User login

Tongue necrosis from temporal arteritis

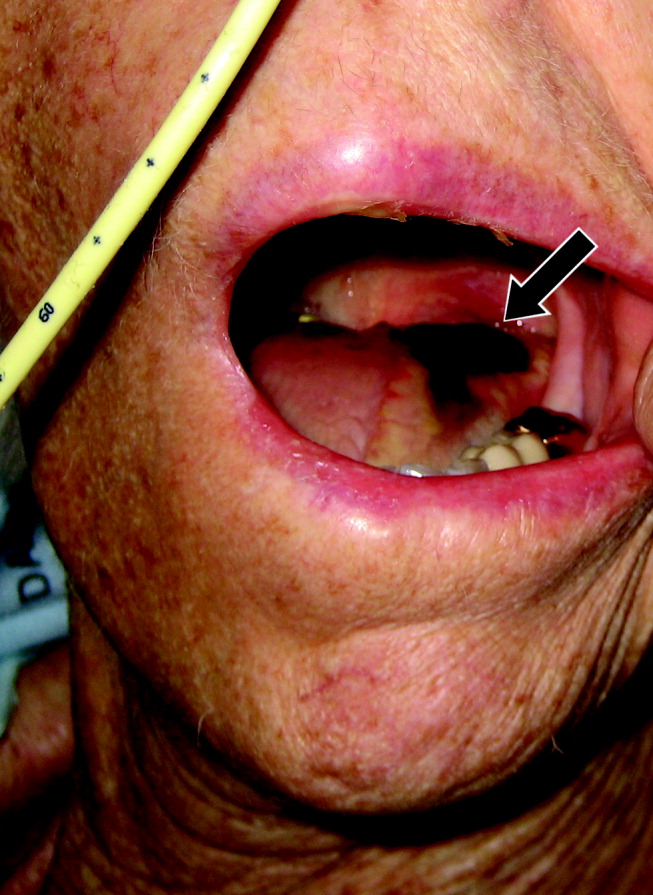

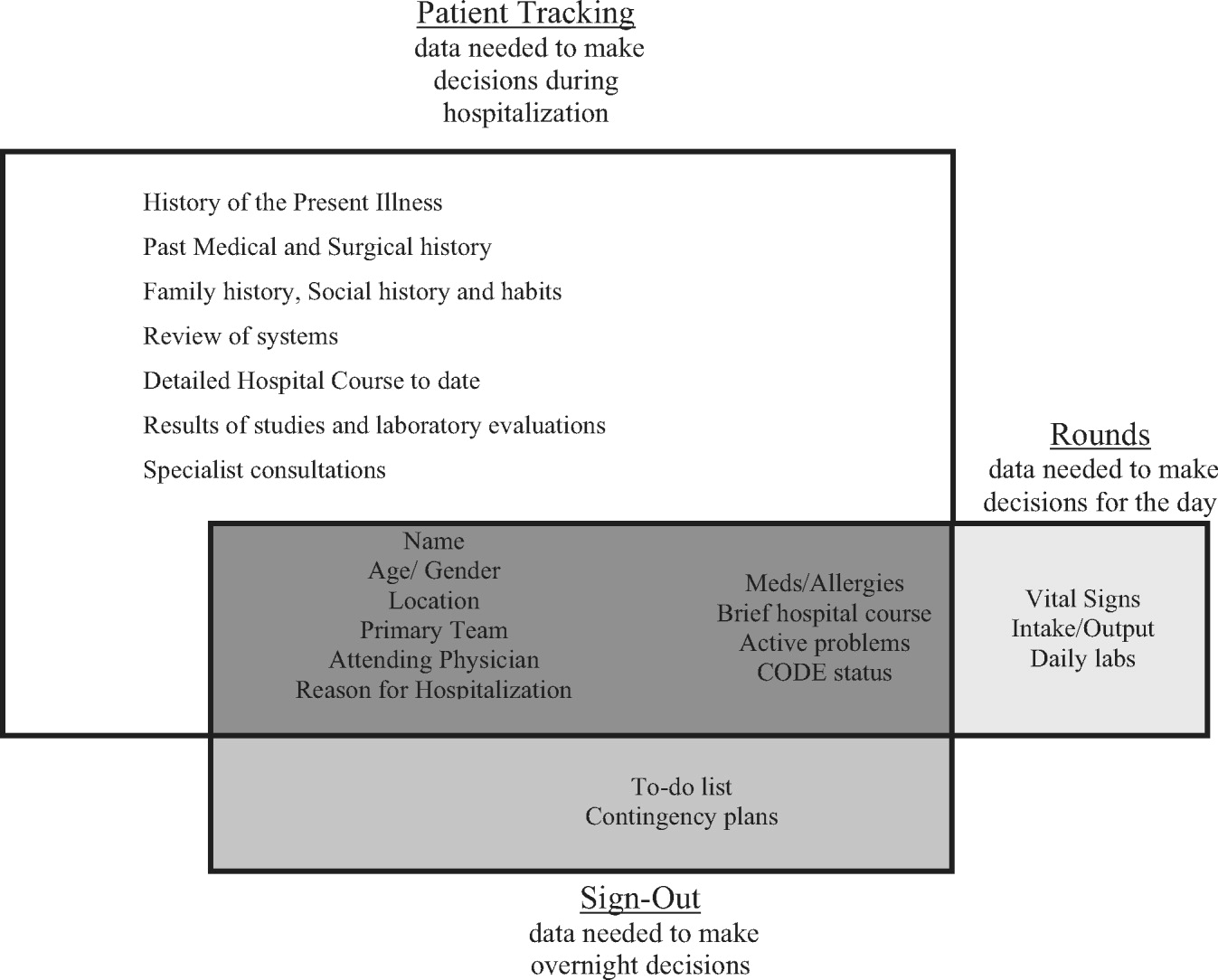

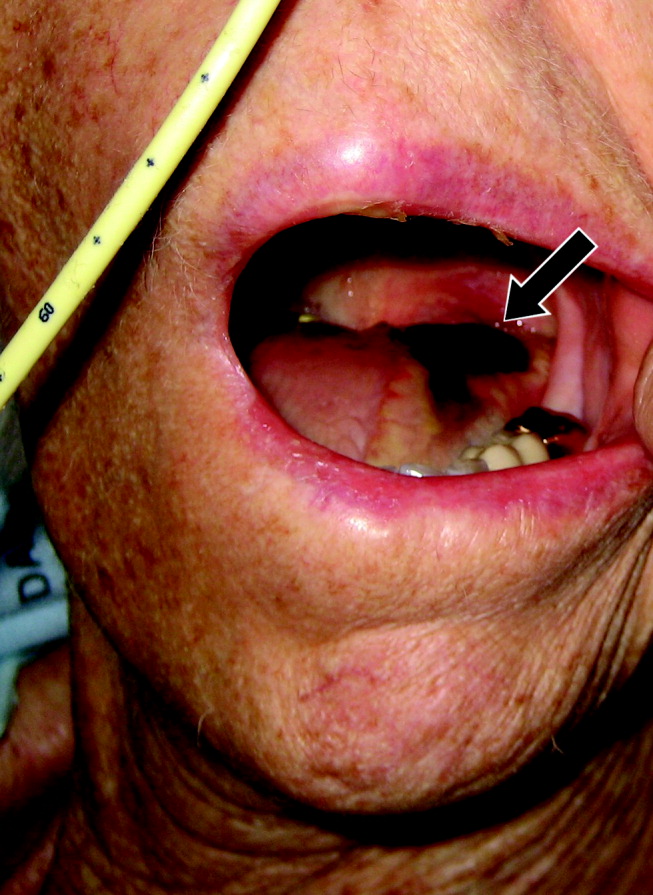

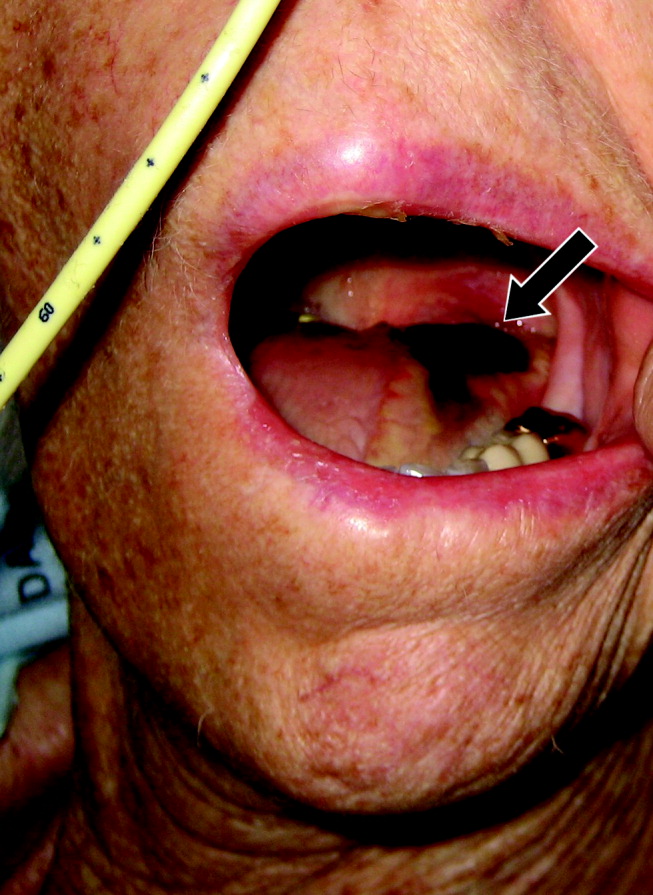

A 77‐year‐old woman with hypothyroidism presented with a 2‐week history of head, neck, jaw, and tongue pain. She had also developed slurred speech and difficulty chewing. On examination she had a temperature of 38.0C. She was without neurological deficits. However, she did have difficulty protruding her tongue, which had a cyanotic appearance and was painful. Laboratory findings showed an erythrocyte sedimentation rate of 68 mm/hr. Temporal arteritis was suspected, and the patient was started on corticosteroids. A subsequent temporal artery biopsy revealed inflammation and thrombus formation consistent with temporal arteritis. On hospital day 3, she developed unilateral ischemia in her tongue, which eventually became necrotic (Fig. 1). Although tongue necrosis is rare, temporal arteritis is the most frequent cause. It is usually unilateral and caused by compromised blood supply as a result of vasculitis in one of the lingual arteries. Other causes of tongue necrosis such as embolus, abscess, syphilis, tongue carcinoma, and Hodgkin's disease should be excluded.1, 2 Although necrotic tongue tissue must sometimes be extensively debrided or resected, our patient required minimal debridement. At follow‐up 1 month later, she was recovering at home with ongoing speech therapy and a corticosteroid taper.

- ,,.Lingual infarction: a review of the literature.Ann Vasc Surg.1992;6:450–452.

- ,.The ESR in the diagnosis and management of the polymyalgia rheumatica/giant cell arteritis syndrome.Ann Rheum Dis.1983;42:168–170.

A 77‐year‐old woman with hypothyroidism presented with a 2‐week history of head, neck, jaw, and tongue pain. She had also developed slurred speech and difficulty chewing. On examination she had a temperature of 38.0C. She was without neurological deficits. However, she did have difficulty protruding her tongue, which had a cyanotic appearance and was painful. Laboratory findings showed an erythrocyte sedimentation rate of 68 mm/hr. Temporal arteritis was suspected, and the patient was started on corticosteroids. A subsequent temporal artery biopsy revealed inflammation and thrombus formation consistent with temporal arteritis. On hospital day 3, she developed unilateral ischemia in her tongue, which eventually became necrotic (Fig. 1). Although tongue necrosis is rare, temporal arteritis is the most frequent cause. It is usually unilateral and caused by compromised blood supply as a result of vasculitis in one of the lingual arteries. Other causes of tongue necrosis such as embolus, abscess, syphilis, tongue carcinoma, and Hodgkin's disease should be excluded.1, 2 Although necrotic tongue tissue must sometimes be extensively debrided or resected, our patient required minimal debridement. At follow‐up 1 month later, she was recovering at home with ongoing speech therapy and a corticosteroid taper.

A 77‐year‐old woman with hypothyroidism presented with a 2‐week history of head, neck, jaw, and tongue pain. She had also developed slurred speech and difficulty chewing. On examination she had a temperature of 38.0C. She was without neurological deficits. However, she did have difficulty protruding her tongue, which had a cyanotic appearance and was painful. Laboratory findings showed an erythrocyte sedimentation rate of 68 mm/hr. Temporal arteritis was suspected, and the patient was started on corticosteroids. A subsequent temporal artery biopsy revealed inflammation and thrombus formation consistent with temporal arteritis. On hospital day 3, she developed unilateral ischemia in her tongue, which eventually became necrotic (Fig. 1). Although tongue necrosis is rare, temporal arteritis is the most frequent cause. It is usually unilateral and caused by compromised blood supply as a result of vasculitis in one of the lingual arteries. Other causes of tongue necrosis such as embolus, abscess, syphilis, tongue carcinoma, and Hodgkin's disease should be excluded.1, 2 Although necrotic tongue tissue must sometimes be extensively debrided or resected, our patient required minimal debridement. At follow‐up 1 month later, she was recovering at home with ongoing speech therapy and a corticosteroid taper.

- ,,.Lingual infarction: a review of the literature.Ann Vasc Surg.1992;6:450–452.

- ,.The ESR in the diagnosis and management of the polymyalgia rheumatica/giant cell arteritis syndrome.Ann Rheum Dis.1983;42:168–170.

- ,,.Lingual infarction: a review of the literature.Ann Vasc Surg.1992;6:450–452.

- ,.The ESR in the diagnosis and management of the polymyalgia rheumatica/giant cell arteritis syndrome.Ann Rheum Dis.1983;42:168–170.

Linezolid‐ and vancomycin‐resistant Enterococcus faecium endocarditis: Successful treatment with tigecycline and daptomycin

Enterococci are a leading cause of endocarditis and nosocomial infections. Vancomycin‐resistant enterococci (VRE) emerged in the 1980s and now represent most nosocomial isolates in the United States. The first case of VRE endocarditis was reported in 1996.1 Although increasing enterococcal antibiotic resistance has prompted increasing reliance on newer antibiotics,2 a recent review of VRE endocarditis noted that survival rates were similar to those for vancomycin‐sensitive enterococcal endocarditis.1 Cure was achieved in several patients with bacteriostatic agents in the absence of valve replacement, but no patients were infected with truly linezolid‐resistant organisms. This case of linezolid‐resistant VRE endocarditis represents the first reported cure of infective endocarditis with a tigecycline‐containing regimen.

CASE REPORT

A 62‐year‐old man presented with hypoglycemia and delirium. His medical history included diabetes mellitus, coronary and peripheral arterial disease, and end‐stage renal disease. He had had endocarditis of an unknown type 12 years prior to admission. He had recently developed septic shock because of a Candida parapsilosis, Enterobacter cloacae, and Staphylococcus epidermidis infection of a peripherally inserted central catheter (PICC) and received 14 days of vancomycin, meropenem, and fluconazole administered through a new PICC. This catheter was not removed, and 39 days after completion of the antibiotic therapy, he developed hypoglycemia, which was attributed to weight loss without adjustment of his insulin regimen. He was afebrile; examination revealed a new 3/6 holosystolic murmur radiating to the axilla. There were no other stigmata of infective endocarditis, and his PICC and arteriovenous fistula sites appeared normal. Delirium resolved after administration of intravenous glucose.

E. faecium grew from all 6 initial blood cultures. A transesophageal echocardiogram revealed a new 3‐mm mitral valve vegetation with perforation and severe regurgitation. He had definite endocarditis on the basis of 2 major criteria.3 He was given vancomycin (1 g IV, then administered by levels), then switched to linezolid (600 mg orally every 12 hours), and finally tigecycline (100 mg IV followed by 50 mg IV every 12 hours) plus daptomycin (6 mg/kg IV every 48 hours) as further sensitivity data became available.

The organism was resistant to ampicillin, chloramphenicol, and linezolid (MIC > 20 g/mL), as well as vancomycin (MIC > 50 g/mL), quinupristin/dalfopristin (MIC 2.5 g/mL), and gentamicin (MIC > 200 g/mL), and demonstrated high‐level streptomycin resistance (>2000 g/mL). It was intermediate to doxycycline (MIC 5 g/mL). It was susceptible to daptomycin (MIC 4 g/mL) and tigecycline (MIC 0.06 g/mL).

Blood cultures done on hospital days 1, 4, 6, and 7 (day 1 of tigecycline) were positive, and multiple cultures were negative from day 10 on. Because of the lack of experience with tigecycline in infective endocarditis, unrevascularized left‐main coronary artery disease, and severe mitral regurgitation, the patient was advised to undergo valve replacement and coronary artery bypass surgery after antibiotic therapy. Because he feared surgical complications, he refused and received 70 days of tigecycline plus daptomycin therapy, which was complicated only by nausea. He remained clinically well and had negative blood cultures 16 weeks after completion of therapy.

DISCUSSION

Tigecycline, the first available glycylcycline, is a minocycline‐derived antibiotic that remains active in the presence of the ribosomal modifications and efflux pumps that mediate tetracycline resistance. Thus, it possesses broad‐spectrum bacteriostatic activity, including activity against VRE. A PubMed search revealed no published data about the use of tigecycline for endocarditis in humans. However, tetracyclines have been used to treat endocarditis due to such organisms as Bartonella, Coxiella burnetti, or methicillin‐resistant Staphylococcus aureus (MRSA), frequently for prolonged courses. Tetracyclines were combined with other antibiotics in 5 published cases of VRE endocarditis. All patients survived; 3 were cured with the tetracycline regimen and 2 with other antimicrobials.1 In animal models of endocarditis, tigecycline stabilized vegetation counts of E. faecalis and reduced vegetation counts of MRSA and 1 strain of E. faecium.4

Daptomycin, the first available cyclic lipopeptide, kills by nonlytic depolarization of the bacterial cell membrane. In a recent study, daptomycin was non‐inferior to vancomycin or antistaphylococcal penicillins for S. aureus bacteremia or endocarditis. Although a few patients had left‐sided endocarditis, only 1 of them experienced a successful outcome with daptomycin therapy, and daptomycin displayed a trend toward higher rates of persistent or relapsing infection.5 Less evidence supports the use of daptomycin for serious enterococcal infections.2 One report noted the deaths of 6 of 10 patients treated with daptomycin for VRE bacteremia, including both patients with endocarditis.6 Daptomycin was used successfully in a case of VRE endocarditis in combination with gentamicin and rifampin for 11 weeks1 and at least 6 other reported cases of VRE bacteremia.7, 8

In summary, despite tigecycline's lack of bactericidal activity or proven efficacy in endocarditis, daptomycin's prior performance in VRE bacteremia, and the isolate's borderline daptomycin susceptibility, prolonged combination therapy resulted in a cure of VRE endocarditis. This success extends the experience with using both agents in the treatment of resistant infections. As linezolid‐resistant VRE and other resistant pathogens become more common, the need for research on treatment options becomes more urgent, and familiarity with novel and lesser‐used antibiotics becomes more crucial for hospitalists.

- ,.Endocarditis due to vancomycin‐resistant enterococci: case report and review of the literature.Clin Infect Dis.2005;41:1134–1142.

- ,.Approaches to vancomycin resistant enterococci.Curr Opin Infect Dis.2004;17:541–547.

- ,,, et al.Proposed modifications to the Duke criteria for the diagnosis of infective endocarditis.Clin Infect Dis.2000;4:633–638.

- ,,, et al.Activity and diffusion of tigecycline (GAR‐936) in experimental enterococcal endocarditis.Antimicrob Agents Chemother.2003;47:216–222.

- ,,, et al.Daptomycin versus standard therapy for bacteremia and endocarditis caused by staphylococcus aureus.New Engl J Med.2006;355:653–665.

- ,,.Daptomycin for the treatment of gram‐positive bacteremia and infective endocarditis: a retrospective case series of 31 patients.Pharmacotherapy.2006;26:347–352.

- ,,,,.Daptomycin in the treatment of vancomycin‐resistant Enterococcus faecium bacteremia in neutropenic patients.J Infect.2007;54:567–571.

- ,,,,.Daptomycin for the treatment of vancomycin resistant Enterococcus faecium bacteremia.Scand J Infect Dis.2006;38:290–292.

Enterococci are a leading cause of endocarditis and nosocomial infections. Vancomycin‐resistant enterococci (VRE) emerged in the 1980s and now represent most nosocomial isolates in the United States. The first case of VRE endocarditis was reported in 1996.1 Although increasing enterococcal antibiotic resistance has prompted increasing reliance on newer antibiotics,2 a recent review of VRE endocarditis noted that survival rates were similar to those for vancomycin‐sensitive enterococcal endocarditis.1 Cure was achieved in several patients with bacteriostatic agents in the absence of valve replacement, but no patients were infected with truly linezolid‐resistant organisms. This case of linezolid‐resistant VRE endocarditis represents the first reported cure of infective endocarditis with a tigecycline‐containing regimen.

CASE REPORT

A 62‐year‐old man presented with hypoglycemia and delirium. His medical history included diabetes mellitus, coronary and peripheral arterial disease, and end‐stage renal disease. He had had endocarditis of an unknown type 12 years prior to admission. He had recently developed septic shock because of a Candida parapsilosis, Enterobacter cloacae, and Staphylococcus epidermidis infection of a peripherally inserted central catheter (PICC) and received 14 days of vancomycin, meropenem, and fluconazole administered through a new PICC. This catheter was not removed, and 39 days after completion of the antibiotic therapy, he developed hypoglycemia, which was attributed to weight loss without adjustment of his insulin regimen. He was afebrile; examination revealed a new 3/6 holosystolic murmur radiating to the axilla. There were no other stigmata of infective endocarditis, and his PICC and arteriovenous fistula sites appeared normal. Delirium resolved after administration of intravenous glucose.

E. faecium grew from all 6 initial blood cultures. A transesophageal echocardiogram revealed a new 3‐mm mitral valve vegetation with perforation and severe regurgitation. He had definite endocarditis on the basis of 2 major criteria.3 He was given vancomycin (1 g IV, then administered by levels), then switched to linezolid (600 mg orally every 12 hours), and finally tigecycline (100 mg IV followed by 50 mg IV every 12 hours) plus daptomycin (6 mg/kg IV every 48 hours) as further sensitivity data became available.

The organism was resistant to ampicillin, chloramphenicol, and linezolid (MIC > 20 g/mL), as well as vancomycin (MIC > 50 g/mL), quinupristin/dalfopristin (MIC 2.5 g/mL), and gentamicin (MIC > 200 g/mL), and demonstrated high‐level streptomycin resistance (>2000 g/mL). It was intermediate to doxycycline (MIC 5 g/mL). It was susceptible to daptomycin (MIC 4 g/mL) and tigecycline (MIC 0.06 g/mL).

Blood cultures done on hospital days 1, 4, 6, and 7 (day 1 of tigecycline) were positive, and multiple cultures were negative from day 10 on. Because of the lack of experience with tigecycline in infective endocarditis, unrevascularized left‐main coronary artery disease, and severe mitral regurgitation, the patient was advised to undergo valve replacement and coronary artery bypass surgery after antibiotic therapy. Because he feared surgical complications, he refused and received 70 days of tigecycline plus daptomycin therapy, which was complicated only by nausea. He remained clinically well and had negative blood cultures 16 weeks after completion of therapy.

DISCUSSION

Tigecycline, the first available glycylcycline, is a minocycline‐derived antibiotic that remains active in the presence of the ribosomal modifications and efflux pumps that mediate tetracycline resistance. Thus, it possesses broad‐spectrum bacteriostatic activity, including activity against VRE. A PubMed search revealed no published data about the use of tigecycline for endocarditis in humans. However, tetracyclines have been used to treat endocarditis due to such organisms as Bartonella, Coxiella burnetti, or methicillin‐resistant Staphylococcus aureus (MRSA), frequently for prolonged courses. Tetracyclines were combined with other antibiotics in 5 published cases of VRE endocarditis. All patients survived; 3 were cured with the tetracycline regimen and 2 with other antimicrobials.1 In animal models of endocarditis, tigecycline stabilized vegetation counts of E. faecalis and reduced vegetation counts of MRSA and 1 strain of E. faecium.4

Daptomycin, the first available cyclic lipopeptide, kills by nonlytic depolarization of the bacterial cell membrane. In a recent study, daptomycin was non‐inferior to vancomycin or antistaphylococcal penicillins for S. aureus bacteremia or endocarditis. Although a few patients had left‐sided endocarditis, only 1 of them experienced a successful outcome with daptomycin therapy, and daptomycin displayed a trend toward higher rates of persistent or relapsing infection.5 Less evidence supports the use of daptomycin for serious enterococcal infections.2 One report noted the deaths of 6 of 10 patients treated with daptomycin for VRE bacteremia, including both patients with endocarditis.6 Daptomycin was used successfully in a case of VRE endocarditis in combination with gentamicin and rifampin for 11 weeks1 and at least 6 other reported cases of VRE bacteremia.7, 8

In summary, despite tigecycline's lack of bactericidal activity or proven efficacy in endocarditis, daptomycin's prior performance in VRE bacteremia, and the isolate's borderline daptomycin susceptibility, prolonged combination therapy resulted in a cure of VRE endocarditis. This success extends the experience with using both agents in the treatment of resistant infections. As linezolid‐resistant VRE and other resistant pathogens become more common, the need for research on treatment options becomes more urgent, and familiarity with novel and lesser‐used antibiotics becomes more crucial for hospitalists.

Enterococci are a leading cause of endocarditis and nosocomial infections. Vancomycin‐resistant enterococci (VRE) emerged in the 1980s and now represent most nosocomial isolates in the United States. The first case of VRE endocarditis was reported in 1996.1 Although increasing enterococcal antibiotic resistance has prompted increasing reliance on newer antibiotics,2 a recent review of VRE endocarditis noted that survival rates were similar to those for vancomycin‐sensitive enterococcal endocarditis.1 Cure was achieved in several patients with bacteriostatic agents in the absence of valve replacement, but no patients were infected with truly linezolid‐resistant organisms. This case of linezolid‐resistant VRE endocarditis represents the first reported cure of infective endocarditis with a tigecycline‐containing regimen.

CASE REPORT

A 62‐year‐old man presented with hypoglycemia and delirium. His medical history included diabetes mellitus, coronary and peripheral arterial disease, and end‐stage renal disease. He had had endocarditis of an unknown type 12 years prior to admission. He had recently developed septic shock because of a Candida parapsilosis, Enterobacter cloacae, and Staphylococcus epidermidis infection of a peripherally inserted central catheter (PICC) and received 14 days of vancomycin, meropenem, and fluconazole administered through a new PICC. This catheter was not removed, and 39 days after completion of the antibiotic therapy, he developed hypoglycemia, which was attributed to weight loss without adjustment of his insulin regimen. He was afebrile; examination revealed a new 3/6 holosystolic murmur radiating to the axilla. There were no other stigmata of infective endocarditis, and his PICC and arteriovenous fistula sites appeared normal. Delirium resolved after administration of intravenous glucose.

E. faecium grew from all 6 initial blood cultures. A transesophageal echocardiogram revealed a new 3‐mm mitral valve vegetation with perforation and severe regurgitation. He had definite endocarditis on the basis of 2 major criteria.3 He was given vancomycin (1 g IV, then administered by levels), then switched to linezolid (600 mg orally every 12 hours), and finally tigecycline (100 mg IV followed by 50 mg IV every 12 hours) plus daptomycin (6 mg/kg IV every 48 hours) as further sensitivity data became available.

The organism was resistant to ampicillin, chloramphenicol, and linezolid (MIC > 20 g/mL), as well as vancomycin (MIC > 50 g/mL), quinupristin/dalfopristin (MIC 2.5 g/mL), and gentamicin (MIC > 200 g/mL), and demonstrated high‐level streptomycin resistance (>2000 g/mL). It was intermediate to doxycycline (MIC 5 g/mL). It was susceptible to daptomycin (MIC 4 g/mL) and tigecycline (MIC 0.06 g/mL).

Blood cultures done on hospital days 1, 4, 6, and 7 (day 1 of tigecycline) were positive, and multiple cultures were negative from day 10 on. Because of the lack of experience with tigecycline in infective endocarditis, unrevascularized left‐main coronary artery disease, and severe mitral regurgitation, the patient was advised to undergo valve replacement and coronary artery bypass surgery after antibiotic therapy. Because he feared surgical complications, he refused and received 70 days of tigecycline plus daptomycin therapy, which was complicated only by nausea. He remained clinically well and had negative blood cultures 16 weeks after completion of therapy.

DISCUSSION

Tigecycline, the first available glycylcycline, is a minocycline‐derived antibiotic that remains active in the presence of the ribosomal modifications and efflux pumps that mediate tetracycline resistance. Thus, it possesses broad‐spectrum bacteriostatic activity, including activity against VRE. A PubMed search revealed no published data about the use of tigecycline for endocarditis in humans. However, tetracyclines have been used to treat endocarditis due to such organisms as Bartonella, Coxiella burnetti, or methicillin‐resistant Staphylococcus aureus (MRSA), frequently for prolonged courses. Tetracyclines were combined with other antibiotics in 5 published cases of VRE endocarditis. All patients survived; 3 were cured with the tetracycline regimen and 2 with other antimicrobials.1 In animal models of endocarditis, tigecycline stabilized vegetation counts of E. faecalis and reduced vegetation counts of MRSA and 1 strain of E. faecium.4

Daptomycin, the first available cyclic lipopeptide, kills by nonlytic depolarization of the bacterial cell membrane. In a recent study, daptomycin was non‐inferior to vancomycin or antistaphylococcal penicillins for S. aureus bacteremia or endocarditis. Although a few patients had left‐sided endocarditis, only 1 of them experienced a successful outcome with daptomycin therapy, and daptomycin displayed a trend toward higher rates of persistent or relapsing infection.5 Less evidence supports the use of daptomycin for serious enterococcal infections.2 One report noted the deaths of 6 of 10 patients treated with daptomycin for VRE bacteremia, including both patients with endocarditis.6 Daptomycin was used successfully in a case of VRE endocarditis in combination with gentamicin and rifampin for 11 weeks1 and at least 6 other reported cases of VRE bacteremia.7, 8

In summary, despite tigecycline's lack of bactericidal activity or proven efficacy in endocarditis, daptomycin's prior performance in VRE bacteremia, and the isolate's borderline daptomycin susceptibility, prolonged combination therapy resulted in a cure of VRE endocarditis. This success extends the experience with using both agents in the treatment of resistant infections. As linezolid‐resistant VRE and other resistant pathogens become more common, the need for research on treatment options becomes more urgent, and familiarity with novel and lesser‐used antibiotics becomes more crucial for hospitalists.

- ,.Endocarditis due to vancomycin‐resistant enterococci: case report and review of the literature.Clin Infect Dis.2005;41:1134–1142.

- ,.Approaches to vancomycin resistant enterococci.Curr Opin Infect Dis.2004;17:541–547.

- ,,, et al.Proposed modifications to the Duke criteria for the diagnosis of infective endocarditis.Clin Infect Dis.2000;4:633–638.

- ,,, et al.Activity and diffusion of tigecycline (GAR‐936) in experimental enterococcal endocarditis.Antimicrob Agents Chemother.2003;47:216–222.

- ,,, et al.Daptomycin versus standard therapy for bacteremia and endocarditis caused by staphylococcus aureus.New Engl J Med.2006;355:653–665.

- ,,.Daptomycin for the treatment of gram‐positive bacteremia and infective endocarditis: a retrospective case series of 31 patients.Pharmacotherapy.2006;26:347–352.

- ,,,,.Daptomycin in the treatment of vancomycin‐resistant Enterococcus faecium bacteremia in neutropenic patients.J Infect.2007;54:567–571.

- ,,,,.Daptomycin for the treatment of vancomycin resistant Enterococcus faecium bacteremia.Scand J Infect Dis.2006;38:290–292.

- ,.Endocarditis due to vancomycin‐resistant enterococci: case report and review of the literature.Clin Infect Dis.2005;41:1134–1142.

- ,.Approaches to vancomycin resistant enterococci.Curr Opin Infect Dis.2004;17:541–547.

- ,,, et al.Proposed modifications to the Duke criteria for the diagnosis of infective endocarditis.Clin Infect Dis.2000;4:633–638.

- ,,, et al.Activity and diffusion of tigecycline (GAR‐936) in experimental enterococcal endocarditis.Antimicrob Agents Chemother.2003;47:216–222.

- ,,, et al.Daptomycin versus standard therapy for bacteremia and endocarditis caused by staphylococcus aureus.New Engl J Med.2006;355:653–665.

- ,,.Daptomycin for the treatment of gram‐positive bacteremia and infective endocarditis: a retrospective case series of 31 patients.Pharmacotherapy.2006;26:347–352.

- ,,,,.Daptomycin in the treatment of vancomycin‐resistant Enterococcus faecium bacteremia in neutropenic patients.J Infect.2007;54:567–571.

- ,,,,.Daptomycin for the treatment of vancomycin resistant Enterococcus faecium bacteremia.Scand J Infect Dis.2006;38:290–292.

Fishing for a Diagnosis

A 54‐year‐old man with hypertension and type 2 diabetes mellitus entered the Chest Pain Evaluation Unit of a teaching hospital after 12 hours of intermittent thoracic discomfort. The pain began during dinner and was sharp, bandlike, and located beneath the sternum and across the entire chest. He had dyspnea but no diaphoresis or nausea. A recumbent position relieved the pain after dinner, but it recurred during the night and again the following morning. He did not smoke and had no family history of coronary artery disease.

A useful approach in evaluating acute chest pain is to employ a hierarchical differential diagnosis that emphasizes life‐threatening disorders requiring prompt recognition and intervention. Most prominent are cardiac ischemia, pericardial tamponade, pneumothorax, pulmonary embolus, esophageal rupture, and aortic dissection. The concurrent dyspnea and retrosternal location and intermittent nature of the pain that this patient has are consistent with myocardial ischemia, but the sharp quality of the pain and the relief gained by being recumbent are atypical. Pain with pericarditis is characteristically pleuritic and often worse when lying down. The pain of pneumothorax is typically unilateral, not intermittent, and unlikely to improve with recumbency. Although pain during eating suggests the possibility of an esophageal source, spontaneous rupture usually follows vomiting. The pain is typically continuous and severe. The pain of pulmonary embolism may be unilateral and pleuritic but often is more diffuse. Relief by recumbency is unusual, but the intermittent nature could suggest recurrent emboli. The patient has a history of hypertension, which predisposes him to aortic dissection, in which the pain is typically sharp, continuous, and severe but occasionally intermittent. Among numerous less urgent diagnoses are esophagitis and thoracic diabetic radiculopathy.

Important features to look for during this patient's examination include: disappearance of the radial pulse during inhalation, a simple screening test that is insensitive but very specific for pericardial tamponade; elevated neck veins, which can occur with tension pneumothorax, massive pulmonary embolism, and pericardial tamponade; pericardial and pleural friction rubs; discrepant blood pressures in the 2 arms, sometimes a sign of aortic dissection; local thoracic tenderness from chest wall disorders; and sensory examination of the chest surface, which is often abnormal in diabetic thoracic radiculopathy. Given this patient's age and history of diabetes, I am most concerned about myocardial ischemia. The most appropriate diagnostic tests include an electrocardiogram and a chest radiograph.

The patient appeared apprehensive but reported no pain. He had a temperature of 36.0 C, heart rate of 95 beats/minute, blood pressure of 138/77 mm Hg, respiratory rate of 16/minute, and oxygen saturation of 99% while breathing ambient air. Blood pressures were equal in both arms. Jugular venous distention was absent, and the lung and cardiac examinations had normal results. His pain did not increase on chest wall palpation. Examination of the abdomen, extremities, and the neurologic system showed normal results.

The results of laboratory tests showed a leukocyte count of 12,700/cm3, with 85% neutrophils, 8% lymphocytes, 6% monocytes, and 1% eosinophils. The hematocrit was 45%, and the platelet count was 172,000/cm3. The results of his chemistry panel were remarkable only for a glucose of 225 mg/dL. An electrocardiogram (ECG) showed a normal sinus rhythm and left anterior fascicular block without acute ST‐ or T‐wave changes. Prior ECGs were unavailable. An anteroposterior radiograph disclosed low lung volumes and bibasilar opacities. No pleural effusion was noted. Serial serum troponin and creatine kinase levels were normal. A Tc‐99m tetrofosmin cardiac nuclear perfusion test performed at rest demonstrated a moderate area of mildly decreased uptake along the inferior wall extending to the apex. An exercise treadmill test, terminated after 1 minute, 45 seconds because of chest pain, provoked no ECG changes diagnostic of ischemic disease.

The absence of elevated jugular venous pressure virtually eliminates pericardial tamponade as a diagnosis, and the chest film excludes pneumothorax. The intermittent nature of the chest pain, the absence on the chest radiograph of such findings as mediastinal gas, left pneumothorax, or hydropneumothorax, and the lack of a predisposing cause make esophageal rupture unlikely. Pulmonary emboli remain a consideration despite the normal oxygen saturation because there is no hypoxemia in a substantial minority of such cases. The normal cardiac enzyme levels and the lack of significant changes on the ECG exclude that a myocardial infarction has recently occurred, but cardiac ischemia remains a possibility, especially because the patient had chest pain on exercise and the nuclear scan indicated diminished blood flow to the inferior left ventricle. Aortic dissection still lurks as a possibility. The inferior wall abnormalities seen on the scan could result from dissection into the right coronary artery, which is more frequently involved than the left, or compression of it by an enlarged aorta, but they also may be artifacts. The leukocytosis may be a nonspecific response to stress but could indicate, although unlikely, infections such as mediastinitis from esophageal rupture or bacterial aortitis.

A conscientious clinician would repeat the history, reexamine the patient, and scrutinize the chest film to determine what the bilateral opacities represent. Given the story so far, however, I might consider a thoracic computed tomography (CT) angiogram because I am most concerned about pulmonary emboli and aortic dissection.

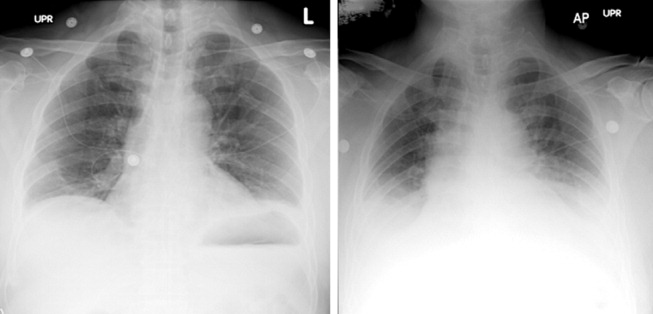

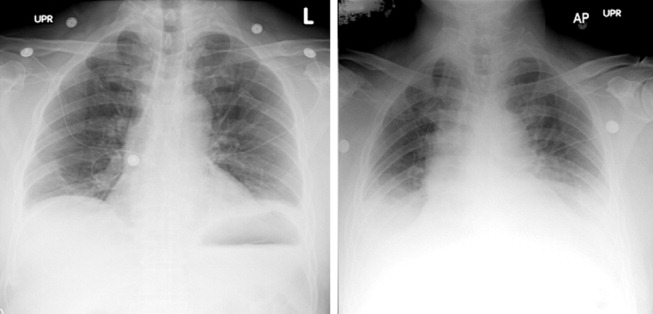

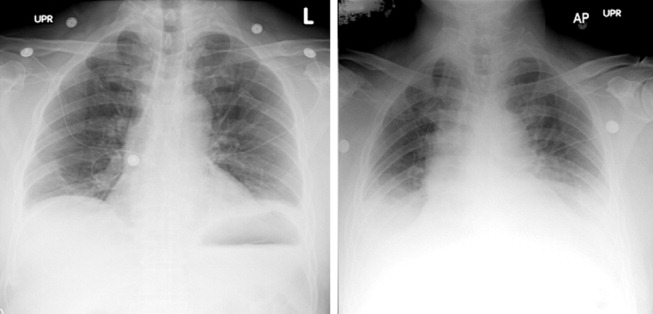

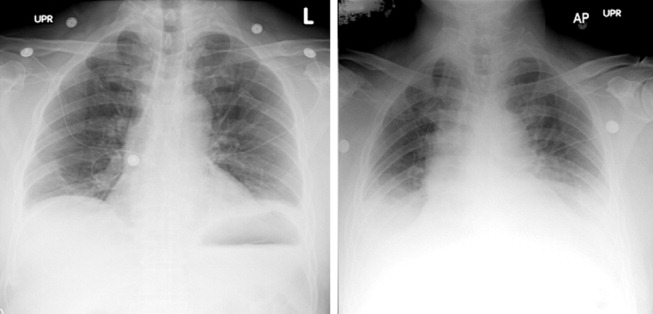

On hospital day 3, the patient had worsening dyspnea and persistent chest pain. His temperature was 39.3C, and his oxygen saturation decreased to 89% while breathing room air. Repeat chest radiography showed new bilateral pleural effusions and increased bibasilar opacification (Fig. 1). His leukocyte count was 19,000/cm3, with 88% neutrophils, 6% lymphocytes, 5% monocytes, and 1% eosinophils. Care was transferred from the chest pain team to an inpatient general medicine ward team. A pulmonary CT angiogram showed no large central clots but suggested emboli in the right superior subsegmental artery and a right upper lobe subsegmental artery. Bilateral pleural effusions were observed, as were bilateral pleural‐based atelectasis or infiltrates in the lower lungs. A hiatal hernia was noted, but no aortic dissection. The patient received supplemental oxygen, intravenous levofloxacin, and unfractionated heparin by continuous infusion.

Without other information, I will assume that the fever is part of the patient's original disease and not a nosocomial infection or drug fever. At this point, a crucial part of the evaluation is examining the CT scan with experienced radiologists to determine whether the abnormalities noted are genuinely convincing for pulmonary emboli. If the findings are equivocal, the next step might be a pulmonary angiogram or the indirect approach of evaluating the leg veins with ultrasound, reasoning that the presence of proximal leg vein thromboses would require anticoagulation in any event.

The patient's worsening chest pain and hypoxemia are consistent with multiple pulmonary emboli. Bilateral pleural effusions and leukocytosis can occur but are uncommon. Because of the fever, another possibility is septic pulmonary emboli, but he has no evidence of suppurative thrombophlebitis of the peripheral veins, apparent infection elsewhere, or previous intravenous drug abuse causing right‐sided endocarditis. An alternative diagnosis is infection of an initially bland pulmonary infarct.

An important consideration is a thoracentesis, depending on how persuasive the CT diagnosis of pulmonary embolism is and the size of the pleural effusions. It should be done before instituting antimicrobial therapy, which may decrease the yield of the cultures, and before starting heparin, which increases the risk of bleeding and occasionally causes a substantial, even fatal hemothorax.

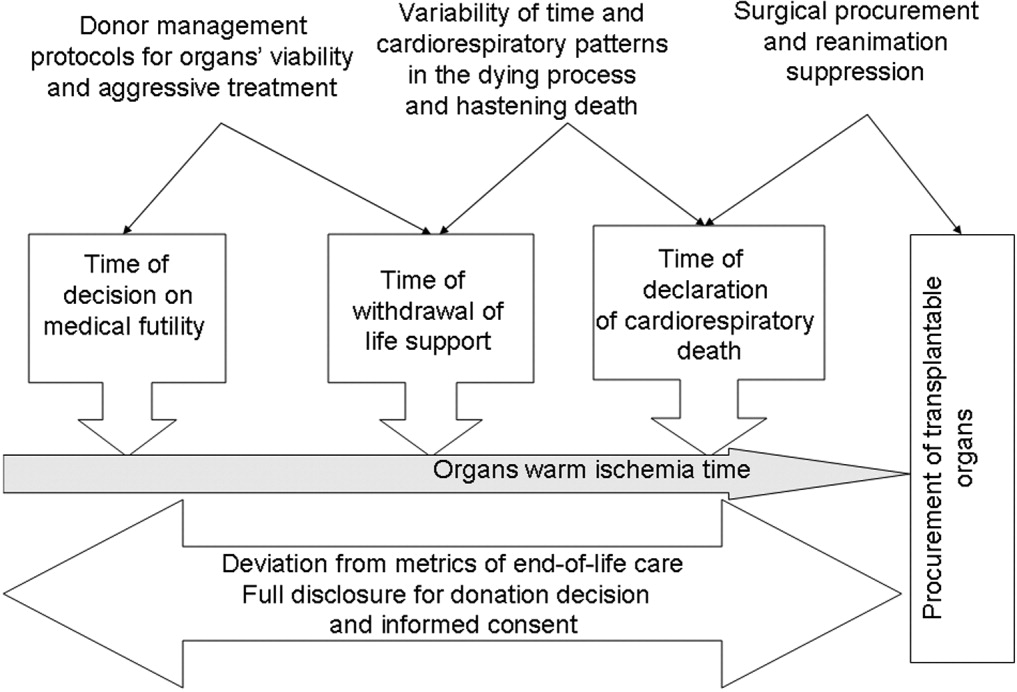

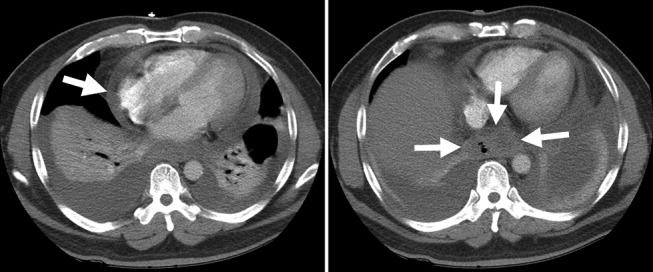

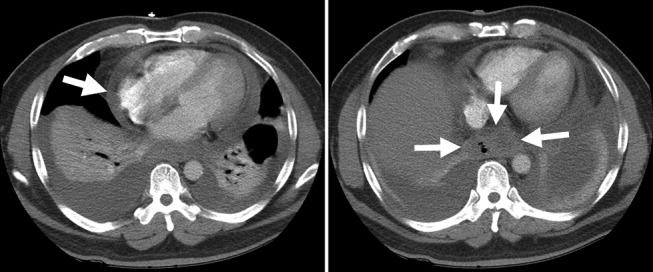

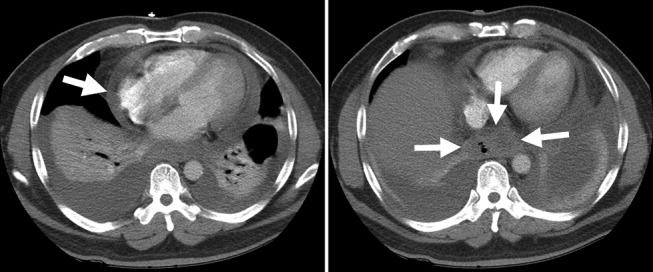

The patient's oxygenation and dyspnea did not improve. Over the next day, he repeatedly mentioned that swallowing, particularly solid foods, worsened his chest pain. He had a temperature of 39.9C, a heart rate of 121 beats/minute, blood pressure of 149/94 mm Hg, a respiratory rate of 28/minute, and oxygen saturation of 93% while breathing 40% oxygen. He had inspiratory splinting, percussive dullness at both lung bases, and distant heart sounds. A contrast esophagogram showed distal narrowing that prevented solid contrast from passing, but no hiatal hernia. Blood and urine cultures obtained before antibiotic therapy were sterile. Duplex ultrasonography of bilateral lower extremities showed no evidence of deep venous thrombosis. A pulmonary angiogram revealed no emboli, and heparin was discontinued. Bilateral thoracentesis yielded grossly bloody fluid. Repeat chest CT (Fig. 2) demonstrated large bilateral effusions, a new large pericardial effusion, and a prominence at the gastroesophageal junction more concerning for a soft‐tissue mass than for a hiatal hernia, although the quality of the study was suboptimal because of an absence of oral contrast.

The CT scan suggests a paraesophageal abscess from an esophageal rupture. As mentioned earlier, if rupture occurs spontaneously, it typically follows retching or vomiting and is called Boerhaave's syndrome. Another consideration is a rupture secondary to an external insult, such as trauma or ingestion of a caustic substance. In evaluating these possibilities, the patient should have been asked 4 questions at the initial interview that I neglected to explicitly highlight earlier. First, what was he eating when he developed the chest pain? Second, did the pain begin during swallowing? Third, did he have previous symptoms suggesting an esophageal disorder such as dysphagia, odynophagia, or heartburn? These might indicate a cancer that could perforate or another problem such as a stricture or disordered esophageal motility that might have caused a swallowed item to lodge in the esophagus. Finally, did he have retching or vomiting? Though not routinely part of the review of systems, the former 2 questions are an appropriate history‐prompted line of questioning of a patient with onset of chest pain while eating.

At this point, a reasonable approach would be an esophagoscopy to delineate any intraluminal problems, such as a cancer or a foreign body. The apparent obstruction seen on barium swallow may be from extrinsic pressure from a paraesophageal abscess. The patient should receive broad‐spectrum antimicrobial therapy effective against oral anaerobes. Although occasionally patients recover with antibiotics alone, surgery is usually required. I am surprised that the original CT scan did not show evidence of an esophageal perforation. Possibly, the hiatal hernia was a paraesophageal abscess poorly characterized because of the lack of oral contrast.

The team, concerned about esophageal perforation, began the patient on intravenous clindamycin. The patient underwent video‐assisted thoracoscopic drainage, which yielded a moderate amount of turbid, bloody fluid from each hemithorax. The pericardium contained approximately 500 cm3 of turbid fluid. Gram stain and culture of these fluids were negative. No esophageal or mediastinal mass was noted during surgery. Intraoperative esophagogastroduodenoscopy with endoscopic ultrasound showed a healing linear mucosal tear in the distal esophagus (Fig. 3) as well as air/fluid collection in the esophageal soft tissue (not shown).

On further questioning postoperatively, the patient reported eating bony fish during the dinner when he first experienced chest pain. The patient received a 21‐day course of oral clindamycin and completely recovered. Five weeks later, a chest CT showed decreased distal esophageal thickening and no mediastinal air.

COMMENTARY

Esophageal perforation is an uncommon but life‐threatening cause of chest pain. In most series iatrogenic injury accounts for more than 70% of cases, whereas most of the other cases have spontaneous (5%20%) or traumatic (4%10%) causes (Table 1).14 Perforation as a complication of ingesting fish bones, although rare, is well described and continues to be reported.57

| Etiology | Percent |

|---|---|

| |

| Iatrogenic | 45%77% |

| Rigid or flexible endoscopy, balloon dilation, Blakemore tube, sclerotherapy, operative injury | |

| Increased intraesophageal pressure (Boerhaave's syndrome) | 5%20% |

| Vomiting or retching, weightlifting, childbirth | |

| Traumatic | 4%10% |

| Penetrating or blunt injury to neck or chest | |

| Ingestion | 0%12% |

| Foreign body, toxic or caustic substance | |

| Miscellaneous | 0%5% |

| Malignancy, Barrett's esophagus, infection, aortic dissection | |

Diagnosis of esophageal perforation secondary to a foreign body may be difficult because of the considerable overlap of symptoms with other causes of chest pain and failure to consider this infrequent condition in the absence of a classic history of retching. To diagnose such a disease, physicians must gather data from various sourcesespecially the history, physical examination, and medical recordformulate hypotheses, integrate results from diagnostic tests, and then assess the importance of the available information in the context of a differential diagnosis. Incorrectly evaluating or failing to obtain essential data can lead to incorrect or delayed diagnoses.

In This Patient's Evaluation, What Prevented Prompt Recognition of Esophageal Perforation?

The critical misstep was an incomplete history, both on arrival and when the patient was transferred to a second team. The presence of risk factors for coronary artery disease led the providers to first consider myocardial ischemia. They failed to ask crucial questions about the onset of the painwhen it occurred during the meal and what he was eatingeven when the patient later complained of odynophagia. As a result of the incomplete history, the providers, puzzled by the patient's ongoing and evolving symptoms, ordered numerous unnecessary diagnostic tests that gave false‐positive results, leading to potentially harmful treatment including anticoagulation. The discussant mentions that the preferred response to a puzzling clinical situation is to return to the bedside and repeat the history, reexamine the patient, and reevaluate available informationsimple steps that can often resolve diagnostic dilemmas.

There is ongoing concern that the history‐taking and physical examination skills of clinicians are in decline.814 Many speculate this is in part due to reliance on increasingly sophisticated diagnostic tests. Providers may overly rely on modern diagnostic tests because of their familiarity with the sensitivity and specificity of such tests, fear of malpractice litigation, diminishing opportunity to elucidate the complete history and physical exam, or lack of confidence in their history‐taking and examination skills.814 Although the rapid development and implementation of advanced diagnostic technologies have had a significant impact on diagnostic accuracy, the estimated rate of disease misdiagnosis remains elevated at 24%.1518 In contrast to technology‐based testing, the history and physical provide an inexpensive, safe, and effective means of at arriving at a correct diagnosis. In outpatient medical visits the history and physical, when completely elicited, result in a correct diagnosis of up to 70%90% of patients.8, 19, 20 Even for illnesses whose diagnosis requires confirmation by a diagnostic test, the definitive test can only be selected after a sufficient history and exam provide an assessment of the pretest probability of disease.

In evaluating chest pain there is an additional potential factor that diminishes reliance on bedside assessment. Modern quality assurance measures and chest pain units encourage clinicians to evaluate patients with chest pain quickly because any delay diminishes the benefits of therapies for acute coronary syndromes. In the emergency room, these patients find themselves on a rapidly moving diagnostic conveyor belt, an approach that is efficient and appropriate given the high prevalence of coronary disease but that also contributes to inattentiveness and error for patients with unusual diagnoses.

How Could Clinicians in Our Case Use Bedside Evidence to Help Differentiate Our Patient?

For most patients with chest pain there is no finding that would change diagnostic probabilities enough to take them off the diagnostic conveyor belt. Nevertheless, several bedside findings can help providers to rank‐order a differential diagnosis, thereby improving the sequence in which diagnostic testing is done. For patients with chest pain the ECG has the highest predictive ability of all studied history, physical exam, and ECG findings (Table 2).21 A history of sharp and positional pain descriptors diminishes the probability of myocardial ischemia.21 Unfortunately, no history, exam, or ECG feature is sensitive enough, either alone or in combination, to effectively rule out myocardial ischemia.

| Finding | Positive LR* |

|---|---|

| Myocardial ischemia | |

| ST segment elevation or Q wave | 22 |

| S3 gallop, blood pressure < 100 mm Hg, or ST segment depression | 3.0 |

| Sharp or positional pain | 0.3 |

| Pulmonary embolism | |

| Low clinical probability | 0.2 |

| Medium clinical probability | 1.8 |

| High clinical probability | 17.1 |

| Aortic dissection | |

| Tearing or ripping pain | 10.8 |

| Focal neurologic deficits | 6.633 |

| Ipsilateral versus contralateral pulse deficit | 5.7 |

| Cardiac tamponade | |

| Pulsus paradoxus > 12 mm Hg | 5.9 |

| Esophageal perforation | |

| Dysphagia, odynophagia, retching, vomiting, or subcutaneous emphysema | ? |

The history and exam can also facilitate differentiation of noncoronary causes of life‐threatening chest pain. The dismal performance of individual bedside findings for pulmonary embolism is what led to development of quantitative D‐dimer assays and objective methods based on bedside evaluation, including the widely used Wells Score.22 This score can be used to classify patients as having low, medium, and high risk of pulmonary embolism, facilitating management decisions after diagnostic imaging is obtained.23 Fewer than half of all patients with thoracic aortic dissection have classic exam findings; however, when present, they can appropriately raise the probability of dissection higher on the differential diagnosis.24 Importantly, no history or exam finding argues against dissection.24 Most patients with cardiac tamponade will have elevated jugular venous pressure (76%100%); however, poor interobserver agreement about this finding may decrease its detection.11, 25, 26 As the discussant notes, total paradox, defined as the palpable pulse disappearing with inspiration, is an insensitive test for tamponade, present in only 23% of patients with the disorder. In contrast, an inspiratory drop in systolic blood pressure of more than 12 mm Hg should prompt consideration for tamponade.11, 26 Commonly taught features of esophageal perforation, including chest pain, dysphagia, odynophagia, prior retching or vomiting, subcutaneous emphysema, dyspnea, and pleural effusions, vary in their reported sensitivity, but their specificity is virtually never reported.27

Like most patients with chest pain, our patient lacked all these symptoms and signs, arguing for myocardial ischemia, although he had a few signs that argued against it (sharp and positional chest pain). After the initial CXR and ECG, further testing with cardiac biomarkers was appropriate, but a fundamental error was made in not returning to the patient's bedside to repeat the interview and examination after the cardiac biomarkers were found to be normal. Had this been done, several cluesdysphagia, onset of pain with eating bony fish, and feverwould have pushed esophageal perforation to the top of the differential diagnosis. Subsequent testing would have led to the correct diagnosis and avoided a potentially harmful diagnostic fishing expedition.

Take‐Home Points

-

Esophageal perforation is an uncommon but life‐threatening cause of chest pain that is difficult to diagnose because of its nonspecific symptoms.

-

An accurate and complete history and exam can reveal signs and symptoms that influence the likelihood of each life‐threatening cause of chest pain. Evaluating patients for these features is vital to the rank ordering of a differential diagnosis and the selection of appropriate diagnostic tests.

-

There is no substitute for repeating the history, reexamining the patient, and reevaluating available information when confronted with a confusing constellation of symptoms.

Acknowledgements

The authors thank Steve McGee for his thoughtful review and comments on the manuscript.

- ,.Esophageal perforations: a 15 year experience.Am J Surg.1982;143:495–503.

- ,,.Esophageal perforation: emphasis on management.Ann Thorac Surg.1996;61:1447–1451; discussion1451–1452.

- ,,,,,.Evolving options in the management of esophageal perforation.Ann Thorac Surg.2004;77:1475–1783.

- ,.Personal management of 57 consecutive patients with esophageal perforation.Am J Surg.2004;187:58–63.

- ,,,,.Perforation of the oesophagus and aorta after eating fish: an unusual cause of chest pain.Emerg Med J.2003;20:385–386.

- ,,,.Esophageal perforation and mediastinitis from fish bone ingestion.South Med J.2003;96:516–520.

- ,,,.A 73‐year‐old man with chest pain 4 days after a fish dinner.Chest.2004;126:294–297.

- ,.The science of the art of the clinical examination.JAMA.1992;267:2650–2652.

- .Clinical skills in the 21st century.Arch Intern Med.1994;154:22–24.

- ,.Pulmonary auscultatory skills during training in internal medicine and family practice.Am J Respir Crit Care Med.1999;159:1119–1124.

- .Evidence‐Based Physical Diagnosis.Philadelphia, PA:Saunders;2001.

- .Simple is beautiful: the neglected power of simple tests.Arch Intern Med.2004;164:2198–2200.

- ,.Pearls and pitfalls in patient care: need to revive traditional clinical values.Am J Med Sci.2004;327:79–85.

- ,. Physical diagnosis: a lost art? Agency for Health Research and Quality. WebM75:29–40.

- .Low‐tech autopsies in the era of high‐tech medicine: continued value for quality assurance and patient safety.JAMA.1998;280:1273–1274.

- ,,,.Has misdiagnosis of appendicitis decreased over time? A population‐based analysis.JAMA.2001;286:1748–1753.

- ,,,.Changes in rates of autopsy‐detected diagnostic errors over time: a systematic review.JAMA.2003;289:2849–2856.

- .Diagnostic Process.J Coll Gen Pract.1963;54:579–589.

- .The importance of the history in the medical clinic and the cost of unnecessary tests.Am Heart J.1980;100:928–931.

- ,.Bedside diagnosis of coronary artery disease: a systematic review.Am J Med.2004;117:334–343.

- ,,, et al.Use of a clinical model for safe management of patients with suspected pulmonary embolism.Ann Intern Med.1998;129:997–1005.

- ,,, et al.Diagnostic pathways in acute pulmonary embolism: recommendations of the PIOPED II investigators.Am J Med.2006;119:1048–1055.

- .Does this patient have an acute thoracic aortic dissection?JAMA.2002;287:2262–2272.

- ,.The rational clinical examination. Does this patient have abnormal central venous pressure?JAMA.1996;275:630–634.

- ,,,.Does this patient with a pericardial effusion have cardiac tamponade?JAMA.2007;297:1810–1818.

- ,.Spontaneous esophageal rupture: a frequently missed diagnosis.Am Surg.1999;65:449–452.

A 54‐year‐old man with hypertension and type 2 diabetes mellitus entered the Chest Pain Evaluation Unit of a teaching hospital after 12 hours of intermittent thoracic discomfort. The pain began during dinner and was sharp, bandlike, and located beneath the sternum and across the entire chest. He had dyspnea but no diaphoresis or nausea. A recumbent position relieved the pain after dinner, but it recurred during the night and again the following morning. He did not smoke and had no family history of coronary artery disease.

A useful approach in evaluating acute chest pain is to employ a hierarchical differential diagnosis that emphasizes life‐threatening disorders requiring prompt recognition and intervention. Most prominent are cardiac ischemia, pericardial tamponade, pneumothorax, pulmonary embolus, esophageal rupture, and aortic dissection. The concurrent dyspnea and retrosternal location and intermittent nature of the pain that this patient has are consistent with myocardial ischemia, but the sharp quality of the pain and the relief gained by being recumbent are atypical. Pain with pericarditis is characteristically pleuritic and often worse when lying down. The pain of pneumothorax is typically unilateral, not intermittent, and unlikely to improve with recumbency. Although pain during eating suggests the possibility of an esophageal source, spontaneous rupture usually follows vomiting. The pain is typically continuous and severe. The pain of pulmonary embolism may be unilateral and pleuritic but often is more diffuse. Relief by recumbency is unusual, but the intermittent nature could suggest recurrent emboli. The patient has a history of hypertension, which predisposes him to aortic dissection, in which the pain is typically sharp, continuous, and severe but occasionally intermittent. Among numerous less urgent diagnoses are esophagitis and thoracic diabetic radiculopathy.

Important features to look for during this patient's examination include: disappearance of the radial pulse during inhalation, a simple screening test that is insensitive but very specific for pericardial tamponade; elevated neck veins, which can occur with tension pneumothorax, massive pulmonary embolism, and pericardial tamponade; pericardial and pleural friction rubs; discrepant blood pressures in the 2 arms, sometimes a sign of aortic dissection; local thoracic tenderness from chest wall disorders; and sensory examination of the chest surface, which is often abnormal in diabetic thoracic radiculopathy. Given this patient's age and history of diabetes, I am most concerned about myocardial ischemia. The most appropriate diagnostic tests include an electrocardiogram and a chest radiograph.

The patient appeared apprehensive but reported no pain. He had a temperature of 36.0 C, heart rate of 95 beats/minute, blood pressure of 138/77 mm Hg, respiratory rate of 16/minute, and oxygen saturation of 99% while breathing ambient air. Blood pressures were equal in both arms. Jugular venous distention was absent, and the lung and cardiac examinations had normal results. His pain did not increase on chest wall palpation. Examination of the abdomen, extremities, and the neurologic system showed normal results.

The results of laboratory tests showed a leukocyte count of 12,700/cm3, with 85% neutrophils, 8% lymphocytes, 6% monocytes, and 1% eosinophils. The hematocrit was 45%, and the platelet count was 172,000/cm3. The results of his chemistry panel were remarkable only for a glucose of 225 mg/dL. An electrocardiogram (ECG) showed a normal sinus rhythm and left anterior fascicular block without acute ST‐ or T‐wave changes. Prior ECGs were unavailable. An anteroposterior radiograph disclosed low lung volumes and bibasilar opacities. No pleural effusion was noted. Serial serum troponin and creatine kinase levels were normal. A Tc‐99m tetrofosmin cardiac nuclear perfusion test performed at rest demonstrated a moderate area of mildly decreased uptake along the inferior wall extending to the apex. An exercise treadmill test, terminated after 1 minute, 45 seconds because of chest pain, provoked no ECG changes diagnostic of ischemic disease.

The absence of elevated jugular venous pressure virtually eliminates pericardial tamponade as a diagnosis, and the chest film excludes pneumothorax. The intermittent nature of the chest pain, the absence on the chest radiograph of such findings as mediastinal gas, left pneumothorax, or hydropneumothorax, and the lack of a predisposing cause make esophageal rupture unlikely. Pulmonary emboli remain a consideration despite the normal oxygen saturation because there is no hypoxemia in a substantial minority of such cases. The normal cardiac enzyme levels and the lack of significant changes on the ECG exclude that a myocardial infarction has recently occurred, but cardiac ischemia remains a possibility, especially because the patient had chest pain on exercise and the nuclear scan indicated diminished blood flow to the inferior left ventricle. Aortic dissection still lurks as a possibility. The inferior wall abnormalities seen on the scan could result from dissection into the right coronary artery, which is more frequently involved than the left, or compression of it by an enlarged aorta, but they also may be artifacts. The leukocytosis may be a nonspecific response to stress but could indicate, although unlikely, infections such as mediastinitis from esophageal rupture or bacterial aortitis.

A conscientious clinician would repeat the history, reexamine the patient, and scrutinize the chest film to determine what the bilateral opacities represent. Given the story so far, however, I might consider a thoracic computed tomography (CT) angiogram because I am most concerned about pulmonary emboli and aortic dissection.

On hospital day 3, the patient had worsening dyspnea and persistent chest pain. His temperature was 39.3C, and his oxygen saturation decreased to 89% while breathing room air. Repeat chest radiography showed new bilateral pleural effusions and increased bibasilar opacification (Fig. 1). His leukocyte count was 19,000/cm3, with 88% neutrophils, 6% lymphocytes, 5% monocytes, and 1% eosinophils. Care was transferred from the chest pain team to an inpatient general medicine ward team. A pulmonary CT angiogram showed no large central clots but suggested emboli in the right superior subsegmental artery and a right upper lobe subsegmental artery. Bilateral pleural effusions were observed, as were bilateral pleural‐based atelectasis or infiltrates in the lower lungs. A hiatal hernia was noted, but no aortic dissection. The patient received supplemental oxygen, intravenous levofloxacin, and unfractionated heparin by continuous infusion.

Without other information, I will assume that the fever is part of the patient's original disease and not a nosocomial infection or drug fever. At this point, a crucial part of the evaluation is examining the CT scan with experienced radiologists to determine whether the abnormalities noted are genuinely convincing for pulmonary emboli. If the findings are equivocal, the next step might be a pulmonary angiogram or the indirect approach of evaluating the leg veins with ultrasound, reasoning that the presence of proximal leg vein thromboses would require anticoagulation in any event.

The patient's worsening chest pain and hypoxemia are consistent with multiple pulmonary emboli. Bilateral pleural effusions and leukocytosis can occur but are uncommon. Because of the fever, another possibility is septic pulmonary emboli, but he has no evidence of suppurative thrombophlebitis of the peripheral veins, apparent infection elsewhere, or previous intravenous drug abuse causing right‐sided endocarditis. An alternative diagnosis is infection of an initially bland pulmonary infarct.

An important consideration is a thoracentesis, depending on how persuasive the CT diagnosis of pulmonary embolism is and the size of the pleural effusions. It should be done before instituting antimicrobial therapy, which may decrease the yield of the cultures, and before starting heparin, which increases the risk of bleeding and occasionally causes a substantial, even fatal hemothorax.

The patient's oxygenation and dyspnea did not improve. Over the next day, he repeatedly mentioned that swallowing, particularly solid foods, worsened his chest pain. He had a temperature of 39.9C, a heart rate of 121 beats/minute, blood pressure of 149/94 mm Hg, a respiratory rate of 28/minute, and oxygen saturation of 93% while breathing 40% oxygen. He had inspiratory splinting, percussive dullness at both lung bases, and distant heart sounds. A contrast esophagogram showed distal narrowing that prevented solid contrast from passing, but no hiatal hernia. Blood and urine cultures obtained before antibiotic therapy were sterile. Duplex ultrasonography of bilateral lower extremities showed no evidence of deep venous thrombosis. A pulmonary angiogram revealed no emboli, and heparin was discontinued. Bilateral thoracentesis yielded grossly bloody fluid. Repeat chest CT (Fig. 2) demonstrated large bilateral effusions, a new large pericardial effusion, and a prominence at the gastroesophageal junction more concerning for a soft‐tissue mass than for a hiatal hernia, although the quality of the study was suboptimal because of an absence of oral contrast.

The CT scan suggests a paraesophageal abscess from an esophageal rupture. As mentioned earlier, if rupture occurs spontaneously, it typically follows retching or vomiting and is called Boerhaave's syndrome. Another consideration is a rupture secondary to an external insult, such as trauma or ingestion of a caustic substance. In evaluating these possibilities, the patient should have been asked 4 questions at the initial interview that I neglected to explicitly highlight earlier. First, what was he eating when he developed the chest pain? Second, did the pain begin during swallowing? Third, did he have previous symptoms suggesting an esophageal disorder such as dysphagia, odynophagia, or heartburn? These might indicate a cancer that could perforate or another problem such as a stricture or disordered esophageal motility that might have caused a swallowed item to lodge in the esophagus. Finally, did he have retching or vomiting? Though not routinely part of the review of systems, the former 2 questions are an appropriate history‐prompted line of questioning of a patient with onset of chest pain while eating.

At this point, a reasonable approach would be an esophagoscopy to delineate any intraluminal problems, such as a cancer or a foreign body. The apparent obstruction seen on barium swallow may be from extrinsic pressure from a paraesophageal abscess. The patient should receive broad‐spectrum antimicrobial therapy effective against oral anaerobes. Although occasionally patients recover with antibiotics alone, surgery is usually required. I am surprised that the original CT scan did not show evidence of an esophageal perforation. Possibly, the hiatal hernia was a paraesophageal abscess poorly characterized because of the lack of oral contrast.

The team, concerned about esophageal perforation, began the patient on intravenous clindamycin. The patient underwent video‐assisted thoracoscopic drainage, which yielded a moderate amount of turbid, bloody fluid from each hemithorax. The pericardium contained approximately 500 cm3 of turbid fluid. Gram stain and culture of these fluids were negative. No esophageal or mediastinal mass was noted during surgery. Intraoperative esophagogastroduodenoscopy with endoscopic ultrasound showed a healing linear mucosal tear in the distal esophagus (Fig. 3) as well as air/fluid collection in the esophageal soft tissue (not shown).

On further questioning postoperatively, the patient reported eating bony fish during the dinner when he first experienced chest pain. The patient received a 21‐day course of oral clindamycin and completely recovered. Five weeks later, a chest CT showed decreased distal esophageal thickening and no mediastinal air.

COMMENTARY

Esophageal perforation is an uncommon but life‐threatening cause of chest pain. In most series iatrogenic injury accounts for more than 70% of cases, whereas most of the other cases have spontaneous (5%20%) or traumatic (4%10%) causes (Table 1).14 Perforation as a complication of ingesting fish bones, although rare, is well described and continues to be reported.57

| Etiology | Percent |

|---|---|

| |

| Iatrogenic | 45%77% |

| Rigid or flexible endoscopy, balloon dilation, Blakemore tube, sclerotherapy, operative injury | |

| Increased intraesophageal pressure (Boerhaave's syndrome) | 5%20% |

| Vomiting or retching, weightlifting, childbirth | |

| Traumatic | 4%10% |

| Penetrating or blunt injury to neck or chest | |

| Ingestion | 0%12% |

| Foreign body, toxic or caustic substance | |

| Miscellaneous | 0%5% |

| Malignancy, Barrett's esophagus, infection, aortic dissection | |

Diagnosis of esophageal perforation secondary to a foreign body may be difficult because of the considerable overlap of symptoms with other causes of chest pain and failure to consider this infrequent condition in the absence of a classic history of retching. To diagnose such a disease, physicians must gather data from various sourcesespecially the history, physical examination, and medical recordformulate hypotheses, integrate results from diagnostic tests, and then assess the importance of the available information in the context of a differential diagnosis. Incorrectly evaluating or failing to obtain essential data can lead to incorrect or delayed diagnoses.

In This Patient's Evaluation, What Prevented Prompt Recognition of Esophageal Perforation?

The critical misstep was an incomplete history, both on arrival and when the patient was transferred to a second team. The presence of risk factors for coronary artery disease led the providers to first consider myocardial ischemia. They failed to ask crucial questions about the onset of the painwhen it occurred during the meal and what he was eatingeven when the patient later complained of odynophagia. As a result of the incomplete history, the providers, puzzled by the patient's ongoing and evolving symptoms, ordered numerous unnecessary diagnostic tests that gave false‐positive results, leading to potentially harmful treatment including anticoagulation. The discussant mentions that the preferred response to a puzzling clinical situation is to return to the bedside and repeat the history, reexamine the patient, and reevaluate available informationsimple steps that can often resolve diagnostic dilemmas.

There is ongoing concern that the history‐taking and physical examination skills of clinicians are in decline.814 Many speculate this is in part due to reliance on increasingly sophisticated diagnostic tests. Providers may overly rely on modern diagnostic tests because of their familiarity with the sensitivity and specificity of such tests, fear of malpractice litigation, diminishing opportunity to elucidate the complete history and physical exam, or lack of confidence in their history‐taking and examination skills.814 Although the rapid development and implementation of advanced diagnostic technologies have had a significant impact on diagnostic accuracy, the estimated rate of disease misdiagnosis remains elevated at 24%.1518 In contrast to technology‐based testing, the history and physical provide an inexpensive, safe, and effective means of at arriving at a correct diagnosis. In outpatient medical visits the history and physical, when completely elicited, result in a correct diagnosis of up to 70%90% of patients.8, 19, 20 Even for illnesses whose diagnosis requires confirmation by a diagnostic test, the definitive test can only be selected after a sufficient history and exam provide an assessment of the pretest probability of disease.

In evaluating chest pain there is an additional potential factor that diminishes reliance on bedside assessment. Modern quality assurance measures and chest pain units encourage clinicians to evaluate patients with chest pain quickly because any delay diminishes the benefits of therapies for acute coronary syndromes. In the emergency room, these patients find themselves on a rapidly moving diagnostic conveyor belt, an approach that is efficient and appropriate given the high prevalence of coronary disease but that also contributes to inattentiveness and error for patients with unusual diagnoses.

How Could Clinicians in Our Case Use Bedside Evidence to Help Differentiate Our Patient?

For most patients with chest pain there is no finding that would change diagnostic probabilities enough to take them off the diagnostic conveyor belt. Nevertheless, several bedside findings can help providers to rank‐order a differential diagnosis, thereby improving the sequence in which diagnostic testing is done. For patients with chest pain the ECG has the highest predictive ability of all studied history, physical exam, and ECG findings (Table 2).21 A history of sharp and positional pain descriptors diminishes the probability of myocardial ischemia.21 Unfortunately, no history, exam, or ECG feature is sensitive enough, either alone or in combination, to effectively rule out myocardial ischemia.

| Finding | Positive LR* |

|---|---|

| Myocardial ischemia | |

| ST segment elevation or Q wave | 22 |

| S3 gallop, blood pressure < 100 mm Hg, or ST segment depression | 3.0 |

| Sharp or positional pain | 0.3 |

| Pulmonary embolism | |

| Low clinical probability | 0.2 |

| Medium clinical probability | 1.8 |

| High clinical probability | 17.1 |

| Aortic dissection | |

| Tearing or ripping pain | 10.8 |

| Focal neurologic deficits | 6.633 |

| Ipsilateral versus contralateral pulse deficit | 5.7 |

| Cardiac tamponade | |

| Pulsus paradoxus > 12 mm Hg | 5.9 |

| Esophageal perforation | |

| Dysphagia, odynophagia, retching, vomiting, or subcutaneous emphysema | ? |

The history and exam can also facilitate differentiation of noncoronary causes of life‐threatening chest pain. The dismal performance of individual bedside findings for pulmonary embolism is what led to development of quantitative D‐dimer assays and objective methods based on bedside evaluation, including the widely used Wells Score.22 This score can be used to classify patients as having low, medium, and high risk of pulmonary embolism, facilitating management decisions after diagnostic imaging is obtained.23 Fewer than half of all patients with thoracic aortic dissection have classic exam findings; however, when present, they can appropriately raise the probability of dissection higher on the differential diagnosis.24 Importantly, no history or exam finding argues against dissection.24 Most patients with cardiac tamponade will have elevated jugular venous pressure (76%100%); however, poor interobserver agreement about this finding may decrease its detection.11, 25, 26 As the discussant notes, total paradox, defined as the palpable pulse disappearing with inspiration, is an insensitive test for tamponade, present in only 23% of patients with the disorder. In contrast, an inspiratory drop in systolic blood pressure of more than 12 mm Hg should prompt consideration for tamponade.11, 26 Commonly taught features of esophageal perforation, including chest pain, dysphagia, odynophagia, prior retching or vomiting, subcutaneous emphysema, dyspnea, and pleural effusions, vary in their reported sensitivity, but their specificity is virtually never reported.27

Like most patients with chest pain, our patient lacked all these symptoms and signs, arguing for myocardial ischemia, although he had a few signs that argued against it (sharp and positional chest pain). After the initial CXR and ECG, further testing with cardiac biomarkers was appropriate, but a fundamental error was made in not returning to the patient's bedside to repeat the interview and examination after the cardiac biomarkers were found to be normal. Had this been done, several cluesdysphagia, onset of pain with eating bony fish, and feverwould have pushed esophageal perforation to the top of the differential diagnosis. Subsequent testing would have led to the correct diagnosis and avoided a potentially harmful diagnostic fishing expedition.

Take‐Home Points

-

Esophageal perforation is an uncommon but life‐threatening cause of chest pain that is difficult to diagnose because of its nonspecific symptoms.

-

An accurate and complete history and exam can reveal signs and symptoms that influence the likelihood of each life‐threatening cause of chest pain. Evaluating patients for these features is vital to the rank ordering of a differential diagnosis and the selection of appropriate diagnostic tests.

-

There is no substitute for repeating the history, reexamining the patient, and reevaluating available information when confronted with a confusing constellation of symptoms.

Acknowledgements

The authors thank Steve McGee for his thoughtful review and comments on the manuscript.

A 54‐year‐old man with hypertension and type 2 diabetes mellitus entered the Chest Pain Evaluation Unit of a teaching hospital after 12 hours of intermittent thoracic discomfort. The pain began during dinner and was sharp, bandlike, and located beneath the sternum and across the entire chest. He had dyspnea but no diaphoresis or nausea. A recumbent position relieved the pain after dinner, but it recurred during the night and again the following morning. He did not smoke and had no family history of coronary artery disease.

A useful approach in evaluating acute chest pain is to employ a hierarchical differential diagnosis that emphasizes life‐threatening disorders requiring prompt recognition and intervention. Most prominent are cardiac ischemia, pericardial tamponade, pneumothorax, pulmonary embolus, esophageal rupture, and aortic dissection. The concurrent dyspnea and retrosternal location and intermittent nature of the pain that this patient has are consistent with myocardial ischemia, but the sharp quality of the pain and the relief gained by being recumbent are atypical. Pain with pericarditis is characteristically pleuritic and often worse when lying down. The pain of pneumothorax is typically unilateral, not intermittent, and unlikely to improve with recumbency. Although pain during eating suggests the possibility of an esophageal source, spontaneous rupture usually follows vomiting. The pain is typically continuous and severe. The pain of pulmonary embolism may be unilateral and pleuritic but often is more diffuse. Relief by recumbency is unusual, but the intermittent nature could suggest recurrent emboli. The patient has a history of hypertension, which predisposes him to aortic dissection, in which the pain is typically sharp, continuous, and severe but occasionally intermittent. Among numerous less urgent diagnoses are esophagitis and thoracic diabetic radiculopathy.

Important features to look for during this patient's examination include: disappearance of the radial pulse during inhalation, a simple screening test that is insensitive but very specific for pericardial tamponade; elevated neck veins, which can occur with tension pneumothorax, massive pulmonary embolism, and pericardial tamponade; pericardial and pleural friction rubs; discrepant blood pressures in the 2 arms, sometimes a sign of aortic dissection; local thoracic tenderness from chest wall disorders; and sensory examination of the chest surface, which is often abnormal in diabetic thoracic radiculopathy. Given this patient's age and history of diabetes, I am most concerned about myocardial ischemia. The most appropriate diagnostic tests include an electrocardiogram and a chest radiograph.

The patient appeared apprehensive but reported no pain. He had a temperature of 36.0 C, heart rate of 95 beats/minute, blood pressure of 138/77 mm Hg, respiratory rate of 16/minute, and oxygen saturation of 99% while breathing ambient air. Blood pressures were equal in both arms. Jugular venous distention was absent, and the lung and cardiac examinations had normal results. His pain did not increase on chest wall palpation. Examination of the abdomen, extremities, and the neurologic system showed normal results.

The results of laboratory tests showed a leukocyte count of 12,700/cm3, with 85% neutrophils, 8% lymphocytes, 6% monocytes, and 1% eosinophils. The hematocrit was 45%, and the platelet count was 172,000/cm3. The results of his chemistry panel were remarkable only for a glucose of 225 mg/dL. An electrocardiogram (ECG) showed a normal sinus rhythm and left anterior fascicular block without acute ST‐ or T‐wave changes. Prior ECGs were unavailable. An anteroposterior radiograph disclosed low lung volumes and bibasilar opacities. No pleural effusion was noted. Serial serum troponin and creatine kinase levels were normal. A Tc‐99m tetrofosmin cardiac nuclear perfusion test performed at rest demonstrated a moderate area of mildly decreased uptake along the inferior wall extending to the apex. An exercise treadmill test, terminated after 1 minute, 45 seconds because of chest pain, provoked no ECG changes diagnostic of ischemic disease.

The absence of elevated jugular venous pressure virtually eliminates pericardial tamponade as a diagnosis, and the chest film excludes pneumothorax. The intermittent nature of the chest pain, the absence on the chest radiograph of such findings as mediastinal gas, left pneumothorax, or hydropneumothorax, and the lack of a predisposing cause make esophageal rupture unlikely. Pulmonary emboli remain a consideration despite the normal oxygen saturation because there is no hypoxemia in a substantial minority of such cases. The normal cardiac enzyme levels and the lack of significant changes on the ECG exclude that a myocardial infarction has recently occurred, but cardiac ischemia remains a possibility, especially because the patient had chest pain on exercise and the nuclear scan indicated diminished blood flow to the inferior left ventricle. Aortic dissection still lurks as a possibility. The inferior wall abnormalities seen on the scan could result from dissection into the right coronary artery, which is more frequently involved than the left, or compression of it by an enlarged aorta, but they also may be artifacts. The leukocytosis may be a nonspecific response to stress but could indicate, although unlikely, infections such as mediastinitis from esophageal rupture or bacterial aortitis.

A conscientious clinician would repeat the history, reexamine the patient, and scrutinize the chest film to determine what the bilateral opacities represent. Given the story so far, however, I might consider a thoracic computed tomography (CT) angiogram because I am most concerned about pulmonary emboli and aortic dissection.

On hospital day 3, the patient had worsening dyspnea and persistent chest pain. His temperature was 39.3C, and his oxygen saturation decreased to 89% while breathing room air. Repeat chest radiography showed new bilateral pleural effusions and increased bibasilar opacification (Fig. 1). His leukocyte count was 19,000/cm3, with 88% neutrophils, 6% lymphocytes, 5% monocytes, and 1% eosinophils. Care was transferred from the chest pain team to an inpatient general medicine ward team. A pulmonary CT angiogram showed no large central clots but suggested emboli in the right superior subsegmental artery and a right upper lobe subsegmental artery. Bilateral pleural effusions were observed, as were bilateral pleural‐based atelectasis or infiltrates in the lower lungs. A hiatal hernia was noted, but no aortic dissection. The patient received supplemental oxygen, intravenous levofloxacin, and unfractionated heparin by continuous infusion.

Without other information, I will assume that the fever is part of the patient's original disease and not a nosocomial infection or drug fever. At this point, a crucial part of the evaluation is examining the CT scan with experienced radiologists to determine whether the abnormalities noted are genuinely convincing for pulmonary emboli. If the findings are equivocal, the next step might be a pulmonary angiogram or the indirect approach of evaluating the leg veins with ultrasound, reasoning that the presence of proximal leg vein thromboses would require anticoagulation in any event.

The patient's worsening chest pain and hypoxemia are consistent with multiple pulmonary emboli. Bilateral pleural effusions and leukocytosis can occur but are uncommon. Because of the fever, another possibility is septic pulmonary emboli, but he has no evidence of suppurative thrombophlebitis of the peripheral veins, apparent infection elsewhere, or previous intravenous drug abuse causing right‐sided endocarditis. An alternative diagnosis is infection of an initially bland pulmonary infarct.