User login

When a Public Health Alert Goes Wrong

At 8:07 am on January 13, 2018, people in Hawaii received an emergency alert advising them to seek shelter from an incoming ballistic missile.

A very long 38 minutes later, the message was retracted via the same systems that had sent it—the Wireless Emergency Alert system, which sends location-based warnings to wireless carrier systems, and the Emergency Alert System, which sends television and radio alerts.

The Federal Communications Commission report that covered the debacle noted that, among other errors, the employee responsible for triggering the false alert believed the missile threat was real. Moreover, the exercise plans did not document a process for disseminating an all-clear message. And on top of that, the established ballistic missile alert checklist did not include a step to notify the Hawaii Emergency Management Agency’s public information officer responsible for communicating with the public, media, other agencies, and other stakeholders during an incident.

Researchers from the CDC and Hawaii Department of Health analyzed tweets sent during 2 periods: early (8:07-8:45 am), the 38 minutes during which the alert circulated; and the late period (8:46-9:24 am), the same amount of elapsed time after the correction had been issued.

They found 4 themes dominated the early period: information processing, information sharing, authentication, and emotional reaction (shock, fear, panic, terror). Information processing was defined as any indication of initial mental processing of the alert. Many of the tweets dealt with coming to terms with the threat.

During the late period, information sharing and emotional reaction persisted, but they were joined by new themes that, according to the researchers, were “fundamentally different” from the early-period themes and reflected reactions to misinformation: denunciation, insufficient knowledge to act, and mistrust of authority. “Insufficient knowledge to act” involved reacting to the lack of a response plan, particularly not knowing how to properly take shelter. Denunciations blamed the emergency warning and response, especially the time it took to correct the mistake. Mistrust of authority involved doubting the emergency alert system or governmental response.

How can a situation like this be better handled? The researchers say public health messaging during an emergency is complicated. For instance, it is influenced by how messages are perceived and interpreted by different people, and by the fact that messages need to be sent over multiple platforms to ensure that the information is disseminated accurately and quickly.

Which is why social media is both a handicap and a boon in public health emergencies. Tweets spread misinformation as fast as information (if not faster), so the first messages are critical. In addition to conveying timely messages, the researchers advise, public health authorities need to address the reactions during each phase of a crisis. They also need to establish credibility to prevent the public from mistrusting the public health message and its issuers.

Most important, perhaps: Alerts should carry clear instructions for persons in the affected area to carry out during an emergency.

At 8:07 am on January 13, 2018, people in Hawaii received an emergency alert advising them to seek shelter from an incoming ballistic missile.

A very long 38 minutes later, the message was retracted via the same systems that had sent it—the Wireless Emergency Alert system, which sends location-based warnings to wireless carrier systems, and the Emergency Alert System, which sends television and radio alerts.

The Federal Communications Commission report that covered the debacle noted that, among other errors, the employee responsible for triggering the false alert believed the missile threat was real. Moreover, the exercise plans did not document a process for disseminating an all-clear message. And on top of that, the established ballistic missile alert checklist did not include a step to notify the Hawaii Emergency Management Agency’s public information officer responsible for communicating with the public, media, other agencies, and other stakeholders during an incident.

Researchers from the CDC and Hawaii Department of Health analyzed tweets sent during 2 periods: early (8:07-8:45 am), the 38 minutes during which the alert circulated; and the late period (8:46-9:24 am), the same amount of elapsed time after the correction had been issued.

They found 4 themes dominated the early period: information processing, information sharing, authentication, and emotional reaction (shock, fear, panic, terror). Information processing was defined as any indication of initial mental processing of the alert. Many of the tweets dealt with coming to terms with the threat.

During the late period, information sharing and emotional reaction persisted, but they were joined by new themes that, according to the researchers, were “fundamentally different” from the early-period themes and reflected reactions to misinformation: denunciation, insufficient knowledge to act, and mistrust of authority. “Insufficient knowledge to act” involved reacting to the lack of a response plan, particularly not knowing how to properly take shelter. Denunciations blamed the emergency warning and response, especially the time it took to correct the mistake. Mistrust of authority involved doubting the emergency alert system or governmental response.

How can a situation like this be better handled? The researchers say public health messaging during an emergency is complicated. For instance, it is influenced by how messages are perceived and interpreted by different people, and by the fact that messages need to be sent over multiple platforms to ensure that the information is disseminated accurately and quickly.

Which is why social media is both a handicap and a boon in public health emergencies. Tweets spread misinformation as fast as information (if not faster), so the first messages are critical. In addition to conveying timely messages, the researchers advise, public health authorities need to address the reactions during each phase of a crisis. They also need to establish credibility to prevent the public from mistrusting the public health message and its issuers.

Most important, perhaps: Alerts should carry clear instructions for persons in the affected area to carry out during an emergency.

At 8:07 am on January 13, 2018, people in Hawaii received an emergency alert advising them to seek shelter from an incoming ballistic missile.

A very long 38 minutes later, the message was retracted via the same systems that had sent it—the Wireless Emergency Alert system, which sends location-based warnings to wireless carrier systems, and the Emergency Alert System, which sends television and radio alerts.

The Federal Communications Commission report that covered the debacle noted that, among other errors, the employee responsible for triggering the false alert believed the missile threat was real. Moreover, the exercise plans did not document a process for disseminating an all-clear message. And on top of that, the established ballistic missile alert checklist did not include a step to notify the Hawaii Emergency Management Agency’s public information officer responsible for communicating with the public, media, other agencies, and other stakeholders during an incident.

Researchers from the CDC and Hawaii Department of Health analyzed tweets sent during 2 periods: early (8:07-8:45 am), the 38 minutes during which the alert circulated; and the late period (8:46-9:24 am), the same amount of elapsed time after the correction had been issued.

They found 4 themes dominated the early period: information processing, information sharing, authentication, and emotional reaction (shock, fear, panic, terror). Information processing was defined as any indication of initial mental processing of the alert. Many of the tweets dealt with coming to terms with the threat.

During the late period, information sharing and emotional reaction persisted, but they were joined by new themes that, according to the researchers, were “fundamentally different” from the early-period themes and reflected reactions to misinformation: denunciation, insufficient knowledge to act, and mistrust of authority. “Insufficient knowledge to act” involved reacting to the lack of a response plan, particularly not knowing how to properly take shelter. Denunciations blamed the emergency warning and response, especially the time it took to correct the mistake. Mistrust of authority involved doubting the emergency alert system or governmental response.

How can a situation like this be better handled? The researchers say public health messaging during an emergency is complicated. For instance, it is influenced by how messages are perceived and interpreted by different people, and by the fact that messages need to be sent over multiple platforms to ensure that the information is disseminated accurately and quickly.

Which is why social media is both a handicap and a boon in public health emergencies. Tweets spread misinformation as fast as information (if not faster), so the first messages are critical. In addition to conveying timely messages, the researchers advise, public health authorities need to address the reactions during each phase of a crisis. They also need to establish credibility to prevent the public from mistrusting the public health message and its issuers.

Most important, perhaps: Alerts should carry clear instructions for persons in the affected area to carry out during an emergency.

Prior authorization an increasing burden

The use of prior authorization for prescriptions and medical services has continued to increase in recent years, despite the consequences to continuity of care, according to a survey by the American Medical Association.

and 41% said that PA for medical services has done the same. The corresponding numbers for 5-year decreases in PAs were 2% and 1%, the AMA reported March 12.

Results of the survey, conducted in December 2018, also show that 85% of physicians believe that prior authorization sometimes, often, or always has a negative effect on the continuity of patients’ care. Almost 70% of respondents said that it is somewhat or extremely difficult to determine when PA is required for a prescription or medical service, and only 8% reported contracting with a health plan that offers programs to exempt physicians from the PA process, the AMA said.

“Physicians follow insurance protocols for prior authorization that require faxing recurring paperwork, multiple phone calls, and hours spent on hold. At the same time, patients’ lives can hang in the balance until health plans decide if needed care will qualify for insurance coverage,” AMA President Barbara L. McAneny, MD, said in a statement.

In January 2018, two organizations representing insurers – America’s Health Insurance Plans and the Blue Cross Blue Shield Association – signed onto a joint consensus statement with the AMA and other health care groups that provided five areas for improvement of the PA process. The current survey results show that “most health plans are not making meaningful progress on reforming the cumbersome prior authorization process,” the AMA said.

The use of prior authorization for prescriptions and medical services has continued to increase in recent years, despite the consequences to continuity of care, according to a survey by the American Medical Association.

and 41% said that PA for medical services has done the same. The corresponding numbers for 5-year decreases in PAs were 2% and 1%, the AMA reported March 12.

Results of the survey, conducted in December 2018, also show that 85% of physicians believe that prior authorization sometimes, often, or always has a negative effect on the continuity of patients’ care. Almost 70% of respondents said that it is somewhat or extremely difficult to determine when PA is required for a prescription or medical service, and only 8% reported contracting with a health plan that offers programs to exempt physicians from the PA process, the AMA said.

“Physicians follow insurance protocols for prior authorization that require faxing recurring paperwork, multiple phone calls, and hours spent on hold. At the same time, patients’ lives can hang in the balance until health plans decide if needed care will qualify for insurance coverage,” AMA President Barbara L. McAneny, MD, said in a statement.

In January 2018, two organizations representing insurers – America’s Health Insurance Plans and the Blue Cross Blue Shield Association – signed onto a joint consensus statement with the AMA and other health care groups that provided five areas for improvement of the PA process. The current survey results show that “most health plans are not making meaningful progress on reforming the cumbersome prior authorization process,” the AMA said.

The use of prior authorization for prescriptions and medical services has continued to increase in recent years, despite the consequences to continuity of care, according to a survey by the American Medical Association.

and 41% said that PA for medical services has done the same. The corresponding numbers for 5-year decreases in PAs were 2% and 1%, the AMA reported March 12.

Results of the survey, conducted in December 2018, also show that 85% of physicians believe that prior authorization sometimes, often, or always has a negative effect on the continuity of patients’ care. Almost 70% of respondents said that it is somewhat or extremely difficult to determine when PA is required for a prescription or medical service, and only 8% reported contracting with a health plan that offers programs to exempt physicians from the PA process, the AMA said.

“Physicians follow insurance protocols for prior authorization that require faxing recurring paperwork, multiple phone calls, and hours spent on hold. At the same time, patients’ lives can hang in the balance until health plans decide if needed care will qualify for insurance coverage,” AMA President Barbara L. McAneny, MD, said in a statement.

In January 2018, two organizations representing insurers – America’s Health Insurance Plans and the Blue Cross Blue Shield Association – signed onto a joint consensus statement with the AMA and other health care groups that provided five areas for improvement of the PA process. The current survey results show that “most health plans are not making meaningful progress on reforming the cumbersome prior authorization process,” the AMA said.

Military Doctors In Crosshairs of a Budget Battle

The move inside the military coincides with efforts by the Trump administration to privatize care for veterans. The Department of Veterans Affairs in February proposed rules that would allow veterans to use private hospitals and clinics if government primary care facilities are not nearby or if they have to wait too long for an appointment.

Shrinking the medical corps within the armed forces is proving more contentious and complex. In 2017, a Republican-controlled Congress mandated changes in what a Senate Armed Services Committee report described as “an under-performing, disjointed health system” with “bloated medical headquarters staffs” and “inevitable turf wars.” The directive sought a greater emphasis for military doctors on combat-related needs while transferring other care to civilian providers.

Details of reductions have yet to be finalized, a military spokeswoman said. But within the system and among alumni, trepidation has increased since Military.com, an online military and veterans organization, reported in January that the Department of Defense had drafted proposals to convert more than 17,000 medical positions into fighting and support positions – a 13 percent reduction in medical personnel.

“That would be a drastic first cut,” said Dr. David Lane, a retired rear admiral and former director of the Walter Reed National Military Medical Center in Bethesda, Md.

At most risk in the current planning are positions that aren’t considered essential to troops overseas, such as training spots for new doctors and jobs that can be outsourced to private physicians and hospitals – obstetricians and primary care doctors, for example. The reductions may also limit the military’s medical humanitarian assistance and relief for foreign natural disasters and disease outbreaks.

Even in war zones, Lane warned, it would be a mistake to downplay the importance of contributions by doctors who do not specialize in trauma. In the 1991 invasion of Kuwait, for instance, cases of diseases and non-battle injuries rather than combat injuries created the most medical work, he said.

Doctors who train in the military’s highly regarded medical school – who have committed to serve in the armed forces after training – and those who do military residencies account for much of the staff serving troops overseas. A major deployment could leave the military flatfooted, said Dr. John Prescott, a former Army physician.

“The majority of folks in the military don’t stay in for their whole career, they stay in for a few years,” Prescott said. “I’m concerned there will be a very small cohort that will be available for deployment in the future.”

The military health system is responsible for more than 1.4 million active-duty and 331,000 reserve personnel, with 54 hospitals and 377 military clinics around the world. Split among the Navy, Army and Air Force, each with its own doctors and hospitals, the service has been targeted for years for overhaul to reduce redundancies and save costs.

The department has already started moving administrative functions under one bureaucracy, called the Defense Health Agency, which is slated to take over the service branch hospitals in 2021.

The budget for the next fiscal year is still being developed and final decisions have not yet been made, a Department of Defense spokeswoman, Lt. Col. Carla Gleason, said in an email. “Any reforms that do result will be driven by the Department’s efforts to ensure our medical personnel are ready to provide battlefield care in support of our forces, and to provide the outstanding medical benefits that Service members, retirees and their families deserve,” she said.

For years, critics of the broad role of the military health services have argued that many medical corps services – such as maternity care and pediatrics on bases – could be provided more effectively by civilian doctors and hospitals.

But Lane said there is too much focus on the high-profile trauma cases on the battlefield “that at the end of the day are a small portion” of medical care. “When we’re trying to put things back together that got broken during a war,” he said, “that’s what you need the most of – pediatricians, public health doctors, primary care doctors.”

Some studies commissioned by the department have concluded private hospitals could deliver less costly care, in part because doctors at hospitals take care of more patients. But the Congressional Budget Office said savings were not at all certain and that military hospitals might be less expensive if the government arranged for greater use of them.

Brad Carson and Morgan Plummer, who held senior jobs in the Department of Defense during President Barack Obama’s administration, argued in a 2016 essay that the military isn’t the best training for surgeons because it doesn’t provide them with a sufficient number of cases to develop expertise.

The military health system “has too much infrastructure, the wrong mix of providers, and predominantly serves the needs of beneficiaries who could easily have their health care needs satisfied by civilian providers at far less cost and with equal or better quality,” they wrote.

The government this year is spending $50 billion on the military health system, including Tricare insurance for more than 9 million active-duty service members, veterans, families and survivors, according to Congress’ budget office. That is roughly a tenth of the military budget. The CBO projected costs are on track to increase to $63 billion in 2033.

Defenders of the system reject the idea that non-wartime jobs can be eliminated without it hurting that core mission.

“Military health care providers between deployments maintain their clinical skills by treating service members and millions of beneficiaries,” Dr. Arthur Kellermann, dean of the school of medicine at the Uniformed Services University in Bethesda, wrote in a 2017 Health Affairs article. “Military hospitals provide valuable platforms for teaching the next generation of uniformed health care professionals and standby capacity for combat casualties.”

Prescott, the former Army doctor, said that the military may have trouble turning to civilian doctors in some regions given physician shortages, which he said the military cuts would exacerbate.

“Most hospitals are already pretty full, most health care providers are pretty busy,” said Prescott, now chief academic officer at the Association of American Medical Colleges.

Doctor shortages would increase if the military cut the slots it now has to train doctors, because there wouldn’t be new civilian residencies created to compensate. “Those positions basically disappear,” he said.

Kathryn Beasley, a retired Navy captain who is director of government relations for health affairs at the Military Officers Association of America, said she was also concerned with unforeseen consequences of dramatic cuts.

“Everything’s tied together, there’s a lot of interdependencies in these things,” she said. “You pull a string on one and you might feel it in an area you don’t expect.”

Kaiser Health News is a nonprofit national health policy news service. It is an editorially independent program of the Henry J. Kaiser Family Foundation that is not affiliated with Kaiser Permanente.

The move inside the military coincides with efforts by the Trump administration to privatize care for veterans. The Department of Veterans Affairs in February proposed rules that would allow veterans to use private hospitals and clinics if government primary care facilities are not nearby or if they have to wait too long for an appointment.

Shrinking the medical corps within the armed forces is proving more contentious and complex. In 2017, a Republican-controlled Congress mandated changes in what a Senate Armed Services Committee report described as “an under-performing, disjointed health system” with “bloated medical headquarters staffs” and “inevitable turf wars.” The directive sought a greater emphasis for military doctors on combat-related needs while transferring other care to civilian providers.

Details of reductions have yet to be finalized, a military spokeswoman said. But within the system and among alumni, trepidation has increased since Military.com, an online military and veterans organization, reported in January that the Department of Defense had drafted proposals to convert more than 17,000 medical positions into fighting and support positions – a 13 percent reduction in medical personnel.

“That would be a drastic first cut,” said Dr. David Lane, a retired rear admiral and former director of the Walter Reed National Military Medical Center in Bethesda, Md.

At most risk in the current planning are positions that aren’t considered essential to troops overseas, such as training spots for new doctors and jobs that can be outsourced to private physicians and hospitals – obstetricians and primary care doctors, for example. The reductions may also limit the military’s medical humanitarian assistance and relief for foreign natural disasters and disease outbreaks.

Even in war zones, Lane warned, it would be a mistake to downplay the importance of contributions by doctors who do not specialize in trauma. In the 1991 invasion of Kuwait, for instance, cases of diseases and non-battle injuries rather than combat injuries created the most medical work, he said.

Doctors who train in the military’s highly regarded medical school – who have committed to serve in the armed forces after training – and those who do military residencies account for much of the staff serving troops overseas. A major deployment could leave the military flatfooted, said Dr. John Prescott, a former Army physician.

“The majority of folks in the military don’t stay in for their whole career, they stay in for a few years,” Prescott said. “I’m concerned there will be a very small cohort that will be available for deployment in the future.”

The military health system is responsible for more than 1.4 million active-duty and 331,000 reserve personnel, with 54 hospitals and 377 military clinics around the world. Split among the Navy, Army and Air Force, each with its own doctors and hospitals, the service has been targeted for years for overhaul to reduce redundancies and save costs.

The department has already started moving administrative functions under one bureaucracy, called the Defense Health Agency, which is slated to take over the service branch hospitals in 2021.

The budget for the next fiscal year is still being developed and final decisions have not yet been made, a Department of Defense spokeswoman, Lt. Col. Carla Gleason, said in an email. “Any reforms that do result will be driven by the Department’s efforts to ensure our medical personnel are ready to provide battlefield care in support of our forces, and to provide the outstanding medical benefits that Service members, retirees and their families deserve,” she said.

For years, critics of the broad role of the military health services have argued that many medical corps services – such as maternity care and pediatrics on bases – could be provided more effectively by civilian doctors and hospitals.

But Lane said there is too much focus on the high-profile trauma cases on the battlefield “that at the end of the day are a small portion” of medical care. “When we’re trying to put things back together that got broken during a war,” he said, “that’s what you need the most of – pediatricians, public health doctors, primary care doctors.”

Some studies commissioned by the department have concluded private hospitals could deliver less costly care, in part because doctors at hospitals take care of more patients. But the Congressional Budget Office said savings were not at all certain and that military hospitals might be less expensive if the government arranged for greater use of them.

Brad Carson and Morgan Plummer, who held senior jobs in the Department of Defense during President Barack Obama’s administration, argued in a 2016 essay that the military isn’t the best training for surgeons because it doesn’t provide them with a sufficient number of cases to develop expertise.

The military health system “has too much infrastructure, the wrong mix of providers, and predominantly serves the needs of beneficiaries who could easily have their health care needs satisfied by civilian providers at far less cost and with equal or better quality,” they wrote.

The government this year is spending $50 billion on the military health system, including Tricare insurance for more than 9 million active-duty service members, veterans, families and survivors, according to Congress’ budget office. That is roughly a tenth of the military budget. The CBO projected costs are on track to increase to $63 billion in 2033.

Defenders of the system reject the idea that non-wartime jobs can be eliminated without it hurting that core mission.

“Military health care providers between deployments maintain their clinical skills by treating service members and millions of beneficiaries,” Dr. Arthur Kellermann, dean of the school of medicine at the Uniformed Services University in Bethesda, wrote in a 2017 Health Affairs article. “Military hospitals provide valuable platforms for teaching the next generation of uniformed health care professionals and standby capacity for combat casualties.”

Prescott, the former Army doctor, said that the military may have trouble turning to civilian doctors in some regions given physician shortages, which he said the military cuts would exacerbate.

“Most hospitals are already pretty full, most health care providers are pretty busy,” said Prescott, now chief academic officer at the Association of American Medical Colleges.

Doctor shortages would increase if the military cut the slots it now has to train doctors, because there wouldn’t be new civilian residencies created to compensate. “Those positions basically disappear,” he said.

Kathryn Beasley, a retired Navy captain who is director of government relations for health affairs at the Military Officers Association of America, said she was also concerned with unforeseen consequences of dramatic cuts.

“Everything’s tied together, there’s a lot of interdependencies in these things,” she said. “You pull a string on one and you might feel it in an area you don’t expect.”

Kaiser Health News is a nonprofit national health policy news service. It is an editorially independent program of the Henry J. Kaiser Family Foundation that is not affiliated with Kaiser Permanente.

The move inside the military coincides with efforts by the Trump administration to privatize care for veterans. The Department of Veterans Affairs in February proposed rules that would allow veterans to use private hospitals and clinics if government primary care facilities are not nearby or if they have to wait too long for an appointment.

Shrinking the medical corps within the armed forces is proving more contentious and complex. In 2017, a Republican-controlled Congress mandated changes in what a Senate Armed Services Committee report described as “an under-performing, disjointed health system” with “bloated medical headquarters staffs” and “inevitable turf wars.” The directive sought a greater emphasis for military doctors on combat-related needs while transferring other care to civilian providers.

Details of reductions have yet to be finalized, a military spokeswoman said. But within the system and among alumni, trepidation has increased since Military.com, an online military and veterans organization, reported in January that the Department of Defense had drafted proposals to convert more than 17,000 medical positions into fighting and support positions – a 13 percent reduction in medical personnel.

“That would be a drastic first cut,” said Dr. David Lane, a retired rear admiral and former director of the Walter Reed National Military Medical Center in Bethesda, Md.

At most risk in the current planning are positions that aren’t considered essential to troops overseas, such as training spots for new doctors and jobs that can be outsourced to private physicians and hospitals – obstetricians and primary care doctors, for example. The reductions may also limit the military’s medical humanitarian assistance and relief for foreign natural disasters and disease outbreaks.

Even in war zones, Lane warned, it would be a mistake to downplay the importance of contributions by doctors who do not specialize in trauma. In the 1991 invasion of Kuwait, for instance, cases of diseases and non-battle injuries rather than combat injuries created the most medical work, he said.

Doctors who train in the military’s highly regarded medical school – who have committed to serve in the armed forces after training – and those who do military residencies account for much of the staff serving troops overseas. A major deployment could leave the military flatfooted, said Dr. John Prescott, a former Army physician.

“The majority of folks in the military don’t stay in for their whole career, they stay in for a few years,” Prescott said. “I’m concerned there will be a very small cohort that will be available for deployment in the future.”

The military health system is responsible for more than 1.4 million active-duty and 331,000 reserve personnel, with 54 hospitals and 377 military clinics around the world. Split among the Navy, Army and Air Force, each with its own doctors and hospitals, the service has been targeted for years for overhaul to reduce redundancies and save costs.

The department has already started moving administrative functions under one bureaucracy, called the Defense Health Agency, which is slated to take over the service branch hospitals in 2021.

The budget for the next fiscal year is still being developed and final decisions have not yet been made, a Department of Defense spokeswoman, Lt. Col. Carla Gleason, said in an email. “Any reforms that do result will be driven by the Department’s efforts to ensure our medical personnel are ready to provide battlefield care in support of our forces, and to provide the outstanding medical benefits that Service members, retirees and their families deserve,” she said.

For years, critics of the broad role of the military health services have argued that many medical corps services – such as maternity care and pediatrics on bases – could be provided more effectively by civilian doctors and hospitals.

But Lane said there is too much focus on the high-profile trauma cases on the battlefield “that at the end of the day are a small portion” of medical care. “When we’re trying to put things back together that got broken during a war,” he said, “that’s what you need the most of – pediatricians, public health doctors, primary care doctors.”

Some studies commissioned by the department have concluded private hospitals could deliver less costly care, in part because doctors at hospitals take care of more patients. But the Congressional Budget Office said savings were not at all certain and that military hospitals might be less expensive if the government arranged for greater use of them.

Brad Carson and Morgan Plummer, who held senior jobs in the Department of Defense during President Barack Obama’s administration, argued in a 2016 essay that the military isn’t the best training for surgeons because it doesn’t provide them with a sufficient number of cases to develop expertise.

The military health system “has too much infrastructure, the wrong mix of providers, and predominantly serves the needs of beneficiaries who could easily have their health care needs satisfied by civilian providers at far less cost and with equal or better quality,” they wrote.

The government this year is spending $50 billion on the military health system, including Tricare insurance for more than 9 million active-duty service members, veterans, families and survivors, according to Congress’ budget office. That is roughly a tenth of the military budget. The CBO projected costs are on track to increase to $63 billion in 2033.

Defenders of the system reject the idea that non-wartime jobs can be eliminated without it hurting that core mission.

“Military health care providers between deployments maintain their clinical skills by treating service members and millions of beneficiaries,” Dr. Arthur Kellermann, dean of the school of medicine at the Uniformed Services University in Bethesda, wrote in a 2017 Health Affairs article. “Military hospitals provide valuable platforms for teaching the next generation of uniformed health care professionals and standby capacity for combat casualties.”

Prescott, the former Army doctor, said that the military may have trouble turning to civilian doctors in some regions given physician shortages, which he said the military cuts would exacerbate.

“Most hospitals are already pretty full, most health care providers are pretty busy,” said Prescott, now chief academic officer at the Association of American Medical Colleges.

Doctor shortages would increase if the military cut the slots it now has to train doctors, because there wouldn’t be new civilian residencies created to compensate. “Those positions basically disappear,” he said.

Kathryn Beasley, a retired Navy captain who is director of government relations for health affairs at the Military Officers Association of America, said she was also concerned with unforeseen consequences of dramatic cuts.

“Everything’s tied together, there’s a lot of interdependencies in these things,” she said. “You pull a string on one and you might feel it in an area you don’t expect.”

Kaiser Health News is a nonprofit national health policy news service. It is an editorially independent program of the Henry J. Kaiser Family Foundation that is not affiliated with Kaiser Permanente.

Deprescribing: Nicolas Badre

In this episode of the MDedge Psychcast, Dr. Lorenzo Norris speaks with Dr. Nicolas Badre about ways to approach reducing dosages or discontinuing medications that are not beneficial. Dr. Badre, who has written about “deprescribing,” is a forensic psychiatrist who holds teaching positions at the University of California San Diego, and the University of San Diego.

Subscribe here:

Amazon

Apple Podcasts

Google Podcasts

Spotify

In this episode of the MDedge Psychcast, Dr. Lorenzo Norris speaks with Dr. Nicolas Badre about ways to approach reducing dosages or discontinuing medications that are not beneficial. Dr. Badre, who has written about “deprescribing,” is a forensic psychiatrist who holds teaching positions at the University of California San Diego, and the University of San Diego.

Subscribe here:

Amazon

Apple Podcasts

Google Podcasts

Spotify

In this episode of the MDedge Psychcast, Dr. Lorenzo Norris speaks with Dr. Nicolas Badre about ways to approach reducing dosages or discontinuing medications that are not beneficial. Dr. Badre, who has written about “deprescribing,” is a forensic psychiatrist who holds teaching positions at the University of California San Diego, and the University of San Diego.

Subscribe here:

Amazon

Apple Podcasts

Google Podcasts

Spotify

Large survey reveals that few MS patients have long-term care insurance

DALLAS – A number of sociodemographic factors may influence health and disability insurance access by individuals with multiple sclerosis, including employment, age, gender, disease duration, marital status, and ethnicity, results from a large survey suggest.

“The last similar work was conducted over 10 years ago and so much has happened in the meantime, including the Great Recession and the introduction of the Affordable Care Act, that offers protection for health care but not for other important types of insurance (short- and long-term disability, long-term care, and life),” lead study author Sarah Planchon, PhD, said in an interview in advance of the meeting held by the Americas Committee for Treatment and Research in Multiple Sclerosis. “MS is one of the most costly chronic diseases today. That is not only because of the cost of disease-modifying therapies but also because of lost employment and income. We wanted to better understand the insurance landscape so that we could in turn educate patients and professionals about the protection these insurances offer and advise them on how to obtain these policies.”

In an effort to evaluate factors that affect insurance access in MS, Dr. Planchon, a project scientist at the Mellen Center for Multiple Sclerosis at the Cleveland Clinic in Ohio, and her colleagues used the North American Research Committee on MS (NARCOMS), iConquerMS, and the National Multiple Sclerosis Society to survey 2,507 individuals with the disease regarding insurance, demographic, health, disability, and employment status. They used covariate-adjusted nominal logistic regression to estimate odds ratios for the likelihood of having or not having a type of insurance. The majority of respondents (83%) were female, their mean age was 54 years, 91% were white, 65% were currently married, and their mean disease duration at the time of the survey was 16 years. In addition, 43% were employed full/part-time, and 29% were not employed or retired because of disability. Nearly all respondents (96%) reported having health insurance, while 59% had life insurance, 29% had private long-term disability insurance, 18% had short-term disability insurance, and 10% had long-term care insurance.

The researchers found that employment status had the greatest impact on insurance coverage. Of those with health insurance, 33% were employed full-time, compared with 89% of those with short-term disability insurance, 42% of those with private long-term disability insurance, 44% of those with long-term care insurance, and 41% of those with life insurance. Logistic regression analyses indicated that respondents employed part time were significantly more likely to have short-term disability insurance if they were currently married (odds ratio, 4.4). Short-term disability insurance was significantly more likely among fully employed patients with disease duration of 5-10 years vs. more than 20 years (OR, 2.0). Private long-term disability insurance was significantly associated with female gender (OR, 1.6), age 50-59 years vs. younger than 40 (OR, 1.6), full-time vs. part-time employment (OR, 2.3), and shorter disease duration (ORs, 1.4-1.6 for 6-10, 11-15, and 16-20 years’ duration). Long-term care insurance was associated with older age (ORs, 2.5 and 4.3 for those aged 50-59 and 60-65 vs. younger than 40), and having excellent or good general health status vs. fair or poor (OR, 1.8). Life insurance was associated with non-Hispanic ethnicity (OR, 1.6), full-time vs. part-time employment (OR, 2.4), older age (ORs, 1.6-1.7 for ages 40-49 and 50-59 vs. younger than 40), and marital status (currently/previously married, ORs, 1.6-2.6). Considering the high rate of survey respondents with health insurance, covariate-adjusted modeling was not applicable.

“The number of people with MS who do not have long-term care insurance was surprisingly high,” Dr. Planchon said. “Although the improved treatment climate recently may decrease the long-term disability levels, we do not yet know this with certainty. A large number of people with MS are likely to need long-term care in the future, which often is a significant financial burden to families.” The findings suggest that clinical care teams “need to initiate early discussions of possible long-term needs with their patients,” she continued. “Incorporation of social work teams, who are familiar with the needs of people with MS and insurance options available to them, within MS specialty practices will bolster the comprehensive care of patients and their families.”

She acknowledged certain limitations of the study, including the low proportion of respondents who were Hispanic/Latino and African American (about 4% each). “The insurance landscape may differ in these groups compared to the majority Caucasian population who responded to this survey,” Dr. Planchon said.

The National Multiple Sclerosis Society funded the study. Dr. Planchon reported having no relevant financial disclosures.

SOURCE: Planchon S et al. ACTRIMS Forum 2019, Abstract P295.

DALLAS – A number of sociodemographic factors may influence health and disability insurance access by individuals with multiple sclerosis, including employment, age, gender, disease duration, marital status, and ethnicity, results from a large survey suggest.

“The last similar work was conducted over 10 years ago and so much has happened in the meantime, including the Great Recession and the introduction of the Affordable Care Act, that offers protection for health care but not for other important types of insurance (short- and long-term disability, long-term care, and life),” lead study author Sarah Planchon, PhD, said in an interview in advance of the meeting held by the Americas Committee for Treatment and Research in Multiple Sclerosis. “MS is one of the most costly chronic diseases today. That is not only because of the cost of disease-modifying therapies but also because of lost employment and income. We wanted to better understand the insurance landscape so that we could in turn educate patients and professionals about the protection these insurances offer and advise them on how to obtain these policies.”

In an effort to evaluate factors that affect insurance access in MS, Dr. Planchon, a project scientist at the Mellen Center for Multiple Sclerosis at the Cleveland Clinic in Ohio, and her colleagues used the North American Research Committee on MS (NARCOMS), iConquerMS, and the National Multiple Sclerosis Society to survey 2,507 individuals with the disease regarding insurance, demographic, health, disability, and employment status. They used covariate-adjusted nominal logistic regression to estimate odds ratios for the likelihood of having or not having a type of insurance. The majority of respondents (83%) were female, their mean age was 54 years, 91% were white, 65% were currently married, and their mean disease duration at the time of the survey was 16 years. In addition, 43% were employed full/part-time, and 29% were not employed or retired because of disability. Nearly all respondents (96%) reported having health insurance, while 59% had life insurance, 29% had private long-term disability insurance, 18% had short-term disability insurance, and 10% had long-term care insurance.

The researchers found that employment status had the greatest impact on insurance coverage. Of those with health insurance, 33% were employed full-time, compared with 89% of those with short-term disability insurance, 42% of those with private long-term disability insurance, 44% of those with long-term care insurance, and 41% of those with life insurance. Logistic regression analyses indicated that respondents employed part time were significantly more likely to have short-term disability insurance if they were currently married (odds ratio, 4.4). Short-term disability insurance was significantly more likely among fully employed patients with disease duration of 5-10 years vs. more than 20 years (OR, 2.0). Private long-term disability insurance was significantly associated with female gender (OR, 1.6), age 50-59 years vs. younger than 40 (OR, 1.6), full-time vs. part-time employment (OR, 2.3), and shorter disease duration (ORs, 1.4-1.6 for 6-10, 11-15, and 16-20 years’ duration). Long-term care insurance was associated with older age (ORs, 2.5 and 4.3 for those aged 50-59 and 60-65 vs. younger than 40), and having excellent or good general health status vs. fair or poor (OR, 1.8). Life insurance was associated with non-Hispanic ethnicity (OR, 1.6), full-time vs. part-time employment (OR, 2.4), older age (ORs, 1.6-1.7 for ages 40-49 and 50-59 vs. younger than 40), and marital status (currently/previously married, ORs, 1.6-2.6). Considering the high rate of survey respondents with health insurance, covariate-adjusted modeling was not applicable.

“The number of people with MS who do not have long-term care insurance was surprisingly high,” Dr. Planchon said. “Although the improved treatment climate recently may decrease the long-term disability levels, we do not yet know this with certainty. A large number of people with MS are likely to need long-term care in the future, which often is a significant financial burden to families.” The findings suggest that clinical care teams “need to initiate early discussions of possible long-term needs with their patients,” she continued. “Incorporation of social work teams, who are familiar with the needs of people with MS and insurance options available to them, within MS specialty practices will bolster the comprehensive care of patients and their families.”

She acknowledged certain limitations of the study, including the low proportion of respondents who were Hispanic/Latino and African American (about 4% each). “The insurance landscape may differ in these groups compared to the majority Caucasian population who responded to this survey,” Dr. Planchon said.

The National Multiple Sclerosis Society funded the study. Dr. Planchon reported having no relevant financial disclosures.

SOURCE: Planchon S et al. ACTRIMS Forum 2019, Abstract P295.

DALLAS – A number of sociodemographic factors may influence health and disability insurance access by individuals with multiple sclerosis, including employment, age, gender, disease duration, marital status, and ethnicity, results from a large survey suggest.

“The last similar work was conducted over 10 years ago and so much has happened in the meantime, including the Great Recession and the introduction of the Affordable Care Act, that offers protection for health care but not for other important types of insurance (short- and long-term disability, long-term care, and life),” lead study author Sarah Planchon, PhD, said in an interview in advance of the meeting held by the Americas Committee for Treatment and Research in Multiple Sclerosis. “MS is one of the most costly chronic diseases today. That is not only because of the cost of disease-modifying therapies but also because of lost employment and income. We wanted to better understand the insurance landscape so that we could in turn educate patients and professionals about the protection these insurances offer and advise them on how to obtain these policies.”

In an effort to evaluate factors that affect insurance access in MS, Dr. Planchon, a project scientist at the Mellen Center for Multiple Sclerosis at the Cleveland Clinic in Ohio, and her colleagues used the North American Research Committee on MS (NARCOMS), iConquerMS, and the National Multiple Sclerosis Society to survey 2,507 individuals with the disease regarding insurance, demographic, health, disability, and employment status. They used covariate-adjusted nominal logistic regression to estimate odds ratios for the likelihood of having or not having a type of insurance. The majority of respondents (83%) were female, their mean age was 54 years, 91% were white, 65% were currently married, and their mean disease duration at the time of the survey was 16 years. In addition, 43% were employed full/part-time, and 29% were not employed or retired because of disability. Nearly all respondents (96%) reported having health insurance, while 59% had life insurance, 29% had private long-term disability insurance, 18% had short-term disability insurance, and 10% had long-term care insurance.

The researchers found that employment status had the greatest impact on insurance coverage. Of those with health insurance, 33% were employed full-time, compared with 89% of those with short-term disability insurance, 42% of those with private long-term disability insurance, 44% of those with long-term care insurance, and 41% of those with life insurance. Logistic regression analyses indicated that respondents employed part time were significantly more likely to have short-term disability insurance if they were currently married (odds ratio, 4.4). Short-term disability insurance was significantly more likely among fully employed patients with disease duration of 5-10 years vs. more than 20 years (OR, 2.0). Private long-term disability insurance was significantly associated with female gender (OR, 1.6), age 50-59 years vs. younger than 40 (OR, 1.6), full-time vs. part-time employment (OR, 2.3), and shorter disease duration (ORs, 1.4-1.6 for 6-10, 11-15, and 16-20 years’ duration). Long-term care insurance was associated with older age (ORs, 2.5 and 4.3 for those aged 50-59 and 60-65 vs. younger than 40), and having excellent or good general health status vs. fair or poor (OR, 1.8). Life insurance was associated with non-Hispanic ethnicity (OR, 1.6), full-time vs. part-time employment (OR, 2.4), older age (ORs, 1.6-1.7 for ages 40-49 and 50-59 vs. younger than 40), and marital status (currently/previously married, ORs, 1.6-2.6). Considering the high rate of survey respondents with health insurance, covariate-adjusted modeling was not applicable.

“The number of people with MS who do not have long-term care insurance was surprisingly high,” Dr. Planchon said. “Although the improved treatment climate recently may decrease the long-term disability levels, we do not yet know this with certainty. A large number of people with MS are likely to need long-term care in the future, which often is a significant financial burden to families.” The findings suggest that clinical care teams “need to initiate early discussions of possible long-term needs with their patients,” she continued. “Incorporation of social work teams, who are familiar with the needs of people with MS and insurance options available to them, within MS specialty practices will bolster the comprehensive care of patients and their families.”

She acknowledged certain limitations of the study, including the low proportion of respondents who were Hispanic/Latino and African American (about 4% each). “The insurance landscape may differ in these groups compared to the majority Caucasian population who responded to this survey,” Dr. Planchon said.

The National Multiple Sclerosis Society funded the study. Dr. Planchon reported having no relevant financial disclosures.

SOURCE: Planchon S et al. ACTRIMS Forum 2019, Abstract P295.

REPORTING FROM ACTRIMS FORUM 2019

Big pharma says it can’t drop drug list prices alone

Top pharmaceutical executives expressed willingness to lower the list prices of their drugs, but only if there were cooperation among all sectors to reform how drugs get from manufacturer to patient.

That theme was common in the testimony of seven pharmaceutical executives before the Senate Finance Committee during a Feb. 26 hearing.

“We are in a system that used to be fit for purpose and really drove enormous savings over the last few years but it is no longer fit for purpose,” Pascal Soriot, executive director and CEO of AstraZeneca, testified before the committee. “It’s one of those situations where nobody in the system can do anything, can fix it by themselves.”

The problem, the executives agreed, is the financial structure of drug delivery that ties list prices and their associated rebates to formulary placement.

“If you went back a few years ago, when we negotiated to get our drugs on formulary, our goal was to have the lowest copay by patients,” Kenneth Frazier, chairman and CEO of Merck, testified before the committee. “Today, the goal is to pay into the supply chain the biggest rebate. That actually puts the patient at a disadvantage since they are the only ones that are paying a portion of the list price. The list price is actually working against the patient.”

When asked why the list prices of prescription drugs are so high, Olivier Brandicourt, MD, CEO of Sanofi, said, “We are trying to get formulary position with those high list price-high rebate. It’s a preferred position. Unfortunately that preferred position doesn’t automatically ensure affordability.”

Mr. Frazier added that if a manufacturer brings a product “with a low list price in this system, you get punished financially and you get no uptake because everyone in the supply chain makes money as a result of a higher list price.”

Executives noted that when accounting for financial incentives such as rebates, discounts, and coupons, net prices for pharmaceuticals have actually come down even as list prices are on the rise to accommodate competition on formulary placement.

But that is obscured at the pharmacy counter, where patients are paying higher and higher out-of-pocket costs because more often than not, payment is tied to the list price of the drug, not the net price after all rebates and other discounts have been taken into consideration.

This is a particular problem in Medicare Part D, said AbbVie Chairman and CEO Richard Gonzalez.

“Due to the structure of the Part D benefit design, patients are charged out-of-pocket costs on a medicine’s list price which does not reflect the market-based rebates that Medicare receives,” he testified.

Despite acknowledging that this is a problem, the executives gathered were hesitant to commit to simply lowering the list prices, or anything for that matter.

The closest the panel came to a commitment to lowering the list prices of their drugs was to do so if all rebates went away in both the public and private sector.

But beyond that, the pharma executives continued to assign responsibility for high out-of-pocket drug costs to other players in the health care system, adding that the only way to change the situation would be to have everyone come to the table simultaneously.

“I understand the dissatisfaction with our industry,” Mr. Frazier said. “I understand why patients are frustrated because they need these medicines and they can’t afford them. I would pledge to do everything that we could, but I would urge you to recognize that the system itself is complex and it is interdependent and no one company can unilaterally lower list prices without running into financial and operating disadvantages that make it impossible to do that. But if we all bring the parties together around the table with the goal of doing what’s best for the patient, I think we can some up with a system that works for all Americans.”

Ultimately, the panel suggested, legislation is going to be required to change the system.

Top pharmaceutical executives expressed willingness to lower the list prices of their drugs, but only if there were cooperation among all sectors to reform how drugs get from manufacturer to patient.

That theme was common in the testimony of seven pharmaceutical executives before the Senate Finance Committee during a Feb. 26 hearing.

“We are in a system that used to be fit for purpose and really drove enormous savings over the last few years but it is no longer fit for purpose,” Pascal Soriot, executive director and CEO of AstraZeneca, testified before the committee. “It’s one of those situations where nobody in the system can do anything, can fix it by themselves.”

The problem, the executives agreed, is the financial structure of drug delivery that ties list prices and their associated rebates to formulary placement.

“If you went back a few years ago, when we negotiated to get our drugs on formulary, our goal was to have the lowest copay by patients,” Kenneth Frazier, chairman and CEO of Merck, testified before the committee. “Today, the goal is to pay into the supply chain the biggest rebate. That actually puts the patient at a disadvantage since they are the only ones that are paying a portion of the list price. The list price is actually working against the patient.”

When asked why the list prices of prescription drugs are so high, Olivier Brandicourt, MD, CEO of Sanofi, said, “We are trying to get formulary position with those high list price-high rebate. It’s a preferred position. Unfortunately that preferred position doesn’t automatically ensure affordability.”

Mr. Frazier added that if a manufacturer brings a product “with a low list price in this system, you get punished financially and you get no uptake because everyone in the supply chain makes money as a result of a higher list price.”

Executives noted that when accounting for financial incentives such as rebates, discounts, and coupons, net prices for pharmaceuticals have actually come down even as list prices are on the rise to accommodate competition on formulary placement.

But that is obscured at the pharmacy counter, where patients are paying higher and higher out-of-pocket costs because more often than not, payment is tied to the list price of the drug, not the net price after all rebates and other discounts have been taken into consideration.

This is a particular problem in Medicare Part D, said AbbVie Chairman and CEO Richard Gonzalez.

“Due to the structure of the Part D benefit design, patients are charged out-of-pocket costs on a medicine’s list price which does not reflect the market-based rebates that Medicare receives,” he testified.

Despite acknowledging that this is a problem, the executives gathered were hesitant to commit to simply lowering the list prices, or anything for that matter.

The closest the panel came to a commitment to lowering the list prices of their drugs was to do so if all rebates went away in both the public and private sector.

But beyond that, the pharma executives continued to assign responsibility for high out-of-pocket drug costs to other players in the health care system, adding that the only way to change the situation would be to have everyone come to the table simultaneously.

“I understand the dissatisfaction with our industry,” Mr. Frazier said. “I understand why patients are frustrated because they need these medicines and they can’t afford them. I would pledge to do everything that we could, but I would urge you to recognize that the system itself is complex and it is interdependent and no one company can unilaterally lower list prices without running into financial and operating disadvantages that make it impossible to do that. But if we all bring the parties together around the table with the goal of doing what’s best for the patient, I think we can some up with a system that works for all Americans.”

Ultimately, the panel suggested, legislation is going to be required to change the system.

Top pharmaceutical executives expressed willingness to lower the list prices of their drugs, but only if there were cooperation among all sectors to reform how drugs get from manufacturer to patient.

That theme was common in the testimony of seven pharmaceutical executives before the Senate Finance Committee during a Feb. 26 hearing.

“We are in a system that used to be fit for purpose and really drove enormous savings over the last few years but it is no longer fit for purpose,” Pascal Soriot, executive director and CEO of AstraZeneca, testified before the committee. “It’s one of those situations where nobody in the system can do anything, can fix it by themselves.”

The problem, the executives agreed, is the financial structure of drug delivery that ties list prices and their associated rebates to formulary placement.

“If you went back a few years ago, when we negotiated to get our drugs on formulary, our goal was to have the lowest copay by patients,” Kenneth Frazier, chairman and CEO of Merck, testified before the committee. “Today, the goal is to pay into the supply chain the biggest rebate. That actually puts the patient at a disadvantage since they are the only ones that are paying a portion of the list price. The list price is actually working against the patient.”

When asked why the list prices of prescription drugs are so high, Olivier Brandicourt, MD, CEO of Sanofi, said, “We are trying to get formulary position with those high list price-high rebate. It’s a preferred position. Unfortunately that preferred position doesn’t automatically ensure affordability.”

Mr. Frazier added that if a manufacturer brings a product “with a low list price in this system, you get punished financially and you get no uptake because everyone in the supply chain makes money as a result of a higher list price.”

Executives noted that when accounting for financial incentives such as rebates, discounts, and coupons, net prices for pharmaceuticals have actually come down even as list prices are on the rise to accommodate competition on formulary placement.

But that is obscured at the pharmacy counter, where patients are paying higher and higher out-of-pocket costs because more often than not, payment is tied to the list price of the drug, not the net price after all rebates and other discounts have been taken into consideration.

This is a particular problem in Medicare Part D, said AbbVie Chairman and CEO Richard Gonzalez.

“Due to the structure of the Part D benefit design, patients are charged out-of-pocket costs on a medicine’s list price which does not reflect the market-based rebates that Medicare receives,” he testified.

Despite acknowledging that this is a problem, the executives gathered were hesitant to commit to simply lowering the list prices, or anything for that matter.

The closest the panel came to a commitment to lowering the list prices of their drugs was to do so if all rebates went away in both the public and private sector.

But beyond that, the pharma executives continued to assign responsibility for high out-of-pocket drug costs to other players in the health care system, adding that the only way to change the situation would be to have everyone come to the table simultaneously.

“I understand the dissatisfaction with our industry,” Mr. Frazier said. “I understand why patients are frustrated because they need these medicines and they can’t afford them. I would pledge to do everything that we could, but I would urge you to recognize that the system itself is complex and it is interdependent and no one company can unilaterally lower list prices without running into financial and operating disadvantages that make it impossible to do that. But if we all bring the parties together around the table with the goal of doing what’s best for the patient, I think we can some up with a system that works for all Americans.”

Ultimately, the panel suggested, legislation is going to be required to change the system.

REPORTING FROM SENATE FINANCE COMMITTEE HEARING

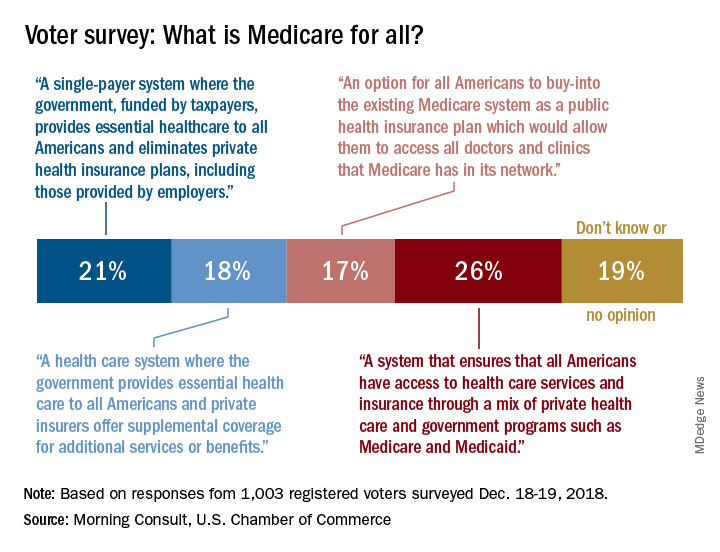

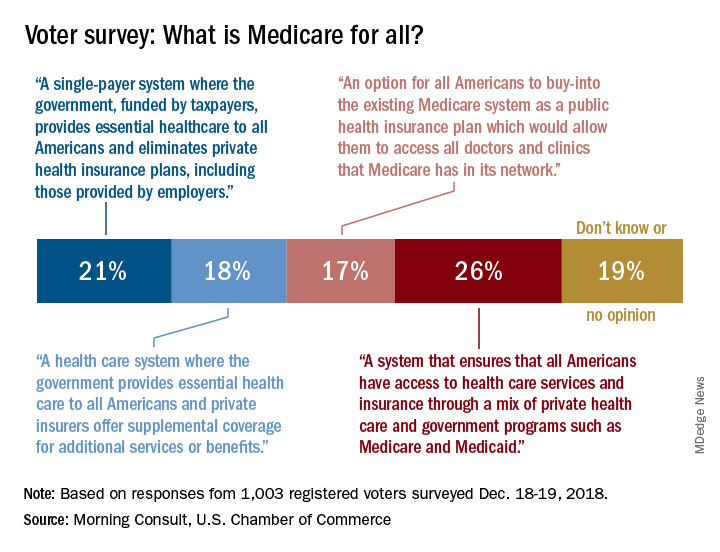

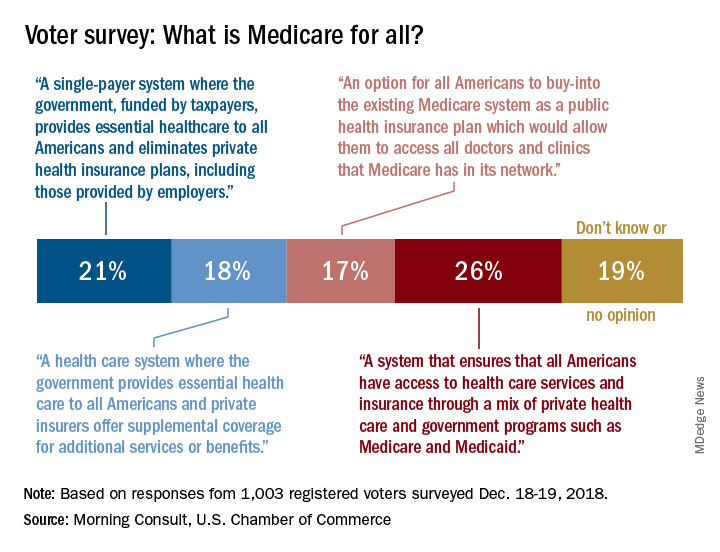

What does 'Medicare for all' mean?

Only about a fifth of Americans correctly identified the description of a Medicare-for-all system in a recent national tracking poll.

Four descriptions of a Medicare-for-all health care system were provided, and only 21% of respondents correctly selected “a single-payer system where the government, funded by taxpayers, provides essential health care to all Americans and eliminates private health insurance plans, including those provided by employers,” according to the tracking poll from the U.S. Chamber of Commerce and digital media company Morning Consult.

The most common selection – chosen by 26% of the 1,003 registered voters who answered the question (about half of all the respondents) – involved “a system that ensures that all Americans have access to health care services and insurance through a mix of private health care and government programs such as Medicare and Medicaid.”

The other choices covered a federal system with available private supplemental coverage and another with the option of buying in to the existing Medicare system, the report said. Another 19% of respondents to the survey, which was conducted Dec. 18-19, said that they didn’t know or had no opinion.

Questions covering other areas of possible future legislation, which were answered by all of the 2,000 respondents, showed strong support for protection against surprise hospital bills (90%), reforming the Affordable Care Act (73%), and protecting the Affordable Care Act (63%), the U.S. Chamber and Morning Consult reported. The survey’s margin of error was plus or minus two percentage points.

Only about a fifth of Americans correctly identified the description of a Medicare-for-all system in a recent national tracking poll.

Four descriptions of a Medicare-for-all health care system were provided, and only 21% of respondents correctly selected “a single-payer system where the government, funded by taxpayers, provides essential health care to all Americans and eliminates private health insurance plans, including those provided by employers,” according to the tracking poll from the U.S. Chamber of Commerce and digital media company Morning Consult.

The most common selection – chosen by 26% of the 1,003 registered voters who answered the question (about half of all the respondents) – involved “a system that ensures that all Americans have access to health care services and insurance through a mix of private health care and government programs such as Medicare and Medicaid.”

The other choices covered a federal system with available private supplemental coverage and another with the option of buying in to the existing Medicare system, the report said. Another 19% of respondents to the survey, which was conducted Dec. 18-19, said that they didn’t know or had no opinion.

Questions covering other areas of possible future legislation, which were answered by all of the 2,000 respondents, showed strong support for protection against surprise hospital bills (90%), reforming the Affordable Care Act (73%), and protecting the Affordable Care Act (63%), the U.S. Chamber and Morning Consult reported. The survey’s margin of error was plus or minus two percentage points.

Only about a fifth of Americans correctly identified the description of a Medicare-for-all system in a recent national tracking poll.

Four descriptions of a Medicare-for-all health care system were provided, and only 21% of respondents correctly selected “a single-payer system where the government, funded by taxpayers, provides essential health care to all Americans and eliminates private health insurance plans, including those provided by employers,” according to the tracking poll from the U.S. Chamber of Commerce and digital media company Morning Consult.

The most common selection – chosen by 26% of the 1,003 registered voters who answered the question (about half of all the respondents) – involved “a system that ensures that all Americans have access to health care services and insurance through a mix of private health care and government programs such as Medicare and Medicaid.”

The other choices covered a federal system with available private supplemental coverage and another with the option of buying in to the existing Medicare system, the report said. Another 19% of respondents to the survey, which was conducted Dec. 18-19, said that they didn’t know or had no opinion.

Questions covering other areas of possible future legislation, which were answered by all of the 2,000 respondents, showed strong support for protection against surprise hospital bills (90%), reforming the Affordable Care Act (73%), and protecting the Affordable Care Act (63%), the U.S. Chamber and Morning Consult reported. The survey’s margin of error was plus or minus two percentage points.

Medicine grapples with COI reporting

Conflict of interest (COI) reporting has moved center stage again in recent months, with some medical journals, professional societies, cancer centers, and academic medical institutions reviewing policies and practices in the wake of a highly publicized disclosure failure last fall at Memorial Sloan Kettering Cancer Center (MSK).

And in some settings, oncologists and other physician researchers are being encouraged to check what the federal Open Payments database says about their payments from industry.

The spotlight is on the field of cancer research and treatment, where MSK’s chief medical officer, José Baselga, MD, PhD, resigned in September 2018 after the New York Times and ProPublica reported that he’d failed to disclose millions of dollars of industry payments and ownership interests in the majority of journal articles he wrote or cowrote over a 4-year period.

COI disclosure issues have a broad reach, however, and the policy reviews, debates, and hashing out of responsibilities that are now taking place likely will have implications for all of medicine.

Among the questions: Who enforces disclosure rules and how should cases of incomplete or inconsistent disclosure be handled? How can COI declarations be made easier for researchers? Should disclosure be based on self-reported relevancy, or more comprehensive in nature?

Such questions are being debated nationally. On Feb. 12, 2019, leaders from academia, journals, and medical societies came together in Washington, D.C., at the offices of the Association of American Medical Colleges (AAMC) for a closed-door meeting focused on COI disclosures. MSK, the Journal of the American Medical Association (JAMA), the American Society of Clinical Oncology (ASCO), and the Council of Medical Specialty Societies led the charge as cosponsors of the meeting.

“We’ve been dealing with disclosure issues in a siloed way in exchanges [between journal editors and authors, for instance, or between speakers and CME providers]. And academic institutions have their own robust disclosure mechanisms that they use internally,” said Heather Pierce, JD, MPH, senior director of science policy and regulatory counsel for the AAMC. “There’s a growing understanding that these conversations need to be happening across these different sectors.”

Pleas for accuracy

At academic medical institutions, conflicts of interest are identified and then managed; it’s common for researchers’ COI management plans to include requirements for disclosure in all presentations and publications.

Journals and professional medical societies require authors and speakers to submit disclosure forms of varying lengths and with differing questions about relationships with industry, often based on the notion of relevancy to the subject at hand. Disclosure forms are reviewed, but editors and other reviewers rely largely – if not entirely – on the honor system.

Dr. Baselga’s disclosure lapses and his subsequent resignation have rattled leaders in each of these settings. Researchers at MSK were instructed to review their COI disclosures and submit corrections when necessary, and in December 2018 the hospital was reportedly evaluating its process for reviewing conflicts of interest, according to reports in the New York Times and ProPublica. (MSK did not respond to requests for comment about actions taken.)

The Dana Farber Cancer Institute in Boston similarly has “been reminding faculty and other researchers” of their disclosure responsibilities and is conducting a review of “all our policies in this area,” a spokeswoman said. And at Fred Hutchinson Cancer Research Center in Seattle, a spokesman said they have established an internal task force to review individual and institutional COI policies to ensure that COIs are “appropriately managed while also enabling research collaborations that bring scientific advances to our patients.”

Other centers contacted for this article, such as the Cleveland Clinic Cancer Center and the Mayo Clinic Cancer Center, said that they have no new reviews ongoing and no plans to change policies at this time.

The heightened attention to disclosure has, in turn, shone a spotlight on increasingly complex physician-industry relationships and on the Open Payments website run by the Centers for Medicare and Medicaid Services. Open Payments is a disclosure program and database that tracks payments made to physicians and teaching hospitals by drug and device companies.

Journalists, including those who reported on Dr. Baselga’s disclosures, have searched the public database for industry payment data. So have other researchers who have studied financial disclosure statements; a study reported in JAMA Oncology last year, for instance, concluded through the use of Open Payments data that about one-third of authors of cancer drug trial reports did not completely disclose payments from trial sponsors (JAMA Oncol. 2018;4[10]:1426-8

In a column published in December 2018 in AAMC News, AAMC President and CEO Darrell G. Kirch, MD, wrote that failures to disclose can raise questions about the integrity of research, whether or not there is an actual conflict. He advised institutions to “encourage faculty to review the information posted about them on the Open Payments website” of the CMS to “ensure it is accurate and consistent with disclosures related to all their professional responsibilities.”

ASCO issues similar advice, encouraging authors and CME speakers and participants of other ASCO activities to double-check their disclosures against other sources, including “publicly reported interactions with companies that may have been inadvertently omitted.”

In the world of journals, the New England Journal of Medicine (NEJM) began asking authors at the end of 2018 to “certify that they have reconciled their disclosures” with the Open Payments database, said Jennifer Zeis, a spokeswoman forthe journal.

Time may tell how well such requests work. When the Institute of Medicine (now called the National Academy of Medicine) called on Congress in 2009 to create a national program requiring pharmaceutical, device, and biotechnology companies to publicly report their payments, it envisioned universities, journals, and others using the program to verify disclosures made to them. But the resulting Open Payments database has limitations – for instance, it doesn’t include payments from companies without FDA-approved products, it is not necessarily up to date, and its payment categories do not necessarily match categories of disclosure.

“Some entries in the Open Payments database need further explanation,” said Ms. Zeis of NEJM. “Some authors, for example, have said that the database does not fully and accurately explain that the funds were disbursed not to them personally, but to their academic institutions.” While the database provides transparency, it also “needs context that’s not currently provided,” she said.

Mistakes in the database can also be “very hard to challenge,” said Clifford A. Hudis, MD, CEO of the American Society of Clinical Oncology, which produces the Journal of Clinical Oncology (JCO).

All in all, he said, “there’s really no timely, comprehensive, and fully reliable source of information with which to verify an individual’s disclosures.”

Policies and practices are also under review at the American Association for Cancer Research (AACR) and the American Society of Hematology (ASH).

The AACR has appointed a panel of experts, including physicians, basic scientists, a patient advocate, and others to conduct “a comprehensive review of [its] disclosure policies and to explore whether any current policies need to be revised,” said Rachel Salis-Silverman, director of public relations. It also will convene a session on COI disclosures at its 2019 annual meeting at the end of March, she said.

ASH, which publishes the journal Blood, is exploring possible changes in its “internal processes with regards to ASH publications,” said Matt Gertzog, deputy executive director of the group. COI disclosure is “more of a journey than a destination,” he said. “We are continuously reflecting on and refining our processes.”

Moving away from ‘relevancy’