User login

Nonhealing Eroded Plaque on an Interdigital Web Space of the Foot

The Diagnosis: Basal Cell Nevus Syndrome

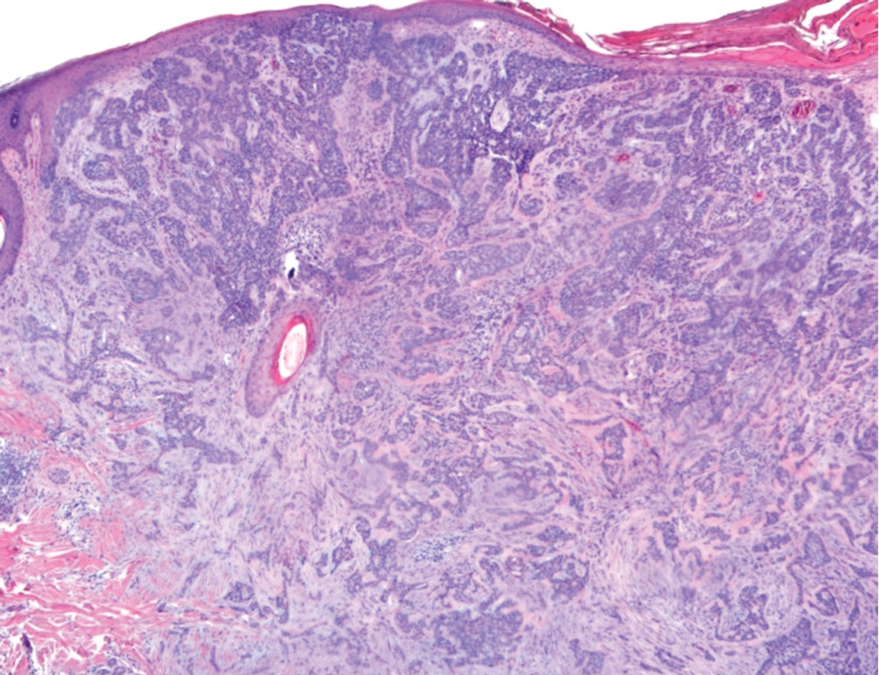

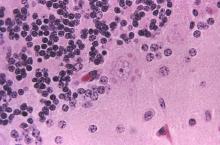

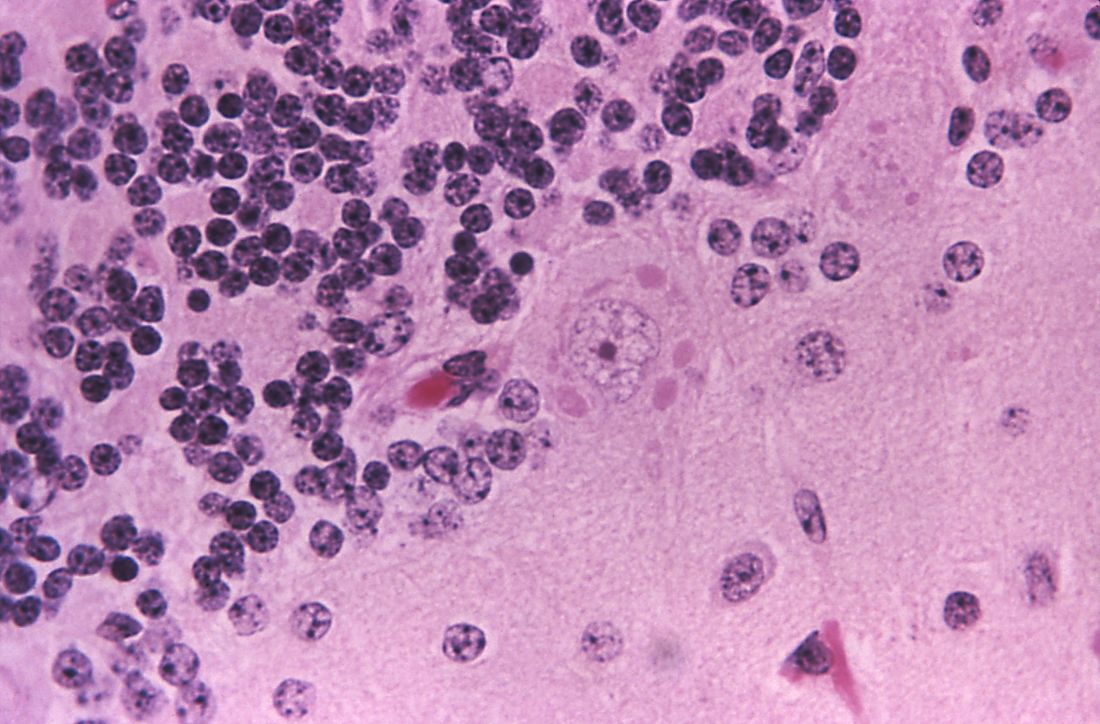

Given the patient’s history of numerous basal cell carcinomas (BCCs), odontogenic keratocysts, palmar pits, and a nonhealing ulcer, the clinical presentation was highly suggestive of interdigital BCC in the setting of basal cell nevus syndrome (BCNS). A shave biopsy was performed revealing islands of basaloid cells with peripheral palisading and a retraction artifact surrounded by fibromyxoid stroma, consistent with nodular and infiltrative BCC (Figure 1).

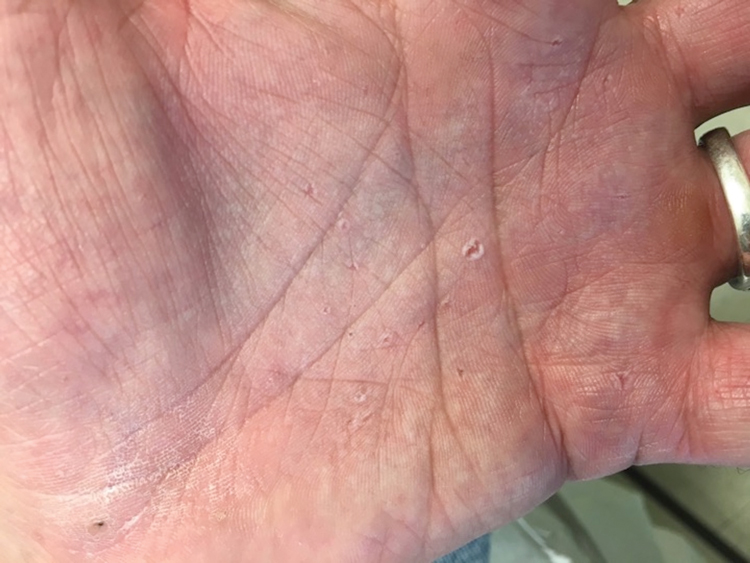

Basal cell nevus syndrome (also known as Gorlin syndrome) is a rare neurocutaneous syndrome that manifests with multiple BCCs; palmar and plantar pits (Figure 2); central nervous system tumors; and skeletal anomalies including jaw cysts, macrocephaly, frontal bossing, and bifid ribs.1 It is an autosomal-dominant condition caused by mutations in the PTCH1 gene, a tumor suppressor gene involved in the Hedgehog signaling pathway.2 Basal cell carcinoma is the most distinctive feature of BCNS, causing notable morbidity. Tumors typically present between puberty and 35 years of age, and patients can have anywhere from a few to thousands of tumors. They rarely become locally aggressive; however, with radiation therapy, proliferation and local invasion may occur within a few years. Therefore, radiotherapy should be avoided in these patients.1

Although the most common sites for BCCs in BCNS are the head, neck, and back, there is a higher rate of occurrence on sun-protected areas in BCNS compared to the general population.3 Our patient presented with interdigital BCC of the foot, which is an extremely rare occurrence. PubMed and Ovid searches using the terms basal cell carcinoma, BCC, foot, interdigital, and nonmelanoma skin cancer revealed only 3 cases of interdigital BCC of the foot. One case was associated with prior surgical trauma, the second presented as a junctional nevus, and the third did not appear to have any associated inciting factors.4-6 Dermatologists need to have a low threshold for biopsy for any unusual nonhealing lesions, especially in the setting of BCNS. Basal cell carcinomas in BCNS cannot be histologically differentiated from sporadic BCCs, and management largely depends on the size, location, recurrence, and number of lesions. Treatment methods range from topical agents to Mohs micrographic surgery.1

Nonhealing lesions of the foot may give an initial clinical impression of infection overlying peripheral vascular disease or diabetes mellitus with the possibility of associated osteomyelitis. Our patient had no clinical history to suggest peripheral vascular disease or diabetes mellitus, and he had palpable dorsalis pedis pulses as well as a normal neurologic examination. Clinicians also may consider fungal infection in the differential diagnosis. Erosio interdigitalis blastomycetica is a superficial yeast infection described as a well-defined, red, shiny plaque found in chronically wet areas, usually affecting the third or fourth interdigital spaces of the fingers.7 However, the lack of improvement with antibiotics and antifungals argued against bacterial or fungal infection in our patient. Although BCC also is a common feature of Bazex Dupré-Christol syndrome, it also is characterized by follicular atrophoderma, milia, hypohidrosis, and hypotrichosis,8 which were not evident in our patient. Pseudomonas hot foot syndrome is characterized by painful, plantar, erythematous nodules after exposure to ontaminated water that typically is self-limited but does respond to antibiotics for Pseudomonas.9

Our patient underwent Mohs micrographic surgery with a complex repair utilizing a full-thickness skin graft. There were no signs of recurrence at 3-month follow-up, and he was counseled on the importance of sun-protective behaviors along with regular dermatologic follow-up.

1. Gorlin RJ. Nevoid basal cell (Gorlin) syndrome. Genet Med. 2004; 6:530-539.

2. Bale A. The nevoid basal cell carcinoma syndrome: genetics and mechanism of carcinogenesis. Cancer Invest. 1997;15:180-186.

3. Goldstein AM, Bale SJ, Peck GL, et al. Sun exposure and basal cell carcinomas in nevoid basal cell carcinoma syndrome. J Am Acad Dermatol. 1993;29:34-41.

4. Silvers SH. Interdigital pedal basal cell carcinoma. Cutis. 1983;31:199-200.

5. Weitzner S. Basal cell carcinoma of toeweb presenting as a junctional nevus. Southwest Med. 1968;49:175.

6. Niwa A, Pimentel E. Basal cell carcinoma in unusual locations. An Bras Dermatol. 2006;81:281-284.

7. Mitchell JH. Erosio interdigitalis blastomycetica. Arch Derm Syphilol. 1922;6:675-679.

8. Kidd A, Carson L, Gregory DW, et al. A Scottish family with Bazex-Dupré-Christol syndrome: follicular atrophoderma, congenital hypotrichosis, and basal cell carcinoma. J Med Genet. 1996;33:493-497.

9. Yu Y, Cheng AS, Wang L, et al. Hot tub folliculitis or hot hand-foot syndrome caused by Pseudomonas aeruginosa. J Am Acad Dermatol. 2007;57:596-600.

The Diagnosis: Basal Cell Nevus Syndrome

Given the patient’s history of numerous basal cell carcinomas (BCCs), odontogenic keratocysts, palmar pits, and a nonhealing ulcer, the clinical presentation was highly suggestive of interdigital BCC in the setting of basal cell nevus syndrome (BCNS). A shave biopsy was performed revealing islands of basaloid cells with peripheral palisading and a retraction artifact surrounded by fibromyxoid stroma, consistent with nodular and infiltrative BCC (Figure 1).

Basal cell nevus syndrome (also known as Gorlin syndrome) is a rare neurocutaneous syndrome that manifests with multiple BCCs; palmar and plantar pits (Figure 2); central nervous system tumors; and skeletal anomalies including jaw cysts, macrocephaly, frontal bossing, and bifid ribs.1 It is an autosomal-dominant condition caused by mutations in the PTCH1 gene, a tumor suppressor gene involved in the Hedgehog signaling pathway.2 Basal cell carcinoma is the most distinctive feature of BCNS, causing notable morbidity. Tumors typically present between puberty and 35 years of age, and patients can have anywhere from a few to thousands of tumors. They rarely become locally aggressive; however, with radiation therapy, proliferation and local invasion may occur within a few years. Therefore, radiotherapy should be avoided in these patients.1

Although the most common sites for BCCs in BCNS are the head, neck, and back, there is a higher rate of occurrence on sun-protected areas in BCNS compared to the general population.3 Our patient presented with interdigital BCC of the foot, which is an extremely rare occurrence. PubMed and Ovid searches using the terms basal cell carcinoma, BCC, foot, interdigital, and nonmelanoma skin cancer revealed only 3 cases of interdigital BCC of the foot. One case was associated with prior surgical trauma, the second presented as a junctional nevus, and the third did not appear to have any associated inciting factors.4-6 Dermatologists need to have a low threshold for biopsy for any unusual nonhealing lesions, especially in the setting of BCNS. Basal cell carcinomas in BCNS cannot be histologically differentiated from sporadic BCCs, and management largely depends on the size, location, recurrence, and number of lesions. Treatment methods range from topical agents to Mohs micrographic surgery.1

Nonhealing lesions of the foot may give an initial clinical impression of infection overlying peripheral vascular disease or diabetes mellitus with the possibility of associated osteomyelitis. Our patient had no clinical history to suggest peripheral vascular disease or diabetes mellitus, and he had palpable dorsalis pedis pulses as well as a normal neurologic examination. Clinicians also may consider fungal infection in the differential diagnosis. Erosio interdigitalis blastomycetica is a superficial yeast infection described as a well-defined, red, shiny plaque found in chronically wet areas, usually affecting the third or fourth interdigital spaces of the fingers.7 However, the lack of improvement with antibiotics and antifungals argued against bacterial or fungal infection in our patient. Although BCC also is a common feature of Bazex Dupré-Christol syndrome, it also is characterized by follicular atrophoderma, milia, hypohidrosis, and hypotrichosis,8 which were not evident in our patient. Pseudomonas hot foot syndrome is characterized by painful, plantar, erythematous nodules after exposure to ontaminated water that typically is self-limited but does respond to antibiotics for Pseudomonas.9

Our patient underwent Mohs micrographic surgery with a complex repair utilizing a full-thickness skin graft. There were no signs of recurrence at 3-month follow-up, and he was counseled on the importance of sun-protective behaviors along with regular dermatologic follow-up.

The Diagnosis: Basal Cell Nevus Syndrome

Given the patient’s history of numerous basal cell carcinomas (BCCs), odontogenic keratocysts, palmar pits, and a nonhealing ulcer, the clinical presentation was highly suggestive of interdigital BCC in the setting of basal cell nevus syndrome (BCNS). A shave biopsy was performed revealing islands of basaloid cells with peripheral palisading and a retraction artifact surrounded by fibromyxoid stroma, consistent with nodular and infiltrative BCC (Figure 1).

Basal cell nevus syndrome (also known as Gorlin syndrome) is a rare neurocutaneous syndrome that manifests with multiple BCCs; palmar and plantar pits (Figure 2); central nervous system tumors; and skeletal anomalies including jaw cysts, macrocephaly, frontal bossing, and bifid ribs.1 It is an autosomal-dominant condition caused by mutations in the PTCH1 gene, a tumor suppressor gene involved in the Hedgehog signaling pathway.2 Basal cell carcinoma is the most distinctive feature of BCNS, causing notable morbidity. Tumors typically present between puberty and 35 years of age, and patients can have anywhere from a few to thousands of tumors. They rarely become locally aggressive; however, with radiation therapy, proliferation and local invasion may occur within a few years. Therefore, radiotherapy should be avoided in these patients.1

Although the most common sites for BCCs in BCNS are the head, neck, and back, there is a higher rate of occurrence on sun-protected areas in BCNS compared to the general population.3 Our patient presented with interdigital BCC of the foot, which is an extremely rare occurrence. PubMed and Ovid searches using the terms basal cell carcinoma, BCC, foot, interdigital, and nonmelanoma skin cancer revealed only 3 cases of interdigital BCC of the foot. One case was associated with prior surgical trauma, the second presented as a junctional nevus, and the third did not appear to have any associated inciting factors.4-6 Dermatologists need to have a low threshold for biopsy for any unusual nonhealing lesions, especially in the setting of BCNS. Basal cell carcinomas in BCNS cannot be histologically differentiated from sporadic BCCs, and management largely depends on the size, location, recurrence, and number of lesions. Treatment methods range from topical agents to Mohs micrographic surgery.1

Nonhealing lesions of the foot may give an initial clinical impression of infection overlying peripheral vascular disease or diabetes mellitus with the possibility of associated osteomyelitis. Our patient had no clinical history to suggest peripheral vascular disease or diabetes mellitus, and he had palpable dorsalis pedis pulses as well as a normal neurologic examination. Clinicians also may consider fungal infection in the differential diagnosis. Erosio interdigitalis blastomycetica is a superficial yeast infection described as a well-defined, red, shiny plaque found in chronically wet areas, usually affecting the third or fourth interdigital spaces of the fingers.7 However, the lack of improvement with antibiotics and antifungals argued against bacterial or fungal infection in our patient. Although BCC also is a common feature of Bazex Dupré-Christol syndrome, it also is characterized by follicular atrophoderma, milia, hypohidrosis, and hypotrichosis,8 which were not evident in our patient. Pseudomonas hot foot syndrome is characterized by painful, plantar, erythematous nodules after exposure to ontaminated water that typically is self-limited but does respond to antibiotics for Pseudomonas.9

Our patient underwent Mohs micrographic surgery with a complex repair utilizing a full-thickness skin graft. There were no signs of recurrence at 3-month follow-up, and he was counseled on the importance of sun-protective behaviors along with regular dermatologic follow-up.

1. Gorlin RJ. Nevoid basal cell (Gorlin) syndrome. Genet Med. 2004; 6:530-539.

2. Bale A. The nevoid basal cell carcinoma syndrome: genetics and mechanism of carcinogenesis. Cancer Invest. 1997;15:180-186.

3. Goldstein AM, Bale SJ, Peck GL, et al. Sun exposure and basal cell carcinomas in nevoid basal cell carcinoma syndrome. J Am Acad Dermatol. 1993;29:34-41.

4. Silvers SH. Interdigital pedal basal cell carcinoma. Cutis. 1983;31:199-200.

5. Weitzner S. Basal cell carcinoma of toeweb presenting as a junctional nevus. Southwest Med. 1968;49:175.

6. Niwa A, Pimentel E. Basal cell carcinoma in unusual locations. An Bras Dermatol. 2006;81:281-284.

7. Mitchell JH. Erosio interdigitalis blastomycetica. Arch Derm Syphilol. 1922;6:675-679.

8. Kidd A, Carson L, Gregory DW, et al. A Scottish family with Bazex-Dupré-Christol syndrome: follicular atrophoderma, congenital hypotrichosis, and basal cell carcinoma. J Med Genet. 1996;33:493-497.

9. Yu Y, Cheng AS, Wang L, et al. Hot tub folliculitis or hot hand-foot syndrome caused by Pseudomonas aeruginosa. J Am Acad Dermatol. 2007;57:596-600.

1. Gorlin RJ. Nevoid basal cell (Gorlin) syndrome. Genet Med. 2004; 6:530-539.

2. Bale A. The nevoid basal cell carcinoma syndrome: genetics and mechanism of carcinogenesis. Cancer Invest. 1997;15:180-186.

3. Goldstein AM, Bale SJ, Peck GL, et al. Sun exposure and basal cell carcinomas in nevoid basal cell carcinoma syndrome. J Am Acad Dermatol. 1993;29:34-41.

4. Silvers SH. Interdigital pedal basal cell carcinoma. Cutis. 1983;31:199-200.

5. Weitzner S. Basal cell carcinoma of toeweb presenting as a junctional nevus. Southwest Med. 1968;49:175.

6. Niwa A, Pimentel E. Basal cell carcinoma in unusual locations. An Bras Dermatol. 2006;81:281-284.

7. Mitchell JH. Erosio interdigitalis blastomycetica. Arch Derm Syphilol. 1922;6:675-679.

8. Kidd A, Carson L, Gregory DW, et al. A Scottish family with Bazex-Dupré-Christol syndrome: follicular atrophoderma, congenital hypotrichosis, and basal cell carcinoma. J Med Genet. 1996;33:493-497.

9. Yu Y, Cheng AS, Wang L, et al. Hot tub folliculitis or hot hand-foot syndrome caused by Pseudomonas aeruginosa. J Am Acad Dermatol. 2007;57:596-600.

A 53-year-old man with a history of numerous basal cell carcinomas and odontogenic keratocysts presented with a nonhealing erosion between the left second and third toes of several months’ duration. He was treated empirically with multiple courses of topical and systemic antibiotics as well as antifungals with minimal improvement. Physical examination revealed a 1.2×0.6-cm eroded plaque with rolled borders on the left second toe web; bilateral palmar pits; diffuse actinic damage; and several well-healed surgical scars on the head, neck, and back. Neurologic examination was normal, and dorsalis pedis pulses were equal and palpable bilaterally.

The HPV vaccine is now recommended for adults aged 27–45: Counseling implications

The US Food and Drug Administration (FDA) recently extended the approval for Gardasil 9 (to prevent HPV-associated cancers, cancer precursors, and genital lesions) to men and women aged 27 to 45.1 In this editorial, we discuss the evolution of the HPV vaccine since its initial approval more than 10 years ago, the benefits of primary prevention with the HPV vaccine, and the case for the FDA’s recent extension of coverage to older men and women.

The evolution of the HPV vaccine

Since recognition in the 1980s and 90s that high-risk strains of HPV, notably HPV types 16 and 18, were linked to cervical cancer, there have been exciting advances in detection and prevention of high-risk HPV infection. About 70% of cervical cancers are attributable to these 2 oncogenic types.2 The first vaccine licensed, Gardasil (Merck), was approved in 2006 for girls and women aged 9 through 26 to prevent HPV-related diseases caused by types 6, 11, 16, and 18.3 The vaccine was effective for prevention of cervical cancer; genital warts; and grades 2 and 3 of cervical, vulvar, and vaginal intraepithelial neoplasia. In 2008, prevention of vulvar and vaginal cancers was added to the indication. By 2009, prevention of genital warts was added, and use in males aged 9 to 15 was approved. By 2010 sufficient data were accumulated to document prevention of anal cancer and anal intraepithelial neoplasia in men and women, and this indication was added.

In 2014 Gardasil 9 was approved to extend coverage to an additional 5 oncogenic HPV types (31, 33, 45, 52, and 58), now covering an additional 20% of cervical cancers, and in 2015 Gardasil 9 indications were expanded to include boys and men 9 to 26 years of age. Immunogenicity studies were performed to infer effectiveness of a 2-dose regimen in boys and girls aged 9 to 14 years, which was recommended by the Advisory Committee on Immunization Practices (ACIP) of the Centers for Disease Control and Prevention (CDC) in late 2016.4

Until October 2018, Gardasil 9 was indicated for prevention of genital warts, cervical, vaginal, vulvar and anal cancers and cancer precursors for males and females aged 9 to 26 years. In October the FDA extended approval of the 3-dose vaccine regimen to men and women up to age 45.

HPV vaccine uptake

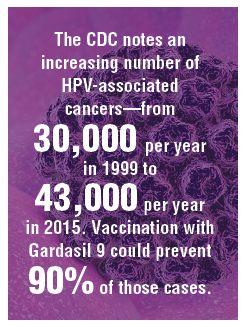

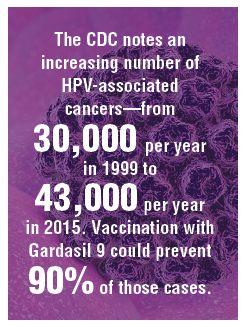

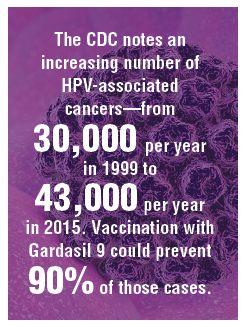

HPV vaccination has been underutilized in the United States. In 2017, a disappointing 49% of adolescents were up to date on vaccination, and 66% had received at least one dose.5 In rural areas the vaccination rates are 11 points lower than in urban regions.6 The CDC notes an increasing number of HPV-associated cancers—from 30,000 per year in 1999 to 43,000 per year in 2015—due mostly to increases in oral and anal carcinomas. Vaccination with Gardasil 9 could prevent 90% of those cases.7

Non-US successes. HPV vaccine uptake in Australia provides an excellent opportunity to study the impact of universally available, school-based vaccinations. In 2007 Australia implemented a program of free HPV vaccination distributed through schools. Boys and girls aged 12 and 13 were targeted that year, with catch-up vaccinations for those aged 13 to 18 in 2007-2009 in schools and for those aged 18 to 26 reached in the community.8

Continue to: Ali and colleagues studied the...

Ali and colleagues studied the preprogram and postprogram incidence of genital warts.9 About 83% received at least 1 dose of vaccine, and 73% of the eligible population completed the 3-dose regimen. There was a significant reduction in warts in both men and women younger than age 21 from 2007 to 2011 (12.1% to 2.2% in men and 11.5% to 0.85% in women). In the 21 to 30 age group there were similar reductions. This study demonstrates that with universal access and public implementation, the rates of HPV-associated disease can be reduced dramatically.

Data informing expanded vaccination ages

Will vaccination of an older population, with presumably many of whom sexually active and at risk for prior exposure to multiple HPV types, have a reasonable impact on lowering HPV-associated cancers? Are HPV-detected lesions in 27- to 45-year-old women the result of reactivation of latent HPV infection, or are they related to new-onset exposure? The FDA reviewed data from 3 studies of HPV vaccination in women aged 27 to 45. The first enrolled women who were naïve to oncogenic HPV types and provided all 3 doses of quadrivalent vaccine were followed for 4 years, along with a comparison group of nonvaccinated women. The second study allowed the nonvaccinated group to receive vaccine in year 4. Both groups were followed up to 10 years with the relevant outcome defined as cumulative incidence of HPV 6/11/16/18-related CIN and condyloma. The third study looked at the same outcomes in a set of all women—whether HPV high-risk naïve or not—after receiving vaccine and followed more than 10 years.7 This last study is most relevant to ObGyns, as it is closest to how we would consider vaccinating our patients.

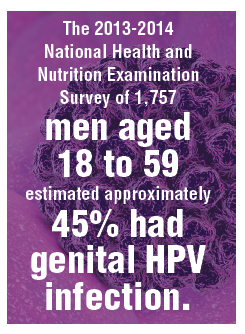

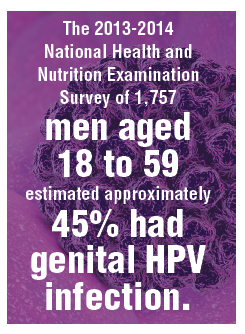

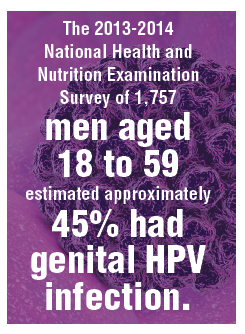

The study findings are reassuring: A large proportion of HPV infections in women between 27 and 45 are the result of new exposure/infection. A study of 420 online daters aged 25 to 65 showed an annual incidence of high-risk HPV types in vaginal swabs of 25.4%, of which 64% were likely new acquisitions.10 The 2013-2014 National Health and Nutrition Examination Survey of 1,757 men aged 18 to 59 estimated approximately 45% had genital HPV infection. There was a bimodal distribution of disease with peaks at 28 to 32 and a larger second peak at 58 to 59 years of age.11 Bottom line: Men and women older than age 26 who are sexually active likely acquire new HPV infections with oncogenic types. Exposure to high-risk HPV types prior to vaccination—as we would expect in the real-world setting—did not eliminate the substantial benefit of immunization.

Based on these study results, and extrapolation to the 9-valent vaccine, the FDA extended the approval of Gardasil 9 to men and women from age 9 to 45. The indications and usage will remain the same: for prevention of cervical, vulvar, vaginal, and anal cancer and genital warts as well as precancerous or dysplastic lesions of the cervix, vulva, vagina, and anus related to HPV types 6, 11, 16, 18, 31, 33, 45, 52, and 58.

Continue to: Impact of the new...

Impact of the new indication on HPV-related disease

As described above, widespread vaccination of young girls and boys is going to have major impact on HPV-related disease, including precancer and cancer. Because there is evidence that older women and men are at risk for new HPV infection,10 there likely will be some benefit from vaccination of adults. It is difficult, however, to extrapolate the degree to which adult vaccination will impact HPV-related disease. This is because we do not fully understand the rates at which new HPV infection in the cervices of older women will progress to high-grade dysplasia or cancer. Further, the pathophysiology of HPV-related cancers at other anogenital sites and new oral-pharyngeal infection is poorly understood in comparison with our knowledge of the natural history of high-risk HPV infection in younger women. That said, because of the outstanding efficacy of HPV vaccination and the low-risk profile, even if the actual impact on prevention of cancer or morbidity from dysplasia is relatively low, adult vaccination benefits outweigh the limited risks.

It may be that increased vaccination and awareness of vaccination for adults may enhance the adherence and acceptance of widespread vaccination of boys and girls. Adult vaccination could create a cultural shift toward HPV vaccination acceptance when adult parents and loved ones of vaccine-age boys and girls have been vaccinated themselves.

Current and future insurance coverage

The Affordable Care Act, otherwise known as Obamacare, mandates coverage for all immunizations recommended by the ACIP. HPV vaccination up to age 26 is fully covered, without copay or deductible. The ACIP did consider extension of the indications for HPV vaccination to men and women up to age 45 at their October 2018 meeting. They are tasked with considering not only safety and efficacy but also the cost effectiveness of implementing vaccination. They continue to study the costs and potential benefits of extending HPV vaccination to age 45. Their recommendations may be determined at the February 2019 meeting—or even later in 2019. The American College of Obstetricians and Gynecologists (ACOG) relies upon ACIP for practice guidance. Once the ACIP has made a determination, and if new guidelines are published in the Morbidity and Mortality Weekly Report, insurance coverage and ACOG guidance will be updated.

How should we react and change practice based on this new indication?

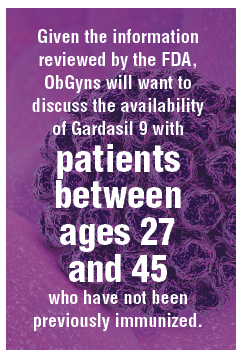

Given the information reviewed by the FDA, ObGyns will want to discuss the availability of Gardasil 9 with our patients between ages 27 and 45 who have not been previously immunized.

Especially for our patients with exposure to multiple or new sexual partners, immunization against oncogenic HPV viral types is effective in providing protection from cancer precursors and cancers of the cervix, vulva, vagina, and anus—and of course from genital warts. They should understand that, until formal recommendations are published by the ACIP, they are likely to be responsible for the cost of the vaccination series. These conversations will also remind our patients to immunize their teens against HPV. The more conversation we have regarding the benefits of vaccination against high-risk HPV types, the more likely we are to be able to achieve the impressive results seen in Australia.

- US Food and Drug Administration website. FDA approves expanded use of Gardasil 9 to include individuals 27 through 45 years old. https://www.fda.gov/NewsEvents/Newsroom/PressAnnouncements/ucm622715.htm. Updated October 9, 2018. Accessed December 27, 2018.

- World Health Organization website. Human papillomavirus (HPV) and cervical cancer. https://www.who.int/news-room/fact-sheets/detail/human-papillomavirus-(hpv)-and-cervical-cancer. February 15, 2018. Accessed December 27, 2018.

- Centers for Disease Control and Prevention website. Human papillomavirus (HPV) vaccine safety. https://www.cdc.gov/vaccinesafety/vaccines/hpv-vaccine.html. Last reviewed October 27, 2015. Accessed December 27, 2018.

- Meites E, Kempe A, Markowitz LE. Use of a 2-dose schedule for human papillomavirus vaccination—updated recommendations of the Advisory Committee on Immunization Practices. MMWR. 2016;65(49):1405–1408.

- AAP News website. Jenko M. CDC: 49% of teens up to date on HPV vaccine. http://www.aappublications.org/news/2018/08/23/vac cinationrates082318. August 23, 2018. Accessed December 27, 2018.

- Walker TY, Elam-Evans LD, Yankey D, et al. National, regional, state, and selected local area vaccination coverage among adolescents aged 13–17 years—United States, 2017. MMWR Morb Mortal Wkly Rep. 2018;67:909-917.

- Montague L. Summary basis for regulatory action. October 5, 2018. https://www.fda.gov/downloads/BiologicsBloodVaccines/Vaccines/ApprovedProducts/UCM622941.pdf. Accessed December 27, 2018.

- Tabrizi SN, Brotherton JM, Kaldor JM, et al. Fall in human papillomavirus prevalence following a national vaccination program. J Infect Dis. 2012;206:1645-1651.

- Ali H, Donovan B, Wand H, et al. Genital warts in young Australians five years into national human papillomavirus vaccination programme: national surveillance data [published correction appears in BMJ. 2013;346:F2942]. BMJ. 2013;346:F2032.

- Winer RL, Hughes JP, Feng Q, et al. Incident detection of high-risk human papillomavirus infections in a cohort of high-risk women aged 25-65 years. J Infect Dis. 2016;214:665-675.

- Han JJ, Beltran TH, Song JW, et al. Prevalence of genital human papillomavirus infection and human papillomavirus vaccination rates among US adult men: National Health and Nutrition Examination Survey (NHANES) 2013-2014. JAMA Oncol. 2017;3:810-816.

The US Food and Drug Administration (FDA) recently extended the approval for Gardasil 9 (to prevent HPV-associated cancers, cancer precursors, and genital lesions) to men and women aged 27 to 45.1 In this editorial, we discuss the evolution of the HPV vaccine since its initial approval more than 10 years ago, the benefits of primary prevention with the HPV vaccine, and the case for the FDA’s recent extension of coverage to older men and women.

The evolution of the HPV vaccine

Since recognition in the 1980s and 90s that high-risk strains of HPV, notably HPV types 16 and 18, were linked to cervical cancer, there have been exciting advances in detection and prevention of high-risk HPV infection. About 70% of cervical cancers are attributable to these 2 oncogenic types.2 The first vaccine licensed, Gardasil (Merck), was approved in 2006 for girls and women aged 9 through 26 to prevent HPV-related diseases caused by types 6, 11, 16, and 18.3 The vaccine was effective for prevention of cervical cancer; genital warts; and grades 2 and 3 of cervical, vulvar, and vaginal intraepithelial neoplasia. In 2008, prevention of vulvar and vaginal cancers was added to the indication. By 2009, prevention of genital warts was added, and use in males aged 9 to 15 was approved. By 2010 sufficient data were accumulated to document prevention of anal cancer and anal intraepithelial neoplasia in men and women, and this indication was added.

In 2014 Gardasil 9 was approved to extend coverage to an additional 5 oncogenic HPV types (31, 33, 45, 52, and 58), now covering an additional 20% of cervical cancers, and in 2015 Gardasil 9 indications were expanded to include boys and men 9 to 26 years of age. Immunogenicity studies were performed to infer effectiveness of a 2-dose regimen in boys and girls aged 9 to 14 years, which was recommended by the Advisory Committee on Immunization Practices (ACIP) of the Centers for Disease Control and Prevention (CDC) in late 2016.4

Until October 2018, Gardasil 9 was indicated for prevention of genital warts, cervical, vaginal, vulvar and anal cancers and cancer precursors for males and females aged 9 to 26 years. In October the FDA extended approval of the 3-dose vaccine regimen to men and women up to age 45.

HPV vaccine uptake

HPV vaccination has been underutilized in the United States. In 2017, a disappointing 49% of adolescents were up to date on vaccination, and 66% had received at least one dose.5 In rural areas the vaccination rates are 11 points lower than in urban regions.6 The CDC notes an increasing number of HPV-associated cancers—from 30,000 per year in 1999 to 43,000 per year in 2015—due mostly to increases in oral and anal carcinomas. Vaccination with Gardasil 9 could prevent 90% of those cases.7

Non-US successes. HPV vaccine uptake in Australia provides an excellent opportunity to study the impact of universally available, school-based vaccinations. In 2007 Australia implemented a program of free HPV vaccination distributed through schools. Boys and girls aged 12 and 13 were targeted that year, with catch-up vaccinations for those aged 13 to 18 in 2007-2009 in schools and for those aged 18 to 26 reached in the community.8

Continue to: Ali and colleagues studied the...

Ali and colleagues studied the preprogram and postprogram incidence of genital warts.9 About 83% received at least 1 dose of vaccine, and 73% of the eligible population completed the 3-dose regimen. There was a significant reduction in warts in both men and women younger than age 21 from 2007 to 2011 (12.1% to 2.2% in men and 11.5% to 0.85% in women). In the 21 to 30 age group there were similar reductions. This study demonstrates that with universal access and public implementation, the rates of HPV-associated disease can be reduced dramatically.

Data informing expanded vaccination ages

Will vaccination of an older population, with presumably many of whom sexually active and at risk for prior exposure to multiple HPV types, have a reasonable impact on lowering HPV-associated cancers? Are HPV-detected lesions in 27- to 45-year-old women the result of reactivation of latent HPV infection, or are they related to new-onset exposure? The FDA reviewed data from 3 studies of HPV vaccination in women aged 27 to 45. The first enrolled women who were naïve to oncogenic HPV types and provided all 3 doses of quadrivalent vaccine were followed for 4 years, along with a comparison group of nonvaccinated women. The second study allowed the nonvaccinated group to receive vaccine in year 4. Both groups were followed up to 10 years with the relevant outcome defined as cumulative incidence of HPV 6/11/16/18-related CIN and condyloma. The third study looked at the same outcomes in a set of all women—whether HPV high-risk naïve or not—after receiving vaccine and followed more than 10 years.7 This last study is most relevant to ObGyns, as it is closest to how we would consider vaccinating our patients.

The study findings are reassuring: A large proportion of HPV infections in women between 27 and 45 are the result of new exposure/infection. A study of 420 online daters aged 25 to 65 showed an annual incidence of high-risk HPV types in vaginal swabs of 25.4%, of which 64% were likely new acquisitions.10 The 2013-2014 National Health and Nutrition Examination Survey of 1,757 men aged 18 to 59 estimated approximately 45% had genital HPV infection. There was a bimodal distribution of disease with peaks at 28 to 32 and a larger second peak at 58 to 59 years of age.11 Bottom line: Men and women older than age 26 who are sexually active likely acquire new HPV infections with oncogenic types. Exposure to high-risk HPV types prior to vaccination—as we would expect in the real-world setting—did not eliminate the substantial benefit of immunization.

Based on these study results, and extrapolation to the 9-valent vaccine, the FDA extended the approval of Gardasil 9 to men and women from age 9 to 45. The indications and usage will remain the same: for prevention of cervical, vulvar, vaginal, and anal cancer and genital warts as well as precancerous or dysplastic lesions of the cervix, vulva, vagina, and anus related to HPV types 6, 11, 16, 18, 31, 33, 45, 52, and 58.

Continue to: Impact of the new...

Impact of the new indication on HPV-related disease

As described above, widespread vaccination of young girls and boys is going to have major impact on HPV-related disease, including precancer and cancer. Because there is evidence that older women and men are at risk for new HPV infection,10 there likely will be some benefit from vaccination of adults. It is difficult, however, to extrapolate the degree to which adult vaccination will impact HPV-related disease. This is because we do not fully understand the rates at which new HPV infection in the cervices of older women will progress to high-grade dysplasia or cancer. Further, the pathophysiology of HPV-related cancers at other anogenital sites and new oral-pharyngeal infection is poorly understood in comparison with our knowledge of the natural history of high-risk HPV infection in younger women. That said, because of the outstanding efficacy of HPV vaccination and the low-risk profile, even if the actual impact on prevention of cancer or morbidity from dysplasia is relatively low, adult vaccination benefits outweigh the limited risks.

It may be that increased vaccination and awareness of vaccination for adults may enhance the adherence and acceptance of widespread vaccination of boys and girls. Adult vaccination could create a cultural shift toward HPV vaccination acceptance when adult parents and loved ones of vaccine-age boys and girls have been vaccinated themselves.

Current and future insurance coverage

The Affordable Care Act, otherwise known as Obamacare, mandates coverage for all immunizations recommended by the ACIP. HPV vaccination up to age 26 is fully covered, without copay or deductible. The ACIP did consider extension of the indications for HPV vaccination to men and women up to age 45 at their October 2018 meeting. They are tasked with considering not only safety and efficacy but also the cost effectiveness of implementing vaccination. They continue to study the costs and potential benefits of extending HPV vaccination to age 45. Their recommendations may be determined at the February 2019 meeting—or even later in 2019. The American College of Obstetricians and Gynecologists (ACOG) relies upon ACIP for practice guidance. Once the ACIP has made a determination, and if new guidelines are published in the Morbidity and Mortality Weekly Report, insurance coverage and ACOG guidance will be updated.

How should we react and change practice based on this new indication?

Given the information reviewed by the FDA, ObGyns will want to discuss the availability of Gardasil 9 with our patients between ages 27 and 45 who have not been previously immunized.

Especially for our patients with exposure to multiple or new sexual partners, immunization against oncogenic HPV viral types is effective in providing protection from cancer precursors and cancers of the cervix, vulva, vagina, and anus—and of course from genital warts. They should understand that, until formal recommendations are published by the ACIP, they are likely to be responsible for the cost of the vaccination series. These conversations will also remind our patients to immunize their teens against HPV. The more conversation we have regarding the benefits of vaccination against high-risk HPV types, the more likely we are to be able to achieve the impressive results seen in Australia.

The US Food and Drug Administration (FDA) recently extended the approval for Gardasil 9 (to prevent HPV-associated cancers, cancer precursors, and genital lesions) to men and women aged 27 to 45.1 In this editorial, we discuss the evolution of the HPV vaccine since its initial approval more than 10 years ago, the benefits of primary prevention with the HPV vaccine, and the case for the FDA’s recent extension of coverage to older men and women.

The evolution of the HPV vaccine

Since recognition in the 1980s and 90s that high-risk strains of HPV, notably HPV types 16 and 18, were linked to cervical cancer, there have been exciting advances in detection and prevention of high-risk HPV infection. About 70% of cervical cancers are attributable to these 2 oncogenic types.2 The first vaccine licensed, Gardasil (Merck), was approved in 2006 for girls and women aged 9 through 26 to prevent HPV-related diseases caused by types 6, 11, 16, and 18.3 The vaccine was effective for prevention of cervical cancer; genital warts; and grades 2 and 3 of cervical, vulvar, and vaginal intraepithelial neoplasia. In 2008, prevention of vulvar and vaginal cancers was added to the indication. By 2009, prevention of genital warts was added, and use in males aged 9 to 15 was approved. By 2010 sufficient data were accumulated to document prevention of anal cancer and anal intraepithelial neoplasia in men and women, and this indication was added.

In 2014 Gardasil 9 was approved to extend coverage to an additional 5 oncogenic HPV types (31, 33, 45, 52, and 58), now covering an additional 20% of cervical cancers, and in 2015 Gardasil 9 indications were expanded to include boys and men 9 to 26 years of age. Immunogenicity studies were performed to infer effectiveness of a 2-dose regimen in boys and girls aged 9 to 14 years, which was recommended by the Advisory Committee on Immunization Practices (ACIP) of the Centers for Disease Control and Prevention (CDC) in late 2016.4

Until October 2018, Gardasil 9 was indicated for prevention of genital warts, cervical, vaginal, vulvar and anal cancers and cancer precursors for males and females aged 9 to 26 years. In October the FDA extended approval of the 3-dose vaccine regimen to men and women up to age 45.

HPV vaccine uptake

HPV vaccination has been underutilized in the United States. In 2017, a disappointing 49% of adolescents were up to date on vaccination, and 66% had received at least one dose.5 In rural areas the vaccination rates are 11 points lower than in urban regions.6 The CDC notes an increasing number of HPV-associated cancers—from 30,000 per year in 1999 to 43,000 per year in 2015—due mostly to increases in oral and anal carcinomas. Vaccination with Gardasil 9 could prevent 90% of those cases.7

Non-US successes. HPV vaccine uptake in Australia provides an excellent opportunity to study the impact of universally available, school-based vaccinations. In 2007 Australia implemented a program of free HPV vaccination distributed through schools. Boys and girls aged 12 and 13 were targeted that year, with catch-up vaccinations for those aged 13 to 18 in 2007-2009 in schools and for those aged 18 to 26 reached in the community.8

Continue to: Ali and colleagues studied the...

Ali and colleagues studied the preprogram and postprogram incidence of genital warts.9 About 83% received at least 1 dose of vaccine, and 73% of the eligible population completed the 3-dose regimen. There was a significant reduction in warts in both men and women younger than age 21 from 2007 to 2011 (12.1% to 2.2% in men and 11.5% to 0.85% in women). In the 21 to 30 age group there were similar reductions. This study demonstrates that with universal access and public implementation, the rates of HPV-associated disease can be reduced dramatically.

Data informing expanded vaccination ages

Will vaccination of an older population, with presumably many of whom sexually active and at risk for prior exposure to multiple HPV types, have a reasonable impact on lowering HPV-associated cancers? Are HPV-detected lesions in 27- to 45-year-old women the result of reactivation of latent HPV infection, or are they related to new-onset exposure? The FDA reviewed data from 3 studies of HPV vaccination in women aged 27 to 45. The first enrolled women who were naïve to oncogenic HPV types and provided all 3 doses of quadrivalent vaccine were followed for 4 years, along with a comparison group of nonvaccinated women. The second study allowed the nonvaccinated group to receive vaccine in year 4. Both groups were followed up to 10 years with the relevant outcome defined as cumulative incidence of HPV 6/11/16/18-related CIN and condyloma. The third study looked at the same outcomes in a set of all women—whether HPV high-risk naïve or not—after receiving vaccine and followed more than 10 years.7 This last study is most relevant to ObGyns, as it is closest to how we would consider vaccinating our patients.

The study findings are reassuring: A large proportion of HPV infections in women between 27 and 45 are the result of new exposure/infection. A study of 420 online daters aged 25 to 65 showed an annual incidence of high-risk HPV types in vaginal swabs of 25.4%, of which 64% were likely new acquisitions.10 The 2013-2014 National Health and Nutrition Examination Survey of 1,757 men aged 18 to 59 estimated approximately 45% had genital HPV infection. There was a bimodal distribution of disease with peaks at 28 to 32 and a larger second peak at 58 to 59 years of age.11 Bottom line: Men and women older than age 26 who are sexually active likely acquire new HPV infections with oncogenic types. Exposure to high-risk HPV types prior to vaccination—as we would expect in the real-world setting—did not eliminate the substantial benefit of immunization.

Based on these study results, and extrapolation to the 9-valent vaccine, the FDA extended the approval of Gardasil 9 to men and women from age 9 to 45. The indications and usage will remain the same: for prevention of cervical, vulvar, vaginal, and anal cancer and genital warts as well as precancerous or dysplastic lesions of the cervix, vulva, vagina, and anus related to HPV types 6, 11, 16, 18, 31, 33, 45, 52, and 58.

Continue to: Impact of the new...

Impact of the new indication on HPV-related disease

As described above, widespread vaccination of young girls and boys is going to have major impact on HPV-related disease, including precancer and cancer. Because there is evidence that older women and men are at risk for new HPV infection,10 there likely will be some benefit from vaccination of adults. It is difficult, however, to extrapolate the degree to which adult vaccination will impact HPV-related disease. This is because we do not fully understand the rates at which new HPV infection in the cervices of older women will progress to high-grade dysplasia or cancer. Further, the pathophysiology of HPV-related cancers at other anogenital sites and new oral-pharyngeal infection is poorly understood in comparison with our knowledge of the natural history of high-risk HPV infection in younger women. That said, because of the outstanding efficacy of HPV vaccination and the low-risk profile, even if the actual impact on prevention of cancer or morbidity from dysplasia is relatively low, adult vaccination benefits outweigh the limited risks.

It may be that increased vaccination and awareness of vaccination for adults may enhance the adherence and acceptance of widespread vaccination of boys and girls. Adult vaccination could create a cultural shift toward HPV vaccination acceptance when adult parents and loved ones of vaccine-age boys and girls have been vaccinated themselves.

Current and future insurance coverage

The Affordable Care Act, otherwise known as Obamacare, mandates coverage for all immunizations recommended by the ACIP. HPV vaccination up to age 26 is fully covered, without copay or deductible. The ACIP did consider extension of the indications for HPV vaccination to men and women up to age 45 at their October 2018 meeting. They are tasked with considering not only safety and efficacy but also the cost effectiveness of implementing vaccination. They continue to study the costs and potential benefits of extending HPV vaccination to age 45. Their recommendations may be determined at the February 2019 meeting—or even later in 2019. The American College of Obstetricians and Gynecologists (ACOG) relies upon ACIP for practice guidance. Once the ACIP has made a determination, and if new guidelines are published in the Morbidity and Mortality Weekly Report, insurance coverage and ACOG guidance will be updated.

How should we react and change practice based on this new indication?

Given the information reviewed by the FDA, ObGyns will want to discuss the availability of Gardasil 9 with our patients between ages 27 and 45 who have not been previously immunized.

Especially for our patients with exposure to multiple or new sexual partners, immunization against oncogenic HPV viral types is effective in providing protection from cancer precursors and cancers of the cervix, vulva, vagina, and anus—and of course from genital warts. They should understand that, until formal recommendations are published by the ACIP, they are likely to be responsible for the cost of the vaccination series. These conversations will also remind our patients to immunize their teens against HPV. The more conversation we have regarding the benefits of vaccination against high-risk HPV types, the more likely we are to be able to achieve the impressive results seen in Australia.

- US Food and Drug Administration website. FDA approves expanded use of Gardasil 9 to include individuals 27 through 45 years old. https://www.fda.gov/NewsEvents/Newsroom/PressAnnouncements/ucm622715.htm. Updated October 9, 2018. Accessed December 27, 2018.

- World Health Organization website. Human papillomavirus (HPV) and cervical cancer. https://www.who.int/news-room/fact-sheets/detail/human-papillomavirus-(hpv)-and-cervical-cancer. February 15, 2018. Accessed December 27, 2018.

- Centers for Disease Control and Prevention website. Human papillomavirus (HPV) vaccine safety. https://www.cdc.gov/vaccinesafety/vaccines/hpv-vaccine.html. Last reviewed October 27, 2015. Accessed December 27, 2018.

- Meites E, Kempe A, Markowitz LE. Use of a 2-dose schedule for human papillomavirus vaccination—updated recommendations of the Advisory Committee on Immunization Practices. MMWR. 2016;65(49):1405–1408.

- AAP News website. Jenko M. CDC: 49% of teens up to date on HPV vaccine. http://www.aappublications.org/news/2018/08/23/vac cinationrates082318. August 23, 2018. Accessed December 27, 2018.

- Walker TY, Elam-Evans LD, Yankey D, et al. National, regional, state, and selected local area vaccination coverage among adolescents aged 13–17 years—United States, 2017. MMWR Morb Mortal Wkly Rep. 2018;67:909-917.

- Montague L. Summary basis for regulatory action. October 5, 2018. https://www.fda.gov/downloads/BiologicsBloodVaccines/Vaccines/ApprovedProducts/UCM622941.pdf. Accessed December 27, 2018.

- Tabrizi SN, Brotherton JM, Kaldor JM, et al. Fall in human papillomavirus prevalence following a national vaccination program. J Infect Dis. 2012;206:1645-1651.

- Ali H, Donovan B, Wand H, et al. Genital warts in young Australians five years into national human papillomavirus vaccination programme: national surveillance data [published correction appears in BMJ. 2013;346:F2942]. BMJ. 2013;346:F2032.

- Winer RL, Hughes JP, Feng Q, et al. Incident detection of high-risk human papillomavirus infections in a cohort of high-risk women aged 25-65 years. J Infect Dis. 2016;214:665-675.

- Han JJ, Beltran TH, Song JW, et al. Prevalence of genital human papillomavirus infection and human papillomavirus vaccination rates among US adult men: National Health and Nutrition Examination Survey (NHANES) 2013-2014. JAMA Oncol. 2017;3:810-816.

- US Food and Drug Administration website. FDA approves expanded use of Gardasil 9 to include individuals 27 through 45 years old. https://www.fda.gov/NewsEvents/Newsroom/PressAnnouncements/ucm622715.htm. Updated October 9, 2018. Accessed December 27, 2018.

- World Health Organization website. Human papillomavirus (HPV) and cervical cancer. https://www.who.int/news-room/fact-sheets/detail/human-papillomavirus-(hpv)-and-cervical-cancer. February 15, 2018. Accessed December 27, 2018.

- Centers for Disease Control and Prevention website. Human papillomavirus (HPV) vaccine safety. https://www.cdc.gov/vaccinesafety/vaccines/hpv-vaccine.html. Last reviewed October 27, 2015. Accessed December 27, 2018.

- Meites E, Kempe A, Markowitz LE. Use of a 2-dose schedule for human papillomavirus vaccination—updated recommendations of the Advisory Committee on Immunization Practices. MMWR. 2016;65(49):1405–1408.

- AAP News website. Jenko M. CDC: 49% of teens up to date on HPV vaccine. http://www.aappublications.org/news/2018/08/23/vac cinationrates082318. August 23, 2018. Accessed December 27, 2018.

- Walker TY, Elam-Evans LD, Yankey D, et al. National, regional, state, and selected local area vaccination coverage among adolescents aged 13–17 years—United States, 2017. MMWR Morb Mortal Wkly Rep. 2018;67:909-917.

- Montague L. Summary basis for regulatory action. October 5, 2018. https://www.fda.gov/downloads/BiologicsBloodVaccines/Vaccines/ApprovedProducts/UCM622941.pdf. Accessed December 27, 2018.

- Tabrizi SN, Brotherton JM, Kaldor JM, et al. Fall in human papillomavirus prevalence following a national vaccination program. J Infect Dis. 2012;206:1645-1651.

- Ali H, Donovan B, Wand H, et al. Genital warts in young Australians five years into national human papillomavirus vaccination programme: national surveillance data [published correction appears in BMJ. 2013;346:F2942]. BMJ. 2013;346:F2032.

- Winer RL, Hughes JP, Feng Q, et al. Incident detection of high-risk human papillomavirus infections in a cohort of high-risk women aged 25-65 years. J Infect Dis. 2016;214:665-675.

- Han JJ, Beltran TH, Song JW, et al. Prevalence of genital human papillomavirus infection and human papillomavirus vaccination rates among US adult men: National Health and Nutrition Examination Survey (NHANES) 2013-2014. JAMA Oncol. 2017;3:810-816.

Puppy bite at yoga retreat leads to rabies death: Prompts health warning

Individuals going to rabies-endemic countries should have a pretrip consultation with a travel health specialist, say authors of a case report describing the death of a woman who sustained a bite from a rabid puppy during a 2017 yoga retreat in rural India.

Preexposure prophylaxis is warranted, especially for individuals expected to be in those countries for long durations, those planning to go to remote areas, or if they plan activities that may put them at risk for rabies exposure, the authors wrote in Morbidity and Mortality Weekly Report.

“In the case of the yoga retreat tour, given the extended length of the tour and the rural and community activities involved, pretravel rabies vaccination should have been considered,” said Julia Murphy, DVM, a veterinarian with the Virginia Department of Health, and her coauthors in the recently published report.

The case also underscores the importance of prompt rabies diagnosis, according to Dr. Murphy and her colleagues: 250 health care workers were assessed for exposure to the patient, 72 (29%) of whom were advised to initiate postexposure prophylaxis and were treated at a cost of nearly a quarter million dollars.

The Virginia woman described in the case report was aged 65 years and had no preexisting health conditions. She had spent more than 2 months on a yoga retreat tour in India and was bitten by a puppy near her hotel in Rishikesh in northern India, according to results of a public health investigation.

That retreat ended on April 7, 2017, according to the report, and on May 3, 2017, the woman started to have pain and paresthesia in her right arm during gardening.

On May 6, she sought care at an urgent care facility, resulting in a diagnosis of carpal tunnel syndrome and a prescription for an NSAID.

The next day, she was evaluated at a hospital for anxiety, insomnia, shortness of breath, and difficulty swallowing water and was given lorazepam for a presumed panic attack. She was discharged and, in her car, experienced claustrophobia and shortness of breath. She returned to the hospital’s ED, received more lorazepam, and was again discharged.

The day after that, she was transported by ambulance to another hospital with increased anxiety, shortness of breath, chest discomfort, and progressive paresthesia; she was found to have elevated cardiac enzymes and underwent emergency cardiac catheterization, which revealed normal arteries.

That evening, the patient became “progressively agitated and combative,” according to the report, and was found to be gasping for air while trying to drink water. When family were questioned about animal exposures, the woman’s husband indicated that she had been bitten on the right hand by a puppy during the yoga retreat, about 6 weeks before the symptoms started.

Once a diagnosis of rabies was confirmed, the woman was started on aggressive treatment but eventually died, according to Dr. Murphy and her coauthors, which made this patient the ninth person in the United States to die from rabies exposure while overseas since 2008. Canine rabies has been eliminated in the United States because of the strict vaccination laws.

“These events underscore the importance of obtaining a thorough pretravel health consultation, particularly when visiting countries with high incidence of emerging or zoonotic pathogens, to ensure awareness of health risks and appropriate pretravel and postexposure health care actions,” they concluded in their report.

Dr. Murphy and her coauthors reported no potential conflicts of interest related to the case report.

SOURCE: Murphy J et al. MMWR Morb Mortal Wkly Rep. 2019 Jan 4;67(5152):1410-4.

Individuals going to rabies-endemic countries should have a pretrip consultation with a travel health specialist, say authors of a case report describing the death of a woman who sustained a bite from a rabid puppy during a 2017 yoga retreat in rural India.

Preexposure prophylaxis is warranted, especially for individuals expected to be in those countries for long durations, those planning to go to remote areas, or if they plan activities that may put them at risk for rabies exposure, the authors wrote in Morbidity and Mortality Weekly Report.

“In the case of the yoga retreat tour, given the extended length of the tour and the rural and community activities involved, pretravel rabies vaccination should have been considered,” said Julia Murphy, DVM, a veterinarian with the Virginia Department of Health, and her coauthors in the recently published report.

The case also underscores the importance of prompt rabies diagnosis, according to Dr. Murphy and her colleagues: 250 health care workers were assessed for exposure to the patient, 72 (29%) of whom were advised to initiate postexposure prophylaxis and were treated at a cost of nearly a quarter million dollars.

The Virginia woman described in the case report was aged 65 years and had no preexisting health conditions. She had spent more than 2 months on a yoga retreat tour in India and was bitten by a puppy near her hotel in Rishikesh in northern India, according to results of a public health investigation.

That retreat ended on April 7, 2017, according to the report, and on May 3, 2017, the woman started to have pain and paresthesia in her right arm during gardening.

On May 6, she sought care at an urgent care facility, resulting in a diagnosis of carpal tunnel syndrome and a prescription for an NSAID.

The next day, she was evaluated at a hospital for anxiety, insomnia, shortness of breath, and difficulty swallowing water and was given lorazepam for a presumed panic attack. She was discharged and, in her car, experienced claustrophobia and shortness of breath. She returned to the hospital’s ED, received more lorazepam, and was again discharged.

The day after that, she was transported by ambulance to another hospital with increased anxiety, shortness of breath, chest discomfort, and progressive paresthesia; she was found to have elevated cardiac enzymes and underwent emergency cardiac catheterization, which revealed normal arteries.

That evening, the patient became “progressively agitated and combative,” according to the report, and was found to be gasping for air while trying to drink water. When family were questioned about animal exposures, the woman’s husband indicated that she had been bitten on the right hand by a puppy during the yoga retreat, about 6 weeks before the symptoms started.

Once a diagnosis of rabies was confirmed, the woman was started on aggressive treatment but eventually died, according to Dr. Murphy and her coauthors, which made this patient the ninth person in the United States to die from rabies exposure while overseas since 2008. Canine rabies has been eliminated in the United States because of the strict vaccination laws.

“These events underscore the importance of obtaining a thorough pretravel health consultation, particularly when visiting countries with high incidence of emerging or zoonotic pathogens, to ensure awareness of health risks and appropriate pretravel and postexposure health care actions,” they concluded in their report.

Dr. Murphy and her coauthors reported no potential conflicts of interest related to the case report.

SOURCE: Murphy J et al. MMWR Morb Mortal Wkly Rep. 2019 Jan 4;67(5152):1410-4.

Individuals going to rabies-endemic countries should have a pretrip consultation with a travel health specialist, say authors of a case report describing the death of a woman who sustained a bite from a rabid puppy during a 2017 yoga retreat in rural India.

Preexposure prophylaxis is warranted, especially for individuals expected to be in those countries for long durations, those planning to go to remote areas, or if they plan activities that may put them at risk for rabies exposure, the authors wrote in Morbidity and Mortality Weekly Report.

“In the case of the yoga retreat tour, given the extended length of the tour and the rural and community activities involved, pretravel rabies vaccination should have been considered,” said Julia Murphy, DVM, a veterinarian with the Virginia Department of Health, and her coauthors in the recently published report.

The case also underscores the importance of prompt rabies diagnosis, according to Dr. Murphy and her colleagues: 250 health care workers were assessed for exposure to the patient, 72 (29%) of whom were advised to initiate postexposure prophylaxis and were treated at a cost of nearly a quarter million dollars.

The Virginia woman described in the case report was aged 65 years and had no preexisting health conditions. She had spent more than 2 months on a yoga retreat tour in India and was bitten by a puppy near her hotel in Rishikesh in northern India, according to results of a public health investigation.

That retreat ended on April 7, 2017, according to the report, and on May 3, 2017, the woman started to have pain and paresthesia in her right arm during gardening.

On May 6, she sought care at an urgent care facility, resulting in a diagnosis of carpal tunnel syndrome and a prescription for an NSAID.

The next day, she was evaluated at a hospital for anxiety, insomnia, shortness of breath, and difficulty swallowing water and was given lorazepam for a presumed panic attack. She was discharged and, in her car, experienced claustrophobia and shortness of breath. She returned to the hospital’s ED, received more lorazepam, and was again discharged.

The day after that, she was transported by ambulance to another hospital with increased anxiety, shortness of breath, chest discomfort, and progressive paresthesia; she was found to have elevated cardiac enzymes and underwent emergency cardiac catheterization, which revealed normal arteries.

That evening, the patient became “progressively agitated and combative,” according to the report, and was found to be gasping for air while trying to drink water. When family were questioned about animal exposures, the woman’s husband indicated that she had been bitten on the right hand by a puppy during the yoga retreat, about 6 weeks before the symptoms started.

Once a diagnosis of rabies was confirmed, the woman was started on aggressive treatment but eventually died, according to Dr. Murphy and her coauthors, which made this patient the ninth person in the United States to die from rabies exposure while overseas since 2008. Canine rabies has been eliminated in the United States because of the strict vaccination laws.

“These events underscore the importance of obtaining a thorough pretravel health consultation, particularly when visiting countries with high incidence of emerging or zoonotic pathogens, to ensure awareness of health risks and appropriate pretravel and postexposure health care actions,” they concluded in their report.

Dr. Murphy and her coauthors reported no potential conflicts of interest related to the case report.

SOURCE: Murphy J et al. MMWR Morb Mortal Wkly Rep. 2019 Jan 4;67(5152):1410-4.

FROM MMWR

Key clinical point: depending on length of trip, location, and activities involved.

Major finding: A Virginia woman died after sustaining a bite from a rabid puppy during a 2017 yoga retreat in rural India.

Study details: Case report including details of the 65-year-old woman’s trip, rabies exposure, symptoms, diagnosis, and eventual death.

Disclosures: Authors reported no potential conflicts of interest.

Source: Murphy J et al. MMWR Morb Mortal Wkly Rep. 2019 Jan 4;67(5152):1410-4.

Danish study finds reassuring data on pregnancy outcomes in atopic dermatitis patients

PARIS – over an 18-year period, which showed no increased risk of pregnancy and birth problems other than modestly increased risks of premature rupture of membranes and neonatal staphylococcal septicemia, according to Jacob P. Thyssen, MD, PhD.

At a session of the European Task Force of Atopic Dermatitis held in conjunction with the annual congress of the European Academy of Dermatology and Venereology, he presented a case control study of 10,668 births to Danish women with atopic dermatitis (AD) during 1997-2014. They were matched 1:10 by age, parity, and birth year to mothers without AD.

The risk of premature rupture of membranes was 15% higher in mothers with AD. And while the increased relative risk of neonatal staphylococcal septicemia was more substantial – a 145% increase – this was in fact a rare complication, observed Dr. Thyssen, a dermatologist at the University of Copenhagen.

There was no significant difference between women with or without AD in rates of preeclampsia, prematurity, pregnancy-induced hypertension, placenta previa, placental abruption, neonatal nonstaphylococcal septicemia, or other complications. The two groups had a similar number of visits to physicians and midwives during pregnancy.

Moreover, although the body mass index was similar in women with or without AD, the risk of gestational diabetes in women with the disease was significantly reduced by 21%; their risk of having a large-for-gestational-age baby with a birth weight of 4,500 g or more was also significantly lower than in controls.

Women received less treatment for AD during their pregnancy than they did beforehand. While pregnant, their disease was managed predominantly with topical corticosteroids and UV therapy. There was very little use of superpotent topical steroids, topical calcineurin inhibitors, or immunosuppressants, although 10% of pregnant women received systemic corticosteroids for their AD.

Dr. Thyssen reported serving as a scientific adviser and paid speaker for Leo Pharma, Roche, Eli Lilly, and Sanofi-Genzyme, although this study was conducted without commercial support.

PARIS – over an 18-year period, which showed no increased risk of pregnancy and birth problems other than modestly increased risks of premature rupture of membranes and neonatal staphylococcal septicemia, according to Jacob P. Thyssen, MD, PhD.

At a session of the European Task Force of Atopic Dermatitis held in conjunction with the annual congress of the European Academy of Dermatology and Venereology, he presented a case control study of 10,668 births to Danish women with atopic dermatitis (AD) during 1997-2014. They were matched 1:10 by age, parity, and birth year to mothers without AD.

The risk of premature rupture of membranes was 15% higher in mothers with AD. And while the increased relative risk of neonatal staphylococcal septicemia was more substantial – a 145% increase – this was in fact a rare complication, observed Dr. Thyssen, a dermatologist at the University of Copenhagen.

There was no significant difference between women with or without AD in rates of preeclampsia, prematurity, pregnancy-induced hypertension, placenta previa, placental abruption, neonatal nonstaphylococcal septicemia, or other complications. The two groups had a similar number of visits to physicians and midwives during pregnancy.

Moreover, although the body mass index was similar in women with or without AD, the risk of gestational diabetes in women with the disease was significantly reduced by 21%; their risk of having a large-for-gestational-age baby with a birth weight of 4,500 g or more was also significantly lower than in controls.

Women received less treatment for AD during their pregnancy than they did beforehand. While pregnant, their disease was managed predominantly with topical corticosteroids and UV therapy. There was very little use of superpotent topical steroids, topical calcineurin inhibitors, or immunosuppressants, although 10% of pregnant women received systemic corticosteroids for their AD.

Dr. Thyssen reported serving as a scientific adviser and paid speaker for Leo Pharma, Roche, Eli Lilly, and Sanofi-Genzyme, although this study was conducted without commercial support.

PARIS – over an 18-year period, which showed no increased risk of pregnancy and birth problems other than modestly increased risks of premature rupture of membranes and neonatal staphylococcal septicemia, according to Jacob P. Thyssen, MD, PhD.

At a session of the European Task Force of Atopic Dermatitis held in conjunction with the annual congress of the European Academy of Dermatology and Venereology, he presented a case control study of 10,668 births to Danish women with atopic dermatitis (AD) during 1997-2014. They were matched 1:10 by age, parity, and birth year to mothers without AD.

The risk of premature rupture of membranes was 15% higher in mothers with AD. And while the increased relative risk of neonatal staphylococcal septicemia was more substantial – a 145% increase – this was in fact a rare complication, observed Dr. Thyssen, a dermatologist at the University of Copenhagen.

There was no significant difference between women with or without AD in rates of preeclampsia, prematurity, pregnancy-induced hypertension, placenta previa, placental abruption, neonatal nonstaphylococcal septicemia, or other complications. The two groups had a similar number of visits to physicians and midwives during pregnancy.

Moreover, although the body mass index was similar in women with or without AD, the risk of gestational diabetes in women with the disease was significantly reduced by 21%; their risk of having a large-for-gestational-age baby with a birth weight of 4,500 g or more was also significantly lower than in controls.

Women received less treatment for AD during their pregnancy than they did beforehand. While pregnant, their disease was managed predominantly with topical corticosteroids and UV therapy. There was very little use of superpotent topical steroids, topical calcineurin inhibitors, or immunosuppressants, although 10% of pregnant women received systemic corticosteroids for their AD.

Dr. Thyssen reported serving as a scientific adviser and paid speaker for Leo Pharma, Roche, Eli Lilly, and Sanofi-Genzyme, although this study was conducted without commercial support.

REPORTING FROM THE EADV CONGRESS

Key clinical point: Birth complications are uncommon for women with atopic dermatitis in pregnancy.

Major finding: The risk of premature rupture of membranes was increased by 15% in women with atopic dermatitis in pregnancy, but their risk of gestational diabetes was reduced by 21%.

Study details: This case control study included 10,668 births to Danish women with atopic dermatitis and 10 times as many matched controls without the disease.

Disclosures: The study presenter reported serving as a scientific adviser and paid speaker for Leo Pharma, Roche, Eli Lilly, and Sanofi-Genzyme, although this study was conducted without commercial support.

Difelikefalin shows promise for hemodialysis-associated itch

PARIS – while achieving across-the-board clinically meaningful improvements in quality of life measures in patients with hemodialysis-associated pruritus in a phase 2 study, Frédérique Menzaghi, PhD, reported at the annual congress of the European Academy of Dermatology and Venereology.

At present there is no approved medication in the United States or Europe for the often intense itching associated with chronic kidney disease. Off-label treatments have limited efficacy.

Dr. Menzaghi is senior vice president for research and development at Cara Therapeutics, which is developing difelikefalin.

More than half – 60% to 70% – of patients on hemodialysis for end-stage renal disease experience chronic pruritus, as do a smaller proportion of individuals with chronic kidney disease (CKD) not requiring dialysis. CKD-associated pruritus is a day-and-night itch that makes life miserable for affected patients. Not only must they endure the predictable complications of skin excoriation, including impetigo, ulcerations, papules, and prurigo nodularis, but they also experience sleep disruption, depressed mood, and a 10%-20% increased mortality risk compared with CKD patients without pruritus.

Difelikefalin is a potent and selective peripheral kappa opioid receptor agonist that doesn’t activate mu or delta opioid receptors. It’s a synthetic drug that mimics endogenous dynorphin. Its key attribute is that it doesn’t cross the blood/brain barrier, so it doesn’t pose a risk for adverse events caused by activation of central opioid receptors. Difelikefalin has two mechanisms of action in CKD-associated pruritus: an antipruritic effect due to inhibition of ion channels responsible for afferent peripheral nerve activity; and an anti-inflammatory effect mediated by activation of kappa opioid receptors expressed by immune system cells, according to Dr. Menzaghi.

She reported on 174 hemodialysis patients with moderate to severe CKD-associated pruritus who were randomized to a double-blind, phase 2, dose-ranging study featuring an intravenous bolus of difelikefalin at 0.5, 1.0, or 1.5 mcg/kg or placebo given immediately after each of the thrice-weekly hemodialysis sessions for 8 weeks.

An oral formulation of difelikefalin is also under investigation for treatment of CKD-associated pruritus. The IV version is being developed for hemodialysis patients because difelikefalin is renally excreted.

“We’re taking advantage of the fact that their kidneys aren’t working. The drug stays in the system until the next dialysis because it can’t be eliminated. It’s quite convenient for these patients,” she explained.

The primary endpoint in the phase 2 study was change from baseline through week 8 in the weekly average of a patient’s daily self-rated 0-10 worst itching intensity numeric rating scale (NRS) scores. All participants had to have a baseline NRS score of at least 4, considered the lower threshold for moderate itch. In fact, the mean baseline score was 6.7-7.1 in the four study arms.

The results

Sixty-four percent of patients on difelikefalin 0.5 mcg/kg – the most effective dose – experienced at least a 3-point reduction, compared with 29% of placebo-treated controls. And a 4-point or greater reduction in NRS from baseline was documented in 51% of patients on difelikefalin at 0.5 mcg/kg, compared with 24% of controls.

Although a 4-point difference is widely considered to represent clinically meaningful improvement in atopic dermatitis studies, Dr. Menzaghi said psychometric analyses of the difelikefalin trial data indicated that a 3-point or greater improvement in NRS score was associated with clinically meaningful change.

“Our data suggest that a 4-point change may not be generalizable to all conditions,” she said.

Hemodialysis patients with severe baseline itch typically improved to moderate itch on difelikefalin, while those with baseline moderate itch – that is, an NRS of 4-6 – dropped down to mild or no itch while on the drug.

“But that’s just a number. The question is, is that really clinically meaningful?” Dr. Menzaghi noted.

The answer, she continued, is yes. A high correlation was seen between reduction in itch intensity and improvement in quality of life. Scores on the 5-D Itch Scale and Skindex-10 improved two- to threefold more in the difelikefalin 0.5-mcg group than in controls. So did scores on the 12-item Medical Outcomes Study Sleep Scale assessing sleep restlessness, awakening during sleep, and trouble falling asleep.

“We think these results suggest that peripheral kappa opioid receptors play an integral role in the modulation of itch signals and represent a primary target for the development of antipruritic agents,” said Dr. Menzaghi.

Indeed, a phase 3 randomized trial of difelikefalin 0.5 mcg/kg versus placebo in 350 hemodialysis patients with CKD-associated itch is ongoing in the United States, Europe, Australia, and Korea. Also ongoing is a phase 2 U.S. study of oral difelikefalin in patients with CKD-associated pruritus, many of whom are not on hemodialysis. In January, the company announced that enrollment in a phase 3 U.S. study of difelikefalin injection (0.5 mcg/kg) in hemodialysis patients with moderate to severe CKD-associated pruritus had been completed. The trials are funded by Cara Therapeutics.

SOURCE: Menzaghi F. EADV Congress, Abstract FC0.4.7.

PARIS – while achieving across-the-board clinically meaningful improvements in quality of life measures in patients with hemodialysis-associated pruritus in a phase 2 study, Frédérique Menzaghi, PhD, reported at the annual congress of the European Academy of Dermatology and Venereology.

At present there is no approved medication in the United States or Europe for the often intense itching associated with chronic kidney disease. Off-label treatments have limited efficacy.

Dr. Menzaghi is senior vice president for research and development at Cara Therapeutics, which is developing difelikefalin.

More than half – 60% to 70% – of patients on hemodialysis for end-stage renal disease experience chronic pruritus, as do a smaller proportion of individuals with chronic kidney disease (CKD) not requiring dialysis. CKD-associated pruritus is a day-and-night itch that makes life miserable for affected patients. Not only must they endure the predictable complications of skin excoriation, including impetigo, ulcerations, papules, and prurigo nodularis, but they also experience sleep disruption, depressed mood, and a 10%-20% increased mortality risk compared with CKD patients without pruritus.

Difelikefalin is a potent and selective peripheral kappa opioid receptor agonist that doesn’t activate mu or delta opioid receptors. It’s a synthetic drug that mimics endogenous dynorphin. Its key attribute is that it doesn’t cross the blood/brain barrier, so it doesn’t pose a risk for adverse events caused by activation of central opioid receptors. Difelikefalin has two mechanisms of action in CKD-associated pruritus: an antipruritic effect due to inhibition of ion channels responsible for afferent peripheral nerve activity; and an anti-inflammatory effect mediated by activation of kappa opioid receptors expressed by immune system cells, according to Dr. Menzaghi.

She reported on 174 hemodialysis patients with moderate to severe CKD-associated pruritus who were randomized to a double-blind, phase 2, dose-ranging study featuring an intravenous bolus of difelikefalin at 0.5, 1.0, or 1.5 mcg/kg or placebo given immediately after each of the thrice-weekly hemodialysis sessions for 8 weeks.

An oral formulation of difelikefalin is also under investigation for treatment of CKD-associated pruritus. The IV version is being developed for hemodialysis patients because difelikefalin is renally excreted.

“We’re taking advantage of the fact that their kidneys aren’t working. The drug stays in the system until the next dialysis because it can’t be eliminated. It’s quite convenient for these patients,” she explained.

The primary endpoint in the phase 2 study was change from baseline through week 8 in the weekly average of a patient’s daily self-rated 0-10 worst itching intensity numeric rating scale (NRS) scores. All participants had to have a baseline NRS score of at least 4, considered the lower threshold for moderate itch. In fact, the mean baseline score was 6.7-7.1 in the four study arms.