User login

Atopic Dermatitis Increases the Risk for Subsequent Autoimmune Disease

Key clinical point: A significant causal relationship was observed between atopic dermatitis (AD) and autoimmune diseases in children, and this was supported by the presence of shared genetic factors.

Major finding: At a follow-up of 12 years, children with vs without AD had a significantly increased risk for autoimmune diseases (adjusted hazard ratio [aHR] 1.27; 95% CI 1.23-1.32), particularly psoriasis vulgaris (aHR 2.55; 95% CI 2.25-2.80). Boys were significantly more susceptible to autoimmune diseases than girls (P for interaction = .04). Sixteen shared genes were identified between AD and autoimmune diseases and were associated with comorbidities, such as asthma and bronchiolitis.

Study details: This large-scale cohort study included 39,832 children with AD born between 2002 and 2018, who were matched with 159,328 children without AD.

Disclosures: This study was supported by the Korea Health Technology R&D. The authors declared no conflicts of interest.

Source: Ahn J, Shin S, Lee GC, et al. Unraveling the link between atopic dermatitis and autoimmune diseases in children: Insights from a large-scale cohort study with 15-year follow-up and shared gene ontology analysis. Allergol Int. 2024 (Jan 17). doi: 10.1016/j.alit.2023.12.005 Source

Key clinical point: A significant causal relationship was observed between atopic dermatitis (AD) and autoimmune diseases in children, and this was supported by the presence of shared genetic factors.

Major finding: At a follow-up of 12 years, children with vs without AD had a significantly increased risk for autoimmune diseases (adjusted hazard ratio [aHR] 1.27; 95% CI 1.23-1.32), particularly psoriasis vulgaris (aHR 2.55; 95% CI 2.25-2.80). Boys were significantly more susceptible to autoimmune diseases than girls (P for interaction = .04). Sixteen shared genes were identified between AD and autoimmune diseases and were associated with comorbidities, such as asthma and bronchiolitis.

Study details: This large-scale cohort study included 39,832 children with AD born between 2002 and 2018, who were matched with 159,328 children without AD.

Disclosures: This study was supported by the Korea Health Technology R&D. The authors declared no conflicts of interest.

Source: Ahn J, Shin S, Lee GC, et al. Unraveling the link between atopic dermatitis and autoimmune diseases in children: Insights from a large-scale cohort study with 15-year follow-up and shared gene ontology analysis. Allergol Int. 2024 (Jan 17). doi: 10.1016/j.alit.2023.12.005 Source

Key clinical point: A significant causal relationship was observed between atopic dermatitis (AD) and autoimmune diseases in children, and this was supported by the presence of shared genetic factors.

Major finding: At a follow-up of 12 years, children with vs without AD had a significantly increased risk for autoimmune diseases (adjusted hazard ratio [aHR] 1.27; 95% CI 1.23-1.32), particularly psoriasis vulgaris (aHR 2.55; 95% CI 2.25-2.80). Boys were significantly more susceptible to autoimmune diseases than girls (P for interaction = .04). Sixteen shared genes were identified between AD and autoimmune diseases and were associated with comorbidities, such as asthma and bronchiolitis.

Study details: This large-scale cohort study included 39,832 children with AD born between 2002 and 2018, who were matched with 159,328 children without AD.

Disclosures: This study was supported by the Korea Health Technology R&D. The authors declared no conflicts of interest.

Source: Ahn J, Shin S, Lee GC, et al. Unraveling the link between atopic dermatitis and autoimmune diseases in children: Insights from a large-scale cohort study with 15-year follow-up and shared gene ontology analysis. Allergol Int. 2024 (Jan 17). doi: 10.1016/j.alit.2023.12.005 Source

Tapinarof Cream Under FDA Review for Atopic Dermatitis Indication

On February 14, Dermavant Sciences announced that the company had submitted a supplemental New Drug Application (sNDA) to the Food and Drug Administration for tapinarof cream, 1%, for treating atopic dermatitis (AD) in adults and children 2 years of age and older.

Tapinarof cream, 1%, is an aryl hydrocarbon receptor agonist marketed under the brand name VTAMA that was approved in 2022 for treating plaque psoriasis in adults.

According to a Dermavant press release, the sNDA is based on positive data from the phase 3 ADORING 1 and ADORING 2 pivotal trials and interim results from the phase 3 ADORING 3 open-label, long-term extension 48-week trial. In ADORING 1 and ADORING 2, tapinarof cream demonstrated statistically significant improvements in the primary endpoint of Validated Investigator Global Assessment for Atopic Dermatitis (vIGA-AD) treatment success, defined as a vIGA-AD score of 0 (clear) or 1 (almost clear) with at least a 2-grade improvement from baseline; demonstrated treatment success over vehicle at week 8; and met all key secondary endpoints with statistical significance, according to the company.

The most common adverse reactions in patients treated with VTAMA cream include folliculitis, nasopharyngitis, contact dermatitis, headache, and pruritus.

On February 14, Dermavant Sciences announced that the company had submitted a supplemental New Drug Application (sNDA) to the Food and Drug Administration for tapinarof cream, 1%, for treating atopic dermatitis (AD) in adults and children 2 years of age and older.

Tapinarof cream, 1%, is an aryl hydrocarbon receptor agonist marketed under the brand name VTAMA that was approved in 2022 for treating plaque psoriasis in adults.

According to a Dermavant press release, the sNDA is based on positive data from the phase 3 ADORING 1 and ADORING 2 pivotal trials and interim results from the phase 3 ADORING 3 open-label, long-term extension 48-week trial. In ADORING 1 and ADORING 2, tapinarof cream demonstrated statistically significant improvements in the primary endpoint of Validated Investigator Global Assessment for Atopic Dermatitis (vIGA-AD) treatment success, defined as a vIGA-AD score of 0 (clear) or 1 (almost clear) with at least a 2-grade improvement from baseline; demonstrated treatment success over vehicle at week 8; and met all key secondary endpoints with statistical significance, according to the company.

The most common adverse reactions in patients treated with VTAMA cream include folliculitis, nasopharyngitis, contact dermatitis, headache, and pruritus.

On February 14, Dermavant Sciences announced that the company had submitted a supplemental New Drug Application (sNDA) to the Food and Drug Administration for tapinarof cream, 1%, for treating atopic dermatitis (AD) in adults and children 2 years of age and older.

Tapinarof cream, 1%, is an aryl hydrocarbon receptor agonist marketed under the brand name VTAMA that was approved in 2022 for treating plaque psoriasis in adults.

According to a Dermavant press release, the sNDA is based on positive data from the phase 3 ADORING 1 and ADORING 2 pivotal trials and interim results from the phase 3 ADORING 3 open-label, long-term extension 48-week trial. In ADORING 1 and ADORING 2, tapinarof cream demonstrated statistically significant improvements in the primary endpoint of Validated Investigator Global Assessment for Atopic Dermatitis (vIGA-AD) treatment success, defined as a vIGA-AD score of 0 (clear) or 1 (almost clear) with at least a 2-grade improvement from baseline; demonstrated treatment success over vehicle at week 8; and met all key secondary endpoints with statistical significance, according to the company.

The most common adverse reactions in patients treated with VTAMA cream include folliculitis, nasopharyngitis, contact dermatitis, headache, and pruritus.

Dupilumab Improves AD Affecting the Hands, Feet

TOPLINE:

compared with placebo.

METHODOLOGY:

- The multinational phase 3 LIBERTY-AD-HAFT trial of adults and adolescents with moderate to severe chronic atopic dermatitis (AD) of the hands, feet, or both included 67 participants at 48 sites randomized to dupilumab monotherapy and 66 to placebo.

- The primary endpoint was the proportion of patients scoring 0 or 1 on Hand and Foot Investigator’s Global Assessment (HF-IGA) at week 16.

- Secondary endpoints were severity and extent of signs, symptom intensity (itch and pain), sleep, and quality of life.

TAKEAWAY:

- At week 16, 27 patients receiving dupilumab vs 11 receiving placebo achieved an HF-IGA score of 0 or 1 (40.3% vs 16.7%; P = .003).

- At week 16, 35 participants receiving dupilumab vs nine receiving placebo improved at least four points in the weekly average of daily HF-Peak Pruritus Numeric Rating Scale (52.2% vs 13.6%; P < .0001).

- At week 16, Quality of Life Hand Eczema Questionnaire results improved in the dupilumab group compared with controls (P < .0001), and weekly average of daily Sleep Numeric Rating Scale results improved in the dupilumab group compared with controls (P < .05).

- The safety profile was similar to the known profile in adults and adolescents with moderate to severe AD.

IN PRACTICE:

The results of the study “support dupilumab” as an “efficacious systemic therapy for moderate to severe H/F AD,” the authors wrote.

SOURCE:

The study, led by Eric L. Simpson, MD, MCR, professor of dermatology at the Oregon Health & Science University in Portland, was published on January 29, 2024, in the Journal of the American Academy of Dermatology.

LIMITATIONS:

The short duration of the study and the large proportion of patients with positive patch tests (31 of 133) suggested that some participants may have had concurrent AD and allergic contact dermatitis, so the effect of dupilumab on those patients needs further evaluation.

DISCLOSURES:

The study was sponsored by Sanofi and Regeneron. All but one author had financial relationships with Sanofi, Regeneron, or both. Several authors were employees of, and may hold stocks or stock options in, Sanofi or Regeneron.

TOPLINE:

compared with placebo.

METHODOLOGY:

- The multinational phase 3 LIBERTY-AD-HAFT trial of adults and adolescents with moderate to severe chronic atopic dermatitis (AD) of the hands, feet, or both included 67 participants at 48 sites randomized to dupilumab monotherapy and 66 to placebo.

- The primary endpoint was the proportion of patients scoring 0 or 1 on Hand and Foot Investigator’s Global Assessment (HF-IGA) at week 16.

- Secondary endpoints were severity and extent of signs, symptom intensity (itch and pain), sleep, and quality of life.

TAKEAWAY:

- At week 16, 27 patients receiving dupilumab vs 11 receiving placebo achieved an HF-IGA score of 0 or 1 (40.3% vs 16.7%; P = .003).

- At week 16, 35 participants receiving dupilumab vs nine receiving placebo improved at least four points in the weekly average of daily HF-Peak Pruritus Numeric Rating Scale (52.2% vs 13.6%; P < .0001).

- At week 16, Quality of Life Hand Eczema Questionnaire results improved in the dupilumab group compared with controls (P < .0001), and weekly average of daily Sleep Numeric Rating Scale results improved in the dupilumab group compared with controls (P < .05).

- The safety profile was similar to the known profile in adults and adolescents with moderate to severe AD.

IN PRACTICE:

The results of the study “support dupilumab” as an “efficacious systemic therapy for moderate to severe H/F AD,” the authors wrote.

SOURCE:

The study, led by Eric L. Simpson, MD, MCR, professor of dermatology at the Oregon Health & Science University in Portland, was published on January 29, 2024, in the Journal of the American Academy of Dermatology.

LIMITATIONS:

The short duration of the study and the large proportion of patients with positive patch tests (31 of 133) suggested that some participants may have had concurrent AD and allergic contact dermatitis, so the effect of dupilumab on those patients needs further evaluation.

DISCLOSURES:

The study was sponsored by Sanofi and Regeneron. All but one author had financial relationships with Sanofi, Regeneron, or both. Several authors were employees of, and may hold stocks or stock options in, Sanofi or Regeneron.

TOPLINE:

compared with placebo.

METHODOLOGY:

- The multinational phase 3 LIBERTY-AD-HAFT trial of adults and adolescents with moderate to severe chronic atopic dermatitis (AD) of the hands, feet, or both included 67 participants at 48 sites randomized to dupilumab monotherapy and 66 to placebo.

- The primary endpoint was the proportion of patients scoring 0 or 1 on Hand and Foot Investigator’s Global Assessment (HF-IGA) at week 16.

- Secondary endpoints were severity and extent of signs, symptom intensity (itch and pain), sleep, and quality of life.

TAKEAWAY:

- At week 16, 27 patients receiving dupilumab vs 11 receiving placebo achieved an HF-IGA score of 0 or 1 (40.3% vs 16.7%; P = .003).

- At week 16, 35 participants receiving dupilumab vs nine receiving placebo improved at least four points in the weekly average of daily HF-Peak Pruritus Numeric Rating Scale (52.2% vs 13.6%; P < .0001).

- At week 16, Quality of Life Hand Eczema Questionnaire results improved in the dupilumab group compared with controls (P < .0001), and weekly average of daily Sleep Numeric Rating Scale results improved in the dupilumab group compared with controls (P < .05).

- The safety profile was similar to the known profile in adults and adolescents with moderate to severe AD.

IN PRACTICE:

The results of the study “support dupilumab” as an “efficacious systemic therapy for moderate to severe H/F AD,” the authors wrote.

SOURCE:

The study, led by Eric L. Simpson, MD, MCR, professor of dermatology at the Oregon Health & Science University in Portland, was published on January 29, 2024, in the Journal of the American Academy of Dermatology.

LIMITATIONS:

The short duration of the study and the large proportion of patients with positive patch tests (31 of 133) suggested that some participants may have had concurrent AD and allergic contact dermatitis, so the effect of dupilumab on those patients needs further evaluation.

DISCLOSURES:

The study was sponsored by Sanofi and Regeneron. All but one author had financial relationships with Sanofi, Regeneron, or both. Several authors were employees of, and may hold stocks or stock options in, Sanofi or Regeneron.

Survey: Dermatology Residents Shortchanged on Sensitive Skin Education

Although sensitive skin affects an estimated 40%-70% of the population, knowledge of the pathophysiology of sensitive skin is incomplete, and consensus is lacking as to the best diagnosis and treatment strategies, and the inclusion of sensitive skin education in dermatology curricula has not been examined, according to Erika T. McCormick, BS, and Adam Friedman, MD, of George Washington University, Washington, DC.

For the study, published in the Journal of Drugs in Dermatology, they developed a 26-question survey for dermatology residents that asked about sensitive skin in dermatology residency training. Participants came from the Orlando Dermatology, Aesthetic, and Surgical Conference email list.

Survey respondents included 214 residents at various levels of training at programs across the United States; 67.1% were female, 92.1% were aged 25-34 years, and 85.5% were in academic or university programs.

Overall, 99% of respondents believed that sensitive skin issues should be part of their residency training to some extent, and 84% reported experiences with patients for whom the chief presenting complaint was sensitive skin.

However, fewer than half (48%) of the residents reported specific resident education in sensitive skin, while 51% reported nonspecific education about sensitive skin education in the context of other skin diseases, and 1% reported no education about sensitive skin.

Less than one-quarter of the respondents who received any sensitive skin education reported feeling comfortable in their ability to diagnose, evaluate, and manage sensitive skin, while those with sensitive skin–specific education were significantly more likely to describe themselves as “very knowledgeable.”

As for treatment approaches, residents with specific sensitive skin education were more likely than were those without sensitive skin–specific training to ask patients about allergies and past reactions to skin products, and to counsel them about environmental triggers.

Notably, 96% of the respondents were not familiar with the Sensitive Skin (SS) Scale–10, a validated measure of sensitive skin severity.

The most common challenges in care of patients with sensitive skin were assessing improvement over time, reported by 25% of respondents, recommending products (23%), and prescribing/medical management (22%). The topics residents expressed most interest in learning about were product recommendations (78%), patient counseling (77%), reviewing research on sensitive skin (70%), diagnosing sensitive skin (67%), using the SS-10 (48%), and clinical research updates (40%).

The findings were limited by several factors including the reliance on self-reports, the researchers noted. However, the results highlight the lack of consensus in treatment of sensitive skin and the need to address this knowledge gap at the residency level, they said.

Improving Tools for Practice

“Many practice patterns and approaches are forged in the fires of training,” corresponding author Dr. Friedman, professor and chair of dermatology and residency program director at George Washington University, said in an interview. “Identifying gaps, especially for heavily prevalent issues, questions, and concerns such as sensitive skin that residents will encounter in practice is important to ensure an educated workforce,” he said.

Education on sensitive skin is lacking because, until recently, research and clinical guidance have been lacking, Dr. Friedman said. The root of the problem is that sensitive skin is mainly considered a symptom, rather than an independent condition, he explained. “Depending on the study, the prevalence of sensitive skin has been reported as high as 70%, with roughly 40% of these patients having no primary skin condition,” he said. This means sensitive skin can be both a symptom and a condition, which causes confusion for clinicians and patients, he added.

“Therefore, in order to overcome this gap, the condition itself at a minimum needs a standard definition and a way to diagnosis, which we fortunately have in the validated research tool known as the SS-10,” said Dr. Friedman.

Almost all residents surveyed in the current study had never heard of the SS-10, but more than half found it to be useful after learning of it through the study survey, he noted.

Looking ahead, greater elucidation of the pathophysiology of sensitive skin is needed to effectively pursue studies of products and treatments for these patients, but the SS-10 can be used to define and monitor the condition to evaluate improvement, he added.

The study was funded by an independent fellowship grant from Galderma. Ms. McCormick is supported by an unrestricted fellowship grant funded by Galderma. Dr. Friedman has served as a consultant for Galderma.

Although sensitive skin affects an estimated 40%-70% of the population, knowledge of the pathophysiology of sensitive skin is incomplete, and consensus is lacking as to the best diagnosis and treatment strategies, and the inclusion of sensitive skin education in dermatology curricula has not been examined, according to Erika T. McCormick, BS, and Adam Friedman, MD, of George Washington University, Washington, DC.

For the study, published in the Journal of Drugs in Dermatology, they developed a 26-question survey for dermatology residents that asked about sensitive skin in dermatology residency training. Participants came from the Orlando Dermatology, Aesthetic, and Surgical Conference email list.

Survey respondents included 214 residents at various levels of training at programs across the United States; 67.1% were female, 92.1% were aged 25-34 years, and 85.5% were in academic or university programs.

Overall, 99% of respondents believed that sensitive skin issues should be part of their residency training to some extent, and 84% reported experiences with patients for whom the chief presenting complaint was sensitive skin.

However, fewer than half (48%) of the residents reported specific resident education in sensitive skin, while 51% reported nonspecific education about sensitive skin education in the context of other skin diseases, and 1% reported no education about sensitive skin.

Less than one-quarter of the respondents who received any sensitive skin education reported feeling comfortable in their ability to diagnose, evaluate, and manage sensitive skin, while those with sensitive skin–specific education were significantly more likely to describe themselves as “very knowledgeable.”

As for treatment approaches, residents with specific sensitive skin education were more likely than were those without sensitive skin–specific training to ask patients about allergies and past reactions to skin products, and to counsel them about environmental triggers.

Notably, 96% of the respondents were not familiar with the Sensitive Skin (SS) Scale–10, a validated measure of sensitive skin severity.

The most common challenges in care of patients with sensitive skin were assessing improvement over time, reported by 25% of respondents, recommending products (23%), and prescribing/medical management (22%). The topics residents expressed most interest in learning about were product recommendations (78%), patient counseling (77%), reviewing research on sensitive skin (70%), diagnosing sensitive skin (67%), using the SS-10 (48%), and clinical research updates (40%).

The findings were limited by several factors including the reliance on self-reports, the researchers noted. However, the results highlight the lack of consensus in treatment of sensitive skin and the need to address this knowledge gap at the residency level, they said.

Improving Tools for Practice

“Many practice patterns and approaches are forged in the fires of training,” corresponding author Dr. Friedman, professor and chair of dermatology and residency program director at George Washington University, said in an interview. “Identifying gaps, especially for heavily prevalent issues, questions, and concerns such as sensitive skin that residents will encounter in practice is important to ensure an educated workforce,” he said.

Education on sensitive skin is lacking because, until recently, research and clinical guidance have been lacking, Dr. Friedman said. The root of the problem is that sensitive skin is mainly considered a symptom, rather than an independent condition, he explained. “Depending on the study, the prevalence of sensitive skin has been reported as high as 70%, with roughly 40% of these patients having no primary skin condition,” he said. This means sensitive skin can be both a symptom and a condition, which causes confusion for clinicians and patients, he added.

“Therefore, in order to overcome this gap, the condition itself at a minimum needs a standard definition and a way to diagnosis, which we fortunately have in the validated research tool known as the SS-10,” said Dr. Friedman.

Almost all residents surveyed in the current study had never heard of the SS-10, but more than half found it to be useful after learning of it through the study survey, he noted.

Looking ahead, greater elucidation of the pathophysiology of sensitive skin is needed to effectively pursue studies of products and treatments for these patients, but the SS-10 can be used to define and monitor the condition to evaluate improvement, he added.

The study was funded by an independent fellowship grant from Galderma. Ms. McCormick is supported by an unrestricted fellowship grant funded by Galderma. Dr. Friedman has served as a consultant for Galderma.

Although sensitive skin affects an estimated 40%-70% of the population, knowledge of the pathophysiology of sensitive skin is incomplete, and consensus is lacking as to the best diagnosis and treatment strategies, and the inclusion of sensitive skin education in dermatology curricula has not been examined, according to Erika T. McCormick, BS, and Adam Friedman, MD, of George Washington University, Washington, DC.

For the study, published in the Journal of Drugs in Dermatology, they developed a 26-question survey for dermatology residents that asked about sensitive skin in dermatology residency training. Participants came from the Orlando Dermatology, Aesthetic, and Surgical Conference email list.

Survey respondents included 214 residents at various levels of training at programs across the United States; 67.1% were female, 92.1% were aged 25-34 years, and 85.5% were in academic or university programs.

Overall, 99% of respondents believed that sensitive skin issues should be part of their residency training to some extent, and 84% reported experiences with patients for whom the chief presenting complaint was sensitive skin.

However, fewer than half (48%) of the residents reported specific resident education in sensitive skin, while 51% reported nonspecific education about sensitive skin education in the context of other skin diseases, and 1% reported no education about sensitive skin.

Less than one-quarter of the respondents who received any sensitive skin education reported feeling comfortable in their ability to diagnose, evaluate, and manage sensitive skin, while those with sensitive skin–specific education were significantly more likely to describe themselves as “very knowledgeable.”

As for treatment approaches, residents with specific sensitive skin education were more likely than were those without sensitive skin–specific training to ask patients about allergies and past reactions to skin products, and to counsel them about environmental triggers.

Notably, 96% of the respondents were not familiar with the Sensitive Skin (SS) Scale–10, a validated measure of sensitive skin severity.

The most common challenges in care of patients with sensitive skin were assessing improvement over time, reported by 25% of respondents, recommending products (23%), and prescribing/medical management (22%). The topics residents expressed most interest in learning about were product recommendations (78%), patient counseling (77%), reviewing research on sensitive skin (70%), diagnosing sensitive skin (67%), using the SS-10 (48%), and clinical research updates (40%).

The findings were limited by several factors including the reliance on self-reports, the researchers noted. However, the results highlight the lack of consensus in treatment of sensitive skin and the need to address this knowledge gap at the residency level, they said.

Improving Tools for Practice

“Many practice patterns and approaches are forged in the fires of training,” corresponding author Dr. Friedman, professor and chair of dermatology and residency program director at George Washington University, said in an interview. “Identifying gaps, especially for heavily prevalent issues, questions, and concerns such as sensitive skin that residents will encounter in practice is important to ensure an educated workforce,” he said.

Education on sensitive skin is lacking because, until recently, research and clinical guidance have been lacking, Dr. Friedman said. The root of the problem is that sensitive skin is mainly considered a symptom, rather than an independent condition, he explained. “Depending on the study, the prevalence of sensitive skin has been reported as high as 70%, with roughly 40% of these patients having no primary skin condition,” he said. This means sensitive skin can be both a symptom and a condition, which causes confusion for clinicians and patients, he added.

“Therefore, in order to overcome this gap, the condition itself at a minimum needs a standard definition and a way to diagnosis, which we fortunately have in the validated research tool known as the SS-10,” said Dr. Friedman.

Almost all residents surveyed in the current study had never heard of the SS-10, but more than half found it to be useful after learning of it through the study survey, he noted.

Looking ahead, greater elucidation of the pathophysiology of sensitive skin is needed to effectively pursue studies of products and treatments for these patients, but the SS-10 can be used to define and monitor the condition to evaluate improvement, he added.

The study was funded by an independent fellowship grant from Galderma. Ms. McCormick is supported by an unrestricted fellowship grant funded by Galderma. Dr. Friedman has served as a consultant for Galderma.

FROM THE JOURNAL OF DRUGS IN DERMATOLOGY

Review Finds No Short-term MACE, VTE risk with JAK Inhibitors For Dermatoses

, at least in the short term, say the authors of a new meta-analysis published in JAMA Dermatology.

Considering data on over 17,000 patients with different dermatoses from 45 placebo-controlled randomized clinical trials with an average follow up of 16 weeks, they found there was no significant increase in the occurrence of major adverse cardiovascular events (MACE) or venous thromboembolism (VTE) in people with dermatoses treated with JAK-STAT inhibitors, compared with placebo.

The I² statistic was 0.00% for both MACE and VTE comparing the two arms, indicating that the results were unlikely to be due to chance. There was no increased risk in MACE between those on placebo and those on JAK-STAT inhibitors, with a risk ratio (RR) of 0.47; or for VTE risk, with an RR of 0.46.

Similar findings were obtained when data were analyzed according to the dermatological condition being treated, mechanism of action of the medication, or whether the medication carried a boxed warning.

These data “suggest inconsistency with established sentiments,” that JAK-STAT inhibitors increase the risk for cardiovascular events, Patrick Ireland, MD, of the University of New South Wales, Randwick, Australia, and coauthors wrote in the article. “This may be owing to the limited time frames in which these rare events could be adequately captured, or the ages of enrolled patients being too young to realize the well established heightened risks of developing MACE and VTE,” they suggested.

However, the findings challenge the notion that the cardiovascular complications of these drugs are the same in all patients; dermatological use may not be associated with the same risks as with use for rheumatologic indications.

Class-Wide Boxed Warning

“JAK-STAT [inhibitors] have had some pretty indemnifying data against their use, with the ORAL [Surveillance] study demonstrating increased all-cause mortality, cardiovascular events, venous thromboembolism, and malignancy,” Dr. Ireland said in an interview.

ORAL Surveillance was an open-label, postmarketing trial conducted in patients with rheumatoid arthritis treated with tofacitinib or a tumor necrosis factor (TNF) inhibitor. The results led the US Food and Drug Administration to require information about the risks of serious heart-related events, cancer, blood clots, and death in a boxed warning for JAK-STAT inhibitors in 2022.

“I think it’s important to recognize that these [ORAL Surveillance participants] are very different patients to the typical dermatological patient being treated with a JAK-STAT [inhibitors], with newer studies demonstrating a much safer profile than initially thought,” Dr. Ireland said.

Examining Risk in Dermatological Conditions

The meta-analysis performed by Dr. Ireland and associates focused specifically on the risk for MACE and VTE in patients being treated for dermatological conditions, and included trials published up until June 2023. Only trials that had included a placebo arm were considered; pooled analyses, long-term extension trial data, post hoc analyses, and pediatric-specific trials were excluded.

Most (25) of the trials were phase 2b or phase 3 trials, 18 were phase 2 to 2b, and two were phase 1 trials. The studies included 12,996 participants, mostly with atopic dermatitis or psoriasis, who were treated with JAK-STAT inhibitors, which included baricitinib (2846 patients), tofacitinib (2470), upadacitinib (2218), abrocitinib (1904), and deucravacitinib (1492), among others. There were 4925 patients on placebo.

Overall, MACE — defined as a combined endpoint of acute myocardial infarction, stroke, cardiovascular mortality, heart failure, and unstable angina, as well as arterial embolism — occurred in 13 of the JAK-STAT inhibitor-treated patients and in four of those on placebo. VTE — defined as deep vein thrombosis, pulmonary embolism, and any unusual site thrombosis — was reported in eight JAK-STAT inhibitor-treated patients and in one patient on placebo.

The pooled incidence ratios for MACE and VTE were calculated as 0.20 per 100 person exposure years (PEY) for JAK-STAT inhibitor treatment and 0.13 PEY for placebo. The pooled RRs comparing the two treatment groups were a respective 1.13 for MACE and 2.79 for VTE, but neither RR reached statistical significance.

No difference was seen between the treatment arms in terms of treatment emergent adverse events (RR, 1.05), serious adverse events (RR, 0.92), or study discontinuation because of adverse events (RR, 0.94).

Reassuring Results?

Dr. Ireland and coauthors said the finding should help to reassure clinicians that the short-term use of JAK-STAT inhibitors in patients with dermatological conditions with low cardiovascular risk profiles “appears to be both safe and well tolerated.” They cautioned, however, that “clinicians must remain judicious” when using these medications for longer periods and in high-risk patient populations.

This was a pragmatic meta-analysis that provides useful information for dermatologists, Adam Friedman, MD, professor and chair of dermatology at George Washington University, Washington, DC, said in an interview.

“When there are safety concerns, I think that’s where data like this are so important to not just allay the fears of practitioners, but also to arm the practitioner with information for when they discuss a possible treatment with a patient,” said Dr. Friedman, who was not involved in the study.

“What’s unique here is that they’re looking at any possible use of JAK inhibitors for dermatological disease,” so this represents patients that dermatologists would be seeing, he added.

“The limitation here is time, we only can say so much about the safety of the medication with the data that we have,” Dr. Friedman said. Almost 4 months is “a good amount of time” to know about the cardiovascular risks, he said, but added, what happens then? Will the risk increase and will patients need to be switched to another medication?

“There’s no line in the sand,” with regard to using a JAK-STAT inhibitor. “If you look at the label, they’re not meant to be used incrementally,” but as ongoing treatment, while considering the needs of the patient and the relative risks and benefits, he said.

With that in mind, “the open label extension studies for all these [JAK-STAT inhibitors] are really, really important to get a sense of ‘do new signals emerge down the road.’ ”

The meta-analysis received no commercial funding. One author of the work reported personal fees from several pharmaceutical companies which were done outside of analysis. Dr. Friedman has received research funding from or acted as a consultant for several pharmaceutical companies including, Incyte, Pfizer, Eli Lily, and AbbVie.

, at least in the short term, say the authors of a new meta-analysis published in JAMA Dermatology.

Considering data on over 17,000 patients with different dermatoses from 45 placebo-controlled randomized clinical trials with an average follow up of 16 weeks, they found there was no significant increase in the occurrence of major adverse cardiovascular events (MACE) or venous thromboembolism (VTE) in people with dermatoses treated with JAK-STAT inhibitors, compared with placebo.

The I² statistic was 0.00% for both MACE and VTE comparing the two arms, indicating that the results were unlikely to be due to chance. There was no increased risk in MACE between those on placebo and those on JAK-STAT inhibitors, with a risk ratio (RR) of 0.47; or for VTE risk, with an RR of 0.46.

Similar findings were obtained when data were analyzed according to the dermatological condition being treated, mechanism of action of the medication, or whether the medication carried a boxed warning.

These data “suggest inconsistency with established sentiments,” that JAK-STAT inhibitors increase the risk for cardiovascular events, Patrick Ireland, MD, of the University of New South Wales, Randwick, Australia, and coauthors wrote in the article. “This may be owing to the limited time frames in which these rare events could be adequately captured, or the ages of enrolled patients being too young to realize the well established heightened risks of developing MACE and VTE,” they suggested.

However, the findings challenge the notion that the cardiovascular complications of these drugs are the same in all patients; dermatological use may not be associated with the same risks as with use for rheumatologic indications.

Class-Wide Boxed Warning

“JAK-STAT [inhibitors] have had some pretty indemnifying data against their use, with the ORAL [Surveillance] study demonstrating increased all-cause mortality, cardiovascular events, venous thromboembolism, and malignancy,” Dr. Ireland said in an interview.

ORAL Surveillance was an open-label, postmarketing trial conducted in patients with rheumatoid arthritis treated with tofacitinib or a tumor necrosis factor (TNF) inhibitor. The results led the US Food and Drug Administration to require information about the risks of serious heart-related events, cancer, blood clots, and death in a boxed warning for JAK-STAT inhibitors in 2022.

“I think it’s important to recognize that these [ORAL Surveillance participants] are very different patients to the typical dermatological patient being treated with a JAK-STAT [inhibitors], with newer studies demonstrating a much safer profile than initially thought,” Dr. Ireland said.

Examining Risk in Dermatological Conditions

The meta-analysis performed by Dr. Ireland and associates focused specifically on the risk for MACE and VTE in patients being treated for dermatological conditions, and included trials published up until June 2023. Only trials that had included a placebo arm were considered; pooled analyses, long-term extension trial data, post hoc analyses, and pediatric-specific trials were excluded.

Most (25) of the trials were phase 2b or phase 3 trials, 18 were phase 2 to 2b, and two were phase 1 trials. The studies included 12,996 participants, mostly with atopic dermatitis or psoriasis, who were treated with JAK-STAT inhibitors, which included baricitinib (2846 patients), tofacitinib (2470), upadacitinib (2218), abrocitinib (1904), and deucravacitinib (1492), among others. There were 4925 patients on placebo.

Overall, MACE — defined as a combined endpoint of acute myocardial infarction, stroke, cardiovascular mortality, heart failure, and unstable angina, as well as arterial embolism — occurred in 13 of the JAK-STAT inhibitor-treated patients and in four of those on placebo. VTE — defined as deep vein thrombosis, pulmonary embolism, and any unusual site thrombosis — was reported in eight JAK-STAT inhibitor-treated patients and in one patient on placebo.

The pooled incidence ratios for MACE and VTE were calculated as 0.20 per 100 person exposure years (PEY) for JAK-STAT inhibitor treatment and 0.13 PEY for placebo. The pooled RRs comparing the two treatment groups were a respective 1.13 for MACE and 2.79 for VTE, but neither RR reached statistical significance.

No difference was seen between the treatment arms in terms of treatment emergent adverse events (RR, 1.05), serious adverse events (RR, 0.92), or study discontinuation because of adverse events (RR, 0.94).

Reassuring Results?

Dr. Ireland and coauthors said the finding should help to reassure clinicians that the short-term use of JAK-STAT inhibitors in patients with dermatological conditions with low cardiovascular risk profiles “appears to be both safe and well tolerated.” They cautioned, however, that “clinicians must remain judicious” when using these medications for longer periods and in high-risk patient populations.

This was a pragmatic meta-analysis that provides useful information for dermatologists, Adam Friedman, MD, professor and chair of dermatology at George Washington University, Washington, DC, said in an interview.

“When there are safety concerns, I think that’s where data like this are so important to not just allay the fears of practitioners, but also to arm the practitioner with information for when they discuss a possible treatment with a patient,” said Dr. Friedman, who was not involved in the study.

“What’s unique here is that they’re looking at any possible use of JAK inhibitors for dermatological disease,” so this represents patients that dermatologists would be seeing, he added.

“The limitation here is time, we only can say so much about the safety of the medication with the data that we have,” Dr. Friedman said. Almost 4 months is “a good amount of time” to know about the cardiovascular risks, he said, but added, what happens then? Will the risk increase and will patients need to be switched to another medication?

“There’s no line in the sand,” with regard to using a JAK-STAT inhibitor. “If you look at the label, they’re not meant to be used incrementally,” but as ongoing treatment, while considering the needs of the patient and the relative risks and benefits, he said.

With that in mind, “the open label extension studies for all these [JAK-STAT inhibitors] are really, really important to get a sense of ‘do new signals emerge down the road.’ ”

The meta-analysis received no commercial funding. One author of the work reported personal fees from several pharmaceutical companies which were done outside of analysis. Dr. Friedman has received research funding from or acted as a consultant for several pharmaceutical companies including, Incyte, Pfizer, Eli Lily, and AbbVie.

, at least in the short term, say the authors of a new meta-analysis published in JAMA Dermatology.

Considering data on over 17,000 patients with different dermatoses from 45 placebo-controlled randomized clinical trials with an average follow up of 16 weeks, they found there was no significant increase in the occurrence of major adverse cardiovascular events (MACE) or venous thromboembolism (VTE) in people with dermatoses treated with JAK-STAT inhibitors, compared with placebo.

The I² statistic was 0.00% for both MACE and VTE comparing the two arms, indicating that the results were unlikely to be due to chance. There was no increased risk in MACE between those on placebo and those on JAK-STAT inhibitors, with a risk ratio (RR) of 0.47; or for VTE risk, with an RR of 0.46.

Similar findings were obtained when data were analyzed according to the dermatological condition being treated, mechanism of action of the medication, or whether the medication carried a boxed warning.

These data “suggest inconsistency with established sentiments,” that JAK-STAT inhibitors increase the risk for cardiovascular events, Patrick Ireland, MD, of the University of New South Wales, Randwick, Australia, and coauthors wrote in the article. “This may be owing to the limited time frames in which these rare events could be adequately captured, or the ages of enrolled patients being too young to realize the well established heightened risks of developing MACE and VTE,” they suggested.

However, the findings challenge the notion that the cardiovascular complications of these drugs are the same in all patients; dermatological use may not be associated with the same risks as with use for rheumatologic indications.

Class-Wide Boxed Warning

“JAK-STAT [inhibitors] have had some pretty indemnifying data against their use, with the ORAL [Surveillance] study demonstrating increased all-cause mortality, cardiovascular events, venous thromboembolism, and malignancy,” Dr. Ireland said in an interview.

ORAL Surveillance was an open-label, postmarketing trial conducted in patients with rheumatoid arthritis treated with tofacitinib or a tumor necrosis factor (TNF) inhibitor. The results led the US Food and Drug Administration to require information about the risks of serious heart-related events, cancer, blood clots, and death in a boxed warning for JAK-STAT inhibitors in 2022.

“I think it’s important to recognize that these [ORAL Surveillance participants] are very different patients to the typical dermatological patient being treated with a JAK-STAT [inhibitors], with newer studies demonstrating a much safer profile than initially thought,” Dr. Ireland said.

Examining Risk in Dermatological Conditions

The meta-analysis performed by Dr. Ireland and associates focused specifically on the risk for MACE and VTE in patients being treated for dermatological conditions, and included trials published up until June 2023. Only trials that had included a placebo arm were considered; pooled analyses, long-term extension trial data, post hoc analyses, and pediatric-specific trials were excluded.

Most (25) of the trials were phase 2b or phase 3 trials, 18 were phase 2 to 2b, and two were phase 1 trials. The studies included 12,996 participants, mostly with atopic dermatitis or psoriasis, who were treated with JAK-STAT inhibitors, which included baricitinib (2846 patients), tofacitinib (2470), upadacitinib (2218), abrocitinib (1904), and deucravacitinib (1492), among others. There were 4925 patients on placebo.

Overall, MACE — defined as a combined endpoint of acute myocardial infarction, stroke, cardiovascular mortality, heart failure, and unstable angina, as well as arterial embolism — occurred in 13 of the JAK-STAT inhibitor-treated patients and in four of those on placebo. VTE — defined as deep vein thrombosis, pulmonary embolism, and any unusual site thrombosis — was reported in eight JAK-STAT inhibitor-treated patients and in one patient on placebo.

The pooled incidence ratios for MACE and VTE were calculated as 0.20 per 100 person exposure years (PEY) for JAK-STAT inhibitor treatment and 0.13 PEY for placebo. The pooled RRs comparing the two treatment groups were a respective 1.13 for MACE and 2.79 for VTE, but neither RR reached statistical significance.

No difference was seen between the treatment arms in terms of treatment emergent adverse events (RR, 1.05), serious adverse events (RR, 0.92), or study discontinuation because of adverse events (RR, 0.94).

Reassuring Results?

Dr. Ireland and coauthors said the finding should help to reassure clinicians that the short-term use of JAK-STAT inhibitors in patients with dermatological conditions with low cardiovascular risk profiles “appears to be both safe and well tolerated.” They cautioned, however, that “clinicians must remain judicious” when using these medications for longer periods and in high-risk patient populations.

This was a pragmatic meta-analysis that provides useful information for dermatologists, Adam Friedman, MD, professor and chair of dermatology at George Washington University, Washington, DC, said in an interview.

“When there are safety concerns, I think that’s where data like this are so important to not just allay the fears of practitioners, but also to arm the practitioner with information for when they discuss a possible treatment with a patient,” said Dr. Friedman, who was not involved in the study.

“What’s unique here is that they’re looking at any possible use of JAK inhibitors for dermatological disease,” so this represents patients that dermatologists would be seeing, he added.

“The limitation here is time, we only can say so much about the safety of the medication with the data that we have,” Dr. Friedman said. Almost 4 months is “a good amount of time” to know about the cardiovascular risks, he said, but added, what happens then? Will the risk increase and will patients need to be switched to another medication?

“There’s no line in the sand,” with regard to using a JAK-STAT inhibitor. “If you look at the label, they’re not meant to be used incrementally,” but as ongoing treatment, while considering the needs of the patient and the relative risks and benefits, he said.

With that in mind, “the open label extension studies for all these [JAK-STAT inhibitors] are really, really important to get a sense of ‘do new signals emerge down the road.’ ”

The meta-analysis received no commercial funding. One author of the work reported personal fees from several pharmaceutical companies which were done outside of analysis. Dr. Friedman has received research funding from or acted as a consultant for several pharmaceutical companies including, Incyte, Pfizer, Eli Lily, and AbbVie.

FROM JAMA DERMATOLOGY

Impact of Ketogenic and Low-Glycemic Diets on Inflammatory Skin Conditions

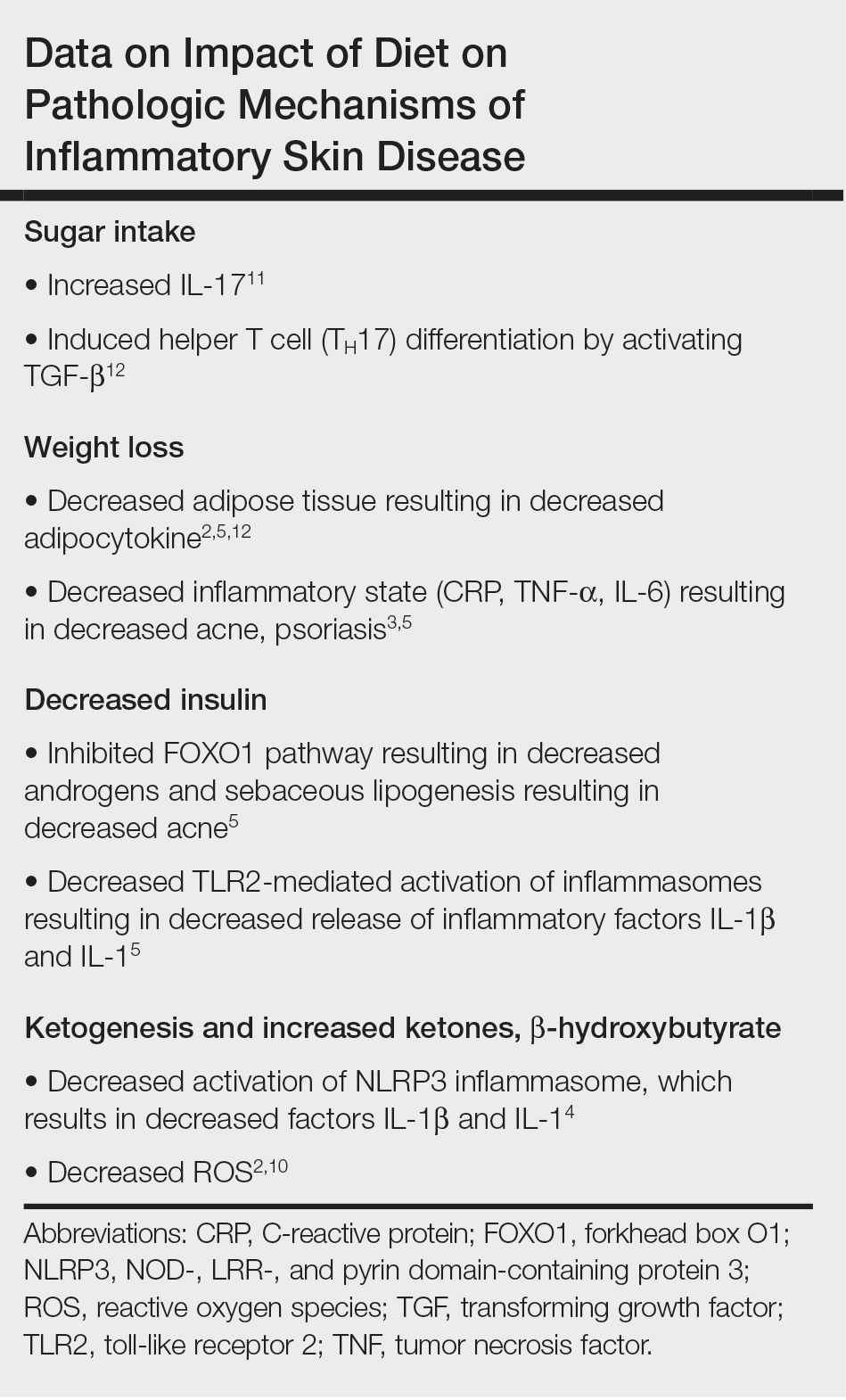

Inflammatory skin conditions often have a relapsing and remitting course and represent a large proportion of chronic skin diseases. Common inflammatory skin disorders include acne, psoriasis, hidradenitis suppurativa (HS), atopic dermatitis (AD), and seborrheic dermatitis (SD).1 Although each of these conditions has a unique pathogenesis, they all are driven by a background of chronic inflammation. It has been reported that diets with high levels of refined carbohydrates and saturated or trans-fatty acids may exacerbate existing inflammation.2 Consequently, dietary interventions, such as the ketogenic and low-glycemic diets, have potential anti-inflammatory and metabolic effects that are being assessed as stand-alone or adjunctive therapies for dermatologic diseases.

Diet may partially influence systemic inflammation through its effect on weight. Higher body mass index and obesity are linked to a low-grade inflammatory state and higher levels of circulating inflammatory markers. Therefore, weight loss leads to decreases in inflammatory cytokines, including C-reactive protein, tumor necrosis factor α, and IL-6.3 These cytokines and metabolic effects overlap with inflammatory skin condition pathways. It also is posited that decreased insulin release associated with weight loss results in decreased sebaceous lipogenesis and androgens, which drive keratinocyte proliferation and acne development.4,5 For instance, in a 2015 meta-analysis of 5 randomized controlled trials on psoriasis, patients in the weight loss intervention group had more substantial reductions in psoriasis area and severity index (PASI) scores compared with controls receiving usual care (P=.004).6 However, in a systematic review of 35 studies on acne vulgaris, overweight and obese patients (defined by a body mass index of ≥23 kg/m2) had similar odds of having acne compared with normal-weight individuals (P=.671).7

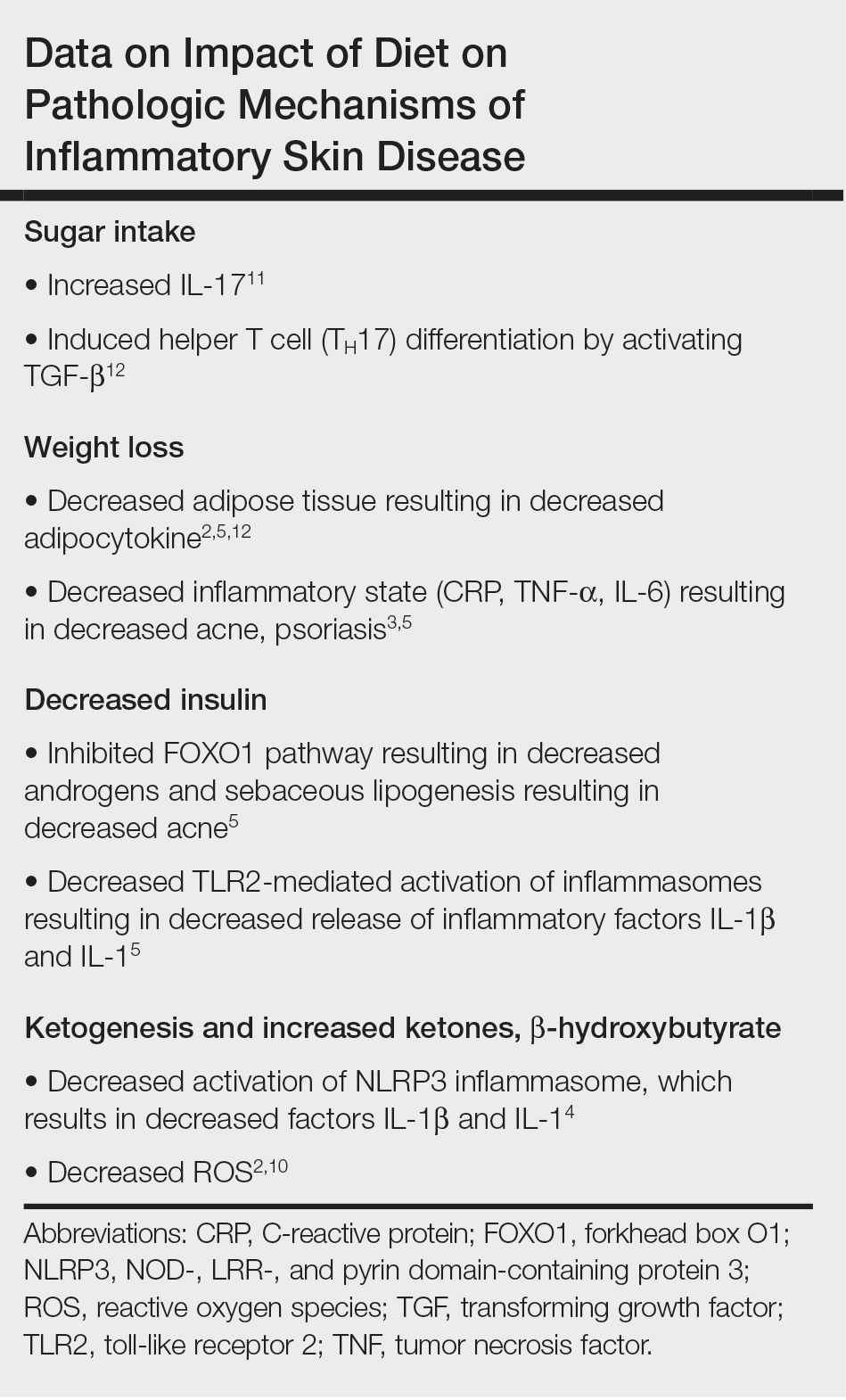

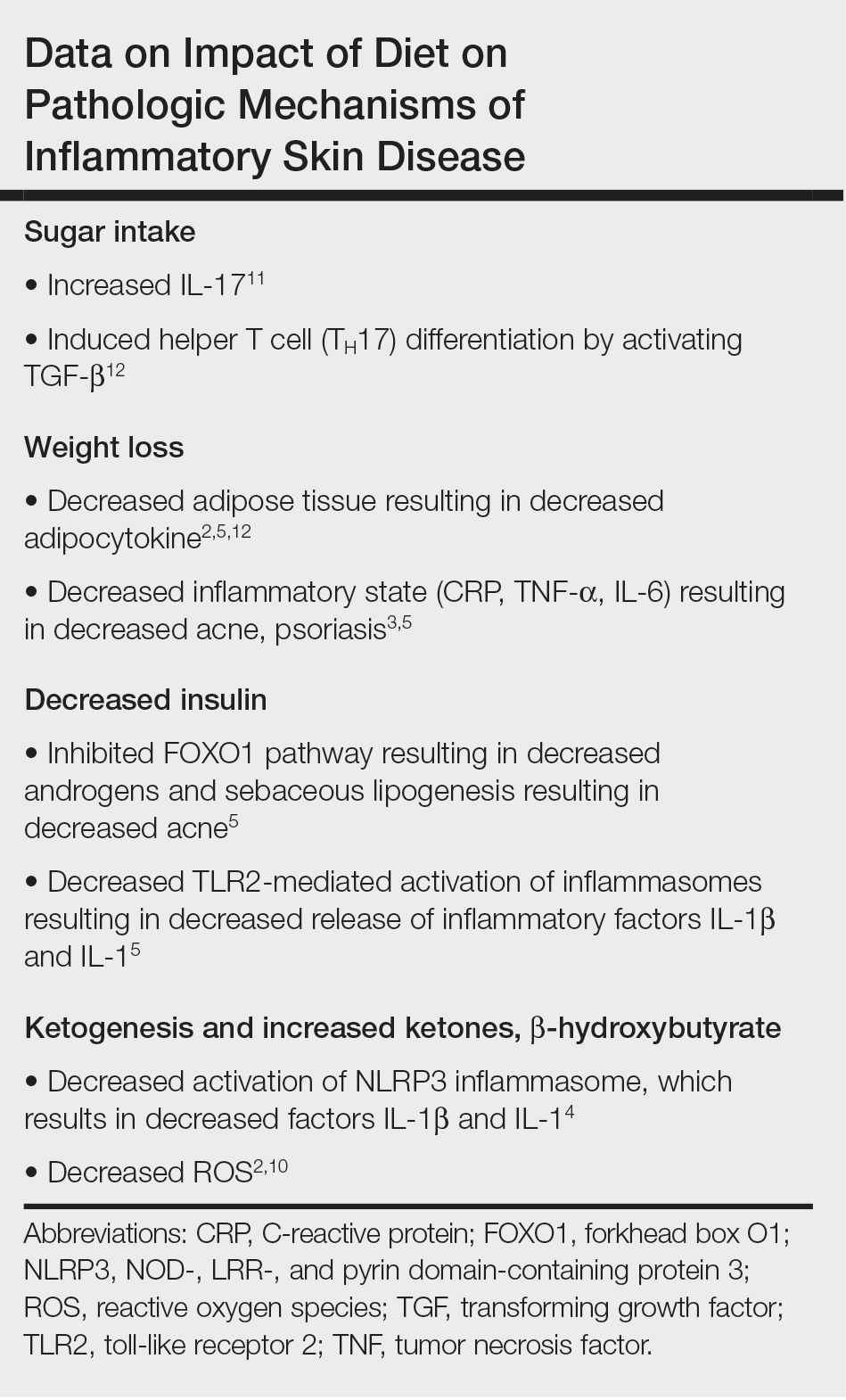

Similar to weight loss, ketogenesis acts as a negative feedback mechanism to reduce insulin release, leading to decreased inflammation and androgens that often exacerbate inflammatory skin diseases.8 Ketogenesis ensues when daily carbohydrate intake is limited to less than 50 g, and long-term adherence to a ketogenic diet results in metabolic reliance on ketone bodies such as acetoacetate, β-hydroxybutyrate, and acetone.9 These metabolites may decrease free radical damage and consequently improve signs and symptoms of acne, psoriasis, and other inflammatory skin diseases.10-12 Similarly, increased ketones also may decrease activation of the NLRP3 (NOD-, LRR-, and Pyrin domain-containing protein 3) inflammasome and therefore reduce inflammatory markers such as IL-1β and IL-1.4,13 Several proposed mechanisms are outlined in the Table.

Collectively, low-glycemic and ketogenic diets have been proposed as potential interventions for reducing inflammatory skin conditions. These dietary approaches are hypothesized to exert their effects by facilitating weight loss, elevating ketone levels, and reducing systemic inflammation. The current review summarizes the existing evidence on ketogenic and low-glycemic diets as treatments for inflammatory skin conditions and evaluates the potential benefits of these dietary interventions in managing and improving outcomes for individuals with inflammatory skin conditions.

Methods

Using PubMed for articles indexed for MEDLINE and Google Scholar, a review of the literature was conducted with a combination of the following search terms: low-glycemic diet, inflammatory, dermatologic, ketogenic diet, inflammation, dermatology, acne, psoriasis, eczema, seborrheic dermatitis, and hidradenitis suppurativa. Reference citations in identified works also were reviewed. Interventional (experimental studies or clinical trials), survey-based, and observational studies that investigated the effects of low-glycemic or ketogenic diets for the treatment of inflammatory skin conditions were included. Inclusion criteria were studies assessing acne, psoriasis, SD, AD, and HS. Exclusion criteria were studies published before 1965; those written in languages other than English; and those analyzing other diets, such as the Mediterranean or low-fat diets. The search yielded a total of 11 observational studies and 4 controlled studies published between 1966 and January 2023. Because this analysis utilized publicly available data and did not qualify as human subject research, institutional review board approval was not required.

Results

Acne Vulgaris—Acne vulgaris is a disease of chronic pilosebaceous inflammation and follicular epithelial proliferation associated with Propionibacterium acnes. The association between acne and low-glycemic diets has been examined in several studies. Diet quality is measured and assessed using the glycemic index (GI), which is the effect of a single food on postprandial blood glucose, and the glycemic load, which is the GI adjusted for carbohydrates per serving.14 High levels of GI and glycemic load are associated with hyperinsulinemia and an increase in insulinlike growth factor 1 concentration that promotes

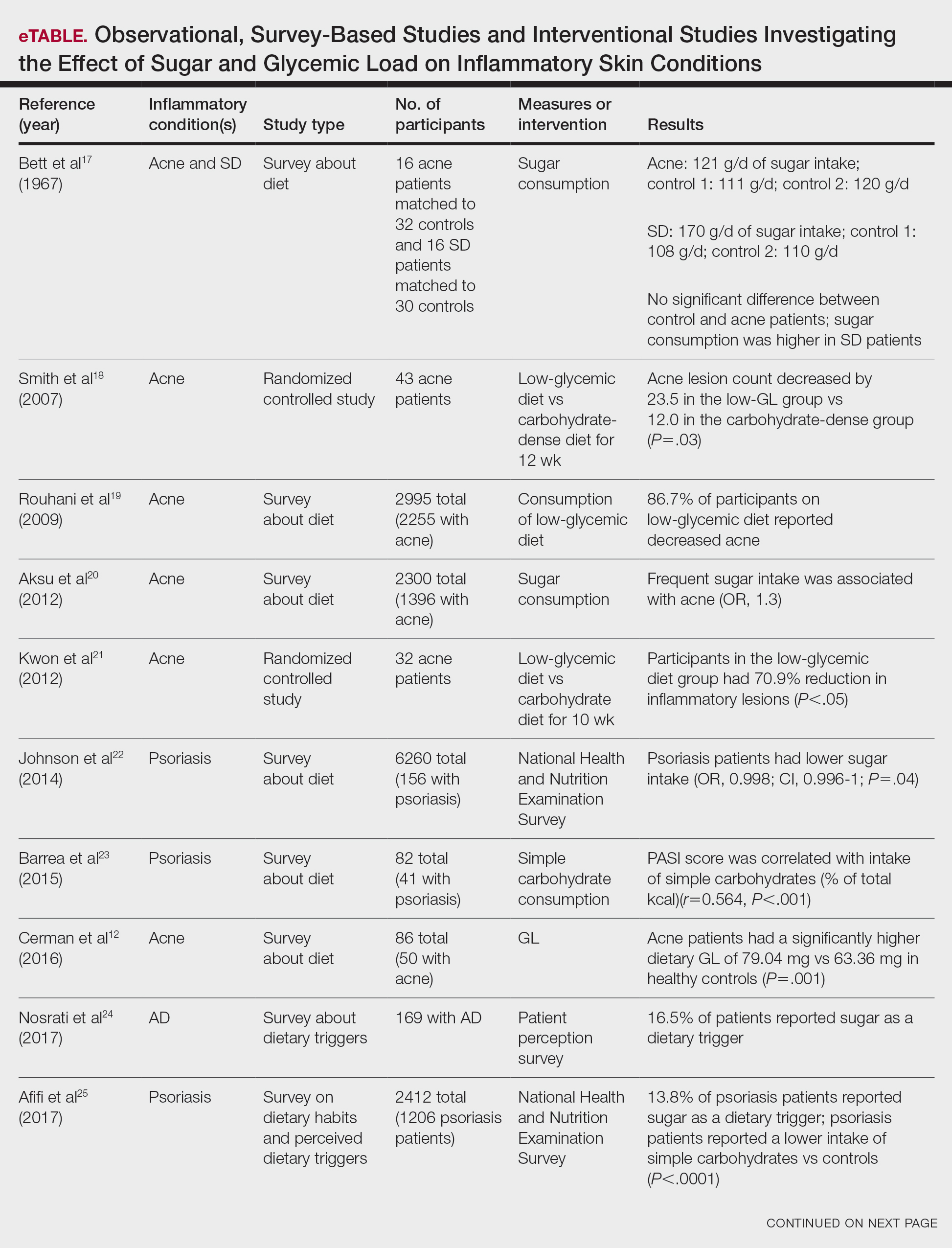

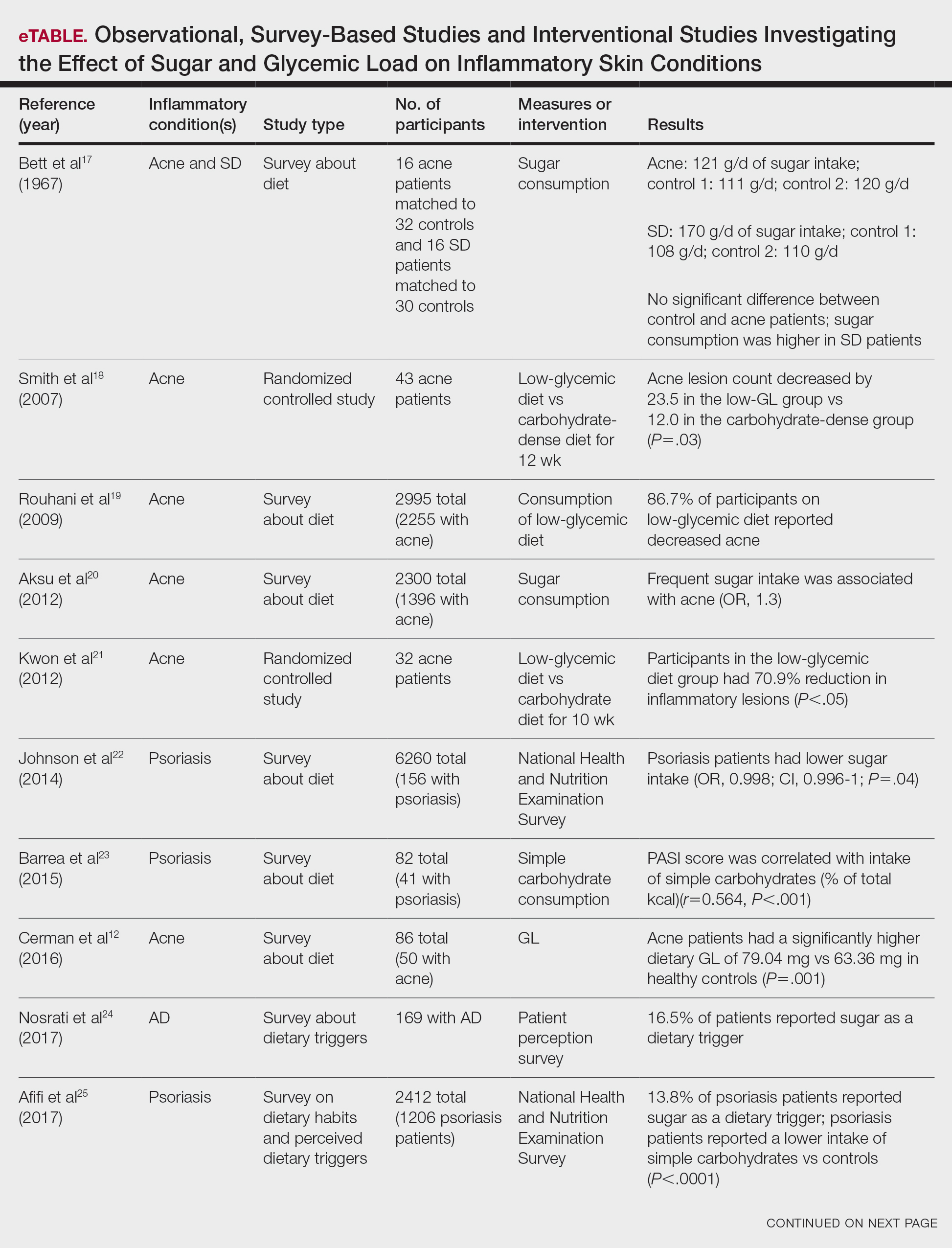

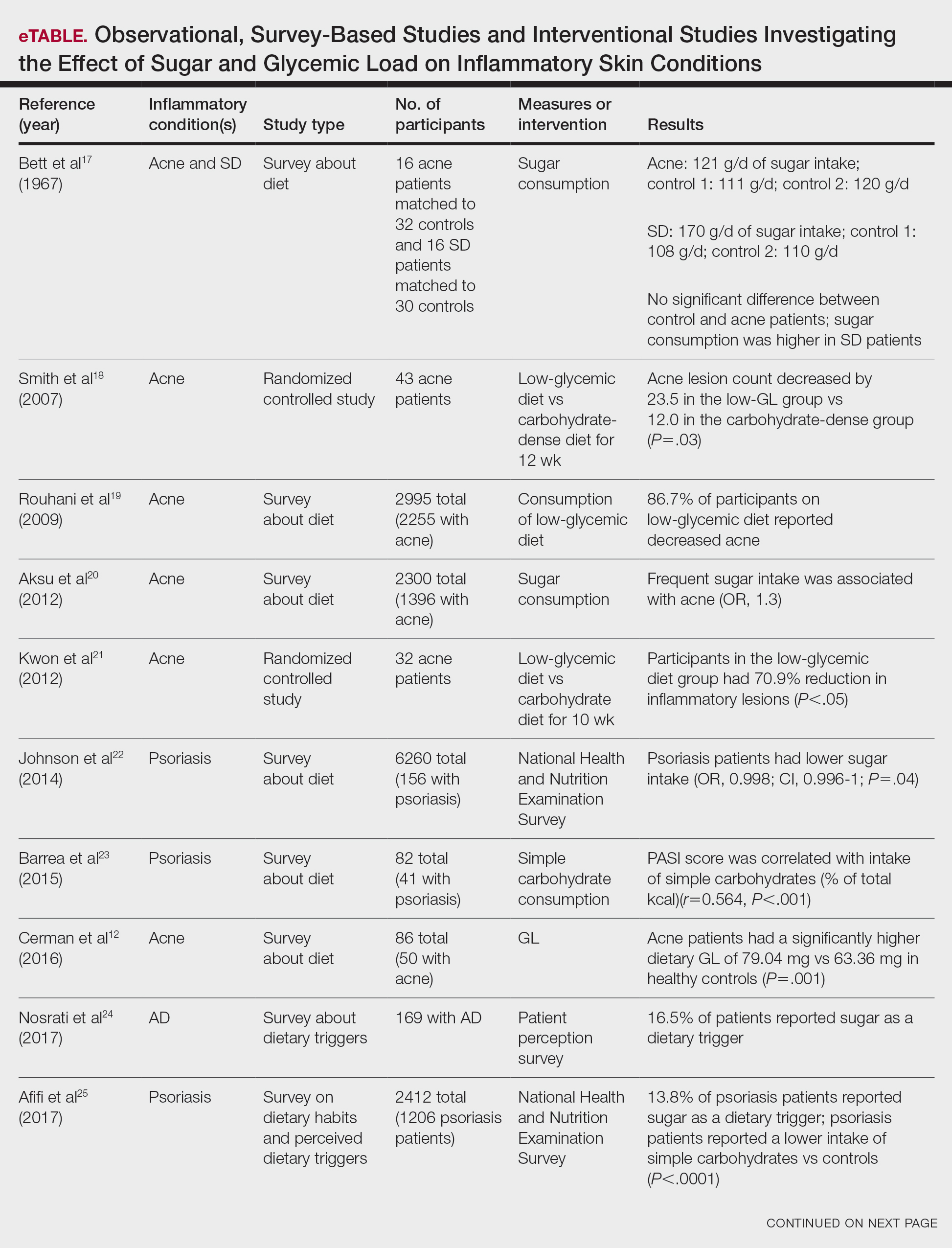

Six survey-based studies evaluated sugar intake in patients with acne compared to healthy matched controls (eTable). Among these studies, 5 reported higher glycemic loads or daily sugar intake in acne patients compared to individuals without acne.12,19,20,26,28 The remaining study was conducted in 1967 and enrolled 16 acne patients and 32 matched controls. It reported no significant difference in sugar intake between the groups (P>.05).17

Smith et al18 randomized 43 male patients aged 15 to 25 years with facial acne into 2 cohorts for 12 weeks, each consuming either a low-glycemic diet (25% protein, 45% low-glycemic food [fruits, whole grains], and 30% fat) or a carbohydrate-dense diet of foods with medium to high GI based on prior documentation of the original diet. Patients were instructed to use a noncomedogenic cleanser as their only acne treatment. At 12 weeks, patients consuming the low-glycemic diet had an average of 23.5 fewer inflammatory lesions, while those in the intervention group had 12.0 fewer lesions (P=.03).18

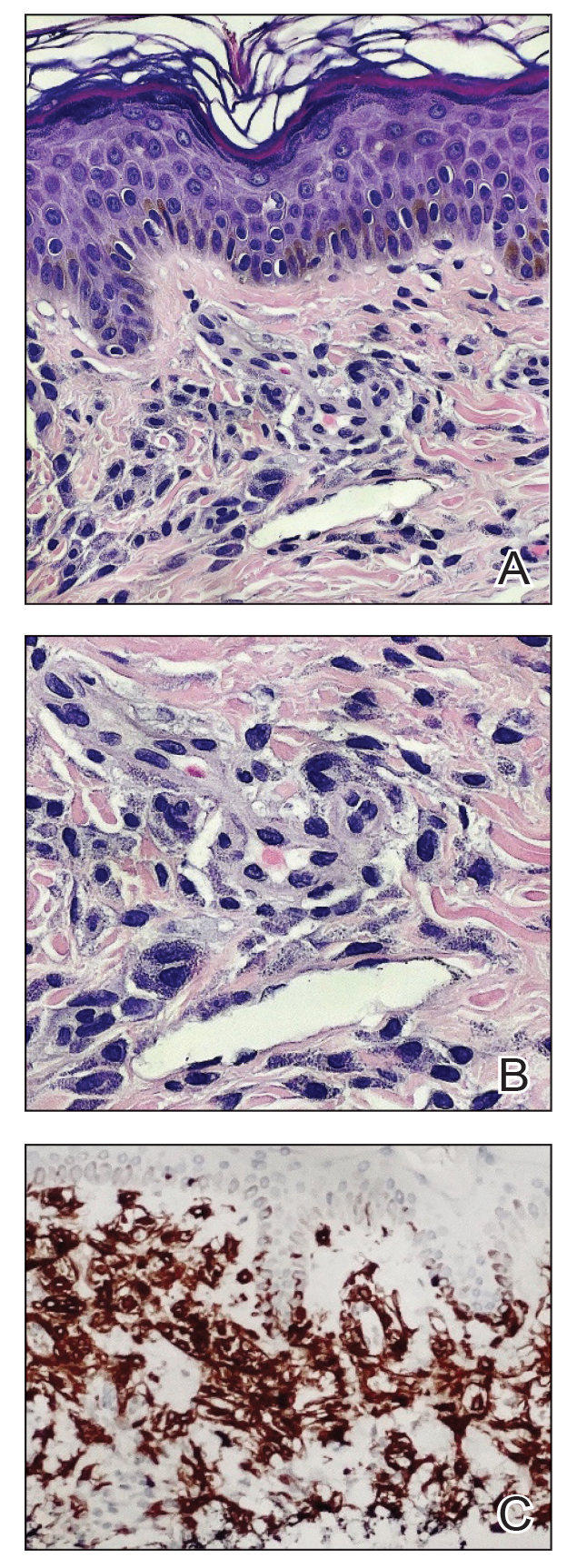

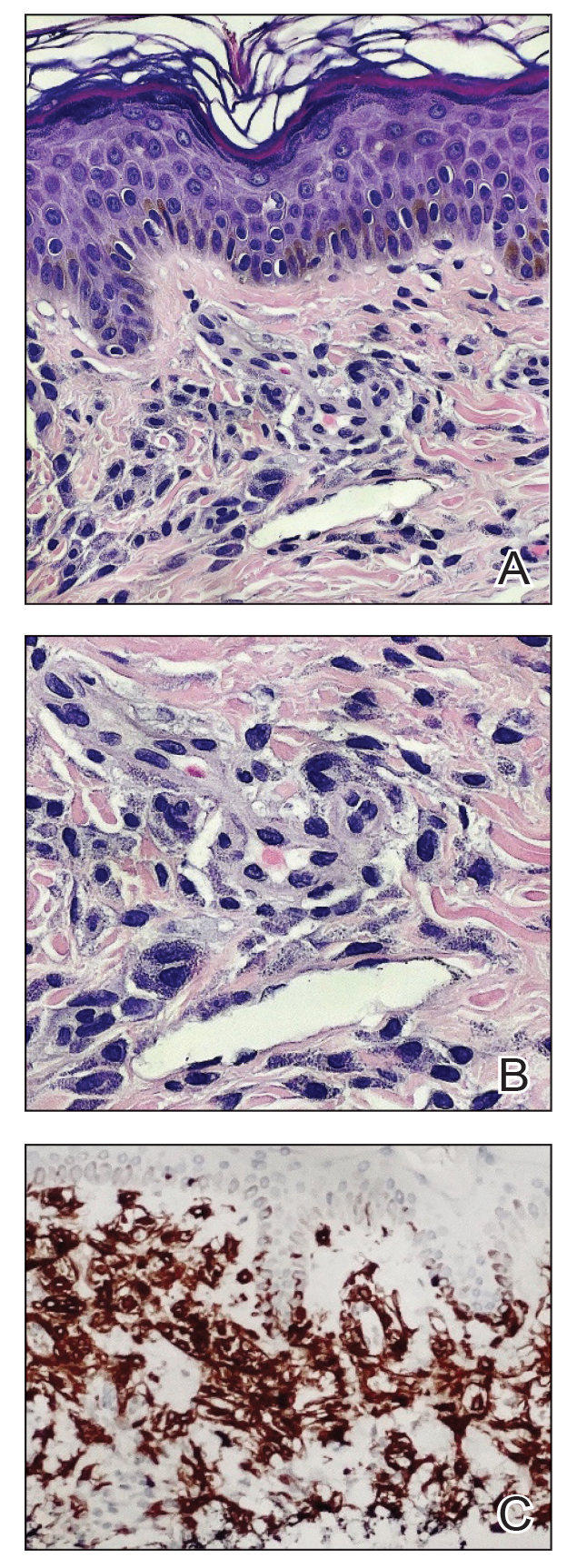

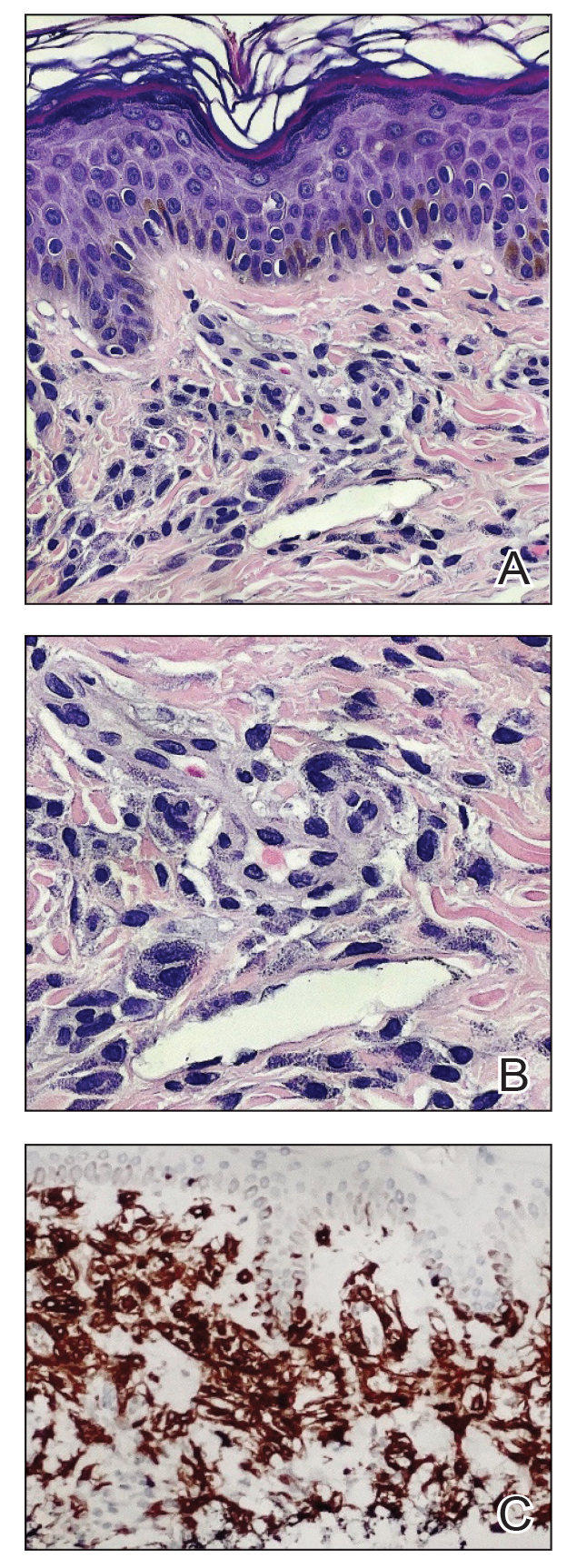

In another controlled study by Kwon et al,21 32 male and female acne patients were randomized to a low-glycemic diet (25% protein, 45% low-glycemic food, and 30% fat) or a standard diet for 10 weeks. Patients on the low-glycemic diet experienced a 70.9% reduction in inflammatory lesions (P<.05). Hematoxylin and eosin staining and image analysis were performed to measure sebaceous gland surface area in the low-glycemic diet group, which decreased from 0.32 to 0.24 mm2 (P=.03). The sebaceous gland surface area in the control group was not reported. Moreover, patients on the low-glycemic diet had reduced IL-8 immunohistochemical staining (decreasing from 2.9 to 1.7 [P=.03]) and sterol regulatory element-binding protein 1 levels (decreasing from 2.6 to 1.3 [P=.03]), suggesting suppression of ongoing inflammation. Patients on the low-glycemic diet had no significant difference in transforming growth factor β1(P=.83). In the control group, there was no difference in IL-8, sterol regulatory element binding protein 1, or transforming growth factor β1 (P>.05) on immunohistochemical staining.21

Psoriasis—Psoriasis is a systemic inflammatory disease characterized by hyperproliferation and aberrant keratinocyte plaque formation. The innate immune response of keratinocytes in response to epidermal damage or infection begins with neutrophil recruitment and dendritic cell activation. Dendritic cell secretion of IL-23 promotes T-cell differentiation into helper T cells (TH1) that subsequently secrete IL-17 and IL-22, thereby stimulating keratinocyte proliferation and eventual plaque formation. The relationship between diet and psoriasis is poorly understood; however, hyperinsulinemia is associated with greater severity of psoriasis.31

Four observational studies examined sugar intake in psoriasis patients. Barrea et al23 conducted a survey-based study of 82 male participants (41 with psoriasis and 41 healthy controls), reporting that PASI score was correlated with intake of simple carbohydrates (percentage of total kilocalorie)(r=0.564, P<.001). Another study by Yamashita et al27 found higher sugar intake in psoriasis patients than controls (P=.003) based on surveys from 70 patients with psoriasis and 70 matched healthy controls.

These findings contrast with 2 survey-based studies by Johnson et al22 and Afifi et al25 of sugar intake in psoriasis patients using the National Health and Nutrition Examination Survey. Johnson et al22 reported reduced sugar intake among 156 psoriasis patients compared with 6104 unmatched controls (odds ratio, 0.998; CI, 0.996-1 [P=.04]) from 2003 to 2006. Similarly, Afifi et al25 reported decreased sugar intake in 1206 psoriasis patients compared with sex- and age-matched controls (P<.0001) in 2009 and 2010. When patients were asked about dietary triggers, 13.8% of psoriasis patients reported sugar as the most common trigger, which was more frequent than alcohol (13.6%), gluten (7.2%), and dairy (6%).25

Castaldo et al29,30 published 2 nonrandomized clinical intervention studies in 2020 and 2021 evaluating the impact of the ketogenic diet on psoriasis. In the first study, 37 psoriasis patients followed a 10-week diet consisting of 4 weeks on a ketogenic diet (500 kcal/d) followed by 6 weeks on a low-caloric Mediterranean diet.29 At the end of the intervention, there was a 17.4% reduction in PASI score, a 33.2-point reduction in itch severity score, and a 13.4-point reduction in the dermatology life quality index score; however, this study did not include a control diet group for comparison.29 The second study included 30 psoriasis patients on a ketogenic diet and 30 control patients without psoriasis on a regular diet.30 The ketogenic diet consisted of 400 to 500 g of vegetables, 20 to 30 g of fat, and a proportion of protein based on body weight with at least 12 g of whey protein and various amino acids. Patients on the ketogenic diet had significant reduction in PASI scores (value relative to clinical features, 1.4916 [P=.007]). Furthermore, concentrations of cytokines IL-2 (P=.04) and IL-1β (P=.006) decreased following the ketogenic diet but were not measured in the control group.30

Seborrheic Dermatitis—Seborrheic dermatitis is associated with overcolonization of Malassezia species near lipid-rich sebaceous glands. Malassezia hydrolyzes free fatty acids, yielding oleic acids and leading to T-cell release of IL-8 and IL-17.32 Literature is sparse regarding how dietary modifications may play a role in disease severity. In a survey study, Bett et al17 compared 16 SD patients to 1:2 matched controls (N=29) to investigate the relationship between sugar consumption and presence of disease. Two control cohorts were selected, 1 from clinic patients diagnosed with verruca and 1 matched by age and sex from a survey-based study at a facility in London, England. Sugar intake was measured both in total grams per day and in “beverage sugar” per day, defined as sugar taken in tea and coffee. There was higher total sugar and higher beverage sugar intake among the SD group compared with both control groups (P<.05).17

Atopic Dermatitis—Atopic dermatitis is a disease of epidermal barrier dysfunction and IgE-mediated allergic sensitization.33 There are several mechanisms by which skin structure may be disrupted. It is well established that filaggrin mutations inhibit stratum corneum maturation and lamellar matrix deposition.34 Upregulation of IL-4–, IL-13–, and IL-17–secreting TH2 cells also is associated with disruption of tight junctions and reduction of filaggrin.35,36 Given that a T cell–mediated inflammatory response is involved in disease pathogenesis, glycemic control is hypothesized to have therapeutic potential.

Nosrati et al24 surveyed 169 AD patients about their perceived dietary triggers through a 61-question survey based on the National Health and Nutrition Examination Survey. Respondents were queried about their perceptions and dietary changes, such as removal or addition of specific food groups and trial of specific diets. Overall, 16.5% of patients reported sugar being a trigger, making it the fourth most common among those surveyed and less common than dairy (24.8%), gluten (18.3%), and alcohol (17.1%).24

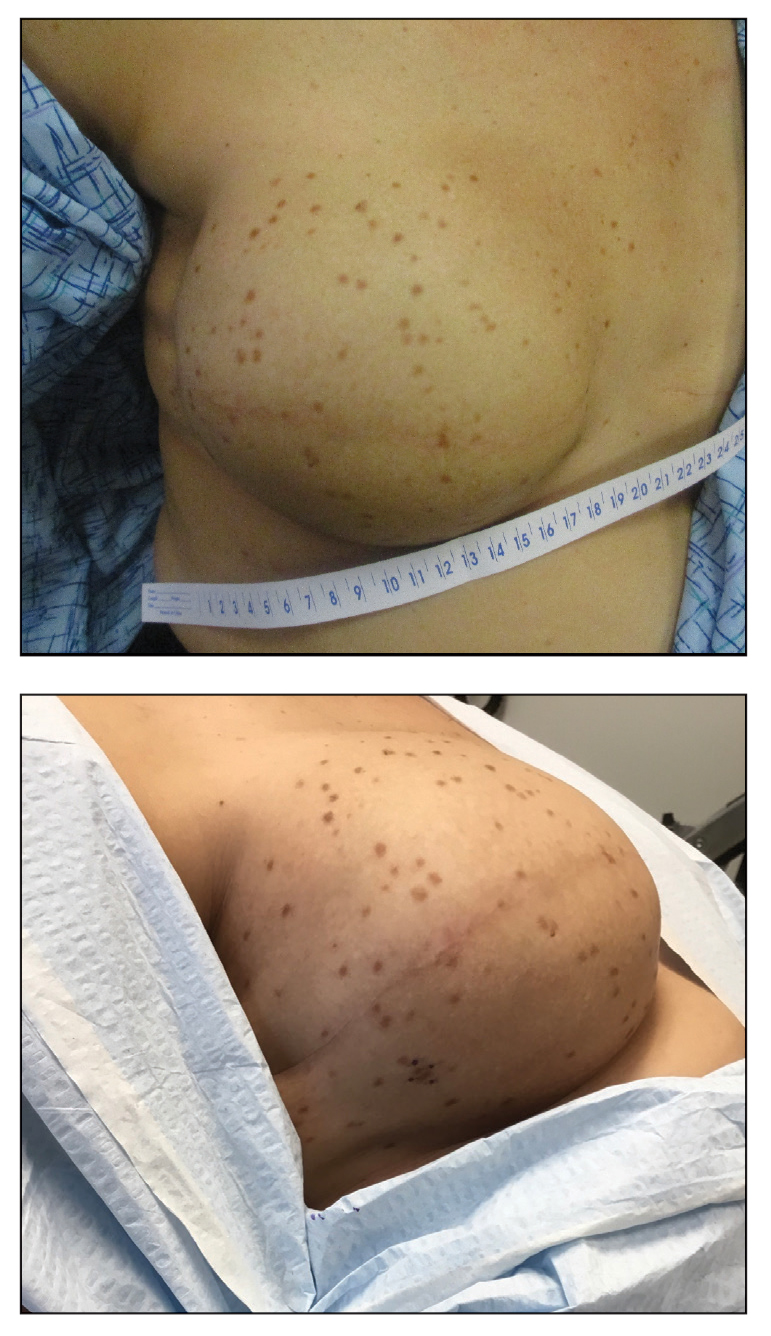

Hidradenitis Suppurativa—Hidradenitis suppurativa is driven by hyperkeratosis, dilatation, and occlusion of pilosebaceous follicular ducts, whose eventual rupture evokes a local acute inflammatory response.37 The inciting event for both acne and HS involves mTOR complex–mediated follicular hyperproliferation andinsulinlike growth factor 1 stimulation of androgen receptors in pilosebaceous glands. Given the similarities between the pathogenesis of acne and HS, it is hypothesized that lifestyle changes, including diet modification, may have a beneficial effect on HS.38-40

Comment

Acne—Overall, there is strong evidence supporting the efficacy of a low-glycemic diet in the treatment of acne. Notably, among the 6 observational studies identified, there was 1 conflicting study by Bett et al17 that did not find a statistically significant difference in glucose intake between acne and control patients. However, this study included only 16 acne patients, whereas the other 5 observational studies included 32 to 2255 patients.17 The strongest evidence supporting low-glycemic dietary interventions in acne treatment is from 2 rigorous randomized clinical trials by Kwon et al21 and Smith et al.18 These trials used intention-to-treat models and maintained consistency in gender, age, and acne treatment protocols across both control and treatment groups. To ensure compliance with dietary interventions, daily telephone calls, food logs, and 24-hour urea sampling were utilized. Acne outcomes were assessed by a dermatologist who remained blinded with well-defined outcome measures. An important limitation of these studies is the difficulty in attributing the observed results solely to reduced glucose intake, as low-glycemic diets often lead to other dietary changes, including reduced fat intake and increased nutrient consumption.18,21

A 2022 systematic review of acne by Meixiong et al41 further reinforced the beneficial effects of low-glycemic diets in the management of acne patients. The group reviewed 6 interventional studies and 28 observational studies to investigate the relationship among acne, dairy, and glycemic content and found an association between decreased glucose and dairy on reduction of acne.41

It is likely that the ketogenic diet, which limits glucose, would be beneficial for acne patients. There may be added benefit through elevated ketone bodies and substantially reduced insulin secretion. However, because there are no observational or interventional studies, further research is needed to draw firm conclusions regarding diet for acne treatment. A randomized clinical trial investigating the effects of the ketogenic diet compared to the low-glycemic diet compared to a regular diet would be valuable.

Psoriasis—Among psoriasis studies, there was a lack of consensus regarding glucose intake and correlation with disease. Among the 4 observational studies, 2 reported increased glucose intake among psoriasis patients and 2 reported decreased glucose intake. It is plausible that the variability in studies is due to differences in sample size and diet heterogeneity among study populations. More specifically, Johnson et al22 and Afifi et al25 analyzed large sample sizes of 6260 and 2412 US participants, respectively, and found decreased sugar intake among psoriasis patients compared to controls. In comparison, Barrea et al23 and Yamashita et al27 analyzed substantially smaller and more specific populations consisting of 82 Italian and 140 Japanese participants, respectively; both reported increased glucose intake among psoriasis patients compared to controls. These seemingly antithetical results may be explained by regional dietary differences, with varying proportions of meats, vegetables, antioxidants, and vitamins.

Moreover, the variation among studies may be further explained by the high prevalence of comorbidities among psoriasis patients. In the study by Barrea et al,23 psoriasis patients had higher fasting glucose (P=.004) and insulin (P=.022) levels than healthy patients. After adjusting for body mass index and metabolic syndrome, the correlation coefficient measuring the relationship between the PASI score and intake of simple carbohydrates changed from r=0.564 (P<.001) to r=0.352 (P=.028). The confounding impact of these comorbidities was further highlighted by Yamashita et al,27 who found statistically significant differences in glucose intake between psoriasis and healthy patients (P=.003). However, they reported diminished significance on additional subgroup analysis accounting for potential comorbidities (P=.994).27 Johnson et al22 and Afifi et al25 did not account for comorbidities; therefore, the 4 observational study results must be interpreted cautiously.

The 2 randomized clinical trials by Castaldo et al29,30 weakly suggest that a ketogenic diet may be beneficial for psoriasis patients. The studies have several notable limitations, including insufficient sample sizes and control groups. Thus, the decreased PASI scores reported in psoriasis patients on the ketogenic diets are challenging to interpret. Additionally, both studies placed patients on highly restrictive diets of 500 kcal/d for 4 weeks. The feasibility of recommending such a diet to patients in clinical practice is questionable. Diets of less than 500 kcal/d may be dangerous for patients with underlying comorbidities and are unlikely to serve as long-term solutions.23 To contextualize our findings, a 2022 review by Chung et al42 examined the impact of various diets—low-caloric, gluten-free, Mediterranean, Western, and ketogenic—on psoriasis and reported insufficient evidence to suggest a benefit to the ketogenic diet for psoriasis patients, though the Mediterranean diet may be well suited for psoriasis patients because of improved cardiovascular health and reduced mortality.

Seborrheic Dermatitis—Sanders et al43 found that patients with a high-fruit diet had lower odds of having SD, while those on a Western diet had higher odds of having SD. Although the study did not measure glycemic load, it is conceivable that the high glycemic load characteristic of the Western diet contributed to these findings.43 However, no studies have investigated the direct link between low-glycemic or ketogenic diets and SD, leaving this area open for further study.

Atopic Dermatitis—It has been hypothesized that mitigating T cell–mediated inflammation via glucose control may contribute to the improvement in AD.35,36 However, in one study, 16.5% of AD patients self-identified sugar as a dietary trigger, ranking fourth among other dietary triggers.24 Thus, the connection between glucose levels and AD warrants further exploration.

Hidradenitis Suppurativa—Given the role of metabolic and hormonal influence in HS as well as the overlapping pathophysiology with acne, it is possible that low-glycemic and ketogenic diets may have a role in improving HS.38-40 However, there is a gap in observation and controlled studies investigating the link between low-glycemic or ketogenic diets and HS.

Conclusion

Our analysis focused on interventional and observational research exploring the effects of low-glycemic and ketogenic diets on associations and treatment of inflammatory skin conditions. There is sufficient evidence to counsel acne patients on the benefits of a low-glycemic diet as an adjunctive treatment for acne. Currently, there is insufficient evidence to recommend a low-glycemic or ketogenic diet as a treatment for patients with any other inflammatory skin disease. Prospective and controlled clinical trials are needed to clarify the utility of dietary interventions for treating inflammatory skin conditions.

- Pickett K, Loveman E, Kalita N, et al. Educational interventions to improve quality of life in people with chronic inflammatory skin diseases: systematic reviews of clinical effectiveness and cost-effectiveness. Health Technol Assess. 2015;19:1-176, v-vi.

- Giugliano D, Ceriello A, Esposito K. The effects of diet on inflammation: emphasis on the metabolic syndrome. J Am Coll Cardiol. 2006;48:677-685.

- Dowlatshahi EA, van der Voort EA, Arends LR, et al. Markers of systemic inflammation in psoriasis: a systematic review and meta-analysis. Br J Dermatol. 2013;169:266-282.

- Youm YH, Nguyen KY, Grant RW, et al. The ketone metabolite beta-hydroxybutyrate blocks NLRP3 inflammasome-mediated inflammatory disease. Nat Med. 2015;21:263-269.

- Melnik BC. Acne vulgaris: the metabolic syndrome of the pilosebaceous follicle. Clin Dermatol. 2018;36:29-40.

- Upala S, Sanguankeo A. Effect of lifestyle weight loss intervention on disease severity in patients with psoriasis: a systematic review and meta-analysis. Int J Obes (Lond). 2015;39:1197-1202.

- Heng AHS, Chew FT. Systematic review of the epidemiology of acne vulgaris. Sci Rep. 2020;10:5754.

- Paoli A, Grimaldi K, Toniolo L, et al. Nutrition and acne: therapeutic potential of ketogenic diets. Skin Pharmacol Physiol. 2012;25:111-117.

- Masood W, Annamaraju P, Khan Suheb MZ, et al. Ketogenic diet. StatPearls. StatPearls Publishing; 2023.

- Fomin DA, McDaniel B, Crane J. The promising potential role of ketones in inflammatory dermatologic disease: a new frontier in treatment research. J Dermatolog Treat. 2017;28:484-487.

- Zhang D, Jin W, Wu R, et al. High glucose intake exacerbates autoimmunity through reactive-oxygen-species-mediated TGF-β cytokine activation. Immunity. 2019;51:671-681.e5.

- Cerman AA, Aktas E, Altunay IK, et al. Dietary glycemic factors, insulin resistance, and adiponectin levels in acne vulgaris. J Am Acad Dermatol. 2016;75:155-162.

- Ferrere G, Tidjani Alou M, Liu P, et al. Ketogenic diet and ketone bodies enhance the anticancer effects of PD-1 blockade. JCI Insight. 2021;6:e145207.

- Burris J, Shikany JM, Rietkerk W, et al. A Low glycemic index and glycemic load diet decreases insulin-like growth factor-1 among adults with moderate and severe acne: a short-duration, 2-week randomized controlled trial. J Acad Nutr Diet. 2018;118:1874-1885.

- Tan JKL, Stein Gold LF, Alexis AF, et al. Current concepts in acne pathogenesis: pathways to inflammation. Semin Cutan Med Surg. 2018;37(3S):S60-S62.

- Kim J, Ochoa MT, Krutzik SR, et al. Activation of toll-like receptor 2 in acne triggers inflammatory cytokine responses. J Immunol. 2002;169:1535-1541.

- Bett DG, Morland J, Yudkin J. Sugar consumption in acne vulgaris and seborrhoeic dermatitis. Br Med J. 1967;3:153-155.

- Smith RN, Mann NJ, Braue A, et al. A low-glycemic-load diet improves symptoms in acne vulgaris patients: a randomized controlled trial. Am J Clin Nutr. 2007;86:107-115.

- Rouhani P, Berman B, Rouhani G. Acne improves with a popular, low glycemic diet from South Beach. J Am Acad Dermatol. 2009;60(Suppl 1):AB14.

- Aksu AE, Metintas S, Saracoglu ZN, et al. Acne: prevalence and relationship with dietary habits in Eskisehir, Turkey. J Eur Acad Dermatol Venereol. 2012;26:1503-1509.

- Kwon HH, Yoon JY, Hong JS, et al. Clinical and histological effect of a low glycaemic load diet in treatment of acne vulgaris in Korean patients: a randomized, controlled trial. Acta Derm Venereol. 2012;92:241-246.

- Johnson JA, Ma C, Kanada KN, et al. Diet and nutrition in psoriasis: analysis of the National Health and Nutrition Examination Survey (NHANES) in the United States. J Eur Acad Dermatol Venereol. 2014;28:327-332.

- Barrea L, Macchia PE, Tarantino G, et al. Nutrition: a key environmental dietary factor in clinical severity and cardio-metabolic risk in psoriatic male patients evaluated by 7-day food-frequency questionnaire. J Transl Med. 2015;13:303.

- Nosrati A, Afifi L, Danesh MJ, et al. Dietary modifications in atopic dermatitis: patient-reported outcomes. J Dermatolog Treat. 2017;28:523-538.

- Afifi L, Danesh MJ, Lee KM, et al. Dietary behaviors in psoriasis: patient-reported outcomes from a U.S. national survey. Dermatol Ther (Heidelb). 2017;7:227-242.

- Burris J, Rietkerk W, Shikany JM, et al. Differences in dietary glycemic load and hormones in New York City adults with no and moderate/severe acne. J Acad Nutr Diet. 2017;117:1375-1383.

- Yamashita H, Morita T, Ito M, et al. Dietary habits in Japanese patients with psoriasis and psoriatic arthritis: low intake of meat in psoriasis and high intake of vitamin A in psoriatic arthritis. J Dermatol. 2019;46:759-769.

- Marson J, Baldwin HE. 12761 Acne, twins, and glycemic index: a sweet pilot study of diet and dietary beliefs. J Am Acad Dermatol. 2020;83(Suppl):AB110.

- Castaldo G, Rastrelli L, Galdo G, et al. Aggressive weight-loss program with a ketogenic induction phase for the treatment of chronic plaque psoriasis: a proof-of-concept, single-arm, open-label clinical trial. Nutrition. 2020;74:110757.

- Castaldo G, Pagano I, Grimaldi M, et al. Effect of very-low-calorie ketogenic diet on psoriasis patients: a nuclear magnetic resonance-based metabolomic study. J Proteome Res. 2021;20:1509-1521.

- Ip W, Kirchhof MG. Glycemic control in the treatment of psoriasis. Dermatology. 2017;233:23-29.

- Vijaya Chandra SH, Srinivas R, Dawson TL Jr, et al. Cutaneous Malassezia: commensal, pathogen, or protector? Front Cell Infect Microbiol. 2020;10:614446.

- David Boothe W, Tarbox JA, Tarbox MB. Atopic dermatitis: pathophysiology. Adv Exp Med Biol. 2017;1027:21-37.

- Guttman-Yassky E, Hanifin JM, Boguniewicz M, et al. The role of phosphodiesterase 4 in the pathophysiology of atopic dermatitis and the perspective for its inhibition. Exp Dermatol. 2019;28:3-10.

- Furue K, Ito T, Tsuji G, et al. The IL-13–OVOL1–FLG axis in atopic dermatitis. Immunology. 2019;158:281-286.

- Renert-Yuval Y, Guttman-Yassky E. New treatments for atopic dermatitis targeting beyond IL-4/IL-13 cytokines. Ann Allergy Asthma Immunol. 2020;124:28-35.

- Sellheyer K, Krahl D. “Hidradenitis suppurativa” is acne inversa! An appeal to (finally) abandon a misnomer. Int J Dermatol. 2005;44:535-540.

- Danby FW, Margesson LJ. Hidradenitis suppurativa. Dermatol Clin. 2010;28:779-793.

- Fernandez JM, Marr KD, Hendricks AJ, et al. Alleviating and exacerbating foods in hidradenitis suppurativa. Dermatol Ther. 2020;33:E14246.

- Yamanaka-Takaichi M, Revankar R, Shih T, et al. Expert consensus on priority research gaps in dietary and lifestyle factors in hidradenitis suppurativa: a Delphi consensus study. Arch Dermatol Res. 2023;315:2129-2136.

- Meixiong J, Ricco C, Vasavda C, et al. Diet and acne: a systematic review. JAAD Int. 2022;7:95-112.

- Chung M, Bartholomew E, Yeroushalmi S, et al. Dietary intervention and supplements in the management of psoriasis: current perspectives. Psoriasis (Auckland). 2022;12:151-176. doi:10.2147/PTT.S328581

- Sanders MGH, Pardo LM, Ginger RS, et al. Association between diet and seborrheic dermatitis: a cross-sectional study. J Invest Dermatol. 2019;139:108-114.

Inflammatory skin conditions often have a relapsing and remitting course and represent a large proportion of chronic skin diseases. Common inflammatory skin disorders include acne, psoriasis, hidradenitis suppurativa (HS), atopic dermatitis (AD), and seborrheic dermatitis (SD).1 Although each of these conditions has a unique pathogenesis, they all are driven by a background of chronic inflammation. It has been reported that diets with high levels of refined carbohydrates and saturated or trans-fatty acids may exacerbate existing inflammation.2 Consequently, dietary interventions, such as the ketogenic and low-glycemic diets, have potential anti-inflammatory and metabolic effects that are being assessed as stand-alone or adjunctive therapies for dermatologic diseases.

Diet may partially influence systemic inflammation through its effect on weight. Higher body mass index and obesity are linked to a low-grade inflammatory state and higher levels of circulating inflammatory markers. Therefore, weight loss leads to decreases in inflammatory cytokines, including C-reactive protein, tumor necrosis factor α, and IL-6.3 These cytokines and metabolic effects overlap with inflammatory skin condition pathways. It also is posited that decreased insulin release associated with weight loss results in decreased sebaceous lipogenesis and androgens, which drive keratinocyte proliferation and acne development.4,5 For instance, in a 2015 meta-analysis of 5 randomized controlled trials on psoriasis, patients in the weight loss intervention group had more substantial reductions in psoriasis area and severity index (PASI) scores compared with controls receiving usual care (P=.004).6 However, in a systematic review of 35 studies on acne vulgaris, overweight and obese patients (defined by a body mass index of ≥23 kg/m2) had similar odds of having acne compared with normal-weight individuals (P=.671).7