User login

Improved cancer survival in states with ACA Medicaid expansion

compared with patients in states that did not adopt the expansion.

The finding comes from an American Cancer Society study of more than 2 million patients with newly diagnosed cancer, published online in the Journal of the National Cancer Institute.

The analysis also showed that the evidence was strongest for malignancies with poor prognosis such as lung, pancreatic, and liver cancer, and also for colorectal cancer.

Importantly, improvements in survival were larger in non-Hispanic Black patients and individuals residing in rural areas, suggesting there was a narrowing of disparities in cancer survival by race and rurality.

“Our findings provide further evidence of the importance of expanding Medicaid eligibility in all states, particularly considering the economic crisis and health care disruptions caused by the COVID-19 pandemic,” said lead author Xuesong Han, PhD, scientific director of health services research at the American Cancer Society, in a statement. “What’s encouraging is the American Rescue Plan Act of 2021 provides new incentives for Medicaid expansion in states that have yet to increase eligibility.”

The ACA provided states with incentives to expand Medicaid eligibility to all low-income adults under 138% federal poverty level, regardless of parental status.

As of last month, just 12 states have not yet opted for Medicaid expansion, even though the American Rescue Plan Act of 2021 provides new incentives for those remaining jurisdictions. But to date, none of the remaining states have taken advantage of these new incentives.

An interactive map showing the status of Medicare expansion by state is available here. The 12 states that have not adopted Medicare expansion (as of April) are Alabama, Florida, Georgia, Kansas, Mississippi, North Carolina, South Carolina, South Dakota, Tennessee, Texas, Wisconsin, and Wyoming.

The benefit of Medicaid expansion on cancer outcomes has already been observed in other studies. The first study to show a survival benefit was presented at the 2020 American Society of Clinical Oncology annual meeting. That analysis showed that cancer mortality declined by 29% in states that expanded Medicaid and by 25% in those that did not. The authors also noted that the greatest mortality benefit was observed in Hispanic patients.

Improved survival with expansion

In the current paper, Dr. Han and colleagues used population-based cancer registries from 42 states and compared data on patients aged 18-62 years who were diagnosed with cancer in a period of 2 years before (2010-2012) and after (2014-2016) ACA Medicaid expansion. They were followed through Sept. 30, 2013, and Dec. 31, 2017, respectively.

The analysis involved a total of 2.5 million patients, of whom 1.52 million lived in states that adopted Medicaid expansion and compared with 1 million patients were in states that did not.

Patients with grouped by sex, race and ethnicity, census tract-level poverty, and rurality. The authors note that non-Hispanic Black patients and those from high poverty areas and nonmetropolitan areas were disproportionately represented in nonexpansion states.

During the 2-year follow-up period, a total of 453,487 deaths occurred (257,950 in expansion states and 195,537 in nonexpansion states).

Overall, patients in expansion states generally had better survival versus those in nonexpansion states, the authors comment. However, for most cancer types, overall survival improved after the ACA for both groups of states.

The 2-year overall survival increased from 80.6% before the ACA to 82.2% post ACA in expansion states and from 78.7% to 80% in nonexpansion states.

This extrapolated to net increase of 0.44 percentage points in expansion states after adjusting for sociodemographic factors. By cancer site, the net increase was greater for colorectal cancer, lung cancer, non-Hodgkin’s lymphoma, pancreatic cancer, and liver cancer.

For Hispanic patients, 2-year survival also increased but was similar in expansion and nonexpansion states, and little net change was associated with Medicaid expansion.

“Our study shows that the increase was largely driven by improvements in survival for cancer types with poor prognosis, suggesting improved access to timely and effective treatments,” said Dr. Han. “It adds to accumulating evidence of the multiple benefits of Medicaid expansion.”

A version of this article first appeared on Medscape.com.

compared with patients in states that did not adopt the expansion.

The finding comes from an American Cancer Society study of more than 2 million patients with newly diagnosed cancer, published online in the Journal of the National Cancer Institute.

The analysis also showed that the evidence was strongest for malignancies with poor prognosis such as lung, pancreatic, and liver cancer, and also for colorectal cancer.

Importantly, improvements in survival were larger in non-Hispanic Black patients and individuals residing in rural areas, suggesting there was a narrowing of disparities in cancer survival by race and rurality.

“Our findings provide further evidence of the importance of expanding Medicaid eligibility in all states, particularly considering the economic crisis and health care disruptions caused by the COVID-19 pandemic,” said lead author Xuesong Han, PhD, scientific director of health services research at the American Cancer Society, in a statement. “What’s encouraging is the American Rescue Plan Act of 2021 provides new incentives for Medicaid expansion in states that have yet to increase eligibility.”

The ACA provided states with incentives to expand Medicaid eligibility to all low-income adults under 138% federal poverty level, regardless of parental status.

As of last month, just 12 states have not yet opted for Medicaid expansion, even though the American Rescue Plan Act of 2021 provides new incentives for those remaining jurisdictions. But to date, none of the remaining states have taken advantage of these new incentives.

An interactive map showing the status of Medicare expansion by state is available here. The 12 states that have not adopted Medicare expansion (as of April) are Alabama, Florida, Georgia, Kansas, Mississippi, North Carolina, South Carolina, South Dakota, Tennessee, Texas, Wisconsin, and Wyoming.

The benefit of Medicaid expansion on cancer outcomes has already been observed in other studies. The first study to show a survival benefit was presented at the 2020 American Society of Clinical Oncology annual meeting. That analysis showed that cancer mortality declined by 29% in states that expanded Medicaid and by 25% in those that did not. The authors also noted that the greatest mortality benefit was observed in Hispanic patients.

Improved survival with expansion

In the current paper, Dr. Han and colleagues used population-based cancer registries from 42 states and compared data on patients aged 18-62 years who were diagnosed with cancer in a period of 2 years before (2010-2012) and after (2014-2016) ACA Medicaid expansion. They were followed through Sept. 30, 2013, and Dec. 31, 2017, respectively.

The analysis involved a total of 2.5 million patients, of whom 1.52 million lived in states that adopted Medicaid expansion and compared with 1 million patients were in states that did not.

Patients with grouped by sex, race and ethnicity, census tract-level poverty, and rurality. The authors note that non-Hispanic Black patients and those from high poverty areas and nonmetropolitan areas were disproportionately represented in nonexpansion states.

During the 2-year follow-up period, a total of 453,487 deaths occurred (257,950 in expansion states and 195,537 in nonexpansion states).

Overall, patients in expansion states generally had better survival versus those in nonexpansion states, the authors comment. However, for most cancer types, overall survival improved after the ACA for both groups of states.

The 2-year overall survival increased from 80.6% before the ACA to 82.2% post ACA in expansion states and from 78.7% to 80% in nonexpansion states.

This extrapolated to net increase of 0.44 percentage points in expansion states after adjusting for sociodemographic factors. By cancer site, the net increase was greater for colorectal cancer, lung cancer, non-Hodgkin’s lymphoma, pancreatic cancer, and liver cancer.

For Hispanic patients, 2-year survival also increased but was similar in expansion and nonexpansion states, and little net change was associated with Medicaid expansion.

“Our study shows that the increase was largely driven by improvements in survival for cancer types with poor prognosis, suggesting improved access to timely and effective treatments,” said Dr. Han. “It adds to accumulating evidence of the multiple benefits of Medicaid expansion.”

A version of this article first appeared on Medscape.com.

compared with patients in states that did not adopt the expansion.

The finding comes from an American Cancer Society study of more than 2 million patients with newly diagnosed cancer, published online in the Journal of the National Cancer Institute.

The analysis also showed that the evidence was strongest for malignancies with poor prognosis such as lung, pancreatic, and liver cancer, and also for colorectal cancer.

Importantly, improvements in survival were larger in non-Hispanic Black patients and individuals residing in rural areas, suggesting there was a narrowing of disparities in cancer survival by race and rurality.

“Our findings provide further evidence of the importance of expanding Medicaid eligibility in all states, particularly considering the economic crisis and health care disruptions caused by the COVID-19 pandemic,” said lead author Xuesong Han, PhD, scientific director of health services research at the American Cancer Society, in a statement. “What’s encouraging is the American Rescue Plan Act of 2021 provides new incentives for Medicaid expansion in states that have yet to increase eligibility.”

The ACA provided states with incentives to expand Medicaid eligibility to all low-income adults under 138% federal poverty level, regardless of parental status.

As of last month, just 12 states have not yet opted for Medicaid expansion, even though the American Rescue Plan Act of 2021 provides new incentives for those remaining jurisdictions. But to date, none of the remaining states have taken advantage of these new incentives.

An interactive map showing the status of Medicare expansion by state is available here. The 12 states that have not adopted Medicare expansion (as of April) are Alabama, Florida, Georgia, Kansas, Mississippi, North Carolina, South Carolina, South Dakota, Tennessee, Texas, Wisconsin, and Wyoming.

The benefit of Medicaid expansion on cancer outcomes has already been observed in other studies. The first study to show a survival benefit was presented at the 2020 American Society of Clinical Oncology annual meeting. That analysis showed that cancer mortality declined by 29% in states that expanded Medicaid and by 25% in those that did not. The authors also noted that the greatest mortality benefit was observed in Hispanic patients.

Improved survival with expansion

In the current paper, Dr. Han and colleagues used population-based cancer registries from 42 states and compared data on patients aged 18-62 years who were diagnosed with cancer in a period of 2 years before (2010-2012) and after (2014-2016) ACA Medicaid expansion. They were followed through Sept. 30, 2013, and Dec. 31, 2017, respectively.

The analysis involved a total of 2.5 million patients, of whom 1.52 million lived in states that adopted Medicaid expansion and compared with 1 million patients were in states that did not.

Patients with grouped by sex, race and ethnicity, census tract-level poverty, and rurality. The authors note that non-Hispanic Black patients and those from high poverty areas and nonmetropolitan areas were disproportionately represented in nonexpansion states.

During the 2-year follow-up period, a total of 453,487 deaths occurred (257,950 in expansion states and 195,537 in nonexpansion states).

Overall, patients in expansion states generally had better survival versus those in nonexpansion states, the authors comment. However, for most cancer types, overall survival improved after the ACA for both groups of states.

The 2-year overall survival increased from 80.6% before the ACA to 82.2% post ACA in expansion states and from 78.7% to 80% in nonexpansion states.

This extrapolated to net increase of 0.44 percentage points in expansion states after adjusting for sociodemographic factors. By cancer site, the net increase was greater for colorectal cancer, lung cancer, non-Hodgkin’s lymphoma, pancreatic cancer, and liver cancer.

For Hispanic patients, 2-year survival also increased but was similar in expansion and nonexpansion states, and little net change was associated with Medicaid expansion.

“Our study shows that the increase was largely driven by improvements in survival for cancer types with poor prognosis, suggesting improved access to timely and effective treatments,” said Dr. Han. “It adds to accumulating evidence of the multiple benefits of Medicaid expansion.”

A version of this article first appeared on Medscape.com.

FDA authorizes Pfizer’s COVID booster for kids ages 5 to 11

emergency use authorization (EUA), allowing the Pfizer-BioNTech COVID-19 booster shot for children ages 5 to 11 who are at least 5 months out from their first vaccine series.

According to the most recent data from the Centers for Disease Control and Prevention, 28.6% of children in this age group have received both initial doses of Pfizer’s COVID-19 vaccine, and 35.3% have received their first dose.

Pfizer’s vaccine trial involving 4,500 children showed few side effects among children younger than 12 who received a booster, or third dose, according to a company statement.

Pfizer asked the FDA for an amended authorization in April, after submitting data showing that a third dose in children between 5 and 11 raised antibodies targeting the Omicron variant by 36 times.

“While it has largely been the case that COVID-19 tends to be less severe in children than adults, the omicron wave has seen more kids getting sick with the disease and being hospitalized, and children may also experience longer-term effects, even following initially mild disease,” FDA Commissioner Robert M. Califf, MD, said in a news release.

A study done by the New York State Department of Health showed the effectiveness of Pfizer’s two-dose vaccine series fell from 68% to 12% 4-5 months after the second dose was given to children 5 to 11 during the Omicron surge. A CDC study published in March also showed that the Pfizer shot reduced the risk of Omicron by 31% in children 5 to 11, a significantly lower rate than for kids 12 to 15, who had a 59% risk reduction after receiving two doses.

To some experts, this data suggest an even greater need for children under 12 to be eligible for a third dose.

“Since authorizing the vaccine for children down to 5 years of age in October 2021, emerging data suggest that vaccine effectiveness against COVID-19 wanes after the second dose of the vaccine in all authorized populations,” says Peter Marks, MD, PhD, the director of the FDA’s Center for Biologics Evaluation and Research.

The CDC still needs to sign off on the shots before they can be allowed. The agency’s Advisory Committee on Immunization Practices is set to meet on May 19 to discuss boosters in this age group.

FDA advisory panels plan to meet next month to discuss allowing Pfizer’s and Moderna’s COVID-19 vaccines for children under 6 years old.

A version of this article first appeared on WebMD.com.

emergency use authorization (EUA), allowing the Pfizer-BioNTech COVID-19 booster shot for children ages 5 to 11 who are at least 5 months out from their first vaccine series.

According to the most recent data from the Centers for Disease Control and Prevention, 28.6% of children in this age group have received both initial doses of Pfizer’s COVID-19 vaccine, and 35.3% have received their first dose.

Pfizer’s vaccine trial involving 4,500 children showed few side effects among children younger than 12 who received a booster, or third dose, according to a company statement.

Pfizer asked the FDA for an amended authorization in April, after submitting data showing that a third dose in children between 5 and 11 raised antibodies targeting the Omicron variant by 36 times.

“While it has largely been the case that COVID-19 tends to be less severe in children than adults, the omicron wave has seen more kids getting sick with the disease and being hospitalized, and children may also experience longer-term effects, even following initially mild disease,” FDA Commissioner Robert M. Califf, MD, said in a news release.

A study done by the New York State Department of Health showed the effectiveness of Pfizer’s two-dose vaccine series fell from 68% to 12% 4-5 months after the second dose was given to children 5 to 11 during the Omicron surge. A CDC study published in March also showed that the Pfizer shot reduced the risk of Omicron by 31% in children 5 to 11, a significantly lower rate than for kids 12 to 15, who had a 59% risk reduction after receiving two doses.

To some experts, this data suggest an even greater need for children under 12 to be eligible for a third dose.

“Since authorizing the vaccine for children down to 5 years of age in October 2021, emerging data suggest that vaccine effectiveness against COVID-19 wanes after the second dose of the vaccine in all authorized populations,” says Peter Marks, MD, PhD, the director of the FDA’s Center for Biologics Evaluation and Research.

The CDC still needs to sign off on the shots before they can be allowed. The agency’s Advisory Committee on Immunization Practices is set to meet on May 19 to discuss boosters in this age group.

FDA advisory panels plan to meet next month to discuss allowing Pfizer’s and Moderna’s COVID-19 vaccines for children under 6 years old.

A version of this article first appeared on WebMD.com.

emergency use authorization (EUA), allowing the Pfizer-BioNTech COVID-19 booster shot for children ages 5 to 11 who are at least 5 months out from their first vaccine series.

According to the most recent data from the Centers for Disease Control and Prevention, 28.6% of children in this age group have received both initial doses of Pfizer’s COVID-19 vaccine, and 35.3% have received their first dose.

Pfizer’s vaccine trial involving 4,500 children showed few side effects among children younger than 12 who received a booster, or third dose, according to a company statement.

Pfizer asked the FDA for an amended authorization in April, after submitting data showing that a third dose in children between 5 and 11 raised antibodies targeting the Omicron variant by 36 times.

“While it has largely been the case that COVID-19 tends to be less severe in children than adults, the omicron wave has seen more kids getting sick with the disease and being hospitalized, and children may also experience longer-term effects, even following initially mild disease,” FDA Commissioner Robert M. Califf, MD, said in a news release.

A study done by the New York State Department of Health showed the effectiveness of Pfizer’s two-dose vaccine series fell from 68% to 12% 4-5 months after the second dose was given to children 5 to 11 during the Omicron surge. A CDC study published in March also showed that the Pfizer shot reduced the risk of Omicron by 31% in children 5 to 11, a significantly lower rate than for kids 12 to 15, who had a 59% risk reduction after receiving two doses.

To some experts, this data suggest an even greater need for children under 12 to be eligible for a third dose.

“Since authorizing the vaccine for children down to 5 years of age in October 2021, emerging data suggest that vaccine effectiveness against COVID-19 wanes after the second dose of the vaccine in all authorized populations,” says Peter Marks, MD, PhD, the director of the FDA’s Center for Biologics Evaluation and Research.

The CDC still needs to sign off on the shots before they can be allowed. The agency’s Advisory Committee on Immunization Practices is set to meet on May 19 to discuss boosters in this age group.

FDA advisory panels plan to meet next month to discuss allowing Pfizer’s and Moderna’s COVID-19 vaccines for children under 6 years old.

A version of this article first appeared on WebMD.com.

FDA working to improve U.S. baby formula supply

The Food and Drug Administration announced on May 10 that it is taking several steps to improve the supply of baby formula in the United States.

The nationwide formula shortage has grown worse in recent weeks due to supply chain issues and a recall of certain Abbott Nutrition products, including major labels such as Similac, Alimentum, and EleCare.

“We recognize that many consumers have been unable to access infant formula and critical medical foods they are accustomed to using and are frustrated by their inability to do so,” FDA Commissioner Robert Califf, MD, said in a statement.

“We are doing everything in our power to ensure there is adequate product available where and when they need it,” he said.

About three-quarters of babies are fed formula for the first 6 months of their lives as a substitute for human milk, Axios reported.

In mid-February, the FDA warned consumers not to use certain powdered infant formula products from Abbott’s facility in Sturgis, Mich. Since then, the FDA has been working with Abbott and other manufacturers to increase the supply in the U.S. market.

“In fact, other infant formula manufacturers are meeting or exceeding capacity levels to meet current demand,” the FDA said in the statement. “Notably, more infant formula was purchased in the month of April than in the month prior to the recall.”

The FDA released a list of steps the agency is taking to increase supply, such as meeting with major infant formula makers to increase output and prioritize product lines in high demand, particularly specialty formulas for infants with allergies or specific diet needs.

But other manufacturers have struggled to quickly increase production because their operations tend to focus on a steady level of supply, according to The New York Times.

“Some industries are very good at ramping up and ramping down,” Rudi Leuschner, PhD, an associate professor of supply chain management at Rutgers Business School, Newark, N.J., told the newspaper.

“You flip a switch and they can produce 10 times as much,” he said. “Baby formula is not that type of a product.”

The FDA is also keeping an eye on the infant formula shortage by using the agency’s 21 Forward food supply chain continuity system. The system was developed during the pandemic to provide a full understanding of how COVID-19 is impacting food supply chains, the FDA said.

The FDA is compiling data on trends for in-stock rates at national and regional levels to understand where infant formula is available and where it should go.

Products are also being brought in from other countries, the FDA said. The agency is trying to speed up the process to get more formula into the U.S. and move it more quickly around the country.

For babies on a special diet, the FDA has decided to release some Abbott products that have been on hold at the Sturgis facility to those who need an urgent supply of metabolic formulas, on a case-by-case basis.

“In these circumstances, the benefit of allowing caregivers, in consultation with their health care providers, to access these products may outweigh the potential risk of bacterial infection,” the FDA said in the statement.

The FDA continues to advise against making homemade infant formulas and recommends talking to the child’s health care provider for recommendations on changing feeding practices or switching to other formulas, if necessary.

A version of this article first appeared on WebMd.com.

The Food and Drug Administration announced on May 10 that it is taking several steps to improve the supply of baby formula in the United States.

The nationwide formula shortage has grown worse in recent weeks due to supply chain issues and a recall of certain Abbott Nutrition products, including major labels such as Similac, Alimentum, and EleCare.

“We recognize that many consumers have been unable to access infant formula and critical medical foods they are accustomed to using and are frustrated by their inability to do so,” FDA Commissioner Robert Califf, MD, said in a statement.

“We are doing everything in our power to ensure there is adequate product available where and when they need it,” he said.

About three-quarters of babies are fed formula for the first 6 months of their lives as a substitute for human milk, Axios reported.

In mid-February, the FDA warned consumers not to use certain powdered infant formula products from Abbott’s facility in Sturgis, Mich. Since then, the FDA has been working with Abbott and other manufacturers to increase the supply in the U.S. market.

“In fact, other infant formula manufacturers are meeting or exceeding capacity levels to meet current demand,” the FDA said in the statement. “Notably, more infant formula was purchased in the month of April than in the month prior to the recall.”

The FDA released a list of steps the agency is taking to increase supply, such as meeting with major infant formula makers to increase output and prioritize product lines in high demand, particularly specialty formulas for infants with allergies or specific diet needs.

But other manufacturers have struggled to quickly increase production because their operations tend to focus on a steady level of supply, according to The New York Times.

“Some industries are very good at ramping up and ramping down,” Rudi Leuschner, PhD, an associate professor of supply chain management at Rutgers Business School, Newark, N.J., told the newspaper.

“You flip a switch and they can produce 10 times as much,” he said. “Baby formula is not that type of a product.”

The FDA is also keeping an eye on the infant formula shortage by using the agency’s 21 Forward food supply chain continuity system. The system was developed during the pandemic to provide a full understanding of how COVID-19 is impacting food supply chains, the FDA said.

The FDA is compiling data on trends for in-stock rates at national and regional levels to understand where infant formula is available and where it should go.

Products are also being brought in from other countries, the FDA said. The agency is trying to speed up the process to get more formula into the U.S. and move it more quickly around the country.

For babies on a special diet, the FDA has decided to release some Abbott products that have been on hold at the Sturgis facility to those who need an urgent supply of metabolic formulas, on a case-by-case basis.

“In these circumstances, the benefit of allowing caregivers, in consultation with their health care providers, to access these products may outweigh the potential risk of bacterial infection,” the FDA said in the statement.

The FDA continues to advise against making homemade infant formulas and recommends talking to the child’s health care provider for recommendations on changing feeding practices or switching to other formulas, if necessary.

A version of this article first appeared on WebMd.com.

The Food and Drug Administration announced on May 10 that it is taking several steps to improve the supply of baby formula in the United States.

The nationwide formula shortage has grown worse in recent weeks due to supply chain issues and a recall of certain Abbott Nutrition products, including major labels such as Similac, Alimentum, and EleCare.

“We recognize that many consumers have been unable to access infant formula and critical medical foods they are accustomed to using and are frustrated by their inability to do so,” FDA Commissioner Robert Califf, MD, said in a statement.

“We are doing everything in our power to ensure there is adequate product available where and when they need it,” he said.

About three-quarters of babies are fed formula for the first 6 months of their lives as a substitute for human milk, Axios reported.

In mid-February, the FDA warned consumers not to use certain powdered infant formula products from Abbott’s facility in Sturgis, Mich. Since then, the FDA has been working with Abbott and other manufacturers to increase the supply in the U.S. market.

“In fact, other infant formula manufacturers are meeting or exceeding capacity levels to meet current demand,” the FDA said in the statement. “Notably, more infant formula was purchased in the month of April than in the month prior to the recall.”

The FDA released a list of steps the agency is taking to increase supply, such as meeting with major infant formula makers to increase output and prioritize product lines in high demand, particularly specialty formulas for infants with allergies or specific diet needs.

But other manufacturers have struggled to quickly increase production because their operations tend to focus on a steady level of supply, according to The New York Times.

“Some industries are very good at ramping up and ramping down,” Rudi Leuschner, PhD, an associate professor of supply chain management at Rutgers Business School, Newark, N.J., told the newspaper.

“You flip a switch and they can produce 10 times as much,” he said. “Baby formula is not that type of a product.”

The FDA is also keeping an eye on the infant formula shortage by using the agency’s 21 Forward food supply chain continuity system. The system was developed during the pandemic to provide a full understanding of how COVID-19 is impacting food supply chains, the FDA said.

The FDA is compiling data on trends for in-stock rates at national and regional levels to understand where infant formula is available and where it should go.

Products are also being brought in from other countries, the FDA said. The agency is trying to speed up the process to get more formula into the U.S. and move it more quickly around the country.

For babies on a special diet, the FDA has decided to release some Abbott products that have been on hold at the Sturgis facility to those who need an urgent supply of metabolic formulas, on a case-by-case basis.

“In these circumstances, the benefit of allowing caregivers, in consultation with their health care providers, to access these products may outweigh the potential risk of bacterial infection,” the FDA said in the statement.

The FDA continues to advise against making homemade infant formulas and recommends talking to the child’s health care provider for recommendations on changing feeding practices or switching to other formulas, if necessary.

A version of this article first appeared on WebMd.com.

Is There a Relationship Between Facility Peer Review Findings and Quality in the Veterans Health Administration?

Hospital leaders report the most common aim of peer review (PR) is to improve quality and patient safety, thus it is a potentially powerful quality improvement (QI) driver.1 “When conducted systematically and credibly, peer review for quality management can result in both short-term and long-term improvements in patient care by revealing areas for improvement in the provision of care,” Veterans Health Administration (VHA) Directive 1190 states. “This ultimately contributes to organizational improvements.” At the same time, there are anecdotal concerns that PR may be used punitively and driven by case outcomes rather than by accepted best practices supporting QI.

Studies of the PR process suggest these concerns are valid. A key tenet of QI is standardization. PR is problematic in that regard; studies show poor interrater reliability for judgments on care, as well as hindsight bias—the fact that raters are strongly influenced by the outcome of care, not the process of care.2-5 There are concerns that case selection or review process when not standardized may be wielded as punitive too.6 In this study, we sought to identify the relationship between PR findings and subsequent institution quality metrics. If PR does lead to an improvement in quality, or if quality concerns are managed within the PR committee, it should be possible to identify a measurable relationship between the PR process and a facility’s subsequent quality measures.

A handful of studies describe the association between PR and quality of care. Itri and colleagues noted that random, not standardized PR in radiology does not achieve reductions in diagnostic error rate.7 However, adoption of just culture principles in PR resulted in a significant improvement in facility leaders’ self-reports of quality measures at surveyed institutions.8 The same author reported that increases in PR standardization and integration with performance improvement activities could explain up to 18% of objective quality measure variation.9

We sought to determine whether a specific aspect of the PR process, the PR committee judgment of quality of care by clinicians, was related to medical center quality in a cross-sectional study of 136 Veterans Health Administration (VHA) medical centers. The VHA is a good source of study because there are standardized PR processes and training for committee members and reviewers. Our hypothesis was that medical centers with a higher number of Level 2 (“most experienced and competent clinicians might have managed the case differently”) and Level 3 (“most experienced and competent providers would have managed the case differently”) PR findings would also have lower quality metric scores for processes and outcomes of care.

Methods

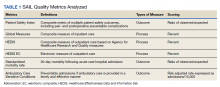

We used PR data from fiscal year 2018 and 2019. VHA PR data are available quarterly and are self-reported by each facility to the VHA Office of Clinical Risk Management. These data are broken down by facility. The following data, when available in both fiscal years 2018 and 2019, were used for this analysis: percent and number of PR that are ranked as level 1, 2, or 3; medical center group (MCG) acuity measure assigned by the VHA (1 is highest, 3 is lowest); and number of PR per 100,000 unique veteran encounters in 2019. Measures of facility quality are drawn from Strategic Analytics for Improvement and Learning (SAIL) data from 2019, which are available quarterly by facility and are rolling for 12 months. SAIL measures processes and outcomes of care. Table 1 indicates which measures are focused on outcomes vs quality processes.

SAS Version 9.2 was used to perform statistical analyses. We used Spearman correlation to estimate the PR and quality relationship.

Results

There were 136 facilities with 2 years of PR data available. The majority of these facilities (89) were highest complexity MCG 1 facilities; 19 were MCG 2, and 28 were MCG 3. Of 13,515 PRs, most of the 9555 PR findings were level 1 (70.7%). The between-facility range of level 2 and 3 findings was large, varying from 3.5% to nearly 70% in 2019 (Table 2). Findings were similar in 2018; facilities level 2 and 3 ratings ranged from 3.6% to 73.5% of all PR findings.

There was no correlation between most quality measures and facility PR findings (Table 3). The only exception was for Global Measures (GM90), an inpatient process of care measure. Unexpectedly, the correlation was positive—facilities with a higher percentage of level 2 and 3 PR findings had better inpatient processes of care SAIL score. The strongest correlation was between 2018 and 2019 PR findings.

Discussion

We hypothesized that a high percentage of level 2 and 3 PR findings would be negatively associated with objective facility measures of care processes in SAIL but we did not see this association. The only quality measure associated with PR findings was GM90, a score of inpatient care processes. However, the association was positive, with better performance associated with more level 2 and 3 PR findings.

The best predictor of the proportion of a facility’s PR findings is the previous year’s PR findings. With an R = 0.59, the previous year findings explain about 35% of the variability in level assignment. Our analysis may describe a new bias in PR, in which committees consistently assign either low or high proportions of level 2 and 3 findings. This correlation could be due to individual PR committee culture or composition, but it does not relate to objective quality measures.

Strengths

For this study we use objective measures of PR processes, the assignment of levels of care.

Limitations

Facilities self-report PR outcomes, so there could be errors in reporting. In addition, this study was cross sectional and not longitudinal and it is possible that change in quality measures over time are correlated with PR findings. Future studies using the VHA PR and SAIL data could evaluate whether changes over time, and perhaps in response to level 2 and 3 findings, would be a more sensitive indicator of the impact of the PR process on quality metrics. Future studies could incorporate the relationship between findings from the All Employee Survey, which is conducted annually, such as psychologic safety, as well as the distance the facility has gone on the high reliability organization journey, with PR findings and SAIL metrics. Finally, PR is focused on the practice of an individual clinician, while SAIL quality metrics reflect facility performance. Interventions possibly stay at the clinician level and do not drive subsequent QI processes.

What does this mean for PR? Since the early 1990s, there have been exhortations from experts to improve PR, by adopting a QI model, or for a deeper integration of PR and QI.1,2,10 Just culture tools, which include QI, are promoted as a means to improve PR.8,11,12 Other studies show PR remains problematic in terms of standardization, incorporation of best practices, redesigning systems of care, or demonstrable improvements to facility safety and care quality.1,4,6,8 Several publications have described interventions to improve PR. Deyo-Svedson discussed a program with standardized training and triggers, much like VHA.13 Itri and colleagues standardized PR in radiology to target areas of known diagnostic error, as well as use the issues assessed in PR to perform QI and education. One example of a successful QI effort involved changing the radiology reporting template to make sure areas that are prone to diagnostic error are addressed.7

Conclusions

Since 35% of PR level variance is correlated with prior year’s results, PR committees should look at increased standardization in reviews and findings. We endorse a strong focus on standardization, application of just culture tools to case reviews, and tighter linkage between process and outcome metrics measured by SAIL and PR case finding. Studies should be performed to pilot interventions to improve the linkage between PR and quality, so that greater and faster gains can be made in quality processes and, leading from this, outcomes. Additionally, future research should investigate why some facilities consistently choose higher or lower PR ratings.

Acknowledgments

We acknowledge Dr. George “Web” Ross for his helpful edits.

1. Edwards MT. In pursuit of quality and safety: an 8-year study of clinical peer review best practices in US hospitals. Int J Qual Health Care. 2018;30(8):602-607. doi:10.1093/intqhc/mzy069

2. Dans PE. Clinical peer Review: burnishing a tarnished icon. Ann Intern Med. 1993;118(7):566-568. doi:10.7326/0003-4819-118-7-199304010-00014

3. Goldman RL. The reliability of peer assessments of quality of care. JAMA. 1992;267(7):958-960. doi:10.1001/jama.1992.03480070074034

4. Swaroop R. Disrupting physician clinical practice peer review. Perm J. 2019;23:18-207. doi:10.7812/TPP/18-207

5. Caplan RA, Posner KL, Cheney FW. Effect of outcome on physician judgments of appropriateness of care. JAMA. 1991;265(15):1957–1960. doi:10.1001/jama.1991.03460150061024

6. Vyas D, Hozain AE. Clinical peer review in the United States: history, legal development and subsequent abuse. World J Gastroenterol. 2014;20(21):6357-6363. doi:10.3748/wjg.v20.i21.6357

7. Itri JN, Donithan A, Patel SH. Random versus nonrandom peer review: a case for more meaningful peer review. J Am Coll Radiol. 2018;15(7):1045-1052. doi:10.1016/j.jacr.2018.03.054

8. Edwards MT. An assessment of the impact of just culture on quality and safety in US hospitals. Am J Med Qual. 2018; 33(5):502-508. doi:10.1177/1062860618768057

9. Edwards MT. The objective impact of clinical peer review on hospital quality and safety. Am J Med Qual. 2011;26(2);110-119. doi:10.1177/1062860610380732

10. Berwick DM. Peer review and quality management: are they compatible?. QRB Qual Rev Bull. 1990;16(7):246-251. doi:10.1016/s0097-5990(16)30377-3

11. Volkar JK, Phrampus P, English D, et al. Institution of just culture physician peer review in an academic medical center. J Patient Saf. 2021;17(7):e689-e693. doi:10.1097/PTS.0000000000000449

12. Burns J, Miller T, Weiss JM, Erdfarb A, Silber D, Goldberg-Stein S. Just culture: practical implementation for radiologist peer review. J Am Coll Radiol. 2019;16(3):384-388. doi:10.1016/j.jacr.2018.10.021

13. Deyo-Svendsen ME, Phillips MR, Albright JK, et al. A systematic approach to clinical peer review in a critical access hospital. Qual Manag Health Care. 2016;25(4):213-218. doi:10.1097/QMH.0000000000000113

Hospital leaders report the most common aim of peer review (PR) is to improve quality and patient safety, thus it is a potentially powerful quality improvement (QI) driver.1 “When conducted systematically and credibly, peer review for quality management can result in both short-term and long-term improvements in patient care by revealing areas for improvement in the provision of care,” Veterans Health Administration (VHA) Directive 1190 states. “This ultimately contributes to organizational improvements.” At the same time, there are anecdotal concerns that PR may be used punitively and driven by case outcomes rather than by accepted best practices supporting QI.

Studies of the PR process suggest these concerns are valid. A key tenet of QI is standardization. PR is problematic in that regard; studies show poor interrater reliability for judgments on care, as well as hindsight bias—the fact that raters are strongly influenced by the outcome of care, not the process of care.2-5 There are concerns that case selection or review process when not standardized may be wielded as punitive too.6 In this study, we sought to identify the relationship between PR findings and subsequent institution quality metrics. If PR does lead to an improvement in quality, or if quality concerns are managed within the PR committee, it should be possible to identify a measurable relationship between the PR process and a facility’s subsequent quality measures.

A handful of studies describe the association between PR and quality of care. Itri and colleagues noted that random, not standardized PR in radiology does not achieve reductions in diagnostic error rate.7 However, adoption of just culture principles in PR resulted in a significant improvement in facility leaders’ self-reports of quality measures at surveyed institutions.8 The same author reported that increases in PR standardization and integration with performance improvement activities could explain up to 18% of objective quality measure variation.9

We sought to determine whether a specific aspect of the PR process, the PR committee judgment of quality of care by clinicians, was related to medical center quality in a cross-sectional study of 136 Veterans Health Administration (VHA) medical centers. The VHA is a good source of study because there are standardized PR processes and training for committee members and reviewers. Our hypothesis was that medical centers with a higher number of Level 2 (“most experienced and competent clinicians might have managed the case differently”) and Level 3 (“most experienced and competent providers would have managed the case differently”) PR findings would also have lower quality metric scores for processes and outcomes of care.

Methods

We used PR data from fiscal year 2018 and 2019. VHA PR data are available quarterly and are self-reported by each facility to the VHA Office of Clinical Risk Management. These data are broken down by facility. The following data, when available in both fiscal years 2018 and 2019, were used for this analysis: percent and number of PR that are ranked as level 1, 2, or 3; medical center group (MCG) acuity measure assigned by the VHA (1 is highest, 3 is lowest); and number of PR per 100,000 unique veteran encounters in 2019. Measures of facility quality are drawn from Strategic Analytics for Improvement and Learning (SAIL) data from 2019, which are available quarterly by facility and are rolling for 12 months. SAIL measures processes and outcomes of care. Table 1 indicates which measures are focused on outcomes vs quality processes.

SAS Version 9.2 was used to perform statistical analyses. We used Spearman correlation to estimate the PR and quality relationship.

Results

There were 136 facilities with 2 years of PR data available. The majority of these facilities (89) were highest complexity MCG 1 facilities; 19 were MCG 2, and 28 were MCG 3. Of 13,515 PRs, most of the 9555 PR findings were level 1 (70.7%). The between-facility range of level 2 and 3 findings was large, varying from 3.5% to nearly 70% in 2019 (Table 2). Findings were similar in 2018; facilities level 2 and 3 ratings ranged from 3.6% to 73.5% of all PR findings.

There was no correlation between most quality measures and facility PR findings (Table 3). The only exception was for Global Measures (GM90), an inpatient process of care measure. Unexpectedly, the correlation was positive—facilities with a higher percentage of level 2 and 3 PR findings had better inpatient processes of care SAIL score. The strongest correlation was between 2018 and 2019 PR findings.

Discussion

We hypothesized that a high percentage of level 2 and 3 PR findings would be negatively associated with objective facility measures of care processes in SAIL but we did not see this association. The only quality measure associated with PR findings was GM90, a score of inpatient care processes. However, the association was positive, with better performance associated with more level 2 and 3 PR findings.

The best predictor of the proportion of a facility’s PR findings is the previous year’s PR findings. With an R = 0.59, the previous year findings explain about 35% of the variability in level assignment. Our analysis may describe a new bias in PR, in which committees consistently assign either low or high proportions of level 2 and 3 findings. This correlation could be due to individual PR committee culture or composition, but it does not relate to objective quality measures.

Strengths

For this study we use objective measures of PR processes, the assignment of levels of care.

Limitations

Facilities self-report PR outcomes, so there could be errors in reporting. In addition, this study was cross sectional and not longitudinal and it is possible that change in quality measures over time are correlated with PR findings. Future studies using the VHA PR and SAIL data could evaluate whether changes over time, and perhaps in response to level 2 and 3 findings, would be a more sensitive indicator of the impact of the PR process on quality metrics. Future studies could incorporate the relationship between findings from the All Employee Survey, which is conducted annually, such as psychologic safety, as well as the distance the facility has gone on the high reliability organization journey, with PR findings and SAIL metrics. Finally, PR is focused on the practice of an individual clinician, while SAIL quality metrics reflect facility performance. Interventions possibly stay at the clinician level and do not drive subsequent QI processes.

What does this mean for PR? Since the early 1990s, there have been exhortations from experts to improve PR, by adopting a QI model, or for a deeper integration of PR and QI.1,2,10 Just culture tools, which include QI, are promoted as a means to improve PR.8,11,12 Other studies show PR remains problematic in terms of standardization, incorporation of best practices, redesigning systems of care, or demonstrable improvements to facility safety and care quality.1,4,6,8 Several publications have described interventions to improve PR. Deyo-Svedson discussed a program with standardized training and triggers, much like VHA.13 Itri and colleagues standardized PR in radiology to target areas of known diagnostic error, as well as use the issues assessed in PR to perform QI and education. One example of a successful QI effort involved changing the radiology reporting template to make sure areas that are prone to diagnostic error are addressed.7

Conclusions

Since 35% of PR level variance is correlated with prior year’s results, PR committees should look at increased standardization in reviews and findings. We endorse a strong focus on standardization, application of just culture tools to case reviews, and tighter linkage between process and outcome metrics measured by SAIL and PR case finding. Studies should be performed to pilot interventions to improve the linkage between PR and quality, so that greater and faster gains can be made in quality processes and, leading from this, outcomes. Additionally, future research should investigate why some facilities consistently choose higher or lower PR ratings.

Acknowledgments

We acknowledge Dr. George “Web” Ross for his helpful edits.

Hospital leaders report the most common aim of peer review (PR) is to improve quality and patient safety, thus it is a potentially powerful quality improvement (QI) driver.1 “When conducted systematically and credibly, peer review for quality management can result in both short-term and long-term improvements in patient care by revealing areas for improvement in the provision of care,” Veterans Health Administration (VHA) Directive 1190 states. “This ultimately contributes to organizational improvements.” At the same time, there are anecdotal concerns that PR may be used punitively and driven by case outcomes rather than by accepted best practices supporting QI.

Studies of the PR process suggest these concerns are valid. A key tenet of QI is standardization. PR is problematic in that regard; studies show poor interrater reliability for judgments on care, as well as hindsight bias—the fact that raters are strongly influenced by the outcome of care, not the process of care.2-5 There are concerns that case selection or review process when not standardized may be wielded as punitive too.6 In this study, we sought to identify the relationship between PR findings and subsequent institution quality metrics. If PR does lead to an improvement in quality, or if quality concerns are managed within the PR committee, it should be possible to identify a measurable relationship between the PR process and a facility’s subsequent quality measures.

A handful of studies describe the association between PR and quality of care. Itri and colleagues noted that random, not standardized PR in radiology does not achieve reductions in diagnostic error rate.7 However, adoption of just culture principles in PR resulted in a significant improvement in facility leaders’ self-reports of quality measures at surveyed institutions.8 The same author reported that increases in PR standardization and integration with performance improvement activities could explain up to 18% of objective quality measure variation.9

We sought to determine whether a specific aspect of the PR process, the PR committee judgment of quality of care by clinicians, was related to medical center quality in a cross-sectional study of 136 Veterans Health Administration (VHA) medical centers. The VHA is a good source of study because there are standardized PR processes and training for committee members and reviewers. Our hypothesis was that medical centers with a higher number of Level 2 (“most experienced and competent clinicians might have managed the case differently”) and Level 3 (“most experienced and competent providers would have managed the case differently”) PR findings would also have lower quality metric scores for processes and outcomes of care.

Methods

We used PR data from fiscal year 2018 and 2019. VHA PR data are available quarterly and are self-reported by each facility to the VHA Office of Clinical Risk Management. These data are broken down by facility. The following data, when available in both fiscal years 2018 and 2019, were used for this analysis: percent and number of PR that are ranked as level 1, 2, or 3; medical center group (MCG) acuity measure assigned by the VHA (1 is highest, 3 is lowest); and number of PR per 100,000 unique veteran encounters in 2019. Measures of facility quality are drawn from Strategic Analytics for Improvement and Learning (SAIL) data from 2019, which are available quarterly by facility and are rolling for 12 months. SAIL measures processes and outcomes of care. Table 1 indicates which measures are focused on outcomes vs quality processes.

SAS Version 9.2 was used to perform statistical analyses. We used Spearman correlation to estimate the PR and quality relationship.

Results

There were 136 facilities with 2 years of PR data available. The majority of these facilities (89) were highest complexity MCG 1 facilities; 19 were MCG 2, and 28 were MCG 3. Of 13,515 PRs, most of the 9555 PR findings were level 1 (70.7%). The between-facility range of level 2 and 3 findings was large, varying from 3.5% to nearly 70% in 2019 (Table 2). Findings were similar in 2018; facilities level 2 and 3 ratings ranged from 3.6% to 73.5% of all PR findings.

There was no correlation between most quality measures and facility PR findings (Table 3). The only exception was for Global Measures (GM90), an inpatient process of care measure. Unexpectedly, the correlation was positive—facilities with a higher percentage of level 2 and 3 PR findings had better inpatient processes of care SAIL score. The strongest correlation was between 2018 and 2019 PR findings.

Discussion

We hypothesized that a high percentage of level 2 and 3 PR findings would be negatively associated with objective facility measures of care processes in SAIL but we did not see this association. The only quality measure associated with PR findings was GM90, a score of inpatient care processes. However, the association was positive, with better performance associated with more level 2 and 3 PR findings.

The best predictor of the proportion of a facility’s PR findings is the previous year’s PR findings. With an R = 0.59, the previous year findings explain about 35% of the variability in level assignment. Our analysis may describe a new bias in PR, in which committees consistently assign either low or high proportions of level 2 and 3 findings. This correlation could be due to individual PR committee culture or composition, but it does not relate to objective quality measures.

Strengths

For this study we use objective measures of PR processes, the assignment of levels of care.

Limitations

Facilities self-report PR outcomes, so there could be errors in reporting. In addition, this study was cross sectional and not longitudinal and it is possible that change in quality measures over time are correlated with PR findings. Future studies using the VHA PR and SAIL data could evaluate whether changes over time, and perhaps in response to level 2 and 3 findings, would be a more sensitive indicator of the impact of the PR process on quality metrics. Future studies could incorporate the relationship between findings from the All Employee Survey, which is conducted annually, such as psychologic safety, as well as the distance the facility has gone on the high reliability organization journey, with PR findings and SAIL metrics. Finally, PR is focused on the practice of an individual clinician, while SAIL quality metrics reflect facility performance. Interventions possibly stay at the clinician level and do not drive subsequent QI processes.

What does this mean for PR? Since the early 1990s, there have been exhortations from experts to improve PR, by adopting a QI model, or for a deeper integration of PR and QI.1,2,10 Just culture tools, which include QI, are promoted as a means to improve PR.8,11,12 Other studies show PR remains problematic in terms of standardization, incorporation of best practices, redesigning systems of care, or demonstrable improvements to facility safety and care quality.1,4,6,8 Several publications have described interventions to improve PR. Deyo-Svedson discussed a program with standardized training and triggers, much like VHA.13 Itri and colleagues standardized PR in radiology to target areas of known diagnostic error, as well as use the issues assessed in PR to perform QI and education. One example of a successful QI effort involved changing the radiology reporting template to make sure areas that are prone to diagnostic error are addressed.7

Conclusions

Since 35% of PR level variance is correlated with prior year’s results, PR committees should look at increased standardization in reviews and findings. We endorse a strong focus on standardization, application of just culture tools to case reviews, and tighter linkage between process and outcome metrics measured by SAIL and PR case finding. Studies should be performed to pilot interventions to improve the linkage between PR and quality, so that greater and faster gains can be made in quality processes and, leading from this, outcomes. Additionally, future research should investigate why some facilities consistently choose higher or lower PR ratings.

Acknowledgments

We acknowledge Dr. George “Web” Ross for his helpful edits.

1. Edwards MT. In pursuit of quality and safety: an 8-year study of clinical peer review best practices in US hospitals. Int J Qual Health Care. 2018;30(8):602-607. doi:10.1093/intqhc/mzy069

2. Dans PE. Clinical peer Review: burnishing a tarnished icon. Ann Intern Med. 1993;118(7):566-568. doi:10.7326/0003-4819-118-7-199304010-00014

3. Goldman RL. The reliability of peer assessments of quality of care. JAMA. 1992;267(7):958-960. doi:10.1001/jama.1992.03480070074034

4. Swaroop R. Disrupting physician clinical practice peer review. Perm J. 2019;23:18-207. doi:10.7812/TPP/18-207

5. Caplan RA, Posner KL, Cheney FW. Effect of outcome on physician judgments of appropriateness of care. JAMA. 1991;265(15):1957–1960. doi:10.1001/jama.1991.03460150061024

6. Vyas D, Hozain AE. Clinical peer review in the United States: history, legal development and subsequent abuse. World J Gastroenterol. 2014;20(21):6357-6363. doi:10.3748/wjg.v20.i21.6357

7. Itri JN, Donithan A, Patel SH. Random versus nonrandom peer review: a case for more meaningful peer review. J Am Coll Radiol. 2018;15(7):1045-1052. doi:10.1016/j.jacr.2018.03.054

8. Edwards MT. An assessment of the impact of just culture on quality and safety in US hospitals. Am J Med Qual. 2018; 33(5):502-508. doi:10.1177/1062860618768057

9. Edwards MT. The objective impact of clinical peer review on hospital quality and safety. Am J Med Qual. 2011;26(2);110-119. doi:10.1177/1062860610380732

10. Berwick DM. Peer review and quality management: are they compatible?. QRB Qual Rev Bull. 1990;16(7):246-251. doi:10.1016/s0097-5990(16)30377-3

11. Volkar JK, Phrampus P, English D, et al. Institution of just culture physician peer review in an academic medical center. J Patient Saf. 2021;17(7):e689-e693. doi:10.1097/PTS.0000000000000449

12. Burns J, Miller T, Weiss JM, Erdfarb A, Silber D, Goldberg-Stein S. Just culture: practical implementation for radiologist peer review. J Am Coll Radiol. 2019;16(3):384-388. doi:10.1016/j.jacr.2018.10.021

13. Deyo-Svendsen ME, Phillips MR, Albright JK, et al. A systematic approach to clinical peer review in a critical access hospital. Qual Manag Health Care. 2016;25(4):213-218. doi:10.1097/QMH.0000000000000113

1. Edwards MT. In pursuit of quality and safety: an 8-year study of clinical peer review best practices in US hospitals. Int J Qual Health Care. 2018;30(8):602-607. doi:10.1093/intqhc/mzy069

2. Dans PE. Clinical peer Review: burnishing a tarnished icon. Ann Intern Med. 1993;118(7):566-568. doi:10.7326/0003-4819-118-7-199304010-00014

3. Goldman RL. The reliability of peer assessments of quality of care. JAMA. 1992;267(7):958-960. doi:10.1001/jama.1992.03480070074034

4. Swaroop R. Disrupting physician clinical practice peer review. Perm J. 2019;23:18-207. doi:10.7812/TPP/18-207

5. Caplan RA, Posner KL, Cheney FW. Effect of outcome on physician judgments of appropriateness of care. JAMA. 1991;265(15):1957–1960. doi:10.1001/jama.1991.03460150061024

6. Vyas D, Hozain AE. Clinical peer review in the United States: history, legal development and subsequent abuse. World J Gastroenterol. 2014;20(21):6357-6363. doi:10.3748/wjg.v20.i21.6357

7. Itri JN, Donithan A, Patel SH. Random versus nonrandom peer review: a case for more meaningful peer review. J Am Coll Radiol. 2018;15(7):1045-1052. doi:10.1016/j.jacr.2018.03.054

8. Edwards MT. An assessment of the impact of just culture on quality and safety in US hospitals. Am J Med Qual. 2018; 33(5):502-508. doi:10.1177/1062860618768057

9. Edwards MT. The objective impact of clinical peer review on hospital quality and safety. Am J Med Qual. 2011;26(2);110-119. doi:10.1177/1062860610380732

10. Berwick DM. Peer review and quality management: are they compatible?. QRB Qual Rev Bull. 1990;16(7):246-251. doi:10.1016/s0097-5990(16)30377-3

11. Volkar JK, Phrampus P, English D, et al. Institution of just culture physician peer review in an academic medical center. J Patient Saf. 2021;17(7):e689-e693. doi:10.1097/PTS.0000000000000449

12. Burns J, Miller T, Weiss JM, Erdfarb A, Silber D, Goldberg-Stein S. Just culture: practical implementation for radiologist peer review. J Am Coll Radiol. 2019;16(3):384-388. doi:10.1016/j.jacr.2018.10.021

13. Deyo-Svendsen ME, Phillips MR, Albright JK, et al. A systematic approach to clinical peer review in a critical access hospital. Qual Manag Health Care. 2016;25(4):213-218. doi:10.1097/QMH.0000000000000113

My choice? Unvaccinated pose outsize risk to vaccinated

according to a mathematical modeling study.

The study, which simulated patterns of infection among vaccinated and unvaccinated populations, showed that, as the populations mixed less, attack rates decreased among vaccinated people (from 15% to 10%) and increased among unvaccinated people (from 62% to 79%). The unvaccinated increasingly became the source of infection, however.

“When the vaccinated and unvaccinated mix, indirect protection is conferred upon the unvaccinated by the buffering effect of vaccinated individuals, and by contrast, risk in the vaccinated goes up,” lead author David Fisman, MD, professor of epidemiology at the University of Toronto, told this news organization.

As the groups mix less and less, the size of the epidemic increases among the unvaccinated and decreases among the vaccinated. “But the impact of the unvaccinated on risk in the vaccinated is disproportionate to the numbers of contacts between the two groups,” said Dr. Fisman.

The study was published online in the Canadian Medical Association Journal.

Relative contributions to risk

The researchers used a model of a respiratory viral disease “similar to SARS-CoV-2 infection with Delta variant.” They included reproduction values to capture the dynamics of the Omicron variant, which was emerging at the time. In the study, vaccines ranged in effectiveness from 40% to 80%. The study incorporated various levels of mixing between a partially vaccinated and an unvaccinated population. The mixing ranged from random mixing to like-with-like mixing (“assortativity”). There were three possible “compartments” of people in the model: those considered susceptible to infection, those considered infected and infectious, and those considered immune because of recovery.

The model showed that, as mixing between the vaccinated and the unvaccinated populations increased, case numbers rose, “with cases in the unvaccinated subpopulation accounting for a substantial proportion of infections.” However, as mixing between the populations decreased, the final attack rate decreased among vaccinated people, but the relative “contribution of risk to vaccinated people caused by infection acquired from contact with unvaccinated people ... increased.”

When the vaccination rate was increased in the model, case numbers among the vaccinated declined “as expected, owing to indirect protective effects,” the researchers noted. But this also “further increased the relative contribution to risk in vaccinated people by those who were unvaccinated.”

Self-regarding risk?

The findings show that “choices made by people who forgo vaccination contribute disproportionately to risk among those who do get vaccinated,” the researchers wrote. “Although risk associated with avoiding vaccination during a virulent pandemic accrues chiefly to those who are unvaccinated, the choice of some individuals to refuse vaccination is likely to affect the health and safety of vaccinated people in a manner disproportionate to the fraction of unvaccinated people in the population.”

The fact that like-with-like mixing cannot mitigate the risk to vaccinated people “undermines the assertion that vaccine choice is best left to the individual and supports strong public actions aimed at enhancing vaccine uptake and limiting access to public spaces for unvaccinated people,” they wrote.

Mandates and passports

“Our model provides support for vaccine mandates and passports during epidemics, such that vaccination is required for people to take part in nonessential activities,” said Dr. Fisman. The choice to not be vaccinated against COVID-19 should not be considered “self-regarding,” he added. “Risk is self-regarding when it only impacts the person engaging in the activity. Something like smoking cigarettes (alone, without others around) creates a lot of risk over time, but if nobody is breathing your secondhand smoke, you’re only creating risk for yourself. By contrast, we regulate, in Ontario, your right to smoke in public indoor spaces such as restaurants, because once other people are around, the risk isn’t self-regarding anymore. You’re creating risk for others.”

The authors also noted that the risks created by the unvaccinated extend beyond those of infection by “creating a risk that those around them may not be able to obtain the care they need.” They recommended that considerations of equity and justice for people who do choose to be vaccinated, as well as those who choose not to be, need to be included in formulating vaccination policy.

Illuminating the discussion

Asked to comment on the study, Matthew Oughton, MD, assistant professor of medicine at McGill University, Montreal, said: “It is easy to dismiss a mathematical model as a series of assumptions that leads to an implausible conclusion. ... However, they can serve to illustrate and, to an extent, quantify the results of complex interactions, and this study does just that.” Dr. Oughton was not involved in the research.

During the past 2 years, the scientific press and the general press have often discussed the individual and collective effects of disease-prevention methods, including nonpharmaceutical interventions. “Models like this can help illuminate those discussions by highlighting important consequences of preventive measures,” said Dr. Oughton, who also works in the division of infectious diseases at the Jewish General Hospital, Montreal.

It’s worth noting that the authors modeled vaccine effectiveness against all infection, “rather than the generally greater and more durable effects we have seen for vaccines in prevention of severe infection,” said Dr. Oughton. He added that the authors did not include the effect of vaccination in reducing forward transmission. “Inclusion of this effect would presumably have reduced overall infectious burden in mixed populations and increased the difference between groups at lower levels of mixing between populations.”

The research was supported by a grant from the Canadian Institutes of Health Research. Dr. Fisman has served on advisory boards related to influenza and SARS-CoV-2 vaccines for Seqirus, Pfizer, AstraZeneca, and Sanofi-Pasteur Vaccines and has served as a legal expert on issues related to COVID-19 epidemiology for the Elementary Teachers Federation of Ontario and the Registered Nurses Association of Ontario. Dr. Oughton disclosed no relevant financial relationships.

A version of this article first appeared on Medscape.com.

according to a mathematical modeling study.

The study, which simulated patterns of infection among vaccinated and unvaccinated populations, showed that, as the populations mixed less, attack rates decreased among vaccinated people (from 15% to 10%) and increased among unvaccinated people (from 62% to 79%). The unvaccinated increasingly became the source of infection, however.

“When the vaccinated and unvaccinated mix, indirect protection is conferred upon the unvaccinated by the buffering effect of vaccinated individuals, and by contrast, risk in the vaccinated goes up,” lead author David Fisman, MD, professor of epidemiology at the University of Toronto, told this news organization.

As the groups mix less and less, the size of the epidemic increases among the unvaccinated and decreases among the vaccinated. “But the impact of the unvaccinated on risk in the vaccinated is disproportionate to the numbers of contacts between the two groups,” said Dr. Fisman.

The study was published online in the Canadian Medical Association Journal.

Relative contributions to risk

The researchers used a model of a respiratory viral disease “similar to SARS-CoV-2 infection with Delta variant.” They included reproduction values to capture the dynamics of the Omicron variant, which was emerging at the time. In the study, vaccines ranged in effectiveness from 40% to 80%. The study incorporated various levels of mixing between a partially vaccinated and an unvaccinated population. The mixing ranged from random mixing to like-with-like mixing (“assortativity”). There were three possible “compartments” of people in the model: those considered susceptible to infection, those considered infected and infectious, and those considered immune because of recovery.

The model showed that, as mixing between the vaccinated and the unvaccinated populations increased, case numbers rose, “with cases in the unvaccinated subpopulation accounting for a substantial proportion of infections.” However, as mixing between the populations decreased, the final attack rate decreased among vaccinated people, but the relative “contribution of risk to vaccinated people caused by infection acquired from contact with unvaccinated people ... increased.”

When the vaccination rate was increased in the model, case numbers among the vaccinated declined “as expected, owing to indirect protective effects,” the researchers noted. But this also “further increased the relative contribution to risk in vaccinated people by those who were unvaccinated.”

Self-regarding risk?

The findings show that “choices made by people who forgo vaccination contribute disproportionately to risk among those who do get vaccinated,” the researchers wrote. “Although risk associated with avoiding vaccination during a virulent pandemic accrues chiefly to those who are unvaccinated, the choice of some individuals to refuse vaccination is likely to affect the health and safety of vaccinated people in a manner disproportionate to the fraction of unvaccinated people in the population.”

The fact that like-with-like mixing cannot mitigate the risk to vaccinated people “undermines the assertion that vaccine choice is best left to the individual and supports strong public actions aimed at enhancing vaccine uptake and limiting access to public spaces for unvaccinated people,” they wrote.

Mandates and passports

“Our model provides support for vaccine mandates and passports during epidemics, such that vaccination is required for people to take part in nonessential activities,” said Dr. Fisman. The choice to not be vaccinated against COVID-19 should not be considered “self-regarding,” he added. “Risk is self-regarding when it only impacts the person engaging in the activity. Something like smoking cigarettes (alone, without others around) creates a lot of risk over time, but if nobody is breathing your secondhand smoke, you’re only creating risk for yourself. By contrast, we regulate, in Ontario, your right to smoke in public indoor spaces such as restaurants, because once other people are around, the risk isn’t self-regarding anymore. You’re creating risk for others.”

The authors also noted that the risks created by the unvaccinated extend beyond those of infection by “creating a risk that those around them may not be able to obtain the care they need.” They recommended that considerations of equity and justice for people who do choose to be vaccinated, as well as those who choose not to be, need to be included in formulating vaccination policy.

Illuminating the discussion

Asked to comment on the study, Matthew Oughton, MD, assistant professor of medicine at McGill University, Montreal, said: “It is easy to dismiss a mathematical model as a series of assumptions that leads to an implausible conclusion. ... However, they can serve to illustrate and, to an extent, quantify the results of complex interactions, and this study does just that.” Dr. Oughton was not involved in the research.

During the past 2 years, the scientific press and the general press have often discussed the individual and collective effects of disease-prevention methods, including nonpharmaceutical interventions. “Models like this can help illuminate those discussions by highlighting important consequences of preventive measures,” said Dr. Oughton, who also works in the division of infectious diseases at the Jewish General Hospital, Montreal.

It’s worth noting that the authors modeled vaccine effectiveness against all infection, “rather than the generally greater and more durable effects we have seen for vaccines in prevention of severe infection,” said Dr. Oughton. He added that the authors did not include the effect of vaccination in reducing forward transmission. “Inclusion of this effect would presumably have reduced overall infectious burden in mixed populations and increased the difference between groups at lower levels of mixing between populations.”

The research was supported by a grant from the Canadian Institutes of Health Research. Dr. Fisman has served on advisory boards related to influenza and SARS-CoV-2 vaccines for Seqirus, Pfizer, AstraZeneca, and Sanofi-Pasteur Vaccines and has served as a legal expert on issues related to COVID-19 epidemiology for the Elementary Teachers Federation of Ontario and the Registered Nurses Association of Ontario. Dr. Oughton disclosed no relevant financial relationships.

A version of this article first appeared on Medscape.com.

according to a mathematical modeling study.

The study, which simulated patterns of infection among vaccinated and unvaccinated populations, showed that, as the populations mixed less, attack rates decreased among vaccinated people (from 15% to 10%) and increased among unvaccinated people (from 62% to 79%). The unvaccinated increasingly became the source of infection, however.

“When the vaccinated and unvaccinated mix, indirect protection is conferred upon the unvaccinated by the buffering effect of vaccinated individuals, and by contrast, risk in the vaccinated goes up,” lead author David Fisman, MD, professor of epidemiology at the University of Toronto, told this news organization.

As the groups mix less and less, the size of the epidemic increases among the unvaccinated and decreases among the vaccinated. “But the impact of the unvaccinated on risk in the vaccinated is disproportionate to the numbers of contacts between the two groups,” said Dr. Fisman.

The study was published online in the Canadian Medical Association Journal.

Relative contributions to risk

The researchers used a model of a respiratory viral disease “similar to SARS-CoV-2 infection with Delta variant.” They included reproduction values to capture the dynamics of the Omicron variant, which was emerging at the time. In the study, vaccines ranged in effectiveness from 40% to 80%. The study incorporated various levels of mixing between a partially vaccinated and an unvaccinated population. The mixing ranged from random mixing to like-with-like mixing (“assortativity”). There were three possible “compartments” of people in the model: those considered susceptible to infection, those considered infected and infectious, and those considered immune because of recovery.

The model showed that, as mixing between the vaccinated and the unvaccinated populations increased, case numbers rose, “with cases in the unvaccinated subpopulation accounting for a substantial proportion of infections.” However, as mixing between the populations decreased, the final attack rate decreased among vaccinated people, but the relative “contribution of risk to vaccinated people caused by infection acquired from contact with unvaccinated people ... increased.”

When the vaccination rate was increased in the model, case numbers among the vaccinated declined “as expected, owing to indirect protective effects,” the researchers noted. But this also “further increased the relative contribution to risk in vaccinated people by those who were unvaccinated.”

Self-regarding risk?