User login

This Tech Will Change Your Practice Sooner Than You Think

Medical innovations don’t happen overnight — but in today’s digital world, they happen pretty fast. Some are advancing faster than you think.

1. Artificial Intelligence (AI) Medical Scribes

You may already be using this or, at the very least, have heard about it.

Physician burnout is a growing problem, with many doctors spending 2 hours on paperwork for every hour with patients. But some doctors, such as Gregory Ator, MD, chief medical informatics officer at the University of Kansas Medical Center, Kansas City, Kansas, have found a better way.

“I have been using it for 9 months now, and it truly is a life changer,” Dr. Ator said of Abridge, an AI helper that transcribes and summarizes his conversations with patients. “Now, I go into the room, place my phone just about anywhere, and I can just listen.” He estimated that the tech saves him between 3 and 10 minutes per patient. “At 20 patients a day, that saves me around 2 hours,” he said.

Bonus: Patients “get a doctor’s full attention instead of just looking at the top of his head while they play with the computer,” Dr. Ator said. “I have yet to have a patient who didn’t think that was a positive thing.”

Several companies are already selling these AI devices, including Ambience Healthcare, Augmedix, Nuance, and Suki, and they offer more than just transcriptions, said John D. Halamka, MD, president of Mayo Clinic Platform, who oversees Mayo’s adoption of AI. They also generate notes for treatment and billing and update data in the electronic health record.

“It’s preparation of documentation based on ambient listening of doctor-patient conversations,” Dr. Halamka explained. “I’m very optimistic about the use of emerging AI technologies to enable every clinician to practice at the top of their license.”

Patricia Garcia, MD, associate clinical information officer for ambulatory care at Stanford Health Care, has spent much of the last year co-running the medical center’s pilot program for AI scribes, and she’s so impressed with the technology that she “expects it’ll become more widely available as an option for any clinician that wants to use it in the next 12-18 months.”

2. Three-Dimensional (3D) Printing

Although 3D-printed organs may not happen anytime soon, the future is here for some 3D-printed prosthetics and implants — everything from dentures to spinal implants to prosthetic fingers and noses.

“In the next few years, I see rapid growth in the use of 3D printing technology across orthopedic surgery,” said Rishin J. Kadakia, MD, an orthopedic surgeon in Atlanta. “It’s becoming more common not just at large academic institutions. More and more providers will turn to using 3D printing technology to help tackle challenging cases that previously did not have good solutions.”

Dr. Kadakia has experienced this firsthand with his patients at the Emory Orthopaedics & Spine Center. One female patient developed talar avascular necrosis due to a bone break she’d sustained in a serious car crash. An ankle and subtalar joint fusion would repair the damage but limit her mobility and change her gait. So instead, in August of 2021, Dr. Kadakia and fellow orthopedic surgeon Jason Bariteau, MD, created for her a 3D-printed cobalt chrome talus implant.

“It provided an opportunity for her to keep her ankle’s range of motion, and also mobilize faster than with a subtalar and ankle joint fusion,” said Dr. Kadakia.

The technology is also playing a role in customized medical devices — patient-specific tools for greater precision — and 3D-printed anatomical models, built to the exact specifications of individual patients. Mayo Clinic already has 3D modeling units in three states, and other hospitals are following suit. The models not only help doctors prepare for complicated surgeries but also can dramatically cut down on costs. A 2021 study from Durham University reported that 3D models helped reduce surgery time by between 1.5 and 2.5 hours in lengthy procedures.

3. Drones

For patients who can’t make it to a pharmacy to pick up their prescriptions, either because of distance or lack of transportation, drones — which can deliver medications onto a customer’s back yard or front porch — offer a compelling solution.

Several companies and hospitals are already experimenting with drones, like WellSpan Health in Pennsylvania, Amazon Pharmacy, and the Cleveland Clinic, which announced a partnership with drone delivery company Zipline and plans to begin prescription deliveries across Northeast Ohio by 2025.

Healthcare systems are just beginning to explore the potential of drone deliveries, for everything from lab samples to medical and surgical supplies — even defibrillators that could arrive at an ailing patient’s front door before an emergency medical technician arrives.

“For many providers, when you take a sample from a patient, that sample waits around for hours until a courier picks up all of the facility’s samples and drives them to an outside facility for processing,” said Hillary Brendzel, head of Zipline’s US Healthcare Practice.

According to a 2022 survey from American Nurse Journal, 71% of nurses said that medical courier delays and errors negatively affected their ability to provide patient care. But with drone delivery, “lab samples can be sent for processing immediately, on-demand, resulting in faster diagnosis, treatment, and ultimately better outcomes,” said Ms. Brendzel.

4. Portable Ultrasound

Within the next 2 years, portable ultrasound — pocket-sized devices that connect to a smartphone or tablet — will become the “21st-century stethoscope,” said Abhilash Hareendranathan, PhD, assistant professor in the Department of Radiology and Diagnostic Imaging at the University of Alberta, in Edmonton, Alberta, Canada.

AI can make these devices easy to use, allowing clinicians with minimal imaging training to capture clear images and understand the results. Dr. Hareendranathan developed the Ultrasound Arm Injury Detection tool, a portable ultrasound that uses AI to detect fracture.

“We plan to introduce this technology in emergency departments, where it could be used by triage nurses to perform quick examinations to detect fractures of the wrist, elbow, or shoulder,” he said.

More pocket-sized scanners like these could “reshape the way diagnostic care is provided in rural and remote communities,” Dr. Hareendranathan said, and will “reduce wait times in crowded emergency departments.” Bill Gates believes enough in portable ultrasound that last September, the Bill & Melinda Gates Foundation granted $44 million to GE HealthCare to develop the technology for under-resourced communities.

5. Virtual Reality (VR)

When RelieVRx became the first US Food and Drug Administration (FDA)–approved VR therapy for chronic back pain in 2021, the technology was used in just a handful of Veterans Affairs (VA) facilities. But today, thousands of VR headsets have been deployed to more than 160 VA medical centers and clinics across the country.

“The VR experiences encompass pain neuroscience education, mindfulness, pleasant and relaxing distraction, and key skills to calm the nervous system,” said Beth Darnall, PhD, director of the Stanford Pain Relief Innovations Lab, who helped design the RelieVRx. She expects VR to go mainstream soon, not just because of increasing evidence that it works but also thanks to the Centers for Medicare & Medicaid Services, which recently issued a Healthcare Common Procedure Coding System code for VR. “This billing infrastructure will encourage adoption and uptake,” she said.

Hundreds of hospitals across the United States have already adopted the technology, for everything from childbirth pain to wound debridement, said Josh Sackman, the president and cofounder of AppliedVR, the company that developed RelieVRx.

“Over the next few years, we may see hundreds more deploy unique applications [for VR] that can handle multiple clinical indications,” he said. “Given the modality’s ability to scale and reduce reliance on pharmacological interventions, it has the power to improve the cost and quality of care.”

Hospital systems like Geisinger and Cedars-Sinai are already finding unique ways to implement the technology, he said, like using VR to reduce “scanxiety” during imaging service.

Other VR innovations are already being introduced, from the Smileyscope, a VR device for children that’s been proven to lessen the pain of a blood draw or intravenous insertion (it was cleared by the FDA last November) to several VR platforms launched by Cedars-Sinai in recent months, for applications that range from gastrointestinal issues to mental health therapy. “There may already be a thousand hospitals using VR in some capacity,” said Brennan Spiegel, MD, director of Health Services Research at Cedars-Sinai.

A version of this article appeared on Medscape.com.

Medical innovations don’t happen overnight — but in today’s digital world, they happen pretty fast. Some are advancing faster than you think.

1. Artificial Intelligence (AI) Medical Scribes

You may already be using this or, at the very least, have heard about it.

Physician burnout is a growing problem, with many doctors spending 2 hours on paperwork for every hour with patients. But some doctors, such as Gregory Ator, MD, chief medical informatics officer at the University of Kansas Medical Center, Kansas City, Kansas, have found a better way.

“I have been using it for 9 months now, and it truly is a life changer,” Dr. Ator said of Abridge, an AI helper that transcribes and summarizes his conversations with patients. “Now, I go into the room, place my phone just about anywhere, and I can just listen.” He estimated that the tech saves him between 3 and 10 minutes per patient. “At 20 patients a day, that saves me around 2 hours,” he said.

Bonus: Patients “get a doctor’s full attention instead of just looking at the top of his head while they play with the computer,” Dr. Ator said. “I have yet to have a patient who didn’t think that was a positive thing.”

Several companies are already selling these AI devices, including Ambience Healthcare, Augmedix, Nuance, and Suki, and they offer more than just transcriptions, said John D. Halamka, MD, president of Mayo Clinic Platform, who oversees Mayo’s adoption of AI. They also generate notes for treatment and billing and update data in the electronic health record.

“It’s preparation of documentation based on ambient listening of doctor-patient conversations,” Dr. Halamka explained. “I’m very optimistic about the use of emerging AI technologies to enable every clinician to practice at the top of their license.”

Patricia Garcia, MD, associate clinical information officer for ambulatory care at Stanford Health Care, has spent much of the last year co-running the medical center’s pilot program for AI scribes, and she’s so impressed with the technology that she “expects it’ll become more widely available as an option for any clinician that wants to use it in the next 12-18 months.”

2. Three-Dimensional (3D) Printing

Although 3D-printed organs may not happen anytime soon, the future is here for some 3D-printed prosthetics and implants — everything from dentures to spinal implants to prosthetic fingers and noses.

“In the next few years, I see rapid growth in the use of 3D printing technology across orthopedic surgery,” said Rishin J. Kadakia, MD, an orthopedic surgeon in Atlanta. “It’s becoming more common not just at large academic institutions. More and more providers will turn to using 3D printing technology to help tackle challenging cases that previously did not have good solutions.”

Dr. Kadakia has experienced this firsthand with his patients at the Emory Orthopaedics & Spine Center. One female patient developed talar avascular necrosis due to a bone break she’d sustained in a serious car crash. An ankle and subtalar joint fusion would repair the damage but limit her mobility and change her gait. So instead, in August of 2021, Dr. Kadakia and fellow orthopedic surgeon Jason Bariteau, MD, created for her a 3D-printed cobalt chrome talus implant.

“It provided an opportunity for her to keep her ankle’s range of motion, and also mobilize faster than with a subtalar and ankle joint fusion,” said Dr. Kadakia.

The technology is also playing a role in customized medical devices — patient-specific tools for greater precision — and 3D-printed anatomical models, built to the exact specifications of individual patients. Mayo Clinic already has 3D modeling units in three states, and other hospitals are following suit. The models not only help doctors prepare for complicated surgeries but also can dramatically cut down on costs. A 2021 study from Durham University reported that 3D models helped reduce surgery time by between 1.5 and 2.5 hours in lengthy procedures.

3. Drones

For patients who can’t make it to a pharmacy to pick up their prescriptions, either because of distance or lack of transportation, drones — which can deliver medications onto a customer’s back yard or front porch — offer a compelling solution.

Several companies and hospitals are already experimenting with drones, like WellSpan Health in Pennsylvania, Amazon Pharmacy, and the Cleveland Clinic, which announced a partnership with drone delivery company Zipline and plans to begin prescription deliveries across Northeast Ohio by 2025.

Healthcare systems are just beginning to explore the potential of drone deliveries, for everything from lab samples to medical and surgical supplies — even defibrillators that could arrive at an ailing patient’s front door before an emergency medical technician arrives.

“For many providers, when you take a sample from a patient, that sample waits around for hours until a courier picks up all of the facility’s samples and drives them to an outside facility for processing,” said Hillary Brendzel, head of Zipline’s US Healthcare Practice.

According to a 2022 survey from American Nurse Journal, 71% of nurses said that medical courier delays and errors negatively affected their ability to provide patient care. But with drone delivery, “lab samples can be sent for processing immediately, on-demand, resulting in faster diagnosis, treatment, and ultimately better outcomes,” said Ms. Brendzel.

4. Portable Ultrasound

Within the next 2 years, portable ultrasound — pocket-sized devices that connect to a smartphone or tablet — will become the “21st-century stethoscope,” said Abhilash Hareendranathan, PhD, assistant professor in the Department of Radiology and Diagnostic Imaging at the University of Alberta, in Edmonton, Alberta, Canada.

AI can make these devices easy to use, allowing clinicians with minimal imaging training to capture clear images and understand the results. Dr. Hareendranathan developed the Ultrasound Arm Injury Detection tool, a portable ultrasound that uses AI to detect fracture.

“We plan to introduce this technology in emergency departments, where it could be used by triage nurses to perform quick examinations to detect fractures of the wrist, elbow, or shoulder,” he said.

More pocket-sized scanners like these could “reshape the way diagnostic care is provided in rural and remote communities,” Dr. Hareendranathan said, and will “reduce wait times in crowded emergency departments.” Bill Gates believes enough in portable ultrasound that last September, the Bill & Melinda Gates Foundation granted $44 million to GE HealthCare to develop the technology for under-resourced communities.

5. Virtual Reality (VR)

When RelieVRx became the first US Food and Drug Administration (FDA)–approved VR therapy for chronic back pain in 2021, the technology was used in just a handful of Veterans Affairs (VA) facilities. But today, thousands of VR headsets have been deployed to more than 160 VA medical centers and clinics across the country.

“The VR experiences encompass pain neuroscience education, mindfulness, pleasant and relaxing distraction, and key skills to calm the nervous system,” said Beth Darnall, PhD, director of the Stanford Pain Relief Innovations Lab, who helped design the RelieVRx. She expects VR to go mainstream soon, not just because of increasing evidence that it works but also thanks to the Centers for Medicare & Medicaid Services, which recently issued a Healthcare Common Procedure Coding System code for VR. “This billing infrastructure will encourage adoption and uptake,” she said.

Hundreds of hospitals across the United States have already adopted the technology, for everything from childbirth pain to wound debridement, said Josh Sackman, the president and cofounder of AppliedVR, the company that developed RelieVRx.

“Over the next few years, we may see hundreds more deploy unique applications [for VR] that can handle multiple clinical indications,” he said. “Given the modality’s ability to scale and reduce reliance on pharmacological interventions, it has the power to improve the cost and quality of care.”

Hospital systems like Geisinger and Cedars-Sinai are already finding unique ways to implement the technology, he said, like using VR to reduce “scanxiety” during imaging service.

Other VR innovations are already being introduced, from the Smileyscope, a VR device for children that’s been proven to lessen the pain of a blood draw or intravenous insertion (it was cleared by the FDA last November) to several VR platforms launched by Cedars-Sinai in recent months, for applications that range from gastrointestinal issues to mental health therapy. “There may already be a thousand hospitals using VR in some capacity,” said Brennan Spiegel, MD, director of Health Services Research at Cedars-Sinai.

A version of this article appeared on Medscape.com.

Medical innovations don’t happen overnight — but in today’s digital world, they happen pretty fast. Some are advancing faster than you think.

1. Artificial Intelligence (AI) Medical Scribes

You may already be using this or, at the very least, have heard about it.

Physician burnout is a growing problem, with many doctors spending 2 hours on paperwork for every hour with patients. But some doctors, such as Gregory Ator, MD, chief medical informatics officer at the University of Kansas Medical Center, Kansas City, Kansas, have found a better way.

“I have been using it for 9 months now, and it truly is a life changer,” Dr. Ator said of Abridge, an AI helper that transcribes and summarizes his conversations with patients. “Now, I go into the room, place my phone just about anywhere, and I can just listen.” He estimated that the tech saves him between 3 and 10 minutes per patient. “At 20 patients a day, that saves me around 2 hours,” he said.

Bonus: Patients “get a doctor’s full attention instead of just looking at the top of his head while they play with the computer,” Dr. Ator said. “I have yet to have a patient who didn’t think that was a positive thing.”

Several companies are already selling these AI devices, including Ambience Healthcare, Augmedix, Nuance, and Suki, and they offer more than just transcriptions, said John D. Halamka, MD, president of Mayo Clinic Platform, who oversees Mayo’s adoption of AI. They also generate notes for treatment and billing and update data in the electronic health record.

“It’s preparation of documentation based on ambient listening of doctor-patient conversations,” Dr. Halamka explained. “I’m very optimistic about the use of emerging AI technologies to enable every clinician to practice at the top of their license.”

Patricia Garcia, MD, associate clinical information officer for ambulatory care at Stanford Health Care, has spent much of the last year co-running the medical center’s pilot program for AI scribes, and she’s so impressed with the technology that she “expects it’ll become more widely available as an option for any clinician that wants to use it in the next 12-18 months.”

2. Three-Dimensional (3D) Printing

Although 3D-printed organs may not happen anytime soon, the future is here for some 3D-printed prosthetics and implants — everything from dentures to spinal implants to prosthetic fingers and noses.

“In the next few years, I see rapid growth in the use of 3D printing technology across orthopedic surgery,” said Rishin J. Kadakia, MD, an orthopedic surgeon in Atlanta. “It’s becoming more common not just at large academic institutions. More and more providers will turn to using 3D printing technology to help tackle challenging cases that previously did not have good solutions.”

Dr. Kadakia has experienced this firsthand with his patients at the Emory Orthopaedics & Spine Center. One female patient developed talar avascular necrosis due to a bone break she’d sustained in a serious car crash. An ankle and subtalar joint fusion would repair the damage but limit her mobility and change her gait. So instead, in August of 2021, Dr. Kadakia and fellow orthopedic surgeon Jason Bariteau, MD, created for her a 3D-printed cobalt chrome talus implant.

“It provided an opportunity for her to keep her ankle’s range of motion, and also mobilize faster than with a subtalar and ankle joint fusion,” said Dr. Kadakia.

The technology is also playing a role in customized medical devices — patient-specific tools for greater precision — and 3D-printed anatomical models, built to the exact specifications of individual patients. Mayo Clinic already has 3D modeling units in three states, and other hospitals are following suit. The models not only help doctors prepare for complicated surgeries but also can dramatically cut down on costs. A 2021 study from Durham University reported that 3D models helped reduce surgery time by between 1.5 and 2.5 hours in lengthy procedures.

3. Drones

For patients who can’t make it to a pharmacy to pick up their prescriptions, either because of distance or lack of transportation, drones — which can deliver medications onto a customer’s back yard or front porch — offer a compelling solution.

Several companies and hospitals are already experimenting with drones, like WellSpan Health in Pennsylvania, Amazon Pharmacy, and the Cleveland Clinic, which announced a partnership with drone delivery company Zipline and plans to begin prescription deliveries across Northeast Ohio by 2025.

Healthcare systems are just beginning to explore the potential of drone deliveries, for everything from lab samples to medical and surgical supplies — even defibrillators that could arrive at an ailing patient’s front door before an emergency medical technician arrives.

“For many providers, when you take a sample from a patient, that sample waits around for hours until a courier picks up all of the facility’s samples and drives them to an outside facility for processing,” said Hillary Brendzel, head of Zipline’s US Healthcare Practice.

According to a 2022 survey from American Nurse Journal, 71% of nurses said that medical courier delays and errors negatively affected their ability to provide patient care. But with drone delivery, “lab samples can be sent for processing immediately, on-demand, resulting in faster diagnosis, treatment, and ultimately better outcomes,” said Ms. Brendzel.

4. Portable Ultrasound

Within the next 2 years, portable ultrasound — pocket-sized devices that connect to a smartphone or tablet — will become the “21st-century stethoscope,” said Abhilash Hareendranathan, PhD, assistant professor in the Department of Radiology and Diagnostic Imaging at the University of Alberta, in Edmonton, Alberta, Canada.

AI can make these devices easy to use, allowing clinicians with minimal imaging training to capture clear images and understand the results. Dr. Hareendranathan developed the Ultrasound Arm Injury Detection tool, a portable ultrasound that uses AI to detect fracture.

“We plan to introduce this technology in emergency departments, where it could be used by triage nurses to perform quick examinations to detect fractures of the wrist, elbow, or shoulder,” he said.

More pocket-sized scanners like these could “reshape the way diagnostic care is provided in rural and remote communities,” Dr. Hareendranathan said, and will “reduce wait times in crowded emergency departments.” Bill Gates believes enough in portable ultrasound that last September, the Bill & Melinda Gates Foundation granted $44 million to GE HealthCare to develop the technology for under-resourced communities.

5. Virtual Reality (VR)

When RelieVRx became the first US Food and Drug Administration (FDA)–approved VR therapy for chronic back pain in 2021, the technology was used in just a handful of Veterans Affairs (VA) facilities. But today, thousands of VR headsets have been deployed to more than 160 VA medical centers and clinics across the country.

“The VR experiences encompass pain neuroscience education, mindfulness, pleasant and relaxing distraction, and key skills to calm the nervous system,” said Beth Darnall, PhD, director of the Stanford Pain Relief Innovations Lab, who helped design the RelieVRx. She expects VR to go mainstream soon, not just because of increasing evidence that it works but also thanks to the Centers for Medicare & Medicaid Services, which recently issued a Healthcare Common Procedure Coding System code for VR. “This billing infrastructure will encourage adoption and uptake,” she said.

Hundreds of hospitals across the United States have already adopted the technology, for everything from childbirth pain to wound debridement, said Josh Sackman, the president and cofounder of AppliedVR, the company that developed RelieVRx.

“Over the next few years, we may see hundreds more deploy unique applications [for VR] that can handle multiple clinical indications,” he said. “Given the modality’s ability to scale and reduce reliance on pharmacological interventions, it has the power to improve the cost and quality of care.”

Hospital systems like Geisinger and Cedars-Sinai are already finding unique ways to implement the technology, he said, like using VR to reduce “scanxiety” during imaging service.

Other VR innovations are already being introduced, from the Smileyscope, a VR device for children that’s been proven to lessen the pain of a blood draw or intravenous insertion (it was cleared by the FDA last November) to several VR platforms launched by Cedars-Sinai in recent months, for applications that range from gastrointestinal issues to mental health therapy. “There may already be a thousand hospitals using VR in some capacity,” said Brennan Spiegel, MD, director of Health Services Research at Cedars-Sinai.

A version of this article appeared on Medscape.com.

The AGA Future Leaders Program: A Mentee-Mentor Triad Perspective

Two of us (Parakkal Deepak and Edward L. Barnes) were part of the American Gastroenterological Association’s (AGA) Future Leaders Program (FLP) class of 2022-2023, and our mentor was Aasma Shaukat. We were invited to share our experiences as participants in the FLP and its impact in our careers.

Why Was the Future Leaders Program Conceived?

To understand this, one must first understand that the AGA, like all other GI professional organizations, relies on volunteer leaders to develop its long-term vision and execute this through strategic initiatives and programs. and understand the governance structure of the AGA to help lead it to face these challenges effectively.

The AGA FLP was thus conceived and launched in 2014-2015 by the founding chairs, Byron Cryer, MD, who is a professor of medicine and associate dean for faculty diversity at University of Texas Southwestern Medical School and Suzanne Rose, MD, MSEd, AGAF, who is a professor of medicine and senior vice dean for medical education at Perelman School of Medicine at the University of Pennsylvania. They envisioned a leadership pathway that would position early career GIs on a track to positively affect the AGA and the field of GI.

How Does One Apply for the Program?

Our FLP cohort applications were invited in October of 2021 and mentees accepted into the program in November 2021. The application process is competitive – applicants are encouraged to detail why they feel they would benefit from the FLP, what existing skillsets they have that can be further enhanced through the program, and what their long-term vision is for their growth as leaders, both within their institution and within the AGA. This is further accompanied by letters of support from their divisional chiefs and other key supervisors within the division who are intimately aware of their leadership potential and career trajectory. This process identified 18 future leaders for our class of 2022-2023.

What Is Involved?

Following acceptance into the AGA Future Leaders Program, we embarked on a series of virtual and in-person meetings with our mentorship triads (one mentor and two mentees) and other mentorship teams over the 18-month program (see Figure). These meetings covered highly focused topics ranging from the role of advocacy in leadership to negotiation and developing a business plan, with ample opportunities for individually tailored mentorship within the mentorship triads.

We also completed personality assessments that helped us understand our strengths and areas of improvement, and ways to use the information to hone our leadership styles.

A large portion of programming and the mentorship experience during the AGA Future Leaders Program is focused on a leadership project that is aimed at addressing a societal driver of interest for the AGA. Examples of these societal drivers of interest include maximizing the role of women in gastroenterology, the role of artificial intelligence in gastroenterology, burnout, and the impact of climate change on gastroenterology. Mentorship triads propose novel methods for addressing these critical issues, outlining the roles that the AGA and other stakeholders may embrace to address these anticipated growing challenges head on.

Our mentorship triad was asked to address the issue of ending disparities within gastroenterology. Given our research and clinical interest in inflammatory bowel disease (IBD), we immediately recognized an opportunity to evaluate and potentially offer solutions for the geographic disparities that exist in the field of IBD. These disparities affect access to care for patients with Crohn’s disease and ulcerative colitis, leading to delays in diagnosis and ultimately effective therapy decisions.

In addition to developing a proposal for the AGA to expand access to care to major IBD centers in rural areas where these disparities exist, we also initiated an examination of geographic disparities in our own multidisciplinary IBD centers (abstract accepted for presentation at Digestive Diseases Week 2024). This allowed us to expand our respective research footprints at our institutions, utilizing new methods of geocoding to directly measure factors affecting clinical outcomes in IBD. Given our in-depth evaluation of this topic as part of our Future Leaders Program training, at the suggestion of our mentor, our mentorship triad also published a commentary on geographic disparities in the Diversity, Equity, and Inclusion sections of Gastroenterology and Clinical Gastroenterology and Hepatology.1, 2

Impact on the Field and Our Careers

Our mentorship triad had the unique experience of having a mentor who had previously participated in the Future Leaders Program as a mentee. As the Future Leaders Program has now enrolled 72 participants, these occasions will likely become more frequent, given the opportunities for career development and growth within the AGA (and our field) that are available after participating in the Future Leaders Program.

To have a mentor with this insight of having been a mentee in the program was invaluable, given her direct experience and understanding of the growth opportunities available, and opportunities to maximize participation in the Future Leaders Program. Additionally, as evidenced by Dr. Shaukat’s recommendations to grow our initial assignment into published commentaries, need statements for our field, and ultimately growing research projects, her keen insights as a mentor were a critical component of our individual growth in the program and the success of our mentorship triad. We benefited from networking with peers and learning about their work, which can lead to future collaborations. We had access to the highly accomplished mentors from diverse settings and learned models of leadership, while developing skills to foster our own leadership style.

In terms of programmatic impact, more than 90% of FLP alumni are serving in AGA leadership on committees, task forces, editorial boards, and councils. What is also important is the impact of content developed by mentee-mentor triads during the FLP cohorts over time. More than 700 GIs have benefited from online leadership development content created by the FLP. Based on our experience, we highly recommend all early career GI physicians to apply!

Dr. Parakkal (@P_DeepakIBDMD) is based in the division of gastroenterology, Washington University in St. Louis (Mo.) School of Medicine. He is supported by a Junior Faculty Development Award from the American College of Gastroenterology and IBD Plexus of the Crohn’s & Colitis Foundation. He has received research support under a sponsored research agreement unrelated to the data in the paper from AbbVie, Arena Pharmaceuticals, Boehringer Ingelheim, Bristol Myers Squibb, Janssen, Prometheus Biosciences, Takeda Pharmaceuticals, Roche-Genentech, and CorEvitas LLC. He has served as a consultant for AbbVie, Boehringer Ingelheim, Bristol Myers Squibb, Scipher Medicine, Fresenius Kabi, Roche-Genentech, and CorEvitas LLC. Dr. Barnes (@EdBarnesMD) is based in the division of gastroenterology and hepatology, University of North Carolina at Chapel Hill. He is supported by National Institutes of Health K23DK127157-01, and has served as a consultant for Eli Lilly, Bristol-Meyers Squibb, and Target RWE. Dr. Shaukat (@AasmaShaukatMD) is based in the division of gastroenterology, New York University, New York. She has served as a consultant for Iterative health, Motus, Freenome, and Geneoscopy. Research support by the Steve and Alex Cohen Foundation.

References

1. Deepak P, Barnes EL, Shaukat A. Health Disparities in Inflammatory Bowel Disease Care Driven by Rural Versus Urban Residence: Challenges and Potential Solutions. Gastroenterology. 2023 July. doi: 10.1053/j.gastro.2023.05.017.

2. Deepak P, Barnes EL, Shaukat A. Health Disparities in Inflammatory Bowel Disease Care Driven by Rural Versus Urban Residence: Challenges and Potential Solutions. Clin Gastroenterol Hepatol. 2023 July. doi: 10.1016/j.cgh.2023.04.006.

Two of us (Parakkal Deepak and Edward L. Barnes) were part of the American Gastroenterological Association’s (AGA) Future Leaders Program (FLP) class of 2022-2023, and our mentor was Aasma Shaukat. We were invited to share our experiences as participants in the FLP and its impact in our careers.

Why Was the Future Leaders Program Conceived?

To understand this, one must first understand that the AGA, like all other GI professional organizations, relies on volunteer leaders to develop its long-term vision and execute this through strategic initiatives and programs. and understand the governance structure of the AGA to help lead it to face these challenges effectively.

The AGA FLP was thus conceived and launched in 2014-2015 by the founding chairs, Byron Cryer, MD, who is a professor of medicine and associate dean for faculty diversity at University of Texas Southwestern Medical School and Suzanne Rose, MD, MSEd, AGAF, who is a professor of medicine and senior vice dean for medical education at Perelman School of Medicine at the University of Pennsylvania. They envisioned a leadership pathway that would position early career GIs on a track to positively affect the AGA and the field of GI.

How Does One Apply for the Program?

Our FLP cohort applications were invited in October of 2021 and mentees accepted into the program in November 2021. The application process is competitive – applicants are encouraged to detail why they feel they would benefit from the FLP, what existing skillsets they have that can be further enhanced through the program, and what their long-term vision is for their growth as leaders, both within their institution and within the AGA. This is further accompanied by letters of support from their divisional chiefs and other key supervisors within the division who are intimately aware of their leadership potential and career trajectory. This process identified 18 future leaders for our class of 2022-2023.

What Is Involved?

Following acceptance into the AGA Future Leaders Program, we embarked on a series of virtual and in-person meetings with our mentorship triads (one mentor and two mentees) and other mentorship teams over the 18-month program (see Figure). These meetings covered highly focused topics ranging from the role of advocacy in leadership to negotiation and developing a business plan, with ample opportunities for individually tailored mentorship within the mentorship triads.

We also completed personality assessments that helped us understand our strengths and areas of improvement, and ways to use the information to hone our leadership styles.

A large portion of programming and the mentorship experience during the AGA Future Leaders Program is focused on a leadership project that is aimed at addressing a societal driver of interest for the AGA. Examples of these societal drivers of interest include maximizing the role of women in gastroenterology, the role of artificial intelligence in gastroenterology, burnout, and the impact of climate change on gastroenterology. Mentorship triads propose novel methods for addressing these critical issues, outlining the roles that the AGA and other stakeholders may embrace to address these anticipated growing challenges head on.

Our mentorship triad was asked to address the issue of ending disparities within gastroenterology. Given our research and clinical interest in inflammatory bowel disease (IBD), we immediately recognized an opportunity to evaluate and potentially offer solutions for the geographic disparities that exist in the field of IBD. These disparities affect access to care for patients with Crohn’s disease and ulcerative colitis, leading to delays in diagnosis and ultimately effective therapy decisions.

In addition to developing a proposal for the AGA to expand access to care to major IBD centers in rural areas where these disparities exist, we also initiated an examination of geographic disparities in our own multidisciplinary IBD centers (abstract accepted for presentation at Digestive Diseases Week 2024). This allowed us to expand our respective research footprints at our institutions, utilizing new methods of geocoding to directly measure factors affecting clinical outcomes in IBD. Given our in-depth evaluation of this topic as part of our Future Leaders Program training, at the suggestion of our mentor, our mentorship triad also published a commentary on geographic disparities in the Diversity, Equity, and Inclusion sections of Gastroenterology and Clinical Gastroenterology and Hepatology.1, 2

Impact on the Field and Our Careers

Our mentorship triad had the unique experience of having a mentor who had previously participated in the Future Leaders Program as a mentee. As the Future Leaders Program has now enrolled 72 participants, these occasions will likely become more frequent, given the opportunities for career development and growth within the AGA (and our field) that are available after participating in the Future Leaders Program.

To have a mentor with this insight of having been a mentee in the program was invaluable, given her direct experience and understanding of the growth opportunities available, and opportunities to maximize participation in the Future Leaders Program. Additionally, as evidenced by Dr. Shaukat’s recommendations to grow our initial assignment into published commentaries, need statements for our field, and ultimately growing research projects, her keen insights as a mentor were a critical component of our individual growth in the program and the success of our mentorship triad. We benefited from networking with peers and learning about their work, which can lead to future collaborations. We had access to the highly accomplished mentors from diverse settings and learned models of leadership, while developing skills to foster our own leadership style.

In terms of programmatic impact, more than 90% of FLP alumni are serving in AGA leadership on committees, task forces, editorial boards, and councils. What is also important is the impact of content developed by mentee-mentor triads during the FLP cohorts over time. More than 700 GIs have benefited from online leadership development content created by the FLP. Based on our experience, we highly recommend all early career GI physicians to apply!

Dr. Parakkal (@P_DeepakIBDMD) is based in the division of gastroenterology, Washington University in St. Louis (Mo.) School of Medicine. He is supported by a Junior Faculty Development Award from the American College of Gastroenterology and IBD Plexus of the Crohn’s & Colitis Foundation. He has received research support under a sponsored research agreement unrelated to the data in the paper from AbbVie, Arena Pharmaceuticals, Boehringer Ingelheim, Bristol Myers Squibb, Janssen, Prometheus Biosciences, Takeda Pharmaceuticals, Roche-Genentech, and CorEvitas LLC. He has served as a consultant for AbbVie, Boehringer Ingelheim, Bristol Myers Squibb, Scipher Medicine, Fresenius Kabi, Roche-Genentech, and CorEvitas LLC. Dr. Barnes (@EdBarnesMD) is based in the division of gastroenterology and hepatology, University of North Carolina at Chapel Hill. He is supported by National Institutes of Health K23DK127157-01, and has served as a consultant for Eli Lilly, Bristol-Meyers Squibb, and Target RWE. Dr. Shaukat (@AasmaShaukatMD) is based in the division of gastroenterology, New York University, New York. She has served as a consultant for Iterative health, Motus, Freenome, and Geneoscopy. Research support by the Steve and Alex Cohen Foundation.

References

1. Deepak P, Barnes EL, Shaukat A. Health Disparities in Inflammatory Bowel Disease Care Driven by Rural Versus Urban Residence: Challenges and Potential Solutions. Gastroenterology. 2023 July. doi: 10.1053/j.gastro.2023.05.017.

2. Deepak P, Barnes EL, Shaukat A. Health Disparities in Inflammatory Bowel Disease Care Driven by Rural Versus Urban Residence: Challenges and Potential Solutions. Clin Gastroenterol Hepatol. 2023 July. doi: 10.1016/j.cgh.2023.04.006.

Two of us (Parakkal Deepak and Edward L. Barnes) were part of the American Gastroenterological Association’s (AGA) Future Leaders Program (FLP) class of 2022-2023, and our mentor was Aasma Shaukat. We were invited to share our experiences as participants in the FLP and its impact in our careers.

Why Was the Future Leaders Program Conceived?

To understand this, one must first understand that the AGA, like all other GI professional organizations, relies on volunteer leaders to develop its long-term vision and execute this through strategic initiatives and programs. and understand the governance structure of the AGA to help lead it to face these challenges effectively.

The AGA FLP was thus conceived and launched in 2014-2015 by the founding chairs, Byron Cryer, MD, who is a professor of medicine and associate dean for faculty diversity at University of Texas Southwestern Medical School and Suzanne Rose, MD, MSEd, AGAF, who is a professor of medicine and senior vice dean for medical education at Perelman School of Medicine at the University of Pennsylvania. They envisioned a leadership pathway that would position early career GIs on a track to positively affect the AGA and the field of GI.

How Does One Apply for the Program?

Our FLP cohort applications were invited in October of 2021 and mentees accepted into the program in November 2021. The application process is competitive – applicants are encouraged to detail why they feel they would benefit from the FLP, what existing skillsets they have that can be further enhanced through the program, and what their long-term vision is for their growth as leaders, both within their institution and within the AGA. This is further accompanied by letters of support from their divisional chiefs and other key supervisors within the division who are intimately aware of their leadership potential and career trajectory. This process identified 18 future leaders for our class of 2022-2023.

What Is Involved?

Following acceptance into the AGA Future Leaders Program, we embarked on a series of virtual and in-person meetings with our mentorship triads (one mentor and two mentees) and other mentorship teams over the 18-month program (see Figure). These meetings covered highly focused topics ranging from the role of advocacy in leadership to negotiation and developing a business plan, with ample opportunities for individually tailored mentorship within the mentorship triads.

We also completed personality assessments that helped us understand our strengths and areas of improvement, and ways to use the information to hone our leadership styles.

A large portion of programming and the mentorship experience during the AGA Future Leaders Program is focused on a leadership project that is aimed at addressing a societal driver of interest for the AGA. Examples of these societal drivers of interest include maximizing the role of women in gastroenterology, the role of artificial intelligence in gastroenterology, burnout, and the impact of climate change on gastroenterology. Mentorship triads propose novel methods for addressing these critical issues, outlining the roles that the AGA and other stakeholders may embrace to address these anticipated growing challenges head on.

Our mentorship triad was asked to address the issue of ending disparities within gastroenterology. Given our research and clinical interest in inflammatory bowel disease (IBD), we immediately recognized an opportunity to evaluate and potentially offer solutions for the geographic disparities that exist in the field of IBD. These disparities affect access to care for patients with Crohn’s disease and ulcerative colitis, leading to delays in diagnosis and ultimately effective therapy decisions.

In addition to developing a proposal for the AGA to expand access to care to major IBD centers in rural areas where these disparities exist, we also initiated an examination of geographic disparities in our own multidisciplinary IBD centers (abstract accepted for presentation at Digestive Diseases Week 2024). This allowed us to expand our respective research footprints at our institutions, utilizing new methods of geocoding to directly measure factors affecting clinical outcomes in IBD. Given our in-depth evaluation of this topic as part of our Future Leaders Program training, at the suggestion of our mentor, our mentorship triad also published a commentary on geographic disparities in the Diversity, Equity, and Inclusion sections of Gastroenterology and Clinical Gastroenterology and Hepatology.1, 2

Impact on the Field and Our Careers

Our mentorship triad had the unique experience of having a mentor who had previously participated in the Future Leaders Program as a mentee. As the Future Leaders Program has now enrolled 72 participants, these occasions will likely become more frequent, given the opportunities for career development and growth within the AGA (and our field) that are available after participating in the Future Leaders Program.

To have a mentor with this insight of having been a mentee in the program was invaluable, given her direct experience and understanding of the growth opportunities available, and opportunities to maximize participation in the Future Leaders Program. Additionally, as evidenced by Dr. Shaukat’s recommendations to grow our initial assignment into published commentaries, need statements for our field, and ultimately growing research projects, her keen insights as a mentor were a critical component of our individual growth in the program and the success of our mentorship triad. We benefited from networking with peers and learning about their work, which can lead to future collaborations. We had access to the highly accomplished mentors from diverse settings and learned models of leadership, while developing skills to foster our own leadership style.

In terms of programmatic impact, more than 90% of FLP alumni are serving in AGA leadership on committees, task forces, editorial boards, and councils. What is also important is the impact of content developed by mentee-mentor triads during the FLP cohorts over time. More than 700 GIs have benefited from online leadership development content created by the FLP. Based on our experience, we highly recommend all early career GI physicians to apply!

Dr. Parakkal (@P_DeepakIBDMD) is based in the division of gastroenterology, Washington University in St. Louis (Mo.) School of Medicine. He is supported by a Junior Faculty Development Award from the American College of Gastroenterology and IBD Plexus of the Crohn’s & Colitis Foundation. He has received research support under a sponsored research agreement unrelated to the data in the paper from AbbVie, Arena Pharmaceuticals, Boehringer Ingelheim, Bristol Myers Squibb, Janssen, Prometheus Biosciences, Takeda Pharmaceuticals, Roche-Genentech, and CorEvitas LLC. He has served as a consultant for AbbVie, Boehringer Ingelheim, Bristol Myers Squibb, Scipher Medicine, Fresenius Kabi, Roche-Genentech, and CorEvitas LLC. Dr. Barnes (@EdBarnesMD) is based in the division of gastroenterology and hepatology, University of North Carolina at Chapel Hill. He is supported by National Institutes of Health K23DK127157-01, and has served as a consultant for Eli Lilly, Bristol-Meyers Squibb, and Target RWE. Dr. Shaukat (@AasmaShaukatMD) is based in the division of gastroenterology, New York University, New York. She has served as a consultant for Iterative health, Motus, Freenome, and Geneoscopy. Research support by the Steve and Alex Cohen Foundation.

References

1. Deepak P, Barnes EL, Shaukat A. Health Disparities in Inflammatory Bowel Disease Care Driven by Rural Versus Urban Residence: Challenges and Potential Solutions. Gastroenterology. 2023 July. doi: 10.1053/j.gastro.2023.05.017.

2. Deepak P, Barnes EL, Shaukat A. Health Disparities in Inflammatory Bowel Disease Care Driven by Rural Versus Urban Residence: Challenges and Potential Solutions. Clin Gastroenterol Hepatol. 2023 July. doi: 10.1016/j.cgh.2023.04.006.

Navigating the Search for a Financial Adviser

As gastroenterologists, we spend innumerable years in medical training with an abrupt and significant increase in our earning potential upon beginning practice. The majority of us also carry a sizeable amount of student loan debt. This combination results in a unique situation that can make us hesitant about how best to set ourselves up financially while also making us vulnerable to potentially predatory financial practices.

Although your initial steps to achieve financial wellness and build wealth can be obtained on your own with some education, a financial adviser becomes indispensable when you have significant assets, a high income, complex finances, and/or are experiencing a major life change. Additionally, as there are so many avenues to invest and grow your capital, a financial adviser can assist in designing a portfolio to best accomplish specific monetary goals. Studies have demonstrated that those working with a financial adviser reduce their single-stock risk and have more significant increase in portfolio value, reducing the total cost associated with their investments’ management.1 Those working with a financial adviser will also net up to a 3% larger annual return, compared with a standard baseline investment plan.2,3

Based on this information, it may appear that working with a personal financial adviser would be a no-brainer. Unfortunately, there is a caveat: There is no legal regulation regarding who can use the title “financial adviser.” It is therefore crucial to be aware of common practices and terminology to best help you identify a reputable financial adviser and reduce your risk of excessive fees or financial loss. This is also a highly personal decision and your search should first begin with understanding why you are looking for an adviser, as this will determine the appropriate type of service to look for.

Types of Advisers

A certified financial planner (CFP) is an expert in estate planning, taxes, retirement saving, and financial planning who has a formal designation by the Certified Financial Planner Board of Standards Inc.4 They must undergo stringent licensing examinations following a 3-year course with required continuing education to maintain their credentials. CFPs are fiduciaries, meaning they must make financial decisions in your best interest, even if they may make less money with that product or investment strategy. In other words, they are beholden to give honest, impartial recommendations to their clients, and may face sanctions by the CFP Board if found to violate its Code of Ethics and Standards of Conduct, which includes failure to act in a fiduciary duty.5

CFPs evaluate your total financial picture, such as investments, insurance policies, and overall current financial position, to develop a comprehensive strategy that will successfully guide you to your financial goal. There are many individuals who may refer to themselves as financial planners without having the CFP designation; while they may offer similar services as above, they will not be required to act as a fiduciary. Hence, it is important to do your due diligence and verify they hold this certification via the CFP Board website: www.cfp.net/verify-a-cfp-professional.

An investment adviser is a legal term from the U.S. Securities and Exchange Commission (SEC) and the Financial Industry Regulatory Authority (FINRA) referring to an individual who provides recommendations and analyses for financial securities such as stock. Both of these agencies ensure investment advisers adhere to regulatory requirements designed to protect client investers. Similar to CFPs, they are held to a fiduciary standard, and their firm is required to register with the SEC or the state of practice based on the amount of assets under management.6

An individual investment adviser must also register with their state as an Investment Adviser Representative (IAR), the distinctive term referring to an individual as opposed to an investment advising firm. Investment advisers are required to pass the extensive Series 65, Uniform Investment Advisor Law Exam, or equivalent, by states requiring licensure.7 They can guide you on the selection of particular investments and portfolio management based on a discussion with you regarding your current financial standing and what fiscal ambitions you wish to achieve.

A financial adviser provides direction on a multitude of financially related topics such as investing, tax laws, and life insurance with the goal to help you reach specific financial objectives. However, this term is often used quite ubiquitously given the lack of formal regulation of the title. Essentially, those with varying types of educational background can give themselves the title of financial adviser.

If a financial adviser buys or sells financial securities such as stocks or bonds, then they must be registered as a licensed broker with the SEC and IAR and pass the Series 6 or Series 7 exam. Unlike CFPs and investment advisers, a financial adviser (if also a licensed broker) is not required to be a fiduciary, and instead works under the suitability standard.8 Suitability requires that financial recommendations made by the adviser are appropriate but not necessarily the best for the client. In fact, these recommendations do not even have to be the most suitable. This is where conflicts of interest can arise with the adviser recommending products and securities that best compensate them while not serving the best return on investment for you.

Making the search for a financial adviser more complex, an individual can be a combination of any of the above, pending the appropriate licensing. For example, a CFP can also be an asset manager and thus hold the title of a financial adviser and/or IAR. A financial adviser may also not directly manage your assets if they have a partnership with a third party or another licensed individual. Questions to ask of your potential financial adviser should therefore include the following:

- What licensure and related education do you have?

- What is your particular area of expertise?

- How long have you been in practice?

- How will you be managing my assets?

Financial Adviser Fee Schedules

Prior to working with a financial adviser, you must also inquire about their fee structure. There are two kinds of fee schedules used by financial advisers: fee-only and fee-based.

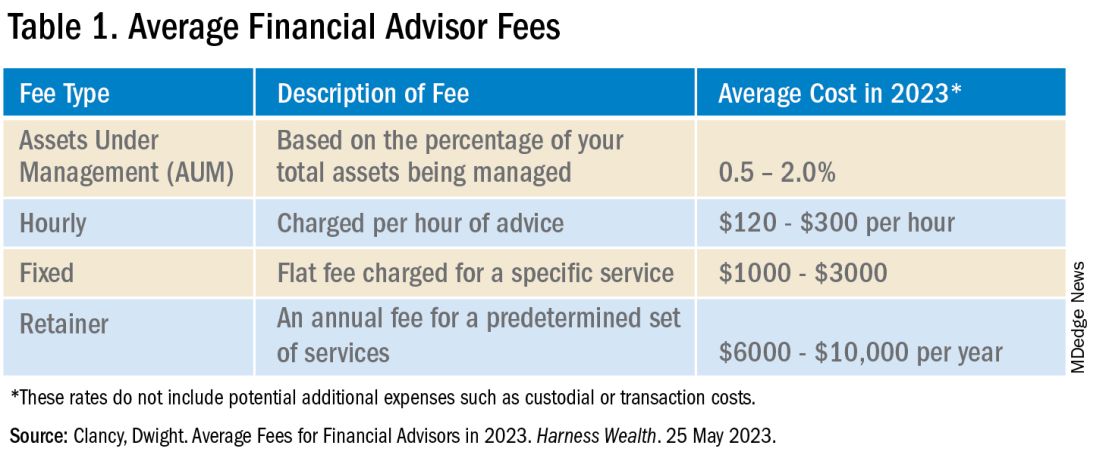

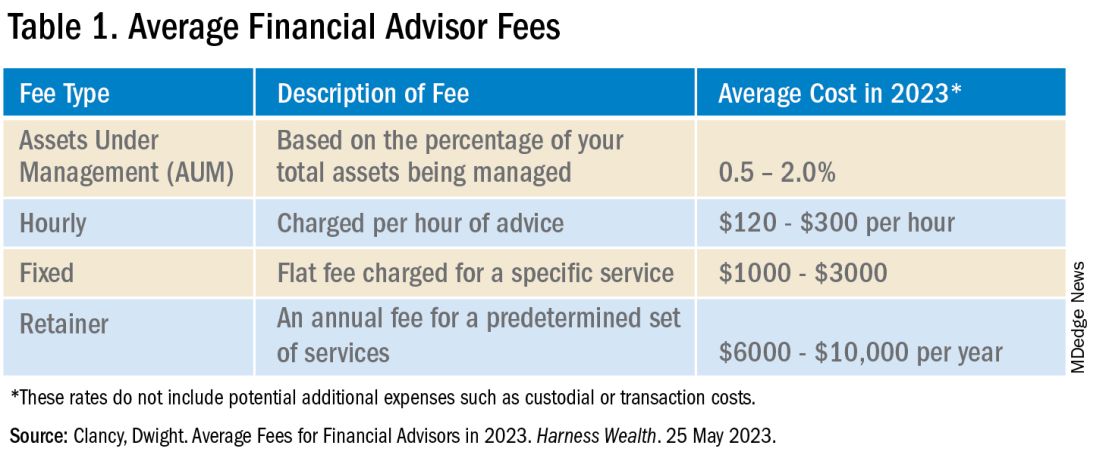

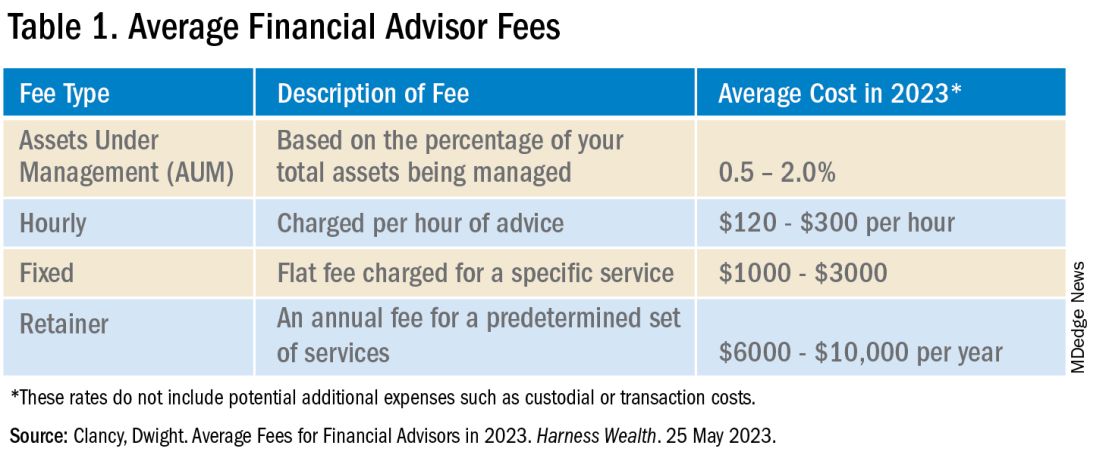

Fee-only advisers receive payment solely for the services they provide. They do not collect commissions from third parties providing the recommended products. There is variability in how this type of payment schedule is structured, encompassing flat fees, hourly rates, or the adviser charging a retainer. The Table below compares the types of fee-only structures and range of charges based on 2023 rates.9 Of note, fee-only advisers serve as fiduciaries.10

Fee-based financial advisers receive payment for services but may also receive commission on specific products they sell to you.9 Most, if not all, financial experts recommend avoiding advisers using commission-based charges given the potential conflict of interest: How can one be absolutely sure this recommended financial product is best for you, knowing your adviser has a financial stake in said item?

In addition to charging the fees above, your financial adviser, if they are actively managing your investment portfolio, will also charge an assets under management (AUM) fee. This is a percentage of the dollar amount within your portfolio. For example, if your adviser charges a 1% AUM rate for your account totaling $100,000, this equates to a $1,000 fee in that calendar year. AUM fees typically decrease as the size of your portfolio increases. As seen in the Table, there is a wide range of the average AUM rate (0.5%–2%); however, an AUM fee approaching 2% is unnecessarily high and consumes a significant portion of your portfolio. Thus, it is recommended to look for a money manager with an approximate 1% AUM fee.

Many of us delay or avoid working with a financial adviser due to the potential perceived risks of having poor portfolio management from an adviser not working in our best interest, along with the concern for excessive fees. In many ways, it is how we counsel our patients. While they can seek medical information on their own, their best care is under the guidance of an expert: a healthcare professional. That being said, personal finance is indeed personal, so I hope this guide helps facilitate your search and increase your financial wellness.

Dr. Luthra is a therapeutic endoscopist at Moffitt Cancer Center, Tampa, Florida, and the founder of The Scope of Finance, a financial wellness education and coaching company focused on physicians. Her interest in financial well-being is thanks to the teachings of her father, an entrepreneur and former Certified Financial Planner (CFP). She can be found on Instagram (thescopeoffinance) and X (@ScopeofFinance). She reports no financial disclosures relevant to this article.

References

1. Pagliaro CA and Utkus SP. Assessing the value of advice. Vanguard. 2019 Sept.

2. Kinniry Jr. FM et al. Putting a value on your value: Quantifying Vanguard Advisor’s Alpha. Vanguard. 2022 July.

3. Horan S. What Are the Benefits of Working with a Financial Advisor? – 2021 Study. Smart Asset. 2023 July 27.

4. Kagan J. Certified Financial PlannerTM(CFP): What It Is and How to Become One. Investopedia. 2023 Aug 3.

5. CFP Board. Our Commitment to Ethical Standards. CFP Board. 2024.

6. Staff of the Investment Adviser Regulation Office Division of Investment Management, U.S. Securities and Exchange Commission. Regulation of Investment Advisers by the U.S. Securities and Exchange Commission. 2013 Mar.

7. Hicks C. Investment Advisor vs. Financial Advisor: There is a Difference. US News & World Report. 2019 June 13.

8. Roberts K. Financial advisor vs. financial planner: What is the difference? Bankrate. 2023 Nov 21.

9. Clancy D. Average Fees for Financial Advisors in 2023. Harness Wealth. 2023 May 25.

10. Palmer B. Fee- vs. Commission-Based Advisor: What’s the Difference? Investopedia. 2023 June 20.

As gastroenterologists, we spend innumerable years in medical training with an abrupt and significant increase in our earning potential upon beginning practice. The majority of us also carry a sizeable amount of student loan debt. This combination results in a unique situation that can make us hesitant about how best to set ourselves up financially while also making us vulnerable to potentially predatory financial practices.

Although your initial steps to achieve financial wellness and build wealth can be obtained on your own with some education, a financial adviser becomes indispensable when you have significant assets, a high income, complex finances, and/or are experiencing a major life change. Additionally, as there are so many avenues to invest and grow your capital, a financial adviser can assist in designing a portfolio to best accomplish specific monetary goals. Studies have demonstrated that those working with a financial adviser reduce their single-stock risk and have more significant increase in portfolio value, reducing the total cost associated with their investments’ management.1 Those working with a financial adviser will also net up to a 3% larger annual return, compared with a standard baseline investment plan.2,3

Based on this information, it may appear that working with a personal financial adviser would be a no-brainer. Unfortunately, there is a caveat: There is no legal regulation regarding who can use the title “financial adviser.” It is therefore crucial to be aware of common practices and terminology to best help you identify a reputable financial adviser and reduce your risk of excessive fees or financial loss. This is also a highly personal decision and your search should first begin with understanding why you are looking for an adviser, as this will determine the appropriate type of service to look for.

Types of Advisers

A certified financial planner (CFP) is an expert in estate planning, taxes, retirement saving, and financial planning who has a formal designation by the Certified Financial Planner Board of Standards Inc.4 They must undergo stringent licensing examinations following a 3-year course with required continuing education to maintain their credentials. CFPs are fiduciaries, meaning they must make financial decisions in your best interest, even if they may make less money with that product or investment strategy. In other words, they are beholden to give honest, impartial recommendations to their clients, and may face sanctions by the CFP Board if found to violate its Code of Ethics and Standards of Conduct, which includes failure to act in a fiduciary duty.5

CFPs evaluate your total financial picture, such as investments, insurance policies, and overall current financial position, to develop a comprehensive strategy that will successfully guide you to your financial goal. There are many individuals who may refer to themselves as financial planners without having the CFP designation; while they may offer similar services as above, they will not be required to act as a fiduciary. Hence, it is important to do your due diligence and verify they hold this certification via the CFP Board website: www.cfp.net/verify-a-cfp-professional.

An investment adviser is a legal term from the U.S. Securities and Exchange Commission (SEC) and the Financial Industry Regulatory Authority (FINRA) referring to an individual who provides recommendations and analyses for financial securities such as stock. Both of these agencies ensure investment advisers adhere to regulatory requirements designed to protect client investers. Similar to CFPs, they are held to a fiduciary standard, and their firm is required to register with the SEC or the state of practice based on the amount of assets under management.6

An individual investment adviser must also register with their state as an Investment Adviser Representative (IAR), the distinctive term referring to an individual as opposed to an investment advising firm. Investment advisers are required to pass the extensive Series 65, Uniform Investment Advisor Law Exam, or equivalent, by states requiring licensure.7 They can guide you on the selection of particular investments and portfolio management based on a discussion with you regarding your current financial standing and what fiscal ambitions you wish to achieve.

A financial adviser provides direction on a multitude of financially related topics such as investing, tax laws, and life insurance with the goal to help you reach specific financial objectives. However, this term is often used quite ubiquitously given the lack of formal regulation of the title. Essentially, those with varying types of educational background can give themselves the title of financial adviser.

If a financial adviser buys or sells financial securities such as stocks or bonds, then they must be registered as a licensed broker with the SEC and IAR and pass the Series 6 or Series 7 exam. Unlike CFPs and investment advisers, a financial adviser (if also a licensed broker) is not required to be a fiduciary, and instead works under the suitability standard.8 Suitability requires that financial recommendations made by the adviser are appropriate but not necessarily the best for the client. In fact, these recommendations do not even have to be the most suitable. This is where conflicts of interest can arise with the adviser recommending products and securities that best compensate them while not serving the best return on investment for you.

Making the search for a financial adviser more complex, an individual can be a combination of any of the above, pending the appropriate licensing. For example, a CFP can also be an asset manager and thus hold the title of a financial adviser and/or IAR. A financial adviser may also not directly manage your assets if they have a partnership with a third party or another licensed individual. Questions to ask of your potential financial adviser should therefore include the following:

- What licensure and related education do you have?

- What is your particular area of expertise?

- How long have you been in practice?

- How will you be managing my assets?

Financial Adviser Fee Schedules

Prior to working with a financial adviser, you must also inquire about their fee structure. There are two kinds of fee schedules used by financial advisers: fee-only and fee-based.

Fee-only advisers receive payment solely for the services they provide. They do not collect commissions from third parties providing the recommended products. There is variability in how this type of payment schedule is structured, encompassing flat fees, hourly rates, or the adviser charging a retainer. The Table below compares the types of fee-only structures and range of charges based on 2023 rates.9 Of note, fee-only advisers serve as fiduciaries.10

Fee-based financial advisers receive payment for services but may also receive commission on specific products they sell to you.9 Most, if not all, financial experts recommend avoiding advisers using commission-based charges given the potential conflict of interest: How can one be absolutely sure this recommended financial product is best for you, knowing your adviser has a financial stake in said item?

In addition to charging the fees above, your financial adviser, if they are actively managing your investment portfolio, will also charge an assets under management (AUM) fee. This is a percentage of the dollar amount within your portfolio. For example, if your adviser charges a 1% AUM rate for your account totaling $100,000, this equates to a $1,000 fee in that calendar year. AUM fees typically decrease as the size of your portfolio increases. As seen in the Table, there is a wide range of the average AUM rate (0.5%–2%); however, an AUM fee approaching 2% is unnecessarily high and consumes a significant portion of your portfolio. Thus, it is recommended to look for a money manager with an approximate 1% AUM fee.

Many of us delay or avoid working with a financial adviser due to the potential perceived risks of having poor portfolio management from an adviser not working in our best interest, along with the concern for excessive fees. In many ways, it is how we counsel our patients. While they can seek medical information on their own, their best care is under the guidance of an expert: a healthcare professional. That being said, personal finance is indeed personal, so I hope this guide helps facilitate your search and increase your financial wellness.

Dr. Luthra is a therapeutic endoscopist at Moffitt Cancer Center, Tampa, Florida, and the founder of The Scope of Finance, a financial wellness education and coaching company focused on physicians. Her interest in financial well-being is thanks to the teachings of her father, an entrepreneur and former Certified Financial Planner (CFP). She can be found on Instagram (thescopeoffinance) and X (@ScopeofFinance). She reports no financial disclosures relevant to this article.

References

1. Pagliaro CA and Utkus SP. Assessing the value of advice. Vanguard. 2019 Sept.

2. Kinniry Jr. FM et al. Putting a value on your value: Quantifying Vanguard Advisor’s Alpha. Vanguard. 2022 July.

3. Horan S. What Are the Benefits of Working with a Financial Advisor? – 2021 Study. Smart Asset. 2023 July 27.

4. Kagan J. Certified Financial PlannerTM(CFP): What It Is and How to Become One. Investopedia. 2023 Aug 3.

5. CFP Board. Our Commitment to Ethical Standards. CFP Board. 2024.

6. Staff of the Investment Adviser Regulation Office Division of Investment Management, U.S. Securities and Exchange Commission. Regulation of Investment Advisers by the U.S. Securities and Exchange Commission. 2013 Mar.

7. Hicks C. Investment Advisor vs. Financial Advisor: There is a Difference. US News & World Report. 2019 June 13.

8. Roberts K. Financial advisor vs. financial planner: What is the difference? Bankrate. 2023 Nov 21.

9. Clancy D. Average Fees for Financial Advisors in 2023. Harness Wealth. 2023 May 25.

10. Palmer B. Fee- vs. Commission-Based Advisor: What’s the Difference? Investopedia. 2023 June 20.

As gastroenterologists, we spend innumerable years in medical training with an abrupt and significant increase in our earning potential upon beginning practice. The majority of us also carry a sizeable amount of student loan debt. This combination results in a unique situation that can make us hesitant about how best to set ourselves up financially while also making us vulnerable to potentially predatory financial practices.

Although your initial steps to achieve financial wellness and build wealth can be obtained on your own with some education, a financial adviser becomes indispensable when you have significant assets, a high income, complex finances, and/or are experiencing a major life change. Additionally, as there are so many avenues to invest and grow your capital, a financial adviser can assist in designing a portfolio to best accomplish specific monetary goals. Studies have demonstrated that those working with a financial adviser reduce their single-stock risk and have more significant increase in portfolio value, reducing the total cost associated with their investments’ management.1 Those working with a financial adviser will also net up to a 3% larger annual return, compared with a standard baseline investment plan.2,3

Based on this information, it may appear that working with a personal financial adviser would be a no-brainer. Unfortunately, there is a caveat: There is no legal regulation regarding who can use the title “financial adviser.” It is therefore crucial to be aware of common practices and terminology to best help you identify a reputable financial adviser and reduce your risk of excessive fees or financial loss. This is also a highly personal decision and your search should first begin with understanding why you are looking for an adviser, as this will determine the appropriate type of service to look for.

Types of Advisers

A certified financial planner (CFP) is an expert in estate planning, taxes, retirement saving, and financial planning who has a formal designation by the Certified Financial Planner Board of Standards Inc.4 They must undergo stringent licensing examinations following a 3-year course with required continuing education to maintain their credentials. CFPs are fiduciaries, meaning they must make financial decisions in your best interest, even if they may make less money with that product or investment strategy. In other words, they are beholden to give honest, impartial recommendations to their clients, and may face sanctions by the CFP Board if found to violate its Code of Ethics and Standards of Conduct, which includes failure to act in a fiduciary duty.5

CFPs evaluate your total financial picture, such as investments, insurance policies, and overall current financial position, to develop a comprehensive strategy that will successfully guide you to your financial goal. There are many individuals who may refer to themselves as financial planners without having the CFP designation; while they may offer similar services as above, they will not be required to act as a fiduciary. Hence, it is important to do your due diligence and verify they hold this certification via the CFP Board website: www.cfp.net/verify-a-cfp-professional.

An investment adviser is a legal term from the U.S. Securities and Exchange Commission (SEC) and the Financial Industry Regulatory Authority (FINRA) referring to an individual who provides recommendations and analyses for financial securities such as stock. Both of these agencies ensure investment advisers adhere to regulatory requirements designed to protect client investers. Similar to CFPs, they are held to a fiduciary standard, and their firm is required to register with the SEC or the state of practice based on the amount of assets under management.6

An individual investment adviser must also register with their state as an Investment Adviser Representative (IAR), the distinctive term referring to an individual as opposed to an investment advising firm. Investment advisers are required to pass the extensive Series 65, Uniform Investment Advisor Law Exam, or equivalent, by states requiring licensure.7 They can guide you on the selection of particular investments and portfolio management based on a discussion with you regarding your current financial standing and what fiscal ambitions you wish to achieve.

A financial adviser provides direction on a multitude of financially related topics such as investing, tax laws, and life insurance with the goal to help you reach specific financial objectives. However, this term is often used quite ubiquitously given the lack of formal regulation of the title. Essentially, those with varying types of educational background can give themselves the title of financial adviser.

If a financial adviser buys or sells financial securities such as stocks or bonds, then they must be registered as a licensed broker with the SEC and IAR and pass the Series 6 or Series 7 exam. Unlike CFPs and investment advisers, a financial adviser (if also a licensed broker) is not required to be a fiduciary, and instead works under the suitability standard.8 Suitability requires that financial recommendations made by the adviser are appropriate but not necessarily the best for the client. In fact, these recommendations do not even have to be the most suitable. This is where conflicts of interest can arise with the adviser recommending products and securities that best compensate them while not serving the best return on investment for you.

Making the search for a financial adviser more complex, an individual can be a combination of any of the above, pending the appropriate licensing. For example, a CFP can also be an asset manager and thus hold the title of a financial adviser and/or IAR. A financial adviser may also not directly manage your assets if they have a partnership with a third party or another licensed individual. Questions to ask of your potential financial adviser should therefore include the following:

- What licensure and related education do you have?

- What is your particular area of expertise?

- How long have you been in practice?

- How will you be managing my assets?

Financial Adviser Fee Schedules

Prior to working with a financial adviser, you must also inquire about their fee structure. There are two kinds of fee schedules used by financial advisers: fee-only and fee-based.

Fee-only advisers receive payment solely for the services they provide. They do not collect commissions from third parties providing the recommended products. There is variability in how this type of payment schedule is structured, encompassing flat fees, hourly rates, or the adviser charging a retainer. The Table below compares the types of fee-only structures and range of charges based on 2023 rates.9 Of note, fee-only advisers serve as fiduciaries.10

Fee-based financial advisers receive payment for services but may also receive commission on specific products they sell to you.9 Most, if not all, financial experts recommend avoiding advisers using commission-based charges given the potential conflict of interest: How can one be absolutely sure this recommended financial product is best for you, knowing your adviser has a financial stake in said item?