User login

Where Loyalty Lies

The question that nearly stumped me came from the back of the room.

I was giving a presentation on the hospital medicine movement to 350 physicians with an organization interested in our rapidly developing specialty. The evolution of hospital medicine is a great story, and I relish telling it. My biggest problem is usually curbing my enthusiasm to fit the time allotted. As an old colleague once told me when I launched into an exhaustive explanation of a simple medical problem: “Rusty, don’t build the watch—just tell me the time!” For this talk, I behaved myself and had managed with 10 minutes to spare for questions.

Then came the question:

“With more than a third of hospitalists directly employed by the hospital I have concerns that the loyalty of the physician will be to the best interests of the institution instead of the patient, don’t you?”

It was certainly thought provoking. The questioner was asking if the source of a physician’s paycheck trumped patient needs. For many hospitalists, our employer is technically not the patient, but the hospital.

Some referring physicians, who put their patients in our care when they hospitalize them, wonder which master we serve. Can that hospitalist in charge of my patient resist the institutional pull to drive down length of stay (LOS) and curtail costs? Whose interests will that physician favor when there is a clash between what my patients might need and the hospital’s bottom line?

I could have simply said: “No, I’m not concerned. Physicians should always act in the interest of their patients over that of the hospital.” But the real answer is far more complex—a synthesis of complementary interests that can appear mutually exclusive.

How? While my response was somewhat less well organized than this column, I attempted to address the complexity of the question by including the profile of hospitalists’ employers, the obligations of the medical staff in any hospital, physician incentives, transparency of performance, checks and balances, and the general principle of managing polarities.

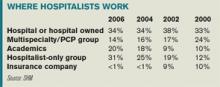

Let’s look at the scope of the issue. Who pays the hospitalist? A third are employed directly by hospitals, a fifth by academic medical centers, and nearly half by multispecialty or hospitalist-only medical groups. Two points emerge from the data. First, employment percentage by hospitals has remained stable, while academic centers and hospitalist-only groups have grown. Second, this employment model is not unique to hospitalists. These same types of practice groups and institutions employ physicians in other specialties, too.

All physicians working in a hospital are members of the active medical staff and must uphold certain core responsibilities. Chief among these are the quality and safety of care, treatment, and services delivered at the institution. That duty applies whether they are solo practitioners or employees of a hospital or independent medical group.

These core obligations are enforced by the organized medical staff through by-laws, rules, and regulations. Further, the medical staff is beholden to operate with the cooperation of hospital administration/management and hospital governance (i.e., the board) to support quality of care within the institution.

These elements are intended to provide a structure for optimizing patient care. But they often collide with the real world in which we physicians operate—a world of competing interests we face daily. While a physician’s fiduciary responsibility is always to the patient, there are often other interests to consider. Who among us has not tried to balance the often conflicting opinions and agendas of the:

- Patient;

- Caregivers/family;

- Hospital;

- Primary care physician;

- Consulting specialists; and

- Insurers.

These conflicts are usually over methods rather than outcomes. If hospitals want to cut LOS, so do patients, who want to sleep in their own beds. Hospitals want to manage costly and scarce resources wisely; patients want judicious use of treatments and tests. Hospitals want to keep costs down; patients want to keep out-of-pocket expenses down.

Are the loyalties of doctors to their patients sometimes at odds? The honest answer is, “Sometimes, yes.” Sometimes hospitals make providing care more challenging. Incentives affect how doctors behave. If bonuses accrue to good infection control, infection rates fall. If bonuses are aligned with keeping costs down, costs likely go down.

But such incentives play a role in how all doctors behave, not just hospitalists employed by a hospital. Self-employed physicians (hospitalists or otherwise) and members of a large medical practice group respond to incentives, as well.

One could argue these doctors might have a greater conflict of interest than hospital-based physicians. Think of the time pressures under which many physicians work, the complexity of the hospital environment, and the burden of paperwork.

Solo private practitioners whose only source of revenue is professional service fees may be inclined to keep patients in the hospital longer because that generates higher fees. They may also have a secondary agenda: Drive higher patient satisfaction by keeping patients in the hospital until they feel completely well, “protecting” them from hospital administrators who want to “prematurely” discharge them.

The real problem with incentives is aligning them with optimal care.

Once we establish that incentives are important, that their ultimate goal is optimal care, the next step is to create transparent, explicit performance criteria. There should be no mystery concerning which behaviors and outcomes physicians are expected to achieve, including those involving quality and safety. Finally, incentives need good checks and balances. There must be a good measurement system for desired performance and a method for keeping tabs to mitigate or eliminate unintended consequences.

All physicians must simultaneously manage the interests of the patient and the interests of the healthcare system—especially the hospital. When these goals are met, patient and system benefit by maximally utilizing precious resources such as inpatient beds, diagnostic and treatment technologies, and drugs. These resources are not limitless and should never be used without a great deal of critical thinking and consideration of alternatives.

There will always be tension between optimizing resources and treatment. Balancing these interests is not a problem to be solved, but a polarity to manage. Polarities are unsolvable because neither pole alone is the right answer. Focusing on one pole to the neglect of the other undermines our efforts to optimize patient needs and propagate a sustainable hospital care system. These alternatives are ongoing and interdependent and must be managed together.

To achieve the right balance, we must establish measures to alert us when one pole “tips” over the other. While I believe physicians, in the face of conflict of interests, must do what is right for the patient, it is also our duty to find ways to balance the interests of all involved. This is the key to a more sustainable, reliable, satisfying healthcare system—and to fulfilling our promise to monitor and self-govern the quality and safety of care we deliver. TH

Dr. Holman is president of SHM. He can be reached at holman.russell@cogenthealthcare.com

The question that nearly stumped me came from the back of the room.

I was giving a presentation on the hospital medicine movement to 350 physicians with an organization interested in our rapidly developing specialty. The evolution of hospital medicine is a great story, and I relish telling it. My biggest problem is usually curbing my enthusiasm to fit the time allotted. As an old colleague once told me when I launched into an exhaustive explanation of a simple medical problem: “Rusty, don’t build the watch—just tell me the time!” For this talk, I behaved myself and had managed with 10 minutes to spare for questions.

Then came the question:

“With more than a third of hospitalists directly employed by the hospital I have concerns that the loyalty of the physician will be to the best interests of the institution instead of the patient, don’t you?”

It was certainly thought provoking. The questioner was asking if the source of a physician’s paycheck trumped patient needs. For many hospitalists, our employer is technically not the patient, but the hospital.

Some referring physicians, who put their patients in our care when they hospitalize them, wonder which master we serve. Can that hospitalist in charge of my patient resist the institutional pull to drive down length of stay (LOS) and curtail costs? Whose interests will that physician favor when there is a clash between what my patients might need and the hospital’s bottom line?

I could have simply said: “No, I’m not concerned. Physicians should always act in the interest of their patients over that of the hospital.” But the real answer is far more complex—a synthesis of complementary interests that can appear mutually exclusive.

How? While my response was somewhat less well organized than this column, I attempted to address the complexity of the question by including the profile of hospitalists’ employers, the obligations of the medical staff in any hospital, physician incentives, transparency of performance, checks and balances, and the general principle of managing polarities.

Let’s look at the scope of the issue. Who pays the hospitalist? A third are employed directly by hospitals, a fifth by academic medical centers, and nearly half by multispecialty or hospitalist-only medical groups. Two points emerge from the data. First, employment percentage by hospitals has remained stable, while academic centers and hospitalist-only groups have grown. Second, this employment model is not unique to hospitalists. These same types of practice groups and institutions employ physicians in other specialties, too.

All physicians working in a hospital are members of the active medical staff and must uphold certain core responsibilities. Chief among these are the quality and safety of care, treatment, and services delivered at the institution. That duty applies whether they are solo practitioners or employees of a hospital or independent medical group.

These core obligations are enforced by the organized medical staff through by-laws, rules, and regulations. Further, the medical staff is beholden to operate with the cooperation of hospital administration/management and hospital governance (i.e., the board) to support quality of care within the institution.

These elements are intended to provide a structure for optimizing patient care. But they often collide with the real world in which we physicians operate—a world of competing interests we face daily. While a physician’s fiduciary responsibility is always to the patient, there are often other interests to consider. Who among us has not tried to balance the often conflicting opinions and agendas of the:

- Patient;

- Caregivers/family;

- Hospital;

- Primary care physician;

- Consulting specialists; and

- Insurers.

These conflicts are usually over methods rather than outcomes. If hospitals want to cut LOS, so do patients, who want to sleep in their own beds. Hospitals want to manage costly and scarce resources wisely; patients want judicious use of treatments and tests. Hospitals want to keep costs down; patients want to keep out-of-pocket expenses down.

Are the loyalties of doctors to their patients sometimes at odds? The honest answer is, “Sometimes, yes.” Sometimes hospitals make providing care more challenging. Incentives affect how doctors behave. If bonuses accrue to good infection control, infection rates fall. If bonuses are aligned with keeping costs down, costs likely go down.

But such incentives play a role in how all doctors behave, not just hospitalists employed by a hospital. Self-employed physicians (hospitalists or otherwise) and members of a large medical practice group respond to incentives, as well.

One could argue these doctors might have a greater conflict of interest than hospital-based physicians. Think of the time pressures under which many physicians work, the complexity of the hospital environment, and the burden of paperwork.

Solo private practitioners whose only source of revenue is professional service fees may be inclined to keep patients in the hospital longer because that generates higher fees. They may also have a secondary agenda: Drive higher patient satisfaction by keeping patients in the hospital until they feel completely well, “protecting” them from hospital administrators who want to “prematurely” discharge them.

The real problem with incentives is aligning them with optimal care.

Once we establish that incentives are important, that their ultimate goal is optimal care, the next step is to create transparent, explicit performance criteria. There should be no mystery concerning which behaviors and outcomes physicians are expected to achieve, including those involving quality and safety. Finally, incentives need good checks and balances. There must be a good measurement system for desired performance and a method for keeping tabs to mitigate or eliminate unintended consequences.

All physicians must simultaneously manage the interests of the patient and the interests of the healthcare system—especially the hospital. When these goals are met, patient and system benefit by maximally utilizing precious resources such as inpatient beds, diagnostic and treatment technologies, and drugs. These resources are not limitless and should never be used without a great deal of critical thinking and consideration of alternatives.

There will always be tension between optimizing resources and treatment. Balancing these interests is not a problem to be solved, but a polarity to manage. Polarities are unsolvable because neither pole alone is the right answer. Focusing on one pole to the neglect of the other undermines our efforts to optimize patient needs and propagate a sustainable hospital care system. These alternatives are ongoing and interdependent and must be managed together.

To achieve the right balance, we must establish measures to alert us when one pole “tips” over the other. While I believe physicians, in the face of conflict of interests, must do what is right for the patient, it is also our duty to find ways to balance the interests of all involved. This is the key to a more sustainable, reliable, satisfying healthcare system—and to fulfilling our promise to monitor and self-govern the quality and safety of care we deliver. TH

Dr. Holman is president of SHM. He can be reached at holman.russell@cogenthealthcare.com

The question that nearly stumped me came from the back of the room.

I was giving a presentation on the hospital medicine movement to 350 physicians with an organization interested in our rapidly developing specialty. The evolution of hospital medicine is a great story, and I relish telling it. My biggest problem is usually curbing my enthusiasm to fit the time allotted. As an old colleague once told me when I launched into an exhaustive explanation of a simple medical problem: “Rusty, don’t build the watch—just tell me the time!” For this talk, I behaved myself and had managed with 10 minutes to spare for questions.

Then came the question:

“With more than a third of hospitalists directly employed by the hospital I have concerns that the loyalty of the physician will be to the best interests of the institution instead of the patient, don’t you?”

It was certainly thought provoking. The questioner was asking if the source of a physician’s paycheck trumped patient needs. For many hospitalists, our employer is technically not the patient, but the hospital.

Some referring physicians, who put their patients in our care when they hospitalize them, wonder which master we serve. Can that hospitalist in charge of my patient resist the institutional pull to drive down length of stay (LOS) and curtail costs? Whose interests will that physician favor when there is a clash between what my patients might need and the hospital’s bottom line?

I could have simply said: “No, I’m not concerned. Physicians should always act in the interest of their patients over that of the hospital.” But the real answer is far more complex—a synthesis of complementary interests that can appear mutually exclusive.

How? While my response was somewhat less well organized than this column, I attempted to address the complexity of the question by including the profile of hospitalists’ employers, the obligations of the medical staff in any hospital, physician incentives, transparency of performance, checks and balances, and the general principle of managing polarities.

Let’s look at the scope of the issue. Who pays the hospitalist? A third are employed directly by hospitals, a fifth by academic medical centers, and nearly half by multispecialty or hospitalist-only medical groups. Two points emerge from the data. First, employment percentage by hospitals has remained stable, while academic centers and hospitalist-only groups have grown. Second, this employment model is not unique to hospitalists. These same types of practice groups and institutions employ physicians in other specialties, too.

All physicians working in a hospital are members of the active medical staff and must uphold certain core responsibilities. Chief among these are the quality and safety of care, treatment, and services delivered at the institution. That duty applies whether they are solo practitioners or employees of a hospital or independent medical group.

These core obligations are enforced by the organized medical staff through by-laws, rules, and regulations. Further, the medical staff is beholden to operate with the cooperation of hospital administration/management and hospital governance (i.e., the board) to support quality of care within the institution.

These elements are intended to provide a structure for optimizing patient care. But they often collide with the real world in which we physicians operate—a world of competing interests we face daily. While a physician’s fiduciary responsibility is always to the patient, there are often other interests to consider. Who among us has not tried to balance the often conflicting opinions and agendas of the:

- Patient;

- Caregivers/family;

- Hospital;

- Primary care physician;

- Consulting specialists; and

- Insurers.

These conflicts are usually over methods rather than outcomes. If hospitals want to cut LOS, so do patients, who want to sleep in their own beds. Hospitals want to manage costly and scarce resources wisely; patients want judicious use of treatments and tests. Hospitals want to keep costs down; patients want to keep out-of-pocket expenses down.

Are the loyalties of doctors to their patients sometimes at odds? The honest answer is, “Sometimes, yes.” Sometimes hospitals make providing care more challenging. Incentives affect how doctors behave. If bonuses accrue to good infection control, infection rates fall. If bonuses are aligned with keeping costs down, costs likely go down.

But such incentives play a role in how all doctors behave, not just hospitalists employed by a hospital. Self-employed physicians (hospitalists or otherwise) and members of a large medical practice group respond to incentives, as well.

One could argue these doctors might have a greater conflict of interest than hospital-based physicians. Think of the time pressures under which many physicians work, the complexity of the hospital environment, and the burden of paperwork.

Solo private practitioners whose only source of revenue is professional service fees may be inclined to keep patients in the hospital longer because that generates higher fees. They may also have a secondary agenda: Drive higher patient satisfaction by keeping patients in the hospital until they feel completely well, “protecting” them from hospital administrators who want to “prematurely” discharge them.

The real problem with incentives is aligning them with optimal care.

Once we establish that incentives are important, that their ultimate goal is optimal care, the next step is to create transparent, explicit performance criteria. There should be no mystery concerning which behaviors and outcomes physicians are expected to achieve, including those involving quality and safety. Finally, incentives need good checks and balances. There must be a good measurement system for desired performance and a method for keeping tabs to mitigate or eliminate unintended consequences.

All physicians must simultaneously manage the interests of the patient and the interests of the healthcare system—especially the hospital. When these goals are met, patient and system benefit by maximally utilizing precious resources such as inpatient beds, diagnostic and treatment technologies, and drugs. These resources are not limitless and should never be used without a great deal of critical thinking and consideration of alternatives.

There will always be tension between optimizing resources and treatment. Balancing these interests is not a problem to be solved, but a polarity to manage. Polarities are unsolvable because neither pole alone is the right answer. Focusing on one pole to the neglect of the other undermines our efforts to optimize patient needs and propagate a sustainable hospital care system. These alternatives are ongoing and interdependent and must be managed together.

To achieve the right balance, we must establish measures to alert us when one pole “tips” over the other. While I believe physicians, in the face of conflict of interests, must do what is right for the patient, it is also our duty to find ways to balance the interests of all involved. This is the key to a more sustainable, reliable, satisfying healthcare system—and to fulfilling our promise to monitor and self-govern the quality and safety of care we deliver. TH

Dr. Holman is president of SHM. He can be reached at holman.russell@cogenthealthcare.com

The Hospitalist as Teacher

In addition to being expert in acute care clinical issues, hospitalists are knowledgeable in the ways and means of the hospital.

As teachers, hospitalists are ideally situated to improve house staff’s proficiency in areas such as evidence-based medicine, effective teamwork, communication, and quality improvement.1 These areas meld with hospitalist core competencies, writes David M. Pressel, MD, PhD, director of Inpatient Service and General Pediatrics at Alfred I. duPont Hospital for Children in Wilmington, Del.

What makes a great hospitalist a great teacher? “I don’t think there is anything special about a hospitalist [that would make him or her] a great teacher as opposed to another kind of physician,” Dr. Pressel says. “The only caveat to that is that presumably the hospitalist has specialized knowledge that they can impart similarly to [how] another doc can [impart information] in their specialized knowledge.”

Good teaching in all specialties has the same core features. But the key component a hospitalist would want to impart, he says, is that the hospitalist should maintain a holistic view of the patient.

In Dr. Pressel’s view, a great teacher loves what he does, has a sense of humor and makes learning fun or enjoyable, makes his lessons interactive, continually learns alongside his students, and knows his strengths and weaknesses.

“A great teacher has a sense of self-awareness as to what they do well and what they don’t do well,” he says. “Some people can be dynamic speakers for a mass audience and hold a lecture hall of 200 in thrall, but one on one, they’re not that strong. Others are the opposite. It is easy to teach people who are smart, dynamic, and interested; it is more challenging for someone who is a bit slower and [finds it] harder to get it.”

A good teacher also models for his trainees, especially in more delicate conversations, such as when giving bad news or asking patients and families to make difficult decisions.

“Residents should be watching you have those kinds of conversations,” says Howard Epstein, MD, a hospitalist and the medical director of the palliative care program at Regions Hospital, St. Paul, Minn. “[Rather than saying], ‘I’m just going to go have a family conference so why don’t you go take care of this, that, and the other thing,’ we should be saying, ‘This is really important. You need to come in and watch me do this now. This is just as important as putting in those discharge orders or putting in that central line.’ ”

Teach versus Coach

Jeffery G. Wiese, MD, associate professor of medicine at Tulane University in New Orleans, has thought a lot about what makes a great teacher and the differences between teaching information and teaching skills. To him it is the difference between teaching and coaching.

Dr. Wiese, who is on SHM’s board of directors, believes medical education is less about the dissemination of knowledge and more about how to apply that knowledge.

“Dissemination of knowledge is requisite but not sufficient,” says Dr. Wiese. “Clinical education is about performance because ultimately it doesn’t matter if the student knows a lot if he or she can’t put it in act for the benefit of their patient. And when you change that paradigm, then you move from being a good teacher to being a great coach.”

Dr. Wiese, who is also director of the Internal Medicine Residency Program and the chief of medicine at Tulane, presented a workshop at the SHM’s annual meeting in May, titled “Great Hospitalist to Great Teacher: Clinical Coaching.”

The five main points of the presentation are represented by the mnemonic VACUM: visualization, anticipation, choosing content that has utility, and motivation.

Visualization

Great teachers empower trainees to visualize how they will use the skill or knowledge for the benefit of the patient. The average lecture on hypotension, for example, disseminates the causes of hypotension and the treatment for each. The great coaching session, however, begins with getting the student to visualize using the skill. “Picture this: You are awakened from sleep on call to see a hypotensive patient,” Dr. Wiese says. “Do you see yourself in the room? Do you see the panic, the fear of those around you? Now visualize feeling the warmth of the patient’s extremities to exclude causes of low vascular resistance. Now imagine feeling the pulse to exclude bradycardia. Are you there? Now see yourself lowering the head of the bed and starting the IV to increase his preload.” The vision makes the content stick in the student’s memory.

Anticipation

“It’s not enough to teach a trainee how to do the skill,” says Dr. Wiese. “You have to anticipate where the trainee is going to get it confused and where the pitfalls are going to be in performing that skill down the road.”

This concept is analogous to that of someone giving directions to their house. Merely giving the student the destination (i.e., what they need to know) is not sufficient. Providing a heads up on where they might take a wrong turn ensures that they arrive at the destination.

In teaching hyperosmolar nonketotic coma (HONKC), for example, a great coach will begin with the warning: “Listen, this is where you could get confused. You might be tempted to ascribe a patient’s delirium to the osmotic effects of the high glucose, and while this can happen, it does not happen with a serum osmolarity of less than 340. You could forget that the cortisol surge that comes from infection is the leading cause of HONKC. Do you see yourself in the emergency department with that patient with HONKC? OK, when it happens, make sure you check the osmolarity; if it’s less than 340, do the lumbar puncture. Meningitis may just be the cause of the delirium and the infection that has caused the HONKC.”

—Jeffery G. Wiese, MD, associate professor of medicine, Tulane University Health Sciences Center, New Orleans

Content With Utility

Teaching the oppressive details about a disease beyond what the student learns from textbooks probably does not have the same utility for them as learning the fundamental principles of how to diagnose, treat, and prognosticate a disease, says Dr. Wiese.

Although most hospitalists train in internal medicine, with a lesser number training in pediatrics or family practice, all hospitalist instructors are still responsible for all students—including those who may be headed for radiology or orthopedics, for instance.

“I can teach the medical content that is of utility to that student’s performance,” Dr. Wiese says, “and I still share responsibility for their performance as an orthopedic surgeon, particularly with respect to how they manage medical disease.” The important lesson is that utility is defined by the learner. “If my student has chosen a future career in orthopedics, the content of the lectures will shift away from high-end internal medicine topics and toward what I think the future orthopedist before me needs to know.”

Motivation

“Should we have to motivate students to be great physicians both professionally and in terms of patient care and knowledge competence?” asks Dr. Wiese. “At the end of the day, the answer should be no; everyone has responsibility for motivating themselves. But, like a great coach, it is still the coach’s responsibly to ensure that when the players are tired, when they’re hungry, when they’ve got other things on their mind, they will stay motivated to want to learn the skill—even before we begin to teach the skill.

“A big portion of that motivation comes from figuring out what their career goals are and helping to link the medical knowledge or the skill that you’re teaching to those hooks, those things that are going to be of interest to them.”

There are four key components to motivation, says Dr. Wiese.

“First, remember the student’s name and use it often,” he says. “Remember that they will not care what you know, until they know that you care. Second, be physical. Reach out with the handshake or pat on the shoulder when things get done correctly. Third, stay focused on their hooks: Couch all content in terms of how they will use it in their future careers, and focus your analogies on their personal interests. For example, if a student likes music, my teaching of heart murmurs is going to use analogies of the song writer and performer.”

Game Time

“The medical knowledge is analogous to the play that the team will run or the skill of throwing the ball, but [there are a lot of other factors that influence what’s needed for] the game-time scenario,” Dr. Wiese says. “It’s how you interact with the clock for the game, how you interact with the referees, how you interact with your team mates, how you interact against the defense.”

To teach in order to prepare your “players” for the realities of the challenge—or the challenges of reality, as the case may be—teachers need to do more than unwittingly repeat the methods used when they were students.

“A student who is learning about a disease from Harrison’s or Cecil’s [textbooks] can focus on all the details and knowledge they need to know,” says Dr. Wiese. “But the thing that they can’t get out of the book and that they really need from the hospitalist coach is all that game-time instruction.”

In other words, hospitalists must consider with their students how to integrate their knowledge into their interactions with the hospital system.

In this era of PDAs, wireless networking, and access to the Internet, hospitalists are way past the point of having to keep all their acquired information in their heads, Dr. Wiese says. “The issue now is how do you ask the right questions and then access that knowledge—and then more importantly, how do you take that knowledge and put it into the ‘play’ that is the patient?” And that is what a student can’t get out of a book, he says—and what they need to get from their coach.

Be an Agent for Change

Don’t automatically transfer the way you learned or the ways you were taught into how you teach your own students. “Learning and teaching are very different,” says Dr. Wiese. “Learning knowledge is focused on the details. Teaching is much more [about] how you put that knowledge into play.”

That kind of transference is easily recognizable in a situation where a student asks “Can you teach me something this afternoon?” and the hospitalist replies, “Well, let me go home tonight and prepare, and then I’ll teach you.”

“What they’re saying is, ‘Let me read up, make a list of facts—maybe worse, maybe put it in PowerPoint,’ ” says Dr. Wiese. “The student could have done that on his or her own.”

Because hospitalists are intimately familiar with the hospital system, they serve as agents of change, Dr. Wiese says.

“Hospitalists are the key group at the first level of being able to take a student or resident or fellow and say, ‘These are the patients, we’re on hospital wards, and let me show you how to put in action the knowledge and skills you have to make a success for your patients,’ ” he says.

Hospitalists know where the system doesn’t work. “The great hospitalist doesn’t [face a problem and think], ‘Oh, woe is me; I’m hopelessly at the whim of the system that is broken,” says Dr. Wiese. “A great hospitalist consistently looks at [the situation] and asks, ‘How can I improve this system?’ The only way that medical students and residents can move out of the helpless role where [they see themselves as] servants of the system is to have hospitalist teachers who have a perspective of themselves as owners and who take responsibility for improving the system. Nothing has to be the way that it is,” says Dr. Wiese. TH

Andrea Sattinger is a frequent contributor to The Hospitalist.

References

- Pressel DM. Hospitalists in medical education: coming to an academic medical center near you. J Natl Med Assoc. 2006 Sep;98(9):1501-1504.

In addition to being expert in acute care clinical issues, hospitalists are knowledgeable in the ways and means of the hospital.

As teachers, hospitalists are ideally situated to improve house staff’s proficiency in areas such as evidence-based medicine, effective teamwork, communication, and quality improvement.1 These areas meld with hospitalist core competencies, writes David M. Pressel, MD, PhD, director of Inpatient Service and General Pediatrics at Alfred I. duPont Hospital for Children in Wilmington, Del.

What makes a great hospitalist a great teacher? “I don’t think there is anything special about a hospitalist [that would make him or her] a great teacher as opposed to another kind of physician,” Dr. Pressel says. “The only caveat to that is that presumably the hospitalist has specialized knowledge that they can impart similarly to [how] another doc can [impart information] in their specialized knowledge.”

Good teaching in all specialties has the same core features. But the key component a hospitalist would want to impart, he says, is that the hospitalist should maintain a holistic view of the patient.

In Dr. Pressel’s view, a great teacher loves what he does, has a sense of humor and makes learning fun or enjoyable, makes his lessons interactive, continually learns alongside his students, and knows his strengths and weaknesses.

“A great teacher has a sense of self-awareness as to what they do well and what they don’t do well,” he says. “Some people can be dynamic speakers for a mass audience and hold a lecture hall of 200 in thrall, but one on one, they’re not that strong. Others are the opposite. It is easy to teach people who are smart, dynamic, and interested; it is more challenging for someone who is a bit slower and [finds it] harder to get it.”

A good teacher also models for his trainees, especially in more delicate conversations, such as when giving bad news or asking patients and families to make difficult decisions.

“Residents should be watching you have those kinds of conversations,” says Howard Epstein, MD, a hospitalist and the medical director of the palliative care program at Regions Hospital, St. Paul, Minn. “[Rather than saying], ‘I’m just going to go have a family conference so why don’t you go take care of this, that, and the other thing,’ we should be saying, ‘This is really important. You need to come in and watch me do this now. This is just as important as putting in those discharge orders or putting in that central line.’ ”

Teach versus Coach

Jeffery G. Wiese, MD, associate professor of medicine at Tulane University in New Orleans, has thought a lot about what makes a great teacher and the differences between teaching information and teaching skills. To him it is the difference between teaching and coaching.

Dr. Wiese, who is on SHM’s board of directors, believes medical education is less about the dissemination of knowledge and more about how to apply that knowledge.

“Dissemination of knowledge is requisite but not sufficient,” says Dr. Wiese. “Clinical education is about performance because ultimately it doesn’t matter if the student knows a lot if he or she can’t put it in act for the benefit of their patient. And when you change that paradigm, then you move from being a good teacher to being a great coach.”

Dr. Wiese, who is also director of the Internal Medicine Residency Program and the chief of medicine at Tulane, presented a workshop at the SHM’s annual meeting in May, titled “Great Hospitalist to Great Teacher: Clinical Coaching.”

The five main points of the presentation are represented by the mnemonic VACUM: visualization, anticipation, choosing content that has utility, and motivation.

Visualization

Great teachers empower trainees to visualize how they will use the skill or knowledge for the benefit of the patient. The average lecture on hypotension, for example, disseminates the causes of hypotension and the treatment for each. The great coaching session, however, begins with getting the student to visualize using the skill. “Picture this: You are awakened from sleep on call to see a hypotensive patient,” Dr. Wiese says. “Do you see yourself in the room? Do you see the panic, the fear of those around you? Now visualize feeling the warmth of the patient’s extremities to exclude causes of low vascular resistance. Now imagine feeling the pulse to exclude bradycardia. Are you there? Now see yourself lowering the head of the bed and starting the IV to increase his preload.” The vision makes the content stick in the student’s memory.

Anticipation

“It’s not enough to teach a trainee how to do the skill,” says Dr. Wiese. “You have to anticipate where the trainee is going to get it confused and where the pitfalls are going to be in performing that skill down the road.”

This concept is analogous to that of someone giving directions to their house. Merely giving the student the destination (i.e., what they need to know) is not sufficient. Providing a heads up on where they might take a wrong turn ensures that they arrive at the destination.

In teaching hyperosmolar nonketotic coma (HONKC), for example, a great coach will begin with the warning: “Listen, this is where you could get confused. You might be tempted to ascribe a patient’s delirium to the osmotic effects of the high glucose, and while this can happen, it does not happen with a serum osmolarity of less than 340. You could forget that the cortisol surge that comes from infection is the leading cause of HONKC. Do you see yourself in the emergency department with that patient with HONKC? OK, when it happens, make sure you check the osmolarity; if it’s less than 340, do the lumbar puncture. Meningitis may just be the cause of the delirium and the infection that has caused the HONKC.”

—Jeffery G. Wiese, MD, associate professor of medicine, Tulane University Health Sciences Center, New Orleans

Content With Utility

Teaching the oppressive details about a disease beyond what the student learns from textbooks probably does not have the same utility for them as learning the fundamental principles of how to diagnose, treat, and prognosticate a disease, says Dr. Wiese.

Although most hospitalists train in internal medicine, with a lesser number training in pediatrics or family practice, all hospitalist instructors are still responsible for all students—including those who may be headed for radiology or orthopedics, for instance.

“I can teach the medical content that is of utility to that student’s performance,” Dr. Wiese says, “and I still share responsibility for their performance as an orthopedic surgeon, particularly with respect to how they manage medical disease.” The important lesson is that utility is defined by the learner. “If my student has chosen a future career in orthopedics, the content of the lectures will shift away from high-end internal medicine topics and toward what I think the future orthopedist before me needs to know.”

Motivation

“Should we have to motivate students to be great physicians both professionally and in terms of patient care and knowledge competence?” asks Dr. Wiese. “At the end of the day, the answer should be no; everyone has responsibility for motivating themselves. But, like a great coach, it is still the coach’s responsibly to ensure that when the players are tired, when they’re hungry, when they’ve got other things on their mind, they will stay motivated to want to learn the skill—even before we begin to teach the skill.

“A big portion of that motivation comes from figuring out what their career goals are and helping to link the medical knowledge or the skill that you’re teaching to those hooks, those things that are going to be of interest to them.”

There are four key components to motivation, says Dr. Wiese.

“First, remember the student’s name and use it often,” he says. “Remember that they will not care what you know, until they know that you care. Second, be physical. Reach out with the handshake or pat on the shoulder when things get done correctly. Third, stay focused on their hooks: Couch all content in terms of how they will use it in their future careers, and focus your analogies on their personal interests. For example, if a student likes music, my teaching of heart murmurs is going to use analogies of the song writer and performer.”

Game Time

“The medical knowledge is analogous to the play that the team will run or the skill of throwing the ball, but [there are a lot of other factors that influence what’s needed for] the game-time scenario,” Dr. Wiese says. “It’s how you interact with the clock for the game, how you interact with the referees, how you interact with your team mates, how you interact against the defense.”

To teach in order to prepare your “players” for the realities of the challenge—or the challenges of reality, as the case may be—teachers need to do more than unwittingly repeat the methods used when they were students.

“A student who is learning about a disease from Harrison’s or Cecil’s [textbooks] can focus on all the details and knowledge they need to know,” says Dr. Wiese. “But the thing that they can’t get out of the book and that they really need from the hospitalist coach is all that game-time instruction.”

In other words, hospitalists must consider with their students how to integrate their knowledge into their interactions with the hospital system.

In this era of PDAs, wireless networking, and access to the Internet, hospitalists are way past the point of having to keep all their acquired information in their heads, Dr. Wiese says. “The issue now is how do you ask the right questions and then access that knowledge—and then more importantly, how do you take that knowledge and put it into the ‘play’ that is the patient?” And that is what a student can’t get out of a book, he says—and what they need to get from their coach.

Be an Agent for Change

Don’t automatically transfer the way you learned or the ways you were taught into how you teach your own students. “Learning and teaching are very different,” says Dr. Wiese. “Learning knowledge is focused on the details. Teaching is much more [about] how you put that knowledge into play.”

That kind of transference is easily recognizable in a situation where a student asks “Can you teach me something this afternoon?” and the hospitalist replies, “Well, let me go home tonight and prepare, and then I’ll teach you.”

“What they’re saying is, ‘Let me read up, make a list of facts—maybe worse, maybe put it in PowerPoint,’ ” says Dr. Wiese. “The student could have done that on his or her own.”

Because hospitalists are intimately familiar with the hospital system, they serve as agents of change, Dr. Wiese says.

“Hospitalists are the key group at the first level of being able to take a student or resident or fellow and say, ‘These are the patients, we’re on hospital wards, and let me show you how to put in action the knowledge and skills you have to make a success for your patients,’ ” he says.

Hospitalists know where the system doesn’t work. “The great hospitalist doesn’t [face a problem and think], ‘Oh, woe is me; I’m hopelessly at the whim of the system that is broken,” says Dr. Wiese. “A great hospitalist consistently looks at [the situation] and asks, ‘How can I improve this system?’ The only way that medical students and residents can move out of the helpless role where [they see themselves as] servants of the system is to have hospitalist teachers who have a perspective of themselves as owners and who take responsibility for improving the system. Nothing has to be the way that it is,” says Dr. Wiese. TH

Andrea Sattinger is a frequent contributor to The Hospitalist.

References

- Pressel DM. Hospitalists in medical education: coming to an academic medical center near you. J Natl Med Assoc. 2006 Sep;98(9):1501-1504.

In addition to being expert in acute care clinical issues, hospitalists are knowledgeable in the ways and means of the hospital.

As teachers, hospitalists are ideally situated to improve house staff’s proficiency in areas such as evidence-based medicine, effective teamwork, communication, and quality improvement.1 These areas meld with hospitalist core competencies, writes David M. Pressel, MD, PhD, director of Inpatient Service and General Pediatrics at Alfred I. duPont Hospital for Children in Wilmington, Del.

What makes a great hospitalist a great teacher? “I don’t think there is anything special about a hospitalist [that would make him or her] a great teacher as opposed to another kind of physician,” Dr. Pressel says. “The only caveat to that is that presumably the hospitalist has specialized knowledge that they can impart similarly to [how] another doc can [impart information] in their specialized knowledge.”

Good teaching in all specialties has the same core features. But the key component a hospitalist would want to impart, he says, is that the hospitalist should maintain a holistic view of the patient.

In Dr. Pressel’s view, a great teacher loves what he does, has a sense of humor and makes learning fun or enjoyable, makes his lessons interactive, continually learns alongside his students, and knows his strengths and weaknesses.

“A great teacher has a sense of self-awareness as to what they do well and what they don’t do well,” he says. “Some people can be dynamic speakers for a mass audience and hold a lecture hall of 200 in thrall, but one on one, they’re not that strong. Others are the opposite. It is easy to teach people who are smart, dynamic, and interested; it is more challenging for someone who is a bit slower and [finds it] harder to get it.”

A good teacher also models for his trainees, especially in more delicate conversations, such as when giving bad news or asking patients and families to make difficult decisions.

“Residents should be watching you have those kinds of conversations,” says Howard Epstein, MD, a hospitalist and the medical director of the palliative care program at Regions Hospital, St. Paul, Minn. “[Rather than saying], ‘I’m just going to go have a family conference so why don’t you go take care of this, that, and the other thing,’ we should be saying, ‘This is really important. You need to come in and watch me do this now. This is just as important as putting in those discharge orders or putting in that central line.’ ”

Teach versus Coach

Jeffery G. Wiese, MD, associate professor of medicine at Tulane University in New Orleans, has thought a lot about what makes a great teacher and the differences between teaching information and teaching skills. To him it is the difference between teaching and coaching.

Dr. Wiese, who is on SHM’s board of directors, believes medical education is less about the dissemination of knowledge and more about how to apply that knowledge.

“Dissemination of knowledge is requisite but not sufficient,” says Dr. Wiese. “Clinical education is about performance because ultimately it doesn’t matter if the student knows a lot if he or she can’t put it in act for the benefit of their patient. And when you change that paradigm, then you move from being a good teacher to being a great coach.”

Dr. Wiese, who is also director of the Internal Medicine Residency Program and the chief of medicine at Tulane, presented a workshop at the SHM’s annual meeting in May, titled “Great Hospitalist to Great Teacher: Clinical Coaching.”

The five main points of the presentation are represented by the mnemonic VACUM: visualization, anticipation, choosing content that has utility, and motivation.

Visualization

Great teachers empower trainees to visualize how they will use the skill or knowledge for the benefit of the patient. The average lecture on hypotension, for example, disseminates the causes of hypotension and the treatment for each. The great coaching session, however, begins with getting the student to visualize using the skill. “Picture this: You are awakened from sleep on call to see a hypotensive patient,” Dr. Wiese says. “Do you see yourself in the room? Do you see the panic, the fear of those around you? Now visualize feeling the warmth of the patient’s extremities to exclude causes of low vascular resistance. Now imagine feeling the pulse to exclude bradycardia. Are you there? Now see yourself lowering the head of the bed and starting the IV to increase his preload.” The vision makes the content stick in the student’s memory.

Anticipation

“It’s not enough to teach a trainee how to do the skill,” says Dr. Wiese. “You have to anticipate where the trainee is going to get it confused and where the pitfalls are going to be in performing that skill down the road.”

This concept is analogous to that of someone giving directions to their house. Merely giving the student the destination (i.e., what they need to know) is not sufficient. Providing a heads up on where they might take a wrong turn ensures that they arrive at the destination.

In teaching hyperosmolar nonketotic coma (HONKC), for example, a great coach will begin with the warning: “Listen, this is where you could get confused. You might be tempted to ascribe a patient’s delirium to the osmotic effects of the high glucose, and while this can happen, it does not happen with a serum osmolarity of less than 340. You could forget that the cortisol surge that comes from infection is the leading cause of HONKC. Do you see yourself in the emergency department with that patient with HONKC? OK, when it happens, make sure you check the osmolarity; if it’s less than 340, do the lumbar puncture. Meningitis may just be the cause of the delirium and the infection that has caused the HONKC.”

—Jeffery G. Wiese, MD, associate professor of medicine, Tulane University Health Sciences Center, New Orleans

Content With Utility

Teaching the oppressive details about a disease beyond what the student learns from textbooks probably does not have the same utility for them as learning the fundamental principles of how to diagnose, treat, and prognosticate a disease, says Dr. Wiese.

Although most hospitalists train in internal medicine, with a lesser number training in pediatrics or family practice, all hospitalist instructors are still responsible for all students—including those who may be headed for radiology or orthopedics, for instance.

“I can teach the medical content that is of utility to that student’s performance,” Dr. Wiese says, “and I still share responsibility for their performance as an orthopedic surgeon, particularly with respect to how they manage medical disease.” The important lesson is that utility is defined by the learner. “If my student has chosen a future career in orthopedics, the content of the lectures will shift away from high-end internal medicine topics and toward what I think the future orthopedist before me needs to know.”

Motivation

“Should we have to motivate students to be great physicians both professionally and in terms of patient care and knowledge competence?” asks Dr. Wiese. “At the end of the day, the answer should be no; everyone has responsibility for motivating themselves. But, like a great coach, it is still the coach’s responsibly to ensure that when the players are tired, when they’re hungry, when they’ve got other things on their mind, they will stay motivated to want to learn the skill—even before we begin to teach the skill.

“A big portion of that motivation comes from figuring out what their career goals are and helping to link the medical knowledge or the skill that you’re teaching to those hooks, those things that are going to be of interest to them.”

There are four key components to motivation, says Dr. Wiese.

“First, remember the student’s name and use it often,” he says. “Remember that they will not care what you know, until they know that you care. Second, be physical. Reach out with the handshake or pat on the shoulder when things get done correctly. Third, stay focused on their hooks: Couch all content in terms of how they will use it in their future careers, and focus your analogies on their personal interests. For example, if a student likes music, my teaching of heart murmurs is going to use analogies of the song writer and performer.”

Game Time

“The medical knowledge is analogous to the play that the team will run or the skill of throwing the ball, but [there are a lot of other factors that influence what’s needed for] the game-time scenario,” Dr. Wiese says. “It’s how you interact with the clock for the game, how you interact with the referees, how you interact with your team mates, how you interact against the defense.”

To teach in order to prepare your “players” for the realities of the challenge—or the challenges of reality, as the case may be—teachers need to do more than unwittingly repeat the methods used when they were students.

“A student who is learning about a disease from Harrison’s or Cecil’s [textbooks] can focus on all the details and knowledge they need to know,” says Dr. Wiese. “But the thing that they can’t get out of the book and that they really need from the hospitalist coach is all that game-time instruction.”

In other words, hospitalists must consider with their students how to integrate their knowledge into their interactions with the hospital system.

In this era of PDAs, wireless networking, and access to the Internet, hospitalists are way past the point of having to keep all their acquired information in their heads, Dr. Wiese says. “The issue now is how do you ask the right questions and then access that knowledge—and then more importantly, how do you take that knowledge and put it into the ‘play’ that is the patient?” And that is what a student can’t get out of a book, he says—and what they need to get from their coach.

Be an Agent for Change

Don’t automatically transfer the way you learned or the ways you were taught into how you teach your own students. “Learning and teaching are very different,” says Dr. Wiese. “Learning knowledge is focused on the details. Teaching is much more [about] how you put that knowledge into play.”

That kind of transference is easily recognizable in a situation where a student asks “Can you teach me something this afternoon?” and the hospitalist replies, “Well, let me go home tonight and prepare, and then I’ll teach you.”

“What they’re saying is, ‘Let me read up, make a list of facts—maybe worse, maybe put it in PowerPoint,’ ” says Dr. Wiese. “The student could have done that on his or her own.”

Because hospitalists are intimately familiar with the hospital system, they serve as agents of change, Dr. Wiese says.

“Hospitalists are the key group at the first level of being able to take a student or resident or fellow and say, ‘These are the patients, we’re on hospital wards, and let me show you how to put in action the knowledge and skills you have to make a success for your patients,’ ” he says.

Hospitalists know where the system doesn’t work. “The great hospitalist doesn’t [face a problem and think], ‘Oh, woe is me; I’m hopelessly at the whim of the system that is broken,” says Dr. Wiese. “A great hospitalist consistently looks at [the situation] and asks, ‘How can I improve this system?’ The only way that medical students and residents can move out of the helpless role where [they see themselves as] servants of the system is to have hospitalist teachers who have a perspective of themselves as owners and who take responsibility for improving the system. Nothing has to be the way that it is,” says Dr. Wiese. TH

Andrea Sattinger is a frequent contributor to The Hospitalist.

References

- Pressel DM. Hospitalists in medical education: coming to an academic medical center near you. J Natl Med Assoc. 2006 Sep;98(9):1501-1504.

Transition Talk

Charles A. Crecelius, MD, of Saint Louis, has experienced best- and worst-case scenarios when his frail elderly patients have been admitted and discharged by local hospitalists.

Best case, he says: “My patient is admitted. I get a call. I’m told what is going on. I’m notified of meaningful changes, and at discharge, I get another call [from the hospitalist].”

But there are wide variations in hospitalist/nursing home relationships, notes Dr. Crecelius, a long-term care physician and president-elect of the American Medical Director’s Association (AMDA).

This was brought home by the case of a patient with a well-documented history of dystonic reaction to toxic lithium levels. The patient was later misdiagnosed as having tardive dyskinesia, a movement disorder. Her much-needed medication was discontinued, and the hospital transferred the patient back to the nursing home in worse condition than before.

“We wasted an entire hospitalization,” Dr. Crecelius recalls ruefully.

The above scenario underscores the importance of a thorough transfer of information when elderly patients move from facility to facility. Interaction between hospitalists and nursing home staff will become increasingly important in light of the growing frail elderly population and the Joint Commission on Accreditation of Health Care Organization’s (JCAHO) push for improved discharge communications.1

By applying a customer service model and continually upgrading transfer documentation, hospital medicine groups can “keep the level of communication where it needs to be,” says Susan S. Cumming, MD, associate medical director of Marin Hospitalist Medical Group at Marin General Hospital in Greenbrae, Calif.

Running a Risk

Dan Osterweil, MD, CMD, is familiar with the hospitalist model through his medical training in Israel during the late 1970s and early 1980s. Hospitalists there routinely handled inpatient care.

Dr. Osterweil, a clinical professor of medicine/geriatric medicine at UCLA, research associate with the UCLA Borun Center for Gerontological Research, and former medical director of the Jewish Home for the Aging in Reseda, Calif., has the opportunity to observe hospitalists deal with nursing homes in his current capacity as a consultant for managed care corporations in Southern California.

“Hospitalists have an excellent understanding of acute care management,” he says. “They do a good on-site job of dealing with immediate problems of the individual, and they’re very efficient and very responsive. But while hospitalists are providing higher competency in the management of intra-hospital care, I think that those I’ve interfaced with fall short on the transitions of care, which is so critical with the nursing home patient.”

Dr. Osterweil recalls one patient who had in place do not resuscitate (DNR) and do not intubate (DNI) orders. But when he was hospitalized, the patient was intubated. “If [the hospitalist] had asked one question of the individual or the caregiver—‘What is the goal of care?’—they would have been able to plan a much smoother transition for that person back to the facility.”

At Lower Bucks Hospital in Bristol, Pa., where long-term care physician Daniel Haimowitz, MD, CMD serves as chairman of internal medicine and chairs the utilization committee, the surrounding community of physicians has responded in a mostly positive way to a new hospitalist program.

However, Dr. Haimowitz has concerns that transitioning admissions of nursing home patients to hospitalists can hinder continuity of care.

Different hospitalists work each shift, and unless the patient has been on the hospitalist service in the past, the admitting hospitalist may know nothing about the patient—and most probably has no relationship with the patient’s family (as the primary care physician would have).

“The family doctor has seen the patient for 20 or 30 years and knows what he or she wants,” Dr. Haimowitz says. “But this patient is brand new to the hospitalist. Unless the hospitalist is really good with communication and takes the extra step to call the physician at the nursing home, I think you run the real risk of duplicating workup or actually not doing what is in the best interest of the patient.”

“While demonstrating improved quality of care for the acutely ill hospitalized patient, hospital medicine has struggled with the fact that it inherently adds more patient hand-offs into the mix,” says Bryce Gartland, MD, medical director for care coordination and director of hospital medicine for Emory University Hospital in Atlanta. “We experience this internally, within our facility and externally when transferring patients into or out of the hospital.”

There is always a potential for what has been called the “voltage drop” when hand-offs occur, agrees Dr. Cumming, whether they’re between hospitalists in the same facility or from hospitalist back to the primary care provider. “We function in a healthcare system that is very individualized,” she says. “When you’re dealing with many different community hospitals that may not be part of the same system, it’s very hard to standardize [transfer processes].”

The standard of care for transferring patients from Marin General Hospital to subacute rehabilitation facilities or to skilled nursing facilities entails a detailed inter-facility transfer form. The form includes a thorough discharge summary, with a separate medication reconciliation form, photocopies of any relevant consultations, and a list of pending lab tests. In concert with the hospital’s case managers, Dr. Cumming and hospitalists on her team also make every effort to speak with patients’ receiving providers to relay a synopsis of what has occurred during their patients’ stay in the hospital.

—Daniel Haimowitz, MD, CMD, chairman of internal medicine, Lower Bucks Hospital, Bristol, Pa.

Avoid Assumptions

Especially in the case of patients with dementia or severe illness prohibiting communication about their condition, a thorough transfer sheet or discharge summary—arriving with the patient or faxed in a timely manner—can help reduce errors and contribute to more seamless resumption of care at the next facility.

Without access to a patient’s history, the opportunity for errors increases. One of Dr. Crecelius’ pet peeves is seeing “history not obtainable” on the hospital’s patient transfer sheet. “A history is always obtainable,” Dr. Crecelius asserts. “You can call the nursing home, the family, or the patient’s physician. That phrase equals, ‘We didn’t bother to take the time.’ There is no such thing as ‘history not obtainable,’ and legally, that will not fly in a court of law.”

Missing or incomplete records necessitate communication between facilities. Dr. Crecelius has also found that hospitalists may not understand the nuances of medication prescription for the elderly—a situation that can be rectified with a phone call.

A case in point: Dr. Crecelius once prescribed theophylline for a bradycardic patient who refused a pacemaker but frequently lost consciousness when his pulse and blood pressure dropped. Although this was an obscure use of the drug, which is primarily a bronchodilator, “it worked to keep the patient’s pulse up so he was not passing out. When he went to the hospital, they stopped the drug, and it took forever to get him discharged. The patient came back to the nursing home in horrible shape. I assume the providers at the hospital thought I was crazy for prescribing theophylline to a frail old person!”

Dr. Crecelius’ prescription for avoiding the above scenario: “If you think the medicine is an odd choice, ask the prescriber why the patient is on it. We need to respect each other and get the information when there is a question.”

Cornerstones of Continuity

Medical directors have addressed continuity of care issues in their own ways. Whenever possible, Dr. Crecelius sees his patients in the hospital. He has also been working as a representative of the Missouri Association of Long-Term Care Physicians with a statewide transition planning committee. The committee is drafting new transfer forms for hospitals and post-acute care facilities.

The Asheville Hospitalist Group, PA has “gone to extraordinary lengths to address the issue of inter-facility transfers,” says Marc Westle, DO, FACP, president and managing partner for the large private group in N.C. His group has coordinated efforts with another group of hospitalists who specialize in managing patients in the Asheville area’s 20-plus nursing homes.

To facilitate transfers to a hospital, the nursing homes send paperwork (including history, physical, and medication records) with patients to the emergency department. When patients are ready for discharge, discharge summaries are dictated stat and faxed to the nursing home. Hospitalists discharging patients pre-order diagnostic tests that will be necessary when the patient returns to the nursing home by noting those tests on discharge orders. In addition, “The nursing home group has a list of all our beeper numbers for direct contact should a question arise,” says Dr. Westle.

Every patient transferred to another facility from Emory University Hospital in Atlanta is accompanied by a three-page transfer form, says Dr. Gartland. Included is a one-page summary of detailed nursing care; a second page listing hospitalization events, including pertinent consults, procedures, diagnoses, pending lab tests, and recommended follow-up; and a detailed medication sheet with discontinuation dates for such medication as antibiotics.

During his time as medical director at the Jewish Home for the Aging, Dr. Osterweil created what he calls his own “pseudo-hospitalist arrangement” to ensure continuity of care. He identified multiphysician groups comprising internists and nephrologists who, between them, could offer 24 hours on-call coverage.

When patients were transported to a local community hospital, Dr. Osterweil or his staff would call one of these physicians, who would take care of the patients when they were admitted to the floor. That arrangement is still in place.

“Any major decisions that are made, we are kept in the loop,” says Dr. Osterweil. “Twenty-four hours before readmission back to the skilled nursing facility, we receive a call letting us know the patient is coming back and his or her issues. The physician group executes a ‘stat’ dictated discharge summary, and the patient leaves the hospital with those orders. This ensures the continuity of care when the patient goes back to the nursing home or the board and care facility.”

Beef Up Communication

Dr. Crecelius concedes that certified medical directors (CMDs) are also often guilty of dropping the ball when it comes to communicating with inpatient provider colleagues.

Care of nursing home patients can be improved if hospitalists and medical directors of nursing homes talk directly on the phone, he says. “I met one wonderful hospitalist who actually showed up at the nursing home to see how the patients that he’d been sending out of the hospital were doing,’’ he recalls. “It was so nice to see the face behind the voice. You can’t get mad at a face!”

However, again demonstrating the range of practice techniques, another hospitalist group in Dr. Crecelius’ area does not do anything beyond faxing him the patient’s diagnosis. “Well, I knew the diagnosis, so that fax is not telling me anything,’’ he says. “And unfortunately, that is their idea of communication.”

The Marin Hospitalist Medical Group makes every effort to ensure communications with receiving facilities are timely and thorough. According to Dr. Cumming, the group has surveyed—and will continue to survey—its referring primary care physicians, whether office or facility-based, for feedback on their performance. Hospital case managers also relay feedback to the hospitalist group, she notes. “We’ve tried to use the customer service model across all the groups of physicians who transfer patients to us and to whom we transfer patients, to keep that level of communication where it needs to be,” she says. Some of the questions they ask of their facilities:

- Are we sending the information you need?

- Do you want to receive all documents with the patient when he or she is transferred, or just a small subset of documents?

- How do you want information delivered? Do you want forms, discharge summaries and other documents faxed to you? Would you prefer a phone call?

- What can we do better?

Dr. Haimowitz’s advice to hospitalists might parallel the advice he recently gave to local a hospital administrators who were considering starting an intensivist program. “If you’re going to do this right, you must have physicians who are sensitive to older patients and what they want,” he says. Quality of life, DNR orders, and goals of care take on subtle gradations when applied to the elderly, he emphasizes.

Absent the time to visit the area nursing homes, hospitalists can always at least call, Dr. Crecelius notes.

Just as a hospitalist or emergency department physician would contact the family to corroborate patient history, they should also call the nursing home. “Speaking with the nurse at the skilled nursing facility, you can access a wealth of information—and save time and effort,” he says.

Improve Transfers

Dr. Haimowitz believes communication—on a form or by phone—is essential. He sees even more opportunity for miscommunication between hospitals and nursing homes because of different recordkeeping systems.

Hospitals are moving increasingly to electronic health records, while nursing homes still rely on paper documentation. “How do you foster communication?” Dr. Haimowitz asks. “How do you get the right people on the same bus? The best transfer sheet in the world is no good if one, it’s not filled out, and two, if it’s not read.”

Disparate systems can be a barrier, but it does not mean you should not try to optimize communication within whatever system you have, says Dr. Cumming.

The Marin Hospitalist Medical Group is setting up a communication system to alert all primary care physicians of pending lab results so such tests do not fall through the cracks after patients are discharged.

In another initiative, the hospital will set up a system to note that any pneumonia or influenza vaccinations performed while the patient was hospitalized are communicated either to PCP or outside facility. The group is also working to urge all local nursing facilities to include records of patients’ recent vaccinations when they are transferred to the hospital.

It’s clear that effective transfers of elderly patients require a concerted effort by all involved. “If you perform a root cause analysis of [transfer] errors, most occur not because of any negligence, but because communication—written or verbal—was not handled as best as it could have been,” Dr. Gartland notes. “Oftentimes, we are just as frustrated as they [nursing facilities] are when patients return to the emergency room unable to communicate their medical conditions, wishes, and the like,” he says. As medical director of care coordination at Emory, he has worked to improve relationships with administrators and physicians in nursing facilities used most often by the hospital. “If people have a vested interest in a relationship, they are more likely to be diligent about the transfer of patients,” he asserts.

Above all, emphasizes Dr. Cumming, “it important to always solicit feedback from your primary care physician ‘clientele.’ They are your clients, much as your patients are, and your hospital is. We’re providing services to all these various groups. Quality patient care is the most important thing that we do, and part of that means that we have to have good transfer of information. Our group recognizes that we are far from perfect; we know we can always do better; and we always have to reassess to make sure that we’re on the right track.” TH

Gretchen Henkel is a frequent contributor to The Hospitalist.

Reference

- Ouslander JG, Osterweil D, Morley J. Medical Care in the Nursing Home. 2nd ed. New York, New York: McGraw-Hill Publishers;1997.

Charles A. Crecelius, MD, of Saint Louis, has experienced best- and worst-case scenarios when his frail elderly patients have been admitted and discharged by local hospitalists.

Best case, he says: “My patient is admitted. I get a call. I’m told what is going on. I’m notified of meaningful changes, and at discharge, I get another call [from the hospitalist].”

But there are wide variations in hospitalist/nursing home relationships, notes Dr. Crecelius, a long-term care physician and president-elect of the American Medical Director’s Association (AMDA).

This was brought home by the case of a patient with a well-documented history of dystonic reaction to toxic lithium levels. The patient was later misdiagnosed as having tardive dyskinesia, a movement disorder. Her much-needed medication was discontinued, and the hospital transferred the patient back to the nursing home in worse condition than before.

“We wasted an entire hospitalization,” Dr. Crecelius recalls ruefully.

The above scenario underscores the importance of a thorough transfer of information when elderly patients move from facility to facility. Interaction between hospitalists and nursing home staff will become increasingly important in light of the growing frail elderly population and the Joint Commission on Accreditation of Health Care Organization’s (JCAHO) push for improved discharge communications.1

By applying a customer service model and continually upgrading transfer documentation, hospital medicine groups can “keep the level of communication where it needs to be,” says Susan S. Cumming, MD, associate medical director of Marin Hospitalist Medical Group at Marin General Hospital in Greenbrae, Calif.

Running a Risk

Dan Osterweil, MD, CMD, is familiar with the hospitalist model through his medical training in Israel during the late 1970s and early 1980s. Hospitalists there routinely handled inpatient care.

Dr. Osterweil, a clinical professor of medicine/geriatric medicine at UCLA, research associate with the UCLA Borun Center for Gerontological Research, and former medical director of the Jewish Home for the Aging in Reseda, Calif., has the opportunity to observe hospitalists deal with nursing homes in his current capacity as a consultant for managed care corporations in Southern California.

“Hospitalists have an excellent understanding of acute care management,” he says. “They do a good on-site job of dealing with immediate problems of the individual, and they’re very efficient and very responsive. But while hospitalists are providing higher competency in the management of intra-hospital care, I think that those I’ve interfaced with fall short on the transitions of care, which is so critical with the nursing home patient.”

Dr. Osterweil recalls one patient who had in place do not resuscitate (DNR) and do not intubate (DNI) orders. But when he was hospitalized, the patient was intubated. “If [the hospitalist] had asked one question of the individual or the caregiver—‘What is the goal of care?’—they would have been able to plan a much smoother transition for that person back to the facility.”

At Lower Bucks Hospital in Bristol, Pa., where long-term care physician Daniel Haimowitz, MD, CMD serves as chairman of internal medicine and chairs the utilization committee, the surrounding community of physicians has responded in a mostly positive way to a new hospitalist program.

However, Dr. Haimowitz has concerns that transitioning admissions of nursing home patients to hospitalists can hinder continuity of care.

Different hospitalists work each shift, and unless the patient has been on the hospitalist service in the past, the admitting hospitalist may know nothing about the patient—and most probably has no relationship with the patient’s family (as the primary care physician would have).

“The family doctor has seen the patient for 20 or 30 years and knows what he or she wants,” Dr. Haimowitz says. “But this patient is brand new to the hospitalist. Unless the hospitalist is really good with communication and takes the extra step to call the physician at the nursing home, I think you run the real risk of duplicating workup or actually not doing what is in the best interest of the patient.”