User login

The SHM Fellow designation: Class of 2021

Spotlight on Tanisha Hamilton, MD, FHM

As we navigate a time unlike any other, it is clear that the value hospitalists provide is growing stronger as the hospital medicine field expands. Many Society of Hospital Medicine members look to its Fellows program as a worthwhile opportunity to distinguish themselves as leaders in the field and accelerate their careers in the specialty.

An active member of SHM since 2012 and member of its 2020 class of Fellows, Tanisha Hamilton, MD, FHM, is one of these ambitious individuals.

Dr. Hamilton is based at Baylor University Medical Center in Dallas, an affiliate of Baylor Scott & White Health. Known for personalized health and wellness care, Dr. Hamilton has more than 14 years of experience in the medical field.

Her love for the hospital medicine specialty is rooted in its diversity and complexity of patient cases – something that she knew would innately complement her personality. She says that an invaluable aspect of working in the field is the ability to interact and connect with people from all walks of life.

“My patients keep me motivated in this space. Learning from my patients and having the responsibility of serving as their advocate is incredibly rewarding,” Dr. Hamilton said. “I hope my patients feel like I’ve helped to make a difference in their lives, if only for just a moment.”

When reflecting on why she joined SHM 8 years ago, Dr. Hamilton said she was encouraged to do so because of its like-minded membership community and professional development opportunities, including the Fellows program.

“I applied to SHM’s Fellows program because I’m committed to the specialty. Hospital medicine is an ever-changing field loaded with opportunities to enhance personal and professional career growth,” said Dr. Hamilton. “To me, SHM’s Fellow in Hospital Medicine [FHM] designation demonstrates the ability to make a contribution to the field and to be an instrument for change.”

She credits receiving her designation as a distinction that has opened doors to other career-enhancing opportunities and networking resources, including an expansive global community, program development at her institution, and positions within SHM. Since earning her FHM designation, Dr. Hamilton has become an engaged member of the annual meeting committee and the North Central Texas Chapter.

“Since we are taking our annual conference virtual for SHM Converge in 2021, I’m excited to see how we can transform a meeting of more than 5,000 attendees into a full digital experience with interactive workshops, exhibits, research competitions, and more,” Dr. Hamilton said. “It’s certainly going to be a challenge, but I know that our meetings department and annual conference committee will make it a success!”

As Dr. Hamilton looks forward in her hospital medicine career, she is committed to making a positive impact on the field and for her patients.

In the future, Dr. Hamilton hopes to share curriculum she recently developed and sponsored around diversity, equity, and inclusion with her team at Baylor University Medical Center.

“Following the tragic deaths of numerous individuals, including Breonna Taylor, Ahmaud Abery, and George Floyd, and other people of color who have died because of COVID-19, I have felt compelled to educate my colleagues on how to curtail systemic racism, sexism, religious discrimination, and xenophobia in health care,” Dr. Hamilton said. “This curriculum includes courses on health disparities and cultural competencies, launching a lecture series, and other educational components.”

While 2020 has been a trying year, Dr. Hamilton remains hopeful for a prosperous future.

“When I think of the future of hospital medicine, I am hopeful that hospitalists will have a more prominent role in changing the direction of our health care system,” she said. “The pandemic has made the world realize the importance of hospital medicine. We, as hospitalists, are a critical part of its infrastructure and its success.”

If you would like to join Dr. Hamilton and other like-minded hospital medicine leaders in accelerating your career, SHM is currently recruiting for the Fellows and Senior Fellows class of 2021. Applications are open until Nov. 20, 2020. These designations are available across a variety of membership categories, including physicians, nurse practitioners, physician assistants, and qualified practice administrators. Dedicated to promoting excellence, innovation, and quality improvement in patient care, Fellows designations provide members with a distinguishing credential as established pioneers in the industry.

For more information and to review your eligibility, visit hospitalmedicine.org/fellows.

Ms. Cowan is a communications specialist at the Society of Hospital Medicine.

Spotlight on Tanisha Hamilton, MD, FHM

Spotlight on Tanisha Hamilton, MD, FHM

As we navigate a time unlike any other, it is clear that the value hospitalists provide is growing stronger as the hospital medicine field expands. Many Society of Hospital Medicine members look to its Fellows program as a worthwhile opportunity to distinguish themselves as leaders in the field and accelerate their careers in the specialty.

An active member of SHM since 2012 and member of its 2020 class of Fellows, Tanisha Hamilton, MD, FHM, is one of these ambitious individuals.

Dr. Hamilton is based at Baylor University Medical Center in Dallas, an affiliate of Baylor Scott & White Health. Known for personalized health and wellness care, Dr. Hamilton has more than 14 years of experience in the medical field.

Her love for the hospital medicine specialty is rooted in its diversity and complexity of patient cases – something that she knew would innately complement her personality. She says that an invaluable aspect of working in the field is the ability to interact and connect with people from all walks of life.

“My patients keep me motivated in this space. Learning from my patients and having the responsibility of serving as their advocate is incredibly rewarding,” Dr. Hamilton said. “I hope my patients feel like I’ve helped to make a difference in their lives, if only for just a moment.”

When reflecting on why she joined SHM 8 years ago, Dr. Hamilton said she was encouraged to do so because of its like-minded membership community and professional development opportunities, including the Fellows program.

“I applied to SHM’s Fellows program because I’m committed to the specialty. Hospital medicine is an ever-changing field loaded with opportunities to enhance personal and professional career growth,” said Dr. Hamilton. “To me, SHM’s Fellow in Hospital Medicine [FHM] designation demonstrates the ability to make a contribution to the field and to be an instrument for change.”

She credits receiving her designation as a distinction that has opened doors to other career-enhancing opportunities and networking resources, including an expansive global community, program development at her institution, and positions within SHM. Since earning her FHM designation, Dr. Hamilton has become an engaged member of the annual meeting committee and the North Central Texas Chapter.

“Since we are taking our annual conference virtual for SHM Converge in 2021, I’m excited to see how we can transform a meeting of more than 5,000 attendees into a full digital experience with interactive workshops, exhibits, research competitions, and more,” Dr. Hamilton said. “It’s certainly going to be a challenge, but I know that our meetings department and annual conference committee will make it a success!”

As Dr. Hamilton looks forward in her hospital medicine career, she is committed to making a positive impact on the field and for her patients.

In the future, Dr. Hamilton hopes to share curriculum she recently developed and sponsored around diversity, equity, and inclusion with her team at Baylor University Medical Center.

“Following the tragic deaths of numerous individuals, including Breonna Taylor, Ahmaud Abery, and George Floyd, and other people of color who have died because of COVID-19, I have felt compelled to educate my colleagues on how to curtail systemic racism, sexism, religious discrimination, and xenophobia in health care,” Dr. Hamilton said. “This curriculum includes courses on health disparities and cultural competencies, launching a lecture series, and other educational components.”

While 2020 has been a trying year, Dr. Hamilton remains hopeful for a prosperous future.

“When I think of the future of hospital medicine, I am hopeful that hospitalists will have a more prominent role in changing the direction of our health care system,” she said. “The pandemic has made the world realize the importance of hospital medicine. We, as hospitalists, are a critical part of its infrastructure and its success.”

If you would like to join Dr. Hamilton and other like-minded hospital medicine leaders in accelerating your career, SHM is currently recruiting for the Fellows and Senior Fellows class of 2021. Applications are open until Nov. 20, 2020. These designations are available across a variety of membership categories, including physicians, nurse practitioners, physician assistants, and qualified practice administrators. Dedicated to promoting excellence, innovation, and quality improvement in patient care, Fellows designations provide members with a distinguishing credential as established pioneers in the industry.

For more information and to review your eligibility, visit hospitalmedicine.org/fellows.

Ms. Cowan is a communications specialist at the Society of Hospital Medicine.

As we navigate a time unlike any other, it is clear that the value hospitalists provide is growing stronger as the hospital medicine field expands. Many Society of Hospital Medicine members look to its Fellows program as a worthwhile opportunity to distinguish themselves as leaders in the field and accelerate their careers in the specialty.

An active member of SHM since 2012 and member of its 2020 class of Fellows, Tanisha Hamilton, MD, FHM, is one of these ambitious individuals.

Dr. Hamilton is based at Baylor University Medical Center in Dallas, an affiliate of Baylor Scott & White Health. Known for personalized health and wellness care, Dr. Hamilton has more than 14 years of experience in the medical field.

Her love for the hospital medicine specialty is rooted in its diversity and complexity of patient cases – something that she knew would innately complement her personality. She says that an invaluable aspect of working in the field is the ability to interact and connect with people from all walks of life.

“My patients keep me motivated in this space. Learning from my patients and having the responsibility of serving as their advocate is incredibly rewarding,” Dr. Hamilton said. “I hope my patients feel like I’ve helped to make a difference in their lives, if only for just a moment.”

When reflecting on why she joined SHM 8 years ago, Dr. Hamilton said she was encouraged to do so because of its like-minded membership community and professional development opportunities, including the Fellows program.

“I applied to SHM’s Fellows program because I’m committed to the specialty. Hospital medicine is an ever-changing field loaded with opportunities to enhance personal and professional career growth,” said Dr. Hamilton. “To me, SHM’s Fellow in Hospital Medicine [FHM] designation demonstrates the ability to make a contribution to the field and to be an instrument for change.”

She credits receiving her designation as a distinction that has opened doors to other career-enhancing opportunities and networking resources, including an expansive global community, program development at her institution, and positions within SHM. Since earning her FHM designation, Dr. Hamilton has become an engaged member of the annual meeting committee and the North Central Texas Chapter.

“Since we are taking our annual conference virtual for SHM Converge in 2021, I’m excited to see how we can transform a meeting of more than 5,000 attendees into a full digital experience with interactive workshops, exhibits, research competitions, and more,” Dr. Hamilton said. “It’s certainly going to be a challenge, but I know that our meetings department and annual conference committee will make it a success!”

As Dr. Hamilton looks forward in her hospital medicine career, she is committed to making a positive impact on the field and for her patients.

In the future, Dr. Hamilton hopes to share curriculum she recently developed and sponsored around diversity, equity, and inclusion with her team at Baylor University Medical Center.

“Following the tragic deaths of numerous individuals, including Breonna Taylor, Ahmaud Abery, and George Floyd, and other people of color who have died because of COVID-19, I have felt compelled to educate my colleagues on how to curtail systemic racism, sexism, religious discrimination, and xenophobia in health care,” Dr. Hamilton said. “This curriculum includes courses on health disparities and cultural competencies, launching a lecture series, and other educational components.”

While 2020 has been a trying year, Dr. Hamilton remains hopeful for a prosperous future.

“When I think of the future of hospital medicine, I am hopeful that hospitalists will have a more prominent role in changing the direction of our health care system,” she said. “The pandemic has made the world realize the importance of hospital medicine. We, as hospitalists, are a critical part of its infrastructure and its success.”

If you would like to join Dr. Hamilton and other like-minded hospital medicine leaders in accelerating your career, SHM is currently recruiting for the Fellows and Senior Fellows class of 2021. Applications are open until Nov. 20, 2020. These designations are available across a variety of membership categories, including physicians, nurse practitioners, physician assistants, and qualified practice administrators. Dedicated to promoting excellence, innovation, and quality improvement in patient care, Fellows designations provide members with a distinguishing credential as established pioneers in the industry.

For more information and to review your eligibility, visit hospitalmedicine.org/fellows.

Ms. Cowan is a communications specialist at the Society of Hospital Medicine.

Burnout risk may be exacerbated by COVID crisis

New kinds of job stress multiply in unusual times

Clarissa Barnes, MD, a hospitalist at Avera McKennan Hospital in Sioux Falls, S.D., and until recently medical director of Avera’s LIGHT Program, a wellness-oriented service for doctors, nurse practitioners, and physician assistants, watched the COVID-19 crisis unfold up close in her community and her hospital. Sioux Falls traced its surge of COVID patients to an outbreak at a local meatpacking plant.

“In the beginning, we didn’t know much about the virus and its communicability, although we have since gotten a better handle on that,” she said. “We had questions: Should we give patients more fluids – or less? Steroids or not? In my experience as a hospitalist I never had patients die every day on my shift, but that was happening with COVID.” The crisis imposed serious stresses on frontline providers, and hospitalists were concerned about personal safety and exposure risk – not just for themselves but for their families.

“The first time I worked on the COVID unit, I moved into the guest room in our home, apart from my husband and our young children,” Dr. Barnes said. “Ultimately I caught the virus, although I have since recovered.” Her experience has highlighted how existing issues of job stress and burnout in hospital medicine have been exacerbated by COVID-19. Even physicians who consider themselves healthy may have little emotional reserve to draw upon in a crisis of this magnitude.

“We are social distancing at work, wearing masks, not eating together with our colleagues – with less camaraderie and social support than we used to have,” she said. “I feel exhausted and there’s no question that my colleagues and I have sacrificed a lot to deal with the pandemic.” Add to that the second front of the COVID-19 crisis, Dr. Barnes said, which is “fighting the medical information wars, trying to correct misinformation put out there by people. Physicians who have been on the front lines of the pandemic know how demoralizing it can be to have people negate your first-hand experience.”

The situation has gotten better in Sioux Falls, Dr. Barnes said, although cases have started rising in the state again. The stress, while not gone, is reduced. For some doctors, “COVID reminded us of why we do what we do. Some of the usual bureaucratic requirements were set aside and we could focus on what our patients needed and how to take care of them.”

Taking job stress seriously

Tiffani Panek, MA, SFHM, CLHM, administrator of the division of hospital medicine at Johns Hopkins Bayview Medical Center in Baltimore, said job stress is a major issue for hospitalist groups.

“We take it seriously here, and use a survey tool to measure morale in our group annually,” she said. “So far, knock on wood, Baltimore has not been one of the big hot spots, but we’ve definitely had waves of COVID patients.”

The Bayview hospitalist group has a diversified set of leaders, including a wellness director. “They’re always checking up on our people, keeping an eye on those who are most vulnerable. One of the stressors we hadn’t thought about before was for our people who live alone. With the isolation and lockdown, they haven’t been able to socialize, so we’ve made direct outreach, asking people how they were doing,” Ms. Panek said. “People know we’ve got their back – professionally and personally. They know, if there’s something we can do to help, we will do it.”

Bayview Medical Center has COVID-specific units and non-COVID units, and has tried to rotate hospitalist assignments because more than a couple days in a row spent wearing full personal protective equipment (PPE) is exhausting, Ms. Panek said. The group also allocated a respite room just outside the biocontainment unit, with a computer and opportunities for providers to just sit and take a breather – with appropriate social distancing. “It’s not fancy, but you just have to wear a mask, not full PPE.”

The Hopkins hospitalist group’s wellness director, Catherine Washburn, MD, also a working hospitalist, said providers are exhausted, and trying to transition to the new normal is a moving target.

“It’s hard for anyone to say what our lives will look like in 6 months,” she said. “People in our group have lost family members to COVID, or postponed major life events, like weddings. We acknowledge losses together as a group, and celebrate things worth celebrating, like babies or birthdays.”

Greatest COVID caseload

Joshua Case, MD, hospitalist medical director for 16 acute care hospitals of Northwell Health serving metropolitan New York City and Long Island, said his group’s hospitalists and other staff worked incredibly hard during the surge of COVID-19 patients in New York. “Northwell likely cared for more COVID patients than any other health care system in the U.S., if not the world.

“It’s vastly different now. We went from a peak of thousands of cases per day down to about 70-90 new cases a day across our system. We’re lucky our system recognized that COVID could be an issue early on, with all of the multifaceted stressors on patient care,” Dr. Case said. “We’ve done whatever we could to give people time off, especially as the census started to come down. We freed up as many supportive mental health services as we could, working with the health system’s employee assistance program.”

Northwell gave out numbers for the psychiatry department, with clinicians available 24/7 for a confidential call, along with outside volunteers and a network of trauma psychologists. “Our system also provided emergency child care for staff, including hospitalists, wherever we could, drawing upon community resources,” Dr. Case added.

“We recognize that we’re all in the same foxhole. That’s been a helpful attitude – recognizing that it’s okay to be upset in a crisis and to have trouble dealing with what’s going on,” he said. “We need to acknowledge that some of us are suffering and try to encourage people to face it head on. For a lot of physicians, especially those who were redeployed here from other departments, it was important just to have us ask if they were doing okay.”

Brian Schroeder, MHA, FACHE, FHM, assistant vice president for hospital and emergency medicine for Atrium Health, based in Charlotte, N.C., said one of the biggest sources of stress on his staff has been the constant pace of change – whether local hospital protocols, state policies, or guidelines from the Centers for Disease Control and Prevention. “The updating is difficult to keep up with. A lot of our physicians get worried and anxious that they’re not following the latest guidelines or correctly doing what they should be doing to care for COVID patients. One thing we’ve done to alleviate some of that fear and anxiety is through weekly huddles with our hospital teams, focusing on changes relevant to their work. We also have weekly ‘all-hands’ meetings for our 250 providers across 13 acute and four postacute facilities.”

Before COVID, it was difficult to get everyone together as one big group from hospitals up to 5 hours apart, but with the Microsoft Teams platform, they can all meet together.

“At the height of the pandemic, we’d convene weekly and share national statistics, organizational statistics, testing updates, changes to protocols,” Mr. Schroeder said. As the pace of change has slowed, these meetings were cut back to monthly. “Our physicians feel we are passing on information as soon as we get it. They know we’ll always tell them what we know.”

Sarah Richards, MD, assistant professor of internal medicine at the University of Nebraska, Omaha, who heads the Society of Hospital Medicine’s Well-Being Task Force, formed to address staff stress in the COVID environment, said there are things that health care systems can do to help mitigate job stress and burnout. But broader issues may need to be addressed at a national level. “SHM is trying to understand work-related stress – and to identify resources that could support doctors, so they can spend more of their time doing what they enjoy most, which is taking care of patients,” she said.

“We also recognize that people have had very different experiences, depending on geography, and at the individual level stressors are experienced very differently,” Dr. Richard noted. “One of the most common stressors we’ve heard from doctors is the challenge of caring for patients who are lonely and isolated in their hospital rooms, suffering and dying in new ways. In low-incidence areas, doctors are expressing guilt because they aren’t under as much stress as their colleagues. In high-incidence areas, doctors are already experiencing posttraumatic stress disorder.”

SHM’s Well-Being Task Force is working on a tool to help normalize these stressors and encourage open conversations about mental health issues. A guide called “HM COVID Check-in Guide for Self & Peers” is designed to help hospitalists break the culture of silence around well-being and burnout during COVID-19 and how people are handling and processing the pandemic experience. It is expected to be completed later this year, Dr. Richards said. Other SHM projects and resources for staff support are also in the works.

The impact on women doctors

In a recent Journal of Hospital Medicine article entitled “Collateral Damage: How COVID-19 is Adversely Impacting Women Physicians,” hospitalist Yemisi Jones, MD, medical director of continuing medical education at Cincinnati Children’s Hospital Medical Center, and colleagues argue that preexisting gender inequities in compensation, academic rank and leadership positions for physicians have made the COVID-19 crisis even more burdensome on female hospitalists.1

“Increased childcare and schooling obligations, coupled with disproportionate household responsibilities and an inability to work from home, will likely result in female hospitalists struggling to meet family needs while pandemic-related work responsibilities are ramping up,” they write. COVID may intensify workplace inequalities, with a lack of recognition of the undue strain that group policies place on women.

“Often women suffer in silence,” said coauthor Jennifer O’Toole, MD, MEd, director of education in the division of hospital medicine at Cincinnati Children’s Hospital Medical Center and program director of the internal medicine–pediatrics residency. “We are not always the best self-advocates, although many of us are working on that.”

When women in hospital medicine take leadership roles, these often tend to involve mutual support activities, taking care of colleagues, and promoting collaborative work environments, Dr. Jones added. The stereotypical example is the committee that organizes celebrations when group members get married or have babies.

These activities can take a lot of time, she said. “We need to pay attention to that kind of role in our groups, because it’s important to the cohesiveness of the group. But it often goes unrecognized and doesn’t translate into the currency of promotion and leadership in medicine. When women go for promotions in the future, how will what happened during the COVID crisis impact their opportunities?”

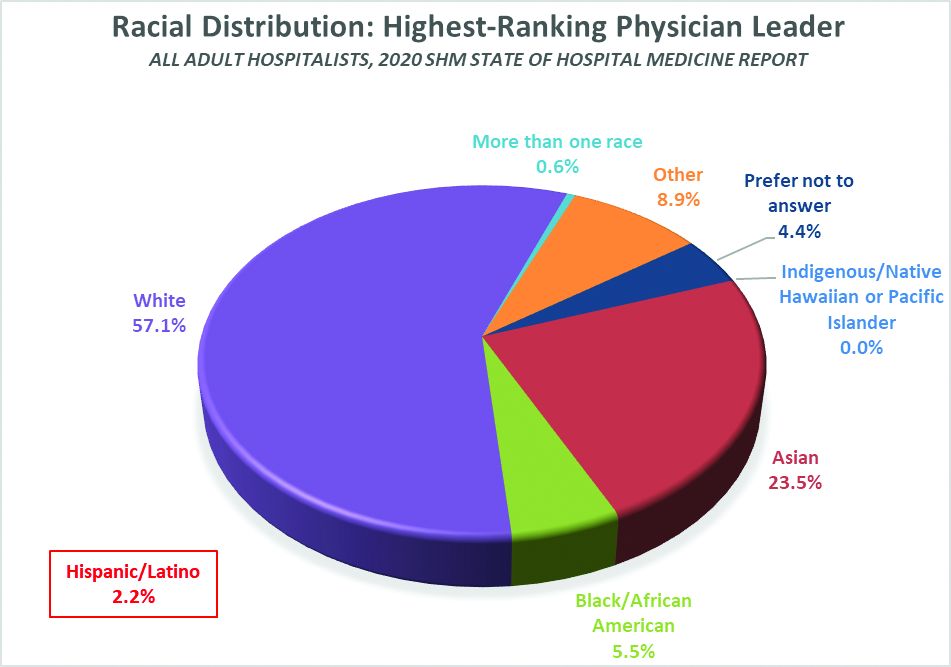

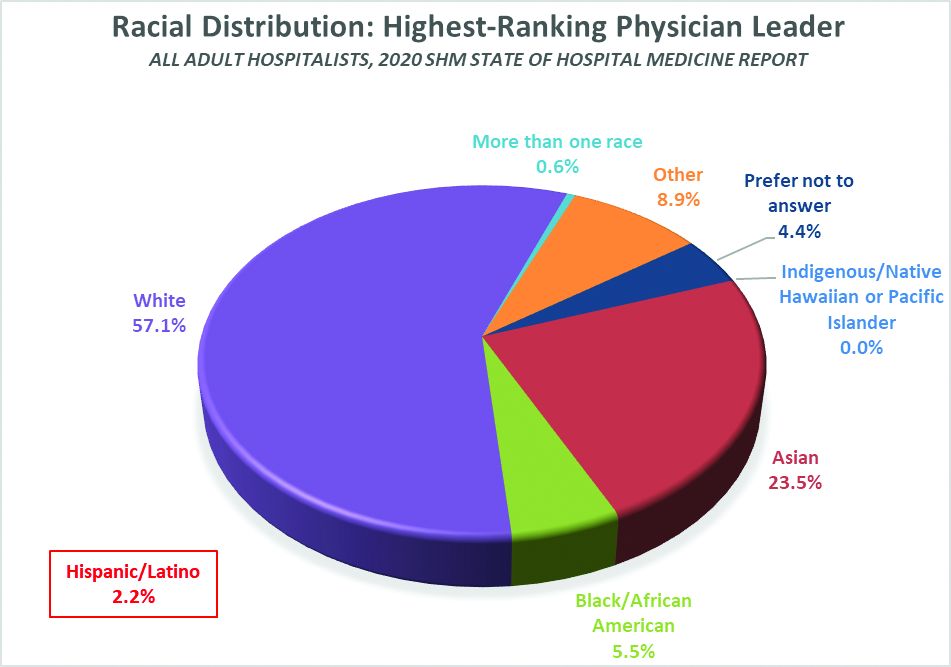

What is the answer to overcoming these systemic inequities? Start with making sure women are part of the leadership team, with responsibilities for group policies, schedules, and other important decisions. “Look at your group’s leadership – particularly the higher positions. If it’s not diverse, ask why. ‘What is it about the structure of our group?’ Make a more concerted effort in your recruitment and retention,” Dr. Jones said.

The JHM article also recommends closely monitoring the direct and indirect effects of COVID-19 on female hospitalists, inquiring specifically about the needs of women in the organization, and ensuring that diversity, inclusion, and equity efforts are not suspended during the pandemic. Gender-based disparities in pay also need a closer look, and not just one time but reviewed periodically and adjusted accordingly.

Mentoring for early career women is important, but more so is sponsorship – someone in a high-level leadership role in the group sponsoring women who are rising up the career ladder, Dr. O’Toole said. “Professional women tend to be overmentored and undersponsored.”

What are the answers?

Ultimately, listening is key to try to help people get through the pandemic, Dr. Washburn said. “People become burned out when they feel leadership doesn’t understand their needs or doesn’t hear their concerns. Our group leaders all do clinical work, so they are seen as one of us. They try very hard; they have listening ears. But listening is just the first step. Next step is to work creatively to get the identified needs met.”

A few years ago, Johns Hopkins developed training in enhanced communication in health care for all hospital providers, including nurses and doctors, encouraging them to get trained in how to actively listen and address their patients’ emotional and social experiences as well as disease, Dr. Washburn explained. Learning how to listen better to patients can enhance skills at listening to colleagues, and vice versa. “We recognize the importance of better communication – for reducing sentinel events in the hospital and also for preventing staff burnout.”

Dr. Barnes also does physician coaching, and says a lot of that work is helping people achieve clarity on their core values. “Healing patients is a core identify for physicians; we want to take care of people. But other things can get in the way of that, and hospitalist groups can work at minimizing those barriers. We also need to learn, as hospitalists, that we work in a group. You need to be creative in how you do your team building, especially now, when you can no longer get together for dinner. Whatever it is, how do we bring our team back together? The biggest source of support for many hospitalists, beyond their family, is the group.”

Dr. Case said there is a longer-term need to study the root causes of burnout in hospitalists and to identify the issues that cause job stress. “What is modifiable? How can we tackle it? I see that as big part of my job every day. Being a physician is hard enough as it is. Let’s work to resolve those issues that add needlessly to the stress.”

“I think the pandemic brought a magnifying glass to how important a concern staff stress is,” Ms. Panek said. Resilience is important.

“We were working in our group on creating a culture that values trust and transparency, and then the COVID crisis hit,” she said. “But you can still keep working on those things. We would not have been as good or as positive as we were in managing this crisis without that preexisting culture to draw upon. We always said it was important. Now we know that’s true.”

Reference

1. Jones Y et al. Collateral Damage: How COVID-19 Is Adversely Impacting Women Physicians. J Hosp Med. 2020 August;15(8):507-9.

New kinds of job stress multiply in unusual times

New kinds of job stress multiply in unusual times

Clarissa Barnes, MD, a hospitalist at Avera McKennan Hospital in Sioux Falls, S.D., and until recently medical director of Avera’s LIGHT Program, a wellness-oriented service for doctors, nurse practitioners, and physician assistants, watched the COVID-19 crisis unfold up close in her community and her hospital. Sioux Falls traced its surge of COVID patients to an outbreak at a local meatpacking plant.

“In the beginning, we didn’t know much about the virus and its communicability, although we have since gotten a better handle on that,” she said. “We had questions: Should we give patients more fluids – or less? Steroids or not? In my experience as a hospitalist I never had patients die every day on my shift, but that was happening with COVID.” The crisis imposed serious stresses on frontline providers, and hospitalists were concerned about personal safety and exposure risk – not just for themselves but for their families.

“The first time I worked on the COVID unit, I moved into the guest room in our home, apart from my husband and our young children,” Dr. Barnes said. “Ultimately I caught the virus, although I have since recovered.” Her experience has highlighted how existing issues of job stress and burnout in hospital medicine have been exacerbated by COVID-19. Even physicians who consider themselves healthy may have little emotional reserve to draw upon in a crisis of this magnitude.

“We are social distancing at work, wearing masks, not eating together with our colleagues – with less camaraderie and social support than we used to have,” she said. “I feel exhausted and there’s no question that my colleagues and I have sacrificed a lot to deal with the pandemic.” Add to that the second front of the COVID-19 crisis, Dr. Barnes said, which is “fighting the medical information wars, trying to correct misinformation put out there by people. Physicians who have been on the front lines of the pandemic know how demoralizing it can be to have people negate your first-hand experience.”

The situation has gotten better in Sioux Falls, Dr. Barnes said, although cases have started rising in the state again. The stress, while not gone, is reduced. For some doctors, “COVID reminded us of why we do what we do. Some of the usual bureaucratic requirements were set aside and we could focus on what our patients needed and how to take care of them.”

Taking job stress seriously

Tiffani Panek, MA, SFHM, CLHM, administrator of the division of hospital medicine at Johns Hopkins Bayview Medical Center in Baltimore, said job stress is a major issue for hospitalist groups.

“We take it seriously here, and use a survey tool to measure morale in our group annually,” she said. “So far, knock on wood, Baltimore has not been one of the big hot spots, but we’ve definitely had waves of COVID patients.”

The Bayview hospitalist group has a diversified set of leaders, including a wellness director. “They’re always checking up on our people, keeping an eye on those who are most vulnerable. One of the stressors we hadn’t thought about before was for our people who live alone. With the isolation and lockdown, they haven’t been able to socialize, so we’ve made direct outreach, asking people how they were doing,” Ms. Panek said. “People know we’ve got their back – professionally and personally. They know, if there’s something we can do to help, we will do it.”

Bayview Medical Center has COVID-specific units and non-COVID units, and has tried to rotate hospitalist assignments because more than a couple days in a row spent wearing full personal protective equipment (PPE) is exhausting, Ms. Panek said. The group also allocated a respite room just outside the biocontainment unit, with a computer and opportunities for providers to just sit and take a breather – with appropriate social distancing. “It’s not fancy, but you just have to wear a mask, not full PPE.”

The Hopkins hospitalist group’s wellness director, Catherine Washburn, MD, also a working hospitalist, said providers are exhausted, and trying to transition to the new normal is a moving target.

“It’s hard for anyone to say what our lives will look like in 6 months,” she said. “People in our group have lost family members to COVID, or postponed major life events, like weddings. We acknowledge losses together as a group, and celebrate things worth celebrating, like babies or birthdays.”

Greatest COVID caseload

Joshua Case, MD, hospitalist medical director for 16 acute care hospitals of Northwell Health serving metropolitan New York City and Long Island, said his group’s hospitalists and other staff worked incredibly hard during the surge of COVID-19 patients in New York. “Northwell likely cared for more COVID patients than any other health care system in the U.S., if not the world.

“It’s vastly different now. We went from a peak of thousands of cases per day down to about 70-90 new cases a day across our system. We’re lucky our system recognized that COVID could be an issue early on, with all of the multifaceted stressors on patient care,” Dr. Case said. “We’ve done whatever we could to give people time off, especially as the census started to come down. We freed up as many supportive mental health services as we could, working with the health system’s employee assistance program.”

Northwell gave out numbers for the psychiatry department, with clinicians available 24/7 for a confidential call, along with outside volunteers and a network of trauma psychologists. “Our system also provided emergency child care for staff, including hospitalists, wherever we could, drawing upon community resources,” Dr. Case added.

“We recognize that we’re all in the same foxhole. That’s been a helpful attitude – recognizing that it’s okay to be upset in a crisis and to have trouble dealing with what’s going on,” he said. “We need to acknowledge that some of us are suffering and try to encourage people to face it head on. For a lot of physicians, especially those who were redeployed here from other departments, it was important just to have us ask if they were doing okay.”

Brian Schroeder, MHA, FACHE, FHM, assistant vice president for hospital and emergency medicine for Atrium Health, based in Charlotte, N.C., said one of the biggest sources of stress on his staff has been the constant pace of change – whether local hospital protocols, state policies, or guidelines from the Centers for Disease Control and Prevention. “The updating is difficult to keep up with. A lot of our physicians get worried and anxious that they’re not following the latest guidelines or correctly doing what they should be doing to care for COVID patients. One thing we’ve done to alleviate some of that fear and anxiety is through weekly huddles with our hospital teams, focusing on changes relevant to their work. We also have weekly ‘all-hands’ meetings for our 250 providers across 13 acute and four postacute facilities.”

Before COVID, it was difficult to get everyone together as one big group from hospitals up to 5 hours apart, but with the Microsoft Teams platform, they can all meet together.

“At the height of the pandemic, we’d convene weekly and share national statistics, organizational statistics, testing updates, changes to protocols,” Mr. Schroeder said. As the pace of change has slowed, these meetings were cut back to monthly. “Our physicians feel we are passing on information as soon as we get it. They know we’ll always tell them what we know.”

Sarah Richards, MD, assistant professor of internal medicine at the University of Nebraska, Omaha, who heads the Society of Hospital Medicine’s Well-Being Task Force, formed to address staff stress in the COVID environment, said there are things that health care systems can do to help mitigate job stress and burnout. But broader issues may need to be addressed at a national level. “SHM is trying to understand work-related stress – and to identify resources that could support doctors, so they can spend more of their time doing what they enjoy most, which is taking care of patients,” she said.

“We also recognize that people have had very different experiences, depending on geography, and at the individual level stressors are experienced very differently,” Dr. Richard noted. “One of the most common stressors we’ve heard from doctors is the challenge of caring for patients who are lonely and isolated in their hospital rooms, suffering and dying in new ways. In low-incidence areas, doctors are expressing guilt because they aren’t under as much stress as their colleagues. In high-incidence areas, doctors are already experiencing posttraumatic stress disorder.”

SHM’s Well-Being Task Force is working on a tool to help normalize these stressors and encourage open conversations about mental health issues. A guide called “HM COVID Check-in Guide for Self & Peers” is designed to help hospitalists break the culture of silence around well-being and burnout during COVID-19 and how people are handling and processing the pandemic experience. It is expected to be completed later this year, Dr. Richards said. Other SHM projects and resources for staff support are also in the works.

The impact on women doctors

In a recent Journal of Hospital Medicine article entitled “Collateral Damage: How COVID-19 is Adversely Impacting Women Physicians,” hospitalist Yemisi Jones, MD, medical director of continuing medical education at Cincinnati Children’s Hospital Medical Center, and colleagues argue that preexisting gender inequities in compensation, academic rank and leadership positions for physicians have made the COVID-19 crisis even more burdensome on female hospitalists.1

“Increased childcare and schooling obligations, coupled with disproportionate household responsibilities and an inability to work from home, will likely result in female hospitalists struggling to meet family needs while pandemic-related work responsibilities are ramping up,” they write. COVID may intensify workplace inequalities, with a lack of recognition of the undue strain that group policies place on women.

“Often women suffer in silence,” said coauthor Jennifer O’Toole, MD, MEd, director of education in the division of hospital medicine at Cincinnati Children’s Hospital Medical Center and program director of the internal medicine–pediatrics residency. “We are not always the best self-advocates, although many of us are working on that.”

When women in hospital medicine take leadership roles, these often tend to involve mutual support activities, taking care of colleagues, and promoting collaborative work environments, Dr. Jones added. The stereotypical example is the committee that organizes celebrations when group members get married or have babies.

These activities can take a lot of time, she said. “We need to pay attention to that kind of role in our groups, because it’s important to the cohesiveness of the group. But it often goes unrecognized and doesn’t translate into the currency of promotion and leadership in medicine. When women go for promotions in the future, how will what happened during the COVID crisis impact their opportunities?”

What is the answer to overcoming these systemic inequities? Start with making sure women are part of the leadership team, with responsibilities for group policies, schedules, and other important decisions. “Look at your group’s leadership – particularly the higher positions. If it’s not diverse, ask why. ‘What is it about the structure of our group?’ Make a more concerted effort in your recruitment and retention,” Dr. Jones said.

The JHM article also recommends closely monitoring the direct and indirect effects of COVID-19 on female hospitalists, inquiring specifically about the needs of women in the organization, and ensuring that diversity, inclusion, and equity efforts are not suspended during the pandemic. Gender-based disparities in pay also need a closer look, and not just one time but reviewed periodically and adjusted accordingly.

Mentoring for early career women is important, but more so is sponsorship – someone in a high-level leadership role in the group sponsoring women who are rising up the career ladder, Dr. O’Toole said. “Professional women tend to be overmentored and undersponsored.”

What are the answers?

Ultimately, listening is key to try to help people get through the pandemic, Dr. Washburn said. “People become burned out when they feel leadership doesn’t understand their needs or doesn’t hear their concerns. Our group leaders all do clinical work, so they are seen as one of us. They try very hard; they have listening ears. But listening is just the first step. Next step is to work creatively to get the identified needs met.”

A few years ago, Johns Hopkins developed training in enhanced communication in health care for all hospital providers, including nurses and doctors, encouraging them to get trained in how to actively listen and address their patients’ emotional and social experiences as well as disease, Dr. Washburn explained. Learning how to listen better to patients can enhance skills at listening to colleagues, and vice versa. “We recognize the importance of better communication – for reducing sentinel events in the hospital and also for preventing staff burnout.”

Dr. Barnes also does physician coaching, and says a lot of that work is helping people achieve clarity on their core values. “Healing patients is a core identify for physicians; we want to take care of people. But other things can get in the way of that, and hospitalist groups can work at minimizing those barriers. We also need to learn, as hospitalists, that we work in a group. You need to be creative in how you do your team building, especially now, when you can no longer get together for dinner. Whatever it is, how do we bring our team back together? The biggest source of support for many hospitalists, beyond their family, is the group.”

Dr. Case said there is a longer-term need to study the root causes of burnout in hospitalists and to identify the issues that cause job stress. “What is modifiable? How can we tackle it? I see that as big part of my job every day. Being a physician is hard enough as it is. Let’s work to resolve those issues that add needlessly to the stress.”

“I think the pandemic brought a magnifying glass to how important a concern staff stress is,” Ms. Panek said. Resilience is important.

“We were working in our group on creating a culture that values trust and transparency, and then the COVID crisis hit,” she said. “But you can still keep working on those things. We would not have been as good or as positive as we were in managing this crisis without that preexisting culture to draw upon. We always said it was important. Now we know that’s true.”

Reference

1. Jones Y et al. Collateral Damage: How COVID-19 Is Adversely Impacting Women Physicians. J Hosp Med. 2020 August;15(8):507-9.

Clarissa Barnes, MD, a hospitalist at Avera McKennan Hospital in Sioux Falls, S.D., and until recently medical director of Avera’s LIGHT Program, a wellness-oriented service for doctors, nurse practitioners, and physician assistants, watched the COVID-19 crisis unfold up close in her community and her hospital. Sioux Falls traced its surge of COVID patients to an outbreak at a local meatpacking plant.

“In the beginning, we didn’t know much about the virus and its communicability, although we have since gotten a better handle on that,” she said. “We had questions: Should we give patients more fluids – or less? Steroids or not? In my experience as a hospitalist I never had patients die every day on my shift, but that was happening with COVID.” The crisis imposed serious stresses on frontline providers, and hospitalists were concerned about personal safety and exposure risk – not just for themselves but for their families.

“The first time I worked on the COVID unit, I moved into the guest room in our home, apart from my husband and our young children,” Dr. Barnes said. “Ultimately I caught the virus, although I have since recovered.” Her experience has highlighted how existing issues of job stress and burnout in hospital medicine have been exacerbated by COVID-19. Even physicians who consider themselves healthy may have little emotional reserve to draw upon in a crisis of this magnitude.

“We are social distancing at work, wearing masks, not eating together with our colleagues – with less camaraderie and social support than we used to have,” she said. “I feel exhausted and there’s no question that my colleagues and I have sacrificed a lot to deal with the pandemic.” Add to that the second front of the COVID-19 crisis, Dr. Barnes said, which is “fighting the medical information wars, trying to correct misinformation put out there by people. Physicians who have been on the front lines of the pandemic know how demoralizing it can be to have people negate your first-hand experience.”

The situation has gotten better in Sioux Falls, Dr. Barnes said, although cases have started rising in the state again. The stress, while not gone, is reduced. For some doctors, “COVID reminded us of why we do what we do. Some of the usual bureaucratic requirements were set aside and we could focus on what our patients needed and how to take care of them.”

Taking job stress seriously

Tiffani Panek, MA, SFHM, CLHM, administrator of the division of hospital medicine at Johns Hopkins Bayview Medical Center in Baltimore, said job stress is a major issue for hospitalist groups.

“We take it seriously here, and use a survey tool to measure morale in our group annually,” she said. “So far, knock on wood, Baltimore has not been one of the big hot spots, but we’ve definitely had waves of COVID patients.”

The Bayview hospitalist group has a diversified set of leaders, including a wellness director. “They’re always checking up on our people, keeping an eye on those who are most vulnerable. One of the stressors we hadn’t thought about before was for our people who live alone. With the isolation and lockdown, they haven’t been able to socialize, so we’ve made direct outreach, asking people how they were doing,” Ms. Panek said. “People know we’ve got their back – professionally and personally. They know, if there’s something we can do to help, we will do it.”

Bayview Medical Center has COVID-specific units and non-COVID units, and has tried to rotate hospitalist assignments because more than a couple days in a row spent wearing full personal protective equipment (PPE) is exhausting, Ms. Panek said. The group also allocated a respite room just outside the biocontainment unit, with a computer and opportunities for providers to just sit and take a breather – with appropriate social distancing. “It’s not fancy, but you just have to wear a mask, not full PPE.”

The Hopkins hospitalist group’s wellness director, Catherine Washburn, MD, also a working hospitalist, said providers are exhausted, and trying to transition to the new normal is a moving target.

“It’s hard for anyone to say what our lives will look like in 6 months,” she said. “People in our group have lost family members to COVID, or postponed major life events, like weddings. We acknowledge losses together as a group, and celebrate things worth celebrating, like babies or birthdays.”

Greatest COVID caseload

Joshua Case, MD, hospitalist medical director for 16 acute care hospitals of Northwell Health serving metropolitan New York City and Long Island, said his group’s hospitalists and other staff worked incredibly hard during the surge of COVID-19 patients in New York. “Northwell likely cared for more COVID patients than any other health care system in the U.S., if not the world.

“It’s vastly different now. We went from a peak of thousands of cases per day down to about 70-90 new cases a day across our system. We’re lucky our system recognized that COVID could be an issue early on, with all of the multifaceted stressors on patient care,” Dr. Case said. “We’ve done whatever we could to give people time off, especially as the census started to come down. We freed up as many supportive mental health services as we could, working with the health system’s employee assistance program.”

Northwell gave out numbers for the psychiatry department, with clinicians available 24/7 for a confidential call, along with outside volunteers and a network of trauma psychologists. “Our system also provided emergency child care for staff, including hospitalists, wherever we could, drawing upon community resources,” Dr. Case added.

“We recognize that we’re all in the same foxhole. That’s been a helpful attitude – recognizing that it’s okay to be upset in a crisis and to have trouble dealing with what’s going on,” he said. “We need to acknowledge that some of us are suffering and try to encourage people to face it head on. For a lot of physicians, especially those who were redeployed here from other departments, it was important just to have us ask if they were doing okay.”

Brian Schroeder, MHA, FACHE, FHM, assistant vice president for hospital and emergency medicine for Atrium Health, based in Charlotte, N.C., said one of the biggest sources of stress on his staff has been the constant pace of change – whether local hospital protocols, state policies, or guidelines from the Centers for Disease Control and Prevention. “The updating is difficult to keep up with. A lot of our physicians get worried and anxious that they’re not following the latest guidelines or correctly doing what they should be doing to care for COVID patients. One thing we’ve done to alleviate some of that fear and anxiety is through weekly huddles with our hospital teams, focusing on changes relevant to their work. We also have weekly ‘all-hands’ meetings for our 250 providers across 13 acute and four postacute facilities.”

Before COVID, it was difficult to get everyone together as one big group from hospitals up to 5 hours apart, but with the Microsoft Teams platform, they can all meet together.

“At the height of the pandemic, we’d convene weekly and share national statistics, organizational statistics, testing updates, changes to protocols,” Mr. Schroeder said. As the pace of change has slowed, these meetings were cut back to monthly. “Our physicians feel we are passing on information as soon as we get it. They know we’ll always tell them what we know.”

Sarah Richards, MD, assistant professor of internal medicine at the University of Nebraska, Omaha, who heads the Society of Hospital Medicine’s Well-Being Task Force, formed to address staff stress in the COVID environment, said there are things that health care systems can do to help mitigate job stress and burnout. But broader issues may need to be addressed at a national level. “SHM is trying to understand work-related stress – and to identify resources that could support doctors, so they can spend more of their time doing what they enjoy most, which is taking care of patients,” she said.

“We also recognize that people have had very different experiences, depending on geography, and at the individual level stressors are experienced very differently,” Dr. Richard noted. “One of the most common stressors we’ve heard from doctors is the challenge of caring for patients who are lonely and isolated in their hospital rooms, suffering and dying in new ways. In low-incidence areas, doctors are expressing guilt because they aren’t under as much stress as their colleagues. In high-incidence areas, doctors are already experiencing posttraumatic stress disorder.”

SHM’s Well-Being Task Force is working on a tool to help normalize these stressors and encourage open conversations about mental health issues. A guide called “HM COVID Check-in Guide for Self & Peers” is designed to help hospitalists break the culture of silence around well-being and burnout during COVID-19 and how people are handling and processing the pandemic experience. It is expected to be completed later this year, Dr. Richards said. Other SHM projects and resources for staff support are also in the works.

The impact on women doctors

In a recent Journal of Hospital Medicine article entitled “Collateral Damage: How COVID-19 is Adversely Impacting Women Physicians,” hospitalist Yemisi Jones, MD, medical director of continuing medical education at Cincinnati Children’s Hospital Medical Center, and colleagues argue that preexisting gender inequities in compensation, academic rank and leadership positions for physicians have made the COVID-19 crisis even more burdensome on female hospitalists.1

“Increased childcare and schooling obligations, coupled with disproportionate household responsibilities and an inability to work from home, will likely result in female hospitalists struggling to meet family needs while pandemic-related work responsibilities are ramping up,” they write. COVID may intensify workplace inequalities, with a lack of recognition of the undue strain that group policies place on women.

“Often women suffer in silence,” said coauthor Jennifer O’Toole, MD, MEd, director of education in the division of hospital medicine at Cincinnati Children’s Hospital Medical Center and program director of the internal medicine–pediatrics residency. “We are not always the best self-advocates, although many of us are working on that.”

When women in hospital medicine take leadership roles, these often tend to involve mutual support activities, taking care of colleagues, and promoting collaborative work environments, Dr. Jones added. The stereotypical example is the committee that organizes celebrations when group members get married or have babies.

These activities can take a lot of time, she said. “We need to pay attention to that kind of role in our groups, because it’s important to the cohesiveness of the group. But it often goes unrecognized and doesn’t translate into the currency of promotion and leadership in medicine. When women go for promotions in the future, how will what happened during the COVID crisis impact their opportunities?”

What is the answer to overcoming these systemic inequities? Start with making sure women are part of the leadership team, with responsibilities for group policies, schedules, and other important decisions. “Look at your group’s leadership – particularly the higher positions. If it’s not diverse, ask why. ‘What is it about the structure of our group?’ Make a more concerted effort in your recruitment and retention,” Dr. Jones said.

The JHM article also recommends closely monitoring the direct and indirect effects of COVID-19 on female hospitalists, inquiring specifically about the needs of women in the organization, and ensuring that diversity, inclusion, and equity efforts are not suspended during the pandemic. Gender-based disparities in pay also need a closer look, and not just one time but reviewed periodically and adjusted accordingly.

Mentoring for early career women is important, but more so is sponsorship – someone in a high-level leadership role in the group sponsoring women who are rising up the career ladder, Dr. O’Toole said. “Professional women tend to be overmentored and undersponsored.”

What are the answers?

Ultimately, listening is key to try to help people get through the pandemic, Dr. Washburn said. “People become burned out when they feel leadership doesn’t understand their needs or doesn’t hear their concerns. Our group leaders all do clinical work, so they are seen as one of us. They try very hard; they have listening ears. But listening is just the first step. Next step is to work creatively to get the identified needs met.”

A few years ago, Johns Hopkins developed training in enhanced communication in health care for all hospital providers, including nurses and doctors, encouraging them to get trained in how to actively listen and address their patients’ emotional and social experiences as well as disease, Dr. Washburn explained. Learning how to listen better to patients can enhance skills at listening to colleagues, and vice versa. “We recognize the importance of better communication – for reducing sentinel events in the hospital and also for preventing staff burnout.”

Dr. Barnes also does physician coaching, and says a lot of that work is helping people achieve clarity on their core values. “Healing patients is a core identify for physicians; we want to take care of people. But other things can get in the way of that, and hospitalist groups can work at minimizing those barriers. We also need to learn, as hospitalists, that we work in a group. You need to be creative in how you do your team building, especially now, when you can no longer get together for dinner. Whatever it is, how do we bring our team back together? The biggest source of support for many hospitalists, beyond their family, is the group.”

Dr. Case said there is a longer-term need to study the root causes of burnout in hospitalists and to identify the issues that cause job stress. “What is modifiable? How can we tackle it? I see that as big part of my job every day. Being a physician is hard enough as it is. Let’s work to resolve those issues that add needlessly to the stress.”

“I think the pandemic brought a magnifying glass to how important a concern staff stress is,” Ms. Panek said. Resilience is important.

“We were working in our group on creating a culture that values trust and transparency, and then the COVID crisis hit,” she said. “But you can still keep working on those things. We would not have been as good or as positive as we were in managing this crisis without that preexisting culture to draw upon. We always said it was important. Now we know that’s true.”

Reference

1. Jones Y et al. Collateral Damage: How COVID-19 Is Adversely Impacting Women Physicians. J Hosp Med. 2020 August;15(8):507-9.

The authority/accountability balance

Evaluating your career trajectory

I have had the pleasure of working on the Society of Hospital Medicine’s signature Leadership Academies since 2010, and I enjoy working with hospital medicine leaders from around the country every year. I started as a hospital medicine leader in 2000 and served during the unprecedented growth of the field when it was “the most rapidly growing specialty in the history of medicine.”

Most businesses dream of having a year of double-digit growth; my department grew an average of 15% annually for more than 10 years. These unique experiences have taught me many lessons and afforded me the opportunity to watch many stars of hospital medicine rise, as well as to learn from several less-scrupulous leaders about the darker side of hospital politics.

One of the lessons I learned the hard way about hospital politics is striking the “Authority/Accountability balance” in your career. I shared this perspective at the SHM annual conference in 2018, at speaking engagements on the West Coast, and with my leadership group at the academies. I am sharing it with you because the feedback I have received has been very positive.

The Authority/Accountability balance is a tool for evaluating your current career trajectory and measuring if it is set up for success or failure. The essence is that your Authority and Accountability need to be balanced for you to be successful in your career, regardless of your station. Everybody from the hospitalist fresh out of residency to the CEO needs to have Authority and Accountability in balance to be successful. And as you use the tool to measure your own potential for success or failure, learn to apply it to those who report to you.

I believe the rising tide lifts all boats and the success of your subordinates, through mentoring and support, will add to your success. There is another, more cynical view of subordinates that can be identified using the Authority/Accountability balance, which I will address.

Authority

In this construct, “Authority” has a much broader meaning than just the ability to tell people what to do. The ability to tell people what to do is important but not sufficient for success in hospital politics.

Financial resources are essential for a successful Authority/Accountability balance – not only the hardware such as computers, telephones, pagers, and so on, but also clerical support, technical support, and analytic support so that you are getting high-quality data on the performance of the members of your hospital medicine group (HMG). These “soft” resources (clerical, technical, and analytical) are often overlooked as needs that HMG leaders must advocate for; I speak with many HMG leaders who remain under-resourced with “soft” assets. However, being appropriately resourced in these areas can be transformational for a group. Hospitalists don’t like doing clerical work, and if you don’t like a menial job assigned to you, you probably won’t do it very well. Having an unlicensed person dedicated to these clerical activities not only will cost less, but will ensure the job is done better.

Reporting structure is critically important, often overlooked, and historically misaligned in HMGs. When hospital medicine was starting in the late 1990s and early 2000s, rapidly growing hospitalist groups were typically led by young, early-career physicians who had chosen hospital medicine as a career. The problem was that they often lacked the seniority and connections at the executive level to advocate for their HMG. All too often the hospitalist group was tucked in under another department or division which, in turn, reported HMG updates and issues to the board of directors and the CEO.

A common reporting structure in the early days was that a senior member of the medical staff, or group, had once worked in the hospital and therefore “understood” the issues and challenges that the hospitalists were facing. It was up to this physician with seniority and connections to advocate for the hospitalists as they saw fit. The problem was that the hospital landscape was, and is, constantly evolving in innumerable ways. These “once removed” reporting structures for HMGs failed to get the required information on the rapidly changing, and evolving, hospitalist landscape to the desks of executives who had the financial and structural control to address the challenges that the hospitalists in the trenches were facing.

Numerous HMGs failed in the early days of hospital medicine because of this type of misaligned reporting structure. This is a lesson that should not be forgotten: Make sure your HMG leader has a seat at the table where executive decisions are made, including but not limited to the board of directors. To be in balance, you have to be “in the room where it happens.”

Accountability

The outcomes that you are responsible for need to be explicit, appropriately resourced with Authority, and clearly spelled out in your job description. Your job description is a document you should know, own, and revisit regularly with whomever you report to, in order to ensure success.

Once you have the Authority side of the equation appropriately resourced, setting outcomes that are a stretch, but still realistic and achievable within the scope of your position, is critical to your success. It is good to think about short-, medium-, and long-term goals, especially if you are in a leadership role. For example, one expectation you will have, regardless of your station, is that you keep up on your email and answer your phone. These are short-term goals that will often be included in your job description. However, taking on a new hospital contract and making sure that it has 24/7 hospitalist coverage, that all the hospitalists are meeting the geometric mean length of stay, and that all the physicians are having 15 encounters per day doesn’t happen immediately. Long-term goals, such as taking on a new hospital contract, are the big-picture stuff that can make or break the career of an HMG leader. Long-term goals also need to be delineated in the job description, along with specific time stamps and the resources you need to accomplish big ticket items – which are spelled out in the Authority side (that is, physician recruiter, secretary, background checks, and so on).

One of the classic misuses of Accountability is the “Fall Guy” scenario. The Fall Guy scenario is often used by cynical hospital and medical group executives to expand their influence while limiting their liability. In the Fall Guy scenario, the executive is surrounded with junior partners who are underpowered with Authority, and then the executive makes decisions for which the junior partners are Accountable. This allows the senior executive to make risky decisions on behalf of the hospital or medical group without the liability of being held accountable when the decision-making process fails. When the risky, and often ill-informed, decision fails, the junior partner who lacked the Authority to make the decision – but held the Accountability for it – becomes the Fall Guy for the failed endeavor. This is a critical outcome that the Authority/Accountability balance can help you avoid, if you use it wisely and properly.

If you find yourself in the Fall Guy position, it is time for a change. The Authority, the Accountability, or both need to change so that they are in better balance. Or your employer needs to change. Changing employers is an outcome worth avoiding, if at all possible. I have scrutinized thousands of resumes in my career, and frequent job changes always wave a red flag to prospective employers. However, changing jobs remains a crucial option if you are being set up for failure when Authority and Accountability are out of balance.

If you are unable to negotiate for the balance that will allow you to be successful with your current group, remember that HMG leaders are a prized commodity and in short supply. Leaving a group that has been your career is hard, but it is better to leave than stay in a position where you are set up for failure as the Fall Guy. Further, the most effective time to expand your Authority is when you are negotiating the terms of a new position. Changing positions is the nuclear option. However, it is better than becoming the Fall Guy, and a change can create opportunities that will accelerate your career and influence, if done right.

When I talk about Authority/Accountability balance, I always counter the Fall Guy with an ignominious historical figure: General George B. McClellan. General McClellan was the commander of the Army of the Potomac during the early years of the American Civil War. General McClellan had the industrial might of the Union north at his beck and call, as well as extraordinary resources for recruiting and retaining soldiers for his army. At every encounter with General Robert E. Lee’s Army of Northern Virginia, General McClellan outnumbered them, sometimes by more than two to one. Yet General McClellan was outfoxed repeatedly for the same reason: He failed to take decisive action.

Every time that McClellan failed, he blamed insufficient resources and told President Lincoln that he needed more troops and more equipment to be successful. In summary, while the Fall Guy scenario needs to be avoided, once you are adequately resourced, success requires taking decisive and strategic action, or you will suffer as did General McClellan. Failing to act when you are appropriately resourced can be just as damaging to your career and credibility as allowing yourself to become the Fall Guy.

Job description

Everybody has somebody that they report to, no matter how high up on the executive ladder they have climbed. Even the CEO must report to the board of directors. And that reporting structure usually involves periodic formal reviews. Your formal review is a good time to go over your job description, note what is relevant, remove what is irrelevant, and add new elements that have evolved in importance since your last review.

Job descriptions take many forms, but they always include a list of qualifications. If you have the job, you have the qualifications, so that is not likely to change. You may become more qualified for a higher-level position, but that is an entirely different discussion. I like to think of a well-written job description as including short-term and long-term goals. Short-term goals are usually the daily stuff that keeps operations running smoothly but garners little attention. Examples would include staying current on your emails, answering your phone, organizing meetings, and regularly attending various committees. Even some of these short-term goals can and will change over time. I always enjoyed quality oversight in my department, but as the department and my responsibilities grew, I realized I couldn’t do everything that I wanted to do. I needed to focus on the things only I could do and delegate those things that could be done by someone else, even though I wanted to continue doing them myself. I created a position for a clinical quality officer, and quality oversight moved off of my job description.

Long-term goals are the aspirational items, such as increasing market share, decreasing readmissions, improving patient satisfaction, and the like. Effective leaders are often focused on these aspirational, long-term goals, but they still must effectively execute their short-term goals. Stephen Covey outlines the dilemma with the “time management matrix” in his seminal work “The 7 Habits of Highly Effective People.” An in-depth discussion is beyond the scope of this article, but the time management matrix places tasks into one of four categories based on urgency and importance, and provides strategies for staying up on short-term goals while continually moving long-term goals forward.If you show up at your review with a list of accomplishments as well as an understanding of how the “time management matrix” affects your responsibilities, your boss will be impressed. It is also worth mentioning that Covey’s first habit is “Proactivity.” He uses the term Proactivity in a much more nuanced form than we typically think of, however. Simply put, Proactivity is the opposite of Reactivity, and it is another invaluable tool for success with those long-term goals that will help you make a name for yourself.

When you show up for your review, be it annual, biannual, or other, be prepared. Not only should you bring your job description and recommendations for how it should be adapted in the changing environment, but also bring examples of your accomplishments since the last review.

I talk with leaders frequently who are hardworking and diligent and hate bragging about their achievements; I get that. At the same time, if you don’t inform your superiors about your successes, there is no guarantee that they will hear about them or understand them in the appropriate context. Bragging about how great you are in the physician’s lounge is annoying; telling your boss about your accomplishments since the last review is critical to maintaining the momentum of past accomplishments. If you are not willing to toot your own horn, there is a very good chance that your horn will remain silent. I don’t think self-promotion comes easily to anyone, and it has to be done with a degree of humility and sensitivity; but it has to be done, so prepare for it.

Look out for yourself and others

We talk about teamwork and collaboration as hospitalists, and SHM is always underscoring the importance of teamwork and highlighting examples of successful teamwork in its many conferences and publications. Most hospital executives are focused on their own careers, however, and many have no reservations about damaging your career (your brand) if they think it will promote theirs. You have to look out for yourself and size up every leadership position you get into.

Physicians can expect their careers to last decades. The average hospital CEO has a tenure of less than 3.5 years, however, and when a new CEO is hired, almost half of chief financial, chief operating, and chief information officers are fired within 9 months. You may be focused on the long-term success of your organization as you plan your career, but many hospital administrators are interested only in short-term gains. It is similar to some members of Congress who are interested only in what they need to do now to win the next election and not in the long-term needs of the country. You should understand this disconnect when dealing with hospital executives, and how you and your credibility can become cannon fodder in their quest for short-term self-preservation.

You have to look out for and take care of yourself as you promote your group. With a better understanding of the Authority/Accountability balance, you have new tools to assess your chances of success and to advocate for yourself so that you and your group can be successful.

Despite my cynicism toward executives in the medical field, I personally advocate for supporting the career development of those around you and advise against furthering your career at the expense of others. Many unscrupulous executives will use this approach, surrounding themselves with Fall Guys, but my experience shows that this is not a sustainable strategy for success. It can lead to short-term gains, but eventually the piper must be paid. Moreover, the most successful medical executives and leaders that I have encountered have been those who genuinely cared about their subordinates, looked out for them, and selflessly promoted their careers.

In the age of social media, tearing others down seems to be the fastest way to get more “likes.” However, I strongly believe that you can’t build up your group, and our profession, just by tearing people down. Lending a helping hand may bring you less attention in the short term, but such action raises your stature, creates loyalty, and leads to sustainable success for the long run.

Dr. McIlraith is the founding chairman of the Hospital Medicine Department at Mercy Medical Group in Sacramento, Calif. He received the SHM Award for Outstanding Service in Hospital Medicine in 2016 and is currently a member of the SHM Practice Management and Awards Committees, as well as the SHM Critical Care Task Force.

Sources

Quinn R. HM Turns 20: A look at the evolution of hospital medicine. The Hospitalist. 2016 August. https://www.the-hospitalist.org/hospitalist/article/121525/hm-turns-20-look-evolution-hospital-medicine

Stephen R. Covey. The 7 Habits of Highly Effective People: Powerful Lessons in Personal Change. Simon & Schuster. 1989.

10 Statistics on CEO Turnover, Recruitment. Becker’s Hospital Review. 2020. https://www.beckershospitalreview.com/hospital-management-administration/10-statistics-on-ceo-turnover-recruitment.html

Evaluating your career trajectory

Evaluating your career trajectory

I have had the pleasure of working on the Society of Hospital Medicine’s signature Leadership Academies since 2010, and I enjoy working with hospital medicine leaders from around the country every year. I started as a hospital medicine leader in 2000 and served during the unprecedented growth of the field when it was “the most rapidly growing specialty in the history of medicine.”

Most businesses dream of having a year of double-digit growth; my department grew an average of 15% annually for more than 10 years. These unique experiences have taught me many lessons and afforded me the opportunity to watch many stars of hospital medicine rise, as well as to learn from several less-scrupulous leaders about the darker side of hospital politics.

One of the lessons I learned the hard way about hospital politics is striking the “Authority/Accountability balance” in your career. I shared this perspective at the SHM annual conference in 2018, at speaking engagements on the West Coast, and with my leadership group at the academies. I am sharing it with you because the feedback I have received has been very positive.

The Authority/Accountability balance is a tool for evaluating your current career trajectory and measuring if it is set up for success or failure. The essence is that your Authority and Accountability need to be balanced for you to be successful in your career, regardless of your station. Everybody from the hospitalist fresh out of residency to the CEO needs to have Authority and Accountability in balance to be successful. And as you use the tool to measure your own potential for success or failure, learn to apply it to those who report to you.

I believe the rising tide lifts all boats and the success of your subordinates, through mentoring and support, will add to your success. There is another, more cynical view of subordinates that can be identified using the Authority/Accountability balance, which I will address.

Authority

In this construct, “Authority” has a much broader meaning than just the ability to tell people what to do. The ability to tell people what to do is important but not sufficient for success in hospital politics.