User login

Hours to Expertise

Glass of wine in one hand and the Sept. 30 copy of Wine Spectator in the other, I intended to relax a bit—the future of hospital medicine not necessarily uppermost in my mind. But then I was struck by an article by Matt Kramer titled “10,000 hours.” In it he discusses the implications Daniel Levitin’s new book This Is Your Brain on Music: The Science of a Human Obsession (Dutton) may have for the field of wine tasting.

Levitin notes that “ten thousand hours of practice is required to achieve the level of mastery associated with being a world-class expert—in anything.” It turns out it doesn’t matter what you are trying to master.

“In study after study of composers, basketball players, fiction writers, ice skaters, concert pianists, chess players, master criminals, and what have you, this number comes up again and again,” he says. “No one has yet found a case in which true world-class expertise was accomplished in less time.” This is consistent with how we learn. “Learning requires the assimilation and consolidation of information in neural tissue,” writes Levitin. “The more experiences we have with something the stronger the memory/learning trace for the experience becomes.”

Ten thousand hours. Are you an expert in hospital medicine? Have you compiled the requisite 10,000 hours? The average hospitalist working approximately 200 shifts a year of 10 to 12 hours each would take four to five years to master the practice of hospital medicine. On the other hand, a provider spending 10 hours a week in the hospital would require 20 years to achieve the numeric equivalent of expert status.

While Levitin was discussing the impact of this calculation on music and Kramer on wine expertise, it struck me as applicable to one of the great debates surrounding hospital medicine. Early in the days of the hospitalist movement, many inside and outside the field opined as to whether hospitals should be the domain of hospitalists and clinics the domain of primary care doctors, without overlap. SHM and I proclaimed hospitals should be open to all providers, regardless of primary practice site.

Over time the argument has died down as the threat of a hospitalist takeover has given way to the realization that many primary care doctors prefer a practice without inpatient obligations.

Recently the American Board of Internal Medicine (ABIM) has decided to move forward with a Recognition of Focused Practice in hospital medicine (RFP-HM) certification. This designation will utilize the structure of the ABIM Maintenance of Certification (MOC) program. It will be available to those who have practiced hospital medicine at least three years, meet inpatient volume requirements, and successfully complete hospital medicine-specific Self-Evaluation Process (SEP) modules, Practice Improvement Modules (PIM) and a secure exam.

This has again raised concerns about the growth and direction of hospital medicine and the implications for internal medicine. Would this confer specialty status to hospitalists while leaving primary care doctors as the remaining generalists? Would this further fracture the field of internal medicine? Would this allow hospital-credentialing boards to preferentially allow only those with RFP-HM to practice within their walls, effectively outlawing the primary care doctor?

Having been a member of the task force that worked on RFP-HM, I can say emphatically that it is not intended to confer specialty status to hospitalists or exalt them above other general internists. Rather, it is meant to recognize that a practitioner has focused his or her practice in a manner that demonstrates greater proficiency in the practice of hospital medicine. While this denotes a presumably higher level of proficiency by RFP-HM providers, it does not mean those without it are not capable providers.

How then should we define who is a capable provider in the hospital setting? According to the Dreyfus Model of Skills Acquisition, as learners develop along the continuum from novice to beginner to competent to proficient to expert, their skills become more developed, letting them tackle more complex issues and tasks more efficiently.

For example, the novice knows that a patient with dyspnea might have pneumonia and orders a chest X-ray but little more. The competent provider realizes many other disease states can cause dyspnea and would assess for those as well, often getting bogged down in extraneous details. The proficient provider immediately focuses on the important details and determines pneumonia as the cause of the dyspnea, applying the proper treatment algorithms with a level of efficiency beyond that of the competent peer.

The expert intuitively diagnoses the pneumonia and prescribes the proper diagnostic and therapeutic evaluation. He does so while considering the patient’s immune status, the impact of the hospital’s antimicrobial resistance patterns, and the potential risks and benefits of short-course antimicrobial therapy—all through the prism of quality core measures, cost, and throughput.

In a healthcare system at best strained and by most evidence severely fractured, we can no longer accept competence as the determinant of a capable provider. Rather, we should use proficiency moving toward expertise as the measuring stick for caring for increasingly more complex patients.

The designation “hospitalist” or even RFP-HM should not determine if one is proficient to practice hospital medicine, just as the designation of primary care provider should not exclude one from practicing in the hospital. Certainly, there are practitioners able to seamlessly cross the inpatient/outpatient boundary without losing a step. However, I suspect the more likely scenario is expertise in one and at best proficiency in the other.

Levitin’s 10,000-hour threshold supports this assumption, as it would take at least 10 years to amass 10,000 hours in each practice setting. Most likely, development of expertise in one arena means mere competence in another. As exhibit A, I tremble at the thought of the mischief I would cause if I took my stethoscope to the primary care clinic.

Instead, the ethical standards of our profession should dictate that each provider determines if they meet this pursuit-of-expertise standard. Employers and credentialing boards need to raise the bar toward expertise, ensuring these thresholds are met.

In the end, hospital or clinic sites should be the domain of capable providers, regardless of their primary practice site. However, we need to recalibrate how we define a capable provider who is moving away from competence toward proficiency verging on expertise. Experience as a surrogate for expertise, more than primary practice setting or RFP-HM status, should be the major determinant for who cares for hospitalized patients. TH

Dr. Glasheen is associate professor of medicine at the University of Colorado at Denver, where he serves as director of the Hospital Medicine Program and the Hospitalist Training Program, and as associate program director of the Internal Medicine Residency Program.

Glass of wine in one hand and the Sept. 30 copy of Wine Spectator in the other, I intended to relax a bit—the future of hospital medicine not necessarily uppermost in my mind. But then I was struck by an article by Matt Kramer titled “10,000 hours.” In it he discusses the implications Daniel Levitin’s new book This Is Your Brain on Music: The Science of a Human Obsession (Dutton) may have for the field of wine tasting.

Levitin notes that “ten thousand hours of practice is required to achieve the level of mastery associated with being a world-class expert—in anything.” It turns out it doesn’t matter what you are trying to master.

“In study after study of composers, basketball players, fiction writers, ice skaters, concert pianists, chess players, master criminals, and what have you, this number comes up again and again,” he says. “No one has yet found a case in which true world-class expertise was accomplished in less time.” This is consistent with how we learn. “Learning requires the assimilation and consolidation of information in neural tissue,” writes Levitin. “The more experiences we have with something the stronger the memory/learning trace for the experience becomes.”

Ten thousand hours. Are you an expert in hospital medicine? Have you compiled the requisite 10,000 hours? The average hospitalist working approximately 200 shifts a year of 10 to 12 hours each would take four to five years to master the practice of hospital medicine. On the other hand, a provider spending 10 hours a week in the hospital would require 20 years to achieve the numeric equivalent of expert status.

While Levitin was discussing the impact of this calculation on music and Kramer on wine expertise, it struck me as applicable to one of the great debates surrounding hospital medicine. Early in the days of the hospitalist movement, many inside and outside the field opined as to whether hospitals should be the domain of hospitalists and clinics the domain of primary care doctors, without overlap. SHM and I proclaimed hospitals should be open to all providers, regardless of primary practice site.

Over time the argument has died down as the threat of a hospitalist takeover has given way to the realization that many primary care doctors prefer a practice without inpatient obligations.

Recently the American Board of Internal Medicine (ABIM) has decided to move forward with a Recognition of Focused Practice in hospital medicine (RFP-HM) certification. This designation will utilize the structure of the ABIM Maintenance of Certification (MOC) program. It will be available to those who have practiced hospital medicine at least three years, meet inpatient volume requirements, and successfully complete hospital medicine-specific Self-Evaluation Process (SEP) modules, Practice Improvement Modules (PIM) and a secure exam.

This has again raised concerns about the growth and direction of hospital medicine and the implications for internal medicine. Would this confer specialty status to hospitalists while leaving primary care doctors as the remaining generalists? Would this further fracture the field of internal medicine? Would this allow hospital-credentialing boards to preferentially allow only those with RFP-HM to practice within their walls, effectively outlawing the primary care doctor?

Having been a member of the task force that worked on RFP-HM, I can say emphatically that it is not intended to confer specialty status to hospitalists or exalt them above other general internists. Rather, it is meant to recognize that a practitioner has focused his or her practice in a manner that demonstrates greater proficiency in the practice of hospital medicine. While this denotes a presumably higher level of proficiency by RFP-HM providers, it does not mean those without it are not capable providers.

How then should we define who is a capable provider in the hospital setting? According to the Dreyfus Model of Skills Acquisition, as learners develop along the continuum from novice to beginner to competent to proficient to expert, their skills become more developed, letting them tackle more complex issues and tasks more efficiently.

For example, the novice knows that a patient with dyspnea might have pneumonia and orders a chest X-ray but little more. The competent provider realizes many other disease states can cause dyspnea and would assess for those as well, often getting bogged down in extraneous details. The proficient provider immediately focuses on the important details and determines pneumonia as the cause of the dyspnea, applying the proper treatment algorithms with a level of efficiency beyond that of the competent peer.

The expert intuitively diagnoses the pneumonia and prescribes the proper diagnostic and therapeutic evaluation. He does so while considering the patient’s immune status, the impact of the hospital’s antimicrobial resistance patterns, and the potential risks and benefits of short-course antimicrobial therapy—all through the prism of quality core measures, cost, and throughput.

In a healthcare system at best strained and by most evidence severely fractured, we can no longer accept competence as the determinant of a capable provider. Rather, we should use proficiency moving toward expertise as the measuring stick for caring for increasingly more complex patients.

The designation “hospitalist” or even RFP-HM should not determine if one is proficient to practice hospital medicine, just as the designation of primary care provider should not exclude one from practicing in the hospital. Certainly, there are practitioners able to seamlessly cross the inpatient/outpatient boundary without losing a step. However, I suspect the more likely scenario is expertise in one and at best proficiency in the other.

Levitin’s 10,000-hour threshold supports this assumption, as it would take at least 10 years to amass 10,000 hours in each practice setting. Most likely, development of expertise in one arena means mere competence in another. As exhibit A, I tremble at the thought of the mischief I would cause if I took my stethoscope to the primary care clinic.

Instead, the ethical standards of our profession should dictate that each provider determines if they meet this pursuit-of-expertise standard. Employers and credentialing boards need to raise the bar toward expertise, ensuring these thresholds are met.

In the end, hospital or clinic sites should be the domain of capable providers, regardless of their primary practice site. However, we need to recalibrate how we define a capable provider who is moving away from competence toward proficiency verging on expertise. Experience as a surrogate for expertise, more than primary practice setting or RFP-HM status, should be the major determinant for who cares for hospitalized patients. TH

Dr. Glasheen is associate professor of medicine at the University of Colorado at Denver, where he serves as director of the Hospital Medicine Program and the Hospitalist Training Program, and as associate program director of the Internal Medicine Residency Program.

Glass of wine in one hand and the Sept. 30 copy of Wine Spectator in the other, I intended to relax a bit—the future of hospital medicine not necessarily uppermost in my mind. But then I was struck by an article by Matt Kramer titled “10,000 hours.” In it he discusses the implications Daniel Levitin’s new book This Is Your Brain on Music: The Science of a Human Obsession (Dutton) may have for the field of wine tasting.

Levitin notes that “ten thousand hours of practice is required to achieve the level of mastery associated with being a world-class expert—in anything.” It turns out it doesn’t matter what you are trying to master.

“In study after study of composers, basketball players, fiction writers, ice skaters, concert pianists, chess players, master criminals, and what have you, this number comes up again and again,” he says. “No one has yet found a case in which true world-class expertise was accomplished in less time.” This is consistent with how we learn. “Learning requires the assimilation and consolidation of information in neural tissue,” writes Levitin. “The more experiences we have with something the stronger the memory/learning trace for the experience becomes.”

Ten thousand hours. Are you an expert in hospital medicine? Have you compiled the requisite 10,000 hours? The average hospitalist working approximately 200 shifts a year of 10 to 12 hours each would take four to five years to master the practice of hospital medicine. On the other hand, a provider spending 10 hours a week in the hospital would require 20 years to achieve the numeric equivalent of expert status.

While Levitin was discussing the impact of this calculation on music and Kramer on wine expertise, it struck me as applicable to one of the great debates surrounding hospital medicine. Early in the days of the hospitalist movement, many inside and outside the field opined as to whether hospitals should be the domain of hospitalists and clinics the domain of primary care doctors, without overlap. SHM and I proclaimed hospitals should be open to all providers, regardless of primary practice site.

Over time the argument has died down as the threat of a hospitalist takeover has given way to the realization that many primary care doctors prefer a practice without inpatient obligations.

Recently the American Board of Internal Medicine (ABIM) has decided to move forward with a Recognition of Focused Practice in hospital medicine (RFP-HM) certification. This designation will utilize the structure of the ABIM Maintenance of Certification (MOC) program. It will be available to those who have practiced hospital medicine at least three years, meet inpatient volume requirements, and successfully complete hospital medicine-specific Self-Evaluation Process (SEP) modules, Practice Improvement Modules (PIM) and a secure exam.

This has again raised concerns about the growth and direction of hospital medicine and the implications for internal medicine. Would this confer specialty status to hospitalists while leaving primary care doctors as the remaining generalists? Would this further fracture the field of internal medicine? Would this allow hospital-credentialing boards to preferentially allow only those with RFP-HM to practice within their walls, effectively outlawing the primary care doctor?

Having been a member of the task force that worked on RFP-HM, I can say emphatically that it is not intended to confer specialty status to hospitalists or exalt them above other general internists. Rather, it is meant to recognize that a practitioner has focused his or her practice in a manner that demonstrates greater proficiency in the practice of hospital medicine. While this denotes a presumably higher level of proficiency by RFP-HM providers, it does not mean those without it are not capable providers.

How then should we define who is a capable provider in the hospital setting? According to the Dreyfus Model of Skills Acquisition, as learners develop along the continuum from novice to beginner to competent to proficient to expert, their skills become more developed, letting them tackle more complex issues and tasks more efficiently.

For example, the novice knows that a patient with dyspnea might have pneumonia and orders a chest X-ray but little more. The competent provider realizes many other disease states can cause dyspnea and would assess for those as well, often getting bogged down in extraneous details. The proficient provider immediately focuses on the important details and determines pneumonia as the cause of the dyspnea, applying the proper treatment algorithms with a level of efficiency beyond that of the competent peer.

The expert intuitively diagnoses the pneumonia and prescribes the proper diagnostic and therapeutic evaluation. He does so while considering the patient’s immune status, the impact of the hospital’s antimicrobial resistance patterns, and the potential risks and benefits of short-course antimicrobial therapy—all through the prism of quality core measures, cost, and throughput.

In a healthcare system at best strained and by most evidence severely fractured, we can no longer accept competence as the determinant of a capable provider. Rather, we should use proficiency moving toward expertise as the measuring stick for caring for increasingly more complex patients.

The designation “hospitalist” or even RFP-HM should not determine if one is proficient to practice hospital medicine, just as the designation of primary care provider should not exclude one from practicing in the hospital. Certainly, there are practitioners able to seamlessly cross the inpatient/outpatient boundary without losing a step. However, I suspect the more likely scenario is expertise in one and at best proficiency in the other.

Levitin’s 10,000-hour threshold supports this assumption, as it would take at least 10 years to amass 10,000 hours in each practice setting. Most likely, development of expertise in one arena means mere competence in another. As exhibit A, I tremble at the thought of the mischief I would cause if I took my stethoscope to the primary care clinic.

Instead, the ethical standards of our profession should dictate that each provider determines if they meet this pursuit-of-expertise standard. Employers and credentialing boards need to raise the bar toward expertise, ensuring these thresholds are met.

In the end, hospital or clinic sites should be the domain of capable providers, regardless of their primary practice site. However, we need to recalibrate how we define a capable provider who is moving away from competence toward proficiency verging on expertise. Experience as a surrogate for expertise, more than primary practice setting or RFP-HM status, should be the major determinant for who cares for hospitalized patients. TH

Dr. Glasheen is associate professor of medicine at the University of Colorado at Denver, where he serves as director of the Hospital Medicine Program and the Hospitalist Training Program, and as associate program director of the Internal Medicine Residency Program.

A Year of Progress

It’s hard to believe eight years have gone by since I came to SHM. More than that, it is strange to think of a world without hospitalists. Hospital medicine is part of the fabric of healthcare; there’s no longer a debate over whether hospitalists are good or bad. Now, the talk is about how hospitalists can help solve so many of the ills that vex our healthcare system.

This year has been an extraordinary year even by SHM standards. Witness our progress in the following areas.

ABIM Progress

In a landmark and revolutionary decision, the American Board of Internal Medicine (ABIM) recommended proceeding with a recognition of focused practice (RFP) in hospital medicine as an option in its maintenance of certification (MOC).

This is the culmination of a strategy SHM laid out three years ago. SHM is working with ABIM to continue to make the MOC process meaningful to hospitalists as the ABIM recommendations wend their way through the American Board of Medical Specialties. SHM continues to reach out to the pediatric and family medicine boards so the RFP can be available to all hospitalists.

JHM Listed

In its first year of publication, the Journal of Hospital Medicine (JHM) has been included in PubMed, the National Institutes of Health online archive of life science journals. JHM now resides among other established journals, fielding a marked increased in submissions for publication.

Quality

SHM received its third consecutive grant from the John A. Hartford Foundation, this one for $1.4 million over three years to develop interventions to improve care transitions for older adults at discharge.

As part of our work to improve quality for our nation’s seniors, SHM is developing discharge-planning tools and implementation strategies to limit the voltage drop in care at discharge. Hartford’s support means funders see that hospitalists, with SHM support, improve quality at their hospitals. SHM has become a leader in discharge planning tools and is helping set standards for transitions of care.

To help give hospitalists tools and resources to effect change on the front lines, SHM continues to develop online resource rooms and unique strategies such as mentored implementation.

We also have several hospitalist leaders on key panels at the National Quality Forum (NQF). The American Medical Association’s Physician Consortium on Practice Improvement has asked SHM to take the lead in forming a coalition for setting transitions-of-care measurements.

When the Institute for Healthcare Improvement needed a physician group to join the announcement of its 5 Million Lives Campaign, it reached out to SHM. President Rusty Holman took the stage to support the initiative, which intends to protect 5 million patients from incidents of medical harm over the next two years.

Further, the Joint Commission on Accreditation of Healthcare Organizations asked SHM to co-sponsor its medication reconciliation workgroup. Lastly, SHM continues to get significant visibility for hospitalists with our leadership of the deep-vein thrombosis awareness coalition of more than 35 organizations.

Annual Meeting

In May, SHM took over the Gaylord Texan in Dallas with professional meeting staging that rivaled older, larger organizations. With banners, Jumbotrons, and devices projecting the SHM logo, we transformed the Gaylord into a “hospitalist city.” We treated the nearly 1,200 attendees to three superlative speakers:

- David Brailer, MD, national coordinator for health information technology, United States Department of Health and Human Services;

- Jonathan Perlin, MD, former undersecretary for health at the Veterans Health Administration and now chief medical officer and senior vice president of quality for Hospital Corporation of America in Nashville; and

- Bob Wachter, MD, professor and chief of the division of hospital medicine at the University of California, San Francisco.

And, we had our largest poster session ever, with more than 200 submissions, and our largest exhibit hall. We plan to take it up a notch in San Diego in April.

Advocacy and Policy

Our presence in Washington, D.C., allows us to be active in Medicare payment reform. SHM leadership has met with senior staff at MedPAC, the organization that makes recommendations to the Centers for Medicare and Medicaid Services and Congress. MedPAC is interested in working with SHM as Medicare attempts to move away from paying for just visits and procedures and toward reimbursement strategies that drive performance and efficiency.

Current, Future Initiatives

In June, SHM forged a partnership with the Society of General Internal Medicine (SGIM) and the Association of Chiefs of General Internal Medicine to hold an academic summit to develop strategies for academic hospitalists to have a strong and sustainable career in teaching, training, and research in hospital medicine. When the Alliance for Academic Internal Medicine developed its proposal to redesign internal medicine training, SHM took the lead in crafting the hospitalist response.

In July, we joined the SGIM and American College of Physicians to hold a consensus conference on transitions of care. This coalition of more than 25 organizations produced a statement as the basis for future standards and measurements. Also in July, SHM worked with key leaders in emergency medicine and others to redefine the management and opportunities in observation units.

We held a multidisciplinary workforce summit in November to examine the challenges and solutions in growing hospital medicine from 20,000 to 40,000 or more physicians.

Diversity

While at times we may seem to focus more on internal-medicine-trained hospitalists, who make up more than 80% of the field, SHM continues to include hospitalists in family medicine and pediatrics, among other specialties. We also are home to nonphysician providers and physician assistants. We are working to support academic hospitalists, small groups, and multistate companies. In our toughest tightrope walk, SHM continues to be relevant and supportive of labor and management in hospital medicine.

Looking to 2008

The growth and influence of hospital medicine is relentless. Maybe 2008 is the year we will see hospitalists practicing in more than 3,000 hospitals or see the specialty grow to more than 25,000 hospitalists. One thing is for sure: SHM, with your suggestions, ideas, and energy, will be on the front lines with you, supporting and advocating a better healthcare system. TH

Dr. Wellikson is CEO of SHM.

It’s hard to believe eight years have gone by since I came to SHM. More than that, it is strange to think of a world without hospitalists. Hospital medicine is part of the fabric of healthcare; there’s no longer a debate over whether hospitalists are good or bad. Now, the talk is about how hospitalists can help solve so many of the ills that vex our healthcare system.

This year has been an extraordinary year even by SHM standards. Witness our progress in the following areas.

ABIM Progress

In a landmark and revolutionary decision, the American Board of Internal Medicine (ABIM) recommended proceeding with a recognition of focused practice (RFP) in hospital medicine as an option in its maintenance of certification (MOC).

This is the culmination of a strategy SHM laid out three years ago. SHM is working with ABIM to continue to make the MOC process meaningful to hospitalists as the ABIM recommendations wend their way through the American Board of Medical Specialties. SHM continues to reach out to the pediatric and family medicine boards so the RFP can be available to all hospitalists.

JHM Listed

In its first year of publication, the Journal of Hospital Medicine (JHM) has been included in PubMed, the National Institutes of Health online archive of life science journals. JHM now resides among other established journals, fielding a marked increased in submissions for publication.

Quality

SHM received its third consecutive grant from the John A. Hartford Foundation, this one for $1.4 million over three years to develop interventions to improve care transitions for older adults at discharge.

As part of our work to improve quality for our nation’s seniors, SHM is developing discharge-planning tools and implementation strategies to limit the voltage drop in care at discharge. Hartford’s support means funders see that hospitalists, with SHM support, improve quality at their hospitals. SHM has become a leader in discharge planning tools and is helping set standards for transitions of care.

To help give hospitalists tools and resources to effect change on the front lines, SHM continues to develop online resource rooms and unique strategies such as mentored implementation.

We also have several hospitalist leaders on key panels at the National Quality Forum (NQF). The American Medical Association’s Physician Consortium on Practice Improvement has asked SHM to take the lead in forming a coalition for setting transitions-of-care measurements.

When the Institute for Healthcare Improvement needed a physician group to join the announcement of its 5 Million Lives Campaign, it reached out to SHM. President Rusty Holman took the stage to support the initiative, which intends to protect 5 million patients from incidents of medical harm over the next two years.

Further, the Joint Commission on Accreditation of Healthcare Organizations asked SHM to co-sponsor its medication reconciliation workgroup. Lastly, SHM continues to get significant visibility for hospitalists with our leadership of the deep-vein thrombosis awareness coalition of more than 35 organizations.

Annual Meeting

In May, SHM took over the Gaylord Texan in Dallas with professional meeting staging that rivaled older, larger organizations. With banners, Jumbotrons, and devices projecting the SHM logo, we transformed the Gaylord into a “hospitalist city.” We treated the nearly 1,200 attendees to three superlative speakers:

- David Brailer, MD, national coordinator for health information technology, United States Department of Health and Human Services;

- Jonathan Perlin, MD, former undersecretary for health at the Veterans Health Administration and now chief medical officer and senior vice president of quality for Hospital Corporation of America in Nashville; and

- Bob Wachter, MD, professor and chief of the division of hospital medicine at the University of California, San Francisco.

And, we had our largest poster session ever, with more than 200 submissions, and our largest exhibit hall. We plan to take it up a notch in San Diego in April.

Advocacy and Policy

Our presence in Washington, D.C., allows us to be active in Medicare payment reform. SHM leadership has met with senior staff at MedPAC, the organization that makes recommendations to the Centers for Medicare and Medicaid Services and Congress. MedPAC is interested in working with SHM as Medicare attempts to move away from paying for just visits and procedures and toward reimbursement strategies that drive performance and efficiency.

Current, Future Initiatives

In June, SHM forged a partnership with the Society of General Internal Medicine (SGIM) and the Association of Chiefs of General Internal Medicine to hold an academic summit to develop strategies for academic hospitalists to have a strong and sustainable career in teaching, training, and research in hospital medicine. When the Alliance for Academic Internal Medicine developed its proposal to redesign internal medicine training, SHM took the lead in crafting the hospitalist response.

In July, we joined the SGIM and American College of Physicians to hold a consensus conference on transitions of care. This coalition of more than 25 organizations produced a statement as the basis for future standards and measurements. Also in July, SHM worked with key leaders in emergency medicine and others to redefine the management and opportunities in observation units.

We held a multidisciplinary workforce summit in November to examine the challenges and solutions in growing hospital medicine from 20,000 to 40,000 or more physicians.

Diversity

While at times we may seem to focus more on internal-medicine-trained hospitalists, who make up more than 80% of the field, SHM continues to include hospitalists in family medicine and pediatrics, among other specialties. We also are home to nonphysician providers and physician assistants. We are working to support academic hospitalists, small groups, and multistate companies. In our toughest tightrope walk, SHM continues to be relevant and supportive of labor and management in hospital medicine.

Looking to 2008

The growth and influence of hospital medicine is relentless. Maybe 2008 is the year we will see hospitalists practicing in more than 3,000 hospitals or see the specialty grow to more than 25,000 hospitalists. One thing is for sure: SHM, with your suggestions, ideas, and energy, will be on the front lines with you, supporting and advocating a better healthcare system. TH

Dr. Wellikson is CEO of SHM.

It’s hard to believe eight years have gone by since I came to SHM. More than that, it is strange to think of a world without hospitalists. Hospital medicine is part of the fabric of healthcare; there’s no longer a debate over whether hospitalists are good or bad. Now, the talk is about how hospitalists can help solve so many of the ills that vex our healthcare system.

This year has been an extraordinary year even by SHM standards. Witness our progress in the following areas.

ABIM Progress

In a landmark and revolutionary decision, the American Board of Internal Medicine (ABIM) recommended proceeding with a recognition of focused practice (RFP) in hospital medicine as an option in its maintenance of certification (MOC).

This is the culmination of a strategy SHM laid out three years ago. SHM is working with ABIM to continue to make the MOC process meaningful to hospitalists as the ABIM recommendations wend their way through the American Board of Medical Specialties. SHM continues to reach out to the pediatric and family medicine boards so the RFP can be available to all hospitalists.

JHM Listed

In its first year of publication, the Journal of Hospital Medicine (JHM) has been included in PubMed, the National Institutes of Health online archive of life science journals. JHM now resides among other established journals, fielding a marked increased in submissions for publication.

Quality

SHM received its third consecutive grant from the John A. Hartford Foundation, this one for $1.4 million over three years to develop interventions to improve care transitions for older adults at discharge.

As part of our work to improve quality for our nation’s seniors, SHM is developing discharge-planning tools and implementation strategies to limit the voltage drop in care at discharge. Hartford’s support means funders see that hospitalists, with SHM support, improve quality at their hospitals. SHM has become a leader in discharge planning tools and is helping set standards for transitions of care.

To help give hospitalists tools and resources to effect change on the front lines, SHM continues to develop online resource rooms and unique strategies such as mentored implementation.

We also have several hospitalist leaders on key panels at the National Quality Forum (NQF). The American Medical Association’s Physician Consortium on Practice Improvement has asked SHM to take the lead in forming a coalition for setting transitions-of-care measurements.

When the Institute for Healthcare Improvement needed a physician group to join the announcement of its 5 Million Lives Campaign, it reached out to SHM. President Rusty Holman took the stage to support the initiative, which intends to protect 5 million patients from incidents of medical harm over the next two years.

Further, the Joint Commission on Accreditation of Healthcare Organizations asked SHM to co-sponsor its medication reconciliation workgroup. Lastly, SHM continues to get significant visibility for hospitalists with our leadership of the deep-vein thrombosis awareness coalition of more than 35 organizations.

Annual Meeting

In May, SHM took over the Gaylord Texan in Dallas with professional meeting staging that rivaled older, larger organizations. With banners, Jumbotrons, and devices projecting the SHM logo, we transformed the Gaylord into a “hospitalist city.” We treated the nearly 1,200 attendees to three superlative speakers:

- David Brailer, MD, national coordinator for health information technology, United States Department of Health and Human Services;

- Jonathan Perlin, MD, former undersecretary for health at the Veterans Health Administration and now chief medical officer and senior vice president of quality for Hospital Corporation of America in Nashville; and

- Bob Wachter, MD, professor and chief of the division of hospital medicine at the University of California, San Francisco.

And, we had our largest poster session ever, with more than 200 submissions, and our largest exhibit hall. We plan to take it up a notch in San Diego in April.

Advocacy and Policy

Our presence in Washington, D.C., allows us to be active in Medicare payment reform. SHM leadership has met with senior staff at MedPAC, the organization that makes recommendations to the Centers for Medicare and Medicaid Services and Congress. MedPAC is interested in working with SHM as Medicare attempts to move away from paying for just visits and procedures and toward reimbursement strategies that drive performance and efficiency.

Current, Future Initiatives

In June, SHM forged a partnership with the Society of General Internal Medicine (SGIM) and the Association of Chiefs of General Internal Medicine to hold an academic summit to develop strategies for academic hospitalists to have a strong and sustainable career in teaching, training, and research in hospital medicine. When the Alliance for Academic Internal Medicine developed its proposal to redesign internal medicine training, SHM took the lead in crafting the hospitalist response.

In July, we joined the SGIM and American College of Physicians to hold a consensus conference on transitions of care. This coalition of more than 25 organizations produced a statement as the basis for future standards and measurements. Also in July, SHM worked with key leaders in emergency medicine and others to redefine the management and opportunities in observation units.

We held a multidisciplinary workforce summit in November to examine the challenges and solutions in growing hospital medicine from 20,000 to 40,000 or more physicians.

Diversity

While at times we may seem to focus more on internal-medicine-trained hospitalists, who make up more than 80% of the field, SHM continues to include hospitalists in family medicine and pediatrics, among other specialties. We also are home to nonphysician providers and physician assistants. We are working to support academic hospitalists, small groups, and multistate companies. In our toughest tightrope walk, SHM continues to be relevant and supportive of labor and management in hospital medicine.

Looking to 2008

The growth and influence of hospital medicine is relentless. Maybe 2008 is the year we will see hospitalists practicing in more than 3,000 hospitals or see the specialty grow to more than 25,000 hospitalists. One thing is for sure: SHM, with your suggestions, ideas, and energy, will be on the front lines with you, supporting and advocating a better healthcare system. TH

Dr. Wellikson is CEO of SHM.

Care & Prayer

Charles Petit, MD, like many healthcare professionals, spends a good deal of time addressing the needs of the underprivileged. Since 2004, he has taken up the cause of the indigenous Miskito Indians of Puerto Lempira, Honduras. He is putting his own money into developing a modern clinic and international medicine program there.

But medicine isn’t his only mission. Dr. Petit, 56, a hospitalist at Palmetto Health Care’s Richland Memorial Hospital in Columbia, S.C., is also an Episcopal priest.

He joined Palmetto Health Senior Care as its first medical director in 1988 and reconnected with the group in 2004—not in his previous role as an office-based physician but as a hospitalist. In between those stints he pursued his ordination and medical missionary work in Africa and Latin America.

As a physician, Dr. Petit says he feels God’s presence at each patient’s bedside. Years ago he wondered how to handle that.

To deepen his connection between medicine and spirituality, he lived in a Christian intentional community in Indiana, Pa., from 1981 to 1988. Gradually, his views on medicine and spirituality crystallized.

“How does God do what he does?” Dr. Petit wondered. “Can medicine put Him to the test? I have seen that prayer works, including a patient miraculously healed of metastatic ovarian cancer. But God isn’t a vending machine. You don’t drop in a prayer and get a healing back.”

The Second Calling

Recognizing he needed something more to integrate medicine and spirituality, Dr. Petit sought a firmer grounding in religious studies.

He moved to Simpsonville, S.C., in 1995 and entered the Episcopal seminary, working as an emergency department doctor to pay the bills. Later, he earned a master’s of divinity from the University of the South in Sewanee, Tenn., in 2003.

His spiritual “internship” was a transitional deaconship from 2003 to 2005, under the Rev. Michael Flanagan, rector at Simpsonville’s Holy Cross Episcopal Church. Both had dual vocations—Flanagan was an engineer who sold electrical equipment for 10 years before ordination. Prior to meeting Dr. Petit, Flanagan was leery of the doctor’s ability to balance pastoral and medical duties.

“Would he be a doctor/priest?” Flanagan wondered. “A priest/doctor? His desire was to meld both and he did. Medicine and spirituality are both in his blood. He sees both as calls from God and connects medicine with spirituality into a holistic view of each person.” He says Dr. Petit “seems to know everything and sucks up knowledge, which he wants to share. He loves being the doctor and having the knowledge to fix the patient’s problem.”

While Dr. Petit keeps his hospitalist and priest roles mostly separate, working with elderly patients sometimes requires the skills of both disciplines. At Richland he wears a clerical collar on pastoral rounds. If a family or patient asks him to pray with them or discuss life’s ending, he does. He has conducted funerals for his own and colleagues’ patients.

“It’s a very powerful experience being both a priest and a doctor,” he says. “I grow so close to the patients and their families that it is natural for me to serve in both roles.”

Honduras Mission

As a seminarian, Dr. Petit took medical mission trips and briefly supported an African orphanage, looking for a cause to call his own. Until his first trip to Puerto Lempira, a village on the Miskito Coast of the Atlantic Ocean.

The abject poverty and medical needs of the Miskito Indians there pulled at him. Early on he enlisted the help of Ennis Whiddon, a builder and Holy Cross parishioner. Whiddon, who usually accompanies Dr. Petit to Puerto Lempira, says of his friend: “I knew him as [an emergency department] doctor first. Then I realized his extraordinary spiritual commitment. I went to Puerto Lempira on his first mission trip and I asked myself why anyone would want to be there, but I knew Chuck couldn’t bear not to be there. I also knew he wasn’t just going to give people two aspirins, come home and pray for them.”

Dr. Petit returns to Puerto Lempira three or four times a year with a team of doctors, seeing several hundred patients a day. During one two-week stint he dispensed $200,000 worth of medication he cadged from drug companies for $600 out of his pocket to rid the town’s youngsters of debilitating parasites.

Dr. Petit works with a Miskito nurse who runs their rudimentary clinic in his absence. He also uses hyperbaric medicine to treat divers whose crippling injuries result from diving deeply using pressurized oxygen tanks and rising too quickly to the surface.

“You wouldn’t believe the indescribably poor facilities we found there,” Whiddon says of the town’s clinic. “You wouldn’t have your dog treated there if you loved your dog.”

Last year Dr. Petit ratcheted up his commitment to Puerto Lempira, dreaming of building a permanent clinic there.

He decided to use his money to buy land to build a clinic, but got stonewalled by a stubborn local bureaucracy.

Then Andres Leone, a like-minded younger doctor who was part of the mission trip, stepped in with handy language and cultural skills. Leone who had attended medical school in Ecuador, is a Lutheran seminarian, and is completing a geriatric hospitalist fellowship at Palmetto Healthcare.

“We were in Puerto Lempira for two weeks and visited the mayor several times to buy land,” Dr. Leone explains. “He said the price was $600,000, which was ridiculous. In the town I overheard some conversations, which led to us meeting the 77-year-old daughter of missionaries. She sold us some of her land and even donated money to help build the clinic, which will be dedicated in her name.”

Thinking big, Dr. Petit is adding an apartment complete with air conditioning and a modern bathroom to the clinic’s blueprint, to attract residents in a to-be-formed international medicine program. As an assistant professor of family medicine at the University of South Carolina’s (USC) School of Medicine, he intends to oversee those residents.

Just back from Puerto Lempira, Dr. Petit finalized the clinic’s design, lined up local workers to figure out how to make concrete building blocks with native materials, and met with Anglican bishop the Right Rev. Lloyd E. Allen, bolstering support for the new clinic and the possibility of HIV outreach. Side by side with Honduran and Cuban doctors, Dr. Petit treated hundreds of Puerto Lempira’s villagers every day.

Back in the Hospital

Dr. Petit always wanted to be a doctor. Although his father suggested he become a hospital orderly, Dr. Petit knew being a physician was his calling, graduating from the University of West Virginia School of Medicine (Morgantown) family medicine program in 1978.

He enjoys hospital medicine as a holistic approach to caring for patients, consistent with his work early in his career.

An earlier 10-year stint as a hospitalist at HealthSouth Rehabilitation Hospital, also at USC, involved teaching residents and students rotating through the hospital, as well as a consultative service for neurosurgical patients at Richland. At Wheeling Hospital early in his career he became comfortable as a generalist, covering intensive care, assisting in surgery, and delivering many babies.

Being a hospitalist keeps that spirit alive. “It gives me the gift of time to spend with patients,” he says. “I try not to tie frail elderly patients down with IVs, Foley catheters, EKG monitors, worries that eating a leafy green vegetable will react badly with their Coumadin [warfarin], and polypharmacy.”

He discusses advanced directives, palliative care, and how the elderly in fragile condition can maintain as much freedom as possible. The hospital medicine group’s accommodating scheduling allows time for his parish duties and medical mission trips.

The group’s medical director, Victor Hirth, MD, describes Dr. Petit as a borderline workaholic who’s always looking for ways to make things better for the practice and patients. “The patients absolutely love him because he takes time to sit and talk to them,” says Dr. Hirth.

Dr. Petit also embraces new technologies. “Our [electronic medical record] makes working with my outpatient colleagues smooth and straightforward.” He relies on a personal digital device assistant for updates on clinical guidelines and optimal drug doses for elderly patients. Integrating a healer’s touch with new technology he says: “While medicine is a science, it’s still an art, a ministry, and a gift.”

What’s Next?

Back in South Carolina, Dr. Petit has picked up his hospitalist and pastoral responsibilities without missing a beat. He looks forward to building the palliative care consulting service and intends to launch a nonprofit corporation to receive donations to support the Puerto Lempira clinic’s construction.

He is planning more mission trips. He thrives on the work. Infused with boundless energy, he’s always looking for more to do.

“I love what I do,” he concludes. “If I felt much better they’d charge me an amusement tax.” TH

Marlene Piturro is a medical writer based in New York.

Charles Petit, MD, like many healthcare professionals, spends a good deal of time addressing the needs of the underprivileged. Since 2004, he has taken up the cause of the indigenous Miskito Indians of Puerto Lempira, Honduras. He is putting his own money into developing a modern clinic and international medicine program there.

But medicine isn’t his only mission. Dr. Petit, 56, a hospitalist at Palmetto Health Care’s Richland Memorial Hospital in Columbia, S.C., is also an Episcopal priest.

He joined Palmetto Health Senior Care as its first medical director in 1988 and reconnected with the group in 2004—not in his previous role as an office-based physician but as a hospitalist. In between those stints he pursued his ordination and medical missionary work in Africa and Latin America.

As a physician, Dr. Petit says he feels God’s presence at each patient’s bedside. Years ago he wondered how to handle that.

To deepen his connection between medicine and spirituality, he lived in a Christian intentional community in Indiana, Pa., from 1981 to 1988. Gradually, his views on medicine and spirituality crystallized.

“How does God do what he does?” Dr. Petit wondered. “Can medicine put Him to the test? I have seen that prayer works, including a patient miraculously healed of metastatic ovarian cancer. But God isn’t a vending machine. You don’t drop in a prayer and get a healing back.”

The Second Calling

Recognizing he needed something more to integrate medicine and spirituality, Dr. Petit sought a firmer grounding in religious studies.

He moved to Simpsonville, S.C., in 1995 and entered the Episcopal seminary, working as an emergency department doctor to pay the bills. Later, he earned a master’s of divinity from the University of the South in Sewanee, Tenn., in 2003.

His spiritual “internship” was a transitional deaconship from 2003 to 2005, under the Rev. Michael Flanagan, rector at Simpsonville’s Holy Cross Episcopal Church. Both had dual vocations—Flanagan was an engineer who sold electrical equipment for 10 years before ordination. Prior to meeting Dr. Petit, Flanagan was leery of the doctor’s ability to balance pastoral and medical duties.

“Would he be a doctor/priest?” Flanagan wondered. “A priest/doctor? His desire was to meld both and he did. Medicine and spirituality are both in his blood. He sees both as calls from God and connects medicine with spirituality into a holistic view of each person.” He says Dr. Petit “seems to know everything and sucks up knowledge, which he wants to share. He loves being the doctor and having the knowledge to fix the patient’s problem.”

While Dr. Petit keeps his hospitalist and priest roles mostly separate, working with elderly patients sometimes requires the skills of both disciplines. At Richland he wears a clerical collar on pastoral rounds. If a family or patient asks him to pray with them or discuss life’s ending, he does. He has conducted funerals for his own and colleagues’ patients.

“It’s a very powerful experience being both a priest and a doctor,” he says. “I grow so close to the patients and their families that it is natural for me to serve in both roles.”

Honduras Mission

As a seminarian, Dr. Petit took medical mission trips and briefly supported an African orphanage, looking for a cause to call his own. Until his first trip to Puerto Lempira, a village on the Miskito Coast of the Atlantic Ocean.

The abject poverty and medical needs of the Miskito Indians there pulled at him. Early on he enlisted the help of Ennis Whiddon, a builder and Holy Cross parishioner. Whiddon, who usually accompanies Dr. Petit to Puerto Lempira, says of his friend: “I knew him as [an emergency department] doctor first. Then I realized his extraordinary spiritual commitment. I went to Puerto Lempira on his first mission trip and I asked myself why anyone would want to be there, but I knew Chuck couldn’t bear not to be there. I also knew he wasn’t just going to give people two aspirins, come home and pray for them.”

Dr. Petit returns to Puerto Lempira three or four times a year with a team of doctors, seeing several hundred patients a day. During one two-week stint he dispensed $200,000 worth of medication he cadged from drug companies for $600 out of his pocket to rid the town’s youngsters of debilitating parasites.

Dr. Petit works with a Miskito nurse who runs their rudimentary clinic in his absence. He also uses hyperbaric medicine to treat divers whose crippling injuries result from diving deeply using pressurized oxygen tanks and rising too quickly to the surface.

“You wouldn’t believe the indescribably poor facilities we found there,” Whiddon says of the town’s clinic. “You wouldn’t have your dog treated there if you loved your dog.”

Last year Dr. Petit ratcheted up his commitment to Puerto Lempira, dreaming of building a permanent clinic there.

He decided to use his money to buy land to build a clinic, but got stonewalled by a stubborn local bureaucracy.

Then Andres Leone, a like-minded younger doctor who was part of the mission trip, stepped in with handy language and cultural skills. Leone who had attended medical school in Ecuador, is a Lutheran seminarian, and is completing a geriatric hospitalist fellowship at Palmetto Healthcare.

“We were in Puerto Lempira for two weeks and visited the mayor several times to buy land,” Dr. Leone explains. “He said the price was $600,000, which was ridiculous. In the town I overheard some conversations, which led to us meeting the 77-year-old daughter of missionaries. She sold us some of her land and even donated money to help build the clinic, which will be dedicated in her name.”

Thinking big, Dr. Petit is adding an apartment complete with air conditioning and a modern bathroom to the clinic’s blueprint, to attract residents in a to-be-formed international medicine program. As an assistant professor of family medicine at the University of South Carolina’s (USC) School of Medicine, he intends to oversee those residents.

Just back from Puerto Lempira, Dr. Petit finalized the clinic’s design, lined up local workers to figure out how to make concrete building blocks with native materials, and met with Anglican bishop the Right Rev. Lloyd E. Allen, bolstering support for the new clinic and the possibility of HIV outreach. Side by side with Honduran and Cuban doctors, Dr. Petit treated hundreds of Puerto Lempira’s villagers every day.

Back in the Hospital

Dr. Petit always wanted to be a doctor. Although his father suggested he become a hospital orderly, Dr. Petit knew being a physician was his calling, graduating from the University of West Virginia School of Medicine (Morgantown) family medicine program in 1978.

He enjoys hospital medicine as a holistic approach to caring for patients, consistent with his work early in his career.

An earlier 10-year stint as a hospitalist at HealthSouth Rehabilitation Hospital, also at USC, involved teaching residents and students rotating through the hospital, as well as a consultative service for neurosurgical patients at Richland. At Wheeling Hospital early in his career he became comfortable as a generalist, covering intensive care, assisting in surgery, and delivering many babies.

Being a hospitalist keeps that spirit alive. “It gives me the gift of time to spend with patients,” he says. “I try not to tie frail elderly patients down with IVs, Foley catheters, EKG monitors, worries that eating a leafy green vegetable will react badly with their Coumadin [warfarin], and polypharmacy.”

He discusses advanced directives, palliative care, and how the elderly in fragile condition can maintain as much freedom as possible. The hospital medicine group’s accommodating scheduling allows time for his parish duties and medical mission trips.

The group’s medical director, Victor Hirth, MD, describes Dr. Petit as a borderline workaholic who’s always looking for ways to make things better for the practice and patients. “The patients absolutely love him because he takes time to sit and talk to them,” says Dr. Hirth.

Dr. Petit also embraces new technologies. “Our [electronic medical record] makes working with my outpatient colleagues smooth and straightforward.” He relies on a personal digital device assistant for updates on clinical guidelines and optimal drug doses for elderly patients. Integrating a healer’s touch with new technology he says: “While medicine is a science, it’s still an art, a ministry, and a gift.”

What’s Next?

Back in South Carolina, Dr. Petit has picked up his hospitalist and pastoral responsibilities without missing a beat. He looks forward to building the palliative care consulting service and intends to launch a nonprofit corporation to receive donations to support the Puerto Lempira clinic’s construction.

He is planning more mission trips. He thrives on the work. Infused with boundless energy, he’s always looking for more to do.

“I love what I do,” he concludes. “If I felt much better they’d charge me an amusement tax.” TH

Marlene Piturro is a medical writer based in New York.

Charles Petit, MD, like many healthcare professionals, spends a good deal of time addressing the needs of the underprivileged. Since 2004, he has taken up the cause of the indigenous Miskito Indians of Puerto Lempira, Honduras. He is putting his own money into developing a modern clinic and international medicine program there.

But medicine isn’t his only mission. Dr. Petit, 56, a hospitalist at Palmetto Health Care’s Richland Memorial Hospital in Columbia, S.C., is also an Episcopal priest.

He joined Palmetto Health Senior Care as its first medical director in 1988 and reconnected with the group in 2004—not in his previous role as an office-based physician but as a hospitalist. In between those stints he pursued his ordination and medical missionary work in Africa and Latin America.

As a physician, Dr. Petit says he feels God’s presence at each patient’s bedside. Years ago he wondered how to handle that.

To deepen his connection between medicine and spirituality, he lived in a Christian intentional community in Indiana, Pa., from 1981 to 1988. Gradually, his views on medicine and spirituality crystallized.

“How does God do what he does?” Dr. Petit wondered. “Can medicine put Him to the test? I have seen that prayer works, including a patient miraculously healed of metastatic ovarian cancer. But God isn’t a vending machine. You don’t drop in a prayer and get a healing back.”

The Second Calling

Recognizing he needed something more to integrate medicine and spirituality, Dr. Petit sought a firmer grounding in religious studies.

He moved to Simpsonville, S.C., in 1995 and entered the Episcopal seminary, working as an emergency department doctor to pay the bills. Later, he earned a master’s of divinity from the University of the South in Sewanee, Tenn., in 2003.

His spiritual “internship” was a transitional deaconship from 2003 to 2005, under the Rev. Michael Flanagan, rector at Simpsonville’s Holy Cross Episcopal Church. Both had dual vocations—Flanagan was an engineer who sold electrical equipment for 10 years before ordination. Prior to meeting Dr. Petit, Flanagan was leery of the doctor’s ability to balance pastoral and medical duties.

“Would he be a doctor/priest?” Flanagan wondered. “A priest/doctor? His desire was to meld both and he did. Medicine and spirituality are both in his blood. He sees both as calls from God and connects medicine with spirituality into a holistic view of each person.” He says Dr. Petit “seems to know everything and sucks up knowledge, which he wants to share. He loves being the doctor and having the knowledge to fix the patient’s problem.”

While Dr. Petit keeps his hospitalist and priest roles mostly separate, working with elderly patients sometimes requires the skills of both disciplines. At Richland he wears a clerical collar on pastoral rounds. If a family or patient asks him to pray with them or discuss life’s ending, he does. He has conducted funerals for his own and colleagues’ patients.

“It’s a very powerful experience being both a priest and a doctor,” he says. “I grow so close to the patients and their families that it is natural for me to serve in both roles.”

Honduras Mission

As a seminarian, Dr. Petit took medical mission trips and briefly supported an African orphanage, looking for a cause to call his own. Until his first trip to Puerto Lempira, a village on the Miskito Coast of the Atlantic Ocean.

The abject poverty and medical needs of the Miskito Indians there pulled at him. Early on he enlisted the help of Ennis Whiddon, a builder and Holy Cross parishioner. Whiddon, who usually accompanies Dr. Petit to Puerto Lempira, says of his friend: “I knew him as [an emergency department] doctor first. Then I realized his extraordinary spiritual commitment. I went to Puerto Lempira on his first mission trip and I asked myself why anyone would want to be there, but I knew Chuck couldn’t bear not to be there. I also knew he wasn’t just going to give people two aspirins, come home and pray for them.”

Dr. Petit returns to Puerto Lempira three or four times a year with a team of doctors, seeing several hundred patients a day. During one two-week stint he dispensed $200,000 worth of medication he cadged from drug companies for $600 out of his pocket to rid the town’s youngsters of debilitating parasites.

Dr. Petit works with a Miskito nurse who runs their rudimentary clinic in his absence. He also uses hyperbaric medicine to treat divers whose crippling injuries result from diving deeply using pressurized oxygen tanks and rising too quickly to the surface.

“You wouldn’t believe the indescribably poor facilities we found there,” Whiddon says of the town’s clinic. “You wouldn’t have your dog treated there if you loved your dog.”

Last year Dr. Petit ratcheted up his commitment to Puerto Lempira, dreaming of building a permanent clinic there.

He decided to use his money to buy land to build a clinic, but got stonewalled by a stubborn local bureaucracy.

Then Andres Leone, a like-minded younger doctor who was part of the mission trip, stepped in with handy language and cultural skills. Leone who had attended medical school in Ecuador, is a Lutheran seminarian, and is completing a geriatric hospitalist fellowship at Palmetto Healthcare.

“We were in Puerto Lempira for two weeks and visited the mayor several times to buy land,” Dr. Leone explains. “He said the price was $600,000, which was ridiculous. In the town I overheard some conversations, which led to us meeting the 77-year-old daughter of missionaries. She sold us some of her land and even donated money to help build the clinic, which will be dedicated in her name.”

Thinking big, Dr. Petit is adding an apartment complete with air conditioning and a modern bathroom to the clinic’s blueprint, to attract residents in a to-be-formed international medicine program. As an assistant professor of family medicine at the University of South Carolina’s (USC) School of Medicine, he intends to oversee those residents.

Just back from Puerto Lempira, Dr. Petit finalized the clinic’s design, lined up local workers to figure out how to make concrete building blocks with native materials, and met with Anglican bishop the Right Rev. Lloyd E. Allen, bolstering support for the new clinic and the possibility of HIV outreach. Side by side with Honduran and Cuban doctors, Dr. Petit treated hundreds of Puerto Lempira’s villagers every day.

Back in the Hospital

Dr. Petit always wanted to be a doctor. Although his father suggested he become a hospital orderly, Dr. Petit knew being a physician was his calling, graduating from the University of West Virginia School of Medicine (Morgantown) family medicine program in 1978.

He enjoys hospital medicine as a holistic approach to caring for patients, consistent with his work early in his career.

An earlier 10-year stint as a hospitalist at HealthSouth Rehabilitation Hospital, also at USC, involved teaching residents and students rotating through the hospital, as well as a consultative service for neurosurgical patients at Richland. At Wheeling Hospital early in his career he became comfortable as a generalist, covering intensive care, assisting in surgery, and delivering many babies.

Being a hospitalist keeps that spirit alive. “It gives me the gift of time to spend with patients,” he says. “I try not to tie frail elderly patients down with IVs, Foley catheters, EKG monitors, worries that eating a leafy green vegetable will react badly with their Coumadin [warfarin], and polypharmacy.”

He discusses advanced directives, palliative care, and how the elderly in fragile condition can maintain as much freedom as possible. The hospital medicine group’s accommodating scheduling allows time for his parish duties and medical mission trips.

The group’s medical director, Victor Hirth, MD, describes Dr. Petit as a borderline workaholic who’s always looking for ways to make things better for the practice and patients. “The patients absolutely love him because he takes time to sit and talk to them,” says Dr. Hirth.

Dr. Petit also embraces new technologies. “Our [electronic medical record] makes working with my outpatient colleagues smooth and straightforward.” He relies on a personal digital device assistant for updates on clinical guidelines and optimal drug doses for elderly patients. Integrating a healer’s touch with new technology he says: “While medicine is a science, it’s still an art, a ministry, and a gift.”

What’s Next?

Back in South Carolina, Dr. Petit has picked up his hospitalist and pastoral responsibilities without missing a beat. He looks forward to building the palliative care consulting service and intends to launch a nonprofit corporation to receive donations to support the Puerto Lempira clinic’s construction.

He is planning more mission trips. He thrives on the work. Infused with boundless energy, he’s always looking for more to do.

“I love what I do,” he concludes. “If I felt much better they’d charge me an amusement tax.” TH

Marlene Piturro is a medical writer based in New York.

Do feeding tubes improve outcomes in patients with dementia?

Case

A 68-year-old cachectic female with a history of Alzheimer’s dementia presents with a slowly progressive decline in functional status. She is bed bound, minimally verbal, and has lost interest in eating.

Her problems with decreased oral intake started when her diet was changed to nectar-thickened liquids. This change was made after the patient was hospitalized multiple times for aspiration pneumonia and she underwent a fluoroscopic swallowing evaluation that revealed aspiration of thin liquids. The patient’s husband requests that a feeding tube be placed so his wife doesn’t “die of pneumonia or starve to death.”

Overview

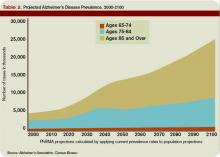

As the U.S. population ages, hospitalists are seeing a steady increase in the average patient age and the prevalence of dementia. Alzheimer’s dementia affects an estimated 4 million to 5 million Americans; this number expected to triple by the year 2050.1

As patients with dementia near the end of life, they often fail to thrive, with less oral intake and more swallowing disorders leading to aspiration. This is when physicians and patient family members must decide whether a feeding tube should be placed.

Placement of a nasogastric or percutaneous endogastric gastrostomy (PEG) feeding tube has become a relatively common medical intervention instituted to maintain or improve a patient’s nutritional status. Prior to 1980, permanent gastric or postpyloric feeding tubes were placed surgically by laparotomy, but the advent of endoscopy and computed tomography (CT) guided procedures offers a simplified procedure requiring only mild sedation and local anesthesia.2

Many patients who suffer multiple bouts of aspiration pneumonia and fail a swallowing evaluation because of an irreversible process are offered a percutaneous feeding tube to maintain nutrition. A feeding tube is also seen as a way to supply nutrition at the end of life in patients no longer able or willing to take food orally.

Although it seems logical that a feeding tube might improve the outcomes of these clinical scenarios, limited literature exists on the topic because of the legal, ethical, emotional, and religious implications a large, randomized, placebo-controlled trial would entail.

Review of the Data

Placement of a PEG has become accepted as a relatively benign procedure, although it is associated with significant morbidity and mortality. Minor complications including pain, abdominal wall ulcers, wound infections, peristomal leakage, and tube displacement occur in approximately 10% of cases.3 Major complications including hemorrhage, bowel or liver perforation, or aspiration occur in 3% of cases.4

These numbers do not account for long-term complications including peristomal infections, leakage problems, or the use of physical restraints to avoid self-extubation.

Aspiration Risk

A common indication for PEG placement is aspiration risk. PEG tubes are often placed in patients who fail swallowing evaluations in order to decrease their risk of aspiration and aspiration pneumonia.

True aspiration pneumonia is thought to originate from an inoculum of oral cavity or nasopharynx bacteria, which placement of a PEG tube would not prevent. Leibovitz, et al., showed that elderly patients with nasogastric or percutaneous feeding tubes are associated with colonization of the oropharynx with more pathogenic bacteria when compared with orally fed patients.5 Thus, the use of PEG tubes might put them at higher risk for pathogenic inoculation.

Aspiration pneumonia occurs in up to 50% of patients with feeding tubes. Studies have shown PEG tube placement decreases lower esophageal sphincter tone, potentially increasing regurgitation risk.6 It has also been shown that aspiration of gastric contents produces a pneumonitis with the resultant inflammatory response allowing for establishment of infection by smaller inoculums of or less virulent organisms.7

Small, randomized trials have shown no decrease in aspiration risk with post-pyloric versus gastric feeding tubes, nasogastric versus percutaneous feeding tubes, or continuous versus intermittent tube feeds.8 There have been no sizable randomized prospective trials to determine if feeding tube placement versus hand feeding patients with end-stage dementia alters aspiration pneumonia risk.

Pressure Ulcers

Patients with end-stage dementia often become bed bound as their disease progresses, and they commonly suffer from pressure ulcers. Pressure ulcers often coexist in patients with malnutrition, and it is well established that patients with biochemical markers of malnutrition are at higher risk for pressure ulcer formation.

Still, no studies show that improved nutrition prevents pressure ulcer formation. In a nursing home population of patients with dementia, a two-year follow-up study showed no significant improvement in pressure ulcer healing or decreased ulcer formation with nutrition by feeding tube.9 These studies are adjusted for independent risk factors for mortality and indication for PEG placement, but we can assume there are confounders that go into the decision for feeding tube placement that are not necessarily identifiable.

Nutritional Status

Family members are often concerned that if the patient is unable to take food by mouth and no feeding tube is placed, then the patient will suffer from the discomfort of starvation and dehydration.

As a patient with a severe dementing illness enters the end stage of his/her clinical course, practitioners frequently make a plan with families to change the goals of care toward keeping the patient comfortable. Comfort is a difficult clinical parameter to measure, but studies in the hospice population of patients with end-stage cancer and AIDS report that the hunger and thirst are transient and improve with ice chips and mouth swabs.10

Despite the lack of evidence of PEG tubes prolonging survival in patients with dementia who are no longer able or willing to take in food orally, it is logical that withholding all hydration or nutritional support will hasten death despite the risks associated with feeding tubes. This is where the ethical argument arises regarding prolonging life of decreasing quality.

In certain medical and legal sectors, artificial nutrition, and hydration are considered a medical intervention. Therefore, the ideals of patient autonomy dictate that the patient’s proxy should decide whether or not the patient would have wanted the intervention after weighing the risks and benefits.

If hospitalists view artificial nutrition as a medical intervention, our moral obligation is to instruct patients and their families about these risks and benefits.

Often, the patient will not clinically improve with artificial nutrition. But we can maintain physiologic processes or at least slow their decline.

Emerging research indicates the standard of care in how we present this information is changing to include presentation of data instead of only using a patient’s suspected beliefs about quality of life.

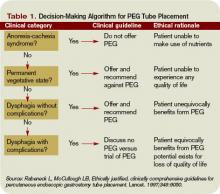

A useful algorithm proposed by Rabeneck, et al., provides comprehensive guidelines for PEG placement in all patient populations based on the reason for PEG consideration.11

Back to the Case

Our patient is likely nearing the end of her life because of end-stage dementia. There is no evidence to suggest placement of a feeding tube would extend her life more than hand feeding.

We know feeding-tube placement could increase aspiration pneumonia risk and significant short- and long-term morbidity and mortality. We can keep her comfortable with small amounts of water, wetting her lips with swabs. If a feeding tube is placed, its use should be evaluated based on the patient’s clinical course. TH

Dr. Pell is an instructor of medicine in the Section of Hospital Medicine at the University of Colorado, Denver.

References

- Gauderer MW, Ponsky JL, Izant RJ Jr. Gastrostomy without laparotomy: a percutaneous endoscopic technique. J Pediatr Surg. 1980;15(6):872-875.

- Hebert LE, Beckett LA, Scherr PA, and Evans DA. Annual incidence of Alzheimer disease in the United States projected to the years 2000 through 2050. Alzheimer Dis Assoc Disord. 2001;15:169-173.

- Grant MD, Rudberg MA, Brody JA. Gastrostomy placement and mortality among hospitalized Medicare beneficiaries. JAMA. 1998;279:1973-1976.

- Finocchiaro C, Galletti R, Rovera G, et al. Percutaneous endoscopic gastrostomy: a long-term follow-up. Nutrition. 1997;13(6):520-523.

- Leibovitz A, Plotnikov G, Habot B, et al. Pathogenic colonization of oral flora in frail elderly patients fed by nasogastric tube or percutaneous enterogastric tube. J Gerontol A Biol Sci Med. 2003;58(1):52-55.

- McCann R. Lack of evidence about tube feeding: food for thought. JAMA. 1999;282(14):1380-1381.

- Cameron JL, Caldini P, Toung J-K, et al. Aspiration pneumonia: physiologic data following experimental Aspiration. Surgery. 1972;72:238.

- Loeb MB, Becker M, Eady A, et al. Interventions to prevent aspiration pneumonia in older adults: a systematic review. JAGS. 2003;51(7):1018-1022.

- Mitchell SL, Kiely DK, Lipsitz LA. The risk factors and impact on survival of feeding tube placement in nursing home residents with severe cognitive impairment. Arch Intern Med. 1997;157:327-332.

- McCann RM, Hall WJ, Groth-Junker A. Comfort care for terminally ill patients: the appropriate use of nutrition and hydration. JAMA. 1994;272:1263-1266.

- Rabeneck L, McCullough LB. Ethically justified, clinically comprehensive guidelines for percutaneous endoscopic gastrostomy tube placement. Lancet. 1997;349(9050):496-498.

Case

A 68-year-old cachectic female with a history of Alzheimer’s dementia presents with a slowly progressive decline in functional status. She is bed bound, minimally verbal, and has lost interest in eating.

Her problems with decreased oral intake started when her diet was changed to nectar-thickened liquids. This change was made after the patient was hospitalized multiple times for aspiration pneumonia and she underwent a fluoroscopic swallowing evaluation that revealed aspiration of thin liquids. The patient’s husband requests that a feeding tube be placed so his wife doesn’t “die of pneumonia or starve to death.”

Overview