User login

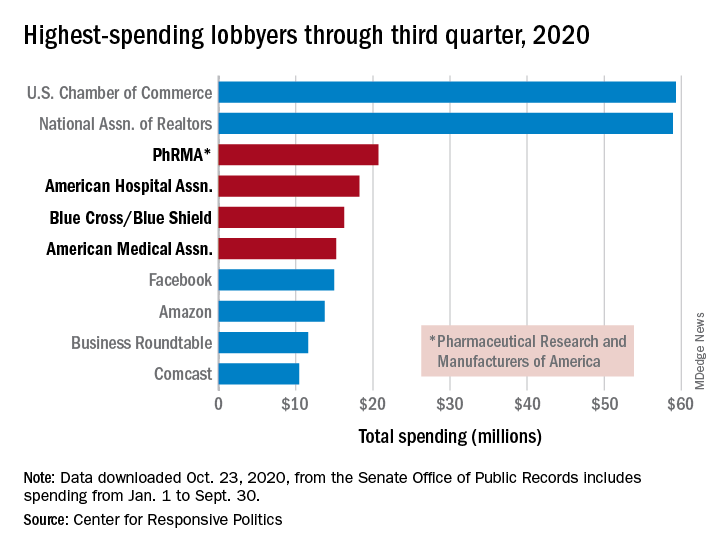

Health sector has spent $464 million on lobbying in 2020

, according to the Center for Responsive Politics.

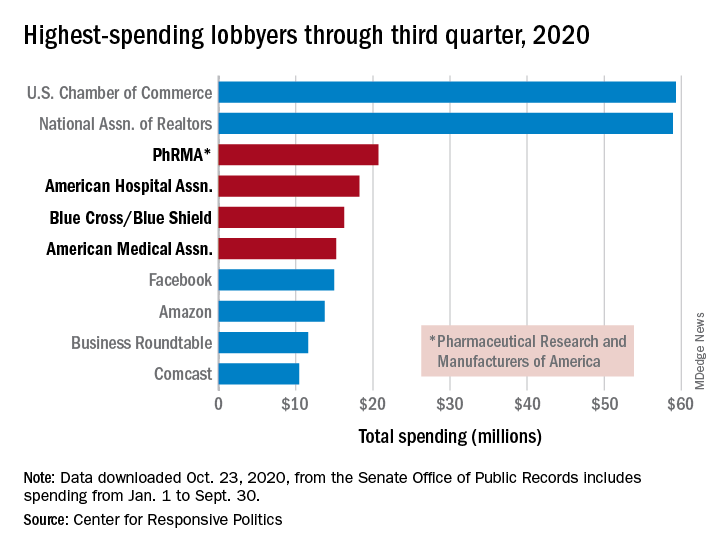

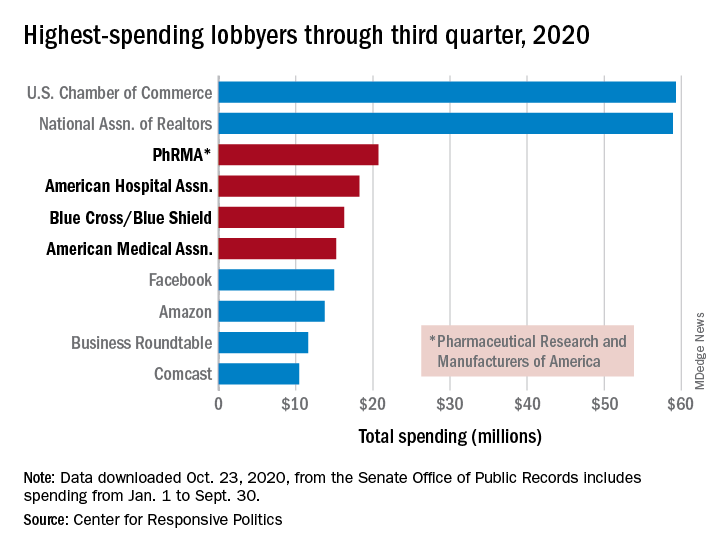

PhRMA spent $20.7 million on lobbying through the end of September, good enough for third on the overall list of U.S. companies and organizations. Three other members of the health sector made the top 10: the American Hospital Association ($18.3 million), BlueCross/BlueShield ($16.3 million), and the American Medical Association ($15.2 million), the center reported.

Total spending by the health sector was $464 million from Jan. 1 to Sept. 30, topping the finance/insurance/real estate sector at $403 million, and miscellaneous business at $371 million. Miscellaneous business is the home of the U.S. Chamber of Commerce, the annual leader in such spending for the last 20 years, based on data from the Senate Office of Public Records.

The largest share of health sector spending came from pharmaceuticals/health products, with a total of almost $233 million, just slightly more than the sector’s four other constituents combined: hospitals/nursing homes ($80 million), health services/HMOs ($75 million), health professionals ($67 million), and miscellaneous health ($9.5 million), the center said on OpenSecrets.org.

Taking one step down from the sector level, that $233 million made pharmaceuticals/health products the highest spending of about 100 industries in 2020, nearly doubling the efforts of electronics manufacturing and equipment ($118 million), which came a distant second. Hospitals/nursing homes was eighth on the industry list, the center noted.

, according to the Center for Responsive Politics.

PhRMA spent $20.7 million on lobbying through the end of September, good enough for third on the overall list of U.S. companies and organizations. Three other members of the health sector made the top 10: the American Hospital Association ($18.3 million), BlueCross/BlueShield ($16.3 million), and the American Medical Association ($15.2 million), the center reported.

Total spending by the health sector was $464 million from Jan. 1 to Sept. 30, topping the finance/insurance/real estate sector at $403 million, and miscellaneous business at $371 million. Miscellaneous business is the home of the U.S. Chamber of Commerce, the annual leader in such spending for the last 20 years, based on data from the Senate Office of Public Records.

The largest share of health sector spending came from pharmaceuticals/health products, with a total of almost $233 million, just slightly more than the sector’s four other constituents combined: hospitals/nursing homes ($80 million), health services/HMOs ($75 million), health professionals ($67 million), and miscellaneous health ($9.5 million), the center said on OpenSecrets.org.

Taking one step down from the sector level, that $233 million made pharmaceuticals/health products the highest spending of about 100 industries in 2020, nearly doubling the efforts of electronics manufacturing and equipment ($118 million), which came a distant second. Hospitals/nursing homes was eighth on the industry list, the center noted.

, according to the Center for Responsive Politics.

PhRMA spent $20.7 million on lobbying through the end of September, good enough for third on the overall list of U.S. companies and organizations. Three other members of the health sector made the top 10: the American Hospital Association ($18.3 million), BlueCross/BlueShield ($16.3 million), and the American Medical Association ($15.2 million), the center reported.

Total spending by the health sector was $464 million from Jan. 1 to Sept. 30, topping the finance/insurance/real estate sector at $403 million, and miscellaneous business at $371 million. Miscellaneous business is the home of the U.S. Chamber of Commerce, the annual leader in such spending for the last 20 years, based on data from the Senate Office of Public Records.

The largest share of health sector spending came from pharmaceuticals/health products, with a total of almost $233 million, just slightly more than the sector’s four other constituents combined: hospitals/nursing homes ($80 million), health services/HMOs ($75 million), health professionals ($67 million), and miscellaneous health ($9.5 million), the center said on OpenSecrets.org.

Taking one step down from the sector level, that $233 million made pharmaceuticals/health products the highest spending of about 100 industries in 2020, nearly doubling the efforts of electronics manufacturing and equipment ($118 million), which came a distant second. Hospitals/nursing homes was eighth on the industry list, the center noted.

CDC panel takes on COVID vaccine rollout, risks, and side effects

Federal advisers who will help determine which Americans get the first COVID vaccines took an in-depth look Oct. 30 at the challenges they face in selecting priority groups.

The Advisory Committee on Immunization Practices (ACIP) of the Centers for Disease Control and Prevention (CDC) will face two key decisions once a COVID vaccine wins clearance from the US Food and Drug Administration (FDA).

ACIP will need to decide whether to recommend its use in adults (the age group in which vaccines are currently being tested). The group will also need to offer direction on which groups should get priority in vaccine allocation, inasmuch as early supplies will not be sufficient to vaccinate everyone.

At the Oct. 30 meeting, CDC’s Kathleen Dooling, MD, MPH, suggested that ACIP plan on tackling these issues as two separate questions when it comes time to weigh in on an approved vaccine. Although there was no formal vote among ACIP members at the meeting, Dooling’s proposal for tackling a future recommendation in a two-part fashion drew positive feedback.

ACIP member Katherine A. Poehling, MD, MPH, suggested that the panel and CDC be ready to reexamine the situation frequently regarding COVID vaccination. “Perhaps we could think about reviewing data on a monthly basis and updating the recommendation, so that we can account for the concerns and balance both the benefits and the [potential] harm,” Poehling said.

Dooling agreed. “Both the vaccine recommendation and allocation will be revisited in what is a very dynamic situation,” Dooling replied to Poehling. “So all new evidence will be brought to ACIP, and certainly the allocation as vaccine distribution proceeds will need to be adjusted accordingly.”

Ethics and limited evidence

During the meeting, ACIP members repeatedly expressed discomfort with the prospect of having to weigh in on widespread use of COVID vaccines on the basis of limited evidence.

Within months, FDA may opt for a special clearance, known as an emergency use authorization (EUA), for one or more of the experimental COVID vaccines now in advanced testing. Many of FDA’s past EUA clearances were granted for test kits. For those EUA approvals, the agency considered risks of false results but not longer-term, direct harm to patients from these products.

With a COVID vaccine, there will be strong pressure to distribute doses as quickly as possible with the hope of curbing the pandemic, which has already led to more than 229,000 deaths in the United States alone and has disrupted lives and economies around the world. But questions will persist about the possibility of serious complications from these vaccines, ACIP members noted.

“My personal struggle is the ethical side and how to balance these two,” said ACIP member Robert L. Atmar, MD, of Baylor College of Medicine, Houston, Texas, who noted that he expects his fellow panelists to share this concern.

Currently, four experimental COVID vaccines likely to be used in the United States have advanced to phase 3 testing. Pfizer Inc and BioNtech have enrolled more than 42,000 participants in a test of their candidate, BNT162b2 vaccine, and rival Moderna has enrolled about 30,000 participants in a test of its mRNA-1273 vaccine, CDC staff said.

The other two advanced COVID vaccine candidates have overcome recent hurdles. AstraZeneca Plc on Oct. 23 announced that FDA had removed a hold on the testing of its AZD1222 vaccine candidate; the trial will enroll approximately 30,000 people. Johnson & Johnson’s Janssen unit also announced that day the lifting of a safety pause for its Ad26.COV2.S vaccine; the phase 3 trial for that vaccine will enroll approximately 60,000 volunteers. Federal agencies, states, and territories have developed plans for future distribution of COVID vaccines, CDC staff said in briefing materials for today’s ACIP meeting.

Several ACIP members raised many of the same concerns that members of an FDA advisory committee raised at a meeting earlier in October. ACIP and FDA advisers honed in on the FDA’s decision to set a median follow-up duration of 2 months in phase 3 trials in connection with expected EUA applications for COVID-19 vaccines.

“I struggle with following people for 2 months after their second vaccination as a time point to start making final decisions about safety,” said ACIP member Sharon E. Frey, MD, a professor at St. Louis University School of Medicine, St. Louis, Missouri. “I just want to put that out there.”

Medical front line, then who?

There is consensus that healthcare workers be in the first stage ― Phase 1 ― of distribution. That recommendation was made in a report from the National Academies of Sciences, Engineering, and Medicine (NASEM). Phase 1A would include first responders; Phase 1B might include people of all ages who have two or more comorbidities that put them at significantly higher risk for COVID-19 or death, as well as older adults living in congregate or overcrowded settings, the NASEM report said.

A presentation from the CDC’s Matthew Biggerstaff, ScD, MPH, underscored challenges in distributing what are expected to be limited initial supplies of COVID vaccines.

Biggerstaff showed several scenarios the CDC’s Data, Analytics, and Modeling Task Force had studied. The initial allocation of vaccines would be for healthcare workers, followed by what the CDC called Phase 1B.

Choices for a rollout may include next giving COVID vaccines to people at high risk, such as persons who have one or more chronic medical conditions, including heart disease, diabetes, kidney disease, or obesity. Other options for the rollout could be to vaccinate people aged 65 years and older or essential workers whose employment puts them in contact with the public, thus raising the risk of contracting the virus.

The CDC’s research found that the greatest impact in preventing death was to initially vaccinate adults aged 65 and older in Phase 1B. The agency staff described this approach as likely to result in an about “1 to 11% increase in averted deaths across the scenarios.”

Initially vaccinating essential workers or high-risk adults in Phase 1B would avert the most infections. The agency staff described this approach as yielding about “1 to 5% increase in averted infections across the scenarios,” Biggerstaff said during his presentation.

The following are other findings of the CDC staff:

The earlier the vaccine rollout relative to increasing transmission, the greater the averted percentage and differences between the strategies.

Differences were not substantial in some scenarios.

The need to continue efforts to slow the spread of COVID-19 should be emphasized.

Adverse effects

ACIP members also heard about strategies for tracking potential side effects of future vaccines. A presentation by Tom Shimabukuro, MD, MPH, MBA, from the CDC’s COVID-19 Vaccine Task Force/Vaccine Safety Team, included details about a new smartphone-based active surveillance program for COVID-19 vaccine safety.

Known as v-safe, this system would use Web-based survey monitoring and incorporate text messaging. It would conduct electronic health checks on vaccine recipients, which would occur daily during the first week post vaccination and weekly thereafter for 6 weeks from the time of vaccination.

Clinicians “can play an important role in helping CDC enroll patients in v-safe at the time of vaccination,” Shimabukuro noted in his presentation. This would add another task, though, for clinicians, the CDC staff noted.

Pregnancy and breastfeeding are special concerns

Of special concern with the rollout of a COVID vaccine are recommendations regarding pregnancy and breastfeeding. Women constitute about 75% of the healthcare workforce, CDC staff noted.

At the time the initial ACIP COVID vaccination recommendations are made, there could be approximately 330,000 healthcare personnel who are pregnant or who have recently given birth. Available data indicate potentially increased risks for severe maternal illness and preterm birth associated with SARS-CoV-2 infection, said CDC’s Megan Wallace, DrPH, MPH, in a presentation for the Friday meeting.

In an Oct. 27 letter to ACIP, Chair Jose Romero, the American College of Obstetricians and Gynecologists (ACOG), urged the panel to ensure that pregnant women and new mothers in the healthcare workforce have priority access to a COVID vaccine. Pregnant and lactating women were “noticeably and alarmingly absent from the NASEM vaccine allocation plan for COVID-19,” wrote Christopher M. Zahn, MD, vice president for practice activities at ACOG, in the letter to Romero.

“ACOG urges ACIP to incorporate pregnant and lactating women clearly and explicitly into its COVID-19 vaccine allocation and prioritization framework,” Zahn wrote. “Should an Emergency Use Authorization be executed for one or more COVID-19 vaccines and provide a permissive recommendation for pregnant and lactating women, pregnant health care workers, pregnant first responders, and pregnant individuals with underlying conditions should be prioritized for vaccination alongside their non-pregnant peers.”

This article first appeared on Medscape.com.

Federal advisers who will help determine which Americans get the first COVID vaccines took an in-depth look Oct. 30 at the challenges they face in selecting priority groups.

The Advisory Committee on Immunization Practices (ACIP) of the Centers for Disease Control and Prevention (CDC) will face two key decisions once a COVID vaccine wins clearance from the US Food and Drug Administration (FDA).

ACIP will need to decide whether to recommend its use in adults (the age group in which vaccines are currently being tested). The group will also need to offer direction on which groups should get priority in vaccine allocation, inasmuch as early supplies will not be sufficient to vaccinate everyone.

At the Oct. 30 meeting, CDC’s Kathleen Dooling, MD, MPH, suggested that ACIP plan on tackling these issues as two separate questions when it comes time to weigh in on an approved vaccine. Although there was no formal vote among ACIP members at the meeting, Dooling’s proposal for tackling a future recommendation in a two-part fashion drew positive feedback.

ACIP member Katherine A. Poehling, MD, MPH, suggested that the panel and CDC be ready to reexamine the situation frequently regarding COVID vaccination. “Perhaps we could think about reviewing data on a monthly basis and updating the recommendation, so that we can account for the concerns and balance both the benefits and the [potential] harm,” Poehling said.

Dooling agreed. “Both the vaccine recommendation and allocation will be revisited in what is a very dynamic situation,” Dooling replied to Poehling. “So all new evidence will be brought to ACIP, and certainly the allocation as vaccine distribution proceeds will need to be adjusted accordingly.”

Ethics and limited evidence

During the meeting, ACIP members repeatedly expressed discomfort with the prospect of having to weigh in on widespread use of COVID vaccines on the basis of limited evidence.

Within months, FDA may opt for a special clearance, known as an emergency use authorization (EUA), for one or more of the experimental COVID vaccines now in advanced testing. Many of FDA’s past EUA clearances were granted for test kits. For those EUA approvals, the agency considered risks of false results but not longer-term, direct harm to patients from these products.

With a COVID vaccine, there will be strong pressure to distribute doses as quickly as possible with the hope of curbing the pandemic, which has already led to more than 229,000 deaths in the United States alone and has disrupted lives and economies around the world. But questions will persist about the possibility of serious complications from these vaccines, ACIP members noted.

“My personal struggle is the ethical side and how to balance these two,” said ACIP member Robert L. Atmar, MD, of Baylor College of Medicine, Houston, Texas, who noted that he expects his fellow panelists to share this concern.

Currently, four experimental COVID vaccines likely to be used in the United States have advanced to phase 3 testing. Pfizer Inc and BioNtech have enrolled more than 42,000 participants in a test of their candidate, BNT162b2 vaccine, and rival Moderna has enrolled about 30,000 participants in a test of its mRNA-1273 vaccine, CDC staff said.

The other two advanced COVID vaccine candidates have overcome recent hurdles. AstraZeneca Plc on Oct. 23 announced that FDA had removed a hold on the testing of its AZD1222 vaccine candidate; the trial will enroll approximately 30,000 people. Johnson & Johnson’s Janssen unit also announced that day the lifting of a safety pause for its Ad26.COV2.S vaccine; the phase 3 trial for that vaccine will enroll approximately 60,000 volunteers. Federal agencies, states, and territories have developed plans for future distribution of COVID vaccines, CDC staff said in briefing materials for today’s ACIP meeting.

Several ACIP members raised many of the same concerns that members of an FDA advisory committee raised at a meeting earlier in October. ACIP and FDA advisers honed in on the FDA’s decision to set a median follow-up duration of 2 months in phase 3 trials in connection with expected EUA applications for COVID-19 vaccines.

“I struggle with following people for 2 months after their second vaccination as a time point to start making final decisions about safety,” said ACIP member Sharon E. Frey, MD, a professor at St. Louis University School of Medicine, St. Louis, Missouri. “I just want to put that out there.”

Medical front line, then who?

There is consensus that healthcare workers be in the first stage ― Phase 1 ― of distribution. That recommendation was made in a report from the National Academies of Sciences, Engineering, and Medicine (NASEM). Phase 1A would include first responders; Phase 1B might include people of all ages who have two or more comorbidities that put them at significantly higher risk for COVID-19 or death, as well as older adults living in congregate or overcrowded settings, the NASEM report said.

A presentation from the CDC’s Matthew Biggerstaff, ScD, MPH, underscored challenges in distributing what are expected to be limited initial supplies of COVID vaccines.

Biggerstaff showed several scenarios the CDC’s Data, Analytics, and Modeling Task Force had studied. The initial allocation of vaccines would be for healthcare workers, followed by what the CDC called Phase 1B.

Choices for a rollout may include next giving COVID vaccines to people at high risk, such as persons who have one or more chronic medical conditions, including heart disease, diabetes, kidney disease, or obesity. Other options for the rollout could be to vaccinate people aged 65 years and older or essential workers whose employment puts them in contact with the public, thus raising the risk of contracting the virus.

The CDC’s research found that the greatest impact in preventing death was to initially vaccinate adults aged 65 and older in Phase 1B. The agency staff described this approach as likely to result in an about “1 to 11% increase in averted deaths across the scenarios.”

Initially vaccinating essential workers or high-risk adults in Phase 1B would avert the most infections. The agency staff described this approach as yielding about “1 to 5% increase in averted infections across the scenarios,” Biggerstaff said during his presentation.

The following are other findings of the CDC staff:

The earlier the vaccine rollout relative to increasing transmission, the greater the averted percentage and differences between the strategies.

Differences were not substantial in some scenarios.

The need to continue efforts to slow the spread of COVID-19 should be emphasized.

Adverse effects

ACIP members also heard about strategies for tracking potential side effects of future vaccines. A presentation by Tom Shimabukuro, MD, MPH, MBA, from the CDC’s COVID-19 Vaccine Task Force/Vaccine Safety Team, included details about a new smartphone-based active surveillance program for COVID-19 vaccine safety.

Known as v-safe, this system would use Web-based survey monitoring and incorporate text messaging. It would conduct electronic health checks on vaccine recipients, which would occur daily during the first week post vaccination and weekly thereafter for 6 weeks from the time of vaccination.

Clinicians “can play an important role in helping CDC enroll patients in v-safe at the time of vaccination,” Shimabukuro noted in his presentation. This would add another task, though, for clinicians, the CDC staff noted.

Pregnancy and breastfeeding are special concerns

Of special concern with the rollout of a COVID vaccine are recommendations regarding pregnancy and breastfeeding. Women constitute about 75% of the healthcare workforce, CDC staff noted.

At the time the initial ACIP COVID vaccination recommendations are made, there could be approximately 330,000 healthcare personnel who are pregnant or who have recently given birth. Available data indicate potentially increased risks for severe maternal illness and preterm birth associated with SARS-CoV-2 infection, said CDC’s Megan Wallace, DrPH, MPH, in a presentation for the Friday meeting.

In an Oct. 27 letter to ACIP, Chair Jose Romero, the American College of Obstetricians and Gynecologists (ACOG), urged the panel to ensure that pregnant women and new mothers in the healthcare workforce have priority access to a COVID vaccine. Pregnant and lactating women were “noticeably and alarmingly absent from the NASEM vaccine allocation plan for COVID-19,” wrote Christopher M. Zahn, MD, vice president for practice activities at ACOG, in the letter to Romero.

“ACOG urges ACIP to incorporate pregnant and lactating women clearly and explicitly into its COVID-19 vaccine allocation and prioritization framework,” Zahn wrote. “Should an Emergency Use Authorization be executed for one or more COVID-19 vaccines and provide a permissive recommendation for pregnant and lactating women, pregnant health care workers, pregnant first responders, and pregnant individuals with underlying conditions should be prioritized for vaccination alongside their non-pregnant peers.”

This article first appeared on Medscape.com.

Federal advisers who will help determine which Americans get the first COVID vaccines took an in-depth look Oct. 30 at the challenges they face in selecting priority groups.

The Advisory Committee on Immunization Practices (ACIP) of the Centers for Disease Control and Prevention (CDC) will face two key decisions once a COVID vaccine wins clearance from the US Food and Drug Administration (FDA).

ACIP will need to decide whether to recommend its use in adults (the age group in which vaccines are currently being tested). The group will also need to offer direction on which groups should get priority in vaccine allocation, inasmuch as early supplies will not be sufficient to vaccinate everyone.

At the Oct. 30 meeting, CDC’s Kathleen Dooling, MD, MPH, suggested that ACIP plan on tackling these issues as two separate questions when it comes time to weigh in on an approved vaccine. Although there was no formal vote among ACIP members at the meeting, Dooling’s proposal for tackling a future recommendation in a two-part fashion drew positive feedback.

ACIP member Katherine A. Poehling, MD, MPH, suggested that the panel and CDC be ready to reexamine the situation frequently regarding COVID vaccination. “Perhaps we could think about reviewing data on a monthly basis and updating the recommendation, so that we can account for the concerns and balance both the benefits and the [potential] harm,” Poehling said.

Dooling agreed. “Both the vaccine recommendation and allocation will be revisited in what is a very dynamic situation,” Dooling replied to Poehling. “So all new evidence will be brought to ACIP, and certainly the allocation as vaccine distribution proceeds will need to be adjusted accordingly.”

Ethics and limited evidence

During the meeting, ACIP members repeatedly expressed discomfort with the prospect of having to weigh in on widespread use of COVID vaccines on the basis of limited evidence.

Within months, FDA may opt for a special clearance, known as an emergency use authorization (EUA), for one or more of the experimental COVID vaccines now in advanced testing. Many of FDA’s past EUA clearances were granted for test kits. For those EUA approvals, the agency considered risks of false results but not longer-term, direct harm to patients from these products.

With a COVID vaccine, there will be strong pressure to distribute doses as quickly as possible with the hope of curbing the pandemic, which has already led to more than 229,000 deaths in the United States alone and has disrupted lives and economies around the world. But questions will persist about the possibility of serious complications from these vaccines, ACIP members noted.

“My personal struggle is the ethical side and how to balance these two,” said ACIP member Robert L. Atmar, MD, of Baylor College of Medicine, Houston, Texas, who noted that he expects his fellow panelists to share this concern.

Currently, four experimental COVID vaccines likely to be used in the United States have advanced to phase 3 testing. Pfizer Inc and BioNtech have enrolled more than 42,000 participants in a test of their candidate, BNT162b2 vaccine, and rival Moderna has enrolled about 30,000 participants in a test of its mRNA-1273 vaccine, CDC staff said.

The other two advanced COVID vaccine candidates have overcome recent hurdles. AstraZeneca Plc on Oct. 23 announced that FDA had removed a hold on the testing of its AZD1222 vaccine candidate; the trial will enroll approximately 30,000 people. Johnson & Johnson’s Janssen unit also announced that day the lifting of a safety pause for its Ad26.COV2.S vaccine; the phase 3 trial for that vaccine will enroll approximately 60,000 volunteers. Federal agencies, states, and territories have developed plans for future distribution of COVID vaccines, CDC staff said in briefing materials for today’s ACIP meeting.

Several ACIP members raised many of the same concerns that members of an FDA advisory committee raised at a meeting earlier in October. ACIP and FDA advisers honed in on the FDA’s decision to set a median follow-up duration of 2 months in phase 3 trials in connection with expected EUA applications for COVID-19 vaccines.

“I struggle with following people for 2 months after their second vaccination as a time point to start making final decisions about safety,” said ACIP member Sharon E. Frey, MD, a professor at St. Louis University School of Medicine, St. Louis, Missouri. “I just want to put that out there.”

Medical front line, then who?

There is consensus that healthcare workers be in the first stage ― Phase 1 ― of distribution. That recommendation was made in a report from the National Academies of Sciences, Engineering, and Medicine (NASEM). Phase 1A would include first responders; Phase 1B might include people of all ages who have two or more comorbidities that put them at significantly higher risk for COVID-19 or death, as well as older adults living in congregate or overcrowded settings, the NASEM report said.

A presentation from the CDC’s Matthew Biggerstaff, ScD, MPH, underscored challenges in distributing what are expected to be limited initial supplies of COVID vaccines.

Biggerstaff showed several scenarios the CDC’s Data, Analytics, and Modeling Task Force had studied. The initial allocation of vaccines would be for healthcare workers, followed by what the CDC called Phase 1B.

Choices for a rollout may include next giving COVID vaccines to people at high risk, such as persons who have one or more chronic medical conditions, including heart disease, diabetes, kidney disease, or obesity. Other options for the rollout could be to vaccinate people aged 65 years and older or essential workers whose employment puts them in contact with the public, thus raising the risk of contracting the virus.

The CDC’s research found that the greatest impact in preventing death was to initially vaccinate adults aged 65 and older in Phase 1B. The agency staff described this approach as likely to result in an about “1 to 11% increase in averted deaths across the scenarios.”

Initially vaccinating essential workers or high-risk adults in Phase 1B would avert the most infections. The agency staff described this approach as yielding about “1 to 5% increase in averted infections across the scenarios,” Biggerstaff said during his presentation.

The following are other findings of the CDC staff:

The earlier the vaccine rollout relative to increasing transmission, the greater the averted percentage and differences between the strategies.

Differences were not substantial in some scenarios.

The need to continue efforts to slow the spread of COVID-19 should be emphasized.

Adverse effects

ACIP members also heard about strategies for tracking potential side effects of future vaccines. A presentation by Tom Shimabukuro, MD, MPH, MBA, from the CDC’s COVID-19 Vaccine Task Force/Vaccine Safety Team, included details about a new smartphone-based active surveillance program for COVID-19 vaccine safety.

Known as v-safe, this system would use Web-based survey monitoring and incorporate text messaging. It would conduct electronic health checks on vaccine recipients, which would occur daily during the first week post vaccination and weekly thereafter for 6 weeks from the time of vaccination.

Clinicians “can play an important role in helping CDC enroll patients in v-safe at the time of vaccination,” Shimabukuro noted in his presentation. This would add another task, though, for clinicians, the CDC staff noted.

Pregnancy and breastfeeding are special concerns

Of special concern with the rollout of a COVID vaccine are recommendations regarding pregnancy and breastfeeding. Women constitute about 75% of the healthcare workforce, CDC staff noted.

At the time the initial ACIP COVID vaccination recommendations are made, there could be approximately 330,000 healthcare personnel who are pregnant or who have recently given birth. Available data indicate potentially increased risks for severe maternal illness and preterm birth associated with SARS-CoV-2 infection, said CDC’s Megan Wallace, DrPH, MPH, in a presentation for the Friday meeting.

In an Oct. 27 letter to ACIP, Chair Jose Romero, the American College of Obstetricians and Gynecologists (ACOG), urged the panel to ensure that pregnant women and new mothers in the healthcare workforce have priority access to a COVID vaccine. Pregnant and lactating women were “noticeably and alarmingly absent from the NASEM vaccine allocation plan for COVID-19,” wrote Christopher M. Zahn, MD, vice president for practice activities at ACOG, in the letter to Romero.

“ACOG urges ACIP to incorporate pregnant and lactating women clearly and explicitly into its COVID-19 vaccine allocation and prioritization framework,” Zahn wrote. “Should an Emergency Use Authorization be executed for one or more COVID-19 vaccines and provide a permissive recommendation for pregnant and lactating women, pregnant health care workers, pregnant first responders, and pregnant individuals with underlying conditions should be prioritized for vaccination alongside their non-pregnant peers.”

This article first appeared on Medscape.com.

HHS extends deadline for patient access to your clinical notes

The Department of Health & Human Services on Oct. 29 extended the deadline for health care groups to provide patients with immediate electronic access to their doctors’ clinical notes as well as test results and reports from pathology and imaging.

The mandate, called “open notes” by many, is part of the 21st Century Cures Act, and will now go into effect April 5.

The announcement comes just 4 days before the previously established Nov. 2 deadline and gives the pandemic as the reason for the delay.

“We are hearing that, while there is strong support for advancing patient access … stakeholders also must manage the needs being experienced during the current pandemic,” Don Rucker, MD, national coordinator for health information technology at HHS, said in a press statement.

“To be clear, the Office of the National Coordinator is not removing the requirements advancing patient access to their health information,” he added.

‘What you make of it’

Scott MacDonald, MD, electronic health record medical director at the University of California, Davis, said his organization is proceeding anyway. “UC Davis is going to start releasing notes and test results on Nov. 12,” he said in an interview.

Other organizations and practices now have more time, he said, but the law stays the same. “There’s no change to the what or why – only to the when,” Dr. MacDonald pointed out.

Vanderbilt University Medical Center in Nashville, Tenn., will take advantage of the extra time, Trent Rosenbloom, MD, MPH, director of patient portals, said in an interview.

“Given the super-short time frame we had to work under as this emerged out from dealing with COVID, we feel that we have not addressed all the potential legal-edge cases such as dealing with adolescent medicine and child abuse,” he said.

On Oct. 21, this news organization reported on the then-imminent start of the new law, which irked many readers. They cited, among other things, the likelihood of patient confusion with fast patient access to all clinical notes.

“To me, the biggest issue is that we speak a foreign language that most outside of medicine don’t speak. Our job is to explain it to the patient at a level they can understand. What will 100% happen now is that a patient will not be able to reconcile what is in the note to what they’ve been told,” Andrew White, MD, wrote in a reader comment.

But benefits of open notes outweigh the risks, say proponents, who claim that doctor-patient communication and trust actually improve with information access and that research indicates other benefits such as improved medication adherence.

Open notes are “what you make of it,” said Marlene Millen, MD, an internist at UC San Diego Health, which has had a pilot open-notes program for 3 years.

“I actually end all of my appointments with: ‘Don’t forget to read your note later,’ ” she said in an interview.

Dr. Millen feared open notes initially but, within the first 3 months of usage, about 15 patients gave her direct feedback on how much they appreciated her notes. “It seemed to really reassure them that they were getting good care.”

Dr. MacDonald and Dr. Millen disclosed no relevant financial relationships.

A version of this article originally appeared on Medscape.com.

The Department of Health & Human Services on Oct. 29 extended the deadline for health care groups to provide patients with immediate electronic access to their doctors’ clinical notes as well as test results and reports from pathology and imaging.

The mandate, called “open notes” by many, is part of the 21st Century Cures Act, and will now go into effect April 5.

The announcement comes just 4 days before the previously established Nov. 2 deadline and gives the pandemic as the reason for the delay.

“We are hearing that, while there is strong support for advancing patient access … stakeholders also must manage the needs being experienced during the current pandemic,” Don Rucker, MD, national coordinator for health information technology at HHS, said in a press statement.

“To be clear, the Office of the National Coordinator is not removing the requirements advancing patient access to their health information,” he added.

‘What you make of it’

Scott MacDonald, MD, electronic health record medical director at the University of California, Davis, said his organization is proceeding anyway. “UC Davis is going to start releasing notes and test results on Nov. 12,” he said in an interview.

Other organizations and practices now have more time, he said, but the law stays the same. “There’s no change to the what or why – only to the when,” Dr. MacDonald pointed out.

Vanderbilt University Medical Center in Nashville, Tenn., will take advantage of the extra time, Trent Rosenbloom, MD, MPH, director of patient portals, said in an interview.

“Given the super-short time frame we had to work under as this emerged out from dealing with COVID, we feel that we have not addressed all the potential legal-edge cases such as dealing with adolescent medicine and child abuse,” he said.

On Oct. 21, this news organization reported on the then-imminent start of the new law, which irked many readers. They cited, among other things, the likelihood of patient confusion with fast patient access to all clinical notes.

“To me, the biggest issue is that we speak a foreign language that most outside of medicine don’t speak. Our job is to explain it to the patient at a level they can understand. What will 100% happen now is that a patient will not be able to reconcile what is in the note to what they’ve been told,” Andrew White, MD, wrote in a reader comment.

But benefits of open notes outweigh the risks, say proponents, who claim that doctor-patient communication and trust actually improve with information access and that research indicates other benefits such as improved medication adherence.

Open notes are “what you make of it,” said Marlene Millen, MD, an internist at UC San Diego Health, which has had a pilot open-notes program for 3 years.

“I actually end all of my appointments with: ‘Don’t forget to read your note later,’ ” she said in an interview.

Dr. Millen feared open notes initially but, within the first 3 months of usage, about 15 patients gave her direct feedback on how much they appreciated her notes. “It seemed to really reassure them that they were getting good care.”

Dr. MacDonald and Dr. Millen disclosed no relevant financial relationships.

A version of this article originally appeared on Medscape.com.

The Department of Health & Human Services on Oct. 29 extended the deadline for health care groups to provide patients with immediate electronic access to their doctors’ clinical notes as well as test results and reports from pathology and imaging.

The mandate, called “open notes” by many, is part of the 21st Century Cures Act, and will now go into effect April 5.

The announcement comes just 4 days before the previously established Nov. 2 deadline and gives the pandemic as the reason for the delay.

“We are hearing that, while there is strong support for advancing patient access … stakeholders also must manage the needs being experienced during the current pandemic,” Don Rucker, MD, national coordinator for health information technology at HHS, said in a press statement.

“To be clear, the Office of the National Coordinator is not removing the requirements advancing patient access to their health information,” he added.

‘What you make of it’

Scott MacDonald, MD, electronic health record medical director at the University of California, Davis, said his organization is proceeding anyway. “UC Davis is going to start releasing notes and test results on Nov. 12,” he said in an interview.

Other organizations and practices now have more time, he said, but the law stays the same. “There’s no change to the what or why – only to the when,” Dr. MacDonald pointed out.

Vanderbilt University Medical Center in Nashville, Tenn., will take advantage of the extra time, Trent Rosenbloom, MD, MPH, director of patient portals, said in an interview.

“Given the super-short time frame we had to work under as this emerged out from dealing with COVID, we feel that we have not addressed all the potential legal-edge cases such as dealing with adolescent medicine and child abuse,” he said.

On Oct. 21, this news organization reported on the then-imminent start of the new law, which irked many readers. They cited, among other things, the likelihood of patient confusion with fast patient access to all clinical notes.

“To me, the biggest issue is that we speak a foreign language that most outside of medicine don’t speak. Our job is to explain it to the patient at a level they can understand. What will 100% happen now is that a patient will not be able to reconcile what is in the note to what they’ve been told,” Andrew White, MD, wrote in a reader comment.

But benefits of open notes outweigh the risks, say proponents, who claim that doctor-patient communication and trust actually improve with information access and that research indicates other benefits such as improved medication adherence.

Open notes are “what you make of it,” said Marlene Millen, MD, an internist at UC San Diego Health, which has had a pilot open-notes program for 3 years.

“I actually end all of my appointments with: ‘Don’t forget to read your note later,’ ” she said in an interview.

Dr. Millen feared open notes initially but, within the first 3 months of usage, about 15 patients gave her direct feedback on how much they appreciated her notes. “It seemed to really reassure them that they were getting good care.”

Dr. MacDonald and Dr. Millen disclosed no relevant financial relationships.

A version of this article originally appeared on Medscape.com.

Florida will investigate all COVID-19 deaths

The Florida Department of Health will investigate the state’s 16,000 coronavirus deaths due to questions about the integrity of the data, according to an announcement issued Wednesday.

State health department officials said the “fatality data reported to the state consistently presents confusion and warrants a rigorous review.” The review is meant to “ensure data integrity.”

“During a pandemic, the public must be able to rely on accurate public health data to make informed decisions,” Scott Rivkees, the surgeon general for Florida, said in the statement.

Among the 95 deaths reported Wednesday for instance, 16 had more than a 2-month separation between the time of testing positive for COVID-19 and passing away, and 5 cases had a 3-month gap. In addition, 11 of the deaths occurred more than a month ago.

The health department then listed data for all 95 cases, including the age, gender, county and the dates of test positivity and death. Palm Beach County had 50 of the COVID-19 deaths.

“To ensure the accuracy of COVID-19 related deaths, the department will be performing additional reviews of all deaths,” Rivkees said. “Timely and accurate data remains a top priority of the Department of Health.”

Last week, Jose Oliva, speaker of the Florida House of Representatives, said medical examiner reports were “often lacking in rigor.” House Democrats then said Republicans were trying to “downplay the death toll,” according to the South Florida Sun Sentinel .

Fred Piccolo Jr., a spokesman for Florida Gov. Ron DeSantis, told the newspaper Wednesday that officials have struggled to obtain timely data. Labs sometimes report test results from weeks before, he added.

“It’s really one of those things that you gotta know if someone is dying of COVID or if they’re not,” Piccolo said. “Then you can legitimately say, here are the numbers.”

Sources

Florida Department of Health, “Florida Surgeon General Implements Additional Review Process for Fatalities Attributed to COVID-19 to Ensure Data Integrity.”

South Florida Sun Sentinel, “Florida to investigate all COVID-19 deaths after questions about ‘integrity’ of data.”

WebMD Health News © 2020

This article first appeared on Medscape.com.

The Florida Department of Health will investigate the state’s 16,000 coronavirus deaths due to questions about the integrity of the data, according to an announcement issued Wednesday.

State health department officials said the “fatality data reported to the state consistently presents confusion and warrants a rigorous review.” The review is meant to “ensure data integrity.”

“During a pandemic, the public must be able to rely on accurate public health data to make informed decisions,” Scott Rivkees, the surgeon general for Florida, said in the statement.

Among the 95 deaths reported Wednesday for instance, 16 had more than a 2-month separation between the time of testing positive for COVID-19 and passing away, and 5 cases had a 3-month gap. In addition, 11 of the deaths occurred more than a month ago.

The health department then listed data for all 95 cases, including the age, gender, county and the dates of test positivity and death. Palm Beach County had 50 of the COVID-19 deaths.

“To ensure the accuracy of COVID-19 related deaths, the department will be performing additional reviews of all deaths,” Rivkees said. “Timely and accurate data remains a top priority of the Department of Health.”

Last week, Jose Oliva, speaker of the Florida House of Representatives, said medical examiner reports were “often lacking in rigor.” House Democrats then said Republicans were trying to “downplay the death toll,” according to the South Florida Sun Sentinel .

Fred Piccolo Jr., a spokesman for Florida Gov. Ron DeSantis, told the newspaper Wednesday that officials have struggled to obtain timely data. Labs sometimes report test results from weeks before, he added.

“It’s really one of those things that you gotta know if someone is dying of COVID or if they’re not,” Piccolo said. “Then you can legitimately say, here are the numbers.”

Sources

Florida Department of Health, “Florida Surgeon General Implements Additional Review Process for Fatalities Attributed to COVID-19 to Ensure Data Integrity.”

South Florida Sun Sentinel, “Florida to investigate all COVID-19 deaths after questions about ‘integrity’ of data.”

WebMD Health News © 2020

This article first appeared on Medscape.com.

The Florida Department of Health will investigate the state’s 16,000 coronavirus deaths due to questions about the integrity of the data, according to an announcement issued Wednesday.

State health department officials said the “fatality data reported to the state consistently presents confusion and warrants a rigorous review.” The review is meant to “ensure data integrity.”

“During a pandemic, the public must be able to rely on accurate public health data to make informed decisions,” Scott Rivkees, the surgeon general for Florida, said in the statement.

Among the 95 deaths reported Wednesday for instance, 16 had more than a 2-month separation between the time of testing positive for COVID-19 and passing away, and 5 cases had a 3-month gap. In addition, 11 of the deaths occurred more than a month ago.

The health department then listed data for all 95 cases, including the age, gender, county and the dates of test positivity and death. Palm Beach County had 50 of the COVID-19 deaths.

“To ensure the accuracy of COVID-19 related deaths, the department will be performing additional reviews of all deaths,” Rivkees said. “Timely and accurate data remains a top priority of the Department of Health.”

Last week, Jose Oliva, speaker of the Florida House of Representatives, said medical examiner reports were “often lacking in rigor.” House Democrats then said Republicans were trying to “downplay the death toll,” according to the South Florida Sun Sentinel .

Fred Piccolo Jr., a spokesman for Florida Gov. Ron DeSantis, told the newspaper Wednesday that officials have struggled to obtain timely data. Labs sometimes report test results from weeks before, he added.

“It’s really one of those things that you gotta know if someone is dying of COVID or if they’re not,” Piccolo said. “Then you can legitimately say, here are the numbers.”

Sources

Florida Department of Health, “Florida Surgeon General Implements Additional Review Process for Fatalities Attributed to COVID-19 to Ensure Data Integrity.”

South Florida Sun Sentinel, “Florida to investigate all COVID-19 deaths after questions about ‘integrity’ of data.”

WebMD Health News © 2020

This article first appeared on Medscape.com.

COVID-19 vaccine standards questioned at FDA advisory meeting

The FDA’s Vaccines and Related Biological Products Advisory Committee met for a wide-ranging discussion beginning around 10 am. The FDA did not ask the panel to weigh in on any particular vaccine. Instead, the FDA asked for the panel’s feedback on a series of questions, including considerations for continuing phase 3 trials if a product were to get an interim clearance known as an emergency use authorization (EUA).

Speakers at the hearing made a variety of requests, including asking for data showing COVID-19 vaccines can prevent serious illness and urging transparency about the agency’s deliberations for each product to be considered.

FDA staff are closely tracking the crop of experimental vaccines that have made it into advanced stages of testing, including products from Pfizer Inc, AstraZeneca, Johnson & Johnson, and Moderna.

‘Time for a reset’

Among the speakers at the public hearing was Peter Lurie, MD, who served as an FDA associate commissioner from 2014 to 2017. Now the president of the Center for Science in the Public Interest, Lurie was among the speakers who asked the agency to make its independence clear.

President Donald Trump has for months been making predictions about COVID-19 vaccine approvals that have been overly optimistic. In one example, the president, who is seeking re-election on November 3, last month spoke about being able to begin distributing a vaccine in October.

“Until now the process of developing candidate vaccines has been inappropriately politicized with an eye on the election calendar, rather than the deliberate timeframe science requires,” Lurie told the FDA advisory panel. “Now is the time for a reset. This committee has a unique opportunity to set a new tone for vaccine deliberations going forward.”

Lurie asked the panel to press the FDA to commit to hold an advisory committee meeting on requests by drugmakers for EUAs. He also asked the panel to demand that informed consent forms and minutes from institutional review board (IRB) discussions of COVID-19 vaccines trials be made public.

Also among the speakers at the public hearing was Peter Doshi, PhD, an associate professor at the University of Maryland School of Pharmacy, who argued that the current trials won’t answer the right questions about the COVID-19 vaccines.

“We could end up with approved vaccines that reduce the risk of mild infection, but do not decrease the risk of hospitalization, ICU use, or death — either at all or by a clinically relevant amount,” Doshi told the panel.

In his presentation, he reiterated points he had made previously, including in an October 21 article in the BMJ, for which he is an associate editor. Doshi also raised these concerns in a September opinion article in The New York Times, co-authored with Eric Topol, MD, director of the Scripps Research Translational Institute and editor-in-chief of Medscape.

Risks of a ‘rushed vaccine’

Other complaints about the FDA’s approach included criticism of a 2-month follow-up time after vaccination, which was seen as too short. ECRI, a nonprofit organization that seeks to improve the safety, quality, and cost-effectiveness of medicines, has argued that approving a weak COVID-19 vaccine might worsen the pandemic.

In an October 21 statement, ECRI noted the risk of a partially effective vaccine, which could be welcomed as a means of slowing transmission of the virus. But public response and attitudes over the past 9 months in the United States suggest that people would relax their precautions as soon as a vaccine is available.

“Resulting infections may offset the vaccine’s impact and end up increasing the mortality and morbidity burden,” ECRI said in the brief.

“The risks and consequences of a rushed vaccine could be very severe if the review is anything shy of thorough,” ECRI Chief Executive Officer Marcus Schabacker, MD, PhD, said in a statement prepared for the hearing.

This article first appeared on Medscape.com.

The FDA’s Vaccines and Related Biological Products Advisory Committee met for a wide-ranging discussion beginning around 10 am. The FDA did not ask the panel to weigh in on any particular vaccine. Instead, the FDA asked for the panel’s feedback on a series of questions, including considerations for continuing phase 3 trials if a product were to get an interim clearance known as an emergency use authorization (EUA).

Speakers at the hearing made a variety of requests, including asking for data showing COVID-19 vaccines can prevent serious illness and urging transparency about the agency’s deliberations for each product to be considered.

FDA staff are closely tracking the crop of experimental vaccines that have made it into advanced stages of testing, including products from Pfizer Inc, AstraZeneca, Johnson & Johnson, and Moderna.

‘Time for a reset’

Among the speakers at the public hearing was Peter Lurie, MD, who served as an FDA associate commissioner from 2014 to 2017. Now the president of the Center for Science in the Public Interest, Lurie was among the speakers who asked the agency to make its independence clear.

President Donald Trump has for months been making predictions about COVID-19 vaccine approvals that have been overly optimistic. In one example, the president, who is seeking re-election on November 3, last month spoke about being able to begin distributing a vaccine in October.

“Until now the process of developing candidate vaccines has been inappropriately politicized with an eye on the election calendar, rather than the deliberate timeframe science requires,” Lurie told the FDA advisory panel. “Now is the time for a reset. This committee has a unique opportunity to set a new tone for vaccine deliberations going forward.”

Lurie asked the panel to press the FDA to commit to hold an advisory committee meeting on requests by drugmakers for EUAs. He also asked the panel to demand that informed consent forms and minutes from institutional review board (IRB) discussions of COVID-19 vaccines trials be made public.

Also among the speakers at the public hearing was Peter Doshi, PhD, an associate professor at the University of Maryland School of Pharmacy, who argued that the current trials won’t answer the right questions about the COVID-19 vaccines.

“We could end up with approved vaccines that reduce the risk of mild infection, but do not decrease the risk of hospitalization, ICU use, or death — either at all or by a clinically relevant amount,” Doshi told the panel.

In his presentation, he reiterated points he had made previously, including in an October 21 article in the BMJ, for which he is an associate editor. Doshi also raised these concerns in a September opinion article in The New York Times, co-authored with Eric Topol, MD, director of the Scripps Research Translational Institute and editor-in-chief of Medscape.

Risks of a ‘rushed vaccine’

Other complaints about the FDA’s approach included criticism of a 2-month follow-up time after vaccination, which was seen as too short. ECRI, a nonprofit organization that seeks to improve the safety, quality, and cost-effectiveness of medicines, has argued that approving a weak COVID-19 vaccine might worsen the pandemic.

In an October 21 statement, ECRI noted the risk of a partially effective vaccine, which could be welcomed as a means of slowing transmission of the virus. But public response and attitudes over the past 9 months in the United States suggest that people would relax their precautions as soon as a vaccine is available.

“Resulting infections may offset the vaccine’s impact and end up increasing the mortality and morbidity burden,” ECRI said in the brief.

“The risks and consequences of a rushed vaccine could be very severe if the review is anything shy of thorough,” ECRI Chief Executive Officer Marcus Schabacker, MD, PhD, said in a statement prepared for the hearing.

This article first appeared on Medscape.com.

The FDA’s Vaccines and Related Biological Products Advisory Committee met for a wide-ranging discussion beginning around 10 am. The FDA did not ask the panel to weigh in on any particular vaccine. Instead, the FDA asked for the panel’s feedback on a series of questions, including considerations for continuing phase 3 trials if a product were to get an interim clearance known as an emergency use authorization (EUA).

Speakers at the hearing made a variety of requests, including asking for data showing COVID-19 vaccines can prevent serious illness and urging transparency about the agency’s deliberations for each product to be considered.

FDA staff are closely tracking the crop of experimental vaccines that have made it into advanced stages of testing, including products from Pfizer Inc, AstraZeneca, Johnson & Johnson, and Moderna.

‘Time for a reset’

Among the speakers at the public hearing was Peter Lurie, MD, who served as an FDA associate commissioner from 2014 to 2017. Now the president of the Center for Science in the Public Interest, Lurie was among the speakers who asked the agency to make its independence clear.

President Donald Trump has for months been making predictions about COVID-19 vaccine approvals that have been overly optimistic. In one example, the president, who is seeking re-election on November 3, last month spoke about being able to begin distributing a vaccine in October.

“Until now the process of developing candidate vaccines has been inappropriately politicized with an eye on the election calendar, rather than the deliberate timeframe science requires,” Lurie told the FDA advisory panel. “Now is the time for a reset. This committee has a unique opportunity to set a new tone for vaccine deliberations going forward.”

Lurie asked the panel to press the FDA to commit to hold an advisory committee meeting on requests by drugmakers for EUAs. He also asked the panel to demand that informed consent forms and minutes from institutional review board (IRB) discussions of COVID-19 vaccines trials be made public.

Also among the speakers at the public hearing was Peter Doshi, PhD, an associate professor at the University of Maryland School of Pharmacy, who argued that the current trials won’t answer the right questions about the COVID-19 vaccines.

“We could end up with approved vaccines that reduce the risk of mild infection, but do not decrease the risk of hospitalization, ICU use, or death — either at all or by a clinically relevant amount,” Doshi told the panel.

In his presentation, he reiterated points he had made previously, including in an October 21 article in the BMJ, for which he is an associate editor. Doshi also raised these concerns in a September opinion article in The New York Times, co-authored with Eric Topol, MD, director of the Scripps Research Translational Institute and editor-in-chief of Medscape.

Risks of a ‘rushed vaccine’

Other complaints about the FDA’s approach included criticism of a 2-month follow-up time after vaccination, which was seen as too short. ECRI, a nonprofit organization that seeks to improve the safety, quality, and cost-effectiveness of medicines, has argued that approving a weak COVID-19 vaccine might worsen the pandemic.

In an October 21 statement, ECRI noted the risk of a partially effective vaccine, which could be welcomed as a means of slowing transmission of the virus. But public response and attitudes over the past 9 months in the United States suggest that people would relax their precautions as soon as a vaccine is available.

“Resulting infections may offset the vaccine’s impact and end up increasing the mortality and morbidity burden,” ECRI said in the brief.

“The risks and consequences of a rushed vaccine could be very severe if the review is anything shy of thorough,” ECRI Chief Executive Officer Marcus Schabacker, MD, PhD, said in a statement prepared for the hearing.

This article first appeared on Medscape.com.

Human Papillomavirus Vaccination in LGBTQ Patients: The Need for Dermatologists on the Front Lines

Human papillomavirus (HPV) is one of the most common sexually transmitted infections in the United States. It is the causative agent of genital warts, as well as cervical, anal, penile, vulvar, vaginal, and some head and neck cancers.1 Development of the HPV vaccine and its introduction into the scheduled vaccine series recommended by the Centers for Disease Control and Prevention (CDC) represented a major public health milestone. The CDC recommends the HPV vaccine for all children beginning at 11 or 12 years of age, even as early as 9 years, regardless of gender identity or sexuality. As of late 2016, the 9-valent formulation (Gardasil 9 [Merck]) is the only HPV vaccine distributed in the United States, and the vaccination schedule depends specifically on age. The Advisory Committee on Immunization Practices (ACIP) of the CDC revised its recommendations in 2019 to include “shared clinical decision-making regarding HPV vaccination . . . for some adults aged 27 through 45 years.”2 This change in policy has notable implications for sexual and gender minority populations, such as lesbian, gay, bisexual, transgender, and queer or questioning (LGBTQ) patients, especially in the context of dermatologic care. Herein, we discuss HPV-related conditions for LGBTQ patients, barriers to vaccine administration, and the role of dermatologists in promoting an increased vaccination rate in the LGBTQ community.

HPV-Related Conditions

A 2019 review of dermatologic care for LGBTQ patients identified many specific health disparities of HPV.3 Specifically, men who have sex with men (MSM) are more likely than heterosexual men to have oral, anal, and penile HPV infections, including high-risk HPV types.3 From 2011 to 2014, 18% and 13% of MSM had oral HPV infection and high-risk oral HPV infection, respectively, compared to only 11% and 7%, respectively, of men who reported never having had a same-sex sexual partner.4

Similarly, despite the CDC’s position that patients with perianal warts might benefit from digital anal examination or referral for standard or high-resolution anoscopy to detect intra-anal warts, improvements in morbidity have not yet been realized. In 2017, anal cancer incidence was 45.9 cases for every 100,000 person-years among human immunodeficiency (HIV)–positive MSM and 5.1 cases for every 100,000 person-years among HIV-negative MSM vs only 1.5 cases for every 100,000 person-years among men in the United States overall.3 Yet the CDC states that there is insufficient evidence to recommend routine anal cancer screening among MSM, even when a patient is HIV positive. Therefore, current screening practices and treatments are insufficient as MSM continue to have a disproportionately higher rate of HPV-associated disease compared to other populations.

Barriers to HPV Vaccine Administration

The HPV vaccination rate among MSM in adolescent populations varies across reports.5-7 Interestingly, a 2016 survey study found that MSM had approximately 2-times greater odds of initiating the HPV vaccine than heterosexual men.8 However, a study specifically sampling young gay and bisexual men (N=428) found that only 13% had received any doses of the HPV vaccine.6

Regardless, HPV vaccination is much less common among all males than it is among all females, and the low rate of vaccination among sexual minority men has a disproportionate impact, given their higher risk for HPV infection.4 Although the HPV vaccination rate increased from 2014 to 2017, the HPV vaccination rate in MSM overall is less than half of the Healthy People 2020 goal of 80%.9 A 2018 review determined that HPV vaccination is a cost-effective strategy for preventing anal cancer in MSM10; yet male patients might still view the HPV vaccine as a “women’s issue” and are less likely to be vaccinated if they are not prompted by health care providers. Additionally, HPV vaccination is remarkably less likely in MSM when patients are older, uninsured, of lower socioeconomic status, or have not disclosed their sexual identity to their health care provider.9 Dermatologists should be mindful of these barriers to promote HPV vaccination in MSM before, or soon after, sexual debut.

Other members of the LGBTQ community, such as women who have sex with women, face notable HPV-related health disparities and would benefit from increased vaccination efforts by dermatologists. Adolescent and young adult women who have sex with women are less likely than heterosexual adolescent and young adult women to receive routine Papanicolaou tests and initiate HPV vaccination, despite having a higher number of lifetime sexual partners and a higher risk for HPV exposure.11 A 2015 survey study (N=3253) found that after adjusting for covariates, only 8.5% of lesbians and 33.2% of bisexual women and girls who had heard of the HPV vaccine had initiated vaccination compared to 28.4% of their heterosexual counterparts.11 The HPV vaccine is an effective public health tool for the prevention of cervical cancer in these populations. A study of women aged 15 to 19 years in the HPV vaccination era (2007-2014) found significant (P<.05) observed population-level decreases in cervical intraepithelial neoplasia incidence across all grades.12

Transgender women also face a high rate of HPV infection, HIV infection, and other structural and financial disparities, such as low insurance coverage, that can limit their access to vaccination. Transgender men have a higher rate of HPV infection than cisgender men, and those with female internal reproductive organs are less likely to receive routine Papanicolaou tests. A 2018 survey study found that approximately one-third of transgender men and women reported initiating the HPV vaccination series,13 but further investigation is required to make balanced comparisons to cisgender patients.

The Role of the Dermatologist

Collectively, these disparities emphasize the need for increased involvement by dermatologists in HPV vaccination efforts for all LGBTQ patients. Adult patients may have concerns about ties of the HPV vaccine to drug manufacturers and the general safety of vaccination. For pediatric patients, parents/guardians also may be concerned about an assumed but not evidence-based increase in sexual promiscuity following HPV vaccination.14 These topics can be challenging to discuss, but dermatologists have the duty to be proactive and initiate conversation about HPV vaccination, as opposed to waiting for patients to express interest. Dermatologists should stress the safety of the vaccine as well as its potential to protect against multiple, even life-threatening diseases. Providers also can explain that the ACIP recommends catch-up vaccination for all individuals through 26 years of age, regardless of sexual orientation or gender identity.

With the ACIP having recently expanded the appropriate age range for HPV vaccination, we encourage dermatologists to engage in education and shared decision-making to ensure that adult patients with specific risk factors receive the HPV vaccine. Because the expanded ACIP recommendations are aimed at vaccination before HPV exposure, vaccination might not be appropriate for all LGBTQ patients. However, eliciting a sexual history with routine patient intake forms or during the clinical encounter ensures equal access to the HPV vaccine.

Greater awareness of HPV-related disparities and barriers to vaccination in LGBTQ populations has the potential to notably decrease HPV-associated mortality and morbidity. Increased involvement by dermatologists contributes to the efforts of other specialties in universal HPV vaccination, regardless of sexual orientation or gender identity—ideally in younger age groups, such that patients receive the vaccine prior to coitarche.

There are many ways that dermatologists can advocate for HPV vaccination. Those in a multispecialty or academic practice can readily refer patients to an associated internist, primary care physician, or vaccination clinic in the same building or institution. Dermatologists in private practice might be able to administer the HPV vaccine themselves or can advocate for patients to receive the vaccine at a local facility of the Department of Health or at a nonprofit organization, such as a Planned Parenthood center. Although pediatricians and family physicians remain front-line providers of these services, dermatologists represent an additional member of a patient’s care team, capable of advocating for this important intervention.

- Brianti P, De Flammineis E, Mercuri SR. Review of HPV-related diseases and cancers. New Microbiol. 2017;40:80-85.

- Meites E, Szilagyi PG, Chesson HW, et al. Human papillomavirus vaccination for adults: updated recommendations of the Advisory Committee on Immunization Practices. MMWR Morb Mortal Wkly Rep. 2019;68:698-702.

- Yeung H, Luk KM, Chen SC, et al. Dermatologic care for lesbian, gay, bisexual, and transgender persons: epidemiology, screening, and disease prevention. J Am Acad Dermatol. 2019;80:591-602.

- Sonawane K, Suk R, Chiao EY, et al. Oral human papillomavirus infection: differences in prevalence between sexes and concordance with genital human papillomavirus infection, NHANES 2011 to 2014. Ann Intern Med. 2017;167:714-724.

- Kosche C, Mansh M, Luskus M, et al. Dermatologic care of sexual and gender minority/LGBTQIA youth, part 2: recognition and management of the unique dermatologic needs of SGM adolescents. Pediatr Dermatol. 2019;35:587-593.

- Reiter PL, McRee A-L, Katz ML, et al. Human papillomavirus vaccination among young adult gay and bisexual men in the United States. Am J Public Health. 2015;105:96-102.

- Charlton BM, Reisner SL, Ag

énor M, et al. Sexual orientation disparities in human papillomavirus vaccination in a longitudinal cohort of U.S. males and females. LGBT Health. 2017;4:202-209. - Agénor M, Peitzmeier SM, Gordon AR, et al. Sexual orientation identity disparities in human papillomavirus vaccination initiation and completion among young adult US women and men. Cancer Causes Control. 2016;27:1187-1196.

- Loretan C, Chamberlain AT, Sanchez T, et al. Trends and characteristics associated with human papillomavirus vaccination uptake among men who have sex with men in the United States, 2014-2017. Sex Transm Dis. 2019;46:465-473.

- Setiawan D, Wondimu A, Ong K, et al. Cost effectiveness of human papillomavirus vaccination for men who have sex with men; reviewing the available evidence. Pharmacoeconomics. 2018;36:929-939.

- Agénor M, Peitzmeier S, Gordon AR, et al. Sexual orientation identity disparities in awareness and initiation of the human papillomavirus vaccine among U.S. women and girls: a national survey. Ann Intern Med. 2015;163:99-106.

- Benard VB, Castle PE, Jenison SA, et al. Population-based incidence rates of cervical intraepithelial neoplasia in the human papillomavirus vaccine era. JAMA Oncol. 2017;3:833-837.

- McRee A-L, Gower AL, Reiter PL. Preventive healthcare services use among transgender young adults. Int J Transgend. 2018;19:417-423.

- Trinidad J. Policy focus: promoting human papilloma virus vaccine to prevent genital warts and cancer. Boston, MA: The Fenway Institute; 2012. https://fenwayhealth.org/documents/the-fenway-institute/policy-briefs/PolicyFocus_HPV_v4_10.09.12.pdf. Accessed September 15, 2020.

Human papillomavirus (HPV) is one of the most common sexually transmitted infections in the United States. It is the causative agent of genital warts, as well as cervical, anal, penile, vulvar, vaginal, and some head and neck cancers.1 Development of the HPV vaccine and its introduction into the scheduled vaccine series recommended by the Centers for Disease Control and Prevention (CDC) represented a major public health milestone. The CDC recommends the HPV vaccine for all children beginning at 11 or 12 years of age, even as early as 9 years, regardless of gender identity or sexuality. As of late 2016, the 9-valent formulation (Gardasil 9 [Merck]) is the only HPV vaccine distributed in the United States, and the vaccination schedule depends specifically on age. The Advisory Committee on Immunization Practices (ACIP) of the CDC revised its recommendations in 2019 to include “shared clinical decision-making regarding HPV vaccination . . . for some adults aged 27 through 45 years.”2 This change in policy has notable implications for sexual and gender minority populations, such as lesbian, gay, bisexual, transgender, and queer or questioning (LGBTQ) patients, especially in the context of dermatologic care. Herein, we discuss HPV-related conditions for LGBTQ patients, barriers to vaccine administration, and the role of dermatologists in promoting an increased vaccination rate in the LGBTQ community.

HPV-Related Conditions

A 2019 review of dermatologic care for LGBTQ patients identified many specific health disparities of HPV.3 Specifically, men who have sex with men (MSM) are more likely than heterosexual men to have oral, anal, and penile HPV infections, including high-risk HPV types.3 From 2011 to 2014, 18% and 13% of MSM had oral HPV infection and high-risk oral HPV infection, respectively, compared to only 11% and 7%, respectively, of men who reported never having had a same-sex sexual partner.4

Similarly, despite the CDC’s position that patients with perianal warts might benefit from digital anal examination or referral for standard or high-resolution anoscopy to detect intra-anal warts, improvements in morbidity have not yet been realized. In 2017, anal cancer incidence was 45.9 cases for every 100,000 person-years among human immunodeficiency (HIV)–positive MSM and 5.1 cases for every 100,000 person-years among HIV-negative MSM vs only 1.5 cases for every 100,000 person-years among men in the United States overall.3 Yet the CDC states that there is insufficient evidence to recommend routine anal cancer screening among MSM, even when a patient is HIV positive. Therefore, current screening practices and treatments are insufficient as MSM continue to have a disproportionately higher rate of HPV-associated disease compared to other populations.

Barriers to HPV Vaccine Administration

The HPV vaccination rate among MSM in adolescent populations varies across reports.5-7 Interestingly, a 2016 survey study found that MSM had approximately 2-times greater odds of initiating the HPV vaccine than heterosexual men.8 However, a study specifically sampling young gay and bisexual men (N=428) found that only 13% had received any doses of the HPV vaccine.6

Regardless, HPV vaccination is much less common among all males than it is among all females, and the low rate of vaccination among sexual minority men has a disproportionate impact, given their higher risk for HPV infection.4 Although the HPV vaccination rate increased from 2014 to 2017, the HPV vaccination rate in MSM overall is less than half of the Healthy People 2020 goal of 80%.9 A 2018 review determined that HPV vaccination is a cost-effective strategy for preventing anal cancer in MSM10; yet male patients might still view the HPV vaccine as a “women’s issue” and are less likely to be vaccinated if they are not prompted by health care providers. Additionally, HPV vaccination is remarkably less likely in MSM when patients are older, uninsured, of lower socioeconomic status, or have not disclosed their sexual identity to their health care provider.9 Dermatologists should be mindful of these barriers to promote HPV vaccination in MSM before, or soon after, sexual debut.

Other members of the LGBTQ community, such as women who have sex with women, face notable HPV-related health disparities and would benefit from increased vaccination efforts by dermatologists. Adolescent and young adult women who have sex with women are less likely than heterosexual adolescent and young adult women to receive routine Papanicolaou tests and initiate HPV vaccination, despite having a higher number of lifetime sexual partners and a higher risk for HPV exposure.11 A 2015 survey study (N=3253) found that after adjusting for covariates, only 8.5% of lesbians and 33.2% of bisexual women and girls who had heard of the HPV vaccine had initiated vaccination compared to 28.4% of their heterosexual counterparts.11 The HPV vaccine is an effective public health tool for the prevention of cervical cancer in these populations. A study of women aged 15 to 19 years in the HPV vaccination era (2007-2014) found significant (P<.05) observed population-level decreases in cervical intraepithelial neoplasia incidence across all grades.12

Transgender women also face a high rate of HPV infection, HIV infection, and other structural and financial disparities, such as low insurance coverage, that can limit their access to vaccination. Transgender men have a higher rate of HPV infection than cisgender men, and those with female internal reproductive organs are less likely to receive routine Papanicolaou tests. A 2018 survey study found that approximately one-third of transgender men and women reported initiating the HPV vaccination series,13 but further investigation is required to make balanced comparisons to cisgender patients.

The Role of the Dermatologist