User login

New screening tool identifies asthma risk in toddlers

A symptom-based screening tool can identify 2-year-olds at increased risk of asthma, persistent symptoms of wheeze, and health care burden by the age of 5, according to researchers.

The validated CHILDhood Asthma Risk Tool (CHART) determines high, moderate, or low risk of asthma based on symptoms reported before the age of 3 years. It also recommends follow-up.

Potentially, CHART could be used “to identify children who need monitoring, timely symptom control, and introduction of preventive therapies,” said Padmaja Subbarao, MD, MSc, associate chief of clinical research at the Hospital for Sick Children, Toronto, and colleagues in JAMA Network Open.

“The implementation of CHART as a first-step screening tool in general practice could promote timely treatment control and, in turn, improve quality of life for patients and reduce the clinical and economic burden of asthma,” they wrote.

Dr. Subbarao and colleagues developed CHART using data from parent questionnaires and 3- and 5-year clinic visits in the CHILD study. Children were categorized as “high risk” when they experienced two or more episodes of wheeze annually at both 3 and 5 years of age, concurrent with ED visits, hospitalizations, asthma medication, or frequent dry cough. Children with only cough episodes or with cough episodes plus one episode of wheeze in the past 12 months were categorized as “low risk.”

“Our unique approach to classification of wheeze symptoms is important because it helps busy practitioners identify the smaller subset of children with more frequent or severe wheezing episodes who have a higher probability of continued symptoms and impaired lung function in adult life among most children with infrequent wheeze,” Dr. Sabbarao and coauthors said.

Their diagnostic study to evaluate CHART’s predictive capacity showed that the tool had the highest proportion of true-positive asthma at 5 years (sensitivity, 50.0%), compared with physicians’ diagnosis at 3 years (sensitivity, 43.5%), and positive standardized modified Asthma Predictive Index (mAPI) at 3 years (sensitivity, 24.4%).

CHART also outperformed physician assessments and mAPI for predicting persistent wheeze at 5 years and provided the highest predictive capacity for subsequent health care use at 5 years of age. The study showed that it identified 20% more children with emergency department visits or hospitalizations than the standardized mAPI (sensitivity 45.5% vs. 25.0%), and approximately 10% more at-risk children than physician diagnosis.

“These findings are especially important given that many hospitalizations are avoidable if appropriate treatment and management of asthma are implemented at primary care,” Dr. Subbarao and colleagues wrote.

CHART has been validated in two external cohorts: a general-population cohort of 2,185 children from the Raine Study in Australia at 5 years of age; and the other a high-risk cohort of 349 children from the Canadian Asthma Primary Prevention Study at 7 years of age.

“We want to highlight the importance of periodic monitoring of wheeze symptoms and simplify the identification of high-risk children for primary care providers and parents or caregivers,” said Dr. Subbarao, who is director of the CHILD study and professor of pediatrics at the University of Toronto.

The tool “does not identify the underlying biology, which could impact the efficacy of our current standard asthma treatment,” Dr. Subbarao emphasized. CHART has not been tested in low-prevalence settings or in countries in which the term “wheeze” is not commonly recognized, she added.

“CHART helps you focus your crystal ball a little bit, look into the future, and see what’s going to happen,” said Harold Farber, MD, a pediatric pulmonologist who was not involved in the study. “It’s useful even if it just confirms what I’m already doing clinically.”

Dr. Farber, who is professor of pediatrics at Baylor College of Medicine and the Texas Children’s Hospital, Houston, cautioned that the predictive value of CHART is based on the diagnosis of asthma, and that this can differ across health care communities. “Between the extremes and what’s considered borderline, there’s a lot of diagnostic variation in what we call asthma,” he explained in an interview. “The diagnosis is, to some extent, subjective.”

However, Dr. Farber agreed that two or more wheezing episodes in the past 12 months – enough to require treatment – puts a child at very high risk for future wheezing. “Kids with a bunch of wheezing problems at 3 years are likely to have wheezing problems at 5. We have to think about what we can do for a toddler today to keep him from wheezing later.”

CHART is simple to use, the investigators said. The information needed can be easily gathered through interviews and parent-reported questionnaires, then put into the electronic medical record to flag children at high risk for further investigation, and well as those at low or moderate risk for monitoring.

Parents and caregivers can also use CHART to document symptoms every 6 months in children older than 1 year of age, said Dr. Subbarao. This information can be brought to the attention of the doctor “to facilitate a deeper discussion,” she suggested.

This study was funded by the Canadian Institutes of Health Research, Allergy, Genes and Environment Network of Centers of Excellence; Don and Debbie Morrison; Women’s and Children Health Research Institute; and Canada Research Chairs. Dr Subbarao reported having no potential conflicts of interest. Coauthor Vanessa Breton, PhD, disclosed being employed by F. Hoffmann-La Roche Ltd., and coauthor Elinor Simons, MD, PhD, reported membership on the Sanofi-Genzyme Data Monitoring Board. No other conflicts of interest were reported by the study authors. Dr Farber disclosed having no potential conflicts of interest.

A symptom-based screening tool can identify 2-year-olds at increased risk of asthma, persistent symptoms of wheeze, and health care burden by the age of 5, according to researchers.

The validated CHILDhood Asthma Risk Tool (CHART) determines high, moderate, or low risk of asthma based on symptoms reported before the age of 3 years. It also recommends follow-up.

Potentially, CHART could be used “to identify children who need monitoring, timely symptom control, and introduction of preventive therapies,” said Padmaja Subbarao, MD, MSc, associate chief of clinical research at the Hospital for Sick Children, Toronto, and colleagues in JAMA Network Open.

“The implementation of CHART as a first-step screening tool in general practice could promote timely treatment control and, in turn, improve quality of life for patients and reduce the clinical and economic burden of asthma,” they wrote.

Dr. Subbarao and colleagues developed CHART using data from parent questionnaires and 3- and 5-year clinic visits in the CHILD study. Children were categorized as “high risk” when they experienced two or more episodes of wheeze annually at both 3 and 5 years of age, concurrent with ED visits, hospitalizations, asthma medication, or frequent dry cough. Children with only cough episodes or with cough episodes plus one episode of wheeze in the past 12 months were categorized as “low risk.”

“Our unique approach to classification of wheeze symptoms is important because it helps busy practitioners identify the smaller subset of children with more frequent or severe wheezing episodes who have a higher probability of continued symptoms and impaired lung function in adult life among most children with infrequent wheeze,” Dr. Sabbarao and coauthors said.

Their diagnostic study to evaluate CHART’s predictive capacity showed that the tool had the highest proportion of true-positive asthma at 5 years (sensitivity, 50.0%), compared with physicians’ diagnosis at 3 years (sensitivity, 43.5%), and positive standardized modified Asthma Predictive Index (mAPI) at 3 years (sensitivity, 24.4%).

CHART also outperformed physician assessments and mAPI for predicting persistent wheeze at 5 years and provided the highest predictive capacity for subsequent health care use at 5 years of age. The study showed that it identified 20% more children with emergency department visits or hospitalizations than the standardized mAPI (sensitivity 45.5% vs. 25.0%), and approximately 10% more at-risk children than physician diagnosis.

“These findings are especially important given that many hospitalizations are avoidable if appropriate treatment and management of asthma are implemented at primary care,” Dr. Subbarao and colleagues wrote.

CHART has been validated in two external cohorts: a general-population cohort of 2,185 children from the Raine Study in Australia at 5 years of age; and the other a high-risk cohort of 349 children from the Canadian Asthma Primary Prevention Study at 7 years of age.

“We want to highlight the importance of periodic monitoring of wheeze symptoms and simplify the identification of high-risk children for primary care providers and parents or caregivers,” said Dr. Subbarao, who is director of the CHILD study and professor of pediatrics at the University of Toronto.

The tool “does not identify the underlying biology, which could impact the efficacy of our current standard asthma treatment,” Dr. Subbarao emphasized. CHART has not been tested in low-prevalence settings or in countries in which the term “wheeze” is not commonly recognized, she added.

“CHART helps you focus your crystal ball a little bit, look into the future, and see what’s going to happen,” said Harold Farber, MD, a pediatric pulmonologist who was not involved in the study. “It’s useful even if it just confirms what I’m already doing clinically.”

Dr. Farber, who is professor of pediatrics at Baylor College of Medicine and the Texas Children’s Hospital, Houston, cautioned that the predictive value of CHART is based on the diagnosis of asthma, and that this can differ across health care communities. “Between the extremes and what’s considered borderline, there’s a lot of diagnostic variation in what we call asthma,” he explained in an interview. “The diagnosis is, to some extent, subjective.”

However, Dr. Farber agreed that two or more wheezing episodes in the past 12 months – enough to require treatment – puts a child at very high risk for future wheezing. “Kids with a bunch of wheezing problems at 3 years are likely to have wheezing problems at 5. We have to think about what we can do for a toddler today to keep him from wheezing later.”

CHART is simple to use, the investigators said. The information needed can be easily gathered through interviews and parent-reported questionnaires, then put into the electronic medical record to flag children at high risk for further investigation, and well as those at low or moderate risk for monitoring.

Parents and caregivers can also use CHART to document symptoms every 6 months in children older than 1 year of age, said Dr. Subbarao. This information can be brought to the attention of the doctor “to facilitate a deeper discussion,” she suggested.

This study was funded by the Canadian Institutes of Health Research, Allergy, Genes and Environment Network of Centers of Excellence; Don and Debbie Morrison; Women’s and Children Health Research Institute; and Canada Research Chairs. Dr Subbarao reported having no potential conflicts of interest. Coauthor Vanessa Breton, PhD, disclosed being employed by F. Hoffmann-La Roche Ltd., and coauthor Elinor Simons, MD, PhD, reported membership on the Sanofi-Genzyme Data Monitoring Board. No other conflicts of interest were reported by the study authors. Dr Farber disclosed having no potential conflicts of interest.

A symptom-based screening tool can identify 2-year-olds at increased risk of asthma, persistent symptoms of wheeze, and health care burden by the age of 5, according to researchers.

The validated CHILDhood Asthma Risk Tool (CHART) determines high, moderate, or low risk of asthma based on symptoms reported before the age of 3 years. It also recommends follow-up.

Potentially, CHART could be used “to identify children who need monitoring, timely symptom control, and introduction of preventive therapies,” said Padmaja Subbarao, MD, MSc, associate chief of clinical research at the Hospital for Sick Children, Toronto, and colleagues in JAMA Network Open.

“The implementation of CHART as a first-step screening tool in general practice could promote timely treatment control and, in turn, improve quality of life for patients and reduce the clinical and economic burden of asthma,” they wrote.

Dr. Subbarao and colleagues developed CHART using data from parent questionnaires and 3- and 5-year clinic visits in the CHILD study. Children were categorized as “high risk” when they experienced two or more episodes of wheeze annually at both 3 and 5 years of age, concurrent with ED visits, hospitalizations, asthma medication, or frequent dry cough. Children with only cough episodes or with cough episodes plus one episode of wheeze in the past 12 months were categorized as “low risk.”

“Our unique approach to classification of wheeze symptoms is important because it helps busy practitioners identify the smaller subset of children with more frequent or severe wheezing episodes who have a higher probability of continued symptoms and impaired lung function in adult life among most children with infrequent wheeze,” Dr. Sabbarao and coauthors said.

Their diagnostic study to evaluate CHART’s predictive capacity showed that the tool had the highest proportion of true-positive asthma at 5 years (sensitivity, 50.0%), compared with physicians’ diagnosis at 3 years (sensitivity, 43.5%), and positive standardized modified Asthma Predictive Index (mAPI) at 3 years (sensitivity, 24.4%).

CHART also outperformed physician assessments and mAPI for predicting persistent wheeze at 5 years and provided the highest predictive capacity for subsequent health care use at 5 years of age. The study showed that it identified 20% more children with emergency department visits or hospitalizations than the standardized mAPI (sensitivity 45.5% vs. 25.0%), and approximately 10% more at-risk children than physician diagnosis.

“These findings are especially important given that many hospitalizations are avoidable if appropriate treatment and management of asthma are implemented at primary care,” Dr. Subbarao and colleagues wrote.

CHART has been validated in two external cohorts: a general-population cohort of 2,185 children from the Raine Study in Australia at 5 years of age; and the other a high-risk cohort of 349 children from the Canadian Asthma Primary Prevention Study at 7 years of age.

“We want to highlight the importance of periodic monitoring of wheeze symptoms and simplify the identification of high-risk children for primary care providers and parents or caregivers,” said Dr. Subbarao, who is director of the CHILD study and professor of pediatrics at the University of Toronto.

The tool “does not identify the underlying biology, which could impact the efficacy of our current standard asthma treatment,” Dr. Subbarao emphasized. CHART has not been tested in low-prevalence settings or in countries in which the term “wheeze” is not commonly recognized, she added.

“CHART helps you focus your crystal ball a little bit, look into the future, and see what’s going to happen,” said Harold Farber, MD, a pediatric pulmonologist who was not involved in the study. “It’s useful even if it just confirms what I’m already doing clinically.”

Dr. Farber, who is professor of pediatrics at Baylor College of Medicine and the Texas Children’s Hospital, Houston, cautioned that the predictive value of CHART is based on the diagnosis of asthma, and that this can differ across health care communities. “Between the extremes and what’s considered borderline, there’s a lot of diagnostic variation in what we call asthma,” he explained in an interview. “The diagnosis is, to some extent, subjective.”

However, Dr. Farber agreed that two or more wheezing episodes in the past 12 months – enough to require treatment – puts a child at very high risk for future wheezing. “Kids with a bunch of wheezing problems at 3 years are likely to have wheezing problems at 5. We have to think about what we can do for a toddler today to keep him from wheezing later.”

CHART is simple to use, the investigators said. The information needed can be easily gathered through interviews and parent-reported questionnaires, then put into the electronic medical record to flag children at high risk for further investigation, and well as those at low or moderate risk for monitoring.

Parents and caregivers can also use CHART to document symptoms every 6 months in children older than 1 year of age, said Dr. Subbarao. This information can be brought to the attention of the doctor “to facilitate a deeper discussion,” she suggested.

This study was funded by the Canadian Institutes of Health Research, Allergy, Genes and Environment Network of Centers of Excellence; Don and Debbie Morrison; Women’s and Children Health Research Institute; and Canada Research Chairs. Dr Subbarao reported having no potential conflicts of interest. Coauthor Vanessa Breton, PhD, disclosed being employed by F. Hoffmann-La Roche Ltd., and coauthor Elinor Simons, MD, PhD, reported membership on the Sanofi-Genzyme Data Monitoring Board. No other conflicts of interest were reported by the study authors. Dr Farber disclosed having no potential conflicts of interest.

FROM JAMA NETWORK OPEN

Would your patient benefit from a monoclonal antibody?

Small-molecule drugs such as aspirin, albuterol, atorvastatin, and lisinopril are the backbone of disease management in family medicine.1 However, large-molecule biological drugs such as monoclonal antibodies (MAbs) are increasingly prescribed to treat common conditions. In the past decade, MAbs comprised 20% of all drug approvals by the US Food and Drug Administration (FDA), and today they represent more than half of drugs currently in development.2 Fifteen MAbs have been approved by the FDA over the past decade for asthma, atopic dermatitis (AD), hyperlipidemia, osteoporosis, and migraine prevention.3 This review details what makes MAbs unique and what you should know about them.

The uniqueness of monoclonal antibodies

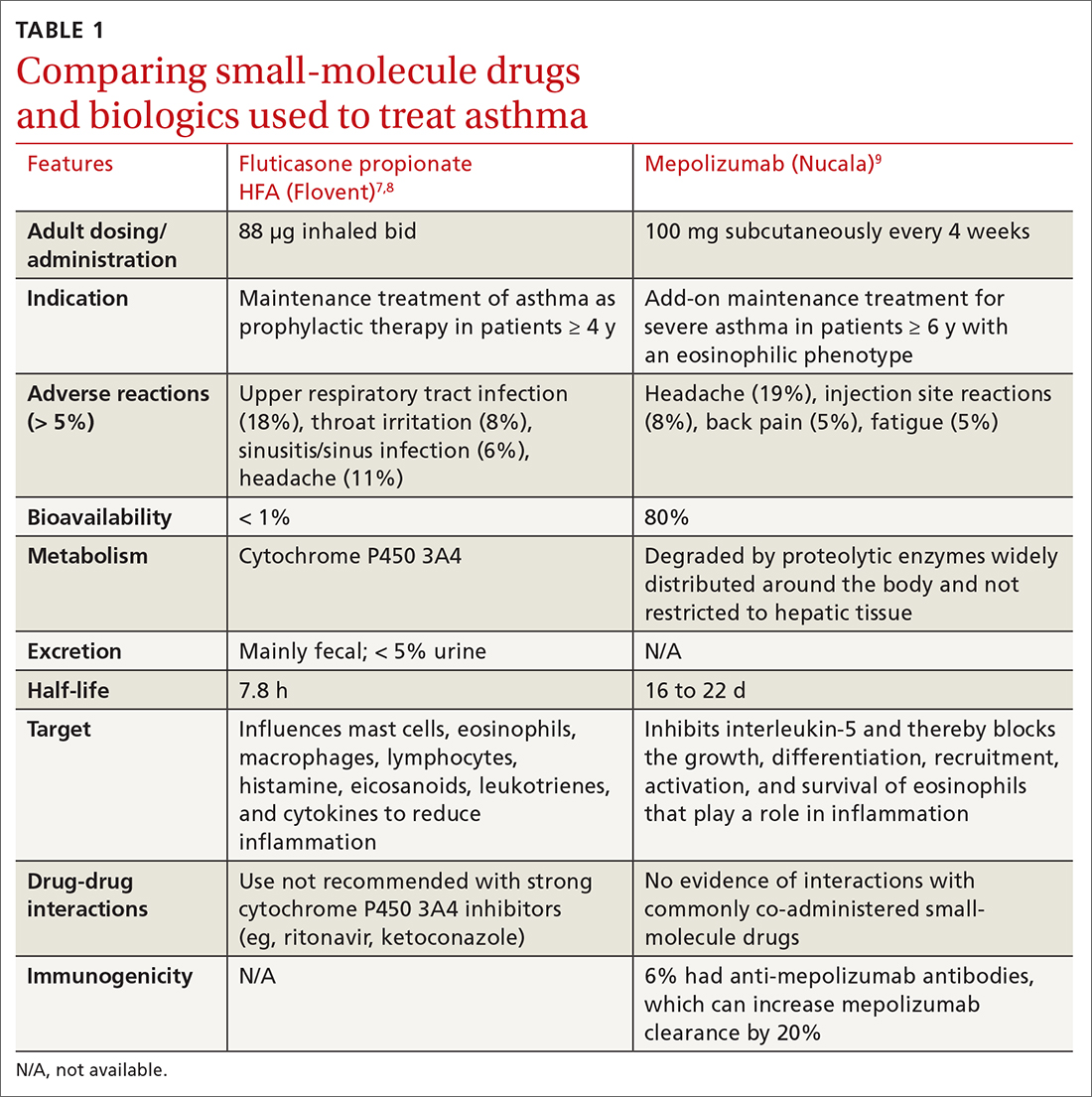

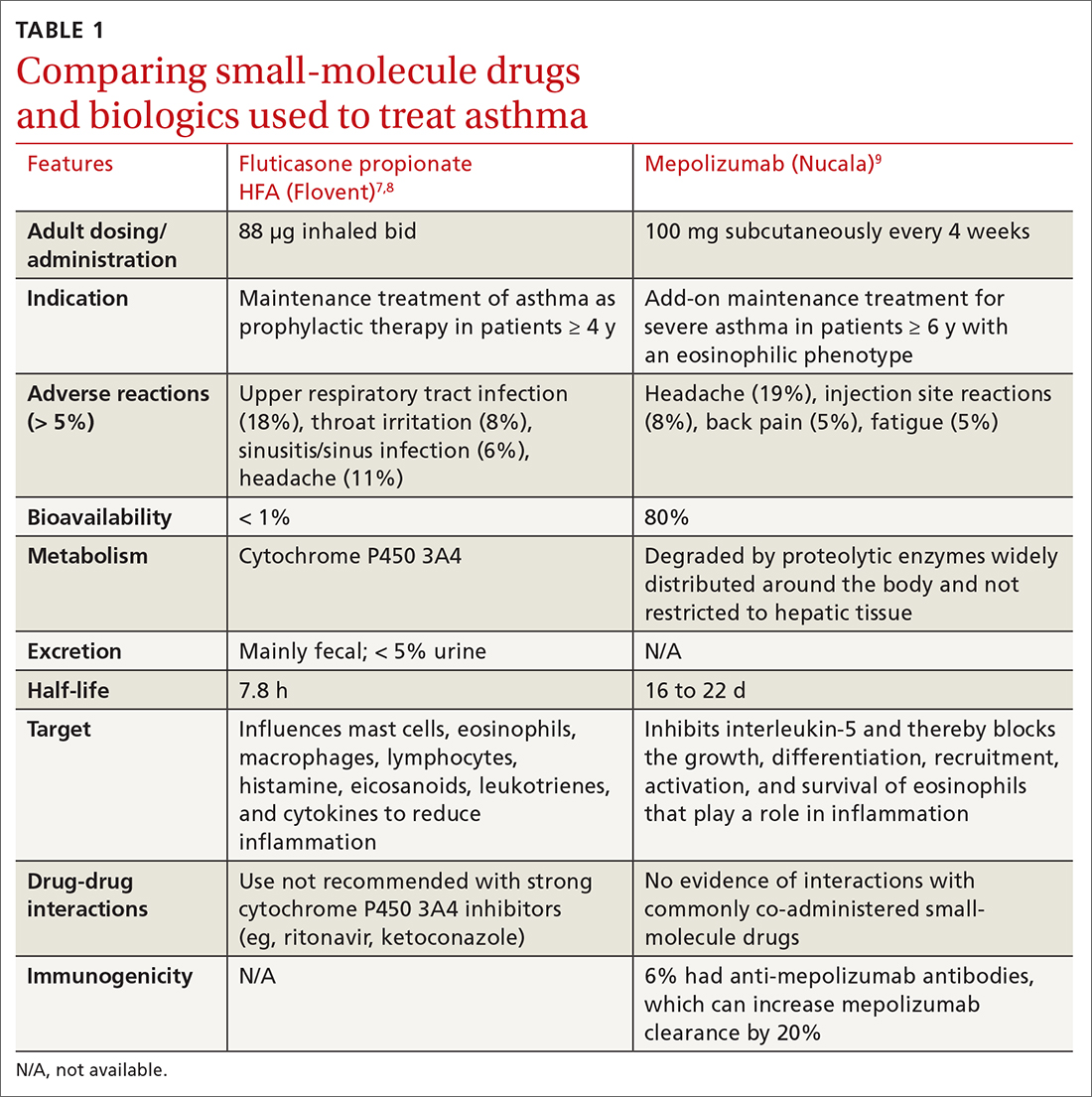

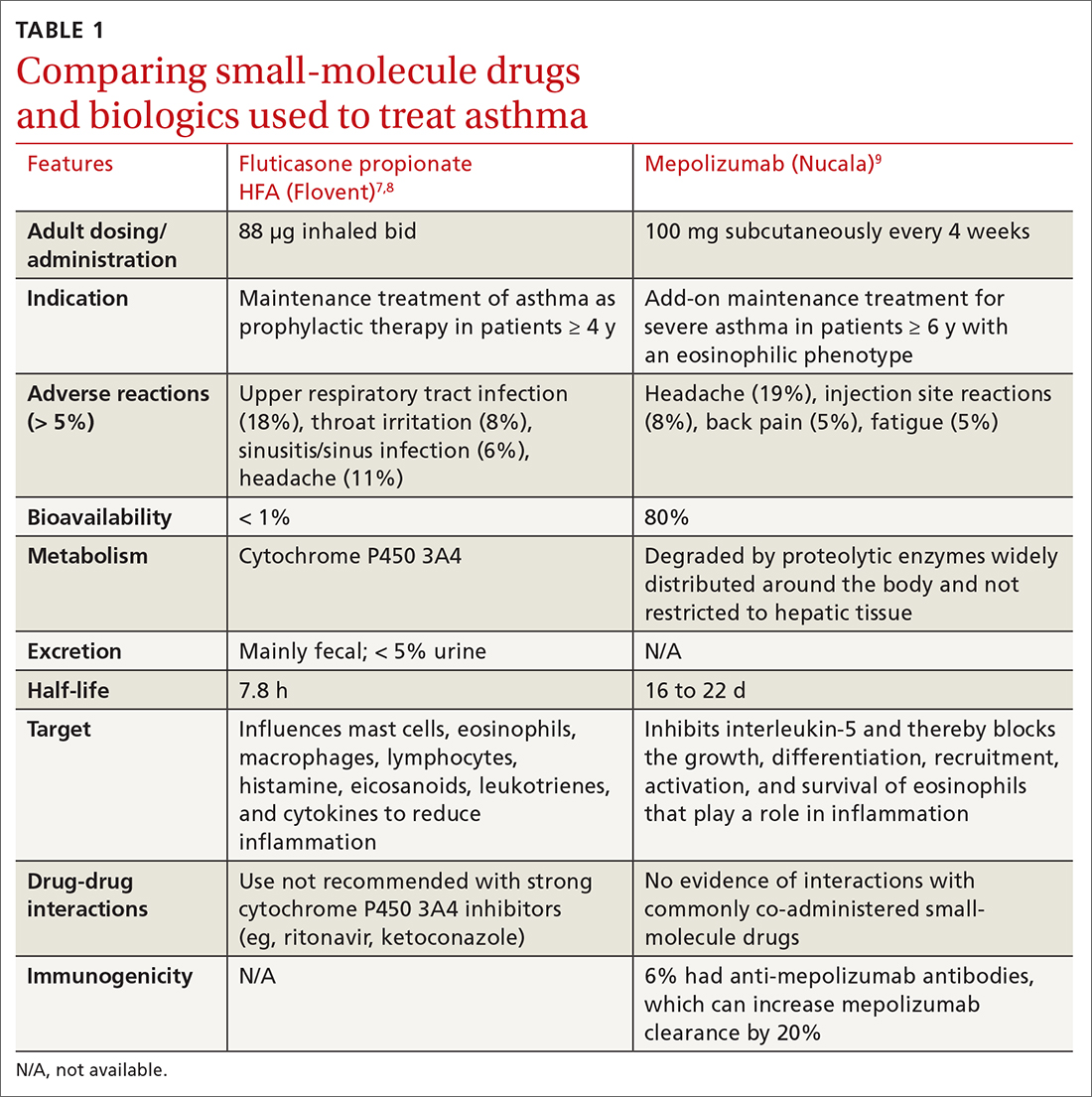

MAbs are biologics, but not all biologics are MAbs—eg, adalimumab (Humira) is a MAb, but etanercept (Enbrel) is not. MAbs are therapeutic proteins made possible by hybridoma technology used to create an antibody with single specificity.4-6 Monoclonal antibodies differ from small-molecule drugs in structure, dosing, route of administration, manufacturing, metabolism, drug interactions, and elimination (TABLE 17-9).

MAbs can be classified as naked, “without any drug or radioactive material attached to them,” or conjugated, “joined to a chemotherapy drug, radioactive isotope, or toxin.”10 MAbs work in several ways, including competitively inhibiting ligand-receptor binding, receptor blockade, or cell elimination from indirect immune system activities such as antibody-dependent cell-mediated cytotoxicity.11,12

Monoclonal antibody uses in family medicine

Asthma

Several MAbs have been approved for use in severe asthma, including but not limited to: omalizumab (Xolair),13 mepolizumab (Nucala),9,14 and dupilumab (Dupixent).15

Omalizumab is a humanized MAb that prevents IgE antibodies from binding to mast cells and basophils, thereby reducing inflammatory mediators.13 A systematic review found that, compared with placebo, omalizumab used in patients with inadequately controlled moderate-to-severe asthma led to significantly fewer asthma exacerbations (absolute risk reduction [ARR], 16% vs 26%; odds ratio [OR] = 0.55; 95% CI, 0.42-0.60; number needed to treat [NNT] = 10) and fewer hospitalizations (ARR, 0.5% vs 3%; OR = 0.16; 95% CI, 0.06-0.42; NNT = 40).13

Significantly more patients in the omalizumab group were able to withdraw from, or reduce, the dose of ICS. GINA recommends omalizumab for patients with positive skin sensitization, total serum IgE ≥ 30 IU/mL, weight within 30 kg to 150 kg, history of childhood asthma and recent exacerbations, and blood eosinophils ≥ 260/mcL.16 Omalizumab is also approved for use in chronic spontaneous urticaria and nasal polyps.

Mepolizumab

Continue to: Another trial found that...

Another trial found that mepolizumab reduced total OCS doses in patients with severe asthma by 50% without increasing exacerbations or worsening asthma control.18 All 3 anti-IL-5 drugs—including not only mepolizumab, but also benralizumab (Fasenra) and reslizumab (Cinqair)—appear to yield similar improvements. A 2017 systematic review found all anti-IL-5 treatments reduced rates of clinically significant asthma exacerbations (treatment with OCS for ≥ 3 days) by roughly 50% in patients with severe eosinophilic asthma and a history of ≥ 2 exacerbations in the past year.

Dupilumab is a humanized MAb that inhibits IL-4 and IL-13, which influence multiple cell types involved in inflammation (eg, mast cells, eosinophils) and inflammatory mediators (histamine, leukotrienes, cytokines).15 In a recent study of patients with uncontrolled asthma, dupilumab 200 mg every 2 weeks compared with placebo showed a modest reduction in the annualized rate of severe asthma exacerbations (0.46 exacerbations vs 0.87, respectively). Dupilumab was effective in patients with blood eosinophil counts ≥ 150/μL but was ineffective in patients with eosinophil counts < 150/μL.15

For patients ≥ 12 years old with severe eosinophilic asthma, GINA recommends using dupilumab as add-on therapy for an initial trial of 4 months at doses of 200 or 300 mg SC every 2 weeks, with preference for 300 mg SC every 2 weeks for OCS-dependent asthma. Dupilumab is approved for use in AD and chronic rhinosinusitis with nasal polyposis. If a biologic agent is not successful after a 4-month trial, consider a 6- to 12-month trial. If efficacy is still minimal, consider switching to an alternative biologic therapy approved for asthma.16

❯ Asthma: Test your skills

Subjective findings: A 19-year-old man presents to your clinic. He has a history of nasal polyps and allergic asthma. At age 18, he was given a diagnosis of severe persistent asthma. He has shortness of breath during waking hours 4 times per week, and treats each of these episodes with albuterol. He also wakes up about twice a week with shortness of breath and has some limitations in normal activities. He reports missing his prescribed fluticasone/salmeterol 500/50 μg, 1 inhalation bid, only once each month. In the last year, he has had 2 exacerbations requiring oral steroids.

Medications: Albuterol 90 μg, 1-2 inhalations, q6h prn; fluticasone/salmeterol 500/50 μg, 1 inhalation bid; tiotropium 1.25 μg, 2 puffs/d; montelukast 10 mg every morning; prednisone 10 mg/d.

Continue to: Objective data

Objective data: Patient is in no apparent distress and afebrile, and oxygen saturation on room air is 97%. Ht, 70 inches; wt, 75 kg. Labs: IgE, 15 IU/mL; serum eosinophils, 315/μL.

Which MAb would be appropriate for this patient? Given that the patient has a blood eosinophil level ≥ 300/μL and severe exacerbations, adult-onset asthma, nasal polyposis, and maintenance OCS at baseline, it would be reasonable to initiate mepolizumab 100 mg SC every 4 weeks, or dupilumab 600 mg once, then 300 mg SC every 2 weeks. Both agents can be self-administered.

Atopic dermatitis

Two MAbs—dupilumab and tralokinumab (Adbry; inhibits IL-13)—are approved for treatment of AD in adults that is uncontrolled with conventional therapy.15,19 Dupilumab is also approved for children ≥ 6 months old.20 Both MAbs are dosed at 600 mg SC, followed by 300 mg every 2 weeks. Dupilumab was compared with placebo in adult patients who had moderate-to-severe AD inadequately controlled on topical corticosteroids (TCSs), to determine the proportion of patients in each group achieving improvement of either 0 or 1 points or ≥ 2 points in the 5-point Investigator Global Assessment (IGA) score from baseline to 16 weeks.21 Thirty-seven percent of patients receiving dupilumab 300 mg SC weekly and 38% of patients receiving dupilumab 300 mg SC every 2 weeks achieved the primary outcome, compared with 10% of those receiving placebo (P < .001).21 Similar IGA scores were reported when dupilumab was combined with TCS, compared with placebo.22

It would be reasonable to consider dupilumab or tralokinumab in patients with: cutaneous atrophy or hypothalamic-pituitary-adrenal axis suppression with TCS, concerns of malignancy with topical calcineurin inhibitors, or problems with the alternative systemic therapies (cyclosporine-induced hypertension, nephrotoxicity, or immunosuppression; azathioprine-induced malignancy; or methotrexate-induced bone marrow suppression, renal impairment, hepatotoxicity, pneumonitis, or gastrointestinal toxicity).23

A distinct advantage of MAbs over other systemic agents in the management of AD is that MAbs do not require frequent monitoring of blood pressure, renal or liver function, complete blood count with differential, electrolytes, or uric acid. Additionally, MAbs have fewer black box warnings and adverse reactions when compared with other systemic agents.

Continue to: Hyperlipidemia

Hyperlipidemia

Three MAbs are approved for use in hyperlipidemia: the angiopoietin-like protein 3 (ANGPTL3) inhibitor evinacumab (Evkeeza)24 and 2 proprotein convertase subtilisin/kexin type 9 (PCSK9) inhibitors, evolocumab (Repatha)25 and alirocumab (Praluent).26

ANGPTL3 inhibitors block ANGPTL3 and reduce endothelial lipase and lipoprotein lipase activity, which in turn decreases low-density lipoprotein cholesterol (LDL-C), high-density lipoprotein cholesterol (HDL-C), and triglyceride formation. PCSK9 inhibitors prevent PCSK9 from binding to LDL receptors, thereby maintaining the number of active LDL receptors and increasing LDL-C removal.

Evinacumab is indicated for homozygous familial hypercholesterolemia and is administered intravenously every 4 weeks. Evinacumab has not been evaluated for effects on cardiovascular morbidity and mortality.

Evolocumab 140 mg SC every 2 weeks or 420 mg SC monthly has been studied in patients on statin therapy with LDL-C ≥ 70 mg/dL. Patients on evolocumab experienced significantly less of the composite endpoint of cardiovascular death, myocardial infarction (MI), stroke, hospitalization for unstable angina, or coronary revascularization compared with placebo (9.8% vs 11.3%; hazard ratio [HR] = 0.85; 95% CI, 0.79-0.92; NNT = 67.27

Alirocumab 75 mg SC every 2 weeks has also been studied in patients receiving statin therapy with LDL-C ≥ 70 mg/dL. Patients taking alirocumab experienced significantly less of the composite endpoint of death from coronary heart disease, nonfatal MI, ischemic stroke, or hospitalization for unstable angina compared with placebo (9.5% vs 11.1%; HR = 0.85; 95% CI, 0.78-0.93; NNT = 63).

Continue to: According to the 2018...

According to the 2018 AHA Cholesterol Guidelines, PCSK9 inhibitors are indicated for patients receiving maximally tolerated LDL-C-lowering therapy (statin and ezetimibe) with LDL-C ≥ 70 mg/dL, if they have had multiple atherosclerotic cardiovascular disease (ASCVD) events or 1 major ASCVD event with multiple high-risk conditions (eg, heterozygous familial hypercholesterolemia, history of coronary artery bypass grafting or percutaneous coronary intervention, hypertension, estimated glomerular filtration rate of 15 to 59 mL/min/1.73m2).29 For patients without prior ASCVD events or high-risk conditions who are receiving maximally tolerated LDL-C-lowering therapy (statin and ezetimibe), PCSK9 inhibitors are indicated if the LDL-C remains ≥ 100 mg/dL.

Osteoporosis

The 2 MAbs approved for use in osteoporosis are the receptor activator of nuclear factor kB ligand (RANKL) inhibitor denosumab (Prolia)30 and the sclerostin inhibitor romosozumab (Evenity).31

Denosumab prevents RANKL from binding to the RANK receptor, thereby inhibiting osteoclast formation and decreasing bone resorption. Denosumab is approved for use in women and men who are at high risk of osteoporotic fracture, including those taking OCSs, men receiving androgen deprivation therapy for prostate cancer, and women receiving adjuvant aromatase inhibitor therapy for breast cancer.

In a 3-year randomized trial, denosumab 60 mg SC every 6 months was compared with placebo in postmenopausal women with T-scores < –2.5, but not < –4.0 at the lumbar spine or total hip. Denosumab significantly reduced new radiographic vertebral fractures (2.3% vs 7.2%; risk ratio [RR] = 0.32; 95% CI, 0.26-0.41; NNT = 21), hip fracture (0.7% vs 1.2%), and nonvertebral fracture (6.5% vs 8.0%).32 Denosumab carries an increased risk of multiple vertebral fractures following discontinuation, skin infections, dermatologic reactions, and severe bone, joint, and muscle pain.

Romosozumab inhibits sclerostin, thereby increasing bone formation and, to a lesser degree, decreasing bone resorption. Romosozumab is approved for use in postmenopausal women at high risk for fracture (ie, those with a history of osteoporotic fracture or multiple risk factors for fracture) or in patients who have not benefited from or are intolerant of other therapies. In one study, postmenopausal women with a T-score of –2.5 to –3.5 at the total hip or femoral neck were randomly assigned to receive either romosozumab 210 mg SC or placebo for 12 months, then each group was switched to denosumab 60 mg SC for 12 months. After the first year, prior to initiating denosumab, patients taking romosozumab experienced significantly fewer new vertebral fractures than patients taking placebo (0.5% vs 1.8%; RR = 0.27; 95% CI, 0.16-0.47; NNT = 77); however, there was no significant difference between the 2 groups with nonvertebral fractures (HR = 0.75; 95% CI, 0.53-1.05).33

Continue to: In another study...

In another study, romosozumab 210 mg SC was compared with alendronate 70 mg weekly, followed by alendronate 70 mg weekly in both groups. Over the first 12 months, patients treated with romosozumab saw a significant reduction in the incidence of new vertebral fractures (4% vs 6.3%; RR = 0.63, P < .003; NNT = 44). Patients treated with romosozumab with alendronate added for another 12 months also saw a significant reduction in new incidence of vertebral fractures (6.2% vs 11.9%; RR = 0.52; P < .001; NNT = 18).34 There was a higher risk of cardiovascular events among patients receiving romosozumab compared with those treated with alendronate, so romosozumab should not be used in individuals who have had an MI or stroke within the previous year.34 Denosumab and romosozumab offer an advantage over some bisphosphonates in that they require less frequent dosing and can be used in patients with renal impairment (creatinine clearance < 35 mL/min, in which zoledronic acid is contraindicated and alendronate is not recommended; < 30 mL/min, in which risedronate and ibandronate are not recommended).

Migraine prevention

Four

Erenumab, fremanezumab, and galcanezumab are all available in subcutaneous autoinjectors (or syringe with fremanezumab). Eptinezumab is an intravenous (IV) infusion given every 3 months.

Erenumab is available in both 70-mg and 140-mg dosing options. Fremanezumab can be given as 225 mg monthly or 675 mg quarterly. Galcanezumab has an initial loading dose of 240 mg followed by 120 mg given monthly. Erenumab targets the CGRP receptor; the others target the CGRP ligand. Eptinezumab has 100% bioavailability and reaches maximum serum concentration sooner than the other antagonists (due to its route of administration), but it must be given in an infusion center. Few insurers approve the use of eptinezumab unless a trial of least 1 of the monthly injectables has failed.

There are no head-to-head studies of the medications in this class. Additionally, differing study designs, definitions, statistical analyses, endpoints, and responder-rate calculations make it challenging to compare them directly against one another. At the very least, all of the CGRP MAbs have efficacy comparable to conventional preventive migraine medications such as propranolol, amitriptyline, and topiramate.40

Continue to: The most commonly reported adverse...

The most commonly reported adverse effect for all 4 CGRPs is injection site reaction, which was highest with the quarterly fremanezumab dose (45%).37 Constipation was most notable with the 140-mg dose of erenumab (3%)35; with the other CGRP MAbs it is comparable to that seen with placebo (< 1%).

Erenumab-induced hypertension has been identified in 61 cases reported through the FDA Adverse Event Reporting System (FAERS) as of 2021.41 This was not reported during MAb development programs, nor was it noted during clinical trials. Blood pressure elevation was seen within 1 week of injection in nearly 50% of the cases, and nearly one-third had pre-existing hypertension.41 Due to these findings, the erenumab prescribing information was updated to include hypertension in its warnings and precautions. It is possible that hypertension could be a class effect, although trial data and posthoc studies have yet to bear that out. Since erenumab was the first CGRP antagonist brought to market (May 2018 vs September 2018 for fremanezumab and galcanezumab), it may have accumulated more FAERS reports. Nearly all studies exclude patients with older age, uncontrolled hypertension, and unstable cardiovascular disease, which could impact data.41

Overall, this class of medications is very well tolerated, easy to use (again, excluding eptinezumab), and maintains a low adverse effect profile, giving added value compared with conventional preventive migraine medications.

The American Headache Society recommends a preventive oral therapy for at least 3 months before trying an alternative medication. After treatment failure with at least 2 oral agents, CGRP MAbs are recommended.42 CGRP antagonists offer convenient dosing, bypass gastrointestinal metabolism (which is useful in patients with nausea/vomiting), and have fewer adverse effects than traditional oral medications.

Worth noting. Several newer oral agents have been recently approved for migraine prevention, including atogepant (Qulipta) and rimegepant (Nurtec), which are also CGRP antagonists. Rimegepant is approved for both acute migraine treatment and prevention.

Continue to: Migraine

❯ Migraine: Test your skills

Subjective findings: A 25-year-old woman presents to your clinic for management of episodic migraines with aura. Her baseline average migraine frequency is 9 headache days/month. Her migraines are becoming more frequent despite treatment. She fears IV medication use and avoids hospitals.

History: Hypertension, irritable bowel syndrome with constipation (IBS-C), and depression. The patient is not pregnant or trying to get pregnant.

Medications: Current medications (for previous 4 months) include propranolol 40 mg at bedtime, linaclotide 145 μg/d, citalopram 20 mg/d, and sumatriptan 50 mg prn. Past medications include venlafaxine 150 mg po bid for 5 months.

What would be appropriate for this patient? This patient meets the criteria for using a CGRP antagonist because she has tried 2 preventive treatments for more than 60 to 90 days. Erenumab is not the best option, given the patient’s history of hypertension and IBS-C. The patient fears hospitals and IV medications, making eptinezumab a less-than-ideal choice. Depending on her insurance, fremanezumab or galcanezumab would be good options at this time.

CGRP antagonists have not been studied or evaluated in pregnancy, but if this patient becomes pregnant, a first-line agent for prevention would be propranolol, and a second-line agent would be a tricyclic antidepressant, memantine, or verapamil. Avoid ergotamines and antiepileptics (topiramate or valproate) in pregnancy.43,44

Continue to: The challenges associated with MAbs

The challenges associated with MAbs

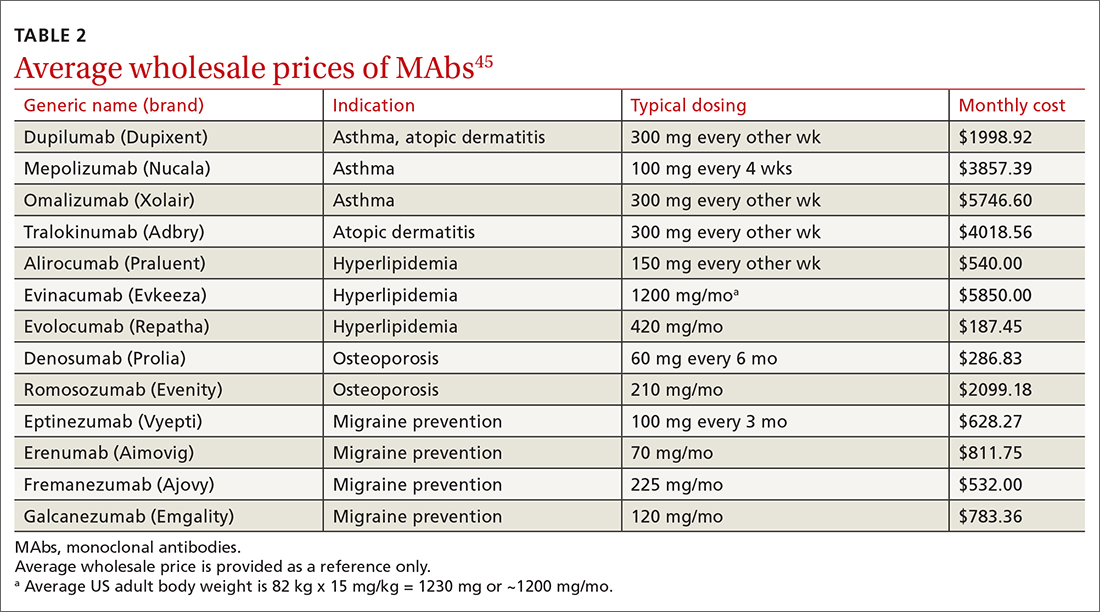

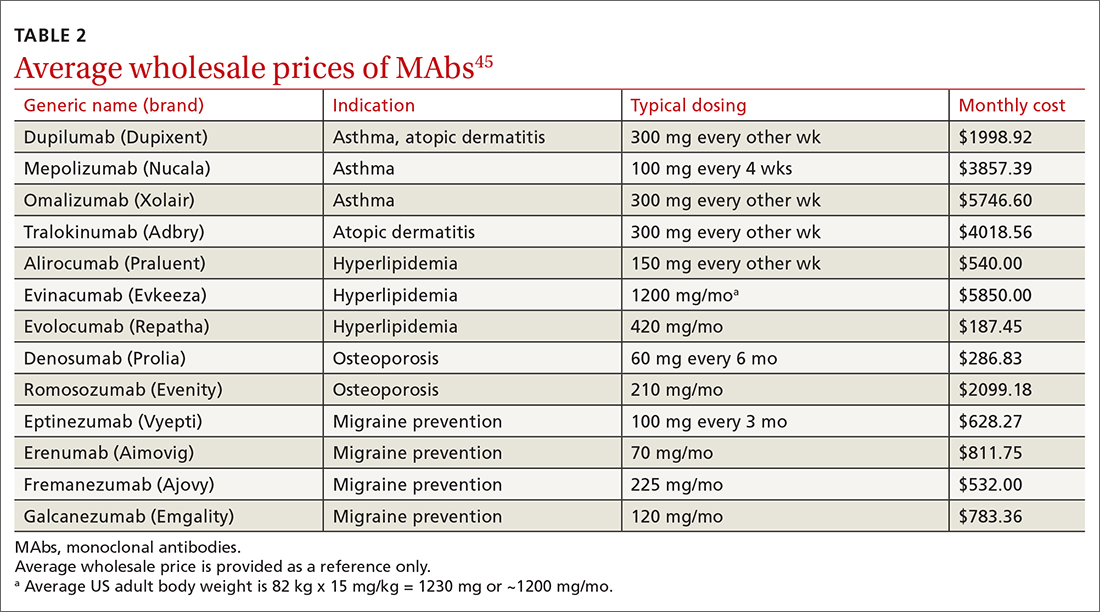

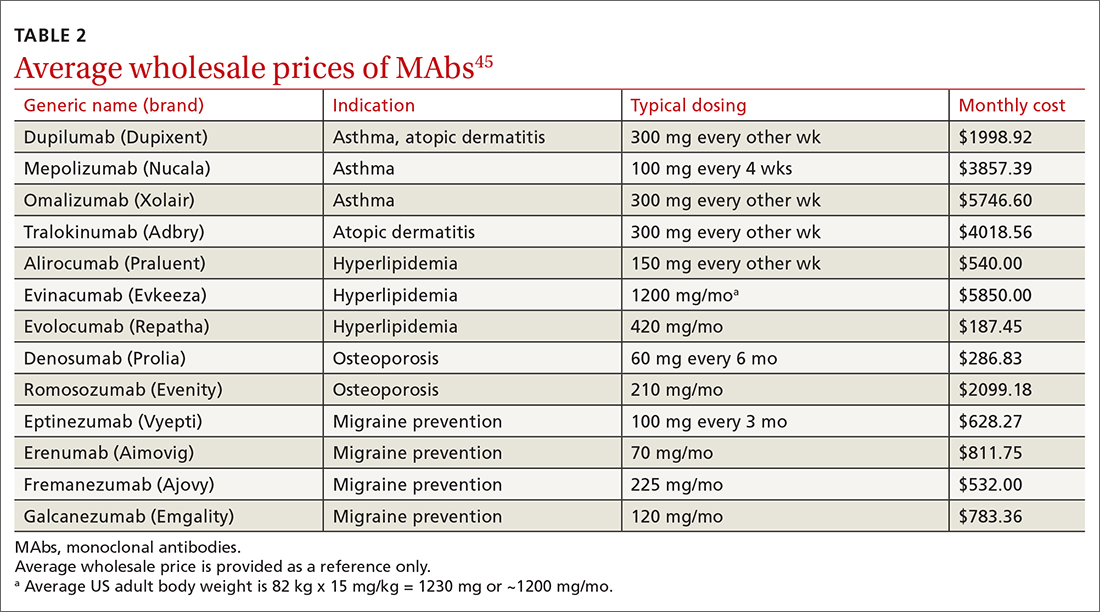

MAbs can be expensive (TABLE 2),45 some prohibitively so. On a population scale, biologics account for around 40% of prescription drug spending and may cost 22 times more than small-molecule drugs.46 Estimates in 2016 showed that MAbs comprise $90.2 billion (43%) of the biologic market.46

MAbs also require prior authorization forms to be submitted. Prior authorization criteria vary by state and by insurance plan. In my (ES) experience, submitting letters of medical necessity justifying the need for therapy or expertise in the disease states for which the MAb is being prescribed help your patient get the medication they need.

Expect to see additional MAbs approved in the future. If the costs come down, adoption of these agents into practice will likely increase.

CORRESPONDENCE

Evelyn Sbar, MD, Texas Tech University Health Sciences Center, 1400 South Coulter Street, Suite 5100, Amarillo, TX 79106; evelyn.sbar@ttuhsc.edu

1. Rui P, Okeyode T. National Ambulatory Medical Care Survey: 2016 national summary tables. National Center for Health Statistics. Accessed June 15, 2022. www.cdc.gov/nchs/data/ahcd/namcs_summary/2016_namcs_web_tables.pdf

2. IDBS. The future of biologics drug development is today. June 27, 2018. Accessed June 15, 2022. www.idbs.com/blog/2018/06/the-future-of-biologics-drug-development-is-today/

3. Antibody therapeutics approved or in regulatory review in the EU or US. Antibody Society. Accessed June 15, 2022. www.antibodysociety.org/resources/approved-antibodies/

4. FDA. Code of Federal Regulations, Title 21, Chapter I, Subchapter F biologics. March 29, 2022. Accessed June 15, 2022. www.accessdata.fda.gov/scripts/cdrh/cfdocs/cfcfr/CFRSearch.cfm?fr=600.3

5. Köhler G, Milstein C. Continuous cultures of fused cells secreting antibody of predefined specificity. Nature. 1975;256:495-497. doi: 10.1038/256495a0

6. Raejewsky K. The advent and rise of monoclonal antibodies. Nature. November 4, 2019. Accessed June 15, 2022. www.nature.com/articles/d41586-019-02840-w

7. Flovent. Prescribing information. GlaxoSmithKline; 2010. Accessed June 15, 2022. www.accessdata.fda.gov/drugsatfda_docs/label/2010/021433s015lbl.pdf

8. NLM. National Center for Biotechnology Information. PubChem. Method for the preparation of fluticasone and related 17beta-carbothioic esters using a novel carbothioic acid synthesis and novel purification methods. Accessed June 15, 2022. pubchem.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/patent/WO-0162722-A2

9. Nucala. Prescribing information. GlaxoSmithKline; 2019. Accessed June 15, 2022. www.accessdata.fda.gov/drugsatfda_docs/label/2019/761122s000lbl.pdf

10. Argyriou AA, Kalofonos HP. Recent advances relating to the clinical application of naked monoclonal antibodies in solid tumors. Mol Med. 2009;15:183-191. doi: 10.2119/molmed.2009.00007

11. Wang W, Wang EQ, Balthasar JP. Monoclonal antibody pharmacokinetics and pharmacodynamics. Clin Pharmacol Ther. 2008;84:548-558. doi: 10.1038/clpt.2008.170

12. Zahavi D, AlDeghaither D, O’Connell A, et al. Enhancing antibody-dependent cell-mediated cytotoxicity: a strategy for improving antibody-based immunotherapy. Antib Ther. 2018;1:7-12. doi: 10.1093/abt/tby002

13. Normansell R, Walker S, Milan SJ, et al. Omalizumab for asthma in adults and children. Cochrane Database Syst Rev. 2014:CD003559. doi: 10.1002/14651858.CD003559.pub4

14. Farne HA, Wilson A, Powell C, et al. Anti-IL5 therapies for asthma. Cochrane Database Syst Rev. 2017;9:CD010834. doi: 10.1002/14651858.CD010834.pub3

15. Castro M, Corren J, Pavord ID, et al. Dupilumab efficacy and safety in moderate-to-severe uncontrolled asthma. N Engl J Med. 2018;378:2486-2496. doi: 10.1056/NEJMoa1804092

16. GINA. Global strategy for asthma management and prevention. 2022 Difficult-to-treat and severe asthma guide—slide set. Accessed June 23, 2022. https://ginasthma.org/severeasthma/

17. Ortega HG, Liu MC, Pavord ID, et al. Mepolizumab treatment in patients with severe eosinophilic asthma. N Engl J Med. 2014;371:1198-1207. doi: 10.1056/NEJMoa1403290

18. Bel EH, Wenzel SE, Thompson PJ, et al. Oral glucocorticoid-sparing effect of mepolizumab in eosinophilic asthma. N Engl J Med. 2014;371:1189-1197. doi: 10.1056/NEJMoa1403291

19. Adbry. Prescribing information. Leo Pharma Inc; 2021. Accessed June 24, 2022. www.accessdata.fda.gov/drugsatfda_docs/nda/2022/761180Orig1s000lbl.pdf

20. Dupixent. Prescribing information. Regeneron Pharmaceuticals; 2022. Accessed October 5, 2022. https://www.regeneron.com/downloads/dupixent_fpi.pdf

21. Simpson EL, Bieber T, Guttman-Yassky E, et al. Two phase 3 trials of dupilumab versus placebo in atopic dermatitis. N Engl J Med. 2016;375:2335-2348. doi: 10.1056/NEJMoa1610020

22. Blauvelt A, de Bruin-Weller M, Gooderham M, et al. Long-term management of moderate-to-severe atopic dermatitis with dupilumab and concomitant topical corticosteroids (LIBERTY AD CHRONOS): a 1-year, randomised, double-blinded, placebo-controlled, phase 3 trial. Lancet. 2017;389:2287-2303. doi: 10.1016/s0140-6736(17)31191-1

23. Sidbury R, Davis DM, Cohen DE, et al. Guidelines of care for the management of atopic dermatitis: section 3. Management and treatment with phototherapy and systemic agents. J Am Acad Dermatol. 2014;71:327-349. doi: 10.1016/j.jaad.2014.03.030

24. Evkeeza. Prescribing information. Regeneron Pharmaceuticals; 2021. Accessed June 24, 2022. https://www.accessdata.fda.gov/drugsatfda_docs/label/2021/761181s000lbl.pdf

25. Repatha. Prescribing information. Amgen; 2015. Accessed June 24, 2022. www.accessdata.fda.gov/drugsatfda_docs/label/2017/125522s014lbl.pdf

26. Praluent. Prescribing information. Sanofi Aventis and Regeneron Pharmaceuticals. 2015. Accessed June 24, 2022. www.accessdata.fda.gov/drugsatfda_docs/label/2017/125559s002lbl.pdf

27. Sabatine MS, Giugliano RP, Keech AC, et al. Evolocumab and clinical outcomes in patients with cardiovascular disease. N Engl J Med. 2017;376:1713-1722. doi: 10.1056/NEJMoa1615664

28. Schwartz GG, Steg PG, Szarek M, et al. Alirocumab and cardiovascular outcomes after acute coronary syndrome. N Engl J Med. 2018;379:2097-2107. doi:10.1056/NEJMoa1801174

29. Grundy SM, Stone NJ, Bailey AL, et al. 2018 AHA/ACC/AACVPR/AAPA/ABC/ACPM/ADA/AGS/APhA/ASPC/NLA/PCNA guideline on the management of blood cholesterol: a report of the American College of Cardiology/American Heart Association Task Force on clinical practice guidelines. J Am Coll Cardiol. 2019;73:e285-e350. doi: 10.1016/j.jacc.2018.11.003

30. Prolia. Prescribing information. Amgen; 2010. Accessed June 24, 2022. www.accessdata.fda.gov/drugsatfda_docs/label/2013/125320s094lbl.pdf

31. Evenity. Prescribing information. Amgen; 2019. Accessed June 24, 2022. www.accessdata.fda.gov/drugsatfda_docs/label/2019/761062s000lbl.pdf

32. Cummings SR, San Martin J, McClung MR, et al. Denosumab for prevention of fractures in postmenopausal women with osteoporosis. N Engl J Med. 2009;361:756-765. doi: 10.1056/NEJMoa0809493

33. Cosman F, Crittenden DB, Adachi JD, et al. Romosozumab treatment in postmenopausal women with osteoporosis. N Engl J Med. 2016;375:1532-1543. doi: 10.1056/NEJMoa1607948

34. Saag KG, Petersen J, Brandi ML, et al. Romosozumab or alendronate for fracture prevention in women with osteoporosis. N Engl J Med. 2017;377:1417-1427. doi: 10.1056/NEJMoa1708322

35. Aimovig. Prescribing information. Amgen; 2018. Accessed June 24, 2022. www.accessdata.fda.gov/drugsatfda_docs/label/2018/761077s000lbl.pdf

36. Vyepti. Prescribing information. Lundbeck Seattle BioPharmaceuticals; 2020. Accessed June 24, 2022. www.accessdata.fda.gov/drugsatfda_docs/label/2020/761119s000lbl.pdf

37. Ajovy. Prescribing information. Teva Pharmaceuticals; 2018. Accessed June 24, 2022. www.accessdata.fda.gov/drugsatfda_docs/label/2018/761089s000lbl.pdf

38. Emgality. Prescribing information. Eli Lilly and Co.; 2018. Accessed June 24, 2022. www.accessdata.fda.gov/drugsatfda_docs/label/2018/761063s000lbl.pdf

39. Edvinsson L, Haanes KA, Warfvinge K, et al. CGRP as the target of new migraine therapies - successful translation from bench to clinic. Nat Rev Neurol. 2018;14:338-350. doi: 10.1038/s41582-018-0003-1

40. Vandervorst F. Van Deun L, Van Dycke A, et al. CGRP monoclonal antibodies in migraine: an efficacy and tolerability comparison with standard prophylactic drugs. J Headache Pain. 2021;22:128. doi: 10.1186/s10194-021-01335-2

41. Saely S, Croteau D, Jawidzik L, et al. Hypertension: a new safety risk for patients treated with erenumab. Headache. 2021;61:202-208. doi: 10.1111/head.14051

42. American Headache Society. The American Headache Society position statement on integrating new migraine treatments into clinical practice. Headache. 2019;59:1-18. doi: 10.1111/head.13456

43. Burch R. Headache in pregnancy and the puerperium. Neurol Clin. 2019;37:31-51. doi: 10.1016/j.ncl.2018.09.004

44. Burch R. Epidemiology and treatment of menstrual migraine and migraine during pregnancy and lactation: a narrative review. Headache. 2020;60:200-216. doi: 10.1111/head.13665

45. Lexi-Comp. Lexi-drug database. Accessed April 4, 2022. https://online.lexi.com/lco/action/login

46. Walker N. Biologics: driving force in pharma. Pharma’s Almanac. June 5, 2017. Accessed June 15, 2020. www.pharmasalmanac.com/articles/biologics-driving-force-in-pharma

Small-molecule drugs such as aspirin, albuterol, atorvastatin, and lisinopril are the backbone of disease management in family medicine.1 However, large-molecule biological drugs such as monoclonal antibodies (MAbs) are increasingly prescribed to treat common conditions. In the past decade, MAbs comprised 20% of all drug approvals by the US Food and Drug Administration (FDA), and today they represent more than half of drugs currently in development.2 Fifteen MAbs have been approved by the FDA over the past decade for asthma, atopic dermatitis (AD), hyperlipidemia, osteoporosis, and migraine prevention.3 This review details what makes MAbs unique and what you should know about them.

The uniqueness of monoclonal antibodies

MAbs are biologics, but not all biologics are MAbs—eg, adalimumab (Humira) is a MAb, but etanercept (Enbrel) is not. MAbs are therapeutic proteins made possible by hybridoma technology used to create an antibody with single specificity.4-6 Monoclonal antibodies differ from small-molecule drugs in structure, dosing, route of administration, manufacturing, metabolism, drug interactions, and elimination (TABLE 17-9).

MAbs can be classified as naked, “without any drug or radioactive material attached to them,” or conjugated, “joined to a chemotherapy drug, radioactive isotope, or toxin.”10 MAbs work in several ways, including competitively inhibiting ligand-receptor binding, receptor blockade, or cell elimination from indirect immune system activities such as antibody-dependent cell-mediated cytotoxicity.11,12

Monoclonal antibody uses in family medicine

Asthma

Several MAbs have been approved for use in severe asthma, including but not limited to: omalizumab (Xolair),13 mepolizumab (Nucala),9,14 and dupilumab (Dupixent).15

Omalizumab is a humanized MAb that prevents IgE antibodies from binding to mast cells and basophils, thereby reducing inflammatory mediators.13 A systematic review found that, compared with placebo, omalizumab used in patients with inadequately controlled moderate-to-severe asthma led to significantly fewer asthma exacerbations (absolute risk reduction [ARR], 16% vs 26%; odds ratio [OR] = 0.55; 95% CI, 0.42-0.60; number needed to treat [NNT] = 10) and fewer hospitalizations (ARR, 0.5% vs 3%; OR = 0.16; 95% CI, 0.06-0.42; NNT = 40).13

Significantly more patients in the omalizumab group were able to withdraw from, or reduce, the dose of ICS. GINA recommends omalizumab for patients with positive skin sensitization, total serum IgE ≥ 30 IU/mL, weight within 30 kg to 150 kg, history of childhood asthma and recent exacerbations, and blood eosinophils ≥ 260/mcL.16 Omalizumab is also approved for use in chronic spontaneous urticaria and nasal polyps.

Mepolizumab

Continue to: Another trial found that...

Another trial found that mepolizumab reduced total OCS doses in patients with severe asthma by 50% without increasing exacerbations or worsening asthma control.18 All 3 anti-IL-5 drugs—including not only mepolizumab, but also benralizumab (Fasenra) and reslizumab (Cinqair)—appear to yield similar improvements. A 2017 systematic review found all anti-IL-5 treatments reduced rates of clinically significant asthma exacerbations (treatment with OCS for ≥ 3 days) by roughly 50% in patients with severe eosinophilic asthma and a history of ≥ 2 exacerbations in the past year.

Dupilumab is a humanized MAb that inhibits IL-4 and IL-13, which influence multiple cell types involved in inflammation (eg, mast cells, eosinophils) and inflammatory mediators (histamine, leukotrienes, cytokines).15 In a recent study of patients with uncontrolled asthma, dupilumab 200 mg every 2 weeks compared with placebo showed a modest reduction in the annualized rate of severe asthma exacerbations (0.46 exacerbations vs 0.87, respectively). Dupilumab was effective in patients with blood eosinophil counts ≥ 150/μL but was ineffective in patients with eosinophil counts < 150/μL.15

For patients ≥ 12 years old with severe eosinophilic asthma, GINA recommends using dupilumab as add-on therapy for an initial trial of 4 months at doses of 200 or 300 mg SC every 2 weeks, with preference for 300 mg SC every 2 weeks for OCS-dependent asthma. Dupilumab is approved for use in AD and chronic rhinosinusitis with nasal polyposis. If a biologic agent is not successful after a 4-month trial, consider a 6- to 12-month trial. If efficacy is still minimal, consider switching to an alternative biologic therapy approved for asthma.16

❯ Asthma: Test your skills

Subjective findings: A 19-year-old man presents to your clinic. He has a history of nasal polyps and allergic asthma. At age 18, he was given a diagnosis of severe persistent asthma. He has shortness of breath during waking hours 4 times per week, and treats each of these episodes with albuterol. He also wakes up about twice a week with shortness of breath and has some limitations in normal activities. He reports missing his prescribed fluticasone/salmeterol 500/50 μg, 1 inhalation bid, only once each month. In the last year, he has had 2 exacerbations requiring oral steroids.

Medications: Albuterol 90 μg, 1-2 inhalations, q6h prn; fluticasone/salmeterol 500/50 μg, 1 inhalation bid; tiotropium 1.25 μg, 2 puffs/d; montelukast 10 mg every morning; prednisone 10 mg/d.

Continue to: Objective data

Objective data: Patient is in no apparent distress and afebrile, and oxygen saturation on room air is 97%. Ht, 70 inches; wt, 75 kg. Labs: IgE, 15 IU/mL; serum eosinophils, 315/μL.

Which MAb would be appropriate for this patient? Given that the patient has a blood eosinophil level ≥ 300/μL and severe exacerbations, adult-onset asthma, nasal polyposis, and maintenance OCS at baseline, it would be reasonable to initiate mepolizumab 100 mg SC every 4 weeks, or dupilumab 600 mg once, then 300 mg SC every 2 weeks. Both agents can be self-administered.

Atopic dermatitis

Two MAbs—dupilumab and tralokinumab (Adbry; inhibits IL-13)—are approved for treatment of AD in adults that is uncontrolled with conventional therapy.15,19 Dupilumab is also approved for children ≥ 6 months old.20 Both MAbs are dosed at 600 mg SC, followed by 300 mg every 2 weeks. Dupilumab was compared with placebo in adult patients who had moderate-to-severe AD inadequately controlled on topical corticosteroids (TCSs), to determine the proportion of patients in each group achieving improvement of either 0 or 1 points or ≥ 2 points in the 5-point Investigator Global Assessment (IGA) score from baseline to 16 weeks.21 Thirty-seven percent of patients receiving dupilumab 300 mg SC weekly and 38% of patients receiving dupilumab 300 mg SC every 2 weeks achieved the primary outcome, compared with 10% of those receiving placebo (P < .001).21 Similar IGA scores were reported when dupilumab was combined with TCS, compared with placebo.22

It would be reasonable to consider dupilumab or tralokinumab in patients with: cutaneous atrophy or hypothalamic-pituitary-adrenal axis suppression with TCS, concerns of malignancy with topical calcineurin inhibitors, or problems with the alternative systemic therapies (cyclosporine-induced hypertension, nephrotoxicity, or immunosuppression; azathioprine-induced malignancy; or methotrexate-induced bone marrow suppression, renal impairment, hepatotoxicity, pneumonitis, or gastrointestinal toxicity).23

A distinct advantage of MAbs over other systemic agents in the management of AD is that MAbs do not require frequent monitoring of blood pressure, renal or liver function, complete blood count with differential, electrolytes, or uric acid. Additionally, MAbs have fewer black box warnings and adverse reactions when compared with other systemic agents.

Continue to: Hyperlipidemia

Hyperlipidemia

Three MAbs are approved for use in hyperlipidemia: the angiopoietin-like protein 3 (ANGPTL3) inhibitor evinacumab (Evkeeza)24 and 2 proprotein convertase subtilisin/kexin type 9 (PCSK9) inhibitors, evolocumab (Repatha)25 and alirocumab (Praluent).26

ANGPTL3 inhibitors block ANGPTL3 and reduce endothelial lipase and lipoprotein lipase activity, which in turn decreases low-density lipoprotein cholesterol (LDL-C), high-density lipoprotein cholesterol (HDL-C), and triglyceride formation. PCSK9 inhibitors prevent PCSK9 from binding to LDL receptors, thereby maintaining the number of active LDL receptors and increasing LDL-C removal.

Evinacumab is indicated for homozygous familial hypercholesterolemia and is administered intravenously every 4 weeks. Evinacumab has not been evaluated for effects on cardiovascular morbidity and mortality.

Evolocumab 140 mg SC every 2 weeks or 420 mg SC monthly has been studied in patients on statin therapy with LDL-C ≥ 70 mg/dL. Patients on evolocumab experienced significantly less of the composite endpoint of cardiovascular death, myocardial infarction (MI), stroke, hospitalization for unstable angina, or coronary revascularization compared with placebo (9.8% vs 11.3%; hazard ratio [HR] = 0.85; 95% CI, 0.79-0.92; NNT = 67.27

Alirocumab 75 mg SC every 2 weeks has also been studied in patients receiving statin therapy with LDL-C ≥ 70 mg/dL. Patients taking alirocumab experienced significantly less of the composite endpoint of death from coronary heart disease, nonfatal MI, ischemic stroke, or hospitalization for unstable angina compared with placebo (9.5% vs 11.1%; HR = 0.85; 95% CI, 0.78-0.93; NNT = 63).

Continue to: According to the 2018...

According to the 2018 AHA Cholesterol Guidelines, PCSK9 inhibitors are indicated for patients receiving maximally tolerated LDL-C-lowering therapy (statin and ezetimibe) with LDL-C ≥ 70 mg/dL, if they have had multiple atherosclerotic cardiovascular disease (ASCVD) events or 1 major ASCVD event with multiple high-risk conditions (eg, heterozygous familial hypercholesterolemia, history of coronary artery bypass grafting or percutaneous coronary intervention, hypertension, estimated glomerular filtration rate of 15 to 59 mL/min/1.73m2).29 For patients without prior ASCVD events or high-risk conditions who are receiving maximally tolerated LDL-C-lowering therapy (statin and ezetimibe), PCSK9 inhibitors are indicated if the LDL-C remains ≥ 100 mg/dL.

Osteoporosis

The 2 MAbs approved for use in osteoporosis are the receptor activator of nuclear factor kB ligand (RANKL) inhibitor denosumab (Prolia)30 and the sclerostin inhibitor romosozumab (Evenity).31

Denosumab prevents RANKL from binding to the RANK receptor, thereby inhibiting osteoclast formation and decreasing bone resorption. Denosumab is approved for use in women and men who are at high risk of osteoporotic fracture, including those taking OCSs, men receiving androgen deprivation therapy for prostate cancer, and women receiving adjuvant aromatase inhibitor therapy for breast cancer.

In a 3-year randomized trial, denosumab 60 mg SC every 6 months was compared with placebo in postmenopausal women with T-scores < –2.5, but not < –4.0 at the lumbar spine or total hip. Denosumab significantly reduced new radiographic vertebral fractures (2.3% vs 7.2%; risk ratio [RR] = 0.32; 95% CI, 0.26-0.41; NNT = 21), hip fracture (0.7% vs 1.2%), and nonvertebral fracture (6.5% vs 8.0%).32 Denosumab carries an increased risk of multiple vertebral fractures following discontinuation, skin infections, dermatologic reactions, and severe bone, joint, and muscle pain.

Romosozumab inhibits sclerostin, thereby increasing bone formation and, to a lesser degree, decreasing bone resorption. Romosozumab is approved for use in postmenopausal women at high risk for fracture (ie, those with a history of osteoporotic fracture or multiple risk factors for fracture) or in patients who have not benefited from or are intolerant of other therapies. In one study, postmenopausal women with a T-score of –2.5 to –3.5 at the total hip or femoral neck were randomly assigned to receive either romosozumab 210 mg SC or placebo for 12 months, then each group was switched to denosumab 60 mg SC for 12 months. After the first year, prior to initiating denosumab, patients taking romosozumab experienced significantly fewer new vertebral fractures than patients taking placebo (0.5% vs 1.8%; RR = 0.27; 95% CI, 0.16-0.47; NNT = 77); however, there was no significant difference between the 2 groups with nonvertebral fractures (HR = 0.75; 95% CI, 0.53-1.05).33

Continue to: In another study...

In another study, romosozumab 210 mg SC was compared with alendronate 70 mg weekly, followed by alendronate 70 mg weekly in both groups. Over the first 12 months, patients treated with romosozumab saw a significant reduction in the incidence of new vertebral fractures (4% vs 6.3%; RR = 0.63, P < .003; NNT = 44). Patients treated with romosozumab with alendronate added for another 12 months also saw a significant reduction in new incidence of vertebral fractures (6.2% vs 11.9%; RR = 0.52; P < .001; NNT = 18).34 There was a higher risk of cardiovascular events among patients receiving romosozumab compared with those treated with alendronate, so romosozumab should not be used in individuals who have had an MI or stroke within the previous year.34 Denosumab and romosozumab offer an advantage over some bisphosphonates in that they require less frequent dosing and can be used in patients with renal impairment (creatinine clearance < 35 mL/min, in which zoledronic acid is contraindicated and alendronate is not recommended; < 30 mL/min, in which risedronate and ibandronate are not recommended).

Migraine prevention

Four

Erenumab, fremanezumab, and galcanezumab are all available in subcutaneous autoinjectors (or syringe with fremanezumab). Eptinezumab is an intravenous (IV) infusion given every 3 months.

Erenumab is available in both 70-mg and 140-mg dosing options. Fremanezumab can be given as 225 mg monthly or 675 mg quarterly. Galcanezumab has an initial loading dose of 240 mg followed by 120 mg given monthly. Erenumab targets the CGRP receptor; the others target the CGRP ligand. Eptinezumab has 100% bioavailability and reaches maximum serum concentration sooner than the other antagonists (due to its route of administration), but it must be given in an infusion center. Few insurers approve the use of eptinezumab unless a trial of least 1 of the monthly injectables has failed.

There are no head-to-head studies of the medications in this class. Additionally, differing study designs, definitions, statistical analyses, endpoints, and responder-rate calculations make it challenging to compare them directly against one another. At the very least, all of the CGRP MAbs have efficacy comparable to conventional preventive migraine medications such as propranolol, amitriptyline, and topiramate.40

Continue to: The most commonly reported adverse...

The most commonly reported adverse effect for all 4 CGRPs is injection site reaction, which was highest with the quarterly fremanezumab dose (45%).37 Constipation was most notable with the 140-mg dose of erenumab (3%)35; with the other CGRP MAbs it is comparable to that seen with placebo (< 1%).

Erenumab-induced hypertension has been identified in 61 cases reported through the FDA Adverse Event Reporting System (FAERS) as of 2021.41 This was not reported during MAb development programs, nor was it noted during clinical trials. Blood pressure elevation was seen within 1 week of injection in nearly 50% of the cases, and nearly one-third had pre-existing hypertension.41 Due to these findings, the erenumab prescribing information was updated to include hypertension in its warnings and precautions. It is possible that hypertension could be a class effect, although trial data and posthoc studies have yet to bear that out. Since erenumab was the first CGRP antagonist brought to market (May 2018 vs September 2018 for fremanezumab and galcanezumab), it may have accumulated more FAERS reports. Nearly all studies exclude patients with older age, uncontrolled hypertension, and unstable cardiovascular disease, which could impact data.41

Overall, this class of medications is very well tolerated, easy to use (again, excluding eptinezumab), and maintains a low adverse effect profile, giving added value compared with conventional preventive migraine medications.

The American Headache Society recommends a preventive oral therapy for at least 3 months before trying an alternative medication. After treatment failure with at least 2 oral agents, CGRP MAbs are recommended.42 CGRP antagonists offer convenient dosing, bypass gastrointestinal metabolism (which is useful in patients with nausea/vomiting), and have fewer adverse effects than traditional oral medications.

Worth noting. Several newer oral agents have been recently approved for migraine prevention, including atogepant (Qulipta) and rimegepant (Nurtec), which are also CGRP antagonists. Rimegepant is approved for both acute migraine treatment and prevention.

Continue to: Migraine

❯ Migraine: Test your skills

Subjective findings: A 25-year-old woman presents to your clinic for management of episodic migraines with aura. Her baseline average migraine frequency is 9 headache days/month. Her migraines are becoming more frequent despite treatment. She fears IV medication use and avoids hospitals.

History: Hypertension, irritable bowel syndrome with constipation (IBS-C), and depression. The patient is not pregnant or trying to get pregnant.

Medications: Current medications (for previous 4 months) include propranolol 40 mg at bedtime, linaclotide 145 μg/d, citalopram 20 mg/d, and sumatriptan 50 mg prn. Past medications include venlafaxine 150 mg po bid for 5 months.

What would be appropriate for this patient? This patient meets the criteria for using a CGRP antagonist because she has tried 2 preventive treatments for more than 60 to 90 days. Erenumab is not the best option, given the patient’s history of hypertension and IBS-C. The patient fears hospitals and IV medications, making eptinezumab a less-than-ideal choice. Depending on her insurance, fremanezumab or galcanezumab would be good options at this time.

CGRP antagonists have not been studied or evaluated in pregnancy, but if this patient becomes pregnant, a first-line agent for prevention would be propranolol, and a second-line agent would be a tricyclic antidepressant, memantine, or verapamil. Avoid ergotamines and antiepileptics (topiramate or valproate) in pregnancy.43,44

Continue to: The challenges associated with MAbs

The challenges associated with MAbs

MAbs can be expensive (TABLE 2),45 some prohibitively so. On a population scale, biologics account for around 40% of prescription drug spending and may cost 22 times more than small-molecule drugs.46 Estimates in 2016 showed that MAbs comprise $90.2 billion (43%) of the biologic market.46

MAbs also require prior authorization forms to be submitted. Prior authorization criteria vary by state and by insurance plan. In my (ES) experience, submitting letters of medical necessity justifying the need for therapy or expertise in the disease states for which the MAb is being prescribed help your patient get the medication they need.

Expect to see additional MAbs approved in the future. If the costs come down, adoption of these agents into practice will likely increase.

CORRESPONDENCE

Evelyn Sbar, MD, Texas Tech University Health Sciences Center, 1400 South Coulter Street, Suite 5100, Amarillo, TX 79106; evelyn.sbar@ttuhsc.edu

Small-molecule drugs such as aspirin, albuterol, atorvastatin, and lisinopril are the backbone of disease management in family medicine.1 However, large-molecule biological drugs such as monoclonal antibodies (MAbs) are increasingly prescribed to treat common conditions. In the past decade, MAbs comprised 20% of all drug approvals by the US Food and Drug Administration (FDA), and today they represent more than half of drugs currently in development.2 Fifteen MAbs have been approved by the FDA over the past decade for asthma, atopic dermatitis (AD), hyperlipidemia, osteoporosis, and migraine prevention.3 This review details what makes MAbs unique and what you should know about them.

The uniqueness of monoclonal antibodies

MAbs are biologics, but not all biologics are MAbs—eg, adalimumab (Humira) is a MAb, but etanercept (Enbrel) is not. MAbs are therapeutic proteins made possible by hybridoma technology used to create an antibody with single specificity.4-6 Monoclonal antibodies differ from small-molecule drugs in structure, dosing, route of administration, manufacturing, metabolism, drug interactions, and elimination (TABLE 17-9).

MAbs can be classified as naked, “without any drug or radioactive material attached to them,” or conjugated, “joined to a chemotherapy drug, radioactive isotope, or toxin.”10 MAbs work in several ways, including competitively inhibiting ligand-receptor binding, receptor blockade, or cell elimination from indirect immune system activities such as antibody-dependent cell-mediated cytotoxicity.11,12

Monoclonal antibody uses in family medicine

Asthma

Several MAbs have been approved for use in severe asthma, including but not limited to: omalizumab (Xolair),13 mepolizumab (Nucala),9,14 and dupilumab (Dupixent).15

Omalizumab is a humanized MAb that prevents IgE antibodies from binding to mast cells and basophils, thereby reducing inflammatory mediators.13 A systematic review found that, compared with placebo, omalizumab used in patients with inadequately controlled moderate-to-severe asthma led to significantly fewer asthma exacerbations (absolute risk reduction [ARR], 16% vs 26%; odds ratio [OR] = 0.55; 95% CI, 0.42-0.60; number needed to treat [NNT] = 10) and fewer hospitalizations (ARR, 0.5% vs 3%; OR = 0.16; 95% CI, 0.06-0.42; NNT = 40).13

Significantly more patients in the omalizumab group were able to withdraw from, or reduce, the dose of ICS. GINA recommends omalizumab for patients with positive skin sensitization, total serum IgE ≥ 30 IU/mL, weight within 30 kg to 150 kg, history of childhood asthma and recent exacerbations, and blood eosinophils ≥ 260/mcL.16 Omalizumab is also approved for use in chronic spontaneous urticaria and nasal polyps.

Mepolizumab

Continue to: Another trial found that...

Another trial found that mepolizumab reduced total OCS doses in patients with severe asthma by 50% without increasing exacerbations or worsening asthma control.18 All 3 anti-IL-5 drugs—including not only mepolizumab, but also benralizumab (Fasenra) and reslizumab (Cinqair)—appear to yield similar improvements. A 2017 systematic review found all anti-IL-5 treatments reduced rates of clinically significant asthma exacerbations (treatment with OCS for ≥ 3 days) by roughly 50% in patients with severe eosinophilic asthma and a history of ≥ 2 exacerbations in the past year.

Dupilumab is a humanized MAb that inhibits IL-4 and IL-13, which influence multiple cell types involved in inflammation (eg, mast cells, eosinophils) and inflammatory mediators (histamine, leukotrienes, cytokines).15 In a recent study of patients with uncontrolled asthma, dupilumab 200 mg every 2 weeks compared with placebo showed a modest reduction in the annualized rate of severe asthma exacerbations (0.46 exacerbations vs 0.87, respectively). Dupilumab was effective in patients with blood eosinophil counts ≥ 150/μL but was ineffective in patients with eosinophil counts < 150/μL.15

For patients ≥ 12 years old with severe eosinophilic asthma, GINA recommends using dupilumab as add-on therapy for an initial trial of 4 months at doses of 200 or 300 mg SC every 2 weeks, with preference for 300 mg SC every 2 weeks for OCS-dependent asthma. Dupilumab is approved for use in AD and chronic rhinosinusitis with nasal polyposis. If a biologic agent is not successful after a 4-month trial, consider a 6- to 12-month trial. If efficacy is still minimal, consider switching to an alternative biologic therapy approved for asthma.16

❯ Asthma: Test your skills

Subjective findings: A 19-year-old man presents to your clinic. He has a history of nasal polyps and allergic asthma. At age 18, he was given a diagnosis of severe persistent asthma. He has shortness of breath during waking hours 4 times per week, and treats each of these episodes with albuterol. He also wakes up about twice a week with shortness of breath and has some limitations in normal activities. He reports missing his prescribed fluticasone/salmeterol 500/50 μg, 1 inhalation bid, only once each month. In the last year, he has had 2 exacerbations requiring oral steroids.

Medications: Albuterol 90 μg, 1-2 inhalations, q6h prn; fluticasone/salmeterol 500/50 μg, 1 inhalation bid; tiotropium 1.25 μg, 2 puffs/d; montelukast 10 mg every morning; prednisone 10 mg/d.

Continue to: Objective data

Objective data: Patient is in no apparent distress and afebrile, and oxygen saturation on room air is 97%. Ht, 70 inches; wt, 75 kg. Labs: IgE, 15 IU/mL; serum eosinophils, 315/μL.

Which MAb would be appropriate for this patient? Given that the patient has a blood eosinophil level ≥ 300/μL and severe exacerbations, adult-onset asthma, nasal polyposis, and maintenance OCS at baseline, it would be reasonable to initiate mepolizumab 100 mg SC every 4 weeks, or dupilumab 600 mg once, then 300 mg SC every 2 weeks. Both agents can be self-administered.

Atopic dermatitis

Two MAbs—dupilumab and tralokinumab (Adbry; inhibits IL-13)—are approved for treatment of AD in adults that is uncontrolled with conventional therapy.15,19 Dupilumab is also approved for children ≥ 6 months old.20 Both MAbs are dosed at 600 mg SC, followed by 300 mg every 2 weeks. Dupilumab was compared with placebo in adult patients who had moderate-to-severe AD inadequately controlled on topical corticosteroids (TCSs), to determine the proportion of patients in each group achieving improvement of either 0 or 1 points or ≥ 2 points in the 5-point Investigator Global Assessment (IGA) score from baseline to 16 weeks.21 Thirty-seven percent of patients receiving dupilumab 300 mg SC weekly and 38% of patients receiving dupilumab 300 mg SC every 2 weeks achieved the primary outcome, compared with 10% of those receiving placebo (P < .001).21 Similar IGA scores were reported when dupilumab was combined with TCS, compared with placebo.22

It would be reasonable to consider dupilumab or tralokinumab in patients with: cutaneous atrophy or hypothalamic-pituitary-adrenal axis suppression with TCS, concerns of malignancy with topical calcineurin inhibitors, or problems with the alternative systemic therapies (cyclosporine-induced hypertension, nephrotoxicity, or immunosuppression; azathioprine-induced malignancy; or methotrexate-induced bone marrow suppression, renal impairment, hepatotoxicity, pneumonitis, or gastrointestinal toxicity).23

A distinct advantage of MAbs over other systemic agents in the management of AD is that MAbs do not require frequent monitoring of blood pressure, renal or liver function, complete blood count with differential, electrolytes, or uric acid. Additionally, MAbs have fewer black box warnings and adverse reactions when compared with other systemic agents.

Continue to: Hyperlipidemia

Hyperlipidemia

Three MAbs are approved for use in hyperlipidemia: the angiopoietin-like protein 3 (ANGPTL3) inhibitor evinacumab (Evkeeza)24 and 2 proprotein convertase subtilisin/kexin type 9 (PCSK9) inhibitors, evolocumab (Repatha)25 and alirocumab (Praluent).26

ANGPTL3 inhibitors block ANGPTL3 and reduce endothelial lipase and lipoprotein lipase activity, which in turn decreases low-density lipoprotein cholesterol (LDL-C), high-density lipoprotein cholesterol (HDL-C), and triglyceride formation. PCSK9 inhibitors prevent PCSK9 from binding to LDL receptors, thereby maintaining the number of active LDL receptors and increasing LDL-C removal.

Evinacumab is indicated for homozygous familial hypercholesterolemia and is administered intravenously every 4 weeks. Evinacumab has not been evaluated for effects on cardiovascular morbidity and mortality.

Evolocumab 140 mg SC every 2 weeks or 420 mg SC monthly has been studied in patients on statin therapy with LDL-C ≥ 70 mg/dL. Patients on evolocumab experienced significantly less of the composite endpoint of cardiovascular death, myocardial infarction (MI), stroke, hospitalization for unstable angina, or coronary revascularization compared with placebo (9.8% vs 11.3%; hazard ratio [HR] = 0.85; 95% CI, 0.79-0.92; NNT = 67.27

Alirocumab 75 mg SC every 2 weeks has also been studied in patients receiving statin therapy with LDL-C ≥ 70 mg/dL. Patients taking alirocumab experienced significantly less of the composite endpoint of death from coronary heart disease, nonfatal MI, ischemic stroke, or hospitalization for unstable angina compared with placebo (9.5% vs 11.1%; HR = 0.85; 95% CI, 0.78-0.93; NNT = 63).

Continue to: According to the 2018...

According to the 2018 AHA Cholesterol Guidelines, PCSK9 inhibitors are indicated for patients receiving maximally tolerated LDL-C-lowering therapy (statin and ezetimibe) with LDL-C ≥ 70 mg/dL, if they have had multiple atherosclerotic cardiovascular disease (ASCVD) events or 1 major ASCVD event with multiple high-risk conditions (eg, heterozygous familial hypercholesterolemia, history of coronary artery bypass grafting or percutaneous coronary intervention, hypertension, estimated glomerular filtration rate of 15 to 59 mL/min/1.73m2).29 For patients without prior ASCVD events or high-risk conditions who are receiving maximally tolerated LDL-C-lowering therapy (statin and ezetimibe), PCSK9 inhibitors are indicated if the LDL-C remains ≥ 100 mg/dL.

Osteoporosis

The 2 MAbs approved for use in osteoporosis are the receptor activator of nuclear factor kB ligand (RANKL) inhibitor denosumab (Prolia)30 and the sclerostin inhibitor romosozumab (Evenity).31

Denosumab prevents RANKL from binding to the RANK receptor, thereby inhibiting osteoclast formation and decreasing bone resorption. Denosumab is approved for use in women and men who are at high risk of osteoporotic fracture, including those taking OCSs, men receiving androgen deprivation therapy for prostate cancer, and women receiving adjuvant aromatase inhibitor therapy for breast cancer.

In a 3-year randomized trial, denosumab 60 mg SC every 6 months was compared with placebo in postmenopausal women with T-scores < –2.5, but not < –4.0 at the lumbar spine or total hip. Denosumab significantly reduced new radiographic vertebral fractures (2.3% vs 7.2%; risk ratio [RR] = 0.32; 95% CI, 0.26-0.41; NNT = 21), hip fracture (0.7% vs 1.2%), and nonvertebral fracture (6.5% vs 8.0%).32 Denosumab carries an increased risk of multiple vertebral fractures following discontinuation, skin infections, dermatologic reactions, and severe bone, joint, and muscle pain.

Romosozumab inhibits sclerostin, thereby increasing bone formation and, to a lesser degree, decreasing bone resorption. Romosozumab is approved for use in postmenopausal women at high risk for fracture (ie, those with a history of osteoporotic fracture or multiple risk factors for fracture) or in patients who have not benefited from or are intolerant of other therapies. In one study, postmenopausal women with a T-score of –2.5 to –3.5 at the total hip or femoral neck were randomly assigned to receive either romosozumab 210 mg SC or placebo for 12 months, then each group was switched to denosumab 60 mg SC for 12 months. After the first year, prior to initiating denosumab, patients taking romosozumab experienced significantly fewer new vertebral fractures than patients taking placebo (0.5% vs 1.8%; RR = 0.27; 95% CI, 0.16-0.47; NNT = 77); however, there was no significant difference between the 2 groups with nonvertebral fractures (HR = 0.75; 95% CI, 0.53-1.05).33

Continue to: In another study...

In another study, romosozumab 210 mg SC was compared with alendronate 70 mg weekly, followed by alendronate 70 mg weekly in both groups. Over the first 12 months, patients treated with romosozumab saw a significant reduction in the incidence of new vertebral fractures (4% vs 6.3%; RR = 0.63, P < .003; NNT = 44). Patients treated with romosozumab with alendronate added for another 12 months also saw a significant reduction in new incidence of vertebral fractures (6.2% vs 11.9%; RR = 0.52; P < .001; NNT = 18).34 There was a higher risk of cardiovascular events among patients receiving romosozumab compared with those treated with alendronate, so romosozumab should not be used in individuals who have had an MI or stroke within the previous year.34 Denosumab and romosozumab offer an advantage over some bisphosphonates in that they require less frequent dosing and can be used in patients with renal impairment (creatinine clearance < 35 mL/min, in which zoledronic acid is contraindicated and alendronate is not recommended; < 30 mL/min, in which risedronate and ibandronate are not recommended).

Migraine prevention

Four

Erenumab, fremanezumab, and galcanezumab are all available in subcutaneous autoinjectors (or syringe with fremanezumab). Eptinezumab is an intravenous (IV) infusion given every 3 months.