User login

Using Co-Design Methods to Create a Patient-Oriented Discharge Summary

From the OpenLab, University Health Network, Toronto, Canada (Dr. Hahn-Goldberg, Dr. Okrainec, Dr. Abrams, Mr. Huynh); School of Health Policy and Management, York University, Toronto (Dr. Hahn-Goldberg); Toronto Central Local Health Integration Network (Ms. Damba); Centre for Addiction and Mental Health, Toronto (Ms. Solomon); and the Department of Medicine, University Health Network, Toronto (Dr. Okrainec, Dr. Abrams).

Abstract

- Objective: To describe the co-design process we under-took to create a patient-oriented discharge summary (PODS) with patients, caregivers, and providers.

- Method: Descriptive report.

- Results: We designed and produced a prototype PODS, based on best practices in information design, graphic design, and patient education. Through a co-design process, patients, health care providers, designers and system planners worked together to establish what content needed to be included, as well as how it would be organized and presented. From an initial prototype, we then refined the PODS through an iterative participatory design process involving patients, including those from hard-to-reach groups such as patients with language barriers and/or low health literacy and patients with a primary psychiatric diagnosis.

- Conclusion: Co-design events and targeted focus groups are very useful for engaging patients and caregivers in the design and development of solutions aimed at improving their experience of care. It is important to include all users, especially those who are harder to reach, such as patients with language barriers and mental health conditions. Engaging health care providers is essential to ensure feasibility of those solutions.

Traditional discharge summaries are written primarily for the patient’s primary care provider and are not designed as tools to support communication between the clinician and patient regarding instructions for patients to follow at home post discharge. A more patient-centered version of the discharge summary is needed to complement the traditional format.

To enhance our patients’ care experience in the post-discharge period, we set out to co-design a patient-oriented discharge summary (PODS) with patients, caregivers, and providers. The main objective of this project was to develop a prototype PODS that not only addressed critical information that patients felt was the most important to know following discharge, but also provided this information in the most comprehensible format at hospitals within the Toronto area. The project focused on reformatting patient-care instructions for patients discharged from inpatient medical wards as these instructions presented the best opportunity for improvement.

This project drew on work done in countries such as India, South Africa, and Pakistan, where challenges with general and health literacy have led to the introduction of simplified discharge forms and medication instructions that place a greater emphasis on visual communication to improve information comprehension. For example, the use of pictograms in patient materials has been shown to increase patient understanding of and compliance with care instructions in these countries [1–3].

We have provided an overview of the PODS project elsewhere [4]. In this article, we describe the co-design process we undertook with patients, health care providers, and designers in creating a PODS.

Design Methods

We used several methods to design and develop the PODS and to engage multiple stakeholders in the design process. Among these methods were innovative techniques for understanding the patient experience of discharge, such as cultural probes [5], where patients were given journals and cameras to document their time at home after discharge, as described by Hahn-Goldberg et al [4]. Other key methods for determining the design of the PODS included:

Patient education consultation. A patient education representative with training and expertise in designing materials for patients with low health literacy was added to the team advisory committee to act as a consultant at all stages of the study. This helped to ensure that we would be following best practices in design for our target population.

Review of literature. We reviewed the literature pertaining to design for patients with low health literacy and language barriers, including the resources available through the patient education department at the University Health Network.

Review of Toronto Central Local Health Integration Network (TCLHIN) hospitals’ tools: current discharge summaries, components they included and how they were formatted.

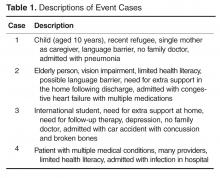

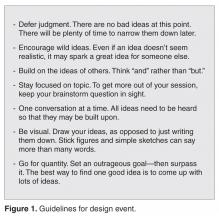

Co-design event. We held an interprofessional design event where teams of patients, health care providers, and designers worked together to create draft PODS for 4 hypothetical patient cases.

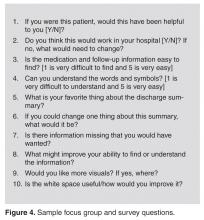

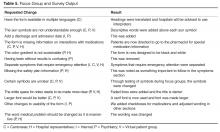

Focus groups and surveys. We used feedback from focus groups and surveys to revise and improve the first PODS prototype.

Insights from the Literature

Studies have shown that multiple interventions tend to increase adherence, that self-management should be encouraged, and that modes of communication other than verbal must be used [6]. Visual cues, such as pictures or symbols, are useful to help with recall of medications and instructions for people with language barriers or limited health literacy [7]. Simplified written instructions and larger fonts have been found to be effective in patients with language barriers or limited health literacy, as have use of illustrated medication schedules [8]. Other guidelines include using short words and sentences, writing directly to the reader, listing important points in list format, and using left justification so there is even spacing between words.

The literature is consistent with our findings from speaking with patient education representatives and patients. Patients and caregivers noted that the PODS should be written in plain language, use large fonts, include illustrations of care and medication schedules, and include headings that are meaningful to the patient. Patients also expressed the desire for charts and lists that they could use while completing their follow-up care plan.

“My mom made me a chart of when to drink water and how much (patient).”

“We were given a sheet to record all feedings (caregiver).”

“We can provide a list of patient meds in a grid format with days of the week and times of day. We use our judgement to give this to patients. It is not standard practice (pharmacist).”

“A discharge form in ‘plain English’ should be standardized (patient).”

The Co-design Event

Solutions resulting from the design event ranged from more traditional discharge summaries that were enhanced with multiple languages and images to make things clear for patients, to solutions including interactive patient portals. There were solutions that came with stickers to color-code your medications, areas for patients to write notes, and checklists for them to keep track of all their follow-up plans.

Refining the Design Using Focus Groups and Surveys

The ideas and concepts generated during the design event were analyzed by the interdisciplinary advisory team at OpenLab. In addition, several team sessions were held with health care

This is a great piece. You guys are doing an awesome job. This would have saved me so much anxiety and fear of doing something wrong when I was discharged. I didn’t want to bother my doctors and went on a hope and prayer. Even my home care people weren’t always sure of what to do. Again this would be a great step forward in easing patients’ fears, especially senior citizens. GREAT WORK. THANKS FOR CARING.

Discussion

Innovative methods such as co-design events and targeted focus groups are very useful for

Future Plans

The PODS template has now been adapted and implemented in several hospitals in Toronto, Canada, using a supported early adopter process [10]. Future plans are to test the impact of the PODS on patient experience and health outcomes using a randomized controlled trial. Also, for now, we have focused on a paper version of PODS, but with the increasing prevalence of electronic health records and consumer-oriented health care apps, future consideration for a digital and mobile version of PODS is warranted.

Conclusion

Patients need to be prepared for discharge so that they can engage in supported self-management once they return home.

Corresponding author: Shoshana Hahn-Goldberg, PhD, 294 Mullen Dr., Thornhill, ON L4J 2P2.

Funding/support: The PODS project has been funded by the Toronto Central Local Health Integration Network.

Financial disclosures: None.

1. Rajesh R, Vidyasagar S, Varma M, Sharma S. Design And evaluation of pictograms for communicating information about adverse drug reactions to antiretroviral therapy in Indian human immunodeficiency virus positive patients. J Pharm Biomed Sci 2012;16:1–11.

2. Dowse R, Ehlers MS. The evaluation of pharmaceutical pictograms in a low-literate South African population. Patient Educ Couns 2001;45:87–99.

3. Clayton M, Syed F, Rashid A, Fayyaz U. Improving illiterate patients’ understanding and adherence to discharge medications. BMJ Qual Improv Rep 2012;1:u496.w167.

4. Hahn-Goldberg S, Okrainec K, Huynh T, et al. Co-creating patient-oriented instructions with patients, caregivers, and providers. J Hosp Med 2015;10:804–7.

5. Gaver B, Dunne T, Pacenti E. Design: cultural probes. Interactions 1999;6:21–9.

6. Sheridan SL, Halpern DJ, Viera AJ, et al. Interventions for individuals with low health literacy: a systematic review. J Health Commun 2011;16 Suppl 3:30–54.

7. Schillinger D, Machtinger EL, Wang F, et al. Language, literacy, and communication regarding medications in an anticoagulation clinic: A comparison of verbal vs. visual assessment. J Health Commun 2006;11:651–4.

8. Chugh A, Williams MV, Grigsby J, Coleman EA. Better transitions: Improving comprehension of discharge instructions. Front Health Serv Manage 2009;25:11–32.

9. IDEO. Design thinking for educators toolkit. 2nd ed. New York: IDEObooks; 2013.

10. Hahn-Goldberg S, Okrainec K, Damba C, et al. Implementing patient oriented discharge summaries (PODS): A multi-site pilot across early adopter hospitals. Healthc Q 2016;19:42–8.

From the OpenLab, University Health Network, Toronto, Canada (Dr. Hahn-Goldberg, Dr. Okrainec, Dr. Abrams, Mr. Huynh); School of Health Policy and Management, York University, Toronto (Dr. Hahn-Goldberg); Toronto Central Local Health Integration Network (Ms. Damba); Centre for Addiction and Mental Health, Toronto (Ms. Solomon); and the Department of Medicine, University Health Network, Toronto (Dr. Okrainec, Dr. Abrams).

Abstract

- Objective: To describe the co-design process we under-took to create a patient-oriented discharge summary (PODS) with patients, caregivers, and providers.

- Method: Descriptive report.

- Results: We designed and produced a prototype PODS, based on best practices in information design, graphic design, and patient education. Through a co-design process, patients, health care providers, designers and system planners worked together to establish what content needed to be included, as well as how it would be organized and presented. From an initial prototype, we then refined the PODS through an iterative participatory design process involving patients, including those from hard-to-reach groups such as patients with language barriers and/or low health literacy and patients with a primary psychiatric diagnosis.

- Conclusion: Co-design events and targeted focus groups are very useful for engaging patients and caregivers in the design and development of solutions aimed at improving their experience of care. It is important to include all users, especially those who are harder to reach, such as patients with language barriers and mental health conditions. Engaging health care providers is essential to ensure feasibility of those solutions.

Traditional discharge summaries are written primarily for the patient’s primary care provider and are not designed as tools to support communication between the clinician and patient regarding instructions for patients to follow at home post discharge. A more patient-centered version of the discharge summary is needed to complement the traditional format.

To enhance our patients’ care experience in the post-discharge period, we set out to co-design a patient-oriented discharge summary (PODS) with patients, caregivers, and providers. The main objective of this project was to develop a prototype PODS that not only addressed critical information that patients felt was the most important to know following discharge, but also provided this information in the most comprehensible format at hospitals within the Toronto area. The project focused on reformatting patient-care instructions for patients discharged from inpatient medical wards as these instructions presented the best opportunity for improvement.

This project drew on work done in countries such as India, South Africa, and Pakistan, where challenges with general and health literacy have led to the introduction of simplified discharge forms and medication instructions that place a greater emphasis on visual communication to improve information comprehension. For example, the use of pictograms in patient materials has been shown to increase patient understanding of and compliance with care instructions in these countries [1–3].

We have provided an overview of the PODS project elsewhere [4]. In this article, we describe the co-design process we undertook with patients, health care providers, and designers in creating a PODS.

Design Methods

We used several methods to design and develop the PODS and to engage multiple stakeholders in the design process. Among these methods were innovative techniques for understanding the patient experience of discharge, such as cultural probes [5], where patients were given journals and cameras to document their time at home after discharge, as described by Hahn-Goldberg et al [4]. Other key methods for determining the design of the PODS included:

Patient education consultation. A patient education representative with training and expertise in designing materials for patients with low health literacy was added to the team advisory committee to act as a consultant at all stages of the study. This helped to ensure that we would be following best practices in design for our target population.

Review of literature. We reviewed the literature pertaining to design for patients with low health literacy and language barriers, including the resources available through the patient education department at the University Health Network.

Review of Toronto Central Local Health Integration Network (TCLHIN) hospitals’ tools: current discharge summaries, components they included and how they were formatted.

Co-design event. We held an interprofessional design event where teams of patients, health care providers, and designers worked together to create draft PODS for 4 hypothetical patient cases.

Focus groups and surveys. We used feedback from focus groups and surveys to revise and improve the first PODS prototype.

Insights from the Literature

Studies have shown that multiple interventions tend to increase adherence, that self-management should be encouraged, and that modes of communication other than verbal must be used [6]. Visual cues, such as pictures or symbols, are useful to help with recall of medications and instructions for people with language barriers or limited health literacy [7]. Simplified written instructions and larger fonts have been found to be effective in patients with language barriers or limited health literacy, as have use of illustrated medication schedules [8]. Other guidelines include using short words and sentences, writing directly to the reader, listing important points in list format, and using left justification so there is even spacing between words.

The literature is consistent with our findings from speaking with patient education representatives and patients. Patients and caregivers noted that the PODS should be written in plain language, use large fonts, include illustrations of care and medication schedules, and include headings that are meaningful to the patient. Patients also expressed the desire for charts and lists that they could use while completing their follow-up care plan.

“My mom made me a chart of when to drink water and how much (patient).”

“We were given a sheet to record all feedings (caregiver).”

“We can provide a list of patient meds in a grid format with days of the week and times of day. We use our judgement to give this to patients. It is not standard practice (pharmacist).”

“A discharge form in ‘plain English’ should be standardized (patient).”

The Co-design Event

Solutions resulting from the design event ranged from more traditional discharge summaries that were enhanced with multiple languages and images to make things clear for patients, to solutions including interactive patient portals. There were solutions that came with stickers to color-code your medications, areas for patients to write notes, and checklists for them to keep track of all their follow-up plans.

Refining the Design Using Focus Groups and Surveys

The ideas and concepts generated during the design event were analyzed by the interdisciplinary advisory team at OpenLab. In addition, several team sessions were held with health care

This is a great piece. You guys are doing an awesome job. This would have saved me so much anxiety and fear of doing something wrong when I was discharged. I didn’t want to bother my doctors and went on a hope and prayer. Even my home care people weren’t always sure of what to do. Again this would be a great step forward in easing patients’ fears, especially senior citizens. GREAT WORK. THANKS FOR CARING.

Discussion

Innovative methods such as co-design events and targeted focus groups are very useful for

Future Plans

The PODS template has now been adapted and implemented in several hospitals in Toronto, Canada, using a supported early adopter process [10]. Future plans are to test the impact of the PODS on patient experience and health outcomes using a randomized controlled trial. Also, for now, we have focused on a paper version of PODS, but with the increasing prevalence of electronic health records and consumer-oriented health care apps, future consideration for a digital and mobile version of PODS is warranted.

Conclusion

Patients need to be prepared for discharge so that they can engage in supported self-management once they return home.

Corresponding author: Shoshana Hahn-Goldberg, PhD, 294 Mullen Dr., Thornhill, ON L4J 2P2.

Funding/support: The PODS project has been funded by the Toronto Central Local Health Integration Network.

Financial disclosures: None.

From the OpenLab, University Health Network, Toronto, Canada (Dr. Hahn-Goldberg, Dr. Okrainec, Dr. Abrams, Mr. Huynh); School of Health Policy and Management, York University, Toronto (Dr. Hahn-Goldberg); Toronto Central Local Health Integration Network (Ms. Damba); Centre for Addiction and Mental Health, Toronto (Ms. Solomon); and the Department of Medicine, University Health Network, Toronto (Dr. Okrainec, Dr. Abrams).

Abstract

- Objective: To describe the co-design process we under-took to create a patient-oriented discharge summary (PODS) with patients, caregivers, and providers.

- Method: Descriptive report.

- Results: We designed and produced a prototype PODS, based on best practices in information design, graphic design, and patient education. Through a co-design process, patients, health care providers, designers and system planners worked together to establish what content needed to be included, as well as how it would be organized and presented. From an initial prototype, we then refined the PODS through an iterative participatory design process involving patients, including those from hard-to-reach groups such as patients with language barriers and/or low health literacy and patients with a primary psychiatric diagnosis.

- Conclusion: Co-design events and targeted focus groups are very useful for engaging patients and caregivers in the design and development of solutions aimed at improving their experience of care. It is important to include all users, especially those who are harder to reach, such as patients with language barriers and mental health conditions. Engaging health care providers is essential to ensure feasibility of those solutions.

Traditional discharge summaries are written primarily for the patient’s primary care provider and are not designed as tools to support communication between the clinician and patient regarding instructions for patients to follow at home post discharge. A more patient-centered version of the discharge summary is needed to complement the traditional format.

To enhance our patients’ care experience in the post-discharge period, we set out to co-design a patient-oriented discharge summary (PODS) with patients, caregivers, and providers. The main objective of this project was to develop a prototype PODS that not only addressed critical information that patients felt was the most important to know following discharge, but also provided this information in the most comprehensible format at hospitals within the Toronto area. The project focused on reformatting patient-care instructions for patients discharged from inpatient medical wards as these instructions presented the best opportunity for improvement.

This project drew on work done in countries such as India, South Africa, and Pakistan, where challenges with general and health literacy have led to the introduction of simplified discharge forms and medication instructions that place a greater emphasis on visual communication to improve information comprehension. For example, the use of pictograms in patient materials has been shown to increase patient understanding of and compliance with care instructions in these countries [1–3].

We have provided an overview of the PODS project elsewhere [4]. In this article, we describe the co-design process we undertook with patients, health care providers, and designers in creating a PODS.

Design Methods

We used several methods to design and develop the PODS and to engage multiple stakeholders in the design process. Among these methods were innovative techniques for understanding the patient experience of discharge, such as cultural probes [5], where patients were given journals and cameras to document their time at home after discharge, as described by Hahn-Goldberg et al [4]. Other key methods for determining the design of the PODS included:

Patient education consultation. A patient education representative with training and expertise in designing materials for patients with low health literacy was added to the team advisory committee to act as a consultant at all stages of the study. This helped to ensure that we would be following best practices in design for our target population.

Review of literature. We reviewed the literature pertaining to design for patients with low health literacy and language barriers, including the resources available through the patient education department at the University Health Network.

Review of Toronto Central Local Health Integration Network (TCLHIN) hospitals’ tools: current discharge summaries, components they included and how they were formatted.

Co-design event. We held an interprofessional design event where teams of patients, health care providers, and designers worked together to create draft PODS for 4 hypothetical patient cases.

Focus groups and surveys. We used feedback from focus groups and surveys to revise and improve the first PODS prototype.

Insights from the Literature

Studies have shown that multiple interventions tend to increase adherence, that self-management should be encouraged, and that modes of communication other than verbal must be used [6]. Visual cues, such as pictures or symbols, are useful to help with recall of medications and instructions for people with language barriers or limited health literacy [7]. Simplified written instructions and larger fonts have been found to be effective in patients with language barriers or limited health literacy, as have use of illustrated medication schedules [8]. Other guidelines include using short words and sentences, writing directly to the reader, listing important points in list format, and using left justification so there is even spacing between words.

The literature is consistent with our findings from speaking with patient education representatives and patients. Patients and caregivers noted that the PODS should be written in plain language, use large fonts, include illustrations of care and medication schedules, and include headings that are meaningful to the patient. Patients also expressed the desire for charts and lists that they could use while completing their follow-up care plan.

“My mom made me a chart of when to drink water and how much (patient).”

“We were given a sheet to record all feedings (caregiver).”

“We can provide a list of patient meds in a grid format with days of the week and times of day. We use our judgement to give this to patients. It is not standard practice (pharmacist).”

“A discharge form in ‘plain English’ should be standardized (patient).”

The Co-design Event

Solutions resulting from the design event ranged from more traditional discharge summaries that were enhanced with multiple languages and images to make things clear for patients, to solutions including interactive patient portals. There were solutions that came with stickers to color-code your medications, areas for patients to write notes, and checklists for them to keep track of all their follow-up plans.

Refining the Design Using Focus Groups and Surveys

The ideas and concepts generated during the design event were analyzed by the interdisciplinary advisory team at OpenLab. In addition, several team sessions were held with health care

This is a great piece. You guys are doing an awesome job. This would have saved me so much anxiety and fear of doing something wrong when I was discharged. I didn’t want to bother my doctors and went on a hope and prayer. Even my home care people weren’t always sure of what to do. Again this would be a great step forward in easing patients’ fears, especially senior citizens. GREAT WORK. THANKS FOR CARING.

Discussion

Innovative methods such as co-design events and targeted focus groups are very useful for

Future Plans

The PODS template has now been adapted and implemented in several hospitals in Toronto, Canada, using a supported early adopter process [10]. Future plans are to test the impact of the PODS on patient experience and health outcomes using a randomized controlled trial. Also, for now, we have focused on a paper version of PODS, but with the increasing prevalence of electronic health records and consumer-oriented health care apps, future consideration for a digital and mobile version of PODS is warranted.

Conclusion

Patients need to be prepared for discharge so that they can engage in supported self-management once they return home.

Corresponding author: Shoshana Hahn-Goldberg, PhD, 294 Mullen Dr., Thornhill, ON L4J 2P2.

Funding/support: The PODS project has been funded by the Toronto Central Local Health Integration Network.

Financial disclosures: None.

1. Rajesh R, Vidyasagar S, Varma M, Sharma S. Design And evaluation of pictograms for communicating information about adverse drug reactions to antiretroviral therapy in Indian human immunodeficiency virus positive patients. J Pharm Biomed Sci 2012;16:1–11.

2. Dowse R, Ehlers MS. The evaluation of pharmaceutical pictograms in a low-literate South African population. Patient Educ Couns 2001;45:87–99.

3. Clayton M, Syed F, Rashid A, Fayyaz U. Improving illiterate patients’ understanding and adherence to discharge medications. BMJ Qual Improv Rep 2012;1:u496.w167.

4. Hahn-Goldberg S, Okrainec K, Huynh T, et al. Co-creating patient-oriented instructions with patients, caregivers, and providers. J Hosp Med 2015;10:804–7.

5. Gaver B, Dunne T, Pacenti E. Design: cultural probes. Interactions 1999;6:21–9.

6. Sheridan SL, Halpern DJ, Viera AJ, et al. Interventions for individuals with low health literacy: a systematic review. J Health Commun 2011;16 Suppl 3:30–54.

7. Schillinger D, Machtinger EL, Wang F, et al. Language, literacy, and communication regarding medications in an anticoagulation clinic: A comparison of verbal vs. visual assessment. J Health Commun 2006;11:651–4.

8. Chugh A, Williams MV, Grigsby J, Coleman EA. Better transitions: Improving comprehension of discharge instructions. Front Health Serv Manage 2009;25:11–32.

9. IDEO. Design thinking for educators toolkit. 2nd ed. New York: IDEObooks; 2013.

10. Hahn-Goldberg S, Okrainec K, Damba C, et al. Implementing patient oriented discharge summaries (PODS): A multi-site pilot across early adopter hospitals. Healthc Q 2016;19:42–8.

1. Rajesh R, Vidyasagar S, Varma M, Sharma S. Design And evaluation of pictograms for communicating information about adverse drug reactions to antiretroviral therapy in Indian human immunodeficiency virus positive patients. J Pharm Biomed Sci 2012;16:1–11.

2. Dowse R, Ehlers MS. The evaluation of pharmaceutical pictograms in a low-literate South African population. Patient Educ Couns 2001;45:87–99.

3. Clayton M, Syed F, Rashid A, Fayyaz U. Improving illiterate patients’ understanding and adherence to discharge medications. BMJ Qual Improv Rep 2012;1:u496.w167.

4. Hahn-Goldberg S, Okrainec K, Huynh T, et al. Co-creating patient-oriented instructions with patients, caregivers, and providers. J Hosp Med 2015;10:804–7.

5. Gaver B, Dunne T, Pacenti E. Design: cultural probes. Interactions 1999;6:21–9.

6. Sheridan SL, Halpern DJ, Viera AJ, et al. Interventions for individuals with low health literacy: a systematic review. J Health Commun 2011;16 Suppl 3:30–54.

7. Schillinger D, Machtinger EL, Wang F, et al. Language, literacy, and communication regarding medications in an anticoagulation clinic: A comparison of verbal vs. visual assessment. J Health Commun 2006;11:651–4.

8. Chugh A, Williams MV, Grigsby J, Coleman EA. Better transitions: Improving comprehension of discharge instructions. Front Health Serv Manage 2009;25:11–32.

9. IDEO. Design thinking for educators toolkit. 2nd ed. New York: IDEObooks; 2013.

10. Hahn-Goldberg S, Okrainec K, Damba C, et al. Implementing patient oriented discharge summaries (PODS): A multi-site pilot across early adopter hospitals. Healthc Q 2016;19:42–8.

Using the Common Sense Model in Daily Clinical Practice for Improving Medication Adherence

From Genoa-QoL Healthcare and the University of Michigan College of Pharmacy, Ann Arbor, MI.

Abstract

- Objective: To review the Common Sense Model, a framework that can be used for understanding patients’ behavior, including taking or not taking medications as prescribed.

- Methods: Descriptive report.

- Results: Medication adherence, a critical component of achieving good patient outcomes and reducing medical costs, is dependent upon patient illness beliefs. The Common Sense Model holds that these beliefs can be categorized as illness identity, cause, consequence, control, and timeline. Effective communication is necessary to understand the beliefs that patients hold and help them understand their condition. Good communication also can allay fears and other emotions that can be disruptive to achieving good outcomes.

- Conclusion: Clinicians should seek to understand their patients’ illness beliefs and collaborate with them to achieve desired health outcomes.

Clinical practice is based on scientific evidence, by which medical problems are diagnosed and treatment recommendations are made. However, the role of the patient may not be completely recognized as an integral part of the process of patient care. The impact of failing to adequately recognize the patient perspective is evident in medication nonadherence. Health psychology research can provide clinicians insight into patients’ perceptions and behavior. This paper reviews the Common Sense Model (CSM), a behavioral model that provides a framework that can be used in understanding patients’ behavior. In this paper I will discuss the model and how it can be a possible strategy for improving adherence.

Making the Case for CSM in Daily Practice

It can be difficult to realize that persons seeking medical attention would not take medications as prescribed by a physician. In fact, studies reveal that on average, 16.4% of prescribed medications will not be picked up from the pharmacy [1]. Of those patients who do pick up their medication, approximately 1 out of 4 will not take them as prescribed [2]. Such medication nonadherence leads to poor health outcomes and increased health care costs [3,4]. There are many reasons for medication nonadherence [5], and there is no single solution to improving medication adherence [6]. A Cochrane review of randomized controlled trials evaluating various interventions intended to enhance patient adherence to prescribed medications for medical conditions found them to have limited effectiveness. Interventions assessed included health and medication information, reminder calls, follow-up assessment of medication therapy, social support, and simplification of the treatment regimen [6]. In an exploratory study of patients with chronic health conditions, Kucukarslan et al found patients’ beliefs about their illness and their medication are integral to their health care decisions [7]. Their findings were consistent with the CSM, which is based on Leventhal’s theory of self-regulation.

Self-regulation theory states that rational people will make decisions to reduce their health threat. Patients’ perceptions of their selves and environments drives their behavior. So in the presence of a health threat, a person will seek to eliminate or reduce that threat. However, coping behavior is complex. A person may decide to follow the advice of his clinician, follow some other advice (from family, friends, advertising, etc.), or do nothing. The premise of self-regulation is that people will choose a common sense approach to their health threat [8]. Therefore, clinicians must understand their patients’ viewpoint of themselves and their health condition so they may help guide them toward healthy outcomes.

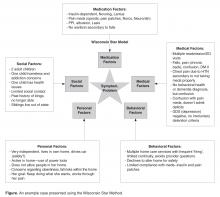

The Common Sense Model

The CSM is a framework for understanding patient behavior when faced with a health threat. It holds that patients form common sense representations of their illness using information from 5 domains [8]: (1) the identity of the illness (the label the patient gives to the condition and symptoms); (2) the cause of the illness; (3) the consequences of the illness (beliefs about how the illness will impact the patient’s well-being); (4) whether the illness can be controlled or cured; and (5) timeline (beliefs about how long the condition will last). A patient may either act to address the health threat or choose to ignore it. Patient emotions are proposed to have a role on patient behavior along with the 5 dimensions of illness perception.

Illness Identity

Illness identity is the label patients place on the health threat; it is most likely not the same as the signs and symptoms clinicians use. Therefore, the first misconnect between physician and patient may be in describing the illness. Chen et al studied illness identity as perceived by patients with hypertension [9,10]. Illness identity was defined as (1) hypertension-related symptoms, (2) symptoms experienced before and after their diagnosis; and (3) symptoms used to predict high blood pressure. Although hypertension is asymptomatic, patients do perceive symptoms such as headache associated with their hypertension. The researchers found those patients who identified more symptoms were more likely to believe that their symptoms caused the hypertension and were correspondingly less likely to use their medication. For them, when the headache subsides, so does the hypertension.

Physicians should find out how patients assess their health condition and provide them tools for evaluating their response to medication. In the case of hypertension, the physician could have the patient check their blood pressure with and without the headache to demonstrate that hypertension occurs even when the patient is not “symptomatic.” The point is to converse with the patient to learn how they view their condition. Clinicians should resist the “urge” to correct patients. Taking time to help patients better understand their condition is important. A misstep:

Patient: I can tell when my blood pressure is high. I get a pounding headache.

Doctor: High blood pressure is an asymptomatic condition. Your headaches are not caused by your high blood pressure.

Patients may choose to ignore the clinician if they feel strongly about how they define their illness. It is better to listen to the patient and offer steps to learn about their health condition. Here is a better response from the physician:

Doctor: You are telling me that you can tell when your blood pressure is high. So when your head aches your pressure is high, right?

Patient: Yes.

Doctor: Let me tell you more about high blood pressure. High blood pressure is also present without headaches...

Illness Causes

There are multiple causative factors patients may associate with their disease. Causes attributed to disease may be based on patient experiences, input from family and friends, and cultural factors. Causes may include emotional state, stress or worry, overwork, genetic predisposition, or environmental factors (eg, pollution). Jessop and Rutter found patients who perceive their condition as due to uncontrollable factors, such as chance, germs, or pollution, were less likely to take their medication [11]. Similar findings were published by Chen et al [9]. They found psychological factors, environmental risk factors (eg, smoking, diet), and even bad luck or chance associated with less likelihood of taking medications as prescribed. Clinicians should explore patients’ perceptions of causes of a condition. Patients strive to eliminate the perceived cause, thus eliminating the need to take medication. In some cultures, bad luck or chance drives patients’ decisions to not take medication, or they believe in fate and do not accept treatment. Whether they feel they can control their condition by eliminating the cause or have a fatalistic view that the cause of their condition is not within their control, the clinician must work with the patient to reduce the impact of misperceptions or significance of perceived causes.

Illness Consequence

Consequence associated with the health condition is an important factor in patient behavior [12]. Patients must understand the specific threats to their health if a condition is left untreated or uncontrolled. Patients’ view of illness consequence may be formed by their own perceived vulnerability or susceptibility and the perceived seriousness of the condition. For example, patients with hypertension should be informed about the impact of high blood pressure on their bodies and the consequence of disability from stroke, dependency on dialysis from kidney failure, or death. They may not consider themselves susceptible to illness since they “feel healthy” and may decide to delay treatment. Patients with conditions such as asthma or heart failure may believe they are cured when their symptoms abate and therefore believe they have no more need for medication. Such patients need education to understand that they are asymptomatic because they are well controlled with medication.

Illness Control

Patients may feel they can control their health condition by changing their behavior, changing their environment, and/or by taking prescribed medication. As discussed earlier, cause and control both work together to form patient beliefs and actions. Patients will take their medications as prescribed if they believe in the effectiveness of medication to control their condition [11,13–15]. Interestingly, Ross found those who felt they had more control over their illness were more likely not to take their medication as prescribed [12]. These persons are more likely to not want to become “dependent” on medication. Their feeling was that they can make changes in their lives and thereby improve their health condition.

Physicians should invite patients’ thoughts as to what should be done to improve their health condition, and collaborate with the patient on an action plan for change if change is expected to improve/control the health condition. Follow-up to assess the patient’s health status longitudinally is necessary.

In this exchange, the patient feels he can control his hypertension on his own:

Doctor: I recommend that you start taking medication to control your blood pressure. Uncontrolled high blood pressure can lead to many health problems.

Patient: I am not ready to start taking medication.

Doctor: What are your reasons?

Patient: I am under a lot of stress at work. Once I get control of this stress, my blood pressure will go down.

Doctor: Getting control of your stress at work is important. Let me tell you more about high blood pressure.

Patient: Okay.

Doctor: There is no one cause of your high blood pressure. Eliminating your work stress will most likely not reduce your blood pressure....

Timeline

Health conditions can be acute, chronic, or cyclical (ie, seasonal); however, patients may have different perceptions of the duration of their health condition. In Kucukarslan et al, some patients did not believe their hypertension was a lifelong condition because they felt they would be able to cure it [7]. For example, as illustrated above, patients may believe that stress causes their hypertension, and if the stress could be controlled, then their blood pressure would normalize. Conversely, Ross et al found that patients who viewed their hypertension as a long-term condition were more likely to believe their medications were necessary and thus more likely to take their medication as prescribed [12]. A lifelong or chronic health condition is a difficult concept for patients to accept, especially ones who may view themselves as too young to have the condition.

Emotions

After being informed about their health condition, patients may feel emotions that are not apparent to the practitioner. These may include worry, depression, anger, anxiety, or fear. Emotions may impact their decision to take medication [12,14]. Listening for patients’ responses to health information provided by the clinician and letting patients know they have been heard will help allay strong negative emotions [16]. Good communication builds trust between the clinician and patient.

Conclusion

Patients receive medical advice from clinicians that may be inconsistent with their beliefs and understanding of their health condition. Studies of medication nonadherence find many factors contribute to it and no one tool to improve medication adherence exists. However, the consequence of medication nonadherence are great and include include worsening condition, increased comorbid disease, and increased health care costs. Understanding patients’ beliefs about their health condition is an important step toward reducing medication nonadherence. The CSM provides a framework for clinicians to guide patients toward effective decision-making. Listening to the patient explain how they view their condition—how they define it, the causes, consequences, how to control it, and how long it will last or if it will progress—are important to the process of working with the patient manage their condition effectively. Clinicians’ reaction to these perceptions are important, and dismissing them may alienate patients. Effective communication is necessary to understand patients’ perspectives and to help them manage their health condition.

Corresponding author: Suzan N. Kucukarslan, PhD, RPh, skucukar@gmail.com.

Financial disclosures: None.

1. Gadkari AS, McHorney CA. Medication non-fulfillment rates and reasons: a narrative systematic review. Curr Med Res Opin 2010;26:683–785.

2. DiMatteo MR. Variations in patients’ adherence to medical recommendations: a quantitative review of 50 years of research. Med Care 2004;42:200–9.

3. Ho PM, Rumsfeld JS, Masoudi FA, et al. The effect of medication non-adherence on hospitalization and mortality among patients with diabetes mellitus. Arch Intern Med 2006;166;1836–41.

4. Benjamin RM. Medication adherence: Helping patients take their medicines as directed. Pub Health Rep 2012;2–3.

5. Osterberg L, Blaschke T. Adherence to medication. N Engl J Med 2005;353:487–97.

6. Haynes RB, Ackloo E, Sahota N, et al. Interventions for enhancing medication adherence. Cochrane Database Syst Rev 2008;(2):CD000011.

7. Kucukarslan SN, Lewis NJW, Shimp LA, et al. Exploring patient experiences with prescription medicines to identify unmet patient needs: implications for research and practice. Res Social Adm Pharm 2012;8:321–332.

8. Leventhal H, Leventhal EA, Contrada RJ. Self-regulation, health, and behavior: a perceptual-cognitive approach. Psychol Health 1998;13:717–33.

9. Chen S-L, Tsai J-C, Chou K-R. Illness perceptions and adherence to therapeutic regimens among patients with hypertension: A structural model approach. Int J Nurs Stud 2011;48:235–45.

10. Chen S-L, Tsai J-C, Lee W-L. The impact of illness perception on adherence to therapeutic regimens of patients with hypertension in Taiwan. J Clin Nurs 2009;18:2234–44.

11. Jessop DC, Rutter DR. Adherence to asthma medication: the role of illness representations. Psychol Health 2003;18:595–612.

12. Ross S, Walker A, MacLeod M. Patient compliance in hypertension:role of illness perceptions and treatment beliefs. J Hum Hypertension 2004;18:607–13.

13 Searle A, Norman P. Thompson R. Vedhara K. A prospective examination of illness belies and coping in patients with type 2 diabetes. Br J Health Psychol 2007;12:621–38.

14. Zugelj U, Zuparnicic M, Komidar L, et al. Self-reported adherence behavior in adolescent hypertensive patients: the role of illness representation and personality. J Pediatr Psychol 2010;35:1049–60.

15. Horne R, Weinman J. Self-regulation and self-management in asthma: exploring the role of illness perception and treatment beliefs in explaining non-adherence to preventer medication. Psychol Health 2002;17:17–32.

16. Northouse LL, Northouse PG. Health communication: strategies for health professionals. Stamford: Prentice Hall; 1998.

From Genoa-QoL Healthcare and the University of Michigan College of Pharmacy, Ann Arbor, MI.

Abstract

- Objective: To review the Common Sense Model, a framework that can be used for understanding patients’ behavior, including taking or not taking medications as prescribed.

- Methods: Descriptive report.

- Results: Medication adherence, a critical component of achieving good patient outcomes and reducing medical costs, is dependent upon patient illness beliefs. The Common Sense Model holds that these beliefs can be categorized as illness identity, cause, consequence, control, and timeline. Effective communication is necessary to understand the beliefs that patients hold and help them understand their condition. Good communication also can allay fears and other emotions that can be disruptive to achieving good outcomes.

- Conclusion: Clinicians should seek to understand their patients’ illness beliefs and collaborate with them to achieve desired health outcomes.

Clinical practice is based on scientific evidence, by which medical problems are diagnosed and treatment recommendations are made. However, the role of the patient may not be completely recognized as an integral part of the process of patient care. The impact of failing to adequately recognize the patient perspective is evident in medication nonadherence. Health psychology research can provide clinicians insight into patients’ perceptions and behavior. This paper reviews the Common Sense Model (CSM), a behavioral model that provides a framework that can be used in understanding patients’ behavior. In this paper I will discuss the model and how it can be a possible strategy for improving adherence.

Making the Case for CSM in Daily Practice

It can be difficult to realize that persons seeking medical attention would not take medications as prescribed by a physician. In fact, studies reveal that on average, 16.4% of prescribed medications will not be picked up from the pharmacy [1]. Of those patients who do pick up their medication, approximately 1 out of 4 will not take them as prescribed [2]. Such medication nonadherence leads to poor health outcomes and increased health care costs [3,4]. There are many reasons for medication nonadherence [5], and there is no single solution to improving medication adherence [6]. A Cochrane review of randomized controlled trials evaluating various interventions intended to enhance patient adherence to prescribed medications for medical conditions found them to have limited effectiveness. Interventions assessed included health and medication information, reminder calls, follow-up assessment of medication therapy, social support, and simplification of the treatment regimen [6]. In an exploratory study of patients with chronic health conditions, Kucukarslan et al found patients’ beliefs about their illness and their medication are integral to their health care decisions [7]. Their findings were consistent with the CSM, which is based on Leventhal’s theory of self-regulation.

Self-regulation theory states that rational people will make decisions to reduce their health threat. Patients’ perceptions of their selves and environments drives their behavior. So in the presence of a health threat, a person will seek to eliminate or reduce that threat. However, coping behavior is complex. A person may decide to follow the advice of his clinician, follow some other advice (from family, friends, advertising, etc.), or do nothing. The premise of self-regulation is that people will choose a common sense approach to their health threat [8]. Therefore, clinicians must understand their patients’ viewpoint of themselves and their health condition so they may help guide them toward healthy outcomes.

The Common Sense Model

The CSM is a framework for understanding patient behavior when faced with a health threat. It holds that patients form common sense representations of their illness using information from 5 domains [8]: (1) the identity of the illness (the label the patient gives to the condition and symptoms); (2) the cause of the illness; (3) the consequences of the illness (beliefs about how the illness will impact the patient’s well-being); (4) whether the illness can be controlled or cured; and (5) timeline (beliefs about how long the condition will last). A patient may either act to address the health threat or choose to ignore it. Patient emotions are proposed to have a role on patient behavior along with the 5 dimensions of illness perception.

Illness Identity

Illness identity is the label patients place on the health threat; it is most likely not the same as the signs and symptoms clinicians use. Therefore, the first misconnect between physician and patient may be in describing the illness. Chen et al studied illness identity as perceived by patients with hypertension [9,10]. Illness identity was defined as (1) hypertension-related symptoms, (2) symptoms experienced before and after their diagnosis; and (3) symptoms used to predict high blood pressure. Although hypertension is asymptomatic, patients do perceive symptoms such as headache associated with their hypertension. The researchers found those patients who identified more symptoms were more likely to believe that their symptoms caused the hypertension and were correspondingly less likely to use their medication. For them, when the headache subsides, so does the hypertension.

Physicians should find out how patients assess their health condition and provide them tools for evaluating their response to medication. In the case of hypertension, the physician could have the patient check their blood pressure with and without the headache to demonstrate that hypertension occurs even when the patient is not “symptomatic.” The point is to converse with the patient to learn how they view their condition. Clinicians should resist the “urge” to correct patients. Taking time to help patients better understand their condition is important. A misstep:

Patient: I can tell when my blood pressure is high. I get a pounding headache.

Doctor: High blood pressure is an asymptomatic condition. Your headaches are not caused by your high blood pressure.

Patients may choose to ignore the clinician if they feel strongly about how they define their illness. It is better to listen to the patient and offer steps to learn about their health condition. Here is a better response from the physician:

Doctor: You are telling me that you can tell when your blood pressure is high. So when your head aches your pressure is high, right?

Patient: Yes.

Doctor: Let me tell you more about high blood pressure. High blood pressure is also present without headaches...

Illness Causes

There are multiple causative factors patients may associate with their disease. Causes attributed to disease may be based on patient experiences, input from family and friends, and cultural factors. Causes may include emotional state, stress or worry, overwork, genetic predisposition, or environmental factors (eg, pollution). Jessop and Rutter found patients who perceive their condition as due to uncontrollable factors, such as chance, germs, or pollution, were less likely to take their medication [11]. Similar findings were published by Chen et al [9]. They found psychological factors, environmental risk factors (eg, smoking, diet), and even bad luck or chance associated with less likelihood of taking medications as prescribed. Clinicians should explore patients’ perceptions of causes of a condition. Patients strive to eliminate the perceived cause, thus eliminating the need to take medication. In some cultures, bad luck or chance drives patients’ decisions to not take medication, or they believe in fate and do not accept treatment. Whether they feel they can control their condition by eliminating the cause or have a fatalistic view that the cause of their condition is not within their control, the clinician must work with the patient to reduce the impact of misperceptions or significance of perceived causes.

Illness Consequence

Consequence associated with the health condition is an important factor in patient behavior [12]. Patients must understand the specific threats to their health if a condition is left untreated or uncontrolled. Patients’ view of illness consequence may be formed by their own perceived vulnerability or susceptibility and the perceived seriousness of the condition. For example, patients with hypertension should be informed about the impact of high blood pressure on their bodies and the consequence of disability from stroke, dependency on dialysis from kidney failure, or death. They may not consider themselves susceptible to illness since they “feel healthy” and may decide to delay treatment. Patients with conditions such as asthma or heart failure may believe they are cured when their symptoms abate and therefore believe they have no more need for medication. Such patients need education to understand that they are asymptomatic because they are well controlled with medication.

Illness Control

Patients may feel they can control their health condition by changing their behavior, changing their environment, and/or by taking prescribed medication. As discussed earlier, cause and control both work together to form patient beliefs and actions. Patients will take their medications as prescribed if they believe in the effectiveness of medication to control their condition [11,13–15]. Interestingly, Ross found those who felt they had more control over their illness were more likely not to take their medication as prescribed [12]. These persons are more likely to not want to become “dependent” on medication. Their feeling was that they can make changes in their lives and thereby improve their health condition.

Physicians should invite patients’ thoughts as to what should be done to improve their health condition, and collaborate with the patient on an action plan for change if change is expected to improve/control the health condition. Follow-up to assess the patient’s health status longitudinally is necessary.

In this exchange, the patient feels he can control his hypertension on his own:

Doctor: I recommend that you start taking medication to control your blood pressure. Uncontrolled high blood pressure can lead to many health problems.

Patient: I am not ready to start taking medication.

Doctor: What are your reasons?

Patient: I am under a lot of stress at work. Once I get control of this stress, my blood pressure will go down.

Doctor: Getting control of your stress at work is important. Let me tell you more about high blood pressure.

Patient: Okay.

Doctor: There is no one cause of your high blood pressure. Eliminating your work stress will most likely not reduce your blood pressure....

Timeline

Health conditions can be acute, chronic, or cyclical (ie, seasonal); however, patients may have different perceptions of the duration of their health condition. In Kucukarslan et al, some patients did not believe their hypertension was a lifelong condition because they felt they would be able to cure it [7]. For example, as illustrated above, patients may believe that stress causes their hypertension, and if the stress could be controlled, then their blood pressure would normalize. Conversely, Ross et al found that patients who viewed their hypertension as a long-term condition were more likely to believe their medications were necessary and thus more likely to take their medication as prescribed [12]. A lifelong or chronic health condition is a difficult concept for patients to accept, especially ones who may view themselves as too young to have the condition.

Emotions

After being informed about their health condition, patients may feel emotions that are not apparent to the practitioner. These may include worry, depression, anger, anxiety, or fear. Emotions may impact their decision to take medication [12,14]. Listening for patients’ responses to health information provided by the clinician and letting patients know they have been heard will help allay strong negative emotions [16]. Good communication builds trust between the clinician and patient.

Conclusion

Patients receive medical advice from clinicians that may be inconsistent with their beliefs and understanding of their health condition. Studies of medication nonadherence find many factors contribute to it and no one tool to improve medication adherence exists. However, the consequence of medication nonadherence are great and include include worsening condition, increased comorbid disease, and increased health care costs. Understanding patients’ beliefs about their health condition is an important step toward reducing medication nonadherence. The CSM provides a framework for clinicians to guide patients toward effective decision-making. Listening to the patient explain how they view their condition—how they define it, the causes, consequences, how to control it, and how long it will last or if it will progress—are important to the process of working with the patient manage their condition effectively. Clinicians’ reaction to these perceptions are important, and dismissing them may alienate patients. Effective communication is necessary to understand patients’ perspectives and to help them manage their health condition.

Corresponding author: Suzan N. Kucukarslan, PhD, RPh, skucukar@gmail.com.

Financial disclosures: None.

From Genoa-QoL Healthcare and the University of Michigan College of Pharmacy, Ann Arbor, MI.

Abstract

- Objective: To review the Common Sense Model, a framework that can be used for understanding patients’ behavior, including taking or not taking medications as prescribed.

- Methods: Descriptive report.

- Results: Medication adherence, a critical component of achieving good patient outcomes and reducing medical costs, is dependent upon patient illness beliefs. The Common Sense Model holds that these beliefs can be categorized as illness identity, cause, consequence, control, and timeline. Effective communication is necessary to understand the beliefs that patients hold and help them understand their condition. Good communication also can allay fears and other emotions that can be disruptive to achieving good outcomes.

- Conclusion: Clinicians should seek to understand their patients’ illness beliefs and collaborate with them to achieve desired health outcomes.

Clinical practice is based on scientific evidence, by which medical problems are diagnosed and treatment recommendations are made. However, the role of the patient may not be completely recognized as an integral part of the process of patient care. The impact of failing to adequately recognize the patient perspective is evident in medication nonadherence. Health psychology research can provide clinicians insight into patients’ perceptions and behavior. This paper reviews the Common Sense Model (CSM), a behavioral model that provides a framework that can be used in understanding patients’ behavior. In this paper I will discuss the model and how it can be a possible strategy for improving adherence.

Making the Case for CSM in Daily Practice

It can be difficult to realize that persons seeking medical attention would not take medications as prescribed by a physician. In fact, studies reveal that on average, 16.4% of prescribed medications will not be picked up from the pharmacy [1]. Of those patients who do pick up their medication, approximately 1 out of 4 will not take them as prescribed [2]. Such medication nonadherence leads to poor health outcomes and increased health care costs [3,4]. There are many reasons for medication nonadherence [5], and there is no single solution to improving medication adherence [6]. A Cochrane review of randomized controlled trials evaluating various interventions intended to enhance patient adherence to prescribed medications for medical conditions found them to have limited effectiveness. Interventions assessed included health and medication information, reminder calls, follow-up assessment of medication therapy, social support, and simplification of the treatment regimen [6]. In an exploratory study of patients with chronic health conditions, Kucukarslan et al found patients’ beliefs about their illness and their medication are integral to their health care decisions [7]. Their findings were consistent with the CSM, which is based on Leventhal’s theory of self-regulation.

Self-regulation theory states that rational people will make decisions to reduce their health threat. Patients’ perceptions of their selves and environments drives their behavior. So in the presence of a health threat, a person will seek to eliminate or reduce that threat. However, coping behavior is complex. A person may decide to follow the advice of his clinician, follow some other advice (from family, friends, advertising, etc.), or do nothing. The premise of self-regulation is that people will choose a common sense approach to their health threat [8]. Therefore, clinicians must understand their patients’ viewpoint of themselves and their health condition so they may help guide them toward healthy outcomes.

The Common Sense Model

The CSM is a framework for understanding patient behavior when faced with a health threat. It holds that patients form common sense representations of their illness using information from 5 domains [8]: (1) the identity of the illness (the label the patient gives to the condition and symptoms); (2) the cause of the illness; (3) the consequences of the illness (beliefs about how the illness will impact the patient’s well-being); (4) whether the illness can be controlled or cured; and (5) timeline (beliefs about how long the condition will last). A patient may either act to address the health threat or choose to ignore it. Patient emotions are proposed to have a role on patient behavior along with the 5 dimensions of illness perception.

Illness Identity

Illness identity is the label patients place on the health threat; it is most likely not the same as the signs and symptoms clinicians use. Therefore, the first misconnect between physician and patient may be in describing the illness. Chen et al studied illness identity as perceived by patients with hypertension [9,10]. Illness identity was defined as (1) hypertension-related symptoms, (2) symptoms experienced before and after their diagnosis; and (3) symptoms used to predict high blood pressure. Although hypertension is asymptomatic, patients do perceive symptoms such as headache associated with their hypertension. The researchers found those patients who identified more symptoms were more likely to believe that their symptoms caused the hypertension and were correspondingly less likely to use their medication. For them, when the headache subsides, so does the hypertension.

Physicians should find out how patients assess their health condition and provide them tools for evaluating their response to medication. In the case of hypertension, the physician could have the patient check their blood pressure with and without the headache to demonstrate that hypertension occurs even when the patient is not “symptomatic.” The point is to converse with the patient to learn how they view their condition. Clinicians should resist the “urge” to correct patients. Taking time to help patients better understand their condition is important. A misstep:

Patient: I can tell when my blood pressure is high. I get a pounding headache.

Doctor: High blood pressure is an asymptomatic condition. Your headaches are not caused by your high blood pressure.

Patients may choose to ignore the clinician if they feel strongly about how they define their illness. It is better to listen to the patient and offer steps to learn about their health condition. Here is a better response from the physician:

Doctor: You are telling me that you can tell when your blood pressure is high. So when your head aches your pressure is high, right?

Patient: Yes.

Doctor: Let me tell you more about high blood pressure. High blood pressure is also present without headaches...

Illness Causes

There are multiple causative factors patients may associate with their disease. Causes attributed to disease may be based on patient experiences, input from family and friends, and cultural factors. Causes may include emotional state, stress or worry, overwork, genetic predisposition, or environmental factors (eg, pollution). Jessop and Rutter found patients who perceive their condition as due to uncontrollable factors, such as chance, germs, or pollution, were less likely to take their medication [11]. Similar findings were published by Chen et al [9]. They found psychological factors, environmental risk factors (eg, smoking, diet), and even bad luck or chance associated with less likelihood of taking medications as prescribed. Clinicians should explore patients’ perceptions of causes of a condition. Patients strive to eliminate the perceived cause, thus eliminating the need to take medication. In some cultures, bad luck or chance drives patients’ decisions to not take medication, or they believe in fate and do not accept treatment. Whether they feel they can control their condition by eliminating the cause or have a fatalistic view that the cause of their condition is not within their control, the clinician must work with the patient to reduce the impact of misperceptions or significance of perceived causes.

Illness Consequence

Consequence associated with the health condition is an important factor in patient behavior [12]. Patients must understand the specific threats to their health if a condition is left untreated or uncontrolled. Patients’ view of illness consequence may be formed by their own perceived vulnerability or susceptibility and the perceived seriousness of the condition. For example, patients with hypertension should be informed about the impact of high blood pressure on their bodies and the consequence of disability from stroke, dependency on dialysis from kidney failure, or death. They may not consider themselves susceptible to illness since they “feel healthy” and may decide to delay treatment. Patients with conditions such as asthma or heart failure may believe they are cured when their symptoms abate and therefore believe they have no more need for medication. Such patients need education to understand that they are asymptomatic because they are well controlled with medication.

Illness Control

Patients may feel they can control their health condition by changing their behavior, changing their environment, and/or by taking prescribed medication. As discussed earlier, cause and control both work together to form patient beliefs and actions. Patients will take their medications as prescribed if they believe in the effectiveness of medication to control their condition [11,13–15]. Interestingly, Ross found those who felt they had more control over their illness were more likely not to take their medication as prescribed [12]. These persons are more likely to not want to become “dependent” on medication. Their feeling was that they can make changes in their lives and thereby improve their health condition.

Physicians should invite patients’ thoughts as to what should be done to improve their health condition, and collaborate with the patient on an action plan for change if change is expected to improve/control the health condition. Follow-up to assess the patient’s health status longitudinally is necessary.

In this exchange, the patient feels he can control his hypertension on his own:

Doctor: I recommend that you start taking medication to control your blood pressure. Uncontrolled high blood pressure can lead to many health problems.

Patient: I am not ready to start taking medication.

Doctor: What are your reasons?

Patient: I am under a lot of stress at work. Once I get control of this stress, my blood pressure will go down.

Doctor: Getting control of your stress at work is important. Let me tell you more about high blood pressure.

Patient: Okay.

Doctor: There is no one cause of your high blood pressure. Eliminating your work stress will most likely not reduce your blood pressure....

Timeline

Health conditions can be acute, chronic, or cyclical (ie, seasonal); however, patients may have different perceptions of the duration of their health condition. In Kucukarslan et al, some patients did not believe their hypertension was a lifelong condition because they felt they would be able to cure it [7]. For example, as illustrated above, patients may believe that stress causes their hypertension, and if the stress could be controlled, then their blood pressure would normalize. Conversely, Ross et al found that patients who viewed their hypertension as a long-term condition were more likely to believe their medications were necessary and thus more likely to take their medication as prescribed [12]. A lifelong or chronic health condition is a difficult concept for patients to accept, especially ones who may view themselves as too young to have the condition.

Emotions

After being informed about their health condition, patients may feel emotions that are not apparent to the practitioner. These may include worry, depression, anger, anxiety, or fear. Emotions may impact their decision to take medication [12,14]. Listening for patients’ responses to health information provided by the clinician and letting patients know they have been heard will help allay strong negative emotions [16]. Good communication builds trust between the clinician and patient.

Conclusion

Patients receive medical advice from clinicians that may be inconsistent with their beliefs and understanding of their health condition. Studies of medication nonadherence find many factors contribute to it and no one tool to improve medication adherence exists. However, the consequence of medication nonadherence are great and include include worsening condition, increased comorbid disease, and increased health care costs. Understanding patients’ beliefs about their health condition is an important step toward reducing medication nonadherence. The CSM provides a framework for clinicians to guide patients toward effective decision-making. Listening to the patient explain how they view their condition—how they define it, the causes, consequences, how to control it, and how long it will last or if it will progress—are important to the process of working with the patient manage their condition effectively. Clinicians’ reaction to these perceptions are important, and dismissing them may alienate patients. Effective communication is necessary to understand patients’ perspectives and to help them manage their health condition.

Corresponding author: Suzan N. Kucukarslan, PhD, RPh, skucukar@gmail.com.

Financial disclosures: None.

1. Gadkari AS, McHorney CA. Medication non-fulfillment rates and reasons: a narrative systematic review. Curr Med Res Opin 2010;26:683–785.

2. DiMatteo MR. Variations in patients’ adherence to medical recommendations: a quantitative review of 50 years of research. Med Care 2004;42:200–9.

3. Ho PM, Rumsfeld JS, Masoudi FA, et al. The effect of medication non-adherence on hospitalization and mortality among patients with diabetes mellitus. Arch Intern Med 2006;166;1836–41.

4. Benjamin RM. Medication adherence: Helping patients take their medicines as directed. Pub Health Rep 2012;2–3.

5. Osterberg L, Blaschke T. Adherence to medication. N Engl J Med 2005;353:487–97.

6. Haynes RB, Ackloo E, Sahota N, et al. Interventions for enhancing medication adherence. Cochrane Database Syst Rev 2008;(2):CD000011.

7. Kucukarslan SN, Lewis NJW, Shimp LA, et al. Exploring patient experiences with prescription medicines to identify unmet patient needs: implications for research and practice. Res Social Adm Pharm 2012;8:321–332.

8. Leventhal H, Leventhal EA, Contrada RJ. Self-regulation, health, and behavior: a perceptual-cognitive approach. Psychol Health 1998;13:717–33.

9. Chen S-L, Tsai J-C, Chou K-R. Illness perceptions and adherence to therapeutic regimens among patients with hypertension: A structural model approach. Int J Nurs Stud 2011;48:235–45.

10. Chen S-L, Tsai J-C, Lee W-L. The impact of illness perception on adherence to therapeutic regimens of patients with hypertension in Taiwan. J Clin Nurs 2009;18:2234–44.

11. Jessop DC, Rutter DR. Adherence to asthma medication: the role of illness representations. Psychol Health 2003;18:595–612.

12. Ross S, Walker A, MacLeod M. Patient compliance in hypertension:role of illness perceptions and treatment beliefs. J Hum Hypertension 2004;18:607–13.

13 Searle A, Norman P. Thompson R. Vedhara K. A prospective examination of illness belies and coping in patients with type 2 diabetes. Br J Health Psychol 2007;12:621–38.

14. Zugelj U, Zuparnicic M, Komidar L, et al. Self-reported adherence behavior in adolescent hypertensive patients: the role of illness representation and personality. J Pediatr Psychol 2010;35:1049–60.

15. Horne R, Weinman J. Self-regulation and self-management in asthma: exploring the role of illness perception and treatment beliefs in explaining non-adherence to preventer medication. Psychol Health 2002;17:17–32.

16. Northouse LL, Northouse PG. Health communication: strategies for health professionals. Stamford: Prentice Hall; 1998.

1. Gadkari AS, McHorney CA. Medication non-fulfillment rates and reasons: a narrative systematic review. Curr Med Res Opin 2010;26:683–785.

2. DiMatteo MR. Variations in patients’ adherence to medical recommendations: a quantitative review of 50 years of research. Med Care 2004;42:200–9.

3. Ho PM, Rumsfeld JS, Masoudi FA, et al. The effect of medication non-adherence on hospitalization and mortality among patients with diabetes mellitus. Arch Intern Med 2006;166;1836–41.

4. Benjamin RM. Medication adherence: Helping patients take their medicines as directed. Pub Health Rep 2012;2–3.

5. Osterberg L, Blaschke T. Adherence to medication. N Engl J Med 2005;353:487–97.

6. Haynes RB, Ackloo E, Sahota N, et al. Interventions for enhancing medication adherence. Cochrane Database Syst Rev 2008;(2):CD000011.

7. Kucukarslan SN, Lewis NJW, Shimp LA, et al. Exploring patient experiences with prescription medicines to identify unmet patient needs: implications for research and practice. Res Social Adm Pharm 2012;8:321–332.

8. Leventhal H, Leventhal EA, Contrada RJ. Self-regulation, health, and behavior: a perceptual-cognitive approach. Psychol Health 1998;13:717–33.

9. Chen S-L, Tsai J-C, Chou K-R. Illness perceptions and adherence to therapeutic regimens among patients with hypertension: A structural model approach. Int J Nurs Stud 2011;48:235–45.

10. Chen S-L, Tsai J-C, Lee W-L. The impact of illness perception on adherence to therapeutic regimens of patients with hypertension in Taiwan. J Clin Nurs 2009;18:2234–44.

11. Jessop DC, Rutter DR. Adherence to asthma medication: the role of illness representations. Psychol Health 2003;18:595–612.

12. Ross S, Walker A, MacLeod M. Patient compliance in hypertension:role of illness perceptions and treatment beliefs. J Hum Hypertension 2004;18:607–13.

13 Searle A, Norman P. Thompson R. Vedhara K. A prospective examination of illness belies and coping in patients with type 2 diabetes. Br J Health Psychol 2007;12:621–38.