User login

Micronutrient Deficiencies in Patients With Inflammatory Bowel Disease

In 2023, ESPEN (the European Society for Clinical Nutrition and Metabolism) published consensus recommendations highlighting the importance of regular monitoring and treatment of nutrient deficiencies in patients with inflammatory bowel disease (IBD) for improved prognosis, mortality, and quality of life.1 Suboptimal nutrition in patients with IBD predominantly results from inflammation of the gastrointestinal (GI) tract leading to malabsorption; however, medications commonly used to manage IBD also can contribute to malnutrition.2,3 Additionally, patients may develop nausea and food avoidance due to medication or the disease itself, leading to nutritional withdrawal and eventual deficiency.4 Even with the development of diets focused on balancing nutritional needs and decreasing inflammation,5 offsetting this aversion to food can be difficult to overcome.2

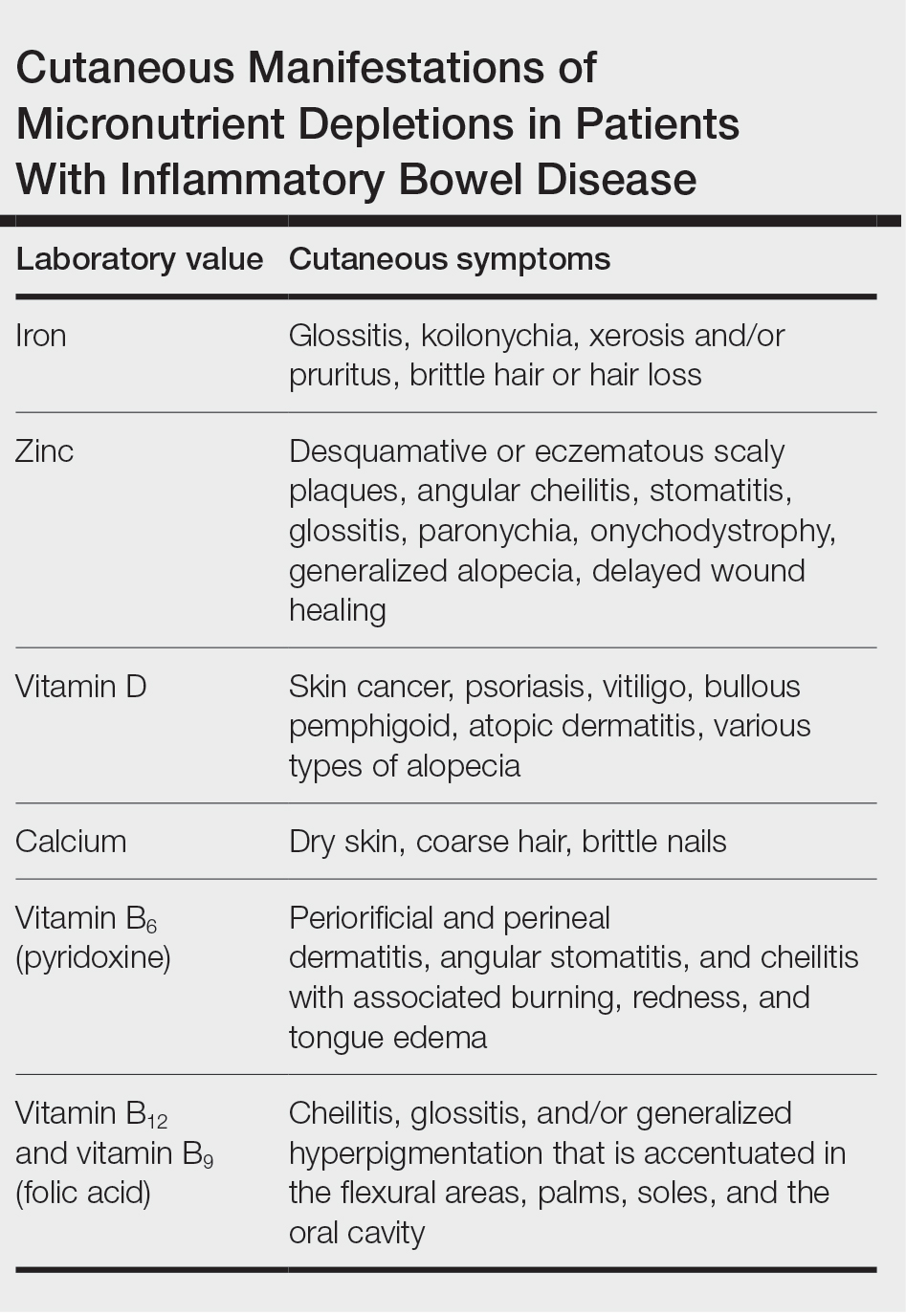

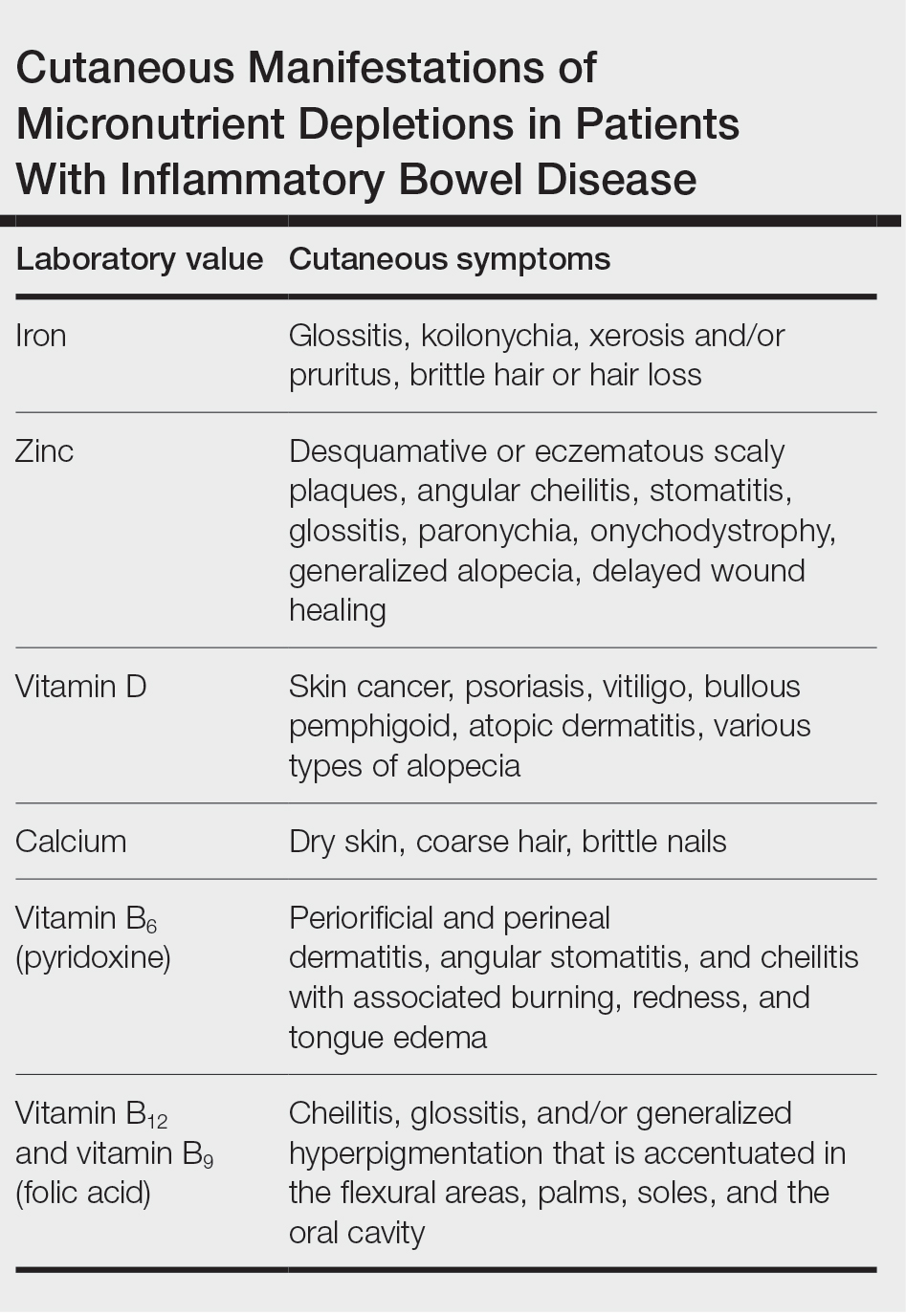

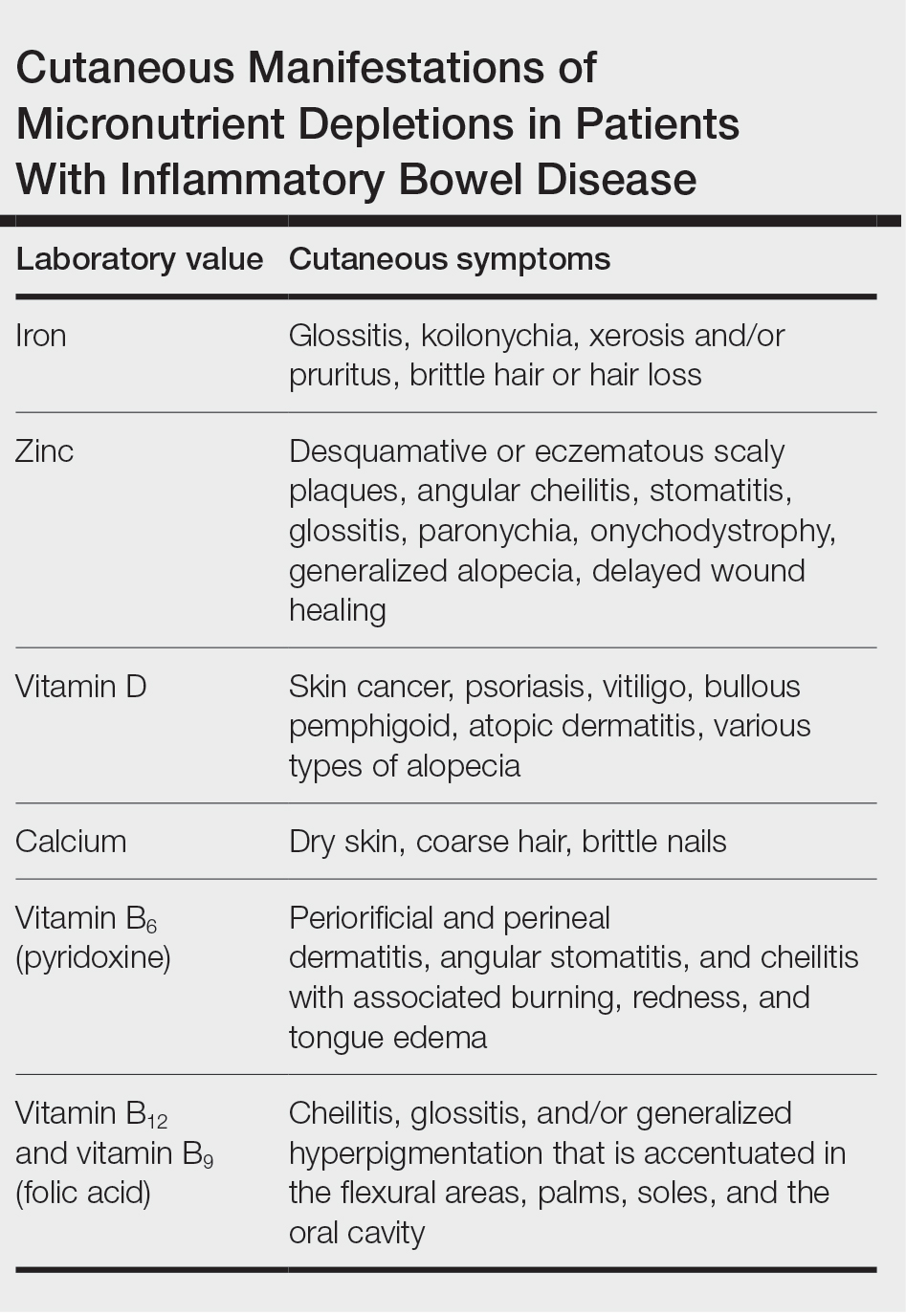

Cutaneous manifestations of IBD are multifaceted and can be secondary to the disease, reactive to or associated with IBD, or effects from nutritional deficiencies. The most common vitamin and nutrient deficiencies in patients with IBD include iron; zinc; calcium; vitamin D; and vitamins B6 (pyridoxine), B9 (folic acid), and B12.6 Malnutrition may manifest with cutaneous disease, and dermatologists can be the first to identify and assess for nutritional deficiencies. In this article, we review the mechanisms of these micronutrient depletions in the context of IBD, their subsequent dermatologic manifestations (Table), and treatment and monitoring guidelines for each deficiency.

Iron

A systematic review conducted from 2007 to 2012 in European patients with IBD (N=2192) found the overall prevalence of anemia in this population to be 24% (95% CI, 18%-31%), with 57% of patients with anemia experiencing iron deficiency.7 Anemia is observed more commonly in patients hospitalized with IBD and is common in patients with both Crohn disease and ulcerative colitis.8

Pathophysiology—Iron is critically important in oxygen transportation throughout the body as a major component of hemoglobin. Physiologically, the low pH of the duodenum and proximal jejunum allows divalent metal transporter 1 to transfer dietary Fe3+ into enterocytes, where it is reduced to the transportable Fe2+.9,10 Distribution of Fe2+ ions from enterocytes relies on ferroportin, an iron-transporting protein, which is heavily regulated by the protein hepcidin.11 Hepcidin, a known acute phase reactant, will increase in the setting of active IBD, causing a depletion of ferroportin and an inability of the body to utilize the stored iron in enterocytes.12 This poor utilization of iron stores combined with blood loss caused by inflammation in the GI tract is the proposed primary mechanism of iron-deficiency anemia observed in patients with IBD.13

Cutaneous Manifestations—From a dermatologic perspective, iron-deficiency anemia can manifest with a wide range of symptoms including glossitis, koilonychia, xerosis and/or pruritus, and brittle hair or hair loss.14,15 Although the underlying pathophysiology of these cutaneous manifestations is not fully understood, there are several theories assessing the mechanisms behind the skin findings of iron deficiency.

Atrophic glossitis has been observed in many patients with iron deficiency and is thought to manifest due to low iron concentrations in the blood, thereby decreasing oxygen delivery to the papillae of the dorsal tongue with resultant atrophy.16,17 Similarly, decreased oxygen delivery to the nail bed capillaries may cause deformities in the nail called koilonychia (or “spoon nails”).18 Iron is a key co-factor in collagen lysyl hydroxylase that promotes collagen binding; iron deficiency may lead to disruptions in the epidermal barrier that can cause pruritus and xerosis.19 An observational study of 200 healthy patients with a primary concern of pruritus found a correlation between low serum ferritin and a higher degree of pruritus (r=−0.768; P<.00001).20

Evidence for iron’s role in hair growth comes from a mouse model study with a mutation in the serine protease TMPRSS6—a protein that regulates hepcidin and iron absorption—which caused an increase in hepcidin production and subsequent systemic iron deficiency. Mice at 4 weeks of age were devoid of all body hair but had substantial regrowth after initiation of a 2-week iron-rich diet, which suggests a connection between iron repletion and hair growth in mice with iron deficiency.21 Additionally, a meta-analysis analyzing the comorbidities of patients with alopecia areata found them to have higher odds (odds ratio [OR]=2.78; 95% CI, 1.23-6.29) of iron-deficiency anemia but no association with IBD (OR=1.48; 95% CI, 0.32-6.82).22

Diagnosis and Monitoring—The American Gastroenterological Association recommends a complete blood cell count (CBC), serum ferritin, transferrin saturation (TfS), and C-reactive protein (CRP) as standard evaluations for iron deficiency in patients with IBD. Patients with active IBD should be screened every 3 months,and patients with inactive disease should be screened every 6 to 12 months.23

Although ferritin and TfS often are used as markers for iron status in healthy individuals, they are positive and negative acute phase reactants, respectively. Using them to assess iron status in patients with IBD may inaccurately represent iron status in the setting of inflammation from the disease.24 The European Crohn’s and Colitis Organisation (ECCO) produced guidelines to define iron deficiency as a TfS less than 20% or a ferritin level less than 30 µg/L in patients without evidence of active IBD and a ferritin level less than 100 µg/L for patients with active inflammation.25

A 2020 multicenter observational study of 202 patients with diagnosed IBD found that the ECCO guideline of ferritin less than 30 µg/L had an area under the receiver operating characteristic (AUROC) curve of 0.69, a sensitivity of 0.43, and a specificity of 0.95 in their population.26 In a sensitivity analysis stratifying patients by CRP level (<10 or ≥10 mg/L), the authors found that for patients with ulcerative colitis and a CRP less than 10 mg/L, a cut-off value of ferritin less than 65 µg/L (AUROC=0.78) had a sensitivity of 0.78 and specificity of 0.76, and a TfS value of less than 16% (AUROC=0.88) had a sensitivity of 0.79 and a specificity of 0.9. In patients with a CRP of 10 mg/L or greater, a cut-off value of ferritin 80 µg/L (AUROC=0.76) had a sensitivity of 0.75 and a specificity of 0.82, and a TfS value of less than 11% (AUROC=0.69) had a sensitivity of 0.79 and a specificity of 0.88. There were no ferritin cut-off values associated with good diagnostic performance (defined as both sensitivity and specificity >0.70) for iron deficiency in patients with Crohn disease.26

The authors recommended using an alternative iron measurement such as soluble transferrin receptor (sTfR)/log ferritin ratio (TfR-F) that is not influenced by active inflammation and has a good correlation with ferritin values (TfR-F: r=0.66; P<.001).26 However, both sTfR and TfR-F have high costs and intermethod variability as well as differences in their reference ranges depending on which laboratory performs the analysis, limiting the accessibility and practicality of easily obtaining these tests.27 Although there may be inaccuracies for standard ferritin or TfS under ECCO guidelines, proposed alternatives have their own limitations, which may make ferritin and TfS the most reasonable evaluations of iron status as long as disease activity status at the time of testing is taken into consideration.

Treatment—Treatment of underlying iron deficiency in patients with IBD requires reversing the cause of the deficiency and supplementing iron. In patients with IBD, the options to supplement iron may be limited by active disease, making oral intake less effective. Oral iron supplementation also is associated with notable GI adverse effects that may be exacerbated in patients with IBD. A systematic review of 43 randomized controlled trials (RCTs) evaluating GI adverse effects (eg, nausea, abdominal pain, diarrhea, constipation, and black or tarry stools) of oral ferrous sulfate compared with placebo or intravenous (IV) iron supplementation in healthy nonanemic individuals found a significant increase in GI adverse effects with oral supplementation (placebo: OR=2.32; P<.0001; IV: OR=3.05; P<.0001).28

Therefore, IV iron repletion may be necessary in patients with IBD and may require numerous infusions depending on the formulation of iron. In an RCT conducted in 2011, patients with iron-deficiency anemia with quiescent or mild to moderate IBD were treated with either IV iron sulfate or ferric carboxymaltose.29 With a primary end point of hemoglobin response greater than 2 g/dL, the authors found that 150 of 240 patients responded to ferric carboxymaltose vs 118 of 235 treated with iron sulfate (P=.004). The dosing for ferric carboxymaltose was 1 to 3 infusions of 500 to 1000 mg of iron and for iron sulfate up to 11 infusions of 200 mg of iron.29

Zinc

A systematic review of zinc deficiency in patients with IBD identified 7 studies including 2413 patients and revealed those with Crohn disease had a higher prevalence of zinc deficiency compared with patients with ulcerative colitis (54% vs 41%).30

Pathophysiology—Zinc serves as a catalytic cofactor for enzymatic activity within proteins and immune cells.31 The homeostasis of zinc is tightly regulated within the brush border of the small intestine by zinc transporters ZIP4 and ZIP1 from the lumen of enterocytes into the bloodstream.32 Inflammation in the small intestine due to Crohn disease can result in zinc malabsorption.

Ranaldi et al33 exposed intestinal cells and zinc-depleted intestinal cells to tumor necrosis factor α media to simulate an inflammatory environment. They measured transepithelial electrical resistance as a surrogate for transmembrane permeability and found that zinc-depleted cells had a statistically significantly higher transepithelial electrical resistance percentage (60% reduction after 4 hours; P<1.10–6) when exposed to tumor necrosis factor α signaling compared with normal intestinal cells. They concluded that zinc deficiency can increase intestinal permeability in the presence of inflammation, creating a cycle of further nutrient malabsorption and inflammation exacerbating IBD symptoms.33

Cutaneous Manifestations—After absorption in the small intestine, approximately 5% of zinc resides in the skin, with the highest concentration in the stratum spinosum.34 A cell study found that keratinocytes in zinc-deficient environments had higher rates of apoptosis compared with cells in normal media. The authors proposed that this higher rate of apoptosis and the resulting inflammation could be a mechanism for developing the desquamative or eczematous scaly plaques that are common cutaneous manifestations of zinc deficiency.35

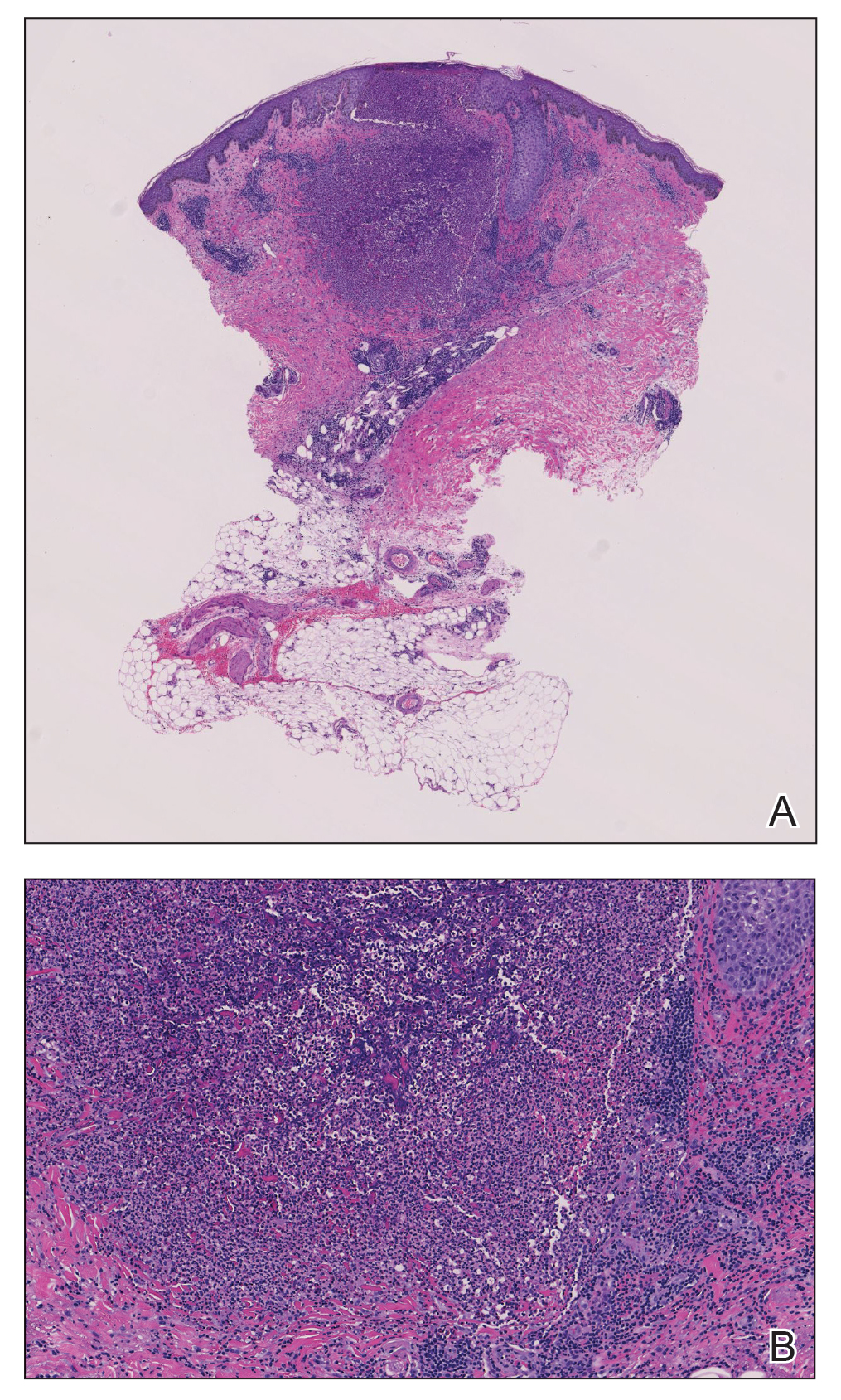

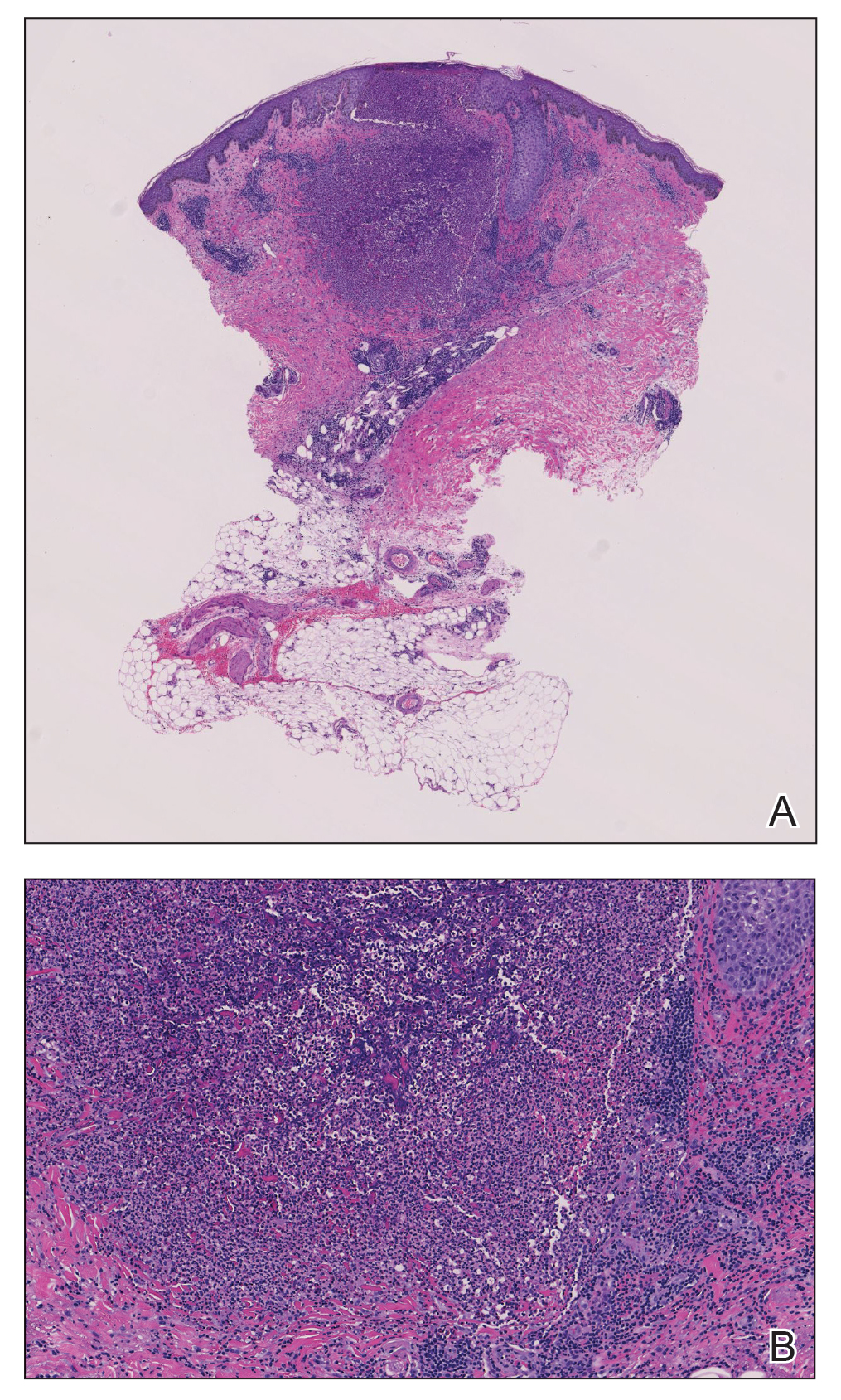

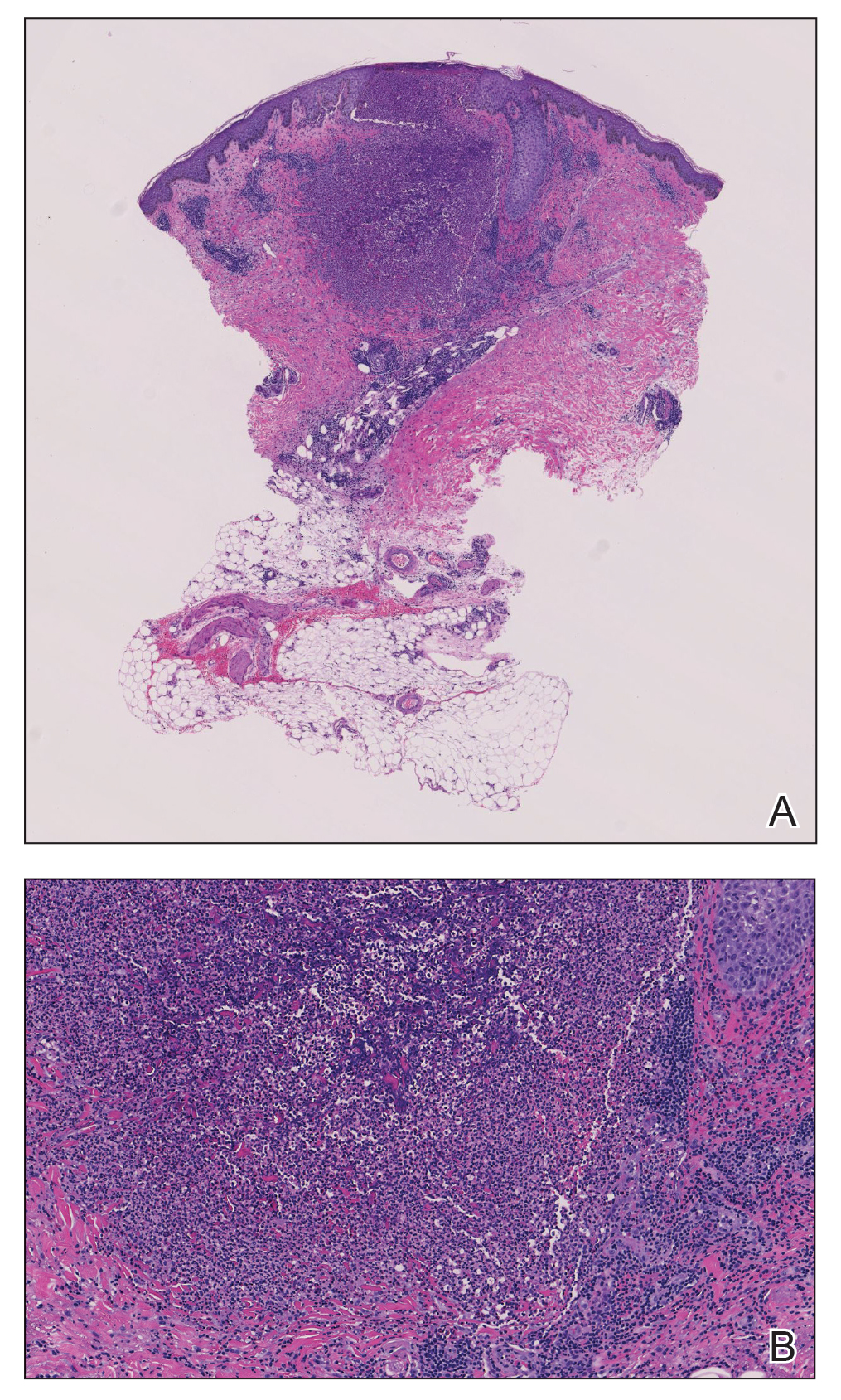

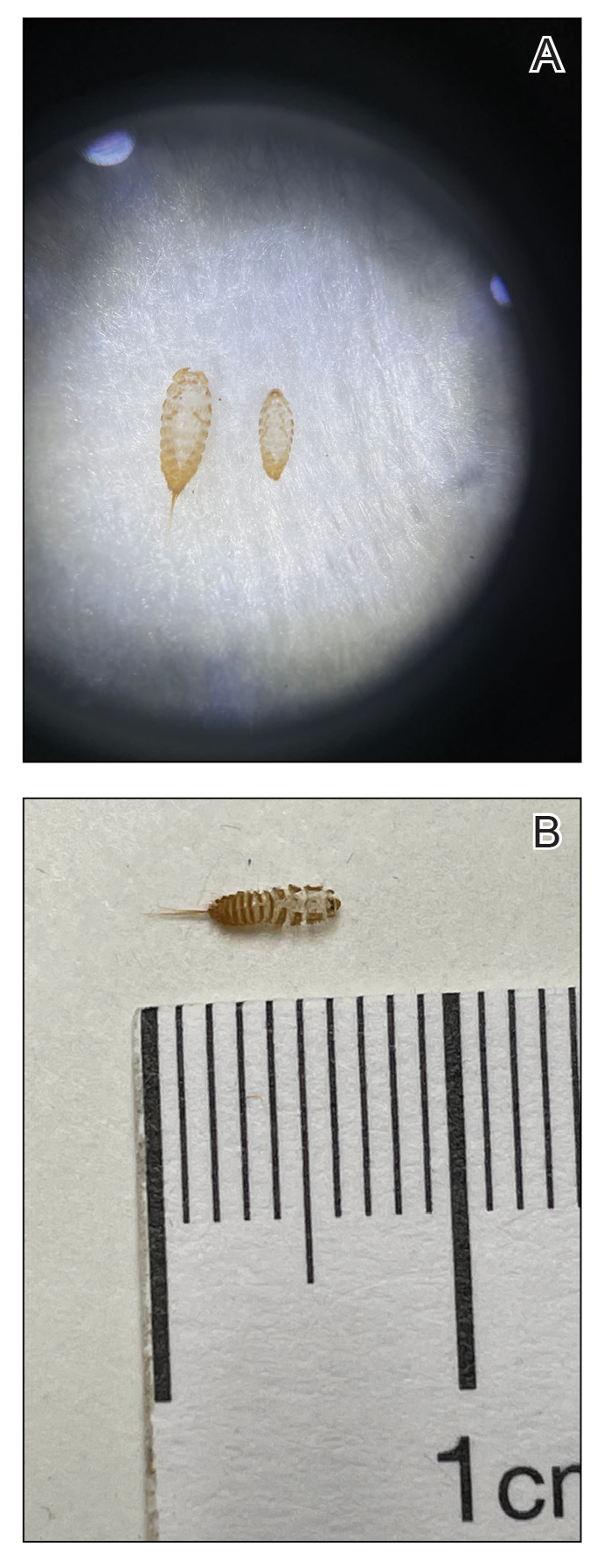

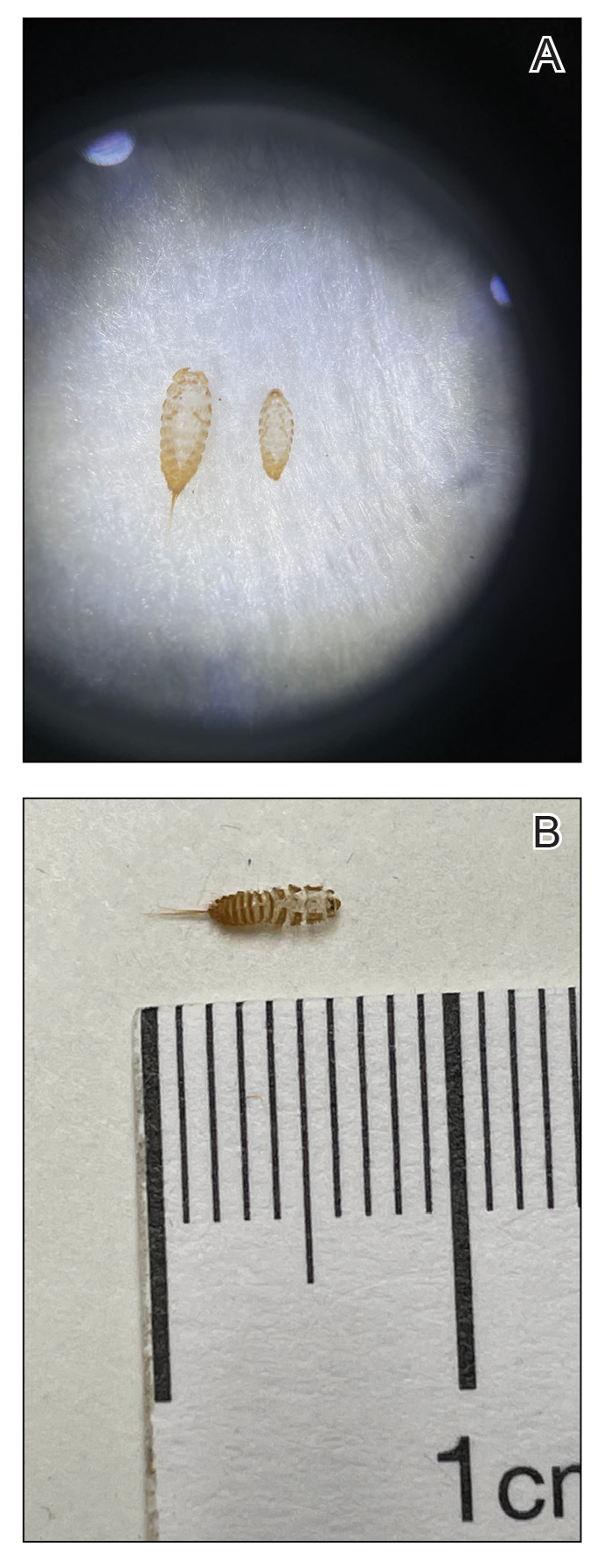

Other cutaneous findings may include angular cheilitis, stomatitis, glossitis, paronychia, onychodystrophy, generalized alopecia, and delayed wound healing.36 The histopathology of these skin lesions is characterized by granular layer loss, epidermal pallor, confluent parakeratosis, spongiosis, dyskeratosis, and psoriasiform hyperplasia.37

Diagnosis and Monitoring—Assessing serum zinc levels is challenging, as they may decrease during states of inflammation.38 A mouse model study showed a 3.1-fold increase (P<.001) in ZIP14 expression in wild-type mice compared with an IL-6 -/- knock-down model after IL-6 exposure. The authors concluded that the upregulation of ZIP14 in the liver due to inflammatory cytokine upregulation decreases zinc availability in serum.39 Additionally, serum zinc can overestimate the level of deficiency in IBD because approximately 75% of serum zinc is bound to albumin, which decreases in the setting of inflammation.40-42

Alternatively, alkaline phosphatase (AP), a zinc-dependent metalloenzyme, may be a better evaluator of zinc status during periods of inflammation. A study in rats evaluated zinc through serum zinc levels and AP levels after a period of induced stress to mimic a short-term inflammatory state.43 The researchers found that total body stores of zinc were unaffected throughout the experiment; only serum zinc declined throughout the experiment duration while AP did not. Because approximately 75% of serum zinc is bound to serum albumin,42 the researchers concluded the induced inflammatory state depleted serum albumin and redistributed zinc to the liver, causing the observed serum zinc changes, while total body zinc levels and AP were largely unaffected in comparison.43 Comorbid conditions such as liver or bone disease can increase AP levels, which limits the utility of AP as a surrogate for zinc in patients with comorbidities.44 However, even in the context of active IBD, serum zinc still is currently considered the best biomarker to evaluate zinc status.45

Treatment—The recommended dose for zinc supplementation is 20 to 40 mg daily with higher doses (>50 mg/d) for patients with malabsorptive syndromes such as IBD.46 It can be administered orally or parenterally. Although rare, zinc replacement therapy may be associated with diarrhea, nausea, vomiting, mild headaches, and fatigue.46 Additional considerations should be taken when repleting other micronutrients with zinc, as calcium and folate can inhibit zinc reabsorption, while zinc itself can inhibit iron and copper reabsorption.47

Vitamin D and Calcium

Low vitamin D levels (<50 nmol/L) and hypocalcemia (<8.8 mg/dL) are common in patients with IBD.48,49

Pathophysiology—Vitamin D levels are maintained via 2 mechanisms. The first mechanism is through the skin, as keratinocytes produce 7-dehydrocholesterol after exposure to UV light, which is converted into previtamin D3 and then thermally isomerizes into vitamin D3. This vitamin D3 is then transported to the liver on vitamin D–binding protein.50 The second mechanism is through oral vitamin D3 that is absorbed through vitamin D receptors in intestinal epithelium and transported to the liver, where it is hydroxylated into 25-hydroxyvitamin D (25[OH]D), then to the kidneys for hydroxylation to 1,25(OH)2D for redistribution throughout the body.50 This activated form of vitamin D regulates calcium absorption in the intestine, and optimal vitamin D levels are necessary to absorb calcium efficiently.51 Inflammation from IBD within the small intestine can downregulate vitamin D receptors, causing malabsorption and decreased serum vitamin D.52

Vitamin D signaling also is vital to maintaining the tight junctions and adherens junctions of the intestinal epithelium. Weakening the permeability of the epithelium further exacerbates malabsorption and subsequent vitamin D deficiency.52 A meta-analysis of 27 studies including 8316 patients with IBD showed low vitamin D levels were associated with increased odds of disease activity (OR=1.53; 95% CI, 1.32-1.77), mucosal inflammation (OR=1.25; 95% CI, 1.06-1.47), and future clinical relapse (OR=1.23; 95% CI, 1.03-1.47) in patients with Crohn disease. The authors concluded that low levels of vitamin D could be used as a potential biomarker of inflammatory status in Crohn disease.53

Vitamin D and calcium are further implicated in maintaining skeletal health,47 while vitamin D specifically helps maintain intestinal homeostasis54 and immune system modulation in the skin.55

Cutaneous Manifestations—Vitamin D is thought to play crucial roles in skin differentiation and proliferation, cutaneous innate immunity, hair follicle cycling, photoprotection, and wound healing.56 Vitamin D deficiency has been observed in a large range of cutaneous diseases including skin cancer, psoriasis, vitiligo, bullous pemphigoid, atopic dermatitis, and various types of alopecia.56-59 It is unclear whether vitamin D deficiency facilitates these disease processes or is merely the consequence of a disrupted cutaneous surface with the inability to complete the first step in vitamin D processing. A 2014 meta-analysis of 290 prospective cohort studies and 172 randomized trials concluded that 25(OH)D deficiency was associated with ill health and did not find causal evidence for any specific disease, dermatologic or otherwise.60 Calcium deficiency may cause epidermal changes including dry skin, coarse hair, and brittle nails.61

Diagnosis and Monitoring—The ECCO guidelines recommend obtaining serum 25(OH)D levels every 3 months in patients with IBD.62 Levels less than 75 nmol/L are considered deficient, and a value less than 30 nmol/L increases the risk for osteomalacia and nutritional rickets, constituting severe vitamin D deficiency.63-65

An observational study of 325 patients with IBD showed a statistically significant negative correlation between serum vitamin D and fecal calprotectin (r=−0.19; P<.001), a stool-based marker for gut inflammation, supporting vitamin D as a potential biomarker in IBD.66

Evaluation of calcium can be done through serum levels in patients with IBD.67 Patients with IBD are at risk for hypoalbuminemia; therefore, consideration should be taken to ensure calcium levels are corrected, as approximately 50% of calcium is bound to albumin or other ions in the body,68 which can be done by adjusting the calcium concentration by 0.02 mmol/L for every 1 g/L of albumin above or below 40 g/L. In the most critically ill patients, a direct ionized calcium blood level should be used instead because the previously mentioned correction calculations are inaccurate when albumin is critically low.69

Treatment—The ECCO guidelines recommend calcium and vitamin D repletion of 500 to 1000 mg and 800 to 1000 U, respectively, in patients with IBD on systemic corticosteroids to prevent the negative effects of bone loss.62 Calcium repletion in patients with IBD who are not on systemic steroids are the same as for the general population.65

Vitamin D repletion also may help decrease IBD activity. In a prospective study, 10,000 IU/d of vitamin D in 10 patients with IBD—adjusted over 12 weeks to a target of 100 to 125 nmol/L of serum 25(OH)D—showed a significant reduction in clinical Crohn activity (P=.019) over the study period.70 In contrast, 2000 IU/d for 3 months in an RCT of 27 patients with Crohn disease found significantly lower CRP (P=.019) and significantly higher self-reported quality of life (P=.037) but nonsignificant decreases in Crohn activity (P=.082) in patients with 25(OH)D levels of 75 nmol/L or higher compared with those with 25(OH)D levels less than 75 nmol/L.71

These discrepancies illustrate the need for expanded clinical trials to elucidate the optimal vitamin D dosing for patients with IBD. Ultimately, assessing vitamin D and calcium status and considering repletion in patients with IBD, especially those with comorbid dermatologic diseases such as poor wound healing, psoriasis, or atopic dermatitis, is important.

Vitamin B6 (Pyridoxine)

Pathophysiology—Pyridoxine is an important coenzyme for many functions including amino acid transamination, fatty acid metabolism, and conversion of tryptophan to niacin. It is absorbed in the jejunum and ileum and subsequently transported to the liver for rephosphorylation and release into its active form.36 An observational study assessing the nutritional status of patients with IBD found that only 5.7% of 105 patients with food records had inadequate dietary intake of pyridoxine, but 29% of all patients with IBD had subnormal pyridoxine levels.72 Additionally, they found no significant difference in the prevalence of subnormal pyridoxine levels in patients with active IBD vs IBD in remission. The authors suggested that the subnormal pyridoxine levels in patients with IBD likely were multifactorial and resulted from malabsorption due to active disease, inflammation, and inadequate intake.72

Cutaneous Manifestations—Cutaneous findings associated with pyridoxine deficiency include periorificial and perineal dermatitis,73 angular stomatitis, and cheilitis with associated burning, redness, and tongue edema.36 Additionally, pyridoxine is involved in the conversion of tryptophan to niacin, and its deficiency may manifest with pellagralike findings.74

Because pyridoxine is critical to protein metabolism, its deficiency may disrupt key cellular structures that rely on protein concentrations to maintain structural integrity. One such structure in the skin that heavily relies on protein concentrations is the ground substance of the extracellular matrix—the amorphous gelatinous spaces that occupy the areas between the extracellular matrix, which consists of cross-linked glycosaminoglycans and proteins.75 Without protein, ground substance increases in viscosity and can disrupt the epidermal barrier, leading to increased transepidermal water loss and ultimately inflammation.76 Although this theory has yet to be validated fully, this is a potential mechanistic explanation for the inflammation in dermal papillae that leads to dermatitis observed in pyridoxine deficiency.

Diagnosis and Monitoring—Direct biomarkers of pyridoxine status are in serum, plasma, erythrocytes, and urine, with the most common measurement in plasma as pyridoxal 5′-phosphate (PLP).77 Plasma PLP concentrations lower than 20 nmol/L are suggestive of deficiency.78 Plasma PLP has shown inverse relationships with acute phase inflammatory markers CRP79 and AP,78 thereby raising concerns for its validity to assess pyridoxine status in patients with symptomatic IBD.80

Alternative evaluations of pyridoxine include tryptophan and methionine loading tests,36 which are measured via urinary excretion and require normal kidney function to be accurate. They should be considered in IBD if necessary, but routine testing, even in patients with symptomatic IBD, is not recommended in the ECCO guidelines. Additional considerations should be taken in patients with altered nutrient requirements such as those who have undergone bowel resection due to highly active disease or those who receive parenteral nutritional supplementation.81

Treatment—Recommendations for oral pyridoxine supplementation range from 25 to 600 mg daily,82 with symptoms typically improving on 100 mg daily.36 Pyridoxine supplementation may have additional benefits for patients with IBD and potentially modulate disease severity. An IL-10 knockout mouse supplemented with pyridoxine had an approximately 60% reduction (P<.05) in inflammation compared to mice deficient in pyridoxine.83 The authors suggest that PLP-dependent enzymes can inhibit further proinflammatory signaling and T-cell migration that can exacerbate IBD. Ultimately, more data is needed before determining the efficacy of pyridoxine supplementation for active IBD.

Vitamin B12 and Vitamin B9 (Folic Acid)

Pathophysiology—Vitamin B12 is reabsorbed in the terminal ileum, the distal portion of the small intestine. The American Gastroenterological Association recommends that patients with a history of extensive ileal disease or prior ileal surgery, which is the case for many patients with Crohn disease, be monitored for vitamin B12 deficiency.23 Monitoring and rapid supplementation of vitamin B12 can prevent pernicious anemia and irreversible neurologic damage that may result from deficiency.84

Folic acid is primarily absorbed in the duodenum and jejunum of the small intestine. A meta-analysis performed in 2017 assessed studies observing folic acid and vitamin B12 levels in 1086 patients with IBD compared with 1484 healthy controls and found an average difference in serum folate concentration of 0.46 nmol/L (P<.001).84 Interestingly, this study did not find a significant difference in serum vitamin B12 levels between patients with IBD and healthy controls, highlighting the mechanism of vitamin B12 deficiency in IBD because only patients with terminal ileal involvement are at risk for malabsorption and subsequent deficiency.

Cutaneous Manifestations—Both vitamin B12 and folic acid deficiency can manifest as cheilitis, glossitis, and/or generalized hyperpigmentation that is accentuated in the flexural areas, palms, soles, and oral cavity.85,86 Systemic symptoms of patients with vitamin B12 and folic acid deficiency include megaloblastic anemia, pallor, and fatigue. A potential mechanism for the hyperpigmentation observed from vitamin B12 deficiency came from an electron microscope study that showed an increased concentration of melanosomes in a patient with deficiency.87

Diagnosis and Monitoring—In patients with suspected vitamin B12 and/or folic acid deficiency, initial evaluation should include a CBC with peripheral smear and serum vitamin B12 and folate levels. In cases for which the diagnosis still is unclear after initial testing,

Treatment—According to the Centers for Disease Control and Prevention, supplementation of vitamin B12 can be done orally with 1000 µg daily in patients with deficiency. In patients with active IBD, oral reabsorption of vitamin B12 can be less effective, making subcutaneous or intramuscular administration (1000 µg/wk for 8 weeks, then monthly for life) better options.89

Patients with IBD managed with methotrexate should be screened carefully for folate deficiency. Methotrexate is a folate analog that sometimes is used for the treatment of IBD. Reversible competitive inhibition of dihydrofolate reductase can precipitate a systemic folic acid decrease.91 Typically, oral folic acid (1 to 5 mg/d) is sufficient to treat folate deficiency, with the ESPEN recommending 5 mg once weekly 24 to 72 hours after methotrexate treatment or 1 mg daily for 5 days per week in patients with IBD.1 Alternative formulations—IV, subcutaneous, or intramuscular—are available for patients who cannot tolerate oral intake.92

Final Thoughts

Dermatologists can be the first to observe the cutaneous manifestations of micronutrient deficiencies. Although the symptoms of each micronutrient deficiency discussed may overlap, attention to small clinical clues in patients with IBD can improve patient outcomes and quality of life. For example, koilonychia with glossitis and xerosis likely is due to iron deficiency, while zinc deficiency should be suspected in patients with scaly eczematous plaques in skin folds. A high level of suspicion for micronutrient deficiencies in patients with IBD should be followed by a complete patient history, review of systems, and thorough clinical examination. A thorough laboratory evaluation can pinpoint nutritional deficiencies in patients with IBD, keeping in mind that specific biomarkers such as ferritin and serum zinc also act as acute phase reactants and should be interpreted in this context. Co-management with gastroenterologists should be a priority in patients with IBD, as gaining control of inflammatory disease is crucial for the prevention of recurrent vitamin and micronutrient deficiencies in addition to long-term health in this population.

- Bischoff SC, Bager P, Escher J, et al. ESPEN guideline on clinical nutrition in inflammatory bowel disease. Clin Nutr. 2023;42:352-379. doi:10.1016/j.clnu.2022.12.004

- Gerasimidis K, McGrogan P, Edwards CA. The aetiology and impact of malnutrition in paediatric inflammator y bowel disease. J Hum Nutr Diet. 2011;24:313-326. doi:10.1111/j.1365-277X.2011.01171.x

- Mentella MC, Scaldaferri F, Pizzoferrato M, et al. Nutrition, IBD and gut microbiota: a review. Nutrients. 2020;12:944. doi:10.3390/nu12040944

- Bonsack O, Caron B, Baumann C, et al. Food avoidance and fasting in patients with inflammatory bowel disease: experience from the Nancy IBD nutrition clinic. United European Gastroenterol J. 2023;11:361-370. doi:10.1002/ueg2.1238521

- Campmans-Kuijpers MJE, Dijkstra G. Food and food groups in inflammatory bowel disease (IBD): the design of the Groningen Anti-Inflammatory Diet (GrAID). Nutrients. 2021;13:1067. doi:10.3390/nu13041067

- Hwang C, Issokson K, Giguere-Rich C, et al. Development and pilot testing of the inflammatory bowel disease nutrition care pathway. Clin Gastroenterol Hepatol. 2020;18:2645-2649.e4. doi:10.1016/j.cgh.2020.06.039

- Filmann N, Rey J, Schneeweiss S, et al. Prevalence of anemia in inflammatory bowel diseases in European countries: a systematic review and individual patient data meta-analysis. Inflamm Bowel Dis. 2014;20:936-945. doi:10.1097/01.MIB.0000442728.74340.fd

- Stein J, Hartmann F, Dignass AU. Diagnosis and management of iron deficiency anemia in patients with IBD. Nat Rev Gastroenterol Hepatol. 2010;7:599-610. doi:10.1038/nrgastro.2010.151

- Ems T, St Lucia K, Huecker MR. Biochemistry, iron absorption. StatPearls [Internet]. Updated April 17, 2023. Accessed March 19, 2024. https://www.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/books/NBK448204/

- Evstatiev R, Gasche C. Iron sensing and signalling. Gut. 2012;61:933-952. doi:10.1136/gut.2010.214312

- Przybyszewska J, Zekanowska E. The role of hepcidin, ferroportin, HCP1, and DMT1 protein in iron absorption in the human digestive tract. Prz Gastroenterol. 2014;9:208-213. doi:10.5114/pg.2014.45102

- Weiss G, Gasche C. Pathogenesis and treatment of anemia in inflammatory bowel disease. Haematologica. 2010;95:175-178. doi:10.3324/haematol.2009.017046

- Kaitha S, Bashir M, Ali T. Iron deficiency anemia in inflammatory bowel disease. World J Gastrointest Pathophysiol. 2015;6:62-72. doi:10.4291/wjgp.v6.i3.62

- Moiz B. Spoon nails: still seen in today’s world. Clin Case Rep. 2018;6:547-548. doi:10.1002/ccr3.1404

- St Pierre SA, Vercellotti GM, Donovan JC, et al. Iron deficiency and diffuse nonscarring scalp alopecia in women: more pieces to the puzzle. J Am Acad Dermatol. 2010;63:1070-1076. doi:10.1016/j.jaad.2009.05.054

- Chiang CP, Yu-Fong Chang J, Wang YP, et al. Anemia, hematinic deficiencies, hyperhomocysteinemia, and serum gastric parietal cell antibody positivity in atrophic glossitis patients with or without microcytosis. J Formos Med Assoc. 2019;118:1401-1407. doi:10.1016/j.jfma.2019.06.004

- Chiang CP, Chang JY, Wang YP, et al. Atrophic glossitis: Etiology, serum autoantibodies, anemia, hematinic deficiencies, hyperhomocysteinemia, and management. J Formos Med Assoc. 2020;119:774-780. doi:10.1016/j.jfma.2019.04.015

- Walker J, Baran R, Vélez N, et al. Koilonychia: an update on pathophysiology, differential diagnosis and clinical relevance. J Eur Acad Dermatol Venereol. 2016;30:1985-1991. doi:10.1111/jdv.13610

- Guo HF, Tsai CL, Terajima M, et al. Pro-metastatic collagen lysyl hydroxylase dimer assemblies stabilized by Fe2+-binding. Nat Commun. 2018;9:512. doi:10.1038/s41467-018-02859-z

- Saini S, Jain AK, Agarwal S, et al. Iron deficiency and pruritus: a cross-sectional analysis to assess its association and relationship. Indian J Dermatol. 2021;66:705. doi:10.4103/ijd.ijd_326_21

- Du X, She E, Gelbart T, et al. The serine protease TMPRSS6 is required to sense iron deficiency. Science. 2008;320:1088-1092. doi:10.1126/science.1157121

- Lee S, Lee H, Lee CH, et al. Comorbidities in alopecia areata: a systematic review and meta-analysis. J Am Acad Dermatol. 2019;80:466-477.e16. doi:10.1016/j.jaad.2018.07.013

- Hashash JG, Elkins J, Lewis JD, et al. AGA Clinical Practice Update on diet and nutritional therapies in patients with inflammatory bowel disease: expert review [published online January 23, 2024]. Gastroenterology. doi:10.1053/j.gastro.2023.11.303

- Choudhuri S, Chowdhury IH, Saha A, et al. Acute monocyte pro- inflammatory response predicts higher positive to negative acute phase reactants ratio and severe hemostatic derangement in dengue fever. Cytokine. 2021;146:155644. doi:10.1016/j.cyto.2021.155644

- Dignass AU, Gasche C, Bettenworth D, et al; European Crohn’s and Colitis Organisation. European consensus on the diagnosis and management of iron deficiency and anaemia in inflammatory bowel diseases. J Crohn’s Colitis. 2015;9:211-222. doi:10.1093/ecco-jcc/jju009

- Daude S, Remen T, Chateau T, et al. Comparative accuracy of ferritin, transferrin saturation and soluble transferrin receptor for the diagnosis of iron deficiency in inflammatory bowel disease. Aliment Pharmacol Ther. 2020;51:1087-1095. doi:10.1111/apt.15739

- Pfeiffer CM, Looker AC. Laboratory methodologies for indicators of iron status: strengths, limitations, and analytical challenges. Am J Clin Nutr. 2017;106(suppl 6):1606S-1614S. doi:10.3945/ajcn.117.155887

- Tolkien Z, Stecher L, Mander AP, et al. Ferrous sulfate supplementation causes significant gastrointestinal side-effects in adults: a systematic review and meta-analysis. PLoS One. 2015;10:e0117383. doi:10.1371/journal.pone.0117383

- Evstatiev R, Marteau P, Iqbal T, et al. FERGIcor, a randomized controlled trial on ferric carboxymaltose for iron deficiency anemia in inflammatory bowel disease. Gastroenterology. 2011;141:846-853.e8532. doi:10.1053/j.gastro.2011.06.005

- Zupo R, Sila A, Castellana F, et al. Prevalence of zinc deficiency in inflammatory bowel disease: a systematic review and meta-analysis. Nutrients. 2022;14:4052. doi:10.3390/nu14194052

- Thompson MW. Regulation of zinc-dependent enzymes by metal carrier proteins. Biometals. 2022;35:187-213. doi:10.1007/s10534-022-00373-w

- Maares M, Haase H. A guide to human zinc absorption: general overview and recent advances of in vitro intestinal models. Nutrients. 2020;12:762. doi:10.3390/nu12030762

- Ranaldi G, Ferruzza S, Canali R, et al. Intracellular zinc is required for intestinal cell survival signals triggered by the inflammatory cytokine TNFα. J Nutr Biochem. 2013;24:967-976. doi:10.1016/j.jnutbio.2012.06.020

- Ogawa Y, Kawamura T, Shimada S. Zinc and skin biology. Arch Biochem Biophys. 2016;611:113-119. doi:10.1016/j.abb.2016.06.003

- Wilson D, Varigos G, Ackland ML. Apoptosis may underlie the pathology of zinc-deficient skin. Immunol Cell Biol. 2006;84:28-37. doi:10.1111/j.1440-1711.2005.01391.x

- Jen M, Yan AC. Syndromes associated with nutritional deficiency and excess. Clin Dermatol. 2010;28:669-685. doi:10.1016/j.clindermatol.2010.03.029

- Gonzalez JR, Botet MV, Sanchez JL. The histopathology of acrodermatitis enteropathica. Am J Dermatopathol. 1982;4:303-311.

- Gammoh NZ, Rink L. Zinc in infection and inflammation. Nutrients. 2017;9:624. doi:10.3390/nu9060624

- Liuzzi JP, Lichten LA, Rivera S, et al. Interleukin-6 regulates the zinc transporter Zip14 in liver and contributes to the hypozincemia of the acute-phase response. Proc Natl Acad Sci U S A. 2005;102:6843-6848. doi:10.1073/pnas.0502257102

- Vermeire S, Van Assche G, Rutgeerts P. Laboratory markers in IBD: useful, magic, or unnecessary toys?. Gut. 2006;55:426-431. doi:10.1136/gut.2005.069476

- Morisaku M, Ito K, Ogiso A, et al. Correlation between serum albumin and serum zinc in malignant lymphoma. Fujita Med J. 2022;8:59-64. doi:10.20407/fmj.2021-006

- Falchuk KH. Effect of acute disease and ACTH on serum zinc proteins. N Engl J Med. 1977:296:1129-1134.

- Naber TH, Baadenhuysen H, Jansen JB, et al. Serum alkaline phosphatase activity during zinc deficiency and long-term inflammatory stress. Clin Chim Acta. 1996;249:109-127. doi:10.1016/0009-8981(96)06281-x

- Lowe D, Sanvictores T, Zubair M, et al. Alkaline phosphatase. StatPearls [Internet]. Updated October 29, 2023. Accessed March 19, 2024. https://www.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/books/NBK459201/

- Krebs NF. Update on zinc deficiency and excess in clinical pediatric practice. Ann Nutr Metab. 2013;62 suppl 1:19-29. doi:10.1159/000348261

- Maxfield L, Shukla S, Crane JS. Zinc deficiency. StatPearls [Internet]. Updated June 28, 2023. Accessed March 25, 2024. https://www.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/books/NBK493231/

- Ghishan FK, Kiela PR. Vitamins and minerals in inflammatory bowel disease. Gastroenterol Clin North Am. 2017;46:797-808. doi:10.1016/j.gtc.2017.08.011

- Caviezel D, Maissen S, Niess JH, et al. High prevalence of vitamin D deficiency among patients with inflammatory bowel disease. Inflamm Intest Dis. 2018;2:200-210. doi:10.1159/000489010

- Jasielska M, Grzybowska-Chlebowczyk U. Hypocalcemia and vitamin D deficiency in children with inflammatory bowel diseases and lactose intolerance. Nutrients. 2021;13:2583. doi:10.3390/nu13082583

- Vernia F, Valvano M, Longo S, et al. Vitamin D in inflammatory bowel diseases. Mechanisms of action and therapeutic implications. Nutrients. 2022;14:269. doi:10.3390/nu14020269

- Khazai N, Judd SE, Tangpricha V. Calcium and vitamin D: skeletal and extraskeletal health. Curr Rheumatol Rep. 2008;10:110-117. doi:10.1007/s11926-008-0020-y

- Domazetovic V, Iantomasi T, Bonanomi AG, et al. Vitamin D regulates claudin-2 and claudin-4 expression in active ulcerative colitis by p-Stat-6 and Smad-7 signaling. Int J Colorectal Dis. 2020;35:1231-1242. doi:10.1007/s00384-020-03576-0

- Gubatan J, Chou ND, Nielsen OH, et al. Systematic review with meta-analysis: association of vitamin D status with clinical outcomes in adult patients with inflammatory bowel disease. Aliment Pharmacol Ther. 2019;50:1146-1158. doi:10.1111/apt.15506

- Fakhoury HMA, Kvietys PR, AlKattan W, et al. Vitamin D and intestinal homeostasis: barrier, microbiota, and immune modulation. J Steroid Biochem Mol Biol. 2020;200:105663. doi:10.1016/j.jsbmb.2020.105663

- Liu PT, Stenger S, Li H, et al. Toll-like receptor triggering of a vitamin D-mediated human antimicrobial response. Science. 2006;311:1770-1773. doi:10.1126/science.1123933

- Mostafa WZ, Hegazy RA. Vitamin D and the skin: focus on a complex relationship: a review. J Adv Res. 2015;6:793-804. doi:10.1016/j.jare.2014.01.011

- Searing DA, Leung DY. Vitamin D in atopic dermatitis, asthma and allergic diseases. Immunol Allergy Clin North Am. 2010;30:397-409.

- Lee YH, Song GG. Association between circulating 25-hydroxyvitamin D levels and psoriasis, and correlation with disease severity: a meta-analysis. Clin Exp Dermatol. 2018;43:529-535.

- Adorini L, Penna G. Control of autoimmune diseases by the vitamin D endocrine system. Nat Clin Pract Rheumatol. 2008;4:404-412.

- Autier P, Boniol M, Pizot C, et al. Vitamin D status and ill health: a systematic review. Lancet Diabetes Endocrinol. 2014;2:76-89. doi:10.1016/S2213-8587(13)70165-7

- Schafer AL, Shoback DM. Hypocalcemia: diagnosis and treatment. In: Feingold KR, Anawalt B, Blackman MR, et al, eds. Endotext [Internet]. Updated January 3, 2016. Accessed March 19, 2024. https://www.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/books/NBK279022/

- Magro F, Gionchetti P, Eliakim R, et al. Third European Evidence-based Consensus on Diagnosis and Management of Ulcerative Colitis. Part 1: Definitions, diagnosis, extra-intestinal manifestations, pregnancy, cancer surveillance, surgery, and ileo-anal pouch disorders. J Crohns Colitis. 2017;11:649-670. doi:10.1093/ecco-jcc/jjx008

- Amrein K, Scherkl M, Hoffmann M, et al. Vitamin D deficiency 2.0: an update on the current status worldwide. Eur J Clin Nutr. 2020;74:1498-1513. doi:10.1038/s41430-020-0558-y

- Munns CF, Shaw N, Kiely M, et al. Global consensus recommendations on prevention and management of nutritional rickets. J Clin Endocrinol Metab. 2016;101:394-415. doi:10.1210/jc.2015-2175

- Institute of Medicine (US) Committee to Review Dietary Reference Intakes for Vitamin D and Calcium; Ross AC, Taylor CL, Yaktine AL, Del Valle HB, eds. Dietary Reference Intakes for Calcium and Vitamin D. National Academies Press (US); 2011.

- Yeaman F, Nguyen A, Abasszade J, et al. Assessing vitamin D as a biomarker in inflammatory bowel disease. JGH Open. 2023;7:953-958. doi:10.1002/jgh3.13010

- Vernia P, Loizos P, Di Giuseppantonio I, et al S. Dietary calcium intake in patients with inflammatory bowel disease. J Crohns Colitis. 2014;8:312-317. doi:10.1016/j.crohns.2013.09.008

- Cooper MS, Gittoes NJ. Diagnosis and management of hypocalcaemia. BMJ. 2008;336:1298-1302. doi:10.1136/bmj.39582.589433.BE

- Kenny CM, Murphy CE, Boyce DS, et al. Things we do for no reason™: calculating a “corrected calcium” level. J Hosp Med. 2021;16:499-501. doi:10.12788/jhm.3619

- Garg M, Rosella O, Rosella G, et al. Evaluation of a 12-week targeted vitamin D supplementation regimen in patients with active inflammatory bowel disease. Clin Nutr. 2018;37:1375-1382. doi:10.1016/j.clnu.2017.06.011

- Raftery T, Martineau AR, Greiller CL, et al. Effects of vitamin D supplementation on intestinal permeability, cathelicidin and disease markers in Crohn’s disease: results from a randomised double-blind placebo-controlled study. United European Gastroenterol J. 2015;3:294-302. doi:10.1177/2050640615572176

- Vagianos K, Bector S, McConnell J, et al. Nutrition assessment of patients with inflammatory bowel disease. JPEN J Parenter Enteral Nutr. 2007;31:311-319. doi:10.1177/0148607107031004311

- Barthelemy H, Chouvet B, Cambazard F. Skin and mucosal manifestations in vitamin deficiency. J Am Acad Dermatol. 1986;15:1263-1274. doi:10.1016/s0190-9622(86)70301-0

- Galimberti F, Mesinkovska NA. Skin findings associated with nutritional deficiencies. Cleve Clin J Med. 2016;83:731-739. doi:10.3949/ccjm.83a.15061

- Elgharably N, Al Abadie M, Al Abadie M, et al. Vitamin B group levels and supplementations in dermatology. Dermatol Reports. 2022;15:9511. doi:10.4081/dr.2022.9511

- Hołubiec P, Leon´czyk M, Staszewski F, et al. Pathophysiology and clinical management of pellagra—a review. Folia Med Cracov. 2021;61:125-137. doi:10.24425/fmc.2021.138956

- Ink SL, Henderson LM. Vitamin B6 metabolism. Annu Rev Nutr. 1984;4:455-470. doi:10.1146/annurev.nu.04.070184.002323

- Brown MJ, Ameer MA, Daley SF, et al. Vitamin B6 deficiency. StatPearls [Internet]. Updated August 8, 2023. Accessed March 25, 2024. https://www.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/books/NBK470579/.

- Vasilaki AT, McMillan DC, Kinsella J, et al. Relation between pyridoxal and pyridoxal phosphate concentrations in plasma, red cells, and white cells in patients with critical illness. Am J Clin Nutr. 2008;88:140-146. doi:10.1093/ajcn/88.1.140

- Chiang EP, Bagley PJ, Selhub J, et al. Abnormal vitamin B(6) status is associated with severity of symptoms in patients with rheumatoid arthritis. Am J Med. 2003;114:283-287. doi:10.1016/s0002-9343(02)01528-0

- Maaser C, Sturm A, Vavricka SR, et al. ECCO-ESGAR guideline for diagnostic assessment in IBD. Part 1: initial diagnosis, monitoring of known IBD, detection of complications. J Crohns Colitis. 2019;13:144-164. doi:10.1093/ecco-jcc/jjy113

- Spinneker A, Sola R, Lemmen V, et al. Vitamin B6 status, deficiency and its consequences—an overview. Nutr Hosp. 2007;22:7-24.

- Selhub J, Byun A, Liu Z, et al. Dietary vitamin B6 intake modulates colonic inflammation in the IL10-/- model of inflammatory bowel disease. J Nutr Biochem. 2013;24:2138-2143. doi:10.1016/j.jnutbio.2013.08.005

- Pan Y, Liu Y, Guo H, et al. Associations between folate and vitamin B12 levels and inflammatory bowel disease: a meta-analysis. Nutrients. 2017;9:382. doi:10.3390/nu9040382

- Brescoll J, Daveluy S. A review of vitamin B12 in dermatology. Am J Clin Dermatol. 2015;16:27-33. doi:10.1007/s40257-014-0107-3

- DiBaise M, Tarleton SM. Hair, nails, and skin: differentiating cutaneous manifestations of micronutrient deficiency. Nutr Clin Pract. 2019;34:490-503. doi:10.1002/ncp.10321

- Mori K, Ando I, Kukita A. Generalized hyperpigmentation of the skin due to vitamin B12 deficiency. J Dermatol. 2001;28:282-285. doi:10.1111/j.1346-8138.2001.tb00134.x

- Green R. Indicators for assessing folate and vitamin B-12 status and for monitoring the efficacy of intervention strategies. Am J Clin Nutr. 2011;94:666S-672S. doi:10.3945/ajcn.110.009613

- NIH Office of Dietary Supplements. Vitamin B12: fact sheet for health professionals. Updated February 27, 2024. Accessed March 19, 2024. https://ods.od.nih.gov/factsheets/VitaminB12-HealthProfessional/

- NIH Office of Dietary Supplements. Folate: fact sheet for health professionals. Updated November 20, 2023. Accessed March 19, 2024. https://ods.od.nih.gov/factsheets/Folate-HealthProfessional/.

- Saibeni S, Bollani S, Losco A, et al. The use of methotrexate for treatment of inflammatory bowel disease in clinical practice. Dig Liver Dis. 2012;44:123-127. doi:10.1016/j.dld.2011.09.015

- Khan KM, Jialal I. Folic acid deficiency. StatPearls [Internet]. Updated June 26, 2023. Accessed March 19, 2024. https://www.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/books/NBK535377/

In 2023, ESPEN (the European Society for Clinical Nutrition and Metabolism) published consensus recommendations highlighting the importance of regular monitoring and treatment of nutrient deficiencies in patients with inflammatory bowel disease (IBD) for improved prognosis, mortality, and quality of life.1 Suboptimal nutrition in patients with IBD predominantly results from inflammation of the gastrointestinal (GI) tract leading to malabsorption; however, medications commonly used to manage IBD also can contribute to malnutrition.2,3 Additionally, patients may develop nausea and food avoidance due to medication or the disease itself, leading to nutritional withdrawal and eventual deficiency.4 Even with the development of diets focused on balancing nutritional needs and decreasing inflammation,5 offsetting this aversion to food can be difficult to overcome.2

Cutaneous manifestations of IBD are multifaceted and can be secondary to the disease, reactive to or associated with IBD, or effects from nutritional deficiencies. The most common vitamin and nutrient deficiencies in patients with IBD include iron; zinc; calcium; vitamin D; and vitamins B6 (pyridoxine), B9 (folic acid), and B12.6 Malnutrition may manifest with cutaneous disease, and dermatologists can be the first to identify and assess for nutritional deficiencies. In this article, we review the mechanisms of these micronutrient depletions in the context of IBD, their subsequent dermatologic manifestations (Table), and treatment and monitoring guidelines for each deficiency.

Iron

A systematic review conducted from 2007 to 2012 in European patients with IBD (N=2192) found the overall prevalence of anemia in this population to be 24% (95% CI, 18%-31%), with 57% of patients with anemia experiencing iron deficiency.7 Anemia is observed more commonly in patients hospitalized with IBD and is common in patients with both Crohn disease and ulcerative colitis.8

Pathophysiology—Iron is critically important in oxygen transportation throughout the body as a major component of hemoglobin. Physiologically, the low pH of the duodenum and proximal jejunum allows divalent metal transporter 1 to transfer dietary Fe3+ into enterocytes, where it is reduced to the transportable Fe2+.9,10 Distribution of Fe2+ ions from enterocytes relies on ferroportin, an iron-transporting protein, which is heavily regulated by the protein hepcidin.11 Hepcidin, a known acute phase reactant, will increase in the setting of active IBD, causing a depletion of ferroportin and an inability of the body to utilize the stored iron in enterocytes.12 This poor utilization of iron stores combined with blood loss caused by inflammation in the GI tract is the proposed primary mechanism of iron-deficiency anemia observed in patients with IBD.13

Cutaneous Manifestations—From a dermatologic perspective, iron-deficiency anemia can manifest with a wide range of symptoms including glossitis, koilonychia, xerosis and/or pruritus, and brittle hair or hair loss.14,15 Although the underlying pathophysiology of these cutaneous manifestations is not fully understood, there are several theories assessing the mechanisms behind the skin findings of iron deficiency.

Atrophic glossitis has been observed in many patients with iron deficiency and is thought to manifest due to low iron concentrations in the blood, thereby decreasing oxygen delivery to the papillae of the dorsal tongue with resultant atrophy.16,17 Similarly, decreased oxygen delivery to the nail bed capillaries may cause deformities in the nail called koilonychia (or “spoon nails”).18 Iron is a key co-factor in collagen lysyl hydroxylase that promotes collagen binding; iron deficiency may lead to disruptions in the epidermal barrier that can cause pruritus and xerosis.19 An observational study of 200 healthy patients with a primary concern of pruritus found a correlation between low serum ferritin and a higher degree of pruritus (r=−0.768; P<.00001).20

Evidence for iron’s role in hair growth comes from a mouse model study with a mutation in the serine protease TMPRSS6—a protein that regulates hepcidin and iron absorption—which caused an increase in hepcidin production and subsequent systemic iron deficiency. Mice at 4 weeks of age were devoid of all body hair but had substantial regrowth after initiation of a 2-week iron-rich diet, which suggests a connection between iron repletion and hair growth in mice with iron deficiency.21 Additionally, a meta-analysis analyzing the comorbidities of patients with alopecia areata found them to have higher odds (odds ratio [OR]=2.78; 95% CI, 1.23-6.29) of iron-deficiency anemia but no association with IBD (OR=1.48; 95% CI, 0.32-6.82).22

Diagnosis and Monitoring—The American Gastroenterological Association recommends a complete blood cell count (CBC), serum ferritin, transferrin saturation (TfS), and C-reactive protein (CRP) as standard evaluations for iron deficiency in patients with IBD. Patients with active IBD should be screened every 3 months,and patients with inactive disease should be screened every 6 to 12 months.23

Although ferritin and TfS often are used as markers for iron status in healthy individuals, they are positive and negative acute phase reactants, respectively. Using them to assess iron status in patients with IBD may inaccurately represent iron status in the setting of inflammation from the disease.24 The European Crohn’s and Colitis Organisation (ECCO) produced guidelines to define iron deficiency as a TfS less than 20% or a ferritin level less than 30 µg/L in patients without evidence of active IBD and a ferritin level less than 100 µg/L for patients with active inflammation.25

A 2020 multicenter observational study of 202 patients with diagnosed IBD found that the ECCO guideline of ferritin less than 30 µg/L had an area under the receiver operating characteristic (AUROC) curve of 0.69, a sensitivity of 0.43, and a specificity of 0.95 in their population.26 In a sensitivity analysis stratifying patients by CRP level (<10 or ≥10 mg/L), the authors found that for patients with ulcerative colitis and a CRP less than 10 mg/L, a cut-off value of ferritin less than 65 µg/L (AUROC=0.78) had a sensitivity of 0.78 and specificity of 0.76, and a TfS value of less than 16% (AUROC=0.88) had a sensitivity of 0.79 and a specificity of 0.9. In patients with a CRP of 10 mg/L or greater, a cut-off value of ferritin 80 µg/L (AUROC=0.76) had a sensitivity of 0.75 and a specificity of 0.82, and a TfS value of less than 11% (AUROC=0.69) had a sensitivity of 0.79 and a specificity of 0.88. There were no ferritin cut-off values associated with good diagnostic performance (defined as both sensitivity and specificity >0.70) for iron deficiency in patients with Crohn disease.26

The authors recommended using an alternative iron measurement such as soluble transferrin receptor (sTfR)/log ferritin ratio (TfR-F) that is not influenced by active inflammation and has a good correlation with ferritin values (TfR-F: r=0.66; P<.001).26 However, both sTfR and TfR-F have high costs and intermethod variability as well as differences in their reference ranges depending on which laboratory performs the analysis, limiting the accessibility and practicality of easily obtaining these tests.27 Although there may be inaccuracies for standard ferritin or TfS under ECCO guidelines, proposed alternatives have their own limitations, which may make ferritin and TfS the most reasonable evaluations of iron status as long as disease activity status at the time of testing is taken into consideration.

Treatment—Treatment of underlying iron deficiency in patients with IBD requires reversing the cause of the deficiency and supplementing iron. In patients with IBD, the options to supplement iron may be limited by active disease, making oral intake less effective. Oral iron supplementation also is associated with notable GI adverse effects that may be exacerbated in patients with IBD. A systematic review of 43 randomized controlled trials (RCTs) evaluating GI adverse effects (eg, nausea, abdominal pain, diarrhea, constipation, and black or tarry stools) of oral ferrous sulfate compared with placebo or intravenous (IV) iron supplementation in healthy nonanemic individuals found a significant increase in GI adverse effects with oral supplementation (placebo: OR=2.32; P<.0001; IV: OR=3.05; P<.0001).28

Therefore, IV iron repletion may be necessary in patients with IBD and may require numerous infusions depending on the formulation of iron. In an RCT conducted in 2011, patients with iron-deficiency anemia with quiescent or mild to moderate IBD were treated with either IV iron sulfate or ferric carboxymaltose.29 With a primary end point of hemoglobin response greater than 2 g/dL, the authors found that 150 of 240 patients responded to ferric carboxymaltose vs 118 of 235 treated with iron sulfate (P=.004). The dosing for ferric carboxymaltose was 1 to 3 infusions of 500 to 1000 mg of iron and for iron sulfate up to 11 infusions of 200 mg of iron.29

Zinc

A systematic review of zinc deficiency in patients with IBD identified 7 studies including 2413 patients and revealed those with Crohn disease had a higher prevalence of zinc deficiency compared with patients with ulcerative colitis (54% vs 41%).30

Pathophysiology—Zinc serves as a catalytic cofactor for enzymatic activity within proteins and immune cells.31 The homeostasis of zinc is tightly regulated within the brush border of the small intestine by zinc transporters ZIP4 and ZIP1 from the lumen of enterocytes into the bloodstream.32 Inflammation in the small intestine due to Crohn disease can result in zinc malabsorption.

Ranaldi et al33 exposed intestinal cells and zinc-depleted intestinal cells to tumor necrosis factor α media to simulate an inflammatory environment. They measured transepithelial electrical resistance as a surrogate for transmembrane permeability and found that zinc-depleted cells had a statistically significantly higher transepithelial electrical resistance percentage (60% reduction after 4 hours; P<1.10–6) when exposed to tumor necrosis factor α signaling compared with normal intestinal cells. They concluded that zinc deficiency can increase intestinal permeability in the presence of inflammation, creating a cycle of further nutrient malabsorption and inflammation exacerbating IBD symptoms.33

Cutaneous Manifestations—After absorption in the small intestine, approximately 5% of zinc resides in the skin, with the highest concentration in the stratum spinosum.34 A cell study found that keratinocytes in zinc-deficient environments had higher rates of apoptosis compared with cells in normal media. The authors proposed that this higher rate of apoptosis and the resulting inflammation could be a mechanism for developing the desquamative or eczematous scaly plaques that are common cutaneous manifestations of zinc deficiency.35

Other cutaneous findings may include angular cheilitis, stomatitis, glossitis, paronychia, onychodystrophy, generalized alopecia, and delayed wound healing.36 The histopathology of these skin lesions is characterized by granular layer loss, epidermal pallor, confluent parakeratosis, spongiosis, dyskeratosis, and psoriasiform hyperplasia.37

Diagnosis and Monitoring—Assessing serum zinc levels is challenging, as they may decrease during states of inflammation.38 A mouse model study showed a 3.1-fold increase (P<.001) in ZIP14 expression in wild-type mice compared with an IL-6 -/- knock-down model after IL-6 exposure. The authors concluded that the upregulation of ZIP14 in the liver due to inflammatory cytokine upregulation decreases zinc availability in serum.39 Additionally, serum zinc can overestimate the level of deficiency in IBD because approximately 75% of serum zinc is bound to albumin, which decreases in the setting of inflammation.40-42

Alternatively, alkaline phosphatase (AP), a zinc-dependent metalloenzyme, may be a better evaluator of zinc status during periods of inflammation. A study in rats evaluated zinc through serum zinc levels and AP levels after a period of induced stress to mimic a short-term inflammatory state.43 The researchers found that total body stores of zinc were unaffected throughout the experiment; only serum zinc declined throughout the experiment duration while AP did not. Because approximately 75% of serum zinc is bound to serum albumin,42 the researchers concluded the induced inflammatory state depleted serum albumin and redistributed zinc to the liver, causing the observed serum zinc changes, while total body zinc levels and AP were largely unaffected in comparison.43 Comorbid conditions such as liver or bone disease can increase AP levels, which limits the utility of AP as a surrogate for zinc in patients with comorbidities.44 However, even in the context of active IBD, serum zinc still is currently considered the best biomarker to evaluate zinc status.45

Treatment—The recommended dose for zinc supplementation is 20 to 40 mg daily with higher doses (>50 mg/d) for patients with malabsorptive syndromes such as IBD.46 It can be administered orally or parenterally. Although rare, zinc replacement therapy may be associated with diarrhea, nausea, vomiting, mild headaches, and fatigue.46 Additional considerations should be taken when repleting other micronutrients with zinc, as calcium and folate can inhibit zinc reabsorption, while zinc itself can inhibit iron and copper reabsorption.47

Vitamin D and Calcium

Low vitamin D levels (<50 nmol/L) and hypocalcemia (<8.8 mg/dL) are common in patients with IBD.48,49

Pathophysiology—Vitamin D levels are maintained via 2 mechanisms. The first mechanism is through the skin, as keratinocytes produce 7-dehydrocholesterol after exposure to UV light, which is converted into previtamin D3 and then thermally isomerizes into vitamin D3. This vitamin D3 is then transported to the liver on vitamin D–binding protein.50 The second mechanism is through oral vitamin D3 that is absorbed through vitamin D receptors in intestinal epithelium and transported to the liver, where it is hydroxylated into 25-hydroxyvitamin D (25[OH]D), then to the kidneys for hydroxylation to 1,25(OH)2D for redistribution throughout the body.50 This activated form of vitamin D regulates calcium absorption in the intestine, and optimal vitamin D levels are necessary to absorb calcium efficiently.51 Inflammation from IBD within the small intestine can downregulate vitamin D receptors, causing malabsorption and decreased serum vitamin D.52

Vitamin D signaling also is vital to maintaining the tight junctions and adherens junctions of the intestinal epithelium. Weakening the permeability of the epithelium further exacerbates malabsorption and subsequent vitamin D deficiency.52 A meta-analysis of 27 studies including 8316 patients with IBD showed low vitamin D levels were associated with increased odds of disease activity (OR=1.53; 95% CI, 1.32-1.77), mucosal inflammation (OR=1.25; 95% CI, 1.06-1.47), and future clinical relapse (OR=1.23; 95% CI, 1.03-1.47) in patients with Crohn disease. The authors concluded that low levels of vitamin D could be used as a potential biomarker of inflammatory status in Crohn disease.53

Vitamin D and calcium are further implicated in maintaining skeletal health,47 while vitamin D specifically helps maintain intestinal homeostasis54 and immune system modulation in the skin.55

Cutaneous Manifestations—Vitamin D is thought to play crucial roles in skin differentiation and proliferation, cutaneous innate immunity, hair follicle cycling, photoprotection, and wound healing.56 Vitamin D deficiency has been observed in a large range of cutaneous diseases including skin cancer, psoriasis, vitiligo, bullous pemphigoid, atopic dermatitis, and various types of alopecia.56-59 It is unclear whether vitamin D deficiency facilitates these disease processes or is merely the consequence of a disrupted cutaneous surface with the inability to complete the first step in vitamin D processing. A 2014 meta-analysis of 290 prospective cohort studies and 172 randomized trials concluded that 25(OH)D deficiency was associated with ill health and did not find causal evidence for any specific disease, dermatologic or otherwise.60 Calcium deficiency may cause epidermal changes including dry skin, coarse hair, and brittle nails.61

Diagnosis and Monitoring—The ECCO guidelines recommend obtaining serum 25(OH)D levels every 3 months in patients with IBD.62 Levels less than 75 nmol/L are considered deficient, and a value less than 30 nmol/L increases the risk for osteomalacia and nutritional rickets, constituting severe vitamin D deficiency.63-65

An observational study of 325 patients with IBD showed a statistically significant negative correlation between serum vitamin D and fecal calprotectin (r=−0.19; P<.001), a stool-based marker for gut inflammation, supporting vitamin D as a potential biomarker in IBD.66

Evaluation of calcium can be done through serum levels in patients with IBD.67 Patients with IBD are at risk for hypoalbuminemia; therefore, consideration should be taken to ensure calcium levels are corrected, as approximately 50% of calcium is bound to albumin or other ions in the body,68 which can be done by adjusting the calcium concentration by 0.02 mmol/L for every 1 g/L of albumin above or below 40 g/L. In the most critically ill patients, a direct ionized calcium blood level should be used instead because the previously mentioned correction calculations are inaccurate when albumin is critically low.69

Treatment—The ECCO guidelines recommend calcium and vitamin D repletion of 500 to 1000 mg and 800 to 1000 U, respectively, in patients with IBD on systemic corticosteroids to prevent the negative effects of bone loss.62 Calcium repletion in patients with IBD who are not on systemic steroids are the same as for the general population.65

Vitamin D repletion also may help decrease IBD activity. In a prospective study, 10,000 IU/d of vitamin D in 10 patients with IBD—adjusted over 12 weeks to a target of 100 to 125 nmol/L of serum 25(OH)D—showed a significant reduction in clinical Crohn activity (P=.019) over the study period.70 In contrast, 2000 IU/d for 3 months in an RCT of 27 patients with Crohn disease found significantly lower CRP (P=.019) and significantly higher self-reported quality of life (P=.037) but nonsignificant decreases in Crohn activity (P=.082) in patients with 25(OH)D levels of 75 nmol/L or higher compared with those with 25(OH)D levels less than 75 nmol/L.71

These discrepancies illustrate the need for expanded clinical trials to elucidate the optimal vitamin D dosing for patients with IBD. Ultimately, assessing vitamin D and calcium status and considering repletion in patients with IBD, especially those with comorbid dermatologic diseases such as poor wound healing, psoriasis, or atopic dermatitis, is important.

Vitamin B6 (Pyridoxine)

Pathophysiology—Pyridoxine is an important coenzyme for many functions including amino acid transamination, fatty acid metabolism, and conversion of tryptophan to niacin. It is absorbed in the jejunum and ileum and subsequently transported to the liver for rephosphorylation and release into its active form.36 An observational study assessing the nutritional status of patients with IBD found that only 5.7% of 105 patients with food records had inadequate dietary intake of pyridoxine, but 29% of all patients with IBD had subnormal pyridoxine levels.72 Additionally, they found no significant difference in the prevalence of subnormal pyridoxine levels in patients with active IBD vs IBD in remission. The authors suggested that the subnormal pyridoxine levels in patients with IBD likely were multifactorial and resulted from malabsorption due to active disease, inflammation, and inadequate intake.72

Cutaneous Manifestations—Cutaneous findings associated with pyridoxine deficiency include periorificial and perineal dermatitis,73 angular stomatitis, and cheilitis with associated burning, redness, and tongue edema.36 Additionally, pyridoxine is involved in the conversion of tryptophan to niacin, and its deficiency may manifest with pellagralike findings.74

Because pyridoxine is critical to protein metabolism, its deficiency may disrupt key cellular structures that rely on protein concentrations to maintain structural integrity. One such structure in the skin that heavily relies on protein concentrations is the ground substance of the extracellular matrix—the amorphous gelatinous spaces that occupy the areas between the extracellular matrix, which consists of cross-linked glycosaminoglycans and proteins.75 Without protein, ground substance increases in viscosity and can disrupt the epidermal barrier, leading to increased transepidermal water loss and ultimately inflammation.76 Although this theory has yet to be validated fully, this is a potential mechanistic explanation for the inflammation in dermal papillae that leads to dermatitis observed in pyridoxine deficiency.

Diagnosis and Monitoring—Direct biomarkers of pyridoxine status are in serum, plasma, erythrocytes, and urine, with the most common measurement in plasma as pyridoxal 5′-phosphate (PLP).77 Plasma PLP concentrations lower than 20 nmol/L are suggestive of deficiency.78 Plasma PLP has shown inverse relationships with acute phase inflammatory markers CRP79 and AP,78 thereby raising concerns for its validity to assess pyridoxine status in patients with symptomatic IBD.80

Alternative evaluations of pyridoxine include tryptophan and methionine loading tests,36 which are measured via urinary excretion and require normal kidney function to be accurate. They should be considered in IBD if necessary, but routine testing, even in patients with symptomatic IBD, is not recommended in the ECCO guidelines. Additional considerations should be taken in patients with altered nutrient requirements such as those who have undergone bowel resection due to highly active disease or those who receive parenteral nutritional supplementation.81

Treatment—Recommendations for oral pyridoxine supplementation range from 25 to 600 mg daily,82 with symptoms typically improving on 100 mg daily.36 Pyridoxine supplementation may have additional benefits for patients with IBD and potentially modulate disease severity. An IL-10 knockout mouse supplemented with pyridoxine had an approximately 60% reduction (P<.05) in inflammation compared to mice deficient in pyridoxine.83 The authors suggest that PLP-dependent enzymes can inhibit further proinflammatory signaling and T-cell migration that can exacerbate IBD. Ultimately, more data is needed before determining the efficacy of pyridoxine supplementation for active IBD.

Vitamin B12 and Vitamin B9 (Folic Acid)

Pathophysiology—Vitamin B12 is reabsorbed in the terminal ileum, the distal portion of the small intestine. The American Gastroenterological Association recommends that patients with a history of extensive ileal disease or prior ileal surgery, which is the case for many patients with Crohn disease, be monitored for vitamin B12 deficiency.23 Monitoring and rapid supplementation of vitamin B12 can prevent pernicious anemia and irreversible neurologic damage that may result from deficiency.84

Folic acid is primarily absorbed in the duodenum and jejunum of the small intestine. A meta-analysis performed in 2017 assessed studies observing folic acid and vitamin B12 levels in 1086 patients with IBD compared with 1484 healthy controls and found an average difference in serum folate concentration of 0.46 nmol/L (P<.001).84 Interestingly, this study did not find a significant difference in serum vitamin B12 levels between patients with IBD and healthy controls, highlighting the mechanism of vitamin B12 deficiency in IBD because only patients with terminal ileal involvement are at risk for malabsorption and subsequent deficiency.

Cutaneous Manifestations—Both vitamin B12 and folic acid deficiency can manifest as cheilitis, glossitis, and/or generalized hyperpigmentation that is accentuated in the flexural areas, palms, soles, and oral cavity.85,86 Systemic symptoms of patients with vitamin B12 and folic acid deficiency include megaloblastic anemia, pallor, and fatigue. A potential mechanism for the hyperpigmentation observed from vitamin B12 deficiency came from an electron microscope study that showed an increased concentration of melanosomes in a patient with deficiency.87

Diagnosis and Monitoring—In patients with suspected vitamin B12 and/or folic acid deficiency, initial evaluation should include a CBC with peripheral smear and serum vitamin B12 and folate levels. In cases for which the diagnosis still is unclear after initial testing,

Treatment—According to the Centers for Disease Control and Prevention, supplementation of vitamin B12 can be done orally with 1000 µg daily in patients with deficiency. In patients with active IBD, oral reabsorption of vitamin B12 can be less effective, making subcutaneous or intramuscular administration (1000 µg/wk for 8 weeks, then monthly for life) better options.89

Patients with IBD managed with methotrexate should be screened carefully for folate deficiency. Methotrexate is a folate analog that sometimes is used for the treatment of IBD. Reversible competitive inhibition of dihydrofolate reductase can precipitate a systemic folic acid decrease.91 Typically, oral folic acid (1 to 5 mg/d) is sufficient to treat folate deficiency, with the ESPEN recommending 5 mg once weekly 24 to 72 hours after methotrexate treatment or 1 mg daily for 5 days per week in patients with IBD.1 Alternative formulations—IV, subcutaneous, or intramuscular—are available for patients who cannot tolerate oral intake.92

Final Thoughts

Dermatologists can be the first to observe the cutaneous manifestations of micronutrient deficiencies. Although the symptoms of each micronutrient deficiency discussed may overlap, attention to small clinical clues in patients with IBD can improve patient outcomes and quality of life. For example, koilonychia with glossitis and xerosis likely is due to iron deficiency, while zinc deficiency should be suspected in patients with scaly eczematous plaques in skin folds. A high level of suspicion for micronutrient deficiencies in patients with IBD should be followed by a complete patient history, review of systems, and thorough clinical examination. A thorough laboratory evaluation can pinpoint nutritional deficiencies in patients with IBD, keeping in mind that specific biomarkers such as ferritin and serum zinc also act as acute phase reactants and should be interpreted in this context. Co-management with gastroenterologists should be a priority in patients with IBD, as gaining control of inflammatory disease is crucial for the prevention of recurrent vitamin and micronutrient deficiencies in addition to long-term health in this population.

In 2023, ESPEN (the European Society for Clinical Nutrition and Metabolism) published consensus recommendations highlighting the importance of regular monitoring and treatment of nutrient deficiencies in patients with inflammatory bowel disease (IBD) for improved prognosis, mortality, and quality of life.1 Suboptimal nutrition in patients with IBD predominantly results from inflammation of the gastrointestinal (GI) tract leading to malabsorption; however, medications commonly used to manage IBD also can contribute to malnutrition.2,3 Additionally, patients may develop nausea and food avoidance due to medication or the disease itself, leading to nutritional withdrawal and eventual deficiency.4 Even with the development of diets focused on balancing nutritional needs and decreasing inflammation,5 offsetting this aversion to food can be difficult to overcome.2

Cutaneous manifestations of IBD are multifaceted and can be secondary to the disease, reactive to or associated with IBD, or effects from nutritional deficiencies. The most common vitamin and nutrient deficiencies in patients with IBD include iron; zinc; calcium; vitamin D; and vitamins B6 (pyridoxine), B9 (folic acid), and B12.6 Malnutrition may manifest with cutaneous disease, and dermatologists can be the first to identify and assess for nutritional deficiencies. In this article, we review the mechanisms of these micronutrient depletions in the context of IBD, their subsequent dermatologic manifestations (Table), and treatment and monitoring guidelines for each deficiency.

Iron

A systematic review conducted from 2007 to 2012 in European patients with IBD (N=2192) found the overall prevalence of anemia in this population to be 24% (95% CI, 18%-31%), with 57% of patients with anemia experiencing iron deficiency.7 Anemia is observed more commonly in patients hospitalized with IBD and is common in patients with both Crohn disease and ulcerative colitis.8

Pathophysiology—Iron is critically important in oxygen transportation throughout the body as a major component of hemoglobin. Physiologically, the low pH of the duodenum and proximal jejunum allows divalent metal transporter 1 to transfer dietary Fe3+ into enterocytes, where it is reduced to the transportable Fe2+.9,10 Distribution of Fe2+ ions from enterocytes relies on ferroportin, an iron-transporting protein, which is heavily regulated by the protein hepcidin.11 Hepcidin, a known acute phase reactant, will increase in the setting of active IBD, causing a depletion of ferroportin and an inability of the body to utilize the stored iron in enterocytes.12 This poor utilization of iron stores combined with blood loss caused by inflammation in the GI tract is the proposed primary mechanism of iron-deficiency anemia observed in patients with IBD.13

Cutaneous Manifestations—From a dermatologic perspective, iron-deficiency anemia can manifest with a wide range of symptoms including glossitis, koilonychia, xerosis and/or pruritus, and brittle hair or hair loss.14,15 Although the underlying pathophysiology of these cutaneous manifestations is not fully understood, there are several theories assessing the mechanisms behind the skin findings of iron deficiency.

Atrophic glossitis has been observed in many patients with iron deficiency and is thought to manifest due to low iron concentrations in the blood, thereby decreasing oxygen delivery to the papillae of the dorsal tongue with resultant atrophy.16,17 Similarly, decreased oxygen delivery to the nail bed capillaries may cause deformities in the nail called koilonychia (or “spoon nails”).18 Iron is a key co-factor in collagen lysyl hydroxylase that promotes collagen binding; iron deficiency may lead to disruptions in the epidermal barrier that can cause pruritus and xerosis.19 An observational study of 200 healthy patients with a primary concern of pruritus found a correlation between low serum ferritin and a higher degree of pruritus (r=−0.768; P<.00001).20

Evidence for iron’s role in hair growth comes from a mouse model study with a mutation in the serine protease TMPRSS6—a protein that regulates hepcidin and iron absorption—which caused an increase in hepcidin production and subsequent systemic iron deficiency. Mice at 4 weeks of age were devoid of all body hair but had substantial regrowth after initiation of a 2-week iron-rich diet, which suggests a connection between iron repletion and hair growth in mice with iron deficiency.21 Additionally, a meta-analysis analyzing the comorbidities of patients with alopecia areata found them to have higher odds (odds ratio [OR]=2.78; 95% CI, 1.23-6.29) of iron-deficiency anemia but no association with IBD (OR=1.48; 95% CI, 0.32-6.82).22

Diagnosis and Monitoring—The American Gastroenterological Association recommends a complete blood cell count (CBC), serum ferritin, transferrin saturation (TfS), and C-reactive protein (CRP) as standard evaluations for iron deficiency in patients with IBD. Patients with active IBD should be screened every 3 months,and patients with inactive disease should be screened every 6 to 12 months.23

Although ferritin and TfS often are used as markers for iron status in healthy individuals, they are positive and negative acute phase reactants, respectively. Using them to assess iron status in patients with IBD may inaccurately represent iron status in the setting of inflammation from the disease.24 The European Crohn’s and Colitis Organisation (ECCO) produced guidelines to define iron deficiency as a TfS less than 20% or a ferritin level less than 30 µg/L in patients without evidence of active IBD and a ferritin level less than 100 µg/L for patients with active inflammation.25

A 2020 multicenter observational study of 202 patients with diagnosed IBD found that the ECCO guideline of ferritin less than 30 µg/L had an area under the receiver operating characteristic (AUROC) curve of 0.69, a sensitivity of 0.43, and a specificity of 0.95 in their population.26 In a sensitivity analysis stratifying patients by CRP level (<10 or ≥10 mg/L), the authors found that for patients with ulcerative colitis and a CRP less than 10 mg/L, a cut-off value of ferritin less than 65 µg/L (AUROC=0.78) had a sensitivity of 0.78 and specificity of 0.76, and a TfS value of less than 16% (AUROC=0.88) had a sensitivity of 0.79 and a specificity of 0.9. In patients with a CRP of 10 mg/L or greater, a cut-off value of ferritin 80 µg/L (AUROC=0.76) had a sensitivity of 0.75 and a specificity of 0.82, and a TfS value of less than 11% (AUROC=0.69) had a sensitivity of 0.79 and a specificity of 0.88. There were no ferritin cut-off values associated with good diagnostic performance (defined as both sensitivity and specificity >0.70) for iron deficiency in patients with Crohn disease.26

The authors recommended using an alternative iron measurement such as soluble transferrin receptor (sTfR)/log ferritin ratio (TfR-F) that is not influenced by active inflammation and has a good correlation with ferritin values (TfR-F: r=0.66; P<.001).26 However, both sTfR and TfR-F have high costs and intermethod variability as well as differences in their reference ranges depending on which laboratory performs the analysis, limiting the accessibility and practicality of easily obtaining these tests.27 Although there may be inaccuracies for standard ferritin or TfS under ECCO guidelines, proposed alternatives have their own limitations, which may make ferritin and TfS the most reasonable evaluations of iron status as long as disease activity status at the time of testing is taken into consideration.