User login

Maintaining and reclaiming hemostasis in laparoscopic surgery

Additional videos from SGS are available here, including these recent offerings:

- Safety and efficiency in the laparoscopic hysterectomy: Techniques to optimize the surgical approach

- Laparoscopic management of bladder fibroids: Surgical tips and tricks

- Laparoscopic techniques for Essure device removal

Additional videos from SGS are available here, including these recent offerings:

- Safety and efficiency in the laparoscopic hysterectomy: Techniques to optimize the surgical approach

- Laparoscopic management of bladder fibroids: Surgical tips and tricks

- Laparoscopic techniques for Essure device removal

Additional videos from SGS are available here, including these recent offerings:

- Safety and efficiency in the laparoscopic hysterectomy: Techniques to optimize the surgical approach

- Laparoscopic management of bladder fibroids: Surgical tips and tricks

- Laparoscopic techniques for Essure device removal

Two-drug combo should be first-line standard of care in advanced endometrial cancer

The combination proved to be noninferior to paclitaxel-doxorubicin-cisplatin (TAP) in terms of response, progression-free survival, and overall survival, and with lower toxicity.

Overall survival was a median of 37 months for TC and 41 months for TAP, and there were more adverse events of grade 3 or higher with TAP.

The data were initially presented at the 2012 annual meeting of the Society of Gynecologic Oncology. In the original presentation, lead author David Scott Miller, MD, said this combination should be the standard of care in this setting. Dr. Miller is professor of obstetrics and gynecology at the University of Texas Southwestern Medical Center, Dallas.

“This subsequent long-term follow-up publication confirmed that,” he said in an interview. “TAP is now rarely used.”

The results have now been published in the Journal of Clinical Oncology.

The Gynecologic Oncology Group 177 trial established TAP about a decade earlier as the standard for systemic treatment of stage III-IV and recurrent endometrial cancer. However, the regimen was associated with substantially more toxicity than doxorubicin-cisplatin.

Phase 2 trials of TC suggested that the combination was active in endometrial cancer, the authors noted. They hypothesized that doxorubicin could be omitted from the regimen and that carboplatin could be substituted for cisplatin.

Equivalent survival, lower toxicity

In the current trial, Dr. Miller and colleagues sought to determine whether TC was therapeutically equivalent or noninferior to TAP with regard to survival outcomes. Secondary endpoints involved the toxicity profile of TC, compared with TAP. The two regimens were also compared with respect to patient-reported neurotoxicity and health-related quality of life (HRQoL).

From 2003 to 2009, 1,381 women with stage III, stage IV, and recurrent endometrial cancers were enrolled in the phase 3 GOG0209 trial. Patients were treated with doxorubicin 45 mg/m2 and cisplatin 50 mg/m2 (day 1), followed by paclitaxel 160 mg/m2 (day 2) with granulocyte colony–stimulating factor or paclitaxel 175 mg/m2 and carboplatin area under the curve 6 (day 1) every 21 days for seven cycles.

After treatment was completed, patients were followed quarterly for 2 years, semiannually for 3 years, and then annually until death. Most of the patients (61%) had measurable or recurrent disease at baseline.

In this updated analysis, with a median follow-up of 124 months, about two-thirds (>65%) of the patients had died; 28% remain alive without evidence of cancer. The adjusted ratio of death hazard of TC versus TAP was 1.002; for progression, the HR of TC to TAP was 1.032.

Median progression-free survival for TAP versus TC was 14 months versus 13 months, and for overall survival, 41 months versus 37 months.

As for adverse events, neutropenic fever was reported in 7% of patients who received TAP and in 6% of those who received TC. The rate of sensory neuropathy was greater among patients who received TAP (26% vs. 20%; P = .40), as was the rate of thrombocytopenia of grade ≥3 (23% vs. 12%), vomiting (7% vs. 4%), diarrhea (6% vs. 2%), and metabolic toxicities (14% vs. 8%). The rate of neutropenia was greater with TC (52% vs. 80%).

Data on HRQoL were collected from the first 538 patients enrolled before March 26, 2007. HRQoL was assessed at baseline and then at 6 weeks, 15 weeks, and 26 weeks. At 6 weeks, the TC group had higher scores on physical well-being and functional well-being (2.1-point difference; 0.3 to approximately 3.9 points; P = .009; effect size, 0.19). There were no statistically significant differences between groups at 15 and 26 weeks.

On the Functional Assessment of Cancer Therapy/GOG-Neurotoxicity four-item measure of sensory neuropathy (FACT/GOG-Ntx) subscale, scores were higher (indicating fewer neurotoxic symptoms) for patients in the TC group by 1.4 points (0.4 to approximately 2.5 points; P = .003; effect size, 0.64) at 26 weeks. There were no statistically significant differences between the groups at 6 and 15 weeks.

Dr. Miller noted that TC became the “backbone or control arm for most subsequent trials,” such as those evaluating immunotherapy and other agents in this setting.

The study was supported by National Cancer Institute grants to the GOG Administrative Office, the GOG Statistical Office, NRG Oncology (1 U10 CA180822), NRG Operations, and the National Cancer Institute Community Oncology Research Program. Dr. Miller has had a consulting or advisory role with Genentech, Tesaro, Eisai, AstraZeneca, Guardant Health, Janssen Oncology, Alexion Pharmaceuticals, Karyopharm Therapeutics, Incyte, Guardant Health, Janssen, Alexion Pharmaceuticals, Clovis Oncology, and Merck Sharp & Dohme; has been on the speakers’ bureaus for Clovis Oncology and Genentech; and has received institutional research funding from US Biotest, Advenchen Laboratories, Millennium, Tesaro, Xenetic Biosciences, Advaxis, Janssen, Aeterna Zentaris, TRACON Pharma, Pfizer, Immunogen, Mateon Therapeutics, and Merck Sharp & Dohme.

A version of this article originally appeared on Medscape.com.

The combination proved to be noninferior to paclitaxel-doxorubicin-cisplatin (TAP) in terms of response, progression-free survival, and overall survival, and with lower toxicity.

Overall survival was a median of 37 months for TC and 41 months for TAP, and there were more adverse events of grade 3 or higher with TAP.

The data were initially presented at the 2012 annual meeting of the Society of Gynecologic Oncology. In the original presentation, lead author David Scott Miller, MD, said this combination should be the standard of care in this setting. Dr. Miller is professor of obstetrics and gynecology at the University of Texas Southwestern Medical Center, Dallas.

“This subsequent long-term follow-up publication confirmed that,” he said in an interview. “TAP is now rarely used.”

The results have now been published in the Journal of Clinical Oncology.

The Gynecologic Oncology Group 177 trial established TAP about a decade earlier as the standard for systemic treatment of stage III-IV and recurrent endometrial cancer. However, the regimen was associated with substantially more toxicity than doxorubicin-cisplatin.

Phase 2 trials of TC suggested that the combination was active in endometrial cancer, the authors noted. They hypothesized that doxorubicin could be omitted from the regimen and that carboplatin could be substituted for cisplatin.

Equivalent survival, lower toxicity

In the current trial, Dr. Miller and colleagues sought to determine whether TC was therapeutically equivalent or noninferior to TAP with regard to survival outcomes. Secondary endpoints involved the toxicity profile of TC, compared with TAP. The two regimens were also compared with respect to patient-reported neurotoxicity and health-related quality of life (HRQoL).

From 2003 to 2009, 1,381 women with stage III, stage IV, and recurrent endometrial cancers were enrolled in the phase 3 GOG0209 trial. Patients were treated with doxorubicin 45 mg/m2 and cisplatin 50 mg/m2 (day 1), followed by paclitaxel 160 mg/m2 (day 2) with granulocyte colony–stimulating factor or paclitaxel 175 mg/m2 and carboplatin area under the curve 6 (day 1) every 21 days for seven cycles.

After treatment was completed, patients were followed quarterly for 2 years, semiannually for 3 years, and then annually until death. Most of the patients (61%) had measurable or recurrent disease at baseline.

In this updated analysis, with a median follow-up of 124 months, about two-thirds (>65%) of the patients had died; 28% remain alive without evidence of cancer. The adjusted ratio of death hazard of TC versus TAP was 1.002; for progression, the HR of TC to TAP was 1.032.

Median progression-free survival for TAP versus TC was 14 months versus 13 months, and for overall survival, 41 months versus 37 months.

As for adverse events, neutropenic fever was reported in 7% of patients who received TAP and in 6% of those who received TC. The rate of sensory neuropathy was greater among patients who received TAP (26% vs. 20%; P = .40), as was the rate of thrombocytopenia of grade ≥3 (23% vs. 12%), vomiting (7% vs. 4%), diarrhea (6% vs. 2%), and metabolic toxicities (14% vs. 8%). The rate of neutropenia was greater with TC (52% vs. 80%).

Data on HRQoL were collected from the first 538 patients enrolled before March 26, 2007. HRQoL was assessed at baseline and then at 6 weeks, 15 weeks, and 26 weeks. At 6 weeks, the TC group had higher scores on physical well-being and functional well-being (2.1-point difference; 0.3 to approximately 3.9 points; P = .009; effect size, 0.19). There were no statistically significant differences between groups at 15 and 26 weeks.

On the Functional Assessment of Cancer Therapy/GOG-Neurotoxicity four-item measure of sensory neuropathy (FACT/GOG-Ntx) subscale, scores were higher (indicating fewer neurotoxic symptoms) for patients in the TC group by 1.4 points (0.4 to approximately 2.5 points; P = .003; effect size, 0.64) at 26 weeks. There were no statistically significant differences between the groups at 6 and 15 weeks.

Dr. Miller noted that TC became the “backbone or control arm for most subsequent trials,” such as those evaluating immunotherapy and other agents in this setting.

The study was supported by National Cancer Institute grants to the GOG Administrative Office, the GOG Statistical Office, NRG Oncology (1 U10 CA180822), NRG Operations, and the National Cancer Institute Community Oncology Research Program. Dr. Miller has had a consulting or advisory role with Genentech, Tesaro, Eisai, AstraZeneca, Guardant Health, Janssen Oncology, Alexion Pharmaceuticals, Karyopharm Therapeutics, Incyte, Guardant Health, Janssen, Alexion Pharmaceuticals, Clovis Oncology, and Merck Sharp & Dohme; has been on the speakers’ bureaus for Clovis Oncology and Genentech; and has received institutional research funding from US Biotest, Advenchen Laboratories, Millennium, Tesaro, Xenetic Biosciences, Advaxis, Janssen, Aeterna Zentaris, TRACON Pharma, Pfizer, Immunogen, Mateon Therapeutics, and Merck Sharp & Dohme.

A version of this article originally appeared on Medscape.com.

The combination proved to be noninferior to paclitaxel-doxorubicin-cisplatin (TAP) in terms of response, progression-free survival, and overall survival, and with lower toxicity.

Overall survival was a median of 37 months for TC and 41 months for TAP, and there were more adverse events of grade 3 or higher with TAP.

The data were initially presented at the 2012 annual meeting of the Society of Gynecologic Oncology. In the original presentation, lead author David Scott Miller, MD, said this combination should be the standard of care in this setting. Dr. Miller is professor of obstetrics and gynecology at the University of Texas Southwestern Medical Center, Dallas.

“This subsequent long-term follow-up publication confirmed that,” he said in an interview. “TAP is now rarely used.”

The results have now been published in the Journal of Clinical Oncology.

The Gynecologic Oncology Group 177 trial established TAP about a decade earlier as the standard for systemic treatment of stage III-IV and recurrent endometrial cancer. However, the regimen was associated with substantially more toxicity than doxorubicin-cisplatin.

Phase 2 trials of TC suggested that the combination was active in endometrial cancer, the authors noted. They hypothesized that doxorubicin could be omitted from the regimen and that carboplatin could be substituted for cisplatin.

Equivalent survival, lower toxicity

In the current trial, Dr. Miller and colleagues sought to determine whether TC was therapeutically equivalent or noninferior to TAP with regard to survival outcomes. Secondary endpoints involved the toxicity profile of TC, compared with TAP. The two regimens were also compared with respect to patient-reported neurotoxicity and health-related quality of life (HRQoL).

From 2003 to 2009, 1,381 women with stage III, stage IV, and recurrent endometrial cancers were enrolled in the phase 3 GOG0209 trial. Patients were treated with doxorubicin 45 mg/m2 and cisplatin 50 mg/m2 (day 1), followed by paclitaxel 160 mg/m2 (day 2) with granulocyte colony–stimulating factor or paclitaxel 175 mg/m2 and carboplatin area under the curve 6 (day 1) every 21 days for seven cycles.

After treatment was completed, patients were followed quarterly for 2 years, semiannually for 3 years, and then annually until death. Most of the patients (61%) had measurable or recurrent disease at baseline.

In this updated analysis, with a median follow-up of 124 months, about two-thirds (>65%) of the patients had died; 28% remain alive without evidence of cancer. The adjusted ratio of death hazard of TC versus TAP was 1.002; for progression, the HR of TC to TAP was 1.032.

Median progression-free survival for TAP versus TC was 14 months versus 13 months, and for overall survival, 41 months versus 37 months.

As for adverse events, neutropenic fever was reported in 7% of patients who received TAP and in 6% of those who received TC. The rate of sensory neuropathy was greater among patients who received TAP (26% vs. 20%; P = .40), as was the rate of thrombocytopenia of grade ≥3 (23% vs. 12%), vomiting (7% vs. 4%), diarrhea (6% vs. 2%), and metabolic toxicities (14% vs. 8%). The rate of neutropenia was greater with TC (52% vs. 80%).

Data on HRQoL were collected from the first 538 patients enrolled before March 26, 2007. HRQoL was assessed at baseline and then at 6 weeks, 15 weeks, and 26 weeks. At 6 weeks, the TC group had higher scores on physical well-being and functional well-being (2.1-point difference; 0.3 to approximately 3.9 points; P = .009; effect size, 0.19). There were no statistically significant differences between groups at 15 and 26 weeks.

On the Functional Assessment of Cancer Therapy/GOG-Neurotoxicity four-item measure of sensory neuropathy (FACT/GOG-Ntx) subscale, scores were higher (indicating fewer neurotoxic symptoms) for patients in the TC group by 1.4 points (0.4 to approximately 2.5 points; P = .003; effect size, 0.64) at 26 weeks. There were no statistically significant differences between the groups at 6 and 15 weeks.

Dr. Miller noted that TC became the “backbone or control arm for most subsequent trials,” such as those evaluating immunotherapy and other agents in this setting.

The study was supported by National Cancer Institute grants to the GOG Administrative Office, the GOG Statistical Office, NRG Oncology (1 U10 CA180822), NRG Operations, and the National Cancer Institute Community Oncology Research Program. Dr. Miller has had a consulting or advisory role with Genentech, Tesaro, Eisai, AstraZeneca, Guardant Health, Janssen Oncology, Alexion Pharmaceuticals, Karyopharm Therapeutics, Incyte, Guardant Health, Janssen, Alexion Pharmaceuticals, Clovis Oncology, and Merck Sharp & Dohme; has been on the speakers’ bureaus for Clovis Oncology and Genentech; and has received institutional research funding from US Biotest, Advenchen Laboratories, Millennium, Tesaro, Xenetic Biosciences, Advaxis, Janssen, Aeterna Zentaris, TRACON Pharma, Pfizer, Immunogen, Mateon Therapeutics, and Merck Sharp & Dohme.

A version of this article originally appeared on Medscape.com.

Menstrual irregularity appears to be predictor of early death

than women with regular or short cycles, reported Yi-Xin Wang, PhD, of Harvard TH Chan School of Public Health, Boston, and associates. This is particularly true in the presence of cardiovascular disease and a history of smoking.

In a peer-reviewed observational study of 79,505 premenopausal women enrolled in the Nurses’ Health Study II, the researchers sought to determine whether a life-long history of irregular or long menstrual cycles was associated with premature death. Patients averaged a mean age of 37.7 years and had no history of cardiovascular disease, cancer, or diabetes at enrollment.

Although irregular and long menstrual cycles are common and frequently linked with an increased risk of major chronic diseases – such as ovarian cancer, coronary heart disease, type 2 diabetes, and mental health problems – in women of reproductive age, actual evidence linking irregular or long menstrual cycles with mortality is scant, the researchers noted in the BMJ.

During the study, participants checked in at ages 14-17 years, 18-22 years, and 29-46 years to report the usual length and regularity of their menstrual cycles. Over 24 years of follow-up, a total of 1,975 premature deaths were noted, including 894 from cancer and 172 from cardiovascular disease.

Irregular cycles appear to bring risks

After considering other possible factors of influence, including age, weight, lifestyle, and family medical history, Dr. Wang and associates noted higher rates of mortality among those consistently reporting irregular cycles than women in the same age ranges with very regular cycles. Specifically, women aged 18-22 years and 29-46 years with cycles of 40 days or more were at greater risk of dying prematurely than were those in the same age ranges with cycles of 26-31 days.

Cardiovascular disease was a stronger predictor of death than cancer or other causes. Also included in the higher-risk group were those who currently smoked.

Among women reporting very regular cycles and women reporting always irregular cycles, mortality rates per 1,000 person-years were 1.05 and 1.23 at ages 14-17 years, 1.00 and 1.37 at ages 18-22 years, and 1.00 and 1.68 at ages 29-46 years, respectively.

The study also found that women reporting irregular cycles or no periods had a higher body mass indexes (28.2 vs. 25.0 kg/m2); were more likely to have conditions including hypertension (13.2% vs. 6.2%), high blood cholesterol levels (23.9% vs. 14.9%), hirsutism (8.4%

vs. 1.8%), or endometriosis (5.9% vs. 4.5%); and uterine fibroids (10.0% vs. 7.8%); and a higher prevalence of family history of diabetes (19.4% vs. 15.8%).

Dr. Wang and associates also observed – using multivariable Cox models – a greater risk of premature death across all categories and all age ranges in women with decreasing menstrual cycle regularity. In models that were fully adjusted, cycle lengths that were 40 days or more or too irregular to estimate from ages 18-22 and 29-46 expressed hazard ratios for premature death at the time of follow-up of 1.34 and 1.40, compared with women in the same age ranges reporting cycle lengths of 26-31 days.

Of note, Dr. Wang and colleagues unexpectedly discovered an increased risk of premature death in women who had used contraceptives between 14-17 years. They suggested that a greater number of women self-reporting contraceptive use in adolescence may have been using contraceptives to manage symptoms of polycystic ovary syndrome (PCOS) and other conditions such as endometriosis.

Relying on the potential inaccuracy inherent in patient recall of their menstrual cycle characteristics, and the likelihood for other unmeasured factors, may have affected study results. Study strengths included the significant number of participants who had a high follow-up rate over many years, and the availability of menstrual cycle data at three different points across the reproductive lifespan.

Because the mechanisms underlying these associations are likely related to the disrupted hormonal environment, the study results “emphasize the need for primary care providers to include menstrual cycle characteristics throughout the reproductive life span as additional vital signs in assessing women’s general health status,” Dr. Wang and colleagues cautioned.

Expert suggests a probable underlying link

“Irregular menstrual cycles in women have long been known to be associated with significant morbidities, including the leading causes of mortality worldwide such as cardiovascular disease and cancer,” Reshef Tal, MD, PhD, assistant professor of obstetrics, gynecology & reproductive sciences at Yale University, New Haven, Conn., said in an interview. “The findings of this large study that irregular menstrual cycles are associated with premature death, most strongly from cardiovascular causes, are therefore not surprising.”

Dr. Tal acknowledged that one probable underlying link is PCOS, which is recognized as the most common hormonal disorder affecting women of reproductive age. The irregular periods that characterize PCOS are tied to a number of metabolic risk factors, including obesity, insulin resistance, dyslipidemia, and hypertension, which increase the long-term risk of cardiovascular disease and cancer of the uterus.

“The study did not have information on patients’ pelvic ultrasound findings and male hormone levels, which would have helped to establish PCOS diagnosis. However, women in this study who had irregular cycles tended to have more hirsutism, high cholesterol, hypertension as well as higher BMI, suggesting that PCOS is at least partly responsible for the observed association with cardiovascular disease. Interestingly, the association between irregular cycles and early mortality was independent of BMI, indicating that mechanisms other than metabolic factors may also play a role,” observed Dr. Tal, who was asked to comment on the study.

“Irregular periods are a symptom and not a disease, so it is important to identify underlying metabolic risk factors. Furthermore, physicians are advised to counsel patients experiencing menstrual irregularity, [to advise them to] maintain a healthy lifestyle and be alert to health changes,” Dr. Tal suggested.

The study was funded by the National Institutes of Health. The investigators had no relevant financial disclosures. Dr. Tal said he had no relevant financial disclosures.

SOURCE: Chavarro J et al. BMJ. 2020. doi: 10.1136/bmj.m3464.

than women with regular or short cycles, reported Yi-Xin Wang, PhD, of Harvard TH Chan School of Public Health, Boston, and associates. This is particularly true in the presence of cardiovascular disease and a history of smoking.

In a peer-reviewed observational study of 79,505 premenopausal women enrolled in the Nurses’ Health Study II, the researchers sought to determine whether a life-long history of irregular or long menstrual cycles was associated with premature death. Patients averaged a mean age of 37.7 years and had no history of cardiovascular disease, cancer, or diabetes at enrollment.

Although irregular and long menstrual cycles are common and frequently linked with an increased risk of major chronic diseases – such as ovarian cancer, coronary heart disease, type 2 diabetes, and mental health problems – in women of reproductive age, actual evidence linking irregular or long menstrual cycles with mortality is scant, the researchers noted in the BMJ.

During the study, participants checked in at ages 14-17 years, 18-22 years, and 29-46 years to report the usual length and regularity of their menstrual cycles. Over 24 years of follow-up, a total of 1,975 premature deaths were noted, including 894 from cancer and 172 from cardiovascular disease.

Irregular cycles appear to bring risks

After considering other possible factors of influence, including age, weight, lifestyle, and family medical history, Dr. Wang and associates noted higher rates of mortality among those consistently reporting irregular cycles than women in the same age ranges with very regular cycles. Specifically, women aged 18-22 years and 29-46 years with cycles of 40 days or more were at greater risk of dying prematurely than were those in the same age ranges with cycles of 26-31 days.

Cardiovascular disease was a stronger predictor of death than cancer or other causes. Also included in the higher-risk group were those who currently smoked.

Among women reporting very regular cycles and women reporting always irregular cycles, mortality rates per 1,000 person-years were 1.05 and 1.23 at ages 14-17 years, 1.00 and 1.37 at ages 18-22 years, and 1.00 and 1.68 at ages 29-46 years, respectively.

The study also found that women reporting irregular cycles or no periods had a higher body mass indexes (28.2 vs. 25.0 kg/m2); were more likely to have conditions including hypertension (13.2% vs. 6.2%), high blood cholesterol levels (23.9% vs. 14.9%), hirsutism (8.4%

vs. 1.8%), or endometriosis (5.9% vs. 4.5%); and uterine fibroids (10.0% vs. 7.8%); and a higher prevalence of family history of diabetes (19.4% vs. 15.8%).

Dr. Wang and associates also observed – using multivariable Cox models – a greater risk of premature death across all categories and all age ranges in women with decreasing menstrual cycle regularity. In models that were fully adjusted, cycle lengths that were 40 days or more or too irregular to estimate from ages 18-22 and 29-46 expressed hazard ratios for premature death at the time of follow-up of 1.34 and 1.40, compared with women in the same age ranges reporting cycle lengths of 26-31 days.

Of note, Dr. Wang and colleagues unexpectedly discovered an increased risk of premature death in women who had used contraceptives between 14-17 years. They suggested that a greater number of women self-reporting contraceptive use in adolescence may have been using contraceptives to manage symptoms of polycystic ovary syndrome (PCOS) and other conditions such as endometriosis.

Relying on the potential inaccuracy inherent in patient recall of their menstrual cycle characteristics, and the likelihood for other unmeasured factors, may have affected study results. Study strengths included the significant number of participants who had a high follow-up rate over many years, and the availability of menstrual cycle data at three different points across the reproductive lifespan.

Because the mechanisms underlying these associations are likely related to the disrupted hormonal environment, the study results “emphasize the need for primary care providers to include menstrual cycle characteristics throughout the reproductive life span as additional vital signs in assessing women’s general health status,” Dr. Wang and colleagues cautioned.

Expert suggests a probable underlying link

“Irregular menstrual cycles in women have long been known to be associated with significant morbidities, including the leading causes of mortality worldwide such as cardiovascular disease and cancer,” Reshef Tal, MD, PhD, assistant professor of obstetrics, gynecology & reproductive sciences at Yale University, New Haven, Conn., said in an interview. “The findings of this large study that irregular menstrual cycles are associated with premature death, most strongly from cardiovascular causes, are therefore not surprising.”

Dr. Tal acknowledged that one probable underlying link is PCOS, which is recognized as the most common hormonal disorder affecting women of reproductive age. The irregular periods that characterize PCOS are tied to a number of metabolic risk factors, including obesity, insulin resistance, dyslipidemia, and hypertension, which increase the long-term risk of cardiovascular disease and cancer of the uterus.

“The study did not have information on patients’ pelvic ultrasound findings and male hormone levels, which would have helped to establish PCOS diagnosis. However, women in this study who had irregular cycles tended to have more hirsutism, high cholesterol, hypertension as well as higher BMI, suggesting that PCOS is at least partly responsible for the observed association with cardiovascular disease. Interestingly, the association between irregular cycles and early mortality was independent of BMI, indicating that mechanisms other than metabolic factors may also play a role,” observed Dr. Tal, who was asked to comment on the study.

“Irregular periods are a symptom and not a disease, so it is important to identify underlying metabolic risk factors. Furthermore, physicians are advised to counsel patients experiencing menstrual irregularity, [to advise them to] maintain a healthy lifestyle and be alert to health changes,” Dr. Tal suggested.

The study was funded by the National Institutes of Health. The investigators had no relevant financial disclosures. Dr. Tal said he had no relevant financial disclosures.

SOURCE: Chavarro J et al. BMJ. 2020. doi: 10.1136/bmj.m3464.

than women with regular or short cycles, reported Yi-Xin Wang, PhD, of Harvard TH Chan School of Public Health, Boston, and associates. This is particularly true in the presence of cardiovascular disease and a history of smoking.

In a peer-reviewed observational study of 79,505 premenopausal women enrolled in the Nurses’ Health Study II, the researchers sought to determine whether a life-long history of irregular or long menstrual cycles was associated with premature death. Patients averaged a mean age of 37.7 years and had no history of cardiovascular disease, cancer, or diabetes at enrollment.

Although irregular and long menstrual cycles are common and frequently linked with an increased risk of major chronic diseases – such as ovarian cancer, coronary heart disease, type 2 diabetes, and mental health problems – in women of reproductive age, actual evidence linking irregular or long menstrual cycles with mortality is scant, the researchers noted in the BMJ.

During the study, participants checked in at ages 14-17 years, 18-22 years, and 29-46 years to report the usual length and regularity of their menstrual cycles. Over 24 years of follow-up, a total of 1,975 premature deaths were noted, including 894 from cancer and 172 from cardiovascular disease.

Irregular cycles appear to bring risks

After considering other possible factors of influence, including age, weight, lifestyle, and family medical history, Dr. Wang and associates noted higher rates of mortality among those consistently reporting irregular cycles than women in the same age ranges with very regular cycles. Specifically, women aged 18-22 years and 29-46 years with cycles of 40 days or more were at greater risk of dying prematurely than were those in the same age ranges with cycles of 26-31 days.

Cardiovascular disease was a stronger predictor of death than cancer or other causes. Also included in the higher-risk group were those who currently smoked.

Among women reporting very regular cycles and women reporting always irregular cycles, mortality rates per 1,000 person-years were 1.05 and 1.23 at ages 14-17 years, 1.00 and 1.37 at ages 18-22 years, and 1.00 and 1.68 at ages 29-46 years, respectively.

The study also found that women reporting irregular cycles or no periods had a higher body mass indexes (28.2 vs. 25.0 kg/m2); were more likely to have conditions including hypertension (13.2% vs. 6.2%), high blood cholesterol levels (23.9% vs. 14.9%), hirsutism (8.4%

vs. 1.8%), or endometriosis (5.9% vs. 4.5%); and uterine fibroids (10.0% vs. 7.8%); and a higher prevalence of family history of diabetes (19.4% vs. 15.8%).

Dr. Wang and associates also observed – using multivariable Cox models – a greater risk of premature death across all categories and all age ranges in women with decreasing menstrual cycle regularity. In models that were fully adjusted, cycle lengths that were 40 days or more or too irregular to estimate from ages 18-22 and 29-46 expressed hazard ratios for premature death at the time of follow-up of 1.34 and 1.40, compared with women in the same age ranges reporting cycle lengths of 26-31 days.

Of note, Dr. Wang and colleagues unexpectedly discovered an increased risk of premature death in women who had used contraceptives between 14-17 years. They suggested that a greater number of women self-reporting contraceptive use in adolescence may have been using contraceptives to manage symptoms of polycystic ovary syndrome (PCOS) and other conditions such as endometriosis.

Relying on the potential inaccuracy inherent in patient recall of their menstrual cycle characteristics, and the likelihood for other unmeasured factors, may have affected study results. Study strengths included the significant number of participants who had a high follow-up rate over many years, and the availability of menstrual cycle data at three different points across the reproductive lifespan.

Because the mechanisms underlying these associations are likely related to the disrupted hormonal environment, the study results “emphasize the need for primary care providers to include menstrual cycle characteristics throughout the reproductive life span as additional vital signs in assessing women’s general health status,” Dr. Wang and colleagues cautioned.

Expert suggests a probable underlying link

“Irregular menstrual cycles in women have long been known to be associated with significant morbidities, including the leading causes of mortality worldwide such as cardiovascular disease and cancer,” Reshef Tal, MD, PhD, assistant professor of obstetrics, gynecology & reproductive sciences at Yale University, New Haven, Conn., said in an interview. “The findings of this large study that irregular menstrual cycles are associated with premature death, most strongly from cardiovascular causes, are therefore not surprising.”

Dr. Tal acknowledged that one probable underlying link is PCOS, which is recognized as the most common hormonal disorder affecting women of reproductive age. The irregular periods that characterize PCOS are tied to a number of metabolic risk factors, including obesity, insulin resistance, dyslipidemia, and hypertension, which increase the long-term risk of cardiovascular disease and cancer of the uterus.

“The study did not have information on patients’ pelvic ultrasound findings and male hormone levels, which would have helped to establish PCOS diagnosis. However, women in this study who had irregular cycles tended to have more hirsutism, high cholesterol, hypertension as well as higher BMI, suggesting that PCOS is at least partly responsible for the observed association with cardiovascular disease. Interestingly, the association between irregular cycles and early mortality was independent of BMI, indicating that mechanisms other than metabolic factors may also play a role,” observed Dr. Tal, who was asked to comment on the study.

“Irregular periods are a symptom and not a disease, so it is important to identify underlying metabolic risk factors. Furthermore, physicians are advised to counsel patients experiencing menstrual irregularity, [to advise them to] maintain a healthy lifestyle and be alert to health changes,” Dr. Tal suggested.

The study was funded by the National Institutes of Health. The investigators had no relevant financial disclosures. Dr. Tal said he had no relevant financial disclosures.

SOURCE: Chavarro J et al. BMJ. 2020. doi: 10.1136/bmj.m3464.

FROM THE BMJ

2020 Update on abnormal uterine bleeding

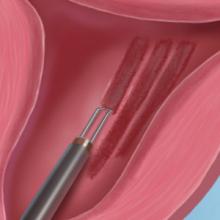

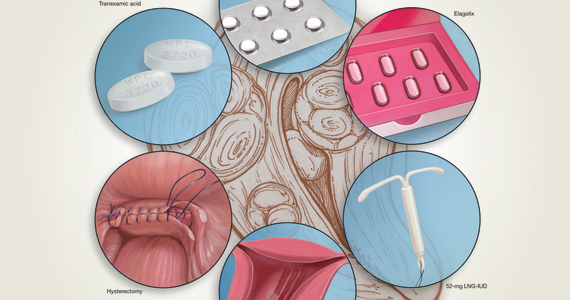

Abnormal uterine bleeding (AUB) continues to be a top reason that women present for gynecologic care. In general, our approach to the management of AUB is to diagnose causes before we prescribe therapy and to offer conservative therapies initially and progress to more invasive measures if indicated.

In this Update, we highlight several new studies that provide evidence for preferential use of certain medical and surgical therapies. In considering conservative therapy for the treatment of AUB, we take a closer look at the efficacy of cyclic progestogens. Another important issue, as more types of endometrial ablation (EA) are being developed and are coming into the market, is the need for additional guidance regarding decisions about EA versus progestin-releasing intrauterine devices (IUDs). Lastly, an unintended consequence of an increased cesarean delivery rate is the development of isthmocele, also known as cesarean scar defect or uterine niche. These defects, which can be bothersome and cause abnormal bleeding, are treated with various techniques. Within the last year, 2 systematic reviews that compare the efficacy of several different approaches and provide guidance have been published.

Is it time to retire cyclic progestogens for the treatment of heavy menstrual bleeding?

Bofill Rodriguez M, Lethaby A, Low C, et al. Cyclical progestogens for heavy menstrual bleeding. Cochrane Database Syst Rev. 2019;(8):CD001016.

In a recent Cochrane Database Systematic Review, Bofill Rodriguez and colleagues looked at the efficacy, safety, and tolerability of oral progestogen therapy for heavy menstrual bleeding.1 They considered progestogen (medroxyprogesterone acetate or norethisterone) in short-cycle use (7 to 10 days in the luteal phase) and long-cycle use (21 days per cycle) in a review of 15 randomized clinical trials (RCTs) that included a total of 1,071 women. As this topic had not been updated in 12 years, this review was essential in demonstrating changes that occurred over the past decade.

The primary outcomes of the analysis were menstrual blood loss and treatment satisfaction. Secondary outcomes included the number of days of bleeding, quality of life, adherence and acceptability of treatment, adverse events, and costs.

Classic progestogens fall short compared with newer approaches

Analysis of the data revealed that short-cycle progestogen was inferior to treatment with tranexamic acid, danazol, and the 65-µg progesterone-releasing IUD (Pg-IUD). Of note, the 65-µg Pg-IUD has been off the market since 2001, and danazol is rarely used in current practice. Furthermore, based on 2 trials, cyclic progestogens demonstrated no clear benefit over nonsteroidal anti-inflammatory drugs. Additionally, long-cycle progestogen therapy was found to be inferior to the 52-mg levonorgestrel-releasing IUD (LNG-IUD), tranexamic acid, and ormeloxifene.

It should be noted that the quality of evidence is still lacking for progestogen therapy, and this study's main limitation is bias, as the women and the researchers were aware of the treatments that were given. This review is helpful, however, for emphasizing the advantage of tranexamic acid and LNG-IUD use in clinical care.

The takeaway. Although it may not necessarily be time to retire the use of cyclic oral progestogens, the 52-mg LNG-IUD or tranexamic acid may be more successful for treating AUB in women who are appropriate candidates.

Cyclic progestogen therapy appears to be less effective for the treatment of AUB when compared with tranexamic acid and the LNG-IUD. It does not appear to be more helpful than nonsteroidal anti-inflammatory drugs. We frequently offer and prescribe tranexamic acid, 1,300 mg 3 times daily, as a medical alternative to hormonal therapy for up to 5 days monthly for women without thromboembolism risk. Lukes and colleagues published an RCT in 2010 that demonstrated a 40% reduction of bleeding in tranexamic acid–treated women compared with an 8.2% reduction in the placebo group.2

Continue to: Endometrial ablation...

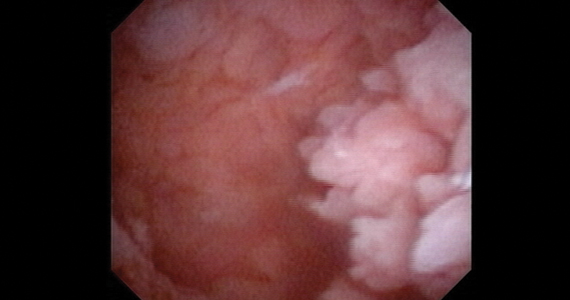

Endometrial ablation: New evidence informs when it could (and could not) be the best option

Bergeron C, Laberge PY, Boutin A, et al. Endometrial ablation or resection versus levonorgestrel intra-uterine system for the treatment of women with heavy menstrual bleeding and a normal uterine cavity: a systematic review with meta-analysis. Hum Reprod Update. 2020;26:302-311.

Vitale SG, Ferrero S, Ciebiera M, et al. Hysteroscopic endometrial resection vs hysterectomy for abnormal uterine bleeding: impact on quality of life and sexuality. Evidence from a systematic review of randomized controlled trials. Curr Opin Obstet Gynecol. 2020;32:159-165.

Two systematic reviews evaluated the efficacy of EA in women with abnormal uterine bleeding. One compared EA with the LNG-IUD and reported on safety and efficacy, while the other compared EA with hysterectomy and reported on quality of life.

Bergeron and colleagues reviewed 13 studies that included 884 women to compare the efficacy and safety of EA or resection with the LNG-IUD for the treatment of premenopausal women with AUB.3 They found no significant differences between EA and the LNG-IUD in terms of subsequent hysterectomy (risk ratio [RR] = 1.3; 95% confidence interval [CI], 0.60-2.11). It was not surprising that, when looking at age, EA was associated with a higher risk for hysterectomy in women younger than age 42 (RR = 5.26; 95% CI, 1.21-22.91). Conversely, subsequent hysterectomy was less likely with EA compared to LNG-IUD use in women older than 42 years. However, statistical significance was not reached in the older group (RR = 0.51; 95% CI, 0.21-1.24).

In the systematic review by Vitale and colleagues, 9 studies met inclusion criteria for a comparison of EA and hysterectomy, with the objective of ascertaining improvement in quality of life and several other measures.4

Although there was significant heterogeneity between assessment tools, both treatment groups experienced similar improvements in quality of life during the first year. However, hysterectomy was more advantageous in terms of improving uterine bleeding and satisfaction in the long term when compared with EA.4

As EA is considered, it is important to continue to counsel about the efficacy of the LNG-IUD, as well as its decreased associated morbidity. Additionally, EA is particularly less effective in younger women.

Continue to: Laparoscopy is best approach for isthomocele management, with caveats...

Laparoscopy is best approach for isthomocele management, with caveats

He Y, Zhong J, Zhou W, et al. Four surgical strategies for the treatment of cesarean scar defect: a systematic review and network meta-analysis. J Minim Invasive Gynecol. 2020;27:593-602.

Vitale SG, Ludwin A, Vilos GA, et al. From hysteroscopy to laparoendoscopic surgery: what is the best surgical approach for symptomatic isthmocele? A systematic review and meta-analysis. Arch Gynecol Obstet. 2020;301:33-52.

The isthmocele (cesarean scar defect, uterine niche), a known complication of cesarean delivery, represents a myometrial defect in the anterior uterine wall that often presents as abnormal uterine bleeding. It also can be a site for pregnancy-related complications, such as invasive placentation, placenta previa, and uterine rupture.

Two systematic reviews compared surgical strategies for treating isthmocele, including laparoscopy, hysteroscopy, combined laparoscopy and hysteroscopy, laparotomy, and vaginal repair.

Laparoscopy reduced isthmocele-associated AUB better than other techniques

A review by He and colleagues analyzed data from 10 pertinent studies (4 RCTs and 6 observational studies) that included 858 patients in total.5 Treatments compared were laparoscopy, hysteroscopy, combined laparoscopy with hysteroscopy, and vaginal repair for reduction of AUB and isthmocele and diverticulum depth.

The authors found no difference in intraoperative bleeding between the 4 surgical methods (laparotomy was not included in this review). Hysteroscopic surgery was associated with the shortest operative time, while laparoscopy was the longest surgery. In terms of reducing intermittent abnormal bleeding and scar depth, laparoscopic surgery performed better than the other 3 methods.

Approach considerations in isthmocele repair

Vitale and colleagues conducted a systematic review that included 33 publications (28 focused on a single surgical technique, 5 compared different techniques) to examine the effectiveness and risks of various surgical approaches for isthmocele in women with AUB, infertility, or for prevention of obstetric complications.6

Results of their analysis in general favored a laparoscopic approach for patients who desired future fertility, with an improvement rate of 92.7%. Hysteroscopic correction had an 85% improvement rate, and vaginal correction had an 82.5% improvement rate.

Although there were no high-level data to suggest a threshold for myometrial thickness in recommending a surgical approach, the authors provided a helpful algorithm for choosing a route based on a patient's fertility desires. For the asymptomatic patient, they suggest no treatment. In symptomatic patients, the laparoscopic approach is the gold standard but requires significant laparoscopic surgical skill, and a hysteroscopic approach may be considered as an alternative route if the residual myometrial defect is greater than 2.5 to 3.5 mm. For patients who are not considering future reproduction, hysteroscopy is the gold standard as long as the residual myometrial thickness is greater than 2.5 to 3.5 mm.

The takeaway. Of the several methods used for surgical isthmocele management, the laparoscopic approach reduced intermittent abnormal bleeding and scar depth better than other methods. It also was associated with the longest surgical duration. Hysteroscopic surgery was the quickest procedure to perform and is effective in removing the upper valve to promote the elimination of the hematocele and symptoms of abnormal bleeding; however, it does not change the anatomic aspects of the isthmocele in terms of myometrial thickness. Some authors suggested that deciding on the surgical route should be based on fertility desires and the residual thickness of the myometrium. ●

In terms of isthmocele repair, the laparoscopic approach is preferred in patients who desire fertility, as long as the surgeon possesses the skill set to perform this difficult surgery, and as long as the residual myometrium is thicker than 2.5 to 3.5 mm.

- Bofill Rodriguez M, Lethaby A, Low C, et al. Cyclical progestogens for heavy menstrual bleeding. Cochrane Database Syst Rev. 2019;(8):CD001016.

- Lukes AS, Moore KA, Muse KN, et al. Tranexamic acid treatment for heavy menstrual bleeding: a randomized controlled study. Obstet Gynecol. 2010;116:865-875.

- Bergeron C, Laberge PY, Boutin A, et al. Endometrial ablation or resection versus levonorgestrel intra-uterine system for the treatment of women with heavy menstrual bleeding and a normal uterine cavity: a systematic review with meta-analysis. Hum Reprod Update. 2020;26:302-311.

- Vitale SG, Ferrero S, Ciebiera M, et al. Hysteroscopic endometrial resection vs hysterectomy for abnormal uterine bleeding: impact on quality of life and sexuality. Evidence from a systematic review of randomized controlled trials. Curr Opin Obstet Gynecol. 2020;32:159-165.

- He Y, Zhong J, Zhou W, et al. Four surgical strategies for the treatment of cesarean scar defect: a systematic review and network meta-analysis. J Minim Invasive Gynecol. 2020;27:593-602.

- Vitale SG, Ludwin A, Vilos GA, et al. From hysteroscopy to laparoendoscopic surgery: what is the best surgical approach for symptomatic isthmocele? A systematic review and meta-analysis. Arch Gynecol Obstet. 2020;301:33-52.

Abnormal uterine bleeding (AUB) continues to be a top reason that women present for gynecologic care. In general, our approach to the management of AUB is to diagnose causes before we prescribe therapy and to offer conservative therapies initially and progress to more invasive measures if indicated.

In this Update, we highlight several new studies that provide evidence for preferential use of certain medical and surgical therapies. In considering conservative therapy for the treatment of AUB, we take a closer look at the efficacy of cyclic progestogens. Another important issue, as more types of endometrial ablation (EA) are being developed and are coming into the market, is the need for additional guidance regarding decisions about EA versus progestin-releasing intrauterine devices (IUDs). Lastly, an unintended consequence of an increased cesarean delivery rate is the development of isthmocele, also known as cesarean scar defect or uterine niche. These defects, which can be bothersome and cause abnormal bleeding, are treated with various techniques. Within the last year, 2 systematic reviews that compare the efficacy of several different approaches and provide guidance have been published.

Is it time to retire cyclic progestogens for the treatment of heavy menstrual bleeding?

Bofill Rodriguez M, Lethaby A, Low C, et al. Cyclical progestogens for heavy menstrual bleeding. Cochrane Database Syst Rev. 2019;(8):CD001016.

In a recent Cochrane Database Systematic Review, Bofill Rodriguez and colleagues looked at the efficacy, safety, and tolerability of oral progestogen therapy for heavy menstrual bleeding.1 They considered progestogen (medroxyprogesterone acetate or norethisterone) in short-cycle use (7 to 10 days in the luteal phase) and long-cycle use (21 days per cycle) in a review of 15 randomized clinical trials (RCTs) that included a total of 1,071 women. As this topic had not been updated in 12 years, this review was essential in demonstrating changes that occurred over the past decade.

The primary outcomes of the analysis were menstrual blood loss and treatment satisfaction. Secondary outcomes included the number of days of bleeding, quality of life, adherence and acceptability of treatment, adverse events, and costs.

Classic progestogens fall short compared with newer approaches

Analysis of the data revealed that short-cycle progestogen was inferior to treatment with tranexamic acid, danazol, and the 65-µg progesterone-releasing IUD (Pg-IUD). Of note, the 65-µg Pg-IUD has been off the market since 2001, and danazol is rarely used in current practice. Furthermore, based on 2 trials, cyclic progestogens demonstrated no clear benefit over nonsteroidal anti-inflammatory drugs. Additionally, long-cycle progestogen therapy was found to be inferior to the 52-mg levonorgestrel-releasing IUD (LNG-IUD), tranexamic acid, and ormeloxifene.

It should be noted that the quality of evidence is still lacking for progestogen therapy, and this study's main limitation is bias, as the women and the researchers were aware of the treatments that were given. This review is helpful, however, for emphasizing the advantage of tranexamic acid and LNG-IUD use in clinical care.

The takeaway. Although it may not necessarily be time to retire the use of cyclic oral progestogens, the 52-mg LNG-IUD or tranexamic acid may be more successful for treating AUB in women who are appropriate candidates.

Cyclic progestogen therapy appears to be less effective for the treatment of AUB when compared with tranexamic acid and the LNG-IUD. It does not appear to be more helpful than nonsteroidal anti-inflammatory drugs. We frequently offer and prescribe tranexamic acid, 1,300 mg 3 times daily, as a medical alternative to hormonal therapy for up to 5 days monthly for women without thromboembolism risk. Lukes and colleagues published an RCT in 2010 that demonstrated a 40% reduction of bleeding in tranexamic acid–treated women compared with an 8.2% reduction in the placebo group.2

Continue to: Endometrial ablation...

Endometrial ablation: New evidence informs when it could (and could not) be the best option

Bergeron C, Laberge PY, Boutin A, et al. Endometrial ablation or resection versus levonorgestrel intra-uterine system for the treatment of women with heavy menstrual bleeding and a normal uterine cavity: a systematic review with meta-analysis. Hum Reprod Update. 2020;26:302-311.

Vitale SG, Ferrero S, Ciebiera M, et al. Hysteroscopic endometrial resection vs hysterectomy for abnormal uterine bleeding: impact on quality of life and sexuality. Evidence from a systematic review of randomized controlled trials. Curr Opin Obstet Gynecol. 2020;32:159-165.

Two systematic reviews evaluated the efficacy of EA in women with abnormal uterine bleeding. One compared EA with the LNG-IUD and reported on safety and efficacy, while the other compared EA with hysterectomy and reported on quality of life.

Bergeron and colleagues reviewed 13 studies that included 884 women to compare the efficacy and safety of EA or resection with the LNG-IUD for the treatment of premenopausal women with AUB.3 They found no significant differences between EA and the LNG-IUD in terms of subsequent hysterectomy (risk ratio [RR] = 1.3; 95% confidence interval [CI], 0.60-2.11). It was not surprising that, when looking at age, EA was associated with a higher risk for hysterectomy in women younger than age 42 (RR = 5.26; 95% CI, 1.21-22.91). Conversely, subsequent hysterectomy was less likely with EA compared to LNG-IUD use in women older than 42 years. However, statistical significance was not reached in the older group (RR = 0.51; 95% CI, 0.21-1.24).

In the systematic review by Vitale and colleagues, 9 studies met inclusion criteria for a comparison of EA and hysterectomy, with the objective of ascertaining improvement in quality of life and several other measures.4

Although there was significant heterogeneity between assessment tools, both treatment groups experienced similar improvements in quality of life during the first year. However, hysterectomy was more advantageous in terms of improving uterine bleeding and satisfaction in the long term when compared with EA.4

As EA is considered, it is important to continue to counsel about the efficacy of the LNG-IUD, as well as its decreased associated morbidity. Additionally, EA is particularly less effective in younger women.

Continue to: Laparoscopy is best approach for isthomocele management, with caveats...

Laparoscopy is best approach for isthomocele management, with caveats

He Y, Zhong J, Zhou W, et al. Four surgical strategies for the treatment of cesarean scar defect: a systematic review and network meta-analysis. J Minim Invasive Gynecol. 2020;27:593-602.

Vitale SG, Ludwin A, Vilos GA, et al. From hysteroscopy to laparoendoscopic surgery: what is the best surgical approach for symptomatic isthmocele? A systematic review and meta-analysis. Arch Gynecol Obstet. 2020;301:33-52.

The isthmocele (cesarean scar defect, uterine niche), a known complication of cesarean delivery, represents a myometrial defect in the anterior uterine wall that often presents as abnormal uterine bleeding. It also can be a site for pregnancy-related complications, such as invasive placentation, placenta previa, and uterine rupture.

Two systematic reviews compared surgical strategies for treating isthmocele, including laparoscopy, hysteroscopy, combined laparoscopy and hysteroscopy, laparotomy, and vaginal repair.

Laparoscopy reduced isthmocele-associated AUB better than other techniques

A review by He and colleagues analyzed data from 10 pertinent studies (4 RCTs and 6 observational studies) that included 858 patients in total.5 Treatments compared were laparoscopy, hysteroscopy, combined laparoscopy with hysteroscopy, and vaginal repair for reduction of AUB and isthmocele and diverticulum depth.

The authors found no difference in intraoperative bleeding between the 4 surgical methods (laparotomy was not included in this review). Hysteroscopic surgery was associated with the shortest operative time, while laparoscopy was the longest surgery. In terms of reducing intermittent abnormal bleeding and scar depth, laparoscopic surgery performed better than the other 3 methods.

Approach considerations in isthmocele repair

Vitale and colleagues conducted a systematic review that included 33 publications (28 focused on a single surgical technique, 5 compared different techniques) to examine the effectiveness and risks of various surgical approaches for isthmocele in women with AUB, infertility, or for prevention of obstetric complications.6

Results of their analysis in general favored a laparoscopic approach for patients who desired future fertility, with an improvement rate of 92.7%. Hysteroscopic correction had an 85% improvement rate, and vaginal correction had an 82.5% improvement rate.

Although there were no high-level data to suggest a threshold for myometrial thickness in recommending a surgical approach, the authors provided a helpful algorithm for choosing a route based on a patient's fertility desires. For the asymptomatic patient, they suggest no treatment. In symptomatic patients, the laparoscopic approach is the gold standard but requires significant laparoscopic surgical skill, and a hysteroscopic approach may be considered as an alternative route if the residual myometrial defect is greater than 2.5 to 3.5 mm. For patients who are not considering future reproduction, hysteroscopy is the gold standard as long as the residual myometrial thickness is greater than 2.5 to 3.5 mm.

The takeaway. Of the several methods used for surgical isthmocele management, the laparoscopic approach reduced intermittent abnormal bleeding and scar depth better than other methods. It also was associated with the longest surgical duration. Hysteroscopic surgery was the quickest procedure to perform and is effective in removing the upper valve to promote the elimination of the hematocele and symptoms of abnormal bleeding; however, it does not change the anatomic aspects of the isthmocele in terms of myometrial thickness. Some authors suggested that deciding on the surgical route should be based on fertility desires and the residual thickness of the myometrium. ●

In terms of isthmocele repair, the laparoscopic approach is preferred in patients who desire fertility, as long as the surgeon possesses the skill set to perform this difficult surgery, and as long as the residual myometrium is thicker than 2.5 to 3.5 mm.

Abnormal uterine bleeding (AUB) continues to be a top reason that women present for gynecologic care. In general, our approach to the management of AUB is to diagnose causes before we prescribe therapy and to offer conservative therapies initially and progress to more invasive measures if indicated.

In this Update, we highlight several new studies that provide evidence for preferential use of certain medical and surgical therapies. In considering conservative therapy for the treatment of AUB, we take a closer look at the efficacy of cyclic progestogens. Another important issue, as more types of endometrial ablation (EA) are being developed and are coming into the market, is the need for additional guidance regarding decisions about EA versus progestin-releasing intrauterine devices (IUDs). Lastly, an unintended consequence of an increased cesarean delivery rate is the development of isthmocele, also known as cesarean scar defect or uterine niche. These defects, which can be bothersome and cause abnormal bleeding, are treated with various techniques. Within the last year, 2 systematic reviews that compare the efficacy of several different approaches and provide guidance have been published.

Is it time to retire cyclic progestogens for the treatment of heavy menstrual bleeding?

Bofill Rodriguez M, Lethaby A, Low C, et al. Cyclical progestogens for heavy menstrual bleeding. Cochrane Database Syst Rev. 2019;(8):CD001016.

In a recent Cochrane Database Systematic Review, Bofill Rodriguez and colleagues looked at the efficacy, safety, and tolerability of oral progestogen therapy for heavy menstrual bleeding.1 They considered progestogen (medroxyprogesterone acetate or norethisterone) in short-cycle use (7 to 10 days in the luteal phase) and long-cycle use (21 days per cycle) in a review of 15 randomized clinical trials (RCTs) that included a total of 1,071 women. As this topic had not been updated in 12 years, this review was essential in demonstrating changes that occurred over the past decade.

The primary outcomes of the analysis were menstrual blood loss and treatment satisfaction. Secondary outcomes included the number of days of bleeding, quality of life, adherence and acceptability of treatment, adverse events, and costs.

Classic progestogens fall short compared with newer approaches

Analysis of the data revealed that short-cycle progestogen was inferior to treatment with tranexamic acid, danazol, and the 65-µg progesterone-releasing IUD (Pg-IUD). Of note, the 65-µg Pg-IUD has been off the market since 2001, and danazol is rarely used in current practice. Furthermore, based on 2 trials, cyclic progestogens demonstrated no clear benefit over nonsteroidal anti-inflammatory drugs. Additionally, long-cycle progestogen therapy was found to be inferior to the 52-mg levonorgestrel-releasing IUD (LNG-IUD), tranexamic acid, and ormeloxifene.

It should be noted that the quality of evidence is still lacking for progestogen therapy, and this study's main limitation is bias, as the women and the researchers were aware of the treatments that were given. This review is helpful, however, for emphasizing the advantage of tranexamic acid and LNG-IUD use in clinical care.

The takeaway. Although it may not necessarily be time to retire the use of cyclic oral progestogens, the 52-mg LNG-IUD or tranexamic acid may be more successful for treating AUB in women who are appropriate candidates.

Cyclic progestogen therapy appears to be less effective for the treatment of AUB when compared with tranexamic acid and the LNG-IUD. It does not appear to be more helpful than nonsteroidal anti-inflammatory drugs. We frequently offer and prescribe tranexamic acid, 1,300 mg 3 times daily, as a medical alternative to hormonal therapy for up to 5 days monthly for women without thromboembolism risk. Lukes and colleagues published an RCT in 2010 that demonstrated a 40% reduction of bleeding in tranexamic acid–treated women compared with an 8.2% reduction in the placebo group.2

Continue to: Endometrial ablation...

Endometrial ablation: New evidence informs when it could (and could not) be the best option

Bergeron C, Laberge PY, Boutin A, et al. Endometrial ablation or resection versus levonorgestrel intra-uterine system for the treatment of women with heavy menstrual bleeding and a normal uterine cavity: a systematic review with meta-analysis. Hum Reprod Update. 2020;26:302-311.

Vitale SG, Ferrero S, Ciebiera M, et al. Hysteroscopic endometrial resection vs hysterectomy for abnormal uterine bleeding: impact on quality of life and sexuality. Evidence from a systematic review of randomized controlled trials. Curr Opin Obstet Gynecol. 2020;32:159-165.

Two systematic reviews evaluated the efficacy of EA in women with abnormal uterine bleeding. One compared EA with the LNG-IUD and reported on safety and efficacy, while the other compared EA with hysterectomy and reported on quality of life.

Bergeron and colleagues reviewed 13 studies that included 884 women to compare the efficacy and safety of EA or resection with the LNG-IUD for the treatment of premenopausal women with AUB.3 They found no significant differences between EA and the LNG-IUD in terms of subsequent hysterectomy (risk ratio [RR] = 1.3; 95% confidence interval [CI], 0.60-2.11). It was not surprising that, when looking at age, EA was associated with a higher risk for hysterectomy in women younger than age 42 (RR = 5.26; 95% CI, 1.21-22.91). Conversely, subsequent hysterectomy was less likely with EA compared to LNG-IUD use in women older than 42 years. However, statistical significance was not reached in the older group (RR = 0.51; 95% CI, 0.21-1.24).

In the systematic review by Vitale and colleagues, 9 studies met inclusion criteria for a comparison of EA and hysterectomy, with the objective of ascertaining improvement in quality of life and several other measures.4

Although there was significant heterogeneity between assessment tools, both treatment groups experienced similar improvements in quality of life during the first year. However, hysterectomy was more advantageous in terms of improving uterine bleeding and satisfaction in the long term when compared with EA.4

As EA is considered, it is important to continue to counsel about the efficacy of the LNG-IUD, as well as its decreased associated morbidity. Additionally, EA is particularly less effective in younger women.

Continue to: Laparoscopy is best approach for isthomocele management, with caveats...

Laparoscopy is best approach for isthomocele management, with caveats

He Y, Zhong J, Zhou W, et al. Four surgical strategies for the treatment of cesarean scar defect: a systematic review and network meta-analysis. J Minim Invasive Gynecol. 2020;27:593-602.

Vitale SG, Ludwin A, Vilos GA, et al. From hysteroscopy to laparoendoscopic surgery: what is the best surgical approach for symptomatic isthmocele? A systematic review and meta-analysis. Arch Gynecol Obstet. 2020;301:33-52.

The isthmocele (cesarean scar defect, uterine niche), a known complication of cesarean delivery, represents a myometrial defect in the anterior uterine wall that often presents as abnormal uterine bleeding. It also can be a site for pregnancy-related complications, such as invasive placentation, placenta previa, and uterine rupture.

Two systematic reviews compared surgical strategies for treating isthmocele, including laparoscopy, hysteroscopy, combined laparoscopy and hysteroscopy, laparotomy, and vaginal repair.

Laparoscopy reduced isthmocele-associated AUB better than other techniques

A review by He and colleagues analyzed data from 10 pertinent studies (4 RCTs and 6 observational studies) that included 858 patients in total.5 Treatments compared were laparoscopy, hysteroscopy, combined laparoscopy with hysteroscopy, and vaginal repair for reduction of AUB and isthmocele and diverticulum depth.

The authors found no difference in intraoperative bleeding between the 4 surgical methods (laparotomy was not included in this review). Hysteroscopic surgery was associated with the shortest operative time, while laparoscopy was the longest surgery. In terms of reducing intermittent abnormal bleeding and scar depth, laparoscopic surgery performed better than the other 3 methods.

Approach considerations in isthmocele repair

Vitale and colleagues conducted a systematic review that included 33 publications (28 focused on a single surgical technique, 5 compared different techniques) to examine the effectiveness and risks of various surgical approaches for isthmocele in women with AUB, infertility, or for prevention of obstetric complications.6

Results of their analysis in general favored a laparoscopic approach for patients who desired future fertility, with an improvement rate of 92.7%. Hysteroscopic correction had an 85% improvement rate, and vaginal correction had an 82.5% improvement rate.

Although there were no high-level data to suggest a threshold for myometrial thickness in recommending a surgical approach, the authors provided a helpful algorithm for choosing a route based on a patient's fertility desires. For the asymptomatic patient, they suggest no treatment. In symptomatic patients, the laparoscopic approach is the gold standard but requires significant laparoscopic surgical skill, and a hysteroscopic approach may be considered as an alternative route if the residual myometrial defect is greater than 2.5 to 3.5 mm. For patients who are not considering future reproduction, hysteroscopy is the gold standard as long as the residual myometrial thickness is greater than 2.5 to 3.5 mm.

The takeaway. Of the several methods used for surgical isthmocele management, the laparoscopic approach reduced intermittent abnormal bleeding and scar depth better than other methods. It also was associated with the longest surgical duration. Hysteroscopic surgery was the quickest procedure to perform and is effective in removing the upper valve to promote the elimination of the hematocele and symptoms of abnormal bleeding; however, it does not change the anatomic aspects of the isthmocele in terms of myometrial thickness. Some authors suggested that deciding on the surgical route should be based on fertility desires and the residual thickness of the myometrium. ●

In terms of isthmocele repair, the laparoscopic approach is preferred in patients who desire fertility, as long as the surgeon possesses the skill set to perform this difficult surgery, and as long as the residual myometrium is thicker than 2.5 to 3.5 mm.

- Bofill Rodriguez M, Lethaby A, Low C, et al. Cyclical progestogens for heavy menstrual bleeding. Cochrane Database Syst Rev. 2019;(8):CD001016.

- Lukes AS, Moore KA, Muse KN, et al. Tranexamic acid treatment for heavy menstrual bleeding: a randomized controlled study. Obstet Gynecol. 2010;116:865-875.

- Bergeron C, Laberge PY, Boutin A, et al. Endometrial ablation or resection versus levonorgestrel intra-uterine system for the treatment of women with heavy menstrual bleeding and a normal uterine cavity: a systematic review with meta-analysis. Hum Reprod Update. 2020;26:302-311.

- Vitale SG, Ferrero S, Ciebiera M, et al. Hysteroscopic endometrial resection vs hysterectomy for abnormal uterine bleeding: impact on quality of life and sexuality. Evidence from a systematic review of randomized controlled trials. Curr Opin Obstet Gynecol. 2020;32:159-165.

- He Y, Zhong J, Zhou W, et al. Four surgical strategies for the treatment of cesarean scar defect: a systematic review and network meta-analysis. J Minim Invasive Gynecol. 2020;27:593-602.

- Vitale SG, Ludwin A, Vilos GA, et al. From hysteroscopy to laparoendoscopic surgery: what is the best surgical approach for symptomatic isthmocele? A systematic review and meta-analysis. Arch Gynecol Obstet. 2020;301:33-52.

- Bofill Rodriguez M, Lethaby A, Low C, et al. Cyclical progestogens for heavy menstrual bleeding. Cochrane Database Syst Rev. 2019;(8):CD001016.

- Lukes AS, Moore KA, Muse KN, et al. Tranexamic acid treatment for heavy menstrual bleeding: a randomized controlled study. Obstet Gynecol. 2010;116:865-875.

- Bergeron C, Laberge PY, Boutin A, et al. Endometrial ablation or resection versus levonorgestrel intra-uterine system for the treatment of women with heavy menstrual bleeding and a normal uterine cavity: a systematic review with meta-analysis. Hum Reprod Update. 2020;26:302-311.

- Vitale SG, Ferrero S, Ciebiera M, et al. Hysteroscopic endometrial resection vs hysterectomy for abnormal uterine bleeding: impact on quality of life and sexuality. Evidence from a systematic review of randomized controlled trials. Curr Opin Obstet Gynecol. 2020;32:159-165.

- He Y, Zhong J, Zhou W, et al. Four surgical strategies for the treatment of cesarean scar defect: a systematic review and network meta-analysis. J Minim Invasive Gynecol. 2020;27:593-602.

- Vitale SG, Ludwin A, Vilos GA, et al. From hysteroscopy to laparoendoscopic surgery: what is the best surgical approach for symptomatic isthmocele? A systematic review and meta-analysis. Arch Gynecol Obstet. 2020;301:33-52.

How effective is elagolix treatment in women with fibroids and HMB?

Simon JA, Al-Hendy A, Archer DF, et al. Elagolix treatment for up to 12 months in women with heavy menstrual bleeding and uterine leiomyomas. Obstet Gynecol. 2020;135:1313-1326.

Expert Commentary

Uterine fibroids are common (occurring in up to 80% of reproductive-age women),1,2 and often associated with heavy menstrual bleeding (HMB). There are surgical and medical options, but typically medical options are used for short periods of time. Elagolix with hormonal add-back therapy was recently approved (May 29, 2020) by the US Food and Drug Administration (FDA) for treatment of HMB in women with uterine fibroids for up to 24 months.

Elagolix is an oral, nonpeptide gonadotropin-releasing hormone antagonist that results in a dose-dependent reduction of gonadotropins and ovarian sex hormones. There are now 2 approved products containing elagolix, with different indications:

- Orilissa. Elagolix was approved in 2018 by the FDA for moderate to severe pain associated with endometriosis. For that indication there are 2 dose options of elagolix (150 mg for up to 2 years and 200 mg for up to 6 months) and there is no hormonal add-back therapy.

- Oriahnn. Elagolix and hormonal add-back therapy was approved in 2020 for HMB associated with uterine fibroids for up to 24 months. The total daily dose of elagolix is 600 mg (elagolix 300 mg in the morning with estradiol 1 mg/norethindrone acetate 0.5 mg and then in the evening elagolix 300 mg and no hormonal add-back).

This new class of drug, GnRH antagonist, is an important one for women’s health, and emerging science will continue to expand its potential uses, such as in reproductive health, as well as long-term efficacy and safety. The difference in daily dose of elagolix for endometriosis (150 mg for 24 months) compared with HMB associated with fibroids (600 mg for 24 months) is why the hormonal add-back therapy is important and allows for protection of bone density.

This is an important manuscript because it highlights a medical option for women with HMB associated with fibroids, which can be used for a long period of time. Further, the improvement in bleeding is both impressive and maintained in the extension study. Approximately 90% of women show improvement in their menstrual bleeding associated with fibroids.

The question of what to do after 24 months of therapy with elagolix and hormonal add-back therapy is an important one, but providers should recognize that the limiting factor with this elagolix and hormonal add-back therapy is bone mineral density (BMD). We will only learn more and more moving forward if this is a clinically meaningful reason for stopping treatment at 24 months. The FDA takes a strict view of safety, and providers must weigh this with the benefit of therapy.

One other highlight between the 2 approved medications is that Orilissa does not have a black box warning, given that there is no hormonal add-back therapy. Oriahnn does have a warning, regarding thromboembolic disorders and vascular events:

- Estrogen and progestin combinations, including Oriahnn, increase the risk of thrombotic or thromboembolic disorders, especially in women at increased risk for these events.

- Oriahnn is contraindicated in women with current or a history of thrombotic or thromboembolic disorders and in women at increased risk for these events, including women over 35 years of age who smoke or women with uncontrolled hypertension.

Continue to: Details about the study...

Details about the study

The study by Simon et al is an extension study (UF-EXTEND), in that women could participate if they had completed 1 of the 2 pivotal studies on elagolix. The pivotal studies (Elaris UF1 and UF2) were both randomized, double-blinded, placebo-controlled studies with up to 6 months of therapy; for UF-EXTEND, however, participants were randomly assigned to either combined elagolix and hormone replacement therapy or elagolix alone for an additional 6 months of therapy. Although it was known that all participants would receive elagolix in UF-EXTEND, those who received hormonal add-back therapy were blinded. All women were then followed up for an additional 12 months after treatment ended.

The efficacy of elagolix was measured by the objective alkaline hematin method for menstrual blood loss with the a priori coprimary endpoints. The elagolix and hormonal add-back therapy group showed objective improvement in menstrual blood loss at 12 months in 87.9% of women in the extension study (89.4% in the elagolix alone group). This compares with 72.2% improvement at 6 months of treatment in the UF1 and UF2 studies for those taking elagolix and hormonal add-back therapy. These findings illustrate maintenance of the efficacy seen within the 6-month pivotal studies using elagolix over an extended amount of time.

The safety of elagolix also was demonstrated in UF-EXTEND. The 3 most common adverse events were similar to those found in Elaris UF1 and UF2 and included hot flushes, headache, and nausea. In the elagolix and hormonal add-back therapy group during the extension study, the percentage with hot flushes was 7%, headache 6%, and nausea 4%. These are small percentages, which is encouraging for providers and women with HMB associated with fibroids.

Effects on bone density

Bone density was evaluated at baseline in the UF1 and UF2 studies, through treatment, and then 12 months after the extended treatment was stopped. The hormonal add-back therapy of estradiol 1 mg/norethindrone acetate 0.5 mg significantly protected bone density. Some women did not have a decrease in bone density, but for those who did the average was less than 5% for the lumbar spine. The lumbar spine is considered the most reactive, so this illustrates the safety that combined therapy offers women with HMB and fibroids.

The lumbar spine is considered the most reactive, so this site is often used as the main focus with BMD studies. As Simon et al show, the lumbar spine mean BMD percent change from baseline for the elagolix with add-back therapy was -1.5% (95% confidence interval [CI], -1.9 to -1.0) in women who received up to 12 months of treatment at month 6 in the extension study. After stopping elagolix with add-back therapy, at 6 months the elagolix with add-back therapy had a Z-score of -0.6% (95% CI, -1.1 to -0.1). This shows a trend toward baseline, or a recovery within a short time from stopping medication.

Continue to: Study strengths and limitations...

Study strengths and limitations

Strengths of this study include its overall design; efficacy endpoints, which were all established a priori; the fact that measurement of menstrual blood loss was done with the objective alkaline hematin method; and the statistical analysis, which is thorough and well presented. This extension study allowed further evaluation of efficacy and safety for elagolix. Although the authors point out that there may be some selection bias in an extension study, the fact that so many women elected to continue into the extended study is a positive reflection of the treatment.