User login

Treatment of Community‐Acquired Pneumonia

In the United States, community‐acquired pneumonia (CAP) leads to nearly 1 million hospitalizations annually, with aggregate costs of hospitalization approaching $9 billion.1, 2 In an effort to improve the appropriate, cost‐effective care for patients with CAP, several professional societies have developed clinical practice guidelines and pathways for pneumonia.37 Although the guidelines address all aspects of care, they devote substantial attention to antibiotic recommendations. Most U.S. guidelines recommend treatment of hospitalized patients with an intravenous beta‐lactam combined with a macrolide, or a fluoroquinolone with activity against Streptococcus pneumoniae. Of the major U.S. CAP practice guidelines, only one6 recommends doxycycline as an alternative to a macrolide for inpatients.

Doxycycline is an attractive alternative to macrolides. Similar to macrolides, doxycycline is active against a wide variety of organisms including atypical bacteria (Chlamydia pneumoniae, Legionella pneumophilus, and Mycoplasma pneumoniae) and is well tolerated.810 In addition, it is inexpensive (cost of $1.00/day [awp] for 100 mg p.o. bid), and rates of tetracycline/doxycycline resistance among S. pneumoniae isolates have remained low, in contrast to the increasing rates of resistance to macrolides and fluoroquinolones.11, 12 The most recent guidelines from the Infectious Diseases Society of America cited limited published clinical data on the effectiveness of doxycycline in CAP as a barrier to increased use.7 Only one study of hospitalized patients has been published in the era of penicillin‐resistant pneumococcus, and this study included only 43 low‐risk patients treated with doxycycline.13 At the university hospital affiliated with the University of California, San Francisco, ceftriaxone plus doxycycline is generally recommended as initial empiric antibiotic therapy for patients hospitalized with CAP, but significant variability in prescribing exists, allowing for comparisons between patients treated with different initial empiric antibiotic regimens. We compared outcomes of hospitalized patients with CAP treated with ceftriaxone plus doxycycline to those of patients treated with alternative initial empiric therapy at an academic medical center.

METHODS

Study Population

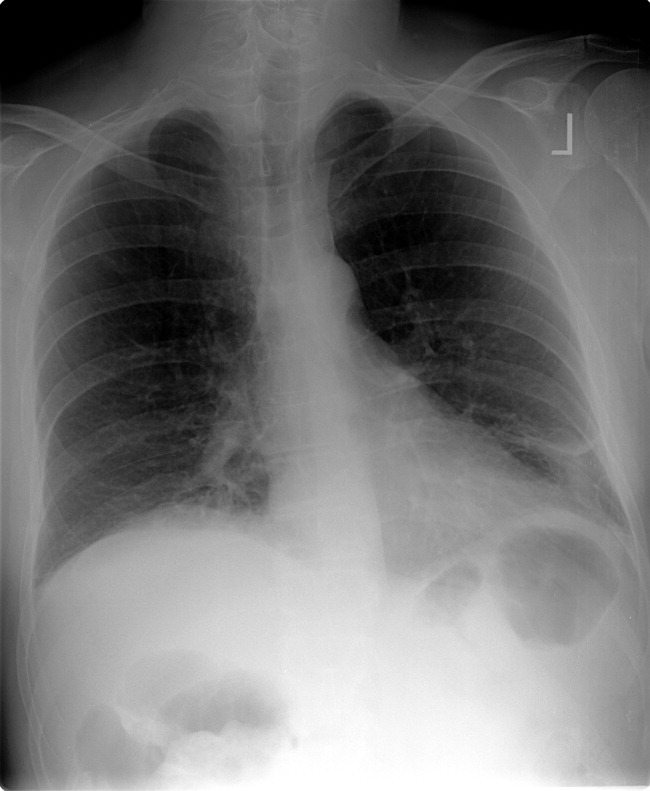

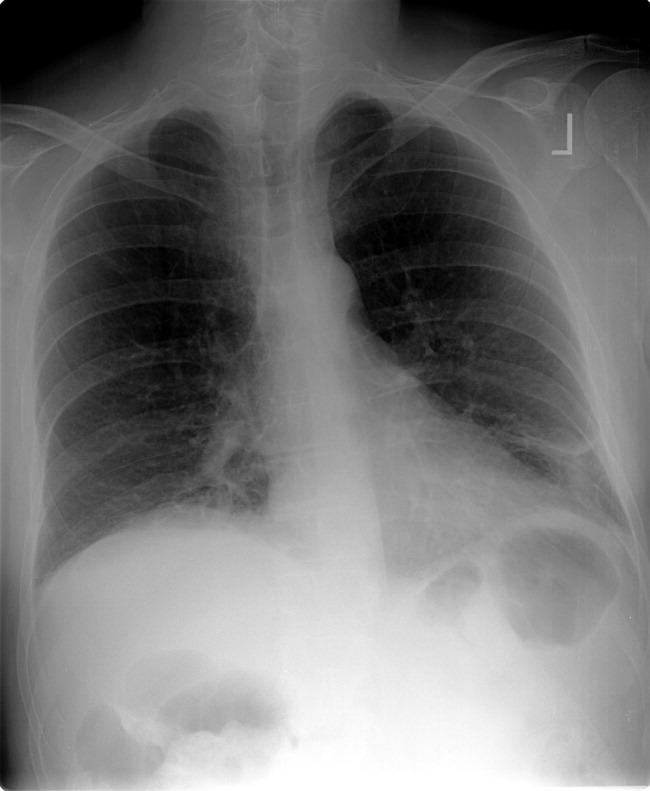

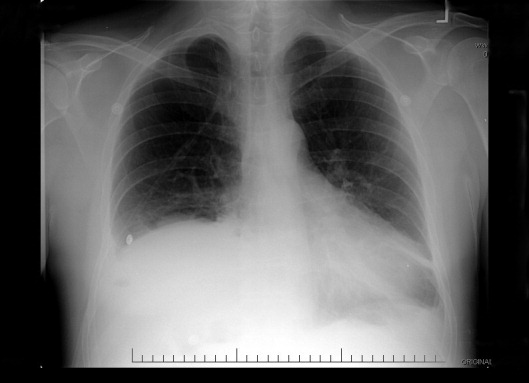

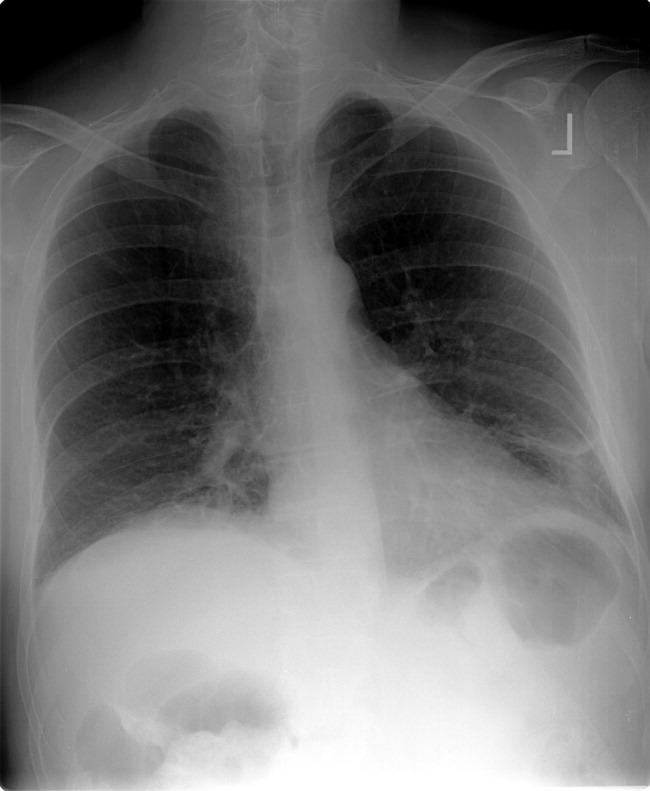

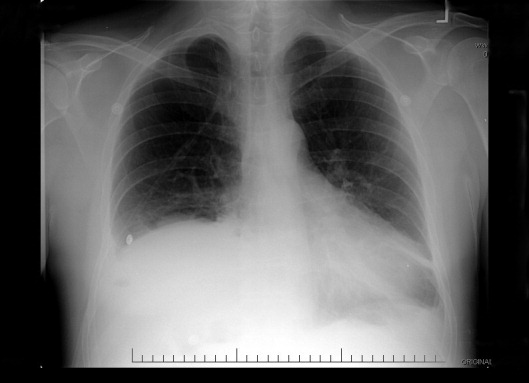

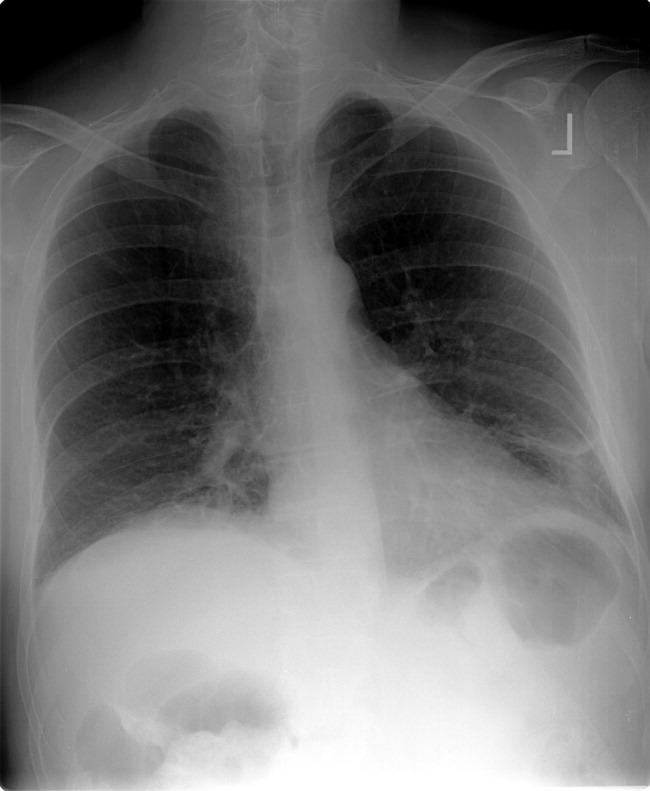

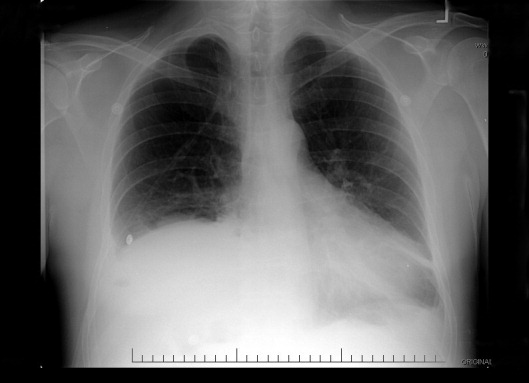

A retrospective cohort study of all adults (age 18 years) discharged from the inpatient general medicine service of Moffitt‐Long Hospital at the University of California, San Francisco, was conducted from January 1999 through July 2001. Eligibility criteria included a principal discharge diagnosis of CAP and a chest radiograph demonstrating an infiltrate within 48 hours of admission. Exclusion criteria included infection with the human immunodeficiency virus, history of organ transplantation or use of immunosuppressive therapy (including prednisone > 15 mg/day), cystic fibrosis, postobstructive pneumonia, active tuberculosis, recent hospitalization (within 10 days), or admission for comfort care. The study protocol and procedures were reviewed and approved by the UCSF Committee for Human Research.

Data Collection

Medical record review by trained research assistants blinded to the research question was used to gather demographic data, comorbid illnesses, physical examination findings on initial presentation, and laboratory or radiographic results on initial presentation. The pneumonia severity index (PSI) score was calculated for each patient using the above data.14 In addition, data were collected on antibiotic allergies, antibiotics used within the 30 days prior to admission, results of sputum or blood cultures, and admission location (intensive care unit [ICU] versus medical floor).

Data from TSI (Transition Systems Inc., Boston, MA), the hospital administrative database, were used to identify the initial empiric antibiotic regimen. All antibiotics prescribed within the first 48 hours of hospitalization were considered initial empiric therapy with few exceptions. Initial empiric therapy was classified as 1) ceftriaxone plus doxycycline (including patients treated with these agents alone in the first 48 hours, as well as patients treated with both agents in the first 24 hours who were switched to alternative therapy [broader coverage] on the second day), or 2) other appropriate therapy (treatment consistent with current national guideline recommendations including at least a beta‐lactam plus a macrolide or a beta‐lactam plus a fluoroquinolone, or fluoroquinolone monotherapy). Patients receiving therapy inconsistent with current national guideline recommendations were excluded.

Outcomes

TSI data were used to identify length of stay, death during the index hospitalization, and return to the emergency department or readmission within 30 days of discharge. The National Death Index was used to identify all deaths that occurred after hospital discharge. The 30‐day mortality data included deaths occurring during the index hospitalization and in the 30 days after the index hospitalization discharge.

Statistical Analysis

For the purposes of this analysis we compared patients treated with ceftriaxone plus doxycycline to patients treated with other appropriate therapy. To examine demographic and clinical differences between the two groups, statistical tests of comparison were performed using chi‐square tests for the dichotomous variables and t tests for the numeric variables, all of which were normally distributed (after log transformation in the case of length of stay).

To adjust for clinical variables that might contribute to differences in outcomes between the two groups, we used backward stepwise logistic regression analysis to construct a propensity score15 for the likelihood of ceftriaxone plus doxycycline use. The propensity score reflected the conditional probability of exposure to ceftriaxone plus doxycycline and allowed for stratification and, subsequently, comparisons by quintiles of propensity score. Propensity scores often have distinct advantages over direct adjustment for a large number of confounding variables and allow direct comparisons between groups with a similar propensity for receiving ceftriaxone plus doxycycline.15 Unlike random assignment of treatment, however, the propensity score cannot balance unmeasured variables that may affect treatment assignment. Thus, the possibility of bias remains. The variables used to build the score included age, presence of comorbid illness, admission from a nursing home or long‐term care facility, antibiotic allergy, prior antibiotic use, PSI score, PSI risk class, diagnosis of aspiration, admission to the ICU, and positive blood cultures. The propensity score was then stratified and used as an adjustment variable in comparisons between groups for in‐hospital mortality, 30‐day mortality, and 30‐day readmission rates. As expected, length of stay was highly skewed and was therefore log‐transformed and compared between groups with adjustment for the propensity score.

To further address issues related to potential selection bias, a separate analysis was performed on a subset of the original cohort that excluded patients for whom ceftriaxone plus doxycycline would not generally be recommended as first‐line therapy. For this analysis, patients admitted from a nursing home or long‐term care facility, patients admitted to the ICU, and patients with a principal diagnosis of aspiration pneumonia were excluded. A propensity score was rederived for this subset, which was used to adjust for differences in outcomes. All statistical procedures were performed using STATA (Ver. 7.0, Stata Corporation, College Station TX).

RESULTS

Patient Characteristics

A total of 341 patients were eligible for analysis. Of this group, 216 were treated with ceftriaxone plus doxycycline and 125 received other appropriate therapy. Both groups of patients were similar in age. Patients treated with ceftriaxone plus doxycycline had a lower median PSI score and fewer comorbid illnesses than did patients treated with other appropriate therapy (Table 1). Blood cultures were positive in 30 (8.8%) of the 341 patients included in the analysis, with S. pneumoniae the most commonly isolated organism (n = 17, 5.0%). Of S. pneumoniae isolates, 4 (24%) were resistant to penicillin (MIC 1 g/mL), and 2 (12%) were resistant to tetracycline (MIC 8 g/mL).

| Ceftriaxone/doxycycline | Other appropriate therapy | |

|---|---|---|

| ||

| Patients (n) | 216 | 125 |

| Age (median) | 76 | 74 |

| PSI Score (median)a | 97 | 108 |

| PSI Risk Class (%)a | ||

| Class I | 9.3 | 5.6 |

| Class II | 11.1 | 8.8 |

| Class III | 21.8 | 13.6 |

| Class IV | 40.7 | 40.0 |

| Class V | 17.1 | 32.0 |

| Comorbid Illness (%)a | 36.1 | 47.2 |

| Nursing Home/LCF (%)a | 5.1 | 14.4 |

| Aspiration (%)a | 3.2 | 20.0 |

| Admission to ICU (%)a | 6.0 | 28.0 |

Common antibiotic choices in patients receiving other appropriate therapy included a beta‐lactam/beta‐lactamase inhibitor plus doxycycline or a macrolide (n = 36, 29%), fluoroquinolone monotherapy (n = 16, 13%), and a variety of other antibiotic combinations with activity against S. pneumoniae and atypical bacteria (n = 52, 42%).

Clinical Outcomes

Analyses of unadjusted outcomes showed that patients treated with ceftriaxone plus doxycycline had significantly lower inpatient (2% vs. 14%, P < .001) and 30‐day (6% vs. 20%, P < .001) mortality compared to patients treated with other regimens (Table 2). Multivariable logistic regression analysis identified three variables (diagnosis of congestive heart failure, admission to the ICU, and the presence of comorbid illness) associated with initial antibiotic selection, which were used to build a propensity score. After adjustment for the propensity score, use of ceftriaxone plus doxycycline remained significantly associated with lower inpatient mortality (OR = 0.26, 95% CI: 0.080.81) and 30‐day mortality (OR = 0.37, 95% CI: 0.170.81). Differences in length of stay and 30‐day readmission rates between the treatment groups were not significant (Table 2).

| Ceftriaxone + doxycycline (n = 216) | Other appropriate therapy (n = 125) | Adjusted odds ratio (95% confidence interval) | |

|---|---|---|---|

| |||

| Inpatient Mortality | 2.3% | 14.4% | 0.26 (0.080.81) |

| 30‐day mortality | 6.0% | 20.0% | 0.37 (0.170.81) |

| Length of stay (median days) | 3.0 | 4.0 | 0.09 (0.250.06)a |

| 30‐day readmission | 10.7% | 12.0% | 0.87 (0.421.81) |

Subset Analysis

To address issues related to selection bias, we performed an analysis of a subset of the patients after excluding those admitted from a nursing home, diagnosed with aspiration, or admitted to the ICU, for whom ceftriaxone plus doxycycline would not be considered recommended (or first‐line) therapy. The two resulting groups were similar, except there were fewer patients with comorbid illness in the ceftriaxone plus doxycycline group (34% vs. 50%, P = .015). The propensity score was rederived for this subset and used for adjustment. Unadjusted and adjusted outcomes are shown in Table 3. Use of ceftriaxone plus doxycycline in this subset also was associated with reduced odds of inpatient mortality (OR = 0.17, 95% CI: 0.040.77). The odds of 30‐day mortality also were reduced but not significantly, as the confidence interval included 1.0 (OR = 0.43, 95% CI: 0.141.31). There were no differences between groups in length of stay or in 30‐day readmission rate.

| Ceftriaxone + doxycycline (n = 188) | Other appropriate therapy (n = 70) | Adjusted odds ratio (95% CI) | |

|---|---|---|---|

| |||

| Age (median years) | 75 | 71 | |

| PSI score (mean) | 95 | 98 | |

| Comorbid illness (%)a | 33.5 | 50.0 | |

| Inpatient mortality | 1.6% | 7.1% | 0.17 (0.040.77) |

| 30‐day mortality | 4.8% | 8.6% | 0.43 (0.141.31) |

| LOS (median days) | 3 | 3 | 0.06 (0.240.12)b |

| 30‐day readmission | 11.9% | 10.0% | 1.31 (0.523.28) |

DISCUSSION

In our hospital setting, the use of ceftriaxone plus doxycycline as the initial empiric antibiotic therapy for patients hospitalized with community‐acquired pneumonia was associated with significantly lower inpatient and 30‐day mortality, even after adjusting for clinical differences between groups. We did not find a difference between regimens in hospital length of stay or 30‐day readmission rate. In case the multivariable model was insufficient to account for the clinical differences (i.e., selection bias) between groups, we also performed an analysis of a subgroup of less severely ill patients by excluding those admitted from nursing homes, those admitted to the intensive care unit, and those with aspiration pneumonia. In this subset, use of ceftriaxone plus doxycycline remained associated with lower inpatient mortality but not with lower 30‐day mortality. Although, as an observational study, the results of our findings could still be a result of residual confounding, we believe the results provide valuable information regarding doxycycline.

Combination therapy with a macrolide, but not doxycycline, is advocated by the practice guidelines of several major U.S. professional societies,3, 4, 7 apparently because of a lack of data on the effectiveness of combination therapy with doxycycline.7 Only one randomized, unblinded study, in 87 low‐risk patients hospitalized with CAP, that compared monotherapy with IV doxycycline versus physician‐determined therapy has been conducted.13 This study found no differences between treatment groups in clinical outcomes but did find that use of doxycycline was associated with shorter hospital stays and reduced costs. Our results, achieved in a real‐world setting in relatively ill hospitalized patients (58% were in PSI risk class IV or V), provide further support for the use of combination therapy with doxycycline.

Hospitalized patients treated with a beta‐lactam in combination with a macrolide are often discharged on macrolide monotherapy. In our population most patients treated with ceftriaxone plus doxycycline were discharged on doxycycline if they required continued therapy (data not shown). In the current era of resistance of Streptococcus pneumoniae to antibiotics, there is good reason to believe doxycycline may perform as well, if not better, than macrolides when hospitalized patients with CAP are discharged on oral monotherapy. Macrolide resistance rates among invasive pneumococcal isolates in the United States doubled from 10% to 20% during a period in which prescriptions for macrolides increased by 13%.12 In addition, a large surveillance study of more than 1500 isolates collected in 1999 and 2000 found that 26% of the isolates were resistant to macrolides, whereas only 16% were resistant to tetracycline.16 In vitro testing against S. Pneumoniae has also suggested that tetracycline resistance overestimates doxycycline resistance.17, 18 More recently, Streptococcus pneumoniae susceptibility data from the SENTRY Antimicrobial Surveillance program reaffirmed doxycycline's in vitro superiority over macrolides.17

Our study had several limitations. The study design adopted precluded determining whether favorable results with the use of ceftriaxone plus doxycycline resulted from an effect unique to this combination of antibiotics, the possible anti‐inflammatory properties of doxycycline alone,19, 20 or unmeasured confounders. For example, processes of care that affect clinical outcomes for patients hospitalized with CAP, such as the timing of antibiotic delivery, the timing of blood cultures, and stability assessment on discharge were not measured in this study. To affect outcomes, these processes of care would need to be differentially distributed between our comparison groups. However, because this study was performed in a single institution during a single interval, it is likely that the performance of these processes of care would be similar for all patients.

In conclusion, ceftriaxone plus doxycycline appears to be an effective, and possibly superior, therapy for patients hospitalized with CAP. Randomized controlled trials of doxycycline‐containing regimens versus other regimens are warranted.

- ,,, et al.Hospitalized pneumonia. Outcomes, treatment patterns, and costs in urban and rural areas.J Gen Intern Med.1996;11:415–421.

- ,,, et al.The cost of treating community‐acquired pneumonia.Clin Ther.1998;20:820–837.

- ,,, et al.Practice guidelines for the management of community‐acquired pneumonia in adults. Infectious Diseases Society of America.Clin Infect Dis.2000;31:347–382.

- ,,, et al.Management of community‐acquired pneumonia in the era of pneumococcal resistance: a report from the Drug‐Resistant Streptococcus pneumoniae Therapeutic Working Group.Arch Intern Med.2000;160:1399–1408.

- ,,, et al.Canadian guidelines for the initial management of community‐acquired pneumonia: an evidence‐based update by the Canadian Infectious Diseases Society and the Canadian Thoracic Society. The Canadian Community‐Acquired Pneumonia Working Group.Clin Infect Dis.2000;31:383–421.

- ,,, et al.Guidelines for the management of adults with community‐acquired pneumonia. Diagnosis, assessment of severity, antimicrobial therapy, and prevention.Am J Respir Crit Care Med.2001;163:1730–1754.

- ,,, et al.Update of practice guidelines for the management of community‐acquired pneumonia in immunocompetent adults.Clin Infect Dis.2003;37:1405–1433

- ,,.Doxycycline.Ther Drug Monit1982;4:115–135

- ,.Chloramphenicol and tetracyclines.Med Clin North Am.1987;71:1155–1168

- ,.Tetracyclines.Med Clin North Am.1995;79:789–801

- ,,, et al.Antibiotic resistance among gram‐negative bacilli in US intensive care units: implications for fluoroquinolone use.JAMA.2003;289:885–888

- ,,, et al.Macrolide resistance among invasive Streptococcus pneumoniae isolates.JAMA.2001;286:1857–1862.

- ,,, et al.Doxycycline is a cost‐effective therapy for hospitalized patients with community‐acquired pneumonia.Arch Intern Med.1999;159:266–270.

- ,,, et al.A prediction rule to identify low‐risk patients with community‐acquired pneumonia.N Engl J Med.1997;336:243–250.

- .Reducing bias in observational studies using subclassification on the propensity score.J Am Stat Assoc.1984;79:516–524

- ,,, et al.Antimicrobial resistance among clinical isolates of Streptococcus pneumoniae in the United States during 1999—2000, including a comparison of resistance rates since 1994—1995.Antimicrob Agents Chemother.2001;45:1721–1729

- ,,.Doxycycline use for community‐acquired pneumonia: contemporary in vitro spectrum of activity against Streptococcus pneumoniae (1999–2002).Diagn Microbiol Infect Dis.2004;49:147–149

- ,,, et al.Doxycycline activity against Streptococcus pneumoniae.Chest.1995;108:1775–1776.

- ,,, et al.Inhibition of enzymatic activity of phospholipases A2 by minocycline and doxycycline.Biochem Pharmacol.1992;44:1165–1170.

- ,,, et al.Doxycycline reduces mortality to lethal endotoxemia by reducing nitric oxide synthesis via an interleukin‐10‐independent mechanism.J Infect Dis.1998;177:489–492.

In the United States, community‐acquired pneumonia (CAP) leads to nearly 1 million hospitalizations annually, with aggregate costs of hospitalization approaching $9 billion.1, 2 In an effort to improve the appropriate, cost‐effective care for patients with CAP, several professional societies have developed clinical practice guidelines and pathways for pneumonia.37 Although the guidelines address all aspects of care, they devote substantial attention to antibiotic recommendations. Most U.S. guidelines recommend treatment of hospitalized patients with an intravenous beta‐lactam combined with a macrolide, or a fluoroquinolone with activity against Streptococcus pneumoniae. Of the major U.S. CAP practice guidelines, only one6 recommends doxycycline as an alternative to a macrolide for inpatients.

Doxycycline is an attractive alternative to macrolides. Similar to macrolides, doxycycline is active against a wide variety of organisms including atypical bacteria (Chlamydia pneumoniae, Legionella pneumophilus, and Mycoplasma pneumoniae) and is well tolerated.810 In addition, it is inexpensive (cost of $1.00/day [awp] for 100 mg p.o. bid), and rates of tetracycline/doxycycline resistance among S. pneumoniae isolates have remained low, in contrast to the increasing rates of resistance to macrolides and fluoroquinolones.11, 12 The most recent guidelines from the Infectious Diseases Society of America cited limited published clinical data on the effectiveness of doxycycline in CAP as a barrier to increased use.7 Only one study of hospitalized patients has been published in the era of penicillin‐resistant pneumococcus, and this study included only 43 low‐risk patients treated with doxycycline.13 At the university hospital affiliated with the University of California, San Francisco, ceftriaxone plus doxycycline is generally recommended as initial empiric antibiotic therapy for patients hospitalized with CAP, but significant variability in prescribing exists, allowing for comparisons between patients treated with different initial empiric antibiotic regimens. We compared outcomes of hospitalized patients with CAP treated with ceftriaxone plus doxycycline to those of patients treated with alternative initial empiric therapy at an academic medical center.

METHODS

Study Population

A retrospective cohort study of all adults (age 18 years) discharged from the inpatient general medicine service of Moffitt‐Long Hospital at the University of California, San Francisco, was conducted from January 1999 through July 2001. Eligibility criteria included a principal discharge diagnosis of CAP and a chest radiograph demonstrating an infiltrate within 48 hours of admission. Exclusion criteria included infection with the human immunodeficiency virus, history of organ transplantation or use of immunosuppressive therapy (including prednisone > 15 mg/day), cystic fibrosis, postobstructive pneumonia, active tuberculosis, recent hospitalization (within 10 days), or admission for comfort care. The study protocol and procedures were reviewed and approved by the UCSF Committee for Human Research.

Data Collection

Medical record review by trained research assistants blinded to the research question was used to gather demographic data, comorbid illnesses, physical examination findings on initial presentation, and laboratory or radiographic results on initial presentation. The pneumonia severity index (PSI) score was calculated for each patient using the above data.14 In addition, data were collected on antibiotic allergies, antibiotics used within the 30 days prior to admission, results of sputum or blood cultures, and admission location (intensive care unit [ICU] versus medical floor).

Data from TSI (Transition Systems Inc., Boston, MA), the hospital administrative database, were used to identify the initial empiric antibiotic regimen. All antibiotics prescribed within the first 48 hours of hospitalization were considered initial empiric therapy with few exceptions. Initial empiric therapy was classified as 1) ceftriaxone plus doxycycline (including patients treated with these agents alone in the first 48 hours, as well as patients treated with both agents in the first 24 hours who were switched to alternative therapy [broader coverage] on the second day), or 2) other appropriate therapy (treatment consistent with current national guideline recommendations including at least a beta‐lactam plus a macrolide or a beta‐lactam plus a fluoroquinolone, or fluoroquinolone monotherapy). Patients receiving therapy inconsistent with current national guideline recommendations were excluded.

Outcomes

TSI data were used to identify length of stay, death during the index hospitalization, and return to the emergency department or readmission within 30 days of discharge. The National Death Index was used to identify all deaths that occurred after hospital discharge. The 30‐day mortality data included deaths occurring during the index hospitalization and in the 30 days after the index hospitalization discharge.

Statistical Analysis

For the purposes of this analysis we compared patients treated with ceftriaxone plus doxycycline to patients treated with other appropriate therapy. To examine demographic and clinical differences between the two groups, statistical tests of comparison were performed using chi‐square tests for the dichotomous variables and t tests for the numeric variables, all of which were normally distributed (after log transformation in the case of length of stay).

To adjust for clinical variables that might contribute to differences in outcomes between the two groups, we used backward stepwise logistic regression analysis to construct a propensity score15 for the likelihood of ceftriaxone plus doxycycline use. The propensity score reflected the conditional probability of exposure to ceftriaxone plus doxycycline and allowed for stratification and, subsequently, comparisons by quintiles of propensity score. Propensity scores often have distinct advantages over direct adjustment for a large number of confounding variables and allow direct comparisons between groups with a similar propensity for receiving ceftriaxone plus doxycycline.15 Unlike random assignment of treatment, however, the propensity score cannot balance unmeasured variables that may affect treatment assignment. Thus, the possibility of bias remains. The variables used to build the score included age, presence of comorbid illness, admission from a nursing home or long‐term care facility, antibiotic allergy, prior antibiotic use, PSI score, PSI risk class, diagnosis of aspiration, admission to the ICU, and positive blood cultures. The propensity score was then stratified and used as an adjustment variable in comparisons between groups for in‐hospital mortality, 30‐day mortality, and 30‐day readmission rates. As expected, length of stay was highly skewed and was therefore log‐transformed and compared between groups with adjustment for the propensity score.

To further address issues related to potential selection bias, a separate analysis was performed on a subset of the original cohort that excluded patients for whom ceftriaxone plus doxycycline would not generally be recommended as first‐line therapy. For this analysis, patients admitted from a nursing home or long‐term care facility, patients admitted to the ICU, and patients with a principal diagnosis of aspiration pneumonia were excluded. A propensity score was rederived for this subset, which was used to adjust for differences in outcomes. All statistical procedures were performed using STATA (Ver. 7.0, Stata Corporation, College Station TX).

RESULTS

Patient Characteristics

A total of 341 patients were eligible for analysis. Of this group, 216 were treated with ceftriaxone plus doxycycline and 125 received other appropriate therapy. Both groups of patients were similar in age. Patients treated with ceftriaxone plus doxycycline had a lower median PSI score and fewer comorbid illnesses than did patients treated with other appropriate therapy (Table 1). Blood cultures were positive in 30 (8.8%) of the 341 patients included in the analysis, with S. pneumoniae the most commonly isolated organism (n = 17, 5.0%). Of S. pneumoniae isolates, 4 (24%) were resistant to penicillin (MIC 1 g/mL), and 2 (12%) were resistant to tetracycline (MIC 8 g/mL).

| Ceftriaxone/doxycycline | Other appropriate therapy | |

|---|---|---|

| ||

| Patients (n) | 216 | 125 |

| Age (median) | 76 | 74 |

| PSI Score (median)a | 97 | 108 |

| PSI Risk Class (%)a | ||

| Class I | 9.3 | 5.6 |

| Class II | 11.1 | 8.8 |

| Class III | 21.8 | 13.6 |

| Class IV | 40.7 | 40.0 |

| Class V | 17.1 | 32.0 |

| Comorbid Illness (%)a | 36.1 | 47.2 |

| Nursing Home/LCF (%)a | 5.1 | 14.4 |

| Aspiration (%)a | 3.2 | 20.0 |

| Admission to ICU (%)a | 6.0 | 28.0 |

Common antibiotic choices in patients receiving other appropriate therapy included a beta‐lactam/beta‐lactamase inhibitor plus doxycycline or a macrolide (n = 36, 29%), fluoroquinolone monotherapy (n = 16, 13%), and a variety of other antibiotic combinations with activity against S. pneumoniae and atypical bacteria (n = 52, 42%).

Clinical Outcomes

Analyses of unadjusted outcomes showed that patients treated with ceftriaxone plus doxycycline had significantly lower inpatient (2% vs. 14%, P < .001) and 30‐day (6% vs. 20%, P < .001) mortality compared to patients treated with other regimens (Table 2). Multivariable logistic regression analysis identified three variables (diagnosis of congestive heart failure, admission to the ICU, and the presence of comorbid illness) associated with initial antibiotic selection, which were used to build a propensity score. After adjustment for the propensity score, use of ceftriaxone plus doxycycline remained significantly associated with lower inpatient mortality (OR = 0.26, 95% CI: 0.080.81) and 30‐day mortality (OR = 0.37, 95% CI: 0.170.81). Differences in length of stay and 30‐day readmission rates between the treatment groups were not significant (Table 2).

| Ceftriaxone + doxycycline (n = 216) | Other appropriate therapy (n = 125) | Adjusted odds ratio (95% confidence interval) | |

|---|---|---|---|

| |||

| Inpatient Mortality | 2.3% | 14.4% | 0.26 (0.080.81) |

| 30‐day mortality | 6.0% | 20.0% | 0.37 (0.170.81) |

| Length of stay (median days) | 3.0 | 4.0 | 0.09 (0.250.06)a |

| 30‐day readmission | 10.7% | 12.0% | 0.87 (0.421.81) |

Subset Analysis

To address issues related to selection bias, we performed an analysis of a subset of the patients after excluding those admitted from a nursing home, diagnosed with aspiration, or admitted to the ICU, for whom ceftriaxone plus doxycycline would not be considered recommended (or first‐line) therapy. The two resulting groups were similar, except there were fewer patients with comorbid illness in the ceftriaxone plus doxycycline group (34% vs. 50%, P = .015). The propensity score was rederived for this subset and used for adjustment. Unadjusted and adjusted outcomes are shown in Table 3. Use of ceftriaxone plus doxycycline in this subset also was associated with reduced odds of inpatient mortality (OR = 0.17, 95% CI: 0.040.77). The odds of 30‐day mortality also were reduced but not significantly, as the confidence interval included 1.0 (OR = 0.43, 95% CI: 0.141.31). There were no differences between groups in length of stay or in 30‐day readmission rate.

| Ceftriaxone + doxycycline (n = 188) | Other appropriate therapy (n = 70) | Adjusted odds ratio (95% CI) | |

|---|---|---|---|

| |||

| Age (median years) | 75 | 71 | |

| PSI score (mean) | 95 | 98 | |

| Comorbid illness (%)a | 33.5 | 50.0 | |

| Inpatient mortality | 1.6% | 7.1% | 0.17 (0.040.77) |

| 30‐day mortality | 4.8% | 8.6% | 0.43 (0.141.31) |

| LOS (median days) | 3 | 3 | 0.06 (0.240.12)b |

| 30‐day readmission | 11.9% | 10.0% | 1.31 (0.523.28) |

DISCUSSION

In our hospital setting, the use of ceftriaxone plus doxycycline as the initial empiric antibiotic therapy for patients hospitalized with community‐acquired pneumonia was associated with significantly lower inpatient and 30‐day mortality, even after adjusting for clinical differences between groups. We did not find a difference between regimens in hospital length of stay or 30‐day readmission rate. In case the multivariable model was insufficient to account for the clinical differences (i.e., selection bias) between groups, we also performed an analysis of a subgroup of less severely ill patients by excluding those admitted from nursing homes, those admitted to the intensive care unit, and those with aspiration pneumonia. In this subset, use of ceftriaxone plus doxycycline remained associated with lower inpatient mortality but not with lower 30‐day mortality. Although, as an observational study, the results of our findings could still be a result of residual confounding, we believe the results provide valuable information regarding doxycycline.

Combination therapy with a macrolide, but not doxycycline, is advocated by the practice guidelines of several major U.S. professional societies,3, 4, 7 apparently because of a lack of data on the effectiveness of combination therapy with doxycycline.7 Only one randomized, unblinded study, in 87 low‐risk patients hospitalized with CAP, that compared monotherapy with IV doxycycline versus physician‐determined therapy has been conducted.13 This study found no differences between treatment groups in clinical outcomes but did find that use of doxycycline was associated with shorter hospital stays and reduced costs. Our results, achieved in a real‐world setting in relatively ill hospitalized patients (58% were in PSI risk class IV or V), provide further support for the use of combination therapy with doxycycline.

Hospitalized patients treated with a beta‐lactam in combination with a macrolide are often discharged on macrolide monotherapy. In our population most patients treated with ceftriaxone plus doxycycline were discharged on doxycycline if they required continued therapy (data not shown). In the current era of resistance of Streptococcus pneumoniae to antibiotics, there is good reason to believe doxycycline may perform as well, if not better, than macrolides when hospitalized patients with CAP are discharged on oral monotherapy. Macrolide resistance rates among invasive pneumococcal isolates in the United States doubled from 10% to 20% during a period in which prescriptions for macrolides increased by 13%.12 In addition, a large surveillance study of more than 1500 isolates collected in 1999 and 2000 found that 26% of the isolates were resistant to macrolides, whereas only 16% were resistant to tetracycline.16 In vitro testing against S. Pneumoniae has also suggested that tetracycline resistance overestimates doxycycline resistance.17, 18 More recently, Streptococcus pneumoniae susceptibility data from the SENTRY Antimicrobial Surveillance program reaffirmed doxycycline's in vitro superiority over macrolides.17

Our study had several limitations. The study design adopted precluded determining whether favorable results with the use of ceftriaxone plus doxycycline resulted from an effect unique to this combination of antibiotics, the possible anti‐inflammatory properties of doxycycline alone,19, 20 or unmeasured confounders. For example, processes of care that affect clinical outcomes for patients hospitalized with CAP, such as the timing of antibiotic delivery, the timing of blood cultures, and stability assessment on discharge were not measured in this study. To affect outcomes, these processes of care would need to be differentially distributed between our comparison groups. However, because this study was performed in a single institution during a single interval, it is likely that the performance of these processes of care would be similar for all patients.

In conclusion, ceftriaxone plus doxycycline appears to be an effective, and possibly superior, therapy for patients hospitalized with CAP. Randomized controlled trials of doxycycline‐containing regimens versus other regimens are warranted.

In the United States, community‐acquired pneumonia (CAP) leads to nearly 1 million hospitalizations annually, with aggregate costs of hospitalization approaching $9 billion.1, 2 In an effort to improve the appropriate, cost‐effective care for patients with CAP, several professional societies have developed clinical practice guidelines and pathways for pneumonia.37 Although the guidelines address all aspects of care, they devote substantial attention to antibiotic recommendations. Most U.S. guidelines recommend treatment of hospitalized patients with an intravenous beta‐lactam combined with a macrolide, or a fluoroquinolone with activity against Streptococcus pneumoniae. Of the major U.S. CAP practice guidelines, only one6 recommends doxycycline as an alternative to a macrolide for inpatients.

Doxycycline is an attractive alternative to macrolides. Similar to macrolides, doxycycline is active against a wide variety of organisms including atypical bacteria (Chlamydia pneumoniae, Legionella pneumophilus, and Mycoplasma pneumoniae) and is well tolerated.810 In addition, it is inexpensive (cost of $1.00/day [awp] for 100 mg p.o. bid), and rates of tetracycline/doxycycline resistance among S. pneumoniae isolates have remained low, in contrast to the increasing rates of resistance to macrolides and fluoroquinolones.11, 12 The most recent guidelines from the Infectious Diseases Society of America cited limited published clinical data on the effectiveness of doxycycline in CAP as a barrier to increased use.7 Only one study of hospitalized patients has been published in the era of penicillin‐resistant pneumococcus, and this study included only 43 low‐risk patients treated with doxycycline.13 At the university hospital affiliated with the University of California, San Francisco, ceftriaxone plus doxycycline is generally recommended as initial empiric antibiotic therapy for patients hospitalized with CAP, but significant variability in prescribing exists, allowing for comparisons between patients treated with different initial empiric antibiotic regimens. We compared outcomes of hospitalized patients with CAP treated with ceftriaxone plus doxycycline to those of patients treated with alternative initial empiric therapy at an academic medical center.

METHODS

Study Population

A retrospective cohort study of all adults (age 18 years) discharged from the inpatient general medicine service of Moffitt‐Long Hospital at the University of California, San Francisco, was conducted from January 1999 through July 2001. Eligibility criteria included a principal discharge diagnosis of CAP and a chest radiograph demonstrating an infiltrate within 48 hours of admission. Exclusion criteria included infection with the human immunodeficiency virus, history of organ transplantation or use of immunosuppressive therapy (including prednisone > 15 mg/day), cystic fibrosis, postobstructive pneumonia, active tuberculosis, recent hospitalization (within 10 days), or admission for comfort care. The study protocol and procedures were reviewed and approved by the UCSF Committee for Human Research.

Data Collection

Medical record review by trained research assistants blinded to the research question was used to gather demographic data, comorbid illnesses, physical examination findings on initial presentation, and laboratory or radiographic results on initial presentation. The pneumonia severity index (PSI) score was calculated for each patient using the above data.14 In addition, data were collected on antibiotic allergies, antibiotics used within the 30 days prior to admission, results of sputum or blood cultures, and admission location (intensive care unit [ICU] versus medical floor).

Data from TSI (Transition Systems Inc., Boston, MA), the hospital administrative database, were used to identify the initial empiric antibiotic regimen. All antibiotics prescribed within the first 48 hours of hospitalization were considered initial empiric therapy with few exceptions. Initial empiric therapy was classified as 1) ceftriaxone plus doxycycline (including patients treated with these agents alone in the first 48 hours, as well as patients treated with both agents in the first 24 hours who were switched to alternative therapy [broader coverage] on the second day), or 2) other appropriate therapy (treatment consistent with current national guideline recommendations including at least a beta‐lactam plus a macrolide or a beta‐lactam plus a fluoroquinolone, or fluoroquinolone monotherapy). Patients receiving therapy inconsistent with current national guideline recommendations were excluded.

Outcomes

TSI data were used to identify length of stay, death during the index hospitalization, and return to the emergency department or readmission within 30 days of discharge. The National Death Index was used to identify all deaths that occurred after hospital discharge. The 30‐day mortality data included deaths occurring during the index hospitalization and in the 30 days after the index hospitalization discharge.

Statistical Analysis

For the purposes of this analysis we compared patients treated with ceftriaxone plus doxycycline to patients treated with other appropriate therapy. To examine demographic and clinical differences between the two groups, statistical tests of comparison were performed using chi‐square tests for the dichotomous variables and t tests for the numeric variables, all of which were normally distributed (after log transformation in the case of length of stay).

To adjust for clinical variables that might contribute to differences in outcomes between the two groups, we used backward stepwise logistic regression analysis to construct a propensity score15 for the likelihood of ceftriaxone plus doxycycline use. The propensity score reflected the conditional probability of exposure to ceftriaxone plus doxycycline and allowed for stratification and, subsequently, comparisons by quintiles of propensity score. Propensity scores often have distinct advantages over direct adjustment for a large number of confounding variables and allow direct comparisons between groups with a similar propensity for receiving ceftriaxone plus doxycycline.15 Unlike random assignment of treatment, however, the propensity score cannot balance unmeasured variables that may affect treatment assignment. Thus, the possibility of bias remains. The variables used to build the score included age, presence of comorbid illness, admission from a nursing home or long‐term care facility, antibiotic allergy, prior antibiotic use, PSI score, PSI risk class, diagnosis of aspiration, admission to the ICU, and positive blood cultures. The propensity score was then stratified and used as an adjustment variable in comparisons between groups for in‐hospital mortality, 30‐day mortality, and 30‐day readmission rates. As expected, length of stay was highly skewed and was therefore log‐transformed and compared between groups with adjustment for the propensity score.

To further address issues related to potential selection bias, a separate analysis was performed on a subset of the original cohort that excluded patients for whom ceftriaxone plus doxycycline would not generally be recommended as first‐line therapy. For this analysis, patients admitted from a nursing home or long‐term care facility, patients admitted to the ICU, and patients with a principal diagnosis of aspiration pneumonia were excluded. A propensity score was rederived for this subset, which was used to adjust for differences in outcomes. All statistical procedures were performed using STATA (Ver. 7.0, Stata Corporation, College Station TX).

RESULTS

Patient Characteristics

A total of 341 patients were eligible for analysis. Of this group, 216 were treated with ceftriaxone plus doxycycline and 125 received other appropriate therapy. Both groups of patients were similar in age. Patients treated with ceftriaxone plus doxycycline had a lower median PSI score and fewer comorbid illnesses than did patients treated with other appropriate therapy (Table 1). Blood cultures were positive in 30 (8.8%) of the 341 patients included in the analysis, with S. pneumoniae the most commonly isolated organism (n = 17, 5.0%). Of S. pneumoniae isolates, 4 (24%) were resistant to penicillin (MIC 1 g/mL), and 2 (12%) were resistant to tetracycline (MIC 8 g/mL).

| Ceftriaxone/doxycycline | Other appropriate therapy | |

|---|---|---|

| ||

| Patients (n) | 216 | 125 |

| Age (median) | 76 | 74 |

| PSI Score (median)a | 97 | 108 |

| PSI Risk Class (%)a | ||

| Class I | 9.3 | 5.6 |

| Class II | 11.1 | 8.8 |

| Class III | 21.8 | 13.6 |

| Class IV | 40.7 | 40.0 |

| Class V | 17.1 | 32.0 |

| Comorbid Illness (%)a | 36.1 | 47.2 |

| Nursing Home/LCF (%)a | 5.1 | 14.4 |

| Aspiration (%)a | 3.2 | 20.0 |

| Admission to ICU (%)a | 6.0 | 28.0 |

Common antibiotic choices in patients receiving other appropriate therapy included a beta‐lactam/beta‐lactamase inhibitor plus doxycycline or a macrolide (n = 36, 29%), fluoroquinolone monotherapy (n = 16, 13%), and a variety of other antibiotic combinations with activity against S. pneumoniae and atypical bacteria (n = 52, 42%).

Clinical Outcomes

Analyses of unadjusted outcomes showed that patients treated with ceftriaxone plus doxycycline had significantly lower inpatient (2% vs. 14%, P < .001) and 30‐day (6% vs. 20%, P < .001) mortality compared to patients treated with other regimens (Table 2). Multivariable logistic regression analysis identified three variables (diagnosis of congestive heart failure, admission to the ICU, and the presence of comorbid illness) associated with initial antibiotic selection, which were used to build a propensity score. After adjustment for the propensity score, use of ceftriaxone plus doxycycline remained significantly associated with lower inpatient mortality (OR = 0.26, 95% CI: 0.080.81) and 30‐day mortality (OR = 0.37, 95% CI: 0.170.81). Differences in length of stay and 30‐day readmission rates between the treatment groups were not significant (Table 2).

| Ceftriaxone + doxycycline (n = 216) | Other appropriate therapy (n = 125) | Adjusted odds ratio (95% confidence interval) | |

|---|---|---|---|

| |||

| Inpatient Mortality | 2.3% | 14.4% | 0.26 (0.080.81) |

| 30‐day mortality | 6.0% | 20.0% | 0.37 (0.170.81) |

| Length of stay (median days) | 3.0 | 4.0 | 0.09 (0.250.06)a |

| 30‐day readmission | 10.7% | 12.0% | 0.87 (0.421.81) |

Subset Analysis

To address issues related to selection bias, we performed an analysis of a subset of the patients after excluding those admitted from a nursing home, diagnosed with aspiration, or admitted to the ICU, for whom ceftriaxone plus doxycycline would not be considered recommended (or first‐line) therapy. The two resulting groups were similar, except there were fewer patients with comorbid illness in the ceftriaxone plus doxycycline group (34% vs. 50%, P = .015). The propensity score was rederived for this subset and used for adjustment. Unadjusted and adjusted outcomes are shown in Table 3. Use of ceftriaxone plus doxycycline in this subset also was associated with reduced odds of inpatient mortality (OR = 0.17, 95% CI: 0.040.77). The odds of 30‐day mortality also were reduced but not significantly, as the confidence interval included 1.0 (OR = 0.43, 95% CI: 0.141.31). There were no differences between groups in length of stay or in 30‐day readmission rate.

| Ceftriaxone + doxycycline (n = 188) | Other appropriate therapy (n = 70) | Adjusted odds ratio (95% CI) | |

|---|---|---|---|

| |||

| Age (median years) | 75 | 71 | |

| PSI score (mean) | 95 | 98 | |

| Comorbid illness (%)a | 33.5 | 50.0 | |

| Inpatient mortality | 1.6% | 7.1% | 0.17 (0.040.77) |

| 30‐day mortality | 4.8% | 8.6% | 0.43 (0.141.31) |

| LOS (median days) | 3 | 3 | 0.06 (0.240.12)b |

| 30‐day readmission | 11.9% | 10.0% | 1.31 (0.523.28) |

DISCUSSION

In our hospital setting, the use of ceftriaxone plus doxycycline as the initial empiric antibiotic therapy for patients hospitalized with community‐acquired pneumonia was associated with significantly lower inpatient and 30‐day mortality, even after adjusting for clinical differences between groups. We did not find a difference between regimens in hospital length of stay or 30‐day readmission rate. In case the multivariable model was insufficient to account for the clinical differences (i.e., selection bias) between groups, we also performed an analysis of a subgroup of less severely ill patients by excluding those admitted from nursing homes, those admitted to the intensive care unit, and those with aspiration pneumonia. In this subset, use of ceftriaxone plus doxycycline remained associated with lower inpatient mortality but not with lower 30‐day mortality. Although, as an observational study, the results of our findings could still be a result of residual confounding, we believe the results provide valuable information regarding doxycycline.

Combination therapy with a macrolide, but not doxycycline, is advocated by the practice guidelines of several major U.S. professional societies,3, 4, 7 apparently because of a lack of data on the effectiveness of combination therapy with doxycycline.7 Only one randomized, unblinded study, in 87 low‐risk patients hospitalized with CAP, that compared monotherapy with IV doxycycline versus physician‐determined therapy has been conducted.13 This study found no differences between treatment groups in clinical outcomes but did find that use of doxycycline was associated with shorter hospital stays and reduced costs. Our results, achieved in a real‐world setting in relatively ill hospitalized patients (58% were in PSI risk class IV or V), provide further support for the use of combination therapy with doxycycline.

Hospitalized patients treated with a beta‐lactam in combination with a macrolide are often discharged on macrolide monotherapy. In our population most patients treated with ceftriaxone plus doxycycline were discharged on doxycycline if they required continued therapy (data not shown). In the current era of resistance of Streptococcus pneumoniae to antibiotics, there is good reason to believe doxycycline may perform as well, if not better, than macrolides when hospitalized patients with CAP are discharged on oral monotherapy. Macrolide resistance rates among invasive pneumococcal isolates in the United States doubled from 10% to 20% during a period in which prescriptions for macrolides increased by 13%.12 In addition, a large surveillance study of more than 1500 isolates collected in 1999 and 2000 found that 26% of the isolates were resistant to macrolides, whereas only 16% were resistant to tetracycline.16 In vitro testing against S. Pneumoniae has also suggested that tetracycline resistance overestimates doxycycline resistance.17, 18 More recently, Streptococcus pneumoniae susceptibility data from the SENTRY Antimicrobial Surveillance program reaffirmed doxycycline's in vitro superiority over macrolides.17

Our study had several limitations. The study design adopted precluded determining whether favorable results with the use of ceftriaxone plus doxycycline resulted from an effect unique to this combination of antibiotics, the possible anti‐inflammatory properties of doxycycline alone,19, 20 or unmeasured confounders. For example, processes of care that affect clinical outcomes for patients hospitalized with CAP, such as the timing of antibiotic delivery, the timing of blood cultures, and stability assessment on discharge were not measured in this study. To affect outcomes, these processes of care would need to be differentially distributed between our comparison groups. However, because this study was performed in a single institution during a single interval, it is likely that the performance of these processes of care would be similar for all patients.

In conclusion, ceftriaxone plus doxycycline appears to be an effective, and possibly superior, therapy for patients hospitalized with CAP. Randomized controlled trials of doxycycline‐containing regimens versus other regimens are warranted.

- ,,, et al.Hospitalized pneumonia. Outcomes, treatment patterns, and costs in urban and rural areas.J Gen Intern Med.1996;11:415–421.

- ,,, et al.The cost of treating community‐acquired pneumonia.Clin Ther.1998;20:820–837.

- ,,, et al.Practice guidelines for the management of community‐acquired pneumonia in adults. Infectious Diseases Society of America.Clin Infect Dis.2000;31:347–382.

- ,,, et al.Management of community‐acquired pneumonia in the era of pneumococcal resistance: a report from the Drug‐Resistant Streptococcus pneumoniae Therapeutic Working Group.Arch Intern Med.2000;160:1399–1408.

- ,,, et al.Canadian guidelines for the initial management of community‐acquired pneumonia: an evidence‐based update by the Canadian Infectious Diseases Society and the Canadian Thoracic Society. The Canadian Community‐Acquired Pneumonia Working Group.Clin Infect Dis.2000;31:383–421.

- ,,, et al.Guidelines for the management of adults with community‐acquired pneumonia. Diagnosis, assessment of severity, antimicrobial therapy, and prevention.Am J Respir Crit Care Med.2001;163:1730–1754.

- ,,, et al.Update of practice guidelines for the management of community‐acquired pneumonia in immunocompetent adults.Clin Infect Dis.2003;37:1405–1433

- ,,.Doxycycline.Ther Drug Monit1982;4:115–135

- ,.Chloramphenicol and tetracyclines.Med Clin North Am.1987;71:1155–1168

- ,.Tetracyclines.Med Clin North Am.1995;79:789–801

- ,,, et al.Antibiotic resistance among gram‐negative bacilli in US intensive care units: implications for fluoroquinolone use.JAMA.2003;289:885–888

- ,,, et al.Macrolide resistance among invasive Streptococcus pneumoniae isolates.JAMA.2001;286:1857–1862.

- ,,, et al.Doxycycline is a cost‐effective therapy for hospitalized patients with community‐acquired pneumonia.Arch Intern Med.1999;159:266–270.

- ,,, et al.A prediction rule to identify low‐risk patients with community‐acquired pneumonia.N Engl J Med.1997;336:243–250.

- .Reducing bias in observational studies using subclassification on the propensity score.J Am Stat Assoc.1984;79:516–524

- ,,, et al.Antimicrobial resistance among clinical isolates of Streptococcus pneumoniae in the United States during 1999—2000, including a comparison of resistance rates since 1994—1995.Antimicrob Agents Chemother.2001;45:1721–1729

- ,,.Doxycycline use for community‐acquired pneumonia: contemporary in vitro spectrum of activity against Streptococcus pneumoniae (1999–2002).Diagn Microbiol Infect Dis.2004;49:147–149

- ,,, et al.Doxycycline activity against Streptococcus pneumoniae.Chest.1995;108:1775–1776.

- ,,, et al.Inhibition of enzymatic activity of phospholipases A2 by minocycline and doxycycline.Biochem Pharmacol.1992;44:1165–1170.

- ,,, et al.Doxycycline reduces mortality to lethal endotoxemia by reducing nitric oxide synthesis via an interleukin‐10‐independent mechanism.J Infect Dis.1998;177:489–492.

- ,,, et al.Hospitalized pneumonia. Outcomes, treatment patterns, and costs in urban and rural areas.J Gen Intern Med.1996;11:415–421.

- ,,, et al.The cost of treating community‐acquired pneumonia.Clin Ther.1998;20:820–837.

- ,,, et al.Practice guidelines for the management of community‐acquired pneumonia in adults. Infectious Diseases Society of America.Clin Infect Dis.2000;31:347–382.

- ,,, et al.Management of community‐acquired pneumonia in the era of pneumococcal resistance: a report from the Drug‐Resistant Streptococcus pneumoniae Therapeutic Working Group.Arch Intern Med.2000;160:1399–1408.

- ,,, et al.Canadian guidelines for the initial management of community‐acquired pneumonia: an evidence‐based update by the Canadian Infectious Diseases Society and the Canadian Thoracic Society. The Canadian Community‐Acquired Pneumonia Working Group.Clin Infect Dis.2000;31:383–421.

- ,,, et al.Guidelines for the management of adults with community‐acquired pneumonia. Diagnosis, assessment of severity, antimicrobial therapy, and prevention.Am J Respir Crit Care Med.2001;163:1730–1754.

- ,,, et al.Update of practice guidelines for the management of community‐acquired pneumonia in immunocompetent adults.Clin Infect Dis.2003;37:1405–1433

- ,,.Doxycycline.Ther Drug Monit1982;4:115–135

- ,.Chloramphenicol and tetracyclines.Med Clin North Am.1987;71:1155–1168

- ,.Tetracyclines.Med Clin North Am.1995;79:789–801

- ,,, et al.Antibiotic resistance among gram‐negative bacilli in US intensive care units: implications for fluoroquinolone use.JAMA.2003;289:885–888

- ,,, et al.Macrolide resistance among invasive Streptococcus pneumoniae isolates.JAMA.2001;286:1857–1862.

- ,,, et al.Doxycycline is a cost‐effective therapy for hospitalized patients with community‐acquired pneumonia.Arch Intern Med.1999;159:266–270.

- ,,, et al.A prediction rule to identify low‐risk patients with community‐acquired pneumonia.N Engl J Med.1997;336:243–250.

- .Reducing bias in observational studies using subclassification on the propensity score.J Am Stat Assoc.1984;79:516–524

- ,,, et al.Antimicrobial resistance among clinical isolates of Streptococcus pneumoniae in the United States during 1999—2000, including a comparison of resistance rates since 1994—1995.Antimicrob Agents Chemother.2001;45:1721–1729

- ,,.Doxycycline use for community‐acquired pneumonia: contemporary in vitro spectrum of activity against Streptococcus pneumoniae (1999–2002).Diagn Microbiol Infect Dis.2004;49:147–149

- ,,, et al.Doxycycline activity against Streptococcus pneumoniae.Chest.1995;108:1775–1776.

- ,,, et al.Inhibition of enzymatic activity of phospholipases A2 by minocycline and doxycycline.Biochem Pharmacol.1992;44:1165–1170.

- ,,, et al.Doxycycline reduces mortality to lethal endotoxemia by reducing nitric oxide synthesis via an interleukin‐10‐independent mechanism.J Infect Dis.1998;177:489–492.

Copyright © 2006 Society of Hospital Medicine

Editorial

You hold in your hands the inaugural issue of the Journal of Hospital Medicine (JHM). Our goal is for JHM to become the premier forum for peer‐reviewed research articles and evidence‐based reviews in the specialty of hospital medicine.

Yes, the specialty of hospital medicine. This official publication of the Society of Hospital Medicine signifies another step forward in the evolution of this specialty. With the publication of JHM the Society of Hospital Medicine continues its pivotal educational and leadership role in shaping the practice of hospital medicine. The Society is dedicated to promoting the highest‐quality care for all hospitalized patients and excellence in hospital medicine through education, advocacy, and research. As part of the Society's effort to improve care and standards, it is providing JHM to all members as part of their membership. We hope that our readership will grow to include individuals involved in all aspects of hospital care.

Packed with the results of new studies and state‐of‐the‐art reviews, JHM is not aimed solely at academicians and voracious readers of the medical literature. Rather, we hope that it fills a practical need to promote lifelong learning in both hospitalists and their hospital colleagues. For example, in this issue, national experts in palliative care and geriatrics summarize the pertinent literature and the important role of such care for hospitalized patients. JHM will also serve as a key venue for hospital medicine researchers to disseminate their findings and for educators to share their knowledge and techniques.

Why bother to create yet another journal? Given the stacks of journals that adorn many of our desks (and some of our chairs and windowsills), do we really need another to get lost among the mail that inundates us? We believe the field of hospital medicine involves a growing body of knowledge deserving of a journal focused solely on it. Hospital medicine evolved from efforts to fill a need identified by overstretched primary care physicians in the late 1980s. Physicians like the cofounders of SHM, John Nelson in Florida and Win Whitcomb in Massachusetts, began careers in a field that today numbers more than 12,000 physicians. Labeled with the moniker hospitalist given us by Bob Wachter and Lee Goldman,1 we now make up the fastest‐growing medical specialty in the United States.2 Yet, until now, no journal was devoted solely to this specialty.

The Journal of Hospital Medicine aims to provide physicians and other health care professionals with continuing insight into the basic and clinical sciences to support informed clinical decision making in the hospital. As hospitalists increasingly take an active role in the successful delivery of bench research discoveries to the bedside and become vigorous participants in the translational and clinical research sought by the National Institutes of Health,3 JHM will disseminate their findings. In addition, we hope to foster balanced debates on medical issues and health care trends that affect hospital medicine and patient care. Nonclinical aspects of hospital medicine also will be featured, including public health and the political, philosophic, ethical, legal, environmental, economic, historical, and cultural issues surrounding hospital care. We especially want to encourage submissions that evaluate projects involving the entire hospital care team: physicians and our colleagues in the hospitalnurses, pharmacists, administrators, physical and occupational therapists, social workers, and case managers.

Two articles (see pages 48 and 57) highlight this inaugural issue. One describes the development of The Core Competencies in Hospital Medicine: A Framework for Curriculum Development (a supplement to this issue), and the other demonstrates how this document can be applied to curriculum development.4, 5 This milestone in the evolution of hospital medicine provides an initial structural framework to guide medical educators in developing curricula that incorporate these competencies into the training and evaluation of students, clinicians‐in‐training, and practicing hospitalists.4 The president and CEO of the American Board of Internal Medicine (ABIM), Christine Cassel, offers her perspective on this landmark document.6 Its timeliness is reflected by the current efforts of the American College of Physicians, the ABIM, and others to redesign the training and the certification requirements of internists. As this supplement demonstrates, the Society of Hospital Medicine will be intimately involved in this process.

After this auspicious start, subsequent issues will include articles in the following categories. Original research articles will report results of randomized controlled trials, evaluations of diagnostic tests, prospective cohort studies, casecontrol studies, and high‐quality observational studies. We are interested in publishing both quantitative and qualitative research. Review articles, especially those targeting the hospital medicine core competencies, are eagerly sought. We also seek descriptions of interventions that transform hospital care delivery in the hospital. For example, accounts of the implementation of quality‐improvement projects and outcomes, including barriers that were overcome or that blocked implementation, would be invaluable to hospitalists throughout the country. Clinical conundrums should describe clinical cases that present diagnostic dilemmas or involve issues of medical errors. To facilitate the professional development of hospitalists, we seek articles focused on their professional development in community, academic, and administrative settings. Examples of leadership topics are managing physician performance, leading and managing change, and self‐evaluation. Teaching tips or descriptions of educational programs or curricula also are desired. For researchers, potential topics include descriptions of specific techniques used for surveys, meta‐analyses, economic evaluations, and statistical analyses.Penetrating point manuscripts, those that go beyond the cutting edge to explain the next potential breakthrough or intervention in the developing field of hospital medicine, may be authored by thought leaders inside and outside the health care field as well as by hospitalists with novel ideas. Equally vital, I want to share the illuminating perspectives of physicians, patients, and families of patients as they reflect on the experience of being in the hospitalhospitalists can enlighten us through their handoffs, and patients and their families can inform us about their view from the hospital bed.

Finally, never forget that this is your journal. Let me know what you like and what changes you think can make it better. Please e‐mail your suggestions, comments, criticisms, and ideas to us at JHMeditor@ hospitalmedicine.org. This is your chance to help shape the practice of hospital medicine and the future of hospital care. I look forward to your guidance. Together we can expand our knowledge and continue to grow in our careers.

The more you see the less you know

The less you find out as you grow

I knew much more then than I do now.

U2, City of Blinding Lights,

How to Dismantle an Atomic Bomb

- ,.The emerging role of “hospitalists” in the American health care system.N Engl J Med.1996;335:514–517.

- .The future of hospital medicine: evolution or revolution?Am J Med.2004;117:446–450.

- .Translational and clinical science—time for a new vision.N Engl J Med2005;35:1621‐1623.

- ,,,,, eds.The core competencies in hospital medicine: development and methodology.J Hosp Med.2006;1:48–56.

- ,,,,.How to use The Core Competencies in Hospital Medicine: A Framework for Curriculum Development.J Hosp Med.2006;1:57–67.

- .Hospital medicine: early successes and challenges ahead.J Hosp Med.2006;1:3–4.

You hold in your hands the inaugural issue of the Journal of Hospital Medicine (JHM). Our goal is for JHM to become the premier forum for peer‐reviewed research articles and evidence‐based reviews in the specialty of hospital medicine.

Yes, the specialty of hospital medicine. This official publication of the Society of Hospital Medicine signifies another step forward in the evolution of this specialty. With the publication of JHM the Society of Hospital Medicine continues its pivotal educational and leadership role in shaping the practice of hospital medicine. The Society is dedicated to promoting the highest‐quality care for all hospitalized patients and excellence in hospital medicine through education, advocacy, and research. As part of the Society's effort to improve care and standards, it is providing JHM to all members as part of their membership. We hope that our readership will grow to include individuals involved in all aspects of hospital care.

Packed with the results of new studies and state‐of‐the‐art reviews, JHM is not aimed solely at academicians and voracious readers of the medical literature. Rather, we hope that it fills a practical need to promote lifelong learning in both hospitalists and their hospital colleagues. For example, in this issue, national experts in palliative care and geriatrics summarize the pertinent literature and the important role of such care for hospitalized patients. JHM will also serve as a key venue for hospital medicine researchers to disseminate their findings and for educators to share their knowledge and techniques.

Why bother to create yet another journal? Given the stacks of journals that adorn many of our desks (and some of our chairs and windowsills), do we really need another to get lost among the mail that inundates us? We believe the field of hospital medicine involves a growing body of knowledge deserving of a journal focused solely on it. Hospital medicine evolved from efforts to fill a need identified by overstretched primary care physicians in the late 1980s. Physicians like the cofounders of SHM, John Nelson in Florida and Win Whitcomb in Massachusetts, began careers in a field that today numbers more than 12,000 physicians. Labeled with the moniker hospitalist given us by Bob Wachter and Lee Goldman,1 we now make up the fastest‐growing medical specialty in the United States.2 Yet, until now, no journal was devoted solely to this specialty.

The Journal of Hospital Medicine aims to provide physicians and other health care professionals with continuing insight into the basic and clinical sciences to support informed clinical decision making in the hospital. As hospitalists increasingly take an active role in the successful delivery of bench research discoveries to the bedside and become vigorous participants in the translational and clinical research sought by the National Institutes of Health,3 JHM will disseminate their findings. In addition, we hope to foster balanced debates on medical issues and health care trends that affect hospital medicine and patient care. Nonclinical aspects of hospital medicine also will be featured, including public health and the political, philosophic, ethical, legal, environmental, economic, historical, and cultural issues surrounding hospital care. We especially want to encourage submissions that evaluate projects involving the entire hospital care team: physicians and our colleagues in the hospitalnurses, pharmacists, administrators, physical and occupational therapists, social workers, and case managers.

Two articles (see pages 48 and 57) highlight this inaugural issue. One describes the development of The Core Competencies in Hospital Medicine: A Framework for Curriculum Development (a supplement to this issue), and the other demonstrates how this document can be applied to curriculum development.4, 5 This milestone in the evolution of hospital medicine provides an initial structural framework to guide medical educators in developing curricula that incorporate these competencies into the training and evaluation of students, clinicians‐in‐training, and practicing hospitalists.4 The president and CEO of the American Board of Internal Medicine (ABIM), Christine Cassel, offers her perspective on this landmark document.6 Its timeliness is reflected by the current efforts of the American College of Physicians, the ABIM, and others to redesign the training and the certification requirements of internists. As this supplement demonstrates, the Society of Hospital Medicine will be intimately involved in this process.

After this auspicious start, subsequent issues will include articles in the following categories. Original research articles will report results of randomized controlled trials, evaluations of diagnostic tests, prospective cohort studies, casecontrol studies, and high‐quality observational studies. We are interested in publishing both quantitative and qualitative research. Review articles, especially those targeting the hospital medicine core competencies, are eagerly sought. We also seek descriptions of interventions that transform hospital care delivery in the hospital. For example, accounts of the implementation of quality‐improvement projects and outcomes, including barriers that were overcome or that blocked implementation, would be invaluable to hospitalists throughout the country. Clinical conundrums should describe clinical cases that present diagnostic dilemmas or involve issues of medical errors. To facilitate the professional development of hospitalists, we seek articles focused on their professional development in community, academic, and administrative settings. Examples of leadership topics are managing physician performance, leading and managing change, and self‐evaluation. Teaching tips or descriptions of educational programs or curricula also are desired. For researchers, potential topics include descriptions of specific techniques used for surveys, meta‐analyses, economic evaluations, and statistical analyses.Penetrating point manuscripts, those that go beyond the cutting edge to explain the next potential breakthrough or intervention in the developing field of hospital medicine, may be authored by thought leaders inside and outside the health care field as well as by hospitalists with novel ideas. Equally vital, I want to share the illuminating perspectives of physicians, patients, and families of patients as they reflect on the experience of being in the hospitalhospitalists can enlighten us through their handoffs, and patients and their families can inform us about their view from the hospital bed.

Finally, never forget that this is your journal. Let me know what you like and what changes you think can make it better. Please e‐mail your suggestions, comments, criticisms, and ideas to us at JHMeditor@ hospitalmedicine.org. This is your chance to help shape the practice of hospital medicine and the future of hospital care. I look forward to your guidance. Together we can expand our knowledge and continue to grow in our careers.

The more you see the less you know

The less you find out as you grow

I knew much more then than I do now.

U2, City of Blinding Lights,

How to Dismantle an Atomic Bomb

You hold in your hands the inaugural issue of the Journal of Hospital Medicine (JHM). Our goal is for JHM to become the premier forum for peer‐reviewed research articles and evidence‐based reviews in the specialty of hospital medicine.

Yes, the specialty of hospital medicine. This official publication of the Society of Hospital Medicine signifies another step forward in the evolution of this specialty. With the publication of JHM the Society of Hospital Medicine continues its pivotal educational and leadership role in shaping the practice of hospital medicine. The Society is dedicated to promoting the highest‐quality care for all hospitalized patients and excellence in hospital medicine through education, advocacy, and research. As part of the Society's effort to improve care and standards, it is providing JHM to all members as part of their membership. We hope that our readership will grow to include individuals involved in all aspects of hospital care.

Packed with the results of new studies and state‐of‐the‐art reviews, JHM is not aimed solely at academicians and voracious readers of the medical literature. Rather, we hope that it fills a practical need to promote lifelong learning in both hospitalists and their hospital colleagues. For example, in this issue, national experts in palliative care and geriatrics summarize the pertinent literature and the important role of such care for hospitalized patients. JHM will also serve as a key venue for hospital medicine researchers to disseminate their findings and for educators to share their knowledge and techniques.

Why bother to create yet another journal? Given the stacks of journals that adorn many of our desks (and some of our chairs and windowsills), do we really need another to get lost among the mail that inundates us? We believe the field of hospital medicine involves a growing body of knowledge deserving of a journal focused solely on it. Hospital medicine evolved from efforts to fill a need identified by overstretched primary care physicians in the late 1980s. Physicians like the cofounders of SHM, John Nelson in Florida and Win Whitcomb in Massachusetts, began careers in a field that today numbers more than 12,000 physicians. Labeled with the moniker hospitalist given us by Bob Wachter and Lee Goldman,1 we now make up the fastest‐growing medical specialty in the United States.2 Yet, until now, no journal was devoted solely to this specialty.

The Journal of Hospital Medicine aims to provide physicians and other health care professionals with continuing insight into the basic and clinical sciences to support informed clinical decision making in the hospital. As hospitalists increasingly take an active role in the successful delivery of bench research discoveries to the bedside and become vigorous participants in the translational and clinical research sought by the National Institutes of Health,3 JHM will disseminate their findings. In addition, we hope to foster balanced debates on medical issues and health care trends that affect hospital medicine and patient care. Nonclinical aspects of hospital medicine also will be featured, including public health and the political, philosophic, ethical, legal, environmental, economic, historical, and cultural issues surrounding hospital care. We especially want to encourage submissions that evaluate projects involving the entire hospital care team: physicians and our colleagues in the hospitalnurses, pharmacists, administrators, physical and occupational therapists, social workers, and case managers.

Two articles (see pages 48 and 57) highlight this inaugural issue. One describes the development of The Core Competencies in Hospital Medicine: A Framework for Curriculum Development (a supplement to this issue), and the other demonstrates how this document can be applied to curriculum development.4, 5 This milestone in the evolution of hospital medicine provides an initial structural framework to guide medical educators in developing curricula that incorporate these competencies into the training and evaluation of students, clinicians‐in‐training, and practicing hospitalists.4 The president and CEO of the American Board of Internal Medicine (ABIM), Christine Cassel, offers her perspective on this landmark document.6 Its timeliness is reflected by the current efforts of the American College of Physicians, the ABIM, and others to redesign the training and the certification requirements of internists. As this supplement demonstrates, the Society of Hospital Medicine will be intimately involved in this process.