User login

Enchondromatosis

Patient history: A 53-year-old female admits with a history of multiple orthopedic, dermatologic, and plastic-surgical procedures. The physical exam is notable for multiple cutaneous hemangiomas.

Salient findings: The images show old fracture deformities of the left fibular shaft and proximal tibia as well as a deformity of the distal femur. The patient has had a left total knee arthroplasty. There are multiple lucent lesions involving the left second, fourth, and fifth rays, with bone deformities. Findings are consistent with multiple chondromas. There is no evidence for malignant degeneration.

Patient population and natural history of disease: Enchondromatosis is a condition of multiple benign ectopic rests of cartilage growing within intramedullary bone, forming lucent lesions and bone expansion on radiographs. The enchondromas can deform and shorten a limb and can predispose the patient to a pathologic fracture. Enchondromas account for 12%-14% of benign bone neoplasms. When associated with cutaneous and visceral hemangiomas, the condition is called Maffucci’s syndrome.

Most patients with Maffucci’s syndrome will develop malignant transformation of at least one enchondroma into a chondrosarcoma (malignant cartilage tumor). Enchondromatosis without hemangiomas is known as Ollier’s disease; about 25% of patients with Ollier’s disease will develop chondrosarcoma by age 40. Both Maffucci’s syndrome and Ollier’s disease are nonhereditary. Metachondromatosis, a condition characterized by multiple enchondromas, is an autosomal dominant condition uniquely associated with osteochondromas.

Management: The physician who evaluates a patient with Maffucci’s syndrome must have a high suspicion for pathologic fracture and malignant degeneration. All bone pain and swelling should be evaluated with plain radiographs. Bone expansion, cortical breakthrough, soft-tissue mass, and deep endosteal scalloping of the cortex are indicative of malignant transformation. These findings are unreliable in the smaller bones of the hands, however, and features of low-grade chondrosarcoma are often indistinguishable from benign enchondromas. Even in the absence of worrisome features on plain radiographs, if clinical suspicion is high, a CT scan and/or an MRI should be performed for further evaluation. Biopsy is often indicated on clinical findings, despite imaging characteristics. Hemangiomas can undergo rapid expansion and are often treated with surgery.

Take-home points:

- Enchondromas are the most common primary neoplasm of the bones in the hand and are benign;

- There is an increased risk of malignant transformation of enchondromas in patients with Ollier’s disease or Maffucci’s syndrome; and

- Biopsy of a lesion may be indicated if clinical suspicion for malignancy is high. TH

Helena Summers is a radiology resident and Erik Summers is a hospitalist at the Mayo Clinic College of Medicine in Rochester, Minn.

Bibliography

- Sun TC, Swee RG, Shives TC, et al. Chondrosarcoma in Maffucci’s syndrome. J Bone Joint Surg Am. 1985 Oct;67(8):1214-1219.

- Schwartz HS, Zimmerman NB, Simon MA, et al. The malignant potential of enchondromatosis. J Bone Joint Surg Am. 1987 Feb;69(2):269-274.

- Chew FS, Maldjian C. Enchondroma and enchondromatosis. emedicine. June 10, 2005. Available at: www.emedicine.com/radio/topic247.htm. Last accessed on March 14, 2007.

Patient history: A 53-year-old female admits with a history of multiple orthopedic, dermatologic, and plastic-surgical procedures. The physical exam is notable for multiple cutaneous hemangiomas.

Salient findings: The images show old fracture deformities of the left fibular shaft and proximal tibia as well as a deformity of the distal femur. The patient has had a left total knee arthroplasty. There are multiple lucent lesions involving the left second, fourth, and fifth rays, with bone deformities. Findings are consistent with multiple chondromas. There is no evidence for malignant degeneration.

Patient population and natural history of disease: Enchondromatosis is a condition of multiple benign ectopic rests of cartilage growing within intramedullary bone, forming lucent lesions and bone expansion on radiographs. The enchondromas can deform and shorten a limb and can predispose the patient to a pathologic fracture. Enchondromas account for 12%-14% of benign bone neoplasms. When associated with cutaneous and visceral hemangiomas, the condition is called Maffucci’s syndrome.

Most patients with Maffucci’s syndrome will develop malignant transformation of at least one enchondroma into a chondrosarcoma (malignant cartilage tumor). Enchondromatosis without hemangiomas is known as Ollier’s disease; about 25% of patients with Ollier’s disease will develop chondrosarcoma by age 40. Both Maffucci’s syndrome and Ollier’s disease are nonhereditary. Metachondromatosis, a condition characterized by multiple enchondromas, is an autosomal dominant condition uniquely associated with osteochondromas.

Management: The physician who evaluates a patient with Maffucci’s syndrome must have a high suspicion for pathologic fracture and malignant degeneration. All bone pain and swelling should be evaluated with plain radiographs. Bone expansion, cortical breakthrough, soft-tissue mass, and deep endosteal scalloping of the cortex are indicative of malignant transformation. These findings are unreliable in the smaller bones of the hands, however, and features of low-grade chondrosarcoma are often indistinguishable from benign enchondromas. Even in the absence of worrisome features on plain radiographs, if clinical suspicion is high, a CT scan and/or an MRI should be performed for further evaluation. Biopsy is often indicated on clinical findings, despite imaging characteristics. Hemangiomas can undergo rapid expansion and are often treated with surgery.

Take-home points:

- Enchondromas are the most common primary neoplasm of the bones in the hand and are benign;

- There is an increased risk of malignant transformation of enchondromas in patients with Ollier’s disease or Maffucci’s syndrome; and

- Biopsy of a lesion may be indicated if clinical suspicion for malignancy is high. TH

Helena Summers is a radiology resident and Erik Summers is a hospitalist at the Mayo Clinic College of Medicine in Rochester, Minn.

Bibliography

- Sun TC, Swee RG, Shives TC, et al. Chondrosarcoma in Maffucci’s syndrome. J Bone Joint Surg Am. 1985 Oct;67(8):1214-1219.

- Schwartz HS, Zimmerman NB, Simon MA, et al. The malignant potential of enchondromatosis. J Bone Joint Surg Am. 1987 Feb;69(2):269-274.

- Chew FS, Maldjian C. Enchondroma and enchondromatosis. emedicine. June 10, 2005. Available at: www.emedicine.com/radio/topic247.htm. Last accessed on March 14, 2007.

Patient history: A 53-year-old female admits with a history of multiple orthopedic, dermatologic, and plastic-surgical procedures. The physical exam is notable for multiple cutaneous hemangiomas.

Salient findings: The images show old fracture deformities of the left fibular shaft and proximal tibia as well as a deformity of the distal femur. The patient has had a left total knee arthroplasty. There are multiple lucent lesions involving the left second, fourth, and fifth rays, with bone deformities. Findings are consistent with multiple chondromas. There is no evidence for malignant degeneration.

Patient population and natural history of disease: Enchondromatosis is a condition of multiple benign ectopic rests of cartilage growing within intramedullary bone, forming lucent lesions and bone expansion on radiographs. The enchondromas can deform and shorten a limb and can predispose the patient to a pathologic fracture. Enchondromas account for 12%-14% of benign bone neoplasms. When associated with cutaneous and visceral hemangiomas, the condition is called Maffucci’s syndrome.

Most patients with Maffucci’s syndrome will develop malignant transformation of at least one enchondroma into a chondrosarcoma (malignant cartilage tumor). Enchondromatosis without hemangiomas is known as Ollier’s disease; about 25% of patients with Ollier’s disease will develop chondrosarcoma by age 40. Both Maffucci’s syndrome and Ollier’s disease are nonhereditary. Metachondromatosis, a condition characterized by multiple enchondromas, is an autosomal dominant condition uniquely associated with osteochondromas.

Management: The physician who evaluates a patient with Maffucci’s syndrome must have a high suspicion for pathologic fracture and malignant degeneration. All bone pain and swelling should be evaluated with plain radiographs. Bone expansion, cortical breakthrough, soft-tissue mass, and deep endosteal scalloping of the cortex are indicative of malignant transformation. These findings are unreliable in the smaller bones of the hands, however, and features of low-grade chondrosarcoma are often indistinguishable from benign enchondromas. Even in the absence of worrisome features on plain radiographs, if clinical suspicion is high, a CT scan and/or an MRI should be performed for further evaluation. Biopsy is often indicated on clinical findings, despite imaging characteristics. Hemangiomas can undergo rapid expansion and are often treated with surgery.

Take-home points:

- Enchondromas are the most common primary neoplasm of the bones in the hand and are benign;

- There is an increased risk of malignant transformation of enchondromas in patients with Ollier’s disease or Maffucci’s syndrome; and

- Biopsy of a lesion may be indicated if clinical suspicion for malignancy is high. TH

Helena Summers is a radiology resident and Erik Summers is a hospitalist at the Mayo Clinic College of Medicine in Rochester, Minn.

Bibliography

- Sun TC, Swee RG, Shives TC, et al. Chondrosarcoma in Maffucci’s syndrome. J Bone Joint Surg Am. 1985 Oct;67(8):1214-1219.

- Schwartz HS, Zimmerman NB, Simon MA, et al. The malignant potential of enchondromatosis. J Bone Joint Surg Am. 1987 Feb;69(2):269-274.

- Chew FS, Maldjian C. Enchondroma and enchondromatosis. emedicine. June 10, 2005. Available at: www.emedicine.com/radio/topic247.htm. Last accessed on March 14, 2007.

The Anorectic Heart

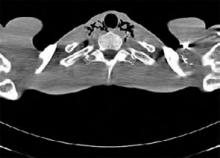

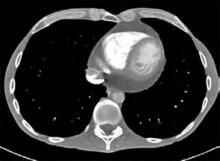

Patient history: A 40-year-old male with a history of anorexia, depression, and recent weight loss presents for a general medical evaluation prompted by his concerned father. A computed tomography (CT) scan of his chest shows a moderate amount of pneumomediastinum (PM) extending superiorly into the tissues of the neck. He also has a moderate-size pericardial effusion. The patient denies symptoms of chest pain, shortness of breath, nausea, vomiting, or recreational drug use. Specifically, the patient admits to a depressed mood, but denies any vomiting, retching, or auto-destructive behavior. He has no history or evidence of underlying pulmonary disease.

Other notable findings consistent with the patient’s eating disorder are a body mass index (BMI) of 15, leukopenia, hyponatremia, bradycardia, and low blood pressure. A subsequent gastrograffin esophagram shows no obvious leaks or abnormalities. The patient is admitted to the hospital, allowed nothing by mouth, and placed on intravenous piperacillin and tazobactam, and nutrition. A transthoracic echocardiogram to evaluate the pericardial effusion on the first hospital day shows early tamponade physiology. Repeat evaluation two days later shows mild right atrial collapse but no evidence of hemodynamic compromise. Inpatient psychiatry consultation is obtained regarding his depression and eating disorder. On the fifth hospital day, a repeat CT scan shows moderate improvement of the PM. The patient is discharged home with outpatient follow-up.

Discussion: PM is defined as free air or gas in the mediastinum and is an uncommon finding. The etiology is usually from the airway, esophagus, or external trauma/surgery. Spontaneous PM occurs in the absence of an apparent identifiable cause and can exist in isolation or in conjunction with pneumothorax and soft-tissue emphysema. Elevated intraalveolar pressures related to mechanical ventilation or activities involving Valsalva maneuvers, along with pre-existing lung disease, account for the majority of pulmonary-related PM.1 Esophageal tear or rupture is another, less common cause of PM. Several case reports of PM in patients with anorexia nervosa exist, and some experts have postulated that one possible mechanism is vomiting or some other auto-destructive behavior.2-4 Loss of pulmonary connective tissue related to prolonged starvation leading to spontaneous pneumothorax and PM has also been postulated using rat models.5

The most common symptoms associated with PM are chest pain, voice change, and cough. In rare cases, PM can lead to decreased cardiac output. Common triggers of spontaneous PM, such as cough, physical exercise, and drug abuse, have been reported. A high percentage of patients with spontaneous PM have underlying pulmonary disease, including asthma and COPD.1 PM in conjunction with Boerhaave’s syndrome may have a mortality rate as high as 50% to 70%. In patients with anorexia nervosa, PM is often seen in conjunction with other advanced findings, including pancytopenia, electrolyte disturbances, bradycardia, and hypotension.

The age and gender of the patient are atypical for anorexia nervosa, although he does indeed have a restrictive eating disorder. The PM and pericardial effusion are additive unique findings that likely relate to his malnourished state and possible auto-destructive behavior.

Management: Spontaneous PM has been managed in a variety of ways, ranging from outpatient radiographic follow-up to close, inpatient monitoring. Identifying the etiology and monitoring for further progression or complications is important. For patients in whom esophageal tear or microperforation is suspected, early surgical consultation is recommended. An acceptable algorithm for patients with suspected esophageal perforation after endoscopy is to begin with a contrast CT scan of the neck and chest with oral contrast or to use a water-soluble contrast (gastrograffin) esophagram followed by a barium swallow if the water-soluble study is negative.6,7 When imaging reveals no leakage, the PM can be followed radiographically—typically after 48 hours and thereafter slowly advancing the diet. TH

Mackram Eleid, MD, works in the Division of Internal Medicine at the Mayo Clinic Arizona (Scottsdale/Phoenix). Joseph Charles, MD, FACP, is an assistant professor of Medicine and division education coordinator in the Mayo Clinic Hospital Arizona, Scottsdale/Phoenix.

References

- Campillo-Soto A, Coll-Salinas A, Soria-Aledo V, et al. [Spontaneous pneumomediastinum: descriptive study of our experience with 36 cases.] [in Spanish] Arch Bronconeumol. 2005;41:528-531.

- Danzer G, Mulzer J, Weber G, et al. Advanced anorexia nervosa, associated with pneumomediastinum, pneumothorax, and soft-tissue emphysema without esophageal lesion. Int J Eat Disord. 2005 Nov;38(3):281-284.

- Brooks AP, Martyn C. Pneumomediastinum in anorexia nervosa. Br Med J. 1979;1:125.

- Chatfield WR, Bowditch JD, Forrest CA. Spontaneous pneumomediastinum complicating anorexia nervosa. Br Med J. 1979 Jan 13;1(6156):200-201.

- Sahebjami H, MacGee J. Changes in connective tissue composition of the lung in starvation and refeeding. Am Rev Respir Dis. 1983;128:644-647.

- Dodds WJ, Stewart ET, Vlymen WJ. Appropriate contrast media for the evaluation of esophageal disruption. Radiology. 1982 Jul;144(2):439-441.

- Ghahremani GG. Radiologic evaluation of suspected gastrointestinal perforations. Radiol Clin North Am. 1993 Nov;31(6):1219-1234.

Patient history: A 40-year-old male with a history of anorexia, depression, and recent weight loss presents for a general medical evaluation prompted by his concerned father. A computed tomography (CT) scan of his chest shows a moderate amount of pneumomediastinum (PM) extending superiorly into the tissues of the neck. He also has a moderate-size pericardial effusion. The patient denies symptoms of chest pain, shortness of breath, nausea, vomiting, or recreational drug use. Specifically, the patient admits to a depressed mood, but denies any vomiting, retching, or auto-destructive behavior. He has no history or evidence of underlying pulmonary disease.

Other notable findings consistent with the patient’s eating disorder are a body mass index (BMI) of 15, leukopenia, hyponatremia, bradycardia, and low blood pressure. A subsequent gastrograffin esophagram shows no obvious leaks or abnormalities. The patient is admitted to the hospital, allowed nothing by mouth, and placed on intravenous piperacillin and tazobactam, and nutrition. A transthoracic echocardiogram to evaluate the pericardial effusion on the first hospital day shows early tamponade physiology. Repeat evaluation two days later shows mild right atrial collapse but no evidence of hemodynamic compromise. Inpatient psychiatry consultation is obtained regarding his depression and eating disorder. On the fifth hospital day, a repeat CT scan shows moderate improvement of the PM. The patient is discharged home with outpatient follow-up.

Discussion: PM is defined as free air or gas in the mediastinum and is an uncommon finding. The etiology is usually from the airway, esophagus, or external trauma/surgery. Spontaneous PM occurs in the absence of an apparent identifiable cause and can exist in isolation or in conjunction with pneumothorax and soft-tissue emphysema. Elevated intraalveolar pressures related to mechanical ventilation or activities involving Valsalva maneuvers, along with pre-existing lung disease, account for the majority of pulmonary-related PM.1 Esophageal tear or rupture is another, less common cause of PM. Several case reports of PM in patients with anorexia nervosa exist, and some experts have postulated that one possible mechanism is vomiting or some other auto-destructive behavior.2-4 Loss of pulmonary connective tissue related to prolonged starvation leading to spontaneous pneumothorax and PM has also been postulated using rat models.5

The most common symptoms associated with PM are chest pain, voice change, and cough. In rare cases, PM can lead to decreased cardiac output. Common triggers of spontaneous PM, such as cough, physical exercise, and drug abuse, have been reported. A high percentage of patients with spontaneous PM have underlying pulmonary disease, including asthma and COPD.1 PM in conjunction with Boerhaave’s syndrome may have a mortality rate as high as 50% to 70%. In patients with anorexia nervosa, PM is often seen in conjunction with other advanced findings, including pancytopenia, electrolyte disturbances, bradycardia, and hypotension.

The age and gender of the patient are atypical for anorexia nervosa, although he does indeed have a restrictive eating disorder. The PM and pericardial effusion are additive unique findings that likely relate to his malnourished state and possible auto-destructive behavior.

Management: Spontaneous PM has been managed in a variety of ways, ranging from outpatient radiographic follow-up to close, inpatient monitoring. Identifying the etiology and monitoring for further progression or complications is important. For patients in whom esophageal tear or microperforation is suspected, early surgical consultation is recommended. An acceptable algorithm for patients with suspected esophageal perforation after endoscopy is to begin with a contrast CT scan of the neck and chest with oral contrast or to use a water-soluble contrast (gastrograffin) esophagram followed by a barium swallow if the water-soluble study is negative.6,7 When imaging reveals no leakage, the PM can be followed radiographically—typically after 48 hours and thereafter slowly advancing the diet. TH

Mackram Eleid, MD, works in the Division of Internal Medicine at the Mayo Clinic Arizona (Scottsdale/Phoenix). Joseph Charles, MD, FACP, is an assistant professor of Medicine and division education coordinator in the Mayo Clinic Hospital Arizona, Scottsdale/Phoenix.

References

- Campillo-Soto A, Coll-Salinas A, Soria-Aledo V, et al. [Spontaneous pneumomediastinum: descriptive study of our experience with 36 cases.] [in Spanish] Arch Bronconeumol. 2005;41:528-531.

- Danzer G, Mulzer J, Weber G, et al. Advanced anorexia nervosa, associated with pneumomediastinum, pneumothorax, and soft-tissue emphysema without esophageal lesion. Int J Eat Disord. 2005 Nov;38(3):281-284.

- Brooks AP, Martyn C. Pneumomediastinum in anorexia nervosa. Br Med J. 1979;1:125.

- Chatfield WR, Bowditch JD, Forrest CA. Spontaneous pneumomediastinum complicating anorexia nervosa. Br Med J. 1979 Jan 13;1(6156):200-201.

- Sahebjami H, MacGee J. Changes in connective tissue composition of the lung in starvation and refeeding. Am Rev Respir Dis. 1983;128:644-647.

- Dodds WJ, Stewart ET, Vlymen WJ. Appropriate contrast media for the evaluation of esophageal disruption. Radiology. 1982 Jul;144(2):439-441.

- Ghahremani GG. Radiologic evaluation of suspected gastrointestinal perforations. Radiol Clin North Am. 1993 Nov;31(6):1219-1234.

Patient history: A 40-year-old male with a history of anorexia, depression, and recent weight loss presents for a general medical evaluation prompted by his concerned father. A computed tomography (CT) scan of his chest shows a moderate amount of pneumomediastinum (PM) extending superiorly into the tissues of the neck. He also has a moderate-size pericardial effusion. The patient denies symptoms of chest pain, shortness of breath, nausea, vomiting, or recreational drug use. Specifically, the patient admits to a depressed mood, but denies any vomiting, retching, or auto-destructive behavior. He has no history or evidence of underlying pulmonary disease.

Other notable findings consistent with the patient’s eating disorder are a body mass index (BMI) of 15, leukopenia, hyponatremia, bradycardia, and low blood pressure. A subsequent gastrograffin esophagram shows no obvious leaks or abnormalities. The patient is admitted to the hospital, allowed nothing by mouth, and placed on intravenous piperacillin and tazobactam, and nutrition. A transthoracic echocardiogram to evaluate the pericardial effusion on the first hospital day shows early tamponade physiology. Repeat evaluation two days later shows mild right atrial collapse but no evidence of hemodynamic compromise. Inpatient psychiatry consultation is obtained regarding his depression and eating disorder. On the fifth hospital day, a repeat CT scan shows moderate improvement of the PM. The patient is discharged home with outpatient follow-up.

Discussion: PM is defined as free air or gas in the mediastinum and is an uncommon finding. The etiology is usually from the airway, esophagus, or external trauma/surgery. Spontaneous PM occurs in the absence of an apparent identifiable cause and can exist in isolation or in conjunction with pneumothorax and soft-tissue emphysema. Elevated intraalveolar pressures related to mechanical ventilation or activities involving Valsalva maneuvers, along with pre-existing lung disease, account for the majority of pulmonary-related PM.1 Esophageal tear or rupture is another, less common cause of PM. Several case reports of PM in patients with anorexia nervosa exist, and some experts have postulated that one possible mechanism is vomiting or some other auto-destructive behavior.2-4 Loss of pulmonary connective tissue related to prolonged starvation leading to spontaneous pneumothorax and PM has also been postulated using rat models.5

The most common symptoms associated with PM are chest pain, voice change, and cough. In rare cases, PM can lead to decreased cardiac output. Common triggers of spontaneous PM, such as cough, physical exercise, and drug abuse, have been reported. A high percentage of patients with spontaneous PM have underlying pulmonary disease, including asthma and COPD.1 PM in conjunction with Boerhaave’s syndrome may have a mortality rate as high as 50% to 70%. In patients with anorexia nervosa, PM is often seen in conjunction with other advanced findings, including pancytopenia, electrolyte disturbances, bradycardia, and hypotension.

The age and gender of the patient are atypical for anorexia nervosa, although he does indeed have a restrictive eating disorder. The PM and pericardial effusion are additive unique findings that likely relate to his malnourished state and possible auto-destructive behavior.

Management: Spontaneous PM has been managed in a variety of ways, ranging from outpatient radiographic follow-up to close, inpatient monitoring. Identifying the etiology and monitoring for further progression or complications is important. For patients in whom esophageal tear or microperforation is suspected, early surgical consultation is recommended. An acceptable algorithm for patients with suspected esophageal perforation after endoscopy is to begin with a contrast CT scan of the neck and chest with oral contrast or to use a water-soluble contrast (gastrograffin) esophagram followed by a barium swallow if the water-soluble study is negative.6,7 When imaging reveals no leakage, the PM can be followed radiographically—typically after 48 hours and thereafter slowly advancing the diet. TH

Mackram Eleid, MD, works in the Division of Internal Medicine at the Mayo Clinic Arizona (Scottsdale/Phoenix). Joseph Charles, MD, FACP, is an assistant professor of Medicine and division education coordinator in the Mayo Clinic Hospital Arizona, Scottsdale/Phoenix.

References

- Campillo-Soto A, Coll-Salinas A, Soria-Aledo V, et al. [Spontaneous pneumomediastinum: descriptive study of our experience with 36 cases.] [in Spanish] Arch Bronconeumol. 2005;41:528-531.

- Danzer G, Mulzer J, Weber G, et al. Advanced anorexia nervosa, associated with pneumomediastinum, pneumothorax, and soft-tissue emphysema without esophageal lesion. Int J Eat Disord. 2005 Nov;38(3):281-284.

- Brooks AP, Martyn C. Pneumomediastinum in anorexia nervosa. Br Med J. 1979;1:125.

- Chatfield WR, Bowditch JD, Forrest CA. Spontaneous pneumomediastinum complicating anorexia nervosa. Br Med J. 1979 Jan 13;1(6156):200-201.

- Sahebjami H, MacGee J. Changes in connective tissue composition of the lung in starvation and refeeding. Am Rev Respir Dis. 1983;128:644-647.

- Dodds WJ, Stewart ET, Vlymen WJ. Appropriate contrast media for the evaluation of esophageal disruption. Radiology. 1982 Jul;144(2):439-441.

- Ghahremani GG. Radiologic evaluation of suspected gastrointestinal perforations. Radiol Clin North Am. 1993 Nov;31(6):1219-1234.

Get Control

This is the first in a series of articles on the four pillars of career satisfaction in hospital medicine.

How do you feel about the hours, compensation, responsibilities, and stresses of your present position? Do you think your job is sustainable—that is, would you be happy to continue your current work for years to come?

Many of today’s hospitalists might not answer the last question with a resounding “yes” because of one or more common factors that lead to chronic dissatisfaction with their careers.

In 2005, SHM formed the Career Satisfaction Task Force (CSTF) to combat this dissatisfaction, charging it with a three-pronged mission: to identify working conditions in hospital medicine that promote success and wellness; to provide resources to enhance career satisfaction; and to promote research into hospitalist career satisfaction and burnout.

“Originally, we were concerned with burnout in hospital medicine,” says CSTF co-chair Sylvia C. W. McKean, MD, FACP, medical director at Brigham and Women's Hospital/Faulkner Hospitalist Service and associate professor of medicine, Harvard Medical School, Boston. “The task force was charged to examine the factors that lead to a long, satisfactory career in hospital medicine.”

New White Paper Available

After reviewing the literature on physician burnout and general career satisfaction, the CSTF created a comprehensive document, “A Challenge for a New Specialty: A White Paper on Hospitalist Career Satisfaction” (available at www.hospitalmedicine.org), which can be used by hospitalists and hospital medicine practices as a toolkit for improving or ensuring job satisfaction.

The white paper outlines the four pillars of career satisfaction: autonomy/control, workload/schedule, reward/recognition, and community/environment. It includes a Job Fit self-evaluation questionnaire and other tools and advice that can be used to gather information and take steps to improve problems identified by the survey.

While the information in the white paper can best be used to improve an entire hospital medicine program, individual hospitalists can also benefit from it. The paper clearly states that an individual hospitalist has the power to influence change within his or her job, perhaps by majority rule. They can find a niche of expertise within their practice; pursue continuing medical education opportunities to promote their areas of expertise; nurture networks with peers; and find a mentor and regularly seek advice.

The First Pillar: Autonomy/Control

Control, or autonomy, refers to the need to be able to affect the key factors that influence job performance. For example, do you have control over when, how, and how quickly you perform a specific task? Do you have some say in task assignment and policies? What about the availability of support staff, supplies, and materials?

“Doctors expect to have control in their jobs, control over the tasks they do, how and when they do those tasks,” says CSTF member Tosha Wetterneck, MD, University of Wisconsin Hospital/Clinics in Madison. “This control helps them cope with stress; take that control away, and they can’t cope as well.”

Autonomy is a problem in hospital medicine because the field is still new and not widely understood. Consequently, hospitalists may end up responsible for additional duties and hours—especially on weekends—that other physicians dump on them.

“In some hospitals, the only doctors who can’t cap [their workloads] are the hospitalists,” reports Dr. McKean.

The best way to ensure you’re comfortable with the autonomy offered by your position is to be aware of what you want—and what you get—when you take your job.

“An individual hospitalist always has a choice of taking a job with the clear understanding of what they’ll have control over,” says Dr. Wetterneck. “However, you have to understand what you as a person need to have control over. You don’t want to get yourself into a position where you don’t have control over the specific areas that matter the most to you.”

An Example of Autonomy

To help clarify how lack of autonomy can make career satisfaction plummet, here is a fictional example of a hospitalist who suddenly lost control in her job:

“I love working in hospital medicine and take my job very seriously. However, two months ago my hospital medicine group assumed responsibility for care of neurosurgical patients, and all hospitalists are now required to provide care to these patients. I find this upsetting—I feel like this is one more step in relegating my colleagues and I to the status of ‘super-residents’ who are responsible for everything that other physicians don’t want to do. I want to have control over which type of patients I see.”

According to the CSTF research, this individual should take the following steps:

Step 1: Assess the situation in the manner outlined in the white paper. The hospitalist should:

- Use the Job Fit questionnaire to profile the control elements of the hospitalist practice;

- Become familiar with the hospital’s leadership and committee structure;

- Understand key payer issues that might affect inpatient care; and

- Review her job description.

After reviewing the role personal autonomy plays within her practice, the hospitalist must consider whether she’s in a position to request a change of duties, or whether her new responsibilities are non-negotiable.

“There are different facets of control,” says Dr. Wetterneck. “Some could make the argument that a hospitalist doesn’t have the skills to take care of neurosurgical patients, that this is out of the realm of reasonable expectations for the job. Others might say that there is reasonable expectation, as long as the hospitalists would get extra learning and extra support from other [subspecialists] that they’d be available for consult.”

Regardless of where you stand on the argument of reasonable expectation of a hospitalist’s responsibilities, what if a new job task simply rubs you the wrong way—to the point where you no longer enjoy your work?

“If it’s truly an issue of ‘I don’t want to do this,’ then it becomes an issue of your fit with your group,” Dr. Wetterneck continues. “If everyone in the group is doing it and you don’t want to, then you need to understand how important this control is for you. Is it important enough to change jobs?”

Step 2: If the answer to that last question is “Yes,” this hospitalist should keep autonomy in mind as she begins a job search. The white paper includes questions to ask herself and her potential employers to ensure she has control in her next position. The diversity of hospitalist responsibilities works in her favor—assuming she’s willing to move to another part of the country.

“You can list all the things that make you happy in a job, and you can probably find every single thing on your list in a hospitalist job somewhere in the U.S.,” speculates Dr. Wetterneck.

Next Month

A discussion of the workload/schedule pillar, which refers to the type, volume, and intensity of a hospitalist's work.

The Only Constant

Working in hospital medicine practically guarantees your job will continually change. Whether it’s a change in responsibilities like the example above, the steady growth of your practice, or even a change in leadership or ownership, hospitalists must go with the flow.

“I definitely think that the job requires a certain amount of flexibility,” says Dr. Wetterneck. “Hospitalists have to understand that their job role will continue to change over time. Therefore, people have to really understand what’s important to them.”

The cost of lack of autonomy—or other job stressors—can be severe.

“If a change [in your job] throws you out of control, this can lead to stress,” Dr. Wetterneck points out. “We know from recent studies that stress has an impact on your health, specifically on cardiovascular disease and mortality.” TH

Jane Jerrard has written for The Hospitalist since 2005.

This is the first in a series of articles on the four pillars of career satisfaction in hospital medicine.

How do you feel about the hours, compensation, responsibilities, and stresses of your present position? Do you think your job is sustainable—that is, would you be happy to continue your current work for years to come?

Many of today’s hospitalists might not answer the last question with a resounding “yes” because of one or more common factors that lead to chronic dissatisfaction with their careers.

In 2005, SHM formed the Career Satisfaction Task Force (CSTF) to combat this dissatisfaction, charging it with a three-pronged mission: to identify working conditions in hospital medicine that promote success and wellness; to provide resources to enhance career satisfaction; and to promote research into hospitalist career satisfaction and burnout.

“Originally, we were concerned with burnout in hospital medicine,” says CSTF co-chair Sylvia C. W. McKean, MD, FACP, medical director at Brigham and Women's Hospital/Faulkner Hospitalist Service and associate professor of medicine, Harvard Medical School, Boston. “The task force was charged to examine the factors that lead to a long, satisfactory career in hospital medicine.”

New White Paper Available

After reviewing the literature on physician burnout and general career satisfaction, the CSTF created a comprehensive document, “A Challenge for a New Specialty: A White Paper on Hospitalist Career Satisfaction” (available at www.hospitalmedicine.org), which can be used by hospitalists and hospital medicine practices as a toolkit for improving or ensuring job satisfaction.

The white paper outlines the four pillars of career satisfaction: autonomy/control, workload/schedule, reward/recognition, and community/environment. It includes a Job Fit self-evaluation questionnaire and other tools and advice that can be used to gather information and take steps to improve problems identified by the survey.

While the information in the white paper can best be used to improve an entire hospital medicine program, individual hospitalists can also benefit from it. The paper clearly states that an individual hospitalist has the power to influence change within his or her job, perhaps by majority rule. They can find a niche of expertise within their practice; pursue continuing medical education opportunities to promote their areas of expertise; nurture networks with peers; and find a mentor and regularly seek advice.

The First Pillar: Autonomy/Control

Control, or autonomy, refers to the need to be able to affect the key factors that influence job performance. For example, do you have control over when, how, and how quickly you perform a specific task? Do you have some say in task assignment and policies? What about the availability of support staff, supplies, and materials?

“Doctors expect to have control in their jobs, control over the tasks they do, how and when they do those tasks,” says CSTF member Tosha Wetterneck, MD, University of Wisconsin Hospital/Clinics in Madison. “This control helps them cope with stress; take that control away, and they can’t cope as well.”

Autonomy is a problem in hospital medicine because the field is still new and not widely understood. Consequently, hospitalists may end up responsible for additional duties and hours—especially on weekends—that other physicians dump on them.

“In some hospitals, the only doctors who can’t cap [their workloads] are the hospitalists,” reports Dr. McKean.

The best way to ensure you’re comfortable with the autonomy offered by your position is to be aware of what you want—and what you get—when you take your job.

“An individual hospitalist always has a choice of taking a job with the clear understanding of what they’ll have control over,” says Dr. Wetterneck. “However, you have to understand what you as a person need to have control over. You don’t want to get yourself into a position where you don’t have control over the specific areas that matter the most to you.”

An Example of Autonomy

To help clarify how lack of autonomy can make career satisfaction plummet, here is a fictional example of a hospitalist who suddenly lost control in her job:

“I love working in hospital medicine and take my job very seriously. However, two months ago my hospital medicine group assumed responsibility for care of neurosurgical patients, and all hospitalists are now required to provide care to these patients. I find this upsetting—I feel like this is one more step in relegating my colleagues and I to the status of ‘super-residents’ who are responsible for everything that other physicians don’t want to do. I want to have control over which type of patients I see.”

According to the CSTF research, this individual should take the following steps:

Step 1: Assess the situation in the manner outlined in the white paper. The hospitalist should:

- Use the Job Fit questionnaire to profile the control elements of the hospitalist practice;

- Become familiar with the hospital’s leadership and committee structure;

- Understand key payer issues that might affect inpatient care; and

- Review her job description.

After reviewing the role personal autonomy plays within her practice, the hospitalist must consider whether she’s in a position to request a change of duties, or whether her new responsibilities are non-negotiable.

“There are different facets of control,” says Dr. Wetterneck. “Some could make the argument that a hospitalist doesn’t have the skills to take care of neurosurgical patients, that this is out of the realm of reasonable expectations for the job. Others might say that there is reasonable expectation, as long as the hospitalists would get extra learning and extra support from other [subspecialists] that they’d be available for consult.”

Regardless of where you stand on the argument of reasonable expectation of a hospitalist’s responsibilities, what if a new job task simply rubs you the wrong way—to the point where you no longer enjoy your work?

“If it’s truly an issue of ‘I don’t want to do this,’ then it becomes an issue of your fit with your group,” Dr. Wetterneck continues. “If everyone in the group is doing it and you don’t want to, then you need to understand how important this control is for you. Is it important enough to change jobs?”

Step 2: If the answer to that last question is “Yes,” this hospitalist should keep autonomy in mind as she begins a job search. The white paper includes questions to ask herself and her potential employers to ensure she has control in her next position. The diversity of hospitalist responsibilities works in her favor—assuming she’s willing to move to another part of the country.

“You can list all the things that make you happy in a job, and you can probably find every single thing on your list in a hospitalist job somewhere in the U.S.,” speculates Dr. Wetterneck.

Next Month

A discussion of the workload/schedule pillar, which refers to the type, volume, and intensity of a hospitalist's work.

The Only Constant

Working in hospital medicine practically guarantees your job will continually change. Whether it’s a change in responsibilities like the example above, the steady growth of your practice, or even a change in leadership or ownership, hospitalists must go with the flow.

“I definitely think that the job requires a certain amount of flexibility,” says Dr. Wetterneck. “Hospitalists have to understand that their job role will continue to change over time. Therefore, people have to really understand what’s important to them.”

The cost of lack of autonomy—or other job stressors—can be severe.

“If a change [in your job] throws you out of control, this can lead to stress,” Dr. Wetterneck points out. “We know from recent studies that stress has an impact on your health, specifically on cardiovascular disease and mortality.” TH

Jane Jerrard has written for The Hospitalist since 2005.

This is the first in a series of articles on the four pillars of career satisfaction in hospital medicine.

How do you feel about the hours, compensation, responsibilities, and stresses of your present position? Do you think your job is sustainable—that is, would you be happy to continue your current work for years to come?

Many of today’s hospitalists might not answer the last question with a resounding “yes” because of one or more common factors that lead to chronic dissatisfaction with their careers.

In 2005, SHM formed the Career Satisfaction Task Force (CSTF) to combat this dissatisfaction, charging it with a three-pronged mission: to identify working conditions in hospital medicine that promote success and wellness; to provide resources to enhance career satisfaction; and to promote research into hospitalist career satisfaction and burnout.

“Originally, we were concerned with burnout in hospital medicine,” says CSTF co-chair Sylvia C. W. McKean, MD, FACP, medical director at Brigham and Women's Hospital/Faulkner Hospitalist Service and associate professor of medicine, Harvard Medical School, Boston. “The task force was charged to examine the factors that lead to a long, satisfactory career in hospital medicine.”

New White Paper Available

After reviewing the literature on physician burnout and general career satisfaction, the CSTF created a comprehensive document, “A Challenge for a New Specialty: A White Paper on Hospitalist Career Satisfaction” (available at www.hospitalmedicine.org), which can be used by hospitalists and hospital medicine practices as a toolkit for improving or ensuring job satisfaction.

The white paper outlines the four pillars of career satisfaction: autonomy/control, workload/schedule, reward/recognition, and community/environment. It includes a Job Fit self-evaluation questionnaire and other tools and advice that can be used to gather information and take steps to improve problems identified by the survey.

While the information in the white paper can best be used to improve an entire hospital medicine program, individual hospitalists can also benefit from it. The paper clearly states that an individual hospitalist has the power to influence change within his or her job, perhaps by majority rule. They can find a niche of expertise within their practice; pursue continuing medical education opportunities to promote their areas of expertise; nurture networks with peers; and find a mentor and regularly seek advice.

The First Pillar: Autonomy/Control

Control, or autonomy, refers to the need to be able to affect the key factors that influence job performance. For example, do you have control over when, how, and how quickly you perform a specific task? Do you have some say in task assignment and policies? What about the availability of support staff, supplies, and materials?

“Doctors expect to have control in their jobs, control over the tasks they do, how and when they do those tasks,” says CSTF member Tosha Wetterneck, MD, University of Wisconsin Hospital/Clinics in Madison. “This control helps them cope with stress; take that control away, and they can’t cope as well.”

Autonomy is a problem in hospital medicine because the field is still new and not widely understood. Consequently, hospitalists may end up responsible for additional duties and hours—especially on weekends—that other physicians dump on them.

“In some hospitals, the only doctors who can’t cap [their workloads] are the hospitalists,” reports Dr. McKean.

The best way to ensure you’re comfortable with the autonomy offered by your position is to be aware of what you want—and what you get—when you take your job.

“An individual hospitalist always has a choice of taking a job with the clear understanding of what they’ll have control over,” says Dr. Wetterneck. “However, you have to understand what you as a person need to have control over. You don’t want to get yourself into a position where you don’t have control over the specific areas that matter the most to you.”

An Example of Autonomy

To help clarify how lack of autonomy can make career satisfaction plummet, here is a fictional example of a hospitalist who suddenly lost control in her job:

“I love working in hospital medicine and take my job very seriously. However, two months ago my hospital medicine group assumed responsibility for care of neurosurgical patients, and all hospitalists are now required to provide care to these patients. I find this upsetting—I feel like this is one more step in relegating my colleagues and I to the status of ‘super-residents’ who are responsible for everything that other physicians don’t want to do. I want to have control over which type of patients I see.”

According to the CSTF research, this individual should take the following steps:

Step 1: Assess the situation in the manner outlined in the white paper. The hospitalist should:

- Use the Job Fit questionnaire to profile the control elements of the hospitalist practice;

- Become familiar with the hospital’s leadership and committee structure;

- Understand key payer issues that might affect inpatient care; and

- Review her job description.

After reviewing the role personal autonomy plays within her practice, the hospitalist must consider whether she’s in a position to request a change of duties, or whether her new responsibilities are non-negotiable.

“There are different facets of control,” says Dr. Wetterneck. “Some could make the argument that a hospitalist doesn’t have the skills to take care of neurosurgical patients, that this is out of the realm of reasonable expectations for the job. Others might say that there is reasonable expectation, as long as the hospitalists would get extra learning and extra support from other [subspecialists] that they’d be available for consult.”

Regardless of where you stand on the argument of reasonable expectation of a hospitalist’s responsibilities, what if a new job task simply rubs you the wrong way—to the point where you no longer enjoy your work?

“If it’s truly an issue of ‘I don’t want to do this,’ then it becomes an issue of your fit with your group,” Dr. Wetterneck continues. “If everyone in the group is doing it and you don’t want to, then you need to understand how important this control is for you. Is it important enough to change jobs?”

Step 2: If the answer to that last question is “Yes,” this hospitalist should keep autonomy in mind as she begins a job search. The white paper includes questions to ask herself and her potential employers to ensure she has control in her next position. The diversity of hospitalist responsibilities works in her favor—assuming she’s willing to move to another part of the country.

“You can list all the things that make you happy in a job, and you can probably find every single thing on your list in a hospitalist job somewhere in the U.S.,” speculates Dr. Wetterneck.

Next Month

A discussion of the workload/schedule pillar, which refers to the type, volume, and intensity of a hospitalist's work.

The Only Constant

Working in hospital medicine practically guarantees your job will continually change. Whether it’s a change in responsibilities like the example above, the steady growth of your practice, or even a change in leadership or ownership, hospitalists must go with the flow.

“I definitely think that the job requires a certain amount of flexibility,” says Dr. Wetterneck. “Hospitalists have to understand that their job role will continue to change over time. Therefore, people have to really understand what’s important to them.”

The cost of lack of autonomy—or other job stressors—can be severe.

“If a change [in your job] throws you out of control, this can lead to stress,” Dr. Wetterneck points out. “We know from recent studies that stress has an impact on your health, specifically on cardiovascular disease and mortality.” TH

Jane Jerrard has written for The Hospitalist since 2005.

Capitol Gains

Nine members of SHM’s Public Policy Committee (PPC), accompanied by several SHM staff members, paid a visit to Capitol Hill early this year.

The group spent Feb. 28 calling on senators, representatives, and congressional staff, as they participated in meetings similar to those included in SHM’s Legislative Advocacy Day, held during the 2006 Annual Meeting. In fact, many of the PPC members had second meetings with legislative staff they had met last May.

“We had already broken some ground with Legislative Day, so some people were familiar with us,” says Ron Angus, MD, Department of Medicine, Presbyterian Hospital of Dallas. “We had a little more time to talk about the issues.”

During their meetings, “We emphasized the different roles that SHM can play, and we tried to get a feel for what it means to have a Democrat-led Congress,” says Jack Percelay, MD, MPH, FAAP, Virtua Health, Ridgewood, N.J.

SHM’s senior adviser for advocacy and government affairs, Laura Allendorf, pronounces it “a very productive day.”

Building on a Foundation

The PPC visits were successful partly because this was the second time SHM had visited representatives, allowing the hospitalists to build on their introductory meetings and spend more time discussing issues and offering help. The committee hopes to continue this trend.

“In the long term, we want to see if we can meet with the same people more frequently,” explains Dr. Angus. Allendorf agrees, saying, “The more often we’re up there, the better.”

There may be many more visits or communications. “I think we’re building something long-term, and it’s going to take a while to do that,” says Dr. Angus. “As we get more comfortable talking to these folks, we’ll work on getting them to contact us when issues first come up. Our goal is to be there at the beginning of the process, rather than the end, when it’s too late to have much impact.”

Another reason the February visits were deemed a success involves whom the PPC met with.

“These meetings were more productive because we were meeting with key staff, people on key committees,” recounts Allendorf. “And [participants] had more visits during the day—each had between five and eight. We made a point to meet with committee staff, staff for key committees, including the House Ways and Means Health Subcommittee, the Senate Finance Committee, the Senate Committee on Appropriations, and the Senate Committee on Health, Education, Labor, and Pensions. We met with committee aides hired to handle special issues like Medicare Part B.”

Targeting these influential offices—particularly the powerful Ways and Means Committee—should have greater impact on healthcare legislation and funding.

Making Inroads with Ways and Means

The entire group ended the day in a meeting with Rep. Shelley Berkley, D-Nev., and her health legislative aide Jeff Davis. Berkley serves on the House Ways and Means Committee and is perceived as “physician-friendly.” Her husband is a nephrologist, and Allendorf describes the lawmaker as “very knowledgeable about the issues” in healthcare. “She’s now in a position to do something; she’ll be a major player,” predicts Allendorf.

“We met with Berkley for five or 10 minutes, then had a roundtable with Jeff Davis from her office,” says Dr. Angus. “We talked about increased funding for AHRQ [Agency for Healthcare Research and Quality] and coordinating quality initiatives being brought to bear in hospitals. We tried to emphasize that when you talk about quality in hospitals, you’re talking about hospitalists.”

With her majority role on a key committee, Berkley is one example of the newly empowered Democrats in office—Democrats who may make a difference in pushing through SHM-sponsored legislation.

Democratic Differences?

Did the PPC members notice a difference since May, with the change of majority party in Congress?

“I could feel it,” says Dr. Angus. “There’s been a huge sea change. Those who felt unempowered last year now feel that there’s a clean slate.”

Dr. Percelay saw a difference in priorities among healthcare issues. “In general, the access issue is much more prominent,” he says. “There’s a sense that we need to do something about healthcare expenses and access for everyone. There’s a recognition of big-picture issues—by both Democrats and Republicans—that we aren’t providing coverage for everyone, and we’re spending too much on it.”

Future Advocacy

The PPC counts its Capitol Hill visit a success. Members want to broaden the influence of SHM and hospitalists by enlisting the help of others.

“We want to identify members who are interested in public policy who live in key areas—areas served by legislators on key committees,” explains Dr. Percelay, “so that they can lobby from a local perspective.” Dr. Angus adds, “Ideally, they’ll interact with their national officials when they’re in their local offices. Also, we’d like members to keep an eye on state and local issues.”

Allendorf points out that these members can be identified and reached though SHM’s online Legislative Action Center at capwiz.com/hospitalmedicine/home. If you receive an e-mail asking you to contact one of your representatives regarding a specific issue, you can take part in the advocacy efforts.

In other plans, says Dr. Angus, “We hope to construct some body of resources that hospitalists who go to D.C. on their own can use to go up to the Hill with information in hand and talk to their Congress people.”

PPC members understand they have their work cut out for them when it comes to increasing awareness of SHM and hospitalists on Capitol Hill.

“This is a long-term investment process,” Dr. Percelay says. “We’re learning as an organization how to conduct our public policy efforts. We’re at the beginning stages of meeting with these people and letting them know what hospitalists can do.” TH

Jane Jerrard writes “Public Policy” for The Hospitalist.

Nine members of SHM’s Public Policy Committee (PPC), accompanied by several SHM staff members, paid a visit to Capitol Hill early this year.

The group spent Feb. 28 calling on senators, representatives, and congressional staff, as they participated in meetings similar to those included in SHM’s Legislative Advocacy Day, held during the 2006 Annual Meeting. In fact, many of the PPC members had second meetings with legislative staff they had met last May.

“We had already broken some ground with Legislative Day, so some people were familiar with us,” says Ron Angus, MD, Department of Medicine, Presbyterian Hospital of Dallas. “We had a little more time to talk about the issues.”

During their meetings, “We emphasized the different roles that SHM can play, and we tried to get a feel for what it means to have a Democrat-led Congress,” says Jack Percelay, MD, MPH, FAAP, Virtua Health, Ridgewood, N.J.

SHM’s senior adviser for advocacy and government affairs, Laura Allendorf, pronounces it “a very productive day.”

Building on a Foundation

The PPC visits were successful partly because this was the second time SHM had visited representatives, allowing the hospitalists to build on their introductory meetings and spend more time discussing issues and offering help. The committee hopes to continue this trend.

“In the long term, we want to see if we can meet with the same people more frequently,” explains Dr. Angus. Allendorf agrees, saying, “The more often we’re up there, the better.”

There may be many more visits or communications. “I think we’re building something long-term, and it’s going to take a while to do that,” says Dr. Angus. “As we get more comfortable talking to these folks, we’ll work on getting them to contact us when issues first come up. Our goal is to be there at the beginning of the process, rather than the end, when it’s too late to have much impact.”

Another reason the February visits were deemed a success involves whom the PPC met with.

“These meetings were more productive because we were meeting with key staff, people on key committees,” recounts Allendorf. “And [participants] had more visits during the day—each had between five and eight. We made a point to meet with committee staff, staff for key committees, including the House Ways and Means Health Subcommittee, the Senate Finance Committee, the Senate Committee on Appropriations, and the Senate Committee on Health, Education, Labor, and Pensions. We met with committee aides hired to handle special issues like Medicare Part B.”

Targeting these influential offices—particularly the powerful Ways and Means Committee—should have greater impact on healthcare legislation and funding.

Making Inroads with Ways and Means

The entire group ended the day in a meeting with Rep. Shelley Berkley, D-Nev., and her health legislative aide Jeff Davis. Berkley serves on the House Ways and Means Committee and is perceived as “physician-friendly.” Her husband is a nephrologist, and Allendorf describes the lawmaker as “very knowledgeable about the issues” in healthcare. “She’s now in a position to do something; she’ll be a major player,” predicts Allendorf.

“We met with Berkley for five or 10 minutes, then had a roundtable with Jeff Davis from her office,” says Dr. Angus. “We talked about increased funding for AHRQ [Agency for Healthcare Research and Quality] and coordinating quality initiatives being brought to bear in hospitals. We tried to emphasize that when you talk about quality in hospitals, you’re talking about hospitalists.”

With her majority role on a key committee, Berkley is one example of the newly empowered Democrats in office—Democrats who may make a difference in pushing through SHM-sponsored legislation.

Democratic Differences?

Did the PPC members notice a difference since May, with the change of majority party in Congress?

“I could feel it,” says Dr. Angus. “There’s been a huge sea change. Those who felt unempowered last year now feel that there’s a clean slate.”

Dr. Percelay saw a difference in priorities among healthcare issues. “In general, the access issue is much more prominent,” he says. “There’s a sense that we need to do something about healthcare expenses and access for everyone. There’s a recognition of big-picture issues—by both Democrats and Republicans—that we aren’t providing coverage for everyone, and we’re spending too much on it.”

Future Advocacy

The PPC counts its Capitol Hill visit a success. Members want to broaden the influence of SHM and hospitalists by enlisting the help of others.

“We want to identify members who are interested in public policy who live in key areas—areas served by legislators on key committees,” explains Dr. Percelay, “so that they can lobby from a local perspective.” Dr. Angus adds, “Ideally, they’ll interact with their national officials when they’re in their local offices. Also, we’d like members to keep an eye on state and local issues.”

Allendorf points out that these members can be identified and reached though SHM’s online Legislative Action Center at capwiz.com/hospitalmedicine/home. If you receive an e-mail asking you to contact one of your representatives regarding a specific issue, you can take part in the advocacy efforts.

In other plans, says Dr. Angus, “We hope to construct some body of resources that hospitalists who go to D.C. on their own can use to go up to the Hill with information in hand and talk to their Congress people.”

PPC members understand they have their work cut out for them when it comes to increasing awareness of SHM and hospitalists on Capitol Hill.

“This is a long-term investment process,” Dr. Percelay says. “We’re learning as an organization how to conduct our public policy efforts. We’re at the beginning stages of meeting with these people and letting them know what hospitalists can do.” TH

Jane Jerrard writes “Public Policy” for The Hospitalist.

Nine members of SHM’s Public Policy Committee (PPC), accompanied by several SHM staff members, paid a visit to Capitol Hill early this year.

The group spent Feb. 28 calling on senators, representatives, and congressional staff, as they participated in meetings similar to those included in SHM’s Legislative Advocacy Day, held during the 2006 Annual Meeting. In fact, many of the PPC members had second meetings with legislative staff they had met last May.

“We had already broken some ground with Legislative Day, so some people were familiar with us,” says Ron Angus, MD, Department of Medicine, Presbyterian Hospital of Dallas. “We had a little more time to talk about the issues.”

During their meetings, “We emphasized the different roles that SHM can play, and we tried to get a feel for what it means to have a Democrat-led Congress,” says Jack Percelay, MD, MPH, FAAP, Virtua Health, Ridgewood, N.J.

SHM’s senior adviser for advocacy and government affairs, Laura Allendorf, pronounces it “a very productive day.”

Building on a Foundation

The PPC visits were successful partly because this was the second time SHM had visited representatives, allowing the hospitalists to build on their introductory meetings and spend more time discussing issues and offering help. The committee hopes to continue this trend.

“In the long term, we want to see if we can meet with the same people more frequently,” explains Dr. Angus. Allendorf agrees, saying, “The more often we’re up there, the better.”

There may be many more visits or communications. “I think we’re building something long-term, and it’s going to take a while to do that,” says Dr. Angus. “As we get more comfortable talking to these folks, we’ll work on getting them to contact us when issues first come up. Our goal is to be there at the beginning of the process, rather than the end, when it’s too late to have much impact.”

Another reason the February visits were deemed a success involves whom the PPC met with.

“These meetings were more productive because we were meeting with key staff, people on key committees,” recounts Allendorf. “And [participants] had more visits during the day—each had between five and eight. We made a point to meet with committee staff, staff for key committees, including the House Ways and Means Health Subcommittee, the Senate Finance Committee, the Senate Committee on Appropriations, and the Senate Committee on Health, Education, Labor, and Pensions. We met with committee aides hired to handle special issues like Medicare Part B.”

Targeting these influential offices—particularly the powerful Ways and Means Committee—should have greater impact on healthcare legislation and funding.

Making Inroads with Ways and Means

The entire group ended the day in a meeting with Rep. Shelley Berkley, D-Nev., and her health legislative aide Jeff Davis. Berkley serves on the House Ways and Means Committee and is perceived as “physician-friendly.” Her husband is a nephrologist, and Allendorf describes the lawmaker as “very knowledgeable about the issues” in healthcare. “She’s now in a position to do something; she’ll be a major player,” predicts Allendorf.

“We met with Berkley for five or 10 minutes, then had a roundtable with Jeff Davis from her office,” says Dr. Angus. “We talked about increased funding for AHRQ [Agency for Healthcare Research and Quality] and coordinating quality initiatives being brought to bear in hospitals. We tried to emphasize that when you talk about quality in hospitals, you’re talking about hospitalists.”

With her majority role on a key committee, Berkley is one example of the newly empowered Democrats in office—Democrats who may make a difference in pushing through SHM-sponsored legislation.

Democratic Differences?

Did the PPC members notice a difference since May, with the change of majority party in Congress?

“I could feel it,” says Dr. Angus. “There’s been a huge sea change. Those who felt unempowered last year now feel that there’s a clean slate.”

Dr. Percelay saw a difference in priorities among healthcare issues. “In general, the access issue is much more prominent,” he says. “There’s a sense that we need to do something about healthcare expenses and access for everyone. There’s a recognition of big-picture issues—by both Democrats and Republicans—that we aren’t providing coverage for everyone, and we’re spending too much on it.”

Future Advocacy

The PPC counts its Capitol Hill visit a success. Members want to broaden the influence of SHM and hospitalists by enlisting the help of others.

“We want to identify members who are interested in public policy who live in key areas—areas served by legislators on key committees,” explains Dr. Percelay, “so that they can lobby from a local perspective.” Dr. Angus adds, “Ideally, they’ll interact with their national officials when they’re in their local offices. Also, we’d like members to keep an eye on state and local issues.”

Allendorf points out that these members can be identified and reached though SHM’s online Legislative Action Center at capwiz.com/hospitalmedicine/home. If you receive an e-mail asking you to contact one of your representatives regarding a specific issue, you can take part in the advocacy efforts.

In other plans, says Dr. Angus, “We hope to construct some body of resources that hospitalists who go to D.C. on their own can use to go up to the Hill with information in hand and talk to their Congress people.”

PPC members understand they have their work cut out for them when it comes to increasing awareness of SHM and hospitalists on Capitol Hill.

“This is a long-term investment process,” Dr. Percelay says. “We’re learning as an organization how to conduct our public policy efforts. We’re at the beginning stages of meeting with these people and letting them know what hospitalists can do.” TH

Jane Jerrard writes “Public Policy” for The Hospitalist.

Physician Payment Reform, P4P, AHRQ

SHM’s Public Policy Committee (PPC) monitors federal legislation and regulations affecting hospital medicine and recommending appropriate action by SHM. SHM works independently and through coalitions with like-minded organizations in pursuit of its policy objectives. This month, I’ll update you on PPC’s major activities in the past six months.

Physician Payment Reform

Late last year, as Congress debated whether to address pending reductions in 2007 Medicare payments to physicians before adjourning, PPC spearheaded a number of activities to influence debate on the issue. These efforts included:

- Sending a letter from then-SHM President Mary Jo Gorman, MD, MBA, to members of the key health committees, urging lawmakers to take action to avert the scheduled 5% cut in Medicare physician fees and enact a positive payment update that accurately reflects increases in practice costs;

- Launching a new advocacy tool that allows SHM members to quickly e-mail their members of Congress in opposition to the pending fee cut. In less than two weeks, 130 members sent nearly 390 messages to the U.S. House of Representatives and the Senate; and

- Lobbying Congress to ensure that any pay-for-reporting program for physicians be voluntary and based on valid measures developed by the medical profession.

The legislation approved by Congress (H.R. 6111) averted the 5% cut, as advocated by SHM, freezing rates at 2006 levels. Continuation of the current payment rates, combined with increases in evaluation and management services proposed by CMS and supported by SHM as part of the five-year review, translated into an average gain per hospitalist of approximately 8.8% on their Medicare billings.

A scheduled 10% cut in 2008 Medicare payments to physicians will dominate this year’s legislative agenda. The PPC will continue to oppose cuts in the physician update and advocate for a more permanent solution to the annual payment reductions caused by the flawed sustainable growth rate.

Pay for Performance

Together with SHM’s Performance and Standards Task Force (PSTF), the PPC has spent countless hours working to position SHM to influence the debate over pay for performance on Capitol Hill and with CMS. This has involved Hill visits by PPC members and staff in addition to conference calls, meetings, and communications with CMS officials. Part of the committee’s role is also to educate SHM members on how their practices will be affected by legislative and regulatory action in this area.

Under the new Physician Quality Reporting Initiative (PQRI) mandated under H.R. 6111, SHM members and other eligible professionals who successfully report quality measures on claims for dates of service from July 1 to Dec. 31 may earn a bonus payment, subject to a cap, of 1.5% of total allowed charges for covered Medicare physician fee schedule services.

Because measures were not originally developed for hospital medicine, PPC, PSTF, and staff actively lobbied CMS and the AMA’s Physician Consortium for Performance Improvement (PCPI) for changes to the measures that would allow wider reporting by SHM members. Significantly, PCPI accepted SHM’s recommendations, paving the way for hospitalist participation in this voluntary program. Had SHM not been at the table, hospitalists would have had only a limited opportunity to qualify for a 1.5% increase in their Medicare payments through participation in the PQRI program. SHM will also take the lead in developing measures on care transitions through the PCPI for 2009, which will position hospital medicine as the premier advocate for this important issue.

Funding for AHRQ

One of SHM’s legislative priorities is to advocate for increased funding for the Agency for Healthcare Research and Quality (AHRQ), whose mission is to improve the quality, safety, efficiency, and effectiveness of healthcare for all Americans. As part of this effort, we participate in the Friends of AHRQ, a voluntary coalition of more than 130 organizations that supports the AHRQ by sending joint letters to key members of Congress, making joint visits to members of Congress and their staff, and holding briefings to demonstrate the importance of AHRQ research.

In March, SHM and 50 other members of the coalition sent a letter to the chairs and ranking members of the House and Senate Appropriations committees recommending that AHRQ receive $350 million in FY 2008, an increase of $31 million over FY 2007. The groups pointed out that while AHRQ is charged with supporting research to improve healthcare quality, reduce costs, advance patient safety, decrease medical errors, eliminate healthcare disparities, and broaden access to essential services, “precarious funding levels threaten the agency’s ability to achieve this important mission, at a time when healthcare costs are at an all-time high.”

Funding for NIH and Other Agencies

SHM also routinely joins with other organizations in urging Congress to increase funding for the National Institutes of Health (NIH) and other public health programs.

A Feb. 26 letter, signed by SHM and 405 other health organizations, urged Congress to increase FY 2008 funding for public health programs by an additional $4 billion, or 7.8%, above the FY 2007 level. The letter states that this increase in the FY 2008 budget for Function 550 discretionary health programs such as NIH, AHRQ, and CDC will “reverse the erosion of support for the continuum of biomedical, behavioral and health services research, community-based disease prevention and health promotion, basic and targeted services for the medically uninsured and those with disabilities, health professions education, and robust regulation of the nation’s food and drug supply.”

Access to Care

Recognizing SHM member interest—and that of the 110th Congress—in initiatives to expand healthcare coverage to the nation’s 47 million uninsured, the PPC is reviewing legislative proposals being considered in this area.

At the committee’s recommendation, SHM sent a letter of support for the Health Partnership Act (S. 325/H.R. 506), which would establish a grant program to promote the development of innovative health coverage initiatives at the state level. In the letter, then-SHM President Mary Jo Gorman, MD, MBA, commended the sponsors for “giving state and local governments the flexibility to test a variety of options for improving access so they can address the unique needs of their uninsured populations.”

She noted that many hospitalist programs exist to manage the burgeoning population of uninsured and underinsured patients who require hospitalization, and offered SHM’s help in moving the bill through Congress.

Grass-roots Advocacy

Politically active members are an organization’s best resource when it comes to influencing healthcare policy on Capitol Hill. Building on the relationships established during SHM’s first Advocacy Day held during the 2006 annual meeting, PPC members traveled to Washington D.C., in February to brief members of Congress and their staffs on SHM’s 2007 legislative priorities, including support for initiatives designed to improve the quality, safety, and cost effectiveness of inpatient medical care.

More than 30 appointments were scheduled with lawmakers and their staffs, many of whom sit on the key congressional committees with jurisdiction over the Medicare and Medicaid programs. Each PPC member had from five to eight visits. They continued the process of educating Congress about the specialty of hospital medicine that began during Advocacy Day and the role of hospitalists in improving the quality of care provided in our nation’s hospitals. It was time well spent. Lawmakers and their staffs were eager to learn about hospital medicine and our support for increased funding for AHRQ, pay-for-reporting, and legislation like the Health Partnership Act.

Allendorf is senior adviser, advocacy and government relations, for SHM.

New Task Force, New Chair, Improved Patient Care

SHM’s HQPS Committee makes tremendous progress

By Shannon Roach

The past year has been successful and productive for the SHM Health Quality and Patient Safety (HQPS) Committee. Under the leadership of Lakshmi Halasyamani, MD, HQPS has strengthened its national leadership role in inpatient quality improvement efforts, most notably in the areas of reducing DVTs, improving glycemic control and management of patients with heart failure. Additionally, HQPS has strengthened relationships with partner organizations and created new alliances. HQPS has participated in the development of training activities and clinical support tools for quality improvement efforts.

Hand-Off Standards

The Hand-Off Standards and Communication Task Force was formed to create a formally recognized set of standards for ensuring optimum communication and continuity of care at the end of a medical professional’s shift or a patient’s change in service. The standards ensure that care is coordinated and that important clinical care issues are effectively managed. The development methodology mirrors that of the Discharge Planning Checklist and includes a literature review, panel of experts, presentation to and input from membership. Vineet Arora, MD, has led this development in collaboration with Sunil Kripalani, MD, Efren Manjarrez, MD, Dan Dressler, MD, Preetha Basaviah, MD, and Lakshmi Halasyamani, MD.

The Hand-Off Standards checklist was unveiled at the 2007 Annual Meeting from May 23-25 in Dallas, where attendees reviewed and voted on the standards in order to provide the Task Force with a final draft to present to the Expert Panel for a final review. Effective hand-offs require program policy, verbal exchange, and content exchange. A research agenda was also proposed to evaluate these standards rigorously, put emphasis on controlled interventions, and to encourage SHM and other organizations to fund research and innovations in this area.

Medication Reconciliation