User login

Upadacitinib is effective and well-tolerated in difficult-to-treat atopic dermatitis

Key clinical point: Upadacitinib is effective and well-tolerated in patients with moderate-to-severe atopic dermatitis (AD) and prior failure to multiple systemic immunosuppressive and biologic therapies.

Major finding: At a median follow-up of 37.5 weeks, the median Investigator’s Global Assessment scores and Numerical Rating Scale itch scores reduced significantly from 3.00 to 1.50 and from 7.00 to 2.25, respectively (both P < .001). The adverse events reported were mostly mild in severity, with acne-like eruptions (25%) and nausea (13%) being the most common.

Study details: This prospective observational single-center study included 48 patients with moderate-to-severe AD receiving 15 mg or 30 mg upadacitinib daily, most of whom (n = 39) had failed other targeted therapies, including other Janus kinase inhibitors and biologics.

Disclosures: This study did not receive any funding. DJ Hijnen declared serving as an investigator and consultant for various sources. The other authors declared no conflicts of interest.

Source: Schlösser AR et al. Upadacitinib treatment in a real-world difficult-to-treat atopic dermatitis patient cohort. J Eur Acad Dermatol Venereol. 2023 (Oct 21). doi: 10.1111/jdv.19581

Key clinical point: Upadacitinib is effective and well-tolerated in patients with moderate-to-severe atopic dermatitis (AD) and prior failure to multiple systemic immunosuppressive and biologic therapies.

Major finding: At a median follow-up of 37.5 weeks, the median Investigator’s Global Assessment scores and Numerical Rating Scale itch scores reduced significantly from 3.00 to 1.50 and from 7.00 to 2.25, respectively (both P < .001). The adverse events reported were mostly mild in severity, with acne-like eruptions (25%) and nausea (13%) being the most common.

Study details: This prospective observational single-center study included 48 patients with moderate-to-severe AD receiving 15 mg or 30 mg upadacitinib daily, most of whom (n = 39) had failed other targeted therapies, including other Janus kinase inhibitors and biologics.

Disclosures: This study did not receive any funding. DJ Hijnen declared serving as an investigator and consultant for various sources. The other authors declared no conflicts of interest.

Source: Schlösser AR et al. Upadacitinib treatment in a real-world difficult-to-treat atopic dermatitis patient cohort. J Eur Acad Dermatol Venereol. 2023 (Oct 21). doi: 10.1111/jdv.19581

Key clinical point: Upadacitinib is effective and well-tolerated in patients with moderate-to-severe atopic dermatitis (AD) and prior failure to multiple systemic immunosuppressive and biologic therapies.

Major finding: At a median follow-up of 37.5 weeks, the median Investigator’s Global Assessment scores and Numerical Rating Scale itch scores reduced significantly from 3.00 to 1.50 and from 7.00 to 2.25, respectively (both P < .001). The adverse events reported were mostly mild in severity, with acne-like eruptions (25%) and nausea (13%) being the most common.

Study details: This prospective observational single-center study included 48 patients with moderate-to-severe AD receiving 15 mg or 30 mg upadacitinib daily, most of whom (n = 39) had failed other targeted therapies, including other Janus kinase inhibitors and biologics.

Disclosures: This study did not receive any funding. DJ Hijnen declared serving as an investigator and consultant for various sources. The other authors declared no conflicts of interest.

Source: Schlösser AR et al. Upadacitinib treatment in a real-world difficult-to-treat atopic dermatitis patient cohort. J Eur Acad Dermatol Venereol. 2023 (Oct 21). doi: 10.1111/jdv.19581

Lebrikizumab rapidly relieves itch and itch-associated sleep loss in AD

Key clinical point: Lebrikizumab monotherapy for 16 weeks significantly reduced itch and itch-associated sleep loss in patients with moderate-to-severe atopic dermatitis (AD).

Major finding: At 16 weeks, a significantly higher number of patients from the ADvocate1 and ADvocate2 trials treated with lebrikizumab vs placebo achieved a ≥ 3-point improvement in the Pruritus Numeric Rating Scale scores (ADvocate1 54.6% vs 19.2%; ADvocate2 49.4% vs 14.0%; both P < .001) and ≥ 1-point improvement in Sleep-Loss Scale scores (ADvocate1 64.1% vs 27.2%; ADvocate2 58.1% vs 21.7%; both P < .001).

Study details: Findings are from a study including patients from the ADvocate1 (n = 424) and ADvocate2 (n = 427) trials who had moderate-to-severe AD and were randomized to receive subcutaneous lebrikizumab or placebo every 2 weeks.

Disclosures: This study was sponsored by Dermira, a wholly owned subsidiary of Eli Lilly and Company. Several authors declared receiving research grants or honoraria from, serving as employees and shareholders of, or having other ties with various sources, including Eli Lilly and Dermira.

Source: Yosipovitch G et al. Lebrikizumab improved itch and reduced the extent of itch interference on sleep in patients with moderate-to-severe atopic dermatitis: Two randomized, placebo-controlled, phase III trials. Br J Dermatol. 2023 (Nov 6). doi: 10.1093/bjd/ljad435

Key clinical point: Lebrikizumab monotherapy for 16 weeks significantly reduced itch and itch-associated sleep loss in patients with moderate-to-severe atopic dermatitis (AD).

Major finding: At 16 weeks, a significantly higher number of patients from the ADvocate1 and ADvocate2 trials treated with lebrikizumab vs placebo achieved a ≥ 3-point improvement in the Pruritus Numeric Rating Scale scores (ADvocate1 54.6% vs 19.2%; ADvocate2 49.4% vs 14.0%; both P < .001) and ≥ 1-point improvement in Sleep-Loss Scale scores (ADvocate1 64.1% vs 27.2%; ADvocate2 58.1% vs 21.7%; both P < .001).

Study details: Findings are from a study including patients from the ADvocate1 (n = 424) and ADvocate2 (n = 427) trials who had moderate-to-severe AD and were randomized to receive subcutaneous lebrikizumab or placebo every 2 weeks.

Disclosures: This study was sponsored by Dermira, a wholly owned subsidiary of Eli Lilly and Company. Several authors declared receiving research grants or honoraria from, serving as employees and shareholders of, or having other ties with various sources, including Eli Lilly and Dermira.

Source: Yosipovitch G et al. Lebrikizumab improved itch and reduced the extent of itch interference on sleep in patients with moderate-to-severe atopic dermatitis: Two randomized, placebo-controlled, phase III trials. Br J Dermatol. 2023 (Nov 6). doi: 10.1093/bjd/ljad435

Key clinical point: Lebrikizumab monotherapy for 16 weeks significantly reduced itch and itch-associated sleep loss in patients with moderate-to-severe atopic dermatitis (AD).

Major finding: At 16 weeks, a significantly higher number of patients from the ADvocate1 and ADvocate2 trials treated with lebrikizumab vs placebo achieved a ≥ 3-point improvement in the Pruritus Numeric Rating Scale scores (ADvocate1 54.6% vs 19.2%; ADvocate2 49.4% vs 14.0%; both P < .001) and ≥ 1-point improvement in Sleep-Loss Scale scores (ADvocate1 64.1% vs 27.2%; ADvocate2 58.1% vs 21.7%; both P < .001).

Study details: Findings are from a study including patients from the ADvocate1 (n = 424) and ADvocate2 (n = 427) trials who had moderate-to-severe AD and were randomized to receive subcutaneous lebrikizumab or placebo every 2 weeks.

Disclosures: This study was sponsored by Dermira, a wholly owned subsidiary of Eli Lilly and Company. Several authors declared receiving research grants or honoraria from, serving as employees and shareholders of, or having other ties with various sources, including Eli Lilly and Dermira.

Source: Yosipovitch G et al. Lebrikizumab improved itch and reduced the extent of itch interference on sleep in patients with moderate-to-severe atopic dermatitis: Two randomized, placebo-controlled, phase III trials. Br J Dermatol. 2023 (Nov 6). doi: 10.1093/bjd/ljad435

AAD updates guidelines for managing AD with phototherapy and systemic therapies

.

The guidelines cover approved and off-label uses of systemic therapies and phototherapy, including new treatments that have become available since the last guidelines were published almost a decade ago. These include biologics and oral Janus kinase (JAK) inhibitors, as well as older oral or injectable immunomodulators and antimetabolites, oral antibiotics, antihistamines, and phosphodiesterase-4 inhibitors. The guidelines rate the existing evidence as “strong” for dupilumab, tralokinumab, abrocitinib, baricitinib, and upadacitinib. They also conditionally recommend phototherapy, as well as cyclosporine, methotrexate, azathioprine, and mycophenolate, but recommend against the use of systemic corticosteroids.

The guidelines update the AAD’s 2014 recommendations for managing AD in adults with phototherapy and systemic therapies. “At that time, prednisone – universally agreed to be the least appropriate chronic therapy for AD – was the only Food and Drug Administration–approved agent,” Robert Sidbury, MD, MPH, who cochaired a 14-member multidisciplinary work group that assembled the guidelines, told this news organization. “This was the driver.”

The latest guidelines were published online in the Journal of the American Academy of Dermatology.

Broad evidence review

Dr. Sidbury, chief of the division of dermatology at Seattle Children’s Hospital, guidelines cochair Dawn M. R. Davis, MD, a dermatologist at the Mayo Clinic, Rochester, Minn., and colleagues conducted a systematic evidence review of phototherapy such as narrowband and broadband UVB and systemic therapies, including biologics such as dupilumab and tralokinumab, JAK inhibitors such as upadacitinib and abrocitinib, and immunosuppressants such as methotrexate and azathioprine.

Next, the work group applied the Grading of Recommendations, Assessment, Development, and Evaluation (GRADE) approach for assessing the certainty of the evidence and formulating and grading clinical recommendations based on relevant randomized trials in the medical literature.

Recommendations, future studies

Of the 11 evidence-based recommendations of therapies for adults with AD refractory to topical medications, the work group ranks 5 as “strong” based on the evidence and the rest as “conditional.” “Strong” implies the benefits clearly outweigh risks and burdens, they apply to most patients in most circumstances, and they fall under good clinical practice. “Conditional” means the benefits and risks are closely balanced for most patients, “but the appropriate action may different depending on the patient or other stakeholder values,” the authors wrote.

In their remarks about phototherapy, the work group noted that most published literature on the topic “reports on the efficacy and safety of narrow band UVB. Wherever possible, use a light source that minimizes the potential for harm under the supervision of a qualified clinician.”

In their remarks about cyclosporine, they noted that evidence suggests an initial dose of 3 mg/kg per day to 5 mg/kg per day is effective, but that the Food and Drug Administration has not approved cyclosporine for use in AD. “The FDA has approved limited-term use (up to 1 year) in psoriasis,” they wrote. “Comorbidities or drug interactions that may exacerbate toxicity make this intervention inappropriate for select patients.” The work group noted that significant research gaps remain in phototherapy, especially trials that compare different phototherapy modalities and those that compare phototherapy with other AD treatment strategies.

“Larger clinical trials would also be helpful for cyclosporine, methotrexate, azathioprine, and mycophenolate to improve the certainty of evidence for those medications,” they added. “Furthermore, formal cost-effectiveness analyses comparing older to newer treatments are needed.”

They recommended the inclusion of active comparator arms in randomized, controlled trials as new systemic therapies continue to be developed and tested.

The work group ranked the level of evidence they reviewed for the therapies from very low to moderate. No therapy was judged to have high evidence. They also cited the short duration of most randomized controlled trials of phototherapy.

Using the guidelines in clinical care

According to Dr. Davis, the topic of which agent if any should be considered “first line” generated robust discussion among the work group members.

“When there are not robust head-to-head trials – and there are not – it is often opinion that governs this decision, and opinion should not, when possible, govern a guideline,” Dr. Davis said. “Accordingly, we determined based upon the evidence agents – plural – that deserve to be considered ‘first line’ but not a single agent.”

In her opinion, the top three considerations regarding use of systemic therapy for AD relate to patient selection and shared decision making. One, standard therapy has failed. Two, diagnosis is assured. And three, “steroid phobia should be considered,” and patients should be “fully informed of risks and benefits of both treating and not treating,” she said.

Dr. Sidbury reported that he serves as an advisory board member for Pfizer, a principal investigator for Regeneron, an investigator for Brickell Biotech and Galderma USA, and a consultant for Galderma Global and Micreos. Dr. Davis reported having no relevant disclosures. Other work group members reported having financial disclosures with many pharmaceutical companies. The study was supported by internal funds from the American Academy of Dermatology.

.

The guidelines cover approved and off-label uses of systemic therapies and phototherapy, including new treatments that have become available since the last guidelines were published almost a decade ago. These include biologics and oral Janus kinase (JAK) inhibitors, as well as older oral or injectable immunomodulators and antimetabolites, oral antibiotics, antihistamines, and phosphodiesterase-4 inhibitors. The guidelines rate the existing evidence as “strong” for dupilumab, tralokinumab, abrocitinib, baricitinib, and upadacitinib. They also conditionally recommend phototherapy, as well as cyclosporine, methotrexate, azathioprine, and mycophenolate, but recommend against the use of systemic corticosteroids.

The guidelines update the AAD’s 2014 recommendations for managing AD in adults with phototherapy and systemic therapies. “At that time, prednisone – universally agreed to be the least appropriate chronic therapy for AD – was the only Food and Drug Administration–approved agent,” Robert Sidbury, MD, MPH, who cochaired a 14-member multidisciplinary work group that assembled the guidelines, told this news organization. “This was the driver.”

The latest guidelines were published online in the Journal of the American Academy of Dermatology.

Broad evidence review

Dr. Sidbury, chief of the division of dermatology at Seattle Children’s Hospital, guidelines cochair Dawn M. R. Davis, MD, a dermatologist at the Mayo Clinic, Rochester, Minn., and colleagues conducted a systematic evidence review of phototherapy such as narrowband and broadband UVB and systemic therapies, including biologics such as dupilumab and tralokinumab, JAK inhibitors such as upadacitinib and abrocitinib, and immunosuppressants such as methotrexate and azathioprine.

Next, the work group applied the Grading of Recommendations, Assessment, Development, and Evaluation (GRADE) approach for assessing the certainty of the evidence and formulating and grading clinical recommendations based on relevant randomized trials in the medical literature.

Recommendations, future studies

Of the 11 evidence-based recommendations of therapies for adults with AD refractory to topical medications, the work group ranks 5 as “strong” based on the evidence and the rest as “conditional.” “Strong” implies the benefits clearly outweigh risks and burdens, they apply to most patients in most circumstances, and they fall under good clinical practice. “Conditional” means the benefits and risks are closely balanced for most patients, “but the appropriate action may different depending on the patient or other stakeholder values,” the authors wrote.

In their remarks about phototherapy, the work group noted that most published literature on the topic “reports on the efficacy and safety of narrow band UVB. Wherever possible, use a light source that minimizes the potential for harm under the supervision of a qualified clinician.”

In their remarks about cyclosporine, they noted that evidence suggests an initial dose of 3 mg/kg per day to 5 mg/kg per day is effective, but that the Food and Drug Administration has not approved cyclosporine for use in AD. “The FDA has approved limited-term use (up to 1 year) in psoriasis,” they wrote. “Comorbidities or drug interactions that may exacerbate toxicity make this intervention inappropriate for select patients.” The work group noted that significant research gaps remain in phototherapy, especially trials that compare different phototherapy modalities and those that compare phototherapy with other AD treatment strategies.

“Larger clinical trials would also be helpful for cyclosporine, methotrexate, azathioprine, and mycophenolate to improve the certainty of evidence for those medications,” they added. “Furthermore, formal cost-effectiveness analyses comparing older to newer treatments are needed.”

They recommended the inclusion of active comparator arms in randomized, controlled trials as new systemic therapies continue to be developed and tested.

The work group ranked the level of evidence they reviewed for the therapies from very low to moderate. No therapy was judged to have high evidence. They also cited the short duration of most randomized controlled trials of phototherapy.

Using the guidelines in clinical care

According to Dr. Davis, the topic of which agent if any should be considered “first line” generated robust discussion among the work group members.

“When there are not robust head-to-head trials – and there are not – it is often opinion that governs this decision, and opinion should not, when possible, govern a guideline,” Dr. Davis said. “Accordingly, we determined based upon the evidence agents – plural – that deserve to be considered ‘first line’ but not a single agent.”

In her opinion, the top three considerations regarding use of systemic therapy for AD relate to patient selection and shared decision making. One, standard therapy has failed. Two, diagnosis is assured. And three, “steroid phobia should be considered,” and patients should be “fully informed of risks and benefits of both treating and not treating,” she said.

Dr. Sidbury reported that he serves as an advisory board member for Pfizer, a principal investigator for Regeneron, an investigator for Brickell Biotech and Galderma USA, and a consultant for Galderma Global and Micreos. Dr. Davis reported having no relevant disclosures. Other work group members reported having financial disclosures with many pharmaceutical companies. The study was supported by internal funds from the American Academy of Dermatology.

.

The guidelines cover approved and off-label uses of systemic therapies and phototherapy, including new treatments that have become available since the last guidelines were published almost a decade ago. These include biologics and oral Janus kinase (JAK) inhibitors, as well as older oral or injectable immunomodulators and antimetabolites, oral antibiotics, antihistamines, and phosphodiesterase-4 inhibitors. The guidelines rate the existing evidence as “strong” for dupilumab, tralokinumab, abrocitinib, baricitinib, and upadacitinib. They also conditionally recommend phototherapy, as well as cyclosporine, methotrexate, azathioprine, and mycophenolate, but recommend against the use of systemic corticosteroids.

The guidelines update the AAD’s 2014 recommendations for managing AD in adults with phototherapy and systemic therapies. “At that time, prednisone – universally agreed to be the least appropriate chronic therapy for AD – was the only Food and Drug Administration–approved agent,” Robert Sidbury, MD, MPH, who cochaired a 14-member multidisciplinary work group that assembled the guidelines, told this news organization. “This was the driver.”

The latest guidelines were published online in the Journal of the American Academy of Dermatology.

Broad evidence review

Dr. Sidbury, chief of the division of dermatology at Seattle Children’s Hospital, guidelines cochair Dawn M. R. Davis, MD, a dermatologist at the Mayo Clinic, Rochester, Minn., and colleagues conducted a systematic evidence review of phototherapy such as narrowband and broadband UVB and systemic therapies, including biologics such as dupilumab and tralokinumab, JAK inhibitors such as upadacitinib and abrocitinib, and immunosuppressants such as methotrexate and azathioprine.

Next, the work group applied the Grading of Recommendations, Assessment, Development, and Evaluation (GRADE) approach for assessing the certainty of the evidence and formulating and grading clinical recommendations based on relevant randomized trials in the medical literature.

Recommendations, future studies

Of the 11 evidence-based recommendations of therapies for adults with AD refractory to topical medications, the work group ranks 5 as “strong” based on the evidence and the rest as “conditional.” “Strong” implies the benefits clearly outweigh risks and burdens, they apply to most patients in most circumstances, and they fall under good clinical practice. “Conditional” means the benefits and risks are closely balanced for most patients, “but the appropriate action may different depending on the patient or other stakeholder values,” the authors wrote.

In their remarks about phototherapy, the work group noted that most published literature on the topic “reports on the efficacy and safety of narrow band UVB. Wherever possible, use a light source that minimizes the potential for harm under the supervision of a qualified clinician.”

In their remarks about cyclosporine, they noted that evidence suggests an initial dose of 3 mg/kg per day to 5 mg/kg per day is effective, but that the Food and Drug Administration has not approved cyclosporine for use in AD. “The FDA has approved limited-term use (up to 1 year) in psoriasis,” they wrote. “Comorbidities or drug interactions that may exacerbate toxicity make this intervention inappropriate for select patients.” The work group noted that significant research gaps remain in phototherapy, especially trials that compare different phototherapy modalities and those that compare phototherapy with other AD treatment strategies.

“Larger clinical trials would also be helpful for cyclosporine, methotrexate, azathioprine, and mycophenolate to improve the certainty of evidence for those medications,” they added. “Furthermore, formal cost-effectiveness analyses comparing older to newer treatments are needed.”

They recommended the inclusion of active comparator arms in randomized, controlled trials as new systemic therapies continue to be developed and tested.

The work group ranked the level of evidence they reviewed for the therapies from very low to moderate. No therapy was judged to have high evidence. They also cited the short duration of most randomized controlled trials of phototherapy.

Using the guidelines in clinical care

According to Dr. Davis, the topic of which agent if any should be considered “first line” generated robust discussion among the work group members.

“When there are not robust head-to-head trials – and there are not – it is often opinion that governs this decision, and opinion should not, when possible, govern a guideline,” Dr. Davis said. “Accordingly, we determined based upon the evidence agents – plural – that deserve to be considered ‘first line’ but not a single agent.”

In her opinion, the top three considerations regarding use of systemic therapy for AD relate to patient selection and shared decision making. One, standard therapy has failed. Two, diagnosis is assured. And three, “steroid phobia should be considered,” and patients should be “fully informed of risks and benefits of both treating and not treating,” she said.

Dr. Sidbury reported that he serves as an advisory board member for Pfizer, a principal investigator for Regeneron, an investigator for Brickell Biotech and Galderma USA, and a consultant for Galderma Global and Micreos. Dr. Davis reported having no relevant disclosures. Other work group members reported having financial disclosures with many pharmaceutical companies. The study was supported by internal funds from the American Academy of Dermatology.

FROM JAMA DERMATOLOGY

Review estimates acne risk with JAK inhibitor therapy

TOPLINE:

, according to an analysis of 25 JAK inhibitor studies.

METHODOLOGY:

- Acne has been reported to be an adverse effect of JAK inhibitors, but not much is known about how common acne is overall and how incidence differs between different JAK inhibitors and the disease being treated.

- For the systematic review and meta-analysis, researchers identified 25 phase 2 or 3 randomized, controlled trials that reported acne as an adverse event associated with the use of JAK inhibitors.

- The study population included 10,839 participants (54% male, 46% female).

- The primary outcome was the incidence of acne following a period of JAK inhibitor use.

TAKEAWAY:

- Overall, the risk of acne was significantly higher among those treated with JAK inhibitors in comparison with patients given placebo in a pooled analysis (odds ratio [OR], 3.83).

- The risk of acne was highest with abrocitinib (OR, 13.47), followed by baricitinib (OR, 4.96), upadacitinib (OR, 4.79), deuruxolitinib (OR, 3.30), and deucravacitinib (OR, 2.64). By JAK inhibitor class, results were as follows: JAK1-specific inhibitors (OR, 4.69), combined JAK1 and JAK2 inhibitors (OR, 3.43), and tyrosine kinase 2 inhibitors (OR, 2.64).

- In a subgroup analysis, risk of acne was higher among patients using JAK inhibitors for dermatologic conditions in comparison with those using JAK inhibitors for nondermatologic conditions (OR, 4.67 vs 1.18).

- Age and gender had no apparent impact on the effect of JAK inhibitor use on acne risk.

IN PRACTICE:

“The occurrence of acne following treatment with certain classes of JAK inhibitors is of potential concern, as this adverse effect may jeopardize treatment adherence among some patients,” the researchers wrote. More studies are needed “to characterize the underlying mechanism of acne with JAK inhibitor use and to identify best practices for treatment,” they added.

SOURCE:

The lead author was Jeremy Martinez, MPH, of Harvard Medical School, Boston. The study was published online in JAMA Dermatology.

LIMITATIONS:

The review was limited by the variable classification and reporting of acne across studies, the potential exclusion of relevant studies, and the small number of studies for certain drugs.

DISCLOSURES:

The studies were mainly funded by the pharmaceutical industry. Mr. Martinez disclosed no relevant financial relationships. Several coauthors have ties with Dexcel Pharma Technologies, AbbVie, Concert, Pfizer, 3Derm Systems, Incyte, Aclaris, Eli Lilly, Concert, Equillium, ASLAN, ACOM, and Boehringer Ingelheim.

A version of this article appeared on Medscape.com.

TOPLINE:

, according to an analysis of 25 JAK inhibitor studies.

METHODOLOGY:

- Acne has been reported to be an adverse effect of JAK inhibitors, but not much is known about how common acne is overall and how incidence differs between different JAK inhibitors and the disease being treated.

- For the systematic review and meta-analysis, researchers identified 25 phase 2 or 3 randomized, controlled trials that reported acne as an adverse event associated with the use of JAK inhibitors.

- The study population included 10,839 participants (54% male, 46% female).

- The primary outcome was the incidence of acne following a period of JAK inhibitor use.

TAKEAWAY:

- Overall, the risk of acne was significantly higher among those treated with JAK inhibitors in comparison with patients given placebo in a pooled analysis (odds ratio [OR], 3.83).

- The risk of acne was highest with abrocitinib (OR, 13.47), followed by baricitinib (OR, 4.96), upadacitinib (OR, 4.79), deuruxolitinib (OR, 3.30), and deucravacitinib (OR, 2.64). By JAK inhibitor class, results were as follows: JAK1-specific inhibitors (OR, 4.69), combined JAK1 and JAK2 inhibitors (OR, 3.43), and tyrosine kinase 2 inhibitors (OR, 2.64).

- In a subgroup analysis, risk of acne was higher among patients using JAK inhibitors for dermatologic conditions in comparison with those using JAK inhibitors for nondermatologic conditions (OR, 4.67 vs 1.18).

- Age and gender had no apparent impact on the effect of JAK inhibitor use on acne risk.

IN PRACTICE:

“The occurrence of acne following treatment with certain classes of JAK inhibitors is of potential concern, as this adverse effect may jeopardize treatment adherence among some patients,” the researchers wrote. More studies are needed “to characterize the underlying mechanism of acne with JAK inhibitor use and to identify best practices for treatment,” they added.

SOURCE:

The lead author was Jeremy Martinez, MPH, of Harvard Medical School, Boston. The study was published online in JAMA Dermatology.

LIMITATIONS:

The review was limited by the variable classification and reporting of acne across studies, the potential exclusion of relevant studies, and the small number of studies for certain drugs.

DISCLOSURES:

The studies were mainly funded by the pharmaceutical industry. Mr. Martinez disclosed no relevant financial relationships. Several coauthors have ties with Dexcel Pharma Technologies, AbbVie, Concert, Pfizer, 3Derm Systems, Incyte, Aclaris, Eli Lilly, Concert, Equillium, ASLAN, ACOM, and Boehringer Ingelheim.

A version of this article appeared on Medscape.com.

TOPLINE:

, according to an analysis of 25 JAK inhibitor studies.

METHODOLOGY:

- Acne has been reported to be an adverse effect of JAK inhibitors, but not much is known about how common acne is overall and how incidence differs between different JAK inhibitors and the disease being treated.

- For the systematic review and meta-analysis, researchers identified 25 phase 2 or 3 randomized, controlled trials that reported acne as an adverse event associated with the use of JAK inhibitors.

- The study population included 10,839 participants (54% male, 46% female).

- The primary outcome was the incidence of acne following a period of JAK inhibitor use.

TAKEAWAY:

- Overall, the risk of acne was significantly higher among those treated with JAK inhibitors in comparison with patients given placebo in a pooled analysis (odds ratio [OR], 3.83).

- The risk of acne was highest with abrocitinib (OR, 13.47), followed by baricitinib (OR, 4.96), upadacitinib (OR, 4.79), deuruxolitinib (OR, 3.30), and deucravacitinib (OR, 2.64). By JAK inhibitor class, results were as follows: JAK1-specific inhibitors (OR, 4.69), combined JAK1 and JAK2 inhibitors (OR, 3.43), and tyrosine kinase 2 inhibitors (OR, 2.64).

- In a subgroup analysis, risk of acne was higher among patients using JAK inhibitors for dermatologic conditions in comparison with those using JAK inhibitors for nondermatologic conditions (OR, 4.67 vs 1.18).

- Age and gender had no apparent impact on the effect of JAK inhibitor use on acne risk.

IN PRACTICE:

“The occurrence of acne following treatment with certain classes of JAK inhibitors is of potential concern, as this adverse effect may jeopardize treatment adherence among some patients,” the researchers wrote. More studies are needed “to characterize the underlying mechanism of acne with JAK inhibitor use and to identify best practices for treatment,” they added.

SOURCE:

The lead author was Jeremy Martinez, MPH, of Harvard Medical School, Boston. The study was published online in JAMA Dermatology.

LIMITATIONS:

The review was limited by the variable classification and reporting of acne across studies, the potential exclusion of relevant studies, and the small number of studies for certain drugs.

DISCLOSURES:

The studies were mainly funded by the pharmaceutical industry. Mr. Martinez disclosed no relevant financial relationships. Several coauthors have ties with Dexcel Pharma Technologies, AbbVie, Concert, Pfizer, 3Derm Systems, Incyte, Aclaris, Eli Lilly, Concert, Equillium, ASLAN, ACOM, and Boehringer Ingelheim.

A version of this article appeared on Medscape.com.

Pustular Eruption on the Face

The Diagnosis: Eczema Herpeticum

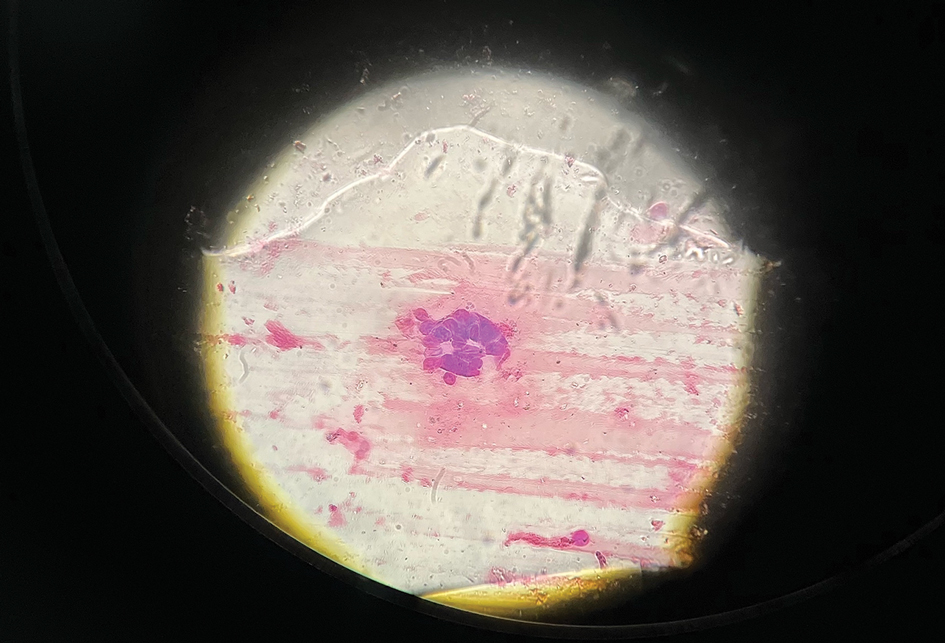

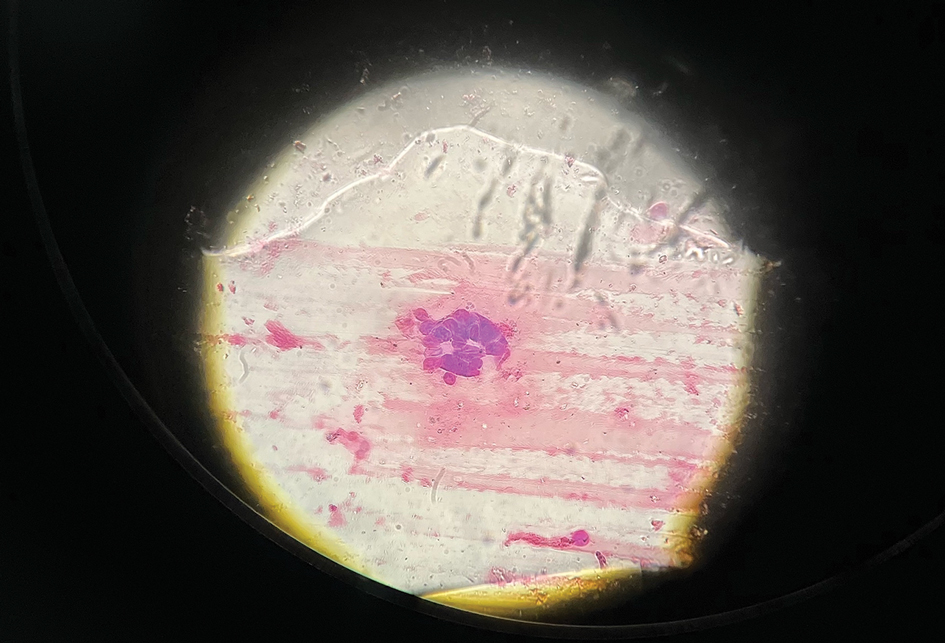

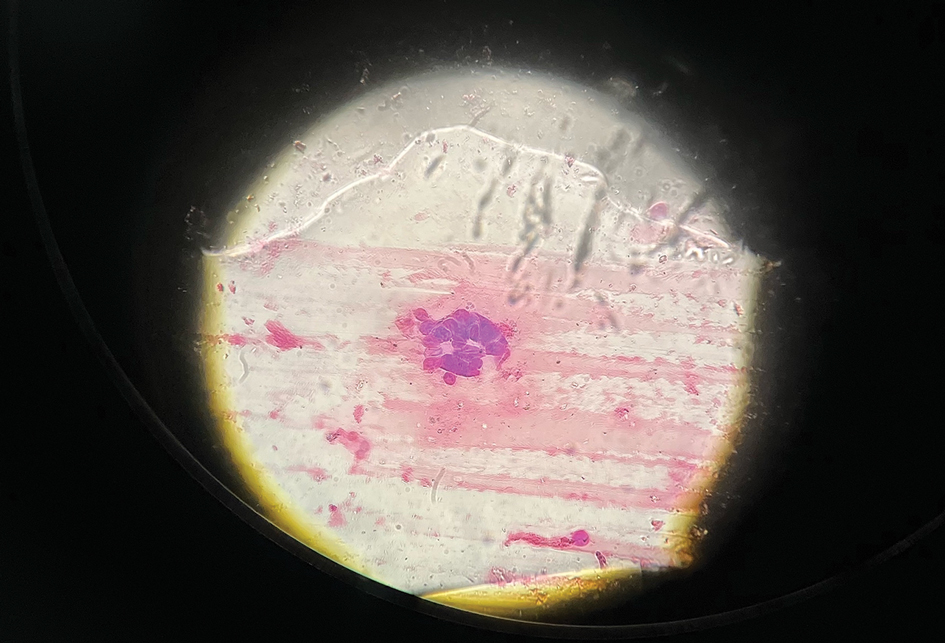

The patient’s condition with worsening facial edema and notable pain prompted a bedside Tzanck smear using a sample from the base of a deroofed forehead vesicle. In addition, a swab of a deroofed lesion was sent for herpes simplex virus and varicella-zoster virus (VZV) polymerase chain reaction (PCR) testing. The Tzanck smear demonstrated ballooning multinucleated syncytial giant cells and eosinophilic inclusion bodies (Figure), which are characteristic of certain herpesviruses including herpes simplex virus and VZV. He was started on intravenous acyclovir while PCR results were pending; the PCR test later confirmed positivity for herpes simplex virus type 1. Treatment was transitioned to oral valacyclovir once the lesions started crusting over. Notable healing and epithelialization of the lesions occurred during his hospital stay, and he was discharged home 5 days after starting treatment. He was counseled on autoinoculation, advised that he was considered infectious until all lesions had crusted over, and encouraged to employ frequent handwashing. Complete resolution of eczema herpeticum (EH) was noted at 3-week follow-up.

Eczema herpeticum (also known as Kaposi varicelliform eruption) is a potentially life-threatening disseminated cutaneous infection caused by herpes simplex virus types 1 and 2 in patients with pre-existing skin disease.1 It typically presents as a complication of atopic dermatitis (AD) but also has been identified as a rare complication in other conditions that disrupt the normal skin barrier, including mycosis fungoides, pemphigus foliaceus, pemphigus vulgaris, Darier disease, pityriasis rubra pilaris, contact dermatitis, and seborrheic dermatitis.1-4

The pathogenesis of EH is multifactorial. Disruption of the stratum corneum; impaired natural killer cell function; early-onset, untreated, or severe AD; disrupted skin microbiota with skewed colonization by Staphylococcus aureus; immunosuppressive AD therapies such as calcineurin inhibitors; eosinophilia; and helper T cell (TH2) cytokine predominance all have been suggested to play a role in the development of EH.5-8

As seen in our patient, EH presents with a sudden eruption of painful or pruritic, grouped, monomorphic, domeshaped vesicles with background swelling and erythema typically on the head, neck, and trunk. Vesicles then progress to punched-out erosions with overlying hemorrhagic crusting that can coalesce to form large denuded areas susceptible to superinfection with bacteria.9 Other accompanying symptoms include high fever, chills, malaise, and lymphadenopathy. Associated inflammation, classically described as erythema, may be difficult to discern in patients with darker skin and appears as hyperpigmentation; therefore, identification of clusters of monomorphic vesicles in areas of pre-existing dermatitis is particularly important for clinical diagnosis in people with darker skin types.

Various tests are available to confirm diagnosis in ambiguous cases. Bedside Tzanck smears can be performed rapidly and are considered positive if characteristic multinucleated giant cells are noted; however, they do not differentiate between the various herpesviruses. Direct fluorescent antibody testing of scraped lesions and viral cultures of swabbed vesicular fluid are equally effective in distinguishing between herpes simplex virus type 1, herpes simplex virus type 2, and VZV; PCR confirms the diagnosis with high specificity and sensitivity.10

In our patient, the initial differential diagnosis included EH, acute generalized exanthematous pustulosis, allergic contact dermatitis, and Orthopoxvirus infection. The positive Tzanck smear reduced the likelihood of a nonviral etiology. Additionally, worsening of the rash despite discontinuation of medications and utilization of topical steroids argued against acute generalized exanthematous pustulosis and allergic contact dermatitis. The laboratory findings reduced the likelihood of drug reaction with eosinophilia and systemic symptoms (DRESS) syndrome, and PCR findings ultimately ruled out Orthopoxvirus infections. Additional differential diagnoses for EH include dermatitis herpetiformis; primary VZV infection; hand, foot, and mouth disease; disseminated zoster infection; disseminated molluscum contagiosum; and eczema coxsackium.

Complications of EH include scarring; herpetic keratitis due to corneal infection, which if left untreated can progress to blindness; and rarely death due to multiorgan failure or septicemia.11 The traditional smallpox vaccine (ACAM2000) is contraindicated in patients with AD and EH, even when AD is in remission. These patients should avoid contact with recently vaccinated individuals.12 An alternative vaccine—Jynneos (Bavarian Nordic)—is available for these patients and their family members.13 Clinicians should be aware of this guideline, especially given the recent mpox (monkeypox) outbreaks.

Mild cases of EH are more common, may sometimes go unnoticed, and self-resolve in healthy patients. Severe cases may require systemic antiviral therapy. Acyclovir and its prodrug valacyclovir are standard treatments for EH. Alternatively, foscarnet or cidofovir can be used in the treatment of acyclovir-resistant thymidine kinase– deficient herpes simplex virus and other acyclovirresistant cases.14 Any secondary bacterial superinfections, usually due to staphylococcal or streptococcal bacteria, should be treated with antibiotics. A thorough ophthalmologic evaluation should be performed for patients with periocular involvement of EH. Empiric treatment should be started immediately, given a relative low toxicity of systemic antiviral therapy and high morbidity and mortality associated with untreated widespread EH.

It is important to maintain a high index of clinical suspicion for EH, especially in patients with pre-existing conditions such as AD who present with systemic symptoms and facial vesicles, pustules, or erosions to ensure prompt diagnosis and appropriate treatment.

- Baaniya B, Agrawal S. Kaposi varicelliform eruption in a patient with pemphigus vulgaris: a case report and review of the literature. Case Rep Dermatol Med. 2020;2020:6695342. doi:10.1155/2020/6695342

- Tayabali K, Pothiwalla H, Lowitt M. Eczema herpeticum in Darier’s disease: a topical storm. J Community Hosp Intern Med Perspect. 2019;9:347. doi:10.1080/20009666.2019.1650590

- Cavalié M, Giacchero D, Cardot-Leccia N, et al. Kaposi’s varicelliform eruption in a patient with pityriasis rubra pilaris (pityriasis rubra pilaris herpeticum). J Eur Acad Dermatol Venereol. 2013;27:1585-1586. doi:10.1111/JDV.12120

- Lee GH, Kim YM, Lee SY, et al. A case of eczema herpeticum with Hailey-Hailey disease. Ann Dermatol. 2009;21:311-314. doi:10.5021/ad.2009.21.3.311

- Seegräber M, Worm M, Werfel T, et al. Recurrent eczema herpeticum— a retrospective European multicenter study evaluating the clinical characteristics of eczema herpeticum cases in atopic dermatitis patients. J Eur Acad Dermatol Venereol. 2020;34:1074-1079. doi:10.1111/JDV.16090

- Kawakami Y, Ando T, Lee J-R, et al. Defective natural killer cell activity in a mouse model of eczema herpeticum. J Allergy Clin Immunol. 2017;139:997-1006.e10. doi:10.1016/j.jaci.2016.06.034

- Beck L, Latchney L, Zaccaro D, et al. Biomarkers of disease severity and Th2 polarity are predictors of risk for eczema herpeticum. J Allergy Clin Immunol. 2008;121:S37-S37. doi:10.1016/j.jaci.2007.12.152

- Kim M, Jung M, Hong SP, et al. Topical calcineurin inhibitors compromise stratum corneum integrity, epidermal permeability and antimicrobial barrier function. Exp Dermatol. 2010; 19:501-510. doi:10.1111/J.1600-0625.2009.00941.X

- Karray M, Kwan E, Souissi A. Kaposi varicelliform eruption. StatPearls [Internet]. StatPearls Publishing; 2023. https://www.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/books/NBK482432/

- Dominguez SR, Pretty K, Hengartner R, et al. Comparison of herpes simplex virus PCR with culture for virus detection in multisource surface swab specimens from neonates [published online September 25, 2018]. J Clin Microbiol. doi:10.1128/JCM.00632-18

- Feye F, De Halleux C, Gillet JB, et al. Exacerbation of atopic dermatitis in the emergency department. Eur J Emerg Med. 2004;11:49-52. doi:10.1097/00063110-200412000-00014

- Casey C, Vellozzi C, Mootrey GT, et al; Vaccinia Case Definition Development Working Group; Advisory Committee on Immunization Practices-Armed Forces Epidemiological Board Smallpox Vaccine Safety Working Group. Surveillance guidelines for smallpox vaccine (vaccinia) adverse reactions. MMWR Recomm Rep. 2006;55:1-16.

- Rao AK, Petersen BW, Whitehill F, et al. Use of JYNNEOS (Smallpox and Monkeypox Vaccine, Live, Nonreplicating) for preexposure vaccination of persons at risk for occupational exposure to orthopoxviruses: recommendations of the Advisory Committee on Immunization Practices—United States, 2022. MMWR Morb Mortal Wkly Rep. 2022;71:734-742. doi:10.15585 /MMWR.MM7122E1

- Piret J, Boivin G. Resistance of herpes simplex viruses to nucleoside analogues: mechanisms, prevalence, and management. Antimicrob Agents Chemother. 2011;55:459. doi:10.1128/AAC.00615-10

The Diagnosis: Eczema Herpeticum

The patient’s condition with worsening facial edema and notable pain prompted a bedside Tzanck smear using a sample from the base of a deroofed forehead vesicle. In addition, a swab of a deroofed lesion was sent for herpes simplex virus and varicella-zoster virus (VZV) polymerase chain reaction (PCR) testing. The Tzanck smear demonstrated ballooning multinucleated syncytial giant cells and eosinophilic inclusion bodies (Figure), which are characteristic of certain herpesviruses including herpes simplex virus and VZV. He was started on intravenous acyclovir while PCR results were pending; the PCR test later confirmed positivity for herpes simplex virus type 1. Treatment was transitioned to oral valacyclovir once the lesions started crusting over. Notable healing and epithelialization of the lesions occurred during his hospital stay, and he was discharged home 5 days after starting treatment. He was counseled on autoinoculation, advised that he was considered infectious until all lesions had crusted over, and encouraged to employ frequent handwashing. Complete resolution of eczema herpeticum (EH) was noted at 3-week follow-up.

Eczema herpeticum (also known as Kaposi varicelliform eruption) is a potentially life-threatening disseminated cutaneous infection caused by herpes simplex virus types 1 and 2 in patients with pre-existing skin disease.1 It typically presents as a complication of atopic dermatitis (AD) but also has been identified as a rare complication in other conditions that disrupt the normal skin barrier, including mycosis fungoides, pemphigus foliaceus, pemphigus vulgaris, Darier disease, pityriasis rubra pilaris, contact dermatitis, and seborrheic dermatitis.1-4

The pathogenesis of EH is multifactorial. Disruption of the stratum corneum; impaired natural killer cell function; early-onset, untreated, or severe AD; disrupted skin microbiota with skewed colonization by Staphylococcus aureus; immunosuppressive AD therapies such as calcineurin inhibitors; eosinophilia; and helper T cell (TH2) cytokine predominance all have been suggested to play a role in the development of EH.5-8

As seen in our patient, EH presents with a sudden eruption of painful or pruritic, grouped, monomorphic, domeshaped vesicles with background swelling and erythema typically on the head, neck, and trunk. Vesicles then progress to punched-out erosions with overlying hemorrhagic crusting that can coalesce to form large denuded areas susceptible to superinfection with bacteria.9 Other accompanying symptoms include high fever, chills, malaise, and lymphadenopathy. Associated inflammation, classically described as erythema, may be difficult to discern in patients with darker skin and appears as hyperpigmentation; therefore, identification of clusters of monomorphic vesicles in areas of pre-existing dermatitis is particularly important for clinical diagnosis in people with darker skin types.

Various tests are available to confirm diagnosis in ambiguous cases. Bedside Tzanck smears can be performed rapidly and are considered positive if characteristic multinucleated giant cells are noted; however, they do not differentiate between the various herpesviruses. Direct fluorescent antibody testing of scraped lesions and viral cultures of swabbed vesicular fluid are equally effective in distinguishing between herpes simplex virus type 1, herpes simplex virus type 2, and VZV; PCR confirms the diagnosis with high specificity and sensitivity.10

In our patient, the initial differential diagnosis included EH, acute generalized exanthematous pustulosis, allergic contact dermatitis, and Orthopoxvirus infection. The positive Tzanck smear reduced the likelihood of a nonviral etiology. Additionally, worsening of the rash despite discontinuation of medications and utilization of topical steroids argued against acute generalized exanthematous pustulosis and allergic contact dermatitis. The laboratory findings reduced the likelihood of drug reaction with eosinophilia and systemic symptoms (DRESS) syndrome, and PCR findings ultimately ruled out Orthopoxvirus infections. Additional differential diagnoses for EH include dermatitis herpetiformis; primary VZV infection; hand, foot, and mouth disease; disseminated zoster infection; disseminated molluscum contagiosum; and eczema coxsackium.

Complications of EH include scarring; herpetic keratitis due to corneal infection, which if left untreated can progress to blindness; and rarely death due to multiorgan failure or septicemia.11 The traditional smallpox vaccine (ACAM2000) is contraindicated in patients with AD and EH, even when AD is in remission. These patients should avoid contact with recently vaccinated individuals.12 An alternative vaccine—Jynneos (Bavarian Nordic)—is available for these patients and their family members.13 Clinicians should be aware of this guideline, especially given the recent mpox (monkeypox) outbreaks.

Mild cases of EH are more common, may sometimes go unnoticed, and self-resolve in healthy patients. Severe cases may require systemic antiviral therapy. Acyclovir and its prodrug valacyclovir are standard treatments for EH. Alternatively, foscarnet or cidofovir can be used in the treatment of acyclovir-resistant thymidine kinase– deficient herpes simplex virus and other acyclovirresistant cases.14 Any secondary bacterial superinfections, usually due to staphylococcal or streptococcal bacteria, should be treated with antibiotics. A thorough ophthalmologic evaluation should be performed for patients with periocular involvement of EH. Empiric treatment should be started immediately, given a relative low toxicity of systemic antiviral therapy and high morbidity and mortality associated with untreated widespread EH.

It is important to maintain a high index of clinical suspicion for EH, especially in patients with pre-existing conditions such as AD who present with systemic symptoms and facial vesicles, pustules, or erosions to ensure prompt diagnosis and appropriate treatment.

The Diagnosis: Eczema Herpeticum

The patient’s condition with worsening facial edema and notable pain prompted a bedside Tzanck smear using a sample from the base of a deroofed forehead vesicle. In addition, a swab of a deroofed lesion was sent for herpes simplex virus and varicella-zoster virus (VZV) polymerase chain reaction (PCR) testing. The Tzanck smear demonstrated ballooning multinucleated syncytial giant cells and eosinophilic inclusion bodies (Figure), which are characteristic of certain herpesviruses including herpes simplex virus and VZV. He was started on intravenous acyclovir while PCR results were pending; the PCR test later confirmed positivity for herpes simplex virus type 1. Treatment was transitioned to oral valacyclovir once the lesions started crusting over. Notable healing and epithelialization of the lesions occurred during his hospital stay, and he was discharged home 5 days after starting treatment. He was counseled on autoinoculation, advised that he was considered infectious until all lesions had crusted over, and encouraged to employ frequent handwashing. Complete resolution of eczema herpeticum (EH) was noted at 3-week follow-up.

Eczema herpeticum (also known as Kaposi varicelliform eruption) is a potentially life-threatening disseminated cutaneous infection caused by herpes simplex virus types 1 and 2 in patients with pre-existing skin disease.1 It typically presents as a complication of atopic dermatitis (AD) but also has been identified as a rare complication in other conditions that disrupt the normal skin barrier, including mycosis fungoides, pemphigus foliaceus, pemphigus vulgaris, Darier disease, pityriasis rubra pilaris, contact dermatitis, and seborrheic dermatitis.1-4

The pathogenesis of EH is multifactorial. Disruption of the stratum corneum; impaired natural killer cell function; early-onset, untreated, or severe AD; disrupted skin microbiota with skewed colonization by Staphylococcus aureus; immunosuppressive AD therapies such as calcineurin inhibitors; eosinophilia; and helper T cell (TH2) cytokine predominance all have been suggested to play a role in the development of EH.5-8

As seen in our patient, EH presents with a sudden eruption of painful or pruritic, grouped, monomorphic, domeshaped vesicles with background swelling and erythema typically on the head, neck, and trunk. Vesicles then progress to punched-out erosions with overlying hemorrhagic crusting that can coalesce to form large denuded areas susceptible to superinfection with bacteria.9 Other accompanying symptoms include high fever, chills, malaise, and lymphadenopathy. Associated inflammation, classically described as erythema, may be difficult to discern in patients with darker skin and appears as hyperpigmentation; therefore, identification of clusters of monomorphic vesicles in areas of pre-existing dermatitis is particularly important for clinical diagnosis in people with darker skin types.

Various tests are available to confirm diagnosis in ambiguous cases. Bedside Tzanck smears can be performed rapidly and are considered positive if characteristic multinucleated giant cells are noted; however, they do not differentiate between the various herpesviruses. Direct fluorescent antibody testing of scraped lesions and viral cultures of swabbed vesicular fluid are equally effective in distinguishing between herpes simplex virus type 1, herpes simplex virus type 2, and VZV; PCR confirms the diagnosis with high specificity and sensitivity.10

In our patient, the initial differential diagnosis included EH, acute generalized exanthematous pustulosis, allergic contact dermatitis, and Orthopoxvirus infection. The positive Tzanck smear reduced the likelihood of a nonviral etiology. Additionally, worsening of the rash despite discontinuation of medications and utilization of topical steroids argued against acute generalized exanthematous pustulosis and allergic contact dermatitis. The laboratory findings reduced the likelihood of drug reaction with eosinophilia and systemic symptoms (DRESS) syndrome, and PCR findings ultimately ruled out Orthopoxvirus infections. Additional differential diagnoses for EH include dermatitis herpetiformis; primary VZV infection; hand, foot, and mouth disease; disseminated zoster infection; disseminated molluscum contagiosum; and eczema coxsackium.

Complications of EH include scarring; herpetic keratitis due to corneal infection, which if left untreated can progress to blindness; and rarely death due to multiorgan failure or septicemia.11 The traditional smallpox vaccine (ACAM2000) is contraindicated in patients with AD and EH, even when AD is in remission. These patients should avoid contact with recently vaccinated individuals.12 An alternative vaccine—Jynneos (Bavarian Nordic)—is available for these patients and their family members.13 Clinicians should be aware of this guideline, especially given the recent mpox (monkeypox) outbreaks.

Mild cases of EH are more common, may sometimes go unnoticed, and self-resolve in healthy patients. Severe cases may require systemic antiviral therapy. Acyclovir and its prodrug valacyclovir are standard treatments for EH. Alternatively, foscarnet or cidofovir can be used in the treatment of acyclovir-resistant thymidine kinase– deficient herpes simplex virus and other acyclovirresistant cases.14 Any secondary bacterial superinfections, usually due to staphylococcal or streptococcal bacteria, should be treated with antibiotics. A thorough ophthalmologic evaluation should be performed for patients with periocular involvement of EH. Empiric treatment should be started immediately, given a relative low toxicity of systemic antiviral therapy and high morbidity and mortality associated with untreated widespread EH.

It is important to maintain a high index of clinical suspicion for EH, especially in patients with pre-existing conditions such as AD who present with systemic symptoms and facial vesicles, pustules, or erosions to ensure prompt diagnosis and appropriate treatment.

- Baaniya B, Agrawal S. Kaposi varicelliform eruption in a patient with pemphigus vulgaris: a case report and review of the literature. Case Rep Dermatol Med. 2020;2020:6695342. doi:10.1155/2020/6695342

- Tayabali K, Pothiwalla H, Lowitt M. Eczema herpeticum in Darier’s disease: a topical storm. J Community Hosp Intern Med Perspect. 2019;9:347. doi:10.1080/20009666.2019.1650590

- Cavalié M, Giacchero D, Cardot-Leccia N, et al. Kaposi’s varicelliform eruption in a patient with pityriasis rubra pilaris (pityriasis rubra pilaris herpeticum). J Eur Acad Dermatol Venereol. 2013;27:1585-1586. doi:10.1111/JDV.12120

- Lee GH, Kim YM, Lee SY, et al. A case of eczema herpeticum with Hailey-Hailey disease. Ann Dermatol. 2009;21:311-314. doi:10.5021/ad.2009.21.3.311

- Seegräber M, Worm M, Werfel T, et al. Recurrent eczema herpeticum— a retrospective European multicenter study evaluating the clinical characteristics of eczema herpeticum cases in atopic dermatitis patients. J Eur Acad Dermatol Venereol. 2020;34:1074-1079. doi:10.1111/JDV.16090

- Kawakami Y, Ando T, Lee J-R, et al. Defective natural killer cell activity in a mouse model of eczema herpeticum. J Allergy Clin Immunol. 2017;139:997-1006.e10. doi:10.1016/j.jaci.2016.06.034

- Beck L, Latchney L, Zaccaro D, et al. Biomarkers of disease severity and Th2 polarity are predictors of risk for eczema herpeticum. J Allergy Clin Immunol. 2008;121:S37-S37. doi:10.1016/j.jaci.2007.12.152

- Kim M, Jung M, Hong SP, et al. Topical calcineurin inhibitors compromise stratum corneum integrity, epidermal permeability and antimicrobial barrier function. Exp Dermatol. 2010; 19:501-510. doi:10.1111/J.1600-0625.2009.00941.X

- Karray M, Kwan E, Souissi A. Kaposi varicelliform eruption. StatPearls [Internet]. StatPearls Publishing; 2023. https://www.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/books/NBK482432/

- Dominguez SR, Pretty K, Hengartner R, et al. Comparison of herpes simplex virus PCR with culture for virus detection in multisource surface swab specimens from neonates [published online September 25, 2018]. J Clin Microbiol. doi:10.1128/JCM.00632-18

- Feye F, De Halleux C, Gillet JB, et al. Exacerbation of atopic dermatitis in the emergency department. Eur J Emerg Med. 2004;11:49-52. doi:10.1097/00063110-200412000-00014

- Casey C, Vellozzi C, Mootrey GT, et al; Vaccinia Case Definition Development Working Group; Advisory Committee on Immunization Practices-Armed Forces Epidemiological Board Smallpox Vaccine Safety Working Group. Surveillance guidelines for smallpox vaccine (vaccinia) adverse reactions. MMWR Recomm Rep. 2006;55:1-16.

- Rao AK, Petersen BW, Whitehill F, et al. Use of JYNNEOS (Smallpox and Monkeypox Vaccine, Live, Nonreplicating) for preexposure vaccination of persons at risk for occupational exposure to orthopoxviruses: recommendations of the Advisory Committee on Immunization Practices—United States, 2022. MMWR Morb Mortal Wkly Rep. 2022;71:734-742. doi:10.15585 /MMWR.MM7122E1

- Piret J, Boivin G. Resistance of herpes simplex viruses to nucleoside analogues: mechanisms, prevalence, and management. Antimicrob Agents Chemother. 2011;55:459. doi:10.1128/AAC.00615-10

- Baaniya B, Agrawal S. Kaposi varicelliform eruption in a patient with pemphigus vulgaris: a case report and review of the literature. Case Rep Dermatol Med. 2020;2020:6695342. doi:10.1155/2020/6695342

- Tayabali K, Pothiwalla H, Lowitt M. Eczema herpeticum in Darier’s disease: a topical storm. J Community Hosp Intern Med Perspect. 2019;9:347. doi:10.1080/20009666.2019.1650590

- Cavalié M, Giacchero D, Cardot-Leccia N, et al. Kaposi’s varicelliform eruption in a patient with pityriasis rubra pilaris (pityriasis rubra pilaris herpeticum). J Eur Acad Dermatol Venereol. 2013;27:1585-1586. doi:10.1111/JDV.12120

- Lee GH, Kim YM, Lee SY, et al. A case of eczema herpeticum with Hailey-Hailey disease. Ann Dermatol. 2009;21:311-314. doi:10.5021/ad.2009.21.3.311

- Seegräber M, Worm M, Werfel T, et al. Recurrent eczema herpeticum— a retrospective European multicenter study evaluating the clinical characteristics of eczema herpeticum cases in atopic dermatitis patients. J Eur Acad Dermatol Venereol. 2020;34:1074-1079. doi:10.1111/JDV.16090

- Kawakami Y, Ando T, Lee J-R, et al. Defective natural killer cell activity in a mouse model of eczema herpeticum. J Allergy Clin Immunol. 2017;139:997-1006.e10. doi:10.1016/j.jaci.2016.06.034

- Beck L, Latchney L, Zaccaro D, et al. Biomarkers of disease severity and Th2 polarity are predictors of risk for eczema herpeticum. J Allergy Clin Immunol. 2008;121:S37-S37. doi:10.1016/j.jaci.2007.12.152

- Kim M, Jung M, Hong SP, et al. Topical calcineurin inhibitors compromise stratum corneum integrity, epidermal permeability and antimicrobial barrier function. Exp Dermatol. 2010; 19:501-510. doi:10.1111/J.1600-0625.2009.00941.X

- Karray M, Kwan E, Souissi A. Kaposi varicelliform eruption. StatPearls [Internet]. StatPearls Publishing; 2023. https://www.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/books/NBK482432/

- Dominguez SR, Pretty K, Hengartner R, et al. Comparison of herpes simplex virus PCR with culture for virus detection in multisource surface swab specimens from neonates [published online September 25, 2018]. J Clin Microbiol. doi:10.1128/JCM.00632-18

- Feye F, De Halleux C, Gillet JB, et al. Exacerbation of atopic dermatitis in the emergency department. Eur J Emerg Med. 2004;11:49-52. doi:10.1097/00063110-200412000-00014

- Casey C, Vellozzi C, Mootrey GT, et al; Vaccinia Case Definition Development Working Group; Advisory Committee on Immunization Practices-Armed Forces Epidemiological Board Smallpox Vaccine Safety Working Group. Surveillance guidelines for smallpox vaccine (vaccinia) adverse reactions. MMWR Recomm Rep. 2006;55:1-16.

- Rao AK, Petersen BW, Whitehill F, et al. Use of JYNNEOS (Smallpox and Monkeypox Vaccine, Live, Nonreplicating) for preexposure vaccination of persons at risk for occupational exposure to orthopoxviruses: recommendations of the Advisory Committee on Immunization Practices—United States, 2022. MMWR Morb Mortal Wkly Rep. 2022;71:734-742. doi:10.15585 /MMWR.MM7122E1

- Piret J, Boivin G. Resistance of herpes simplex viruses to nucleoside analogues: mechanisms, prevalence, and management. Antimicrob Agents Chemother. 2011;55:459. doi:10.1128/AAC.00615-10

A 52-year-old man developed a sudden eruption of small pustules on background erythema and edema covering the forehead, nasal bridge, periorbital region, cheeks, and perioral region on day 3 of hospitalization in the intensive care unit for management of septic shock secondary to a complicated urinary tract infection. He had a medical history of benign prostatic hyperplasia, sarcoidosis, and atopic dermatitis. He initially presented to the emergency department with fever, chills, and dysuria of 2 days’ duration. Because he received ceftriaxone, vancomycin, ciprofloxacin, and tamsulosin while hospitalized for the infection, the primary medical team suspected a drug reaction and empirically started applying hydrocortisone cream 2.5%. The rash continued to spread over the ensuing day, prompting a dermatology consultation to rule out a drug eruption and to help guide further management. The patient was in substantial distress and pain. Physical examination revealed numerous discrete and confluent monomorphic pustules on background erythema with faint collarettes of scale covering most of the face. Substantial periorbital and facial edema forced the eyes closed. There was no mucous membrane involvement. A review of systems was negative for dyspnea and dysphagia, and the rash was not present elsewhere on the body. Ophthalmologic evaluation revealed no ocular involvement or vision changes. Laboratory studies demonstrated neutrophilia (17.27×109 cells/L [reference range, 2.0–6.9×109 cells/L]). The eosinophil count, blood urea nitrogen/creatinine, and liver function tests were within reference range.

Dupilumab-associated lymphoid reactions require caution

, according to a study published in JAMA Dermatology

The potential for such reactions requires diagnosing AD carefully, monitoring patients on dupilumab for new and unusual symptoms, and thoroughly working up suspicious LRs, according to an accompanying editorial and experts interviewed for this article.

“Dupilumab has become such an important first-line systemic medication for our patients with moderate to severe atopic dermatitis. It’s important for us to understand everything we can about its use in the real world – both good and bad,”Raj Chovatiya, MD, PhD, MSCI, assistant professor of dermatology at Northwestern University, Chicago, said in an interview. He was uninvolved with either publication.

Robert Sidbury, MD, MPH, added that, although the affected patient group was small, studying lymphoid reactions associated with dupilumab is important because of the risk for diagnostic misadventure that these reactions carry. He is a professor of pediatrics and division head of dermatology at Seattle Children’s Hospital and the University of Washington, Seattle.

“AD and MF are easily confused for one another at baseline,” explained Dr. Sidbury, who was not involved with the study or editorial. “Dupilumab is known to make AD better and theoretically could help MF via its effect on interleukin (IL)–13, yet case reports of exacerbation and/or unmasking of MF are out there.”

For the study, researchers retrospectively examined records of 530 patients with AD treated with dupilumab at the University Medical Center Utrecht (the Netherlands). Reviewing pretreatment biopsies revealed that among 14 (2.6%) patients who developed clinical suspicion of cutaneous T-cell lymphoma (CTCL) while on treatment, three actually had preexisting MF.

All 14 patients with LR initially responded to dupilumab then developed worsening symptoms at a median of 4 months. Patients reported that the worsening lesions looked and felt different than did previous lesions, with symptoms including burning/pain and an appearance of generalized erythematous maculopapular plaques, sometimes with severe lichenification, on the lower trunk and upper thighs.

The 14 patients’ posttreatment biopsies showed an atypical lymphoid infiltrate with lichenoid or perivascular distribution and intraepithelial T-cell lymphocytes. Whereas patients with MF had hyperconvoluted cerebriform lymphocytes aligned in the epidermal basal layer at the dermoepidermal junction, the 11 with LR had similar-looking lesions dispersed throughout the upper epidermis.

Immunohistochemically, both groups had a dysregulated (mostly increased) CD4:CD8 ratio. CD30 overexpression, usually absent in early-stage MF, affected only patients with LR and one patient with advanced MF. In addition, patients with LR maintained pan–T-cell antigens (CD2, CD3, and CD5), whereas those with MF did not. The 11 patients with LR experienced biopsy-confirmed resolution once they discontinued dupilumab.

It is reassuring that the LRs resolved after dupilumab discontinuation, writes the author of the accompanying editorial, Joan Guitart, MD, chief of dermatopathology at Northwestern University. Nevertheless, he added, such patients deserve “a comprehensive workup including skin biopsy with T-cell receptor clonality assay, blood cell counts with flow cytometry analysis, serum lactate dehydrogenase, and documentation of possible adenopathy, followed with imaging studies and/or local biopsies in cases with abnormal results.”

The possibility that these LRs may represent a first step toward lymphoma requires dermatologists to remain vigilant in ruling out MF, Dr. Guitart wrote, particularly in atypical presentations such as adult-onset AD, cases lacking a history of AD, and cases involving erythrodermic and other uncharacteristic presentations such as plaques, nodules, or spared flexural sites.

For dermatopathologists, Dr. Guitart recommended a cautious approach that resists overdiagnosing MF and acknowledging that insufficient evidence exists to report such reactions as benign. The fact that one study patient had both MF and LR raises concerns that the LR may not always be reversible, Dr. Guitart added.

Clinicians and patients must consider the possibility of dupilumab-induced LR as part of the shared decision-making process and risk-benefit calculus, Dr. Sidbury said. In cases involving unexpected responses or atypical presentations, he added, clinicians must have a low threshold for stopping dupilumab.

For patients who must discontinue dupilumab because of LR, the list of treatment options is growing. “While more investigation is required to understand the role of newer IL-13–blocking biologics and JAK inhibitors among patients experiencing lymphoid reactions,” said Dr. Chovatiya, “traditional atopic dermatitis therapies like narrowband UVB phototherapy and the oral immunosuppressant methotrexate may be reassuring in this population.” Conversely, cyclosporine has been associated with progression of MF.

Also reassuring, said Dr. Sidbury and Dr. Chovatiya, is the rarity of LR overall. Dr. Sidbury said, “The numbers of patients in whom LR or onset/exacerbation of MF occurs is extraordinarily low when compared to those helped immeasurably by dupilumab.”

Dr. Sidbury added that the study and accompanying editorial also will alert clinicians to the potential for newer AD biologics that target solely IL-13 and not IL-4/13, as dupilumab does. “If the deregulated response leading to LR and potentially MF in the affected few is driven by IL-4 inhibition,” he said, “drugs such as tralokinumab (Adbry), lebrikizumab (once approved), and perhaps other newer options might calm AD without causing LRs.”

(Lebrikizumab is not yet approved. In an Oct. 2 press release, Eli Lilly and Company, developer of lebrikizumab, said that it would address issues the U.S. Food and Drug Administration had raised about a third-party manufacturing facility that arose during evaluation of the lebrikizumab biologic license application.)

Study limitations include the fact that most patients who experienced LR had already undergone skin biopsies before dupilumab treatment, which suggests that they had a more atypical AD presentation from the start. The authors add that their having treated all study patients in a tertiary referral hospital indicates a hard-to-treat AD subpopulation.

Study authors reported relationships with several biologic drug manufacturers including Sanofi and Regeneron (dupilumab), LEO Pharma (tralokinumab), and Eli Lilly (lebrikizumab). However, none of these companies provided support for the study.

Dr. Sidbury has been an investigator for Regeneron, Pfizer, and Galderma and a consultant for LEO Pharma and Eli Lilly. Dr. Chovatiya has served as an advisor, consultant, speaker, and investigator for Sanofi and Regeneron. Dr. Guitart reported no conflicts of interest.

A version of this article appeared on Medscape.com.

, according to a study published in JAMA Dermatology

The potential for such reactions requires diagnosing AD carefully, monitoring patients on dupilumab for new and unusual symptoms, and thoroughly working up suspicious LRs, according to an accompanying editorial and experts interviewed for this article.

“Dupilumab has become such an important first-line systemic medication for our patients with moderate to severe atopic dermatitis. It’s important for us to understand everything we can about its use in the real world – both good and bad,”Raj Chovatiya, MD, PhD, MSCI, assistant professor of dermatology at Northwestern University, Chicago, said in an interview. He was uninvolved with either publication.

Robert Sidbury, MD, MPH, added that, although the affected patient group was small, studying lymphoid reactions associated with dupilumab is important because of the risk for diagnostic misadventure that these reactions carry. He is a professor of pediatrics and division head of dermatology at Seattle Children’s Hospital and the University of Washington, Seattle.

“AD and MF are easily confused for one another at baseline,” explained Dr. Sidbury, who was not involved with the study or editorial. “Dupilumab is known to make AD better and theoretically could help MF via its effect on interleukin (IL)–13, yet case reports of exacerbation and/or unmasking of MF are out there.”

For the study, researchers retrospectively examined records of 530 patients with AD treated with dupilumab at the University Medical Center Utrecht (the Netherlands). Reviewing pretreatment biopsies revealed that among 14 (2.6%) patients who developed clinical suspicion of cutaneous T-cell lymphoma (CTCL) while on treatment, three actually had preexisting MF.

All 14 patients with LR initially responded to dupilumab then developed worsening symptoms at a median of 4 months. Patients reported that the worsening lesions looked and felt different than did previous lesions, with symptoms including burning/pain and an appearance of generalized erythematous maculopapular plaques, sometimes with severe lichenification, on the lower trunk and upper thighs.

The 14 patients’ posttreatment biopsies showed an atypical lymphoid infiltrate with lichenoid or perivascular distribution and intraepithelial T-cell lymphocytes. Whereas patients with MF had hyperconvoluted cerebriform lymphocytes aligned in the epidermal basal layer at the dermoepidermal junction, the 11 with LR had similar-looking lesions dispersed throughout the upper epidermis.

Immunohistochemically, both groups had a dysregulated (mostly increased) CD4:CD8 ratio. CD30 overexpression, usually absent in early-stage MF, affected only patients with LR and one patient with advanced MF. In addition, patients with LR maintained pan–T-cell antigens (CD2, CD3, and CD5), whereas those with MF did not. The 11 patients with LR experienced biopsy-confirmed resolution once they discontinued dupilumab.

It is reassuring that the LRs resolved after dupilumab discontinuation, writes the author of the accompanying editorial, Joan Guitart, MD, chief of dermatopathology at Northwestern University. Nevertheless, he added, such patients deserve “a comprehensive workup including skin biopsy with T-cell receptor clonality assay, blood cell counts with flow cytometry analysis, serum lactate dehydrogenase, and documentation of possible adenopathy, followed with imaging studies and/or local biopsies in cases with abnormal results.”

The possibility that these LRs may represent a first step toward lymphoma requires dermatologists to remain vigilant in ruling out MF, Dr. Guitart wrote, particularly in atypical presentations such as adult-onset AD, cases lacking a history of AD, and cases involving erythrodermic and other uncharacteristic presentations such as plaques, nodules, or spared flexural sites.

For dermatopathologists, Dr. Guitart recommended a cautious approach that resists overdiagnosing MF and acknowledging that insufficient evidence exists to report such reactions as benign. The fact that one study patient had both MF and LR raises concerns that the LR may not always be reversible, Dr. Guitart added.

Clinicians and patients must consider the possibility of dupilumab-induced LR as part of the shared decision-making process and risk-benefit calculus, Dr. Sidbury said. In cases involving unexpected responses or atypical presentations, he added, clinicians must have a low threshold for stopping dupilumab.

For patients who must discontinue dupilumab because of LR, the list of treatment options is growing. “While more investigation is required to understand the role of newer IL-13–blocking biologics and JAK inhibitors among patients experiencing lymphoid reactions,” said Dr. Chovatiya, “traditional atopic dermatitis therapies like narrowband UVB phototherapy and the oral immunosuppressant methotrexate may be reassuring in this population.” Conversely, cyclosporine has been associated with progression of MF.

Also reassuring, said Dr. Sidbury and Dr. Chovatiya, is the rarity of LR overall. Dr. Sidbury said, “The numbers of patients in whom LR or onset/exacerbation of MF occurs is extraordinarily low when compared to those helped immeasurably by dupilumab.”

Dr. Sidbury added that the study and accompanying editorial also will alert clinicians to the potential for newer AD biologics that target solely IL-13 and not IL-4/13, as dupilumab does. “If the deregulated response leading to LR and potentially MF in the affected few is driven by IL-4 inhibition,” he said, “drugs such as tralokinumab (Adbry), lebrikizumab (once approved), and perhaps other newer options might calm AD without causing LRs.”

(Lebrikizumab is not yet approved. In an Oct. 2 press release, Eli Lilly and Company, developer of lebrikizumab, said that it would address issues the U.S. Food and Drug Administration had raised about a third-party manufacturing facility that arose during evaluation of the lebrikizumab biologic license application.)

Study limitations include the fact that most patients who experienced LR had already undergone skin biopsies before dupilumab treatment, which suggests that they had a more atypical AD presentation from the start. The authors add that their having treated all study patients in a tertiary referral hospital indicates a hard-to-treat AD subpopulation.

Study authors reported relationships with several biologic drug manufacturers including Sanofi and Regeneron (dupilumab), LEO Pharma (tralokinumab), and Eli Lilly (lebrikizumab). However, none of these companies provided support for the study.

Dr. Sidbury has been an investigator for Regeneron, Pfizer, and Galderma and a consultant for LEO Pharma and Eli Lilly. Dr. Chovatiya has served as an advisor, consultant, speaker, and investigator for Sanofi and Regeneron. Dr. Guitart reported no conflicts of interest.

A version of this article appeared on Medscape.com.

, according to a study published in JAMA Dermatology

The potential for such reactions requires diagnosing AD carefully, monitoring patients on dupilumab for new and unusual symptoms, and thoroughly working up suspicious LRs, according to an accompanying editorial and experts interviewed for this article.

“Dupilumab has become such an important first-line systemic medication for our patients with moderate to severe atopic dermatitis. It’s important for us to understand everything we can about its use in the real world – both good and bad,”Raj Chovatiya, MD, PhD, MSCI, assistant professor of dermatology at Northwestern University, Chicago, said in an interview. He was uninvolved with either publication.

Robert Sidbury, MD, MPH, added that, although the affected patient group was small, studying lymphoid reactions associated with dupilumab is important because of the risk for diagnostic misadventure that these reactions carry. He is a professor of pediatrics and division head of dermatology at Seattle Children’s Hospital and the University of Washington, Seattle.

“AD and MF are easily confused for one another at baseline,” explained Dr. Sidbury, who was not involved with the study or editorial. “Dupilumab is known to make AD better and theoretically could help MF via its effect on interleukin (IL)–13, yet case reports of exacerbation and/or unmasking of MF are out there.”

For the study, researchers retrospectively examined records of 530 patients with AD treated with dupilumab at the University Medical Center Utrecht (the Netherlands). Reviewing pretreatment biopsies revealed that among 14 (2.6%) patients who developed clinical suspicion of cutaneous T-cell lymphoma (CTCL) while on treatment, three actually had preexisting MF.

All 14 patients with LR initially responded to dupilumab then developed worsening symptoms at a median of 4 months. Patients reported that the worsening lesions looked and felt different than did previous lesions, with symptoms including burning/pain and an appearance of generalized erythematous maculopapular plaques, sometimes with severe lichenification, on the lower trunk and upper thighs.

The 14 patients’ posttreatment biopsies showed an atypical lymphoid infiltrate with lichenoid or perivascular distribution and intraepithelial T-cell lymphocytes. Whereas patients with MF had hyperconvoluted cerebriform lymphocytes aligned in the epidermal basal layer at the dermoepidermal junction, the 11 with LR had similar-looking lesions dispersed throughout the upper epidermis.