User login

Assessment of Same-Day Naloxone Availability in New Mexico Pharmacies

From the Department of Medicine, University of California San Diego (Dr. Haponyuk), Department of Emergency Medicine, University of Tennessee (Dr. Dejong), the Department of Family Medicine, University of New Mexico (Dr. Gutfrucht), and the Department of Internal Medicine, University of New Mexico (Dr. Barrett)

Objective: Naloxone availability can reduce the risk of death from opioid overdoses, although prescriber, legislative, and payment barriers to accessing this life-saving medication exist. A previously underreported barrier involves same-day availability, the lack of which may force patients to travel to multiple pharmacies and having delays in access or risking not filling their prescription. This study sought to determine same-day availability of naloxone in pharmacies in the state of New Mexico.

Methods: Same-day availability of naloxone was assessed via an audit survey.

Results: Of the 183 pharamacies screened, only 84.7% had same-day availability, including only 72% in Albuquerque, the state’s most populous city/municipality.

Conclusion: These results highlight the extent of a previously underexplored challenge to patient care and barrier to patient safety, and future directions for more patient-centered care.

Keywords: naloxone; barriers to care; opioid overdose prevention.

The US is enduring an ongoing epidemic of deaths due to opioid use, which have increased in frequency since the onset of the COVID-19 pandemic.1 One strategy to reduce the risk of mortality from opioid use is to ensure the widespread availability of naloxone. Individual states have implemented harm reduction strategies to increase access to naloxone, including improving availability via a statewide standing order that it may be dispensed without a prescription.2,3 Such naloxone access laws are being widely adopted and are believed to reduce overdose deaths.4

There are many barriers to patients receiving naloxone despite their clinicians providing a prescription for it, including stigmatization, financial cost, and local availability.5-9 However, the stigma associated with naloxone extends to both patients and pharmacists. Pharmacists in West Virginia, for example, showed widespread concerns about having naloxone available for patients to purchase over the counter, for fear that increasing naloxone access may increase overdoses.6 A study in Tennessee also found pharmacists hesitant to recommend naloxone.7 Another study of rural pharmacies in Georgia found that just over half carried naloxone despite a state law that naloxone be available without a prescription.8 Challenges are not limited to rural areas, however; a study in Philadelphia found that more than one-third of pharmacies required a prescription to dispense naloxone, contrary to state law.9 Thus, in a rapidly changing regulatory environment, there are many evolving barriers to patients receiving naloxone.

New Mexico has an opioid overdose rate higher than the national average, coming in 15th out of 50 states when last ranked in 2018, with overdose rates that vary across demographic variables.10 Consequently, New Mexico state law added language requiring clinicians prescribing opioids for 5 days or longer to co-prescribe naloxone along with written information on how to administer the opioid antagonist.11 New Mexico is also a geographically large state with a relatively low overall population characterized by striking health disparities, particularly as related to access to care.

The purpose of this study is to describe the same-day availability of naloxone throughout the state of New Mexico after a change in state law requiring co-prescription was enacted, to help identify challenges to patients receiving it. Comprehensive examination of barriers to patients accessing this life-saving medication can advise strategies to both improve patient-centered care and potentially reduce deaths.

Methods

To better understand barriers to patients obtaining naloxone, in July and August of 2019 we performed an audit (“secret shopper”) study of all pharmacies in the state, posing as patients wishing to obtain naloxone. A publicly available list of every pharmacy in New Mexico was used to identify 89 pharmacies in Albuquerque (the most populous city in New Mexico) and 106 pharmacies throughout the rest of the state.12

Every pharmacy was called via a publicly available phone number during business hours (confirmed via an internet search), at least 2 hours prior to closing. One of 3 researchers telephoned pharmacies posing as a patient and inquired whether naloxone would be available for pick up the same day. If the pharmacy confirmed it was available that day, the call concluded. If naloxone was unavailable for same day pick up, researchers asked when it would be next available. Each pharmacy was called once, and neither insurance information nor cost was offered or requested. All questions were asked in English by native English speakers.

All responses were recorded in a secure spreadsheet. Once all responses were received and reviewed, they were characterized in discrete response categories: same day, within 1 to 2 days, within 3 to 4 days, within a week, or unsure/unknown. Naloxone availability was also tracked by city/municipality, and this was compared to the state’s population distribution.

No personally identifiable information was obtained. This study was Institutional Review Board exempt.

Results

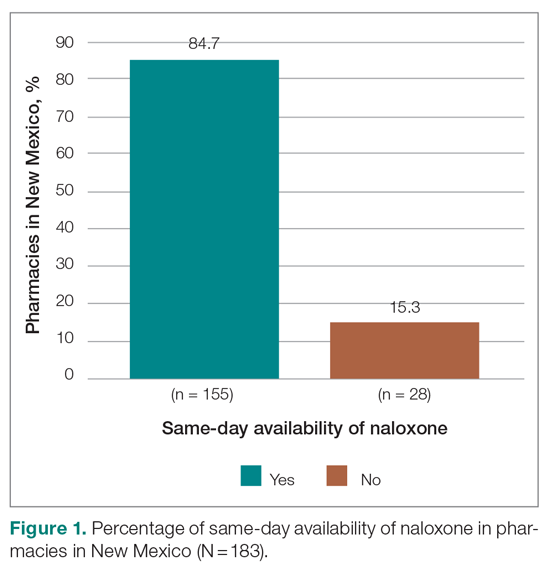

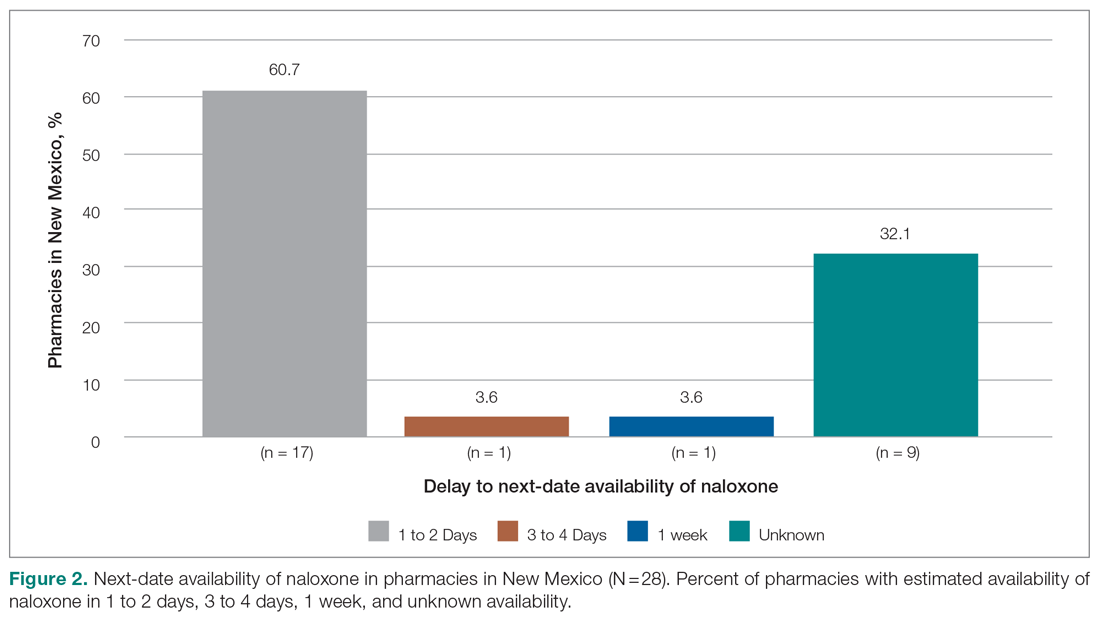

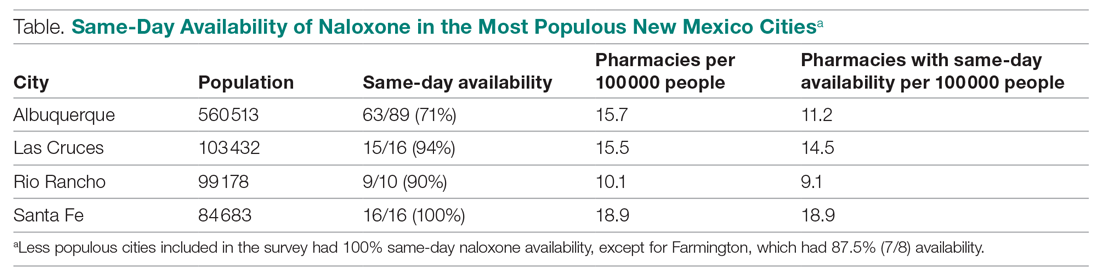

Responses were recorded from 183 pharmacies. Seventeen locations were eliminated from our analysis because their phone system was inoperable or the pharmacy was permanently closed. Of the pharmacies reached, 84.7% (155/183) reported they have naloxone available for pick up on the same day (Figure 1). Of the 15.3% (28) pharmacies that did not have same-day availability, 60.7% (17 pharmacies) reported availability in 1 to 2 days, 3.6% had availability in 3 to 4 days, 3.6% had availability in 1 week, and 32.1% were unsure of next availability (Figure 2). More than one-third of the state’s patients reside in municipalities where naloxone is immediately available in at least 72% of pharmacies (Table).13

Discussion

Increased access to naloxone at the state and community level is associated with reduced risk for death from overdose, and, consequently, widespread availability is recommended.14-17 Statewide real-time pharmacy availability of naloxone—as patients would experience availability—has not been previously reported. These findings suggest unpredictable same-day availability that may affect experience and care outcomes. That other studies have found similar challenges in naloxone availability in other municipalities and regions suggests this barrier to access is widespread,6-9 and likely affects patients throughout the country.

Many patients have misgivings about naloxone, and it places an undue burden on them to travel to multiple pharmacies or take repeated trips to fill prescriptions. Additionally, patients without reliable transportation may be unable to return at a later date. Although we found most pharmacies in New Mexico without immediate availability of naloxone reported they could have it within several days, such a delay may reduce the likelihood that patients will fill their prescription at all. It is also concerning that many pharmacies are unsure of when naloxone will be available, particularly when some of these may be the only pharmacy easily accessible to patients or the one where they regularly fill their prescriptions.

Barriers to naloxone availability requires further study due to possible negative consequences for patient safety and risks for exacerbating health disparities among vulnerable populations. Further research may focus on examining the effects on patients when naloxone dispensing is delayed or impossible, why there is variability in naloxone availability between different pharmacies and municipalities, the reasons for uncertainty when naloxone will be available, and effective solutions. Expanded naloxone distribution in community locations and in clinics offers one potential patient-centered solution that should be explored, but it is likely that more widespread and systemic solutions will require policy and regulatory changes at the state and national levels.

Limitations of this study include that the findings may be relevant for solely 1 state, such as in the case of state-specific barriers to keeping naloxone in stock that we are unaware of. However, it is unclear why that would be the case, and it is more likely that similar barriers are pervasive. Additionally, repeat phone calls, which we did not follow up with, may have yielded more pharmacies with naloxone availability. However, due to the stigma associated with obtaining naloxone, it may be that patients will not make multiple calls either—highlighting how important real-time availability is.

Conclusion

Urgent solutions are needed to address the epidemic of deaths from opioid overdoses. Naloxone availability is an important tool for reducing these deaths, resulting in numerous state laws attempting to increase access. Despite this, there are persistent barriers to patients receiving naloxone, including a lack of same-day availability at pharmacies. Our results suggest that this underexplored barrier is widespread. Improving both availability and accessibility of naloxone may include legislative policy solutions as well as patient-oriented solutions, such as distribution in clinics and hospitals when opioid prescriptions are first written. Further research should be conducted to determine patient-centered, effective solutions that can improve outcomes.

Corresponding author: Eileen Barrett, MD, MPH, Department of Internal Medicine, University of New Mexico; ebarrett@salud.unm.edu.

Financial disclosures: None.

1. Mason M, Welch SB, Arunkumar P, et al. Notes from the field: opioid overdose deaths before, during, and after an 11-week COVID-19 stay-at-home order—Cook County, Illinois, January 1, 2018–October 6, 2020. MMWR Morb Mortal Wkly Rep. 2021;70(10):362-363. doi:10.15585/mmwr.mm7010a3

2. Kaiser Family Foundation. Opioid overdose death rates and all drug overdose death rates per 100,000 population (age-adjusted). Accessed October 6, 2021. https://www.kff.org/other/state-indicator/opioid-overdose-death

3. Sohn M, Talbert JC, Huang Z, et al. Association of naloxone coprescription laws with naloxone prescription dispensing in the United States. JAMA Netw Open. 2019;2(6):e196215. doi:10.1001/jamanetworkopen.2019.6215

4. Smart R, Pardo B, Davis CS. Systematic review of the emerging literature on the effectiveness of naloxone access laws in the United States. Addiction. 2021;116(1):6-17. doi:10.1111/add.15163

5. Mueller SR, Koester S, Glanz JM, et al. Attitudes toward naloxone prescribing in clinical settings: a qualitative study of patients prescribed high dose opioids for chronic non-cancer pain. J Gen Intern Med. 2017;32(3):277-283. doi:10.1007/s11606-016-3895-8

6. Thornton JD, Lyvers E, Scott VGG, Dwibedi N. Pharmacists’ readiness to provide naloxone in community pharmacies in West Virginia. J Am Pharm Assoc (2003). 2017;57(2S):S12-S18.e4. doi:10.1016/j.japh.2016.12.070

7. Spivey C, Wilder A, Chisholm-Burns MA, et al. Evaluation of naloxone access, pricing, and barriers to dispensing in Tennessee retail community pharmacies. J Am Pharm Assoc (2003). 2020;60(5):694-701.e1. doi:10.1016/j.japh.2020.01.030

8. Nguyen JL, Gilbert LR, Beasley L, et al. Availability of naloxone at rural Georgia pharmacies, 2019. JAMA Netw Open. 2020;3(2):e1921227. doi:10.1001/jamanetworkopen.2019.21227

9. Guadamuz JS, Alexander GC, Chaudhri T, et al. Availability and cost of naloxone nasal spray at pharmacies in Philadelphia, Pennsylvania. JAMA Netw Open. 2019;2(6):e195388. doi:10.1001/jamanetworkopen.2019.5388

10. Edge K. Changes in drug overdose mortality in New Mexico. New Mexico Epidemiology. July 2020 (3). https://www.nmhealth.org/data/view/report/2402/

11. Senate Bill 221. 54th Legislature, State of New Mexico, First Session, 2019 (introduced by William P. Soules). Accessed October 6, 2021. https://nmlegis.gov/Sessions/19%20Regular/bills/senate/SB0221.pdf

12. GoodRx. Find pharmacies in New Mexico. Accessed October 6, 2021. https://www.goodrx.com/pharmacy-near-me/all/nm

13. U.S. Census Bureau. QuickFacts: New Mexico. Accessed October 6, 2021. https://www.census.gov/quickfacts/NM

14. Linas BP, Savinkina A, Madushani RWMA, et al. Projected estimates of opioid mortality after community-level interventions. JAMA Netw Open. 2021;4(2):e2037259. doi:10.1001/jamanetworkopen.2020.37259

15. You HS, Ha J, Kang CY, et al. Regional variation in states’ naloxone accessibility laws in association with opioid overdose death rates—observational study (STROBE compliant). Medicine (Baltimore). 2020;99(22):e20033. doi:10.1097/MD.0000000000020033

16. Pew Charitable Trusts. Expanded access to naloxone can curb opioid overdose deaths. October 20, 2020. Accessed October 6, 2021. https://www.

17. Centers for Disease Control and Prevention. Still not enough naloxone where it’s most needed. August 6, 2019. Accessed October 6, 2021. https://www.cdc.gov/media/releases/2019/p0806-naloxone.html

From the Department of Medicine, University of California San Diego (Dr. Haponyuk), Department of Emergency Medicine, University of Tennessee (Dr. Dejong), the Department of Family Medicine, University of New Mexico (Dr. Gutfrucht), and the Department of Internal Medicine, University of New Mexico (Dr. Barrett)

Objective: Naloxone availability can reduce the risk of death from opioid overdoses, although prescriber, legislative, and payment barriers to accessing this life-saving medication exist. A previously underreported barrier involves same-day availability, the lack of which may force patients to travel to multiple pharmacies and having delays in access or risking not filling their prescription. This study sought to determine same-day availability of naloxone in pharmacies in the state of New Mexico.

Methods: Same-day availability of naloxone was assessed via an audit survey.

Results: Of the 183 pharamacies screened, only 84.7% had same-day availability, including only 72% in Albuquerque, the state’s most populous city/municipality.

Conclusion: These results highlight the extent of a previously underexplored challenge to patient care and barrier to patient safety, and future directions for more patient-centered care.

Keywords: naloxone; barriers to care; opioid overdose prevention.

The US is enduring an ongoing epidemic of deaths due to opioid use, which have increased in frequency since the onset of the COVID-19 pandemic.1 One strategy to reduce the risk of mortality from opioid use is to ensure the widespread availability of naloxone. Individual states have implemented harm reduction strategies to increase access to naloxone, including improving availability via a statewide standing order that it may be dispensed without a prescription.2,3 Such naloxone access laws are being widely adopted and are believed to reduce overdose deaths.4

There are many barriers to patients receiving naloxone despite their clinicians providing a prescription for it, including stigmatization, financial cost, and local availability.5-9 However, the stigma associated with naloxone extends to both patients and pharmacists. Pharmacists in West Virginia, for example, showed widespread concerns about having naloxone available for patients to purchase over the counter, for fear that increasing naloxone access may increase overdoses.6 A study in Tennessee also found pharmacists hesitant to recommend naloxone.7 Another study of rural pharmacies in Georgia found that just over half carried naloxone despite a state law that naloxone be available without a prescription.8 Challenges are not limited to rural areas, however; a study in Philadelphia found that more than one-third of pharmacies required a prescription to dispense naloxone, contrary to state law.9 Thus, in a rapidly changing regulatory environment, there are many evolving barriers to patients receiving naloxone.

New Mexico has an opioid overdose rate higher than the national average, coming in 15th out of 50 states when last ranked in 2018, with overdose rates that vary across demographic variables.10 Consequently, New Mexico state law added language requiring clinicians prescribing opioids for 5 days or longer to co-prescribe naloxone along with written information on how to administer the opioid antagonist.11 New Mexico is also a geographically large state with a relatively low overall population characterized by striking health disparities, particularly as related to access to care.

The purpose of this study is to describe the same-day availability of naloxone throughout the state of New Mexico after a change in state law requiring co-prescription was enacted, to help identify challenges to patients receiving it. Comprehensive examination of barriers to patients accessing this life-saving medication can advise strategies to both improve patient-centered care and potentially reduce deaths.

Methods

To better understand barriers to patients obtaining naloxone, in July and August of 2019 we performed an audit (“secret shopper”) study of all pharmacies in the state, posing as patients wishing to obtain naloxone. A publicly available list of every pharmacy in New Mexico was used to identify 89 pharmacies in Albuquerque (the most populous city in New Mexico) and 106 pharmacies throughout the rest of the state.12

Every pharmacy was called via a publicly available phone number during business hours (confirmed via an internet search), at least 2 hours prior to closing. One of 3 researchers telephoned pharmacies posing as a patient and inquired whether naloxone would be available for pick up the same day. If the pharmacy confirmed it was available that day, the call concluded. If naloxone was unavailable for same day pick up, researchers asked when it would be next available. Each pharmacy was called once, and neither insurance information nor cost was offered or requested. All questions were asked in English by native English speakers.

All responses were recorded in a secure spreadsheet. Once all responses were received and reviewed, they were characterized in discrete response categories: same day, within 1 to 2 days, within 3 to 4 days, within a week, or unsure/unknown. Naloxone availability was also tracked by city/municipality, and this was compared to the state’s population distribution.

No personally identifiable information was obtained. This study was Institutional Review Board exempt.

Results

Responses were recorded from 183 pharmacies. Seventeen locations were eliminated from our analysis because their phone system was inoperable or the pharmacy was permanently closed. Of the pharmacies reached, 84.7% (155/183) reported they have naloxone available for pick up on the same day (Figure 1). Of the 15.3% (28) pharmacies that did not have same-day availability, 60.7% (17 pharmacies) reported availability in 1 to 2 days, 3.6% had availability in 3 to 4 days, 3.6% had availability in 1 week, and 32.1% were unsure of next availability (Figure 2). More than one-third of the state’s patients reside in municipalities where naloxone is immediately available in at least 72% of pharmacies (Table).13

Discussion

Increased access to naloxone at the state and community level is associated with reduced risk for death from overdose, and, consequently, widespread availability is recommended.14-17 Statewide real-time pharmacy availability of naloxone—as patients would experience availability—has not been previously reported. These findings suggest unpredictable same-day availability that may affect experience and care outcomes. That other studies have found similar challenges in naloxone availability in other municipalities and regions suggests this barrier to access is widespread,6-9 and likely affects patients throughout the country.

Many patients have misgivings about naloxone, and it places an undue burden on them to travel to multiple pharmacies or take repeated trips to fill prescriptions. Additionally, patients without reliable transportation may be unable to return at a later date. Although we found most pharmacies in New Mexico without immediate availability of naloxone reported they could have it within several days, such a delay may reduce the likelihood that patients will fill their prescription at all. It is also concerning that many pharmacies are unsure of when naloxone will be available, particularly when some of these may be the only pharmacy easily accessible to patients or the one where they regularly fill their prescriptions.

Barriers to naloxone availability requires further study due to possible negative consequences for patient safety and risks for exacerbating health disparities among vulnerable populations. Further research may focus on examining the effects on patients when naloxone dispensing is delayed or impossible, why there is variability in naloxone availability between different pharmacies and municipalities, the reasons for uncertainty when naloxone will be available, and effective solutions. Expanded naloxone distribution in community locations and in clinics offers one potential patient-centered solution that should be explored, but it is likely that more widespread and systemic solutions will require policy and regulatory changes at the state and national levels.

Limitations of this study include that the findings may be relevant for solely 1 state, such as in the case of state-specific barriers to keeping naloxone in stock that we are unaware of. However, it is unclear why that would be the case, and it is more likely that similar barriers are pervasive. Additionally, repeat phone calls, which we did not follow up with, may have yielded more pharmacies with naloxone availability. However, due to the stigma associated with obtaining naloxone, it may be that patients will not make multiple calls either—highlighting how important real-time availability is.

Conclusion

Urgent solutions are needed to address the epidemic of deaths from opioid overdoses. Naloxone availability is an important tool for reducing these deaths, resulting in numerous state laws attempting to increase access. Despite this, there are persistent barriers to patients receiving naloxone, including a lack of same-day availability at pharmacies. Our results suggest that this underexplored barrier is widespread. Improving both availability and accessibility of naloxone may include legislative policy solutions as well as patient-oriented solutions, such as distribution in clinics and hospitals when opioid prescriptions are first written. Further research should be conducted to determine patient-centered, effective solutions that can improve outcomes.

Corresponding author: Eileen Barrett, MD, MPH, Department of Internal Medicine, University of New Mexico; ebarrett@salud.unm.edu.

Financial disclosures: None.

From the Department of Medicine, University of California San Diego (Dr. Haponyuk), Department of Emergency Medicine, University of Tennessee (Dr. Dejong), the Department of Family Medicine, University of New Mexico (Dr. Gutfrucht), and the Department of Internal Medicine, University of New Mexico (Dr. Barrett)

Objective: Naloxone availability can reduce the risk of death from opioid overdoses, although prescriber, legislative, and payment barriers to accessing this life-saving medication exist. A previously underreported barrier involves same-day availability, the lack of which may force patients to travel to multiple pharmacies and having delays in access or risking not filling their prescription. This study sought to determine same-day availability of naloxone in pharmacies in the state of New Mexico.

Methods: Same-day availability of naloxone was assessed via an audit survey.

Results: Of the 183 pharamacies screened, only 84.7% had same-day availability, including only 72% in Albuquerque, the state’s most populous city/municipality.

Conclusion: These results highlight the extent of a previously underexplored challenge to patient care and barrier to patient safety, and future directions for more patient-centered care.

Keywords: naloxone; barriers to care; opioid overdose prevention.

The US is enduring an ongoing epidemic of deaths due to opioid use, which have increased in frequency since the onset of the COVID-19 pandemic.1 One strategy to reduce the risk of mortality from opioid use is to ensure the widespread availability of naloxone. Individual states have implemented harm reduction strategies to increase access to naloxone, including improving availability via a statewide standing order that it may be dispensed without a prescription.2,3 Such naloxone access laws are being widely adopted and are believed to reduce overdose deaths.4

There are many barriers to patients receiving naloxone despite their clinicians providing a prescription for it, including stigmatization, financial cost, and local availability.5-9 However, the stigma associated with naloxone extends to both patients and pharmacists. Pharmacists in West Virginia, for example, showed widespread concerns about having naloxone available for patients to purchase over the counter, for fear that increasing naloxone access may increase overdoses.6 A study in Tennessee also found pharmacists hesitant to recommend naloxone.7 Another study of rural pharmacies in Georgia found that just over half carried naloxone despite a state law that naloxone be available without a prescription.8 Challenges are not limited to rural areas, however; a study in Philadelphia found that more than one-third of pharmacies required a prescription to dispense naloxone, contrary to state law.9 Thus, in a rapidly changing regulatory environment, there are many evolving barriers to patients receiving naloxone.

New Mexico has an opioid overdose rate higher than the national average, coming in 15th out of 50 states when last ranked in 2018, with overdose rates that vary across demographic variables.10 Consequently, New Mexico state law added language requiring clinicians prescribing opioids for 5 days or longer to co-prescribe naloxone along with written information on how to administer the opioid antagonist.11 New Mexico is also a geographically large state with a relatively low overall population characterized by striking health disparities, particularly as related to access to care.

The purpose of this study is to describe the same-day availability of naloxone throughout the state of New Mexico after a change in state law requiring co-prescription was enacted, to help identify challenges to patients receiving it. Comprehensive examination of barriers to patients accessing this life-saving medication can advise strategies to both improve patient-centered care and potentially reduce deaths.

Methods

To better understand barriers to patients obtaining naloxone, in July and August of 2019 we performed an audit (“secret shopper”) study of all pharmacies in the state, posing as patients wishing to obtain naloxone. A publicly available list of every pharmacy in New Mexico was used to identify 89 pharmacies in Albuquerque (the most populous city in New Mexico) and 106 pharmacies throughout the rest of the state.12

Every pharmacy was called via a publicly available phone number during business hours (confirmed via an internet search), at least 2 hours prior to closing. One of 3 researchers telephoned pharmacies posing as a patient and inquired whether naloxone would be available for pick up the same day. If the pharmacy confirmed it was available that day, the call concluded. If naloxone was unavailable for same day pick up, researchers asked when it would be next available. Each pharmacy was called once, and neither insurance information nor cost was offered or requested. All questions were asked in English by native English speakers.

All responses were recorded in a secure spreadsheet. Once all responses were received and reviewed, they were characterized in discrete response categories: same day, within 1 to 2 days, within 3 to 4 days, within a week, or unsure/unknown. Naloxone availability was also tracked by city/municipality, and this was compared to the state’s population distribution.

No personally identifiable information was obtained. This study was Institutional Review Board exempt.

Results

Responses were recorded from 183 pharmacies. Seventeen locations were eliminated from our analysis because their phone system was inoperable or the pharmacy was permanently closed. Of the pharmacies reached, 84.7% (155/183) reported they have naloxone available for pick up on the same day (Figure 1). Of the 15.3% (28) pharmacies that did not have same-day availability, 60.7% (17 pharmacies) reported availability in 1 to 2 days, 3.6% had availability in 3 to 4 days, 3.6% had availability in 1 week, and 32.1% were unsure of next availability (Figure 2). More than one-third of the state’s patients reside in municipalities where naloxone is immediately available in at least 72% of pharmacies (Table).13

Discussion

Increased access to naloxone at the state and community level is associated with reduced risk for death from overdose, and, consequently, widespread availability is recommended.14-17 Statewide real-time pharmacy availability of naloxone—as patients would experience availability—has not been previously reported. These findings suggest unpredictable same-day availability that may affect experience and care outcomes. That other studies have found similar challenges in naloxone availability in other municipalities and regions suggests this barrier to access is widespread,6-9 and likely affects patients throughout the country.

Many patients have misgivings about naloxone, and it places an undue burden on them to travel to multiple pharmacies or take repeated trips to fill prescriptions. Additionally, patients without reliable transportation may be unable to return at a later date. Although we found most pharmacies in New Mexico without immediate availability of naloxone reported they could have it within several days, such a delay may reduce the likelihood that patients will fill their prescription at all. It is also concerning that many pharmacies are unsure of when naloxone will be available, particularly when some of these may be the only pharmacy easily accessible to patients or the one where they regularly fill their prescriptions.

Barriers to naloxone availability requires further study due to possible negative consequences for patient safety and risks for exacerbating health disparities among vulnerable populations. Further research may focus on examining the effects on patients when naloxone dispensing is delayed or impossible, why there is variability in naloxone availability between different pharmacies and municipalities, the reasons for uncertainty when naloxone will be available, and effective solutions. Expanded naloxone distribution in community locations and in clinics offers one potential patient-centered solution that should be explored, but it is likely that more widespread and systemic solutions will require policy and regulatory changes at the state and national levels.

Limitations of this study include that the findings may be relevant for solely 1 state, such as in the case of state-specific barriers to keeping naloxone in stock that we are unaware of. However, it is unclear why that would be the case, and it is more likely that similar barriers are pervasive. Additionally, repeat phone calls, which we did not follow up with, may have yielded more pharmacies with naloxone availability. However, due to the stigma associated with obtaining naloxone, it may be that patients will not make multiple calls either—highlighting how important real-time availability is.

Conclusion

Urgent solutions are needed to address the epidemic of deaths from opioid overdoses. Naloxone availability is an important tool for reducing these deaths, resulting in numerous state laws attempting to increase access. Despite this, there are persistent barriers to patients receiving naloxone, including a lack of same-day availability at pharmacies. Our results suggest that this underexplored barrier is widespread. Improving both availability and accessibility of naloxone may include legislative policy solutions as well as patient-oriented solutions, such as distribution in clinics and hospitals when opioid prescriptions are first written. Further research should be conducted to determine patient-centered, effective solutions that can improve outcomes.

Corresponding author: Eileen Barrett, MD, MPH, Department of Internal Medicine, University of New Mexico; ebarrett@salud.unm.edu.

Financial disclosures: None.

1. Mason M, Welch SB, Arunkumar P, et al. Notes from the field: opioid overdose deaths before, during, and after an 11-week COVID-19 stay-at-home order—Cook County, Illinois, January 1, 2018–October 6, 2020. MMWR Morb Mortal Wkly Rep. 2021;70(10):362-363. doi:10.15585/mmwr.mm7010a3

2. Kaiser Family Foundation. Opioid overdose death rates and all drug overdose death rates per 100,000 population (age-adjusted). Accessed October 6, 2021. https://www.kff.org/other/state-indicator/opioid-overdose-death

3. Sohn M, Talbert JC, Huang Z, et al. Association of naloxone coprescription laws with naloxone prescription dispensing in the United States. JAMA Netw Open. 2019;2(6):e196215. doi:10.1001/jamanetworkopen.2019.6215

4. Smart R, Pardo B, Davis CS. Systematic review of the emerging literature on the effectiveness of naloxone access laws in the United States. Addiction. 2021;116(1):6-17. doi:10.1111/add.15163

5. Mueller SR, Koester S, Glanz JM, et al. Attitudes toward naloxone prescribing in clinical settings: a qualitative study of patients prescribed high dose opioids for chronic non-cancer pain. J Gen Intern Med. 2017;32(3):277-283. doi:10.1007/s11606-016-3895-8

6. Thornton JD, Lyvers E, Scott VGG, Dwibedi N. Pharmacists’ readiness to provide naloxone in community pharmacies in West Virginia. J Am Pharm Assoc (2003). 2017;57(2S):S12-S18.e4. doi:10.1016/j.japh.2016.12.070

7. Spivey C, Wilder A, Chisholm-Burns MA, et al. Evaluation of naloxone access, pricing, and barriers to dispensing in Tennessee retail community pharmacies. J Am Pharm Assoc (2003). 2020;60(5):694-701.e1. doi:10.1016/j.japh.2020.01.030

8. Nguyen JL, Gilbert LR, Beasley L, et al. Availability of naloxone at rural Georgia pharmacies, 2019. JAMA Netw Open. 2020;3(2):e1921227. doi:10.1001/jamanetworkopen.2019.21227

9. Guadamuz JS, Alexander GC, Chaudhri T, et al. Availability and cost of naloxone nasal spray at pharmacies in Philadelphia, Pennsylvania. JAMA Netw Open. 2019;2(6):e195388. doi:10.1001/jamanetworkopen.2019.5388

10. Edge K. Changes in drug overdose mortality in New Mexico. New Mexico Epidemiology. July 2020 (3). https://www.nmhealth.org/data/view/report/2402/

11. Senate Bill 221. 54th Legislature, State of New Mexico, First Session, 2019 (introduced by William P. Soules). Accessed October 6, 2021. https://nmlegis.gov/Sessions/19%20Regular/bills/senate/SB0221.pdf

12. GoodRx. Find pharmacies in New Mexico. Accessed October 6, 2021. https://www.goodrx.com/pharmacy-near-me/all/nm

13. U.S. Census Bureau. QuickFacts: New Mexico. Accessed October 6, 2021. https://www.census.gov/quickfacts/NM

14. Linas BP, Savinkina A, Madushani RWMA, et al. Projected estimates of opioid mortality after community-level interventions. JAMA Netw Open. 2021;4(2):e2037259. doi:10.1001/jamanetworkopen.2020.37259

15. You HS, Ha J, Kang CY, et al. Regional variation in states’ naloxone accessibility laws in association with opioid overdose death rates—observational study (STROBE compliant). Medicine (Baltimore). 2020;99(22):e20033. doi:10.1097/MD.0000000000020033

16. Pew Charitable Trusts. Expanded access to naloxone can curb opioid overdose deaths. October 20, 2020. Accessed October 6, 2021. https://www.

17. Centers for Disease Control and Prevention. Still not enough naloxone where it’s most needed. August 6, 2019. Accessed October 6, 2021. https://www.cdc.gov/media/releases/2019/p0806-naloxone.html

1. Mason M, Welch SB, Arunkumar P, et al. Notes from the field: opioid overdose deaths before, during, and after an 11-week COVID-19 stay-at-home order—Cook County, Illinois, January 1, 2018–October 6, 2020. MMWR Morb Mortal Wkly Rep. 2021;70(10):362-363. doi:10.15585/mmwr.mm7010a3

2. Kaiser Family Foundation. Opioid overdose death rates and all drug overdose death rates per 100,000 population (age-adjusted). Accessed October 6, 2021. https://www.kff.org/other/state-indicator/opioid-overdose-death

3. Sohn M, Talbert JC, Huang Z, et al. Association of naloxone coprescription laws with naloxone prescription dispensing in the United States. JAMA Netw Open. 2019;2(6):e196215. doi:10.1001/jamanetworkopen.2019.6215

4. Smart R, Pardo B, Davis CS. Systematic review of the emerging literature on the effectiveness of naloxone access laws in the United States. Addiction. 2021;116(1):6-17. doi:10.1111/add.15163

5. Mueller SR, Koester S, Glanz JM, et al. Attitudes toward naloxone prescribing in clinical settings: a qualitative study of patients prescribed high dose opioids for chronic non-cancer pain. J Gen Intern Med. 2017;32(3):277-283. doi:10.1007/s11606-016-3895-8

6. Thornton JD, Lyvers E, Scott VGG, Dwibedi N. Pharmacists’ readiness to provide naloxone in community pharmacies in West Virginia. J Am Pharm Assoc (2003). 2017;57(2S):S12-S18.e4. doi:10.1016/j.japh.2016.12.070

7. Spivey C, Wilder A, Chisholm-Burns MA, et al. Evaluation of naloxone access, pricing, and barriers to dispensing in Tennessee retail community pharmacies. J Am Pharm Assoc (2003). 2020;60(5):694-701.e1. doi:10.1016/j.japh.2020.01.030

8. Nguyen JL, Gilbert LR, Beasley L, et al. Availability of naloxone at rural Georgia pharmacies, 2019. JAMA Netw Open. 2020;3(2):e1921227. doi:10.1001/jamanetworkopen.2019.21227

9. Guadamuz JS, Alexander GC, Chaudhri T, et al. Availability and cost of naloxone nasal spray at pharmacies in Philadelphia, Pennsylvania. JAMA Netw Open. 2019;2(6):e195388. doi:10.1001/jamanetworkopen.2019.5388

10. Edge K. Changes in drug overdose mortality in New Mexico. New Mexico Epidemiology. July 2020 (3). https://www.nmhealth.org/data/view/report/2402/

11. Senate Bill 221. 54th Legislature, State of New Mexico, First Session, 2019 (introduced by William P. Soules). Accessed October 6, 2021. https://nmlegis.gov/Sessions/19%20Regular/bills/senate/SB0221.pdf

12. GoodRx. Find pharmacies in New Mexico. Accessed October 6, 2021. https://www.goodrx.com/pharmacy-near-me/all/nm

13. U.S. Census Bureau. QuickFacts: New Mexico. Accessed October 6, 2021. https://www.census.gov/quickfacts/NM

14. Linas BP, Savinkina A, Madushani RWMA, et al. Projected estimates of opioid mortality after community-level interventions. JAMA Netw Open. 2021;4(2):e2037259. doi:10.1001/jamanetworkopen.2020.37259

15. You HS, Ha J, Kang CY, et al. Regional variation in states’ naloxone accessibility laws in association with opioid overdose death rates—observational study (STROBE compliant). Medicine (Baltimore). 2020;99(22):e20033. doi:10.1097/MD.0000000000020033

16. Pew Charitable Trusts. Expanded access to naloxone can curb opioid overdose deaths. October 20, 2020. Accessed October 6, 2021. https://www.

17. Centers for Disease Control and Prevention. Still not enough naloxone where it’s most needed. August 6, 2019. Accessed October 6, 2021. https://www.cdc.gov/media/releases/2019/p0806-naloxone.html

Positive Outcomes Following a Multidisciplinary Approach in the Diagnosis and Prevention of Hospital Delirium

From the Department of Neurology, Cedars-Sinai Medical Center, Los Angeles, CA (Drs. Ching, Darwish, Li, Wong, Simpson, and Funk), the Department of Anesthesia, Cedars-Sinai Medical Center, Los Angeles, CA (Keith Siegel), and the Department of Psychiatry, Cedars-Sinai Medical Center, Los Angeles, CA (Dr. Bamgbose).

Objectives: To reduce the incidence and duration of delirium among patients in a hospital ward through standardized delirium screening tools and nonpharmacologic interventions. To advance nursing-focused education on delirium-prevention strategies. To measure the efficacy of the interventions with the aim of reproducing best practices.

Background: Delirium is associated with poor patient outcomes but may be preventable in a significant percentage of hospitalized patients.

Methods: Following nursing-focused education to prevent delirium, we prospectively evaluated patient care outcomes in a consecutive series of patients who were admitted to a hospital medical-surgical ward within a 25-week period. All patients who had at least 1 Confusion Assessment Method (CAM) documented by a nurse during hospitalization met our inclusion criteria (N = 353). Standards for Quality Improvement Reporting Excellence guidelines were adhered to.

Results: There were 187 patients in the control group, and 166 in the postintervention group. Compared to the control group, the postintervention group had a significant decrease in the incidence of delirium during hospitalization (14.4% vs 4.2%) and a significant decrease in the mean percentage of tested nursing shifts with 1 or more positive CAM (4.9% vs 1.1%). Significant differences in secondary outcomes between the control and postintervention groups included median length of stay (6 days vs 4 days), mean length of stay (8.5 days vs 5.9 days), and use of an indwelling urinary catheter (9.1% vs 2.4%).

Conclusion: A multimodal strategy involving nursing-focused training and nonpharmacologic interventions to address hospital delirium is associated with improved patient care outcomes and nursing confidence. Nurses play an integral role in the early recognition and prevention of hospital delirium, which directly translates to reducing burdens in both patient functionality and health care costs.

Delirium is a disorder characterized by inattention and acute changes in cognition. It is defined by the American Psychiatric Association’s fifth edition of the Diagnostic and Statistical Manual of Mental Disorders as a disturbance in attention, awareness, and cognition over hours to a few days that is not better explained by a preexisting, established, or other evolving neurocognitive disorder.1 Delirium is common yet often under-recognized among hospitalized patients, particularly in the elderly. The incidence of delirium in elderly patients on admission is estimated to be 11% to 25%, and an additional 29% to 31% of elderly patients will develop delirium during the hospitalization.2 Delirium costs the health care system an estimated $38 billion to $152 billion per year.3 It is associated with negative outcomes, such as increased new placements to nursing homes, increased mortality, increased risk of dementia, and further cognitive deterioration among patients with dementia.4-6

Despite its prevalence, delirium may be preventable in a significant percentage of hospitalized patients. Targeted intervention strategies, such as frequent reorientation, maximizing sleep, early mobilization, restricting use of psychoactive medications, and addressing hearing or vision impairment, have been demonstrated to significantly reduce the incidence of hospital delirium.7,8 To achieve these goals, we explored the use of a multimodal strategy centered on nursing education. We integrated consistent, standardized delirium screening and nonpharmacologic interventions as part of a preventative protocol to reduce the incidence of delirium in the hospital ward.

Methods

We evaluated a consecutive series of patients who were admitted to a designated hospital medical-surgical ward within a 25-week period between October 2019 and April 2020. All patients during this period who had at least 1 Confusion Assessment Method (CAM) documented by a nurse during hospitalization met our inclusion criteria. Patients who did not have a CAM documented were excluded from the analysis. Delirium was defined according to the CAM diagnostic algorithm.9

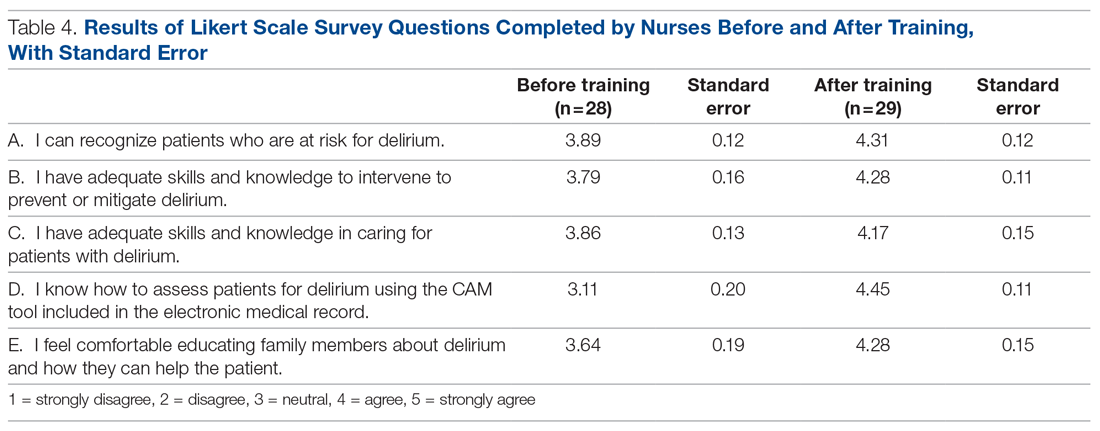

Core nursing staff regularly assigned to the ward completed a multimodal training program designed to improve recognition, documentation, and prevention of hospital delirium. Prior to the training, the nurses completed a 5-point Likert scale survey assessing their level of confidence with recognizing delirium risk factors, preventing delirium, addressing delirium, utilizing the CAM tool, and educating others about delirium. Nurses completed the same survey after the study period ended.

The training curriculum for nurses began with an online module reviewing the epidemiology and risk factors for delirium. Nurses then participated in a series of in-service training sessions led by a team of physicians, during which the CAM and nonpharmacologic delirium prevention measures were reviewed then practiced first-hand. Nursing staff attended an in-person lecture reviewing the current body of literature on delirium risk factors and effective nursing interventions. After formal training was completed, nurses were instructed to document CAM screens

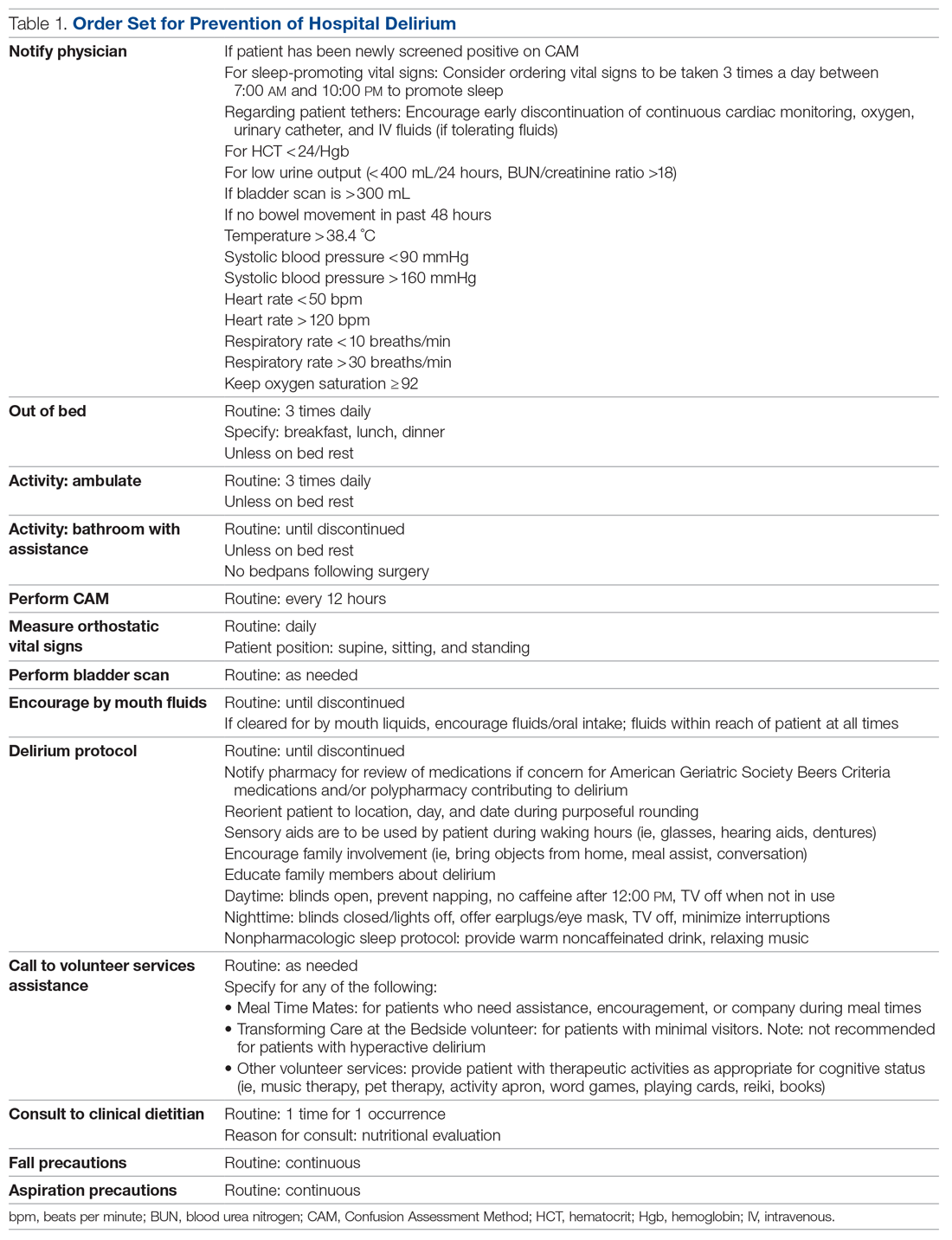

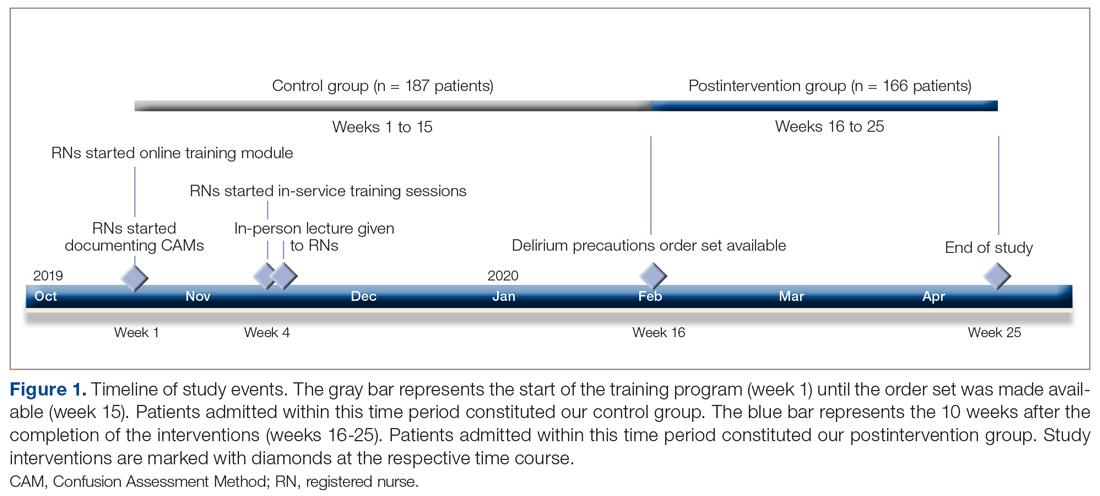

Patients admitted to the hospital unit from the start of the training program (week 1) until the order set was made available (week 15) constituted our control group. The postintervention study group consisted of patients admitted for 10 weeks after the completion of the interventions (weeks 16-25). A timeline of the study events is shown in Figure 1.

Patient demographics and hospital-stay metrics determined a priori were attained via the Cedars-Sinai Enterprise Information Services core. Age, sex, medical history, and incidence of surgery with anesthesia during hospitalization were recorded. The Charlson Comorbidity Index was calculated from patients’ listed diagnoses following discharge. Primary outcomes included incidence of patients with delirium during hospitalization, percentage of tested shifts with positive CAM screens, length of hospital stay, and survival. Secondary outcomes included measures associated with delirium, including the use of chemical restraints, physical restraints, sitters, indwelling urinary catheters, and new psychiatry and neurology consults. Chemical restraints were defined as administration of a new antipsychotic medication or benzodiazepine for the specific indication of hyperactive delirium or agitation.

Statistical analysis was conducted by a statistician, using R version 3.6.3.10P values of < .05 were considered significant. Categorical variables were analyzed using Fisher’s exact test. Continuous variables were analyzed with Welch’s t-test or, for highly skewed continuous variables, with Wilcoxon rank-sum test or Mood’s median test. All patient data were anonymized and stored securely in accordance with institutional guidelines.

Our project was deemed to represent nonhuman subject research and therefore did not require Institutional Review Board (IRB) approval upon review by our institution’s IRB committee and Office of Research Compliance and Quality Improvement. Standards for Quality Improvement Reporting Excellence (SQUIRE 2.0) guidelines were adhered to (Supplementary File can be found at mdedge.com/jcomjournal).

Results

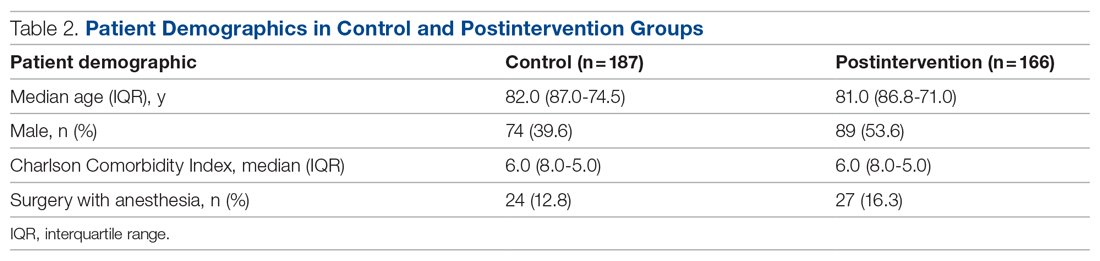

We evaluated 353 patients who met our inclusion criteria: 187 in the control group, and 166 in the postintervention group. Ten patients were readmitted to the ward after their initial discharge; only the initial admission encounters were included in our analysis. Median age, sex, median Charlson Comorbidity Index, and incidence of surgery with anesthesia during hospitalization were comparable between the control and postintervention groups and are summarized in Table 2.

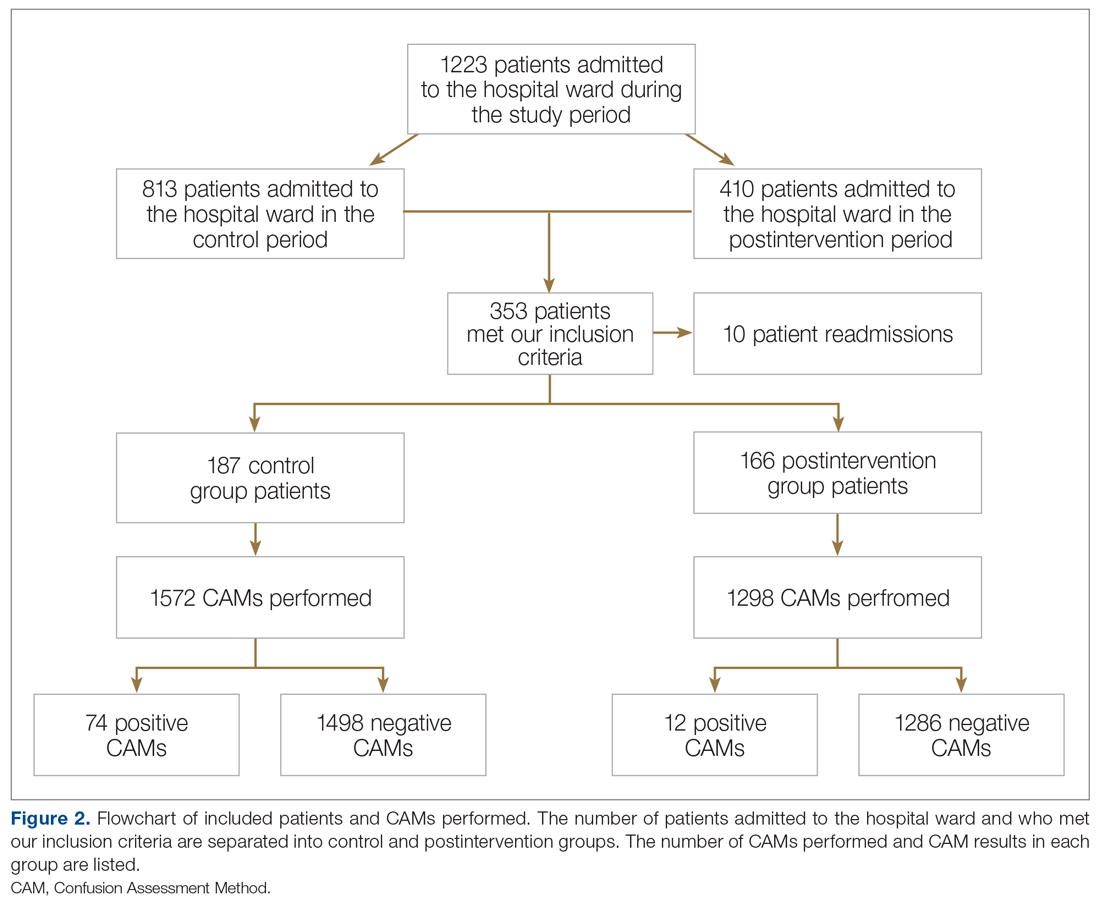

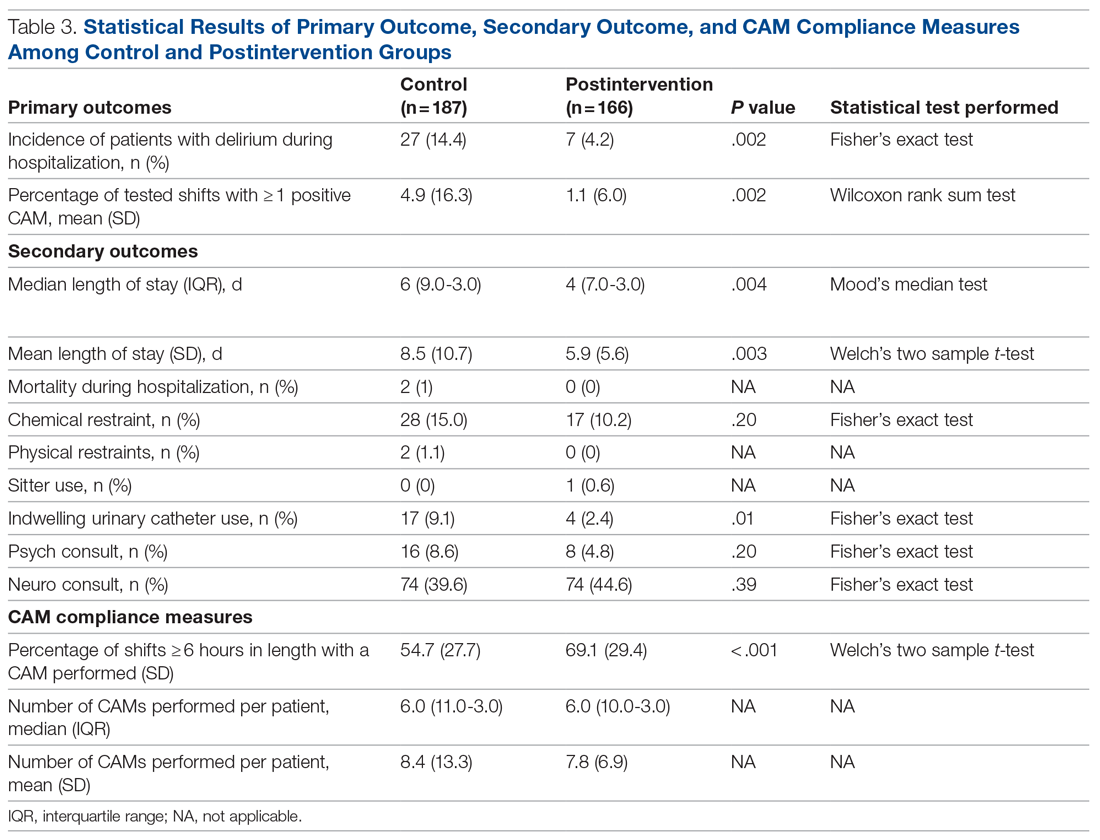

In the control group, 1572 CAMs were performed, with 74 positive CAMs recorded among 27 patients with delirium. In the postintervention group, 1298 CAMs were performed, with 12 positive CAMs recorded among 7 patients with delirium (Figure 2). Primary and secondary outcomes, as well as CAM compliance measures, are summarized in Table 3.

Compared to the control group, the postintervention group had a significant decrease in the incidence of delirium during hospitalization (14.4% vs 4.2%, P = .002) and a significant decrease in the mean percentage of tested nursing shifts with 1 or more positive CAM (4.9% vs 1.1%, P = .002). Significant differences in secondary outcomes between the control and postintervention groups included median length of stay (6 days vs 4 days, P = .004), mean length of stay (8.5 days vs 5.9 days, P = .003), and use of an indwelling urinary catheter (9.1% vs 2.4%, P = .012). There was a trend towards decreased incidence of chemical restraints and psychiatry consults, which did not reach statistical significance. Differences in mortality during hospitalization, physical restraint use, and sitter use could not be assessed due to low incidence.

Compliance with nursing CAM assessments was evaluated. Compared to the control group, the postintervention group saw a significant increase in the percentage of shifts with a CAM performed (54.7% vs 69.1%, P < .001). The median and mean number of CAMs performed per patient were similar between the control and postintervention groups.

Results of nursing surveys completed before and after the training program are listed in Table 4. After training, nurses had a greater level of confidence with recognizing delirium risk factors, preventing delirium, addressing delirium, utilizing the CAM tool, and educating others about delirium.

Discussion

Our study utilized a standardized delirium assessment tool to compare patient cohorts before and after nurse-targeted training interventions on delirium recognition and prevention. Our interventions emphasized nonpharmacologic intervention strategies, which are recommended as first-line in the management of patients with delirium.11 Patients were not excluded from the analysis based on preexisting medical conditions or recent surgery with anesthesia, to allow for conditions that are representative of community hospitals. We also did not use an inclusion criterion based on age; however, the majority of our patients were greater than 70 years old, representing those at highest risk for delirium.2 Significant outcomes among patients in the postintervention group include decreased incidence of delirium, lower average length of stay, decreased indwelling urinary catheter use, and increased compliance with delirium screening by nursing staff.

While the study’s focus was primarily on delirium prevention rather than treatment, these strategies may also have conferred the benefit of reversing delirium symptoms. In addition to measuring incidence of delirium, our primary outcome of percentage of tested shifts with 1 or more positive CAM was intended to assess the overall duration in which patients had delirium during their hospitalization. The reduction in shifts with positive CAMs observed in the postintervention group is notable, given that a significant percentage of patients with hospital delirium have the potential for symptom reversibility.12

Multiple studies have shown that admitted patients who develop delirium experience prolonged hospital stays, often up to 5 to 10 days longer.12-14 The decreased incidence and duration of delirium in our postintervention group is a reasonable explanation for the observed decrease in average length of stay. Our study is in line with previously documented initiatives that show that nonpharmacologic interventions can effectively address downstream health and fiscal sequelae of hospital delirium. For example, a volunteer-based initiative named the Hospital Elder Life Program, from which elements in our order set were modeled after, demonstrated significant reductions in delirium incidence, length of stay, and health care costs.14-16 Other initiatives that focused on educational training for nurses to assess and prevent delirium have also demonstrated similar positive results.17-19 Our study provides a model for effective nursing-focused education that can be reproduced in the hospital setting.

Unlike some other studies, which identified delirium based only on physician assessments, our initiative utilized the CAM performed by floor nurses to identify delirium. While this method

Our study demonstrated an increase in the overall compliance with the CAM screening during the postintervention period, which is significant given the under-recognition of delirium by health care professionals.20 We attribute this increase to greater realized importance and a higher level of confidence from nursing staff in recognizing and addressing delirium, as supported by survey data. While the increased screening of patients should be considered a positive outcome, it also poses the possibility that the observed decrease in delirium incidence in the postintervention group was in fact due to more CAMs performed on patients without delirium. Likewise, nurses may have become more adept at recognizing true delirium, as opposed to delirium mimics, in the latter period of the study.

Perhaps the greatest limitation of our study is the variability in performing and recording CAMs, as some patients had multiple CAMs recorded while others did not have any CAMs recorded. This may have been affected in part by the increase in COVID-19 cases in our hospital towards the latter half of the study, which resulted in changes in nursing assignments as well as patient comorbidities in ways that cannot be easily quantified. Given the limited size of our patient cohorts, certain outcomes, such as the use of sitters, physical restraints, and in-hospital mortality, were unable to be assessed for changes statistically. Causative relationships between our interventions and associated outcome measures are necessarily limited in a binary comparison between control and postintervention groups.

Within these limitations, our study demonstrates promising results in core dimensions of patient care. We anticipate further quality improvement initiatives involving greater numbers of nursing staff and patients to better quantify the impact of nonpharmacologic nursing-centered interventions for preventing hospital delirium.

Conclusion

A multimodal strategy involving nursing-focused training and nonpharmacologic interventions to address hospital delirium is associated with improved patient care outcomes and nursing confidence. Nurses play an integral role in the early recognition and prevention of hospital delirium, which directly translates to reducing burdens in both patient functionality and health care costs. Education and tools to equip nurses to perform standardized delirium screening and interventions should be prioritized.

Acknowledgment: The authors thanks Olena Svetlov, NP, Oscar Abarca, Jose Chavez, and Jenita Gutierrez.

Corresponding author: Jason Ching, MD, Department of Neurology, Cedars-Sinai Medical Center, 8700 Beverly Blvd, Los Angeles, CA 90048; jason.ching@cshs.org.

Financial disclosures: None.

Funding: This research was supported by NIH National Center for Advancing Translational Science (NCATS) UCLA CTSI Grant Number UL1TR001881.

1. American Psychiatric Association. Diagnostic and Statistical Manual of Mental Disorders, 5th edition. American Psychiatric Association; 2013.

2. Vasilevskis EE, Han JH, Hughes CG, et al. Epidemiology and risk factors for delirium across hospital settings. Best Pract Res Clin Anaesthesiol. 2012;26(3):277-287. doi:10.1016/j.bpa.2012.07003

3. Leslie DL, Marcantonio ER, Zhang Y, et al. One-year health care costs associated with delirium in the elderly population. Arch Intern Med. 2008;168(1):27-32. doi:10.1001/archinternmed.2007.4

4. McCusker J, Cole M, Abrahamowicz M, et al. Delirium predicts 12-month mortality. Arch Intern Med. 2002;162(4):457-463. doi:10.1001/archinte.162.4.457

5. Witlox J, Eurelings LS, de Jonghe JF, et al. Delirium in elderly patients and the risk of postdischarge mortality, institutionalization, and dementia: a meta-analysis. JAMA. 2010;304(4):443-451. doi:10.1001/jama.2010.1013

6. Gross AL, Jones RN, Habtemariam DA, et al. Delirium and long-term cognitive trajectory among persons with dementia. Arch Intern Med. 2012;172(17):1324-1331. doi:10.1001/archinternmed.2012.3203

7. Inouye SK. Prevention of delirium in hospitalized older patients: risk factors and targeted intervention strategies. Ann Med. 2000;32(4):257-263. doi:10.3109/07853890009011770

8. Siddiqi N, Harrison JK, Clegg A, et al. Interventions for preventing delirium in hospitalised non-ICU patients. Cochrane Database Syst Rev. 2016;3:CD005563. doi:10.1002/14651858.CD005563.pub3

9. Inouye SK, van Dyck CH, Alessi CA, et al. Clarifying confusion: the confusion assessment method. A new method for detection of delirium. Ann Intern Med. 1990;113(12):941-948. doi:10.7326/0003-4819-113-12-941

10. R Core Team. R: A Language and Environment for Statistical Computing. R Foundation for Statistical Computing; 2017.

11. Fong TG, Tulebaev SR, Inouye SK. Delirium in elderly adults: diagnosis, prevention and treatment. Nat Rev Neurol. 2009;5(4):210-220. doi:10.1038/nrneurol.2009.24

12. Siddiqi N, House AO, Holmes JD. Occurrence and outcome of delirium in medical in-patients: a systematic literature review. Age Ageing. 2006;35(4):350-364. doi:10.1093/ageing/afl005

13. Ely EW, Shintani A, Truman B, et al. Delirium as a predictor of mortality in mechanically ventilated patients in the intensive care unit. JAMA. 2004;291(14):1753-1762. doi:10.1001/jama.291.14.1753

14. Chen CC, Lin MT, Tien YW, et al. Modified Hospital Elder Life Program: effects on abdominal surgery patients. J Am Coll Surg. 2011;213(2):245-252. doi:10.1016/j.jamcollsurg.2011.05.004

15. Zaubler TS, Murphy K, Rizzuto L, et al. Quality improvement and cost savings with multicomponent delirium interventions: replication of the Hospital Elder Life Program in a community hospital. Psychosomatics. 2013;54(3):219-226. doi:10.1016/j.psym.2013.01.010

16. Rubin FH, Neal K, Fenlon K, et al. Sustainability and scalability of the Hospital Elder Life Program at a community hospital. J Am Geriatr Soc. 2011;59(2):359-365. doi:10.1111/j.1532-5415.2010.03243.x

17. Milisen K, Foreman MD, Abraham IL, et al. A nurse-led interdisciplinary intervention program for delirium in elderly hip-fracture patients. J Am Geriatr Soc. 2001;49(5):523-532. doi:10.1046/j.1532-5415.2001.49109.x

18. Lundström M, Edlund A, Karlsson S, et al. A multifactorial intervention program reduces the duration of delirium, length of hospitalization, and mortality in delirious patients. J Am Geriatr Soc. 2005;53(4):622-628. doi:10.1111/j.1532-5415.2005.53210.x

19. Tabet N, Hudson S, Sweeney V, et al. An educational intervention can prevent delirium on acute medical wards. Age Ageing. 2005;34(2):152-156. doi:10.1093/ageing/afi0320. Han JH, Zimmerman EE, Cutler N, et al. Delirium in older emergency department patients: recognition, risk factors, and psychomotor subtypes. Acad Emerg Med. 2009;16(3):193-200. doi:10.1111/j.1553-2712.2008.00339.x

From the Department of Neurology, Cedars-Sinai Medical Center, Los Angeles, CA (Drs. Ching, Darwish, Li, Wong, Simpson, and Funk), the Department of Anesthesia, Cedars-Sinai Medical Center, Los Angeles, CA (Keith Siegel), and the Department of Psychiatry, Cedars-Sinai Medical Center, Los Angeles, CA (Dr. Bamgbose).

Objectives: To reduce the incidence and duration of delirium among patients in a hospital ward through standardized delirium screening tools and nonpharmacologic interventions. To advance nursing-focused education on delirium-prevention strategies. To measure the efficacy of the interventions with the aim of reproducing best practices.

Background: Delirium is associated with poor patient outcomes but may be preventable in a significant percentage of hospitalized patients.

Methods: Following nursing-focused education to prevent delirium, we prospectively evaluated patient care outcomes in a consecutive series of patients who were admitted to a hospital medical-surgical ward within a 25-week period. All patients who had at least 1 Confusion Assessment Method (CAM) documented by a nurse during hospitalization met our inclusion criteria (N = 353). Standards for Quality Improvement Reporting Excellence guidelines were adhered to.

Results: There were 187 patients in the control group, and 166 in the postintervention group. Compared to the control group, the postintervention group had a significant decrease in the incidence of delirium during hospitalization (14.4% vs 4.2%) and a significant decrease in the mean percentage of tested nursing shifts with 1 or more positive CAM (4.9% vs 1.1%). Significant differences in secondary outcomes between the control and postintervention groups included median length of stay (6 days vs 4 days), mean length of stay (8.5 days vs 5.9 days), and use of an indwelling urinary catheter (9.1% vs 2.4%).

Conclusion: A multimodal strategy involving nursing-focused training and nonpharmacologic interventions to address hospital delirium is associated with improved patient care outcomes and nursing confidence. Nurses play an integral role in the early recognition and prevention of hospital delirium, which directly translates to reducing burdens in both patient functionality and health care costs.

Delirium is a disorder characterized by inattention and acute changes in cognition. It is defined by the American Psychiatric Association’s fifth edition of the Diagnostic and Statistical Manual of Mental Disorders as a disturbance in attention, awareness, and cognition over hours to a few days that is not better explained by a preexisting, established, or other evolving neurocognitive disorder.1 Delirium is common yet often under-recognized among hospitalized patients, particularly in the elderly. The incidence of delirium in elderly patients on admission is estimated to be 11% to 25%, and an additional 29% to 31% of elderly patients will develop delirium during the hospitalization.2 Delirium costs the health care system an estimated $38 billion to $152 billion per year.3 It is associated with negative outcomes, such as increased new placements to nursing homes, increased mortality, increased risk of dementia, and further cognitive deterioration among patients with dementia.4-6

Despite its prevalence, delirium may be preventable in a significant percentage of hospitalized patients. Targeted intervention strategies, such as frequent reorientation, maximizing sleep, early mobilization, restricting use of psychoactive medications, and addressing hearing or vision impairment, have been demonstrated to significantly reduce the incidence of hospital delirium.7,8 To achieve these goals, we explored the use of a multimodal strategy centered on nursing education. We integrated consistent, standardized delirium screening and nonpharmacologic interventions as part of a preventative protocol to reduce the incidence of delirium in the hospital ward.

Methods

We evaluated a consecutive series of patients who were admitted to a designated hospital medical-surgical ward within a 25-week period between October 2019 and April 2020. All patients during this period who had at least 1 Confusion Assessment Method (CAM) documented by a nurse during hospitalization met our inclusion criteria. Patients who did not have a CAM documented were excluded from the analysis. Delirium was defined according to the CAM diagnostic algorithm.9

Core nursing staff regularly assigned to the ward completed a multimodal training program designed to improve recognition, documentation, and prevention of hospital delirium. Prior to the training, the nurses completed a 5-point Likert scale survey assessing their level of confidence with recognizing delirium risk factors, preventing delirium, addressing delirium, utilizing the CAM tool, and educating others about delirium. Nurses completed the same survey after the study period ended.

The training curriculum for nurses began with an online module reviewing the epidemiology and risk factors for delirium. Nurses then participated in a series of in-service training sessions led by a team of physicians, during which the CAM and nonpharmacologic delirium prevention measures were reviewed then practiced first-hand. Nursing staff attended an in-person lecture reviewing the current body of literature on delirium risk factors and effective nursing interventions. After formal training was completed, nurses were instructed to document CAM screens

Patients admitted to the hospital unit from the start of the training program (week 1) until the order set was made available (week 15) constituted our control group. The postintervention study group consisted of patients admitted for 10 weeks after the completion of the interventions (weeks 16-25). A timeline of the study events is shown in Figure 1.

Patient demographics and hospital-stay metrics determined a priori were attained via the Cedars-Sinai Enterprise Information Services core. Age, sex, medical history, and incidence of surgery with anesthesia during hospitalization were recorded. The Charlson Comorbidity Index was calculated from patients’ listed diagnoses following discharge. Primary outcomes included incidence of patients with delirium during hospitalization, percentage of tested shifts with positive CAM screens, length of hospital stay, and survival. Secondary outcomes included measures associated with delirium, including the use of chemical restraints, physical restraints, sitters, indwelling urinary catheters, and new psychiatry and neurology consults. Chemical restraints were defined as administration of a new antipsychotic medication or benzodiazepine for the specific indication of hyperactive delirium or agitation.

Statistical analysis was conducted by a statistician, using R version 3.6.3.10P values of < .05 were considered significant. Categorical variables were analyzed using Fisher’s exact test. Continuous variables were analyzed with Welch’s t-test or, for highly skewed continuous variables, with Wilcoxon rank-sum test or Mood’s median test. All patient data were anonymized and stored securely in accordance with institutional guidelines.

Our project was deemed to represent nonhuman subject research and therefore did not require Institutional Review Board (IRB) approval upon review by our institution’s IRB committee and Office of Research Compliance and Quality Improvement. Standards for Quality Improvement Reporting Excellence (SQUIRE 2.0) guidelines were adhered to (Supplementary File can be found at mdedge.com/jcomjournal).

Results

We evaluated 353 patients who met our inclusion criteria: 187 in the control group, and 166 in the postintervention group. Ten patients were readmitted to the ward after their initial discharge; only the initial admission encounters were included in our analysis. Median age, sex, median Charlson Comorbidity Index, and incidence of surgery with anesthesia during hospitalization were comparable between the control and postintervention groups and are summarized in Table 2.

In the control group, 1572 CAMs were performed, with 74 positive CAMs recorded among 27 patients with delirium. In the postintervention group, 1298 CAMs were performed, with 12 positive CAMs recorded among 7 patients with delirium (Figure 2). Primary and secondary outcomes, as well as CAM compliance measures, are summarized in Table 3.

Compared to the control group, the postintervention group had a significant decrease in the incidence of delirium during hospitalization (14.4% vs 4.2%, P = .002) and a significant decrease in the mean percentage of tested nursing shifts with 1 or more positive CAM (4.9% vs 1.1%, P = .002). Significant differences in secondary outcomes between the control and postintervention groups included median length of stay (6 days vs 4 days, P = .004), mean length of stay (8.5 days vs 5.9 days, P = .003), and use of an indwelling urinary catheter (9.1% vs 2.4%, P = .012). There was a trend towards decreased incidence of chemical restraints and psychiatry consults, which did not reach statistical significance. Differences in mortality during hospitalization, physical restraint use, and sitter use could not be assessed due to low incidence.

Compliance with nursing CAM assessments was evaluated. Compared to the control group, the postintervention group saw a significant increase in the percentage of shifts with a CAM performed (54.7% vs 69.1%, P < .001). The median and mean number of CAMs performed per patient were similar between the control and postintervention groups.

Results of nursing surveys completed before and after the training program are listed in Table 4. After training, nurses had a greater level of confidence with recognizing delirium risk factors, preventing delirium, addressing delirium, utilizing the CAM tool, and educating others about delirium.

Discussion

Our study utilized a standardized delirium assessment tool to compare patient cohorts before and after nurse-targeted training interventions on delirium recognition and prevention. Our interventions emphasized nonpharmacologic intervention strategies, which are recommended as first-line in the management of patients with delirium.11 Patients were not excluded from the analysis based on preexisting medical conditions or recent surgery with anesthesia, to allow for conditions that are representative of community hospitals. We also did not use an inclusion criterion based on age; however, the majority of our patients were greater than 70 years old, representing those at highest risk for delirium.2 Significant outcomes among patients in the postintervention group include decreased incidence of delirium, lower average length of stay, decreased indwelling urinary catheter use, and increased compliance with delirium screening by nursing staff.

While the study’s focus was primarily on delirium prevention rather than treatment, these strategies may also have conferred the benefit of reversing delirium symptoms. In addition to measuring incidence of delirium, our primary outcome of percentage of tested shifts with 1 or more positive CAM was intended to assess the overall duration in which patients had delirium during their hospitalization. The reduction in shifts with positive CAMs observed in the postintervention group is notable, given that a significant percentage of patients with hospital delirium have the potential for symptom reversibility.12

Multiple studies have shown that admitted patients who develop delirium experience prolonged hospital stays, often up to 5 to 10 days longer.12-14 The decreased incidence and duration of delirium in our postintervention group is a reasonable explanation for the observed decrease in average length of stay. Our study is in line with previously documented initiatives that show that nonpharmacologic interventions can effectively address downstream health and fiscal sequelae of hospital delirium. For example, a volunteer-based initiative named the Hospital Elder Life Program, from which elements in our order set were modeled after, demonstrated significant reductions in delirium incidence, length of stay, and health care costs.14-16 Other initiatives that focused on educational training for nurses to assess and prevent delirium have also demonstrated similar positive results.17-19 Our study provides a model for effective nursing-focused education that can be reproduced in the hospital setting.

Unlike some other studies, which identified delirium based only on physician assessments, our initiative utilized the CAM performed by floor nurses to identify delirium. While this method

Our study demonstrated an increase in the overall compliance with the CAM screening during the postintervention period, which is significant given the under-recognition of delirium by health care professionals.20 We attribute this increase to greater realized importance and a higher level of confidence from nursing staff in recognizing and addressing delirium, as supported by survey data. While the increased screening of patients should be considered a positive outcome, it also poses the possibility that the observed decrease in delirium incidence in the postintervention group was in fact due to more CAMs performed on patients without delirium. Likewise, nurses may have become more adept at recognizing true delirium, as opposed to delirium mimics, in the latter period of the study.

Perhaps the greatest limitation of our study is the variability in performing and recording CAMs, as some patients had multiple CAMs recorded while others did not have any CAMs recorded. This may have been affected in part by the increase in COVID-19 cases in our hospital towards the latter half of the study, which resulted in changes in nursing assignments as well as patient comorbidities in ways that cannot be easily quantified. Given the limited size of our patient cohorts, certain outcomes, such as the use of sitters, physical restraints, and in-hospital mortality, were unable to be assessed for changes statistically. Causative relationships between our interventions and associated outcome measures are necessarily limited in a binary comparison between control and postintervention groups.

Within these limitations, our study demonstrates promising results in core dimensions of patient care. We anticipate further quality improvement initiatives involving greater numbers of nursing staff and patients to better quantify the impact of nonpharmacologic nursing-centered interventions for preventing hospital delirium.

Conclusion

A multimodal strategy involving nursing-focused training and nonpharmacologic interventions to address hospital delirium is associated with improved patient care outcomes and nursing confidence. Nurses play an integral role in the early recognition and prevention of hospital delirium, which directly translates to reducing burdens in both patient functionality and health care costs. Education and tools to equip nurses to perform standardized delirium screening and interventions should be prioritized.

Acknowledgment: The authors thanks Olena Svetlov, NP, Oscar Abarca, Jose Chavez, and Jenita Gutierrez.

Corresponding author: Jason Ching, MD, Department of Neurology, Cedars-Sinai Medical Center, 8700 Beverly Blvd, Los Angeles, CA 90048; jason.ching@cshs.org.

Financial disclosures: None.

Funding: This research was supported by NIH National Center for Advancing Translational Science (NCATS) UCLA CTSI Grant Number UL1TR001881.

From the Department of Neurology, Cedars-Sinai Medical Center, Los Angeles, CA (Drs. Ching, Darwish, Li, Wong, Simpson, and Funk), the Department of Anesthesia, Cedars-Sinai Medical Center, Los Angeles, CA (Keith Siegel), and the Department of Psychiatry, Cedars-Sinai Medical Center, Los Angeles, CA (Dr. Bamgbose).

Objectives: To reduce the incidence and duration of delirium among patients in a hospital ward through standardized delirium screening tools and nonpharmacologic interventions. To advance nursing-focused education on delirium-prevention strategies. To measure the efficacy of the interventions with the aim of reproducing best practices.

Background: Delirium is associated with poor patient outcomes but may be preventable in a significant percentage of hospitalized patients.

Methods: Following nursing-focused education to prevent delirium, we prospectively evaluated patient care outcomes in a consecutive series of patients who were admitted to a hospital medical-surgical ward within a 25-week period. All patients who had at least 1 Confusion Assessment Method (CAM) documented by a nurse during hospitalization met our inclusion criteria (N = 353). Standards for Quality Improvement Reporting Excellence guidelines were adhered to.

Results: There were 187 patients in the control group, and 166 in the postintervention group. Compared to the control group, the postintervention group had a significant decrease in the incidence of delirium during hospitalization (14.4% vs 4.2%) and a significant decrease in the mean percentage of tested nursing shifts with 1 or more positive CAM (4.9% vs 1.1%). Significant differences in secondary outcomes between the control and postintervention groups included median length of stay (6 days vs 4 days), mean length of stay (8.5 days vs 5.9 days), and use of an indwelling urinary catheter (9.1% vs 2.4%).

Conclusion: A multimodal strategy involving nursing-focused training and nonpharmacologic interventions to address hospital delirium is associated with improved patient care outcomes and nursing confidence. Nurses play an integral role in the early recognition and prevention of hospital delirium, which directly translates to reducing burdens in both patient functionality and health care costs.

Delirium is a disorder characterized by inattention and acute changes in cognition. It is defined by the American Psychiatric Association’s fifth edition of the Diagnostic and Statistical Manual of Mental Disorders as a disturbance in attention, awareness, and cognition over hours to a few days that is not better explained by a preexisting, established, or other evolving neurocognitive disorder.1 Delirium is common yet often under-recognized among hospitalized patients, particularly in the elderly. The incidence of delirium in elderly patients on admission is estimated to be 11% to 25%, and an additional 29% to 31% of elderly patients will develop delirium during the hospitalization.2 Delirium costs the health care system an estimated $38 billion to $152 billion per year.3 It is associated with negative outcomes, such as increased new placements to nursing homes, increased mortality, increased risk of dementia, and further cognitive deterioration among patients with dementia.4-6

Despite its prevalence, delirium may be preventable in a significant percentage of hospitalized patients. Targeted intervention strategies, such as frequent reorientation, maximizing sleep, early mobilization, restricting use of psychoactive medications, and addressing hearing or vision impairment, have been demonstrated to significantly reduce the incidence of hospital delirium.7,8 To achieve these goals, we explored the use of a multimodal strategy centered on nursing education. We integrated consistent, standardized delirium screening and nonpharmacologic interventions as part of a preventative protocol to reduce the incidence of delirium in the hospital ward.

Methods