User login

Quality and Quantity of the Elbow Arthroscopy Literature: A Systematic Review and Meta-Analysis

Although elbow arthroscopy was first described in the 1930s, it has become increasingly popular in the last 30 years.1 While initially considered as a tool for diagnosis and loose body removal, indications have expanded to include treatment of osteochondritis dissecans (OCD), treatment of lateral epicondylitis, fixation of fractures, and others.2-5 Miyake and colleagues6 found a significant improvement in range of motion, both flexion and extension, and outcome scores when elbow arthroscopy was used to remove impinging osteophytes. Babaqi and colleagues7 found significant improvement in pain, satisfaction, and outcome scores in 31 patients who underwent elbow arthroscopy for lateral epicondylitis refractory to nonsurgical management. The technical difficulty of the procedure, lower frequency of pathology amenable to arthroscopic intervention, and potential neurovascular complications make the elbow less frequently evaluated with the arthroscope vs other joints, such as the knee and shoulder.2,8,9

Geographic distribution of subjects undergoing elbow arthroscopy, the indications used, surgical techniques being performed, and their associated clinical outcomes have received little to no recognition in the peer-reviewed literature.10 Differences in the elbow arthroscopy literature include characteristics related to the patient (age, gender, hand dominance, duration of symptoms), study (level of evidence, number of subjects, number of participating centers, design), indication (lateral epicondylitis, loose bodies, olecranon osteophytes, OCD), surgical technique, and outcome. Evidence-based medicine and clinical practice guidelines direct surgeons in clinical decision-making. Payers investigate the cost of surgical interventions and the value that surgery may provide, while following trends in different surgical techniques. Regulatory agencies and associations emphasize subjective patient-reported outcomes as the primary outcome measured in high-quality trials. Thus, in discussion of complex surgical interventions such as elbow arthroscopy, it is important to characterize the studies, subjects, and surgeries across the world to understand the geographic similarities and differences to optimize care in this clinical situation.

The goal of this study was to perform a systematic review and meta-analysis of elbow arthroscopy literature to identify and compare the characteristics of the studies published, the subjects analyzed, and surgical techniques performed across continents and countries to answer these questions: “Across the world, what demographic of patients are undergoing elbow arthroscopy, what are the most common indications for elbow arthroscopy, and how good is the evidence?” The authors hypothesized that patients who undergo elbow arthroscopy will be largely age <40 years, the most common indication for elbow arthroscopy will be a release/débridement, and the evidence for elbow arthroscopy will be poor. Also, no significant differences will exist in elbow arthroscopy publications, subjects, outcomes, and techniques based on continent/country of publication.

Methods

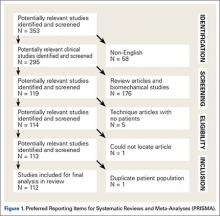

A systematic review was conducted according to Preferred Reporting Items for Systematic Reviews and Meta-Analyses (PRISMA) guidelines using a PRISMA checklist.11 Systematic review registration was performed using the International Prospective Register of Ongoing Systematic Reviews (PROSPERO; registration number, CRD42014010580; registration date, July 15, 2014).12 Two study authors independently conducted the search on June 23, 2014 using the following databases: Medline, Cochrane Central Register of Controlled Trials, SportDiscus, and CINAHL. The electronic search citation algorithm used was: (elbow) AND arthroscopy) NOT shoulder) NOT knee) NOT ankle) NOT wrist) NOT hip) NOT dog) NOT cadaver). English language Level I-IV evidence (2012 update by the Oxford Centre for Evidence-Based Medicine13) clinical studies were eligible for inclusion into this study. Abstracts were ineligible for inclusion. All references in selected studies were cross-referenced for inclusion if they were missed during the initial search. Duplicate subject publications within separate unique studies were not reported twice. The study with longer duration follow-up, higher level of evidence, greater number of subjects, or more detailed subject, surgical technique, or outcome reporting was retained for inclusion. Level V evidence reviews, expert opinion articles, letters to the editor, basic science, biomechanical studies, open elbow surgery, imaging, surgical technique, and classification studies were excluded.

All included patients underwent elbow arthroscopy for either intra- or extra-articular elbow pathology (ulnotrochlear osteoarthritis, lateral epicondylitis, rheumatoid arthritis, post-traumatic contracture, osteonecrosis of the capitellum or radial head, osteoid osteoma, and others). There was no minimum follow-up duration or rehabilitation requirement. The study and subject demographic parameters that we analyzed included year of publication, years of subject enrollment, presence of study financial conflict of interest, number of subjects and elbows, elbow dominance, gender, age, body mass index, diagnoses treated, type of anesthesia (block or general), and surgical positioning. Postoperative splint application and pain management, and whether a continuous passive motion machine was used and whether a drain was placed were recorded. Clinical outcome scores were DASH (Disability of the Arm, Shoulder, and Hand), Morrey score, MEPS (Mayo Elbow Performance Score), Andrews-Carson score, Timmerman-Andrews score, LES (Liverpool Elbow Score), Tegner score, HSS (Hospital for Special Surgery Score), VAS (Visual Analog Scale), EFA (Elbow Functional Assessment), Short Form-12 (SF-12), Short Form-36 (SF-36), Kerlan-Jobe Orthopaedic Clinic (KJOC) Shoulder and Elbow Questionnaire, and MAESS (Modified Andrews Elbow Scoring System). Radiographs, computed tomography (CT), computed tomography arthrography (CTA), magnetic resonance imaging (MRI), and magnetic resonance arthrography (MRA) data were extracted when available. Range of motion (flexion, extension, supination, and pronation) and grip strength data, both preoperative and postoperative, were extracted when available. Study methodological quality was evaluated using the Modified Coleman Methodology Score (MCMS).14

Statistical Analysis

Study descriptive statistics were calculated. Continuous variable data were reported as weighted means ± weighted standard deviations. Categorical variable data were reported as frequencies with percentages. For all statistical analysis either measured and calculated from study data extraction or directly reported from the individual studies, P < .05 was considered statistically significant. Study, subject, and surgical outcomes data were compared using 1-way analysis of variance (ANOVA) tests. Where applicable, study, subject, and surgical outcomes data were also compared using 2-sample and 2-proportion Z-test calculators with α .05 because of the difference in sample sizes between compared groups. To examine trends over time, Pearson’s correlation coefficients were calculated. For the purposes of analysis, the indications of “osteoarthritis,” “arthrofibrosis,” “loose body removal,” “ulnotrochlear osteoarthritis causing stiffness,” “post-traumatic contracture/stiffness,” and “post-operative elbow contracture” were combined into the indication “release and débridement.” For the 3 most common indications for arthroscopy (OCD, lateral epicondylitis, and release and débridement) data were combined into 5-year increments to overcome the smaller sample size within each of these categories, and Pearson’s correlation coefficients were calculated to determine if number of reported cases covaried with year period. Within these 3 diagnoses, ANOVA analyses were performed to determine whether the number of cases differed between continents and countries.

Results

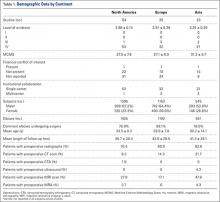

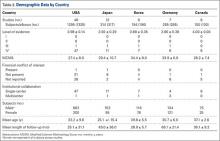

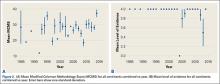

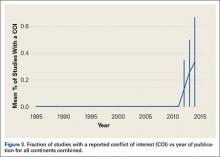

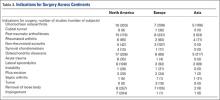

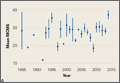

A total of 353 studies were located, and, after implementation of the exclusion criteria, 112 studies were included in the final analysis (Figure 1; 3093 subjects; 3168 elbows; 64% male; mean age, 34.9 ± 14.68 years). There was a mean of 33.4 ± 26.02 months of follow-up, and 75% of surgeries involved the dominant elbow (Table 1). Most studies were level IV evidence (94.6%), had a low MCMS (mean 28.1 ± 8.06; poor rating), and were single-center investigations (94.6%). Most studies did not report financial conflicts of interest (56.3%) (Tables 1 and 2). From 1985 through 2014, the number of publications significantly increased with time (P = .004) among all continents. The MCMS was unchanged over time (P = .247) (Figure 2A), as was the level of evidence (P = .094) (Figure 2B). Conflicts of interest significantly increased with time (P = .025) (Figure 3).

Among continents, North America published the largest number of studies (54), and had the largest number of patients (1395) and elbow surgeries (1425) (Table 1). The United States published the largest number of studies (43%). There were no significant differences between age (P = .331), length of follow-up (P = .403), MCMS (P = .123), and level of evidence (P = .288) between continents. Of the 32 studies that reported the use of preoperative MRI, studies from Asia reported significantly more MRI scans than those from other continents (P = .040); there were no other significant differences between continents in reference to preoperative imaging studies or other demographic information.

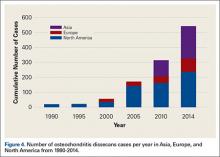

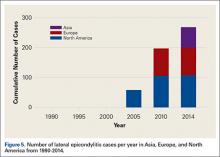

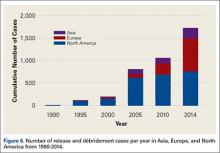

The most common surgical indications were OCD (Figure 4), lateral epicondylitis (Figure 5), and release and débridement (Figure 6, Table 3; all studies listed indications). The number of reported cases for these 3 indications significantly increased over time (OCD P = .005, lateral epicondylitis P = .044, release and débridement P = .042) but did not significantly differ between regions (P > .05 in all cases).

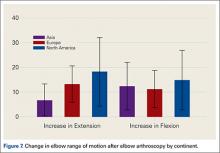

Thirty-two (28.6%) studies reported the use of outcome measures (16 different outcome scores were used by the included studies). Asia reported outcome measures in 9 of 23 studies (39%), Europe in 12 of 35 studies (34%) and North America in 11 of 54 (20%) of studies. The MEPS was the most frequently used outcome score in 9.8% of studies, followed by VAS for pain in 5.3% of cases. North American studies reported a significantly higher increase in extension after elbow arthroscopy than Asia (P = .0432) (Figure 7), with no differences in flexion (P = .699), pronation (P = .376), or supination (P = .408). No significant differences were observed between continents in the type of anesthesia chosen (general anesthesia [P = .94] or regional anesthesia [P = .85]). Asia and Europe performed elbow arthroscopy most frequently in the lateral decubitus position, while North American studies most often used the supine position (Table 4).

Twenty (17.9%) studies reported the use of a postoperative splint, 12 (10.7%) studies reported use of a drain, 2 (1.79%) studies reported use of a hinged elbow brace, 9 (8.03%) studies reported use of a continuous passive motion machine postoperatively, and 3 (2.68%) studies reported use of an indwelling axillary catheter for postoperative pain management. Of 130 reported surgical complications (4.1%), the most frequent complication was transient sensory ulnar nerve palsy (1.5%), followed by persistent wound drainage (.76%), and transient sensory radial nerve palsy (.38%). Other reported complications included infection (.22%), transient sensory palsy of the median nerve (.19%), heterotopic ossification (.13%), complete transection of the ulnar nerve (.10%), loose body formation (.06%), hematoma formation (.06%), transient sensory palsy of the posterior interosseous (.06%), or anterior interosseous nerve (.03%), and complete transection of the radial (.03%), or median nerve (.03%).

Discussion

Elbow arthroscopy is an evolving surgical procedure that is used to treat intra- and extra-articular pathologies of the elbow. Outcomes of elbow arthroscopy for certain conditions have generally been reported as good, with improvements seen in pain, functional scores, and range of motion.6,15-17 The authors’ hypotheses were mostly confirmed in that the average age of patients undergoing elbow arthroscopy was <40 years, release/débridement was one of the most common indications (along with lateral epicondylitis and OCD), and the general evidence for elbow arthroscopy was poor. Also, there were almost no differences between continents/countries related to patient indications, preoperative imaging, anesthesia choice, indications, postoperative protocols, and outcomes (although the number of studies that reported outcomes was low and could have skewed the results), with the exception of a higher number of preoperative MRI scans in Asia. Some of the notable findings of this study included: 1) the number of studies published on elbow arthroscopy is significantly increasing with time, despite a lack of improvement in the level of evidence; 2) the majority of studies on elbow arthroscopy do not report a surgical outcome score; and 3) the number of reported cases for the 3 most common indications significantly increased over time (OCD, P = .005; lateral epicondylitis, P = .044; release and débridement, P = .042) but did not differ between regions (P > .05 in all cases).

The indications for elbow arthroscopy have grown dramatically in the past 2 decades to include both intra- and extra-articular pathologies.18 Despite this increase in the number of indications for elbow arthroscopy, the study did not find a significant difference between countries/continents in the indications each used for elbow arthroscopy patients. There was a trend towards an increase in OCD cases in all continents, especially Asia (Figure 4), with time. Interestingly, while not statistically significant, there was variation among countries for surgical indications. In North America, removal of loose bodies accounts for 18% of patients, while in Europe this accounted for only 9% and in Asia for 1%. Post-traumatic stiffness was the indication for elbow arthroscopy in Europe in 19% of patients vs 7% in North America and 10% in Asia. In Asia, OCD accounts for 40% of arthroscopies, 7% in Europe, and 14% in North America (Figure 4) (Table 3).

This study demonstrated that the mean increase in elbow extension gained after surgery in North America was significantly greater when compared with studies from Asia, but the gain in flexion, pronation, and supination was similar across continents. The underlying cause of this difference in improvement in elbow extension between nations is unclear, although differences in diagnosis could account for some variation. This study did not examine differences in rehabilitation protocols, and certainly, it is plausible that protocol variations by country could account for some discrepancy. Furthermore, differences in functional needs may vary by continent and could have driven this result.

This study found no routine reporting of outcome scores by elbow arthroscopy studies from any continent, and that when outcome scores are reported, there is substantial inconsistency with regard to the actual scoring system used. No continent reported outcome scores in more than 40% of the studies published from that area, and the variation of outcome scores used, even from a single region, was large. This makes comparing clinical outcomes between studies difficult, even when performing identical procedures for identical indications, because there is no standardized method of reporting outcomes. To allow comparison of studies and generalizability of the results to different populations, a more standardized approach to outcome reporting needs to be instituted in the elbow arthroscopy literature. To date, there is no standardized score that has been validated for reporting clinical outcomes after elbow arthroscopy.19 Hence, it is not surprising that there were 16 different outcome scores reported throughout the 112 studies analyzed in this review, with the most frequent score, the MEPS, reported in a total of 10 studies. As medicine moves towards pay scales that are based on patient outcomes, it will become more important to define a clear outcome score that can be used to assess these patients, and reliably report scores. This will allow comparison of patients across nations to determine the best surgical treatment for different clinical problems. A validation study comparing these outcome scores to determine which score best summarizes the patient’s level of pain and function after surgery would be beneficial, because this could identify 1 score that could be standardized to allow comparison among reported outcomes.

Limitations

This study had several limitations. Despite having 2 authors search independently for studies, some studies could have been missed during the search process, introducing possible selection bias. Including only published studies could have introduced publication bias. Numerous studies did not report all the variables the authors examined. This could have skewed some results, and had additional variables been reported, could have altered the data to show significant differences in some measured variables. Because this study did not compare outcome measures for varying pathologies, conclusions cannot be drawn on the best treatment options for different indications. Case reports could have lowered the MCMS score and the average in studies reporting outcomes. Furthermore, the poor quality of the underlying data used in this study could limit the validity/generalizability of the results because this is a systematic review, and its level of evidence is only as high as the studies it includes. Because the primary aim was to report on demographics, this study did not examine concomitant pathology at the time of surgery or rehabilitation protocols.

Conclusion

The quantity, but not the quality, of arthroscopic elbow publications has significantly increased over time. Most patients undergo elbow arthroscopy for lateral epicondylitis, OCD, and release and débridement. Pathology and indications do not appear to differ geographically with more men undergoing elbow arthroscopy than women.

1. Khanchandani P. Elbow arthroscopy: review of the literature and case reports. Case Rep Orthop. 2012;2012:478214.

2. Dodson CC, Nho SJ, Williams RJ 3rd, Altchek DW. Elbow arthroscopy. J Am Acad Orthop Surg. 2008;16(10):574-585.

3. Takahara M, Mura N, Sasaki J, Harada M, Ogino T. Classification, treatment, and outcome of osteochondritis dissecans of the humeral capitellum. Surgical technique. J Bone Joint Surg Am. 2008;90(suppl 2 Pt 1):47-62.

4. Kelly EW, Morrey BF, O’Driscoll SW. Complications of elbow arthroscopy. J Bone Joint Surg Am. 2001;83-A(1):25-34.

5. Rajeev A, Pooley J. Lateral compartment cartilage changes and lateral elbow pain. Acta Orthop Belg. 2009;75(1):37-40.

6. Miyake J, Shimada K, Oka K, et al. Arthroscopic debridement in the treatment of patients with osteoarthritis of the elbow, based on computer simulation. Bone Joint J. 2014;96-B(2):237-241.

7. Babaqi AA, Kotb MM, Said HG, AbdelHamid MM, ElKady HA, ElAssal MA. Short-term evaluation of arthroscopic management of tennis elbow; including resection of radio-capitellar capsular complex. J Orthop. 2014;11(2):82-86.

8. Gay DM, Raphael BS, Weiland AJ. Revision arthroscopic contracture release in the elbow resulting in an ulnar nerve transection: a case report. J Bone Joint Surg Am. 2010;92(5):1246-1249.

9. Haapaniemi T, Berggren M, Adolfsson L. Complete transection of the median and radial nerves during arthroscopic release of post-traumatic elbow contracture. Arthroscopy. 1999;15(7):784-787.

10. Yeoh KM, King GJ, Faber KJ, Glazebrook MA, Athwal GS. Evidence-based indications for elbow arthroscopy. Arthroscopy. 2012;28(2):272-282.

11. Liberati A, Altman DG, Tetzlaff J, et al. The PRISMA statement for reporting systematic reviews and meta-analyses of studies that evaluate health care interventions: explanation and elaboration. BMJ. 2009;339:b2700.

12. PROSPERO. International Prospective Register of Ongoing Systematic Reviews. The University of York CfRaDP-Iprosr-v. 2013 [cited 2014]. http://www.crd.york.ac.uk/PROSPERO/. Accessed March 17, 2016.

13. Oxford Centre for Evidence-Based Medicine - levels of evidence (March 2009). Centre for Evidence-Based Medicine Web site. http://www.cebm.net/oxford-centre-evidence-based-medicine-levels-evidence-march-2009/. Accessed July 6, 2016.

14. Cowan J, Lozano-Calderόn S, Ring D. Quality of prospective controlled randomized trials. Analysis of trials of treatment for lateral epicondylitis as an example. J Bone Joint Surg Am. 2007;89(8):1693-1699.

15. Jones GS, Savoie FH 3rd. Arthroscopic capsular release of flexion contractures (arthrofibrosis) of the elbow. Arthroscopy. 1993;9(3):277-283.

16. O’Brien MJ, Lee Murphy R, Savoie FH 3rd. A preliminary report of acute and subacute arthroscopic repair of the radial ulnohumeral ligament after elbow dislocation in the high-demand patient. Arthroscopy. 2014;30(6):679-687.

17. Rhyou IH, Kim KW. Is posterior synovial plica excision necessary for refractory lateral epicondylitis of the elbow? Clin Orthop Relat Res. 2013;471(1):284-290.

18. Jerosch J, Schunck J. Arthroscopic treatment of lateral epicondylitis: indication, technique and early results. Knee Surg Sports Traumatol Arthrosc. 2006;14(4):379-382.

19. Tijssen M, van Cingel R, van Melick N, de Visser E. Patient-Reported Outcome questionnaires for hip arthroscopy: a systematic review of the psychometric evidence. BMC Musculoskelet Disord. 2011;12:117.

Although elbow arthroscopy was first described in the 1930s, it has become increasingly popular in the last 30 years.1 While initially considered as a tool for diagnosis and loose body removal, indications have expanded to include treatment of osteochondritis dissecans (OCD), treatment of lateral epicondylitis, fixation of fractures, and others.2-5 Miyake and colleagues6 found a significant improvement in range of motion, both flexion and extension, and outcome scores when elbow arthroscopy was used to remove impinging osteophytes. Babaqi and colleagues7 found significant improvement in pain, satisfaction, and outcome scores in 31 patients who underwent elbow arthroscopy for lateral epicondylitis refractory to nonsurgical management. The technical difficulty of the procedure, lower frequency of pathology amenable to arthroscopic intervention, and potential neurovascular complications make the elbow less frequently evaluated with the arthroscope vs other joints, such as the knee and shoulder.2,8,9

Geographic distribution of subjects undergoing elbow arthroscopy, the indications used, surgical techniques being performed, and their associated clinical outcomes have received little to no recognition in the peer-reviewed literature.10 Differences in the elbow arthroscopy literature include characteristics related to the patient (age, gender, hand dominance, duration of symptoms), study (level of evidence, number of subjects, number of participating centers, design), indication (lateral epicondylitis, loose bodies, olecranon osteophytes, OCD), surgical technique, and outcome. Evidence-based medicine and clinical practice guidelines direct surgeons in clinical decision-making. Payers investigate the cost of surgical interventions and the value that surgery may provide, while following trends in different surgical techniques. Regulatory agencies and associations emphasize subjective patient-reported outcomes as the primary outcome measured in high-quality trials. Thus, in discussion of complex surgical interventions such as elbow arthroscopy, it is important to characterize the studies, subjects, and surgeries across the world to understand the geographic similarities and differences to optimize care in this clinical situation.

The goal of this study was to perform a systematic review and meta-analysis of elbow arthroscopy literature to identify and compare the characteristics of the studies published, the subjects analyzed, and surgical techniques performed across continents and countries to answer these questions: “Across the world, what demographic of patients are undergoing elbow arthroscopy, what are the most common indications for elbow arthroscopy, and how good is the evidence?” The authors hypothesized that patients who undergo elbow arthroscopy will be largely age <40 years, the most common indication for elbow arthroscopy will be a release/débridement, and the evidence for elbow arthroscopy will be poor. Also, no significant differences will exist in elbow arthroscopy publications, subjects, outcomes, and techniques based on continent/country of publication.

Methods

A systematic review was conducted according to Preferred Reporting Items for Systematic Reviews and Meta-Analyses (PRISMA) guidelines using a PRISMA checklist.11 Systematic review registration was performed using the International Prospective Register of Ongoing Systematic Reviews (PROSPERO; registration number, CRD42014010580; registration date, July 15, 2014).12 Two study authors independently conducted the search on June 23, 2014 using the following databases: Medline, Cochrane Central Register of Controlled Trials, SportDiscus, and CINAHL. The electronic search citation algorithm used was: (elbow) AND arthroscopy) NOT shoulder) NOT knee) NOT ankle) NOT wrist) NOT hip) NOT dog) NOT cadaver). English language Level I-IV evidence (2012 update by the Oxford Centre for Evidence-Based Medicine13) clinical studies were eligible for inclusion into this study. Abstracts were ineligible for inclusion. All references in selected studies were cross-referenced for inclusion if they were missed during the initial search. Duplicate subject publications within separate unique studies were not reported twice. The study with longer duration follow-up, higher level of evidence, greater number of subjects, or more detailed subject, surgical technique, or outcome reporting was retained for inclusion. Level V evidence reviews, expert opinion articles, letters to the editor, basic science, biomechanical studies, open elbow surgery, imaging, surgical technique, and classification studies were excluded.

All included patients underwent elbow arthroscopy for either intra- or extra-articular elbow pathology (ulnotrochlear osteoarthritis, lateral epicondylitis, rheumatoid arthritis, post-traumatic contracture, osteonecrosis of the capitellum or radial head, osteoid osteoma, and others). There was no minimum follow-up duration or rehabilitation requirement. The study and subject demographic parameters that we analyzed included year of publication, years of subject enrollment, presence of study financial conflict of interest, number of subjects and elbows, elbow dominance, gender, age, body mass index, diagnoses treated, type of anesthesia (block or general), and surgical positioning. Postoperative splint application and pain management, and whether a continuous passive motion machine was used and whether a drain was placed were recorded. Clinical outcome scores were DASH (Disability of the Arm, Shoulder, and Hand), Morrey score, MEPS (Mayo Elbow Performance Score), Andrews-Carson score, Timmerman-Andrews score, LES (Liverpool Elbow Score), Tegner score, HSS (Hospital for Special Surgery Score), VAS (Visual Analog Scale), EFA (Elbow Functional Assessment), Short Form-12 (SF-12), Short Form-36 (SF-36), Kerlan-Jobe Orthopaedic Clinic (KJOC) Shoulder and Elbow Questionnaire, and MAESS (Modified Andrews Elbow Scoring System). Radiographs, computed tomography (CT), computed tomography arthrography (CTA), magnetic resonance imaging (MRI), and magnetic resonance arthrography (MRA) data were extracted when available. Range of motion (flexion, extension, supination, and pronation) and grip strength data, both preoperative and postoperative, were extracted when available. Study methodological quality was evaluated using the Modified Coleman Methodology Score (MCMS).14

Statistical Analysis

Study descriptive statistics were calculated. Continuous variable data were reported as weighted means ± weighted standard deviations. Categorical variable data were reported as frequencies with percentages. For all statistical analysis either measured and calculated from study data extraction or directly reported from the individual studies, P < .05 was considered statistically significant. Study, subject, and surgical outcomes data were compared using 1-way analysis of variance (ANOVA) tests. Where applicable, study, subject, and surgical outcomes data were also compared using 2-sample and 2-proportion Z-test calculators with α .05 because of the difference in sample sizes between compared groups. To examine trends over time, Pearson’s correlation coefficients were calculated. For the purposes of analysis, the indications of “osteoarthritis,” “arthrofibrosis,” “loose body removal,” “ulnotrochlear osteoarthritis causing stiffness,” “post-traumatic contracture/stiffness,” and “post-operative elbow contracture” were combined into the indication “release and débridement.” For the 3 most common indications for arthroscopy (OCD, lateral epicondylitis, and release and débridement) data were combined into 5-year increments to overcome the smaller sample size within each of these categories, and Pearson’s correlation coefficients were calculated to determine if number of reported cases covaried with year period. Within these 3 diagnoses, ANOVA analyses were performed to determine whether the number of cases differed between continents and countries.

Results

A total of 353 studies were located, and, after implementation of the exclusion criteria, 112 studies were included in the final analysis (Figure 1; 3093 subjects; 3168 elbows; 64% male; mean age, 34.9 ± 14.68 years). There was a mean of 33.4 ± 26.02 months of follow-up, and 75% of surgeries involved the dominant elbow (Table 1). Most studies were level IV evidence (94.6%), had a low MCMS (mean 28.1 ± 8.06; poor rating), and were single-center investigations (94.6%). Most studies did not report financial conflicts of interest (56.3%) (Tables 1 and 2). From 1985 through 2014, the number of publications significantly increased with time (P = .004) among all continents. The MCMS was unchanged over time (P = .247) (Figure 2A), as was the level of evidence (P = .094) (Figure 2B). Conflicts of interest significantly increased with time (P = .025) (Figure 3).

Among continents, North America published the largest number of studies (54), and had the largest number of patients (1395) and elbow surgeries (1425) (Table 1). The United States published the largest number of studies (43%). There were no significant differences between age (P = .331), length of follow-up (P = .403), MCMS (P = .123), and level of evidence (P = .288) between continents. Of the 32 studies that reported the use of preoperative MRI, studies from Asia reported significantly more MRI scans than those from other continents (P = .040); there were no other significant differences between continents in reference to preoperative imaging studies or other demographic information.

The most common surgical indications were OCD (Figure 4), lateral epicondylitis (Figure 5), and release and débridement (Figure 6, Table 3; all studies listed indications). The number of reported cases for these 3 indications significantly increased over time (OCD P = .005, lateral epicondylitis P = .044, release and débridement P = .042) but did not significantly differ between regions (P > .05 in all cases).

Thirty-two (28.6%) studies reported the use of outcome measures (16 different outcome scores were used by the included studies). Asia reported outcome measures in 9 of 23 studies (39%), Europe in 12 of 35 studies (34%) and North America in 11 of 54 (20%) of studies. The MEPS was the most frequently used outcome score in 9.8% of studies, followed by VAS for pain in 5.3% of cases. North American studies reported a significantly higher increase in extension after elbow arthroscopy than Asia (P = .0432) (Figure 7), with no differences in flexion (P = .699), pronation (P = .376), or supination (P = .408). No significant differences were observed between continents in the type of anesthesia chosen (general anesthesia [P = .94] or regional anesthesia [P = .85]). Asia and Europe performed elbow arthroscopy most frequently in the lateral decubitus position, while North American studies most often used the supine position (Table 4).

Twenty (17.9%) studies reported the use of a postoperative splint, 12 (10.7%) studies reported use of a drain, 2 (1.79%) studies reported use of a hinged elbow brace, 9 (8.03%) studies reported use of a continuous passive motion machine postoperatively, and 3 (2.68%) studies reported use of an indwelling axillary catheter for postoperative pain management. Of 130 reported surgical complications (4.1%), the most frequent complication was transient sensory ulnar nerve palsy (1.5%), followed by persistent wound drainage (.76%), and transient sensory radial nerve palsy (.38%). Other reported complications included infection (.22%), transient sensory palsy of the median nerve (.19%), heterotopic ossification (.13%), complete transection of the ulnar nerve (.10%), loose body formation (.06%), hematoma formation (.06%), transient sensory palsy of the posterior interosseous (.06%), or anterior interosseous nerve (.03%), and complete transection of the radial (.03%), or median nerve (.03%).

Discussion

Elbow arthroscopy is an evolving surgical procedure that is used to treat intra- and extra-articular pathologies of the elbow. Outcomes of elbow arthroscopy for certain conditions have generally been reported as good, with improvements seen in pain, functional scores, and range of motion.6,15-17 The authors’ hypotheses were mostly confirmed in that the average age of patients undergoing elbow arthroscopy was <40 years, release/débridement was one of the most common indications (along with lateral epicondylitis and OCD), and the general evidence for elbow arthroscopy was poor. Also, there were almost no differences between continents/countries related to patient indications, preoperative imaging, anesthesia choice, indications, postoperative protocols, and outcomes (although the number of studies that reported outcomes was low and could have skewed the results), with the exception of a higher number of preoperative MRI scans in Asia. Some of the notable findings of this study included: 1) the number of studies published on elbow arthroscopy is significantly increasing with time, despite a lack of improvement in the level of evidence; 2) the majority of studies on elbow arthroscopy do not report a surgical outcome score; and 3) the number of reported cases for the 3 most common indications significantly increased over time (OCD, P = .005; lateral epicondylitis, P = .044; release and débridement, P = .042) but did not differ between regions (P > .05 in all cases).

The indications for elbow arthroscopy have grown dramatically in the past 2 decades to include both intra- and extra-articular pathologies.18 Despite this increase in the number of indications for elbow arthroscopy, the study did not find a significant difference between countries/continents in the indications each used for elbow arthroscopy patients. There was a trend towards an increase in OCD cases in all continents, especially Asia (Figure 4), with time. Interestingly, while not statistically significant, there was variation among countries for surgical indications. In North America, removal of loose bodies accounts for 18% of patients, while in Europe this accounted for only 9% and in Asia for 1%. Post-traumatic stiffness was the indication for elbow arthroscopy in Europe in 19% of patients vs 7% in North America and 10% in Asia. In Asia, OCD accounts for 40% of arthroscopies, 7% in Europe, and 14% in North America (Figure 4) (Table 3).

This study demonstrated that the mean increase in elbow extension gained after surgery in North America was significantly greater when compared with studies from Asia, but the gain in flexion, pronation, and supination was similar across continents. The underlying cause of this difference in improvement in elbow extension between nations is unclear, although differences in diagnosis could account for some variation. This study did not examine differences in rehabilitation protocols, and certainly, it is plausible that protocol variations by country could account for some discrepancy. Furthermore, differences in functional needs may vary by continent and could have driven this result.

This study found no routine reporting of outcome scores by elbow arthroscopy studies from any continent, and that when outcome scores are reported, there is substantial inconsistency with regard to the actual scoring system used. No continent reported outcome scores in more than 40% of the studies published from that area, and the variation of outcome scores used, even from a single region, was large. This makes comparing clinical outcomes between studies difficult, even when performing identical procedures for identical indications, because there is no standardized method of reporting outcomes. To allow comparison of studies and generalizability of the results to different populations, a more standardized approach to outcome reporting needs to be instituted in the elbow arthroscopy literature. To date, there is no standardized score that has been validated for reporting clinical outcomes after elbow arthroscopy.19 Hence, it is not surprising that there were 16 different outcome scores reported throughout the 112 studies analyzed in this review, with the most frequent score, the MEPS, reported in a total of 10 studies. As medicine moves towards pay scales that are based on patient outcomes, it will become more important to define a clear outcome score that can be used to assess these patients, and reliably report scores. This will allow comparison of patients across nations to determine the best surgical treatment for different clinical problems. A validation study comparing these outcome scores to determine which score best summarizes the patient’s level of pain and function after surgery would be beneficial, because this could identify 1 score that could be standardized to allow comparison among reported outcomes.

Limitations

This study had several limitations. Despite having 2 authors search independently for studies, some studies could have been missed during the search process, introducing possible selection bias. Including only published studies could have introduced publication bias. Numerous studies did not report all the variables the authors examined. This could have skewed some results, and had additional variables been reported, could have altered the data to show significant differences in some measured variables. Because this study did not compare outcome measures for varying pathologies, conclusions cannot be drawn on the best treatment options for different indications. Case reports could have lowered the MCMS score and the average in studies reporting outcomes. Furthermore, the poor quality of the underlying data used in this study could limit the validity/generalizability of the results because this is a systematic review, and its level of evidence is only as high as the studies it includes. Because the primary aim was to report on demographics, this study did not examine concomitant pathology at the time of surgery or rehabilitation protocols.

Conclusion

The quantity, but not the quality, of arthroscopic elbow publications has significantly increased over time. Most patients undergo elbow arthroscopy for lateral epicondylitis, OCD, and release and débridement. Pathology and indications do not appear to differ geographically with more men undergoing elbow arthroscopy than women.

Although elbow arthroscopy was first described in the 1930s, it has become increasingly popular in the last 30 years.1 While initially considered as a tool for diagnosis and loose body removal, indications have expanded to include treatment of osteochondritis dissecans (OCD), treatment of lateral epicondylitis, fixation of fractures, and others.2-5 Miyake and colleagues6 found a significant improvement in range of motion, both flexion and extension, and outcome scores when elbow arthroscopy was used to remove impinging osteophytes. Babaqi and colleagues7 found significant improvement in pain, satisfaction, and outcome scores in 31 patients who underwent elbow arthroscopy for lateral epicondylitis refractory to nonsurgical management. The technical difficulty of the procedure, lower frequency of pathology amenable to arthroscopic intervention, and potential neurovascular complications make the elbow less frequently evaluated with the arthroscope vs other joints, such as the knee and shoulder.2,8,9

Geographic distribution of subjects undergoing elbow arthroscopy, the indications used, surgical techniques being performed, and their associated clinical outcomes have received little to no recognition in the peer-reviewed literature.10 Differences in the elbow arthroscopy literature include characteristics related to the patient (age, gender, hand dominance, duration of symptoms), study (level of evidence, number of subjects, number of participating centers, design), indication (lateral epicondylitis, loose bodies, olecranon osteophytes, OCD), surgical technique, and outcome. Evidence-based medicine and clinical practice guidelines direct surgeons in clinical decision-making. Payers investigate the cost of surgical interventions and the value that surgery may provide, while following trends in different surgical techniques. Regulatory agencies and associations emphasize subjective patient-reported outcomes as the primary outcome measured in high-quality trials. Thus, in discussion of complex surgical interventions such as elbow arthroscopy, it is important to characterize the studies, subjects, and surgeries across the world to understand the geographic similarities and differences to optimize care in this clinical situation.

The goal of this study was to perform a systematic review and meta-analysis of elbow arthroscopy literature to identify and compare the characteristics of the studies published, the subjects analyzed, and surgical techniques performed across continents and countries to answer these questions: “Across the world, what demographic of patients are undergoing elbow arthroscopy, what are the most common indications for elbow arthroscopy, and how good is the evidence?” The authors hypothesized that patients who undergo elbow arthroscopy will be largely age <40 years, the most common indication for elbow arthroscopy will be a release/débridement, and the evidence for elbow arthroscopy will be poor. Also, no significant differences will exist in elbow arthroscopy publications, subjects, outcomes, and techniques based on continent/country of publication.

Methods

A systematic review was conducted according to Preferred Reporting Items for Systematic Reviews and Meta-Analyses (PRISMA) guidelines using a PRISMA checklist.11 Systematic review registration was performed using the International Prospective Register of Ongoing Systematic Reviews (PROSPERO; registration number, CRD42014010580; registration date, July 15, 2014).12 Two study authors independently conducted the search on June 23, 2014 using the following databases: Medline, Cochrane Central Register of Controlled Trials, SportDiscus, and CINAHL. The electronic search citation algorithm used was: (elbow) AND arthroscopy) NOT shoulder) NOT knee) NOT ankle) NOT wrist) NOT hip) NOT dog) NOT cadaver). English language Level I-IV evidence (2012 update by the Oxford Centre for Evidence-Based Medicine13) clinical studies were eligible for inclusion into this study. Abstracts were ineligible for inclusion. All references in selected studies were cross-referenced for inclusion if they were missed during the initial search. Duplicate subject publications within separate unique studies were not reported twice. The study with longer duration follow-up, higher level of evidence, greater number of subjects, or more detailed subject, surgical technique, or outcome reporting was retained for inclusion. Level V evidence reviews, expert opinion articles, letters to the editor, basic science, biomechanical studies, open elbow surgery, imaging, surgical technique, and classification studies were excluded.

All included patients underwent elbow arthroscopy for either intra- or extra-articular elbow pathology (ulnotrochlear osteoarthritis, lateral epicondylitis, rheumatoid arthritis, post-traumatic contracture, osteonecrosis of the capitellum or radial head, osteoid osteoma, and others). There was no minimum follow-up duration or rehabilitation requirement. The study and subject demographic parameters that we analyzed included year of publication, years of subject enrollment, presence of study financial conflict of interest, number of subjects and elbows, elbow dominance, gender, age, body mass index, diagnoses treated, type of anesthesia (block or general), and surgical positioning. Postoperative splint application and pain management, and whether a continuous passive motion machine was used and whether a drain was placed were recorded. Clinical outcome scores were DASH (Disability of the Arm, Shoulder, and Hand), Morrey score, MEPS (Mayo Elbow Performance Score), Andrews-Carson score, Timmerman-Andrews score, LES (Liverpool Elbow Score), Tegner score, HSS (Hospital for Special Surgery Score), VAS (Visual Analog Scale), EFA (Elbow Functional Assessment), Short Form-12 (SF-12), Short Form-36 (SF-36), Kerlan-Jobe Orthopaedic Clinic (KJOC) Shoulder and Elbow Questionnaire, and MAESS (Modified Andrews Elbow Scoring System). Radiographs, computed tomography (CT), computed tomography arthrography (CTA), magnetic resonance imaging (MRI), and magnetic resonance arthrography (MRA) data were extracted when available. Range of motion (flexion, extension, supination, and pronation) and grip strength data, both preoperative and postoperative, were extracted when available. Study methodological quality was evaluated using the Modified Coleman Methodology Score (MCMS).14

Statistical Analysis

Study descriptive statistics were calculated. Continuous variable data were reported as weighted means ± weighted standard deviations. Categorical variable data were reported as frequencies with percentages. For all statistical analysis either measured and calculated from study data extraction or directly reported from the individual studies, P < .05 was considered statistically significant. Study, subject, and surgical outcomes data were compared using 1-way analysis of variance (ANOVA) tests. Where applicable, study, subject, and surgical outcomes data were also compared using 2-sample and 2-proportion Z-test calculators with α .05 because of the difference in sample sizes between compared groups. To examine trends over time, Pearson’s correlation coefficients were calculated. For the purposes of analysis, the indications of “osteoarthritis,” “arthrofibrosis,” “loose body removal,” “ulnotrochlear osteoarthritis causing stiffness,” “post-traumatic contracture/stiffness,” and “post-operative elbow contracture” were combined into the indication “release and débridement.” For the 3 most common indications for arthroscopy (OCD, lateral epicondylitis, and release and débridement) data were combined into 5-year increments to overcome the smaller sample size within each of these categories, and Pearson’s correlation coefficients were calculated to determine if number of reported cases covaried with year period. Within these 3 diagnoses, ANOVA analyses were performed to determine whether the number of cases differed between continents and countries.

Results

A total of 353 studies were located, and, after implementation of the exclusion criteria, 112 studies were included in the final analysis (Figure 1; 3093 subjects; 3168 elbows; 64% male; mean age, 34.9 ± 14.68 years). There was a mean of 33.4 ± 26.02 months of follow-up, and 75% of surgeries involved the dominant elbow (Table 1). Most studies were level IV evidence (94.6%), had a low MCMS (mean 28.1 ± 8.06; poor rating), and were single-center investigations (94.6%). Most studies did not report financial conflicts of interest (56.3%) (Tables 1 and 2). From 1985 through 2014, the number of publications significantly increased with time (P = .004) among all continents. The MCMS was unchanged over time (P = .247) (Figure 2A), as was the level of evidence (P = .094) (Figure 2B). Conflicts of interest significantly increased with time (P = .025) (Figure 3).

Among continents, North America published the largest number of studies (54), and had the largest number of patients (1395) and elbow surgeries (1425) (Table 1). The United States published the largest number of studies (43%). There were no significant differences between age (P = .331), length of follow-up (P = .403), MCMS (P = .123), and level of evidence (P = .288) between continents. Of the 32 studies that reported the use of preoperative MRI, studies from Asia reported significantly more MRI scans than those from other continents (P = .040); there were no other significant differences between continents in reference to preoperative imaging studies or other demographic information.

The most common surgical indications were OCD (Figure 4), lateral epicondylitis (Figure 5), and release and débridement (Figure 6, Table 3; all studies listed indications). The number of reported cases for these 3 indications significantly increased over time (OCD P = .005, lateral epicondylitis P = .044, release and débridement P = .042) but did not significantly differ between regions (P > .05 in all cases).

Thirty-two (28.6%) studies reported the use of outcome measures (16 different outcome scores were used by the included studies). Asia reported outcome measures in 9 of 23 studies (39%), Europe in 12 of 35 studies (34%) and North America in 11 of 54 (20%) of studies. The MEPS was the most frequently used outcome score in 9.8% of studies, followed by VAS for pain in 5.3% of cases. North American studies reported a significantly higher increase in extension after elbow arthroscopy than Asia (P = .0432) (Figure 7), with no differences in flexion (P = .699), pronation (P = .376), or supination (P = .408). No significant differences were observed between continents in the type of anesthesia chosen (general anesthesia [P = .94] or regional anesthesia [P = .85]). Asia and Europe performed elbow arthroscopy most frequently in the lateral decubitus position, while North American studies most often used the supine position (Table 4).

Twenty (17.9%) studies reported the use of a postoperative splint, 12 (10.7%) studies reported use of a drain, 2 (1.79%) studies reported use of a hinged elbow brace, 9 (8.03%) studies reported use of a continuous passive motion machine postoperatively, and 3 (2.68%) studies reported use of an indwelling axillary catheter for postoperative pain management. Of 130 reported surgical complications (4.1%), the most frequent complication was transient sensory ulnar nerve palsy (1.5%), followed by persistent wound drainage (.76%), and transient sensory radial nerve palsy (.38%). Other reported complications included infection (.22%), transient sensory palsy of the median nerve (.19%), heterotopic ossification (.13%), complete transection of the ulnar nerve (.10%), loose body formation (.06%), hematoma formation (.06%), transient sensory palsy of the posterior interosseous (.06%), or anterior interosseous nerve (.03%), and complete transection of the radial (.03%), or median nerve (.03%).

Discussion

Elbow arthroscopy is an evolving surgical procedure that is used to treat intra- and extra-articular pathologies of the elbow. Outcomes of elbow arthroscopy for certain conditions have generally been reported as good, with improvements seen in pain, functional scores, and range of motion.6,15-17 The authors’ hypotheses were mostly confirmed in that the average age of patients undergoing elbow arthroscopy was <40 years, release/débridement was one of the most common indications (along with lateral epicondylitis and OCD), and the general evidence for elbow arthroscopy was poor. Also, there were almost no differences between continents/countries related to patient indications, preoperative imaging, anesthesia choice, indications, postoperative protocols, and outcomes (although the number of studies that reported outcomes was low and could have skewed the results), with the exception of a higher number of preoperative MRI scans in Asia. Some of the notable findings of this study included: 1) the number of studies published on elbow arthroscopy is significantly increasing with time, despite a lack of improvement in the level of evidence; 2) the majority of studies on elbow arthroscopy do not report a surgical outcome score; and 3) the number of reported cases for the 3 most common indications significantly increased over time (OCD, P = .005; lateral epicondylitis, P = .044; release and débridement, P = .042) but did not differ between regions (P > .05 in all cases).

The indications for elbow arthroscopy have grown dramatically in the past 2 decades to include both intra- and extra-articular pathologies.18 Despite this increase in the number of indications for elbow arthroscopy, the study did not find a significant difference between countries/continents in the indications each used for elbow arthroscopy patients. There was a trend towards an increase in OCD cases in all continents, especially Asia (Figure 4), with time. Interestingly, while not statistically significant, there was variation among countries for surgical indications. In North America, removal of loose bodies accounts for 18% of patients, while in Europe this accounted for only 9% and in Asia for 1%. Post-traumatic stiffness was the indication for elbow arthroscopy in Europe in 19% of patients vs 7% in North America and 10% in Asia. In Asia, OCD accounts for 40% of arthroscopies, 7% in Europe, and 14% in North America (Figure 4) (Table 3).

This study demonstrated that the mean increase in elbow extension gained after surgery in North America was significantly greater when compared with studies from Asia, but the gain in flexion, pronation, and supination was similar across continents. The underlying cause of this difference in improvement in elbow extension between nations is unclear, although differences in diagnosis could account for some variation. This study did not examine differences in rehabilitation protocols, and certainly, it is plausible that protocol variations by country could account for some discrepancy. Furthermore, differences in functional needs may vary by continent and could have driven this result.

This study found no routine reporting of outcome scores by elbow arthroscopy studies from any continent, and that when outcome scores are reported, there is substantial inconsistency with regard to the actual scoring system used. No continent reported outcome scores in more than 40% of the studies published from that area, and the variation of outcome scores used, even from a single region, was large. This makes comparing clinical outcomes between studies difficult, even when performing identical procedures for identical indications, because there is no standardized method of reporting outcomes. To allow comparison of studies and generalizability of the results to different populations, a more standardized approach to outcome reporting needs to be instituted in the elbow arthroscopy literature. To date, there is no standardized score that has been validated for reporting clinical outcomes after elbow arthroscopy.19 Hence, it is not surprising that there were 16 different outcome scores reported throughout the 112 studies analyzed in this review, with the most frequent score, the MEPS, reported in a total of 10 studies. As medicine moves towards pay scales that are based on patient outcomes, it will become more important to define a clear outcome score that can be used to assess these patients, and reliably report scores. This will allow comparison of patients across nations to determine the best surgical treatment for different clinical problems. A validation study comparing these outcome scores to determine which score best summarizes the patient’s level of pain and function after surgery would be beneficial, because this could identify 1 score that could be standardized to allow comparison among reported outcomes.

Limitations

This study had several limitations. Despite having 2 authors search independently for studies, some studies could have been missed during the search process, introducing possible selection bias. Including only published studies could have introduced publication bias. Numerous studies did not report all the variables the authors examined. This could have skewed some results, and had additional variables been reported, could have altered the data to show significant differences in some measured variables. Because this study did not compare outcome measures for varying pathologies, conclusions cannot be drawn on the best treatment options for different indications. Case reports could have lowered the MCMS score and the average in studies reporting outcomes. Furthermore, the poor quality of the underlying data used in this study could limit the validity/generalizability of the results because this is a systematic review, and its level of evidence is only as high as the studies it includes. Because the primary aim was to report on demographics, this study did not examine concomitant pathology at the time of surgery or rehabilitation protocols.

Conclusion

The quantity, but not the quality, of arthroscopic elbow publications has significantly increased over time. Most patients undergo elbow arthroscopy for lateral epicondylitis, OCD, and release and débridement. Pathology and indications do not appear to differ geographically with more men undergoing elbow arthroscopy than women.

1. Khanchandani P. Elbow arthroscopy: review of the literature and case reports. Case Rep Orthop. 2012;2012:478214.

2. Dodson CC, Nho SJ, Williams RJ 3rd, Altchek DW. Elbow arthroscopy. J Am Acad Orthop Surg. 2008;16(10):574-585.

3. Takahara M, Mura N, Sasaki J, Harada M, Ogino T. Classification, treatment, and outcome of osteochondritis dissecans of the humeral capitellum. Surgical technique. J Bone Joint Surg Am. 2008;90(suppl 2 Pt 1):47-62.

4. Kelly EW, Morrey BF, O’Driscoll SW. Complications of elbow arthroscopy. J Bone Joint Surg Am. 2001;83-A(1):25-34.

5. Rajeev A, Pooley J. Lateral compartment cartilage changes and lateral elbow pain. Acta Orthop Belg. 2009;75(1):37-40.

6. Miyake J, Shimada K, Oka K, et al. Arthroscopic debridement in the treatment of patients with osteoarthritis of the elbow, based on computer simulation. Bone Joint J. 2014;96-B(2):237-241.

7. Babaqi AA, Kotb MM, Said HG, AbdelHamid MM, ElKady HA, ElAssal MA. Short-term evaluation of arthroscopic management of tennis elbow; including resection of radio-capitellar capsular complex. J Orthop. 2014;11(2):82-86.

8. Gay DM, Raphael BS, Weiland AJ. Revision arthroscopic contracture release in the elbow resulting in an ulnar nerve transection: a case report. J Bone Joint Surg Am. 2010;92(5):1246-1249.

9. Haapaniemi T, Berggren M, Adolfsson L. Complete transection of the median and radial nerves during arthroscopic release of post-traumatic elbow contracture. Arthroscopy. 1999;15(7):784-787.

10. Yeoh KM, King GJ, Faber KJ, Glazebrook MA, Athwal GS. Evidence-based indications for elbow arthroscopy. Arthroscopy. 2012;28(2):272-282.

11. Liberati A, Altman DG, Tetzlaff J, et al. The PRISMA statement for reporting systematic reviews and meta-analyses of studies that evaluate health care interventions: explanation and elaboration. BMJ. 2009;339:b2700.

12. PROSPERO. International Prospective Register of Ongoing Systematic Reviews. The University of York CfRaDP-Iprosr-v. 2013 [cited 2014]. http://www.crd.york.ac.uk/PROSPERO/. Accessed March 17, 2016.

13. Oxford Centre for Evidence-Based Medicine - levels of evidence (March 2009). Centre for Evidence-Based Medicine Web site. http://www.cebm.net/oxford-centre-evidence-based-medicine-levels-evidence-march-2009/. Accessed July 6, 2016.

14. Cowan J, Lozano-Calderόn S, Ring D. Quality of prospective controlled randomized trials. Analysis of trials of treatment for lateral epicondylitis as an example. J Bone Joint Surg Am. 2007;89(8):1693-1699.

15. Jones GS, Savoie FH 3rd. Arthroscopic capsular release of flexion contractures (arthrofibrosis) of the elbow. Arthroscopy. 1993;9(3):277-283.

16. O’Brien MJ, Lee Murphy R, Savoie FH 3rd. A preliminary report of acute and subacute arthroscopic repair of the radial ulnohumeral ligament after elbow dislocation in the high-demand patient. Arthroscopy. 2014;30(6):679-687.

17. Rhyou IH, Kim KW. Is posterior synovial plica excision necessary for refractory lateral epicondylitis of the elbow? Clin Orthop Relat Res. 2013;471(1):284-290.

18. Jerosch J, Schunck J. Arthroscopic treatment of lateral epicondylitis: indication, technique and early results. Knee Surg Sports Traumatol Arthrosc. 2006;14(4):379-382.

19. Tijssen M, van Cingel R, van Melick N, de Visser E. Patient-Reported Outcome questionnaires for hip arthroscopy: a systematic review of the psychometric evidence. BMC Musculoskelet Disord. 2011;12:117.

1. Khanchandani P. Elbow arthroscopy: review of the literature and case reports. Case Rep Orthop. 2012;2012:478214.

2. Dodson CC, Nho SJ, Williams RJ 3rd, Altchek DW. Elbow arthroscopy. J Am Acad Orthop Surg. 2008;16(10):574-585.

3. Takahara M, Mura N, Sasaki J, Harada M, Ogino T. Classification, treatment, and outcome of osteochondritis dissecans of the humeral capitellum. Surgical technique. J Bone Joint Surg Am. 2008;90(suppl 2 Pt 1):47-62.

4. Kelly EW, Morrey BF, O’Driscoll SW. Complications of elbow arthroscopy. J Bone Joint Surg Am. 2001;83-A(1):25-34.

5. Rajeev A, Pooley J. Lateral compartment cartilage changes and lateral elbow pain. Acta Orthop Belg. 2009;75(1):37-40.

6. Miyake J, Shimada K, Oka K, et al. Arthroscopic debridement in the treatment of patients with osteoarthritis of the elbow, based on computer simulation. Bone Joint J. 2014;96-B(2):237-241.

7. Babaqi AA, Kotb MM, Said HG, AbdelHamid MM, ElKady HA, ElAssal MA. Short-term evaluation of arthroscopic management of tennis elbow; including resection of radio-capitellar capsular complex. J Orthop. 2014;11(2):82-86.

8. Gay DM, Raphael BS, Weiland AJ. Revision arthroscopic contracture release in the elbow resulting in an ulnar nerve transection: a case report. J Bone Joint Surg Am. 2010;92(5):1246-1249.

9. Haapaniemi T, Berggren M, Adolfsson L. Complete transection of the median and radial nerves during arthroscopic release of post-traumatic elbow contracture. Arthroscopy. 1999;15(7):784-787.

10. Yeoh KM, King GJ, Faber KJ, Glazebrook MA, Athwal GS. Evidence-based indications for elbow arthroscopy. Arthroscopy. 2012;28(2):272-282.

11. Liberati A, Altman DG, Tetzlaff J, et al. The PRISMA statement for reporting systematic reviews and meta-analyses of studies that evaluate health care interventions: explanation and elaboration. BMJ. 2009;339:b2700.

12. PROSPERO. International Prospective Register of Ongoing Systematic Reviews. The University of York CfRaDP-Iprosr-v. 2013 [cited 2014]. http://www.crd.york.ac.uk/PROSPERO/. Accessed March 17, 2016.

13. Oxford Centre for Evidence-Based Medicine - levels of evidence (March 2009). Centre for Evidence-Based Medicine Web site. http://www.cebm.net/oxford-centre-evidence-based-medicine-levels-evidence-march-2009/. Accessed July 6, 2016.

14. Cowan J, Lozano-Calderόn S, Ring D. Quality of prospective controlled randomized trials. Analysis of trials of treatment for lateral epicondylitis as an example. J Bone Joint Surg Am. 2007;89(8):1693-1699.

15. Jones GS, Savoie FH 3rd. Arthroscopic capsular release of flexion contractures (arthrofibrosis) of the elbow. Arthroscopy. 1993;9(3):277-283.

16. O’Brien MJ, Lee Murphy R, Savoie FH 3rd. A preliminary report of acute and subacute arthroscopic repair of the radial ulnohumeral ligament after elbow dislocation in the high-demand patient. Arthroscopy. 2014;30(6):679-687.

17. Rhyou IH, Kim KW. Is posterior synovial plica excision necessary for refractory lateral epicondylitis of the elbow? Clin Orthop Relat Res. 2013;471(1):284-290.

18. Jerosch J, Schunck J. Arthroscopic treatment of lateral epicondylitis: indication, technique and early results. Knee Surg Sports Traumatol Arthrosc. 2006;14(4):379-382.

19. Tijssen M, van Cingel R, van Melick N, de Visser E. Patient-Reported Outcome questionnaires for hip arthroscopy: a systematic review of the psychometric evidence. BMC Musculoskelet Disord. 2011;12:117.

A Picture Is Worth a Thousand Words: Unconscious Bias in the Residency Application Process?

Applying for a residency program can be a stressful process for medical students. It is a combination of applying for a job in the “real world” and applying to a college or medical school. In certain fields of medicine or surgery, there may be over 600 residency applications for 40 to 80 interviewee slots. Different specialties, as well as programs within a given specialty, take a different number of residents per year. This can vary from 1 to over 20 available spots, depending on the field of medicine or surgery as well as the specific program. Orthopedic surgery residencies, for example, can match between 2 and 12 residents each year. During the 2013–2014 academic year at our institution, there were over 600 applications received for approximately 50 interview slots for a class of 5 orthopedic surgery residents. Nationally, according to publicly available 2013 National Resident Matching Program (NRMP) data, a total of 1038 applicants (833 US medical school seniors) applied for 693 spots in orthopedic surgery, of which 692 were filled, indicating that orthopedic surgery remains one of the most desired fields among medical school seniors.1 Looking at the statistics provided by the NRMP data, orthopedic applicants remain some of the most competitive, with proportionally higher board scores, publication numbers, and grades, among other factors.1

Each individual program has its own method for sifting through the applications. At some institutions, the individual “in charge” of the selection committee may look through all applications initially, narrow them down, and then distribute them to the other members of the selection committee to determine the final interviewee list. At other institutions, the initial group of applications may be divided and distributed to the committee members so that each member reviews the applications and ultimately decides upon the interview candidates.

The Electronic Residency Application Service (ERAS) application includes the applicant’s name, birth city, current place of residence, education history, standardized test scores, grades achieved during medical school, letters of recommendation, personal statement, extracurricular activities, volunteer activities, research experience, and languages spoken, along with several other pieces of data, all intended to be able to give the committee a better understanding of the applicant. Interestingly, however, the application also includes a photograph of the applicant.

Countless authors have demonstrated that we make assumptions and reach conclusions without even being aware that this is occurring. This is the theory of “unconscious bias.”2-5 Unconscious bias applies to how we perceive other people, and occurs when subconscious beliefs or unrecognized stereotypes about specific characteristics, including gender, ethnicity, religion, socioeconomic status, age, and sexual orientation, result in an automatic and unconscious reaction and/or behavior.6 Unconscious bias has the ability to affect everything from how health care is delivered to how employees are hired.7-12 We are all biased, and becoming aware of our biases will help us mitigate them in the workplace.

Title VII of the Civil Rights Act of 1964 requires that employers rely solely on job-related qualifications, and not physical characteristics, in their interviewing and hiring process. The US Equal Employment Opportunity Commission (EEOC), the federal agency that enforces Title VII, includes asking for photographs during the application stage on its list of prohibited practices for employers.13 It is our belief that including a photograph in the ERAS application, prior to the selection of interview candidates, may produce unconscious bias in the decision for granting (or not granting) an interview, and this component of the application should be eliminated.

Using a wide spectrum of cultural backgrounds in employers, Dion and colleagues14 demonstrated that the “what is beautiful is good” bias is present in all cultures when prospective employees are closely matched in qualification. Attractive individuals are thought to have better professional lives and stable marital relationships and personalities, according to previous studies.14 There has been much research aimed at determining if physical attractiveness is a factor in hiring, and the evidence suggests that the more attractive the applicant is, the greater the chances of being hired.15 Specifically, Watkins and Johnston15 have found that attractive people are thought to have better personalities than less attractive people, and that a photograph can influence the hiring decision process.

Bradley Ruffle at Ben-Gurion University and Ze’ev Shtudiner at Ariel University looked at what happens when job hunters include photographs with their curricula vitae (CV), as is the norm in much of Europe and Asia.16 For over 2500 job postings, they sent 2 identical résumés: one with a photograph and one without a photograph. An equal number of male and female applicants were sent to each posting, as were an equal number of attractive and plain-looking photographs; applications without photographs were also sent as a control group. For men, the results were as expected: CVs of “attractive” men were more likely to elicit a response from the employer (19.7%) compared with those of no-picture men (13.7%) and plain-looking men (9.2%). Interestingly, men who were viewed as “plain-looking” were better off not including a photograph. For the female applicants, however, the results were unexpected: CVs of women without a picture elicited the highest response rate (16.6%), while CVs of “plain-looking” women (13.6%) and of “attractive” women (12.8%) were less likely to receive a response.16

It is an unfortunate reality that personal preference, bias, and, in some cases, discriminatory hiring practices all factor into the selection process.17 This is why, as described above, the EEOC includes asking for photographs during the application stage on its list of prohibited practices for employers.13 The EEOC website also states: “If needed for identification purposes, a photograph may be obtained after an offer of employment is made and accepted.”13 In the residency application scenario, once an applicant has been granted an interview, a photograph can be taken on the day of the interview. With so many interviewees, this may help the interviewers to remember the interviewee. At this point in the process, the applicant has already been granted the interview. The bias associated with merely looking at a photograph is thus eliminated. This is in accordance with Title VII and is clearly different than including a photograph in the initial application, which directly violates Title VII.

Reviewers of applicants may have an unconscious bias due to the applicant’s attractiveness, race, sex, ethnicity, etc. Other, subtler forms of bias may also be present. Without realizing it, people may judge the quality of the photograph, or even what the applicant was wearing in the photograph. In orthopedic surgery, for example, there may be bias in the “size” of the applicant regardless of sex. Reviewers may unconsciously think how is he/she going to hold the leg, cut a rod, reduce a hip, etc. Without even realizing it, this may sway the person reviewing the application to choose one applicant over another. This may occur regardless of the applicant’s actual qualifications as based on the previously described factors, including test scores, grades during medical school, letters of recommendation, personal statement, extracurricular activities, volunteer activities, and research experience.

Unconscious bias is present in everyone. In an ideal world, one would be able to eliminate all sources of unconscious bias in the application process. Bias due to attending an Ivy League school versus a state school, bias due to where the applicant is from, bias due to who wrote the letter of recommendation, along with various other sources of unconscious bias, would be able to be eliminated. Unfortunately, this is not possible. What is possible, however, is to remove the photograph from the application process and to comply with Title VII of the Civil Rights Act of 1964.

1. National Resident Matching Program, Data Release and Research Committee. Results of the 2013 NRMP Applicant Survey by Preferred Specialty and Applicant Type. Washington, DC: National Resident Matching Program; 2013. www.nrmp.org/wp-content/uploads/2013/08/applicantresultsbyspecialty2013.pdf. Accessed July 20, 2015.

2. Santry HP, Wren SM. The role of unconscious bias in surgical safety and outcomes. Surg Clin North Am. 2012;92(1):137–151.

3. Greenwald AG, McGhee DE, Schwartz JL. Measuring individual differences in implicit cognition: the implicit association test. J Pers Soc Psychol. 1998;74(6):1464–1480.

4. Greenwald AG, Poehlman TA, Uhlmann EL, Banaji MR. Understanding and using the Implicit Association Test: III. Meta-analysis of predictive validity. J Pers Soc Psychol. 2009;97(1):17–41.

5. Plessner H, Banse R. Attitude measurement using the Implicit Association Test (IAT). Z Exp Psychol. 2001;48(2):82–84.

6. Chapman EN, Kaatz A, Carnes M. Physicians and implicit bias: how doctors may unwittingly perpetuate health care disparities. J Gen Intern Med. 2013;28(11):1504–1510.

7. What you don’t know: the science of unconscious bias and what to do about it in the search and recruitment process [e-learning seminar]. Association of American Medical Colleges website. https://www.aamc.org/members/leadership/catalog/178420/unconscious_bias.html. Accessed July 14, 2015.

8. Haider AH, Schneider EB, Sriram N, et al. Unconscious race and class bias: its association with decision making by trauma and acute care surgeons. J Trauma Acute Care Surg. 2014;77(3):409–416.

9. Blair IV, Steiner JF, Hanratty R, et al. An investigation of associations between clinicians’ ethnic or racial bias and hypertension treatment, medication adherence and blood pressure control. J Gen Intern Med. 2014;29(7):987–995.

10. Ravenell J, Ogedegbe G. Unconscious bias and real-world hypertension outcomes: advancing disparities research. J Gen Intern Med. 2014;29(7):973–975.

11. van Ryn M, Saha S. Exploring unconscious bias in disparities research and medical education. JAMA. 2011;306(9):995–996.

12. Puhl RM, Moss-Racusin CA, Schwartz MB, Brownell KD. Weight stigmatization and bias reduction: perspectives of overweight and obese adults. Health Educ Res. 2008;23(2):347–358.

13. Prohibited employment policies/practices. US Equal Employment Opportunity Commission website. http://www.eeoc.gov/laws/practices/. Accessed July 14, 2015.

14. Dion K, Berscheid E, Walster E. What is beautiful is good. J Pers Soc Psychol. 1972;24(3):285–290.

15. Watkins LM, Johnston L. Screening job applicants: the impact of physical attractiveness and application quality. Int J Selection Assess. 2000;8(2):76–84.

16. Ruffle BJ, Shtudiner Z. Are good-looking people more employable? Manage Sci. http://dx.doi.org/10.1287/mnsc.2014.1927. Published May 29, 2014. Accessed July 14, 2015.

17. Lemay EP Jr, Clark MS, Greenberg A. What is beautiful is good because what is beautiful is desired: physical attractiveness stereotyping as projection of interpersonal goals. Pers Soc Psychol Bull. 2010;36(3):339–353.

Applying for a residency program can be a stressful process for medical students. It is a combination of applying for a job in the “real world” and applying to a college or medical school. In certain fields of medicine or surgery, there may be over 600 residency applications for 40 to 80 interviewee slots. Different specialties, as well as programs within a given specialty, take a different number of residents per year. This can vary from 1 to over 20 available spots, depending on the field of medicine or surgery as well as the specific program. Orthopedic surgery residencies, for example, can match between 2 and 12 residents each year. During the 2013–2014 academic year at our institution, there were over 600 applications received for approximately 50 interview slots for a class of 5 orthopedic surgery residents. Nationally, according to publicly available 2013 National Resident Matching Program (NRMP) data, a total of 1038 applicants (833 US medical school seniors) applied for 693 spots in orthopedic surgery, of which 692 were filled, indicating that orthopedic surgery remains one of the most desired fields among medical school seniors.1 Looking at the statistics provided by the NRMP data, orthopedic applicants remain some of the most competitive, with proportionally higher board scores, publication numbers, and grades, among other factors.1

Each individual program has its own method for sifting through the applications. At some institutions, the individual “in charge” of the selection committee may look through all applications initially, narrow them down, and then distribute them to the other members of the selection committee to determine the final interviewee list. At other institutions, the initial group of applications may be divided and distributed to the committee members so that each member reviews the applications and ultimately decides upon the interview candidates.