User login

Improving Physicians’ Bowel Documentation on Geriatric Wards

From Sheffield Teaching Hospitals, Sheffield, UK, S5 7AU.

Objective: Constipation is widely prevalent in older adults and may result in complications such as urinary retention, delirium, and bowel obstruction. Previous studies have indicated that while the nursing staff do well in completing stool charts, doctors monitor them infrequently. This project aimed to improve the documentation of bowel movement by doctors on ward rounds to 85%, by the end of a 3-month period.

Methods: Baseline, postintervention, and sustainability data were collected from inpatient notes on weekdays on a geriatric ward in Northern General Hospital, Sheffield, UK. Posters and stickers of the poo emoji were placed on walls and in inpatient notes, respectively, as a reminder.

Results: Data on bowel activity documentation were collected from 28 patients. The baseline data showed that bowel activity was monitored daily on the ward 60.49% of the time. However, following the interventions, there was a significant increase in documentation, to 86.78%. The sustainability study showed that bowel activity was documented on the ward 56.56% of the time.

Conclusion: This study shows how a strong initial effect on behavioral change can be accomplished through simple interventions such as stickers and posters. As most wards currently still use paper notes, this is a generalizable model that other wards can trial. However, this study also shows the difficulty in maintaining behavioral change over extended periods of time.

Keywords: bowel movement; documentation; obstruction; constipation; geriatrics; incontinence; junior doctor; quality improvement.

Constipation is widely prevalent in the elderly, encountered frequently in both community and hospital medicine.1 Its estimated prevalence in adults over 84 years old is 34% for women and 25% for men, rising to up to 80% for long-term care residents.2

Chronic constipation is generally characterized by unsatisfactory defecation due to infrequent bowel emptying or difficulty with stool passage, which may lead to incomplete evacuation.2-4 Constipation in the elderly, in addition to causing abdominal pain, nausea, and reduced appetite, may result in complications such as fecal incontinence (and overflow diarrhea), urinary retention, delirium, and bowel obstruction, which may in result in life-threatening perforation.5,6 For inpatients on geriatric wards, these consequences may increase morbidity and mortality, while prolonging hospital stays, thereby also increasing exposure to hospital-acquired infections.7 Furthermore, constipation is also associated with impaired health-related quality of life.8

Management includes treating the cause, stopping contributing medications, early mobilization, diet modification, and, if all else fails, prescription laxatives. Therefore, early identification and appropriate treatment of constipation is beneficial in inpatient care, as well as when planning safe and patient-centered discharges.

Given the risks and complications of constipation in the elderly, we, a group of Foundation Year 2 (FY2) doctors in the UK Foundation Programme, decided to explore how doctors can help to recognize this condition early. Regular bowel movement documentation in patient notes on ward rounds is crucial, as it has been shown to reduce constipation-associated complications.5 However, complications from constipation can take significant amounts of time to develop and, therefore, documenting bowel movements on a daily basis is not necessary.

Based on these observations along with targets set out in previous studies,7 our aim was to improve documentation of bowel movement on ward rounds to 85% by March 2020.

Methods

Before the data collection process, a fishbone diagram was designed to identify the potential causes of poor documentation of bowel movement on geriatric wards. There were several aspects that were reviewed, including, for example, patients, health care professionals, organizational policies, procedures, and equipment. It was then decided to focus on raising awareness of the documentation of bowel movement by doctors specifically.

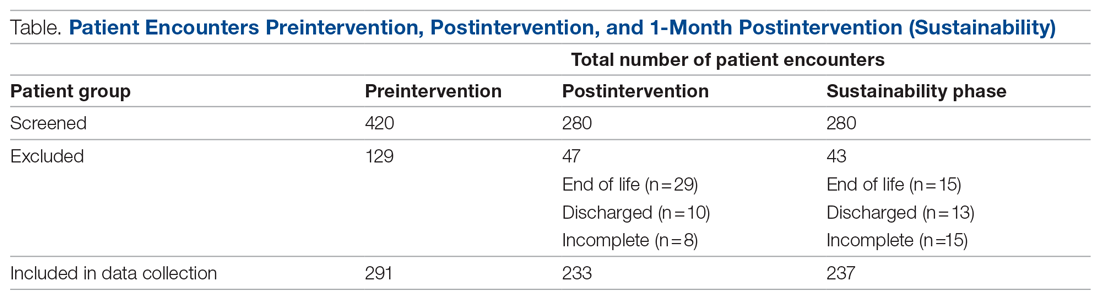

Retrospective data were collected from the inpatient paper notes of 28 patients on Brearley 6, a geriatric ward at the Northern General Hospital within Sheffield Teaching Hospitals (STH), on weekdays over a 3-week period. The baseline data collected included the bed number of the patient, whether or not bowel movement on initial ward round was documented, and whether it was the junior, registrar, or consultant leading the ward round. End-of-life and discharged patients were excluded (Table).

The interventions consisted of posters and stickers. Posters were displayed on Brearley 6, including the doctors’ office, nurses’ station, and around the bays where notes were kept, in order to emphasize their importance. The stickers of the poo emoji were also printed and placed at the front of each set of inpatient paper notes as a reminder for the doctor documenting on the ward round. The interventions were also introduced in the morning board meeting to ensure all staff on Brearley 6 were aware of them.

Data were collected on weekdays over a 3-week period starting 2 weeks after the interventions were put in place (Table). In order to assess that the intervention had been sustained, data were again collected 1 month later over a 2-week period (Table). Microsoft Excel (Microsoft Corporation, Redmond, Washington, USA) was used to analyze all data, and control charts were used to assess variability in the data.

Results

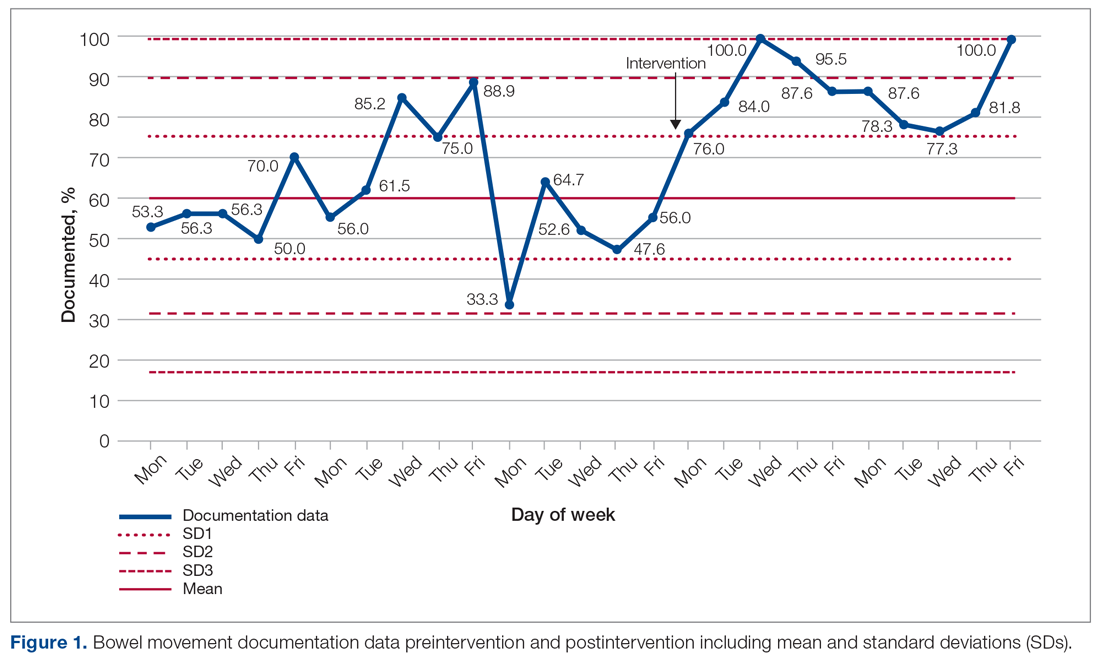

The baseline data showed that bowel movement was documented 60.49% of the time by doctors on the initial ward round before intervention, as illustrated in Figure 1. There was no evidence of an out-of-control process in this baseline data set.

The comparison between the preintervention and postintervention data is illustrated in Figure 1. The postintervention data, which were taken 2 weeks after intervention, showed a significant increase in the documentation of bowel movements, to 86.78%. The figure displays a number of features consistent with an out-of-control process: beyond limits (≥ 1 points beyond control limits), Zone A rule (2 out of 3 consecutive points beyond 2 standard deviations from the mean), Zone B rule (4 out of 5 consecutive points beyond 1 standard deviation from the mean), and Zone C rule (≥ 8 consecutive points on 1 side of the mean). These findings demonstrate a special cause variation in the documentation of bowel movements.

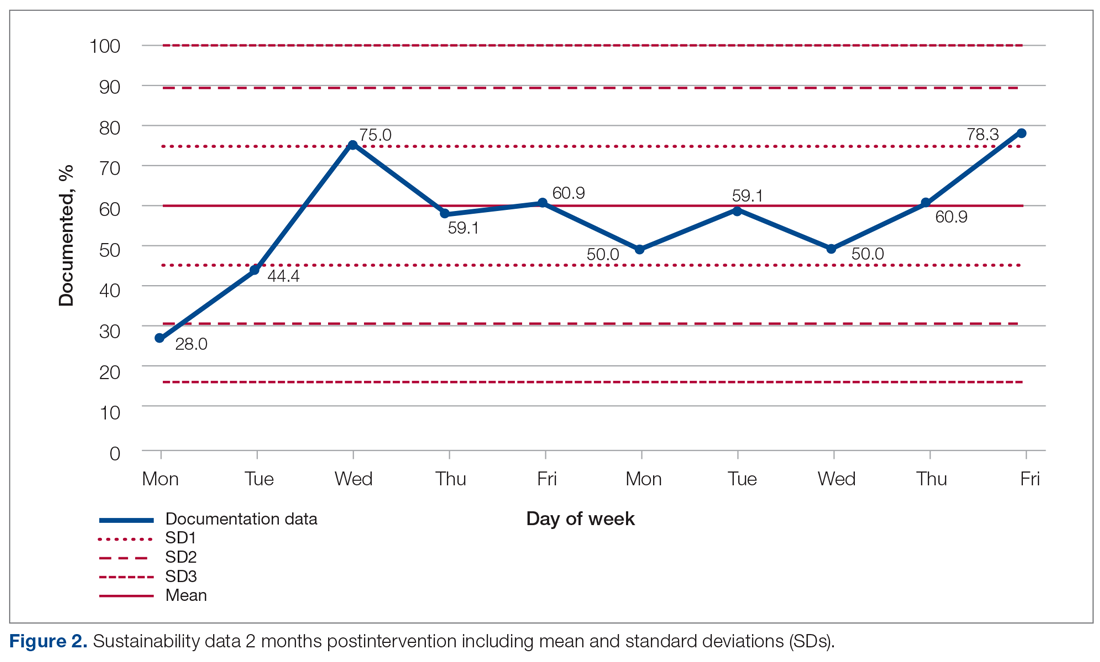

Figure 2 shows the sustainability of the intervention, which averaged 56.56% postintervention nearly 2 months later. The data returned to preintervention variability levels.

Discussion

Our project explored an important issue that was frequently encountered by department clinicians. Our team of FY2 doctors, in general, had little experience with quality improvement. We have developed our understanding and experience through planning, making, and measuring improvement.

It was challenging deciding on how to deal with the problem. A number of ways were considered to improve the paper rounding chart, but the nursing team had already planned to make changes to it. Bowel activity is mainly documented by nursing staff, but there was no specific protocol for recognizing constipation and when to inform the medical team. We decided to focus on doctors’ documentation in patient notes during the ward round, as this is where the decision regarding management of bowels is made, including interventions that could only be done by doctors, such as prescribing laxatives.

Strom et al9 have described a number of successful quality improvement interventions, and we decided to follow the authors’ guidance to implement a reminder system strategy using both posters and stickers to prompt doctors to document bowel activity. Both of these were simple, and the text on the poster was concise. The only cost incurred on the project was from printing the stickers; this totalled £2.99 (US $4.13). Individual stickers for each ward round entry were considered but not used, as it would create an additional task for doctors.

The data initially indicated that the interventions had their desired effect. However, this positive change was unsustainable, most likely suggesting that the novelty of the stickers and posters wore off at some point, leading to junior doctors no longer noticing them. Further Plan-Do-Study-Act cycles should examine the reasons why the change is difficult to sustain and implement new policies that aim to overcome them.

There were a number of limitations to this study. A patient could be discharged before data collection, which was done twice weekly. This could have resulted in missed data during the collection period. In addition, the accuracy of the documentation is dependent on nursing staff correctly recording—as well as the doctors correctly viewing—all sources of information on bowel activity. Observer bias is possible, too, as a steering group member was involved in data collection. Their awareness of the project could cause a positive skew in the data. And, unfortunately, the project came to an abrupt end because of COVID-19 cases on the ward.

We examined the daily documentation of bowel activity, which may not be necessary considering that internationally recognized constipation classifications, such as the Rome III criteria, define constipation as fewer than 3 bowel movements per week.10 However, the data collection sheet did not include patient identifiers, so it was impossible to determine whether bowel activity had been documented 3 or more times per week for each patient. This is important because a clinician may only decide to act if there is no bowel movement activity for 3 or more days.

Because our data were collected on a single geriatric ward, which had an emphasis on Parkinson’s disease, it is unclear whether our findings are generalizable to other clinical areas in STH. However, constipation is common in the elderly, so it is likely to be relevant to other wards, as more than a third of STH hospital beds are occupied by patients aged 75 years and older.11

Conclusion

Overall, our study highlights the fact that monitoring bowel activity is important on a geriatric ward. Recognizing constipation early prevents complications and delays to discharge. As mentioned earlier, our aim was achieved initially but not sustained. Therefore, future development should focus on sustainability. For example, laxative-focused ward rounds have shown to be effective at recognizing and preventing constipation by intervening early.12 Future cycles that we considered included using an electronic reminder on the hospital IT system, as the trust is aiming to introduce electronic documentation. Focus could also be placed on improving documentation in bowel charts by ward staff. This could be achieved by organizing regular educational sessions on the complications of constipation and when to inform the medical team regarding concerns.

Acknowledgments: The authors thank Dr. Jamie Kapur, Sheffield Teaching Hospitals, for his guidance and supervision, as well as our collaborators: Rachel Hallam, Claire Walker, Monisha Chakravorty, and Hamza Khan.

Corresponding author: Alexander P. Noar, BMBCh, BA, 10 Stanhope Gardens, London, N6 5TS; alecnoar@live.co.uk.

Financial disclosures: None.

1. Forootan M, Bagheri N, Darvishi M. Chronic constipation: A review of literature. Medicine (Baltimore). 2018;97:e10631. doi:10.1097/MD.00000000000.10631

2. Schuster BG, Kosar L, Kamrul R. Constipation in older adults: stepwise approach to keep things moving. Can Fam Physician. 2015;61:152-158.

3. Gray JR. What is chronic constipation? Definition and diagnosis. Can J Gastroenterol. 2011;25 (Suppl B):7B-10B.

4. American Gastroenterological Association, Bharucha AE, Dorn SD, Lembo A, Pressman A. American Gastroenterological Association medical position statement on constipation. Gastroenterology. 2013;144:211-217. doi:10.1053/j.gastro.2012.10.029

5. Maung TZ, Singh K. Regular monitoring with stool chart prevents constipation, urinary retention and delirium in elderly patients: an audit leading to clinical effectiveness, efficiency and patient centredness. Future Healthc J. 2019;6(Suppl 2):3. doi:10.7861/futurehosp.6-2s-s3

6. Mostafa SM, Bhandari S, Ritchie G, et al. Constipation and its implications in the critically ill patient. Br J Anaesth. 2003;91:815-819. doi:10.1093/bja/aeg275

7. Jackson R, Cheng P, Moreman S, et al. “The constipation conundrum”: Improving recognition of constipation on a gastroenterology ward. BMJ Qual Improv Rep. 2016;5(1):u212167.w3007. doi:10.1136/bmjquality.u212167.w3007

8. Rao S, Go JT. Update on the management of constipation in the elderly: new treatment options. Clin Interv Aging. 2010;5:163-171. doi:10.2147/cia.s8100

9. Strom KL. Quality improvement interventions: what works? J Healthc Qual. 2001;23(5):4-24. doi:10.1111/j.1945-1474.2001.tb00368.x

10. De Giorgio R, Ruggeri E, Stanghellini V, et al. Chronic constipation in the elderly: a primer for the gastroenterologist. BMC Gastroenterol. 2015;15:130. doi:10.1186/s12876-015-366-3

11. The Health Foundation. Improving the flow of older people. April 2013. Accessed August 11, 2021. https://www.england.nhs.uk/wp-content/uploads/2013/08/sheff-study.pdf

12. Linton A. Improving management of constipation in an inpatient setting using a care bundle. BMJ Qual Improv Rep. 2014;3(1):u201903.w1002. doi:10.1136/bmjquality.u201903.w1002

From Sheffield Teaching Hospitals, Sheffield, UK, S5 7AU.

Objective: Constipation is widely prevalent in older adults and may result in complications such as urinary retention, delirium, and bowel obstruction. Previous studies have indicated that while the nursing staff do well in completing stool charts, doctors monitor them infrequently. This project aimed to improve the documentation of bowel movement by doctors on ward rounds to 85%, by the end of a 3-month period.

Methods: Baseline, postintervention, and sustainability data were collected from inpatient notes on weekdays on a geriatric ward in Northern General Hospital, Sheffield, UK. Posters and stickers of the poo emoji were placed on walls and in inpatient notes, respectively, as a reminder.

Results: Data on bowel activity documentation were collected from 28 patients. The baseline data showed that bowel activity was monitored daily on the ward 60.49% of the time. However, following the interventions, there was a significant increase in documentation, to 86.78%. The sustainability study showed that bowel activity was documented on the ward 56.56% of the time.

Conclusion: This study shows how a strong initial effect on behavioral change can be accomplished through simple interventions such as stickers and posters. As most wards currently still use paper notes, this is a generalizable model that other wards can trial. However, this study also shows the difficulty in maintaining behavioral change over extended periods of time.

Keywords: bowel movement; documentation; obstruction; constipation; geriatrics; incontinence; junior doctor; quality improvement.

Constipation is widely prevalent in the elderly, encountered frequently in both community and hospital medicine.1 Its estimated prevalence in adults over 84 years old is 34% for women and 25% for men, rising to up to 80% for long-term care residents.2

Chronic constipation is generally characterized by unsatisfactory defecation due to infrequent bowel emptying or difficulty with stool passage, which may lead to incomplete evacuation.2-4 Constipation in the elderly, in addition to causing abdominal pain, nausea, and reduced appetite, may result in complications such as fecal incontinence (and overflow diarrhea), urinary retention, delirium, and bowel obstruction, which may in result in life-threatening perforation.5,6 For inpatients on geriatric wards, these consequences may increase morbidity and mortality, while prolonging hospital stays, thereby also increasing exposure to hospital-acquired infections.7 Furthermore, constipation is also associated with impaired health-related quality of life.8

Management includes treating the cause, stopping contributing medications, early mobilization, diet modification, and, if all else fails, prescription laxatives. Therefore, early identification and appropriate treatment of constipation is beneficial in inpatient care, as well as when planning safe and patient-centered discharges.

Given the risks and complications of constipation in the elderly, we, a group of Foundation Year 2 (FY2) doctors in the UK Foundation Programme, decided to explore how doctors can help to recognize this condition early. Regular bowel movement documentation in patient notes on ward rounds is crucial, as it has been shown to reduce constipation-associated complications.5 However, complications from constipation can take significant amounts of time to develop and, therefore, documenting bowel movements on a daily basis is not necessary.

Based on these observations along with targets set out in previous studies,7 our aim was to improve documentation of bowel movement on ward rounds to 85% by March 2020.

Methods

Before the data collection process, a fishbone diagram was designed to identify the potential causes of poor documentation of bowel movement on geriatric wards. There were several aspects that were reviewed, including, for example, patients, health care professionals, organizational policies, procedures, and equipment. It was then decided to focus on raising awareness of the documentation of bowel movement by doctors specifically.

Retrospective data were collected from the inpatient paper notes of 28 patients on Brearley 6, a geriatric ward at the Northern General Hospital within Sheffield Teaching Hospitals (STH), on weekdays over a 3-week period. The baseline data collected included the bed number of the patient, whether or not bowel movement on initial ward round was documented, and whether it was the junior, registrar, or consultant leading the ward round. End-of-life and discharged patients were excluded (Table).

The interventions consisted of posters and stickers. Posters were displayed on Brearley 6, including the doctors’ office, nurses’ station, and around the bays where notes were kept, in order to emphasize their importance. The stickers of the poo emoji were also printed and placed at the front of each set of inpatient paper notes as a reminder for the doctor documenting on the ward round. The interventions were also introduced in the morning board meeting to ensure all staff on Brearley 6 were aware of them.

Data were collected on weekdays over a 3-week period starting 2 weeks after the interventions were put in place (Table). In order to assess that the intervention had been sustained, data were again collected 1 month later over a 2-week period (Table). Microsoft Excel (Microsoft Corporation, Redmond, Washington, USA) was used to analyze all data, and control charts were used to assess variability in the data.

Results

The baseline data showed that bowel movement was documented 60.49% of the time by doctors on the initial ward round before intervention, as illustrated in Figure 1. There was no evidence of an out-of-control process in this baseline data set.

The comparison between the preintervention and postintervention data is illustrated in Figure 1. The postintervention data, which were taken 2 weeks after intervention, showed a significant increase in the documentation of bowel movements, to 86.78%. The figure displays a number of features consistent with an out-of-control process: beyond limits (≥ 1 points beyond control limits), Zone A rule (2 out of 3 consecutive points beyond 2 standard deviations from the mean), Zone B rule (4 out of 5 consecutive points beyond 1 standard deviation from the mean), and Zone C rule (≥ 8 consecutive points on 1 side of the mean). These findings demonstrate a special cause variation in the documentation of bowel movements.

Figure 2 shows the sustainability of the intervention, which averaged 56.56% postintervention nearly 2 months later. The data returned to preintervention variability levels.

Discussion

Our project explored an important issue that was frequently encountered by department clinicians. Our team of FY2 doctors, in general, had little experience with quality improvement. We have developed our understanding and experience through planning, making, and measuring improvement.

It was challenging deciding on how to deal with the problem. A number of ways were considered to improve the paper rounding chart, but the nursing team had already planned to make changes to it. Bowel activity is mainly documented by nursing staff, but there was no specific protocol for recognizing constipation and when to inform the medical team. We decided to focus on doctors’ documentation in patient notes during the ward round, as this is where the decision regarding management of bowels is made, including interventions that could only be done by doctors, such as prescribing laxatives.

Strom et al9 have described a number of successful quality improvement interventions, and we decided to follow the authors’ guidance to implement a reminder system strategy using both posters and stickers to prompt doctors to document bowel activity. Both of these were simple, and the text on the poster was concise. The only cost incurred on the project was from printing the stickers; this totalled £2.99 (US $4.13). Individual stickers for each ward round entry were considered but not used, as it would create an additional task for doctors.

The data initially indicated that the interventions had their desired effect. However, this positive change was unsustainable, most likely suggesting that the novelty of the stickers and posters wore off at some point, leading to junior doctors no longer noticing them. Further Plan-Do-Study-Act cycles should examine the reasons why the change is difficult to sustain and implement new policies that aim to overcome them.

There were a number of limitations to this study. A patient could be discharged before data collection, which was done twice weekly. This could have resulted in missed data during the collection period. In addition, the accuracy of the documentation is dependent on nursing staff correctly recording—as well as the doctors correctly viewing—all sources of information on bowel activity. Observer bias is possible, too, as a steering group member was involved in data collection. Their awareness of the project could cause a positive skew in the data. And, unfortunately, the project came to an abrupt end because of COVID-19 cases on the ward.

We examined the daily documentation of bowel activity, which may not be necessary considering that internationally recognized constipation classifications, such as the Rome III criteria, define constipation as fewer than 3 bowel movements per week.10 However, the data collection sheet did not include patient identifiers, so it was impossible to determine whether bowel activity had been documented 3 or more times per week for each patient. This is important because a clinician may only decide to act if there is no bowel movement activity for 3 or more days.

Because our data were collected on a single geriatric ward, which had an emphasis on Parkinson’s disease, it is unclear whether our findings are generalizable to other clinical areas in STH. However, constipation is common in the elderly, so it is likely to be relevant to other wards, as more than a third of STH hospital beds are occupied by patients aged 75 years and older.11

Conclusion

Overall, our study highlights the fact that monitoring bowel activity is important on a geriatric ward. Recognizing constipation early prevents complications and delays to discharge. As mentioned earlier, our aim was achieved initially but not sustained. Therefore, future development should focus on sustainability. For example, laxative-focused ward rounds have shown to be effective at recognizing and preventing constipation by intervening early.12 Future cycles that we considered included using an electronic reminder on the hospital IT system, as the trust is aiming to introduce electronic documentation. Focus could also be placed on improving documentation in bowel charts by ward staff. This could be achieved by organizing regular educational sessions on the complications of constipation and when to inform the medical team regarding concerns.

Acknowledgments: The authors thank Dr. Jamie Kapur, Sheffield Teaching Hospitals, for his guidance and supervision, as well as our collaborators: Rachel Hallam, Claire Walker, Monisha Chakravorty, and Hamza Khan.

Corresponding author: Alexander P. Noar, BMBCh, BA, 10 Stanhope Gardens, London, N6 5TS; alecnoar@live.co.uk.

Financial disclosures: None.

From Sheffield Teaching Hospitals, Sheffield, UK, S5 7AU.

Objective: Constipation is widely prevalent in older adults and may result in complications such as urinary retention, delirium, and bowel obstruction. Previous studies have indicated that while the nursing staff do well in completing stool charts, doctors monitor them infrequently. This project aimed to improve the documentation of bowel movement by doctors on ward rounds to 85%, by the end of a 3-month period.

Methods: Baseline, postintervention, and sustainability data were collected from inpatient notes on weekdays on a geriatric ward in Northern General Hospital, Sheffield, UK. Posters and stickers of the poo emoji were placed on walls and in inpatient notes, respectively, as a reminder.

Results: Data on bowel activity documentation were collected from 28 patients. The baseline data showed that bowel activity was monitored daily on the ward 60.49% of the time. However, following the interventions, there was a significant increase in documentation, to 86.78%. The sustainability study showed that bowel activity was documented on the ward 56.56% of the time.

Conclusion: This study shows how a strong initial effect on behavioral change can be accomplished through simple interventions such as stickers and posters. As most wards currently still use paper notes, this is a generalizable model that other wards can trial. However, this study also shows the difficulty in maintaining behavioral change over extended periods of time.

Keywords: bowel movement; documentation; obstruction; constipation; geriatrics; incontinence; junior doctor; quality improvement.

Constipation is widely prevalent in the elderly, encountered frequently in both community and hospital medicine.1 Its estimated prevalence in adults over 84 years old is 34% for women and 25% for men, rising to up to 80% for long-term care residents.2

Chronic constipation is generally characterized by unsatisfactory defecation due to infrequent bowel emptying or difficulty with stool passage, which may lead to incomplete evacuation.2-4 Constipation in the elderly, in addition to causing abdominal pain, nausea, and reduced appetite, may result in complications such as fecal incontinence (and overflow diarrhea), urinary retention, delirium, and bowel obstruction, which may in result in life-threatening perforation.5,6 For inpatients on geriatric wards, these consequences may increase morbidity and mortality, while prolonging hospital stays, thereby also increasing exposure to hospital-acquired infections.7 Furthermore, constipation is also associated with impaired health-related quality of life.8

Management includes treating the cause, stopping contributing medications, early mobilization, diet modification, and, if all else fails, prescription laxatives. Therefore, early identification and appropriate treatment of constipation is beneficial in inpatient care, as well as when planning safe and patient-centered discharges.

Given the risks and complications of constipation in the elderly, we, a group of Foundation Year 2 (FY2) doctors in the UK Foundation Programme, decided to explore how doctors can help to recognize this condition early. Regular bowel movement documentation in patient notes on ward rounds is crucial, as it has been shown to reduce constipation-associated complications.5 However, complications from constipation can take significant amounts of time to develop and, therefore, documenting bowel movements on a daily basis is not necessary.

Based on these observations along with targets set out in previous studies,7 our aim was to improve documentation of bowel movement on ward rounds to 85% by March 2020.

Methods

Before the data collection process, a fishbone diagram was designed to identify the potential causes of poor documentation of bowel movement on geriatric wards. There were several aspects that were reviewed, including, for example, patients, health care professionals, organizational policies, procedures, and equipment. It was then decided to focus on raising awareness of the documentation of bowel movement by doctors specifically.

Retrospective data were collected from the inpatient paper notes of 28 patients on Brearley 6, a geriatric ward at the Northern General Hospital within Sheffield Teaching Hospitals (STH), on weekdays over a 3-week period. The baseline data collected included the bed number of the patient, whether or not bowel movement on initial ward round was documented, and whether it was the junior, registrar, or consultant leading the ward round. End-of-life and discharged patients were excluded (Table).

The interventions consisted of posters and stickers. Posters were displayed on Brearley 6, including the doctors’ office, nurses’ station, and around the bays where notes were kept, in order to emphasize their importance. The stickers of the poo emoji were also printed and placed at the front of each set of inpatient paper notes as a reminder for the doctor documenting on the ward round. The interventions were also introduced in the morning board meeting to ensure all staff on Brearley 6 were aware of them.

Data were collected on weekdays over a 3-week period starting 2 weeks after the interventions were put in place (Table). In order to assess that the intervention had been sustained, data were again collected 1 month later over a 2-week period (Table). Microsoft Excel (Microsoft Corporation, Redmond, Washington, USA) was used to analyze all data, and control charts were used to assess variability in the data.

Results

The baseline data showed that bowel movement was documented 60.49% of the time by doctors on the initial ward round before intervention, as illustrated in Figure 1. There was no evidence of an out-of-control process in this baseline data set.

The comparison between the preintervention and postintervention data is illustrated in Figure 1. The postintervention data, which were taken 2 weeks after intervention, showed a significant increase in the documentation of bowel movements, to 86.78%. The figure displays a number of features consistent with an out-of-control process: beyond limits (≥ 1 points beyond control limits), Zone A rule (2 out of 3 consecutive points beyond 2 standard deviations from the mean), Zone B rule (4 out of 5 consecutive points beyond 1 standard deviation from the mean), and Zone C rule (≥ 8 consecutive points on 1 side of the mean). These findings demonstrate a special cause variation in the documentation of bowel movements.

Figure 2 shows the sustainability of the intervention, which averaged 56.56% postintervention nearly 2 months later. The data returned to preintervention variability levels.

Discussion

Our project explored an important issue that was frequently encountered by department clinicians. Our team of FY2 doctors, in general, had little experience with quality improvement. We have developed our understanding and experience through planning, making, and measuring improvement.

It was challenging deciding on how to deal with the problem. A number of ways were considered to improve the paper rounding chart, but the nursing team had already planned to make changes to it. Bowel activity is mainly documented by nursing staff, but there was no specific protocol for recognizing constipation and when to inform the medical team. We decided to focus on doctors’ documentation in patient notes during the ward round, as this is where the decision regarding management of bowels is made, including interventions that could only be done by doctors, such as prescribing laxatives.

Strom et al9 have described a number of successful quality improvement interventions, and we decided to follow the authors’ guidance to implement a reminder system strategy using both posters and stickers to prompt doctors to document bowel activity. Both of these were simple, and the text on the poster was concise. The only cost incurred on the project was from printing the stickers; this totalled £2.99 (US $4.13). Individual stickers for each ward round entry were considered but not used, as it would create an additional task for doctors.

The data initially indicated that the interventions had their desired effect. However, this positive change was unsustainable, most likely suggesting that the novelty of the stickers and posters wore off at some point, leading to junior doctors no longer noticing them. Further Plan-Do-Study-Act cycles should examine the reasons why the change is difficult to sustain and implement new policies that aim to overcome them.

There were a number of limitations to this study. A patient could be discharged before data collection, which was done twice weekly. This could have resulted in missed data during the collection period. In addition, the accuracy of the documentation is dependent on nursing staff correctly recording—as well as the doctors correctly viewing—all sources of information on bowel activity. Observer bias is possible, too, as a steering group member was involved in data collection. Their awareness of the project could cause a positive skew in the data. And, unfortunately, the project came to an abrupt end because of COVID-19 cases on the ward.

We examined the daily documentation of bowel activity, which may not be necessary considering that internationally recognized constipation classifications, such as the Rome III criteria, define constipation as fewer than 3 bowel movements per week.10 However, the data collection sheet did not include patient identifiers, so it was impossible to determine whether bowel activity had been documented 3 or more times per week for each patient. This is important because a clinician may only decide to act if there is no bowel movement activity for 3 or more days.

Because our data were collected on a single geriatric ward, which had an emphasis on Parkinson’s disease, it is unclear whether our findings are generalizable to other clinical areas in STH. However, constipation is common in the elderly, so it is likely to be relevant to other wards, as more than a third of STH hospital beds are occupied by patients aged 75 years and older.11

Conclusion

Overall, our study highlights the fact that monitoring bowel activity is important on a geriatric ward. Recognizing constipation early prevents complications and delays to discharge. As mentioned earlier, our aim was achieved initially but not sustained. Therefore, future development should focus on sustainability. For example, laxative-focused ward rounds have shown to be effective at recognizing and preventing constipation by intervening early.12 Future cycles that we considered included using an electronic reminder on the hospital IT system, as the trust is aiming to introduce electronic documentation. Focus could also be placed on improving documentation in bowel charts by ward staff. This could be achieved by organizing regular educational sessions on the complications of constipation and when to inform the medical team regarding concerns.

Acknowledgments: The authors thank Dr. Jamie Kapur, Sheffield Teaching Hospitals, for his guidance and supervision, as well as our collaborators: Rachel Hallam, Claire Walker, Monisha Chakravorty, and Hamza Khan.

Corresponding author: Alexander P. Noar, BMBCh, BA, 10 Stanhope Gardens, London, N6 5TS; alecnoar@live.co.uk.

Financial disclosures: None.

1. Forootan M, Bagheri N, Darvishi M. Chronic constipation: A review of literature. Medicine (Baltimore). 2018;97:e10631. doi:10.1097/MD.00000000000.10631

2. Schuster BG, Kosar L, Kamrul R. Constipation in older adults: stepwise approach to keep things moving. Can Fam Physician. 2015;61:152-158.

3. Gray JR. What is chronic constipation? Definition and diagnosis. Can J Gastroenterol. 2011;25 (Suppl B):7B-10B.

4. American Gastroenterological Association, Bharucha AE, Dorn SD, Lembo A, Pressman A. American Gastroenterological Association medical position statement on constipation. Gastroenterology. 2013;144:211-217. doi:10.1053/j.gastro.2012.10.029

5. Maung TZ, Singh K. Regular monitoring with stool chart prevents constipation, urinary retention and delirium in elderly patients: an audit leading to clinical effectiveness, efficiency and patient centredness. Future Healthc J. 2019;6(Suppl 2):3. doi:10.7861/futurehosp.6-2s-s3

6. Mostafa SM, Bhandari S, Ritchie G, et al. Constipation and its implications in the critically ill patient. Br J Anaesth. 2003;91:815-819. doi:10.1093/bja/aeg275

7. Jackson R, Cheng P, Moreman S, et al. “The constipation conundrum”: Improving recognition of constipation on a gastroenterology ward. BMJ Qual Improv Rep. 2016;5(1):u212167.w3007. doi:10.1136/bmjquality.u212167.w3007

8. Rao S, Go JT. Update on the management of constipation in the elderly: new treatment options. Clin Interv Aging. 2010;5:163-171. doi:10.2147/cia.s8100

9. Strom KL. Quality improvement interventions: what works? J Healthc Qual. 2001;23(5):4-24. doi:10.1111/j.1945-1474.2001.tb00368.x

10. De Giorgio R, Ruggeri E, Stanghellini V, et al. Chronic constipation in the elderly: a primer for the gastroenterologist. BMC Gastroenterol. 2015;15:130. doi:10.1186/s12876-015-366-3

11. The Health Foundation. Improving the flow of older people. April 2013. Accessed August 11, 2021. https://www.england.nhs.uk/wp-content/uploads/2013/08/sheff-study.pdf

12. Linton A. Improving management of constipation in an inpatient setting using a care bundle. BMJ Qual Improv Rep. 2014;3(1):u201903.w1002. doi:10.1136/bmjquality.u201903.w1002

1. Forootan M, Bagheri N, Darvishi M. Chronic constipation: A review of literature. Medicine (Baltimore). 2018;97:e10631. doi:10.1097/MD.00000000000.10631

2. Schuster BG, Kosar L, Kamrul R. Constipation in older adults: stepwise approach to keep things moving. Can Fam Physician. 2015;61:152-158.

3. Gray JR. What is chronic constipation? Definition and diagnosis. Can J Gastroenterol. 2011;25 (Suppl B):7B-10B.

4. American Gastroenterological Association, Bharucha AE, Dorn SD, Lembo A, Pressman A. American Gastroenterological Association medical position statement on constipation. Gastroenterology. 2013;144:211-217. doi:10.1053/j.gastro.2012.10.029

5. Maung TZ, Singh K. Regular monitoring with stool chart prevents constipation, urinary retention and delirium in elderly patients: an audit leading to clinical effectiveness, efficiency and patient centredness. Future Healthc J. 2019;6(Suppl 2):3. doi:10.7861/futurehosp.6-2s-s3

6. Mostafa SM, Bhandari S, Ritchie G, et al. Constipation and its implications in the critically ill patient. Br J Anaesth. 2003;91:815-819. doi:10.1093/bja/aeg275

7. Jackson R, Cheng P, Moreman S, et al. “The constipation conundrum”: Improving recognition of constipation on a gastroenterology ward. BMJ Qual Improv Rep. 2016;5(1):u212167.w3007. doi:10.1136/bmjquality.u212167.w3007

8. Rao S, Go JT. Update on the management of constipation in the elderly: new treatment options. Clin Interv Aging. 2010;5:163-171. doi:10.2147/cia.s8100

9. Strom KL. Quality improvement interventions: what works? J Healthc Qual. 2001;23(5):4-24. doi:10.1111/j.1945-1474.2001.tb00368.x

10. De Giorgio R, Ruggeri E, Stanghellini V, et al. Chronic constipation in the elderly: a primer for the gastroenterologist. BMC Gastroenterol. 2015;15:130. doi:10.1186/s12876-015-366-3

11. The Health Foundation. Improving the flow of older people. April 2013. Accessed August 11, 2021. https://www.england.nhs.uk/wp-content/uploads/2013/08/sheff-study.pdf

12. Linton A. Improving management of constipation in an inpatient setting using a care bundle. BMJ Qual Improv Rep. 2014;3(1):u201903.w1002. doi:10.1136/bmjquality.u201903.w1002

Feasibility of a Saliva-Based COVID-19 Screening Program in Abu Dhabi Primary Schools

From Health Center, New York University Abu Dhabi, Abu Dhabi, United Arab Emirates (Dr. Virji and Aisha Al Hamiz), Public Health, Abu Dhabi Public Health Center, Abu Dhabi, United Arab Emirates (Drs. Al Hajeri, Al Shehhi, Al Memari, and Ahlam Al Maskari), College of Medicine and Health Sciences, Khalifa University, Abu Dhabi, United Arab Emirates, Department of Medicine, Sheikh Shakhbout Medical City, Abu Dhabi, United Arab Emirates (Dr. Alhajri), Public Health Research Center, New York University Abu Dhabi, Abu Dhabi, United Arab Emirates, Oxford University Hospitals NHS Foundation Trust, Oxford, England, and the MRC Epidemiology Unit, University of Cambridge, Cambridge, England (Dr. Ali).

Objective: The pandemic has forced closures of primary schools, resulting in loss of learning time on a global scale. In addition to face coverings, social distancing, and hand hygiene, an efficient testing method is important to mitigate the spread of COVID-19 in schools. We evaluated the feasibility of a saliva-based SARS-CoV-2 polymerase chain reaction testing program among 18 primary schools in the Emirate of Abu Dhabi, United Arab Emirates. Qualitative results show that children 4 to 5 years old had difficulty producing an adequate saliva specimen compared to those 6 to 12 years old.

Methods: A short training video on saliva collection beforehand helps demystify the process for students and parents alike. Informed consent was challenging yet should be done beforehand by school health nurses or other medical professionals to reassure parents and maximize participation.

Results: Telephone interviews with school administrators resulted in an 83% response rate. Overall, 93% of school administrators had a positive experience with saliva testing and felt the program improved the safety of their schools. The ongoing use of saliva testing for SARS-CoV-2 was supported by 73% of respondents.

Conclusion: On-campus saliva testing is a feasible option for primary schools to screen for COVID-19 in their student population to help keep their campuses safe and open for learning.

Keywords: COVID-19; saliva testing; mitigation; primary school.

The COVID-19 pandemic is a leading cause of morbidity and mortality worldwide and continues to exhaust health care resources on a large scale.1 Efficient testing is critical to identify cases early and to help mitigate the deleterious effects of the pandemic.2 Saliva polymerase chain reaction (PCR) nucleic acid amplification testing (NAAT) is more comfortable than nasopharyngeal (NP) NAAT and has been validated as a test for SARS-CoV-2.1 Although children are less susceptible to severe disease, primary schools are considered a vector for transmission and community spread.3 Efficient and scalable methods of routine testing are needed globally to help keep schools open. Saliva testing has proven a useful resource for this population.4,5

Abu Dhabi is the largest Emirate in the United Arab Emirates (UAE), with an estimated population of 2.5 million.6 The first case of COVID-19 was discovered in the UAE on January 29, 2020.7 The UAE has been recognized worldwide for its robust pandemic response. Along with the coordinated and swift application of public health measures, the country has one of the highest COVID-19 testing rates per capita and one of the highest vaccination rates worldwide.8,9 The Abu Dhabi Public Health Center (ADPHC) works alongside the Ministry of Education (MOE) to establish testing, quarantine, and general safety guidelines for primary schools. In December 2020, the ADPHC partnered with a local, accredited diagnostic laboratory to test the feasibility of a saliva-based screening program for COVID-19 directly on school campuses for 18 primary schools in the Emirate.

Saliva-based PCR testing for COVID-19 was approved for use in schools in the UAE on January 24, 2021.10 As part of a greater mitigation strategy to reduce both school-based transmission and, hence, community spread, the ADPHC focused its on-site testing program on children aged 4 to 12 years. The program required collaboration among medical professionals, school administrators and teachers, students, and parents. Our study evaluates the feasibility of implementing a saliva-based COVID-19 screening program directly on primary school campuses involving children as young as 4 years of age.

Methods

The ADPHC, in collaboration with G42 Biogenix Labs, conducted a saliva SARS-CoV-2 NAAT testing program in 18 primary schools in the Emirate. Schools were selected based on outbreak prevalence at the time and focused on “hot spot” areas. The school on-site saliva testing program included children aged 4 to 12 years old in a “bubble” attendance model during the school day. This model involved children being assigned to groups or “pods.” This allowed us to limit a potential outbreak to a single pod, as opposed to risk exposing the entire school, should a single student test positive. The well-established SalivaDirect protocol developed at Yale University was used for testing and included an RNA extraction-free, RT-qPCR method for SARS-CoV-2 detection.11

We conducted a qualitative study involving telephone interviews of school administrators to evaluate their experience with the ADPHC testing program at their schools. In addition, we interviewed the G42 Biogenix Lab providers to understand the logistics that supported on-campus collection of saliva specimens for this age group. We also gathered the attitudes of school children before and after testing. This study was reviewed and approved by the Abu Dhabi Health Research and Technology Committee and the Institutional Review Board (IRB), New York University Abu Dhabi (NYUAD).

Sample and recruitment

The original sample collection of saliva specimens was performed by the ADPHC in collaboration with G42 Biogenix Lab providers on school campuses between December 6 and December 10, 2020. During this time, schools operated in a hybrid teaching model, where learning took place both online and in person. Infection control measures were deployed based on ADPHC standards and guidelines. Nurses utilized appropriate patient protective equipment, frequent hand hygiene, and social distancing during the collection process. Inclusion criteria included asymptomatic students aged 4 to 12 years attending in-person classes on campus. Students with respiratory symptoms who were asked to stay home or those not attending in-person classes were excluded.

Data collection

Data with regard to school children’s attitudes before and after testing were compiled through an online survey sent randomly to participants postintervention. Data from school administrators were collected through video and telephone interviews between April 14 and April 29, 2021. We first interviewed G42 Biogenix Lab providers to obtain previously acquired qualitative and quantitative data, which were collected during the intervention itself. After obtaining this information, we designed a questionnaire and proceeded with a structured interview process for school officials.

We interviewed school principals and administrators to collect their overall experiences with the saliva testing program. Before starting each interview, we established the interviewees preferred language, either English or Arabic. We then introduced the meeting attendees and provided study details, aims, and objectives, and described collaborating entities. We obtained verbal informed consent from a script approved by the NYUAD IRB and then proceeded with the interview, which included 4 questions. The first 3 questions were answered on a 5-point Likert scale model that consisted of 5 answer options: 5 being completely agree, 4 agree, 3 somewhat agree, 2 somewhat disagree, and 1 completely disagree. The fourth question invited open-ended feedback and comments on the following statements:

- I believe the COVID-19 saliva testing program improved the safety for my school campus.

- Our community had an overall positive experience with the COVID saliva testing.

- We would like to continue a saliva-based COVID testing program on our school campus.

- Please provide any additional comments you feel important about the program.

During the interview, we transcribed the answers as the interviewee was answering. We then translated those in Arabic into English and collected the data in 1 Excel spreadsheet. School interviewees and school names were de-identified in the collection and storage process.

Results

A total of 2011 saliva samples were collected from 18 different primary school campuses. Samples were sent the same day to G42 Biogenix Labs in Abu Dhabi for COVID PCR testing. A team consisting of 5 doctors providing general oversight, along with 2 to 6 nurses per site, were able to manage the collection process for all 18 school campuses. Samples were collected between 8

Sample stations were set up in either the school auditorium or gymnasium to ensure appropriate crowd control and ventilation. Teachers and other school staff, including public safety, were able to manage lines and the shuttling of students back and forth from classes to testing stations, which allowed medical staff to focus on sample collection.

Informed consent was obtained by prior electronic communication to parents from school staff, asking them to agree to allow their child to participate in the testing program. Informed consent was identified as a challenge: Getting parents to understand that saliva testing was more comfortable than NP testing, and that the results were only being used to help keep the school safe, took time. School staff are used to obtaining consent from parents for field trips, but this was clearly more challenging for them.

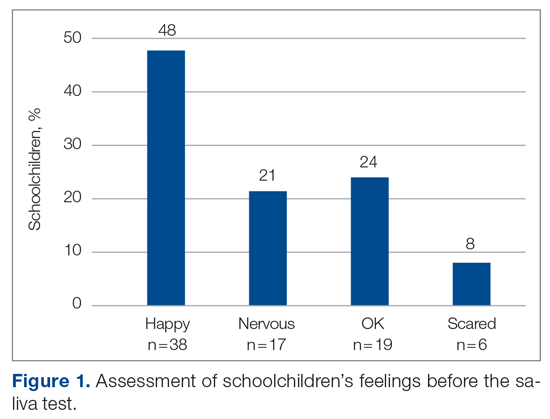

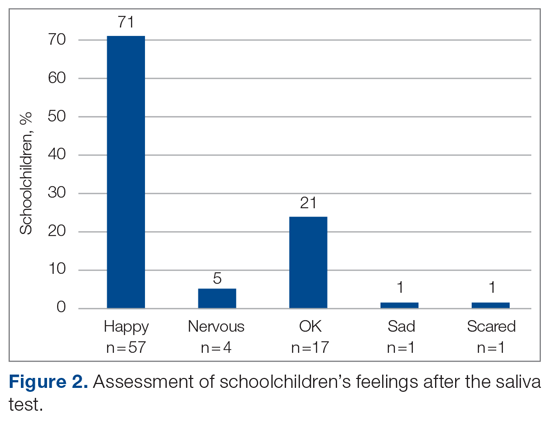

The saliva collection process per child took more time than expected. Children fasted for 45 minutes before saliva collection. We used an active drool technique, which required children to pool saliva in their mouth then express it into a collection tube. Adults can generally do this on command, but we found it took 10 to 12 minutes per child. Saliva production was cued by asking the children to think about food, and by showing them pictures and TV commercials depicting food. Children 4 to 5 years old had more difficulty with the process despite active cueing, while those 6 to 12 years old had an easier time with the process. We collected data on a cohort of 80 children regarding their attitudes pre (Figure 1) and post collection (Figure 2). Children felt happier, less nervous, and less scared after collection than before collection. This trend reassured us that future collections would be easier for students.

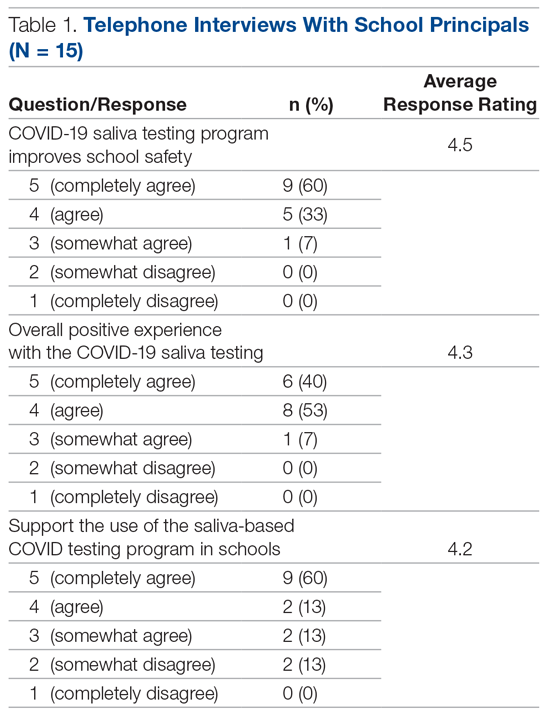

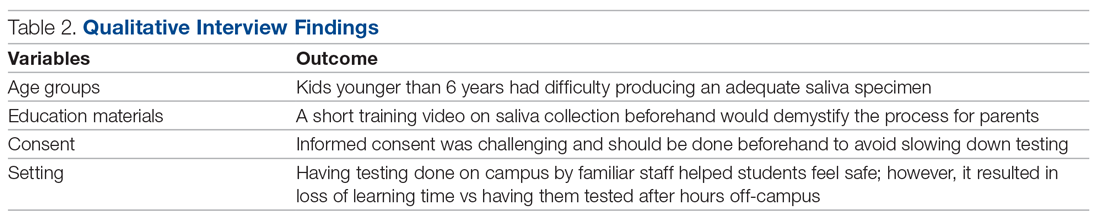

A total of 15 of 18 school principals completed the telephone interview, yielding a response rate of 83%. Overall, 93% of the school principals agreed or completely agreed that the COVID-19 saliva testing program improved school safety; 93% agreed or completely agreed that they had an overall positive experience with the program; and 73% supported the ongoing use of saliva testing in their schools (Table 1). Administrators’ open-ended comments on their experience were positive overall (Table 2).

Discussion

By March 2020, many kindergarten to grade 12 public and private schools suspended in-person classes due to the pandemic and turned to online learning platforms. The negative impact of school closures on academic achievement is projected to be significant.7,12,13 Ensuring schools can stay open and run operations safely will require routine SARS-CoV-2 testing. Our study investigated the feasibility of routine saliva testing on children aged 4 to 12 years on their school campuses. The ADPHC school on-site saliva testing program involved bringing lab providers onto 18 primary school campuses and required cooperation among parents, students, school administrators, and health care professionals.

Children younger than 6 years had difficulty producing an adequate saliva specimen, whereas those 6 to 12 years did so with relative ease when cued by thoughts or pictures of food while waiting in line for collection. Schools considering on-site testing programs should consider the age range of 6 to 12 years as a viable age range for saliva screening. Children should fast for a minimum of 45 minutes prior to saliva collection and should be cued by thoughts of food, food pictures, or food commercials. Setting up a sampling station close to the cafeteria where students can smell meal preparation may also help.14,15 Sampling before breakfast or lunch, when children are potentially at their hungriest, should also be considered.

The greatest challenge was obtaining informed consent from parents who were not yet familiar with the reliability of saliva testing as a tool for SARS-CoV-2 screening or with the saliva collection process as a whole. Informed consent was initially done electronically, lacking direct human interaction to answer parents’ questions. Parents who refused had a follow-up call from the school nurse to further explain the logistics and rationale for saliva screening. Having medical professionals directly answer parents’ questions was helpful. Parents were reassured that the process was painless, confidential, and only to be used for school safety purposes. Despite school administrators being experienced in obtaining consent from parents for field trips, obtaining informed consent for a medical testing procedure is more complicated, and parents aren’t accustomed to providing such consent in a school environment. Schools considering on-site testing should ensure that their school nurse or other health care providers are on the front line obtaining informed consent and allaying parents’ fears.

School staff were able to effectively provide crowd control for testing, and children felt at ease being in a familiar environment. Teachers and public safety officers are well-equipped at managing the shuttling of students to class, to lunch, to physical education, and, finally, to dismissal. They were equally equipped at handling the logistics of students to and from testing, including minimizing crowds and helping students feel at ease during the process. This effective collaboration allowed the lab personnel to focus on sample collection and storage, while school staff managed all other aspects of the children’s safety and care.

Conclusion

Overall, school administrators had a positive experience with the testing program, felt the program improved the safety of their schools, and supported the ongoing use of saliva testing for SARS-CoV-2 on their school campuses. Children aged 6 years and older were able to provide adequate saliva samples, and children felt happier and less nervous after the process, indicating repeatability. Our findings highlight the feasibility of an integrated on-site saliva testing model for primary school campuses. Further research is needed to determine the scalability of such a model and whether the added compliance and safety of on-site testing compensates for the potential loss of learning time that testing during school hours would require.

Corresponding author: Ayaz Virji, MD, New York University Abu Dhabi, PO Box 129188, Abu Dhabi, United Arab Emirates; av102@nyu.edu.

Financial disclosures: None.

1. Kuehn BM. Despite improvements, COVID-19’s health care disruptions persist. JAMA. 2021;325(23):2335. doi:10.1001/jama.2021.9134

2. National Institute on Aging. Why COVID-19 testing is the key to getting back to normal. September 4, 2020. Accessed September 8, 2021. https://www.nia.nih.gov/news/why-covid-19-testing-key-getting-back-normal

3. Centers for Disease Control and Prevention. Science brief: Transmission of SARS-CoV-2 in K-12 schools. Updated July 9, 2021. Accessed September 8, 2021. https://www.cdc.gov/coronavirus/2019-ncov/science/science-briefs/transmission_k_12_schools.html

4. Butler-Laporte G, Lawandi A, Schiller I, et al. Comparison of saliva and nasopharyngeal swab nucleic acid amplification testing for detection of SARS-CoV-2: a systematic review and meta-analysis. JAMA Intern Med. 2021;181(3):353-360. doi:10.1001/jamainternmed.2020.8876

5. Al Suwaidi H, Senok A, Varghese R, et al. Saliva for molecular detection of SARS-CoV-2 in school-age children. Clin Microbiol Infect. 2021;27(9):1330-1335. doi:10.1016/j.cmi.2021.02.009

6. Abu Dhabi. Accessed September 8, 2021. https://u.ae/en/about-the-uae/the-seven-emirates/abu-dhabi

7. Alsuwaidi AR, Al Hosani FI, Al Memari S, et al. Seroprevalence of COVID-19 infection in the Emirate of Abu Dhabi, United Arab Emirates: a population-based cross-sectional study. Int J Epidemiol. 2021;50(4):1077-1090. doi:10.1093/ije/dyab077

8. Al Hosany F, Ganesan S, Al Memari S, et al. Response to COVID-19 pandemic in the UAE: a public health perspective. J Glob Health. 2021;11:03050. doi:10.7189/jogh.11.03050

9. Bremmer I. The best global responses to the COVID-19 pandemic, 1 year later. Time Magazine. Updated February 23, 2021. Accessed September 8, 2021. https://time.com/5851633/best-global-responses-covid-19/

10. Department of Health, Abu Dhabi. Laboratory diagnostic test for COVID-19: update regarding saliva-based testing using RT-PCR test. 2021.

11. Vogels C, Brackney DE, Kalinich CC, et al. SalivaDirect: RNA extraction-free SARS-CoV-2 diagnostics. Protocols.io. Accessed September 8, 2021. https://www.protocols.io/view/salivadirect-rna-extraction-free-sars-cov-2-diagno-bh6jj9cn?version_warning=no

12. Education Endowment Foundation. Impact of school closures on the attainment gap: rapid evidence assessment. June 2020. Accessed September 8, 2021. https://www.researchgate.net/publication/342501263_EEF_2020_-_Impact_of_School_Closures_on_the_Attainment_Gap

13. United Nations. Policy brief: Education during COVID-19 and beyond. Accessed September 8, 2021. https://www.un.org/development/desa/dspd/wp-content/uploads/sites/22/2020/08/sg_policy_brief_covid-19_and_education_august_2020.pdf

14. Schiffman SS, Miletic ID. Effect of taste and smell on secretion rate of salivary IgA in elderly and young persons. J Nutr Health Aging. 1999;3(3):158-164.

15. Lee VM, Linden RW. The effect of odours on stimulated parotid salivary flow in humans. Physiol Behav. 1992;52(6):1121-1125. doi:10.1016/0031-9384(92)90470-m

From Health Center, New York University Abu Dhabi, Abu Dhabi, United Arab Emirates (Dr. Virji and Aisha Al Hamiz), Public Health, Abu Dhabi Public Health Center, Abu Dhabi, United Arab Emirates (Drs. Al Hajeri, Al Shehhi, Al Memari, and Ahlam Al Maskari), College of Medicine and Health Sciences, Khalifa University, Abu Dhabi, United Arab Emirates, Department of Medicine, Sheikh Shakhbout Medical City, Abu Dhabi, United Arab Emirates (Dr. Alhajri), Public Health Research Center, New York University Abu Dhabi, Abu Dhabi, United Arab Emirates, Oxford University Hospitals NHS Foundation Trust, Oxford, England, and the MRC Epidemiology Unit, University of Cambridge, Cambridge, England (Dr. Ali).

Objective: The pandemic has forced closures of primary schools, resulting in loss of learning time on a global scale. In addition to face coverings, social distancing, and hand hygiene, an efficient testing method is important to mitigate the spread of COVID-19 in schools. We evaluated the feasibility of a saliva-based SARS-CoV-2 polymerase chain reaction testing program among 18 primary schools in the Emirate of Abu Dhabi, United Arab Emirates. Qualitative results show that children 4 to 5 years old had difficulty producing an adequate saliva specimen compared to those 6 to 12 years old.

Methods: A short training video on saliva collection beforehand helps demystify the process for students and parents alike. Informed consent was challenging yet should be done beforehand by school health nurses or other medical professionals to reassure parents and maximize participation.

Results: Telephone interviews with school administrators resulted in an 83% response rate. Overall, 93% of school administrators had a positive experience with saliva testing and felt the program improved the safety of their schools. The ongoing use of saliva testing for SARS-CoV-2 was supported by 73% of respondents.

Conclusion: On-campus saliva testing is a feasible option for primary schools to screen for COVID-19 in their student population to help keep their campuses safe and open for learning.

Keywords: COVID-19; saliva testing; mitigation; primary school.

The COVID-19 pandemic is a leading cause of morbidity and mortality worldwide and continues to exhaust health care resources on a large scale.1 Efficient testing is critical to identify cases early and to help mitigate the deleterious effects of the pandemic.2 Saliva polymerase chain reaction (PCR) nucleic acid amplification testing (NAAT) is more comfortable than nasopharyngeal (NP) NAAT and has been validated as a test for SARS-CoV-2.1 Although children are less susceptible to severe disease, primary schools are considered a vector for transmission and community spread.3 Efficient and scalable methods of routine testing are needed globally to help keep schools open. Saliva testing has proven a useful resource for this population.4,5

Abu Dhabi is the largest Emirate in the United Arab Emirates (UAE), with an estimated population of 2.5 million.6 The first case of COVID-19 was discovered in the UAE on January 29, 2020.7 The UAE has been recognized worldwide for its robust pandemic response. Along with the coordinated and swift application of public health measures, the country has one of the highest COVID-19 testing rates per capita and one of the highest vaccination rates worldwide.8,9 The Abu Dhabi Public Health Center (ADPHC) works alongside the Ministry of Education (MOE) to establish testing, quarantine, and general safety guidelines for primary schools. In December 2020, the ADPHC partnered with a local, accredited diagnostic laboratory to test the feasibility of a saliva-based screening program for COVID-19 directly on school campuses for 18 primary schools in the Emirate.

Saliva-based PCR testing for COVID-19 was approved for use in schools in the UAE on January 24, 2021.10 As part of a greater mitigation strategy to reduce both school-based transmission and, hence, community spread, the ADPHC focused its on-site testing program on children aged 4 to 12 years. The program required collaboration among medical professionals, school administrators and teachers, students, and parents. Our study evaluates the feasibility of implementing a saliva-based COVID-19 screening program directly on primary school campuses involving children as young as 4 years of age.

Methods

The ADPHC, in collaboration with G42 Biogenix Labs, conducted a saliva SARS-CoV-2 NAAT testing program in 18 primary schools in the Emirate. Schools were selected based on outbreak prevalence at the time and focused on “hot spot” areas. The school on-site saliva testing program included children aged 4 to 12 years old in a “bubble” attendance model during the school day. This model involved children being assigned to groups or “pods.” This allowed us to limit a potential outbreak to a single pod, as opposed to risk exposing the entire school, should a single student test positive. The well-established SalivaDirect protocol developed at Yale University was used for testing and included an RNA extraction-free, RT-qPCR method for SARS-CoV-2 detection.11

We conducted a qualitative study involving telephone interviews of school administrators to evaluate their experience with the ADPHC testing program at their schools. In addition, we interviewed the G42 Biogenix Lab providers to understand the logistics that supported on-campus collection of saliva specimens for this age group. We also gathered the attitudes of school children before and after testing. This study was reviewed and approved by the Abu Dhabi Health Research and Technology Committee and the Institutional Review Board (IRB), New York University Abu Dhabi (NYUAD).

Sample and recruitment

The original sample collection of saliva specimens was performed by the ADPHC in collaboration with G42 Biogenix Lab providers on school campuses between December 6 and December 10, 2020. During this time, schools operated in a hybrid teaching model, where learning took place both online and in person. Infection control measures were deployed based on ADPHC standards and guidelines. Nurses utilized appropriate patient protective equipment, frequent hand hygiene, and social distancing during the collection process. Inclusion criteria included asymptomatic students aged 4 to 12 years attending in-person classes on campus. Students with respiratory symptoms who were asked to stay home or those not attending in-person classes were excluded.

Data collection

Data with regard to school children’s attitudes before and after testing were compiled through an online survey sent randomly to participants postintervention. Data from school administrators were collected through video and telephone interviews between April 14 and April 29, 2021. We first interviewed G42 Biogenix Lab providers to obtain previously acquired qualitative and quantitative data, which were collected during the intervention itself. After obtaining this information, we designed a questionnaire and proceeded with a structured interview process for school officials.

We interviewed school principals and administrators to collect their overall experiences with the saliva testing program. Before starting each interview, we established the interviewees preferred language, either English or Arabic. We then introduced the meeting attendees and provided study details, aims, and objectives, and described collaborating entities. We obtained verbal informed consent from a script approved by the NYUAD IRB and then proceeded with the interview, which included 4 questions. The first 3 questions were answered on a 5-point Likert scale model that consisted of 5 answer options: 5 being completely agree, 4 agree, 3 somewhat agree, 2 somewhat disagree, and 1 completely disagree. The fourth question invited open-ended feedback and comments on the following statements:

- I believe the COVID-19 saliva testing program improved the safety for my school campus.

- Our community had an overall positive experience with the COVID saliva testing.

- We would like to continue a saliva-based COVID testing program on our school campus.

- Please provide any additional comments you feel important about the program.

During the interview, we transcribed the answers as the interviewee was answering. We then translated those in Arabic into English and collected the data in 1 Excel spreadsheet. School interviewees and school names were de-identified in the collection and storage process.

Results

A total of 2011 saliva samples were collected from 18 different primary school campuses. Samples were sent the same day to G42 Biogenix Labs in Abu Dhabi for COVID PCR testing. A team consisting of 5 doctors providing general oversight, along with 2 to 6 nurses per site, were able to manage the collection process for all 18 school campuses. Samples were collected between 8

Sample stations were set up in either the school auditorium or gymnasium to ensure appropriate crowd control and ventilation. Teachers and other school staff, including public safety, were able to manage lines and the shuttling of students back and forth from classes to testing stations, which allowed medical staff to focus on sample collection.

Informed consent was obtained by prior electronic communication to parents from school staff, asking them to agree to allow their child to participate in the testing program. Informed consent was identified as a challenge: Getting parents to understand that saliva testing was more comfortable than NP testing, and that the results were only being used to help keep the school safe, took time. School staff are used to obtaining consent from parents for field trips, but this was clearly more challenging for them.

The saliva collection process per child took more time than expected. Children fasted for 45 minutes before saliva collection. We used an active drool technique, which required children to pool saliva in their mouth then express it into a collection tube. Adults can generally do this on command, but we found it took 10 to 12 minutes per child. Saliva production was cued by asking the children to think about food, and by showing them pictures and TV commercials depicting food. Children 4 to 5 years old had more difficulty with the process despite active cueing, while those 6 to 12 years old had an easier time with the process. We collected data on a cohort of 80 children regarding their attitudes pre (Figure 1) and post collection (Figure 2). Children felt happier, less nervous, and less scared after collection than before collection. This trend reassured us that future collections would be easier for students.

A total of 15 of 18 school principals completed the telephone interview, yielding a response rate of 83%. Overall, 93% of the school principals agreed or completely agreed that the COVID-19 saliva testing program improved school safety; 93% agreed or completely agreed that they had an overall positive experience with the program; and 73% supported the ongoing use of saliva testing in their schools (Table 1). Administrators’ open-ended comments on their experience were positive overall (Table 2).

Discussion

By March 2020, many kindergarten to grade 12 public and private schools suspended in-person classes due to the pandemic and turned to online learning platforms. The negative impact of school closures on academic achievement is projected to be significant.7,12,13 Ensuring schools can stay open and run operations safely will require routine SARS-CoV-2 testing. Our study investigated the feasibility of routine saliva testing on children aged 4 to 12 years on their school campuses. The ADPHC school on-site saliva testing program involved bringing lab providers onto 18 primary school campuses and required cooperation among parents, students, school administrators, and health care professionals.

Children younger than 6 years had difficulty producing an adequate saliva specimen, whereas those 6 to 12 years did so with relative ease when cued by thoughts or pictures of food while waiting in line for collection. Schools considering on-site testing programs should consider the age range of 6 to 12 years as a viable age range for saliva screening. Children should fast for a minimum of 45 minutes prior to saliva collection and should be cued by thoughts of food, food pictures, or food commercials. Setting up a sampling station close to the cafeteria where students can smell meal preparation may also help.14,15 Sampling before breakfast or lunch, when children are potentially at their hungriest, should also be considered.

The greatest challenge was obtaining informed consent from parents who were not yet familiar with the reliability of saliva testing as a tool for SARS-CoV-2 screening or with the saliva collection process as a whole. Informed consent was initially done electronically, lacking direct human interaction to answer parents’ questions. Parents who refused had a follow-up call from the school nurse to further explain the logistics and rationale for saliva screening. Having medical professionals directly answer parents’ questions was helpful. Parents were reassured that the process was painless, confidential, and only to be used for school safety purposes. Despite school administrators being experienced in obtaining consent from parents for field trips, obtaining informed consent for a medical testing procedure is more complicated, and parents aren’t accustomed to providing such consent in a school environment. Schools considering on-site testing should ensure that their school nurse or other health care providers are on the front line obtaining informed consent and allaying parents’ fears.

School staff were able to effectively provide crowd control for testing, and children felt at ease being in a familiar environment. Teachers and public safety officers are well-equipped at managing the shuttling of students to class, to lunch, to physical education, and, finally, to dismissal. They were equally equipped at handling the logistics of students to and from testing, including minimizing crowds and helping students feel at ease during the process. This effective collaboration allowed the lab personnel to focus on sample collection and storage, while school staff managed all other aspects of the children’s safety and care.

Conclusion

Overall, school administrators had a positive experience with the testing program, felt the program improved the safety of their schools, and supported the ongoing use of saliva testing for SARS-CoV-2 on their school campuses. Children aged 6 years and older were able to provide adequate saliva samples, and children felt happier and less nervous after the process, indicating repeatability. Our findings highlight the feasibility of an integrated on-site saliva testing model for primary school campuses. Further research is needed to determine the scalability of such a model and whether the added compliance and safety of on-site testing compensates for the potential loss of learning time that testing during school hours would require.

Corresponding author: Ayaz Virji, MD, New York University Abu Dhabi, PO Box 129188, Abu Dhabi, United Arab Emirates; av102@nyu.edu.

Financial disclosures: None.

From Health Center, New York University Abu Dhabi, Abu Dhabi, United Arab Emirates (Dr. Virji and Aisha Al Hamiz), Public Health, Abu Dhabi Public Health Center, Abu Dhabi, United Arab Emirates (Drs. Al Hajeri, Al Shehhi, Al Memari, and Ahlam Al Maskari), College of Medicine and Health Sciences, Khalifa University, Abu Dhabi, United Arab Emirates, Department of Medicine, Sheikh Shakhbout Medical City, Abu Dhabi, United Arab Emirates (Dr. Alhajri), Public Health Research Center, New York University Abu Dhabi, Abu Dhabi, United Arab Emirates, Oxford University Hospitals NHS Foundation Trust, Oxford, England, and the MRC Epidemiology Unit, University of Cambridge, Cambridge, England (Dr. Ali).

Objective: The pandemic has forced closures of primary schools, resulting in loss of learning time on a global scale. In addition to face coverings, social distancing, and hand hygiene, an efficient testing method is important to mitigate the spread of COVID-19 in schools. We evaluated the feasibility of a saliva-based SARS-CoV-2 polymerase chain reaction testing program among 18 primary schools in the Emirate of Abu Dhabi, United Arab Emirates. Qualitative results show that children 4 to 5 years old had difficulty producing an adequate saliva specimen compared to those 6 to 12 years old.

Methods: A short training video on saliva collection beforehand helps demystify the process for students and parents alike. Informed consent was challenging yet should be done beforehand by school health nurses or other medical professionals to reassure parents and maximize participation.

Results: Telephone interviews with school administrators resulted in an 83% response rate. Overall, 93% of school administrators had a positive experience with saliva testing and felt the program improved the safety of their schools. The ongoing use of saliva testing for SARS-CoV-2 was supported by 73% of respondents.

Conclusion: On-campus saliva testing is a feasible option for primary schools to screen for COVID-19 in their student population to help keep their campuses safe and open for learning.

Keywords: COVID-19; saliva testing; mitigation; primary school.

The COVID-19 pandemic is a leading cause of morbidity and mortality worldwide and continues to exhaust health care resources on a large scale.1 Efficient testing is critical to identify cases early and to help mitigate the deleterious effects of the pandemic.2 Saliva polymerase chain reaction (PCR) nucleic acid amplification testing (NAAT) is more comfortable than nasopharyngeal (NP) NAAT and has been validated as a test for SARS-CoV-2.1 Although children are less susceptible to severe disease, primary schools are considered a vector for transmission and community spread.3 Efficient and scalable methods of routine testing are needed globally to help keep schools open. Saliva testing has proven a useful resource for this population.4,5

Abu Dhabi is the largest Emirate in the United Arab Emirates (UAE), with an estimated population of 2.5 million.6 The first case of COVID-19 was discovered in the UAE on January 29, 2020.7 The UAE has been recognized worldwide for its robust pandemic response. Along with the coordinated and swift application of public health measures, the country has one of the highest COVID-19 testing rates per capita and one of the highest vaccination rates worldwide.8,9 The Abu Dhabi Public Health Center (ADPHC) works alongside the Ministry of Education (MOE) to establish testing, quarantine, and general safety guidelines for primary schools. In December 2020, the ADPHC partnered with a local, accredited diagnostic laboratory to test the feasibility of a saliva-based screening program for COVID-19 directly on school campuses for 18 primary schools in the Emirate.

Saliva-based PCR testing for COVID-19 was approved for use in schools in the UAE on January 24, 2021.10 As part of a greater mitigation strategy to reduce both school-based transmission and, hence, community spread, the ADPHC focused its on-site testing program on children aged 4 to 12 years. The program required collaboration among medical professionals, school administrators and teachers, students, and parents. Our study evaluates the feasibility of implementing a saliva-based COVID-19 screening program directly on primary school campuses involving children as young as 4 years of age.

Methods