User login

CYP450 interactions between illicit substances and prescription medications

Ms. L, age 37, presents to psychiatric emergency services with command auditory hallucinations, ideas of reference, and suicidal ideation.

Ms. L has a 22-year history of schizophrenia. Additionally, she has a history of cocaine use disorder (in remission for 12 years), cannabis use disorder (in remission for 6 months), type 2 diabetes mellitus, and hypertension. Her psychotic symptoms are well controlled on a regimen of

On interview, Ms. L reports smoking cannabis each day for the past month and using $400 worth of cocaine over 2 days. She is experiencing intense guilt over these relapses and is admitted to the inpatient adult psychiatry unit. On admission, Ms. L’s clozapine and norclozapine trough levels (drawn approximately 12 hours after last administration documented by the ACT member) are 300 and 275 ng/mL, respectively. Generally, clozapine levels >350 to 420 ng/mL are considered therapeutic, and a clozapine-to-norclozapine ratio of 2:1 is desirable for maximum efficacy and tolerability. Because Ms. L’s clozapine level is <350 and her ratio is approximately 1:1, her clozapine treatment is subtherapeutic.

Because Ms. L has a history of documented adherence to and benefit from her current medication regimen, no changes are made during her 3-week hospital stay. She notices a gradual reduction in auditory hallucinations, no longer wants to harm herself, and is motivated to regain sobriety.

At the time of discharge, Ms. L’s clozapine and norclozapine trough levels are 550 and 250 ng/mL, respectively, which indicates a more favorable clozapine-to-norclozapine ratio of approximately 2:1 and a clozapine level greater than the recommended minimum threshold of 350 ng/mL. While cocaine ingestion presumably played a role in her acute decompensation, the treatment team determined that Ms. L’s relapse to cannabis use likely contributed to low clozapine levels by induction of cytochrome P450 (CYP) 1A2, and subsequently led to the delayed recovery of symptom control.1

The use of illicit substances is a widespread, growing problem. According to the 2017 National Survey on Drug Use and Health, 11.5% of Americans age ≥12 had used an illicit substance (ie, use of marijuana, cocaine, heroin, hallucinogens, inhalants, or methamphetamine, or misuse of prescription psychotherapeutics) in the past month.2 While illicit substance use is of particular public health interest due to a known increase in mortality and health care spending, there has been little discussion of the impact of illicit drug use on concurrent pharmacologic therapy. Just as prescription medications have pharmacokinetic drug–drug interactions with each other, so do illicit substances, though far less is known about their impact on the treatment of medical conditions.

Pharmacokinetic interactions

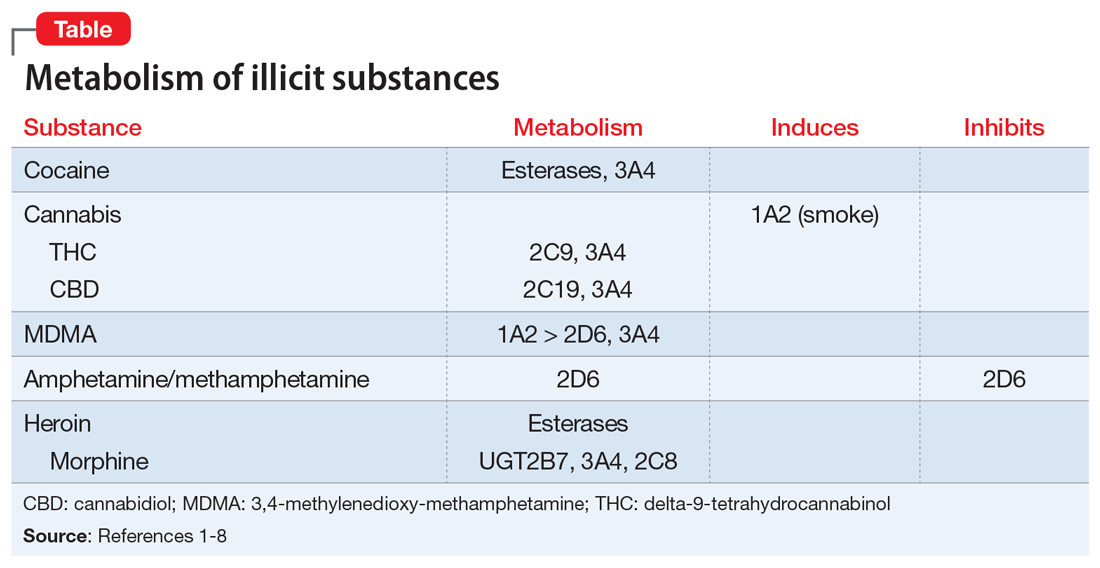

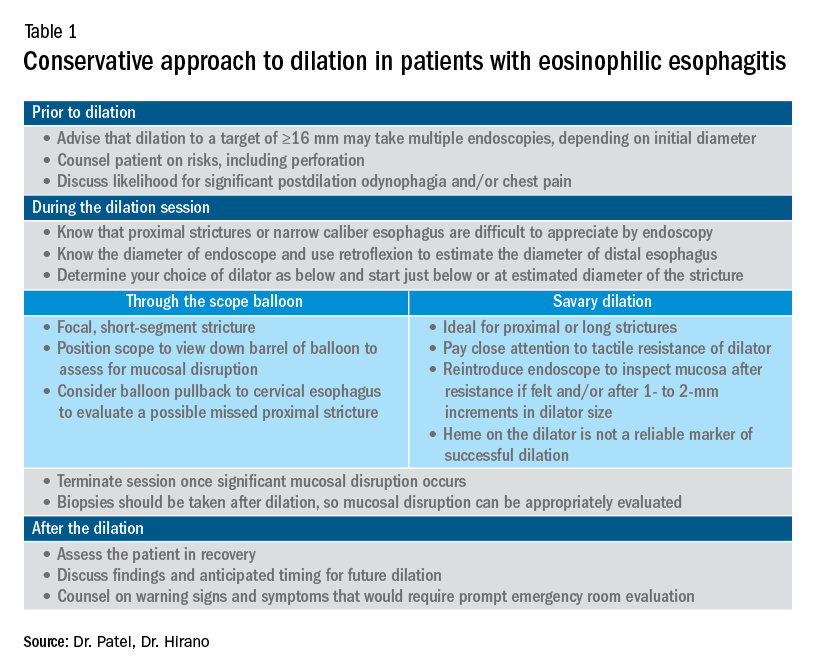

Key pharmacokinetic interactions have been reported with cocaine, marijuana, amphetamines, and opioids. The Table1-8 summarizes the metabolism of illicit substances.

Continue to: Cocaine

Cocaine is largely metabolized by serum esterases such as pseudocholinesterase, human carboxylesterase-1 (hCE-1), and human carboxylesterase-2 (hCE-2), to inactive metabolites benzoylecgonine (35% to 45%) and ecgonine (32% to 49%).2 However, a smaller portion (2.6% to 6.2%) undergoes hepatic N-demethylation by CYP3A4 to norcocaine.3 Norcocaine is an active metabolite responsible for some of the toxic effects of cocaine (eg, hepatotoxicity).4,5 Several commonly prescribed medications are known inducers of CYP3A4 (eg, phenytoin, carbamazepine) and may lead to increased levels of the toxic metabolite when used concurrently with cocaine. Additionally, the use of cocaine with acetylcholinesterase inhibitors, such as donepezil, may lead to reduction of serum esterases and shunt cocaine metabolism toward the hepatic pathway, thus increasing norcocaine formation.3

Cannabis. The metabolism and drug–drug interactions of cannabis can be separated by its 2 main components: delta-9-tetrahydrocannabinol (THC) and cannabidiol (CBD). A review conducted in 2014 concluded that THC is primarily metabolized by CYP2C9 and 3A4, while CBD is metabolized by CYP2C19 and 3A4.6 Oral administration of ketoconazole, a CYP3A4 inhibitor, along with cannabis extract has been shown to increase the maximum concentration (Cmax) and area under the curve (AUC) of THC by 1.2- and 1.8-fold, respectively, while increasing both Cmaxand AUC of CBD by 2-fold.6 In addition, CYP2C9 poor metabolizers have been shown to experience significant increases in THC exposure and reductions in metabolite formation, further supporting the role of CYP enzymes in cannabis metabolism.6

There is also evidence of enzyme induction by cannabis. Individuals who reported smoking marijuana experienced greater clearance of theophylline, a substrate of CYP1A2, than did those who reported not smoking marijuana.1,6 As with cigarette smoking, this effect appears to be a direct result of the hydrocarbons found in marijuana smoke rather than the cannabis itself, as there is a lack of evidence for enzyme induction when the drug is orally ingested.6

Amphetamine and methamphetamine appear to be both substrates and competitive inhibitors of CYP2D6.7 Rats administered quinidine (a strong 2D6 inhibitor) had 2-fold elevations in AUC and decreased clearance of amphetamine and its metabolites.8 Amphetamine-related recreational drugs, such as 3,4-methylenedioxy-methamphetamine (MDMA) and 3,4-methylenedioxyamphetamine (MDA), are substrates of CYP2D6 and CYP3A4, while MDMA also undergoes substantial metabolism by CYP1A2.3,7,9

Opioids. Heroin is metabolized to 6‑monoacetylmorphine (6-MAM) and morphine by hCE-1, hCE-2, and pseudocholinesterase, and has minimal impact on CYP enzymes. However, while morphine is primarily metabolized to inactive metabolites by UGT2B7, it does undergo minor metabolism through CYP3A4 and 2C8 pathways, creating potential for drug interactions with medications that inhibit or induce CYP3A4.10

Continue to: An underappreciated risk of illicit substance use

An underappreciated risk of illicit substance use

There is a paucity of evidence regarding the metabolism and pharmacokinetic interactions with illicit substances, and further research is needed. Despite the absence of comprehensive data on the subject, the available information indicates the use of illicit substances may have a significant impact on medications used to treat comorbid conditions. Alternatively, those medications may affect the kinetics of recreationally used substances. The risk of adverse consequences of drug–drug interactions is yet another reason patients should be encouraged to avoid use of substances and seek treatment for substance use disorders. When determining the most appropriate therapy for comorbid conditions for patients who are using illicit substances and are likely to continue to do so, clinicians should take into consideration potential interactions among prescription medications and the specific illicit substances the patient uses.

Related Resources

- Lindsey W, Stewart D, Childress D. Drug interactions between common illicit drugs and prescription therapies. Am J Drug Alcohol Abuse. 2012;38(4):334-343.

- Maurer H, Sauer C, Theobald D. Toxicokinetics of drugs of abuse: current knowledge of the isoenzymes involved in the human metabolism of tetrahydrocannabinol, cocaine, heroin, morphine, and codeine. Ther Drug Monit. 2006;28(3):447-453.

- Dean A. Illicit drugs and drug interactions. Pharmacist. 2006;25(9):684-689.

Drug Brand Names

Carbamazepine • Carbatrol, Tegretol

Clozapine • Clozaril

Donepezil • Aricept

Ketoconazole • Nizoral

Paliperidone palmitate • Invega sustenna

Phenytoin • Dilantin, Phenytek

Quinidine • Cardioquin, Duraquin

Theophylline • Elixophylline, Theochron

1. Jusko WJ, Schentag JJ, Clark JH, et al. Enhanced biotransformation of theophylline in marihuana and tobacco smokers. Clin Pharmacol Ther. 1978;24(4):405-410.

2. Substance Abuse and Mental Health Services Administration. Results from the 2017 National Survey on Drug Use and Health: Detailed Tables. https://www.samhsa.gov/data/sites/default/files/cbhsq-reports/NSDUHDetailedTabs2017/NSDUHDetailedTabs2017.htm#tab1-1A. Published 2019. Accessed February 7, 2020.

3. Quinn D, Wodak A, Day R. Pharmacokinetic and pharmacodynamic principles of illicit drug use and treatment of illicit drug users. Clin Pharmacokinet. 1997;33(5):344-400.

4. Ndikum-Moffor FM, Schoeb TR, Roberts SM. Liver toxicity from norcocaine nitroxide, an N-oxidative metabolite of cocaine. J Pharmacol Exp Ther. 1998;284(1):413-419.

5. Pellinen P, Honkakoski P, Stenbäck F, et al. Cocaine N-demethylation and the metabolism-related hepatotoxicity can be prevented by cytochrome P450 3A inhibitors. Eur J Pharmacol. 1994;270(1):35-43.

6. Stout S, Cimino N. Exogenous cannabinoids as substrates, inhibitors, and inducers of human drug metabolizing enzymes: a systematic review. Drug Metab Rev. 2013;46(1):86-95.

7. Kraemer T, Maurer H. Toxicokinetics of amphetamines: metabolism and toxicokinetic data of designer drugs, amphetamine, methamphetamine, and their N-alkyl derivatives. Ther Drug Monit. 2002;24(2):277-289.

8. Markowitz J, Patrick K. Pharmacokinetic and pharmacodynamic drug interactions in the treatment of attention-deficit hyperactivity disorder. Clin Pharmacokinet. 2001;40(10):753-772.

9. Kreth K, Kovar K, Schwab M, et al. Identification of the human cytochromes P450 involved in the oxidative metabolism of “ecstasy”-related designer drugs. Biochem Pharmacol. 2000;59(12):1563-1571.

10. Meyer M, Maurer H. Absorption, distribution, metabolism and excretion pharmacogenomics of drugs of abuse. Pharmacogenomics. 2011;12(2):215-233.

Ms. L, age 37, presents to psychiatric emergency services with command auditory hallucinations, ideas of reference, and suicidal ideation.

Ms. L has a 22-year history of schizophrenia. Additionally, she has a history of cocaine use disorder (in remission for 12 years), cannabis use disorder (in remission for 6 months), type 2 diabetes mellitus, and hypertension. Her psychotic symptoms are well controlled on a regimen of

On interview, Ms. L reports smoking cannabis each day for the past month and using $400 worth of cocaine over 2 days. She is experiencing intense guilt over these relapses and is admitted to the inpatient adult psychiatry unit. On admission, Ms. L’s clozapine and norclozapine trough levels (drawn approximately 12 hours after last administration documented by the ACT member) are 300 and 275 ng/mL, respectively. Generally, clozapine levels >350 to 420 ng/mL are considered therapeutic, and a clozapine-to-norclozapine ratio of 2:1 is desirable for maximum efficacy and tolerability. Because Ms. L’s clozapine level is <350 and her ratio is approximately 1:1, her clozapine treatment is subtherapeutic.

Because Ms. L has a history of documented adherence to and benefit from her current medication regimen, no changes are made during her 3-week hospital stay. She notices a gradual reduction in auditory hallucinations, no longer wants to harm herself, and is motivated to regain sobriety.

At the time of discharge, Ms. L’s clozapine and norclozapine trough levels are 550 and 250 ng/mL, respectively, which indicates a more favorable clozapine-to-norclozapine ratio of approximately 2:1 and a clozapine level greater than the recommended minimum threshold of 350 ng/mL. While cocaine ingestion presumably played a role in her acute decompensation, the treatment team determined that Ms. L’s relapse to cannabis use likely contributed to low clozapine levels by induction of cytochrome P450 (CYP) 1A2, and subsequently led to the delayed recovery of symptom control.1

The use of illicit substances is a widespread, growing problem. According to the 2017 National Survey on Drug Use and Health, 11.5% of Americans age ≥12 had used an illicit substance (ie, use of marijuana, cocaine, heroin, hallucinogens, inhalants, or methamphetamine, or misuse of prescription psychotherapeutics) in the past month.2 While illicit substance use is of particular public health interest due to a known increase in mortality and health care spending, there has been little discussion of the impact of illicit drug use on concurrent pharmacologic therapy. Just as prescription medications have pharmacokinetic drug–drug interactions with each other, so do illicit substances, though far less is known about their impact on the treatment of medical conditions.

Pharmacokinetic interactions

Key pharmacokinetic interactions have been reported with cocaine, marijuana, amphetamines, and opioids. The Table1-8 summarizes the metabolism of illicit substances.

Continue to: Cocaine

Cocaine is largely metabolized by serum esterases such as pseudocholinesterase, human carboxylesterase-1 (hCE-1), and human carboxylesterase-2 (hCE-2), to inactive metabolites benzoylecgonine (35% to 45%) and ecgonine (32% to 49%).2 However, a smaller portion (2.6% to 6.2%) undergoes hepatic N-demethylation by CYP3A4 to norcocaine.3 Norcocaine is an active metabolite responsible for some of the toxic effects of cocaine (eg, hepatotoxicity).4,5 Several commonly prescribed medications are known inducers of CYP3A4 (eg, phenytoin, carbamazepine) and may lead to increased levels of the toxic metabolite when used concurrently with cocaine. Additionally, the use of cocaine with acetylcholinesterase inhibitors, such as donepezil, may lead to reduction of serum esterases and shunt cocaine metabolism toward the hepatic pathway, thus increasing norcocaine formation.3

Cannabis. The metabolism and drug–drug interactions of cannabis can be separated by its 2 main components: delta-9-tetrahydrocannabinol (THC) and cannabidiol (CBD). A review conducted in 2014 concluded that THC is primarily metabolized by CYP2C9 and 3A4, while CBD is metabolized by CYP2C19 and 3A4.6 Oral administration of ketoconazole, a CYP3A4 inhibitor, along with cannabis extract has been shown to increase the maximum concentration (Cmax) and area under the curve (AUC) of THC by 1.2- and 1.8-fold, respectively, while increasing both Cmaxand AUC of CBD by 2-fold.6 In addition, CYP2C9 poor metabolizers have been shown to experience significant increases in THC exposure and reductions in metabolite formation, further supporting the role of CYP enzymes in cannabis metabolism.6

There is also evidence of enzyme induction by cannabis. Individuals who reported smoking marijuana experienced greater clearance of theophylline, a substrate of CYP1A2, than did those who reported not smoking marijuana.1,6 As with cigarette smoking, this effect appears to be a direct result of the hydrocarbons found in marijuana smoke rather than the cannabis itself, as there is a lack of evidence for enzyme induction when the drug is orally ingested.6

Amphetamine and methamphetamine appear to be both substrates and competitive inhibitors of CYP2D6.7 Rats administered quinidine (a strong 2D6 inhibitor) had 2-fold elevations in AUC and decreased clearance of amphetamine and its metabolites.8 Amphetamine-related recreational drugs, such as 3,4-methylenedioxy-methamphetamine (MDMA) and 3,4-methylenedioxyamphetamine (MDA), are substrates of CYP2D6 and CYP3A4, while MDMA also undergoes substantial metabolism by CYP1A2.3,7,9

Opioids. Heroin is metabolized to 6‑monoacetylmorphine (6-MAM) and morphine by hCE-1, hCE-2, and pseudocholinesterase, and has minimal impact on CYP enzymes. However, while morphine is primarily metabolized to inactive metabolites by UGT2B7, it does undergo minor metabolism through CYP3A4 and 2C8 pathways, creating potential for drug interactions with medications that inhibit or induce CYP3A4.10

Continue to: An underappreciated risk of illicit substance use

An underappreciated risk of illicit substance use

There is a paucity of evidence regarding the metabolism and pharmacokinetic interactions with illicit substances, and further research is needed. Despite the absence of comprehensive data on the subject, the available information indicates the use of illicit substances may have a significant impact on medications used to treat comorbid conditions. Alternatively, those medications may affect the kinetics of recreationally used substances. The risk of adverse consequences of drug–drug interactions is yet another reason patients should be encouraged to avoid use of substances and seek treatment for substance use disorders. When determining the most appropriate therapy for comorbid conditions for patients who are using illicit substances and are likely to continue to do so, clinicians should take into consideration potential interactions among prescription medications and the specific illicit substances the patient uses.

Related Resources

- Lindsey W, Stewart D, Childress D. Drug interactions between common illicit drugs and prescription therapies. Am J Drug Alcohol Abuse. 2012;38(4):334-343.

- Maurer H, Sauer C, Theobald D. Toxicokinetics of drugs of abuse: current knowledge of the isoenzymes involved in the human metabolism of tetrahydrocannabinol, cocaine, heroin, morphine, and codeine. Ther Drug Monit. 2006;28(3):447-453.

- Dean A. Illicit drugs and drug interactions. Pharmacist. 2006;25(9):684-689.

Drug Brand Names

Carbamazepine • Carbatrol, Tegretol

Clozapine • Clozaril

Donepezil • Aricept

Ketoconazole • Nizoral

Paliperidone palmitate • Invega sustenna

Phenytoin • Dilantin, Phenytek

Quinidine • Cardioquin, Duraquin

Theophylline • Elixophylline, Theochron

Ms. L, age 37, presents to psychiatric emergency services with command auditory hallucinations, ideas of reference, and suicidal ideation.

Ms. L has a 22-year history of schizophrenia. Additionally, she has a history of cocaine use disorder (in remission for 12 years), cannabis use disorder (in remission for 6 months), type 2 diabetes mellitus, and hypertension. Her psychotic symptoms are well controlled on a regimen of

On interview, Ms. L reports smoking cannabis each day for the past month and using $400 worth of cocaine over 2 days. She is experiencing intense guilt over these relapses and is admitted to the inpatient adult psychiatry unit. On admission, Ms. L’s clozapine and norclozapine trough levels (drawn approximately 12 hours after last administration documented by the ACT member) are 300 and 275 ng/mL, respectively. Generally, clozapine levels >350 to 420 ng/mL are considered therapeutic, and a clozapine-to-norclozapine ratio of 2:1 is desirable for maximum efficacy and tolerability. Because Ms. L’s clozapine level is <350 and her ratio is approximately 1:1, her clozapine treatment is subtherapeutic.

Because Ms. L has a history of documented adherence to and benefit from her current medication regimen, no changes are made during her 3-week hospital stay. She notices a gradual reduction in auditory hallucinations, no longer wants to harm herself, and is motivated to regain sobriety.

At the time of discharge, Ms. L’s clozapine and norclozapine trough levels are 550 and 250 ng/mL, respectively, which indicates a more favorable clozapine-to-norclozapine ratio of approximately 2:1 and a clozapine level greater than the recommended minimum threshold of 350 ng/mL. While cocaine ingestion presumably played a role in her acute decompensation, the treatment team determined that Ms. L’s relapse to cannabis use likely contributed to low clozapine levels by induction of cytochrome P450 (CYP) 1A2, and subsequently led to the delayed recovery of symptom control.1

The use of illicit substances is a widespread, growing problem. According to the 2017 National Survey on Drug Use and Health, 11.5% of Americans age ≥12 had used an illicit substance (ie, use of marijuana, cocaine, heroin, hallucinogens, inhalants, or methamphetamine, or misuse of prescription psychotherapeutics) in the past month.2 While illicit substance use is of particular public health interest due to a known increase in mortality and health care spending, there has been little discussion of the impact of illicit drug use on concurrent pharmacologic therapy. Just as prescription medications have pharmacokinetic drug–drug interactions with each other, so do illicit substances, though far less is known about their impact on the treatment of medical conditions.

Pharmacokinetic interactions

Key pharmacokinetic interactions have been reported with cocaine, marijuana, amphetamines, and opioids. The Table1-8 summarizes the metabolism of illicit substances.

Continue to: Cocaine

Cocaine is largely metabolized by serum esterases such as pseudocholinesterase, human carboxylesterase-1 (hCE-1), and human carboxylesterase-2 (hCE-2), to inactive metabolites benzoylecgonine (35% to 45%) and ecgonine (32% to 49%).2 However, a smaller portion (2.6% to 6.2%) undergoes hepatic N-demethylation by CYP3A4 to norcocaine.3 Norcocaine is an active metabolite responsible for some of the toxic effects of cocaine (eg, hepatotoxicity).4,5 Several commonly prescribed medications are known inducers of CYP3A4 (eg, phenytoin, carbamazepine) and may lead to increased levels of the toxic metabolite when used concurrently with cocaine. Additionally, the use of cocaine with acetylcholinesterase inhibitors, such as donepezil, may lead to reduction of serum esterases and shunt cocaine metabolism toward the hepatic pathway, thus increasing norcocaine formation.3

Cannabis. The metabolism and drug–drug interactions of cannabis can be separated by its 2 main components: delta-9-tetrahydrocannabinol (THC) and cannabidiol (CBD). A review conducted in 2014 concluded that THC is primarily metabolized by CYP2C9 and 3A4, while CBD is metabolized by CYP2C19 and 3A4.6 Oral administration of ketoconazole, a CYP3A4 inhibitor, along with cannabis extract has been shown to increase the maximum concentration (Cmax) and area under the curve (AUC) of THC by 1.2- and 1.8-fold, respectively, while increasing both Cmaxand AUC of CBD by 2-fold.6 In addition, CYP2C9 poor metabolizers have been shown to experience significant increases in THC exposure and reductions in metabolite formation, further supporting the role of CYP enzymes in cannabis metabolism.6

There is also evidence of enzyme induction by cannabis. Individuals who reported smoking marijuana experienced greater clearance of theophylline, a substrate of CYP1A2, than did those who reported not smoking marijuana.1,6 As with cigarette smoking, this effect appears to be a direct result of the hydrocarbons found in marijuana smoke rather than the cannabis itself, as there is a lack of evidence for enzyme induction when the drug is orally ingested.6

Amphetamine and methamphetamine appear to be both substrates and competitive inhibitors of CYP2D6.7 Rats administered quinidine (a strong 2D6 inhibitor) had 2-fold elevations in AUC and decreased clearance of amphetamine and its metabolites.8 Amphetamine-related recreational drugs, such as 3,4-methylenedioxy-methamphetamine (MDMA) and 3,4-methylenedioxyamphetamine (MDA), are substrates of CYP2D6 and CYP3A4, while MDMA also undergoes substantial metabolism by CYP1A2.3,7,9

Opioids. Heroin is metabolized to 6‑monoacetylmorphine (6-MAM) and morphine by hCE-1, hCE-2, and pseudocholinesterase, and has minimal impact on CYP enzymes. However, while morphine is primarily metabolized to inactive metabolites by UGT2B7, it does undergo minor metabolism through CYP3A4 and 2C8 pathways, creating potential for drug interactions with medications that inhibit or induce CYP3A4.10

Continue to: An underappreciated risk of illicit substance use

An underappreciated risk of illicit substance use

There is a paucity of evidence regarding the metabolism and pharmacokinetic interactions with illicit substances, and further research is needed. Despite the absence of comprehensive data on the subject, the available information indicates the use of illicit substances may have a significant impact on medications used to treat comorbid conditions. Alternatively, those medications may affect the kinetics of recreationally used substances. The risk of adverse consequences of drug–drug interactions is yet another reason patients should be encouraged to avoid use of substances and seek treatment for substance use disorders. When determining the most appropriate therapy for comorbid conditions for patients who are using illicit substances and are likely to continue to do so, clinicians should take into consideration potential interactions among prescription medications and the specific illicit substances the patient uses.

Related Resources

- Lindsey W, Stewart D, Childress D. Drug interactions between common illicit drugs and prescription therapies. Am J Drug Alcohol Abuse. 2012;38(4):334-343.

- Maurer H, Sauer C, Theobald D. Toxicokinetics of drugs of abuse: current knowledge of the isoenzymes involved in the human metabolism of tetrahydrocannabinol, cocaine, heroin, morphine, and codeine. Ther Drug Monit. 2006;28(3):447-453.

- Dean A. Illicit drugs and drug interactions. Pharmacist. 2006;25(9):684-689.

Drug Brand Names

Carbamazepine • Carbatrol, Tegretol

Clozapine • Clozaril

Donepezil • Aricept

Ketoconazole • Nizoral

Paliperidone palmitate • Invega sustenna

Phenytoin • Dilantin, Phenytek

Quinidine • Cardioquin, Duraquin

Theophylline • Elixophylline, Theochron

1. Jusko WJ, Schentag JJ, Clark JH, et al. Enhanced biotransformation of theophylline in marihuana and tobacco smokers. Clin Pharmacol Ther. 1978;24(4):405-410.

2. Substance Abuse and Mental Health Services Administration. Results from the 2017 National Survey on Drug Use and Health: Detailed Tables. https://www.samhsa.gov/data/sites/default/files/cbhsq-reports/NSDUHDetailedTabs2017/NSDUHDetailedTabs2017.htm#tab1-1A. Published 2019. Accessed February 7, 2020.

3. Quinn D, Wodak A, Day R. Pharmacokinetic and pharmacodynamic principles of illicit drug use and treatment of illicit drug users. Clin Pharmacokinet. 1997;33(5):344-400.

4. Ndikum-Moffor FM, Schoeb TR, Roberts SM. Liver toxicity from norcocaine nitroxide, an N-oxidative metabolite of cocaine. J Pharmacol Exp Ther. 1998;284(1):413-419.

5. Pellinen P, Honkakoski P, Stenbäck F, et al. Cocaine N-demethylation and the metabolism-related hepatotoxicity can be prevented by cytochrome P450 3A inhibitors. Eur J Pharmacol. 1994;270(1):35-43.

6. Stout S, Cimino N. Exogenous cannabinoids as substrates, inhibitors, and inducers of human drug metabolizing enzymes: a systematic review. Drug Metab Rev. 2013;46(1):86-95.

7. Kraemer T, Maurer H. Toxicokinetics of amphetamines: metabolism and toxicokinetic data of designer drugs, amphetamine, methamphetamine, and their N-alkyl derivatives. Ther Drug Monit. 2002;24(2):277-289.

8. Markowitz J, Patrick K. Pharmacokinetic and pharmacodynamic drug interactions in the treatment of attention-deficit hyperactivity disorder. Clin Pharmacokinet. 2001;40(10):753-772.

9. Kreth K, Kovar K, Schwab M, et al. Identification of the human cytochromes P450 involved in the oxidative metabolism of “ecstasy”-related designer drugs. Biochem Pharmacol. 2000;59(12):1563-1571.

10. Meyer M, Maurer H. Absorption, distribution, metabolism and excretion pharmacogenomics of drugs of abuse. Pharmacogenomics. 2011;12(2):215-233.

1. Jusko WJ, Schentag JJ, Clark JH, et al. Enhanced biotransformation of theophylline in marihuana and tobacco smokers. Clin Pharmacol Ther. 1978;24(4):405-410.

2. Substance Abuse and Mental Health Services Administration. Results from the 2017 National Survey on Drug Use and Health: Detailed Tables. https://www.samhsa.gov/data/sites/default/files/cbhsq-reports/NSDUHDetailedTabs2017/NSDUHDetailedTabs2017.htm#tab1-1A. Published 2019. Accessed February 7, 2020.

3. Quinn D, Wodak A, Day R. Pharmacokinetic and pharmacodynamic principles of illicit drug use and treatment of illicit drug users. Clin Pharmacokinet. 1997;33(5):344-400.

4. Ndikum-Moffor FM, Schoeb TR, Roberts SM. Liver toxicity from norcocaine nitroxide, an N-oxidative metabolite of cocaine. J Pharmacol Exp Ther. 1998;284(1):413-419.

5. Pellinen P, Honkakoski P, Stenbäck F, et al. Cocaine N-demethylation and the metabolism-related hepatotoxicity can be prevented by cytochrome P450 3A inhibitors. Eur J Pharmacol. 1994;270(1):35-43.

6. Stout S, Cimino N. Exogenous cannabinoids as substrates, inhibitors, and inducers of human drug metabolizing enzymes: a systematic review. Drug Metab Rev. 2013;46(1):86-95.

7. Kraemer T, Maurer H. Toxicokinetics of amphetamines: metabolism and toxicokinetic data of designer drugs, amphetamine, methamphetamine, and their N-alkyl derivatives. Ther Drug Monit. 2002;24(2):277-289.

8. Markowitz J, Patrick K. Pharmacokinetic and pharmacodynamic drug interactions in the treatment of attention-deficit hyperactivity disorder. Clin Pharmacokinet. 2001;40(10):753-772.

9. Kreth K, Kovar K, Schwab M, et al. Identification of the human cytochromes P450 involved in the oxidative metabolism of “ecstasy”-related designer drugs. Biochem Pharmacol. 2000;59(12):1563-1571.

10. Meyer M, Maurer H. Absorption, distribution, metabolism and excretion pharmacogenomics of drugs of abuse. Pharmacogenomics. 2011;12(2):215-233.

When the worry is worse than the actual illness

CASE Distraught over a medical illness

Ms. S, age 16, presents to the emergency department (ED) accompanied by her mother with superficial lacerations on her arm. Ms. S states, “I cut my arm because I was afraid I was going to do something serious if I didn’t get to go to the ED.” She says that 6 months earlier, she was diagnosed with superior mesenteric artery syndrome (SMAS), a rare, potentially life-threatening condition that occurs when the duodenum is compressed between the aorta and the superior mesenteric artery, causing a partial or complete blockage of the duodenum. Since receiving this diagnosis, Ms. S reports feeling anxious, depressed, and overwhelmed by both the pain she is experiencing from her illness and uncertainty about her prognosis.

HISTORY In pain and isolated

Since being diagnosed with SMAS, Ms. S has had approximately 30 medical and 7 ED visits for SMAS-related pain. Ms. S was referred to the outpatient clinic for ongoing support and treatment for SMAS.

Because of her pain and anxiety, Ms. S, a junior in high school, no longer attends school but has been working with a tutor. Ms. S says that some of her loneliness and hopelessness are due to the social isolation of being tutored at home. She states that she has been “out of sight and out of mind” from her friends. She also reports feeling different from them due to the pain brought on by SMAS.

Ms. S and her mother live in public housing. Ms. S says that overall, she has a good relationship with her mother, but that in certain situations, her mother’s anxiety causes her significant frustration and anxiety.

EVALUATION Transient suicidal thoughts

A physical examination reveals superficial lacerations to Ms. S’s left arm. Although she appears thin, her current body mass index (BMI) is 20.4 kg/m2, which is within normal range. She says she sees herself as “underweight” and “not fat at all.” Ms. S reports that she likes food and enjoyed eating until it became too painful following her SMAS diagnosis. Ms. S denies a history of binging or purging. Results from her laboratory workup and all values are within normal limits.

During the initial interview, Ms. S’s mother says they came to the ED because Ms. S urgently needs a psychiatric evaluation so she can be cleared for gastrointestinal (GI) surgery and placement of a nasogastric tube. Her mother says a surgeon from a different hospital told them that her insurance company required a psychiatric evaluation to rule out anorexia nervosa before they would authorize the GI surgery. When asked why psychiatry at this hospital was not consulted, Ms. S’s mother does not answer.

When asked about the symptoms she has been experiencing, Ms. S says that her sleep has been poor because of increased pain and excessive worrying about her health. She has limited her food intake. Ms. S reports that after eating, she lays on her left side to alleviate pain and help the food move through her body.

Continue to: Ms. S says...

Ms. S says she feels anxious and depressed due to her SMAS diagnosis, her mother’s online research and oversharing of poor prognoses, and being isolated from her friends. Most of her time outside the home is spent attending medical appointments with specialists. Several months ago, Ms. S had seen a psychotherapist, but her mother was unhappy with the treatment recommendations, which included seeking care from a nutritionist and joining group therapy. Ms. S’s mother says she ended her daughter’s psychotherapy because she was unable to obtain a signature ruling out anorexia nervosa within the first few appointments.

Ms. S also says she has had passive suicidal thoughts during the past month, usually twice a week. She reports that these thoughts lasted as long as several hours and were difficult to control, but she has no specific plan or intent. Ms. S denies current suicidal thoughts or ideation, and works with the treatment team to complete a safety plan, which she signs. Other than her recent visit to the ED, Ms. S denies any other thoughts or behaviors of self-injury or suicide.

[polldaddy:10586905]

The authors’ observations

The treatment team considered the following conditions as part of Ms. S’s differential diagnosis:

Major depressive disorder. The team was able to rule out MDD because Ms. S’s depression was attributed to SMAS. Ms. S reported that all depressive symptoms were manageable or nonexistent before the onset of pain from SMAS. There was no direct pathophysiological consequence of another medical condition. Ms. S was clear that her symptoms of anxiety and depression began after she was isolated from her friends and began having difficulty understanding her diagnosis and prognosis.

Anorexia nervosa also was ruled out. According to the DSM-5, a diagnosis of anorexia nervosa requires the following 3 criteria1:

- restriction of food intake resulting in significantly low body weight (defined as weight that is less than “minimally normal”) relative to age, gender, or development

- intense fear of gaining weight, or persistent behaviors that interfere with weight gain

- disturbance in the way in which one’s body weight or shape is experienced, undue influence of body weight or shape on self-evaluation, or lack of insight with regard to seriousness of current low body weight.

Continue to: Although Ms. S appeared...

Although Ms. S appeared thin, her BMI was within normal range. She added that she likes food and enjoyed eating, but that her medical condition made it too painful. Lastly, Ms. S denied a history of binging or purging.

Somatic symptom disorder.

Factitious disorder imposed on self. An individual with FDIS chronically stimulates, induces, or aggravates illnesses to gain the status of being a patient.

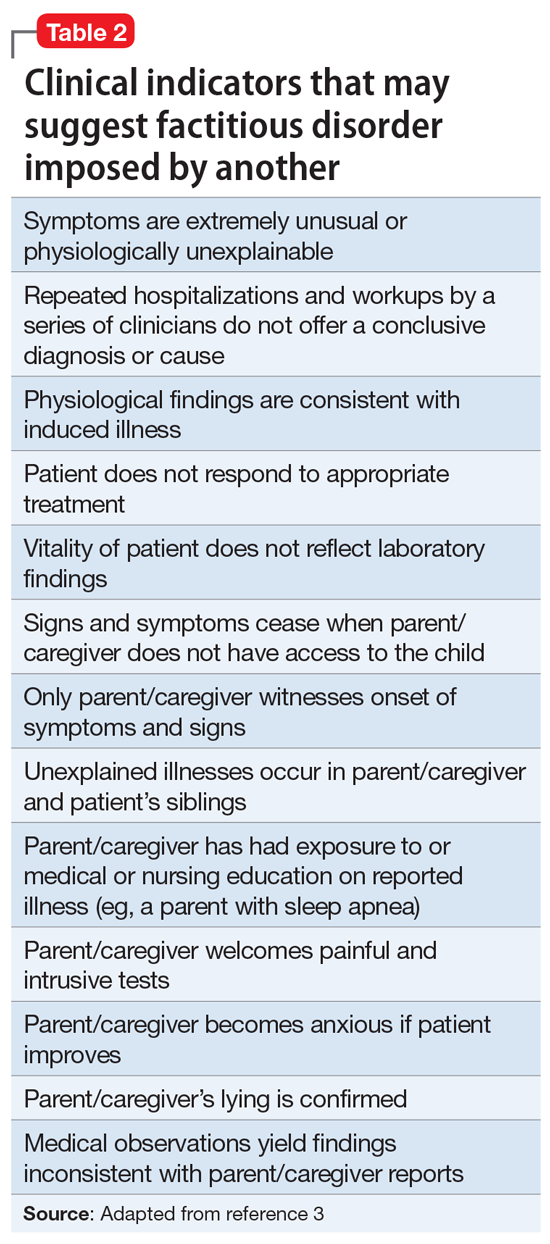

Factitious disorder imposed on another is the deliberate feigning or production of symptoms in another individual who is under the perpetrator’s supervision.1Table 23 lists clinical indicators that raise suspicion for FDIA.

Before a diagnosis of somatic symptom disorder, FDIS, or FDIA could be established or ruled out, it was imperative to gather collateral information from other clinicians involved in Ms. S’s care. Ms. S and her mother had sought out help from a pediatric surgeon, a pediatric gastroenterologist, a pediatrician, and a psychotherapist.

Continue to: EVALUATION Collateral information

EVALUATION Collateral information

After Ms. S’s mother signs consent forms for exchange of information, the treatment team reaches out to the other clinicians. The therapist confirms that Ms. S’s mother had ended her daughter’s treatment after she was unable to quickly obtain documentation to rule out anorexia nervosa.

Both the pediatric surgeon and gastroenterologist report concerns of FDIA, which is why both clinicians had referred Ms. S and her mother to psychiatry. The pediatric surgeon states that on one occasion when he interviewed Ms. S separately from her mother, she seemed to be going down a checklist of symptoms. The surgeon reports that there was a partial occlusion of the superior mesenteric artery, confirming the diagnosis of SMAS, but he believed it was not severe enough to explain the symptoms Ms. S reported. The surgeon had scheduled another imaging appointment for 1 month later.

The pediatric gastroenterologist reports that Ms. S’s mother had demanded surgery and nasogastric tube placement for her daughter, which raised suspicion of FDIA. The gastroenterologist had convinced Ms. S and her mother to start low-dose doxepin, 20 mg twice a day, for anxiety, sleep, and abdominal pain.

Lastly, the pediatrician reports that she had not seen Ms. S for several months but stated that Ms. S always has been in the low normal BMI range. The pediatrician also reports that 6 months ago, the patient and her mother were frantically visiting EDs and scheduling doctor’s appointments.

[polldaddy:10586906]

The authors’ observations

The treatment team decided that Ms. S was not in imminent danger, and felt it was important to keep her in treatment without raising her mother’s suspicion. The team agreed to raise these concerns to the police, child protective services, and risk management if Ms. S’s health suddenly deteriorated or if her mother decided to remove Ms. S from our care.

Continue to: The treatment team...

The treatment team at the outpatient psychiatry clinic agreed that Ms. S did not currently meet criteria for anorexia nervosa, MDD, FDIS, or FDIA. However, Ms. S reported worries particular to persistent abdominal pain that was exacerbated by either eating or going to bed at night, which indicated that somatic symptom disorder was her likely diagnosis. Further, she endorsed a high level of anxiety and depression with regard to this somatic complaint that interfered with her daily activities and consumed an excessive amount of time, which also pointed to somatic symptom disorder. As a result of this diagnosis, the treatment team helped Ms. S manage her somatic symptoms and monitored for any other changes in her symptoms

Generally, cognitive-behavioral therapy (CBT) and mindfulness-based therapy may help relieve symptoms associated with somatic symptom disorder.4

TREATMENT Therapy sessions and medication management

At the psychiatric clinic, Ms. S is scheduled for biweekly therapy sessions with a social worker and biweekly appointments with a senior psychiatry resident for medication management. At each visit, Ms. S’s vital signs, height, and weight are measured. In the therapy sessions, she is taught mindfulness skills as well as CBT. The senior psychiatry resident maintains regular communication with the other clinicians involved in Ms. S’s care.

After the first month of treatment, Ms. S undergoes repeat imaging at the gastroenterologist’s office that indicates her SMAS is no longer occluded. Ms. S continues to report somatic symptoms, but with mild improvement.

Over the course of approximately 4 months, Ms. S begins to show signs of improvement in her pain, anxiety, and depression. Ms. S begins to feel well enough to get a summer job at a nursing home and expresses enthusiasm when her weight begins to increase. Her mother also became enthused and verbalized her appreciation that her daughter appeared to be improving.

Continue to: In the fall...

In the fall, Ms. S returns to high school for her senior year but has difficulty getting back into the routine and relating to her old friends. Ms. S continues to perseverate on thoughts of getting sick and her physical symptoms become overwhelming once again. She continues to be focused on any new symptoms she experiences, and to limit the types of foods she eats due to fear of the abdominal pain returning.

After several more months of psychiatric treatment, Ms. S reports significant relief from her abdominal pain, and no longer seeks corrective surgery for her SMAS. Although she occasionally struggles with perseverating thoughts and anxiety about her somatic symptoms such as abdominal pain and worrying about the types of foods she eats and becoming ill, she continues to work through symptoms of her somatic symptom disorder.

The authors’ observations

The main challenge of somatic symptom disorder is the patient’s “abnormal illness behavior.”2,5,6 For pediatric patients, there may an association between a parent’s psychological status and the patient’s somatic symptoms. Abdominal symptoms in a pediatric patient have a strong association with a parent who presents with depression, anxiety, or somatization. The effects of the parent’s psychological status could also manifest in the form of modeling catastrophic thinking or through reinforcement. Parents with certain traits, such as disproportionate worry about pain, may pay more attention to their child’s symptoms, and hence, reward the child when he/she reports somatic symptoms.7,8 In the case of Ms. S, her mother did not participate in therapy and the mother’s psychiatric history was never obtained.

OUTCOMES Making personal strides

Ms. S continues to use mindfulness skills as well as CBT to manage her symptoms of somatic symptom disorder. She continues to celebrate her weight gains, denies any thoughts of suicide or self-harm behaviors, and prepares for college by scheduling campus visits and completing admissions applications.

Bottom Line

Patients with somatic symptom disorder tend to have very high levels of worry about illness. Somatic symptoms in such patients may or may not have a medical explanation. Accurate diagnosis and careful management are necessary to reduce patient distress. Cognitive-behavioral therapy and mindfulness-based therapy may help relieve symptoms associated with this disorder.

Related Resources

- Henningsen P. Management of somatic symptom disorder. Dialogues Clin Neurosci. 2018;20(1):23-91.

- Rosic T, Kalra S, Samaan Z. Somatic symptom disorder, a new DSM-5 diagnosis of an old clinical challenge. BMJ Case Rep. 2016: bcr2015212553. doi: 10.1136/bcr-2015-212553.

Drug Brand Name

Doxepin • Silenor

1. Diagnostic and statistical manual of mental disorders, 5th ed. Washington, DC: American Psychiatric Association; 2013.

2. Stern T, Freudenreich O, Smith F, et al. Massachusetts General Hospital Handbook of General Hospital Psychiatry, 7th ed. New York, NY: Elsevier; 2017.

3. Feldman MD, Eisendrath SJ. The spectrum of factitious disorders. Washington, DC: American Psychiatric Association; 1997.

4. Sadock BJ, Sadock VA, Ruiz P. Kaplan & Sadock’s synopsis of psychiatry: behavioral sciences/clinical psychiatry, 11th ed. Philadelphia, PA: Wolters Kluwer; 2014:470.

5. Pilowsky I. The concept of abnormal illness behavior. Psychosomatics. 1990;31(2):207-213.

6. Kirmayer LJ, Looper KJ. Abnormal illness behavior: physiological, psychological and social dimensions of coping with stress. Curr Opin Psychiatry. 2006;19(1):54-60.

7. Walker LS, Garber J, Greene JW. Somatic complaints in pediatric patients: a prospective study of the role of negative life events, child social and academic competence, and parental somatic symptoms. J Consult Clin Psychology. 1994;62(6):1213-1221.

8. Van Oudenhove L, Levy RL, Crowell MD, et al. Biopsychosocial aspects of functional gastrointestinal disorders: how central and environmental processes contribute to the development and expression of functional gastrointestinal disorders. Gastroenterology. 2016;150(6):1355-1367.

CASE Distraught over a medical illness

Ms. S, age 16, presents to the emergency department (ED) accompanied by her mother with superficial lacerations on her arm. Ms. S states, “I cut my arm because I was afraid I was going to do something serious if I didn’t get to go to the ED.” She says that 6 months earlier, she was diagnosed with superior mesenteric artery syndrome (SMAS), a rare, potentially life-threatening condition that occurs when the duodenum is compressed between the aorta and the superior mesenteric artery, causing a partial or complete blockage of the duodenum. Since receiving this diagnosis, Ms. S reports feeling anxious, depressed, and overwhelmed by both the pain she is experiencing from her illness and uncertainty about her prognosis.

HISTORY In pain and isolated

Since being diagnosed with SMAS, Ms. S has had approximately 30 medical and 7 ED visits for SMAS-related pain. Ms. S was referred to the outpatient clinic for ongoing support and treatment for SMAS.

Because of her pain and anxiety, Ms. S, a junior in high school, no longer attends school but has been working with a tutor. Ms. S says that some of her loneliness and hopelessness are due to the social isolation of being tutored at home. She states that she has been “out of sight and out of mind” from her friends. She also reports feeling different from them due to the pain brought on by SMAS.

Ms. S and her mother live in public housing. Ms. S says that overall, she has a good relationship with her mother, but that in certain situations, her mother’s anxiety causes her significant frustration and anxiety.

EVALUATION Transient suicidal thoughts

A physical examination reveals superficial lacerations to Ms. S’s left arm. Although she appears thin, her current body mass index (BMI) is 20.4 kg/m2, which is within normal range. She says she sees herself as “underweight” and “not fat at all.” Ms. S reports that she likes food and enjoyed eating until it became too painful following her SMAS diagnosis. Ms. S denies a history of binging or purging. Results from her laboratory workup and all values are within normal limits.

During the initial interview, Ms. S’s mother says they came to the ED because Ms. S urgently needs a psychiatric evaluation so she can be cleared for gastrointestinal (GI) surgery and placement of a nasogastric tube. Her mother says a surgeon from a different hospital told them that her insurance company required a psychiatric evaluation to rule out anorexia nervosa before they would authorize the GI surgery. When asked why psychiatry at this hospital was not consulted, Ms. S’s mother does not answer.

When asked about the symptoms she has been experiencing, Ms. S says that her sleep has been poor because of increased pain and excessive worrying about her health. She has limited her food intake. Ms. S reports that after eating, she lays on her left side to alleviate pain and help the food move through her body.

Continue to: Ms. S says...

Ms. S says she feels anxious and depressed due to her SMAS diagnosis, her mother’s online research and oversharing of poor prognoses, and being isolated from her friends. Most of her time outside the home is spent attending medical appointments with specialists. Several months ago, Ms. S had seen a psychotherapist, but her mother was unhappy with the treatment recommendations, which included seeking care from a nutritionist and joining group therapy. Ms. S’s mother says she ended her daughter’s psychotherapy because she was unable to obtain a signature ruling out anorexia nervosa within the first few appointments.

Ms. S also says she has had passive suicidal thoughts during the past month, usually twice a week. She reports that these thoughts lasted as long as several hours and were difficult to control, but she has no specific plan or intent. Ms. S denies current suicidal thoughts or ideation, and works with the treatment team to complete a safety plan, which she signs. Other than her recent visit to the ED, Ms. S denies any other thoughts or behaviors of self-injury or suicide.

[polldaddy:10586905]

The authors’ observations

The treatment team considered the following conditions as part of Ms. S’s differential diagnosis:

Major depressive disorder. The team was able to rule out MDD because Ms. S’s depression was attributed to SMAS. Ms. S reported that all depressive symptoms were manageable or nonexistent before the onset of pain from SMAS. There was no direct pathophysiological consequence of another medical condition. Ms. S was clear that her symptoms of anxiety and depression began after she was isolated from her friends and began having difficulty understanding her diagnosis and prognosis.

Anorexia nervosa also was ruled out. According to the DSM-5, a diagnosis of anorexia nervosa requires the following 3 criteria1:

- restriction of food intake resulting in significantly low body weight (defined as weight that is less than “minimally normal”) relative to age, gender, or development

- intense fear of gaining weight, or persistent behaviors that interfere with weight gain

- disturbance in the way in which one’s body weight or shape is experienced, undue influence of body weight or shape on self-evaluation, or lack of insight with regard to seriousness of current low body weight.

Continue to: Although Ms. S appeared...

Although Ms. S appeared thin, her BMI was within normal range. She added that she likes food and enjoyed eating, but that her medical condition made it too painful. Lastly, Ms. S denied a history of binging or purging.

Somatic symptom disorder.

Factitious disorder imposed on self. An individual with FDIS chronically stimulates, induces, or aggravates illnesses to gain the status of being a patient.

Factitious disorder imposed on another is the deliberate feigning or production of symptoms in another individual who is under the perpetrator’s supervision.1Table 23 lists clinical indicators that raise suspicion for FDIA.

Before a diagnosis of somatic symptom disorder, FDIS, or FDIA could be established or ruled out, it was imperative to gather collateral information from other clinicians involved in Ms. S’s care. Ms. S and her mother had sought out help from a pediatric surgeon, a pediatric gastroenterologist, a pediatrician, and a psychotherapist.

Continue to: EVALUATION Collateral information

EVALUATION Collateral information

After Ms. S’s mother signs consent forms for exchange of information, the treatment team reaches out to the other clinicians. The therapist confirms that Ms. S’s mother had ended her daughter’s treatment after she was unable to quickly obtain documentation to rule out anorexia nervosa.

Both the pediatric surgeon and gastroenterologist report concerns of FDIA, which is why both clinicians had referred Ms. S and her mother to psychiatry. The pediatric surgeon states that on one occasion when he interviewed Ms. S separately from her mother, she seemed to be going down a checklist of symptoms. The surgeon reports that there was a partial occlusion of the superior mesenteric artery, confirming the diagnosis of SMAS, but he believed it was not severe enough to explain the symptoms Ms. S reported. The surgeon had scheduled another imaging appointment for 1 month later.

The pediatric gastroenterologist reports that Ms. S’s mother had demanded surgery and nasogastric tube placement for her daughter, which raised suspicion of FDIA. The gastroenterologist had convinced Ms. S and her mother to start low-dose doxepin, 20 mg twice a day, for anxiety, sleep, and abdominal pain.

Lastly, the pediatrician reports that she had not seen Ms. S for several months but stated that Ms. S always has been in the low normal BMI range. The pediatrician also reports that 6 months ago, the patient and her mother were frantically visiting EDs and scheduling doctor’s appointments.

[polldaddy:10586906]

The authors’ observations

The treatment team decided that Ms. S was not in imminent danger, and felt it was important to keep her in treatment without raising her mother’s suspicion. The team agreed to raise these concerns to the police, child protective services, and risk management if Ms. S’s health suddenly deteriorated or if her mother decided to remove Ms. S from our care.

Continue to: The treatment team...

The treatment team at the outpatient psychiatry clinic agreed that Ms. S did not currently meet criteria for anorexia nervosa, MDD, FDIS, or FDIA. However, Ms. S reported worries particular to persistent abdominal pain that was exacerbated by either eating or going to bed at night, which indicated that somatic symptom disorder was her likely diagnosis. Further, she endorsed a high level of anxiety and depression with regard to this somatic complaint that interfered with her daily activities and consumed an excessive amount of time, which also pointed to somatic symptom disorder. As a result of this diagnosis, the treatment team helped Ms. S manage her somatic symptoms and monitored for any other changes in her symptoms

Generally, cognitive-behavioral therapy (CBT) and mindfulness-based therapy may help relieve symptoms associated with somatic symptom disorder.4

TREATMENT Therapy sessions and medication management

At the psychiatric clinic, Ms. S is scheduled for biweekly therapy sessions with a social worker and biweekly appointments with a senior psychiatry resident for medication management. At each visit, Ms. S’s vital signs, height, and weight are measured. In the therapy sessions, she is taught mindfulness skills as well as CBT. The senior psychiatry resident maintains regular communication with the other clinicians involved in Ms. S’s care.

After the first month of treatment, Ms. S undergoes repeat imaging at the gastroenterologist’s office that indicates her SMAS is no longer occluded. Ms. S continues to report somatic symptoms, but with mild improvement.

Over the course of approximately 4 months, Ms. S begins to show signs of improvement in her pain, anxiety, and depression. Ms. S begins to feel well enough to get a summer job at a nursing home and expresses enthusiasm when her weight begins to increase. Her mother also became enthused and verbalized her appreciation that her daughter appeared to be improving.

Continue to: In the fall...

In the fall, Ms. S returns to high school for her senior year but has difficulty getting back into the routine and relating to her old friends. Ms. S continues to perseverate on thoughts of getting sick and her physical symptoms become overwhelming once again. She continues to be focused on any new symptoms she experiences, and to limit the types of foods she eats due to fear of the abdominal pain returning.

After several more months of psychiatric treatment, Ms. S reports significant relief from her abdominal pain, and no longer seeks corrective surgery for her SMAS. Although she occasionally struggles with perseverating thoughts and anxiety about her somatic symptoms such as abdominal pain and worrying about the types of foods she eats and becoming ill, she continues to work through symptoms of her somatic symptom disorder.

The authors’ observations

The main challenge of somatic symptom disorder is the patient’s “abnormal illness behavior.”2,5,6 For pediatric patients, there may an association between a parent’s psychological status and the patient’s somatic symptoms. Abdominal symptoms in a pediatric patient have a strong association with a parent who presents with depression, anxiety, or somatization. The effects of the parent’s psychological status could also manifest in the form of modeling catastrophic thinking or through reinforcement. Parents with certain traits, such as disproportionate worry about pain, may pay more attention to their child’s symptoms, and hence, reward the child when he/she reports somatic symptoms.7,8 In the case of Ms. S, her mother did not participate in therapy and the mother’s psychiatric history was never obtained.

OUTCOMES Making personal strides

Ms. S continues to use mindfulness skills as well as CBT to manage her symptoms of somatic symptom disorder. She continues to celebrate her weight gains, denies any thoughts of suicide or self-harm behaviors, and prepares for college by scheduling campus visits and completing admissions applications.

Bottom Line

Patients with somatic symptom disorder tend to have very high levels of worry about illness. Somatic symptoms in such patients may or may not have a medical explanation. Accurate diagnosis and careful management are necessary to reduce patient distress. Cognitive-behavioral therapy and mindfulness-based therapy may help relieve symptoms associated with this disorder.

Related Resources

- Henningsen P. Management of somatic symptom disorder. Dialogues Clin Neurosci. 2018;20(1):23-91.

- Rosic T, Kalra S, Samaan Z. Somatic symptom disorder, a new DSM-5 diagnosis of an old clinical challenge. BMJ Case Rep. 2016: bcr2015212553. doi: 10.1136/bcr-2015-212553.

Drug Brand Name

Doxepin • Silenor

CASE Distraught over a medical illness

Ms. S, age 16, presents to the emergency department (ED) accompanied by her mother with superficial lacerations on her arm. Ms. S states, “I cut my arm because I was afraid I was going to do something serious if I didn’t get to go to the ED.” She says that 6 months earlier, she was diagnosed with superior mesenteric artery syndrome (SMAS), a rare, potentially life-threatening condition that occurs when the duodenum is compressed between the aorta and the superior mesenteric artery, causing a partial or complete blockage of the duodenum. Since receiving this diagnosis, Ms. S reports feeling anxious, depressed, and overwhelmed by both the pain she is experiencing from her illness and uncertainty about her prognosis.

HISTORY In pain and isolated

Since being diagnosed with SMAS, Ms. S has had approximately 30 medical and 7 ED visits for SMAS-related pain. Ms. S was referred to the outpatient clinic for ongoing support and treatment for SMAS.

Because of her pain and anxiety, Ms. S, a junior in high school, no longer attends school but has been working with a tutor. Ms. S says that some of her loneliness and hopelessness are due to the social isolation of being tutored at home. She states that she has been “out of sight and out of mind” from her friends. She also reports feeling different from them due to the pain brought on by SMAS.

Ms. S and her mother live in public housing. Ms. S says that overall, she has a good relationship with her mother, but that in certain situations, her mother’s anxiety causes her significant frustration and anxiety.

EVALUATION Transient suicidal thoughts

A physical examination reveals superficial lacerations to Ms. S’s left arm. Although she appears thin, her current body mass index (BMI) is 20.4 kg/m2, which is within normal range. She says she sees herself as “underweight” and “not fat at all.” Ms. S reports that she likes food and enjoyed eating until it became too painful following her SMAS diagnosis. Ms. S denies a history of binging or purging. Results from her laboratory workup and all values are within normal limits.

During the initial interview, Ms. S’s mother says they came to the ED because Ms. S urgently needs a psychiatric evaluation so she can be cleared for gastrointestinal (GI) surgery and placement of a nasogastric tube. Her mother says a surgeon from a different hospital told them that her insurance company required a psychiatric evaluation to rule out anorexia nervosa before they would authorize the GI surgery. When asked why psychiatry at this hospital was not consulted, Ms. S’s mother does not answer.

When asked about the symptoms she has been experiencing, Ms. S says that her sleep has been poor because of increased pain and excessive worrying about her health. She has limited her food intake. Ms. S reports that after eating, she lays on her left side to alleviate pain and help the food move through her body.

Continue to: Ms. S says...

Ms. S says she feels anxious and depressed due to her SMAS diagnosis, her mother’s online research and oversharing of poor prognoses, and being isolated from her friends. Most of her time outside the home is spent attending medical appointments with specialists. Several months ago, Ms. S had seen a psychotherapist, but her mother was unhappy with the treatment recommendations, which included seeking care from a nutritionist and joining group therapy. Ms. S’s mother says she ended her daughter’s psychotherapy because she was unable to obtain a signature ruling out anorexia nervosa within the first few appointments.

Ms. S also says she has had passive suicidal thoughts during the past month, usually twice a week. She reports that these thoughts lasted as long as several hours and were difficult to control, but she has no specific plan or intent. Ms. S denies current suicidal thoughts or ideation, and works with the treatment team to complete a safety plan, which she signs. Other than her recent visit to the ED, Ms. S denies any other thoughts or behaviors of self-injury or suicide.

[polldaddy:10586905]

The authors’ observations

The treatment team considered the following conditions as part of Ms. S’s differential diagnosis:

Major depressive disorder. The team was able to rule out MDD because Ms. S’s depression was attributed to SMAS. Ms. S reported that all depressive symptoms were manageable or nonexistent before the onset of pain from SMAS. There was no direct pathophysiological consequence of another medical condition. Ms. S was clear that her symptoms of anxiety and depression began after she was isolated from her friends and began having difficulty understanding her diagnosis and prognosis.

Anorexia nervosa also was ruled out. According to the DSM-5, a diagnosis of anorexia nervosa requires the following 3 criteria1:

- restriction of food intake resulting in significantly low body weight (defined as weight that is less than “minimally normal”) relative to age, gender, or development

- intense fear of gaining weight, or persistent behaviors that interfere with weight gain

- disturbance in the way in which one’s body weight or shape is experienced, undue influence of body weight or shape on self-evaluation, or lack of insight with regard to seriousness of current low body weight.

Continue to: Although Ms. S appeared...

Although Ms. S appeared thin, her BMI was within normal range. She added that she likes food and enjoyed eating, but that her medical condition made it too painful. Lastly, Ms. S denied a history of binging or purging.

Somatic symptom disorder.

Factitious disorder imposed on self. An individual with FDIS chronically stimulates, induces, or aggravates illnesses to gain the status of being a patient.

Factitious disorder imposed on another is the deliberate feigning or production of symptoms in another individual who is under the perpetrator’s supervision.1Table 23 lists clinical indicators that raise suspicion for FDIA.

Before a diagnosis of somatic symptom disorder, FDIS, or FDIA could be established or ruled out, it was imperative to gather collateral information from other clinicians involved in Ms. S’s care. Ms. S and her mother had sought out help from a pediatric surgeon, a pediatric gastroenterologist, a pediatrician, and a psychotherapist.

Continue to: EVALUATION Collateral information

EVALUATION Collateral information

After Ms. S’s mother signs consent forms for exchange of information, the treatment team reaches out to the other clinicians. The therapist confirms that Ms. S’s mother had ended her daughter’s treatment after she was unable to quickly obtain documentation to rule out anorexia nervosa.

Both the pediatric surgeon and gastroenterologist report concerns of FDIA, which is why both clinicians had referred Ms. S and her mother to psychiatry. The pediatric surgeon states that on one occasion when he interviewed Ms. S separately from her mother, she seemed to be going down a checklist of symptoms. The surgeon reports that there was a partial occlusion of the superior mesenteric artery, confirming the diagnosis of SMAS, but he believed it was not severe enough to explain the symptoms Ms. S reported. The surgeon had scheduled another imaging appointment for 1 month later.

The pediatric gastroenterologist reports that Ms. S’s mother had demanded surgery and nasogastric tube placement for her daughter, which raised suspicion of FDIA. The gastroenterologist had convinced Ms. S and her mother to start low-dose doxepin, 20 mg twice a day, for anxiety, sleep, and abdominal pain.

Lastly, the pediatrician reports that she had not seen Ms. S for several months but stated that Ms. S always has been in the low normal BMI range. The pediatrician also reports that 6 months ago, the patient and her mother were frantically visiting EDs and scheduling doctor’s appointments.

[polldaddy:10586906]

The authors’ observations

The treatment team decided that Ms. S was not in imminent danger, and felt it was important to keep her in treatment without raising her mother’s suspicion. The team agreed to raise these concerns to the police, child protective services, and risk management if Ms. S’s health suddenly deteriorated or if her mother decided to remove Ms. S from our care.

Continue to: The treatment team...

The treatment team at the outpatient psychiatry clinic agreed that Ms. S did not currently meet criteria for anorexia nervosa, MDD, FDIS, or FDIA. However, Ms. S reported worries particular to persistent abdominal pain that was exacerbated by either eating or going to bed at night, which indicated that somatic symptom disorder was her likely diagnosis. Further, she endorsed a high level of anxiety and depression with regard to this somatic complaint that interfered with her daily activities and consumed an excessive amount of time, which also pointed to somatic symptom disorder. As a result of this diagnosis, the treatment team helped Ms. S manage her somatic symptoms and monitored for any other changes in her symptoms

Generally, cognitive-behavioral therapy (CBT) and mindfulness-based therapy may help relieve symptoms associated with somatic symptom disorder.4

TREATMENT Therapy sessions and medication management

At the psychiatric clinic, Ms. S is scheduled for biweekly therapy sessions with a social worker and biweekly appointments with a senior psychiatry resident for medication management. At each visit, Ms. S’s vital signs, height, and weight are measured. In the therapy sessions, she is taught mindfulness skills as well as CBT. The senior psychiatry resident maintains regular communication with the other clinicians involved in Ms. S’s care.

After the first month of treatment, Ms. S undergoes repeat imaging at the gastroenterologist’s office that indicates her SMAS is no longer occluded. Ms. S continues to report somatic symptoms, but with mild improvement.

Over the course of approximately 4 months, Ms. S begins to show signs of improvement in her pain, anxiety, and depression. Ms. S begins to feel well enough to get a summer job at a nursing home and expresses enthusiasm when her weight begins to increase. Her mother also became enthused and verbalized her appreciation that her daughter appeared to be improving.

Continue to: In the fall...

In the fall, Ms. S returns to high school for her senior year but has difficulty getting back into the routine and relating to her old friends. Ms. S continues to perseverate on thoughts of getting sick and her physical symptoms become overwhelming once again. She continues to be focused on any new symptoms she experiences, and to limit the types of foods she eats due to fear of the abdominal pain returning.

After several more months of psychiatric treatment, Ms. S reports significant relief from her abdominal pain, and no longer seeks corrective surgery for her SMAS. Although she occasionally struggles with perseverating thoughts and anxiety about her somatic symptoms such as abdominal pain and worrying about the types of foods she eats and becoming ill, she continues to work through symptoms of her somatic symptom disorder.

The authors’ observations

The main challenge of somatic symptom disorder is the patient’s “abnormal illness behavior.”2,5,6 For pediatric patients, there may an association between a parent’s psychological status and the patient’s somatic symptoms. Abdominal symptoms in a pediatric patient have a strong association with a parent who presents with depression, anxiety, or somatization. The effects of the parent’s psychological status could also manifest in the form of modeling catastrophic thinking or through reinforcement. Parents with certain traits, such as disproportionate worry about pain, may pay more attention to their child’s symptoms, and hence, reward the child when he/she reports somatic symptoms.7,8 In the case of Ms. S, her mother did not participate in therapy and the mother’s psychiatric history was never obtained.

OUTCOMES Making personal strides

Ms. S continues to use mindfulness skills as well as CBT to manage her symptoms of somatic symptom disorder. She continues to celebrate her weight gains, denies any thoughts of suicide or self-harm behaviors, and prepares for college by scheduling campus visits and completing admissions applications.

Bottom Line

Patients with somatic symptom disorder tend to have very high levels of worry about illness. Somatic symptoms in such patients may or may not have a medical explanation. Accurate diagnosis and careful management are necessary to reduce patient distress. Cognitive-behavioral therapy and mindfulness-based therapy may help relieve symptoms associated with this disorder.

Related Resources

- Henningsen P. Management of somatic symptom disorder. Dialogues Clin Neurosci. 2018;20(1):23-91.

- Rosic T, Kalra S, Samaan Z. Somatic symptom disorder, a new DSM-5 diagnosis of an old clinical challenge. BMJ Case Rep. 2016: bcr2015212553. doi: 10.1136/bcr-2015-212553.

Drug Brand Name

Doxepin • Silenor

1. Diagnostic and statistical manual of mental disorders, 5th ed. Washington, DC: American Psychiatric Association; 2013.

2. Stern T, Freudenreich O, Smith F, et al. Massachusetts General Hospital Handbook of General Hospital Psychiatry, 7th ed. New York, NY: Elsevier; 2017.

3. Feldman MD, Eisendrath SJ. The spectrum of factitious disorders. Washington, DC: American Psychiatric Association; 1997.

4. Sadock BJ, Sadock VA, Ruiz P. Kaplan & Sadock’s synopsis of psychiatry: behavioral sciences/clinical psychiatry, 11th ed. Philadelphia, PA: Wolters Kluwer; 2014:470.

5. Pilowsky I. The concept of abnormal illness behavior. Psychosomatics. 1990;31(2):207-213.

6. Kirmayer LJ, Looper KJ. Abnormal illness behavior: physiological, psychological and social dimensions of coping with stress. Curr Opin Psychiatry. 2006;19(1):54-60.

7. Walker LS, Garber J, Greene JW. Somatic complaints in pediatric patients: a prospective study of the role of negative life events, child social and academic competence, and parental somatic symptoms. J Consult Clin Psychology. 1994;62(6):1213-1221.

8. Van Oudenhove L, Levy RL, Crowell MD, et al. Biopsychosocial aspects of functional gastrointestinal disorders: how central and environmental processes contribute to the development and expression of functional gastrointestinal disorders. Gastroenterology. 2016;150(6):1355-1367.

1. Diagnostic and statistical manual of mental disorders, 5th ed. Washington, DC: American Psychiatric Association; 2013.

2. Stern T, Freudenreich O, Smith F, et al. Massachusetts General Hospital Handbook of General Hospital Psychiatry, 7th ed. New York, NY: Elsevier; 2017.

3. Feldman MD, Eisendrath SJ. The spectrum of factitious disorders. Washington, DC: American Psychiatric Association; 1997.

4. Sadock BJ, Sadock VA, Ruiz P. Kaplan & Sadock’s synopsis of psychiatry: behavioral sciences/clinical psychiatry, 11th ed. Philadelphia, PA: Wolters Kluwer; 2014:470.

5. Pilowsky I. The concept of abnormal illness behavior. Psychosomatics. 1990;31(2):207-213.

6. Kirmayer LJ, Looper KJ. Abnormal illness behavior: physiological, psychological and social dimensions of coping with stress. Curr Opin Psychiatry. 2006;19(1):54-60.

7. Walker LS, Garber J, Greene JW. Somatic complaints in pediatric patients: a prospective study of the role of negative life events, child social and academic competence, and parental somatic symptoms. J Consult Clin Psychology. 1994;62(6):1213-1221.

8. Van Oudenhove L, Levy RL, Crowell MD, et al. Biopsychosocial aspects of functional gastrointestinal disorders: how central and environmental processes contribute to the development and expression of functional gastrointestinal disorders. Gastroenterology. 2016;150(6):1355-1367.

What to tell parents whose child saw them having sex

Many parents find themselves in a difficult situation when their child accidentally sees them having sex. These patients may ask us, as their clinicians, if they should discuss the incident with their child, and if so, what to say. If parents do not address the subject appropriately, their child might be confused and uncomfortable with his/her interpretation of the encounter.1 Some older research suggests that after witnessing their parents in a sexual encounter, children may have difficulty with affectional love, fears of being alone, or feelings of vulnerability.2,3 Clinicians may find themselves at a loss when parents ask them how to handle these situations. Although there are no evidence-based guidelines to consult, consider the following suggestions:

Relax. For patients who have not yet experienced this situation, tell them it is important not to panic if their child witnesses them having sex. They should cover their bodies and calmly respond to their child’s presence. Calm responsiveness is a key to diffusing this awkward situation. Otherwise, children may sense their parents’ embarrassment and conclude that sex is shameful. Parents should gently explain to their child that they are having a private, adult moment. They should ask their child if something is needed immediately, or if it could wait.

Accept that it happened. Parents should not avoid discussing the incident, but should promptly follow up with their child at an appropriate time and place. Waiting for a child to raise the topic puts the responsibility on him/her, instead of on the parent. Although some forthright children may ask questions, others may feel too ashamed or nervous to broach the topic and will prefer their parents to take the lead.

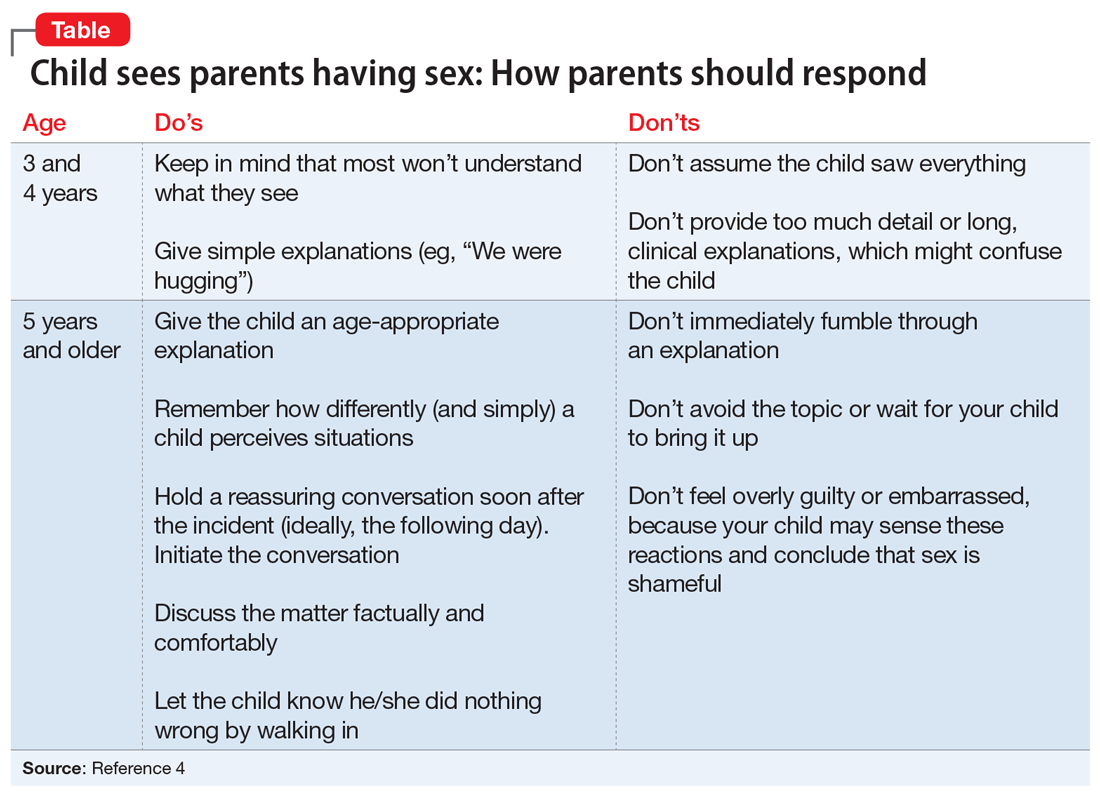

Discuss what happened. Tell parents to explore their child’s impression of what he/she saw. Tailoring the discussion to the child’s age is important. For example, a 3-year-old might wonder if anyone was harmed, and might need reassurance, whereas a 12-year-old is likely to have a better understanding of sex but still feel uncomfortable. Educational conversations about sexuality might be appropriate for children age 8 to 12. The parents’ goal should be to answer questions honestly without oversharing, and to leave the door open—so to speak—for future conversations.

Recommend that parents use plain, factual language to answer any questions their child asks. Statements such as “We were having a private, adult moment” can be helpful. Parents can categorize sex as a universal activity that is not harmful or scary by telling their child something such as, “This is what all parents do.” Parents should avoid providing unnecessary information or answering questions their child is not asking. The Table4 offers guidance on how parents might handle such conversations.

Consider potentially positive outcomes. Although parents may feel guilty or describe this as a terrible situation, remind them that there are some potentially healthy outcomes. For example, such incidents may help reassure the child that their parents love each other, which might give him/her a sense of happiness and security.

Take steps to prevent this from happening again. Advise parents to lock the door when having sex. Remind them to consider the proximity of rooms because their child might hear noises and become curious.

1. Blum HP. On the concept and consequences of the primal scene. Psychoanal Q. 1979;48(1):27-47.

2. Hoyt MF. On the psychology and psychopathology of primal-scene experience. J Am Acad Psychoanal. 1980;8(3):311-335.

3. Ikonen P, Rechardt E. On the universal nature of primal scene fantasies. Int J Psychoanal. 1984;65(pt 1):63-72.

4. Pelly J. Four things my four-year-old already knows about sex. Today’s Parent. https://www.todaysparent.com/family/parenting/4-things-my-4-year-old-already-knows-about-sex/. Published February 1, 2020. Accessed June 20, 2020.

Many parents find themselves in a difficult situation when their child accidentally sees them having sex. These patients may ask us, as their clinicians, if they should discuss the incident with their child, and if so, what to say. If parents do not address the subject appropriately, their child might be confused and uncomfortable with his/her interpretation of the encounter.1 Some older research suggests that after witnessing their parents in a sexual encounter, children may have difficulty with affectional love, fears of being alone, or feelings of vulnerability.2,3 Clinicians may find themselves at a loss when parents ask them how to handle these situations. Although there are no evidence-based guidelines to consult, consider the following suggestions:

Relax. For patients who have not yet experienced this situation, tell them it is important not to panic if their child witnesses them having sex. They should cover their bodies and calmly respond to their child’s presence. Calm responsiveness is a key to diffusing this awkward situation. Otherwise, children may sense their parents’ embarrassment and conclude that sex is shameful. Parents should gently explain to their child that they are having a private, adult moment. They should ask their child if something is needed immediately, or if it could wait.

Accept that it happened. Parents should not avoid discussing the incident, but should promptly follow up with their child at an appropriate time and place. Waiting for a child to raise the topic puts the responsibility on him/her, instead of on the parent. Although some forthright children may ask questions, others may feel too ashamed or nervous to broach the topic and will prefer their parents to take the lead.