User login

Identifying and Treating Nonalcoholic Fatty Liver Disease

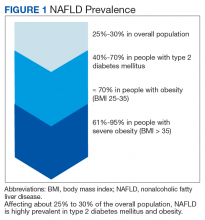

Nonalcoholic fatty liver disease (NAFLD) is a silent epidemic affecting nearly 1 in 3 Americans and is increasing within the Veterans Health Administration (VHA).1,2 NAFLD independently increases the risk of type 2 diabetes mellitus (

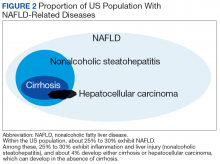

In most patients (80%), NAFLD progresses slowly over decades. The progression is related to continuing insulin resistance.15,16 Greater disease progression is seen in patients with T2DM or concomitant chronic liver disease (such as hepatitis C).10,11,16 Patients with NAFLD who develop advanced fibrosis or cirrhosis experience increased rates of overall mortality, liver-related events, and liver transplantation.1,9,17,18 Within the VHA, NAFLD is the third most common cause of cirrhosis and HCC, occurring at an average age of 66 and 70 years, respectively.19

Although no pharmaceuticals are yet approved to treat NAFLD, even modest weight loss is beneficial. For example, weight loss > 4% improves fatty liver, ≥ 7% improves liver inflammation, and ≥ 10% decreases liver fibrosis (or scarring).21-23 In patients with a prior lack of success with weight loss, weight loss medications may be beneficial for short-term use.24 When comparing the effects of diet, exercise, obesity pharmacotherapy, and combinations for these approaches, intensive lifestyle modification with exercise had the greatest, most enduring benefit.25 Additionally, bariatric (weight loss) surgery has significantly improved health and liver-related outcomes for patients with NASH.26

In at-risk veterans, NAFLD has myriad negative effects on health and QOL. To improve its early identification and management in the VHA, we summarize strategies that all providers can use to screen and treat patients for this condition.

Screening for Advanced Fibrosis

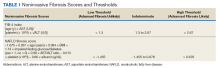

Advanced fibrosis in NAFLD is diagnosed by analyzing adequately sized liver biopsies.27,28 However, noninvasive approaches to quantify advanced fibrosis by imaging or use of a simple fibrosis prediction score also are available. Imaging modalities include measuring liver stiffness, using transient elastography (FibroScan, Waltham, MA) or magnetic resonance elastography.1,29-31 Fibrosis prediction scores use common clinical and laboratory data to predict the presence or absence of advanced fibrosis (Table 1).29

Does This Patient Have NAFLD?

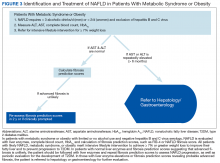

To identify NAFLD, patients with metabolic syndrome and modest or no alcohol use are first assessed for liver injury with ALT, AST, and complete blood count (Figure 3; Case 1).16

Next, common underlying liver diseases that cause liver injury should be excluded by hepatitis B and C virus serology.11,16 Other underlying liver diseases are uncommon and should be assessed only if clinically indicated.

Evaluation of fasting glucose or hemoglobin A1c (HbA1c)can identify undiagnosed T2DM. NAFL, or simple steatosis, is independently associated with an increased risk of T2DM, cardiovascular and kidney disease, yet not overall mortality.16 Over 10 to 20 years, few patients (4%) with simple steatosis progress to cirrhosis.39

In NAFLD, simple steatosis can resolve, and NASH can significantly improve with 7% to 10% weight loss.16,23,40 Patients with simple steatosis on imaging and normal liver enzymes should be monitored with periodic liver enzymes and fibrosis prediction scores (eg, FIB-4) and encouraged to pursue intensive lifestyle intervention.16,33 Without weight loss and exercise interventions metabolic syndrome, T2DM, and NAFLD may progress.

Patients with combined liver steatosis and liver enzyme elevations may exhibit NASH and warrant an evaluation by a hepatologist or gastroenterologist for consideration of additional testing or liver biopsy.16

Encouraging Patients to Pursue Intensive Lifestyle InterventionS

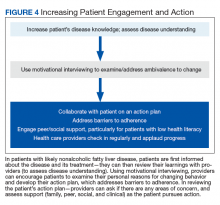

Most veterans wish to collaborate in their care (Table 3, Figure 4) yet experience many barriers, such as low health literacy, high rates of comorbidities, and ongoing drug/alcohol misuse.43,44

In addition to patient education, motivational interviewing significantly improves weight loss, resulting in a 3.3 lb (1.5 kg) increased weight loss in the intervention group vs the control group in weight loss studies.46

To start the conversation, the health care provider can explain that

- Why would you want to lose weight and exercise?

- How might you go about it in order to succeed?

- What are the 3 best reasons for you to do it?

- How important is it for you to make this change, and why? The provider can also ask the patient to quantify on a scale of 1 to 10: (a) How likely is it that they will make each required change? (b) How hard will each change be for them?

- The provider then summarizes the patient’s reasons for wanting change, how he/she can effect change, what their best reasons are, and how to successfully change. The provider then asks a final question:

- So what do you think you will do?

Most patients report feeling engaged, empowered, open, and understood with motivational interviewing. People are “persuaded by what they hear themselves say,” increasing motivation to change.47

This personalized action plan facilitates successful health behavior change.48 Action plans should integrate daily routines. For example, by placing the scale near the toothbrush, daily weighing is encouraged. Daily weighing is associated with significantly greater weight loss and less weight regain.49 In a 6-month, randomized controlled weight loss trial in men and women, daily weighing (using a scale that automatically transmitted weight data), with weekly e-mails and tailored feedback yielded an overall 9% weight loss and increased use of exercise and diet behaviors associated with weight loss in comparison with those who weighed themselves less than weekly.50 This simple daily measure seems to reinforce a patient’s action plan.

Adherence to an action plan significantly improves with patient education, peer or social support, and addressing barriers to adherence.51 For example, by providing support with weekly text messaging of “How are you?” and addressing the issues that patients reported in a large randomized treatment trial, adherence was significantly improved.52 In VHA patients with low health literacy, peer support or telephone coaching also has proven effective in increasing weight loss and glycemic control in patients with T2DM.53,54 Providing multidisciplinary team support during intensive lifestyle intervention, providers can partner with patients to address questions or issues and applaud progress.

Effective VHA interventions

In an ethnically diverse population of patients with prediabetes, up to 7% weight loss was observed in the Diabetes Prevention Program (DPP).55 In this study patients were randomized to placebo; metformin 850 mg twice daily; or a lifestyle-modification program in which they received one-on-one culturally sensitive, individualized lessons in diet, moderate exercise (≥ 150 minutes weekly), and behavior modification from case managers over 16 sessions. Lessons were reinforced in both group and individual sessions. This intervention was associated with an average of 6% weight loss at 6 months (half of participants attained 7% weight loss) and a 58% decrease in the rate of progression to T2DM over a nearly 3-year follow-up of this population with prediabetes compared with that of the placebo group.55 Over a 15-year follow-up, the intensive lifestyle intervention group sustained a 27% decrease in the incidence of T2DM compared with that of the placebo group.56 To emulate the success of the DPP in the VHA, a web-based DPP-like study in female veterans was performed with online coaching and daily weighing. This study achieved a 5.2% weight loss from baseline at 4 months.57

To improve outcomes, the VHA MOVE! Weight Management Program has been revised to include more sustained intervention (16 sessions) and multiple modes for participating—in person, by telephone, via video, via MOVE! Coach phone app, or any combination.58 Using shared decision making between patients with NAFLD and their providers, a customized MOVE! weight loss program can be developed to enable sustained intensive lifestyle intervention: hypocaloric diet, ≥ 150 minutes of moderate exercise weekly, and behavioral change.

In addition to intensive lifestyle intervention, a prospective study found that bariatric surgery significantly improved outcomes in patients with NASH, with most patients experiencing resolution of their NASH and nearly half exhibiting significantly improved fibrosis.26 In the VHA, bariatric surgery has yielded excellent long-term outcomes, with 21% sustained weight loss from baseline (vs matched nonsurgical population) at 10 years postoperatively in patients undergoing Roux-en-Y gastric bypass.59 Bariatric surgery also results in long-term remission of T2DM in most patients and significant improvement in hypertension and dyslipidemia.60 The risks of bariatric surgery include 3% serious complications, 1% reoperation rates, and 0.4% 30-day mortality.61,62 Bariatric surgery can be considered in patients with BMI > 40 or in patients with BMI > 35 who have comorbidities and do not have decompensated cirrhosis.63,64

Beyond weight loss, more favorable liver-related outcomes and lower rates of advanced liver fibrosis are observed in those consuming filtered coffee; a reduction in liver steatosis also is observed with adherence to a Mediterranean diet.65,66 In NAFLD, statins may improve liver chemistries and fibrosis; this class of medications can be used safely even in the presence of an elevated ALT.11,67

Conclusion

Nonalcoholic fatty liver disease independently increases the risk of T2DM, cardiovascular disease and kidney disease. With its rates increasing in the VHA, earlier identification and intervention is warranted in patients at high risk (ie, those with metabolic syndrome, obesity, and T2DM).2

NASH is more frequent in those with liver enzyme elevations or with an elevated FIB-4 and is associated with a long-term risk of cirrhosis. These patients merit referral to hepatology or gastroenterology for further evaluation and consideration of a liver biopsy to identify NASH. Patients with likely NAFLD without liver enzyme elevations can be further evaluated with FIB-4 scores to assess their probability of advanced liver fibrosis and potential need for referral to hepatology or gastroenterology.

Early NAFLD detection and intervention with intensive lifestyle modifications has the potential to avert progression to advanced fibrosis—and its associated increased overall and liver-related mortality, and impaired QOL.3,16,18 Although FIB-4 is a validated predictor of advanced fibrosis, this score is not yet used nationally to identify and risk stratify NAFLD in the VHA. Additionally, the very low use of VHA diet/exercise programs in eligible patients contributes to NAFLD progression.68 The cost-effective DPP has successfully yielded weight loss in patients with prediabetes and decreases in the incidence of T2DM through motivational interviewing and intensive lifestyle intervention.55

To improve NAFLD management, providers can successfully engage patients through motivational interviewing for intensive lifestyle intervention. Their resulting weight loss is enhanced with a personalized action plan, daily weighing, and peer support. When NAFLD is identified in patients with metabolic risk factors, the probability of advanced fibrosis is easily assessed in those with elevated FIB-4 scores who merit gastrointestinal referral.33,37

In all those identified with NAFLD, disease information should be provided to patients and their families. Intensive lifestyle modification targeting a ≥ 7% weight loss is recommended; motivational interviewing can increase commitment to change and yield a customized action plan for sustained weight loss. Working with the support and encouragement of their team of primary care providers, dieticians, and MOVE! coaches, patients can actively engage to improve their NAFLD and overall health.

1. Rinella ME. Nonalcoholic fatty liver disease: a systematic review. JAMA. 2015;313(22):2263-2273.

2. Kanwal F, Kramer JR, Duan Z, et al. Trends in the burden of nonalcoholic fatty liver disease in a United States cohort of veterans. Clin Gastroenterol Hepatol. 2016;14(2):301-308.

3. Golabi P, Otgonsuren M, Cable R, et al. Non-alcoholic fatty liver disease (NAFLD) is associated with impairment of Health Related Quality of Life (HRQOL). Health Qual Life Outcomes. 2016;14(1):18.

4. Targher G, Bertolini L, Padovani R, et al. Prevalence of nonalcoholic fatty liver disease and its association with cardiovascular disease among type 2 diabetic patients. Diabetes Care. 2007;30(5):1212-1218.

5. Argo CK, Caldwell SH. Epidemiology and natural history of non-alcoholic steatohepatitis. Clin Liver Dis. 2009;13(4):511-531.

6. Centers for Disease Control and Prevention. About Prediabetes & Type 2 Diabetes. https://www.cdc.gov/diabetes/prevention/prediabetes-type2/index.html. Updated June 11, 2018. Accessed November 7, 2018.

7. Littman AJ, Jacobson IG, Boyko EJ, Powell TM, Smith TC; Millennium Cohort Study Team. Weight change following US military service. Int J Obes (Lond). 2013;37(2):244-253.

8. Breland JY, Phibbs CS, Hoggatt KJ, et al. The obesity epidemic in the Veterans Health Administration: prevalence among key populations of women and men veterans. J Gen Intern Med. 2017;32(suppl 1):11-17.

9. Angulo P, Hui JM, Marchesini G, et al. The NAFLD fibrosis score: a noninvasive system that identifies liver fibrosis in patients with NAFLD. Hepatology. 2007;45(4):846-854.

10. Bazick J, Donithan M, Neuschwander-Tetri BA, et al. Clinical model for NASH and advanced fibrosis in adult patients with diabetes and NAFLD: guidelines for referral in NAFLD. Diabetes Care. 2015;38(7):1347-1355.

11. Chalasani N, Younossi Z, Lavine JE, et al. The diagnosis and management of nonalcoholic fatty liver disease: Practice guidance from the American Association for the Study of Liver Diseases. Hepatology. 2018;67(1):328-357.

12. Bril F, Barb D, Portillo‐Sanchez P, et al. Metabolic and histological implications of intrahepatic triglyceride content in nonalcoholic fatty liver disease. Hepatology. 2017;65(4):1132-1144.

13. Diehl AM, Day C. Cause, pathogenesis, and treatment of nonalcoholic steatohepatitis. N Engl J Med. 2017;377(21):2063-2072.

14. Nasr P, Ignatova S, Kechagias S, Ekstedt M. Natural history of nonalcoholic fatty liver disease: a prospective follow-up study with serial biopsies. Hepatol Commun. 2018;27(2):199-210.

15. Singh S, Allen AM, Wang Z, Prokop LJ, Murad MH, Loomba R. Fibrosis progression in nonalcoholic fatty liver vs nonalcoholic steatohepatitis: a systematic review and meta-analysis of paired-biopsy studies. Clin Gastroenterol Hepatol. 2015;13(4):643-654.

16. European Association for the Study of the Liver (EASL); European Association for the Study of Diabetes (EASD); European Association for the Study of Obesity (EASO). EASL-EASD-EASO clinical practice guidelines for the management of non-alcoholic fatty liver disease. J Hepatol. 2016;64(6):1388-1402.

17. Younossi ZM, Blissett D, Blissett R, et al. The economic and clinical burden of nonalcoholic fatty liver disease in the United States and Europe. Hepatology. 2016;64(5):1577-1586.

18. Angulo P, Kleiner DE, Dam-Larsen S, et al. Liver fibrosis, but no other histologic features, is associated with long-term outcomes of patients with nonalcoholic fatty liver disease. Gastroenterology. 2015;149(2):389-397.

19. Beste LA, Leipertz SL, Green PK, Dominitz JA, Ross D, Ioannou GN. Trends in burden of cirrhosis and hepatocellular carcinoma by underlying liver disease in US Veterans, 2001-2013. Gastroenterology 2015;149(6):1471-1482.

20. Mittal S, El-Serag HB, Sada YH, et al. Hepatocellular carcinoma in the absence of cirrhosis in United States veterans is associated with nonalcoholic fatty liver disease. Clin Gastroenterol Hepatol. 2016;14(1):124-131.

21. Kenneally S, Sier JH, Moore JB. Efficacy of dietary and physical activity intervention in non-alcoholic fatty liver disease: a systematic review. BMJ Open Gastroenterol. 2017;4(1):e000139.

22. Thoma C, Day CP, Trenell MI. Lifestyle interventions for the treatment of non-alcoholic fatty liver disease in adults: a systematic review. J Hepatol. 2012;56(1):255-266.

23. Vilar-Gomez E, Martinez-Perez Y, Calzadilla-Bertot L, et al. Weight loss through lifestyle modification significantly reduces features of nonalcoholic steatohepatitis. Gastroenterology. 2015;149(2):367-378.

24. Apovian CM, Aronne LJ, Bessesen DH, et al; Endocrine Society. Pharmacological management of obesity: an endocrine society clinical practice guideline. J Clin Endocrinol Metab. 2015;100(2):342-362.

25. Haw JS, Galaviz KI, Straus AN, et al. Long-term sustainability of diabetes prevention approaches: a systematic review and meta-analysis of randomized clinical trials. JAMA Intern Med. 2017;177(12):1808-1817.

26. Lassailly G, Caiazzo R, Buob D, et al. Bariatric surgery reduces features of nonalcoholic steatohepatitis in morbidly obese patients. Gastroenterology. 2015;149(2):379-388.

27. Kleiner DE, Brunt EM, Van Natta M, et al; Nonalcoholic Steatohepatitis Clinical Research Network. Design and validation of a histological scoring system for nonalcoholic fatty liver disease. Hepatology. 2005;41(6):1313-1321.

28. Bedossa P; FLIP Pathology Consortium. Utility and appropriateness of the fatty liver inhibition of progression (FLIP) algorithm and steatosis, activity, and fibrosis (SAF) score in the evaluation of biopsies of nonalcoholic fatty liver disease. Hepatology. 2014;60(2):565-567.

29. Tapper EB, Sengupta N, Hunink MG, Afdhal NH, Lai M. Cost-effective evaluation of nonalcoholic fatty liver disease with NAFLD fibrosis score and vibration controlled transient elastography. Am J Gastroenterol. 2015;110(9):1298-1304.

30. Cui J, Ang B, Haufe W, et al. Comparative diagnostic accuracy of magnetic resonance elastography vs. eight clinical prediction rules for non‐invasive diagnosis of advanced fibrosis in biopsy‐proven non‐alcoholic fatty liver disease: a prospective study. Aliment Pharmacol Ther. 2015;41(12):1271-1280.

31. Tapper EB, Lok AS-F. Use of liver imaging and biopsy in clinical practice. N Engl J Med . 2017;377(8):756-768.

32. Sterling RK, Lissen E, Clumeck N; APRICOT Clinical Investigators. Development of a simple noninvasive index to predict significant fibrosis in patients with HIV/HCV coinfection. Hepatology. 2006;43(6):1317-1325.

33. Imler T. Indiana University School of Medicine - GIHep calculators. http://gihep.com/calculators/hepatology/fibrosis-4-score. Published 2018. Accessed November 7, 2018.

34. Sun W, Cui H , Li N, et al. Comparison of FIB-4 index, NAFLD fibrosis score and BARD score for prediction of advanced fibrosis in adult patients with non-alcoholic fatty liver disease: a meta-analysis study. Hepatol Res. 2016;46(9):862-870.

35. Imler T, Indiana University School of Medicine - GIHep calculators. http://gihep.com/calculators/hepatology/nafld-fibrosis-score. Published 2018. Accessed November 7, 2018.

36. Harrison SA, Oliver D, Arnold HL, Gogia S, Neuschwander-Tetri BA. Development and validation of a simple NAFLD clinical scoring system for identifying patients without advanced disease. Gut. 2008;57(10):1441-1447.

37. Patel YA, Gifford EJ, Glass LM, et al. Identifying non-alcoholic fatty liver disease advanced fibrosis in the Veterans Health Administration. Dig Dis Sci. 2018;63(9): 2259-2266.

38. Armstrong MJ, Houlihan DD, Bentham L, et al. Presence and severity of non-alcoholic fatty liver disease in a large prospective primary care cohort. J Hepatol. 2012;56(1):234-240.

39. Matteoni CA, Younossi ZM, Gramlich T, Boparai N, Liu YC, McCullough AJ. Nonalcoholic fatty liver disease: a spectrum of clinical and pathological severity. Gastroenterology. 1999;116(6):1413-1419.

40. Promrat K, Kleiner DE, Niemeier HM, et al. Randomized controlled trial testing the effects of weight loss on nonalcoholic steatohepatitis. Hepatology. 2010;51(1):121-129.

41. Mofrad P, Contos MJ, Haque M, et al. Clinical and histologic spectrum of nonalcoholic fatty liver disease associated with normal ALT values. Hepatology. 2003;37(6):1286-1292.

42. Portillo-Sanchez P, Bril F, Maximos M, et al. High prevalence of nonalcoholic fatty liver disease in patients With Type 2 Diabetes Mellitus and Normal Plasma Aminotransferase Levels. J Clin Endocrinol Metab 2015;100(6):2231-2238.

43. Rodriguez V, Andrade AD, Garcia-Retamero R, et al. Health literacy, numeracy, and graphical literacy among veterans in primary care and their effect on shared decision making and trust in physicians. J Health Commun. 2013;18(suppl 1):273-289.

44. Kramer JR, Kanwal F, Richardson P, Mei M, El-Serag HB. Gaps in the achievement of effectiveness of HCV treatment in national VA practice. J Hepatol. 2012;56(2):320-325.

45. Veterans Health Administration. Non-alcoholic fatty liver: information for patients. https://www.hepatitis.va.gov/pdf/NAFL.pdf. Published September 2017. Accessed November 7, 2018.

46. Armstrong MJ, Mottershead TA, Ronksley PE, Sigal RJ, Campbell TS, Hemmelgarn BR. Motivational interviewing to improve weight loss in overweight and/or obese patients: a systematic review and meta-analysis of randomized controlled trials. Obes Rev. 2011;12(9):709-723.

47. Miller WR, Rollnick S. Motivational Interviewing: Helping People Change. Guilford Press: NY, New York; 2013.

48. Leventhal H, Leventhal EA, Breland JY. Cognitive science speaks to the “common sense” of chronic illness management. Ann Behav Med. 2011;41(2):152-163.

49. Zheng Y, Klem ML, Sereika SM, Danford CA, Ewing LJ, Burke LE. Self-weighing in weight management: a systematic literature review. Obesity (Silver Spring). 2015;23(2):256-265.

50. Steinberg DM, Bennett GG, Askew S, Tate DF. Weighing every day matters; daily weighing improves weight loss and adoption of weight control behaviors. J Acad Nutr Diet. 2015;115(4):511-518.

51. Charania MR, Marshall KJ, Lyles CM; HIV/AIDS Prevention Research Synthesis (PRS) Team. Identification of evidence-based interventions for promoting HIV medication adherence: findings from a systematic review of U.S.-based studies, 1996-2011. AIDS Behav. 2014;18(4):646-660.

52. Lester RT, Ritvo P, Mills EJ, et al. Effects of a mobile phone short message service on antiretroviral treatment adherence in Kenya (WelTel Kenya1): a randomised trial. Lancet 2010;376(9755):1838-1845.

53. Dutton GR, Phillips JM, Kukkamalla M, Cherrington AL, Safford MM. Pilot study evaluating the feasibility and initial outcomes of a primary care weight loss intervention with peer coaches. Diabetes Educ. 2015:41(3):361-368.

54. Fisher EB, Coufal MM, Parada H, et al. Peer support in health care and prevention: Cultural, organizational, and dissemination issues. Annu Rev Public Health. 2014;35(1):363-383.

55. Diabetes Prevention Program Research Group. Reduction in the incidence of type 2 diabetes with lifestyle intervention or metformin. N Engl J Med. 2002;(346):393-403.

56. Diabetes Prevention Program Research Group. Long-term effects of lifestyle intervention or metformin on diabetes development and microvascular complications over 15-year follow-up: the Diabetes Prevention Program Outcomes Study. Lancet Diabetes Endocrinol. 2015;3(11):866-875.

57. Moin T, Ertl K, Schneider J, et al. Women veterans’ experience with a web-based diabetes prevention program: a qualitative study to inform future practice. J Med Internet Res. 2015;17(5):e127.

58. US Department of Veterans Affairs. MOVE! Weight management program. https://www.move.va.gov/MOVE/index.asp. Updated October 5, 2018. Accessed November 7, 2018.

59. Maciejewski ML, Arterburn DE, Van Scoyoc L, et al. Bariatric surgery and long-term durability of weight loss. JAMA Surg. 2016;151(11):1046-1055.

60. Adams TD, Davidson LE, Litwin SE, et al. Weight and metabolic outcomes 12 years after gastric bypass. N Engl J Med. 2017;377(12):1143-1155.

61. Dimick JB, Nicholas LH, Ryan AM, Thumma JR, Birkmeyer JD. Bariatric surgery complications beforevs after implementation of a national policy restricting coverage to centers of excellence. JAMA. 2013;309(8):792-799.

62. The Longitudinal Assessment of Bariatric Surgery (LABS) Consortium, Flum DR, Belle SH, et al. Perioperative safety in the longitudinal assessment of bariatric surgery. N Engl J Med. 2009;361(5):445-454.

63. Brito JP, Montori VM, Davis AM; Delegates of the 2nd Diabetes Surgery Summit. Metabolic surgery in the treatment algorithm for type 2 diabetes: a joint statement by international diabetes organizations. JAMA. 2017;317(6):635-636.

64. Mosko JD, Nguyen GC. Increased perioperative mortality following bariatric surgery among patients with cirrhosis. Clin Gastroenterol Hepatol. 2011;9(10):897-901.

65. Saab S, Mallam D, Cox GA 2nd, Tong MJ. Impact of coffee on liver diseases: a systematic review. Liver Int. 2014;34(4):495-504.

66. Ryan MC, Itsiopoulos C, Thodis T, et al. The Mediterranean diet improves hepatic steatosis and insulin sensitivity in individuals with non-alcoholic fatty liver disease. J Hepatol. 2013;59(1):138-143.

67. Musso G, Gambino R, Cassader M, Pagano G. A meta‐analysis of randomized trials for the treatment of nonalcoholic fatty liver disease. Hepatology. 2010;52(1):79-104.

68. Patel Y, Gifford EJ, Glass LM, et al. Risk factors for biopsy-proven non-alcoholic fatty liver disease progression in the Veterans Health Administration. Aliment Pharmacol Ther. 2018;47(2):268-278.

Nonalcoholic fatty liver disease (NAFLD) is a silent epidemic affecting nearly 1 in 3 Americans and is increasing within the Veterans Health Administration (VHA).1,2 NAFLD independently increases the risk of type 2 diabetes mellitus (

In most patients (80%), NAFLD progresses slowly over decades. The progression is related to continuing insulin resistance.15,16 Greater disease progression is seen in patients with T2DM or concomitant chronic liver disease (such as hepatitis C).10,11,16 Patients with NAFLD who develop advanced fibrosis or cirrhosis experience increased rates of overall mortality, liver-related events, and liver transplantation.1,9,17,18 Within the VHA, NAFLD is the third most common cause of cirrhosis and HCC, occurring at an average age of 66 and 70 years, respectively.19

Although no pharmaceuticals are yet approved to treat NAFLD, even modest weight loss is beneficial. For example, weight loss > 4% improves fatty liver, ≥ 7% improves liver inflammation, and ≥ 10% decreases liver fibrosis (or scarring).21-23 In patients with a prior lack of success with weight loss, weight loss medications may be beneficial for short-term use.24 When comparing the effects of diet, exercise, obesity pharmacotherapy, and combinations for these approaches, intensive lifestyle modification with exercise had the greatest, most enduring benefit.25 Additionally, bariatric (weight loss) surgery has significantly improved health and liver-related outcomes for patients with NASH.26

In at-risk veterans, NAFLD has myriad negative effects on health and QOL. To improve its early identification and management in the VHA, we summarize strategies that all providers can use to screen and treat patients for this condition.

Screening for Advanced Fibrosis

Advanced fibrosis in NAFLD is diagnosed by analyzing adequately sized liver biopsies.27,28 However, noninvasive approaches to quantify advanced fibrosis by imaging or use of a simple fibrosis prediction score also are available. Imaging modalities include measuring liver stiffness, using transient elastography (FibroScan, Waltham, MA) or magnetic resonance elastography.1,29-31 Fibrosis prediction scores use common clinical and laboratory data to predict the presence or absence of advanced fibrosis (Table 1).29

Does This Patient Have NAFLD?

To identify NAFLD, patients with metabolic syndrome and modest or no alcohol use are first assessed for liver injury with ALT, AST, and complete blood count (Figure 3; Case 1).16

Next, common underlying liver diseases that cause liver injury should be excluded by hepatitis B and C virus serology.11,16 Other underlying liver diseases are uncommon and should be assessed only if clinically indicated.

Evaluation of fasting glucose or hemoglobin A1c (HbA1c)can identify undiagnosed T2DM. NAFL, or simple steatosis, is independently associated with an increased risk of T2DM, cardiovascular and kidney disease, yet not overall mortality.16 Over 10 to 20 years, few patients (4%) with simple steatosis progress to cirrhosis.39

In NAFLD, simple steatosis can resolve, and NASH can significantly improve with 7% to 10% weight loss.16,23,40 Patients with simple steatosis on imaging and normal liver enzymes should be monitored with periodic liver enzymes and fibrosis prediction scores (eg, FIB-4) and encouraged to pursue intensive lifestyle intervention.16,33 Without weight loss and exercise interventions metabolic syndrome, T2DM, and NAFLD may progress.

Patients with combined liver steatosis and liver enzyme elevations may exhibit NASH and warrant an evaluation by a hepatologist or gastroenterologist for consideration of additional testing or liver biopsy.16

Encouraging Patients to Pursue Intensive Lifestyle InterventionS

Most veterans wish to collaborate in their care (Table 3, Figure 4) yet experience many barriers, such as low health literacy, high rates of comorbidities, and ongoing drug/alcohol misuse.43,44

In addition to patient education, motivational interviewing significantly improves weight loss, resulting in a 3.3 lb (1.5 kg) increased weight loss in the intervention group vs the control group in weight loss studies.46

To start the conversation, the health care provider can explain that

- Why would you want to lose weight and exercise?

- How might you go about it in order to succeed?

- What are the 3 best reasons for you to do it?

- How important is it for you to make this change, and why? The provider can also ask the patient to quantify on a scale of 1 to 10: (a) How likely is it that they will make each required change? (b) How hard will each change be for them?

- The provider then summarizes the patient’s reasons for wanting change, how he/she can effect change, what their best reasons are, and how to successfully change. The provider then asks a final question:

- So what do you think you will do?

Most patients report feeling engaged, empowered, open, and understood with motivational interviewing. People are “persuaded by what they hear themselves say,” increasing motivation to change.47

This personalized action plan facilitates successful health behavior change.48 Action plans should integrate daily routines. For example, by placing the scale near the toothbrush, daily weighing is encouraged. Daily weighing is associated with significantly greater weight loss and less weight regain.49 In a 6-month, randomized controlled weight loss trial in men and women, daily weighing (using a scale that automatically transmitted weight data), with weekly e-mails and tailored feedback yielded an overall 9% weight loss and increased use of exercise and diet behaviors associated with weight loss in comparison with those who weighed themselves less than weekly.50 This simple daily measure seems to reinforce a patient’s action plan.

Adherence to an action plan significantly improves with patient education, peer or social support, and addressing barriers to adherence.51 For example, by providing support with weekly text messaging of “How are you?” and addressing the issues that patients reported in a large randomized treatment trial, adherence was significantly improved.52 In VHA patients with low health literacy, peer support or telephone coaching also has proven effective in increasing weight loss and glycemic control in patients with T2DM.53,54 Providing multidisciplinary team support during intensive lifestyle intervention, providers can partner with patients to address questions or issues and applaud progress.

Effective VHA interventions

In an ethnically diverse population of patients with prediabetes, up to 7% weight loss was observed in the Diabetes Prevention Program (DPP).55 In this study patients were randomized to placebo; metformin 850 mg twice daily; or a lifestyle-modification program in which they received one-on-one culturally sensitive, individualized lessons in diet, moderate exercise (≥ 150 minutes weekly), and behavior modification from case managers over 16 sessions. Lessons were reinforced in both group and individual sessions. This intervention was associated with an average of 6% weight loss at 6 months (half of participants attained 7% weight loss) and a 58% decrease in the rate of progression to T2DM over a nearly 3-year follow-up of this population with prediabetes compared with that of the placebo group.55 Over a 15-year follow-up, the intensive lifestyle intervention group sustained a 27% decrease in the incidence of T2DM compared with that of the placebo group.56 To emulate the success of the DPP in the VHA, a web-based DPP-like study in female veterans was performed with online coaching and daily weighing. This study achieved a 5.2% weight loss from baseline at 4 months.57

To improve outcomes, the VHA MOVE! Weight Management Program has been revised to include more sustained intervention (16 sessions) and multiple modes for participating—in person, by telephone, via video, via MOVE! Coach phone app, or any combination.58 Using shared decision making between patients with NAFLD and their providers, a customized MOVE! weight loss program can be developed to enable sustained intensive lifestyle intervention: hypocaloric diet, ≥ 150 minutes of moderate exercise weekly, and behavioral change.

In addition to intensive lifestyle intervention, a prospective study found that bariatric surgery significantly improved outcomes in patients with NASH, with most patients experiencing resolution of their NASH and nearly half exhibiting significantly improved fibrosis.26 In the VHA, bariatric surgery has yielded excellent long-term outcomes, with 21% sustained weight loss from baseline (vs matched nonsurgical population) at 10 years postoperatively in patients undergoing Roux-en-Y gastric bypass.59 Bariatric surgery also results in long-term remission of T2DM in most patients and significant improvement in hypertension and dyslipidemia.60 The risks of bariatric surgery include 3% serious complications, 1% reoperation rates, and 0.4% 30-day mortality.61,62 Bariatric surgery can be considered in patients with BMI > 40 or in patients with BMI > 35 who have comorbidities and do not have decompensated cirrhosis.63,64

Beyond weight loss, more favorable liver-related outcomes and lower rates of advanced liver fibrosis are observed in those consuming filtered coffee; a reduction in liver steatosis also is observed with adherence to a Mediterranean diet.65,66 In NAFLD, statins may improve liver chemistries and fibrosis; this class of medications can be used safely even in the presence of an elevated ALT.11,67

Conclusion

Nonalcoholic fatty liver disease independently increases the risk of T2DM, cardiovascular disease and kidney disease. With its rates increasing in the VHA, earlier identification and intervention is warranted in patients at high risk (ie, those with metabolic syndrome, obesity, and T2DM).2

NASH is more frequent in those with liver enzyme elevations or with an elevated FIB-4 and is associated with a long-term risk of cirrhosis. These patients merit referral to hepatology or gastroenterology for further evaluation and consideration of a liver biopsy to identify NASH. Patients with likely NAFLD without liver enzyme elevations can be further evaluated with FIB-4 scores to assess their probability of advanced liver fibrosis and potential need for referral to hepatology or gastroenterology.

Early NAFLD detection and intervention with intensive lifestyle modifications has the potential to avert progression to advanced fibrosis—and its associated increased overall and liver-related mortality, and impaired QOL.3,16,18 Although FIB-4 is a validated predictor of advanced fibrosis, this score is not yet used nationally to identify and risk stratify NAFLD in the VHA. Additionally, the very low use of VHA diet/exercise programs in eligible patients contributes to NAFLD progression.68 The cost-effective DPP has successfully yielded weight loss in patients with prediabetes and decreases in the incidence of T2DM through motivational interviewing and intensive lifestyle intervention.55

To improve NAFLD management, providers can successfully engage patients through motivational interviewing for intensive lifestyle intervention. Their resulting weight loss is enhanced with a personalized action plan, daily weighing, and peer support. When NAFLD is identified in patients with metabolic risk factors, the probability of advanced fibrosis is easily assessed in those with elevated FIB-4 scores who merit gastrointestinal referral.33,37

In all those identified with NAFLD, disease information should be provided to patients and their families. Intensive lifestyle modification targeting a ≥ 7% weight loss is recommended; motivational interviewing can increase commitment to change and yield a customized action plan for sustained weight loss. Working with the support and encouragement of their team of primary care providers, dieticians, and MOVE! coaches, patients can actively engage to improve their NAFLD and overall health.

Nonalcoholic fatty liver disease (NAFLD) is a silent epidemic affecting nearly 1 in 3 Americans and is increasing within the Veterans Health Administration (VHA).1,2 NAFLD independently increases the risk of type 2 diabetes mellitus (

In most patients (80%), NAFLD progresses slowly over decades. The progression is related to continuing insulin resistance.15,16 Greater disease progression is seen in patients with T2DM or concomitant chronic liver disease (such as hepatitis C).10,11,16 Patients with NAFLD who develop advanced fibrosis or cirrhosis experience increased rates of overall mortality, liver-related events, and liver transplantation.1,9,17,18 Within the VHA, NAFLD is the third most common cause of cirrhosis and HCC, occurring at an average age of 66 and 70 years, respectively.19

Although no pharmaceuticals are yet approved to treat NAFLD, even modest weight loss is beneficial. For example, weight loss > 4% improves fatty liver, ≥ 7% improves liver inflammation, and ≥ 10% decreases liver fibrosis (or scarring).21-23 In patients with a prior lack of success with weight loss, weight loss medications may be beneficial for short-term use.24 When comparing the effects of diet, exercise, obesity pharmacotherapy, and combinations for these approaches, intensive lifestyle modification with exercise had the greatest, most enduring benefit.25 Additionally, bariatric (weight loss) surgery has significantly improved health and liver-related outcomes for patients with NASH.26

In at-risk veterans, NAFLD has myriad negative effects on health and QOL. To improve its early identification and management in the VHA, we summarize strategies that all providers can use to screen and treat patients for this condition.

Screening for Advanced Fibrosis

Advanced fibrosis in NAFLD is diagnosed by analyzing adequately sized liver biopsies.27,28 However, noninvasive approaches to quantify advanced fibrosis by imaging or use of a simple fibrosis prediction score also are available. Imaging modalities include measuring liver stiffness, using transient elastography (FibroScan, Waltham, MA) or magnetic resonance elastography.1,29-31 Fibrosis prediction scores use common clinical and laboratory data to predict the presence or absence of advanced fibrosis (Table 1).29

Does This Patient Have NAFLD?

To identify NAFLD, patients with metabolic syndrome and modest or no alcohol use are first assessed for liver injury with ALT, AST, and complete blood count (Figure 3; Case 1).16

Next, common underlying liver diseases that cause liver injury should be excluded by hepatitis B and C virus serology.11,16 Other underlying liver diseases are uncommon and should be assessed only if clinically indicated.

Evaluation of fasting glucose or hemoglobin A1c (HbA1c)can identify undiagnosed T2DM. NAFL, or simple steatosis, is independently associated with an increased risk of T2DM, cardiovascular and kidney disease, yet not overall mortality.16 Over 10 to 20 years, few patients (4%) with simple steatosis progress to cirrhosis.39

In NAFLD, simple steatosis can resolve, and NASH can significantly improve with 7% to 10% weight loss.16,23,40 Patients with simple steatosis on imaging and normal liver enzymes should be monitored with periodic liver enzymes and fibrosis prediction scores (eg, FIB-4) and encouraged to pursue intensive lifestyle intervention.16,33 Without weight loss and exercise interventions metabolic syndrome, T2DM, and NAFLD may progress.

Patients with combined liver steatosis and liver enzyme elevations may exhibit NASH and warrant an evaluation by a hepatologist or gastroenterologist for consideration of additional testing or liver biopsy.16

Encouraging Patients to Pursue Intensive Lifestyle InterventionS

Most veterans wish to collaborate in their care (Table 3, Figure 4) yet experience many barriers, such as low health literacy, high rates of comorbidities, and ongoing drug/alcohol misuse.43,44

In addition to patient education, motivational interviewing significantly improves weight loss, resulting in a 3.3 lb (1.5 kg) increased weight loss in the intervention group vs the control group in weight loss studies.46

To start the conversation, the health care provider can explain that

- Why would you want to lose weight and exercise?

- How might you go about it in order to succeed?

- What are the 3 best reasons for you to do it?

- How important is it for you to make this change, and why? The provider can also ask the patient to quantify on a scale of 1 to 10: (a) How likely is it that they will make each required change? (b) How hard will each change be for them?

- The provider then summarizes the patient’s reasons for wanting change, how he/she can effect change, what their best reasons are, and how to successfully change. The provider then asks a final question:

- So what do you think you will do?

Most patients report feeling engaged, empowered, open, and understood with motivational interviewing. People are “persuaded by what they hear themselves say,” increasing motivation to change.47

This personalized action plan facilitates successful health behavior change.48 Action plans should integrate daily routines. For example, by placing the scale near the toothbrush, daily weighing is encouraged. Daily weighing is associated with significantly greater weight loss and less weight regain.49 In a 6-month, randomized controlled weight loss trial in men and women, daily weighing (using a scale that automatically transmitted weight data), with weekly e-mails and tailored feedback yielded an overall 9% weight loss and increased use of exercise and diet behaviors associated with weight loss in comparison with those who weighed themselves less than weekly.50 This simple daily measure seems to reinforce a patient’s action plan.

Adherence to an action plan significantly improves with patient education, peer or social support, and addressing barriers to adherence.51 For example, by providing support with weekly text messaging of “How are you?” and addressing the issues that patients reported in a large randomized treatment trial, adherence was significantly improved.52 In VHA patients with low health literacy, peer support or telephone coaching also has proven effective in increasing weight loss and glycemic control in patients with T2DM.53,54 Providing multidisciplinary team support during intensive lifestyle intervention, providers can partner with patients to address questions or issues and applaud progress.

Effective VHA interventions

In an ethnically diverse population of patients with prediabetes, up to 7% weight loss was observed in the Diabetes Prevention Program (DPP).55 In this study patients were randomized to placebo; metformin 850 mg twice daily; or a lifestyle-modification program in which they received one-on-one culturally sensitive, individualized lessons in diet, moderate exercise (≥ 150 minutes weekly), and behavior modification from case managers over 16 sessions. Lessons were reinforced in both group and individual sessions. This intervention was associated with an average of 6% weight loss at 6 months (half of participants attained 7% weight loss) and a 58% decrease in the rate of progression to T2DM over a nearly 3-year follow-up of this population with prediabetes compared with that of the placebo group.55 Over a 15-year follow-up, the intensive lifestyle intervention group sustained a 27% decrease in the incidence of T2DM compared with that of the placebo group.56 To emulate the success of the DPP in the VHA, a web-based DPP-like study in female veterans was performed with online coaching and daily weighing. This study achieved a 5.2% weight loss from baseline at 4 months.57

To improve outcomes, the VHA MOVE! Weight Management Program has been revised to include more sustained intervention (16 sessions) and multiple modes for participating—in person, by telephone, via video, via MOVE! Coach phone app, or any combination.58 Using shared decision making between patients with NAFLD and their providers, a customized MOVE! weight loss program can be developed to enable sustained intensive lifestyle intervention: hypocaloric diet, ≥ 150 minutes of moderate exercise weekly, and behavioral change.

In addition to intensive lifestyle intervention, a prospective study found that bariatric surgery significantly improved outcomes in patients with NASH, with most patients experiencing resolution of their NASH and nearly half exhibiting significantly improved fibrosis.26 In the VHA, bariatric surgery has yielded excellent long-term outcomes, with 21% sustained weight loss from baseline (vs matched nonsurgical population) at 10 years postoperatively in patients undergoing Roux-en-Y gastric bypass.59 Bariatric surgery also results in long-term remission of T2DM in most patients and significant improvement in hypertension and dyslipidemia.60 The risks of bariatric surgery include 3% serious complications, 1% reoperation rates, and 0.4% 30-day mortality.61,62 Bariatric surgery can be considered in patients with BMI > 40 or in patients with BMI > 35 who have comorbidities and do not have decompensated cirrhosis.63,64

Beyond weight loss, more favorable liver-related outcomes and lower rates of advanced liver fibrosis are observed in those consuming filtered coffee; a reduction in liver steatosis also is observed with adherence to a Mediterranean diet.65,66 In NAFLD, statins may improve liver chemistries and fibrosis; this class of medications can be used safely even in the presence of an elevated ALT.11,67

Conclusion

Nonalcoholic fatty liver disease independently increases the risk of T2DM, cardiovascular disease and kidney disease. With its rates increasing in the VHA, earlier identification and intervention is warranted in patients at high risk (ie, those with metabolic syndrome, obesity, and T2DM).2

NASH is more frequent in those with liver enzyme elevations or with an elevated FIB-4 and is associated with a long-term risk of cirrhosis. These patients merit referral to hepatology or gastroenterology for further evaluation and consideration of a liver biopsy to identify NASH. Patients with likely NAFLD without liver enzyme elevations can be further evaluated with FIB-4 scores to assess their probability of advanced liver fibrosis and potential need for referral to hepatology or gastroenterology.

Early NAFLD detection and intervention with intensive lifestyle modifications has the potential to avert progression to advanced fibrosis—and its associated increased overall and liver-related mortality, and impaired QOL.3,16,18 Although FIB-4 is a validated predictor of advanced fibrosis, this score is not yet used nationally to identify and risk stratify NAFLD in the VHA. Additionally, the very low use of VHA diet/exercise programs in eligible patients contributes to NAFLD progression.68 The cost-effective DPP has successfully yielded weight loss in patients with prediabetes and decreases in the incidence of T2DM through motivational interviewing and intensive lifestyle intervention.55

To improve NAFLD management, providers can successfully engage patients through motivational interviewing for intensive lifestyle intervention. Their resulting weight loss is enhanced with a personalized action plan, daily weighing, and peer support. When NAFLD is identified in patients with metabolic risk factors, the probability of advanced fibrosis is easily assessed in those with elevated FIB-4 scores who merit gastrointestinal referral.33,37

In all those identified with NAFLD, disease information should be provided to patients and their families. Intensive lifestyle modification targeting a ≥ 7% weight loss is recommended; motivational interviewing can increase commitment to change and yield a customized action plan for sustained weight loss. Working with the support and encouragement of their team of primary care providers, dieticians, and MOVE! coaches, patients can actively engage to improve their NAFLD and overall health.

1. Rinella ME. Nonalcoholic fatty liver disease: a systematic review. JAMA. 2015;313(22):2263-2273.

2. Kanwal F, Kramer JR, Duan Z, et al. Trends in the burden of nonalcoholic fatty liver disease in a United States cohort of veterans. Clin Gastroenterol Hepatol. 2016;14(2):301-308.

3. Golabi P, Otgonsuren M, Cable R, et al. Non-alcoholic fatty liver disease (NAFLD) is associated with impairment of Health Related Quality of Life (HRQOL). Health Qual Life Outcomes. 2016;14(1):18.

4. Targher G, Bertolini L, Padovani R, et al. Prevalence of nonalcoholic fatty liver disease and its association with cardiovascular disease among type 2 diabetic patients. Diabetes Care. 2007;30(5):1212-1218.

5. Argo CK, Caldwell SH. Epidemiology and natural history of non-alcoholic steatohepatitis. Clin Liver Dis. 2009;13(4):511-531.

6. Centers for Disease Control and Prevention. About Prediabetes & Type 2 Diabetes. https://www.cdc.gov/diabetes/prevention/prediabetes-type2/index.html. Updated June 11, 2018. Accessed November 7, 2018.

7. Littman AJ, Jacobson IG, Boyko EJ, Powell TM, Smith TC; Millennium Cohort Study Team. Weight change following US military service. Int J Obes (Lond). 2013;37(2):244-253.

8. Breland JY, Phibbs CS, Hoggatt KJ, et al. The obesity epidemic in the Veterans Health Administration: prevalence among key populations of women and men veterans. J Gen Intern Med. 2017;32(suppl 1):11-17.

9. Angulo P, Hui JM, Marchesini G, et al. The NAFLD fibrosis score: a noninvasive system that identifies liver fibrosis in patients with NAFLD. Hepatology. 2007;45(4):846-854.

10. Bazick J, Donithan M, Neuschwander-Tetri BA, et al. Clinical model for NASH and advanced fibrosis in adult patients with diabetes and NAFLD: guidelines for referral in NAFLD. Diabetes Care. 2015;38(7):1347-1355.

11. Chalasani N, Younossi Z, Lavine JE, et al. The diagnosis and management of nonalcoholic fatty liver disease: Practice guidance from the American Association for the Study of Liver Diseases. Hepatology. 2018;67(1):328-357.

12. Bril F, Barb D, Portillo‐Sanchez P, et al. Metabolic and histological implications of intrahepatic triglyceride content in nonalcoholic fatty liver disease. Hepatology. 2017;65(4):1132-1144.

13. Diehl AM, Day C. Cause, pathogenesis, and treatment of nonalcoholic steatohepatitis. N Engl J Med. 2017;377(21):2063-2072.

14. Nasr P, Ignatova S, Kechagias S, Ekstedt M. Natural history of nonalcoholic fatty liver disease: a prospective follow-up study with serial biopsies. Hepatol Commun. 2018;27(2):199-210.

15. Singh S, Allen AM, Wang Z, Prokop LJ, Murad MH, Loomba R. Fibrosis progression in nonalcoholic fatty liver vs nonalcoholic steatohepatitis: a systematic review and meta-analysis of paired-biopsy studies. Clin Gastroenterol Hepatol. 2015;13(4):643-654.

16. European Association for the Study of the Liver (EASL); European Association for the Study of Diabetes (EASD); European Association for the Study of Obesity (EASO). EASL-EASD-EASO clinical practice guidelines for the management of non-alcoholic fatty liver disease. J Hepatol. 2016;64(6):1388-1402.

17. Younossi ZM, Blissett D, Blissett R, et al. The economic and clinical burden of nonalcoholic fatty liver disease in the United States and Europe. Hepatology. 2016;64(5):1577-1586.

18. Angulo P, Kleiner DE, Dam-Larsen S, et al. Liver fibrosis, but no other histologic features, is associated with long-term outcomes of patients with nonalcoholic fatty liver disease. Gastroenterology. 2015;149(2):389-397.

19. Beste LA, Leipertz SL, Green PK, Dominitz JA, Ross D, Ioannou GN. Trends in burden of cirrhosis and hepatocellular carcinoma by underlying liver disease in US Veterans, 2001-2013. Gastroenterology 2015;149(6):1471-1482.

20. Mittal S, El-Serag HB, Sada YH, et al. Hepatocellular carcinoma in the absence of cirrhosis in United States veterans is associated with nonalcoholic fatty liver disease. Clin Gastroenterol Hepatol. 2016;14(1):124-131.

21. Kenneally S, Sier JH, Moore JB. Efficacy of dietary and physical activity intervention in non-alcoholic fatty liver disease: a systematic review. BMJ Open Gastroenterol. 2017;4(1):e000139.

22. Thoma C, Day CP, Trenell MI. Lifestyle interventions for the treatment of non-alcoholic fatty liver disease in adults: a systematic review. J Hepatol. 2012;56(1):255-266.

23. Vilar-Gomez E, Martinez-Perez Y, Calzadilla-Bertot L, et al. Weight loss through lifestyle modification significantly reduces features of nonalcoholic steatohepatitis. Gastroenterology. 2015;149(2):367-378.

24. Apovian CM, Aronne LJ, Bessesen DH, et al; Endocrine Society. Pharmacological management of obesity: an endocrine society clinical practice guideline. J Clin Endocrinol Metab. 2015;100(2):342-362.

25. Haw JS, Galaviz KI, Straus AN, et al. Long-term sustainability of diabetes prevention approaches: a systematic review and meta-analysis of randomized clinical trials. JAMA Intern Med. 2017;177(12):1808-1817.

26. Lassailly G, Caiazzo R, Buob D, et al. Bariatric surgery reduces features of nonalcoholic steatohepatitis in morbidly obese patients. Gastroenterology. 2015;149(2):379-388.

27. Kleiner DE, Brunt EM, Van Natta M, et al; Nonalcoholic Steatohepatitis Clinical Research Network. Design and validation of a histological scoring system for nonalcoholic fatty liver disease. Hepatology. 2005;41(6):1313-1321.

28. Bedossa P; FLIP Pathology Consortium. Utility and appropriateness of the fatty liver inhibition of progression (FLIP) algorithm and steatosis, activity, and fibrosis (SAF) score in the evaluation of biopsies of nonalcoholic fatty liver disease. Hepatology. 2014;60(2):565-567.

29. Tapper EB, Sengupta N, Hunink MG, Afdhal NH, Lai M. Cost-effective evaluation of nonalcoholic fatty liver disease with NAFLD fibrosis score and vibration controlled transient elastography. Am J Gastroenterol. 2015;110(9):1298-1304.

30. Cui J, Ang B, Haufe W, et al. Comparative diagnostic accuracy of magnetic resonance elastography vs. eight clinical prediction rules for non‐invasive diagnosis of advanced fibrosis in biopsy‐proven non‐alcoholic fatty liver disease: a prospective study. Aliment Pharmacol Ther. 2015;41(12):1271-1280.

31. Tapper EB, Lok AS-F. Use of liver imaging and biopsy in clinical practice. N Engl J Med . 2017;377(8):756-768.

32. Sterling RK, Lissen E, Clumeck N; APRICOT Clinical Investigators. Development of a simple noninvasive index to predict significant fibrosis in patients with HIV/HCV coinfection. Hepatology. 2006;43(6):1317-1325.

33. Imler T. Indiana University School of Medicine - GIHep calculators. http://gihep.com/calculators/hepatology/fibrosis-4-score. Published 2018. Accessed November 7, 2018.

34. Sun W, Cui H , Li N, et al. Comparison of FIB-4 index, NAFLD fibrosis score and BARD score for prediction of advanced fibrosis in adult patients with non-alcoholic fatty liver disease: a meta-analysis study. Hepatol Res. 2016;46(9):862-870.

35. Imler T, Indiana University School of Medicine - GIHep calculators. http://gihep.com/calculators/hepatology/nafld-fibrosis-score. Published 2018. Accessed November 7, 2018.

36. Harrison SA, Oliver D, Arnold HL, Gogia S, Neuschwander-Tetri BA. Development and validation of a simple NAFLD clinical scoring system for identifying patients without advanced disease. Gut. 2008;57(10):1441-1447.

37. Patel YA, Gifford EJ, Glass LM, et al. Identifying non-alcoholic fatty liver disease advanced fibrosis in the Veterans Health Administration. Dig Dis Sci. 2018;63(9): 2259-2266.

38. Armstrong MJ, Houlihan DD, Bentham L, et al. Presence and severity of non-alcoholic fatty liver disease in a large prospective primary care cohort. J Hepatol. 2012;56(1):234-240.

39. Matteoni CA, Younossi ZM, Gramlich T, Boparai N, Liu YC, McCullough AJ. Nonalcoholic fatty liver disease: a spectrum of clinical and pathological severity. Gastroenterology. 1999;116(6):1413-1419.

40. Promrat K, Kleiner DE, Niemeier HM, et al. Randomized controlled trial testing the effects of weight loss on nonalcoholic steatohepatitis. Hepatology. 2010;51(1):121-129.

41. Mofrad P, Contos MJ, Haque M, et al. Clinical and histologic spectrum of nonalcoholic fatty liver disease associated with normal ALT values. Hepatology. 2003;37(6):1286-1292.

42. Portillo-Sanchez P, Bril F, Maximos M, et al. High prevalence of nonalcoholic fatty liver disease in patients With Type 2 Diabetes Mellitus and Normal Plasma Aminotransferase Levels. J Clin Endocrinol Metab 2015;100(6):2231-2238.

43. Rodriguez V, Andrade AD, Garcia-Retamero R, et al. Health literacy, numeracy, and graphical literacy among veterans in primary care and their effect on shared decision making and trust in physicians. J Health Commun. 2013;18(suppl 1):273-289.

44. Kramer JR, Kanwal F, Richardson P, Mei M, El-Serag HB. Gaps in the achievement of effectiveness of HCV treatment in national VA practice. J Hepatol. 2012;56(2):320-325.

45. Veterans Health Administration. Non-alcoholic fatty liver: information for patients. https://www.hepatitis.va.gov/pdf/NAFL.pdf. Published September 2017. Accessed November 7, 2018.

46. Armstrong MJ, Mottershead TA, Ronksley PE, Sigal RJ, Campbell TS, Hemmelgarn BR. Motivational interviewing to improve weight loss in overweight and/or obese patients: a systematic review and meta-analysis of randomized controlled trials. Obes Rev. 2011;12(9):709-723.

47. Miller WR, Rollnick S. Motivational Interviewing: Helping People Change. Guilford Press: NY, New York; 2013.

48. Leventhal H, Leventhal EA, Breland JY. Cognitive science speaks to the “common sense” of chronic illness management. Ann Behav Med. 2011;41(2):152-163.

49. Zheng Y, Klem ML, Sereika SM, Danford CA, Ewing LJ, Burke LE. Self-weighing in weight management: a systematic literature review. Obesity (Silver Spring). 2015;23(2):256-265.

50. Steinberg DM, Bennett GG, Askew S, Tate DF. Weighing every day matters; daily weighing improves weight loss and adoption of weight control behaviors. J Acad Nutr Diet. 2015;115(4):511-518.

51. Charania MR, Marshall KJ, Lyles CM; HIV/AIDS Prevention Research Synthesis (PRS) Team. Identification of evidence-based interventions for promoting HIV medication adherence: findings from a systematic review of U.S.-based studies, 1996-2011. AIDS Behav. 2014;18(4):646-660.

52. Lester RT, Ritvo P, Mills EJ, et al. Effects of a mobile phone short message service on antiretroviral treatment adherence in Kenya (WelTel Kenya1): a randomised trial. Lancet 2010;376(9755):1838-1845.

53. Dutton GR, Phillips JM, Kukkamalla M, Cherrington AL, Safford MM. Pilot study evaluating the feasibility and initial outcomes of a primary care weight loss intervention with peer coaches. Diabetes Educ. 2015:41(3):361-368.

54. Fisher EB, Coufal MM, Parada H, et al. Peer support in health care and prevention: Cultural, organizational, and dissemination issues. Annu Rev Public Health. 2014;35(1):363-383.

55. Diabetes Prevention Program Research Group. Reduction in the incidence of type 2 diabetes with lifestyle intervention or metformin. N Engl J Med. 2002;(346):393-403.

56. Diabetes Prevention Program Research Group. Long-term effects of lifestyle intervention or metformin on diabetes development and microvascular complications over 15-year follow-up: the Diabetes Prevention Program Outcomes Study. Lancet Diabetes Endocrinol. 2015;3(11):866-875.

57. Moin T, Ertl K, Schneider J, et al. Women veterans’ experience with a web-based diabetes prevention program: a qualitative study to inform future practice. J Med Internet Res. 2015;17(5):e127.

58. US Department of Veterans Affairs. MOVE! Weight management program. https://www.move.va.gov/MOVE/index.asp. Updated October 5, 2018. Accessed November 7, 2018.

59. Maciejewski ML, Arterburn DE, Van Scoyoc L, et al. Bariatric surgery and long-term durability of weight loss. JAMA Surg. 2016;151(11):1046-1055.

60. Adams TD, Davidson LE, Litwin SE, et al. Weight and metabolic outcomes 12 years after gastric bypass. N Engl J Med. 2017;377(12):1143-1155.

61. Dimick JB, Nicholas LH, Ryan AM, Thumma JR, Birkmeyer JD. Bariatric surgery complications beforevs after implementation of a national policy restricting coverage to centers of excellence. JAMA. 2013;309(8):792-799.

62. The Longitudinal Assessment of Bariatric Surgery (LABS) Consortium, Flum DR, Belle SH, et al. Perioperative safety in the longitudinal assessment of bariatric surgery. N Engl J Med. 2009;361(5):445-454.

63. Brito JP, Montori VM, Davis AM; Delegates of the 2nd Diabetes Surgery Summit. Metabolic surgery in the treatment algorithm for type 2 diabetes: a joint statement by international diabetes organizations. JAMA. 2017;317(6):635-636.

64. Mosko JD, Nguyen GC. Increased perioperative mortality following bariatric surgery among patients with cirrhosis. Clin Gastroenterol Hepatol. 2011;9(10):897-901.

65. Saab S, Mallam D, Cox GA 2nd, Tong MJ. Impact of coffee on liver diseases: a systematic review. Liver Int. 2014;34(4):495-504.

66. Ryan MC, Itsiopoulos C, Thodis T, et al. The Mediterranean diet improves hepatic steatosis and insulin sensitivity in individuals with non-alcoholic fatty liver disease. J Hepatol. 2013;59(1):138-143.

67. Musso G, Gambino R, Cassader M, Pagano G. A meta‐analysis of randomized trials for the treatment of nonalcoholic fatty liver disease. Hepatology. 2010;52(1):79-104.

68. Patel Y, Gifford EJ, Glass LM, et al. Risk factors for biopsy-proven non-alcoholic fatty liver disease progression in the Veterans Health Administration. Aliment Pharmacol Ther. 2018;47(2):268-278.

1. Rinella ME. Nonalcoholic fatty liver disease: a systematic review. JAMA. 2015;313(22):2263-2273.

2. Kanwal F, Kramer JR, Duan Z, et al. Trends in the burden of nonalcoholic fatty liver disease in a United States cohort of veterans. Clin Gastroenterol Hepatol. 2016;14(2):301-308.

3. Golabi P, Otgonsuren M, Cable R, et al. Non-alcoholic fatty liver disease (NAFLD) is associated with impairment of Health Related Quality of Life (HRQOL). Health Qual Life Outcomes. 2016;14(1):18.

4. Targher G, Bertolini L, Padovani R, et al. Prevalence of nonalcoholic fatty liver disease and its association with cardiovascular disease among type 2 diabetic patients. Diabetes Care. 2007;30(5):1212-1218.

5. Argo CK, Caldwell SH. Epidemiology and natural history of non-alcoholic steatohepatitis. Clin Liver Dis. 2009;13(4):511-531.

6. Centers for Disease Control and Prevention. About Prediabetes & Type 2 Diabetes. https://www.cdc.gov/diabetes/prevention/prediabetes-type2/index.html. Updated June 11, 2018. Accessed November 7, 2018.

7. Littman AJ, Jacobson IG, Boyko EJ, Powell TM, Smith TC; Millennium Cohort Study Team. Weight change following US military service. Int J Obes (Lond). 2013;37(2):244-253.

8. Breland JY, Phibbs CS, Hoggatt KJ, et al. The obesity epidemic in the Veterans Health Administration: prevalence among key populations of women and men veterans. J Gen Intern Med. 2017;32(suppl 1):11-17.

9. Angulo P, Hui JM, Marchesini G, et al. The NAFLD fibrosis score: a noninvasive system that identifies liver fibrosis in patients with NAFLD. Hepatology. 2007;45(4):846-854.

10. Bazick J, Donithan M, Neuschwander-Tetri BA, et al. Clinical model for NASH and advanced fibrosis in adult patients with diabetes and NAFLD: guidelines for referral in NAFLD. Diabetes Care. 2015;38(7):1347-1355.

11. Chalasani N, Younossi Z, Lavine JE, et al. The diagnosis and management of nonalcoholic fatty liver disease: Practice guidance from the American Association for the Study of Liver Diseases. Hepatology. 2018;67(1):328-357.

12. Bril F, Barb D, Portillo‐Sanchez P, et al. Metabolic and histological implications of intrahepatic triglyceride content in nonalcoholic fatty liver disease. Hepatology. 2017;65(4):1132-1144.

13. Diehl AM, Day C. Cause, pathogenesis, and treatment of nonalcoholic steatohepatitis. N Engl J Med. 2017;377(21):2063-2072.

14. Nasr P, Ignatova S, Kechagias S, Ekstedt M. Natural history of nonalcoholic fatty liver disease: a prospective follow-up study with serial biopsies. Hepatol Commun. 2018;27(2):199-210.

15. Singh S, Allen AM, Wang Z, Prokop LJ, Murad MH, Loomba R. Fibrosis progression in nonalcoholic fatty liver vs nonalcoholic steatohepatitis: a systematic review and meta-analysis of paired-biopsy studies. Clin Gastroenterol Hepatol. 2015;13(4):643-654.

16. European Association for the Study of the Liver (EASL); European Association for the Study of Diabetes (EASD); European Association for the Study of Obesity (EASO). EASL-EASD-EASO clinical practice guidelines for the management of non-alcoholic fatty liver disease. J Hepatol. 2016;64(6):1388-1402.

17. Younossi ZM, Blissett D, Blissett R, et al. The economic and clinical burden of nonalcoholic fatty liver disease in the United States and Europe. Hepatology. 2016;64(5):1577-1586.

18. Angulo P, Kleiner DE, Dam-Larsen S, et al. Liver fibrosis, but no other histologic features, is associated with long-term outcomes of patients with nonalcoholic fatty liver disease. Gastroenterology. 2015;149(2):389-397.

19. Beste LA, Leipertz SL, Green PK, Dominitz JA, Ross D, Ioannou GN. Trends in burden of cirrhosis and hepatocellular carcinoma by underlying liver disease in US Veterans, 2001-2013. Gastroenterology 2015;149(6):1471-1482.

20. Mittal S, El-Serag HB, Sada YH, et al. Hepatocellular carcinoma in the absence of cirrhosis in United States veterans is associated with nonalcoholic fatty liver disease. Clin Gastroenterol Hepatol. 2016;14(1):124-131.

21. Kenneally S, Sier JH, Moore JB. Efficacy of dietary and physical activity intervention in non-alcoholic fatty liver disease: a systematic review. BMJ Open Gastroenterol. 2017;4(1):e000139.

22. Thoma C, Day CP, Trenell MI. Lifestyle interventions for the treatment of non-alcoholic fatty liver disease in adults: a systematic review. J Hepatol. 2012;56(1):255-266.

23. Vilar-Gomez E, Martinez-Perez Y, Calzadilla-Bertot L, et al. Weight loss through lifestyle modification significantly reduces features of nonalcoholic steatohepatitis. Gastroenterology. 2015;149(2):367-378.

24. Apovian CM, Aronne LJ, Bessesen DH, et al; Endocrine Society. Pharmacological management of obesity: an endocrine society clinical practice guideline. J Clin Endocrinol Metab. 2015;100(2):342-362.

25. Haw JS, Galaviz KI, Straus AN, et al. Long-term sustainability of diabetes prevention approaches: a systematic review and meta-analysis of randomized clinical trials. JAMA Intern Med. 2017;177(12):1808-1817.

26. Lassailly G, Caiazzo R, Buob D, et al. Bariatric surgery reduces features of nonalcoholic steatohepatitis in morbidly obese patients. Gastroenterology. 2015;149(2):379-388.

27. Kleiner DE, Brunt EM, Van Natta M, et al; Nonalcoholic Steatohepatitis Clinical Research Network. Design and validation of a histological scoring system for nonalcoholic fatty liver disease. Hepatology. 2005;41(6):1313-1321.

28. Bedossa P; FLIP Pathology Consortium. Utility and appropriateness of the fatty liver inhibition of progression (FLIP) algorithm and steatosis, activity, and fibrosis (SAF) score in the evaluation of biopsies of nonalcoholic fatty liver disease. Hepatology. 2014;60(2):565-567.

29. Tapper EB, Sengupta N, Hunink MG, Afdhal NH, Lai M. Cost-effective evaluation of nonalcoholic fatty liver disease with NAFLD fibrosis score and vibration controlled transient elastography. Am J Gastroenterol. 2015;110(9):1298-1304.

30. Cui J, Ang B, Haufe W, et al. Comparative diagnostic accuracy of magnetic resonance elastography vs. eight clinical prediction rules for non‐invasive diagnosis of advanced fibrosis in biopsy‐proven non‐alcoholic fatty liver disease: a prospective study. Aliment Pharmacol Ther. 2015;41(12):1271-1280.

31. Tapper EB, Lok AS-F. Use of liver imaging and biopsy in clinical practice. N Engl J Med . 2017;377(8):756-768.

32. Sterling RK, Lissen E, Clumeck N; APRICOT Clinical Investigators. Development of a simple noninvasive index to predict significant fibrosis in patients with HIV/HCV coinfection. Hepatology. 2006;43(6):1317-1325.

33. Imler T. Indiana University School of Medicine - GIHep calculators. http://gihep.com/calculators/hepatology/fibrosis-4-score. Published 2018. Accessed November 7, 2018.

34. Sun W, Cui H , Li N, et al. Comparison of FIB-4 index, NAFLD fibrosis score and BARD score for prediction of advanced fibrosis in adult patients with non-alcoholic fatty liver disease: a meta-analysis study. Hepatol Res. 2016;46(9):862-870.

35. Imler T, Indiana University School of Medicine - GIHep calculators. http://gihep.com/calculators/hepatology/nafld-fibrosis-score. Published 2018. Accessed November 7, 2018.

36. Harrison SA, Oliver D, Arnold HL, Gogia S, Neuschwander-Tetri BA. Development and validation of a simple NAFLD clinical scoring system for identifying patients without advanced disease. Gut. 2008;57(10):1441-1447.

37. Patel YA, Gifford EJ, Glass LM, et al. Identifying non-alcoholic fatty liver disease advanced fibrosis in the Veterans Health Administration. Dig Dis Sci. 2018;63(9): 2259-2266.

38. Armstrong MJ, Houlihan DD, Bentham L, et al. Presence and severity of non-alcoholic fatty liver disease in a large prospective primary care cohort. J Hepatol. 2012;56(1):234-240.

39. Matteoni CA, Younossi ZM, Gramlich T, Boparai N, Liu YC, McCullough AJ. Nonalcoholic fatty liver disease: a spectrum of clinical and pathological severity. Gastroenterology. 1999;116(6):1413-1419.

40. Promrat K, Kleiner DE, Niemeier HM, et al. Randomized controlled trial testing the effects of weight loss on nonalcoholic steatohepatitis. Hepatology. 2010;51(1):121-129.

41. Mofrad P, Contos MJ, Haque M, et al. Clinical and histologic spectrum of nonalcoholic fatty liver disease associated with normal ALT values. Hepatology. 2003;37(6):1286-1292.

42. Portillo-Sanchez P, Bril F, Maximos M, et al. High prevalence of nonalcoholic fatty liver disease in patients With Type 2 Diabetes Mellitus and Normal Plasma Aminotransferase Levels. J Clin Endocrinol Metab 2015;100(6):2231-2238.

43. Rodriguez V, Andrade AD, Garcia-Retamero R, et al. Health literacy, numeracy, and graphical literacy among veterans in primary care and their effect on shared decision making and trust in physicians. J Health Commun. 2013;18(suppl 1):273-289.

44. Kramer JR, Kanwal F, Richardson P, Mei M, El-Serag HB. Gaps in the achievement of effectiveness of HCV treatment in national VA practice. J Hepatol. 2012;56(2):320-325.

45. Veterans Health Administration. Non-alcoholic fatty liver: information for patients. https://www.hepatitis.va.gov/pdf/NAFL.pdf. Published September 2017. Accessed November 7, 2018.

46. Armstrong MJ, Mottershead TA, Ronksley PE, Sigal RJ, Campbell TS, Hemmelgarn BR. Motivational interviewing to improve weight loss in overweight and/or obese patients: a systematic review and meta-analysis of randomized controlled trials. Obes Rev. 2011;12(9):709-723.

47. Miller WR, Rollnick S. Motivational Interviewing: Helping People Change. Guilford Press: NY, New York; 2013.

48. Leventhal H, Leventhal EA, Breland JY. Cognitive science speaks to the “common sense” of chronic illness management. Ann Behav Med. 2011;41(2):152-163.

49. Zheng Y, Klem ML, Sereika SM, Danford CA, Ewing LJ, Burke LE. Self-weighing in weight management: a systematic literature review. Obesity (Silver Spring). 2015;23(2):256-265.

50. Steinberg DM, Bennett GG, Askew S, Tate DF. Weighing every day matters; daily weighing improves weight loss and adoption of weight control behaviors. J Acad Nutr Diet. 2015;115(4):511-518.

51. Charania MR, Marshall KJ, Lyles CM; HIV/AIDS Prevention Research Synthesis (PRS) Team. Identification of evidence-based interventions for promoting HIV medication adherence: findings from a systematic review of U.S.-based studies, 1996-2011. AIDS Behav. 2014;18(4):646-660.

52. Lester RT, Ritvo P, Mills EJ, et al. Effects of a mobile phone short message service on antiretroviral treatment adherence in Kenya (WelTel Kenya1): a randomised trial. Lancet 2010;376(9755):1838-1845.

53. Dutton GR, Phillips JM, Kukkamalla M, Cherrington AL, Safford MM. Pilot study evaluating the feasibility and initial outcomes of a primary care weight loss intervention with peer coaches. Diabetes Educ. 2015:41(3):361-368.

54. Fisher EB, Coufal MM, Parada H, et al. Peer support in health care and prevention: Cultural, organizational, and dissemination issues. Annu Rev Public Health. 2014;35(1):363-383.

55. Diabetes Prevention Program Research Group. Reduction in the incidence of type 2 diabetes with lifestyle intervention or metformin. N Engl J Med. 2002;(346):393-403.

56. Diabetes Prevention Program Research Group. Long-term effects of lifestyle intervention or metformin on diabetes development and microvascular complications over 15-year follow-up: the Diabetes Prevention Program Outcomes Study. Lancet Diabetes Endocrinol. 2015;3(11):866-875.

57. Moin T, Ertl K, Schneider J, et al. Women veterans’ experience with a web-based diabetes prevention program: a qualitative study to inform future practice. J Med Internet Res. 2015;17(5):e127.

58. US Department of Veterans Affairs. MOVE! Weight management program. https://www.move.va.gov/MOVE/index.asp. Updated October 5, 2018. Accessed November 7, 2018.

59. Maciejewski ML, Arterburn DE, Van Scoyoc L, et al. Bariatric surgery and long-term durability of weight loss. JAMA Surg. 2016;151(11):1046-1055.

60. Adams TD, Davidson LE, Litwin SE, et al. Weight and metabolic outcomes 12 years after gastric bypass. N Engl J Med. 2017;377(12):1143-1155.

61. Dimick JB, Nicholas LH, Ryan AM, Thumma JR, Birkmeyer JD. Bariatric surgery complications beforevs after implementation of a national policy restricting coverage to centers of excellence. JAMA. 2013;309(8):792-799.

62. The Longitudinal Assessment of Bariatric Surgery (LABS) Consortium, Flum DR, Belle SH, et al. Perioperative safety in the longitudinal assessment of bariatric surgery. N Engl J Med. 2009;361(5):445-454.

63. Brito JP, Montori VM, Davis AM; Delegates of the 2nd Diabetes Surgery Summit. Metabolic surgery in the treatment algorithm for type 2 diabetes: a joint statement by international diabetes organizations. JAMA. 2017;317(6):635-636.

64. Mosko JD, Nguyen GC. Increased perioperative mortality following bariatric surgery among patients with cirrhosis. Clin Gastroenterol Hepatol. 2011;9(10):897-901.

65. Saab S, Mallam D, Cox GA 2nd, Tong MJ. Impact of coffee on liver diseases: a systematic review. Liver Int. 2014;34(4):495-504.

66. Ryan MC, Itsiopoulos C, Thodis T, et al. The Mediterranean diet improves hepatic steatosis and insulin sensitivity in individuals with non-alcoholic fatty liver disease. J Hepatol. 2013;59(1):138-143.

67. Musso G, Gambino R, Cassader M, Pagano G. A meta‐analysis of randomized trials for the treatment of nonalcoholic fatty liver disease. Hepatology. 2010;52(1):79-104.

68. Patel Y, Gifford EJ, Glass LM, et al. Risk factors for biopsy-proven non-alcoholic fatty liver disease progression in the Veterans Health Administration. Aliment Pharmacol Ther. 2018;47(2):268-278.

A Veteran With Acute Progressive Encephalopathy of Unknown Etiology

Case Presentation. A 70-year-old US Marine Corps veteran of the Vietnam War with no significant past medical history was brought by ambulance to VA Boston Healthcare System (VABHS) after being found on the floor at home by his wife, awake, but with minimally coherent speech. He was moving all extremities, and there was no loss of bowel or bladder continence. He had last been seen well by his wife 30 minutes prior. When emergency medical services arrived, his finger stick blood glucose and vital signs were within normal range. In the emergency department, he was able to state his first name but then continuously repeated “7/11” to other questions. A neurologic examination revealed intact cranial nerves, full strength in all extremities, and normal reflexes. A National Institute of Health Stroke Scale (NIHSS) was 3, and a code stroke was activated. At the time of presentation, the patient was an active smoker of 15 cigarettes per day for 50 years and did not use alcohol or recreational drugs.

► Jonathan Li, MD, Chief Medical Resident, VABHS and Beth Israel Deaconess Medical Center (BIDMC). Dr. Fehnel, the patient’s medical team was most worried about a transient ischemic attack (TIA) or cerebrovascular accident (CVA). Is his presentation consistent with these diagnoses, and what else is on your differential diagnosis?