User login

Principal Investigations

What can you do with a quarter of a million dollars? In some places, that amount can buy a home that can shelter a family for decades. In other places, it is enough to pay annual malpractice insurance premiums for physicians practicing in high-risk specialties—with a little left over.

But if you wanted to use that money for an enduring healthcare project that would provide the most good for the most people, how would you do it? Hospitalists can look to the Agency for Healthcare Research and Quality (AHRQ) for stellar examples of well-invested dollars with excellent return.

AHRQ Funding

With a staff of approximately 300, the tiny AHRQ is the lead federal agency charged with improving the quality, safety, efficiency, and effectiveness of healthcare for all Americans. It creates a priority research agenda annually, and funds studies in areas where improvement is deemed most needed. These include patient safety, data development, pharmaceutical outcomes, and other areas described on its Web site (www.ahrq.gov/).

In 2005, AHRQ announced its Partnerships in Implementing Patient Safety (PIPS) and committed up to $9 million in total costs to fund new grants of less than $300,000 per year, lasting two years. AHRQ indicated that eligible safe practice intervention projects would be required to include “tool kits,” and a comprehensive implementation tool kit to help others overcome barriers and allay adoption concerns. AHRQ’s goal was and is to disseminate funded projects’ perfected tools widely for adaptation and/or adoption by diverse healthcare settings.

AHRQ asked that principal investigators (PIs) be experienced senior level individuals familiar with implementing change in healthcare settings. Their expectation was that PIs would devote at least 15% of their time to the project for its duration. Thus the competitive challenge to potential PIs was great:

- Select a worthy project from among the endless areas where healthcare needs improvement, and then plan specific, realistic, achievable interventions that could create measurable improvement over two years;

- Implement the program; and

- Develop a plan and tools so basic and user-friendly that they could feasibly be applied in not just the local practice setting, but in other healthcare settings.

Although the size and duration of the awards varied, many of the 17 projects they funded received slightly more than a quarter of a million dollars. Among the funded projects, two boast hospitalists as their PIs and address areas of obvious concern in most healthcare settings. Greg Maynard, MD, MS, at the University of California, San Diego, was funded to implement a venous thromboembolism (VTE) intervention program. And Mark V. Williams, MD, FACP, professor of medicine, Emory University School of Medicine, Atlanta, and editor of the Journal of Hospital Medicine, was funded to implement a discharge bundle of patient safety interventions respectively.

Stalking the Silent Killer

Dr. Maynard’s project, “Optimal Prevention of Hospital Acquired Venous Thromboembolism,” focuses on eliminating preventable hospital-acquired VTE at an academic healthcare facility that has a large population of Hispanic patients.

The project’s timeliness and utility is clear: Although the exact incidence of VTE is unknown, experts estimate that approximately 260,000 are clinically recognized annually in acutely hospitalized patients.1 Pulmonary embolism (PE) resulting from deep vein thrombosis (DVT) is the most common cause of preventable hospital death, the majority of hospitalized patients with risk factors for DVT receive no prophylaxis, and the rate of fatal PE more than doubles between age 50 and 80.2,3 The problem is easily recognizable, but “Getting people to do what they need to do to prevent VTE can be hard,” says Dr. Maynard.

This project was carefully planned. It used a rigorous quality improvement process, involving all appropriate clinicians, nurses, managers, and technical support personnel.

Dr. Maynard and his team anticipated roadblocks and negotiated in advance to reduce their effects. They accepted that when patients are hospitalized, things frequently happen that cause physicians to stop VTE prophylaxis: A hemoglobin or platelet count may fall, the patient may have difficulty taking the drug, or the patient’s status may change abruptly. Or the prophylaxis might be accidentally discontinued—perhaps when a patient is transferred.

The team also looked at other institutions’ solutions. Then, using a basic understanding of the ways in which their process was missing VTE prophylaxis opportunities, they built interventions.

This team considered logistics carefully because it was clear that the only intervention that could decrease risk would have to be repetitive in nature. “The process we ultimately selected is very, very quick, yet valid,” says Dr. Maynard, while acknowledging that presenting any intervention repeatedly has the potential to interfere with care. “Other models require the physician to use math and add points. This one does not, and takes only seconds.”

Beginning April 19, 2006, the University of California, San Diego (UCSD) will introduce an intervention that presents a VTE risk assessment screen on every patient who is admitted. This process inquires about the need for prophylaxis every three days for the duration of hospitalization, and physicians cannot skip the screen. If risk factors are present and bleeding risk is not, the screen presents appropriate VTE options.

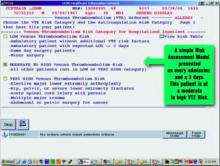

For example, the system will suggest enoxaparin 40 mg daily, enoxaparin 30 mg twice daily, or appropriately dosed warfarin for a high-risk orthopedic surgery patient who has no bleeding risk. Every three days, the process repeats itself, making explicit decisions or suggestions about appropriate prophylaxis. (Figure 1, below, shows a sample screen for a patient with moderately high risk.

Much evidence about VTE is still being gathered. For example, opinions vary about when to start prophylaxis or how long to continue it. Dr. Maynard and his team also addressed real versus relative contraindications—another area of debate among clinicians. Many clinicians are uncertain about how soon after surgery to restart VTE prophylaxis. After orthopedic spine surgery, for example, some might start it on day five, while others may not restart prophylaxis even after day 10. At UCSD, clinical stakeholders in the process came to consensus, and now all restart by day seven.

The tool kit UCSD is developing recognizes that every institution is unique. Those that choose to implement a similar program must identify their baseline rate of VTE and monitor change over time to determine if progress is being made. Every institution must define adequate VTE prophylaxis and tailor the tools appropriately.

Wait? No Need

One compelling aspect of Dr. Maynard’s project is that some of UCSD’s VTE tools are already available on the SHM Web site in the “VTE Resource Room.” With or without AHRQ funding, UCSD planned to develop and implement a VTE awareness program. UCSD’s grant department provided the support Dr. Maynard and his colleagues needed to apply for the AHRQ funding, and Dr. Maynard says the funding they received helped UCSD “disseminate the program better and to carry it out with more rigor.”

UCSD worked with SHM to develop the tool kit. In return, SHM is providing and promoting the VTE tool kit at no charge to interested parties. Additionally, SHM recently received funding via an unrestricted sponsorship to create a mentored implementation project for the “VTE Resource Room.” Interested institutions will be mentored by UCSD staff who have experience with the tool kit.

Over time, Dr. Maynard will measure the effects of the intervention to ensure it is working. In addition to creating a malleable tool kit, UCSD research hospitalists will examine race, gender, and age to determine the effects of these on the likelihood of getting adequate prophylaxis.

Hospital Patient Safe-D(ischarge)

Dr. Williams and his colleagues at Emory University and the University of Ottawa received funding for “Hospital Patient Safe-D(ischarge): A Discharge Bundle for Patients,” a program that builds on previous AHRQ funding. This intervention implements a “discharge bundle” of patient safety interventions to improve patient transition from the hospital to home or another healthcare setting.

“We hope that every patient will undergo discharge, and of course the majority do, but the discharge process has almost been treated as an afterthought,” explains Dr. Williams. “Doctors spend a lot of time on diagnosis and treatment, but not on discharge. This process of transition from total care with a call button, lots of nursing attention, daily visits from the doctor, and delivered meals to greater independence, has not been well researched.”

What little research exists tends to indicate that discharge processes are very heterogeneous.

So far, Dr. Williams’ team’s examination of the process has produced only one surprise: The team has discovered that the discharge process is even more capricious than they suspected. As patients prepare to leave the hospital, what could and should be an orderly process that educates and prepares patients to assume responsibility for their own care in a new and better way is often interrupted or disjointed.

Preparing patients for discharge once fell to the nursing staff. As nursing faces staffing shortages and expanded roles, the discharge process often belongs to everyone and to no one. That physicians’ discharge visits pay much less than the time required to do it well also complicates the problem. The researchers were not surprised, however, to learn that many patients do not know their diagnosis or treatment plan as discharge is imminent. Their goal is to develop a consistent, comprehensive discharge process that will be a national model.

Here again, the precepts of continuous quality improvement are apparent. Dr. Williams’ team’s effort represents collaboration among physicians, pharmacists, nurses, and patients; involves SHM and several other professional organizations; and calls upon an advisory committee consisting of nationally recognized patient care and safety experts.

The discharge bundle of patient safety interventions—a concept advocated by the Joint Commission on Accreditation of Healthcare Organizations and other quality-promoting groups—adds a post-discharge continuity check to medication reconciliation and patient-centered education at discharge.

The four project phases—implement, evaluate, develop a tool, and disseminate the discharge bundle—overlap and ensure success.

Dr. Williams believes that the group of patients most likely to benefit from this intervention is the elderly. “The elderly bear the greatest burden of chronic disease and typically have several concurrent health problems,” he says.

Educating elders at the time of discharge should decrease the medication error rate and improve adherence to other treatments and recommended lifestyle changes. To gauge the appropriateness of the discharge bundle, John Banja, PhD, an expert in communication and safety, observes the discharge process directly. All communications must be patient-centered, and thus presented in a manner that patients will understand and appreciate. Banja relies on his background in patient safety and disability/rehabilitation to assess the discharge process.

Initial enrollment in this study seems successful. More than 50 patients have consented to participate, but Banja projects a need for 200 to complete the entire process. Recently, the team increased its planned maximum accrual to 300 to increase the statistical power of their findings. The participants like the program because most of them find discharge somewhat discomforting. Patients know they have knowledge gaps and appreciate clinicians’ efforts to fill those gaps seamlessly. A small investment of time can prevent problems after discharge.

Added Value

Clearly, the findings from these AHRQ-funded studies have the potential to reduce morbidity and mortality in a logarithmic manner as other institutions adapt these new tool kits. Dr. Williams indicates that recipients of PIPS funding receive more than just funding and the satisfaction of creating tools that will help all Americans.

“The AHRQ sponsors quarterly conference calls for all participants, regardless of their research topic, and an annual meeting in June to bring all investigators together,” he says.

The opportunity to learn how others address problems, plan interventions, and tackle hurdles proves invaluable. In addition, being privy to interim study results or learning how others handle research dilemmas helps hospitalists expand their skill sets.

Listening to Drs. Maynard and Williams is a not-so-subtle reminder that every hospital needs a well-structured quality improvement plan, and that hospitalists are essential in the plan’s success. Every hospitalist needs an understanding of the precepts these PIs used to earn this well-deserved funding: interdisciplinary and professional organization collaboration, good communication, realistic planning, managing change by measuring, and above all, sharing success. TH

Jeannette Yeznach Wick, RPh, MBA, FASCP, is a freelance medical writer based in Arlington, Va.

References

- Anderson FA Jr, Wheeler HB, Goldberg RJ, et al. A population-based perspective of the hospital incidence and case-fatality rates of deep vein thrombosis and pulmonary embolism. The Worcester DVT Study. Arch Intern Med. 1991 May;151(5):933-938.

- Clagett GP, Anderson FA Jr, Heit J, et al. Prevention of venous thromboembolism. Chest. 1995 Oct;108(4 Suppl):312S-334S.

- Geerts WH, Heit JA, Clagett GP, et al. Prevention of venous thromboembolism. Chest. 2001;119(1 Suppl):132S-175S.

What can you do with a quarter of a million dollars? In some places, that amount can buy a home that can shelter a family for decades. In other places, it is enough to pay annual malpractice insurance premiums for physicians practicing in high-risk specialties—with a little left over.

But if you wanted to use that money for an enduring healthcare project that would provide the most good for the most people, how would you do it? Hospitalists can look to the Agency for Healthcare Research and Quality (AHRQ) for stellar examples of well-invested dollars with excellent return.

AHRQ Funding

With a staff of approximately 300, the tiny AHRQ is the lead federal agency charged with improving the quality, safety, efficiency, and effectiveness of healthcare for all Americans. It creates a priority research agenda annually, and funds studies in areas where improvement is deemed most needed. These include patient safety, data development, pharmaceutical outcomes, and other areas described on its Web site (www.ahrq.gov/).

In 2005, AHRQ announced its Partnerships in Implementing Patient Safety (PIPS) and committed up to $9 million in total costs to fund new grants of less than $300,000 per year, lasting two years. AHRQ indicated that eligible safe practice intervention projects would be required to include “tool kits,” and a comprehensive implementation tool kit to help others overcome barriers and allay adoption concerns. AHRQ’s goal was and is to disseminate funded projects’ perfected tools widely for adaptation and/or adoption by diverse healthcare settings.

AHRQ asked that principal investigators (PIs) be experienced senior level individuals familiar with implementing change in healthcare settings. Their expectation was that PIs would devote at least 15% of their time to the project for its duration. Thus the competitive challenge to potential PIs was great:

- Select a worthy project from among the endless areas where healthcare needs improvement, and then plan specific, realistic, achievable interventions that could create measurable improvement over two years;

- Implement the program; and

- Develop a plan and tools so basic and user-friendly that they could feasibly be applied in not just the local practice setting, but in other healthcare settings.

Although the size and duration of the awards varied, many of the 17 projects they funded received slightly more than a quarter of a million dollars. Among the funded projects, two boast hospitalists as their PIs and address areas of obvious concern in most healthcare settings. Greg Maynard, MD, MS, at the University of California, San Diego, was funded to implement a venous thromboembolism (VTE) intervention program. And Mark V. Williams, MD, FACP, professor of medicine, Emory University School of Medicine, Atlanta, and editor of the Journal of Hospital Medicine, was funded to implement a discharge bundle of patient safety interventions respectively.

Stalking the Silent Killer

Dr. Maynard’s project, “Optimal Prevention of Hospital Acquired Venous Thromboembolism,” focuses on eliminating preventable hospital-acquired VTE at an academic healthcare facility that has a large population of Hispanic patients.

The project’s timeliness and utility is clear: Although the exact incidence of VTE is unknown, experts estimate that approximately 260,000 are clinically recognized annually in acutely hospitalized patients.1 Pulmonary embolism (PE) resulting from deep vein thrombosis (DVT) is the most common cause of preventable hospital death, the majority of hospitalized patients with risk factors for DVT receive no prophylaxis, and the rate of fatal PE more than doubles between age 50 and 80.2,3 The problem is easily recognizable, but “Getting people to do what they need to do to prevent VTE can be hard,” says Dr. Maynard.

This project was carefully planned. It used a rigorous quality improvement process, involving all appropriate clinicians, nurses, managers, and technical support personnel.

Dr. Maynard and his team anticipated roadblocks and negotiated in advance to reduce their effects. They accepted that when patients are hospitalized, things frequently happen that cause physicians to stop VTE prophylaxis: A hemoglobin or platelet count may fall, the patient may have difficulty taking the drug, or the patient’s status may change abruptly. Or the prophylaxis might be accidentally discontinued—perhaps when a patient is transferred.

The team also looked at other institutions’ solutions. Then, using a basic understanding of the ways in which their process was missing VTE prophylaxis opportunities, they built interventions.

This team considered logistics carefully because it was clear that the only intervention that could decrease risk would have to be repetitive in nature. “The process we ultimately selected is very, very quick, yet valid,” says Dr. Maynard, while acknowledging that presenting any intervention repeatedly has the potential to interfere with care. “Other models require the physician to use math and add points. This one does not, and takes only seconds.”

Beginning April 19, 2006, the University of California, San Diego (UCSD) will introduce an intervention that presents a VTE risk assessment screen on every patient who is admitted. This process inquires about the need for prophylaxis every three days for the duration of hospitalization, and physicians cannot skip the screen. If risk factors are present and bleeding risk is not, the screen presents appropriate VTE options.

For example, the system will suggest enoxaparin 40 mg daily, enoxaparin 30 mg twice daily, or appropriately dosed warfarin for a high-risk orthopedic surgery patient who has no bleeding risk. Every three days, the process repeats itself, making explicit decisions or suggestions about appropriate prophylaxis. (Figure 1, below, shows a sample screen for a patient with moderately high risk.

Much evidence about VTE is still being gathered. For example, opinions vary about when to start prophylaxis or how long to continue it. Dr. Maynard and his team also addressed real versus relative contraindications—another area of debate among clinicians. Many clinicians are uncertain about how soon after surgery to restart VTE prophylaxis. After orthopedic spine surgery, for example, some might start it on day five, while others may not restart prophylaxis even after day 10. At UCSD, clinical stakeholders in the process came to consensus, and now all restart by day seven.

The tool kit UCSD is developing recognizes that every institution is unique. Those that choose to implement a similar program must identify their baseline rate of VTE and monitor change over time to determine if progress is being made. Every institution must define adequate VTE prophylaxis and tailor the tools appropriately.

Wait? No Need

One compelling aspect of Dr. Maynard’s project is that some of UCSD’s VTE tools are already available on the SHM Web site in the “VTE Resource Room.” With or without AHRQ funding, UCSD planned to develop and implement a VTE awareness program. UCSD’s grant department provided the support Dr. Maynard and his colleagues needed to apply for the AHRQ funding, and Dr. Maynard says the funding they received helped UCSD “disseminate the program better and to carry it out with more rigor.”

UCSD worked with SHM to develop the tool kit. In return, SHM is providing and promoting the VTE tool kit at no charge to interested parties. Additionally, SHM recently received funding via an unrestricted sponsorship to create a mentored implementation project for the “VTE Resource Room.” Interested institutions will be mentored by UCSD staff who have experience with the tool kit.

Over time, Dr. Maynard will measure the effects of the intervention to ensure it is working. In addition to creating a malleable tool kit, UCSD research hospitalists will examine race, gender, and age to determine the effects of these on the likelihood of getting adequate prophylaxis.

Hospital Patient Safe-D(ischarge)

Dr. Williams and his colleagues at Emory University and the University of Ottawa received funding for “Hospital Patient Safe-D(ischarge): A Discharge Bundle for Patients,” a program that builds on previous AHRQ funding. This intervention implements a “discharge bundle” of patient safety interventions to improve patient transition from the hospital to home or another healthcare setting.

“We hope that every patient will undergo discharge, and of course the majority do, but the discharge process has almost been treated as an afterthought,” explains Dr. Williams. “Doctors spend a lot of time on diagnosis and treatment, but not on discharge. This process of transition from total care with a call button, lots of nursing attention, daily visits from the doctor, and delivered meals to greater independence, has not been well researched.”

What little research exists tends to indicate that discharge processes are very heterogeneous.

So far, Dr. Williams’ team’s examination of the process has produced only one surprise: The team has discovered that the discharge process is even more capricious than they suspected. As patients prepare to leave the hospital, what could and should be an orderly process that educates and prepares patients to assume responsibility for their own care in a new and better way is often interrupted or disjointed.

Preparing patients for discharge once fell to the nursing staff. As nursing faces staffing shortages and expanded roles, the discharge process often belongs to everyone and to no one. That physicians’ discharge visits pay much less than the time required to do it well also complicates the problem. The researchers were not surprised, however, to learn that many patients do not know their diagnosis or treatment plan as discharge is imminent. Their goal is to develop a consistent, comprehensive discharge process that will be a national model.

Here again, the precepts of continuous quality improvement are apparent. Dr. Williams’ team’s effort represents collaboration among physicians, pharmacists, nurses, and patients; involves SHM and several other professional organizations; and calls upon an advisory committee consisting of nationally recognized patient care and safety experts.

The discharge bundle of patient safety interventions—a concept advocated by the Joint Commission on Accreditation of Healthcare Organizations and other quality-promoting groups—adds a post-discharge continuity check to medication reconciliation and patient-centered education at discharge.

The four project phases—implement, evaluate, develop a tool, and disseminate the discharge bundle—overlap and ensure success.

Dr. Williams believes that the group of patients most likely to benefit from this intervention is the elderly. “The elderly bear the greatest burden of chronic disease and typically have several concurrent health problems,” he says.

Educating elders at the time of discharge should decrease the medication error rate and improve adherence to other treatments and recommended lifestyle changes. To gauge the appropriateness of the discharge bundle, John Banja, PhD, an expert in communication and safety, observes the discharge process directly. All communications must be patient-centered, and thus presented in a manner that patients will understand and appreciate. Banja relies on his background in patient safety and disability/rehabilitation to assess the discharge process.

Initial enrollment in this study seems successful. More than 50 patients have consented to participate, but Banja projects a need for 200 to complete the entire process. Recently, the team increased its planned maximum accrual to 300 to increase the statistical power of their findings. The participants like the program because most of them find discharge somewhat discomforting. Patients know they have knowledge gaps and appreciate clinicians’ efforts to fill those gaps seamlessly. A small investment of time can prevent problems after discharge.

Added Value

Clearly, the findings from these AHRQ-funded studies have the potential to reduce morbidity and mortality in a logarithmic manner as other institutions adapt these new tool kits. Dr. Williams indicates that recipients of PIPS funding receive more than just funding and the satisfaction of creating tools that will help all Americans.

“The AHRQ sponsors quarterly conference calls for all participants, regardless of their research topic, and an annual meeting in June to bring all investigators together,” he says.

The opportunity to learn how others address problems, plan interventions, and tackle hurdles proves invaluable. In addition, being privy to interim study results or learning how others handle research dilemmas helps hospitalists expand their skill sets.

Listening to Drs. Maynard and Williams is a not-so-subtle reminder that every hospital needs a well-structured quality improvement plan, and that hospitalists are essential in the plan’s success. Every hospitalist needs an understanding of the precepts these PIs used to earn this well-deserved funding: interdisciplinary and professional organization collaboration, good communication, realistic planning, managing change by measuring, and above all, sharing success. TH

Jeannette Yeznach Wick, RPh, MBA, FASCP, is a freelance medical writer based in Arlington, Va.

References

- Anderson FA Jr, Wheeler HB, Goldberg RJ, et al. A population-based perspective of the hospital incidence and case-fatality rates of deep vein thrombosis and pulmonary embolism. The Worcester DVT Study. Arch Intern Med. 1991 May;151(5):933-938.

- Clagett GP, Anderson FA Jr, Heit J, et al. Prevention of venous thromboembolism. Chest. 1995 Oct;108(4 Suppl):312S-334S.

- Geerts WH, Heit JA, Clagett GP, et al. Prevention of venous thromboembolism. Chest. 2001;119(1 Suppl):132S-175S.

What can you do with a quarter of a million dollars? In some places, that amount can buy a home that can shelter a family for decades. In other places, it is enough to pay annual malpractice insurance premiums for physicians practicing in high-risk specialties—with a little left over.

But if you wanted to use that money for an enduring healthcare project that would provide the most good for the most people, how would you do it? Hospitalists can look to the Agency for Healthcare Research and Quality (AHRQ) for stellar examples of well-invested dollars with excellent return.

AHRQ Funding

With a staff of approximately 300, the tiny AHRQ is the lead federal agency charged with improving the quality, safety, efficiency, and effectiveness of healthcare for all Americans. It creates a priority research agenda annually, and funds studies in areas where improvement is deemed most needed. These include patient safety, data development, pharmaceutical outcomes, and other areas described on its Web site (www.ahrq.gov/).

In 2005, AHRQ announced its Partnerships in Implementing Patient Safety (PIPS) and committed up to $9 million in total costs to fund new grants of less than $300,000 per year, lasting two years. AHRQ indicated that eligible safe practice intervention projects would be required to include “tool kits,” and a comprehensive implementation tool kit to help others overcome barriers and allay adoption concerns. AHRQ’s goal was and is to disseminate funded projects’ perfected tools widely for adaptation and/or adoption by diverse healthcare settings.

AHRQ asked that principal investigators (PIs) be experienced senior level individuals familiar with implementing change in healthcare settings. Their expectation was that PIs would devote at least 15% of their time to the project for its duration. Thus the competitive challenge to potential PIs was great:

- Select a worthy project from among the endless areas where healthcare needs improvement, and then plan specific, realistic, achievable interventions that could create measurable improvement over two years;

- Implement the program; and

- Develop a plan and tools so basic and user-friendly that they could feasibly be applied in not just the local practice setting, but in other healthcare settings.

Although the size and duration of the awards varied, many of the 17 projects they funded received slightly more than a quarter of a million dollars. Among the funded projects, two boast hospitalists as their PIs and address areas of obvious concern in most healthcare settings. Greg Maynard, MD, MS, at the University of California, San Diego, was funded to implement a venous thromboembolism (VTE) intervention program. And Mark V. Williams, MD, FACP, professor of medicine, Emory University School of Medicine, Atlanta, and editor of the Journal of Hospital Medicine, was funded to implement a discharge bundle of patient safety interventions respectively.

Stalking the Silent Killer

Dr. Maynard’s project, “Optimal Prevention of Hospital Acquired Venous Thromboembolism,” focuses on eliminating preventable hospital-acquired VTE at an academic healthcare facility that has a large population of Hispanic patients.

The project’s timeliness and utility is clear: Although the exact incidence of VTE is unknown, experts estimate that approximately 260,000 are clinically recognized annually in acutely hospitalized patients.1 Pulmonary embolism (PE) resulting from deep vein thrombosis (DVT) is the most common cause of preventable hospital death, the majority of hospitalized patients with risk factors for DVT receive no prophylaxis, and the rate of fatal PE more than doubles between age 50 and 80.2,3 The problem is easily recognizable, but “Getting people to do what they need to do to prevent VTE can be hard,” says Dr. Maynard.

This project was carefully planned. It used a rigorous quality improvement process, involving all appropriate clinicians, nurses, managers, and technical support personnel.

Dr. Maynard and his team anticipated roadblocks and negotiated in advance to reduce their effects. They accepted that when patients are hospitalized, things frequently happen that cause physicians to stop VTE prophylaxis: A hemoglobin or platelet count may fall, the patient may have difficulty taking the drug, or the patient’s status may change abruptly. Or the prophylaxis might be accidentally discontinued—perhaps when a patient is transferred.

The team also looked at other institutions’ solutions. Then, using a basic understanding of the ways in which their process was missing VTE prophylaxis opportunities, they built interventions.

This team considered logistics carefully because it was clear that the only intervention that could decrease risk would have to be repetitive in nature. “The process we ultimately selected is very, very quick, yet valid,” says Dr. Maynard, while acknowledging that presenting any intervention repeatedly has the potential to interfere with care. “Other models require the physician to use math and add points. This one does not, and takes only seconds.”

Beginning April 19, 2006, the University of California, San Diego (UCSD) will introduce an intervention that presents a VTE risk assessment screen on every patient who is admitted. This process inquires about the need for prophylaxis every three days for the duration of hospitalization, and physicians cannot skip the screen. If risk factors are present and bleeding risk is not, the screen presents appropriate VTE options.

For example, the system will suggest enoxaparin 40 mg daily, enoxaparin 30 mg twice daily, or appropriately dosed warfarin for a high-risk orthopedic surgery patient who has no bleeding risk. Every three days, the process repeats itself, making explicit decisions or suggestions about appropriate prophylaxis. (Figure 1, below, shows a sample screen for a patient with moderately high risk.

Much evidence about VTE is still being gathered. For example, opinions vary about when to start prophylaxis or how long to continue it. Dr. Maynard and his team also addressed real versus relative contraindications—another area of debate among clinicians. Many clinicians are uncertain about how soon after surgery to restart VTE prophylaxis. After orthopedic spine surgery, for example, some might start it on day five, while others may not restart prophylaxis even after day 10. At UCSD, clinical stakeholders in the process came to consensus, and now all restart by day seven.

The tool kit UCSD is developing recognizes that every institution is unique. Those that choose to implement a similar program must identify their baseline rate of VTE and monitor change over time to determine if progress is being made. Every institution must define adequate VTE prophylaxis and tailor the tools appropriately.

Wait? No Need

One compelling aspect of Dr. Maynard’s project is that some of UCSD’s VTE tools are already available on the SHM Web site in the “VTE Resource Room.” With or without AHRQ funding, UCSD planned to develop and implement a VTE awareness program. UCSD’s grant department provided the support Dr. Maynard and his colleagues needed to apply for the AHRQ funding, and Dr. Maynard says the funding they received helped UCSD “disseminate the program better and to carry it out with more rigor.”

UCSD worked with SHM to develop the tool kit. In return, SHM is providing and promoting the VTE tool kit at no charge to interested parties. Additionally, SHM recently received funding via an unrestricted sponsorship to create a mentored implementation project for the “VTE Resource Room.” Interested institutions will be mentored by UCSD staff who have experience with the tool kit.

Over time, Dr. Maynard will measure the effects of the intervention to ensure it is working. In addition to creating a malleable tool kit, UCSD research hospitalists will examine race, gender, and age to determine the effects of these on the likelihood of getting adequate prophylaxis.

Hospital Patient Safe-D(ischarge)

Dr. Williams and his colleagues at Emory University and the University of Ottawa received funding for “Hospital Patient Safe-D(ischarge): A Discharge Bundle for Patients,” a program that builds on previous AHRQ funding. This intervention implements a “discharge bundle” of patient safety interventions to improve patient transition from the hospital to home or another healthcare setting.

“We hope that every patient will undergo discharge, and of course the majority do, but the discharge process has almost been treated as an afterthought,” explains Dr. Williams. “Doctors spend a lot of time on diagnosis and treatment, but not on discharge. This process of transition from total care with a call button, lots of nursing attention, daily visits from the doctor, and delivered meals to greater independence, has not been well researched.”

What little research exists tends to indicate that discharge processes are very heterogeneous.

So far, Dr. Williams’ team’s examination of the process has produced only one surprise: The team has discovered that the discharge process is even more capricious than they suspected. As patients prepare to leave the hospital, what could and should be an orderly process that educates and prepares patients to assume responsibility for their own care in a new and better way is often interrupted or disjointed.

Preparing patients for discharge once fell to the nursing staff. As nursing faces staffing shortages and expanded roles, the discharge process often belongs to everyone and to no one. That physicians’ discharge visits pay much less than the time required to do it well also complicates the problem. The researchers were not surprised, however, to learn that many patients do not know their diagnosis or treatment plan as discharge is imminent. Their goal is to develop a consistent, comprehensive discharge process that will be a national model.

Here again, the precepts of continuous quality improvement are apparent. Dr. Williams’ team’s effort represents collaboration among physicians, pharmacists, nurses, and patients; involves SHM and several other professional organizations; and calls upon an advisory committee consisting of nationally recognized patient care and safety experts.

The discharge bundle of patient safety interventions—a concept advocated by the Joint Commission on Accreditation of Healthcare Organizations and other quality-promoting groups—adds a post-discharge continuity check to medication reconciliation and patient-centered education at discharge.

The four project phases—implement, evaluate, develop a tool, and disseminate the discharge bundle—overlap and ensure success.

Dr. Williams believes that the group of patients most likely to benefit from this intervention is the elderly. “The elderly bear the greatest burden of chronic disease and typically have several concurrent health problems,” he says.

Educating elders at the time of discharge should decrease the medication error rate and improve adherence to other treatments and recommended lifestyle changes. To gauge the appropriateness of the discharge bundle, John Banja, PhD, an expert in communication and safety, observes the discharge process directly. All communications must be patient-centered, and thus presented in a manner that patients will understand and appreciate. Banja relies on his background in patient safety and disability/rehabilitation to assess the discharge process.

Initial enrollment in this study seems successful. More than 50 patients have consented to participate, but Banja projects a need for 200 to complete the entire process. Recently, the team increased its planned maximum accrual to 300 to increase the statistical power of their findings. The participants like the program because most of them find discharge somewhat discomforting. Patients know they have knowledge gaps and appreciate clinicians’ efforts to fill those gaps seamlessly. A small investment of time can prevent problems after discharge.

Added Value

Clearly, the findings from these AHRQ-funded studies have the potential to reduce morbidity and mortality in a logarithmic manner as other institutions adapt these new tool kits. Dr. Williams indicates that recipients of PIPS funding receive more than just funding and the satisfaction of creating tools that will help all Americans.

“The AHRQ sponsors quarterly conference calls for all participants, regardless of their research topic, and an annual meeting in June to bring all investigators together,” he says.

The opportunity to learn how others address problems, plan interventions, and tackle hurdles proves invaluable. In addition, being privy to interim study results or learning how others handle research dilemmas helps hospitalists expand their skill sets.

Listening to Drs. Maynard and Williams is a not-so-subtle reminder that every hospital needs a well-structured quality improvement plan, and that hospitalists are essential in the plan’s success. Every hospitalist needs an understanding of the precepts these PIs used to earn this well-deserved funding: interdisciplinary and professional organization collaboration, good communication, realistic planning, managing change by measuring, and above all, sharing success. TH

Jeannette Yeznach Wick, RPh, MBA, FASCP, is a freelance medical writer based in Arlington, Va.

References

- Anderson FA Jr, Wheeler HB, Goldberg RJ, et al. A population-based perspective of the hospital incidence and case-fatality rates of deep vein thrombosis and pulmonary embolism. The Worcester DVT Study. Arch Intern Med. 1991 May;151(5):933-938.

- Clagett GP, Anderson FA Jr, Heit J, et al. Prevention of venous thromboembolism. Chest. 1995 Oct;108(4 Suppl):312S-334S.

- Geerts WH, Heit JA, Clagett GP, et al. Prevention of venous thromboembolism. Chest. 2001;119(1 Suppl):132S-175S.

Listen Between the Lines

When an elderly person is admitted to the hospital, Adrienne Green, MD, sees an opportunity for something beyond addressing the medical issues at hand.

“One of the key issues that is important for practical, everyday care is trying to figure out how the elderly are not functioning well at home,” says Dr. Green, an associate clinical professor of medicine at the University of California at San Francisco and a member of UCSF’s hospitalist group. “I think we do a great job of managing their diseases, but what we don’t do very well is helping them out with other things [such as coping with] their losses and the fact that they may be just barely hanging on at home in terms of their ability to care for themselves; and this hospitalization may really have set them back.”

Eva Chittenden, MD, an assistant clinical professor of medicine, also at UCSF, agrees. “Many hospitalists are so focused on the hospital that they’re not thinking about the ‘before the hospital’ and the ‘after the hospital,’” she says.

But after identifying the challenges that elderly patients face, communication itself may be challenging. Elderly individuals struggle with issues of control and allowing people to tell them what they need to change in their lives may not be an easy task. What are the best ways to communicate with hospitalized elderly patients to facilitate the best “whole-person” care?

—David Solie, MS, PA

Under the Radar Screen

The hospitalists interviewed for this article agreed that getting a broader picture of an elderly patient’s health and well-being involves discovering how they are really doing at home. Dr. Green asks simple questions, particularly about activities of daily living, such as whether they’re doing their own shopping and cooking. She also involves the family, “because very frequently the patient will say, ‘I’m doing fine,’ and the family member is in the background shaking their head.”

She also looks for clues about whether the patient needs more help at home, whether they are compliant with their medications, and if not, why (e.g., can they open their medicine bottles)?

“I frequently have the elderly patients evaluated for home care just to get someone into their house … ,” says Dr. Green. “I think that probably 80% of our patients who are over 80 who come into the hospital have things in their homes that are not safe, such as throw rugs.” Even if patients are basically doing OK, “if I can get some home care for them, I know we’ll uncover a ton [of things that can be improved],” she says. “These patients may have … kind of snuck under the radar screen of their families and their primary [care physician], and I think the hospitalization kind of opens that up in some ways.”

Facing Resistance

Even if issues are uncovered by means of interviews and home-health visits, however, many elderly patients present a particular communication challenge. This, says David Solie, MS, PA, author of How to Say It to Seniors: Closing the Communication Gap with Our Elders, is because of the difference in circumstances and current experiences between the elderly and their hospitalist providers.1 It is common knowledge that younger people go through stages of development, but the elderly do, too, says Solie, who is medical director and CEO of Second Opinion Insurance Services in Woodland Hills, Calif., a brokerage that specializes in the insurance needs of impaired-risk, elderly individuals.

The last human developmental stage compels elderly adults to work hard at maintaining control over their lives in the face of almost daily losses. A big part of the losses they experience involve their health and functioning, and the ways different patients cope with loss and the perceived stresses of healthcare have been analyzed and categorized.2-5

But in addition to loss of control, the elderly also face the daunting task of discovering what their legacy will be—what will live on after they die. “The way our elders communicate contains clues to the urgency they feel in trying to resolve these items on their agendas,” writes Solie. “In almost every conversation with older adults, control and legacy issues rise to the surface.”

A Matter of Loss

By the time a person is old (over 70) or old-old (over 85) their losses may have manifested in many areas: They’ve lost:

- Parents;

- Other relatives—perhaps including children;

- Friends;

- Places of residence (both homes and the familiarity of cities or towns);

- Possessions;

- Other relationships (sometimes other healthcare providers);

- Careers;

- Consultative authority (“ours is not a culture that values the wisdom of our elders,” writes Solie);

- Identity;

- Financial independence;

- Habits and pleasures;

- Physical space (the room at their son or daughter’s or in assisted living or the nursing home can’t compare to the homes, gardens, and expanses of view they may have had as younger people), and, of course; and

- Physical and mental capacities.

Sometimes the losses elders sustain occur in rapid-fire sequence, with little or no recovery time in between.1,6

It is no wonder that older adults, in one way or another, exhibit what we consider resistance to their changing lives. In terms of a hospitalization, this may mean saying “no” to medications, individual providers, tests, surgery, home-health visits, or something as small as being talked to or touched in what they perceive as a disturbing, overly familiar, or mechanized manner.

“Many patients are resistant to having people come into their homes and help them, and at the same time they are resistant to going to a skilled nursing care facility,” says Dr. Green, “and it has to do with their [feelings of the] loss of independence and control over their lives.”

“It’s very easy if you’re in medicine to normalize your context of the hospital,” says Solie. “In other words, the hospital seems familiar to you and you’re very comfortable moving around there, and mainly because you’re in control. You’re the doctor … and you move in the hospital in order to make things happen and you never feel all that threatened. But when you bring an older person who already has a heightened sensitivity toward losing control into the hospital—this complex, technological world of medicine—and they have the cumulative disadvantage of being sick,” says Solie, “it’s really important to remember that there will probably be no other state that they’ll be in, except maybe nursing home care, where they will feel so out of control.”

A good first step in communicating with older patients is to quickly develop a rapport with them and show them you recognize what they’re up against.7 “They really want to know whether or not I get it,” says Solie.

The way you communicate that you get it, he says, is fairly straightforward: When I’m first interacting with the patient, I say, “if you are like my [other] elderly patients … I’m sure you’re feeling a lot of anxiety over [not having much] control and, first of all, I want to assure you that I’m going to make sure you understand the choices and help you make all the decisions. And … I’m definitely going to … put everything in a language that you understand. But if I’m not successful, I’m going to employ someone from your family. We’re going to work together. Even though you’re hospitalized and even though you’re fighting this illness (or whatever the condition might be), you still [have] the right to make choices, and my goal is to partner with you. My expertise is medicine, but you have an expertise in your life.”

In other words, you are signaling that you recognize that control is the issue. Acknowledge the loss, ask about the value of the event or decision to the patient, ask what you can do to help them deal with their feelings or make up their minds. It also allows you to remind an older patient’s children that control is a big and normal concern for their mother or father.

—Eva Chittenden, MD

Hospitalists at a Different Time and Place

The elderly desperately need people who can serve them as natural healers, who are not constantly in a hurry, and who care what they are thinking and feeling. How can hospitalists relate to those who are in the midst of life review and who are hanging on to an escaping control? How can they serve their patients in a way that meets all needs?

Fighting—with denial or ignorance—the resistance that patients might put up will more than likely provoke them. A fight for control can undermine and sabotage the best intentions of the provider and the greatest wishes for the patient to experience comfort or regain health and well-being. Rather than justifying wresting control from elderly patients because it’s for their own good, advises Solie, what we must do instead is to “step back, hand them the control baton, and allow them to run with it.”1

A person’s admission to the hospital “might be such a huge crisis for them, whereas for us it’s our routine work,” says Dr. Chittenden, who practices as a hospitalist and also works on her institution’s inpatient palliative care service. “And many people who are hospitalists—who are even in their late 20s, 30s, 40s—have been totally healthy their whole life, so it is hard to relate to what it’s like to be older and to be losing function, losing friends who are also dying, losing their house … . I think that it can be very helpful for the hospitalist to take a little more time and explore some of those issues [of loss and legacy]. I try to meet the person where they’re at and try to understand what their goals, needs, ... and fears are [as well as] their functional status.”

Allowing older patients to engage with you about their lives and their pasts is a privilege for any healthcare provider. Engaging with them in a way that will help facilitate their loosening the reins on control may expedite and allow greater quality into their healthcare. It may provide an opening whereby you can order that home-health visit with less struggle.

Create Openings

“There are a lot of different ‘on-ramps’ to asking the life-review questions, which are extremely comforting,” says Solie. “For example, you might say, ‘Mary, I notice that you were born in Iowa. You know, my family on my father’s side came from Iowa. Where were you raised?’ And ‘Do you have a big family on your farm, because my aunt had cows.’”

Once you get a response that engages the patient, then you “are in the slipstream. Physicians have such a high experience curve, they see so many patients,” he says. “They don’t have to go very far into their inventory of experiences [to find one] that essentially matches up with that patient.”

Any kind of comment that will key you in to their background experience can help establish some kind of foundation for relationship. Another example: “You know, Mary, I was working with this woman who was about your age and she was raised in the Midwest and was dealing with some of these issues of congestive heart failure, and one of her big concerns was something that I didn’t appreciate until I understood what an impact it was having on her life.”

This kind of communication, says Solie, can help to relieve some of the patient’s control anxieties, “because she feels that if I ‘get it,’ she’s open to what I have to say, such as, ‘The first thing, we have to deal with is there is too much fluid going on in your body and it’s putting a big strain on your heart, so the first couple days all we did for that [other] woman was try to pull some fluid off and keep everything in balance.’”

You’ve communicated that you have a plan, that you can be trusted, and that you will help her to exercise as much control as possible. Creating and accessing those openings is also “the ideal way to weave the family into this whole life-review process, which is where the patient lives, psychologically and emotionally, when outside the hospital environment,” he says. “We become so myopic when we’re caught in the hospital environment that the world becomes a narrow tunnel and we forget the greater matrix outside that we’re all connected to.”

The Boon of Biology

Whereas the physiology and anatomy of humans deteriorate with time, some of the changes in mental processes in old age may actually enhance the ability to reflect and make informed judgments. Solie’s view is that what younger people may view as slow behavior, confusing speech patterns, and physical frailty don’t hinder the tasks that are before the elderly. On the contrary, they assist the fulfillment of their developmental agendas to feel in control when they’re losing control and to let go enough to reveal the legacy that will survive after they go.

Research on the aging brain indicates that changes in brain chemistry facilitate the life-review process.1,6 In general, reflection is the normal mode of existence for elderly adults and their primary focus. Thus, viewing them as diminished because they communicate differently than younger people do is doing them a disservice.

Those slowed mental processes, Dr. Chittenden concurs, “are conducive to reflection. Someone younger will pathologize it. … I agree that we don’t value the slowing down process, but I also think that when this population is in the hospital we are tending to look at loss of functional status or the quick mental traits that we value as opposed to [that which is] adaptive [and] that enables them to look at things differently and reflect.”

The key to connecting the dots of where they are and where they need to be (both medically and psychosocially), as well as how they occur to their providers and their families as opposed to how they occur to themselves, is to listen to and speak with them by making use of what you know about this stage of their life as it affects their communication. You can do this, says Solie, by invoking the “access code,” which is “to clearly understand that at the top of their agenda—no matter what else is happening—is the need for control and the need to develop and go after a legacy, and that means life review. If you know that, you will never lose your reference point with them.”

Communication Habits of the Elderly

Solie identifies some verbal behaviors that are common in older people. In many cases these behaviors may reveal something between the lines.

- Lack of urgency. Older people need more time to decide things. Accept that slower pace as normal. Don’t take it personally. Adjust your schedule to allow time to deliver news or ask for choices and then allow time for them to discuss with their families or contemplate on their own; return to them at a later time. Become expert at spontaneous facilitation. Use your access code to get their attention and gain their trust.

- Nonlinear conversations. Although older patients may appear to wander off topic, they may do so in the urge to ground themselves in what their priorities are, what their feelings are, what their choices will be. Signal you’re willing to listen and that you’re tuned in to the content, even if you don’t know where it is leading. (Obviously, someone who is demented or delirious presents a different scenario altogether, and depression is common and frequently overlooked.) Listen for patterns and themes. Nonlinear conversations can lead to spontaneous revelations and great insights for your patients and for yourself and can help patients revisit life dramas that test and clarify values. This, too, is a part of healthcare.

- Repetition and attention to details. In situations when dementia is ruled out, a patient’s repetition may indicate a means to emphasize an important point or value. Keep in mind, too, that as we age, we all repeat stories to some degree. Details in stories may be the means by which older adults connect to their pasts and may also serve as clues to what is important to these people. Don’t assume details demand any action on your part. You are only being asked to listen as the older person sorts things out.

- Uncoupling. Solie describes uncoupling as any time an older person appears to disconnect from you in the course of a conversation. For a professional, this can feel as if you are dismissed or ignored just when you think you’ve hit the mark with a comment or question. Go back and assess the information you’ve gathered by doing some verification. Rethink the objective: Any action that works against their maintaining control and discovering a legacy will produce uncoupling.

“I try to be aware of when I’m losing people,” says Dr. Chittenden of this phenomenon. “I would say, ‘I seem to be losing you and I’m wondering what you’re thinking right now.’ I would try to find out where they’re at and if it was something I said that didn’t gel with them, didn’t make sense to them, or wasn’t their priority.” This is something, she emphasizes, that a hospitalist needs to watch for with patients of all ages. “Whether you’re older or younger,” she says, the communication can be complicated because “you’re … in the hospital culture and the priorities of doctors are so often different from the priorities of patients.”

Conclusion

Older and especially old-old individuals in some ways live in an era other than the one traversed by the young and middle-aged.6 Their purposes, agendas, and mission are different and the slowing down of their functioning can facilitate their attempts to put their lives into perspective and manage what control they can still exercise or are still allowed. Viewing older patients with the utmost respect and acknowledging the challenges they face at these last phases of their lives can better help you to partner with them and their families in their care. TH

Andrea Sattinger also writes about the importance of apology in this issue.

References

- Solie D. How to Say it to Seniors: Closing the Communication Gap with Our Elders. New York: Prentice Hall Press; 2004.

- Chochinov HM, Cann BJ. Interventions to enhance the spiritual aspects of dying. J Palliat Med. 2005;8:Suppl 1:S103-115.

- Dennis KE. Patients' control and the information imperative: clarification and confirmation. Nurs Res. 1990;39(3):162-166.

- Kiesler DJ, Auerbach SM. Integrating measurement of control and affiliation in studies of physician-patient interaction: the interpersonal circumplex. Soc Sci Med. 2003;57(9):1707-1722.

- Breemhaar B, Visser AP, Kleijnen JG. Perceptions and behaviour among elderly hospital patients: description and explanation of age differences in satisfaction, knowledge, emotions and behaviour. Soc Sci Med. 1990;31(12):1377-1385.

- Pipher M. Another Country: Navigating the Emotional Terrain of Our Elders. New York: Riverhead Books; 1999.

- Barnett PB. Rapport and the hospitalist. Am J Med. 2001;111:31S-35S.

When an elderly person is admitted to the hospital, Adrienne Green, MD, sees an opportunity for something beyond addressing the medical issues at hand.

“One of the key issues that is important for practical, everyday care is trying to figure out how the elderly are not functioning well at home,” says Dr. Green, an associate clinical professor of medicine at the University of California at San Francisco and a member of UCSF’s hospitalist group. “I think we do a great job of managing their diseases, but what we don’t do very well is helping them out with other things [such as coping with] their losses and the fact that they may be just barely hanging on at home in terms of their ability to care for themselves; and this hospitalization may really have set them back.”

Eva Chittenden, MD, an assistant clinical professor of medicine, also at UCSF, agrees. “Many hospitalists are so focused on the hospital that they’re not thinking about the ‘before the hospital’ and the ‘after the hospital,’” she says.

But after identifying the challenges that elderly patients face, communication itself may be challenging. Elderly individuals struggle with issues of control and allowing people to tell them what they need to change in their lives may not be an easy task. What are the best ways to communicate with hospitalized elderly patients to facilitate the best “whole-person” care?

—David Solie, MS, PA

Under the Radar Screen

The hospitalists interviewed for this article agreed that getting a broader picture of an elderly patient’s health and well-being involves discovering how they are really doing at home. Dr. Green asks simple questions, particularly about activities of daily living, such as whether they’re doing their own shopping and cooking. She also involves the family, “because very frequently the patient will say, ‘I’m doing fine,’ and the family member is in the background shaking their head.”

She also looks for clues about whether the patient needs more help at home, whether they are compliant with their medications, and if not, why (e.g., can they open their medicine bottles)?

“I frequently have the elderly patients evaluated for home care just to get someone into their house … ,” says Dr. Green. “I think that probably 80% of our patients who are over 80 who come into the hospital have things in their homes that are not safe, such as throw rugs.” Even if patients are basically doing OK, “if I can get some home care for them, I know we’ll uncover a ton [of things that can be improved],” she says. “These patients may have … kind of snuck under the radar screen of their families and their primary [care physician], and I think the hospitalization kind of opens that up in some ways.”

Facing Resistance

Even if issues are uncovered by means of interviews and home-health visits, however, many elderly patients present a particular communication challenge. This, says David Solie, MS, PA, author of How to Say It to Seniors: Closing the Communication Gap with Our Elders, is because of the difference in circumstances and current experiences between the elderly and their hospitalist providers.1 It is common knowledge that younger people go through stages of development, but the elderly do, too, says Solie, who is medical director and CEO of Second Opinion Insurance Services in Woodland Hills, Calif., a brokerage that specializes in the insurance needs of impaired-risk, elderly individuals.

The last human developmental stage compels elderly adults to work hard at maintaining control over their lives in the face of almost daily losses. A big part of the losses they experience involve their health and functioning, and the ways different patients cope with loss and the perceived stresses of healthcare have been analyzed and categorized.2-5

But in addition to loss of control, the elderly also face the daunting task of discovering what their legacy will be—what will live on after they die. “The way our elders communicate contains clues to the urgency they feel in trying to resolve these items on their agendas,” writes Solie. “In almost every conversation with older adults, control and legacy issues rise to the surface.”

A Matter of Loss

By the time a person is old (over 70) or old-old (over 85) their losses may have manifested in many areas: They’ve lost:

- Parents;

- Other relatives—perhaps including children;

- Friends;

- Places of residence (both homes and the familiarity of cities or towns);

- Possessions;

- Other relationships (sometimes other healthcare providers);

- Careers;

- Consultative authority (“ours is not a culture that values the wisdom of our elders,” writes Solie);

- Identity;

- Financial independence;

- Habits and pleasures;

- Physical space (the room at their son or daughter’s or in assisted living or the nursing home can’t compare to the homes, gardens, and expanses of view they may have had as younger people), and, of course; and

- Physical and mental capacities.

Sometimes the losses elders sustain occur in rapid-fire sequence, with little or no recovery time in between.1,6

It is no wonder that older adults, in one way or another, exhibit what we consider resistance to their changing lives. In terms of a hospitalization, this may mean saying “no” to medications, individual providers, tests, surgery, home-health visits, or something as small as being talked to or touched in what they perceive as a disturbing, overly familiar, or mechanized manner.

“Many patients are resistant to having people come into their homes and help them, and at the same time they are resistant to going to a skilled nursing care facility,” says Dr. Green, “and it has to do with their [feelings of the] loss of independence and control over their lives.”

“It’s very easy if you’re in medicine to normalize your context of the hospital,” says Solie. “In other words, the hospital seems familiar to you and you’re very comfortable moving around there, and mainly because you’re in control. You’re the doctor … and you move in the hospital in order to make things happen and you never feel all that threatened. But when you bring an older person who already has a heightened sensitivity toward losing control into the hospital—this complex, technological world of medicine—and they have the cumulative disadvantage of being sick,” says Solie, “it’s really important to remember that there will probably be no other state that they’ll be in, except maybe nursing home care, where they will feel so out of control.”

A good first step in communicating with older patients is to quickly develop a rapport with them and show them you recognize what they’re up against.7 “They really want to know whether or not I get it,” says Solie.

The way you communicate that you get it, he says, is fairly straightforward: When I’m first interacting with the patient, I say, “if you are like my [other] elderly patients … I’m sure you’re feeling a lot of anxiety over [not having much] control and, first of all, I want to assure you that I’m going to make sure you understand the choices and help you make all the decisions. And … I’m definitely going to … put everything in a language that you understand. But if I’m not successful, I’m going to employ someone from your family. We’re going to work together. Even though you’re hospitalized and even though you’re fighting this illness (or whatever the condition might be), you still [have] the right to make choices, and my goal is to partner with you. My expertise is medicine, but you have an expertise in your life.”

In other words, you are signaling that you recognize that control is the issue. Acknowledge the loss, ask about the value of the event or decision to the patient, ask what you can do to help them deal with their feelings or make up their minds. It also allows you to remind an older patient’s children that control is a big and normal concern for their mother or father.

—Eva Chittenden, MD

Hospitalists at a Different Time and Place

The elderly desperately need people who can serve them as natural healers, who are not constantly in a hurry, and who care what they are thinking and feeling. How can hospitalists relate to those who are in the midst of life review and who are hanging on to an escaping control? How can they serve their patients in a way that meets all needs?

Fighting—with denial or ignorance—the resistance that patients might put up will more than likely provoke them. A fight for control can undermine and sabotage the best intentions of the provider and the greatest wishes for the patient to experience comfort or regain health and well-being. Rather than justifying wresting control from elderly patients because it’s for their own good, advises Solie, what we must do instead is to “step back, hand them the control baton, and allow them to run with it.”1

A person’s admission to the hospital “might be such a huge crisis for them, whereas for us it’s our routine work,” says Dr. Chittenden, who practices as a hospitalist and also works on her institution’s inpatient palliative care service. “And many people who are hospitalists—who are even in their late 20s, 30s, 40s—have been totally healthy their whole life, so it is hard to relate to what it’s like to be older and to be losing function, losing friends who are also dying, losing their house … . I think that it can be very helpful for the hospitalist to take a little more time and explore some of those issues [of loss and legacy]. I try to meet the person where they’re at and try to understand what their goals, needs, ... and fears are [as well as] their functional status.”

Allowing older patients to engage with you about their lives and their pasts is a privilege for any healthcare provider. Engaging with them in a way that will help facilitate their loosening the reins on control may expedite and allow greater quality into their healthcare. It may provide an opening whereby you can order that home-health visit with less struggle.

Create Openings

“There are a lot of different ‘on-ramps’ to asking the life-review questions, which are extremely comforting,” says Solie. “For example, you might say, ‘Mary, I notice that you were born in Iowa. You know, my family on my father’s side came from Iowa. Where were you raised?’ And ‘Do you have a big family on your farm, because my aunt had cows.’”

Once you get a response that engages the patient, then you “are in the slipstream. Physicians have such a high experience curve, they see so many patients,” he says. “They don’t have to go very far into their inventory of experiences [to find one] that essentially matches up with that patient.”

Any kind of comment that will key you in to their background experience can help establish some kind of foundation for relationship. Another example: “You know, Mary, I was working with this woman who was about your age and she was raised in the Midwest and was dealing with some of these issues of congestive heart failure, and one of her big concerns was something that I didn’t appreciate until I understood what an impact it was having on her life.”

This kind of communication, says Solie, can help to relieve some of the patient’s control anxieties, “because she feels that if I ‘get it,’ she’s open to what I have to say, such as, ‘The first thing, we have to deal with is there is too much fluid going on in your body and it’s putting a big strain on your heart, so the first couple days all we did for that [other] woman was try to pull some fluid off and keep everything in balance.’”

You’ve communicated that you have a plan, that you can be trusted, and that you will help her to exercise as much control as possible. Creating and accessing those openings is also “the ideal way to weave the family into this whole life-review process, which is where the patient lives, psychologically and emotionally, when outside the hospital environment,” he says. “We become so myopic when we’re caught in the hospital environment that the world becomes a narrow tunnel and we forget the greater matrix outside that we’re all connected to.”

The Boon of Biology

Whereas the physiology and anatomy of humans deteriorate with time, some of the changes in mental processes in old age may actually enhance the ability to reflect and make informed judgments. Solie’s view is that what younger people may view as slow behavior, confusing speech patterns, and physical frailty don’t hinder the tasks that are before the elderly. On the contrary, they assist the fulfillment of their developmental agendas to feel in control when they’re losing control and to let go enough to reveal the legacy that will survive after they go.

Research on the aging brain indicates that changes in brain chemistry facilitate the life-review process.1,6 In general, reflection is the normal mode of existence for elderly adults and their primary focus. Thus, viewing them as diminished because they communicate differently than younger people do is doing them a disservice.

Those slowed mental processes, Dr. Chittenden concurs, “are conducive to reflection. Someone younger will pathologize it. … I agree that we don’t value the slowing down process, but I also think that when this population is in the hospital we are tending to look at loss of functional status or the quick mental traits that we value as opposed to [that which is] adaptive [and] that enables them to look at things differently and reflect.”

The key to connecting the dots of where they are and where they need to be (both medically and psychosocially), as well as how they occur to their providers and their families as opposed to how they occur to themselves, is to listen to and speak with them by making use of what you know about this stage of their life as it affects their communication. You can do this, says Solie, by invoking the “access code,” which is “to clearly understand that at the top of their agenda—no matter what else is happening—is the need for control and the need to develop and go after a legacy, and that means life review. If you know that, you will never lose your reference point with them.”

Communication Habits of the Elderly

Solie identifies some verbal behaviors that are common in older people. In many cases these behaviors may reveal something between the lines.

- Lack of urgency. Older people need more time to decide things. Accept that slower pace as normal. Don’t take it personally. Adjust your schedule to allow time to deliver news or ask for choices and then allow time for them to discuss with their families or contemplate on their own; return to them at a later time. Become expert at spontaneous facilitation. Use your access code to get their attention and gain their trust.

- Nonlinear conversations. Although older patients may appear to wander off topic, they may do so in the urge to ground themselves in what their priorities are, what their feelings are, what their choices will be. Signal you’re willing to listen and that you’re tuned in to the content, even if you don’t know where it is leading. (Obviously, someone who is demented or delirious presents a different scenario altogether, and depression is common and frequently overlooked.) Listen for patterns and themes. Nonlinear conversations can lead to spontaneous revelations and great insights for your patients and for yourself and can help patients revisit life dramas that test and clarify values. This, too, is a part of healthcare.

- Repetition and attention to details. In situations when dementia is ruled out, a patient’s repetition may indicate a means to emphasize an important point or value. Keep in mind, too, that as we age, we all repeat stories to some degree. Details in stories may be the means by which older adults connect to their pasts and may also serve as clues to what is important to these people. Don’t assume details demand any action on your part. You are only being asked to listen as the older person sorts things out.

- Uncoupling. Solie describes uncoupling as any time an older person appears to disconnect from you in the course of a conversation. For a professional, this can feel as if you are dismissed or ignored just when you think you’ve hit the mark with a comment or question. Go back and assess the information you’ve gathered by doing some verification. Rethink the objective: Any action that works against their maintaining control and discovering a legacy will produce uncoupling.

“I try to be aware of when I’m losing people,” says Dr. Chittenden of this phenomenon. “I would say, ‘I seem to be losing you and I’m wondering what you’re thinking right now.’ I would try to find out where they’re at and if it was something I said that didn’t gel with them, didn’t make sense to them, or wasn’t their priority.” This is something, she emphasizes, that a hospitalist needs to watch for with patients of all ages. “Whether you’re older or younger,” she says, the communication can be complicated because “you’re … in the hospital culture and the priorities of doctors are so often different from the priorities of patients.”

Conclusion

Older and especially old-old individuals in some ways live in an era other than the one traversed by the young and middle-aged.6 Their purposes, agendas, and mission are different and the slowing down of their functioning can facilitate their attempts to put their lives into perspective and manage what control they can still exercise or are still allowed. Viewing older patients with the utmost respect and acknowledging the challenges they face at these last phases of their lives can better help you to partner with them and their families in their care. TH

Andrea Sattinger also writes about the importance of apology in this issue.

References

- Solie D. How to Say it to Seniors: Closing the Communication Gap with Our Elders. New York: Prentice Hall Press; 2004.

- Chochinov HM, Cann BJ. Interventions to enhance the spiritual aspects of dying. J Palliat Med. 2005;8:Suppl 1:S103-115.

- Dennis KE. Patients' control and the information imperative: clarification and confirmation. Nurs Res. 1990;39(3):162-166.