User login

Penicillin Allergy Delabeling Can Decrease Antibiotic Resistance, Reduce Costs, and Optimize Patient Outcomes

Antibiotics are one of the most frequently prescribed medications in both inpatient and outpatient settings.1,2 More than 266 million courses of antibiotics are prescribed annually in the outpatient setting; 49.9% of hospitalized patients were prescribed ≥ 1 antibiotic during their hospitalization.1,2 Among all classes of antibiotics, penicillins are prescribed due to their clinical efficacy, cost-effectiveness, and general safety for all ages. Unfortunately, penicillins also are the most common drug allergy listed in medical records. Patients with this allergy are consistently treated with broad-spectrum antibiotics, have more antibiotic resistant infections, incur higher health care costs, and experience more adverse effects (AEs).3,4

Drug allergies are distinguished by different immune mechanisms, including IgE-mediated reaction, T-lymphocyte-mediated mild skin reactions, and severe cutaneous adverse reactions (SCAR), or other systemic immune syndromes, such as hemolytic anemia, nephritis, and rash with eosinophilia.3 Although drug allergies should be a concern, compelling evidence shows that > 90% of patients labeled with a penicillin allergy are not allergic to penicillins (and associated β-lactams).3,4 Although this evidence is growing, clinicians still hesitate to prescribe penicillin, and patients are similarly anxious to take them. This article reviews the health care consequences of penicillin allergy and the application of this information to military medicine and readiness.

Penicillin Allergy Prevalence

Since their approval for public use in 1945, penicillins have been one of the most often prescribed antibiotics due to their clinical efficacy for many types of infections.3 However, 8 to 10% of the US population and up to 15% of hospitalized patients have a documented penicillin allergy, which limits the ability to use these effective antibiotics.3,4 Once a patient is labeled with a penicillin allergy, many clinicians avoid prescribing all β-lactam antibiotics to patients. Clinicians also avoid prescribing cephalosporins due to the concern for potential cross-reactivity (at a rate of about 2%, which is lower than previously reported).3 These reported allergies are often not clear and range from patients avoiding penicillins because their parents exhibited allergies, they had a symptom that was not likely allergic (ie, nausea, headache, itching with no rash), being told by their parents that they had a rash as a child, or experiencing severe anaphylaxis or other systemic reaction.3,4 Despite the high rates of documented penicillin allergy, studies now show that most patients do not have a serious allergy; < 1% of the population has a true immune-mediated penicillin allergy.3,4

Broad-Spectrum Antibiotic Risks

Even though penicillin allergies are often not confirmed, many patients are treated with alternative antibiotics. Unfortunately, most alternative antibiotics are not as effective or as safe as penicillin.3,4 Twenty percent of hospitalized patients will experience an AE related to their antibiotic; 19.3% of emergency department visits for adverse drug reactions (ADRs) are from antibiotics.5,6 Sulfonamides, clindamycin, and quinolones were the antibiotics most commonly associated with AEs.6

In a large database study over a 3-year period, > 400,000 hospitalizations were analyzed in patients matched for admission type, with and without a penicillin allergy in their medical record.7 Those with a documented penicillin allergy had longer hospitalizations; were treated with broad-spectrum antibiotics; and had increased rates of Clostridium difficile (C difficile), methicillin-resistant Staphylococcus aureus (MRSA), and vancomycin-resistant Enterococcus (VRE).7,8 In addition to being first-line treatment for many common infections, penicillins often are used for dental, perinatal, and perioperative prophylaxis.1,3 Nearly 25 million antibiotics are prescribed annually by dentists.1 If a patient has a penicillin allergy listed in their medical record, they will inevitably receive a second- or third-line treatment that is less effective and has higher risks. Common alternative antibiotics include clindamycin, fluoroquinolones, macrolides, and vancomycin.3,7,8

Clindamycin and fluoroquinolones are associated with C difficile infections.9,10 Fluoroquinolones come with a boxed warning for known serious ADRs, including tendon rupture, peripheral neuropathy, central nervous system effects, and are known for causing cardiac reactions such as QT prolongation, life-threatening arrhythmias, and cardiovascular death.11,12 Fluoroquinolones are associated with an increased risk for VRE and MRSA, in more than any other antibiotic classes.3,7,12,13

Macrolides, such as azithromycin and clarithromycin, are another common class of antibiotics used as an alternative for penicillins. Both are used frequently for upper respiratory infections. Known ADRs to macrolides include gastrointestinal adverse effects (AEs) (ie, nausea, vomiting, diarrhea, and abdominal pain), liver toxicity (ie, abnormal liver function tests, hepatitis, and liver failure), and cardiac risks (ie, QT prolongation and sudden death). When compared with amoxicillin, there was an increased risk for cardiovascular mortality in those patients receiving macrolides.14,15

Vancomycin is known for its potential to cause “red man syndrome,” an infusion-related reaction causing redness and itching as well as nephrotoxic and hematologic effects requiring close monitoring.3 Vancomycin is less effective than methicillin in clearing MRSA or other sensitive pathogens; however, vancomycin is used in patients with a penicillin allergy label.16-18 Intrapartum antibiotic use of vancomycin for group B streptococcus infection was associated with clinically significant morbidity and ADRs.19,20 Perioperatively, patients with penicillin allergies developed more surgical site infections due to the use of second-line antibiotics, such as vancomycin or others.21

Cost of Penicillin Allergies

Penicillin allergy plays an important role in rising health care costs. In 2017, health care spending reached 17.9% of the gross domestic product.22 Macy and Contreras demonstrated the significantly higher costs associated with having a reported (and unverified) penicillin allergy in a matched cohort study. Inferred for the extra hospital use, the penicillin allergy group cost the health care system $64,626,630 more than for the group who did not have a penicillin allergy label.7 A subsequent study by Macy and Contreras of both inpatient and outpatient settings showed a potential savings of $2,000 per patient per year in health care expenses with the testing and delabeling of penicillin allergies.23 Use of newer and broad-spectrum antibiotics also are more costly and contribute to higher health care costs.24

When these potential savings are applied to the military insurance population of 9.4 million beneficiaries (TRICARE, including active duty, their dependents, and all retirees participating in the program), the results showed that this could impart a savings of nearly $1.7 billion annually, using the model by Macy and Contreras.23,25,26

Previously with colleagues, I reviewed penicillin’s role in military history, compiled data from relevant studies from military penicillin allergy rates and delabeling efforts, and calculated the potential economic impact of penicillin allergies along with the benefits of testing.26 Calculations were estimated using the TRICARE beneficiary population (9.4 million) × the estimated prevalence (10%) to get an estimate of 940,000 TRICARE patients with penicillin allergy in their medical record.25 If 90% of those patients were delabeled, this would equal 846,000 TRICARE patients. When multiplied by the potential savings of $2,000 per patient per year, the estimated savings would be $1,692,000,000 annually.23,26

Current literature provides compelling evidence that all health care plans should use penicillin allergy testing and delabeling programs.3,23,26 As most patients with a history of penicillin allergy in their medical records do not have a verified allergy, delabeling those who do not have a true allergy will have individual, public health, and cost benefits.3,7,23,26

Antibiotic Stewardship

Antibiotic stewardship programs are now mandated to combat antibiotic resistance.3,27 This program is supported by major medical organizations, including the Centers for Disease Control and Prevention, Society for Healthcare Epidemiology of America, Infectious Disease Society of America, and the American Academy of Allergy Asthma and Immunology.3 Given the role of broad-spectrum antibiotics in antibiotic resistance, penicillin allergy testing and delabeling is an important component of these programs.3

In the US, > 2 million people acquire antibiotic resistant infections annually; 23,000 people die of these infections.27 More than 250,000 illnesses and 14,000 deaths annually are due to C difficile.27 There are many factors contributing to the increase in antibiotic resistance; however, one established and consistent factor is the use of broad-spectrum antibiotics. Further, broad-spectrum antibiotics are often used when first-line agents, such as penicillins, cannot be used due to a reported “allergy.” In addition, there are fewer novel antibiotics being developed, and as they are introduced, pathogens develop resistance to these new agents.27

Military Relevance

Infectious diseases have always accompanied military activity.28-30 Despite preventive programs such as vaccinations, hygiene measures, and prophylactic antibiotics, military personnel are at increased risk for infections due to the military’s mobile nature and crowded living situations.28-30 This situation has operational relevance from basic training, deployments, and combat operations to peacetime activities.

Military recruits are treated routinely with penicillin G benzathine as standard prophylaxis against streptococcal infections.26,30 A recent study by the Marine Corps Recruiting Depot in San Diego, California showed that in a cohort of 402 young healthy male recruits, only 5 (1.5%) had a positive reaction to penicillin testing and challenge over a 21-month period.31 The delabeled other 397 (98.5%) marine recruits were able to receive benzathine penicillin prophylaxis successfully.31 Recruits with a penicillin allergy who had a positive test or were not tested received azithromycin (or erythromycin at some recruit training locations).26,31 Military members may need to operate in remote or austere locations; the ability to use penicillins is important for readiness.

Evaluation and Management of Reported Penicillin Allergy

Verifying penicillin allergies is an important first step in optimizing medical care and decreasing resistance and ADRs.3,4,32,33 Although allergists can provide specialized evaluation, due to the high prevalence of penicillin allergy in the US, all health care team members, including clinicians and pharmacists, should be educated about penicillin allergies and be able to implement evaluations in both inpatient and outpatient settings. Reactions to any of the penicillins should be considered, including the natural penicillins (penicillin V, etc), antistaphylococcal penicillins (dicloxacillin), aminopenicillins (amoxicillin and ampicillin), and extended-spectrum penicillins (piperacillin).3 A thorough history, including the prior reaction (age, type of reaction) and subsequent tolerance are helpful in stratifying patients.3,26

Patient Risk Levels

Based on the clinical history, patients would fall into 4 categories from low risk, medium risk, high risk, to do not test/use.3,32,33 Low-risk patients are those who report mild or nonallergic symptoms (ie, gastrointestinal symptoms, headache, yeast infection, etc), remote cutaneous reactions (> 10 years), or in those with a family history of penicillin allergy.3,32,33 Low-risk patients often can be safely tested with an oral challenge. Although there are different approaches to the oral challenge, a single amoxicillin dose of 250 mg followed by 1 hour of direct monitoring is usually sufficient.3,32,33

Medium-risk patients have a more recent (< 1 year) history of pruritic rashes, urticaria, and/or angioedema without a history of severe or systemic reactions. These patients benefit from negative skin testing prior to an oral challenge, which can be performed by trained clinicians or pharmacists or an allergist. However, due to limited availability of skin testing and the potential for false positive testing with skin tests, a single dose or graded challenge would be a reasonable approach as well.3,32,33

High-risk patients are those with severe symptoms (anaphylaxis), a history of reactions to other β-lactam antibiotics, and/or recurrent reactions to antibiotics. These patients benefit from a formal evaluation by an allergist and skin testing prior to challenge.3,32,33 Testing and/or challenge should not be performed in patients who report a history of severe cutaneous reactions (blistering rash, such as Stevens Johnson syndrome), hemolytic anemia, serum sickness, drug fever, and other organ dysfunction.3,4,31,32

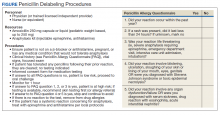

The Figure describes a published questionnaire, personnel, resources, and procedures for penicillin delabeling.26 Although skin testing is reliable in revealing a immunoglobulin E-mediated penicillin allergy, there is potential for false positives.32,33 The oral amoxicillin challenge effectively clears the patient for future penicillin administration.3,32-34 In high-risk patients, desensitization should be considered if penicillins (or cephalosporins) are required as first-line treatment. A test dose (one-tenth dose, higher or lower depending on route of administration, historic reaction, clinical status, and level of certainty of prior reaction) may be considered in low- to moderate-risk patients, depending on the indication for the use of the antibiotics.32

Penicillin evaluation pathways can occur in both inpatient and outpatient settings where antibiotics will be prescribed.32-34 There are several proposed pathways, including a screening questionnaire to determine the penicillin allergy risk.26,32,33 Implementation of perioperative testing has been successful in decreasing the rates of vancomycin use and lessening the morbidity associated with use of second-line antibiotics.35 Many hospitals throughout the country have implemented standardized penicillin delabeling programs.3,32-34

Conclusions

Penicillin allergies are an important barrier to effective antibiotic treatments and are associated with worse outcomes and higher economic costs.3,7,23,26,34 Therefore, in addition to vaccinations, infection control measures, and public health education, penicillin allergy verification and delabeling programs should be a proactive component of military medical readiness and all antibiotic stewardship initiatives in all health care settings.29 Given the many issues and negative impact of having a penicillin allergy label, penicillin delabeling will allow service members to be treated with the necessary antibiotics with fewer adverse complications, and return them to health and readiness for operational duties. In the current standardization of the Defense Health Agency, implementing this program across all services would have significant clinical, public health, and cost benefits for patients, the health care team, taxpayers, and the community at large.

Many patients report an allergy to penicillin, but only a small portion have a current true immune-mediated allergy. Given the clinical, public health, and economic costs associated with a penicillin allergy label, evaluation and clearance of penicillin allergies is a simple method that would improve clinical outcomes, decrease AEs to high-risk alternative broad-spectrum antibiotics, and prevent the spread of antibiotic resistance. In the military, penicillin delabeling improves readiness with optimal antibiotic options and avoidance of unnecessary risks of using alternative antibiotics, expediting return to full duty for military personnel.

1. Centers for Disease Control and Prevention. Outpatient antibiotic prescriptions-United States, 2014. https://www.cdc.gov/antibiotic-use/community/pdfs/annual-reportsummary_2014.pdf. Accessed August 15, 2020.

2. Magill SS, Edwards JR, Beldavs ZG, et al. Prevalence of antimicrobial use in US acute care hospitals, May-September 2011. JAMA. 2014;312(14):1438-1446. doi:10.1001/jama.2014.12923

3. Shenoy ES, Macy E, Rowe T, Blumenthal KG. Evaluation and management of penicillin allergy. JAMA. 2019;321:188-199. doi:10.1001/jama.2018.19283

4. Har D, Solensky R. Penicillin and beta-lactam hypersensitivity. Immunol Allergy Clin North Am. 2017;37(4):643-662. doi:10.1016/j.iac.2017.07.001

5. Tamma PD, Avdic E, Li DX, Dzintars K, Cosgrove SE. Association of adverse events with antibiotic use in hospitalized patients. JAMA Intern Med. 2017;177(9):1308-1315. doi:10.1001/jamainternmed.2017.1938

6. Shebab N, Patel PR, Srinivasan A, Budnitz DS. Emergency department visits for antibiotic-associated adverse events. Clin Infect Dis. 2008;47(6):735-743. doi:10.1086/591126

7. Macy E, Contreras R. Healthcare use and serious infection prevalence associated with penicillin “allergy” in hospitalized patients: a cohort study. J Allergy Clin Immunol. 2014;133(3):790-796. doi:10.1016/j.jaci.2013.09.021

8. Blumenthal KG, Lu N, Zhang Y, Li Y, Walensky RP, Choi HK. Risk of methicillin resistant Staphylococcal aureus and Clostridium difficile in patients with a documented penicillin allergy: population-based matched cohort study. BMJ. 2018;361:k2400. doi:10.1136/bmj.k2400

9. Loo VG, Poirier L, Miller MA, et al. A predominantly clonal multi-institutional outbreak of Clostridium difficile associated diarrhea with high morbidity and mortality. N Engl J Med. 2005;353(23):2442-2449. doi:10.1056/NEJMoa051639

10. Pepin J, Saheb N, Coulombe MA, et al. Emergence of fluoroquinolone as the predominant risk factor for Clostridium difficile-associated diarrhea: a cohort study during an epidemic in Quebec. Clin Infect Dis. 2005;41(9):1254-1260. doi:10.1086/496986

11. Chou HW, Wang JL, Chang CH, et al. Risks of cardiac arrhythmia and mortality among patients using new-generation macrolides, fluoroquinolones, and β-lactam/β-lactamase inhibitors: a Taiwanese nationwide study. Clin Infec Dis. 2015;60(4):566-577. doi:10.1093/cid/ciu914

12. Rao GA, Mann JR, Shoaibi A, et al. Azithromycin and levofloxacin use and increased risk of cardiac arrhythmia and death. Ann Fam Med. 2014;12(2):121-127. doi:10.1370/afm.1601

13. LeBlanc L, Pepin J, Toulouse K, et al. Fluoroquinolone and risk for methicillin-resistant Staphylococcus aureus, Canada. Emerg Infect Dis. 2006;12(9):1398-1405. doi:10.3201/eid1209.060397

14. Schembri S, Williamson PA, Short PM, et al. Cardiovascular events after clarithromycin use in lower respiratory tract infections: analysis of two prospective cohort studies. BMJ. 2013;346:f1245. doi:10.1136/bmj.f1235

15. Ray WA, Murray KT, Hall K, Arbogast PG, Stein CM. Azithromycin and the risk of cardiovascular death. N Engl J Med. 2012;366(20):1881-1890. doi:10.1056/NEJMoa1003833

16. McDaniel JS, Perencevich EN, Diekema DJ, et al. Comparative effectiveness of beta-lactams versus vancomycin for treatment of methicillin-susceptible Staphylococcus aureus bloodstream infections among 122 hospitals. Clin Infect Dis. 2015;61(3):361-367. doi:10.1093/cid/civ308

17. Wong D, Wong T, Romney M, Leung V. Comparison of outcomes in patients with methicillin-susceptible Staphylococcus aureus (MSSA) bacteremia who are treated with β-lactam vs vancomycin empiric therapy: a retrospective cohort study. BMC Infect Dis. 2016;16:224. doi:10.1186/s12879-016-1564-5

18. Blumenthal KG, Shenoy ES, Huang M, et al. The impact of reporting a prior penicillin allergy on the treatment of methicillin-sensitivity Staphylococcus aureus bacteremia. PLoS One. 2016;11(7):e0159406. doi:10.1371/journal.pone.0159406

19. Verani JR, McGee L, Schrag SJ; . Prevention of perinatal group B streptococcal disease. MMWR Recomm Rep. 2010;59(RR-10):1-36.

20. Desai SH, Kaplan MS, Chen Q, Macy EM. Morbidity in pregnant women associated with unverified penicillin allergies, antibiotic use, and group B Streptococcus infections. Perm J. 2017;21:16-080. doi:10.7812/TPP/16-080

21. Blumenthal KG, Ryan EE, Li Y, Lee H, Kuhlen JL, Shenoy ES. The impact of a reported penicillin allergy on surgical site infection risk. Clin Infect Dis. 2018;66(3):329-336. doi:10.1093/cid/cix794

22. National Health Expenditures 2017 Highlights. Centers for Medicare & Medicaid services. https://www.cms.gov/Research-Statistics-Data-and-Systems/Statistics-Trends-and-Reports/NationalHealthExpendData/Downloads/highlights.pdf. Accessed August 25, 2020.

23. Macy E, Shu YH. The effect of penicillin allergy testing on future health care utilization: a matched cohort study. J Allergy Clin Immunol Pract. 2017;5(3):705-710. doi:10.1016/j.jaip.2017.02.012

24. Picard M, Begin P, Bouchard H, et al. Treatment of patients with a history of penicillin allergy in a large tertiary-care academic hospital. J Allergy Clin Immunol Pract. 2013;1(3):252-257. doi:10.1016/j.jaip.2013.01.006

25. US Department of Defense. Beneficiary population statistics. https://health.mil/I-Am-A/Media/Media-Center/Patient-Population-Statistics. Accessed August 25, 2020.

26. Lee RU, Banks TA, Waibel KH, Rodriguez RG. Penicillin allergy…maybe not? The military relevance for penicillin testing and de-labeling. Mil Med. 2019;184(3-4):e163-e168. doi:10.1093/milmed/usy194

27. Antibiotic resistance threats in the United States, 2013. Centers for Disease Control and Prevention. https://www.cdc.gov/drugresistance/threat-report-2013/index.html. Accessed May 10, 2019.

28. Gray GC, Callahan JD, Hawksworth AW, Fisher CA, Gaydos JC. Respiratory diseases among U.S. military personnel: countering emerging threats. Emerg Infect Dis. 1999;5(3):379-385. doi:10.3201/eid0503.990308

29. Beaumier CM, Gomez-Rubio AM, Hotez PJ, Weina PJ. United States military tropical medicine: extraordinary legacy, uncertain future. PLoS Negl Trop Dis. 2013;7(12):e2448. doi:10.1371/journal.pntd.0002448

30. Thomas RJ, Conwill DE, Morton DE, et al. Penicillin prophylaxis for streptococcal infections in the United States Navy and Marine Corps recruit camps, 1951-1985. Rev Infect Dis. 1988;10(1):125-130. doi:10.1093/clinids/10.1.125

31. Tucker MH, Lomas CM, Ramchandar N, Waldram JD. Amoxicillin challenge without penicillin skin testing in evaluation of penicillin allergy in a cohort of Marine recruits. J Allergy Clin Immunol Pract. 2017;5(3):813-815. doi:10.1016/j.jaip.2017.01.023

32. Blumenthal KG, Shenoy ES, Wolfson AR, et al. Addressing inpatient beta-lactam allergies: a multihospital implementation. J Allergy Clin Immunol Pract. 2017;5(3):616-625. doi:10.1016/j.jaip.2017.02.019

33. Kuruvilla M, Shih J, Patel K, Scanlon N. Direct oral amoxicillin challenge without preliminary skin testing in adult patients with allergy and at low risk with reported penicillin allergy. Allergy Asthma Proc. 2019;40(1):57-61. doi:10.2500/aap.2019.40.4184

34. Banks TA, Tucker M, Macy E. Evaluating penicillin allergies without skin testing. Curr Allergy Asthma Rep. 2019;19(5):27. doi:10.1007/s11882-019-0854-6

35. Park M, Markus P, Matesic

Antibiotics are one of the most frequently prescribed medications in both inpatient and outpatient settings.1,2 More than 266 million courses of antibiotics are prescribed annually in the outpatient setting; 49.9% of hospitalized patients were prescribed ≥ 1 antibiotic during their hospitalization.1,2 Among all classes of antibiotics, penicillins are prescribed due to their clinical efficacy, cost-effectiveness, and general safety for all ages. Unfortunately, penicillins also are the most common drug allergy listed in medical records. Patients with this allergy are consistently treated with broad-spectrum antibiotics, have more antibiotic resistant infections, incur higher health care costs, and experience more adverse effects (AEs).3,4

Drug allergies are distinguished by different immune mechanisms, including IgE-mediated reaction, T-lymphocyte-mediated mild skin reactions, and severe cutaneous adverse reactions (SCAR), or other systemic immune syndromes, such as hemolytic anemia, nephritis, and rash with eosinophilia.3 Although drug allergies should be a concern, compelling evidence shows that > 90% of patients labeled with a penicillin allergy are not allergic to penicillins (and associated β-lactams).3,4 Although this evidence is growing, clinicians still hesitate to prescribe penicillin, and patients are similarly anxious to take them. This article reviews the health care consequences of penicillin allergy and the application of this information to military medicine and readiness.

Penicillin Allergy Prevalence

Since their approval for public use in 1945, penicillins have been one of the most often prescribed antibiotics due to their clinical efficacy for many types of infections.3 However, 8 to 10% of the US population and up to 15% of hospitalized patients have a documented penicillin allergy, which limits the ability to use these effective antibiotics.3,4 Once a patient is labeled with a penicillin allergy, many clinicians avoid prescribing all β-lactam antibiotics to patients. Clinicians also avoid prescribing cephalosporins due to the concern for potential cross-reactivity (at a rate of about 2%, which is lower than previously reported).3 These reported allergies are often not clear and range from patients avoiding penicillins because their parents exhibited allergies, they had a symptom that was not likely allergic (ie, nausea, headache, itching with no rash), being told by their parents that they had a rash as a child, or experiencing severe anaphylaxis or other systemic reaction.3,4 Despite the high rates of documented penicillin allergy, studies now show that most patients do not have a serious allergy; < 1% of the population has a true immune-mediated penicillin allergy.3,4

Broad-Spectrum Antibiotic Risks

Even though penicillin allergies are often not confirmed, many patients are treated with alternative antibiotics. Unfortunately, most alternative antibiotics are not as effective or as safe as penicillin.3,4 Twenty percent of hospitalized patients will experience an AE related to their antibiotic; 19.3% of emergency department visits for adverse drug reactions (ADRs) are from antibiotics.5,6 Sulfonamides, clindamycin, and quinolones were the antibiotics most commonly associated with AEs.6

In a large database study over a 3-year period, > 400,000 hospitalizations were analyzed in patients matched for admission type, with and without a penicillin allergy in their medical record.7 Those with a documented penicillin allergy had longer hospitalizations; were treated with broad-spectrum antibiotics; and had increased rates of Clostridium difficile (C difficile), methicillin-resistant Staphylococcus aureus (MRSA), and vancomycin-resistant Enterococcus (VRE).7,8 In addition to being first-line treatment for many common infections, penicillins often are used for dental, perinatal, and perioperative prophylaxis.1,3 Nearly 25 million antibiotics are prescribed annually by dentists.1 If a patient has a penicillin allergy listed in their medical record, they will inevitably receive a second- or third-line treatment that is less effective and has higher risks. Common alternative antibiotics include clindamycin, fluoroquinolones, macrolides, and vancomycin.3,7,8

Clindamycin and fluoroquinolones are associated with C difficile infections.9,10 Fluoroquinolones come with a boxed warning for known serious ADRs, including tendon rupture, peripheral neuropathy, central nervous system effects, and are known for causing cardiac reactions such as QT prolongation, life-threatening arrhythmias, and cardiovascular death.11,12 Fluoroquinolones are associated with an increased risk for VRE and MRSA, in more than any other antibiotic classes.3,7,12,13

Macrolides, such as azithromycin and clarithromycin, are another common class of antibiotics used as an alternative for penicillins. Both are used frequently for upper respiratory infections. Known ADRs to macrolides include gastrointestinal adverse effects (AEs) (ie, nausea, vomiting, diarrhea, and abdominal pain), liver toxicity (ie, abnormal liver function tests, hepatitis, and liver failure), and cardiac risks (ie, QT prolongation and sudden death). When compared with amoxicillin, there was an increased risk for cardiovascular mortality in those patients receiving macrolides.14,15

Vancomycin is known for its potential to cause “red man syndrome,” an infusion-related reaction causing redness and itching as well as nephrotoxic and hematologic effects requiring close monitoring.3 Vancomycin is less effective than methicillin in clearing MRSA or other sensitive pathogens; however, vancomycin is used in patients with a penicillin allergy label.16-18 Intrapartum antibiotic use of vancomycin for group B streptococcus infection was associated with clinically significant morbidity and ADRs.19,20 Perioperatively, patients with penicillin allergies developed more surgical site infections due to the use of second-line antibiotics, such as vancomycin or others.21

Cost of Penicillin Allergies

Penicillin allergy plays an important role in rising health care costs. In 2017, health care spending reached 17.9% of the gross domestic product.22 Macy and Contreras demonstrated the significantly higher costs associated with having a reported (and unverified) penicillin allergy in a matched cohort study. Inferred for the extra hospital use, the penicillin allergy group cost the health care system $64,626,630 more than for the group who did not have a penicillin allergy label.7 A subsequent study by Macy and Contreras of both inpatient and outpatient settings showed a potential savings of $2,000 per patient per year in health care expenses with the testing and delabeling of penicillin allergies.23 Use of newer and broad-spectrum antibiotics also are more costly and contribute to higher health care costs.24

When these potential savings are applied to the military insurance population of 9.4 million beneficiaries (TRICARE, including active duty, their dependents, and all retirees participating in the program), the results showed that this could impart a savings of nearly $1.7 billion annually, using the model by Macy and Contreras.23,25,26

Previously with colleagues, I reviewed penicillin’s role in military history, compiled data from relevant studies from military penicillin allergy rates and delabeling efforts, and calculated the potential economic impact of penicillin allergies along with the benefits of testing.26 Calculations were estimated using the TRICARE beneficiary population (9.4 million) × the estimated prevalence (10%) to get an estimate of 940,000 TRICARE patients with penicillin allergy in their medical record.25 If 90% of those patients were delabeled, this would equal 846,000 TRICARE patients. When multiplied by the potential savings of $2,000 per patient per year, the estimated savings would be $1,692,000,000 annually.23,26

Current literature provides compelling evidence that all health care plans should use penicillin allergy testing and delabeling programs.3,23,26 As most patients with a history of penicillin allergy in their medical records do not have a verified allergy, delabeling those who do not have a true allergy will have individual, public health, and cost benefits.3,7,23,26

Antibiotic Stewardship

Antibiotic stewardship programs are now mandated to combat antibiotic resistance.3,27 This program is supported by major medical organizations, including the Centers for Disease Control and Prevention, Society for Healthcare Epidemiology of America, Infectious Disease Society of America, and the American Academy of Allergy Asthma and Immunology.3 Given the role of broad-spectrum antibiotics in antibiotic resistance, penicillin allergy testing and delabeling is an important component of these programs.3

In the US, > 2 million people acquire antibiotic resistant infections annually; 23,000 people die of these infections.27 More than 250,000 illnesses and 14,000 deaths annually are due to C difficile.27 There are many factors contributing to the increase in antibiotic resistance; however, one established and consistent factor is the use of broad-spectrum antibiotics. Further, broad-spectrum antibiotics are often used when first-line agents, such as penicillins, cannot be used due to a reported “allergy.” In addition, there are fewer novel antibiotics being developed, and as they are introduced, pathogens develop resistance to these new agents.27

Military Relevance

Infectious diseases have always accompanied military activity.28-30 Despite preventive programs such as vaccinations, hygiene measures, and prophylactic antibiotics, military personnel are at increased risk for infections due to the military’s mobile nature and crowded living situations.28-30 This situation has operational relevance from basic training, deployments, and combat operations to peacetime activities.

Military recruits are treated routinely with penicillin G benzathine as standard prophylaxis against streptococcal infections.26,30 A recent study by the Marine Corps Recruiting Depot in San Diego, California showed that in a cohort of 402 young healthy male recruits, only 5 (1.5%) had a positive reaction to penicillin testing and challenge over a 21-month period.31 The delabeled other 397 (98.5%) marine recruits were able to receive benzathine penicillin prophylaxis successfully.31 Recruits with a penicillin allergy who had a positive test or were not tested received azithromycin (or erythromycin at some recruit training locations).26,31 Military members may need to operate in remote or austere locations; the ability to use penicillins is important for readiness.

Evaluation and Management of Reported Penicillin Allergy

Verifying penicillin allergies is an important first step in optimizing medical care and decreasing resistance and ADRs.3,4,32,33 Although allergists can provide specialized evaluation, due to the high prevalence of penicillin allergy in the US, all health care team members, including clinicians and pharmacists, should be educated about penicillin allergies and be able to implement evaluations in both inpatient and outpatient settings. Reactions to any of the penicillins should be considered, including the natural penicillins (penicillin V, etc), antistaphylococcal penicillins (dicloxacillin), aminopenicillins (amoxicillin and ampicillin), and extended-spectrum penicillins (piperacillin).3 A thorough history, including the prior reaction (age, type of reaction) and subsequent tolerance are helpful in stratifying patients.3,26

Patient Risk Levels

Based on the clinical history, patients would fall into 4 categories from low risk, medium risk, high risk, to do not test/use.3,32,33 Low-risk patients are those who report mild or nonallergic symptoms (ie, gastrointestinal symptoms, headache, yeast infection, etc), remote cutaneous reactions (> 10 years), or in those with a family history of penicillin allergy.3,32,33 Low-risk patients often can be safely tested with an oral challenge. Although there are different approaches to the oral challenge, a single amoxicillin dose of 250 mg followed by 1 hour of direct monitoring is usually sufficient.3,32,33

Medium-risk patients have a more recent (< 1 year) history of pruritic rashes, urticaria, and/or angioedema without a history of severe or systemic reactions. These patients benefit from negative skin testing prior to an oral challenge, which can be performed by trained clinicians or pharmacists or an allergist. However, due to limited availability of skin testing and the potential for false positive testing with skin tests, a single dose or graded challenge would be a reasonable approach as well.3,32,33

High-risk patients are those with severe symptoms (anaphylaxis), a history of reactions to other β-lactam antibiotics, and/or recurrent reactions to antibiotics. These patients benefit from a formal evaluation by an allergist and skin testing prior to challenge.3,32,33 Testing and/or challenge should not be performed in patients who report a history of severe cutaneous reactions (blistering rash, such as Stevens Johnson syndrome), hemolytic anemia, serum sickness, drug fever, and other organ dysfunction.3,4,31,32

The Figure describes a published questionnaire, personnel, resources, and procedures for penicillin delabeling.26 Although skin testing is reliable in revealing a immunoglobulin E-mediated penicillin allergy, there is potential for false positives.32,33 The oral amoxicillin challenge effectively clears the patient for future penicillin administration.3,32-34 In high-risk patients, desensitization should be considered if penicillins (or cephalosporins) are required as first-line treatment. A test dose (one-tenth dose, higher or lower depending on route of administration, historic reaction, clinical status, and level of certainty of prior reaction) may be considered in low- to moderate-risk patients, depending on the indication for the use of the antibiotics.32

Penicillin evaluation pathways can occur in both inpatient and outpatient settings where antibiotics will be prescribed.32-34 There are several proposed pathways, including a screening questionnaire to determine the penicillin allergy risk.26,32,33 Implementation of perioperative testing has been successful in decreasing the rates of vancomycin use and lessening the morbidity associated with use of second-line antibiotics.35 Many hospitals throughout the country have implemented standardized penicillin delabeling programs.3,32-34

Conclusions

Penicillin allergies are an important barrier to effective antibiotic treatments and are associated with worse outcomes and higher economic costs.3,7,23,26,34 Therefore, in addition to vaccinations, infection control measures, and public health education, penicillin allergy verification and delabeling programs should be a proactive component of military medical readiness and all antibiotic stewardship initiatives in all health care settings.29 Given the many issues and negative impact of having a penicillin allergy label, penicillin delabeling will allow service members to be treated with the necessary antibiotics with fewer adverse complications, and return them to health and readiness for operational duties. In the current standardization of the Defense Health Agency, implementing this program across all services would have significant clinical, public health, and cost benefits for patients, the health care team, taxpayers, and the community at large.

Many patients report an allergy to penicillin, but only a small portion have a current true immune-mediated allergy. Given the clinical, public health, and economic costs associated with a penicillin allergy label, evaluation and clearance of penicillin allergies is a simple method that would improve clinical outcomes, decrease AEs to high-risk alternative broad-spectrum antibiotics, and prevent the spread of antibiotic resistance. In the military, penicillin delabeling improves readiness with optimal antibiotic options and avoidance of unnecessary risks of using alternative antibiotics, expediting return to full duty for military personnel.

Antibiotics are one of the most frequently prescribed medications in both inpatient and outpatient settings.1,2 More than 266 million courses of antibiotics are prescribed annually in the outpatient setting; 49.9% of hospitalized patients were prescribed ≥ 1 antibiotic during their hospitalization.1,2 Among all classes of antibiotics, penicillins are prescribed due to their clinical efficacy, cost-effectiveness, and general safety for all ages. Unfortunately, penicillins also are the most common drug allergy listed in medical records. Patients with this allergy are consistently treated with broad-spectrum antibiotics, have more antibiotic resistant infections, incur higher health care costs, and experience more adverse effects (AEs).3,4

Drug allergies are distinguished by different immune mechanisms, including IgE-mediated reaction, T-lymphocyte-mediated mild skin reactions, and severe cutaneous adverse reactions (SCAR), or other systemic immune syndromes, such as hemolytic anemia, nephritis, and rash with eosinophilia.3 Although drug allergies should be a concern, compelling evidence shows that > 90% of patients labeled with a penicillin allergy are not allergic to penicillins (and associated β-lactams).3,4 Although this evidence is growing, clinicians still hesitate to prescribe penicillin, and patients are similarly anxious to take them. This article reviews the health care consequences of penicillin allergy and the application of this information to military medicine and readiness.

Penicillin Allergy Prevalence

Since their approval for public use in 1945, penicillins have been one of the most often prescribed antibiotics due to their clinical efficacy for many types of infections.3 However, 8 to 10% of the US population and up to 15% of hospitalized patients have a documented penicillin allergy, which limits the ability to use these effective antibiotics.3,4 Once a patient is labeled with a penicillin allergy, many clinicians avoid prescribing all β-lactam antibiotics to patients. Clinicians also avoid prescribing cephalosporins due to the concern for potential cross-reactivity (at a rate of about 2%, which is lower than previously reported).3 These reported allergies are often not clear and range from patients avoiding penicillins because their parents exhibited allergies, they had a symptom that was not likely allergic (ie, nausea, headache, itching with no rash), being told by their parents that they had a rash as a child, or experiencing severe anaphylaxis or other systemic reaction.3,4 Despite the high rates of documented penicillin allergy, studies now show that most patients do not have a serious allergy; < 1% of the population has a true immune-mediated penicillin allergy.3,4

Broad-Spectrum Antibiotic Risks

Even though penicillin allergies are often not confirmed, many patients are treated with alternative antibiotics. Unfortunately, most alternative antibiotics are not as effective or as safe as penicillin.3,4 Twenty percent of hospitalized patients will experience an AE related to their antibiotic; 19.3% of emergency department visits for adverse drug reactions (ADRs) are from antibiotics.5,6 Sulfonamides, clindamycin, and quinolones were the antibiotics most commonly associated with AEs.6

In a large database study over a 3-year period, > 400,000 hospitalizations were analyzed in patients matched for admission type, with and without a penicillin allergy in their medical record.7 Those with a documented penicillin allergy had longer hospitalizations; were treated with broad-spectrum antibiotics; and had increased rates of Clostridium difficile (C difficile), methicillin-resistant Staphylococcus aureus (MRSA), and vancomycin-resistant Enterococcus (VRE).7,8 In addition to being first-line treatment for many common infections, penicillins often are used for dental, perinatal, and perioperative prophylaxis.1,3 Nearly 25 million antibiotics are prescribed annually by dentists.1 If a patient has a penicillin allergy listed in their medical record, they will inevitably receive a second- or third-line treatment that is less effective and has higher risks. Common alternative antibiotics include clindamycin, fluoroquinolones, macrolides, and vancomycin.3,7,8

Clindamycin and fluoroquinolones are associated with C difficile infections.9,10 Fluoroquinolones come with a boxed warning for known serious ADRs, including tendon rupture, peripheral neuropathy, central nervous system effects, and are known for causing cardiac reactions such as QT prolongation, life-threatening arrhythmias, and cardiovascular death.11,12 Fluoroquinolones are associated with an increased risk for VRE and MRSA, in more than any other antibiotic classes.3,7,12,13

Macrolides, such as azithromycin and clarithromycin, are another common class of antibiotics used as an alternative for penicillins. Both are used frequently for upper respiratory infections. Known ADRs to macrolides include gastrointestinal adverse effects (AEs) (ie, nausea, vomiting, diarrhea, and abdominal pain), liver toxicity (ie, abnormal liver function tests, hepatitis, and liver failure), and cardiac risks (ie, QT prolongation and sudden death). When compared with amoxicillin, there was an increased risk for cardiovascular mortality in those patients receiving macrolides.14,15

Vancomycin is known for its potential to cause “red man syndrome,” an infusion-related reaction causing redness and itching as well as nephrotoxic and hematologic effects requiring close monitoring.3 Vancomycin is less effective than methicillin in clearing MRSA or other sensitive pathogens; however, vancomycin is used in patients with a penicillin allergy label.16-18 Intrapartum antibiotic use of vancomycin for group B streptococcus infection was associated with clinically significant morbidity and ADRs.19,20 Perioperatively, patients with penicillin allergies developed more surgical site infections due to the use of second-line antibiotics, such as vancomycin or others.21

Cost of Penicillin Allergies

Penicillin allergy plays an important role in rising health care costs. In 2017, health care spending reached 17.9% of the gross domestic product.22 Macy and Contreras demonstrated the significantly higher costs associated with having a reported (and unverified) penicillin allergy in a matched cohort study. Inferred for the extra hospital use, the penicillin allergy group cost the health care system $64,626,630 more than for the group who did not have a penicillin allergy label.7 A subsequent study by Macy and Contreras of both inpatient and outpatient settings showed a potential savings of $2,000 per patient per year in health care expenses with the testing and delabeling of penicillin allergies.23 Use of newer and broad-spectrum antibiotics also are more costly and contribute to higher health care costs.24

When these potential savings are applied to the military insurance population of 9.4 million beneficiaries (TRICARE, including active duty, their dependents, and all retirees participating in the program), the results showed that this could impart a savings of nearly $1.7 billion annually, using the model by Macy and Contreras.23,25,26

Previously with colleagues, I reviewed penicillin’s role in military history, compiled data from relevant studies from military penicillin allergy rates and delabeling efforts, and calculated the potential economic impact of penicillin allergies along with the benefits of testing.26 Calculations were estimated using the TRICARE beneficiary population (9.4 million) × the estimated prevalence (10%) to get an estimate of 940,000 TRICARE patients with penicillin allergy in their medical record.25 If 90% of those patients were delabeled, this would equal 846,000 TRICARE patients. When multiplied by the potential savings of $2,000 per patient per year, the estimated savings would be $1,692,000,000 annually.23,26

Current literature provides compelling evidence that all health care plans should use penicillin allergy testing and delabeling programs.3,23,26 As most patients with a history of penicillin allergy in their medical records do not have a verified allergy, delabeling those who do not have a true allergy will have individual, public health, and cost benefits.3,7,23,26

Antibiotic Stewardship

Antibiotic stewardship programs are now mandated to combat antibiotic resistance.3,27 This program is supported by major medical organizations, including the Centers for Disease Control and Prevention, Society for Healthcare Epidemiology of America, Infectious Disease Society of America, and the American Academy of Allergy Asthma and Immunology.3 Given the role of broad-spectrum antibiotics in antibiotic resistance, penicillin allergy testing and delabeling is an important component of these programs.3

In the US, > 2 million people acquire antibiotic resistant infections annually; 23,000 people die of these infections.27 More than 250,000 illnesses and 14,000 deaths annually are due to C difficile.27 There are many factors contributing to the increase in antibiotic resistance; however, one established and consistent factor is the use of broad-spectrum antibiotics. Further, broad-spectrum antibiotics are often used when first-line agents, such as penicillins, cannot be used due to a reported “allergy.” In addition, there are fewer novel antibiotics being developed, and as they are introduced, pathogens develop resistance to these new agents.27

Military Relevance

Infectious diseases have always accompanied military activity.28-30 Despite preventive programs such as vaccinations, hygiene measures, and prophylactic antibiotics, military personnel are at increased risk for infections due to the military’s mobile nature and crowded living situations.28-30 This situation has operational relevance from basic training, deployments, and combat operations to peacetime activities.

Military recruits are treated routinely with penicillin G benzathine as standard prophylaxis against streptococcal infections.26,30 A recent study by the Marine Corps Recruiting Depot in San Diego, California showed that in a cohort of 402 young healthy male recruits, only 5 (1.5%) had a positive reaction to penicillin testing and challenge over a 21-month period.31 The delabeled other 397 (98.5%) marine recruits were able to receive benzathine penicillin prophylaxis successfully.31 Recruits with a penicillin allergy who had a positive test or were not tested received azithromycin (or erythromycin at some recruit training locations).26,31 Military members may need to operate in remote or austere locations; the ability to use penicillins is important for readiness.

Evaluation and Management of Reported Penicillin Allergy

Verifying penicillin allergies is an important first step in optimizing medical care and decreasing resistance and ADRs.3,4,32,33 Although allergists can provide specialized evaluation, due to the high prevalence of penicillin allergy in the US, all health care team members, including clinicians and pharmacists, should be educated about penicillin allergies and be able to implement evaluations in both inpatient and outpatient settings. Reactions to any of the penicillins should be considered, including the natural penicillins (penicillin V, etc), antistaphylococcal penicillins (dicloxacillin), aminopenicillins (amoxicillin and ampicillin), and extended-spectrum penicillins (piperacillin).3 A thorough history, including the prior reaction (age, type of reaction) and subsequent tolerance are helpful in stratifying patients.3,26

Patient Risk Levels

Based on the clinical history, patients would fall into 4 categories from low risk, medium risk, high risk, to do not test/use.3,32,33 Low-risk patients are those who report mild or nonallergic symptoms (ie, gastrointestinal symptoms, headache, yeast infection, etc), remote cutaneous reactions (> 10 years), or in those with a family history of penicillin allergy.3,32,33 Low-risk patients often can be safely tested with an oral challenge. Although there are different approaches to the oral challenge, a single amoxicillin dose of 250 mg followed by 1 hour of direct monitoring is usually sufficient.3,32,33

Medium-risk patients have a more recent (< 1 year) history of pruritic rashes, urticaria, and/or angioedema without a history of severe or systemic reactions. These patients benefit from negative skin testing prior to an oral challenge, which can be performed by trained clinicians or pharmacists or an allergist. However, due to limited availability of skin testing and the potential for false positive testing with skin tests, a single dose or graded challenge would be a reasonable approach as well.3,32,33

High-risk patients are those with severe symptoms (anaphylaxis), a history of reactions to other β-lactam antibiotics, and/or recurrent reactions to antibiotics. These patients benefit from a formal evaluation by an allergist and skin testing prior to challenge.3,32,33 Testing and/or challenge should not be performed in patients who report a history of severe cutaneous reactions (blistering rash, such as Stevens Johnson syndrome), hemolytic anemia, serum sickness, drug fever, and other organ dysfunction.3,4,31,32

The Figure describes a published questionnaire, personnel, resources, and procedures for penicillin delabeling.26 Although skin testing is reliable in revealing a immunoglobulin E-mediated penicillin allergy, there is potential for false positives.32,33 The oral amoxicillin challenge effectively clears the patient for future penicillin administration.3,32-34 In high-risk patients, desensitization should be considered if penicillins (or cephalosporins) are required as first-line treatment. A test dose (one-tenth dose, higher or lower depending on route of administration, historic reaction, clinical status, and level of certainty of prior reaction) may be considered in low- to moderate-risk patients, depending on the indication for the use of the antibiotics.32

Penicillin evaluation pathways can occur in both inpatient and outpatient settings where antibiotics will be prescribed.32-34 There are several proposed pathways, including a screening questionnaire to determine the penicillin allergy risk.26,32,33 Implementation of perioperative testing has been successful in decreasing the rates of vancomycin use and lessening the morbidity associated with use of second-line antibiotics.35 Many hospitals throughout the country have implemented standardized penicillin delabeling programs.3,32-34

Conclusions

Penicillin allergies are an important barrier to effective antibiotic treatments and are associated with worse outcomes and higher economic costs.3,7,23,26,34 Therefore, in addition to vaccinations, infection control measures, and public health education, penicillin allergy verification and delabeling programs should be a proactive component of military medical readiness and all antibiotic stewardship initiatives in all health care settings.29 Given the many issues and negative impact of having a penicillin allergy label, penicillin delabeling will allow service members to be treated with the necessary antibiotics with fewer adverse complications, and return them to health and readiness for operational duties. In the current standardization of the Defense Health Agency, implementing this program across all services would have significant clinical, public health, and cost benefits for patients, the health care team, taxpayers, and the community at large.

Many patients report an allergy to penicillin, but only a small portion have a current true immune-mediated allergy. Given the clinical, public health, and economic costs associated with a penicillin allergy label, evaluation and clearance of penicillin allergies is a simple method that would improve clinical outcomes, decrease AEs to high-risk alternative broad-spectrum antibiotics, and prevent the spread of antibiotic resistance. In the military, penicillin delabeling improves readiness with optimal antibiotic options and avoidance of unnecessary risks of using alternative antibiotics, expediting return to full duty for military personnel.

1. Centers for Disease Control and Prevention. Outpatient antibiotic prescriptions-United States, 2014. https://www.cdc.gov/antibiotic-use/community/pdfs/annual-reportsummary_2014.pdf. Accessed August 15, 2020.

2. Magill SS, Edwards JR, Beldavs ZG, et al. Prevalence of antimicrobial use in US acute care hospitals, May-September 2011. JAMA. 2014;312(14):1438-1446. doi:10.1001/jama.2014.12923

3. Shenoy ES, Macy E, Rowe T, Blumenthal KG. Evaluation and management of penicillin allergy. JAMA. 2019;321:188-199. doi:10.1001/jama.2018.19283

4. Har D, Solensky R. Penicillin and beta-lactam hypersensitivity. Immunol Allergy Clin North Am. 2017;37(4):643-662. doi:10.1016/j.iac.2017.07.001

5. Tamma PD, Avdic E, Li DX, Dzintars K, Cosgrove SE. Association of adverse events with antibiotic use in hospitalized patients. JAMA Intern Med. 2017;177(9):1308-1315. doi:10.1001/jamainternmed.2017.1938

6. Shebab N, Patel PR, Srinivasan A, Budnitz DS. Emergency department visits for antibiotic-associated adverse events. Clin Infect Dis. 2008;47(6):735-743. doi:10.1086/591126

7. Macy E, Contreras R. Healthcare use and serious infection prevalence associated with penicillin “allergy” in hospitalized patients: a cohort study. J Allergy Clin Immunol. 2014;133(3):790-796. doi:10.1016/j.jaci.2013.09.021

8. Blumenthal KG, Lu N, Zhang Y, Li Y, Walensky RP, Choi HK. Risk of methicillin resistant Staphylococcal aureus and Clostridium difficile in patients with a documented penicillin allergy: population-based matched cohort study. BMJ. 2018;361:k2400. doi:10.1136/bmj.k2400

9. Loo VG, Poirier L, Miller MA, et al. A predominantly clonal multi-institutional outbreak of Clostridium difficile associated diarrhea with high morbidity and mortality. N Engl J Med. 2005;353(23):2442-2449. doi:10.1056/NEJMoa051639

10. Pepin J, Saheb N, Coulombe MA, et al. Emergence of fluoroquinolone as the predominant risk factor for Clostridium difficile-associated diarrhea: a cohort study during an epidemic in Quebec. Clin Infect Dis. 2005;41(9):1254-1260. doi:10.1086/496986

11. Chou HW, Wang JL, Chang CH, et al. Risks of cardiac arrhythmia and mortality among patients using new-generation macrolides, fluoroquinolones, and β-lactam/β-lactamase inhibitors: a Taiwanese nationwide study. Clin Infec Dis. 2015;60(4):566-577. doi:10.1093/cid/ciu914

12. Rao GA, Mann JR, Shoaibi A, et al. Azithromycin and levofloxacin use and increased risk of cardiac arrhythmia and death. Ann Fam Med. 2014;12(2):121-127. doi:10.1370/afm.1601

13. LeBlanc L, Pepin J, Toulouse K, et al. Fluoroquinolone and risk for methicillin-resistant Staphylococcus aureus, Canada. Emerg Infect Dis. 2006;12(9):1398-1405. doi:10.3201/eid1209.060397

14. Schembri S, Williamson PA, Short PM, et al. Cardiovascular events after clarithromycin use in lower respiratory tract infections: analysis of two prospective cohort studies. BMJ. 2013;346:f1245. doi:10.1136/bmj.f1235

15. Ray WA, Murray KT, Hall K, Arbogast PG, Stein CM. Azithromycin and the risk of cardiovascular death. N Engl J Med. 2012;366(20):1881-1890. doi:10.1056/NEJMoa1003833

16. McDaniel JS, Perencevich EN, Diekema DJ, et al. Comparative effectiveness of beta-lactams versus vancomycin for treatment of methicillin-susceptible Staphylococcus aureus bloodstream infections among 122 hospitals. Clin Infect Dis. 2015;61(3):361-367. doi:10.1093/cid/civ308

17. Wong D, Wong T, Romney M, Leung V. Comparison of outcomes in patients with methicillin-susceptible Staphylococcus aureus (MSSA) bacteremia who are treated with β-lactam vs vancomycin empiric therapy: a retrospective cohort study. BMC Infect Dis. 2016;16:224. doi:10.1186/s12879-016-1564-5

18. Blumenthal KG, Shenoy ES, Huang M, et al. The impact of reporting a prior penicillin allergy on the treatment of methicillin-sensitivity Staphylococcus aureus bacteremia. PLoS One. 2016;11(7):e0159406. doi:10.1371/journal.pone.0159406

19. Verani JR, McGee L, Schrag SJ; . Prevention of perinatal group B streptococcal disease. MMWR Recomm Rep. 2010;59(RR-10):1-36.

20. Desai SH, Kaplan MS, Chen Q, Macy EM. Morbidity in pregnant women associated with unverified penicillin allergies, antibiotic use, and group B Streptococcus infections. Perm J. 2017;21:16-080. doi:10.7812/TPP/16-080

21. Blumenthal KG, Ryan EE, Li Y, Lee H, Kuhlen JL, Shenoy ES. The impact of a reported penicillin allergy on surgical site infection risk. Clin Infect Dis. 2018;66(3):329-336. doi:10.1093/cid/cix794

22. National Health Expenditures 2017 Highlights. Centers for Medicare & Medicaid services. https://www.cms.gov/Research-Statistics-Data-and-Systems/Statistics-Trends-and-Reports/NationalHealthExpendData/Downloads/highlights.pdf. Accessed August 25, 2020.

23. Macy E, Shu YH. The effect of penicillin allergy testing on future health care utilization: a matched cohort study. J Allergy Clin Immunol Pract. 2017;5(3):705-710. doi:10.1016/j.jaip.2017.02.012

24. Picard M, Begin P, Bouchard H, et al. Treatment of patients with a history of penicillin allergy in a large tertiary-care academic hospital. J Allergy Clin Immunol Pract. 2013;1(3):252-257. doi:10.1016/j.jaip.2013.01.006

25. US Department of Defense. Beneficiary population statistics. https://health.mil/I-Am-A/Media/Media-Center/Patient-Population-Statistics. Accessed August 25, 2020.

26. Lee RU, Banks TA, Waibel KH, Rodriguez RG. Penicillin allergy…maybe not? The military relevance for penicillin testing and de-labeling. Mil Med. 2019;184(3-4):e163-e168. doi:10.1093/milmed/usy194

27. Antibiotic resistance threats in the United States, 2013. Centers for Disease Control and Prevention. https://www.cdc.gov/drugresistance/threat-report-2013/index.html. Accessed May 10, 2019.

28. Gray GC, Callahan JD, Hawksworth AW, Fisher CA, Gaydos JC. Respiratory diseases among U.S. military personnel: countering emerging threats. Emerg Infect Dis. 1999;5(3):379-385. doi:10.3201/eid0503.990308

29. Beaumier CM, Gomez-Rubio AM, Hotez PJ, Weina PJ. United States military tropical medicine: extraordinary legacy, uncertain future. PLoS Negl Trop Dis. 2013;7(12):e2448. doi:10.1371/journal.pntd.0002448

30. Thomas RJ, Conwill DE, Morton DE, et al. Penicillin prophylaxis for streptococcal infections in the United States Navy and Marine Corps recruit camps, 1951-1985. Rev Infect Dis. 1988;10(1):125-130. doi:10.1093/clinids/10.1.125

31. Tucker MH, Lomas CM, Ramchandar N, Waldram JD. Amoxicillin challenge without penicillin skin testing in evaluation of penicillin allergy in a cohort of Marine recruits. J Allergy Clin Immunol Pract. 2017;5(3):813-815. doi:10.1016/j.jaip.2017.01.023

32. Blumenthal KG, Shenoy ES, Wolfson AR, et al. Addressing inpatient beta-lactam allergies: a multihospital implementation. J Allergy Clin Immunol Pract. 2017;5(3):616-625. doi:10.1016/j.jaip.2017.02.019

33. Kuruvilla M, Shih J, Patel K, Scanlon N. Direct oral amoxicillin challenge without preliminary skin testing in adult patients with allergy and at low risk with reported penicillin allergy. Allergy Asthma Proc. 2019;40(1):57-61. doi:10.2500/aap.2019.40.4184

34. Banks TA, Tucker M, Macy E. Evaluating penicillin allergies without skin testing. Curr Allergy Asthma Rep. 2019;19(5):27. doi:10.1007/s11882-019-0854-6

35. Park M, Markus P, Matesic

1. Centers for Disease Control and Prevention. Outpatient antibiotic prescriptions-United States, 2014. https://www.cdc.gov/antibiotic-use/community/pdfs/annual-reportsummary_2014.pdf. Accessed August 15, 2020.

2. Magill SS, Edwards JR, Beldavs ZG, et al. Prevalence of antimicrobial use in US acute care hospitals, May-September 2011. JAMA. 2014;312(14):1438-1446. doi:10.1001/jama.2014.12923

3. Shenoy ES, Macy E, Rowe T, Blumenthal KG. Evaluation and management of penicillin allergy. JAMA. 2019;321:188-199. doi:10.1001/jama.2018.19283

4. Har D, Solensky R. Penicillin and beta-lactam hypersensitivity. Immunol Allergy Clin North Am. 2017;37(4):643-662. doi:10.1016/j.iac.2017.07.001

5. Tamma PD, Avdic E, Li DX, Dzintars K, Cosgrove SE. Association of adverse events with antibiotic use in hospitalized patients. JAMA Intern Med. 2017;177(9):1308-1315. doi:10.1001/jamainternmed.2017.1938

6. Shebab N, Patel PR, Srinivasan A, Budnitz DS. Emergency department visits for antibiotic-associated adverse events. Clin Infect Dis. 2008;47(6):735-743. doi:10.1086/591126

7. Macy E, Contreras R. Healthcare use and serious infection prevalence associated with penicillin “allergy” in hospitalized patients: a cohort study. J Allergy Clin Immunol. 2014;133(3):790-796. doi:10.1016/j.jaci.2013.09.021

8. Blumenthal KG, Lu N, Zhang Y, Li Y, Walensky RP, Choi HK. Risk of methicillin resistant Staphylococcal aureus and Clostridium difficile in patients with a documented penicillin allergy: population-based matched cohort study. BMJ. 2018;361:k2400. doi:10.1136/bmj.k2400

9. Loo VG, Poirier L, Miller MA, et al. A predominantly clonal multi-institutional outbreak of Clostridium difficile associated diarrhea with high morbidity and mortality. N Engl J Med. 2005;353(23):2442-2449. doi:10.1056/NEJMoa051639

10. Pepin J, Saheb N, Coulombe MA, et al. Emergence of fluoroquinolone as the predominant risk factor for Clostridium difficile-associated diarrhea: a cohort study during an epidemic in Quebec. Clin Infect Dis. 2005;41(9):1254-1260. doi:10.1086/496986

11. Chou HW, Wang JL, Chang CH, et al. Risks of cardiac arrhythmia and mortality among patients using new-generation macrolides, fluoroquinolones, and β-lactam/β-lactamase inhibitors: a Taiwanese nationwide study. Clin Infec Dis. 2015;60(4):566-577. doi:10.1093/cid/ciu914

12. Rao GA, Mann JR, Shoaibi A, et al. Azithromycin and levofloxacin use and increased risk of cardiac arrhythmia and death. Ann Fam Med. 2014;12(2):121-127. doi:10.1370/afm.1601

13. LeBlanc L, Pepin J, Toulouse K, et al. Fluoroquinolone and risk for methicillin-resistant Staphylococcus aureus, Canada. Emerg Infect Dis. 2006;12(9):1398-1405. doi:10.3201/eid1209.060397

14. Schembri S, Williamson PA, Short PM, et al. Cardiovascular events after clarithromycin use in lower respiratory tract infections: analysis of two prospective cohort studies. BMJ. 2013;346:f1245. doi:10.1136/bmj.f1235

15. Ray WA, Murray KT, Hall K, Arbogast PG, Stein CM. Azithromycin and the risk of cardiovascular death. N Engl J Med. 2012;366(20):1881-1890. doi:10.1056/NEJMoa1003833

16. McDaniel JS, Perencevich EN, Diekema DJ, et al. Comparative effectiveness of beta-lactams versus vancomycin for treatment of methicillin-susceptible Staphylococcus aureus bloodstream infections among 122 hospitals. Clin Infect Dis. 2015;61(3):361-367. doi:10.1093/cid/civ308

17. Wong D, Wong T, Romney M, Leung V. Comparison of outcomes in patients with methicillin-susceptible Staphylococcus aureus (MSSA) bacteremia who are treated with β-lactam vs vancomycin empiric therapy: a retrospective cohort study. BMC Infect Dis. 2016;16:224. doi:10.1186/s12879-016-1564-5

18. Blumenthal KG, Shenoy ES, Huang M, et al. The impact of reporting a prior penicillin allergy on the treatment of methicillin-sensitivity Staphylococcus aureus bacteremia. PLoS One. 2016;11(7):e0159406. doi:10.1371/journal.pone.0159406

19. Verani JR, McGee L, Schrag SJ; . Prevention of perinatal group B streptococcal disease. MMWR Recomm Rep. 2010;59(RR-10):1-36.

20. Desai SH, Kaplan MS, Chen Q, Macy EM. Morbidity in pregnant women associated with unverified penicillin allergies, antibiotic use, and group B Streptococcus infections. Perm J. 2017;21:16-080. doi:10.7812/TPP/16-080

21. Blumenthal KG, Ryan EE, Li Y, Lee H, Kuhlen JL, Shenoy ES. The impact of a reported penicillin allergy on surgical site infection risk. Clin Infect Dis. 2018;66(3):329-336. doi:10.1093/cid/cix794

22. National Health Expenditures 2017 Highlights. Centers for Medicare & Medicaid services. https://www.cms.gov/Research-Statistics-Data-and-Systems/Statistics-Trends-and-Reports/NationalHealthExpendData/Downloads/highlights.pdf. Accessed August 25, 2020.

23. Macy E, Shu YH. The effect of penicillin allergy testing on future health care utilization: a matched cohort study. J Allergy Clin Immunol Pract. 2017;5(3):705-710. doi:10.1016/j.jaip.2017.02.012

24. Picard M, Begin P, Bouchard H, et al. Treatment of patients with a history of penicillin allergy in a large tertiary-care academic hospital. J Allergy Clin Immunol Pract. 2013;1(3):252-257. doi:10.1016/j.jaip.2013.01.006

25. US Department of Defense. Beneficiary population statistics. https://health.mil/I-Am-A/Media/Media-Center/Patient-Population-Statistics. Accessed August 25, 2020.

26. Lee RU, Banks TA, Waibel KH, Rodriguez RG. Penicillin allergy…maybe not? The military relevance for penicillin testing and de-labeling. Mil Med. 2019;184(3-4):e163-e168. doi:10.1093/milmed/usy194

27. Antibiotic resistance threats in the United States, 2013. Centers for Disease Control and Prevention. https://www.cdc.gov/drugresistance/threat-report-2013/index.html. Accessed May 10, 2019.

28. Gray GC, Callahan JD, Hawksworth AW, Fisher CA, Gaydos JC. Respiratory diseases among U.S. military personnel: countering emerging threats. Emerg Infect Dis. 1999;5(3):379-385. doi:10.3201/eid0503.990308

29. Beaumier CM, Gomez-Rubio AM, Hotez PJ, Weina PJ. United States military tropical medicine: extraordinary legacy, uncertain future. PLoS Negl Trop Dis. 2013;7(12):e2448. doi:10.1371/journal.pntd.0002448

30. Thomas RJ, Conwill DE, Morton DE, et al. Penicillin prophylaxis for streptococcal infections in the United States Navy and Marine Corps recruit camps, 1951-1985. Rev Infect Dis. 1988;10(1):125-130. doi:10.1093/clinids/10.1.125

31. Tucker MH, Lomas CM, Ramchandar N, Waldram JD. Amoxicillin challenge without penicillin skin testing in evaluation of penicillin allergy in a cohort of Marine recruits. J Allergy Clin Immunol Pract. 2017;5(3):813-815. doi:10.1016/j.jaip.2017.01.023

32. Blumenthal KG, Shenoy ES, Wolfson AR, et al. Addressing inpatient beta-lactam allergies: a multihospital implementation. J Allergy Clin Immunol Pract. 2017;5(3):616-625. doi:10.1016/j.jaip.2017.02.019

33. Kuruvilla M, Shih J, Patel K, Scanlon N. Direct oral amoxicillin challenge without preliminary skin testing in adult patients with allergy and at low risk with reported penicillin allergy. Allergy Asthma Proc. 2019;40(1):57-61. doi:10.2500/aap.2019.40.4184

34. Banks TA, Tucker M, Macy E. Evaluating penicillin allergies without skin testing. Curr Allergy Asthma Rep. 2019;19(5):27. doi:10.1007/s11882-019-0854-6

35. Park M, Markus P, Matesic

CDC flips, acknowledges aerosol spread of COVID-19

The information reiterates, however, that “COVID-19 is thought to spread mainly through close contact from person to person, including between people who are physically near each other (within about 6 feet). People who are infected but do not show symptoms can also spread the virus to others.”

In a statement to the media, the CDC said, “Today’s update acknowledges the existence of some published reports showing limited, uncommon circumstances where people with COVID-19 infected others who were more than 6 feet away or shortly after the COVID-19–positive person left an area. In these instances, transmission occurred in poorly ventilated and enclosed spaces that often involved activities that caused heavier breathing, like singing or exercise. Such environments and activities may contribute to the buildup of virus-carrying particles.”

“This is HUGE and been long delayed. But glad it’s now CDC official,” tweeted Eric Feigl-Ding, MD, an epidemiologist and health economist at Harvard University, Boston on Oct. 5.

The CDC announcement follows an abrupt flip-flop on information last month surrounding the aerosol spread of the virus.

Information deleted from website last month

On September 18, the CDC had added to its existing guidance that the virus is spread “through respiratory droplets or small particles, such as those in aerosols, produced when an infected person coughs, sneezes, sings, talks, or breathes. These particles can be inhaled into the nose, mouth, airways, and lungs and cause infection.”

The CDC then deleted that guidance on Sept. 21, saying it was a draft update released in error.

A key element of the now-deleted guidance said, “this is thought to be the main way the virus spreads.”

The information updated today reverses the now-deleted guidance and says aerosol transmission is not the main way the virus spreads.

It states that people who are within 6 feet of a person with COVID-19 or have direct contact with that person have the greatest risk of infection.

The CDC reiterated in the statement to the media today, “People can protect themselves from the virus that causes COVID-19 by staying at least 6 feet away from others, wearing a mask that covers their nose and mouth, washing their hands frequently, cleaning touched surfaces often, and staying home when sick.”

Among the journals that have published evidence on aerosol spread is Clinical Infectious Diseases, which, on July 6, published the paper, “It Is Time to Address Airborne Transmission of Coronavirus Disease 2019,” which was supported by 239 scientists.

The authors wrote, “there is significant potential for inhalation exposure to viruses in microscopic respiratory droplets (microdroplets) at short to medium distances (up to several meters, or room scale).”

Aerosols and airborne transmission “are the only way to explain super-spreader events we are seeing,” said Kimberly Prather, PhD, an atmospheric chemist at the University of California at San Diego, in an interview Oct. 5 with the Washington Post.

Dr. Prather added that, once aerosolization is acknowledged, this becomes a “fixable” problem through proper ventilation.

“Wear masks at all times indoors when others are present,” Dr. Prather said. But when inside, she said, there’s no such thing as a completely safe social distance.

This article first appeared on Medscape.com.

The information reiterates, however, that “COVID-19 is thought to spread mainly through close contact from person to person, including between people who are physically near each other (within about 6 feet). People who are infected but do not show symptoms can also spread the virus to others.”

In a statement to the media, the CDC said, “Today’s update acknowledges the existence of some published reports showing limited, uncommon circumstances where people with COVID-19 infected others who were more than 6 feet away or shortly after the COVID-19–positive person left an area. In these instances, transmission occurred in poorly ventilated and enclosed spaces that often involved activities that caused heavier breathing, like singing or exercise. Such environments and activities may contribute to the buildup of virus-carrying particles.”

“This is HUGE and been long delayed. But glad it’s now CDC official,” tweeted Eric Feigl-Ding, MD, an epidemiologist and health economist at Harvard University, Boston on Oct. 5.

The CDC announcement follows an abrupt flip-flop on information last month surrounding the aerosol spread of the virus.

Information deleted from website last month

On September 18, the CDC had added to its existing guidance that the virus is spread “through respiratory droplets or small particles, such as those in aerosols, produced when an infected person coughs, sneezes, sings, talks, or breathes. These particles can be inhaled into the nose, mouth, airways, and lungs and cause infection.”

The CDC then deleted that guidance on Sept. 21, saying it was a draft update released in error.

A key element of the now-deleted guidance said, “this is thought to be the main way the virus spreads.”

The information updated today reverses the now-deleted guidance and says aerosol transmission is not the main way the virus spreads.

It states that people who are within 6 feet of a person with COVID-19 or have direct contact with that person have the greatest risk of infection.

The CDC reiterated in the statement to the media today, “People can protect themselves from the virus that causes COVID-19 by staying at least 6 feet away from others, wearing a mask that covers their nose and mouth, washing their hands frequently, cleaning touched surfaces often, and staying home when sick.”

Among the journals that have published evidence on aerosol spread is Clinical Infectious Diseases, which, on July 6, published the paper, “It Is Time to Address Airborne Transmission of Coronavirus Disease 2019,” which was supported by 239 scientists.

The authors wrote, “there is significant potential for inhalation exposure to viruses in microscopic respiratory droplets (microdroplets) at short to medium distances (up to several meters, or room scale).”

Aerosols and airborne transmission “are the only way to explain super-spreader events we are seeing,” said Kimberly Prather, PhD, an atmospheric chemist at the University of California at San Diego, in an interview Oct. 5 with the Washington Post.

Dr. Prather added that, once aerosolization is acknowledged, this becomes a “fixable” problem through proper ventilation.

“Wear masks at all times indoors when others are present,” Dr. Prather said. But when inside, she said, there’s no such thing as a completely safe social distance.

This article first appeared on Medscape.com.

The information reiterates, however, that “COVID-19 is thought to spread mainly through close contact from person to person, including between people who are physically near each other (within about 6 feet). People who are infected but do not show symptoms can also spread the virus to others.”

In a statement to the media, the CDC said, “Today’s update acknowledges the existence of some published reports showing limited, uncommon circumstances where people with COVID-19 infected others who were more than 6 feet away or shortly after the COVID-19–positive person left an area. In these instances, transmission occurred in poorly ventilated and enclosed spaces that often involved activities that caused heavier breathing, like singing or exercise. Such environments and activities may contribute to the buildup of virus-carrying particles.”

“This is HUGE and been long delayed. But glad it’s now CDC official,” tweeted Eric Feigl-Ding, MD, an epidemiologist and health economist at Harvard University, Boston on Oct. 5.

The CDC announcement follows an abrupt flip-flop on information last month surrounding the aerosol spread of the virus.

Information deleted from website last month

On September 18, the CDC had added to its existing guidance that the virus is spread “through respiratory droplets or small particles, such as those in aerosols, produced when an infected person coughs, sneezes, sings, talks, or breathes. These particles can be inhaled into the nose, mouth, airways, and lungs and cause infection.”