User login

SARS-CoV-2 crosses placenta and infects brains of two infants: ‘This is a first’

, according to a study published online today in Pediatrics .

One of the infants died at 13 months and the other remained in hospice care at time of manuscript submission.

Lead author Merline Benny, MD, with the division of neonatology, department of pediatrics at University of Miami, and colleagues briefed reporters today ahead of the release.

“This is a first,” said senior author Shahnaz Duara, MD, medical director of the Neonatal Intensive Care Unit at Holtz Children’s Hospital, Miami, explaining it is the first study to confirm cross-placental SARS-CoV-2 transmission leading to brain injury in a newborn.

Both infants negative for the virus at birth

The two infants were admitted in the early days of the pandemic in the Delta wave to the neonatal ICU at Holtz Children’s Hospital at University of Miami/Jackson Memorial Medical Center.

Both infants tested negative for the virus at birth, but had significantly elevated SARS-CoV-2 antibodies in their blood, indicating that either antibodies crossed the placenta, or the virus crossed and the immune response was the baby’s.

Dr. Benny explained that the researchers have seen, to this point, more than 700 mother/infant pairs in whom the mother tested positive for COVID in Jackson hospital.

Most who tested positive for COVID were asymptomatic and most of the mothers and infants left the hospital without complications.

“However, (these) two babies had a very unusual clinical picture,” Dr. Benny said.

Those infants were born to mothers who became COVID positive in the second trimester and delivered a few weeks later.

Seizures started on day 1 of life

The babies began to seize from the first day of life. They had profound low tone (hypotonia) in their clinical exam, Dr. Benny explained.

“We had absolutely no good explanation for the early seizures and the degree of brain injury we saw,” Dr. Duara said.

Dr. Benny said that as their bodies grew, they had very small head circumference. Unlike some babies born with the Zika virus, these babies were not microcephalic at birth. Brain imaging on the two babies indicated significant brain atrophy, and neurodevelopment exams showed significant delay.

Discussions began with the center’s multidisciplinary team including neurologists, pathologists, neuroradiologists, and obstetricians who cared for both the mothers and the babies.

The experts examined the placentas and found some characteristic COVID changes and presence of the COVID virus. This was accompanied by increased markers for inflammation and a severe reduction in a hormone critical for placental health and brain development.

Examining the infant’s autopsy findings further raised suspicions of maternal transmission, something that had not been documented before.

Coauthor Ali G. Saad, MD, pediatric and perinatal pathology director at Miami, said, “I have seen literally thousands of brains in autopsies over the last 14 years, and this was the most dramatic case of leukoencephalopathy or loss of white matter in a patient with no significant reason. That’s what triggered the investigation.”

Mothers had very different presentations

Coauthor Michael J. Paidas, MD, with the department of obstetrics, gynecology, and reproductive sciences at Miami, pointed out that the circumstances of the two mothers, who were in their 20s, were very different.

One mother delivered at 32 weeks and had a very severe COVID presentation and spent a month in the intensive care unit. The team decided to deliver the child to save the mother, Dr. Paidas said.

In contrast, the other mother had asymptomatic COVID infection in the second trimester and delivered at full term.

He said one of the early suspicions in the babies’ presentations was hypoxic ischemic encephalopathy. “But it wasn’t lack of blood flow to the placenta that caused this,” he said. “As best we can tell, it was the viral infection.”

Instances are rare

The researchers emphasized that these instances are rare and have not been seen before or since the period of this study to their knowledge.

Dr. Duara said, “This is something we want to alert the medical community to more than the general public. We do not want the lay public to be panicked. We’re trying to understand what made these two pregnancies different, so we can direct research towards protecting vulnerable babies.”

Previous data have indicated a relatively benign status in infants who test negative for the COVID virus after birth. Dr. Benny added that COVID vaccination has been found safe in pregnancy and both vaccination and breastfeeding can help passage of antibodies to the infant and help protect the baby. Because these cases happened in the early days of the pandemic, no vaccines were available.

Dr. Paidas received funding from BioIncept to study hypoxic-ischemic encephalopathy with Preimplantation Factor, is a scientific advisory board member, and has stock options. Dr. Paidas and coauthor Dr. Jayakumar are coinventors of SPIKENET, University of Miami, patent pending 2023. The other authors have no conflicts of interest to disclose.

, according to a study published online today in Pediatrics .

One of the infants died at 13 months and the other remained in hospice care at time of manuscript submission.

Lead author Merline Benny, MD, with the division of neonatology, department of pediatrics at University of Miami, and colleagues briefed reporters today ahead of the release.

“This is a first,” said senior author Shahnaz Duara, MD, medical director of the Neonatal Intensive Care Unit at Holtz Children’s Hospital, Miami, explaining it is the first study to confirm cross-placental SARS-CoV-2 transmission leading to brain injury in a newborn.

Both infants negative for the virus at birth

The two infants were admitted in the early days of the pandemic in the Delta wave to the neonatal ICU at Holtz Children’s Hospital at University of Miami/Jackson Memorial Medical Center.

Both infants tested negative for the virus at birth, but had significantly elevated SARS-CoV-2 antibodies in their blood, indicating that either antibodies crossed the placenta, or the virus crossed and the immune response was the baby’s.

Dr. Benny explained that the researchers have seen, to this point, more than 700 mother/infant pairs in whom the mother tested positive for COVID in Jackson hospital.

Most who tested positive for COVID were asymptomatic and most of the mothers and infants left the hospital without complications.

“However, (these) two babies had a very unusual clinical picture,” Dr. Benny said.

Those infants were born to mothers who became COVID positive in the second trimester and delivered a few weeks later.

Seizures started on day 1 of life

The babies began to seize from the first day of life. They had profound low tone (hypotonia) in their clinical exam, Dr. Benny explained.

“We had absolutely no good explanation for the early seizures and the degree of brain injury we saw,” Dr. Duara said.

Dr. Benny said that as their bodies grew, they had very small head circumference. Unlike some babies born with the Zika virus, these babies were not microcephalic at birth. Brain imaging on the two babies indicated significant brain atrophy, and neurodevelopment exams showed significant delay.

Discussions began with the center’s multidisciplinary team including neurologists, pathologists, neuroradiologists, and obstetricians who cared for both the mothers and the babies.

The experts examined the placentas and found some characteristic COVID changes and presence of the COVID virus. This was accompanied by increased markers for inflammation and a severe reduction in a hormone critical for placental health and brain development.

Examining the infant’s autopsy findings further raised suspicions of maternal transmission, something that had not been documented before.

Coauthor Ali G. Saad, MD, pediatric and perinatal pathology director at Miami, said, “I have seen literally thousands of brains in autopsies over the last 14 years, and this was the most dramatic case of leukoencephalopathy or loss of white matter in a patient with no significant reason. That’s what triggered the investigation.”

Mothers had very different presentations

Coauthor Michael J. Paidas, MD, with the department of obstetrics, gynecology, and reproductive sciences at Miami, pointed out that the circumstances of the two mothers, who were in their 20s, were very different.

One mother delivered at 32 weeks and had a very severe COVID presentation and spent a month in the intensive care unit. The team decided to deliver the child to save the mother, Dr. Paidas said.

In contrast, the other mother had asymptomatic COVID infection in the second trimester and delivered at full term.

He said one of the early suspicions in the babies’ presentations was hypoxic ischemic encephalopathy. “But it wasn’t lack of blood flow to the placenta that caused this,” he said. “As best we can tell, it was the viral infection.”

Instances are rare

The researchers emphasized that these instances are rare and have not been seen before or since the period of this study to their knowledge.

Dr. Duara said, “This is something we want to alert the medical community to more than the general public. We do not want the lay public to be panicked. We’re trying to understand what made these two pregnancies different, so we can direct research towards protecting vulnerable babies.”

Previous data have indicated a relatively benign status in infants who test negative for the COVID virus after birth. Dr. Benny added that COVID vaccination has been found safe in pregnancy and both vaccination and breastfeeding can help passage of antibodies to the infant and help protect the baby. Because these cases happened in the early days of the pandemic, no vaccines were available.

Dr. Paidas received funding from BioIncept to study hypoxic-ischemic encephalopathy with Preimplantation Factor, is a scientific advisory board member, and has stock options. Dr. Paidas and coauthor Dr. Jayakumar are coinventors of SPIKENET, University of Miami, patent pending 2023. The other authors have no conflicts of interest to disclose.

, according to a study published online today in Pediatrics .

One of the infants died at 13 months and the other remained in hospice care at time of manuscript submission.

Lead author Merline Benny, MD, with the division of neonatology, department of pediatrics at University of Miami, and colleagues briefed reporters today ahead of the release.

“This is a first,” said senior author Shahnaz Duara, MD, medical director of the Neonatal Intensive Care Unit at Holtz Children’s Hospital, Miami, explaining it is the first study to confirm cross-placental SARS-CoV-2 transmission leading to brain injury in a newborn.

Both infants negative for the virus at birth

The two infants were admitted in the early days of the pandemic in the Delta wave to the neonatal ICU at Holtz Children’s Hospital at University of Miami/Jackson Memorial Medical Center.

Both infants tested negative for the virus at birth, but had significantly elevated SARS-CoV-2 antibodies in their blood, indicating that either antibodies crossed the placenta, or the virus crossed and the immune response was the baby’s.

Dr. Benny explained that the researchers have seen, to this point, more than 700 mother/infant pairs in whom the mother tested positive for COVID in Jackson hospital.

Most who tested positive for COVID were asymptomatic and most of the mothers and infants left the hospital without complications.

“However, (these) two babies had a very unusual clinical picture,” Dr. Benny said.

Those infants were born to mothers who became COVID positive in the second trimester and delivered a few weeks later.

Seizures started on day 1 of life

The babies began to seize from the first day of life. They had profound low tone (hypotonia) in their clinical exam, Dr. Benny explained.

“We had absolutely no good explanation for the early seizures and the degree of brain injury we saw,” Dr. Duara said.

Dr. Benny said that as their bodies grew, they had very small head circumference. Unlike some babies born with the Zika virus, these babies were not microcephalic at birth. Brain imaging on the two babies indicated significant brain atrophy, and neurodevelopment exams showed significant delay.

Discussions began with the center’s multidisciplinary team including neurologists, pathologists, neuroradiologists, and obstetricians who cared for both the mothers and the babies.

The experts examined the placentas and found some characteristic COVID changes and presence of the COVID virus. This was accompanied by increased markers for inflammation and a severe reduction in a hormone critical for placental health and brain development.

Examining the infant’s autopsy findings further raised suspicions of maternal transmission, something that had not been documented before.

Coauthor Ali G. Saad, MD, pediatric and perinatal pathology director at Miami, said, “I have seen literally thousands of brains in autopsies over the last 14 years, and this was the most dramatic case of leukoencephalopathy or loss of white matter in a patient with no significant reason. That’s what triggered the investigation.”

Mothers had very different presentations

Coauthor Michael J. Paidas, MD, with the department of obstetrics, gynecology, and reproductive sciences at Miami, pointed out that the circumstances of the two mothers, who were in their 20s, were very different.

One mother delivered at 32 weeks and had a very severe COVID presentation and spent a month in the intensive care unit. The team decided to deliver the child to save the mother, Dr. Paidas said.

In contrast, the other mother had asymptomatic COVID infection in the second trimester and delivered at full term.

He said one of the early suspicions in the babies’ presentations was hypoxic ischemic encephalopathy. “But it wasn’t lack of blood flow to the placenta that caused this,” he said. “As best we can tell, it was the viral infection.”

Instances are rare

The researchers emphasized that these instances are rare and have not been seen before or since the period of this study to their knowledge.

Dr. Duara said, “This is something we want to alert the medical community to more than the general public. We do not want the lay public to be panicked. We’re trying to understand what made these two pregnancies different, so we can direct research towards protecting vulnerable babies.”

Previous data have indicated a relatively benign status in infants who test negative for the COVID virus after birth. Dr. Benny added that COVID vaccination has been found safe in pregnancy and both vaccination and breastfeeding can help passage of antibodies to the infant and help protect the baby. Because these cases happened in the early days of the pandemic, no vaccines were available.

Dr. Paidas received funding from BioIncept to study hypoxic-ischemic encephalopathy with Preimplantation Factor, is a scientific advisory board member, and has stock options. Dr. Paidas and coauthor Dr. Jayakumar are coinventors of SPIKENET, University of Miami, patent pending 2023. The other authors have no conflicts of interest to disclose.

FROM PEDIATRICS

COVID can mimic prostate cancer symptoms

This patient has a strong likelihood of aggressive prostate cancer, right? If that same patient also presents with severe, burning bone pain with no precipitating trauma to the area and rest and over-the-counter painkillers are not helping, you’d think, “check for metastases,” right?

That patient was me in late January 2023.

As a research scientist member of the American Urological Association, I knew enough to know I had to consult my urologist ASAP.

With the above symptoms, I’ll admit I was scared. Fortunately, if that’s the right word, I was no stranger to a rapid, dramatic spike in PSA. In 2021 I was temporarily living in a new city, and I wanted to form a relationship with a good local urologist. The urologist that I was referred to gave me a thorough consultation, including a vigorous digital rectal exam (DRE) and sent me across the street for a blood draw.

To my shock, my PSA had spiked over 2 points, to 9.9 from 7.8 a few months earlier. I freaked. Had my 3-cm tumor burst out into an aggressive cancer? Research on PubMed provided an array of studies showing what could cause PSA to suddenly rise, including a DRE performed 72 hours before the blood draw.1 A week later, my PSA was back down to its normal 7.6.

But in January 2023, I had none of those previously reported experiences that could suddenly trigger a spike in PSA, like a DRE or riding on a thin bicycle seat for a few hours before the lab visit.

The COVID effect

I went back to PubMed and found a new circumstance that could cause a surge in PSA: COVID-19. A recent study2 of 91 men with benign prostatic hypertrophy by researchers in Turkey found that PSA spiked from 0 to 5 points during the COVID infection period and up to 2 points higher 3 months after the infection had cleared. I had tested positive for COVID-19 in mid-December 2022, 4 weeks before my 9.9 PSA reading.

Using Google translate, I communicated with the team in Turkey and found out that the PSA spike can last up to 6 months.

That study helps explain why my PSA dropped over 1.5 points to 8.5 just 2 weeks after the 9.9 reading, with the expectation that it would return to its previous normal of 7.8 within 6 months of infection with SARS-CoV-2. To be safe, my urologist scheduled another PSA test in May, along with an updated multiparametric MRI, which may be followed by an in-bore MRI-guided biopsy of the 3-cm tumor if the mass has enlarged.

COVID-19 pain

What about my burning bone pain in my upper right humerus and right rotator cuff that was not precipitated by trauma or strain? A radiograph found no evidence of metastasis, thank goodness. And my research showed that several studies3 have found that COVID-19 can cause burning musculoskeletal pain, including enthesopathy, which is what I had per the radiology report. So my PSA spike and searing pain were likely consequences of the infection.

To avoid the risk for a gross misdiagnosis after a radical spike in PSA, the informed urologist should ask the patient if he has had COVID-19 in the previous 6 months. Overlooking that question could lead to the wrong diagnostic decisions about a rapid jump in PSA or unexplained bone pain.

References

1. Bossens MM et al. Eur J Cancer. 1995;31A:682-5.

2. Cinislioglu AE et al. Urology. 2022;159:16-21.

3. Ciaffi J et al. Joint Bone Spine. 2021;88:105158.

Dr. Keller is founder of the Keller Research Institute, Jacksonville, Fla. He reported serving as a research scientist for the American Urological Association, serving on the advisory board of Active Surveillance Patient’s International, and serving on the boards of numerous nonprofit organizations.

A version of this article first appeared on Medscape.com.

This patient has a strong likelihood of aggressive prostate cancer, right? If that same patient also presents with severe, burning bone pain with no precipitating trauma to the area and rest and over-the-counter painkillers are not helping, you’d think, “check for metastases,” right?

That patient was me in late January 2023.

As a research scientist member of the American Urological Association, I knew enough to know I had to consult my urologist ASAP.

With the above symptoms, I’ll admit I was scared. Fortunately, if that’s the right word, I was no stranger to a rapid, dramatic spike in PSA. In 2021 I was temporarily living in a new city, and I wanted to form a relationship with a good local urologist. The urologist that I was referred to gave me a thorough consultation, including a vigorous digital rectal exam (DRE) and sent me across the street for a blood draw.

To my shock, my PSA had spiked over 2 points, to 9.9 from 7.8 a few months earlier. I freaked. Had my 3-cm tumor burst out into an aggressive cancer? Research on PubMed provided an array of studies showing what could cause PSA to suddenly rise, including a DRE performed 72 hours before the blood draw.1 A week later, my PSA was back down to its normal 7.6.

But in January 2023, I had none of those previously reported experiences that could suddenly trigger a spike in PSA, like a DRE or riding on a thin bicycle seat for a few hours before the lab visit.

The COVID effect

I went back to PubMed and found a new circumstance that could cause a surge in PSA: COVID-19. A recent study2 of 91 men with benign prostatic hypertrophy by researchers in Turkey found that PSA spiked from 0 to 5 points during the COVID infection period and up to 2 points higher 3 months after the infection had cleared. I had tested positive for COVID-19 in mid-December 2022, 4 weeks before my 9.9 PSA reading.

Using Google translate, I communicated with the team in Turkey and found out that the PSA spike can last up to 6 months.

That study helps explain why my PSA dropped over 1.5 points to 8.5 just 2 weeks after the 9.9 reading, with the expectation that it would return to its previous normal of 7.8 within 6 months of infection with SARS-CoV-2. To be safe, my urologist scheduled another PSA test in May, along with an updated multiparametric MRI, which may be followed by an in-bore MRI-guided biopsy of the 3-cm tumor if the mass has enlarged.

COVID-19 pain

What about my burning bone pain in my upper right humerus and right rotator cuff that was not precipitated by trauma or strain? A radiograph found no evidence of metastasis, thank goodness. And my research showed that several studies3 have found that COVID-19 can cause burning musculoskeletal pain, including enthesopathy, which is what I had per the radiology report. So my PSA spike and searing pain were likely consequences of the infection.

To avoid the risk for a gross misdiagnosis after a radical spike in PSA, the informed urologist should ask the patient if he has had COVID-19 in the previous 6 months. Overlooking that question could lead to the wrong diagnostic decisions about a rapid jump in PSA or unexplained bone pain.

References

1. Bossens MM et al. Eur J Cancer. 1995;31A:682-5.

2. Cinislioglu AE et al. Urology. 2022;159:16-21.

3. Ciaffi J et al. Joint Bone Spine. 2021;88:105158.

Dr. Keller is founder of the Keller Research Institute, Jacksonville, Fla. He reported serving as a research scientist for the American Urological Association, serving on the advisory board of Active Surveillance Patient’s International, and serving on the boards of numerous nonprofit organizations.

A version of this article first appeared on Medscape.com.

This patient has a strong likelihood of aggressive prostate cancer, right? If that same patient also presents with severe, burning bone pain with no precipitating trauma to the area and rest and over-the-counter painkillers are not helping, you’d think, “check for metastases,” right?

That patient was me in late January 2023.

As a research scientist member of the American Urological Association, I knew enough to know I had to consult my urologist ASAP.

With the above symptoms, I’ll admit I was scared. Fortunately, if that’s the right word, I was no stranger to a rapid, dramatic spike in PSA. In 2021 I was temporarily living in a new city, and I wanted to form a relationship with a good local urologist. The urologist that I was referred to gave me a thorough consultation, including a vigorous digital rectal exam (DRE) and sent me across the street for a blood draw.

To my shock, my PSA had spiked over 2 points, to 9.9 from 7.8 a few months earlier. I freaked. Had my 3-cm tumor burst out into an aggressive cancer? Research on PubMed provided an array of studies showing what could cause PSA to suddenly rise, including a DRE performed 72 hours before the blood draw.1 A week later, my PSA was back down to its normal 7.6.

But in January 2023, I had none of those previously reported experiences that could suddenly trigger a spike in PSA, like a DRE or riding on a thin bicycle seat for a few hours before the lab visit.

The COVID effect

I went back to PubMed and found a new circumstance that could cause a surge in PSA: COVID-19. A recent study2 of 91 men with benign prostatic hypertrophy by researchers in Turkey found that PSA spiked from 0 to 5 points during the COVID infection period and up to 2 points higher 3 months after the infection had cleared. I had tested positive for COVID-19 in mid-December 2022, 4 weeks before my 9.9 PSA reading.

Using Google translate, I communicated with the team in Turkey and found out that the PSA spike can last up to 6 months.

That study helps explain why my PSA dropped over 1.5 points to 8.5 just 2 weeks after the 9.9 reading, with the expectation that it would return to its previous normal of 7.8 within 6 months of infection with SARS-CoV-2. To be safe, my urologist scheduled another PSA test in May, along with an updated multiparametric MRI, which may be followed by an in-bore MRI-guided biopsy of the 3-cm tumor if the mass has enlarged.

COVID-19 pain

What about my burning bone pain in my upper right humerus and right rotator cuff that was not precipitated by trauma or strain? A radiograph found no evidence of metastasis, thank goodness. And my research showed that several studies3 have found that COVID-19 can cause burning musculoskeletal pain, including enthesopathy, which is what I had per the radiology report. So my PSA spike and searing pain were likely consequences of the infection.

To avoid the risk for a gross misdiagnosis after a radical spike in PSA, the informed urologist should ask the patient if he has had COVID-19 in the previous 6 months. Overlooking that question could lead to the wrong diagnostic decisions about a rapid jump in PSA or unexplained bone pain.

References

1. Bossens MM et al. Eur J Cancer. 1995;31A:682-5.

2. Cinislioglu AE et al. Urology. 2022;159:16-21.

3. Ciaffi J et al. Joint Bone Spine. 2021;88:105158.

Dr. Keller is founder of the Keller Research Institute, Jacksonville, Fla. He reported serving as a research scientist for the American Urological Association, serving on the advisory board of Active Surveillance Patient’s International, and serving on the boards of numerous nonprofit organizations.

A version of this article first appeared on Medscape.com.

Factors linked with increased VTE risk in COVID outpatients

Though VTE risk is well studied and significant in those hospitalized with COVID, little is known about the risk in the outpatient setting, said the authors of the new research published online in JAMA Network Open.

The study was conducted at two integrated health care delivery systems in northern and southern California. Data were gathered from the Kaiser Permanente Virtual Data Warehouse and electronic health records.

Nearly 400,000 patients studied

Researchers, led by Margaret Fang, MD, with the division of hospital medicine, University of California, San Francisco, identified 398,530 outpatients with COVID-19 from Jan. 1, 2020, through Jan. 31, 2021.

VTE risk was low overall for ambulatory COVID patients.

“It is a reassuring study,” Dr. Fang said in an interview.

The researchers found that the risk is highest in the first 30 days after COVID-19 diagnosis (unadjusted rate, 0.58; 95% confidence interval, 0.51-0.67 per 100 person-years vs. 0.09; 95% CI, 0.08-0.11 per 100 person-years after 30 days).

Factors linked with high VTE risk

They also found that several factors were linked with a higher risk of blood clots in the study population, including being at least 55 years old; being male; having a history of blood clots or thrombophilia; and a body mass index (BMI) of at least 30 kg/m2.

The authors write, “These findings may help identify subsets of patients with COVID-19 who could benefit from VTE preventive strategies and more intensive short-term surveillance.”

Are routine anticoagulants justified?

Previously, randomized clinical trials have found that hospitalized patients with moderate COVID-19 may benefit from therapeutically dosed heparin anticoagulants but that therapeutic anticoagulation had no net benefit – and perhaps could even harm – patients who were critically ill with COVID.

“[M]uch less is known about the optimal thromboprophylaxis strategy for people with milder presentations of COVID-19 who do not require hospitalization,” they write.

Mild COVID VTE risk similar to general population

The authors note that rates of blood clots linked with COVID-19 are not much higher than the average blood clot rate in the general population, which is about 0.1-0.2 per 100 person-years.

Therefore, the results don’t justify routine administration of anticoagulation given the costs, inconvenience, and bleeding risks, they acknowledge.

Dr. Fang told this publication that it’s hard to know what to tell patients, given the overall low VTE risk. She said their study wasn’t designed to advise when to give prophylaxis.

Physicians should inform patients of their higher risk

“We should tell our patients who fall into these risk categories that blood clot is a concern after the development of COVID, especially in those first 30 days. And some people might benefit from increased surveillance,” Dr. Fang said.

”I think this study would support ongoing studies that look at whether selected patients benefit from VTE prophylaxis, for example low-dose anticoagulants,” she said.

Dr. Fang said the subgroup factors they found increased risk of blood clots for all patients, not just COVID-19 patients. It’s not clear why factors such as being male may increase blood clot risk, though that is consistent with previous literature, but higher risk with higher BMI might be related to a combination of inflammation or decreased mobility, she said.

Unanswered questions

Robert H. Hopkins Jr., MD, says the study helps answer a couple of important questions – that the VTE risk in nonhospitalized COVID-19 patients is low and when and for which patients risk may be highest.

However, there are several unanswered questions that argue against routine initiation of anticoagulants, notes the professor of internal medicine and pediatrics chief, division of general internal medicine, at University of Arkansas for Medical Sciences, Little Rock.

One is the change in the COVID variant landscape.

“We do not know whether rates of VTE are same or lower or higher with current circulating variants,” Dr. Hopkins said.

The authors acknowledge this as a limitation. Study data predate Omicron and subvariants, which appear to lower clinical severity, so it’s unclear whether VTE risk is different in this Omicron era.

Dr. Hopkins added another unknown: “We do not know whether vaccination affects rates of VTE in ambulatory breakthrough infection.”

Dr. Hopkins and the authors also note the lack of a control group in the study, to better compare risk.

Coauthor Dr. Prasad reports consultant fees from EpiExcellence LLC outside the submitted work. Coauthor Dr. Go reports grants paid to the division of research, Kaiser Permanente Northern California, from CSL Behring, Novartis, Bristol Meyers Squibb/Pfizer Alliance, and Janssen outside the submitted work.

The research was funded through Patient-Centered Outcomes Research Institute.

Dr. Hopkins reports no relevant financial relationships.

Though VTE risk is well studied and significant in those hospitalized with COVID, little is known about the risk in the outpatient setting, said the authors of the new research published online in JAMA Network Open.

The study was conducted at two integrated health care delivery systems in northern and southern California. Data were gathered from the Kaiser Permanente Virtual Data Warehouse and electronic health records.

Nearly 400,000 patients studied

Researchers, led by Margaret Fang, MD, with the division of hospital medicine, University of California, San Francisco, identified 398,530 outpatients with COVID-19 from Jan. 1, 2020, through Jan. 31, 2021.

VTE risk was low overall for ambulatory COVID patients.

“It is a reassuring study,” Dr. Fang said in an interview.

The researchers found that the risk is highest in the first 30 days after COVID-19 diagnosis (unadjusted rate, 0.58; 95% confidence interval, 0.51-0.67 per 100 person-years vs. 0.09; 95% CI, 0.08-0.11 per 100 person-years after 30 days).

Factors linked with high VTE risk

They also found that several factors were linked with a higher risk of blood clots in the study population, including being at least 55 years old; being male; having a history of blood clots or thrombophilia; and a body mass index (BMI) of at least 30 kg/m2.

The authors write, “These findings may help identify subsets of patients with COVID-19 who could benefit from VTE preventive strategies and more intensive short-term surveillance.”

Are routine anticoagulants justified?

Previously, randomized clinical trials have found that hospitalized patients with moderate COVID-19 may benefit from therapeutically dosed heparin anticoagulants but that therapeutic anticoagulation had no net benefit – and perhaps could even harm – patients who were critically ill with COVID.

“[M]uch less is known about the optimal thromboprophylaxis strategy for people with milder presentations of COVID-19 who do not require hospitalization,” they write.

Mild COVID VTE risk similar to general population

The authors note that rates of blood clots linked with COVID-19 are not much higher than the average blood clot rate in the general population, which is about 0.1-0.2 per 100 person-years.

Therefore, the results don’t justify routine administration of anticoagulation given the costs, inconvenience, and bleeding risks, they acknowledge.

Dr. Fang told this publication that it’s hard to know what to tell patients, given the overall low VTE risk. She said their study wasn’t designed to advise when to give prophylaxis.

Physicians should inform patients of their higher risk

“We should tell our patients who fall into these risk categories that blood clot is a concern after the development of COVID, especially in those first 30 days. And some people might benefit from increased surveillance,” Dr. Fang said.

”I think this study would support ongoing studies that look at whether selected patients benefit from VTE prophylaxis, for example low-dose anticoagulants,” she said.

Dr. Fang said the subgroup factors they found increased risk of blood clots for all patients, not just COVID-19 patients. It’s not clear why factors such as being male may increase blood clot risk, though that is consistent with previous literature, but higher risk with higher BMI might be related to a combination of inflammation or decreased mobility, she said.

Unanswered questions

Robert H. Hopkins Jr., MD, says the study helps answer a couple of important questions – that the VTE risk in nonhospitalized COVID-19 patients is low and when and for which patients risk may be highest.

However, there are several unanswered questions that argue against routine initiation of anticoagulants, notes the professor of internal medicine and pediatrics chief, division of general internal medicine, at University of Arkansas for Medical Sciences, Little Rock.

One is the change in the COVID variant landscape.

“We do not know whether rates of VTE are same or lower or higher with current circulating variants,” Dr. Hopkins said.

The authors acknowledge this as a limitation. Study data predate Omicron and subvariants, which appear to lower clinical severity, so it’s unclear whether VTE risk is different in this Omicron era.

Dr. Hopkins added another unknown: “We do not know whether vaccination affects rates of VTE in ambulatory breakthrough infection.”

Dr. Hopkins and the authors also note the lack of a control group in the study, to better compare risk.

Coauthor Dr. Prasad reports consultant fees from EpiExcellence LLC outside the submitted work. Coauthor Dr. Go reports grants paid to the division of research, Kaiser Permanente Northern California, from CSL Behring, Novartis, Bristol Meyers Squibb/Pfizer Alliance, and Janssen outside the submitted work.

The research was funded through Patient-Centered Outcomes Research Institute.

Dr. Hopkins reports no relevant financial relationships.

Though VTE risk is well studied and significant in those hospitalized with COVID, little is known about the risk in the outpatient setting, said the authors of the new research published online in JAMA Network Open.

The study was conducted at two integrated health care delivery systems in northern and southern California. Data were gathered from the Kaiser Permanente Virtual Data Warehouse and electronic health records.

Nearly 400,000 patients studied

Researchers, led by Margaret Fang, MD, with the division of hospital medicine, University of California, San Francisco, identified 398,530 outpatients with COVID-19 from Jan. 1, 2020, through Jan. 31, 2021.

VTE risk was low overall for ambulatory COVID patients.

“It is a reassuring study,” Dr. Fang said in an interview.

The researchers found that the risk is highest in the first 30 days after COVID-19 diagnosis (unadjusted rate, 0.58; 95% confidence interval, 0.51-0.67 per 100 person-years vs. 0.09; 95% CI, 0.08-0.11 per 100 person-years after 30 days).

Factors linked with high VTE risk

They also found that several factors were linked with a higher risk of blood clots in the study population, including being at least 55 years old; being male; having a history of blood clots or thrombophilia; and a body mass index (BMI) of at least 30 kg/m2.

The authors write, “These findings may help identify subsets of patients with COVID-19 who could benefit from VTE preventive strategies and more intensive short-term surveillance.”

Are routine anticoagulants justified?

Previously, randomized clinical trials have found that hospitalized patients with moderate COVID-19 may benefit from therapeutically dosed heparin anticoagulants but that therapeutic anticoagulation had no net benefit – and perhaps could even harm – patients who were critically ill with COVID.

“[M]uch less is known about the optimal thromboprophylaxis strategy for people with milder presentations of COVID-19 who do not require hospitalization,” they write.

Mild COVID VTE risk similar to general population

The authors note that rates of blood clots linked with COVID-19 are not much higher than the average blood clot rate in the general population, which is about 0.1-0.2 per 100 person-years.

Therefore, the results don’t justify routine administration of anticoagulation given the costs, inconvenience, and bleeding risks, they acknowledge.

Dr. Fang told this publication that it’s hard to know what to tell patients, given the overall low VTE risk. She said their study wasn’t designed to advise when to give prophylaxis.

Physicians should inform patients of their higher risk

“We should tell our patients who fall into these risk categories that blood clot is a concern after the development of COVID, especially in those first 30 days. And some people might benefit from increased surveillance,” Dr. Fang said.

”I think this study would support ongoing studies that look at whether selected patients benefit from VTE prophylaxis, for example low-dose anticoagulants,” she said.

Dr. Fang said the subgroup factors they found increased risk of blood clots for all patients, not just COVID-19 patients. It’s not clear why factors such as being male may increase blood clot risk, though that is consistent with previous literature, but higher risk with higher BMI might be related to a combination of inflammation or decreased mobility, she said.

Unanswered questions

Robert H. Hopkins Jr., MD, says the study helps answer a couple of important questions – that the VTE risk in nonhospitalized COVID-19 patients is low and when and for which patients risk may be highest.

However, there are several unanswered questions that argue against routine initiation of anticoagulants, notes the professor of internal medicine and pediatrics chief, division of general internal medicine, at University of Arkansas for Medical Sciences, Little Rock.

One is the change in the COVID variant landscape.

“We do not know whether rates of VTE are same or lower or higher with current circulating variants,” Dr. Hopkins said.

The authors acknowledge this as a limitation. Study data predate Omicron and subvariants, which appear to lower clinical severity, so it’s unclear whether VTE risk is different in this Omicron era.

Dr. Hopkins added another unknown: “We do not know whether vaccination affects rates of VTE in ambulatory breakthrough infection.”

Dr. Hopkins and the authors also note the lack of a control group in the study, to better compare risk.

Coauthor Dr. Prasad reports consultant fees from EpiExcellence LLC outside the submitted work. Coauthor Dr. Go reports grants paid to the division of research, Kaiser Permanente Northern California, from CSL Behring, Novartis, Bristol Meyers Squibb/Pfizer Alliance, and Janssen outside the submitted work.

The research was funded through Patient-Centered Outcomes Research Institute.

Dr. Hopkins reports no relevant financial relationships.

FROM JAMA NETWORK OPEN

Even mild COVID is hard on the brain

early research suggests.

“Our results suggest a severe pattern of changes in how the brain communicates as well as its structure, mainly in people with anxiety and depression with long-COVID syndrome, which affects so many people,” study investigator Clarissa Yasuda, MD, PhD, from University of Campinas, São Paulo, said in a news release.

“The magnitude of these changes suggests that they could lead to problems with memory and thinking skills, so we need to be exploring holistic treatments even for people mildly affected by COVID-19,” Dr. Yasuda added.

The findings were released March 6 ahead of the study’s scheduled presentation at the annual meeting of the American Academy of Neurology.

Brain shrinkage

Some studies have shown a high prevalence of symptoms of anxiety and depression in COVID-19 survivors, but few have investigated the associated cerebral changes, Dr. Yasuda told this news organization.

The study included 254 adults (177 women, 77 men, median age 41 years) who had mild COVID-19 a median of 82 days earlier. A total of 102 had symptoms of both anxiety and depression, and 152 had no such symptoms.

On brain imaging, those with COVID-19 and anxiety and depression had atrophy in the limbic area of the brain, which plays a role in memory and emotional processing.

No shrinkage in this area was evident in people who had COVID-19 without anxiety and depression or in a healthy control group of individuals without COVID-19.

The researchers also observed a “severe” pattern of abnormal cerebral functional connectivity in those with COVID-19 and anxiety and depression.

In this functional connectivity analysis, individuals with COVID-19 and anxiety and depression had widespread functional changes in each of the 12 networks assessed, while those with COVID-19 but without symptoms of anxiety and depression showed changes in only 5 networks.

Mechanisms unclear

“Unfortunately, the underpinning mechanisms associated with brain changes and neuropsychiatric dysfunction after COVID-19 infection are unclear,” Dr. Yasuda told this news organization.

“Some studies have demonstrated an association between symptoms of anxiety and depression with inflammation. However, we hypothesize that these cerebral alterations may result from a more complex interaction of social, psychological, and systemic stressors, including inflammation. It is indeed intriguing that such alterations are present in individuals who presented mild acute infection,” Dr. Yasuda added.

“Symptoms of anxiety and depression are frequently observed after COVID-19 and are part of long-COVID syndrome for some individuals. These symptoms require adequate treatment to improve the quality of life, cognition, and work capacity,” she said.

Treating these symptoms may induce “brain plasticity, which may result in some degree of gray matter increase and eventually prevent further structural and functional damage,” Dr. Yasuda said.

A limitation of the study was that symptoms of anxiety and depression were self-reported, meaning people may have misjudged or misreported symptoms.

Commenting on the findings for this news organization, Cyrus Raji, MD, PhD, with the Mallinckrodt Institute of Radiology, Washington University, St. Louis, said the idea that COVID-19 is bad for the brain isn’t new. Dr. Raji was not involved with the study.

Early in the pandemic, Dr. Raji and colleagues published a paper detailing COVID-19’s effects on the brain, and Dr. Raji followed it up with a TED talk on the subject.

“Within the growing framework of what we already know about COVID-19 infection and its adverse effects on the brain, this work incrementally adds to this knowledge by identifying functional and structural neuroimaging abnormalities related to anxiety and depression in persons suffering from COVID-19 infection,” Dr. Raji said.

The study was supported by the São Paulo Research Foundation. The authors have no relevant disclosures. Raji is a consultant for Brainreader, Apollo Health, Pacific Neuroscience Foundation, and Neurevolution LLC.

early research suggests.

“Our results suggest a severe pattern of changes in how the brain communicates as well as its structure, mainly in people with anxiety and depression with long-COVID syndrome, which affects so many people,” study investigator Clarissa Yasuda, MD, PhD, from University of Campinas, São Paulo, said in a news release.

“The magnitude of these changes suggests that they could lead to problems with memory and thinking skills, so we need to be exploring holistic treatments even for people mildly affected by COVID-19,” Dr. Yasuda added.

The findings were released March 6 ahead of the study’s scheduled presentation at the annual meeting of the American Academy of Neurology.

Brain shrinkage

Some studies have shown a high prevalence of symptoms of anxiety and depression in COVID-19 survivors, but few have investigated the associated cerebral changes, Dr. Yasuda told this news organization.

The study included 254 adults (177 women, 77 men, median age 41 years) who had mild COVID-19 a median of 82 days earlier. A total of 102 had symptoms of both anxiety and depression, and 152 had no such symptoms.

On brain imaging, those with COVID-19 and anxiety and depression had atrophy in the limbic area of the brain, which plays a role in memory and emotional processing.

No shrinkage in this area was evident in people who had COVID-19 without anxiety and depression or in a healthy control group of individuals without COVID-19.

The researchers also observed a “severe” pattern of abnormal cerebral functional connectivity in those with COVID-19 and anxiety and depression.

In this functional connectivity analysis, individuals with COVID-19 and anxiety and depression had widespread functional changes in each of the 12 networks assessed, while those with COVID-19 but without symptoms of anxiety and depression showed changes in only 5 networks.

Mechanisms unclear

“Unfortunately, the underpinning mechanisms associated with brain changes and neuropsychiatric dysfunction after COVID-19 infection are unclear,” Dr. Yasuda told this news organization.

“Some studies have demonstrated an association between symptoms of anxiety and depression with inflammation. However, we hypothesize that these cerebral alterations may result from a more complex interaction of social, psychological, and systemic stressors, including inflammation. It is indeed intriguing that such alterations are present in individuals who presented mild acute infection,” Dr. Yasuda added.

“Symptoms of anxiety and depression are frequently observed after COVID-19 and are part of long-COVID syndrome for some individuals. These symptoms require adequate treatment to improve the quality of life, cognition, and work capacity,” she said.

Treating these symptoms may induce “brain plasticity, which may result in some degree of gray matter increase and eventually prevent further structural and functional damage,” Dr. Yasuda said.

A limitation of the study was that symptoms of anxiety and depression were self-reported, meaning people may have misjudged or misreported symptoms.

Commenting on the findings for this news organization, Cyrus Raji, MD, PhD, with the Mallinckrodt Institute of Radiology, Washington University, St. Louis, said the idea that COVID-19 is bad for the brain isn’t new. Dr. Raji was not involved with the study.

Early in the pandemic, Dr. Raji and colleagues published a paper detailing COVID-19’s effects on the brain, and Dr. Raji followed it up with a TED talk on the subject.

“Within the growing framework of what we already know about COVID-19 infection and its adverse effects on the brain, this work incrementally adds to this knowledge by identifying functional and structural neuroimaging abnormalities related to anxiety and depression in persons suffering from COVID-19 infection,” Dr. Raji said.

The study was supported by the São Paulo Research Foundation. The authors have no relevant disclosures. Raji is a consultant for Brainreader, Apollo Health, Pacific Neuroscience Foundation, and Neurevolution LLC.

early research suggests.

“Our results suggest a severe pattern of changes in how the brain communicates as well as its structure, mainly in people with anxiety and depression with long-COVID syndrome, which affects so many people,” study investigator Clarissa Yasuda, MD, PhD, from University of Campinas, São Paulo, said in a news release.

“The magnitude of these changes suggests that they could lead to problems with memory and thinking skills, so we need to be exploring holistic treatments even for people mildly affected by COVID-19,” Dr. Yasuda added.

The findings were released March 6 ahead of the study’s scheduled presentation at the annual meeting of the American Academy of Neurology.

Brain shrinkage

Some studies have shown a high prevalence of symptoms of anxiety and depression in COVID-19 survivors, but few have investigated the associated cerebral changes, Dr. Yasuda told this news organization.

The study included 254 adults (177 women, 77 men, median age 41 years) who had mild COVID-19 a median of 82 days earlier. A total of 102 had symptoms of both anxiety and depression, and 152 had no such symptoms.

On brain imaging, those with COVID-19 and anxiety and depression had atrophy in the limbic area of the brain, which plays a role in memory and emotional processing.

No shrinkage in this area was evident in people who had COVID-19 without anxiety and depression or in a healthy control group of individuals without COVID-19.

The researchers also observed a “severe” pattern of abnormal cerebral functional connectivity in those with COVID-19 and anxiety and depression.

In this functional connectivity analysis, individuals with COVID-19 and anxiety and depression had widespread functional changes in each of the 12 networks assessed, while those with COVID-19 but without symptoms of anxiety and depression showed changes in only 5 networks.

Mechanisms unclear

“Unfortunately, the underpinning mechanisms associated with brain changes and neuropsychiatric dysfunction after COVID-19 infection are unclear,” Dr. Yasuda told this news organization.

“Some studies have demonstrated an association between symptoms of anxiety and depression with inflammation. However, we hypothesize that these cerebral alterations may result from a more complex interaction of social, psychological, and systemic stressors, including inflammation. It is indeed intriguing that such alterations are present in individuals who presented mild acute infection,” Dr. Yasuda added.

“Symptoms of anxiety and depression are frequently observed after COVID-19 and are part of long-COVID syndrome for some individuals. These symptoms require adequate treatment to improve the quality of life, cognition, and work capacity,” she said.

Treating these symptoms may induce “brain plasticity, which may result in some degree of gray matter increase and eventually prevent further structural and functional damage,” Dr. Yasuda said.

A limitation of the study was that symptoms of anxiety and depression were self-reported, meaning people may have misjudged or misreported symptoms.

Commenting on the findings for this news organization, Cyrus Raji, MD, PhD, with the Mallinckrodt Institute of Radiology, Washington University, St. Louis, said the idea that COVID-19 is bad for the brain isn’t new. Dr. Raji was not involved with the study.

Early in the pandemic, Dr. Raji and colleagues published a paper detailing COVID-19’s effects on the brain, and Dr. Raji followed it up with a TED talk on the subject.

“Within the growing framework of what we already know about COVID-19 infection and its adverse effects on the brain, this work incrementally adds to this knowledge by identifying functional and structural neuroimaging abnormalities related to anxiety and depression in persons suffering from COVID-19 infection,” Dr. Raji said.

The study was supported by the São Paulo Research Foundation. The authors have no relevant disclosures. Raji is a consultant for Brainreader, Apollo Health, Pacific Neuroscience Foundation, and Neurevolution LLC.

COVID-19 shot appears to reduce diabetes risk, even after Omicron

new data suggest.

The findings, from more than 20,000 patients in the Cedars-Sinai Health System in Los Angeles, suggest that “continued efforts to prevent COVID-19 infection may be beneficial to patient health until we develop better understanding of the effects of potential long-term effects of COVID-19,” lead author Alan C. Kwan, MD, of the department of cardiology at Cedars Sinai’s Smidt Heart Institute, said in an interview.

Several studies conducted early in the pandemic suggested increased risks for both new-onset diabetes and cardiometabolic diseases following COVID-19 infection, possibly because of persistent inflammation contributing to insulin resistance.

However, it hasn’t been clear if those risks have persisted with the more recent predominance of the less-virulent Omicron variant or whether the COVID-19 vaccine influences the risk. This new study suggests that both are the case.

“Our results verify that the risk of developing type 2 diabetes after a COVID-19 infection was not just an early observation but, in fact, a real risk that has, unfortunately, persisted through the Omicron era,” Dr. Kwan noted.

“While the level of evidence by our study and others may not reach the degree needed to affect formal guidelines at this time, we believe it is reasonable to have increased clinical suspicion for diabetes after COVID-19 infection and a lower threshold for testing,” he added.

Moreover, “we believe that our study and others suggest the potential role of COVID-19 to affect cardiovascular risk, and so both prevention of COVID-19 infection, through reasonable personal practices and vaccination, and an increased attention to cardiovascular health after COVID-19 infection is warranted.”

The findings were published online in JAMA Network Open.

Dr. Kwan and colleagues analyzed data for a total of 23,709 patients treated (inpatient and outpatient) for at least one COVID-19 infection between March 2020 and June 2022.

Rates of new-onset diabetes (using ICD-10 codes, primarily type 2 diabetes), hypertension, and hyperlipidemia were all elevated in the 90 days following COVID-19 infection compared with the 90 days prior. The same was true of two diagnoses unrelated to COVID-19, urinary tract infection and gastroesophageal reflux, used as benchmarks of health care engagement.

The highest odds for post versus preinfection were for diabetes (odds ratio, 2.35; P < .001), followed by hypertension (OR, 1.54; P < .001), the benchmark diagnoses (OR, 1.42; P < .001), and hyperlipidemia (OR, 1.22; P = .03).

Following adjustments, the risk versus the benchmark conditions for new-onset diabetes before versus after COVID-19 was significantly elevated (OR, 1.58; P < .001), while the risks for hypertension and hyperlipidemia versus benchmark diagnoses were not (OR, 1.06; P = .52 and 0.91, P = .43, respectively).

The diabetes risk after versus before COVID-19 infection was higher among those who had not been vaccinated (OR, 1.78; P < .001), compared with those who had received the vaccine (OR, 1.07; P = .80).

However, there was no significant interaction between vaccination and diabetes diagnosis (P = .08). “For this reason, we believe our data are suggestive of a protective effect in the population who received vaccination prior to infection, but [this is] not definitive,” Dr. Kwan said.

There were no apparent interactions by age, sex, or pre-existing cardiovascular risk factors, including hypertension or hyperlipidemia. Age, sex, and timing of index infection regarding the Omicron variant were not associated with an increased risk of a new cardiometabolic diagnosis before or after COVID-19 infection in any of the models.

Dr. Kwan said in an interview: “We have continued to be surprised by the evolving understanding of the SARS-CoV-2 virus and the effects on human health. In the beginning of the pandemic it was framed as a purely respiratory virus, which we now know to be a severely limited description of all of its potential effects on the human body. We believe that our research and others raise a concern for increased cardiometabolic risk after COVID infection.”

He added that, “while knowledge is incomplete on this topic, we believe that clinical providers may wish to have a higher degree of suspicion for both diabetes and risk of future cardiac events in patients after COVID infection, and that continued efforts to prevent COVID infection may be beneficial to patient health until we develop better understanding of the potential long-term effects of COVID.”

This study was funded by the Erika J. Glazer Family Foundation, the Doris Duke Charitable Foundation, and grants from the National Institutes of Health. Dr. Kwan reported receiving grants from the Doris Duke Charitable Foundation during the conduct of the study.

A version of this article originally appeared on Medscape.com.

new data suggest.

The findings, from more than 20,000 patients in the Cedars-Sinai Health System in Los Angeles, suggest that “continued efforts to prevent COVID-19 infection may be beneficial to patient health until we develop better understanding of the effects of potential long-term effects of COVID-19,” lead author Alan C. Kwan, MD, of the department of cardiology at Cedars Sinai’s Smidt Heart Institute, said in an interview.

Several studies conducted early in the pandemic suggested increased risks for both new-onset diabetes and cardiometabolic diseases following COVID-19 infection, possibly because of persistent inflammation contributing to insulin resistance.

However, it hasn’t been clear if those risks have persisted with the more recent predominance of the less-virulent Omicron variant or whether the COVID-19 vaccine influences the risk. This new study suggests that both are the case.

“Our results verify that the risk of developing type 2 diabetes after a COVID-19 infection was not just an early observation but, in fact, a real risk that has, unfortunately, persisted through the Omicron era,” Dr. Kwan noted.

“While the level of evidence by our study and others may not reach the degree needed to affect formal guidelines at this time, we believe it is reasonable to have increased clinical suspicion for diabetes after COVID-19 infection and a lower threshold for testing,” he added.

Moreover, “we believe that our study and others suggest the potential role of COVID-19 to affect cardiovascular risk, and so both prevention of COVID-19 infection, through reasonable personal practices and vaccination, and an increased attention to cardiovascular health after COVID-19 infection is warranted.”

The findings were published online in JAMA Network Open.

Dr. Kwan and colleagues analyzed data for a total of 23,709 patients treated (inpatient and outpatient) for at least one COVID-19 infection between March 2020 and June 2022.

Rates of new-onset diabetes (using ICD-10 codes, primarily type 2 diabetes), hypertension, and hyperlipidemia were all elevated in the 90 days following COVID-19 infection compared with the 90 days prior. The same was true of two diagnoses unrelated to COVID-19, urinary tract infection and gastroesophageal reflux, used as benchmarks of health care engagement.

The highest odds for post versus preinfection were for diabetes (odds ratio, 2.35; P < .001), followed by hypertension (OR, 1.54; P < .001), the benchmark diagnoses (OR, 1.42; P < .001), and hyperlipidemia (OR, 1.22; P = .03).

Following adjustments, the risk versus the benchmark conditions for new-onset diabetes before versus after COVID-19 was significantly elevated (OR, 1.58; P < .001), while the risks for hypertension and hyperlipidemia versus benchmark diagnoses were not (OR, 1.06; P = .52 and 0.91, P = .43, respectively).

The diabetes risk after versus before COVID-19 infection was higher among those who had not been vaccinated (OR, 1.78; P < .001), compared with those who had received the vaccine (OR, 1.07; P = .80).

However, there was no significant interaction between vaccination and diabetes diagnosis (P = .08). “For this reason, we believe our data are suggestive of a protective effect in the population who received vaccination prior to infection, but [this is] not definitive,” Dr. Kwan said.

There were no apparent interactions by age, sex, or pre-existing cardiovascular risk factors, including hypertension or hyperlipidemia. Age, sex, and timing of index infection regarding the Omicron variant were not associated with an increased risk of a new cardiometabolic diagnosis before or after COVID-19 infection in any of the models.

Dr. Kwan said in an interview: “We have continued to be surprised by the evolving understanding of the SARS-CoV-2 virus and the effects on human health. In the beginning of the pandemic it was framed as a purely respiratory virus, which we now know to be a severely limited description of all of its potential effects on the human body. We believe that our research and others raise a concern for increased cardiometabolic risk after COVID infection.”

He added that, “while knowledge is incomplete on this topic, we believe that clinical providers may wish to have a higher degree of suspicion for both diabetes and risk of future cardiac events in patients after COVID infection, and that continued efforts to prevent COVID infection may be beneficial to patient health until we develop better understanding of the potential long-term effects of COVID.”

This study was funded by the Erika J. Glazer Family Foundation, the Doris Duke Charitable Foundation, and grants from the National Institutes of Health. Dr. Kwan reported receiving grants from the Doris Duke Charitable Foundation during the conduct of the study.

A version of this article originally appeared on Medscape.com.

new data suggest.

The findings, from more than 20,000 patients in the Cedars-Sinai Health System in Los Angeles, suggest that “continued efforts to prevent COVID-19 infection may be beneficial to patient health until we develop better understanding of the effects of potential long-term effects of COVID-19,” lead author Alan C. Kwan, MD, of the department of cardiology at Cedars Sinai’s Smidt Heart Institute, said in an interview.

Several studies conducted early in the pandemic suggested increased risks for both new-onset diabetes and cardiometabolic diseases following COVID-19 infection, possibly because of persistent inflammation contributing to insulin resistance.

However, it hasn’t been clear if those risks have persisted with the more recent predominance of the less-virulent Omicron variant or whether the COVID-19 vaccine influences the risk. This new study suggests that both are the case.

“Our results verify that the risk of developing type 2 diabetes after a COVID-19 infection was not just an early observation but, in fact, a real risk that has, unfortunately, persisted through the Omicron era,” Dr. Kwan noted.

“While the level of evidence by our study and others may not reach the degree needed to affect formal guidelines at this time, we believe it is reasonable to have increased clinical suspicion for diabetes after COVID-19 infection and a lower threshold for testing,” he added.

Moreover, “we believe that our study and others suggest the potential role of COVID-19 to affect cardiovascular risk, and so both prevention of COVID-19 infection, through reasonable personal practices and vaccination, and an increased attention to cardiovascular health after COVID-19 infection is warranted.”

The findings were published online in JAMA Network Open.

Dr. Kwan and colleagues analyzed data for a total of 23,709 patients treated (inpatient and outpatient) for at least one COVID-19 infection between March 2020 and June 2022.

Rates of new-onset diabetes (using ICD-10 codes, primarily type 2 diabetes), hypertension, and hyperlipidemia were all elevated in the 90 days following COVID-19 infection compared with the 90 days prior. The same was true of two diagnoses unrelated to COVID-19, urinary tract infection and gastroesophageal reflux, used as benchmarks of health care engagement.

The highest odds for post versus preinfection were for diabetes (odds ratio, 2.35; P < .001), followed by hypertension (OR, 1.54; P < .001), the benchmark diagnoses (OR, 1.42; P < .001), and hyperlipidemia (OR, 1.22; P = .03).

Following adjustments, the risk versus the benchmark conditions for new-onset diabetes before versus after COVID-19 was significantly elevated (OR, 1.58; P < .001), while the risks for hypertension and hyperlipidemia versus benchmark diagnoses were not (OR, 1.06; P = .52 and 0.91, P = .43, respectively).

The diabetes risk after versus before COVID-19 infection was higher among those who had not been vaccinated (OR, 1.78; P < .001), compared with those who had received the vaccine (OR, 1.07; P = .80).

However, there was no significant interaction between vaccination and diabetes diagnosis (P = .08). “For this reason, we believe our data are suggestive of a protective effect in the population who received vaccination prior to infection, but [this is] not definitive,” Dr. Kwan said.

There were no apparent interactions by age, sex, or pre-existing cardiovascular risk factors, including hypertension or hyperlipidemia. Age, sex, and timing of index infection regarding the Omicron variant were not associated with an increased risk of a new cardiometabolic diagnosis before or after COVID-19 infection in any of the models.

Dr. Kwan said in an interview: “We have continued to be surprised by the evolving understanding of the SARS-CoV-2 virus and the effects on human health. In the beginning of the pandemic it was framed as a purely respiratory virus, which we now know to be a severely limited description of all of its potential effects on the human body. We believe that our research and others raise a concern for increased cardiometabolic risk after COVID infection.”

He added that, “while knowledge is incomplete on this topic, we believe that clinical providers may wish to have a higher degree of suspicion for both diabetes and risk of future cardiac events in patients after COVID infection, and that continued efforts to prevent COVID infection may be beneficial to patient health until we develop better understanding of the potential long-term effects of COVID.”

This study was funded by the Erika J. Glazer Family Foundation, the Doris Duke Charitable Foundation, and grants from the National Institutes of Health. Dr. Kwan reported receiving grants from the Doris Duke Charitable Foundation during the conduct of the study.

A version of this article originally appeared on Medscape.com.

FROM JAMA NETWORK OPEN

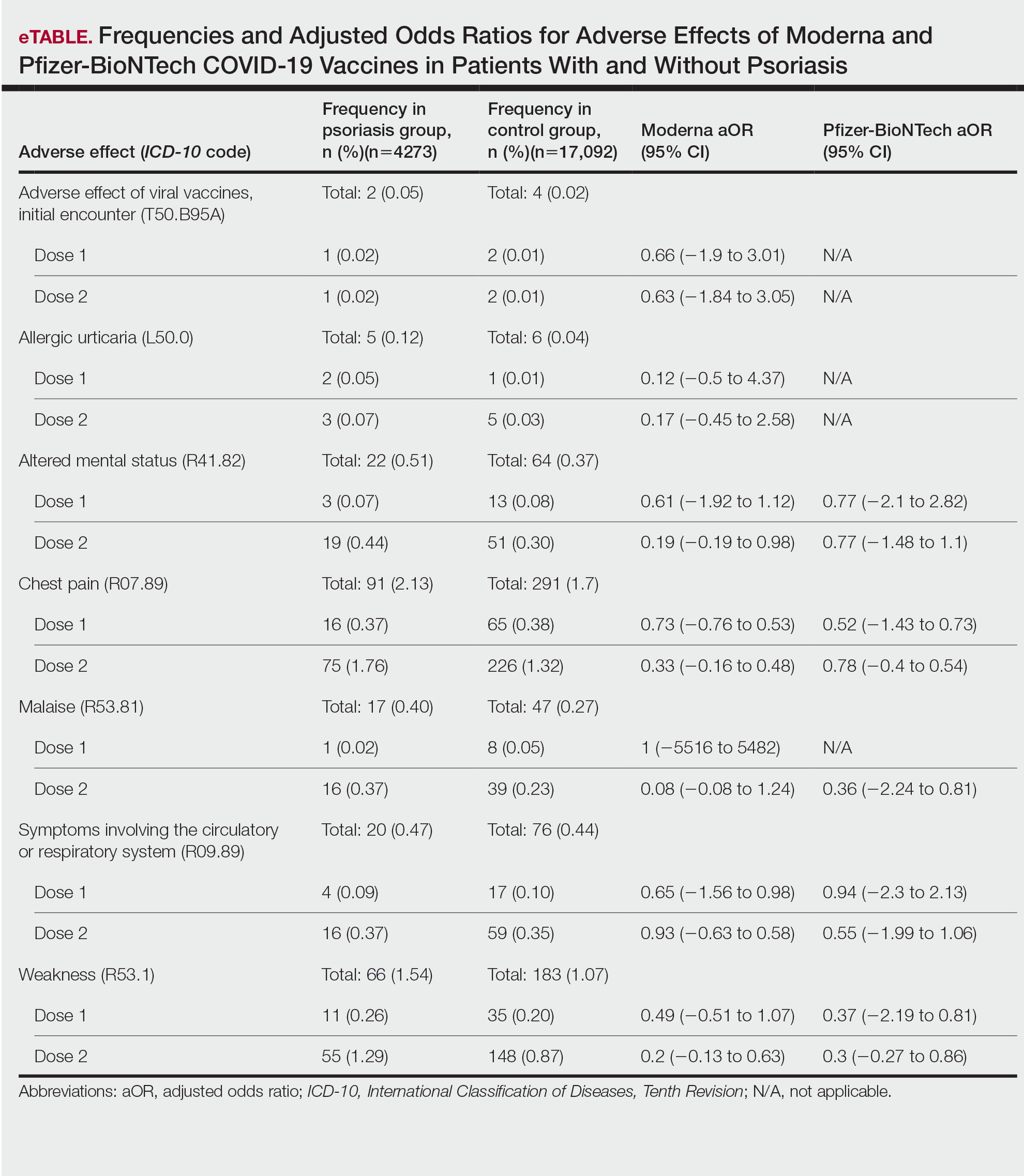

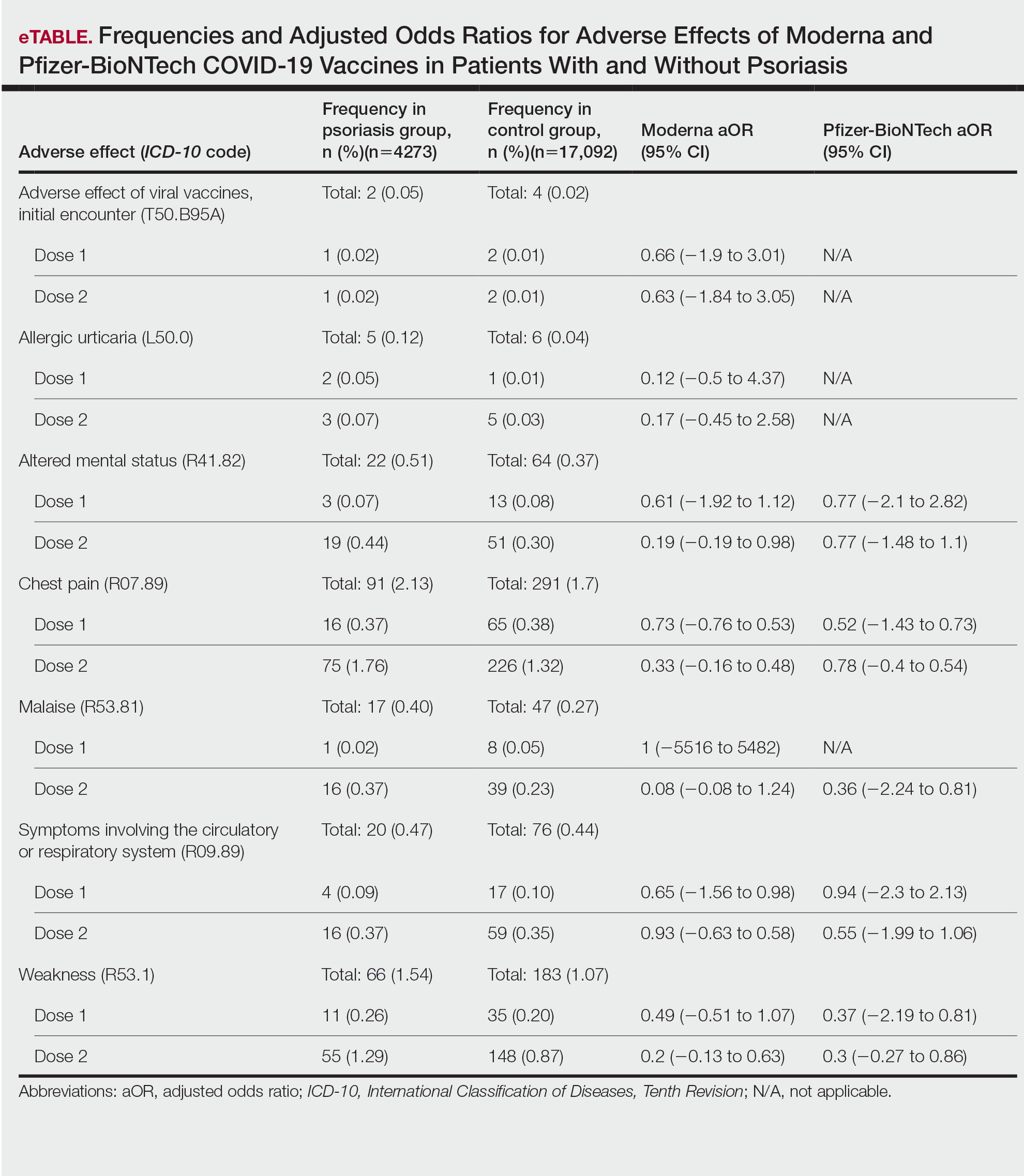

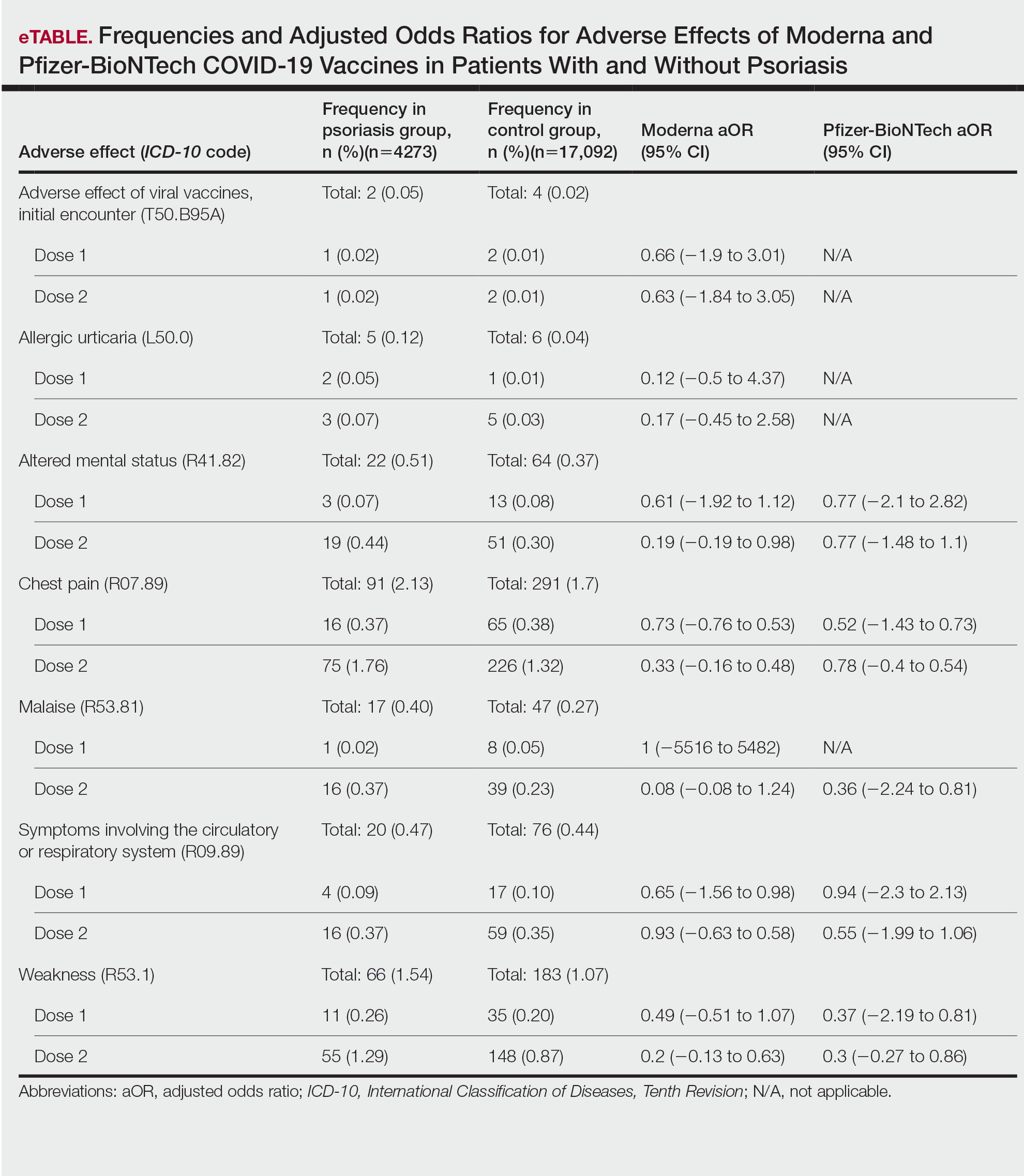

Adverse Effects of the COVID-19 Vaccine in Patients With Psoriasis

To the Editor:

Because the SARS-CoV-2 virus is constantly changing, routine vaccination to prevent COVID-19 infection is recommended. The messenger RNA (mRNA) vaccines from Pfizer-BioNTech and Moderna as well as the Ad26.COV2.S (Johnson & Johnson) and NVX-CoV2373 (Novavax) vaccines are the most commonly used COVID-19 vaccines in the United States. Adverse effects following vaccination against SARS-CoV-2 are well documented; recent studies report a small incidence of adverse effects in the general population, with most being minor (eg, headache, fever, muscle pain).1,2 Interestingly, reports of exacerbation of psoriasis and new-onset psoriasis following COVID-19 vaccination suggest a potential association.3,4 However, the literature investigating the vaccine adverse effect profile in this demographic is scarce. We examined the incidence of adverse effects from SARS-CoV-2 vaccines in patients with psoriasis.

This retrospective cohort study used the COVID-19 Research Database (https://covid19researchdatabase.org/) to examine the adverse effects following the first and second doses of the mRNA vaccines in patients with and without psoriasis. The sample size for the Ad26.COV2.S vaccine was too small to analyze.

Claims were evaluated from August to October 2021 for 2 diagnoses of psoriasis prior to January 1, 2020, using the International Classification of Diseases, Tenth Revision (ICD-10) code L40.9 to increase the positive predictive value and ensure that the diagnosis preceded the COVID-19 pandemic. Patients younger than 18 years and those who did not receive 2 doses of a SARS-CoV-2 vaccine were excluded. Controls who did not have a diagnosis of psoriasis were matched for age, sex, and hypertension at a 4:1 ratio. Hypertension represented the most common comorbidity that could feasibly be controlled for in this study population. Other comorbidities recorded included obesity, type 2 diabetes mellitus, congestive heart failure, asthma, chronic obstructive pulmonary disease, chronic ischemic heart disease, rhinitis, and chronic kidney disease.

Common adverse effects as long as 30 days after vaccination were identified using ICD-10 codes. Adverse effects of interest were anaphylactic reaction, initial encounter of adverse effect of viral vaccines, fever, allergic urticaria, weakness, altered mental status, malaise, allergic reaction, chest pain, symptoms involving circulatory or respiratory systems, localized rash, axillary lymphadenopathy, infection, and myocarditis.5 Poisson regression was performed using Stata 17 analytical software.

We identified 4273 patients with psoriasis and 17,092 controls who received mRNA COVID-19 vaccines (Table). Adjusted odds ratios (aORs) for doses 1 and 2 were calculated for each vaccine (eTable). Adverse effects with sufficient data to generate an aOR included weakness, altered mental status, malaise, chest pain, and symptoms involving the circulatory or respiratory system. The aORs for allergic urticaria and initial encounter of adverse effect of viral vaccines were only calculated for the Moderna mRNA vaccine due to low sample size.

This study demonstrated that patients with psoriasis do not appear to have a significantly increased risk of adverse effects from mRNA SARS-CoV-2 vaccines. Although the ORs in this study were not significant, most recorded adverse effects demonstrated an aOR less than 1, suggesting that there might be a lower risk of certain adverse effects in psoriasis patients. This could be explained by the immunomodulatory effects of certain systemic psoriasis treatments that might influence the adverse effect presentation.

The study is limited by the lack of treatment data, small sample size, and the fact that it did not assess flares or worsening of psoriasis with the vaccines. Underreporting of adverse effects by patients and underdiagnosis of adverse effects secondary to SARS-CoV-2 vaccines due to its novel nature, incompletely understood consequences, and limited ICD-10 codes associated with adverse effects all contributed to the small sample size.

Our findings suggest that the risk for immediate adverse effects from the mRNA SARS-CoV-2 vaccines is not increased among psoriasis patients. However, the impact of immunomodulatory agents on vaccine efficacy and expected adverse effects should be investigated. As more individuals receive the COVID-19 vaccine, the adverse effect profile in patients with psoriasis is an important area of investigation.

- Singh A, Khillan R, Mishra Y, et al. The safety profile of COVID-19 vaccinations in the United States. Am J Infect Control. 2022;50:15-19. doi: 10.1016/j.ajic.2021.10.015

- Beatty AL, Peyser ND, Butcher XE, et al. Analysis of COVID-19 vaccine type and adverse effects following vaccination. JAMA Netw Open. 2021;4:e2140364. doi:10.1001/jamanetworkopen.2021.40364

- Bellinato F, Maurelli M, Gisondi P, et al. Cutaneous adverse reactions associated with SARS-CoV-2 vaccines. J Clin Med. 2021;10:5344. doi:10.3390/jcm10225344

- Elamin S, Hinds F, Tolland J. De novo generalized pustular psoriasis following Oxford-AstraZeneca COVID-19 vaccine. Clin Exp Dermatol. 2022;47:153-155. doi:10.1111/ced.14895

- Remer EE. Coding COVID-19 vaccination. ICD10monitor. Published March 2, 2021. Updated October 18, 2022. Accessed January 17, 2023. https://icd10monitor.medlearn.com/coding-covid-19-vaccination/

To the Editor:

Because the SARS-CoV-2 virus is constantly changing, routine vaccination to prevent COVID-19 infection is recommended. The messenger RNA (mRNA) vaccines from Pfizer-BioNTech and Moderna as well as the Ad26.COV2.S (Johnson & Johnson) and NVX-CoV2373 (Novavax) vaccines are the most commonly used COVID-19 vaccines in the United States. Adverse effects following vaccination against SARS-CoV-2 are well documented; recent studies report a small incidence of adverse effects in the general population, with most being minor (eg, headache, fever, muscle pain).1,2 Interestingly, reports of exacerbation of psoriasis and new-onset psoriasis following COVID-19 vaccination suggest a potential association.3,4 However, the literature investigating the vaccine adverse effect profile in this demographic is scarce. We examined the incidence of adverse effects from SARS-CoV-2 vaccines in patients with psoriasis.

This retrospective cohort study used the COVID-19 Research Database (https://covid19researchdatabase.org/) to examine the adverse effects following the first and second doses of the mRNA vaccines in patients with and without psoriasis. The sample size for the Ad26.COV2.S vaccine was too small to analyze.

Claims were evaluated from August to October 2021 for 2 diagnoses of psoriasis prior to January 1, 2020, using the International Classification of Diseases, Tenth Revision (ICD-10) code L40.9 to increase the positive predictive value and ensure that the diagnosis preceded the COVID-19 pandemic. Patients younger than 18 years and those who did not receive 2 doses of a SARS-CoV-2 vaccine were excluded. Controls who did not have a diagnosis of psoriasis were matched for age, sex, and hypertension at a 4:1 ratio. Hypertension represented the most common comorbidity that could feasibly be controlled for in this study population. Other comorbidities recorded included obesity, type 2 diabetes mellitus, congestive heart failure, asthma, chronic obstructive pulmonary disease, chronic ischemic heart disease, rhinitis, and chronic kidney disease.

Common adverse effects as long as 30 days after vaccination were identified using ICD-10 codes. Adverse effects of interest were anaphylactic reaction, initial encounter of adverse effect of viral vaccines, fever, allergic urticaria, weakness, altered mental status, malaise, allergic reaction, chest pain, symptoms involving circulatory or respiratory systems, localized rash, axillary lymphadenopathy, infection, and myocarditis.5 Poisson regression was performed using Stata 17 analytical software.

We identified 4273 patients with psoriasis and 17,092 controls who received mRNA COVID-19 vaccines (Table). Adjusted odds ratios (aORs) for doses 1 and 2 were calculated for each vaccine (eTable). Adverse effects with sufficient data to generate an aOR included weakness, altered mental status, malaise, chest pain, and symptoms involving the circulatory or respiratory system. The aORs for allergic urticaria and initial encounter of adverse effect of viral vaccines were only calculated for the Moderna mRNA vaccine due to low sample size.

This study demonstrated that patients with psoriasis do not appear to have a significantly increased risk of adverse effects from mRNA SARS-CoV-2 vaccines. Although the ORs in this study were not significant, most recorded adverse effects demonstrated an aOR less than 1, suggesting that there might be a lower risk of certain adverse effects in psoriasis patients. This could be explained by the immunomodulatory effects of certain systemic psoriasis treatments that might influence the adverse effect presentation.

The study is limited by the lack of treatment data, small sample size, and the fact that it did not assess flares or worsening of psoriasis with the vaccines. Underreporting of adverse effects by patients and underdiagnosis of adverse effects secondary to SARS-CoV-2 vaccines due to its novel nature, incompletely understood consequences, and limited ICD-10 codes associated with adverse effects all contributed to the small sample size.