User login

Expanding Hospitalist Roles to Public Health

The field of hospital medicine came into being in response to numerous factors involving physicians, patients, and hospitals themselves1 Now, years later, hospital medicine is a specialty that is growing, both in size and sophistication such that the role of the hospitalist is constantly evolving.2 A compelling function that has not yet been clearly articulated is the opportunity for hospitalists to serve as public health practitioners in their unique clinical environment. There is precedence for the power of collaboration between medicine and public health as has been seen with emergency medicine's willingness to embrace opportunities to advance public health.35

In public health, the programs, services, and institutions involved emphasize the prevention of disease and the health needs of the population as a whole. Public health activities vary with changing technology and social values, but the goals remain the same: to reduce the amount of disease, premature death, and disease‐associated discomfort and disability in the population.6 The authors of a leading textbook of public health, Scutchfield and Keck, contend that the most important skill for public health practice is the capacity to visualize the potential for health that exists in a community.6

Hospitalists care for a distinct subset of the general populationinpatients, only a small percentage of society in a given year. Yet over time hospitalists affect a substantial subset of the larger population that uses considerable health care resources.79 Furthermore, hospitalization can be a sentinel event with public health implications (eg, newly diagnosed HIV infection or acute myocardial infarction in a patient with an extended family of cigarette smokers). This presents an opportunity to educate and counsel both the patient and the patient's social network. One model of public health practice by hospitalists is to influence the patient, his or her family, and the community by touching and inspiring the hospitalized patient.

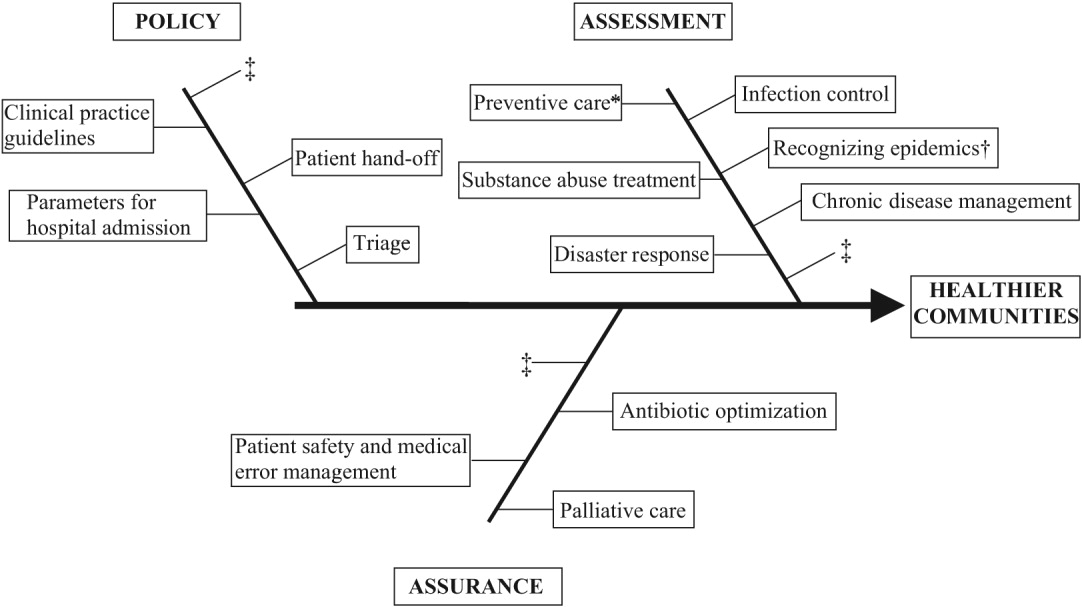

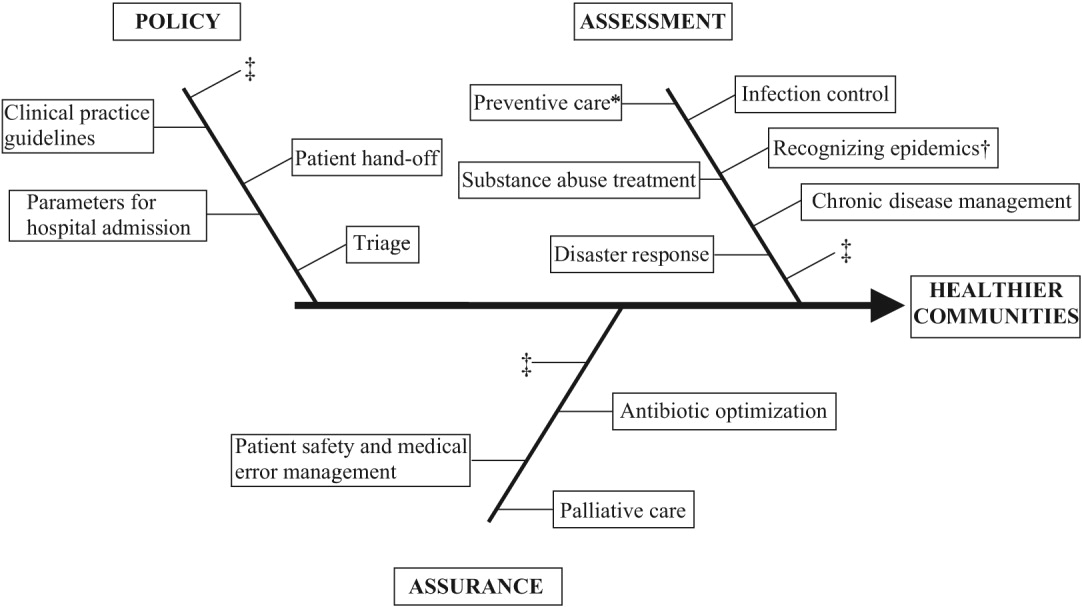

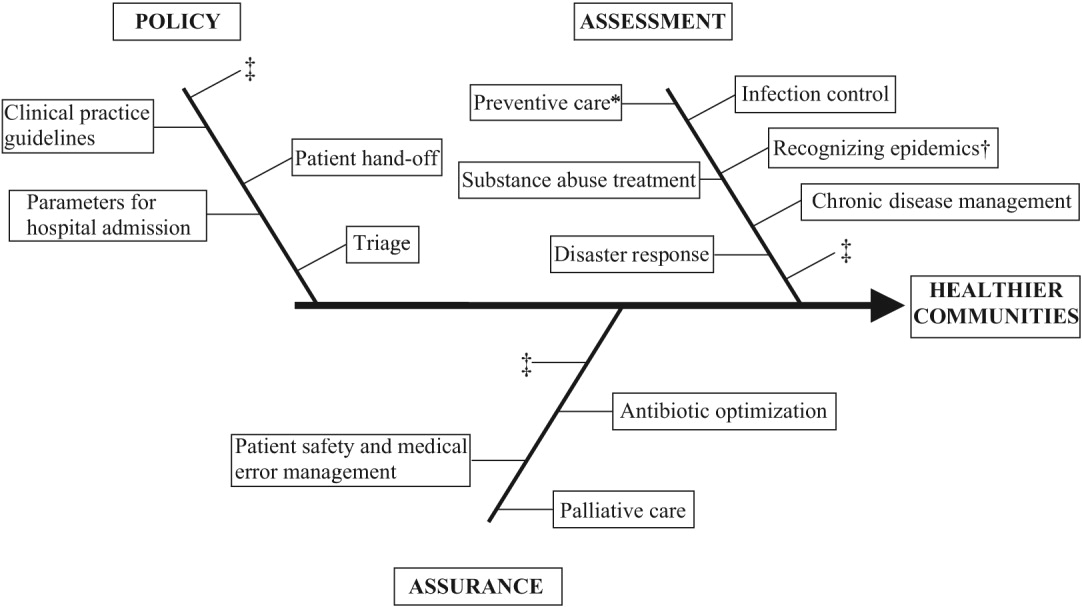

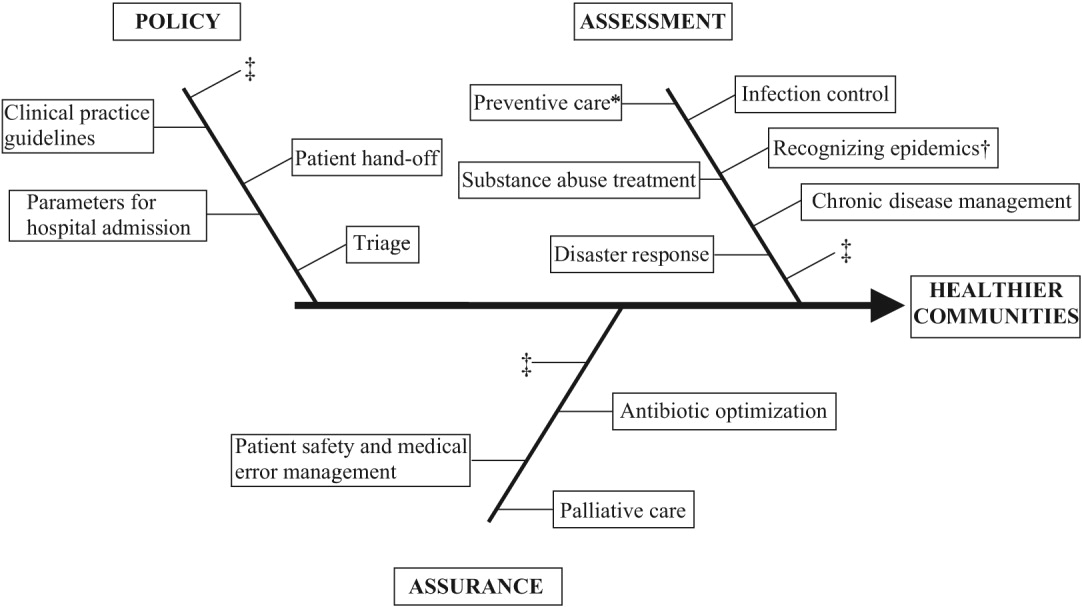

Hospitalists are already involved in many of the core functions of public health (assessment, assurance, and policy development; Fig. 1).10 Achieving ongoing success in this arena means developing hospitalists who are consciously in tune with their roles as public health practitioners.

In this article we define the specific public health contributions that hospitalists have made and describe the possibilities for further innovative advances. To this end, we outline specific public health roles under the broad categories of assessment, assurance, and policy. We point to advances in public health accomplished by hospitalists as well as those being performed by nonhospitalists in the hospital setting. We conclude by describing some of the barriers to and implications of hospitalists taking on public health roles.

ASSESSMENT

Assessment is the systematic collection, analysis, and dissemination of health status information.10 These activities include disease surveillance and investigation of acute outbreaks or changes in the epidemiology of chronic diseases. Assessment also involves understanding the health of a population and the key determinants of a population's health from a variety of perspectives: physical, biological, behavioral, social, cultural, and spiritual.6 Human health has been defined as a state characterized by anatomic integrity; ability to perform personally valued family work and community roles; ability to deal with physical, biologic, and social stress; a feeling of well‐being; and freedom from the risk of disease and untimely death.6 Hospitalists interact with individuals at times of stress and acute illness and thus have a unique opportunity to assess the strength, viability, and resources available to individuals. Key roles that may fall within the auspices of assessment in hospital medicine are infection control, epidemic recognition, disaster response, preventive care, substance abuse treatment, and chronic disease management.

Infection Control

Physicians caring for inpatients have a crucial stake in controlling hospital infection as exemplified by the work of Flanders et al. on preventing nosocomial infections, especially nosocomial pneumonia.11 They describe specific strategies to prevent iatrogenic spread such as washing hands before and after patient contact, establishing guidelines against the use of artificial fingernails, using indwelling devices such as catheters only when absolutely necessary, and using sterile barriers.11 Hospitalists such as Sanjay Saint have led the way in studying methods to reduce bladder catheterization, which has been associated with urinary tract infections12; others have collaborated on work to prevent infections in nursing homes.13 Given the importance of this field, there is room for further hospitalist involvement. Novel methods for infection control in hospitals have been studied by nonhospitalists such as Wisnivesky, who prospectively validated a clinical decision rule to predict the need for respiratory isolation of inpatients with suspected tuberculosis (TB). This prediction rule, which is based on clinical and chest radiographic findings, was able to accurately identify patients at low risk for TB from among inpatients with suspected active pulmonary TB isolated on admission to the hospital.14 Retrospective application of the prediction rule showed respiratory precautions were inappropriately implemented for a third of patients.14 These studies are examples of empiric public health research performed in the inpatient setting. In the infection control domain, candidate issues for further study could include interventions aimed at reducing rates of Clostridium difficile, developing programs for standardized surveillance of hospital infection, validating electronic markers for nosocomial infection, and taking innovative approaches to improving hand‐washing practices in the hospital.15, 16

Recognizing Epidemics

An excellent example of the importance of hospitalists embracing public health and remembering their patients are part of a community was the severe acute respiratory syndrome (SARS) outbreak in Toronto, Ontario, Canada. The outbreak is thought to have begun with a single traveler. With the transfer of patients and the movement of visitors and health care workers among facilities, SARS quickly spread through Toronto, making it the largest SARS‐affected area outside Asia.17 Approximately a month after the outbreak was recognized in Toronto, it was thought to be over, and the World Health Organization (WHO) removed Toronto from its SARS‐affected list.17 Unfortunately, patients with unrecognized SARS remained in health care institutions, including a patient transferred to a rehabilitation center. Infection quickly spread again, resulting in a second phase of the outbreak.17

The SARS outbreak served as a reminder that a global public health system is essential and taught many lessons17 germane to pandemics that recur annually (eg, influenza viruses) as well those that episodically threaten the health of the population (eg, avian flu). Proposed actions to prevent a repeat of the scenario that occurred with SARS in Toronto include assessing the current facilities (eg, isolation rooms and respiratory masks) at each institution, identifying health care workers willing to serve as an outbreak team, and the hiring staff to train hospital personnel in personal protective equipment (PPE) and infection control policies.18 The Centers for Disease Control and Prevention (CDC) contends that planning for the possibility of a virulent pandemic at the local, national, and global levels is critical to limiting the mortality and morbidity should such occur.19, 20 In a previous article, Pile and Gordon declared hospitalists are key players in institutional efforts to prepare for a viral pandemic such as influenza and should be aware of lessons that may be applied from responses to pandemics such as SARS.19 Well placed to recognize clinical trends that may herald epidemics, hospitalists can fulfill some of the necessary public health responsibilities delineated above.

Disaster Response

Natural disasters and terrorism are in the forefront of the popular press and are also high priorities in health care and public health.21 Terrorism and natural disasters cause significant injury, illness, and death.22 Hospital‐based health care providers fulfill a variety of roles when terrorist acts and disasters occur, including reporting, diagnosing, and managing illness, providing preventive measures (eg, vaccines and preparedness kits), preventing the secondary spread of disease, assisting in the investigation of the causes of disease outbreaks, participating in preparedness planning, and evaluating preparedness policies and programs.22 The experience gained in the aftermaths of Hurricanes Katrina and Rita with their unprecedented death, injury, destruction, and displacement should help to guide future response and recovery activities.23 Hospitalists were at the forefront of delivering care, living in their hospitals for days after Hurricane Katrina. Without question, hospitalists will be called on again to serve those affected by disasters.

Preventive Care

For many patients admitted to the hospital, meeting a hospitalist is their first encounter with a physician in years.24, 25 In these instances, hospitalists must ensure that patients' immunizations are up‐to‐date and arrange appropriate follow‐up care with primary care providers. Greenwald described an important role that hospitalists could play in HIV prevention by promoting HIV testing in the hospital.26 The CDC recently confirmed the wisdom of this approach and estimates that the 250,000 to 1.2 million people in the United States with HIV infection who do not know their serostatus play a significant role in HIV transmission.26, 27 In an effort to promote testing, the CDC has initiated a program aimed at incorporating HIV testing into routine medical care, as recommended by others.28 More than a quarter of patients with HIV in the United States are diagnosed in the hospital, and for many other patients, hospitalization is their only real opportunity to be tested.26, 29 Similarly, when hospitalists find elevated cholesterol or triglycerides in routine evaluations of patients who present with chest pain, they have to decide whether to initiate lipid‐lowering medications.30 The hospitalist is sometimes the only physician that patients repeatedly admitted, may see over prolonged periods. It follows that if hospitalists are remiss in delivering preventive care to such patients, they lose the opportunity to positively affect their long‐term health. In practice, hospitalists perform myriad preventive‐care functions, although there is scant literature supporting this role. Hospitalists have an opportunity to collaborate in research projects of hospital‐initiated preventive care that measure outcomes at the community level.

Substance Abuse

In the Unites States, 25%‐40% of hospital admissions are related to substance abuse and its sequelae.31 These patients frequently are admitted to general medicine services for detoxification or treatment of substance‐abuse‐related morbidity, although some American hospitals have specialized treatment and detoxification centers. There is a pressing need for more models of comprehensive care that address the complex issues of addiction, including the biological, social, cultural, spiritual, and developmental needs of patients.32

Hospitalists routinely counsel their patients with substance abuse problems and often consult a chemical dependency counselor, who provides patients with additional information about outpatient or inpatient facilities that may help them after their hospitalization. Unfortunately, because of the natural history of substance abuse, many of these patients are rehospitalized with the same problems even after going through rehabilitation. The adoption of a public health philosophy and approach by hospitalists may assist patients who have addictions through innovative multidisciplinary interventions while these patient are being detoxified. Traditionally, these responsibilities have fallen to primary care providers and psychologists in substance abuse medicine; but, as mentioned previously, many such patients are rehospitalized before they make it to their follow‐up appointments.

In a study examining smoking cessation practices among Norwegian hospital physicians, 98% of the doctors stated they ask their patients about their smoking habits, but fewer than 7% of these physicians regularly offer smoking‐cessation counseling, hand out materials, or give patients other advice about smoking cessation.33 That study illustrates that hospital doctors often ask about problems but can certainly improve in terms of intervention and follow‐up. Other works by nonhospitalist physicians have examined the real potential of inpatient interventions for smoking cessation. Most of this work involves a multidisciplinary approach that relies heavily on nurses. For example, Davies et al. evaluated the effectiveness of a hospital‐based intervention for smoking cessation among low‐income smokers using public health methodologies. The intervention was effective and promising as a way to affect smokers in underserved communities.34

Chronic Disease Management

Public health roles involving chronic disease management include surveillance, intervention design, and implementation of control programs.6 Given their access to data on hospitalized patients, hospitalists can carry out surveillance and empirical population‐based research about hospitalized patients with chronic illnesses. Thoughtfully designed protocols can measure the success of interventions initiated in patients while hospitalized, with further data collection and follow‐up after patients have returned to the community.35 Such endeavors can improve the likelihood that patients with chronic conditions are effectively referred to programs that will maintain their health and functional status.36 If hospitalists consider themselves public health providers, encounters with these hospitalized patients will go beyond noting that their chronic conditions are stable and instead will lay the groundwork to prospectively control these conditions. This approach would have the potential to reduce the number of future hospitalizations and lead to healthier communities.37 To truly carry this out effectively, coordinated collaboration between primary care providers and hospitalists will be necessary.

ASSURANCE

Assurance is the provision of access to necessary health services. It entails efforts to solve problems that threaten the health of populations and empowers individuals to maintain their own health. This is accomplished by either encouraging action, delegating to other entities (private or public sector), mandating specific requirements through regulation, or providing services directly.10 Hospitalist teams aim to ensure that the high‐quality services needed to protect the health of their community (hospitalized patients) are available and that this population receives proper consideration in the allocation of resources. The few studies to date that have directly examined the quality of care that hospitalists provide38 have done so using evidence‐based measures believed to correlate with improved health care outcomes.38 The ambiguities in assessing quality may in part limit such studies.39 Specific hospitalist roles that fall under the assurance umbrella include antibiotic optimization, palliative care, patient safety, and medical error management.

Antibiotic Optimization

Inappropriate use of antimicrobial treatment for infectious diseases has cost and public health implications.40 These inappropriate uses include giving antibiotics when not indicated, overusing broad‐spectrum antibiotics, making mismatches between microbes and medicines when cultures and information on test sensitivity are available, and using intravenous formulations when oral therapy would suffice.41 The public health impact goes way beyond increasing selective pressure for antimicrobial resistance to include safety, adverse events, and increased costs to both patient and hospitals.40 At our institution, the hospital medicine service and infectious disease division have jointly developed and implemented an intervention to reduce inappropriate antibiotic use. At other institutions, hospitalist teams have developed protocols for treating infectious diseases commonly encountered in the hospitalized patient.42 The recommendations of both Amin and Reddy for management of community‐ and hospital‐acquired pneumonia acknowledged that through establishment of clinical care pathways, variation in prescribing patterns among hospitalists can be decreased while optimizing outcomes.42 The work of Williams and colleagues is another example of advances by hospitalists. They reviewed the literature to determine that the use of combination antibiotics as empiric therapy for community‐acquired pneumonia is superior to the use of a single effective antibiotic in treating bacteremic patients with pneumococcal community‐acquired pneumonia.43

Palliative Care

Mortality is a vital outcome measure of public health research and interventions. Not surprisingly, many people are hospitalized in the final months of their life and often die in a hospital. Pantilat showed that hospitalists can respond to these circumstances and have the opportunity to improve care of the dying.4446 Muir et al. evaluated the convergence of the fields of palliative care medicine and hospital medicine and reviewed the opportunities for mutual education and improved patient care.47 They described how the confluence of the changing nature and site of death in the United States coupled with the reorganization of hospital care provides a strategic opportunity to improve end‐of‐life care.47 Hospitalists can ensure that care of the dying is delivered with skill, compassion, and expertise. And so it is imperative they be trained to accomplish this objective.47, 49

Fortunately, hospitalists already appear to enhance patientphysician communication. Auerbach looked at communication, care patterns, and outcomes of dying patients, comparing patients being cared for by hospitalists with those being care for by community‐based physicians. Hospitalists had discussions with patients or their families about care more often than did nonhospitalist physicians (91% versus 73%, respectively, P = .006).49 Because the delivery of high‐quality palliative care is time consuming and complex, alternative models for billing or the use of physician extenders or consultants may be necessary at some institutions.

Patient Safety and Medical Error Management

Hospitalists have been in the forefront of promoting a culture of patient safety.50 Their continuous presence in the hospital and their interactions with members of health care teams from multiple disciplines who share this goal make them important facilitators. Hospitalists have increasing involvement in systems‐based efforts aimed at reducing medical errors.50 Hospitalists are being asked to lead committees that adopt multidisciplinary approaches to reduce adverse events, morbidity, and mortality.50 These committees often have representation from pharmacy, nursing, and other key hospital stakeholders including from the administration.51 Quality assurance activities assess locally collected data and compare results with local and national benchmarks. There are several published examples of hospitalists engaged in patient safety and medical error management. For example, Shojania et al compiled evidence based safety practices in an effort to promote patient safety.52, 53 Schnipper studied the role of pharmacist counseling in preventing adverse drug events (ADEs) after hospitalization and found that pharmacist medication review, patient counseling, and telephone follow‐up were associated with a lower rate of preventable ADEs 30 days after hospital discharge.54 Moreover, Syed paired hospitalists and pharmacists to collaboratively prescribe medications appropriately. In one study there were fewer medication errors and adverse drug reactions in patients treated by a team led by hospitalists than in those treated by the control group, made up of nonhospitalist attendings.55

POLICY

Policy development defines health control goals and objectives and develops implementation plans for those goals.10 By necessity, it operates at the intersection of legislative, political, and regulatory processes.10 At many institutions, hospitalists have been involved in the development of policies ensuring that the core functions of assessment and assurance are addressed and maintained. In fact, hospitalists report that development of quality assurance and practice guidelines accounts for most of their nonclinical time.56 This role of hospitalists is supported by anecdotal reports rather than published empiric evidence.57 For example, at Johns Hopkins Bayview Medical Center, hospitalist‐led teams have developed triage and patient handoff policies designed to improve patient safety. Parameters for admission to the general medicine ward have been elaborated and are periodically refined by the hospitalist team.

Another area that falls within the genre of policy is development of clinical practice guidelines. Guidelines for the treatment of pneumonia, congestive heart failure, deep‐vein thrombosis prophylaxis, alcohol and drug withdrawal, pain management, delirium, and chronic obstructive pulmonary disease have been developed by nonhospitalists.58, 59 These areas are considered core competencies in hospital medicine, and as such, hospitalists have an obligation to review and refine these guidelines to ensure the best provision of care to our patients.59

Hospitalists have been engaged in upholding guidelines that affect community practice. For example, in a study comparing treatment of patients admitted with congestive heart failure by hospitalists compared with that by nonhospitalists, hospitalists were found to be more likely to document left ventricular function, a core measure of quality as defined by JCAHO.39, 60 Knowledge about cardiac function can direct future care for patients when they return to the community and into the care of their primary care providers. In another example, Rifkin found that patients with community‐acquired pneumonia treated by hospitalists were more rapidly converted to oral antibiotics from intravenous antibiotics, facilitating a shorter length of stay,61 which reduced the opportunity for nosocomial infections to propagate. Because hospitalists are skilled at following guidelines,59 it follows that they should seize the opportunity to develop more of them.

As the hospitalist movement continues to grow, hospitalists will likely be engaged in implementing citywide, statewide, and even national policies that ensure optimal care of the hospitalized patient.

BARRIERS TO HOSPITALISTS FOCUSING ON PUBLIC HEALTH

Hospitalists are involved in public health activities even though they may not recognize the extent of this involvement. However, there may be some drawbacks to hospitalists viewing each patient encounter as an opportunity for a public health intervention. First, in viewing a patient as part of a cohort, the individual needs of the patient may be overlooked. There is inherent tension between population‐based and individual‐based care, which is a challenge. Second, hospitalists are busy clinicians who may be most highly valued because of their focus on efficiency and cost savings in the acute care setting. This factor alone may prevent substantive involvement by hospitalists in public health practice. Moving beyond the management of an acute illness may interfere with this efficiency and cost effectiveness from the hospital's perspective. However, interventions that promote health and prevent or reduce rehospitalizations may be cost effective to society in the long run. Third, current billing systems do not adequately reward or reimburse providers for the extra time that may be necessary to engage in public health practice. Fourth, hospitalists may not have the awareness, interest, training, or commitment to engage in public health practice. Finally, there may not be effective collaboration and communication systems between primary care providers and hospitalists. This barrier limits or hinders many possibilities for the effective execution of several public health initiatives.

CONCLUSIONS AND IMPLICATIONS

Hospitalists and the specialty of hospital medicine materialized because of myriad economic forces and the need to provide safe, high‐quality care to hospitalized patients. In this article we have described the ways in which hospitalists can be explicitly involved in public health practice. Traditionally, physicians caring for hospitalized patients have collected information through histories and physical examinations, interpreted laboratory data and tests, and formulated assessments and plans of care. To become public health practitioners, hospitalists have to go beyond these tasks and consider public health thought processes, such as problem‐solving paradigms and theories of behavior change. In adopting this public health perspective, hospitalists may begin to think of a patient in the context of the larger community in order to define the problems facing the community, not just the patient, determine the magnitude of such problems, identify key stakeholders, create intervention/prevention strategies, set priorities and recommend interventions, and implement and evaluate those interventions. This approach forces providers to move beyond the physicianpatient model and draw on public health models to invoke change. Hopefully, future research will further convince hospitalists of the benefits of this approach. Although it may be easier to defer care and management decisions to an outpatient physician, data suggest that intervening when patients are in the hospital may be most effective.62, 63 For example, is it possible that patients are more likely to quit smoking when they are sick in the hospital than when they are in their usual state of health on a routine visit at their primary care provider's office?64 Further, although deferring care to a primary care provider (PCP) may be easier, it is not always possible given these barriers: (1) some patients are routinely rehospitalized, precluding primary care visits, (2) some recommendations may not be received by PCPs, and (3) PCPpatient encounters are brief and the agendas full, and there are limited resources to address recommendations from the hospital.

As hospitalists become more involved in public health practice, their collaboration with physicians and researchers in other fields, nurses, policymakers, and administrators will expand. Succeeding in this arena requires integrity, motivation, capacity, understanding, knowledge, and experience.65 It is hoped that hospitalists will embrace the opportunity and master the requisite skill set necessary to practice in and advance this field. As hospitalist fellowship programs are developed, public health practice skills could be incorporated into the curriculum. Currently 6 of 16 fellowship programs offer either a master of public health degree or public health courses.66 Public health skills can also be taught at Society of Hospital Medicine meetings and other continuing medical education events.

With the evolution of hospital medicine, hospitalists have to be malleable in order to optimally meet the needs of the population they serve. The possibilities are endless.

- ,.The Hospitalist movement 5 years later.JAMA.2002;287:487–494.

- Hospitals and Health Networks. Hospitalists: a specialty coming into its own. Available at: http://www.hhmag.com. Accessed February 27,2006.

- ,,.Emergency medicine and public health: new steps in old directions.Ann Emerg Med.2001;38:675–683.

- ,, et al.A public health approach to emergency medicine: preparing for the twenty‐first century.Acad Emerg Med.1994;1:277–286.

- ,.Emergency medicine in population‐based systems of care.Ann Emerg Med.1997;30:800–803.

- ,.Principles of Public Health Practice.Albany, NY:Delmar Publishing;1997.

- Centers for Medicare and Medicaid. Health care spending and growth rate continue to decline in 2004. Available at: http://www.cms.hhs.gov. Accessed October 31,2006.

- ,,, et al.National health expenditures, 2002.Health Care Financ Rev. Summer2004;25:4.

- ,,, et al.Health spending Projections Through 2015: Changes on the Horizon.Health Affairs2006;25:w61–w73.

- Institute of Medicine.Recommendations from the Future of Public Health. InThe Future of the Public's Health.Washington, DC:National Academic Press;2003:411–420.

- ,,.Nosocomial pneumonia: state of the science.Am J Infect Control.2006;34:84–93.

- ,,,,.A reminder reduces urinary catheterization in hospitalized patients.Jt Comm J Qual Patient Saf.2005;31:455–462.

- ,,,.Preventing infections in nursing homes: A survey of infection control practices in southeast Michigan.Am J Infect Control.2005;33:489–492.

- ,,,.Prospective validation of a prediction model for isolating inpatients with suspected pulmonary tuberculosis.Arch Intern Med.2005;165:453–457.

- ,.The Hospital Infection Standardised Surveillance (HISS) programme: analysis of a two‐year pilot.J Hosp Infect.2003;53:259–267.

- ,,,.A Laboratory‐Based, Hospital‐Wide, Electronic Marker for Nosocomial Infection.Am J Clin Pathol.2006;125:34–39.

- ,,.Severe acute respiratory syndrome.Arch Pathol Lab Med.2004;128:1346–1350.

- ,,.Severe acute respiratory syndrome: responses of the healthcare system to a global epidemic.Curr Opin Otolaryngol Head Neck Surg.2005;13:161–164.

- ,.Pandemic influenza and the hospitalist: apocalypse when?J Hosp Med.2006;1:118–123.

- Center for Disease Control and Prevention. Pandemic Influenza information for Health Professionals. Available at: http://www.cdc.gov/flu/pandemic/. Accessed October 31,2006.

- .US health policy in the aftermath of Hurricane Katrina.JAMA.2006;295:437–40

- Levy B,Sidel V, eds.Terrorism and Public Health.New York:Oxford University Press;2003.

- Centers for Disease Control and Prevention (CDC).Public health response to Hurricanes Katrina and Rita—United States 2005.MMWR Morb Mortal Wkly Rep.2006;55:229–231.

- ,,,,,.Racial and ethnic disparities in health: a view from the South Bronx.J Health Care Poor Underserved.2006;17:116–127.

- ,.Williams E. Health Seeking behaviors of African Americans: implications for health administration.J Health Hum Serv Adm.2005;28(1):68–95.

- .Routine rapid HIV testing in hospitals: another opportunity for hospitalists to improve care.J Hosp Med.2006;1:106–112.

- Centers for Disease Control and Prevention.Advancing HIV prevention: new strategies for a changing epidemic—United States, 2003.MMWR Morb Mortal Wkly Rep.2003;52:329–332.

- ,,, et al.Expanded screening for HIV in the United States—an analysis of cost‐effectiveness.N Engl J Med.2005;352:586–595.

- ,,,.Identifying undiagnosed human immunodeficiency virus: the yield for routine, voluntary, inpatient testing.Arch Intern Med.2002;162:887–892.

- ,,,,.Insufficient treatment of hypercholestrolemia among patients hospitalized with chest pain.Clin Cardiol.2006;29:259–262.

- .Medical management of alcoholic patients. In:Kissen B,Besleiter H, eds.Treatment and Rehabilitation of the Chronic Alcoholic.New York:Plenum Publishing Co.;1997.

- ,,.An integral approach to substance abuse.J Psychoactive Drugs.2005;37:363–371.

- ,,, et al.Smoking cessation practice among Norwegian hospital physicians.Tiddskr Nor laegeforen.2000;120:1629–1632.

- ,, et al.Evaluation of an intervention for hospitalized African American smokers.Am J Health Behav.2005;29:228–239.

- .Falling through the cracks: challenges and opportunities for improving transitional care for persons with continuous complex care needs [review].J Am Geriatr Soc.2003;51:549–555.

- ,,,,.Advances in hospital medicine: a review of key articles from the literature.Med Clin N Am.2002;86:797–823.

- ,,,,,.Comprehensive discharge planning with post discharge support for older patients with congestive heart failure.JAMA.2004;291:1358–1367.

- ,.The impact of hospitalists on the cost and quality of inpatient care in the United States: a research synthesis.Med Care Res Rev.2005;62:379–406.

- ,,,,,Quality of care for patients hospitalized with heart failure: assessing the impact of hospitalists.Arch Intern Med.2002;162:1251–1256.

- ,,,.Educational interventions to improve antibiotic use in the community: report from the International Forum on Antibiotic Resistance (IFAR) colloquim, 2002.Lancet Infect Dis.2004;4:44–53.

- ,,, et al.Systematic review of antimicrobial drug prescribing in hospitals.Emerg Infect Dis.2006;12:211–216.

- ,,,,,,.Recommendations for management of community and hospital acquired pneumonia‐the hospitalist perspective.Curr Opin Pulm Med.2004;10(suppl 1):S23–S27.

- ,,,,.Advances in hospital medicine: a review of key articles from the literature.Med Clin N Am.2002;86:797–823.

- .End‐of‐life care for the hospitalized patient.Med Clin N Am.2002;86:749–770.

- ,.Palliative care for patients with heart failure.JAMA.2004;291:2476–2482.

- ,.Prevalence and structure of palliative care services in California hospitals.Arch Intern Med.2003;163:1084–1088.

- ,.Palliative care and the hospitalist: an opportunity for cross‐fertilization.J Med.2001;111:10S–14S.

- .Palliative care in hospitals.J Hosp Med.2006;1:21–28.

- ,.End‐of‐life care in a voluntary hospitalist model: effects on communication, process of care, and patient symptoms.Am J Med.2004;116:669–675.

- ,,,Understanding medical error and improving patient safety in the inpatient setting,Med Clin N Am2002;86:847–867.

- , The hospitalist movement: ten issues to consider, hospital practice. Available at: http://www.hosppract.com/issues/1999/02/wachter.htm. Accessed March 14,2006.

- Shojania KG,Duncan BW,McDonald KM,Wachter RM, eds.Making health care safer: a critical analysis of patient safety practices. Evidence Report/Technology Assessment No. 43 from the Agency for Healthcare Research and Quality: AHRQ Publication No. 01‐E058;2001. Available at: http://www.ahrq.gov/clinic/ptsafety/.

- ,,,.Safe but sound: patient safety meets evidence‐based medicine.JAMA.2002;288:508–513.

- ,,, et al.Role of pharmacist counseling in preventing adverse drug events after hospitalization.Arch Intern Med.2006;166:565–571.

- Hospitalists, pharmacists partner to cut errors: shorter lengths of stay, lower med costs result. HealthCare Benchmarks and Quality Improvement.American Health Consultants, Inc.,2005.

- ,,,.Hospitalists and the practice of inpatient medicine: results of a survey of the National Association of Inpatient Physicians.Ann Intern Med.1999;130:343–349.

- ,,,,.Core competencies in hospital medicine: Development and methodology.J Hosp Med.2006;1:48–56.

- National guideline clearing house. Available at: http://www.guideline.gov. Accessed June 26,2006.

- ,,,,, eds.The core competencies in hospital medicine.J Hosp Med.2006;1(suppl 1).

- Joint Commission on Accreditation of Healthcare Organizations. Core Measures overview. Available at: http://www.jcaho.org/perfeas/coremeas/cm.ovrvw.html. Accessed February 1,2006.

- ,,,.,Comparison of processes and outcomes of pneumonia care between hospitalists and community‐based primary care physicians.Mayo Clin Proc.2002;77:1053–1058.

- ,.The effectiveness of a nursing inpatient smoking cessation program in individuals with cardiovascular disease.Nurs Res.2005;54:243–254.

- ,,,,,.Evaluation of an intervention for hospitalized African American smokers.Am J Health Behav.2005;29:228–239.

- .Smoking cessation: the case for hospital‐based interventions.Prof Nurse.2003;19(3):145–148..

- . Dee Hock's management principles, in his own words. Fast Company.1996;5:79. Available at: http://www.fastcompany.com/magazine/05/dee2.html.

- ,,,.Hospital Medicine Fellowships: Works in progress.Am J Med.2006;119(1):72.e1–e7.

The field of hospital medicine came into being in response to numerous factors involving physicians, patients, and hospitals themselves1 Now, years later, hospital medicine is a specialty that is growing, both in size and sophistication such that the role of the hospitalist is constantly evolving.2 A compelling function that has not yet been clearly articulated is the opportunity for hospitalists to serve as public health practitioners in their unique clinical environment. There is precedence for the power of collaboration between medicine and public health as has been seen with emergency medicine's willingness to embrace opportunities to advance public health.35

In public health, the programs, services, and institutions involved emphasize the prevention of disease and the health needs of the population as a whole. Public health activities vary with changing technology and social values, but the goals remain the same: to reduce the amount of disease, premature death, and disease‐associated discomfort and disability in the population.6 The authors of a leading textbook of public health, Scutchfield and Keck, contend that the most important skill for public health practice is the capacity to visualize the potential for health that exists in a community.6

Hospitalists care for a distinct subset of the general populationinpatients, only a small percentage of society in a given year. Yet over time hospitalists affect a substantial subset of the larger population that uses considerable health care resources.79 Furthermore, hospitalization can be a sentinel event with public health implications (eg, newly diagnosed HIV infection or acute myocardial infarction in a patient with an extended family of cigarette smokers). This presents an opportunity to educate and counsel both the patient and the patient's social network. One model of public health practice by hospitalists is to influence the patient, his or her family, and the community by touching and inspiring the hospitalized patient.

Hospitalists are already involved in many of the core functions of public health (assessment, assurance, and policy development; Fig. 1).10 Achieving ongoing success in this arena means developing hospitalists who are consciously in tune with their roles as public health practitioners.

In this article we define the specific public health contributions that hospitalists have made and describe the possibilities for further innovative advances. To this end, we outline specific public health roles under the broad categories of assessment, assurance, and policy. We point to advances in public health accomplished by hospitalists as well as those being performed by nonhospitalists in the hospital setting. We conclude by describing some of the barriers to and implications of hospitalists taking on public health roles.

ASSESSMENT

Assessment is the systematic collection, analysis, and dissemination of health status information.10 These activities include disease surveillance and investigation of acute outbreaks or changes in the epidemiology of chronic diseases. Assessment also involves understanding the health of a population and the key determinants of a population's health from a variety of perspectives: physical, biological, behavioral, social, cultural, and spiritual.6 Human health has been defined as a state characterized by anatomic integrity; ability to perform personally valued family work and community roles; ability to deal with physical, biologic, and social stress; a feeling of well‐being; and freedom from the risk of disease and untimely death.6 Hospitalists interact with individuals at times of stress and acute illness and thus have a unique opportunity to assess the strength, viability, and resources available to individuals. Key roles that may fall within the auspices of assessment in hospital medicine are infection control, epidemic recognition, disaster response, preventive care, substance abuse treatment, and chronic disease management.

Infection Control

Physicians caring for inpatients have a crucial stake in controlling hospital infection as exemplified by the work of Flanders et al. on preventing nosocomial infections, especially nosocomial pneumonia.11 They describe specific strategies to prevent iatrogenic spread such as washing hands before and after patient contact, establishing guidelines against the use of artificial fingernails, using indwelling devices such as catheters only when absolutely necessary, and using sterile barriers.11 Hospitalists such as Sanjay Saint have led the way in studying methods to reduce bladder catheterization, which has been associated with urinary tract infections12; others have collaborated on work to prevent infections in nursing homes.13 Given the importance of this field, there is room for further hospitalist involvement. Novel methods for infection control in hospitals have been studied by nonhospitalists such as Wisnivesky, who prospectively validated a clinical decision rule to predict the need for respiratory isolation of inpatients with suspected tuberculosis (TB). This prediction rule, which is based on clinical and chest radiographic findings, was able to accurately identify patients at low risk for TB from among inpatients with suspected active pulmonary TB isolated on admission to the hospital.14 Retrospective application of the prediction rule showed respiratory precautions were inappropriately implemented for a third of patients.14 These studies are examples of empiric public health research performed in the inpatient setting. In the infection control domain, candidate issues for further study could include interventions aimed at reducing rates of Clostridium difficile, developing programs for standardized surveillance of hospital infection, validating electronic markers for nosocomial infection, and taking innovative approaches to improving hand‐washing practices in the hospital.15, 16

Recognizing Epidemics

An excellent example of the importance of hospitalists embracing public health and remembering their patients are part of a community was the severe acute respiratory syndrome (SARS) outbreak in Toronto, Ontario, Canada. The outbreak is thought to have begun with a single traveler. With the transfer of patients and the movement of visitors and health care workers among facilities, SARS quickly spread through Toronto, making it the largest SARS‐affected area outside Asia.17 Approximately a month after the outbreak was recognized in Toronto, it was thought to be over, and the World Health Organization (WHO) removed Toronto from its SARS‐affected list.17 Unfortunately, patients with unrecognized SARS remained in health care institutions, including a patient transferred to a rehabilitation center. Infection quickly spread again, resulting in a second phase of the outbreak.17

The SARS outbreak served as a reminder that a global public health system is essential and taught many lessons17 germane to pandemics that recur annually (eg, influenza viruses) as well those that episodically threaten the health of the population (eg, avian flu). Proposed actions to prevent a repeat of the scenario that occurred with SARS in Toronto include assessing the current facilities (eg, isolation rooms and respiratory masks) at each institution, identifying health care workers willing to serve as an outbreak team, and the hiring staff to train hospital personnel in personal protective equipment (PPE) and infection control policies.18 The Centers for Disease Control and Prevention (CDC) contends that planning for the possibility of a virulent pandemic at the local, national, and global levels is critical to limiting the mortality and morbidity should such occur.19, 20 In a previous article, Pile and Gordon declared hospitalists are key players in institutional efforts to prepare for a viral pandemic such as influenza and should be aware of lessons that may be applied from responses to pandemics such as SARS.19 Well placed to recognize clinical trends that may herald epidemics, hospitalists can fulfill some of the necessary public health responsibilities delineated above.

Disaster Response

Natural disasters and terrorism are in the forefront of the popular press and are also high priorities in health care and public health.21 Terrorism and natural disasters cause significant injury, illness, and death.22 Hospital‐based health care providers fulfill a variety of roles when terrorist acts and disasters occur, including reporting, diagnosing, and managing illness, providing preventive measures (eg, vaccines and preparedness kits), preventing the secondary spread of disease, assisting in the investigation of the causes of disease outbreaks, participating in preparedness planning, and evaluating preparedness policies and programs.22 The experience gained in the aftermaths of Hurricanes Katrina and Rita with their unprecedented death, injury, destruction, and displacement should help to guide future response and recovery activities.23 Hospitalists were at the forefront of delivering care, living in their hospitals for days after Hurricane Katrina. Without question, hospitalists will be called on again to serve those affected by disasters.

Preventive Care

For many patients admitted to the hospital, meeting a hospitalist is their first encounter with a physician in years.24, 25 In these instances, hospitalists must ensure that patients' immunizations are up‐to‐date and arrange appropriate follow‐up care with primary care providers. Greenwald described an important role that hospitalists could play in HIV prevention by promoting HIV testing in the hospital.26 The CDC recently confirmed the wisdom of this approach and estimates that the 250,000 to 1.2 million people in the United States with HIV infection who do not know their serostatus play a significant role in HIV transmission.26, 27 In an effort to promote testing, the CDC has initiated a program aimed at incorporating HIV testing into routine medical care, as recommended by others.28 More than a quarter of patients with HIV in the United States are diagnosed in the hospital, and for many other patients, hospitalization is their only real opportunity to be tested.26, 29 Similarly, when hospitalists find elevated cholesterol or triglycerides in routine evaluations of patients who present with chest pain, they have to decide whether to initiate lipid‐lowering medications.30 The hospitalist is sometimes the only physician that patients repeatedly admitted, may see over prolonged periods. It follows that if hospitalists are remiss in delivering preventive care to such patients, they lose the opportunity to positively affect their long‐term health. In practice, hospitalists perform myriad preventive‐care functions, although there is scant literature supporting this role. Hospitalists have an opportunity to collaborate in research projects of hospital‐initiated preventive care that measure outcomes at the community level.

Substance Abuse

In the Unites States, 25%‐40% of hospital admissions are related to substance abuse and its sequelae.31 These patients frequently are admitted to general medicine services for detoxification or treatment of substance‐abuse‐related morbidity, although some American hospitals have specialized treatment and detoxification centers. There is a pressing need for more models of comprehensive care that address the complex issues of addiction, including the biological, social, cultural, spiritual, and developmental needs of patients.32

Hospitalists routinely counsel their patients with substance abuse problems and often consult a chemical dependency counselor, who provides patients with additional information about outpatient or inpatient facilities that may help them after their hospitalization. Unfortunately, because of the natural history of substance abuse, many of these patients are rehospitalized with the same problems even after going through rehabilitation. The adoption of a public health philosophy and approach by hospitalists may assist patients who have addictions through innovative multidisciplinary interventions while these patient are being detoxified. Traditionally, these responsibilities have fallen to primary care providers and psychologists in substance abuse medicine; but, as mentioned previously, many such patients are rehospitalized before they make it to their follow‐up appointments.

In a study examining smoking cessation practices among Norwegian hospital physicians, 98% of the doctors stated they ask their patients about their smoking habits, but fewer than 7% of these physicians regularly offer smoking‐cessation counseling, hand out materials, or give patients other advice about smoking cessation.33 That study illustrates that hospital doctors often ask about problems but can certainly improve in terms of intervention and follow‐up. Other works by nonhospitalist physicians have examined the real potential of inpatient interventions for smoking cessation. Most of this work involves a multidisciplinary approach that relies heavily on nurses. For example, Davies et al. evaluated the effectiveness of a hospital‐based intervention for smoking cessation among low‐income smokers using public health methodologies. The intervention was effective and promising as a way to affect smokers in underserved communities.34

Chronic Disease Management

Public health roles involving chronic disease management include surveillance, intervention design, and implementation of control programs.6 Given their access to data on hospitalized patients, hospitalists can carry out surveillance and empirical population‐based research about hospitalized patients with chronic illnesses. Thoughtfully designed protocols can measure the success of interventions initiated in patients while hospitalized, with further data collection and follow‐up after patients have returned to the community.35 Such endeavors can improve the likelihood that patients with chronic conditions are effectively referred to programs that will maintain their health and functional status.36 If hospitalists consider themselves public health providers, encounters with these hospitalized patients will go beyond noting that their chronic conditions are stable and instead will lay the groundwork to prospectively control these conditions. This approach would have the potential to reduce the number of future hospitalizations and lead to healthier communities.37 To truly carry this out effectively, coordinated collaboration between primary care providers and hospitalists will be necessary.

ASSURANCE

Assurance is the provision of access to necessary health services. It entails efforts to solve problems that threaten the health of populations and empowers individuals to maintain their own health. This is accomplished by either encouraging action, delegating to other entities (private or public sector), mandating specific requirements through regulation, or providing services directly.10 Hospitalist teams aim to ensure that the high‐quality services needed to protect the health of their community (hospitalized patients) are available and that this population receives proper consideration in the allocation of resources. The few studies to date that have directly examined the quality of care that hospitalists provide38 have done so using evidence‐based measures believed to correlate with improved health care outcomes.38 The ambiguities in assessing quality may in part limit such studies.39 Specific hospitalist roles that fall under the assurance umbrella include antibiotic optimization, palliative care, patient safety, and medical error management.

Antibiotic Optimization

Inappropriate use of antimicrobial treatment for infectious diseases has cost and public health implications.40 These inappropriate uses include giving antibiotics when not indicated, overusing broad‐spectrum antibiotics, making mismatches between microbes and medicines when cultures and information on test sensitivity are available, and using intravenous formulations when oral therapy would suffice.41 The public health impact goes way beyond increasing selective pressure for antimicrobial resistance to include safety, adverse events, and increased costs to both patient and hospitals.40 At our institution, the hospital medicine service and infectious disease division have jointly developed and implemented an intervention to reduce inappropriate antibiotic use. At other institutions, hospitalist teams have developed protocols for treating infectious diseases commonly encountered in the hospitalized patient.42 The recommendations of both Amin and Reddy for management of community‐ and hospital‐acquired pneumonia acknowledged that through establishment of clinical care pathways, variation in prescribing patterns among hospitalists can be decreased while optimizing outcomes.42 The work of Williams and colleagues is another example of advances by hospitalists. They reviewed the literature to determine that the use of combination antibiotics as empiric therapy for community‐acquired pneumonia is superior to the use of a single effective antibiotic in treating bacteremic patients with pneumococcal community‐acquired pneumonia.43

Palliative Care

Mortality is a vital outcome measure of public health research and interventions. Not surprisingly, many people are hospitalized in the final months of their life and often die in a hospital. Pantilat showed that hospitalists can respond to these circumstances and have the opportunity to improve care of the dying.4446 Muir et al. evaluated the convergence of the fields of palliative care medicine and hospital medicine and reviewed the opportunities for mutual education and improved patient care.47 They described how the confluence of the changing nature and site of death in the United States coupled with the reorganization of hospital care provides a strategic opportunity to improve end‐of‐life care.47 Hospitalists can ensure that care of the dying is delivered with skill, compassion, and expertise. And so it is imperative they be trained to accomplish this objective.47, 49

Fortunately, hospitalists already appear to enhance patientphysician communication. Auerbach looked at communication, care patterns, and outcomes of dying patients, comparing patients being cared for by hospitalists with those being care for by community‐based physicians. Hospitalists had discussions with patients or their families about care more often than did nonhospitalist physicians (91% versus 73%, respectively, P = .006).49 Because the delivery of high‐quality palliative care is time consuming and complex, alternative models for billing or the use of physician extenders or consultants may be necessary at some institutions.

Patient Safety and Medical Error Management

Hospitalists have been in the forefront of promoting a culture of patient safety.50 Their continuous presence in the hospital and their interactions with members of health care teams from multiple disciplines who share this goal make them important facilitators. Hospitalists have increasing involvement in systems‐based efforts aimed at reducing medical errors.50 Hospitalists are being asked to lead committees that adopt multidisciplinary approaches to reduce adverse events, morbidity, and mortality.50 These committees often have representation from pharmacy, nursing, and other key hospital stakeholders including from the administration.51 Quality assurance activities assess locally collected data and compare results with local and national benchmarks. There are several published examples of hospitalists engaged in patient safety and medical error management. For example, Shojania et al compiled evidence based safety practices in an effort to promote patient safety.52, 53 Schnipper studied the role of pharmacist counseling in preventing adverse drug events (ADEs) after hospitalization and found that pharmacist medication review, patient counseling, and telephone follow‐up were associated with a lower rate of preventable ADEs 30 days after hospital discharge.54 Moreover, Syed paired hospitalists and pharmacists to collaboratively prescribe medications appropriately. In one study there were fewer medication errors and adverse drug reactions in patients treated by a team led by hospitalists than in those treated by the control group, made up of nonhospitalist attendings.55

POLICY

Policy development defines health control goals and objectives and develops implementation plans for those goals.10 By necessity, it operates at the intersection of legislative, political, and regulatory processes.10 At many institutions, hospitalists have been involved in the development of policies ensuring that the core functions of assessment and assurance are addressed and maintained. In fact, hospitalists report that development of quality assurance and practice guidelines accounts for most of their nonclinical time.56 This role of hospitalists is supported by anecdotal reports rather than published empiric evidence.57 For example, at Johns Hopkins Bayview Medical Center, hospitalist‐led teams have developed triage and patient handoff policies designed to improve patient safety. Parameters for admission to the general medicine ward have been elaborated and are periodically refined by the hospitalist team.

Another area that falls within the genre of policy is development of clinical practice guidelines. Guidelines for the treatment of pneumonia, congestive heart failure, deep‐vein thrombosis prophylaxis, alcohol and drug withdrawal, pain management, delirium, and chronic obstructive pulmonary disease have been developed by nonhospitalists.58, 59 These areas are considered core competencies in hospital medicine, and as such, hospitalists have an obligation to review and refine these guidelines to ensure the best provision of care to our patients.59

Hospitalists have been engaged in upholding guidelines that affect community practice. For example, in a study comparing treatment of patients admitted with congestive heart failure by hospitalists compared with that by nonhospitalists, hospitalists were found to be more likely to document left ventricular function, a core measure of quality as defined by JCAHO.39, 60 Knowledge about cardiac function can direct future care for patients when they return to the community and into the care of their primary care providers. In another example, Rifkin found that patients with community‐acquired pneumonia treated by hospitalists were more rapidly converted to oral antibiotics from intravenous antibiotics, facilitating a shorter length of stay,61 which reduced the opportunity for nosocomial infections to propagate. Because hospitalists are skilled at following guidelines,59 it follows that they should seize the opportunity to develop more of them.

As the hospitalist movement continues to grow, hospitalists will likely be engaged in implementing citywide, statewide, and even national policies that ensure optimal care of the hospitalized patient.

BARRIERS TO HOSPITALISTS FOCUSING ON PUBLIC HEALTH

Hospitalists are involved in public health activities even though they may not recognize the extent of this involvement. However, there may be some drawbacks to hospitalists viewing each patient encounter as an opportunity for a public health intervention. First, in viewing a patient as part of a cohort, the individual needs of the patient may be overlooked. There is inherent tension between population‐based and individual‐based care, which is a challenge. Second, hospitalists are busy clinicians who may be most highly valued because of their focus on efficiency and cost savings in the acute care setting. This factor alone may prevent substantive involvement by hospitalists in public health practice. Moving beyond the management of an acute illness may interfere with this efficiency and cost effectiveness from the hospital's perspective. However, interventions that promote health and prevent or reduce rehospitalizations may be cost effective to society in the long run. Third, current billing systems do not adequately reward or reimburse providers for the extra time that may be necessary to engage in public health practice. Fourth, hospitalists may not have the awareness, interest, training, or commitment to engage in public health practice. Finally, there may not be effective collaboration and communication systems between primary care providers and hospitalists. This barrier limits or hinders many possibilities for the effective execution of several public health initiatives.

CONCLUSIONS AND IMPLICATIONS

Hospitalists and the specialty of hospital medicine materialized because of myriad economic forces and the need to provide safe, high‐quality care to hospitalized patients. In this article we have described the ways in which hospitalists can be explicitly involved in public health practice. Traditionally, physicians caring for hospitalized patients have collected information through histories and physical examinations, interpreted laboratory data and tests, and formulated assessments and plans of care. To become public health practitioners, hospitalists have to go beyond these tasks and consider public health thought processes, such as problem‐solving paradigms and theories of behavior change. In adopting this public health perspective, hospitalists may begin to think of a patient in the context of the larger community in order to define the problems facing the community, not just the patient, determine the magnitude of such problems, identify key stakeholders, create intervention/prevention strategies, set priorities and recommend interventions, and implement and evaluate those interventions. This approach forces providers to move beyond the physicianpatient model and draw on public health models to invoke change. Hopefully, future research will further convince hospitalists of the benefits of this approach. Although it may be easier to defer care and management decisions to an outpatient physician, data suggest that intervening when patients are in the hospital may be most effective.62, 63 For example, is it possible that patients are more likely to quit smoking when they are sick in the hospital than when they are in their usual state of health on a routine visit at their primary care provider's office?64 Further, although deferring care to a primary care provider (PCP) may be easier, it is not always possible given these barriers: (1) some patients are routinely rehospitalized, precluding primary care visits, (2) some recommendations may not be received by PCPs, and (3) PCPpatient encounters are brief and the agendas full, and there are limited resources to address recommendations from the hospital.

As hospitalists become more involved in public health practice, their collaboration with physicians and researchers in other fields, nurses, policymakers, and administrators will expand. Succeeding in this arena requires integrity, motivation, capacity, understanding, knowledge, and experience.65 It is hoped that hospitalists will embrace the opportunity and master the requisite skill set necessary to practice in and advance this field. As hospitalist fellowship programs are developed, public health practice skills could be incorporated into the curriculum. Currently 6 of 16 fellowship programs offer either a master of public health degree or public health courses.66 Public health skills can also be taught at Society of Hospital Medicine meetings and other continuing medical education events.

With the evolution of hospital medicine, hospitalists have to be malleable in order to optimally meet the needs of the population they serve. The possibilities are endless.

The field of hospital medicine came into being in response to numerous factors involving physicians, patients, and hospitals themselves1 Now, years later, hospital medicine is a specialty that is growing, both in size and sophistication such that the role of the hospitalist is constantly evolving.2 A compelling function that has not yet been clearly articulated is the opportunity for hospitalists to serve as public health practitioners in their unique clinical environment. There is precedence for the power of collaboration between medicine and public health as has been seen with emergency medicine's willingness to embrace opportunities to advance public health.35

In public health, the programs, services, and institutions involved emphasize the prevention of disease and the health needs of the population as a whole. Public health activities vary with changing technology and social values, but the goals remain the same: to reduce the amount of disease, premature death, and disease‐associated discomfort and disability in the population.6 The authors of a leading textbook of public health, Scutchfield and Keck, contend that the most important skill for public health practice is the capacity to visualize the potential for health that exists in a community.6

Hospitalists care for a distinct subset of the general populationinpatients, only a small percentage of society in a given year. Yet over time hospitalists affect a substantial subset of the larger population that uses considerable health care resources.79 Furthermore, hospitalization can be a sentinel event with public health implications (eg, newly diagnosed HIV infection or acute myocardial infarction in a patient with an extended family of cigarette smokers). This presents an opportunity to educate and counsel both the patient and the patient's social network. One model of public health practice by hospitalists is to influence the patient, his or her family, and the community by touching and inspiring the hospitalized patient.

Hospitalists are already involved in many of the core functions of public health (assessment, assurance, and policy development; Fig. 1).10 Achieving ongoing success in this arena means developing hospitalists who are consciously in tune with their roles as public health practitioners.

In this article we define the specific public health contributions that hospitalists have made and describe the possibilities for further innovative advances. To this end, we outline specific public health roles under the broad categories of assessment, assurance, and policy. We point to advances in public health accomplished by hospitalists as well as those being performed by nonhospitalists in the hospital setting. We conclude by describing some of the barriers to and implications of hospitalists taking on public health roles.

ASSESSMENT

Assessment is the systematic collection, analysis, and dissemination of health status information.10 These activities include disease surveillance and investigation of acute outbreaks or changes in the epidemiology of chronic diseases. Assessment also involves understanding the health of a population and the key determinants of a population's health from a variety of perspectives: physical, biological, behavioral, social, cultural, and spiritual.6 Human health has been defined as a state characterized by anatomic integrity; ability to perform personally valued family work and community roles; ability to deal with physical, biologic, and social stress; a feeling of well‐being; and freedom from the risk of disease and untimely death.6 Hospitalists interact with individuals at times of stress and acute illness and thus have a unique opportunity to assess the strength, viability, and resources available to individuals. Key roles that may fall within the auspices of assessment in hospital medicine are infection control, epidemic recognition, disaster response, preventive care, substance abuse treatment, and chronic disease management.

Infection Control

Physicians caring for inpatients have a crucial stake in controlling hospital infection as exemplified by the work of Flanders et al. on preventing nosocomial infections, especially nosocomial pneumonia.11 They describe specific strategies to prevent iatrogenic spread such as washing hands before and after patient contact, establishing guidelines against the use of artificial fingernails, using indwelling devices such as catheters only when absolutely necessary, and using sterile barriers.11 Hospitalists such as Sanjay Saint have led the way in studying methods to reduce bladder catheterization, which has been associated with urinary tract infections12; others have collaborated on work to prevent infections in nursing homes.13 Given the importance of this field, there is room for further hospitalist involvement. Novel methods for infection control in hospitals have been studied by nonhospitalists such as Wisnivesky, who prospectively validated a clinical decision rule to predict the need for respiratory isolation of inpatients with suspected tuberculosis (TB). This prediction rule, which is based on clinical and chest radiographic findings, was able to accurately identify patients at low risk for TB from among inpatients with suspected active pulmonary TB isolated on admission to the hospital.14 Retrospective application of the prediction rule showed respiratory precautions were inappropriately implemented for a third of patients.14 These studies are examples of empiric public health research performed in the inpatient setting. In the infection control domain, candidate issues for further study could include interventions aimed at reducing rates of Clostridium difficile, developing programs for standardized surveillance of hospital infection, validating electronic markers for nosocomial infection, and taking innovative approaches to improving hand‐washing practices in the hospital.15, 16

Recognizing Epidemics

An excellent example of the importance of hospitalists embracing public health and remembering their patients are part of a community was the severe acute respiratory syndrome (SARS) outbreak in Toronto, Ontario, Canada. The outbreak is thought to have begun with a single traveler. With the transfer of patients and the movement of visitors and health care workers among facilities, SARS quickly spread through Toronto, making it the largest SARS‐affected area outside Asia.17 Approximately a month after the outbreak was recognized in Toronto, it was thought to be over, and the World Health Organization (WHO) removed Toronto from its SARS‐affected list.17 Unfortunately, patients with unrecognized SARS remained in health care institutions, including a patient transferred to a rehabilitation center. Infection quickly spread again, resulting in a second phase of the outbreak.17

The SARS outbreak served as a reminder that a global public health system is essential and taught many lessons17 germane to pandemics that recur annually (eg, influenza viruses) as well those that episodically threaten the health of the population (eg, avian flu). Proposed actions to prevent a repeat of the scenario that occurred with SARS in Toronto include assessing the current facilities (eg, isolation rooms and respiratory masks) at each institution, identifying health care workers willing to serve as an outbreak team, and the hiring staff to train hospital personnel in personal protective equipment (PPE) and infection control policies.18 The Centers for Disease Control and Prevention (CDC) contends that planning for the possibility of a virulent pandemic at the local, national, and global levels is critical to limiting the mortality and morbidity should such occur.19, 20 In a previous article, Pile and Gordon declared hospitalists are key players in institutional efforts to prepare for a viral pandemic such as influenza and should be aware of lessons that may be applied from responses to pandemics such as SARS.19 Well placed to recognize clinical trends that may herald epidemics, hospitalists can fulfill some of the necessary public health responsibilities delineated above.

Disaster Response

Natural disasters and terrorism are in the forefront of the popular press and are also high priorities in health care and public health.21 Terrorism and natural disasters cause significant injury, illness, and death.22 Hospital‐based health care providers fulfill a variety of roles when terrorist acts and disasters occur, including reporting, diagnosing, and managing illness, providing preventive measures (eg, vaccines and preparedness kits), preventing the secondary spread of disease, assisting in the investigation of the causes of disease outbreaks, participating in preparedness planning, and evaluating preparedness policies and programs.22 The experience gained in the aftermaths of Hurricanes Katrina and Rita with their unprecedented death, injury, destruction, and displacement should help to guide future response and recovery activities.23 Hospitalists were at the forefront of delivering care, living in their hospitals for days after Hurricane Katrina. Without question, hospitalists will be called on again to serve those affected by disasters.

Preventive Care

For many patients admitted to the hospital, meeting a hospitalist is their first encounter with a physician in years.24, 25 In these instances, hospitalists must ensure that patients' immunizations are up‐to‐date and arrange appropriate follow‐up care with primary care providers. Greenwald described an important role that hospitalists could play in HIV prevention by promoting HIV testing in the hospital.26 The CDC recently confirmed the wisdom of this approach and estimates that the 250,000 to 1.2 million people in the United States with HIV infection who do not know their serostatus play a significant role in HIV transmission.26, 27 In an effort to promote testing, the CDC has initiated a program aimed at incorporating HIV testing into routine medical care, as recommended by others.28 More than a quarter of patients with HIV in the United States are diagnosed in the hospital, and for many other patients, hospitalization is their only real opportunity to be tested.26, 29 Similarly, when hospitalists find elevated cholesterol or triglycerides in routine evaluations of patients who present with chest pain, they have to decide whether to initiate lipid‐lowering medications.30 The hospitalist is sometimes the only physician that patients repeatedly admitted, may see over prolonged periods. It follows that if hospitalists are remiss in delivering preventive care to such patients, they lose the opportunity to positively affect their long‐term health. In practice, hospitalists perform myriad preventive‐care functions, although there is scant literature supporting this role. Hospitalists have an opportunity to collaborate in research projects of hospital‐initiated preventive care that measure outcomes at the community level.

Substance Abuse

In the Unites States, 25%‐40% of hospital admissions are related to substance abuse and its sequelae.31 These patients frequently are admitted to general medicine services for detoxification or treatment of substance‐abuse‐related morbidity, although some American hospitals have specialized treatment and detoxification centers. There is a pressing need for more models of comprehensive care that address the complex issues of addiction, including the biological, social, cultural, spiritual, and developmental needs of patients.32

Hospitalists routinely counsel their patients with substance abuse problems and often consult a chemical dependency counselor, who provides patients with additional information about outpatient or inpatient facilities that may help them after their hospitalization. Unfortunately, because of the natural history of substance abuse, many of these patients are rehospitalized with the same problems even after going through rehabilitation. The adoption of a public health philosophy and approach by hospitalists may assist patients who have addictions through innovative multidisciplinary interventions while these patient are being detoxified. Traditionally, these responsibilities have fallen to primary care providers and psychologists in substance abuse medicine; but, as mentioned previously, many such patients are rehospitalized before they make it to their follow‐up appointments.

In a study examining smoking cessation practices among Norwegian hospital physicians, 98% of the doctors stated they ask their patients about their smoking habits, but fewer than 7% of these physicians regularly offer smoking‐cessation counseling, hand out materials, or give patients other advice about smoking cessation.33 That study illustrates that hospital doctors often ask about problems but can certainly improve in terms of intervention and follow‐up. Other works by nonhospitalist physicians have examined the real potential of inpatient interventions for smoking cessation. Most of this work involves a multidisciplinary approach that relies heavily on nurses. For example, Davies et al. evaluated the effectiveness of a hospital‐based intervention for smoking cessation among low‐income smokers using public health methodologies. The intervention was effective and promising as a way to affect smokers in underserved communities.34

Chronic Disease Management

Public health roles involving chronic disease management include surveillance, intervention design, and implementation of control programs.6 Given their access to data on hospitalized patients, hospitalists can carry out surveillance and empirical population‐based research about hospitalized patients with chronic illnesses. Thoughtfully designed protocols can measure the success of interventions initiated in patients while hospitalized, with further data collection and follow‐up after patients have returned to the community.35 Such endeavors can improve the likelihood that patients with chronic conditions are effectively referred to programs that will maintain their health and functional status.36 If hospitalists consider themselves public health providers, encounters with these hospitalized patients will go beyond noting that their chronic conditions are stable and instead will lay the groundwork to prospectively control these conditions. This approach would have the potential to reduce the number of future hospitalizations and lead to healthier communities.37 To truly carry this out effectively, coordinated collaboration between primary care providers and hospitalists will be necessary.

ASSURANCE