User login

ADHD: Only half the diagnosis in an adult with inattention?

Overlapping symptoms may obscure comorbid bipolar illness

An adult with function-impairing inattention could have attention-deficit/hyperactivity disorder (ADHD), bipolar disorder (BD), or both. Comorbid ADHD and BD often is unrecognized, however, because patients are more likely to report ADHD-related symptoms than manic symptoms.1

To help you recognize comorbid ADHD/BD—and protect adults who might switch into mania if given stimulants or antidepressants—this article describes a hierarchy to diagnose and treat this comorbidity. Based on the evidence and our experience, we:

- discuss how to differentiate between these disorders with overlapping symptoms

- provide tools and suggestions to screen for BD and adult ADHD

- offer 3 algorithms to guide your diagnosis and choice of medications.

Clinical challenges

Prevalence is unclear. Adult ADHD—with an estimated prevalence of 4.4%2—is more common than BD. Lifetime prevalences of BD types I and II are 1.6% and 0.5%, respectively.3 Studies of ADHD/BD comorbidity suggest wide-ranging prevalence rates:

Underdiagnosis. Adult ADHD/BD is a more severe illness than ADHD or BD alone and is highly comorbid with agoraphobia, social phobia, posttraumatic stress disorder, and alcohol or drug addiction. Adults with ADHD/BD have more frequent affective episodes, suicide attempts, violence, and legal problems.4 Diagnosing this comorbidity remains a challenge, however, because:

- identifying which symptoms are caused by which disorder can be difficult

- BD tends to be underdiagnosed9

- patients often misidentify, underreport, or deny manic symptoms1,10,11

- if a patient presents with active bipolar symptoms, DSM-IV-TR criteria require that ADHD not be diagnosed until mood symptoms are resolved.

Overlapping symptoms. ADHD and bipolar mania share some DSM-IV-TR diagnostic criteria, including talkativeness, distractibility, increased activity or physical restlessness, and loss of social inhibitions (Table 1).12 Overlapping symptoms also are notable within ADHD diagnostic criteria (Table 2). In the inattention category, for example, “easily distracted by extraneous stimuli,” “difficulty sustaining attention in tasks,” and “fails to give close attention to details” are considered 3 separate symptoms. In the hyperactivity category, “often leaves seat,” “often runs about or climbs excessively,” and “often on the go, or often acts as if driven by a motor” are 3 separate symptoms.

Given ADHD’s relatively loose diagnostic criteria and high comorbidity in adults with mood disorders, the question of whether adult ADHD/BD represents comorbidity or diagnostic overlap remains unresolved. For the clinician, the disorders’ nonoverlapping features (Table 1) can assist with the differential diagnosis. For example:

- ADHD symptoms tend to be chronic and BD symptoms episodic.

- ADHD patients may have high energy but lack increased productivity seen in BD patients.

- ADHD patients do not need less sleep or have inflated self-esteem like symptomatic BD patients.

- Psychotic symptoms such as hallucinations or delusions might be present in severe BD but are absent in ADHD.

Table 1

Overlap between DSM-IV-TR diagnostic criteria for ADHD and bipolar mania

| Overlapping symptoms | |

|---|---|

| ADHD | Bipolar mania |

| Talks excessively | More talkative than usual |

| Easily distracted/jumps from one activity to the next | Distractibility or constant changes in activity or plans |

| Fidgets Difficulty remaining seated Runs or climbs about inappropriately Difficulty playing quietly On the go as if driven by a motor | Increased activity or physical restlessness |

| Interrupts or butts in uninvited Blurts out answers | Loss of normal social inhibitions |

| Nonoverlapping symptoms | |

| ADHD Forgetful in daily activities Difficulty awaiting turn Difficulty organizing self Loses things Avoids sustained mental effort Does not seem to listen Difficulty following through on instructions/fails to finish work Difficulty sustaining attention Fails to give close attention to details/makes careless mistakes | |

| Bipolar mania Inflated self-esteem/grandiosity Increase in goal-directed activity Flight of ideas Decreased need for sleep Excessive involvement in pleasurable activities with disregard for potential adverse consequences Marked sexual energy or sexual indiscretions | |

| ADHD: attention-deficit/hyperactivity disorder | |

| Source: Adapted and reprinted with permission from reference 12 | |

Table 2

DSM-IV-TR diagnostic criteria for attention-deficit/ hyperactivity disorder

| Inattention |

≥6 symptoms have persisted ≥6 months to a degree that is maladaptive and inconsistent with developmental level. The patient often:

|

| Hyperactivity/impulsivity |

≥6 symptoms have persisted ≥6 months to a degree that is maladaptive and inconsistent with developmental level. The patient often:

|

| Diagnosis requires evidence of inattention or hyperactivity/impulsivity or both |

| Some hyperactive/impulsive or inattentive symptoms that caused impairment were present before age 7 |

| Some impairment from symptoms is present in ≥2 settings (such as at school, work, or home) |

| Symptoms do not occur exclusively during the course of a pervasive developmental disorder, schizophrenia, or other psychotic disorder and are not better accounted for by another mental disorder (mood disorder, anxiety disorder, dissociative disorder, or a personality disorder) |

| Source: DSM-IV-TR |

Mood symptoms first

A diagnostic hierarchy is implicit in DSM-IV-TR; anxiety disorders are not diagnosed during an active major depressive or manic episode, and schizophrenia is not diagnosed on the basis of psychotic symptoms during an active major depressive or manic episode. Mood disorders sit atop this implied diagnostic hierarchy and must be ruled out before psychotic or anxiety disorders are diagnosed. Similarly, most personality disorders are not diagnosed during an active mood or psychotic episode.

Diagnosing adult ADHD when a patient is actively depressed or manic is inconsistent with this hierarchy and conflicts with extensive nosologic literature.13 We suggest that ADHD—a cognitive-behavioral problem—not be diagnosed solely on symptoms observed when a patient is experiencing a mood episode or psychotic illness.

Bipolar disorder. Two useful mnemonics (Table 3) assist in screening for DSM-IV-TR symptoms of BD type I:

- Pure mania consists of euphoric mood and ≥3 of 7 DIGFAST criteria, or irritable mood and ≥4 of 7 DIGFAST criteria

- Mixed mania consists of depressed mood with ≥4 of 7 DIGFAST criteria and ≥4 of 8 SIGECAPS criteria.

To be diagnostic, these symptoms must cause substantial social or occupational dysfunction and be present at least 1 week. Diagnose BD type I if a patient has experienced a single pure or mixed manic episode at any time, unless the episode had a medical cause such as hyperthyroidism or antidepressant use. Because patients with mixed episodes experience depressed mood, assess any patient with clinical depression for manic symptoms. Otherwise, a patient with a mixed episode could be misdiagnosed as having unipolar depression instead of BD type I.14

BD type II also has been observed in patients with comorbid adult ADHD/BD.4,6 The main difference between BD types I and II is that manic symptoms in type II are not severe enough to cause functional impairment or psychotic symptoms.15

Adult ADHD. The clinical interview seeking evidence of inattention and hyperactivity/impulsivity remains the basis of adult ADHD diagnosis (Table 2). Key areas are:

- the patient’s past and current functional impairment

- whether substantial impairment occurs in at least 2 areas of life (such as school, work, or home).

Take medical, educational, social, psychological, and vocational histories, and rule out other conditions before concluding that adult ADHD is the appropriate diagnosis.16 In adult ADHD, inattentive symptoms become far more prominent, about twice as common as hyperactive symptoms.17 Inattentive symptoms may manifest as neglect, poor time management, motivational deficits, or poor concentration that results in forgetfulness, distractibility, item misplacement, or excessive mistakes in paperwork.18 When impulsive symptoms persist in adults, they may manifest as automobile accidents or low tolerance for frustration, which may lead to frequent job changes and unstable, interrupted interpersonal relationships.18

Neuropsychological testing is not required to make an adult ADHD diagnosis but can help establish the breadth of symptoms or comorbidity.17 Rating scales can screen, gather data (including presence and severity of symptoms), and measure treatment response.16 Commonly used rating scales include:

- Conners’ Adult ADHD Rating Scales19

- Brown Attention Deficit Disorder Rating Scale for Adults20

- Adult ADHD Self-Report Scale.21

When using rating scales, remember that adult psychopathology can distort perceptions, and some self-report scales have questionable reliability.16

Table 3

Mnemonics for diagnostic symptoms of pure and mixed bipolar mania

| DIGFAST* for bipolar mania symptoms | SIGECAPS† bipolar depression symptoms |

|---|---|

| Distractibility Insomnia Grandiosity Flight of ideas Activities Speech Thoughtlessness | Sleep Interest Guilt Energy Concentration Appetite Psychomotor Suicide |

| Pure mania: Euphoric mood with ≥3 DIGFAST criteria or irritable mood with ≥4 DIGFAST criteria. | |

| Mixed mania: Depressed mood with ≥4 DIGFAST criteria and ≥4 SIGECAPS criteria. | |

| * Developed by William Falk, MD | |

| †Developed by Carey Gross, MD | |

| Source: Adapted from Ghaemi SN. Mood disorders. New York: Lippincott, Williams, & Wilkins; 2003 | |

Treatment recommendations

Limited data. We found only 1 study on adult ADHD/BD treatment. In this open trial,22 36 adults with comorbid ADHD and BD received bupropion SR, up to 200 mg bid, for ADHD symptoms while maintained on mood stabilizers, antipsychotics, or both. Improvement was defined as ≥30% reduction in ADHD Symptom Checklist Scale scores, without concurrent mania. After 6 weeks, 82% of patients had improved; 1 dropped out at week 2 because of hypomanic activation. Methodologic limitations included trial design (non-randomized, nonblinded, short duration) and patient selection (90% of subjects had BD type II).

In the absence of adequate data on adult ADHD/BD, studies in children suggest:

- stimulants may not be effective for ADHD symptoms in patients with active manic or depressive symptoms

- mood stabilization is a prerequisite for successful pharmacologic treatment of ADHD in patients with both ADHD and manic or depressive symptoms.23,24

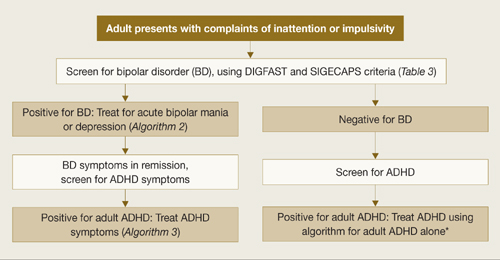

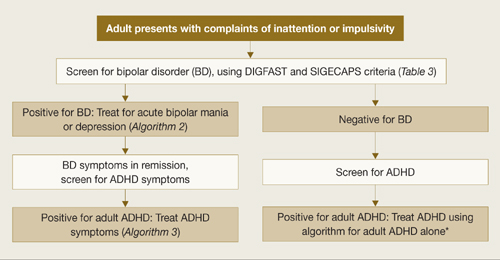

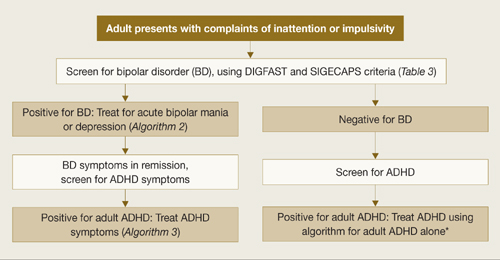

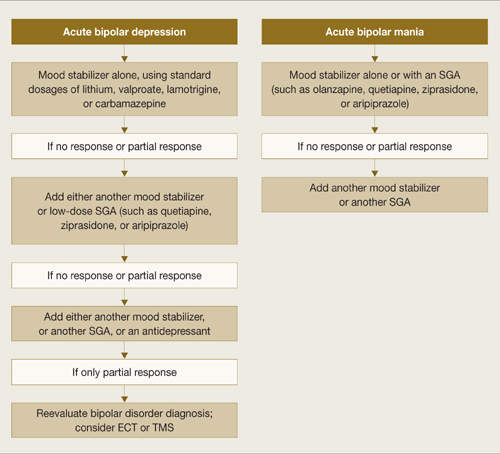

Follow the hierarchy. First treat acute mood symptoms, then reevaluate and possibly treat ADHD symptoms if they persist during euthymia (Algorithm 1). When a patient meets criteria for adult ADHD/BD, first stabilize bipolar manic or depressive symptoms (Algorithm 2). For acute mania, treat with standard mood stabilizers (lithium, valproate, lamotrigine, or carbamazepine) with or without a second-generation antipsychotic.25 Starting stimulants for ADHD when patients have active mood symptoms is sub-optimal and potentially harmful because of the risk of inducing mania. For acute bipolar depression, adjunctive antidepressant treatment has been found to be no more effective than a mood stabilizer alone.26

After bipolar symptoms respond or remit, reassess for adult ADHD. If ADHD symptoms persist during euthymia, additional treatment may be indicated.

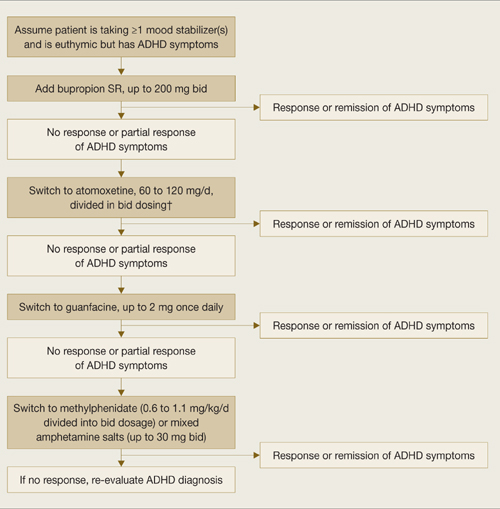

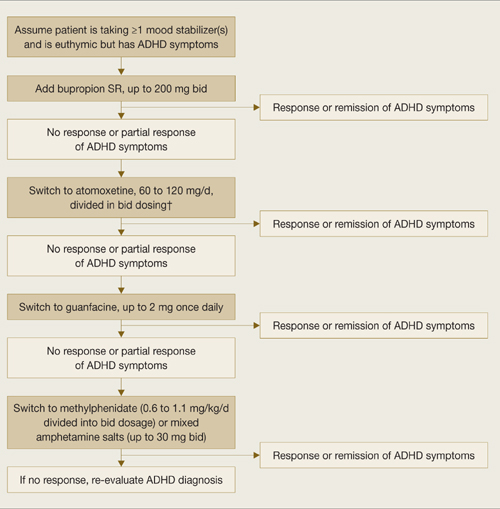

Very little evidence exists on treating adult ADHD/BD; as mentioned, bupropion is the only medication studied in this population. For adult ADHD alone, clinical trials have showed varying efficacy with bupropion,27,28 atomoxetine,29 venlafaxine,30,31 desipramine,32 methylphenidate,33 mixed amphetamine salts,34 and guanfacine.35 Whether these treatments can be generalized as safe and efficacious for comorbid adult ADHD/BD is unclear. Nonetheless, we suggest using bupropion first, followed by atomoxetine or guanfacine before you consider amphetamine stimulants (Algorithm 3).

Algorithm 1

Hierarchy for diagnosis and treatment of adult ADHD/BD

ADHD: attention-deficit/hyperactivity disorder; BD: bipolar disorder

*Adler LA, Chua HC. Management of ADHD in adults. J Clin Psychiatry 2002;63(suppl 12):29-35.

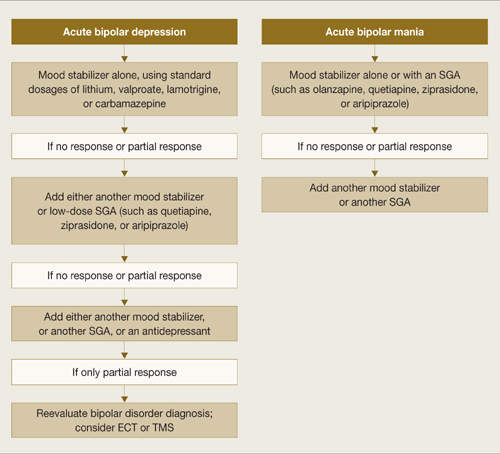

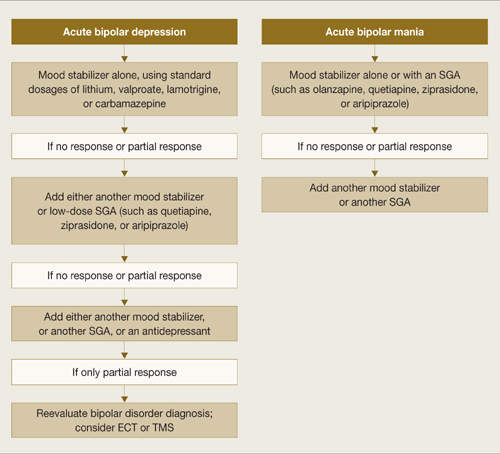

Algorithm 2

Treating acute episodes of bipolar disorder

ECT: electroconvulsive therapy; SGA: second-generation antipsychotic; TMS: transcranial magnetic stimulation

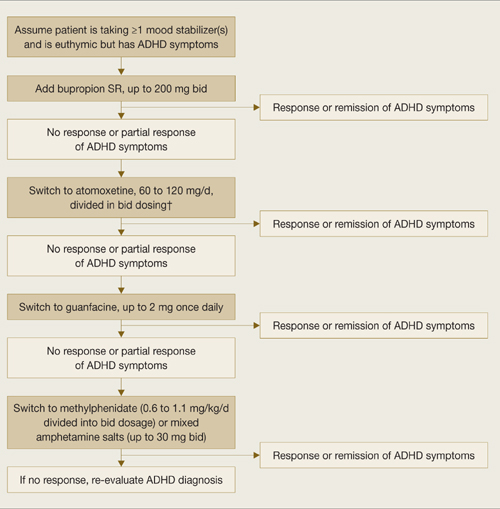

Algorithm 3

Suggested approach to adult ADHD with comorbid BD*

* Based on data extrapolated from samples of patients with ADHD alone because of very limited data in ADHD/BD samples.

† We recommend against combining antidepressants and stimulants because of additive risks of mania in BD. Discontinue stimulant or antidepressant if manic symptoms appear or rapid cycling emerges.

Reducing mania risk

Antidepressants and stimulants may help adults with ADHD alone, but risks of mania and rapid cycling limit their use in adults with ADHD/BD.

Stimulants and mania. One study found a 17% manic switch rate when methylphenidate (≤10 mg bid) was given to 14 bipolar depressed adults (10 BD type I, 2 BD type II, and 2 with secondary mania) taking mood stabilizers.36 A chart review of 82 bipolar children not taking mood stabilizers found an 18% switch rate with methylphenidate or amphetamine.37 Another chart review of 80 children with BD type I found that past amphetamine treatment (but not history of ADHD diagnosis or antidepressant treatment) was associated with more severe bipolar illness.38

No studies have examined predictors of amphetamine-induced mania. In our clinical experience, triggers are similar to those that can cause antidepressant-induced mania, such as:

- recent manic episodes

- current rapid cycling

- past antidepressant-induced mania.

Antidepressants and mania. When 64 patients with acute bipolar depression received both antidepressants and mood stabilizers in a randomized, double-blind trial, switch rates into mania or hypomania were 10% for bupropion, 9% for sertraline, and 29% for venlafaxine.39 In a meta analysis of clinical trials using selective serotonin reuptake inhibitors (SSRIs) or tricyclic antidepressants (TCAs), the manic switch rate was threefold higher with TCAs than SSRIs.40 Antidepressant use in bipolar patients was associated with rapid cycling in the only randomized study of this topic.41

Insufficient data exist to clarify whether mania induction with antidepressants is dose-dependent.42 Factors associated with antidepressant-induced mania include:

- previous antidepressant-induced mania

- family history of BD

- exposure to multiple antidepressant trials42

- history of substance abuse and/or dependence.43

Related resources

- Bipolar disorder information and resources. www.psycheducation.org.

- ADHD Information and resources. www.adhdnews.com.

- Phelps J. Why am I still depressed? Recognizing and managing the ups and downs of bipolar II and soft bipolar disorder. New York: McGraw-Hill; 2006.

Drug brand names

- Amphetamine/Dextroamphetamine • Adderall

- Aripiprazole • Abilify

- Atomoxetine • Strattera

- Bupropion • Wellbutrin

- Carbamazepine • Tegretol

- Desipramine • Norpramin

- Dextroamphetamine • Dexedrine

- Guanfacine • Tenex

- Lamotrigine • Lamictal

- Lithium • Eskalith, Lithobid

- Methylphenidate • Ritalin

- Quetiapine • Seroquel

- Sertraline • Zoloft

- Valproate • Depakote

- Venlafaxine • Effexor

- Ziprasidone • Geodon

Disclosures

Dr. Wingo reports no financial relationship with any company whose products are mentioned in this article or with manufacturers of competing products.

Dr. Ghaemi receives research grants from GlaxoSmithKline and Pfizer and is a speaker for GlaxoSmithKline, AstraZeneca, Pfizer, and Abbott Laboratories. Neither he nor his family hold equity positions in pharmaceutical companies.

1. Ghaemi SN, Stoll AL, Pope HG, Jr, et al. Lack of insight in bipolar disorder. The acute manic episode. J Nerv Ment Dis 1995;183(7):464-7.

2. Kessler RC, Adler L, Barkley R, et al. The prevalence and correlates of adult ADHD in the United States: results from the National Comorbidity Survey Replication. Am J Psychiatry 2006;163(4):716-23.

3. Sadock BJ, Sadock VA, eds. Synopsis of psychiatry, 9th ed. Philadelphia: Lippincott Williams & Wilkins; 2003.

4. Nierenberg AA, Miyahara S, Spencer T, et al. Clinical and diagnostic implications of lifetime attention-deficit/hyperactivity disorder comorbidity in adults with bipolar disorder: data from the first 1000 STEP-BD participants. Biol Psychiatry 2005;57(11):1467-73.

5. Tamam L, Tuglu C, Karatas G, et al. Adult attention-deficit hyperactivity disorder in patients with bipolar I disorder in remission: preliminary study. Psychiatry Clin Neurosci 2006;60(4):480-5.

6. Wilens TE, Biederman J, Wozniak J, et al. Can adults with attention-deficit/hyperactivity disorder be distinguished from those with comorbid bipolar disorder? Findings from a sample of clinically referred adults. Biol Psychiatry 2003;54(1):1-8.

7. McGough JJ, Smalley SL, McCracken JT, et al. Psychiatric comorbidity in adult attention deficit hyperactivity disorder: findings from multiplex families. Am J Psychiatry 2005;162(9):1621-7.

8. Faraone SV, Biederman J, Spencer T, et al. Diagnosing adult attention deficit hyperactivity disorder: are late onset and subthreshold diagnoses valid? Am J Psychiatry 2006;163(10):1720-9.

9. Ghaemi SN, Sachs GS, Chiou AM, et al. Is bipolar disorder still underdiagnosed? Are antidepressants overutilized? J Affect Disord 1999;52(1-3):135-44.

10. Keitner GI, Solomon DA, Ryan CE, et al. Prodromal and residual symptoms in bipolar I disorder. Compr Psychiatry 1996;37(5):362-7.

11. Bowden CL. Strategies to reduce misdiagnosis of bipolar depression. Psychiatr Serv 2001;52(1):51-5.

12. Kent L, Craddock N. Is there a relationship between attention deficit hyperactivity disorder and bipolar disorder? J Affect Disord 2003;73(3):211-21.

13. Surtees PG, Kendell RE. The hierarchy model of psychiatric symptomatology: an investigation based on present state examination ratings. Br J Psychiatry 1979;135:438-43.

14. Benazzi F. Symptoms of depression as possible markers of bipolar II disorder. Prog Neuropsychopharmacol Biol Psychiatry 2006;30(3):471-7.

15. Diagnostic and Statistical Manual of Mental Disorders, 4th ed., text rev. Washington, DC: American Psychiatric Association; 2000.

16. Murphy KR, Adler LA. Assessing attention-deficit hyperactivity disorder in adults: focus on rating scales. J Clin Psychiatry 2004;65(suppl 3):12-17.

17. Adler LA. Diagnosing adult attention deficit hyperactivity disorder. Primary Psychiatry 2006;13(suppl 3):9-10.

18. Montano B. Diagnosis and treatment of ADHD in adults in primary care. J Clin Psychiatry 2004;65(suppl 3):18-21.

19. Conners CK, Erhardt D, Sparrow E. Conners’ Adult ADHD Rating Scales (CAARS). North Tonawanda, NY: Multi-Health Systems; 1999.

20. Brown TE. Brown Attention Deficit Disorder Scales. San Antonio, TX: The Psychological Corporation; 1996.

21. Adler LA, Kessler RC, Spencer T. Adult ADHD Self-report Scale v1.1 (ASRS-v1.1) Symptom Checklist. World Health Organization. Available at: http://www.med.nyu.edu/psych/assets/adhdscreen18.pdf. Accessed May 7, 2007.

22. Wilens TE, Prince JB, Spencer T, et al. An open trial of bupropion for the treatment of adults with attention-deficit/hyperactivity disorder and bipolar disorder. Biol Psychiatry 2003;54(1):9-16.

23. Biederman J, Mick E, Prince J, et al. Systematic chart review of the pharmacologic treatment of comorbid attention deficit hyperactivity disorder in youth with bipolar disorder. J Child Adolesc Psychopharmacol 1999;9(4):247-56.

24. Daviss WB, Bentivoglio P, Racusin R, et al. Bupropion sustained release in adolescents with comorbid attention-deficit/hyperactivity disorder and depression. J Am Acad Child Adolesc Psychiatry 2001;40(3):307-14.

25. Scherk H, Pajonk FG, Leucht SL. Second-generation antipsychotic agents in the treatment of acute mania. Arch Gen Psychiatry 2007;64:442-55.

26. Sachs GS, Nierenberg AA, Calabrese JR, et al. Effectiveness of adjunctive antidepressant treatment for bipolar depression. N Engl J Med 2007:356:(17):1711-22.

27. Wilens TE, Haight BR, Horrigan JP, et al. Bupropion XL in adults with attention deficit hyperactivity disorder: a randomized, placebo controlled study. Biol Psychiatry 2005;57:793-801.

28. Wilens TE, Spencer TJ, Biederman J, et al. A controlled clinical trial of bupropion for attention deficit hyperactivity disorder in adults. Am J Psychiatry 2001;158(2):282-8.

29. Michelson D, Adler LA, Spencer T, et al. Atomoxetine in adults with ADHD: two randomized, placebo controlled studies. Biol Psychiatry 2003;53:112-20.

30. Adler LA, Resnick S, Kunz M, Devinsky O. Open-label trial of venlafaxine in adults with attention deficit disorder. Psychopharmacol Bull 1995;31(4):785-8.

31. Hedges D, Reimherr FW, Rogers A, et al. An open trial of venlafaxine in adult patients with attention deficit hyperactivity disorder. Psychopharmacol Bull 1995;31(4):779-83.

32. Wilens TE, Biederman J, Prince J, et al. Six-week, double-blind, placebo-controlled study of desipramine for adult attention deficit hyperactivity disorder. Am J Psychiatry 1996;153(9):1147-53.

33. Faraone SV, Spencer T, Aleardi M, et al. Meta analysis of the efficacy of methylphenidate for treating adult attention deficit hyperactivity disorder. J Clin Psychopharmacol 2004;24(1):24-8.

34. Spencer T, Biederman J, Wilens TE, et al. Efficacy of a mixed amphetamine salts compound in adults with attention deficit hyperactivity disorder. Arch Gen Psychiatry 2001;58:775-82.

35. Taylor FB, Russo J. Comparing guanfacine and dextroamphetamine for the treatment of adult attention deficit hyperactivity disorder. J Clin Psychopharmacol 2000;21(2):223-8.

36. El-Mallakh RS. An open study of methylphenidate in bipolar depression. Bipolar Disord 2000;2(1):56-9.

37. Faedda GL, Baldessarini RJ, Glovinsky IP, et al. Treatment-emergent mania in pediatric bipolar disorder: a retrospective case review. J Affect Disord 2004;82(1):149-58.

38. Soutullo CA, DelBello MP, Ochsner JE, et al. Severity of bipolarity in hospitalized manic adolescents with history of stimulant or antidepressant treatment. J Affect Disord 2002;70(3):323-7.

39. Post RM, Altshuler LL, Leverich GS, et al. Mood switch in bipolar depression: comparison of adjunctive venlafaxine, bupropion and sertraline. Br J Psychiatry 2006;189:124-31.

40. Peet M. Induction of mania with selective serotonin re-uptake inhibitors and tricyclic antidepressants. Br J Psychiatry 1994;164(4):549-50.

41. Wehr TA, Sack DA, Rosenthal NE, Cowdry RW. Rapid cycling affective disorder: contributing factors and treatment responses in 51 patients. Am J Psychiatry 1988;145(2):179-84.

42. Goldberg JF. When do antidepressants worsen the course of bipolar disorder? J Psychiatr Pract. 2003;9(3):181-94.

43. Goldberg JF, Whiteside JE. The association between substance abuse and antidepressant-induced mania in bipolar disorder: a preliminary study. J Clin Psychiatry 2002;63(9):791-5.

Overlapping symptoms may obscure comorbid bipolar illness

An adult with function-impairing inattention could have attention-deficit/hyperactivity disorder (ADHD), bipolar disorder (BD), or both. Comorbid ADHD and BD often is unrecognized, however, because patients are more likely to report ADHD-related symptoms than manic symptoms.1

To help you recognize comorbid ADHD/BD—and protect adults who might switch into mania if given stimulants or antidepressants—this article describes a hierarchy to diagnose and treat this comorbidity. Based on the evidence and our experience, we:

- discuss how to differentiate between these disorders with overlapping symptoms

- provide tools and suggestions to screen for BD and adult ADHD

- offer 3 algorithms to guide your diagnosis and choice of medications.

Clinical challenges

Prevalence is unclear. Adult ADHD—with an estimated prevalence of 4.4%2—is more common than BD. Lifetime prevalences of BD types I and II are 1.6% and 0.5%, respectively.3 Studies of ADHD/BD comorbidity suggest wide-ranging prevalence rates:

Underdiagnosis. Adult ADHD/BD is a more severe illness than ADHD or BD alone and is highly comorbid with agoraphobia, social phobia, posttraumatic stress disorder, and alcohol or drug addiction. Adults with ADHD/BD have more frequent affective episodes, suicide attempts, violence, and legal problems.4 Diagnosing this comorbidity remains a challenge, however, because:

- identifying which symptoms are caused by which disorder can be difficult

- BD tends to be underdiagnosed9

- patients often misidentify, underreport, or deny manic symptoms1,10,11

- if a patient presents with active bipolar symptoms, DSM-IV-TR criteria require that ADHD not be diagnosed until mood symptoms are resolved.

Overlapping symptoms. ADHD and bipolar mania share some DSM-IV-TR diagnostic criteria, including talkativeness, distractibility, increased activity or physical restlessness, and loss of social inhibitions (Table 1).12 Overlapping symptoms also are notable within ADHD diagnostic criteria (Table 2). In the inattention category, for example, “easily distracted by extraneous stimuli,” “difficulty sustaining attention in tasks,” and “fails to give close attention to details” are considered 3 separate symptoms. In the hyperactivity category, “often leaves seat,” “often runs about or climbs excessively,” and “often on the go, or often acts as if driven by a motor” are 3 separate symptoms.

Given ADHD’s relatively loose diagnostic criteria and high comorbidity in adults with mood disorders, the question of whether adult ADHD/BD represents comorbidity or diagnostic overlap remains unresolved. For the clinician, the disorders’ nonoverlapping features (Table 1) can assist with the differential diagnosis. For example:

- ADHD symptoms tend to be chronic and BD symptoms episodic.

- ADHD patients may have high energy but lack increased productivity seen in BD patients.

- ADHD patients do not need less sleep or have inflated self-esteem like symptomatic BD patients.

- Psychotic symptoms such as hallucinations or delusions might be present in severe BD but are absent in ADHD.

Table 1

Overlap between DSM-IV-TR diagnostic criteria for ADHD and bipolar mania

| Overlapping symptoms | |

|---|---|

| ADHD | Bipolar mania |

| Talks excessively | More talkative than usual |

| Easily distracted/jumps from one activity to the next | Distractibility or constant changes in activity or plans |

| Fidgets Difficulty remaining seated Runs or climbs about inappropriately Difficulty playing quietly On the go as if driven by a motor | Increased activity or physical restlessness |

| Interrupts or butts in uninvited Blurts out answers | Loss of normal social inhibitions |

| Nonoverlapping symptoms | |

| ADHD Forgetful in daily activities Difficulty awaiting turn Difficulty organizing self Loses things Avoids sustained mental effort Does not seem to listen Difficulty following through on instructions/fails to finish work Difficulty sustaining attention Fails to give close attention to details/makes careless mistakes | |

| Bipolar mania Inflated self-esteem/grandiosity Increase in goal-directed activity Flight of ideas Decreased need for sleep Excessive involvement in pleasurable activities with disregard for potential adverse consequences Marked sexual energy or sexual indiscretions | |

| ADHD: attention-deficit/hyperactivity disorder | |

| Source: Adapted and reprinted with permission from reference 12 | |

Table 2

DSM-IV-TR diagnostic criteria for attention-deficit/ hyperactivity disorder

| Inattention |

≥6 symptoms have persisted ≥6 months to a degree that is maladaptive and inconsistent with developmental level. The patient often:

|

| Hyperactivity/impulsivity |

≥6 symptoms have persisted ≥6 months to a degree that is maladaptive and inconsistent with developmental level. The patient often:

|

| Diagnosis requires evidence of inattention or hyperactivity/impulsivity or both |

| Some hyperactive/impulsive or inattentive symptoms that caused impairment were present before age 7 |

| Some impairment from symptoms is present in ≥2 settings (such as at school, work, or home) |

| Symptoms do not occur exclusively during the course of a pervasive developmental disorder, schizophrenia, or other psychotic disorder and are not better accounted for by another mental disorder (mood disorder, anxiety disorder, dissociative disorder, or a personality disorder) |

| Source: DSM-IV-TR |

Mood symptoms first

A diagnostic hierarchy is implicit in DSM-IV-TR; anxiety disorders are not diagnosed during an active major depressive or manic episode, and schizophrenia is not diagnosed on the basis of psychotic symptoms during an active major depressive or manic episode. Mood disorders sit atop this implied diagnostic hierarchy and must be ruled out before psychotic or anxiety disorders are diagnosed. Similarly, most personality disorders are not diagnosed during an active mood or psychotic episode.

Diagnosing adult ADHD when a patient is actively depressed or manic is inconsistent with this hierarchy and conflicts with extensive nosologic literature.13 We suggest that ADHD—a cognitive-behavioral problem—not be diagnosed solely on symptoms observed when a patient is experiencing a mood episode or psychotic illness.

Bipolar disorder. Two useful mnemonics (Table 3) assist in screening for DSM-IV-TR symptoms of BD type I:

- Pure mania consists of euphoric mood and ≥3 of 7 DIGFAST criteria, or irritable mood and ≥4 of 7 DIGFAST criteria

- Mixed mania consists of depressed mood with ≥4 of 7 DIGFAST criteria and ≥4 of 8 SIGECAPS criteria.

To be diagnostic, these symptoms must cause substantial social or occupational dysfunction and be present at least 1 week. Diagnose BD type I if a patient has experienced a single pure or mixed manic episode at any time, unless the episode had a medical cause such as hyperthyroidism or antidepressant use. Because patients with mixed episodes experience depressed mood, assess any patient with clinical depression for manic symptoms. Otherwise, a patient with a mixed episode could be misdiagnosed as having unipolar depression instead of BD type I.14

BD type II also has been observed in patients with comorbid adult ADHD/BD.4,6 The main difference between BD types I and II is that manic symptoms in type II are not severe enough to cause functional impairment or psychotic symptoms.15

Adult ADHD. The clinical interview seeking evidence of inattention and hyperactivity/impulsivity remains the basis of adult ADHD diagnosis (Table 2). Key areas are:

- the patient’s past and current functional impairment

- whether substantial impairment occurs in at least 2 areas of life (such as school, work, or home).

Take medical, educational, social, psychological, and vocational histories, and rule out other conditions before concluding that adult ADHD is the appropriate diagnosis.16 In adult ADHD, inattentive symptoms become far more prominent, about twice as common as hyperactive symptoms.17 Inattentive symptoms may manifest as neglect, poor time management, motivational deficits, or poor concentration that results in forgetfulness, distractibility, item misplacement, or excessive mistakes in paperwork.18 When impulsive symptoms persist in adults, they may manifest as automobile accidents or low tolerance for frustration, which may lead to frequent job changes and unstable, interrupted interpersonal relationships.18

Neuropsychological testing is not required to make an adult ADHD diagnosis but can help establish the breadth of symptoms or comorbidity.17 Rating scales can screen, gather data (including presence and severity of symptoms), and measure treatment response.16 Commonly used rating scales include:

- Conners’ Adult ADHD Rating Scales19

- Brown Attention Deficit Disorder Rating Scale for Adults20

- Adult ADHD Self-Report Scale.21

When using rating scales, remember that adult psychopathology can distort perceptions, and some self-report scales have questionable reliability.16

Table 3

Mnemonics for diagnostic symptoms of pure and mixed bipolar mania

| DIGFAST* for bipolar mania symptoms | SIGECAPS† bipolar depression symptoms |

|---|---|

| Distractibility Insomnia Grandiosity Flight of ideas Activities Speech Thoughtlessness | Sleep Interest Guilt Energy Concentration Appetite Psychomotor Suicide |

| Pure mania: Euphoric mood with ≥3 DIGFAST criteria or irritable mood with ≥4 DIGFAST criteria. | |

| Mixed mania: Depressed mood with ≥4 DIGFAST criteria and ≥4 SIGECAPS criteria. | |

| * Developed by William Falk, MD | |

| †Developed by Carey Gross, MD | |

| Source: Adapted from Ghaemi SN. Mood disorders. New York: Lippincott, Williams, & Wilkins; 2003 | |

Treatment recommendations

Limited data. We found only 1 study on adult ADHD/BD treatment. In this open trial,22 36 adults with comorbid ADHD and BD received bupropion SR, up to 200 mg bid, for ADHD symptoms while maintained on mood stabilizers, antipsychotics, or both. Improvement was defined as ≥30% reduction in ADHD Symptom Checklist Scale scores, without concurrent mania. After 6 weeks, 82% of patients had improved; 1 dropped out at week 2 because of hypomanic activation. Methodologic limitations included trial design (non-randomized, nonblinded, short duration) and patient selection (90% of subjects had BD type II).

In the absence of adequate data on adult ADHD/BD, studies in children suggest:

- stimulants may not be effective for ADHD symptoms in patients with active manic or depressive symptoms

- mood stabilization is a prerequisite for successful pharmacologic treatment of ADHD in patients with both ADHD and manic or depressive symptoms.23,24

Follow the hierarchy. First treat acute mood symptoms, then reevaluate and possibly treat ADHD symptoms if they persist during euthymia (Algorithm 1). When a patient meets criteria for adult ADHD/BD, first stabilize bipolar manic or depressive symptoms (Algorithm 2). For acute mania, treat with standard mood stabilizers (lithium, valproate, lamotrigine, or carbamazepine) with or without a second-generation antipsychotic.25 Starting stimulants for ADHD when patients have active mood symptoms is sub-optimal and potentially harmful because of the risk of inducing mania. For acute bipolar depression, adjunctive antidepressant treatment has been found to be no more effective than a mood stabilizer alone.26

After bipolar symptoms respond or remit, reassess for adult ADHD. If ADHD symptoms persist during euthymia, additional treatment may be indicated.

Very little evidence exists on treating adult ADHD/BD; as mentioned, bupropion is the only medication studied in this population. For adult ADHD alone, clinical trials have showed varying efficacy with bupropion,27,28 atomoxetine,29 venlafaxine,30,31 desipramine,32 methylphenidate,33 mixed amphetamine salts,34 and guanfacine.35 Whether these treatments can be generalized as safe and efficacious for comorbid adult ADHD/BD is unclear. Nonetheless, we suggest using bupropion first, followed by atomoxetine or guanfacine before you consider amphetamine stimulants (Algorithm 3).

Algorithm 1

Hierarchy for diagnosis and treatment of adult ADHD/BD

ADHD: attention-deficit/hyperactivity disorder; BD: bipolar disorder

*Adler LA, Chua HC. Management of ADHD in adults. J Clin Psychiatry 2002;63(suppl 12):29-35.

Algorithm 2

Treating acute episodes of bipolar disorder

ECT: electroconvulsive therapy; SGA: second-generation antipsychotic; TMS: transcranial magnetic stimulation

Algorithm 3

Suggested approach to adult ADHD with comorbid BD*

* Based on data extrapolated from samples of patients with ADHD alone because of very limited data in ADHD/BD samples.

† We recommend against combining antidepressants and stimulants because of additive risks of mania in BD. Discontinue stimulant or antidepressant if manic symptoms appear or rapid cycling emerges.

Reducing mania risk

Antidepressants and stimulants may help adults with ADHD alone, but risks of mania and rapid cycling limit their use in adults with ADHD/BD.

Stimulants and mania. One study found a 17% manic switch rate when methylphenidate (≤10 mg bid) was given to 14 bipolar depressed adults (10 BD type I, 2 BD type II, and 2 with secondary mania) taking mood stabilizers.36 A chart review of 82 bipolar children not taking mood stabilizers found an 18% switch rate with methylphenidate or amphetamine.37 Another chart review of 80 children with BD type I found that past amphetamine treatment (but not history of ADHD diagnosis or antidepressant treatment) was associated with more severe bipolar illness.38

No studies have examined predictors of amphetamine-induced mania. In our clinical experience, triggers are similar to those that can cause antidepressant-induced mania, such as:

- recent manic episodes

- current rapid cycling

- past antidepressant-induced mania.

Antidepressants and mania. When 64 patients with acute bipolar depression received both antidepressants and mood stabilizers in a randomized, double-blind trial, switch rates into mania or hypomania were 10% for bupropion, 9% for sertraline, and 29% for venlafaxine.39 In a meta analysis of clinical trials using selective serotonin reuptake inhibitors (SSRIs) or tricyclic antidepressants (TCAs), the manic switch rate was threefold higher with TCAs than SSRIs.40 Antidepressant use in bipolar patients was associated with rapid cycling in the only randomized study of this topic.41

Insufficient data exist to clarify whether mania induction with antidepressants is dose-dependent.42 Factors associated with antidepressant-induced mania include:

- previous antidepressant-induced mania

- family history of BD

- exposure to multiple antidepressant trials42

- history of substance abuse and/or dependence.43

Related resources

- Bipolar disorder information and resources. www.psycheducation.org.

- ADHD Information and resources. www.adhdnews.com.

- Phelps J. Why am I still depressed? Recognizing and managing the ups and downs of bipolar II and soft bipolar disorder. New York: McGraw-Hill; 2006.

Drug brand names

- Amphetamine/Dextroamphetamine • Adderall

- Aripiprazole • Abilify

- Atomoxetine • Strattera

- Bupropion • Wellbutrin

- Carbamazepine • Tegretol

- Desipramine • Norpramin

- Dextroamphetamine • Dexedrine

- Guanfacine • Tenex

- Lamotrigine • Lamictal

- Lithium • Eskalith, Lithobid

- Methylphenidate • Ritalin

- Quetiapine • Seroquel

- Sertraline • Zoloft

- Valproate • Depakote

- Venlafaxine • Effexor

- Ziprasidone • Geodon

Disclosures

Dr. Wingo reports no financial relationship with any company whose products are mentioned in this article or with manufacturers of competing products.

Dr. Ghaemi receives research grants from GlaxoSmithKline and Pfizer and is a speaker for GlaxoSmithKline, AstraZeneca, Pfizer, and Abbott Laboratories. Neither he nor his family hold equity positions in pharmaceutical companies.

Overlapping symptoms may obscure comorbid bipolar illness

An adult with function-impairing inattention could have attention-deficit/hyperactivity disorder (ADHD), bipolar disorder (BD), or both. Comorbid ADHD and BD often is unrecognized, however, because patients are more likely to report ADHD-related symptoms than manic symptoms.1

To help you recognize comorbid ADHD/BD—and protect adults who might switch into mania if given stimulants or antidepressants—this article describes a hierarchy to diagnose and treat this comorbidity. Based on the evidence and our experience, we:

- discuss how to differentiate between these disorders with overlapping symptoms

- provide tools and suggestions to screen for BD and adult ADHD

- offer 3 algorithms to guide your diagnosis and choice of medications.

Clinical challenges

Prevalence is unclear. Adult ADHD—with an estimated prevalence of 4.4%2—is more common than BD. Lifetime prevalences of BD types I and II are 1.6% and 0.5%, respectively.3 Studies of ADHD/BD comorbidity suggest wide-ranging prevalence rates:

Underdiagnosis. Adult ADHD/BD is a more severe illness than ADHD or BD alone and is highly comorbid with agoraphobia, social phobia, posttraumatic stress disorder, and alcohol or drug addiction. Adults with ADHD/BD have more frequent affective episodes, suicide attempts, violence, and legal problems.4 Diagnosing this comorbidity remains a challenge, however, because:

- identifying which symptoms are caused by which disorder can be difficult

- BD tends to be underdiagnosed9

- patients often misidentify, underreport, or deny manic symptoms1,10,11

- if a patient presents with active bipolar symptoms, DSM-IV-TR criteria require that ADHD not be diagnosed until mood symptoms are resolved.

Overlapping symptoms. ADHD and bipolar mania share some DSM-IV-TR diagnostic criteria, including talkativeness, distractibility, increased activity or physical restlessness, and loss of social inhibitions (Table 1).12 Overlapping symptoms also are notable within ADHD diagnostic criteria (Table 2). In the inattention category, for example, “easily distracted by extraneous stimuli,” “difficulty sustaining attention in tasks,” and “fails to give close attention to details” are considered 3 separate symptoms. In the hyperactivity category, “often leaves seat,” “often runs about or climbs excessively,” and “often on the go, or often acts as if driven by a motor” are 3 separate symptoms.

Given ADHD’s relatively loose diagnostic criteria and high comorbidity in adults with mood disorders, the question of whether adult ADHD/BD represents comorbidity or diagnostic overlap remains unresolved. For the clinician, the disorders’ nonoverlapping features (Table 1) can assist with the differential diagnosis. For example:

- ADHD symptoms tend to be chronic and BD symptoms episodic.

- ADHD patients may have high energy but lack increased productivity seen in BD patients.

- ADHD patients do not need less sleep or have inflated self-esteem like symptomatic BD patients.

- Psychotic symptoms such as hallucinations or delusions might be present in severe BD but are absent in ADHD.

Table 1

Overlap between DSM-IV-TR diagnostic criteria for ADHD and bipolar mania

| Overlapping symptoms | |

|---|---|

| ADHD | Bipolar mania |

| Talks excessively | More talkative than usual |

| Easily distracted/jumps from one activity to the next | Distractibility or constant changes in activity or plans |

| Fidgets Difficulty remaining seated Runs or climbs about inappropriately Difficulty playing quietly On the go as if driven by a motor | Increased activity or physical restlessness |

| Interrupts or butts in uninvited Blurts out answers | Loss of normal social inhibitions |

| Nonoverlapping symptoms | |

| ADHD Forgetful in daily activities Difficulty awaiting turn Difficulty organizing self Loses things Avoids sustained mental effort Does not seem to listen Difficulty following through on instructions/fails to finish work Difficulty sustaining attention Fails to give close attention to details/makes careless mistakes | |

| Bipolar mania Inflated self-esteem/grandiosity Increase in goal-directed activity Flight of ideas Decreased need for sleep Excessive involvement in pleasurable activities with disregard for potential adverse consequences Marked sexual energy or sexual indiscretions | |

| ADHD: attention-deficit/hyperactivity disorder | |

| Source: Adapted and reprinted with permission from reference 12 | |

Table 2

DSM-IV-TR diagnostic criteria for attention-deficit/ hyperactivity disorder

| Inattention |

≥6 symptoms have persisted ≥6 months to a degree that is maladaptive and inconsistent with developmental level. The patient often:

|

| Hyperactivity/impulsivity |

≥6 symptoms have persisted ≥6 months to a degree that is maladaptive and inconsistent with developmental level. The patient often:

|

| Diagnosis requires evidence of inattention or hyperactivity/impulsivity or both |

| Some hyperactive/impulsive or inattentive symptoms that caused impairment were present before age 7 |

| Some impairment from symptoms is present in ≥2 settings (such as at school, work, or home) |

| Symptoms do not occur exclusively during the course of a pervasive developmental disorder, schizophrenia, or other psychotic disorder and are not better accounted for by another mental disorder (mood disorder, anxiety disorder, dissociative disorder, or a personality disorder) |

| Source: DSM-IV-TR |

Mood symptoms first

A diagnostic hierarchy is implicit in DSM-IV-TR; anxiety disorders are not diagnosed during an active major depressive or manic episode, and schizophrenia is not diagnosed on the basis of psychotic symptoms during an active major depressive or manic episode. Mood disorders sit atop this implied diagnostic hierarchy and must be ruled out before psychotic or anxiety disorders are diagnosed. Similarly, most personality disorders are not diagnosed during an active mood or psychotic episode.

Diagnosing adult ADHD when a patient is actively depressed or manic is inconsistent with this hierarchy and conflicts with extensive nosologic literature.13 We suggest that ADHD—a cognitive-behavioral problem—not be diagnosed solely on symptoms observed when a patient is experiencing a mood episode or psychotic illness.

Bipolar disorder. Two useful mnemonics (Table 3) assist in screening for DSM-IV-TR symptoms of BD type I:

- Pure mania consists of euphoric mood and ≥3 of 7 DIGFAST criteria, or irritable mood and ≥4 of 7 DIGFAST criteria

- Mixed mania consists of depressed mood with ≥4 of 7 DIGFAST criteria and ≥4 of 8 SIGECAPS criteria.

To be diagnostic, these symptoms must cause substantial social or occupational dysfunction and be present at least 1 week. Diagnose BD type I if a patient has experienced a single pure or mixed manic episode at any time, unless the episode had a medical cause such as hyperthyroidism or antidepressant use. Because patients with mixed episodes experience depressed mood, assess any patient with clinical depression for manic symptoms. Otherwise, a patient with a mixed episode could be misdiagnosed as having unipolar depression instead of BD type I.14

BD type II also has been observed in patients with comorbid adult ADHD/BD.4,6 The main difference between BD types I and II is that manic symptoms in type II are not severe enough to cause functional impairment or psychotic symptoms.15

Adult ADHD. The clinical interview seeking evidence of inattention and hyperactivity/impulsivity remains the basis of adult ADHD diagnosis (Table 2). Key areas are:

- the patient’s past and current functional impairment

- whether substantial impairment occurs in at least 2 areas of life (such as school, work, or home).

Take medical, educational, social, psychological, and vocational histories, and rule out other conditions before concluding that adult ADHD is the appropriate diagnosis.16 In adult ADHD, inattentive symptoms become far more prominent, about twice as common as hyperactive symptoms.17 Inattentive symptoms may manifest as neglect, poor time management, motivational deficits, or poor concentration that results in forgetfulness, distractibility, item misplacement, or excessive mistakes in paperwork.18 When impulsive symptoms persist in adults, they may manifest as automobile accidents or low tolerance for frustration, which may lead to frequent job changes and unstable, interrupted interpersonal relationships.18

Neuropsychological testing is not required to make an adult ADHD diagnosis but can help establish the breadth of symptoms or comorbidity.17 Rating scales can screen, gather data (including presence and severity of symptoms), and measure treatment response.16 Commonly used rating scales include:

- Conners’ Adult ADHD Rating Scales19

- Brown Attention Deficit Disorder Rating Scale for Adults20

- Adult ADHD Self-Report Scale.21

When using rating scales, remember that adult psychopathology can distort perceptions, and some self-report scales have questionable reliability.16

Table 3

Mnemonics for diagnostic symptoms of pure and mixed bipolar mania

| DIGFAST* for bipolar mania symptoms | SIGECAPS† bipolar depression symptoms |

|---|---|

| Distractibility Insomnia Grandiosity Flight of ideas Activities Speech Thoughtlessness | Sleep Interest Guilt Energy Concentration Appetite Psychomotor Suicide |

| Pure mania: Euphoric mood with ≥3 DIGFAST criteria or irritable mood with ≥4 DIGFAST criteria. | |

| Mixed mania: Depressed mood with ≥4 DIGFAST criteria and ≥4 SIGECAPS criteria. | |

| * Developed by William Falk, MD | |

| †Developed by Carey Gross, MD | |

| Source: Adapted from Ghaemi SN. Mood disorders. New York: Lippincott, Williams, & Wilkins; 2003 | |

Treatment recommendations

Limited data. We found only 1 study on adult ADHD/BD treatment. In this open trial,22 36 adults with comorbid ADHD and BD received bupropion SR, up to 200 mg bid, for ADHD symptoms while maintained on mood stabilizers, antipsychotics, or both. Improvement was defined as ≥30% reduction in ADHD Symptom Checklist Scale scores, without concurrent mania. After 6 weeks, 82% of patients had improved; 1 dropped out at week 2 because of hypomanic activation. Methodologic limitations included trial design (non-randomized, nonblinded, short duration) and patient selection (90% of subjects had BD type II).

In the absence of adequate data on adult ADHD/BD, studies in children suggest:

- stimulants may not be effective for ADHD symptoms in patients with active manic or depressive symptoms

- mood stabilization is a prerequisite for successful pharmacologic treatment of ADHD in patients with both ADHD and manic or depressive symptoms.23,24

Follow the hierarchy. First treat acute mood symptoms, then reevaluate and possibly treat ADHD symptoms if they persist during euthymia (Algorithm 1). When a patient meets criteria for adult ADHD/BD, first stabilize bipolar manic or depressive symptoms (Algorithm 2). For acute mania, treat with standard mood stabilizers (lithium, valproate, lamotrigine, or carbamazepine) with or without a second-generation antipsychotic.25 Starting stimulants for ADHD when patients have active mood symptoms is sub-optimal and potentially harmful because of the risk of inducing mania. For acute bipolar depression, adjunctive antidepressant treatment has been found to be no more effective than a mood stabilizer alone.26

After bipolar symptoms respond or remit, reassess for adult ADHD. If ADHD symptoms persist during euthymia, additional treatment may be indicated.

Very little evidence exists on treating adult ADHD/BD; as mentioned, bupropion is the only medication studied in this population. For adult ADHD alone, clinical trials have showed varying efficacy with bupropion,27,28 atomoxetine,29 venlafaxine,30,31 desipramine,32 methylphenidate,33 mixed amphetamine salts,34 and guanfacine.35 Whether these treatments can be generalized as safe and efficacious for comorbid adult ADHD/BD is unclear. Nonetheless, we suggest using bupropion first, followed by atomoxetine or guanfacine before you consider amphetamine stimulants (Algorithm 3).

Algorithm 1

Hierarchy for diagnosis and treatment of adult ADHD/BD

ADHD: attention-deficit/hyperactivity disorder; BD: bipolar disorder

*Adler LA, Chua HC. Management of ADHD in adults. J Clin Psychiatry 2002;63(suppl 12):29-35.

Algorithm 2

Treating acute episodes of bipolar disorder

ECT: electroconvulsive therapy; SGA: second-generation antipsychotic; TMS: transcranial magnetic stimulation

Algorithm 3

Suggested approach to adult ADHD with comorbid BD*

* Based on data extrapolated from samples of patients with ADHD alone because of very limited data in ADHD/BD samples.

† We recommend against combining antidepressants and stimulants because of additive risks of mania in BD. Discontinue stimulant or antidepressant if manic symptoms appear or rapid cycling emerges.

Reducing mania risk

Antidepressants and stimulants may help adults with ADHD alone, but risks of mania and rapid cycling limit their use in adults with ADHD/BD.

Stimulants and mania. One study found a 17% manic switch rate when methylphenidate (≤10 mg bid) was given to 14 bipolar depressed adults (10 BD type I, 2 BD type II, and 2 with secondary mania) taking mood stabilizers.36 A chart review of 82 bipolar children not taking mood stabilizers found an 18% switch rate with methylphenidate or amphetamine.37 Another chart review of 80 children with BD type I found that past amphetamine treatment (but not history of ADHD diagnosis or antidepressant treatment) was associated with more severe bipolar illness.38

No studies have examined predictors of amphetamine-induced mania. In our clinical experience, triggers are similar to those that can cause antidepressant-induced mania, such as:

- recent manic episodes

- current rapid cycling

- past antidepressant-induced mania.

Antidepressants and mania. When 64 patients with acute bipolar depression received both antidepressants and mood stabilizers in a randomized, double-blind trial, switch rates into mania or hypomania were 10% for bupropion, 9% for sertraline, and 29% for venlafaxine.39 In a meta analysis of clinical trials using selective serotonin reuptake inhibitors (SSRIs) or tricyclic antidepressants (TCAs), the manic switch rate was threefold higher with TCAs than SSRIs.40 Antidepressant use in bipolar patients was associated with rapid cycling in the only randomized study of this topic.41

Insufficient data exist to clarify whether mania induction with antidepressants is dose-dependent.42 Factors associated with antidepressant-induced mania include:

- previous antidepressant-induced mania

- family history of BD

- exposure to multiple antidepressant trials42

- history of substance abuse and/or dependence.43

Related resources

- Bipolar disorder information and resources. www.psycheducation.org.

- ADHD Information and resources. www.adhdnews.com.

- Phelps J. Why am I still depressed? Recognizing and managing the ups and downs of bipolar II and soft bipolar disorder. New York: McGraw-Hill; 2006.

Drug brand names

- Amphetamine/Dextroamphetamine • Adderall

- Aripiprazole • Abilify

- Atomoxetine • Strattera

- Bupropion • Wellbutrin

- Carbamazepine • Tegretol

- Desipramine • Norpramin

- Dextroamphetamine • Dexedrine

- Guanfacine • Tenex

- Lamotrigine • Lamictal

- Lithium • Eskalith, Lithobid

- Methylphenidate • Ritalin

- Quetiapine • Seroquel

- Sertraline • Zoloft

- Valproate • Depakote

- Venlafaxine • Effexor

- Ziprasidone • Geodon

Disclosures

Dr. Wingo reports no financial relationship with any company whose products are mentioned in this article or with manufacturers of competing products.

Dr. Ghaemi receives research grants from GlaxoSmithKline and Pfizer and is a speaker for GlaxoSmithKline, AstraZeneca, Pfizer, and Abbott Laboratories. Neither he nor his family hold equity positions in pharmaceutical companies.

1. Ghaemi SN, Stoll AL, Pope HG, Jr, et al. Lack of insight in bipolar disorder. The acute manic episode. J Nerv Ment Dis 1995;183(7):464-7.

2. Kessler RC, Adler L, Barkley R, et al. The prevalence and correlates of adult ADHD in the United States: results from the National Comorbidity Survey Replication. Am J Psychiatry 2006;163(4):716-23.

3. Sadock BJ, Sadock VA, eds. Synopsis of psychiatry, 9th ed. Philadelphia: Lippincott Williams & Wilkins; 2003.

4. Nierenberg AA, Miyahara S, Spencer T, et al. Clinical and diagnostic implications of lifetime attention-deficit/hyperactivity disorder comorbidity in adults with bipolar disorder: data from the first 1000 STEP-BD participants. Biol Psychiatry 2005;57(11):1467-73.

5. Tamam L, Tuglu C, Karatas G, et al. Adult attention-deficit hyperactivity disorder in patients with bipolar I disorder in remission: preliminary study. Psychiatry Clin Neurosci 2006;60(4):480-5.

6. Wilens TE, Biederman J, Wozniak J, et al. Can adults with attention-deficit/hyperactivity disorder be distinguished from those with comorbid bipolar disorder? Findings from a sample of clinically referred adults. Biol Psychiatry 2003;54(1):1-8.

7. McGough JJ, Smalley SL, McCracken JT, et al. Psychiatric comorbidity in adult attention deficit hyperactivity disorder: findings from multiplex families. Am J Psychiatry 2005;162(9):1621-7.

8. Faraone SV, Biederman J, Spencer T, et al. Diagnosing adult attention deficit hyperactivity disorder: are late onset and subthreshold diagnoses valid? Am J Psychiatry 2006;163(10):1720-9.

9. Ghaemi SN, Sachs GS, Chiou AM, et al. Is bipolar disorder still underdiagnosed? Are antidepressants overutilized? J Affect Disord 1999;52(1-3):135-44.

10. Keitner GI, Solomon DA, Ryan CE, et al. Prodromal and residual symptoms in bipolar I disorder. Compr Psychiatry 1996;37(5):362-7.

11. Bowden CL. Strategies to reduce misdiagnosis of bipolar depression. Psychiatr Serv 2001;52(1):51-5.

12. Kent L, Craddock N. Is there a relationship between attention deficit hyperactivity disorder and bipolar disorder? J Affect Disord 2003;73(3):211-21.

13. Surtees PG, Kendell RE. The hierarchy model of psychiatric symptomatology: an investigation based on present state examination ratings. Br J Psychiatry 1979;135:438-43.

14. Benazzi F. Symptoms of depression as possible markers of bipolar II disorder. Prog Neuropsychopharmacol Biol Psychiatry 2006;30(3):471-7.

15. Diagnostic and Statistical Manual of Mental Disorders, 4th ed., text rev. Washington, DC: American Psychiatric Association; 2000.

16. Murphy KR, Adler LA. Assessing attention-deficit hyperactivity disorder in adults: focus on rating scales. J Clin Psychiatry 2004;65(suppl 3):12-17.

17. Adler LA. Diagnosing adult attention deficit hyperactivity disorder. Primary Psychiatry 2006;13(suppl 3):9-10.

18. Montano B. Diagnosis and treatment of ADHD in adults in primary care. J Clin Psychiatry 2004;65(suppl 3):18-21.

19. Conners CK, Erhardt D, Sparrow E. Conners’ Adult ADHD Rating Scales (CAARS). North Tonawanda, NY: Multi-Health Systems; 1999.

20. Brown TE. Brown Attention Deficit Disorder Scales. San Antonio, TX: The Psychological Corporation; 1996.

21. Adler LA, Kessler RC, Spencer T. Adult ADHD Self-report Scale v1.1 (ASRS-v1.1) Symptom Checklist. World Health Organization. Available at: http://www.med.nyu.edu/psych/assets/adhdscreen18.pdf. Accessed May 7, 2007.

22. Wilens TE, Prince JB, Spencer T, et al. An open trial of bupropion for the treatment of adults with attention-deficit/hyperactivity disorder and bipolar disorder. Biol Psychiatry 2003;54(1):9-16.

23. Biederman J, Mick E, Prince J, et al. Systematic chart review of the pharmacologic treatment of comorbid attention deficit hyperactivity disorder in youth with bipolar disorder. J Child Adolesc Psychopharmacol 1999;9(4):247-56.

24. Daviss WB, Bentivoglio P, Racusin R, et al. Bupropion sustained release in adolescents with comorbid attention-deficit/hyperactivity disorder and depression. J Am Acad Child Adolesc Psychiatry 2001;40(3):307-14.

25. Scherk H, Pajonk FG, Leucht SL. Second-generation antipsychotic agents in the treatment of acute mania. Arch Gen Psychiatry 2007;64:442-55.

26. Sachs GS, Nierenberg AA, Calabrese JR, et al. Effectiveness of adjunctive antidepressant treatment for bipolar depression. N Engl J Med 2007:356:(17):1711-22.

27. Wilens TE, Haight BR, Horrigan JP, et al. Bupropion XL in adults with attention deficit hyperactivity disorder: a randomized, placebo controlled study. Biol Psychiatry 2005;57:793-801.

28. Wilens TE, Spencer TJ, Biederman J, et al. A controlled clinical trial of bupropion for attention deficit hyperactivity disorder in adults. Am J Psychiatry 2001;158(2):282-8.

29. Michelson D, Adler LA, Spencer T, et al. Atomoxetine in adults with ADHD: two randomized, placebo controlled studies. Biol Psychiatry 2003;53:112-20.

30. Adler LA, Resnick S, Kunz M, Devinsky O. Open-label trial of venlafaxine in adults with attention deficit disorder. Psychopharmacol Bull 1995;31(4):785-8.

31. Hedges D, Reimherr FW, Rogers A, et al. An open trial of venlafaxine in adult patients with attention deficit hyperactivity disorder. Psychopharmacol Bull 1995;31(4):779-83.

32. Wilens TE, Biederman J, Prince J, et al. Six-week, double-blind, placebo-controlled study of desipramine for adult attention deficit hyperactivity disorder. Am J Psychiatry 1996;153(9):1147-53.

33. Faraone SV, Spencer T, Aleardi M, et al. Meta analysis of the efficacy of methylphenidate for treating adult attention deficit hyperactivity disorder. J Clin Psychopharmacol 2004;24(1):24-8.

34. Spencer T, Biederman J, Wilens TE, et al. Efficacy of a mixed amphetamine salts compound in adults with attention deficit hyperactivity disorder. Arch Gen Psychiatry 2001;58:775-82.

35. Taylor FB, Russo J. Comparing guanfacine and dextroamphetamine for the treatment of adult attention deficit hyperactivity disorder. J Clin Psychopharmacol 2000;21(2):223-8.

36. El-Mallakh RS. An open study of methylphenidate in bipolar depression. Bipolar Disord 2000;2(1):56-9.

37. Faedda GL, Baldessarini RJ, Glovinsky IP, et al. Treatment-emergent mania in pediatric bipolar disorder: a retrospective case review. J Affect Disord 2004;82(1):149-58.

38. Soutullo CA, DelBello MP, Ochsner JE, et al. Severity of bipolarity in hospitalized manic adolescents with history of stimulant or antidepressant treatment. J Affect Disord 2002;70(3):323-7.

39. Post RM, Altshuler LL, Leverich GS, et al. Mood switch in bipolar depression: comparison of adjunctive venlafaxine, bupropion and sertraline. Br J Psychiatry 2006;189:124-31.

40. Peet M. Induction of mania with selective serotonin re-uptake inhibitors and tricyclic antidepressants. Br J Psychiatry 1994;164(4):549-50.

41. Wehr TA, Sack DA, Rosenthal NE, Cowdry RW. Rapid cycling affective disorder: contributing factors and treatment responses in 51 patients. Am J Psychiatry 1988;145(2):179-84.

42. Goldberg JF. When do antidepressants worsen the course of bipolar disorder? J Psychiatr Pract. 2003;9(3):181-94.

43. Goldberg JF, Whiteside JE. The association between substance abuse and antidepressant-induced mania in bipolar disorder: a preliminary study. J Clin Psychiatry 2002;63(9):791-5.

1. Ghaemi SN, Stoll AL, Pope HG, Jr, et al. Lack of insight in bipolar disorder. The acute manic episode. J Nerv Ment Dis 1995;183(7):464-7.

2. Kessler RC, Adler L, Barkley R, et al. The prevalence and correlates of adult ADHD in the United States: results from the National Comorbidity Survey Replication. Am J Psychiatry 2006;163(4):716-23.

3. Sadock BJ, Sadock VA, eds. Synopsis of psychiatry, 9th ed. Philadelphia: Lippincott Williams & Wilkins; 2003.

4. Nierenberg AA, Miyahara S, Spencer T, et al. Clinical and diagnostic implications of lifetime attention-deficit/hyperactivity disorder comorbidity in adults with bipolar disorder: data from the first 1000 STEP-BD participants. Biol Psychiatry 2005;57(11):1467-73.

5. Tamam L, Tuglu C, Karatas G, et al. Adult attention-deficit hyperactivity disorder in patients with bipolar I disorder in remission: preliminary study. Psychiatry Clin Neurosci 2006;60(4):480-5.

6. Wilens TE, Biederman J, Wozniak J, et al. Can adults with attention-deficit/hyperactivity disorder be distinguished from those with comorbid bipolar disorder? Findings from a sample of clinically referred adults. Biol Psychiatry 2003;54(1):1-8.

7. McGough JJ, Smalley SL, McCracken JT, et al. Psychiatric comorbidity in adult attention deficit hyperactivity disorder: findings from multiplex families. Am J Psychiatry 2005;162(9):1621-7.

8. Faraone SV, Biederman J, Spencer T, et al. Diagnosing adult attention deficit hyperactivity disorder: are late onset and subthreshold diagnoses valid? Am J Psychiatry 2006;163(10):1720-9.

9. Ghaemi SN, Sachs GS, Chiou AM, et al. Is bipolar disorder still underdiagnosed? Are antidepressants overutilized? J Affect Disord 1999;52(1-3):135-44.

10. Keitner GI, Solomon DA, Ryan CE, et al. Prodromal and residual symptoms in bipolar I disorder. Compr Psychiatry 1996;37(5):362-7.

11. Bowden CL. Strategies to reduce misdiagnosis of bipolar depression. Psychiatr Serv 2001;52(1):51-5.

12. Kent L, Craddock N. Is there a relationship between attention deficit hyperactivity disorder and bipolar disorder? J Affect Disord 2003;73(3):211-21.

13. Surtees PG, Kendell RE. The hierarchy model of psychiatric symptomatology: an investigation based on present state examination ratings. Br J Psychiatry 1979;135:438-43.

14. Benazzi F. Symptoms of depression as possible markers of bipolar II disorder. Prog Neuropsychopharmacol Biol Psychiatry 2006;30(3):471-7.

15. Diagnostic and Statistical Manual of Mental Disorders, 4th ed., text rev. Washington, DC: American Psychiatric Association; 2000.

16. Murphy KR, Adler LA. Assessing attention-deficit hyperactivity disorder in adults: focus on rating scales. J Clin Psychiatry 2004;65(suppl 3):12-17.

17. Adler LA. Diagnosing adult attention deficit hyperactivity disorder. Primary Psychiatry 2006;13(suppl 3):9-10.

18. Montano B. Diagnosis and treatment of ADHD in adults in primary care. J Clin Psychiatry 2004;65(suppl 3):18-21.

19. Conners CK, Erhardt D, Sparrow E. Conners’ Adult ADHD Rating Scales (CAARS). North Tonawanda, NY: Multi-Health Systems; 1999.

20. Brown TE. Brown Attention Deficit Disorder Scales. San Antonio, TX: The Psychological Corporation; 1996.

21. Adler LA, Kessler RC, Spencer T. Adult ADHD Self-report Scale v1.1 (ASRS-v1.1) Symptom Checklist. World Health Organization. Available at: http://www.med.nyu.edu/psych/assets/adhdscreen18.pdf. Accessed May 7, 2007.

22. Wilens TE, Prince JB, Spencer T, et al. An open trial of bupropion for the treatment of adults with attention-deficit/hyperactivity disorder and bipolar disorder. Biol Psychiatry 2003;54(1):9-16.

23. Biederman J, Mick E, Prince J, et al. Systematic chart review of the pharmacologic treatment of comorbid attention deficit hyperactivity disorder in youth with bipolar disorder. J Child Adolesc Psychopharmacol 1999;9(4):247-56.

24. Daviss WB, Bentivoglio P, Racusin R, et al. Bupropion sustained release in adolescents with comorbid attention-deficit/hyperactivity disorder and depression. J Am Acad Child Adolesc Psychiatry 2001;40(3):307-14.

25. Scherk H, Pajonk FG, Leucht SL. Second-generation antipsychotic agents in the treatment of acute mania. Arch Gen Psychiatry 2007;64:442-55.

26. Sachs GS, Nierenberg AA, Calabrese JR, et al. Effectiveness of adjunctive antidepressant treatment for bipolar depression. N Engl J Med 2007:356:(17):1711-22.

27. Wilens TE, Haight BR, Horrigan JP, et al. Bupropion XL in adults with attention deficit hyperactivity disorder: a randomized, placebo controlled study. Biol Psychiatry 2005;57:793-801.

28. Wilens TE, Spencer TJ, Biederman J, et al. A controlled clinical trial of bupropion for attention deficit hyperactivity disorder in adults. Am J Psychiatry 2001;158(2):282-8.

29. Michelson D, Adler LA, Spencer T, et al. Atomoxetine in adults with ADHD: two randomized, placebo controlled studies. Biol Psychiatry 2003;53:112-20.

30. Adler LA, Resnick S, Kunz M, Devinsky O. Open-label trial of venlafaxine in adults with attention deficit disorder. Psychopharmacol Bull 1995;31(4):785-8.

31. Hedges D, Reimherr FW, Rogers A, et al. An open trial of venlafaxine in adult patients with attention deficit hyperactivity disorder. Psychopharmacol Bull 1995;31(4):779-83.

32. Wilens TE, Biederman J, Prince J, et al. Six-week, double-blind, placebo-controlled study of desipramine for adult attention deficit hyperactivity disorder. Am J Psychiatry 1996;153(9):1147-53.

33. Faraone SV, Spencer T, Aleardi M, et al. Meta analysis of the efficacy of methylphenidate for treating adult attention deficit hyperactivity disorder. J Clin Psychopharmacol 2004;24(1):24-8.

34. Spencer T, Biederman J, Wilens TE, et al. Efficacy of a mixed amphetamine salts compound in adults with attention deficit hyperactivity disorder. Arch Gen Psychiatry 2001;58:775-82.

35. Taylor FB, Russo J. Comparing guanfacine and dextroamphetamine for the treatment of adult attention deficit hyperactivity disorder. J Clin Psychopharmacol 2000;21(2):223-8.

36. El-Mallakh RS. An open study of methylphenidate in bipolar depression. Bipolar Disord 2000;2(1):56-9.

37. Faedda GL, Baldessarini RJ, Glovinsky IP, et al. Treatment-emergent mania in pediatric bipolar disorder: a retrospective case review. J Affect Disord 2004;82(1):149-58.

38. Soutullo CA, DelBello MP, Ochsner JE, et al. Severity of bipolarity in hospitalized manic adolescents with history of stimulant or antidepressant treatment. J Affect Disord 2002;70(3):323-7.

39. Post RM, Altshuler LL, Leverich GS, et al. Mood switch in bipolar depression: comparison of adjunctive venlafaxine, bupropion and sertraline. Br J Psychiatry 2006;189:124-31.

40. Peet M. Induction of mania with selective serotonin re-uptake inhibitors and tricyclic antidepressants. Br J Psychiatry 1994;164(4):549-50.

41. Wehr TA, Sack DA, Rosenthal NE, Cowdry RW. Rapid cycling affective disorder: contributing factors and treatment responses in 51 patients. Am J Psychiatry 1988;145(2):179-84.

42. Goldberg JF. When do antidepressants worsen the course of bipolar disorder? J Psychiatr Pract. 2003;9(3):181-94.

43. Goldberg JF, Whiteside JE. The association between substance abuse and antidepressant-induced mania in bipolar disorder: a preliminary study. J Clin Psychiatry 2002;63(9):791-5.

The Hospital as College

The hospital is the only proper college in which to rear a true disciple of Aesculapius.—John Abernethy (1764-1831), surgeon and teacher

With this quote Sir William Osler began his address, “The Hospital as a College?” to the Academy of Medicine in New York in 1903. His second quote for this report was from the famed physician Oliver Wendell Holmes Sr. in 1867:

“The most essential part of a student’s instruction is obtained, as I believe, not in the lecture room, but at the bedside. Nothing seen there is lost: the rhythms of disease are learned by frequent repetition: its unforeseen occurrence stamp themselves indelibly on the memory. Before the student is aware of what he had acquired he has learned the aspects and causes and probable issue of the disease he has seen with his teacher and the proper mode of dealing with them, as far as his master knows.”

In his report Osler was celebrating a quarter century’s success in education. He demanded a better general education for students, a lengthened period for professional study, and the substitution of theoretical by practical learning. He wanted the student not to learn only from dissecting the sympathetic nervous system but to learn to “take a blood pressure observation” with a kymograph (an instrument used to record the temporal variations of any physiological or muscular process; it consists essentially of a revolving drum, bearing a record sheet on which a stylus travels).

Osler observed that there should be no teaching without a patient for a text: “The whole of medicine is in observation” that the teacher’s art is educating the student’s finger to feel and eyes to see. Give the student good methods and a proper point of view, and experience will do the rest.

Osler expressed confidence that students would keep the hospital physician from slovenliness and improve the care of patients. He was also concerned that “we ask too much of the resident physicians, whose number has not increased in proportion to the enormous amount of work thrust upon them.” Students were the answer, the proto-scut-monkey.

The practicality of working out of a teaching hospital was outlined at length in Osler’s report. The student’s third year should begin with a systematic physical diagnosis course, first in history taking, then in writing reports. Concurrently, a physical examination course should be given several days a week with individual cases assigned to students to follow, and instruction is accessing the literature. Next comes clinical microscopy—an essential in an era where there was often no lab to call upon. In general, medical clinic occurs one day a week when interesting cases are brought from the wards. Of note, committees were appointed to report on every case of pneumonia.

In revamping medical education Osler brought the third-year students to the outpatient clinic and the fourth-year students to the wards. What implication does this have for us as hospitalists?

I have no pretensions about being another Osler (I am barely a Newman on my best days), but still my colleagues and I trudge along in our teaching duties. What education do we really do? I sat down after reading Osler’s paper, stimulated by a tangential question from the esteemed Tom Baudenistel, MD, and decided to see exactly whom we were teaching.

First there are medical students. We are faculty on their first-year selectives, offering a shadow experience. We staff the introduction to physical exam courses in second year. Third-year students rotate on our services, and seniors take our elective as well as taking acting internships on our teaching services. We act as mentors and interest group leaders. There is certainly more to this list. We also spend time teaching NP and PA students.

The internal medicine residents rotate on our hospitalist services, and we staff the general medical services. We interact with them daily when they are on consult services, trying to set a role model. General medicine, geriatric, and hospital medicine fellows rotate through as well.

We also teach the nurses on services and through in-services and daily rounds to cement the working relationship and improve communication. We teach each other. A day rarely goes by without a colleague passing on a tasty medical tidbit. (Of course, for me, a tabla blanca, no shortage of space for pearls). And finally we teach our patients and their families. Every day we do this, and if we don’t then we are missing the point of our profession entirely.

Each party—patient or student—has something to learn from us, but more importantly we have something to learn from them. Osler wrote that “The stimulus of their presence (the student) neutralizes the clinical apathy certain, sooner or later, to beset the man who makes lonely “rounds” with his house physician.”

One hundred years plus later, much of what was written is still true: Whether in a teaching institution or making “lonely rounds” we must strive to continue to educate ourselves, our colleagues, and our patients. And what better place to do it than the hospital? TH

Dr. Newman is the physician editor of The Hospitalist. He’s also consultant, Hospital Internal Medicine, and assistant professor of internal medicine and medical history, Mayo Clinic College of Medicine, Rochester, Minn.

Bibliography

Osler W (Sir) Aequanimitas. 1945. The Blakiston Company, Philadelphia. p. 311-327.

The hospital is the only proper college in which to rear a true disciple of Aesculapius.—John Abernethy (1764-1831), surgeon and teacher

With this quote Sir William Osler began his address, “The Hospital as a College?” to the Academy of Medicine in New York in 1903. His second quote for this report was from the famed physician Oliver Wendell Holmes Sr. in 1867:

“The most essential part of a student’s instruction is obtained, as I believe, not in the lecture room, but at the bedside. Nothing seen there is lost: the rhythms of disease are learned by frequent repetition: its unforeseen occurrence stamp themselves indelibly on the memory. Before the student is aware of what he had acquired he has learned the aspects and causes and probable issue of the disease he has seen with his teacher and the proper mode of dealing with them, as far as his master knows.”

In his report Osler was celebrating a quarter century’s success in education. He demanded a better general education for students, a lengthened period for professional study, and the substitution of theoretical by practical learning. He wanted the student not to learn only from dissecting the sympathetic nervous system but to learn to “take a blood pressure observation” with a kymograph (an instrument used to record the temporal variations of any physiological or muscular process; it consists essentially of a revolving drum, bearing a record sheet on which a stylus travels).

Osler observed that there should be no teaching without a patient for a text: “The whole of medicine is in observation” that the teacher’s art is educating the student’s finger to feel and eyes to see. Give the student good methods and a proper point of view, and experience will do the rest.