User login

Assessment of Consolidated Mail Outpatient Pharmacy Utilization in the Indian Health Service

Consolidated mail outpatient pharmacy (CMOP) is an automated prescription order processing and delivery system developed by the US Department of Veterans Affairs (VA) in 1994 to provide medications to VA patients.1 In fiscal year (FY) 2016, CMOP filled about 80% of VA outpatient prescriptions.2

Formalized by the 2010 Memorandum of Understanding between Indian Health Service (IHS) and VA, CMOP is a partnership undertaken to improve the delivery of care to patients by both agencies.3 The number of prescriptions filled by CMOP for IHS patients increased from 1,972 in FY 2010 to 840,109 in FY 2018.4 In the fourth quarter of FY 2018, there were 94 CMOP-enrolled IHS federal and tribal sites.5 It is only appropriate that a growing number of IHS sites are adopting CMOP considering the evidence for mail-order pharmacy on better patient adherence, improved health outcomes, and potential cost savings.6-9 Furthermore, using a centralized pharmacy operation, such as CMOP, can lead to better quality services.10

Crownpoint Health Care Facility (CHCF) serves > 30,000 American Indians and is in Crownpoint, New Mexico, a small community of about 3,000 people.11 Most of the patients served by the facility live in distant places. Many of these underserved patients do not have a stable means of transportation.12 Therefore, these patients may have difficulty traveling to the facility for their health care needs, including medication pickups. More than 2.5 million American Indians and Alaska Natives IHS beneficiaries face similar challenges due to the rurality of their communities.13 CMOP can be a method to increase access to care for this vulnerable population. However, the utilization of CMOP varies significantly among IHS facilities. While some IHS facilities process large numbers of prescriptions through CMOP, other facilities process few, if any. There also are IHS facilities, such as CHCF, which are at the initial stage of implementing CMOP or trying to increase the volume of prescriptions processed through CMOP. Although the utilization of CMOP has grown exponentially among IHS facilities, there is currently no available resource that summarizes the relative advantages and disadvantages, the challenges and opportunities, and the strengths and weaknesses of implementing CMOP for IHS facilities

Methods

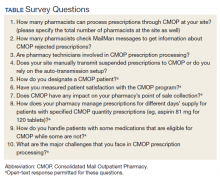

A questionnaire encompassing various aspects of CMOP prescription processing was developed and distributed to the primary CMOP contacts for IHS facilities. The questionnaire was first distributed by e-mail on December 19, 2018. It was e-mailed for a second time on January 16, 2019, and the questionnaire was open for responses until the end of January 2019 (Table).

Results

Forty-four of 94 CMOP-enrolled IHS sites responded to the questionnaire. Most sites train the majority of their pharmacists in CMOP prescription processing. Overall, 310 of 347 pharmacists (89%) in these 44 IHS sites can process prescriptions through CMOP. Thirty-one sites have all their pharmacists trained in CMOP prescription processing. Only 1 facility had less than half (2 of 17 pharmacists) of its pharmacists trained in CMOP prescription processing. More than half the total number of pharmacists, 185 out of 347 (53%), check electronic messages via Resource and Patient Management System (RPMS) MailMan to get information about prescriptions rejected by CMOP. Twenty sites have all their pharmacists check messages about CMOP rejections. However, 2 facilities reported that they do not check the rejection messages at all. Twenty-six of the 44 responding sites (59%) transmit prescriptions to CMOP manually in the electronic system. The rest (18 of 44) rely on the auto-transmission (AT) setup to transmit the CMOP-suspended prescriptions at specified times of the day.

Half the sites (8 of 16) that rely on patients asking for prescriptions to be mailed at the time of refill request do not use any method to designate a CMOP patient. Twenty-four sites use the narrative field on the patient’s profile in RPMS, the health information system used by most IHS facilities, to designate CMOP patients. Eighteen sites use pop-up messages on ScriptPro, a pharmacy automation system, as a designation method. Most of the sites (12 of 15) that use both RPMS and ScriptPro designation methods do not require patients to ask for prescriptions to be mailed at the time of refill request; prescriptions for these patients are routed through CMOP unless patients request otherwise. Only 3 of 44 sites use both methods and rely on patients asking for prescriptions to be mailed at the time of refill request. Some other reported designation methods were using the electronic health record (EHR) posting box, keeping a manual list of CMOP patients, and solely utilizing the Prescription Mail Delivery field in RPMS. Three sites also noted that they keep manual lists to auto-refill prescriptions through CMOP.

Thirty sites (68%) reported that they process every prescription through CMOP even if the patient had prescriptions with specified CMOP quantities. Only 8 sites (18%) said that they used the local mail-out program to keep the same days’ supply for all medication orders. For patients with CMOP-ineligible prescriptions, 34 of the 44 sites (77%) process the eligible prescriptions through CMOP and refill the rest of the prescriptions locally. Six sites (14%) process all medication orders locally for patients with any CMOP-ineligible prescriptions.

Only 12 of 44 sites (27%) involve pharmacy technicians in CMOP prescription processing. Five sites have technicians process prescription refills through CMOP. Two of these sites mentioned the strategy of technicians suspending the prescriptions to be sent to CMOP on the refill due date. Other technician roles included tracking CMOP packages, checking electronic messages for CMOP rejections, and signing up patients for CMOP.

Only 3 of the 44 sites (7%) have measured patient satisfaction with the CMOP program. One of these 3 sites reported that the overall satisfaction was high with CMOP. This site administered the survey to patients who came to the clinic for appointments. The second facility called patients and asked for their feedback. The third site conducted the survey by using student pharmacists. Two sites reported that they use the survey results from the CMOP-conducted patient satisfaction surveys, although they have not measured patient satisfaction at their specific facilities.

Most sites have not assessed CMOP’s impact on their insurance (point of sale) collections. However, 13 sites (30%) reported that they believe they are losing on collections by utilizing CMOP. The use of repackaged products by CMOP, which are usually nonreimbursable, is an issue that was mentioned multiple times. In contrast, 2 sites mentioned that CMOP has led to increased insurance collections for their facilities.

Discussion

The utility of CMOP among the responding IHS sites varies quite significantly. Some sites appreciate the convenience of CMOP while acknowledging its limitations, such as the possible decrease in insurance collections, lengthy prescription processing time, or medication backorders. However, some sites have reserved CMOP for special circumstances (eg, mailing refrigerated items to the patient’s street address) due to various complexities that may come with CMOP. One site reported that it compares IHS contract drug prices with VA contract drug prices quarterly to determine which prescriptions should be sent through CMOP.

Most of the IHS pharmacists (89%) are trained in CMOP prescription processing. If an IHS site wants to increase its volume of CMOP prescriptions, it is sensible to train as many pharmacists as possible so that the responsibility does not fall on a few pharmacists. Newly hired pharmacists can receive guidance from trained pharmacists. Designation methods for CMOP patients can be beneficial for these pharmacists to identify CMOP-enrolled patients, especially if the site does not require patients to ask for prescriptions to be mailed at the time of refill request. Only 3 sites (7%) use multiple designation methods in addition to relying on patients to ask for prescriptions to be mailed. Proper implementation of designation methods can remove this extra burden on patients. Conversely, requiring patients to ask for prescriptions to be sent through CMOP can prevent spontaneous mail-outs if a CMOP-designated patient wants to pick up prescriptions locally. Overall, 16 sites (36%) rely on patients asking for prescriptions to be mailed.

One of the main benefits of CMOP is the ability to mail refrigerated items. Local pharmacy mail-out programs may not have this ability. Patients at rural locations often use post office (PO) boxes because they are unable to receive postal services at their physical addresses; however, they may receive packages through United Parcel Service (UPS) at their physical addresses. CMOP uses UPS to send refrigerated items, but UPS does not deliver to PO boxes. Therefore, remotely located sites like CHCF have difficulty in fully optimizing this benefit. One solution is documenting both the physical and mailing addresses on the patient’s EHR, which enables CMOP to send refrigerated items to the patient’s home address via UPS and mail the rest of the prescriptions to the patient’s PO box address with the US Postal Service. The physical address must be listed above the PO box address to ensure that refrigerated items are not rejected by CMOP. Furthermore, both the physical address and the PO box address must be in the same city for this method to work. Two sites noted mailing refrigerated items as one of the major challenges in CMOP prescription processing.

CMOP-enrolled patients must be educated about requesting medications 7 to 10 days before they run out. There is no standard time line for prescriptions filled by CMOP. However, 1 site reported that it may take up to “10 days from time requested to mailbox.” This delay leads to pharmacies facing a dilemma as processing prescriptions too early can lead to insurance rejections, but processing them too late can lead to the patient not receiving the medication by the time they run out of their current supply. However, CMOP provides the ability to track prescriptions sent through CMOP. Pharmacists and technicians need to have access to BestWay Parcel Services Client Portal (genco-mms.bestwayparcel.com) to track CMOP packages. Tracking CMOP prescriptions is a way pharmacy technicians can be involved in CMOP prescription processing. Technicians seem to be underutilized, as only 27% of the responding sites utilize them to some degree in the CMOP process. One site delegated the responsibility of checking CMOP rejection messages to pharmacy technicians. Since 2 of the responding sites do not check CMOP rejection messages at all, this is an excellent opportunity to get pharmacy technicians involved.

A CMOP auto-refill program can potentially be utilized to avoid missed or late medications. In an auto-refill program, a pharmacist can refill prescriptions through CMOP on the due date without a patient request. They may get rejected by insurance the first time they are processed through CMOP for refilling too early if the processing time is taken into account. However, the subsequent refills do not have to consider the CMOP processing time as they would already be synchronized based on the last refill date. Though, if CMOP is out of stock on a medication and it is expected to be available soon, CMOP may take a few extra days to either fill the prescription or reject it if the drug stays unavailable. One of the sites reported “the amount of time [CMOP] holds medications if they are out of stock” as “the hardest thing to work around.” A couple of sites also mentioned the longer than usual delay in processing prescriptions by CMOP during the holidays as one of the major challenges.

CMOP use of repackaged products also may lead insurance companies to deny reimbursement. Repackaged products are usually cheaper to buy.14 However, most insurances do not reimburse for prescriptions filled with these products.15 The local drug file on RPMS may have a national drug code (NDC) that is reimbursable by insurance, but CMOP will change it to the repackaged NDC if they are filling the prescription with a repackaged product. One potential solution to this problem would be filling these prescriptions locally. Furthermore, insurance claims are processed when the prescriptions are filled by CMOP. Sites cannot return/cancel the prescription anymore at that point. Therefore, the inability to see real-time rejections as the medication orders are processed on-site makes it challenging to prevent avoidable insurance rejections, such as a refill too soon. One site calculated that it lost $26,386.45 by utilizing CMOP from January 9, 2018 to December 12, 2018. However, it is unclear whether this loss was representative of other sites. It is also worth noting that IHS sites can save a substantial amount of money on certain products by utilizing CMOP because VA buys these products at a reduced price.16

CMOP-transmitted prescriptions can be rejected for various reasons, such as CMOP manufacturer’s backorder, a different quantity from CMOP stock size, etc. Information about these rejected prescriptions is accessed through electronic messages on RPMS. CMOP does not dispense less than a full, unopened package for most over-the-counter (OTC) medications. The quantity on these prescriptions must be equal to or multiples of the package size for them to be filled by CMOP. This can lead to a patient having prescriptions with different days’ supplies, which results in various refill due dates. If a site has a local mail-out program available, it can potentially keep the same days’ supply for all prescriptions by mailing these OTC medications locally rather than utilizing CMOP. However, this can partially negate CMOP’s benefit of reduced workload.

CMOP also has specified quantities on some prescription medications. One survey respondent viewed “the quantity and day supply required by CMOP” as a negative influence on the site’s insurance collection. It is possible that CMOP does not carry all the medications that a CMOP-enrolled patient is prescribed. Most sites (77%) still send eligible prescriptions through CMOP for the patients who also have CMOP-ineligible prescriptions. There are a small number of sites (14%) that utilize local mail-out program for the patients with any CMOP-ineligible prescriptions, possibly to simplify the process. Schedule II controlled substances cannot be processed through CMOP either; however, facilities may have local policies that prohibit mailing any controlled substances.

Prescriptions can be manually transmitted to CMOP, or they can be automatically transmitted based on the run time and frequency of the auto-transmission setup. The prescriptions that are waiting to be transmitted to CMOP must be in the “suspended” status. The apparent advantage of relying on auto-transmission is that you do not have to complete the steps manually to transmit suspended CMOP prescriptions, thereby making the process more convenient. However, the manual transmission can be utilized as a checkpoint to verify that prescriptions were properly suspended for CMOP, as the prescription status changes from “S” (suspended) to “AT” once the transmission is completed. If a prescription is not properly suspended for CMOP, the status will remain as S even after manual transmission. More than half (59%) of the responding sites must find the manual transmission feature useful as they use it either over or in addition to the auto-transmission setup.

Despite the challenges, many IHS sites process thousands of monthly prescriptions through CMOP. Of the 94 CMOP-enrolled IHS sites, 17 processed > 1,000 prescriptions from March 27, 2019 to April 25, 2019.17 Five sites processed > 5,000 prescriptions.17 At the rate of > 5,000 prescriptions per month, the yearly CMOP prescription count will be > 60,000. That is more than one-third of the prescriptions processed by CHCF in 2018. By handling these prescriptions through CMOP, it can decrease pharmacy filling and dispensing workload, thereby freeing pharmacists to participate in other services.18 Furthermore, implementing CMOP does not incur any cost for the IHS site. There is a nondrug cost for each prescription that is filled through CMOP. This cost was $2.67 during FY 2016.19 The fee covers prescription vial, label, packaging for mail, postage, personnel, building overhead, and equipment capitalization.19 The nondrug cost of filling a prescription locally at the site can potentially exceed the cost charged by CMOP.19

A lack of objective data exists to assess the net impact of CMOP on patients. Different theoretical assumptions can be made, such as CMOP resulting in better patient adherence. However, there is no objective information about how much CMOP improves patient adherence if it does at all. Though J.D. Power US Pharmacy Study ranks CMOP as “among the best” mail-order pharmacies in customer satisfaction, only 3 of the 44 responding sites have measured patient satisfaction locally.20 Only 1 site had objective data about CMOP’s impact on the point of sale. Therefore, it is currently difficult to perform a cost-benefit analysis of the CMOP program. There are opportunities for further studies on these topics.

Limitations

One limitation of this study is that < 50% of the CMOP-enrolled sites (44 of 94) responded to the questionnaire. It is possible that the facilities that had a significantly positive or negative experience with CMOP were more inclined to share their views. Therefore, it is difficult to conclude whether the responding sites are an accurate representative sample. Another limitation of the study was the questionnaire design and the reliance on free-text responses as opposed to structured data. The free-text responses had to be analyzed manually to determine whether they fall in the same category, thereby increasing the risk of interpretation error.

Conclusion

CMOP has its unique challenges but provides many benefits that local pharmacy mail-out programs may not possess, such as the abilities to mail refrigerated items and track packages. One must be familiar with CMOP’s various idiosyncrasies to make the best use of the program. Extensive staff education and orientation for new staff members must be done to familiarize them with the program. Nevertheless, the successful implementation of CMOP can lead to reduced pharmacy workload while increasing access to care for patients with transportation issues.

Acknowledgments

The authors thank LCDR Karsten Smith, PharmD, BCGP, the IHS CMOP Coordinator for providing the list of primary CMOP contacts and CDR Kendall Van Tyle, PharmD, BCPS, for proofreading the article.

1. US Department of Veterans Affairs, Office of Inspector General. Audit of Consolidated Mail Outpatient Pharmacy contract management. https://www.va.gov/oig/52/reports/2009/VAOIG-09-00026-143.pdf. Published June 10, 2009. Accessed June 11, 2020.

2. US Department of Veterans Affairs. Pharmacy Benefits Management Services. VA mail order pharmacy. https://www.pbm.va.gov/PBM/CMOP/VA_Mail_Order_Pharmacy.asp. Updated July 18, 2018. Accessed July 16, 2019.

3. US Department of Veterans Affairs. Memorandum of understanding between the Department of Veterans Affairs (VA) and Indian Health Service (IHS). https://www.va.gov/TRIBALGOVERNMENT/docs/Signed2010VA-IHSMOU.pdf. Published October 1, 2010. Accessed June 11, 2020.

4. US Department of Veterans Affairs, Office of Tribal Government Relations, Office of Rural Health, US Department of Health and Human Services, Indian Health Service. U.S. Department of Veterans Affairs and Indian Health Service memorandum of understanding annual report fiscal year 2018. https://www.ruralhealth.va.gov/docs/VA-IHS_MOU_AnnualReport_FY2018_FINAL.pdf. Published December 2018. Accessed June 11, 2020.

5. Karsten S. CMOP items of interest. Published October 12, 2018. [Nonpublic document]

6. Fernandez EV, McDaniel JA, Carroll NV. Examination of the link between medication adherence and use of mail-order pharmacies in chronic disease states. J Manag Care Spec Pharm. 2016;22(11):1247‐1259. doi:10.18553/jmcp.2016.22.11.1247

7. Schwab P, Racsa P, Rascati K, Mourer M, Meah Y, Worley K. A retrospective database study comparing diabetes-related medication adherence and health outcomes for mail-order versus community pharmacy. J Manag Care Spec Pharm. 2019;25(3):332‐340. doi:10.18553/jmcp.2019.25.3.332

8. Schmittdiel JA, Karter AJ, Dyer W, et al. The comparative effectiveness of mail order pharmacy use vs. local pharmacy use on LDL-C control in new statin users. J Gen Intern Med. 2011;26(12):1396‐1402. doi:10.1007/s11606-011-1805-7

9. Devine S, Vlahiotis A, Sundar H. A comparison of diabetes medication adherence and healthcare costs in patients using mail order pharmacy and retail pharmacy. J Med Econ. 2010;13(2):203‐211. doi:10.3111/13696991003741801

10. Kappenman AM, Ragsdale R, Rim MH, Tyler LS, Nickman NA. Implementation of a centralized mail-order pharmacy service. Am J Health Syst Pharm. 2019;76(suppl 3):S74‐S78. doi:10.1093/ajhp/zxz138

11. US Department of Health and Human Services, Indian Health Service. Crownpoint service unit. www.ihs.gov/crownpoint. Accessed June 11, 2020.

12. Chaco P. Roads and transportation on the Navajo Nation. https://obamawhitehouse.archives.gov/microsite/blog/31387?page=135. Published February 15, 2012. Accessed June 11, 2020.

13. US Department of Health and Human Services, Indian Health Service. Disparities. www.ihs.gov/newsroom/factsheets/disparities. Updated October 2019. Accessed June 11, 2020.

14. Golden State Medical Supply. National contracts. www.gsms.us/wp-content/uploads/2018/10/National-Contracts-Flyer.pdf. Updated October 4, 2018. Accessed June 11, 2020.

15. Arizona Health Care Cost Containment System. IHS/Tribal provider billing manual chapter 9, hospital and clinic services. www.azahcccs.gov/PlansProviders/Downloads/IHS-TribalManual/IHS-Chap09HospClinic.pdf. Updated February 28, 2019. Accessed June 11, 2020.

16. US Department of Veterans Affairs, Office of Inspector General. The impact of VA allowing government agencies to be excluded from temporary price reductions on federal supply schedule pharmaceutical contracts. www.va.gov/oig/pubs/VAOIG-18-04451-06.pdf. Published October 30, 2019. Accessed June 11, 2020.

17. Karsten S. IHS Billing Report-Apr. Indian Health Service SharePoint. Published May 3, 2019. [Nonpublic document]

18. Aragon BR, Pierce RA 2nd, Jones WN. VA CMOPs: producing a pattern of quality and efficiency in government. J Am Pharm Assoc (2003). 2012;52(6):810‐815. doi:10.1331/JAPhA.2012.11075

19. Todd W. VA-IHS Consolidated Mail Outpatient Pharmacy program (CMOP). www.npaihb.org/wp-content/uploads/2017/01/CMOP-Slides-for-Portland-Area-Tribal-Sites.pdf. Published 2017. Accessed June 11, 2020.

20. J.D. Power. Pharmacy customers slow to adopt digital offerings but satisfaction increases when they do, J.D. Power finds. www.jdpower.com/business/press-releases/2019-us-pharmacy-study. Published August 20, 2019. Accessed June 11, 2020.

Consolidated mail outpatient pharmacy (CMOP) is an automated prescription order processing and delivery system developed by the US Department of Veterans Affairs (VA) in 1994 to provide medications to VA patients.1 In fiscal year (FY) 2016, CMOP filled about 80% of VA outpatient prescriptions.2

Formalized by the 2010 Memorandum of Understanding between Indian Health Service (IHS) and VA, CMOP is a partnership undertaken to improve the delivery of care to patients by both agencies.3 The number of prescriptions filled by CMOP for IHS patients increased from 1,972 in FY 2010 to 840,109 in FY 2018.4 In the fourth quarter of FY 2018, there were 94 CMOP-enrolled IHS federal and tribal sites.5 It is only appropriate that a growing number of IHS sites are adopting CMOP considering the evidence for mail-order pharmacy on better patient adherence, improved health outcomes, and potential cost savings.6-9 Furthermore, using a centralized pharmacy operation, such as CMOP, can lead to better quality services.10

Crownpoint Health Care Facility (CHCF) serves > 30,000 American Indians and is in Crownpoint, New Mexico, a small community of about 3,000 people.11 Most of the patients served by the facility live in distant places. Many of these underserved patients do not have a stable means of transportation.12 Therefore, these patients may have difficulty traveling to the facility for their health care needs, including medication pickups. More than 2.5 million American Indians and Alaska Natives IHS beneficiaries face similar challenges due to the rurality of their communities.13 CMOP can be a method to increase access to care for this vulnerable population. However, the utilization of CMOP varies significantly among IHS facilities. While some IHS facilities process large numbers of prescriptions through CMOP, other facilities process few, if any. There also are IHS facilities, such as CHCF, which are at the initial stage of implementing CMOP or trying to increase the volume of prescriptions processed through CMOP. Although the utilization of CMOP has grown exponentially among IHS facilities, there is currently no available resource that summarizes the relative advantages and disadvantages, the challenges and opportunities, and the strengths and weaknesses of implementing CMOP for IHS facilities

Methods

A questionnaire encompassing various aspects of CMOP prescription processing was developed and distributed to the primary CMOP contacts for IHS facilities. The questionnaire was first distributed by e-mail on December 19, 2018. It was e-mailed for a second time on January 16, 2019, and the questionnaire was open for responses until the end of January 2019 (Table).

Results

Forty-four of 94 CMOP-enrolled IHS sites responded to the questionnaire. Most sites train the majority of their pharmacists in CMOP prescription processing. Overall, 310 of 347 pharmacists (89%) in these 44 IHS sites can process prescriptions through CMOP. Thirty-one sites have all their pharmacists trained in CMOP prescription processing. Only 1 facility had less than half (2 of 17 pharmacists) of its pharmacists trained in CMOP prescription processing. More than half the total number of pharmacists, 185 out of 347 (53%), check electronic messages via Resource and Patient Management System (RPMS) MailMan to get information about prescriptions rejected by CMOP. Twenty sites have all their pharmacists check messages about CMOP rejections. However, 2 facilities reported that they do not check the rejection messages at all. Twenty-six of the 44 responding sites (59%) transmit prescriptions to CMOP manually in the electronic system. The rest (18 of 44) rely on the auto-transmission (AT) setup to transmit the CMOP-suspended prescriptions at specified times of the day.

Half the sites (8 of 16) that rely on patients asking for prescriptions to be mailed at the time of refill request do not use any method to designate a CMOP patient. Twenty-four sites use the narrative field on the patient’s profile in RPMS, the health information system used by most IHS facilities, to designate CMOP patients. Eighteen sites use pop-up messages on ScriptPro, a pharmacy automation system, as a designation method. Most of the sites (12 of 15) that use both RPMS and ScriptPro designation methods do not require patients to ask for prescriptions to be mailed at the time of refill request; prescriptions for these patients are routed through CMOP unless patients request otherwise. Only 3 of 44 sites use both methods and rely on patients asking for prescriptions to be mailed at the time of refill request. Some other reported designation methods were using the electronic health record (EHR) posting box, keeping a manual list of CMOP patients, and solely utilizing the Prescription Mail Delivery field in RPMS. Three sites also noted that they keep manual lists to auto-refill prescriptions through CMOP.

Thirty sites (68%) reported that they process every prescription through CMOP even if the patient had prescriptions with specified CMOP quantities. Only 8 sites (18%) said that they used the local mail-out program to keep the same days’ supply for all medication orders. For patients with CMOP-ineligible prescriptions, 34 of the 44 sites (77%) process the eligible prescriptions through CMOP and refill the rest of the prescriptions locally. Six sites (14%) process all medication orders locally for patients with any CMOP-ineligible prescriptions.

Only 12 of 44 sites (27%) involve pharmacy technicians in CMOP prescription processing. Five sites have technicians process prescription refills through CMOP. Two of these sites mentioned the strategy of technicians suspending the prescriptions to be sent to CMOP on the refill due date. Other technician roles included tracking CMOP packages, checking electronic messages for CMOP rejections, and signing up patients for CMOP.

Only 3 of the 44 sites (7%) have measured patient satisfaction with the CMOP program. One of these 3 sites reported that the overall satisfaction was high with CMOP. This site administered the survey to patients who came to the clinic for appointments. The second facility called patients and asked for their feedback. The third site conducted the survey by using student pharmacists. Two sites reported that they use the survey results from the CMOP-conducted patient satisfaction surveys, although they have not measured patient satisfaction at their specific facilities.

Most sites have not assessed CMOP’s impact on their insurance (point of sale) collections. However, 13 sites (30%) reported that they believe they are losing on collections by utilizing CMOP. The use of repackaged products by CMOP, which are usually nonreimbursable, is an issue that was mentioned multiple times. In contrast, 2 sites mentioned that CMOP has led to increased insurance collections for their facilities.

Discussion

The utility of CMOP among the responding IHS sites varies quite significantly. Some sites appreciate the convenience of CMOP while acknowledging its limitations, such as the possible decrease in insurance collections, lengthy prescription processing time, or medication backorders. However, some sites have reserved CMOP for special circumstances (eg, mailing refrigerated items to the patient’s street address) due to various complexities that may come with CMOP. One site reported that it compares IHS contract drug prices with VA contract drug prices quarterly to determine which prescriptions should be sent through CMOP.

Most of the IHS pharmacists (89%) are trained in CMOP prescription processing. If an IHS site wants to increase its volume of CMOP prescriptions, it is sensible to train as many pharmacists as possible so that the responsibility does not fall on a few pharmacists. Newly hired pharmacists can receive guidance from trained pharmacists. Designation methods for CMOP patients can be beneficial for these pharmacists to identify CMOP-enrolled patients, especially if the site does not require patients to ask for prescriptions to be mailed at the time of refill request. Only 3 sites (7%) use multiple designation methods in addition to relying on patients to ask for prescriptions to be mailed. Proper implementation of designation methods can remove this extra burden on patients. Conversely, requiring patients to ask for prescriptions to be sent through CMOP can prevent spontaneous mail-outs if a CMOP-designated patient wants to pick up prescriptions locally. Overall, 16 sites (36%) rely on patients asking for prescriptions to be mailed.

One of the main benefits of CMOP is the ability to mail refrigerated items. Local pharmacy mail-out programs may not have this ability. Patients at rural locations often use post office (PO) boxes because they are unable to receive postal services at their physical addresses; however, they may receive packages through United Parcel Service (UPS) at their physical addresses. CMOP uses UPS to send refrigerated items, but UPS does not deliver to PO boxes. Therefore, remotely located sites like CHCF have difficulty in fully optimizing this benefit. One solution is documenting both the physical and mailing addresses on the patient’s EHR, which enables CMOP to send refrigerated items to the patient’s home address via UPS and mail the rest of the prescriptions to the patient’s PO box address with the US Postal Service. The physical address must be listed above the PO box address to ensure that refrigerated items are not rejected by CMOP. Furthermore, both the physical address and the PO box address must be in the same city for this method to work. Two sites noted mailing refrigerated items as one of the major challenges in CMOP prescription processing.

CMOP-enrolled patients must be educated about requesting medications 7 to 10 days before they run out. There is no standard time line for prescriptions filled by CMOP. However, 1 site reported that it may take up to “10 days from time requested to mailbox.” This delay leads to pharmacies facing a dilemma as processing prescriptions too early can lead to insurance rejections, but processing them too late can lead to the patient not receiving the medication by the time they run out of their current supply. However, CMOP provides the ability to track prescriptions sent through CMOP. Pharmacists and technicians need to have access to BestWay Parcel Services Client Portal (genco-mms.bestwayparcel.com) to track CMOP packages. Tracking CMOP prescriptions is a way pharmacy technicians can be involved in CMOP prescription processing. Technicians seem to be underutilized, as only 27% of the responding sites utilize them to some degree in the CMOP process. One site delegated the responsibility of checking CMOP rejection messages to pharmacy technicians. Since 2 of the responding sites do not check CMOP rejection messages at all, this is an excellent opportunity to get pharmacy technicians involved.

A CMOP auto-refill program can potentially be utilized to avoid missed or late medications. In an auto-refill program, a pharmacist can refill prescriptions through CMOP on the due date without a patient request. They may get rejected by insurance the first time they are processed through CMOP for refilling too early if the processing time is taken into account. However, the subsequent refills do not have to consider the CMOP processing time as they would already be synchronized based on the last refill date. Though, if CMOP is out of stock on a medication and it is expected to be available soon, CMOP may take a few extra days to either fill the prescription or reject it if the drug stays unavailable. One of the sites reported “the amount of time [CMOP] holds medications if they are out of stock” as “the hardest thing to work around.” A couple of sites also mentioned the longer than usual delay in processing prescriptions by CMOP during the holidays as one of the major challenges.

CMOP use of repackaged products also may lead insurance companies to deny reimbursement. Repackaged products are usually cheaper to buy.14 However, most insurances do not reimburse for prescriptions filled with these products.15 The local drug file on RPMS may have a national drug code (NDC) that is reimbursable by insurance, but CMOP will change it to the repackaged NDC if they are filling the prescription with a repackaged product. One potential solution to this problem would be filling these prescriptions locally. Furthermore, insurance claims are processed when the prescriptions are filled by CMOP. Sites cannot return/cancel the prescription anymore at that point. Therefore, the inability to see real-time rejections as the medication orders are processed on-site makes it challenging to prevent avoidable insurance rejections, such as a refill too soon. One site calculated that it lost $26,386.45 by utilizing CMOP from January 9, 2018 to December 12, 2018. However, it is unclear whether this loss was representative of other sites. It is also worth noting that IHS sites can save a substantial amount of money on certain products by utilizing CMOP because VA buys these products at a reduced price.16

CMOP-transmitted prescriptions can be rejected for various reasons, such as CMOP manufacturer’s backorder, a different quantity from CMOP stock size, etc. Information about these rejected prescriptions is accessed through electronic messages on RPMS. CMOP does not dispense less than a full, unopened package for most over-the-counter (OTC) medications. The quantity on these prescriptions must be equal to or multiples of the package size for them to be filled by CMOP. This can lead to a patient having prescriptions with different days’ supplies, which results in various refill due dates. If a site has a local mail-out program available, it can potentially keep the same days’ supply for all prescriptions by mailing these OTC medications locally rather than utilizing CMOP. However, this can partially negate CMOP’s benefit of reduced workload.

CMOP also has specified quantities on some prescription medications. One survey respondent viewed “the quantity and day supply required by CMOP” as a negative influence on the site’s insurance collection. It is possible that CMOP does not carry all the medications that a CMOP-enrolled patient is prescribed. Most sites (77%) still send eligible prescriptions through CMOP for the patients who also have CMOP-ineligible prescriptions. There are a small number of sites (14%) that utilize local mail-out program for the patients with any CMOP-ineligible prescriptions, possibly to simplify the process. Schedule II controlled substances cannot be processed through CMOP either; however, facilities may have local policies that prohibit mailing any controlled substances.

Prescriptions can be manually transmitted to CMOP, or they can be automatically transmitted based on the run time and frequency of the auto-transmission setup. The prescriptions that are waiting to be transmitted to CMOP must be in the “suspended” status. The apparent advantage of relying on auto-transmission is that you do not have to complete the steps manually to transmit suspended CMOP prescriptions, thereby making the process more convenient. However, the manual transmission can be utilized as a checkpoint to verify that prescriptions were properly suspended for CMOP, as the prescription status changes from “S” (suspended) to “AT” once the transmission is completed. If a prescription is not properly suspended for CMOP, the status will remain as S even after manual transmission. More than half (59%) of the responding sites must find the manual transmission feature useful as they use it either over or in addition to the auto-transmission setup.

Despite the challenges, many IHS sites process thousands of monthly prescriptions through CMOP. Of the 94 CMOP-enrolled IHS sites, 17 processed > 1,000 prescriptions from March 27, 2019 to April 25, 2019.17 Five sites processed > 5,000 prescriptions.17 At the rate of > 5,000 prescriptions per month, the yearly CMOP prescription count will be > 60,000. That is more than one-third of the prescriptions processed by CHCF in 2018. By handling these prescriptions through CMOP, it can decrease pharmacy filling and dispensing workload, thereby freeing pharmacists to participate in other services.18 Furthermore, implementing CMOP does not incur any cost for the IHS site. There is a nondrug cost for each prescription that is filled through CMOP. This cost was $2.67 during FY 2016.19 The fee covers prescription vial, label, packaging for mail, postage, personnel, building overhead, and equipment capitalization.19 The nondrug cost of filling a prescription locally at the site can potentially exceed the cost charged by CMOP.19

A lack of objective data exists to assess the net impact of CMOP on patients. Different theoretical assumptions can be made, such as CMOP resulting in better patient adherence. However, there is no objective information about how much CMOP improves patient adherence if it does at all. Though J.D. Power US Pharmacy Study ranks CMOP as “among the best” mail-order pharmacies in customer satisfaction, only 3 of the 44 responding sites have measured patient satisfaction locally.20 Only 1 site had objective data about CMOP’s impact on the point of sale. Therefore, it is currently difficult to perform a cost-benefit analysis of the CMOP program. There are opportunities for further studies on these topics.

Limitations

One limitation of this study is that < 50% of the CMOP-enrolled sites (44 of 94) responded to the questionnaire. It is possible that the facilities that had a significantly positive or negative experience with CMOP were more inclined to share their views. Therefore, it is difficult to conclude whether the responding sites are an accurate representative sample. Another limitation of the study was the questionnaire design and the reliance on free-text responses as opposed to structured data. The free-text responses had to be analyzed manually to determine whether they fall in the same category, thereby increasing the risk of interpretation error.

Conclusion

CMOP has its unique challenges but provides many benefits that local pharmacy mail-out programs may not possess, such as the abilities to mail refrigerated items and track packages. One must be familiar with CMOP’s various idiosyncrasies to make the best use of the program. Extensive staff education and orientation for new staff members must be done to familiarize them with the program. Nevertheless, the successful implementation of CMOP can lead to reduced pharmacy workload while increasing access to care for patients with transportation issues.

Acknowledgments

The authors thank LCDR Karsten Smith, PharmD, BCGP, the IHS CMOP Coordinator for providing the list of primary CMOP contacts and CDR Kendall Van Tyle, PharmD, BCPS, for proofreading the article.

Consolidated mail outpatient pharmacy (CMOP) is an automated prescription order processing and delivery system developed by the US Department of Veterans Affairs (VA) in 1994 to provide medications to VA patients.1 In fiscal year (FY) 2016, CMOP filled about 80% of VA outpatient prescriptions.2

Formalized by the 2010 Memorandum of Understanding between Indian Health Service (IHS) and VA, CMOP is a partnership undertaken to improve the delivery of care to patients by both agencies.3 The number of prescriptions filled by CMOP for IHS patients increased from 1,972 in FY 2010 to 840,109 in FY 2018.4 In the fourth quarter of FY 2018, there were 94 CMOP-enrolled IHS federal and tribal sites.5 It is only appropriate that a growing number of IHS sites are adopting CMOP considering the evidence for mail-order pharmacy on better patient adherence, improved health outcomes, and potential cost savings.6-9 Furthermore, using a centralized pharmacy operation, such as CMOP, can lead to better quality services.10

Crownpoint Health Care Facility (CHCF) serves > 30,000 American Indians and is in Crownpoint, New Mexico, a small community of about 3,000 people.11 Most of the patients served by the facility live in distant places. Many of these underserved patients do not have a stable means of transportation.12 Therefore, these patients may have difficulty traveling to the facility for their health care needs, including medication pickups. More than 2.5 million American Indians and Alaska Natives IHS beneficiaries face similar challenges due to the rurality of their communities.13 CMOP can be a method to increase access to care for this vulnerable population. However, the utilization of CMOP varies significantly among IHS facilities. While some IHS facilities process large numbers of prescriptions through CMOP, other facilities process few, if any. There also are IHS facilities, such as CHCF, which are at the initial stage of implementing CMOP or trying to increase the volume of prescriptions processed through CMOP. Although the utilization of CMOP has grown exponentially among IHS facilities, there is currently no available resource that summarizes the relative advantages and disadvantages, the challenges and opportunities, and the strengths and weaknesses of implementing CMOP for IHS facilities

Methods

A questionnaire encompassing various aspects of CMOP prescription processing was developed and distributed to the primary CMOP contacts for IHS facilities. The questionnaire was first distributed by e-mail on December 19, 2018. It was e-mailed for a second time on January 16, 2019, and the questionnaire was open for responses until the end of January 2019 (Table).

Results

Forty-four of 94 CMOP-enrolled IHS sites responded to the questionnaire. Most sites train the majority of their pharmacists in CMOP prescription processing. Overall, 310 of 347 pharmacists (89%) in these 44 IHS sites can process prescriptions through CMOP. Thirty-one sites have all their pharmacists trained in CMOP prescription processing. Only 1 facility had less than half (2 of 17 pharmacists) of its pharmacists trained in CMOP prescription processing. More than half the total number of pharmacists, 185 out of 347 (53%), check electronic messages via Resource and Patient Management System (RPMS) MailMan to get information about prescriptions rejected by CMOP. Twenty sites have all their pharmacists check messages about CMOP rejections. However, 2 facilities reported that they do not check the rejection messages at all. Twenty-six of the 44 responding sites (59%) transmit prescriptions to CMOP manually in the electronic system. The rest (18 of 44) rely on the auto-transmission (AT) setup to transmit the CMOP-suspended prescriptions at specified times of the day.

Half the sites (8 of 16) that rely on patients asking for prescriptions to be mailed at the time of refill request do not use any method to designate a CMOP patient. Twenty-four sites use the narrative field on the patient’s profile in RPMS, the health information system used by most IHS facilities, to designate CMOP patients. Eighteen sites use pop-up messages on ScriptPro, a pharmacy automation system, as a designation method. Most of the sites (12 of 15) that use both RPMS and ScriptPro designation methods do not require patients to ask for prescriptions to be mailed at the time of refill request; prescriptions for these patients are routed through CMOP unless patients request otherwise. Only 3 of 44 sites use both methods and rely on patients asking for prescriptions to be mailed at the time of refill request. Some other reported designation methods were using the electronic health record (EHR) posting box, keeping a manual list of CMOP patients, and solely utilizing the Prescription Mail Delivery field in RPMS. Three sites also noted that they keep manual lists to auto-refill prescriptions through CMOP.

Thirty sites (68%) reported that they process every prescription through CMOP even if the patient had prescriptions with specified CMOP quantities. Only 8 sites (18%) said that they used the local mail-out program to keep the same days’ supply for all medication orders. For patients with CMOP-ineligible prescriptions, 34 of the 44 sites (77%) process the eligible prescriptions through CMOP and refill the rest of the prescriptions locally. Six sites (14%) process all medication orders locally for patients with any CMOP-ineligible prescriptions.

Only 12 of 44 sites (27%) involve pharmacy technicians in CMOP prescription processing. Five sites have technicians process prescription refills through CMOP. Two of these sites mentioned the strategy of technicians suspending the prescriptions to be sent to CMOP on the refill due date. Other technician roles included tracking CMOP packages, checking electronic messages for CMOP rejections, and signing up patients for CMOP.

Only 3 of the 44 sites (7%) have measured patient satisfaction with the CMOP program. One of these 3 sites reported that the overall satisfaction was high with CMOP. This site administered the survey to patients who came to the clinic for appointments. The second facility called patients and asked for their feedback. The third site conducted the survey by using student pharmacists. Two sites reported that they use the survey results from the CMOP-conducted patient satisfaction surveys, although they have not measured patient satisfaction at their specific facilities.

Most sites have not assessed CMOP’s impact on their insurance (point of sale) collections. However, 13 sites (30%) reported that they believe they are losing on collections by utilizing CMOP. The use of repackaged products by CMOP, which are usually nonreimbursable, is an issue that was mentioned multiple times. In contrast, 2 sites mentioned that CMOP has led to increased insurance collections for their facilities.

Discussion

The utility of CMOP among the responding IHS sites varies quite significantly. Some sites appreciate the convenience of CMOP while acknowledging its limitations, such as the possible decrease in insurance collections, lengthy prescription processing time, or medication backorders. However, some sites have reserved CMOP for special circumstances (eg, mailing refrigerated items to the patient’s street address) due to various complexities that may come with CMOP. One site reported that it compares IHS contract drug prices with VA contract drug prices quarterly to determine which prescriptions should be sent through CMOP.

Most of the IHS pharmacists (89%) are trained in CMOP prescription processing. If an IHS site wants to increase its volume of CMOP prescriptions, it is sensible to train as many pharmacists as possible so that the responsibility does not fall on a few pharmacists. Newly hired pharmacists can receive guidance from trained pharmacists. Designation methods for CMOP patients can be beneficial for these pharmacists to identify CMOP-enrolled patients, especially if the site does not require patients to ask for prescriptions to be mailed at the time of refill request. Only 3 sites (7%) use multiple designation methods in addition to relying on patients to ask for prescriptions to be mailed. Proper implementation of designation methods can remove this extra burden on patients. Conversely, requiring patients to ask for prescriptions to be sent through CMOP can prevent spontaneous mail-outs if a CMOP-designated patient wants to pick up prescriptions locally. Overall, 16 sites (36%) rely on patients asking for prescriptions to be mailed.

One of the main benefits of CMOP is the ability to mail refrigerated items. Local pharmacy mail-out programs may not have this ability. Patients at rural locations often use post office (PO) boxes because they are unable to receive postal services at their physical addresses; however, they may receive packages through United Parcel Service (UPS) at their physical addresses. CMOP uses UPS to send refrigerated items, but UPS does not deliver to PO boxes. Therefore, remotely located sites like CHCF have difficulty in fully optimizing this benefit. One solution is documenting both the physical and mailing addresses on the patient’s EHR, which enables CMOP to send refrigerated items to the patient’s home address via UPS and mail the rest of the prescriptions to the patient’s PO box address with the US Postal Service. The physical address must be listed above the PO box address to ensure that refrigerated items are not rejected by CMOP. Furthermore, both the physical address and the PO box address must be in the same city for this method to work. Two sites noted mailing refrigerated items as one of the major challenges in CMOP prescription processing.

CMOP-enrolled patients must be educated about requesting medications 7 to 10 days before they run out. There is no standard time line for prescriptions filled by CMOP. However, 1 site reported that it may take up to “10 days from time requested to mailbox.” This delay leads to pharmacies facing a dilemma as processing prescriptions too early can lead to insurance rejections, but processing them too late can lead to the patient not receiving the medication by the time they run out of their current supply. However, CMOP provides the ability to track prescriptions sent through CMOP. Pharmacists and technicians need to have access to BestWay Parcel Services Client Portal (genco-mms.bestwayparcel.com) to track CMOP packages. Tracking CMOP prescriptions is a way pharmacy technicians can be involved in CMOP prescription processing. Technicians seem to be underutilized, as only 27% of the responding sites utilize them to some degree in the CMOP process. One site delegated the responsibility of checking CMOP rejection messages to pharmacy technicians. Since 2 of the responding sites do not check CMOP rejection messages at all, this is an excellent opportunity to get pharmacy technicians involved.

A CMOP auto-refill program can potentially be utilized to avoid missed or late medications. In an auto-refill program, a pharmacist can refill prescriptions through CMOP on the due date without a patient request. They may get rejected by insurance the first time they are processed through CMOP for refilling too early if the processing time is taken into account. However, the subsequent refills do not have to consider the CMOP processing time as they would already be synchronized based on the last refill date. Though, if CMOP is out of stock on a medication and it is expected to be available soon, CMOP may take a few extra days to either fill the prescription or reject it if the drug stays unavailable. One of the sites reported “the amount of time [CMOP] holds medications if they are out of stock” as “the hardest thing to work around.” A couple of sites also mentioned the longer than usual delay in processing prescriptions by CMOP during the holidays as one of the major challenges.

CMOP use of repackaged products also may lead insurance companies to deny reimbursement. Repackaged products are usually cheaper to buy.14 However, most insurances do not reimburse for prescriptions filled with these products.15 The local drug file on RPMS may have a national drug code (NDC) that is reimbursable by insurance, but CMOP will change it to the repackaged NDC if they are filling the prescription with a repackaged product. One potential solution to this problem would be filling these prescriptions locally. Furthermore, insurance claims are processed when the prescriptions are filled by CMOP. Sites cannot return/cancel the prescription anymore at that point. Therefore, the inability to see real-time rejections as the medication orders are processed on-site makes it challenging to prevent avoidable insurance rejections, such as a refill too soon. One site calculated that it lost $26,386.45 by utilizing CMOP from January 9, 2018 to December 12, 2018. However, it is unclear whether this loss was representative of other sites. It is also worth noting that IHS sites can save a substantial amount of money on certain products by utilizing CMOP because VA buys these products at a reduced price.16

CMOP-transmitted prescriptions can be rejected for various reasons, such as CMOP manufacturer’s backorder, a different quantity from CMOP stock size, etc. Information about these rejected prescriptions is accessed through electronic messages on RPMS. CMOP does not dispense less than a full, unopened package for most over-the-counter (OTC) medications. The quantity on these prescriptions must be equal to or multiples of the package size for them to be filled by CMOP. This can lead to a patient having prescriptions with different days’ supplies, which results in various refill due dates. If a site has a local mail-out program available, it can potentially keep the same days’ supply for all prescriptions by mailing these OTC medications locally rather than utilizing CMOP. However, this can partially negate CMOP’s benefit of reduced workload.

CMOP also has specified quantities on some prescription medications. One survey respondent viewed “the quantity and day supply required by CMOP” as a negative influence on the site’s insurance collection. It is possible that CMOP does not carry all the medications that a CMOP-enrolled patient is prescribed. Most sites (77%) still send eligible prescriptions through CMOP for the patients who also have CMOP-ineligible prescriptions. There are a small number of sites (14%) that utilize local mail-out program for the patients with any CMOP-ineligible prescriptions, possibly to simplify the process. Schedule II controlled substances cannot be processed through CMOP either; however, facilities may have local policies that prohibit mailing any controlled substances.

Prescriptions can be manually transmitted to CMOP, or they can be automatically transmitted based on the run time and frequency of the auto-transmission setup. The prescriptions that are waiting to be transmitted to CMOP must be in the “suspended” status. The apparent advantage of relying on auto-transmission is that you do not have to complete the steps manually to transmit suspended CMOP prescriptions, thereby making the process more convenient. However, the manual transmission can be utilized as a checkpoint to verify that prescriptions were properly suspended for CMOP, as the prescription status changes from “S” (suspended) to “AT” once the transmission is completed. If a prescription is not properly suspended for CMOP, the status will remain as S even after manual transmission. More than half (59%) of the responding sites must find the manual transmission feature useful as they use it either over or in addition to the auto-transmission setup.

Despite the challenges, many IHS sites process thousands of monthly prescriptions through CMOP. Of the 94 CMOP-enrolled IHS sites, 17 processed > 1,000 prescriptions from March 27, 2019 to April 25, 2019.17 Five sites processed > 5,000 prescriptions.17 At the rate of > 5,000 prescriptions per month, the yearly CMOP prescription count will be > 60,000. That is more than one-third of the prescriptions processed by CHCF in 2018. By handling these prescriptions through CMOP, it can decrease pharmacy filling and dispensing workload, thereby freeing pharmacists to participate in other services.18 Furthermore, implementing CMOP does not incur any cost for the IHS site. There is a nondrug cost for each prescription that is filled through CMOP. This cost was $2.67 during FY 2016.19 The fee covers prescription vial, label, packaging for mail, postage, personnel, building overhead, and equipment capitalization.19 The nondrug cost of filling a prescription locally at the site can potentially exceed the cost charged by CMOP.19

A lack of objective data exists to assess the net impact of CMOP on patients. Different theoretical assumptions can be made, such as CMOP resulting in better patient adherence. However, there is no objective information about how much CMOP improves patient adherence if it does at all. Though J.D. Power US Pharmacy Study ranks CMOP as “among the best” mail-order pharmacies in customer satisfaction, only 3 of the 44 responding sites have measured patient satisfaction locally.20 Only 1 site had objective data about CMOP’s impact on the point of sale. Therefore, it is currently difficult to perform a cost-benefit analysis of the CMOP program. There are opportunities for further studies on these topics.

Limitations

One limitation of this study is that < 50% of the CMOP-enrolled sites (44 of 94) responded to the questionnaire. It is possible that the facilities that had a significantly positive or negative experience with CMOP were more inclined to share their views. Therefore, it is difficult to conclude whether the responding sites are an accurate representative sample. Another limitation of the study was the questionnaire design and the reliance on free-text responses as opposed to structured data. The free-text responses had to be analyzed manually to determine whether they fall in the same category, thereby increasing the risk of interpretation error.

Conclusion

CMOP has its unique challenges but provides many benefits that local pharmacy mail-out programs may not possess, such as the abilities to mail refrigerated items and track packages. One must be familiar with CMOP’s various idiosyncrasies to make the best use of the program. Extensive staff education and orientation for new staff members must be done to familiarize them with the program. Nevertheless, the successful implementation of CMOP can lead to reduced pharmacy workload while increasing access to care for patients with transportation issues.

Acknowledgments

The authors thank LCDR Karsten Smith, PharmD, BCGP, the IHS CMOP Coordinator for providing the list of primary CMOP contacts and CDR Kendall Van Tyle, PharmD, BCPS, for proofreading the article.

1. US Department of Veterans Affairs, Office of Inspector General. Audit of Consolidated Mail Outpatient Pharmacy contract management. https://www.va.gov/oig/52/reports/2009/VAOIG-09-00026-143.pdf. Published June 10, 2009. Accessed June 11, 2020.

2. US Department of Veterans Affairs. Pharmacy Benefits Management Services. VA mail order pharmacy. https://www.pbm.va.gov/PBM/CMOP/VA_Mail_Order_Pharmacy.asp. Updated July 18, 2018. Accessed July 16, 2019.

3. US Department of Veterans Affairs. Memorandum of understanding between the Department of Veterans Affairs (VA) and Indian Health Service (IHS). https://www.va.gov/TRIBALGOVERNMENT/docs/Signed2010VA-IHSMOU.pdf. Published October 1, 2010. Accessed June 11, 2020.

4. US Department of Veterans Affairs, Office of Tribal Government Relations, Office of Rural Health, US Department of Health and Human Services, Indian Health Service. U.S. Department of Veterans Affairs and Indian Health Service memorandum of understanding annual report fiscal year 2018. https://www.ruralhealth.va.gov/docs/VA-IHS_MOU_AnnualReport_FY2018_FINAL.pdf. Published December 2018. Accessed June 11, 2020.

5. Karsten S. CMOP items of interest. Published October 12, 2018. [Nonpublic document]

6. Fernandez EV, McDaniel JA, Carroll NV. Examination of the link between medication adherence and use of mail-order pharmacies in chronic disease states. J Manag Care Spec Pharm. 2016;22(11):1247‐1259. doi:10.18553/jmcp.2016.22.11.1247

7. Schwab P, Racsa P, Rascati K, Mourer M, Meah Y, Worley K. A retrospective database study comparing diabetes-related medication adherence and health outcomes for mail-order versus community pharmacy. J Manag Care Spec Pharm. 2019;25(3):332‐340. doi:10.18553/jmcp.2019.25.3.332

8. Schmittdiel JA, Karter AJ, Dyer W, et al. The comparative effectiveness of mail order pharmacy use vs. local pharmacy use on LDL-C control in new statin users. J Gen Intern Med. 2011;26(12):1396‐1402. doi:10.1007/s11606-011-1805-7

9. Devine S, Vlahiotis A, Sundar H. A comparison of diabetes medication adherence and healthcare costs in patients using mail order pharmacy and retail pharmacy. J Med Econ. 2010;13(2):203‐211. doi:10.3111/13696991003741801

10. Kappenman AM, Ragsdale R, Rim MH, Tyler LS, Nickman NA. Implementation of a centralized mail-order pharmacy service. Am J Health Syst Pharm. 2019;76(suppl 3):S74‐S78. doi:10.1093/ajhp/zxz138

11. US Department of Health and Human Services, Indian Health Service. Crownpoint service unit. www.ihs.gov/crownpoint. Accessed June 11, 2020.

12. Chaco P. Roads and transportation on the Navajo Nation. https://obamawhitehouse.archives.gov/microsite/blog/31387?page=135. Published February 15, 2012. Accessed June 11, 2020.

13. US Department of Health and Human Services, Indian Health Service. Disparities. www.ihs.gov/newsroom/factsheets/disparities. Updated October 2019. Accessed June 11, 2020.

14. Golden State Medical Supply. National contracts. www.gsms.us/wp-content/uploads/2018/10/National-Contracts-Flyer.pdf. Updated October 4, 2018. Accessed June 11, 2020.

15. Arizona Health Care Cost Containment System. IHS/Tribal provider billing manual chapter 9, hospital and clinic services. www.azahcccs.gov/PlansProviders/Downloads/IHS-TribalManual/IHS-Chap09HospClinic.pdf. Updated February 28, 2019. Accessed June 11, 2020.

16. US Department of Veterans Affairs, Office of Inspector General. The impact of VA allowing government agencies to be excluded from temporary price reductions on federal supply schedule pharmaceutical contracts. www.va.gov/oig/pubs/VAOIG-18-04451-06.pdf. Published October 30, 2019. Accessed June 11, 2020.

17. Karsten S. IHS Billing Report-Apr. Indian Health Service SharePoint. Published May 3, 2019. [Nonpublic document]

18. Aragon BR, Pierce RA 2nd, Jones WN. VA CMOPs: producing a pattern of quality and efficiency in government. J Am Pharm Assoc (2003). 2012;52(6):810‐815. doi:10.1331/JAPhA.2012.11075

19. Todd W. VA-IHS Consolidated Mail Outpatient Pharmacy program (CMOP). www.npaihb.org/wp-content/uploads/2017/01/CMOP-Slides-for-Portland-Area-Tribal-Sites.pdf. Published 2017. Accessed June 11, 2020.

20. J.D. Power. Pharmacy customers slow to adopt digital offerings but satisfaction increases when they do, J.D. Power finds. www.jdpower.com/business/press-releases/2019-us-pharmacy-study. Published August 20, 2019. Accessed June 11, 2020.

1. US Department of Veterans Affairs, Office of Inspector General. Audit of Consolidated Mail Outpatient Pharmacy contract management. https://www.va.gov/oig/52/reports/2009/VAOIG-09-00026-143.pdf. Published June 10, 2009. Accessed June 11, 2020.

2. US Department of Veterans Affairs. Pharmacy Benefits Management Services. VA mail order pharmacy. https://www.pbm.va.gov/PBM/CMOP/VA_Mail_Order_Pharmacy.asp. Updated July 18, 2018. Accessed July 16, 2019.

3. US Department of Veterans Affairs. Memorandum of understanding between the Department of Veterans Affairs (VA) and Indian Health Service (IHS). https://www.va.gov/TRIBALGOVERNMENT/docs/Signed2010VA-IHSMOU.pdf. Published October 1, 2010. Accessed June 11, 2020.

4. US Department of Veterans Affairs, Office of Tribal Government Relations, Office of Rural Health, US Department of Health and Human Services, Indian Health Service. U.S. Department of Veterans Affairs and Indian Health Service memorandum of understanding annual report fiscal year 2018. https://www.ruralhealth.va.gov/docs/VA-IHS_MOU_AnnualReport_FY2018_FINAL.pdf. Published December 2018. Accessed June 11, 2020.

5. Karsten S. CMOP items of interest. Published October 12, 2018. [Nonpublic document]

6. Fernandez EV, McDaniel JA, Carroll NV. Examination of the link between medication adherence and use of mail-order pharmacies in chronic disease states. J Manag Care Spec Pharm. 2016;22(11):1247‐1259. doi:10.18553/jmcp.2016.22.11.1247

7. Schwab P, Racsa P, Rascati K, Mourer M, Meah Y, Worley K. A retrospective database study comparing diabetes-related medication adherence and health outcomes for mail-order versus community pharmacy. J Manag Care Spec Pharm. 2019;25(3):332‐340. doi:10.18553/jmcp.2019.25.3.332

8. Schmittdiel JA, Karter AJ, Dyer W, et al. The comparative effectiveness of mail order pharmacy use vs. local pharmacy use on LDL-C control in new statin users. J Gen Intern Med. 2011;26(12):1396‐1402. doi:10.1007/s11606-011-1805-7

9. Devine S, Vlahiotis A, Sundar H. A comparison of diabetes medication adherence and healthcare costs in patients using mail order pharmacy and retail pharmacy. J Med Econ. 2010;13(2):203‐211. doi:10.3111/13696991003741801

10. Kappenman AM, Ragsdale R, Rim MH, Tyler LS, Nickman NA. Implementation of a centralized mail-order pharmacy service. Am J Health Syst Pharm. 2019;76(suppl 3):S74‐S78. doi:10.1093/ajhp/zxz138

11. US Department of Health and Human Services, Indian Health Service. Crownpoint service unit. www.ihs.gov/crownpoint. Accessed June 11, 2020.

12. Chaco P. Roads and transportation on the Navajo Nation. https://obamawhitehouse.archives.gov/microsite/blog/31387?page=135. Published February 15, 2012. Accessed June 11, 2020.

13. US Department of Health and Human Services, Indian Health Service. Disparities. www.ihs.gov/newsroom/factsheets/disparities. Updated October 2019. Accessed June 11, 2020.

14. Golden State Medical Supply. National contracts. www.gsms.us/wp-content/uploads/2018/10/National-Contracts-Flyer.pdf. Updated October 4, 2018. Accessed June 11, 2020.

15. Arizona Health Care Cost Containment System. IHS/Tribal provider billing manual chapter 9, hospital and clinic services. www.azahcccs.gov/PlansProviders/Downloads/IHS-TribalManual/IHS-Chap09HospClinic.pdf. Updated February 28, 2019. Accessed June 11, 2020.

16. US Department of Veterans Affairs, Office of Inspector General. The impact of VA allowing government agencies to be excluded from temporary price reductions on federal supply schedule pharmaceutical contracts. www.va.gov/oig/pubs/VAOIG-18-04451-06.pdf. Published October 30, 2019. Accessed June 11, 2020.

17. Karsten S. IHS Billing Report-Apr. Indian Health Service SharePoint. Published May 3, 2019. [Nonpublic document]

18. Aragon BR, Pierce RA 2nd, Jones WN. VA CMOPs: producing a pattern of quality and efficiency in government. J Am Pharm Assoc (2003). 2012;52(6):810‐815. doi:10.1331/JAPhA.2012.11075

19. Todd W. VA-IHS Consolidated Mail Outpatient Pharmacy program (CMOP). www.npaihb.org/wp-content/uploads/2017/01/CMOP-Slides-for-Portland-Area-Tribal-Sites.pdf. Published 2017. Accessed June 11, 2020.

20. J.D. Power. Pharmacy customers slow to adopt digital offerings but satisfaction increases when they do, J.D. Power finds. www.jdpower.com/business/press-releases/2019-us-pharmacy-study. Published August 20, 2019. Accessed June 11, 2020.

Telemedicine: Navigating legal issues

In the first 2 articles of this series, “Telemedicine: A primer for today’s ObGyn” and “Telemedicine: Common hurdles and proper coding for ObGyns,” which appeared in the May and June issues of

Legal issues surrounding telemedicine

There are numerous legal, regulatory, and compliance issues that existed before the pandemic that likely will continue to be of concern postpandemic. Although the recent 1135 waiver (allowing Medicare to pay for office, hospital, and other visits furnished via telehealth)1 and other regulations are now in place for almost every aspect of telemedicine, virtual medicine is not a free-for-all (even though it may seem like it). Practicing ethical telemedicine entails abiding by numerous federal and state-specific laws and requirements. It is important to be aware of the laws in each state in which your patients are located and to practice according to the requirements of these laws. This often requires consultation with an experienced health care attorney who is knowledgeable about the use of telemedicine and who can help you with issues surrounding:

- Malpractice insurance. It is an important first step to contact your practice’s malpractice insurance carrier and confirm coverage for telemedicine visits. Telemedicine visits are considered the same as in-person visits when determining scope of practice and malpractice liability. Nevertheless, a best practice is to have written verification from your malpractice carrier about the types of telemedicine services and claims for which your ObGyn practice is covered. Additionally, if you care for patients virtually who live in a state in which you are not licensed, check with your carrier to determine if potential claims will be covered.

- Corporate practice laws. These laws require that your practice be governed by a health care professional and not someone with a nonmedical background. This becomes important if you are looking to create a virtual practice in another state. States that prohibit the corporate practice of medicine have state-specific mandates that require strict adherence. Consult with a health care attorney before entering into a business arrangement with a nonphysician or corporate entity.

- Delegation agreement requirements. These laws require physician collaboration and/or supervision of allied health care workers such as nurse practitioners (NPs) and physician assistants (PAs) and may limit the number of allied health care providers that a physician may supervise. Many states are allowing allied health care workers to practice at the top of their license, but this is still state specific. Thus, it is an important issue to consider, especially for practices that rely heavily on the services of advanced practice registered nurses (APRNs), for example, who have a broad scope of practice and who may be qualified to care for many common ObGyn problems.

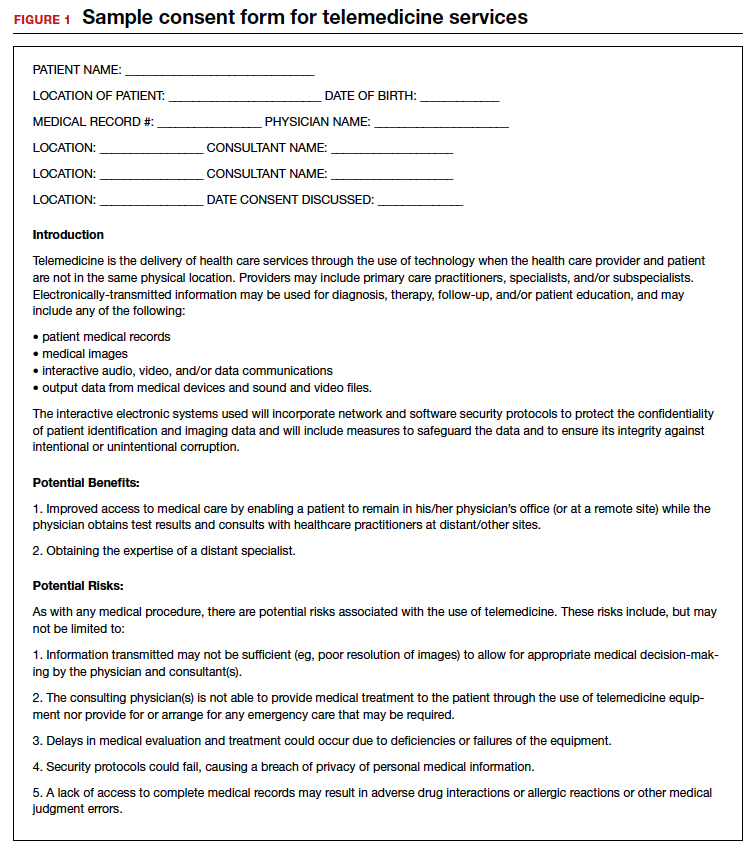

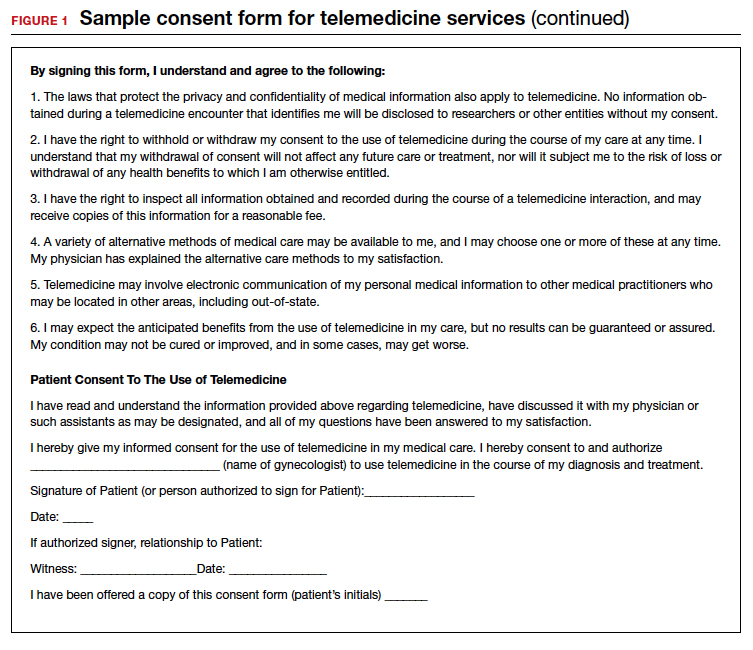

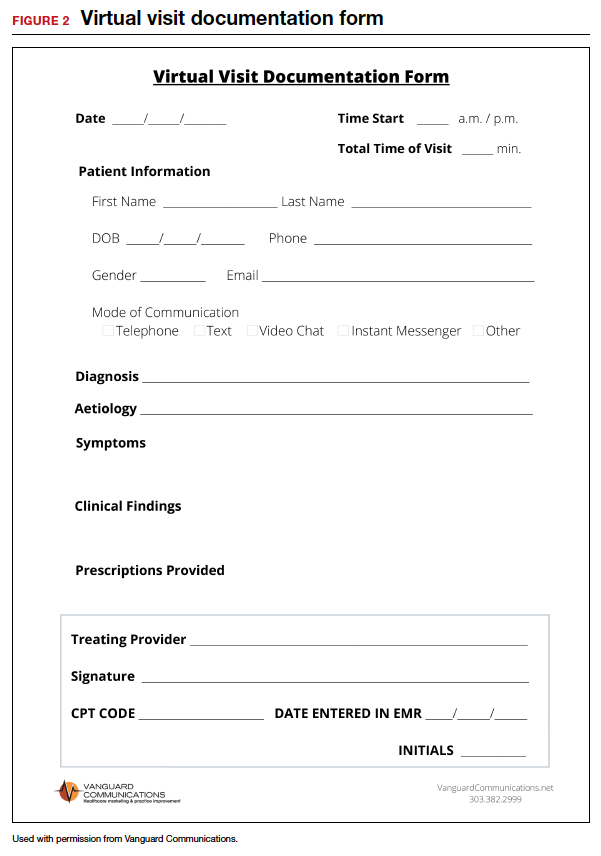

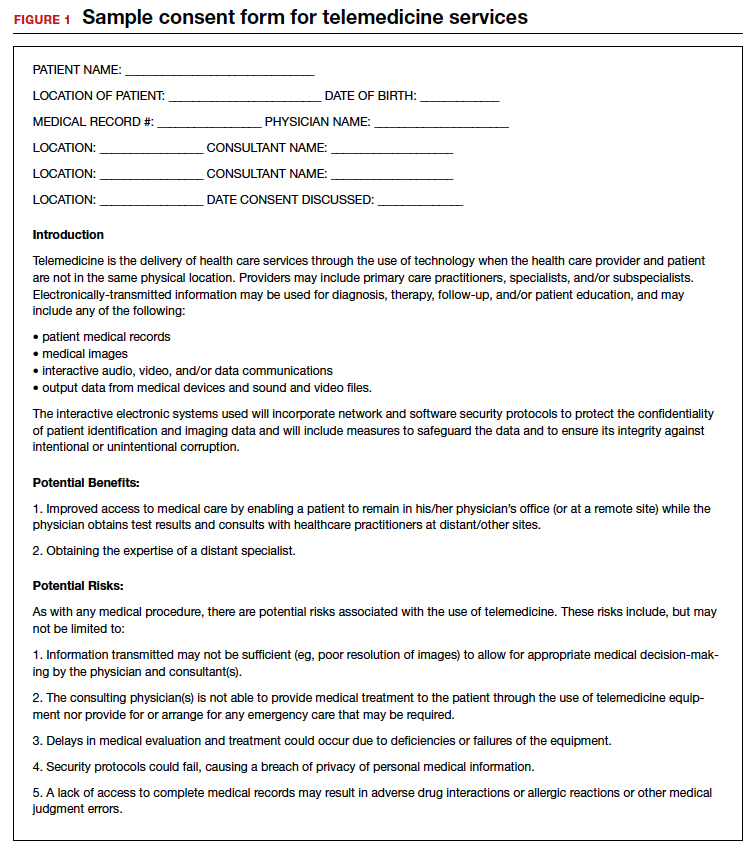

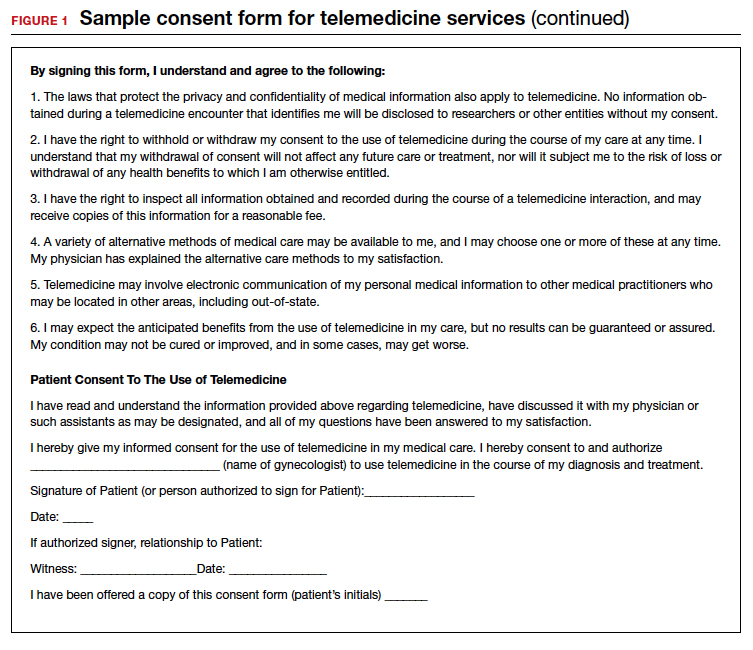

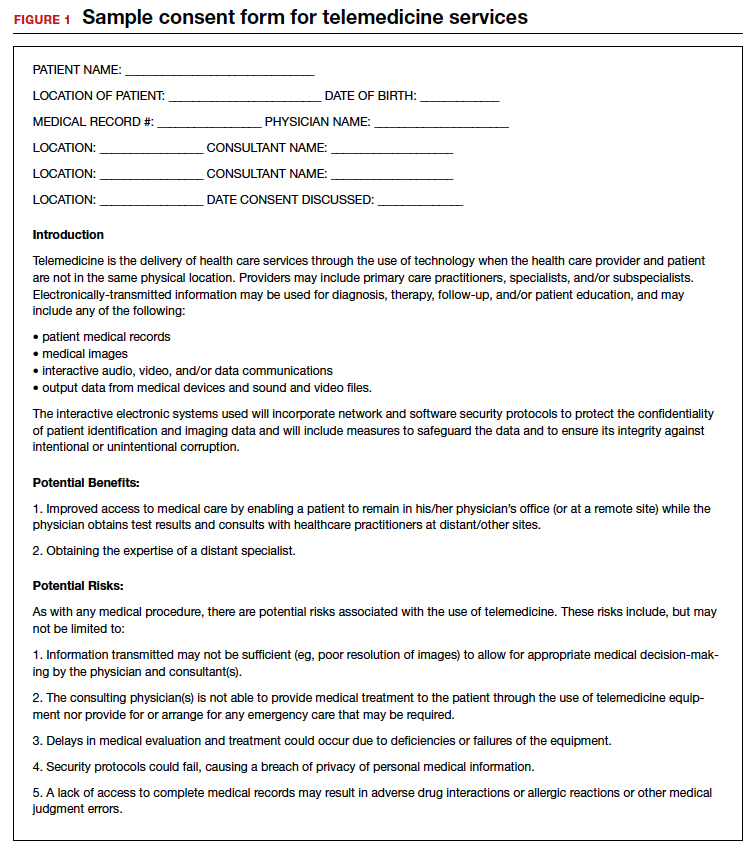

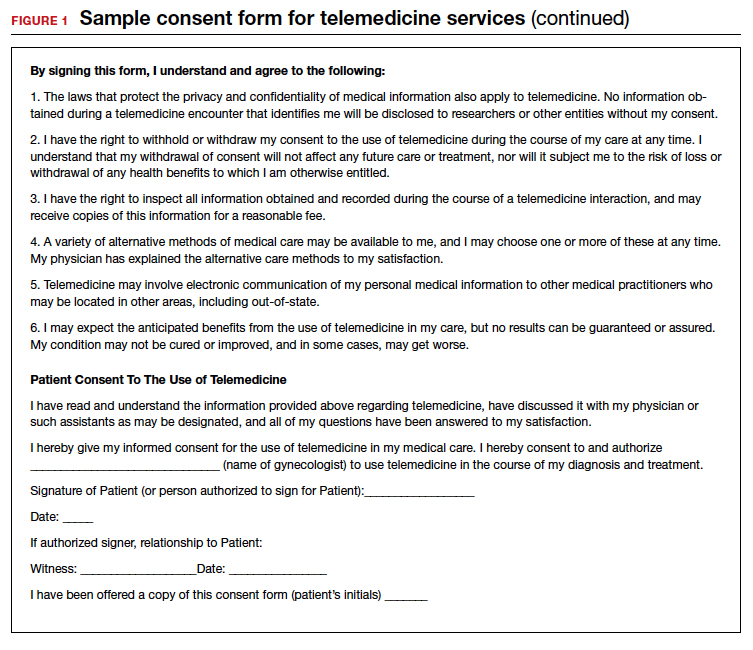

- Informed consent requirements. Some states have no requirements regarding consent for a virtual visit. Others require either written or verbal consent. In states that do not require informed consent, it is best practice to nevertheless obtain either written or oral consent and to document in the patient’s record that consent was obtained before initiating a virtual visit. The consent should follow state-mandated disclosures, as well as the practice’s policies regarding billing, scheduling, and cancellations of telemedicine visits.

- Interstate licensing laws. Because of the COVID-19 pandemic, federal and state licensure waivers are in place to allow physicians to care for patients outside the physician’s home state, but these waivers likely will be lifted postpandemic. Once waivers are lifted, physicians will need to be licensed not only in the state in which they practice but also in the state where the patient is located at the time of treatment. Even physicians who practice in states that belong to the Interstate Medical Licensure Compact2 must apply for and obtain a license to practice within Compact member states. Membership in the Interstate Medical Licensure Compact expedites the licensure process, but does not alleviate the need to obtain a license to practice in each member state. To ensure compliance with interstate licensure laws, seek advice from a health care attorney specializing in telemedicine.

- Drug monitoring laws. The Ryan Haight Online Pharmacy Consumer Protection Act of 20083 implemented a requirement that physicians have at least one in-person, face-to-face visit with patients before prescribing a controlled substance for the first time. Because state laws may vary, we suggest consulting with a health care attorney to understand your state’s requirements for prescribing controlled substances to new patients and when using telemedicine (see “Prescription drugs” at https://www.cdc.gov/phlp/publications/topic/prescription.html for more information).

- Data privacy and security. From a content perspective, health care data and personally identifiable information are extremely rich, which makes electronic health records (EHRs), or the digital form of patients’ medical histories and other data, particularly tempting targets for hackers and cyber criminals. We caution that services such as Facetime and Skype are not encrypted; they have been granted waivers for telemedicine use, but these waivers are probably not going to be permanent once the COVID-19 crisis passes.

- HIPAA compliance. Generally—and certainly under normal circumstances—telemedicine is subject to the same rules governing protected health information (PHI) as any other technology and process used in physician practices. The Health Insurance Portability and Accountability Act (HIPAA) Security Rule includes guidelines on telemedicine and stipulates that only authorized users should have access to ePHI, that a system of secure communication must be established to protect the security of ePHI, and that a system to monitor communications must be maintained, among other requirements.4 Third parties that provide telemedicine, data storage, and other services, with a few exceptions, must have a business associate agreement (BAA) with a covered entity. Covered entities include health care providers, health plans, and health and health care clearinghouses. Such an agreement should include specific language that ensures that HIPAA requirements will be met and that governs permitted and required uses of PHI, strictly limits other uses of PHI, and establishes appropriate safeguards and steps that must be taken in the event of a breach or disallowed disclosure of PHI. Best practice requires that providers establish robust protocols, policies, and processes for handling sensitive information.

During the COVID-19 pandemic, however, certain HIPAA restrictions relating to telemedicine have been temporarily waived by the US Department of Health and Human Services (HHS). More specifically, HHS Secretary Alex Azar has exercised his authority to waive sanctions against covered hospitals for noncompliance with requirements: to obtain a patient’s consent to speak with family members or friends involved in the patient’s care, to distribute a notice of privacy practices, to request privacy restrictions, to request confidential communications, and the use of nonpublic facing audio and video communications products, among others.5 These are temporary measures only; once the national public health emergency has passed or at the HHS Secretary’s discretion based on new developments, this position on discretionary nonenforcement may end.

Continue to: Crisis creates opportunity: The future of telemedicine...

Crisis creates opportunity: The future of telemedicine

It was just a few years ago when the use of telemedicine was relegated to treating patients in only rural areas or those located a great distance from brick and mortar practices. But the pandemic, along with the coincident relaxation of the Centers for Medicare and Medicaid Services’ (CMS) requirements for conducting telemedicine visits has made the technology highly attractive to ObGyns who can now treat many patients 24/7 from their homes using laptops and even mobile devices. In addition, the pandemic has prompted an expansion of current procedural terminology (CPT) codes that makes it possible to bill patients for telemedicine services and be appropriately compensated.

Thus, as awful as COVID-19 is, we can conclude that it has provided us with opportunities. We predict that when the crisis has abated, although the current relaxation of HIPAA guidelines will probably be rescinded, restrictions will not likely return to precoronavirus status; changes will certainly be made, and telemedicine will likely become part and parcel of caring for ObGyn patients.