User login

Doc groups pushing back on Part B drug reimbursement proposal

The Centers for Medicare & Medicaid Services in October 2018 issued an “advance notice of proposed rulemaking with comment” outlining a test that would pay for Part B drugs with price points more closely aligned with international rates through the use of private sector vendors that would negotiate drug prices, procure the products, distribute them to physicians and hospitals, and take on the responsibility of billing Medicare.

Although the so-called International Pricing Index (IPI) model is not fully fleshed out in the regulatory filing, one of the key details that has been announced is that the demonstration project would have mandatory participation. This did not sit well with medical societies offering feedback to CMS.

The American College of Rheumatology stated in comments filed with the agency that “we do not support mandatory demonstration projects.”

The American Society of Clinical Oncology echoed that sentiment in Dec. 31, 2018, comments filed with the agency. “ASCO cannot support a mandatory demonstration program,” the group noted. “We are concerned about losing access points to oncology care provided by oncology practices, especially in rural, underserved, and low-income areas that are already struggling to deliver care.”

And while the Community Oncology Alliance also spoke against making participation in the IPI model demonstration project mandatory, it went further with its criticism of the proposal.

“COA does not support the IPI Model as proposed in the pre-proposed rule published by [CMS] because we have serious concerns about its impact on cancer patient care and even its legality,” the group said in Dec. 31, 2018, comments filed with the agency, adding that “mandatory demonstration projects are clearly not in the charter of CMMI [Center for Medicare & Medicaid Innovation] as written into law by Congress. If CMS believes that CMMI has the power via statute to effectively amend Medicare law – in this case the Part B drug reimbursement rate for at least 50% of Part B providers – it (CMS representing the Executive branch) either has overstepped its constitutional boundaries separating the powers of government branches or Congress has effectively handed over its powers to the Executive branch. That would either be illegal or unconstitutional, with the latter case invalidating the section of the law that created and funded CMMI.”

While none of the groups offered support to the IPI demonstration project, all offered suggestions on what could be done to improve on the details outlined in the advance notice of proposed rulemaking.

The American Academy of Dermatology Association, which like other groups took exception to CMS’ “insinuation” in its regulatory pre-proposal that physicians select treatments based on reimbursement ahead of patient need, suggested in Dec. 19, 2018, comments to the agency that drugs on the Food and Drug Administration’s drug shortage list be excluded from the list.

It also expressed concerns regarding access if a drug goes without international reference pricing because a manufacturer chooses not to sell in certain countries.

“AADA is concerned that this model could result in patients losing access to some drugs when a distributor and manufacturer are unable to agree on a price,” the group said. Similarly, the lag in setting a reference price after a new product is introduced could also create access issues.

AADA also took issue with the fact that vendors could not offer physicians and hospitals volume-based incentive payments or rebates but did not have the same prohibition from vendors receiving such incentives. “Under this proposal, CMS should prohibit vendors from prioritizing drug availability or excluding some drugs from distribution to physicians based on discounts provided by manufacturers. CMS will need to monitor utilization to ensure access to necessary treatments is not delayed or impeded.”

AADA also wants more clarity in how providers will be selected to participate.

The American College of Rheumatology expressed concern that “the administrative difficulties that would be associated with utilizing vendors could lead some practices to lose the ability to provide infusion services. Specifically, we are concerned that the added administrative burden of proposed interactions with the vendors in the model exceeds any inherent benefits to practice.” It added that CMS needs to look at how a potentially mandatory participation could affect specialty physician shortages.

The ACR made a number of recommendations, including making the IPI model participation voluntary; allowing for an exit for participants if the program is not working for them; providing incentives that could increase gross reimbursement; increasing provider reimbursement to cover the expenses associated with dealing with vendors; and making sure the agency is adequately tracking the effect on patient access.

ASCO used its comments to reiterate previous comments provided to the agency on revising the competitive acquisition program (CAP), a failed program that used third-party vendors as suppliers for Part B drugs. Among its suggestions were making the program voluntary; ensuring it does not result in an aggregate reduction in payments to oncology practices; ensuring a CAP does not result in interruption in care; and restricting its burdensome utilization management requirements.

The Community Oncology Alliance said it is working on an alternative to the IPI model, one that could contain a number of provisions, such as tiered average sales price-based reimbursement; clinically appropriate utilization management techniques; and drug prices that are lowered without artificial international price indexing.

The American Medical Association in Dec. 20, 2018, comments to the agency outlined a number of principles that any new vendor-based program needs to include, such as being voluntary; providing supplemental payments to cover the cost of special handling and storage of Part B drugs; flexibility to ensure various ordering issues; preventing variation in treatments for patients; and prohibiting vendors from restricting access using utilization management techniques.

The AMA also offered a range of suggestions for the IPI model, including measuring timeliness of deliveries in hours, not days; prohibiting vendors from withholding shipments of subsequent treatments if the initial claim has not been processed; making all treatment options available, even for off-label use; and getting guarantees from vendors on the availability of next-day delivery to any location where the patient is being treated.

Likewise, the AMA suggested that CMS should not set unreasonable deadlines for claims submissions and should provide an adequate number of vendors to ensure choice and access.

“We are also concerned about the impact of the proposed IPI model and its overall impact on costs to physician practices,” the AMA said in its comment letter. “The Administration proposes to allow the vendors to charge administrative fees to physician practices as part of their agreement to provide drug products to those practices included in the model. While we understand that third-party vendors must have a financial incentive in order to participate in the program, allowing vendors to charge physician practices administrative fees would add new, potentially significant increased costs to physicians in acquiring and providing treatments to patients without adequate changes to the reimbursement model to compensate for these costs.”

The AMA said that lower reimbursement combined with administrative fees would likely make the model untenable for physician practices unless changes to the reimbursement model were made.

The AMA also took issue with the focus on single-source drugs and biologics indexed with international pricing, which could create access issues.

“We urge CMS to undertake modeling and simulation of the impact if vendors are unable to obtain these drugs at the reimbursement amount,” the AMA stated in its comment letter. “There is a distinct possibility of immediate adverse patient impact if none of the vendors are able to secure needed clinical treatments.”

The Centers for Medicare & Medicaid Services in October 2018 issued an “advance notice of proposed rulemaking with comment” outlining a test that would pay for Part B drugs with price points more closely aligned with international rates through the use of private sector vendors that would negotiate drug prices, procure the products, distribute them to physicians and hospitals, and take on the responsibility of billing Medicare.

Although the so-called International Pricing Index (IPI) model is not fully fleshed out in the regulatory filing, one of the key details that has been announced is that the demonstration project would have mandatory participation. This did not sit well with medical societies offering feedback to CMS.

The American College of Rheumatology stated in comments filed with the agency that “we do not support mandatory demonstration projects.”

The American Society of Clinical Oncology echoed that sentiment in Dec. 31, 2018, comments filed with the agency. “ASCO cannot support a mandatory demonstration program,” the group noted. “We are concerned about losing access points to oncology care provided by oncology practices, especially in rural, underserved, and low-income areas that are already struggling to deliver care.”

And while the Community Oncology Alliance also spoke against making participation in the IPI model demonstration project mandatory, it went further with its criticism of the proposal.

“COA does not support the IPI Model as proposed in the pre-proposed rule published by [CMS] because we have serious concerns about its impact on cancer patient care and even its legality,” the group said in Dec. 31, 2018, comments filed with the agency, adding that “mandatory demonstration projects are clearly not in the charter of CMMI [Center for Medicare & Medicaid Innovation] as written into law by Congress. If CMS believes that CMMI has the power via statute to effectively amend Medicare law – in this case the Part B drug reimbursement rate for at least 50% of Part B providers – it (CMS representing the Executive branch) either has overstepped its constitutional boundaries separating the powers of government branches or Congress has effectively handed over its powers to the Executive branch. That would either be illegal or unconstitutional, with the latter case invalidating the section of the law that created and funded CMMI.”

While none of the groups offered support to the IPI demonstration project, all offered suggestions on what could be done to improve on the details outlined in the advance notice of proposed rulemaking.

The American Academy of Dermatology Association, which like other groups took exception to CMS’ “insinuation” in its regulatory pre-proposal that physicians select treatments based on reimbursement ahead of patient need, suggested in Dec. 19, 2018, comments to the agency that drugs on the Food and Drug Administration’s drug shortage list be excluded from the list.

It also expressed concerns regarding access if a drug goes without international reference pricing because a manufacturer chooses not to sell in certain countries.

“AADA is concerned that this model could result in patients losing access to some drugs when a distributor and manufacturer are unable to agree on a price,” the group said. Similarly, the lag in setting a reference price after a new product is introduced could also create access issues.

AADA also took issue with the fact that vendors could not offer physicians and hospitals volume-based incentive payments or rebates but did not have the same prohibition from vendors receiving such incentives. “Under this proposal, CMS should prohibit vendors from prioritizing drug availability or excluding some drugs from distribution to physicians based on discounts provided by manufacturers. CMS will need to monitor utilization to ensure access to necessary treatments is not delayed or impeded.”

AADA also wants more clarity in how providers will be selected to participate.

The American College of Rheumatology expressed concern that “the administrative difficulties that would be associated with utilizing vendors could lead some practices to lose the ability to provide infusion services. Specifically, we are concerned that the added administrative burden of proposed interactions with the vendors in the model exceeds any inherent benefits to practice.” It added that CMS needs to look at how a potentially mandatory participation could affect specialty physician shortages.

The ACR made a number of recommendations, including making the IPI model participation voluntary; allowing for an exit for participants if the program is not working for them; providing incentives that could increase gross reimbursement; increasing provider reimbursement to cover the expenses associated with dealing with vendors; and making sure the agency is adequately tracking the effect on patient access.

ASCO used its comments to reiterate previous comments provided to the agency on revising the competitive acquisition program (CAP), a failed program that used third-party vendors as suppliers for Part B drugs. Among its suggestions were making the program voluntary; ensuring it does not result in an aggregate reduction in payments to oncology practices; ensuring a CAP does not result in interruption in care; and restricting its burdensome utilization management requirements.

The Community Oncology Alliance said it is working on an alternative to the IPI model, one that could contain a number of provisions, such as tiered average sales price-based reimbursement; clinically appropriate utilization management techniques; and drug prices that are lowered without artificial international price indexing.

The American Medical Association in Dec. 20, 2018, comments to the agency outlined a number of principles that any new vendor-based program needs to include, such as being voluntary; providing supplemental payments to cover the cost of special handling and storage of Part B drugs; flexibility to ensure various ordering issues; preventing variation in treatments for patients; and prohibiting vendors from restricting access using utilization management techniques.

The AMA also offered a range of suggestions for the IPI model, including measuring timeliness of deliveries in hours, not days; prohibiting vendors from withholding shipments of subsequent treatments if the initial claim has not been processed; making all treatment options available, even for off-label use; and getting guarantees from vendors on the availability of next-day delivery to any location where the patient is being treated.

Likewise, the AMA suggested that CMS should not set unreasonable deadlines for claims submissions and should provide an adequate number of vendors to ensure choice and access.

“We are also concerned about the impact of the proposed IPI model and its overall impact on costs to physician practices,” the AMA said in its comment letter. “The Administration proposes to allow the vendors to charge administrative fees to physician practices as part of their agreement to provide drug products to those practices included in the model. While we understand that third-party vendors must have a financial incentive in order to participate in the program, allowing vendors to charge physician practices administrative fees would add new, potentially significant increased costs to physicians in acquiring and providing treatments to patients without adequate changes to the reimbursement model to compensate for these costs.”

The AMA said that lower reimbursement combined with administrative fees would likely make the model untenable for physician practices unless changes to the reimbursement model were made.

The AMA also took issue with the focus on single-source drugs and biologics indexed with international pricing, which could create access issues.

“We urge CMS to undertake modeling and simulation of the impact if vendors are unable to obtain these drugs at the reimbursement amount,” the AMA stated in its comment letter. “There is a distinct possibility of immediate adverse patient impact if none of the vendors are able to secure needed clinical treatments.”

The Centers for Medicare & Medicaid Services in October 2018 issued an “advance notice of proposed rulemaking with comment” outlining a test that would pay for Part B drugs with price points more closely aligned with international rates through the use of private sector vendors that would negotiate drug prices, procure the products, distribute them to physicians and hospitals, and take on the responsibility of billing Medicare.

Although the so-called International Pricing Index (IPI) model is not fully fleshed out in the regulatory filing, one of the key details that has been announced is that the demonstration project would have mandatory participation. This did not sit well with medical societies offering feedback to CMS.

The American College of Rheumatology stated in comments filed with the agency that “we do not support mandatory demonstration projects.”

The American Society of Clinical Oncology echoed that sentiment in Dec. 31, 2018, comments filed with the agency. “ASCO cannot support a mandatory demonstration program,” the group noted. “We are concerned about losing access points to oncology care provided by oncology practices, especially in rural, underserved, and low-income areas that are already struggling to deliver care.”

And while the Community Oncology Alliance also spoke against making participation in the IPI model demonstration project mandatory, it went further with its criticism of the proposal.

“COA does not support the IPI Model as proposed in the pre-proposed rule published by [CMS] because we have serious concerns about its impact on cancer patient care and even its legality,” the group said in Dec. 31, 2018, comments filed with the agency, adding that “mandatory demonstration projects are clearly not in the charter of CMMI [Center for Medicare & Medicaid Innovation] as written into law by Congress. If CMS believes that CMMI has the power via statute to effectively amend Medicare law – in this case the Part B drug reimbursement rate for at least 50% of Part B providers – it (CMS representing the Executive branch) either has overstepped its constitutional boundaries separating the powers of government branches or Congress has effectively handed over its powers to the Executive branch. That would either be illegal or unconstitutional, with the latter case invalidating the section of the law that created and funded CMMI.”

While none of the groups offered support to the IPI demonstration project, all offered suggestions on what could be done to improve on the details outlined in the advance notice of proposed rulemaking.

The American Academy of Dermatology Association, which like other groups took exception to CMS’ “insinuation” in its regulatory pre-proposal that physicians select treatments based on reimbursement ahead of patient need, suggested in Dec. 19, 2018, comments to the agency that drugs on the Food and Drug Administration’s drug shortage list be excluded from the list.

It also expressed concerns regarding access if a drug goes without international reference pricing because a manufacturer chooses not to sell in certain countries.

“AADA is concerned that this model could result in patients losing access to some drugs when a distributor and manufacturer are unable to agree on a price,” the group said. Similarly, the lag in setting a reference price after a new product is introduced could also create access issues.

AADA also took issue with the fact that vendors could not offer physicians and hospitals volume-based incentive payments or rebates but did not have the same prohibition from vendors receiving such incentives. “Under this proposal, CMS should prohibit vendors from prioritizing drug availability or excluding some drugs from distribution to physicians based on discounts provided by manufacturers. CMS will need to monitor utilization to ensure access to necessary treatments is not delayed or impeded.”

AADA also wants more clarity in how providers will be selected to participate.

The American College of Rheumatology expressed concern that “the administrative difficulties that would be associated with utilizing vendors could lead some practices to lose the ability to provide infusion services. Specifically, we are concerned that the added administrative burden of proposed interactions with the vendors in the model exceeds any inherent benefits to practice.” It added that CMS needs to look at how a potentially mandatory participation could affect specialty physician shortages.

The ACR made a number of recommendations, including making the IPI model participation voluntary; allowing for an exit for participants if the program is not working for them; providing incentives that could increase gross reimbursement; increasing provider reimbursement to cover the expenses associated with dealing with vendors; and making sure the agency is adequately tracking the effect on patient access.

ASCO used its comments to reiterate previous comments provided to the agency on revising the competitive acquisition program (CAP), a failed program that used third-party vendors as suppliers for Part B drugs. Among its suggestions were making the program voluntary; ensuring it does not result in an aggregate reduction in payments to oncology practices; ensuring a CAP does not result in interruption in care; and restricting its burdensome utilization management requirements.

The Community Oncology Alliance said it is working on an alternative to the IPI model, one that could contain a number of provisions, such as tiered average sales price-based reimbursement; clinically appropriate utilization management techniques; and drug prices that are lowered without artificial international price indexing.

The American Medical Association in Dec. 20, 2018, comments to the agency outlined a number of principles that any new vendor-based program needs to include, such as being voluntary; providing supplemental payments to cover the cost of special handling and storage of Part B drugs; flexibility to ensure various ordering issues; preventing variation in treatments for patients; and prohibiting vendors from restricting access using utilization management techniques.

The AMA also offered a range of suggestions for the IPI model, including measuring timeliness of deliveries in hours, not days; prohibiting vendors from withholding shipments of subsequent treatments if the initial claim has not been processed; making all treatment options available, even for off-label use; and getting guarantees from vendors on the availability of next-day delivery to any location where the patient is being treated.

Likewise, the AMA suggested that CMS should not set unreasonable deadlines for claims submissions and should provide an adequate number of vendors to ensure choice and access.

“We are also concerned about the impact of the proposed IPI model and its overall impact on costs to physician practices,” the AMA said in its comment letter. “The Administration proposes to allow the vendors to charge administrative fees to physician practices as part of their agreement to provide drug products to those practices included in the model. While we understand that third-party vendors must have a financial incentive in order to participate in the program, allowing vendors to charge physician practices administrative fees would add new, potentially significant increased costs to physicians in acquiring and providing treatments to patients without adequate changes to the reimbursement model to compensate for these costs.”

The AMA said that lower reimbursement combined with administrative fees would likely make the model untenable for physician practices unless changes to the reimbursement model were made.

The AMA also took issue with the focus on single-source drugs and biologics indexed with international pricing, which could create access issues.

“We urge CMS to undertake modeling and simulation of the impact if vendors are unable to obtain these drugs at the reimbursement amount,” the AMA stated in its comment letter. “There is a distinct possibility of immediate adverse patient impact if none of the vendors are able to secure needed clinical treatments.”

Idiopathic Granulomatous Mastitis

Idiopathic granulomatous mastitis (IGM) is rare during pregnancy; it typically is seen in women of childbearing potential from 6 months to 6 years postpartum.1 Because of a temporal association with breastfeeding, it is believed that hyperprolactinemia2 or an immune response to local lobular secretions might play a role in pathogenesis. Early misdiagnosis as bacterial mastitis is common, prompting multiple antibiotic regimens. When antibiotics fail, patients are worked up for inflammatory breast cancer, given the nonhealing breast nodules. Mammography, ultrasonography, and fine-needle aspiration often are unable to rule out carcinoma, warranting excisional biopsies of nodules. The patient is then referred to rheumatology for potential sarcoidosis or to dermatology for IGM. In either case, the workup should be similar, but additional history focused on behavior and medications is essential in suspected IGM, given the association with hyperprolactinemia.

Because IGM is rare, there are no randomized, placebo-controlled trials of treatment efficacy. In many cases, patients undergo complete mastectomy, which is curative but may be psychologically and physically impactful in young women. In some cases, high-dose corticosteroids have been successful; however, because the IGM process can last longer than 2 years, patients treated in this manner are exposed to steroid morbidities.1

We report 3 cases of IGM that add to the literature on possible contributing factors, clinical presentations, and treatments for this disease. We also demonstrate that appropriate trigger identification and steroid-sparing agents, specifically methotrexate, can be breast-saving as they can alleviate this debilitating condition, obviating the need for radical surgical intervention.

CASE REPORTS

Patient 1

A 40-year-old woman with a 4-year history of breastfeeding noted a grape-sized nodule on the left breast that grew to the size of a grapefruit after 2 weeks. Ulceration and drainage periodically occurred, forming pink plaques along the lateral aspects of the breast after healing. Her primary care provider suspected infectious mastitis; she was given an oral antibiotic (cephalexin) and intravenous antibiotics without improvement.

Imaging

Subsequent magnetic resonance imaging revealed a large, irregular, enhancing mass within the outer left breast (6.5 cm at greatest dimension) with additional surrounding amorphous enhancement highly suspicious for malignancy. There also were multiple prominent left axillary lymph nodes, with the largest demonstrating a cortical thickness of 8 mm.

Biopsy

Core breast biopsy showed benign tissue with fat necrosis. Fine-needle aspiration revealed few benign ductal cells and rare histiocytes; because these findings were nondiagnostic and cancer was still a consideration, the patient underwent excisional biopsy.

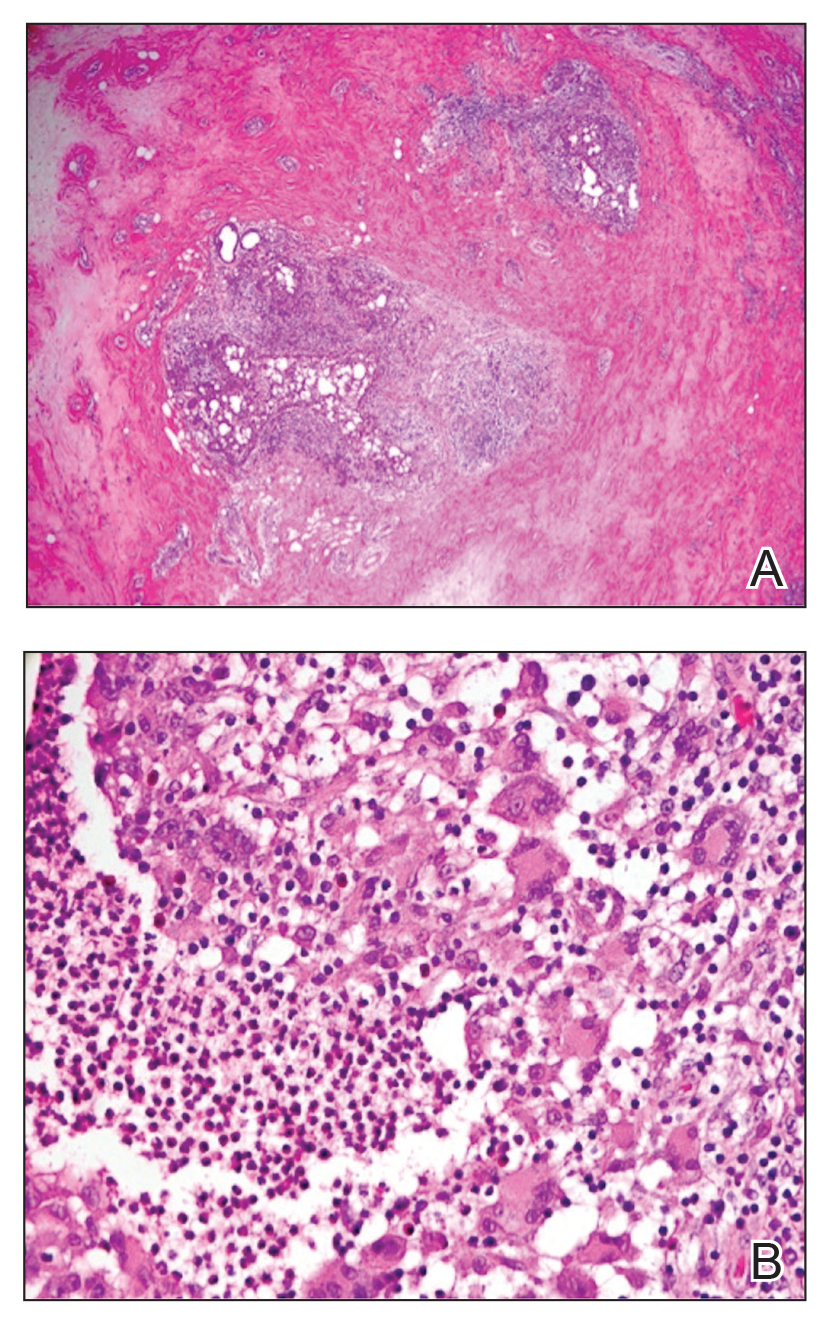

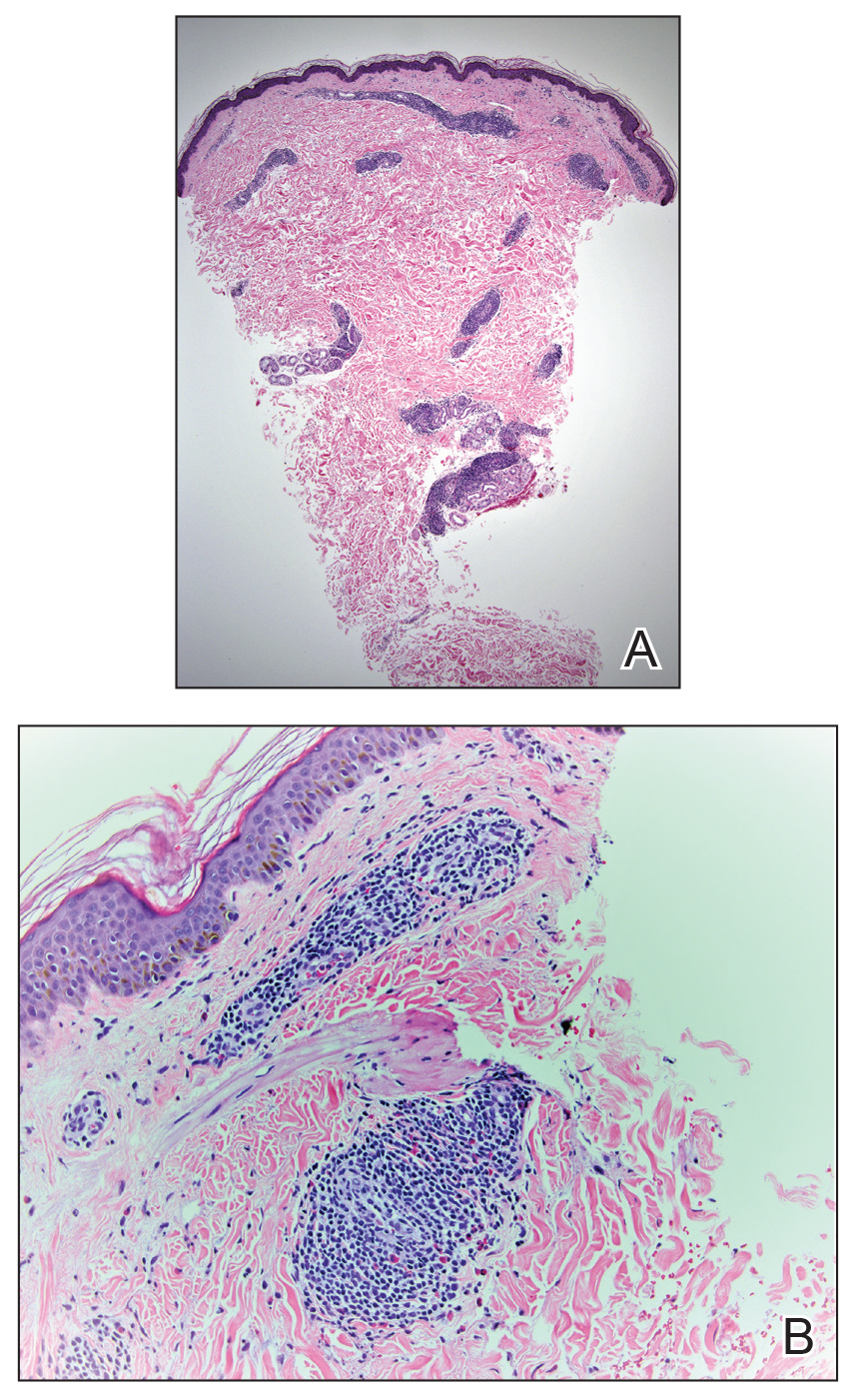

Histologic sections of breast tissue showed extensive lobulocentric inflammation comprising histiocytes and lymphocytes, with neutrophils admixed and forming microabscesses (Figure 1A). Multinucleated giant cells and single-cell necrosis were seen, but true caseous necrosis was absent (Figure 1B). Duct spaces often contained inflammatory cells or secretions. Special stains for fungal and acid-fast bacterial microorganisms were negative.

Referral to Dermatology

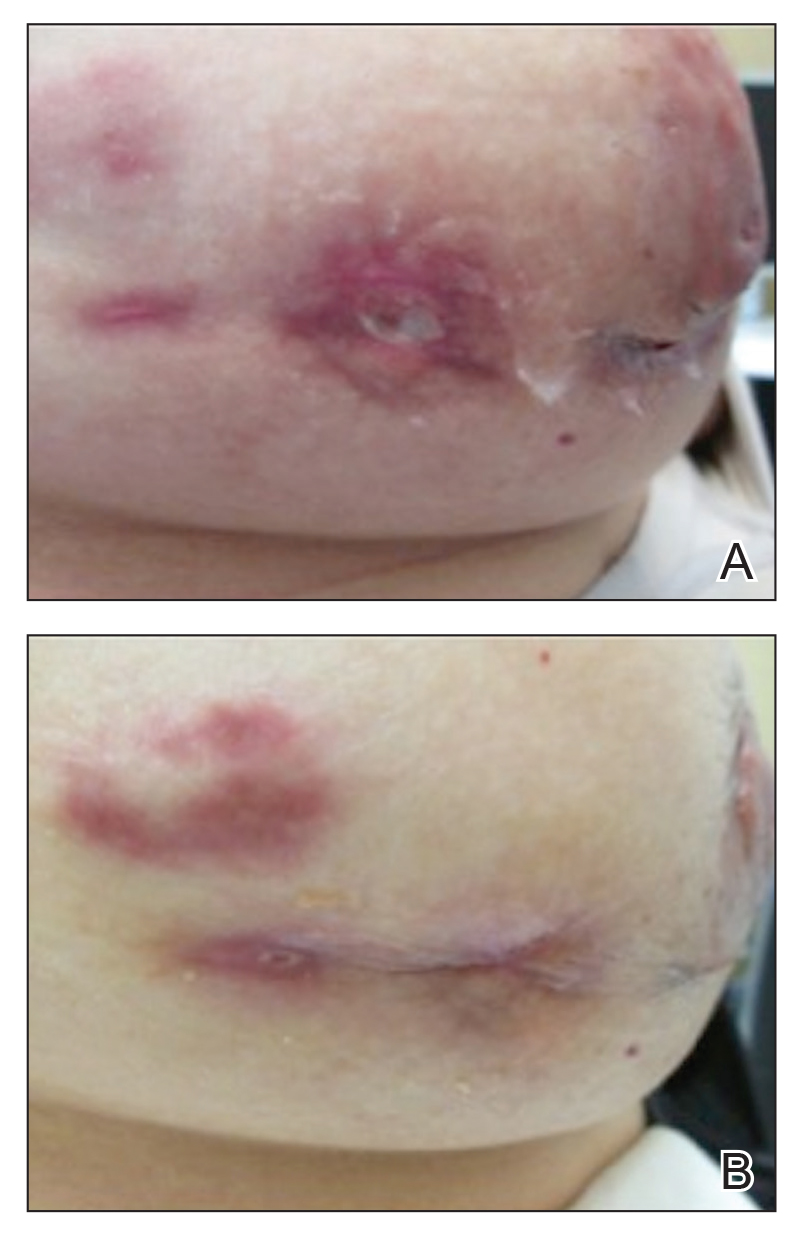

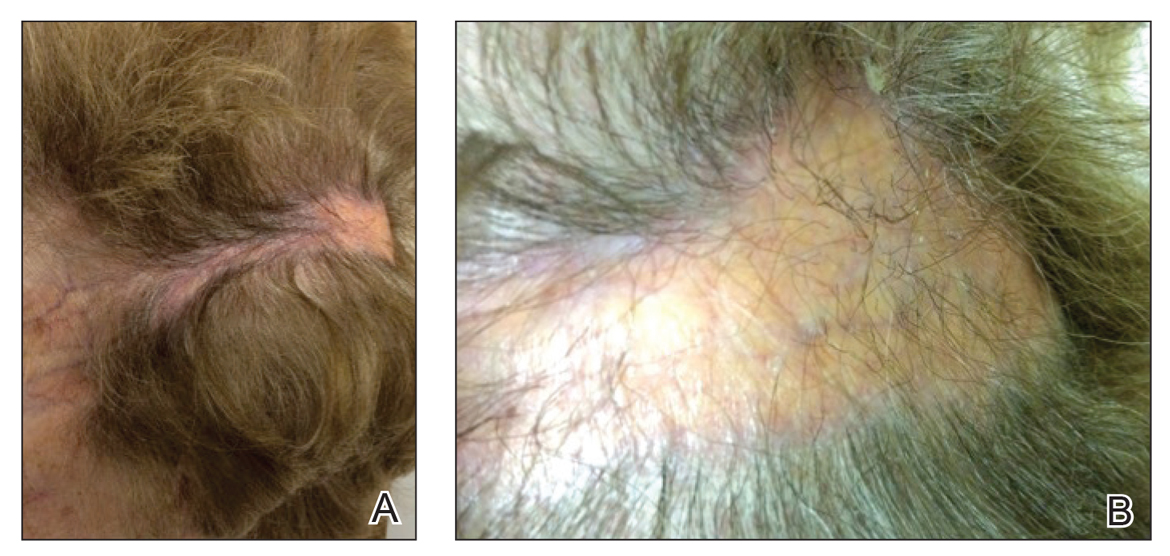

Granulomatous lobular mastitis was diagnosed, and the patient was referred to dermatology. On presentation to dermatology, the left breast showed a 6-cm area of firm induration and overlying peau d’orange change to the epidermis (Figure 2A). Based on pathologic analysis, she was worked up for a possible granulomatous etiology. Negative purified protein derivative (tuberculin)(PPD) and a normal chest radiograph ruled out tuberculosis. Normal chest radiography, serum Ca2+ and angiotensin-converting enzyme (ACE) levels, and ophthalmology examination ruled out sarcoidosis.

The patient reported she continued breastfeeding her 4-year-old son. Additionally, she had been started on trazadone and buspirone for alcohol abuse recovery, then switched to and maintained on fluoxetine 1 year before developing these symptoms.

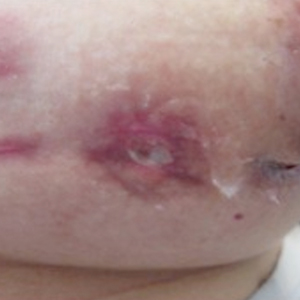

Buspirone, fluoxetine, and prolonged breastfeeding all contribute to hyperprolactinemia, a possible trigger of IGM. The patient was therefore advised to stop breastfeeding and to be switched from fluoxetine to a medication that would not increase the prolactin level. She did not require methotrexate treatment because her condition resolved rapidly after breastfeeding and fluoxetine were discontinued (Figure 2B).

B, Resolution after discontinuation of breastfeeding and fluoxetine.

Patient 2

A 40-year-old woman with no history of breastfeeding who gave birth 4.5 years prior presented to her primary care provider with a painful breast lump and rash on the right breast of 2 months’ duration. Infectious mastitis was suspected; she was given cephalexin and clindamycin without improvement of symptoms.

Imaging

Mammography and ultrasonography were nondiagnostic.

Biopsy

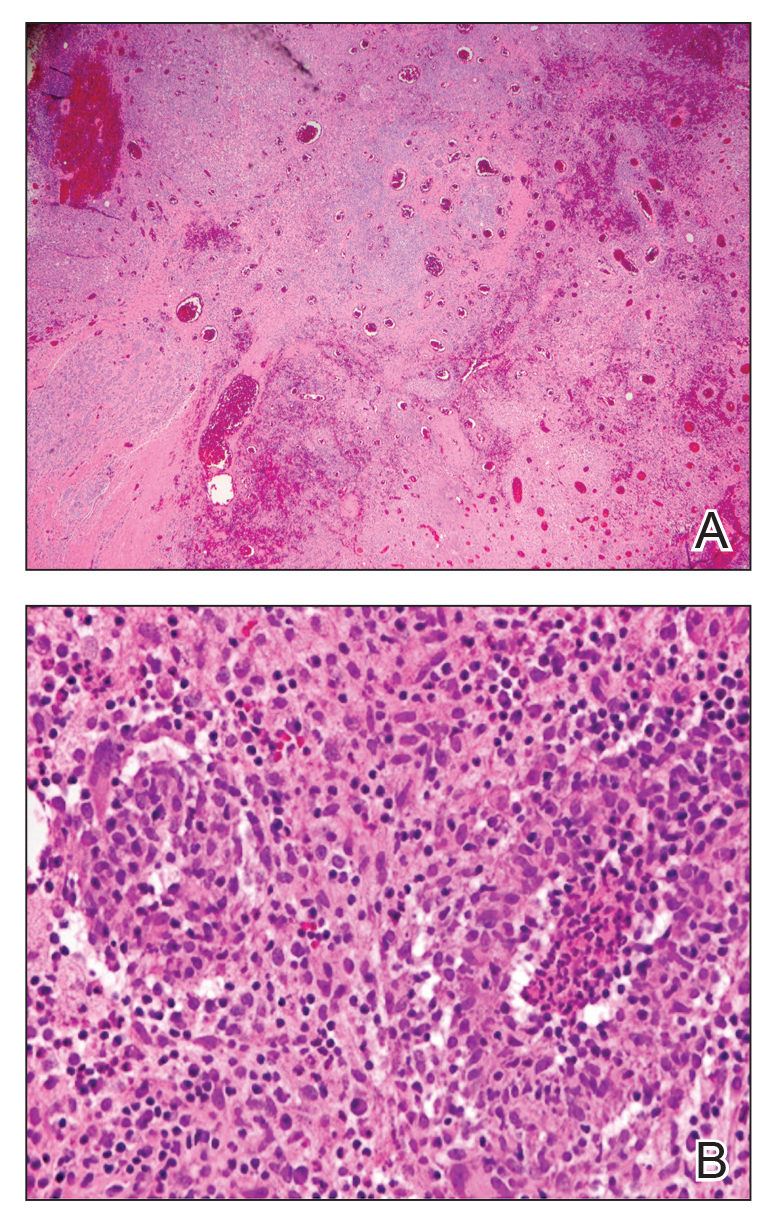

Breast biopsy showed tissue with large expanses of histiocytes, neutrophils, lymphocytes, plasma cells, and multinucleated giant cells (Figure 3A). Many discrete granulomas were seen against this mixed inflammatory background, associated with focal fat necrosis (Figure 3B). Special stains were negative for microorganisms. Histologic findings were consistent with granulomatous mastitis.

Referral to Dermatology

On presentation to dermatology, the patient was worked up for a possible granulomatous etiology, which included a negative PPD, as well as a normal chest radiograph, serum Ca2+ and ACE levels, and ophthalmology examination. Review of symptoms (ROS),medical history, and medication review were unremarkable.

By exclusion, the patient was given a diagnosis of IGM and started on methotrexate (15 mg weekly) with folic acid (1 mg daily). The condition of the right breast improved within 4 weeks of starting methotrexate; however, methotrexate was increased to 30 mg weekly because of occasional flares. The patient remained on methotrexate without further IGM flares for 8 months compared to prior unremitting pain and drainage. She was then tapered from methotrexate over 6 weeks without additional flares.

Patient 3

A 27-year-old woman who gave birth 2 years prior and discontinued breastfeeding 6 weeks after delivery noted bilateral breast rashes for several months. The lesions were growing in size, tender, and draining. Her primary care provider suspected infectious mastitis and prescribed antibiotics, which were ineffective.

Biopsy

Breast core biopsy showed histologic findings similar to patients 1 and 2, including lobulocentric mixed inflammation, neutrophilic microabscesses, and scattered discrete granulomas. Microorganisms were not found using special stains. Breast cancer was ruled out, and granulomatous mastitis was diagnosed.

Referral to Dermatology

Two years earlier, the patient tested positive for latent tuberculosis and was prescribed a 9-month regimen of isoniazid. At the current presentation, she did not have symptoms of active tuberculosis on ROS (ie, no cough, hemoptysis, weight loss, night sweats); a chest radiograph was normal. Additionally, serum Ca2+ and ACE levels as well as an ophthalmology examination were normal, and she was not taking any medications known to increase the prolactin level.

The patient was started on methotrexate (12.5 mg weekly) and folic acid (1 mg daily). She had 1 IGM flare and was given a tapering regimen of prednisone. She received methotrexate for 14 months, tapered during the final 3 months. She has been off methotrexate for 3 years without IGM flares and appears to be in complete remission.

COMMENT

We report 3 cases of IGM, which contribute to the literature on possible presentations, causes, and conservative treatment of this rare connective-tissue disorder.

Differential Diagnosis

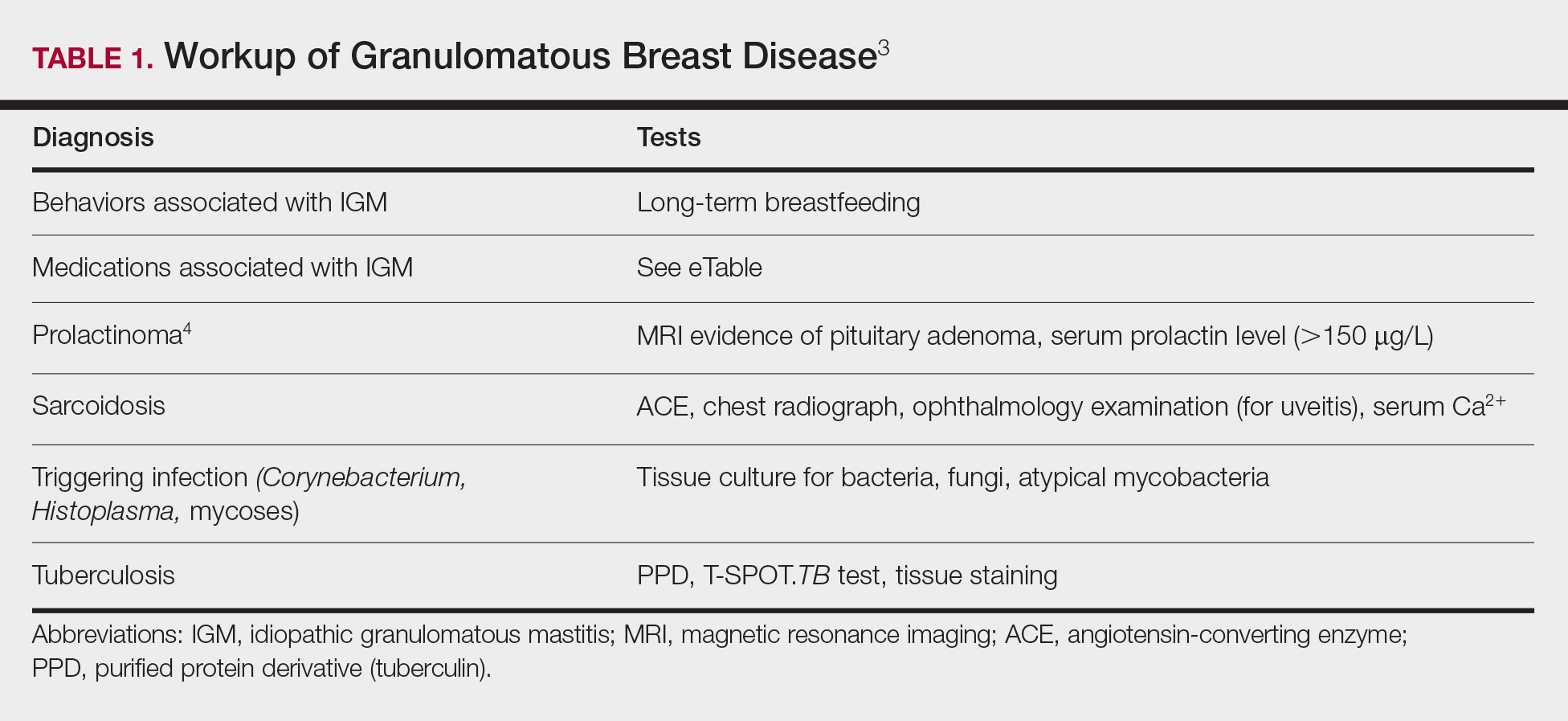

The time between recognition of symptoms and diagnosis and treatment of IGM often is prolonged because IGM can present similarly to other disorders, such as infection, breast cancer, tuberculosis, and sarcoidosis. Idiopathic granulomatous mastitis is a diagnosis of exclusion, made after obtaining evidence of granulomatous inflammation on breast biopsy and ruling out other granulomatous disorders, such as tuberculosis and sarcoidosis (Table 1).3,4

Tuberculosis

A full ROS and a PPD test or T-SPOT.TB test can be helpful in ruling out tuberculosis; because anergy occurs in some patients, tuberculosis should be evaluated in the context of known immunosuppression or human immunodeficiency virus status, or in the case of miliary tuberculosis.

Chest radiography findings classically showing upper lobe infiltrates with cavities in active tuberculosis also should be sought.3 Ziehl-Neelsen staining of 2 sputum specimens, assessed by conventional light microscopy at the time of tissue biopsy has 64% sensitivity and 98% specificity for detecting Mycobacterium tuberculosis; auramine O staining, examined with light-emitting diode fluorescence microscopy, has 73% sensitivity and 93% specificity.5

Sarcoidosis

Because more than 90% of sarcoid patients have lung disease, a chest radiograph is used to screen for hilar lymphadenopathy.3 An elevated serum ACE level also can be helpful in diagnosis, but patients do not always have increased ACE, which can occur in other diseases, such as hyperthyroidism and miliary tuberculosis. Sarcoid granulomas can increase active vitamin D production, which in turn increases serum Ca2+ in 10% of sarcoid patients. Last, an ophthalmology evaluation should be obtained to rule out anterior or posterior uveitis that can occur in sarcoidosis and initially remain asymptomatic.3 Once these other causes of granulomatous inflammation have been ruled out, a diagnosis of IGM can be made.

Prolactinoma

Prolactinoma is an important cause of hyperprolactinemia that can be screened for based on ROS and the serum prolactin level. Prolactinoma can cause oligomenorrhea or amenorrhea and galactorrhea in 90% and 80% of premenopausal women, respectively, as well as erectile dysfunction and decreased libido in men. Infertility, headache, and visual impairment may be experienced in both sexes.4

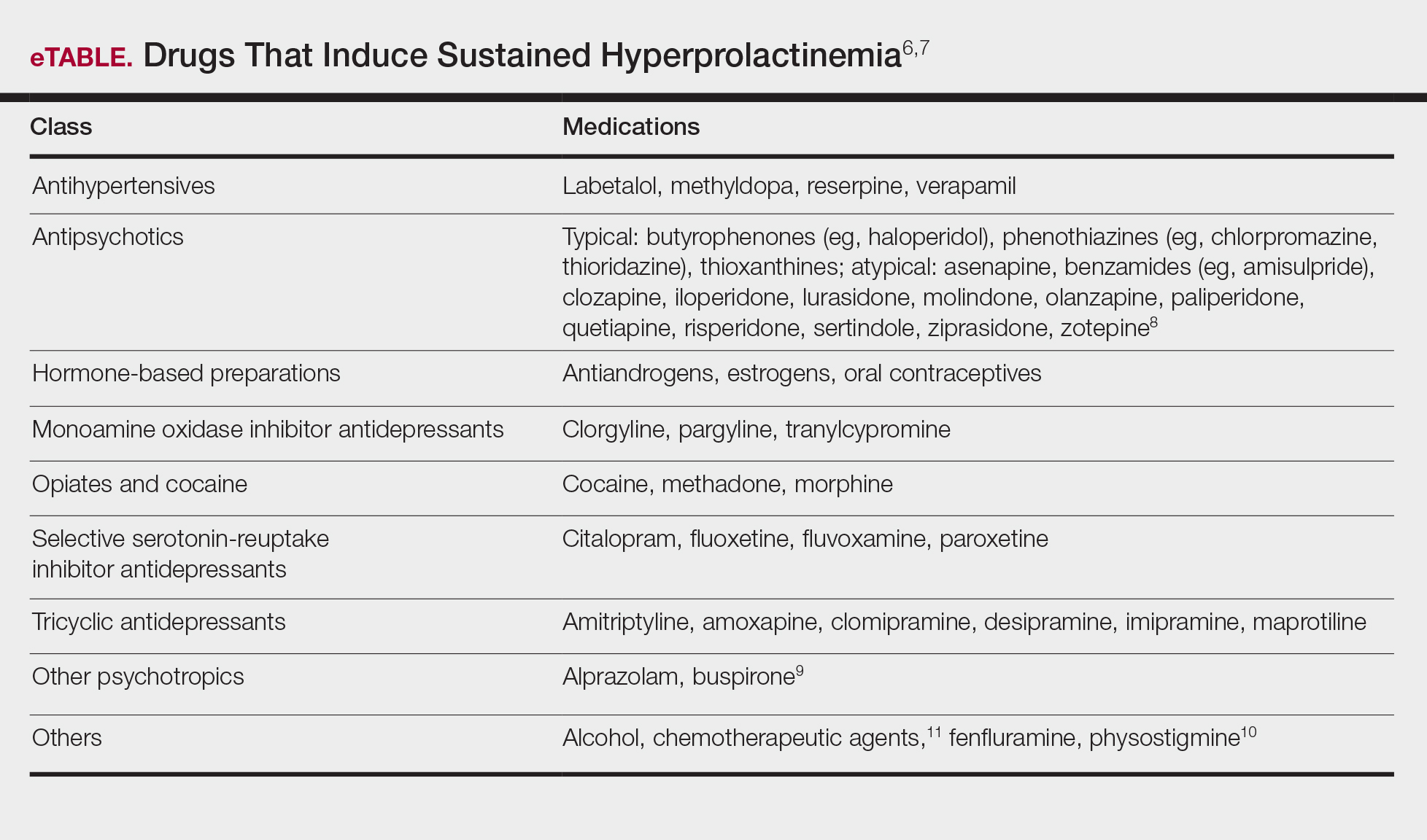

A normal prolactin level is less than 25 μg/L; more than 25 μg/L but less than 100 μg/L usually is due to certain drugs (eTable),6-11 estrogen, or idiopathic reasons; and more than 150 μg/L usually is due to prolactinoma.5 In many cases, removal of hyperprolactinemia-precipitating factors can resolve disease, as in patient 1. If symptoms continue or precipitating factors are absent, IGM symptom-based treatment should be administered.

Course and Management

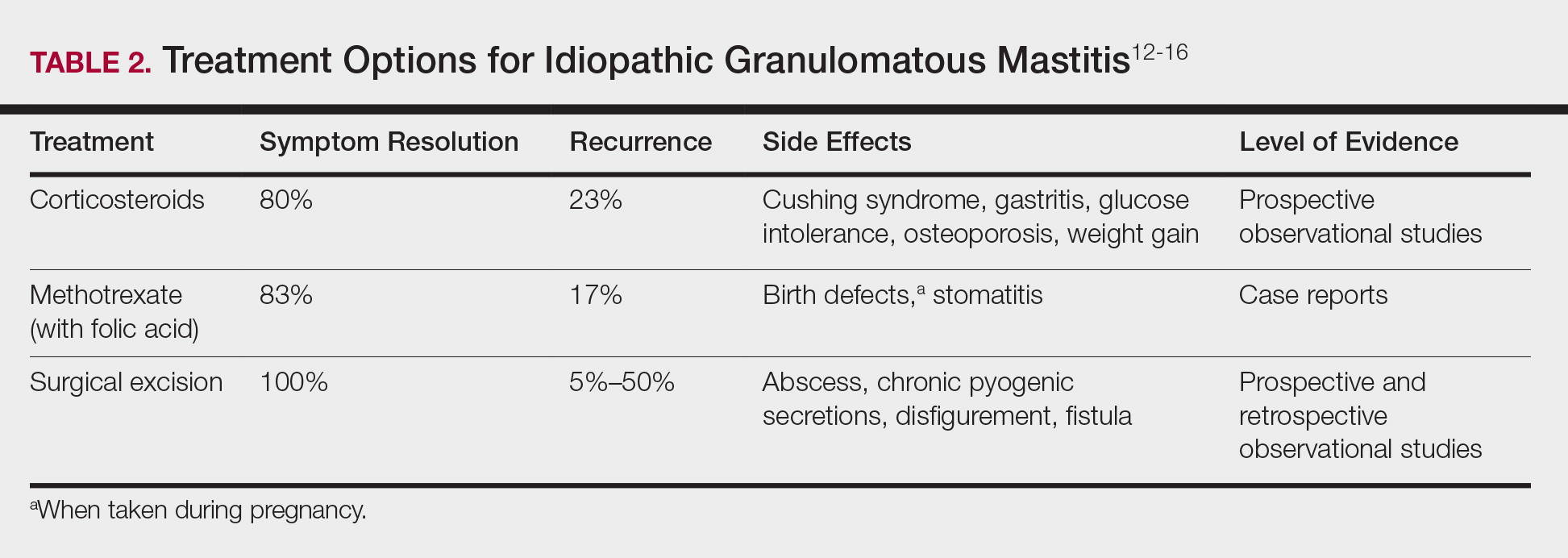

Idiopathic granulomatous mastitis is self-limited and usually resolves within 2 years. Therefore, the goal of treatment is to suppress associated pain and drainage until the active inflammatory phase of IGM self-resolves. An established protocol for treating IGM does not exist, but common treatments include corticosteroids, methotrexate, and limited or wide surgical excision (Table 2).12-16 Before beginning any of these treatments, IGM triggers, such as breastfeeding and drugs that induce hyperprolactinemia, should be removed.

It is important to consider which treatment option is best for limiting disease recurrence and adverse effects (AEs). Keep in mind that the available data are limited, as there are no randomized controlled trials looking at these treatments. Nevertheless, we recommend methotrexate as first line because it resolves granulomatous inflammation symptoms without invasive surgery, while limiting corticosteroid AEs.12

With or without concurrent use of corticosteroids, surgical excision typically is the mainstay of treatment. However, surgical excision of IGM lesions can be complicated by abscess formation, fistula, and chronic pyogenic secretions, in addition to a 5% to 50% rate of recurrence of disease.12-14 Limited excision often is insufficient; therefore, wide local excision, in which negative margins around granulomatous inflammation are obtained, is the surgical modality of choice.14 Wide local excision can be disfiguring to the breast in young women affected by IGM, making it an undesirable treatment option.

Corticosteroids often have been used to treat IGM, but their efficacy is variable, symptoms can recur upon drug removal, and remarkable AEs can result from long-term use.12 Additionally, corticosteroid therapy often is used in combination with excision, making it difficult to determine the extent to which corticosteroids or excision are more beneficial. In a prospective observational study, corticosteroid therapy alone resolved 80% of IGM symptoms after 159 days on average. After complete symptom resolution, 23% of patients had disease recurrence.9 Observed AEs included gastritis, weight gain, osteoporosis, glucose intolerance, and Cushing syndrome.12,15

Methotrexate for IGM has not been reviewed in a randomized controlled trial; case reports have shown 83% symptom resolution, with 17% recurrence and limited long-term AEs.12 Because the active phase of IGM can persist for 2 years, immunosuppressive therapy with limited AEs is necessary. Many AEs can occur when high-dose methotrexate is given for cancer treatment. Low-dose methotrexate has been extensively studied in long-term treatment of rheumatoid arthritis. Adverse effects may include gastrointestinal tract upset and hepatic dysfunction, which are limited when given with folic acid.

Regardless of folic acid cotreatment, stomatitis may occur. Women should use an effective method of birth control because severe birth defects may occur on even low-dose methotrexate.16

Compared to corticosteroid or surgical treatment, we recommend low-dose methotrexate therapy based on its high efficacy with limited AEs. An occasional mild flare of IGM symptoms with methotrexate is not unusual. If it occurs, corticosteroids can be added and tapered for as long as 2 weeks to speed up resolution of flares while reducing long-term AEs of corticosteroids.

Surgical excision can be performed in cases refractory to all systemic therapies.

CONCLUSION

Idiopathic granulomatous mastitis is a rare granulomatous breast disorder that can have a prolonged time to diagnosis, delaying proper treatment. Many cases self-resolve, but more severe cases can persist for a long period before adequate symptomatic treatment is achieved by methotrexate, corticosteroids, or surgical excision. Before using these therapies, it is important to identify and remove contributing factors, such as long-term breastfeeding and drugs that induce hyperprolactinemia. Improving the rate of IGM diagnosis and treatment would greatly benefit these patients. We report 1 case in which removal of possible precipitating IGM factors led to symptom resolution and 2 cases in which methotrexate was an effective IGM treatment that limited the need for invasive procedures and corticosteroid AEs.

1. Patel RA, Strickland P, Sankara IR, et al. Idiopathic granulomatous mastitis: case reports and review of literature. J Gen Intern Med. 2010;25:270-273.

2. Bellavia M, Damiano G, Palumbo VD, et al. Granulomatous mastitis during chronic antidepressant therapy: is it possible a conservative therapeutic approach? J Breast Cancer. 2012;15:371-372.

3. Longo D, Fauci A, Kasper D, et al. Harrison’s Principles of Internal Medicine. 18th ed. New York, NY: McGraw-Hill; 2012.

4. Davis JL, Cattamanchi A, Cuevas LE, et al. Diagnostic accuracy of same-day microscopy versus standard microscopy for pulmonary tuberculosis: a systematic review and meta-analysis. Lancet Infect Dis. 2013;13:147-154.

5. Casanueva FF, Molitch ME, Schlechte JA, et al. Guidelines of the Pituitary Society for the diagnosis and management of prolactinomas. Clin Endocrinol (Oxf). 2006;65:265-273.

6. Akbulut S, Arikanoglu Z, Senol A, et al. Is methotrexate an acceptable treatment in the management of idiopathic granulomatous mastitis? Arch Gynecol Obstet. 2011;284:1189-1195.

7. Bani-Hani KE, Yaghan RJ, Matalka II, et al. Idiopathic granulomatous mastitis: time to avoid unnecessary mastectomies. Breast J. 2004;10:318-322.

8. Asoglu O, Ozmen V, Karanlik H, et al. Feasibility of surgical management in patients with granulomatous mastitis. Breast J. 2005;11:108-114.

9. Pandey TS, Mackinnon JC, Bressler L, et al. Idiopathic granulomatous mastitis—a prospective study of 49 women and treatment outcomes with steroid therapy. Breast J. 2014;20:258-266.

10. Shea B, Swinden MV, Tanjong Ghogomu E, et al. Folic acid and folinic acid for reducing side effects in patients receiving methotrexate for rheumatoid arthritis. Cochrane Database Syst Rev. 2013;5:CD000951.

11. Molitch ME. Drugs and prolactin. Pituitary. 2008;11:209-218.

12.

13.

14.

15.

16.

Idiopathic granulomatous mastitis (IGM) is rare during pregnancy; it typically is seen in women of childbearing potential from 6 months to 6 years postpartum.1 Because of a temporal association with breastfeeding, it is believed that hyperprolactinemia2 or an immune response to local lobular secretions might play a role in pathogenesis. Early misdiagnosis as bacterial mastitis is common, prompting multiple antibiotic regimens. When antibiotics fail, patients are worked up for inflammatory breast cancer, given the nonhealing breast nodules. Mammography, ultrasonography, and fine-needle aspiration often are unable to rule out carcinoma, warranting excisional biopsies of nodules. The patient is then referred to rheumatology for potential sarcoidosis or to dermatology for IGM. In either case, the workup should be similar, but additional history focused on behavior and medications is essential in suspected IGM, given the association with hyperprolactinemia.

Because IGM is rare, there are no randomized, placebo-controlled trials of treatment efficacy. In many cases, patients undergo complete mastectomy, which is curative but may be psychologically and physically impactful in young women. In some cases, high-dose corticosteroids have been successful; however, because the IGM process can last longer than 2 years, patients treated in this manner are exposed to steroid morbidities.1

We report 3 cases of IGM that add to the literature on possible contributing factors, clinical presentations, and treatments for this disease. We also demonstrate that appropriate trigger identification and steroid-sparing agents, specifically methotrexate, can be breast-saving as they can alleviate this debilitating condition, obviating the need for radical surgical intervention.

CASE REPORTS

Patient 1

A 40-year-old woman with a 4-year history of breastfeeding noted a grape-sized nodule on the left breast that grew to the size of a grapefruit after 2 weeks. Ulceration and drainage periodically occurred, forming pink plaques along the lateral aspects of the breast after healing. Her primary care provider suspected infectious mastitis; she was given an oral antibiotic (cephalexin) and intravenous antibiotics without improvement.

Imaging

Subsequent magnetic resonance imaging revealed a large, irregular, enhancing mass within the outer left breast (6.5 cm at greatest dimension) with additional surrounding amorphous enhancement highly suspicious for malignancy. There also were multiple prominent left axillary lymph nodes, with the largest demonstrating a cortical thickness of 8 mm.

Biopsy

Core breast biopsy showed benign tissue with fat necrosis. Fine-needle aspiration revealed few benign ductal cells and rare histiocytes; because these findings were nondiagnostic and cancer was still a consideration, the patient underwent excisional biopsy.

Histologic sections of breast tissue showed extensive lobulocentric inflammation comprising histiocytes and lymphocytes, with neutrophils admixed and forming microabscesses (Figure 1A). Multinucleated giant cells and single-cell necrosis were seen, but true caseous necrosis was absent (Figure 1B). Duct spaces often contained inflammatory cells or secretions. Special stains for fungal and acid-fast bacterial microorganisms were negative.

Referral to Dermatology

Granulomatous lobular mastitis was diagnosed, and the patient was referred to dermatology. On presentation to dermatology, the left breast showed a 6-cm area of firm induration and overlying peau d’orange change to the epidermis (Figure 2A). Based on pathologic analysis, she was worked up for a possible granulomatous etiology. Negative purified protein derivative (tuberculin)(PPD) and a normal chest radiograph ruled out tuberculosis. Normal chest radiography, serum Ca2+ and angiotensin-converting enzyme (ACE) levels, and ophthalmology examination ruled out sarcoidosis.

The patient reported she continued breastfeeding her 4-year-old son. Additionally, she had been started on trazadone and buspirone for alcohol abuse recovery, then switched to and maintained on fluoxetine 1 year before developing these symptoms.

Buspirone, fluoxetine, and prolonged breastfeeding all contribute to hyperprolactinemia, a possible trigger of IGM. The patient was therefore advised to stop breastfeeding and to be switched from fluoxetine to a medication that would not increase the prolactin level. She did not require methotrexate treatment because her condition resolved rapidly after breastfeeding and fluoxetine were discontinued (Figure 2B).

B, Resolution after discontinuation of breastfeeding and fluoxetine.

Patient 2

A 40-year-old woman with no history of breastfeeding who gave birth 4.5 years prior presented to her primary care provider with a painful breast lump and rash on the right breast of 2 months’ duration. Infectious mastitis was suspected; she was given cephalexin and clindamycin without improvement of symptoms.

Imaging

Mammography and ultrasonography were nondiagnostic.

Biopsy

Breast biopsy showed tissue with large expanses of histiocytes, neutrophils, lymphocytes, plasma cells, and multinucleated giant cells (Figure 3A). Many discrete granulomas were seen against this mixed inflammatory background, associated with focal fat necrosis (Figure 3B). Special stains were negative for microorganisms. Histologic findings were consistent with granulomatous mastitis.

Referral to Dermatology

On presentation to dermatology, the patient was worked up for a possible granulomatous etiology, which included a negative PPD, as well as a normal chest radiograph, serum Ca2+ and ACE levels, and ophthalmology examination. Review of symptoms (ROS),medical history, and medication review were unremarkable.

By exclusion, the patient was given a diagnosis of IGM and started on methotrexate (15 mg weekly) with folic acid (1 mg daily). The condition of the right breast improved within 4 weeks of starting methotrexate; however, methotrexate was increased to 30 mg weekly because of occasional flares. The patient remained on methotrexate without further IGM flares for 8 months compared to prior unremitting pain and drainage. She was then tapered from methotrexate over 6 weeks without additional flares.

Patient 3

A 27-year-old woman who gave birth 2 years prior and discontinued breastfeeding 6 weeks after delivery noted bilateral breast rashes for several months. The lesions were growing in size, tender, and draining. Her primary care provider suspected infectious mastitis and prescribed antibiotics, which were ineffective.

Biopsy

Breast core biopsy showed histologic findings similar to patients 1 and 2, including lobulocentric mixed inflammation, neutrophilic microabscesses, and scattered discrete granulomas. Microorganisms were not found using special stains. Breast cancer was ruled out, and granulomatous mastitis was diagnosed.

Referral to Dermatology

Two years earlier, the patient tested positive for latent tuberculosis and was prescribed a 9-month regimen of isoniazid. At the current presentation, she did not have symptoms of active tuberculosis on ROS (ie, no cough, hemoptysis, weight loss, night sweats); a chest radiograph was normal. Additionally, serum Ca2+ and ACE levels as well as an ophthalmology examination were normal, and she was not taking any medications known to increase the prolactin level.

The patient was started on methotrexate (12.5 mg weekly) and folic acid (1 mg daily). She had 1 IGM flare and was given a tapering regimen of prednisone. She received methotrexate for 14 months, tapered during the final 3 months. She has been off methotrexate for 3 years without IGM flares and appears to be in complete remission.

COMMENT

We report 3 cases of IGM, which contribute to the literature on possible presentations, causes, and conservative treatment of this rare connective-tissue disorder.

Differential Diagnosis

The time between recognition of symptoms and diagnosis and treatment of IGM often is prolonged because IGM can present similarly to other disorders, such as infection, breast cancer, tuberculosis, and sarcoidosis. Idiopathic granulomatous mastitis is a diagnosis of exclusion, made after obtaining evidence of granulomatous inflammation on breast biopsy and ruling out other granulomatous disorders, such as tuberculosis and sarcoidosis (Table 1).3,4

Tuberculosis

A full ROS and a PPD test or T-SPOT.TB test can be helpful in ruling out tuberculosis; because anergy occurs in some patients, tuberculosis should be evaluated in the context of known immunosuppression or human immunodeficiency virus status, or in the case of miliary tuberculosis.

Chest radiography findings classically showing upper lobe infiltrates with cavities in active tuberculosis also should be sought.3 Ziehl-Neelsen staining of 2 sputum specimens, assessed by conventional light microscopy at the time of tissue biopsy has 64% sensitivity and 98% specificity for detecting Mycobacterium tuberculosis; auramine O staining, examined with light-emitting diode fluorescence microscopy, has 73% sensitivity and 93% specificity.5

Sarcoidosis

Because more than 90% of sarcoid patients have lung disease, a chest radiograph is used to screen for hilar lymphadenopathy.3 An elevated serum ACE level also can be helpful in diagnosis, but patients do not always have increased ACE, which can occur in other diseases, such as hyperthyroidism and miliary tuberculosis. Sarcoid granulomas can increase active vitamin D production, which in turn increases serum Ca2+ in 10% of sarcoid patients. Last, an ophthalmology evaluation should be obtained to rule out anterior or posterior uveitis that can occur in sarcoidosis and initially remain asymptomatic.3 Once these other causes of granulomatous inflammation have been ruled out, a diagnosis of IGM can be made.

Prolactinoma

Prolactinoma is an important cause of hyperprolactinemia that can be screened for based on ROS and the serum prolactin level. Prolactinoma can cause oligomenorrhea or amenorrhea and galactorrhea in 90% and 80% of premenopausal women, respectively, as well as erectile dysfunction and decreased libido in men. Infertility, headache, and visual impairment may be experienced in both sexes.4

A normal prolactin level is less than 25 μg/L; more than 25 μg/L but less than 100 μg/L usually is due to certain drugs (eTable),6-11 estrogen, or idiopathic reasons; and more than 150 μg/L usually is due to prolactinoma.5 In many cases, removal of hyperprolactinemia-precipitating factors can resolve disease, as in patient 1. If symptoms continue or precipitating factors are absent, IGM symptom-based treatment should be administered.

Course and Management

Idiopathic granulomatous mastitis is self-limited and usually resolves within 2 years. Therefore, the goal of treatment is to suppress associated pain and drainage until the active inflammatory phase of IGM self-resolves. An established protocol for treating IGM does not exist, but common treatments include corticosteroids, methotrexate, and limited or wide surgical excision (Table 2).12-16 Before beginning any of these treatments, IGM triggers, such as breastfeeding and drugs that induce hyperprolactinemia, should be removed.

It is important to consider which treatment option is best for limiting disease recurrence and adverse effects (AEs). Keep in mind that the available data are limited, as there are no randomized controlled trials looking at these treatments. Nevertheless, we recommend methotrexate as first line because it resolves granulomatous inflammation symptoms without invasive surgery, while limiting corticosteroid AEs.12

With or without concurrent use of corticosteroids, surgical excision typically is the mainstay of treatment. However, surgical excision of IGM lesions can be complicated by abscess formation, fistula, and chronic pyogenic secretions, in addition to a 5% to 50% rate of recurrence of disease.12-14 Limited excision often is insufficient; therefore, wide local excision, in which negative margins around granulomatous inflammation are obtained, is the surgical modality of choice.14 Wide local excision can be disfiguring to the breast in young women affected by IGM, making it an undesirable treatment option.

Corticosteroids often have been used to treat IGM, but their efficacy is variable, symptoms can recur upon drug removal, and remarkable AEs can result from long-term use.12 Additionally, corticosteroid therapy often is used in combination with excision, making it difficult to determine the extent to which corticosteroids or excision are more beneficial. In a prospective observational study, corticosteroid therapy alone resolved 80% of IGM symptoms after 159 days on average. After complete symptom resolution, 23% of patients had disease recurrence.9 Observed AEs included gastritis, weight gain, osteoporosis, glucose intolerance, and Cushing syndrome.12,15

Methotrexate for IGM has not been reviewed in a randomized controlled trial; case reports have shown 83% symptom resolution, with 17% recurrence and limited long-term AEs.12 Because the active phase of IGM can persist for 2 years, immunosuppressive therapy with limited AEs is necessary. Many AEs can occur when high-dose methotrexate is given for cancer treatment. Low-dose methotrexate has been extensively studied in long-term treatment of rheumatoid arthritis. Adverse effects may include gastrointestinal tract upset and hepatic dysfunction, which are limited when given with folic acid.

Regardless of folic acid cotreatment, stomatitis may occur. Women should use an effective method of birth control because severe birth defects may occur on even low-dose methotrexate.16

Compared to corticosteroid or surgical treatment, we recommend low-dose methotrexate therapy based on its high efficacy with limited AEs. An occasional mild flare of IGM symptoms with methotrexate is not unusual. If it occurs, corticosteroids can be added and tapered for as long as 2 weeks to speed up resolution of flares while reducing long-term AEs of corticosteroids.

Surgical excision can be performed in cases refractory to all systemic therapies.

CONCLUSION

Idiopathic granulomatous mastitis is a rare granulomatous breast disorder that can have a prolonged time to diagnosis, delaying proper treatment. Many cases self-resolve, but more severe cases can persist for a long period before adequate symptomatic treatment is achieved by methotrexate, corticosteroids, or surgical excision. Before using these therapies, it is important to identify and remove contributing factors, such as long-term breastfeeding and drugs that induce hyperprolactinemia. Improving the rate of IGM diagnosis and treatment would greatly benefit these patients. We report 1 case in which removal of possible precipitating IGM factors led to symptom resolution and 2 cases in which methotrexate was an effective IGM treatment that limited the need for invasive procedures and corticosteroid AEs.

Idiopathic granulomatous mastitis (IGM) is rare during pregnancy; it typically is seen in women of childbearing potential from 6 months to 6 years postpartum.1 Because of a temporal association with breastfeeding, it is believed that hyperprolactinemia2 or an immune response to local lobular secretions might play a role in pathogenesis. Early misdiagnosis as bacterial mastitis is common, prompting multiple antibiotic regimens. When antibiotics fail, patients are worked up for inflammatory breast cancer, given the nonhealing breast nodules. Mammography, ultrasonography, and fine-needle aspiration often are unable to rule out carcinoma, warranting excisional biopsies of nodules. The patient is then referred to rheumatology for potential sarcoidosis or to dermatology for IGM. In either case, the workup should be similar, but additional history focused on behavior and medications is essential in suspected IGM, given the association with hyperprolactinemia.

Because IGM is rare, there are no randomized, placebo-controlled trials of treatment efficacy. In many cases, patients undergo complete mastectomy, which is curative but may be psychologically and physically impactful in young women. In some cases, high-dose corticosteroids have been successful; however, because the IGM process can last longer than 2 years, patients treated in this manner are exposed to steroid morbidities.1

We report 3 cases of IGM that add to the literature on possible contributing factors, clinical presentations, and treatments for this disease. We also demonstrate that appropriate trigger identification and steroid-sparing agents, specifically methotrexate, can be breast-saving as they can alleviate this debilitating condition, obviating the need for radical surgical intervention.

CASE REPORTS

Patient 1

A 40-year-old woman with a 4-year history of breastfeeding noted a grape-sized nodule on the left breast that grew to the size of a grapefruit after 2 weeks. Ulceration and drainage periodically occurred, forming pink plaques along the lateral aspects of the breast after healing. Her primary care provider suspected infectious mastitis; she was given an oral antibiotic (cephalexin) and intravenous antibiotics without improvement.

Imaging

Subsequent magnetic resonance imaging revealed a large, irregular, enhancing mass within the outer left breast (6.5 cm at greatest dimension) with additional surrounding amorphous enhancement highly suspicious for malignancy. There also were multiple prominent left axillary lymph nodes, with the largest demonstrating a cortical thickness of 8 mm.

Biopsy

Core breast biopsy showed benign tissue with fat necrosis. Fine-needle aspiration revealed few benign ductal cells and rare histiocytes; because these findings were nondiagnostic and cancer was still a consideration, the patient underwent excisional biopsy.

Histologic sections of breast tissue showed extensive lobulocentric inflammation comprising histiocytes and lymphocytes, with neutrophils admixed and forming microabscesses (Figure 1A). Multinucleated giant cells and single-cell necrosis were seen, but true caseous necrosis was absent (Figure 1B). Duct spaces often contained inflammatory cells or secretions. Special stains for fungal and acid-fast bacterial microorganisms were negative.

Referral to Dermatology

Granulomatous lobular mastitis was diagnosed, and the patient was referred to dermatology. On presentation to dermatology, the left breast showed a 6-cm area of firm induration and overlying peau d’orange change to the epidermis (Figure 2A). Based on pathologic analysis, she was worked up for a possible granulomatous etiology. Negative purified protein derivative (tuberculin)(PPD) and a normal chest radiograph ruled out tuberculosis. Normal chest radiography, serum Ca2+ and angiotensin-converting enzyme (ACE) levels, and ophthalmology examination ruled out sarcoidosis.

The patient reported she continued breastfeeding her 4-year-old son. Additionally, she had been started on trazadone and buspirone for alcohol abuse recovery, then switched to and maintained on fluoxetine 1 year before developing these symptoms.

Buspirone, fluoxetine, and prolonged breastfeeding all contribute to hyperprolactinemia, a possible trigger of IGM. The patient was therefore advised to stop breastfeeding and to be switched from fluoxetine to a medication that would not increase the prolactin level. She did not require methotrexate treatment because her condition resolved rapidly after breastfeeding and fluoxetine were discontinued (Figure 2B).

B, Resolution after discontinuation of breastfeeding and fluoxetine.

Patient 2

A 40-year-old woman with no history of breastfeeding who gave birth 4.5 years prior presented to her primary care provider with a painful breast lump and rash on the right breast of 2 months’ duration. Infectious mastitis was suspected; she was given cephalexin and clindamycin without improvement of symptoms.

Imaging

Mammography and ultrasonography were nondiagnostic.

Biopsy

Breast biopsy showed tissue with large expanses of histiocytes, neutrophils, lymphocytes, plasma cells, and multinucleated giant cells (Figure 3A). Many discrete granulomas were seen against this mixed inflammatory background, associated with focal fat necrosis (Figure 3B). Special stains were negative for microorganisms. Histologic findings were consistent with granulomatous mastitis.

Referral to Dermatology

On presentation to dermatology, the patient was worked up for a possible granulomatous etiology, which included a negative PPD, as well as a normal chest radiograph, serum Ca2+ and ACE levels, and ophthalmology examination. Review of symptoms (ROS),medical history, and medication review were unremarkable.

By exclusion, the patient was given a diagnosis of IGM and started on methotrexate (15 mg weekly) with folic acid (1 mg daily). The condition of the right breast improved within 4 weeks of starting methotrexate; however, methotrexate was increased to 30 mg weekly because of occasional flares. The patient remained on methotrexate without further IGM flares for 8 months compared to prior unremitting pain and drainage. She was then tapered from methotrexate over 6 weeks without additional flares.

Patient 3

A 27-year-old woman who gave birth 2 years prior and discontinued breastfeeding 6 weeks after delivery noted bilateral breast rashes for several months. The lesions were growing in size, tender, and draining. Her primary care provider suspected infectious mastitis and prescribed antibiotics, which were ineffective.

Biopsy

Breast core biopsy showed histologic findings similar to patients 1 and 2, including lobulocentric mixed inflammation, neutrophilic microabscesses, and scattered discrete granulomas. Microorganisms were not found using special stains. Breast cancer was ruled out, and granulomatous mastitis was diagnosed.

Referral to Dermatology

Two years earlier, the patient tested positive for latent tuberculosis and was prescribed a 9-month regimen of isoniazid. At the current presentation, she did not have symptoms of active tuberculosis on ROS (ie, no cough, hemoptysis, weight loss, night sweats); a chest radiograph was normal. Additionally, serum Ca2+ and ACE levels as well as an ophthalmology examination were normal, and she was not taking any medications known to increase the prolactin level.

The patient was started on methotrexate (12.5 mg weekly) and folic acid (1 mg daily). She had 1 IGM flare and was given a tapering regimen of prednisone. She received methotrexate for 14 months, tapered during the final 3 months. She has been off methotrexate for 3 years without IGM flares and appears to be in complete remission.

COMMENT

We report 3 cases of IGM, which contribute to the literature on possible presentations, causes, and conservative treatment of this rare connective-tissue disorder.

Differential Diagnosis

The time between recognition of symptoms and diagnosis and treatment of IGM often is prolonged because IGM can present similarly to other disorders, such as infection, breast cancer, tuberculosis, and sarcoidosis. Idiopathic granulomatous mastitis is a diagnosis of exclusion, made after obtaining evidence of granulomatous inflammation on breast biopsy and ruling out other granulomatous disorders, such as tuberculosis and sarcoidosis (Table 1).3,4

Tuberculosis

A full ROS and a PPD test or T-SPOT.TB test can be helpful in ruling out tuberculosis; because anergy occurs in some patients, tuberculosis should be evaluated in the context of known immunosuppression or human immunodeficiency virus status, or in the case of miliary tuberculosis.

Chest radiography findings classically showing upper lobe infiltrates with cavities in active tuberculosis also should be sought.3 Ziehl-Neelsen staining of 2 sputum specimens, assessed by conventional light microscopy at the time of tissue biopsy has 64% sensitivity and 98% specificity for detecting Mycobacterium tuberculosis; auramine O staining, examined with light-emitting diode fluorescence microscopy, has 73% sensitivity and 93% specificity.5

Sarcoidosis

Because more than 90% of sarcoid patients have lung disease, a chest radiograph is used to screen for hilar lymphadenopathy.3 An elevated serum ACE level also can be helpful in diagnosis, but patients do not always have increased ACE, which can occur in other diseases, such as hyperthyroidism and miliary tuberculosis. Sarcoid granulomas can increase active vitamin D production, which in turn increases serum Ca2+ in 10% of sarcoid patients. Last, an ophthalmology evaluation should be obtained to rule out anterior or posterior uveitis that can occur in sarcoidosis and initially remain asymptomatic.3 Once these other causes of granulomatous inflammation have been ruled out, a diagnosis of IGM can be made.

Prolactinoma

Prolactinoma is an important cause of hyperprolactinemia that can be screened for based on ROS and the serum prolactin level. Prolactinoma can cause oligomenorrhea or amenorrhea and galactorrhea in 90% and 80% of premenopausal women, respectively, as well as erectile dysfunction and decreased libido in men. Infertility, headache, and visual impairment may be experienced in both sexes.4

A normal prolactin level is less than 25 μg/L; more than 25 μg/L but less than 100 μg/L usually is due to certain drugs (eTable),6-11 estrogen, or idiopathic reasons; and more than 150 μg/L usually is due to prolactinoma.5 In many cases, removal of hyperprolactinemia-precipitating factors can resolve disease, as in patient 1. If symptoms continue or precipitating factors are absent, IGM symptom-based treatment should be administered.

Course and Management

Idiopathic granulomatous mastitis is self-limited and usually resolves within 2 years. Therefore, the goal of treatment is to suppress associated pain and drainage until the active inflammatory phase of IGM self-resolves. An established protocol for treating IGM does not exist, but common treatments include corticosteroids, methotrexate, and limited or wide surgical excision (Table 2).12-16 Before beginning any of these treatments, IGM triggers, such as breastfeeding and drugs that induce hyperprolactinemia, should be removed.

It is important to consider which treatment option is best for limiting disease recurrence and adverse effects (AEs). Keep in mind that the available data are limited, as there are no randomized controlled trials looking at these treatments. Nevertheless, we recommend methotrexate as first line because it resolves granulomatous inflammation symptoms without invasive surgery, while limiting corticosteroid AEs.12

With or without concurrent use of corticosteroids, surgical excision typically is the mainstay of treatment. However, surgical excision of IGM lesions can be complicated by abscess formation, fistula, and chronic pyogenic secretions, in addition to a 5% to 50% rate of recurrence of disease.12-14 Limited excision often is insufficient; therefore, wide local excision, in which negative margins around granulomatous inflammation are obtained, is the surgical modality of choice.14 Wide local excision can be disfiguring to the breast in young women affected by IGM, making it an undesirable treatment option.

Corticosteroids often have been used to treat IGM, but their efficacy is variable, symptoms can recur upon drug removal, and remarkable AEs can result from long-term use.12 Additionally, corticosteroid therapy often is used in combination with excision, making it difficult to determine the extent to which corticosteroids or excision are more beneficial. In a prospective observational study, corticosteroid therapy alone resolved 80% of IGM symptoms after 159 days on average. After complete symptom resolution, 23% of patients had disease recurrence.9 Observed AEs included gastritis, weight gain, osteoporosis, glucose intolerance, and Cushing syndrome.12,15

Methotrexate for IGM has not been reviewed in a randomized controlled trial; case reports have shown 83% symptom resolution, with 17% recurrence and limited long-term AEs.12 Because the active phase of IGM can persist for 2 years, immunosuppressive therapy with limited AEs is necessary. Many AEs can occur when high-dose methotrexate is given for cancer treatment. Low-dose methotrexate has been extensively studied in long-term treatment of rheumatoid arthritis. Adverse effects may include gastrointestinal tract upset and hepatic dysfunction, which are limited when given with folic acid.

Regardless of folic acid cotreatment, stomatitis may occur. Women should use an effective method of birth control because severe birth defects may occur on even low-dose methotrexate.16

Compared to corticosteroid or surgical treatment, we recommend low-dose methotrexate therapy based on its high efficacy with limited AEs. An occasional mild flare of IGM symptoms with methotrexate is not unusual. If it occurs, corticosteroids can be added and tapered for as long as 2 weeks to speed up resolution of flares while reducing long-term AEs of corticosteroids.

Surgical excision can be performed in cases refractory to all systemic therapies.

CONCLUSION

Idiopathic granulomatous mastitis is a rare granulomatous breast disorder that can have a prolonged time to diagnosis, delaying proper treatment. Many cases self-resolve, but more severe cases can persist for a long period before adequate symptomatic treatment is achieved by methotrexate, corticosteroids, or surgical excision. Before using these therapies, it is important to identify and remove contributing factors, such as long-term breastfeeding and drugs that induce hyperprolactinemia. Improving the rate of IGM diagnosis and treatment would greatly benefit these patients. We report 1 case in which removal of possible precipitating IGM factors led to symptom resolution and 2 cases in which methotrexate was an effective IGM treatment that limited the need for invasive procedures and corticosteroid AEs.

1. Patel RA, Strickland P, Sankara IR, et al. Idiopathic granulomatous mastitis: case reports and review of literature. J Gen Intern Med. 2010;25:270-273.

2. Bellavia M, Damiano G, Palumbo VD, et al. Granulomatous mastitis during chronic antidepressant therapy: is it possible a conservative therapeutic approach? J Breast Cancer. 2012;15:371-372.

3. Longo D, Fauci A, Kasper D, et al. Harrison’s Principles of Internal Medicine. 18th ed. New York, NY: McGraw-Hill; 2012.

4. Davis JL, Cattamanchi A, Cuevas LE, et al. Diagnostic accuracy of same-day microscopy versus standard microscopy for pulmonary tuberculosis: a systematic review and meta-analysis. Lancet Infect Dis. 2013;13:147-154.

5. Casanueva FF, Molitch ME, Schlechte JA, et al. Guidelines of the Pituitary Society for the diagnosis and management of prolactinomas. Clin Endocrinol (Oxf). 2006;65:265-273.

6. Akbulut S, Arikanoglu Z, Senol A, et al. Is methotrexate an acceptable treatment in the management of idiopathic granulomatous mastitis? Arch Gynecol Obstet. 2011;284:1189-1195.

7. Bani-Hani KE, Yaghan RJ, Matalka II, et al. Idiopathic granulomatous mastitis: time to avoid unnecessary mastectomies. Breast J. 2004;10:318-322.

8. Asoglu O, Ozmen V, Karanlik H, et al. Feasibility of surgical management in patients with granulomatous mastitis. Breast J. 2005;11:108-114.

9. Pandey TS, Mackinnon JC, Bressler L, et al. Idiopathic granulomatous mastitis—a prospective study of 49 women and treatment outcomes with steroid therapy. Breast J. 2014;20:258-266.

10. Shea B, Swinden MV, Tanjong Ghogomu E, et al. Folic acid and folinic acid for reducing side effects in patients receiving methotrexate for rheumatoid arthritis. Cochrane Database Syst Rev. 2013;5:CD000951.

11. Molitch ME. Drugs and prolactin. Pituitary. 2008;11:209-218.

12.

13.

14.

15.

16.

1. Patel RA, Strickland P, Sankara IR, et al. Idiopathic granulomatous mastitis: case reports and review of literature. J Gen Intern Med. 2010;25:270-273.

2. Bellavia M, Damiano G, Palumbo VD, et al. Granulomatous mastitis during chronic antidepressant therapy: is it possible a conservative therapeutic approach? J Breast Cancer. 2012;15:371-372.

3. Longo D, Fauci A, Kasper D, et al. Harrison’s Principles of Internal Medicine. 18th ed. New York, NY: McGraw-Hill; 2012.

4. Davis JL, Cattamanchi A, Cuevas LE, et al. Diagnostic accuracy of same-day microscopy versus standard microscopy for pulmonary tuberculosis: a systematic review and meta-analysis. Lancet Infect Dis. 2013;13:147-154.

5. Casanueva FF, Molitch ME, Schlechte JA, et al. Guidelines of the Pituitary Society for the diagnosis and management of prolactinomas. Clin Endocrinol (Oxf). 2006;65:265-273.

6. Akbulut S, Arikanoglu Z, Senol A, et al. Is methotrexate an acceptable treatment in the management of idiopathic granulomatous mastitis? Arch Gynecol Obstet. 2011;284:1189-1195.

7. Bani-Hani KE, Yaghan RJ, Matalka II, et al. Idiopathic granulomatous mastitis: time to avoid unnecessary mastectomies. Breast J. 2004;10:318-322.

8. Asoglu O, Ozmen V, Karanlik H, et al. Feasibility of surgical management in patients with granulomatous mastitis. Breast J. 2005;11:108-114.

9. Pandey TS, Mackinnon JC, Bressler L, et al. Idiopathic granulomatous mastitis—a prospective study of 49 women and treatment outcomes with steroid therapy. Breast J. 2014;20:258-266.

10. Shea B, Swinden MV, Tanjong Ghogomu E, et al. Folic acid and folinic acid for reducing side effects in patients receiving methotrexate for rheumatoid arthritis. Cochrane Database Syst Rev. 2013;5:CD000951.

11. Molitch ME. Drugs and prolactin. Pituitary. 2008;11:209-218.

12.

13.

14.

15.

16.

Practice Points

- Idiopathic granulomatous mastitis (IGM) is a painful and scarring rare granulomatous breast disorder that can have a prolonged time to diagnosis that delays proper treatment.

- The pathogenesis of IGM remains poorly understood. The temporal association of the disorder with breastfeeding suggests that hyperprolactinemia or an immune response to local lobular secretions might play a role.

- Although many cases of IGM resolve without treatment, more severe cases can persist for a long period before adequate symptomatic treatment is provided with methotrexate, corticosteroids, or surgical excision.

- Before any of these therapies are applied, however, contributing factors, such as long-term breastfeeding and drugs that induce hyperprolactinemia, should be identified and withdrawn.

En Coup de Sabre

En coup de sabre (ECDS) is a rare subtype of linear scleroderma that is limited to the hemiface in a unilateral distribution. The lesional skin first exhibits contraction and stiffness that lead to characteristic fibrotic plaques with associated linear alopecia.1 The pansclerotic plaques are ivory in color with hyperpigmented to violaceous borders extending as a paramedian band on the frontoparietal scalp.2,3 The skin lesions bear resemblance to the stroke of the sabre sword, giving the condition its unique name. Many patients initially present with concerns of frontal scalp alopecia.3 Linear morphea, including the ECDS subtype, is predominantly seen in children and women, usually presenting within the first 2 decades of life.1,4

The differential diagnoses of ECDS include focal dermal hypoplasia, steroid atrophy, localized morphea, and lupus profundus.5 En coup de sabre should be distinguished from progressive hemifacial atrophy (PHA)(also known as Parry-Romberg syndrome).6 Progressive hemifacial atrophy presents as unilateral atrophy of the face involving skin, subcutaneous tissue, muscle, and underlying bone in the distribution of the trigeminal nerve.1 Both PHA and ECDS exist on a spectrum of linear scleroderma and may coexist in the same patient.6

There is a strong association with extracutaneous neurologic involvement, including seizures, ocular abnormalities, trigeminal neuralgia, and headache.7-10 One study examining ECDS and PHA demonstrated that 44% (19/43) of patients who underwent central nervous system imaging had abnormal findings.11 The majority of patients had magnetic resonance imaging with or without contrast, computed tomography, or both. The most common findings on T2-weighted images were white matter hyperintensities, mostly in subcortical and periventricular regions. The findings were bilateral in 61% (11/18) of patients and ipsilateral to the lesion in 33% (6/18) of patients.11 We present a case of ECDS masquerading as alopecia in a 77-year-old woman.

Case Report

A 77-year-old white woman presented with a chief concern of hair loss on the scalp that had been present since 12 years of age. During her adult life, the scalp lesion remained unchanged with no associated symptoms. Her medical history was remarkable for hypertension and non–insulin-dependent diabetes mellitus. The patient denied any history of seizure disorders, facial paralysis, or neurologic deficits.

Comment

Etiology and Presentation