User login

Get Clear on Delirium

Delirium—also known as acute confusional state—is a common and potentially serious condition for hospitalized geriatric patients. It is believed to complicate hospital stays for more than 2.3 million older people, account for more than 17.5 million in patient days, and cost more than $4 billion in Medicare expenditures.1

Many experts believe the numbers may be higher because clinical staff too often automatically attribute patients’ symptoms to age-related dementia.

Delirium is many times more likely to occur in older people.2 Because patients older than 65 account for nearly half of all inpatient days, hospitalists must be readily able to identify the signs and symptoms of delirium—as well as what factors put certain patients at an increased risk for developing delirium. Hospitalists with this knowledge and ability will be better equipped to reduce the risk for delirium in their patients and more effectively treat delirium when it occurs.

“Assuming that the patient’s confusion is a normal state for him or her, without speaking to the patient’s family or caregivers to establish the baseline mental status for the patient, is probably the biggest reason delirium is so often misdiagnosed and, consequently, left untreated,” says Sharon Inouye, MD, of the Institute for Aging Research, Hebrew SeniorLife and Harvard Medical School.

Define and Diagnose Delirium

Delirium is a temporary state of mental confusion and fluctuating consciousness. Patients are unable to focus their thoughts or pay attention, are confused about their environment and individuals, and unsure about their daily routines. They may exhibit subtle or startling personality changes. Some people may become withdrawn and lethargic, while others become agitated or hyperactive. Some patients experience visual and/or auditory hallucinations and become paranoid.

Changes in sleep patterns are a typical manifestation of delirium. The patient may experience anything from mild insomnia to complete reversal of the sleep-wake cycle. All symptoms may fluctuate in severity as the day progresses, and it is common for delirious patients to become more agitated and confused at night.

Dementia is a chronic problem that develops over time. Delirium is acute—usually developing over hours or days. While patients with pre-existing dementia, brain trauma, cerebrovascular accident, or brain tumor are at higher risk for developing delirium, don’t automatically attribute unusual behavior in a geriatric patient to one of these diagnoses—especially if the behavioral change is sudden.

It is vital to obtain a solid history to determine the patient’s baseline mental status. The patient may not be the most reliable source of information regarding his or her normal level of cognition—particularly if he or she is beginning to show signs that may indicate delirium. Make every effort to question the patient’s family members and caregivers thoroughly to determine the patient’s normal level of functioning.

“The trick is that you have to have a nursing staff you can trust and who is attentive enough to changes in behavior—keeping in mind that they’ve only known the patient for a short time,” says Jonathan Flacker, MD, assistant professor of medicine at Emory University in Atlanta. “You have to rely a lot on the families and caregivers. You have to know whether the patient’s behavior is new or not, and sometimes that’s hard to establish.”

A simple tool nursing staff can use to monitor the patient’s mental status is the Confusion Assessment Method (CAM). The CAM is easy to use and interpret and only takes moments to complete. When staff on each shift use this tool and accurately document the results, it can help identify early changes that may indicate the onset of delirium.3

In addition to the CAM, other tools that can assist in cognitive assessment of the patient can include The Mini-Cog Assessment Instrument for Dementia, The Clock Draw Test, The Short Portable Mental Status Questionnaire (SPMSQ), The Geriatric Depression Scale, The Folstein Mini-Mental Status Exam, and The Digit Span Test.

Identify Etiology

Once the physician has determined that a patient is suffering from delirium, the challenge is to identify and treat the cause.

“It is important to remember that older folks often have atypical presentation of symptoms for medical problems,” says Dr. Inouye. “Physicians and clinical staff need to carefully consider all of the patient’s signs and symptoms, regardless of how insignificant they may seem.”

The physician can then order additional diagnostic tests based on the findings of the physical examination, which may include CBC, serum chemistry group, urinalysis, serum and urine drug screens, and possibly diagnostic radiographic studies as indicated.

Assessment must also include a careful review of the patient’s medications—possibly with input from a pharmacist. To do this, obtain a complete list of medications the patient was taking prior to admission to compare with the medications the patient is taking currently. Consider the possible effects of:

- Medications that have been discontinued;

- New medications;

- Changes in dosage;

- Possible drug interactions; and

- Possible drug toxicities that may require additional lab testing.

Pay attention to psychoactive medications the patient is taking, such as sedative-hypnotic agents, narcotics, and antidepressants. It is important to note whether the patient has recently received anesthesia or pain medications.4 It is also important to determine whether the patient has a history of alcohol or drug dependency.

“The first thing I would think if a patient is not acting right is drugs—some new drug that we’re administering or some drug that he or she is withdrawing from,” says O’Neil Pyke, MD, medical director of the Hamot Hospitalist Group in Erie, Pa. “You have to consider the possibility of side effects, drug interactions, and withdrawals. You also have to recognize polypharmacology as a major risk factor and try to curtail unnecessary medications.”

Dr. Flacker cautions that even once a problem has been identified, the physician must follow through on the complete examination and evaluation of the patient, keeping in mind that the cause for delirium may be multifactorial. “The problem is that like a lot of things in older folks, if you look for ‘the’ cause, you’re likely to be frustrated,” he says. “It’s often a combination of stressors causing the patient’s delirium.”

Treatment

Once the underlying problem or problems have been identified, treat those medical conditions accordingly—by administering antibiotics, fluids, and electrolytes as needed and adjusting or discontinuing medications.

However, resolution of the etiologic cause does not necessarily mean the symptoms of delirium will spontaneously resolve. These symptoms likely will require specific interventions to reorient the patient.

Encourage family members to participate in these efforts and spend as much time as possible with the patient. It may also be helpful to have family members bring in a few familiar items from the patient’s home—such as family photographs—to help calm and reassure the patient.

David Meyers, MD, hospitalist and chief of inpatient medicine at the Veterans Administration Medical Center in Madison, Wis., says: “You can use very simple modifications that really don’t take much time or effort. It’s really trying to recreate the patient’s environment and getting him or her to identify with certain things.”

To help the patient remain oriented to time and assist with disturbances in sleep patterns, staff should turn lights on and off and open and close curtains and blinds at the appropriate times. Make wall calendars and clocks visible to the patient. Try to keep the patient as active as possible during the day and minimize sleep interruptions.

Maintain as calm an environment for the patient as possible, minimizing ambient noise and activity. Place the patient in a room without a roommate if possible, close enough to the nurses’ station to facilitate close observation—but not so close that they’re disturbed by beepers, telephones, monitors, and other noises. Keep televisions at a reasonable volume and turned off when no one is watching. However, don’t isolate or abandon the patient, or let him/her spend too much time in bed. Assist the patient with mobilization several times daily.

If the patient has a vision or hearing impairment, staff and family should make every effort to ensure that the patient has access to and uses the appropriate corrective devices.4 Staff will also need to pay special attention to ensure that the patient eats appropriately, maintains an adequate fluid intake, and is assisted to the restroom regularly.

If safety concerns make it absolutely necessary to use physical restraints on a delirious patient, remember to explain all actions and instructions in clear, simple terms, using a low, calm tone of voice. Apply restraints carefully, release at frequent intervals, and discontinue as soon as possible. The patient likely will not understand why he or she is being restrained—and this lack of comprehension can worsen the patient’s fear and agitation.4,5

If nonpharmacologic interventions are not effective in controlling the patient’s agitation, physicians may prescribe antipsychotic agents and intermediate-acting benzodiazepines to immediately control an extremely agitated patient. However, some antipsychotic drugs can have anticholinergic side effects, which may aggravate delirium. Benzodiazepines can also exacerbate the patient’s delirious symptoms in the long term. Use these medications only for initial control of the patient’s behavior, and reduce and discontinue as soon as possible.

Dr. Meyers encourages consultation by a geriatrician. “The biggest consult service I utilize for suggestion of treatment options is geriatrics,” he says. “They’re very good at working with the patient and family and thinking of other behavioral and medical modifications.

“We can’t give a pill to reverse delirium. This is a shift in paradigm from what physicians are taught. In this setting, you actually want to get rid of medications and limit interventions.”

Remember to reassure patients and their families that most people recover fully if delirium is rapidly identified and treated. However, also caution them that some of the patient’s symptoms may persist for weeks or months, and improvement may occur slowly. Discharge from the hospital may be in the patient’s best interest—but the persistence of symptoms may necessitate home healthcare or temporary nursing home placement.

“In the absence of an acute medical problem, it may be preferable to get the patient to a less acute setting that can be more orienting and more therapeutic,” says Dr. Flacker.

While experts agree that it is not possible to prevent every case of delirium, knowing what puts patients at higher risk gives us the ability to reduce that risk for many patients.

In 1999, Dr. Inouye and her colleagues at the Yale University School of Medicine developed The Hospital Elder Life Program (HELP). The HELP program utilizes a trained interdisciplinary team consisting of a geriatric nurse-specialist, specially trained Elder Life specialists, trained volunteers, geriatrician, and other consultants (such as a certified therapeutic recreation specialist, a physical therapist, a pharmacist, and a nutritionist) to address six facets of delirium risk:

- Orientation. Provide daily communication and a daily schedule on a dry-erase board or chalkboard;

- Therapeutic activities. A variety of cognitively stimulating, fun activities like word games, reminiscence, trivia, or current events;

- Early mobilization. Get all patients up and walking three times a day;

- Vision and hearing adaptations;

- Feeding assistance and hydration assistance with encouragement/companionship during meals; and

- Sleep enhancement. Provide a nonpharmacologic sleep protocol, such as warm milk or herbal tea, backrub, and relaxation music.

A study of the HELP program published in The New England Journal of Medicine showed a 40% reduction in risk for delirium when these measures were applied to at-risk patients included in the study. Implementing the program cost $6,341 per case of delirium prevented. That is significantly less than the estimated cost associated with preventing other hospital complications, such as falls and myocardial infarction.

Prevention is preferable to treatment. But when delirium cannot be prevented, Dr. Inouye concludes with this advice for hospitalists: “Recognition is huge. The single most important thing that hospitalists can do for patients suffering from delirium is to know the signs and symptoms and recognize them when they occur. Earlier recognition means earlier intervention—and that is what’s in the best interest of the patient.” TH

Sheri Polley is a frequent contributor to The Hospitalist.

References

- Inouye SK, Bogardus ST, Charpentier PA, et al. A multicomponent intervention to prevent delirium in hospitalized older patients. N Engl J Med.1999 Mar 4;340:669-676.

- Rummans TA, Evans JM, Krahn LE, Fleming KC. Delirium in elderly patients: Evaluation and management. Mayo Clinic Web site. Available at www.mayoclinicproceedings.com/inside.asp?AID=4031&UID. Last accessed May 14, 2007.

- Clinical Toolbox for Geriatric Care. Society of Hospital Medicine Web site. Available at www.hospitalmedicine.org/geriresource/toolbox/howto.htm. Last accessed May 2, 2007.

- McGowan NC, Locala JA. Delirium. The Cleveland Clinic Web site. Available at www.clevelandclinicmeded.com/diseasemanagement/psychiatry/delirium/delirum1.htm. Last accessed May 15, 2007.

- Restraint Alternative Menu. Clinical Toolbox for Geriatric Care 2004 Society of Hospital Medicine. Available at www.hospitalmedicine.org/geriresource/toolbox/howto.htm. Last accessed May 2, 2007.

Delirium—also known as acute confusional state—is a common and potentially serious condition for hospitalized geriatric patients. It is believed to complicate hospital stays for more than 2.3 million older people, account for more than 17.5 million in patient days, and cost more than $4 billion in Medicare expenditures.1

Many experts believe the numbers may be higher because clinical staff too often automatically attribute patients’ symptoms to age-related dementia.

Delirium is many times more likely to occur in older people.2 Because patients older than 65 account for nearly half of all inpatient days, hospitalists must be readily able to identify the signs and symptoms of delirium—as well as what factors put certain patients at an increased risk for developing delirium. Hospitalists with this knowledge and ability will be better equipped to reduce the risk for delirium in their patients and more effectively treat delirium when it occurs.

“Assuming that the patient’s confusion is a normal state for him or her, without speaking to the patient’s family or caregivers to establish the baseline mental status for the patient, is probably the biggest reason delirium is so often misdiagnosed and, consequently, left untreated,” says Sharon Inouye, MD, of the Institute for Aging Research, Hebrew SeniorLife and Harvard Medical School.

Define and Diagnose Delirium

Delirium is a temporary state of mental confusion and fluctuating consciousness. Patients are unable to focus their thoughts or pay attention, are confused about their environment and individuals, and unsure about their daily routines. They may exhibit subtle or startling personality changes. Some people may become withdrawn and lethargic, while others become agitated or hyperactive. Some patients experience visual and/or auditory hallucinations and become paranoid.

Changes in sleep patterns are a typical manifestation of delirium. The patient may experience anything from mild insomnia to complete reversal of the sleep-wake cycle. All symptoms may fluctuate in severity as the day progresses, and it is common for delirious patients to become more agitated and confused at night.

Dementia is a chronic problem that develops over time. Delirium is acute—usually developing over hours or days. While patients with pre-existing dementia, brain trauma, cerebrovascular accident, or brain tumor are at higher risk for developing delirium, don’t automatically attribute unusual behavior in a geriatric patient to one of these diagnoses—especially if the behavioral change is sudden.

It is vital to obtain a solid history to determine the patient’s baseline mental status. The patient may not be the most reliable source of information regarding his or her normal level of cognition—particularly if he or she is beginning to show signs that may indicate delirium. Make every effort to question the patient’s family members and caregivers thoroughly to determine the patient’s normal level of functioning.

“The trick is that you have to have a nursing staff you can trust and who is attentive enough to changes in behavior—keeping in mind that they’ve only known the patient for a short time,” says Jonathan Flacker, MD, assistant professor of medicine at Emory University in Atlanta. “You have to rely a lot on the families and caregivers. You have to know whether the patient’s behavior is new or not, and sometimes that’s hard to establish.”

A simple tool nursing staff can use to monitor the patient’s mental status is the Confusion Assessment Method (CAM). The CAM is easy to use and interpret and only takes moments to complete. When staff on each shift use this tool and accurately document the results, it can help identify early changes that may indicate the onset of delirium.3

In addition to the CAM, other tools that can assist in cognitive assessment of the patient can include The Mini-Cog Assessment Instrument for Dementia, The Clock Draw Test, The Short Portable Mental Status Questionnaire (SPMSQ), The Geriatric Depression Scale, The Folstein Mini-Mental Status Exam, and The Digit Span Test.

Identify Etiology

Once the physician has determined that a patient is suffering from delirium, the challenge is to identify and treat the cause.

“It is important to remember that older folks often have atypical presentation of symptoms for medical problems,” says Dr. Inouye. “Physicians and clinical staff need to carefully consider all of the patient’s signs and symptoms, regardless of how insignificant they may seem.”

The physician can then order additional diagnostic tests based on the findings of the physical examination, which may include CBC, serum chemistry group, urinalysis, serum and urine drug screens, and possibly diagnostic radiographic studies as indicated.

Assessment must also include a careful review of the patient’s medications—possibly with input from a pharmacist. To do this, obtain a complete list of medications the patient was taking prior to admission to compare with the medications the patient is taking currently. Consider the possible effects of:

- Medications that have been discontinued;

- New medications;

- Changes in dosage;

- Possible drug interactions; and

- Possible drug toxicities that may require additional lab testing.

Pay attention to psychoactive medications the patient is taking, such as sedative-hypnotic agents, narcotics, and antidepressants. It is important to note whether the patient has recently received anesthesia or pain medications.4 It is also important to determine whether the patient has a history of alcohol or drug dependency.

“The first thing I would think if a patient is not acting right is drugs—some new drug that we’re administering or some drug that he or she is withdrawing from,” says O’Neil Pyke, MD, medical director of the Hamot Hospitalist Group in Erie, Pa. “You have to consider the possibility of side effects, drug interactions, and withdrawals. You also have to recognize polypharmacology as a major risk factor and try to curtail unnecessary medications.”

Dr. Flacker cautions that even once a problem has been identified, the physician must follow through on the complete examination and evaluation of the patient, keeping in mind that the cause for delirium may be multifactorial. “The problem is that like a lot of things in older folks, if you look for ‘the’ cause, you’re likely to be frustrated,” he says. “It’s often a combination of stressors causing the patient’s delirium.”

Treatment

Once the underlying problem or problems have been identified, treat those medical conditions accordingly—by administering antibiotics, fluids, and electrolytes as needed and adjusting or discontinuing medications.

However, resolution of the etiologic cause does not necessarily mean the symptoms of delirium will spontaneously resolve. These symptoms likely will require specific interventions to reorient the patient.

Encourage family members to participate in these efforts and spend as much time as possible with the patient. It may also be helpful to have family members bring in a few familiar items from the patient’s home—such as family photographs—to help calm and reassure the patient.

David Meyers, MD, hospitalist and chief of inpatient medicine at the Veterans Administration Medical Center in Madison, Wis., says: “You can use very simple modifications that really don’t take much time or effort. It’s really trying to recreate the patient’s environment and getting him or her to identify with certain things.”

To help the patient remain oriented to time and assist with disturbances in sleep patterns, staff should turn lights on and off and open and close curtains and blinds at the appropriate times. Make wall calendars and clocks visible to the patient. Try to keep the patient as active as possible during the day and minimize sleep interruptions.

Maintain as calm an environment for the patient as possible, minimizing ambient noise and activity. Place the patient in a room without a roommate if possible, close enough to the nurses’ station to facilitate close observation—but not so close that they’re disturbed by beepers, telephones, monitors, and other noises. Keep televisions at a reasonable volume and turned off when no one is watching. However, don’t isolate or abandon the patient, or let him/her spend too much time in bed. Assist the patient with mobilization several times daily.

If the patient has a vision or hearing impairment, staff and family should make every effort to ensure that the patient has access to and uses the appropriate corrective devices.4 Staff will also need to pay special attention to ensure that the patient eats appropriately, maintains an adequate fluid intake, and is assisted to the restroom regularly.

If safety concerns make it absolutely necessary to use physical restraints on a delirious patient, remember to explain all actions and instructions in clear, simple terms, using a low, calm tone of voice. Apply restraints carefully, release at frequent intervals, and discontinue as soon as possible. The patient likely will not understand why he or she is being restrained—and this lack of comprehension can worsen the patient’s fear and agitation.4,5

If nonpharmacologic interventions are not effective in controlling the patient’s agitation, physicians may prescribe antipsychotic agents and intermediate-acting benzodiazepines to immediately control an extremely agitated patient. However, some antipsychotic drugs can have anticholinergic side effects, which may aggravate delirium. Benzodiazepines can also exacerbate the patient’s delirious symptoms in the long term. Use these medications only for initial control of the patient’s behavior, and reduce and discontinue as soon as possible.

Dr. Meyers encourages consultation by a geriatrician. “The biggest consult service I utilize for suggestion of treatment options is geriatrics,” he says. “They’re very good at working with the patient and family and thinking of other behavioral and medical modifications.

“We can’t give a pill to reverse delirium. This is a shift in paradigm from what physicians are taught. In this setting, you actually want to get rid of medications and limit interventions.”

Remember to reassure patients and their families that most people recover fully if delirium is rapidly identified and treated. However, also caution them that some of the patient’s symptoms may persist for weeks or months, and improvement may occur slowly. Discharge from the hospital may be in the patient’s best interest—but the persistence of symptoms may necessitate home healthcare or temporary nursing home placement.

“In the absence of an acute medical problem, it may be preferable to get the patient to a less acute setting that can be more orienting and more therapeutic,” says Dr. Flacker.

While experts agree that it is not possible to prevent every case of delirium, knowing what puts patients at higher risk gives us the ability to reduce that risk for many patients.

In 1999, Dr. Inouye and her colleagues at the Yale University School of Medicine developed The Hospital Elder Life Program (HELP). The HELP program utilizes a trained interdisciplinary team consisting of a geriatric nurse-specialist, specially trained Elder Life specialists, trained volunteers, geriatrician, and other consultants (such as a certified therapeutic recreation specialist, a physical therapist, a pharmacist, and a nutritionist) to address six facets of delirium risk:

- Orientation. Provide daily communication and a daily schedule on a dry-erase board or chalkboard;

- Therapeutic activities. A variety of cognitively stimulating, fun activities like word games, reminiscence, trivia, or current events;

- Early mobilization. Get all patients up and walking three times a day;

- Vision and hearing adaptations;

- Feeding assistance and hydration assistance with encouragement/companionship during meals; and

- Sleep enhancement. Provide a nonpharmacologic sleep protocol, such as warm milk or herbal tea, backrub, and relaxation music.

A study of the HELP program published in The New England Journal of Medicine showed a 40% reduction in risk for delirium when these measures were applied to at-risk patients included in the study. Implementing the program cost $6,341 per case of delirium prevented. That is significantly less than the estimated cost associated with preventing other hospital complications, such as falls and myocardial infarction.

Prevention is preferable to treatment. But when delirium cannot be prevented, Dr. Inouye concludes with this advice for hospitalists: “Recognition is huge. The single most important thing that hospitalists can do for patients suffering from delirium is to know the signs and symptoms and recognize them when they occur. Earlier recognition means earlier intervention—and that is what’s in the best interest of the patient.” TH

Sheri Polley is a frequent contributor to The Hospitalist.

References

- Inouye SK, Bogardus ST, Charpentier PA, et al. A multicomponent intervention to prevent delirium in hospitalized older patients. N Engl J Med.1999 Mar 4;340:669-676.

- Rummans TA, Evans JM, Krahn LE, Fleming KC. Delirium in elderly patients: Evaluation and management. Mayo Clinic Web site. Available at www.mayoclinicproceedings.com/inside.asp?AID=4031&UID. Last accessed May 14, 2007.

- Clinical Toolbox for Geriatric Care. Society of Hospital Medicine Web site. Available at www.hospitalmedicine.org/geriresource/toolbox/howto.htm. Last accessed May 2, 2007.

- McGowan NC, Locala JA. Delirium. The Cleveland Clinic Web site. Available at www.clevelandclinicmeded.com/diseasemanagement/psychiatry/delirium/delirum1.htm. Last accessed May 15, 2007.

- Restraint Alternative Menu. Clinical Toolbox for Geriatric Care 2004 Society of Hospital Medicine. Available at www.hospitalmedicine.org/geriresource/toolbox/howto.htm. Last accessed May 2, 2007.

Delirium—also known as acute confusional state—is a common and potentially serious condition for hospitalized geriatric patients. It is believed to complicate hospital stays for more than 2.3 million older people, account for more than 17.5 million in patient days, and cost more than $4 billion in Medicare expenditures.1

Many experts believe the numbers may be higher because clinical staff too often automatically attribute patients’ symptoms to age-related dementia.

Delirium is many times more likely to occur in older people.2 Because patients older than 65 account for nearly half of all inpatient days, hospitalists must be readily able to identify the signs and symptoms of delirium—as well as what factors put certain patients at an increased risk for developing delirium. Hospitalists with this knowledge and ability will be better equipped to reduce the risk for delirium in their patients and more effectively treat delirium when it occurs.

“Assuming that the patient’s confusion is a normal state for him or her, without speaking to the patient’s family or caregivers to establish the baseline mental status for the patient, is probably the biggest reason delirium is so often misdiagnosed and, consequently, left untreated,” says Sharon Inouye, MD, of the Institute for Aging Research, Hebrew SeniorLife and Harvard Medical School.

Define and Diagnose Delirium

Delirium is a temporary state of mental confusion and fluctuating consciousness. Patients are unable to focus their thoughts or pay attention, are confused about their environment and individuals, and unsure about their daily routines. They may exhibit subtle or startling personality changes. Some people may become withdrawn and lethargic, while others become agitated or hyperactive. Some patients experience visual and/or auditory hallucinations and become paranoid.

Changes in sleep patterns are a typical manifestation of delirium. The patient may experience anything from mild insomnia to complete reversal of the sleep-wake cycle. All symptoms may fluctuate in severity as the day progresses, and it is common for delirious patients to become more agitated and confused at night.

Dementia is a chronic problem that develops over time. Delirium is acute—usually developing over hours or days. While patients with pre-existing dementia, brain trauma, cerebrovascular accident, or brain tumor are at higher risk for developing delirium, don’t automatically attribute unusual behavior in a geriatric patient to one of these diagnoses—especially if the behavioral change is sudden.

It is vital to obtain a solid history to determine the patient’s baseline mental status. The patient may not be the most reliable source of information regarding his or her normal level of cognition—particularly if he or she is beginning to show signs that may indicate delirium. Make every effort to question the patient’s family members and caregivers thoroughly to determine the patient’s normal level of functioning.

“The trick is that you have to have a nursing staff you can trust and who is attentive enough to changes in behavior—keeping in mind that they’ve only known the patient for a short time,” says Jonathan Flacker, MD, assistant professor of medicine at Emory University in Atlanta. “You have to rely a lot on the families and caregivers. You have to know whether the patient’s behavior is new or not, and sometimes that’s hard to establish.”

A simple tool nursing staff can use to monitor the patient’s mental status is the Confusion Assessment Method (CAM). The CAM is easy to use and interpret and only takes moments to complete. When staff on each shift use this tool and accurately document the results, it can help identify early changes that may indicate the onset of delirium.3

In addition to the CAM, other tools that can assist in cognitive assessment of the patient can include The Mini-Cog Assessment Instrument for Dementia, The Clock Draw Test, The Short Portable Mental Status Questionnaire (SPMSQ), The Geriatric Depression Scale, The Folstein Mini-Mental Status Exam, and The Digit Span Test.

Identify Etiology

Once the physician has determined that a patient is suffering from delirium, the challenge is to identify and treat the cause.

“It is important to remember that older folks often have atypical presentation of symptoms for medical problems,” says Dr. Inouye. “Physicians and clinical staff need to carefully consider all of the patient’s signs and symptoms, regardless of how insignificant they may seem.”

The physician can then order additional diagnostic tests based on the findings of the physical examination, which may include CBC, serum chemistry group, urinalysis, serum and urine drug screens, and possibly diagnostic radiographic studies as indicated.

Assessment must also include a careful review of the patient’s medications—possibly with input from a pharmacist. To do this, obtain a complete list of medications the patient was taking prior to admission to compare with the medications the patient is taking currently. Consider the possible effects of:

- Medications that have been discontinued;

- New medications;

- Changes in dosage;

- Possible drug interactions; and

- Possible drug toxicities that may require additional lab testing.

Pay attention to psychoactive medications the patient is taking, such as sedative-hypnotic agents, narcotics, and antidepressants. It is important to note whether the patient has recently received anesthesia or pain medications.4 It is also important to determine whether the patient has a history of alcohol or drug dependency.

“The first thing I would think if a patient is not acting right is drugs—some new drug that we’re administering or some drug that he or she is withdrawing from,” says O’Neil Pyke, MD, medical director of the Hamot Hospitalist Group in Erie, Pa. “You have to consider the possibility of side effects, drug interactions, and withdrawals. You also have to recognize polypharmacology as a major risk factor and try to curtail unnecessary medications.”

Dr. Flacker cautions that even once a problem has been identified, the physician must follow through on the complete examination and evaluation of the patient, keeping in mind that the cause for delirium may be multifactorial. “The problem is that like a lot of things in older folks, if you look for ‘the’ cause, you’re likely to be frustrated,” he says. “It’s often a combination of stressors causing the patient’s delirium.”

Treatment

Once the underlying problem or problems have been identified, treat those medical conditions accordingly—by administering antibiotics, fluids, and electrolytes as needed and adjusting or discontinuing medications.

However, resolution of the etiologic cause does not necessarily mean the symptoms of delirium will spontaneously resolve. These symptoms likely will require specific interventions to reorient the patient.

Encourage family members to participate in these efforts and spend as much time as possible with the patient. It may also be helpful to have family members bring in a few familiar items from the patient’s home—such as family photographs—to help calm and reassure the patient.

David Meyers, MD, hospitalist and chief of inpatient medicine at the Veterans Administration Medical Center in Madison, Wis., says: “You can use very simple modifications that really don’t take much time or effort. It’s really trying to recreate the patient’s environment and getting him or her to identify with certain things.”

To help the patient remain oriented to time and assist with disturbances in sleep patterns, staff should turn lights on and off and open and close curtains and blinds at the appropriate times. Make wall calendars and clocks visible to the patient. Try to keep the patient as active as possible during the day and minimize sleep interruptions.

Maintain as calm an environment for the patient as possible, minimizing ambient noise and activity. Place the patient in a room without a roommate if possible, close enough to the nurses’ station to facilitate close observation—but not so close that they’re disturbed by beepers, telephones, monitors, and other noises. Keep televisions at a reasonable volume and turned off when no one is watching. However, don’t isolate or abandon the patient, or let him/her spend too much time in bed. Assist the patient with mobilization several times daily.

If the patient has a vision or hearing impairment, staff and family should make every effort to ensure that the patient has access to and uses the appropriate corrective devices.4 Staff will also need to pay special attention to ensure that the patient eats appropriately, maintains an adequate fluid intake, and is assisted to the restroom regularly.

If safety concerns make it absolutely necessary to use physical restraints on a delirious patient, remember to explain all actions and instructions in clear, simple terms, using a low, calm tone of voice. Apply restraints carefully, release at frequent intervals, and discontinue as soon as possible. The patient likely will not understand why he or she is being restrained—and this lack of comprehension can worsen the patient’s fear and agitation.4,5

If nonpharmacologic interventions are not effective in controlling the patient’s agitation, physicians may prescribe antipsychotic agents and intermediate-acting benzodiazepines to immediately control an extremely agitated patient. However, some antipsychotic drugs can have anticholinergic side effects, which may aggravate delirium. Benzodiazepines can also exacerbate the patient’s delirious symptoms in the long term. Use these medications only for initial control of the patient’s behavior, and reduce and discontinue as soon as possible.

Dr. Meyers encourages consultation by a geriatrician. “The biggest consult service I utilize for suggestion of treatment options is geriatrics,” he says. “They’re very good at working with the patient and family and thinking of other behavioral and medical modifications.

“We can’t give a pill to reverse delirium. This is a shift in paradigm from what physicians are taught. In this setting, you actually want to get rid of medications and limit interventions.”

Remember to reassure patients and their families that most people recover fully if delirium is rapidly identified and treated. However, also caution them that some of the patient’s symptoms may persist for weeks or months, and improvement may occur slowly. Discharge from the hospital may be in the patient’s best interest—but the persistence of symptoms may necessitate home healthcare or temporary nursing home placement.

“In the absence of an acute medical problem, it may be preferable to get the patient to a less acute setting that can be more orienting and more therapeutic,” says Dr. Flacker.

While experts agree that it is not possible to prevent every case of delirium, knowing what puts patients at higher risk gives us the ability to reduce that risk for many patients.

In 1999, Dr. Inouye and her colleagues at the Yale University School of Medicine developed The Hospital Elder Life Program (HELP). The HELP program utilizes a trained interdisciplinary team consisting of a geriatric nurse-specialist, specially trained Elder Life specialists, trained volunteers, geriatrician, and other consultants (such as a certified therapeutic recreation specialist, a physical therapist, a pharmacist, and a nutritionist) to address six facets of delirium risk:

- Orientation. Provide daily communication and a daily schedule on a dry-erase board or chalkboard;

- Therapeutic activities. A variety of cognitively stimulating, fun activities like word games, reminiscence, trivia, or current events;

- Early mobilization. Get all patients up and walking three times a day;

- Vision and hearing adaptations;

- Feeding assistance and hydration assistance with encouragement/companionship during meals; and

- Sleep enhancement. Provide a nonpharmacologic sleep protocol, such as warm milk or herbal tea, backrub, and relaxation music.

A study of the HELP program published in The New England Journal of Medicine showed a 40% reduction in risk for delirium when these measures were applied to at-risk patients included in the study. Implementing the program cost $6,341 per case of delirium prevented. That is significantly less than the estimated cost associated with preventing other hospital complications, such as falls and myocardial infarction.

Prevention is preferable to treatment. But when delirium cannot be prevented, Dr. Inouye concludes with this advice for hospitalists: “Recognition is huge. The single most important thing that hospitalists can do for patients suffering from delirium is to know the signs and symptoms and recognize them when they occur. Earlier recognition means earlier intervention—and that is what’s in the best interest of the patient.” TH

Sheri Polley is a frequent contributor to The Hospitalist.

References

- Inouye SK, Bogardus ST, Charpentier PA, et al. A multicomponent intervention to prevent delirium in hospitalized older patients. N Engl J Med.1999 Mar 4;340:669-676.

- Rummans TA, Evans JM, Krahn LE, Fleming KC. Delirium in elderly patients: Evaluation and management. Mayo Clinic Web site. Available at www.mayoclinicproceedings.com/inside.asp?AID=4031&UID. Last accessed May 14, 2007.

- Clinical Toolbox for Geriatric Care. Society of Hospital Medicine Web site. Available at www.hospitalmedicine.org/geriresource/toolbox/howto.htm. Last accessed May 2, 2007.

- McGowan NC, Locala JA. Delirium. The Cleveland Clinic Web site. Available at www.clevelandclinicmeded.com/diseasemanagement/psychiatry/delirium/delirum1.htm. Last accessed May 15, 2007.

- Restraint Alternative Menu. Clinical Toolbox for Geriatric Care 2004 Society of Hospital Medicine. Available at www.hospitalmedicine.org/geriresource/toolbox/howto.htm. Last accessed May 2, 2007.

Bullied into Botched Care

Bullying, intimidation, verbal abuse—these behaviors negatively affect self-esteem, feelings of competence, and workplace morale. And they can devastate hospital professionals and their patients.

When 2,095 healthcare providers (1,565 nurses, 354 pharmacists, and 176 others) responded to an Institute for Safe Medication Practices (ISMP) survey on intimidation in their healthcare setting, remarkable data were collected.1

Perhaps the most alarming statistic in the 2003-2004 study was that 7% of respondents (n=147) reported they had been involved in a medication error allowed to occur partly because the respondents were afraid to question the prescriber’s decision. At a large urban trauma center in the northeastern United States, nurses listed intimidation as one of the barriers to implementing a sharps safety program.2

Nurses’ Perceptions

Research over the past decade has spotlighted intimidation in healthcare.3

“Bullying and harassment still happen in many areas of medicine,” says David M. Pressel, MD, PhD, hospitalist and director, Inpatient Service, Division of General Pediatrics at Alfred I. duPont Hospital for Children in Wilmington, Del. “The question is, how do you monitor yourself to make sure you aren’t falling into that hierarchical frame of mind that could intervene in great teaching and learning and great patient care?”

Dr. Pressel and his partner, David I. Rappaport, MD, also a pediatric hospitalist at duPont, have focused on the literature pertaining to nurse-physician relationships. Research shows that intimidation impedes nurse recruitment, retention, and satisfaction. In one study, 90% of nurses reported experiencing at least one episode of verbal abuse.4 A 1997 study examining the effects of intimidation on 35 pediatric nurses over a three-month period found that 25 (71.4%) of them reported being yelled at or loudly admonished. Sixteen (45.7%) had been victims of insults. Thirty (85.7%) were spoken to in a condescending manner. One-third of nurses believed that such behavior was “part of the job.”

Although studies have differed as to the most common source of this abuse—patients and families or physicians—a study of pediatric nurses reported a similar incidence from both sources.5 And, nurses are often guilty of verbally abusing each other.6

When the duPont pediatric hospitalist team began performing more family-centered rounds, they began to appreciate the nurse-physician relationship. “We have worked hard to have a charge nurse and oftentimes the bedside nurse with us when we round,” Dr. Rappaport says. Speculating that rounding with hospitalists allowed nurses to feel more part of the team, Dr. Rappaport says know the medical plan, consolidate efforts such that pages to residents were reduced, and generally improve communication. They heard from participating nurses that it made a tremendous difference. This prompted them to conduct their research.

“Our study looked at the nurse-physician relationship globally, not intimidation or abuse specifically,” says Dr. Rappaport. Along with their nurse colleague Norine Watson, RN, Drs. Pressel and Rappaport are examining the relationship between nurses and different categories of physicians: how nurses perceive interactions between nurses and surgical residents, surgical attendings, community physicians, pediatric residents, and pediatric hospitalists.

“Early data suggest that hospitalists may work more effectively with nurses because they share many of the same goals,” says Dr. Rappaport. “As hospital leaders, hospitalists can also improve working conditions for nurses by providing more accessible, efficient, and effective care. Presumably, improved collaboration will also include decreased intimidation or abuse from physicians and also probably from dissatisfied patients and families.”

Avoiding the trap of communicating in a manner that is too direct and might be construed as abusive requires self-awareness and the realization that people receive information in different ways, says Dr. Pressel. Standard professional behavior is the key. Beyond that, the challenge is giving feedback constructively and in a positive manner.

“Hospitalists [may be] more in tune with the needs of nurses than nonhospitalists,” says Dr. Rappaport. “I think that is one of our strengths. We need to continue to facilitate very strong relationships between nurses and physicians because without good nursing care, hospitalists simply cannot provide good medical care.”

There is another way hospitalists can help address verbal abuse. “Studies consistently show that nurses are hesitant to report episodes of verbal abuse,” Dr. Rappaport says, “whether it is from a family, a patient, a physician, or a fellow nurse. Fewer than one in five nurses reports these episodes. One thing that hospitalists can do is work with hospital administration to create an environment that is more proactive in addressing these concerns and allowing nurses to feel more support in this area.”

Only 60% of respondents to the ISMP survey felt their organization had clearly defined an effective process for handling disagreements with a medication order’s safety. Only about a third felt the process facilitated their bypassing an intimidating prescriber or their own supervisor if necessary. Although 70% of respondents reported that they thought their organization or manager would support them if they reported intimidating behavior, only 39% of respondents believed their organization was dealing effectively with intimidating behavior.

Untapped Source

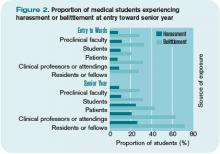

Perceptions of intimidation also occur among trainees. When 2,884 students from the class of 2003 at 16 U.S. medical schools completed questionnaires at various times during training, 27% reported having been “harassed” by house staff, 21% by faculty, and 25% by patients.7 Further, 71% reported having been “belittled” by house staff, 63% by faculty, and 43% by patients.

Mistreated students were significantly more likely to have suffered stress, be depressed or suicidal, and less likely to report being glad they trained as a physician.

—David I. Rappaport, MD, pediatric hospitalist, Alfred I. Dupont Hospital for Children, Wilmington, Del.

This may have an underlying effect on the potential to monitor for patient safety.8,9 Because errors and near misses often result from miscommunication, medical students may be adept at preventing certain types of errors. Students’ observation skills may be just as keen, if not more so, than their more clinically proficient healthcare teammates.8 In four cases from two U.S. academic health centers reported by medical students Samuel Seiden, Cynthia Galvan, and Ruth Lamm in 2006, medical students demonstrated keen attention to detail and appropriately characterized problematic situations with patients—adding another layer of defense within systems safeguarding against patient harm.8 Yet of the 76% of medical students who had observed a medical error, only about half of the students reported the errors to a resident or an attending, despite having received patient-safety training; only 7% reported having used an electronic medical error reporting system.10

By Example

Some intimidation in medical education may be the result of anger toward students and residents over a lack of medical knowledge, says Jeffery G. Wiese, MD, associate professor of Medicine at Tulane University in New Orleans and member of the SHM Board of Directors. “It is natural to feel [that anger]; people abhor in others what they most detest in themselves,’’ he says. “As physicians, a lack of medical knowledge is what we detest in ourselves. But a student’s ignorance is usually a product of where she is in her training; that’s why she is with you.”

—Jeffery G. Wiese, MD, associate professor of Medicine at Tulane University, New Orleans

Anger alienates students, absolving them of the guilt of not knowing the information, and demotivating them from learning it. “The lesson to be communicated is that it is OK not to know, but it is not OK to continue to not know,” Dr. Wiese says. “Reprimands should be reserved for the student who does not know, and then after being taught or asked to look it up, continues to not know.”

“The average physician who practices for 30 years will take care of roughly 80,000 people,” estimates Dr. Wiese. “That’s an arithmetic contribution and there is nothing wrong with that. But if you really want to change the world, teaching is the rule. The same 30 years invested in teaching will indirectly affect 400 million people,” he says. “Even better, if you can train your students and residents in the value of coaching their students and residents, well, now you’re talking about 10 billion people that you can affect over the course of a career.”

The question to ask yourself, says Dr. Wiese, is: Do you want to change the world? “If you do, this is the way to do it,” he says.

“For the 30 years in your career, focus on clinical coaching and getting others to clinically coach. That way, especially if you have the right motives in your heart, the right vision for the way you want to see the profession practiced, and the way you want patient care performed, that’s your shot at changing the world.” TH

Andrea Sattinger is a frequent contributor to The Hospitalist.

References

- Institute for Safe Medication Practice. Intimidation: practitioners speak up about this unresolved problem (Part I). Available at w.ismp.org/Newsletters/acutecare/articles/20040311_2.asp. Last accessed June 27, 2007.

- Hagstrom AM. Perceived barriers to implementation of a successful sharps safety program. AORN J. 2006;83(2):391-7.

- Porto G, Lauve R. Disruptive clinician behavior: a persistent threat to patient safety. Patient Safety Qual Healthc. 2006 Jul-Aug;3:16-24.

- Manderino MA, Berkey N. Verbal abuse of staff nurses by physicians. J Prof Nurs. 1997;13(1):48-55.

- Pejic AR. Verbal abuse: A problem for pediatric nurses. Pediatr Nurs. 2005;31(4):271-279.

- Rowe MM, Sherlock H. Stress and verbal abuse in nursing: do burned out nurses eat their young? J Nurs Manag. 2005May;13(3):242-248.

- Frank E, Carrera JS, Stratton T, et al. Experiences of belittlement and harassment and their correlates among medical students in the United States: longitudinal survey. BMJ. 2006 Sep 30;333(7570):682.

- Seiden SC, Galvan C, Lamm R. Role of medical students in preventing patient harm and enhancing patient safety. Qual Saf Health Care. 2006 Aug;15(4):272-276.

- Wood DF. Bullying and harassment in medical schools. BMJ. 2006 Sep 30;333(7570):664-665.

- Madigosky WS, Headrick LA, Nelson K, et al. Changing and sustaining medical students’ knowledge, skills, and attitudes about patient safety and medical fallibility. Acad Med. 2006 Jan;81(1):94-101.

- Institute for Safe Medication Practice. Intimidation: Mapping a plan for cultural change in healthcare (Part II). Available at www.ismp.org/Newsletters/acutecare/articles/20040325.asp Last accessed July 2, 2007.

Bullying, intimidation, verbal abuse—these behaviors negatively affect self-esteem, feelings of competence, and workplace morale. And they can devastate hospital professionals and their patients.

When 2,095 healthcare providers (1,565 nurses, 354 pharmacists, and 176 others) responded to an Institute for Safe Medication Practices (ISMP) survey on intimidation in their healthcare setting, remarkable data were collected.1

Perhaps the most alarming statistic in the 2003-2004 study was that 7% of respondents (n=147) reported they had been involved in a medication error allowed to occur partly because the respondents were afraid to question the prescriber’s decision. At a large urban trauma center in the northeastern United States, nurses listed intimidation as one of the barriers to implementing a sharps safety program.2

Nurses’ Perceptions

Research over the past decade has spotlighted intimidation in healthcare.3

“Bullying and harassment still happen in many areas of medicine,” says David M. Pressel, MD, PhD, hospitalist and director, Inpatient Service, Division of General Pediatrics at Alfred I. duPont Hospital for Children in Wilmington, Del. “The question is, how do you monitor yourself to make sure you aren’t falling into that hierarchical frame of mind that could intervene in great teaching and learning and great patient care?”

Dr. Pressel and his partner, David I. Rappaport, MD, also a pediatric hospitalist at duPont, have focused on the literature pertaining to nurse-physician relationships. Research shows that intimidation impedes nurse recruitment, retention, and satisfaction. In one study, 90% of nurses reported experiencing at least one episode of verbal abuse.4 A 1997 study examining the effects of intimidation on 35 pediatric nurses over a three-month period found that 25 (71.4%) of them reported being yelled at or loudly admonished. Sixteen (45.7%) had been victims of insults. Thirty (85.7%) were spoken to in a condescending manner. One-third of nurses believed that such behavior was “part of the job.”

Although studies have differed as to the most common source of this abuse—patients and families or physicians—a study of pediatric nurses reported a similar incidence from both sources.5 And, nurses are often guilty of verbally abusing each other.6

When the duPont pediatric hospitalist team began performing more family-centered rounds, they began to appreciate the nurse-physician relationship. “We have worked hard to have a charge nurse and oftentimes the bedside nurse with us when we round,” Dr. Rappaport says. Speculating that rounding with hospitalists allowed nurses to feel more part of the team, Dr. Rappaport says know the medical plan, consolidate efforts such that pages to residents were reduced, and generally improve communication. They heard from participating nurses that it made a tremendous difference. This prompted them to conduct their research.

“Our study looked at the nurse-physician relationship globally, not intimidation or abuse specifically,” says Dr. Rappaport. Along with their nurse colleague Norine Watson, RN, Drs. Pressel and Rappaport are examining the relationship between nurses and different categories of physicians: how nurses perceive interactions between nurses and surgical residents, surgical attendings, community physicians, pediatric residents, and pediatric hospitalists.

“Early data suggest that hospitalists may work more effectively with nurses because they share many of the same goals,” says Dr. Rappaport. “As hospital leaders, hospitalists can also improve working conditions for nurses by providing more accessible, efficient, and effective care. Presumably, improved collaboration will also include decreased intimidation or abuse from physicians and also probably from dissatisfied patients and families.”

Avoiding the trap of communicating in a manner that is too direct and might be construed as abusive requires self-awareness and the realization that people receive information in different ways, says Dr. Pressel. Standard professional behavior is the key. Beyond that, the challenge is giving feedback constructively and in a positive manner.

“Hospitalists [may be] more in tune with the needs of nurses than nonhospitalists,” says Dr. Rappaport. “I think that is one of our strengths. We need to continue to facilitate very strong relationships between nurses and physicians because without good nursing care, hospitalists simply cannot provide good medical care.”

There is another way hospitalists can help address verbal abuse. “Studies consistently show that nurses are hesitant to report episodes of verbal abuse,” Dr. Rappaport says, “whether it is from a family, a patient, a physician, or a fellow nurse. Fewer than one in five nurses reports these episodes. One thing that hospitalists can do is work with hospital administration to create an environment that is more proactive in addressing these concerns and allowing nurses to feel more support in this area.”

Only 60% of respondents to the ISMP survey felt their organization had clearly defined an effective process for handling disagreements with a medication order’s safety. Only about a third felt the process facilitated their bypassing an intimidating prescriber or their own supervisor if necessary. Although 70% of respondents reported that they thought their organization or manager would support them if they reported intimidating behavior, only 39% of respondents believed their organization was dealing effectively with intimidating behavior.

Untapped Source

Perceptions of intimidation also occur among trainees. When 2,884 students from the class of 2003 at 16 U.S. medical schools completed questionnaires at various times during training, 27% reported having been “harassed” by house staff, 21% by faculty, and 25% by patients.7 Further, 71% reported having been “belittled” by house staff, 63% by faculty, and 43% by patients.

Mistreated students were significantly more likely to have suffered stress, be depressed or suicidal, and less likely to report being glad they trained as a physician.

—David I. Rappaport, MD, pediatric hospitalist, Alfred I. Dupont Hospital for Children, Wilmington, Del.

This may have an underlying effect on the potential to monitor for patient safety.8,9 Because errors and near misses often result from miscommunication, medical students may be adept at preventing certain types of errors. Students’ observation skills may be just as keen, if not more so, than their more clinically proficient healthcare teammates.8 In four cases from two U.S. academic health centers reported by medical students Samuel Seiden, Cynthia Galvan, and Ruth Lamm in 2006, medical students demonstrated keen attention to detail and appropriately characterized problematic situations with patients—adding another layer of defense within systems safeguarding against patient harm.8 Yet of the 76% of medical students who had observed a medical error, only about half of the students reported the errors to a resident or an attending, despite having received patient-safety training; only 7% reported having used an electronic medical error reporting system.10

By Example

Some intimidation in medical education may be the result of anger toward students and residents over a lack of medical knowledge, says Jeffery G. Wiese, MD, associate professor of Medicine at Tulane University in New Orleans and member of the SHM Board of Directors. “It is natural to feel [that anger]; people abhor in others what they most detest in themselves,’’ he says. “As physicians, a lack of medical knowledge is what we detest in ourselves. But a student’s ignorance is usually a product of where she is in her training; that’s why she is with you.”

—Jeffery G. Wiese, MD, associate professor of Medicine at Tulane University, New Orleans

Anger alienates students, absolving them of the guilt of not knowing the information, and demotivating them from learning it. “The lesson to be communicated is that it is OK not to know, but it is not OK to continue to not know,” Dr. Wiese says. “Reprimands should be reserved for the student who does not know, and then after being taught or asked to look it up, continues to not know.”

“The average physician who practices for 30 years will take care of roughly 80,000 people,” estimates Dr. Wiese. “That’s an arithmetic contribution and there is nothing wrong with that. But if you really want to change the world, teaching is the rule. The same 30 years invested in teaching will indirectly affect 400 million people,” he says. “Even better, if you can train your students and residents in the value of coaching their students and residents, well, now you’re talking about 10 billion people that you can affect over the course of a career.”

The question to ask yourself, says Dr. Wiese, is: Do you want to change the world? “If you do, this is the way to do it,” he says.

“For the 30 years in your career, focus on clinical coaching and getting others to clinically coach. That way, especially if you have the right motives in your heart, the right vision for the way you want to see the profession practiced, and the way you want patient care performed, that’s your shot at changing the world.” TH

Andrea Sattinger is a frequent contributor to The Hospitalist.

References

- Institute for Safe Medication Practice. Intimidation: practitioners speak up about this unresolved problem (Part I). Available at w.ismp.org/Newsletters/acutecare/articles/20040311_2.asp. Last accessed June 27, 2007.

- Hagstrom AM. Perceived barriers to implementation of a successful sharps safety program. AORN J. 2006;83(2):391-7.

- Porto G, Lauve R. Disruptive clinician behavior: a persistent threat to patient safety. Patient Safety Qual Healthc. 2006 Jul-Aug;3:16-24.

- Manderino MA, Berkey N. Verbal abuse of staff nurses by physicians. J Prof Nurs. 1997;13(1):48-55.

- Pejic AR. Verbal abuse: A problem for pediatric nurses. Pediatr Nurs. 2005;31(4):271-279.

- Rowe MM, Sherlock H. Stress and verbal abuse in nursing: do burned out nurses eat their young? J Nurs Manag. 2005May;13(3):242-248.

- Frank E, Carrera JS, Stratton T, et al. Experiences of belittlement and harassment and their correlates among medical students in the United States: longitudinal survey. BMJ. 2006 Sep 30;333(7570):682.

- Seiden SC, Galvan C, Lamm R. Role of medical students in preventing patient harm and enhancing patient safety. Qual Saf Health Care. 2006 Aug;15(4):272-276.

- Wood DF. Bullying and harassment in medical schools. BMJ. 2006 Sep 30;333(7570):664-665.

- Madigosky WS, Headrick LA, Nelson K, et al. Changing and sustaining medical students’ knowledge, skills, and attitudes about patient safety and medical fallibility. Acad Med. 2006 Jan;81(1):94-101.

- Institute for Safe Medication Practice. Intimidation: Mapping a plan for cultural change in healthcare (Part II). Available at www.ismp.org/Newsletters/acutecare/articles/20040325.asp Last accessed July 2, 2007.

Bullying, intimidation, verbal abuse—these behaviors negatively affect self-esteem, feelings of competence, and workplace morale. And they can devastate hospital professionals and their patients.

When 2,095 healthcare providers (1,565 nurses, 354 pharmacists, and 176 others) responded to an Institute for Safe Medication Practices (ISMP) survey on intimidation in their healthcare setting, remarkable data were collected.1

Perhaps the most alarming statistic in the 2003-2004 study was that 7% of respondents (n=147) reported they had been involved in a medication error allowed to occur partly because the respondents were afraid to question the prescriber’s decision. At a large urban trauma center in the northeastern United States, nurses listed intimidation as one of the barriers to implementing a sharps safety program.2

Nurses’ Perceptions

Research over the past decade has spotlighted intimidation in healthcare.3

“Bullying and harassment still happen in many areas of medicine,” says David M. Pressel, MD, PhD, hospitalist and director, Inpatient Service, Division of General Pediatrics at Alfred I. duPont Hospital for Children in Wilmington, Del. “The question is, how do you monitor yourself to make sure you aren’t falling into that hierarchical frame of mind that could intervene in great teaching and learning and great patient care?”

Dr. Pressel and his partner, David I. Rappaport, MD, also a pediatric hospitalist at duPont, have focused on the literature pertaining to nurse-physician relationships. Research shows that intimidation impedes nurse recruitment, retention, and satisfaction. In one study, 90% of nurses reported experiencing at least one episode of verbal abuse.4 A 1997 study examining the effects of intimidation on 35 pediatric nurses over a three-month period found that 25 (71.4%) of them reported being yelled at or loudly admonished. Sixteen (45.7%) had been victims of insults. Thirty (85.7%) were spoken to in a condescending manner. One-third of nurses believed that such behavior was “part of the job.”

Although studies have differed as to the most common source of this abuse—patients and families or physicians—a study of pediatric nurses reported a similar incidence from both sources.5 And, nurses are often guilty of verbally abusing each other.6

When the duPont pediatric hospitalist team began performing more family-centered rounds, they began to appreciate the nurse-physician relationship. “We have worked hard to have a charge nurse and oftentimes the bedside nurse with us when we round,” Dr. Rappaport says. Speculating that rounding with hospitalists allowed nurses to feel more part of the team, Dr. Rappaport says know the medical plan, consolidate efforts such that pages to residents were reduced, and generally improve communication. They heard from participating nurses that it made a tremendous difference. This prompted them to conduct their research.

“Our study looked at the nurse-physician relationship globally, not intimidation or abuse specifically,” says Dr. Rappaport. Along with their nurse colleague Norine Watson, RN, Drs. Pressel and Rappaport are examining the relationship between nurses and different categories of physicians: how nurses perceive interactions between nurses and surgical residents, surgical attendings, community physicians, pediatric residents, and pediatric hospitalists.

“Early data suggest that hospitalists may work more effectively with nurses because they share many of the same goals,” says Dr. Rappaport. “As hospital leaders, hospitalists can also improve working conditions for nurses by providing more accessible, efficient, and effective care. Presumably, improved collaboration will also include decreased intimidation or abuse from physicians and also probably from dissatisfied patients and families.”

Avoiding the trap of communicating in a manner that is too direct and might be construed as abusive requires self-awareness and the realization that people receive information in different ways, says Dr. Pressel. Standard professional behavior is the key. Beyond that, the challenge is giving feedback constructively and in a positive manner.

“Hospitalists [may be] more in tune with the needs of nurses than nonhospitalists,” says Dr. Rappaport. “I think that is one of our strengths. We need to continue to facilitate very strong relationships between nurses and physicians because without good nursing care, hospitalists simply cannot provide good medical care.”

There is another way hospitalists can help address verbal abuse. “Studies consistently show that nurses are hesitant to report episodes of verbal abuse,” Dr. Rappaport says, “whether it is from a family, a patient, a physician, or a fellow nurse. Fewer than one in five nurses reports these episodes. One thing that hospitalists can do is work with hospital administration to create an environment that is more proactive in addressing these concerns and allowing nurses to feel more support in this area.”

Only 60% of respondents to the ISMP survey felt their organization had clearly defined an effective process for handling disagreements with a medication order’s safety. Only about a third felt the process facilitated their bypassing an intimidating prescriber or their own supervisor if necessary. Although 70% of respondents reported that they thought their organization or manager would support them if they reported intimidating behavior, only 39% of respondents believed their organization was dealing effectively with intimidating behavior.

Untapped Source

Perceptions of intimidation also occur among trainees. When 2,884 students from the class of 2003 at 16 U.S. medical schools completed questionnaires at various times during training, 27% reported having been “harassed” by house staff, 21% by faculty, and 25% by patients.7 Further, 71% reported having been “belittled” by house staff, 63% by faculty, and 43% by patients.

Mistreated students were significantly more likely to have suffered stress, be depressed or suicidal, and less likely to report being glad they trained as a physician.

—David I. Rappaport, MD, pediatric hospitalist, Alfred I. Dupont Hospital for Children, Wilmington, Del.

This may have an underlying effect on the potential to monitor for patient safety.8,9 Because errors and near misses often result from miscommunication, medical students may be adept at preventing certain types of errors. Students’ observation skills may be just as keen, if not more so, than their more clinically proficient healthcare teammates.8 In four cases from two U.S. academic health centers reported by medical students Samuel Seiden, Cynthia Galvan, and Ruth Lamm in 2006, medical students demonstrated keen attention to detail and appropriately characterized problematic situations with patients—adding another layer of defense within systems safeguarding against patient harm.8 Yet of the 76% of medical students who had observed a medical error, only about half of the students reported the errors to a resident or an attending, despite having received patient-safety training; only 7% reported having used an electronic medical error reporting system.10

By Example

Some intimidation in medical education may be the result of anger toward students and residents over a lack of medical knowledge, says Jeffery G. Wiese, MD, associate professor of Medicine at Tulane University in New Orleans and member of the SHM Board of Directors. “It is natural to feel [that anger]; people abhor in others what they most detest in themselves,’’ he says. “As physicians, a lack of medical knowledge is what we detest in ourselves. But a student’s ignorance is usually a product of where she is in her training; that’s why she is with you.”

—Jeffery G. Wiese, MD, associate professor of Medicine at Tulane University, New Orleans

Anger alienates students, absolving them of the guilt of not knowing the information, and demotivating them from learning it. “The lesson to be communicated is that it is OK not to know, but it is not OK to continue to not know,” Dr. Wiese says. “Reprimands should be reserved for the student who does not know, and then after being taught or asked to look it up, continues to not know.”

“The average physician who practices for 30 years will take care of roughly 80,000 people,” estimates Dr. Wiese. “That’s an arithmetic contribution and there is nothing wrong with that. But if you really want to change the world, teaching is the rule. The same 30 years invested in teaching will indirectly affect 400 million people,” he says. “Even better, if you can train your students and residents in the value of coaching their students and residents, well, now you’re talking about 10 billion people that you can affect over the course of a career.”

The question to ask yourself, says Dr. Wiese, is: Do you want to change the world? “If you do, this is the way to do it,” he says.

“For the 30 years in your career, focus on clinical coaching and getting others to clinically coach. That way, especially if you have the right motives in your heart, the right vision for the way you want to see the profession practiced, and the way you want patient care performed, that’s your shot at changing the world.” TH

Andrea Sattinger is a frequent contributor to The Hospitalist.

References

- Institute for Safe Medication Practice. Intimidation: practitioners speak up about this unresolved problem (Part I). Available at w.ismp.org/Newsletters/acutecare/articles/20040311_2.asp. Last accessed June 27, 2007.

- Hagstrom AM. Perceived barriers to implementation of a successful sharps safety program. AORN J. 2006;83(2):391-7.

- Porto G, Lauve R. Disruptive clinician behavior: a persistent threat to patient safety. Patient Safety Qual Healthc. 2006 Jul-Aug;3:16-24.

- Manderino MA, Berkey N. Verbal abuse of staff nurses by physicians. J Prof Nurs. 1997;13(1):48-55.

- Pejic AR. Verbal abuse: A problem for pediatric nurses. Pediatr Nurs. 2005;31(4):271-279.

- Rowe MM, Sherlock H. Stress and verbal abuse in nursing: do burned out nurses eat their young? J Nurs Manag. 2005May;13(3):242-248.

- Frank E, Carrera JS, Stratton T, et al. Experiences of belittlement and harassment and their correlates among medical students in the United States: longitudinal survey. BMJ. 2006 Sep 30;333(7570):682.

- Seiden SC, Galvan C, Lamm R. Role of medical students in preventing patient harm and enhancing patient safety. Qual Saf Health Care. 2006 Aug;15(4):272-276.

- Wood DF. Bullying and harassment in medical schools. BMJ. 2006 Sep 30;333(7570):664-665.

- Madigosky WS, Headrick LA, Nelson K, et al. Changing and sustaining medical students’ knowledge, skills, and attitudes about patient safety and medical fallibility. Acad Med. 2006 Jan;81(1):94-101.

- Institute for Safe Medication Practice. Intimidation: Mapping a plan for cultural change in healthcare (Part II). Available at www.ismp.org/Newsletters/acutecare/articles/20040325.asp Last accessed July 2, 2007.

Pediatric Predictions

In reflecting on the history of pediatric hospital medicine (HM), I have identified a widening schism between inpatient and outpatient pediatrics as the major threat to HM. Here, I follow Bob Wachter’s lead from SHM’s May annual meeting and detail key steps for pediatric HM in the upcoming 10 years.

Define the field: The SHM Pediatric Committee and the Ambulatory Pediatric Association’s (APA) hospital medicine special interest group are collaborating to publish a list of core clinical procedural and systems domains for pediatric hospital medicine.

This will provide a blueprint of how we have defined our field and supply a framework for pediatric acute care residency tracks, hospitalist electives, hospitalist fellowships, and maintenance of certification (MOC). Related characterizations of the field are available through pediatric hospital medicine textbooks. The Pediatric Research in Inpatient Settings (PRIS) network is studying the epidemiology of pediatric HM practice to provide an evidence basis for these expert decrees.

Individual programs should use these resources to help develop program-specific hospitalist privilege materials based on documented patient acuity, volume, and hospital medicine CME activities. The specific criteria and privileges will differ based on differences in job description between and within tertiary care centers and community hospitals—but all will include the general pediatric ward.

Develop MOC Appropriate for Pediatric Hospitalists: The American Board of Internal Medicine has officially approved the creation of a Focused Recognition of Hospital Medicine through its MOC system. A final decision rests with the American Board of Medical Specialties.

Pediatric hospitalists will do well to wait several years to examine the results of these efforts before deciding whether to pursue a similar designation from the American Board of Pediatrics. In the meantime, we should be on a fast track to create specific pediatric HM materials that will meet the 2010 MOC requirements.

There are at least 1,500 practicing pediatric hospitalists. This is equal to the number of board-certified pediatric ED physicians (1,446) and considerably more than the number of pulmonologists (821). Certainly these numbers merit development of MOC materials specifical to pediatric HM. The American Academy of Pediatrics (AAP) is developing an inpatient Education in Quality Improvement for Pediatric Practice (eQIPP) asthma model. SHM may be able to develop a transitions-of-care personal information manager and/or self-evaluation program (SEP) module appropriate for adult and pediatric hospitalists.

The only things missing are a comprehensive inpatient SEP and a closed-book exam. Pediatric hospitalists are here to stay. The American Board of Pediatrics (ABP) will best fulfill its responsibility to the public by creating an MOC program germane to pediatric HM. The actual designation on the MOC doesn’t need to be changed in 2010, but hospitalists recertifying in 2010 should be participating in relevant activities.

Expand pediatric HM (post-) graduate medical education: The increasing number of hospitalists will undoubtedly influence pediatric graduate medical education.

The ABP’s Residency Review and Redesign in Pediatrics project, which looks at global reform of pediatric residency training, should allow for acute care pediatric residency tracks. These would be amenable to pediatricians planning careers in HM, emergency medicine, and critical care.