User login

Acellular Dermal Matrix in Rotator Cuff Surgery

Rotator cuff repairs (RCRs) can be challenging due to poor tendon quality and the inability of tendon to heal to bone. Smoking, age over 63 years, fatty infiltration, and massive cuff tears are all factors implicated in increased failure rates.1-3 Tears >3 cm have a structural failure rate ranging from 11% to 95% in the literature.1-5 Massive tears (tears >5 cm or involving 2 or more tendons) are even more complex and have failure rates of 20% to 90%.5,6 The weakest link in the RCR construct is the suture-tendon interface, and suture pullout through the tendon is thought to be the most common method of failure.6 The purpose of this review is to examine whether literature supports the use of acellular dermal matrices (ADMs) in rotator cuff surgery.

The high rate of structural failures after RCR has led surgeons to seek means to augment repairs and new means of reconstruction for irreparable tears. Freeze dried allograft tendons have been used historically with mixed results, including reports of complete graft failures and foreign body reaction.7-10 Porcine intestinal submucosal membrane “patches” gained popularity due to off-the- shelf availability of the graft. However, these were found to have poor outcomes with early graft rejection and intense inflammatory reaction.11,12 Recently, ADMs have gained significant interest due to favorable biomechanical properties and clinical outcomes.13-19

An ADM is an allograft composed of mostly type I collagen that is processed to remove donor cells while preserving the extracellular matrix. There are several commercially available ADMs with different methods of processing and sterilization, as well as handling characteristics.20,21 In vivo studies have demonstrated that removing the cellular components allows infiltration of native cellular agents, such as fibroblasts, vascular tissue, and tenocytes, while causing minimal host inflammatory reaction.21-23 In addition, superior suture pullout strength has been demonstrated by multiple benchtop and preclinical studies.23,24 Therefore, ADMs play a dual role of strengthening the repair while allowing infiltration of host cells and growth factors to potentially promote healing at the repair site.

Emerging Evidence

Multiple biomechanical studies have evaluated ADMs in RC models.24-28 Barber and colleagues24 demonstrated that ADM had significantly higher loads to failure (229 N) than porcine skin (128 N), bovine skin (76 N), and porcine small intestine submucosa (32 N) (P < .001). In another study, Barber and colleagues25 subsequently demonstrated, in a cadaver RC tear model, an increase in mean failure strength in augmented repairs with ADM (325 N) compared to cadaveric controls (273 N) (P = .047).

A subsequent study by Barber and Aziz-Jacobo26 compared ADMs to a control model of allograft RC. The ADMs had significantly higher tensile modulus (P < .001) and higher suture retention measure by a single-pull destructive test of a simple vertical stitch (P < .05) than the RC allograft. The ultimate load to failure of the ADM model was higher than the RC allograft control (523±154 N vs 208±115 N); however, this difference did not reach statistical significance.26 Beitzel and colleagues27 evaluated ADM augmentation in a cadaver RC model and found a statistically significant increase in load to failure in ADM augmented repairs vs nonaugmented controls, (575.8 N vs 348.9 N, P = .025). Ely and colleagues28 also demonstrated that repairs augmented with ADM had a higher load to failure (643 N vs 551 N) and less gap formation (2.2 mm vs 2.8 mm) compared to controls, although this difference was not statistically significant.

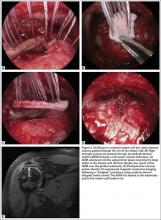

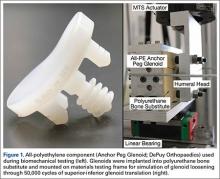

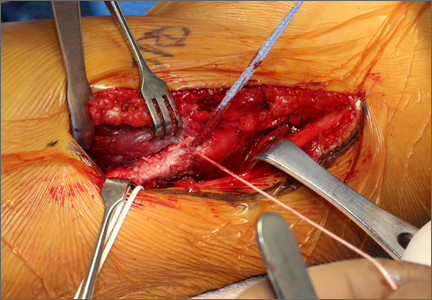

These biomechanical studies have been translated to clinical findings. A level II, prospective, randomized controlled study by Barber and colleagues29 evaluated 42 patients with >3 cm, 2-tendon RCTs repaired arthroscopically.Twenty-two patients were randomized to single-row arthroscopic repair, and 20 patients to single-row arthroscopic repair augmented by ADM by an onlay technique (Figure 1) as described by Labbé.30 At average follow-up of 24 months, 85% of the augmented repairs were intact on magnetic resonance imaging (MRI) at follow-up, compared to 40% in the control group (P < .05). Agrawal31 retrospectively reviewed 14 patients with either RCTs >3 cm or recurrent RCT (may be <3 cm) that were arthroscopically repaired with a double-row technique with ADM augmentation. Postoperative MRI obtained at average of 16.8 months revealed 85.7% of repairs to be intact, with 14.3% having recurrent tears of <1 cm. Rotini and colleagues32 evaluated a smaller subset of 5 patients with large/massive primary cuff tears, arthroscopically repaired with double-row technique and ADM augmentation. Follow-up MRI at an average of 1 year demonstrated 3 intact repairs, 1 partial recurrence, and 1 complete recurrence. These clinical studies demonstrate that RCRs augmented with ADM have a much higher rate of structural integrity on postoperative imaging compared to what has been previously reported in the literature.1-6

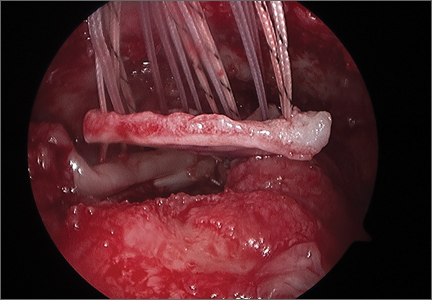

Although an “off-label” indication, the use of ADM in massive RC tears has been described with good clinical results.14,17,19,33 The ADM is used to bridge the gap by suturing it to the edge of the retracted tendon and anchoring it to the tuberosity (Figures 2A-2E). Improvement in pain, function, and active range of motion can be achieved. Burkhead and colleagues14 obtained postoperative MRIs at average follow-up of 1.2 years and found only 3 of 11 repairs with evidence of re-tear, all noted to be smaller than preoperative tears. Gupta and colleagues17 obtained postoperative ultrasounds in 24 patients at average 3 years and showed 76% of tears to be fully intact, with the remaining 24% having only a partial tear, and 0% with full re-tears. Venouziou and colleagues19 evaluated 14 patients with minimum 18-month follow-up and Kokkalis and colleagues33 evaluated 21 patients with a 29-month follow-up; both described successful clinical outcomes but did not provide postoperative imaging evaluation. Multiple studies have adapted this technique to a fully arthroscopic method and have had similarly positive results clinically and with MRI.13,16,18,34,35 Bond and colleagues13 reported 16 cases with massive irreparable tears repaired arthroscopically with ADM to span the tendon gap. At an average follow-up of 26.8 months, 75% had good or excellent clinical results, and at an average of 1 year postoperatively 13 of 16 cases had an intact repair on gadolinium enhanced MRI.13 These studies suggest that ADM can be used for bridging massive irreparable RC tears with good clinical and radiographic outcomes.

Superior capsule reconstruction is a biomechanically proven concept that has been described in previous studies.36,37 In the original technique, autologous tensor fascia lata (TFL) is anchored from the glenoid margin to the greater tuberosity footprint to restore the superior stability of the glenohumeral joint, without altering the native glenohumeral contact forces.38 This concept has gained popularity in the United States, but with the use of an ADM instead of harvesting TFL (Figures 3A, 3B). However, there are no published biomechanical or clinical studies with the use of ADM in superior capsular reconstruction.

Conclusion

The use of ADM is an emerging solution for augmenting primary RCRs and the treatment of irreparable RC tears. The biomechanical and clinical studies summarized support the use of ADM in RC surgery. Further randomized studies are needed to add to the growing evidence on the use of ADMs.

1. Green A. Chronic massive rotator cuff tears: evaluation and management. J Am Acad Orthop Surg. 2003;11(5):321-331.

2. Boileau P, Brassart N, Watkinson DJ, Carles M, Hatzidakis AM, Krishnan SG. Arthroscopic repair of full-thickness tears of the supraspinatus: does the tendon really heal? J Bone Joint Surg Am. 2005;87(6):1229-1240.

3. Iannotti JP, Deutsch A, Green A, et al. Time to failure after rotator cuff repair: a prospective imaging study. J Bone Joint Surg Am. 2013;95(11):965-971.

4. Karas EH, Iannotti JP. Failed repair of the rotator cuff: evaluation and treatment of complications. Instr Course Lect. 1998;47:87-95.

5. Burkhart SS. Biomechanics of rotator cuff repair: converting the ritual to a science. Instr Course Lect. 1998;47:43-50.

6. Derwin KA, Badylak SF, Steinmann SP, Iannotti JP. Extracellular matrix scaffold devices for rotator cuff repair. J Shoulder Elbow Surg. 2010;19:467-476.

7. Neviaser JS, Neviaser RJ, Neviaser TJ. The repair of chronic massive ruptures of the rotator cuff of the shoulder by use of a freeze-dried rotator cuff. J Bone Joint Surg Am. 1978;60(5):681-684.

8. Ito J, Morioka T. Surgical treatment for large and massive tears of the rotator cuff. Int Orthop. 2003;27(4):228-231.

9. Nasca RJ. The use of freeze-dried allografts in the management of global rotator cuff tears. Clin Orthop Related Res. 1988;228:218-226.

10. Moore DR, Cain EL, Schwartz ML, Clancy WG Jr. Allograft reconstruction for massive, irreparable rotator cuff tears. Am J Sports Med. 2006;34(3):392-396.

11. Walton JR, Bowman NK, Khatib Y, Linklater J, Murrell GA. Restore orthobiologic implant: not recommended for augmentation of rotator cuff repairs. J Bone Joint Surg Am. 2007;89(4):786-791.

12. Iannotti JP, Codsi MJ, Kwon YW, Derwin K, Ciccone J, Brems JJ. Porcine small intestine submucosa augmentation of surgical repair of chronic two-tendon rotator cuff tears. A randomized, controlled trial. J Bone Joint Surg Am. 2006;88(6):1238-1244.

13. Bond JL, Dopirak RM, Higgins J, Burns J, Snyder SJ. Arthroscopic replacement of massive, irreparable rotator cuff tears using a GraftJacket allograft: technique and preliminary results. Arthroscopy. 2008;24(4):403-409.

14. Burkhead WZ Jr, Schiffern SC, Krishnan SG. Use of Graft Jacket as an augmentation for massive rotator cuff tears. Semin Arthoplasty. 2007;18(1):11-18.

15. Dehler T, Pennings AL, ElMaraghy AW. Dermal allograft reconstruction of a chronic pectoralis major tear. J Shoulder Elbow Surg. 2013;22(10):e18-e22.

16. Dopirak R, Bond JL, Snyder SJ. Arthroscopic total rotator cuff replacement with an acellular dermal allograft matrix. Int J Shoulder Surg. 2007;1(1):7-15.

17. Gupta AK, Hug K, Berkoff DJ, et al. Dermal tissue allograft for the repair of massive irreparable rotator cuff tears. Am J Sports Med. 2012;40(1):141-147.

18. Modi A, Singh HP, Pandey R, Armstrong A. Management of irreparable rotator cuff tears with the GraftJacket allograft as an interpositional graft. Shoulder Elbow. 2013;5(3):188-194.

19. Venouziou AI, Kokkalis ZT, Sotereanos DG. Human dermal allograft interposition for the reconstruction of massive irreparable rotator cuff tears. Am J Orthop. 2013;42(2):63-70.

20. Acevedo DC, Shore B, Mirzayan R. Orthopedic applications of acellular human dermal allograft for shoulder and elbow surgery. Orthop Clin North Am. 2015;46(3):377-388.

21. Beniker D, McQuillan D, Livesey S, et al. The use of acellular dermal matrix as a scaffold for periosteum replacement. Orthopedics. 2003;26(5 Suppl):s591-s596.

22. Smith RD, Carr A, Dakin SG, Snelling SJ, Yapp C, Hakimi O. The response of tenocytes to commercial scaffolds used for rotator cuff repair. Eur Cell Mater. 2016;31:107-118.

23. Adams JE, Zobitz ME, Reach JS Jr, An KN, Steinmann SP. Rotator cuff repair using an acellular dermal matrix graft: an in vivo study in a canine model. Arthroscopy. 2006;22(7):700-709.

24. Barber FA, Herbert MA, Coons DA. Tendon augmentation grafts: biomechanical failure loads and failure patterns. Arthroscopy. 2006;22(5):534-538.

25. Barber FA, Herbert MA, Boothby MH. Ultimate tensile failure loads of a human dermal allograft rotator cuff augmentation. Arthroscopy. 2008;24(1):20-24.

26. Barber AF, Aziz-Jacobo J. Biomechanical testing of commercially available soft-tissue augmentation materials. Arthroscopy. 2009;25(11):1233-1239.

27. Beitzel K, Chowaniec DM, McCarthy MB, et al. Stability of double-row rotator cuff repair is not adversely affected by scaffold interposition between tendon and bone. Am J Sports Med. 2012;40(5):1148-1154.

28. Ely EE, Figueroa NM, Gilot GJ. Biomechanical analysis of rotator cuff repairs with extraccellular matrix graft augmentation. Orthopedics. 2014;37(9):608-614.

29. Barber AF, Burns JP, Deutsch A, Labbé MR, Litchfield RB. A prospective, randomized evaluation of acellular human dermal matrix augmentation for arthroscopic rotator cuff repair. Arthroscopy. 2012;28(1):8-15.

30. Labbé MR. Arthroscopic technique for patch augmentation of rotator cuff repairs. Arthroscopy. 2006;22(1):1136.e1-e6.

31. Agrawal V. Healing rates for challenging rotator cuff tears utilizing an acellular human dermal reinforcement graft. Int J Shoulder Surg. 2012;6(2):36-44.

32. Rotini R, Marinelli A, Guerra E, et al. Human dermal matrix scaffold augmentation for large and massive rotator cuff repairs: preliminary clinical and MRI results at 1-year follow-up. Musculoskelet Surg. 2011;95 Suppl 1:S13-S23.

33. Kokkalis ZT, Mavrogenis AF, Scarlat M, et al. Human dermal allograft for massive rotator cuff tears. Orthopedics. 2014;37(12):e1108-e1116.

34. Wong I, Burns J, Snyder S. Arthroscopic GraftJacket repair of rotator cuff tears. J Shoulder Elbow Surg. 2010;19(2 Suppl):104-109.

35. Snyder SJ, Bond JL. Technique for arthroscopic replacement of severely damaged rotator cuff using “GraftJacket” allograft. Oper Tech Sports Med. 2007;15(2):86-94.

36. Mihata T, McGarry MH, Pirolo JM, Kinoshita M, Lee TQ. Superior capsule reconstruction to restore superior stability in irreparable rotator cuff tears: a biomechanical cadaveric study. Am J Sports Med. 2012;40(10):2248-2255.

37. Mihata T, McGarry MH, Kahn T, Goldberg I, Neo M, Lee TQ. Biomechanical role of capsular continuity in superior capsule reconstruction for irreparable tears of the supraspinatus tendon. Am J Sports Med. 2016;44(6):1423-1430.

38. Mihata T, Lee TQ, Watanabe C, et al. Clinical results of arthroscopic superior capsule reconstruction for irreparable rotator cuff tears. Arthroscopy. 2013;29(3):459-470.

Rotator cuff repairs (RCRs) can be challenging due to poor tendon quality and the inability of tendon to heal to bone. Smoking, age over 63 years, fatty infiltration, and massive cuff tears are all factors implicated in increased failure rates.1-3 Tears >3 cm have a structural failure rate ranging from 11% to 95% in the literature.1-5 Massive tears (tears >5 cm or involving 2 or more tendons) are even more complex and have failure rates of 20% to 90%.5,6 The weakest link in the RCR construct is the suture-tendon interface, and suture pullout through the tendon is thought to be the most common method of failure.6 The purpose of this review is to examine whether literature supports the use of acellular dermal matrices (ADMs) in rotator cuff surgery.

The high rate of structural failures after RCR has led surgeons to seek means to augment repairs and new means of reconstruction for irreparable tears. Freeze dried allograft tendons have been used historically with mixed results, including reports of complete graft failures and foreign body reaction.7-10 Porcine intestinal submucosal membrane “patches” gained popularity due to off-the- shelf availability of the graft. However, these were found to have poor outcomes with early graft rejection and intense inflammatory reaction.11,12 Recently, ADMs have gained significant interest due to favorable biomechanical properties and clinical outcomes.13-19

An ADM is an allograft composed of mostly type I collagen that is processed to remove donor cells while preserving the extracellular matrix. There are several commercially available ADMs with different methods of processing and sterilization, as well as handling characteristics.20,21 In vivo studies have demonstrated that removing the cellular components allows infiltration of native cellular agents, such as fibroblasts, vascular tissue, and tenocytes, while causing minimal host inflammatory reaction.21-23 In addition, superior suture pullout strength has been demonstrated by multiple benchtop and preclinical studies.23,24 Therefore, ADMs play a dual role of strengthening the repair while allowing infiltration of host cells and growth factors to potentially promote healing at the repair site.

Emerging Evidence

Multiple biomechanical studies have evaluated ADMs in RC models.24-28 Barber and colleagues24 demonstrated that ADM had significantly higher loads to failure (229 N) than porcine skin (128 N), bovine skin (76 N), and porcine small intestine submucosa (32 N) (P < .001). In another study, Barber and colleagues25 subsequently demonstrated, in a cadaver RC tear model, an increase in mean failure strength in augmented repairs with ADM (325 N) compared to cadaveric controls (273 N) (P = .047).

A subsequent study by Barber and Aziz-Jacobo26 compared ADMs to a control model of allograft RC. The ADMs had significantly higher tensile modulus (P < .001) and higher suture retention measure by a single-pull destructive test of a simple vertical stitch (P < .05) than the RC allograft. The ultimate load to failure of the ADM model was higher than the RC allograft control (523±154 N vs 208±115 N); however, this difference did not reach statistical significance.26 Beitzel and colleagues27 evaluated ADM augmentation in a cadaver RC model and found a statistically significant increase in load to failure in ADM augmented repairs vs nonaugmented controls, (575.8 N vs 348.9 N, P = .025). Ely and colleagues28 also demonstrated that repairs augmented with ADM had a higher load to failure (643 N vs 551 N) and less gap formation (2.2 mm vs 2.8 mm) compared to controls, although this difference was not statistically significant.

These biomechanical studies have been translated to clinical findings. A level II, prospective, randomized controlled study by Barber and colleagues29 evaluated 42 patients with >3 cm, 2-tendon RCTs repaired arthroscopically.Twenty-two patients were randomized to single-row arthroscopic repair, and 20 patients to single-row arthroscopic repair augmented by ADM by an onlay technique (Figure 1) as described by Labbé.30 At average follow-up of 24 months, 85% of the augmented repairs were intact on magnetic resonance imaging (MRI) at follow-up, compared to 40% in the control group (P < .05). Agrawal31 retrospectively reviewed 14 patients with either RCTs >3 cm or recurrent RCT (may be <3 cm) that were arthroscopically repaired with a double-row technique with ADM augmentation. Postoperative MRI obtained at average of 16.8 months revealed 85.7% of repairs to be intact, with 14.3% having recurrent tears of <1 cm. Rotini and colleagues32 evaluated a smaller subset of 5 patients with large/massive primary cuff tears, arthroscopically repaired with double-row technique and ADM augmentation. Follow-up MRI at an average of 1 year demonstrated 3 intact repairs, 1 partial recurrence, and 1 complete recurrence. These clinical studies demonstrate that RCRs augmented with ADM have a much higher rate of structural integrity on postoperative imaging compared to what has been previously reported in the literature.1-6

Although an “off-label” indication, the use of ADM in massive RC tears has been described with good clinical results.14,17,19,33 The ADM is used to bridge the gap by suturing it to the edge of the retracted tendon and anchoring it to the tuberosity (Figures 2A-2E). Improvement in pain, function, and active range of motion can be achieved. Burkhead and colleagues14 obtained postoperative MRIs at average follow-up of 1.2 years and found only 3 of 11 repairs with evidence of re-tear, all noted to be smaller than preoperative tears. Gupta and colleagues17 obtained postoperative ultrasounds in 24 patients at average 3 years and showed 76% of tears to be fully intact, with the remaining 24% having only a partial tear, and 0% with full re-tears. Venouziou and colleagues19 evaluated 14 patients with minimum 18-month follow-up and Kokkalis and colleagues33 evaluated 21 patients with a 29-month follow-up; both described successful clinical outcomes but did not provide postoperative imaging evaluation. Multiple studies have adapted this technique to a fully arthroscopic method and have had similarly positive results clinically and with MRI.13,16,18,34,35 Bond and colleagues13 reported 16 cases with massive irreparable tears repaired arthroscopically with ADM to span the tendon gap. At an average follow-up of 26.8 months, 75% had good or excellent clinical results, and at an average of 1 year postoperatively 13 of 16 cases had an intact repair on gadolinium enhanced MRI.13 These studies suggest that ADM can be used for bridging massive irreparable RC tears with good clinical and radiographic outcomes.

Superior capsule reconstruction is a biomechanically proven concept that has been described in previous studies.36,37 In the original technique, autologous tensor fascia lata (TFL) is anchored from the glenoid margin to the greater tuberosity footprint to restore the superior stability of the glenohumeral joint, without altering the native glenohumeral contact forces.38 This concept has gained popularity in the United States, but with the use of an ADM instead of harvesting TFL (Figures 3A, 3B). However, there are no published biomechanical or clinical studies with the use of ADM in superior capsular reconstruction.

Conclusion

The use of ADM is an emerging solution for augmenting primary RCRs and the treatment of irreparable RC tears. The biomechanical and clinical studies summarized support the use of ADM in RC surgery. Further randomized studies are needed to add to the growing evidence on the use of ADMs.

Rotator cuff repairs (RCRs) can be challenging due to poor tendon quality and the inability of tendon to heal to bone. Smoking, age over 63 years, fatty infiltration, and massive cuff tears are all factors implicated in increased failure rates.1-3 Tears >3 cm have a structural failure rate ranging from 11% to 95% in the literature.1-5 Massive tears (tears >5 cm or involving 2 or more tendons) are even more complex and have failure rates of 20% to 90%.5,6 The weakest link in the RCR construct is the suture-tendon interface, and suture pullout through the tendon is thought to be the most common method of failure.6 The purpose of this review is to examine whether literature supports the use of acellular dermal matrices (ADMs) in rotator cuff surgery.

The high rate of structural failures after RCR has led surgeons to seek means to augment repairs and new means of reconstruction for irreparable tears. Freeze dried allograft tendons have been used historically with mixed results, including reports of complete graft failures and foreign body reaction.7-10 Porcine intestinal submucosal membrane “patches” gained popularity due to off-the- shelf availability of the graft. However, these were found to have poor outcomes with early graft rejection and intense inflammatory reaction.11,12 Recently, ADMs have gained significant interest due to favorable biomechanical properties and clinical outcomes.13-19

An ADM is an allograft composed of mostly type I collagen that is processed to remove donor cells while preserving the extracellular matrix. There are several commercially available ADMs with different methods of processing and sterilization, as well as handling characteristics.20,21 In vivo studies have demonstrated that removing the cellular components allows infiltration of native cellular agents, such as fibroblasts, vascular tissue, and tenocytes, while causing minimal host inflammatory reaction.21-23 In addition, superior suture pullout strength has been demonstrated by multiple benchtop and preclinical studies.23,24 Therefore, ADMs play a dual role of strengthening the repair while allowing infiltration of host cells and growth factors to potentially promote healing at the repair site.

Emerging Evidence

Multiple biomechanical studies have evaluated ADMs in RC models.24-28 Barber and colleagues24 demonstrated that ADM had significantly higher loads to failure (229 N) than porcine skin (128 N), bovine skin (76 N), and porcine small intestine submucosa (32 N) (P < .001). In another study, Barber and colleagues25 subsequently demonstrated, in a cadaver RC tear model, an increase in mean failure strength in augmented repairs with ADM (325 N) compared to cadaveric controls (273 N) (P = .047).

A subsequent study by Barber and Aziz-Jacobo26 compared ADMs to a control model of allograft RC. The ADMs had significantly higher tensile modulus (P < .001) and higher suture retention measure by a single-pull destructive test of a simple vertical stitch (P < .05) than the RC allograft. The ultimate load to failure of the ADM model was higher than the RC allograft control (523±154 N vs 208±115 N); however, this difference did not reach statistical significance.26 Beitzel and colleagues27 evaluated ADM augmentation in a cadaver RC model and found a statistically significant increase in load to failure in ADM augmented repairs vs nonaugmented controls, (575.8 N vs 348.9 N, P = .025). Ely and colleagues28 also demonstrated that repairs augmented with ADM had a higher load to failure (643 N vs 551 N) and less gap formation (2.2 mm vs 2.8 mm) compared to controls, although this difference was not statistically significant.

These biomechanical studies have been translated to clinical findings. A level II, prospective, randomized controlled study by Barber and colleagues29 evaluated 42 patients with >3 cm, 2-tendon RCTs repaired arthroscopically.Twenty-two patients were randomized to single-row arthroscopic repair, and 20 patients to single-row arthroscopic repair augmented by ADM by an onlay technique (Figure 1) as described by Labbé.30 At average follow-up of 24 months, 85% of the augmented repairs were intact on magnetic resonance imaging (MRI) at follow-up, compared to 40% in the control group (P < .05). Agrawal31 retrospectively reviewed 14 patients with either RCTs >3 cm or recurrent RCT (may be <3 cm) that were arthroscopically repaired with a double-row technique with ADM augmentation. Postoperative MRI obtained at average of 16.8 months revealed 85.7% of repairs to be intact, with 14.3% having recurrent tears of <1 cm. Rotini and colleagues32 evaluated a smaller subset of 5 patients with large/massive primary cuff tears, arthroscopically repaired with double-row technique and ADM augmentation. Follow-up MRI at an average of 1 year demonstrated 3 intact repairs, 1 partial recurrence, and 1 complete recurrence. These clinical studies demonstrate that RCRs augmented with ADM have a much higher rate of structural integrity on postoperative imaging compared to what has been previously reported in the literature.1-6

Although an “off-label” indication, the use of ADM in massive RC tears has been described with good clinical results.14,17,19,33 The ADM is used to bridge the gap by suturing it to the edge of the retracted tendon and anchoring it to the tuberosity (Figures 2A-2E). Improvement in pain, function, and active range of motion can be achieved. Burkhead and colleagues14 obtained postoperative MRIs at average follow-up of 1.2 years and found only 3 of 11 repairs with evidence of re-tear, all noted to be smaller than preoperative tears. Gupta and colleagues17 obtained postoperative ultrasounds in 24 patients at average 3 years and showed 76% of tears to be fully intact, with the remaining 24% having only a partial tear, and 0% with full re-tears. Venouziou and colleagues19 evaluated 14 patients with minimum 18-month follow-up and Kokkalis and colleagues33 evaluated 21 patients with a 29-month follow-up; both described successful clinical outcomes but did not provide postoperative imaging evaluation. Multiple studies have adapted this technique to a fully arthroscopic method and have had similarly positive results clinically and with MRI.13,16,18,34,35 Bond and colleagues13 reported 16 cases with massive irreparable tears repaired arthroscopically with ADM to span the tendon gap. At an average follow-up of 26.8 months, 75% had good or excellent clinical results, and at an average of 1 year postoperatively 13 of 16 cases had an intact repair on gadolinium enhanced MRI.13 These studies suggest that ADM can be used for bridging massive irreparable RC tears with good clinical and radiographic outcomes.

Superior capsule reconstruction is a biomechanically proven concept that has been described in previous studies.36,37 In the original technique, autologous tensor fascia lata (TFL) is anchored from the glenoid margin to the greater tuberosity footprint to restore the superior stability of the glenohumeral joint, without altering the native glenohumeral contact forces.38 This concept has gained popularity in the United States, but with the use of an ADM instead of harvesting TFL (Figures 3A, 3B). However, there are no published biomechanical or clinical studies with the use of ADM in superior capsular reconstruction.

Conclusion

The use of ADM is an emerging solution for augmenting primary RCRs and the treatment of irreparable RC tears. The biomechanical and clinical studies summarized support the use of ADM in RC surgery. Further randomized studies are needed to add to the growing evidence on the use of ADMs.

1. Green A. Chronic massive rotator cuff tears: evaluation and management. J Am Acad Orthop Surg. 2003;11(5):321-331.

2. Boileau P, Brassart N, Watkinson DJ, Carles M, Hatzidakis AM, Krishnan SG. Arthroscopic repair of full-thickness tears of the supraspinatus: does the tendon really heal? J Bone Joint Surg Am. 2005;87(6):1229-1240.

3. Iannotti JP, Deutsch A, Green A, et al. Time to failure after rotator cuff repair: a prospective imaging study. J Bone Joint Surg Am. 2013;95(11):965-971.

4. Karas EH, Iannotti JP. Failed repair of the rotator cuff: evaluation and treatment of complications. Instr Course Lect. 1998;47:87-95.

5. Burkhart SS. Biomechanics of rotator cuff repair: converting the ritual to a science. Instr Course Lect. 1998;47:43-50.

6. Derwin KA, Badylak SF, Steinmann SP, Iannotti JP. Extracellular matrix scaffold devices for rotator cuff repair. J Shoulder Elbow Surg. 2010;19:467-476.

7. Neviaser JS, Neviaser RJ, Neviaser TJ. The repair of chronic massive ruptures of the rotator cuff of the shoulder by use of a freeze-dried rotator cuff. J Bone Joint Surg Am. 1978;60(5):681-684.

8. Ito J, Morioka T. Surgical treatment for large and massive tears of the rotator cuff. Int Orthop. 2003;27(4):228-231.

9. Nasca RJ. The use of freeze-dried allografts in the management of global rotator cuff tears. Clin Orthop Related Res. 1988;228:218-226.

10. Moore DR, Cain EL, Schwartz ML, Clancy WG Jr. Allograft reconstruction for massive, irreparable rotator cuff tears. Am J Sports Med. 2006;34(3):392-396.

11. Walton JR, Bowman NK, Khatib Y, Linklater J, Murrell GA. Restore orthobiologic implant: not recommended for augmentation of rotator cuff repairs. J Bone Joint Surg Am. 2007;89(4):786-791.

12. Iannotti JP, Codsi MJ, Kwon YW, Derwin K, Ciccone J, Brems JJ. Porcine small intestine submucosa augmentation of surgical repair of chronic two-tendon rotator cuff tears. A randomized, controlled trial. J Bone Joint Surg Am. 2006;88(6):1238-1244.

13. Bond JL, Dopirak RM, Higgins J, Burns J, Snyder SJ. Arthroscopic replacement of massive, irreparable rotator cuff tears using a GraftJacket allograft: technique and preliminary results. Arthroscopy. 2008;24(4):403-409.

14. Burkhead WZ Jr, Schiffern SC, Krishnan SG. Use of Graft Jacket as an augmentation for massive rotator cuff tears. Semin Arthoplasty. 2007;18(1):11-18.

15. Dehler T, Pennings AL, ElMaraghy AW. Dermal allograft reconstruction of a chronic pectoralis major tear. J Shoulder Elbow Surg. 2013;22(10):e18-e22.

16. Dopirak R, Bond JL, Snyder SJ. Arthroscopic total rotator cuff replacement with an acellular dermal allograft matrix. Int J Shoulder Surg. 2007;1(1):7-15.

17. Gupta AK, Hug K, Berkoff DJ, et al. Dermal tissue allograft for the repair of massive irreparable rotator cuff tears. Am J Sports Med. 2012;40(1):141-147.

18. Modi A, Singh HP, Pandey R, Armstrong A. Management of irreparable rotator cuff tears with the GraftJacket allograft as an interpositional graft. Shoulder Elbow. 2013;5(3):188-194.

19. Venouziou AI, Kokkalis ZT, Sotereanos DG. Human dermal allograft interposition for the reconstruction of massive irreparable rotator cuff tears. Am J Orthop. 2013;42(2):63-70.

20. Acevedo DC, Shore B, Mirzayan R. Orthopedic applications of acellular human dermal allograft for shoulder and elbow surgery. Orthop Clin North Am. 2015;46(3):377-388.

21. Beniker D, McQuillan D, Livesey S, et al. The use of acellular dermal matrix as a scaffold for periosteum replacement. Orthopedics. 2003;26(5 Suppl):s591-s596.

22. Smith RD, Carr A, Dakin SG, Snelling SJ, Yapp C, Hakimi O. The response of tenocytes to commercial scaffolds used for rotator cuff repair. Eur Cell Mater. 2016;31:107-118.

23. Adams JE, Zobitz ME, Reach JS Jr, An KN, Steinmann SP. Rotator cuff repair using an acellular dermal matrix graft: an in vivo study in a canine model. Arthroscopy. 2006;22(7):700-709.

24. Barber FA, Herbert MA, Coons DA. Tendon augmentation grafts: biomechanical failure loads and failure patterns. Arthroscopy. 2006;22(5):534-538.

25. Barber FA, Herbert MA, Boothby MH. Ultimate tensile failure loads of a human dermal allograft rotator cuff augmentation. Arthroscopy. 2008;24(1):20-24.

26. Barber AF, Aziz-Jacobo J. Biomechanical testing of commercially available soft-tissue augmentation materials. Arthroscopy. 2009;25(11):1233-1239.

27. Beitzel K, Chowaniec DM, McCarthy MB, et al. Stability of double-row rotator cuff repair is not adversely affected by scaffold interposition between tendon and bone. Am J Sports Med. 2012;40(5):1148-1154.

28. Ely EE, Figueroa NM, Gilot GJ. Biomechanical analysis of rotator cuff repairs with extraccellular matrix graft augmentation. Orthopedics. 2014;37(9):608-614.

29. Barber AF, Burns JP, Deutsch A, Labbé MR, Litchfield RB. A prospective, randomized evaluation of acellular human dermal matrix augmentation for arthroscopic rotator cuff repair. Arthroscopy. 2012;28(1):8-15.

30. Labbé MR. Arthroscopic technique for patch augmentation of rotator cuff repairs. Arthroscopy. 2006;22(1):1136.e1-e6.

31. Agrawal V. Healing rates for challenging rotator cuff tears utilizing an acellular human dermal reinforcement graft. Int J Shoulder Surg. 2012;6(2):36-44.

32. Rotini R, Marinelli A, Guerra E, et al. Human dermal matrix scaffold augmentation for large and massive rotator cuff repairs: preliminary clinical and MRI results at 1-year follow-up. Musculoskelet Surg. 2011;95 Suppl 1:S13-S23.

33. Kokkalis ZT, Mavrogenis AF, Scarlat M, et al. Human dermal allograft for massive rotator cuff tears. Orthopedics. 2014;37(12):e1108-e1116.

34. Wong I, Burns J, Snyder S. Arthroscopic GraftJacket repair of rotator cuff tears. J Shoulder Elbow Surg. 2010;19(2 Suppl):104-109.

35. Snyder SJ, Bond JL. Technique for arthroscopic replacement of severely damaged rotator cuff using “GraftJacket” allograft. Oper Tech Sports Med. 2007;15(2):86-94.

36. Mihata T, McGarry MH, Pirolo JM, Kinoshita M, Lee TQ. Superior capsule reconstruction to restore superior stability in irreparable rotator cuff tears: a biomechanical cadaveric study. Am J Sports Med. 2012;40(10):2248-2255.

37. Mihata T, McGarry MH, Kahn T, Goldberg I, Neo M, Lee TQ. Biomechanical role of capsular continuity in superior capsule reconstruction for irreparable tears of the supraspinatus tendon. Am J Sports Med. 2016;44(6):1423-1430.

38. Mihata T, Lee TQ, Watanabe C, et al. Clinical results of arthroscopic superior capsule reconstruction for irreparable rotator cuff tears. Arthroscopy. 2013;29(3):459-470.

1. Green A. Chronic massive rotator cuff tears: evaluation and management. J Am Acad Orthop Surg. 2003;11(5):321-331.

2. Boileau P, Brassart N, Watkinson DJ, Carles M, Hatzidakis AM, Krishnan SG. Arthroscopic repair of full-thickness tears of the supraspinatus: does the tendon really heal? J Bone Joint Surg Am. 2005;87(6):1229-1240.

3. Iannotti JP, Deutsch A, Green A, et al. Time to failure after rotator cuff repair: a prospective imaging study. J Bone Joint Surg Am. 2013;95(11):965-971.

4. Karas EH, Iannotti JP. Failed repair of the rotator cuff: evaluation and treatment of complications. Instr Course Lect. 1998;47:87-95.

5. Burkhart SS. Biomechanics of rotator cuff repair: converting the ritual to a science. Instr Course Lect. 1998;47:43-50.

6. Derwin KA, Badylak SF, Steinmann SP, Iannotti JP. Extracellular matrix scaffold devices for rotator cuff repair. J Shoulder Elbow Surg. 2010;19:467-476.

7. Neviaser JS, Neviaser RJ, Neviaser TJ. The repair of chronic massive ruptures of the rotator cuff of the shoulder by use of a freeze-dried rotator cuff. J Bone Joint Surg Am. 1978;60(5):681-684.

8. Ito J, Morioka T. Surgical treatment for large and massive tears of the rotator cuff. Int Orthop. 2003;27(4):228-231.

9. Nasca RJ. The use of freeze-dried allografts in the management of global rotator cuff tears. Clin Orthop Related Res. 1988;228:218-226.

10. Moore DR, Cain EL, Schwartz ML, Clancy WG Jr. Allograft reconstruction for massive, irreparable rotator cuff tears. Am J Sports Med. 2006;34(3):392-396.

11. Walton JR, Bowman NK, Khatib Y, Linklater J, Murrell GA. Restore orthobiologic implant: not recommended for augmentation of rotator cuff repairs. J Bone Joint Surg Am. 2007;89(4):786-791.

12. Iannotti JP, Codsi MJ, Kwon YW, Derwin K, Ciccone J, Brems JJ. Porcine small intestine submucosa augmentation of surgical repair of chronic two-tendon rotator cuff tears. A randomized, controlled trial. J Bone Joint Surg Am. 2006;88(6):1238-1244.

13. Bond JL, Dopirak RM, Higgins J, Burns J, Snyder SJ. Arthroscopic replacement of massive, irreparable rotator cuff tears using a GraftJacket allograft: technique and preliminary results. Arthroscopy. 2008;24(4):403-409.

14. Burkhead WZ Jr, Schiffern SC, Krishnan SG. Use of Graft Jacket as an augmentation for massive rotator cuff tears. Semin Arthoplasty. 2007;18(1):11-18.

15. Dehler T, Pennings AL, ElMaraghy AW. Dermal allograft reconstruction of a chronic pectoralis major tear. J Shoulder Elbow Surg. 2013;22(10):e18-e22.

16. Dopirak R, Bond JL, Snyder SJ. Arthroscopic total rotator cuff replacement with an acellular dermal allograft matrix. Int J Shoulder Surg. 2007;1(1):7-15.

17. Gupta AK, Hug K, Berkoff DJ, et al. Dermal tissue allograft for the repair of massive irreparable rotator cuff tears. Am J Sports Med. 2012;40(1):141-147.

18. Modi A, Singh HP, Pandey R, Armstrong A. Management of irreparable rotator cuff tears with the GraftJacket allograft as an interpositional graft. Shoulder Elbow. 2013;5(3):188-194.

19. Venouziou AI, Kokkalis ZT, Sotereanos DG. Human dermal allograft interposition for the reconstruction of massive irreparable rotator cuff tears. Am J Orthop. 2013;42(2):63-70.

20. Acevedo DC, Shore B, Mirzayan R. Orthopedic applications of acellular human dermal allograft for shoulder and elbow surgery. Orthop Clin North Am. 2015;46(3):377-388.

21. Beniker D, McQuillan D, Livesey S, et al. The use of acellular dermal matrix as a scaffold for periosteum replacement. Orthopedics. 2003;26(5 Suppl):s591-s596.

22. Smith RD, Carr A, Dakin SG, Snelling SJ, Yapp C, Hakimi O. The response of tenocytes to commercial scaffolds used for rotator cuff repair. Eur Cell Mater. 2016;31:107-118.

23. Adams JE, Zobitz ME, Reach JS Jr, An KN, Steinmann SP. Rotator cuff repair using an acellular dermal matrix graft: an in vivo study in a canine model. Arthroscopy. 2006;22(7):700-709.

24. Barber FA, Herbert MA, Coons DA. Tendon augmentation grafts: biomechanical failure loads and failure patterns. Arthroscopy. 2006;22(5):534-538.

25. Barber FA, Herbert MA, Boothby MH. Ultimate tensile failure loads of a human dermal allograft rotator cuff augmentation. Arthroscopy. 2008;24(1):20-24.

26. Barber AF, Aziz-Jacobo J. Biomechanical testing of commercially available soft-tissue augmentation materials. Arthroscopy. 2009;25(11):1233-1239.

27. Beitzel K, Chowaniec DM, McCarthy MB, et al. Stability of double-row rotator cuff repair is not adversely affected by scaffold interposition between tendon and bone. Am J Sports Med. 2012;40(5):1148-1154.

28. Ely EE, Figueroa NM, Gilot GJ. Biomechanical analysis of rotator cuff repairs with extraccellular matrix graft augmentation. Orthopedics. 2014;37(9):608-614.

29. Barber AF, Burns JP, Deutsch A, Labbé MR, Litchfield RB. A prospective, randomized evaluation of acellular human dermal matrix augmentation for arthroscopic rotator cuff repair. Arthroscopy. 2012;28(1):8-15.

30. Labbé MR. Arthroscopic technique for patch augmentation of rotator cuff repairs. Arthroscopy. 2006;22(1):1136.e1-e6.

31. Agrawal V. Healing rates for challenging rotator cuff tears utilizing an acellular human dermal reinforcement graft. Int J Shoulder Surg. 2012;6(2):36-44.

32. Rotini R, Marinelli A, Guerra E, et al. Human dermal matrix scaffold augmentation for large and massive rotator cuff repairs: preliminary clinical and MRI results at 1-year follow-up. Musculoskelet Surg. 2011;95 Suppl 1:S13-S23.

33. Kokkalis ZT, Mavrogenis AF, Scarlat M, et al. Human dermal allograft for massive rotator cuff tears. Orthopedics. 2014;37(12):e1108-e1116.

34. Wong I, Burns J, Snyder S. Arthroscopic GraftJacket repair of rotator cuff tears. J Shoulder Elbow Surg. 2010;19(2 Suppl):104-109.

35. Snyder SJ, Bond JL. Technique for arthroscopic replacement of severely damaged rotator cuff using “GraftJacket” allograft. Oper Tech Sports Med. 2007;15(2):86-94.

36. Mihata T, McGarry MH, Pirolo JM, Kinoshita M, Lee TQ. Superior capsule reconstruction to restore superior stability in irreparable rotator cuff tears: a biomechanical cadaveric study. Am J Sports Med. 2012;40(10):2248-2255.

37. Mihata T, McGarry MH, Kahn T, Goldberg I, Neo M, Lee TQ. Biomechanical role of capsular continuity in superior capsule reconstruction for irreparable tears of the supraspinatus tendon. Am J Sports Med. 2016;44(6):1423-1430.

38. Mihata T, Lee TQ, Watanabe C, et al. Clinical results of arthroscopic superior capsule reconstruction for irreparable rotator cuff tears. Arthroscopy. 2013;29(3):459-470.

Platelet-Rich Plasma (PRP) in Orthopedic Sports Medicine

Platelet-rich plasma (PRP) is a refined product of autologous blood with a platelet concentration greater than that of whole blood. It is prepared via plasmapheresis utilizing a 2-stage centrifugation process and more than 40 commercially available systems are marketed to concentrate whole blood to PRP.1 It is rich in biologic factors (growth factors, cytokines, proteins, cellular components) essential to the body’s response to injury. For this reason, it was first used in oromaxillofacial surgery in the 1950s, but its effects on the musculoskeletal system have yet to be clearly elucidated.2 However, this lack of clarity has not deterred its widespread use among orthopedic surgeons. In this review, we aim to delineate the current understanding of PRP and its proven effectiveness in the treatment of rotator cuff tears, knee osteoarthritis, ulnar collateral ligament (UCL) tears, lateral epicondylitis, hamstring injuries, and Achilles tendinopathy.

Rotator Cuff Tears

Rotator cuff tears are one of the most common etiologies for shoulder pain and disability. The incidence continues to increase with the active aging population.3 Rotator cuff tears treated with arthroscopic repair have exhibited satisfactory pain relief and functional outcomes.4-7 Despite advances in fixation techniques, the quality and speed of tendon-to-bone healing remains unpredictable, with repaired tendons exhibiting inferior mechanical properties that are susceptible to re-tear.8-10

Numerous studies have investigated PRP application during arthroscopic rotator cuff repair (RCR) in an attempt to enhance and accelerate the repair process.11-15 However, wide variability exists among protocols of how and when PRP is utilized to augment the repair. Warth and colleagues16 performed a meta-analysis of 11 Level I/II studies evaluating RCR with PRP augmentation. With regards to clinical outcome scores, they found no significant difference in pre- and postoperative American Shoulder and Elbow Surgeons (ASES), Constant, Disability of the Arm, Shoulder and Hand (DASH), or visual analog scale (VAS) pain scores between those patients with or without PRP augmentation. However, they did note a significant increase in Constant scores when PRP was delivered to the tendon-bone interface rather than over the surface of the repair site. There was no significant difference in structural outcomes (evaluated by magnetic resonance imaging [MRI] re-tear rates) between those RCRs with and without PRP augmentation, except in those tears >3 cm in anterior-posterior length using double-row technique, with the PRP group exhibiting a significantly decreased re-tear rate (25.9% vs 57.1%).16 Zhao and colleagues17 reported similar results in a meta-analysis of 8 randomized controlled trials, exhibiting no significant differences in clinical outcome scores or re-tear rates after RCR with and without PRP augmentation. Overall, most studies have failed to demonstrate a significant benefit with regards to re-tear rates or shoulder-specific outcomes with the addition of PRP during arthroscopic RCR.

Knee Osteoarthritis

Osteoarthritis is the most common musculoskeletal disorder, with an estimated prevalence of 10% of the world’s population age 60 years and older.18 The knee is commonly symptomatic, resulting in pain, disability, and significant healthcare costs. Novel biologic, nonoperative therapies, including intra-articular viscosupplementation and PRP injections, have been proposed to treat the early stages of osteoarthritis to provide symptomatic relief and delay surgical intervention.

A multitude of studies have been performed investigating the effects of PRP on knee osteoarthritis, revealing mixed results.19-22 Campbell and colleagues23 published a 2015 systematic review of 3 overlapping meta-analyses comparing the outcomes of intra-articular injection of PRP vs control (hyaluronic acid [HA] or placebo) in 3278 knees. They reported a significant improvement in patient outcome scores for the PRP group when compared to control from 2 to 12 months after injection, but due to significant differences within the included studies, the ideal number of injections or time intervals between injections remains unclear. Meheux and colleagues24 reported a 2016 systematic review including 6 studies (817 knees) comparing PRP and HA injections. They demonstrated significantly better improvements in Western Ontario and McMaster Universities Arthritis Index (WOMAC) outcome scores with PRP vs HA injections at 3 and 12 months postinjection. Similarly, Smith25 conducted a Food and Drug Administration-sanctioned, randomized, double-blind, placebo-controlled clinical trial investigating the effects of intra-articular leukocyte-poor autologous conditioned plasma (ACP) in 30 patients. He reported an improvement in the ACP treatment group WOMAC scores by 78% compared to 7% improvement in the placebo group after 12 months. Despite the heterogeneity amongst studies, the majority of published data suggests better symptomatic relief in patients with early knee degenerative changes, and use of PRP may be considered in this population.

Ulnar Collateral Ligament Injuries

The anterior band of the UCL of the elbow provides stability to valgus stress. Overhead, high-velocity throwing athletes may cause repetitive injury to the UCL, resulting in partial or complete tears of the ligament. This may result in medial elbow pain, as well as decreased throwing velocity and accuracy. Athletes with complete UCL tears have few nonoperative treatment options and generally, operative treatment with UCL reconstruction is recommended for those athletes desiring to return to sport. However, it remains unclear how to definitively treat athletes with partial UCL tears. Recently, there has been an interest in treating these injuries with PRP in conjunction with physical therapy to facilitate a more predictable outcome.

Podesta and colleagues26 published a case series of 34 athletes with MRI-diagnosed partial UCL tears who underwent ultrasound-guided UCL injections and physical therapy. At an average follow-up of 70 weeks, they reported an average return to play (RTP) of 12 weeks, with significant improvements in Kerlan-Jobe Orthopaedic Clinic (KJOC) and DASH outcome scores, and decreased dynamic ulnohumeral joint widening to valgus stress on ultrasound. Most athletes (30/34) returned to their previous level of play, and 1 patient underwent subsequent UCL reconstruction. This study demonstrates that PRP may be used in conjunction with physical therapy and an interval throwing program for the treatment of partial UCL tears, but without a comparison control group, more studies are necessary to delineate the role of PRP in this population.

Lateral Elbow Epicondylitis

Lateral elbow epicondylitis, also known as “tennis elbow,” is thought to be caused by repetitive wrist extension and is more likely to present in patients with various comorbidities such as rotator cuff pathology or a history of smoking.27-29 The condition typically presents as radiating pain centered about the lateral epicondyle. Annual incidence ranges from 0.34% to 3%, with the most recent large-scale, population-based study estimating that nearly 1 million individuals in the United States develop lateral elbow epicondylitis each year.30 For the majority of patients, symptoms resolve after 6 to 12 months of various nonoperative or minimally invasive treatments.31-33 Those who develop chronic symptoms (>12 months) may benefit from surgical intervention.34 The use of PRP has become a contentious topic of debate in treating lateral epicondylitis. Its use and efficacy have been empirically examined and compared among more traditional treatments.35-37

In a small case-series of 6 patients, contrast-enhanced ultrasound imaging was utilized to demonstrate that PRP injection therapy may induce vascularization of the myotendinous junction of the common extensor tendon up to 6 months following injection.38 These physiologic changes may precede observable clinical improvements. Brklijac and colleagues39 prospectively followed 34 patients who had refractory symptoms despite conservative treatment and elected to undergo injection with PRP. At a mean follow-up of 26 weeks, 88.2% of the patients demonstrated improvements on their Oxford Elbow Score (OES). While potentially promising, case series lack large sample sizes, longitudinal analysis, and adequate control groups for comparative analyses of treatments, thereby increasing the likelihood of unintended selection bias.

Randomized controlled trials have demonstrated no difference between PRP and corticosteroid (CS) injection treatments in the short term for symptomatic lateral elbow epicondylitis. At 15 days, 1 month, and 6 months postinjection, no significant difference was found between PRP and CS injections in dynamometer strength measurements nor patient outcome scores (VAS, DASH, OES, and Mayo Clinic Performance Index for Elbow [MMCPIE]).40,41 In fact, multiple randomized controlled trials have demonstrated PRP to be less effective at 1 and 3 months compared to CS injections, as assessed by the Patient Rated Tennis-Elbow Evaluation (PRTEE) questionnaire, VAS, MMCPIE, and Nirschl scores.42,43 One mid-term, multi-center randomized controlled trial published by Mishra and colleagues44 compared PRP injections to an active control group, demonstrating a significant improvement in VAS pain scores at 24 weeks, but no difference in the PRTEE outcome. The available evidence indicates PRP injection therapy remains limited in utility for treatment of lateral epicondylitis, particularly in the short term when compared to CS injections. In the midterm to long term, PRP therapy may provide some benefit, but ultimately, well-designed prospective randomized controlled trials are needed to delineate the effects of PRP versus the natural course of tendon healing and symptom resolution.

Hamstring Injuries

Acute hamstring injuries are common across all levels and types of sport, particularly those in which sprinting or running is involved. While there is no consensus within the literature on how RTP after hamstring injury should be managed or defined, most injuries seem to resolve around 3 to 6 weeks.45 The proximal myotendinous junction of the long head of the biceps femoris and semitendinosus are commonly associated with significant pain and edema after acute hamstring injury.46 The amount of edema resulting from grade 1 and 2 hamstring injuries has been found to correlate (minimally) with time to RTP in elite athletes.47 PRP injection near the proximal myotendinous hamstring origin has been theorized to help speed the recovery process after acute hamstring injury. To date, the literature demonstrates mixed and limited benefit of PRP injection therapy for acute hamstring injury.

Few studies have shown improvements of PRP therapy over typical nonoperative management (rest, physical therapy, nonsteroidal anti-inflammatory drugs) in acute hamstring injury, but the results must be interpreted carefully.48,49 Wetzel and colleagues48 retrospectively reviewed 17 patients with acute hamstring injury, 12 of whom failed typical management and received PRP injection at the hamstring origin. This group demonstrated significant improvements in their VAS and Nirschl scores at follow-up, whereas the 5 patients who did not receive the injection did not. However, this study exhibited significant limitations inherent to a retrospective review with a small sample size. Hamid and colleagues49 conducted a randomized controlled trial of 24 athletes with diagnosed grade 2a acute hamstring injuries, comparing autologous PRP therapy combined with a rehabilitation program versus rehabilitation program alone. RTP, changes in pain severity (Brief Pain Injury-Short Form [BPI-SF] questions 2-6), and pain interference (BPI-SF questions 9A-9G) scores over time were examined. Athletes in the PRP group exhibited no difference in outcomes scores, but returned to play sooner than controls (26.7 vs 42.5 days).

Mejia and Bradley50 have reported their experience in treating 12 National Football League (NFL) players with acute MRI grade 1 or 2 hamstring injuries with a series of PRP injections at the site of injury. They found a 1-game difference in earlier RTP when compared to the predicted RTP based on MRI grading. Similarly, Hamid and colleagues49 performed a randomized control trial published in 2014, reporting an earlier RTP (26.7 vs 42.5 days) when comparing single PRP injection vs rehabilitation alone in 28 patients diagnosed with acute ultrasound grade 2 hamstring injuries. On the contrary, a small case-control study of NFL players and a retrospective cohort study of athletes with severe hamstring injuries demonstrated no difference in RTP when PRP injected patients were compared with controls.51,52 Larger randomized controlled trials have demonstrated comparable results, including a study of 90 professional athletes in whom a single PRP injection did not decrease RTP or lessen the risk of re-injury at 2 and 6 months.53 In another large multicenter randomized controlled trial examining 80 competitive and recreational athletes, PRP did not accelerate RTP, lessen the risk of 2-month or 1-year re-injury rate, or improve secondary measures of MRI parameters, subjective patient satisfaction, or the hamstring outcome score.54 Although further study is warranted, available evidence suggests limited utility of PRP injection in the treatment of acute hamstring injuries.

Achilles Tendinopathy

Noninsertional Achilles tendinopathy is a common source of pain for both recreational and competitive athletes. Typically thought of as an overuse syndrome, Achilles tendinopathy may result in significant pain and swelling, often at the site of its tenuous blood supply, approximately 2 to 7 cm proximal to its insertion.55 Conservative management frequently begins with rest, activity/shoe modification, physical therapy, and eccentric loading exercises.56 For those whom conservative management has failed to reduce symptoms after 6 months, more invasive treatment options may be considered. Peritendinous PRP injection has become an alternative approach in treating Achilles tendinopathy refractory to conservative treatment.

In the few randomized controlled trials published, the data demonstrates no significant improvements in clinical outcomes from PRP injection for Achilles tendinopathy. Kearney and colleagues57 conducted a pilot study of 20 patients randomized into PRP injection or eccentric loading program for mid-substance Achilles tendinopathy, in which Victorian Institute of Sports Assessment (VISA-A), EuroQol 5 dimensions questionnaire (EQ-5D), and complications associated with the injection were recorded at 6 weeks, 3 months, and 6 months. Although this was a pilot study with a small sample size, no significant difference was found between groups across these time periods. Similarly, de Vos and colleagues58,59 conducted a double-blind randomized controlled trial of 54 patients with chronic mid-substance Achilles tendinopathy and randomized them into eccentric exercise therapy with either a PRP injection or a saline injected placebo groups. VISA-A scores were recorded and imaging parameters assessing tendon structure by ultrasonographic tissue characterization and color Doppler ultrasonography were taken with follow-up at 6, 12, and 24 weeks. VISA-A scores improved significantly in both groups after 24 weeks, but the difference was not statistically significant between groups. In addition, tendon structure and neovascularization (exhibited by color Doppler ultrasonography) improved in both groups, with no significant difference between groups. The current literature does not support the use of PRP in treatment of Achilles tendinopathy, as it has failed to reveal additional benefits over conventional treatment alone. Future prospective, well-designed randomized controlled trials with large sample sizes will need to be conducted to ultimately conclude whether or not PRP deserves a role in the treatment of Achilles tendinopathy.

Summary

In theory, the use of PRP within orthopedic surgery makes a great deal of sense to accelerate and augment the healing process of the aforementioned musculoskeletal injuries. However, the vast majority of published literature is Level III and IV evidence. Future research may provide the missing critical information of optimal growth factor, platelet, and leukocyte concentrations necessary for the desired effect, as well as the appropriate delivery method and timing of PRP application in different target tissues. Evidence-based guidelines to direct the use of PRP will benefit from more homogenous, repeatable, and randomized controlled trials.

1. Hsu WK, Mishra A, Rodeo SR, et al. Platelet-rich plasma in orthopaedic applications: evidence-based recommendations for treatment. J Am Acad Orthop Surg. 2013;21(12):739-748.

2. Marx RE. Platelet-rich plasma: evidence to support its use. J Oral Maxillofac Surg. 2004;62(4):489-496.

3. Jo CH, Kim JE, Yoon KS, et al. Does platelet-rich plasma accelerate recovery after rotator cuff repair? A prospective cohort study. Am J Sports Med. 2011;39(10):2082-2090.

4. Burkhart SS, Danaceau SM, Pearce CE Jr. Arthroscopic rotator cuff repair: Analysis of results by tear size and by repair technique-margin convergence versus direct tendon-to-bone repair. Arthroscopy. 2001;17(9):905-912.

5. Severud EL, Ruotolo C, Abbott DD, Nottage WM. All-arthroscopic versus mini-open rotator cuff repair: A long-term retrospective outcome comparison. Arthroscopy. 2003;19(3):234-238.

6. Huang R, Wang S, Wang Y, Qin X, Sun Y. Systematic review of all-arthroscopic versus mini-open repair of rotator cuff tears: a meta-analysis. Sci Rep. 2016;6:22857.

7. Watson EM, Sonnabend DH. Outcome of rotator cuff repair. J Shoulder Elbow Surg. 2002;11(3):201-211.

8. Butler DL, Juncosa N, Dressler MR. Functional efficacy of tendon repair processes. Annu Rev Biomed Eng. 2004;6:303-329.

9. Galatz LM, Ball CM, Teefey SA, Middleton WD, Yamaguchi K. The outcome and repair integrity of completely arthroscopically repaired large and massive rotator cuff tears. J Bone Joint Surg Am. 2004;86-A(2):219-224.

10. Lafosse L, Brozska R, Toussaint B, Gobezie R. The outcome and structural integrity of arthroscopic rotator cuff repair with use of the double-row suture anchor technique. J Bone Joint Surg Am. 2007;89(7):1533-1541.

11. Castricini R, Longo UG, De Benedetto M, et al. Platelet-rich plasma augmentation for arthroscopic rotator cuff repair: a randomized controlled trial. Am J Sports Med. 2011;39(2):258-265.

12. Randelli P, Arrigoni P, Ragone V, Aliprandi A, Cabitza P. Platelet rich plasma in arthroscopic rotator cuff repair: a prospective RCT study, 2-year follow-up. J Shoulder Elbow Surg. 2011;20(4):518-528.

13. Weber SC, Kauffman JI, Parise C, Weber SJ, Katz SD. Platelet-rich fibrin matrix in the management of arthroscopic repair of the rotator cuff: a prospective, randomized, double-blinded study. Am J Sports Med. 2013;41(2):263-270.

14. Gumina S, Campagna V, Ferrazza G, et al. Use of platelet-leukocyte membrane in arthroscopic repair of large rotator cuff tears: a prospective randomized study. J Bone Joint Surg Am. 2012;94(15):1345-1352.

15. Rodeo SA, Delos D, Williams RJ, Adler RS, Pearle A, Warren RF. The effect of platelet-rich fibrin matrix on rotator cuff tendon healing: a prospective, randomized clinical study. Am J Sports Med. 2012;40(6):1234-1241.

16. Warth RJ, Dornan GJ, James EW, Horan MP, Millett PJ. Clinical and structural outcomes after arthroscopic repair of full-thickness rotator cuff tears with and without platelet-rich product supplementation: a meta-analysis and meta-regression. Arthroscopy. 2015;31(2):306-320.

17. Zhao JG, Zhao L, Jiang YX, Wang ZL, Wang J, Zhang P. Platelet-rich plasma in arthroscopic rotator cuff repair: a meta-analysis of randomized controlled trials. Arthroscopy. 2015;31(1):125-135.

18. Glyn-Jones S, Palmer AJ, Agricola R, et al. Osteoarthritis. Lancet. 2015;386(9991):376-387.

19. Cerza F, Carni S, Carcangiu A, et al. Comparison between hyaluronic acid and platelet-rich plasma, intra-articular infiltration in the treatment of gonarthrosis. Am J Sports Med. 2012;40(12):2822-2827.

20. Filardo G, Kon E, Di Martino A, et al. Platelet-rich plasma vs hyaluronic acid to treat knee degenerative pathology: study design and preliminary results of a randomized controlled trial. BMC Musculoskelet Disord. 2012;13:229.

21. Patel S, Dhillon MS, Aggarwal S, Marwaha N, Jain A. Treatment with platelet-rich plasma is more effective than placebo for knee osteoarthritis: a prospective, double-blind, randomized trial. Am J Sports Med. 2013;41(2):356-364.

22. Sanchez M, Fiz N, Azofra J, et al. A randomized clinical trial evaluating plasma rich in growth factors (PRGF-Endoret) versus hyaluronic acid in the short-term treatment of symptomatic knee osteoarthritis. Arthroscopy. 2012;28(8):1070-1078.

23. Campbell KA, Saltzman BM, Mascarenhas R, et al. Does intra-articular platelet-rich plasma injection provide clinically superior outcomes compared with other therapies in the treatment of knee osteoarthritis? A systematic review of overlapping meta-analyses. Arthroscopy. 2015;31(11):2213-2221.

24. Meheux CJ, McCulloch PC, Lintner DM, Varner KE, Harris JD. Efficacy of intra-articular platelet-rich plasma injections in knee osteoarthritis: A systematic review. Arthroscopy. 2016;32(3):495-505.

25. Smith PA. Intra-articular autologous conditioned plasma injections provide safe and efficacious treatment for knee osteoarthritis: An FDA-sanctioned, randomized, double-blind, placebo-controlled clinical trial. Am J Sports Med. 2016;44(4):884-891.

26. Podesta L, Crow SA, Volkmer D, Bert T, Yocum LA. Treatment of partial ulnar collateral ligament tears in the elbow with platelet-rich plasma. Am J Sports Med. 2013;41(7):1689-1694.

27. Herquelot E, Gueguen A, Roquelaure Y, et al. Work-related risk factors for incidence of lateral epicondylitis in a large working population. Scand J Work Environ Health. 2013;39(6):578-588.

28. Titchener AG, Fakis A, Tambe AA, Smith C, Hubbard RB, Clark DI. Risk factors in lateral epicondylitis (tennis elbow): a case-control study. J Hand Surg Eur Vol. 2013;38(2):159-164.

29. Gruchow HW, Pelletier D. An epidemiologic study of tennis elbow. Incidence, recurrence, and effectiveness of prevention strategies. Am J Sports Med. 1979;7(4):234-238.

30. Sanders TL Jr, Maradit Kremers H, Bryan AJ, Ransom JE, Smith J, Morrey BF. The epidemiology and health care burden of tennis elbow: a population-based study. Am J Sports Med. 2015;43(5):1066-1071.

31. Coonrad RW, Hooper WR. Tennis elbow: its course, natural history, conservative and surgical management. J Bone Joint Surg Am. 1973;55(6):1177-1182.

32. Taylor SA, Hannafin JA. Evaluation and management of elbow tendinopathy. Sports Health. 2012;4(5):384-393.

33. Sims SE, Miller K, Elfar JC, Hammert WC. Non-surgical treatment of lateral epicondylitis: a systematic review of randomized controlled trials. Hand (NY). 2014;9(4):419-446.

34. Brummel J, Baker CL 3rd, Hopkins R, Baker CL Jr. Epicondylitis: lateral. Sports Med Arthrosc. 2014;22(3):e1-e6.

35. de Vos RJ, Windt J, Weir A. Strong evidence against platelet-rich plasma injections for chronic lateral epicondylar tendinopathy: a systematic review. Br J Sports Med. 2014;48(12):952-956.

36. Ahmad Z, Brooks R, Kang SN, et al. The effect of platelet-rich plasma on clinical outcomes in lateral epicondylitis. Arthroscopy. 2013;29(11):1851-1862.

37. Arirachakaran A, Sukthuayat A, Sisayanarane T, Laoratanavoraphong S, Kanchanatawan W, Kongtharvonskul J. Platelet-rich plasma versus autologous blood versus steroid injection in lateral epicondylitis: systematic review and network meta-analysis. J Orthop Traumatol. 2016;17(2):101-112.

38. Chaudhury S, de La Lama M, Adler RS, et al. Platelet-rich plasma for the treatment of lateral epicondylitis: sonographic assessment of tendon morphology and vascularity (pilot study). Skeletal Radiol. 2013;42(1):91-97.

39. Brkljac M, Kumar S, Kalloo D, Hirehal K. The effect of platelet-rich plasma injection on lateral epicondylitis following failed conservative management. J Orthop. 2015;12(Suppl 2):S166-S170.

40. Yadav R, Kothari SY, Borah D. Comparison of local injection of platelet rich plasma and corticosteroids in the treatment of lateral epicondylitis of humerus. J Clin Diagn Res. 2015;9(7):RC05-RC07.

41. Gautam VK, Verma S, Batra S, Bhatnagar N, Arora S. Platelet-rich plasma versus corticosteroid injection for recalcitrant lateral epicondylitis: clinical and ultrasonographic evaluation. J Orthop Surg (Hong Kong). 2015;23(1):1-5.

42. Krogh TP, Fredberg U, Stengaard-Pedersen K, Christensen R, Jensen P, Ellingsen T. Treatment of lateral epicondylitis with platelet-rich plasma, glucocorticoid, or saline: a randomized, double-blind, placebo-controlled trial. Am J Sports Med. 2013;41(3):625-635.

43. Behera P, Dhillon M, Aggarwal S, Marwaha N, Prakash M. Leukocyte-poor platelet-rich plasma versus bupivacaine for recalcitrant lateral epicondylar tendinopathy. J Orthop Surg (Hong Kong). 2015;23(1):6-10.

44. Mishra AK, Skrepnik NV, Edwards SG, et al. Efficacy of platelet-rich plasma for chronic tennis elbow: a double-blind, prospective, multicenter, randomized controlled trial of 230 patients. Am J Sports Med. 2014;42(2):463-471.

45. van der Horst N, van de Hoef S, Reurink G, Huisstede B, Backx F. Return to play after hamstring injuries: a qualitative systematic review of definitions and criteria. Sports Med. 2016;46(6):899-912.

46. Crema MD, Guermazi A, Tol JL, Niu J, Hamilton B, Roemer FW. Acute hamstring injury in football players: Association between anatomical location and extent of injury-A large single-center MRI report. J Sci Med Sport. 2016;19(4):317-322.

47. Ekstrand J, Lee JC, Healy JC. MRI findings and return to play in football: a prospective analysis of 255 hamstring injuries in the UEFA Elite Club Injury Study. Br J Sports Med. 2016;50(12):738-743.

48. Wetzel RJ, Patel RM, Terry MA. Platelet-rich plasma as an effective treatment for proximal hamstring injuries. Orthopedics. 2013;36(1):e64-e70.

49. Hamid A, Mohamed Ali MR, Yusof A, George J, Lee LP. Platelet-rich plasma injections for the treatment of hamstring injuries: a randomized controlled trial. Am J Sports Med. 2014;42(10):2410-2418.

50. Mejia HA, Bradley JP. The effects of platelet-rich plasma on muscle: basic science and clinical application. Operative Techniques in Sports Medicine. 2011;19(3):149-153.

51. Guillodo Y, Madouas G, Simon T, Le Dauphin H, Saraux A. Platelet-rich plasma (PRP) treatment of sports-related severe acute hamstring injuries. Muscles Ligaments Tendons J. 2015;5(4):284-288.

52. Rettig AC, Meyer S, Bhadra AK. Platelet-rich plasma in addition to rehabilitation for acute hamstring injuries in NFL players: Clinical effects and time to return to play. Orthop J Sports Med. 2013;1(1):2325967113494354.

53. Hamilton B, Tol JL, Almusa E, et al. Platelet-rich plasma does not enhance return to play in hamstring injuries: a randomised controlled trial. Br J Sports Med. 2015;49(14):943-950.

54. Reurink G, Goudswaard GJ, Moen MH, et al. Rationale, secondary outcome scores and 1-year follow-up of a randomised trial of platelet-rich plasma injections in acute hamstring muscle injury: the Dutch Hamstring Injection Therapy study. Br J Sports Med. 2015;49(18):1206-1212.

55. Kujala UM, Sarna S, Kaprio J. Cumulative incidence of achilles tendon rupture and tendinopathy in male former elite athletes. Clin J Sport Med. 2005;15(3):133-135.

56. Alfredson H. Clinical commentary of the evolution of the treatment for chronic painful mid-portion Achilles tendinopathy. Braz J Phys Ther. 2015;19(5):429-432.

57. Kearney RS, Parsons N, Costa ML. Achilles tendinopathy management: A pilot randomised controlled trial comparing platelet-rich plasma injection with an eccentric loading programme. Bone Joint Res. 2013;2(10):227-232.

58. de Vos RJ, Weir A, Tol JL, Verhaar JA, Weinans H, van Schie HT. No effects of PRP on ultrasonographic tendon structure and neovascularisation in chronic midportion Achilles tendinopathy. Br J Sports Med. 2011;45(5):387-392.

59. de Vos RJ, Weir A, van Schie HT, et al. Platelet-rich plasma injection for chronic Achilles tendinopathy: a randomized controlled trial. JAMA. 2010;303(2):144-149.

Platelet-rich plasma (PRP) is a refined product of autologous blood with a platelet concentration greater than that of whole blood. It is prepared via plasmapheresis utilizing a 2-stage centrifugation process and more than 40 commercially available systems are marketed to concentrate whole blood to PRP.1 It is rich in biologic factors (growth factors, cytokines, proteins, cellular components) essential to the body’s response to injury. For this reason, it was first used in oromaxillofacial surgery in the 1950s, but its effects on the musculoskeletal system have yet to be clearly elucidated.2 However, this lack of clarity has not deterred its widespread use among orthopedic surgeons. In this review, we aim to delineate the current understanding of PRP and its proven effectiveness in the treatment of rotator cuff tears, knee osteoarthritis, ulnar collateral ligament (UCL) tears, lateral epicondylitis, hamstring injuries, and Achilles tendinopathy.

Rotator Cuff Tears

Rotator cuff tears are one of the most common etiologies for shoulder pain and disability. The incidence continues to increase with the active aging population.3 Rotator cuff tears treated with arthroscopic repair have exhibited satisfactory pain relief and functional outcomes.4-7 Despite advances in fixation techniques, the quality and speed of tendon-to-bone healing remains unpredictable, with repaired tendons exhibiting inferior mechanical properties that are susceptible to re-tear.8-10

Numerous studies have investigated PRP application during arthroscopic rotator cuff repair (RCR) in an attempt to enhance and accelerate the repair process.11-15 However, wide variability exists among protocols of how and when PRP is utilized to augment the repair. Warth and colleagues16 performed a meta-analysis of 11 Level I/II studies evaluating RCR with PRP augmentation. With regards to clinical outcome scores, they found no significant difference in pre- and postoperative American Shoulder and Elbow Surgeons (ASES), Constant, Disability of the Arm, Shoulder and Hand (DASH), or visual analog scale (VAS) pain scores between those patients with or without PRP augmentation. However, they did note a significant increase in Constant scores when PRP was delivered to the tendon-bone interface rather than over the surface of the repair site. There was no significant difference in structural outcomes (evaluated by magnetic resonance imaging [MRI] re-tear rates) between those RCRs with and without PRP augmentation, except in those tears >3 cm in anterior-posterior length using double-row technique, with the PRP group exhibiting a significantly decreased re-tear rate (25.9% vs 57.1%).16 Zhao and colleagues17 reported similar results in a meta-analysis of 8 randomized controlled trials, exhibiting no significant differences in clinical outcome scores or re-tear rates after RCR with and without PRP augmentation. Overall, most studies have failed to demonstrate a significant benefit with regards to re-tear rates or shoulder-specific outcomes with the addition of PRP during arthroscopic RCR.

Knee Osteoarthritis

Osteoarthritis is the most common musculoskeletal disorder, with an estimated prevalence of 10% of the world’s population age 60 years and older.18 The knee is commonly symptomatic, resulting in pain, disability, and significant healthcare costs. Novel biologic, nonoperative therapies, including intra-articular viscosupplementation and PRP injections, have been proposed to treat the early stages of osteoarthritis to provide symptomatic relief and delay surgical intervention.

A multitude of studies have been performed investigating the effects of PRP on knee osteoarthritis, revealing mixed results.19-22 Campbell and colleagues23 published a 2015 systematic review of 3 overlapping meta-analyses comparing the outcomes of intra-articular injection of PRP vs control (hyaluronic acid [HA] or placebo) in 3278 knees. They reported a significant improvement in patient outcome scores for the PRP group when compared to control from 2 to 12 months after injection, but due to significant differences within the included studies, the ideal number of injections or time intervals between injections remains unclear. Meheux and colleagues24 reported a 2016 systematic review including 6 studies (817 knees) comparing PRP and HA injections. They demonstrated significantly better improvements in Western Ontario and McMaster Universities Arthritis Index (WOMAC) outcome scores with PRP vs HA injections at 3 and 12 months postinjection. Similarly, Smith25 conducted a Food and Drug Administration-sanctioned, randomized, double-blind, placebo-controlled clinical trial investigating the effects of intra-articular leukocyte-poor autologous conditioned plasma (ACP) in 30 patients. He reported an improvement in the ACP treatment group WOMAC scores by 78% compared to 7% improvement in the placebo group after 12 months. Despite the heterogeneity amongst studies, the majority of published data suggests better symptomatic relief in patients with early knee degenerative changes, and use of PRP may be considered in this population.

Ulnar Collateral Ligament Injuries

The anterior band of the UCL of the elbow provides stability to valgus stress. Overhead, high-velocity throwing athletes may cause repetitive injury to the UCL, resulting in partial or complete tears of the ligament. This may result in medial elbow pain, as well as decreased throwing velocity and accuracy. Athletes with complete UCL tears have few nonoperative treatment options and generally, operative treatment with UCL reconstruction is recommended for those athletes desiring to return to sport. However, it remains unclear how to definitively treat athletes with partial UCL tears. Recently, there has been an interest in treating these injuries with PRP in conjunction with physical therapy to facilitate a more predictable outcome.

Podesta and colleagues26 published a case series of 34 athletes with MRI-diagnosed partial UCL tears who underwent ultrasound-guided UCL injections and physical therapy. At an average follow-up of 70 weeks, they reported an average return to play (RTP) of 12 weeks, with significant improvements in Kerlan-Jobe Orthopaedic Clinic (KJOC) and DASH outcome scores, and decreased dynamic ulnohumeral joint widening to valgus stress on ultrasound. Most athletes (30/34) returned to their previous level of play, and 1 patient underwent subsequent UCL reconstruction. This study demonstrates that PRP may be used in conjunction with physical therapy and an interval throwing program for the treatment of partial UCL tears, but without a comparison control group, more studies are necessary to delineate the role of PRP in this population.

Lateral Elbow Epicondylitis