User login

U.S. influenza activity widespread to start 2018

As far as the influenza virus is concerned, the new year started in the same way as the old one ended: with almost half of the states at the highest level of flu activity, according to the Centers for Disease Control and Prevention.

For the week ending Jan. 6, 2018, there were 23 states – including California, Illinois, and Texas – at level 10 on the CDC’s 1-10 scale for influenza-like illness (ILI) activity, which was up from 22 for the last full week of 2017. Joining the 23 states in the “high” range were New Jersey and Ohio at level 9 and Colorado at level 8, the CDC’s influenza division reported Jan. 12.

Seven flu-related pediatric deaths were reported during the week ending Jan. 6, although one occurred during the week ending Dec. 16 and two were during the week ending Dec. 23. There have been a total of 20 pediatric deaths related to influenza so far for the 2017-2018 season, the CDC said. In 2016-2017, there were 110 pediatric deaths from the flu.

As far as the influenza virus is concerned, the new year started in the same way as the old one ended: with almost half of the states at the highest level of flu activity, according to the Centers for Disease Control and Prevention.

For the week ending Jan. 6, 2018, there were 23 states – including California, Illinois, and Texas – at level 10 on the CDC’s 1-10 scale for influenza-like illness (ILI) activity, which was up from 22 for the last full week of 2017. Joining the 23 states in the “high” range were New Jersey and Ohio at level 9 and Colorado at level 8, the CDC’s influenza division reported Jan. 12.

Seven flu-related pediatric deaths were reported during the week ending Jan. 6, although one occurred during the week ending Dec. 16 and two were during the week ending Dec. 23. There have been a total of 20 pediatric deaths related to influenza so far for the 2017-2018 season, the CDC said. In 2016-2017, there were 110 pediatric deaths from the flu.

As far as the influenza virus is concerned, the new year started in the same way as the old one ended: with almost half of the states at the highest level of flu activity, according to the Centers for Disease Control and Prevention.

For the week ending Jan. 6, 2018, there were 23 states – including California, Illinois, and Texas – at level 10 on the CDC’s 1-10 scale for influenza-like illness (ILI) activity, which was up from 22 for the last full week of 2017. Joining the 23 states in the “high” range were New Jersey and Ohio at level 9 and Colorado at level 8, the CDC’s influenza division reported Jan. 12.

Seven flu-related pediatric deaths were reported during the week ending Jan. 6, although one occurred during the week ending Dec. 16 and two were during the week ending Dec. 23. There have been a total of 20 pediatric deaths related to influenza so far for the 2017-2018 season, the CDC said. In 2016-2017, there were 110 pediatric deaths from the flu.

Don’t give up on influenza vaccine

I suspect most health care providers have heard the complaint, “The vaccine doesn’t work. One year I got the vaccine, and I still came down with the flu.”

Over the years, I’ve polished my responses to vaccine naysayers.

Influenza vaccine doesn’t protect you against every virus that can cause cold and flu symptoms. It only prevents influenza. It’s possible you had a different virus, such as adenovirus, coronavirus, parainfluenza virus, or respiratory syncytial virus.

Some years, the vaccine works better than others because there is a mismatch between the viruses chosen for the vaccine, and the viruses that end up circulating. Even when it doesn’t prevent flu, the vaccine can potentially reduce the severity of illness.

The discussion became a little more complicated in 2016 when the Centers for Disease Control and Prevention Advisory Committee on Immunization Practices withdrew its support for the live attenuated influenza virus vaccine (LAIV4) because of concerns about effectiveness. During the 2015-2016 influenza season, LAIV4 demonstrated no statistically significant effectiveness in children 2-17 years of age against H1N1pdm09, the predominant influenza strain. Fortunately, inactivated injectable vaccine did offer protection. An estimated 41.8 million children aged 6 months to 17 years ultimately received this vaccine during the 2016-2017 influenza season.

Now with the 2017-2018 influenza season in full swing, some media reports are proclaiming the influenza vaccine is only 10% effective this year. This claim is based on an interim analysis of data from the most recent flu season in Australia and the effectiveness of the vaccine against the circulating H3N2 virus strain. News from the U.S. CDC is more encouraging. The H3N2 virus contained in this year’s vaccine is the same as that used last year, and so far, circulating H3N2 viruses in the United States are similar to the vaccine virus. Public health officials suggest that we can hope that the vaccine works as well as it did last year, when overall vaccine effectiveness against all circulating flu viruses was 39%, and effectiveness against the H3N2 virus specifically was 32%.

I’m upping my game when talking to parents about flu vaccine. I mention one study conducted between 2010 and 2012 in which influenza immunization reduced a child’s risk of being admitted to an intensive care unit with flu by 74% (J Infect Dis. 2014 Sep 1;210[5]:674-83). I emphasize that flu vaccine reduces the chance that a child will die from flu. According to a study published in 2017, influenza vaccine reduced the risk of death from flu by 65% in healthy children and 51% in children with high-risk medical conditions (Pediatrics. 2017 May. doi: 10.1542/peds.2016-4244).

When I’m talking to trainees, I no longer just focus on the match between circulating strains of flu and vaccine strains. I mention that viruses used to produce most seasonal flu vaccines are grown in eggs, a process that can result in minor antigenic changes in the hemagglutinin protein, especially in H3N2 viruses. These “egg-adapted changes” may result in a vaccine that stimulates a less effective immune response, even with a good match between circulating strains and vaccine strains. For example, Zost et al. found that the H3N2 virus that emerged during the 2014-2015 season possessed a new hemagglutinin-associated glycosylation site (Proc Natl Acad Sci U S A. 2017 Nov 21;114[47]:12578-83). Although this virus was represented in the 2016-2017 influenza vaccine, the egg-adapted version lost the glycosylation site, resulting in decreased vaccine immunogenicity and less protection against H3N2 viruses circulating in the community.

The real take-home message here is that we need better flu vaccines. In the short term, cell-based flu vaccines that use virus grown in animal cells are a potential alternative to egg-based vaccines. In the long term, we need a universal flu vaccine. The National Institute of Allergy and Infectious Diseases is prioritizing work on a vaccine that could provide long-lasting protection against multiple subtypes of the virus. According to a report on the National Institutes of Health website, such a vaccine could “eliminate the need to update and administer the seasonal flu vaccine each year and could provide protection against newly emerging flu strains,” including those with the potential to cause a pandemic. The NIH researchers acknowledge, however, that achieving this goal will require “a broad range of expertise and substantial resources.”

Until new vaccines are available, we need to do a better job of using available, albeit imperfect, flu vaccines. During the 2016-2017 season, only 59% of children 6 months to 17 years were immunized, and there were 110 influenza-associated deaths in children, according to the CDC. It’s likely that some of these were preventable.

The total magnitude of suffering associated with flu is more difficult to quantify, but anecdotes can be illuminating. A friend recently diagnosed with influenza shared her experience via Facebook. “Rough night. I’m seconds away from a meltdown. My body aches so bad that I can’t get comfortable on the couch or my bed. Can’t breathe, and I cough until I vomit. My head is about to burst along with my ears. Just took a hot bath hoping that would help. I don’t know what else to do. The flu really sucks.”

Indeed. Even a 1 in 10 chance of preventing the flu is better than no chance at all.

Dr. Bryant is a pediatrician specializing in infectious diseases at the University of Louisville (Ky.) and Norton Children’s Hospital in Louisville. She said she had no relevant financial disclosures. Email her at pdnews@frontlinemedcom.com.

I suspect most health care providers have heard the complaint, “The vaccine doesn’t work. One year I got the vaccine, and I still came down with the flu.”

Over the years, I’ve polished my responses to vaccine naysayers.

Influenza vaccine doesn’t protect you against every virus that can cause cold and flu symptoms. It only prevents influenza. It’s possible you had a different virus, such as adenovirus, coronavirus, parainfluenza virus, or respiratory syncytial virus.

Some years, the vaccine works better than others because there is a mismatch between the viruses chosen for the vaccine, and the viruses that end up circulating. Even when it doesn’t prevent flu, the vaccine can potentially reduce the severity of illness.

The discussion became a little more complicated in 2016 when the Centers for Disease Control and Prevention Advisory Committee on Immunization Practices withdrew its support for the live attenuated influenza virus vaccine (LAIV4) because of concerns about effectiveness. During the 2015-2016 influenza season, LAIV4 demonstrated no statistically significant effectiveness in children 2-17 years of age against H1N1pdm09, the predominant influenza strain. Fortunately, inactivated injectable vaccine did offer protection. An estimated 41.8 million children aged 6 months to 17 years ultimately received this vaccine during the 2016-2017 influenza season.

Now with the 2017-2018 influenza season in full swing, some media reports are proclaiming the influenza vaccine is only 10% effective this year. This claim is based on an interim analysis of data from the most recent flu season in Australia and the effectiveness of the vaccine against the circulating H3N2 virus strain. News from the U.S. CDC is more encouraging. The H3N2 virus contained in this year’s vaccine is the same as that used last year, and so far, circulating H3N2 viruses in the United States are similar to the vaccine virus. Public health officials suggest that we can hope that the vaccine works as well as it did last year, when overall vaccine effectiveness against all circulating flu viruses was 39%, and effectiveness against the H3N2 virus specifically was 32%.

I’m upping my game when talking to parents about flu vaccine. I mention one study conducted between 2010 and 2012 in which influenza immunization reduced a child’s risk of being admitted to an intensive care unit with flu by 74% (J Infect Dis. 2014 Sep 1;210[5]:674-83). I emphasize that flu vaccine reduces the chance that a child will die from flu. According to a study published in 2017, influenza vaccine reduced the risk of death from flu by 65% in healthy children and 51% in children with high-risk medical conditions (Pediatrics. 2017 May. doi: 10.1542/peds.2016-4244).

When I’m talking to trainees, I no longer just focus on the match between circulating strains of flu and vaccine strains. I mention that viruses used to produce most seasonal flu vaccines are grown in eggs, a process that can result in minor antigenic changes in the hemagglutinin protein, especially in H3N2 viruses. These “egg-adapted changes” may result in a vaccine that stimulates a less effective immune response, even with a good match between circulating strains and vaccine strains. For example, Zost et al. found that the H3N2 virus that emerged during the 2014-2015 season possessed a new hemagglutinin-associated glycosylation site (Proc Natl Acad Sci U S A. 2017 Nov 21;114[47]:12578-83). Although this virus was represented in the 2016-2017 influenza vaccine, the egg-adapted version lost the glycosylation site, resulting in decreased vaccine immunogenicity and less protection against H3N2 viruses circulating in the community.

The real take-home message here is that we need better flu vaccines. In the short term, cell-based flu vaccines that use virus grown in animal cells are a potential alternative to egg-based vaccines. In the long term, we need a universal flu vaccine. The National Institute of Allergy and Infectious Diseases is prioritizing work on a vaccine that could provide long-lasting protection against multiple subtypes of the virus. According to a report on the National Institutes of Health website, such a vaccine could “eliminate the need to update and administer the seasonal flu vaccine each year and could provide protection against newly emerging flu strains,” including those with the potential to cause a pandemic. The NIH researchers acknowledge, however, that achieving this goal will require “a broad range of expertise and substantial resources.”

Until new vaccines are available, we need to do a better job of using available, albeit imperfect, flu vaccines. During the 2016-2017 season, only 59% of children 6 months to 17 years were immunized, and there were 110 influenza-associated deaths in children, according to the CDC. It’s likely that some of these were preventable.

The total magnitude of suffering associated with flu is more difficult to quantify, but anecdotes can be illuminating. A friend recently diagnosed with influenza shared her experience via Facebook. “Rough night. I’m seconds away from a meltdown. My body aches so bad that I can’t get comfortable on the couch or my bed. Can’t breathe, and I cough until I vomit. My head is about to burst along with my ears. Just took a hot bath hoping that would help. I don’t know what else to do. The flu really sucks.”

Indeed. Even a 1 in 10 chance of preventing the flu is better than no chance at all.

Dr. Bryant is a pediatrician specializing in infectious diseases at the University of Louisville (Ky.) and Norton Children’s Hospital in Louisville. She said she had no relevant financial disclosures. Email her at pdnews@frontlinemedcom.com.

I suspect most health care providers have heard the complaint, “The vaccine doesn’t work. One year I got the vaccine, and I still came down with the flu.”

Over the years, I’ve polished my responses to vaccine naysayers.

Influenza vaccine doesn’t protect you against every virus that can cause cold and flu symptoms. It only prevents influenza. It’s possible you had a different virus, such as adenovirus, coronavirus, parainfluenza virus, or respiratory syncytial virus.

Some years, the vaccine works better than others because there is a mismatch between the viruses chosen for the vaccine, and the viruses that end up circulating. Even when it doesn’t prevent flu, the vaccine can potentially reduce the severity of illness.

The discussion became a little more complicated in 2016 when the Centers for Disease Control and Prevention Advisory Committee on Immunization Practices withdrew its support for the live attenuated influenza virus vaccine (LAIV4) because of concerns about effectiveness. During the 2015-2016 influenza season, LAIV4 demonstrated no statistically significant effectiveness in children 2-17 years of age against H1N1pdm09, the predominant influenza strain. Fortunately, inactivated injectable vaccine did offer protection. An estimated 41.8 million children aged 6 months to 17 years ultimately received this vaccine during the 2016-2017 influenza season.

Now with the 2017-2018 influenza season in full swing, some media reports are proclaiming the influenza vaccine is only 10% effective this year. This claim is based on an interim analysis of data from the most recent flu season in Australia and the effectiveness of the vaccine against the circulating H3N2 virus strain. News from the U.S. CDC is more encouraging. The H3N2 virus contained in this year’s vaccine is the same as that used last year, and so far, circulating H3N2 viruses in the United States are similar to the vaccine virus. Public health officials suggest that we can hope that the vaccine works as well as it did last year, when overall vaccine effectiveness against all circulating flu viruses was 39%, and effectiveness against the H3N2 virus specifically was 32%.

I’m upping my game when talking to parents about flu vaccine. I mention one study conducted between 2010 and 2012 in which influenza immunization reduced a child’s risk of being admitted to an intensive care unit with flu by 74% (J Infect Dis. 2014 Sep 1;210[5]:674-83). I emphasize that flu vaccine reduces the chance that a child will die from flu. According to a study published in 2017, influenza vaccine reduced the risk of death from flu by 65% in healthy children and 51% in children with high-risk medical conditions (Pediatrics. 2017 May. doi: 10.1542/peds.2016-4244).

When I’m talking to trainees, I no longer just focus on the match between circulating strains of flu and vaccine strains. I mention that viruses used to produce most seasonal flu vaccines are grown in eggs, a process that can result in minor antigenic changes in the hemagglutinin protein, especially in H3N2 viruses. These “egg-adapted changes” may result in a vaccine that stimulates a less effective immune response, even with a good match between circulating strains and vaccine strains. For example, Zost et al. found that the H3N2 virus that emerged during the 2014-2015 season possessed a new hemagglutinin-associated glycosylation site (Proc Natl Acad Sci U S A. 2017 Nov 21;114[47]:12578-83). Although this virus was represented in the 2016-2017 influenza vaccine, the egg-adapted version lost the glycosylation site, resulting in decreased vaccine immunogenicity and less protection against H3N2 viruses circulating in the community.

The real take-home message here is that we need better flu vaccines. In the short term, cell-based flu vaccines that use virus grown in animal cells are a potential alternative to egg-based vaccines. In the long term, we need a universal flu vaccine. The National Institute of Allergy and Infectious Diseases is prioritizing work on a vaccine that could provide long-lasting protection against multiple subtypes of the virus. According to a report on the National Institutes of Health website, such a vaccine could “eliminate the need to update and administer the seasonal flu vaccine each year and could provide protection against newly emerging flu strains,” including those with the potential to cause a pandemic. The NIH researchers acknowledge, however, that achieving this goal will require “a broad range of expertise and substantial resources.”

Until new vaccines are available, we need to do a better job of using available, albeit imperfect, flu vaccines. During the 2016-2017 season, only 59% of children 6 months to 17 years were immunized, and there were 110 influenza-associated deaths in children, according to the CDC. It’s likely that some of these were preventable.

The total magnitude of suffering associated with flu is more difficult to quantify, but anecdotes can be illuminating. A friend recently diagnosed with influenza shared her experience via Facebook. “Rough night. I’m seconds away from a meltdown. My body aches so bad that I can’t get comfortable on the couch or my bed. Can’t breathe, and I cough until I vomit. My head is about to burst along with my ears. Just took a hot bath hoping that would help. I don’t know what else to do. The flu really sucks.”

Indeed. Even a 1 in 10 chance of preventing the flu is better than no chance at all.

Dr. Bryant is a pediatrician specializing in infectious diseases at the University of Louisville (Ky.) and Norton Children’s Hospital in Louisville. She said she had no relevant financial disclosures. Email her at pdnews@frontlinemedcom.com.

Majority of influenza-related deaths among hospitalized patients occur after discharge

SAN DIEGO – Over half of hospitalized, influenza-related deaths occurred within 30 days of discharge, according to a study presented at an annual scientific meeting on infectious diseases.

As physicians and pharmaceutical companies attempt to measure the burden of seasonal influenza, discharged patients are currently not considered as much as they should be, according to investigators.

Among 968 deceased patients studied, 444 (46%) died in hospital, while 524 (54%) died within 30 days of discharge.

Investigators conducted a retrospective study of 15,562 patients hospitalized for influenza-related cases between 2014 and 2015, as recorded in Influenza-Associated Hospitalizations Surveillance (FluSurv-NET), a database of the Centers for Disease Control and Prevention.

The majority of the studied patients were women (55%) and the majority were white.

Those who died were more likely to have been admitted to the hospital immediately after influenza onset, with 26% of those who died after discharge and 22% of those who died in hospital having been admitted the same day. In contrast, 13% of those who lived past 30 days were admitted immediately after onset.

A total of 46% of those who died after hospitalization had a length of stay longer than 1 week, compared to 15% of those who lived.

Among patients who died after discharge, 356 (68%) died within 2 weeks of discharge, with the highest number of deaths occurring within the first few days, according to presenter Craig McGowan of the Influenza Division of the CDC in Atlanta.

Age also seemed to be a possible mortality predictor, according to Mr. McGowan and his fellow investigators. “Those who died were more likely to be elderly, and those who died after discharge were even more likely to be 85 [years or older] than those who died during their influenza-related hospitalizations,” said Mr. McGowan, who added that patients aged 85 years and older made up more than half of those who died after discharge.

Patients who died in hospital were significantly more likely to have influenza listed as a cause of death. Overall, influenza-related and non–influenza-related respiratory issues were the two most common causes of death listed on death certificates of patients who died during hospitalization or within 14 days of discharge, while cardiovascular or other symptoms were listed for those who died between 15 and 30 days after discharge.

Admission and discharge locations among patients who did not die were almost 80% from a private residence to a private residence, while observations of those who died revealed a different pattern. “Those individuals who died after discharge were almost evenly split between admission from a nursing home or a private residence,” Mr. McGowan said. “Those who were admitted from the nursing home were almost exclusively discharged to either hospice care or back to a nursing home.”

Mr. McGowan noted rehospitalization to be a significant factor among those who died, with 34% of deaths occurring back in the hospital after initial discharge.

Influenza testing of studied patients was given at clinicians’ discretion, which may make the sample not generalizable to the overall influenza population, and the investigators included only bivariate associations, which means there were likely confounding effects that could not be accounted for.

Mr. McGowan and his fellow investigators plan to expand their research by determining underlying causes of death in these patients, to create more accurate estimates of influenza-associated mortality.

Mr. McGowan reported no relevant financial disclosures.

ezimmerman@frontlinemedcom.com

SOURCE: McGowan, C., et al., ID Week 2017, Abstract 951.

SAN DIEGO – Over half of hospitalized, influenza-related deaths occurred within 30 days of discharge, according to a study presented at an annual scientific meeting on infectious diseases.

As physicians and pharmaceutical companies attempt to measure the burden of seasonal influenza, discharged patients are currently not considered as much as they should be, according to investigators.

Among 968 deceased patients studied, 444 (46%) died in hospital, while 524 (54%) died within 30 days of discharge.

Investigators conducted a retrospective study of 15,562 patients hospitalized for influenza-related cases between 2014 and 2015, as recorded in Influenza-Associated Hospitalizations Surveillance (FluSurv-NET), a database of the Centers for Disease Control and Prevention.

The majority of the studied patients were women (55%) and the majority were white.

Those who died were more likely to have been admitted to the hospital immediately after influenza onset, with 26% of those who died after discharge and 22% of those who died in hospital having been admitted the same day. In contrast, 13% of those who lived past 30 days were admitted immediately after onset.

A total of 46% of those who died after hospitalization had a length of stay longer than 1 week, compared to 15% of those who lived.

Among patients who died after discharge, 356 (68%) died within 2 weeks of discharge, with the highest number of deaths occurring within the first few days, according to presenter Craig McGowan of the Influenza Division of the CDC in Atlanta.

Age also seemed to be a possible mortality predictor, according to Mr. McGowan and his fellow investigators. “Those who died were more likely to be elderly, and those who died after discharge were even more likely to be 85 [years or older] than those who died during their influenza-related hospitalizations,” said Mr. McGowan, who added that patients aged 85 years and older made up more than half of those who died after discharge.

Patients who died in hospital were significantly more likely to have influenza listed as a cause of death. Overall, influenza-related and non–influenza-related respiratory issues were the two most common causes of death listed on death certificates of patients who died during hospitalization or within 14 days of discharge, while cardiovascular or other symptoms were listed for those who died between 15 and 30 days after discharge.

Admission and discharge locations among patients who did not die were almost 80% from a private residence to a private residence, while observations of those who died revealed a different pattern. “Those individuals who died after discharge were almost evenly split between admission from a nursing home or a private residence,” Mr. McGowan said. “Those who were admitted from the nursing home were almost exclusively discharged to either hospice care or back to a nursing home.”

Mr. McGowan noted rehospitalization to be a significant factor among those who died, with 34% of deaths occurring back in the hospital after initial discharge.

Influenza testing of studied patients was given at clinicians’ discretion, which may make the sample not generalizable to the overall influenza population, and the investigators included only bivariate associations, which means there were likely confounding effects that could not be accounted for.

Mr. McGowan and his fellow investigators plan to expand their research by determining underlying causes of death in these patients, to create more accurate estimates of influenza-associated mortality.

Mr. McGowan reported no relevant financial disclosures.

ezimmerman@frontlinemedcom.com

SOURCE: McGowan, C., et al., ID Week 2017, Abstract 951.

SAN DIEGO – Over half of hospitalized, influenza-related deaths occurred within 30 days of discharge, according to a study presented at an annual scientific meeting on infectious diseases.

As physicians and pharmaceutical companies attempt to measure the burden of seasonal influenza, discharged patients are currently not considered as much as they should be, according to investigators.

Among 968 deceased patients studied, 444 (46%) died in hospital, while 524 (54%) died within 30 days of discharge.

Investigators conducted a retrospective study of 15,562 patients hospitalized for influenza-related cases between 2014 and 2015, as recorded in Influenza-Associated Hospitalizations Surveillance (FluSurv-NET), a database of the Centers for Disease Control and Prevention.

The majority of the studied patients were women (55%) and the majority were white.

Those who died were more likely to have been admitted to the hospital immediately after influenza onset, with 26% of those who died after discharge and 22% of those who died in hospital having been admitted the same day. In contrast, 13% of those who lived past 30 days were admitted immediately after onset.

A total of 46% of those who died after hospitalization had a length of stay longer than 1 week, compared to 15% of those who lived.

Among patients who died after discharge, 356 (68%) died within 2 weeks of discharge, with the highest number of deaths occurring within the first few days, according to presenter Craig McGowan of the Influenza Division of the CDC in Atlanta.

Age also seemed to be a possible mortality predictor, according to Mr. McGowan and his fellow investigators. “Those who died were more likely to be elderly, and those who died after discharge were even more likely to be 85 [years or older] than those who died during their influenza-related hospitalizations,” said Mr. McGowan, who added that patients aged 85 years and older made up more than half of those who died after discharge.

Patients who died in hospital were significantly more likely to have influenza listed as a cause of death. Overall, influenza-related and non–influenza-related respiratory issues were the two most common causes of death listed on death certificates of patients who died during hospitalization or within 14 days of discharge, while cardiovascular or other symptoms were listed for those who died between 15 and 30 days after discharge.

Admission and discharge locations among patients who did not die were almost 80% from a private residence to a private residence, while observations of those who died revealed a different pattern. “Those individuals who died after discharge were almost evenly split between admission from a nursing home or a private residence,” Mr. McGowan said. “Those who were admitted from the nursing home were almost exclusively discharged to either hospice care or back to a nursing home.”

Mr. McGowan noted rehospitalization to be a significant factor among those who died, with 34% of deaths occurring back in the hospital after initial discharge.

Influenza testing of studied patients was given at clinicians’ discretion, which may make the sample not generalizable to the overall influenza population, and the investigators included only bivariate associations, which means there were likely confounding effects that could not be accounted for.

Mr. McGowan and his fellow investigators plan to expand their research by determining underlying causes of death in these patients, to create more accurate estimates of influenza-associated mortality.

Mr. McGowan reported no relevant financial disclosures.

ezimmerman@frontlinemedcom.com

SOURCE: McGowan, C., et al., ID Week 2017, Abstract 951.

AT IDWEEK 2017

Key clinical point:

Major finding: Among patients who died with confirmed influenza, 46% died in hospital, while 54% died within 30 days of discharge.

Data source: Retrospective study of 15,562 influenza patients hospitalized or within 30 days of discharge between 2014 and 2015, recorded in Influenza-Associated Hospitalizations Surveillance (FluSurv-NET).

Disclosures: Mr. McGowen reported no relevant financial disclosures.

Inpatient antiviral treatment reduces ICU admissions among influenza patients

SAN DIEGO – Administering inpatient antiviral influenza treatment may reduce admissions to the ICU among adults hospitalized with flu, according to a study presented at ID Week 2017, an infectious diseases meeting.

While interventions did not directly affect flu-related deaths, lower ICU admission rates could reduce morbidity as well as ease the financial burden felt during the influenza season.

Investigators retrospectively studied 4,679 influenza patients admitted to Canadian Immunization Research Network Serious Outcomes Surveillance (SOS) Network hospitals during 2011-2014. Of the 54% of patients given inpatient antiviral treatment, the risk of being admitted to the ICU was reduced by 90% (odds ratio, 0.10;95% confidence interval, 0.08-0.13; P less than .001).

Antiviral treatment was not protective against death outcomes in patients with either influenza A or influenza B (OR, 0.9; 95% CI, 0.7-1.2; P =.454).

The median age of patients was 70 years, with a majority older than 75 years(41%); the majority presented with one or more comorbidities (89%), and had influenza A (72%).

Researchers found that, of the 4,679 patients studied, 798 (16%) were admitted to the ICU, 511 (11%) required mechanical ventilation, and the average length of hospital stay was 11 days.

Of those studied, 444 (9%) died within 30 days of discharge.

Researchers also found that only 38% of those studied had received the current seasonal vaccine upon admittance. However, these numbers may be skewed from the general population, because patients who have not taken the vaccine are more likely to be hospitalized.

Along with the results of antivirals on hospitalized patients, researchers wanted to uncover how the effectiveness of inpatient vaccine administration would vary based on treatment timing, said presenter Zach Shaffelburg of the Canadian Center for Vaccinology, Dalhousie University, Halifax, NS.

Even when administered 4.28 days after symptom onset, antiviral treatments in patients proved to be associated with significant reductions in ICU admissions and the need for mechanical ventilation.

The investigators concluded that antivirals show a strong association with positive effects on serious, influenza-related outcomes in hospitalized patients and, while therapy remained effective with later treatment start, patients would benefit the most from initiation as soon as possible.

Currently, the U.S. Centers for Disease Control and Prevention and the Canadian Immunization Research Network (CIRN) have guidelines instructing best practice for inpatient antiviral treatment, however the number of hospitalized patients given treatment has declined in Canada since 2009, according to Mr. Shaffelburg.

The reason more patients were not receiving inpatient antiviral treatment may be related to studies of different populations that failed to show significant impact, Mr. Shaffelburg suggested during a question and answer session following the presentation: “I think a lot of that comes from outpatient studies that involve patients who are younger and quite healthy [who received] antivirals, and it showed a very minimal impact,” Mr. Shaffelburg said. “So a lot of people saw that study and thought, ‘What’s that point of giving it if it’s not going to make an impact?’ ”

Mr. Shaffelburg and his colleagues are planning to continue their study of inpatient antiviral treatment, focusing more on the effectiveness of treatment in relation to time administered after onset.

Mr. Shaffelburg reported having no disclosures. The study was funded by the CIRN SOS network, Canadian Institutes for Health Research, and a partnership with GlaxoSmithKline Biologicals. Some of the investigators were GSK employees or received grant funding from the company.

ezimmerman@frontlinemedcom.com

SOURCE: Shaffelburg Z et al. IDWeek 2017 Abstract 890.

SAN DIEGO – Administering inpatient antiviral influenza treatment may reduce admissions to the ICU among adults hospitalized with flu, according to a study presented at ID Week 2017, an infectious diseases meeting.

While interventions did not directly affect flu-related deaths, lower ICU admission rates could reduce morbidity as well as ease the financial burden felt during the influenza season.

Investigators retrospectively studied 4,679 influenza patients admitted to Canadian Immunization Research Network Serious Outcomes Surveillance (SOS) Network hospitals during 2011-2014. Of the 54% of patients given inpatient antiviral treatment, the risk of being admitted to the ICU was reduced by 90% (odds ratio, 0.10;95% confidence interval, 0.08-0.13; P less than .001).

Antiviral treatment was not protective against death outcomes in patients with either influenza A or influenza B (OR, 0.9; 95% CI, 0.7-1.2; P =.454).

The median age of patients was 70 years, with a majority older than 75 years(41%); the majority presented with one or more comorbidities (89%), and had influenza A (72%).

Researchers found that, of the 4,679 patients studied, 798 (16%) were admitted to the ICU, 511 (11%) required mechanical ventilation, and the average length of hospital stay was 11 days.

Of those studied, 444 (9%) died within 30 days of discharge.

Researchers also found that only 38% of those studied had received the current seasonal vaccine upon admittance. However, these numbers may be skewed from the general population, because patients who have not taken the vaccine are more likely to be hospitalized.

Along with the results of antivirals on hospitalized patients, researchers wanted to uncover how the effectiveness of inpatient vaccine administration would vary based on treatment timing, said presenter Zach Shaffelburg of the Canadian Center for Vaccinology, Dalhousie University, Halifax, NS.

Even when administered 4.28 days after symptom onset, antiviral treatments in patients proved to be associated with significant reductions in ICU admissions and the need for mechanical ventilation.

The investigators concluded that antivirals show a strong association with positive effects on serious, influenza-related outcomes in hospitalized patients and, while therapy remained effective with later treatment start, patients would benefit the most from initiation as soon as possible.

Currently, the U.S. Centers for Disease Control and Prevention and the Canadian Immunization Research Network (CIRN) have guidelines instructing best practice for inpatient antiviral treatment, however the number of hospitalized patients given treatment has declined in Canada since 2009, according to Mr. Shaffelburg.

The reason more patients were not receiving inpatient antiviral treatment may be related to studies of different populations that failed to show significant impact, Mr. Shaffelburg suggested during a question and answer session following the presentation: “I think a lot of that comes from outpatient studies that involve patients who are younger and quite healthy [who received] antivirals, and it showed a very minimal impact,” Mr. Shaffelburg said. “So a lot of people saw that study and thought, ‘What’s that point of giving it if it’s not going to make an impact?’ ”

Mr. Shaffelburg and his colleagues are planning to continue their study of inpatient antiviral treatment, focusing more on the effectiveness of treatment in relation to time administered after onset.

Mr. Shaffelburg reported having no disclosures. The study was funded by the CIRN SOS network, Canadian Institutes for Health Research, and a partnership with GlaxoSmithKline Biologicals. Some of the investigators were GSK employees or received grant funding from the company.

ezimmerman@frontlinemedcom.com

SOURCE: Shaffelburg Z et al. IDWeek 2017 Abstract 890.

SAN DIEGO – Administering inpatient antiviral influenza treatment may reduce admissions to the ICU among adults hospitalized with flu, according to a study presented at ID Week 2017, an infectious diseases meeting.

While interventions did not directly affect flu-related deaths, lower ICU admission rates could reduce morbidity as well as ease the financial burden felt during the influenza season.

Investigators retrospectively studied 4,679 influenza patients admitted to Canadian Immunization Research Network Serious Outcomes Surveillance (SOS) Network hospitals during 2011-2014. Of the 54% of patients given inpatient antiviral treatment, the risk of being admitted to the ICU was reduced by 90% (odds ratio, 0.10;95% confidence interval, 0.08-0.13; P less than .001).

Antiviral treatment was not protective against death outcomes in patients with either influenza A or influenza B (OR, 0.9; 95% CI, 0.7-1.2; P =.454).

The median age of patients was 70 years, with a majority older than 75 years(41%); the majority presented with one or more comorbidities (89%), and had influenza A (72%).

Researchers found that, of the 4,679 patients studied, 798 (16%) were admitted to the ICU, 511 (11%) required mechanical ventilation, and the average length of hospital stay was 11 days.

Of those studied, 444 (9%) died within 30 days of discharge.

Researchers also found that only 38% of those studied had received the current seasonal vaccine upon admittance. However, these numbers may be skewed from the general population, because patients who have not taken the vaccine are more likely to be hospitalized.

Along with the results of antivirals on hospitalized patients, researchers wanted to uncover how the effectiveness of inpatient vaccine administration would vary based on treatment timing, said presenter Zach Shaffelburg of the Canadian Center for Vaccinology, Dalhousie University, Halifax, NS.

Even when administered 4.28 days after symptom onset, antiviral treatments in patients proved to be associated with significant reductions in ICU admissions and the need for mechanical ventilation.

The investigators concluded that antivirals show a strong association with positive effects on serious, influenza-related outcomes in hospitalized patients and, while therapy remained effective with later treatment start, patients would benefit the most from initiation as soon as possible.

Currently, the U.S. Centers for Disease Control and Prevention and the Canadian Immunization Research Network (CIRN) have guidelines instructing best practice for inpatient antiviral treatment, however the number of hospitalized patients given treatment has declined in Canada since 2009, according to Mr. Shaffelburg.

The reason more patients were not receiving inpatient antiviral treatment may be related to studies of different populations that failed to show significant impact, Mr. Shaffelburg suggested during a question and answer session following the presentation: “I think a lot of that comes from outpatient studies that involve patients who are younger and quite healthy [who received] antivirals, and it showed a very minimal impact,” Mr. Shaffelburg said. “So a lot of people saw that study and thought, ‘What’s that point of giving it if it’s not going to make an impact?’ ”

Mr. Shaffelburg and his colleagues are planning to continue their study of inpatient antiviral treatment, focusing more on the effectiveness of treatment in relation to time administered after onset.

Mr. Shaffelburg reported having no disclosures. The study was funded by the CIRN SOS network, Canadian Institutes for Health Research, and a partnership with GlaxoSmithKline Biologicals. Some of the investigators were GSK employees or received grant funding from the company.

ezimmerman@frontlinemedcom.com

SOURCE: Shaffelburg Z et al. IDWeek 2017 Abstract 890.

REPORTING FROM ID WEEK 2017

Key clinical point:

Major finding: Patients who received antiviral treatment were significantly less likely to go to the ICU or need mechanical ventilation (OR, 0.10; 95% CI, 0.08-0.13; P less than .001).

Study details: Study of 4,679 hospitalized influenza patients admitted to the Canadian Immunization Research Network Serious Outcomes Surveillance (CIRN SOS) network hospitals between 2011 to 2014.

Disclosures: Mr. Shaffelburg reported having no disclosures. The study was funded by the CIRN SOS network, Canadian Institutes for Health Research, and a partnership with GlaxoSmithKline Biologicals. Some of the investigators were GSK employees or received grant funding from the company.

Source: Shaffelburg Z et al. IDWeek 2017 Abstract 890.

Expanded hospital testing improves respiratory pathogen detection

SAN DIEGO – Systematic testing of acute respiratory illness patients can increase the likelihood of finding relevant pathogens, according to a study presented at an annual scientific meeting on infectious diseases.

Currently, hospitals conduct either nonroutine assessments or rely heavily on clinical laboratory testing among severe acute respiratory illness patients, which can lead to missing clinically key viruses.

Systematic testing expands on tests ordered and carried out at hospitals, expanding on them by testing for influenza, respiratory syncytial virus (RSV), human metapneumovirus, rhinovirus and enterovirus, adenovirus, coronavirus, and parainfluenza viruses 1-4. To test the efficacy of systematic testing, investigators studied 2,216 severe acute respiratory illness patients hospitalized in one of three hospitals in Minnesota during September 2015-August 2016. Patients were predominantly younger than 5 years old (57%) and had one or more chronic medical condition (63%).

Detection of at least one virus increased from 1,062 patients (48%) to 1,600 patients (72%) when comparing clinically ordered tests against expanded, systematic RT-PCR testing conducted through the Minnesota Health Department (MDH).

By patient age, viral detection increased by 27%, 24%, 18%, and 21% for patients aged younger than 5 years, 5-17 years, 18-64 years, and 65 years and older, respectively. Except for influenza viruses and RSV, the proportions of viruses identified, regardless of age, were all lower in hospital testing, compared with MDH testing.

“RSV targeting was almost systematic among children less than 5 years, but [accounted for] only 28% of RSV detection,” said Dr. Steffen in her presentation. “A smaller proportion of other respiratory viruses, including the human metapneumovirus, were detected at the hospital, and this was especially true for adults.”

Patients with rhinovirus and enterovirus saw a difference between hospital and expanded testing, increasing from a little over 300 patients detected, to nearly 800 patients.

“Patients admitted to the ICU were less likely to have a pathogen detection than those not admitted to the ICU, and those with one or more chronic medical condition had lower viral detection than those without,” Dr. Steffens said. “While testing at MDH did increase the percent of patients in each category, trends remained consistent and significant.”

Since testing information was only collected for patients with positive test results at the hospital, investigators were not able to compare testing practices between patients with and without viruses. This study may also have underrepresented pathogens detected through means other than the hospital laboratory, like rapid tests in emergency departments. The study was also limited by the short time frame of only 1 year.

The presenters reported no relevant financial disclosures.

ezimmerman@frontlinemedcom.com

SOURCE: Steffens A et al. Abstract 885.

SAN DIEGO – Systematic testing of acute respiratory illness patients can increase the likelihood of finding relevant pathogens, according to a study presented at an annual scientific meeting on infectious diseases.

Currently, hospitals conduct either nonroutine assessments or rely heavily on clinical laboratory testing among severe acute respiratory illness patients, which can lead to missing clinically key viruses.

Systematic testing expands on tests ordered and carried out at hospitals, expanding on them by testing for influenza, respiratory syncytial virus (RSV), human metapneumovirus, rhinovirus and enterovirus, adenovirus, coronavirus, and parainfluenza viruses 1-4. To test the efficacy of systematic testing, investigators studied 2,216 severe acute respiratory illness patients hospitalized in one of three hospitals in Minnesota during September 2015-August 2016. Patients were predominantly younger than 5 years old (57%) and had one or more chronic medical condition (63%).

Detection of at least one virus increased from 1,062 patients (48%) to 1,600 patients (72%) when comparing clinically ordered tests against expanded, systematic RT-PCR testing conducted through the Minnesota Health Department (MDH).

By patient age, viral detection increased by 27%, 24%, 18%, and 21% for patients aged younger than 5 years, 5-17 years, 18-64 years, and 65 years and older, respectively. Except for influenza viruses and RSV, the proportions of viruses identified, regardless of age, were all lower in hospital testing, compared with MDH testing.

“RSV targeting was almost systematic among children less than 5 years, but [accounted for] only 28% of RSV detection,” said Dr. Steffen in her presentation. “A smaller proportion of other respiratory viruses, including the human metapneumovirus, were detected at the hospital, and this was especially true for adults.”

Patients with rhinovirus and enterovirus saw a difference between hospital and expanded testing, increasing from a little over 300 patients detected, to nearly 800 patients.

“Patients admitted to the ICU were less likely to have a pathogen detection than those not admitted to the ICU, and those with one or more chronic medical condition had lower viral detection than those without,” Dr. Steffens said. “While testing at MDH did increase the percent of patients in each category, trends remained consistent and significant.”

Since testing information was only collected for patients with positive test results at the hospital, investigators were not able to compare testing practices between patients with and without viruses. This study may also have underrepresented pathogens detected through means other than the hospital laboratory, like rapid tests in emergency departments. The study was also limited by the short time frame of only 1 year.

The presenters reported no relevant financial disclosures.

ezimmerman@frontlinemedcom.com

SOURCE: Steffens A et al. Abstract 885.

SAN DIEGO – Systematic testing of acute respiratory illness patients can increase the likelihood of finding relevant pathogens, according to a study presented at an annual scientific meeting on infectious diseases.

Currently, hospitals conduct either nonroutine assessments or rely heavily on clinical laboratory testing among severe acute respiratory illness patients, which can lead to missing clinically key viruses.

Systematic testing expands on tests ordered and carried out at hospitals, expanding on them by testing for influenza, respiratory syncytial virus (RSV), human metapneumovirus, rhinovirus and enterovirus, adenovirus, coronavirus, and parainfluenza viruses 1-4. To test the efficacy of systematic testing, investigators studied 2,216 severe acute respiratory illness patients hospitalized in one of three hospitals in Minnesota during September 2015-August 2016. Patients were predominantly younger than 5 years old (57%) and had one or more chronic medical condition (63%).

Detection of at least one virus increased from 1,062 patients (48%) to 1,600 patients (72%) when comparing clinically ordered tests against expanded, systematic RT-PCR testing conducted through the Minnesota Health Department (MDH).

By patient age, viral detection increased by 27%, 24%, 18%, and 21% for patients aged younger than 5 years, 5-17 years, 18-64 years, and 65 years and older, respectively. Except for influenza viruses and RSV, the proportions of viruses identified, regardless of age, were all lower in hospital testing, compared with MDH testing.

“RSV targeting was almost systematic among children less than 5 years, but [accounted for] only 28% of RSV detection,” said Dr. Steffen in her presentation. “A smaller proportion of other respiratory viruses, including the human metapneumovirus, were detected at the hospital, and this was especially true for adults.”

Patients with rhinovirus and enterovirus saw a difference between hospital and expanded testing, increasing from a little over 300 patients detected, to nearly 800 patients.

“Patients admitted to the ICU were less likely to have a pathogen detection than those not admitted to the ICU, and those with one or more chronic medical condition had lower viral detection than those without,” Dr. Steffens said. “While testing at MDH did increase the percent of patients in each category, trends remained consistent and significant.”

Since testing information was only collected for patients with positive test results at the hospital, investigators were not able to compare testing practices between patients with and without viruses. This study may also have underrepresented pathogens detected through means other than the hospital laboratory, like rapid tests in emergency departments. The study was also limited by the short time frame of only 1 year.

The presenters reported no relevant financial disclosures.

ezimmerman@frontlinemedcom.com

SOURCE: Steffens A et al. Abstract 885.

REPORTING FROM ID WEEK 2017

Key clinical point:

Major finding: Among 2,216 patients studied, 1,600 (72%) were found to have at least one respiratory virus through expanded testing, compared with 1,062 (48%) patients tested through clincian-directed testing.

Study details: 2,351 severe acute respiratory illness patients hospitalized in one of three hospitals in Minnesota.

Disclosures: The presenter reported no relevant financial disclosures.

Source: Steffens A et al. Abstract 885.

Chinese school-based flu vaccination program reduced outbreaks

, said Yang Pan, PhD, of the Institute for Infectious Disease and Endemic Disease Control, Beijing Center for Disease Prevention and Control, and associates.

School-based trivalent inactivated influenza vaccination programs generally occurred Oct. 15-Nov. 30 each year since 2007, with greater than 50% vaccination coverage. In an 11-year retrospective study of school outbreaks of influenza in elementary, middle, and high schools in the Beijing area during Sept. 1, 2006-March 31, 2017, there were 286 febrile outbreaks in schools, involving 6,863 children.

During the 11 years, a mismatch between circulating strains and vaccine strains was identified in two influenza seasons, such as “the A(H3N2) 3C.1 (vaccine strain)-A(H3N2) 3C.3a (circulating strains) mismatch in 2014-2015, the B(Yamagata) Clade 2 (vaccine strain)-B(Yamagata) Clade 3 (circulating strain) mismatch in the 2014-2015 influenza season, and B(Yamagata) (vaccine strain)-B(Victoria) (circulating strains) mismatch in 2015-2016,” they reported.

A combination of high flu vaccine coverage because of school-based vaccinations and a good vaccine match reduced influenza outbreaks in schools by 89% (odds ratio, 0.111), Dr. Pan and associates concluded.

“The school-based influenza vaccination program has been in operation for nearly 10 years in the Beijing area, is unique in China, and is one of the few school-based influenza programs in the world,” the researchers explained. “These data can inform and improve vaccination policy locally and nationally.”

Read more in Vaccine (2017 Nov 8. doi: 10.1016/j.vaccine.2017.10.096).

, said Yang Pan, PhD, of the Institute for Infectious Disease and Endemic Disease Control, Beijing Center for Disease Prevention and Control, and associates.

School-based trivalent inactivated influenza vaccination programs generally occurred Oct. 15-Nov. 30 each year since 2007, with greater than 50% vaccination coverage. In an 11-year retrospective study of school outbreaks of influenza in elementary, middle, and high schools in the Beijing area during Sept. 1, 2006-March 31, 2017, there were 286 febrile outbreaks in schools, involving 6,863 children.

During the 11 years, a mismatch between circulating strains and vaccine strains was identified in two influenza seasons, such as “the A(H3N2) 3C.1 (vaccine strain)-A(H3N2) 3C.3a (circulating strains) mismatch in 2014-2015, the B(Yamagata) Clade 2 (vaccine strain)-B(Yamagata) Clade 3 (circulating strain) mismatch in the 2014-2015 influenza season, and B(Yamagata) (vaccine strain)-B(Victoria) (circulating strains) mismatch in 2015-2016,” they reported.

A combination of high flu vaccine coverage because of school-based vaccinations and a good vaccine match reduced influenza outbreaks in schools by 89% (odds ratio, 0.111), Dr. Pan and associates concluded.

“The school-based influenza vaccination program has been in operation for nearly 10 years in the Beijing area, is unique in China, and is one of the few school-based influenza programs in the world,” the researchers explained. “These data can inform and improve vaccination policy locally and nationally.”

Read more in Vaccine (2017 Nov 8. doi: 10.1016/j.vaccine.2017.10.096).

, said Yang Pan, PhD, of the Institute for Infectious Disease and Endemic Disease Control, Beijing Center for Disease Prevention and Control, and associates.

School-based trivalent inactivated influenza vaccination programs generally occurred Oct. 15-Nov. 30 each year since 2007, with greater than 50% vaccination coverage. In an 11-year retrospective study of school outbreaks of influenza in elementary, middle, and high schools in the Beijing area during Sept. 1, 2006-March 31, 2017, there were 286 febrile outbreaks in schools, involving 6,863 children.

During the 11 years, a mismatch between circulating strains and vaccine strains was identified in two influenza seasons, such as “the A(H3N2) 3C.1 (vaccine strain)-A(H3N2) 3C.3a (circulating strains) mismatch in 2014-2015, the B(Yamagata) Clade 2 (vaccine strain)-B(Yamagata) Clade 3 (circulating strain) mismatch in the 2014-2015 influenza season, and B(Yamagata) (vaccine strain)-B(Victoria) (circulating strains) mismatch in 2015-2016,” they reported.

A combination of high flu vaccine coverage because of school-based vaccinations and a good vaccine match reduced influenza outbreaks in schools by 89% (odds ratio, 0.111), Dr. Pan and associates concluded.

“The school-based influenza vaccination program has been in operation for nearly 10 years in the Beijing area, is unique in China, and is one of the few school-based influenza programs in the world,” the researchers explained. “These data can inform and improve vaccination policy locally and nationally.”

Read more in Vaccine (2017 Nov 8. doi: 10.1016/j.vaccine.2017.10.096).

FROM VACCINE

Public health hazard: Bring your flu to work day

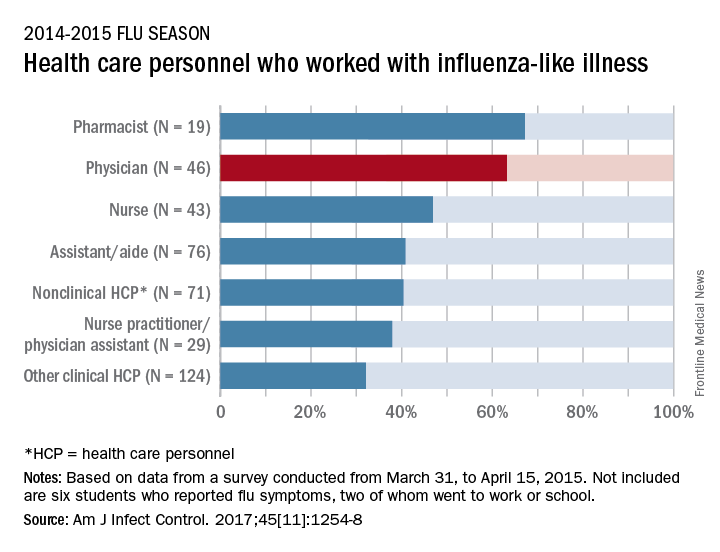

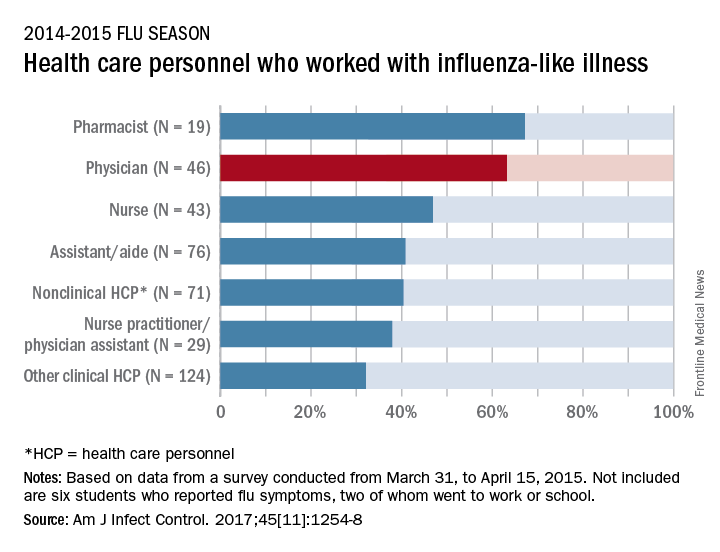

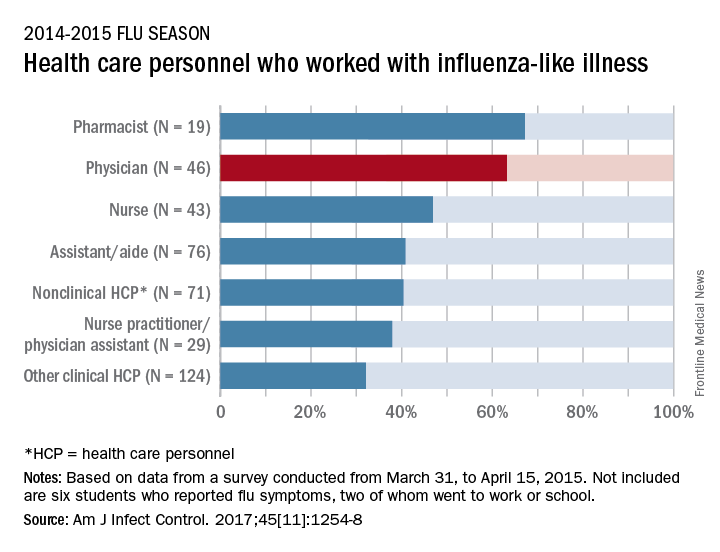

Slightly more than 41% of health care personnel who had the flu during the 2014-2015 influenza season went to work while they were ill, according to an annual survey.

Physicians, however, were well above this average, with 63% reporting they had worked with an influenza-like illness (ILI); they were not quite as far above average as pharmacists, though, who had a 67% rate of “presenteeism” – the highest among all of the health care occupations included in the survey, said Sophia Chiu, MD, MPH, of the Centers for Disease Control and Prevention’s National Institute for Occupational Safety and Health, and her associates.

“The statistics are alarming. At least one earlier study has shown that patients who are exposed to a health care worker who is sick are five times more likely to get a health care–associated infection,” Dr. Chiu said in a separate written statement.

For the study, ILI was defined as “fever (without a specified temperature cutoff) and sore throat or cough.” The “nonclinical personnel” category included managers, food service workers, and janitors, while the “other clinical personnel” category included technicians and technologists. The annual Internet panel survey was conducted from March 31, 2015, to April 15, 2015, and 414 of its 1,914 respondents self-reported having an ILI, of whom 183 said that they worked during their illness, Dr. Chiu and her associates said.

The investigators are all CDC employees. The respondents were recruited from Internet panels operated by Survey Sampling International through a contract with Abt Associates.

Slightly more than 41% of health care personnel who had the flu during the 2014-2015 influenza season went to work while they were ill, according to an annual survey.

Physicians, however, were well above this average, with 63% reporting they had worked with an influenza-like illness (ILI); they were not quite as far above average as pharmacists, though, who had a 67% rate of “presenteeism” – the highest among all of the health care occupations included in the survey, said Sophia Chiu, MD, MPH, of the Centers for Disease Control and Prevention’s National Institute for Occupational Safety and Health, and her associates.

“The statistics are alarming. At least one earlier study has shown that patients who are exposed to a health care worker who is sick are five times more likely to get a health care–associated infection,” Dr. Chiu said in a separate written statement.

For the study, ILI was defined as “fever (without a specified temperature cutoff) and sore throat or cough.” The “nonclinical personnel” category included managers, food service workers, and janitors, while the “other clinical personnel” category included technicians and technologists. The annual Internet panel survey was conducted from March 31, 2015, to April 15, 2015, and 414 of its 1,914 respondents self-reported having an ILI, of whom 183 said that they worked during their illness, Dr. Chiu and her associates said.

The investigators are all CDC employees. The respondents were recruited from Internet panels operated by Survey Sampling International through a contract with Abt Associates.

Slightly more than 41% of health care personnel who had the flu during the 2014-2015 influenza season went to work while they were ill, according to an annual survey.

Physicians, however, were well above this average, with 63% reporting they had worked with an influenza-like illness (ILI); they were not quite as far above average as pharmacists, though, who had a 67% rate of “presenteeism” – the highest among all of the health care occupations included in the survey, said Sophia Chiu, MD, MPH, of the Centers for Disease Control and Prevention’s National Institute for Occupational Safety and Health, and her associates.

“The statistics are alarming. At least one earlier study has shown that patients who are exposed to a health care worker who is sick are five times more likely to get a health care–associated infection,” Dr. Chiu said in a separate written statement.

For the study, ILI was defined as “fever (without a specified temperature cutoff) and sore throat or cough.” The “nonclinical personnel” category included managers, food service workers, and janitors, while the “other clinical personnel” category included technicians and technologists. The annual Internet panel survey was conducted from March 31, 2015, to April 15, 2015, and 414 of its 1,914 respondents self-reported having an ILI, of whom 183 said that they worked during their illness, Dr. Chiu and her associates said.

The investigators are all CDC employees. The respondents were recruited from Internet panels operated by Survey Sampling International through a contract with Abt Associates.

FROM THE AMERICAN JOURNAL OF INFECTION CONTROL

In-hospital outcomes are better for vaccinated H1N1 patients

TORONTO – Patients who received an influenza vaccination but still required hospitalization for H1N1 influenza had better outcomes, compared with unvaccinated patients, according to findings from a retrospective study.

In the hospital, vaccinated patients had significantly lower rates of acute kidney injury (6% vs. 35%; P = .038) and were more likely to be satisfactorily managed with noninvasive mechanical ventilation (41% vs. 6%; P = .004).

Dr. Chandak and her colleagues studied 72 cases of seasonal influenza requiring hospitalization from September 2015 to April 2016 at Berkshire Medical Center, a 300-bed teaching hospital in western Massachusetts. Based on rapid polymerase chain reaction testing, 51 of these patients were positive for H1N1, of which 38 had received a seasonal flu vaccine.

H1N1 patients who had received vaccination were significantly older (70.4 years vs. 59.6 years; P = .016) and were more often smokers (76% vs. 38%; P = .017), compared with patients who were unvaccinated.

The finding that the unvaccinated patients were younger and still had poorer outcomes, “emphasizes the need for widespread vaccination,” Dr. Chandak said.

There were several parameters that trended in favor of vaccination, but did not reach statistical significance due to the relatively small sample size, Dr. Chandak said. These included a trend towards more ICU admission in the unvaccinated, compared with vaccinated patients (21% and 12%, respectively; P = .699), a longer ICU stay (1.7 days and 0.2 days; P = .144), more multiorgan dysfunction syndrome (12% and 6%; P = .654), and more acute respiratory distress syndrome (6% and 0%; P = .547). Vasopressors were needed in a similar proportion of patients (12% of both groups).

During the 2009-2010 flu season, H1N1 was the cause of about 61 million cases of influenza in the United States, 274,000 hospitalizations, and 12,470 deaths, Dr. Chandak reported.

Since the 2010-2011 influenza season, the trivalent influenza vaccine has included antigen from the 2009 pandemic H1N1 influenza A virus. This has prevented between 700,000 and 1.5 million cases of H1N1, up to 10,000 hospitalizations, and as many as 500 deaths, according to surveillance data (Emerg Infect Dis. 2013;19[3]:439-48).

The viral subtype made a strong reappearance in the 2015-2016 flu season when it was again the predominant viral subtype of the season, according to the CDC. Most studies have looked at the effectiveness of the vaccine, but have not studied critical care outcomes in vaccinated versus unvaccinated patients, Dr. Chandak noted.

Dr. Chandak reported having no financial disclosures.

Daniel Ouellette, MD, FCCP, comments: “I never take the flu vaccine,” my patient stated, following my suggestion that she be inoculated. “It makes me sick.”

I reflected on the cases of influenza patients that I took care of the previous year in the ICU: the 50-year-old man with no comorbidities who died in respiratory failure; the 32-year-old pregnant woman who survived a 3-month hospitalization during which she was treated with ECMO and suffered irreversible kidney failure. “I take it every year,” I told her.

While the influenza vaccine may not prevent all cases of influenza, those who develop influenza may have an attenuated illness. Data from Chandak and colleagues affirm improved outcomes in patients who receive the vaccine and still develop influenza.

Daniel Ouellette, MD, FCCP, comments: “I never take the flu vaccine,” my patient stated, following my suggestion that she be inoculated. “It makes me sick.”

I reflected on the cases of influenza patients that I took care of the previous year in the ICU: the 50-year-old man with no comorbidities who died in respiratory failure; the 32-year-old pregnant woman who survived a 3-month hospitalization during which she was treated with ECMO and suffered irreversible kidney failure. “I take it every year,” I told her.

While the influenza vaccine may not prevent all cases of influenza, those who develop influenza may have an attenuated illness. Data from Chandak and colleagues affirm improved outcomes in patients who receive the vaccine and still develop influenza.

Daniel Ouellette, MD, FCCP, comments: “I never take the flu vaccine,” my patient stated, following my suggestion that she be inoculated. “It makes me sick.”

I reflected on the cases of influenza patients that I took care of the previous year in the ICU: the 50-year-old man with no comorbidities who died in respiratory failure; the 32-year-old pregnant woman who survived a 3-month hospitalization during which she was treated with ECMO and suffered irreversible kidney failure. “I take it every year,” I told her.

While the influenza vaccine may not prevent all cases of influenza, those who develop influenza may have an attenuated illness. Data from Chandak and colleagues affirm improved outcomes in patients who receive the vaccine and still develop influenza.

TORONTO – Patients who received an influenza vaccination but still required hospitalization for H1N1 influenza had better outcomes, compared with unvaccinated patients, according to findings from a retrospective study.

In the hospital, vaccinated patients had significantly lower rates of acute kidney injury (6% vs. 35%; P = .038) and were more likely to be satisfactorily managed with noninvasive mechanical ventilation (41% vs. 6%; P = .004).

Dr. Chandak and her colleagues studied 72 cases of seasonal influenza requiring hospitalization from September 2015 to April 2016 at Berkshire Medical Center, a 300-bed teaching hospital in western Massachusetts. Based on rapid polymerase chain reaction testing, 51 of these patients were positive for H1N1, of which 38 had received a seasonal flu vaccine.

H1N1 patients who had received vaccination were significantly older (70.4 years vs. 59.6 years; P = .016) and were more often smokers (76% vs. 38%; P = .017), compared with patients who were unvaccinated.

The finding that the unvaccinated patients were younger and still had poorer outcomes, “emphasizes the need for widespread vaccination,” Dr. Chandak said.

There were several parameters that trended in favor of vaccination, but did not reach statistical significance due to the relatively small sample size, Dr. Chandak said. These included a trend towards more ICU admission in the unvaccinated, compared with vaccinated patients (21% and 12%, respectively; P = .699), a longer ICU stay (1.7 days and 0.2 days; P = .144), more multiorgan dysfunction syndrome (12% and 6%; P = .654), and more acute respiratory distress syndrome (6% and 0%; P = .547). Vasopressors were needed in a similar proportion of patients (12% of both groups).

During the 2009-2010 flu season, H1N1 was the cause of about 61 million cases of influenza in the United States, 274,000 hospitalizations, and 12,470 deaths, Dr. Chandak reported.

Since the 2010-2011 influenza season, the trivalent influenza vaccine has included antigen from the 2009 pandemic H1N1 influenza A virus. This has prevented between 700,000 and 1.5 million cases of H1N1, up to 10,000 hospitalizations, and as many as 500 deaths, according to surveillance data (Emerg Infect Dis. 2013;19[3]:439-48).

The viral subtype made a strong reappearance in the 2015-2016 flu season when it was again the predominant viral subtype of the season, according to the CDC. Most studies have looked at the effectiveness of the vaccine, but have not studied critical care outcomes in vaccinated versus unvaccinated patients, Dr. Chandak noted.

Dr. Chandak reported having no financial disclosures.

TORONTO – Patients who received an influenza vaccination but still required hospitalization for H1N1 influenza had better outcomes, compared with unvaccinated patients, according to findings from a retrospective study.

In the hospital, vaccinated patients had significantly lower rates of acute kidney injury (6% vs. 35%; P = .038) and were more likely to be satisfactorily managed with noninvasive mechanical ventilation (41% vs. 6%; P = .004).

Dr. Chandak and her colleagues studied 72 cases of seasonal influenza requiring hospitalization from September 2015 to April 2016 at Berkshire Medical Center, a 300-bed teaching hospital in western Massachusetts. Based on rapid polymerase chain reaction testing, 51 of these patients were positive for H1N1, of which 38 had received a seasonal flu vaccine.

H1N1 patients who had received vaccination were significantly older (70.4 years vs. 59.6 years; P = .016) and were more often smokers (76% vs. 38%; P = .017), compared with patients who were unvaccinated.

The finding that the unvaccinated patients were younger and still had poorer outcomes, “emphasizes the need for widespread vaccination,” Dr. Chandak said.

There were several parameters that trended in favor of vaccination, but did not reach statistical significance due to the relatively small sample size, Dr. Chandak said. These included a trend towards more ICU admission in the unvaccinated, compared with vaccinated patients (21% and 12%, respectively; P = .699), a longer ICU stay (1.7 days and 0.2 days; P = .144), more multiorgan dysfunction syndrome (12% and 6%; P = .654), and more acute respiratory distress syndrome (6% and 0%; P = .547). Vasopressors were needed in a similar proportion of patients (12% of both groups).

During the 2009-2010 flu season, H1N1 was the cause of about 61 million cases of influenza in the United States, 274,000 hospitalizations, and 12,470 deaths, Dr. Chandak reported.

Since the 2010-2011 influenza season, the trivalent influenza vaccine has included antigen from the 2009 pandemic H1N1 influenza A virus. This has prevented between 700,000 and 1.5 million cases of H1N1, up to 10,000 hospitalizations, and as many as 500 deaths, according to surveillance data (Emerg Infect Dis. 2013;19[3]:439-48).

The viral subtype made a strong reappearance in the 2015-2016 flu season when it was again the predominant viral subtype of the season, according to the CDC. Most studies have looked at the effectiveness of the vaccine, but have not studied critical care outcomes in vaccinated versus unvaccinated patients, Dr. Chandak noted.

Dr. Chandak reported having no financial disclosures.

AT CHEST 2017

Key clinical point:

Major finding: Unvaccinated patients had a significantly higher risk of acute kidney injury (35% vs. 6%; P = .038) and were less likely to be managed with noninvasive mechanical ventilation (6% vs. 41%; P = .004).

Data source: Retrospective analysis including 72 reported influenza cases, 51 (71%) testing positive for H1N1.

Disclosures: Dr. Chandak reported having no financial disclosures.

Nearly 80% of health care personnel stepped up for flu shots

Nearly four out of five health care personnel in the United States received a flu vaccination during the 2016-2017 flu season, but a majority of those working in long-term care settings were not vaccinated, based on data from an Internet survey of more than 2,000 individuals that was conducted by the Centers for Disease Control and Prevention.

A total of 78.6% of the survey’s respondents said they’d been vaccinated during the 2016-2017 season. Vaccination coverage for health care personnel overall has remained in the 77%-79% range in recent years, but that represents an increase from 64% in 2010-2011.

“As in previous seasons, the highest coverage was among HCP whose workplace had vaccination requirements,” noted Carla L. Black, PhD, of the CDC, and colleagues (MMWR Morb Mortal Wkly Rep. 2017 Sep 29;66[38]:1009-15). The researchers reviewed data collected from an Internet panel survey of 2,438 health care personnel between March 28, 2017, and April 19, 2017.

Physicians boasted the highest vaccination coverage in 2016-2017 (96%), followed by pharmacists (94%), nurses (93%), nurse practitioners and physician assistants (92%), other clinical providers (80%), nonclinical health care providers (74%), and aides and assistants (69%).

Flu vaccination rates were highest among HCPs working in a hospital setting (92%); 94% of survey respondents in hospitals reported either having a vaccination requirement at work or being provided at least 1 day of on-site vaccination.

Vaccination rates were lowest among health care personnel in long-term care settings (68%), where only 26% reported a workplace vaccination requirement. However, vaccination rates in long-term care rose to 90% when employers required vaccination.

The report’s findings were limited by several factors, including the use of a volunteer sample, the reliance on self-reports, and the potential differences between Internet survey results and population-based estimates of flu vaccination.

However, “in the absence of vaccination requirements, the findings in this study support the recommendations found in the Guide to Community Preventive Services, which include active promotion of on-site vaccination at no cost or low cost to increase influenza vaccination coverage among HCPs,” the researchers said.

The researchers had no financial conflicts to disclose.

Nearly four out of five health care personnel in the United States received a flu vaccination during the 2016-2017 flu season, but a majority of those working in long-term care settings were not vaccinated, based on data from an Internet survey of more than 2,000 individuals that was conducted by the Centers for Disease Control and Prevention.

A total of 78.6% of the survey’s respondents said they’d been vaccinated during the 2016-2017 season. Vaccination coverage for health care personnel overall has remained in the 77%-79% range in recent years, but that represents an increase from 64% in 2010-2011.

“As in previous seasons, the highest coverage was among HCP whose workplace had vaccination requirements,” noted Carla L. Black, PhD, of the CDC, and colleagues (MMWR Morb Mortal Wkly Rep. 2017 Sep 29;66[38]:1009-15). The researchers reviewed data collected from an Internet panel survey of 2,438 health care personnel between March 28, 2017, and April 19, 2017.

Physicians boasted the highest vaccination coverage in 2016-2017 (96%), followed by pharmacists (94%), nurses (93%), nurse practitioners and physician assistants (92%), other clinical providers (80%), nonclinical health care providers (74%), and aides and assistants (69%).

Flu vaccination rates were highest among HCPs working in a hospital setting (92%); 94% of survey respondents in hospitals reported either having a vaccination requirement at work or being provided at least 1 day of on-site vaccination.

Vaccination rates were lowest among health care personnel in long-term care settings (68%), where only 26% reported a workplace vaccination requirement. However, vaccination rates in long-term care rose to 90% when employers required vaccination.