User login

Wax Stripping and Isotretinoin Treatment: A Warning Not to Be Missed

To the Editor:

Oral isotretinoin is a widely used treatment modality in dermatologic practice that is highly effective for severe and recalcitrant acne vulgaris in addition to other conditions. Its use is accompanied by a variety of side effects that are mainly mucocutaneous. These dose-dependent side effects are experienced by almost all patients treated with this medication.1

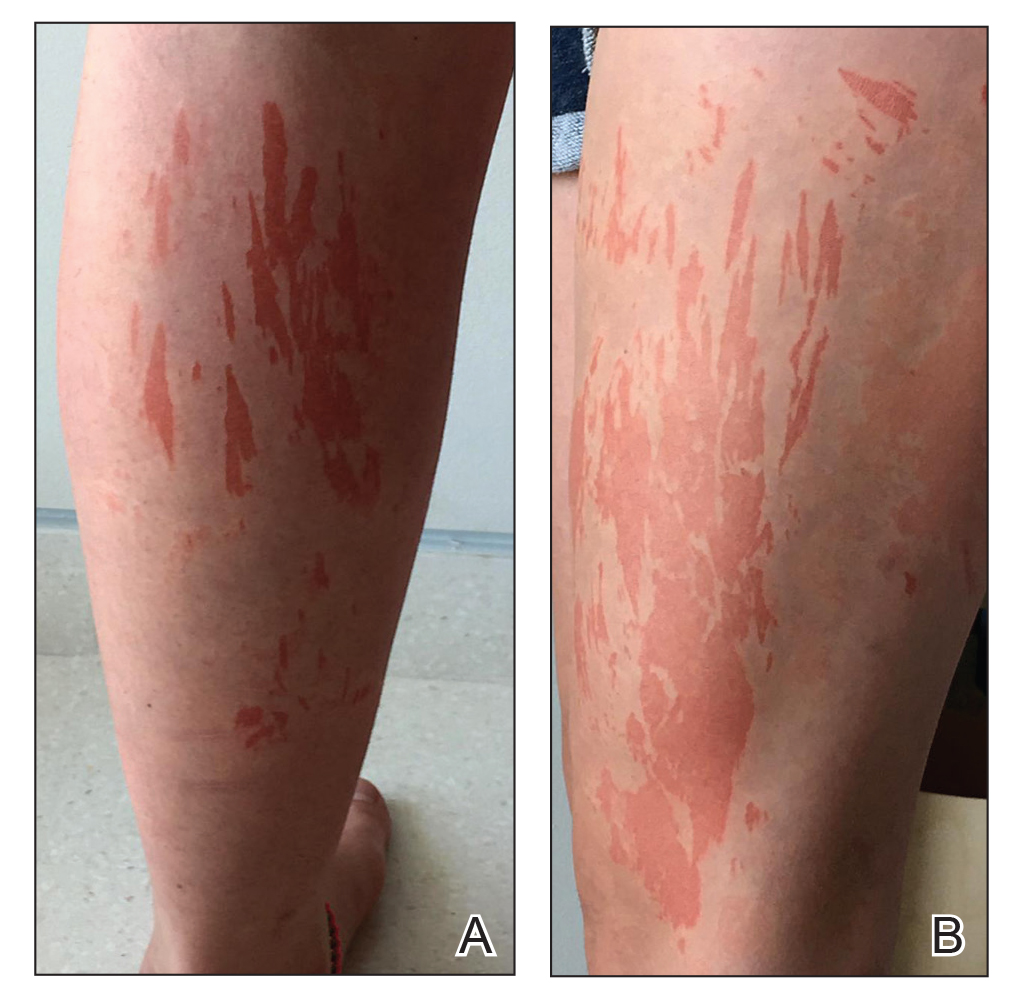

A generally healthy 14-year-old adolescent girl presented with severe widespread erosions located in a linear pattern corresponding to areas of wax depilation on the shins and thighs (Figure). Approximately 5 months prior, the patient started oral isotretinoin 40 mg daily for severe and recalcitrant acne vulgaris. She was not taking other medications. After 4 months of treatment, during which the acne lesions improved and the patient experienced only mild xerosis and cheilitis, the dosage was increased to 60 mg daily. Three weeks later, the patient underwent wax depilation, which resulted in the erosions.

Oral isotretinoin treatment leads to structural and functional changes to the skin, related to epidermal dyscohesion and sebo-suppression. Although these changes may not be clinically evident in all patients, they still make the skin much more sensitive to external mechanical stimuli.1 Wax depilation commonly is used for treating excess hair on the body. Because it exerts remarkable mechanical stress on the epidermis, it may lead to epidermal stripping in patients taking isotretinoin, manifesting as widespread erosions and resulting in notable patient distress.

Dermatologists typically advise patients to avoid wax epilation while being treated with isotretinoin; however, some patients do not adhere to this recommendation. Also, there are dermatologists who are not aware of this potential side effect. In one survey (N=54), only 4% of consulting dermatologists were aware of this complication.2 A PubMed search of articles indexed for MEDLINE using the terms isotretinoin and wax revealed that this severe side effect with isotretinoin has been reported only 4 times in the medical literature.2-5 The fact that wax epilation should be avoided during isotretinoin treatment previously was not included in the prescribing information. It currently is included in the isotretinoin prescribing information6 with an indication not to perform wax depilation for 6 months after stopping treatment. This case should serve as a reminder to avoid wax depilation during isotretinoin treatment.

- Del Rosso JQ. Clinical relevance of skin barrier changes associated with the use of oral isotretinoin: the importance of barrier repair therapy in patient management. J Drugs Dermatol. 2013;12:626-631.

Woollons A, Price ML. Roaccutane and wax epilation: a cautionary tale. Br J Dermatol. 1997;137:839-840. - Egido Romo M. Isotretinoin and wax epilation. Br J Dermatol. 1991;124:393.

- Holmes SC, Thomson J. Isotretinoin and skin fragility. Br J Dermatol. 1995;132:165.

- Turel-Ermertcan A, Sahin MT, Yurtman D, et al. Inappropriate treatments at beauty centers: a case report of burns caused by hot wax stripping. J Dermatol. 2004;31:854-855.

- Accutane. Package insert. Roche; 2008.

To the Editor:

Oral isotretinoin is a widely used treatment modality in dermatologic practice that is highly effective for severe and recalcitrant acne vulgaris in addition to other conditions. Its use is accompanied by a variety of side effects that are mainly mucocutaneous. These dose-dependent side effects are experienced by almost all patients treated with this medication.1

A generally healthy 14-year-old adolescent girl presented with severe widespread erosions located in a linear pattern corresponding to areas of wax depilation on the shins and thighs (Figure). Approximately 5 months prior, the patient started oral isotretinoin 40 mg daily for severe and recalcitrant acne vulgaris. She was not taking other medications. After 4 months of treatment, during which the acne lesions improved and the patient experienced only mild xerosis and cheilitis, the dosage was increased to 60 mg daily. Three weeks later, the patient underwent wax depilation, which resulted in the erosions.

Oral isotretinoin treatment leads to structural and functional changes to the skin, related to epidermal dyscohesion and sebo-suppression. Although these changes may not be clinically evident in all patients, they still make the skin much more sensitive to external mechanical stimuli.1 Wax depilation commonly is used for treating excess hair on the body. Because it exerts remarkable mechanical stress on the epidermis, it may lead to epidermal stripping in patients taking isotretinoin, manifesting as widespread erosions and resulting in notable patient distress.

Dermatologists typically advise patients to avoid wax epilation while being treated with isotretinoin; however, some patients do not adhere to this recommendation. Also, there are dermatologists who are not aware of this potential side effect. In one survey (N=54), only 4% of consulting dermatologists were aware of this complication.2 A PubMed search of articles indexed for MEDLINE using the terms isotretinoin and wax revealed that this severe side effect with isotretinoin has been reported only 4 times in the medical literature.2-5 The fact that wax epilation should be avoided during isotretinoin treatment previously was not included in the prescribing information. It currently is included in the isotretinoin prescribing information6 with an indication not to perform wax depilation for 6 months after stopping treatment. This case should serve as a reminder to avoid wax depilation during isotretinoin treatment.

To the Editor:

Oral isotretinoin is a widely used treatment modality in dermatologic practice that is highly effective for severe and recalcitrant acne vulgaris in addition to other conditions. Its use is accompanied by a variety of side effects that are mainly mucocutaneous. These dose-dependent side effects are experienced by almost all patients treated with this medication.1

A generally healthy 14-year-old adolescent girl presented with severe widespread erosions located in a linear pattern corresponding to areas of wax depilation on the shins and thighs (Figure). Approximately 5 months prior, the patient started oral isotretinoin 40 mg daily for severe and recalcitrant acne vulgaris. She was not taking other medications. After 4 months of treatment, during which the acne lesions improved and the patient experienced only mild xerosis and cheilitis, the dosage was increased to 60 mg daily. Three weeks later, the patient underwent wax depilation, which resulted in the erosions.

Oral isotretinoin treatment leads to structural and functional changes to the skin, related to epidermal dyscohesion and sebo-suppression. Although these changes may not be clinically evident in all patients, they still make the skin much more sensitive to external mechanical stimuli.1 Wax depilation commonly is used for treating excess hair on the body. Because it exerts remarkable mechanical stress on the epidermis, it may lead to epidermal stripping in patients taking isotretinoin, manifesting as widespread erosions and resulting in notable patient distress.

Dermatologists typically advise patients to avoid wax epilation while being treated with isotretinoin; however, some patients do not adhere to this recommendation. Also, there are dermatologists who are not aware of this potential side effect. In one survey (N=54), only 4% of consulting dermatologists were aware of this complication.2 A PubMed search of articles indexed for MEDLINE using the terms isotretinoin and wax revealed that this severe side effect with isotretinoin has been reported only 4 times in the medical literature.2-5 The fact that wax epilation should be avoided during isotretinoin treatment previously was not included in the prescribing information. It currently is included in the isotretinoin prescribing information6 with an indication not to perform wax depilation for 6 months after stopping treatment. This case should serve as a reminder to avoid wax depilation during isotretinoin treatment.

- Del Rosso JQ. Clinical relevance of skin barrier changes associated with the use of oral isotretinoin: the importance of barrier repair therapy in patient management. J Drugs Dermatol. 2013;12:626-631.

Woollons A, Price ML. Roaccutane and wax epilation: a cautionary tale. Br J Dermatol. 1997;137:839-840. - Egido Romo M. Isotretinoin and wax epilation. Br J Dermatol. 1991;124:393.

- Holmes SC, Thomson J. Isotretinoin and skin fragility. Br J Dermatol. 1995;132:165.

- Turel-Ermertcan A, Sahin MT, Yurtman D, et al. Inappropriate treatments at beauty centers: a case report of burns caused by hot wax stripping. J Dermatol. 2004;31:854-855.

- Accutane. Package insert. Roche; 2008.

- Del Rosso JQ. Clinical relevance of skin barrier changes associated with the use of oral isotretinoin: the importance of barrier repair therapy in patient management. J Drugs Dermatol. 2013;12:626-631.

Woollons A, Price ML. Roaccutane and wax epilation: a cautionary tale. Br J Dermatol. 1997;137:839-840. - Egido Romo M. Isotretinoin and wax epilation. Br J Dermatol. 1991;124:393.

- Holmes SC, Thomson J. Isotretinoin and skin fragility. Br J Dermatol. 1995;132:165.

- Turel-Ermertcan A, Sahin MT, Yurtman D, et al. Inappropriate treatments at beauty centers: a case report of burns caused by hot wax stripping. J Dermatol. 2004;31:854-855.

- Accutane. Package insert. Roche; 2008.

Practice Points

- Oral isotretinoin treatment leads to structural and functional changes to the skin, making it much more sensitive to external mechanical stimuli.

- Wax depilation may lead to epidermal stripping in patients taking isotretinoin and therefore should be avoided in these patients.

Is it possible to classify dermatologists and internists into different patterns of prescribing behavior?

An exploratory analysis recently published in the Journal of the American Academy of Dermatology examines whether it is possible to classify dermatologists and internists into different patterns of prescribing behavior for patients with acne.

“Prior research has highlighted that prescribing for acne may not be aligned with guideline recommendations, including the overuse of oral antibiotics and lack of use of concomitant topical medications such as topical retinoids,” the study’s corresponding author, John S. Barbieri, MD, MBA, of the department of dermatology at the University of Pennsylvania, Philadelphia, said in an interview.

“In addition, there is substantial variation in prescribing practices among clinicians. . By identifying such groups, it would facilitate future qualitative interviews to understand factors that might contribute to clinicians having certain prescribing patterns, which could help guide implementation science work to better align practices with evidence and guidelines.”

For the study, which appeared online on March 1, Dr. Barbieri and colleague David J. Margolis, MD, PhD, professor of dermatology and epidemiology at the University of Pennsylvania, evaluated all clinical encounters associated with an ICD-9 or ICD-10 code for acne that occurred in the university’s departments of dermatology and internal medicine between Jan. 1, 2011, and Dec. 31, 2019. They used a machine-learning method known as k-means clustering to cluster clinicians based on their relative use of acne medications, as well as the ratio of spironolactone versus tetracycline use among female patients and stratified their analyses by specialty.

Of the 116 dermatologists included in the analysis, the researchers identified three clusters. The first cluster included 17 dermatologists (14.7%) and was characterized by low use of topical retinoids, high use of oral tetracycline, and low use of spironolactone, compared with oral antibiotics, among women with acne. Physicians in this cluster were more likely to be male and to have more years in practice.

The second cluster included 46 dermatologists (39.6%) and was marked by high use of spironolactone and low use of isotretinoin. The third cluster included 53 dermatologists (45.7%) and was characterized by high use of topical retinoids and frequent use of systemic medications.

Of the 86 internists included in the study, the researchers identified three clusters. The first cluster included 39 internists (45.4%) and was characterized by low use of topical retinoids, high use of oral tetracycline, and limited use of spironolactone. The second cluster included 34 internists (39.5%) and was marked by low use of topical retinoids and systemic medications. The third cluster included 13 clinicians (15.1%), most of whom were nurse practitioners, physician assistants, and other advanced practice providers. This cluster was characterized by high use of topical retinoids and relatively high use of spironolactone.

“There are likely opportunities to improve the use of topical retinoids by internists caring for patients with acne, since these are a first-line treatment option that may be underutilized by internists,” Dr. Barbieri said in the interview. “Future work is needed to identify underlying factors associated with different prescribing phenotypes among both dermatologists and internists. By understanding these factors, we can develop implementation science efforts to align prescribing behavior with best practices based on the guidelines and available evidence.”

He acknowledged certain limitations of the analysis, including its single-center design and the lack of data on patient characteristics. “Future studies are needed to examine whether our results generalize to other settings,” he said.

Dr. Barbieri disclosed that he receives partial salary support through a Pfizer Fellowship in Dermatology Patient Oriented Research grant to the Trustees of the University of Pennsylvania. The authors had no other disclosures.

An exploratory analysis recently published in the Journal of the American Academy of Dermatology examines whether it is possible to classify dermatologists and internists into different patterns of prescribing behavior for patients with acne.

“Prior research has highlighted that prescribing for acne may not be aligned with guideline recommendations, including the overuse of oral antibiotics and lack of use of concomitant topical medications such as topical retinoids,” the study’s corresponding author, John S. Barbieri, MD, MBA, of the department of dermatology at the University of Pennsylvania, Philadelphia, said in an interview.

“In addition, there is substantial variation in prescribing practices among clinicians. . By identifying such groups, it would facilitate future qualitative interviews to understand factors that might contribute to clinicians having certain prescribing patterns, which could help guide implementation science work to better align practices with evidence and guidelines.”

For the study, which appeared online on March 1, Dr. Barbieri and colleague David J. Margolis, MD, PhD, professor of dermatology and epidemiology at the University of Pennsylvania, evaluated all clinical encounters associated with an ICD-9 or ICD-10 code for acne that occurred in the university’s departments of dermatology and internal medicine between Jan. 1, 2011, and Dec. 31, 2019. They used a machine-learning method known as k-means clustering to cluster clinicians based on their relative use of acne medications, as well as the ratio of spironolactone versus tetracycline use among female patients and stratified their analyses by specialty.

Of the 116 dermatologists included in the analysis, the researchers identified three clusters. The first cluster included 17 dermatologists (14.7%) and was characterized by low use of topical retinoids, high use of oral tetracycline, and low use of spironolactone, compared with oral antibiotics, among women with acne. Physicians in this cluster were more likely to be male and to have more years in practice.

The second cluster included 46 dermatologists (39.6%) and was marked by high use of spironolactone and low use of isotretinoin. The third cluster included 53 dermatologists (45.7%) and was characterized by high use of topical retinoids and frequent use of systemic medications.

Of the 86 internists included in the study, the researchers identified three clusters. The first cluster included 39 internists (45.4%) and was characterized by low use of topical retinoids, high use of oral tetracycline, and limited use of spironolactone. The second cluster included 34 internists (39.5%) and was marked by low use of topical retinoids and systemic medications. The third cluster included 13 clinicians (15.1%), most of whom were nurse practitioners, physician assistants, and other advanced practice providers. This cluster was characterized by high use of topical retinoids and relatively high use of spironolactone.

“There are likely opportunities to improve the use of topical retinoids by internists caring for patients with acne, since these are a first-line treatment option that may be underutilized by internists,” Dr. Barbieri said in the interview. “Future work is needed to identify underlying factors associated with different prescribing phenotypes among both dermatologists and internists. By understanding these factors, we can develop implementation science efforts to align prescribing behavior with best practices based on the guidelines and available evidence.”

He acknowledged certain limitations of the analysis, including its single-center design and the lack of data on patient characteristics. “Future studies are needed to examine whether our results generalize to other settings,” he said.

Dr. Barbieri disclosed that he receives partial salary support through a Pfizer Fellowship in Dermatology Patient Oriented Research grant to the Trustees of the University of Pennsylvania. The authors had no other disclosures.

An exploratory analysis recently published in the Journal of the American Academy of Dermatology examines whether it is possible to classify dermatologists and internists into different patterns of prescribing behavior for patients with acne.

“Prior research has highlighted that prescribing for acne may not be aligned with guideline recommendations, including the overuse of oral antibiotics and lack of use of concomitant topical medications such as topical retinoids,” the study’s corresponding author, John S. Barbieri, MD, MBA, of the department of dermatology at the University of Pennsylvania, Philadelphia, said in an interview.

“In addition, there is substantial variation in prescribing practices among clinicians. . By identifying such groups, it would facilitate future qualitative interviews to understand factors that might contribute to clinicians having certain prescribing patterns, which could help guide implementation science work to better align practices with evidence and guidelines.”

For the study, which appeared online on March 1, Dr. Barbieri and colleague David J. Margolis, MD, PhD, professor of dermatology and epidemiology at the University of Pennsylvania, evaluated all clinical encounters associated with an ICD-9 or ICD-10 code for acne that occurred in the university’s departments of dermatology and internal medicine between Jan. 1, 2011, and Dec. 31, 2019. They used a machine-learning method known as k-means clustering to cluster clinicians based on their relative use of acne medications, as well as the ratio of spironolactone versus tetracycline use among female patients and stratified their analyses by specialty.

Of the 116 dermatologists included in the analysis, the researchers identified three clusters. The first cluster included 17 dermatologists (14.7%) and was characterized by low use of topical retinoids, high use of oral tetracycline, and low use of spironolactone, compared with oral antibiotics, among women with acne. Physicians in this cluster were more likely to be male and to have more years in practice.

The second cluster included 46 dermatologists (39.6%) and was marked by high use of spironolactone and low use of isotretinoin. The third cluster included 53 dermatologists (45.7%) and was characterized by high use of topical retinoids and frequent use of systemic medications.

Of the 86 internists included in the study, the researchers identified three clusters. The first cluster included 39 internists (45.4%) and was characterized by low use of topical retinoids, high use of oral tetracycline, and limited use of spironolactone. The second cluster included 34 internists (39.5%) and was marked by low use of topical retinoids and systemic medications. The third cluster included 13 clinicians (15.1%), most of whom were nurse practitioners, physician assistants, and other advanced practice providers. This cluster was characterized by high use of topical retinoids and relatively high use of spironolactone.

“There are likely opportunities to improve the use of topical retinoids by internists caring for patients with acne, since these are a first-line treatment option that may be underutilized by internists,” Dr. Barbieri said in the interview. “Future work is needed to identify underlying factors associated with different prescribing phenotypes among both dermatologists and internists. By understanding these factors, we can develop implementation science efforts to align prescribing behavior with best practices based on the guidelines and available evidence.”

He acknowledged certain limitations of the analysis, including its single-center design and the lack of data on patient characteristics. “Future studies are needed to examine whether our results generalize to other settings,” he said.

Dr. Barbieri disclosed that he receives partial salary support through a Pfizer Fellowship in Dermatology Patient Oriented Research grant to the Trustees of the University of Pennsylvania. The authors had no other disclosures.

Emerging treatments for molluscum contagiosum and acne show promise

, but that could soon change, according to Leon H. Kircik, MD.

“The treatment of molluscum is still an unmet need,” Dr. Kircik, clinical professor of dermatology at the Icahn School of Medicine at Mount Sinai, New York, said at the Orlando Dermatology Aesthetic and Clinical Conference. However, a proprietary drug-device combination of cantharidin 0.7% administered through a single-use precision applicator, which has been tested in phase 3 studies, is currently under FDA review. The manufacturer, Verrica Pharmaceuticals resubmitted a new drug application for the product, VP-102, in December 2020.

“VP-102 features a visualization agent so the injector can see which lesions have been treated, as well as a bittering agent to mitigate oral ingestion by children. Complete clearance at 12 weeks ranged from 46% to 54% of patients, while lesion count reduction compared with baseline ranged from 69% to 82%.”

Acne

In August, 2020, clascoterone 1% cream was approved for the treatment of acne in patients 12 years and older, a development that Dr. Kircik said “can be a game changer in acne treatment.” Clascoterone cream 1% exhibits strong, selective anti-androgen activity by targeting androgen receptors in the skin, not systemically. “It limits or blocks transcription of androgen responsive genes, but it also has an anti-inflammatory effect and an anti-sebum effect,” he explained.

According to results from two phase 3 trials of the product, a response of clear or almost clear on the IGA scale at week 12 was achieved in 18.4% of those on treatment vs. 9% of those on vehicle in one study (P less than .001) and 20.3% vs. 6.5%, respectively, in the second study (P less than .001). Clascoterone is also being evaluated for treating androgenetic alopecia.

In Dr. Kircik’s clinical experience, retinoids can be helpful for patients with moderate to severe acne. “We always use them for anticomedogenic effects, but we also know that they have anti-inflammatory effects,” he said. “They actually inhibit toll-like receptor activity. They also inhibit the AP-1 pathway by causing a reduction in inflammatory signaling associated with collagen degradation and scarring.”

The most recent retinoid to be approved for the topical treatment of acne was 0.005% trifarotene cream, in 2019, for patients aged 9 years and older. “But when we got the results, it was not that exciting,” a difference of about 3.6 (mean) inflammatory lesion reduction between the active and the vehicle arm, said Dr. Kircik, medical director of Physicians Skin Care in Louisville, Ky. “According to the package insert, treatment side effects included mild to moderate erythema in 59% of patients, scaling in 65%, dryness in 69%, and stinging/burning in 56%, which makes it difficult to use in our clinical practice.”

The drug was also tested for treating truncal acne. However, one comparative study showed that tazarotene 0.045% lotion spread an average of 36.7 square centimeters farther than the trifarotene cream, which makes the tazarotene lotion easier to use on the chest and back, he said.

Dr. Kircik also discussed 4% minocycline, a hydrophobic, topical foam formulation of minocycline that was approved by the FDA in 2019 for the treatment of moderate to severe acne, for patients aged 9 and older. In a 12-week study that involved 1,488 patients (mean age was about 20 years), investigators observed a 56% reduction in inflammatory lesion count among those treated with minocycline 4%, compared with 43% in the vehicle group.

Dr. Kircik, one of the authors of the study, noted that the hydrophobic composition of minocycline 4% allows for stable and efficient delivery of an inherently unstable active pharmaceutical ingredient such as minocycline. “It’s free of primary irritants such as surfactants and short chain alcohols, which makes it much more tolerable,” he said. “The unique physical foam characteristics facilitate ease of application and absorption at target sites.”

Dr. Kircik reported that he serves as a consultant and/or adviser to numerous pharmaceutical companies, including Galderma, the manufacturer of trifarotene cream.

dbrunk@mdedge.com

, but that could soon change, according to Leon H. Kircik, MD.

“The treatment of molluscum is still an unmet need,” Dr. Kircik, clinical professor of dermatology at the Icahn School of Medicine at Mount Sinai, New York, said at the Orlando Dermatology Aesthetic and Clinical Conference. However, a proprietary drug-device combination of cantharidin 0.7% administered through a single-use precision applicator, which has been tested in phase 3 studies, is currently under FDA review. The manufacturer, Verrica Pharmaceuticals resubmitted a new drug application for the product, VP-102, in December 2020.

“VP-102 features a visualization agent so the injector can see which lesions have been treated, as well as a bittering agent to mitigate oral ingestion by children. Complete clearance at 12 weeks ranged from 46% to 54% of patients, while lesion count reduction compared with baseline ranged from 69% to 82%.”

Acne

In August, 2020, clascoterone 1% cream was approved for the treatment of acne in patients 12 years and older, a development that Dr. Kircik said “can be a game changer in acne treatment.” Clascoterone cream 1% exhibits strong, selective anti-androgen activity by targeting androgen receptors in the skin, not systemically. “It limits or blocks transcription of androgen responsive genes, but it also has an anti-inflammatory effect and an anti-sebum effect,” he explained.

According to results from two phase 3 trials of the product, a response of clear or almost clear on the IGA scale at week 12 was achieved in 18.4% of those on treatment vs. 9% of those on vehicle in one study (P less than .001) and 20.3% vs. 6.5%, respectively, in the second study (P less than .001). Clascoterone is also being evaluated for treating androgenetic alopecia.

In Dr. Kircik’s clinical experience, retinoids can be helpful for patients with moderate to severe acne. “We always use them for anticomedogenic effects, but we also know that they have anti-inflammatory effects,” he said. “They actually inhibit toll-like receptor activity. They also inhibit the AP-1 pathway by causing a reduction in inflammatory signaling associated with collagen degradation and scarring.”

The most recent retinoid to be approved for the topical treatment of acne was 0.005% trifarotene cream, in 2019, for patients aged 9 years and older. “But when we got the results, it was not that exciting,” a difference of about 3.6 (mean) inflammatory lesion reduction between the active and the vehicle arm, said Dr. Kircik, medical director of Physicians Skin Care in Louisville, Ky. “According to the package insert, treatment side effects included mild to moderate erythema in 59% of patients, scaling in 65%, dryness in 69%, and stinging/burning in 56%, which makes it difficult to use in our clinical practice.”

The drug was also tested for treating truncal acne. However, one comparative study showed that tazarotene 0.045% lotion spread an average of 36.7 square centimeters farther than the trifarotene cream, which makes the tazarotene lotion easier to use on the chest and back, he said.

Dr. Kircik also discussed 4% minocycline, a hydrophobic, topical foam formulation of minocycline that was approved by the FDA in 2019 for the treatment of moderate to severe acne, for patients aged 9 and older. In a 12-week study that involved 1,488 patients (mean age was about 20 years), investigators observed a 56% reduction in inflammatory lesion count among those treated with minocycline 4%, compared with 43% in the vehicle group.

Dr. Kircik, one of the authors of the study, noted that the hydrophobic composition of minocycline 4% allows for stable and efficient delivery of an inherently unstable active pharmaceutical ingredient such as minocycline. “It’s free of primary irritants such as surfactants and short chain alcohols, which makes it much more tolerable,” he said. “The unique physical foam characteristics facilitate ease of application and absorption at target sites.”

Dr. Kircik reported that he serves as a consultant and/or adviser to numerous pharmaceutical companies, including Galderma, the manufacturer of trifarotene cream.

dbrunk@mdedge.com

, but that could soon change, according to Leon H. Kircik, MD.

“The treatment of molluscum is still an unmet need,” Dr. Kircik, clinical professor of dermatology at the Icahn School of Medicine at Mount Sinai, New York, said at the Orlando Dermatology Aesthetic and Clinical Conference. However, a proprietary drug-device combination of cantharidin 0.7% administered through a single-use precision applicator, which has been tested in phase 3 studies, is currently under FDA review. The manufacturer, Verrica Pharmaceuticals resubmitted a new drug application for the product, VP-102, in December 2020.

“VP-102 features a visualization agent so the injector can see which lesions have been treated, as well as a bittering agent to mitigate oral ingestion by children. Complete clearance at 12 weeks ranged from 46% to 54% of patients, while lesion count reduction compared with baseline ranged from 69% to 82%.”

Acne

In August, 2020, clascoterone 1% cream was approved for the treatment of acne in patients 12 years and older, a development that Dr. Kircik said “can be a game changer in acne treatment.” Clascoterone cream 1% exhibits strong, selective anti-androgen activity by targeting androgen receptors in the skin, not systemically. “It limits or blocks transcription of androgen responsive genes, but it also has an anti-inflammatory effect and an anti-sebum effect,” he explained.

According to results from two phase 3 trials of the product, a response of clear or almost clear on the IGA scale at week 12 was achieved in 18.4% of those on treatment vs. 9% of those on vehicle in one study (P less than .001) and 20.3% vs. 6.5%, respectively, in the second study (P less than .001). Clascoterone is also being evaluated for treating androgenetic alopecia.

In Dr. Kircik’s clinical experience, retinoids can be helpful for patients with moderate to severe acne. “We always use them for anticomedogenic effects, but we also know that they have anti-inflammatory effects,” he said. “They actually inhibit toll-like receptor activity. They also inhibit the AP-1 pathway by causing a reduction in inflammatory signaling associated with collagen degradation and scarring.”

The most recent retinoid to be approved for the topical treatment of acne was 0.005% trifarotene cream, in 2019, for patients aged 9 years and older. “But when we got the results, it was not that exciting,” a difference of about 3.6 (mean) inflammatory lesion reduction between the active and the vehicle arm, said Dr. Kircik, medical director of Physicians Skin Care in Louisville, Ky. “According to the package insert, treatment side effects included mild to moderate erythema in 59% of patients, scaling in 65%, dryness in 69%, and stinging/burning in 56%, which makes it difficult to use in our clinical practice.”

The drug was also tested for treating truncal acne. However, one comparative study showed that tazarotene 0.045% lotion spread an average of 36.7 square centimeters farther than the trifarotene cream, which makes the tazarotene lotion easier to use on the chest and back, he said.

Dr. Kircik also discussed 4% minocycline, a hydrophobic, topical foam formulation of minocycline that was approved by the FDA in 2019 for the treatment of moderate to severe acne, for patients aged 9 and older. In a 12-week study that involved 1,488 patients (mean age was about 20 years), investigators observed a 56% reduction in inflammatory lesion count among those treated with minocycline 4%, compared with 43% in the vehicle group.

Dr. Kircik, one of the authors of the study, noted that the hydrophobic composition of minocycline 4% allows for stable and efficient delivery of an inherently unstable active pharmaceutical ingredient such as minocycline. “It’s free of primary irritants such as surfactants and short chain alcohols, which makes it much more tolerable,” he said. “The unique physical foam characteristics facilitate ease of application and absorption at target sites.”

Dr. Kircik reported that he serves as a consultant and/or adviser to numerous pharmaceutical companies, including Galderma, the manufacturer of trifarotene cream.

dbrunk@mdedge.com

FROM ODAC 2021

Expert calls for paradigm shift in lab monitoring of some dermatology drugs

From time to time, Joslyn Kirby, MD, asks other physicians about their experience with certain medications used in dermatology, especially when something new hits the market.

“Sometimes I get an answer like, ‘The last time I used that medicine, my patient needed a liver transplant,’ ” Dr. Kirby, associate professor of dermatology, Penn State University, Hershey, said during the Orlando Dermatology Aesthetic and Clinical Conference. “It’s typically a story of something rare, uncommon, and awful. The challenge with an anecdote is that for all its power, it has a lower level of evidence. But it sticks with us and influences us more than a better level of evidence because it’s a situation and a story that we might relate to.”

Dr. Kirby said that when she thinks about managing side effects from drugs used in dermatology, it usually relates to something common and low-risk such as sore, dry skin with isotretinoin use. In contrast, if there is an uncommon but serious side effect, then mitigation rather than management is key. “I want to mitigate the risk – meaning warn my patient about it or be careful about how I select my patients when it is a serious side effect that happens infrequently,” she said. “The worst combination is a frequent and severe side effect. That is something we should avoid, for sure.”

Isotretinoin

But another aspect of prescribing a new drug for patients can be less clear-cut, Dr. Kirby continued, such as the rationale for routine lab monitoring. She began by discussing one of her male patients with moderate to severe acne. After he failed oral antibiotics and topical retinoids, she recommended isotretinoin, which carries a risk of hypertriglyceridemia-associated pancreatitis. “Early in my career, I was getting a lot of monthly labs in patients on this drug that were totally normal and not influencing my practice,” Dr. Kirby recalled. “We’ve seen studies coming out on isotretinoin lab monitoring, showing us that we can keep our patients safe and that we really don’t need to be checking labs as often, because lab changes are infrequent.”

In one of those studies, researchers evaluated 1,863 patients treated with isotretinoin for acne between Jan. 1, 2008, and June 30, 2017 (J Am Acad Dermatol. 2020 Jan;82[1]:72-9).Over time, fewer than 1% of patients screened developed grade 3 or greater triglyceride testing abnormalities, while fewer than 0.5% developed liver function testing (LFT) abnormalities. Authors of a separate systematic review concluded that for patients on isotretinoin therapy without elevated baseline triglycerides, or risk thereof, monitoring triglycerides is of little value (Br J Dermatol. 2017 Oct;177[4]:960-6). Of the 25 patients in the analysis who developed pancreatitis on isotretinoin, only 3 had elevated triglycerides at baseline.

“I was taught that I need to check triglycerides frequently due to the risk of pancreatitis developing with isotretinoin use,” Dr. Kirby said. “Lipid changes on therapy are expected, but they tend to peak early, meaning the first 3 months of treatment when we’re ramping up from a starting dose to a maintenance dose. It’s rare for somebody to be a late bloomer, meaning that they have totally normal labs in the first 3 months and then suddenly develop an abnormality. People are either going to demonstrate an abnormality early or not have one at all.”

When Dr. Kirby starts patients on isotretinoin, she orders baseline LFTs and a lipid panel and repeats them 60 days later. “If everything is fine or only mildly high, we don’t do more testing, only a review of systems,” she said. “This is valuable to our patients because fear of needles and fainting peak during adolescence.”

Spironolactone

The clinical use of regularly monitoring potassium levels in young women taking spironolactone for acne has also been questioned. The drug has been linked to an increased risk for hyperkalemia, but the prevalence is unclear. “I got a lot of normal potassium levels in these patients [when] I was in training and I really questioned, ‘Why am I doing this? What is the rationale?’ ” Dr. Kirby said.

In a study that informed her own practice, researchers reviewed the rate of hyperkalemia in 974 healthy young women taking spironolactone for acne or for an endocrine disorder with associated acne between Dec. 1, 2000, and March 31, 2014 (JAMA Dermatol. 2015 Sep;151[9]:941-4). Of the total of 1,802 serum potassium measurements taken during treatment, 13 (0.72%) were mildly elevated levels and none of the patients had a potassium level above 5.5 mEq/L. Retesting within 1 to 3 weeks in 6 of 13 patients with elevated levels found that potassium levels were normal. “The recommendation for spironolactone in healthy women is not to check the potassium level,” Dr. Kirby said, adding that she does counsel patients about the risk of breast tenderness (which can occur 5% to 40% of the time) and spotting (which can occur in 10% to 20% of patients). Gynecomastia can occur in 10% to 30% of men, which is one of the reasons she does not use spironolactone in male patients.

TB testing and biologics

Whether or not to test for TB in patients with psoriasis taking biologic therapies represents another conundrum, she continued. Patients taking biologics are at risk of reactivation of latent TB infection, but in her experience, package inserts contain language like “perform TB testing at baseline, then periodically,” or “use at baseline, then with active TB symptoms,” and “after treatment is discontinued.”

“What the inserts didn’t recommend was to perform TB testing every year, which is what my routine had been,” Dr. Kirby said. “In the United States, thankfully we don’t have a lot of TB.” In a study that informed her own practice, researchers at a single academic medical center retrospectively reviewed the TB seroconversion rate among 316 patients treated with second-generation biologics (J Am Acad Dermatol. 2020 Oct 1;S0190-9622[20]32676-1. doi: 10.1016/j.jaad.2020.09.075). It found that only six patients (2%) converted and had a positive TB test later during treatment with the biologic. “Of these six people, all had grown up outside the U.S., had traveled outside of the U.S., or were in a group living situation,” said Dr. Kirby, who was not affiliated with the study.

“This informs our rationale for how we can do this testing. If insurance requires it every year, fine. But if they don’t, I ask patients about travel, about their living situation, and how they’re feeling. If everything’s going great, I don’t order TB testing. I do favor the interferon-gamma release assays because they’re a lot more effective than PPDs [purified protein derivative skin tests]. Also, PPDs are difficult for patients who have a low rate of returning to have that test read.”

Terbinafine for onychomycosis

Dr. Kirby also discussed the rationale for ordering regular LFTs in patients taking terbinafine for onychomycosis. “There is a risk of drug-induced liver injury from taking terbinafine, but it’s rare,” she said. “Can we be thoughtful about which patients we expose?”

Evidence suggests that patients with hyperkeratosis greater than 2 mm, with nail matrix involvement, with 50% or more of the nail involved, or having concomitant peripheral vascular disease and diabetes are recalcitrant to treatment with terbinafine

(J Am Acad Dermatol. 2019 Apr;80[4]:853-67). “If we can frame this risk, then we can frame it for our patients,” she said. “We’re more likely to cause liver injury with an antibiotic. When it comes to an oral antifungal, itraconazole is more likely than terbinafine to cause liver injury. The rate of liver injury with terbinafine is only about 2 out of 100,000. It’s five times more likely with itraconazole and 21 times more likely with Augmentin.”

She recommends obtaining a baseline LFT in patients starting terbinafine therapy “to make sure their liver is normal from the start.” In addition, she advised, “let them know that there is a TB seroconversion risk of about 1 in 50,000 people, and that if it happens there would be symptomatic changes. They would maybe notice pruritus and have a darkening in their urine, and they’d have some flu-like symptoms, which would mean stop the drug and get some care.”

Dr. Kirby emphasized that a patient’s propensity for developing drug-induced liver injury from terbinafine use is not predictable from LFT monitoring. “What you’re more likely to find is an asymptomatic LFT rise in about 1% of people,” she said.

She disclosed that she has received honoraria from AbbVie, ChemoCentryx, Incyte, Janssen, Novartis, and UCB Pharma.

From time to time, Joslyn Kirby, MD, asks other physicians about their experience with certain medications used in dermatology, especially when something new hits the market.

“Sometimes I get an answer like, ‘The last time I used that medicine, my patient needed a liver transplant,’ ” Dr. Kirby, associate professor of dermatology, Penn State University, Hershey, said during the Orlando Dermatology Aesthetic and Clinical Conference. “It’s typically a story of something rare, uncommon, and awful. The challenge with an anecdote is that for all its power, it has a lower level of evidence. But it sticks with us and influences us more than a better level of evidence because it’s a situation and a story that we might relate to.”

Dr. Kirby said that when she thinks about managing side effects from drugs used in dermatology, it usually relates to something common and low-risk such as sore, dry skin with isotretinoin use. In contrast, if there is an uncommon but serious side effect, then mitigation rather than management is key. “I want to mitigate the risk – meaning warn my patient about it or be careful about how I select my patients when it is a serious side effect that happens infrequently,” she said. “The worst combination is a frequent and severe side effect. That is something we should avoid, for sure.”

Isotretinoin

But another aspect of prescribing a new drug for patients can be less clear-cut, Dr. Kirby continued, such as the rationale for routine lab monitoring. She began by discussing one of her male patients with moderate to severe acne. After he failed oral antibiotics and topical retinoids, she recommended isotretinoin, which carries a risk of hypertriglyceridemia-associated pancreatitis. “Early in my career, I was getting a lot of monthly labs in patients on this drug that were totally normal and not influencing my practice,” Dr. Kirby recalled. “We’ve seen studies coming out on isotretinoin lab monitoring, showing us that we can keep our patients safe and that we really don’t need to be checking labs as often, because lab changes are infrequent.”

In one of those studies, researchers evaluated 1,863 patients treated with isotretinoin for acne between Jan. 1, 2008, and June 30, 2017 (J Am Acad Dermatol. 2020 Jan;82[1]:72-9).Over time, fewer than 1% of patients screened developed grade 3 or greater triglyceride testing abnormalities, while fewer than 0.5% developed liver function testing (LFT) abnormalities. Authors of a separate systematic review concluded that for patients on isotretinoin therapy without elevated baseline triglycerides, or risk thereof, monitoring triglycerides is of little value (Br J Dermatol. 2017 Oct;177[4]:960-6). Of the 25 patients in the analysis who developed pancreatitis on isotretinoin, only 3 had elevated triglycerides at baseline.

“I was taught that I need to check triglycerides frequently due to the risk of pancreatitis developing with isotretinoin use,” Dr. Kirby said. “Lipid changes on therapy are expected, but they tend to peak early, meaning the first 3 months of treatment when we’re ramping up from a starting dose to a maintenance dose. It’s rare for somebody to be a late bloomer, meaning that they have totally normal labs in the first 3 months and then suddenly develop an abnormality. People are either going to demonstrate an abnormality early or not have one at all.”

When Dr. Kirby starts patients on isotretinoin, she orders baseline LFTs and a lipid panel and repeats them 60 days later. “If everything is fine or only mildly high, we don’t do more testing, only a review of systems,” she said. “This is valuable to our patients because fear of needles and fainting peak during adolescence.”

Spironolactone

The clinical use of regularly monitoring potassium levels in young women taking spironolactone for acne has also been questioned. The drug has been linked to an increased risk for hyperkalemia, but the prevalence is unclear. “I got a lot of normal potassium levels in these patients [when] I was in training and I really questioned, ‘Why am I doing this? What is the rationale?’ ” Dr. Kirby said.

In a study that informed her own practice, researchers reviewed the rate of hyperkalemia in 974 healthy young women taking spironolactone for acne or for an endocrine disorder with associated acne between Dec. 1, 2000, and March 31, 2014 (JAMA Dermatol. 2015 Sep;151[9]:941-4). Of the total of 1,802 serum potassium measurements taken during treatment, 13 (0.72%) were mildly elevated levels and none of the patients had a potassium level above 5.5 mEq/L. Retesting within 1 to 3 weeks in 6 of 13 patients with elevated levels found that potassium levels were normal. “The recommendation for spironolactone in healthy women is not to check the potassium level,” Dr. Kirby said, adding that she does counsel patients about the risk of breast tenderness (which can occur 5% to 40% of the time) and spotting (which can occur in 10% to 20% of patients). Gynecomastia can occur in 10% to 30% of men, which is one of the reasons she does not use spironolactone in male patients.

TB testing and biologics

Whether or not to test for TB in patients with psoriasis taking biologic therapies represents another conundrum, she continued. Patients taking biologics are at risk of reactivation of latent TB infection, but in her experience, package inserts contain language like “perform TB testing at baseline, then periodically,” or “use at baseline, then with active TB symptoms,” and “after treatment is discontinued.”

“What the inserts didn’t recommend was to perform TB testing every year, which is what my routine had been,” Dr. Kirby said. “In the United States, thankfully we don’t have a lot of TB.” In a study that informed her own practice, researchers at a single academic medical center retrospectively reviewed the TB seroconversion rate among 316 patients treated with second-generation biologics (J Am Acad Dermatol. 2020 Oct 1;S0190-9622[20]32676-1. doi: 10.1016/j.jaad.2020.09.075). It found that only six patients (2%) converted and had a positive TB test later during treatment with the biologic. “Of these six people, all had grown up outside the U.S., had traveled outside of the U.S., or were in a group living situation,” said Dr. Kirby, who was not affiliated with the study.

“This informs our rationale for how we can do this testing. If insurance requires it every year, fine. But if they don’t, I ask patients about travel, about their living situation, and how they’re feeling. If everything’s going great, I don’t order TB testing. I do favor the interferon-gamma release assays because they’re a lot more effective than PPDs [purified protein derivative skin tests]. Also, PPDs are difficult for patients who have a low rate of returning to have that test read.”

Terbinafine for onychomycosis

Dr. Kirby also discussed the rationale for ordering regular LFTs in patients taking terbinafine for onychomycosis. “There is a risk of drug-induced liver injury from taking terbinafine, but it’s rare,” she said. “Can we be thoughtful about which patients we expose?”

Evidence suggests that patients with hyperkeratosis greater than 2 mm, with nail matrix involvement, with 50% or more of the nail involved, or having concomitant peripheral vascular disease and diabetes are recalcitrant to treatment with terbinafine

(J Am Acad Dermatol. 2019 Apr;80[4]:853-67). “If we can frame this risk, then we can frame it for our patients,” she said. “We’re more likely to cause liver injury with an antibiotic. When it comes to an oral antifungal, itraconazole is more likely than terbinafine to cause liver injury. The rate of liver injury with terbinafine is only about 2 out of 100,000. It’s five times more likely with itraconazole and 21 times more likely with Augmentin.”

She recommends obtaining a baseline LFT in patients starting terbinafine therapy “to make sure their liver is normal from the start.” In addition, she advised, “let them know that there is a TB seroconversion risk of about 1 in 50,000 people, and that if it happens there would be symptomatic changes. They would maybe notice pruritus and have a darkening in their urine, and they’d have some flu-like symptoms, which would mean stop the drug and get some care.”

Dr. Kirby emphasized that a patient’s propensity for developing drug-induced liver injury from terbinafine use is not predictable from LFT monitoring. “What you’re more likely to find is an asymptomatic LFT rise in about 1% of people,” she said.

She disclosed that she has received honoraria from AbbVie, ChemoCentryx, Incyte, Janssen, Novartis, and UCB Pharma.

From time to time, Joslyn Kirby, MD, asks other physicians about their experience with certain medications used in dermatology, especially when something new hits the market.

“Sometimes I get an answer like, ‘The last time I used that medicine, my patient needed a liver transplant,’ ” Dr. Kirby, associate professor of dermatology, Penn State University, Hershey, said during the Orlando Dermatology Aesthetic and Clinical Conference. “It’s typically a story of something rare, uncommon, and awful. The challenge with an anecdote is that for all its power, it has a lower level of evidence. But it sticks with us and influences us more than a better level of evidence because it’s a situation and a story that we might relate to.”

Dr. Kirby said that when she thinks about managing side effects from drugs used in dermatology, it usually relates to something common and low-risk such as sore, dry skin with isotretinoin use. In contrast, if there is an uncommon but serious side effect, then mitigation rather than management is key. “I want to mitigate the risk – meaning warn my patient about it or be careful about how I select my patients when it is a serious side effect that happens infrequently,” she said. “The worst combination is a frequent and severe side effect. That is something we should avoid, for sure.”

Isotretinoin

But another aspect of prescribing a new drug for patients can be less clear-cut, Dr. Kirby continued, such as the rationale for routine lab monitoring. She began by discussing one of her male patients with moderate to severe acne. After he failed oral antibiotics and topical retinoids, she recommended isotretinoin, which carries a risk of hypertriglyceridemia-associated pancreatitis. “Early in my career, I was getting a lot of monthly labs in patients on this drug that were totally normal and not influencing my practice,” Dr. Kirby recalled. “We’ve seen studies coming out on isotretinoin lab monitoring, showing us that we can keep our patients safe and that we really don’t need to be checking labs as often, because lab changes are infrequent.”

In one of those studies, researchers evaluated 1,863 patients treated with isotretinoin for acne between Jan. 1, 2008, and June 30, 2017 (J Am Acad Dermatol. 2020 Jan;82[1]:72-9).Over time, fewer than 1% of patients screened developed grade 3 or greater triglyceride testing abnormalities, while fewer than 0.5% developed liver function testing (LFT) abnormalities. Authors of a separate systematic review concluded that for patients on isotretinoin therapy without elevated baseline triglycerides, or risk thereof, monitoring triglycerides is of little value (Br J Dermatol. 2017 Oct;177[4]:960-6). Of the 25 patients in the analysis who developed pancreatitis on isotretinoin, only 3 had elevated triglycerides at baseline.

“I was taught that I need to check triglycerides frequently due to the risk of pancreatitis developing with isotretinoin use,” Dr. Kirby said. “Lipid changes on therapy are expected, but they tend to peak early, meaning the first 3 months of treatment when we’re ramping up from a starting dose to a maintenance dose. It’s rare for somebody to be a late bloomer, meaning that they have totally normal labs in the first 3 months and then suddenly develop an abnormality. People are either going to demonstrate an abnormality early or not have one at all.”

When Dr. Kirby starts patients on isotretinoin, she orders baseline LFTs and a lipid panel and repeats them 60 days later. “If everything is fine or only mildly high, we don’t do more testing, only a review of systems,” she said. “This is valuable to our patients because fear of needles and fainting peak during adolescence.”

Spironolactone

The clinical use of regularly monitoring potassium levels in young women taking spironolactone for acne has also been questioned. The drug has been linked to an increased risk for hyperkalemia, but the prevalence is unclear. “I got a lot of normal potassium levels in these patients [when] I was in training and I really questioned, ‘Why am I doing this? What is the rationale?’ ” Dr. Kirby said.

In a study that informed her own practice, researchers reviewed the rate of hyperkalemia in 974 healthy young women taking spironolactone for acne or for an endocrine disorder with associated acne between Dec. 1, 2000, and March 31, 2014 (JAMA Dermatol. 2015 Sep;151[9]:941-4). Of the total of 1,802 serum potassium measurements taken during treatment, 13 (0.72%) were mildly elevated levels and none of the patients had a potassium level above 5.5 mEq/L. Retesting within 1 to 3 weeks in 6 of 13 patients with elevated levels found that potassium levels were normal. “The recommendation for spironolactone in healthy women is not to check the potassium level,” Dr. Kirby said, adding that she does counsel patients about the risk of breast tenderness (which can occur 5% to 40% of the time) and spotting (which can occur in 10% to 20% of patients). Gynecomastia can occur in 10% to 30% of men, which is one of the reasons she does not use spironolactone in male patients.

TB testing and biologics

Whether or not to test for TB in patients with psoriasis taking biologic therapies represents another conundrum, she continued. Patients taking biologics are at risk of reactivation of latent TB infection, but in her experience, package inserts contain language like “perform TB testing at baseline, then periodically,” or “use at baseline, then with active TB symptoms,” and “after treatment is discontinued.”

“What the inserts didn’t recommend was to perform TB testing every year, which is what my routine had been,” Dr. Kirby said. “In the United States, thankfully we don’t have a lot of TB.” In a study that informed her own practice, researchers at a single academic medical center retrospectively reviewed the TB seroconversion rate among 316 patients treated with second-generation biologics (J Am Acad Dermatol. 2020 Oct 1;S0190-9622[20]32676-1. doi: 10.1016/j.jaad.2020.09.075). It found that only six patients (2%) converted and had a positive TB test later during treatment with the biologic. “Of these six people, all had grown up outside the U.S., had traveled outside of the U.S., or were in a group living situation,” said Dr. Kirby, who was not affiliated with the study.

“This informs our rationale for how we can do this testing. If insurance requires it every year, fine. But if they don’t, I ask patients about travel, about their living situation, and how they’re feeling. If everything’s going great, I don’t order TB testing. I do favor the interferon-gamma release assays because they’re a lot more effective than PPDs [purified protein derivative skin tests]. Also, PPDs are difficult for patients who have a low rate of returning to have that test read.”

Terbinafine for onychomycosis

Dr. Kirby also discussed the rationale for ordering regular LFTs in patients taking terbinafine for onychomycosis. “There is a risk of drug-induced liver injury from taking terbinafine, but it’s rare,” she said. “Can we be thoughtful about which patients we expose?”

Evidence suggests that patients with hyperkeratosis greater than 2 mm, with nail matrix involvement, with 50% or more of the nail involved, or having concomitant peripheral vascular disease and diabetes are recalcitrant to treatment with terbinafine

(J Am Acad Dermatol. 2019 Apr;80[4]:853-67). “If we can frame this risk, then we can frame it for our patients,” she said. “We’re more likely to cause liver injury with an antibiotic. When it comes to an oral antifungal, itraconazole is more likely than terbinafine to cause liver injury. The rate of liver injury with terbinafine is only about 2 out of 100,000. It’s five times more likely with itraconazole and 21 times more likely with Augmentin.”

She recommends obtaining a baseline LFT in patients starting terbinafine therapy “to make sure their liver is normal from the start.” In addition, she advised, “let them know that there is a TB seroconversion risk of about 1 in 50,000 people, and that if it happens there would be symptomatic changes. They would maybe notice pruritus and have a darkening in their urine, and they’d have some flu-like symptoms, which would mean stop the drug and get some care.”

Dr. Kirby emphasized that a patient’s propensity for developing drug-induced liver injury from terbinafine use is not predictable from LFT monitoring. “What you’re more likely to find is an asymptomatic LFT rise in about 1% of people,” she said.

She disclosed that she has received honoraria from AbbVie, ChemoCentryx, Incyte, Janssen, Novartis, and UCB Pharma.

FROM ODAC 2021

The cutaneous benefits of bee venom, Part I: Atopic dermatitis and acne

Honeybees, Apis mellifera, play an important role in the web of life. We rely on bees for pollinating approximately one-third of our crops, including multiple fruits, vegetables, nuts, and seeds.1,2 Bees are also instrumental in the propagation of other plants, flower nectar, and flower pollen. A. mellifera, the European honeybee, is the main pollinator in Europe and North America, but other species, including A. cerana, A. dorsata, A. floria, A. andreniformis, A. koschevnikov, and A. laboriosa, yield honey.3 Honey, propolis, and royal jelly, along with beeswax and bee pollen, are among some of the celebrated bee products that have been found to confer health benefits to human beings.4,5 Bee venom, a toxin bees use for protection, is a convoluted combination of peptides and toxic proteins such as phospholipase A2 (PLA2) and melittin that has garnered significant scientific attention of late and is used to treat various inflammatory conditions.6-8 This column will focus on the investigation of the use of bee venom to treat atopic dermatitis (AD) and acne.

Atopic dermatitis

In 2013, Kim et al. assessed the impact of bee venom on AD-related symptoms in mice, finding that it attenuated the effects of AD-simulating compounds in 48 of 80 patients injected subcutaneously. They concluded that bee venom acted by suppressing mast cell degranulation and proinflammatory cytokine expression.9 Three years later, You et al. conducted a double-blind, randomized, base-controlled multicenter study of 136 patients with AD to ascertain the effects of a bee venom emollient. For 4 weeks, patients applied an emollient with bee venom and silk protein or a vehicle lacking bee venom twice daily. Eczema area and severity index (EASI) scores were significantly lower in the bee venom group, as were the visual analogue scale (VAS) scores. The investigators concluded that bee venom is an effective and safe therapeutic choice for treating patients with AD.10 Further, in 2018, Shin et al. demonstrated that PLA2 derived from bee venom mitigates atopic skin inflammation via the CD206 mannose receptor. They had previously shown in a mouse model that PLA2 from bee venom exerts such activity against AD-like lesions induced by 2,4-dinitrochlorobenzene (DNCB) and house dust mite (Dermatophagoides farinae) extract.11 Gu et al. observed later that year that intraperitoneal administration of bee venom eased the symptoms of ovalbumin-induced AD-like skin lesions in an experimental mouse model. Bee venom also lowered serum immunoglobulin E levels and suppressed infiltration of eosinophils and mast cells. They concluded that bee venom is a viable alternative for attenuating the allergic skin inflammation characteristic of AD.12 At the end of 2018, An et al. reported on the use of an in vivo female Balb/c mouse AD model in which 1-chloro-DNCB acted as inducer in cultures of human keratinocytes, stimulated by TNF-alpha/IFN-gamma. The investigators found that bee venom and melittin displayed robust antiatopic effects as evidenced by reduced lesions. The bee products were also found to have hindered elevated expression of various chemokines and proinflammatory cytokines. The authors suggested that bee venom and melittin appear to warrant consideration as a topical treatment for AD.13 In 2019, Kim et al. demonstrated in mice that bee venom eases the symptoms of AD by inactivating the complement system, particularly through CD55 induction, which might account for its effectiveness in AD treatment in humans, they suggested.6 Early in 2020, Lee et al. demonstrated in a Balb/c mouse model that bee venom appears to be a possible therapeutic macromolecule for treating phthalic anhydride-induced AD.7

Acne

In 2013, in vitro experiments by Han et al. showed that purified bee venom exhibited antimicrobial activity, in a concentration-dependent manner, against Cutibacterium acnes (or Propionibacterium acnes). They followed up with a small randomized, double-blind, controlled trial with 12 subjects who were treated with cosmetics with pure bee venom or cosmetics without it for two weeks. The group receiving bee venom experienced significantly fewer inflammatory and noninflammatory lesions, and a significant decline in adenosine triphosphate levels (a 57.5% reduction) was noted in subjects in the bee venom group, with a nonsignificant decrease of 4.7% observed in the control group. The investigators concluded the purified bee venom may be suitable as an antiacne agent.14 Using a mouse model, An et al. studied the therapeutic effects of bee venom against C. acnes–induced skin inflammation. They found that bee venom significantly diminished the volume of infiltrated inflammatory cells in the treated mice, compared with untreated mice. Bee venom also decreased expression levels of tumor necrosis factor (TNF)-α, and interleukin (IL)-1beta and suppressed Toll-like receptor (TLR)2 and CD14 expression in C. acnes–injected tissue. The investigators concluded that bee venom imparts notable anti-inflammatory activity and has potential for use in treating acne and as an anti-inflammatory agent in skin care.15

In 2015, Kim et al. studied the influence of bee venom against C. acnes–induced inflammation in human keratinocytes (HaCaT) and monocytes (THP-1). They found that bee venom successfully suppressed the secretion of interferon-gamma, IL-1beta, IL-8, and TNF-alpha. It also galvanized the expression of IL-8 and TLR2 in HaCaT cells but hampered their expression in heat-killed C. acnes. The researchers concluded that bee venom displays considerable anti-inflammatory activity against C. acnes and warrants consideration as an alternative to antibiotic acne treatment.16 It is worth noting that early that year, in a comprehensive database review to evaluate the effects and safety of a wide range of complementary treatments for acne, Cao et al. found, among 35 studies including parallel-group randomized controlled trials, that one trial indicated bee venom was superior to control in lowering the number of acne lesions.17

Conclusion

More research, in the form of randomized, controlled trials, is required before bee venom can be incorporated into the dermatologic armamentarium as a first-line therapy for common and vexing cutaneous conditions. Nevertheless, .

Dr. Baumann is a private practice dermatologist, researcher, author, and entrepreneur who practices in Miami. She founded the Cosmetic Dermatology Center at the University of Miami in 1997. Dr. Baumann has written two textbooks and a New York Times Best Sellers book for consumers. Dr. Baumann has received funding for advisory boards and/or clinical research trials from Allergan, Galderma, Revance, Evolus, and Burt’s Bees. She is the CEO of Skin Type Solutions Inc., a company that independently tests skin care products and makes recommendations to physicians on which skin care technologies are best. Write to her at dermnews@mdedge.com.

References

1. Walsh B. The plight of the honeybee: Mass deaths in bee colonies may mean disaster for farmers – and your favorite Foods. Time Magazine, 2013 Aug 19.

2. Klein AM et al. Proc Biol Sci. 2007 Feb 7;274(1608):303-13. doi: 10.1098/rspb.2006.3721.

3. Ediriweera ER and Premarathna NY. AYU. 2012 Apr;33(2):178-82. doi: 10.4103/0974-8520.105233.

4. Baumann, L. Honey/Propolis/Royal Jelly. In Cosmeceuticals and Cosmetic Ingredients. New York:McGraw-Hill; 2014:203-212.

5. Cornara L et al. Front Pharmacol. 2017 Jun 28;8:412. doi: 10.3389/fphar.2017.00412.

6. Kim Y et al. Toxins (Basel). 2019 Apr 26;11(5):239. doi: 10.3390/toxins11050239.

7. Lee YJ et al. Inflammopharmacology. 2020 Feb;28(1):253-63. doi: 10.1007/s10787-019-00646-w.

8. Lee G and Bae H. Molecules. 2016 May 11;21(5):616. doi: 10.3390/molecules21050616.

9. Kim KH et al. Int J Clin Exp Pathol. 2013 Nov 15;6(12):2896-903.

10. You CE et al. Ann Dermatol. 2016 Oct;28(5):593-9. doi: 10.5021/ad.2016.28.5.593.

11. Shin D et al. Toxins (Basel). 2018 Apr 2;10(4):146. doi: 10.3390/toxins10040146.

12. Gu H et al. Mol Med Rep. 2018 Oct;18(4):3711-8. doi: 10.3892/mmr.2018.9398.

13. An HJ et al. Br J Pharmacol. 2018 Dec;175(23):4310-24. doi: 10.1111/bph.14487.

14. Han SM et al. J Integr Med. 2013 Sep;11(5):320-6. doi: 10.3736/jintegrmed2013043.

15. An HJ et al. Int J Mol Med. 2014 Nov;34(5):1341-8. doi: 10.3892/ijmm.2014.1933.

16. Kim JY et al. Int J Mol Med. 2015 Jun;35(6):1651-6. doi: 10.3892/ijmm.2015.2180.

17. Cao H et al. Cochrane Database Syst Rev. 2015 Jan 19;1:CD009436. doi: 10.1002/14651858.CD009436.pub2.

Honeybees, Apis mellifera, play an important role in the web of life. We rely on bees for pollinating approximately one-third of our crops, including multiple fruits, vegetables, nuts, and seeds.1,2 Bees are also instrumental in the propagation of other plants, flower nectar, and flower pollen. A. mellifera, the European honeybee, is the main pollinator in Europe and North America, but other species, including A. cerana, A. dorsata, A. floria, A. andreniformis, A. koschevnikov, and A. laboriosa, yield honey.3 Honey, propolis, and royal jelly, along with beeswax and bee pollen, are among some of the celebrated bee products that have been found to confer health benefits to human beings.4,5 Bee venom, a toxin bees use for protection, is a convoluted combination of peptides and toxic proteins such as phospholipase A2 (PLA2) and melittin that has garnered significant scientific attention of late and is used to treat various inflammatory conditions.6-8 This column will focus on the investigation of the use of bee venom to treat atopic dermatitis (AD) and acne.

Atopic dermatitis

In 2013, Kim et al. assessed the impact of bee venom on AD-related symptoms in mice, finding that it attenuated the effects of AD-simulating compounds in 48 of 80 patients injected subcutaneously. They concluded that bee venom acted by suppressing mast cell degranulation and proinflammatory cytokine expression.9 Three years later, You et al. conducted a double-blind, randomized, base-controlled multicenter study of 136 patients with AD to ascertain the effects of a bee venom emollient. For 4 weeks, patients applied an emollient with bee venom and silk protein or a vehicle lacking bee venom twice daily. Eczema area and severity index (EASI) scores were significantly lower in the bee venom group, as were the visual analogue scale (VAS) scores. The investigators concluded that bee venom is an effective and safe therapeutic choice for treating patients with AD.10 Further, in 2018, Shin et al. demonstrated that PLA2 derived from bee venom mitigates atopic skin inflammation via the CD206 mannose receptor. They had previously shown in a mouse model that PLA2 from bee venom exerts such activity against AD-like lesions induced by 2,4-dinitrochlorobenzene (DNCB) and house dust mite (Dermatophagoides farinae) extract.11 Gu et al. observed later that year that intraperitoneal administration of bee venom eased the symptoms of ovalbumin-induced AD-like skin lesions in an experimental mouse model. Bee venom also lowered serum immunoglobulin E levels and suppressed infiltration of eosinophils and mast cells. They concluded that bee venom is a viable alternative for attenuating the allergic skin inflammation characteristic of AD.12 At the end of 2018, An et al. reported on the use of an in vivo female Balb/c mouse AD model in which 1-chloro-DNCB acted as inducer in cultures of human keratinocytes, stimulated by TNF-alpha/IFN-gamma. The investigators found that bee venom and melittin displayed robust antiatopic effects as evidenced by reduced lesions. The bee products were also found to have hindered elevated expression of various chemokines and proinflammatory cytokines. The authors suggested that bee venom and melittin appear to warrant consideration as a topical treatment for AD.13 In 2019, Kim et al. demonstrated in mice that bee venom eases the symptoms of AD by inactivating the complement system, particularly through CD55 induction, which might account for its effectiveness in AD treatment in humans, they suggested.6 Early in 2020, Lee et al. demonstrated in a Balb/c mouse model that bee venom appears to be a possible therapeutic macromolecule for treating phthalic anhydride-induced AD.7

Acne

In 2013, in vitro experiments by Han et al. showed that purified bee venom exhibited antimicrobial activity, in a concentration-dependent manner, against Cutibacterium acnes (or Propionibacterium acnes). They followed up with a small randomized, double-blind, controlled trial with 12 subjects who were treated with cosmetics with pure bee venom or cosmetics without it for two weeks. The group receiving bee venom experienced significantly fewer inflammatory and noninflammatory lesions, and a significant decline in adenosine triphosphate levels (a 57.5% reduction) was noted in subjects in the bee venom group, with a nonsignificant decrease of 4.7% observed in the control group. The investigators concluded the purified bee venom may be suitable as an antiacne agent.14 Using a mouse model, An et al. studied the therapeutic effects of bee venom against C. acnes–induced skin inflammation. They found that bee venom significantly diminished the volume of infiltrated inflammatory cells in the treated mice, compared with untreated mice. Bee venom also decreased expression levels of tumor necrosis factor (TNF)-α, and interleukin (IL)-1beta and suppressed Toll-like receptor (TLR)2 and CD14 expression in C. acnes–injected tissue. The investigators concluded that bee venom imparts notable anti-inflammatory activity and has potential for use in treating acne and as an anti-inflammatory agent in skin care.15

In 2015, Kim et al. studied the influence of bee venom against C. acnes–induced inflammation in human keratinocytes (HaCaT) and monocytes (THP-1). They found that bee venom successfully suppressed the secretion of interferon-gamma, IL-1beta, IL-8, and TNF-alpha. It also galvanized the expression of IL-8 and TLR2 in HaCaT cells but hampered their expression in heat-killed C. acnes. The researchers concluded that bee venom displays considerable anti-inflammatory activity against C. acnes and warrants consideration as an alternative to antibiotic acne treatment.16 It is worth noting that early that year, in a comprehensive database review to evaluate the effects and safety of a wide range of complementary treatments for acne, Cao et al. found, among 35 studies including parallel-group randomized controlled trials, that one trial indicated bee venom was superior to control in lowering the number of acne lesions.17

Conclusion

More research, in the form of randomized, controlled trials, is required before bee venom can be incorporated into the dermatologic armamentarium as a first-line therapy for common and vexing cutaneous conditions. Nevertheless, .

Dr. Baumann is a private practice dermatologist, researcher, author, and entrepreneur who practices in Miami. She founded the Cosmetic Dermatology Center at the University of Miami in 1997. Dr. Baumann has written two textbooks and a New York Times Best Sellers book for consumers. Dr. Baumann has received funding for advisory boards and/or clinical research trials from Allergan, Galderma, Revance, Evolus, and Burt’s Bees. She is the CEO of Skin Type Solutions Inc., a company that independently tests skin care products and makes recommendations to physicians on which skin care technologies are best. Write to her at dermnews@mdedge.com.

References

1. Walsh B. The plight of the honeybee: Mass deaths in bee colonies may mean disaster for farmers – and your favorite Foods. Time Magazine, 2013 Aug 19.

2. Klein AM et al. Proc Biol Sci. 2007 Feb 7;274(1608):303-13. doi: 10.1098/rspb.2006.3721.

3. Ediriweera ER and Premarathna NY. AYU. 2012 Apr;33(2):178-82. doi: 10.4103/0974-8520.105233.

4. Baumann, L. Honey/Propolis/Royal Jelly. In Cosmeceuticals and Cosmetic Ingredients. New York:McGraw-Hill; 2014:203-212.

5. Cornara L et al. Front Pharmacol. 2017 Jun 28;8:412. doi: 10.3389/fphar.2017.00412.

6. Kim Y et al. Toxins (Basel). 2019 Apr 26;11(5):239. doi: 10.3390/toxins11050239.

7. Lee YJ et al. Inflammopharmacology. 2020 Feb;28(1):253-63. doi: 10.1007/s10787-019-00646-w.

8. Lee G and Bae H. Molecules. 2016 May 11;21(5):616. doi: 10.3390/molecules21050616.

9. Kim KH et al. Int J Clin Exp Pathol. 2013 Nov 15;6(12):2896-903.

10. You CE et al. Ann Dermatol. 2016 Oct;28(5):593-9. doi: 10.5021/ad.2016.28.5.593.

11. Shin D et al. Toxins (Basel). 2018 Apr 2;10(4):146. doi: 10.3390/toxins10040146.

12. Gu H et al. Mol Med Rep. 2018 Oct;18(4):3711-8. doi: 10.3892/mmr.2018.9398.

13. An HJ et al. Br J Pharmacol. 2018 Dec;175(23):4310-24. doi: 10.1111/bph.14487.

14. Han SM et al. J Integr Med. 2013 Sep;11(5):320-6. doi: 10.3736/jintegrmed2013043.

15. An HJ et al. Int J Mol Med. 2014 Nov;34(5):1341-8. doi: 10.3892/ijmm.2014.1933.

16. Kim JY et al. Int J Mol Med. 2015 Jun;35(6):1651-6. doi: 10.3892/ijmm.2015.2180.

17. Cao H et al. Cochrane Database Syst Rev. 2015 Jan 19;1:CD009436. doi: 10.1002/14651858.CD009436.pub2.

Honeybees, Apis mellifera, play an important role in the web of life. We rely on bees for pollinating approximately one-third of our crops, including multiple fruits, vegetables, nuts, and seeds.1,2 Bees are also instrumental in the propagation of other plants, flower nectar, and flower pollen. A. mellifera, the European honeybee, is the main pollinator in Europe and North America, but other species, including A. cerana, A. dorsata, A. floria, A. andreniformis, A. koschevnikov, and A. laboriosa, yield honey.3 Honey, propolis, and royal jelly, along with beeswax and bee pollen, are among some of the celebrated bee products that have been found to confer health benefits to human beings.4,5 Bee venom, a toxin bees use for protection, is a convoluted combination of peptides and toxic proteins such as phospholipase A2 (PLA2) and melittin that has garnered significant scientific attention of late and is used to treat various inflammatory conditions.6-8 This column will focus on the investigation of the use of bee venom to treat atopic dermatitis (AD) and acne.

Atopic dermatitis