User login

In reply: Aleukemic leukemia cutis

In Reply: We greatly appreciate our reader’s interest and response. He brings up a very good point. We have reviewed the reports and discussed it with our pathologists. On page 85, the sentence that begins, “The findings were consistent with leukemic T cells with monocytic differentiation” should actually read, “The findings were consistent with leukemic cells with monocytic differentiation.” The patient was appropriately treated for acute myeloid leukemia.

In Reply: We greatly appreciate our reader’s interest and response. He brings up a very good point. We have reviewed the reports and discussed it with our pathologists. On page 85, the sentence that begins, “The findings were consistent with leukemic T cells with monocytic differentiation” should actually read, “The findings were consistent with leukemic cells with monocytic differentiation.” The patient was appropriately treated for acute myeloid leukemia.

In Reply: We greatly appreciate our reader’s interest and response. He brings up a very good point. We have reviewed the reports and discussed it with our pathologists. On page 85, the sentence that begins, “The findings were consistent with leukemic T cells with monocytic differentiation” should actually read, “The findings were consistent with leukemic cells with monocytic differentiation.” The patient was appropriately treated for acute myeloid leukemia.

Leadership and Professional Development: The Healing Power of Laughter

“The most radical act anyone can commit is to be happy.”

—Patch Adams

“The most radical act anyone can commit is to be happy.”

—Patch Adams

“The most radical act anyone can commit is to be happy.”

—Patch Adams

© 2019 Society of Hospital Medicine

Women Veterans Call Center Now Offers Text Feature

“What is my veteran status?” “Should I receive any benefits from VA, like the GI Bill?”

Now women veterans have another convenient way to get answers to questions like those. Texting 855.829.6636 (855.VA.WOMEN) connects women veterans to the Women Veterans Call Center, where they will find information about VA benefits, health care, and resources. The new texting feature aligns the service with those of other VA call centers, the VA says.

Women are among the fastest-growing veteran demographics , the VA says, accounting for > 30% of the increase in veterans who served between 2014 and 2018. The number of women using VA health care services has tripled since 2000 from about 160,000 to > 500,000. But the VA has found that women veterans underuse VA care, largely due to a lack of knowledge about benefits, services, and their eligibility for them. As the number of women veterans continues to grow, the VA says, it is expanding its outreach to ensure they receive enrollment and benefits information through user-friendly and responsive means. The VA says it works to meet the unique requirements of women, “offering privacy, dignity, and sensitivity to gender-specific needs.” In addition to linking callers to information, the call center staff make direct referrals to Women Veteran Program Managers at every VAMC.

Since 2013, the call center has received nearly 83,000 inbound calls and has initiated almost 1.3 million outbound calls, resulting in communication with > 650,000 veterans.

Staffed by trained, compassionate female VA employees (many are also veterans), the call center is available Monday through Friday 8 am to 10 pm ET and Saturdays from 8 am to 6:30 pm ET. Veterans can call for themselves or on behalf of another woman veteran. Calls are free and confidential, texts and chats are anonymous. Veterans can call as often as they like, the VA says—“until you have the answer to your questions.”

For more information about the Women Veterans Call Center, visit https://www.womenshealth.va.gov/programoverview/wvcc.asp.

“What is my veteran status?” “Should I receive any benefits from VA, like the GI Bill?”

Now women veterans have another convenient way to get answers to questions like those. Texting 855.829.6636 (855.VA.WOMEN) connects women veterans to the Women Veterans Call Center, where they will find information about VA benefits, health care, and resources. The new texting feature aligns the service with those of other VA call centers, the VA says.

Women are among the fastest-growing veteran demographics , the VA says, accounting for > 30% of the increase in veterans who served between 2014 and 2018. The number of women using VA health care services has tripled since 2000 from about 160,000 to > 500,000. But the VA has found that women veterans underuse VA care, largely due to a lack of knowledge about benefits, services, and their eligibility for them. As the number of women veterans continues to grow, the VA says, it is expanding its outreach to ensure they receive enrollment and benefits information through user-friendly and responsive means. The VA says it works to meet the unique requirements of women, “offering privacy, dignity, and sensitivity to gender-specific needs.” In addition to linking callers to information, the call center staff make direct referrals to Women Veteran Program Managers at every VAMC.

Since 2013, the call center has received nearly 83,000 inbound calls and has initiated almost 1.3 million outbound calls, resulting in communication with > 650,000 veterans.

Staffed by trained, compassionate female VA employees (many are also veterans), the call center is available Monday through Friday 8 am to 10 pm ET and Saturdays from 8 am to 6:30 pm ET. Veterans can call for themselves or on behalf of another woman veteran. Calls are free and confidential, texts and chats are anonymous. Veterans can call as often as they like, the VA says—“until you have the answer to your questions.”

For more information about the Women Veterans Call Center, visit https://www.womenshealth.va.gov/programoverview/wvcc.asp.

“What is my veteran status?” “Should I receive any benefits from VA, like the GI Bill?”

Now women veterans have another convenient way to get answers to questions like those. Texting 855.829.6636 (855.VA.WOMEN) connects women veterans to the Women Veterans Call Center, where they will find information about VA benefits, health care, and resources. The new texting feature aligns the service with those of other VA call centers, the VA says.

Women are among the fastest-growing veteran demographics , the VA says, accounting for > 30% of the increase in veterans who served between 2014 and 2018. The number of women using VA health care services has tripled since 2000 from about 160,000 to > 500,000. But the VA has found that women veterans underuse VA care, largely due to a lack of knowledge about benefits, services, and their eligibility for them. As the number of women veterans continues to grow, the VA says, it is expanding its outreach to ensure they receive enrollment and benefits information through user-friendly and responsive means. The VA says it works to meet the unique requirements of women, “offering privacy, dignity, and sensitivity to gender-specific needs.” In addition to linking callers to information, the call center staff make direct referrals to Women Veteran Program Managers at every VAMC.

Since 2013, the call center has received nearly 83,000 inbound calls and has initiated almost 1.3 million outbound calls, resulting in communication with > 650,000 veterans.

Staffed by trained, compassionate female VA employees (many are also veterans), the call center is available Monday through Friday 8 am to 10 pm ET and Saturdays from 8 am to 6:30 pm ET. Veterans can call for themselves or on behalf of another woman veteran. Calls are free and confidential, texts and chats are anonymous. Veterans can call as often as they like, the VA says—“until you have the answer to your questions.”

For more information about the Women Veterans Call Center, visit https://www.womenshealth.va.gov/programoverview/wvcc.asp.

Looking for the Link Between Smoking and STDs

Cigarette smoking has been linked to the diagnosis of bacterial vaginosis (BV) and other genital infections including herpes simplex virus type 2, Chlamydia trachomatis, and oral and genital human papillomavirus (HPV). Nicotine’s major metabolite, cotinine, has been found to concentrate in cervical mucus.

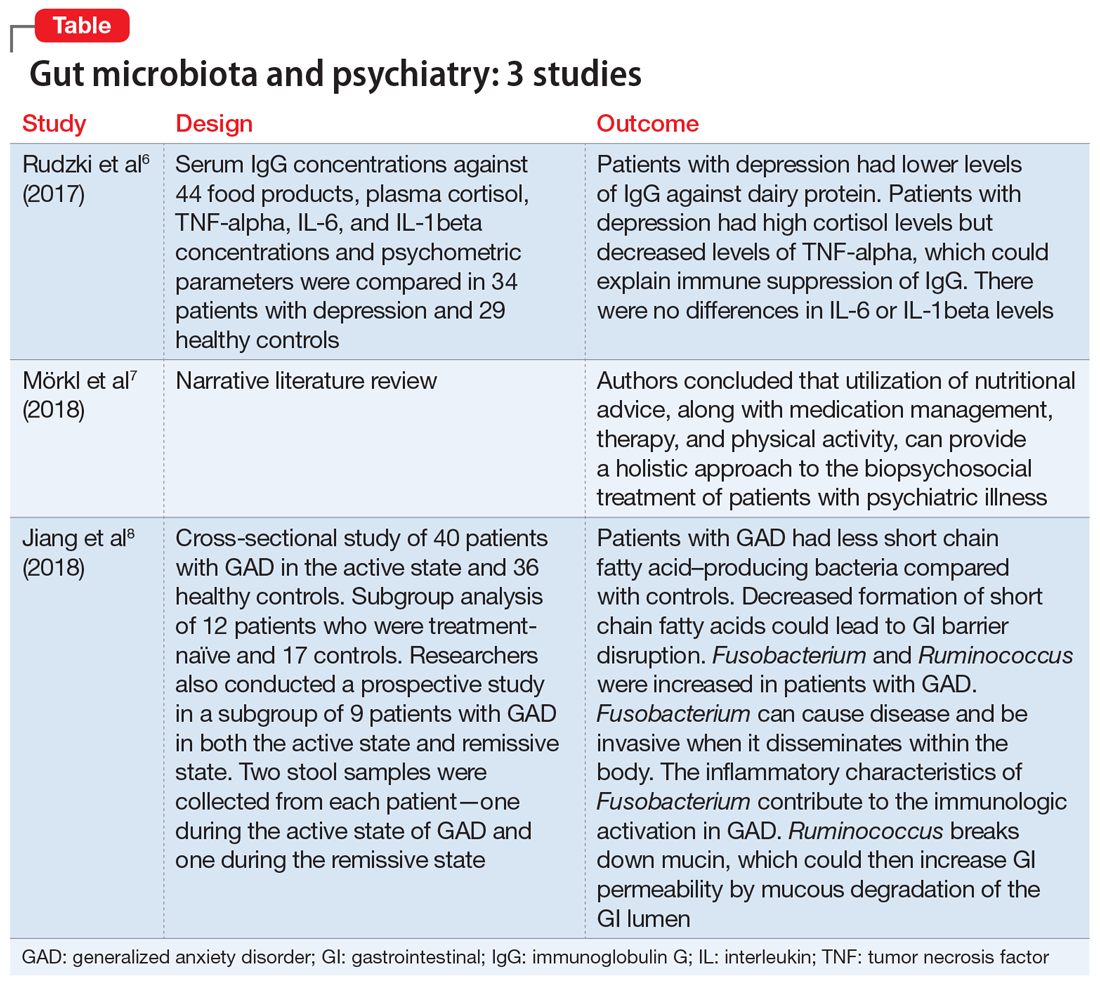

In 2014, researchers from Montana State University confirmed that the composition of the vaginal microbiota is “strongly associated with smoking.” They reported that women whose vaginal microbiota lacked significant numbers of Lactobacillus spp were 25-fold more likely to report current smoking than those with microbiota dominated by Lactobacillus crispatus (L crispatus). The researchers note that most Lactobacillus spp are thought to provide broad-spectrum protection to pathogenic infections by reducing vaginal pH.

But what is the mechanistic link between smoking and its effects on the vaginal microenvironment? The researchers conducted further study to assess the metabolome, a set of small molecule chemicals that includes host and microbial-produced and modified biomolecules as well as exogenous chemicals. The metabolome is an important characteristic of the vaginal microenvironment; the researchers say; differences in some metabolites are associated with functional variations of the vaginal microbiota.

The analysis revealed samples clustered into 3 community state types (CSTs): CST-I (L crispatus dominated), CST-III (L iners dominated) and CST-IV (low Lactobacillus). Overall, smoking did not affect the vaginal metabolome after controlling for CSTs, but the researchers identified “an extensive and diverse range” of vaginal metabolites for which profiles were affected by both the microbiology and smoking status. They found 607 compounds in 36 women, including 12 metabolites that differed significantly between smokers and nonsmokers. Bacterial composition was the most pronounced driver of the vaginal metabolome, they say, associated with changes in 57% of all metabolites. As expected, nicotine, cotinine, and hydroxycotinine were markedly elevated in smokers’ vaginas.

Another “key finding,” the researchers say, was a significant increase in the abundance of various biogenic amines among smokers, far more pronounced in women with a low level of Lactobacillus. Biogenic amines are essential, they note, to mammalian and bacterial physiology. (Several are implicated in the “fishy” odor of BV.)

Their study serves as a pilot study, the researchers say, for future examinations of the connections between smoking and poor gynecologic and reproductive health outcomes.

Cigarette smoking has been linked to the diagnosis of bacterial vaginosis (BV) and other genital infections including herpes simplex virus type 2, Chlamydia trachomatis, and oral and genital human papillomavirus (HPV). Nicotine’s major metabolite, cotinine, has been found to concentrate in cervical mucus.

In 2014, researchers from Montana State University confirmed that the composition of the vaginal microbiota is “strongly associated with smoking.” They reported that women whose vaginal microbiota lacked significant numbers of Lactobacillus spp were 25-fold more likely to report current smoking than those with microbiota dominated by Lactobacillus crispatus (L crispatus). The researchers note that most Lactobacillus spp are thought to provide broad-spectrum protection to pathogenic infections by reducing vaginal pH.

But what is the mechanistic link between smoking and its effects on the vaginal microenvironment? The researchers conducted further study to assess the metabolome, a set of small molecule chemicals that includes host and microbial-produced and modified biomolecules as well as exogenous chemicals. The metabolome is an important characteristic of the vaginal microenvironment; the researchers say; differences in some metabolites are associated with functional variations of the vaginal microbiota.

The analysis revealed samples clustered into 3 community state types (CSTs): CST-I (L crispatus dominated), CST-III (L iners dominated) and CST-IV (low Lactobacillus). Overall, smoking did not affect the vaginal metabolome after controlling for CSTs, but the researchers identified “an extensive and diverse range” of vaginal metabolites for which profiles were affected by both the microbiology and smoking status. They found 607 compounds in 36 women, including 12 metabolites that differed significantly between smokers and nonsmokers. Bacterial composition was the most pronounced driver of the vaginal metabolome, they say, associated with changes in 57% of all metabolites. As expected, nicotine, cotinine, and hydroxycotinine were markedly elevated in smokers’ vaginas.

Another “key finding,” the researchers say, was a significant increase in the abundance of various biogenic amines among smokers, far more pronounced in women with a low level of Lactobacillus. Biogenic amines are essential, they note, to mammalian and bacterial physiology. (Several are implicated in the “fishy” odor of BV.)

Their study serves as a pilot study, the researchers say, for future examinations of the connections between smoking and poor gynecologic and reproductive health outcomes.

Cigarette smoking has been linked to the diagnosis of bacterial vaginosis (BV) and other genital infections including herpes simplex virus type 2, Chlamydia trachomatis, and oral and genital human papillomavirus (HPV). Nicotine’s major metabolite, cotinine, has been found to concentrate in cervical mucus.

In 2014, researchers from Montana State University confirmed that the composition of the vaginal microbiota is “strongly associated with smoking.” They reported that women whose vaginal microbiota lacked significant numbers of Lactobacillus spp were 25-fold more likely to report current smoking than those with microbiota dominated by Lactobacillus crispatus (L crispatus). The researchers note that most Lactobacillus spp are thought to provide broad-spectrum protection to pathogenic infections by reducing vaginal pH.

But what is the mechanistic link between smoking and its effects on the vaginal microenvironment? The researchers conducted further study to assess the metabolome, a set of small molecule chemicals that includes host and microbial-produced and modified biomolecules as well as exogenous chemicals. The metabolome is an important characteristic of the vaginal microenvironment; the researchers say; differences in some metabolites are associated with functional variations of the vaginal microbiota.

The analysis revealed samples clustered into 3 community state types (CSTs): CST-I (L crispatus dominated), CST-III (L iners dominated) and CST-IV (low Lactobacillus). Overall, smoking did not affect the vaginal metabolome after controlling for CSTs, but the researchers identified “an extensive and diverse range” of vaginal metabolites for which profiles were affected by both the microbiology and smoking status. They found 607 compounds in 36 women, including 12 metabolites that differed significantly between smokers and nonsmokers. Bacterial composition was the most pronounced driver of the vaginal metabolome, they say, associated with changes in 57% of all metabolites. As expected, nicotine, cotinine, and hydroxycotinine were markedly elevated in smokers’ vaginas.

Another “key finding,” the researchers say, was a significant increase in the abundance of various biogenic amines among smokers, far more pronounced in women with a low level of Lactobacillus. Biogenic amines are essential, they note, to mammalian and bacterial physiology. (Several are implicated in the “fishy” odor of BV.)

Their study serves as a pilot study, the researchers say, for future examinations of the connections between smoking and poor gynecologic and reproductive health outcomes.

May 2019 Advances in Hematology and Oncology

Click for Credit: Migraine & stroke risk; Aspirin for CV events; more

Here are 5 articles from the May issue of Clinician Reviews (individual articles are valid for one year from date of publication—expiration dates below):

1. Subclinical hypothyroidism boosts immediate risk of heart failure

To take the posttest, go to: https://bit.ly/2IK0YiL

Expires January 24, 2020

2. Meta-analysis supports aspirin to reduce cardiovascular events

To take the posttest, go to: https://bit.ly/2GJLgSB

Expires January 24, 2020

3. Age of migraine onset may affect stroke risk

To take the posttest, go to: https://bit.ly/2ZAJ5YR

Expires January 24, 2020

4. Women with RA have reduced chance of live birth after assisted reproduction treatment

To take the posttest, go to: https://bit.ly/2VvKRLF

Expires January 27, 2020

5. New SLE disease activity measure beats SLEDAI-2K

To take the posttest, go to: https://bit.ly/2W8SVPA

Expires January 31, 2020

Here are 5 articles from the May issue of Clinician Reviews (individual articles are valid for one year from date of publication—expiration dates below):

1. Subclinical hypothyroidism boosts immediate risk of heart failure

To take the posttest, go to: https://bit.ly/2IK0YiL

Expires January 24, 2020

2. Meta-analysis supports aspirin to reduce cardiovascular events

To take the posttest, go to: https://bit.ly/2GJLgSB

Expires January 24, 2020

3. Age of migraine onset may affect stroke risk

To take the posttest, go to: https://bit.ly/2ZAJ5YR

Expires January 24, 2020

4. Women with RA have reduced chance of live birth after assisted reproduction treatment

To take the posttest, go to: https://bit.ly/2VvKRLF

Expires January 27, 2020

5. New SLE disease activity measure beats SLEDAI-2K

To take the posttest, go to: https://bit.ly/2W8SVPA

Expires January 31, 2020

Here are 5 articles from the May issue of Clinician Reviews (individual articles are valid for one year from date of publication—expiration dates below):

1. Subclinical hypothyroidism boosts immediate risk of heart failure

To take the posttest, go to: https://bit.ly/2IK0YiL

Expires January 24, 2020

2. Meta-analysis supports aspirin to reduce cardiovascular events

To take the posttest, go to: https://bit.ly/2GJLgSB

Expires January 24, 2020

3. Age of migraine onset may affect stroke risk

To take the posttest, go to: https://bit.ly/2ZAJ5YR

Expires January 24, 2020

4. Women with RA have reduced chance of live birth after assisted reproduction treatment

To take the posttest, go to: https://bit.ly/2VvKRLF

Expires January 27, 2020

5. New SLE disease activity measure beats SLEDAI-2K

To take the posttest, go to: https://bit.ly/2W8SVPA

Expires January 31, 2020

Racing thoughts: What to consider

Have you ever had times in your life when you had a tremendous amount of energy, like too much energy, with racing thoughts? I initially ask patients this question when evaluating for bipolar disorder. Some patients insist that they have racing thoughts—thoughts occurring at a rate faster than they can be expressed through speech1—but not episodes of hyperactivity. This response suggests that some patients can have racing thoughts without a diagnosis of bipolar disorder.

Among the patients I treat, racing thoughts vary in severity, duration, and treatment. When untreated, a patient’s racing thoughts may range from a mild disturbance lasting a few days to a more severe disturbance occurring daily. In this article, I suggest treatments that may help ameliorate racing thoughts, and describe possible causes that include, but are not limited to, mood disorders.

Major depressive disorder

Many patients with major depressive disorder (MDD) have racing thoughts that often go unrecognized, and this symptom is associated with more severe depression.2 Those with a DSM-5 diagnosis of MDD with mixed features could experience prolonged racing thoughts during a major depressive episode.1 Untreated racing thoughts may explain why many patients with MDD do not improve with an antidepressant alone.3 These patients might benefit from augmentation with a mood stabilizer such as lithium4 or a second-generation antipsychotic.5

Other potential causes

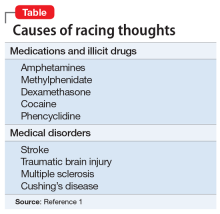

Racing thoughts are a symptom, not a diagnosis. Apprehension and anxiety could cause racing thoughts that do not require treatment with a mood stabilizer or antipsychotic. Patients who often worry about having panic attacks or experience severe chronic stress may have racing thoughts. Also, some patients may be taking medications or illicit drugs or have a medical disorder that could cause symptoms of mania or hypomania that include racing thoughts (Table1).

In summary, when caring for a patient who reports having racing thoughts, consider:

- whether that patient actually does have racing thoughts

- the potential causes, severity, duration, and treatment of the racing thoughts

- the possibility that for a patient with MDD, augmenting an antidepressant with a mood stabilizer or antipsychotic could decrease racing thoughts, thereby helping to alleviate many cases of MDD.

1. Diagnostic and statistical manual of mental disorders, 5th ed. Washington, DC: American Psychiatric Association; 2013.

2. Benazzi F. Unipolar depression with racing thoughts: a bipolar spectrum disorder? Psychiatry Clin Neurosci. 2005;59:570-575.

3. Undurraga J, Baldessarini RJ. Randomized, placebo-controlled trials of antidepressants for acute major depression: thirty-year meta-analytic review. Neuropsychopharmacology. 2012;37(4):851-864.

4. Bauer M, Adli M, Bschor T, et al. Lithium’s emerging role in the treatment of refractory major depressive episodes: augmentation of antidepressants. Neuropsychobiology. 2010;62(1):36-42.

5. Nelson JC, Papakostas GI. Atypical antipsychotic augmentation in major depressive disorder: a meta-analysis of placebo-controlled randomized trials. Am J Psychiatry. 2009;166(9):980-991.

Have you ever had times in your life when you had a tremendous amount of energy, like too much energy, with racing thoughts? I initially ask patients this question when evaluating for bipolar disorder. Some patients insist that they have racing thoughts—thoughts occurring at a rate faster than they can be expressed through speech1—but not episodes of hyperactivity. This response suggests that some patients can have racing thoughts without a diagnosis of bipolar disorder.

Among the patients I treat, racing thoughts vary in severity, duration, and treatment. When untreated, a patient’s racing thoughts may range from a mild disturbance lasting a few days to a more severe disturbance occurring daily. In this article, I suggest treatments that may help ameliorate racing thoughts, and describe possible causes that include, but are not limited to, mood disorders.

Major depressive disorder

Many patients with major depressive disorder (MDD) have racing thoughts that often go unrecognized, and this symptom is associated with more severe depression.2 Those with a DSM-5 diagnosis of MDD with mixed features could experience prolonged racing thoughts during a major depressive episode.1 Untreated racing thoughts may explain why many patients with MDD do not improve with an antidepressant alone.3 These patients might benefit from augmentation with a mood stabilizer such as lithium4 or a second-generation antipsychotic.5

Other potential causes

Racing thoughts are a symptom, not a diagnosis. Apprehension and anxiety could cause racing thoughts that do not require treatment with a mood stabilizer or antipsychotic. Patients who often worry about having panic attacks or experience severe chronic stress may have racing thoughts. Also, some patients may be taking medications or illicit drugs or have a medical disorder that could cause symptoms of mania or hypomania that include racing thoughts (Table1).

In summary, when caring for a patient who reports having racing thoughts, consider:

- whether that patient actually does have racing thoughts

- the potential causes, severity, duration, and treatment of the racing thoughts

- the possibility that for a patient with MDD, augmenting an antidepressant with a mood stabilizer or antipsychotic could decrease racing thoughts, thereby helping to alleviate many cases of MDD.

Have you ever had times in your life when you had a tremendous amount of energy, like too much energy, with racing thoughts? I initially ask patients this question when evaluating for bipolar disorder. Some patients insist that they have racing thoughts—thoughts occurring at a rate faster than they can be expressed through speech1—but not episodes of hyperactivity. This response suggests that some patients can have racing thoughts without a diagnosis of bipolar disorder.

Among the patients I treat, racing thoughts vary in severity, duration, and treatment. When untreated, a patient’s racing thoughts may range from a mild disturbance lasting a few days to a more severe disturbance occurring daily. In this article, I suggest treatments that may help ameliorate racing thoughts, and describe possible causes that include, but are not limited to, mood disorders.

Major depressive disorder

Many patients with major depressive disorder (MDD) have racing thoughts that often go unrecognized, and this symptom is associated with more severe depression.2 Those with a DSM-5 diagnosis of MDD with mixed features could experience prolonged racing thoughts during a major depressive episode.1 Untreated racing thoughts may explain why many patients with MDD do not improve with an antidepressant alone.3 These patients might benefit from augmentation with a mood stabilizer such as lithium4 or a second-generation antipsychotic.5

Other potential causes

Racing thoughts are a symptom, not a diagnosis. Apprehension and anxiety could cause racing thoughts that do not require treatment with a mood stabilizer or antipsychotic. Patients who often worry about having panic attacks or experience severe chronic stress may have racing thoughts. Also, some patients may be taking medications or illicit drugs or have a medical disorder that could cause symptoms of mania or hypomania that include racing thoughts (Table1).

In summary, when caring for a patient who reports having racing thoughts, consider:

- whether that patient actually does have racing thoughts

- the potential causes, severity, duration, and treatment of the racing thoughts

- the possibility that for a patient with MDD, augmenting an antidepressant with a mood stabilizer or antipsychotic could decrease racing thoughts, thereby helping to alleviate many cases of MDD.

1. Diagnostic and statistical manual of mental disorders, 5th ed. Washington, DC: American Psychiatric Association; 2013.

2. Benazzi F. Unipolar depression with racing thoughts: a bipolar spectrum disorder? Psychiatry Clin Neurosci. 2005;59:570-575.

3. Undurraga J, Baldessarini RJ. Randomized, placebo-controlled trials of antidepressants for acute major depression: thirty-year meta-analytic review. Neuropsychopharmacology. 2012;37(4):851-864.

4. Bauer M, Adli M, Bschor T, et al. Lithium’s emerging role in the treatment of refractory major depressive episodes: augmentation of antidepressants. Neuropsychobiology. 2010;62(1):36-42.

5. Nelson JC, Papakostas GI. Atypical antipsychotic augmentation in major depressive disorder: a meta-analysis of placebo-controlled randomized trials. Am J Psychiatry. 2009;166(9):980-991.

1. Diagnostic and statistical manual of mental disorders, 5th ed. Washington, DC: American Psychiatric Association; 2013.

2. Benazzi F. Unipolar depression with racing thoughts: a bipolar spectrum disorder? Psychiatry Clin Neurosci. 2005;59:570-575.

3. Undurraga J, Baldessarini RJ. Randomized, placebo-controlled trials of antidepressants for acute major depression: thirty-year meta-analytic review. Neuropsychopharmacology. 2012;37(4):851-864.

4. Bauer M, Adli M, Bschor T, et al. Lithium’s emerging role in the treatment of refractory major depressive episodes: augmentation of antidepressants. Neuropsychobiology. 2010;62(1):36-42.

5. Nelson JC, Papakostas GI. Atypical antipsychotic augmentation in major depressive disorder: a meta-analysis of placebo-controlled randomized trials. Am J Psychiatry. 2009;166(9):980-991.

Does your patient have postpartum OCD?

Childbirth is a trigger for first-onse

In one prospective study of 461 women who recently gave birth, researchers found the prevalence of OCD symptoms was 11% at 2 weeks postpartum.1 Mothers with OCD may have time-consuming or functionally impairing obsessions and/or compulsions that can include:

- anticipatory anxiety of contamination (eg, germs, illness)

- thoughts of accidental or intentional harm to their infant

- compulsions comprised of cleaning and checking behaviors

- avoidance of situations

- thought suppression.

Because both clinicians and patients may not be aware of the effects of childbirth on women with OCD, postpartum OCD may go underdiagnosed or be misdiagnosed as major depressive disorder (MDD) or an anxiety disorder. Additionally, women with OCD who lack insight or have delusional beliefs might be misdiagnosed with postpartum psychosis.

Here I offer methods to help effectively identify OCD in postpartum women, and suggest how to implement an individualized treatment approach.

Keys to identification and diagnosis

Mothers who present with postpartum anxiety or depression may have obsessions and compulsions. It is important to specifically screen for these symptoms because some mothers may be reluctant to discuss the content of their thoughts or behaviors.

Screen women who present with postpartum anxiety or depression for obsessions and compulsions by using questions based on DSM-5 criteria,2 such as:

- Do you have unpleasant thoughts, urges, or images that repeatedly enter your mind?

- Do you feel driven to perform certain behaviors or mental acts over and over again?

A validated scale, such as the Yale-Brown Obsessive Compulsive Scale (Y-BOCS),3 can also be used to screen for obsessive/compulsive symptoms in these patients.

Continue to: Evaluate women who endorse...

Evaluate women who endorse obsessions or compulsions for OCD. Women who meet diagnostic criteria for OCD should also be assessed for common psychiatric comorbidities, including MDD, anxiety disorders, or bipolar disorder. Obsessive-compulsive disorder with absent insight and delusional beliefs should be differentiated from postpartum psychosis, which is often a manifestation of bipolar disorder.

Treatment: What to consider

When selecting a treatment, consider factors such as symptom severity, psychiatric comorbidities, the patient’s insight into her OCD symptoms, patient preference, and breastfeeding status. Cognitive-behavioral therapy with exposure response prevention is indicated for patients with mild to moderate OCD. Pharmacotherapy should be reserved for individuals with severe OCD. Selective serotonin reuptake inhibitors (SSRIs) are the mainstay pharmacologic treatment of postpartum OCD; however, there are currently no randomized controlled trials of SSRIs for women with postpartum OCD. Augmentation with quetiapine should be considered for women who have an inadequate response to SSRIs.

Acknowledgment

The author thanks Christine Baczynski for her help with the preparation of this article.

1. Miller ES, Chu C, Gollan J, et al. Obsessive-compulsive symptoms during the postpartum period. A prospective cohort. J Reprod Med. 2013;58(3-4):115-122.

2. American Psychiatric Association. Diagnostic and Statistical Manual of Mental Disorders, 5th ed. Washington, DC: American Psychiatric Association; 2013.

3. Goodman WK, Price LH, Rasmussen SA, et al. The Yale-Brown Obsessive Compulsive Scale. I. Development, use, and reliability. Arch Gen Psychiatry. 1989;46(11):1006-1011.

Childbirth is a trigger for first-onse

In one prospective study of 461 women who recently gave birth, researchers found the prevalence of OCD symptoms was 11% at 2 weeks postpartum.1 Mothers with OCD may have time-consuming or functionally impairing obsessions and/or compulsions that can include:

- anticipatory anxiety of contamination (eg, germs, illness)

- thoughts of accidental or intentional harm to their infant

- compulsions comprised of cleaning and checking behaviors

- avoidance of situations

- thought suppression.

Because both clinicians and patients may not be aware of the effects of childbirth on women with OCD, postpartum OCD may go underdiagnosed or be misdiagnosed as major depressive disorder (MDD) or an anxiety disorder. Additionally, women with OCD who lack insight or have delusional beliefs might be misdiagnosed with postpartum psychosis.

Here I offer methods to help effectively identify OCD in postpartum women, and suggest how to implement an individualized treatment approach.

Keys to identification and diagnosis

Mothers who present with postpartum anxiety or depression may have obsessions and compulsions. It is important to specifically screen for these symptoms because some mothers may be reluctant to discuss the content of their thoughts or behaviors.

Screen women who present with postpartum anxiety or depression for obsessions and compulsions by using questions based on DSM-5 criteria,2 such as:

- Do you have unpleasant thoughts, urges, or images that repeatedly enter your mind?

- Do you feel driven to perform certain behaviors or mental acts over and over again?

A validated scale, such as the Yale-Brown Obsessive Compulsive Scale (Y-BOCS),3 can also be used to screen for obsessive/compulsive symptoms in these patients.

Continue to: Evaluate women who endorse...

Evaluate women who endorse obsessions or compulsions for OCD. Women who meet diagnostic criteria for OCD should also be assessed for common psychiatric comorbidities, including MDD, anxiety disorders, or bipolar disorder. Obsessive-compulsive disorder with absent insight and delusional beliefs should be differentiated from postpartum psychosis, which is often a manifestation of bipolar disorder.

Treatment: What to consider

When selecting a treatment, consider factors such as symptom severity, psychiatric comorbidities, the patient’s insight into her OCD symptoms, patient preference, and breastfeeding status. Cognitive-behavioral therapy with exposure response prevention is indicated for patients with mild to moderate OCD. Pharmacotherapy should be reserved for individuals with severe OCD. Selective serotonin reuptake inhibitors (SSRIs) are the mainstay pharmacologic treatment of postpartum OCD; however, there are currently no randomized controlled trials of SSRIs for women with postpartum OCD. Augmentation with quetiapine should be considered for women who have an inadequate response to SSRIs.

Acknowledgment

The author thanks Christine Baczynski for her help with the preparation of this article.

Childbirth is a trigger for first-onse

In one prospective study of 461 women who recently gave birth, researchers found the prevalence of OCD symptoms was 11% at 2 weeks postpartum.1 Mothers with OCD may have time-consuming or functionally impairing obsessions and/or compulsions that can include:

- anticipatory anxiety of contamination (eg, germs, illness)

- thoughts of accidental or intentional harm to their infant

- compulsions comprised of cleaning and checking behaviors

- avoidance of situations

- thought suppression.

Because both clinicians and patients may not be aware of the effects of childbirth on women with OCD, postpartum OCD may go underdiagnosed or be misdiagnosed as major depressive disorder (MDD) or an anxiety disorder. Additionally, women with OCD who lack insight or have delusional beliefs might be misdiagnosed with postpartum psychosis.

Here I offer methods to help effectively identify OCD in postpartum women, and suggest how to implement an individualized treatment approach.

Keys to identification and diagnosis

Mothers who present with postpartum anxiety or depression may have obsessions and compulsions. It is important to specifically screen for these symptoms because some mothers may be reluctant to discuss the content of their thoughts or behaviors.

Screen women who present with postpartum anxiety or depression for obsessions and compulsions by using questions based on DSM-5 criteria,2 such as:

- Do you have unpleasant thoughts, urges, or images that repeatedly enter your mind?

- Do you feel driven to perform certain behaviors or mental acts over and over again?

A validated scale, such as the Yale-Brown Obsessive Compulsive Scale (Y-BOCS),3 can also be used to screen for obsessive/compulsive symptoms in these patients.

Continue to: Evaluate women who endorse...

Evaluate women who endorse obsessions or compulsions for OCD. Women who meet diagnostic criteria for OCD should also be assessed for common psychiatric comorbidities, including MDD, anxiety disorders, or bipolar disorder. Obsessive-compulsive disorder with absent insight and delusional beliefs should be differentiated from postpartum psychosis, which is often a manifestation of bipolar disorder.

Treatment: What to consider

When selecting a treatment, consider factors such as symptom severity, psychiatric comorbidities, the patient’s insight into her OCD symptoms, patient preference, and breastfeeding status. Cognitive-behavioral therapy with exposure response prevention is indicated for patients with mild to moderate OCD. Pharmacotherapy should be reserved for individuals with severe OCD. Selective serotonin reuptake inhibitors (SSRIs) are the mainstay pharmacologic treatment of postpartum OCD; however, there are currently no randomized controlled trials of SSRIs for women with postpartum OCD. Augmentation with quetiapine should be considered for women who have an inadequate response to SSRIs.

Acknowledgment

The author thanks Christine Baczynski for her help with the preparation of this article.

1. Miller ES, Chu C, Gollan J, et al. Obsessive-compulsive symptoms during the postpartum period. A prospective cohort. J Reprod Med. 2013;58(3-4):115-122.

2. American Psychiatric Association. Diagnostic and Statistical Manual of Mental Disorders, 5th ed. Washington, DC: American Psychiatric Association; 2013.

3. Goodman WK, Price LH, Rasmussen SA, et al. The Yale-Brown Obsessive Compulsive Scale. I. Development, use, and reliability. Arch Gen Psychiatry. 1989;46(11):1006-1011.

1. Miller ES, Chu C, Gollan J, et al. Obsessive-compulsive symptoms during the postpartum period. A prospective cohort. J Reprod Med. 2013;58(3-4):115-122.

2. American Psychiatric Association. Diagnostic and Statistical Manual of Mental Disorders, 5th ed. Washington, DC: American Psychiatric Association; 2013.

3. Goodman WK, Price LH, Rasmussen SA, et al. The Yale-Brown Obsessive Compulsive Scale. I. Development, use, and reliability. Arch Gen Psychiatry. 1989;46(11):1006-1011.

Young, angry, and in need of a liver transplant

CASE Rash, fever, extreme lethargy; multiple hospital visits

Ms. L, age 21, a single woman with a history of major depressive disorder (MDD), is directly admitted from an outside community hospital to our tertiary care academic hospital with acute liver failure.

One month earlier, Ms. L had an argument with her family and punched a wall, fracturing her hand. Following the episode, Ms. L’s primary care physician (PCP) prescribed valproic acid, 500 mg/d, to address “mood swings,” which included angry outbursts and irritability. According to her PCP, no baseline laboratory tests were ordered for Ms. L when she started valproic acid because she was young and otherwise healthy.

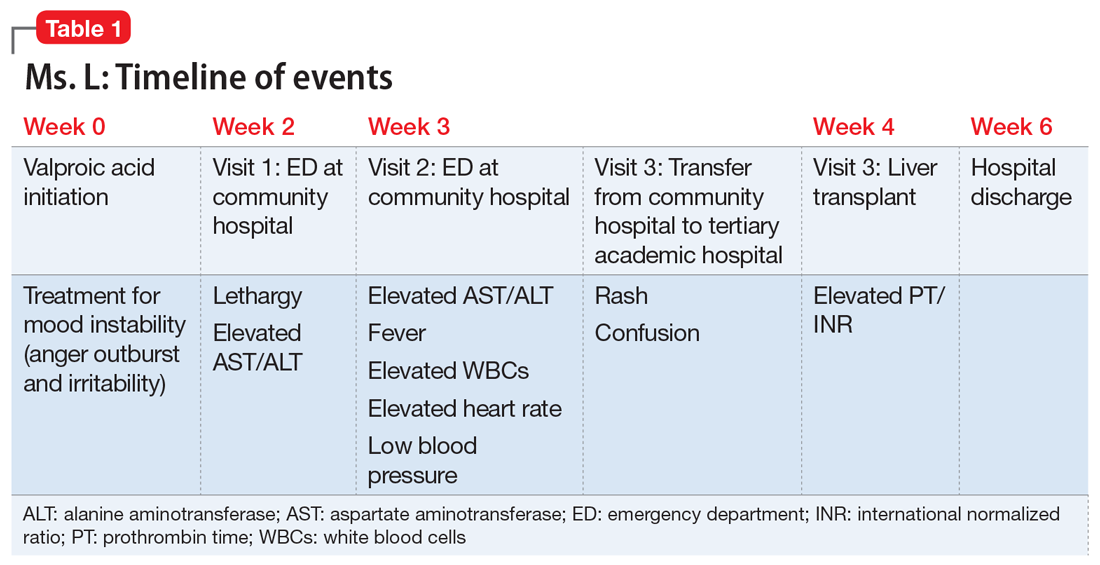

After Ms. L had been taking valproic acid for approximately 2 weeks, her mother noticed she became extremely lethargic and took her to the emergency department (ED) of a community hospital (Visit 1) (Table 1). At this time, her laboratory results were notable for an aspartate aminotransferase (AST) level of 303 IU/L (reference range: 8 to 40 IU/L) and an alanine aminotransferase (ALT) level of 241 IU/L (reference range: 20 to 60 IU/L). She also underwent a liver ultrasound, urine toxicology screen, blood alcohol level, and acetaminophen level; the results of all of these tests were unremarkable. Her valproic acid level was within therapeutic limits, consistent with patient adherence; her ammonia level was within normal limits. At Visit 1, Ms. L’s transaminitis was presumed to be secondary to valproic acid. The ED clinicians told her to stop taking valproic acid and discharged her. Her PCP did not give her any follow-up instructions for further laboratory tests or any other recommendations.

During the next week, even though she stopped taking the valproic acid as instructed, Ms. L developed a rash and fever, and continued to have lethargy and general malaise. When she returned to the ED (Visit 2) (Table 1), she was febrile, tachycardic, and hypotensive, with an elevated white blood cell count, eosinophilia, low platelets, and elevated liver function tests. At Visit 2, she was alert and oriented to person, place, time, and situation. Ms. L insisted that she had not overdosed on any medications, or used illicit drugs or alcohol. A test for hepatitis C was negative. Her ammonia level was 58 µmol/L (reference range: 11 to 32 µmol/L). Ms. L received N-acetylcysteine (NAC), prednisone, diphenhydramine, famotidine, and ibuprofen before she was transferred to our tertiary care hospital.

When she arrives at our facility (Visit 3) (Table 1), Ms. L is admitted with acute liver failure. She has an ALT level of 4,091 IU/L, and an AST level of 2,049 IU/L. Ms. L’s mother says that her daughter had been taking sertraline for depression for “some time” with no adverse effects, although she is not clear on the dose or frequency. Her mother says that Ms. L generally likes to spend most of her time at home, and does not believe her daughter is a danger to herself or others. Ms. L’s mother could not describe any episodes of mania or recurrent, dangerous anger episodes. Ms. L has no other medical history and has otherwise been healthy.

On hospital Day 2, Ms. L’s ammonia level is 72 µmol/L, which is slightly elevated. The hepatology team confirms that Ms. L may require a liver transplantation. The primary team consults the inpatient psychiatry consultation-liaison (C-L) team for a pre-transplant psychiatric evaluation.

[polldaddy:10307646]

The authors’ observations

The differential diagnosis for Ms. L was broad and included both accidental and intentional medication overdose. The primary team consulted the inpatient psychiatry C-L team not only for a pre-transplant evaluation, but also to assess for possible overdose.

Continue to: A review of the records...

A review of the records from Visit 1 and Visit 2 at the outside hospital found no acetaminophen in Ms. L’s system and verified that there was no evidence of a current valproic acid overdose. Ms. L had stated that she had not overdosed on any other medications or used any illicit drugs or alcohol. Ms. L’s complex symptoms—namely fever, acute liver failure, and rash—were more consistent with an adverse effect of valproic acid or possibly an inherent autoimmune process.

Liver damage from valproic acid

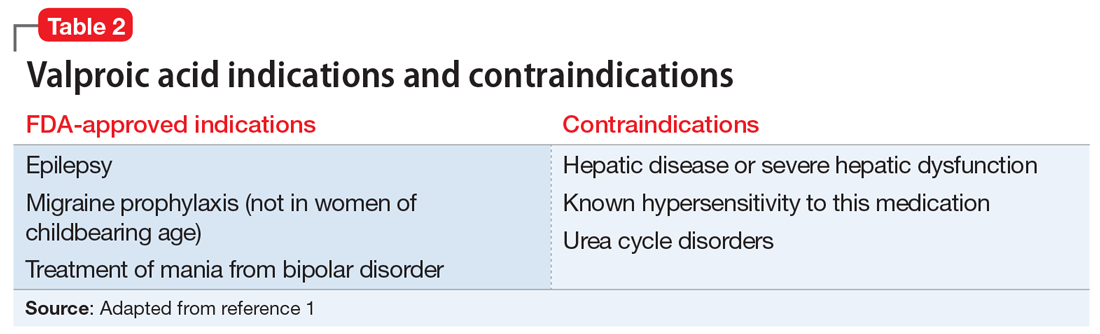

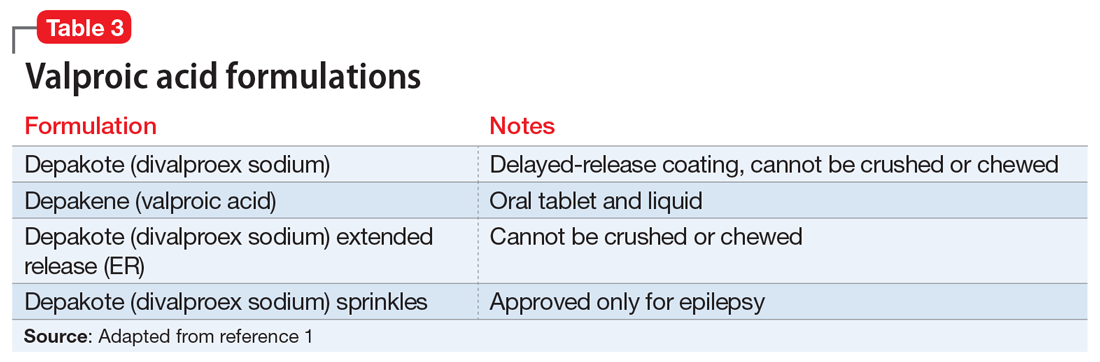

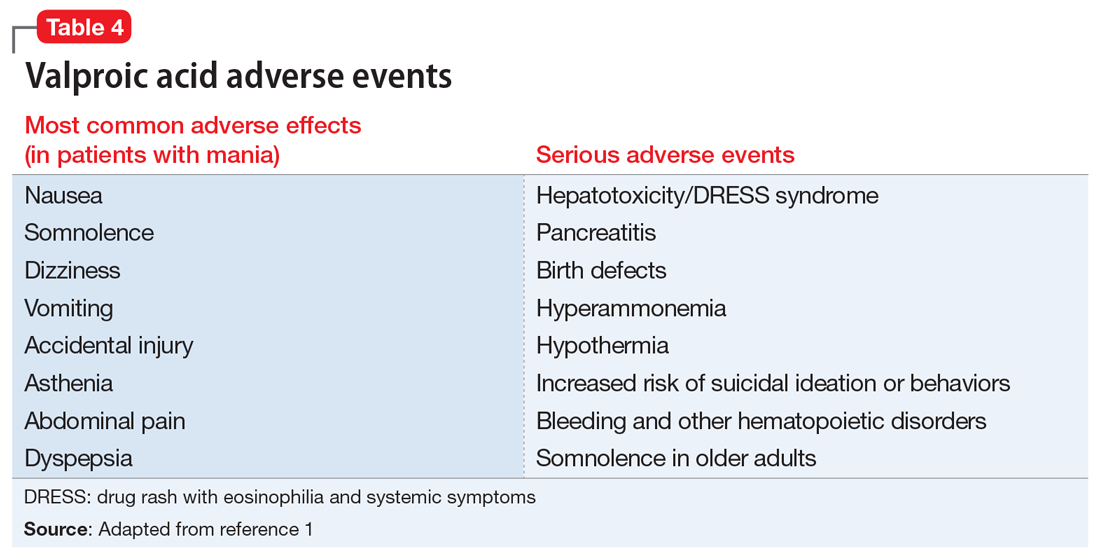

Valproic acid is FDA-approved for treating bipolar disorder, epilepsy, and migraine headaches1 (Table 21). Common adverse effects include nausea, vomiting, sleepiness, and dry mouth. Rarely, valproic acid can impair liver function. While receiving valproic acid, 5% to 10% of patients develop elevated ALT levels, but most are asymptomatic and resolve with time, even if the patient continues taking valproic acid.2 Valproic acid hepatotoxicity resulting in liver transplantation for a healthy patient is extremely rare (Table 31). Liver failure, both fatal and non-fatal, is more prevalent in patients concurrently taking other medications, such as antiepileptics, benzodiazepines, and antipsychotics, as compared with patients receiving only valproic acid.3

There are 3 clinically distinguishable forms of hepatotoxicity due to valproic acid2:

- hyperammonemia

- acute liver failure and jaundice

- Myriad ProReye-like syndrome, which is generally seen in children.

In case reports of hyperammonemia due to valproic acid, previously healthy patients experience confusion, lethargy, and eventual coma in the context of elevated serum ammonia levels; these symptoms resolved upon discontinuing valproic acid.4,5 Liver function remained normal, with normal to near-normal liver enzymes and bilirubin.3 Hyperammonemia and resulting encephalopathy generally occurred within 1 to 3 weeks after initiation of valproate therapy, with resolution of hyperammonemia and resulting symptoms within a few days after stopping valproic acid.2-4

At Visit 2, Ms. L’s presentation was not initially consistent with hepatic encephalopathy. She was alert and oriented to person, place, time, and situation. Additionally, Ms. L’s presenting problem was elevated liver function tests, not elevated ammonia levels. At Visit 2, her ammonia level was 58 µmol/L; on Day 2 (Visit 3) of her hospital stay, her ammonia level was 72 µmol/L (slightly elevated).

Continue to: At Visit 2 in the ED...

At Visit 2 in the ED, Ms. L was started on NAC because the team suspected she was experiencing drug rash with eosinophilia and systemic symptoms (DRESS) syndrome. This syndrome is characterized by extensive rash, fever, and involvement of at least 1 internal organ. It is a variation of a drug-induced hypersensitivity syndrome. Ms. L’s unremarkable valproic acid levels combined with the psychiatry assessment ruled out valproic hepatotoxicity due to overdose, either intentional or accidental.

In case reports, patients who developed acute liver failure due to valproic acid typically had a hepatitis-like syndrome consisting of moderate elevation in liver enzymes, jaundice, and liver failure necessitating transplantation after at least 1 month of treatment with valproic acid.2 In addition to the typical hepatitis-like syndrome resulting from valproic acid, case reports have also linked treatment with valproic acid to DRESS syndrome.2 This syndrome is known to occur with anticonvulsants such as phenobarbital, lamotrigine, and phenytoin, but there are only a few reported cases of DRESS syndrome due to valproic acid therapy alone.6 Drug rash with eosinophilia and systemic symptoms syndrome differs from other acute liver failure cases in that patients also develop lymphadenopathy, fever, and rash.2,6,7 Patients with DRESS syndrome typically respond to corticosteroid therapy and discontinuation of valproic acid, and the liver damage resolves after several weeks, without a need for transplantation.2,6,7

Ms. L seemed to have similarities to DRESS syndrome. However, the severity of her liver damage, which might require transplantation even after only 2 weeks of valproic acid therapy, initially led the hepatology and C-L teams to consider her presentation similar to severe hepatitis-like cases.

EVALUATION Consent for transplantation

As an inpatient, Ms. L undergoes further laboratory testing. Her hepatic function panel demonstrates a total protein level of 4.8 g/dL, an albumin level of 2.0 g/dL, total bilirubin level of 12.2 mg/dL, and alkaline phosphatase of 166 IU/L. Her laboratory results indicate a prothrombin time (PT) of 77.4 seconds, partial thromboplastin time of 61.5 seconds, and PT international normalized ratio (INR) of 9.6. Ms. L’s basic metabolic panel is within normal limits except for a blood urea nitrogen level of 6 mg/dL, glucose level of 136 mg/dL, and calcium level of 7.0 mg/dL. Her complete blood count indicates a white blood cell count of 12.1, hemoglobin of 10.3 g/dL, hematocrit of 30.4%, mean corpuscular volume of 85.9 fL, and platelet count of 84. Her lipase level is normal at 49 U/L. Her serum acetaminophen concentration is <3.0 mcg/mL, valproic acid level was <2 µg/mL, and she is negative for hepatitis A, B, and C. A urine toxicology screen and testing for herpes simplex, rapid plasma reagin, and human immunodeficiency virus are all negative. Results from several auto-antibodies tests are negative and within normal limits, except filamentous actin (F-actin) antibody, which is slightly higher than normal at 21.4 ELISA units. Based on these results, Ms. L’s liver failure seemed most likely secondary to a reaction to valproic acid.

During her pre-transplant psychiatric evaluation, Ms. L is found to be a poor historian with minimal speech production, flat affect, and clouded sensorium. She denies overdosing on her prescribed valproic acid or sertraline, reports no current suicidal ideation, and does not want to die. She accurately recalls her correct daily dosing of each medication, and verifies that she stopped taking valproic acid 2 weeks ago after being advised to do so by the ED clinicians at Visit 2. She continued to take sertraline until Visit 2. She denied any past or present episodes consistent with mania, which was consistent with her mother’s report.

Continue to: Ms. L becomes agitated...

Ms. L becomes agitated upon further questioning, and requests immediate discharge so that she can return to her family. The evaluation is postponed briefly.

When they reconvene, the C-L team performs a decision-making capacity evaluation, which reveals that Ms. L’s mood and affect are consistent with fear of her impending liver transplant and being alone and approximately 2 hours from her family. This is likely complicated by delirium due to hepatotoxicity. Further discussion between Ms. L and the multidisciplinary team focuses on the risks, benefits, adverse effects of, and alternatives to her current treatment; the possibility of needing a liver transplantation; and how to help her family with transportation to the hospital. Following the discussion, Ms. L is fully cooperative with further treatment, and the pre-transplant psychiatric evaluation is completed.

On physical examination, Ms. L is noted to have a widespread morbilliform rash covering 50% to 60% of her body.

[polldaddy:10307651]

The authors’ observations

L-carnitine supplementation

Multiple studies have shown that supplementation with L-carnitine may increase survival from severe hepatotoxicity due to valproic acid.8,9 Valproic acid may contribute to carnitine deficiency due to its inhibition of carnitine biosynthesis via a decrease in alpha-ketoglutarate concentration.8 Hepatotoxicity or hyperammonemia due to valproic acid may be potentiated by a carnitine deficiency, either pre-existing or resulting from valproic acid.8 L-carnitine supplementation has hastened the decrease of valproic acid–induced ammonemia in a dose-dependent manner,10 and it is currently recommended in cases of valproic acid toxicity, especially in children.8 Children at high risk for developing carnitine deficiency who need to receive valproic acid can be given carnitine supplementation.11 It is not known whether L-carnitine is clinically effective in protecting the liver or hastening liver recovery,8 but it is believed that it might prevent adverse effects of hepatotoxicity and hyperammonemia, especially in patients who receive long-term valproic acid therapy.12

TREATMENT Decompensation and transplantation

Ms. L’s treatment regimen includes NAC, lactulose, and L-carnitine supplementation. During the course of Ms. L’s hospital stay, her liver enzymes begin to trend downward, but her INR and PT remain elevated.

Continue to: On hospital Day 6...

On hospital Day 6, she develops more severe symptoms of hepatic encephalopathy, with significant altered mental status and inattention. Ms. L is transferred to the ICU, intubated, and placed on the liver transplant list.

On hospital Day 9, she undergoes a liver transplantation.

[polldaddy:10307652]

The authors’ observations

Baseline laboratory testing should have been conducted prior to initiating valproic acid. As Ms. L’s symptoms worsened, better communication with her PCP and closer monitoring after starting valproic acid might have resulted in more immediate care. Early recognition of her symptoms and decompensation may have triggered earlier inpatient admission and/or transfer to a tertiary care facility for observation and treatment. Additionally, repeat laboratory testing and instructions on when to return to the ED should have been provided at Visit 1.

This case demonstrates the need for all clinicians who prescribe valproic acid to remain diligent about the accurate diagnosis of mood and behavioral symptoms, knowing when psychotropic medications are indicated, and carefully considering and discussing even rare, potentially life-threatening adverse effects of all medications with patients.

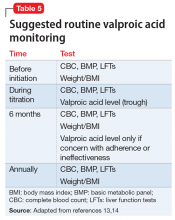

Although rare, after starting valproic acid, a patient may experience a rapid decompensation and life-threatening illness. Ideally, clinicians should closely monitor patients after initiating valproic acid (Table 41). Clinicians must have a clear knowledge of the recommended monitoring and indications for hospitalization and treatment when they note adverse effects such as elevated liver enzymes or transaminitis (Table 513,14). Even after stopping valproic acid, patients who have experienced adverse events should be closely monitored to ensure complete resolution.

Continue to: Consider patient-specific factors

Consider patient-specific factors

Consider the mental state, intellectual capacity, and social support of each patient before initiating valproic acid. Its use as a mood stabilizer for “mood swings” outside of the context of bipolar disorder is questionable. Valproic acid is FDA-approved for treating bipolar disorder and seizures, but not for anger outbursts/irritability. Prior to starting valproic acid, Ms. L may have benefited from alternative nonpharmacologic treatments, such as psychotherapy, for her anger outbursts and poor coping skills. Therapeutic techniques that focused on helping her acquire better coping mechanisms may have been useful, especially because her mood symptoms did not meet criteria for bipolar disorder, and her depression had long been controlled with sertraline monotherapy.

OUTCOME Discharged after 20 days

Ms. L stays in the hospital for 10 days after receiving her liver transplant. She has low appetite and some difficulty with sleep after the transplant; therefore, the C-L team recommends mirtazapine, 15 mg/d. She has no behavioral problems during her stay, and is set up with home health, case management, and psychiatry follow-up. On hospital Day 20, she is discharged.

Bottom Line

Use caution when prescribing valproic acid, even in young, otherwise healthy patients. Although rare, some patients may experience a rapid decompensation and life-threatening illness after starting valproic acid. When prescribing valproic acid, ensure close follow-up after initiation, including mental status examinations, physical examinations, and laboratory testing.

Related Resource

- Doroudgar S, Chou TI. How to modify psychotropic therapy for patients who have liver dysfunction. Current Psychiatry. 2014;13(12):46-49.

Drug Brand Names

Diphenhydramine • Benadryl

Famotidine • Fluxid, Pepcid

Lamotrigine • Lamictal

Mirtazapine • Remeron

N-acetylcysteine • Mucomyst

Phenobarbital • Luminal

Phenytoin • Dilantin

Prednisone • Cortan, Deltasone

Sertraline • Zoloft

Valproic acid • Depakene

1. Depakote [package insert]. North Chicago, IL: AbbVie, Inc.; 2019.

2. National Institutes of Health. U.S. Department of Health and Human Services. Drug Record: Valproate. https://livertox.nlm.nih.gov/Valproate.htm. Updated October 30, 2018. Accessed March 21, 2019.

3. Schmid MM, Freudenmann RW, Keller F, et al. Non-fatal and fatal liver failure associated with valproic acid. Pharmacopsychiatry. 2013;46(2):63-68.

4. Patel N, Landry KB, Fargason RE, et al. Reversible encephalopathy due to valproic acid induced hyperammonemia in a patient with Bipolar I disorder: a cautionary report. Psychopharmacol Bull. 2017;47(1):40-44.

5. Eze E, Workman M, Donley B. Hyperammonemia and coma developed by a woman treated with valproic acid for affective disorder. Psychiatr Serv. 1998;49(10):1358-1359.

6. Darban M and Bagheri B. Drug reaction with eosinophilia and systemic symptoms induced by valproic acid: a case report. Iran Red Crescent Med J. 2016;18(9): e35825.

7. van Zoelen MA, de Graaf M, van Dijk MR, et al. Valproic acid-induced DRESS syndrome with acute liver failure. Neth J Med. 2012;70(3):155.

8. Lheureux PE, Hantson P. Carnitine in the treatment of valproic acid-induced toxicity. Clin Toxicol (Phila). 2009;47(2):101-111.

9. Bohan TP, Helton E, McDonald I, et al. Effect of L-carnitine treatment for valproate-induced hepatotoxicity. Neurology. 2001;56(10):1405-1409.

10. Böhles H, Sewell AC, Wenzel D. The effect of carnitine supplementation in valproate-induced hyperammonaemia. Acta Paediatr. 1996;85(4):446-449.

11. Raskind JY, El-Chaar GM. The role of carnitine supplementation during valproic acid therapy. Ann Pharmacother. 2000;34(5):630-638.

12. Romero-Falcón A, de la Santa-Belda E, García-Contreras R, et al. A case of valproate-associated hepatotoxicity treated with L-carnitine. Eur J Intern Med. 2003;14(5):338-340.

13. National Institute for Health and Clinical Excellence. Bipolar disorder: the management of bipolar disorder in adults, children, and adolescents, in primary and secondary care. https://www.nice.org.uk/guidance/cg185. Updated April 2018. Accessed March 21, 2019.

14 . Hirschfeld RMA, Bowden CL, Gitlin MJ, et al. Practice guideline for the treatment of patients with biopolar disorder: second edition. American Psychiatric Association. https://psychiatryonline.org/pb/assets/raw/sitewide/practice_guidelines/guidelines/bipolar.pdf. Published 2002. Accessed March 21, 2019.

CASE Rash, fever, extreme lethargy; multiple hospital visits

Ms. L, age 21, a single woman with a history of major depressive disorder (MDD), is directly admitted from an outside community hospital to our tertiary care academic hospital with acute liver failure.

One month earlier, Ms. L had an argument with her family and punched a wall, fracturing her hand. Following the episode, Ms. L’s primary care physician (PCP) prescribed valproic acid, 500 mg/d, to address “mood swings,” which included angry outbursts and irritability. According to her PCP, no baseline laboratory tests were ordered for Ms. L when she started valproic acid because she was young and otherwise healthy.

After Ms. L had been taking valproic acid for approximately 2 weeks, her mother noticed she became extremely lethargic and took her to the emergency department (ED) of a community hospital (Visit 1) (Table 1). At this time, her laboratory results were notable for an aspartate aminotransferase (AST) level of 303 IU/L (reference range: 8 to 40 IU/L) and an alanine aminotransferase (ALT) level of 241 IU/L (reference range: 20 to 60 IU/L). She also underwent a liver ultrasound, urine toxicology screen, blood alcohol level, and acetaminophen level; the results of all of these tests were unremarkable. Her valproic acid level was within therapeutic limits, consistent with patient adherence; her ammonia level was within normal limits. At Visit 1, Ms. L’s transaminitis was presumed to be secondary to valproic acid. The ED clinicians told her to stop taking valproic acid and discharged her. Her PCP did not give her any follow-up instructions for further laboratory tests or any other recommendations.

During the next week, even though she stopped taking the valproic acid as instructed, Ms. L developed a rash and fever, and continued to have lethargy and general malaise. When she returned to the ED (Visit 2) (Table 1), she was febrile, tachycardic, and hypotensive, with an elevated white blood cell count, eosinophilia, low platelets, and elevated liver function tests. At Visit 2, she was alert and oriented to person, place, time, and situation. Ms. L insisted that she had not overdosed on any medications, or used illicit drugs or alcohol. A test for hepatitis C was negative. Her ammonia level was 58 µmol/L (reference range: 11 to 32 µmol/L). Ms. L received N-acetylcysteine (NAC), prednisone, diphenhydramine, famotidine, and ibuprofen before she was transferred to our tertiary care hospital.

When she arrives at our facility (Visit 3) (Table 1), Ms. L is admitted with acute liver failure. She has an ALT level of 4,091 IU/L, and an AST level of 2,049 IU/L. Ms. L’s mother says that her daughter had been taking sertraline for depression for “some time” with no adverse effects, although she is not clear on the dose or frequency. Her mother says that Ms. L generally likes to spend most of her time at home, and does not believe her daughter is a danger to herself or others. Ms. L’s mother could not describe any episodes of mania or recurrent, dangerous anger episodes. Ms. L has no other medical history and has otherwise been healthy.

On hospital Day 2, Ms. L’s ammonia level is 72 µmol/L, which is slightly elevated. The hepatology team confirms that Ms. L may require a liver transplantation. The primary team consults the inpatient psychiatry consultation-liaison (C-L) team for a pre-transplant psychiatric evaluation.

[polldaddy:10307646]

The authors’ observations

The differential diagnosis for Ms. L was broad and included both accidental and intentional medication overdose. The primary team consulted the inpatient psychiatry C-L team not only for a pre-transplant evaluation, but also to assess for possible overdose.

Continue to: A review of the records...

A review of the records from Visit 1 and Visit 2 at the outside hospital found no acetaminophen in Ms. L’s system and verified that there was no evidence of a current valproic acid overdose. Ms. L had stated that she had not overdosed on any other medications or used any illicit drugs or alcohol. Ms. L’s complex symptoms—namely fever, acute liver failure, and rash—were more consistent with an adverse effect of valproic acid or possibly an inherent autoimmune process.

Liver damage from valproic acid

Valproic acid is FDA-approved for treating bipolar disorder, epilepsy, and migraine headaches1 (Table 21). Common adverse effects include nausea, vomiting, sleepiness, and dry mouth. Rarely, valproic acid can impair liver function. While receiving valproic acid, 5% to 10% of patients develop elevated ALT levels, but most are asymptomatic and resolve with time, even if the patient continues taking valproic acid.2 Valproic acid hepatotoxicity resulting in liver transplantation for a healthy patient is extremely rare (Table 31). Liver failure, both fatal and non-fatal, is more prevalent in patients concurrently taking other medications, such as antiepileptics, benzodiazepines, and antipsychotics, as compared with patients receiving only valproic acid.3

There are 3 clinically distinguishable forms of hepatotoxicity due to valproic acid2:

- hyperammonemia

- acute liver failure and jaundice

- Myriad ProReye-like syndrome, which is generally seen in children.

In case reports of hyperammonemia due to valproic acid, previously healthy patients experience confusion, lethargy, and eventual coma in the context of elevated serum ammonia levels; these symptoms resolved upon discontinuing valproic acid.4,5 Liver function remained normal, with normal to near-normal liver enzymes and bilirubin.3 Hyperammonemia and resulting encephalopathy generally occurred within 1 to 3 weeks after initiation of valproate therapy, with resolution of hyperammonemia and resulting symptoms within a few days after stopping valproic acid.2-4

At Visit 2, Ms. L’s presentation was not initially consistent with hepatic encephalopathy. She was alert and oriented to person, place, time, and situation. Additionally, Ms. L’s presenting problem was elevated liver function tests, not elevated ammonia levels. At Visit 2, her ammonia level was 58 µmol/L; on Day 2 (Visit 3) of her hospital stay, her ammonia level was 72 µmol/L (slightly elevated).

Continue to: At Visit 2 in the ED...

At Visit 2 in the ED, Ms. L was started on NAC because the team suspected she was experiencing drug rash with eosinophilia and systemic symptoms (DRESS) syndrome. This syndrome is characterized by extensive rash, fever, and involvement of at least 1 internal organ. It is a variation of a drug-induced hypersensitivity syndrome. Ms. L’s unremarkable valproic acid levels combined with the psychiatry assessment ruled out valproic hepatotoxicity due to overdose, either intentional or accidental.

In case reports, patients who developed acute liver failure due to valproic acid typically had a hepatitis-like syndrome consisting of moderate elevation in liver enzymes, jaundice, and liver failure necessitating transplantation after at least 1 month of treatment with valproic acid.2 In addition to the typical hepatitis-like syndrome resulting from valproic acid, case reports have also linked treatment with valproic acid to DRESS syndrome.2 This syndrome is known to occur with anticonvulsants such as phenobarbital, lamotrigine, and phenytoin, but there are only a few reported cases of DRESS syndrome due to valproic acid therapy alone.6 Drug rash with eosinophilia and systemic symptoms syndrome differs from other acute liver failure cases in that patients also develop lymphadenopathy, fever, and rash.2,6,7 Patients with DRESS syndrome typically respond to corticosteroid therapy and discontinuation of valproic acid, and the liver damage resolves after several weeks, without a need for transplantation.2,6,7

Ms. L seemed to have similarities to DRESS syndrome. However, the severity of her liver damage, which might require transplantation even after only 2 weeks of valproic acid therapy, initially led the hepatology and C-L teams to consider her presentation similar to severe hepatitis-like cases.

EVALUATION Consent for transplantation

As an inpatient, Ms. L undergoes further laboratory testing. Her hepatic function panel demonstrates a total protein level of 4.8 g/dL, an albumin level of 2.0 g/dL, total bilirubin level of 12.2 mg/dL, and alkaline phosphatase of 166 IU/L. Her laboratory results indicate a prothrombin time (PT) of 77.4 seconds, partial thromboplastin time of 61.5 seconds, and PT international normalized ratio (INR) of 9.6. Ms. L’s basic metabolic panel is within normal limits except for a blood urea nitrogen level of 6 mg/dL, glucose level of 136 mg/dL, and calcium level of 7.0 mg/dL. Her complete blood count indicates a white blood cell count of 12.1, hemoglobin of 10.3 g/dL, hematocrit of 30.4%, mean corpuscular volume of 85.9 fL, and platelet count of 84. Her lipase level is normal at 49 U/L. Her serum acetaminophen concentration is <3.0 mcg/mL, valproic acid level was <2 µg/mL, and she is negative for hepatitis A, B, and C. A urine toxicology screen and testing for herpes simplex, rapid plasma reagin, and human immunodeficiency virus are all negative. Results from several auto-antibodies tests are negative and within normal limits, except filamentous actin (F-actin) antibody, which is slightly higher than normal at 21.4 ELISA units. Based on these results, Ms. L’s liver failure seemed most likely secondary to a reaction to valproic acid.

During her pre-transplant psychiatric evaluation, Ms. L is found to be a poor historian with minimal speech production, flat affect, and clouded sensorium. She denies overdosing on her prescribed valproic acid or sertraline, reports no current suicidal ideation, and does not want to die. She accurately recalls her correct daily dosing of each medication, and verifies that she stopped taking valproic acid 2 weeks ago after being advised to do so by the ED clinicians at Visit 2. She continued to take sertraline until Visit 2. She denied any past or present episodes consistent with mania, which was consistent with her mother’s report.

Continue to: Ms. L becomes agitated...

Ms. L becomes agitated upon further questioning, and requests immediate discharge so that she can return to her family. The evaluation is postponed briefly.

When they reconvene, the C-L team performs a decision-making capacity evaluation, which reveals that Ms. L’s mood and affect are consistent with fear of her impending liver transplant and being alone and approximately 2 hours from her family. This is likely complicated by delirium due to hepatotoxicity. Further discussion between Ms. L and the multidisciplinary team focuses on the risks, benefits, adverse effects of, and alternatives to her current treatment; the possibility of needing a liver transplantation; and how to help her family with transportation to the hospital. Following the discussion, Ms. L is fully cooperative with further treatment, and the pre-transplant psychiatric evaluation is completed.

On physical examination, Ms. L is noted to have a widespread morbilliform rash covering 50% to 60% of her body.

[polldaddy:10307651]

The authors’ observations

L-carnitine supplementation

Multiple studies have shown that supplementation with L-carnitine may increase survival from severe hepatotoxicity due to valproic acid.8,9 Valproic acid may contribute to carnitine deficiency due to its inhibition of carnitine biosynthesis via a decrease in alpha-ketoglutarate concentration.8 Hepatotoxicity or hyperammonemia due to valproic acid may be potentiated by a carnitine deficiency, either pre-existing or resulting from valproic acid.8 L-carnitine supplementation has hastened the decrease of valproic acid–induced ammonemia in a dose-dependent manner,10 and it is currently recommended in cases of valproic acid toxicity, especially in children.8 Children at high risk for developing carnitine deficiency who need to receive valproic acid can be given carnitine supplementation.11 It is not known whether L-carnitine is clinically effective in protecting the liver or hastening liver recovery,8 but it is believed that it might prevent adverse effects of hepatotoxicity and hyperammonemia, especially in patients who receive long-term valproic acid therapy.12

TREATMENT Decompensation and transplantation

Ms. L’s treatment regimen includes NAC, lactulose, and L-carnitine supplementation. During the course of Ms. L’s hospital stay, her liver enzymes begin to trend downward, but her INR and PT remain elevated.

Continue to: On hospital Day 6...

On hospital Day 6, she develops more severe symptoms of hepatic encephalopathy, with significant altered mental status and inattention. Ms. L is transferred to the ICU, intubated, and placed on the liver transplant list.

On hospital Day 9, she undergoes a liver transplantation.

[polldaddy:10307652]

The authors’ observations

Baseline laboratory testing should have been conducted prior to initiating valproic acid. As Ms. L’s symptoms worsened, better communication with her PCP and closer monitoring after starting valproic acid might have resulted in more immediate care. Early recognition of her symptoms and decompensation may have triggered earlier inpatient admission and/or transfer to a tertiary care facility for observation and treatment. Additionally, repeat laboratory testing and instructions on when to return to the ED should have been provided at Visit 1.

This case demonstrates the need for all clinicians who prescribe valproic acid to remain diligent about the accurate diagnosis of mood and behavioral symptoms, knowing when psychotropic medications are indicated, and carefully considering and discussing even rare, potentially life-threatening adverse effects of all medications with patients.

Although rare, after starting valproic acid, a patient may experience a rapid decompensation and life-threatening illness. Ideally, clinicians should closely monitor patients after initiating valproic acid (Table 41). Clinicians must have a clear knowledge of the recommended monitoring and indications for hospitalization and treatment when they note adverse effects such as elevated liver enzymes or transaminitis (Table 513,14). Even after stopping valproic acid, patients who have experienced adverse events should be closely monitored to ensure complete resolution.

Continue to: Consider patient-specific factors

Consider patient-specific factors

Consider the mental state, intellectual capacity, and social support of each patient before initiating valproic acid. Its use as a mood stabilizer for “mood swings” outside of the context of bipolar disorder is questionable. Valproic acid is FDA-approved for treating bipolar disorder and seizures, but not for anger outbursts/irritability. Prior to starting valproic acid, Ms. L may have benefited from alternative nonpharmacologic treatments, such as psychotherapy, for her anger outbursts and poor coping skills. Therapeutic techniques that focused on helping her acquire better coping mechanisms may have been useful, especially because her mood symptoms did not meet criteria for bipolar disorder, and her depression had long been controlled with sertraline monotherapy.

OUTCOME Discharged after 20 days

Ms. L stays in the hospital for 10 days after receiving her liver transplant. She has low appetite and some difficulty with sleep after the transplant; therefore, the C-L team recommends mirtazapine, 15 mg/d. She has no behavioral problems during her stay, and is set up with home health, case management, and psychiatry follow-up. On hospital Day 20, she is discharged.

Bottom Line

Use caution when prescribing valproic acid, even in young, otherwise healthy patients. Although rare, some patients may experience a rapid decompensation and life-threatening illness after starting valproic acid. When prescribing valproic acid, ensure close follow-up after initiation, including mental status examinations, physical examinations, and laboratory testing.

Related Resource

- Doroudgar S, Chou TI. How to modify psychotropic therapy for patients who have liver dysfunction. Current Psychiatry. 2014;13(12):46-49.

Drug Brand Names

Diphenhydramine • Benadryl

Famotidine • Fluxid, Pepcid

Lamotrigine • Lamictal

Mirtazapine • Remeron

N-acetylcysteine • Mucomyst

Phenobarbital • Luminal

Phenytoin • Dilantin

Prednisone • Cortan, Deltasone

Sertraline • Zoloft

Valproic acid • Depakene

CASE Rash, fever, extreme lethargy; multiple hospital visits

Ms. L, age 21, a single woman with a history of major depressive disorder (MDD), is directly admitted from an outside community hospital to our tertiary care academic hospital with acute liver failure.

One month earlier, Ms. L had an argument with her family and punched a wall, fracturing her hand. Following the episode, Ms. L’s primary care physician (PCP) prescribed valproic acid, 500 mg/d, to address “mood swings,” which included angry outbursts and irritability. According to her PCP, no baseline laboratory tests were ordered for Ms. L when she started valproic acid because she was young and otherwise healthy.

After Ms. L had been taking valproic acid for approximately 2 weeks, her mother noticed she became extremely lethargic and took her to the emergency department (ED) of a community hospital (Visit 1) (Table 1). At this time, her laboratory results were notable for an aspartate aminotransferase (AST) level of 303 IU/L (reference range: 8 to 40 IU/L) and an alanine aminotransferase (ALT) level of 241 IU/L (reference range: 20 to 60 IU/L). She also underwent a liver ultrasound, urine toxicology screen, blood alcohol level, and acetaminophen level; the results of all of these tests were unremarkable. Her valproic acid level was within therapeutic limits, consistent with patient adherence; her ammonia level was within normal limits. At Visit 1, Ms. L’s transaminitis was presumed to be secondary to valproic acid. The ED clinicians told her to stop taking valproic acid and discharged her. Her PCP did not give her any follow-up instructions for further laboratory tests or any other recommendations.

During the next week, even though she stopped taking the valproic acid as instructed, Ms. L developed a rash and fever, and continued to have lethargy and general malaise. When she returned to the ED (Visit 2) (Table 1), she was febrile, tachycardic, and hypotensive, with an elevated white blood cell count, eosinophilia, low platelets, and elevated liver function tests. At Visit 2, she was alert and oriented to person, place, time, and situation. Ms. L insisted that she had not overdosed on any medications, or used illicit drugs or alcohol. A test for hepatitis C was negative. Her ammonia level was 58 µmol/L (reference range: 11 to 32 µmol/L). Ms. L received N-acetylcysteine (NAC), prednisone, diphenhydramine, famotidine, and ibuprofen before she was transferred to our tertiary care hospital.

When she arrives at our facility (Visit 3) (Table 1), Ms. L is admitted with acute liver failure. She has an ALT level of 4,091 IU/L, and an AST level of 2,049 IU/L. Ms. L’s mother says that her daughter had been taking sertraline for depression for “some time” with no adverse effects, although she is not clear on the dose or frequency. Her mother says that Ms. L generally likes to spend most of her time at home, and does not believe her daughter is a danger to herself or others. Ms. L’s mother could not describe any episodes of mania or recurrent, dangerous anger episodes. Ms. L has no other medical history and has otherwise been healthy.

On hospital Day 2, Ms. L’s ammonia level is 72 µmol/L, which is slightly elevated. The hepatology team confirms that Ms. L may require a liver transplantation. The primary team consults the inpatient psychiatry consultation-liaison (C-L) team for a pre-transplant psychiatric evaluation.

[polldaddy:10307646]

The authors’ observations

The differential diagnosis for Ms. L was broad and included both accidental and intentional medication overdose. The primary team consulted the inpatient psychiatry C-L team not only for a pre-transplant evaluation, but also to assess for possible overdose.

Continue to: A review of the records...