User login

What I want people to know about the Chauvin verdict

I woke up from a nap on Tuesday, April 20, to a barrage of text messages and social media alerts about the Derek Chauvin verdict. Messages varied in content, from “let’s celebrate,” to “just so exciting,” to “finally.” As I took in the sentiments of others, I could barely sense what, if any, sentiments I had of my own.

There I sat, a Black DEI [diversity, equity, and inclusion] consultant who calls herself a “psychiatrist-activist,” but slept through the landmark court decision for policing African Americans and felt almost nothing about it.

However, I did have feelings about other matters such as the slide decks due for my client, sending reassuring text messages about the hospitalization of a friend’s child, and the 2 weeks of patient notes on my to-do list. So why did I feel emotionally flatlined about an issue that should stimulate the opposite – emotional intensity?

The answer to “why” could be attributed to a number of psychological buzz words like trauma, grief, desensitization, dissociation, numbness, or my new favorite term, languishing.

Despite the applicability of any of the above, I think my emotional flattening has more to do with the fact that in addition to the guilty verdict, I also woke up to news that 16-year-old Ma’Khia Bryant had been shot by a police officer in Columbus, Ohio.

I asked myself: How can anyone find time to grieve, nevertheless celebrate when (young) Black people continue to be killed by the police?

While it hurts to see individuals who look like me being shot by police, or even emboldened citizens, my hurt likely pales in comparison to someone who grew up surrounded by police gun violence. I grew up solidly middle class, lived in a house at the end of a cul-de-sac in a semi-gated community, and have many years ahead of me to reach my earning potential as a physician in one of the most liberal cities in the nation. While I have the skin color that puts me at risk of being shot by police due to racism, I am in a cushy position compared to other Black people who live in cities or neighborhoods with more police shootings.

Given this line of thinking, it seems clearer to me why I do not feel like celebrating, but instead, feel grateful to be alive. Not only do I feel grateful to be alive, but alive with the emotional stamina to help White people understand their contributions to the widespread oppression that keeps our society rooted in white supremacy.

This brings me to my point of what I want people, especially physicians, to know about the guilty verdict of Derek Chauvin: Some of us cannot really celebrate until there is actual police reform. This is not to say that anyone is wrong to celebrate, as long as there is an understanding that .

Meanwhile, White men like Kyle Rittenhouse who are peaceably arrested after shooting a man with a semi-automatic weapon receive donations from a Virginia police lieutenant; a policeman who, in a possible world, could one day pull me over while driving through Virginia given its proximity to Washington D.C., where I currently live.

Black and Brown people cannot fully celebrate until there is actual police reform, and reform across American institutions like the health care system. Celebration comes when the leaders who run schools, hospitals, and courtrooms look more like the numbers actually reflected in U.S. racial demographics and look less like Derek Chauvin.

Until there are more doctors who look like the racial breakdown of the nation, Black and Brown patients can never fully trust their primary care doctors, orthopedic surgeons, and psychiatrists who are White. While this reality may sound harsh, it is the reality for many of us who are dealing with trauma, grief, desensitization, dissociation, emotional numbness, or languishment resulting from racist experiences.

People of color cannot and will not stop protesting in the streets, being the one who always brings up race in the meeting, or disagreeing that the new changes are “not enough” until there is actual anti-racist institutional reform. More importantly, the efforts of people of color can be made more powerful working collectively with White allies.

But we need White allies who recognize their tendency to perceive “progress” in racial equality. We need White allies who recognize that despite the passage of the Civil Rights Act, the two-time election of a Black president, and the guilty verdict of Derek Chauvin, there is still so much work to do.

Dr. Cyrus is assistant professor in the department of psychiatry at Johns Hopkins University, Baltimore. She reports no relevant financial relationships.

A version of this article first appeared on Medscape.com.

I woke up from a nap on Tuesday, April 20, to a barrage of text messages and social media alerts about the Derek Chauvin verdict. Messages varied in content, from “let’s celebrate,” to “just so exciting,” to “finally.” As I took in the sentiments of others, I could barely sense what, if any, sentiments I had of my own.

There I sat, a Black DEI [diversity, equity, and inclusion] consultant who calls herself a “psychiatrist-activist,” but slept through the landmark court decision for policing African Americans and felt almost nothing about it.

However, I did have feelings about other matters such as the slide decks due for my client, sending reassuring text messages about the hospitalization of a friend’s child, and the 2 weeks of patient notes on my to-do list. So why did I feel emotionally flatlined about an issue that should stimulate the opposite – emotional intensity?

The answer to “why” could be attributed to a number of psychological buzz words like trauma, grief, desensitization, dissociation, numbness, or my new favorite term, languishing.

Despite the applicability of any of the above, I think my emotional flattening has more to do with the fact that in addition to the guilty verdict, I also woke up to news that 16-year-old Ma’Khia Bryant had been shot by a police officer in Columbus, Ohio.

I asked myself: How can anyone find time to grieve, nevertheless celebrate when (young) Black people continue to be killed by the police?

While it hurts to see individuals who look like me being shot by police, or even emboldened citizens, my hurt likely pales in comparison to someone who grew up surrounded by police gun violence. I grew up solidly middle class, lived in a house at the end of a cul-de-sac in a semi-gated community, and have many years ahead of me to reach my earning potential as a physician in one of the most liberal cities in the nation. While I have the skin color that puts me at risk of being shot by police due to racism, I am in a cushy position compared to other Black people who live in cities or neighborhoods with more police shootings.

Given this line of thinking, it seems clearer to me why I do not feel like celebrating, but instead, feel grateful to be alive. Not only do I feel grateful to be alive, but alive with the emotional stamina to help White people understand their contributions to the widespread oppression that keeps our society rooted in white supremacy.

This brings me to my point of what I want people, especially physicians, to know about the guilty verdict of Derek Chauvin: Some of us cannot really celebrate until there is actual police reform. This is not to say that anyone is wrong to celebrate, as long as there is an understanding that .

Meanwhile, White men like Kyle Rittenhouse who are peaceably arrested after shooting a man with a semi-automatic weapon receive donations from a Virginia police lieutenant; a policeman who, in a possible world, could one day pull me over while driving through Virginia given its proximity to Washington D.C., where I currently live.

Black and Brown people cannot fully celebrate until there is actual police reform, and reform across American institutions like the health care system. Celebration comes when the leaders who run schools, hospitals, and courtrooms look more like the numbers actually reflected in U.S. racial demographics and look less like Derek Chauvin.

Until there are more doctors who look like the racial breakdown of the nation, Black and Brown patients can never fully trust their primary care doctors, orthopedic surgeons, and psychiatrists who are White. While this reality may sound harsh, it is the reality for many of us who are dealing with trauma, grief, desensitization, dissociation, emotional numbness, or languishment resulting from racist experiences.

People of color cannot and will not stop protesting in the streets, being the one who always brings up race in the meeting, or disagreeing that the new changes are “not enough” until there is actual anti-racist institutional reform. More importantly, the efforts of people of color can be made more powerful working collectively with White allies.

But we need White allies who recognize their tendency to perceive “progress” in racial equality. We need White allies who recognize that despite the passage of the Civil Rights Act, the two-time election of a Black president, and the guilty verdict of Derek Chauvin, there is still so much work to do.

Dr. Cyrus is assistant professor in the department of psychiatry at Johns Hopkins University, Baltimore. She reports no relevant financial relationships.

A version of this article first appeared on Medscape.com.

I woke up from a nap on Tuesday, April 20, to a barrage of text messages and social media alerts about the Derek Chauvin verdict. Messages varied in content, from “let’s celebrate,” to “just so exciting,” to “finally.” As I took in the sentiments of others, I could barely sense what, if any, sentiments I had of my own.

There I sat, a Black DEI [diversity, equity, and inclusion] consultant who calls herself a “psychiatrist-activist,” but slept through the landmark court decision for policing African Americans and felt almost nothing about it.

However, I did have feelings about other matters such as the slide decks due for my client, sending reassuring text messages about the hospitalization of a friend’s child, and the 2 weeks of patient notes on my to-do list. So why did I feel emotionally flatlined about an issue that should stimulate the opposite – emotional intensity?

The answer to “why” could be attributed to a number of psychological buzz words like trauma, grief, desensitization, dissociation, numbness, or my new favorite term, languishing.

Despite the applicability of any of the above, I think my emotional flattening has more to do with the fact that in addition to the guilty verdict, I also woke up to news that 16-year-old Ma’Khia Bryant had been shot by a police officer in Columbus, Ohio.

I asked myself: How can anyone find time to grieve, nevertheless celebrate when (young) Black people continue to be killed by the police?

While it hurts to see individuals who look like me being shot by police, or even emboldened citizens, my hurt likely pales in comparison to someone who grew up surrounded by police gun violence. I grew up solidly middle class, lived in a house at the end of a cul-de-sac in a semi-gated community, and have many years ahead of me to reach my earning potential as a physician in one of the most liberal cities in the nation. While I have the skin color that puts me at risk of being shot by police due to racism, I am in a cushy position compared to other Black people who live in cities or neighborhoods with more police shootings.

Given this line of thinking, it seems clearer to me why I do not feel like celebrating, but instead, feel grateful to be alive. Not only do I feel grateful to be alive, but alive with the emotional stamina to help White people understand their contributions to the widespread oppression that keeps our society rooted in white supremacy.

This brings me to my point of what I want people, especially physicians, to know about the guilty verdict of Derek Chauvin: Some of us cannot really celebrate until there is actual police reform. This is not to say that anyone is wrong to celebrate, as long as there is an understanding that .

Meanwhile, White men like Kyle Rittenhouse who are peaceably arrested after shooting a man with a semi-automatic weapon receive donations from a Virginia police lieutenant; a policeman who, in a possible world, could one day pull me over while driving through Virginia given its proximity to Washington D.C., where I currently live.

Black and Brown people cannot fully celebrate until there is actual police reform, and reform across American institutions like the health care system. Celebration comes when the leaders who run schools, hospitals, and courtrooms look more like the numbers actually reflected in U.S. racial demographics and look less like Derek Chauvin.

Until there are more doctors who look like the racial breakdown of the nation, Black and Brown patients can never fully trust their primary care doctors, orthopedic surgeons, and psychiatrists who are White. While this reality may sound harsh, it is the reality for many of us who are dealing with trauma, grief, desensitization, dissociation, emotional numbness, or languishment resulting from racist experiences.

People of color cannot and will not stop protesting in the streets, being the one who always brings up race in the meeting, or disagreeing that the new changes are “not enough” until there is actual anti-racist institutional reform. More importantly, the efforts of people of color can be made more powerful working collectively with White allies.

But we need White allies who recognize their tendency to perceive “progress” in racial equality. We need White allies who recognize that despite the passage of the Civil Rights Act, the two-time election of a Black president, and the guilty verdict of Derek Chauvin, there is still so much work to do.

Dr. Cyrus is assistant professor in the department of psychiatry at Johns Hopkins University, Baltimore. She reports no relevant financial relationships.

A version of this article first appeared on Medscape.com.

Chauvin guilty verdict: Now it’s time to get to work

On Tuesday, April 20, the country braced for the impact of the trial verdict in death of George Floyd. Despite the case having what many would consider an overwhelming amount of evidence pointing toward conviction, if we’re completely honest, the country – and particularly the African American community – had significant doubts that the jury would render a guilty verdict.

In the hour leading up to the announcement, people and images dominated my thoughts; Tamir Rice, Breonna Taylor, Eric Garner, Rashard Brooks, and most recently, Daunte Wright. With the deaths of these Black Americans and many others as historical context, I took a stoic stance and held my breath as the verdict was read. Former Minneapolis Police Officer Derek Chauvin was found guilty of second-degree murder, third-degree murder, and second-degree manslaughter.

As Mr. Chauvin was remanded to custody and led away in handcuffs, it was clear there were no “winners” in this verdict. Mr. Floyd is still dead, and violent encounters experienced by Black Americans continue at a vastly disproportionate rate. The result is far from true justice, but what we as a country do have is a moment of accountability – and perhaps an opportunity for true system-level reform.

The final report of the President’s Task Force on 21st Century Policing, released in May 2015, recommended major policy changes at the federal level and developed key pillars aimed at promoting effective crime reduction while building public trust. Based on this report, four key takeaways are relevant to any discussion of police reform. All are vitally important, but two stand out as particularly relevant in the aftermath of the verdict. One of the key recommendations was “embracing a guardian – rather than a warrior mindset” in an effort to build trust and legitimacy. Another was ensuring that “peace officer and standards training (POST) boards include mandatory Crisis Intervention Training.”

As health professionals, we know that the ultimate effectiveness of any intervention is based upon the amount of shared trust and collaboration in the patient-physician relationship. As a consultation-liaison psychiatrist, I’ve been trained to recognize that, when requested to consult on a case, I’m frequently not making a medical diagnosis or delivering an intervention; I’m helping the team and patient reestablish trust in each other. Communication skills and techniques help start a dialogue, but you will ultimately fall short of shared understanding without trust. The underpinning of trust could begin with a commitment to procedural justice. Procedural justice, as described in The Justice Collaboratory of Yale Law School, “speaks to the idea of fair processes and how the quality of their experiences strongly impacts people’s perception of fairness.” There are four central tenets of procedural justice:

- Whether they were treated with dignity and respect.

- Whether they were given voice.

- Whether the decision-maker was neutral and transparent.

- Whether the decision-maker conveyed trustworthy motives.

These four tenets have been researched and shown to improve the trust and confidence a community has in police, and lay the foundation for creating a standard set of shared interests and values.

As health professionals, there are many aspects of procedural justice that we can and should embrace, particularly as we come to our reckoning with the use of restraints in medical settings.

Building on the work of the Task Force on 21st Century Policing, the National Initiative for Building Community Trust and Justice, from January 2015 through December 2018, implemented a six-city intervention aimed at generating measurable improvements in officer behavior, public safety, and community trust in police. The National Initiative was organized around three principal ideas: procedural justice, implicit bias training, and reconciliation and candid conversations about law enforcement’s historic role in racial tensions.

In addition to the recommendations of the federal government and independent institutions, national-level health policy organizations have made clear statements regarding police brutality and the need for systemic reform to address police brutality and systemic racism. In 2018, the American Psychiatric Association released a position statement on Police Brutality and Black Males. This was then followed in 2020 with a joint statement from the National Medical Association and the APA condemning systemic racism and police violence against Black Americans. Other health policy associations, including the American Medical Association and the American Association of Medical Colleges, have made clear statements condemning systemic racism and police brutality.

In the aftermath of the verdict, we also saw something very different. In our partisan country, there appeared to be uniform common ground. Statements were made acknowledging the importance of this historic moment, from police unions, and both political parties, and various invested grassroots organizations. In short, we may have true agreement and motivation to take the next hard steps in police reform for this country. There will be policy discussions and new mandates for training, and certainly a push to ban the use of lethal techniques, such as choke holds. While helpful, these will ultimately fall short unless we hold ourselves accountable for a true culture change.

The challenge of implementing procedural justice shouldn’t be just a law enforcement challenge, and it shouldn’t fall on the shoulders of communities with high crime areas. In other words, no single racial group should own it. Ultimately, procedural justice will need to be embraced by all of us.

On April 20, as I watched the verdict, my oldest daughter watched with me, and she asked, “What do you think, Dad?” I responded: “It’s accountability and an opportunity.” She nodded her head with resolve. She then grabbed her smartphone and jumped into social media and proclaimed in her very knowledgeable teenage voice, “See Dad, one voice is cool, but many voices in unison is better; time to get to work!” To Darnella Frazier, who captured the crime on video at age 17, and all in your generation who dare to hold us accountable, I salute you. I thank you for forcing us to look even when it was painful and not ignore the humanity of our fellow man. It is indeed time to get to work.

Dr. Norris is associate dean of student affairs and administration at George Washington University, Washington. He has no disclosures.

On Tuesday, April 20, the country braced for the impact of the trial verdict in death of George Floyd. Despite the case having what many would consider an overwhelming amount of evidence pointing toward conviction, if we’re completely honest, the country – and particularly the African American community – had significant doubts that the jury would render a guilty verdict.

In the hour leading up to the announcement, people and images dominated my thoughts; Tamir Rice, Breonna Taylor, Eric Garner, Rashard Brooks, and most recently, Daunte Wright. With the deaths of these Black Americans and many others as historical context, I took a stoic stance and held my breath as the verdict was read. Former Minneapolis Police Officer Derek Chauvin was found guilty of second-degree murder, third-degree murder, and second-degree manslaughter.

As Mr. Chauvin was remanded to custody and led away in handcuffs, it was clear there were no “winners” in this verdict. Mr. Floyd is still dead, and violent encounters experienced by Black Americans continue at a vastly disproportionate rate. The result is far from true justice, but what we as a country do have is a moment of accountability – and perhaps an opportunity for true system-level reform.

The final report of the President’s Task Force on 21st Century Policing, released in May 2015, recommended major policy changes at the federal level and developed key pillars aimed at promoting effective crime reduction while building public trust. Based on this report, four key takeaways are relevant to any discussion of police reform. All are vitally important, but two stand out as particularly relevant in the aftermath of the verdict. One of the key recommendations was “embracing a guardian – rather than a warrior mindset” in an effort to build trust and legitimacy. Another was ensuring that “peace officer and standards training (POST) boards include mandatory Crisis Intervention Training.”

As health professionals, we know that the ultimate effectiveness of any intervention is based upon the amount of shared trust and collaboration in the patient-physician relationship. As a consultation-liaison psychiatrist, I’ve been trained to recognize that, when requested to consult on a case, I’m frequently not making a medical diagnosis or delivering an intervention; I’m helping the team and patient reestablish trust in each other. Communication skills and techniques help start a dialogue, but you will ultimately fall short of shared understanding without trust. The underpinning of trust could begin with a commitment to procedural justice. Procedural justice, as described in The Justice Collaboratory of Yale Law School, “speaks to the idea of fair processes and how the quality of their experiences strongly impacts people’s perception of fairness.” There are four central tenets of procedural justice:

- Whether they were treated with dignity and respect.

- Whether they were given voice.

- Whether the decision-maker was neutral and transparent.

- Whether the decision-maker conveyed trustworthy motives.

These four tenets have been researched and shown to improve the trust and confidence a community has in police, and lay the foundation for creating a standard set of shared interests and values.

As health professionals, there are many aspects of procedural justice that we can and should embrace, particularly as we come to our reckoning with the use of restraints in medical settings.

Building on the work of the Task Force on 21st Century Policing, the National Initiative for Building Community Trust and Justice, from January 2015 through December 2018, implemented a six-city intervention aimed at generating measurable improvements in officer behavior, public safety, and community trust in police. The National Initiative was organized around three principal ideas: procedural justice, implicit bias training, and reconciliation and candid conversations about law enforcement’s historic role in racial tensions.

In addition to the recommendations of the federal government and independent institutions, national-level health policy organizations have made clear statements regarding police brutality and the need for systemic reform to address police brutality and systemic racism. In 2018, the American Psychiatric Association released a position statement on Police Brutality and Black Males. This was then followed in 2020 with a joint statement from the National Medical Association and the APA condemning systemic racism and police violence against Black Americans. Other health policy associations, including the American Medical Association and the American Association of Medical Colleges, have made clear statements condemning systemic racism and police brutality.

In the aftermath of the verdict, we also saw something very different. In our partisan country, there appeared to be uniform common ground. Statements were made acknowledging the importance of this historic moment, from police unions, and both political parties, and various invested grassroots organizations. In short, we may have true agreement and motivation to take the next hard steps in police reform for this country. There will be policy discussions and new mandates for training, and certainly a push to ban the use of lethal techniques, such as choke holds. While helpful, these will ultimately fall short unless we hold ourselves accountable for a true culture change.

The challenge of implementing procedural justice shouldn’t be just a law enforcement challenge, and it shouldn’t fall on the shoulders of communities with high crime areas. In other words, no single racial group should own it. Ultimately, procedural justice will need to be embraced by all of us.

On April 20, as I watched the verdict, my oldest daughter watched with me, and she asked, “What do you think, Dad?” I responded: “It’s accountability and an opportunity.” She nodded her head with resolve. She then grabbed her smartphone and jumped into social media and proclaimed in her very knowledgeable teenage voice, “See Dad, one voice is cool, but many voices in unison is better; time to get to work!” To Darnella Frazier, who captured the crime on video at age 17, and all in your generation who dare to hold us accountable, I salute you. I thank you for forcing us to look even when it was painful and not ignore the humanity of our fellow man. It is indeed time to get to work.

Dr. Norris is associate dean of student affairs and administration at George Washington University, Washington. He has no disclosures.

On Tuesday, April 20, the country braced for the impact of the trial verdict in death of George Floyd. Despite the case having what many would consider an overwhelming amount of evidence pointing toward conviction, if we’re completely honest, the country – and particularly the African American community – had significant doubts that the jury would render a guilty verdict.

In the hour leading up to the announcement, people and images dominated my thoughts; Tamir Rice, Breonna Taylor, Eric Garner, Rashard Brooks, and most recently, Daunte Wright. With the deaths of these Black Americans and many others as historical context, I took a stoic stance and held my breath as the verdict was read. Former Minneapolis Police Officer Derek Chauvin was found guilty of second-degree murder, third-degree murder, and second-degree manslaughter.

As Mr. Chauvin was remanded to custody and led away in handcuffs, it was clear there were no “winners” in this verdict. Mr. Floyd is still dead, and violent encounters experienced by Black Americans continue at a vastly disproportionate rate. The result is far from true justice, but what we as a country do have is a moment of accountability – and perhaps an opportunity for true system-level reform.

The final report of the President’s Task Force on 21st Century Policing, released in May 2015, recommended major policy changes at the federal level and developed key pillars aimed at promoting effective crime reduction while building public trust. Based on this report, four key takeaways are relevant to any discussion of police reform. All are vitally important, but two stand out as particularly relevant in the aftermath of the verdict. One of the key recommendations was “embracing a guardian – rather than a warrior mindset” in an effort to build trust and legitimacy. Another was ensuring that “peace officer and standards training (POST) boards include mandatory Crisis Intervention Training.”

As health professionals, we know that the ultimate effectiveness of any intervention is based upon the amount of shared trust and collaboration in the patient-physician relationship. As a consultation-liaison psychiatrist, I’ve been trained to recognize that, when requested to consult on a case, I’m frequently not making a medical diagnosis or delivering an intervention; I’m helping the team and patient reestablish trust in each other. Communication skills and techniques help start a dialogue, but you will ultimately fall short of shared understanding without trust. The underpinning of trust could begin with a commitment to procedural justice. Procedural justice, as described in The Justice Collaboratory of Yale Law School, “speaks to the idea of fair processes and how the quality of their experiences strongly impacts people’s perception of fairness.” There are four central tenets of procedural justice:

- Whether they were treated with dignity and respect.

- Whether they were given voice.

- Whether the decision-maker was neutral and transparent.

- Whether the decision-maker conveyed trustworthy motives.

These four tenets have been researched and shown to improve the trust and confidence a community has in police, and lay the foundation for creating a standard set of shared interests and values.

As health professionals, there are many aspects of procedural justice that we can and should embrace, particularly as we come to our reckoning with the use of restraints in medical settings.

Building on the work of the Task Force on 21st Century Policing, the National Initiative for Building Community Trust and Justice, from January 2015 through December 2018, implemented a six-city intervention aimed at generating measurable improvements in officer behavior, public safety, and community trust in police. The National Initiative was organized around three principal ideas: procedural justice, implicit bias training, and reconciliation and candid conversations about law enforcement’s historic role in racial tensions.

In addition to the recommendations of the federal government and independent institutions, national-level health policy organizations have made clear statements regarding police brutality and the need for systemic reform to address police brutality and systemic racism. In 2018, the American Psychiatric Association released a position statement on Police Brutality and Black Males. This was then followed in 2020 with a joint statement from the National Medical Association and the APA condemning systemic racism and police violence against Black Americans. Other health policy associations, including the American Medical Association and the American Association of Medical Colleges, have made clear statements condemning systemic racism and police brutality.

In the aftermath of the verdict, we also saw something very different. In our partisan country, there appeared to be uniform common ground. Statements were made acknowledging the importance of this historic moment, from police unions, and both political parties, and various invested grassroots organizations. In short, we may have true agreement and motivation to take the next hard steps in police reform for this country. There will be policy discussions and new mandates for training, and certainly a push to ban the use of lethal techniques, such as choke holds. While helpful, these will ultimately fall short unless we hold ourselves accountable for a true culture change.

The challenge of implementing procedural justice shouldn’t be just a law enforcement challenge, and it shouldn’t fall on the shoulders of communities with high crime areas. In other words, no single racial group should own it. Ultimately, procedural justice will need to be embraced by all of us.

On April 20, as I watched the verdict, my oldest daughter watched with me, and she asked, “What do you think, Dad?” I responded: “It’s accountability and an opportunity.” She nodded her head with resolve. She then grabbed her smartphone and jumped into social media and proclaimed in her very knowledgeable teenage voice, “See Dad, one voice is cool, but many voices in unison is better; time to get to work!” To Darnella Frazier, who captured the crime on video at age 17, and all in your generation who dare to hold us accountable, I salute you. I thank you for forcing us to look even when it was painful and not ignore the humanity of our fellow man. It is indeed time to get to work.

Dr. Norris is associate dean of student affairs and administration at George Washington University, Washington. He has no disclosures.

PTSD linked to ischemic heart disease

A study using data from Veterans Health Administration (VHA) electronic medical records shows a significant association between posttraumatic stress disorder (PTSD) among female veterans and an increased risk for incident ischemic heart disease (IHD).

The increased risk for IHD was highest among women younger than 40 with PTSD, and among racial and ethnic minorities.

“These women have been emerging as important targets for cardiovascular prevention, and our study suggests that PTSD may be an important psychosocial risk factor for IHD in these individuals,” wrote the researchers, led by Ramin Ebrahimi, MD, department of medicine, cardiology section, Veterans Affairs Greater Los Angeles Health Care System. “With the number of women veterans growing, it is critical to appreciate the health care needs of this relatively young and diverse patient population.”

The study results also have “important implications for earlier and more aggressive IHD risk assessment, monitoring and management in vulnerable women veterans,” they added. “Indeed, our findings support recent calls for cardiovascular risk screening in younger individuals and for the need to harness a broad range of clinicians who routinely treat younger women to maximize prevention efforts.”

The article was published online in JAMA Cardiology on March 17.

Increasing number of VHA users

“As an interventional cardiologist and the director of the cardiac catheterization laboratory, I noticed a significant number of the patients referred to the cath lab carried a diagnosis of posttraumatic stress disorder,” Dr. Ebrahimi said in an interview. “This intrigued me and started my journey into trying to understand how psychiatric disorders in general, and PTSD, may impact/interact with cardiovascular disorders,” he added.

The number of female veterans in the military has been increasing, and they now make up about 10% of the 20 million American veterans; that number is projected to exceed 2.2 million in the next 20 years, the authors wrote. Female veterans are also the fastest growing group of users of the VHA, they added.

IHD is the leading cause of death in women in the United States, despite the advancements in prevention and treatment. Although women are twice as likely to develop PTSD as are men, and it is even more likely in female veterans, much of the research has predominately been on male veterans, the authors wrote.

For this retrospective study, which used data from the VHA Corporate Data Warehouse, the authors examined a cohort of female veterans who were 18 years or older who had used the VHA health care system between Jan. 1, 2000, and Dec. 31, 2017.

Of the 828,997 female veterans, 151,030 had PTSD. Women excluded from the study were those who did not have any clinical encounters after their index visit, participants who had a diagnosis of IHD at or before the index visit, and those with incident IHD within 90 days of the index visit, allowing time between a PTSD diagnosis and IHD.

Propensity score matching on age at index visit, the number of previous visits, and the presence of traditional and female-specific cardiovascular risk factors, as well as mental and physical health conditions, was conducted to identify female veterans ever diagnosed with PTSD, who were matched in a 1:2 ratio to those never diagnosed with PTSD. In all, 132,923 women with PTSD and 265,846 women without PTSD were included, and data were analyzed for the period of Oct. 1, 2018, to Oct. 30, 2020.

IHD was defined as new-onset coronary artery disease, angina, or myocardial infarction–based ICD-9 and ICD-10 diagnostic codes. Age, race, and ethnicity were self-reported.

The analytic sample consisted of relatively young female veterans (mean [SD] age at baseline, 40.1 [12.2] years) of various races (White, 57.6%; Black, 29.8%) and ethnicities, the authors reported.

Of the 9,940 women who experienced incident IHD during follow-up, 5,559 did not have PTSD (2.1% of the overall population examined) and 4,381 had PTSD (3.3%). PTSD was significantly associated with an increased risk for IHD. Over the median follow-up of 4.9 years, female veterans with PTSD had a 44% higher rate of developing incident IHD compared with the female veterans without PTSD (hazard ratio [HR], 1.44; 95% confidence interval [CI], 1.38-1.50).

In addition, those with PTSD who developed IHD were younger at diagnosis (mean [SD] age, 55.5 [9.7]) than were patients without PTSD (mean [SD] age, 57.8 [10.7]). Effect sizes were largest in the group younger than 40 years (HR, 1.72; 95% CI, 1.55-1.90) and decreased for older participants (HR for those ≥60 years, 1.24; 95% CI, 1.12-1.38)

The authors found a 49% to 66% increase in risk for IHD associated with PTSD in Black women (HR, 1.49; 95% CI, 1.38-1.62) and those identified as non-White and non-Black (HR, 1.66; 95%, 1.33-2.08).

Women of all ethnic groups with PTSD were at higher risk of developing IHD, but this was especially true for Hispanic/Latina women (HR, 1.50; 95% CI 1.22-1.84), they noted.

The authors reported some limitations to their findings. The analytic sample could result in a lower ascertainment of certain conditions, such as psychiatric disorders, they wrote. Substance disorders were low in this study, possibly because of the younger age of female veterans in the sample. Because this study used VHA electronic medical records data, medical care outside of the VHA that was not paid for by the VHA could not be considered.

In addition, although this study used a large sample of female veterans, the findings cannot be generalized to female veterans outside of the VHA system, nonveteran women, or men, the researchers wrote.

A call to action

In an accompanying comment, Beth E. Cohen, MD, of the University of California, San Francisco, and the San Francisco Veterans Affairs Health Care System, points out that the physical implications for psychosocial conditions, including depression and PTSD, have been recognized for quite some time. For example, results of the INTERHEART case-control study of 30,000 people showed stress, depression, and stressful life events accounted for one-third the population-attributable risk for myocardial infarction.

As was also noted by Dr. Ebrahimi and colleagues, much of the current research has been on male veterans, yet types of trauma differ among genders; women experience higher rates of military sexual trauma but lower rates of combat trauma, Dr. Cohen wrote. The PTSD symptoms, trajectory, and biological effects can differ for women and men, as can the pathogenesis, presentation, and outcomes of cardiovascular disease (CVD).

These findings, she said, “are an important extension of the prior literature and represent the largest study in female veterans to date. Although methods differ across studies, the magnitude of risk associated with PTSD was consistent with that found in prior studies of male veterans and nonveteran samples.”

The assessment of age-specific risk is also a strength of the study, “and has implications for clinical practice, because PTSD-associated risk was greatest in a younger group in whom CVD may be overlooked.”

Dr. Cohen addressed the limitations outlined by the authors, including ascertainment bias, severity of PTSD symptoms, and their chronicity, but added that “even in the context of these limitations, this study illustrates the importance of PTSD to the health of women veterans and the additional work needed to reduce their CVD risk.”

Clinical questions remain, she added. Screens for PTSD are widely used in the VHA, yet no studies have examined whether screening or early detection decrease CVD risk. In addition, no evidence suggests that screening for or treatment of PTSD improves cardiovascular outcomes.

“Given the challenges of answering these questions in observational studies, it will be important to incorporate measures of CVD risk and outcomes in trials of behavioral and medical therapies for patients with PTSD,” she wrote.

She added that collaborations among multidisciplinary patient care teams will be important. “The findings of this study represent a call to action for this important work to understand the cardiovascular effects of PTSD and improve the health and well-being of women veterans,” Dr. Cohen concluded.

This research was supported by Investigator-Initiated Research Award from the Department of Defense U.S. Army Medical Research and Material Command Congressionally Directed Medical Research Programs (Dr. Ebrahimi) and in part by grants from the VA Informatics and Computing Infrastructure and the Offices of Research and Development at the Northport, Durham, and Greater Los Angeles Veterans Affairs medical centers. Dr. Ebrahimi reported receiving grants from the Department of Defense during the conduct of the study. Disclosures for other authors are available in the paper. Dr. Cohen reports no disclosures.

A version of this article first appeared on Medscape.com.

A study using data from Veterans Health Administration (VHA) electronic medical records shows a significant association between posttraumatic stress disorder (PTSD) among female veterans and an increased risk for incident ischemic heart disease (IHD).

The increased risk for IHD was highest among women younger than 40 with PTSD, and among racial and ethnic minorities.

“These women have been emerging as important targets for cardiovascular prevention, and our study suggests that PTSD may be an important psychosocial risk factor for IHD in these individuals,” wrote the researchers, led by Ramin Ebrahimi, MD, department of medicine, cardiology section, Veterans Affairs Greater Los Angeles Health Care System. “With the number of women veterans growing, it is critical to appreciate the health care needs of this relatively young and diverse patient population.”

The study results also have “important implications for earlier and more aggressive IHD risk assessment, monitoring and management in vulnerable women veterans,” they added. “Indeed, our findings support recent calls for cardiovascular risk screening in younger individuals and for the need to harness a broad range of clinicians who routinely treat younger women to maximize prevention efforts.”

The article was published online in JAMA Cardiology on March 17.

Increasing number of VHA users

“As an interventional cardiologist and the director of the cardiac catheterization laboratory, I noticed a significant number of the patients referred to the cath lab carried a diagnosis of posttraumatic stress disorder,” Dr. Ebrahimi said in an interview. “This intrigued me and started my journey into trying to understand how psychiatric disorders in general, and PTSD, may impact/interact with cardiovascular disorders,” he added.

The number of female veterans in the military has been increasing, and they now make up about 10% of the 20 million American veterans; that number is projected to exceed 2.2 million in the next 20 years, the authors wrote. Female veterans are also the fastest growing group of users of the VHA, they added.

IHD is the leading cause of death in women in the United States, despite the advancements in prevention and treatment. Although women are twice as likely to develop PTSD as are men, and it is even more likely in female veterans, much of the research has predominately been on male veterans, the authors wrote.

For this retrospective study, which used data from the VHA Corporate Data Warehouse, the authors examined a cohort of female veterans who were 18 years or older who had used the VHA health care system between Jan. 1, 2000, and Dec. 31, 2017.

Of the 828,997 female veterans, 151,030 had PTSD. Women excluded from the study were those who did not have any clinical encounters after their index visit, participants who had a diagnosis of IHD at or before the index visit, and those with incident IHD within 90 days of the index visit, allowing time between a PTSD diagnosis and IHD.

Propensity score matching on age at index visit, the number of previous visits, and the presence of traditional and female-specific cardiovascular risk factors, as well as mental and physical health conditions, was conducted to identify female veterans ever diagnosed with PTSD, who were matched in a 1:2 ratio to those never diagnosed with PTSD. In all, 132,923 women with PTSD and 265,846 women without PTSD were included, and data were analyzed for the period of Oct. 1, 2018, to Oct. 30, 2020.

IHD was defined as new-onset coronary artery disease, angina, or myocardial infarction–based ICD-9 and ICD-10 diagnostic codes. Age, race, and ethnicity were self-reported.

The analytic sample consisted of relatively young female veterans (mean [SD] age at baseline, 40.1 [12.2] years) of various races (White, 57.6%; Black, 29.8%) and ethnicities, the authors reported.

Of the 9,940 women who experienced incident IHD during follow-up, 5,559 did not have PTSD (2.1% of the overall population examined) and 4,381 had PTSD (3.3%). PTSD was significantly associated with an increased risk for IHD. Over the median follow-up of 4.9 years, female veterans with PTSD had a 44% higher rate of developing incident IHD compared with the female veterans without PTSD (hazard ratio [HR], 1.44; 95% confidence interval [CI], 1.38-1.50).

In addition, those with PTSD who developed IHD were younger at diagnosis (mean [SD] age, 55.5 [9.7]) than were patients without PTSD (mean [SD] age, 57.8 [10.7]). Effect sizes were largest in the group younger than 40 years (HR, 1.72; 95% CI, 1.55-1.90) and decreased for older participants (HR for those ≥60 years, 1.24; 95% CI, 1.12-1.38)

The authors found a 49% to 66% increase in risk for IHD associated with PTSD in Black women (HR, 1.49; 95% CI, 1.38-1.62) and those identified as non-White and non-Black (HR, 1.66; 95%, 1.33-2.08).

Women of all ethnic groups with PTSD were at higher risk of developing IHD, but this was especially true for Hispanic/Latina women (HR, 1.50; 95% CI 1.22-1.84), they noted.

The authors reported some limitations to their findings. The analytic sample could result in a lower ascertainment of certain conditions, such as psychiatric disorders, they wrote. Substance disorders were low in this study, possibly because of the younger age of female veterans in the sample. Because this study used VHA electronic medical records data, medical care outside of the VHA that was not paid for by the VHA could not be considered.

In addition, although this study used a large sample of female veterans, the findings cannot be generalized to female veterans outside of the VHA system, nonveteran women, or men, the researchers wrote.

A call to action

In an accompanying comment, Beth E. Cohen, MD, of the University of California, San Francisco, and the San Francisco Veterans Affairs Health Care System, points out that the physical implications for psychosocial conditions, including depression and PTSD, have been recognized for quite some time. For example, results of the INTERHEART case-control study of 30,000 people showed stress, depression, and stressful life events accounted for one-third the population-attributable risk for myocardial infarction.

As was also noted by Dr. Ebrahimi and colleagues, much of the current research has been on male veterans, yet types of trauma differ among genders; women experience higher rates of military sexual trauma but lower rates of combat trauma, Dr. Cohen wrote. The PTSD symptoms, trajectory, and biological effects can differ for women and men, as can the pathogenesis, presentation, and outcomes of cardiovascular disease (CVD).

These findings, she said, “are an important extension of the prior literature and represent the largest study in female veterans to date. Although methods differ across studies, the magnitude of risk associated with PTSD was consistent with that found in prior studies of male veterans and nonveteran samples.”

The assessment of age-specific risk is also a strength of the study, “and has implications for clinical practice, because PTSD-associated risk was greatest in a younger group in whom CVD may be overlooked.”

Dr. Cohen addressed the limitations outlined by the authors, including ascertainment bias, severity of PTSD symptoms, and their chronicity, but added that “even in the context of these limitations, this study illustrates the importance of PTSD to the health of women veterans and the additional work needed to reduce their CVD risk.”

Clinical questions remain, she added. Screens for PTSD are widely used in the VHA, yet no studies have examined whether screening or early detection decrease CVD risk. In addition, no evidence suggests that screening for or treatment of PTSD improves cardiovascular outcomes.

“Given the challenges of answering these questions in observational studies, it will be important to incorporate measures of CVD risk and outcomes in trials of behavioral and medical therapies for patients with PTSD,” she wrote.

She added that collaborations among multidisciplinary patient care teams will be important. “The findings of this study represent a call to action for this important work to understand the cardiovascular effects of PTSD and improve the health and well-being of women veterans,” Dr. Cohen concluded.

This research was supported by Investigator-Initiated Research Award from the Department of Defense U.S. Army Medical Research and Material Command Congressionally Directed Medical Research Programs (Dr. Ebrahimi) and in part by grants from the VA Informatics and Computing Infrastructure and the Offices of Research and Development at the Northport, Durham, and Greater Los Angeles Veterans Affairs medical centers. Dr. Ebrahimi reported receiving grants from the Department of Defense during the conduct of the study. Disclosures for other authors are available in the paper. Dr. Cohen reports no disclosures.

A version of this article first appeared on Medscape.com.

A study using data from Veterans Health Administration (VHA) electronic medical records shows a significant association between posttraumatic stress disorder (PTSD) among female veterans and an increased risk for incident ischemic heart disease (IHD).

The increased risk for IHD was highest among women younger than 40 with PTSD, and among racial and ethnic minorities.

“These women have been emerging as important targets for cardiovascular prevention, and our study suggests that PTSD may be an important psychosocial risk factor for IHD in these individuals,” wrote the researchers, led by Ramin Ebrahimi, MD, department of medicine, cardiology section, Veterans Affairs Greater Los Angeles Health Care System. “With the number of women veterans growing, it is critical to appreciate the health care needs of this relatively young and diverse patient population.”

The study results also have “important implications for earlier and more aggressive IHD risk assessment, monitoring and management in vulnerable women veterans,” they added. “Indeed, our findings support recent calls for cardiovascular risk screening in younger individuals and for the need to harness a broad range of clinicians who routinely treat younger women to maximize prevention efforts.”

The article was published online in JAMA Cardiology on March 17.

Increasing number of VHA users

“As an interventional cardiologist and the director of the cardiac catheterization laboratory, I noticed a significant number of the patients referred to the cath lab carried a diagnosis of posttraumatic stress disorder,” Dr. Ebrahimi said in an interview. “This intrigued me and started my journey into trying to understand how psychiatric disorders in general, and PTSD, may impact/interact with cardiovascular disorders,” he added.

The number of female veterans in the military has been increasing, and they now make up about 10% of the 20 million American veterans; that number is projected to exceed 2.2 million in the next 20 years, the authors wrote. Female veterans are also the fastest growing group of users of the VHA, they added.

IHD is the leading cause of death in women in the United States, despite the advancements in prevention and treatment. Although women are twice as likely to develop PTSD as are men, and it is even more likely in female veterans, much of the research has predominately been on male veterans, the authors wrote.

For this retrospective study, which used data from the VHA Corporate Data Warehouse, the authors examined a cohort of female veterans who were 18 years or older who had used the VHA health care system between Jan. 1, 2000, and Dec. 31, 2017.

Of the 828,997 female veterans, 151,030 had PTSD. Women excluded from the study were those who did not have any clinical encounters after their index visit, participants who had a diagnosis of IHD at or before the index visit, and those with incident IHD within 90 days of the index visit, allowing time between a PTSD diagnosis and IHD.

Propensity score matching on age at index visit, the number of previous visits, and the presence of traditional and female-specific cardiovascular risk factors, as well as mental and physical health conditions, was conducted to identify female veterans ever diagnosed with PTSD, who were matched in a 1:2 ratio to those never diagnosed with PTSD. In all, 132,923 women with PTSD and 265,846 women without PTSD were included, and data were analyzed for the period of Oct. 1, 2018, to Oct. 30, 2020.

IHD was defined as new-onset coronary artery disease, angina, or myocardial infarction–based ICD-9 and ICD-10 diagnostic codes. Age, race, and ethnicity were self-reported.

The analytic sample consisted of relatively young female veterans (mean [SD] age at baseline, 40.1 [12.2] years) of various races (White, 57.6%; Black, 29.8%) and ethnicities, the authors reported.

Of the 9,940 women who experienced incident IHD during follow-up, 5,559 did not have PTSD (2.1% of the overall population examined) and 4,381 had PTSD (3.3%). PTSD was significantly associated with an increased risk for IHD. Over the median follow-up of 4.9 years, female veterans with PTSD had a 44% higher rate of developing incident IHD compared with the female veterans without PTSD (hazard ratio [HR], 1.44; 95% confidence interval [CI], 1.38-1.50).

In addition, those with PTSD who developed IHD were younger at diagnosis (mean [SD] age, 55.5 [9.7]) than were patients without PTSD (mean [SD] age, 57.8 [10.7]). Effect sizes were largest in the group younger than 40 years (HR, 1.72; 95% CI, 1.55-1.90) and decreased for older participants (HR for those ≥60 years, 1.24; 95% CI, 1.12-1.38)

The authors found a 49% to 66% increase in risk for IHD associated with PTSD in Black women (HR, 1.49; 95% CI, 1.38-1.62) and those identified as non-White and non-Black (HR, 1.66; 95%, 1.33-2.08).

Women of all ethnic groups with PTSD were at higher risk of developing IHD, but this was especially true for Hispanic/Latina women (HR, 1.50; 95% CI 1.22-1.84), they noted.

The authors reported some limitations to their findings. The analytic sample could result in a lower ascertainment of certain conditions, such as psychiatric disorders, they wrote. Substance disorders were low in this study, possibly because of the younger age of female veterans in the sample. Because this study used VHA electronic medical records data, medical care outside of the VHA that was not paid for by the VHA could not be considered.

In addition, although this study used a large sample of female veterans, the findings cannot be generalized to female veterans outside of the VHA system, nonveteran women, or men, the researchers wrote.

A call to action

In an accompanying comment, Beth E. Cohen, MD, of the University of California, San Francisco, and the San Francisco Veterans Affairs Health Care System, points out that the physical implications for psychosocial conditions, including depression and PTSD, have been recognized for quite some time. For example, results of the INTERHEART case-control study of 30,000 people showed stress, depression, and stressful life events accounted for one-third the population-attributable risk for myocardial infarction.

As was also noted by Dr. Ebrahimi and colleagues, much of the current research has been on male veterans, yet types of trauma differ among genders; women experience higher rates of military sexual trauma but lower rates of combat trauma, Dr. Cohen wrote. The PTSD symptoms, trajectory, and biological effects can differ for women and men, as can the pathogenesis, presentation, and outcomes of cardiovascular disease (CVD).

These findings, she said, “are an important extension of the prior literature and represent the largest study in female veterans to date. Although methods differ across studies, the magnitude of risk associated with PTSD was consistent with that found in prior studies of male veterans and nonveteran samples.”

The assessment of age-specific risk is also a strength of the study, “and has implications for clinical practice, because PTSD-associated risk was greatest in a younger group in whom CVD may be overlooked.”

Dr. Cohen addressed the limitations outlined by the authors, including ascertainment bias, severity of PTSD symptoms, and their chronicity, but added that “even in the context of these limitations, this study illustrates the importance of PTSD to the health of women veterans and the additional work needed to reduce their CVD risk.”

Clinical questions remain, she added. Screens for PTSD are widely used in the VHA, yet no studies have examined whether screening or early detection decrease CVD risk. In addition, no evidence suggests that screening for or treatment of PTSD improves cardiovascular outcomes.

“Given the challenges of answering these questions in observational studies, it will be important to incorporate measures of CVD risk and outcomes in trials of behavioral and medical therapies for patients with PTSD,” she wrote.

She added that collaborations among multidisciplinary patient care teams will be important. “The findings of this study represent a call to action for this important work to understand the cardiovascular effects of PTSD and improve the health and well-being of women veterans,” Dr. Cohen concluded.

This research was supported by Investigator-Initiated Research Award from the Department of Defense U.S. Army Medical Research and Material Command Congressionally Directed Medical Research Programs (Dr. Ebrahimi) and in part by grants from the VA Informatics and Computing Infrastructure and the Offices of Research and Development at the Northport, Durham, and Greater Los Angeles Veterans Affairs medical centers. Dr. Ebrahimi reported receiving grants from the Department of Defense during the conduct of the study. Disclosures for other authors are available in the paper. Dr. Cohen reports no disclosures.

A version of this article first appeared on Medscape.com.

Adjunctive MDMA safe, effective for severe PTSD

Adding 3,4-methylenedioxymethamphetamine (MDMA) to integrative psychotherapy may significantly improve symptoms and well-being for patients with severe posttraumatic stress disorder, including those with the dissociative subtype, new research suggests.

MAPP1 is the first phase 3 randomized controlled trial of MDMA-assisted therapy in this population. Participants who received the active treatment showed greater improvement in PTSD symptoms, mood, and empathy in comparison with participants who received placebo.

MDMA was “extremely effective, particularly for a subpopulation that ordinarily does not respond well to conventional treatment,” study coinvestigator Bessel van der Kolk, MD, professor of psychiatry at Boston University School of Medicine, told delegates attending the virtual European Psychiatric Association (EPA) 2021 Congress.

Growing interest

, particularly because failure rates with most available evidence-based treatments have been relatively high.

As previously reported by this news organization, in 2017, the U.S. Food and Drug Administration approved the trial design of Dr. van der Kolk’s and colleagues’ MAPP1 study after granting MDMA breakthrough designation.

The MAPP1 investigators assessed 90 patients with PTSD (mean age, 41 years; 77% White; 66% women) from 50 sites. For the majority of patients (84%), trauma history was developmental. “In other words, trauma [occurred] very early in life, usually at the hands of their own caregivers,” Dr. van der Kolk noted.

In addition, 18% of the patients were veterans, and 12% had combat exposure. The average duration of PTSD before enrollment was 18 years. All patients underwent screening and three preparatory psychotherapy sessions at enrollment.

Participants were randomly assigned to receive MDMA 80 mg or 120 mg (n = 46) or placebo (n = 44) followed by three integrative psychotherapy sessions lasting a total of 8 hours. A supplemental dose of 40 or 60 mg of MDMA could be administered from 1.5 to 2 hours after the first dose.

The patients stayed in the laboratory on the evening of the treatment session and attended a debriefing the next morning. The session was repeated a month later and again a month after that. In between, patients had telephone contact with the raters, who were blinded to the treatment received.

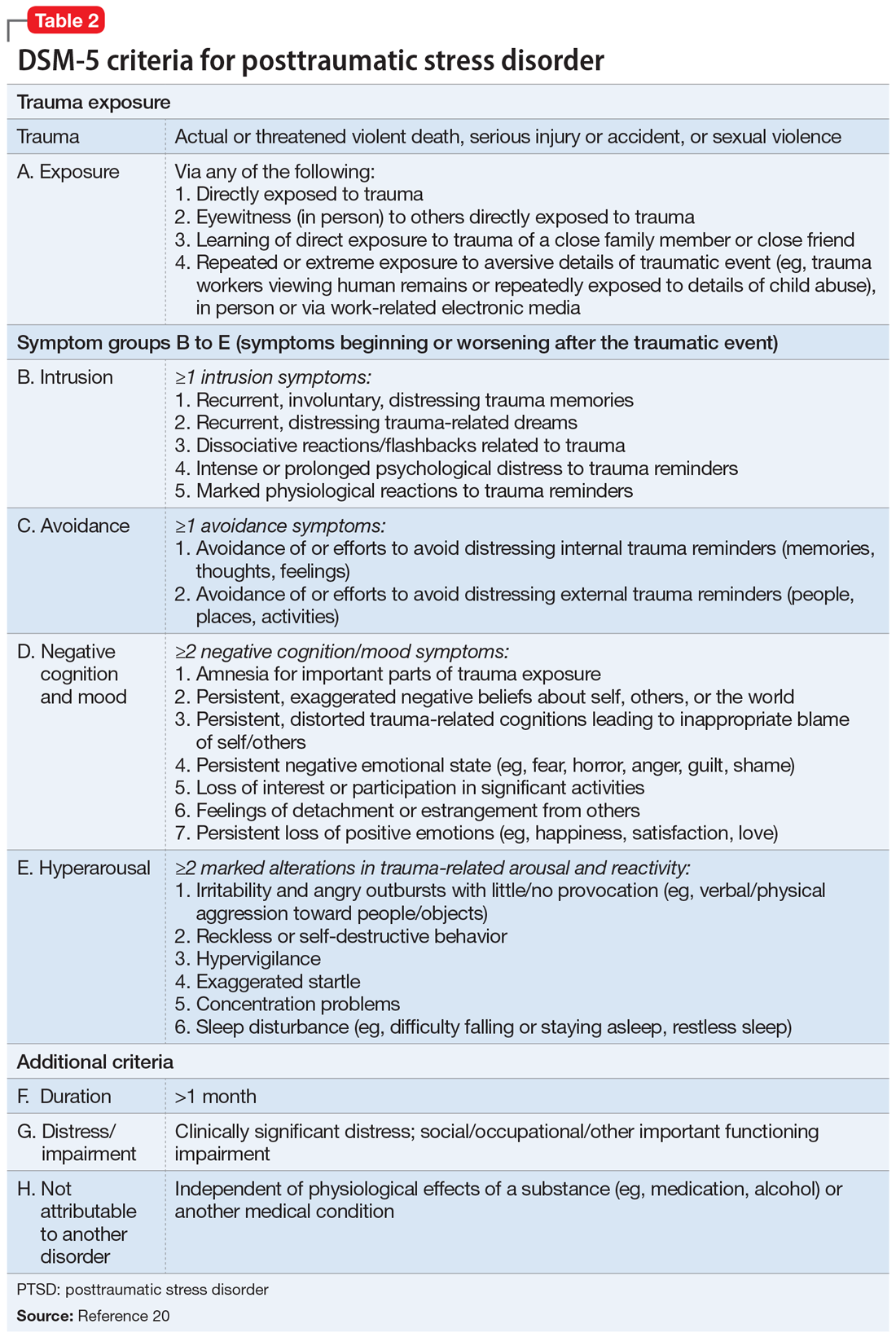

Follow-up assessments were conducted 2 months after the third treatment session and again at 12 months. The primary outcome measure was change in Clinician Administered PTSD Scale for DSM 5 (CAPS-5) score from baseline.

‘Dramatic improvement’

Results showed that both the MDMA and placebo groups experienced a statistically significant improvement in PTSD symptoms, “but MDMA had a dramatically significant improvement, with an effect size of over 0.9,” Dr. van der Kolk said.

The MDMA group also reported enhanced mood and well-being, increased responsiveness to emotional and sensory stimuli, a greater sense of closeness to other people, and a greater feeling of empathy.

Patients also reported having heightened openness, “and clearly the issue of empathy for themselves and others was a very large part of the process,” said Dr. van der Kolk.

“But for me, the most interesting part of the study is that the Adverse Childhood Experiences scale had no effect,” he noted. In other words, “the amount of childhood adverse experiences did not predict outcomes, which was very surprising because usually those patients are very treatment resistant.”

Dr. van der Kolk added that the dissociative subtype of PTSD was first described in the DSM-5 and that patients are “notoriously unresponsive to most unconventional treatments.”

In the current study, 13 patients met the criteria for the subtype, and investigators found they “did better than people with classical PTSD,” Dr. van der Kolk said. He added that this is a “very, very important finding.”

Carefully controlled

Overall, 82% of patients reported a significant improvement by the end of the study; 56% reported that they no longer had PTSD.

In addition, 67% of patients no longer met diagnostic criteria for PTSD. These included patients who had crossed over to active treatment from the placebo group.

Eleven patients (12%) experienced relapse by 12 months; in nine of the cases, this was due to the presence of additional stressors.

There were “very few adverse side effects” during the study, Dr. van der Kolk noted. In addition, “there were really no serious mental side effects,” despite the patients’ “opening up so much very painful material,” he added.

The most common adverse events among the MDMA group were muscle tightness (63%), decreased appetite (52%), nausea (30%), hyperhidrosis (20%), and feeling cold (20%). These effects were “quite small [and] the sort of side effects you would expect in response to an amphetamine substance like MDMA,” said Dr. van der Kolk.

“An important reason why we think the side effect profile is so good is because the study was extremely carefully done, very carefully controlled,” he added. “There was a great deal of support, [and] we paid an enormous amount of attention to creating a very safe context in which this drug was being used.”

However, he expressed concern that “as people see the very good results, they may skimp a little bit on the creation of the context and not have as careful a psychotherapy protocol as we had here.”

‘On the right track’

Commenting on the findings for this news organization, David Nutt, MD, PhD, Edmond J. Safra Professor of Neuropsychopharmacology, Imperial College London, said the results are proof that the investigators’ “earlier smaller trials of MDMA were on the right track.”

“This larger and multicenter trial shows that MDMA therapy can be broadened into newer research groups, which augurs well for the much larger rollout that will be required once it gets a license,” said Dr. Nutt, who was not involved with the research.

He added, “the prior evidence of the safety of MDMA has [now] been confirmed.”

The study represents an “important step in the path to the clinical use of MDMA for PTSD,” Dr. Nutt said.

The study was sponsored by the Multidisciplinary Association for Psychedelic Studies. The investigators and Dr. Nutt have reported no relevant financial relationships.

A version of this article first appeared on Medscape.com.

Adding 3,4-methylenedioxymethamphetamine (MDMA) to integrative psychotherapy may significantly improve symptoms and well-being for patients with severe posttraumatic stress disorder, including those with the dissociative subtype, new research suggests.

MAPP1 is the first phase 3 randomized controlled trial of MDMA-assisted therapy in this population. Participants who received the active treatment showed greater improvement in PTSD symptoms, mood, and empathy in comparison with participants who received placebo.

MDMA was “extremely effective, particularly for a subpopulation that ordinarily does not respond well to conventional treatment,” study coinvestigator Bessel van der Kolk, MD, professor of psychiatry at Boston University School of Medicine, told delegates attending the virtual European Psychiatric Association (EPA) 2021 Congress.

Growing interest

, particularly because failure rates with most available evidence-based treatments have been relatively high.

As previously reported by this news organization, in 2017, the U.S. Food and Drug Administration approved the trial design of Dr. van der Kolk’s and colleagues’ MAPP1 study after granting MDMA breakthrough designation.

The MAPP1 investigators assessed 90 patients with PTSD (mean age, 41 years; 77% White; 66% women) from 50 sites. For the majority of patients (84%), trauma history was developmental. “In other words, trauma [occurred] very early in life, usually at the hands of their own caregivers,” Dr. van der Kolk noted.

In addition, 18% of the patients were veterans, and 12% had combat exposure. The average duration of PTSD before enrollment was 18 years. All patients underwent screening and three preparatory psychotherapy sessions at enrollment.

Participants were randomly assigned to receive MDMA 80 mg or 120 mg (n = 46) or placebo (n = 44) followed by three integrative psychotherapy sessions lasting a total of 8 hours. A supplemental dose of 40 or 60 mg of MDMA could be administered from 1.5 to 2 hours after the first dose.

The patients stayed in the laboratory on the evening of the treatment session and attended a debriefing the next morning. The session was repeated a month later and again a month after that. In between, patients had telephone contact with the raters, who were blinded to the treatment received.

Follow-up assessments were conducted 2 months after the third treatment session and again at 12 months. The primary outcome measure was change in Clinician Administered PTSD Scale for DSM 5 (CAPS-5) score from baseline.

‘Dramatic improvement’

Results showed that both the MDMA and placebo groups experienced a statistically significant improvement in PTSD symptoms, “but MDMA had a dramatically significant improvement, with an effect size of over 0.9,” Dr. van der Kolk said.

The MDMA group also reported enhanced mood and well-being, increased responsiveness to emotional and sensory stimuli, a greater sense of closeness to other people, and a greater feeling of empathy.

Patients also reported having heightened openness, “and clearly the issue of empathy for themselves and others was a very large part of the process,” said Dr. van der Kolk.

“But for me, the most interesting part of the study is that the Adverse Childhood Experiences scale had no effect,” he noted. In other words, “the amount of childhood adverse experiences did not predict outcomes, which was very surprising because usually those patients are very treatment resistant.”

Dr. van der Kolk added that the dissociative subtype of PTSD was first described in the DSM-5 and that patients are “notoriously unresponsive to most unconventional treatments.”

In the current study, 13 patients met the criteria for the subtype, and investigators found they “did better than people with classical PTSD,” Dr. van der Kolk said. He added that this is a “very, very important finding.”

Carefully controlled

Overall, 82% of patients reported a significant improvement by the end of the study; 56% reported that they no longer had PTSD.

In addition, 67% of patients no longer met diagnostic criteria for PTSD. These included patients who had crossed over to active treatment from the placebo group.

Eleven patients (12%) experienced relapse by 12 months; in nine of the cases, this was due to the presence of additional stressors.

There were “very few adverse side effects” during the study, Dr. van der Kolk noted. In addition, “there were really no serious mental side effects,” despite the patients’ “opening up so much very painful material,” he added.

The most common adverse events among the MDMA group were muscle tightness (63%), decreased appetite (52%), nausea (30%), hyperhidrosis (20%), and feeling cold (20%). These effects were “quite small [and] the sort of side effects you would expect in response to an amphetamine substance like MDMA,” said Dr. van der Kolk.

“An important reason why we think the side effect profile is so good is because the study was extremely carefully done, very carefully controlled,” he added. “There was a great deal of support, [and] we paid an enormous amount of attention to creating a very safe context in which this drug was being used.”

However, he expressed concern that “as people see the very good results, they may skimp a little bit on the creation of the context and not have as careful a psychotherapy protocol as we had here.”

‘On the right track’

Commenting on the findings for this news organization, David Nutt, MD, PhD, Edmond J. Safra Professor of Neuropsychopharmacology, Imperial College London, said the results are proof that the investigators’ “earlier smaller trials of MDMA were on the right track.”

“This larger and multicenter trial shows that MDMA therapy can be broadened into newer research groups, which augurs well for the much larger rollout that will be required once it gets a license,” said Dr. Nutt, who was not involved with the research.

He added, “the prior evidence of the safety of MDMA has [now] been confirmed.”

The study represents an “important step in the path to the clinical use of MDMA for PTSD,” Dr. Nutt said.

The study was sponsored by the Multidisciplinary Association for Psychedelic Studies. The investigators and Dr. Nutt have reported no relevant financial relationships.

A version of this article first appeared on Medscape.com.

Adding 3,4-methylenedioxymethamphetamine (MDMA) to integrative psychotherapy may significantly improve symptoms and well-being for patients with severe posttraumatic stress disorder, including those with the dissociative subtype, new research suggests.

MAPP1 is the first phase 3 randomized controlled trial of MDMA-assisted therapy in this population. Participants who received the active treatment showed greater improvement in PTSD symptoms, mood, and empathy in comparison with participants who received placebo.

MDMA was “extremely effective, particularly for a subpopulation that ordinarily does not respond well to conventional treatment,” study coinvestigator Bessel van der Kolk, MD, professor of psychiatry at Boston University School of Medicine, told delegates attending the virtual European Psychiatric Association (EPA) 2021 Congress.

Growing interest

, particularly because failure rates with most available evidence-based treatments have been relatively high.

As previously reported by this news organization, in 2017, the U.S. Food and Drug Administration approved the trial design of Dr. van der Kolk’s and colleagues’ MAPP1 study after granting MDMA breakthrough designation.

The MAPP1 investigators assessed 90 patients with PTSD (mean age, 41 years; 77% White; 66% women) from 50 sites. For the majority of patients (84%), trauma history was developmental. “In other words, trauma [occurred] very early in life, usually at the hands of their own caregivers,” Dr. van der Kolk noted.

In addition, 18% of the patients were veterans, and 12% had combat exposure. The average duration of PTSD before enrollment was 18 years. All patients underwent screening and three preparatory psychotherapy sessions at enrollment.

Participants were randomly assigned to receive MDMA 80 mg or 120 mg (n = 46) or placebo (n = 44) followed by three integrative psychotherapy sessions lasting a total of 8 hours. A supplemental dose of 40 or 60 mg of MDMA could be administered from 1.5 to 2 hours after the first dose.

The patients stayed in the laboratory on the evening of the treatment session and attended a debriefing the next morning. The session was repeated a month later and again a month after that. In between, patients had telephone contact with the raters, who were blinded to the treatment received.

Follow-up assessments were conducted 2 months after the third treatment session and again at 12 months. The primary outcome measure was change in Clinician Administered PTSD Scale for DSM 5 (CAPS-5) score from baseline.

‘Dramatic improvement’

Results showed that both the MDMA and placebo groups experienced a statistically significant improvement in PTSD symptoms, “but MDMA had a dramatically significant improvement, with an effect size of over 0.9,” Dr. van der Kolk said.

The MDMA group also reported enhanced mood and well-being, increased responsiveness to emotional and sensory stimuli, a greater sense of closeness to other people, and a greater feeling of empathy.

Patients also reported having heightened openness, “and clearly the issue of empathy for themselves and others was a very large part of the process,” said Dr. van der Kolk.

“But for me, the most interesting part of the study is that the Adverse Childhood Experiences scale had no effect,” he noted. In other words, “the amount of childhood adverse experiences did not predict outcomes, which was very surprising because usually those patients are very treatment resistant.”

Dr. van der Kolk added that the dissociative subtype of PTSD was first described in the DSM-5 and that patients are “notoriously unresponsive to most unconventional treatments.”

In the current study, 13 patients met the criteria for the subtype, and investigators found they “did better than people with classical PTSD,” Dr. van der Kolk said. He added that this is a “very, very important finding.”

Carefully controlled

Overall, 82% of patients reported a significant improvement by the end of the study; 56% reported that they no longer had PTSD.

In addition, 67% of patients no longer met diagnostic criteria for PTSD. These included patients who had crossed over to active treatment from the placebo group.

Eleven patients (12%) experienced relapse by 12 months; in nine of the cases, this was due to the presence of additional stressors.

There were “very few adverse side effects” during the study, Dr. van der Kolk noted. In addition, “there were really no serious mental side effects,” despite the patients’ “opening up so much very painful material,” he added.

The most common adverse events among the MDMA group were muscle tightness (63%), decreased appetite (52%), nausea (30%), hyperhidrosis (20%), and feeling cold (20%). These effects were “quite small [and] the sort of side effects you would expect in response to an amphetamine substance like MDMA,” said Dr. van der Kolk.