User login

Treating the pregnant patient with opioid addiction

OBG Management : How has the opioid crisis affected women in general?

Mishka Terplan, MD: Everyone is aware that we are experiencing a massive opioid crisis in the United States, and from a historical perspective, this is at least the third or fourth significant opioid epidemic in our nation’s history.1 It is similar in some ways to the very first one, which also featured a large proportion of women and also was driven initially by physician prescribing practices. However, the magnitude of this crisis is unparalleled compared with prior opioid epidemics.

There are lots of reasons why women are overrepresented in this crisis. There are gender-based differences in pain—chronic pain syndromes are more common in women. In addition, we have a gender bias in prescribing opioids and prescribe more opioids to women (especially older women) than to men. Cultural differences also contribute. As providers, we tend not to think of women as people who use drugs or people who develop addictions the same way as we think of these risks and behaviors for men. Therefore, compared with men, we are less likely to screen, assess, or refer women for substance use, misuse, and addiction. All of this adds up to creating a crisis in which women are increasingly the face of the epidemic.

OBG Management : What are the concerns about opioid addiction and pregnant women specifically?

Dr. Terplan: Addiction is a chronic condition, just like diabetes or depression, and the same principles that we think of in terms of optimizing maternal and newborn health apply to addiction. Ideally, we want, for women with chronic diseases to have stable disease at the time of conception and through pregnancy. We know this maximizes birth outcomes.

Unfortunately, there is a massive treatment gap in the United States. Most people with addiction receive no treatment. Only 11% of people with a substance use disorder report receipt of treatment. By contrast, more than 70% of people with depression, hypertension, or diabetes receive care. This treatment gap is also present in pregnancy. Among use disorders, treatment receipt is highest for opioid use disorder; however, nationally, at best, 25% of pregnant women with opioid addiction receive any care.

In other words, when we encounter addiction clinically, it is often untreated addiction. Therefore, many times providers will have women presenting to care who are both pregnant and have untreated addiction. From both a public health and a clinical practice perspective, the salient distinction is not between people with addiction and those without but between people with treated disease and people with untreated disease.

Untreated addiction is a serious medical condition. It is associated with preterm delivery and low birth weight infants. It is associated with acquisition and transmission of HIV and hepatitis C. It is associated with overdose and overdose death. By contrast, treated addiction is associated with term delivery and normal weight infants. Pharmacotherapies for opioid use disorder stabilize the intrauterine environment and allow for normal fetal growth. Pharmacotherapies for opioid use disorder help to structure and stabilize the mom’s social circumstance, providing a platform to deliver prenatal care and essential social services. And pharmacotherapies for opioid use disorder protect women and their fetuses from overdose and from overdose deaths. The goal of management of addiction in pregnancy is treatment of the underlying condition, treating the addiction.

Continue to: OBG Management...

OBG Management : What should the ObGyn do when faced with a patient who might have an addiction?

Dr. Terplan: The good news is that there are lots of recently published guidance documents from the World Health Organization,2 the American College of Obstetricians and Gynecologists (ACOG),3 and the Substance Abuse and Mental Health Services Administration (SAMHSA),4 and there have been a whole series of trainings throughout the United States organized by both ACOG and SAMHSA.

There is also a collaboration between ACOG and the American Society of Addiction Medicine (ASAM) to provide buprenorphine waiver trainings specifically designed for ObGyns. Check both the ACOG and ASAM pages for details. I encourage every provider to get a waiver to prescribe buprenorphine. There are about 30 ObGyns who are also board certified in addiction medicine in the United States, and all of us are more than happy to help our colleagues in the clinical care of this population, a population that all of us really enjoy taking care of.

Although care in pregnancy is important, we must not forget about the postpartum period. Generally speaking, women do quite well during pregnancy in terms of treatment. Postpartum, however, is a vulnerable period, where relapse happens, where gaps in care happen, where child welfare involvement and sometimes child removal happens, which can be very stressful for anyone much less somebody with a substance use disorder. Recent data demonstrate that one of the leading causes of maternal mortality in the US in from overdose, and most of these deaths occur in the postpartum period.5 Regardless of what happens during pregnancy, it is essential that we be able to link and continue care for women with opioid use disorder throughout the postpartum period.

OBG Management : How do you treat opioid use disorder in pregnancy?

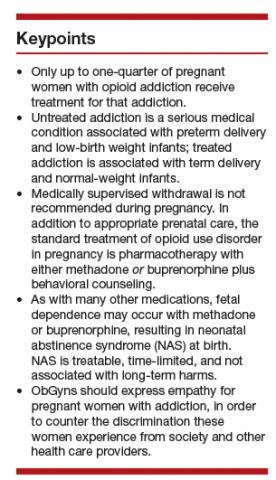

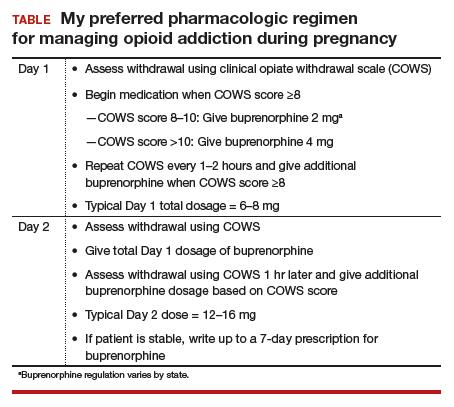

Dr. Terplan: The standard of care for treatment of opioid use disorder in pregnancy is pharmacotherapy with either methadone or buprenorphine (TABLE) plus behavioral counseling—ideally, co-located with prenatal care. The evidence base for pharmacotherapy for opioid use disorder in pregnancy is supported by every single professional society that has ever issued guidance on this, from the World Health Organization to ACOG, to ASAM, to the Royal College in the UK as well as Canadian and Australian obstetrics and gynecology societies; literally every single professional society supports medication.

The core principle of maternal fetal medicine rests upon the fact that chronic conditions need to be treated and that treated illness improves birth outcomes. For both maternal and fetal health, treated addiction is way better than untreated addiction. One concern people have regarding methadone and buprenorphine is the development of dependence. Dependence is a physiologic effect of medication and occurs with opioids, as well as with many other medications, such as antidepressants and most hypertensive agents. For the fetus, dependence means that at the time of delivery, the infant may go into withdrawal, which is also called neonatal abstinence syndrome. Neonatal abstinence syndrome is an expected outcome of in-utero opioid exposure. It is a time-limited and treatable condition. Prospective data do not demonstrate any long-term harms among infants whose mothers received pharmacotherapy for opioid use disorder during pregnancy.6

The treatment for neonatal abstinence syndrome is costly, especially when in a neonatal intensive care unit. It can be quite concerning to a new mother to have an infant that has to spend extra time in the hospital and sometimes be medicated for management of withdrawal.

There has been a renewed interest amongst ObGyns in investigating medically-supervised withdrawal during pregnancy. Although there are remaining questions, overall, the literature does not support withdrawal during pregnancy—mostly because withdrawal is associated with relapse, and relapse is associated with cessation of care (both prenatal care and addiction treatment), acquisition and transmission of HIV and Hepatitis C, and overdose and overdose death. The pertinent clinical and public health goal is the treatment of the chronic condition of addiction during pregnancy. The standard of care remains pharmacotherapy plus behavioral counseling for the treatment of opioid use disorder in pregnancy.

Clinical care, however, is both evidence-based and person-centered. All of us who have worked in this field, long before there was attention to the opioid crisis, all of us have provided medically-supervised withdrawal of a pregnant person, and that is because we understand the principles of care. When evidence-based care conflicts with person-centered care, the ethical course is the provision of person-centered care. Patients have the right of refusal. If someone wants to discontinue medication, I have tapered the medication during pregnancy, but continued to provide (and often increase) behavioral counseling and prenatal care.

Treated addiction is better for the fetus than untreated addiction. Untreated opioid addiction is associated with preterm birth and low birth weight. These obstetric risks are not because of the opioid per se, but because of the repeated cycles of withdrawal that an individual with untreated addiction experiences. People with untreated addiction are not getting “high” when they use, they are just becoming a little bit less sick. It is this repeated cycle of withdrawal that stresses the fetus, which leads to preterm delivery and low birth weight.

Medications for opioid use disorder are long-acting and dosed daily. In contrast to the repeated cycles of fetal withdrawal in untreated addiction, pharmacotherapy stabilizes the intrauterine environment. There is no cyclic, repeated, stressful withdrawal, and consequentially, the fetus grows normally and delivers at term. Obstetric risk is from repeated cyclic withdrawal more than from opioid exposure itself.

Continue to: OBG Management...

OBG Management : Research reports that women are not using all of the opioids that are prescribed to them after a cesarean delivery. What are the risks for addiction in this setting?

Dr. Terplan: I mark a distinction between use (ie, using something as prescribed) and misuse, which means using a prescribed medication not in the manner in which it was prescribed, or using somebody else’s medications, or using an illicit substance. And I differentiate use and misuse from addiction, which is a behavioral condition, a disease. There has been a lot of attention paid to opioid prescribing in general and in particular postdelivery and post–cesarean delivery, which is one of the most common operative procedures in the United States.

It seems clear from the literature that we have overprescribed opioids postdelivery, and a small number of women, about 1 in 300 will continue an opioid script.7 This means that 1 in 300 women who received an opioid prescription following delivery present for care and get another opioid prescription filled. Now, that is a small number at the level of the individual, but because we do so many cesarean deliveries, this is a large number of women at the level of the population. This does not mean, however, that 1 in 300 women who received opioids after cesarean delivery are going to become addicted to them. It just means that 1 in 300 will continue the prescription. Prescription continuation is a risk factor for opioid misuse, and opioid misuse is on the pathway toward addiction.

Most people who use substances do not develop an addiction to that substance. We know from the opioid literature that at most only 10% of people who receive chronic opioid therapy will meet criteria for opioid use disorder.8 Now 10% is not 100%, nor is it 0%, but because we prescribed so many opioids to so many people for so long, the absolute number of people with opioid use disorder from physician opioid prescribing is large, even though the risk at the level of the individual is not as large as people think.

OBG Management : From your experience in treating addiction during pregnancy, are there clinical pearls you would like to share with ObGyns?

Dr. Terplan: There are a couple of takeaways. One is that all women are motivated to maximize their health and that of their baby to be, and every pregnant woman engages in behavioral change; in fact most women quit or cutback substance use during pregnancy. But some can’t. Those that can’t likely have a substance use disorder. We think of addiction as a chronic condition, centered in the brain, but the primary symptoms of addiction are behaviors. The salient feature of addiction is continued use despite adverse consequences; using something that you know is harming yourself and others but you can’t stop using it. In other words, continuing substance use during pregnancy. When we see clinically a pregnant woman who is using a substance, 99% of the time we are seeing a pregnant woman who has the condition of addiction, and what she needs is treatment. She does not need to be told that injecting heroin is unsafe for her and her fetus, she knows that. What she needs is treatment.

The second point is that pregnant women who use drugs and pregnant women with addiction experience a real specific and strong form of discrimination by providers, by other people with addiction, by the legal system, and by their friends and families. Caring for people who have substance use disorder is grounded in human rights, which means treating people with dignity and respect. It is important for providers to have empathy, especially for pregnant people who use drugs, to counter the discrimination they experience from society and from other health care providers.

Continue to: OBG Management...

OBG Management : Are there specific ways in which ObGyns can show empathy when speaking with a pregnant woman who likely has addiction?

Dr. Terplan: In general when we talk to people about drug use, it is important to ask their permission to talk about it. For example, “Is it okay if I ask you some questions about smoking, drinking, and other drugs?” If someone says, “No, I don’t want you to ask those questions,” we have to respect that. Assessment of substance use should be a universal part of all medical care, as substance use, misuse, and addiction are essential domains of wellness, but I think we should ask permission before screening.

One of the really good things about prenatal care is that people come back; we have multiple visits across the gestational period. The behavioral work of addiction treatment rests upon a strong therapeutic alliance. If you do not respect your patient, then there is no way you can achieve a therapeutic alliance. Asking permission, and then respecting somebody’s answers, I think goes a really long way to establishing a strong therapeutic alliance, which is the basis of any medical care.

- Terplan M. Women and the opioid crisis: historical context and public health solutions. Fertil Steril. 2017;108:195-199.

- Management of substance abuse. World Health Organization website. https://www.who.int/substance_abuse/activities/treatment_opioid_dependence/en/. Accessed March 20, 2019.

- Committee on Obstetric Practice. Committee Opinion No. 711: Opioid use and opioid use disorder in pregnancy. Obstet Gynecol. 2017;130(2):e81-e94.

- Substance Abuse and Mental Health Services Administration. Clinical guidance for treating pregnant and parenting women with opioid use disorder and their infants. HHS Publication No. (SMA) 18-5054. Rockville, MD: Substance Abuse and Mental Health Services Administration; 2018.

- Metz TD, Royner P, Hoffman MC, et al. Maternal deaths from suicide and overdose in Colorado, 2004-2012. Obstet Gynecol. 2016;128:1233-1240.

- Kaltenbach K, O’Grady E, Heil SH, et al. Prenatal exposure to methadone or buprenorphine: early childhood developmental outcomes. Drug Alcohol Depend. 2018;185:40-49.

- Bateman BT, Franklin JM, Bykov K, et al. Persistent opioid use following cesarean delivery: patterns and predictors among opioid-naive women. Am J Obstet Gynecol. 2016;215:353.e1-353.e18.

OBG Management : How has the opioid crisis affected women in general?

Mishka Terplan, MD: Everyone is aware that we are experiencing a massive opioid crisis in the United States, and from a historical perspective, this is at least the third or fourth significant opioid epidemic in our nation’s history.1 It is similar in some ways to the very first one, which also featured a large proportion of women and also was driven initially by physician prescribing practices. However, the magnitude of this crisis is unparalleled compared with prior opioid epidemics.

There are lots of reasons why women are overrepresented in this crisis. There are gender-based differences in pain—chronic pain syndromes are more common in women. In addition, we have a gender bias in prescribing opioids and prescribe more opioids to women (especially older women) than to men. Cultural differences also contribute. As providers, we tend not to think of women as people who use drugs or people who develop addictions the same way as we think of these risks and behaviors for men. Therefore, compared with men, we are less likely to screen, assess, or refer women for substance use, misuse, and addiction. All of this adds up to creating a crisis in which women are increasingly the face of the epidemic.

OBG Management : What are the concerns about opioid addiction and pregnant women specifically?

Dr. Terplan: Addiction is a chronic condition, just like diabetes or depression, and the same principles that we think of in terms of optimizing maternal and newborn health apply to addiction. Ideally, we want, for women with chronic diseases to have stable disease at the time of conception and through pregnancy. We know this maximizes birth outcomes.

Unfortunately, there is a massive treatment gap in the United States. Most people with addiction receive no treatment. Only 11% of people with a substance use disorder report receipt of treatment. By contrast, more than 70% of people with depression, hypertension, or diabetes receive care. This treatment gap is also present in pregnancy. Among use disorders, treatment receipt is highest for opioid use disorder; however, nationally, at best, 25% of pregnant women with opioid addiction receive any care.

In other words, when we encounter addiction clinically, it is often untreated addiction. Therefore, many times providers will have women presenting to care who are both pregnant and have untreated addiction. From both a public health and a clinical practice perspective, the salient distinction is not between people with addiction and those without but between people with treated disease and people with untreated disease.

Untreated addiction is a serious medical condition. It is associated with preterm delivery and low birth weight infants. It is associated with acquisition and transmission of HIV and hepatitis C. It is associated with overdose and overdose death. By contrast, treated addiction is associated with term delivery and normal weight infants. Pharmacotherapies for opioid use disorder stabilize the intrauterine environment and allow for normal fetal growth. Pharmacotherapies for opioid use disorder help to structure and stabilize the mom’s social circumstance, providing a platform to deliver prenatal care and essential social services. And pharmacotherapies for opioid use disorder protect women and their fetuses from overdose and from overdose deaths. The goal of management of addiction in pregnancy is treatment of the underlying condition, treating the addiction.

Continue to: OBG Management...

OBG Management : What should the ObGyn do when faced with a patient who might have an addiction?

Dr. Terplan: The good news is that there are lots of recently published guidance documents from the World Health Organization,2 the American College of Obstetricians and Gynecologists (ACOG),3 and the Substance Abuse and Mental Health Services Administration (SAMHSA),4 and there have been a whole series of trainings throughout the United States organized by both ACOG and SAMHSA.

There is also a collaboration between ACOG and the American Society of Addiction Medicine (ASAM) to provide buprenorphine waiver trainings specifically designed for ObGyns. Check both the ACOG and ASAM pages for details. I encourage every provider to get a waiver to prescribe buprenorphine. There are about 30 ObGyns who are also board certified in addiction medicine in the United States, and all of us are more than happy to help our colleagues in the clinical care of this population, a population that all of us really enjoy taking care of.

Although care in pregnancy is important, we must not forget about the postpartum period. Generally speaking, women do quite well during pregnancy in terms of treatment. Postpartum, however, is a vulnerable period, where relapse happens, where gaps in care happen, where child welfare involvement and sometimes child removal happens, which can be very stressful for anyone much less somebody with a substance use disorder. Recent data demonstrate that one of the leading causes of maternal mortality in the US in from overdose, and most of these deaths occur in the postpartum period.5 Regardless of what happens during pregnancy, it is essential that we be able to link and continue care for women with opioid use disorder throughout the postpartum period.

OBG Management : How do you treat opioid use disorder in pregnancy?

Dr. Terplan: The standard of care for treatment of opioid use disorder in pregnancy is pharmacotherapy with either methadone or buprenorphine (TABLE) plus behavioral counseling—ideally, co-located with prenatal care. The evidence base for pharmacotherapy for opioid use disorder in pregnancy is supported by every single professional society that has ever issued guidance on this, from the World Health Organization to ACOG, to ASAM, to the Royal College in the UK as well as Canadian and Australian obstetrics and gynecology societies; literally every single professional society supports medication.

The core principle of maternal fetal medicine rests upon the fact that chronic conditions need to be treated and that treated illness improves birth outcomes. For both maternal and fetal health, treated addiction is way better than untreated addiction. One concern people have regarding methadone and buprenorphine is the development of dependence. Dependence is a physiologic effect of medication and occurs with opioids, as well as with many other medications, such as antidepressants and most hypertensive agents. For the fetus, dependence means that at the time of delivery, the infant may go into withdrawal, which is also called neonatal abstinence syndrome. Neonatal abstinence syndrome is an expected outcome of in-utero opioid exposure. It is a time-limited and treatable condition. Prospective data do not demonstrate any long-term harms among infants whose mothers received pharmacotherapy for opioid use disorder during pregnancy.6

The treatment for neonatal abstinence syndrome is costly, especially when in a neonatal intensive care unit. It can be quite concerning to a new mother to have an infant that has to spend extra time in the hospital and sometimes be medicated for management of withdrawal.

There has been a renewed interest amongst ObGyns in investigating medically-supervised withdrawal during pregnancy. Although there are remaining questions, overall, the literature does not support withdrawal during pregnancy—mostly because withdrawal is associated with relapse, and relapse is associated with cessation of care (both prenatal care and addiction treatment), acquisition and transmission of HIV and Hepatitis C, and overdose and overdose death. The pertinent clinical and public health goal is the treatment of the chronic condition of addiction during pregnancy. The standard of care remains pharmacotherapy plus behavioral counseling for the treatment of opioid use disorder in pregnancy.

Clinical care, however, is both evidence-based and person-centered. All of us who have worked in this field, long before there was attention to the opioid crisis, all of us have provided medically-supervised withdrawal of a pregnant person, and that is because we understand the principles of care. When evidence-based care conflicts with person-centered care, the ethical course is the provision of person-centered care. Patients have the right of refusal. If someone wants to discontinue medication, I have tapered the medication during pregnancy, but continued to provide (and often increase) behavioral counseling and prenatal care.

Treated addiction is better for the fetus than untreated addiction. Untreated opioid addiction is associated with preterm birth and low birth weight. These obstetric risks are not because of the opioid per se, but because of the repeated cycles of withdrawal that an individual with untreated addiction experiences. People with untreated addiction are not getting “high” when they use, they are just becoming a little bit less sick. It is this repeated cycle of withdrawal that stresses the fetus, which leads to preterm delivery and low birth weight.

Medications for opioid use disorder are long-acting and dosed daily. In contrast to the repeated cycles of fetal withdrawal in untreated addiction, pharmacotherapy stabilizes the intrauterine environment. There is no cyclic, repeated, stressful withdrawal, and consequentially, the fetus grows normally and delivers at term. Obstetric risk is from repeated cyclic withdrawal more than from opioid exposure itself.

Continue to: OBG Management...

OBG Management : Research reports that women are not using all of the opioids that are prescribed to them after a cesarean delivery. What are the risks for addiction in this setting?

Dr. Terplan: I mark a distinction between use (ie, using something as prescribed) and misuse, which means using a prescribed medication not in the manner in which it was prescribed, or using somebody else’s medications, or using an illicit substance. And I differentiate use and misuse from addiction, which is a behavioral condition, a disease. There has been a lot of attention paid to opioid prescribing in general and in particular postdelivery and post–cesarean delivery, which is one of the most common operative procedures in the United States.

It seems clear from the literature that we have overprescribed opioids postdelivery, and a small number of women, about 1 in 300 will continue an opioid script.7 This means that 1 in 300 women who received an opioid prescription following delivery present for care and get another opioid prescription filled. Now, that is a small number at the level of the individual, but because we do so many cesarean deliveries, this is a large number of women at the level of the population. This does not mean, however, that 1 in 300 women who received opioids after cesarean delivery are going to become addicted to them. It just means that 1 in 300 will continue the prescription. Prescription continuation is a risk factor for opioid misuse, and opioid misuse is on the pathway toward addiction.

Most people who use substances do not develop an addiction to that substance. We know from the opioid literature that at most only 10% of people who receive chronic opioid therapy will meet criteria for opioid use disorder.8 Now 10% is not 100%, nor is it 0%, but because we prescribed so many opioids to so many people for so long, the absolute number of people with opioid use disorder from physician opioid prescribing is large, even though the risk at the level of the individual is not as large as people think.

OBG Management : From your experience in treating addiction during pregnancy, are there clinical pearls you would like to share with ObGyns?

Dr. Terplan: There are a couple of takeaways. One is that all women are motivated to maximize their health and that of their baby to be, and every pregnant woman engages in behavioral change; in fact most women quit or cutback substance use during pregnancy. But some can’t. Those that can’t likely have a substance use disorder. We think of addiction as a chronic condition, centered in the brain, but the primary symptoms of addiction are behaviors. The salient feature of addiction is continued use despite adverse consequences; using something that you know is harming yourself and others but you can’t stop using it. In other words, continuing substance use during pregnancy. When we see clinically a pregnant woman who is using a substance, 99% of the time we are seeing a pregnant woman who has the condition of addiction, and what she needs is treatment. She does not need to be told that injecting heroin is unsafe for her and her fetus, she knows that. What she needs is treatment.

The second point is that pregnant women who use drugs and pregnant women with addiction experience a real specific and strong form of discrimination by providers, by other people with addiction, by the legal system, and by their friends and families. Caring for people who have substance use disorder is grounded in human rights, which means treating people with dignity and respect. It is important for providers to have empathy, especially for pregnant people who use drugs, to counter the discrimination they experience from society and from other health care providers.

Continue to: OBG Management...

OBG Management : Are there specific ways in which ObGyns can show empathy when speaking with a pregnant woman who likely has addiction?

Dr. Terplan: In general when we talk to people about drug use, it is important to ask their permission to talk about it. For example, “Is it okay if I ask you some questions about smoking, drinking, and other drugs?” If someone says, “No, I don’t want you to ask those questions,” we have to respect that. Assessment of substance use should be a universal part of all medical care, as substance use, misuse, and addiction are essential domains of wellness, but I think we should ask permission before screening.

One of the really good things about prenatal care is that people come back; we have multiple visits across the gestational period. The behavioral work of addiction treatment rests upon a strong therapeutic alliance. If you do not respect your patient, then there is no way you can achieve a therapeutic alliance. Asking permission, and then respecting somebody’s answers, I think goes a really long way to establishing a strong therapeutic alliance, which is the basis of any medical care.

OBG Management : How has the opioid crisis affected women in general?

Mishka Terplan, MD: Everyone is aware that we are experiencing a massive opioid crisis in the United States, and from a historical perspective, this is at least the third or fourth significant opioid epidemic in our nation’s history.1 It is similar in some ways to the very first one, which also featured a large proportion of women and also was driven initially by physician prescribing practices. However, the magnitude of this crisis is unparalleled compared with prior opioid epidemics.

There are lots of reasons why women are overrepresented in this crisis. There are gender-based differences in pain—chronic pain syndromes are more common in women. In addition, we have a gender bias in prescribing opioids and prescribe more opioids to women (especially older women) than to men. Cultural differences also contribute. As providers, we tend not to think of women as people who use drugs or people who develop addictions the same way as we think of these risks and behaviors for men. Therefore, compared with men, we are less likely to screen, assess, or refer women for substance use, misuse, and addiction. All of this adds up to creating a crisis in which women are increasingly the face of the epidemic.

OBG Management : What are the concerns about opioid addiction and pregnant women specifically?

Dr. Terplan: Addiction is a chronic condition, just like diabetes or depression, and the same principles that we think of in terms of optimizing maternal and newborn health apply to addiction. Ideally, we want, for women with chronic diseases to have stable disease at the time of conception and through pregnancy. We know this maximizes birth outcomes.

Unfortunately, there is a massive treatment gap in the United States. Most people with addiction receive no treatment. Only 11% of people with a substance use disorder report receipt of treatment. By contrast, more than 70% of people with depression, hypertension, or diabetes receive care. This treatment gap is also present in pregnancy. Among use disorders, treatment receipt is highest for opioid use disorder; however, nationally, at best, 25% of pregnant women with opioid addiction receive any care.

In other words, when we encounter addiction clinically, it is often untreated addiction. Therefore, many times providers will have women presenting to care who are both pregnant and have untreated addiction. From both a public health and a clinical practice perspective, the salient distinction is not between people with addiction and those without but between people with treated disease and people with untreated disease.

Untreated addiction is a serious medical condition. It is associated with preterm delivery and low birth weight infants. It is associated with acquisition and transmission of HIV and hepatitis C. It is associated with overdose and overdose death. By contrast, treated addiction is associated with term delivery and normal weight infants. Pharmacotherapies for opioid use disorder stabilize the intrauterine environment and allow for normal fetal growth. Pharmacotherapies for opioid use disorder help to structure and stabilize the mom’s social circumstance, providing a platform to deliver prenatal care and essential social services. And pharmacotherapies for opioid use disorder protect women and their fetuses from overdose and from overdose deaths. The goal of management of addiction in pregnancy is treatment of the underlying condition, treating the addiction.

Continue to: OBG Management...

OBG Management : What should the ObGyn do when faced with a patient who might have an addiction?

Dr. Terplan: The good news is that there are lots of recently published guidance documents from the World Health Organization,2 the American College of Obstetricians and Gynecologists (ACOG),3 and the Substance Abuse and Mental Health Services Administration (SAMHSA),4 and there have been a whole series of trainings throughout the United States organized by both ACOG and SAMHSA.

There is also a collaboration between ACOG and the American Society of Addiction Medicine (ASAM) to provide buprenorphine waiver trainings specifically designed for ObGyns. Check both the ACOG and ASAM pages for details. I encourage every provider to get a waiver to prescribe buprenorphine. There are about 30 ObGyns who are also board certified in addiction medicine in the United States, and all of us are more than happy to help our colleagues in the clinical care of this population, a population that all of us really enjoy taking care of.

Although care in pregnancy is important, we must not forget about the postpartum period. Generally speaking, women do quite well during pregnancy in terms of treatment. Postpartum, however, is a vulnerable period, where relapse happens, where gaps in care happen, where child welfare involvement and sometimes child removal happens, which can be very stressful for anyone much less somebody with a substance use disorder. Recent data demonstrate that one of the leading causes of maternal mortality in the US in from overdose, and most of these deaths occur in the postpartum period.5 Regardless of what happens during pregnancy, it is essential that we be able to link and continue care for women with opioid use disorder throughout the postpartum period.

OBG Management : How do you treat opioid use disorder in pregnancy?

Dr. Terplan: The standard of care for treatment of opioid use disorder in pregnancy is pharmacotherapy with either methadone or buprenorphine (TABLE) plus behavioral counseling—ideally, co-located with prenatal care. The evidence base for pharmacotherapy for opioid use disorder in pregnancy is supported by every single professional society that has ever issued guidance on this, from the World Health Organization to ACOG, to ASAM, to the Royal College in the UK as well as Canadian and Australian obstetrics and gynecology societies; literally every single professional society supports medication.

The core principle of maternal fetal medicine rests upon the fact that chronic conditions need to be treated and that treated illness improves birth outcomes. For both maternal and fetal health, treated addiction is way better than untreated addiction. One concern people have regarding methadone and buprenorphine is the development of dependence. Dependence is a physiologic effect of medication and occurs with opioids, as well as with many other medications, such as antidepressants and most hypertensive agents. For the fetus, dependence means that at the time of delivery, the infant may go into withdrawal, which is also called neonatal abstinence syndrome. Neonatal abstinence syndrome is an expected outcome of in-utero opioid exposure. It is a time-limited and treatable condition. Prospective data do not demonstrate any long-term harms among infants whose mothers received pharmacotherapy for opioid use disorder during pregnancy.6

The treatment for neonatal abstinence syndrome is costly, especially when in a neonatal intensive care unit. It can be quite concerning to a new mother to have an infant that has to spend extra time in the hospital and sometimes be medicated for management of withdrawal.

There has been a renewed interest amongst ObGyns in investigating medically-supervised withdrawal during pregnancy. Although there are remaining questions, overall, the literature does not support withdrawal during pregnancy—mostly because withdrawal is associated with relapse, and relapse is associated with cessation of care (both prenatal care and addiction treatment), acquisition and transmission of HIV and Hepatitis C, and overdose and overdose death. The pertinent clinical and public health goal is the treatment of the chronic condition of addiction during pregnancy. The standard of care remains pharmacotherapy plus behavioral counseling for the treatment of opioid use disorder in pregnancy.

Clinical care, however, is both evidence-based and person-centered. All of us who have worked in this field, long before there was attention to the opioid crisis, all of us have provided medically-supervised withdrawal of a pregnant person, and that is because we understand the principles of care. When evidence-based care conflicts with person-centered care, the ethical course is the provision of person-centered care. Patients have the right of refusal. If someone wants to discontinue medication, I have tapered the medication during pregnancy, but continued to provide (and often increase) behavioral counseling and prenatal care.

Treated addiction is better for the fetus than untreated addiction. Untreated opioid addiction is associated with preterm birth and low birth weight. These obstetric risks are not because of the opioid per se, but because of the repeated cycles of withdrawal that an individual with untreated addiction experiences. People with untreated addiction are not getting “high” when they use, they are just becoming a little bit less sick. It is this repeated cycle of withdrawal that stresses the fetus, which leads to preterm delivery and low birth weight.

Medications for opioid use disorder are long-acting and dosed daily. In contrast to the repeated cycles of fetal withdrawal in untreated addiction, pharmacotherapy stabilizes the intrauterine environment. There is no cyclic, repeated, stressful withdrawal, and consequentially, the fetus grows normally and delivers at term. Obstetric risk is from repeated cyclic withdrawal more than from opioid exposure itself.

Continue to: OBG Management...

OBG Management : Research reports that women are not using all of the opioids that are prescribed to them after a cesarean delivery. What are the risks for addiction in this setting?

Dr. Terplan: I mark a distinction between use (ie, using something as prescribed) and misuse, which means using a prescribed medication not in the manner in which it was prescribed, or using somebody else’s medications, or using an illicit substance. And I differentiate use and misuse from addiction, which is a behavioral condition, a disease. There has been a lot of attention paid to opioid prescribing in general and in particular postdelivery and post–cesarean delivery, which is one of the most common operative procedures in the United States.

It seems clear from the literature that we have overprescribed opioids postdelivery, and a small number of women, about 1 in 300 will continue an opioid script.7 This means that 1 in 300 women who received an opioid prescription following delivery present for care and get another opioid prescription filled. Now, that is a small number at the level of the individual, but because we do so many cesarean deliveries, this is a large number of women at the level of the population. This does not mean, however, that 1 in 300 women who received opioids after cesarean delivery are going to become addicted to them. It just means that 1 in 300 will continue the prescription. Prescription continuation is a risk factor for opioid misuse, and opioid misuse is on the pathway toward addiction.

Most people who use substances do not develop an addiction to that substance. We know from the opioid literature that at most only 10% of people who receive chronic opioid therapy will meet criteria for opioid use disorder.8 Now 10% is not 100%, nor is it 0%, but because we prescribed so many opioids to so many people for so long, the absolute number of people with opioid use disorder from physician opioid prescribing is large, even though the risk at the level of the individual is not as large as people think.

OBG Management : From your experience in treating addiction during pregnancy, are there clinical pearls you would like to share with ObGyns?

Dr. Terplan: There are a couple of takeaways. One is that all women are motivated to maximize their health and that of their baby to be, and every pregnant woman engages in behavioral change; in fact most women quit or cutback substance use during pregnancy. But some can’t. Those that can’t likely have a substance use disorder. We think of addiction as a chronic condition, centered in the brain, but the primary symptoms of addiction are behaviors. The salient feature of addiction is continued use despite adverse consequences; using something that you know is harming yourself and others but you can’t stop using it. In other words, continuing substance use during pregnancy. When we see clinically a pregnant woman who is using a substance, 99% of the time we are seeing a pregnant woman who has the condition of addiction, and what she needs is treatment. She does not need to be told that injecting heroin is unsafe for her and her fetus, she knows that. What she needs is treatment.

The second point is that pregnant women who use drugs and pregnant women with addiction experience a real specific and strong form of discrimination by providers, by other people with addiction, by the legal system, and by their friends and families. Caring for people who have substance use disorder is grounded in human rights, which means treating people with dignity and respect. It is important for providers to have empathy, especially for pregnant people who use drugs, to counter the discrimination they experience from society and from other health care providers.

Continue to: OBG Management...

OBG Management : Are there specific ways in which ObGyns can show empathy when speaking with a pregnant woman who likely has addiction?

Dr. Terplan: In general when we talk to people about drug use, it is important to ask their permission to talk about it. For example, “Is it okay if I ask you some questions about smoking, drinking, and other drugs?” If someone says, “No, I don’t want you to ask those questions,” we have to respect that. Assessment of substance use should be a universal part of all medical care, as substance use, misuse, and addiction are essential domains of wellness, but I think we should ask permission before screening.

One of the really good things about prenatal care is that people come back; we have multiple visits across the gestational period. The behavioral work of addiction treatment rests upon a strong therapeutic alliance. If you do not respect your patient, then there is no way you can achieve a therapeutic alliance. Asking permission, and then respecting somebody’s answers, I think goes a really long way to establishing a strong therapeutic alliance, which is the basis of any medical care.

- Terplan M. Women and the opioid crisis: historical context and public health solutions. Fertil Steril. 2017;108:195-199.

- Management of substance abuse. World Health Organization website. https://www.who.int/substance_abuse/activities/treatment_opioid_dependence/en/. Accessed March 20, 2019.

- Committee on Obstetric Practice. Committee Opinion No. 711: Opioid use and opioid use disorder in pregnancy. Obstet Gynecol. 2017;130(2):e81-e94.

- Substance Abuse and Mental Health Services Administration. Clinical guidance for treating pregnant and parenting women with opioid use disorder and their infants. HHS Publication No. (SMA) 18-5054. Rockville, MD: Substance Abuse and Mental Health Services Administration; 2018.

- Metz TD, Royner P, Hoffman MC, et al. Maternal deaths from suicide and overdose in Colorado, 2004-2012. Obstet Gynecol. 2016;128:1233-1240.

- Kaltenbach K, O’Grady E, Heil SH, et al. Prenatal exposure to methadone or buprenorphine: early childhood developmental outcomes. Drug Alcohol Depend. 2018;185:40-49.

- Bateman BT, Franklin JM, Bykov K, et al. Persistent opioid use following cesarean delivery: patterns and predictors among opioid-naive women. Am J Obstet Gynecol. 2016;215:353.e1-353.e18.

- Terplan M. Women and the opioid crisis: historical context and public health solutions. Fertil Steril. 2017;108:195-199.

- Management of substance abuse. World Health Organization website. https://www.who.int/substance_abuse/activities/treatment_opioid_dependence/en/. Accessed March 20, 2019.

- Committee on Obstetric Practice. Committee Opinion No. 711: Opioid use and opioid use disorder in pregnancy. Obstet Gynecol. 2017;130(2):e81-e94.

- Substance Abuse and Mental Health Services Administration. Clinical guidance for treating pregnant and parenting women with opioid use disorder and their infants. HHS Publication No. (SMA) 18-5054. Rockville, MD: Substance Abuse and Mental Health Services Administration; 2018.

- Metz TD, Royner P, Hoffman MC, et al. Maternal deaths from suicide and overdose in Colorado, 2004-2012. Obstet Gynecol. 2016;128:1233-1240.

- Kaltenbach K, O’Grady E, Heil SH, et al. Prenatal exposure to methadone or buprenorphine: early childhood developmental outcomes. Drug Alcohol Depend. 2018;185:40-49.

- Bateman BT, Franklin JM, Bykov K, et al. Persistent opioid use following cesarean delivery: patterns and predictors among opioid-naive women. Am J Obstet Gynecol. 2016;215:353.e1-353.e18.

Mortality rates higher in affiliates, compared with top-ranked hospitals

The sharing of a top-ranked cancer hospital brand across affiliate hospitals doesn’t necessarily guarantee the same quality of care, a new study suggests.

In a paper published in JAMA Network Open, researchers presented the outcomes of a cross-sectional study of 29,228 patients aged over 65 years who underwent complex cancer surgery at either 59 top-ranked hospitals or 343 affiliated hospitals.

The researchers saw a significant 40% higher 90-day mortality rate among patients who underwent complex cancer surgery at one of the affiliate hospitals, compared with those who were treated at the top-ranked hospitals (P less than .001), even after adjusting for factors such as age, comorbidity score, procedure type, and admission type.

“This is not entirely surprising, as affiliated hospitals are generally smaller, less likely to be teaching hospitals, and perform complex surgical procedures with less frequency (lower volume) when compared with top-ranked hospitals,” wrote Jessica R. Hoag, PhD, from the department of surgery at Yale University, New Haven, Conn., and her coauthors. However, including hospital characteristics in the models attenuated but did not eliminate the differences in mortality rates between top-ranked and affiliate hospitals.

The difference in 90-day mortality was particularly evident for gastrectomy, where there was a 100% higher 90-day mortality rate in affiliate hospitals, compared with top-ranked hospitals (P less than .001). The mortality rate for pancreaticoduodenectomy was 59% higher in affiliate hospitals, compared with top-ranked hospitals (P = .009); for colectomy it was 32% higher (P = .001), and for lobectomy it was 34% higher (P = .03).

The only procedure where the mortality rate was not statistically significantly different between top-ranked and affiliate hospitals was esophagectomy (odds ratio, 1.48; P = .06).

When the authors looked at standardized mortality ratios for the top-ranked and affiliate hospitals, they found that 41 of the 49 top-ranked hospitals had lower mortality ratios than their collective affiliates. In 37 cases, the difference in standardized mortality ratios between the top-ranked hospital and its affiliates was statistically significant.

Overall, 39 of the 49 top-ranked hospitals had better standardized mortality ratios than the national average, compared with 17 of the affiliated networks.

The authors wrote that their findings were important because previous studies showed affiliation status played a significant role in which hospital patients choose for their treatment.

“As a result, there is cause for concern that a proportion of the U.S. public could misinterpret brand sharing as indicating equivalent care,” they wrote, suggesting that one way to reduce mortality might therefore be to direct patients with the most risky and complex surgical requirements to top-ranked hospitals rather than affiliates, although acknowledged this might be challenging to implement.

One author reported receiving funding from the Centers for Medicare & Medicaid Services, one reported advisory board and steering committee positions with the private medical sector, and one reported receiving nonfinancial support from private industry outside the submitted work. No other conflicts of interest were reported.

SOURCE: Hoag JR et al. JAMA Netw Open. 2019 Apr 12. doi: 10.1001/jamanetworkopen.2019.1912.

Network affiliations with top-ranked hospitals could help expand access to high-quality cancer care and reduce travel times for patients who live too far away to access the top-ranked hospital itself. However, this study shows that the outcomes and quality of the flagship hospital do not necessarily translate to the affiliate hospitals in the network.

While affiliate hospitals are likely to deal with smaller numbers of complex patients and are less likely to be teaching hospitals, they do offer a way to potentially leverage their affiliation with top-ranked hospitals to improve the overall quality of care for cancer patients. The challenge is to work out how best to do this and to identify which patients are likely to do just as well at an affiliate hospital and which patients will be optimally treated at the flagship hospital.

Lesly A. Dossett, MD, MPH, is from the department of surgery at the University of Michigan, Ann Arbor. These comments are adapted from an accompanying editorial (JAMA Netw Open. 2019 Apr 12. doi:10.1001/jamanetworkopen.2019.1910). No conflicts of interest were reported.

Network affiliations with top-ranked hospitals could help expand access to high-quality cancer care and reduce travel times for patients who live too far away to access the top-ranked hospital itself. However, this study shows that the outcomes and quality of the flagship hospital do not necessarily translate to the affiliate hospitals in the network.

While affiliate hospitals are likely to deal with smaller numbers of complex patients and are less likely to be teaching hospitals, they do offer a way to potentially leverage their affiliation with top-ranked hospitals to improve the overall quality of care for cancer patients. The challenge is to work out how best to do this and to identify which patients are likely to do just as well at an affiliate hospital and which patients will be optimally treated at the flagship hospital.

Lesly A. Dossett, MD, MPH, is from the department of surgery at the University of Michigan, Ann Arbor. These comments are adapted from an accompanying editorial (JAMA Netw Open. 2019 Apr 12. doi:10.1001/jamanetworkopen.2019.1910). No conflicts of interest were reported.

Network affiliations with top-ranked hospitals could help expand access to high-quality cancer care and reduce travel times for patients who live too far away to access the top-ranked hospital itself. However, this study shows that the outcomes and quality of the flagship hospital do not necessarily translate to the affiliate hospitals in the network.

While affiliate hospitals are likely to deal with smaller numbers of complex patients and are less likely to be teaching hospitals, they do offer a way to potentially leverage their affiliation with top-ranked hospitals to improve the overall quality of care for cancer patients. The challenge is to work out how best to do this and to identify which patients are likely to do just as well at an affiliate hospital and which patients will be optimally treated at the flagship hospital.

Lesly A. Dossett, MD, MPH, is from the department of surgery at the University of Michigan, Ann Arbor. These comments are adapted from an accompanying editorial (JAMA Netw Open. 2019 Apr 12. doi:10.1001/jamanetworkopen.2019.1910). No conflicts of interest were reported.

The sharing of a top-ranked cancer hospital brand across affiliate hospitals doesn’t necessarily guarantee the same quality of care, a new study suggests.

In a paper published in JAMA Network Open, researchers presented the outcomes of a cross-sectional study of 29,228 patients aged over 65 years who underwent complex cancer surgery at either 59 top-ranked hospitals or 343 affiliated hospitals.

The researchers saw a significant 40% higher 90-day mortality rate among patients who underwent complex cancer surgery at one of the affiliate hospitals, compared with those who were treated at the top-ranked hospitals (P less than .001), even after adjusting for factors such as age, comorbidity score, procedure type, and admission type.

“This is not entirely surprising, as affiliated hospitals are generally smaller, less likely to be teaching hospitals, and perform complex surgical procedures with less frequency (lower volume) when compared with top-ranked hospitals,” wrote Jessica R. Hoag, PhD, from the department of surgery at Yale University, New Haven, Conn., and her coauthors. However, including hospital characteristics in the models attenuated but did not eliminate the differences in mortality rates between top-ranked and affiliate hospitals.

The difference in 90-day mortality was particularly evident for gastrectomy, where there was a 100% higher 90-day mortality rate in affiliate hospitals, compared with top-ranked hospitals (P less than .001). The mortality rate for pancreaticoduodenectomy was 59% higher in affiliate hospitals, compared with top-ranked hospitals (P = .009); for colectomy it was 32% higher (P = .001), and for lobectomy it was 34% higher (P = .03).

The only procedure where the mortality rate was not statistically significantly different between top-ranked and affiliate hospitals was esophagectomy (odds ratio, 1.48; P = .06).

When the authors looked at standardized mortality ratios for the top-ranked and affiliate hospitals, they found that 41 of the 49 top-ranked hospitals had lower mortality ratios than their collective affiliates. In 37 cases, the difference in standardized mortality ratios between the top-ranked hospital and its affiliates was statistically significant.

Overall, 39 of the 49 top-ranked hospitals had better standardized mortality ratios than the national average, compared with 17 of the affiliated networks.

The authors wrote that their findings were important because previous studies showed affiliation status played a significant role in which hospital patients choose for their treatment.

“As a result, there is cause for concern that a proportion of the U.S. public could misinterpret brand sharing as indicating equivalent care,” they wrote, suggesting that one way to reduce mortality might therefore be to direct patients with the most risky and complex surgical requirements to top-ranked hospitals rather than affiliates, although acknowledged this might be challenging to implement.

One author reported receiving funding from the Centers for Medicare & Medicaid Services, one reported advisory board and steering committee positions with the private medical sector, and one reported receiving nonfinancial support from private industry outside the submitted work. No other conflicts of interest were reported.

SOURCE: Hoag JR et al. JAMA Netw Open. 2019 Apr 12. doi: 10.1001/jamanetworkopen.2019.1912.

The sharing of a top-ranked cancer hospital brand across affiliate hospitals doesn’t necessarily guarantee the same quality of care, a new study suggests.

In a paper published in JAMA Network Open, researchers presented the outcomes of a cross-sectional study of 29,228 patients aged over 65 years who underwent complex cancer surgery at either 59 top-ranked hospitals or 343 affiliated hospitals.

The researchers saw a significant 40% higher 90-day mortality rate among patients who underwent complex cancer surgery at one of the affiliate hospitals, compared with those who were treated at the top-ranked hospitals (P less than .001), even after adjusting for factors such as age, comorbidity score, procedure type, and admission type.

“This is not entirely surprising, as affiliated hospitals are generally smaller, less likely to be teaching hospitals, and perform complex surgical procedures with less frequency (lower volume) when compared with top-ranked hospitals,” wrote Jessica R. Hoag, PhD, from the department of surgery at Yale University, New Haven, Conn., and her coauthors. However, including hospital characteristics in the models attenuated but did not eliminate the differences in mortality rates between top-ranked and affiliate hospitals.

The difference in 90-day mortality was particularly evident for gastrectomy, where there was a 100% higher 90-day mortality rate in affiliate hospitals, compared with top-ranked hospitals (P less than .001). The mortality rate for pancreaticoduodenectomy was 59% higher in affiliate hospitals, compared with top-ranked hospitals (P = .009); for colectomy it was 32% higher (P = .001), and for lobectomy it was 34% higher (P = .03).

The only procedure where the mortality rate was not statistically significantly different between top-ranked and affiliate hospitals was esophagectomy (odds ratio, 1.48; P = .06).

When the authors looked at standardized mortality ratios for the top-ranked and affiliate hospitals, they found that 41 of the 49 top-ranked hospitals had lower mortality ratios than their collective affiliates. In 37 cases, the difference in standardized mortality ratios between the top-ranked hospital and its affiliates was statistically significant.

Overall, 39 of the 49 top-ranked hospitals had better standardized mortality ratios than the national average, compared with 17 of the affiliated networks.

The authors wrote that their findings were important because previous studies showed affiliation status played a significant role in which hospital patients choose for their treatment.

“As a result, there is cause for concern that a proportion of the U.S. public could misinterpret brand sharing as indicating equivalent care,” they wrote, suggesting that one way to reduce mortality might therefore be to direct patients with the most risky and complex surgical requirements to top-ranked hospitals rather than affiliates, although acknowledged this might be challenging to implement.

One author reported receiving funding from the Centers for Medicare & Medicaid Services, one reported advisory board and steering committee positions with the private medical sector, and one reported receiving nonfinancial support from private industry outside the submitted work. No other conflicts of interest were reported.

SOURCE: Hoag JR et al. JAMA Netw Open. 2019 Apr 12. doi: 10.1001/jamanetworkopen.2019.1912.

FROM JAMA NETWORK OPEN

Leveraging consumer technology in gastroenterology practice

SAN FRANCISCO – Dr. Michael Docktor, a pediatric gastroenterologist at Boston Hospital, described myriad digital tools that physicians – especially gastroenterologists – as well as patients are now using. Some tools may be implemented to track stool output or diet for diseases like irritable bowel syndrome or Crohn’s disease, he said in an interview at the AGA Tech Summit, sponsored by the AGA Center for GI Innovation and Technology.

There are patient-facing applications that provide data that can be used by both patients and their physicians to better understand the disease. These data can help in diagnosis and management and give the GI doctor a “window into the 99% of the time that they aren’t with the patient.” Other apps can build a timeline of the disease that can help the patient get a better understanding of their disease and learn to distinguish a flare from a bad day with poor food choices. Dr. Docktor described the AGA Tech Summit as a place to try out new ideas and work with like-minded doctors.

SAN FRANCISCO – Dr. Michael Docktor, a pediatric gastroenterologist at Boston Hospital, described myriad digital tools that physicians – especially gastroenterologists – as well as patients are now using. Some tools may be implemented to track stool output or diet for diseases like irritable bowel syndrome or Crohn’s disease, he said in an interview at the AGA Tech Summit, sponsored by the AGA Center for GI Innovation and Technology.

There are patient-facing applications that provide data that can be used by both patients and their physicians to better understand the disease. These data can help in diagnosis and management and give the GI doctor a “window into the 99% of the time that they aren’t with the patient.” Other apps can build a timeline of the disease that can help the patient get a better understanding of their disease and learn to distinguish a flare from a bad day with poor food choices. Dr. Docktor described the AGA Tech Summit as a place to try out new ideas and work with like-minded doctors.

SAN FRANCISCO – Dr. Michael Docktor, a pediatric gastroenterologist at Boston Hospital, described myriad digital tools that physicians – especially gastroenterologists – as well as patients are now using. Some tools may be implemented to track stool output or diet for diseases like irritable bowel syndrome or Crohn’s disease, he said in an interview at the AGA Tech Summit, sponsored by the AGA Center for GI Innovation and Technology.

There are patient-facing applications that provide data that can be used by both patients and their physicians to better understand the disease. These data can help in diagnosis and management and give the GI doctor a “window into the 99% of the time that they aren’t with the patient.” Other apps can build a timeline of the disease that can help the patient get a better understanding of their disease and learn to distinguish a flare from a bad day with poor food choices. Dr. Docktor described the AGA Tech Summit as a place to try out new ideas and work with like-minded doctors.

REPORTING FROM 2019 AGA TECH SUMMIT

Obeticholic acid reversed NASH liver fibrosis in phase 3 trial

VIENNA – making obeticholic acid the first agent proven to improve the course of this disease.

“There is no doubt that with these data we have changed the treatment” of nonalcoholic steatohepatitis (NASH), Zobair M. Younossi, MD, of Inova Fairfax Medical Campus in Falls Church, Va., said at the meeting sponsored by the European Association for the Study of the Liver. “We are at a watershed moment” in NASH treatment, Dr. Younossi added in a video interview.

Until now “we have had no effective treatments for NASH. This is the first success in a phase 3 trial; obeticholic acid looks very promising,” commented Philip N. Newsome, PhD, professor of experimental hepatology at the University of Birmingham (England).

Obeticholic acid (OCA), an agonist of the farnesoid X receptor, already has Food and Drug Administration marketing approval for the indication of primary biliary cholangitis, a much rarer disease than NASH.

The REGENERATE (Randomized Global Phase 3 Study to Evaluate the Impact on NASH With Fibrosis of Obeticholic Acid Treatment) trial has so far enrolled 931 patients at about 350 sites in 20 countries, including the United States, and followed them during 18 months of treatment, the prespecified time for an interim analysis. The study enrolled adults with biopsy-proven NASH and generally focused on patients with either stage 2 or 3 liver fibrosis and a nonalcoholic fatty liver disease activity score of at least 4. Enrolled patients averaged about 55 years old, slightly more than half the enrolled patients had type 2 diabetes, and more than half had stage 3 fibrosis.

The study design included two coprimary endpoints, and specified that a statistically significant finding for either outcome meant a positive trial result, but the design also prespecified that the benefit would need to meet a stringent definition of statistical significance, compared with placebo patients, with a P value of no more than .01. REGENERATE tested two different OCA dosages, 10 mg or 25 mg, once daily. The results showed a trend for benefit from the smaller dosage, but these effects did not achieve statistical significance.

For the primary endpoint of regression of liver fibrosis by at least one stage with no worsening of NASH the intention-to-treat analysis showed after 18 months a 13% rate with placebo, a 21% rate with the 10-mg dosage, and a 23% rate with the 25-mg dosage, a statistically significant improvement over placebo for the higher dosage.

The second primary endpoint was resolution of NASH without worsening liver fibrosis, which occurred in 8% of placebo patients, 11% of patients on 10 mg OCA/day and 12% of those on 25 mg/day. The differences between each of the active groups and the controls were not statistically significant for this endpoint.

Among the 931 enrolled patients 668 (72%) actually received treatment fully consistent with the study protocol, and among these per-protocol patients the benefit from 25 mg/day OCA was even more striking: a 28% rate of fibrosis regression, compared with 13% in the control patients. Regression by at least two fibrotic stages occurred in 5% of placebo patients and 13% of those on 25 mg/day OCA. Many treated patients also showed normalizations of liver enzyme levels.

Adverse events on OCA were mostly mild or moderate, with similar rates of serious adverse events in the OCA groups and in control patients. The most common adverse effect on OCA treatment was pruritus, a previously described effect, reported by 51% of patients on the 25 mg/day dosage and by 19% of control patients.

REGENERATE will continue until a goal level of endpoint events occur, and may eventually enroll as many as 2,400 patients and extend for a few more years. By then, Dr. Younossi said, he hopes that an analysis will be possible of “harder” endpoints than fibrosis, such as development of cirrhosis. He noted, however, that the FDA has designated fibrosis regression as a valid surrogate endpoint for assessing treatment efficacy for NASH.

Already on the U.S. market, a single 10-mg OCA pill currently retails for almost $230; a 25-mg formulation is not currently marketed. Dr. Younossi said that subsequent studies will assess the cost-effectiveness of OCA treatment for NASH. He also hopes that further study of patient characteristics will identify which NASH patients are most likely to respond to OCA. Eventually, OCA may be part of a multidrug strategy for treating this disease, Dr. Younossi said.

REGENERATE was sponsored by Intercept, the company that markets obeticholic acid (Ocaliva). Dr. Younossi is a consultant to and has received research funding from Intercept. He has also been a consultant to Bristol-Myers Squibb, Gilead, GlaxoSmithKline, Novartis, Novo Nordisk, Quest, Siemens, Terns Pharmaceutical, and Viking Therapeutics. Dr. Newsome has been a consultant or speaker for Intercept as well as Boehringer Ingelheim, Dignity Sciences, Johnson & Johnson, Novo Nordisk, and Shire, and he has received research funding from Pharmaxis and Boehringer Ingelheim.

VIENNA – making obeticholic acid the first agent proven to improve the course of this disease.

“There is no doubt that with these data we have changed the treatment” of nonalcoholic steatohepatitis (NASH), Zobair M. Younossi, MD, of Inova Fairfax Medical Campus in Falls Church, Va., said at the meeting sponsored by the European Association for the Study of the Liver. “We are at a watershed moment” in NASH treatment, Dr. Younossi added in a video interview.

Until now “we have had no effective treatments for NASH. This is the first success in a phase 3 trial; obeticholic acid looks very promising,” commented Philip N. Newsome, PhD, professor of experimental hepatology at the University of Birmingham (England).

Obeticholic acid (OCA), an agonist of the farnesoid X receptor, already has Food and Drug Administration marketing approval for the indication of primary biliary cholangitis, a much rarer disease than NASH.

The REGENERATE (Randomized Global Phase 3 Study to Evaluate the Impact on NASH With Fibrosis of Obeticholic Acid Treatment) trial has so far enrolled 931 patients at about 350 sites in 20 countries, including the United States, and followed them during 18 months of treatment, the prespecified time for an interim analysis. The study enrolled adults with biopsy-proven NASH and generally focused on patients with either stage 2 or 3 liver fibrosis and a nonalcoholic fatty liver disease activity score of at least 4. Enrolled patients averaged about 55 years old, slightly more than half the enrolled patients had type 2 diabetes, and more than half had stage 3 fibrosis.

The study design included two coprimary endpoints, and specified that a statistically significant finding for either outcome meant a positive trial result, but the design also prespecified that the benefit would need to meet a stringent definition of statistical significance, compared with placebo patients, with a P value of no more than .01. REGENERATE tested two different OCA dosages, 10 mg or 25 mg, once daily. The results showed a trend for benefit from the smaller dosage, but these effects did not achieve statistical significance.

For the primary endpoint of regression of liver fibrosis by at least one stage with no worsening of NASH the intention-to-treat analysis showed after 18 months a 13% rate with placebo, a 21% rate with the 10-mg dosage, and a 23% rate with the 25-mg dosage, a statistically significant improvement over placebo for the higher dosage.

The second primary endpoint was resolution of NASH without worsening liver fibrosis, which occurred in 8% of placebo patients, 11% of patients on 10 mg OCA/day and 12% of those on 25 mg/day. The differences between each of the active groups and the controls were not statistically significant for this endpoint.

Among the 931 enrolled patients 668 (72%) actually received treatment fully consistent with the study protocol, and among these per-protocol patients the benefit from 25 mg/day OCA was even more striking: a 28% rate of fibrosis regression, compared with 13% in the control patients. Regression by at least two fibrotic stages occurred in 5% of placebo patients and 13% of those on 25 mg/day OCA. Many treated patients also showed normalizations of liver enzyme levels.

Adverse events on OCA were mostly mild or moderate, with similar rates of serious adverse events in the OCA groups and in control patients. The most common adverse effect on OCA treatment was pruritus, a previously described effect, reported by 51% of patients on the 25 mg/day dosage and by 19% of control patients.

REGENERATE will continue until a goal level of endpoint events occur, and may eventually enroll as many as 2,400 patients and extend for a few more years. By then, Dr. Younossi said, he hopes that an analysis will be possible of “harder” endpoints than fibrosis, such as development of cirrhosis. He noted, however, that the FDA has designated fibrosis regression as a valid surrogate endpoint for assessing treatment efficacy for NASH.

Already on the U.S. market, a single 10-mg OCA pill currently retails for almost $230; a 25-mg formulation is not currently marketed. Dr. Younossi said that subsequent studies will assess the cost-effectiveness of OCA treatment for NASH. He also hopes that further study of patient characteristics will identify which NASH patients are most likely to respond to OCA. Eventually, OCA may be part of a multidrug strategy for treating this disease, Dr. Younossi said.

REGENERATE was sponsored by Intercept, the company that markets obeticholic acid (Ocaliva). Dr. Younossi is a consultant to and has received research funding from Intercept. He has also been a consultant to Bristol-Myers Squibb, Gilead, GlaxoSmithKline, Novartis, Novo Nordisk, Quest, Siemens, Terns Pharmaceutical, and Viking Therapeutics. Dr. Newsome has been a consultant or speaker for Intercept as well as Boehringer Ingelheim, Dignity Sciences, Johnson & Johnson, Novo Nordisk, and Shire, and he has received research funding from Pharmaxis and Boehringer Ingelheim.

VIENNA – making obeticholic acid the first agent proven to improve the course of this disease.

“There is no doubt that with these data we have changed the treatment” of nonalcoholic steatohepatitis (NASH), Zobair M. Younossi, MD, of Inova Fairfax Medical Campus in Falls Church, Va., said at the meeting sponsored by the European Association for the Study of the Liver. “We are at a watershed moment” in NASH treatment, Dr. Younossi added in a video interview.

Until now “we have had no effective treatments for NASH. This is the first success in a phase 3 trial; obeticholic acid looks very promising,” commented Philip N. Newsome, PhD, professor of experimental hepatology at the University of Birmingham (England).

Obeticholic acid (OCA), an agonist of the farnesoid X receptor, already has Food and Drug Administration marketing approval for the indication of primary biliary cholangitis, a much rarer disease than NASH.

The REGENERATE (Randomized Global Phase 3 Study to Evaluate the Impact on NASH With Fibrosis of Obeticholic Acid Treatment) trial has so far enrolled 931 patients at about 350 sites in 20 countries, including the United States, and followed them during 18 months of treatment, the prespecified time for an interim analysis. The study enrolled adults with biopsy-proven NASH and generally focused on patients with either stage 2 or 3 liver fibrosis and a nonalcoholic fatty liver disease activity score of at least 4. Enrolled patients averaged about 55 years old, slightly more than half the enrolled patients had type 2 diabetes, and more than half had stage 3 fibrosis.

The study design included two coprimary endpoints, and specified that a statistically significant finding for either outcome meant a positive trial result, but the design also prespecified that the benefit would need to meet a stringent definition of statistical significance, compared with placebo patients, with a P value of no more than .01. REGENERATE tested two different OCA dosages, 10 mg or 25 mg, once daily. The results showed a trend for benefit from the smaller dosage, but these effects did not achieve statistical significance.

For the primary endpoint of regression of liver fibrosis by at least one stage with no worsening of NASH the intention-to-treat analysis showed after 18 months a 13% rate with placebo, a 21% rate with the 10-mg dosage, and a 23% rate with the 25-mg dosage, a statistically significant improvement over placebo for the higher dosage.

The second primary endpoint was resolution of NASH without worsening liver fibrosis, which occurred in 8% of placebo patients, 11% of patients on 10 mg OCA/day and 12% of those on 25 mg/day. The differences between each of the active groups and the controls were not statistically significant for this endpoint.

Among the 931 enrolled patients 668 (72%) actually received treatment fully consistent with the study protocol, and among these per-protocol patients the benefit from 25 mg/day OCA was even more striking: a 28% rate of fibrosis regression, compared with 13% in the control patients. Regression by at least two fibrotic stages occurred in 5% of placebo patients and 13% of those on 25 mg/day OCA. Many treated patients also showed normalizations of liver enzyme levels.

Adverse events on OCA were mostly mild or moderate, with similar rates of serious adverse events in the OCA groups and in control patients. The most common adverse effect on OCA treatment was pruritus, a previously described effect, reported by 51% of patients on the 25 mg/day dosage and by 19% of control patients.

REGENERATE will continue until a goal level of endpoint events occur, and may eventually enroll as many as 2,400 patients and extend for a few more years. By then, Dr. Younossi said, he hopes that an analysis will be possible of “harder” endpoints than fibrosis, such as development of cirrhosis. He noted, however, that the FDA has designated fibrosis regression as a valid surrogate endpoint for assessing treatment efficacy for NASH.

Already on the U.S. market, a single 10-mg OCA pill currently retails for almost $230; a 25-mg formulation is not currently marketed. Dr. Younossi said that subsequent studies will assess the cost-effectiveness of OCA treatment for NASH. He also hopes that further study of patient characteristics will identify which NASH patients are most likely to respond to OCA. Eventually, OCA may be part of a multidrug strategy for treating this disease, Dr. Younossi said.