User login

Understanding the Singapore COVID-19 Experience: Implications for Hospital Medicine

One of the worst public health threats of our generation, coronavirus disease 2019 (COVID-19), first emerged in Wuhan, China, in December 2019 and quickly spread to Singapore, Hong Kong, and Taiwan. These three countries have been praised for their control of the pandemic,1,2 while the number of cases worldwide, including those in the United States, has soared. Political alignment, centralized and integrated healthcare systems, small size, effective technology deployment, widespread testing combined with contact tracing and isolation, and personal protective equipment (PPE) availability underscore their successes.1,3-5 Although these factors differ starkly from those currently employed in the United States, a better understanding their experience may positively influence the myriad US responses. We describe some salient features of Singapore’s infection preparedness, provide examples of how these features guided the National University Hospital (NUH) Singapore COVID-19 response, and illustrate how one facet of the NUH response was translated to develop a new care model at the University of California, San Francisco (UCSF).

THE SINGAPORE EXPERIENCE OVER TIME

Singapore, a small island country (278 square miles) city-state in Southeast Asia has a population of 5.8 million people. Most Singaporeans receive their inpatient care in the public hospitals that are organized and resourced through the Singapore Ministry of Health (MOH). In 2003, severe acute respiratory syndrome (SARS) infected 238 people and killed 33 over 3 months in Singapore, which led to a significant economic downturn. Singapore’s initial SARS experience unveiled limitations in infrastructure, staff preparedness, virus control methodology, and centralized crisis systems. Lessons gleaned from the SARS experience laid the foundation for Singapore’s subsequent disaster preparedness.6

Post-SARS, the MOH created structures and systems to prepare Singapore for future epidemics. All public hospitals expanded isolation capacity by constructing new units or repurposing existing ones and creating colocated Emergency Department (ED) isolation facilities. Additionally, the MOH commissioned the National Centre for Infectious Diseases, a 330-bed high-level isolation hospital.7 They also mandated hospital systems to regularly practice mass casualty and infectious (including respiratory) crisis responses through externally evaluated simulation.8 These are orchestrated down to the smallest detail and involve staff at all levels. For example, healthcare workers (HCW) being “deployed” outside of their specialty, housekeepers practicing novel hazardous waste disposal, and security guards managing crowds interact throughout the exercise.

The testing and viral spread control challenges during SARS spawned hospital-system epidemiology capacity building. Infectious diseases reporting guidelines were refined, and communication channels enhanced to include cross-hospital information sharing and direct lines of communication for epidemiology groups to and from the MOH. Enhanced contact tracing methodologies were adopted and practiced regularly. In addition, material stockpiles, supplies, and supply chains were recalibrated.

The Singapore government also adopted the Disease Outbreak Response System Condition (DORSCON) system,9 a color-coded framework for pandemic response that guides activation of crisis interventions broadly (such as temperature screening at airports and restrictions to travel and internal movements), as well as within the healthcare setting.

In addition to prompting these notable preparedness efforts, SARS had a palpable impact on Singaporeans’ collective psychology both within and outside of the hospital system. The very close-knit medical community lost colleagues during the crisis, and the larger community deeply felt the health and economic costs of this crisis.10 The resulting “respect” or “healthy fear” for infectious crises continues to the present day.

THE SINGAPORE COVID-19 RESPONSE: NATIONAL UNIVERSITY HOSPITAL EXPERIENCE

The NUH is a 1,200-bed public tertiary care academic health center in Singapore. Before the first COVID-19 case was diagnosed in Singapore, NUH joined forces with its broader health system, university resources (schools of medicine and public health), and international partners to refine the existing structures and systems in response to this new infectious threat.

One of these structures included the existing NUH ED negative-pressure “fever facility.” In the ED triage, patients are routinely screened for infectious diseases such as H1N1, MERS-CoV, and measles. In early January, these screening criteria were evolved to adapt to COVID-19. High-risk patients bypass common waiting areas and are sent directly to the fever facility for management. From there, patients requiring admission are sent to one of the inpatient isolation wards, each with over 21 negative-pressure isolation rooms. To expand isolation capacity, lower-priority patients were relocated, and the existing negative- and neutral-pressure rooms were converted into COVID-19 pandemic wards.

The pandemic wards are staffed by nurses with previous isolation experience and Internal Medicine and Subspecialty Medicine physicians and trainees working closely with Infectious Diseases experts. Pandemic Ward teams are sequestered from other clinical and administrative teams, wear hospital-laundered scrubs, and use PPE-conserving practices. These strategies, implemented at the outset, are based on international guidelines contextualized to local needs and include extended use (up to 6 hours) of N95 respirators for the pandemic wards, and surgical masks in all other clinical areas. Notably, there have been no documented transmissions to HCW or patients at NUH. The workforce was maximized by limiting nonurgent clinical, administrative, research, and teaching activities.

In February, COVID-19 testing was initiated internally and deployed widely. NUH, at the time of this writing, has performed more than 6,000 swabs with up to 200 tests run per day (with 80 confirmed cases). Testing at this scale has allowed NUH to ensure: (a) prompt isolation of patients, even those with mild symptoms, (b) deisolation of those testing negative thus conserving PPE and isolation facilities, (c) a better understanding of the epidemiology and the wide range of clinical manifestations of COVID-19, and (d) early comprehensive contact tracing including mildly symptomatic patients.

The MOH plays a central role in coordinating COVID-19 activities and supports individual hospital systems such as NUH. Some of their crisis leadership strategies include daily text messages distributed countrywide, two-way communication channels that ensure feedback loops with hospital executives, epidemiology specialists, and operational workgroups, and engendering interhospital collaboration.11

A US HOSPITAL MEDICINE RESPONSE: UC SAN FRANCISCO

In the United States, the Joint Commission provides structures, tools, and processes for hospital systems to prepare for disasters.12 Many hospital systems have experience with natural disasters which, similar to Singapore’s planning, ensures structures and systems are in place during a crisis. Although these are transferable to multiple types of disasters, the US healthcare system’s direct experience with infectious crises is limited. A fairly distinctive facet—and an asset of US healthcare—is the role of hospitalists.

Hospitalists care for the majority of medical inpatients across the United States,13 and as such, they currently, and will increasingly, play a major role in the US COVID-19 response. This is the case at the UCSF Helen Diller Medical Center at Parnassus Heights (UCSFMC), a 600-bed academic medical center. To learn from other’s early experiences with COVID-19, UCSF Health System leadership connected with many outside health systems including NUH. As one of its multiple pandemic responses, they engaged the UCSFMC Division of Hospital Medicine (DHM), a division that includes 117 hospitalists, to work with hospital and health system leadership and launch a respiratory isolation unit (RIU) modeled after the NUH pandemic ward. The aim of the RIU is to group inpatients with either confirmed or suspected COVID-19 patients who do not require critical care.

An interdisciplinary work group comprising hospitalists, infectious disease specialists, emergency department clinicians, nursing, rehabilitation experts, hospital epidemiology and infection-prevention leaders, safety specialists, and systems engineers was assembled to repurpose an existing medical unit and establish new care models for the RIU. This workgroup created clinical guidelines and workflows, and RIU leaders actively solicit feedback from the staff to advance these standards.

Hospitalists and nurses who volunteered to work on the UCSF attending-staffed RIU received extensive training, including online and widely available in-person PPE training delivered by infection-prevention experts. The RIU hospitalists engage with hospitalists nationwide through ongoing conference calls to share best practices and clinical cases. Patients are admitted by hospitalists to the RIU via the emergency department or directly from ambulatory sites. All RIU providers and staff are screened daily for symptoms prior to starting their shifts, wear hospital-laundered scrubs on the unit, and remain on the unit for the duration of their shift. Hospitalists and nurses communicate regularly to cluster their patient visits and interventions while specialists provide virtual consults (as deemed safe and appropriate) to optimize PPE conservation and decrease overall exposure. The Health System establishes and revises PPE protocols based on CDC guidelines, best available evidence, and supply chain realities. These guidelines are evolving and currently include surgical mask, gown, gloves, and eye protection for all patient interactions with suspected or confirmed COVID-19 and respirator use during aerosol-generating procedures. Research studies (eg, clinical trials and evaluations), informatics efforts (eg, patient flow dashboards), and healthcare technology innovations (eg, tablets for telehealth and video visits) are continually integrated into the RIU infrastructure. Robust attention to the well-being of everyone working on the unit includes chaplain visits, daily debriefs, meal delivery, and palliative care service support, which enrich the unit experience and instill a culture of unity.

MOVING FORWARD

The structures and systems born out of the 2003 SARS experience and the “test, trace, and isolate” strategy were arguably key drivers to flatten Singapore’s epidemic curve early in the pandemic.3 Even with these in place, Singapore is now experiencing a second wave with a significantly higher caseload.14 In response, the government instituted strict social distancing measures on April 3, closing schools and most workplaces. This suggests that the COVID-19 pandemic may fluctuate over time and that varying types and levels of interventions will be required to maintain long-term control. The NUH team describes experiencing cognitive overload given the ever-changing nature and volume of information and fatigue due to the effort required and duration of this crisis. New programs addressing these challenges are being developed and rapidly deployed.

Despite early testing limitations and newly minted systems, San Francisco is cautiously optimistic about its epidemic curve. Since the March 17, 2020, “shelter in place” order, COVID-19 hospitalizations have remained manageable and constant.15 This has afforded healthcare systems including UCSF critical time to evolve its clinical operations (eg, the RIU) and to leverage its academic culture coordinating its bench research, global health, epidemiology, clinical research, informatics, and clinical enterprise scholars and experts to advance COVID-19 science and inform pandemic solutions. Although the UCSF frontline teams are challenged by the stresses of being in the throes of the pandemic amidst a rapidly changing landscape (including changes in PPE and testing recommendations specifically), they are working together to build team resilience for what may come.

CONCLUSION

The world is facing a pandemic of tremendous proportions, and the United States is in the midst of a wave the height of which is yet to be seen. As Fisher and colleagues wrote in 2011, “Our response to infectious disease outbreaks is born out of past experience.”4 Singapore and NUH’s structures and systems that were put into place demonstrate this—they are timely, have been effective thus far, and will be tested in this next wave. “However, no two outbreaks are the same,” the authors wrote, “so an understanding of the infectious agent as well as the environment confronting it is fundamental to the response.”4 In the United States, hospitalists are a key asset in our environment to confront this virus. The UCSF experience exemplifies that, by combining new ideas from another system with on-the-ground expertise while working hand-in-hand with the hospital and health system, hospitalists can be a critical facet of the pandemic response. Hospitalists’ intrinsic abilities to collaborate, learn, and innovate will enable them to not only meet this challenge now but also to transform practices and capacities to respond to crises into the future.

Acknowledgment

Bradley Sharpe, MD, Division Chief, Division of Hospital Medicine, University of California, San Francisco, California, for his input on conception and critical review of this manuscript.

1. Wang CJ, Ng CY, Brook RH. Response to COVID-19 in Taiwan: big data analytics, new technology, and proactive testing. JAMA. 2020. https://doi.org/10.1001/jama.2020.3151.

2. Legido-Quigley H, Asgari N, Teo YY, et al. Are high-performing health systems resilient against the COVID-19 epidemic? Lancet. 2020;395(10227):848-850. https://doi.org/10.1016/S0140-6736(20)30551-1.

3. Wong JEL, Leo YS, Tan CC. COVID-19 in Singapore—current experience: critical global issues that require attention and action. JAMA. 2020;323(13):1243-1244. https://doi.org/10.1001/jama.2020.2467.

4. Fisher D, Hui DS, Gao Z, et al. Pandemic response lessons from influenza H1N1 2009 in Asia. Respirology. 2011;16(6):876-882. https://doi.org/ 10.1111/j.1440-1843.2011.02003.x.

5. Wong ATY, Chen H, Liu SH, et al. From SARS to avian influenza preparedness in Hong Kong. Clin Infect Dis. 2017;64(suppl_2):S98-S104. https://doi.org/ 10.1093/cid/cix123.

6. Tan CC. SARS in Singapore--key lessons from an epidemic. Ann Acad Med Singapore. 2006;35(5):345-349.

7. National Centre for Infectious Diseases. About NCID. https://www.ncid.sg/About-NCID/Pages/default.aspx. Accessed April 5, 2020.

8. Cutter J. Preparing for an influenza pandemic in Singapore. Ann Acad Med Singapore. 2008;37(6):497-503.

9. Singapore Ministry of Health. What do the different DORSCON levels mean. http://www.gov.sg/article/what-do-the-different-dorscon-levels-mean. Accessed April 5, 2020.

10. Lee J-W, McKibbin WJ. Estimating the global economic costs of SARS. In: Knobler S, Mahmoud A, Lemon S, et al, eds. Institute of Medicine (US) Forum on Microbial Threats. Washington, DC: National Academies Press (US); 2004.

11. James EH, Wooten L. Leadership as (un)usual: how to display competence in times of crisis. Organ Dyn. 2005;34(2):141-152. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.orgdyn.2005.03.005

12. The Joint Commission. Emergency Management: Coronavirus Resources. 2020. https://www.jointcommission.org/covid-19/. Accessed April 4, 2020.

13. Wachter RM, Goldman L. Zero to 50,000 – the 20th anniversary of the hospitalist. N Engl J Med. 2016;375(11):1009-1011. https://doi.org/10.1056/NEJMp1607958.

14. Singapore Ministry of Health. Official Update of COVID-19 Situation in Singapore. 2020. https://experience.arcgis.com/experience/7e30edc490a5441a874f9efe67bd8b89. Accessed April 5, 2020.

15. Chronicle Digital Team. Coronavirus tracker. San Francisco Chronicle. https://projects.sfchronicle.com/2020/coronavirus-map/. Accessed April 5, 2020.

One of the worst public health threats of our generation, coronavirus disease 2019 (COVID-19), first emerged in Wuhan, China, in December 2019 and quickly spread to Singapore, Hong Kong, and Taiwan. These three countries have been praised for their control of the pandemic,1,2 while the number of cases worldwide, including those in the United States, has soared. Political alignment, centralized and integrated healthcare systems, small size, effective technology deployment, widespread testing combined with contact tracing and isolation, and personal protective equipment (PPE) availability underscore their successes.1,3-5 Although these factors differ starkly from those currently employed in the United States, a better understanding their experience may positively influence the myriad US responses. We describe some salient features of Singapore’s infection preparedness, provide examples of how these features guided the National University Hospital (NUH) Singapore COVID-19 response, and illustrate how one facet of the NUH response was translated to develop a new care model at the University of California, San Francisco (UCSF).

THE SINGAPORE EXPERIENCE OVER TIME

Singapore, a small island country (278 square miles) city-state in Southeast Asia has a population of 5.8 million people. Most Singaporeans receive their inpatient care in the public hospitals that are organized and resourced through the Singapore Ministry of Health (MOH). In 2003, severe acute respiratory syndrome (SARS) infected 238 people and killed 33 over 3 months in Singapore, which led to a significant economic downturn. Singapore’s initial SARS experience unveiled limitations in infrastructure, staff preparedness, virus control methodology, and centralized crisis systems. Lessons gleaned from the SARS experience laid the foundation for Singapore’s subsequent disaster preparedness.6

Post-SARS, the MOH created structures and systems to prepare Singapore for future epidemics. All public hospitals expanded isolation capacity by constructing new units or repurposing existing ones and creating colocated Emergency Department (ED) isolation facilities. Additionally, the MOH commissioned the National Centre for Infectious Diseases, a 330-bed high-level isolation hospital.7 They also mandated hospital systems to regularly practice mass casualty and infectious (including respiratory) crisis responses through externally evaluated simulation.8 These are orchestrated down to the smallest detail and involve staff at all levels. For example, healthcare workers (HCW) being “deployed” outside of their specialty, housekeepers practicing novel hazardous waste disposal, and security guards managing crowds interact throughout the exercise.

The testing and viral spread control challenges during SARS spawned hospital-system epidemiology capacity building. Infectious diseases reporting guidelines were refined, and communication channels enhanced to include cross-hospital information sharing and direct lines of communication for epidemiology groups to and from the MOH. Enhanced contact tracing methodologies were adopted and practiced regularly. In addition, material stockpiles, supplies, and supply chains were recalibrated.

The Singapore government also adopted the Disease Outbreak Response System Condition (DORSCON) system,9 a color-coded framework for pandemic response that guides activation of crisis interventions broadly (such as temperature screening at airports and restrictions to travel and internal movements), as well as within the healthcare setting.

In addition to prompting these notable preparedness efforts, SARS had a palpable impact on Singaporeans’ collective psychology both within and outside of the hospital system. The very close-knit medical community lost colleagues during the crisis, and the larger community deeply felt the health and economic costs of this crisis.10 The resulting “respect” or “healthy fear” for infectious crises continues to the present day.

THE SINGAPORE COVID-19 RESPONSE: NATIONAL UNIVERSITY HOSPITAL EXPERIENCE

The NUH is a 1,200-bed public tertiary care academic health center in Singapore. Before the first COVID-19 case was diagnosed in Singapore, NUH joined forces with its broader health system, university resources (schools of medicine and public health), and international partners to refine the existing structures and systems in response to this new infectious threat.

One of these structures included the existing NUH ED negative-pressure “fever facility.” In the ED triage, patients are routinely screened for infectious diseases such as H1N1, MERS-CoV, and measles. In early January, these screening criteria were evolved to adapt to COVID-19. High-risk patients bypass common waiting areas and are sent directly to the fever facility for management. From there, patients requiring admission are sent to one of the inpatient isolation wards, each with over 21 negative-pressure isolation rooms. To expand isolation capacity, lower-priority patients were relocated, and the existing negative- and neutral-pressure rooms were converted into COVID-19 pandemic wards.

The pandemic wards are staffed by nurses with previous isolation experience and Internal Medicine and Subspecialty Medicine physicians and trainees working closely with Infectious Diseases experts. Pandemic Ward teams are sequestered from other clinical and administrative teams, wear hospital-laundered scrubs, and use PPE-conserving practices. These strategies, implemented at the outset, are based on international guidelines contextualized to local needs and include extended use (up to 6 hours) of N95 respirators for the pandemic wards, and surgical masks in all other clinical areas. Notably, there have been no documented transmissions to HCW or patients at NUH. The workforce was maximized by limiting nonurgent clinical, administrative, research, and teaching activities.

In February, COVID-19 testing was initiated internally and deployed widely. NUH, at the time of this writing, has performed more than 6,000 swabs with up to 200 tests run per day (with 80 confirmed cases). Testing at this scale has allowed NUH to ensure: (a) prompt isolation of patients, even those with mild symptoms, (b) deisolation of those testing negative thus conserving PPE and isolation facilities, (c) a better understanding of the epidemiology and the wide range of clinical manifestations of COVID-19, and (d) early comprehensive contact tracing including mildly symptomatic patients.

The MOH plays a central role in coordinating COVID-19 activities and supports individual hospital systems such as NUH. Some of their crisis leadership strategies include daily text messages distributed countrywide, two-way communication channels that ensure feedback loops with hospital executives, epidemiology specialists, and operational workgroups, and engendering interhospital collaboration.11

A US HOSPITAL MEDICINE RESPONSE: UC SAN FRANCISCO

In the United States, the Joint Commission provides structures, tools, and processes for hospital systems to prepare for disasters.12 Many hospital systems have experience with natural disasters which, similar to Singapore’s planning, ensures structures and systems are in place during a crisis. Although these are transferable to multiple types of disasters, the US healthcare system’s direct experience with infectious crises is limited. A fairly distinctive facet—and an asset of US healthcare—is the role of hospitalists.

Hospitalists care for the majority of medical inpatients across the United States,13 and as such, they currently, and will increasingly, play a major role in the US COVID-19 response. This is the case at the UCSF Helen Diller Medical Center at Parnassus Heights (UCSFMC), a 600-bed academic medical center. To learn from other’s early experiences with COVID-19, UCSF Health System leadership connected with many outside health systems including NUH. As one of its multiple pandemic responses, they engaged the UCSFMC Division of Hospital Medicine (DHM), a division that includes 117 hospitalists, to work with hospital and health system leadership and launch a respiratory isolation unit (RIU) modeled after the NUH pandemic ward. The aim of the RIU is to group inpatients with either confirmed or suspected COVID-19 patients who do not require critical care.

An interdisciplinary work group comprising hospitalists, infectious disease specialists, emergency department clinicians, nursing, rehabilitation experts, hospital epidemiology and infection-prevention leaders, safety specialists, and systems engineers was assembled to repurpose an existing medical unit and establish new care models for the RIU. This workgroup created clinical guidelines and workflows, and RIU leaders actively solicit feedback from the staff to advance these standards.

Hospitalists and nurses who volunteered to work on the UCSF attending-staffed RIU received extensive training, including online and widely available in-person PPE training delivered by infection-prevention experts. The RIU hospitalists engage with hospitalists nationwide through ongoing conference calls to share best practices and clinical cases. Patients are admitted by hospitalists to the RIU via the emergency department or directly from ambulatory sites. All RIU providers and staff are screened daily for symptoms prior to starting their shifts, wear hospital-laundered scrubs on the unit, and remain on the unit for the duration of their shift. Hospitalists and nurses communicate regularly to cluster their patient visits and interventions while specialists provide virtual consults (as deemed safe and appropriate) to optimize PPE conservation and decrease overall exposure. The Health System establishes and revises PPE protocols based on CDC guidelines, best available evidence, and supply chain realities. These guidelines are evolving and currently include surgical mask, gown, gloves, and eye protection for all patient interactions with suspected or confirmed COVID-19 and respirator use during aerosol-generating procedures. Research studies (eg, clinical trials and evaluations), informatics efforts (eg, patient flow dashboards), and healthcare technology innovations (eg, tablets for telehealth and video visits) are continually integrated into the RIU infrastructure. Robust attention to the well-being of everyone working on the unit includes chaplain visits, daily debriefs, meal delivery, and palliative care service support, which enrich the unit experience and instill a culture of unity.

MOVING FORWARD

The structures and systems born out of the 2003 SARS experience and the “test, trace, and isolate” strategy were arguably key drivers to flatten Singapore’s epidemic curve early in the pandemic.3 Even with these in place, Singapore is now experiencing a second wave with a significantly higher caseload.14 In response, the government instituted strict social distancing measures on April 3, closing schools and most workplaces. This suggests that the COVID-19 pandemic may fluctuate over time and that varying types and levels of interventions will be required to maintain long-term control. The NUH team describes experiencing cognitive overload given the ever-changing nature and volume of information and fatigue due to the effort required and duration of this crisis. New programs addressing these challenges are being developed and rapidly deployed.

Despite early testing limitations and newly minted systems, San Francisco is cautiously optimistic about its epidemic curve. Since the March 17, 2020, “shelter in place” order, COVID-19 hospitalizations have remained manageable and constant.15 This has afforded healthcare systems including UCSF critical time to evolve its clinical operations (eg, the RIU) and to leverage its academic culture coordinating its bench research, global health, epidemiology, clinical research, informatics, and clinical enterprise scholars and experts to advance COVID-19 science and inform pandemic solutions. Although the UCSF frontline teams are challenged by the stresses of being in the throes of the pandemic amidst a rapidly changing landscape (including changes in PPE and testing recommendations specifically), they are working together to build team resilience for what may come.

CONCLUSION

The world is facing a pandemic of tremendous proportions, and the United States is in the midst of a wave the height of which is yet to be seen. As Fisher and colleagues wrote in 2011, “Our response to infectious disease outbreaks is born out of past experience.”4 Singapore and NUH’s structures and systems that were put into place demonstrate this—they are timely, have been effective thus far, and will be tested in this next wave. “However, no two outbreaks are the same,” the authors wrote, “so an understanding of the infectious agent as well as the environment confronting it is fundamental to the response.”4 In the United States, hospitalists are a key asset in our environment to confront this virus. The UCSF experience exemplifies that, by combining new ideas from another system with on-the-ground expertise while working hand-in-hand with the hospital and health system, hospitalists can be a critical facet of the pandemic response. Hospitalists’ intrinsic abilities to collaborate, learn, and innovate will enable them to not only meet this challenge now but also to transform practices and capacities to respond to crises into the future.

Acknowledgment

Bradley Sharpe, MD, Division Chief, Division of Hospital Medicine, University of California, San Francisco, California, for his input on conception and critical review of this manuscript.

One of the worst public health threats of our generation, coronavirus disease 2019 (COVID-19), first emerged in Wuhan, China, in December 2019 and quickly spread to Singapore, Hong Kong, and Taiwan. These three countries have been praised for their control of the pandemic,1,2 while the number of cases worldwide, including those in the United States, has soared. Political alignment, centralized and integrated healthcare systems, small size, effective technology deployment, widespread testing combined with contact tracing and isolation, and personal protective equipment (PPE) availability underscore their successes.1,3-5 Although these factors differ starkly from those currently employed in the United States, a better understanding their experience may positively influence the myriad US responses. We describe some salient features of Singapore’s infection preparedness, provide examples of how these features guided the National University Hospital (NUH) Singapore COVID-19 response, and illustrate how one facet of the NUH response was translated to develop a new care model at the University of California, San Francisco (UCSF).

THE SINGAPORE EXPERIENCE OVER TIME

Singapore, a small island country (278 square miles) city-state in Southeast Asia has a population of 5.8 million people. Most Singaporeans receive their inpatient care in the public hospitals that are organized and resourced through the Singapore Ministry of Health (MOH). In 2003, severe acute respiratory syndrome (SARS) infected 238 people and killed 33 over 3 months in Singapore, which led to a significant economic downturn. Singapore’s initial SARS experience unveiled limitations in infrastructure, staff preparedness, virus control methodology, and centralized crisis systems. Lessons gleaned from the SARS experience laid the foundation for Singapore’s subsequent disaster preparedness.6

Post-SARS, the MOH created structures and systems to prepare Singapore for future epidemics. All public hospitals expanded isolation capacity by constructing new units or repurposing existing ones and creating colocated Emergency Department (ED) isolation facilities. Additionally, the MOH commissioned the National Centre for Infectious Diseases, a 330-bed high-level isolation hospital.7 They also mandated hospital systems to regularly practice mass casualty and infectious (including respiratory) crisis responses through externally evaluated simulation.8 These are orchestrated down to the smallest detail and involve staff at all levels. For example, healthcare workers (HCW) being “deployed” outside of their specialty, housekeepers practicing novel hazardous waste disposal, and security guards managing crowds interact throughout the exercise.

The testing and viral spread control challenges during SARS spawned hospital-system epidemiology capacity building. Infectious diseases reporting guidelines were refined, and communication channels enhanced to include cross-hospital information sharing and direct lines of communication for epidemiology groups to and from the MOH. Enhanced contact tracing methodologies were adopted and practiced regularly. In addition, material stockpiles, supplies, and supply chains were recalibrated.

The Singapore government also adopted the Disease Outbreak Response System Condition (DORSCON) system,9 a color-coded framework for pandemic response that guides activation of crisis interventions broadly (such as temperature screening at airports and restrictions to travel and internal movements), as well as within the healthcare setting.

In addition to prompting these notable preparedness efforts, SARS had a palpable impact on Singaporeans’ collective psychology both within and outside of the hospital system. The very close-knit medical community lost colleagues during the crisis, and the larger community deeply felt the health and economic costs of this crisis.10 The resulting “respect” or “healthy fear” for infectious crises continues to the present day.

THE SINGAPORE COVID-19 RESPONSE: NATIONAL UNIVERSITY HOSPITAL EXPERIENCE

The NUH is a 1,200-bed public tertiary care academic health center in Singapore. Before the first COVID-19 case was diagnosed in Singapore, NUH joined forces with its broader health system, university resources (schools of medicine and public health), and international partners to refine the existing structures and systems in response to this new infectious threat.

One of these structures included the existing NUH ED negative-pressure “fever facility.” In the ED triage, patients are routinely screened for infectious diseases such as H1N1, MERS-CoV, and measles. In early January, these screening criteria were evolved to adapt to COVID-19. High-risk patients bypass common waiting areas and are sent directly to the fever facility for management. From there, patients requiring admission are sent to one of the inpatient isolation wards, each with over 21 negative-pressure isolation rooms. To expand isolation capacity, lower-priority patients were relocated, and the existing negative- and neutral-pressure rooms were converted into COVID-19 pandemic wards.

The pandemic wards are staffed by nurses with previous isolation experience and Internal Medicine and Subspecialty Medicine physicians and trainees working closely with Infectious Diseases experts. Pandemic Ward teams are sequestered from other clinical and administrative teams, wear hospital-laundered scrubs, and use PPE-conserving practices. These strategies, implemented at the outset, are based on international guidelines contextualized to local needs and include extended use (up to 6 hours) of N95 respirators for the pandemic wards, and surgical masks in all other clinical areas. Notably, there have been no documented transmissions to HCW or patients at NUH. The workforce was maximized by limiting nonurgent clinical, administrative, research, and teaching activities.

In February, COVID-19 testing was initiated internally and deployed widely. NUH, at the time of this writing, has performed more than 6,000 swabs with up to 200 tests run per day (with 80 confirmed cases). Testing at this scale has allowed NUH to ensure: (a) prompt isolation of patients, even those with mild symptoms, (b) deisolation of those testing negative thus conserving PPE and isolation facilities, (c) a better understanding of the epidemiology and the wide range of clinical manifestations of COVID-19, and (d) early comprehensive contact tracing including mildly symptomatic patients.

The MOH plays a central role in coordinating COVID-19 activities and supports individual hospital systems such as NUH. Some of their crisis leadership strategies include daily text messages distributed countrywide, two-way communication channels that ensure feedback loops with hospital executives, epidemiology specialists, and operational workgroups, and engendering interhospital collaboration.11

A US HOSPITAL MEDICINE RESPONSE: UC SAN FRANCISCO

In the United States, the Joint Commission provides structures, tools, and processes for hospital systems to prepare for disasters.12 Many hospital systems have experience with natural disasters which, similar to Singapore’s planning, ensures structures and systems are in place during a crisis. Although these are transferable to multiple types of disasters, the US healthcare system’s direct experience with infectious crises is limited. A fairly distinctive facet—and an asset of US healthcare—is the role of hospitalists.

Hospitalists care for the majority of medical inpatients across the United States,13 and as such, they currently, and will increasingly, play a major role in the US COVID-19 response. This is the case at the UCSF Helen Diller Medical Center at Parnassus Heights (UCSFMC), a 600-bed academic medical center. To learn from other’s early experiences with COVID-19, UCSF Health System leadership connected with many outside health systems including NUH. As one of its multiple pandemic responses, they engaged the UCSFMC Division of Hospital Medicine (DHM), a division that includes 117 hospitalists, to work with hospital and health system leadership and launch a respiratory isolation unit (RIU) modeled after the NUH pandemic ward. The aim of the RIU is to group inpatients with either confirmed or suspected COVID-19 patients who do not require critical care.

An interdisciplinary work group comprising hospitalists, infectious disease specialists, emergency department clinicians, nursing, rehabilitation experts, hospital epidemiology and infection-prevention leaders, safety specialists, and systems engineers was assembled to repurpose an existing medical unit and establish new care models for the RIU. This workgroup created clinical guidelines and workflows, and RIU leaders actively solicit feedback from the staff to advance these standards.

Hospitalists and nurses who volunteered to work on the UCSF attending-staffed RIU received extensive training, including online and widely available in-person PPE training delivered by infection-prevention experts. The RIU hospitalists engage with hospitalists nationwide through ongoing conference calls to share best practices and clinical cases. Patients are admitted by hospitalists to the RIU via the emergency department or directly from ambulatory sites. All RIU providers and staff are screened daily for symptoms prior to starting their shifts, wear hospital-laundered scrubs on the unit, and remain on the unit for the duration of their shift. Hospitalists and nurses communicate regularly to cluster their patient visits and interventions while specialists provide virtual consults (as deemed safe and appropriate) to optimize PPE conservation and decrease overall exposure. The Health System establishes and revises PPE protocols based on CDC guidelines, best available evidence, and supply chain realities. These guidelines are evolving and currently include surgical mask, gown, gloves, and eye protection for all patient interactions with suspected or confirmed COVID-19 and respirator use during aerosol-generating procedures. Research studies (eg, clinical trials and evaluations), informatics efforts (eg, patient flow dashboards), and healthcare technology innovations (eg, tablets for telehealth and video visits) are continually integrated into the RIU infrastructure. Robust attention to the well-being of everyone working on the unit includes chaplain visits, daily debriefs, meal delivery, and palliative care service support, which enrich the unit experience and instill a culture of unity.

MOVING FORWARD

The structures and systems born out of the 2003 SARS experience and the “test, trace, and isolate” strategy were arguably key drivers to flatten Singapore’s epidemic curve early in the pandemic.3 Even with these in place, Singapore is now experiencing a second wave with a significantly higher caseload.14 In response, the government instituted strict social distancing measures on April 3, closing schools and most workplaces. This suggests that the COVID-19 pandemic may fluctuate over time and that varying types and levels of interventions will be required to maintain long-term control. The NUH team describes experiencing cognitive overload given the ever-changing nature and volume of information and fatigue due to the effort required and duration of this crisis. New programs addressing these challenges are being developed and rapidly deployed.

Despite early testing limitations and newly minted systems, San Francisco is cautiously optimistic about its epidemic curve. Since the March 17, 2020, “shelter in place” order, COVID-19 hospitalizations have remained manageable and constant.15 This has afforded healthcare systems including UCSF critical time to evolve its clinical operations (eg, the RIU) and to leverage its academic culture coordinating its bench research, global health, epidemiology, clinical research, informatics, and clinical enterprise scholars and experts to advance COVID-19 science and inform pandemic solutions. Although the UCSF frontline teams are challenged by the stresses of being in the throes of the pandemic amidst a rapidly changing landscape (including changes in PPE and testing recommendations specifically), they are working together to build team resilience for what may come.

CONCLUSION

The world is facing a pandemic of tremendous proportions, and the United States is in the midst of a wave the height of which is yet to be seen. As Fisher and colleagues wrote in 2011, “Our response to infectious disease outbreaks is born out of past experience.”4 Singapore and NUH’s structures and systems that were put into place demonstrate this—they are timely, have been effective thus far, and will be tested in this next wave. “However, no two outbreaks are the same,” the authors wrote, “so an understanding of the infectious agent as well as the environment confronting it is fundamental to the response.”4 In the United States, hospitalists are a key asset in our environment to confront this virus. The UCSF experience exemplifies that, by combining new ideas from another system with on-the-ground expertise while working hand-in-hand with the hospital and health system, hospitalists can be a critical facet of the pandemic response. Hospitalists’ intrinsic abilities to collaborate, learn, and innovate will enable them to not only meet this challenge now but also to transform practices and capacities to respond to crises into the future.

Acknowledgment

Bradley Sharpe, MD, Division Chief, Division of Hospital Medicine, University of California, San Francisco, California, for his input on conception and critical review of this manuscript.

1. Wang CJ, Ng CY, Brook RH. Response to COVID-19 in Taiwan: big data analytics, new technology, and proactive testing. JAMA. 2020. https://doi.org/10.1001/jama.2020.3151.

2. Legido-Quigley H, Asgari N, Teo YY, et al. Are high-performing health systems resilient against the COVID-19 epidemic? Lancet. 2020;395(10227):848-850. https://doi.org/10.1016/S0140-6736(20)30551-1.

3. Wong JEL, Leo YS, Tan CC. COVID-19 in Singapore—current experience: critical global issues that require attention and action. JAMA. 2020;323(13):1243-1244. https://doi.org/10.1001/jama.2020.2467.

4. Fisher D, Hui DS, Gao Z, et al. Pandemic response lessons from influenza H1N1 2009 in Asia. Respirology. 2011;16(6):876-882. https://doi.org/ 10.1111/j.1440-1843.2011.02003.x.

5. Wong ATY, Chen H, Liu SH, et al. From SARS to avian influenza preparedness in Hong Kong. Clin Infect Dis. 2017;64(suppl_2):S98-S104. https://doi.org/ 10.1093/cid/cix123.

6. Tan CC. SARS in Singapore--key lessons from an epidemic. Ann Acad Med Singapore. 2006;35(5):345-349.

7. National Centre for Infectious Diseases. About NCID. https://www.ncid.sg/About-NCID/Pages/default.aspx. Accessed April 5, 2020.

8. Cutter J. Preparing for an influenza pandemic in Singapore. Ann Acad Med Singapore. 2008;37(6):497-503.

9. Singapore Ministry of Health. What do the different DORSCON levels mean. http://www.gov.sg/article/what-do-the-different-dorscon-levels-mean. Accessed April 5, 2020.

10. Lee J-W, McKibbin WJ. Estimating the global economic costs of SARS. In: Knobler S, Mahmoud A, Lemon S, et al, eds. Institute of Medicine (US) Forum on Microbial Threats. Washington, DC: National Academies Press (US); 2004.

11. James EH, Wooten L. Leadership as (un)usual: how to display competence in times of crisis. Organ Dyn. 2005;34(2):141-152. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.orgdyn.2005.03.005

12. The Joint Commission. Emergency Management: Coronavirus Resources. 2020. https://www.jointcommission.org/covid-19/. Accessed April 4, 2020.

13. Wachter RM, Goldman L. Zero to 50,000 – the 20th anniversary of the hospitalist. N Engl J Med. 2016;375(11):1009-1011. https://doi.org/10.1056/NEJMp1607958.

14. Singapore Ministry of Health. Official Update of COVID-19 Situation in Singapore. 2020. https://experience.arcgis.com/experience/7e30edc490a5441a874f9efe67bd8b89. Accessed April 5, 2020.

15. Chronicle Digital Team. Coronavirus tracker. San Francisco Chronicle. https://projects.sfchronicle.com/2020/coronavirus-map/. Accessed April 5, 2020.

1. Wang CJ, Ng CY, Brook RH. Response to COVID-19 in Taiwan: big data analytics, new technology, and proactive testing. JAMA. 2020. https://doi.org/10.1001/jama.2020.3151.

2. Legido-Quigley H, Asgari N, Teo YY, et al. Are high-performing health systems resilient against the COVID-19 epidemic? Lancet. 2020;395(10227):848-850. https://doi.org/10.1016/S0140-6736(20)30551-1.

3. Wong JEL, Leo YS, Tan CC. COVID-19 in Singapore—current experience: critical global issues that require attention and action. JAMA. 2020;323(13):1243-1244. https://doi.org/10.1001/jama.2020.2467.

4. Fisher D, Hui DS, Gao Z, et al. Pandemic response lessons from influenza H1N1 2009 in Asia. Respirology. 2011;16(6):876-882. https://doi.org/ 10.1111/j.1440-1843.2011.02003.x.

5. Wong ATY, Chen H, Liu SH, et al. From SARS to avian influenza preparedness in Hong Kong. Clin Infect Dis. 2017;64(suppl_2):S98-S104. https://doi.org/ 10.1093/cid/cix123.

6. Tan CC. SARS in Singapore--key lessons from an epidemic. Ann Acad Med Singapore. 2006;35(5):345-349.

7. National Centre for Infectious Diseases. About NCID. https://www.ncid.sg/About-NCID/Pages/default.aspx. Accessed April 5, 2020.

8. Cutter J. Preparing for an influenza pandemic in Singapore. Ann Acad Med Singapore. 2008;37(6):497-503.

9. Singapore Ministry of Health. What do the different DORSCON levels mean. http://www.gov.sg/article/what-do-the-different-dorscon-levels-mean. Accessed April 5, 2020.

10. Lee J-W, McKibbin WJ. Estimating the global economic costs of SARS. In: Knobler S, Mahmoud A, Lemon S, et al, eds. Institute of Medicine (US) Forum on Microbial Threats. Washington, DC: National Academies Press (US); 2004.

11. James EH, Wooten L. Leadership as (un)usual: how to display competence in times of crisis. Organ Dyn. 2005;34(2):141-152. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.orgdyn.2005.03.005

12. The Joint Commission. Emergency Management: Coronavirus Resources. 2020. https://www.jointcommission.org/covid-19/. Accessed April 4, 2020.

13. Wachter RM, Goldman L. Zero to 50,000 – the 20th anniversary of the hospitalist. N Engl J Med. 2016;375(11):1009-1011. https://doi.org/10.1056/NEJMp1607958.

14. Singapore Ministry of Health. Official Update of COVID-19 Situation in Singapore. 2020. https://experience.arcgis.com/experience/7e30edc490a5441a874f9efe67bd8b89. Accessed April 5, 2020.

15. Chronicle Digital Team. Coronavirus tracker. San Francisco Chronicle. https://projects.sfchronicle.com/2020/coronavirus-map/. Accessed April 5, 2020.

© 2020 Society of Hospital Medicine

Hospitalist and Internal Medicine Leaders’ Perspectives of Early Discharge Challenges at Academic Medical Centers

The discharge process is a critical bottleneck for efficient patient flow through the hospital. Delayed discharges translate into delays in admissions and other patient transitions, often leading to excess costs, patient dissatisfaction, and even patient harm.1-3 The emergency department is particularly impacted by these delays; bottlenecks there lead to overcrowding, increased overall hospital length of stay, and increased risks for bad outcomes during hospitalization.2

Academic medical centers in particular may struggle with delayed discharges. In a typical teaching hospital, a team composed of an attending physician and housestaff share responsibility for determining the discharge plan. Additionally, clinical teaching activities may affect the process and quality of discharge.4-6

The prevalence and causes of delayed discharges vary greatly.7-9 To improve efficiency around discharge, many hospitals have launched initiatives designed to discharge patients earlier in the day, including goal setting (“discharge by noon”), scheduling discharge appointments, and using quality-improvement methods, such as Lean Methodology (LEAN), to remove inefficiencies within discharge processes.10-12 However, there are few data on the prevalence and effectiveness of different strategies.

The aim of this study was to survey academic hospitalist and general internal medicine physician leaders to elicit their perspectives on the factors contributing to discharge timing and the relative importance and effectiveness of early-discharge initiatives.

METHODS

Study Design, Participants, and Oversight

We obtained a list of 115 university-affiliated hospitals associated with a residency program and, in most cases, a medical school from Vizient Inc. (formerly University HealthSystem Consortium), an alliance of academic medical centers and affiliated hospitals. Each member institution submits clinical data to allow for the benchmarking of outcomes to drive transparency and quality improvement.13 More than 95% of the nation’s academic medical centers and affiliated hospitals participate in this collaborative. Vizient works with members but does not set nor promote quality metrics, such as discharge timeliness. E-mail addresses for hospital medicine physician leaders (eg, division chief) of major academic medical centers were obtained from each institution via publicly available data (eg, the institution’s website). When an institution did not have a hospital medicine section, we identified the division chief of general internal medicine. The University of California, San Francisco Institutional Review Board approved this study.

Survey Development and Domains

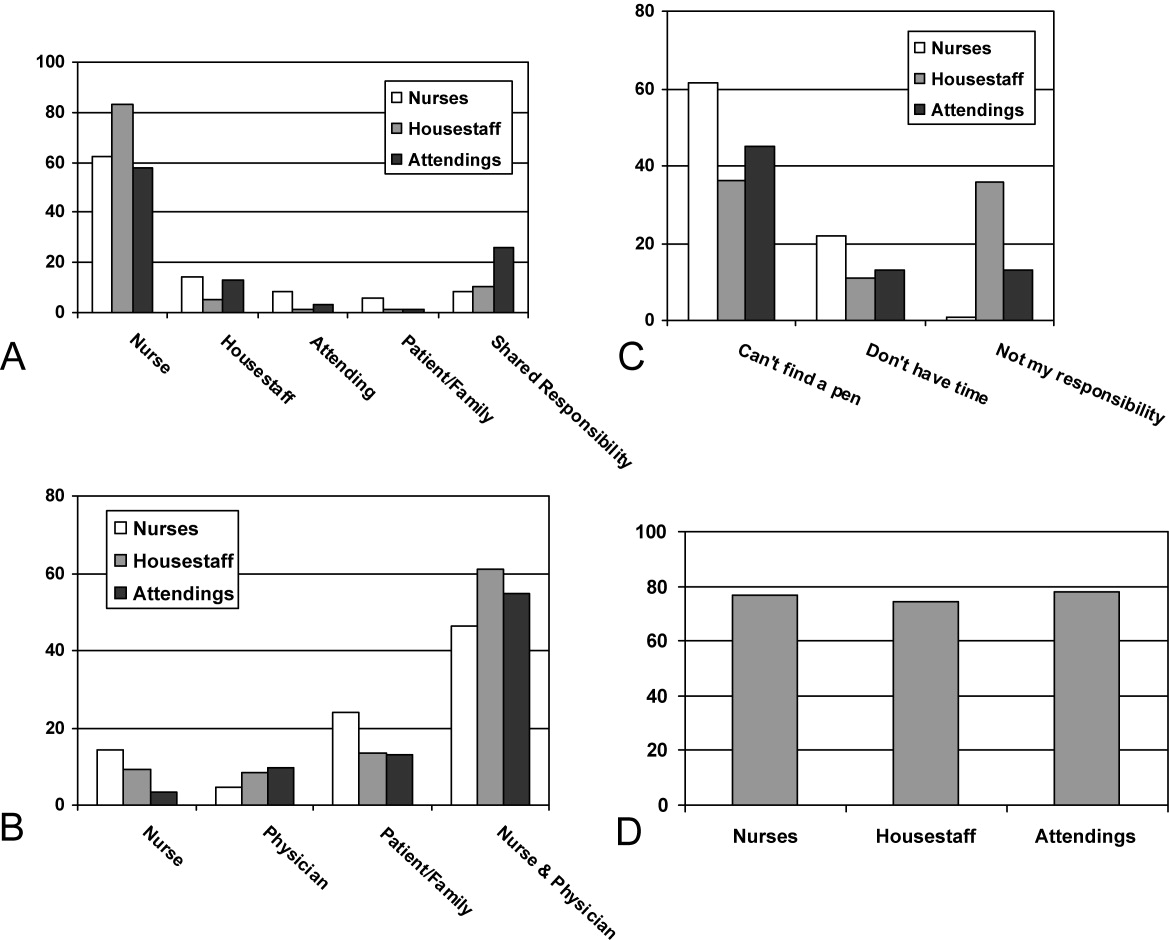

We developed a 30-item survey to evaluate 5 main domains of interest: current discharge practices, degree of prioritization of early discharge on the inpatient service, barriers to timely discharge, prevalence and perceived effectiveness of implemented early-discharge initiatives, and barriers to implementation of early-discharge initiatives.

Respondents were first asked to identify their institutions’ goals for discharge time. They were then asked to compare the priority of early-discharge initiatives to other departmental quality-improvement initiatives, such as reducing 30-day readmissions, improving interpreter use, and improving patient satisfaction. Next, respondents were asked to estimate the degree to which clinical or patient factors contributed to delays in discharge. Respondents were then asked whether specific early-discharge initiatives, such as changes to rounding practices or communication interventions, were implemented at their institutions and, if so, the perceived effectiveness of these initiatives at meeting discharge targets. We piloted the questions locally with physicians and researchers prior to finalizing the survey.

Data Collection

We sent surveys via an online platform (Research Electronic Data Capture).14 Nonresponders were sent 2 e-mail reminders and then a follow-up telephone call asking them to complete the survey. Only 1 survey per academic medical center was collected. Any respondent who completed the survey within 2 weeks of receiving it was entered to win a Kindle Fire.

Data Analysis

We summarized survey responses using descriptive statistics. Analysis was completed in IBM SPSS version 22 (Armonk, NY).

RESULTS

Survey Respondent and Institutional Characteristics

Of the 115 institutions surveyed, we received 61 responses (response rate of 53%), with 39 (64%) respondents from divisions of hospital medicine and 22 (36%) from divisions of general internal medicine. A majority (n = 53; 87%) stated their medicine services have a combination of teaching (with residents) and nonteaching (without residents) teams. Thirty-nine (64%) reported having daily multidisciplinary rounds.

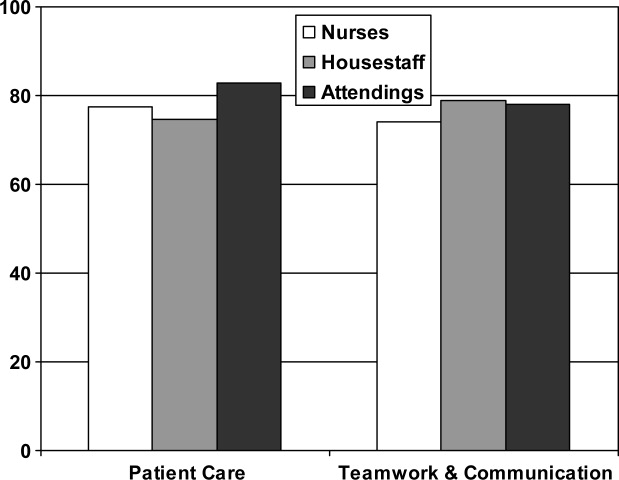

Early Discharge as a Priority

Forty-seven (77%) institutional representatives strongly agreed or agreed that early discharge was a priority, with discharge by noon being the most common target time (n = 23; 38%). Thirty (50%) respondents rated early discharge as more important than improving interpreter use for non-English-speaking patients and equally important as reducing 30-day readmissions (n = 29; 48%) and improving patient satisfaction (n = 27; 44%).

Factors Delaying Discharge

The most common factors perceived as delaying discharge were considered external to the hospital, such as postacute care bed availability or scheduled (eg, ambulance) transport delays (n = 48; 79%), followed by patient factors such as patient transport issues (n = 44; 72%). Less commonly reported were workflow issues, such as competing primary team priorities or case manager bandwidth (n = 38; 62%; Table 1).

Initiatives to Improve Discharge

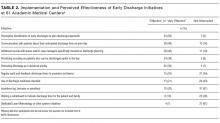

The most commonly implemented initiatives perceived as effective at improving discharge times were the preemptive identification of early discharges to plan discharge paperwork (n = 34; 56%), communication with patients about anticipated discharge time on the day prior to discharge (n = 29; 48%), and the implementation of additional rounds between physician teams and case managers specifically around discharge planning (n = 28; 46%). Initiatives not commonly implemented included regular audit of and feedback on discharge times to providers and teams (n = 21; 34%), the use of a discharge readiness checklist (n = 26; 43%), incentives such as bonuses or penalties (n = 37; 61%), the use of a whiteboard to indicate discharge times (n = 23; 38%), and dedicated quality-improvement approaches such as LEAN (n = 37; 61%; Table 2).

DISCUSSION

Our study suggests early discharge for medicine patients is a priority among academic institutions. Hospitalist and general internal medicine physician leaders in our study generally attributed delayed discharges to external factors, particularly unavailability of postacute care facilities and transportation delays. Having issues with finding postacute care placements is consistent with previous findings by Selker et al.15 and Carey et al.8 This is despite the 20-year difference between Selker et al.’s study and the current study, reflecting a continued opportunity for improvement, including stronger partnerships with local and regional postacute care facilities to expedite care transition and stronger discharge-planning efforts early in the admission process. Efforts in postacute care placement may be particularly important for Medicaid-insured and uninsured patients.

Our responders, hospitalist and internal medicine physician leaders, did not perceive the additional responsibilities of teaching and supervising trainees to be factors that significantly delayed patient discharge. This is in contrast to previous studies, which attributed delays in discharge to prolonged clinical decision-making related to teaching and supervision.4-6,8 This discrepancy may be due to the fact that we only surveyed single physician leaders at each institution and not residents. Our finding warrants further investigation to understand the degree to which resident skills may impact discharge planning and processes.

Institutions represented in our study have attempted a variety of initiatives promoting earlier discharge, with varying levels of perceived success. Initiatives perceived to be the most effective by hospital leaders centered on 2 main areas: (1) changing individual provider practice and (2) anticipatory discharge preparation. Interestingly, this is in discordance with the main factors labeled as causing delays in discharges, such as obtaining postacute care beds, busy case managers, and competing demands on primary teams. We hypothesize this may be because such changes require organization- or system-level changes and are perceived as more arduous than changes at the individual level. In addition, changes to individual provider behavior may be more cost- and time-effective than more systemic initiatives.

Our findings are consistent with the work published by Wertheimer and colleagues,11 who show that additional afternoon interdisciplinary rounds can help identify patients who may be discharged before noon the next day. In their study, identifying such patients in advance improved the overall early-discharge rate the following day.

Our findings should be interpreted in light of several limitations. Our survey only considers the perspectives of hospitalist and general internal medicine physician leaders at academic medical centers that are part of the Vizient Inc. collaborative. They do not represent all academic or community-based medical centers. Although the perceived effectiveness of some initiatives was high, we did not collect empirical data to support these claims or to determine which initiative had the greatest relative impact on discharge timeliness. Lastly, we did not obtain resident, nursing, or case manager perspectives on discharge practices. Given their roles as frontline providers, we may have missed these alternative perspectives.

Our study shows there is a strong interest in increasing early discharges in an effort to improve hospital throughput and patient flow.

Acknowledgments

The authors thank all participants who completed the survey and Danielle Carrier at Vizient Inc. (formally University HealthSystem Consortium) for her assistance in obtaining data.

Disclosures

Hemali Patel, Margaret Fang, Michelle Mourad, Adrienne Green, Ryan Murphy, and James Harrison report no conflicts of interest. At the time the research was conducted, Robert Wachter reported that he is a member of the Lucian Leape Institute at the National Patient Safety Foundation (no compensation except travel expenses); recently chaired an advisory board to England’s National Health Service (NHS) reviewing the NHS’s digital health strategy (no compensation except travel expenses); has a contract with UCSF from the Agency for Healthcare Research and Quality to edit a patient-safety website; receives compensation from John Wiley & Sons for writing a blog; receives royalties from Lippincott Williams & Wilkins and McGraw-Hill Education for writing and/or editing several books; receives stock options for serving on the board of Acuity Medical Management Systems; receives a yearly stipend for serving on the board of The Doctors Company; serves on the scientific advisory boards for amino.com, PatientSafe Solutions Inc., Twine, and EarlySense (for which he receives stock options); has a small royalty stake in CareWeb, a hospital communication tool developed at UCSF; and holds the Marc and Lynne Benioff Endowed Chair in Hospital Medicine and the Holly Smith Distinguished Professorship in Science and Medicine at UCSF.

1. Khanna S, Boyle J, Good N, Lind J. Impact of admission and discharge peak times on hospital overcrowding. Stud Health Technol Inform. 2011;168:82-88. PubMed

2. White BA, Biddinger PD, Chang Y, Grabowski B, Carignan S, Brown DFM. Boarding Inpatients in the Emergency Department Increases Discharged Patient Length of Stay. J Emerg Med. 2013;44(1):230-235. doi:10.1016/j.jemermed.2012.05.007. PubMed

3. Derlet RW, Richards JR. Overcrowding in the nation’s emergency departments: complex causes and disturbing effects. Ann Emerg Med. 2000;35(1):63-68. PubMed

4. da Silva SA, Valácio RA, Botelho FC, Amaral CFS. Reasons for discharge delays in teaching hospitals. Rev Saúde Pública. 2014;48(2):314-321. doi:10.1590/S0034-8910.2014048004971. PubMed

5. Greysen SR, Schiliro D, Horwitz LI, Curry L, Bradley EH. “Out of Sight, Out of Mind”: Housestaff Perceptions of Quality-Limiting Factors in Discharge Care at Teaching Hospitals. J Hosp Med Off Publ Soc Hosp Med. 2012;7(5):376-381. doi:10.1002/jhm.1928. PubMed

6. Goldman J, Reeves S, Wu R, Silver I, MacMillan K, Kitto S. Medical Residents and Interprofessional Interactions in Discharge: An Ethnographic Exploration of Factors That Affect Negotiation. J Gen Intern Med. 2015;30(10):1454-1460. doi:10.1007/s11606-015-3306-6. PubMed

7. Okoniewska B, Santana MJ, Groshaus H, et al. Barriers to discharge in an acute care medical teaching unit: a qualitative analysis of health providers’ perceptions. J Multidiscip Healthc. 2015;8:83-89. doi:10.2147/JMDH.S72633. PubMed

8. Carey MR, Sheth H, Scott Braithwaite R. A Prospective Study of Reasons for Prolonged Hospitalizations on a General Medicine Teaching Service. J Gen Intern Med. 2005;20(2):108-115. doi:10.1111/j.1525-1497.2005.40269.x. PubMed

9. Kim CS, Hart AL, Paretti RF, et al. Excess Hospitalization Days in an Academic Medical Center: Perceptions of Hospitalists and Discharge Planners. Am J Manag Care. 2011;17(2):e34-e42. http://www.ajmc.com/journals/issue/2011/2011-2-vol17-n2/AJMC_11feb_Kim_WebX_e34to42/. Accessed on October 26, 2016.

10. Gershengorn HB, Kocher R, Factor P. Management Strategies to Effect Change in Intensive Care Units: Lessons from the World of Business. Part II. Quality-Improvement Strategies. Ann Am Thorac Soc. 2014;11(3):444-453. doi:10.1513/AnnalsATS.201311-392AS. PubMed

11. Wertheimer B, Jacobs REA, Bailey M, et al. Discharge before noon: An achievable hospital goal. J Hosp Med. 2014;9(4):210-214. doi:10.1002/jhm.2154. PubMed

12. Manning DM, Tammel KJ, Blegen RN, et al. In-room display of day and time patient is anticipated to leave hospital: a “discharge appointment.” J Hosp Med. 2007;2(1):13-16. doi:10.1002/jhm.146. PubMed

13. Networks for academic medical centers. https://www.vizientinc.com/Our-networks/Networks-for-academic-medical-centers. Accessed on July 13, 2017.

14. Harris PA, Taylor R, Thielke R, Payne J, Gonzalez N, Conde JG. Research Electronic Data Capture (REDCap) - A metadata-driven methodology and workflow process for providing translational research informatics support. J Biomed Inform. 2009;42(2):377-381. doi:10.1016/j.jbi.2008.08.010. PubMed

15. Selker HP, Beshansky JR, Pauker SG, Kassirer JP. The epidemiology of delays in a teaching hospital. The development and use of a tool that detects unnecessary hospital days. Med Care. 1989;27(2):112-129. PubMed

The discharge process is a critical bottleneck for efficient patient flow through the hospital. Delayed discharges translate into delays in admissions and other patient transitions, often leading to excess costs, patient dissatisfaction, and even patient harm.1-3 The emergency department is particularly impacted by these delays; bottlenecks there lead to overcrowding, increased overall hospital length of stay, and increased risks for bad outcomes during hospitalization.2

Academic medical centers in particular may struggle with delayed discharges. In a typical teaching hospital, a team composed of an attending physician and housestaff share responsibility for determining the discharge plan. Additionally, clinical teaching activities may affect the process and quality of discharge.4-6

The prevalence and causes of delayed discharges vary greatly.7-9 To improve efficiency around discharge, many hospitals have launched initiatives designed to discharge patients earlier in the day, including goal setting (“discharge by noon”), scheduling discharge appointments, and using quality-improvement methods, such as Lean Methodology (LEAN), to remove inefficiencies within discharge processes.10-12 However, there are few data on the prevalence and effectiveness of different strategies.

The aim of this study was to survey academic hospitalist and general internal medicine physician leaders to elicit their perspectives on the factors contributing to discharge timing and the relative importance and effectiveness of early-discharge initiatives.

METHODS

Study Design, Participants, and Oversight

We obtained a list of 115 university-affiliated hospitals associated with a residency program and, in most cases, a medical school from Vizient Inc. (formerly University HealthSystem Consortium), an alliance of academic medical centers and affiliated hospitals. Each member institution submits clinical data to allow for the benchmarking of outcomes to drive transparency and quality improvement.13 More than 95% of the nation’s academic medical centers and affiliated hospitals participate in this collaborative. Vizient works with members but does not set nor promote quality metrics, such as discharge timeliness. E-mail addresses for hospital medicine physician leaders (eg, division chief) of major academic medical centers were obtained from each institution via publicly available data (eg, the institution’s website). When an institution did not have a hospital medicine section, we identified the division chief of general internal medicine. The University of California, San Francisco Institutional Review Board approved this study.

Survey Development and Domains

We developed a 30-item survey to evaluate 5 main domains of interest: current discharge practices, degree of prioritization of early discharge on the inpatient service, barriers to timely discharge, prevalence and perceived effectiveness of implemented early-discharge initiatives, and barriers to implementation of early-discharge initiatives.

Respondents were first asked to identify their institutions’ goals for discharge time. They were then asked to compare the priority of early-discharge initiatives to other departmental quality-improvement initiatives, such as reducing 30-day readmissions, improving interpreter use, and improving patient satisfaction. Next, respondents were asked to estimate the degree to which clinical or patient factors contributed to delays in discharge. Respondents were then asked whether specific early-discharge initiatives, such as changes to rounding practices or communication interventions, were implemented at their institutions and, if so, the perceived effectiveness of these initiatives at meeting discharge targets. We piloted the questions locally with physicians and researchers prior to finalizing the survey.

Data Collection

We sent surveys via an online platform (Research Electronic Data Capture).14 Nonresponders were sent 2 e-mail reminders and then a follow-up telephone call asking them to complete the survey. Only 1 survey per academic medical center was collected. Any respondent who completed the survey within 2 weeks of receiving it was entered to win a Kindle Fire.

Data Analysis

We summarized survey responses using descriptive statistics. Analysis was completed in IBM SPSS version 22 (Armonk, NY).

RESULTS

Survey Respondent and Institutional Characteristics

Of the 115 institutions surveyed, we received 61 responses (response rate of 53%), with 39 (64%) respondents from divisions of hospital medicine and 22 (36%) from divisions of general internal medicine. A majority (n = 53; 87%) stated their medicine services have a combination of teaching (with residents) and nonteaching (without residents) teams. Thirty-nine (64%) reported having daily multidisciplinary rounds.

Early Discharge as a Priority

Forty-seven (77%) institutional representatives strongly agreed or agreed that early discharge was a priority, with discharge by noon being the most common target time (n = 23; 38%). Thirty (50%) respondents rated early discharge as more important than improving interpreter use for non-English-speaking patients and equally important as reducing 30-day readmissions (n = 29; 48%) and improving patient satisfaction (n = 27; 44%).

Factors Delaying Discharge

The most common factors perceived as delaying discharge were considered external to the hospital, such as postacute care bed availability or scheduled (eg, ambulance) transport delays (n = 48; 79%), followed by patient factors such as patient transport issues (n = 44; 72%). Less commonly reported were workflow issues, such as competing primary team priorities or case manager bandwidth (n = 38; 62%; Table 1).

Initiatives to Improve Discharge

The most commonly implemented initiatives perceived as effective at improving discharge times were the preemptive identification of early discharges to plan discharge paperwork (n = 34; 56%), communication with patients about anticipated discharge time on the day prior to discharge (n = 29; 48%), and the implementation of additional rounds between physician teams and case managers specifically around discharge planning (n = 28; 46%). Initiatives not commonly implemented included regular audit of and feedback on discharge times to providers and teams (n = 21; 34%), the use of a discharge readiness checklist (n = 26; 43%), incentives such as bonuses or penalties (n = 37; 61%), the use of a whiteboard to indicate discharge times (n = 23; 38%), and dedicated quality-improvement approaches such as LEAN (n = 37; 61%; Table 2).

DISCUSSION

Our study suggests early discharge for medicine patients is a priority among academic institutions. Hospitalist and general internal medicine physician leaders in our study generally attributed delayed discharges to external factors, particularly unavailability of postacute care facilities and transportation delays. Having issues with finding postacute care placements is consistent with previous findings by Selker et al.15 and Carey et al.8 This is despite the 20-year difference between Selker et al.’s study and the current study, reflecting a continued opportunity for improvement, including stronger partnerships with local and regional postacute care facilities to expedite care transition and stronger discharge-planning efforts early in the admission process. Efforts in postacute care placement may be particularly important for Medicaid-insured and uninsured patients.

Our responders, hospitalist and internal medicine physician leaders, did not perceive the additional responsibilities of teaching and supervising trainees to be factors that significantly delayed patient discharge. This is in contrast to previous studies, which attributed delays in discharge to prolonged clinical decision-making related to teaching and supervision.4-6,8 This discrepancy may be due to the fact that we only surveyed single physician leaders at each institution and not residents. Our finding warrants further investigation to understand the degree to which resident skills may impact discharge planning and processes.

Institutions represented in our study have attempted a variety of initiatives promoting earlier discharge, with varying levels of perceived success. Initiatives perceived to be the most effective by hospital leaders centered on 2 main areas: (1) changing individual provider practice and (2) anticipatory discharge preparation. Interestingly, this is in discordance with the main factors labeled as causing delays in discharges, such as obtaining postacute care beds, busy case managers, and competing demands on primary teams. We hypothesize this may be because such changes require organization- or system-level changes and are perceived as more arduous than changes at the individual level. In addition, changes to individual provider behavior may be more cost- and time-effective than more systemic initiatives.

Our findings are consistent with the work published by Wertheimer and colleagues,11 who show that additional afternoon interdisciplinary rounds can help identify patients who may be discharged before noon the next day. In their study, identifying such patients in advance improved the overall early-discharge rate the following day.

Our findings should be interpreted in light of several limitations. Our survey only considers the perspectives of hospitalist and general internal medicine physician leaders at academic medical centers that are part of the Vizient Inc. collaborative. They do not represent all academic or community-based medical centers. Although the perceived effectiveness of some initiatives was high, we did not collect empirical data to support these claims or to determine which initiative had the greatest relative impact on discharge timeliness. Lastly, we did not obtain resident, nursing, or case manager perspectives on discharge practices. Given their roles as frontline providers, we may have missed these alternative perspectives.

Our study shows there is a strong interest in increasing early discharges in an effort to improve hospital throughput and patient flow.

Acknowledgments

The authors thank all participants who completed the survey and Danielle Carrier at Vizient Inc. (formally University HealthSystem Consortium) for her assistance in obtaining data.

Disclosures

Hemali Patel, Margaret Fang, Michelle Mourad, Adrienne Green, Ryan Murphy, and James Harrison report no conflicts of interest. At the time the research was conducted, Robert Wachter reported that he is a member of the Lucian Leape Institute at the National Patient Safety Foundation (no compensation except travel expenses); recently chaired an advisory board to England’s National Health Service (NHS) reviewing the NHS’s digital health strategy (no compensation except travel expenses); has a contract with UCSF from the Agency for Healthcare Research and Quality to edit a patient-safety website; receives compensation from John Wiley & Sons for writing a blog; receives royalties from Lippincott Williams & Wilkins and McGraw-Hill Education for writing and/or editing several books; receives stock options for serving on the board of Acuity Medical Management Systems; receives a yearly stipend for serving on the board of The Doctors Company; serves on the scientific advisory boards for amino.com, PatientSafe Solutions Inc., Twine, and EarlySense (for which he receives stock options); has a small royalty stake in CareWeb, a hospital communication tool developed at UCSF; and holds the Marc and Lynne Benioff Endowed Chair in Hospital Medicine and the Holly Smith Distinguished Professorship in Science and Medicine at UCSF.

The discharge process is a critical bottleneck for efficient patient flow through the hospital. Delayed discharges translate into delays in admissions and other patient transitions, often leading to excess costs, patient dissatisfaction, and even patient harm.1-3 The emergency department is particularly impacted by these delays; bottlenecks there lead to overcrowding, increased overall hospital length of stay, and increased risks for bad outcomes during hospitalization.2

Academic medical centers in particular may struggle with delayed discharges. In a typical teaching hospital, a team composed of an attending physician and housestaff share responsibility for determining the discharge plan. Additionally, clinical teaching activities may affect the process and quality of discharge.4-6

The prevalence and causes of delayed discharges vary greatly.7-9 To improve efficiency around discharge, many hospitals have launched initiatives designed to discharge patients earlier in the day, including goal setting (“discharge by noon”), scheduling discharge appointments, and using quality-improvement methods, such as Lean Methodology (LEAN), to remove inefficiencies within discharge processes.10-12 However, there are few data on the prevalence and effectiveness of different strategies.

The aim of this study was to survey academic hospitalist and general internal medicine physician leaders to elicit their perspectives on the factors contributing to discharge timing and the relative importance and effectiveness of early-discharge initiatives.

METHODS

Study Design, Participants, and Oversight

We obtained a list of 115 university-affiliated hospitals associated with a residency program and, in most cases, a medical school from Vizient Inc. (formerly University HealthSystem Consortium), an alliance of academic medical centers and affiliated hospitals. Each member institution submits clinical data to allow for the benchmarking of outcomes to drive transparency and quality improvement.13 More than 95% of the nation’s academic medical centers and affiliated hospitals participate in this collaborative. Vizient works with members but does not set nor promote quality metrics, such as discharge timeliness. E-mail addresses for hospital medicine physician leaders (eg, division chief) of major academic medical centers were obtained from each institution via publicly available data (eg, the institution’s website). When an institution did not have a hospital medicine section, we identified the division chief of general internal medicine. The University of California, San Francisco Institutional Review Board approved this study.

Survey Development and Domains

We developed a 30-item survey to evaluate 5 main domains of interest: current discharge practices, degree of prioritization of early discharge on the inpatient service, barriers to timely discharge, prevalence and perceived effectiveness of implemented early-discharge initiatives, and barriers to implementation of early-discharge initiatives.