User login

Quality and Quantity of the Elbow Arthroscopy Literature: A Systematic Review and Meta-Analysis

Although elbow arthroscopy was first described in the 1930s, it has become increasingly popular in the last 30 years.1 While initially considered as a tool for diagnosis and loose body removal, indications have expanded to include treatment of osteochondritis dissecans (OCD), treatment of lateral epicondylitis, fixation of fractures, and others.2-5 Miyake and colleagues6 found a significant improvement in range of motion, both flexion and extension, and outcome scores when elbow arthroscopy was used to remove impinging osteophytes. Babaqi and colleagues7 found significant improvement in pain, satisfaction, and outcome scores in 31 patients who underwent elbow arthroscopy for lateral epicondylitis refractory to nonsurgical management. The technical difficulty of the procedure, lower frequency of pathology amenable to arthroscopic intervention, and potential neurovascular complications make the elbow less frequently evaluated with the arthroscope vs other joints, such as the knee and shoulder.2,8,9

Geographic distribution of subjects undergoing elbow arthroscopy, the indications used, surgical techniques being performed, and their associated clinical outcomes have received little to no recognition in the peer-reviewed literature.10 Differences in the elbow arthroscopy literature include characteristics related to the patient (age, gender, hand dominance, duration of symptoms), study (level of evidence, number of subjects, number of participating centers, design), indication (lateral epicondylitis, loose bodies, olecranon osteophytes, OCD), surgical technique, and outcome. Evidence-based medicine and clinical practice guidelines direct surgeons in clinical decision-making. Payers investigate the cost of surgical interventions and the value that surgery may provide, while following trends in different surgical techniques. Regulatory agencies and associations emphasize subjective patient-reported outcomes as the primary outcome measured in high-quality trials. Thus, in discussion of complex surgical interventions such as elbow arthroscopy, it is important to characterize the studies, subjects, and surgeries across the world to understand the geographic similarities and differences to optimize care in this clinical situation.

The goal of this study was to perform a systematic review and meta-analysis of elbow arthroscopy literature to identify and compare the characteristics of the studies published, the subjects analyzed, and surgical techniques performed across continents and countries to answer these questions: “Across the world, what demographic of patients are undergoing elbow arthroscopy, what are the most common indications for elbow arthroscopy, and how good is the evidence?” The authors hypothesized that patients who undergo elbow arthroscopy will be largely age <40 years, the most common indication for elbow arthroscopy will be a release/débridement, and the evidence for elbow arthroscopy will be poor. Also, no significant differences will exist in elbow arthroscopy publications, subjects, outcomes, and techniques based on continent/country of publication.

Methods

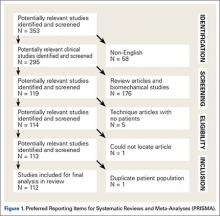

A systematic review was conducted according to Preferred Reporting Items for Systematic Reviews and Meta-Analyses (PRISMA) guidelines using a PRISMA checklist.11 Systematic review registration was performed using the International Prospective Register of Ongoing Systematic Reviews (PROSPERO; registration number, CRD42014010580; registration date, July 15, 2014).12 Two study authors independently conducted the search on June 23, 2014 using the following databases: Medline, Cochrane Central Register of Controlled Trials, SportDiscus, and CINAHL. The electronic search citation algorithm used was: (elbow) AND arthroscopy) NOT shoulder) NOT knee) NOT ankle) NOT wrist) NOT hip) NOT dog) NOT cadaver). English language Level I-IV evidence (2012 update by the Oxford Centre for Evidence-Based Medicine13) clinical studies were eligible for inclusion into this study. Abstracts were ineligible for inclusion. All references in selected studies were cross-referenced for inclusion if they were missed during the initial search. Duplicate subject publications within separate unique studies were not reported twice. The study with longer duration follow-up, higher level of evidence, greater number of subjects, or more detailed subject, surgical technique, or outcome reporting was retained for inclusion. Level V evidence reviews, expert opinion articles, letters to the editor, basic science, biomechanical studies, open elbow surgery, imaging, surgical technique, and classification studies were excluded.

All included patients underwent elbow arthroscopy for either intra- or extra-articular elbow pathology (ulnotrochlear osteoarthritis, lateral epicondylitis, rheumatoid arthritis, post-traumatic contracture, osteonecrosis of the capitellum or radial head, osteoid osteoma, and others). There was no minimum follow-up duration or rehabilitation requirement. The study and subject demographic parameters that we analyzed included year of publication, years of subject enrollment, presence of study financial conflict of interest, number of subjects and elbows, elbow dominance, gender, age, body mass index, diagnoses treated, type of anesthesia (block or general), and surgical positioning. Postoperative splint application and pain management, and whether a continuous passive motion machine was used and whether a drain was placed were recorded. Clinical outcome scores were DASH (Disability of the Arm, Shoulder, and Hand), Morrey score, MEPS (Mayo Elbow Performance Score), Andrews-Carson score, Timmerman-Andrews score, LES (Liverpool Elbow Score), Tegner score, HSS (Hospital for Special Surgery Score), VAS (Visual Analog Scale), EFA (Elbow Functional Assessment), Short Form-12 (SF-12), Short Form-36 (SF-36), Kerlan-Jobe Orthopaedic Clinic (KJOC) Shoulder and Elbow Questionnaire, and MAESS (Modified Andrews Elbow Scoring System). Radiographs, computed tomography (CT), computed tomography arthrography (CTA), magnetic resonance imaging (MRI), and magnetic resonance arthrography (MRA) data were extracted when available. Range of motion (flexion, extension, supination, and pronation) and grip strength data, both preoperative and postoperative, were extracted when available. Study methodological quality was evaluated using the Modified Coleman Methodology Score (MCMS).14

Statistical Analysis

Study descriptive statistics were calculated. Continuous variable data were reported as weighted means ± weighted standard deviations. Categorical variable data were reported as frequencies with percentages. For all statistical analysis either measured and calculated from study data extraction or directly reported from the individual studies, P < .05 was considered statistically significant. Study, subject, and surgical outcomes data were compared using 1-way analysis of variance (ANOVA) tests. Where applicable, study, subject, and surgical outcomes data were also compared using 2-sample and 2-proportion Z-test calculators with α .05 because of the difference in sample sizes between compared groups. To examine trends over time, Pearson’s correlation coefficients were calculated. For the purposes of analysis, the indications of “osteoarthritis,” “arthrofibrosis,” “loose body removal,” “ulnotrochlear osteoarthritis causing stiffness,” “post-traumatic contracture/stiffness,” and “post-operative elbow contracture” were combined into the indication “release and débridement.” For the 3 most common indications for arthroscopy (OCD, lateral epicondylitis, and release and débridement) data were combined into 5-year increments to overcome the smaller sample size within each of these categories, and Pearson’s correlation coefficients were calculated to determine if number of reported cases covaried with year period. Within these 3 diagnoses, ANOVA analyses were performed to determine whether the number of cases differed between continents and countries.

Results

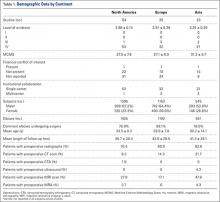

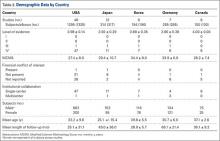

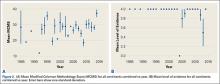

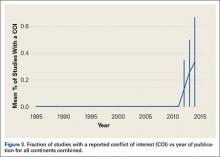

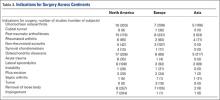

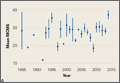

A total of 353 studies were located, and, after implementation of the exclusion criteria, 112 studies were included in the final analysis (Figure 1; 3093 subjects; 3168 elbows; 64% male; mean age, 34.9 ± 14.68 years). There was a mean of 33.4 ± 26.02 months of follow-up, and 75% of surgeries involved the dominant elbow (Table 1). Most studies were level IV evidence (94.6%), had a low MCMS (mean 28.1 ± 8.06; poor rating), and were single-center investigations (94.6%). Most studies did not report financial conflicts of interest (56.3%) (Tables 1 and 2). From 1985 through 2014, the number of publications significantly increased with time (P = .004) among all continents. The MCMS was unchanged over time (P = .247) (Figure 2A), as was the level of evidence (P = .094) (Figure 2B). Conflicts of interest significantly increased with time (P = .025) (Figure 3).

Among continents, North America published the largest number of studies (54), and had the largest number of patients (1395) and elbow surgeries (1425) (Table 1). The United States published the largest number of studies (43%). There were no significant differences between age (P = .331), length of follow-up (P = .403), MCMS (P = .123), and level of evidence (P = .288) between continents. Of the 32 studies that reported the use of preoperative MRI, studies from Asia reported significantly more MRI scans than those from other continents (P = .040); there were no other significant differences between continents in reference to preoperative imaging studies or other demographic information.

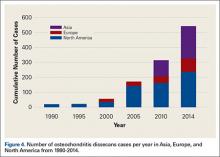

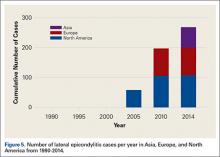

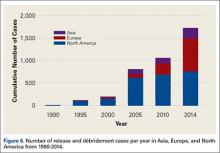

The most common surgical indications were OCD (Figure 4), lateral epicondylitis (Figure 5), and release and débridement (Figure 6, Table 3; all studies listed indications). The number of reported cases for these 3 indications significantly increased over time (OCD P = .005, lateral epicondylitis P = .044, release and débridement P = .042) but did not significantly differ between regions (P > .05 in all cases).

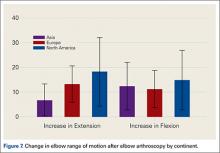

Thirty-two (28.6%) studies reported the use of outcome measures (16 different outcome scores were used by the included studies). Asia reported outcome measures in 9 of 23 studies (39%), Europe in 12 of 35 studies (34%) and North America in 11 of 54 (20%) of studies. The MEPS was the most frequently used outcome score in 9.8% of studies, followed by VAS for pain in 5.3% of cases. North American studies reported a significantly higher increase in extension after elbow arthroscopy than Asia (P = .0432) (Figure 7), with no differences in flexion (P = .699), pronation (P = .376), or supination (P = .408). No significant differences were observed between continents in the type of anesthesia chosen (general anesthesia [P = .94] or regional anesthesia [P = .85]). Asia and Europe performed elbow arthroscopy most frequently in the lateral decubitus position, while North American studies most often used the supine position (Table 4).

Twenty (17.9%) studies reported the use of a postoperative splint, 12 (10.7%) studies reported use of a drain, 2 (1.79%) studies reported use of a hinged elbow brace, 9 (8.03%) studies reported use of a continuous passive motion machine postoperatively, and 3 (2.68%) studies reported use of an indwelling axillary catheter for postoperative pain management. Of 130 reported surgical complications (4.1%), the most frequent complication was transient sensory ulnar nerve palsy (1.5%), followed by persistent wound drainage (.76%), and transient sensory radial nerve palsy (.38%). Other reported complications included infection (.22%), transient sensory palsy of the median nerve (.19%), heterotopic ossification (.13%), complete transection of the ulnar nerve (.10%), loose body formation (.06%), hematoma formation (.06%), transient sensory palsy of the posterior interosseous (.06%), or anterior interosseous nerve (.03%), and complete transection of the radial (.03%), or median nerve (.03%).

Discussion

Elbow arthroscopy is an evolving surgical procedure that is used to treat intra- and extra-articular pathologies of the elbow. Outcomes of elbow arthroscopy for certain conditions have generally been reported as good, with improvements seen in pain, functional scores, and range of motion.6,15-17 The authors’ hypotheses were mostly confirmed in that the average age of patients undergoing elbow arthroscopy was <40 years, release/débridement was one of the most common indications (along with lateral epicondylitis and OCD), and the general evidence for elbow arthroscopy was poor. Also, there were almost no differences between continents/countries related to patient indications, preoperative imaging, anesthesia choice, indications, postoperative protocols, and outcomes (although the number of studies that reported outcomes was low and could have skewed the results), with the exception of a higher number of preoperative MRI scans in Asia. Some of the notable findings of this study included: 1) the number of studies published on elbow arthroscopy is significantly increasing with time, despite a lack of improvement in the level of evidence; 2) the majority of studies on elbow arthroscopy do not report a surgical outcome score; and 3) the number of reported cases for the 3 most common indications significantly increased over time (OCD, P = .005; lateral epicondylitis, P = .044; release and débridement, P = .042) but did not differ between regions (P > .05 in all cases).

The indications for elbow arthroscopy have grown dramatically in the past 2 decades to include both intra- and extra-articular pathologies.18 Despite this increase in the number of indications for elbow arthroscopy, the study did not find a significant difference between countries/continents in the indications each used for elbow arthroscopy patients. There was a trend towards an increase in OCD cases in all continents, especially Asia (Figure 4), with time. Interestingly, while not statistically significant, there was variation among countries for surgical indications. In North America, removal of loose bodies accounts for 18% of patients, while in Europe this accounted for only 9% and in Asia for 1%. Post-traumatic stiffness was the indication for elbow arthroscopy in Europe in 19% of patients vs 7% in North America and 10% in Asia. In Asia, OCD accounts for 40% of arthroscopies, 7% in Europe, and 14% in North America (Figure 4) (Table 3).

This study demonstrated that the mean increase in elbow extension gained after surgery in North America was significantly greater when compared with studies from Asia, but the gain in flexion, pronation, and supination was similar across continents. The underlying cause of this difference in improvement in elbow extension between nations is unclear, although differences in diagnosis could account for some variation. This study did not examine differences in rehabilitation protocols, and certainly, it is plausible that protocol variations by country could account for some discrepancy. Furthermore, differences in functional needs may vary by continent and could have driven this result.

This study found no routine reporting of outcome scores by elbow arthroscopy studies from any continent, and that when outcome scores are reported, there is substantial inconsistency with regard to the actual scoring system used. No continent reported outcome scores in more than 40% of the studies published from that area, and the variation of outcome scores used, even from a single region, was large. This makes comparing clinical outcomes between studies difficult, even when performing identical procedures for identical indications, because there is no standardized method of reporting outcomes. To allow comparison of studies and generalizability of the results to different populations, a more standardized approach to outcome reporting needs to be instituted in the elbow arthroscopy literature. To date, there is no standardized score that has been validated for reporting clinical outcomes after elbow arthroscopy.19 Hence, it is not surprising that there were 16 different outcome scores reported throughout the 112 studies analyzed in this review, with the most frequent score, the MEPS, reported in a total of 10 studies. As medicine moves towards pay scales that are based on patient outcomes, it will become more important to define a clear outcome score that can be used to assess these patients, and reliably report scores. This will allow comparison of patients across nations to determine the best surgical treatment for different clinical problems. A validation study comparing these outcome scores to determine which score best summarizes the patient’s level of pain and function after surgery would be beneficial, because this could identify 1 score that could be standardized to allow comparison among reported outcomes.

Limitations

This study had several limitations. Despite having 2 authors search independently for studies, some studies could have been missed during the search process, introducing possible selection bias. Including only published studies could have introduced publication bias. Numerous studies did not report all the variables the authors examined. This could have skewed some results, and had additional variables been reported, could have altered the data to show significant differences in some measured variables. Because this study did not compare outcome measures for varying pathologies, conclusions cannot be drawn on the best treatment options for different indications. Case reports could have lowered the MCMS score and the average in studies reporting outcomes. Furthermore, the poor quality of the underlying data used in this study could limit the validity/generalizability of the results because this is a systematic review, and its level of evidence is only as high as the studies it includes. Because the primary aim was to report on demographics, this study did not examine concomitant pathology at the time of surgery or rehabilitation protocols.

Conclusion

The quantity, but not the quality, of arthroscopic elbow publications has significantly increased over time. Most patients undergo elbow arthroscopy for lateral epicondylitis, OCD, and release and débridement. Pathology and indications do not appear to differ geographically with more men undergoing elbow arthroscopy than women.

1. Khanchandani P. Elbow arthroscopy: review of the literature and case reports. Case Rep Orthop. 2012;2012:478214.

2. Dodson CC, Nho SJ, Williams RJ 3rd, Altchek DW. Elbow arthroscopy. J Am Acad Orthop Surg. 2008;16(10):574-585.

3. Takahara M, Mura N, Sasaki J, Harada M, Ogino T. Classification, treatment, and outcome of osteochondritis dissecans of the humeral capitellum. Surgical technique. J Bone Joint Surg Am. 2008;90(suppl 2 Pt 1):47-62.

4. Kelly EW, Morrey BF, O’Driscoll SW. Complications of elbow arthroscopy. J Bone Joint Surg Am. 2001;83-A(1):25-34.

5. Rajeev A, Pooley J. Lateral compartment cartilage changes and lateral elbow pain. Acta Orthop Belg. 2009;75(1):37-40.

6. Miyake J, Shimada K, Oka K, et al. Arthroscopic debridement in the treatment of patients with osteoarthritis of the elbow, based on computer simulation. Bone Joint J. 2014;96-B(2):237-241.

7. Babaqi AA, Kotb MM, Said HG, AbdelHamid MM, ElKady HA, ElAssal MA. Short-term evaluation of arthroscopic management of tennis elbow; including resection of radio-capitellar capsular complex. J Orthop. 2014;11(2):82-86.

8. Gay DM, Raphael BS, Weiland AJ. Revision arthroscopic contracture release in the elbow resulting in an ulnar nerve transection: a case report. J Bone Joint Surg Am. 2010;92(5):1246-1249.

9. Haapaniemi T, Berggren M, Adolfsson L. Complete transection of the median and radial nerves during arthroscopic release of post-traumatic elbow contracture. Arthroscopy. 1999;15(7):784-787.

10. Yeoh KM, King GJ, Faber KJ, Glazebrook MA, Athwal GS. Evidence-based indications for elbow arthroscopy. Arthroscopy. 2012;28(2):272-282.

11. Liberati A, Altman DG, Tetzlaff J, et al. The PRISMA statement for reporting systematic reviews and meta-analyses of studies that evaluate health care interventions: explanation and elaboration. BMJ. 2009;339:b2700.

12. PROSPERO. International Prospective Register of Ongoing Systematic Reviews. The University of York CfRaDP-Iprosr-v. 2013 [cited 2014]. http://www.crd.york.ac.uk/PROSPERO/. Accessed March 17, 2016.

13. Oxford Centre for Evidence-Based Medicine - levels of evidence (March 2009). Centre for Evidence-Based Medicine Web site. http://www.cebm.net/oxford-centre-evidence-based-medicine-levels-evidence-march-2009/. Accessed July 6, 2016.

14. Cowan J, Lozano-Calderόn S, Ring D. Quality of prospective controlled randomized trials. Analysis of trials of treatment for lateral epicondylitis as an example. J Bone Joint Surg Am. 2007;89(8):1693-1699.

15. Jones GS, Savoie FH 3rd. Arthroscopic capsular release of flexion contractures (arthrofibrosis) of the elbow. Arthroscopy. 1993;9(3):277-283.

16. O’Brien MJ, Lee Murphy R, Savoie FH 3rd. A preliminary report of acute and subacute arthroscopic repair of the radial ulnohumeral ligament after elbow dislocation in the high-demand patient. Arthroscopy. 2014;30(6):679-687.

17. Rhyou IH, Kim KW. Is posterior synovial plica excision necessary for refractory lateral epicondylitis of the elbow? Clin Orthop Relat Res. 2013;471(1):284-290.

18. Jerosch J, Schunck J. Arthroscopic treatment of lateral epicondylitis: indication, technique and early results. Knee Surg Sports Traumatol Arthrosc. 2006;14(4):379-382.

19. Tijssen M, van Cingel R, van Melick N, de Visser E. Patient-Reported Outcome questionnaires for hip arthroscopy: a systematic review of the psychometric evidence. BMC Musculoskelet Disord. 2011;12:117.

Although elbow arthroscopy was first described in the 1930s, it has become increasingly popular in the last 30 years.1 While initially considered as a tool for diagnosis and loose body removal, indications have expanded to include treatment of osteochondritis dissecans (OCD), treatment of lateral epicondylitis, fixation of fractures, and others.2-5 Miyake and colleagues6 found a significant improvement in range of motion, both flexion and extension, and outcome scores when elbow arthroscopy was used to remove impinging osteophytes. Babaqi and colleagues7 found significant improvement in pain, satisfaction, and outcome scores in 31 patients who underwent elbow arthroscopy for lateral epicondylitis refractory to nonsurgical management. The technical difficulty of the procedure, lower frequency of pathology amenable to arthroscopic intervention, and potential neurovascular complications make the elbow less frequently evaluated with the arthroscope vs other joints, such as the knee and shoulder.2,8,9

Geographic distribution of subjects undergoing elbow arthroscopy, the indications used, surgical techniques being performed, and their associated clinical outcomes have received little to no recognition in the peer-reviewed literature.10 Differences in the elbow arthroscopy literature include characteristics related to the patient (age, gender, hand dominance, duration of symptoms), study (level of evidence, number of subjects, number of participating centers, design), indication (lateral epicondylitis, loose bodies, olecranon osteophytes, OCD), surgical technique, and outcome. Evidence-based medicine and clinical practice guidelines direct surgeons in clinical decision-making. Payers investigate the cost of surgical interventions and the value that surgery may provide, while following trends in different surgical techniques. Regulatory agencies and associations emphasize subjective patient-reported outcomes as the primary outcome measured in high-quality trials. Thus, in discussion of complex surgical interventions such as elbow arthroscopy, it is important to characterize the studies, subjects, and surgeries across the world to understand the geographic similarities and differences to optimize care in this clinical situation.

The goal of this study was to perform a systematic review and meta-analysis of elbow arthroscopy literature to identify and compare the characteristics of the studies published, the subjects analyzed, and surgical techniques performed across continents and countries to answer these questions: “Across the world, what demographic of patients are undergoing elbow arthroscopy, what are the most common indications for elbow arthroscopy, and how good is the evidence?” The authors hypothesized that patients who undergo elbow arthroscopy will be largely age <40 years, the most common indication for elbow arthroscopy will be a release/débridement, and the evidence for elbow arthroscopy will be poor. Also, no significant differences will exist in elbow arthroscopy publications, subjects, outcomes, and techniques based on continent/country of publication.

Methods

A systematic review was conducted according to Preferred Reporting Items for Systematic Reviews and Meta-Analyses (PRISMA) guidelines using a PRISMA checklist.11 Systematic review registration was performed using the International Prospective Register of Ongoing Systematic Reviews (PROSPERO; registration number, CRD42014010580; registration date, July 15, 2014).12 Two study authors independently conducted the search on June 23, 2014 using the following databases: Medline, Cochrane Central Register of Controlled Trials, SportDiscus, and CINAHL. The electronic search citation algorithm used was: (elbow) AND arthroscopy) NOT shoulder) NOT knee) NOT ankle) NOT wrist) NOT hip) NOT dog) NOT cadaver). English language Level I-IV evidence (2012 update by the Oxford Centre for Evidence-Based Medicine13) clinical studies were eligible for inclusion into this study. Abstracts were ineligible for inclusion. All references in selected studies were cross-referenced for inclusion if they were missed during the initial search. Duplicate subject publications within separate unique studies were not reported twice. The study with longer duration follow-up, higher level of evidence, greater number of subjects, or more detailed subject, surgical technique, or outcome reporting was retained for inclusion. Level V evidence reviews, expert opinion articles, letters to the editor, basic science, biomechanical studies, open elbow surgery, imaging, surgical technique, and classification studies were excluded.

All included patients underwent elbow arthroscopy for either intra- or extra-articular elbow pathology (ulnotrochlear osteoarthritis, lateral epicondylitis, rheumatoid arthritis, post-traumatic contracture, osteonecrosis of the capitellum or radial head, osteoid osteoma, and others). There was no minimum follow-up duration or rehabilitation requirement. The study and subject demographic parameters that we analyzed included year of publication, years of subject enrollment, presence of study financial conflict of interest, number of subjects and elbows, elbow dominance, gender, age, body mass index, diagnoses treated, type of anesthesia (block or general), and surgical positioning. Postoperative splint application and pain management, and whether a continuous passive motion machine was used and whether a drain was placed were recorded. Clinical outcome scores were DASH (Disability of the Arm, Shoulder, and Hand), Morrey score, MEPS (Mayo Elbow Performance Score), Andrews-Carson score, Timmerman-Andrews score, LES (Liverpool Elbow Score), Tegner score, HSS (Hospital for Special Surgery Score), VAS (Visual Analog Scale), EFA (Elbow Functional Assessment), Short Form-12 (SF-12), Short Form-36 (SF-36), Kerlan-Jobe Orthopaedic Clinic (KJOC) Shoulder and Elbow Questionnaire, and MAESS (Modified Andrews Elbow Scoring System). Radiographs, computed tomography (CT), computed tomography arthrography (CTA), magnetic resonance imaging (MRI), and magnetic resonance arthrography (MRA) data were extracted when available. Range of motion (flexion, extension, supination, and pronation) and grip strength data, both preoperative and postoperative, were extracted when available. Study methodological quality was evaluated using the Modified Coleman Methodology Score (MCMS).14

Statistical Analysis

Study descriptive statistics were calculated. Continuous variable data were reported as weighted means ± weighted standard deviations. Categorical variable data were reported as frequencies with percentages. For all statistical analysis either measured and calculated from study data extraction or directly reported from the individual studies, P < .05 was considered statistically significant. Study, subject, and surgical outcomes data were compared using 1-way analysis of variance (ANOVA) tests. Where applicable, study, subject, and surgical outcomes data were also compared using 2-sample and 2-proportion Z-test calculators with α .05 because of the difference in sample sizes between compared groups. To examine trends over time, Pearson’s correlation coefficients were calculated. For the purposes of analysis, the indications of “osteoarthritis,” “arthrofibrosis,” “loose body removal,” “ulnotrochlear osteoarthritis causing stiffness,” “post-traumatic contracture/stiffness,” and “post-operative elbow contracture” were combined into the indication “release and débridement.” For the 3 most common indications for arthroscopy (OCD, lateral epicondylitis, and release and débridement) data were combined into 5-year increments to overcome the smaller sample size within each of these categories, and Pearson’s correlation coefficients were calculated to determine if number of reported cases covaried with year period. Within these 3 diagnoses, ANOVA analyses were performed to determine whether the number of cases differed between continents and countries.

Results

A total of 353 studies were located, and, after implementation of the exclusion criteria, 112 studies were included in the final analysis (Figure 1; 3093 subjects; 3168 elbows; 64% male; mean age, 34.9 ± 14.68 years). There was a mean of 33.4 ± 26.02 months of follow-up, and 75% of surgeries involved the dominant elbow (Table 1). Most studies were level IV evidence (94.6%), had a low MCMS (mean 28.1 ± 8.06; poor rating), and were single-center investigations (94.6%). Most studies did not report financial conflicts of interest (56.3%) (Tables 1 and 2). From 1985 through 2014, the number of publications significantly increased with time (P = .004) among all continents. The MCMS was unchanged over time (P = .247) (Figure 2A), as was the level of evidence (P = .094) (Figure 2B). Conflicts of interest significantly increased with time (P = .025) (Figure 3).

Among continents, North America published the largest number of studies (54), and had the largest number of patients (1395) and elbow surgeries (1425) (Table 1). The United States published the largest number of studies (43%). There were no significant differences between age (P = .331), length of follow-up (P = .403), MCMS (P = .123), and level of evidence (P = .288) between continents. Of the 32 studies that reported the use of preoperative MRI, studies from Asia reported significantly more MRI scans than those from other continents (P = .040); there were no other significant differences between continents in reference to preoperative imaging studies or other demographic information.

The most common surgical indications were OCD (Figure 4), lateral epicondylitis (Figure 5), and release and débridement (Figure 6, Table 3; all studies listed indications). The number of reported cases for these 3 indications significantly increased over time (OCD P = .005, lateral epicondylitis P = .044, release and débridement P = .042) but did not significantly differ between regions (P > .05 in all cases).

Thirty-two (28.6%) studies reported the use of outcome measures (16 different outcome scores were used by the included studies). Asia reported outcome measures in 9 of 23 studies (39%), Europe in 12 of 35 studies (34%) and North America in 11 of 54 (20%) of studies. The MEPS was the most frequently used outcome score in 9.8% of studies, followed by VAS for pain in 5.3% of cases. North American studies reported a significantly higher increase in extension after elbow arthroscopy than Asia (P = .0432) (Figure 7), with no differences in flexion (P = .699), pronation (P = .376), or supination (P = .408). No significant differences were observed between continents in the type of anesthesia chosen (general anesthesia [P = .94] or regional anesthesia [P = .85]). Asia and Europe performed elbow arthroscopy most frequently in the lateral decubitus position, while North American studies most often used the supine position (Table 4).

Twenty (17.9%) studies reported the use of a postoperative splint, 12 (10.7%) studies reported use of a drain, 2 (1.79%) studies reported use of a hinged elbow brace, 9 (8.03%) studies reported use of a continuous passive motion machine postoperatively, and 3 (2.68%) studies reported use of an indwelling axillary catheter for postoperative pain management. Of 130 reported surgical complications (4.1%), the most frequent complication was transient sensory ulnar nerve palsy (1.5%), followed by persistent wound drainage (.76%), and transient sensory radial nerve palsy (.38%). Other reported complications included infection (.22%), transient sensory palsy of the median nerve (.19%), heterotopic ossification (.13%), complete transection of the ulnar nerve (.10%), loose body formation (.06%), hematoma formation (.06%), transient sensory palsy of the posterior interosseous (.06%), or anterior interosseous nerve (.03%), and complete transection of the radial (.03%), or median nerve (.03%).

Discussion

Elbow arthroscopy is an evolving surgical procedure that is used to treat intra- and extra-articular pathologies of the elbow. Outcomes of elbow arthroscopy for certain conditions have generally been reported as good, with improvements seen in pain, functional scores, and range of motion.6,15-17 The authors’ hypotheses were mostly confirmed in that the average age of patients undergoing elbow arthroscopy was <40 years, release/débridement was one of the most common indications (along with lateral epicondylitis and OCD), and the general evidence for elbow arthroscopy was poor. Also, there were almost no differences between continents/countries related to patient indications, preoperative imaging, anesthesia choice, indications, postoperative protocols, and outcomes (although the number of studies that reported outcomes was low and could have skewed the results), with the exception of a higher number of preoperative MRI scans in Asia. Some of the notable findings of this study included: 1) the number of studies published on elbow arthroscopy is significantly increasing with time, despite a lack of improvement in the level of evidence; 2) the majority of studies on elbow arthroscopy do not report a surgical outcome score; and 3) the number of reported cases for the 3 most common indications significantly increased over time (OCD, P = .005; lateral epicondylitis, P = .044; release and débridement, P = .042) but did not differ between regions (P > .05 in all cases).

The indications for elbow arthroscopy have grown dramatically in the past 2 decades to include both intra- and extra-articular pathologies.18 Despite this increase in the number of indications for elbow arthroscopy, the study did not find a significant difference between countries/continents in the indications each used for elbow arthroscopy patients. There was a trend towards an increase in OCD cases in all continents, especially Asia (Figure 4), with time. Interestingly, while not statistically significant, there was variation among countries for surgical indications. In North America, removal of loose bodies accounts for 18% of patients, while in Europe this accounted for only 9% and in Asia for 1%. Post-traumatic stiffness was the indication for elbow arthroscopy in Europe in 19% of patients vs 7% in North America and 10% in Asia. In Asia, OCD accounts for 40% of arthroscopies, 7% in Europe, and 14% in North America (Figure 4) (Table 3).

This study demonstrated that the mean increase in elbow extension gained after surgery in North America was significantly greater when compared with studies from Asia, but the gain in flexion, pronation, and supination was similar across continents. The underlying cause of this difference in improvement in elbow extension between nations is unclear, although differences in diagnosis could account for some variation. This study did not examine differences in rehabilitation protocols, and certainly, it is plausible that protocol variations by country could account for some discrepancy. Furthermore, differences in functional needs may vary by continent and could have driven this result.

This study found no routine reporting of outcome scores by elbow arthroscopy studies from any continent, and that when outcome scores are reported, there is substantial inconsistency with regard to the actual scoring system used. No continent reported outcome scores in more than 40% of the studies published from that area, and the variation of outcome scores used, even from a single region, was large. This makes comparing clinical outcomes between studies difficult, even when performing identical procedures for identical indications, because there is no standardized method of reporting outcomes. To allow comparison of studies and generalizability of the results to different populations, a more standardized approach to outcome reporting needs to be instituted in the elbow arthroscopy literature. To date, there is no standardized score that has been validated for reporting clinical outcomes after elbow arthroscopy.19 Hence, it is not surprising that there were 16 different outcome scores reported throughout the 112 studies analyzed in this review, with the most frequent score, the MEPS, reported in a total of 10 studies. As medicine moves towards pay scales that are based on patient outcomes, it will become more important to define a clear outcome score that can be used to assess these patients, and reliably report scores. This will allow comparison of patients across nations to determine the best surgical treatment for different clinical problems. A validation study comparing these outcome scores to determine which score best summarizes the patient’s level of pain and function after surgery would be beneficial, because this could identify 1 score that could be standardized to allow comparison among reported outcomes.

Limitations

This study had several limitations. Despite having 2 authors search independently for studies, some studies could have been missed during the search process, introducing possible selection bias. Including only published studies could have introduced publication bias. Numerous studies did not report all the variables the authors examined. This could have skewed some results, and had additional variables been reported, could have altered the data to show significant differences in some measured variables. Because this study did not compare outcome measures for varying pathologies, conclusions cannot be drawn on the best treatment options for different indications. Case reports could have lowered the MCMS score and the average in studies reporting outcomes. Furthermore, the poor quality of the underlying data used in this study could limit the validity/generalizability of the results because this is a systematic review, and its level of evidence is only as high as the studies it includes. Because the primary aim was to report on demographics, this study did not examine concomitant pathology at the time of surgery or rehabilitation protocols.

Conclusion

The quantity, but not the quality, of arthroscopic elbow publications has significantly increased over time. Most patients undergo elbow arthroscopy for lateral epicondylitis, OCD, and release and débridement. Pathology and indications do not appear to differ geographically with more men undergoing elbow arthroscopy than women.

Although elbow arthroscopy was first described in the 1930s, it has become increasingly popular in the last 30 years.1 While initially considered as a tool for diagnosis and loose body removal, indications have expanded to include treatment of osteochondritis dissecans (OCD), treatment of lateral epicondylitis, fixation of fractures, and others.2-5 Miyake and colleagues6 found a significant improvement in range of motion, both flexion and extension, and outcome scores when elbow arthroscopy was used to remove impinging osteophytes. Babaqi and colleagues7 found significant improvement in pain, satisfaction, and outcome scores in 31 patients who underwent elbow arthroscopy for lateral epicondylitis refractory to nonsurgical management. The technical difficulty of the procedure, lower frequency of pathology amenable to arthroscopic intervention, and potential neurovascular complications make the elbow less frequently evaluated with the arthroscope vs other joints, such as the knee and shoulder.2,8,9

Geographic distribution of subjects undergoing elbow arthroscopy, the indications used, surgical techniques being performed, and their associated clinical outcomes have received little to no recognition in the peer-reviewed literature.10 Differences in the elbow arthroscopy literature include characteristics related to the patient (age, gender, hand dominance, duration of symptoms), study (level of evidence, number of subjects, number of participating centers, design), indication (lateral epicondylitis, loose bodies, olecranon osteophytes, OCD), surgical technique, and outcome. Evidence-based medicine and clinical practice guidelines direct surgeons in clinical decision-making. Payers investigate the cost of surgical interventions and the value that surgery may provide, while following trends in different surgical techniques. Regulatory agencies and associations emphasize subjective patient-reported outcomes as the primary outcome measured in high-quality trials. Thus, in discussion of complex surgical interventions such as elbow arthroscopy, it is important to characterize the studies, subjects, and surgeries across the world to understand the geographic similarities and differences to optimize care in this clinical situation.

The goal of this study was to perform a systematic review and meta-analysis of elbow arthroscopy literature to identify and compare the characteristics of the studies published, the subjects analyzed, and surgical techniques performed across continents and countries to answer these questions: “Across the world, what demographic of patients are undergoing elbow arthroscopy, what are the most common indications for elbow arthroscopy, and how good is the evidence?” The authors hypothesized that patients who undergo elbow arthroscopy will be largely age <40 years, the most common indication for elbow arthroscopy will be a release/débridement, and the evidence for elbow arthroscopy will be poor. Also, no significant differences will exist in elbow arthroscopy publications, subjects, outcomes, and techniques based on continent/country of publication.

Methods

A systematic review was conducted according to Preferred Reporting Items for Systematic Reviews and Meta-Analyses (PRISMA) guidelines using a PRISMA checklist.11 Systematic review registration was performed using the International Prospective Register of Ongoing Systematic Reviews (PROSPERO; registration number, CRD42014010580; registration date, July 15, 2014).12 Two study authors independently conducted the search on June 23, 2014 using the following databases: Medline, Cochrane Central Register of Controlled Trials, SportDiscus, and CINAHL. The electronic search citation algorithm used was: (elbow) AND arthroscopy) NOT shoulder) NOT knee) NOT ankle) NOT wrist) NOT hip) NOT dog) NOT cadaver). English language Level I-IV evidence (2012 update by the Oxford Centre for Evidence-Based Medicine13) clinical studies were eligible for inclusion into this study. Abstracts were ineligible for inclusion. All references in selected studies were cross-referenced for inclusion if they were missed during the initial search. Duplicate subject publications within separate unique studies were not reported twice. The study with longer duration follow-up, higher level of evidence, greater number of subjects, or more detailed subject, surgical technique, or outcome reporting was retained for inclusion. Level V evidence reviews, expert opinion articles, letters to the editor, basic science, biomechanical studies, open elbow surgery, imaging, surgical technique, and classification studies were excluded.

All included patients underwent elbow arthroscopy for either intra- or extra-articular elbow pathology (ulnotrochlear osteoarthritis, lateral epicondylitis, rheumatoid arthritis, post-traumatic contracture, osteonecrosis of the capitellum or radial head, osteoid osteoma, and others). There was no minimum follow-up duration or rehabilitation requirement. The study and subject demographic parameters that we analyzed included year of publication, years of subject enrollment, presence of study financial conflict of interest, number of subjects and elbows, elbow dominance, gender, age, body mass index, diagnoses treated, type of anesthesia (block or general), and surgical positioning. Postoperative splint application and pain management, and whether a continuous passive motion machine was used and whether a drain was placed were recorded. Clinical outcome scores were DASH (Disability of the Arm, Shoulder, and Hand), Morrey score, MEPS (Mayo Elbow Performance Score), Andrews-Carson score, Timmerman-Andrews score, LES (Liverpool Elbow Score), Tegner score, HSS (Hospital for Special Surgery Score), VAS (Visual Analog Scale), EFA (Elbow Functional Assessment), Short Form-12 (SF-12), Short Form-36 (SF-36), Kerlan-Jobe Orthopaedic Clinic (KJOC) Shoulder and Elbow Questionnaire, and MAESS (Modified Andrews Elbow Scoring System). Radiographs, computed tomography (CT), computed tomography arthrography (CTA), magnetic resonance imaging (MRI), and magnetic resonance arthrography (MRA) data were extracted when available. Range of motion (flexion, extension, supination, and pronation) and grip strength data, both preoperative and postoperative, were extracted when available. Study methodological quality was evaluated using the Modified Coleman Methodology Score (MCMS).14

Statistical Analysis

Study descriptive statistics were calculated. Continuous variable data were reported as weighted means ± weighted standard deviations. Categorical variable data were reported as frequencies with percentages. For all statistical analysis either measured and calculated from study data extraction or directly reported from the individual studies, P < .05 was considered statistically significant. Study, subject, and surgical outcomes data were compared using 1-way analysis of variance (ANOVA) tests. Where applicable, study, subject, and surgical outcomes data were also compared using 2-sample and 2-proportion Z-test calculators with α .05 because of the difference in sample sizes between compared groups. To examine trends over time, Pearson’s correlation coefficients were calculated. For the purposes of analysis, the indications of “osteoarthritis,” “arthrofibrosis,” “loose body removal,” “ulnotrochlear osteoarthritis causing stiffness,” “post-traumatic contracture/stiffness,” and “post-operative elbow contracture” were combined into the indication “release and débridement.” For the 3 most common indications for arthroscopy (OCD, lateral epicondylitis, and release and débridement) data were combined into 5-year increments to overcome the smaller sample size within each of these categories, and Pearson’s correlation coefficients were calculated to determine if number of reported cases covaried with year period. Within these 3 diagnoses, ANOVA analyses were performed to determine whether the number of cases differed between continents and countries.

Results

A total of 353 studies were located, and, after implementation of the exclusion criteria, 112 studies were included in the final analysis (Figure 1; 3093 subjects; 3168 elbows; 64% male; mean age, 34.9 ± 14.68 years). There was a mean of 33.4 ± 26.02 months of follow-up, and 75% of surgeries involved the dominant elbow (Table 1). Most studies were level IV evidence (94.6%), had a low MCMS (mean 28.1 ± 8.06; poor rating), and were single-center investigations (94.6%). Most studies did not report financial conflicts of interest (56.3%) (Tables 1 and 2). From 1985 through 2014, the number of publications significantly increased with time (P = .004) among all continents. The MCMS was unchanged over time (P = .247) (Figure 2A), as was the level of evidence (P = .094) (Figure 2B). Conflicts of interest significantly increased with time (P = .025) (Figure 3).

Among continents, North America published the largest number of studies (54), and had the largest number of patients (1395) and elbow surgeries (1425) (Table 1). The United States published the largest number of studies (43%). There were no significant differences between age (P = .331), length of follow-up (P = .403), MCMS (P = .123), and level of evidence (P = .288) between continents. Of the 32 studies that reported the use of preoperative MRI, studies from Asia reported significantly more MRI scans than those from other continents (P = .040); there were no other significant differences between continents in reference to preoperative imaging studies or other demographic information.

The most common surgical indications were OCD (Figure 4), lateral epicondylitis (Figure 5), and release and débridement (Figure 6, Table 3; all studies listed indications). The number of reported cases for these 3 indications significantly increased over time (OCD P = .005, lateral epicondylitis P = .044, release and débridement P = .042) but did not significantly differ between regions (P > .05 in all cases).

Thirty-two (28.6%) studies reported the use of outcome measures (16 different outcome scores were used by the included studies). Asia reported outcome measures in 9 of 23 studies (39%), Europe in 12 of 35 studies (34%) and North America in 11 of 54 (20%) of studies. The MEPS was the most frequently used outcome score in 9.8% of studies, followed by VAS for pain in 5.3% of cases. North American studies reported a significantly higher increase in extension after elbow arthroscopy than Asia (P = .0432) (Figure 7), with no differences in flexion (P = .699), pronation (P = .376), or supination (P = .408). No significant differences were observed between continents in the type of anesthesia chosen (general anesthesia [P = .94] or regional anesthesia [P = .85]). Asia and Europe performed elbow arthroscopy most frequently in the lateral decubitus position, while North American studies most often used the supine position (Table 4).

Twenty (17.9%) studies reported the use of a postoperative splint, 12 (10.7%) studies reported use of a drain, 2 (1.79%) studies reported use of a hinged elbow brace, 9 (8.03%) studies reported use of a continuous passive motion machine postoperatively, and 3 (2.68%) studies reported use of an indwelling axillary catheter for postoperative pain management. Of 130 reported surgical complications (4.1%), the most frequent complication was transient sensory ulnar nerve palsy (1.5%), followed by persistent wound drainage (.76%), and transient sensory radial nerve palsy (.38%). Other reported complications included infection (.22%), transient sensory palsy of the median nerve (.19%), heterotopic ossification (.13%), complete transection of the ulnar nerve (.10%), loose body formation (.06%), hematoma formation (.06%), transient sensory palsy of the posterior interosseous (.06%), or anterior interosseous nerve (.03%), and complete transection of the radial (.03%), or median nerve (.03%).

Discussion

Elbow arthroscopy is an evolving surgical procedure that is used to treat intra- and extra-articular pathologies of the elbow. Outcomes of elbow arthroscopy for certain conditions have generally been reported as good, with improvements seen in pain, functional scores, and range of motion.6,15-17 The authors’ hypotheses were mostly confirmed in that the average age of patients undergoing elbow arthroscopy was <40 years, release/débridement was one of the most common indications (along with lateral epicondylitis and OCD), and the general evidence for elbow arthroscopy was poor. Also, there were almost no differences between continents/countries related to patient indications, preoperative imaging, anesthesia choice, indications, postoperative protocols, and outcomes (although the number of studies that reported outcomes was low and could have skewed the results), with the exception of a higher number of preoperative MRI scans in Asia. Some of the notable findings of this study included: 1) the number of studies published on elbow arthroscopy is significantly increasing with time, despite a lack of improvement in the level of evidence; 2) the majority of studies on elbow arthroscopy do not report a surgical outcome score; and 3) the number of reported cases for the 3 most common indications significantly increased over time (OCD, P = .005; lateral epicondylitis, P = .044; release and débridement, P = .042) but did not differ between regions (P > .05 in all cases).

The indications for elbow arthroscopy have grown dramatically in the past 2 decades to include both intra- and extra-articular pathologies.18 Despite this increase in the number of indications for elbow arthroscopy, the study did not find a significant difference between countries/continents in the indications each used for elbow arthroscopy patients. There was a trend towards an increase in OCD cases in all continents, especially Asia (Figure 4), with time. Interestingly, while not statistically significant, there was variation among countries for surgical indications. In North America, removal of loose bodies accounts for 18% of patients, while in Europe this accounted for only 9% and in Asia for 1%. Post-traumatic stiffness was the indication for elbow arthroscopy in Europe in 19% of patients vs 7% in North America and 10% in Asia. In Asia, OCD accounts for 40% of arthroscopies, 7% in Europe, and 14% in North America (Figure 4) (Table 3).

This study demonstrated that the mean increase in elbow extension gained after surgery in North America was significantly greater when compared with studies from Asia, but the gain in flexion, pronation, and supination was similar across continents. The underlying cause of this difference in improvement in elbow extension between nations is unclear, although differences in diagnosis could account for some variation. This study did not examine differences in rehabilitation protocols, and certainly, it is plausible that protocol variations by country could account for some discrepancy. Furthermore, differences in functional needs may vary by continent and could have driven this result.

This study found no routine reporting of outcome scores by elbow arthroscopy studies from any continent, and that when outcome scores are reported, there is substantial inconsistency with regard to the actual scoring system used. No continent reported outcome scores in more than 40% of the studies published from that area, and the variation of outcome scores used, even from a single region, was large. This makes comparing clinical outcomes between studies difficult, even when performing identical procedures for identical indications, because there is no standardized method of reporting outcomes. To allow comparison of studies and generalizability of the results to different populations, a more standardized approach to outcome reporting needs to be instituted in the elbow arthroscopy literature. To date, there is no standardized score that has been validated for reporting clinical outcomes after elbow arthroscopy.19 Hence, it is not surprising that there were 16 different outcome scores reported throughout the 112 studies analyzed in this review, with the most frequent score, the MEPS, reported in a total of 10 studies. As medicine moves towards pay scales that are based on patient outcomes, it will become more important to define a clear outcome score that can be used to assess these patients, and reliably report scores. This will allow comparison of patients across nations to determine the best surgical treatment for different clinical problems. A validation study comparing these outcome scores to determine which score best summarizes the patient’s level of pain and function after surgery would be beneficial, because this could identify 1 score that could be standardized to allow comparison among reported outcomes.

Limitations

This study had several limitations. Despite having 2 authors search independently for studies, some studies could have been missed during the search process, introducing possible selection bias. Including only published studies could have introduced publication bias. Numerous studies did not report all the variables the authors examined. This could have skewed some results, and had additional variables been reported, could have altered the data to show significant differences in some measured variables. Because this study did not compare outcome measures for varying pathologies, conclusions cannot be drawn on the best treatment options for different indications. Case reports could have lowered the MCMS score and the average in studies reporting outcomes. Furthermore, the poor quality of the underlying data used in this study could limit the validity/generalizability of the results because this is a systematic review, and its level of evidence is only as high as the studies it includes. Because the primary aim was to report on demographics, this study did not examine concomitant pathology at the time of surgery or rehabilitation protocols.

Conclusion

The quantity, but not the quality, of arthroscopic elbow publications has significantly increased over time. Most patients undergo elbow arthroscopy for lateral epicondylitis, OCD, and release and débridement. Pathology and indications do not appear to differ geographically with more men undergoing elbow arthroscopy than women.

1. Khanchandani P. Elbow arthroscopy: review of the literature and case reports. Case Rep Orthop. 2012;2012:478214.

2. Dodson CC, Nho SJ, Williams RJ 3rd, Altchek DW. Elbow arthroscopy. J Am Acad Orthop Surg. 2008;16(10):574-585.

3. Takahara M, Mura N, Sasaki J, Harada M, Ogino T. Classification, treatment, and outcome of osteochondritis dissecans of the humeral capitellum. Surgical technique. J Bone Joint Surg Am. 2008;90(suppl 2 Pt 1):47-62.

4. Kelly EW, Morrey BF, O’Driscoll SW. Complications of elbow arthroscopy. J Bone Joint Surg Am. 2001;83-A(1):25-34.

5. Rajeev A, Pooley J. Lateral compartment cartilage changes and lateral elbow pain. Acta Orthop Belg. 2009;75(1):37-40.

6. Miyake J, Shimada K, Oka K, et al. Arthroscopic debridement in the treatment of patients with osteoarthritis of the elbow, based on computer simulation. Bone Joint J. 2014;96-B(2):237-241.

7. Babaqi AA, Kotb MM, Said HG, AbdelHamid MM, ElKady HA, ElAssal MA. Short-term evaluation of arthroscopic management of tennis elbow; including resection of radio-capitellar capsular complex. J Orthop. 2014;11(2):82-86.

8. Gay DM, Raphael BS, Weiland AJ. Revision arthroscopic contracture release in the elbow resulting in an ulnar nerve transection: a case report. J Bone Joint Surg Am. 2010;92(5):1246-1249.

9. Haapaniemi T, Berggren M, Adolfsson L. Complete transection of the median and radial nerves during arthroscopic release of post-traumatic elbow contracture. Arthroscopy. 1999;15(7):784-787.

10. Yeoh KM, King GJ, Faber KJ, Glazebrook MA, Athwal GS. Evidence-based indications for elbow arthroscopy. Arthroscopy. 2012;28(2):272-282.

11. Liberati A, Altman DG, Tetzlaff J, et al. The PRISMA statement for reporting systematic reviews and meta-analyses of studies that evaluate health care interventions: explanation and elaboration. BMJ. 2009;339:b2700.

12. PROSPERO. International Prospective Register of Ongoing Systematic Reviews. The University of York CfRaDP-Iprosr-v. 2013 [cited 2014]. http://www.crd.york.ac.uk/PROSPERO/. Accessed March 17, 2016.

13. Oxford Centre for Evidence-Based Medicine - levels of evidence (March 2009). Centre for Evidence-Based Medicine Web site. http://www.cebm.net/oxford-centre-evidence-based-medicine-levels-evidence-march-2009/. Accessed July 6, 2016.

14. Cowan J, Lozano-Calderόn S, Ring D. Quality of prospective controlled randomized trials. Analysis of trials of treatment for lateral epicondylitis as an example. J Bone Joint Surg Am. 2007;89(8):1693-1699.

15. Jones GS, Savoie FH 3rd. Arthroscopic capsular release of flexion contractures (arthrofibrosis) of the elbow. Arthroscopy. 1993;9(3):277-283.

16. O’Brien MJ, Lee Murphy R, Savoie FH 3rd. A preliminary report of acute and subacute arthroscopic repair of the radial ulnohumeral ligament after elbow dislocation in the high-demand patient. Arthroscopy. 2014;30(6):679-687.

17. Rhyou IH, Kim KW. Is posterior synovial plica excision necessary for refractory lateral epicondylitis of the elbow? Clin Orthop Relat Res. 2013;471(1):284-290.

18. Jerosch J, Schunck J. Arthroscopic treatment of lateral epicondylitis: indication, technique and early results. Knee Surg Sports Traumatol Arthrosc. 2006;14(4):379-382.

19. Tijssen M, van Cingel R, van Melick N, de Visser E. Patient-Reported Outcome questionnaires for hip arthroscopy: a systematic review of the psychometric evidence. BMC Musculoskelet Disord. 2011;12:117.

1. Khanchandani P. Elbow arthroscopy: review of the literature and case reports. Case Rep Orthop. 2012;2012:478214.

2. Dodson CC, Nho SJ, Williams RJ 3rd, Altchek DW. Elbow arthroscopy. J Am Acad Orthop Surg. 2008;16(10):574-585.

3. Takahara M, Mura N, Sasaki J, Harada M, Ogino T. Classification, treatment, and outcome of osteochondritis dissecans of the humeral capitellum. Surgical technique. J Bone Joint Surg Am. 2008;90(suppl 2 Pt 1):47-62.

4. Kelly EW, Morrey BF, O’Driscoll SW. Complications of elbow arthroscopy. J Bone Joint Surg Am. 2001;83-A(1):25-34.

5. Rajeev A, Pooley J. Lateral compartment cartilage changes and lateral elbow pain. Acta Orthop Belg. 2009;75(1):37-40.

6. Miyake J, Shimada K, Oka K, et al. Arthroscopic debridement in the treatment of patients with osteoarthritis of the elbow, based on computer simulation. Bone Joint J. 2014;96-B(2):237-241.

7. Babaqi AA, Kotb MM, Said HG, AbdelHamid MM, ElKady HA, ElAssal MA. Short-term evaluation of arthroscopic management of tennis elbow; including resection of radio-capitellar capsular complex. J Orthop. 2014;11(2):82-86.

8. Gay DM, Raphael BS, Weiland AJ. Revision arthroscopic contracture release in the elbow resulting in an ulnar nerve transection: a case report. J Bone Joint Surg Am. 2010;92(5):1246-1249.

9. Haapaniemi T, Berggren M, Adolfsson L. Complete transection of the median and radial nerves during arthroscopic release of post-traumatic elbow contracture. Arthroscopy. 1999;15(7):784-787.

10. Yeoh KM, King GJ, Faber KJ, Glazebrook MA, Athwal GS. Evidence-based indications for elbow arthroscopy. Arthroscopy. 2012;28(2):272-282.

11. Liberati A, Altman DG, Tetzlaff J, et al. The PRISMA statement for reporting systematic reviews and meta-analyses of studies that evaluate health care interventions: explanation and elaboration. BMJ. 2009;339:b2700.

12. PROSPERO. International Prospective Register of Ongoing Systematic Reviews. The University of York CfRaDP-Iprosr-v. 2013 [cited 2014]. http://www.crd.york.ac.uk/PROSPERO/. Accessed March 17, 2016.

13. Oxford Centre for Evidence-Based Medicine - levels of evidence (March 2009). Centre for Evidence-Based Medicine Web site. http://www.cebm.net/oxford-centre-evidence-based-medicine-levels-evidence-march-2009/. Accessed July 6, 2016.

14. Cowan J, Lozano-Calderόn S, Ring D. Quality of prospective controlled randomized trials. Analysis of trials of treatment for lateral epicondylitis as an example. J Bone Joint Surg Am. 2007;89(8):1693-1699.

15. Jones GS, Savoie FH 3rd. Arthroscopic capsular release of flexion contractures (arthrofibrosis) of the elbow. Arthroscopy. 1993;9(3):277-283.

16. O’Brien MJ, Lee Murphy R, Savoie FH 3rd. A preliminary report of acute and subacute arthroscopic repair of the radial ulnohumeral ligament after elbow dislocation in the high-demand patient. Arthroscopy. 2014;30(6):679-687.

17. Rhyou IH, Kim KW. Is posterior synovial plica excision necessary for refractory lateral epicondylitis of the elbow? Clin Orthop Relat Res. 2013;471(1):284-290.

18. Jerosch J, Schunck J. Arthroscopic treatment of lateral epicondylitis: indication, technique and early results. Knee Surg Sports Traumatol Arthrosc. 2006;14(4):379-382.

19. Tijssen M, van Cingel R, van Melick N, de Visser E. Patient-Reported Outcome questionnaires for hip arthroscopy: a systematic review of the psychometric evidence. BMC Musculoskelet Disord. 2011;12:117.

Orthopedic Resident Education and Patient Safety

The mantra “See one, do one, teach one” is a longstanding cliché in surgical education. Although this mantra does not apply literally in the case of complex modern orthopedic procedures, the reality is that all surgical education, including orthopedic surgery residency, involves learning “on the job” in the clinic, emergency room, and operating room. In conjunction with a sound basis of textbook learning and observation, orthopedic residents receive graduated patient care responsibilities leading to the goal of entering independent practice at the conclusion of 5 years of residency.

Moreover, the academic medical centers involved in orthopedic resident education often also serve as referral centers for patients with challenging problems and multiple comorbidities, so that attending physicians teaching orthopedic residents must balance educating residents with caring for complex patients. In contrast to their physicians’ dual focus on patient care and resident education, some patients are hesitant to allow residents to participate in their surgical care, fearing increased errors and complications due to resident inexperience.1,2 How do we address these patients’ legitimate concerns while continuing to provide the on-the-job training experience so important to resident education?

Does Orthopedic Resident Surgical Education Affect Patient Safety?

The sparse literature generally suggests that orthopedic resident involvement in patient care may lengthen procedures but is not associated with substantively worse patient outcomes. Studies at single centers found that resident involvement in adolescent idiopathic scoliosis surgery and hip and knee arthroplasty leads to slightly longer operative times, without increased complication rates or clinical outcomes.3,4 One study found significantly less acetabular anteversion in resident-involved total hip arthroplasty cases, although there was no difference in dislocation rate, other complications, or patient clinical outcome.5 These single-center studies showing no change in patient complications or outcomes based on resident involvement could reflect unique experiences that do not generalize beyond a few academic medical centers. Alternatively, the relatively small patient samples may leave these studies underpowered to detect small changes in patient complication rates.

Recently, several studies in the orthopedic literature have addressed the role of resident involvement in patient complications using the large American College of Surgeons National Surgical Quality Improvement Program (ACS-NSQIP) database.6-11 This database contains high-quality information from over 400 hospitals across the United States about whether residents were involved with a surgery, as well as patient comorbidities, operative variables, and 30-day postoperative complications. These studies have found that resident participation is associated with either a decreased rate of complications or no change in the complication rate for common orthopedic surgeries, though the studies have corroborated the small increase in operative time associated with resident involvement.6-9 Interestingly, other ACS-NSQIP database studies failed to identify a “July effect” of increased complications due to resident inexperience at the beginning of the residency academic year.10,11

These studies suggest that, based on current evidence, patients can be reassured that orthopedic resident participation in surgery does not increase complication rates. Moreover, there is no evidence that having orthopedic surgery at the beginning of the residency academic year in July results in a higher complication rate. Although operative time for cases involving residents is on the order of 10 to 15 minutes longer, this small difference in operative time has not translated into differences in patient outcomes or complications. It is worth noting that hospital billing for surgical procedures may take operative time into account based on duration of anesthesia. Appropriate resident training, then, should not be expected to harm patient safety. Resident training should include educational preparation prior to the operating room, intraoperative supervision, and graduated responsibility appropriate to resident training level and skill level.

Have Recent Changes in Orthopedic Resident Education Improved Patient Safety?

Fifteen years ago, the Institute of Medicine published its seminal work, To Err is Human: Building a Safer Health System, highlighting medical errors leading to patient injury and death.12 In 2003, the Accreditation Council for Graduate Medical Education (ACGME) implemented resident work-hour restrictions (subsequently refined in 2011) designed to improve resident education, promote resident well-being, and maximize patient safety.13 The work-hour regulations have been met with mixed reactions, with orthopedic surgeon–authors expressing concerns that the work-hour limits compromise resident education and professionalism in patient care without leading to any proven increase in patient safety.13-15 These views are supported by a recent systematic review of the orthopedic literature, which found that, while work-hour changes have subjectively improved resident quality of life and fatigue, there has been no clear benefit to resident education or patient safety.14 A review of the overall surgery literature similarly found no benefit for resident education and no improvement in patient outcomes associated with the work-hour regulations, with some of the literature suggesting increased complications for high-acuity patients.16 Patient safety, a major impetus behind the work-hour regulations, appears not to be impacted by the regulations except in limited circumstances, though additional studies more specific to common orthopedic procedures and to orthopedic patients could provide additional insight.

Orthopedic resident education standards are constantly changing in an effort to improve education, quality of care, and patient safety. Recently, the ACGME and American Board of Orthopaedic Surgery (ABOS) have implemented clinical “milestones” for evaluating residents’ competency based on knowledge and skill rather than postgraduate year (PGY).15,17 Education of orthopedic PGY-1 residents (interns) has evolved in the last 2 years as well, with 6 months of orthopedic rotations and surgical skills training now required.18 Additionally, the use of surgical simulation in orthopedic resident education has been rapidly increasing, particularly for arthroscopic surgery.19 Whether these recent changes improve patient care remains unclear, and future studies should address whether these changes objectively improve orthopedic surgical education, patient care, and patient safety.

Conclusions

Patients inquiring about resident involvement in their orthopedic procedure can be counseled that available evidence shows resident involvement does not hinder patient safety and does not increase complications. In the author’s opinion, academic medical centers with orthopedic residents involved in patient care may provide superior patient care and expertise in complex, challenging cases. In addition, we should strive to improve patients’ awareness of the orthopedic resident education process and the multiple recent changes designed to improve both resident education and patient care and safety.

1. Holt G, Nunn T, Gregori A. Ethical dilemmas in orthopaedic surgical training. J Bone Joint Surg Am. 2008;90(12):2798-2803. doi:10.2106/JBJS.H.00910.

2. Chiong W. Justifying patient risks associated with medical education. JAMA. 2007;298(9):1046-1048. doi:10.1001/jama.298.9.1046.

3. Woolson ST, Kang MN. A comparison of the results of total hip and knee arthroplasty performed on a teaching service or a private practice service. J Bone Joint Surg Am. 2007;89(3):601-607. doi:10.2106/JBJS.F.00584.

4. Auerbach JD, Lonner BS, Antonacci MD, Kean KE. Perioperative outcomes and complications related to teaching residents and fellows in scoliosis surgery. Spine. 2008;33(10):1113-1118. doi:10.1097/BRS.0b013e31816f69cf.

5. Moran M, Yap SL, Walmsley P, Brenkel IJ. Clinical and radiologic outcome of total hip arthroplasty performed by trainee compared with consultant orthopedic surgeons. J Arthroplasty. 2004;19(7):853-857. doi:10.1016/j.arth.2004.06.026.

6. Haughom BD, Schairer WW, Hellman MD, Yi PH, Levine BR. Does resident involvement impact post-operative complications following primary total knee arthroplasty? An analysis of 24,529 cases. J Arthroplasty. 2014;29(7):1468-1472.e2. doi:10.1016/j.arth.2014.02.036.

7. Edelstein AI, Lovecchio FC, Saha S, Hsu WK, Kim JYS. Impact of resident involvement on orthopaedic surgery outcomes: an analysis of 30,628 patients from the American College of Surgeons National Surgical Quality Improvement Program Database. J Bone Joint Surg Am. 2014;96(15):e131. doi:10.2106/JBJS.M.00660.

8. Haughom BD, Schairer WW, Hellman MD, Yi PH, Levine BR. Resident involvement does not influence complication after total hip arthroplasty: an analysis of 13,109 cases. J Arthroplasty. 2014;29(10):1919-1924. doi:10.1016/j.arth.2014.06.003.

9. Pugely AJ, Gao Y, Martin CT, Callagh JJ, Weinstein SL, Marsh JL. The effect of resident participation on short-term outcomes after orthopaedic surgery. Clin Orthop Relat Res. 2014;472(7):2290-2300. doi:10.1007/s11999-014-3567-0.

10. Bohl DD, Fu MC, Gruskay JA, Basques BA, Golinvaux NS, Grauer JN. “July effect” in elective spine surgery: analysis of the American College of Surgeons National Surgical Quality Improvement Program database. Spine. 2014;39(7):603-611. doi:10.1097/BRS.0000000000000196.

11. Bohl DD, Fu MC, Golinvaux NS, Basques BA, Gruskay JA, Grauer JN. The “July effect” in primary total hip and knee arthroplasty: analysis of 21,434 cases from the ACS-NSQIP database. J Arthroplasty. 2014;29(7):1332-1338. doi:10.1016/j.arth.2014.02.008.

12. Institute of Medicine Committee on Quality of Health Care in America. To Err Is Human: Building a Safer Health System. Kohn LT, Corrigan JM, Donaldson MS, eds. Washington, DC: National Academies Press; 2000.

13. Levine WN, Spang RC. ACGME duty hour requirements: perceptions and impact on resident training and patient care. J Am Acad Orthop Surg. 2014;22(9):535-544. doi:10.5435/JAAOS-22-09-535.

14. Harris JD, Staheli G, LeClere L, Andersone D, McCormick F. What effects have resident work-hour changes had on education, quality of life, and safety? A systematic review. Clin Orthop Relat Res. 2015;473(5):1600-1608. doi:10.1007/s11999-014-3968-0.

15. Peabody T, Nestler S, Marx C, Pellegrini V. Resident duty-hour restrictions-who are we protecting?: AOA critical issues. J Bone Joint Surg Am. 2012;94(17):e131. doi:10.2106/JBJS.J.01685.

16. Ahmed N, Devitt KS, Keshet I, et al. A systematic review of the effects of resident duty hour restrictions in surgery: impact on resident wellness, training, and patient outcomes. Ann Surg. 2014;259(6):1041-1053. doi:10.1097/SLA.0000000000000595.

17. Tosti R. Will the new milestone requirements improve residency training? Am J Orthop. 2013;42(12):E109-E110.

18. Dougherty PJ, Marcus RE. ACGME and ABOS changes for the orthopaedic surgery PGY-1 (intern) year. Clin Orthop Relat Res. 2013;471(11):3412-3416. doi:10.1007/s11999-013-3227-9.

19. Frank RM, Erickson B, Frank JM, et al. Utility of modern arthroscopic simulator training models. Arthroscopy. 2014;30(1):121-133. doi:10.1016/j.arthro.2013.09.084.

The mantra “See one, do one, teach one” is a longstanding cliché in surgical education. Although this mantra does not apply literally in the case of complex modern orthopedic procedures, the reality is that all surgical education, including orthopedic surgery residency, involves learning “on the job” in the clinic, emergency room, and operating room. In conjunction with a sound basis of textbook learning and observation, orthopedic residents receive graduated patient care responsibilities leading to the goal of entering independent practice at the conclusion of 5 years of residency.

Moreover, the academic medical centers involved in orthopedic resident education often also serve as referral centers for patients with challenging problems and multiple comorbidities, so that attending physicians teaching orthopedic residents must balance educating residents with caring for complex patients. In contrast to their physicians’ dual focus on patient care and resident education, some patients are hesitant to allow residents to participate in their surgical care, fearing increased errors and complications due to resident inexperience.1,2 How do we address these patients’ legitimate concerns while continuing to provide the on-the-job training experience so important to resident education?

Does Orthopedic Resident Surgical Education Affect Patient Safety?