User login

Without Ginsburg, judicial threats to the ACA, reproductive rights heighten

On Feb. 27, 2018, I got an email from the Heritage Foundation that alerted me to a news conference that afternoon held by Republican attorneys general of Texas and other states. It was referred to only as a “discussion about the Affordable Care Act lawsuit.”

I sent the following note to my editor: “I’m off to the Hill anyway. I could stop by this. You never know what it might morph into.”

Few people took that case very seriously – barely a handful of reporters attended the news conference. But it has now “morphed into” the latest existential threat to the Affordable Care Act, scheduled for oral arguments at the Supreme Court a week after the general election in November. And with the death of Justice Ruth Bader Ginsburg on Friday, that case could well morph into the threat that brings down the law in its entirety.

Democrats are raising alarms about the future of the law without Ms. Ginsburg. House Speaker Nancy Pelosi, speaking on ABC’s “This Week” Sunday morning, said that part of the strategy by President Trump and Senate Republicans to quickly fill her seat was to help undermine the ACA.

“The president is rushing to make some kind of a decision because … Nov. 10 is when the arguments begin on the Affordable Care Act,” she said. “He doesn’t want to crush the virus. He wants to crush the Affordable Care Act.”

Ms. Ginsburg’s death could throw an already chaotic general election campaign during a pandemic into even more turmoil.

Let’s take them one at a time.

The ACA under fire – again

The GOP attorneys general argued in February 2018 that the Republican-sponsored tax cut bill Congress passed two months earlier had rendered the ACA unconstitutional by reducing to zero the ACA’s penalty for not having insurance. They based their argument on Chief Justice John Roberts’ 2012 conclusion that the ACA was valid, interpreting that penalty as a constitutionally appropriate tax.

Most legal scholars, including several who challenged the law before the Supreme Court in 2012 and again in 2015, find the argument that the entire law should fall to be unconvincing. “If courts invalidate an entire law merely because Congress eliminates or revises one part, as happened here, that may well inhibit necessary reform of federal legislation in the future by turning it into an ‘all or nothing’ proposition,” wrote a group of conservative and liberal law professors in a brief filed in the case.

Still, in December 2018, U.S. District Judge Reed O’Connor in Texas accepted the GOP argument and declared the law unconstitutional. In December 2019, a three-judge 5th Circuit appeals court panel in New Orleans agreed that without the penalty the requirement to buy insurance is unconstitutional. But it sent the case back to Mr. O’Connor to suggest that perhaps the entire law need not fall.

Not wanting to wait the months or years that reconsideration would take, Democratic attorneys general defending the ACA asked the Supreme Court to hear the case this year. (Democrats are defending the law in court because the Trump administration decided to support the GOP attorneys general’s case.) The court agreed to take the case but scheduled arguments for the week after the November election.

While the fate of the ACA was and is a live political issue, few legal observers were terribly worried about the legal outcome of the case, now known as Texas v. California, if only because the case seemed much weaker than the 2012 and 2015 cases in which Mr. Roberts joined the court’s four liberals. In the 2015 case, which challenged the validity of federal tax subsidies helping millions of Americans buy health insurance on the ACA’s marketplaces, both Mr. Roberts and now-retired Justice Anthony Kennedy voted to uphold the law.

But without Ms. Ginsburg, the case could wind up in a 4-4 tie, even if Mr. Roberts supports the law’s constitutionality. That could let the lower-court ruling stand, although it would not be binding on other courts outside of the 5th Circuit. The court could also put off the arguments or, if the Republican Senate replaces Ms. Ginsburg with another conservative justice before arguments are heard, Republicans could secure a 5-4 ruling against the law. Some court observers argue that Justice Brett Kavanaugh has not favored invalidating an entire statute if only part of it is flawed and might not approve overturning the ACA. Still, what started out as an effort to energize Republican voters for the 2018 midterms after Congress failed to “repeal and replace” the health law in 2017 could end up throwing the nation’s entire health system into chaos.

At least 20 million Americans – and likely many more who sought coverage since the start of the coronavirus pandemic — who buy insurance through the ACA marketplaces or have Medicaid through the law’s expansion could lose coverage right away. Many millions more would lose the law’s popular protections guaranteeing coverage for people with preexisting health conditions, including those who have had COVID-19.

Adult children under age 26 years would no longer be guaranteed the right to remain on their parents’ health plans, and Medicare patients would lose enhanced prescription drug coverage. Women would lose guaranteed access to birth control at no out-of-pocket cost.

But a sudden elimination would affect more than just health care consumers. Insurance companies, drug companies, hospitals, and doctors have all changed the way they do business because of incentives and penalties in the health law. If it’s struck down, many of the “rules of the road” would literally be wiped away, including billing and payment mechanisms.

A new Democratic president could not drop the lawsuit because the Trump administration is not the plaintiff (the GOP attorneys general are). But a Democratic Congress and president could in theory make the entire issue go away by reinstating the penalty for failure to have insurance, even at a minimal amount. However, as far as the health law goes, for now, nothing is a sure thing.

As Nicholas Bagley, a law professor at the University of Michigan, Ann Arbor, who specializes in health issues, tweeted: “Among other things, the Affordable Care Act now dangles from a thread.”

Reproductive rights

A woman’s right to abortion – and even to birth control – also has been hanging by a thread at the high court for more than a decade. This past term, Mr. Roberts joined the liberals to invalidate a Louisiana law that would have closed most of the state’s abortion clinics, but he made it clear it was not a vote for abortion rights. The Louisiana law was too similar to a Texas law the court (without his vote) struck down in 2016, Mr. Roberts argued.

Ms. Ginsburg had been a stalwart supporter of reproductive freedom for women. In her nearly 3 decades on the court, she always voted with backers of abortion rights and birth control and led the dissenters in 2007 when the court upheld a federal ban on a specific abortion procedure.

Adding a justice opposed to abortion to the bench – which is what Trump has promised his supporters – would almost certainly tilt the court in favor of far more dramatic restrictions on the procedure and possibly an overturn of the landmark 1973 ruling Roe v. Wade.

But not only is abortion on the line: The court in recent years has repeatedly ruled that employers with religious objections can refuse to provide contraception.

And waiting in the lower-court pipeline are cases involving federal funding of Planned Parenthood in both the Medicaid and federal family planning programs, and the ability of individual health workers to decline to participate in abortion and other procedures.

For Ms. Ginsburg, those issues came down to a clear question of a woman’s guarantee of equal status under the law.

“Women, it is now acknowledged, have the talent, capacity, and right ‘to participate equally in the economic and social life of the Nation,’ ” she wrote in her dissent in that 2007 abortion case. “Their ability to realize their full potential, the Court recognized, is intimately connected to ‘their ability to control their reproductive lives.’ ”

Kaiser Health News is a nonprofit news service covering health issues. It is an editorially independent program of KFF (Kaiser Family Foundation), which is not affiliated with Kaiser Permanente.

On Feb. 27, 2018, I got an email from the Heritage Foundation that alerted me to a news conference that afternoon held by Republican attorneys general of Texas and other states. It was referred to only as a “discussion about the Affordable Care Act lawsuit.”

I sent the following note to my editor: “I’m off to the Hill anyway. I could stop by this. You never know what it might morph into.”

Few people took that case very seriously – barely a handful of reporters attended the news conference. But it has now “morphed into” the latest existential threat to the Affordable Care Act, scheduled for oral arguments at the Supreme Court a week after the general election in November. And with the death of Justice Ruth Bader Ginsburg on Friday, that case could well morph into the threat that brings down the law in its entirety.

Democrats are raising alarms about the future of the law without Ms. Ginsburg. House Speaker Nancy Pelosi, speaking on ABC’s “This Week” Sunday morning, said that part of the strategy by President Trump and Senate Republicans to quickly fill her seat was to help undermine the ACA.

“The president is rushing to make some kind of a decision because … Nov. 10 is when the arguments begin on the Affordable Care Act,” she said. “He doesn’t want to crush the virus. He wants to crush the Affordable Care Act.”

Ms. Ginsburg’s death could throw an already chaotic general election campaign during a pandemic into even more turmoil.

Let’s take them one at a time.

The ACA under fire – again

The GOP attorneys general argued in February 2018 that the Republican-sponsored tax cut bill Congress passed two months earlier had rendered the ACA unconstitutional by reducing to zero the ACA’s penalty for not having insurance. They based their argument on Chief Justice John Roberts’ 2012 conclusion that the ACA was valid, interpreting that penalty as a constitutionally appropriate tax.

Most legal scholars, including several who challenged the law before the Supreme Court in 2012 and again in 2015, find the argument that the entire law should fall to be unconvincing. “If courts invalidate an entire law merely because Congress eliminates or revises one part, as happened here, that may well inhibit necessary reform of federal legislation in the future by turning it into an ‘all or nothing’ proposition,” wrote a group of conservative and liberal law professors in a brief filed in the case.

Still, in December 2018, U.S. District Judge Reed O’Connor in Texas accepted the GOP argument and declared the law unconstitutional. In December 2019, a three-judge 5th Circuit appeals court panel in New Orleans agreed that without the penalty the requirement to buy insurance is unconstitutional. But it sent the case back to Mr. O’Connor to suggest that perhaps the entire law need not fall.

Not wanting to wait the months or years that reconsideration would take, Democratic attorneys general defending the ACA asked the Supreme Court to hear the case this year. (Democrats are defending the law in court because the Trump administration decided to support the GOP attorneys general’s case.) The court agreed to take the case but scheduled arguments for the week after the November election.

While the fate of the ACA was and is a live political issue, few legal observers were terribly worried about the legal outcome of the case, now known as Texas v. California, if only because the case seemed much weaker than the 2012 and 2015 cases in which Mr. Roberts joined the court’s four liberals. In the 2015 case, which challenged the validity of federal tax subsidies helping millions of Americans buy health insurance on the ACA’s marketplaces, both Mr. Roberts and now-retired Justice Anthony Kennedy voted to uphold the law.

But without Ms. Ginsburg, the case could wind up in a 4-4 tie, even if Mr. Roberts supports the law’s constitutionality. That could let the lower-court ruling stand, although it would not be binding on other courts outside of the 5th Circuit. The court could also put off the arguments or, if the Republican Senate replaces Ms. Ginsburg with another conservative justice before arguments are heard, Republicans could secure a 5-4 ruling against the law. Some court observers argue that Justice Brett Kavanaugh has not favored invalidating an entire statute if only part of it is flawed and might not approve overturning the ACA. Still, what started out as an effort to energize Republican voters for the 2018 midterms after Congress failed to “repeal and replace” the health law in 2017 could end up throwing the nation’s entire health system into chaos.

At least 20 million Americans – and likely many more who sought coverage since the start of the coronavirus pandemic — who buy insurance through the ACA marketplaces or have Medicaid through the law’s expansion could lose coverage right away. Many millions more would lose the law’s popular protections guaranteeing coverage for people with preexisting health conditions, including those who have had COVID-19.

Adult children under age 26 years would no longer be guaranteed the right to remain on their parents’ health plans, and Medicare patients would lose enhanced prescription drug coverage. Women would lose guaranteed access to birth control at no out-of-pocket cost.

But a sudden elimination would affect more than just health care consumers. Insurance companies, drug companies, hospitals, and doctors have all changed the way they do business because of incentives and penalties in the health law. If it’s struck down, many of the “rules of the road” would literally be wiped away, including billing and payment mechanisms.

A new Democratic president could not drop the lawsuit because the Trump administration is not the plaintiff (the GOP attorneys general are). But a Democratic Congress and president could in theory make the entire issue go away by reinstating the penalty for failure to have insurance, even at a minimal amount. However, as far as the health law goes, for now, nothing is a sure thing.

As Nicholas Bagley, a law professor at the University of Michigan, Ann Arbor, who specializes in health issues, tweeted: “Among other things, the Affordable Care Act now dangles from a thread.”

Reproductive rights

A woman’s right to abortion – and even to birth control – also has been hanging by a thread at the high court for more than a decade. This past term, Mr. Roberts joined the liberals to invalidate a Louisiana law that would have closed most of the state’s abortion clinics, but he made it clear it was not a vote for abortion rights. The Louisiana law was too similar to a Texas law the court (without his vote) struck down in 2016, Mr. Roberts argued.

Ms. Ginsburg had been a stalwart supporter of reproductive freedom for women. In her nearly 3 decades on the court, she always voted with backers of abortion rights and birth control and led the dissenters in 2007 when the court upheld a federal ban on a specific abortion procedure.

Adding a justice opposed to abortion to the bench – which is what Trump has promised his supporters – would almost certainly tilt the court in favor of far more dramatic restrictions on the procedure and possibly an overturn of the landmark 1973 ruling Roe v. Wade.

But not only is abortion on the line: The court in recent years has repeatedly ruled that employers with religious objections can refuse to provide contraception.

And waiting in the lower-court pipeline are cases involving federal funding of Planned Parenthood in both the Medicaid and federal family planning programs, and the ability of individual health workers to decline to participate in abortion and other procedures.

For Ms. Ginsburg, those issues came down to a clear question of a woman’s guarantee of equal status under the law.

“Women, it is now acknowledged, have the talent, capacity, and right ‘to participate equally in the economic and social life of the Nation,’ ” she wrote in her dissent in that 2007 abortion case. “Their ability to realize their full potential, the Court recognized, is intimately connected to ‘their ability to control their reproductive lives.’ ”

Kaiser Health News is a nonprofit news service covering health issues. It is an editorially independent program of KFF (Kaiser Family Foundation), which is not affiliated with Kaiser Permanente.

On Feb. 27, 2018, I got an email from the Heritage Foundation that alerted me to a news conference that afternoon held by Republican attorneys general of Texas and other states. It was referred to only as a “discussion about the Affordable Care Act lawsuit.”

I sent the following note to my editor: “I’m off to the Hill anyway. I could stop by this. You never know what it might morph into.”

Few people took that case very seriously – barely a handful of reporters attended the news conference. But it has now “morphed into” the latest existential threat to the Affordable Care Act, scheduled for oral arguments at the Supreme Court a week after the general election in November. And with the death of Justice Ruth Bader Ginsburg on Friday, that case could well morph into the threat that brings down the law in its entirety.

Democrats are raising alarms about the future of the law without Ms. Ginsburg. House Speaker Nancy Pelosi, speaking on ABC’s “This Week” Sunday morning, said that part of the strategy by President Trump and Senate Republicans to quickly fill her seat was to help undermine the ACA.

“The president is rushing to make some kind of a decision because … Nov. 10 is when the arguments begin on the Affordable Care Act,” she said. “He doesn’t want to crush the virus. He wants to crush the Affordable Care Act.”

Ms. Ginsburg’s death could throw an already chaotic general election campaign during a pandemic into even more turmoil.

Let’s take them one at a time.

The ACA under fire – again

The GOP attorneys general argued in February 2018 that the Republican-sponsored tax cut bill Congress passed two months earlier had rendered the ACA unconstitutional by reducing to zero the ACA’s penalty for not having insurance. They based their argument on Chief Justice John Roberts’ 2012 conclusion that the ACA was valid, interpreting that penalty as a constitutionally appropriate tax.

Most legal scholars, including several who challenged the law before the Supreme Court in 2012 and again in 2015, find the argument that the entire law should fall to be unconvincing. “If courts invalidate an entire law merely because Congress eliminates or revises one part, as happened here, that may well inhibit necessary reform of federal legislation in the future by turning it into an ‘all or nothing’ proposition,” wrote a group of conservative and liberal law professors in a brief filed in the case.

Still, in December 2018, U.S. District Judge Reed O’Connor in Texas accepted the GOP argument and declared the law unconstitutional. In December 2019, a three-judge 5th Circuit appeals court panel in New Orleans agreed that without the penalty the requirement to buy insurance is unconstitutional. But it sent the case back to Mr. O’Connor to suggest that perhaps the entire law need not fall.

Not wanting to wait the months or years that reconsideration would take, Democratic attorneys general defending the ACA asked the Supreme Court to hear the case this year. (Democrats are defending the law in court because the Trump administration decided to support the GOP attorneys general’s case.) The court agreed to take the case but scheduled arguments for the week after the November election.

While the fate of the ACA was and is a live political issue, few legal observers were terribly worried about the legal outcome of the case, now known as Texas v. California, if only because the case seemed much weaker than the 2012 and 2015 cases in which Mr. Roberts joined the court’s four liberals. In the 2015 case, which challenged the validity of federal tax subsidies helping millions of Americans buy health insurance on the ACA’s marketplaces, both Mr. Roberts and now-retired Justice Anthony Kennedy voted to uphold the law.

But without Ms. Ginsburg, the case could wind up in a 4-4 tie, even if Mr. Roberts supports the law’s constitutionality. That could let the lower-court ruling stand, although it would not be binding on other courts outside of the 5th Circuit. The court could also put off the arguments or, if the Republican Senate replaces Ms. Ginsburg with another conservative justice before arguments are heard, Republicans could secure a 5-4 ruling against the law. Some court observers argue that Justice Brett Kavanaugh has not favored invalidating an entire statute if only part of it is flawed and might not approve overturning the ACA. Still, what started out as an effort to energize Republican voters for the 2018 midterms after Congress failed to “repeal and replace” the health law in 2017 could end up throwing the nation’s entire health system into chaos.

At least 20 million Americans – and likely many more who sought coverage since the start of the coronavirus pandemic — who buy insurance through the ACA marketplaces or have Medicaid through the law’s expansion could lose coverage right away. Many millions more would lose the law’s popular protections guaranteeing coverage for people with preexisting health conditions, including those who have had COVID-19.

Adult children under age 26 years would no longer be guaranteed the right to remain on their parents’ health plans, and Medicare patients would lose enhanced prescription drug coverage. Women would lose guaranteed access to birth control at no out-of-pocket cost.

But a sudden elimination would affect more than just health care consumers. Insurance companies, drug companies, hospitals, and doctors have all changed the way they do business because of incentives and penalties in the health law. If it’s struck down, many of the “rules of the road” would literally be wiped away, including billing and payment mechanisms.

A new Democratic president could not drop the lawsuit because the Trump administration is not the plaintiff (the GOP attorneys general are). But a Democratic Congress and president could in theory make the entire issue go away by reinstating the penalty for failure to have insurance, even at a minimal amount. However, as far as the health law goes, for now, nothing is a sure thing.

As Nicholas Bagley, a law professor at the University of Michigan, Ann Arbor, who specializes in health issues, tweeted: “Among other things, the Affordable Care Act now dangles from a thread.”

Reproductive rights

A woman’s right to abortion – and even to birth control – also has been hanging by a thread at the high court for more than a decade. This past term, Mr. Roberts joined the liberals to invalidate a Louisiana law that would have closed most of the state’s abortion clinics, but he made it clear it was not a vote for abortion rights. The Louisiana law was too similar to a Texas law the court (without his vote) struck down in 2016, Mr. Roberts argued.

Ms. Ginsburg had been a stalwart supporter of reproductive freedom for women. In her nearly 3 decades on the court, she always voted with backers of abortion rights and birth control and led the dissenters in 2007 when the court upheld a federal ban on a specific abortion procedure.

Adding a justice opposed to abortion to the bench – which is what Trump has promised his supporters – would almost certainly tilt the court in favor of far more dramatic restrictions on the procedure and possibly an overturn of the landmark 1973 ruling Roe v. Wade.

But not only is abortion on the line: The court in recent years has repeatedly ruled that employers with religious objections can refuse to provide contraception.

And waiting in the lower-court pipeline are cases involving federal funding of Planned Parenthood in both the Medicaid and federal family planning programs, and the ability of individual health workers to decline to participate in abortion and other procedures.

For Ms. Ginsburg, those issues came down to a clear question of a woman’s guarantee of equal status under the law.

“Women, it is now acknowledged, have the talent, capacity, and right ‘to participate equally in the economic and social life of the Nation,’ ” she wrote in her dissent in that 2007 abortion case. “Their ability to realize their full potential, the Court recognized, is intimately connected to ‘their ability to control their reproductive lives.’ ”

Kaiser Health News is a nonprofit news service covering health issues. It is an editorially independent program of KFF (Kaiser Family Foundation), which is not affiliated with Kaiser Permanente.

Major changes in Medicare billing are planned for January 2021: Some specialties fare better than others

The Centers for Medicare and Medicaid Services (CMS) finalized an increase in the relative value of evaluation and management (E/M) service codes effective January 1, 2021, which results in an overall decrease in the payment for procedural services in the Medicare program. (Due to the mandate for budget neutrality, an increase in relative value units [RVUs] for E/M resulted in a large decrease in the conversion factor—the number of dollars per RVU). This has increased payments for endocrinologists, rheumatologists, and family medicine clinicians and decreased payments for radiologists, pathologists, and surgeons.

In a major win for physicians, CMS proposes to simplify documentation requirements for billing and focus on the complexity of the medical decision making (MDM) or the total time needed to care for the patient on the date of the service as the foundation for determining the relative value of the service. Therefore, there is no more counting bullets—ie, we don’t have to perform a comprehensive physical exam or review of systems to achieve a high level code! Prior to this change, time was only available for coding purposes when counseling and coordination of care was the predominant service (>50%), and only face-to-face time with the patient was considered. Effective January 1, for office and other outpatient services, total time on the calendar date of the encounter will be used. This acknowledges the intensity and value of non–face-to-face work.

Acting through CMS, the federal government influences greatly the US health care system. CMS is an agency in the Department of Health and Human Services that administers the Medicare program and partners with state governments to administer the Health Insurance Exchanges, Medicaid, and the Children’s Health Insurance programs (CHIP).1 In addition, CMS is responsible for enforcing quality care standards in long-term care facilities and clinical laboratories and the implementation of the Health Insurance Portability and Accountability Act.1

In January, CMS plans the following major changes to coding and documentation2,3:

- Selection of the level of E/M service will no longer require documentation of bullet points in the history, physical exam, and MDM. The simplified system allows physicians and qualified health care professionals to code either by total time (both face-to-face and non–face-to-face) on the date of the encounter or by level of MDM.

- For established office patients, 5 levels of office-based evaluation and management services will be retained. CMS had initially proposed to reduce the number of office-based E/M codes from 5 to 3, combining code levels 2, 3, and 4 into 1 code.4 However, after receiving feedback from professional societies and the public, CMS abandoned the plan for radical simplification of coding levels.2,3 Implementation of their proposal would have resulted in the same payment for treatment of a hang nail as for a complex gyn patient with multiple medical problems. Both patient advocacy groups and professional societies argued that incentives originally were misaligned.

- For new office patients, since both 99201 and 99202 require straightforward MDM, the level 1 code (99201) has been eliminated, reducing the number of code levels from 5 to 4.

- History and physical exam will no longer be used to determine code level for office E/M codes. These elements will be required only as medically appropriate. This means that documentation review will no longer focus on “bean counting” the elements in the history and physical exam.

- Following a reassessment of the actual time required to provide E/M services in real-life practice, CMS plans to markedly increase the relative value of office visits for established patients and modestly increase the relative value of office visits for new patients. CMS operates under the principle of “neutral budgeting,” meaning that an increase of the relative value of E/M codes will result in a decrease in the payment for procedural codes. The actual RVUs for procedural services do not change; however, budget neutrality requires a decrease in the dollar conversion factor. The proposed changes will increase the payment for E/M services and decrease payments for procedural services.

Continue to: Refocusing practice on MDM complexity...

Refocusing practice on MDM complexity

The practice of medicine is a calling with great rewards. Prominent among those rewards are improving the health of women, children, and the community, developing deep and trusting relationships with patients, families, and clinical colleagues. The practice of medicine is also replete with a host of punishing administrative burdens, including prior authorizations, clunky electronic medical records, poorly designed quality metrics that are applied to clinicians, and billing compliance rules that emphasize the repetitive documentation of clinical information with minimal value.

Some of the most irritating aspects of medical practice are the CMS rules governing medical record documentation required for billing ambulatory office visits. Current coding compliance focuses on counting the number of systems reviewed in the review of systems; the documentation of past history, social history, and family history; the number of organs and organ elements examined during the physical examination; and the complexity of MDM.

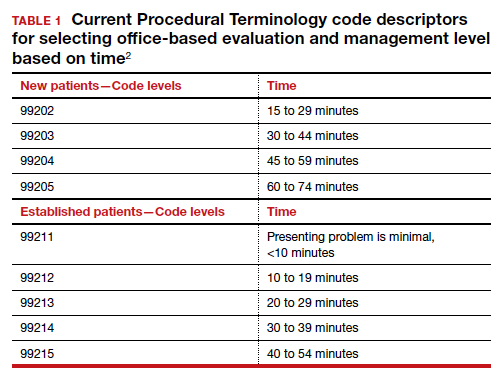

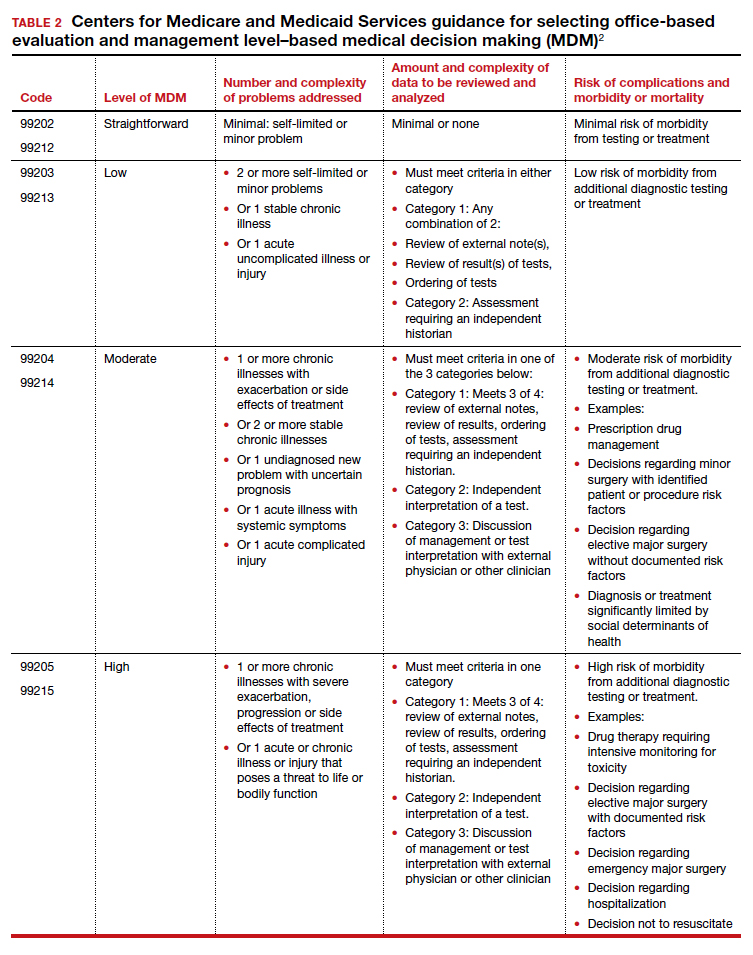

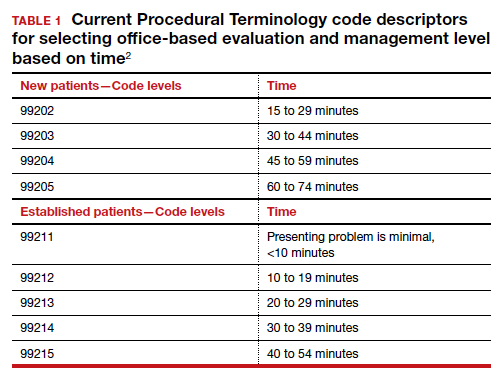

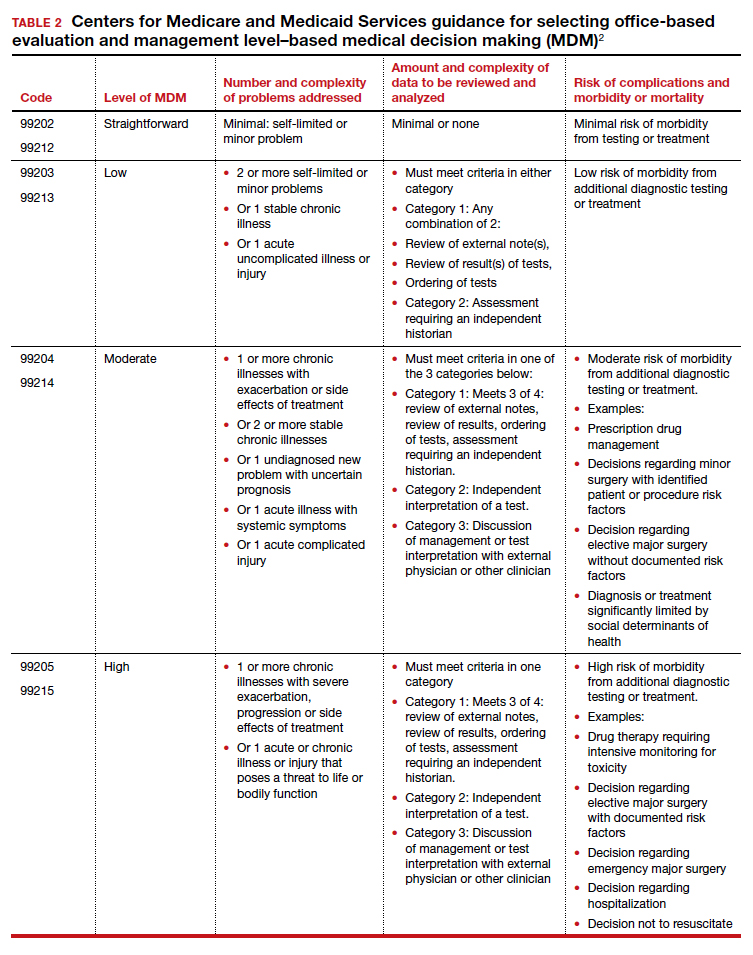

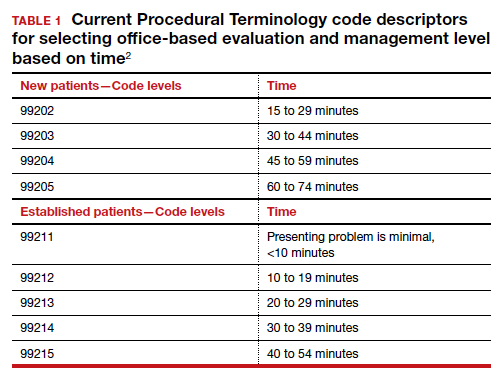

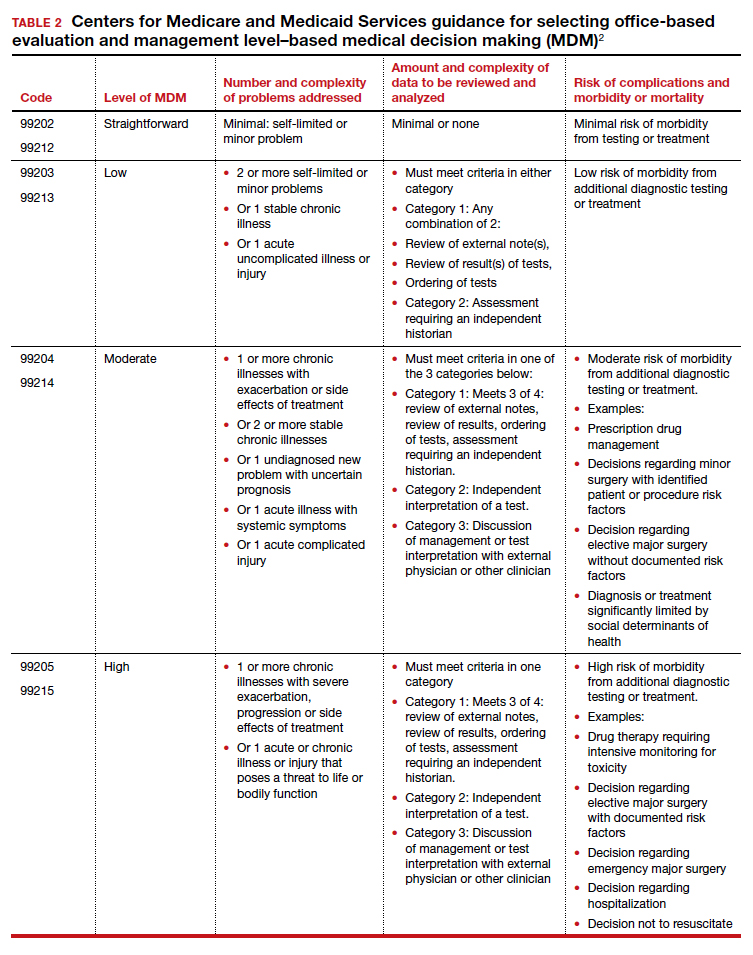

In January 2021, CMS plans to adopt new Current Procedural Terminology (CPT) code descriptors for the office and other outpatient E/M services that sunset most of the “bean-counting” metrics and emphasize the importance of the complexity of MDM in guiding selection of a correct code.2 Beginning in January 2021, clinicians will have the option of selecting an E/M code level based on the total amount of time required to provide the office visit service or the complexity of MDM. When selecting a code level based on MDM the new guidance emphasizes the importance of reviewing notes from other clinicians, reviewing test results, ordering of tests, and discussing and coordinating the care of the patient with other treating physicians. These changes reflect a better understanding of what is most important in good medical practice, promoting better patient care. TABLES 1 and 2 provide the initial guidance from CMS concerning selection of E/M code level based on time and MDM, respectively.2 The guidance for using MDM to select an E/M code level is likely to evolve following implementation, so stay tuned. When using MDM to select a code, 2 of the 3 general categories are required to select that level of service.

Increase in the valuation of office-based E/M services

The Medicare Physician Fee Schedule uses a resource-based relative value system to determine time and intensity of the work of clinical practice. This system recognizes 3 major factors that influence the resources required to provide a service:

- work of the clinician

- practice expense for technical components

- cost of professional liability insurance.

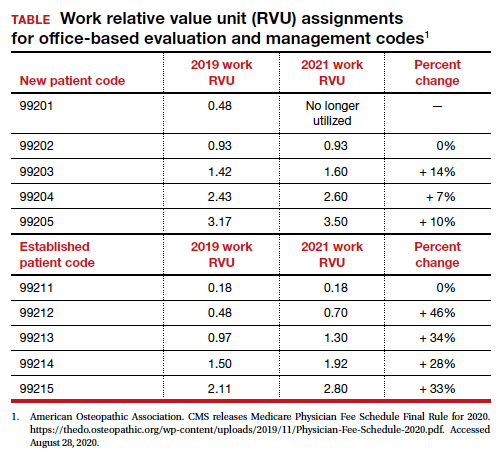

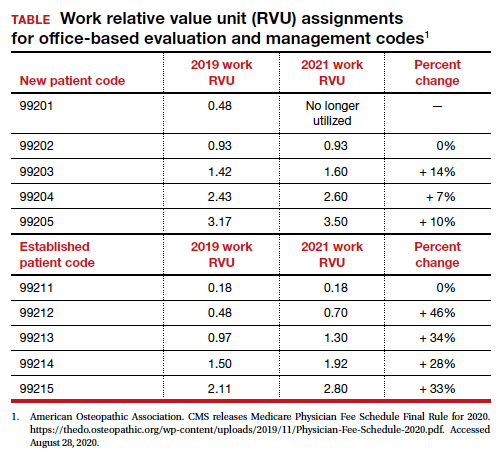

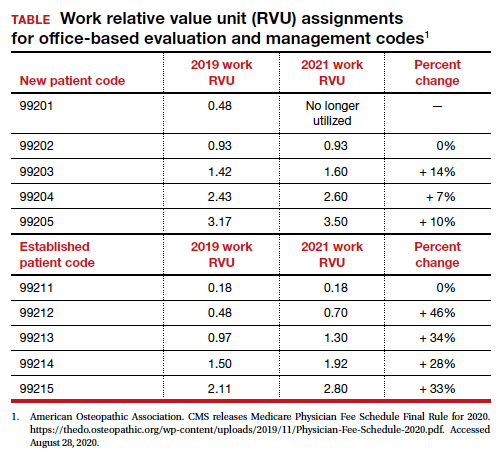

Many primary care professional associations have long contended that CMS has undervalued office-based E/M services relative to procedures, resulting in the devaluing of primary care practice. After the CPT code descriptors were updated by the CPT editorial panel, 52 specialty societies surveyed their members to provide inputs to CMS on the time and intensity of the office and other outpatient E/M codes as currently practiced. The American Medical Association’s Specialty Society Resource-Based Relative Value Scale Update Committee (RUC) reviewed the surveys and provided new inputs via open comment to CMS. CMS has responded to this feedback with a review of the intensity of clinical work required to provide an ambulatory visit service. In response to the review, CMS proposes to accept the recommendations of the RUC representing the house of medicine and increase the work and practice expense relative value assigned to new and established office visit codes. Overall, the combination of changes in relative values assigned for the work of the clinician and the expense of practice, increases the total value of office-based E/M codes for new patients by 7% to 14% and for established patients from 28% to 46% (see supplemental table in the sidebar at the end of this article).

Continue to: Decreased payments for procedural services...

Decreased payments for procedural services

Medicare is required to offset increased payment in one arena of health care delivery with decreased payment in other arenas of care, thereby achieving “budget-neutrality.” As detailed above, CMS plans to increase Medicare payments for office-based E/M services. Payment for services is calculated by multiplying the total RVUs for a particular service by a “conversion factor” (ie, number of dollars per RVU). To achieve budget-neutrality, CMS has proposed substantially reducing the conversion factor for 2021 (from $36.09 to $32.26), which will effectively decrease Medicare payments for procedural services since their RVUs have not changed. While the AMA RUC and many specialty societies continue to strongly advocate for the E/M work RVU increases to be included in the E/M components of 10- and 90-day global services, CMS has proposed to implement them only for “stand alone” E/M services.

Organizations are lobbying to delay or prevent the planned decrease in conversion factor, which results in substantial declines in payment for procedural services. (See "What do the Medicare billing changes mean for the Obstetrical Bundled services?" at the end of this article.) Due to the economic and clinical practice challenges caused by the coronavirus disease 2019 (COVID-19) pandemic it would be best if CMS did not reduce payments to physicians who are experts in procedural health care, thereby avoiding the risk of reduced access to these vital services.

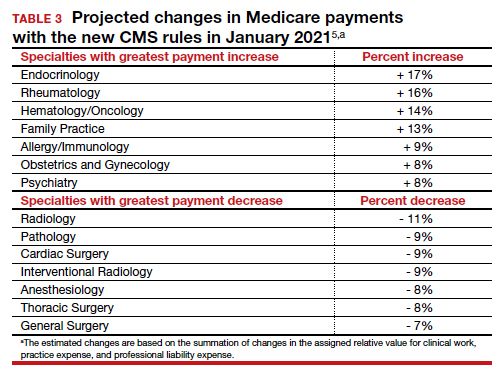

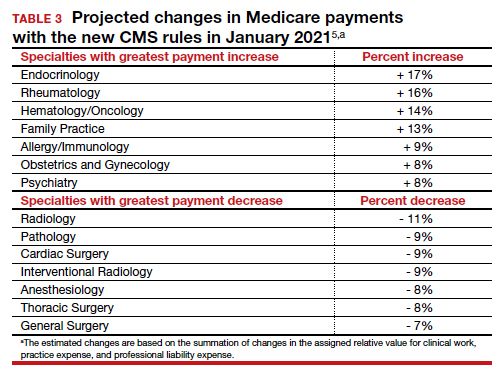

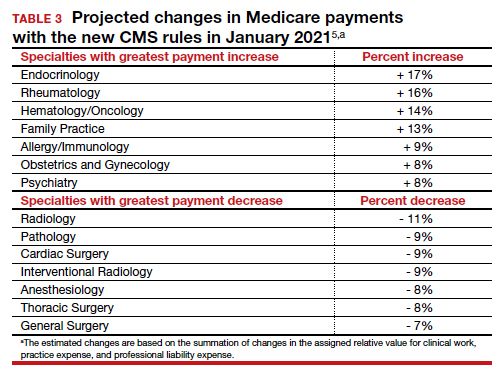

If the current CMS changes in payment are implemented, endocrinologists, rheumatologists, and family physicians will have an increase in payment, and radiologists, pathologists, and surgeons will have a decrease in payment (TABLE 3).6 Obstetrics and gynecology is projected to have an 8% increase in Medicare payment. However, if an obstetrician-gynecologist derives most of their Medicare payments from surgical procedures, they are likely to have a decrease in payment from Medicare. Other payers will be incorporating the new coding structure for 2021; however, their payment structures and conversion factors are likely to vary. It is important to note that the RVUs for procedures have not changed. The budget neutrality adjustment resulted in a much lower conversion factor and therefore a decrease in payment for those specialties whose RVUs did not increase.

Bottom line

Working through the Medicare, Medicaid, and CHIP programs, CMS can influence greatly the practice of medicine including medical record documentation practices and payment rates for every clinical service. CMS proposes to end the onerous “bean counting” approach to billing compliance and refocus on the complexity of MDM as the foundation for selecting a billing code level. This change is long overdue, valuing the effective management of complex patients in office practice. Hopefully, CMS will reverse the planned reduction in the payment for procedural services, preserving patient access to important health care services. ●

The CY 2020 Medicare Physician Fee Schedule Final Rule was published electronically in the Federal Register on November 1, 2019. This final rule aligns the evaluation and management (E/M) coding and payment with changes recommended by the Current Procedural Terminology (CPT) Editorial Panel and American Medical Association’s (AMA) Specialty Society Resource-Based Relative Value Scale Update Committee (RUC) for office/outpatient E/M visits. Unfortunately, the Centers for Medicare and Medicaid Services (CMS) did not agree with the RUC, AMA, and specialty societies that the E/M payment changes should be applicable across all global services that incorporate E/M visits—despite the fact that the values proposed by the RUC incorporated survey data from 52 specialties, representing most of medicine (including those specialties that predominantly perform procedures). Specifically, CMS expressed the view that the number of E/M visits within the 10- and 90-day global codes, as well as the maternity care bundle, were difficult to validate; therefore, the increased values would not be distributed to those procedural services.

Many professional societies expressed significant concerns about the resulting budget neutrality adjustments that would occur effective January 2021. The great news for ObGyns is that the American College of Obstetricians and Gynecologists (ACOG) was able to respond directly to CMS’s concerns with data to support the number of prenatal visits within the Obstetrical Bundle. Tapping into a de-identified, cloud-based data set of prenatal records—representing more than 1,100 obstetric providers with close to 30,000 recently completed pregnancies—ACOG was able to document both a mean and median number of prenatal visits across a broad geographic, payer, and patient demographic that supported the 13 prenatal visits in the Obstetrical Bundle.

With ACOG’s advocacy and ability to provide data to CMS, the proposed physician fee schedule rule for 2021 has proposed to incorporate the E/M increased reimbursement into the prenatal care codes. Now we urge the CMS to finalize this proposal. Although Medicare pays for a tiny number of pregnancies annually, we hope that all payers, including Medicaid and managed care plans, will agree with this acknowledgement of the increased work of evaluation and management that obstetricians provide during prenatal care. Join ACOG in telling CMS to finalize their proposal to increase the values of the global obstetric codes: https://acog.quorum.us/campaign/28579/.

- Centers for Medicare and Medicaid Services. https://www.cms.gov/. Accessed August 28, 2020.

- American Medical Association. CPT Evaluation and Management (E/M) Office or Other Outpatient (99202-99215) and Prolonged Services (99354, 99355, 99356, 99XXX) Code and Guideline Changes. 2019. https://www.ama-assn.org /system/files/2019-06/cpt-office-prolonged-svs -code-changes.pdf. Accessed August 28, 2020.

- The American Academy of Family Physicians. Family medicine updates. Ann Fam Med. 2020;18:84-85. doi: 10.1370/afm.2508.

- Centers for Medicare and Medicaid Services. Final policy, payment and quality provisions changes to the Medicare Physician Fee Schedule for calendar year 2019. November 1, 2018. https://www.cms.gov/newsroom/fact-sheets /final-policy-payment-and-quality-provisionschanges-medicare-physician-fee-schedulecalendar-year. Accessed August 28, 2020.

- Department of Health and Human Services; Centers for Medicare and Medicaid Services. 42 CFR Parts 410, 414, 415, 423, 424, and 425. Federal Register. 2020;85(159). https://www.govinfo.gov /content/pkg/FR-2020-08-17/pdf/2020-17127 .pdf. Accessed August 28, 2020.

The Centers for Medicare and Medicaid Services (CMS) finalized an increase in the relative value of evaluation and management (E/M) service codes effective January 1, 2021, which results in an overall decrease in the payment for procedural services in the Medicare program. (Due to the mandate for budget neutrality, an increase in relative value units [RVUs] for E/M resulted in a large decrease in the conversion factor—the number of dollars per RVU). This has increased payments for endocrinologists, rheumatologists, and family medicine clinicians and decreased payments for radiologists, pathologists, and surgeons.

In a major win for physicians, CMS proposes to simplify documentation requirements for billing and focus on the complexity of the medical decision making (MDM) or the total time needed to care for the patient on the date of the service as the foundation for determining the relative value of the service. Therefore, there is no more counting bullets—ie, we don’t have to perform a comprehensive physical exam or review of systems to achieve a high level code! Prior to this change, time was only available for coding purposes when counseling and coordination of care was the predominant service (>50%), and only face-to-face time with the patient was considered. Effective January 1, for office and other outpatient services, total time on the calendar date of the encounter will be used. This acknowledges the intensity and value of non–face-to-face work.

Acting through CMS, the federal government influences greatly the US health care system. CMS is an agency in the Department of Health and Human Services that administers the Medicare program and partners with state governments to administer the Health Insurance Exchanges, Medicaid, and the Children’s Health Insurance programs (CHIP).1 In addition, CMS is responsible for enforcing quality care standards in long-term care facilities and clinical laboratories and the implementation of the Health Insurance Portability and Accountability Act.1

In January, CMS plans the following major changes to coding and documentation2,3:

- Selection of the level of E/M service will no longer require documentation of bullet points in the history, physical exam, and MDM. The simplified system allows physicians and qualified health care professionals to code either by total time (both face-to-face and non–face-to-face) on the date of the encounter or by level of MDM.

- For established office patients, 5 levels of office-based evaluation and management services will be retained. CMS had initially proposed to reduce the number of office-based E/M codes from 5 to 3, combining code levels 2, 3, and 4 into 1 code.4 However, after receiving feedback from professional societies and the public, CMS abandoned the plan for radical simplification of coding levels.2,3 Implementation of their proposal would have resulted in the same payment for treatment of a hang nail as for a complex gyn patient with multiple medical problems. Both patient advocacy groups and professional societies argued that incentives originally were misaligned.

- For new office patients, since both 99201 and 99202 require straightforward MDM, the level 1 code (99201) has been eliminated, reducing the number of code levels from 5 to 4.

- History and physical exam will no longer be used to determine code level for office E/M codes. These elements will be required only as medically appropriate. This means that documentation review will no longer focus on “bean counting” the elements in the history and physical exam.

- Following a reassessment of the actual time required to provide E/M services in real-life practice, CMS plans to markedly increase the relative value of office visits for established patients and modestly increase the relative value of office visits for new patients. CMS operates under the principle of “neutral budgeting,” meaning that an increase of the relative value of E/M codes will result in a decrease in the payment for procedural codes. The actual RVUs for procedural services do not change; however, budget neutrality requires a decrease in the dollar conversion factor. The proposed changes will increase the payment for E/M services and decrease payments for procedural services.

Continue to: Refocusing practice on MDM complexity...

Refocusing practice on MDM complexity

The practice of medicine is a calling with great rewards. Prominent among those rewards are improving the health of women, children, and the community, developing deep and trusting relationships with patients, families, and clinical colleagues. The practice of medicine is also replete with a host of punishing administrative burdens, including prior authorizations, clunky electronic medical records, poorly designed quality metrics that are applied to clinicians, and billing compliance rules that emphasize the repetitive documentation of clinical information with minimal value.

Some of the most irritating aspects of medical practice are the CMS rules governing medical record documentation required for billing ambulatory office visits. Current coding compliance focuses on counting the number of systems reviewed in the review of systems; the documentation of past history, social history, and family history; the number of organs and organ elements examined during the physical examination; and the complexity of MDM.

In January 2021, CMS plans to adopt new Current Procedural Terminology (CPT) code descriptors for the office and other outpatient E/M services that sunset most of the “bean-counting” metrics and emphasize the importance of the complexity of MDM in guiding selection of a correct code.2 Beginning in January 2021, clinicians will have the option of selecting an E/M code level based on the total amount of time required to provide the office visit service or the complexity of MDM. When selecting a code level based on MDM the new guidance emphasizes the importance of reviewing notes from other clinicians, reviewing test results, ordering of tests, and discussing and coordinating the care of the patient with other treating physicians. These changes reflect a better understanding of what is most important in good medical practice, promoting better patient care. TABLES 1 and 2 provide the initial guidance from CMS concerning selection of E/M code level based on time and MDM, respectively.2 The guidance for using MDM to select an E/M code level is likely to evolve following implementation, so stay tuned. When using MDM to select a code, 2 of the 3 general categories are required to select that level of service.

Increase in the valuation of office-based E/M services

The Medicare Physician Fee Schedule uses a resource-based relative value system to determine time and intensity of the work of clinical practice. This system recognizes 3 major factors that influence the resources required to provide a service:

- work of the clinician

- practice expense for technical components

- cost of professional liability insurance.

Many primary care professional associations have long contended that CMS has undervalued office-based E/M services relative to procedures, resulting in the devaluing of primary care practice. After the CPT code descriptors were updated by the CPT editorial panel, 52 specialty societies surveyed their members to provide inputs to CMS on the time and intensity of the office and other outpatient E/M codes as currently practiced. The American Medical Association’s Specialty Society Resource-Based Relative Value Scale Update Committee (RUC) reviewed the surveys and provided new inputs via open comment to CMS. CMS has responded to this feedback with a review of the intensity of clinical work required to provide an ambulatory visit service. In response to the review, CMS proposes to accept the recommendations of the RUC representing the house of medicine and increase the work and practice expense relative value assigned to new and established office visit codes. Overall, the combination of changes in relative values assigned for the work of the clinician and the expense of practice, increases the total value of office-based E/M codes for new patients by 7% to 14% and for established patients from 28% to 46% (see supplemental table in the sidebar at the end of this article).

Continue to: Decreased payments for procedural services...

Decreased payments for procedural services

Medicare is required to offset increased payment in one arena of health care delivery with decreased payment in other arenas of care, thereby achieving “budget-neutrality.” As detailed above, CMS plans to increase Medicare payments for office-based E/M services. Payment for services is calculated by multiplying the total RVUs for a particular service by a “conversion factor” (ie, number of dollars per RVU). To achieve budget-neutrality, CMS has proposed substantially reducing the conversion factor for 2021 (from $36.09 to $32.26), which will effectively decrease Medicare payments for procedural services since their RVUs have not changed. While the AMA RUC and many specialty societies continue to strongly advocate for the E/M work RVU increases to be included in the E/M components of 10- and 90-day global services, CMS has proposed to implement them only for “stand alone” E/M services.

Organizations are lobbying to delay or prevent the planned decrease in conversion factor, which results in substantial declines in payment for procedural services. (See "What do the Medicare billing changes mean for the Obstetrical Bundled services?" at the end of this article.) Due to the economic and clinical practice challenges caused by the coronavirus disease 2019 (COVID-19) pandemic it would be best if CMS did not reduce payments to physicians who are experts in procedural health care, thereby avoiding the risk of reduced access to these vital services.

If the current CMS changes in payment are implemented, endocrinologists, rheumatologists, and family physicians will have an increase in payment, and radiologists, pathologists, and surgeons will have a decrease in payment (TABLE 3).6 Obstetrics and gynecology is projected to have an 8% increase in Medicare payment. However, if an obstetrician-gynecologist derives most of their Medicare payments from surgical procedures, they are likely to have a decrease in payment from Medicare. Other payers will be incorporating the new coding structure for 2021; however, their payment structures and conversion factors are likely to vary. It is important to note that the RVUs for procedures have not changed. The budget neutrality adjustment resulted in a much lower conversion factor and therefore a decrease in payment for those specialties whose RVUs did not increase.

Bottom line

Working through the Medicare, Medicaid, and CHIP programs, CMS can influence greatly the practice of medicine including medical record documentation practices and payment rates for every clinical service. CMS proposes to end the onerous “bean counting” approach to billing compliance and refocus on the complexity of MDM as the foundation for selecting a billing code level. This change is long overdue, valuing the effective management of complex patients in office practice. Hopefully, CMS will reverse the planned reduction in the payment for procedural services, preserving patient access to important health care services. ●

The CY 2020 Medicare Physician Fee Schedule Final Rule was published electronically in the Federal Register on November 1, 2019. This final rule aligns the evaluation and management (E/M) coding and payment with changes recommended by the Current Procedural Terminology (CPT) Editorial Panel and American Medical Association’s (AMA) Specialty Society Resource-Based Relative Value Scale Update Committee (RUC) for office/outpatient E/M visits. Unfortunately, the Centers for Medicare and Medicaid Services (CMS) did not agree with the RUC, AMA, and specialty societies that the E/M payment changes should be applicable across all global services that incorporate E/M visits—despite the fact that the values proposed by the RUC incorporated survey data from 52 specialties, representing most of medicine (including those specialties that predominantly perform procedures). Specifically, CMS expressed the view that the number of E/M visits within the 10- and 90-day global codes, as well as the maternity care bundle, were difficult to validate; therefore, the increased values would not be distributed to those procedural services.

Many professional societies expressed significant concerns about the resulting budget neutrality adjustments that would occur effective January 2021. The great news for ObGyns is that the American College of Obstetricians and Gynecologists (ACOG) was able to respond directly to CMS’s concerns with data to support the number of prenatal visits within the Obstetrical Bundle. Tapping into a de-identified, cloud-based data set of prenatal records—representing more than 1,100 obstetric providers with close to 30,000 recently completed pregnancies—ACOG was able to document both a mean and median number of prenatal visits across a broad geographic, payer, and patient demographic that supported the 13 prenatal visits in the Obstetrical Bundle.

With ACOG’s advocacy and ability to provide data to CMS, the proposed physician fee schedule rule for 2021 has proposed to incorporate the E/M increased reimbursement into the prenatal care codes. Now we urge the CMS to finalize this proposal. Although Medicare pays for a tiny number of pregnancies annually, we hope that all payers, including Medicaid and managed care plans, will agree with this acknowledgement of the increased work of evaluation and management that obstetricians provide during prenatal care. Join ACOG in telling CMS to finalize their proposal to increase the values of the global obstetric codes: https://acog.quorum.us/campaign/28579/.

The Centers for Medicare and Medicaid Services (CMS) finalized an increase in the relative value of evaluation and management (E/M) service codes effective January 1, 2021, which results in an overall decrease in the payment for procedural services in the Medicare program. (Due to the mandate for budget neutrality, an increase in relative value units [RVUs] for E/M resulted in a large decrease in the conversion factor—the number of dollars per RVU). This has increased payments for endocrinologists, rheumatologists, and family medicine clinicians and decreased payments for radiologists, pathologists, and surgeons.

In a major win for physicians, CMS proposes to simplify documentation requirements for billing and focus on the complexity of the medical decision making (MDM) or the total time needed to care for the patient on the date of the service as the foundation for determining the relative value of the service. Therefore, there is no more counting bullets—ie, we don’t have to perform a comprehensive physical exam or review of systems to achieve a high level code! Prior to this change, time was only available for coding purposes when counseling and coordination of care was the predominant service (>50%), and only face-to-face time with the patient was considered. Effective January 1, for office and other outpatient services, total time on the calendar date of the encounter will be used. This acknowledges the intensity and value of non–face-to-face work.

Acting through CMS, the federal government influences greatly the US health care system. CMS is an agency in the Department of Health and Human Services that administers the Medicare program and partners with state governments to administer the Health Insurance Exchanges, Medicaid, and the Children’s Health Insurance programs (CHIP).1 In addition, CMS is responsible for enforcing quality care standards in long-term care facilities and clinical laboratories and the implementation of the Health Insurance Portability and Accountability Act.1

In January, CMS plans the following major changes to coding and documentation2,3:

- Selection of the level of E/M service will no longer require documentation of bullet points in the history, physical exam, and MDM. The simplified system allows physicians and qualified health care professionals to code either by total time (both face-to-face and non–face-to-face) on the date of the encounter or by level of MDM.

- For established office patients, 5 levels of office-based evaluation and management services will be retained. CMS had initially proposed to reduce the number of office-based E/M codes from 5 to 3, combining code levels 2, 3, and 4 into 1 code.4 However, after receiving feedback from professional societies and the public, CMS abandoned the plan for radical simplification of coding levels.2,3 Implementation of their proposal would have resulted in the same payment for treatment of a hang nail as for a complex gyn patient with multiple medical problems. Both patient advocacy groups and professional societies argued that incentives originally were misaligned.

- For new office patients, since both 99201 and 99202 require straightforward MDM, the level 1 code (99201) has been eliminated, reducing the number of code levels from 5 to 4.

- History and physical exam will no longer be used to determine code level for office E/M codes. These elements will be required only as medically appropriate. This means that documentation review will no longer focus on “bean counting” the elements in the history and physical exam.

- Following a reassessment of the actual time required to provide E/M services in real-life practice, CMS plans to markedly increase the relative value of office visits for established patients and modestly increase the relative value of office visits for new patients. CMS operates under the principle of “neutral budgeting,” meaning that an increase of the relative value of E/M codes will result in a decrease in the payment for procedural codes. The actual RVUs for procedural services do not change; however, budget neutrality requires a decrease in the dollar conversion factor. The proposed changes will increase the payment for E/M services and decrease payments for procedural services.

Continue to: Refocusing practice on MDM complexity...

Refocusing practice on MDM complexity

The practice of medicine is a calling with great rewards. Prominent among those rewards are improving the health of women, children, and the community, developing deep and trusting relationships with patients, families, and clinical colleagues. The practice of medicine is also replete with a host of punishing administrative burdens, including prior authorizations, clunky electronic medical records, poorly designed quality metrics that are applied to clinicians, and billing compliance rules that emphasize the repetitive documentation of clinical information with minimal value.

Some of the most irritating aspects of medical practice are the CMS rules governing medical record documentation required for billing ambulatory office visits. Current coding compliance focuses on counting the number of systems reviewed in the review of systems; the documentation of past history, social history, and family history; the number of organs and organ elements examined during the physical examination; and the complexity of MDM.

In January 2021, CMS plans to adopt new Current Procedural Terminology (CPT) code descriptors for the office and other outpatient E/M services that sunset most of the “bean-counting” metrics and emphasize the importance of the complexity of MDM in guiding selection of a correct code.2 Beginning in January 2021, clinicians will have the option of selecting an E/M code level based on the total amount of time required to provide the office visit service or the complexity of MDM. When selecting a code level based on MDM the new guidance emphasizes the importance of reviewing notes from other clinicians, reviewing test results, ordering of tests, and discussing and coordinating the care of the patient with other treating physicians. These changes reflect a better understanding of what is most important in good medical practice, promoting better patient care. TABLES 1 and 2 provide the initial guidance from CMS concerning selection of E/M code level based on time and MDM, respectively.2 The guidance for using MDM to select an E/M code level is likely to evolve following implementation, so stay tuned. When using MDM to select a code, 2 of the 3 general categories are required to select that level of service.

Increase in the valuation of office-based E/M services

The Medicare Physician Fee Schedule uses a resource-based relative value system to determine time and intensity of the work of clinical practice. This system recognizes 3 major factors that influence the resources required to provide a service:

- work of the clinician

- practice expense for technical components

- cost of professional liability insurance.

Many primary care professional associations have long contended that CMS has undervalued office-based E/M services relative to procedures, resulting in the devaluing of primary care practice. After the CPT code descriptors were updated by the CPT editorial panel, 52 specialty societies surveyed their members to provide inputs to CMS on the time and intensity of the office and other outpatient E/M codes as currently practiced. The American Medical Association’s Specialty Society Resource-Based Relative Value Scale Update Committee (RUC) reviewed the surveys and provided new inputs via open comment to CMS. CMS has responded to this feedback with a review of the intensity of clinical work required to provide an ambulatory visit service. In response to the review, CMS proposes to accept the recommendations of the RUC representing the house of medicine and increase the work and practice expense relative value assigned to new and established office visit codes. Overall, the combination of changes in relative values assigned for the work of the clinician and the expense of practice, increases the total value of office-based E/M codes for new patients by 7% to 14% and for established patients from 28% to 46% (see supplemental table in the sidebar at the end of this article).

Continue to: Decreased payments for procedural services...

Decreased payments for procedural services

Medicare is required to offset increased payment in one arena of health care delivery with decreased payment in other arenas of care, thereby achieving “budget-neutrality.” As detailed above, CMS plans to increase Medicare payments for office-based E/M services. Payment for services is calculated by multiplying the total RVUs for a particular service by a “conversion factor” (ie, number of dollars per RVU). To achieve budget-neutrality, CMS has proposed substantially reducing the conversion factor for 2021 (from $36.09 to $32.26), which will effectively decrease Medicare payments for procedural services since their RVUs have not changed. While the AMA RUC and many specialty societies continue to strongly advocate for the E/M work RVU increases to be included in the E/M components of 10- and 90-day global services, CMS has proposed to implement them only for “stand alone” E/M services.

Organizations are lobbying to delay or prevent the planned decrease in conversion factor, which results in substantial declines in payment for procedural services. (See "What do the Medicare billing changes mean for the Obstetrical Bundled services?" at the end of this article.) Due to the economic and clinical practice challenges caused by the coronavirus disease 2019 (COVID-19) pandemic it would be best if CMS did not reduce payments to physicians who are experts in procedural health care, thereby avoiding the risk of reduced access to these vital services.

If the current CMS changes in payment are implemented, endocrinologists, rheumatologists, and family physicians will have an increase in payment, and radiologists, pathologists, and surgeons will have a decrease in payment (TABLE 3).6 Obstetrics and gynecology is projected to have an 8% increase in Medicare payment. However, if an obstetrician-gynecologist derives most of their Medicare payments from surgical procedures, they are likely to have a decrease in payment from Medicare. Other payers will be incorporating the new coding structure for 2021; however, their payment structures and conversion factors are likely to vary. It is important to note that the RVUs for procedures have not changed. The budget neutrality adjustment resulted in a much lower conversion factor and therefore a decrease in payment for those specialties whose RVUs did not increase.

Bottom line

Working through the Medicare, Medicaid, and CHIP programs, CMS can influence greatly the practice of medicine including medical record documentation practices and payment rates for every clinical service. CMS proposes to end the onerous “bean counting” approach to billing compliance and refocus on the complexity of MDM as the foundation for selecting a billing code level. This change is long overdue, valuing the effective management of complex patients in office practice. Hopefully, CMS will reverse the planned reduction in the payment for procedural services, preserving patient access to important health care services. ●

The CY 2020 Medicare Physician Fee Schedule Final Rule was published electronically in the Federal Register on November 1, 2019. This final rule aligns the evaluation and management (E/M) coding and payment with changes recommended by the Current Procedural Terminology (CPT) Editorial Panel and American Medical Association’s (AMA) Specialty Society Resource-Based Relative Value Scale Update Committee (RUC) for office/outpatient E/M visits. Unfortunately, the Centers for Medicare and Medicaid Services (CMS) did not agree with the RUC, AMA, and specialty societies that the E/M payment changes should be applicable across all global services that incorporate E/M visits—despite the fact that the values proposed by the RUC incorporated survey data from 52 specialties, representing most of medicine (including those specialties that predominantly perform procedures). Specifically, CMS expressed the view that the number of E/M visits within the 10- and 90-day global codes, as well as the maternity care bundle, were difficult to validate; therefore, the increased values would not be distributed to those procedural services.

Many professional societies expressed significant concerns about the resulting budget neutrality adjustments that would occur effective January 2021. The great news for ObGyns is that the American College of Obstetricians and Gynecologists (ACOG) was able to respond directly to CMS’s concerns with data to support the number of prenatal visits within the Obstetrical Bundle. Tapping into a de-identified, cloud-based data set of prenatal records—representing more than 1,100 obstetric providers with close to 30,000 recently completed pregnancies—ACOG was able to document both a mean and median number of prenatal visits across a broad geographic, payer, and patient demographic that supported the 13 prenatal visits in the Obstetrical Bundle.

With ACOG’s advocacy and ability to provide data to CMS, the proposed physician fee schedule rule for 2021 has proposed to incorporate the E/M increased reimbursement into the prenatal care codes. Now we urge the CMS to finalize this proposal. Although Medicare pays for a tiny number of pregnancies annually, we hope that all payers, including Medicaid and managed care plans, will agree with this acknowledgement of the increased work of evaluation and management that obstetricians provide during prenatal care. Join ACOG in telling CMS to finalize their proposal to increase the values of the global obstetric codes: https://acog.quorum.us/campaign/28579/.

- Centers for Medicare and Medicaid Services. https://www.cms.gov/. Accessed August 28, 2020.

- American Medical Association. CPT Evaluation and Management (E/M) Office or Other Outpatient (99202-99215) and Prolonged Services (99354, 99355, 99356, 99XXX) Code and Guideline Changes. 2019. https://www.ama-assn.org /system/files/2019-06/cpt-office-prolonged-svs -code-changes.pdf. Accessed August 28, 2020.

- The American Academy of Family Physicians. Family medicine updates. Ann Fam Med. 2020;18:84-85. doi: 10.1370/afm.2508.

- Centers for Medicare and Medicaid Services. Final policy, payment and quality provisions changes to the Medicare Physician Fee Schedule for calendar year 2019. November 1, 2018. https://www.cms.gov/newsroom/fact-sheets /final-policy-payment-and-quality-provisionschanges-medicare-physician-fee-schedulecalendar-year. Accessed August 28, 2020.

- Department of Health and Human Services; Centers for Medicare and Medicaid Services. 42 CFR Parts 410, 414, 415, 423, 424, and 425. Federal Register. 2020;85(159). https://www.govinfo.gov /content/pkg/FR-2020-08-17/pdf/2020-17127 .pdf. Accessed August 28, 2020.

- Centers for Medicare and Medicaid Services. https://www.cms.gov/. Accessed August 28, 2020.

- American Medical Association. CPT Evaluation and Management (E/M) Office or Other Outpatient (99202-99215) and Prolonged Services (99354, 99355, 99356, 99XXX) Code and Guideline Changes. 2019. https://www.ama-assn.org /system/files/2019-06/cpt-office-prolonged-svs -code-changes.pdf. Accessed August 28, 2020.

- The American Academy of Family Physicians. Family medicine updates. Ann Fam Med. 2020;18:84-85. doi: 10.1370/afm.2508.

- Centers for Medicare and Medicaid Services. Final policy, payment and quality provisions changes to the Medicare Physician Fee Schedule for calendar year 2019. November 1, 2018. https://www.cms.gov/newsroom/fact-sheets /final-policy-payment-and-quality-provisionschanges-medicare-physician-fee-schedulecalendar-year. Accessed August 28, 2020.

- Department of Health and Human Services; Centers for Medicare and Medicaid Services. 42 CFR Parts 410, 414, 415, 423, 424, and 425. Federal Register. 2020;85(159). https://www.govinfo.gov /content/pkg/FR-2020-08-17/pdf/2020-17127 .pdf. Accessed August 28, 2020.

Lifting the restrictions on mifepristone during COVID-19: A step in the right direction

Mifepristone is a safe, effective, and well-tolerated medication for managing miscarriage and for medical abortion when combined with misoprostol.1,2 Since the US Food and Drug Administration (FDA) approved its use in 2000, more than 4 million women have used this medication.3 The combination of mifepristone with misoprostol was used for 39% of all US abortions in 2017.4 Approximately 10% of all clinically recognized pregnancies end in miscarriages, and many are safely managed with either misoprostol alone or with the combination of mifepristone and misoprostol.5

The issue

The prescription and distribution of mifepristone is highly regulated by the FDA via requirements outlined in the Risk Evaluation and Mitigation Strategies (REMS) drug safety program. The FDA may determine a REMS is necessary for a specific drug to ensure the benefits of a drug outweigh the potential risks. A REMS may include an informative package insert for patients, follow-up communication to prescribers—including letters, safety protocols or recommended laboratory tests, or Elements to Assure Safe Use (ETASU). ETASU are types of REMS that are placed on medications that have significant potential for serious adverse effects, and without such restrictions FDA approval would be rescinded.

Are mifepristone requirements fairly applied?

The 3 ETASU restrictions on the distribution of mifepristone are in-person dispensation, prescriber certification, and patient signatures on special forms.6 The in-person dispensing requirement is applied to only 16 other medications (one of which is Mifeprex, the brand version of mifepristone), and Mifeprex/mifepristone are the only ones deemed safe for self-administration—meaning that patients receive the drug from a clinic but then may take it at a site of their choosing. The prescriber certification requirement places expectations on providers to account for distribution of doses and keep records of serial numbers (in effect, having clinicians act as both physician and pharmacist, as most medications are distributed and recorded in pharmacies). The patient form was recommended for elimination in 2016 due to its duplicative information and burden on patients—a recommendation that was then overruled by the FDA commissioner.7

These 3 requirements placed on mifepristone specifically target dosages for use related to abortions and miscarriages. Mifepristone is used to treat other medical conditions, with much higher doses, without the same restrictions—in fact, the FDA has allowed much higher doses of mifepristone to be mailed directly to a patient when prescribed for different disorders. The American College of Obstetricians and Gynecologists (ACOG) has long opposed the burdensome REMS requirements on mifepristone for reproductive health indications.8

Arguments regarding the safety of mifepristone must be understood in the context of how the medication is taken, and the unique difference with other medications that must be administered by physicians or in health care facilities. Mifepristone is self-administered, and the desired effect—evacuation of uterine contents—typically occurs after a patient takes the accompanying medication misoprostol, which is some 24 to 72 hours later. This timeframe makes it highly unlikely that any patient would be in the presence of their provider at the time of medication effect, thus an in-person dispensing requirement has no medical bearing on the outcome of the health of the patient.

REMS changes during the COVID-19 pandemic

The coronavirus disease 2019 (COVID-19) pandemic has necessarily changed the structure of REMS and ETASU requirements for many medications, with changes made in order to mitigate viral transmission through the limitation of unnecessary visits to clinics or hospitals. The FDA announced in March of 2020 that it would not enforce pre-prescription requirements, such as laboratory or magnetic resonance imaging results, for many medications (including those more toxic than mifepristone), and that it would lift the requirement for in-person dispensation of several medications.9 Also in March 2020 the Department of Health and Human Services Secretary (HHS) and the Drug Enforcement Agency (DEA) activated a “telemedicine exception” to allow physicians to use telemedicine to satisfy mandatory requirements for prescribing controlled substances, including opioids.10

Despite repeated pleas from organizations, individuals, and physician groups, the FDA continued to enforce the REMS/ETASU for mifepristone as the pandemic decimated communities. Importantly, the pandemic has not had an equal effect on all communities, and the disparities highlighted in outcomes as related to COVID-19 are also reflected in disparities to access to reproductive choices.11 By enforcing REMS/ETASU for mifepristone during a global pandemic, the FDA has placed additional burden on women and people who menstruate. As offices and clinics have closed, and as many jobs have evaporated, additional barriers have emerged, such as lack of childcare, fewer transportation options, and decreased clinic appointments.

As the pandemic continues to affect communities in the United States, ACOG has issued guidance recommending assessment for eligibility for medical abortion remotely, and has encouraged the use of telemedicine and other remote interactions for its members and patients to limit transmission of the virus.

The lawsuit

On May 27, 2020, the American Civil Liberties Union (ACLU) (on behalf of ACOG, the Council of University Chairs of Obstetrics and Gynecology, New York State Academy of Family Physicians, SisterSong, and Honor MacNaughton, MD) filed a civil action against the FDA and HHS challenging the requirement for in-person dispensing of mifepristone and associated ETASU requirements during the COVID-19 pandemic. The plaintiffs sought this injunction based on the claim that these restrictions during the pandemic infringe on the constitutional rights to patients’ privacy and liberty and to equal protection of the law as protected by the Due Process Clause of the Fifth Amendment. Additionally, the ACLU and other organizations said these unnecessary restrictions place patients, providers, and staff at unnecessary risk of viral exposure amidst a global pandemic.

The verdict

On July 13, 2020, a federal court granted the preliminary injunction to suspend FDA’s enforcement of the in-person requirements of mifepristone for abortion during the COVID-19 pandemic. The court denied the motion for suspension of in-person restrictions as applied to miscarriage management. The preliminary injunction applies nationwide without geographic limitation. It will remain in effect until the end of the litigation or for 30 days following the expiration of the public health emergency.

What the outcome means

This injunction is a step in the right direction for patients and providers to allow for autonomy and clinical practice guided by clinician expertise. However, this ruling remains narrow. Patients must be counseled about mifepristone via telemedicine and sign a Patient Agreement Form, which must be returned electronically or by mail. Patients must receive a copy of the mifepristone medication guide, and dispensing of mifepristone must still be conducted by or under the supervision of a certified provider. The medication may not be dispensed by retail pharmacies, thus requiring providers to arrange for mailing of prescriptions to patients. Given state-based legal statutes regarding mailing of medications, this injunction may not lead to an immediate increase in access to care. In addition, patients seeking management for miscarriage must go to clinic to have mifepristone dispensed and thus risk exposure to viral transmission.

What now?

The regulation of mifepristone—in spite of excellent safety and specifically for the narrow purpose of administration in the setting of abortion and miscarriage care—is by definition a discriminatory practice against patients and providers. As clinicians, we are duty-bound to speak out against injustices to our practices and our patients. At a local level, we can work to implement safe practices in the setting of this injunction and continue to work on a national level to ensure this injunction becomes permanent and with more broad scope to eliminate all of the REMS requirements for mifepristone.

ACTION ITEMS