User login

New Take on Elder Care

Families often note that after older relatives return home from the hospital, something is wrong with them.

While the acute condition that brought a relative into the hospital has been remedied, major functional and cognitive deficits such as confusion, falls, and difficulty with basic activities of daily living remain.

This post-hospital decline may not be appreciated by hospital clinicians, perhaps because the problems do not become visible until the patient is home. However, these problems place significant burdens on patients and families.

Following discharge for an acute hospitalization, about a third of older patients will have a major new disability that threatens their ability to live independently.1 Among community-dwelling elders, half of all new disability occurs within a month of hospitalization.2 It isn’t surprising that nursing home placement has grown more common for medical hospitalizations, even for seemingly reversible medical problems.

Older adults will make up an increasing number of the patients cared for by hospitalists. The Acute Care for Elders (ACE) unit model of care focuses on preventing functional decline and increasing discharges to home.

In 2005, leadership of the San Francisco General Hospital Medical Center (SFGHMC) committed to improving care for hospitalized elders by adopting the ACE model.3

The ACE model combats hospital-acquired disability by improving care processes for older patients.

Major motivating factors for the change included demographic and quality-of-care imperatives. After a nine-month planning process, the SFGHMC ACE unit opened in February.

Rationale

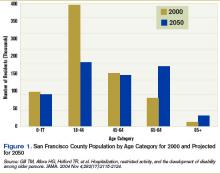

Largely driven by the baby boom, the number of California seniors older than 65 will double from 3.5 million to 7 million over the next 40 years, and those older than 85 will triple from about 500,000 to 1.5 million. In San Francisco, changes will be even more dramatic as the number of residents over 65 increases from 14% of the population to 32%.4 (See Figure 1, right).

In California, people 65 to 84 are almost three times as likely to be hospitalized as those between 45 and 64. If rates of hospitalization do not change, an increase in hospitalized older adults will occur as the baby boom generation ages.

In addition, hospitalization can be hazardous for older adults, with increased risk for functional and cognitive disability and adverse events.5-7 As a result, hospitalization-associated disability represents a growing threat to the independence of the older population. A variety of changes to usual care have been adopted in an effort to reduce the hazards of hospitalization in the elderly.8-11

ACE Model

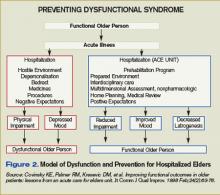

The ACE unit model, proven to reduce the risk of hospital-acquired disability in the elderly, is based on the Model of Dysfunction for Hospitalized Elders.12 (See Figure 2, p. 23)

This model outlines how processes of hospital care for the elderly promote physical impairment and depressed mood, leading to dysfunction. Counterproduc-tive factors in older adults include a hostile environment (lack of natural sunlight, high-glare floors, poor way-finding cues, high noise levels), depersonalization (lack of personal effects, clothing, and usual daily routines), bed rest through multiple tethers or inattention, medicines inappropriate in the elderly or given at inappropriate doses, procedures, and negative expectations (usually that the patient will require nursing home placement after admission).

These processes are the targets of the ACE intervention. The idea is to improve quality of care for the elderly by promoting rehabilitation and preventing disability.

The ACE unit addresses these issues through a “prehabilitation program.” The ACE unit is a physical location in the hospital with 10 beds. Care is redesigned by placing the patient at the center of restorative efforts of an interdisciplinary team consisting of an advanced practice nurse, a social worker, an occupational and a physical therapist, a nutritionist, a pharmacist, and a medical director. This ACE Unit team meets daily to review and plan care for all patients. Recommendations for nursing care and rehabilitation evaluation are implemented by the ACE team directly. Other recommendations, such as changing medications or considering alternative approaches to common geriatric syndromes are communicated to the primary team, which maintains overall responsibility for the care of the patient.

Each patient’s assessment is multidimensional, with an emphasis on nonpharmacologic interventions where practical. For example, an emphasis is placed on after-dinner exercise such as walking and socializing to promote sleep and reduce medication use. Nursing-care plans were revised to promote mobility, discourage inappropriate Foley use, and encourage adequate hydration and nutrition.

Recommendations are communicated to the primary team via a recommendation form placed in the physician-order section and text pages. The unit’s medical director and pharmacist review medications. Recommendations that involve medication changes are discussed with the primary team, which write all medication orders. Home planning begins on the day of admission.

Prior to opening the unit, the ACE unit social worker met with key city and county agencies including Aging and Adult Services, the Public Guardian, In-Home Supportive Services, and community nursing homes to introduce the unit and plan for an effective and safe transition.

All staff expect patients to maintain prehospital physical functioning. When possible, patients are expected to wear their own clothes, eat all their meals in a common dining room, and ambulate or exercise daily.

We considered establishing criteria for admission.13 We have not adopted formal criteria for patients 65 or older, presence of medical non-surgical condition(s) that require(s) acute hospitalization, and no need for telemetry or chemotherapy. As we learn how best to serve our hospitalized older adult population with the resources of the unit, we will re-evaluate targeting criteria. Most of our admissions are from the emergency department (ED), and the remainder are from other units in the hospital.

Challenges

Key challenges in opening the new service include securing commitment and resources from organizational leaders and key stakeholders; incorporation of the ACE unit concept in an academic training center; hiring key staff, especially the geriatric clinical nurse specialist and pharmacist positions; and completing the environmental rehabilitation on a limited budget.

While gaps in the care of the geriatric patient population were well identified at SFGHMC as far back as 1996 by a multidisciplinary task force, no actions on recommendations were taken, for several key reasons.

First, an executive level administrator or physician champion was not a member of the task force. Second, the organization did not have a department or regulatory mandate to address the gaps in the care of the elderly patients. Third, there was no link between the hospital strategic plan and the recommendations.

By 2004, these issues were largely addressed. A new chief nursing officer with a background in quality improvement understood the demographic and quality imperatives to improve care for hospitalized older adults.

That same year, the Hospital Executive Committee incorporated patient safety into the hospital strategic plan. This resulted in a successful business plan for an ACE Unit and geriatric consultation service linked to organizational strategy.

Funding was allocated for a medical director and a clinical nurse specialist in fiscal year 2005-2006. In addition, a grant was obtained from the SFGH Foundation to fund equipment, renovations, and staff education/training.

The original ACE unit concept involved expert, interdisciplinary geriatric assessment and communication of suggestions via a paper-based chart.

Initially, we felt the primary medical team should round with the ACE team, preferably at the bedside. However, informal focus groups held with the residents suggested this would happen infrequently.

The demands on the medical teams of completing patient rounds before morning attending rounds were cited as the main reason that model wouldn’t work.

We have implemented the following methods to promote communication between the ACE unit team and the primary medical team:

- Medical teams are encouraged to attend ACE unit rounds while on bedside rounds. This provides an opportunity to model the team-delivered care for house staff and medical students, an ACGME requirement;

- Suggestions to change medications are directly text-paged to the house staff; and

- Recommendations are summarized in a communication sheet left in the chart (this not a permanent part of the medical record).

We plan on using the text-paging more widely once the unit has wireless computer capability. Despite this, there are occasions where a team is not aware of a recommendation or new emphasis in the care plan. We are considering additional ways to improve communication such as attending the primary team attending rounds.

In California and other states there is a shortage of clinical pharmacists and masters-prepared nurses with expertise in geriatrics.14-16 The advanced practice nurse performs a vital role in raising the level of knowledge, skills, and attitudes for the nursing staff on the ACE unit.

In addition, we see the ACE unit as a drop in the pond; we feel a responsibility to expand nursing geriatric competency throughout appropriate hospital areas. Thus, this nursing role is at the center of preparing the hospital to care for an older patient population.

This position remained unfilled for almost a year despite an intensive national search. This prompted us to incorporate the geriatric resource nurse model into our unit while we continued our recruitment.

Although we have successfully concluded our search for a nursing leader for the ACE unit, we have yet to hire a clinical pharmacist.

The rehabilitation of the unit would not have been possible without foundation support. As a public hospital with many competing demands, monies are limited for the rehabilitation required to create a more welcoming, safer environment for the older patient. In this case, the hospital foundation and a local foundation made grants to the ACE unit to allow us to change the environment.

These grants have allowed for significant changes to the unit, including elevated toilet seats, high-backed chairs, handrails, unit-based physical therapy equipment, and activities to promote non-pharmacological approaches to agitation.

Readiness for Change

All levels of hospital staff embraced the ACE unit concept. Department leaders in rehabilitation, nutrition, social work, and pharmacy felt ACE unit principles would improve care delivery over usual care.

Early on, department leaders and medical staff enthusiastically participated on a steering committee to help guide implementation efforts. In addition, when we offered geriatric resource nurse training to our nursing staff, more than 20 out of 50 unit nurses expressed interest.

Staff from all departments represented on the ACE unit team also expressed interest in and attended the three days of training. This provided baseline knowledge of common geriatric syndromes in hospitalized older patients for all team members. This been helpful during ACE team discussions.

Although medical residents felt they could not consistently attend ACE rounds, they appreciated potential benefits of the unit:

- Different perspectives could provide a wider range of evaluation and treatment recommendations for their patients;

- The co-location of key disciplines could result in overall time savings in calling for and ordering evaluations;

- The reduced likelihood that key interventions such as mobilization, feeding, catheter removal, and medication review would be missed; and

- The opportunity to learn principles of geriatric care through attending ACE rounds (when possible).

Medical staff in other departments immediately accepted the rationale for the unit.

Many expressed interest in expanding the concept to their departments, especially orthopedics, general surgery, and the ED. Although unfamiliar with specific interventions to improve care for hospitalized elders, the underlying concepts of patient-centered, team-delivered care with a focus on function resonated with most medical staff.

Next Steps

The unit is still in startup mode. Our major areas of focus are:

- Evaluating and improving team dynamics: We have engaged with researchers to evaluate our team dynamics and intervene where necessary to promote a high-functioning team.17

- Developing a culture of performance improvement: One of the hallmarks of high-functioning teams are measures of performance that are team-derived and reflect work product that the team can control.17

We are putting into place processes to measure key quality parameters including length of stay; nursing home placement; readmission rate, inappropriate catheter use; inappropriate medication prescribing; incidence of delirium, falls, and pressure ulcers; functional and cognitive status at admission and discharge; and patient satisfaction.

The orders set used by admitting residents are the standard general medical ward admission set and need revision for the ACE unit.

- Developing a research program: Our goal is to develop a research program evaluating interventions to prevent post-hospital degeneration of elders’ health. There is a dearth of research on improving hospital care for older, vulnerable adults.

- Expanding philanthropy support: The unit has benefited tremendously from philanthropy. In a relatively resource-poor setting, this allowed for rapid engagement with designers and vendors to remake the environment. We plan to expand our outreach efforts to interested philanthropists.

Summary

The ACE unit model can improve care for hospitalized older adults.

It requires a sustained level of commitment from hospital leaders, a focus on patient-centered, team-delivered care, sensitivity to communication modalities with primary caregivers, an awareness of the market for key professionals required, and flexibility to respond effectively to the many challenges that will emerge in implementing this model locally. TH

Dr. Pierluissi is medical director of the ACE unit at the San Francisco General Hospital. Susan Currin is the hospital’s chief nursing officer.

References

- Covinsky KE, Palmer RM, Fortinsky RH, et al. Loss of independence in activities of daily living in older adults hospitalized with medical illnesses: increased vulnerability with age. J Am Geriatr Soc. 2003;51(4):451-458.

- Gill TM, Allore HG, Holford TR, et al. Hospitalization, restricted activity, and the development of disability among older persons. JAMA. 2004 Nov 3;292(17):2115-2124

- Landefeld CS, Palmer RM, Kresevic DM, et al. A randomized trial of care in a hospital medical unit especially designed to improve the functional outcomes of acutely ill older patients. N Engl J Med. 1995 May 18;332(20):1338-1344.

- State of California, Department of Finance. Race/Ethnic Population with Age and Sex Detail, 2000–2050; 2004: Sacramento, Calif.

- Creditor MC. Hazards of hospitalization of the elderly. Ann Intern Med. 1993 Feb 1;118(3):219-223.

- Inouye SK. Delirium in older persons. N Engl J Med. 2006 Jun 8;354(23):2509-2511; author reply 2509-11. Comment on: N Engl J Med. 2006 Mar 16;354(11):1157-1165.

- Brennan TA, Leape LL, Laird NM, et al. Incidence of adverse events and negligence in hospitalized patients. Results of the Harvard Medical Practice Study I. N Engl J Med. 1991 Feb 7;324(6):370-376. Comment in: N Engl J Med. 1991 Jul 18;325(3):210.

- Cohen HJ, Feussner JR, Weinberger M, et al. A controlled trial of inpatient and outpatient geriatric evaluation and management. N Engl J Med. 2002 Mar 21;346(12):905-912. Comment in: Curr Surg. 2004 May-Jun;61(3):266-74. N Engl J Med. 2002 Aug 1;347(5):371-373; author reply 371-373; author reply 371-3: N Engl J Med. 2002 Mar 21;346(12):874.

- Inouye SK, Bogardus ST Jr, Charpentier PA, et al. A multicomponent intervention to prevent delirium in hospitalized older patients. N Engl J Med. 1999 Mar 4;340(9):669-676. Comment in: N Engl J Med. 1999 Jul 29;341(5):369-370; author reply 370. N Engl J Med. 1999 Mar 4;340(9):720-721.

- Reuben DB, Borok GM, Wolde-Tsadik G, et al. A randomized trial of comprehensive geriatric assessment in the care of hospitalized patients. N Engl J Med. 1995 May 18;332(20):1345-1350. Comment in: N Engl J Med. 1995 May 18;332(20):1376-1378.

- Leff B, Burton L, Mader SL, et al. Hospital at home: feasibility and outcomes of a program to provide hospital-level care at home for acutely ill older patients. Ann Intern Med. 2005 Dec 6;143(11):798-808. Comment in: Ann Intern Med. 2005 Dec 6;143(11):840-1. Ann Intern Med. 2006 Mar 21;144(6):456. Summary for patients in:Ann Intern Med. 2005 Dec 6;143(11):I56.

- Covinsky KE, Palmer RM, Kresevic DM, et. al. Improving functional outcomes in older patients: lessons from an acute care for elders unit. Jt Comm J Qual Improv. 1998 Feb;24(2):63-76.

- Wieland D, Rubenstein LZ. What do we know about patient targeting in geriatric evaluation and management (GEM) programs? Aging (Milano). 1996 Oct; 8(5):297-310.

- Spetz J, Dyer W. Forecasts of the Registered Nurse Workforce in California. 2005, University of California, San Francisco: San Francisco.

- Fleming KC, Evans JM, Chutka DS. Caregiver and clinician shortages in an aging nation. Mayo Clin Proc. 2003 Aug;78(8):1026-1040.

- Knapp KK, Quist RM, Walton SM, et al. Update on the pharmacist shortage: National and state data through 2003. Am J Health Syst Pharm. 2005 Mar 1;62(5):492-499.

- Katzenbach JR, Smith DK. The Discipline of Teams. Harv Bus Rev. July-August 2005:1-9.

Families often note that after older relatives return home from the hospital, something is wrong with them.

While the acute condition that brought a relative into the hospital has been remedied, major functional and cognitive deficits such as confusion, falls, and difficulty with basic activities of daily living remain.

This post-hospital decline may not be appreciated by hospital clinicians, perhaps because the problems do not become visible until the patient is home. However, these problems place significant burdens on patients and families.

Following discharge for an acute hospitalization, about a third of older patients will have a major new disability that threatens their ability to live independently.1 Among community-dwelling elders, half of all new disability occurs within a month of hospitalization.2 It isn’t surprising that nursing home placement has grown more common for medical hospitalizations, even for seemingly reversible medical problems.

Older adults will make up an increasing number of the patients cared for by hospitalists. The Acute Care for Elders (ACE) unit model of care focuses on preventing functional decline and increasing discharges to home.

In 2005, leadership of the San Francisco General Hospital Medical Center (SFGHMC) committed to improving care for hospitalized elders by adopting the ACE model.3

The ACE model combats hospital-acquired disability by improving care processes for older patients.

Major motivating factors for the change included demographic and quality-of-care imperatives. After a nine-month planning process, the SFGHMC ACE unit opened in February.

Rationale

Largely driven by the baby boom, the number of California seniors older than 65 will double from 3.5 million to 7 million over the next 40 years, and those older than 85 will triple from about 500,000 to 1.5 million. In San Francisco, changes will be even more dramatic as the number of residents over 65 increases from 14% of the population to 32%.4 (See Figure 1, right).

In California, people 65 to 84 are almost three times as likely to be hospitalized as those between 45 and 64. If rates of hospitalization do not change, an increase in hospitalized older adults will occur as the baby boom generation ages.

In addition, hospitalization can be hazardous for older adults, with increased risk for functional and cognitive disability and adverse events.5-7 As a result, hospitalization-associated disability represents a growing threat to the independence of the older population. A variety of changes to usual care have been adopted in an effort to reduce the hazards of hospitalization in the elderly.8-11

ACE Model

The ACE unit model, proven to reduce the risk of hospital-acquired disability in the elderly, is based on the Model of Dysfunction for Hospitalized Elders.12 (See Figure 2, p. 23)

This model outlines how processes of hospital care for the elderly promote physical impairment and depressed mood, leading to dysfunction. Counterproduc-tive factors in older adults include a hostile environment (lack of natural sunlight, high-glare floors, poor way-finding cues, high noise levels), depersonalization (lack of personal effects, clothing, and usual daily routines), bed rest through multiple tethers or inattention, medicines inappropriate in the elderly or given at inappropriate doses, procedures, and negative expectations (usually that the patient will require nursing home placement after admission).

These processes are the targets of the ACE intervention. The idea is to improve quality of care for the elderly by promoting rehabilitation and preventing disability.

The ACE unit addresses these issues through a “prehabilitation program.” The ACE unit is a physical location in the hospital with 10 beds. Care is redesigned by placing the patient at the center of restorative efforts of an interdisciplinary team consisting of an advanced practice nurse, a social worker, an occupational and a physical therapist, a nutritionist, a pharmacist, and a medical director. This ACE Unit team meets daily to review and plan care for all patients. Recommendations for nursing care and rehabilitation evaluation are implemented by the ACE team directly. Other recommendations, such as changing medications or considering alternative approaches to common geriatric syndromes are communicated to the primary team, which maintains overall responsibility for the care of the patient.

Each patient’s assessment is multidimensional, with an emphasis on nonpharmacologic interventions where practical. For example, an emphasis is placed on after-dinner exercise such as walking and socializing to promote sleep and reduce medication use. Nursing-care plans were revised to promote mobility, discourage inappropriate Foley use, and encourage adequate hydration and nutrition.

Recommendations are communicated to the primary team via a recommendation form placed in the physician-order section and text pages. The unit’s medical director and pharmacist review medications. Recommendations that involve medication changes are discussed with the primary team, which write all medication orders. Home planning begins on the day of admission.

Prior to opening the unit, the ACE unit social worker met with key city and county agencies including Aging and Adult Services, the Public Guardian, In-Home Supportive Services, and community nursing homes to introduce the unit and plan for an effective and safe transition.

All staff expect patients to maintain prehospital physical functioning. When possible, patients are expected to wear their own clothes, eat all their meals in a common dining room, and ambulate or exercise daily.

We considered establishing criteria for admission.13 We have not adopted formal criteria for patients 65 or older, presence of medical non-surgical condition(s) that require(s) acute hospitalization, and no need for telemetry or chemotherapy. As we learn how best to serve our hospitalized older adult population with the resources of the unit, we will re-evaluate targeting criteria. Most of our admissions are from the emergency department (ED), and the remainder are from other units in the hospital.

Challenges

Key challenges in opening the new service include securing commitment and resources from organizational leaders and key stakeholders; incorporation of the ACE unit concept in an academic training center; hiring key staff, especially the geriatric clinical nurse specialist and pharmacist positions; and completing the environmental rehabilitation on a limited budget.

While gaps in the care of the geriatric patient population were well identified at SFGHMC as far back as 1996 by a multidisciplinary task force, no actions on recommendations were taken, for several key reasons.

First, an executive level administrator or physician champion was not a member of the task force. Second, the organization did not have a department or regulatory mandate to address the gaps in the care of the elderly patients. Third, there was no link between the hospital strategic plan and the recommendations.

By 2004, these issues were largely addressed. A new chief nursing officer with a background in quality improvement understood the demographic and quality imperatives to improve care for hospitalized older adults.

That same year, the Hospital Executive Committee incorporated patient safety into the hospital strategic plan. This resulted in a successful business plan for an ACE Unit and geriatric consultation service linked to organizational strategy.

Funding was allocated for a medical director and a clinical nurse specialist in fiscal year 2005-2006. In addition, a grant was obtained from the SFGH Foundation to fund equipment, renovations, and staff education/training.

The original ACE unit concept involved expert, interdisciplinary geriatric assessment and communication of suggestions via a paper-based chart.

Initially, we felt the primary medical team should round with the ACE team, preferably at the bedside. However, informal focus groups held with the residents suggested this would happen infrequently.

The demands on the medical teams of completing patient rounds before morning attending rounds were cited as the main reason that model wouldn’t work.

We have implemented the following methods to promote communication between the ACE unit team and the primary medical team:

- Medical teams are encouraged to attend ACE unit rounds while on bedside rounds. This provides an opportunity to model the team-delivered care for house staff and medical students, an ACGME requirement;

- Suggestions to change medications are directly text-paged to the house staff; and

- Recommendations are summarized in a communication sheet left in the chart (this not a permanent part of the medical record).

We plan on using the text-paging more widely once the unit has wireless computer capability. Despite this, there are occasions where a team is not aware of a recommendation or new emphasis in the care plan. We are considering additional ways to improve communication such as attending the primary team attending rounds.

In California and other states there is a shortage of clinical pharmacists and masters-prepared nurses with expertise in geriatrics.14-16 The advanced practice nurse performs a vital role in raising the level of knowledge, skills, and attitudes for the nursing staff on the ACE unit.

In addition, we see the ACE unit as a drop in the pond; we feel a responsibility to expand nursing geriatric competency throughout appropriate hospital areas. Thus, this nursing role is at the center of preparing the hospital to care for an older patient population.

This position remained unfilled for almost a year despite an intensive national search. This prompted us to incorporate the geriatric resource nurse model into our unit while we continued our recruitment.

Although we have successfully concluded our search for a nursing leader for the ACE unit, we have yet to hire a clinical pharmacist.

The rehabilitation of the unit would not have been possible without foundation support. As a public hospital with many competing demands, monies are limited for the rehabilitation required to create a more welcoming, safer environment for the older patient. In this case, the hospital foundation and a local foundation made grants to the ACE unit to allow us to change the environment.

These grants have allowed for significant changes to the unit, including elevated toilet seats, high-backed chairs, handrails, unit-based physical therapy equipment, and activities to promote non-pharmacological approaches to agitation.

Readiness for Change

All levels of hospital staff embraced the ACE unit concept. Department leaders in rehabilitation, nutrition, social work, and pharmacy felt ACE unit principles would improve care delivery over usual care.

Early on, department leaders and medical staff enthusiastically participated on a steering committee to help guide implementation efforts. In addition, when we offered geriatric resource nurse training to our nursing staff, more than 20 out of 50 unit nurses expressed interest.

Staff from all departments represented on the ACE unit team also expressed interest in and attended the three days of training. This provided baseline knowledge of common geriatric syndromes in hospitalized older patients for all team members. This been helpful during ACE team discussions.

Although medical residents felt they could not consistently attend ACE rounds, they appreciated potential benefits of the unit:

- Different perspectives could provide a wider range of evaluation and treatment recommendations for their patients;

- The co-location of key disciplines could result in overall time savings in calling for and ordering evaluations;

- The reduced likelihood that key interventions such as mobilization, feeding, catheter removal, and medication review would be missed; and

- The opportunity to learn principles of geriatric care through attending ACE rounds (when possible).

Medical staff in other departments immediately accepted the rationale for the unit.

Many expressed interest in expanding the concept to their departments, especially orthopedics, general surgery, and the ED. Although unfamiliar with specific interventions to improve care for hospitalized elders, the underlying concepts of patient-centered, team-delivered care with a focus on function resonated with most medical staff.

Next Steps

The unit is still in startup mode. Our major areas of focus are:

- Evaluating and improving team dynamics: We have engaged with researchers to evaluate our team dynamics and intervene where necessary to promote a high-functioning team.17

- Developing a culture of performance improvement: One of the hallmarks of high-functioning teams are measures of performance that are team-derived and reflect work product that the team can control.17

We are putting into place processes to measure key quality parameters including length of stay; nursing home placement; readmission rate, inappropriate catheter use; inappropriate medication prescribing; incidence of delirium, falls, and pressure ulcers; functional and cognitive status at admission and discharge; and patient satisfaction.

The orders set used by admitting residents are the standard general medical ward admission set and need revision for the ACE unit.

- Developing a research program: Our goal is to develop a research program evaluating interventions to prevent post-hospital degeneration of elders’ health. There is a dearth of research on improving hospital care for older, vulnerable adults.

- Expanding philanthropy support: The unit has benefited tremendously from philanthropy. In a relatively resource-poor setting, this allowed for rapid engagement with designers and vendors to remake the environment. We plan to expand our outreach efforts to interested philanthropists.

Summary

The ACE unit model can improve care for hospitalized older adults.

It requires a sustained level of commitment from hospital leaders, a focus on patient-centered, team-delivered care, sensitivity to communication modalities with primary caregivers, an awareness of the market for key professionals required, and flexibility to respond effectively to the many challenges that will emerge in implementing this model locally. TH

Dr. Pierluissi is medical director of the ACE unit at the San Francisco General Hospital. Susan Currin is the hospital’s chief nursing officer.

References

- Covinsky KE, Palmer RM, Fortinsky RH, et al. Loss of independence in activities of daily living in older adults hospitalized with medical illnesses: increased vulnerability with age. J Am Geriatr Soc. 2003;51(4):451-458.

- Gill TM, Allore HG, Holford TR, et al. Hospitalization, restricted activity, and the development of disability among older persons. JAMA. 2004 Nov 3;292(17):2115-2124

- Landefeld CS, Palmer RM, Kresevic DM, et al. A randomized trial of care in a hospital medical unit especially designed to improve the functional outcomes of acutely ill older patients. N Engl J Med. 1995 May 18;332(20):1338-1344.

- State of California, Department of Finance. Race/Ethnic Population with Age and Sex Detail, 2000–2050; 2004: Sacramento, Calif.

- Creditor MC. Hazards of hospitalization of the elderly. Ann Intern Med. 1993 Feb 1;118(3):219-223.

- Inouye SK. Delirium in older persons. N Engl J Med. 2006 Jun 8;354(23):2509-2511; author reply 2509-11. Comment on: N Engl J Med. 2006 Mar 16;354(11):1157-1165.

- Brennan TA, Leape LL, Laird NM, et al. Incidence of adverse events and negligence in hospitalized patients. Results of the Harvard Medical Practice Study I. N Engl J Med. 1991 Feb 7;324(6):370-376. Comment in: N Engl J Med. 1991 Jul 18;325(3):210.

- Cohen HJ, Feussner JR, Weinberger M, et al. A controlled trial of inpatient and outpatient geriatric evaluation and management. N Engl J Med. 2002 Mar 21;346(12):905-912. Comment in: Curr Surg. 2004 May-Jun;61(3):266-74. N Engl J Med. 2002 Aug 1;347(5):371-373; author reply 371-373; author reply 371-3: N Engl J Med. 2002 Mar 21;346(12):874.

- Inouye SK, Bogardus ST Jr, Charpentier PA, et al. A multicomponent intervention to prevent delirium in hospitalized older patients. N Engl J Med. 1999 Mar 4;340(9):669-676. Comment in: N Engl J Med. 1999 Jul 29;341(5):369-370; author reply 370. N Engl J Med. 1999 Mar 4;340(9):720-721.

- Reuben DB, Borok GM, Wolde-Tsadik G, et al. A randomized trial of comprehensive geriatric assessment in the care of hospitalized patients. N Engl J Med. 1995 May 18;332(20):1345-1350. Comment in: N Engl J Med. 1995 May 18;332(20):1376-1378.

- Leff B, Burton L, Mader SL, et al. Hospital at home: feasibility and outcomes of a program to provide hospital-level care at home for acutely ill older patients. Ann Intern Med. 2005 Dec 6;143(11):798-808. Comment in: Ann Intern Med. 2005 Dec 6;143(11):840-1. Ann Intern Med. 2006 Mar 21;144(6):456. Summary for patients in:Ann Intern Med. 2005 Dec 6;143(11):I56.

- Covinsky KE, Palmer RM, Kresevic DM, et. al. Improving functional outcomes in older patients: lessons from an acute care for elders unit. Jt Comm J Qual Improv. 1998 Feb;24(2):63-76.

- Wieland D, Rubenstein LZ. What do we know about patient targeting in geriatric evaluation and management (GEM) programs? Aging (Milano). 1996 Oct; 8(5):297-310.

- Spetz J, Dyer W. Forecasts of the Registered Nurse Workforce in California. 2005, University of California, San Francisco: San Francisco.

- Fleming KC, Evans JM, Chutka DS. Caregiver and clinician shortages in an aging nation. Mayo Clin Proc. 2003 Aug;78(8):1026-1040.

- Knapp KK, Quist RM, Walton SM, et al. Update on the pharmacist shortage: National and state data through 2003. Am J Health Syst Pharm. 2005 Mar 1;62(5):492-499.

- Katzenbach JR, Smith DK. The Discipline of Teams. Harv Bus Rev. July-August 2005:1-9.

Families often note that after older relatives return home from the hospital, something is wrong with them.

While the acute condition that brought a relative into the hospital has been remedied, major functional and cognitive deficits such as confusion, falls, and difficulty with basic activities of daily living remain.

This post-hospital decline may not be appreciated by hospital clinicians, perhaps because the problems do not become visible until the patient is home. However, these problems place significant burdens on patients and families.

Following discharge for an acute hospitalization, about a third of older patients will have a major new disability that threatens their ability to live independently.1 Among community-dwelling elders, half of all new disability occurs within a month of hospitalization.2 It isn’t surprising that nursing home placement has grown more common for medical hospitalizations, even for seemingly reversible medical problems.

Older adults will make up an increasing number of the patients cared for by hospitalists. The Acute Care for Elders (ACE) unit model of care focuses on preventing functional decline and increasing discharges to home.

In 2005, leadership of the San Francisco General Hospital Medical Center (SFGHMC) committed to improving care for hospitalized elders by adopting the ACE model.3

The ACE model combats hospital-acquired disability by improving care processes for older patients.

Major motivating factors for the change included demographic and quality-of-care imperatives. After a nine-month planning process, the SFGHMC ACE unit opened in February.

Rationale

Largely driven by the baby boom, the number of California seniors older than 65 will double from 3.5 million to 7 million over the next 40 years, and those older than 85 will triple from about 500,000 to 1.5 million. In San Francisco, changes will be even more dramatic as the number of residents over 65 increases from 14% of the population to 32%.4 (See Figure 1, right).

In California, people 65 to 84 are almost three times as likely to be hospitalized as those between 45 and 64. If rates of hospitalization do not change, an increase in hospitalized older adults will occur as the baby boom generation ages.

In addition, hospitalization can be hazardous for older adults, with increased risk for functional and cognitive disability and adverse events.5-7 As a result, hospitalization-associated disability represents a growing threat to the independence of the older population. A variety of changes to usual care have been adopted in an effort to reduce the hazards of hospitalization in the elderly.8-11

ACE Model

The ACE unit model, proven to reduce the risk of hospital-acquired disability in the elderly, is based on the Model of Dysfunction for Hospitalized Elders.12 (See Figure 2, p. 23)

This model outlines how processes of hospital care for the elderly promote physical impairment and depressed mood, leading to dysfunction. Counterproduc-tive factors in older adults include a hostile environment (lack of natural sunlight, high-glare floors, poor way-finding cues, high noise levels), depersonalization (lack of personal effects, clothing, and usual daily routines), bed rest through multiple tethers or inattention, medicines inappropriate in the elderly or given at inappropriate doses, procedures, and negative expectations (usually that the patient will require nursing home placement after admission).

These processes are the targets of the ACE intervention. The idea is to improve quality of care for the elderly by promoting rehabilitation and preventing disability.

The ACE unit addresses these issues through a “prehabilitation program.” The ACE unit is a physical location in the hospital with 10 beds. Care is redesigned by placing the patient at the center of restorative efforts of an interdisciplinary team consisting of an advanced practice nurse, a social worker, an occupational and a physical therapist, a nutritionist, a pharmacist, and a medical director. This ACE Unit team meets daily to review and plan care for all patients. Recommendations for nursing care and rehabilitation evaluation are implemented by the ACE team directly. Other recommendations, such as changing medications or considering alternative approaches to common geriatric syndromes are communicated to the primary team, which maintains overall responsibility for the care of the patient.

Each patient’s assessment is multidimensional, with an emphasis on nonpharmacologic interventions where practical. For example, an emphasis is placed on after-dinner exercise such as walking and socializing to promote sleep and reduce medication use. Nursing-care plans were revised to promote mobility, discourage inappropriate Foley use, and encourage adequate hydration and nutrition.

Recommendations are communicated to the primary team via a recommendation form placed in the physician-order section and text pages. The unit’s medical director and pharmacist review medications. Recommendations that involve medication changes are discussed with the primary team, which write all medication orders. Home planning begins on the day of admission.

Prior to opening the unit, the ACE unit social worker met with key city and county agencies including Aging and Adult Services, the Public Guardian, In-Home Supportive Services, and community nursing homes to introduce the unit and plan for an effective and safe transition.

All staff expect patients to maintain prehospital physical functioning. When possible, patients are expected to wear their own clothes, eat all their meals in a common dining room, and ambulate or exercise daily.

We considered establishing criteria for admission.13 We have not adopted formal criteria for patients 65 or older, presence of medical non-surgical condition(s) that require(s) acute hospitalization, and no need for telemetry or chemotherapy. As we learn how best to serve our hospitalized older adult population with the resources of the unit, we will re-evaluate targeting criteria. Most of our admissions are from the emergency department (ED), and the remainder are from other units in the hospital.

Challenges

Key challenges in opening the new service include securing commitment and resources from organizational leaders and key stakeholders; incorporation of the ACE unit concept in an academic training center; hiring key staff, especially the geriatric clinical nurse specialist and pharmacist positions; and completing the environmental rehabilitation on a limited budget.

While gaps in the care of the geriatric patient population were well identified at SFGHMC as far back as 1996 by a multidisciplinary task force, no actions on recommendations were taken, for several key reasons.

First, an executive level administrator or physician champion was not a member of the task force. Second, the organization did not have a department or regulatory mandate to address the gaps in the care of the elderly patients. Third, there was no link between the hospital strategic plan and the recommendations.

By 2004, these issues were largely addressed. A new chief nursing officer with a background in quality improvement understood the demographic and quality imperatives to improve care for hospitalized older adults.

That same year, the Hospital Executive Committee incorporated patient safety into the hospital strategic plan. This resulted in a successful business plan for an ACE Unit and geriatric consultation service linked to organizational strategy.

Funding was allocated for a medical director and a clinical nurse specialist in fiscal year 2005-2006. In addition, a grant was obtained from the SFGH Foundation to fund equipment, renovations, and staff education/training.

The original ACE unit concept involved expert, interdisciplinary geriatric assessment and communication of suggestions via a paper-based chart.

Initially, we felt the primary medical team should round with the ACE team, preferably at the bedside. However, informal focus groups held with the residents suggested this would happen infrequently.

The demands on the medical teams of completing patient rounds before morning attending rounds were cited as the main reason that model wouldn’t work.

We have implemented the following methods to promote communication between the ACE unit team and the primary medical team:

- Medical teams are encouraged to attend ACE unit rounds while on bedside rounds. This provides an opportunity to model the team-delivered care for house staff and medical students, an ACGME requirement;

- Suggestions to change medications are directly text-paged to the house staff; and

- Recommendations are summarized in a communication sheet left in the chart (this not a permanent part of the medical record).

We plan on using the text-paging more widely once the unit has wireless computer capability. Despite this, there are occasions where a team is not aware of a recommendation or new emphasis in the care plan. We are considering additional ways to improve communication such as attending the primary team attending rounds.

In California and other states there is a shortage of clinical pharmacists and masters-prepared nurses with expertise in geriatrics.14-16 The advanced practice nurse performs a vital role in raising the level of knowledge, skills, and attitudes for the nursing staff on the ACE unit.

In addition, we see the ACE unit as a drop in the pond; we feel a responsibility to expand nursing geriatric competency throughout appropriate hospital areas. Thus, this nursing role is at the center of preparing the hospital to care for an older patient population.

This position remained unfilled for almost a year despite an intensive national search. This prompted us to incorporate the geriatric resource nurse model into our unit while we continued our recruitment.

Although we have successfully concluded our search for a nursing leader for the ACE unit, we have yet to hire a clinical pharmacist.

The rehabilitation of the unit would not have been possible without foundation support. As a public hospital with many competing demands, monies are limited for the rehabilitation required to create a more welcoming, safer environment for the older patient. In this case, the hospital foundation and a local foundation made grants to the ACE unit to allow us to change the environment.

These grants have allowed for significant changes to the unit, including elevated toilet seats, high-backed chairs, handrails, unit-based physical therapy equipment, and activities to promote non-pharmacological approaches to agitation.

Readiness for Change

All levels of hospital staff embraced the ACE unit concept. Department leaders in rehabilitation, nutrition, social work, and pharmacy felt ACE unit principles would improve care delivery over usual care.

Early on, department leaders and medical staff enthusiastically participated on a steering committee to help guide implementation efforts. In addition, when we offered geriatric resource nurse training to our nursing staff, more than 20 out of 50 unit nurses expressed interest.

Staff from all departments represented on the ACE unit team also expressed interest in and attended the three days of training. This provided baseline knowledge of common geriatric syndromes in hospitalized older patients for all team members. This been helpful during ACE team discussions.

Although medical residents felt they could not consistently attend ACE rounds, they appreciated potential benefits of the unit:

- Different perspectives could provide a wider range of evaluation and treatment recommendations for their patients;

- The co-location of key disciplines could result in overall time savings in calling for and ordering evaluations;

- The reduced likelihood that key interventions such as mobilization, feeding, catheter removal, and medication review would be missed; and

- The opportunity to learn principles of geriatric care through attending ACE rounds (when possible).

Medical staff in other departments immediately accepted the rationale for the unit.

Many expressed interest in expanding the concept to their departments, especially orthopedics, general surgery, and the ED. Although unfamiliar with specific interventions to improve care for hospitalized elders, the underlying concepts of patient-centered, team-delivered care with a focus on function resonated with most medical staff.

Next Steps

The unit is still in startup mode. Our major areas of focus are:

- Evaluating and improving team dynamics: We have engaged with researchers to evaluate our team dynamics and intervene where necessary to promote a high-functioning team.17

- Developing a culture of performance improvement: One of the hallmarks of high-functioning teams are measures of performance that are team-derived and reflect work product that the team can control.17

We are putting into place processes to measure key quality parameters including length of stay; nursing home placement; readmission rate, inappropriate catheter use; inappropriate medication prescribing; incidence of delirium, falls, and pressure ulcers; functional and cognitive status at admission and discharge; and patient satisfaction.

The orders set used by admitting residents are the standard general medical ward admission set and need revision for the ACE unit.

- Developing a research program: Our goal is to develop a research program evaluating interventions to prevent post-hospital degeneration of elders’ health. There is a dearth of research on improving hospital care for older, vulnerable adults.

- Expanding philanthropy support: The unit has benefited tremendously from philanthropy. In a relatively resource-poor setting, this allowed for rapid engagement with designers and vendors to remake the environment. We plan to expand our outreach efforts to interested philanthropists.

Summary

The ACE unit model can improve care for hospitalized older adults.

It requires a sustained level of commitment from hospital leaders, a focus on patient-centered, team-delivered care, sensitivity to communication modalities with primary caregivers, an awareness of the market for key professionals required, and flexibility to respond effectively to the many challenges that will emerge in implementing this model locally. TH

Dr. Pierluissi is medical director of the ACE unit at the San Francisco General Hospital. Susan Currin is the hospital’s chief nursing officer.

References

- Covinsky KE, Palmer RM, Fortinsky RH, et al. Loss of independence in activities of daily living in older adults hospitalized with medical illnesses: increased vulnerability with age. J Am Geriatr Soc. 2003;51(4):451-458.

- Gill TM, Allore HG, Holford TR, et al. Hospitalization, restricted activity, and the development of disability among older persons. JAMA. 2004 Nov 3;292(17):2115-2124

- Landefeld CS, Palmer RM, Kresevic DM, et al. A randomized trial of care in a hospital medical unit especially designed to improve the functional outcomes of acutely ill older patients. N Engl J Med. 1995 May 18;332(20):1338-1344.

- State of California, Department of Finance. Race/Ethnic Population with Age and Sex Detail, 2000–2050; 2004: Sacramento, Calif.

- Creditor MC. Hazards of hospitalization of the elderly. Ann Intern Med. 1993 Feb 1;118(3):219-223.

- Inouye SK. Delirium in older persons. N Engl J Med. 2006 Jun 8;354(23):2509-2511; author reply 2509-11. Comment on: N Engl J Med. 2006 Mar 16;354(11):1157-1165.

- Brennan TA, Leape LL, Laird NM, et al. Incidence of adverse events and negligence in hospitalized patients. Results of the Harvard Medical Practice Study I. N Engl J Med. 1991 Feb 7;324(6):370-376. Comment in: N Engl J Med. 1991 Jul 18;325(3):210.

- Cohen HJ, Feussner JR, Weinberger M, et al. A controlled trial of inpatient and outpatient geriatric evaluation and management. N Engl J Med. 2002 Mar 21;346(12):905-912. Comment in: Curr Surg. 2004 May-Jun;61(3):266-74. N Engl J Med. 2002 Aug 1;347(5):371-373; author reply 371-373; author reply 371-3: N Engl J Med. 2002 Mar 21;346(12):874.

- Inouye SK, Bogardus ST Jr, Charpentier PA, et al. A multicomponent intervention to prevent delirium in hospitalized older patients. N Engl J Med. 1999 Mar 4;340(9):669-676. Comment in: N Engl J Med. 1999 Jul 29;341(5):369-370; author reply 370. N Engl J Med. 1999 Mar 4;340(9):720-721.

- Reuben DB, Borok GM, Wolde-Tsadik G, et al. A randomized trial of comprehensive geriatric assessment in the care of hospitalized patients. N Engl J Med. 1995 May 18;332(20):1345-1350. Comment in: N Engl J Med. 1995 May 18;332(20):1376-1378.

- Leff B, Burton L, Mader SL, et al. Hospital at home: feasibility and outcomes of a program to provide hospital-level care at home for acutely ill older patients. Ann Intern Med. 2005 Dec 6;143(11):798-808. Comment in: Ann Intern Med. 2005 Dec 6;143(11):840-1. Ann Intern Med. 2006 Mar 21;144(6):456. Summary for patients in:Ann Intern Med. 2005 Dec 6;143(11):I56.

- Covinsky KE, Palmer RM, Kresevic DM, et. al. Improving functional outcomes in older patients: lessons from an acute care for elders unit. Jt Comm J Qual Improv. 1998 Feb;24(2):63-76.

- Wieland D, Rubenstein LZ. What do we know about patient targeting in geriatric evaluation and management (GEM) programs? Aging (Milano). 1996 Oct; 8(5):297-310.

- Spetz J, Dyer W. Forecasts of the Registered Nurse Workforce in California. 2005, University of California, San Francisco: San Francisco.

- Fleming KC, Evans JM, Chutka DS. Caregiver and clinician shortages in an aging nation. Mayo Clin Proc. 2003 Aug;78(8):1026-1040.

- Knapp KK, Quist RM, Walton SM, et al. Update on the pharmacist shortage: National and state data through 2003. Am J Health Syst Pharm. 2005 Mar 1;62(5):492-499.

- Katzenbach JR, Smith DK. The Discipline of Teams. Harv Bus Rev. July-August 2005:1-9.

The Power of “Sorry”

Like many people, we like to sing while secure in the anonymity of our cars. This morning, one of us was wailing along with Elton John as he sang “Sorry Seems to Be the Hardest Word”:

It’s sad, so sad

Why can’t we talk it over

Oh, it seems to me

That sorry seems to be the hardest word.

That verse frames a critical legal question physicians regularly encounter: how to communicate with patients after an unexpected outcome. More precisely, should a physician apologize to a patient who suffers complications because of that physician’s treatment?

Traditionally, after a patient suffered a complication, defense lawyers were reluctant to allow the physician to express apologies or regret. The defense lawyer feared the apology would be treated as an “admission against interest.” In other words, the defense lawyer wanted to prevent a plaintiff’s lawyer from someday arguing that the physician’s apology was an admission of negligence or wrongdoing.

But the lawyer’s strategy fails. The patient wants the physician to apologize for an error. In fact, the patient distrusts a physician who does not admit errors.

‘‘Although a physician may wish to tell a patient when he has made a mistake, lawyers often order doctors to say nothing,’’ wrote University of Florida law professor Jonathan R. Cohen in the Southern California Law Review.1 “The physician’s silence may then trigger the patient’s anger. This alienation may then prompt the patient to sue.”

These observations are consistent with studies demonstrating that patients are far less to sue when provided with a full explanation and apology.2

Certainly no physician wants to make a statement that a plaintiff’s lawyer will use against him in court. But the same physician rationally wants to take any steps that might prevent the patient from feeling as though he or she needs to consult with a plaintiff’s lawyer. So, what’s a physician to do when caught between the hospital’s lawsuit-fearing attorney and a patient who expects his doctor to communicate with her honestly and forthrightly?

Fortunately, several state legislatures have recognized this tension and passed legislation that encourages physicians to apologize without facing the prospect that a plaintiff’s lawyer will argue that the physician apologized only because he knew he did something wrong. An example best illustrates how such “I’m sorry” statutes work.

Dr. Smith is treating a 22-year-old patient, John Elway, for a fractured fibula. Dr. Smith sees no signs of neurological compromise while the patient is in a cast. After the cast is removed, it appears the patient has lost function in the leg because the cast was too tight. The patient was a star college athlete who was expected to be drafted into the NFL, but now likely won’t be drafted. Dr. Smith tells the patient: “It’s my fault this happened. I’m really sorry that I didn’t pick up on this sooner.”

Does Dr. Smith’s statement come into evidence in court? Does part of it? The answers probably depend upon which state’s apology statute is applied. Massachusetts was one of the first states to pass an apology statute. It reads:

Statements, writings, or benevolent gestures expressing sympathy or a general sense of benevolence relating to the pain, suffering or death of a person involved in an accident and made to the person or to the family of such a person shall be inadmissible as evidence of an admission of liability in a civil action.

Significantly, the Massachusetts statute applies to people “involved in an accident,” which might imply that it is limited to automobile accidents or workplace accidents. The Massachusetts statute prevents this limited construction by providing a broad definition of “accident,” including any “occurrence resulting in injury or death to one or more persons which is not the result of a willful action by a party.” This definition would encompass ordinary medical negligence.

It would seem clear that the statute would protect Dr. Smith if he simply stated: “I want you to know how sorry I am this happened. I feel awful that you experienced this complication.”

But if Dr. Smith said, “It’s my fault this happened,” would the Massachusetts statute protect Dr. Smith? That’s a much harder call. Saying “It’s my fault” is technically not an expression of “sympathy or a general act of benevolence.” There no clear answer under Massachusetts law. But we believe the result would probably depend on whether the judge hearing the case thought this statement occurred during an overall act of apology.

The answer is clearer in California. That state’s apology statute reads:

The portion of statements, writings, or benevolent gestures expressing sympathy or a general sense of benevolence relating to the pain, suffering or death of a person involved in an accident and made to that person or to the family of that person shall be inadmissible as evidence of an admission of liability in a civil action. A statement of fault, however, which is part of, or in addition to, any of the above shall not be inadmissible pursuant to this section.

California draws a clear distinction between “the portion of statements ... expressing sympathy or a general sense of benevolence” and “a statement of fault.”

In our scenario, the jury would almost certainly be able to hear Dr. Smith’s statement, “It’s my fault this happened.” Critics of California’s law believe it creates too narrow a window for physicians to believe that plaintiff’s lawyers will not use their apology against them in a lawsuit.3

While Dr. Smith’s statement is likely to come into evidence in California, it’s also clear the opposite would occur in Colorado. Colorado’s apology statute, which specifically applies to medical malpractice actions, reads:

In any civil action brought by an alleged victim of an unanticipated outcome of medical care ... any and all statements … expressing apology, fault, sympathy, commiseration, condolence, compassion or a general sense of benevolence ... shall be inadmissible as evidence of an admission of liability or as evidence of an admission against interest.

Because Colorado’s statute specifically renders statements of “fault” inadmissible, a jury would not be able to consider any of Dr. Smith’s statements made during the course of his apology. Colorado’s law provides the physician with the most protection. Critics of Colorado’s law believe it’s unfair for physicians to admit fault to their patients in the hospital, then deny liability after the patient files a lawsuit.

Twenty-six other states have passed apology statutes; each works a bit differently. The choice of words matters. Legally, there is a big difference between a physician telling a patient, “I’m sorry about your pain” or saying, “It’s my fault you’re in pain.”

While apologies are valuable and important in relationships of trust—including the relationship between physicians and patients—we suggest you consult an experienced lawyer when crafting an apology to make sure it conveys your sympathies without opening a door to liability. TH

Patrick O’Rourke works in the Office of University Counsel, Department of Litigation, Denver.

References

- Cohen JR. Advising clients to apologize. Southern California Law Review. 1999;72:1009-1131.

- Hickson GB, Clayton EW, Githens PB, et al. Factors that prompted families to file medical malpractice claims following perinatal injuries. JAMA. 1992 Mar;267(10):1359-1363.

- Eisenberg D. When doctors say, “We’re sorry.” Time. 2005 Aug 15;166(7):50-52.

Like many people, we like to sing while secure in the anonymity of our cars. This morning, one of us was wailing along with Elton John as he sang “Sorry Seems to Be the Hardest Word”:

It’s sad, so sad

Why can’t we talk it over

Oh, it seems to me

That sorry seems to be the hardest word.

That verse frames a critical legal question physicians regularly encounter: how to communicate with patients after an unexpected outcome. More precisely, should a physician apologize to a patient who suffers complications because of that physician’s treatment?

Traditionally, after a patient suffered a complication, defense lawyers were reluctant to allow the physician to express apologies or regret. The defense lawyer feared the apology would be treated as an “admission against interest.” In other words, the defense lawyer wanted to prevent a plaintiff’s lawyer from someday arguing that the physician’s apology was an admission of negligence or wrongdoing.

But the lawyer’s strategy fails. The patient wants the physician to apologize for an error. In fact, the patient distrusts a physician who does not admit errors.

‘‘Although a physician may wish to tell a patient when he has made a mistake, lawyers often order doctors to say nothing,’’ wrote University of Florida law professor Jonathan R. Cohen in the Southern California Law Review.1 “The physician’s silence may then trigger the patient’s anger. This alienation may then prompt the patient to sue.”

These observations are consistent with studies demonstrating that patients are far less to sue when provided with a full explanation and apology.2

Certainly no physician wants to make a statement that a plaintiff’s lawyer will use against him in court. But the same physician rationally wants to take any steps that might prevent the patient from feeling as though he or she needs to consult with a plaintiff’s lawyer. So, what’s a physician to do when caught between the hospital’s lawsuit-fearing attorney and a patient who expects his doctor to communicate with her honestly and forthrightly?

Fortunately, several state legislatures have recognized this tension and passed legislation that encourages physicians to apologize without facing the prospect that a plaintiff’s lawyer will argue that the physician apologized only because he knew he did something wrong. An example best illustrates how such “I’m sorry” statutes work.

Dr. Smith is treating a 22-year-old patient, John Elway, for a fractured fibula. Dr. Smith sees no signs of neurological compromise while the patient is in a cast. After the cast is removed, it appears the patient has lost function in the leg because the cast was too tight. The patient was a star college athlete who was expected to be drafted into the NFL, but now likely won’t be drafted. Dr. Smith tells the patient: “It’s my fault this happened. I’m really sorry that I didn’t pick up on this sooner.”

Does Dr. Smith’s statement come into evidence in court? Does part of it? The answers probably depend upon which state’s apology statute is applied. Massachusetts was one of the first states to pass an apology statute. It reads:

Statements, writings, or benevolent gestures expressing sympathy or a general sense of benevolence relating to the pain, suffering or death of a person involved in an accident and made to the person or to the family of such a person shall be inadmissible as evidence of an admission of liability in a civil action.

Significantly, the Massachusetts statute applies to people “involved in an accident,” which might imply that it is limited to automobile accidents or workplace accidents. The Massachusetts statute prevents this limited construction by providing a broad definition of “accident,” including any “occurrence resulting in injury or death to one or more persons which is not the result of a willful action by a party.” This definition would encompass ordinary medical negligence.

It would seem clear that the statute would protect Dr. Smith if he simply stated: “I want you to know how sorry I am this happened. I feel awful that you experienced this complication.”

But if Dr. Smith said, “It’s my fault this happened,” would the Massachusetts statute protect Dr. Smith? That’s a much harder call. Saying “It’s my fault” is technically not an expression of “sympathy or a general act of benevolence.” There no clear answer under Massachusetts law. But we believe the result would probably depend on whether the judge hearing the case thought this statement occurred during an overall act of apology.

The answer is clearer in California. That state’s apology statute reads:

The portion of statements, writings, or benevolent gestures expressing sympathy or a general sense of benevolence relating to the pain, suffering or death of a person involved in an accident and made to that person or to the family of that person shall be inadmissible as evidence of an admission of liability in a civil action. A statement of fault, however, which is part of, or in addition to, any of the above shall not be inadmissible pursuant to this section.

California draws a clear distinction between “the portion of statements ... expressing sympathy or a general sense of benevolence” and “a statement of fault.”

In our scenario, the jury would almost certainly be able to hear Dr. Smith’s statement, “It’s my fault this happened.” Critics of California’s law believe it creates too narrow a window for physicians to believe that plaintiff’s lawyers will not use their apology against them in a lawsuit.3

While Dr. Smith’s statement is likely to come into evidence in California, it’s also clear the opposite would occur in Colorado. Colorado’s apology statute, which specifically applies to medical malpractice actions, reads:

In any civil action brought by an alleged victim of an unanticipated outcome of medical care ... any and all statements … expressing apology, fault, sympathy, commiseration, condolence, compassion or a general sense of benevolence ... shall be inadmissible as evidence of an admission of liability or as evidence of an admission against interest.

Because Colorado’s statute specifically renders statements of “fault” inadmissible, a jury would not be able to consider any of Dr. Smith’s statements made during the course of his apology. Colorado’s law provides the physician with the most protection. Critics of Colorado’s law believe it’s unfair for physicians to admit fault to their patients in the hospital, then deny liability after the patient files a lawsuit.

Twenty-six other states have passed apology statutes; each works a bit differently. The choice of words matters. Legally, there is a big difference between a physician telling a patient, “I’m sorry about your pain” or saying, “It’s my fault you’re in pain.”

While apologies are valuable and important in relationships of trust—including the relationship between physicians and patients—we suggest you consult an experienced lawyer when crafting an apology to make sure it conveys your sympathies without opening a door to liability. TH

Patrick O’Rourke works in the Office of University Counsel, Department of Litigation, Denver.

References

- Cohen JR. Advising clients to apologize. Southern California Law Review. 1999;72:1009-1131.

- Hickson GB, Clayton EW, Githens PB, et al. Factors that prompted families to file medical malpractice claims following perinatal injuries. JAMA. 1992 Mar;267(10):1359-1363.

- Eisenberg D. When doctors say, “We’re sorry.” Time. 2005 Aug 15;166(7):50-52.

Like many people, we like to sing while secure in the anonymity of our cars. This morning, one of us was wailing along with Elton John as he sang “Sorry Seems to Be the Hardest Word”:

It’s sad, so sad

Why can’t we talk it over

Oh, it seems to me

That sorry seems to be the hardest word.

That verse frames a critical legal question physicians regularly encounter: how to communicate with patients after an unexpected outcome. More precisely, should a physician apologize to a patient who suffers complications because of that physician’s treatment?

Traditionally, after a patient suffered a complication, defense lawyers were reluctant to allow the physician to express apologies or regret. The defense lawyer feared the apology would be treated as an “admission against interest.” In other words, the defense lawyer wanted to prevent a plaintiff’s lawyer from someday arguing that the physician’s apology was an admission of negligence or wrongdoing.

But the lawyer’s strategy fails. The patient wants the physician to apologize for an error. In fact, the patient distrusts a physician who does not admit errors.

‘‘Although a physician may wish to tell a patient when he has made a mistake, lawyers often order doctors to say nothing,’’ wrote University of Florida law professor Jonathan R. Cohen in the Southern California Law Review.1 “The physician’s silence may then trigger the patient’s anger. This alienation may then prompt the patient to sue.”

These observations are consistent with studies demonstrating that patients are far less to sue when provided with a full explanation and apology.2

Certainly no physician wants to make a statement that a plaintiff’s lawyer will use against him in court. But the same physician rationally wants to take any steps that might prevent the patient from feeling as though he or she needs to consult with a plaintiff’s lawyer. So, what’s a physician to do when caught between the hospital’s lawsuit-fearing attorney and a patient who expects his doctor to communicate with her honestly and forthrightly?

Fortunately, several state legislatures have recognized this tension and passed legislation that encourages physicians to apologize without facing the prospect that a plaintiff’s lawyer will argue that the physician apologized only because he knew he did something wrong. An example best illustrates how such “I’m sorry” statutes work.

Dr. Smith is treating a 22-year-old patient, John Elway, for a fractured fibula. Dr. Smith sees no signs of neurological compromise while the patient is in a cast. After the cast is removed, it appears the patient has lost function in the leg because the cast was too tight. The patient was a star college athlete who was expected to be drafted into the NFL, but now likely won’t be drafted. Dr. Smith tells the patient: “It’s my fault this happened. I’m really sorry that I didn’t pick up on this sooner.”

Does Dr. Smith’s statement come into evidence in court? Does part of it? The answers probably depend upon which state’s apology statute is applied. Massachusetts was one of the first states to pass an apology statute. It reads:

Statements, writings, or benevolent gestures expressing sympathy or a general sense of benevolence relating to the pain, suffering or death of a person involved in an accident and made to the person or to the family of such a person shall be inadmissible as evidence of an admission of liability in a civil action.

Significantly, the Massachusetts statute applies to people “involved in an accident,” which might imply that it is limited to automobile accidents or workplace accidents. The Massachusetts statute prevents this limited construction by providing a broad definition of “accident,” including any “occurrence resulting in injury or death to one or more persons which is not the result of a willful action by a party.” This definition would encompass ordinary medical negligence.

It would seem clear that the statute would protect Dr. Smith if he simply stated: “I want you to know how sorry I am this happened. I feel awful that you experienced this complication.”

But if Dr. Smith said, “It’s my fault this happened,” would the Massachusetts statute protect Dr. Smith? That’s a much harder call. Saying “It’s my fault” is technically not an expression of “sympathy or a general act of benevolence.” There no clear answer under Massachusetts law. But we believe the result would probably depend on whether the judge hearing the case thought this statement occurred during an overall act of apology.

The answer is clearer in California. That state’s apology statute reads:

The portion of statements, writings, or benevolent gestures expressing sympathy or a general sense of benevolence relating to the pain, suffering or death of a person involved in an accident and made to that person or to the family of that person shall be inadmissible as evidence of an admission of liability in a civil action. A statement of fault, however, which is part of, or in addition to, any of the above shall not be inadmissible pursuant to this section.

California draws a clear distinction between “the portion of statements ... expressing sympathy or a general sense of benevolence” and “a statement of fault.”

In our scenario, the jury would almost certainly be able to hear Dr. Smith’s statement, “It’s my fault this happened.” Critics of California’s law believe it creates too narrow a window for physicians to believe that plaintiff’s lawyers will not use their apology against them in a lawsuit.3

While Dr. Smith’s statement is likely to come into evidence in California, it’s also clear the opposite would occur in Colorado. Colorado’s apology statute, which specifically applies to medical malpractice actions, reads:

In any civil action brought by an alleged victim of an unanticipated outcome of medical care ... any and all statements … expressing apology, fault, sympathy, commiseration, condolence, compassion or a general sense of benevolence ... shall be inadmissible as evidence of an admission of liability or as evidence of an admission against interest.

Because Colorado’s statute specifically renders statements of “fault” inadmissible, a jury would not be able to consider any of Dr. Smith’s statements made during the course of his apology. Colorado’s law provides the physician with the most protection. Critics of Colorado’s law believe it’s unfair for physicians to admit fault to their patients in the hospital, then deny liability after the patient files a lawsuit.

Twenty-six other states have passed apology statutes; each works a bit differently. The choice of words matters. Legally, there is a big difference between a physician telling a patient, “I’m sorry about your pain” or saying, “It’s my fault you’re in pain.”

While apologies are valuable and important in relationships of trust—including the relationship between physicians and patients—we suggest you consult an experienced lawyer when crafting an apology to make sure it conveys your sympathies without opening a door to liability. TH

Patrick O’Rourke works in the Office of University Counsel, Department of Litigation, Denver.

References

- Cohen JR. Advising clients to apologize. Southern California Law Review. 1999;72:1009-1131.

- Hickson GB, Clayton EW, Githens PB, et al. Factors that prompted families to file medical malpractice claims following perinatal injuries. JAMA. 1992 Mar;267(10):1359-1363.

- Eisenberg D. When doctors say, “We’re sorry.” Time. 2005 Aug 15;166(7):50-52.

Is P4P Paying off?

Pay for performance (P4P) has been the hottest topic among physicians for quite a while. Perhaps the time has come to ask: Is it worth the hype?

“In terms of organized pay-for-performance programs, we’re at the very beginning of seeing pay for performance in action,” says Patrick J. Torcson, MD, MMM, FACP, member of SHM’s Public Policy Committee and director of hospital medicine at St. Tammany Parish Hospital in Covington, La.

Although P4P is still in its infancy, one major demonstration trial is complete, and researchers have begun to mine results for indications of success.

The largest national P4P trial to date is the Centers for Medicare and Medicaid (CMS)/Premier Hospital Quality Incentive Demonstration Project, which involved more than 260 hospitals reporting on 34 quality measures from October 2003 through September 2006. The measures were grouped in five clinical areas: acute myocardial infarction, heart failure, coronary artery bypass graft, pneumonia, and hip and knee replacement.

Hospitals in the top 10% for each of the quality measures received a 2% bonus of their Medicare payments for the measured condition; hospitals in the top 20% received a 1% bonus; and hospitals in the bottom 20% returned 1% to 2% of their diagnosis-related group (DRG) payments.

CMS has paid $17.55 million in incentives to the top-tier, participating hospitals and reported savings of $1.4 billion in terms of avoidable deaths, complications and readmissions prevented, and shortened lengths of stay.