User login

Noisy incubators could stunt infant hearing

Incubators save the lives of many babies, but new data suggest that the ambient noise associated with the incubator experience could put babies’ hearing and language development skills at risk.

Previous studies have shown that the neonatal intensive care unit is a noisy environment, but specific data on levels of sound inside and outside incubators are limited, wrote Christoph Reuter, MA, a musicology professor at the University of Vienna, and colleagues.

“By the age of 3 years, deficits in language acquisition are detectable in nearly 50% of very preterm infants,” and high levels of NICU noise have been cited as possible contributors to this increased risk, the researchers say.

In a study published in Frontiers in Pediatrics, the researchers aimed to compare real-life NICU noise with previously reported levels to describe the sound characteristics and to identify resonance characteristics inside an incubator.

The study was conducted at the Pediatric Simulation Center at the Medical University of Vienna. The researchers placed a simulation mannequin with an ear microphone inside an incubator. They also placed microphones outside the incubator to collect measures of outside noise and activity involved in NICU care.

Data regarding sound were collected for 11 environmental noises and 12 incubator handlings using weighted and unweighted decibel levels. Specific environmental noises included starting the incubator engine; environmental noise with incubator off; environmental noise with incubator on; normal conversation; light conversation; laughter; telephone sounds; the infusion pump alarm; the monitor alarm (anomaly); the monitor alarm (emergency); and blood pressure measurement.

The 12 incubator handling noises included those associated with water flap, water pouring into the incubator, incubator doors opening properly, incubators doors closing properly, incubator doors closing improperly, hatch closing, hatch opening, incubator drawer, neighbor incubator doors closing (1.82 m distance), taking a stethoscope from the incubator wall, putting a stethoscope on the incubator, and suctioning tube. Noise from six levels of respiratory support was also measured.

The researchers reported that the incubator tended to dampen most sounds but also that some sounds resonated inside the incubator, which raised the interior noise level by as much as 28 decibels.

Most of the measures using both A-weighted decibels (dBA) and sound pressure level decibels (dBSPL) were above the 45-decibel level for neonatal sound exposure recommended by the American Academy of Pediatrics. The measurements (dBA) versus unweighted (dBSPL) are limited in that they are designed to measure low levels of sound and therefore might underestimate proportions of high and low frequencies at stronger levels, the researchers acknowledge.

Overall, most measures were clustered in the 55-75 decibel range, although some sound levels for incubator handling, while below levels previously reported in the literature, reached approximately 100 decibels.

The noise involved inside the incubator was not perceived as loud by those working with the incubator, the researchers note.

As for resonance inside the incubator, the researchers measured a low-frequency main resonance of 97 Hz, but they write that this resonance can be hard to capture in weighted measurements. However, the resonance means that “noises from the outside sound more tonal inside the incubator, booming and muffled as well as less rough or noisy,” and sounds inside the incubator are similarly affected, the researchers say.

“Most of the noise situations described in this manuscript far exceed not only the recommendation of the AAP but also international guidelines provided by the World Health Organization and the U.S. Environmental Protection Agency,” which recommend, respectively, maximum dBA levels of 35 dBA and 45 dBA for daytime and 30 dBA and 35 dBA for night, the researchers indicate.

Potential long-term implications are that babies who spend time in the NICU are at risk for hearing impairment, which could lead to delays in language acquisition, they say.

The findings were limited by several factors, including the variance among the incubators, which prevents generalizability, the researchers note. Other limitations include the use of a simulation room rather than everyday conditions, in which the environmental sounds would likely be even louder.

However, the results provide insights into the specifics of incubator and NICU noise and suggest that sound be a consideration in the development and promotion of incubators to help protect the hearing of the infants inside them, the researchers conclude.

A generalist’s take

“This is an interesting study looking at the level and character of the sound experienced by preterm infants inside an incubator and how it may compare to sounds experienced within the mother’s womb,” said Tim Joos, MD, a Seattle-based clinician with a combination internal medicine/pediatrics practice, in an interview.

In society at large, “there has been more focus lately on the general environment and its effect on health, and this study is a unique take on this concept,” he said. “Although in general the incubators work to dampen external sounds, low-frequency sounds may actually resonate more inside the incubators, and taps on the outside or inside of the incubator itself are amplified within the incubator,” he noted. “It is sad but not surprising that the decibel levels experienced by the infants in the incubators exceed the recommended levels recommended by AAP.”

As for additional research, “it would be interesting to see the results of trials looking at various short- or long-term outcomes experienced by infants exposed to a lower-level noise compared to the current levels,” Dr. Joos told this news organization.

A neonatologist’s perspective

“As the field of neonatology advances, we are caring for an ever-growing number of extremely preterm infants,” said Caitlin M. Drumm, MD, of Walter Reed National Military Medical Center, Bethesda, Md., in an interview.

“These infants will spend the first few months of their lives within an incubator in the neonatal intensive care unit, so it is important to understand the potential long-term implications of environmental effects on these vulnerable patients,” she said.

“As in prior studies, it was not surprising that essentially every environmental, handling, or respiratory intervention led to noise levels higher than the limit recommended by the American Academy of Pediatrics,” Dr. Drumm said. “What was surprising was just how high above the 45-dB recommended noise limit many environmental stimuli are. For example, the authors cite respiratory flow rates of 8 L/min or higher as risky for hearing health at 84.72 dBSPL, “ she said.

The key message for clinicians is to be aware of noise levels in the NICU, Dr. Drumm said. “Environmental stimuli as simple as putting a stethoscope on the incubator lead to noise levels well above the limit recommended by the American Academy of Pediatrics. The entire NICU care team has a role to play in minimizing environmental sound hazards for our most critically ill patients.”

Looking ahead, “future research should focus on providing more information correlating neonatal environmental sound exposure to long-term hearing and neurodevelopmental outcomes,” she said.

The study received no outside funding. The researchers report no relevant financial relationships. Dr. Joos serves on the editorial advisory board of Pediatric News. Dr. Drumm has disclosed no relevant financial relationships.

A version of this article first appeared on Medscape.com.

Incubators save the lives of many babies, but new data suggest that the ambient noise associated with the incubator experience could put babies’ hearing and language development skills at risk.

Previous studies have shown that the neonatal intensive care unit is a noisy environment, but specific data on levels of sound inside and outside incubators are limited, wrote Christoph Reuter, MA, a musicology professor at the University of Vienna, and colleagues.

“By the age of 3 years, deficits in language acquisition are detectable in nearly 50% of very preterm infants,” and high levels of NICU noise have been cited as possible contributors to this increased risk, the researchers say.

In a study published in Frontiers in Pediatrics, the researchers aimed to compare real-life NICU noise with previously reported levels to describe the sound characteristics and to identify resonance characteristics inside an incubator.

The study was conducted at the Pediatric Simulation Center at the Medical University of Vienna. The researchers placed a simulation mannequin with an ear microphone inside an incubator. They also placed microphones outside the incubator to collect measures of outside noise and activity involved in NICU care.

Data regarding sound were collected for 11 environmental noises and 12 incubator handlings using weighted and unweighted decibel levels. Specific environmental noises included starting the incubator engine; environmental noise with incubator off; environmental noise with incubator on; normal conversation; light conversation; laughter; telephone sounds; the infusion pump alarm; the monitor alarm (anomaly); the monitor alarm (emergency); and blood pressure measurement.

The 12 incubator handling noises included those associated with water flap, water pouring into the incubator, incubator doors opening properly, incubators doors closing properly, incubator doors closing improperly, hatch closing, hatch opening, incubator drawer, neighbor incubator doors closing (1.82 m distance), taking a stethoscope from the incubator wall, putting a stethoscope on the incubator, and suctioning tube. Noise from six levels of respiratory support was also measured.

The researchers reported that the incubator tended to dampen most sounds but also that some sounds resonated inside the incubator, which raised the interior noise level by as much as 28 decibels.

Most of the measures using both A-weighted decibels (dBA) and sound pressure level decibels (dBSPL) were above the 45-decibel level for neonatal sound exposure recommended by the American Academy of Pediatrics. The measurements (dBA) versus unweighted (dBSPL) are limited in that they are designed to measure low levels of sound and therefore might underestimate proportions of high and low frequencies at stronger levels, the researchers acknowledge.

Overall, most measures were clustered in the 55-75 decibel range, although some sound levels for incubator handling, while below levels previously reported in the literature, reached approximately 100 decibels.

The noise involved inside the incubator was not perceived as loud by those working with the incubator, the researchers note.

As for resonance inside the incubator, the researchers measured a low-frequency main resonance of 97 Hz, but they write that this resonance can be hard to capture in weighted measurements. However, the resonance means that “noises from the outside sound more tonal inside the incubator, booming and muffled as well as less rough or noisy,” and sounds inside the incubator are similarly affected, the researchers say.

“Most of the noise situations described in this manuscript far exceed not only the recommendation of the AAP but also international guidelines provided by the World Health Organization and the U.S. Environmental Protection Agency,” which recommend, respectively, maximum dBA levels of 35 dBA and 45 dBA for daytime and 30 dBA and 35 dBA for night, the researchers indicate.

Potential long-term implications are that babies who spend time in the NICU are at risk for hearing impairment, which could lead to delays in language acquisition, they say.

The findings were limited by several factors, including the variance among the incubators, which prevents generalizability, the researchers note. Other limitations include the use of a simulation room rather than everyday conditions, in which the environmental sounds would likely be even louder.

However, the results provide insights into the specifics of incubator and NICU noise and suggest that sound be a consideration in the development and promotion of incubators to help protect the hearing of the infants inside them, the researchers conclude.

A generalist’s take

“This is an interesting study looking at the level and character of the sound experienced by preterm infants inside an incubator and how it may compare to sounds experienced within the mother’s womb,” said Tim Joos, MD, a Seattle-based clinician with a combination internal medicine/pediatrics practice, in an interview.

In society at large, “there has been more focus lately on the general environment and its effect on health, and this study is a unique take on this concept,” he said. “Although in general the incubators work to dampen external sounds, low-frequency sounds may actually resonate more inside the incubators, and taps on the outside or inside of the incubator itself are amplified within the incubator,” he noted. “It is sad but not surprising that the decibel levels experienced by the infants in the incubators exceed the recommended levels recommended by AAP.”

As for additional research, “it would be interesting to see the results of trials looking at various short- or long-term outcomes experienced by infants exposed to a lower-level noise compared to the current levels,” Dr. Joos told this news organization.

A neonatologist’s perspective

“As the field of neonatology advances, we are caring for an ever-growing number of extremely preterm infants,” said Caitlin M. Drumm, MD, of Walter Reed National Military Medical Center, Bethesda, Md., in an interview.

“These infants will spend the first few months of their lives within an incubator in the neonatal intensive care unit, so it is important to understand the potential long-term implications of environmental effects on these vulnerable patients,” she said.

“As in prior studies, it was not surprising that essentially every environmental, handling, or respiratory intervention led to noise levels higher than the limit recommended by the American Academy of Pediatrics,” Dr. Drumm said. “What was surprising was just how high above the 45-dB recommended noise limit many environmental stimuli are. For example, the authors cite respiratory flow rates of 8 L/min or higher as risky for hearing health at 84.72 dBSPL, “ she said.

The key message for clinicians is to be aware of noise levels in the NICU, Dr. Drumm said. “Environmental stimuli as simple as putting a stethoscope on the incubator lead to noise levels well above the limit recommended by the American Academy of Pediatrics. The entire NICU care team has a role to play in minimizing environmental sound hazards for our most critically ill patients.”

Looking ahead, “future research should focus on providing more information correlating neonatal environmental sound exposure to long-term hearing and neurodevelopmental outcomes,” she said.

The study received no outside funding. The researchers report no relevant financial relationships. Dr. Joos serves on the editorial advisory board of Pediatric News. Dr. Drumm has disclosed no relevant financial relationships.

A version of this article first appeared on Medscape.com.

Incubators save the lives of many babies, but new data suggest that the ambient noise associated with the incubator experience could put babies’ hearing and language development skills at risk.

Previous studies have shown that the neonatal intensive care unit is a noisy environment, but specific data on levels of sound inside and outside incubators are limited, wrote Christoph Reuter, MA, a musicology professor at the University of Vienna, and colleagues.

“By the age of 3 years, deficits in language acquisition are detectable in nearly 50% of very preterm infants,” and high levels of NICU noise have been cited as possible contributors to this increased risk, the researchers say.

In a study published in Frontiers in Pediatrics, the researchers aimed to compare real-life NICU noise with previously reported levels to describe the sound characteristics and to identify resonance characteristics inside an incubator.

The study was conducted at the Pediatric Simulation Center at the Medical University of Vienna. The researchers placed a simulation mannequin with an ear microphone inside an incubator. They also placed microphones outside the incubator to collect measures of outside noise and activity involved in NICU care.

Data regarding sound were collected for 11 environmental noises and 12 incubator handlings using weighted and unweighted decibel levels. Specific environmental noises included starting the incubator engine; environmental noise with incubator off; environmental noise with incubator on; normal conversation; light conversation; laughter; telephone sounds; the infusion pump alarm; the monitor alarm (anomaly); the monitor alarm (emergency); and blood pressure measurement.

The 12 incubator handling noises included those associated with water flap, water pouring into the incubator, incubator doors opening properly, incubators doors closing properly, incubator doors closing improperly, hatch closing, hatch opening, incubator drawer, neighbor incubator doors closing (1.82 m distance), taking a stethoscope from the incubator wall, putting a stethoscope on the incubator, and suctioning tube. Noise from six levels of respiratory support was also measured.

The researchers reported that the incubator tended to dampen most sounds but also that some sounds resonated inside the incubator, which raised the interior noise level by as much as 28 decibels.

Most of the measures using both A-weighted decibels (dBA) and sound pressure level decibels (dBSPL) were above the 45-decibel level for neonatal sound exposure recommended by the American Academy of Pediatrics. The measurements (dBA) versus unweighted (dBSPL) are limited in that they are designed to measure low levels of sound and therefore might underestimate proportions of high and low frequencies at stronger levels, the researchers acknowledge.

Overall, most measures were clustered in the 55-75 decibel range, although some sound levels for incubator handling, while below levels previously reported in the literature, reached approximately 100 decibels.

The noise involved inside the incubator was not perceived as loud by those working with the incubator, the researchers note.

As for resonance inside the incubator, the researchers measured a low-frequency main resonance of 97 Hz, but they write that this resonance can be hard to capture in weighted measurements. However, the resonance means that “noises from the outside sound more tonal inside the incubator, booming and muffled as well as less rough or noisy,” and sounds inside the incubator are similarly affected, the researchers say.

“Most of the noise situations described in this manuscript far exceed not only the recommendation of the AAP but also international guidelines provided by the World Health Organization and the U.S. Environmental Protection Agency,” which recommend, respectively, maximum dBA levels of 35 dBA and 45 dBA for daytime and 30 dBA and 35 dBA for night, the researchers indicate.

Potential long-term implications are that babies who spend time in the NICU are at risk for hearing impairment, which could lead to delays in language acquisition, they say.

The findings were limited by several factors, including the variance among the incubators, which prevents generalizability, the researchers note. Other limitations include the use of a simulation room rather than everyday conditions, in which the environmental sounds would likely be even louder.

However, the results provide insights into the specifics of incubator and NICU noise and suggest that sound be a consideration in the development and promotion of incubators to help protect the hearing of the infants inside them, the researchers conclude.

A generalist’s take

“This is an interesting study looking at the level and character of the sound experienced by preterm infants inside an incubator and how it may compare to sounds experienced within the mother’s womb,” said Tim Joos, MD, a Seattle-based clinician with a combination internal medicine/pediatrics practice, in an interview.

In society at large, “there has been more focus lately on the general environment and its effect on health, and this study is a unique take on this concept,” he said. “Although in general the incubators work to dampen external sounds, low-frequency sounds may actually resonate more inside the incubators, and taps on the outside or inside of the incubator itself are amplified within the incubator,” he noted. “It is sad but not surprising that the decibel levels experienced by the infants in the incubators exceed the recommended levels recommended by AAP.”

As for additional research, “it would be interesting to see the results of trials looking at various short- or long-term outcomes experienced by infants exposed to a lower-level noise compared to the current levels,” Dr. Joos told this news organization.

A neonatologist’s perspective

“As the field of neonatology advances, we are caring for an ever-growing number of extremely preterm infants,” said Caitlin M. Drumm, MD, of Walter Reed National Military Medical Center, Bethesda, Md., in an interview.

“These infants will spend the first few months of their lives within an incubator in the neonatal intensive care unit, so it is important to understand the potential long-term implications of environmental effects on these vulnerable patients,” she said.

“As in prior studies, it was not surprising that essentially every environmental, handling, or respiratory intervention led to noise levels higher than the limit recommended by the American Academy of Pediatrics,” Dr. Drumm said. “What was surprising was just how high above the 45-dB recommended noise limit many environmental stimuli are. For example, the authors cite respiratory flow rates of 8 L/min or higher as risky for hearing health at 84.72 dBSPL, “ she said.

The key message for clinicians is to be aware of noise levels in the NICU, Dr. Drumm said. “Environmental stimuli as simple as putting a stethoscope on the incubator lead to noise levels well above the limit recommended by the American Academy of Pediatrics. The entire NICU care team has a role to play in minimizing environmental sound hazards for our most critically ill patients.”

Looking ahead, “future research should focus on providing more information correlating neonatal environmental sound exposure to long-term hearing and neurodevelopmental outcomes,” she said.

The study received no outside funding. The researchers report no relevant financial relationships. Dr. Joos serves on the editorial advisory board of Pediatric News. Dr. Drumm has disclosed no relevant financial relationships.

A version of this article first appeared on Medscape.com.

Autism: Is it in the water?

This transcript has been edited for clarity.

Few diseases have stymied explanation like autism spectrum disorder (ASD). We know that the prevalence has been increasing dramatically, but we aren’t quite sure whether that is because of more screening and awareness or more fundamental changes. We know that much of the risk appears to be genetic, but there may be 1,000 genes involved in the syndrome. We know that certain environmental exposures, like pollution, might increase the risk – perhaps on a susceptible genetic background – but we’re not really sure which exposures are most harmful.

So, the search continues, across all domains of inquiry from cell culture to large epidemiologic analyses. And this week, a new player enters the field, and, as they say, it’s something in the water.

We’re talking about this paper, by Zeyan Liew and colleagues, appearing in JAMA Pediatrics.

Using the incredibly robust health data infrastructure in Denmark, the researchers were able to identify 8,842 children born between 2000 and 2013 with ASD and matched each one to five control kids of the same sex and age without autism.

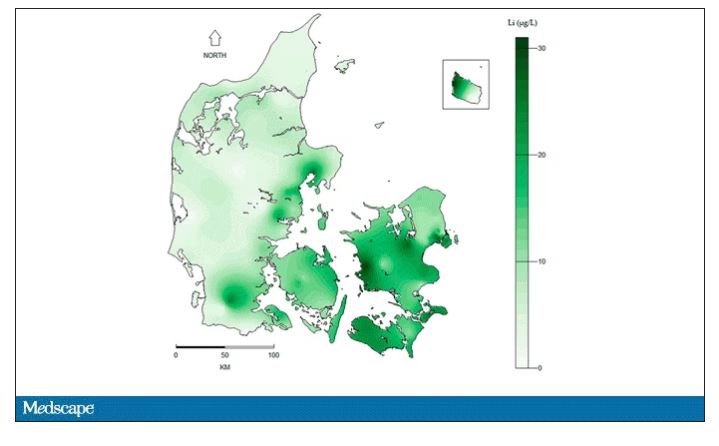

They then mapped the location the mothers of these kids lived while they were pregnant – down to 5 meters resolution, actually – to groundwater lithium levels.

Once that was done, the analysis was straightforward. Would moms who were pregnant in areas with higher groundwater lithium levels be more likely to have kids with ASD?

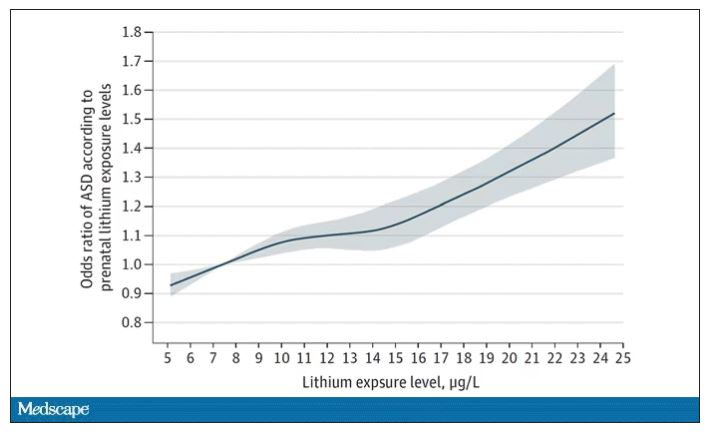

The results show a rather steady and consistent association between higher lithium levels in groundwater and the prevalence of ASD in children.

We’re not talking huge numbers, but moms who lived in the areas of the highest quartile of lithium were about 46% more likely to have a child with ASD. That’s a relative risk, of course – this would be like an increase from 1 in 100 kids to 1.5 in 100 kids. But still, it’s intriguing.

But the case is far from closed here.

Groundwater concentration of lithium and the amount of lithium a pregnant mother ingests are not the same thing. It does turn out that virtually all drinking water in Denmark comes from groundwater sources – but not all lithium comes from drinking water. There are plenty of dietary sources of lithium as well. And, of course, there is medical lithium, but we’ll get to that in a second.

First, let’s talk about those lithium measurements. They were taken in 2013 – after all these kids were born. The authors acknowledge this limitation but show a high correlation between measured levels in 2013 and earlier measured levels from prior studies, suggesting that lithium levels in a given area are quite constant over time. That’s great – but if lithium levels are constant over time, this study does nothing to shed light on why autism diagnoses seem to be increasing.

Let’s put some numbers to the lithium concentrations the authors examined. The average was about 12 mcg/L.

As a reminder, a standard therapeutic dose of lithium used for bipolar disorder is like 600 mg. That means you’d need to drink more than 2,500 of those 5-gallon jugs that sit on your water cooler, per day, to approximate the dose you’d get from a lithium tablet. Of course, small doses can still cause toxicity – but I wanted to put this in perspective.

Also, we have some data on pregnant women who take medical lithium. An analysis of nine studies showed that first-trimester lithium use may be associated with congenital malformations – particularly some specific heart malformations – and some birth complications. But three of four separate studies looking at longer-term neurodevelopmental outcomes did not find any effect on development, attainment of milestones, or IQ. One study of 15 kids exposed to medical lithium in utero did note minor neurologic dysfunction in one child and a low verbal IQ in another – but that’s a very small study.

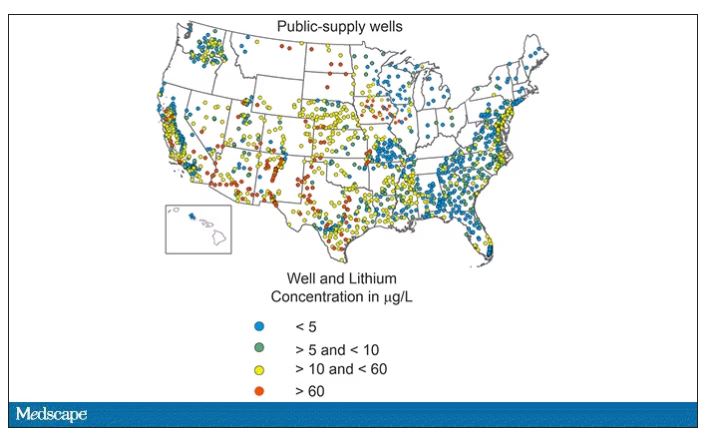

Of course, lithium levels vary around the world as well. The U.S. Geological Survey examined lithium content in groundwater in the United States, as you can see here.

Our numbers are pretty similar to Denmark’s – in the 0-60 range. But an area in the Argentine Andes has levels as high as 1,600 mcg/L. A study of 194 babies from that area found higher lithium exposure was associated with lower fetal size, but I haven’t seen follow-up on neurodevelopmental outcomes.

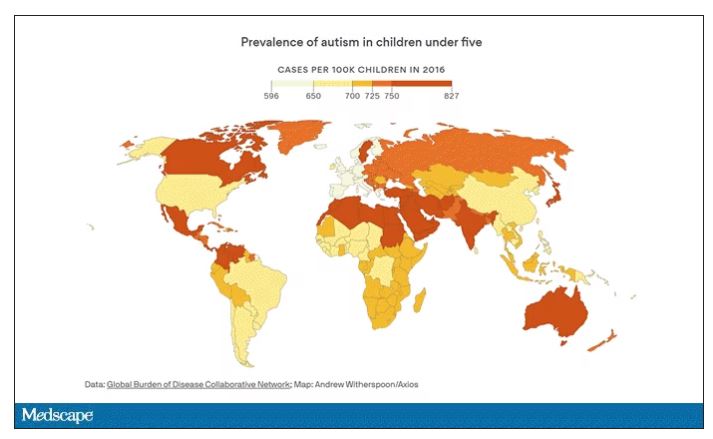

The point is that there is a lot of variability here. It would be really interesting to map groundwater lithium levels to autism rates around the world. As a teaser, I will point out that, if you look at worldwide autism rates, you may be able to convince yourself that they are higher in more arid climates, and arid climates tend to have more groundwater lithium. But I’m really reaching here. More work needs to be done.

And I hope it is done quickly. Lithium is in the midst of becoming a very important commodity thanks to the shift to electric vehicles. While we can hope that recycling will claim most of those batteries at the end of their life, some will escape reclamation and potentially put more lithium into the drinking water. I’d like to know how risky that is before it happens.

F. Perry Wilson, MD, MSCE, is an associate professor of medicine and director of Yale’s Clinical and Translational Research Accelerator. He has disclosed no relevant financial relationships. His science communication work can be found in the Huffington Post, on NPR, and here on Medscape. He tweets @fperrywilson and his new book, “How Medicine Works and When It Doesn’t”, is available now.

A version of this article originally appeared on Medscape.com.

This transcript has been edited for clarity.

Few diseases have stymied explanation like autism spectrum disorder (ASD). We know that the prevalence has been increasing dramatically, but we aren’t quite sure whether that is because of more screening and awareness or more fundamental changes. We know that much of the risk appears to be genetic, but there may be 1,000 genes involved in the syndrome. We know that certain environmental exposures, like pollution, might increase the risk – perhaps on a susceptible genetic background – but we’re not really sure which exposures are most harmful.

So, the search continues, across all domains of inquiry from cell culture to large epidemiologic analyses. And this week, a new player enters the field, and, as they say, it’s something in the water.

We’re talking about this paper, by Zeyan Liew and colleagues, appearing in JAMA Pediatrics.

Using the incredibly robust health data infrastructure in Denmark, the researchers were able to identify 8,842 children born between 2000 and 2013 with ASD and matched each one to five control kids of the same sex and age without autism.

They then mapped the location the mothers of these kids lived while they were pregnant – down to 5 meters resolution, actually – to groundwater lithium levels.

Once that was done, the analysis was straightforward. Would moms who were pregnant in areas with higher groundwater lithium levels be more likely to have kids with ASD?

The results show a rather steady and consistent association between higher lithium levels in groundwater and the prevalence of ASD in children.

We’re not talking huge numbers, but moms who lived in the areas of the highest quartile of lithium were about 46% more likely to have a child with ASD. That’s a relative risk, of course – this would be like an increase from 1 in 100 kids to 1.5 in 100 kids. But still, it’s intriguing.

But the case is far from closed here.

Groundwater concentration of lithium and the amount of lithium a pregnant mother ingests are not the same thing. It does turn out that virtually all drinking water in Denmark comes from groundwater sources – but not all lithium comes from drinking water. There are plenty of dietary sources of lithium as well. And, of course, there is medical lithium, but we’ll get to that in a second.

First, let’s talk about those lithium measurements. They were taken in 2013 – after all these kids were born. The authors acknowledge this limitation but show a high correlation between measured levels in 2013 and earlier measured levels from prior studies, suggesting that lithium levels in a given area are quite constant over time. That’s great – but if lithium levels are constant over time, this study does nothing to shed light on why autism diagnoses seem to be increasing.

Let’s put some numbers to the lithium concentrations the authors examined. The average was about 12 mcg/L.

As a reminder, a standard therapeutic dose of lithium used for bipolar disorder is like 600 mg. That means you’d need to drink more than 2,500 of those 5-gallon jugs that sit on your water cooler, per day, to approximate the dose you’d get from a lithium tablet. Of course, small doses can still cause toxicity – but I wanted to put this in perspective.

Also, we have some data on pregnant women who take medical lithium. An analysis of nine studies showed that first-trimester lithium use may be associated with congenital malformations – particularly some specific heart malformations – and some birth complications. But three of four separate studies looking at longer-term neurodevelopmental outcomes did not find any effect on development, attainment of milestones, or IQ. One study of 15 kids exposed to medical lithium in utero did note minor neurologic dysfunction in one child and a low verbal IQ in another – but that’s a very small study.

Of course, lithium levels vary around the world as well. The U.S. Geological Survey examined lithium content in groundwater in the United States, as you can see here.

Our numbers are pretty similar to Denmark’s – in the 0-60 range. But an area in the Argentine Andes has levels as high as 1,600 mcg/L. A study of 194 babies from that area found higher lithium exposure was associated with lower fetal size, but I haven’t seen follow-up on neurodevelopmental outcomes.

The point is that there is a lot of variability here. It would be really interesting to map groundwater lithium levels to autism rates around the world. As a teaser, I will point out that, if you look at worldwide autism rates, you may be able to convince yourself that they are higher in more arid climates, and arid climates tend to have more groundwater lithium. But I’m really reaching here. More work needs to be done.

And I hope it is done quickly. Lithium is in the midst of becoming a very important commodity thanks to the shift to electric vehicles. While we can hope that recycling will claim most of those batteries at the end of their life, some will escape reclamation and potentially put more lithium into the drinking water. I’d like to know how risky that is before it happens.

F. Perry Wilson, MD, MSCE, is an associate professor of medicine and director of Yale’s Clinical and Translational Research Accelerator. He has disclosed no relevant financial relationships. His science communication work can be found in the Huffington Post, on NPR, and here on Medscape. He tweets @fperrywilson and his new book, “How Medicine Works and When It Doesn’t”, is available now.

A version of this article originally appeared on Medscape.com.

This transcript has been edited for clarity.

Few diseases have stymied explanation like autism spectrum disorder (ASD). We know that the prevalence has been increasing dramatically, but we aren’t quite sure whether that is because of more screening and awareness or more fundamental changes. We know that much of the risk appears to be genetic, but there may be 1,000 genes involved in the syndrome. We know that certain environmental exposures, like pollution, might increase the risk – perhaps on a susceptible genetic background – but we’re not really sure which exposures are most harmful.

So, the search continues, across all domains of inquiry from cell culture to large epidemiologic analyses. And this week, a new player enters the field, and, as they say, it’s something in the water.

We’re talking about this paper, by Zeyan Liew and colleagues, appearing in JAMA Pediatrics.

Using the incredibly robust health data infrastructure in Denmark, the researchers were able to identify 8,842 children born between 2000 and 2013 with ASD and matched each one to five control kids of the same sex and age without autism.

They then mapped the location the mothers of these kids lived while they were pregnant – down to 5 meters resolution, actually – to groundwater lithium levels.

Once that was done, the analysis was straightforward. Would moms who were pregnant in areas with higher groundwater lithium levels be more likely to have kids with ASD?

The results show a rather steady and consistent association between higher lithium levels in groundwater and the prevalence of ASD in children.

We’re not talking huge numbers, but moms who lived in the areas of the highest quartile of lithium were about 46% more likely to have a child with ASD. That’s a relative risk, of course – this would be like an increase from 1 in 100 kids to 1.5 in 100 kids. But still, it’s intriguing.

But the case is far from closed here.

Groundwater concentration of lithium and the amount of lithium a pregnant mother ingests are not the same thing. It does turn out that virtually all drinking water in Denmark comes from groundwater sources – but not all lithium comes from drinking water. There are plenty of dietary sources of lithium as well. And, of course, there is medical lithium, but we’ll get to that in a second.

First, let’s talk about those lithium measurements. They were taken in 2013 – after all these kids were born. The authors acknowledge this limitation but show a high correlation between measured levels in 2013 and earlier measured levels from prior studies, suggesting that lithium levels in a given area are quite constant over time. That’s great – but if lithium levels are constant over time, this study does nothing to shed light on why autism diagnoses seem to be increasing.

Let’s put some numbers to the lithium concentrations the authors examined. The average was about 12 mcg/L.

As a reminder, a standard therapeutic dose of lithium used for bipolar disorder is like 600 mg. That means you’d need to drink more than 2,500 of those 5-gallon jugs that sit on your water cooler, per day, to approximate the dose you’d get from a lithium tablet. Of course, small doses can still cause toxicity – but I wanted to put this in perspective.

Also, we have some data on pregnant women who take medical lithium. An analysis of nine studies showed that first-trimester lithium use may be associated with congenital malformations – particularly some specific heart malformations – and some birth complications. But three of four separate studies looking at longer-term neurodevelopmental outcomes did not find any effect on development, attainment of milestones, or IQ. One study of 15 kids exposed to medical lithium in utero did note minor neurologic dysfunction in one child and a low verbal IQ in another – but that’s a very small study.

Of course, lithium levels vary around the world as well. The U.S. Geological Survey examined lithium content in groundwater in the United States, as you can see here.

Our numbers are pretty similar to Denmark’s – in the 0-60 range. But an area in the Argentine Andes has levels as high as 1,600 mcg/L. A study of 194 babies from that area found higher lithium exposure was associated with lower fetal size, but I haven’t seen follow-up on neurodevelopmental outcomes.

The point is that there is a lot of variability here. It would be really interesting to map groundwater lithium levels to autism rates around the world. As a teaser, I will point out that, if you look at worldwide autism rates, you may be able to convince yourself that they are higher in more arid climates, and arid climates tend to have more groundwater lithium. But I’m really reaching here. More work needs to be done.

And I hope it is done quickly. Lithium is in the midst of becoming a very important commodity thanks to the shift to electric vehicles. While we can hope that recycling will claim most of those batteries at the end of their life, some will escape reclamation and potentially put more lithium into the drinking water. I’d like to know how risky that is before it happens.

F. Perry Wilson, MD, MSCE, is an associate professor of medicine and director of Yale’s Clinical and Translational Research Accelerator. He has disclosed no relevant financial relationships. His science communication work can be found in the Huffington Post, on NPR, and here on Medscape. He tweets @fperrywilson and his new book, “How Medicine Works and When It Doesn’t”, is available now.

A version of this article originally appeared on Medscape.com.

Autism rates trending upwards, CDC reports

Childhood autism rates have ticked up once again, according to the latest data from Centers for Disease Control and Prevention.

According to the CDC, 1 in 36 (2.8%) 8-year-old children have been identified with autism spectrum disorder (ASD) – up from the previous 2018 estimate of 1 in 44 (2.3%).

The updated data come from 11 communities in the Autism and Developmental Disabilities Monitoring (ADDM) network and were published online in Morbidity and Mortality Weekly Report.

A separate report in the MMWR on 4-year-old children in the same 11 communities highlights the impact of COVID-19, showing disruptions in progress in early autism detection.

In the early months of the pandemic, 4-year-old children were less likely to have an evaluation or be identified with ASD than 8-year-old children when they were the same age. This coincides with interruptions in childcare and health care services during the COVID-19 pandemic.

“Disruptions due to the pandemic in the timely evaluation of children and delays in connecting children to the services and support they need could have long-lasting effects,” Karen Remley, MD, director of CDC’s National Center on Birth Defects and Developmental Disabilities, said in a statement.

“The data in this report can help communities better understand how the pandemic impacted early identification of autism in young children and anticipate future needs as these children get older,” Dr. Remley noted.

Shifting demographics

The latest data also show that ASD prevalence among Asian, Black, and Hispanic children was at least 30% higher in 2020 than in 2018, and ASD prevalence among White children was 14.6% higher than in 2018.

For the first time, according to the CDC, the percentage of 8-year-old Asian/Pacific Islander (3.3%), Hispanic (3.2%) and Black (2.9%) children identified with autism was higher than the percentage of 8-year-old White children (2.4%).

This is the opposite of racial and ethnic differences seen in previous ADDM reports for 8-year-olds. These shifts may reflect improved screening, awareness, and access to services among historically underserved groups, the CDC said.

Disparities for co-occurring intellectual disability have also persisted, with a higher percentage of Black children with autism identified with intellectual disability compared with White, Hispanic, or Asian/Pacific Islander children with autism. These differences could relate in part to access to services that diagnose and support children with autism, the CDC noted.

Overall, autism prevalence within the 11 ADDM communities was nearly four times higher for boys than girls. However, it’s the first time that the prevalence of autism among 8-year-old girls has topped 1%.

Community differences

Autism prevalence in the 11 ADDM communities ranged from 1 in 43 (2.3%) children in Maryland to 1 in 22 (4.5%) in California – variations that could be due to how communities identify children with autism.

This variability affords an opportunity to compare local policies and models for delivering diagnostic and interventional services that could enhance autism identification and provide more comprehensive support to people with autism, the CDC said.

A version of this article first appeared on Medscape.com.

Childhood autism rates have ticked up once again, according to the latest data from Centers for Disease Control and Prevention.

According to the CDC, 1 in 36 (2.8%) 8-year-old children have been identified with autism spectrum disorder (ASD) – up from the previous 2018 estimate of 1 in 44 (2.3%).

The updated data come from 11 communities in the Autism and Developmental Disabilities Monitoring (ADDM) network and were published online in Morbidity and Mortality Weekly Report.

A separate report in the MMWR on 4-year-old children in the same 11 communities highlights the impact of COVID-19, showing disruptions in progress in early autism detection.

In the early months of the pandemic, 4-year-old children were less likely to have an evaluation or be identified with ASD than 8-year-old children when they were the same age. This coincides with interruptions in childcare and health care services during the COVID-19 pandemic.

“Disruptions due to the pandemic in the timely evaluation of children and delays in connecting children to the services and support they need could have long-lasting effects,” Karen Remley, MD, director of CDC’s National Center on Birth Defects and Developmental Disabilities, said in a statement.

“The data in this report can help communities better understand how the pandemic impacted early identification of autism in young children and anticipate future needs as these children get older,” Dr. Remley noted.

Shifting demographics

The latest data also show that ASD prevalence among Asian, Black, and Hispanic children was at least 30% higher in 2020 than in 2018, and ASD prevalence among White children was 14.6% higher than in 2018.

For the first time, according to the CDC, the percentage of 8-year-old Asian/Pacific Islander (3.3%), Hispanic (3.2%) and Black (2.9%) children identified with autism was higher than the percentage of 8-year-old White children (2.4%).

This is the opposite of racial and ethnic differences seen in previous ADDM reports for 8-year-olds. These shifts may reflect improved screening, awareness, and access to services among historically underserved groups, the CDC said.

Disparities for co-occurring intellectual disability have also persisted, with a higher percentage of Black children with autism identified with intellectual disability compared with White, Hispanic, or Asian/Pacific Islander children with autism. These differences could relate in part to access to services that diagnose and support children with autism, the CDC noted.

Overall, autism prevalence within the 11 ADDM communities was nearly four times higher for boys than girls. However, it’s the first time that the prevalence of autism among 8-year-old girls has topped 1%.

Community differences

Autism prevalence in the 11 ADDM communities ranged from 1 in 43 (2.3%) children in Maryland to 1 in 22 (4.5%) in California – variations that could be due to how communities identify children with autism.

This variability affords an opportunity to compare local policies and models for delivering diagnostic and interventional services that could enhance autism identification and provide more comprehensive support to people with autism, the CDC said.

A version of this article first appeared on Medscape.com.

Childhood autism rates have ticked up once again, according to the latest data from Centers for Disease Control and Prevention.

According to the CDC, 1 in 36 (2.8%) 8-year-old children have been identified with autism spectrum disorder (ASD) – up from the previous 2018 estimate of 1 in 44 (2.3%).

The updated data come from 11 communities in the Autism and Developmental Disabilities Monitoring (ADDM) network and were published online in Morbidity and Mortality Weekly Report.

A separate report in the MMWR on 4-year-old children in the same 11 communities highlights the impact of COVID-19, showing disruptions in progress in early autism detection.

In the early months of the pandemic, 4-year-old children were less likely to have an evaluation or be identified with ASD than 8-year-old children when they were the same age. This coincides with interruptions in childcare and health care services during the COVID-19 pandemic.

“Disruptions due to the pandemic in the timely evaluation of children and delays in connecting children to the services and support they need could have long-lasting effects,” Karen Remley, MD, director of CDC’s National Center on Birth Defects and Developmental Disabilities, said in a statement.

“The data in this report can help communities better understand how the pandemic impacted early identification of autism in young children and anticipate future needs as these children get older,” Dr. Remley noted.

Shifting demographics

The latest data also show that ASD prevalence among Asian, Black, and Hispanic children was at least 30% higher in 2020 than in 2018, and ASD prevalence among White children was 14.6% higher than in 2018.

For the first time, according to the CDC, the percentage of 8-year-old Asian/Pacific Islander (3.3%), Hispanic (3.2%) and Black (2.9%) children identified with autism was higher than the percentage of 8-year-old White children (2.4%).

This is the opposite of racial and ethnic differences seen in previous ADDM reports for 8-year-olds. These shifts may reflect improved screening, awareness, and access to services among historically underserved groups, the CDC said.

Disparities for co-occurring intellectual disability have also persisted, with a higher percentage of Black children with autism identified with intellectual disability compared with White, Hispanic, or Asian/Pacific Islander children with autism. These differences could relate in part to access to services that diagnose and support children with autism, the CDC noted.

Overall, autism prevalence within the 11 ADDM communities was nearly four times higher for boys than girls. However, it’s the first time that the prevalence of autism among 8-year-old girls has topped 1%.

Community differences

Autism prevalence in the 11 ADDM communities ranged from 1 in 43 (2.3%) children in Maryland to 1 in 22 (4.5%) in California – variations that could be due to how communities identify children with autism.

This variability affords an opportunity to compare local policies and models for delivering diagnostic and interventional services that could enhance autism identification and provide more comprehensive support to people with autism, the CDC said.

A version of this article first appeared on Medscape.com.

COVID in pregnancy may affect boys’ neurodevelopment: Study

Boys born to mothers infected with SARS‐CoV‐2 during pregnancy may be more likely to receive a diagnosis of a neurodevelopmental disorder by age 12 months, according to new research.

Andrea G. Edlow, MD, MSc, with Massachusetts General Hospital and Harvard Medical School in Boston, and colleagues examined data from 18,355 births between March 1, 2020, and May 31, 2021, at eight hospitals across two health systems in Massachusetts.

Of these births, 883 (4.8%) were to individuals who tested positive for SARS‐CoV‐2 during pregnancy. Among the children exposed to SARS‐CoV‐2 in the womb, 26 (3%) received a neurodevelopmental diagnosis, including disorders of motor function, speech and language, and psychological development, by age 1 year. In the group unexposed to the virus, 1.8% received such a diagnosis.

After adjusting for factors such as race, insurance, maternal age, and preterm birth, Dr. Edlow’s group found that a positive test for SARS-CoV-2 during pregnancy was associated with an increased risk for neurodevelopmental diagnoses at 12 months among boys (adjusted odds ratio, 1.94; 95% confidence interval, 1.12-3.17; P = .01), but not among girls.

In a subset of children with data available at 18 months, the correlation among boys at that age was less pronounced and not statistically significant (aOR, 1.42; 95% CI, 0.92-2.11; P = .10).

The findings were published online in JAMA Network Open

Prior epidemiological research has suggested that maternal infection during pregnancy is associated with heightened risk for a range of neurodevelopmental disorders, including autism and schizophrenia, in offspring, the authors wrote.

“The neurodevelopmental risk associated with maternal SARS-CoV-2 infection was disproportionately high in male infants, consistent with the known increased vulnerability of males in the face of prenatal adverse exposures,” Dr. Edlow said in a news release about the findings.

Larger studies and longer follow‐up are needed to confirm and reliably estimate the risk, the researchers said.

“It is not clear that the changes we can detect at 12 and 18 months will be indicative of persistent risks for disorders such as autism spectrum disorder, intellectual disability, or schizophrenia,” they write.

New data published online by the Centers for Disease Control and Prevention show that in 11 communities in 2020, 1 in 36 (2.8%) 8-year-old children had been identified with autism spectrum disorder, an increase from 2.3% in 2018. The data also show that the early months of the pandemic may have disrupted autism detection efforts among 4-year-olds.

The investigators were supported by grants from the National Institutes of Health and the Simons Foundation Autism Research Initiative. Coauthors disclosed consulting for or receiving personal fees from biotechnology and pharmaceutical companies.

A version of this article first appeared on Medscape.com.

Boys born to mothers infected with SARS‐CoV‐2 during pregnancy may be more likely to receive a diagnosis of a neurodevelopmental disorder by age 12 months, according to new research.

Andrea G. Edlow, MD, MSc, with Massachusetts General Hospital and Harvard Medical School in Boston, and colleagues examined data from 18,355 births between March 1, 2020, and May 31, 2021, at eight hospitals across two health systems in Massachusetts.

Of these births, 883 (4.8%) were to individuals who tested positive for SARS‐CoV‐2 during pregnancy. Among the children exposed to SARS‐CoV‐2 in the womb, 26 (3%) received a neurodevelopmental diagnosis, including disorders of motor function, speech and language, and psychological development, by age 1 year. In the group unexposed to the virus, 1.8% received such a diagnosis.

After adjusting for factors such as race, insurance, maternal age, and preterm birth, Dr. Edlow’s group found that a positive test for SARS-CoV-2 during pregnancy was associated with an increased risk for neurodevelopmental diagnoses at 12 months among boys (adjusted odds ratio, 1.94; 95% confidence interval, 1.12-3.17; P = .01), but not among girls.

In a subset of children with data available at 18 months, the correlation among boys at that age was less pronounced and not statistically significant (aOR, 1.42; 95% CI, 0.92-2.11; P = .10).

The findings were published online in JAMA Network Open

Prior epidemiological research has suggested that maternal infection during pregnancy is associated with heightened risk for a range of neurodevelopmental disorders, including autism and schizophrenia, in offspring, the authors wrote.

“The neurodevelopmental risk associated with maternal SARS-CoV-2 infection was disproportionately high in male infants, consistent with the known increased vulnerability of males in the face of prenatal adverse exposures,” Dr. Edlow said in a news release about the findings.

Larger studies and longer follow‐up are needed to confirm and reliably estimate the risk, the researchers said.

“It is not clear that the changes we can detect at 12 and 18 months will be indicative of persistent risks for disorders such as autism spectrum disorder, intellectual disability, or schizophrenia,” they write.

New data published online by the Centers for Disease Control and Prevention show that in 11 communities in 2020, 1 in 36 (2.8%) 8-year-old children had been identified with autism spectrum disorder, an increase from 2.3% in 2018. The data also show that the early months of the pandemic may have disrupted autism detection efforts among 4-year-olds.

The investigators were supported by grants from the National Institutes of Health and the Simons Foundation Autism Research Initiative. Coauthors disclosed consulting for or receiving personal fees from biotechnology and pharmaceutical companies.

A version of this article first appeared on Medscape.com.

Boys born to mothers infected with SARS‐CoV‐2 during pregnancy may be more likely to receive a diagnosis of a neurodevelopmental disorder by age 12 months, according to new research.

Andrea G. Edlow, MD, MSc, with Massachusetts General Hospital and Harvard Medical School in Boston, and colleagues examined data from 18,355 births between March 1, 2020, and May 31, 2021, at eight hospitals across two health systems in Massachusetts.

Of these births, 883 (4.8%) were to individuals who tested positive for SARS‐CoV‐2 during pregnancy. Among the children exposed to SARS‐CoV‐2 in the womb, 26 (3%) received a neurodevelopmental diagnosis, including disorders of motor function, speech and language, and psychological development, by age 1 year. In the group unexposed to the virus, 1.8% received such a diagnosis.

After adjusting for factors such as race, insurance, maternal age, and preterm birth, Dr. Edlow’s group found that a positive test for SARS-CoV-2 during pregnancy was associated with an increased risk for neurodevelopmental diagnoses at 12 months among boys (adjusted odds ratio, 1.94; 95% confidence interval, 1.12-3.17; P = .01), but not among girls.

In a subset of children with data available at 18 months, the correlation among boys at that age was less pronounced and not statistically significant (aOR, 1.42; 95% CI, 0.92-2.11; P = .10).

The findings were published online in JAMA Network Open

Prior epidemiological research has suggested that maternal infection during pregnancy is associated with heightened risk for a range of neurodevelopmental disorders, including autism and schizophrenia, in offspring, the authors wrote.

“The neurodevelopmental risk associated with maternal SARS-CoV-2 infection was disproportionately high in male infants, consistent with the known increased vulnerability of males in the face of prenatal adverse exposures,” Dr. Edlow said in a news release about the findings.

Larger studies and longer follow‐up are needed to confirm and reliably estimate the risk, the researchers said.

“It is not clear that the changes we can detect at 12 and 18 months will be indicative of persistent risks for disorders such as autism spectrum disorder, intellectual disability, or schizophrenia,” they write.

New data published online by the Centers for Disease Control and Prevention show that in 11 communities in 2020, 1 in 36 (2.8%) 8-year-old children had been identified with autism spectrum disorder, an increase from 2.3% in 2018. The data also show that the early months of the pandemic may have disrupted autism detection efforts among 4-year-olds.

The investigators were supported by grants from the National Institutes of Health and the Simons Foundation Autism Research Initiative. Coauthors disclosed consulting for or receiving personal fees from biotechnology and pharmaceutical companies.

A version of this article first appeared on Medscape.com.

FROM JAMA NETWORK OPEN

Children with ASD less likely to get vision screening

Children with autism spectrum disorder (ASD) are significantly less likely to have vision screening at well visits for 3- to 5-year-olds than are typically developing children, researchers have found.

The report, by Kimberly Hoover, MD, of Thomas Jefferson University in Philadelphia, and colleagues, was published online in Pediatrics.

While 59.9% of children without ASD got vision screening in these visits, only 36.5% of children with ASD got the screening. Both screening rates miss the mark set by American Academy of Pediatrics guidelines.

The AAP recommends “annual instrument-based vision screening, if available, at well visits for children starting at age 12 months to 3 years, and direct visual acuity testing beginning at 4 years of age. However, in children with developmental delays, the AAP recommends instrument-based screening, such as photoscreening, as a useful alternative at any age.”

Racial, age disparities as well

Racial disparities were evident in the data as well. Of the children who had ASD, Black children had the lowest rates of screening (27.6%), while the rate for White children was 39.7%. The rate for other/multiracial children with ASD was 39.8%.

The lowest rates of screening occurred in the youngest children, at the 3-year visit.

The researchers analyzed data from 63,829 well-child visits between January 2016 and December 2019, collected from the large primary care database PEDSnet.

Photoscreening vs. acuity screening

The authors pointed out that children with ASD are less likely to complete a vision test, which can be problematic in a busy primary care office.

“Children with ASD were significantly less likely to have at least one completed vision screening (43.2%) compared with children without ASD (72.1%; P <. 01),” the authors wrote, “with only 6.9% of children with ASD having had two or more vision screenings compared with 22.3% of children without ASD.”

The researchers saw higher vision test completion rates with photoscreening, using a sophisticated camera, compared with acuity screening, which uses a wall chart and requires responses.

Less patient participation is required for photoscreening and it can be done in less than 2 minutes.

If ability to complete the vision tests is a concern, the authors wrote, photoscreening may be a better solution.

Photoscreening takes 90 seconds

“Photoscreening has high sensitivity in detecting ocular conditions in children with ASD and has an average screening time of 90 seconds, and [it has] been validated in both children with ASD and developmental delays,” the authors wrote.

Andrew Adesman, MD, chief of developmental and behavioral pediatrics at Cohen Children’s Medical Center in New Hyde Park, N.Y., said the authors of this study quantify the gap between need and reality for vision tests for those with ASD.

“Other studies have shown that children on the autism spectrum have more than three times greater risk of having eye disease or vision problems,” he said in an interview. “You’ve got a high-risk population in need of assessment and the likelihood of them getting an assessment is much reduced.”

He said in addition to attention problems in taking the test, vision screening may get lost in the plethora of concerns parents want to talk about in well-child visits.

“If you’re the parent of a child with developmental delays, language delays, poor social engagement, there are a multitude of things the visit could be focused on and it may be that vision screening possibly gets compromised or not done,” Dr. Adesman said.

That, he said, may be a focus area for improving the screening numbers.

Neither parents nor providers should forget that vision screening is important, despite the myriad other issues to address, he said. “They don’t have to take a long time.”

When it comes to vision problems and children, “the earlier they’re identified the better,” Dr. Adesman says, particularly to identify the need for eye muscle surgery or corrective lenses, the two major interventions for strabismus or refractive error.

“If those problems are significant and go untreated, there’s a risk of loss of vision in the affected eye,” he said.

Reimbursement concerns for photoscreening

This study strongly supports the use of routine photoscreening to help eliminate the vision screening gap in children with ASD, the authors wrote.

They noted, however, that would require insurance reimbursement for primary care practices to effectively use that screening.

The researchers advised, “Providers treating patients with race, ethnicity, region, or age categories that reduce the adjusted odds of photoscreening can take steps in their practices to address these disparities, particularly in children with ASD.”

The study authors and Dr. Adesman reported no relevant financial relationships.

Children with autism spectrum disorder (ASD) are significantly less likely to have vision screening at well visits for 3- to 5-year-olds than are typically developing children, researchers have found.

The report, by Kimberly Hoover, MD, of Thomas Jefferson University in Philadelphia, and colleagues, was published online in Pediatrics.

While 59.9% of children without ASD got vision screening in these visits, only 36.5% of children with ASD got the screening. Both screening rates miss the mark set by American Academy of Pediatrics guidelines.

The AAP recommends “annual instrument-based vision screening, if available, at well visits for children starting at age 12 months to 3 years, and direct visual acuity testing beginning at 4 years of age. However, in children with developmental delays, the AAP recommends instrument-based screening, such as photoscreening, as a useful alternative at any age.”

Racial, age disparities as well

Racial disparities were evident in the data as well. Of the children who had ASD, Black children had the lowest rates of screening (27.6%), while the rate for White children was 39.7%. The rate for other/multiracial children with ASD was 39.8%.

The lowest rates of screening occurred in the youngest children, at the 3-year visit.

The researchers analyzed data from 63,829 well-child visits between January 2016 and December 2019, collected from the large primary care database PEDSnet.

Photoscreening vs. acuity screening

The authors pointed out that children with ASD are less likely to complete a vision test, which can be problematic in a busy primary care office.

“Children with ASD were significantly less likely to have at least one completed vision screening (43.2%) compared with children without ASD (72.1%; P <. 01),” the authors wrote, “with only 6.9% of children with ASD having had two or more vision screenings compared with 22.3% of children without ASD.”

The researchers saw higher vision test completion rates with photoscreening, using a sophisticated camera, compared with acuity screening, which uses a wall chart and requires responses.

Less patient participation is required for photoscreening and it can be done in less than 2 minutes.

If ability to complete the vision tests is a concern, the authors wrote, photoscreening may be a better solution.

Photoscreening takes 90 seconds

“Photoscreening has high sensitivity in detecting ocular conditions in children with ASD and has an average screening time of 90 seconds, and [it has] been validated in both children with ASD and developmental delays,” the authors wrote.

Andrew Adesman, MD, chief of developmental and behavioral pediatrics at Cohen Children’s Medical Center in New Hyde Park, N.Y., said the authors of this study quantify the gap between need and reality for vision tests for those with ASD.

“Other studies have shown that children on the autism spectrum have more than three times greater risk of having eye disease or vision problems,” he said in an interview. “You’ve got a high-risk population in need of assessment and the likelihood of them getting an assessment is much reduced.”

He said in addition to attention problems in taking the test, vision screening may get lost in the plethora of concerns parents want to talk about in well-child visits.

“If you’re the parent of a child with developmental delays, language delays, poor social engagement, there are a multitude of things the visit could be focused on and it may be that vision screening possibly gets compromised or not done,” Dr. Adesman said.

That, he said, may be a focus area for improving the screening numbers.

Neither parents nor providers should forget that vision screening is important, despite the myriad other issues to address, he said. “They don’t have to take a long time.”

When it comes to vision problems and children, “the earlier they’re identified the better,” Dr. Adesman says, particularly to identify the need for eye muscle surgery or corrective lenses, the two major interventions for strabismus or refractive error.

“If those problems are significant and go untreated, there’s a risk of loss of vision in the affected eye,” he said.

Reimbursement concerns for photoscreening

This study strongly supports the use of routine photoscreening to help eliminate the vision screening gap in children with ASD, the authors wrote.

They noted, however, that would require insurance reimbursement for primary care practices to effectively use that screening.

The researchers advised, “Providers treating patients with race, ethnicity, region, or age categories that reduce the adjusted odds of photoscreening can take steps in their practices to address these disparities, particularly in children with ASD.”

The study authors and Dr. Adesman reported no relevant financial relationships.

Children with autism spectrum disorder (ASD) are significantly less likely to have vision screening at well visits for 3- to 5-year-olds than are typically developing children, researchers have found.

The report, by Kimberly Hoover, MD, of Thomas Jefferson University in Philadelphia, and colleagues, was published online in Pediatrics.

While 59.9% of children without ASD got vision screening in these visits, only 36.5% of children with ASD got the screening. Both screening rates miss the mark set by American Academy of Pediatrics guidelines.

The AAP recommends “annual instrument-based vision screening, if available, at well visits for children starting at age 12 months to 3 years, and direct visual acuity testing beginning at 4 years of age. However, in children with developmental delays, the AAP recommends instrument-based screening, such as photoscreening, as a useful alternative at any age.”

Racial, age disparities as well

Racial disparities were evident in the data as well. Of the children who had ASD, Black children had the lowest rates of screening (27.6%), while the rate for White children was 39.7%. The rate for other/multiracial children with ASD was 39.8%.

The lowest rates of screening occurred in the youngest children, at the 3-year visit.

The researchers analyzed data from 63,829 well-child visits between January 2016 and December 2019, collected from the large primary care database PEDSnet.

Photoscreening vs. acuity screening

The authors pointed out that children with ASD are less likely to complete a vision test, which can be problematic in a busy primary care office.

“Children with ASD were significantly less likely to have at least one completed vision screening (43.2%) compared with children without ASD (72.1%; P <. 01),” the authors wrote, “with only 6.9% of children with ASD having had two or more vision screenings compared with 22.3% of children without ASD.”

The researchers saw higher vision test completion rates with photoscreening, using a sophisticated camera, compared with acuity screening, which uses a wall chart and requires responses.

Less patient participation is required for photoscreening and it can be done in less than 2 minutes.

If ability to complete the vision tests is a concern, the authors wrote, photoscreening may be a better solution.

Photoscreening takes 90 seconds

“Photoscreening has high sensitivity in detecting ocular conditions in children with ASD and has an average screening time of 90 seconds, and [it has] been validated in both children with ASD and developmental delays,” the authors wrote.

Andrew Adesman, MD, chief of developmental and behavioral pediatrics at Cohen Children’s Medical Center in New Hyde Park, N.Y., said the authors of this study quantify the gap between need and reality for vision tests for those with ASD.

“Other studies have shown that children on the autism spectrum have more than three times greater risk of having eye disease or vision problems,” he said in an interview. “You’ve got a high-risk population in need of assessment and the likelihood of them getting an assessment is much reduced.”

He said in addition to attention problems in taking the test, vision screening may get lost in the plethora of concerns parents want to talk about in well-child visits.

“If you’re the parent of a child with developmental delays, language delays, poor social engagement, there are a multitude of things the visit could be focused on and it may be that vision screening possibly gets compromised or not done,” Dr. Adesman said.

That, he said, may be a focus area for improving the screening numbers.

Neither parents nor providers should forget that vision screening is important, despite the myriad other issues to address, he said. “They don’t have to take a long time.”

When it comes to vision problems and children, “the earlier they’re identified the better,” Dr. Adesman says, particularly to identify the need for eye muscle surgery or corrective lenses, the two major interventions for strabismus or refractive error.

“If those problems are significant and go untreated, there’s a risk of loss of vision in the affected eye,” he said.

Reimbursement concerns for photoscreening

This study strongly supports the use of routine photoscreening to help eliminate the vision screening gap in children with ASD, the authors wrote.

They noted, however, that would require insurance reimbursement for primary care practices to effectively use that screening.

The researchers advised, “Providers treating patients with race, ethnicity, region, or age categories that reduce the adjusted odds of photoscreening can take steps in their practices to address these disparities, particularly in children with ASD.”

The study authors and Dr. Adesman reported no relevant financial relationships.

FROM PEDIATRICS

Once-daily stimulant for ADHD safe, effective at 1 year

new research shows.

Results from a phase 3, multicenter, dose-optimization, open-label safety study of Azstarys (KemPharm) found that most treatment-emergent adverse events (TEAEs) were mild to moderate.

“This data show that Azstarys remains safe and effective for the treatment of ADHD when given for up to a year,” lead investigator Ann Childress, MD, president of the Center for Psychiatry and Behavioral Medicine, Las Vegas, said in an interview.

The study was published online in the Journal of Child and Adolescent Psychopharmacology.

Safety at 1 year

The drug is a combination of extended-release serdexmethylphenidate (SDX), KemPharm’s prodrug of dexmethylphenidate, coformulated with immediate-release d-MPH.

SDX is converted to d-MPH after it is absorbed in the gastrointestinal tract. The d-MPH is released gradually throughout the day, providing quick symptom control with the d-MPH and extended control with SDX.

Azstarys was approved by the Food and Drug Administration in 2021 on the basis of results from a laboratory classroom phase 3 trial, which showed significant improvement in ADHD symptoms, compared with placebo.

For this study, the second phase 3 trial of Azstarys, investigators analyzed data from 282 children aged 6-12 years in the United States, including 70 who participated in an earlier 1-month efficacy trial.

After screening and a 3-week dose-optimization phase for new participants, patients received once-daily treatment with doses of 26.1 mg/5.2 mg, 39.2 mg/7.8 mg, or 52.3 mg/10.4 mg of SDX/d-MPH.

After 1 year of treatment, 60.1% of participants reported at least one TEAE, the majority of which were moderate. Twelve patients reported severe TEAEs. Six children (2.5%) discontinued the study because of a TEAE during the treatment phase.

The investigators also measured growth and changes in sleep with the Children’s Sleep Habits Questionnaire during the 12-month study. Sleep improved on most measures and the impact on growth was mild.

There were no life-threatening TEAEs and no deaths reported during the study.

The most common TEAEs during the treatment phase were decreased appetite, upper respiratory tract infection, nasopharyngitis, decreased weight, irritability, and increased weight.

Efficacy at 1 year

ADHD symptoms improved considerably after 1 month of treatment, with responses continuing at 1 year.

At baseline, participants’ mean ADHD Rating Scale–5 score was 41.5. After 1 month of treatment, scores averaged 16.1, a decline of –25.3 (P < .001).

The mean score stabilized in the 12-15 range for the remainder of the study. After 1 year of treatment, ADHD symptoms had decreased approximately 70% from baseline.

Investigators found similar results in clinical severity. After 1 month of treatment, the average Clinical Global Impressions–Severity (CGI-S) scale score was 2.5, a decline of –2.2 (P < .0001).

CGI-S scale scores remained in the 2.2-2.4 range for the remainder of the study.

These results, combined with the results of the original classroom trial, suggest Azstarys may offer advantages over other ADHD drugs, Dr. Childress said.

“In the laboratory classroom trial, subjects taking Azstarys completed significantly more math problems than subjects taking placebo beginning at 30 minutes and up to 13 hours after dosing,” Dr. Childress said. “No other methylphenidate extended-release product currently marketed in the United States has a 13-hour duration of effect.”

‘Reassuring data’

Commenting on the findings, Aditya Pawar, MD, a child and adolescent psychiatrist with the Kennedy Krieger Institute and an assistant professor of psychiatry and behavioral sciences at Johns Hopkins University, Baltimore, said that the study suggests the drug may be a valuable addition to ADHD treatment options for pediatric patients.

“The study provides reassuring data on the safety of stimulants in patients without significant history of cardiac events or blood pressure changes, which are usual concerns among patients and clinicians despite the evidence supporting safety, said Dr. Pawar, who was not part of the study.

“Additionally, the 1-year data on efficacy and safety of a new stimulant medication is valuable for clinicians looking for sustained relief for their patients, despite the limitations of an open-label trial,” she added.

Overall, the safety data reported in the study are fairly consistent with the safety profile of other methylphenidates used for treating ADHD, Dr. Pawar said.

However, she noted, the study does have some limitations, including its open-label design and lack of blinding. The research also excluded children with autism, disruptive mood dysregulation disorders, and other common comorbidities of ADHD, which may limit the generalizability of the results.