think a workload much higher than this is reasonable during the start-up phase.

The Role of Physician Extenders

Many hospitalists rely on physician extenders such as physician assistants and nurse practitioners. In academia, physician extenders have traditionally worked only in specialty areas of inpatient care such as orthopedics, oncology, or cardiology. The great unknown, however, is how extenders perform in an environment where they are asked to work with both complex and varied patients. We have seen that the training of many extenders is often not enough for them to take on the role envisioned for them in this kind of service. Over time they may develop the skill set, but there is much on-the-job learning that requires dedicated physician time. A realistic census for a physician assistant (PA) taking care of complex academic medical patients is likely to be 4 to 6. The incremental impact of extenders on a service’s total work capacity is not entirely additive, given the need for physician oversight and the need to maximize revenue by using shared visit billing. Despite these limitations, however, we believe that extenders are helpful, especially given the inefficiencies of day-to-day patient care in academic centers.

The University of Michigan

Medicine Faculty Hospitalist Service

Our own program was designed around an original goal of moving 2000 patients from the resident services. This figure was derived from a per-intern workload target of 25 to 30 admissions per month. Based on our modeling of various ways to share admissions, we ultimately settled on a system that alternates admissions with the resident services after each service admits a “baseline” number of patients. This allowed us to variably offload patients based on day-to-day variation in admission volumes. Our service is staffed 24 hours a day with a total of eight full-time physicians and four physician assistants. We have three physicians and two‑three physician assistants during the day (7 a.m. to 7 p.m.) to coincide with the bulk of the workload. There is one doctor at night (7 p.m. to 7 a.m.) for our entire service, and our hospitalists work an average of 50-55 hours a week during 18 shifts a month. Each hospitalist (working with a PA) averages from 8 to 12 billable encounters a day. We maintain a maximum daily census of 30-35 patients and admit up to 10 patients a day. Given these workloads, we do not come close to financial self-sufficiency, but this is not unique to our program.

Funding and Finances

For most institutions a non-resident service represents incremental faculty members without any significant incremental professional fee revenue. The billings on the new service really are just a shift in revenue from the resident services. In addition, given the high clinical workload and current market conditions, the salaries of hospitalists hired for such services tend to be on average $15,000 to $20,000 above that of hospitalists hired onto a traditional resident-based service. There is some opportunity for increased revenue capture because of 24-hour attending presence, but the incremental gain is unlikely to be enough to create financial self-sufficiency. In our program there has been an increase in department-wide consultative revenue as specialized patients are now placed on our general medical service where they were previously cared for by residents and a specialty attending. In addition, we have improved our charge capture by a small margin. This extra revenue will not, however, come close to offsetting our overall cost. Many programs therefore require hospital support to be viable. Given the strong incentives for hospitals to ensure compliance with ACGME rules and maintain maximal inpatient occupancy, many hospitals can be convinced to provide funding.

We argue strongly that the creation of programs developed primarily to deal with residency work hours should be viewed separately from the funding of existing or new resident-based hospitalist programs. Similar to how resident salaries are paid for by the hospital (via federal graduate medical education funding), the cost of a new hospitalist service that is created to replace residents should come from the hospital. Programs should exercise caution in using existing paradigms such as reduction in LOS or decrease in cost as a basis for funding. There is little data comparing resident-based care to non-resident-based hospital care in a tertiary center, and what little that exists does not necessarily suggest a cost benefit (5). In addition, there is a significant future risk if such proposed benefits do not become a reality

New Roles and Responsibilities

Once established, many programs will be asked to take on additional tasks that were previously performed by trainees or other faculty. This is especially true of nighttime tasks. Many programs are asked to run code-blue teams, supervise procedures at night, supervise sedation in radiology, triage patients in the ER, provide emergent patient coverage for other services: the list can go on and on. The challenge is accepting some and rejecting others without being seen as non-cooperative.

We strongly believe that taking on some of these tasks provides significant added value for non-resident programs, something that becomes vital in the long-run once the urgency of work-hours compliance has passed. Programs should pick wisely and move slowly when adding additional roles. Whatever roles are added, it is vital that ample consideration is given to the impact on workload and faculty satisfaction. Many of these roles may also present an opportunity to garner additional revenue, whether through billing or direct payment from the hospital.

The Challenges of Academia: Separate and Unequal

The greatest challenge that all major academic hospitalist programs will face will be how to create satisfying long-term faculty positions that involve providing direct inpatient care without the assistance of housestaff (6). There is already a growing problem of physician dissatisfaction among clinical-track faculty in many academic centers where the emphasis on clinical productivity has usurped the missions of teaching and research. The challenges faced by academic hospitalists working without residents are even greater than those faced by existing clinical faculty.

The first consideration for academic programs is whether to create two classes of hospitalists within the same program: those that work primarily with residents and those that do not. In our program we had an already established group of classic hospitalist-educators who worked only on resident-staffed services when we were asked to create a non-resident service. Our easiest option, therefore, was to hire new faculty whose sole responsibility is staffing a non-resident service. With this has come a significant struggle on how to ensure faculty satisfaction and avoid creating a split within the hospitalist program. We also struggle with how to administer such a program and whether leadership should have clinical roles on both services (we currently do not).

For many new programs, it may be easier to create one uniform faculty role that mixes non-resident-based and resident-based service duties and avoids the appearance of two classes of hospitalists. For many mature programs, however, the only option may be to hire new faculty who predominantly work on non-resident services. For these groups, we believe that differences in the positions must be addressed. One solution to this problem is creating viable teaching roles for these new faculty. Options that we are examing include medical student teaching, training allied-health professionals, and some involvement in resident education during the night and at regularly scheduled daytime lectures. Each of these roles requires time and will come at the expense of efficiency or work capacity. We also have struggled to create program-level rapport. We have encouraged weekly meetings and have found that clinically oriented collaboration such as case conferences and quality-improvement initiatives seem to provide the best way for the entire faculty to interact. Another solution that has been offered is to create a vigorous inpatient research agenda that uses the non-resident services as the laboratory; we encourage this approach but feel that it may not be a realistic near-term goal for many programs.

In the end, however, while creating these roles will add to faculty satisfaction and long-term viability, there will be ongoing problems similar to those faced by academic primary care faculty who have limited interactions with residents. Our program relies on junior-level faculty who are in transition between residency and further training or faculty who aspire to eventually grow into more traditional academic teaching roles and take on a more hybridized role. There is likely to be value in this variety, and we imagine that large academic programs will have faculty that run the gamut from those who are primarily research focused to those who spend most of their time in direct front-line patient care.

Results: Work Hours Success

Since the implementation of our non-housestaff service, we have seen dramatic improvements in resident work-hours compliance. Prior to our service, 40% of residents were in violation of the 80-hour week and the “24+6” hour shift limit. After successfully removing 15% of the total inpatient (non-ICU) census from resident-coverage, there have been only sporadic violations during the first 3 months of operation. Therefore, violations of the 80-hour work week rules have been virtually eliminated. Our residents have widely praised the new service and overall morale in the residency program has improved. Yet despite what has been perceived as a significant reduction in resident patient load, there are continued violations of the “24+6”-hour shift rule. In fact many have suggested that violation of the “24+6”-hour rule is a reflection of the competing tension between compliance with external regulation and our residents’ professionalism and dedication to patients. While further reductions in volume might help (although even our residents say that this might jeopardize their education), the more likely solution to this problem is both culture change over time and some re-engineering of the timing of resident shifts.

Conclusions

We envision that in the next few years, non-resident services will exist in almost every major medical center. As our experience highlights, these services can be an effective solution to the resident work-hours problem. We caution, however, that implementation is not an easy task. To be successful, programs should invest significant time in the planning stages and have clear goals in mind. Staffing and finances are likely to remain challenging as is the creation of academically viable roles. Eventually, however, we believe these services will succeed. Their growth will add to the future standing of hospital medicine in academic centers by creating a more diverse group of hospitalist faculty who focus on research, education, and, increasingly, quality patient care.

References

- Croasdale, M. “Johns Hopkins penalized for resident hour violations.” AMNews. Sept. 15, 2003.

- Mehes, A. “Med school could forfeit residency accreditation.” Yale Daily News. Oct. 25, 2002.

- Accreditation Council on Graduate Medical Education: Program Requirements for Residency Education in Internal Medicine. July, 2004. http://www.acgme.org/acWebsite/RRC_140/140_prIndex.asp. Last accessed November 17, 2004.

- Boex JR, Leahy PJ. Understanding residents’ work: moving beyond counting hours to assessing educational value. Acad Med. 2003;78:939-944.

- Halasyamani L, Valenstein P, Friedlander M, Cowen M. A comparison of two hospitalist models with traditional care in a community teaching hospital. Society of Hospital Medicine Annual Meeting (Abstract), April 2004.

- Saint S, Flanders SA. Hospitalists in teaching hospitals: opportunities but not without danger. J Gen Intern Med. 2004;Apr;19(4):392-3.

Dr. Parekh can be contacted at viparekh@umich.edu.

Dr. Flanders can be contacted at flanders@umich.edu.

In July of 2003, the Accreditation Council for Graduate Medical Education (ACGME) implemented new rules that restricted resident work hours to no more than 80 per week and restricted continuous duty to no more than 30 hours (24 hours plus 6 hours for transfer of care, the “24+6” rule). As a result, many major academic medical centers face the problem of handling increasing inpatient volume and ensuring compliance with these new work-hours regulations. The problem has become more pressing as several major academic centers have been cited for work-hours violations by the ACGME, and significant public attention has focused on the impact of excessive work hours on patient safety (1, 2).

Given the success of hospitalists in efficiently managing patents in many non-academic environments, one proposed solution has been the creation of hospitalist services to care for patients independent of residents. These services reduce the volume on resident-based services and therefore reduce resident work hours. We have recently implemented our own non-housestaff service at the University of Michigan and in this article describe the challenges and lessons learned.

Planning a Program

The first step for any institution contemplating the creation of a non-resident service is to establish clear goals. Frequently, decisions on the level and scope of uncovered services are made without any rigorous analysis of the data or without a clear idea of what it is that your program should be doing.

Goals for Resident-Service Census and Volume

The first task for any program is to understand what patient volume must be removed to ensure work-hours compliance without impeding the educational experience of the housestaff . Unfortunately, there is little published opinion on optimal resident workload, and the ACGME is surprisingly silent on this vital issue. While the ACGME does proscribe exceeding theoretical maximum workloads for internal medicine, they cite no minimum or ideal patient census (3). In the absence of firm guidelines, it is important to gather data on both the day-to-day variation of inpatient admissions and volume along with peak admission times (usually early evening). The residency program is likely to offer monthly data or a rough guess at what they think is needed. This can be misleading and does not appreciate the variability of patient flow. It is the “peaks’ that are often remembered, whereas the “troughs” are easily forgotten. Vital data elements that should be obtained include the daily admission volume for each resident-service over the course of the past year. We used this data to calculate average per-intern admission volumes and to project what future volume would be under a variety of possible scenarios, including removing a fixed number of patients per day, creating intern-admissions caps or alternating admissions between residents and hospitalists. We then discussed these models and their projected impact on the residents with residency leadership before settling upon our final model.

Structural Reform of the Resident Services

Besides the question of volume, there is also the issue of whether the new service will also be used to create other structural changes in the resident services. Some areas that programs may consider include modification of the existing call rotation such as reducing or eliminating short-call, changing the frequency of long-call, or implementing limitations on night-time admissions to the housestaff.

Each of these possibilities comes with its own structural needs, so it is vital to decide whether any of these changes are to be attempted.

Patient Complexity

There is significant temptation to use established hospitalist workload standards and apply them to non-resident services in academia. To do so is to invite disaster. The complexity of patients on most academic internal medicine services is quite different from the average community service. One big variable to address here is whether or not the new hospitalist service will have a selected patient population (such as low-complexity or “non-teaching” cases). Without specifically selected low-complexity cases, most hospitalist programs will realize that established community work standards do not apply.

Academic Inefficiencies and Workload

Much of what residents do on a day-to-day basis involves pushing their patients through the inefficient and complex maze of an academic medical center. It seems ridiculous to think that one faculty member can replace the work that was previously performed by an attending, a senior resident, and two interns, yet this is what many programs are actually proposing when they suggest that the “established” work load of 15 patients per day per hospitalist could work in academia.

What is an ideal workload in academia? Our answer is based both on our experience and on work-flow analysis of residents, which suggests that less than 20% of their time is actually spent in direct educational activities (4). We suggest that the acceptable workload for a hospitalist in a major academic center managing patients of equivalent complexity as the residents is slightly higher than what a senior resident alone can reasonably handle. In our institution we have had a service without interns, staffed with senior residents and one attending for several years. In institutions without this structure, one could look at what senior residents do on their intern’s days off. In our experience approximately 8-10 patients/day seems to be an acceptable workload that allowed the residents to provide quality care within the confines of a 10 to 12 hour day. This translates into an attending workload of 9-11 patients/day. We acknowledge that with time, an attending may develop more efficient practices than a senior resident but do not think a workload much higher than this is reasonable during the start-up phase.

The Role of Physician Extenders

Many hospitalists rely on physician extenders such as physician assistants and nurse practitioners. In academia, physician extenders have traditionally worked only in specialty areas of inpatient care such as orthopedics, oncology, or cardiology. The great unknown, however, is how extenders perform in an environment where they are asked to work with both complex and varied patients. We have seen that the training of many extenders is often not enough for them to take on the role envisioned for them in this kind of service. Over time they may develop the skill set, but there is much on-the-job learning that requires dedicated physician time. A realistic census for a physician assistant (PA) taking care of complex academic medical patients is likely to be 4 to 6. The incremental impact of extenders on a service’s total work capacity is not entirely additive, given the need for physician oversight and the need to maximize revenue by using shared visit billing. Despite these limitations, however, we believe that extenders are helpful, especially given the inefficiencies of day-to-day patient care in academic centers.

The University of Michigan

Medicine Faculty Hospitalist Service

Our own program was designed around an original goal of moving 2000 patients from the resident services. This figure was derived from a per-intern workload target of 25 to 30 admissions per month. Based on our modeling of various ways to share admissions, we ultimately settled on a system that alternates admissions with the resident services after each service admits a “baseline” number of patients. This allowed us to variably offload patients based on day-to-day variation in admission volumes. Our service is staffed 24 hours a day with a total of eight full-time physicians and four physician assistants. We have three physicians and two‑three physician assistants during the day (7 a.m. to 7 p.m.) to coincide with the bulk of the workload. There is one doctor at night (7 p.m. to 7 a.m.) for our entire service, and our hospitalists work an average of 50-55 hours a week during 18 shifts a month. Each hospitalist (working with a PA) averages from 8 to 12 billable encounters a day. We maintain a maximum daily census of 30-35 patients and admit up to 10 patients a day. Given these workloads, we do not come close to financial self-sufficiency, but this is not unique to our program.

Funding and Finances

For most institutions a non-resident service represents incremental faculty members without any significant incremental professional fee revenue. The billings on the new service really are just a shift in revenue from the resident services. In addition, given the high clinical workload and current market conditions, the salaries of hospitalists hired for such services tend to be on average $15,000 to $20,000 above that of hospitalists hired onto a traditional resident-based service. There is some opportunity for increased revenue capture because of 24-hour attending presence, but the incremental gain is unlikely to be enough to create financial self-sufficiency. In our program there has been an increase in department-wide consultative revenue as specialized patients are now placed on our general medical service where they were previously cared for by residents and a specialty attending. In addition, we have improved our charge capture by a small margin. This extra revenue will not, however, come close to offsetting our overall cost. Many programs therefore require hospital support to be viable. Given the strong incentives for hospitals to ensure compliance with ACGME rules and maintain maximal inpatient occupancy, many hospitals can be convinced to provide funding.

We argue strongly that the creation of programs developed primarily to deal with residency work hours should be viewed separately from the funding of existing or new resident-based hospitalist programs. Similar to how resident salaries are paid for by the hospital (via federal graduate medical education funding), the cost of a new hospitalist service that is created to replace residents should come from the hospital. Programs should exercise caution in using existing paradigms such as reduction in LOS or decrease in cost as a basis for funding. There is little data comparing resident-based care to non-resident-based hospital care in a tertiary center, and what little that exists does not necessarily suggest a cost benefit (5). In addition, there is a significant future risk if such proposed benefits do not become a reality

New Roles and Responsibilities

Once established, many programs will be asked to take on additional tasks that were previously performed by trainees or other faculty. This is especially true of nighttime tasks. Many programs are asked to run code-blue teams, supervise procedures at night, supervise sedation in radiology, triage patients in the ER, provide emergent patient coverage for other services: the list can go on and on. The challenge is accepting some and rejecting others without being seen as non-cooperative.

We strongly believe that taking on some of these tasks provides significant added value for non-resident programs, something that becomes vital in the long-run once the urgency of work-hours compliance has passed. Programs should pick wisely and move slowly when adding additional roles. Whatever roles are added, it is vital that ample consideration is given to the impact on workload and faculty satisfaction. Many of these roles may also present an opportunity to garner additional revenue, whether through billing or direct payment from the hospital.

The Challenges of Academia: Separate and Unequal

The greatest challenge that all major academic hospitalist programs will face will be how to create satisfying long-term faculty positions that involve providing direct inpatient care without the assistance of housestaff (6). There is already a growing problem of physician dissatisfaction among clinical-track faculty in many academic centers where the emphasis on clinical productivity has usurped the missions of teaching and research. The challenges faced by academic hospitalists working without residents are even greater than those faced by existing clinical faculty.

The first consideration for academic programs is whether to create two classes of hospitalists within the same program: those that work primarily with residents and those that do not. In our program we had an already established group of classic hospitalist-educators who worked only on resident-staffed services when we were asked to create a non-resident service. Our easiest option, therefore, was to hire new faculty whose sole responsibility is staffing a non-resident service. With this has come a significant struggle on how to ensure faculty satisfaction and avoid creating a split within the hospitalist program. We also struggle with how to administer such a program and whether leadership should have clinical roles on both services (we currently do not).

For many new programs, it may be easier to create one uniform faculty role that mixes non-resident-based and resident-based service duties and avoids the appearance of two classes of hospitalists. For many mature programs, however, the only option may be to hire new faculty who predominantly work on non-resident services. For these groups, we believe that differences in the positions must be addressed. One solution to this problem is creating viable teaching roles for these new faculty. Options that we are examing include medical student teaching, training allied-health professionals, and some involvement in resident education during the night and at regularly scheduled daytime lectures. Each of these roles requires time and will come at the expense of efficiency or work capacity. We also have struggled to create program-level rapport. We have encouraged weekly meetings and have found that clinically oriented collaboration such as case conferences and quality-improvement initiatives seem to provide the best way for the entire faculty to interact. Another solution that has been offered is to create a vigorous inpatient research agenda that uses the non-resident services as the laboratory; we encourage this approach but feel that it may not be a realistic near-term goal for many programs.

In the end, however, while creating these roles will add to faculty satisfaction and long-term viability, there will be ongoing problems similar to those faced by academic primary care faculty who have limited interactions with residents. Our program relies on junior-level faculty who are in transition between residency and further training or faculty who aspire to eventually grow into more traditional academic teaching roles and take on a more hybridized role. There is likely to be value in this variety, and we imagine that large academic programs will have faculty that run the gamut from those who are primarily research focused to those who spend most of their time in direct front-line patient care.

Results: Work Hours Success

Since the implementation of our non-housestaff service, we have seen dramatic improvements in resident work-hours compliance. Prior to our service, 40% of residents were in violation of the 80-hour week and the “24+6” hour shift limit. After successfully removing 15% of the total inpatient (non-ICU) census from resident-coverage, there have been only sporadic violations during the first 3 months of operation. Therefore, violations of the 80-hour work week rules have been virtually eliminated. Our residents have widely praised the new service and overall morale in the residency program has improved. Yet despite what has been perceived as a significant reduction in resident patient load, there are continued violations of the “24+6”-hour shift rule. In fact many have suggested that violation of the “24+6”-hour rule is a reflection of the competing tension between compliance with external regulation and our residents’ professionalism and dedication to patients. While further reductions in volume might help (although even our residents say that this might jeopardize their education), the more likely solution to this problem is both culture change over time and some re-engineering of the timing of resident shifts.

Conclusions