User login

Bringing you the latest news, research and reviews, exclusive interviews, podcasts, quizzes, and more.

div[contains(@class, 'read-next-article')]

div[contains(@class, 'nav-primary')]

nav[contains(@class, 'nav-primary')]

section[contains(@class, 'footer-nav-section-wrapper')]

nav[contains(@class, 'nav-ce-stack nav-ce-stack__large-screen')]

header[@id='header']

div[contains(@class, 'header__large-screen')]

div[contains(@class, 'read-next-article')]

div[contains(@class, 'main-prefix')]

div[contains(@class, 'nav-primary')]

nav[contains(@class, 'nav-primary')]

section[contains(@class, 'footer-nav-section-wrapper')]

footer[@id='footer']

section[contains(@class, 'nav-hidden')]

div[contains(@class, 'ce-card-content')]

nav[contains(@class, 'nav-ce-stack')]

div[contains(@class, 'view-medstat-quiz-listing-panes')]

div[contains(@class, 'pane-article-sidebar-latest-news')]

FDA approves tirzepatide for treating obesity

Eli Lilly will market tirzepatide injections for weight management under the trade name Zepbound. It was approved in May 2022 for treating type 2 diabetes. The new indication is for adults with either obesity, defined as a body mass index of 30 kg/m2 or greater, or overweight, with a BMI of 27 or greater with at least one weight-related comorbidity, including hypertension, type 2 diabetes, or dyslipidemia.

“Obesity and overweight are serious conditions that can be associated with some of the leading causes of death, such as heart disease, stroke, and diabetes,” said John Sharretts, MD, director of the division of diabetes, lipid disorders, and obesity in the FDA’s Center for Drug Evaluation and Research. “In light of increasing rates of both obesity and overweight in the United States, today’s approval addresses an unmet medical need.”

A once-weekly injection, tirzepatide reduces appetite by activating two gut hormones, glucagonlike peptide–1 (GLP-1) and glucose-dependent insulinotropic polypeptide (GIP). The dosage is increased over 4-20 weeks to achieve a weekly dose target of 5 mg, 10 mg, or 15 mg maximum.

Efficacy was established in two pivotal randomized, double-blind, placebo-controlled trials of adults with obesity or overweight plus another condition. One trial measured weight reduction after 72 weeks in a total of 2,519 patients without diabetes who received either 5 mg, 10 mg or 15 mg of tirzepatide once weekly. Those who received the 15-mg dose achieved on average 18% of their initial body weight, compared with placebo.

The other pivotal trial enrolled a total of 938 patients with type 2 diabetes. These patients achieved an average weight loss of 12% with once-weekly tirzepatide compared to placebo.

Another trial, which was presented at the 2023 Obesity Week meeting and was published in Nature Medicine, showed clinically meaningful added weight loss for adults with obesity who did not have diabetes and who had already experienced weight loss of at least 5% after a 12-week intensive lifestyle intervention.

Another trial, which was reported at the 2023 annual meeting of the European Association for the Study of Diabetes, found that tirzepatide continued to produce “highly significant weight loss” when the drug was continued in a 1-year follow-up trial. Those who discontinued taking the drug regained some weight but not all.

Tirzepatide can cause gastrointestinal side effects, such as nausea, diarrhea, vomiting, constipation, and abdominal pain or discomfort. Site reactions, hypersensitivity, hair loss, burping, and gastrointestinal reflux disease have also been reported.

The medication should not be used by patients with a personal or family history of medullary thyroid cancer or by patients with multiple endocrine neoplasia syndrome type 2. It should also not be used in combination with Mounjaro or another GLP-1 receptor agonist. The safety and effectiveness of the coadministration of tirzepatide with other medications for weight management have not been established.

Zepbound should go to market in the United States by the end of 2023, with an anticipated monthly list price of $1,060, according to a news release from Eli Lilly.

A version of this article first appeared on Medscape.com.

Eli Lilly will market tirzepatide injections for weight management under the trade name Zepbound. It was approved in May 2022 for treating type 2 diabetes. The new indication is for adults with either obesity, defined as a body mass index of 30 kg/m2 or greater, or overweight, with a BMI of 27 or greater with at least one weight-related comorbidity, including hypertension, type 2 diabetes, or dyslipidemia.

“Obesity and overweight are serious conditions that can be associated with some of the leading causes of death, such as heart disease, stroke, and diabetes,” said John Sharretts, MD, director of the division of diabetes, lipid disorders, and obesity in the FDA’s Center for Drug Evaluation and Research. “In light of increasing rates of both obesity and overweight in the United States, today’s approval addresses an unmet medical need.”

A once-weekly injection, tirzepatide reduces appetite by activating two gut hormones, glucagonlike peptide–1 (GLP-1) and glucose-dependent insulinotropic polypeptide (GIP). The dosage is increased over 4-20 weeks to achieve a weekly dose target of 5 mg, 10 mg, or 15 mg maximum.

Efficacy was established in two pivotal randomized, double-blind, placebo-controlled trials of adults with obesity or overweight plus another condition. One trial measured weight reduction after 72 weeks in a total of 2,519 patients without diabetes who received either 5 mg, 10 mg or 15 mg of tirzepatide once weekly. Those who received the 15-mg dose achieved on average 18% of their initial body weight, compared with placebo.

The other pivotal trial enrolled a total of 938 patients with type 2 diabetes. These patients achieved an average weight loss of 12% with once-weekly tirzepatide compared to placebo.

Another trial, which was presented at the 2023 Obesity Week meeting and was published in Nature Medicine, showed clinically meaningful added weight loss for adults with obesity who did not have diabetes and who had already experienced weight loss of at least 5% after a 12-week intensive lifestyle intervention.

Another trial, which was reported at the 2023 annual meeting of the European Association for the Study of Diabetes, found that tirzepatide continued to produce “highly significant weight loss” when the drug was continued in a 1-year follow-up trial. Those who discontinued taking the drug regained some weight but not all.

Tirzepatide can cause gastrointestinal side effects, such as nausea, diarrhea, vomiting, constipation, and abdominal pain or discomfort. Site reactions, hypersensitivity, hair loss, burping, and gastrointestinal reflux disease have also been reported.

The medication should not be used by patients with a personal or family history of medullary thyroid cancer or by patients with multiple endocrine neoplasia syndrome type 2. It should also not be used in combination with Mounjaro or another GLP-1 receptor agonist. The safety and effectiveness of the coadministration of tirzepatide with other medications for weight management have not been established.

Zepbound should go to market in the United States by the end of 2023, with an anticipated monthly list price of $1,060, according to a news release from Eli Lilly.

A version of this article first appeared on Medscape.com.

Eli Lilly will market tirzepatide injections for weight management under the trade name Zepbound. It was approved in May 2022 for treating type 2 diabetes. The new indication is for adults with either obesity, defined as a body mass index of 30 kg/m2 or greater, or overweight, with a BMI of 27 or greater with at least one weight-related comorbidity, including hypertension, type 2 diabetes, or dyslipidemia.

“Obesity and overweight are serious conditions that can be associated with some of the leading causes of death, such as heart disease, stroke, and diabetes,” said John Sharretts, MD, director of the division of diabetes, lipid disorders, and obesity in the FDA’s Center for Drug Evaluation and Research. “In light of increasing rates of both obesity and overweight in the United States, today’s approval addresses an unmet medical need.”

A once-weekly injection, tirzepatide reduces appetite by activating two gut hormones, glucagonlike peptide–1 (GLP-1) and glucose-dependent insulinotropic polypeptide (GIP). The dosage is increased over 4-20 weeks to achieve a weekly dose target of 5 mg, 10 mg, or 15 mg maximum.

Efficacy was established in two pivotal randomized, double-blind, placebo-controlled trials of adults with obesity or overweight plus another condition. One trial measured weight reduction after 72 weeks in a total of 2,519 patients without diabetes who received either 5 mg, 10 mg or 15 mg of tirzepatide once weekly. Those who received the 15-mg dose achieved on average 18% of their initial body weight, compared with placebo.

The other pivotal trial enrolled a total of 938 patients with type 2 diabetes. These patients achieved an average weight loss of 12% with once-weekly tirzepatide compared to placebo.

Another trial, which was presented at the 2023 Obesity Week meeting and was published in Nature Medicine, showed clinically meaningful added weight loss for adults with obesity who did not have diabetes and who had already experienced weight loss of at least 5% after a 12-week intensive lifestyle intervention.

Another trial, which was reported at the 2023 annual meeting of the European Association for the Study of Diabetes, found that tirzepatide continued to produce “highly significant weight loss” when the drug was continued in a 1-year follow-up trial. Those who discontinued taking the drug regained some weight but not all.

Tirzepatide can cause gastrointestinal side effects, such as nausea, diarrhea, vomiting, constipation, and abdominal pain or discomfort. Site reactions, hypersensitivity, hair loss, burping, and gastrointestinal reflux disease have also been reported.

The medication should not be used by patients with a personal or family history of medullary thyroid cancer or by patients with multiple endocrine neoplasia syndrome type 2. It should also not be used in combination with Mounjaro or another GLP-1 receptor agonist. The safety and effectiveness of the coadministration of tirzepatide with other medications for weight management have not been established.

Zepbound should go to market in the United States by the end of 2023, with an anticipated monthly list price of $1,060, according to a news release from Eli Lilly.

A version of this article first appeared on Medscape.com.

Review estimates acne risk with JAK inhibitor therapy

TOPLINE:

, according to an analysis of 25 JAK inhibitor studies.

METHODOLOGY:

- Acne has been reported to be an adverse effect of JAK inhibitors, but not much is known about how common acne is overall and how incidence differs between different JAK inhibitors and the disease being treated.

- For the systematic review and meta-analysis, researchers identified 25 phase 2 or 3 randomized, controlled trials that reported acne as an adverse event associated with the use of JAK inhibitors.

- The study population included 10,839 participants (54% male, 46% female).

- The primary outcome was the incidence of acne following a period of JAK inhibitor use.

TAKEAWAY:

- Overall, the risk of acne was significantly higher among those treated with JAK inhibitors in comparison with patients given placebo in a pooled analysis (odds ratio [OR], 3.83).

- The risk of acne was highest with abrocitinib (OR, 13.47), followed by baricitinib (OR, 4.96), upadacitinib (OR, 4.79), deuruxolitinib (OR, 3.30), and deucravacitinib (OR, 2.64). By JAK inhibitor class, results were as follows: JAK1-specific inhibitors (OR, 4.69), combined JAK1 and JAK2 inhibitors (OR, 3.43), and tyrosine kinase 2 inhibitors (OR, 2.64).

- In a subgroup analysis, risk of acne was higher among patients using JAK inhibitors for dermatologic conditions in comparison with those using JAK inhibitors for nondermatologic conditions (OR, 4.67 vs 1.18).

- Age and gender had no apparent impact on the effect of JAK inhibitor use on acne risk.

IN PRACTICE:

“The occurrence of acne following treatment with certain classes of JAK inhibitors is of potential concern, as this adverse effect may jeopardize treatment adherence among some patients,” the researchers wrote. More studies are needed “to characterize the underlying mechanism of acne with JAK inhibitor use and to identify best practices for treatment,” they added.

SOURCE:

The lead author was Jeremy Martinez, MPH, of Harvard Medical School, Boston. The study was published online in JAMA Dermatology.

LIMITATIONS:

The review was limited by the variable classification and reporting of acne across studies, the potential exclusion of relevant studies, and the small number of studies for certain drugs.

DISCLOSURES:

The studies were mainly funded by the pharmaceutical industry. Mr. Martinez disclosed no relevant financial relationships. Several coauthors have ties with Dexcel Pharma Technologies, AbbVie, Concert, Pfizer, 3Derm Systems, Incyte, Aclaris, Eli Lilly, Concert, Equillium, ASLAN, ACOM, and Boehringer Ingelheim.

A version of this article appeared on Medscape.com.

TOPLINE:

, according to an analysis of 25 JAK inhibitor studies.

METHODOLOGY:

- Acne has been reported to be an adverse effect of JAK inhibitors, but not much is known about how common acne is overall and how incidence differs between different JAK inhibitors and the disease being treated.

- For the systematic review and meta-analysis, researchers identified 25 phase 2 or 3 randomized, controlled trials that reported acne as an adverse event associated with the use of JAK inhibitors.

- The study population included 10,839 participants (54% male, 46% female).

- The primary outcome was the incidence of acne following a period of JAK inhibitor use.

TAKEAWAY:

- Overall, the risk of acne was significantly higher among those treated with JAK inhibitors in comparison with patients given placebo in a pooled analysis (odds ratio [OR], 3.83).

- The risk of acne was highest with abrocitinib (OR, 13.47), followed by baricitinib (OR, 4.96), upadacitinib (OR, 4.79), deuruxolitinib (OR, 3.30), and deucravacitinib (OR, 2.64). By JAK inhibitor class, results were as follows: JAK1-specific inhibitors (OR, 4.69), combined JAK1 and JAK2 inhibitors (OR, 3.43), and tyrosine kinase 2 inhibitors (OR, 2.64).

- In a subgroup analysis, risk of acne was higher among patients using JAK inhibitors for dermatologic conditions in comparison with those using JAK inhibitors for nondermatologic conditions (OR, 4.67 vs 1.18).

- Age and gender had no apparent impact on the effect of JAK inhibitor use on acne risk.

IN PRACTICE:

“The occurrence of acne following treatment with certain classes of JAK inhibitors is of potential concern, as this adverse effect may jeopardize treatment adherence among some patients,” the researchers wrote. More studies are needed “to characterize the underlying mechanism of acne with JAK inhibitor use and to identify best practices for treatment,” they added.

SOURCE:

The lead author was Jeremy Martinez, MPH, of Harvard Medical School, Boston. The study was published online in JAMA Dermatology.

LIMITATIONS:

The review was limited by the variable classification and reporting of acne across studies, the potential exclusion of relevant studies, and the small number of studies for certain drugs.

DISCLOSURES:

The studies were mainly funded by the pharmaceutical industry. Mr. Martinez disclosed no relevant financial relationships. Several coauthors have ties with Dexcel Pharma Technologies, AbbVie, Concert, Pfizer, 3Derm Systems, Incyte, Aclaris, Eli Lilly, Concert, Equillium, ASLAN, ACOM, and Boehringer Ingelheim.

A version of this article appeared on Medscape.com.

TOPLINE:

, according to an analysis of 25 JAK inhibitor studies.

METHODOLOGY:

- Acne has been reported to be an adverse effect of JAK inhibitors, but not much is known about how common acne is overall and how incidence differs between different JAK inhibitors and the disease being treated.

- For the systematic review and meta-analysis, researchers identified 25 phase 2 or 3 randomized, controlled trials that reported acne as an adverse event associated with the use of JAK inhibitors.

- The study population included 10,839 participants (54% male, 46% female).

- The primary outcome was the incidence of acne following a period of JAK inhibitor use.

TAKEAWAY:

- Overall, the risk of acne was significantly higher among those treated with JAK inhibitors in comparison with patients given placebo in a pooled analysis (odds ratio [OR], 3.83).

- The risk of acne was highest with abrocitinib (OR, 13.47), followed by baricitinib (OR, 4.96), upadacitinib (OR, 4.79), deuruxolitinib (OR, 3.30), and deucravacitinib (OR, 2.64). By JAK inhibitor class, results were as follows: JAK1-specific inhibitors (OR, 4.69), combined JAK1 and JAK2 inhibitors (OR, 3.43), and tyrosine kinase 2 inhibitors (OR, 2.64).

- In a subgroup analysis, risk of acne was higher among patients using JAK inhibitors for dermatologic conditions in comparison with those using JAK inhibitors for nondermatologic conditions (OR, 4.67 vs 1.18).

- Age and gender had no apparent impact on the effect of JAK inhibitor use on acne risk.

IN PRACTICE:

“The occurrence of acne following treatment with certain classes of JAK inhibitors is of potential concern, as this adverse effect may jeopardize treatment adherence among some patients,” the researchers wrote. More studies are needed “to characterize the underlying mechanism of acne with JAK inhibitor use and to identify best practices for treatment,” they added.

SOURCE:

The lead author was Jeremy Martinez, MPH, of Harvard Medical School, Boston. The study was published online in JAMA Dermatology.

LIMITATIONS:

The review was limited by the variable classification and reporting of acne across studies, the potential exclusion of relevant studies, and the small number of studies for certain drugs.

DISCLOSURES:

The studies were mainly funded by the pharmaceutical industry. Mr. Martinez disclosed no relevant financial relationships. Several coauthors have ties with Dexcel Pharma Technologies, AbbVie, Concert, Pfizer, 3Derm Systems, Incyte, Aclaris, Eli Lilly, Concert, Equillium, ASLAN, ACOM, and Boehringer Ingelheim.

A version of this article appeared on Medscape.com.

Newer antiobesity meds lower the body’s defended fat mass

The current highly effective antiobesity medications approved for treating obesity (semaglutide), under review (tirzepatide), or in late-stage clinical trials “appear to lower the body’s target and defended fat mass [set point]” but do not permanently fix it at a lower point, Lee M. Kaplan, MD, PhD, explained in a lecture during the annual meeting of the Obesity Society.

It is very likely that patients with obesity will have to take these antiobesity medications “forever,” he said, “until we identify and can repair the cellular and molecular mechanisms that the body uses to regulate body fat mass throughout the life cycle and that are dysfunctional in obesity.”

“The body is able to regulate fat mass at multiple stages during development,” Dr. Kaplan, from Massachusetts General Hospital and Harvard Medical School, Boston, explained, “and when it doesn’t do it appropriately, that becomes the physiological basis of obesity.”

The loss of baby fat, as well as fat changes during puberty, menopause, aging, and, in particular, during and after pregnancy, “all occur without conscious or purposeful input,” he noted.

The body uses food intake and energy expenditure to reach and defend its intended fat mass, and there is an evolutionary benefit to doing this.

For example, people recovering from an acute illness can regain the lost fat and weight. A woman can support a pregnancy and lactation by increasing fat mass.

However, “the idea that [with antiobesity medications] we should be aiming for a fixed lower amount of fat is probably not a good idea.” Dr. Kaplan cautioned.

People need the flexibility to recover lost fat and weight after an acute illness or injury, and pregnant women need to gain an appropriate amount of body fat to support pregnancy and lactation.

Intermittent therapy: A practical strategy?

The long-term benefit of antiobesity medications requires continuous use, Dr. Kaplan noted. For example, in the STEP 1 trial of semaglutide in patients with obesity and without diabetes, when treatment was stopped at 68 weeks, average weight increased through 120 weeks, although it did not return to baseline levels.

Intermittent antiobesity therapy may be an effective, “very practical strategy” to maintain weight loss, which would also “address current challenges of high cost, limited drug availability, and inadequate access to care.”

“Until we have strategies for decreasing the cost of effective obesity treatment, and ensuring more equitable access to obesity care,” Dr. Kaplan said, “optimizing algorithms for the use of intermittent therapy may be an effective stopgap measure.”

Dr. Kaplan is or has recently been a paid consultant for Eli Lilly, Novo Nordisk, and multiple pharmaceutical companies developing antiobesity medications.

A version of this article appeared on Medscape.com.

The current highly effective antiobesity medications approved for treating obesity (semaglutide), under review (tirzepatide), or in late-stage clinical trials “appear to lower the body’s target and defended fat mass [set point]” but do not permanently fix it at a lower point, Lee M. Kaplan, MD, PhD, explained in a lecture during the annual meeting of the Obesity Society.

It is very likely that patients with obesity will have to take these antiobesity medications “forever,” he said, “until we identify and can repair the cellular and molecular mechanisms that the body uses to regulate body fat mass throughout the life cycle and that are dysfunctional in obesity.”

“The body is able to regulate fat mass at multiple stages during development,” Dr. Kaplan, from Massachusetts General Hospital and Harvard Medical School, Boston, explained, “and when it doesn’t do it appropriately, that becomes the physiological basis of obesity.”

The loss of baby fat, as well as fat changes during puberty, menopause, aging, and, in particular, during and after pregnancy, “all occur without conscious or purposeful input,” he noted.

The body uses food intake and energy expenditure to reach and defend its intended fat mass, and there is an evolutionary benefit to doing this.

For example, people recovering from an acute illness can regain the lost fat and weight. A woman can support a pregnancy and lactation by increasing fat mass.

However, “the idea that [with antiobesity medications] we should be aiming for a fixed lower amount of fat is probably not a good idea.” Dr. Kaplan cautioned.

People need the flexibility to recover lost fat and weight after an acute illness or injury, and pregnant women need to gain an appropriate amount of body fat to support pregnancy and lactation.

Intermittent therapy: A practical strategy?

The long-term benefit of antiobesity medications requires continuous use, Dr. Kaplan noted. For example, in the STEP 1 trial of semaglutide in patients with obesity and without diabetes, when treatment was stopped at 68 weeks, average weight increased through 120 weeks, although it did not return to baseline levels.

Intermittent antiobesity therapy may be an effective, “very practical strategy” to maintain weight loss, which would also “address current challenges of high cost, limited drug availability, and inadequate access to care.”

“Until we have strategies for decreasing the cost of effective obesity treatment, and ensuring more equitable access to obesity care,” Dr. Kaplan said, “optimizing algorithms for the use of intermittent therapy may be an effective stopgap measure.”

Dr. Kaplan is or has recently been a paid consultant for Eli Lilly, Novo Nordisk, and multiple pharmaceutical companies developing antiobesity medications.

A version of this article appeared on Medscape.com.

The current highly effective antiobesity medications approved for treating obesity (semaglutide), under review (tirzepatide), or in late-stage clinical trials “appear to lower the body’s target and defended fat mass [set point]” but do not permanently fix it at a lower point, Lee M. Kaplan, MD, PhD, explained in a lecture during the annual meeting of the Obesity Society.

It is very likely that patients with obesity will have to take these antiobesity medications “forever,” he said, “until we identify and can repair the cellular and molecular mechanisms that the body uses to regulate body fat mass throughout the life cycle and that are dysfunctional in obesity.”

“The body is able to regulate fat mass at multiple stages during development,” Dr. Kaplan, from Massachusetts General Hospital and Harvard Medical School, Boston, explained, “and when it doesn’t do it appropriately, that becomes the physiological basis of obesity.”

The loss of baby fat, as well as fat changes during puberty, menopause, aging, and, in particular, during and after pregnancy, “all occur without conscious or purposeful input,” he noted.

The body uses food intake and energy expenditure to reach and defend its intended fat mass, and there is an evolutionary benefit to doing this.

For example, people recovering from an acute illness can regain the lost fat and weight. A woman can support a pregnancy and lactation by increasing fat mass.

However, “the idea that [with antiobesity medications] we should be aiming for a fixed lower amount of fat is probably not a good idea.” Dr. Kaplan cautioned.

People need the flexibility to recover lost fat and weight after an acute illness or injury, and pregnant women need to gain an appropriate amount of body fat to support pregnancy and lactation.

Intermittent therapy: A practical strategy?

The long-term benefit of antiobesity medications requires continuous use, Dr. Kaplan noted. For example, in the STEP 1 trial of semaglutide in patients with obesity and without diabetes, when treatment was stopped at 68 weeks, average weight increased through 120 weeks, although it did not return to baseline levels.

Intermittent antiobesity therapy may be an effective, “very practical strategy” to maintain weight loss, which would also “address current challenges of high cost, limited drug availability, and inadequate access to care.”

“Until we have strategies for decreasing the cost of effective obesity treatment, and ensuring more equitable access to obesity care,” Dr. Kaplan said, “optimizing algorithms for the use of intermittent therapy may be an effective stopgap measure.”

Dr. Kaplan is or has recently been a paid consultant for Eli Lilly, Novo Nordisk, and multiple pharmaceutical companies developing antiobesity medications.

A version of this article appeared on Medscape.com.

FROM OBESITYWEEK® 2023

Pustular Eruption on the Face

The Diagnosis: Eczema Herpeticum

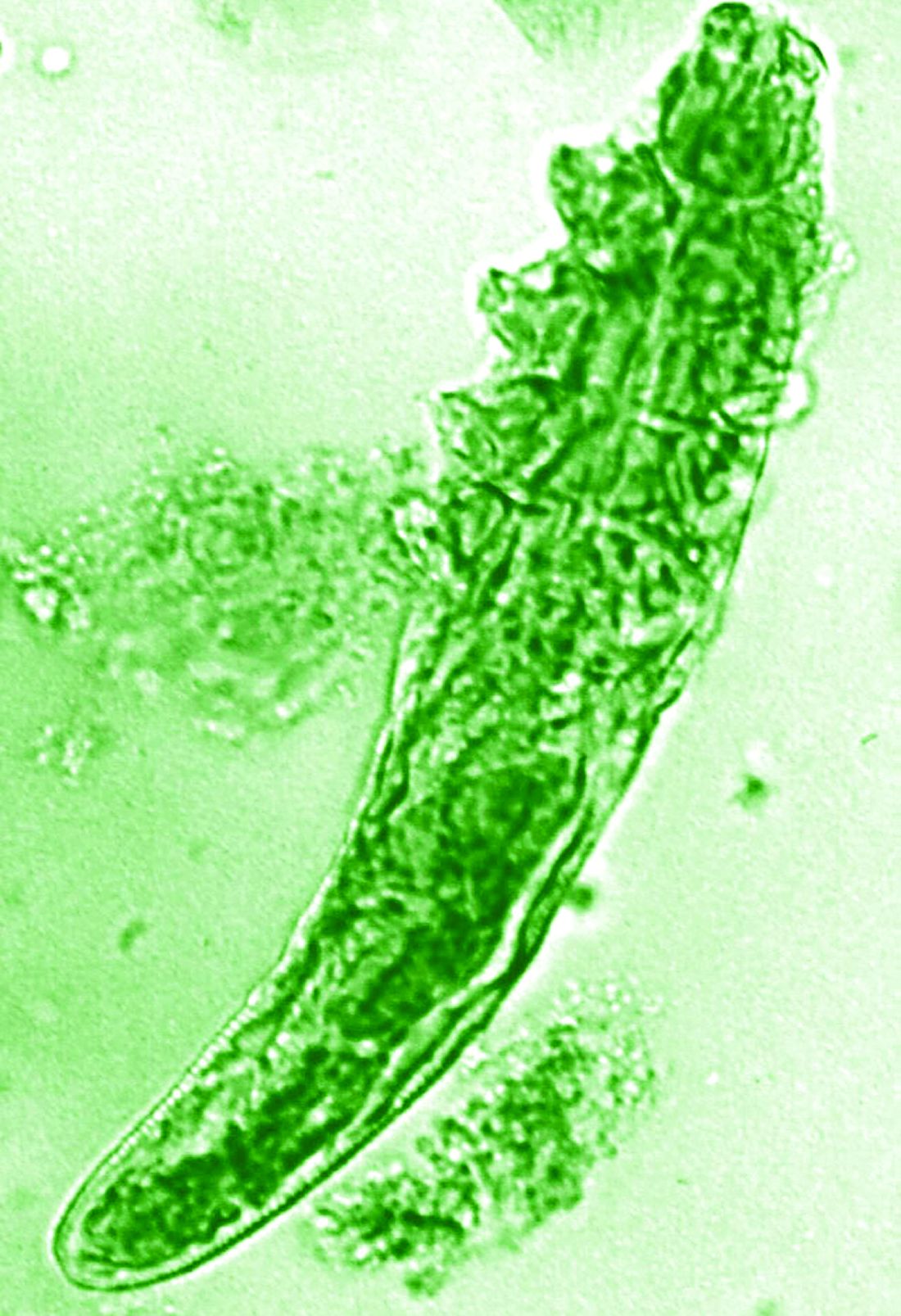

The patient’s condition with worsening facial edema and notable pain prompted a bedside Tzanck smear using a sample from the base of a deroofed forehead vesicle. In addition, a swab of a deroofed lesion was sent for herpes simplex virus and varicella-zoster virus (VZV) polymerase chain reaction (PCR) testing. The Tzanck smear demonstrated ballooning multinucleated syncytial giant cells and eosinophilic inclusion bodies (Figure), which are characteristic of certain herpesviruses including herpes simplex virus and VZV. He was started on intravenous acyclovir while PCR results were pending; the PCR test later confirmed positivity for herpes simplex virus type 1. Treatment was transitioned to oral valacyclovir once the lesions started crusting over. Notable healing and epithelialization of the lesions occurred during his hospital stay, and he was discharged home 5 days after starting treatment. He was counseled on autoinoculation, advised that he was considered infectious until all lesions had crusted over, and encouraged to employ frequent handwashing. Complete resolution of eczema herpeticum (EH) was noted at 3-week follow-up.

Eczema herpeticum (also known as Kaposi varicelliform eruption) is a potentially life-threatening disseminated cutaneous infection caused by herpes simplex virus types 1 and 2 in patients with pre-existing skin disease.1 It typically presents as a complication of atopic dermatitis (AD) but also has been identified as a rare complication in other conditions that disrupt the normal skin barrier, including mycosis fungoides, pemphigus foliaceus, pemphigus vulgaris, Darier disease, pityriasis rubra pilaris, contact dermatitis, and seborrheic dermatitis.1-4

The pathogenesis of EH is multifactorial. Disruption of the stratum corneum; impaired natural killer cell function; early-onset, untreated, or severe AD; disrupted skin microbiota with skewed colonization by Staphylococcus aureus; immunosuppressive AD therapies such as calcineurin inhibitors; eosinophilia; and helper T cell (TH2) cytokine predominance all have been suggested to play a role in the development of EH.5-8

As seen in our patient, EH presents with a sudden eruption of painful or pruritic, grouped, monomorphic, domeshaped vesicles with background swelling and erythema typically on the head, neck, and trunk. Vesicles then progress to punched-out erosions with overlying hemorrhagic crusting that can coalesce to form large denuded areas susceptible to superinfection with bacteria.9 Other accompanying symptoms include high fever, chills, malaise, and lymphadenopathy. Associated inflammation, classically described as erythema, may be difficult to discern in patients with darker skin and appears as hyperpigmentation; therefore, identification of clusters of monomorphic vesicles in areas of pre-existing dermatitis is particularly important for clinical diagnosis in people with darker skin types.

Various tests are available to confirm diagnosis in ambiguous cases. Bedside Tzanck smears can be performed rapidly and are considered positive if characteristic multinucleated giant cells are noted; however, they do not differentiate between the various herpesviruses. Direct fluorescent antibody testing of scraped lesions and viral cultures of swabbed vesicular fluid are equally effective in distinguishing between herpes simplex virus type 1, herpes simplex virus type 2, and VZV; PCR confirms the diagnosis with high specificity and sensitivity.10

In our patient, the initial differential diagnosis included EH, acute generalized exanthematous pustulosis, allergic contact dermatitis, and Orthopoxvirus infection. The positive Tzanck smear reduced the likelihood of a nonviral etiology. Additionally, worsening of the rash despite discontinuation of medications and utilization of topical steroids argued against acute generalized exanthematous pustulosis and allergic contact dermatitis. The laboratory findings reduced the likelihood of drug reaction with eosinophilia and systemic symptoms (DRESS) syndrome, and PCR findings ultimately ruled out Orthopoxvirus infections. Additional differential diagnoses for EH include dermatitis herpetiformis; primary VZV infection; hand, foot, and mouth disease; disseminated zoster infection; disseminated molluscum contagiosum; and eczema coxsackium.

Complications of EH include scarring; herpetic keratitis due to corneal infection, which if left untreated can progress to blindness; and rarely death due to multiorgan failure or septicemia.11 The traditional smallpox vaccine (ACAM2000) is contraindicated in patients with AD and EH, even when AD is in remission. These patients should avoid contact with recently vaccinated individuals.12 An alternative vaccine—Jynneos (Bavarian Nordic)—is available for these patients and their family members.13 Clinicians should be aware of this guideline, especially given the recent mpox (monkeypox) outbreaks.

Mild cases of EH are more common, may sometimes go unnoticed, and self-resolve in healthy patients. Severe cases may require systemic antiviral therapy. Acyclovir and its prodrug valacyclovir are standard treatments for EH. Alternatively, foscarnet or cidofovir can be used in the treatment of acyclovir-resistant thymidine kinase– deficient herpes simplex virus and other acyclovirresistant cases.14 Any secondary bacterial superinfections, usually due to staphylococcal or streptococcal bacteria, should be treated with antibiotics. A thorough ophthalmologic evaluation should be performed for patients with periocular involvement of EH. Empiric treatment should be started immediately, given a relative low toxicity of systemic antiviral therapy and high morbidity and mortality associated with untreated widespread EH.

It is important to maintain a high index of clinical suspicion for EH, especially in patients with pre-existing conditions such as AD who present with systemic symptoms and facial vesicles, pustules, or erosions to ensure prompt diagnosis and appropriate treatment.

- Baaniya B, Agrawal S. Kaposi varicelliform eruption in a patient with pemphigus vulgaris: a case report and review of the literature. Case Rep Dermatol Med. 2020;2020:6695342. doi:10.1155/2020/6695342

- Tayabali K, Pothiwalla H, Lowitt M. Eczema herpeticum in Darier’s disease: a topical storm. J Community Hosp Intern Med Perspect. 2019;9:347. doi:10.1080/20009666.2019.1650590

- Cavalié M, Giacchero D, Cardot-Leccia N, et al. Kaposi’s varicelliform eruption in a patient with pityriasis rubra pilaris (pityriasis rubra pilaris herpeticum). J Eur Acad Dermatol Venereol. 2013;27:1585-1586. doi:10.1111/JDV.12120

- Lee GH, Kim YM, Lee SY, et al. A case of eczema herpeticum with Hailey-Hailey disease. Ann Dermatol. 2009;21:311-314. doi:10.5021/ad.2009.21.3.311

- Seegräber M, Worm M, Werfel T, et al. Recurrent eczema herpeticum— a retrospective European multicenter study evaluating the clinical characteristics of eczema herpeticum cases in atopic dermatitis patients. J Eur Acad Dermatol Venereol. 2020;34:1074-1079. doi:10.1111/JDV.16090

- Kawakami Y, Ando T, Lee J-R, et al. Defective natural killer cell activity in a mouse model of eczema herpeticum. J Allergy Clin Immunol. 2017;139:997-1006.e10. doi:10.1016/j.jaci.2016.06.034

- Beck L, Latchney L, Zaccaro D, et al. Biomarkers of disease severity and Th2 polarity are predictors of risk for eczema herpeticum. J Allergy Clin Immunol. 2008;121:S37-S37. doi:10.1016/j.jaci.2007.12.152

- Kim M, Jung M, Hong SP, et al. Topical calcineurin inhibitors compromise stratum corneum integrity, epidermal permeability and antimicrobial barrier function. Exp Dermatol. 2010; 19:501-510. doi:10.1111/J.1600-0625.2009.00941.X

- Karray M, Kwan E, Souissi A. Kaposi varicelliform eruption. StatPearls [Internet]. StatPearls Publishing; 2023. https://www.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/books/NBK482432/

- Dominguez SR, Pretty K, Hengartner R, et al. Comparison of herpes simplex virus PCR with culture for virus detection in multisource surface swab specimens from neonates [published online September 25, 2018]. J Clin Microbiol. doi:10.1128/JCM.00632-18

- Feye F, De Halleux C, Gillet JB, et al. Exacerbation of atopic dermatitis in the emergency department. Eur J Emerg Med. 2004;11:49-52. doi:10.1097/00063110-200412000-00014

- Casey C, Vellozzi C, Mootrey GT, et al; Vaccinia Case Definition Development Working Group; Advisory Committee on Immunization Practices-Armed Forces Epidemiological Board Smallpox Vaccine Safety Working Group. Surveillance guidelines for smallpox vaccine (vaccinia) adverse reactions. MMWR Recomm Rep. 2006;55:1-16.

- Rao AK, Petersen BW, Whitehill F, et al. Use of JYNNEOS (Smallpox and Monkeypox Vaccine, Live, Nonreplicating) for preexposure vaccination of persons at risk for occupational exposure to orthopoxviruses: recommendations of the Advisory Committee on Immunization Practices—United States, 2022. MMWR Morb Mortal Wkly Rep. 2022;71:734-742. doi:10.15585 /MMWR.MM7122E1

- Piret J, Boivin G. Resistance of herpes simplex viruses to nucleoside analogues: mechanisms, prevalence, and management. Antimicrob Agents Chemother. 2011;55:459. doi:10.1128/AAC.00615-10

The Diagnosis: Eczema Herpeticum

The patient’s condition with worsening facial edema and notable pain prompted a bedside Tzanck smear using a sample from the base of a deroofed forehead vesicle. In addition, a swab of a deroofed lesion was sent for herpes simplex virus and varicella-zoster virus (VZV) polymerase chain reaction (PCR) testing. The Tzanck smear demonstrated ballooning multinucleated syncytial giant cells and eosinophilic inclusion bodies (Figure), which are characteristic of certain herpesviruses including herpes simplex virus and VZV. He was started on intravenous acyclovir while PCR results were pending; the PCR test later confirmed positivity for herpes simplex virus type 1. Treatment was transitioned to oral valacyclovir once the lesions started crusting over. Notable healing and epithelialization of the lesions occurred during his hospital stay, and he was discharged home 5 days after starting treatment. He was counseled on autoinoculation, advised that he was considered infectious until all lesions had crusted over, and encouraged to employ frequent handwashing. Complete resolution of eczema herpeticum (EH) was noted at 3-week follow-up.

Eczema herpeticum (also known as Kaposi varicelliform eruption) is a potentially life-threatening disseminated cutaneous infection caused by herpes simplex virus types 1 and 2 in patients with pre-existing skin disease.1 It typically presents as a complication of atopic dermatitis (AD) but also has been identified as a rare complication in other conditions that disrupt the normal skin barrier, including mycosis fungoides, pemphigus foliaceus, pemphigus vulgaris, Darier disease, pityriasis rubra pilaris, contact dermatitis, and seborrheic dermatitis.1-4

The pathogenesis of EH is multifactorial. Disruption of the stratum corneum; impaired natural killer cell function; early-onset, untreated, or severe AD; disrupted skin microbiota with skewed colonization by Staphylococcus aureus; immunosuppressive AD therapies such as calcineurin inhibitors; eosinophilia; and helper T cell (TH2) cytokine predominance all have been suggested to play a role in the development of EH.5-8

As seen in our patient, EH presents with a sudden eruption of painful or pruritic, grouped, monomorphic, domeshaped vesicles with background swelling and erythema typically on the head, neck, and trunk. Vesicles then progress to punched-out erosions with overlying hemorrhagic crusting that can coalesce to form large denuded areas susceptible to superinfection with bacteria.9 Other accompanying symptoms include high fever, chills, malaise, and lymphadenopathy. Associated inflammation, classically described as erythema, may be difficult to discern in patients with darker skin and appears as hyperpigmentation; therefore, identification of clusters of monomorphic vesicles in areas of pre-existing dermatitis is particularly important for clinical diagnosis in people with darker skin types.

Various tests are available to confirm diagnosis in ambiguous cases. Bedside Tzanck smears can be performed rapidly and are considered positive if characteristic multinucleated giant cells are noted; however, they do not differentiate between the various herpesviruses. Direct fluorescent antibody testing of scraped lesions and viral cultures of swabbed vesicular fluid are equally effective in distinguishing between herpes simplex virus type 1, herpes simplex virus type 2, and VZV; PCR confirms the diagnosis with high specificity and sensitivity.10

In our patient, the initial differential diagnosis included EH, acute generalized exanthematous pustulosis, allergic contact dermatitis, and Orthopoxvirus infection. The positive Tzanck smear reduced the likelihood of a nonviral etiology. Additionally, worsening of the rash despite discontinuation of medications and utilization of topical steroids argued against acute generalized exanthematous pustulosis and allergic contact dermatitis. The laboratory findings reduced the likelihood of drug reaction with eosinophilia and systemic symptoms (DRESS) syndrome, and PCR findings ultimately ruled out Orthopoxvirus infections. Additional differential diagnoses for EH include dermatitis herpetiformis; primary VZV infection; hand, foot, and mouth disease; disseminated zoster infection; disseminated molluscum contagiosum; and eczema coxsackium.

Complications of EH include scarring; herpetic keratitis due to corneal infection, which if left untreated can progress to blindness; and rarely death due to multiorgan failure or septicemia.11 The traditional smallpox vaccine (ACAM2000) is contraindicated in patients with AD and EH, even when AD is in remission. These patients should avoid contact with recently vaccinated individuals.12 An alternative vaccine—Jynneos (Bavarian Nordic)—is available for these patients and their family members.13 Clinicians should be aware of this guideline, especially given the recent mpox (monkeypox) outbreaks.

Mild cases of EH are more common, may sometimes go unnoticed, and self-resolve in healthy patients. Severe cases may require systemic antiviral therapy. Acyclovir and its prodrug valacyclovir are standard treatments for EH. Alternatively, foscarnet or cidofovir can be used in the treatment of acyclovir-resistant thymidine kinase– deficient herpes simplex virus and other acyclovirresistant cases.14 Any secondary bacterial superinfections, usually due to staphylococcal or streptococcal bacteria, should be treated with antibiotics. A thorough ophthalmologic evaluation should be performed for patients with periocular involvement of EH. Empiric treatment should be started immediately, given a relative low toxicity of systemic antiviral therapy and high morbidity and mortality associated with untreated widespread EH.

It is important to maintain a high index of clinical suspicion for EH, especially in patients with pre-existing conditions such as AD who present with systemic symptoms and facial vesicles, pustules, or erosions to ensure prompt diagnosis and appropriate treatment.

The Diagnosis: Eczema Herpeticum

The patient’s condition with worsening facial edema and notable pain prompted a bedside Tzanck smear using a sample from the base of a deroofed forehead vesicle. In addition, a swab of a deroofed lesion was sent for herpes simplex virus and varicella-zoster virus (VZV) polymerase chain reaction (PCR) testing. The Tzanck smear demonstrated ballooning multinucleated syncytial giant cells and eosinophilic inclusion bodies (Figure), which are characteristic of certain herpesviruses including herpes simplex virus and VZV. He was started on intravenous acyclovir while PCR results were pending; the PCR test later confirmed positivity for herpes simplex virus type 1. Treatment was transitioned to oral valacyclovir once the lesions started crusting over. Notable healing and epithelialization of the lesions occurred during his hospital stay, and he was discharged home 5 days after starting treatment. He was counseled on autoinoculation, advised that he was considered infectious until all lesions had crusted over, and encouraged to employ frequent handwashing. Complete resolution of eczema herpeticum (EH) was noted at 3-week follow-up.

Eczema herpeticum (also known as Kaposi varicelliform eruption) is a potentially life-threatening disseminated cutaneous infection caused by herpes simplex virus types 1 and 2 in patients with pre-existing skin disease.1 It typically presents as a complication of atopic dermatitis (AD) but also has been identified as a rare complication in other conditions that disrupt the normal skin barrier, including mycosis fungoides, pemphigus foliaceus, pemphigus vulgaris, Darier disease, pityriasis rubra pilaris, contact dermatitis, and seborrheic dermatitis.1-4

The pathogenesis of EH is multifactorial. Disruption of the stratum corneum; impaired natural killer cell function; early-onset, untreated, or severe AD; disrupted skin microbiota with skewed colonization by Staphylococcus aureus; immunosuppressive AD therapies such as calcineurin inhibitors; eosinophilia; and helper T cell (TH2) cytokine predominance all have been suggested to play a role in the development of EH.5-8

As seen in our patient, EH presents with a sudden eruption of painful or pruritic, grouped, monomorphic, domeshaped vesicles with background swelling and erythema typically on the head, neck, and trunk. Vesicles then progress to punched-out erosions with overlying hemorrhagic crusting that can coalesce to form large denuded areas susceptible to superinfection with bacteria.9 Other accompanying symptoms include high fever, chills, malaise, and lymphadenopathy. Associated inflammation, classically described as erythema, may be difficult to discern in patients with darker skin and appears as hyperpigmentation; therefore, identification of clusters of monomorphic vesicles in areas of pre-existing dermatitis is particularly important for clinical diagnosis in people with darker skin types.

Various tests are available to confirm diagnosis in ambiguous cases. Bedside Tzanck smears can be performed rapidly and are considered positive if characteristic multinucleated giant cells are noted; however, they do not differentiate between the various herpesviruses. Direct fluorescent antibody testing of scraped lesions and viral cultures of swabbed vesicular fluid are equally effective in distinguishing between herpes simplex virus type 1, herpes simplex virus type 2, and VZV; PCR confirms the diagnosis with high specificity and sensitivity.10

In our patient, the initial differential diagnosis included EH, acute generalized exanthematous pustulosis, allergic contact dermatitis, and Orthopoxvirus infection. The positive Tzanck smear reduced the likelihood of a nonviral etiology. Additionally, worsening of the rash despite discontinuation of medications and utilization of topical steroids argued against acute generalized exanthematous pustulosis and allergic contact dermatitis. The laboratory findings reduced the likelihood of drug reaction with eosinophilia and systemic symptoms (DRESS) syndrome, and PCR findings ultimately ruled out Orthopoxvirus infections. Additional differential diagnoses for EH include dermatitis herpetiformis; primary VZV infection; hand, foot, and mouth disease; disseminated zoster infection; disseminated molluscum contagiosum; and eczema coxsackium.

Complications of EH include scarring; herpetic keratitis due to corneal infection, which if left untreated can progress to blindness; and rarely death due to multiorgan failure or septicemia.11 The traditional smallpox vaccine (ACAM2000) is contraindicated in patients with AD and EH, even when AD is in remission. These patients should avoid contact with recently vaccinated individuals.12 An alternative vaccine—Jynneos (Bavarian Nordic)—is available for these patients and their family members.13 Clinicians should be aware of this guideline, especially given the recent mpox (monkeypox) outbreaks.

Mild cases of EH are more common, may sometimes go unnoticed, and self-resolve in healthy patients. Severe cases may require systemic antiviral therapy. Acyclovir and its prodrug valacyclovir are standard treatments for EH. Alternatively, foscarnet or cidofovir can be used in the treatment of acyclovir-resistant thymidine kinase– deficient herpes simplex virus and other acyclovirresistant cases.14 Any secondary bacterial superinfections, usually due to staphylococcal or streptococcal bacteria, should be treated with antibiotics. A thorough ophthalmologic evaluation should be performed for patients with periocular involvement of EH. Empiric treatment should be started immediately, given a relative low toxicity of systemic antiviral therapy and high morbidity and mortality associated with untreated widespread EH.

It is important to maintain a high index of clinical suspicion for EH, especially in patients with pre-existing conditions such as AD who present with systemic symptoms and facial vesicles, pustules, or erosions to ensure prompt diagnosis and appropriate treatment.

- Baaniya B, Agrawal S. Kaposi varicelliform eruption in a patient with pemphigus vulgaris: a case report and review of the literature. Case Rep Dermatol Med. 2020;2020:6695342. doi:10.1155/2020/6695342

- Tayabali K, Pothiwalla H, Lowitt M. Eczema herpeticum in Darier’s disease: a topical storm. J Community Hosp Intern Med Perspect. 2019;9:347. doi:10.1080/20009666.2019.1650590

- Cavalié M, Giacchero D, Cardot-Leccia N, et al. Kaposi’s varicelliform eruption in a patient with pityriasis rubra pilaris (pityriasis rubra pilaris herpeticum). J Eur Acad Dermatol Venereol. 2013;27:1585-1586. doi:10.1111/JDV.12120

- Lee GH, Kim YM, Lee SY, et al. A case of eczema herpeticum with Hailey-Hailey disease. Ann Dermatol. 2009;21:311-314. doi:10.5021/ad.2009.21.3.311

- Seegräber M, Worm M, Werfel T, et al. Recurrent eczema herpeticum— a retrospective European multicenter study evaluating the clinical characteristics of eczema herpeticum cases in atopic dermatitis patients. J Eur Acad Dermatol Venereol. 2020;34:1074-1079. doi:10.1111/JDV.16090

- Kawakami Y, Ando T, Lee J-R, et al. Defective natural killer cell activity in a mouse model of eczema herpeticum. J Allergy Clin Immunol. 2017;139:997-1006.e10. doi:10.1016/j.jaci.2016.06.034

- Beck L, Latchney L, Zaccaro D, et al. Biomarkers of disease severity and Th2 polarity are predictors of risk for eczema herpeticum. J Allergy Clin Immunol. 2008;121:S37-S37. doi:10.1016/j.jaci.2007.12.152

- Kim M, Jung M, Hong SP, et al. Topical calcineurin inhibitors compromise stratum corneum integrity, epidermal permeability and antimicrobial barrier function. Exp Dermatol. 2010; 19:501-510. doi:10.1111/J.1600-0625.2009.00941.X

- Karray M, Kwan E, Souissi A. Kaposi varicelliform eruption. StatPearls [Internet]. StatPearls Publishing; 2023. https://www.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/books/NBK482432/

- Dominguez SR, Pretty K, Hengartner R, et al. Comparison of herpes simplex virus PCR with culture for virus detection in multisource surface swab specimens from neonates [published online September 25, 2018]. J Clin Microbiol. doi:10.1128/JCM.00632-18

- Feye F, De Halleux C, Gillet JB, et al. Exacerbation of atopic dermatitis in the emergency department. Eur J Emerg Med. 2004;11:49-52. doi:10.1097/00063110-200412000-00014

- Casey C, Vellozzi C, Mootrey GT, et al; Vaccinia Case Definition Development Working Group; Advisory Committee on Immunization Practices-Armed Forces Epidemiological Board Smallpox Vaccine Safety Working Group. Surveillance guidelines for smallpox vaccine (vaccinia) adverse reactions. MMWR Recomm Rep. 2006;55:1-16.

- Rao AK, Petersen BW, Whitehill F, et al. Use of JYNNEOS (Smallpox and Monkeypox Vaccine, Live, Nonreplicating) for preexposure vaccination of persons at risk for occupational exposure to orthopoxviruses: recommendations of the Advisory Committee on Immunization Practices—United States, 2022. MMWR Morb Mortal Wkly Rep. 2022;71:734-742. doi:10.15585 /MMWR.MM7122E1

- Piret J, Boivin G. Resistance of herpes simplex viruses to nucleoside analogues: mechanisms, prevalence, and management. Antimicrob Agents Chemother. 2011;55:459. doi:10.1128/AAC.00615-10

- Baaniya B, Agrawal S. Kaposi varicelliform eruption in a patient with pemphigus vulgaris: a case report and review of the literature. Case Rep Dermatol Med. 2020;2020:6695342. doi:10.1155/2020/6695342

- Tayabali K, Pothiwalla H, Lowitt M. Eczema herpeticum in Darier’s disease: a topical storm. J Community Hosp Intern Med Perspect. 2019;9:347. doi:10.1080/20009666.2019.1650590

- Cavalié M, Giacchero D, Cardot-Leccia N, et al. Kaposi’s varicelliform eruption in a patient with pityriasis rubra pilaris (pityriasis rubra pilaris herpeticum). J Eur Acad Dermatol Venereol. 2013;27:1585-1586. doi:10.1111/JDV.12120

- Lee GH, Kim YM, Lee SY, et al. A case of eczema herpeticum with Hailey-Hailey disease. Ann Dermatol. 2009;21:311-314. doi:10.5021/ad.2009.21.3.311

- Seegräber M, Worm M, Werfel T, et al. Recurrent eczema herpeticum— a retrospective European multicenter study evaluating the clinical characteristics of eczema herpeticum cases in atopic dermatitis patients. J Eur Acad Dermatol Venereol. 2020;34:1074-1079. doi:10.1111/JDV.16090

- Kawakami Y, Ando T, Lee J-R, et al. Defective natural killer cell activity in a mouse model of eczema herpeticum. J Allergy Clin Immunol. 2017;139:997-1006.e10. doi:10.1016/j.jaci.2016.06.034

- Beck L, Latchney L, Zaccaro D, et al. Biomarkers of disease severity and Th2 polarity are predictors of risk for eczema herpeticum. J Allergy Clin Immunol. 2008;121:S37-S37. doi:10.1016/j.jaci.2007.12.152

- Kim M, Jung M, Hong SP, et al. Topical calcineurin inhibitors compromise stratum corneum integrity, epidermal permeability and antimicrobial barrier function. Exp Dermatol. 2010; 19:501-510. doi:10.1111/J.1600-0625.2009.00941.X

- Karray M, Kwan E, Souissi A. Kaposi varicelliform eruption. StatPearls [Internet]. StatPearls Publishing; 2023. https://www.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/books/NBK482432/

- Dominguez SR, Pretty K, Hengartner R, et al. Comparison of herpes simplex virus PCR with culture for virus detection in multisource surface swab specimens from neonates [published online September 25, 2018]. J Clin Microbiol. doi:10.1128/JCM.00632-18

- Feye F, De Halleux C, Gillet JB, et al. Exacerbation of atopic dermatitis in the emergency department. Eur J Emerg Med. 2004;11:49-52. doi:10.1097/00063110-200412000-00014

- Casey C, Vellozzi C, Mootrey GT, et al; Vaccinia Case Definition Development Working Group; Advisory Committee on Immunization Practices-Armed Forces Epidemiological Board Smallpox Vaccine Safety Working Group. Surveillance guidelines for smallpox vaccine (vaccinia) adverse reactions. MMWR Recomm Rep. 2006;55:1-16.

- Rao AK, Petersen BW, Whitehill F, et al. Use of JYNNEOS (Smallpox and Monkeypox Vaccine, Live, Nonreplicating) for preexposure vaccination of persons at risk for occupational exposure to orthopoxviruses: recommendations of the Advisory Committee on Immunization Practices—United States, 2022. MMWR Morb Mortal Wkly Rep. 2022;71:734-742. doi:10.15585 /MMWR.MM7122E1

- Piret J, Boivin G. Resistance of herpes simplex viruses to nucleoside analogues: mechanisms, prevalence, and management. Antimicrob Agents Chemother. 2011;55:459. doi:10.1128/AAC.00615-10

A 52-year-old man developed a sudden eruption of small pustules on background erythema and edema covering the forehead, nasal bridge, periorbital region, cheeks, and perioral region on day 3 of hospitalization in the intensive care unit for management of septic shock secondary to a complicated urinary tract infection. He had a medical history of benign prostatic hyperplasia, sarcoidosis, and atopic dermatitis. He initially presented to the emergency department with fever, chills, and dysuria of 2 days’ duration. Because he received ceftriaxone, vancomycin, ciprofloxacin, and tamsulosin while hospitalized for the infection, the primary medical team suspected a drug reaction and empirically started applying hydrocortisone cream 2.5%. The rash continued to spread over the ensuing day, prompting a dermatology consultation to rule out a drug eruption and to help guide further management. The patient was in substantial distress and pain. Physical examination revealed numerous discrete and confluent monomorphic pustules on background erythema with faint collarettes of scale covering most of the face. Substantial periorbital and facial edema forced the eyes closed. There was no mucous membrane involvement. A review of systems was negative for dyspnea and dysphagia, and the rash was not present elsewhere on the body. Ophthalmologic evaluation revealed no ocular involvement or vision changes. Laboratory studies demonstrated neutrophilia (17.27×109 cells/L [reference range, 2.0–6.9×109 cells/L]). The eosinophil count, blood urea nitrogen/creatinine, and liver function tests were within reference range.

Topical ivermectin study sheds light on dysbiosis in rosacea

, according to a report presented at the recent European Academy of Dermatology and Venereology (EADV) 2023 Congress.

“This is the first hint that the host’s cutaneous microbiome plays a secondary role in the immunopathogenesis of rosacea,” said Bernard Homey, MD, director of the department of dermatology at University Hospital Düsseldorf in Germany.

“In rosacea, we are well aware of trigger factors such as stress, UV light, heat, cold, food, and alcohol,” he said. “We are also well aware that there is an increase in Demodex mites in the pilosebaceous unit.”

Research over the past decade has also started to look at the potential role of the skin microbiome in the disease process, but answers have remained “largely elusive,” Dr. Homey said.

Ivermectin helps, but how?

Ivermectin 1% cream (Soolantra) has been approved by the U.S. Food and Drug Administration since 2014 for the treatment of the inflammatory lesions that are characteristic of rosacea, but its mechanism of action is not clear.

Dr. Homey presented the results of a study of 61 patients designed to look at how ivermectin might be working in the treatment of people with rosacea and investigate if there was any relation to the skin microbiome and transcriptome of patients.

The trial included 41 individuals with papulopustular rosacea and 20 individuals who did not have rosacea. For all patients, surface skin biopsies were performed twice 30 days apart using cyanoacrylate glue; patients with rosacea were treated with topical ivermectin 1% between biopsies. Skin samples obtained at day 0 and day 30 were examined under the microscope, and Demodex counts (mites/cm2) of skin and RNA sequencing of the cutaneous microbiome were undertaken.

The mean age of the patients with rosacea was 54.9 years, and the mean Demodex counts before and after treatment were a respective 7.2 cm2 and 0.9 cm2.

Using the Investigator’s General Assessment to assess the severity of rosacea, Homey reported that 43.9% of patients with rosacea had a decrease in scores at day 30, indicating improvement.

In addition, topical ivermectin resulted in a marked or total decrease in Demodex mite density for 87.5% of patients (n = 24) who were identified as having the mites.

Skin microbiome changes seen

As a form of quality control, skin microbiome changes among the patients were compared with control patients using 16S rRNA sequencing.

“The taxa we find within the cutaneous niche of inflammatory lesions of rosacea patients are significantly different from healthy volunteers,” Dr. Homey said.

Cutibacterium species are predominant in healthy control persons but are not present when there is inflammation in patients with rosacea. Instead, staphylococcus species “take over the niche, similar to atopic dermatitis,” he noted.

Looking at how treatment with ivermectin influences the organisms, the decrease in C. acnes seen in patients with rosacea persisted despite treatment, and the abundance of Staphylococcus epidermidis, S. hominis, and S. capitis increased further. This suggests a possible protective or homeostatic role of C. acnes but a pathogenic role for staphylococci, explained Dr. Homey.

“Surprisingly, although inflammatory lesions decrease, patients get better, the cutaneous microbiome does not revert to homeostatic conditions during topical ivermectin treatment,” he observed.

There is, of course, variability among individuals.

Dr. Homey also reported that Snodgrassella alvi – a microorganism believed to reside in the gut of Demodex folliculorum mites – was found in the skin microbiome of patients with rosacea before but not after ivermectin treatment. This may mean that this microorganism could be partially triggering inflammation in rosacea patients.

Looking at the transcriptome of patients, Dr. Homey said that there was downregulation of distinct genes that might make for more favorable conditions for Demodex mites.

Moreover, insufficient upregulation of interleukin-17 pathways might be working together with barrier defects in the skin and metabolic changes to “pave the way” for colonization by S. epidermidis.

Pulling it together

Dr. Homey and associates conclude in their abstract that the findings “support that rosacea lesions are associated with dysbiosis.”

Although treatment with ivermectin did not normalize the skin’s microbiome, it was associated with a decrease in Demodex mite density and the reduction of microbes associated with Demodex.

Margarida Gonçalo, MD, PhD, professor of dermatology at the University of Coimbra in Portugal, who cochaired the late-breaking news session where the data were presented, asked whether healthy and affected skin in patients with rosacea had been compared, rather than comparing the skin of rosacea lesions with healthy control samples.

“No, we did not this, as this is methodologically a little bit more difficult,” Dr. Homey responded.

Also cochairing the session was Michel Gilliet, MD, chair of the department of dermatology at the University Hospital CHUV in Lausanne, Switzerland. He commented that these “data suggest that there’s an intimate link between Demodex and the skin microbiota and dysbiosis in in rosacea.”

Dr. Gilliet added: “You have a whole dysbiosis going on in rosacea, which is probably only dependent on these bacteria.”

It would be “very interesting,” as a “proof-of-concept” study, to look at whether depleting Demodex would also delete S. alvi, he suggested.

The study was funded by Galderma. Dr. Homey has acted as a consultant, speaker or investigator for many pharmaceutical companies including Galderma.

A version of this article first appeared on Medscape.com.

, according to a report presented at the recent European Academy of Dermatology and Venereology (EADV) 2023 Congress.

“This is the first hint that the host’s cutaneous microbiome plays a secondary role in the immunopathogenesis of rosacea,” said Bernard Homey, MD, director of the department of dermatology at University Hospital Düsseldorf in Germany.

“In rosacea, we are well aware of trigger factors such as stress, UV light, heat, cold, food, and alcohol,” he said. “We are also well aware that there is an increase in Demodex mites in the pilosebaceous unit.”

Research over the past decade has also started to look at the potential role of the skin microbiome in the disease process, but answers have remained “largely elusive,” Dr. Homey said.

Ivermectin helps, but how?

Ivermectin 1% cream (Soolantra) has been approved by the U.S. Food and Drug Administration since 2014 for the treatment of the inflammatory lesions that are characteristic of rosacea, but its mechanism of action is not clear.

Dr. Homey presented the results of a study of 61 patients designed to look at how ivermectin might be working in the treatment of people with rosacea and investigate if there was any relation to the skin microbiome and transcriptome of patients.

The trial included 41 individuals with papulopustular rosacea and 20 individuals who did not have rosacea. For all patients, surface skin biopsies were performed twice 30 days apart using cyanoacrylate glue; patients with rosacea were treated with topical ivermectin 1% between biopsies. Skin samples obtained at day 0 and day 30 were examined under the microscope, and Demodex counts (mites/cm2) of skin and RNA sequencing of the cutaneous microbiome were undertaken.

The mean age of the patients with rosacea was 54.9 years, and the mean Demodex counts before and after treatment were a respective 7.2 cm2 and 0.9 cm2.

Using the Investigator’s General Assessment to assess the severity of rosacea, Homey reported that 43.9% of patients with rosacea had a decrease in scores at day 30, indicating improvement.

In addition, topical ivermectin resulted in a marked or total decrease in Demodex mite density for 87.5% of patients (n = 24) who were identified as having the mites.

Skin microbiome changes seen

As a form of quality control, skin microbiome changes among the patients were compared with control patients using 16S rRNA sequencing.

“The taxa we find within the cutaneous niche of inflammatory lesions of rosacea patients are significantly different from healthy volunteers,” Dr. Homey said.

Cutibacterium species are predominant in healthy control persons but are not present when there is inflammation in patients with rosacea. Instead, staphylococcus species “take over the niche, similar to atopic dermatitis,” he noted.

Looking at how treatment with ivermectin influences the organisms, the decrease in C. acnes seen in patients with rosacea persisted despite treatment, and the abundance of Staphylococcus epidermidis, S. hominis, and S. capitis increased further. This suggests a possible protective or homeostatic role of C. acnes but a pathogenic role for staphylococci, explained Dr. Homey.

“Surprisingly, although inflammatory lesions decrease, patients get better, the cutaneous microbiome does not revert to homeostatic conditions during topical ivermectin treatment,” he observed.

There is, of course, variability among individuals.

Dr. Homey also reported that Snodgrassella alvi – a microorganism believed to reside in the gut of Demodex folliculorum mites – was found in the skin microbiome of patients with rosacea before but not after ivermectin treatment. This may mean that this microorganism could be partially triggering inflammation in rosacea patients.

Looking at the transcriptome of patients, Dr. Homey said that there was downregulation of distinct genes that might make for more favorable conditions for Demodex mites.

Moreover, insufficient upregulation of interleukin-17 pathways might be working together with barrier defects in the skin and metabolic changes to “pave the way” for colonization by S. epidermidis.

Pulling it together

Dr. Homey and associates conclude in their abstract that the findings “support that rosacea lesions are associated with dysbiosis.”

Although treatment with ivermectin did not normalize the skin’s microbiome, it was associated with a decrease in Demodex mite density and the reduction of microbes associated with Demodex.

Margarida Gonçalo, MD, PhD, professor of dermatology at the University of Coimbra in Portugal, who cochaired the late-breaking news session where the data were presented, asked whether healthy and affected skin in patients with rosacea had been compared, rather than comparing the skin of rosacea lesions with healthy control samples.

“No, we did not this, as this is methodologically a little bit more difficult,” Dr. Homey responded.

Also cochairing the session was Michel Gilliet, MD, chair of the department of dermatology at the University Hospital CHUV in Lausanne, Switzerland. He commented that these “data suggest that there’s an intimate link between Demodex and the skin microbiota and dysbiosis in in rosacea.”

Dr. Gilliet added: “You have a whole dysbiosis going on in rosacea, which is probably only dependent on these bacteria.”

It would be “very interesting,” as a “proof-of-concept” study, to look at whether depleting Demodex would also delete S. alvi, he suggested.

The study was funded by Galderma. Dr. Homey has acted as a consultant, speaker or investigator for many pharmaceutical companies including Galderma.

A version of this article first appeared on Medscape.com.

, according to a report presented at the recent European Academy of Dermatology and Venereology (EADV) 2023 Congress.

“This is the first hint that the host’s cutaneous microbiome plays a secondary role in the immunopathogenesis of rosacea,” said Bernard Homey, MD, director of the department of dermatology at University Hospital Düsseldorf in Germany.

“In rosacea, we are well aware of trigger factors such as stress, UV light, heat, cold, food, and alcohol,” he said. “We are also well aware that there is an increase in Demodex mites in the pilosebaceous unit.”

Research over the past decade has also started to look at the potential role of the skin microbiome in the disease process, but answers have remained “largely elusive,” Dr. Homey said.

Ivermectin helps, but how?

Ivermectin 1% cream (Soolantra) has been approved by the U.S. Food and Drug Administration since 2014 for the treatment of the inflammatory lesions that are characteristic of rosacea, but its mechanism of action is not clear.

Dr. Homey presented the results of a study of 61 patients designed to look at how ivermectin might be working in the treatment of people with rosacea and investigate if there was any relation to the skin microbiome and transcriptome of patients.

The trial included 41 individuals with papulopustular rosacea and 20 individuals who did not have rosacea. For all patients, surface skin biopsies were performed twice 30 days apart using cyanoacrylate glue; patients with rosacea were treated with topical ivermectin 1% between biopsies. Skin samples obtained at day 0 and day 30 were examined under the microscope, and Demodex counts (mites/cm2) of skin and RNA sequencing of the cutaneous microbiome were undertaken.

The mean age of the patients with rosacea was 54.9 years, and the mean Demodex counts before and after treatment were a respective 7.2 cm2 and 0.9 cm2.

Using the Investigator’s General Assessment to assess the severity of rosacea, Homey reported that 43.9% of patients with rosacea had a decrease in scores at day 30, indicating improvement.

In addition, topical ivermectin resulted in a marked or total decrease in Demodex mite density for 87.5% of patients (n = 24) who were identified as having the mites.

Skin microbiome changes seen

As a form of quality control, skin microbiome changes among the patients were compared with control patients using 16S rRNA sequencing.

“The taxa we find within the cutaneous niche of inflammatory lesions of rosacea patients are significantly different from healthy volunteers,” Dr. Homey said.

Cutibacterium species are predominant in healthy control persons but are not present when there is inflammation in patients with rosacea. Instead, staphylococcus species “take over the niche, similar to atopic dermatitis,” he noted.

Looking at how treatment with ivermectin influences the organisms, the decrease in C. acnes seen in patients with rosacea persisted despite treatment, and the abundance of Staphylococcus epidermidis, S. hominis, and S. capitis increased further. This suggests a possible protective or homeostatic role of C. acnes but a pathogenic role for staphylococci, explained Dr. Homey.

“Surprisingly, although inflammatory lesions decrease, patients get better, the cutaneous microbiome does not revert to homeostatic conditions during topical ivermectin treatment,” he observed.

There is, of course, variability among individuals.

Dr. Homey also reported that Snodgrassella alvi – a microorganism believed to reside in the gut of Demodex folliculorum mites – was found in the skin microbiome of patients with rosacea before but not after ivermectin treatment. This may mean that this microorganism could be partially triggering inflammation in rosacea patients.

Looking at the transcriptome of patients, Dr. Homey said that there was downregulation of distinct genes that might make for more favorable conditions for Demodex mites.

Moreover, insufficient upregulation of interleukin-17 pathways might be working together with barrier defects in the skin and metabolic changes to “pave the way” for colonization by S. epidermidis.

Pulling it together

Dr. Homey and associates conclude in their abstract that the findings “support that rosacea lesions are associated with dysbiosis.”

Although treatment with ivermectin did not normalize the skin’s microbiome, it was associated with a decrease in Demodex mite density and the reduction of microbes associated with Demodex.

Margarida Gonçalo, MD, PhD, professor of dermatology at the University of Coimbra in Portugal, who cochaired the late-breaking news session where the data were presented, asked whether healthy and affected skin in patients with rosacea had been compared, rather than comparing the skin of rosacea lesions with healthy control samples.

“No, we did not this, as this is methodologically a little bit more difficult,” Dr. Homey responded.

Also cochairing the session was Michel Gilliet, MD, chair of the department of dermatology at the University Hospital CHUV in Lausanne, Switzerland. He commented that these “data suggest that there’s an intimate link between Demodex and the skin microbiota and dysbiosis in in rosacea.”

Dr. Gilliet added: “You have a whole dysbiosis going on in rosacea, which is probably only dependent on these bacteria.”

It would be “very interesting,” as a “proof-of-concept” study, to look at whether depleting Demodex would also delete S. alvi, he suggested.

The study was funded by Galderma. Dr. Homey has acted as a consultant, speaker or investigator for many pharmaceutical companies including Galderma.

A version of this article first appeared on Medscape.com.

FROM EADV 2023

A new long COVID explanation: Low serotonin levels?

Could antidepressants hold the key to treating long COVID? The study even points to a possible treatment.

Serotonin is a neurotransmitter that has many functions in the body and is targeted by the most commonly prescribed antidepressants – the selective serotonin reuptake inhibitors.

Serotonin is widely studied for its effects on the brain – it regulates the messaging between neurons, affecting sleep, mood, and memory. It is present in the gut, is found in cells along the gastrointestinal tract, and is absorbed by blood platelets. Gut serotonin, known as circulating serotonin, is responsible for a host of other functions, including the regulation of blood flow, body temperature, and digestion.

Low levels of serotonin could result in any number of seemingly unrelated symptoms, as in the case of long COVID, experts say. The condition affects about 7% of Americans and is associated with a wide range of health problems, including fatigue, shortness of breath, neurological symptoms, joint pain, blood clots, heart palpitations, and digestive problems.

Long COVID is difficult to treat because researchers haven’t been able to pinpoint the underlying mechanisms that cause prolonged illness after a SARS-CoV-2 infection, said study author Christoph A. Thaiss, PhD, an assistant professor of microbiology at the Perelman School of Medicine at the University of Pennsylvania.

The hope is that this study could have implications for new treatments, he said.

“Long COVID can have manifestations not only in the brain but in many different parts of the body, so it’s possible that serotonin reductions are involved in many different aspects of the disease,” said Dr. Thaiss.

Dr. Thaiss’s study, published in the journal Cell, found lower serotonin levels in long COVID patients, compared with patients who were diagnosed with acute COVID-19 but who fully recovered.

His team found that reductions in serotonin were driven by low levels of circulating SARS-CoV-2 virus that caused persistent inflammation as well as an inability of the body to absorb tryptophan, an amino acid that’s a precursor to serotonin. Overactive blood platelets were also shown to play a role; they serve as the primary means of serotonin absorption.

The study doesn’t make any recommendations for treatment, but understanding the role of serotonin in long COVID opens the door to a host of novel ideas that could set the stage for clinical trials and affect care.

“The study gives us a few possible targets that could be used in future clinical studies,” Dr. Thaiss said.

Persistent circulating virus is one of the drivers of low serotonin levels, said study author Michael Peluso, MD, an assistant research professor of infectious medicine at the University of California, San Francisco, School of Medicine. This points to the need to reduce viral load using antiviral medications like nirmatrelvir/ritonavir (Paxlovid), which is approved by the U.S. Food and Drug Administration for the treatment of COVID-19, and VV116, which has not yet been approved for use against COVID.

Research published in the New England Journal of Medicine found that the oral antiviral agent VV116 was as effective as nirmatrelvir/ritonavir in reducing the body’s viral load and aiding recovery from SARS-CoV-2 infection. Paxlovid has also been shown to reduce the likelihood of getting long COVID after an acute SARS-CoV-2 infection.

Researchers are investigating ways to target serotonin levels directly, potentially using SSRIs. But first they need to study whether improvement in serotonin level makes a difference.

“What we need now is a good clinical trial to see whether altering levels of serotonin in people with long COVID will lead to symptom relief,” Dr. Peluso said.

Indeed, the research did show that the SSRI fluoxetine, as well as a glycine-tryptophan supplement, improved cognitive function in SARS-CoV-2-infected rodent models, which were used in a portion of the study.

David F. Putrino, PhD, who runs the long COVID clinic at Mount Sinai Health System in New York City, said the research is helping “to paint a biological picture” that’s in line with other research on the mechanisms that cause long COVID symptoms.

But Dr. Putrino, who was not involved in the study, cautions against treating long COVID patients with SSRIs or any other treatment that increases serotonin before testing patients to determine whether their serotonin levels are actually lower than those of healthy persons.

“We don’t want to assume that every patient with long COVID is going to have lower serotonin levels,” said Dr. Putrino.