User login

Using (dynamic) ultrasound to make an earlier diagnosis of endometriosis

Can you provide some background on endometriosis and the importance of early diagnosis?

Dr. Goldstein: Endometriosis is an inflammatory condition, characterized by endometrial tissue at sites outside the uterus—this definition comes from the World Endometriosis Society.

Endometriosis is said to affect about 10% of women of reproductive age, and if you look at a group, a subset of women with pelvic pain or infertility, the numbers rise to the range of 35% to 50%. It can present in a multitude of locations, mainly in the pelvis, although occasionally even in places like the lung. When it occurs in the uterus, it is known as adenomyosis; when it occurs inside the ovary, it can cause an endometrioma (or what is sometimes referred to as chocolate cyst of the ovary), but you can see endometriotic implants anywhere in the peritoneum—along the urinary tract, rectum, uterosacral ligaments, rectovaginal septum, and even the vaginal wall occasionally.

What I am really interested in is an earlier diagnosis of superficial endometriosis, and it should be apparent to the reader why this is important—the quality of life from pain from endometriosis can be debilitating. It can be a source of infertility, a source of menstrual irregularities, and a source of not only quality of life but also economic consequences. Many women can also undergo as much as a 7-year delay in diagnosis, so the need for a timely diagnosis and initiation of treatment is extremely important.

What is the role of ultrasound in endometriosis diagnostics?

Dr. Goldstein: In an article that I authored 31 years ago, I wrote that there was a difference between an ultrasound examination by referral and examining one’s patients with ultrasound. I coined a phrase: the “ultrasound-enhanced bimanual exam.” I believed that this term should become a routine part of the overall gynecologic exam. I wanted people to think about the bimanual that we had done for at least half a century, which, in my opinion, consists of 2 components:

- An objective component: Is this uterus normal? Is it enlarged or irregular in contour, suggesting maybe fibroids? Is an ovary enlarged? If so, does it feel cystic or solid?

- A subjective component: Does this patient have tenderness through the pelvis. Is there normal mobility of the pelvic organs?

Part of the thesis was that the objective portion could be replaced by an image that could be produced in seconds, dependent on the operator’s training and availability of equipment. The subjective portion, however, depended on the experience and, often, nuance of the examiner. Lately, I have been seeking to expand that thesis by having the imager use examination as part of their overall imaging—this is the concept of dynamic imaging.

Can you expand on the concept of dynamic ultrasound in this setting?

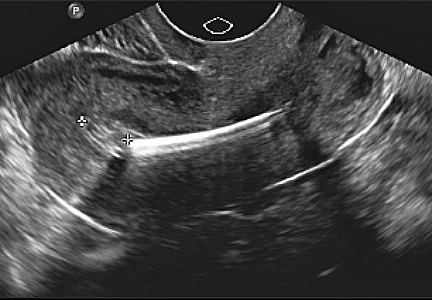

Dr. Goldstein: Presently, most imagers take a multitude of pictures, what I would call 2-dimensional snapshots, to illustrate anatomy. This is usually done by a sonographer, or a technician, who collects the images for viewing by the physician, who then often does so without holding the transducer. Increasing utilization of remote tools like teleradiology only makes this more likely, and for a minority of people who may use video clips instead of still images, they are still simply representations of anatomy. The guidelines for pelvic ultrasound are the underpinning of the expectation of those who are scanning the female pelvis. With dynamic imaging, the operator uses their other hand on the abdomen as well as some motion with the probe to see if they can elicit pain with the vaginal probe, checking for mobility, asking the patient to bear down. Whether you are a sonographer, a radiologist, or an ObGyn, dynamic imaging can bring the examination process into the imager’s hands.

Can you tell us more about the indications for pelvic sonography for endometriosis and what data can you give to support this?

Dr. Goldstein: There is a document titled “Ultrasound Examination of the Female Pelvis,” that was originally developed by the American Institute of Ultrasound in Medicine (AIUM). In this document, there are about 19 different indications for pelvic sonography (in no defined order), and it is interesting that the first indication listed is evaluation of pelvic pain. Well, I would ask you, how do you evaluate pelvic pain with a series of anatomic images? If you have a classic ovarian endometrioma, or you have a classic hydrosalpinx, you can surmise that these are the source of the pain that the patient is reporting. But how do you properly evaluate pain with just an anatomic image? Thus, the need to use dynamic assessment.

There was a concept first introduced by my colleague, Dr. Ilan Timor, known as the sliding organ sign, that was mainly used to determine if 2 structures were adherent or separate. This involved use of the abdominal hand, liberal use of the probe moving in and out, and under real-time vision, examining the patient with the ultrasound transducer; this is the concept of dynamic ultrasound. This practice can be expanded to verify if there is pelvic tenderness and can be a significant part of the nonlaparoscopic, presumptive diagnosis of endometriosis, even when there is no ovarian endometrioma.

To support this theory, I would point you toward a classic article by E Okaro and colleagues in the British Journal of OB-GYN. This study took 120 consecutive women with chronic pelvic pain who were scheduled for laparoscopy, but performed a transvaginal ultrasound prior, and they looked for anatomic abnormalities and divided this into hard markers and soft markers. Hard markers were obvious endometriomas and hydrosalpinges, while soft markers included things like reduced ovarian mobility, site-specific pelvic tenderness, and presence of loculated peritoneal fluid in the pelvis. These were typical of chronic pelvic pain patients that ranged from late teens to almost menopausal, as the average age was about 30 years old.

Patients had experienced pain for anywhere from 6 months to 12 years, but the average was about 4 years. At laparoscopy, 58% of these patients had pelvic pathology, and 42% had a normal pelvis. Of the 58% with pathology, the overwhelming majority—about 51 of 70 women—had endometriosis alone, and another 7 had endometriosis with adhesions. A normal ultrasound, based on the absence of hard markers, was found in 96 of 120 women. Thus, 24 of the 120 women had an abnormal scan based on the presence of these hard markers. At laparoscopy, all 24 women had abnormal laparoscopies. Of those 96 women who would have had a normal ultrasound, based on the anatomic absence of some pathology, 53% had an abnormal scan based on the presence of these soft markers while the remaining women had no soft- or hard-markers suggesting any pelvic pathology. At laparoscopy, 73% of the patients with soft markers had pelvic pathology and 27% had a normal laparoscopy. Of 45 patients who had a normal, transvaginal ultrasound, 9 were found to have small evidence of endometriosis without discrete endometriomas at laparoscopy.

To summarize the study data, 100% of patients with hard markers and chronic pelvic pain had abnormal anatomy at laparoscopy, but 73% of patients who had soft markers but otherwise would have been interpreted as normal anatomic findings had evidence of pelvic pathology. Such an approach, if used, could lead to a reduction in the number of unnecessary laparoscopies.

What it really boils down to is, if you have 100 women with chronic pelvic pain, are you willing to treat 100 patients without laparoscopy, knowing that 73 are going to have a positive laparoscopy and will require treatment anyway? You would treat 27% with a pharmaceutical agent that may provide relief of their pain, or may not, depending on what the true etiology was. I would be willing to do so, as a positive predictive value of 73% makes doing that worthwhile, and I believe a majority of clinicians would agree.

Do you have any other tips or ways to improve the reader’s understanding of transvaginal ultrasound?

Dr. Goldstein: Pelvic organs have mobility. If a premenopausal woman is examined in lithotomy position, if the ovaries are freely mobile, by gravity, they are going to go lateral to the uterus and are seen immediately adjacent to the iliac vessels. But remember, iliac vessels are retroperitoneal as they are outside the peritoneal cavity. If you were to turn that patient onto all fours, so that the ovaries are freely mobile, they are going to move somewhat toward the anterior abdominal wall. When an ovary is seen in a nonanatomic position, it could be normal or it could be held up by a loop of bowel, but it may indicate adhesions. This is where this sliding organ sign and liberal use of the other hand on the lower abdomen can be extremely important. The reader should also understand that our ability to localize ovaries on ultrasound depends on the amount of folliculogenesis. Follicles are black circles that are sonolucent, because they contain fluid, so they make it easy to localize ovaries, but also their anatomic position relative to the iliac vessels. However, there is a caveat—which is, sometimes an ovary might look like it is behind the uterus and not in its normal anatomic location. When dynamic imaging is used, you are able to cajole that ovary to move lateral and sit on top of the iliac vessels, which can enable you make the proper diagnosis.

Can you provide some background on endometriosis and the importance of early diagnosis?

Dr. Goldstein: Endometriosis is an inflammatory condition, characterized by endometrial tissue at sites outside the uterus—this definition comes from the World Endometriosis Society.

Endometriosis is said to affect about 10% of women of reproductive age, and if you look at a group, a subset of women with pelvic pain or infertility, the numbers rise to the range of 35% to 50%. It can present in a multitude of locations, mainly in the pelvis, although occasionally even in places like the lung. When it occurs in the uterus, it is known as adenomyosis; when it occurs inside the ovary, it can cause an endometrioma (or what is sometimes referred to as chocolate cyst of the ovary), but you can see endometriotic implants anywhere in the peritoneum—along the urinary tract, rectum, uterosacral ligaments, rectovaginal septum, and even the vaginal wall occasionally.

What I am really interested in is an earlier diagnosis of superficial endometriosis, and it should be apparent to the reader why this is important—the quality of life from pain from endometriosis can be debilitating. It can be a source of infertility, a source of menstrual irregularities, and a source of not only quality of life but also economic consequences. Many women can also undergo as much as a 7-year delay in diagnosis, so the need for a timely diagnosis and initiation of treatment is extremely important.

What is the role of ultrasound in endometriosis diagnostics?

Dr. Goldstein: In an article that I authored 31 years ago, I wrote that there was a difference between an ultrasound examination by referral and examining one’s patients with ultrasound. I coined a phrase: the “ultrasound-enhanced bimanual exam.” I believed that this term should become a routine part of the overall gynecologic exam. I wanted people to think about the bimanual that we had done for at least half a century, which, in my opinion, consists of 2 components:

- An objective component: Is this uterus normal? Is it enlarged or irregular in contour, suggesting maybe fibroids? Is an ovary enlarged? If so, does it feel cystic or solid?

- A subjective component: Does this patient have tenderness through the pelvis. Is there normal mobility of the pelvic organs?

Part of the thesis was that the objective portion could be replaced by an image that could be produced in seconds, dependent on the operator’s training and availability of equipment. The subjective portion, however, depended on the experience and, often, nuance of the examiner. Lately, I have been seeking to expand that thesis by having the imager use examination as part of their overall imaging—this is the concept of dynamic imaging.

Can you expand on the concept of dynamic ultrasound in this setting?

Dr. Goldstein: Presently, most imagers take a multitude of pictures, what I would call 2-dimensional snapshots, to illustrate anatomy. This is usually done by a sonographer, or a technician, who collects the images for viewing by the physician, who then often does so without holding the transducer. Increasing utilization of remote tools like teleradiology only makes this more likely, and for a minority of people who may use video clips instead of still images, they are still simply representations of anatomy. The guidelines for pelvic ultrasound are the underpinning of the expectation of those who are scanning the female pelvis. With dynamic imaging, the operator uses their other hand on the abdomen as well as some motion with the probe to see if they can elicit pain with the vaginal probe, checking for mobility, asking the patient to bear down. Whether you are a sonographer, a radiologist, or an ObGyn, dynamic imaging can bring the examination process into the imager’s hands.

Can you tell us more about the indications for pelvic sonography for endometriosis and what data can you give to support this?

Dr. Goldstein: There is a document titled “Ultrasound Examination of the Female Pelvis,” that was originally developed by the American Institute of Ultrasound in Medicine (AIUM). In this document, there are about 19 different indications for pelvic sonography (in no defined order), and it is interesting that the first indication listed is evaluation of pelvic pain. Well, I would ask you, how do you evaluate pelvic pain with a series of anatomic images? If you have a classic ovarian endometrioma, or you have a classic hydrosalpinx, you can surmise that these are the source of the pain that the patient is reporting. But how do you properly evaluate pain with just an anatomic image? Thus, the need to use dynamic assessment.

There was a concept first introduced by my colleague, Dr. Ilan Timor, known as the sliding organ sign, that was mainly used to determine if 2 structures were adherent or separate. This involved use of the abdominal hand, liberal use of the probe moving in and out, and under real-time vision, examining the patient with the ultrasound transducer; this is the concept of dynamic ultrasound. This practice can be expanded to verify if there is pelvic tenderness and can be a significant part of the nonlaparoscopic, presumptive diagnosis of endometriosis, even when there is no ovarian endometrioma.

To support this theory, I would point you toward a classic article by E Okaro and colleagues in the British Journal of OB-GYN. This study took 120 consecutive women with chronic pelvic pain who were scheduled for laparoscopy, but performed a transvaginal ultrasound prior, and they looked for anatomic abnormalities and divided this into hard markers and soft markers. Hard markers were obvious endometriomas and hydrosalpinges, while soft markers included things like reduced ovarian mobility, site-specific pelvic tenderness, and presence of loculated peritoneal fluid in the pelvis. These were typical of chronic pelvic pain patients that ranged from late teens to almost menopausal, as the average age was about 30 years old.

Patients had experienced pain for anywhere from 6 months to 12 years, but the average was about 4 years. At laparoscopy, 58% of these patients had pelvic pathology, and 42% had a normal pelvis. Of the 58% with pathology, the overwhelming majority—about 51 of 70 women—had endometriosis alone, and another 7 had endometriosis with adhesions. A normal ultrasound, based on the absence of hard markers, was found in 96 of 120 women. Thus, 24 of the 120 women had an abnormal scan based on the presence of these hard markers. At laparoscopy, all 24 women had abnormal laparoscopies. Of those 96 women who would have had a normal ultrasound, based on the anatomic absence of some pathology, 53% had an abnormal scan based on the presence of these soft markers while the remaining women had no soft- or hard-markers suggesting any pelvic pathology. At laparoscopy, 73% of the patients with soft markers had pelvic pathology and 27% had a normal laparoscopy. Of 45 patients who had a normal, transvaginal ultrasound, 9 were found to have small evidence of endometriosis without discrete endometriomas at laparoscopy.

To summarize the study data, 100% of patients with hard markers and chronic pelvic pain had abnormal anatomy at laparoscopy, but 73% of patients who had soft markers but otherwise would have been interpreted as normal anatomic findings had evidence of pelvic pathology. Such an approach, if used, could lead to a reduction in the number of unnecessary laparoscopies.

What it really boils down to is, if you have 100 women with chronic pelvic pain, are you willing to treat 100 patients without laparoscopy, knowing that 73 are going to have a positive laparoscopy and will require treatment anyway? You would treat 27% with a pharmaceutical agent that may provide relief of their pain, or may not, depending on what the true etiology was. I would be willing to do so, as a positive predictive value of 73% makes doing that worthwhile, and I believe a majority of clinicians would agree.

Do you have any other tips or ways to improve the reader’s understanding of transvaginal ultrasound?

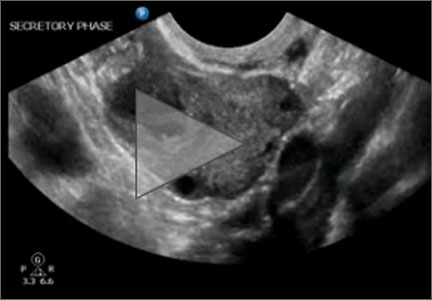

Dr. Goldstein: Pelvic organs have mobility. If a premenopausal woman is examined in lithotomy position, if the ovaries are freely mobile, by gravity, they are going to go lateral to the uterus and are seen immediately adjacent to the iliac vessels. But remember, iliac vessels are retroperitoneal as they are outside the peritoneal cavity. If you were to turn that patient onto all fours, so that the ovaries are freely mobile, they are going to move somewhat toward the anterior abdominal wall. When an ovary is seen in a nonanatomic position, it could be normal or it could be held up by a loop of bowel, but it may indicate adhesions. This is where this sliding organ sign and liberal use of the other hand on the lower abdomen can be extremely important. The reader should also understand that our ability to localize ovaries on ultrasound depends on the amount of folliculogenesis. Follicles are black circles that are sonolucent, because they contain fluid, so they make it easy to localize ovaries, but also their anatomic position relative to the iliac vessels. However, there is a caveat—which is, sometimes an ovary might look like it is behind the uterus and not in its normal anatomic location. When dynamic imaging is used, you are able to cajole that ovary to move lateral and sit on top of the iliac vessels, which can enable you make the proper diagnosis.

Can you provide some background on endometriosis and the importance of early diagnosis?

Dr. Goldstein: Endometriosis is an inflammatory condition, characterized by endometrial tissue at sites outside the uterus—this definition comes from the World Endometriosis Society.

Endometriosis is said to affect about 10% of women of reproductive age, and if you look at a group, a subset of women with pelvic pain or infertility, the numbers rise to the range of 35% to 50%. It can present in a multitude of locations, mainly in the pelvis, although occasionally even in places like the lung. When it occurs in the uterus, it is known as adenomyosis; when it occurs inside the ovary, it can cause an endometrioma (or what is sometimes referred to as chocolate cyst of the ovary), but you can see endometriotic implants anywhere in the peritoneum—along the urinary tract, rectum, uterosacral ligaments, rectovaginal septum, and even the vaginal wall occasionally.

What I am really interested in is an earlier diagnosis of superficial endometriosis, and it should be apparent to the reader why this is important—the quality of life from pain from endometriosis can be debilitating. It can be a source of infertility, a source of menstrual irregularities, and a source of not only quality of life but also economic consequences. Many women can also undergo as much as a 7-year delay in diagnosis, so the need for a timely diagnosis and initiation of treatment is extremely important.

What is the role of ultrasound in endometriosis diagnostics?

Dr. Goldstein: In an article that I authored 31 years ago, I wrote that there was a difference between an ultrasound examination by referral and examining one’s patients with ultrasound. I coined a phrase: the “ultrasound-enhanced bimanual exam.” I believed that this term should become a routine part of the overall gynecologic exam. I wanted people to think about the bimanual that we had done for at least half a century, which, in my opinion, consists of 2 components:

- An objective component: Is this uterus normal? Is it enlarged or irregular in contour, suggesting maybe fibroids? Is an ovary enlarged? If so, does it feel cystic or solid?

- A subjective component: Does this patient have tenderness through the pelvis. Is there normal mobility of the pelvic organs?

Part of the thesis was that the objective portion could be replaced by an image that could be produced in seconds, dependent on the operator’s training and availability of equipment. The subjective portion, however, depended on the experience and, often, nuance of the examiner. Lately, I have been seeking to expand that thesis by having the imager use examination as part of their overall imaging—this is the concept of dynamic imaging.

Can you expand on the concept of dynamic ultrasound in this setting?

Dr. Goldstein: Presently, most imagers take a multitude of pictures, what I would call 2-dimensional snapshots, to illustrate anatomy. This is usually done by a sonographer, or a technician, who collects the images for viewing by the physician, who then often does so without holding the transducer. Increasing utilization of remote tools like teleradiology only makes this more likely, and for a minority of people who may use video clips instead of still images, they are still simply representations of anatomy. The guidelines for pelvic ultrasound are the underpinning of the expectation of those who are scanning the female pelvis. With dynamic imaging, the operator uses their other hand on the abdomen as well as some motion with the probe to see if they can elicit pain with the vaginal probe, checking for mobility, asking the patient to bear down. Whether you are a sonographer, a radiologist, or an ObGyn, dynamic imaging can bring the examination process into the imager’s hands.

Can you tell us more about the indications for pelvic sonography for endometriosis and what data can you give to support this?

Dr. Goldstein: There is a document titled “Ultrasound Examination of the Female Pelvis,” that was originally developed by the American Institute of Ultrasound in Medicine (AIUM). In this document, there are about 19 different indications for pelvic sonography (in no defined order), and it is interesting that the first indication listed is evaluation of pelvic pain. Well, I would ask you, how do you evaluate pelvic pain with a series of anatomic images? If you have a classic ovarian endometrioma, or you have a classic hydrosalpinx, you can surmise that these are the source of the pain that the patient is reporting. But how do you properly evaluate pain with just an anatomic image? Thus, the need to use dynamic assessment.

There was a concept first introduced by my colleague, Dr. Ilan Timor, known as the sliding organ sign, that was mainly used to determine if 2 structures were adherent or separate. This involved use of the abdominal hand, liberal use of the probe moving in and out, and under real-time vision, examining the patient with the ultrasound transducer; this is the concept of dynamic ultrasound. This practice can be expanded to verify if there is pelvic tenderness and can be a significant part of the nonlaparoscopic, presumptive diagnosis of endometriosis, even when there is no ovarian endometrioma.

To support this theory, I would point you toward a classic article by E Okaro and colleagues in the British Journal of OB-GYN. This study took 120 consecutive women with chronic pelvic pain who were scheduled for laparoscopy, but performed a transvaginal ultrasound prior, and they looked for anatomic abnormalities and divided this into hard markers and soft markers. Hard markers were obvious endometriomas and hydrosalpinges, while soft markers included things like reduced ovarian mobility, site-specific pelvic tenderness, and presence of loculated peritoneal fluid in the pelvis. These were typical of chronic pelvic pain patients that ranged from late teens to almost menopausal, as the average age was about 30 years old.

Patients had experienced pain for anywhere from 6 months to 12 years, but the average was about 4 years. At laparoscopy, 58% of these patients had pelvic pathology, and 42% had a normal pelvis. Of the 58% with pathology, the overwhelming majority—about 51 of 70 women—had endometriosis alone, and another 7 had endometriosis with adhesions. A normal ultrasound, based on the absence of hard markers, was found in 96 of 120 women. Thus, 24 of the 120 women had an abnormal scan based on the presence of these hard markers. At laparoscopy, all 24 women had abnormal laparoscopies. Of those 96 women who would have had a normal ultrasound, based on the anatomic absence of some pathology, 53% had an abnormal scan based on the presence of these soft markers while the remaining women had no soft- or hard-markers suggesting any pelvic pathology. At laparoscopy, 73% of the patients with soft markers had pelvic pathology and 27% had a normal laparoscopy. Of 45 patients who had a normal, transvaginal ultrasound, 9 were found to have small evidence of endometriosis without discrete endometriomas at laparoscopy.

To summarize the study data, 100% of patients with hard markers and chronic pelvic pain had abnormal anatomy at laparoscopy, but 73% of patients who had soft markers but otherwise would have been interpreted as normal anatomic findings had evidence of pelvic pathology. Such an approach, if used, could lead to a reduction in the number of unnecessary laparoscopies.

What it really boils down to is, if you have 100 women with chronic pelvic pain, are you willing to treat 100 patients without laparoscopy, knowing that 73 are going to have a positive laparoscopy and will require treatment anyway? You would treat 27% with a pharmaceutical agent that may provide relief of their pain, or may not, depending on what the true etiology was. I would be willing to do so, as a positive predictive value of 73% makes doing that worthwhile, and I believe a majority of clinicians would agree.

Do you have any other tips or ways to improve the reader’s understanding of transvaginal ultrasound?

Dr. Goldstein: Pelvic organs have mobility. If a premenopausal woman is examined in lithotomy position, if the ovaries are freely mobile, by gravity, they are going to go lateral to the uterus and are seen immediately adjacent to the iliac vessels. But remember, iliac vessels are retroperitoneal as they are outside the peritoneal cavity. If you were to turn that patient onto all fours, so that the ovaries are freely mobile, they are going to move somewhat toward the anterior abdominal wall. When an ovary is seen in a nonanatomic position, it could be normal or it could be held up by a loop of bowel, but it may indicate adhesions. This is where this sliding organ sign and liberal use of the other hand on the lower abdomen can be extremely important. The reader should also understand that our ability to localize ovaries on ultrasound depends on the amount of folliculogenesis. Follicles are black circles that are sonolucent, because they contain fluid, so they make it easy to localize ovaries, but also their anatomic position relative to the iliac vessels. However, there is a caveat—which is, sometimes an ovary might look like it is behind the uterus and not in its normal anatomic location. When dynamic imaging is used, you are able to cajole that ovary to move lateral and sit on top of the iliac vessels, which can enable you make the proper diagnosis.

Can a drug FDA approved for endometriosis become a mainstay for nonsurgical treatment of HMB in women with fibroids?

Schlaff WD, Ackerman RT, Al-Hendy A, et al. Elagolix for heavy menstrual bleeding in women with uterine fibroids. N Engl J Med. 2020;382:328-340.

Expert Commentary

Any women’s health care provider is extremely aware of how common uterine fibroids (leiomyomas) are in reproductive-aged women. Bleeding associated with such fibroids is a common source of medical morbidity and reduced quality of life for many patients. The mainstay treatment approach for such patients has been surgical, which over time has become minimally invasive. Finding a nonsurgical treatment for patients with fibroid-associated HMB is of huge importance. The recent failure of the selective progesterone receptor modulator ulipristal acetate to be approved by the US Food and Drug Administration (FDA) was a significant setback to finding an excellent option for medical management. A gonadotropin-releasing hormone (GnRH) antagonist like elagolix could become an incredibly important “arrow in the quiver” of women’s health clinicians.

Details about elagolix

As mentioned, elagolix was FDA approved in 2-dose regimens for the treatment of dysmenorrhea, nonmenstrual pelvic pain, and dyspareunia associated with endometriosis. One would expect that such a GnRH antagonist would reduce or eliminate HMB in patients with fibroids, although formal study had never been undertaken. Previous studies of elagolix had shown the most common adverse reaction to be vasomotor symptoms—hot flashes and night sweats. In addition, the drug shows a dose-dependent decrease in bone mineral density (BMD), although its effect on long-term bone health and future fracture risk is unknown.1

Study specifics. The current study by Schlaff and colleagues was performed including 3 arms: a placebo arm, an elagolix 300 mg twice daily arm, and a third arm that received elagolix 300 mg twice daily and hormonal “add-back” therapy in the form of estradiol 1 mg and norethindrone acetate 0.5 mg daily. The authors actually report on two phase 3 six-month trials that were identical, double-blind, and randomized in nature. Both trials involved approximately 400 women. About 70% of the study participants overall were black, and the average age was approximately 42 years (range, 18 to 51). At baseline, BMD scores were mostly in the normal range. HMB for inclusion was defined as a volume of more than 80 mL per month.

The primary end point was menstrual blood loss volume less than 80 mL in the final month and at least a 50% reduction in menstrual blood loss from baseline to the final month. In the placebo group, only 9% and 10%, respectively, met these criteria.

Continue to: Results...

Results. In the first study group, 84% of those receiving elagolix alone achieved the primary end point, while the group that received elagolix plus add-back therapy had 69% success.

In the second study, both the elagolix group and the add-back group showed that 77% of patients met the primary end point criteria.

The incidences of hot flashes in the elagolix-alone groups were 64% and 43%, respectively, while with add-back therapy, they were 20% in both trials. In the placebo groups, 9% and 4% of participants reported hot flashes. At 6 months, the elagolix-only groups in both trials lost more BMD than the placebo groups, while BMD loss in both add-back groups was not statistically significant from the placebo groups.

Study strengths

Schlaff and colleagues conducted a very well-designed study. The two phase 3 clinical trials in preparation for drug approval were thorough and well reported. The authors are to be commended for including nearly 70% black women as study participants, since this is a racial group known to be affected by HMB resulting from fibroids.

Another strength was the addition of add-back therapy to the doses of elagolix. Concerns about bone loss from a health perspective and vasomotor symptoms from a quality-of-life perspective are not insignificant with elagolix-alone treatment, and proof that add-back therapy significantly diminishes or attenuates the efficacy of this entity is extremely important.

Elagolix is currently available (albeit not in the dosing regimen used in the current study or with built-in add-back therapy), and these study results offer an encouraging nonsurgical approach to HMB. The addition of add-back therapy to this oral GnRH antagonist will allow greater patient acceptance from a quality-of-life point of view because of diminution of vasomotor symptoms while maintaining BMD.

STEVEN R. GOLDSTEIN, MD

- Taylor HS, Giudice LC, Lessey BA, et al. Treatment of endometriosis-associated pain with elagolix, an oral GnRH antagonist. N Engl J Med. 2017;377:28-40.

Schlaff WD, Ackerman RT, Al-Hendy A, et al. Elagolix for heavy menstrual bleeding in women with uterine fibroids. N Engl J Med. 2020;382:328-340.

Expert Commentary

Any women’s health care provider is extremely aware of how common uterine fibroids (leiomyomas) are in reproductive-aged women. Bleeding associated with such fibroids is a common source of medical morbidity and reduced quality of life for many patients. The mainstay treatment approach for such patients has been surgical, which over time has become minimally invasive. Finding a nonsurgical treatment for patients with fibroid-associated HMB is of huge importance. The recent failure of the selective progesterone receptor modulator ulipristal acetate to be approved by the US Food and Drug Administration (FDA) was a significant setback to finding an excellent option for medical management. A gonadotropin-releasing hormone (GnRH) antagonist like elagolix could become an incredibly important “arrow in the quiver” of women’s health clinicians.

Details about elagolix

As mentioned, elagolix was FDA approved in 2-dose regimens for the treatment of dysmenorrhea, nonmenstrual pelvic pain, and dyspareunia associated with endometriosis. One would expect that such a GnRH antagonist would reduce or eliminate HMB in patients with fibroids, although formal study had never been undertaken. Previous studies of elagolix had shown the most common adverse reaction to be vasomotor symptoms—hot flashes and night sweats. In addition, the drug shows a dose-dependent decrease in bone mineral density (BMD), although its effect on long-term bone health and future fracture risk is unknown.1

Study specifics. The current study by Schlaff and colleagues was performed including 3 arms: a placebo arm, an elagolix 300 mg twice daily arm, and a third arm that received elagolix 300 mg twice daily and hormonal “add-back” therapy in the form of estradiol 1 mg and norethindrone acetate 0.5 mg daily. The authors actually report on two phase 3 six-month trials that were identical, double-blind, and randomized in nature. Both trials involved approximately 400 women. About 70% of the study participants overall were black, and the average age was approximately 42 years (range, 18 to 51). At baseline, BMD scores were mostly in the normal range. HMB for inclusion was defined as a volume of more than 80 mL per month.

The primary end point was menstrual blood loss volume less than 80 mL in the final month and at least a 50% reduction in menstrual blood loss from baseline to the final month. In the placebo group, only 9% and 10%, respectively, met these criteria.

Continue to: Results...

Results. In the first study group, 84% of those receiving elagolix alone achieved the primary end point, while the group that received elagolix plus add-back therapy had 69% success.

In the second study, both the elagolix group and the add-back group showed that 77% of patients met the primary end point criteria.

The incidences of hot flashes in the elagolix-alone groups were 64% and 43%, respectively, while with add-back therapy, they were 20% in both trials. In the placebo groups, 9% and 4% of participants reported hot flashes. At 6 months, the elagolix-only groups in both trials lost more BMD than the placebo groups, while BMD loss in both add-back groups was not statistically significant from the placebo groups.

Study strengths

Schlaff and colleagues conducted a very well-designed study. The two phase 3 clinical trials in preparation for drug approval were thorough and well reported. The authors are to be commended for including nearly 70% black women as study participants, since this is a racial group known to be affected by HMB resulting from fibroids.

Another strength was the addition of add-back therapy to the doses of elagolix. Concerns about bone loss from a health perspective and vasomotor symptoms from a quality-of-life perspective are not insignificant with elagolix-alone treatment, and proof that add-back therapy significantly diminishes or attenuates the efficacy of this entity is extremely important.

Elagolix is currently available (albeit not in the dosing regimen used in the current study or with built-in add-back therapy), and these study results offer an encouraging nonsurgical approach to HMB. The addition of add-back therapy to this oral GnRH antagonist will allow greater patient acceptance from a quality-of-life point of view because of diminution of vasomotor symptoms while maintaining BMD.

STEVEN R. GOLDSTEIN, MD

Schlaff WD, Ackerman RT, Al-Hendy A, et al. Elagolix for heavy menstrual bleeding in women with uterine fibroids. N Engl J Med. 2020;382:328-340.

Expert Commentary

Any women’s health care provider is extremely aware of how common uterine fibroids (leiomyomas) are in reproductive-aged women. Bleeding associated with such fibroids is a common source of medical morbidity and reduced quality of life for many patients. The mainstay treatment approach for such patients has been surgical, which over time has become minimally invasive. Finding a nonsurgical treatment for patients with fibroid-associated HMB is of huge importance. The recent failure of the selective progesterone receptor modulator ulipristal acetate to be approved by the US Food and Drug Administration (FDA) was a significant setback to finding an excellent option for medical management. A gonadotropin-releasing hormone (GnRH) antagonist like elagolix could become an incredibly important “arrow in the quiver” of women’s health clinicians.

Details about elagolix

As mentioned, elagolix was FDA approved in 2-dose regimens for the treatment of dysmenorrhea, nonmenstrual pelvic pain, and dyspareunia associated with endometriosis. One would expect that such a GnRH antagonist would reduce or eliminate HMB in patients with fibroids, although formal study had never been undertaken. Previous studies of elagolix had shown the most common adverse reaction to be vasomotor symptoms—hot flashes and night sweats. In addition, the drug shows a dose-dependent decrease in bone mineral density (BMD), although its effect on long-term bone health and future fracture risk is unknown.1

Study specifics. The current study by Schlaff and colleagues was performed including 3 arms: a placebo arm, an elagolix 300 mg twice daily arm, and a third arm that received elagolix 300 mg twice daily and hormonal “add-back” therapy in the form of estradiol 1 mg and norethindrone acetate 0.5 mg daily. The authors actually report on two phase 3 six-month trials that were identical, double-blind, and randomized in nature. Both trials involved approximately 400 women. About 70% of the study participants overall were black, and the average age was approximately 42 years (range, 18 to 51). At baseline, BMD scores were mostly in the normal range. HMB for inclusion was defined as a volume of more than 80 mL per month.

The primary end point was menstrual blood loss volume less than 80 mL in the final month and at least a 50% reduction in menstrual blood loss from baseline to the final month. In the placebo group, only 9% and 10%, respectively, met these criteria.

Continue to: Results...

Results. In the first study group, 84% of those receiving elagolix alone achieved the primary end point, while the group that received elagolix plus add-back therapy had 69% success.

In the second study, both the elagolix group and the add-back group showed that 77% of patients met the primary end point criteria.

The incidences of hot flashes in the elagolix-alone groups were 64% and 43%, respectively, while with add-back therapy, they were 20% in both trials. In the placebo groups, 9% and 4% of participants reported hot flashes. At 6 months, the elagolix-only groups in both trials lost more BMD than the placebo groups, while BMD loss in both add-back groups was not statistically significant from the placebo groups.

Study strengths

Schlaff and colleagues conducted a very well-designed study. The two phase 3 clinical trials in preparation for drug approval were thorough and well reported. The authors are to be commended for including nearly 70% black women as study participants, since this is a racial group known to be affected by HMB resulting from fibroids.

Another strength was the addition of add-back therapy to the doses of elagolix. Concerns about bone loss from a health perspective and vasomotor symptoms from a quality-of-life perspective are not insignificant with elagolix-alone treatment, and proof that add-back therapy significantly diminishes or attenuates the efficacy of this entity is extremely important.

Elagolix is currently available (albeit not in the dosing regimen used in the current study or with built-in add-back therapy), and these study results offer an encouraging nonsurgical approach to HMB. The addition of add-back therapy to this oral GnRH antagonist will allow greater patient acceptance from a quality-of-life point of view because of diminution of vasomotor symptoms while maintaining BMD.

STEVEN R. GOLDSTEIN, MD

- Taylor HS, Giudice LC, Lessey BA, et al. Treatment of endometriosis-associated pain with elagolix, an oral GnRH antagonist. N Engl J Med. 2017;377:28-40.

- Taylor HS, Giudice LC, Lessey BA, et al. Treatment of endometriosis-associated pain with elagolix, an oral GnRH antagonist. N Engl J Med. 2017;377:28-40.

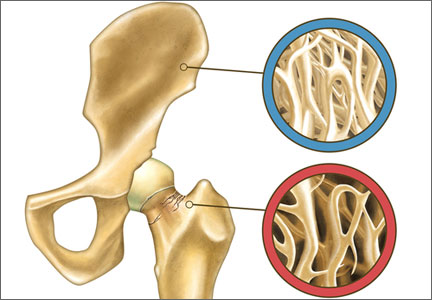

2014 Update on osteoporosis

Gynecologists are “first-line” providers for the diagnosis and treatment of osteoporosis in women. Lest you doubt the importance of this fact, consider that there are more osteoporotic fractures annually in the United States than all myocardial infarctions, strokes, breast cancers, and gynecologic malignancies combined. It is our duty to stay abreast of current developments in the diagnosis and treatment of this potentially devastating skeletal disorder as our patients live longer and longer.

In this article, I present recent studies on:

- the use of conjugated estrogens and bazedoxifene (Duavee) to manage hot flashes and menopausal bone loss

- the need for adequate levels of vitamin D to maintain bone and overall health, with sunlight exposure remaining a viable option

- a reinterpretation of the findings on estrogen and fracture risk from the Women’s Health Initiative (WHI)

- the effects of selective serotonin reuptake inhibitors (SSRIs) on bone mineral density (BMD)

- development of blosozumab, a new agent in the fight against osteoporosis and fracture.

FIRST TISSUE-SELECTIVE ESTROGEN COMPLEX PROTECTS AGAINST BONE LOSS WITHOUT AFFECTING ENDOMETRIAL AND BREAST TISSUE

Komm BS, Mirkin S, Jenkins SN. Development of conjugated estrogens/bazedoxifene, the first tissue selective estrogen complex (TSEC) for management of menopausal hot flashes and postmenopausal bone loss. Steroids. 2014;90:71–81.

Pinkerton JV, Harvey JA, Lindsay R, et al; SMART-5 Investigators. Effects of bazedoxifene/conjugated estrogens on the endometrium and bone: a randomized trial. J Clin Endocrinol Metab. 2014;99(2):e189–e198.

Conjugated estrogens combined with the selective estrogen receptor modulator (SERM) bazedoxifene (Duavee) are a new option to alleviate menopausal symptoms and prevent postmenopausal bone loss. The rationale for development of the tissue-selective estrogen complex (TSEC) was to combine the benefits of conjugated estrogens with the SERM’s ability to offset estrogenic stimulation of the endometrium and breast.

TSECs offer a progestin-free alternative to traditional hormone therapy for women with a uterus. In preclinical studies, investigators found evidence to support bazedoxifene as the SERM of choice and demonstrated that, by combining it with conjugated estrogens, they could provide an optimal balance of estrogen-receptor agonist/antagonist activity, compared with other potential TSEC pairings. Clinical study results confirmed the efficacy of this combination in maintaining bone mass.

Given separately, conjugated estrogens and bazedoxifene each protect against the loss of BMD and help prevent fracture in postmenopausal women.

Findings in key populations

Komm and colleagues describe substudies of the Selective estrogens, Menopause, and Response to Therapy (SMART) trials to evaluate the combination of conjugated estrogens and SERMs to prevent osteoporosis in postmenopausal women with a uterus. One SMART-1 trial included two osteoporosis prevention substudies that evaluated the combination of conjugated estrogens and bazedoxifene in different subpopulations:

- women more than 5 years past the last menstrual period with a lumbar spine or hip BMD T-score between –1 and –2.5 plus one other risk factor for osteoporosis (n = 1,454)

- women 1 to 5 years past their last menstrual period (the interval during which bone loss is greatest) with at least one risk factor for osteoporosis (n = 861).

All doses of conjugated estrogens and bazedoxifene significantly increased the adjusted mean percentage of change in BMD of the lumbar spine from baseline to 24 months (a primary endpoint), compared with placebo, which was associated with decreases in BMD (P<.001). Findings were similar for total hip BMD.

In a separate study, Pinkerton and colleagues found that the dose of conjugated estrogens (0.45 mg) and bazedoxifene (20 mg) approved by the US Food and Drug Administration does not cause a change in breast density or thickness of the endometrium, nor does it increase breast pain, compared with placebo.

WHAT THIS EVIDENCE MEANS FOR PRACTICE

This newly available TSEC—a combination of conjugated estrogens (0.45 mg) and bazedoxifene (20 mg)—is an effective, well-tolerated alternative to traditional estrogen-progestin hormone therapy for relief of menopausal symptoms and prevention of osteoporosis in postmenopausal women with a uterus.

DON’T EXCLUDE SUNLIGHT FROM THE BONE–HEALTH EQUATION

Holick MF. Sunlight, ultraviolet radiation, vitamin D, and skin cancer: how much sunlight do we need? Adv Exp Med Biol. 2014;810:1–16.

Many people think of vitamin D as the “sunshine vitamin.” During exposure to sunlight, ultraviolet photons enter the skin and convert 7-dehydrocholesterol to previtamin D3, which, in turn, is converted to vitamin D3.

Throughout most of human history, people have depended on sunlight for vitamin D. Variables such as skin pigmentation, sunscreen use, aging, time of day, season, and latitude dramatically affect previtamin synthesis.

Although vitamin D deficiency was thought to have been conquered, it is now recognized that more than 50% of the world’s population is at risk for vitamin D insufficiency or low levels of 25-hydroxyvitamin D. Among the reasons are inadequate fortification of foods with vitamin D and a misconception that most balanced diets contain adequate vitamin D.

Deficiency of this vitamin causes growth retardation and rickets in children and osteomalacia in adults and can precipitate and exacerbate osteopenia or osteoporosis and increase the risk of fracture in adults.

Some evidence also suggests that vitamin D deficiency may have other serious consequences, including an increased risk for common cancers and autoimmune, infectious, and cardiovascular diseases.

In this review, Holick argues that we need to remind our patients of the beneficial effects of moderate sunlight.

WHAT THIS EVIDENCE MEANS FOR PRACTICE

There is no question that sufficient levels of vitamin D are vital to bone health, and perhaps to overall health in numerous other organ systems as well. The pendulum of our concern over skin cancers may have moved too far in the direction of sun avoidance. In reality, moderate sunlight as a source of vitamin D is still appropriate for many of our patients.

WHEN IT COMES TO ESTROGEN AND BONE, BENEFITS OUTWEIGH RISKS

de Villiers TJ. 8th Pieter van Keep Memorial Lecture. Estrogen and bone: have we completed a full circle? [published online ahead of print September 22, 2014]. Climacteric. 2014;17(suppl 2):4–7. doi:10.3109/13697137.2014.953047.

In the WHI estrogen-progestin arm, fracture rates were reported as hazard ratios:

- hip fracture, 0.66 (95% confidence interval [CI], 0.45–0.98)

- clinical vertebral fracture, 0.66 (95% CI, 0.44–0.98)

- nonvertebral fractures, 0.77 (95% CI, 0.69–0.86).

In the estrogen-only arm of the WHI, reductions in the rates of fracture were reported as percentages and were similar:

- 39% reduction in hip fracture, compared with placebo

- 38% reduction in clinical vertebral fracture

- 21% reduction in total fractures.

All of these reductions were statistically significant.

Despite the excellent anti-fracture efficacy demonstrated in the WHI, investigators concluded that the risks of hormone therapy outweighed the benefits in the general postmenopausal population.

Why we should reconsider estrogen for bone health

In his presidential address to the International Menopause Society (cited above), de Villiers observed that, in the WHI:

- Only clinical fractures were recorded. Unlike all other fracture trials, routine radiographs were not obtained to record morphometric fractures. This decision, he believes (and I concur), led to a significant understatement of estrogen’s protective effects against vertebral fracture.

- The general population studied had a low risk of fracture, with an average spinal T-score of –1.3. This, too, contributed to an understatement of estrogen’s protective effects, compared with the findings of other randomized controlled trials involving patients at much higher risk.

- From a bone-centric point of view, the WHI findings represent a favorable ratio of benefits to risks.

No bone-active drugs are completely free of potential adverse effects and restrictions, many of which become apparent only after FDA approval and general use of the drug. Bisphosphonates have been implicated in atrial fibrillation, osteonecrosis of the jaw, and atypical femur shaft fracture after extended use. Like estrogen, SERMs can increase the risk of death from deep venous thrombosis and stroke.

WHAT THIS EVIDENCE MEANS FOR PRACTICE

Estrogen is the only agent proved to be effective against all types of osteoporotic fractures during primary analysis of a large randomized controlled trial. This efficacy is of special importance for the patient with osteopenia who is at risk for fracture. Estrogen remains a serious option for the prevention of postmenopausal bone loss and osteoporosis-related fractures, especially in younger patients. Individualization of therapy is key.

COUNSEL SSRI AND SNRI USERS THAT BMD MAY DECLINE OVER THE LONG TERM

Ak E, Bulut SD, Bulut S, et al. Evaluation of the effect of selective serotonin reuptake inhibitors on bone mineral density: an observational cross-sectional study [published online ahead of print September 4, 2014]. Osteoporos Int. doi:10.10007/s00198-014-2859-2.

Moura C, Bernatsky S, Ambrahamowicz M, et al. Antidepressant use and 10-year incident fracture risk: the population-based Canadian Multicentre Osteoporosis Study (CaMoS). Osteoporos Int. 2014;25(5):1473–1481.

Bruyère O, Reginster J-V. Osteoporosis in patients taking selective serotonin reuptake inhibitors: a focus on fracture outcome [published online ahead of print August 5, 2014]. Endocrine. doi:10.1007/s12020-014-0357-0.

Evidence from longitudinal, cross-sectional, and prospective cohort studies suggests that the use of antidepressants at therapeutic doses is associated with a reduction in BMD and an increase in the risk of falls and fracture. These associations have been demonstrated in several distinct populations using various study designs, and with bone density, bone loss, or fractures as outcomes. They remain consistent even after adjustment for confounding variables such as age, body mass index, lifestyle factors such as alcohol and tobacco use, and fracture history.

Ak and colleagues recruited 60 patients given a diagnosis of generalized anxiety disorder and treated with paroxetine, sertraline, or citalopram for at least 12 months, comparing their BMD with that of 40 healthy volunteers. BMD was measured by dual-energy x-ray absorptiometry at the femoral and lumbar regions. BMD of the L2–L4 vertebrae, total lumbar vertebrae, and femoral intertrochanteric region, as well as total femoral Z-scores and femoral Ward’s region T-scores, were lower in the treatment group (P<.05). There was a significant negative correlation between the duration of treatment and the change in BMD values.

Moura and colleagues reviewed data from a large prospective Canadian cohort to assess the association between SSRIs, serotonin and norepinephrine reuptake inhibitors (SNRIs), and fracture in adults aged 50 and older. They used the Canadian Multicentre Osteoporosis Study (CaMos), a prospective, randomly selected, population-based community cohort.

Among 6,645 subjects, 192 (2.9%) were using SSRIs or SNRIs, or both, at baseline. During the 10-year study period, 978 participants (14.7%) experienced at least one fragility fracture. SSRI/SNRI use was associated with an increased risk of fragility fracture (hazard ratio [HR], 1.88; 95% CI, 1.48–2.39). After controlling for multiple risk factors, previous falls, and BMD of the hip and lumbar bone, the adjusted hazard ratio for current SSRI/SNRI use remained elevated (HR, 1.68; 95% CI, 1.32–2.14). The authors concluded that these results lend additional support to an association between SSRI/SNRI use and fragility fractures.

A few possible underlying mechanisms support the biological plausibility of these observations. One explanation is that increased fracture risk is mediated simply by falling. Another explanation could involve the influence of serotonin on bone. Besides their effects on balance, SSRIs may influence bone turnover and BMD. Whatever the mechanism, sufficient evidence exists to warrant the addition of SSRIs to the list of medications that contribute to osteoporosis.

Antidepressant use is not listed as a secondary cause of osteoporosis in the FRAX algorithm. Because the association between SSRI use and fracture risk appears to be independent of BMD, it may be useful to consider the possibility of including it in FRAX.

WHAT THIS EVIDENCE MEANS FOR PRACTICE

Consider BMD assessment for patients who take an SSRI, or who take an SSRI and have additional risk factors for fracture. Given the body of data on this issue, it seems appropriate to expect providers of SSRIs to conduct at least some discussion of bone health with patients.

IN THE PIPELINE: A HIGHLY EFFECTIVE AGENT TARGETING SCLEROSTIN

Recker R, Benson C, Matsumoto T, et al. A randomized, double-blind phase 2 clinical trial of blosozumab, a sclerostin antibody, in postmenopausal women with low bone mineral density [published online ahead of print September 5, 2014]. J Bone Miner Res. doi:10.1002/jbmr.2351.

Sclerostin is a protein secreted by osteocytes that negatively regulates the formation of mineralized bone matrix and bone mass. Recker and colleagues conducted a randomized, double-blind, placebo-

controlled, multicenter, phase 2 clinical trial of blosozumab, a humanized monoclonal antibody targeted against sclerostin. The year-long trial involved 120 postmenopausal women with low BMD (lumbar spine T-score, –2.0 to –3.5) who were randomly allocated to:

- subcutaneous blosozumab 180 mg every 4 weeks

- subcutaneous blosozumab 180 mg every 2 weeks

- subcutaneous blosozumab 270 mg every 2 weeks

- placebo.

All groups also received calcium and vitamin D and underwent serial measurement of spine and hip BMD and testing of biochemical markers of bone turnover. The mean age was 65.8 years, and the mean lumbar spine T-score was –2.8.

Women treated with blosozumab experienced statistically significant, dose-related increases in spine, femoral neck, and total hip BMD, compared with placebo. In the highest dose group, BMD increased 17.7% from baseline at the spine and 6.2% at the total hip. Biochemical markers of bone formation increased rapidly during treatment with blosozumab, trending toward pretreatment levels by the study’s end. CTX, a biochemical marker of bone resorption, decreased early during blosozumab treatment to a concentration lower than that in the placebo group by 2 weeks, and it remained low throughout treatment.

Mild injection-site reactions were reported more frequently with blosozumab than with placebo.

WHAT THIS EVIDENCE MEANS FOR PRACTICE

Although blosozumab is not yet available, clinicians should be aware of the potential of sclerostin-antibody therapies like it. Such therapies appear to have substantial anabolic effects on the skeleton and may become promising agents in the treatment of osteoporosis.

Share your thoughts on this article! Send your Letter to the Editor to rbarbieri@frontlinemedcom.com. Please include your name and the city and state in which you practice.

Gynecologists are “first-line” providers for the diagnosis and treatment of osteoporosis in women. Lest you doubt the importance of this fact, consider that there are more osteoporotic fractures annually in the United States than all myocardial infarctions, strokes, breast cancers, and gynecologic malignancies combined. It is our duty to stay abreast of current developments in the diagnosis and treatment of this potentially devastating skeletal disorder as our patients live longer and longer.

In this article, I present recent studies on:

- the use of conjugated estrogens and bazedoxifene (Duavee) to manage hot flashes and menopausal bone loss

- the need for adequate levels of vitamin D to maintain bone and overall health, with sunlight exposure remaining a viable option

- a reinterpretation of the findings on estrogen and fracture risk from the Women’s Health Initiative (WHI)

- the effects of selective serotonin reuptake inhibitors (SSRIs) on bone mineral density (BMD)

- development of blosozumab, a new agent in the fight against osteoporosis and fracture.

FIRST TISSUE-SELECTIVE ESTROGEN COMPLEX PROTECTS AGAINST BONE LOSS WITHOUT AFFECTING ENDOMETRIAL AND BREAST TISSUE

Komm BS, Mirkin S, Jenkins SN. Development of conjugated estrogens/bazedoxifene, the first tissue selective estrogen complex (TSEC) for management of menopausal hot flashes and postmenopausal bone loss. Steroids. 2014;90:71–81.

Pinkerton JV, Harvey JA, Lindsay R, et al; SMART-5 Investigators. Effects of bazedoxifene/conjugated estrogens on the endometrium and bone: a randomized trial. J Clin Endocrinol Metab. 2014;99(2):e189–e198.

Conjugated estrogens combined with the selective estrogen receptor modulator (SERM) bazedoxifene (Duavee) are a new option to alleviate menopausal symptoms and prevent postmenopausal bone loss. The rationale for development of the tissue-selective estrogen complex (TSEC) was to combine the benefits of conjugated estrogens with the SERM’s ability to offset estrogenic stimulation of the endometrium and breast.

TSECs offer a progestin-free alternative to traditional hormone therapy for women with a uterus. In preclinical studies, investigators found evidence to support bazedoxifene as the SERM of choice and demonstrated that, by combining it with conjugated estrogens, they could provide an optimal balance of estrogen-receptor agonist/antagonist activity, compared with other potential TSEC pairings. Clinical study results confirmed the efficacy of this combination in maintaining bone mass.

Given separately, conjugated estrogens and bazedoxifene each protect against the loss of BMD and help prevent fracture in postmenopausal women.

Findings in key populations

Komm and colleagues describe substudies of the Selective estrogens, Menopause, and Response to Therapy (SMART) trials to evaluate the combination of conjugated estrogens and SERMs to prevent osteoporosis in postmenopausal women with a uterus. One SMART-1 trial included two osteoporosis prevention substudies that evaluated the combination of conjugated estrogens and bazedoxifene in different subpopulations:

- women more than 5 years past the last menstrual period with a lumbar spine or hip BMD T-score between –1 and –2.5 plus one other risk factor for osteoporosis (n = 1,454)

- women 1 to 5 years past their last menstrual period (the interval during which bone loss is greatest) with at least one risk factor for osteoporosis (n = 861).

All doses of conjugated estrogens and bazedoxifene significantly increased the adjusted mean percentage of change in BMD of the lumbar spine from baseline to 24 months (a primary endpoint), compared with placebo, which was associated with decreases in BMD (P<.001). Findings were similar for total hip BMD.

In a separate study, Pinkerton and colleagues found that the dose of conjugated estrogens (0.45 mg) and bazedoxifene (20 mg) approved by the US Food and Drug Administration does not cause a change in breast density or thickness of the endometrium, nor does it increase breast pain, compared with placebo.

WHAT THIS EVIDENCE MEANS FOR PRACTICE

This newly available TSEC—a combination of conjugated estrogens (0.45 mg) and bazedoxifene (20 mg)—is an effective, well-tolerated alternative to traditional estrogen-progestin hormone therapy for relief of menopausal symptoms and prevention of osteoporosis in postmenopausal women with a uterus.

DON’T EXCLUDE SUNLIGHT FROM THE BONE–HEALTH EQUATION

Holick MF. Sunlight, ultraviolet radiation, vitamin D, and skin cancer: how much sunlight do we need? Adv Exp Med Biol. 2014;810:1–16.

Many people think of vitamin D as the “sunshine vitamin.” During exposure to sunlight, ultraviolet photons enter the skin and convert 7-dehydrocholesterol to previtamin D3, which, in turn, is converted to vitamin D3.

Throughout most of human history, people have depended on sunlight for vitamin D. Variables such as skin pigmentation, sunscreen use, aging, time of day, season, and latitude dramatically affect previtamin synthesis.

Although vitamin D deficiency was thought to have been conquered, it is now recognized that more than 50% of the world’s population is at risk for vitamin D insufficiency or low levels of 25-hydroxyvitamin D. Among the reasons are inadequate fortification of foods with vitamin D and a misconception that most balanced diets contain adequate vitamin D.

Deficiency of this vitamin causes growth retardation and rickets in children and osteomalacia in adults and can precipitate and exacerbate osteopenia or osteoporosis and increase the risk of fracture in adults.

Some evidence also suggests that vitamin D deficiency may have other serious consequences, including an increased risk for common cancers and autoimmune, infectious, and cardiovascular diseases.

In this review, Holick argues that we need to remind our patients of the beneficial effects of moderate sunlight.

WHAT THIS EVIDENCE MEANS FOR PRACTICE

There is no question that sufficient levels of vitamin D are vital to bone health, and perhaps to overall health in numerous other organ systems as well. The pendulum of our concern over skin cancers may have moved too far in the direction of sun avoidance. In reality, moderate sunlight as a source of vitamin D is still appropriate for many of our patients.

WHEN IT COMES TO ESTROGEN AND BONE, BENEFITS OUTWEIGH RISKS

de Villiers TJ. 8th Pieter van Keep Memorial Lecture. Estrogen and bone: have we completed a full circle? [published online ahead of print September 22, 2014]. Climacteric. 2014;17(suppl 2):4–7. doi:10.3109/13697137.2014.953047.

In the WHI estrogen-progestin arm, fracture rates were reported as hazard ratios:

- hip fracture, 0.66 (95% confidence interval [CI], 0.45–0.98)

- clinical vertebral fracture, 0.66 (95% CI, 0.44–0.98)

- nonvertebral fractures, 0.77 (95% CI, 0.69–0.86).

In the estrogen-only arm of the WHI, reductions in the rates of fracture were reported as percentages and were similar:

- 39% reduction in hip fracture, compared with placebo

- 38% reduction in clinical vertebral fracture

- 21% reduction in total fractures.

All of these reductions were statistically significant.

Despite the excellent anti-fracture efficacy demonstrated in the WHI, investigators concluded that the risks of hormone therapy outweighed the benefits in the general postmenopausal population.

Why we should reconsider estrogen for bone health

In his presidential address to the International Menopause Society (cited above), de Villiers observed that, in the WHI:

- Only clinical fractures were recorded. Unlike all other fracture trials, routine radiographs were not obtained to record morphometric fractures. This decision, he believes (and I concur), led to a significant understatement of estrogen’s protective effects against vertebral fracture.

- The general population studied had a low risk of fracture, with an average spinal T-score of –1.3. This, too, contributed to an understatement of estrogen’s protective effects, compared with the findings of other randomized controlled trials involving patients at much higher risk.

- From a bone-centric point of view, the WHI findings represent a favorable ratio of benefits to risks.

No bone-active drugs are completely free of potential adverse effects and restrictions, many of which become apparent only after FDA approval and general use of the drug. Bisphosphonates have been implicated in atrial fibrillation, osteonecrosis of the jaw, and atypical femur shaft fracture after extended use. Like estrogen, SERMs can increase the risk of death from deep venous thrombosis and stroke.

WHAT THIS EVIDENCE MEANS FOR PRACTICE

Estrogen is the only agent proved to be effective against all types of osteoporotic fractures during primary analysis of a large randomized controlled trial. This efficacy is of special importance for the patient with osteopenia who is at risk for fracture. Estrogen remains a serious option for the prevention of postmenopausal bone loss and osteoporosis-related fractures, especially in younger patients. Individualization of therapy is key.

COUNSEL SSRI AND SNRI USERS THAT BMD MAY DECLINE OVER THE LONG TERM

Ak E, Bulut SD, Bulut S, et al. Evaluation of the effect of selective serotonin reuptake inhibitors on bone mineral density: an observational cross-sectional study [published online ahead of print September 4, 2014]. Osteoporos Int. doi:10.10007/s00198-014-2859-2.

Moura C, Bernatsky S, Ambrahamowicz M, et al. Antidepressant use and 10-year incident fracture risk: the population-based Canadian Multicentre Osteoporosis Study (CaMoS). Osteoporos Int. 2014;25(5):1473–1481.

Bruyère O, Reginster J-V. Osteoporosis in patients taking selective serotonin reuptake inhibitors: a focus on fracture outcome [published online ahead of print August 5, 2014]. Endocrine. doi:10.1007/s12020-014-0357-0.

Evidence from longitudinal, cross-sectional, and prospective cohort studies suggests that the use of antidepressants at therapeutic doses is associated with a reduction in BMD and an increase in the risk of falls and fracture. These associations have been demonstrated in several distinct populations using various study designs, and with bone density, bone loss, or fractures as outcomes. They remain consistent even after adjustment for confounding variables such as age, body mass index, lifestyle factors such as alcohol and tobacco use, and fracture history.

Ak and colleagues recruited 60 patients given a diagnosis of generalized anxiety disorder and treated with paroxetine, sertraline, or citalopram for at least 12 months, comparing their BMD with that of 40 healthy volunteers. BMD was measured by dual-energy x-ray absorptiometry at the femoral and lumbar regions. BMD of the L2–L4 vertebrae, total lumbar vertebrae, and femoral intertrochanteric region, as well as total femoral Z-scores and femoral Ward’s region T-scores, were lower in the treatment group (P<.05). There was a significant negative correlation between the duration of treatment and the change in BMD values.

Moura and colleagues reviewed data from a large prospective Canadian cohort to assess the association between SSRIs, serotonin and norepinephrine reuptake inhibitors (SNRIs), and fracture in adults aged 50 and older. They used the Canadian Multicentre Osteoporosis Study (CaMos), a prospective, randomly selected, population-based community cohort.

Among 6,645 subjects, 192 (2.9%) were using SSRIs or SNRIs, or both, at baseline. During the 10-year study period, 978 participants (14.7%) experienced at least one fragility fracture. SSRI/SNRI use was associated with an increased risk of fragility fracture (hazard ratio [HR], 1.88; 95% CI, 1.48–2.39). After controlling for multiple risk factors, previous falls, and BMD of the hip and lumbar bone, the adjusted hazard ratio for current SSRI/SNRI use remained elevated (HR, 1.68; 95% CI, 1.32–2.14). The authors concluded that these results lend additional support to an association between SSRI/SNRI use and fragility fractures.

A few possible underlying mechanisms support the biological plausibility of these observations. One explanation is that increased fracture risk is mediated simply by falling. Another explanation could involve the influence of serotonin on bone. Besides their effects on balance, SSRIs may influence bone turnover and BMD. Whatever the mechanism, sufficient evidence exists to warrant the addition of SSRIs to the list of medications that contribute to osteoporosis.

Antidepressant use is not listed as a secondary cause of osteoporosis in the FRAX algorithm. Because the association between SSRI use and fracture risk appears to be independent of BMD, it may be useful to consider the possibility of including it in FRAX.

WHAT THIS EVIDENCE MEANS FOR PRACTICE

Consider BMD assessment for patients who take an SSRI, or who take an SSRI and have additional risk factors for fracture. Given the body of data on this issue, it seems appropriate to expect providers of SSRIs to conduct at least some discussion of bone health with patients.

IN THE PIPELINE: A HIGHLY EFFECTIVE AGENT TARGETING SCLEROSTIN

Recker R, Benson C, Matsumoto T, et al. A randomized, double-blind phase 2 clinical trial of blosozumab, a sclerostin antibody, in postmenopausal women with low bone mineral density [published online ahead of print September 5, 2014]. J Bone Miner Res. doi:10.1002/jbmr.2351.

Sclerostin is a protein secreted by osteocytes that negatively regulates the formation of mineralized bone matrix and bone mass. Recker and colleagues conducted a randomized, double-blind, placebo-

controlled, multicenter, phase 2 clinical trial of blosozumab, a humanized monoclonal antibody targeted against sclerostin. The year-long trial involved 120 postmenopausal women with low BMD (lumbar spine T-score, –2.0 to –3.5) who were randomly allocated to:

- subcutaneous blosozumab 180 mg every 4 weeks

- subcutaneous blosozumab 180 mg every 2 weeks

- subcutaneous blosozumab 270 mg every 2 weeks

- placebo.

All groups also received calcium and vitamin D and underwent serial measurement of spine and hip BMD and testing of biochemical markers of bone turnover. The mean age was 65.8 years, and the mean lumbar spine T-score was –2.8.

Women treated with blosozumab experienced statistically significant, dose-related increases in spine, femoral neck, and total hip BMD, compared with placebo. In the highest dose group, BMD increased 17.7% from baseline at the spine and 6.2% at the total hip. Biochemical markers of bone formation increased rapidly during treatment with blosozumab, trending toward pretreatment levels by the study’s end. CTX, a biochemical marker of bone resorption, decreased early during blosozumab treatment to a concentration lower than that in the placebo group by 2 weeks, and it remained low throughout treatment.

Mild injection-site reactions were reported more frequently with blosozumab than with placebo.

WHAT THIS EVIDENCE MEANS FOR PRACTICE

Although blosozumab is not yet available, clinicians should be aware of the potential of sclerostin-antibody therapies like it. Such therapies appear to have substantial anabolic effects on the skeleton and may become promising agents in the treatment of osteoporosis.

Share your thoughts on this article! Send your Letter to the Editor to rbarbieri@frontlinemedcom.com. Please include your name and the city and state in which you practice.

Gynecologists are “first-line” providers for the diagnosis and treatment of osteoporosis in women. Lest you doubt the importance of this fact, consider that there are more osteoporotic fractures annually in the United States than all myocardial infarctions, strokes, breast cancers, and gynecologic malignancies combined. It is our duty to stay abreast of current developments in the diagnosis and treatment of this potentially devastating skeletal disorder as our patients live longer and longer.

In this article, I present recent studies on:

- the use of conjugated estrogens and bazedoxifene (Duavee) to manage hot flashes and menopausal bone loss

- the need for adequate levels of vitamin D to maintain bone and overall health, with sunlight exposure remaining a viable option

- a reinterpretation of the findings on estrogen and fracture risk from the Women’s Health Initiative (WHI)

- the effects of selective serotonin reuptake inhibitors (SSRIs) on bone mineral density (BMD)

- development of blosozumab, a new agent in the fight against osteoporosis and fracture.

FIRST TISSUE-SELECTIVE ESTROGEN COMPLEX PROTECTS AGAINST BONE LOSS WITHOUT AFFECTING ENDOMETRIAL AND BREAST TISSUE

Komm BS, Mirkin S, Jenkins SN. Development of conjugated estrogens/bazedoxifene, the first tissue selective estrogen complex (TSEC) for management of menopausal hot flashes and postmenopausal bone loss. Steroids. 2014;90:71–81.

Pinkerton JV, Harvey JA, Lindsay R, et al; SMART-5 Investigators. Effects of bazedoxifene/conjugated estrogens on the endometrium and bone: a randomized trial. J Clin Endocrinol Metab. 2014;99(2):e189–e198.

Conjugated estrogens combined with the selective estrogen receptor modulator (SERM) bazedoxifene (Duavee) are a new option to alleviate menopausal symptoms and prevent postmenopausal bone loss. The rationale for development of the tissue-selective estrogen complex (TSEC) was to combine the benefits of conjugated estrogens with the SERM’s ability to offset estrogenic stimulation of the endometrium and breast.

TSECs offer a progestin-free alternative to traditional hormone therapy for women with a uterus. In preclinical studies, investigators found evidence to support bazedoxifene as the SERM of choice and demonstrated that, by combining it with conjugated estrogens, they could provide an optimal balance of estrogen-receptor agonist/antagonist activity, compared with other potential TSEC pairings. Clinical study results confirmed the efficacy of this combination in maintaining bone mass.

Given separately, conjugated estrogens and bazedoxifene each protect against the loss of BMD and help prevent fracture in postmenopausal women.

Findings in key populations

Komm and colleagues describe substudies of the Selective estrogens, Menopause, and Response to Therapy (SMART) trials to evaluate the combination of conjugated estrogens and SERMs to prevent osteoporosis in postmenopausal women with a uterus. One SMART-1 trial included two osteoporosis prevention substudies that evaluated the combination of conjugated estrogens and bazedoxifene in different subpopulations:

- women more than 5 years past the last menstrual period with a lumbar spine or hip BMD T-score between –1 and –2.5 plus one other risk factor for osteoporosis (n = 1,454)

- women 1 to 5 years past their last menstrual period (the interval during which bone loss is greatest) with at least one risk factor for osteoporosis (n = 861).

All doses of conjugated estrogens and bazedoxifene significantly increased the adjusted mean percentage of change in BMD of the lumbar spine from baseline to 24 months (a primary endpoint), compared with placebo, which was associated with decreases in BMD (P<.001). Findings were similar for total hip BMD.

In a separate study, Pinkerton and colleagues found that the dose of conjugated estrogens (0.45 mg) and bazedoxifene (20 mg) approved by the US Food and Drug Administration does not cause a change in breast density or thickness of the endometrium, nor does it increase breast pain, compared with placebo.

WHAT THIS EVIDENCE MEANS FOR PRACTICE

This newly available TSEC—a combination of conjugated estrogens (0.45 mg) and bazedoxifene (20 mg)—is an effective, well-tolerated alternative to traditional estrogen-progestin hormone therapy for relief of menopausal symptoms and prevention of osteoporosis in postmenopausal women with a uterus.

DON’T EXCLUDE SUNLIGHT FROM THE BONE–HEALTH EQUATION

Holick MF. Sunlight, ultraviolet radiation, vitamin D, and skin cancer: how much sunlight do we need? Adv Exp Med Biol. 2014;810:1–16.

Many people think of vitamin D as the “sunshine vitamin.” During exposure to sunlight, ultraviolet photons enter the skin and convert 7-dehydrocholesterol to previtamin D3, which, in turn, is converted to vitamin D3.