User login

Lesions on face, arms, and legs

The FP suspected that the patient had sarcoidosis, based on the infiltrated plaques and their distribution on her face. The appearance of the lesions was similar to images he’d seen online of lupus pernio, a pathognomonic finding of sarcoidosis. The FP recommended a punch biopsy of one of the lesions, and the patient consented.

(See the Watch & Learn video on “Punch biopsy.”)

The FP also sent the patient for a chest x-ray, which showed bilateral hilar adenopathy consistent with sarcoidosis. Histopathology of the biopsy also showed sarcoidosis. Chest radiographic involvement is seen in almost 90% of patients with sarcoidosis and is used in staging the disease. Stage I disease shows bilateral hilar lymphadenopathy (BHL). Stage II disease shows BHL plus pulmonary infiltrates. Stage III disease shows pulmonary infiltrates without BHL. Stage IV disease shows pulmonary fibrosis. In this case, the patient had stage I disease.

The FP prescribed topical 0.1% triamcinolone ointment in an 80 g tube and instructed the patient to apply it to all of the areas involved. Although this medication typically comes in a 15 g or 30 g tube, the FP knew that these quantities would be insufficient. He had also read that a mid-potency steroid would be permissible on the face for this diagnosis. Not having any experience with sarcoidosis, the FP referred the patient to Dermatology and Pulmonology.

The dermatologist started the patient on oral prednisone 40 mg/d and awaited the completion of the patient’s baseline labs before beginning a steroid sparing agent such as methotrexate. Treatments for sarcoidosis include topical steroids, systemic steroids, methotrexate, azathioprine, and biologics (with adalimumab and infliximab having the greatest evidence for effectiveness).

Photos and text for Photo Rounds Friday courtesy of Richard P. Usatine, MD. This case was adapted from: Bae E, Bae Y, Sarabi K, et al. Sarcoidosis. In: Usatine R, Smith M, Mayeaux EJ, et al. Color Atlas and Synopsis of Family Medicine. 3rd ed. New York, NY: McGraw-Hill; 2019:1153-1160.

To learn more about the newest 3rd edition of the Color Atlas and Synopsis of Family Medicine, see: https://www.amazon.com/Color-Atlas-Synopsis-Family-Medicine/dp/1259862046/

You can get the Color Atlas of Family Medicine app by clicking on this link: usatinemedia.com

The FP suspected that the patient had sarcoidosis, based on the infiltrated plaques and their distribution on her face. The appearance of the lesions was similar to images he’d seen online of lupus pernio, a pathognomonic finding of sarcoidosis. The FP recommended a punch biopsy of one of the lesions, and the patient consented.

(See the Watch & Learn video on “Punch biopsy.”)

The FP also sent the patient for a chest x-ray, which showed bilateral hilar adenopathy consistent with sarcoidosis. Histopathology of the biopsy also showed sarcoidosis. Chest radiographic involvement is seen in almost 90% of patients with sarcoidosis and is used in staging the disease. Stage I disease shows bilateral hilar lymphadenopathy (BHL). Stage II disease shows BHL plus pulmonary infiltrates. Stage III disease shows pulmonary infiltrates without BHL. Stage IV disease shows pulmonary fibrosis. In this case, the patient had stage I disease.

The FP prescribed topical 0.1% triamcinolone ointment in an 80 g tube and instructed the patient to apply it to all of the areas involved. Although this medication typically comes in a 15 g or 30 g tube, the FP knew that these quantities would be insufficient. He had also read that a mid-potency steroid would be permissible on the face for this diagnosis. Not having any experience with sarcoidosis, the FP referred the patient to Dermatology and Pulmonology.

The dermatologist started the patient on oral prednisone 40 mg/d and awaited the completion of the patient’s baseline labs before beginning a steroid sparing agent such as methotrexate. Treatments for sarcoidosis include topical steroids, systemic steroids, methotrexate, azathioprine, and biologics (with adalimumab and infliximab having the greatest evidence for effectiveness).

Photos and text for Photo Rounds Friday courtesy of Richard P. Usatine, MD. This case was adapted from: Bae E, Bae Y, Sarabi K, et al. Sarcoidosis. In: Usatine R, Smith M, Mayeaux EJ, et al. Color Atlas and Synopsis of Family Medicine. 3rd ed. New York, NY: McGraw-Hill; 2019:1153-1160.

To learn more about the newest 3rd edition of the Color Atlas and Synopsis of Family Medicine, see: https://www.amazon.com/Color-Atlas-Synopsis-Family-Medicine/dp/1259862046/

You can get the Color Atlas of Family Medicine app by clicking on this link: usatinemedia.com

The FP suspected that the patient had sarcoidosis, based on the infiltrated plaques and their distribution on her face. The appearance of the lesions was similar to images he’d seen online of lupus pernio, a pathognomonic finding of sarcoidosis. The FP recommended a punch biopsy of one of the lesions, and the patient consented.

(See the Watch & Learn video on “Punch biopsy.”)

The FP also sent the patient for a chest x-ray, which showed bilateral hilar adenopathy consistent with sarcoidosis. Histopathology of the biopsy also showed sarcoidosis. Chest radiographic involvement is seen in almost 90% of patients with sarcoidosis and is used in staging the disease. Stage I disease shows bilateral hilar lymphadenopathy (BHL). Stage II disease shows BHL plus pulmonary infiltrates. Stage III disease shows pulmonary infiltrates without BHL. Stage IV disease shows pulmonary fibrosis. In this case, the patient had stage I disease.

The FP prescribed topical 0.1% triamcinolone ointment in an 80 g tube and instructed the patient to apply it to all of the areas involved. Although this medication typically comes in a 15 g or 30 g tube, the FP knew that these quantities would be insufficient. He had also read that a mid-potency steroid would be permissible on the face for this diagnosis. Not having any experience with sarcoidosis, the FP referred the patient to Dermatology and Pulmonology.

The dermatologist started the patient on oral prednisone 40 mg/d and awaited the completion of the patient’s baseline labs before beginning a steroid sparing agent such as methotrexate. Treatments for sarcoidosis include topical steroids, systemic steroids, methotrexate, azathioprine, and biologics (with adalimumab and infliximab having the greatest evidence for effectiveness).

Photos and text for Photo Rounds Friday courtesy of Richard P. Usatine, MD. This case was adapted from: Bae E, Bae Y, Sarabi K, et al. Sarcoidosis. In: Usatine R, Smith M, Mayeaux EJ, et al. Color Atlas and Synopsis of Family Medicine. 3rd ed. New York, NY: McGraw-Hill; 2019:1153-1160.

To learn more about the newest 3rd edition of the Color Atlas and Synopsis of Family Medicine, see: https://www.amazon.com/Color-Atlas-Synopsis-Family-Medicine/dp/1259862046/

You can get the Color Atlas of Family Medicine app by clicking on this link: usatinemedia.com

Can You Put Your Finger on the Diagnosis?

An 8-year-old boy is brought in for evaluation of a collection of blisters on his finger, near the nail. The problem manifested about 6 days ago. The affected area is tender to touch. The child reportedly feels well, with no fever or malaise.

The patient has an extensive personal and family history of atopy. Since birth, he has had dry, sensitive skin and has experienced episodes of eczema, seasonal allergies, and asthma. Three months ago, he was admitted to the hospital with eczema herpeticum and successfully treated with IV acyclovir.

EXAMINATION

A cluster of vesicles is seen in the lateral perionychial area of the left third finger. Very modest erythema surrounds the vesicles, which contain cloudy yellow fluid suggestive of pus. There is a palpable lymph node in the left epitrochlear area.

The child is afebrile and in no distress. Patches of mild eczema are seen on the extremities and trunk.

What’s the diagnosis?

DISCUSSION

The lesion on this child’s finger is a herpetic whitlow. Patients with atopy are often susceptible to all types of skin infections: bacterial, fungal, and viral. In fact, human papillomavirus infection manifesting as multiple warts is not uncommon in this population. Nor is herpes simplex virus (HSV) infection, of which this case represents 1 manifestation.

A culture could have been done to confirm the diagnosis, but that would entail opening a vesicle to collect the fluid and then waiting at least 2 weeks for the results. By then, this whitlow would have long since resolved.

As with all HSV infections in the immunocompetent, treatment with acyclovir must be started in the first 2 to 3 days to have any effect—so such treatment in this case would be useless. If the herpetic whitlow were to recur in the same location, prompt treatment could be initiated, which would likely shorten the disease course and reduce symptoms.

Another HSV infection seen almost exclusively in atopic patients is eczema herpeticum (also known as Kaposi varicelliform eruption). This diffuse infection comprises dozens of tiny papulovesicular lesions, mostly concentrated on the face but often spilling down onto the chest. Patients with Darier disease or seborrheic dermatitis can also acquire it.

TAKE-HOME LEARNING POINTS

- Patients with atopy, especially children, are susceptible to all kinds of skin infections—fungal, bacterial, and viral.

- Herpes simplex virus (HSV) can appear in almost any location, including on fingers, but can also manifest as diffuse papulovesicular lesions on the face and chest of atopic patients.

- The blisters/vesicles of HSV are often pus-filled and usually provoke regional adenopathy.

- If diagnosed early enough, herpetic whitlows can be successfully treated with oral acyclovir; this doesn’t provide a cure but does stop the particular episode.

An 8-year-old boy is brought in for evaluation of a collection of blisters on his finger, near the nail. The problem manifested about 6 days ago. The affected area is tender to touch. The child reportedly feels well, with no fever or malaise.

The patient has an extensive personal and family history of atopy. Since birth, he has had dry, sensitive skin and has experienced episodes of eczema, seasonal allergies, and asthma. Three months ago, he was admitted to the hospital with eczema herpeticum and successfully treated with IV acyclovir.

EXAMINATION

A cluster of vesicles is seen in the lateral perionychial area of the left third finger. Very modest erythema surrounds the vesicles, which contain cloudy yellow fluid suggestive of pus. There is a palpable lymph node in the left epitrochlear area.

The child is afebrile and in no distress. Patches of mild eczema are seen on the extremities and trunk.

What’s the diagnosis?

DISCUSSION

The lesion on this child’s finger is a herpetic whitlow. Patients with atopy are often susceptible to all types of skin infections: bacterial, fungal, and viral. In fact, human papillomavirus infection manifesting as multiple warts is not uncommon in this population. Nor is herpes simplex virus (HSV) infection, of which this case represents 1 manifestation.

A culture could have been done to confirm the diagnosis, but that would entail opening a vesicle to collect the fluid and then waiting at least 2 weeks for the results. By then, this whitlow would have long since resolved.

As with all HSV infections in the immunocompetent, treatment with acyclovir must be started in the first 2 to 3 days to have any effect—so such treatment in this case would be useless. If the herpetic whitlow were to recur in the same location, prompt treatment could be initiated, which would likely shorten the disease course and reduce symptoms.

Another HSV infection seen almost exclusively in atopic patients is eczema herpeticum (also known as Kaposi varicelliform eruption). This diffuse infection comprises dozens of tiny papulovesicular lesions, mostly concentrated on the face but often spilling down onto the chest. Patients with Darier disease or seborrheic dermatitis can also acquire it.

TAKE-HOME LEARNING POINTS

- Patients with atopy, especially children, are susceptible to all kinds of skin infections—fungal, bacterial, and viral.

- Herpes simplex virus (HSV) can appear in almost any location, including on fingers, but can also manifest as diffuse papulovesicular lesions on the face and chest of atopic patients.

- The blisters/vesicles of HSV are often pus-filled and usually provoke regional adenopathy.

- If diagnosed early enough, herpetic whitlows can be successfully treated with oral acyclovir; this doesn’t provide a cure but does stop the particular episode.

An 8-year-old boy is brought in for evaluation of a collection of blisters on his finger, near the nail. The problem manifested about 6 days ago. The affected area is tender to touch. The child reportedly feels well, with no fever or malaise.

The patient has an extensive personal and family history of atopy. Since birth, he has had dry, sensitive skin and has experienced episodes of eczema, seasonal allergies, and asthma. Three months ago, he was admitted to the hospital with eczema herpeticum and successfully treated with IV acyclovir.

EXAMINATION

A cluster of vesicles is seen in the lateral perionychial area of the left third finger. Very modest erythema surrounds the vesicles, which contain cloudy yellow fluid suggestive of pus. There is a palpable lymph node in the left epitrochlear area.

The child is afebrile and in no distress. Patches of mild eczema are seen on the extremities and trunk.

What’s the diagnosis?

DISCUSSION

The lesion on this child’s finger is a herpetic whitlow. Patients with atopy are often susceptible to all types of skin infections: bacterial, fungal, and viral. In fact, human papillomavirus infection manifesting as multiple warts is not uncommon in this population. Nor is herpes simplex virus (HSV) infection, of which this case represents 1 manifestation.

A culture could have been done to confirm the diagnosis, but that would entail opening a vesicle to collect the fluid and then waiting at least 2 weeks for the results. By then, this whitlow would have long since resolved.

As with all HSV infections in the immunocompetent, treatment with acyclovir must be started in the first 2 to 3 days to have any effect—so such treatment in this case would be useless. If the herpetic whitlow were to recur in the same location, prompt treatment could be initiated, which would likely shorten the disease course and reduce symptoms.

Another HSV infection seen almost exclusively in atopic patients is eczema herpeticum (also known as Kaposi varicelliform eruption). This diffuse infection comprises dozens of tiny papulovesicular lesions, mostly concentrated on the face but often spilling down onto the chest. Patients with Darier disease or seborrheic dermatitis can also acquire it.

TAKE-HOME LEARNING POINTS

- Patients with atopy, especially children, are susceptible to all kinds of skin infections—fungal, bacterial, and viral.

- Herpes simplex virus (HSV) can appear in almost any location, including on fingers, but can also manifest as diffuse papulovesicular lesions on the face and chest of atopic patients.

- The blisters/vesicles of HSV are often pus-filled and usually provoke regional adenopathy.

- If diagnosed early enough, herpetic whitlows can be successfully treated with oral acyclovir; this doesn’t provide a cure but does stop the particular episode.

Poverty, incarceration may drive deaths from drug use

High rates of both incarceration and reduced household income are significantly associated with drug-related deaths in the United States, based a regression analysis of several decades of data.

“More than half a million drug-related deaths have occurred in the USA in the past three and half decades, however, no studies have investigated the association between these deaths and the expansion of the incarcerated population,” wrote Elias Nosrati, PhD, of the University of Oxford (England) and colleagues.

The researchers reviewed previously unavailable data on jail and prison incarceration at the county level from the nonprofit Vera Institute of Justice in New York, as well as mortality data from the U.S. National Vital Statistics System. The analysis was published in the Lancet Public Health.

After adjustment for multiple confounding variables, each standard deviation in admission rates to local jails (an average of 7,018 per 100,000 population) was associated with a significant 1.5% increase in drug-related deaths, and each standard deviation in admission rates to state prisons (an average of 254.6 per 100,000 population) was associated with a significant 2.6% increase in drug-related deaths, reported Dr. Nosrati and colleagues.

“On average, the researchers wrote. In addition, each standard-deviation decrease in median household income was associated with a 12.8% increase in drug-related deaths within counties.

The findings were limited by several factors, including the observational nature of the study, the potential skewing of results because of missing data from some counties, and the inability to examine support for individuals released from jail or prison, the researchers noted.

However, the results suggest that, “when coupled with economic hardship, the operations of the prison and jail systems constitute an upstream determinant of despair, whereby regular exposures to neighborhood violence, unstable social and family relationships, and psychosocial stress trigger destructive behaviours,” they wrote.

In an accompanying comment, James LePage, PhD, wrote that current laws regarding trespassing, loitering, and vagrancy “unfairly criminalize individuals of low economic status and homeless individuals” by increasing their likelihood of interaction with the legal system and thus increasing the incarceration rate in this population.

“Future studies should focus on racial and ethnic biases in arrests and sentencing, and the subsequent effect on drug-related mortality,” wrote Dr. LePage of the VA North Texas Health Care System in Dallas.

Neither the researchers in the main study nor Dr. LePage had financial conflicts to disclose.

SOURCE: Nosrati E et al. Lancet Public Health. 2019 Jul 3;4:e326-33.

High rates of both incarceration and reduced household income are significantly associated with drug-related deaths in the United States, based a regression analysis of several decades of data.

“More than half a million drug-related deaths have occurred in the USA in the past three and half decades, however, no studies have investigated the association between these deaths and the expansion of the incarcerated population,” wrote Elias Nosrati, PhD, of the University of Oxford (England) and colleagues.

The researchers reviewed previously unavailable data on jail and prison incarceration at the county level from the nonprofit Vera Institute of Justice in New York, as well as mortality data from the U.S. National Vital Statistics System. The analysis was published in the Lancet Public Health.

After adjustment for multiple confounding variables, each standard deviation in admission rates to local jails (an average of 7,018 per 100,000 population) was associated with a significant 1.5% increase in drug-related deaths, and each standard deviation in admission rates to state prisons (an average of 254.6 per 100,000 population) was associated with a significant 2.6% increase in drug-related deaths, reported Dr. Nosrati and colleagues.

“On average, the researchers wrote. In addition, each standard-deviation decrease in median household income was associated with a 12.8% increase in drug-related deaths within counties.

The findings were limited by several factors, including the observational nature of the study, the potential skewing of results because of missing data from some counties, and the inability to examine support for individuals released from jail or prison, the researchers noted.

However, the results suggest that, “when coupled with economic hardship, the operations of the prison and jail systems constitute an upstream determinant of despair, whereby regular exposures to neighborhood violence, unstable social and family relationships, and psychosocial stress trigger destructive behaviours,” they wrote.

In an accompanying comment, James LePage, PhD, wrote that current laws regarding trespassing, loitering, and vagrancy “unfairly criminalize individuals of low economic status and homeless individuals” by increasing their likelihood of interaction with the legal system and thus increasing the incarceration rate in this population.

“Future studies should focus on racial and ethnic biases in arrests and sentencing, and the subsequent effect on drug-related mortality,” wrote Dr. LePage of the VA North Texas Health Care System in Dallas.

Neither the researchers in the main study nor Dr. LePage had financial conflicts to disclose.

SOURCE: Nosrati E et al. Lancet Public Health. 2019 Jul 3;4:e326-33.

High rates of both incarceration and reduced household income are significantly associated with drug-related deaths in the United States, based a regression analysis of several decades of data.

“More than half a million drug-related deaths have occurred in the USA in the past three and half decades, however, no studies have investigated the association between these deaths and the expansion of the incarcerated population,” wrote Elias Nosrati, PhD, of the University of Oxford (England) and colleagues.

The researchers reviewed previously unavailable data on jail and prison incarceration at the county level from the nonprofit Vera Institute of Justice in New York, as well as mortality data from the U.S. National Vital Statistics System. The analysis was published in the Lancet Public Health.

After adjustment for multiple confounding variables, each standard deviation in admission rates to local jails (an average of 7,018 per 100,000 population) was associated with a significant 1.5% increase in drug-related deaths, and each standard deviation in admission rates to state prisons (an average of 254.6 per 100,000 population) was associated with a significant 2.6% increase in drug-related deaths, reported Dr. Nosrati and colleagues.

“On average, the researchers wrote. In addition, each standard-deviation decrease in median household income was associated with a 12.8% increase in drug-related deaths within counties.

The findings were limited by several factors, including the observational nature of the study, the potential skewing of results because of missing data from some counties, and the inability to examine support for individuals released from jail or prison, the researchers noted.

However, the results suggest that, “when coupled with economic hardship, the operations of the prison and jail systems constitute an upstream determinant of despair, whereby regular exposures to neighborhood violence, unstable social and family relationships, and psychosocial stress trigger destructive behaviours,” they wrote.

In an accompanying comment, James LePage, PhD, wrote that current laws regarding trespassing, loitering, and vagrancy “unfairly criminalize individuals of low economic status and homeless individuals” by increasing their likelihood of interaction with the legal system and thus increasing the incarceration rate in this population.

“Future studies should focus on racial and ethnic biases in arrests and sentencing, and the subsequent effect on drug-related mortality,” wrote Dr. LePage of the VA North Texas Health Care System in Dallas.

Neither the researchers in the main study nor Dr. LePage had financial conflicts to disclose.

SOURCE: Nosrati E et al. Lancet Public Health. 2019 Jul 3;4:e326-33.

FROM THE LANCET PUBLIC HEALTH

Key clinical point: Reduced household income and increased incarceration are significantly associated with drug-related deaths in the U.S. population.

Major finding: High incarceration rates are associated with an increase in drug-related deaths of more than 50% at the county level.

Study details: The data come from a regression analysis of data from multiple institutions, including the U.S. National Vital Statistics System and the Institute for Health Metrics and Evaluation, as well as incarceration data from the Vera Institute of Justice for 2,640 U.S. counties from 1983 to 2014.

Disclosures: The researchers had no financial conflicts to disclose.

Source: Nosrati E et al. Lancet Public Health. 2019 Jul 3;4:e326-33.

Testicular Cancer: Diagnosis and Treatment

Malignant testicular neoplasms can arise from either the germ cells or sex-cord stromal cells, with the former comprising approximately 95% of all testicular cancers (Table 1). Germ cell tumors may contain a single histology or a mix of multiple histologies. For clinical decision making, testicular tumors are categorized as either pure seminoma (no nonseminomatous elements present) or nonseminomatous germ cell tumors (NSGCT). The prevalence of seminoma and NSGCT is roughly equal. If a testicular tumor contains both seminomatous and nonseminomatous components, it is called a mixed germ cell tumor. Because of similarities in biological behavior, the approach to treatment of mixed germ cell tumors is similar to that for NSGCT.

The key points to remember for testicular cancer are:

- With early diagnosis and aggressive multidisciplinary therapy, the overwhelming majority of patients can be cured;

- Specialized care is often critical and affects outcomes; and

- Survivorship, or post-treatment care, is very important for these patients, as they often have lifespan of several decades and a unique set of short- and long-term treatment-related complications.

Developmental Biology and Genetics

The developmental biology of germ cells and germ cell neoplasms is beyond the scope of this review, and interested readers are recommended to refer to pertinent articles on the topic.1,2 A characteristic genetic marker of all germ cell tumors is an isochromosome of the short arm of chromosome 12, i(12p). This is present in testicular tumors regardless of histologic subtype as well as in carcinoma-in-situ. In germ cell tumors without i(12p) karyotype, excess 12p genetic material consisting of repetitive segments has been found, suggesting that this is an early and potentially critical change in oncogenesis.3 Several recent studies have revealed a diverse genomic landscape in testicular cancers, including KIT, KRAS and NRAS mutations in addition to a hyperdiploid karyotype.4,5

Evaluation and Diagnosis

Case Presentation

A 23-year-old Caucasian man presents to a primary care clinic for a pre-employment history and physical exam. He reports testicular pain on the sexually transmitted infections screening questionnaire. On examination, the physician finds a firm, mobile, minimally-tender, 1.5-cm mass in the inferior aspect of left testicle. No contralateral testicular mass or inguinal lymphadenopathy is noted, and a detailed physical exam is otherwise unremarkable. The physician immediately orders an ultrasound of the testicles, which shows a 1.5-cm hypoechoic mass in the inferior aspect of the left testicle, with an unremarkable contralateral testicle. After discussion of the results, the patient is referred a urologic oncologist with expertise in testicular cancer for further care.

The urologic oncologist orders a computed tomography (CT) abdomen and pelvis with and without contrast, which shows a 1.8-cm pathologic-appearing retroperitoneal lymph node at the level of the left renal vein. Chest radiograph with anteroposterior and lateral views is unremarkable. Tumor markers are as follows: beta human chorionic gonadotropin (beta-HCG) 8 mIU/mL (normal range, 0–4 mIU/mL), alpha-fetoprotein (AFP) 2 ng/mL (normal range, 0–8.5 ng/mL), and lactate dehydrogenase (LDH) 195 U/L (normal range, 119–213 U/L).

What is the approach to the initial workup and diagnosis of testicular cancer?

Clinical Presentation and Physical Exam

The majority of testicular cancers are diagnosed on work-up of a nodule or painless swelling of one testicle, usually noted incidentally by the patient. Approximately 30% to 40% of patients complain of a dull ache or heavy sensation in the lower abdomen, perianal area, or scrotum, while acute pain is the presenting symptom in 10%.3

In approximately 10% of patients, the presenting symptom is a result of distant metastatic involvement, such as cough and dyspnea on exertion (pulmonary or mediastinal metastasis), intractable bone pain (skeletal metastasis), intractable back/flank pain, presence of psoas sign or unexplained lower extremity deep vein thrombosis (bulky retroperitoneal metastasis), or central nervous system symptoms (vertebral, spinal or brain metastasis). Constitutional symptoms (unexplained weight loss, anorexia, fatigue) often accompany these symptoms.3

Rarely (5% or less), testicular cancer may present with systemic endocrine symptoms or paraneoplastic symptoms. Gynecomastia is the most common in this category, occurring in approximately 2% of germ cell tumors and more commonly (20%–30%) in Leydig cell tumors of testis.6 Classically, these patients are either 6- to 10-year-old boys with precocious puberty or young men (mid 20s-mid 30s) with a combination of testicular mass, gynecomastia, loss of libido, and impotence. Workup typically reveals increased beta-HCG levels in blood.

Anti-Ma2-antibody-associated limbic encephalitis is the most common (and still quite rare) paraneoplastic complication associated with testicular germ cell tumors. The Ma2 antigen is selectively expressed in the neuronal nucleoli of normal brain tissue and the testicular tumor of the patient. Importantly, in a subset of these patients, the treatment of testicular cancer may result in improvement of symptoms of encephalitis.7

The first step in the diagnosis of testicular neoplasm is a physical exam. This should include a bimanual examination of the scrotal contents, starting with the normal contralateral testis. Normal testicle has a homogeneous texture and consistency, is freely movable, and is separable from the epididymis. Any firm, hard, or fixed mass within the substance of the tunica albuginea should be considered suspicious until proven otherwise. Spread to the epididymis or spermatic cord occurs in 10% to 15% of patients and examination should include these structures as well.3 A comprehensive system-wise examination for features of metastatic spread as discussed above should then be performed. If the patient has cryptorchidism, ultrasound is a mandatory part of the diagnostic workup.

If clinical evaluation suggests a possibility of testicular cancer, the patient must be counseled to undergo an expedited diagnostic workup and specialist evaluation, as a prompt diagnosis and treatment is key to not only improving the likelihood of cure, but also minimizing the treatments needed to achieve it.

Role of Imaging

Scrotal Ultrasound

Scrotal ultrasound is the first imaging modality used in the diagnostic workup of patient with suspected testicular cancer. Bilateral scrotal ultrasound can detect lesions as small as 1 to 2 mm in diameter and help differentiate intratesticular lesions from extrinsic masses. A cystic mass on ultrasound is unlikely to be malignant. Seminomas appear as well-defined hypoechoic lesions without cystic areas, while NSGCTs are typically inhomogeneous with calcifications, cystic areas, and indistinct margins. However, this distinction is not always apparent or reliable. Ultrasound alone is also insufficient for tumor staging.8 For these reasons, a radical inguinal orchiectomy must be pursued for accurate determination of histology and local stage.

If testicular ultrasound shows a suspicious intratesticular mass, the following workup is typically done:

- Measurement of serum tumor markers (beta-HCG, AFP and LDH);

- CT abdomen and pelvis with and without contrast;

- Chest radiograph anteroposterior and lateral views, or CT chest with and without contrast if clinically indicated;

- Any additional focal imaging based on symptoms (eg, magnetic resonance imaging [MRI] scan with and without contrast to evaluate the brain if the patient has CNS symptoms).

CT Scan

CT scan is the preferred imaging modality for staging of testicular cancers, specifically for evaluation of the retroperitoneum, as it is the predominant site for metastases.9 CT scan should encompass the abdomen and pelvis, and contrast-enhanced sequences should be obtained unless medically contraindicated. CT scan of the chest (if not initially done) is compulsory should a CT of abdomen and pelvis and/or a chest radiograph show abnormal findings.

The sensitivity and specificity of CT scans for detection of nodal metastases can vary significantly based on the cutoff. For example, in a series of 70 patients using a cutoff of 10 mm, the sensitivity and specificity of CT scans for patients undergoing retroperitoneal lymph node dissection were 37% and 100%, respectively.10 In the same study, a cutoff of 4 mm increased the sensitivity to 93% and decreased the specificity to 58%. The current general consensus for this cutoff value is 8 to 10 mm measured in the short axis in the transverse (axial) plane.

Approximately 20% of men with clinical stage I testicular cancer (ie, those with non-enlarged retroperitoneal lymph nodes) who do not undergo any adjuvant therapy will have disease relapse in the retroperitoneum, suggesting that they had occult micrometastases that were missed on the initial CT scans.11,12

MRI/Radionuclide Bone Scan/PET Scan

Abdominal or pelvic MRI, whole-body radionuclide bone scan, and positron emission tomography (PET) scans are almost never needed as part of the initial staging workup for testicular cancers due to several limitations, including a high false-negative rate, specifically for the PET scans, and lack of any additional value compared with CT and testicular ultrasound alone.9,13,14 If necessary, these should only be ordered after a multidisciplinary oncology consultation to prevent unnecessary delays in treatment, inappropriate changes to treatment, and unnecessary increases in cost of care.

Tumor Markers, Biopsy, and Staging

What is the role of tumor markers in the management of testicular cancers?

Serum AFP, beta-hCG, and LDH have a well-established role as tumor markers in testicular cancer. The alpha subunit of hCG is shared between multiple pituitary hormones and hence does not serve as a specific marker for testicular cancer. Serum levels of AFP and/or beta-hCG are elevated in approximately 80% percent of men with NSGCTs, even in absence of metastatic spread. On the other hand, serum beta-hCG is elevated in less than 20% and AFP is not elevated in pure seminomas.3

Tumor markers by themselves are not sufficiently sensitive or specific for the diagnosis of testicular cancer, in general, or to differentiate among its subtypes. Despite this limitation, marked elevations in these markers are rarely due to causes other than germ cell tumor. For example, serum beta-hCG concentrations greater than 10,000 mIU/mL occur only in germ cell tumors, trophoblastic differentiation of a primary lung or gastric cancer, gestational trophoblastic disease, or pregnancy. Serum AFP concentrations greater than 10,000 ng/mL occur almost exclusively in germ cell tumors and hepatocellular carcinoma.15

The pattern of marker elevation may play an important role in management of testicular cancer patients. For example, in our practice, several patients have had discordant serum tumor markers and pathology results (eg, elevated AFP with pure seminoma on orchiectomy). One of these patients was treated with adjuvant retroperitoneal lymph node dissection, which confirmed that he had a NSGCT with a seminoma, choriocarcinoma, and teratoma on pathology evaluation of retroperitoneal lymph nodes.

Serum tumor markers have 2 additional critical roles—(1) in the American Joint Committee on Cancer (AJCC)/Union for International Cancer Control (UICC) staging16 and International Germ Cell Cancer Collaboration Group (IGCCCG) risk stratification of testicular cancer,17 and (2) in post-treatment disease monitoring.

Is a testicular biopsy necessary for diagnosis?

A testicular biopsy is almost never pursued to confirm the diagnosis of testicular cancer. There is a concern that percutaneous testicular biopsy, which is associated with scrotal skin violation, can adversely affect outcomes due to tumor seeding of scrotal sac or metastatic spread into the inguinal nodes via scrotal skin lymphatics.

Tissue diagnosis is made by radical orchiectomy in a majority of cases. Rarely in our practice, we obtain a biopsy of metastatic lesion for a tissue diagnosis. This is only done in cases where chemotherapy must be started urgently to prevent worsening of complications from metastatic spread. This decision should be made only after a multidisciplinary consultation with urologic and medical oncology teams.

How is testicular cancer staged?

Both seminomatous and nonseminomatous germ cell tumors of the testis are staged using the AJCC/UICC staging system, which incorporates assessments of the primary tumor (T), lymph nodes (N), and distant metastases (M) and serum tumor marker values (S). Details of this staging system are beyond the scope of this review and further information can be obtained through the AJCC website (www.cancerstaging.org). This TNMS staging enables a prognostic assessment and helps with the therapeutic approach.

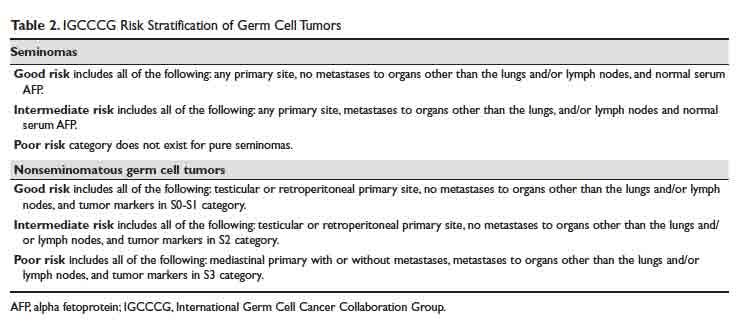

For patients with advanced germ cell tumors, a risk group classification developed by the IGCCCG is used to classify patients into good-risk, intermediate-risk, and poor-risk category (Table 2). This classification has been extensively validated for the past 2 decades, provides important prognostic information, and helps inform therapy decisions.

Treatment

Case 1 Continued

Based on the patient’s imaging and biomarker results, the patient undergoes a left radical inguinal orchiectomy. The physician’s operative note mentions that the left testicle was delivered without violation of scrotal integrity. A pathology report shows pure spermatocytic seminoma (unifocal, 1.4 cm size) with negative margins and no evidence of lymphovascular invasion. No lymph nodes are identified in the resection specimen. Post-orchiectomy markers are “negative,” meaning within normal range. After discussions with medical and radiation oncology physicians, the patient opts to pursue active surveillance.

Surgery alone followed by active surveillance is an appropriate option for this patient, as the likelihood of recurrence is low and most recurrences can be subsequently salvaged using treatment options detailed below.

What are the therapeutic options for testicular cancer?

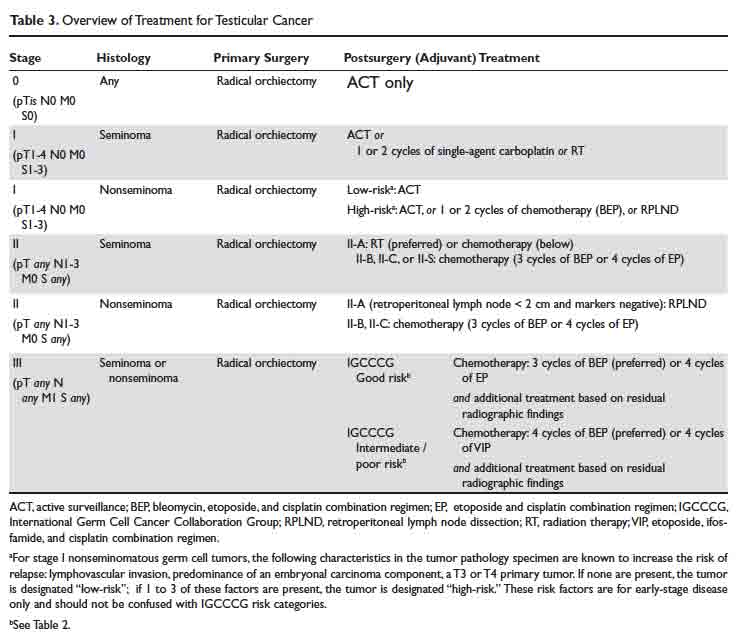

An overview of management for most testicular cancers is presented in Table 3. Note that the actual treatments are significantly more complex and need a comprehensive multidisciplinary consultation (urologic, medical and radiation oncology) at centers with specialized testicular cancer teams, if possible.

Fertility Preservation

All patients initiating treatment for testicular cancer must be offered options for fertility preservation and consultation with a reproductive health team, if available. At the time of diagnosis, approximately 50% patients have some degree of impairment in spermatogenesis, but with effective fertility preservation, successful pregnancy can occur for as many as 30% to 60% of patients.18,19

Orchiectomy

Radical inguinal orchiectomy with high ligation of the spermatic cord at the level of the internal ring is the procedure of choice for suspected testicular cancer. The goal is to provide a definitive tissue diagnosis and local tumor control with minimal morbidity. It can be performed under general, regional, or local anesthesia. Depending on the complexity and surgical expertise, it can be done in an inpatient or outpatient setting. During the procedure, the testicle is delivered from the scrotum through an incision in the inguinal region and then resected. A testicular prosthesis is usually inserted, with resultant excellent cosmetic and patient satisfaction outcomes.20

Testicular sparing surgery (TSS) has been explored as an alternative to radical orchiectomy but is not considered a standard-of-care option at this time. Small studies have shown evidence for comparable short-term oncologic outcomes in a very select group of patients, generally with solitary tumors < 2 cm in size and solitary testicle. If this is being considered as an option, we recommended obtaining a consultation from a urologist at a high-volume center. For a majority of patients, the value of a TSS is diminished due to excellent anatomic/cosmetic outcomes with a testicular prosthesis implanted during the radical orchiectomy, and resumption of sexual functions by the unaffected contralateral testicle.

Retroperitoneal Lymph Node Dissection

As discussed, conventional cross-sectional imaging has a high false-negative rate for detection of retroperitoneal involvement. General indications for RPLND in various stages and histologies of testicular cancer germ cell tumors are outlined in Table 3. Seminoma tends to most commonly metastasize to retroperitoneum, but RPLND for seminoma is generally reserved for a very small subset of these patients. Patterns of metastases of NSGCT (except choriocarcinoma) are considered to be well-defined. In a series of patients with stage II NSGCTs, left-sided tumors metastasized to the pre- and para-aortic nodes in 88% and 86% of cases, respectively (drainage basin of left testicular vein); and right-sided tumors involved the interaortocaval nodes in 93% of patients.3 Inguinal and pelvic nodal metastases may rarely be seen and should not be used to rule out the diagnosis of testicular cancer.

Choriocarcinoma is an exception to this pattern of retroperitoneal spread, as it tends to have a higher likelihood of hematogenous metastases to distant organs. Compared with NSGCTs, pure seminomas are either localized to the testis (80% of all cases) or limited to the retroperitoneum (an additional 15% of all cases) at presentation.3

Depending on the case and expertise of the surgical team, robotic or open RPLND can be performed.21 Regardless of the approach used, RPLND remains a technically challenging surgery. The retroperitoneal “landing zone” lymph nodes lie in close proximity to, and are often densely adherent to, the abdominal great vessels. Complication rates vary widely in the reported literature, but can be as high as 50%.21-23 As detailed in Table 2, the number and size of involved retroperitoneal lymph nodes have prognostic importance.

In summary, RPLND is considered to be a viable option for a subset of early-stage NSGCT (T1-3, N0-2, M0) and for those with advanced seminoma, NSGCT, or mixed germ cell tumors with post-chemotherapy residual disease.

Systemic Chemotherapy

Except for the single-agent carboplatin, most chemotherapy regimens used to treat testicular cancer are combinations of 2 or more chemotherapy agents. For this review, we will focus on the 3 most commonly used regimens: bleomycin, etoposide, and cisplatin (BEP), etoposide and cisplatin (EP), and etoposide, ifosfamide, and cisplatin (VIP).

The core principles of testicular cancer chemotherapy are:

- Minimize dose interruptions, delays, or reductions, as these adversely affect outcomes without clearly improving side effect profile;

- Do not substitute carboplatin for cisplatin in combination regimens because carboplatin-containing combination regimens have been shown to result in significantly poorer outcomes in multiple trials of adults with germ cell tumors;24-27 and

- Give myeloid growth factor support, if necessary.

BEP

The standard BEP regimen comprises a 21-day cycle with bleomycin 30 units on days 1, 8, and 15; etoposide 100 mg/m2 on days 1 to 5; and cisplatin 20 mg/m2 on days 1 to 5. Number of cycles varies based on histology and stage (Table 3). A strong justification to maintain treatment intensity comes from the Australian and New Zealand Germ Cell Trial Group trial. In this study, 166 men were randomly assigned to treatment using 3 cycles of standard BEP or 4 cycles of a modified BEP regimen (bleomycin 30 units day 1; etoposide 120 mg/m2 days 1 to 3; cisplatin 100 mg/m2 day 1) every 21 days. This trial was stopped at interim analyses because the modified BEP arm was inferior to the standard BEP arm. With a median follow-up of 8.5 years, 8-year overall survival was 92% with standard BEP and 83% with modified BEP (P = 0.037).28

Bleomycin used in the BEP regimen has been associated with uncommon but potentially fatal pulmonary toxicity that tends to present as interstitial pneumonitis, which may ultimately progress to fibrosis or bronchiolitis obliterans with organizing pneumonia.29 This has led to evaluation of EP as an alternative to BEP.

EP

The standard EP regimen consists of a 21-day cycle with etoposide 100 mg/m2 on days 1 to 5, and cisplatin 20 mg/m2 on days 1 to 5. Due to conflicting data from multiple randomized trials, there is considerable debate in the field regarding whether 4 cycles of EP are equivalent to 3 cycles of BEP.30,31 The benefit of the EP regimen is that it avoids the higher rates of pulmonary, cutaneous, and neurologic toxicities associated bleomycin, but it does result in the patient receiving an up to 33% higher cumulative dose of cisplatin and etoposide due to the extra cycle of treatment. This has important implications in terms of tolerability and side effects, including delayed toxicities such as second malignancies, which increase with a higher cumulative dose of these agents (etoposide in particular).

VIP

The standard VIP regimen consists of a 21-day cycle with etoposide 75 mg/m2 on days 1 to 5; cisplatin 20 mg/m2 on days 1 to 5; ifosfamide 1200 mg/m2 on days 1 to 5; and mesna 120 mg/m2 IV push on day 1 followed by 1200 mg/m2 on days 1 to 5. For patients with intermediate- or poor-risk disease, 4 cycles of VIP has demonstrated comparable efficacy but higher rates of hematologic toxicities compared with 4 cycles of BEP.32-34 It remains an option for upfront treatment of patients who are not good candidates for a bleomycin-based regimen, and for patients who need salvage chemotherapy.

Adverse Effects of Chemotherapy

Acute and late chemotherapy toxicities vary significantly between regimens depending on the chemotherapy drugs used. Bleomycin-induced pneumonitis may masquerade as a “pneumonia,” which can lead to a delay in diagnosis or institution of treatment, as well as institution of an incorrect treatment (for example, there is a concern that bleomycin toxicity can be precipitated or worsened by a high fraction of inspired oxygen). Chemotherapy-associated neutropenia tends to occur a few days (7–10 days) after initiation of chemotherapy, and neutrophil counts recover without intervention in most patients after an additional 7 to 10 days. Myeloid growth factor support (eg, filgrastim, pegfilgrastim) can be given to patients either prophylactically (if they had an episode of febrile or prolonged neutropenia with the preceding cycle) or secondarily if they present with neutropenia (an absolute neutrophil count ≤ 500 cells/µL) with fever or active infection. Such interventions tend to shorten the duration of neutropenia but does not affect overall survival. Patients with asymptomatic neutropenia do not benefit from growth factor use.35

Stem Cell Transplant

Autologous stem cell transplant (SCT) is the preferred type of SCT for patients with testicular cancer and involves delivery of high doses of chemotherapy followed by infusion of patient-derived myeloid stem cells. While the details of this treatment are outside the scope of this review, decades of experience has shown that this is an effective curative option for a subset of patients with poor prognosis, such as those with platinum-refractory or relapsed disease.36

Clinical Trials

Due to excellent clinical outcomes with front-line therapy, as described, and the relatively low incidence of testicular and other germ cell tumors, clinical trial options for patients with testicular cancer are limited. The TIGER trial is an ongoing international, randomized, phase 3 trial comparing conventional TIP (paclitaxel, ifosfamide, and cisplatin) chemotherapy with high-dose chemotherapy with SCT as the first salvage treatment for relapsed/refractory germ cell tumors (NCT02375204). It is enrolling at multiple centers in the United States and results are expected in 2022. At least 2 ongoing trials are evaluating the role of immunotherapy in patients with relapsed/refractory germ cell tumors (NCT03081923 and NCT03726281). Cluster of differentiation antigen-30 (CD30) has emerged as a potential target of interest in germ cell tumors, and brentuximab vedotin, an anti-CD30 monoclonal antibody, is undergoing evaluation in a phase 2 trial of CD-30–expressing germ cell tumors (NCT01851200). This trial has completed enrollment and results are expected to be available in late 2019 or early 2020.

When possible, patients with relapsed/refractory germ cell tumors should be referred to centers of excellence with access to either testicular/germ-cell tumor specific clinical trials or phase 1 clinical trials.

Radiation Therapy

Adjuvant radiation to the retroperitoneum has a role in the management of stage I and IIA seminomas (Table 3). In a randomized noninferiority trial of radiation therapy versus single-dose carboplatin in stage I seminoma patients, 5-year recurrence-free survival was comparable at approximately 95% in either arm.37,38 In a retrospective database review of 2437 patients receiving either radiation therapy or multi-agent chemotherapy for stage II seminoma, the 5-year survival exceeded 90% in both treatment groups.39 Typically, a total of 30 to 36 Gy of radiation is delivered to para-aortic and ipsilateral external iliac lymph nodes (“dog-leg” field), followed by an optional boost to the involved nodal areas.40 Radiation is associated with acute side effects such as fatigue, gastrointestinal effects, myelosuppression as well as late side effects such as second cancers in the irradiated field (eg, sarcoma, bladder cancer).

Evaluation of Treatment Response

Monitoring of treatment response is fairly straightforward for patients with testicular cancer. Our practice is the following:

- Measure tumor markers on day 1 of each chemotherapy cycle and 3 to 4 weeks after completion of treatment.

- CT of the chest, abdomen, and pelvis with intravenous contrast prior to chemotherapy and upon completion of chemotherapy. Interim imaging is only needed for a small subset of patients with additional clinical indications (eg, new symptoms, lack of improvement in existing symptoms).

- For patients with stage II/III seminoma who have a residual mass ≥ 3 cm on post-treatment CT scan, a PET-CT scan is indicated 6 to 8 weeks after the completion of chemotherapy to determine the need for further treatment.

Active Surveillance

Because testicular cancer has high cure rates even when patients have disease relapse after primary therapy, and additional therapies have significant short- and long-term side effects in these generally young patients, active surveillance is a critical option used in the management of testicular cancer.41

Patients must be counseled that active surveillance is a form of treatment itself in that it involves close clinical and radiographic monitoring. Because there is a risk of disease relapse, patients opting to undergo active surveillance must fully understand the risks of disease recurrence and be willing to abide by the recommended follow-up schedule.

Surveillance is necessary for a minimum of 5 years and possibly 10 years following orchiectomy, and most relapses tend to occur within the first 2 years. Late relapses such as skeletal metastatic disease from seminoma have been reported to occur more than 15 years after orchiectomy, but are generally rare and unpredictable.

The general guidelines for active surveillance are as follows:

For patients with seminoma, history and physical exam and tumor marker assessment should be performed every 3 to 6 months for the first year, then every 6 to 12 months in years 2 and 3, and then annually. CT of the abdomen and pelvis should be done at 3, 6, and 12 months, every 6 to 12 months in years 2 and 3, and then every 12 to 24 months in years 4 and 5. A chest radiograph is performed only if clinically indicated, as the likelihood of distant metastatic recurrence is low.

For patients with nonseminoma, history and physical exam and tumor markers assessment should be performed every 2 to 3 months for first 2 years, every 4 to 6 months in years 3 and 4, and then annually. CT of the abdomen and pelvis should be obtained every 4 to 6 months in year 1, gradually decreasing to annually in year 3 or 4. Chest radiograph is indicated at 4 and 12 months and annually thereafter for stage IA disease. For those with stage IB disease, chest radiograph is indicated every 2 months during the first year and then gradually decreasing to annually beginning year 5.

These recommendations are expected to change over time, and treating physicians are recommended to exercise discretion and consider the patient and tumor characteristics to develop the optimal surveillance plan.

Conclusion

Testicular cancer is the most common cancer afflicting young men. Prompt diagnostic workup initiated in a primary care or hospital setting followed by a referral to a multidisciplinary team of urologists, medical oncologists, and radiation oncologists enables cure in a majority of patients. For patients with stage I seminoma, a radical inguinal orchiectomy followed by active surveillance may offer the best long-term outcome with minimal side effects. For patients with relapsed/refractory testicular cancers, clinical trial participation is strongly encouraged. Patients with a history of testicular cancer benefit from robust survivorship care tailored to their prior therapies. This can be safely delivered through their primary care providers in collaboration with the multidisciplinary oncology team.

1. van der Zwan YG, Biermann K, Wolffenbuttel KP, et al. Gonadal maldevelopment as risk factor for germ cell cancer: towards a clinical decision model. Eur Urol. 2015; 67:692–701.

2. Pierce JL, Frazier AL, Amatruda JF. Pediatric germ cell tumors: a developmental perspective. Adv Urol. 2018 Feb 4;2018.

3. Bosl GJ, Motzer RJ. Testicular germ-cell cancer. N Engl J Med. 1997;337:242-253.

4. Pyle LC, Nathanson KL. Genetic changes associated with testicular cancer susceptibility. Semin Oncol. 2016;43:575-581.

5. Shen H, Shih J, Hollern DP, et al. Integrated molecular characterization of testicular germ cell tumors. Cell Rep. 2018;23:3392-3406.

6. Barry M, Rao A, Lauer R. Sex cord-stromal tumors of the testis. In: Pagliaro L, ed. Rare Genitourinary Tumors. Cham: Springer International Publishing; 2016: 231-251.

7. Dalmau J, Graus F, Villarejo A, et al. Clinical analysis of anti-Ma2-associated encephalitis. Brain J Neurol. 2004;127:1831-1844.

8. Coursey Moreno C, Small WC, Camacho JC, et al. Testicular tumors: what radiologists need to know—differential diagnosis, staging, and management. RadioGraphics. 2015;35:400-415.

9. Kreydin EI, Barrisford GW, Feldman AS, Preston MA. Testicular cancer: what the radiologist needs to know. Am J Roentgenol. 2013;200:1215-1225.

10. Hilton S, Herr HW, Teitcher JB, et al. CT detection of retroperitoneal lymph node metastases in patients with clinical stage I testicular nonseminomatous germ cell cancer: assessment of size and distribution criteria. Am J Roentgenol. 1997;169:521-525.

11. Thompson PI, Nixon J, Harvey VJ. Disease relapse in patients with stage I nonseminomatous germ cell tumor of the testis on active surveillance. J Clin Oncol. 1988;6:1597-1603.

12. Nicolai N, Pizzocaro G. A surveillance study of clinical stage I nonseminomatous germ cell tumors of the testis: 10-year followup. J Urol. 1995;154:1045-1049.

13. Kok HK, Leong S, Torreggiani WC. Is magnetic resonance imaging comparable with computed tomography in the diagnosis of retroperitoneal metastasis in patients with testicular cancer? Can Assoc Radiol J. 2014;65:196-198.

14. Hale GR, Teplitsky S, Truong H, et al. Lymph node imaging in testicular cancer. Transl Androl Urol. 2018;7:864-874.

15. Honecker F, Aparicio J, Berney D, et al. ESMO Consensus Conference on testicular germ cell cancer: diagnosis, treatment and follow-up. Ann Oncol. 2018;29:1658-1686.

16. Paner GP, Stadler WM, Hansel DE, et al. Updates in the Eighth Edition of the Tumor-Node-Metastasis Staging Classification for Urologic Cancers. Eur Urol. 2018;73:560-569.

17. International Germ Cell Cancer Collaborative Group. International Germ Cell Consensus Classification: a prognostic factor-based staging system for metastatic germ cell cancers. International Germ Cell Cancer Collaborative Group. J Clin Oncol. 1997;15:594-603.

18. Lopategui DM, Ibrahim E, Aballa TC, et al. Effect of a formal oncofertility program on fertility preservation rates-first year experience. Transl Androl Urol. 2018;7:S271-S275.

19. Moody JA, Ahmed K, Horsfield C, et al. Fertility preservation in testicular cancer - predictors of spermatogenesis. BJU Int. 2018;122:236-242.

20. Dieckmann KP, Anheuser P, Schmidt S, et al. Testicular prostheses in patients with testicular cancer - acceptance rate and patient satisfaction. BMC Urol. 2015;15:16.

21. Schwen ZR, Gupta M, Pierorazio PM. A review of outcomes and technique for the robotic-assisted laparoscopic retroperitoneal lymph node dissection for testicular cancer. Adv Urol. 2018;2146080.

22. Singh P, Yadav S, Mahapatra S, Seth A. Outcomes following retroperitoneal lymph node dissection in postchemotherapy residual masses in advanced testicular germ cell tumors. Indian J Urol. 2016;32:40-44.

23. Heidenreich A, Thüer D, Polyakov S. Postchemotherapy retroperitoneal lymph node dissection in advanced germ cell tumours of the testis. Eur Urol. 2008;53:260-272.

24. Bajorin DF, Sarosdy MF, Pfister DG, et al. Randomized trial of etoposide and cisplatin versus etoposide and carboplatin in patients with good-risk germ cell tumors: a multiinstitutional study. J Clin Oncol. 1993;11:598-606.

25. Bokemeyer C, Köhrmann O, Tischler J, et al. A randomized trial of cisplatin, etoposide and bleomycin (PEB) versus carboplatin, etoposide and bleomycin (CEB) for patients with “good-risk” metastatic non-seminomatous germ cell tumors. Ann Oncol. 1996;7:1015-1021.

26. Horwich A, Sleijfer DT, Fosså SD, et al. Randomized trial of bleomycin, etoposide, and cisplatin compared with bleomycin, etoposide, and carboplatin in good-prognosis metastatic nonseminomatous germ cell cancer: a Multiinstitutional Medical Research Council/European Organization for Research and Treatment of Cancer Trial. J Clin Oncol. 1997;15:1844-1852.

27. Shaikh F, Nathan PC, Hale J, et al. Is there a role for carboplatin in the treatment of malignant germ cell tumors? A systematic review of adult and pediatric trials. Pediatr Blood Cancer. 2013;60:587-592.

28. Grimison PS, Stockler MR, Thomson DB, et al. Comparison of two standard chemotherapy regimens for good-prognosis germ cell tumors: updated analysis of a randomized trial. J Natl Cancer Inst. 2010;102:1253-1262.

29. Reinert T, da Rocha Baldotto CS, Nunes FAP, de Souza Scheliga AA. Bleomycin-induced lung injury. J Cancer Res. 2013;480608.

30. Jones RH, Vasey PA. Part II: Testicular cancer—management of advanced disease. Lancet Oncol. 2003;4:738-747.

31. Jankilevich G. BEP versus EP for treatment of metastatic germ-cell tumours. Lancet Oncol. 2004;5, 146.

32. Nichols CR, Catalano PJ, Crawford ED, et al. Randomized comparison of cisplatin and etoposide and either bleomycin or ifosfamide in treatment of advanced disseminated germ cell tumors: an Eastern Cooperative Oncology Group, Southwest Oncology Group, and Cancer and Leukemia Group B Study. J Clin Oncol. 1998;16:12871293.

33. Hinton S, Catalano PJ, Einhorn LH, et al. Cisplatin, etoposide and either bleomycin or ifosfamide in the treatment of disseminated germ cell tumors: final analysis of an intergroup trial. Cancer. 2003;97: 1869-1875.

34. de Wit R, Stoter G, Sleijfer DT, et al. Four cycles of BEP vs four cycles of VIP in patients with intermediate-prognosis metastatic testicular non-seminoma: a randomized study of the EORTC Genitourinary Tract Cancer Cooperative Group. European Organization for Research and Treatment of Cancer. Br J Cancer. 1998;78:828-832.

35. Mhaskar R, Clark OA, Lyman G, et al. Colony-stimulating factors for chemotherapy-induced febrile neutropenia. Cochrane Database Syst. Rev. 2014;CD003039.

36. Adra N, Abonour R, Althouse SK, et al. High-dose chemotherapy and autologous peripheral-blood stem-cell transplantation for relapsed metastatic germ cell tumors: The Indiana University experience. J Clin Oncol. 2017;35:1096-1102.

37. Oliver RT, Mason MD, Mead GM, et al. Radiotherapy versus single-dose carboplatin in adjuvant treatment of stage I seminoma: a randomised trial. Lancet. 2005;366:293-300.

38. Oliver RT, Mead GM, Rustin GJ, et al. Randomized trial of carboplatin versus radiotherapy for stage I seminoma: mature results on relapse and contralateral testis cancer rates in MRC TE19/EORTC 30982 study (ISRCTN27163214). J Clin Oncol. 2011;29:957-962.

39. Glaser SM, Vargo JA, Balasubramani GK, Beriwal S. Stage II testicular seminoma: patterns of care and survival by treatment strategy. Clin Oncol. 2016;28:513-521.

40. Boujelbene N, Cosinschi A, Boujelbene N, et al. Pure seminoma: A review and update. Radiat Oncol. 2011;6:90.

41. Nichols CR, Roth B, Albers P, et al. Active surveillance is the preferred approach to clinical stage I testicular cancer. J Clin Oncol. 2013;31;3490-3493.

Malignant testicular neoplasms can arise from either the germ cells or sex-cord stromal cells, with the former comprising approximately 95% of all testicular cancers (Table 1). Germ cell tumors may contain a single histology or a mix of multiple histologies. For clinical decision making, testicular tumors are categorized as either pure seminoma (no nonseminomatous elements present) or nonseminomatous germ cell tumors (NSGCT). The prevalence of seminoma and NSGCT is roughly equal. If a testicular tumor contains both seminomatous and nonseminomatous components, it is called a mixed germ cell tumor. Because of similarities in biological behavior, the approach to treatment of mixed germ cell tumors is similar to that for NSGCT.

The key points to remember for testicular cancer are:

- With early diagnosis and aggressive multidisciplinary therapy, the overwhelming majority of patients can be cured;

- Specialized care is often critical and affects outcomes; and

- Survivorship, or post-treatment care, is very important for these patients, as they often have lifespan of several decades and a unique set of short- and long-term treatment-related complications.

Developmental Biology and Genetics

The developmental biology of germ cells and germ cell neoplasms is beyond the scope of this review, and interested readers are recommended to refer to pertinent articles on the topic.1,2 A characteristic genetic marker of all germ cell tumors is an isochromosome of the short arm of chromosome 12, i(12p). This is present in testicular tumors regardless of histologic subtype as well as in carcinoma-in-situ. In germ cell tumors without i(12p) karyotype, excess 12p genetic material consisting of repetitive segments has been found, suggesting that this is an early and potentially critical change in oncogenesis.3 Several recent studies have revealed a diverse genomic landscape in testicular cancers, including KIT, KRAS and NRAS mutations in addition to a hyperdiploid karyotype.4,5

Evaluation and Diagnosis

Case Presentation

A 23-year-old Caucasian man presents to a primary care clinic for a pre-employment history and physical exam. He reports testicular pain on the sexually transmitted infections screening questionnaire. On examination, the physician finds a firm, mobile, minimally-tender, 1.5-cm mass in the inferior aspect of left testicle. No contralateral testicular mass or inguinal lymphadenopathy is noted, and a detailed physical exam is otherwise unremarkable. The physician immediately orders an ultrasound of the testicles, which shows a 1.5-cm hypoechoic mass in the inferior aspect of the left testicle, with an unremarkable contralateral testicle. After discussion of the results, the patient is referred a urologic oncologist with expertise in testicular cancer for further care.

The urologic oncologist orders a computed tomography (CT) abdomen and pelvis with and without contrast, which shows a 1.8-cm pathologic-appearing retroperitoneal lymph node at the level of the left renal vein. Chest radiograph with anteroposterior and lateral views is unremarkable. Tumor markers are as follows: beta human chorionic gonadotropin (beta-HCG) 8 mIU/mL (normal range, 0–4 mIU/mL), alpha-fetoprotein (AFP) 2 ng/mL (normal range, 0–8.5 ng/mL), and lactate dehydrogenase (LDH) 195 U/L (normal range, 119–213 U/L).

What is the approach to the initial workup and diagnosis of testicular cancer?

Clinical Presentation and Physical Exam

The majority of testicular cancers are diagnosed on work-up of a nodule or painless swelling of one testicle, usually noted incidentally by the patient. Approximately 30% to 40% of patients complain of a dull ache or heavy sensation in the lower abdomen, perianal area, or scrotum, while acute pain is the presenting symptom in 10%.3

In approximately 10% of patients, the presenting symptom is a result of distant metastatic involvement, such as cough and dyspnea on exertion (pulmonary or mediastinal metastasis), intractable bone pain (skeletal metastasis), intractable back/flank pain, presence of psoas sign or unexplained lower extremity deep vein thrombosis (bulky retroperitoneal metastasis), or central nervous system symptoms (vertebral, spinal or brain metastasis). Constitutional symptoms (unexplained weight loss, anorexia, fatigue) often accompany these symptoms.3

Rarely (5% or less), testicular cancer may present with systemic endocrine symptoms or paraneoplastic symptoms. Gynecomastia is the most common in this category, occurring in approximately 2% of germ cell tumors and more commonly (20%–30%) in Leydig cell tumors of testis.6 Classically, these patients are either 6- to 10-year-old boys with precocious puberty or young men (mid 20s-mid 30s) with a combination of testicular mass, gynecomastia, loss of libido, and impotence. Workup typically reveals increased beta-HCG levels in blood.

Anti-Ma2-antibody-associated limbic encephalitis is the most common (and still quite rare) paraneoplastic complication associated with testicular germ cell tumors. The Ma2 antigen is selectively expressed in the neuronal nucleoli of normal brain tissue and the testicular tumor of the patient. Importantly, in a subset of these patients, the treatment of testicular cancer may result in improvement of symptoms of encephalitis.7

The first step in the diagnosis of testicular neoplasm is a physical exam. This should include a bimanual examination of the scrotal contents, starting with the normal contralateral testis. Normal testicle has a homogeneous texture and consistency, is freely movable, and is separable from the epididymis. Any firm, hard, or fixed mass within the substance of the tunica albuginea should be considered suspicious until proven otherwise. Spread to the epididymis or spermatic cord occurs in 10% to 15% of patients and examination should include these structures as well.3 A comprehensive system-wise examination for features of metastatic spread as discussed above should then be performed. If the patient has cryptorchidism, ultrasound is a mandatory part of the diagnostic workup.

If clinical evaluation suggests a possibility of testicular cancer, the patient must be counseled to undergo an expedited diagnostic workup and specialist evaluation, as a prompt diagnosis and treatment is key to not only improving the likelihood of cure, but also minimizing the treatments needed to achieve it.

Role of Imaging

Scrotal Ultrasound

Scrotal ultrasound is the first imaging modality used in the diagnostic workup of patient with suspected testicular cancer. Bilateral scrotal ultrasound can detect lesions as small as 1 to 2 mm in diameter and help differentiate intratesticular lesions from extrinsic masses. A cystic mass on ultrasound is unlikely to be malignant. Seminomas appear as well-defined hypoechoic lesions without cystic areas, while NSGCTs are typically inhomogeneous with calcifications, cystic areas, and indistinct margins. However, this distinction is not always apparent or reliable. Ultrasound alone is also insufficient for tumor staging.8 For these reasons, a radical inguinal orchiectomy must be pursued for accurate determination of histology and local stage.

If testicular ultrasound shows a suspicious intratesticular mass, the following workup is typically done:

- Measurement of serum tumor markers (beta-HCG, AFP and LDH);

- CT abdomen and pelvis with and without contrast;

- Chest radiograph anteroposterior and lateral views, or CT chest with and without contrast if clinically indicated;

- Any additional focal imaging based on symptoms (eg, magnetic resonance imaging [MRI] scan with and without contrast to evaluate the brain if the patient has CNS symptoms).

CT Scan

CT scan is the preferred imaging modality for staging of testicular cancers, specifically for evaluation of the retroperitoneum, as it is the predominant site for metastases.9 CT scan should encompass the abdomen and pelvis, and contrast-enhanced sequences should be obtained unless medically contraindicated. CT scan of the chest (if not initially done) is compulsory should a CT of abdomen and pelvis and/or a chest radiograph show abnormal findings.

The sensitivity and specificity of CT scans for detection of nodal metastases can vary significantly based on the cutoff. For example, in a series of 70 patients using a cutoff of 10 mm, the sensitivity and specificity of CT scans for patients undergoing retroperitoneal lymph node dissection were 37% and 100%, respectively.10 In the same study, a cutoff of 4 mm increased the sensitivity to 93% and decreased the specificity to 58%. The current general consensus for this cutoff value is 8 to 10 mm measured in the short axis in the transverse (axial) plane.

Approximately 20% of men with clinical stage I testicular cancer (ie, those with non-enlarged retroperitoneal lymph nodes) who do not undergo any adjuvant therapy will have disease relapse in the retroperitoneum, suggesting that they had occult micrometastases that were missed on the initial CT scans.11,12

MRI/Radionuclide Bone Scan/PET Scan

Abdominal or pelvic MRI, whole-body radionuclide bone scan, and positron emission tomography (PET) scans are almost never needed as part of the initial staging workup for testicular cancers due to several limitations, including a high false-negative rate, specifically for the PET scans, and lack of any additional value compared with CT and testicular ultrasound alone.9,13,14 If necessary, these should only be ordered after a multidisciplinary oncology consultation to prevent unnecessary delays in treatment, inappropriate changes to treatment, and unnecessary increases in cost of care.

Tumor Markers, Biopsy, and Staging

What is the role of tumor markers in the management of testicular cancers?

Serum AFP, beta-hCG, and LDH have a well-established role as tumor markers in testicular cancer. The alpha subunit of hCG is shared between multiple pituitary hormones and hence does not serve as a specific marker for testicular cancer. Serum levels of AFP and/or beta-hCG are elevated in approximately 80% percent of men with NSGCTs, even in absence of metastatic spread. On the other hand, serum beta-hCG is elevated in less than 20% and AFP is not elevated in pure seminomas.3

Tumor markers by themselves are not sufficiently sensitive or specific for the diagnosis of testicular cancer, in general, or to differentiate among its subtypes. Despite this limitation, marked elevations in these markers are rarely due to causes other than germ cell tumor. For example, serum beta-hCG concentrations greater than 10,000 mIU/mL occur only in germ cell tumors, trophoblastic differentiation of a primary lung or gastric cancer, gestational trophoblastic disease, or pregnancy. Serum AFP concentrations greater than 10,000 ng/mL occur almost exclusively in germ cell tumors and hepatocellular carcinoma.15

The pattern of marker elevation may play an important role in management of testicular cancer patients. For example, in our practice, several patients have had discordant serum tumor markers and pathology results (eg, elevated AFP with pure seminoma on orchiectomy). One of these patients was treated with adjuvant retroperitoneal lymph node dissection, which confirmed that he had a NSGCT with a seminoma, choriocarcinoma, and teratoma on pathology evaluation of retroperitoneal lymph nodes.

Serum tumor markers have 2 additional critical roles—(1) in the American Joint Committee on Cancer (AJCC)/Union for International Cancer Control (UICC) staging16 and International Germ Cell Cancer Collaboration Group (IGCCCG) risk stratification of testicular cancer,17 and (2) in post-treatment disease monitoring.

Is a testicular biopsy necessary for diagnosis?

A testicular biopsy is almost never pursued to confirm the diagnosis of testicular cancer. There is a concern that percutaneous testicular biopsy, which is associated with scrotal skin violation, can adversely affect outcomes due to tumor seeding of scrotal sac or metastatic spread into the inguinal nodes via scrotal skin lymphatics.

Tissue diagnosis is made by radical orchiectomy in a majority of cases. Rarely in our practice, we obtain a biopsy of metastatic lesion for a tissue diagnosis. This is only done in cases where chemotherapy must be started urgently to prevent worsening of complications from metastatic spread. This decision should be made only after a multidisciplinary consultation with urologic and medical oncology teams.

How is testicular cancer staged?

Both seminomatous and nonseminomatous germ cell tumors of the testis are staged using the AJCC/UICC staging system, which incorporates assessments of the primary tumor (T), lymph nodes (N), and distant metastases (M) and serum tumor marker values (S). Details of this staging system are beyond the scope of this review and further information can be obtained through the AJCC website (www.cancerstaging.org). This TNMS staging enables a prognostic assessment and helps with the therapeutic approach.

For patients with advanced germ cell tumors, a risk group classification developed by the IGCCCG is used to classify patients into good-risk, intermediate-risk, and poor-risk category (Table 2). This classification has been extensively validated for the past 2 decades, provides important prognostic information, and helps inform therapy decisions.

Treatment

Case 1 Continued

Based on the patient’s imaging and biomarker results, the patient undergoes a left radical inguinal orchiectomy. The physician’s operative note mentions that the left testicle was delivered without violation of scrotal integrity. A pathology report shows pure spermatocytic seminoma (unifocal, 1.4 cm size) with negative margins and no evidence of lymphovascular invasion. No lymph nodes are identified in the resection specimen. Post-orchiectomy markers are “negative,” meaning within normal range. After discussions with medical and radiation oncology physicians, the patient opts to pursue active surveillance.

Surgery alone followed by active surveillance is an appropriate option for this patient, as the likelihood of recurrence is low and most recurrences can be subsequently salvaged using treatment options detailed below.

What are the therapeutic options for testicular cancer?

An overview of management for most testicular cancers is presented in Table 3. Note that the actual treatments are significantly more complex and need a comprehensive multidisciplinary consultation (urologic, medical and radiation oncology) at centers with specialized testicular cancer teams, if possible.

Fertility Preservation

All patients initiating treatment for testicular cancer must be offered options for fertility preservation and consultation with a reproductive health team, if available. At the time of diagnosis, approximately 50% patients have some degree of impairment in spermatogenesis, but with effective fertility preservation, successful pregnancy can occur for as many as 30% to 60% of patients.18,19

Orchiectomy

Radical inguinal orchiectomy with high ligation of the spermatic cord at the level of the internal ring is the procedure of choice for suspected testicular cancer. The goal is to provide a definitive tissue diagnosis and local tumor control with minimal morbidity. It can be performed under general, regional, or local anesthesia. Depending on the complexity and surgical expertise, it can be done in an inpatient or outpatient setting. During the procedure, the testicle is delivered from the scrotum through an incision in the inguinal region and then resected. A testicular prosthesis is usually inserted, with resultant excellent cosmetic and patient satisfaction outcomes.20