User login

UCSF Hospitalist Mini‐College

I hear and I forget, I see and I remember, I do and I understand.

Confucius

Hospital medicine, first described in 1996,[1] is the fastest growing specialty in United States medical history, now with approximately 40,000 practitioners.[2] Although hospitalists undoubtedly learned many of their key clinical skills during residency training, there is no hospitalist‐specific residency training pathway and a limited number of largely research‐oriented fellowships.[3] Furthermore, hospitalists are often asked to care for surgical patients, those with acute neurologic disorders, and patients in intensive care units, while also contributing to quality improvement and patient safety initiatives.[4] This suggests that the vast majority of hospitalists have not had specific training in many key competencies for the field.[5]

Continuing medical education (CME) has traditionally been the mechanism to maintain, develop, or increase the knowledge, skills, and professional performance of physicians.[6] Most CME activities, including those for hospitalists, are staged as live events in hotel conference rooms or as local events in a similarly passive learning environment (eg, grand rounds and medical staff meetings). Online programs, audiotapes, and expanding electronic media provide increasing and alternate methods for hospitalists to obtain their required CME. All of these activities passively deliver content to a group of diverse and experienced learners. They fail to take advantage of adult learning principles and may have little direct impact on professional practice.[7, 8] Traditional CME is often derided as a barrier to innovative educational methods for these reasons, as adults learn best through active participation, when the information is relevant and practically applied.[9, 10]

To provide practicing hospitalists with necessary continuing education, we designed the University of California, San Francisco (UCSF) Hospitalist Mini‐College (UHMC). This 3‐day course brings adult learners to the bedside for small‐group and active learning focused on content areas relevant to today's hospitalists. We describe the development, content, outcomes, and lessons learned from UHMC's first 5 years.

METHODS

Program Development

We aimed to develop a program that focused on curricular topics that would be highly valued by practicing hospitalists delivered in an active learning small‐group environment. We first conducted an informal needs assessment of community‐based hospitalists to better understand their roles and determine their perceptions of gaps in hospitalist training compared to current requirements for practice. We then reviewed available CME events targeting hospitalists and compared these curricula to the gaps discovered from the needs assessment. We also reviewed the Society of Hospital Medicine's core competencies to further identify gaps in scope of practice.[4] Finally, we reviewed the literature to identify CME curricular innovations in the clinical setting and found no published reports.

Program Setting, Participants, and Faculty

The UHMC course was developed and offered first in 2008 as a precourse to the UCSF Management of the Hospitalized Medicine course, a traditional CME offering that occurs annually in a hotel setting.[11] The UHMC takes place on the campus of UCSF Medical Center, a 600‐bed academic medical center in San Francisco. Registered participants were required to complete limited credentialing paperwork, which allowed them to directly observe clinical care and interact with hospitalized patients. Participants were not involved in any clinical decision making for the patients they met or examined. The course was limited to a maximum of 33 participants annually to optimize active participation, small‐group bedside activities, and a personalized learning experience. UCSF faculty selected to teach in the UHMC were chosen based on exemplary clinical and teaching skills. They collaborated with course directors in the development of their session‐specific goals and curriculum.

Program Description

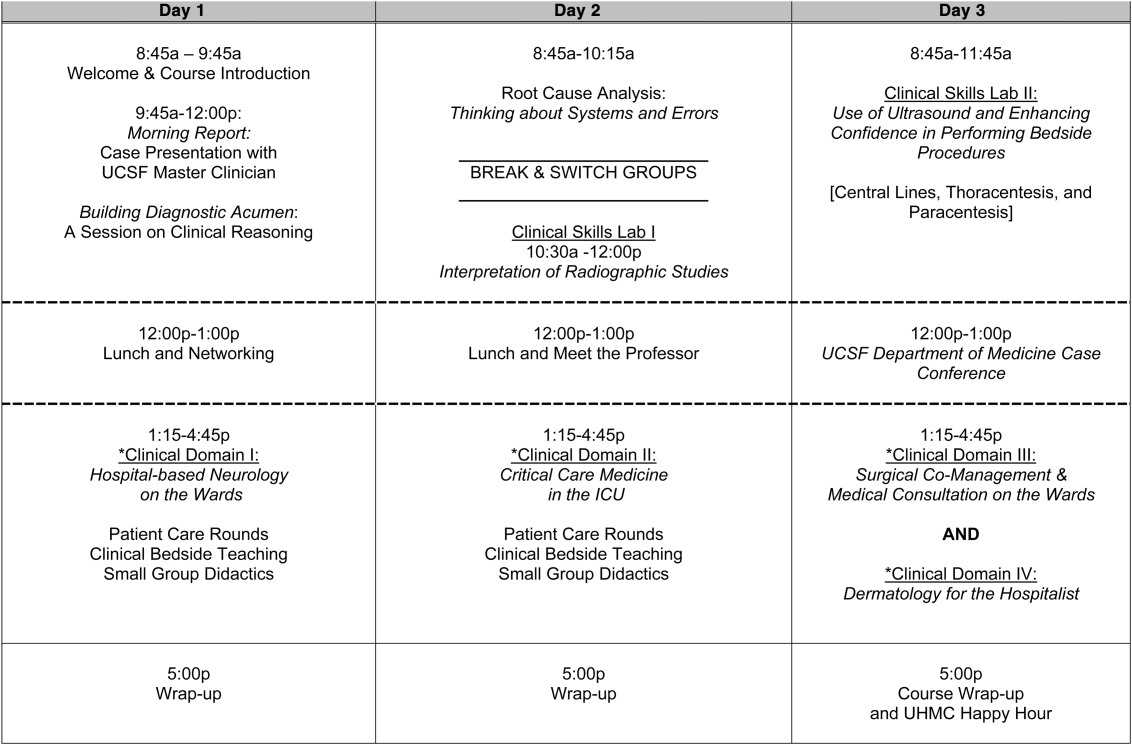

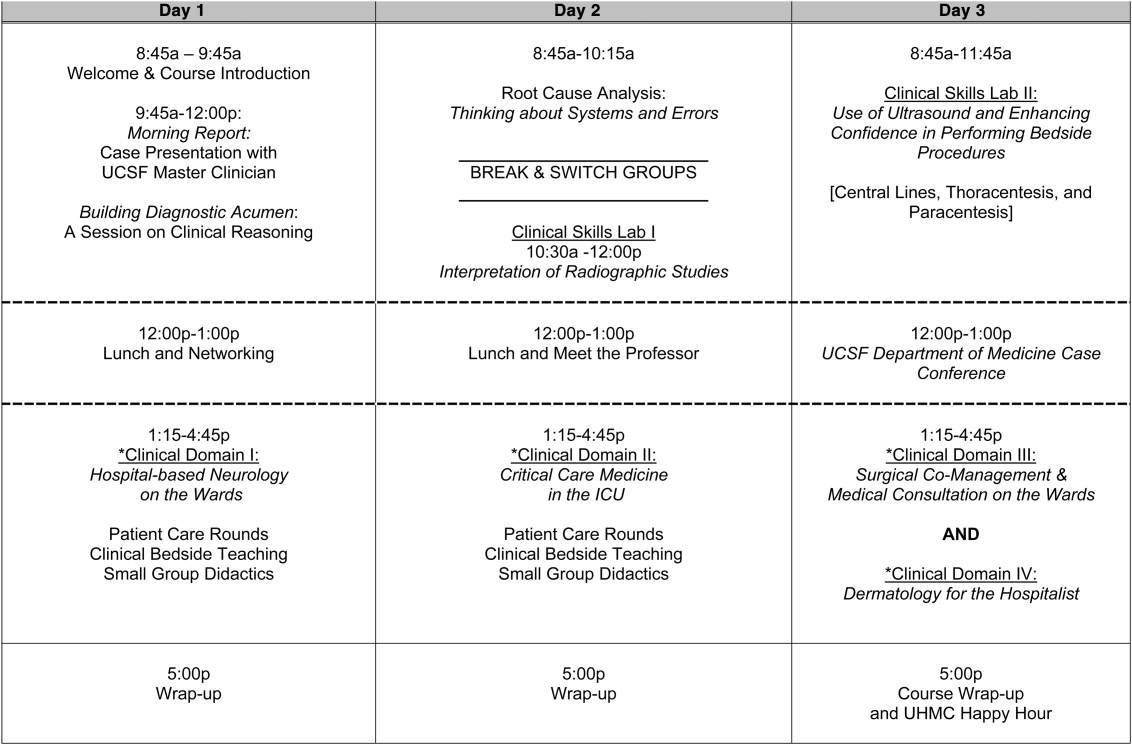

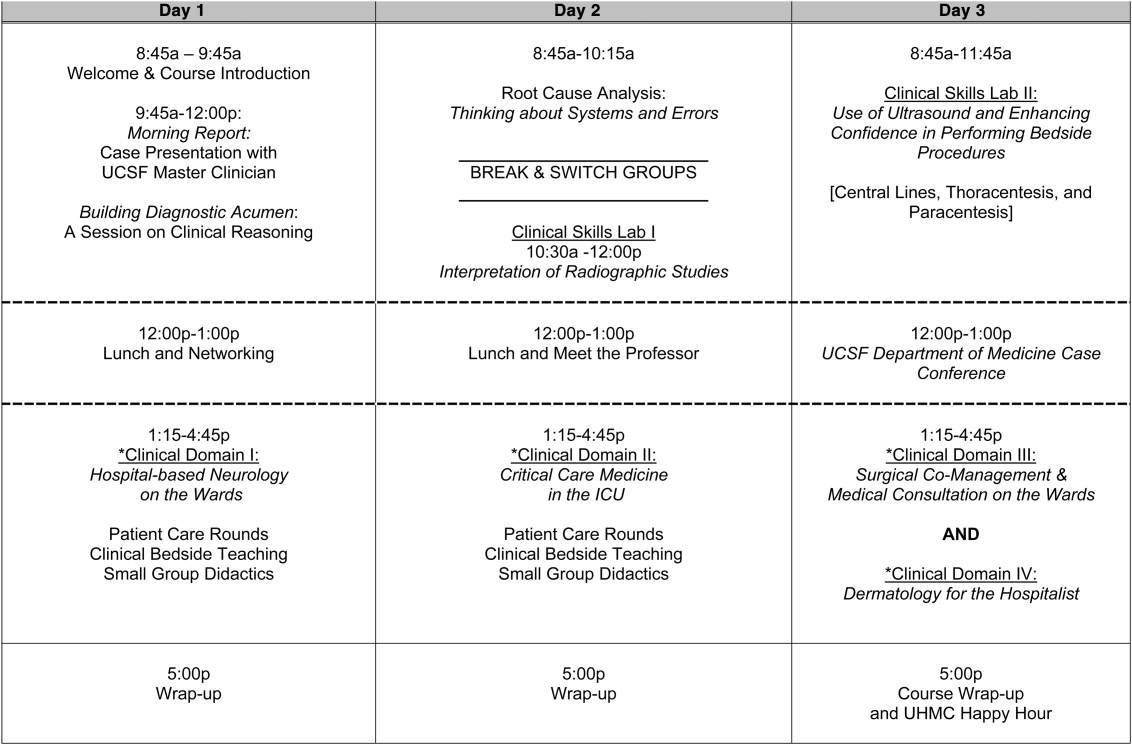

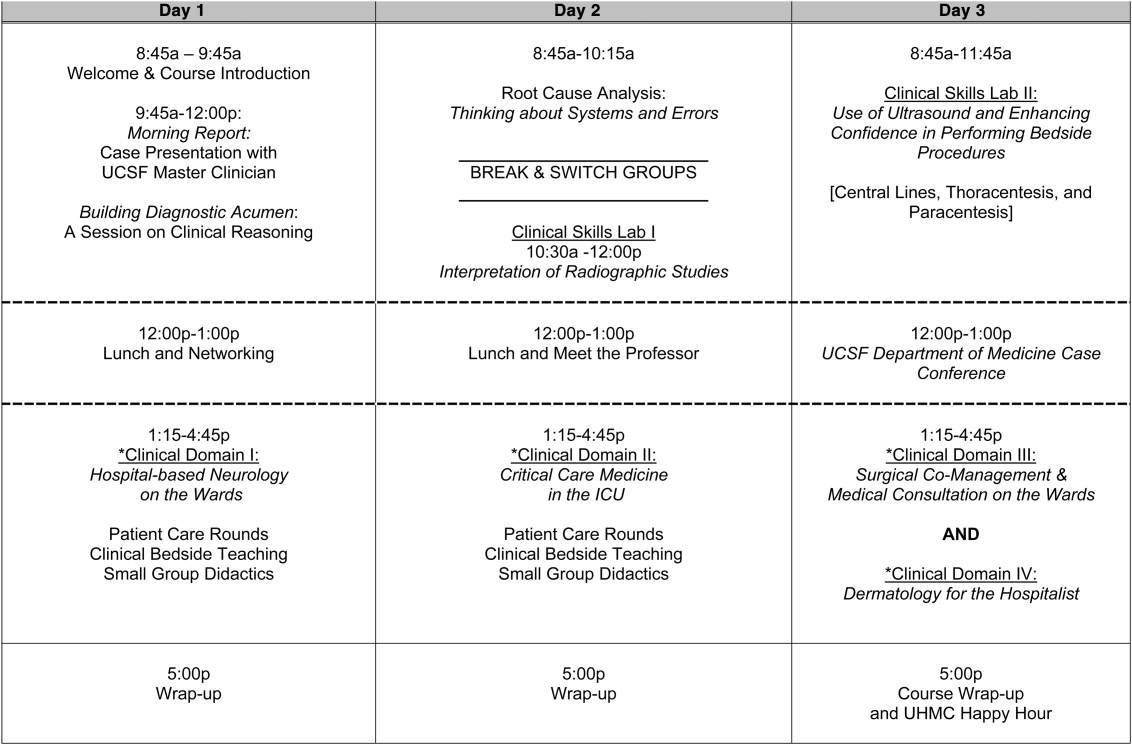

Figure 1 is a representative calendar view of the 3‐day UHMC course. The curricular topics were selected based on the findings from our needs assessment, our ability to deliver that curriculum using our small‐group active learning framework, and to minimize overlap with content of the larger course. Course curriculum was refined annually based on participant feedback and course director observations.

The program was built on a structure of 4 clinical domains and 2 clinical skills labs. The clinical domains included: (1) Hospital‐Based Neurology, (2) Critical Care Medicine in the Intensive Care Unit, (3) Surgical Comanagement and Medical Consultation, and (4) Hospital‐Based Dermatology. Participants were divided into 3 groups of 10 participants each and rotated through each domain in the afternoons. The clinical skills labs included: (1) Interpretation of Radiographic Studies and (2) Use of Ultrasound and Enhancing Confidence in Performing Bedside Procedures. We also developed specific sessions to teach about patient safety and to allow course attendees to participate in traditional academic learning vehicles (eg, a Morning Report and Morbidity and Mortality case conference). Below, we describe each session's format and content.

Clinical Domains

Hospital‐Based Neurology

Attendees participated in both bedside evaluation and case‐based discussions of common neurologic conditions seen in the hospital. In small groups of 5, participants were assigned patients to examine on the neurology ward. After their evaluations, they reported their findings to fellow participants and the faculty, setting the foundation for discussion of clinical management, review of neuroimaging, and exploration of current evidence to inform the patient's diagnosis and management. Participants and faculty then returned to the bedside to hone neurologic examination skills and complete the learning process. Given the unpredictability of what conditions would be represented on the ward in a given day, review of commonly seen conditions was always a focus, such as stroke, seizures, delirium, and neurologic examination pearls.

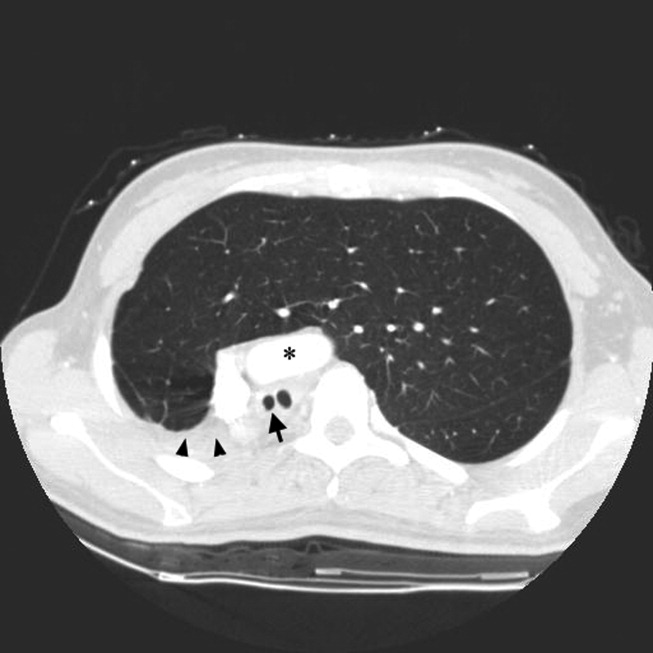

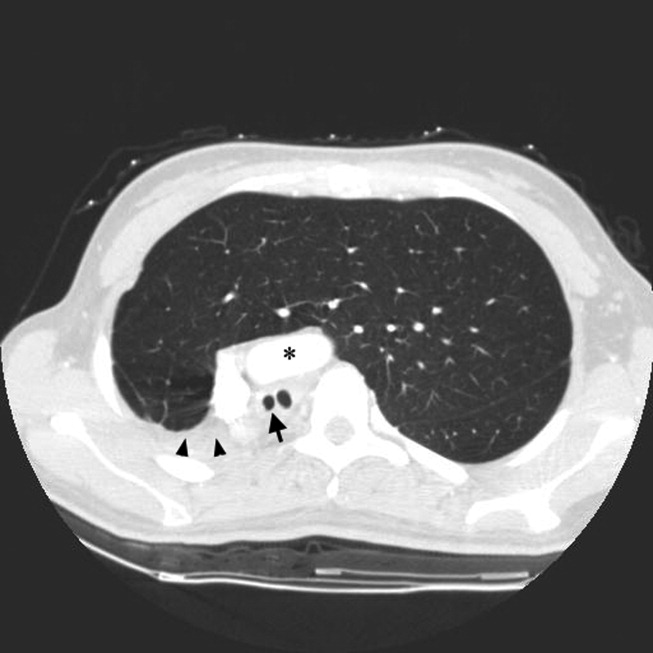

Critical Care

Attendees participated in case‐based discussions of common clinical conditions with similar review of current evidence, relevant imaging, and bedside exam pearls for the intubated patient. For this domain, attendees also participated in an advanced simulation tutorial in ventilator management, which was then applied at the bedside of intubated patients. Specific topics covered include sepsis, decompensated chronic obstructive lung disease, vasopressor selection, novel therapies in critically ill patients, and use of clinical pathways and protocols for improved quality of care.

Surgical Comanagement and Medical Consultation

Attendees participated in case‐based discussions applying current evidence to perioperative controversies and the care of the surgical patient. They also discussed the expanding role of the hospitalist in nonmedical patients.

Hospital‐Based Dermatology

Attendees participated in bedside evaluation of acute skin eruptions based on available patients admitted to the hospital. They discussed the approach to skin eruptions, key diagnoses, and when dermatologists should be consulted for their expertise. Specific topics included drug reactions, the red leg, life‐threating conditions (eg, Stevens‐Johnson syndrome), and dermatologic examination pearls. This domain was added in 2010.

Clinical Skills Labs

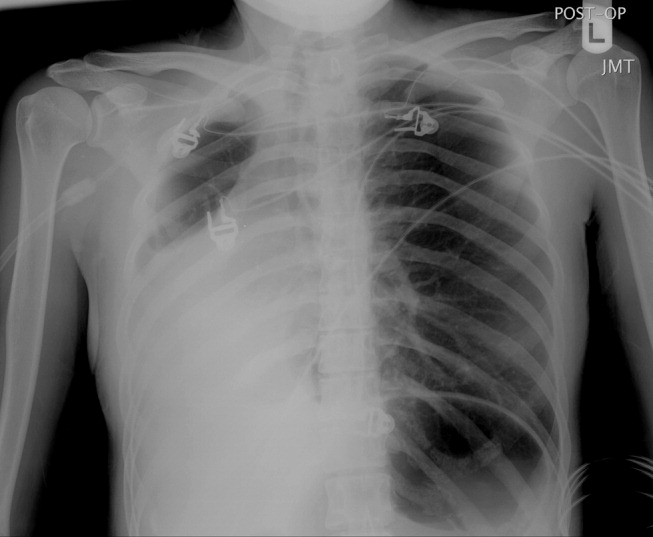

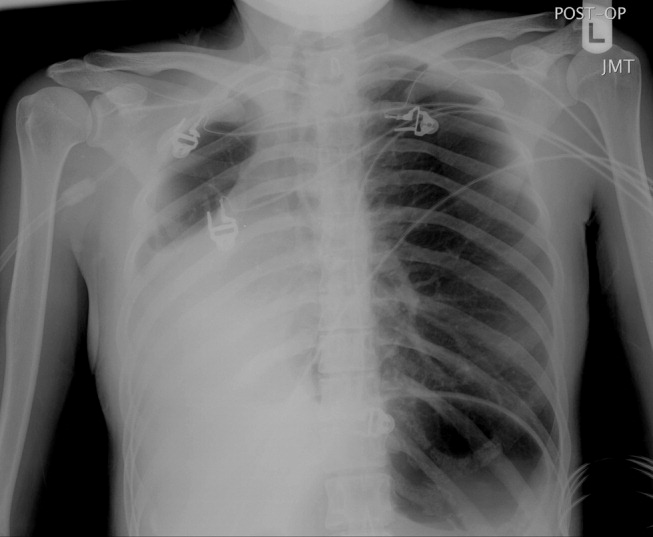

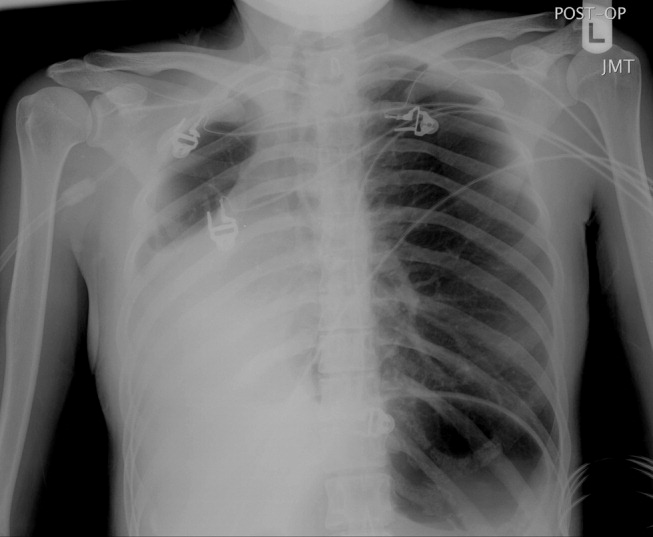

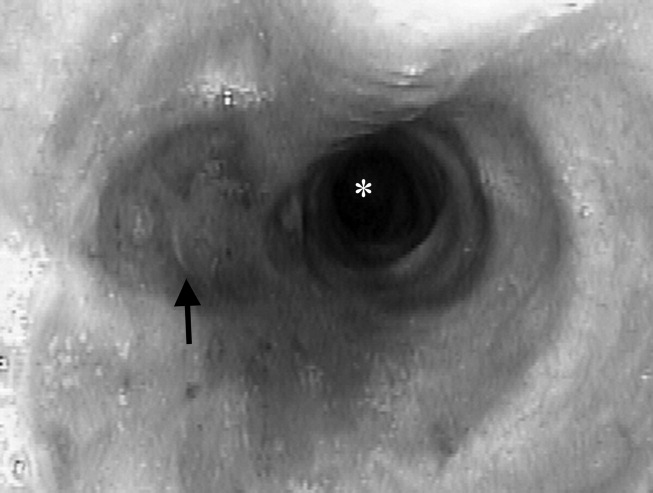

Radiology

In groups of 15, attendees reviewed common radiographs that hospitalists frequently order or evaluate (eg, chest x‐rays; kidney, ureter, and bladder; placement of endotracheal or feeding tube). They also reviewed the most relevant and not‐to‐miss findings on other commonly ordered studies such as abdominal or brain computerized tomography scans.

Hospital Procedures With Bedside Ultrasound

Attendees participated in a half‐day session to gain experience with the following procedures: paracentesis, lumbar puncture, thoracentesis, and central lines. They participated in an initial overview of procedural safety followed by hands‐on application sessions, in which they rotated through clinical workstations in groups of 5. At each work station, they were provided an opportunity to practice techniques, including the safe use of ultrasound on both live (standardized patients) and simulation models.

Other Sessions

Building Diagnostic Acumen and Clinical Reasoning

The opening session of the UHMC reintroduces attendees to the traditional academic morning report format, in which a case is presented and participants are asked to assess the information, develop differential diagnoses, discuss management options, and consider their own clinical reasoning skills. This provides frameworks for diagnostic reasoning, highlights common cognitive errors, and teaches attendees how to develop expertise in their own diagnostic thinking. The session also sets the stage and expectation for active learning and participation in the UHMC.

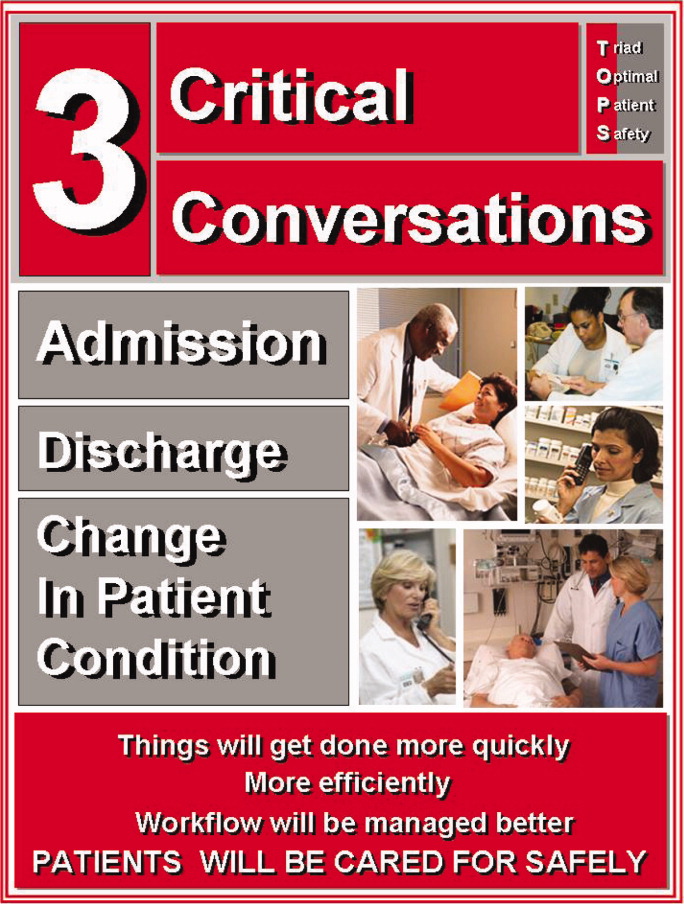

Root Cause Analysis and Systems Thinking

As the only nonclinical session in the UHMC, this session introduces participants to systems thinking and patient safety. Attendees participate in a root cause analysis role play surrounding a serious medical error and discuss the implications, their reflections, and then propose solutions through interactive table discussions. The session also emphasizes the key role hospitalists should play in improving patient safety.

Clinical Case Conference

Attendees participated in the weekly UCSF Department of Medicine Morbidity and Mortality conference. This is a traditional case conference that brings together learners, expert discussants, and an interesting or challenging case. This allows attendees to synthesize much of the course learning through active participation in the case discussion. Rather than creating a new conference for the participants, we brought the participants to the existing conference as part of their UHMC immersion experience.

Meet the Professor

Attendees participated in an informal discussion with a national leader (R.M.W.) in hospital medicine. This allowed for an interactive exchange of ideas and an understanding of the field overall.

Online Search Strategies

This interactive computer lab session allowed participants to explore the ever‐expanding number of online resources to answer clinical queries. This session was replaced in 2010 with the dermatology clinical domain based on participant feedback.

Program Evaluation

Participants completed a pre‐UHMC survey that provided demographic information and attributes about themselves, their clinical practice, and experience. Participants also completed course evaluations consistent with Accreditation Council for Continuing Medical Education standards following the program. The questions asked for each activity were rated on a 1‐to‐5 scale (1=poor, 5=excellent) and also included open‐ended questions to assess overall experiences.

RESULTS

Participant Demographics

During the first 5 years of the UHMC, 152 participants enrolled and completed the program; 91% completed the pre‐UHMC survey and 89% completed the postcourse evaluation. Table 1 describes the self‐reported participant demographics, including years in practice, number of hospitalist jobs, overall job satisfaction, and time spent doing clinical work. Overall, 68% of all participants had been self‐described hospitalists for <4 years, with 62% holding only 1 hospitalist job during that time; 77% reported being pretty or very satisfied with their jobs, and 72% reported clinical care as the attribute they love most in their job. Table 2 highlights the type of work attendees participate in within their clinical practice. More than half manage patients with neurologic disorders and care for critically ill patients, whereas virtually all perform preoperative medical evaluations and medical consultation

| Question | Response Options | 2008 (n=4) | 2009 (n=26) | 2010 (n=29) | 2011 (n=31) | 2012 (n=28) | Average (n=138) |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| |||||||

| How long have you been a hospitalist? | <2 years | 52% | 35% | 37% | 30% | 25% | 36% |

| 24 years | 26% | 39% | 30% | 30% | 38% | 32% | |

| 510 years | 11% | 17% | 15% | 26% | 29% | 20% | |

| >10 years | 11% | 9% | 18% | 14% | 8% | 12% | |

| How many hospitalist jobs have you had? | 1 | 63% | 61% | 62% | 62% | 58% | 62% |

| 2 to 3 | 37% | 35% | 23% | 35% | 29% | 32% | |

| >3 | 0% | 4% | 15% | 1% | 13% | 5% | |

| How satisfied are you with your current position? | Not satisfied | 1% | 4% | 4% | 4% | 0% | 4% |

| Somewhat satisfied | 11% | 13% | 39% | 17% | 17% | 19% | |

| Pretty satisfied | 59% | 52% | 35% | 57% | 38% | 48% | |

| Very satisfied | 26% | 30% | 23% | 22% | 46% | 29% | |

| What do you love most about your job? | Clinical care | 85% | 61% | 65% | 84% | 67% | 72% |

| Teaching | 1% | 17% | 12% | 1% | 4% | 7% | |

| QI or safety work | 0% | 4% | 0% | 1% | 8% | 3% | |

| Other (not specified) | 14% | 18% | 23% | 14% | 21% | 18% | |

| What percent of your time is spent doing clinical care? | 100% | 39% | 36% | 52% | 46% | 58% | 46% |

| 75%100% | 58% | 50% | 37% | 42% | 33% | 44% | |

| 5075% | 0% | 9% | 11% | 12% | 4% | 7% | |

| 25%50% | 4% | 5% | 0% | 0% | 5% | 3% | |

| <25% | 0% | 0% | 0% | 0% | 0% | 0% | |

| Question | Response Options | 2008 (n=24) | 2009 (n=26) | 2010 (n=29) | 2011 (n=31) | 2012 (n=28) | Average(n=138) |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| |||||||

| Do you primarily manage patients with neurologic disorders in your hospital? | Yes | 62% | 50% | 62% | 62% | 63% | 60% |

| Do you primarily manage critically ill ICU patients in your hospital? | Yes and without an intensivist | 19% | 23% | 19% | 27% | 21% | 22% |

| Yes but with an intensivist | 54% | 50% | 44% | 42% | 67% | 51% | |

| No | 27% | 27% | 37% | 31% | 13% | 27% | |

| Do you perform preoperative medical evaluations and medical consultation? | Yes | 96% | 91% | 96% | 96% | 92% | 94% |

| Which of the following describes your role in the care of surgical patients? | Traditional medical consultant | 33% | 28% | 28% | 30% | 24% | 29% |

| Comanagement (shared responsibility with surgeon) | 33% | 34% | 42% | 39% | 35% | 37% | |

| Attending of record with surgeon acting as consultant | 26% | 24% | 26% | 30% | 35% | 28% | |

| Do you have bedside ultrasound available in your daily practice? | Yes | 38% | 32% | 52% | 34% | 38% | 39% |

Participant Experience

Overall, participants rated the quality of the UHMC course highly (4.65; 15 scale). The neurology clinical domain (4.83) and clinical reasoning session (4.72) were the highest‐rated sessions. Compared to all UCSF CME course offerings between January 2010 and September 2012, the UHMC rated higher than the cumulative overall rating from those 227 courses (4.65 vs 4.44). For UCSF CME courses offered in 2011 and 2012, 78% of participants (n=11,447) reported a high or definite likelihood to change practice. For UHMC participants during the same time period (n=57), 98% reported a similar likelihood to change practice. Table 3 provides selected participant comments from their postcourse evaluations.

|

| Great pearls, broad ranging discussion of many controversial and common topics, and I loved the teaching format. |

| I thought the conception of the teaching model was really effectivehands‐on exams in small groups, each demonstrating a different part of the neurologic exam, followed by presentation and discussion, and ending in bedside rounds with the teaching faculty. |

| Excellent review of key topicswide variety of useful and practical points. Very high application value. |

| Great course. I'd take it again and again. It was a superb opportunity to review technique, equipment, and clinical decision making. |

| Overall outstanding course! Very informative and fun. Format was great. |

| Forward and clinically relevant. Like the bedside teaching and how they did it.The small size of the course and the close attention paid by the faculty teaching the course combined with the opportunity to see and examine patients in the hospital was outstanding. |

DISCUSSION

We developed an innovative CME program that brought participants to an academic health center for a participatory, hands‐on, and small‐group experience. They learned about topics relevant to today's hospitalists, rated the experience very highly, and reported a nearly unanimous likelihood to change their practice. Reflecting on our program's first 5 years, there were several lessons learned that may guide others committed to providing a similar CME experience.

First, hospital medicine is a dynamic field. Conducting a needs assessment to match clinical topics to what attendees required in their own practice was critical. Iterative changes from year to year reflected formal participant feedback as well as informal conversations with the teaching faculty. For instance, attendees were not only interested in the clinical topics but often wanted to see examples of clinical pathways, order sets, and other systems in place to improve care for patients with common conditions. Our participant presurvey also helped identify and reinforce the curricular topics that teaching faculty focused on each year. Being responsive to the changing needs of hospitalists and the environment is a crucial part of providing a relevant CME experience.

We also used an innovative approach to teaching, founded in adult and effective CME learning principles. CME activities are geared toward adult physicians, and studies of their effectiveness recommend that sessions should be interactive and utilize multiple modalities of learning.[12] When attendees actively participate and are provided an opportunity to practice skills, it may have a positive effect on patient outcomes.[13] All UHMC faculty were required to couple presentations of the latest evidence for clinical topics with small‐group and hands‐on learning modalities. This also required that we utilize a teaching faculty known for both their clinical expertise and teaching recognition. Together, the learning modalities and the teaching faculty likely accounted for the highly rated course experience and likelihood to change practice.

Finally, our course brought participants to an academic medical center and into the mix of clinical care as opposed to the more traditional hotel venue. This was necessary to deliver the curriculum as described, but also had the unexpected benefit of energizing the participants. Many had not been in a teaching setting since their residency training, and bringing them back into this milieu motivated them to learn and share their inspiration. As there are no published studies of CME experiences in the clinical environment, this observation is noteworthy and deserves to be explored and evaluated further.

What are the limitations of our approach to bringing CME to the bedside? First, the economics of an intensive 3‐day course with a maximum of 33 attendees are far different than those of a large hotel‐based offering. There are no exhibitors or outside contributions. The cost of the course to participants is $2500 (discounted if attending the larger course as well), which is 2 to 3 times higher than most traditional CME courses of the same length. Although the cost is high, the course has sold out each year with a waiting list. Part of the cost is also faculty time. The time, preparation, and need to teach on the fly to meet the differing participant educational needs is fundamentally different than delivering a single lecture in a hotel conference room. Not surprisingly, our faculty enjoy this teaching opportunity and find it equally unique and valuable; no faculty have dropped out of teaching the course, and many describe it as 1 of the teaching highlights of the year. Scalability of the UHMC is challenging for these reasons, but our model could be replicated in other teaching institutions, even as a local offering for their own providers.

In summary, we developed a hospital‐based, highly interactive, small‐group CME course that emphasizes case‐based teaching. The course has sold out each year, and evaluations suggest that it is highly valued and is meeting curricular goals better than more traditional CME courses. We hope our course description and success may motivate others to consider moving beyond the traditional CME for hospitalists and explore further innovations. With the field growing and changing at a rapid pace, innovative CME experiences will be necessary to assure that hospitalists continue to provide exemplary and safe care to their patients.

Acknowledgements

The authors thank Kapo Tam for her program management of the UHMC, and Katherine Li and Zachary Martin for their invaluable administrative support and coordination. The authors are also indebted to faculty colleagues for their time and roles in teaching within the program. They include Gupreet Dhaliwal, Andy Josephson, Vanja Douglas, Michelle Milic, Brian Daniels, Quinny Cheng, Lindy Fox, Diane Sliwka, Ralph Wang, and Thomas Urbania.

Disclosure: Nothing to report.

- , . The emerging role of “hospitalists” in the American health care system. N Engl J Med. 1996;337(7):514–517.

- Society of Hospital Medicine. Available at: http://www.hospitalmedicine.org/Content/NavigationMenu/Membership2/HospitalFocusedPractice/Hospital_Focused_Pra.htm. Accessed October 1, 2013.

- , , , . Hospital medicine fellowships: works in progress. Am J Med. 2006;119(1):72.e1–e7.

- Society of Hospital Medicine. Core competencies in hospital medicine. Available at: http://www.hospitalmedicine.org/Content/NavigationMenu/Education/CoreCurriculum/Core_Competencies.htm. Accessed October 1, 2013.

- , . The expanding role of hospitalists in the United States. Swiss Med Wkly. 2006;136(37‐38);591–596.

- Accreditation Council for Continuing Medical Education. CME content: definition and examples Available at: http://www.accme.org/requirements/accreditation‐requirements‐cme‐providers/policies‐and‐definitions/cme‐content‐definition‐and‐examples. Accessed October 1, 2013.

- , , , . Changing physician performance. A systematic review of the effect of continuing medical education strategies. JAMA. 1995;274(9):700–705.

- , . Continuing medical education and the physician as a learner: guide to the evidence. JAMA. 2002;288(9):1057–1060.

- , , , , . Barriers to innovation in continuing medical eduation. J Contin Educ Health Prof. 2008;28(3):148–156.

- . Adult learning theory for the 21st century. In: Merriam S. Thrid Update on Adult Learning Theory: New Directions for Adult and Continuing Education. San Francisco, CA: Jossey‐Bass; 2008:93–98.

- .UCSF management of the hospitalized patient CME course. Available at: http://www.ucsfcme.com/2014/MDM14P01/info.html. Accessed October 1, 2013.

- Continuing medical education effect on practice performance: effectiveness of continuing medical education: American College or Chest Physicians evidence‐based educational guidelines. Chest. 2009;135(3 suppl);42S–48S.

- Continuing medical education effect on clinical outcomes: effectiveness of continuing medical education: American College or Chest Physicians evidence‐based educational guidelines. Chest. 2009;135(3 suppl);49S–55S.

I hear and I forget, I see and I remember, I do and I understand.

Confucius

Hospital medicine, first described in 1996,[1] is the fastest growing specialty in United States medical history, now with approximately 40,000 practitioners.[2] Although hospitalists undoubtedly learned many of their key clinical skills during residency training, there is no hospitalist‐specific residency training pathway and a limited number of largely research‐oriented fellowships.[3] Furthermore, hospitalists are often asked to care for surgical patients, those with acute neurologic disorders, and patients in intensive care units, while also contributing to quality improvement and patient safety initiatives.[4] This suggests that the vast majority of hospitalists have not had specific training in many key competencies for the field.[5]

Continuing medical education (CME) has traditionally been the mechanism to maintain, develop, or increase the knowledge, skills, and professional performance of physicians.[6] Most CME activities, including those for hospitalists, are staged as live events in hotel conference rooms or as local events in a similarly passive learning environment (eg, grand rounds and medical staff meetings). Online programs, audiotapes, and expanding electronic media provide increasing and alternate methods for hospitalists to obtain their required CME. All of these activities passively deliver content to a group of diverse and experienced learners. They fail to take advantage of adult learning principles and may have little direct impact on professional practice.[7, 8] Traditional CME is often derided as a barrier to innovative educational methods for these reasons, as adults learn best through active participation, when the information is relevant and practically applied.[9, 10]

To provide practicing hospitalists with necessary continuing education, we designed the University of California, San Francisco (UCSF) Hospitalist Mini‐College (UHMC). This 3‐day course brings adult learners to the bedside for small‐group and active learning focused on content areas relevant to today's hospitalists. We describe the development, content, outcomes, and lessons learned from UHMC's first 5 years.

METHODS

Program Development

We aimed to develop a program that focused on curricular topics that would be highly valued by practicing hospitalists delivered in an active learning small‐group environment. We first conducted an informal needs assessment of community‐based hospitalists to better understand their roles and determine their perceptions of gaps in hospitalist training compared to current requirements for practice. We then reviewed available CME events targeting hospitalists and compared these curricula to the gaps discovered from the needs assessment. We also reviewed the Society of Hospital Medicine's core competencies to further identify gaps in scope of practice.[4] Finally, we reviewed the literature to identify CME curricular innovations in the clinical setting and found no published reports.

Program Setting, Participants, and Faculty

The UHMC course was developed and offered first in 2008 as a precourse to the UCSF Management of the Hospitalized Medicine course, a traditional CME offering that occurs annually in a hotel setting.[11] The UHMC takes place on the campus of UCSF Medical Center, a 600‐bed academic medical center in San Francisco. Registered participants were required to complete limited credentialing paperwork, which allowed them to directly observe clinical care and interact with hospitalized patients. Participants were not involved in any clinical decision making for the patients they met or examined. The course was limited to a maximum of 33 participants annually to optimize active participation, small‐group bedside activities, and a personalized learning experience. UCSF faculty selected to teach in the UHMC were chosen based on exemplary clinical and teaching skills. They collaborated with course directors in the development of their session‐specific goals and curriculum.

Program Description

Figure 1 is a representative calendar view of the 3‐day UHMC course. The curricular topics were selected based on the findings from our needs assessment, our ability to deliver that curriculum using our small‐group active learning framework, and to minimize overlap with content of the larger course. Course curriculum was refined annually based on participant feedback and course director observations.

The program was built on a structure of 4 clinical domains and 2 clinical skills labs. The clinical domains included: (1) Hospital‐Based Neurology, (2) Critical Care Medicine in the Intensive Care Unit, (3) Surgical Comanagement and Medical Consultation, and (4) Hospital‐Based Dermatology. Participants were divided into 3 groups of 10 participants each and rotated through each domain in the afternoons. The clinical skills labs included: (1) Interpretation of Radiographic Studies and (2) Use of Ultrasound and Enhancing Confidence in Performing Bedside Procedures. We also developed specific sessions to teach about patient safety and to allow course attendees to participate in traditional academic learning vehicles (eg, a Morning Report and Morbidity and Mortality case conference). Below, we describe each session's format and content.

Clinical Domains

Hospital‐Based Neurology

Attendees participated in both bedside evaluation and case‐based discussions of common neurologic conditions seen in the hospital. In small groups of 5, participants were assigned patients to examine on the neurology ward. After their evaluations, they reported their findings to fellow participants and the faculty, setting the foundation for discussion of clinical management, review of neuroimaging, and exploration of current evidence to inform the patient's diagnosis and management. Participants and faculty then returned to the bedside to hone neurologic examination skills and complete the learning process. Given the unpredictability of what conditions would be represented on the ward in a given day, review of commonly seen conditions was always a focus, such as stroke, seizures, delirium, and neurologic examination pearls.

Critical Care

Attendees participated in case‐based discussions of common clinical conditions with similar review of current evidence, relevant imaging, and bedside exam pearls for the intubated patient. For this domain, attendees also participated in an advanced simulation tutorial in ventilator management, which was then applied at the bedside of intubated patients. Specific topics covered include sepsis, decompensated chronic obstructive lung disease, vasopressor selection, novel therapies in critically ill patients, and use of clinical pathways and protocols for improved quality of care.

Surgical Comanagement and Medical Consultation

Attendees participated in case‐based discussions applying current evidence to perioperative controversies and the care of the surgical patient. They also discussed the expanding role of the hospitalist in nonmedical patients.

Hospital‐Based Dermatology

Attendees participated in bedside evaluation of acute skin eruptions based on available patients admitted to the hospital. They discussed the approach to skin eruptions, key diagnoses, and when dermatologists should be consulted for their expertise. Specific topics included drug reactions, the red leg, life‐threating conditions (eg, Stevens‐Johnson syndrome), and dermatologic examination pearls. This domain was added in 2010.

Clinical Skills Labs

Radiology

In groups of 15, attendees reviewed common radiographs that hospitalists frequently order or evaluate (eg, chest x‐rays; kidney, ureter, and bladder; placement of endotracheal or feeding tube). They also reviewed the most relevant and not‐to‐miss findings on other commonly ordered studies such as abdominal or brain computerized tomography scans.

Hospital Procedures With Bedside Ultrasound

Attendees participated in a half‐day session to gain experience with the following procedures: paracentesis, lumbar puncture, thoracentesis, and central lines. They participated in an initial overview of procedural safety followed by hands‐on application sessions, in which they rotated through clinical workstations in groups of 5. At each work station, they were provided an opportunity to practice techniques, including the safe use of ultrasound on both live (standardized patients) and simulation models.

Other Sessions

Building Diagnostic Acumen and Clinical Reasoning

The opening session of the UHMC reintroduces attendees to the traditional academic morning report format, in which a case is presented and participants are asked to assess the information, develop differential diagnoses, discuss management options, and consider their own clinical reasoning skills. This provides frameworks for diagnostic reasoning, highlights common cognitive errors, and teaches attendees how to develop expertise in their own diagnostic thinking. The session also sets the stage and expectation for active learning and participation in the UHMC.

Root Cause Analysis and Systems Thinking

As the only nonclinical session in the UHMC, this session introduces participants to systems thinking and patient safety. Attendees participate in a root cause analysis role play surrounding a serious medical error and discuss the implications, their reflections, and then propose solutions through interactive table discussions. The session also emphasizes the key role hospitalists should play in improving patient safety.

Clinical Case Conference

Attendees participated in the weekly UCSF Department of Medicine Morbidity and Mortality conference. This is a traditional case conference that brings together learners, expert discussants, and an interesting or challenging case. This allows attendees to synthesize much of the course learning through active participation in the case discussion. Rather than creating a new conference for the participants, we brought the participants to the existing conference as part of their UHMC immersion experience.

Meet the Professor

Attendees participated in an informal discussion with a national leader (R.M.W.) in hospital medicine. This allowed for an interactive exchange of ideas and an understanding of the field overall.

Online Search Strategies

This interactive computer lab session allowed participants to explore the ever‐expanding number of online resources to answer clinical queries. This session was replaced in 2010 with the dermatology clinical domain based on participant feedback.

Program Evaluation

Participants completed a pre‐UHMC survey that provided demographic information and attributes about themselves, their clinical practice, and experience. Participants also completed course evaluations consistent with Accreditation Council for Continuing Medical Education standards following the program. The questions asked for each activity were rated on a 1‐to‐5 scale (1=poor, 5=excellent) and also included open‐ended questions to assess overall experiences.

RESULTS

Participant Demographics

During the first 5 years of the UHMC, 152 participants enrolled and completed the program; 91% completed the pre‐UHMC survey and 89% completed the postcourse evaluation. Table 1 describes the self‐reported participant demographics, including years in practice, number of hospitalist jobs, overall job satisfaction, and time spent doing clinical work. Overall, 68% of all participants had been self‐described hospitalists for <4 years, with 62% holding only 1 hospitalist job during that time; 77% reported being pretty or very satisfied with their jobs, and 72% reported clinical care as the attribute they love most in their job. Table 2 highlights the type of work attendees participate in within their clinical practice. More than half manage patients with neurologic disorders and care for critically ill patients, whereas virtually all perform preoperative medical evaluations and medical consultation

| Question | Response Options | 2008 (n=4) | 2009 (n=26) | 2010 (n=29) | 2011 (n=31) | 2012 (n=28) | Average (n=138) |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| |||||||

| How long have you been a hospitalist? | <2 years | 52% | 35% | 37% | 30% | 25% | 36% |

| 24 years | 26% | 39% | 30% | 30% | 38% | 32% | |

| 510 years | 11% | 17% | 15% | 26% | 29% | 20% | |

| >10 years | 11% | 9% | 18% | 14% | 8% | 12% | |

| How many hospitalist jobs have you had? | 1 | 63% | 61% | 62% | 62% | 58% | 62% |

| 2 to 3 | 37% | 35% | 23% | 35% | 29% | 32% | |

| >3 | 0% | 4% | 15% | 1% | 13% | 5% | |

| How satisfied are you with your current position? | Not satisfied | 1% | 4% | 4% | 4% | 0% | 4% |

| Somewhat satisfied | 11% | 13% | 39% | 17% | 17% | 19% | |

| Pretty satisfied | 59% | 52% | 35% | 57% | 38% | 48% | |

| Very satisfied | 26% | 30% | 23% | 22% | 46% | 29% | |

| What do you love most about your job? | Clinical care | 85% | 61% | 65% | 84% | 67% | 72% |

| Teaching | 1% | 17% | 12% | 1% | 4% | 7% | |

| QI or safety work | 0% | 4% | 0% | 1% | 8% | 3% | |

| Other (not specified) | 14% | 18% | 23% | 14% | 21% | 18% | |

| What percent of your time is spent doing clinical care? | 100% | 39% | 36% | 52% | 46% | 58% | 46% |

| 75%100% | 58% | 50% | 37% | 42% | 33% | 44% | |

| 5075% | 0% | 9% | 11% | 12% | 4% | 7% | |

| 25%50% | 4% | 5% | 0% | 0% | 5% | 3% | |

| <25% | 0% | 0% | 0% | 0% | 0% | 0% | |

| Question | Response Options | 2008 (n=24) | 2009 (n=26) | 2010 (n=29) | 2011 (n=31) | 2012 (n=28) | Average(n=138) |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| |||||||

| Do you primarily manage patients with neurologic disorders in your hospital? | Yes | 62% | 50% | 62% | 62% | 63% | 60% |

| Do you primarily manage critically ill ICU patients in your hospital? | Yes and without an intensivist | 19% | 23% | 19% | 27% | 21% | 22% |

| Yes but with an intensivist | 54% | 50% | 44% | 42% | 67% | 51% | |

| No | 27% | 27% | 37% | 31% | 13% | 27% | |

| Do you perform preoperative medical evaluations and medical consultation? | Yes | 96% | 91% | 96% | 96% | 92% | 94% |

| Which of the following describes your role in the care of surgical patients? | Traditional medical consultant | 33% | 28% | 28% | 30% | 24% | 29% |

| Comanagement (shared responsibility with surgeon) | 33% | 34% | 42% | 39% | 35% | 37% | |

| Attending of record with surgeon acting as consultant | 26% | 24% | 26% | 30% | 35% | 28% | |

| Do you have bedside ultrasound available in your daily practice? | Yes | 38% | 32% | 52% | 34% | 38% | 39% |

Participant Experience

Overall, participants rated the quality of the UHMC course highly (4.65; 15 scale). The neurology clinical domain (4.83) and clinical reasoning session (4.72) were the highest‐rated sessions. Compared to all UCSF CME course offerings between January 2010 and September 2012, the UHMC rated higher than the cumulative overall rating from those 227 courses (4.65 vs 4.44). For UCSF CME courses offered in 2011 and 2012, 78% of participants (n=11,447) reported a high or definite likelihood to change practice. For UHMC participants during the same time period (n=57), 98% reported a similar likelihood to change practice. Table 3 provides selected participant comments from their postcourse evaluations.

|

| Great pearls, broad ranging discussion of many controversial and common topics, and I loved the teaching format. |

| I thought the conception of the teaching model was really effectivehands‐on exams in small groups, each demonstrating a different part of the neurologic exam, followed by presentation and discussion, and ending in bedside rounds with the teaching faculty. |

| Excellent review of key topicswide variety of useful and practical points. Very high application value. |

| Great course. I'd take it again and again. It was a superb opportunity to review technique, equipment, and clinical decision making. |

| Overall outstanding course! Very informative and fun. Format was great. |

| Forward and clinically relevant. Like the bedside teaching and how they did it.The small size of the course and the close attention paid by the faculty teaching the course combined with the opportunity to see and examine patients in the hospital was outstanding. |

DISCUSSION

We developed an innovative CME program that brought participants to an academic health center for a participatory, hands‐on, and small‐group experience. They learned about topics relevant to today's hospitalists, rated the experience very highly, and reported a nearly unanimous likelihood to change their practice. Reflecting on our program's first 5 years, there were several lessons learned that may guide others committed to providing a similar CME experience.

First, hospital medicine is a dynamic field. Conducting a needs assessment to match clinical topics to what attendees required in their own practice was critical. Iterative changes from year to year reflected formal participant feedback as well as informal conversations with the teaching faculty. For instance, attendees were not only interested in the clinical topics but often wanted to see examples of clinical pathways, order sets, and other systems in place to improve care for patients with common conditions. Our participant presurvey also helped identify and reinforce the curricular topics that teaching faculty focused on each year. Being responsive to the changing needs of hospitalists and the environment is a crucial part of providing a relevant CME experience.

We also used an innovative approach to teaching, founded in adult and effective CME learning principles. CME activities are geared toward adult physicians, and studies of their effectiveness recommend that sessions should be interactive and utilize multiple modalities of learning.[12] When attendees actively participate and are provided an opportunity to practice skills, it may have a positive effect on patient outcomes.[13] All UHMC faculty were required to couple presentations of the latest evidence for clinical topics with small‐group and hands‐on learning modalities. This also required that we utilize a teaching faculty known for both their clinical expertise and teaching recognition. Together, the learning modalities and the teaching faculty likely accounted for the highly rated course experience and likelihood to change practice.

Finally, our course brought participants to an academic medical center and into the mix of clinical care as opposed to the more traditional hotel venue. This was necessary to deliver the curriculum as described, but also had the unexpected benefit of energizing the participants. Many had not been in a teaching setting since their residency training, and bringing them back into this milieu motivated them to learn and share their inspiration. As there are no published studies of CME experiences in the clinical environment, this observation is noteworthy and deserves to be explored and evaluated further.

What are the limitations of our approach to bringing CME to the bedside? First, the economics of an intensive 3‐day course with a maximum of 33 attendees are far different than those of a large hotel‐based offering. There are no exhibitors or outside contributions. The cost of the course to participants is $2500 (discounted if attending the larger course as well), which is 2 to 3 times higher than most traditional CME courses of the same length. Although the cost is high, the course has sold out each year with a waiting list. Part of the cost is also faculty time. The time, preparation, and need to teach on the fly to meet the differing participant educational needs is fundamentally different than delivering a single lecture in a hotel conference room. Not surprisingly, our faculty enjoy this teaching opportunity and find it equally unique and valuable; no faculty have dropped out of teaching the course, and many describe it as 1 of the teaching highlights of the year. Scalability of the UHMC is challenging for these reasons, but our model could be replicated in other teaching institutions, even as a local offering for their own providers.

In summary, we developed a hospital‐based, highly interactive, small‐group CME course that emphasizes case‐based teaching. The course has sold out each year, and evaluations suggest that it is highly valued and is meeting curricular goals better than more traditional CME courses. We hope our course description and success may motivate others to consider moving beyond the traditional CME for hospitalists and explore further innovations. With the field growing and changing at a rapid pace, innovative CME experiences will be necessary to assure that hospitalists continue to provide exemplary and safe care to their patients.

Acknowledgements

The authors thank Kapo Tam for her program management of the UHMC, and Katherine Li and Zachary Martin for their invaluable administrative support and coordination. The authors are also indebted to faculty colleagues for their time and roles in teaching within the program. They include Gupreet Dhaliwal, Andy Josephson, Vanja Douglas, Michelle Milic, Brian Daniels, Quinny Cheng, Lindy Fox, Diane Sliwka, Ralph Wang, and Thomas Urbania.

Disclosure: Nothing to report.

I hear and I forget, I see and I remember, I do and I understand.

Confucius

Hospital medicine, first described in 1996,[1] is the fastest growing specialty in United States medical history, now with approximately 40,000 practitioners.[2] Although hospitalists undoubtedly learned many of their key clinical skills during residency training, there is no hospitalist‐specific residency training pathway and a limited number of largely research‐oriented fellowships.[3] Furthermore, hospitalists are often asked to care for surgical patients, those with acute neurologic disorders, and patients in intensive care units, while also contributing to quality improvement and patient safety initiatives.[4] This suggests that the vast majority of hospitalists have not had specific training in many key competencies for the field.[5]

Continuing medical education (CME) has traditionally been the mechanism to maintain, develop, or increase the knowledge, skills, and professional performance of physicians.[6] Most CME activities, including those for hospitalists, are staged as live events in hotel conference rooms or as local events in a similarly passive learning environment (eg, grand rounds and medical staff meetings). Online programs, audiotapes, and expanding electronic media provide increasing and alternate methods for hospitalists to obtain their required CME. All of these activities passively deliver content to a group of diverse and experienced learners. They fail to take advantage of adult learning principles and may have little direct impact on professional practice.[7, 8] Traditional CME is often derided as a barrier to innovative educational methods for these reasons, as adults learn best through active participation, when the information is relevant and practically applied.[9, 10]

To provide practicing hospitalists with necessary continuing education, we designed the University of California, San Francisco (UCSF) Hospitalist Mini‐College (UHMC). This 3‐day course brings adult learners to the bedside for small‐group and active learning focused on content areas relevant to today's hospitalists. We describe the development, content, outcomes, and lessons learned from UHMC's first 5 years.

METHODS

Program Development

We aimed to develop a program that focused on curricular topics that would be highly valued by practicing hospitalists delivered in an active learning small‐group environment. We first conducted an informal needs assessment of community‐based hospitalists to better understand their roles and determine their perceptions of gaps in hospitalist training compared to current requirements for practice. We then reviewed available CME events targeting hospitalists and compared these curricula to the gaps discovered from the needs assessment. We also reviewed the Society of Hospital Medicine's core competencies to further identify gaps in scope of practice.[4] Finally, we reviewed the literature to identify CME curricular innovations in the clinical setting and found no published reports.

Program Setting, Participants, and Faculty

The UHMC course was developed and offered first in 2008 as a precourse to the UCSF Management of the Hospitalized Medicine course, a traditional CME offering that occurs annually in a hotel setting.[11] The UHMC takes place on the campus of UCSF Medical Center, a 600‐bed academic medical center in San Francisco. Registered participants were required to complete limited credentialing paperwork, which allowed them to directly observe clinical care and interact with hospitalized patients. Participants were not involved in any clinical decision making for the patients they met or examined. The course was limited to a maximum of 33 participants annually to optimize active participation, small‐group bedside activities, and a personalized learning experience. UCSF faculty selected to teach in the UHMC were chosen based on exemplary clinical and teaching skills. They collaborated with course directors in the development of their session‐specific goals and curriculum.

Program Description

Figure 1 is a representative calendar view of the 3‐day UHMC course. The curricular topics were selected based on the findings from our needs assessment, our ability to deliver that curriculum using our small‐group active learning framework, and to minimize overlap with content of the larger course. Course curriculum was refined annually based on participant feedback and course director observations.

The program was built on a structure of 4 clinical domains and 2 clinical skills labs. The clinical domains included: (1) Hospital‐Based Neurology, (2) Critical Care Medicine in the Intensive Care Unit, (3) Surgical Comanagement and Medical Consultation, and (4) Hospital‐Based Dermatology. Participants were divided into 3 groups of 10 participants each and rotated through each domain in the afternoons. The clinical skills labs included: (1) Interpretation of Radiographic Studies and (2) Use of Ultrasound and Enhancing Confidence in Performing Bedside Procedures. We also developed specific sessions to teach about patient safety and to allow course attendees to participate in traditional academic learning vehicles (eg, a Morning Report and Morbidity and Mortality case conference). Below, we describe each session's format and content.

Clinical Domains

Hospital‐Based Neurology

Attendees participated in both bedside evaluation and case‐based discussions of common neurologic conditions seen in the hospital. In small groups of 5, participants were assigned patients to examine on the neurology ward. After their evaluations, they reported their findings to fellow participants and the faculty, setting the foundation for discussion of clinical management, review of neuroimaging, and exploration of current evidence to inform the patient's diagnosis and management. Participants and faculty then returned to the bedside to hone neurologic examination skills and complete the learning process. Given the unpredictability of what conditions would be represented on the ward in a given day, review of commonly seen conditions was always a focus, such as stroke, seizures, delirium, and neurologic examination pearls.

Critical Care

Attendees participated in case‐based discussions of common clinical conditions with similar review of current evidence, relevant imaging, and bedside exam pearls for the intubated patient. For this domain, attendees also participated in an advanced simulation tutorial in ventilator management, which was then applied at the bedside of intubated patients. Specific topics covered include sepsis, decompensated chronic obstructive lung disease, vasopressor selection, novel therapies in critically ill patients, and use of clinical pathways and protocols for improved quality of care.

Surgical Comanagement and Medical Consultation

Attendees participated in case‐based discussions applying current evidence to perioperative controversies and the care of the surgical patient. They also discussed the expanding role of the hospitalist in nonmedical patients.

Hospital‐Based Dermatology

Attendees participated in bedside evaluation of acute skin eruptions based on available patients admitted to the hospital. They discussed the approach to skin eruptions, key diagnoses, and when dermatologists should be consulted for their expertise. Specific topics included drug reactions, the red leg, life‐threating conditions (eg, Stevens‐Johnson syndrome), and dermatologic examination pearls. This domain was added in 2010.

Clinical Skills Labs

Radiology

In groups of 15, attendees reviewed common radiographs that hospitalists frequently order or evaluate (eg, chest x‐rays; kidney, ureter, and bladder; placement of endotracheal or feeding tube). They also reviewed the most relevant and not‐to‐miss findings on other commonly ordered studies such as abdominal or brain computerized tomography scans.

Hospital Procedures With Bedside Ultrasound

Attendees participated in a half‐day session to gain experience with the following procedures: paracentesis, lumbar puncture, thoracentesis, and central lines. They participated in an initial overview of procedural safety followed by hands‐on application sessions, in which they rotated through clinical workstations in groups of 5. At each work station, they were provided an opportunity to practice techniques, including the safe use of ultrasound on both live (standardized patients) and simulation models.

Other Sessions

Building Diagnostic Acumen and Clinical Reasoning

The opening session of the UHMC reintroduces attendees to the traditional academic morning report format, in which a case is presented and participants are asked to assess the information, develop differential diagnoses, discuss management options, and consider their own clinical reasoning skills. This provides frameworks for diagnostic reasoning, highlights common cognitive errors, and teaches attendees how to develop expertise in their own diagnostic thinking. The session also sets the stage and expectation for active learning and participation in the UHMC.

Root Cause Analysis and Systems Thinking

As the only nonclinical session in the UHMC, this session introduces participants to systems thinking and patient safety. Attendees participate in a root cause analysis role play surrounding a serious medical error and discuss the implications, their reflections, and then propose solutions through interactive table discussions. The session also emphasizes the key role hospitalists should play in improving patient safety.

Clinical Case Conference

Attendees participated in the weekly UCSF Department of Medicine Morbidity and Mortality conference. This is a traditional case conference that brings together learners, expert discussants, and an interesting or challenging case. This allows attendees to synthesize much of the course learning through active participation in the case discussion. Rather than creating a new conference for the participants, we brought the participants to the existing conference as part of their UHMC immersion experience.

Meet the Professor

Attendees participated in an informal discussion with a national leader (R.M.W.) in hospital medicine. This allowed for an interactive exchange of ideas and an understanding of the field overall.

Online Search Strategies

This interactive computer lab session allowed participants to explore the ever‐expanding number of online resources to answer clinical queries. This session was replaced in 2010 with the dermatology clinical domain based on participant feedback.

Program Evaluation

Participants completed a pre‐UHMC survey that provided demographic information and attributes about themselves, their clinical practice, and experience. Participants also completed course evaluations consistent with Accreditation Council for Continuing Medical Education standards following the program. The questions asked for each activity were rated on a 1‐to‐5 scale (1=poor, 5=excellent) and also included open‐ended questions to assess overall experiences.

RESULTS

Participant Demographics

During the first 5 years of the UHMC, 152 participants enrolled and completed the program; 91% completed the pre‐UHMC survey and 89% completed the postcourse evaluation. Table 1 describes the self‐reported participant demographics, including years in practice, number of hospitalist jobs, overall job satisfaction, and time spent doing clinical work. Overall, 68% of all participants had been self‐described hospitalists for <4 years, with 62% holding only 1 hospitalist job during that time; 77% reported being pretty or very satisfied with their jobs, and 72% reported clinical care as the attribute they love most in their job. Table 2 highlights the type of work attendees participate in within their clinical practice. More than half manage patients with neurologic disorders and care for critically ill patients, whereas virtually all perform preoperative medical evaluations and medical consultation

| Question | Response Options | 2008 (n=4) | 2009 (n=26) | 2010 (n=29) | 2011 (n=31) | 2012 (n=28) | Average (n=138) |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| |||||||

| How long have you been a hospitalist? | <2 years | 52% | 35% | 37% | 30% | 25% | 36% |

| 24 years | 26% | 39% | 30% | 30% | 38% | 32% | |

| 510 years | 11% | 17% | 15% | 26% | 29% | 20% | |

| >10 years | 11% | 9% | 18% | 14% | 8% | 12% | |

| How many hospitalist jobs have you had? | 1 | 63% | 61% | 62% | 62% | 58% | 62% |

| 2 to 3 | 37% | 35% | 23% | 35% | 29% | 32% | |

| >3 | 0% | 4% | 15% | 1% | 13% | 5% | |

| How satisfied are you with your current position? | Not satisfied | 1% | 4% | 4% | 4% | 0% | 4% |

| Somewhat satisfied | 11% | 13% | 39% | 17% | 17% | 19% | |

| Pretty satisfied | 59% | 52% | 35% | 57% | 38% | 48% | |

| Very satisfied | 26% | 30% | 23% | 22% | 46% | 29% | |

| What do you love most about your job? | Clinical care | 85% | 61% | 65% | 84% | 67% | 72% |

| Teaching | 1% | 17% | 12% | 1% | 4% | 7% | |

| QI or safety work | 0% | 4% | 0% | 1% | 8% | 3% | |

| Other (not specified) | 14% | 18% | 23% | 14% | 21% | 18% | |

| What percent of your time is spent doing clinical care? | 100% | 39% | 36% | 52% | 46% | 58% | 46% |

| 75%100% | 58% | 50% | 37% | 42% | 33% | 44% | |

| 5075% | 0% | 9% | 11% | 12% | 4% | 7% | |

| 25%50% | 4% | 5% | 0% | 0% | 5% | 3% | |

| <25% | 0% | 0% | 0% | 0% | 0% | 0% | |

| Question | Response Options | 2008 (n=24) | 2009 (n=26) | 2010 (n=29) | 2011 (n=31) | 2012 (n=28) | Average(n=138) |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| |||||||

| Do you primarily manage patients with neurologic disorders in your hospital? | Yes | 62% | 50% | 62% | 62% | 63% | 60% |

| Do you primarily manage critically ill ICU patients in your hospital? | Yes and without an intensivist | 19% | 23% | 19% | 27% | 21% | 22% |

| Yes but with an intensivist | 54% | 50% | 44% | 42% | 67% | 51% | |

| No | 27% | 27% | 37% | 31% | 13% | 27% | |

| Do you perform preoperative medical evaluations and medical consultation? | Yes | 96% | 91% | 96% | 96% | 92% | 94% |

| Which of the following describes your role in the care of surgical patients? | Traditional medical consultant | 33% | 28% | 28% | 30% | 24% | 29% |

| Comanagement (shared responsibility with surgeon) | 33% | 34% | 42% | 39% | 35% | 37% | |

| Attending of record with surgeon acting as consultant | 26% | 24% | 26% | 30% | 35% | 28% | |

| Do you have bedside ultrasound available in your daily practice? | Yes | 38% | 32% | 52% | 34% | 38% | 39% |

Participant Experience

Overall, participants rated the quality of the UHMC course highly (4.65; 15 scale). The neurology clinical domain (4.83) and clinical reasoning session (4.72) were the highest‐rated sessions. Compared to all UCSF CME course offerings between January 2010 and September 2012, the UHMC rated higher than the cumulative overall rating from those 227 courses (4.65 vs 4.44). For UCSF CME courses offered in 2011 and 2012, 78% of participants (n=11,447) reported a high or definite likelihood to change practice. For UHMC participants during the same time period (n=57), 98% reported a similar likelihood to change practice. Table 3 provides selected participant comments from their postcourse evaluations.

|

| Great pearls, broad ranging discussion of many controversial and common topics, and I loved the teaching format. |

| I thought the conception of the teaching model was really effectivehands‐on exams in small groups, each demonstrating a different part of the neurologic exam, followed by presentation and discussion, and ending in bedside rounds with the teaching faculty. |

| Excellent review of key topicswide variety of useful and practical points. Very high application value. |

| Great course. I'd take it again and again. It was a superb opportunity to review technique, equipment, and clinical decision making. |

| Overall outstanding course! Very informative and fun. Format was great. |

| Forward and clinically relevant. Like the bedside teaching and how they did it.The small size of the course and the close attention paid by the faculty teaching the course combined with the opportunity to see and examine patients in the hospital was outstanding. |

DISCUSSION

We developed an innovative CME program that brought participants to an academic health center for a participatory, hands‐on, and small‐group experience. They learned about topics relevant to today's hospitalists, rated the experience very highly, and reported a nearly unanimous likelihood to change their practice. Reflecting on our program's first 5 years, there were several lessons learned that may guide others committed to providing a similar CME experience.

First, hospital medicine is a dynamic field. Conducting a needs assessment to match clinical topics to what attendees required in their own practice was critical. Iterative changes from year to year reflected formal participant feedback as well as informal conversations with the teaching faculty. For instance, attendees were not only interested in the clinical topics but often wanted to see examples of clinical pathways, order sets, and other systems in place to improve care for patients with common conditions. Our participant presurvey also helped identify and reinforce the curricular topics that teaching faculty focused on each year. Being responsive to the changing needs of hospitalists and the environment is a crucial part of providing a relevant CME experience.

We also used an innovative approach to teaching, founded in adult and effective CME learning principles. CME activities are geared toward adult physicians, and studies of their effectiveness recommend that sessions should be interactive and utilize multiple modalities of learning.[12] When attendees actively participate and are provided an opportunity to practice skills, it may have a positive effect on patient outcomes.[13] All UHMC faculty were required to couple presentations of the latest evidence for clinical topics with small‐group and hands‐on learning modalities. This also required that we utilize a teaching faculty known for both their clinical expertise and teaching recognition. Together, the learning modalities and the teaching faculty likely accounted for the highly rated course experience and likelihood to change practice.

Finally, our course brought participants to an academic medical center and into the mix of clinical care as opposed to the more traditional hotel venue. This was necessary to deliver the curriculum as described, but also had the unexpected benefit of energizing the participants. Many had not been in a teaching setting since their residency training, and bringing them back into this milieu motivated them to learn and share their inspiration. As there are no published studies of CME experiences in the clinical environment, this observation is noteworthy and deserves to be explored and evaluated further.

What are the limitations of our approach to bringing CME to the bedside? First, the economics of an intensive 3‐day course with a maximum of 33 attendees are far different than those of a large hotel‐based offering. There are no exhibitors or outside contributions. The cost of the course to participants is $2500 (discounted if attending the larger course as well), which is 2 to 3 times higher than most traditional CME courses of the same length. Although the cost is high, the course has sold out each year with a waiting list. Part of the cost is also faculty time. The time, preparation, and need to teach on the fly to meet the differing participant educational needs is fundamentally different than delivering a single lecture in a hotel conference room. Not surprisingly, our faculty enjoy this teaching opportunity and find it equally unique and valuable; no faculty have dropped out of teaching the course, and many describe it as 1 of the teaching highlights of the year. Scalability of the UHMC is challenging for these reasons, but our model could be replicated in other teaching institutions, even as a local offering for their own providers.

In summary, we developed a hospital‐based, highly interactive, small‐group CME course that emphasizes case‐based teaching. The course has sold out each year, and evaluations suggest that it is highly valued and is meeting curricular goals better than more traditional CME courses. We hope our course description and success may motivate others to consider moving beyond the traditional CME for hospitalists and explore further innovations. With the field growing and changing at a rapid pace, innovative CME experiences will be necessary to assure that hospitalists continue to provide exemplary and safe care to their patients.

Acknowledgements

The authors thank Kapo Tam for her program management of the UHMC, and Katherine Li and Zachary Martin for their invaluable administrative support and coordination. The authors are also indebted to faculty colleagues for their time and roles in teaching within the program. They include Gupreet Dhaliwal, Andy Josephson, Vanja Douglas, Michelle Milic, Brian Daniels, Quinny Cheng, Lindy Fox, Diane Sliwka, Ralph Wang, and Thomas Urbania.

Disclosure: Nothing to report.

- , . The emerging role of “hospitalists” in the American health care system. N Engl J Med. 1996;337(7):514–517.

- Society of Hospital Medicine. Available at: http://www.hospitalmedicine.org/Content/NavigationMenu/Membership2/HospitalFocusedPractice/Hospital_Focused_Pra.htm. Accessed October 1, 2013.

- , , , . Hospital medicine fellowships: works in progress. Am J Med. 2006;119(1):72.e1–e7.

- Society of Hospital Medicine. Core competencies in hospital medicine. Available at: http://www.hospitalmedicine.org/Content/NavigationMenu/Education/CoreCurriculum/Core_Competencies.htm. Accessed October 1, 2013.

- , . The expanding role of hospitalists in the United States. Swiss Med Wkly. 2006;136(37‐38);591–596.

- Accreditation Council for Continuing Medical Education. CME content: definition and examples Available at: http://www.accme.org/requirements/accreditation‐requirements‐cme‐providers/policies‐and‐definitions/cme‐content‐definition‐and‐examples. Accessed October 1, 2013.

- , , , . Changing physician performance. A systematic review of the effect of continuing medical education strategies. JAMA. 1995;274(9):700–705.

- , . Continuing medical education and the physician as a learner: guide to the evidence. JAMA. 2002;288(9):1057–1060.

- , , , , . Barriers to innovation in continuing medical eduation. J Contin Educ Health Prof. 2008;28(3):148–156.

- . Adult learning theory for the 21st century. In: Merriam S. Thrid Update on Adult Learning Theory: New Directions for Adult and Continuing Education. San Francisco, CA: Jossey‐Bass; 2008:93–98.

- .UCSF management of the hospitalized patient CME course. Available at: http://www.ucsfcme.com/2014/MDM14P01/info.html. Accessed October 1, 2013.

- Continuing medical education effect on practice performance: effectiveness of continuing medical education: American College or Chest Physicians evidence‐based educational guidelines. Chest. 2009;135(3 suppl);42S–48S.

- Continuing medical education effect on clinical outcomes: effectiveness of continuing medical education: American College or Chest Physicians evidence‐based educational guidelines. Chest. 2009;135(3 suppl);49S–55S.

- , . The emerging role of “hospitalists” in the American health care system. N Engl J Med. 1996;337(7):514–517.

- Society of Hospital Medicine. Available at: http://www.hospitalmedicine.org/Content/NavigationMenu/Membership2/HospitalFocusedPractice/Hospital_Focused_Pra.htm. Accessed October 1, 2013.

- , , , . Hospital medicine fellowships: works in progress. Am J Med. 2006;119(1):72.e1–e7.

- Society of Hospital Medicine. Core competencies in hospital medicine. Available at: http://www.hospitalmedicine.org/Content/NavigationMenu/Education/CoreCurriculum/Core_Competencies.htm. Accessed October 1, 2013.

- , . The expanding role of hospitalists in the United States. Swiss Med Wkly. 2006;136(37‐38);591–596.

- Accreditation Council for Continuing Medical Education. CME content: definition and examples Available at: http://www.accme.org/requirements/accreditation‐requirements‐cme‐providers/policies‐and‐definitions/cme‐content‐definition‐and‐examples. Accessed October 1, 2013.

- , , , . Changing physician performance. A systematic review of the effect of continuing medical education strategies. JAMA. 1995;274(9):700–705.

- , . Continuing medical education and the physician as a learner: guide to the evidence. JAMA. 2002;288(9):1057–1060.

- , , , , . Barriers to innovation in continuing medical eduation. J Contin Educ Health Prof. 2008;28(3):148–156.

- . Adult learning theory for the 21st century. In: Merriam S. Thrid Update on Adult Learning Theory: New Directions for Adult and Continuing Education. San Francisco, CA: Jossey‐Bass; 2008:93–98.

- .UCSF management of the hospitalized patient CME course. Available at: http://www.ucsfcme.com/2014/MDM14P01/info.html. Accessed October 1, 2013.

- Continuing medical education effect on practice performance: effectiveness of continuing medical education: American College or Chest Physicians evidence‐based educational guidelines. Chest. 2009;135(3 suppl);42S–48S.

- Continuing medical education effect on clinical outcomes: effectiveness of continuing medical education: American College or Chest Physicians evidence‐based educational guidelines. Chest. 2009;135(3 suppl);49S–55S.

Teamwork in Hospitals

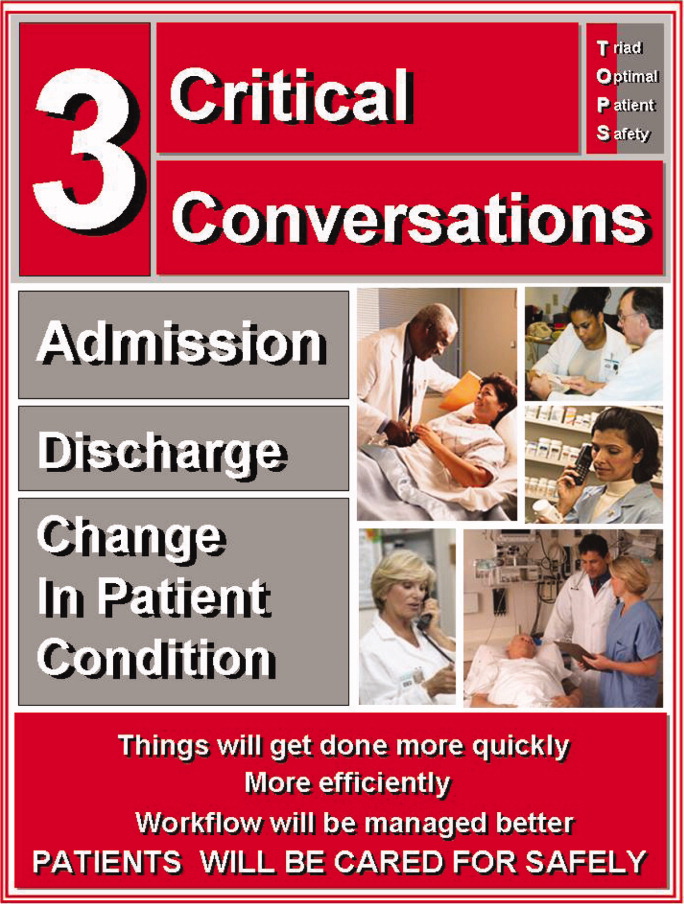

Teamwork is important in providing high‐quality hospital care. Despite tremendous efforts in the 10 years since publication of the Institute of Medicine's To Err is Human report,1 hospitalized patients remain at risk for adverse events (AEs).2 Although many AEs are not preventable, a large portion of those which are identified as preventable can be attributed to communication and teamwork failures.35 A Joint Commission study indicated that communication failures were the root cause for two‐thirds of the 3548 sentinel events reported from 1995 to 2005.6 Another study, involving interviews of resident physicians about recent medical mishaps, found that communication failures contributed to 91% of the AEs they reported.5

Teamwork also plays an important role in other aspects of hospital care delivery. Patients' ratings of nurse‐physician coordination correlate with their overall perception of the quality of care received.7, 8 A study of Veterans Health Administration (VHA) hospitals found that teamwork culture was significantly and positively associated with overall patient satisfaction.9 Another VHA study found that hospitals with higher teamwork culture ratings had lower nurse resignations rates.10 Furthermore, poor teamwork within hospitals may have an adverse effect on financial performance, as a result of inefficiencies in physician and nurse workflow.11

Some organizations are capable of operating in complex, hazardous environments while maintaining exceptional performance over long periods of time. These high reliability organizations (HRO) include aircraft carriers, air traffic control systems, and nuclear power plants, and are characterized by their preoccupation with failure, reluctance to simplify interpretations, sensitivity to operations, commitment to resilience, and deference to expertise.12, 13 Preoccupation with failure is manifested by an organization's efforts to avoid complacency and persist in the search for additional risks. Reluctance to simplify interpretations is exemplified by an interest in pursuing a deep understanding of the issues that arise. Sensitivity to operations is the close attention paid to input from front‐line personnel and processes. Commitment to resilience relates to an organization's ability to contain errors once they occur and mitigate harm. Deference to expertise describes the practice of having authority migrate to the people with the most expertise, regardless of rank. Collectively, these qualities produce a state of mindfulness, allowing teams to anticipate and become aware of unexpected events, yet also quickly contain and learn from them. Recent publications have highlighted the need for hospitals to learn from HROs and the teams within them.14, 15

Recognizing the importance of teamwork in hospitals, senior leadership from the American College of Physician Executives (ACPE), the American Hospital Association (AHA), the American Organization of Nurse Executives (AONE), and the Society of Hospital Medicine (SHM) established the High Performance Teams and the Hospital of the Future project. This collaborative learning effort aims to redesign care delivery to provide optimal value to hospitalized patients. As an initial step, the High Performance Teams and the Hospital of the Future project team completed a literature review related to teamwork in hospitals. The purpose of this report is to summarize the current understanding of teamwork, describe interventions designed to improve teamwork, and make practical recommendations for hospitals to assess and improve teamwork‐related performance. We approach teamwork from the hospitalized patient's perspective, and restrict our discussion to interactions occurring among healthcare professionals within the hospital. We recognize the importance of teamwork at all points in the continuum of patient care. Highly functional inpatient teams should be integrated into an overall system of coordinated and collaborative care.

TEAMWORK: DEFINITION AND CONSTRUCTS

Physicians, nurses, and other healthcare professionals spend a great deal of their time on communication and coordination of care activities.1618 In spite of this and the patient safety concerns previously noted, interpersonal communication skills and teamwork have been historically underemphasized in professional training.1922 A team is defined as 2 or more individuals with specified roles interacting adaptively, interdependently, and dynamically toward a shared and common goal.23 Elements of effective teamwork have been identified through research conducted in aviation, the military, and more recently, healthcare. Salas and colleagues have synthesized this research into 5 core components: team leadership, mutual performance monitoring, backup behavior, adaptability, and team orientation (see Table 1).23 Additionally, 3 supporting and coordinating mechanisms are essential for effective teamwork: shared mental model, closed‐loop communication, and mutual trust (see Table 1).23 High‐performing teams use these elements to develop a culture for speaking up, and situational awareness among team members. Situational awareness refers to a person's perception and understanding of their dynamic environment, and human errors often result from a lack of such awareness.24 These teamwork constructs provide the foundational basis for understanding how hospitals can identify teamwork challenges, assess team performance, and design effective interventions.

| Teamwork | Definition | Behavioral Examples |

|---|---|---|

| ||

| Component | ||

| Team leadership | The leader directs and coordinates team members activities | Facilitate team problem solving; |

| Provide performance expectations; | ||

| Clarify team member roles; | ||

| Assist in conflict resolution | ||

| Mutual performance monitoring | Team members are able to monitor one another's performance | Identify mistakes and lapses in other team member actions; |

| Provide feedback to fellow team members to facilitate self‐correction | ||

| Backup behavior | Team members anticipate and respond to one another's needs | Recognize workload distribution problem; |

| Shift work responsibilities to underutilized members | ||

| Adaptability | The team adjusts strategies based on new information | Identify cues that change has occurred and develop plan to deal with changes; |

| Remain vigilant to change in internal and external environment | ||

| Team orientation | Team members prioritize team goals above individual goals | Take into account alternate solutions by teammates; |

| Increased task involvement, information sharing, and participatory goal setting | ||

| Coordinating mechanism | ||

| Shared mental model | An organizing knowledge of the task of the team and how members will interact to achieve their goal | Anticipate and predict each other's needs; |

| Identify changes in team, task, or teammates | ||

| Closed‐loop communication | Acknowledgement and confirmation of information received | Follow up with team members to ensure message received; |

| Acknowledge that message was received; | ||

| Clarify information received | ||

| Mutual trust | Shared belief that team members will perform their roles | Share information; |

| Willingly admit mistakes and accept feedback | ||

CHALLENGES TO EFFECTIVE TEAMWORK